User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Hospital medicine and palliative care: Wearing both hats

Dr. Barbara Egan leads SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group

Editor’s note: Each month, the Society of Hospitalist Medicine puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help improve the care of hospitalized patients.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Barbara Egan, MD, FACP, SFHM, chief of the hospital medicine service in the department of medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Barbara has been a member of SHM since 2005, is dual certified in hospital medicine and palliative care, and is the chair of SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group.

When did you first hear about SHM, and why did you decide to become a member?

I first learned about SHM when I was an internal medicine resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in the early 2000s. BWH had an extremely strong hospitalist group; the staff I worked with served as powerful role models for me and inspired my interest in becoming a hospitalist. One of my attendings suggested that I join SHM, which I did right after I graduated from residency. I attended my first SHM Annual Conference in 2005. By then, I was working as a hospitalist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. SHM and the field of hospital medicine have exploded since my career first began, and I am happy to have grown alongside them. Similarly, our hospital medicine group here at MSKCC has dramatically grown, from 1 hospitalist (me) to more than 30!

How did you get involved with SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group, and what has the work group accomplished since you joined?

I was honored to be invited to join SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group in 2017 by Wendy Anderson, MD, a colleague and now a friend from University of California, San Francisco. Wendy is a visionary leader who practices and researches at the intersection of palliative care and hospital medicine. She and I met during 2015, when we were both invited to join a collaboration between SHM and the Hastings Center in Garrison, N.Y., which was aimed at improving hospitalists’ ability to provide outstanding care to hospitalized patients with life-limiting illnesses. That collaboration resulted in the Improving Communication about Serious Illness–Implementation Guide, a compilation of resources and best practices.

Wendy was chairing the SHM Palliative Care Work Group and invited me to join, which I did with great enthusiasm. This group consists of several passionate and brilliant hospitalists whose practices, in a variety of ways, involve both hospital medicine and palliative medicine. I was so honored when Wendy passed the baton to me last spring and invited me to chair the Work Group. I am lucky to have the opportunity to collaborate with this group of dynamic individuals, and we are well supported by an outstanding SHM staff member, Nick Marzano.

Are there any new projects that the work group is currently focusing on?

The primary focus of SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group is educational. That is, we aim to assess and help meet the educational needs of hospitalists, thereby helping to empower them to be outstanding providers of primary palliative care to seriously ill, hospitalized patients. To that end, we were very proud to orchestrate a palliative care mini-track for the first time at HM18. To our group’s delight, the attendance and reviews of that track were great. Thus, we were invited to further expand the palliative care offerings at HM19. We are busy planning for HM19: a full-day pre-course in palliative medicine; several podium presentations which will touch on ethical challenges, symptom management, prognostication, and other important topics; and a workshop in communication skills.

What led to your dual certification and how do your two specialties overlap?

I am board certified in internal medicine with Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine by virtue of my clinical training and my primary clinical practice as a hospitalist. As a hospitalist in a cancer center, I spend most of my time caring for patients with late- and end-stage malignancy. As such, early in my career, I had to develop a broad base of palliative medical skills, such as pain and symptom management and communication skills. I find this work extremely rewarding, albeit emotionally taxing. I have learned to redefine what clinical “success” looks like – my patients often have unfixable medical problems, but I can always strive to improve their lives in some way, even if that means helping to provide them with a painless, dignified death as opposed to curing them.

When the American Board of Medical Specialties established a board certification in Hospice and Palliative Medicine, there briefly existed a pathway to be “grandfathered” in, i.e., to qualify for board certification through an examination and clinical experience, as opposed to a fellowship. I jumped at the chance to formalize my palliative care skills and experience, and I attained board certification in 2012. This allowed me to further diversify my clinical practice here at MSKCC.

Hospital medicine is still my first love, and I spend most of my time practicing as a hospitalist on our solid tumor services. But now I also spend several weeks each year attending as a consultant on our inpatient supportive care service. In that role, I am able to collaborate with a fantastic multidisciplinary team consisting of MDs, NPs, a chaplain, a pharmacist, a social worker, and integrative medicine practitioners. I also love the opportunity to teach and mentor our palliative medicine fellows.

To me, the opportunity to marry hospital medicine and palliative medicine in my career was a natural fit. Hospitalists, particularly those caring exclusively for cancer patients like I do, need to provide excellent palliative care to our patients every day. The opportunity to further my training and to obtain board certification was a golden one, and I love being able to wear both hats here at MSKCC.

Ms. Steele is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Barbara Egan leads SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group

Dr. Barbara Egan leads SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group

Editor’s note: Each month, the Society of Hospitalist Medicine puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help improve the care of hospitalized patients.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Barbara Egan, MD, FACP, SFHM, chief of the hospital medicine service in the department of medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Barbara has been a member of SHM since 2005, is dual certified in hospital medicine and palliative care, and is the chair of SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group.

When did you first hear about SHM, and why did you decide to become a member?

I first learned about SHM when I was an internal medicine resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in the early 2000s. BWH had an extremely strong hospitalist group; the staff I worked with served as powerful role models for me and inspired my interest in becoming a hospitalist. One of my attendings suggested that I join SHM, which I did right after I graduated from residency. I attended my first SHM Annual Conference in 2005. By then, I was working as a hospitalist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. SHM and the field of hospital medicine have exploded since my career first began, and I am happy to have grown alongside them. Similarly, our hospital medicine group here at MSKCC has dramatically grown, from 1 hospitalist (me) to more than 30!

How did you get involved with SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group, and what has the work group accomplished since you joined?

I was honored to be invited to join SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group in 2017 by Wendy Anderson, MD, a colleague and now a friend from University of California, San Francisco. Wendy is a visionary leader who practices and researches at the intersection of palliative care and hospital medicine. She and I met during 2015, when we were both invited to join a collaboration between SHM and the Hastings Center in Garrison, N.Y., which was aimed at improving hospitalists’ ability to provide outstanding care to hospitalized patients with life-limiting illnesses. That collaboration resulted in the Improving Communication about Serious Illness–Implementation Guide, a compilation of resources and best practices.

Wendy was chairing the SHM Palliative Care Work Group and invited me to join, which I did with great enthusiasm. This group consists of several passionate and brilliant hospitalists whose practices, in a variety of ways, involve both hospital medicine and palliative medicine. I was so honored when Wendy passed the baton to me last spring and invited me to chair the Work Group. I am lucky to have the opportunity to collaborate with this group of dynamic individuals, and we are well supported by an outstanding SHM staff member, Nick Marzano.

Are there any new projects that the work group is currently focusing on?

The primary focus of SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group is educational. That is, we aim to assess and help meet the educational needs of hospitalists, thereby helping to empower them to be outstanding providers of primary palliative care to seriously ill, hospitalized patients. To that end, we were very proud to orchestrate a palliative care mini-track for the first time at HM18. To our group’s delight, the attendance and reviews of that track were great. Thus, we were invited to further expand the palliative care offerings at HM19. We are busy planning for HM19: a full-day pre-course in palliative medicine; several podium presentations which will touch on ethical challenges, symptom management, prognostication, and other important topics; and a workshop in communication skills.

What led to your dual certification and how do your two specialties overlap?

I am board certified in internal medicine with Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine by virtue of my clinical training and my primary clinical practice as a hospitalist. As a hospitalist in a cancer center, I spend most of my time caring for patients with late- and end-stage malignancy. As such, early in my career, I had to develop a broad base of palliative medical skills, such as pain and symptom management and communication skills. I find this work extremely rewarding, albeit emotionally taxing. I have learned to redefine what clinical “success” looks like – my patients often have unfixable medical problems, but I can always strive to improve their lives in some way, even if that means helping to provide them with a painless, dignified death as opposed to curing them.

When the American Board of Medical Specialties established a board certification in Hospice and Palliative Medicine, there briefly existed a pathway to be “grandfathered” in, i.e., to qualify for board certification through an examination and clinical experience, as opposed to a fellowship. I jumped at the chance to formalize my palliative care skills and experience, and I attained board certification in 2012. This allowed me to further diversify my clinical practice here at MSKCC.

Hospital medicine is still my first love, and I spend most of my time practicing as a hospitalist on our solid tumor services. But now I also spend several weeks each year attending as a consultant on our inpatient supportive care service. In that role, I am able to collaborate with a fantastic multidisciplinary team consisting of MDs, NPs, a chaplain, a pharmacist, a social worker, and integrative medicine practitioners. I also love the opportunity to teach and mentor our palliative medicine fellows.

To me, the opportunity to marry hospital medicine and palliative medicine in my career was a natural fit. Hospitalists, particularly those caring exclusively for cancer patients like I do, need to provide excellent palliative care to our patients every day. The opportunity to further my training and to obtain board certification was a golden one, and I love being able to wear both hats here at MSKCC.

Ms. Steele is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: Each month, the Society of Hospitalist Medicine puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help improve the care of hospitalized patients.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Barbara Egan, MD, FACP, SFHM, chief of the hospital medicine service in the department of medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Barbara has been a member of SHM since 2005, is dual certified in hospital medicine and palliative care, and is the chair of SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group.

When did you first hear about SHM, and why did you decide to become a member?

I first learned about SHM when I was an internal medicine resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in the early 2000s. BWH had an extremely strong hospitalist group; the staff I worked with served as powerful role models for me and inspired my interest in becoming a hospitalist. One of my attendings suggested that I join SHM, which I did right after I graduated from residency. I attended my first SHM Annual Conference in 2005. By then, I was working as a hospitalist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. SHM and the field of hospital medicine have exploded since my career first began, and I am happy to have grown alongside them. Similarly, our hospital medicine group here at MSKCC has dramatically grown, from 1 hospitalist (me) to more than 30!

How did you get involved with SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group, and what has the work group accomplished since you joined?

I was honored to be invited to join SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group in 2017 by Wendy Anderson, MD, a colleague and now a friend from University of California, San Francisco. Wendy is a visionary leader who practices and researches at the intersection of palliative care and hospital medicine. She and I met during 2015, when we were both invited to join a collaboration between SHM and the Hastings Center in Garrison, N.Y., which was aimed at improving hospitalists’ ability to provide outstanding care to hospitalized patients with life-limiting illnesses. That collaboration resulted in the Improving Communication about Serious Illness–Implementation Guide, a compilation of resources and best practices.

Wendy was chairing the SHM Palliative Care Work Group and invited me to join, which I did with great enthusiasm. This group consists of several passionate and brilliant hospitalists whose practices, in a variety of ways, involve both hospital medicine and palliative medicine. I was so honored when Wendy passed the baton to me last spring and invited me to chair the Work Group. I am lucky to have the opportunity to collaborate with this group of dynamic individuals, and we are well supported by an outstanding SHM staff member, Nick Marzano.

Are there any new projects that the work group is currently focusing on?

The primary focus of SHM’s Palliative Care Work Group is educational. That is, we aim to assess and help meet the educational needs of hospitalists, thereby helping to empower them to be outstanding providers of primary palliative care to seriously ill, hospitalized patients. To that end, we were very proud to orchestrate a palliative care mini-track for the first time at HM18. To our group’s delight, the attendance and reviews of that track were great. Thus, we were invited to further expand the palliative care offerings at HM19. We are busy planning for HM19: a full-day pre-course in palliative medicine; several podium presentations which will touch on ethical challenges, symptom management, prognostication, and other important topics; and a workshop in communication skills.

What led to your dual certification and how do your two specialties overlap?

I am board certified in internal medicine with Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine by virtue of my clinical training and my primary clinical practice as a hospitalist. As a hospitalist in a cancer center, I spend most of my time caring for patients with late- and end-stage malignancy. As such, early in my career, I had to develop a broad base of palliative medical skills, such as pain and symptom management and communication skills. I find this work extremely rewarding, albeit emotionally taxing. I have learned to redefine what clinical “success” looks like – my patients often have unfixable medical problems, but I can always strive to improve their lives in some way, even if that means helping to provide them with a painless, dignified death as opposed to curing them.

When the American Board of Medical Specialties established a board certification in Hospice and Palliative Medicine, there briefly existed a pathway to be “grandfathered” in, i.e., to qualify for board certification through an examination and clinical experience, as opposed to a fellowship. I jumped at the chance to formalize my palliative care skills and experience, and I attained board certification in 2012. This allowed me to further diversify my clinical practice here at MSKCC.

Hospital medicine is still my first love, and I spend most of my time practicing as a hospitalist on our solid tumor services. But now I also spend several weeks each year attending as a consultant on our inpatient supportive care service. In that role, I am able to collaborate with a fantastic multidisciplinary team consisting of MDs, NPs, a chaplain, a pharmacist, a social worker, and integrative medicine practitioners. I also love the opportunity to teach and mentor our palliative medicine fellows.

To me, the opportunity to marry hospital medicine and palliative medicine in my career was a natural fit. Hospitalists, particularly those caring exclusively for cancer patients like I do, need to provide excellent palliative care to our patients every day. The opportunity to further my training and to obtain board certification was a golden one, and I love being able to wear both hats here at MSKCC.

Ms. Steele is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Reducing alarm fatigue

Monitoring from a centralized location

Hospitalists hearing the constant noise from cardiac telemetry monitoring systems can experience alarm fatigue – a nationwide phenomenon that can lead to an increase in patient deaths.

The American Heart Association reports that fewer than one in four adults survived an in-hospital cardiac arrest in 2013; other studies showed that up to 44% of inpatient cardiac arrests were not detected appropriately, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Clinicians at the Cleveland Clinic have tried centralized monitoring to address the problem. They’ve established a “mission control” center, where off-site personnel monitor sensors and high-definition cameras and vital signs such as blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration. On-site action is requested when appropriate; unimportant alarms are dismissed.

In August 2016, results from the first 13 months of the Cleveland Clinic program were published in JAMA. They revealed that the monitoring system could help reduce rates of unimportant alarms with no increase in cardiopulmonary arrest events. The centralized unit monitored 99,048 patient orders, and ultimately detected serious problems and accurately notified on-site staff for 79% of 3,243 events, which included a rhythm and/or rate change within 1 hour or less of the event. Accurate notification to on-site hospital staff was more than 84%.

Since then, improvements to the system have continued, according to Cleveland Clinic, and include doubling the number of monitored patients per technician and improved clinical outcomes.

Reference

Cleveland Clinic: Consult QD – An update on the centralized cardiac telemetry monitoring unit

Monitoring from a centralized location

Monitoring from a centralized location

Hospitalists hearing the constant noise from cardiac telemetry monitoring systems can experience alarm fatigue – a nationwide phenomenon that can lead to an increase in patient deaths.

The American Heart Association reports that fewer than one in four adults survived an in-hospital cardiac arrest in 2013; other studies showed that up to 44% of inpatient cardiac arrests were not detected appropriately, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Clinicians at the Cleveland Clinic have tried centralized monitoring to address the problem. They’ve established a “mission control” center, where off-site personnel monitor sensors and high-definition cameras and vital signs such as blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration. On-site action is requested when appropriate; unimportant alarms are dismissed.

In August 2016, results from the first 13 months of the Cleveland Clinic program were published in JAMA. They revealed that the monitoring system could help reduce rates of unimportant alarms with no increase in cardiopulmonary arrest events. The centralized unit monitored 99,048 patient orders, and ultimately detected serious problems and accurately notified on-site staff for 79% of 3,243 events, which included a rhythm and/or rate change within 1 hour or less of the event. Accurate notification to on-site hospital staff was more than 84%.

Since then, improvements to the system have continued, according to Cleveland Clinic, and include doubling the number of monitored patients per technician and improved clinical outcomes.

Reference

Cleveland Clinic: Consult QD – An update on the centralized cardiac telemetry monitoring unit

Hospitalists hearing the constant noise from cardiac telemetry monitoring systems can experience alarm fatigue – a nationwide phenomenon that can lead to an increase in patient deaths.

The American Heart Association reports that fewer than one in four adults survived an in-hospital cardiac arrest in 2013; other studies showed that up to 44% of inpatient cardiac arrests were not detected appropriately, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Clinicians at the Cleveland Clinic have tried centralized monitoring to address the problem. They’ve established a “mission control” center, where off-site personnel monitor sensors and high-definition cameras and vital signs such as blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration. On-site action is requested when appropriate; unimportant alarms are dismissed.

In August 2016, results from the first 13 months of the Cleveland Clinic program were published in JAMA. They revealed that the monitoring system could help reduce rates of unimportant alarms with no increase in cardiopulmonary arrest events. The centralized unit monitored 99,048 patient orders, and ultimately detected serious problems and accurately notified on-site staff for 79% of 3,243 events, which included a rhythm and/or rate change within 1 hour or less of the event. Accurate notification to on-site hospital staff was more than 84%.

Since then, improvements to the system have continued, according to Cleveland Clinic, and include doubling the number of monitored patients per technician and improved clinical outcomes.

Reference

Cleveland Clinic: Consult QD – An update on the centralized cardiac telemetry monitoring unit

Readmission to non-index hospital following acute stroke linked to worse outcomes

ATLANTA – Following an acute stroke, optimizing stroke secondary prevention measures, medical complications, and transitions of care is essential to reducing 30-day readmissions and improving patient outcomes, a large analysis of national data showed.

“Care that is fragmented with readmissions to other hospitals results not only in more expensive care and longer length of stay but also increased mortality for our acute stroke patients,” lead study author Laura K. Stein, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

In 2017, a study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database demonstrated that 12.1% of patients with acute ischemic stroke were readmitted within 30 days (Stroke 2017;48:1386-8). It cited that 89.6% were unplanned and 12.9% were preventable. “However, this study did not examine whether patients were admitted to the discharging hospital or a different hospital,” said Dr. Stein, a neurologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “Furthermore, it did not include metrics such as cost, length of stay, and mortality with 30-day readmissions. Hospitals are increasingly held accountable and penalized for metrics such as length of stay and 30-day readmissions.”

In 2010, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services introduced the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in an attempt to decrease readmissions following hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. “In 2012, CMS started reducing Medicare payments for hospitals with excess readmissions,” said Dr. Stein, who is a fellowship-trained stroke specialist. “While readmission to the same hospital has great implications for hospital systems, any readmission has great implications for patients.”

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, Dr. Stein and her colleagues drew from the 2013 Nationwide Readmissions Database to examine in-hospital outcomes associated with 30-day readmission to a different hospital for acute ischemic stroke. They used ICD-9 codes to identify index stroke admissions and all-cause readmissions. Outcomes of interest were length of stay, total charges, and in-hospital mortality during the 30-day readmission. The main predictor was readmission to another hospital, compared with readmission to the same hospital as the index acute stroke admission. The researchers used linear regression for the outcomes of length of stay and charges, and logistic regression for in-hospital mortality. They adjusted for several variables during the index admission, including age, sex, vascular risk factors, hospital bed size, teaching hospital status, insurance status, discharge destination, National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural location classification, length of stay, and total charges.

Of 24,545 acute stroke patients readmitted within 30 days, 7,274 (30%) were readmitted to a different hospital. The top three reasons for readmission were acute cerebrovascular disease, septicemia, and renal failure. In fully adjusted models, readmission to a different hospital was associated with an increased length of stay of 0.97 days (P less than .0001) and a mean of $7,677.28 greater total charges, compared with readmission to the same hospital (P less than .0001). The fully adjusted odds ratio for in-hospital mortality during readmission was 1.17 for readmission to another hospital vs. readmission to the same hospital (P = .0079).

“While it is conceivable that cost and length of stay could be higher with readmission to a different hospital because of a need for additional testing with a lack of familiarity with the patient, it is concerning that mortality is higher,” Dr. Stein said. “These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing secondary stroke prevention and medical complications following acute stroke before discharge. Additionally, they emphasize the importance of good transitions of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting (whether that’s to a rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, or home) and accessibility of the discharging stroke team after discharge.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its reliance of administrative data, which could include misclassification of diagnoses and comorbidities based on ICD-9 codes. “However, we have chosen ICD-9 codes for stroke that have been previously validated in the literature,” Dr. Stein said. “For instance, the validated codes for stroke as the primary discharge diagnosis have a sensitivity of 74%, specificity of 95%, and positive predictive value of 88%. Second, we do not know stroke subtype or severity of stroke. Third, we do not know what the transitions of care plan were when the patients left the hospital following index acute ischemic stroke admission and why these patients ended up being readmitted to a different hospital rather than the one that treated them for their acute stroke.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stein L et al. Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S149. Abstract M127.

ATLANTA – Following an acute stroke, optimizing stroke secondary prevention measures, medical complications, and transitions of care is essential to reducing 30-day readmissions and improving patient outcomes, a large analysis of national data showed.

“Care that is fragmented with readmissions to other hospitals results not only in more expensive care and longer length of stay but also increased mortality for our acute stroke patients,” lead study author Laura K. Stein, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

In 2017, a study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database demonstrated that 12.1% of patients with acute ischemic stroke were readmitted within 30 days (Stroke 2017;48:1386-8). It cited that 89.6% were unplanned and 12.9% were preventable. “However, this study did not examine whether patients were admitted to the discharging hospital or a different hospital,” said Dr. Stein, a neurologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “Furthermore, it did not include metrics such as cost, length of stay, and mortality with 30-day readmissions. Hospitals are increasingly held accountable and penalized for metrics such as length of stay and 30-day readmissions.”

In 2010, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services introduced the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in an attempt to decrease readmissions following hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. “In 2012, CMS started reducing Medicare payments for hospitals with excess readmissions,” said Dr. Stein, who is a fellowship-trained stroke specialist. “While readmission to the same hospital has great implications for hospital systems, any readmission has great implications for patients.”

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, Dr. Stein and her colleagues drew from the 2013 Nationwide Readmissions Database to examine in-hospital outcomes associated with 30-day readmission to a different hospital for acute ischemic stroke. They used ICD-9 codes to identify index stroke admissions and all-cause readmissions. Outcomes of interest were length of stay, total charges, and in-hospital mortality during the 30-day readmission. The main predictor was readmission to another hospital, compared with readmission to the same hospital as the index acute stroke admission. The researchers used linear regression for the outcomes of length of stay and charges, and logistic regression for in-hospital mortality. They adjusted for several variables during the index admission, including age, sex, vascular risk factors, hospital bed size, teaching hospital status, insurance status, discharge destination, National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural location classification, length of stay, and total charges.

Of 24,545 acute stroke patients readmitted within 30 days, 7,274 (30%) were readmitted to a different hospital. The top three reasons for readmission were acute cerebrovascular disease, septicemia, and renal failure. In fully adjusted models, readmission to a different hospital was associated with an increased length of stay of 0.97 days (P less than .0001) and a mean of $7,677.28 greater total charges, compared with readmission to the same hospital (P less than .0001). The fully adjusted odds ratio for in-hospital mortality during readmission was 1.17 for readmission to another hospital vs. readmission to the same hospital (P = .0079).

“While it is conceivable that cost and length of stay could be higher with readmission to a different hospital because of a need for additional testing with a lack of familiarity with the patient, it is concerning that mortality is higher,” Dr. Stein said. “These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing secondary stroke prevention and medical complications following acute stroke before discharge. Additionally, they emphasize the importance of good transitions of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting (whether that’s to a rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, or home) and accessibility of the discharging stroke team after discharge.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its reliance of administrative data, which could include misclassification of diagnoses and comorbidities based on ICD-9 codes. “However, we have chosen ICD-9 codes for stroke that have been previously validated in the literature,” Dr. Stein said. “For instance, the validated codes for stroke as the primary discharge diagnosis have a sensitivity of 74%, specificity of 95%, and positive predictive value of 88%. Second, we do not know stroke subtype or severity of stroke. Third, we do not know what the transitions of care plan were when the patients left the hospital following index acute ischemic stroke admission and why these patients ended up being readmitted to a different hospital rather than the one that treated them for their acute stroke.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stein L et al. Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S149. Abstract M127.

ATLANTA – Following an acute stroke, optimizing stroke secondary prevention measures, medical complications, and transitions of care is essential to reducing 30-day readmissions and improving patient outcomes, a large analysis of national data showed.

“Care that is fragmented with readmissions to other hospitals results not only in more expensive care and longer length of stay but also increased mortality for our acute stroke patients,” lead study author Laura K. Stein, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

In 2017, a study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database demonstrated that 12.1% of patients with acute ischemic stroke were readmitted within 30 days (Stroke 2017;48:1386-8). It cited that 89.6% were unplanned and 12.9% were preventable. “However, this study did not examine whether patients were admitted to the discharging hospital or a different hospital,” said Dr. Stein, a neurologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “Furthermore, it did not include metrics such as cost, length of stay, and mortality with 30-day readmissions. Hospitals are increasingly held accountable and penalized for metrics such as length of stay and 30-day readmissions.”

In 2010, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services introduced the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in an attempt to decrease readmissions following hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. “In 2012, CMS started reducing Medicare payments for hospitals with excess readmissions,” said Dr. Stein, who is a fellowship-trained stroke specialist. “While readmission to the same hospital has great implications for hospital systems, any readmission has great implications for patients.”

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, Dr. Stein and her colleagues drew from the 2013 Nationwide Readmissions Database to examine in-hospital outcomes associated with 30-day readmission to a different hospital for acute ischemic stroke. They used ICD-9 codes to identify index stroke admissions and all-cause readmissions. Outcomes of interest were length of stay, total charges, and in-hospital mortality during the 30-day readmission. The main predictor was readmission to another hospital, compared with readmission to the same hospital as the index acute stroke admission. The researchers used linear regression for the outcomes of length of stay and charges, and logistic regression for in-hospital mortality. They adjusted for several variables during the index admission, including age, sex, vascular risk factors, hospital bed size, teaching hospital status, insurance status, discharge destination, National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural location classification, length of stay, and total charges.

Of 24,545 acute stroke patients readmitted within 30 days, 7,274 (30%) were readmitted to a different hospital. The top three reasons for readmission were acute cerebrovascular disease, septicemia, and renal failure. In fully adjusted models, readmission to a different hospital was associated with an increased length of stay of 0.97 days (P less than .0001) and a mean of $7,677.28 greater total charges, compared with readmission to the same hospital (P less than .0001). The fully adjusted odds ratio for in-hospital mortality during readmission was 1.17 for readmission to another hospital vs. readmission to the same hospital (P = .0079).

“While it is conceivable that cost and length of stay could be higher with readmission to a different hospital because of a need for additional testing with a lack of familiarity with the patient, it is concerning that mortality is higher,” Dr. Stein said. “These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing secondary stroke prevention and medical complications following acute stroke before discharge. Additionally, they emphasize the importance of good transitions of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting (whether that’s to a rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, or home) and accessibility of the discharging stroke team after discharge.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its reliance of administrative data, which could include misclassification of diagnoses and comorbidities based on ICD-9 codes. “However, we have chosen ICD-9 codes for stroke that have been previously validated in the literature,” Dr. Stein said. “For instance, the validated codes for stroke as the primary discharge diagnosis have a sensitivity of 74%, specificity of 95%, and positive predictive value of 88%. Second, we do not know stroke subtype or severity of stroke. Third, we do not know what the transitions of care plan were when the patients left the hospital following index acute ischemic stroke admission and why these patients ended up being readmitted to a different hospital rather than the one that treated them for their acute stroke.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stein L et al. Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S149. Abstract M127.

REPORTING FROM ANA 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The adjusted odds ratio for in-hospital mortality during readmission was 1.17 for readmission to another hospital vs. readmission to the same hospital (P = .0079).

Study details: A review of 24,545 acute stroke patients 2013 from the Nationwide Readmissions Database.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Stein L et al. Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S149. Abstract M127.

Blood test may obviate need for head CTs in brain trauma evaluation

SAN DIEGO – A biomarker test based on the presence of two proteins in the blood appears to be suitable for ruling out significant intracranial injuries in patients with a history of mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) without the need for a CT head scan, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

according to Jeffrey J. Bazarian, MD, professor of emergency medicine, University of Rochester (New York).

In the ALERT-TBI study, which evaluated the biomarker test, 1,959 patients with suspected TBI at 22 participating EDs in the United States and Europe were enrolled and available for analysis. All had mild TBI as defined as a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13-15.

The treating ED physician’s decision to order a head CT scan was the major criterion for study entry. All enrolled patients had their blood drawn within 12 hours in order to quantify two biomarkers, C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).

The biomarker test for TBI was negative when the UCH-L1 value was less than 327 pg/mL and the GFAP was less than 22 pg/mL; the test was positive if either value was at this threshold or higher. To evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of this dual-biomarker test, results were correlated with head CT scans read by two neurologists blinded to the biomarker values.

The mean age of the study population was 48.8 years and slightly more than half were male. About half of the suspected TBI in these patients was attributed to falls and about one third to motor vehicle accidents.

Typical of TBI with GCS scores in the mild range, only 6% of the patients had a positive CT head scan. Of the 125 positive CT scans, the most common injury detected on CT scan was subarachnoid hemorrhage followed by subdural hematoma.

Of the 671 negative biomarker tests, 668 had normal head CT scans. Of the three false positives, one included a cavernous malformation that may have been present prior to the TBI. The others were a small subarachnoid hemorrhage and a small subdural hematoma. Overall the negative predictive value was 99.6% and the sensitivity was 97.6%.

Although the biomarker specificity was only 36% with an even-lower positive predictive value, the goal of the test was to rule out significant TBI to avoid the need for CT scan. On this basis, the biomarker test, which is being developed under the proprietary name Banyan BTI, appears to be promising. The data, according to Dr. Bazarian, have been submitted to the Food and Drug Administration.

“Head CT scans are the current standard for evaluating intracranial injuries after TBI, but they are overused, based on the high proportion that do not show an injury,” said Dr. Bazarian. Although he does not know the disposition of the FDA application, he said, based on these data, “I would definitely be using this test if it were available.”

SAN DIEGO – A biomarker test based on the presence of two proteins in the blood appears to be suitable for ruling out significant intracranial injuries in patients with a history of mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) without the need for a CT head scan, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

according to Jeffrey J. Bazarian, MD, professor of emergency medicine, University of Rochester (New York).

In the ALERT-TBI study, which evaluated the biomarker test, 1,959 patients with suspected TBI at 22 participating EDs in the United States and Europe were enrolled and available for analysis. All had mild TBI as defined as a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13-15.

The treating ED physician’s decision to order a head CT scan was the major criterion for study entry. All enrolled patients had their blood drawn within 12 hours in order to quantify two biomarkers, C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).

The biomarker test for TBI was negative when the UCH-L1 value was less than 327 pg/mL and the GFAP was less than 22 pg/mL; the test was positive if either value was at this threshold or higher. To evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of this dual-biomarker test, results were correlated with head CT scans read by two neurologists blinded to the biomarker values.

The mean age of the study population was 48.8 years and slightly more than half were male. About half of the suspected TBI in these patients was attributed to falls and about one third to motor vehicle accidents.

Typical of TBI with GCS scores in the mild range, only 6% of the patients had a positive CT head scan. Of the 125 positive CT scans, the most common injury detected on CT scan was subarachnoid hemorrhage followed by subdural hematoma.

Of the 671 negative biomarker tests, 668 had normal head CT scans. Of the three false positives, one included a cavernous malformation that may have been present prior to the TBI. The others were a small subarachnoid hemorrhage and a small subdural hematoma. Overall the negative predictive value was 99.6% and the sensitivity was 97.6%.

Although the biomarker specificity was only 36% with an even-lower positive predictive value, the goal of the test was to rule out significant TBI to avoid the need for CT scan. On this basis, the biomarker test, which is being developed under the proprietary name Banyan BTI, appears to be promising. The data, according to Dr. Bazarian, have been submitted to the Food and Drug Administration.

“Head CT scans are the current standard for evaluating intracranial injuries after TBI, but they are overused, based on the high proportion that do not show an injury,” said Dr. Bazarian. Although he does not know the disposition of the FDA application, he said, based on these data, “I would definitely be using this test if it were available.”

SAN DIEGO – A biomarker test based on the presence of two proteins in the blood appears to be suitable for ruling out significant intracranial injuries in patients with a history of mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) without the need for a CT head scan, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

according to Jeffrey J. Bazarian, MD, professor of emergency medicine, University of Rochester (New York).

In the ALERT-TBI study, which evaluated the biomarker test, 1,959 patients with suspected TBI at 22 participating EDs in the United States and Europe were enrolled and available for analysis. All had mild TBI as defined as a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13-15.

The treating ED physician’s decision to order a head CT scan was the major criterion for study entry. All enrolled patients had their blood drawn within 12 hours in order to quantify two biomarkers, C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).

The biomarker test for TBI was negative when the UCH-L1 value was less than 327 pg/mL and the GFAP was less than 22 pg/mL; the test was positive if either value was at this threshold or higher. To evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of this dual-biomarker test, results were correlated with head CT scans read by two neurologists blinded to the biomarker values.

The mean age of the study population was 48.8 years and slightly more than half were male. About half of the suspected TBI in these patients was attributed to falls and about one third to motor vehicle accidents.

Typical of TBI with GCS scores in the mild range, only 6% of the patients had a positive CT head scan. Of the 125 positive CT scans, the most common injury detected on CT scan was subarachnoid hemorrhage followed by subdural hematoma.

Of the 671 negative biomarker tests, 668 had normal head CT scans. Of the three false positives, one included a cavernous malformation that may have been present prior to the TBI. The others were a small subarachnoid hemorrhage and a small subdural hematoma. Overall the negative predictive value was 99.6% and the sensitivity was 97.6%.

Although the biomarker specificity was only 36% with an even-lower positive predictive value, the goal of the test was to rule out significant TBI to avoid the need for CT scan. On this basis, the biomarker test, which is being developed under the proprietary name Banyan BTI, appears to be promising. The data, according to Dr. Bazarian, have been submitted to the Food and Drug Administration.

“Head CT scans are the current standard for evaluating intracranial injuries after TBI, but they are overused, based on the high proportion that do not show an injury,” said Dr. Bazarian. Although he does not know the disposition of the FDA application, he said, based on these data, “I would definitely be using this test if it were available.”

FROM ACEP 2018

Key clinical point: In patients with mild head trauma, a simple blood test may eliminate need and cost for routine CT scans.

Major finding: In patients a history of head trauma, the biomarker test had a 99.6% negative predictive value in ruling out injury.

Study details: Prospective, controlled registration study.

Disclosures: Dr. Bazarian reported no financial relationships relevant to this study, which was in part funded by Banyan Biomarkers.

DAPT’s benefit after stroke or TIA clusters in first 21 days

MONTREAL – The optimal length for dual antiplatelet therapy in patients who have just had a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack is 21 days, a duration of combined treatment that maximized protection against major ischemic events while minimizing the extra risk for a major hemorrhage, according to a prespecified analysis of data from the POINT trial.

The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial randomized 4,881 patients with a very recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack and without atrial fibrillation to treatment with either clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone for 90 days. Compared with aspirin alone, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) cut the incidence of a major ischemic event by a relative 25% but also more than doubled the rate of major hemorrhage (New Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 19;377[3]:215-25).

The new, prespecified analysis looked at outcomes on a week-by-week basis over the course of 90 days of treatment, and showed that during the first 21 days the rate of major ischemic events was 5.6% among patients on aspirin only and 3.6% among those on DAPT, a statistically significant 35% relative cut in these adverse outcomes by using DAPT, Jordan J. Elm, PhD, reported at the World Stroke Congress. During the subsequent 69 days on treatment, the incidence of major ischemic events was roughly 1% in both arms of the study, showing that after 3 weeks the incremental benefit from DAPT disappeared, said Dr. Elm, a biostatistician at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

In contrast, the doubled rate of major hemorrhages (mostly reversible gastrointestinal bleeds) with DAPT, compared with aspirin alone, occurred at a relatively uniform rate throughout the 90 days of treatment, meaning that limiting DAPT to just 21 days could prevent many of the excess hemorrhages.

“These results suggest that limiting clopidogrel plus aspirin use to 21 days may maximize benefit and reduce risk,” Dr. Elm said, especially in light of the findings confirming the efficacy of 21 days of DAPT following a minor stroke or TIA that had been reported several years ago in the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) trial (New Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 4;369[1]:11-9).

Although the new finding from the POINT results came in a secondary analysis, it’s statistically legitimate and should be taken into account when writing treatment guidelines, she said, emphasizing that “this is a very important analysis that is not just hypothesis generating.”

Another finding from the new analysis was that a large number of major ischemic events, and hence a large number of the events prevented by DAPT, occurred in the first 2 days following the index event, a finding made possible because the POINT investigators enrolled patients and started treatment within 12 hours of the qualifying events.

“It’s better to start treatment early,” Dr. Elm noted, but she also highlighted that major ischemic events continued to accumulate during days 3-21, suggesting that patients could still benefit from DAPT even if treatment did not start until 24 or 48 hours after their index event.

POINT received no commercial funding aside from study drugs supplied by Sanofi. Dr. Elm reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Elm JJ et al. World Stroke Congress, Late-breaking session.

The new model using data from the POINT trial confirms what had been previously shown in the CHANCE trial – that 21 days is a sensible cutoff for dual antiplatelet treatment for patients immediately following a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack. Treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy for 21 days provides the same added benefit as 90 days of treatment but with less excess bleeding. The new findings confirm that the CHANCE results were not specific to a Chinese population.

For the time being, clopidogrel is the evidence-based antiplatelet drug to pair with aspirin for this indication. Clopidogrel has the advantages of being generic, cheap, available, and familiar. It’s possible that another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor (Brilinta), might work even better, but that needs to be proven to justify the added expense of a brand-name antiplatelet drug.

Mike Sharma, MD , is a stroke neurologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. He has been an advisor to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. He made these comments in an interview.

The new model using data from the POINT trial confirms what had been previously shown in the CHANCE trial – that 21 days is a sensible cutoff for dual antiplatelet treatment for patients immediately following a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack. Treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy for 21 days provides the same added benefit as 90 days of treatment but with less excess bleeding. The new findings confirm that the CHANCE results were not specific to a Chinese population.

For the time being, clopidogrel is the evidence-based antiplatelet drug to pair with aspirin for this indication. Clopidogrel has the advantages of being generic, cheap, available, and familiar. It’s possible that another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor (Brilinta), might work even better, but that needs to be proven to justify the added expense of a brand-name antiplatelet drug.

Mike Sharma, MD , is a stroke neurologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. He has been an advisor to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. He made these comments in an interview.

The new model using data from the POINT trial confirms what had been previously shown in the CHANCE trial – that 21 days is a sensible cutoff for dual antiplatelet treatment for patients immediately following a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack. Treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy for 21 days provides the same added benefit as 90 days of treatment but with less excess bleeding. The new findings confirm that the CHANCE results were not specific to a Chinese population.

For the time being, clopidogrel is the evidence-based antiplatelet drug to pair with aspirin for this indication. Clopidogrel has the advantages of being generic, cheap, available, and familiar. It’s possible that another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor (Brilinta), might work even better, but that needs to be proven to justify the added expense of a brand-name antiplatelet drug.

Mike Sharma, MD , is a stroke neurologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. He has been an advisor to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. He made these comments in an interview.

MONTREAL – The optimal length for dual antiplatelet therapy in patients who have just had a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack is 21 days, a duration of combined treatment that maximized protection against major ischemic events while minimizing the extra risk for a major hemorrhage, according to a prespecified analysis of data from the POINT trial.

The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial randomized 4,881 patients with a very recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack and without atrial fibrillation to treatment with either clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone for 90 days. Compared with aspirin alone, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) cut the incidence of a major ischemic event by a relative 25% but also more than doubled the rate of major hemorrhage (New Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 19;377[3]:215-25).

The new, prespecified analysis looked at outcomes on a week-by-week basis over the course of 90 days of treatment, and showed that during the first 21 days the rate of major ischemic events was 5.6% among patients on aspirin only and 3.6% among those on DAPT, a statistically significant 35% relative cut in these adverse outcomes by using DAPT, Jordan J. Elm, PhD, reported at the World Stroke Congress. During the subsequent 69 days on treatment, the incidence of major ischemic events was roughly 1% in both arms of the study, showing that after 3 weeks the incremental benefit from DAPT disappeared, said Dr. Elm, a biostatistician at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

In contrast, the doubled rate of major hemorrhages (mostly reversible gastrointestinal bleeds) with DAPT, compared with aspirin alone, occurred at a relatively uniform rate throughout the 90 days of treatment, meaning that limiting DAPT to just 21 days could prevent many of the excess hemorrhages.

“These results suggest that limiting clopidogrel plus aspirin use to 21 days may maximize benefit and reduce risk,” Dr. Elm said, especially in light of the findings confirming the efficacy of 21 days of DAPT following a minor stroke or TIA that had been reported several years ago in the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) trial (New Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 4;369[1]:11-9).

Although the new finding from the POINT results came in a secondary analysis, it’s statistically legitimate and should be taken into account when writing treatment guidelines, she said, emphasizing that “this is a very important analysis that is not just hypothesis generating.”

Another finding from the new analysis was that a large number of major ischemic events, and hence a large number of the events prevented by DAPT, occurred in the first 2 days following the index event, a finding made possible because the POINT investigators enrolled patients and started treatment within 12 hours of the qualifying events.

“It’s better to start treatment early,” Dr. Elm noted, but she also highlighted that major ischemic events continued to accumulate during days 3-21, suggesting that patients could still benefit from DAPT even if treatment did not start until 24 or 48 hours after their index event.

POINT received no commercial funding aside from study drugs supplied by Sanofi. Dr. Elm reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Elm JJ et al. World Stroke Congress, Late-breaking session.

MONTREAL – The optimal length for dual antiplatelet therapy in patients who have just had a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack is 21 days, a duration of combined treatment that maximized protection against major ischemic events while minimizing the extra risk for a major hemorrhage, according to a prespecified analysis of data from the POINT trial.

The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial randomized 4,881 patients with a very recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack and without atrial fibrillation to treatment with either clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone for 90 days. Compared with aspirin alone, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) cut the incidence of a major ischemic event by a relative 25% but also more than doubled the rate of major hemorrhage (New Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 19;377[3]:215-25).

The new, prespecified analysis looked at outcomes on a week-by-week basis over the course of 90 days of treatment, and showed that during the first 21 days the rate of major ischemic events was 5.6% among patients on aspirin only and 3.6% among those on DAPT, a statistically significant 35% relative cut in these adverse outcomes by using DAPT, Jordan J. Elm, PhD, reported at the World Stroke Congress. During the subsequent 69 days on treatment, the incidence of major ischemic events was roughly 1% in both arms of the study, showing that after 3 weeks the incremental benefit from DAPT disappeared, said Dr. Elm, a biostatistician at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

In contrast, the doubled rate of major hemorrhages (mostly reversible gastrointestinal bleeds) with DAPT, compared with aspirin alone, occurred at a relatively uniform rate throughout the 90 days of treatment, meaning that limiting DAPT to just 21 days could prevent many of the excess hemorrhages.

“These results suggest that limiting clopidogrel plus aspirin use to 21 days may maximize benefit and reduce risk,” Dr. Elm said, especially in light of the findings confirming the efficacy of 21 days of DAPT following a minor stroke or TIA that had been reported several years ago in the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) trial (New Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 4;369[1]:11-9).

Although the new finding from the POINT results came in a secondary analysis, it’s statistically legitimate and should be taken into account when writing treatment guidelines, she said, emphasizing that “this is a very important analysis that is not just hypothesis generating.”

Another finding from the new analysis was that a large number of major ischemic events, and hence a large number of the events prevented by DAPT, occurred in the first 2 days following the index event, a finding made possible because the POINT investigators enrolled patients and started treatment within 12 hours of the qualifying events.

“It’s better to start treatment early,” Dr. Elm noted, but she also highlighted that major ischemic events continued to accumulate during days 3-21, suggesting that patients could still benefit from DAPT even if treatment did not start until 24 or 48 hours after their index event.

POINT received no commercial funding aside from study drugs supplied by Sanofi. Dr. Elm reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Elm JJ et al. World Stroke Congress, Late-breaking session.

REPORTING FROM THE WORLD STROKE CONGRESS

Key clinical point: All of DAPT’s extra benefit over aspirin alone in recent stroke or transient ischemic attack patients happened during the first 21 days.

Major finding: During the first 21 days, DAPT cut major ischemic events by 35%, compared with aspirin only.

Study details: A prespecified, secondary analysis from POINT, a multicenter, randomized trial with 4,881 patients.

Disclosures: POINT received no commercial funding aside from study drugs supplied by Sanofi. Dr. Elm had no disclosures.

Source: Elm JJ et al. World Stroke Congress, Late-breaking session.

“You have a pending query”

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

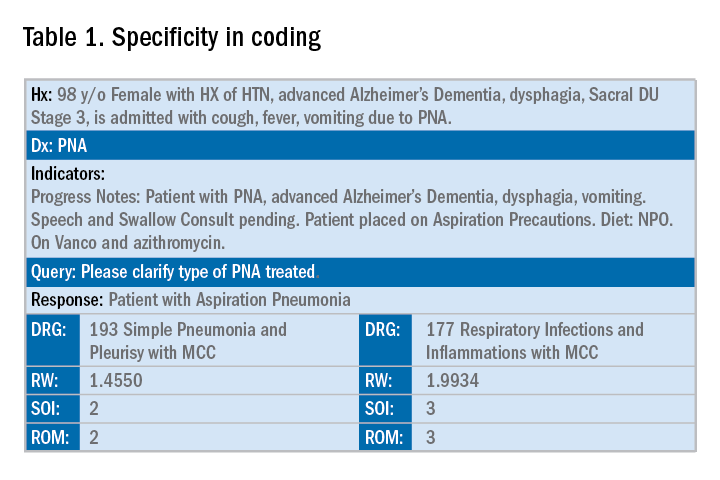

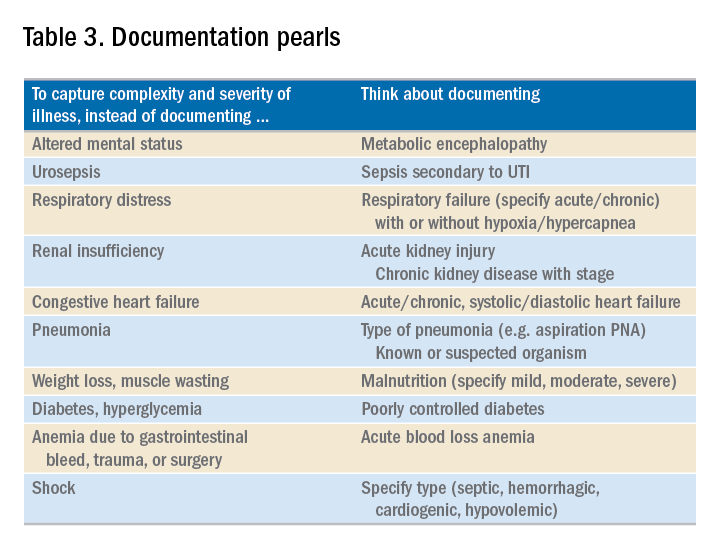

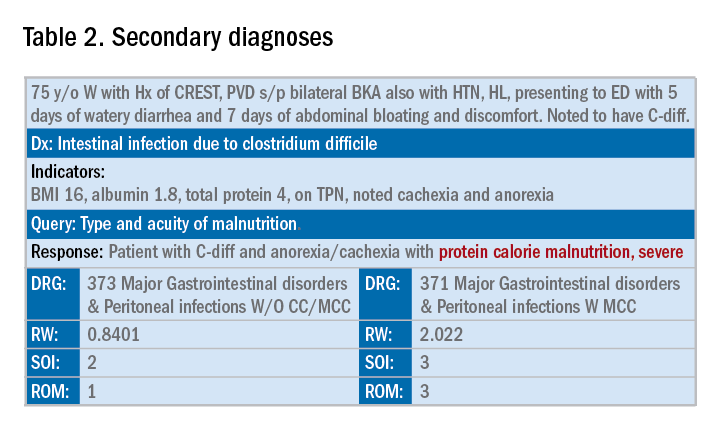

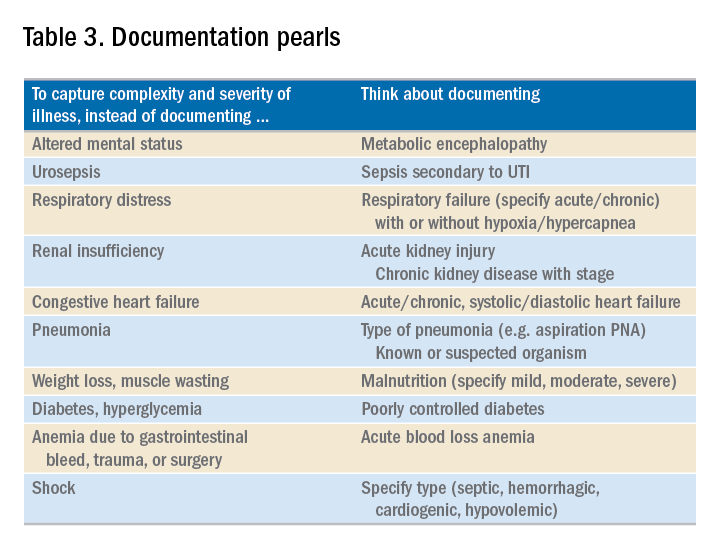

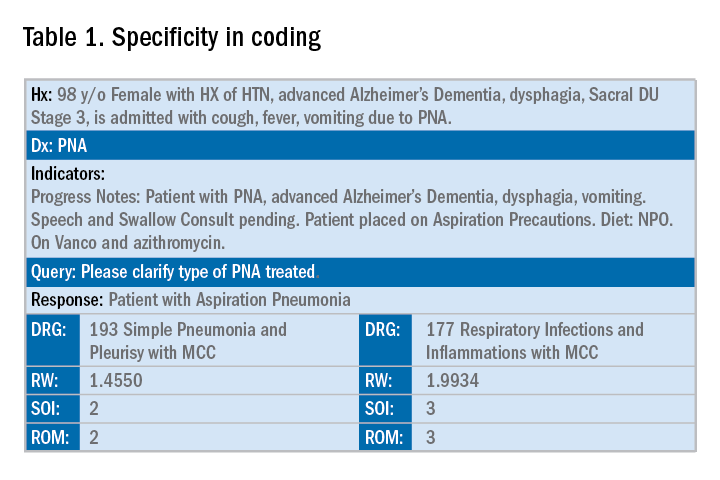

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

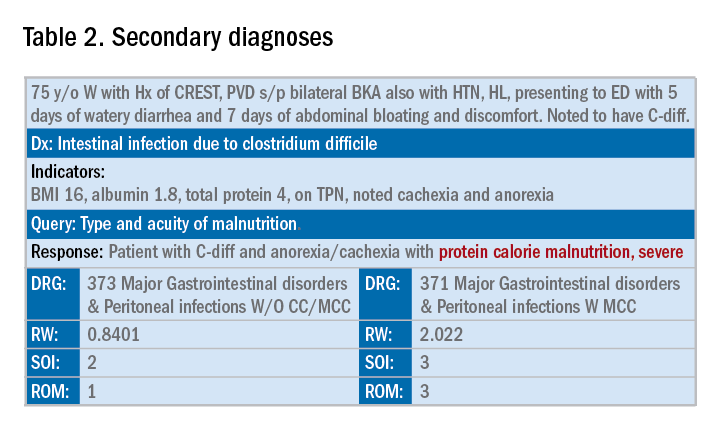

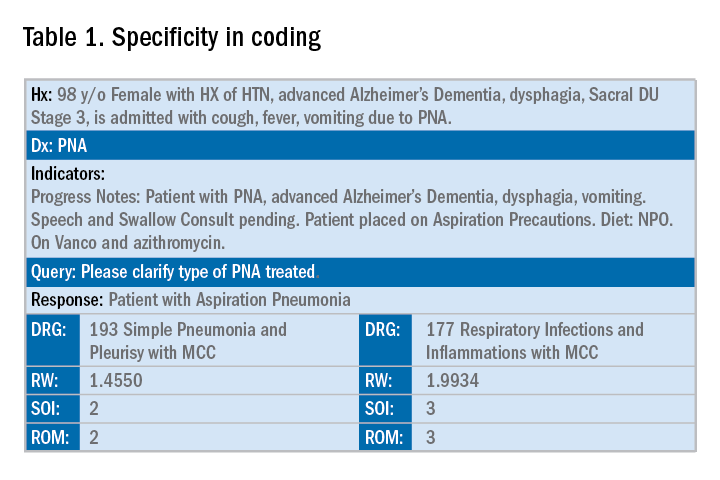

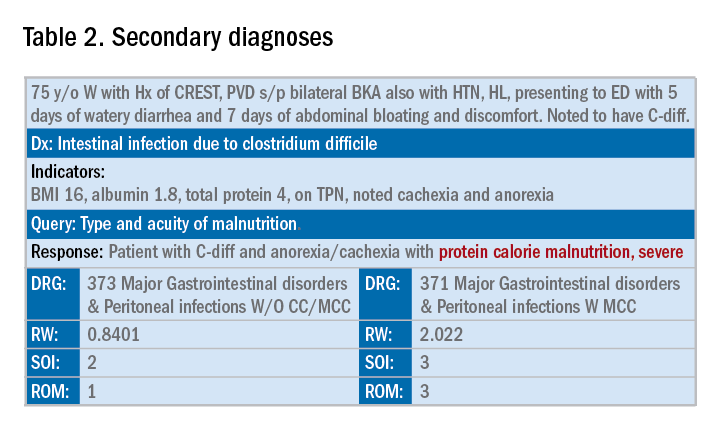

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

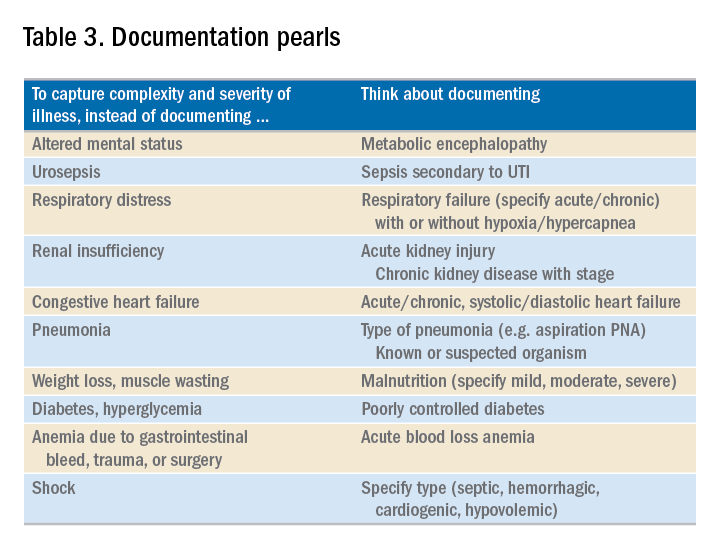

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.