User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Opioids and hospital medicine: What can we do?

I recently attended a local Charleston (S.C.) Medical Society meeting, the theme of which was the opioid crisis. Although at the time I did not see a perfect relevance of this crisis to hospital medicine, I attended anyway, hoping to gain some pearls of wisdom regarding what my role in this epidemic could be.

I was already certainly aware of the extent of the opioid epidemic, including some startling statistics. For example, the burden of the crisis totaled $95 billion in the United States in 2016 from lost productivity and health care and criminal justice system expenses.1 But I was still not certain what my specific role could be in doing something about it.

The main speaker at the meeting was Nanci Steadman Shipman, the mother of a 19-year-old college student who had accidentally overdosed on heroin the year prior. She told the story of his upbringing, which was in an upper-middle-class suburban neighborhood, full of family, friends, and loving support. When her son was 15 years old, he suffered a leg injury during his lacrosse season, which led to a hospital stay, a surgery, and a prolonged recovery. It was during this period of time that, unbeknownst to his family, he became addicted to opioids.

Over the years, Nanci’s son found ever more creative mechanisms to procure various opioids, eventually resorting to heroin, which was remarkably cheap and easy to find. All the while in high school, he maintained good grades, remained active in sports, and had a normal social circle of friends. It was not until his first year of college that his mother started to worry that something might be wrong. In less than a year, her son quit sports, and his grades spiraled. Despite ongoing family support and extensive rehab, he suffered more than one setback and accidentally overdosed.

After her son’s death, Nanci started a nonprofit organization, Wake Up Carolina.2 Its mission is to fight drug abuse among adolescents and young adults. They use a combination of education, awareness, prevention, and recovery tactics to achieve their task. In the meantime, they try to diminish the shame and secrecy among families suffering from opioid addiction. During Nanci’s presentation at the medical society meeting, the message she conveyed to us – an audience full of physicians – was simple: We can either be part of the problem or part of the solution; we all have a duty to help and a role to play in this crisis. Whether a patient is exposed first inside the hospital or outside of it, for a short period of time or for a long one, every opioid exposure comes with a risk. Nanci’s story was incredibly affecting and made me rethink my personal role in this epidemic; how might I have contributed to this, and what could I do differently?

Shortly after her son died, her younger son suffered a femur fracture during a football game. You can imagine the horror her family felt knowing that he would need some pain medication for his acute injury. Nanci and her family were able to work with the medical and surgical teams, and through multimodal pain regimens, her son received little to no opioids during the hospital stay and was able to recover from the fracture with reasonable pain levels. She expressed gratitude that the hospital teams were willing to listen to her and her family’s concerns and offer both pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapies for her son’s recovery, which allayed their fears about opioids.

From this incredibly powerful and moving story of one family’s experience, I was able to gather some very meaningful, evidence-based, and tangible practices that I could implement in my own organization. These might even help other hospitalists take an active role in stemming this sadly growing epidemic.

As hospitalists, we should work on the following:

- Improve our personal knowledge of and skills in utilizing multimodal pain therapies regardless of the etiology of the pain. These should include both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.

- Use consultants to assist us with difficult cases. Depending on our practice setting, we should utilize consultants who can give us good advice on nonopioid pain management regimens, such as palliative care.

- Try to influence the practice of surgeons and other specialties that consult us, to help shape prescribing patterns that include nonopioid medical regimens, and to get doctors used to entertaining nonpharmacologic pain-reducing interventions.

- Limit the volume of prescription opioids written to our patients at the time of hospital discharge. There is mounting literature that suggests leftover prescriptions can be the start of an opioid addiction for a family member.

- Educate ourselves and our patients about any local “take back” programs that allow for safe, secure, and anonymous drops of prescription medications. This may reduce opioids getting into the hands of someone who might later become addicted.

- Find out whether our hospitals or health systems have a pain or opioid oversight group or team, and if not, see whether there is interest in starting one.

- Look into local community activist programs to partner with for education, awareness, prevention, or treatment options (such as Wake Up Carolina).

- Work with local resources (for example, case management, social workers, psychiatrists) to learn about and utilize local options for rehabilitation. We should actively and openly discuss these options with any patients known or suspected to be addicted.

- Make a valiant attempt to remove any unconscious bias against people who have become addicted to opioids. Continuing the social stigma of addiction only spurs the shame and secrecy.

Please share other ideas or suggestions you may have regarding the role hospitalists can have in curbing this growing epidemic.

References

1. “Burden of opioid crisis reached $95 billion in 2016; private sector hit hardest.” Altarum press release. Nov 16, 2017.

2. Wake Up Carolina website.

I recently attended a local Charleston (S.C.) Medical Society meeting, the theme of which was the opioid crisis. Although at the time I did not see a perfect relevance of this crisis to hospital medicine, I attended anyway, hoping to gain some pearls of wisdom regarding what my role in this epidemic could be.

I was already certainly aware of the extent of the opioid epidemic, including some startling statistics. For example, the burden of the crisis totaled $95 billion in the United States in 2016 from lost productivity and health care and criminal justice system expenses.1 But I was still not certain what my specific role could be in doing something about it.

The main speaker at the meeting was Nanci Steadman Shipman, the mother of a 19-year-old college student who had accidentally overdosed on heroin the year prior. She told the story of his upbringing, which was in an upper-middle-class suburban neighborhood, full of family, friends, and loving support. When her son was 15 years old, he suffered a leg injury during his lacrosse season, which led to a hospital stay, a surgery, and a prolonged recovery. It was during this period of time that, unbeknownst to his family, he became addicted to opioids.

Over the years, Nanci’s son found ever more creative mechanisms to procure various opioids, eventually resorting to heroin, which was remarkably cheap and easy to find. All the while in high school, he maintained good grades, remained active in sports, and had a normal social circle of friends. It was not until his first year of college that his mother started to worry that something might be wrong. In less than a year, her son quit sports, and his grades spiraled. Despite ongoing family support and extensive rehab, he suffered more than one setback and accidentally overdosed.

After her son’s death, Nanci started a nonprofit organization, Wake Up Carolina.2 Its mission is to fight drug abuse among adolescents and young adults. They use a combination of education, awareness, prevention, and recovery tactics to achieve their task. In the meantime, they try to diminish the shame and secrecy among families suffering from opioid addiction. During Nanci’s presentation at the medical society meeting, the message she conveyed to us – an audience full of physicians – was simple: We can either be part of the problem or part of the solution; we all have a duty to help and a role to play in this crisis. Whether a patient is exposed first inside the hospital or outside of it, for a short period of time or for a long one, every opioid exposure comes with a risk. Nanci’s story was incredibly affecting and made me rethink my personal role in this epidemic; how might I have contributed to this, and what could I do differently?

Shortly after her son died, her younger son suffered a femur fracture during a football game. You can imagine the horror her family felt knowing that he would need some pain medication for his acute injury. Nanci and her family were able to work with the medical and surgical teams, and through multimodal pain regimens, her son received little to no opioids during the hospital stay and was able to recover from the fracture with reasonable pain levels. She expressed gratitude that the hospital teams were willing to listen to her and her family’s concerns and offer both pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapies for her son’s recovery, which allayed their fears about opioids.

From this incredibly powerful and moving story of one family’s experience, I was able to gather some very meaningful, evidence-based, and tangible practices that I could implement in my own organization. These might even help other hospitalists take an active role in stemming this sadly growing epidemic.

As hospitalists, we should work on the following:

- Improve our personal knowledge of and skills in utilizing multimodal pain therapies regardless of the etiology of the pain. These should include both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.

- Use consultants to assist us with difficult cases. Depending on our practice setting, we should utilize consultants who can give us good advice on nonopioid pain management regimens, such as palliative care.

- Try to influence the practice of surgeons and other specialties that consult us, to help shape prescribing patterns that include nonopioid medical regimens, and to get doctors used to entertaining nonpharmacologic pain-reducing interventions.

- Limit the volume of prescription opioids written to our patients at the time of hospital discharge. There is mounting literature that suggests leftover prescriptions can be the start of an opioid addiction for a family member.

- Educate ourselves and our patients about any local “take back” programs that allow for safe, secure, and anonymous drops of prescription medications. This may reduce opioids getting into the hands of someone who might later become addicted.

- Find out whether our hospitals or health systems have a pain or opioid oversight group or team, and if not, see whether there is interest in starting one.

- Look into local community activist programs to partner with for education, awareness, prevention, or treatment options (such as Wake Up Carolina).

- Work with local resources (for example, case management, social workers, psychiatrists) to learn about and utilize local options for rehabilitation. We should actively and openly discuss these options with any patients known or suspected to be addicted.

- Make a valiant attempt to remove any unconscious bias against people who have become addicted to opioids. Continuing the social stigma of addiction only spurs the shame and secrecy.

Please share other ideas or suggestions you may have regarding the role hospitalists can have in curbing this growing epidemic.

References

1. “Burden of opioid crisis reached $95 billion in 2016; private sector hit hardest.” Altarum press release. Nov 16, 2017.

2. Wake Up Carolina website.

I recently attended a local Charleston (S.C.) Medical Society meeting, the theme of which was the opioid crisis. Although at the time I did not see a perfect relevance of this crisis to hospital medicine, I attended anyway, hoping to gain some pearls of wisdom regarding what my role in this epidemic could be.

I was already certainly aware of the extent of the opioid epidemic, including some startling statistics. For example, the burden of the crisis totaled $95 billion in the United States in 2016 from lost productivity and health care and criminal justice system expenses.1 But I was still not certain what my specific role could be in doing something about it.

The main speaker at the meeting was Nanci Steadman Shipman, the mother of a 19-year-old college student who had accidentally overdosed on heroin the year prior. She told the story of his upbringing, which was in an upper-middle-class suburban neighborhood, full of family, friends, and loving support. When her son was 15 years old, he suffered a leg injury during his lacrosse season, which led to a hospital stay, a surgery, and a prolonged recovery. It was during this period of time that, unbeknownst to his family, he became addicted to opioids.

Over the years, Nanci’s son found ever more creative mechanisms to procure various opioids, eventually resorting to heroin, which was remarkably cheap and easy to find. All the while in high school, he maintained good grades, remained active in sports, and had a normal social circle of friends. It was not until his first year of college that his mother started to worry that something might be wrong. In less than a year, her son quit sports, and his grades spiraled. Despite ongoing family support and extensive rehab, he suffered more than one setback and accidentally overdosed.

After her son’s death, Nanci started a nonprofit organization, Wake Up Carolina.2 Its mission is to fight drug abuse among adolescents and young adults. They use a combination of education, awareness, prevention, and recovery tactics to achieve their task. In the meantime, they try to diminish the shame and secrecy among families suffering from opioid addiction. During Nanci’s presentation at the medical society meeting, the message she conveyed to us – an audience full of physicians – was simple: We can either be part of the problem or part of the solution; we all have a duty to help and a role to play in this crisis. Whether a patient is exposed first inside the hospital or outside of it, for a short period of time or for a long one, every opioid exposure comes with a risk. Nanci’s story was incredibly affecting and made me rethink my personal role in this epidemic; how might I have contributed to this, and what could I do differently?

Shortly after her son died, her younger son suffered a femur fracture during a football game. You can imagine the horror her family felt knowing that he would need some pain medication for his acute injury. Nanci and her family were able to work with the medical and surgical teams, and through multimodal pain regimens, her son received little to no opioids during the hospital stay and was able to recover from the fracture with reasonable pain levels. She expressed gratitude that the hospital teams were willing to listen to her and her family’s concerns and offer both pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapies for her son’s recovery, which allayed their fears about opioids.

From this incredibly powerful and moving story of one family’s experience, I was able to gather some very meaningful, evidence-based, and tangible practices that I could implement in my own organization. These might even help other hospitalists take an active role in stemming this sadly growing epidemic.

As hospitalists, we should work on the following:

- Improve our personal knowledge of and skills in utilizing multimodal pain therapies regardless of the etiology of the pain. These should include both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.

- Use consultants to assist us with difficult cases. Depending on our practice setting, we should utilize consultants who can give us good advice on nonopioid pain management regimens, such as palliative care.

- Try to influence the practice of surgeons and other specialties that consult us, to help shape prescribing patterns that include nonopioid medical regimens, and to get doctors used to entertaining nonpharmacologic pain-reducing interventions.

- Limit the volume of prescription opioids written to our patients at the time of hospital discharge. There is mounting literature that suggests leftover prescriptions can be the start of an opioid addiction for a family member.

- Educate ourselves and our patients about any local “take back” programs that allow for safe, secure, and anonymous drops of prescription medications. This may reduce opioids getting into the hands of someone who might later become addicted.

- Find out whether our hospitals or health systems have a pain or opioid oversight group or team, and if not, see whether there is interest in starting one.

- Look into local community activist programs to partner with for education, awareness, prevention, or treatment options (such as Wake Up Carolina).

- Work with local resources (for example, case management, social workers, psychiatrists) to learn about and utilize local options for rehabilitation. We should actively and openly discuss these options with any patients known or suspected to be addicted.

- Make a valiant attempt to remove any unconscious bias against people who have become addicted to opioids. Continuing the social stigma of addiction only spurs the shame and secrecy.

Please share other ideas or suggestions you may have regarding the role hospitalists can have in curbing this growing epidemic.

References

1. “Burden of opioid crisis reached $95 billion in 2016; private sector hit hardest.” Altarum press release. Nov 16, 2017.

2. Wake Up Carolina website.

New C. difficile guidelines recommend fecal microbiota transplants

.

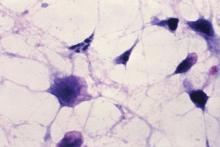

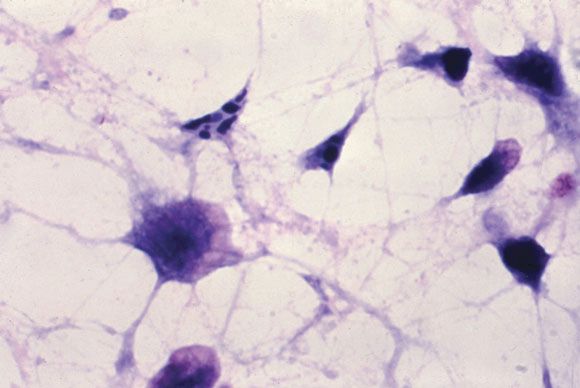

The updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children, published in the Feb. 15 edition of Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085), address changes in management and diagnosis of the infection, and include recommendations for pediatric infection. The guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America were lasted published in 2010.

One of the strongest recommendations was on the use of FMTs to treat recurrent C. difficile infection after the failure of antibiotic therapy.

“Anecdotal treatment success rates of fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent CDI [C. difficile infection] have been high regardless of route of instillation of feces, and have ranged between 77% and 94% with administration via the proximal small bowel; the highest success rates (80%-100%) have been associated with instillation of feces via the colon,” they wrote.

The guidelines also addressed what the authors described as the “evolving controversy” over the best methods for diagnosis, pointing out that there is little consensus about the best laboratory testing method.

“Given these various conundrums and the paucity of large prospective studies, the recommendations, while strong in some instances, are based upon a very low to low quality of evidence,” the authors said.

That aside, they advised that patients with unexplained and new-onset diarrhea (three or more unformed stools in 24 hours) were the preferred target population for testing for C. difficile infection. The most sensitive method of diagnosis in patients with clinical symptoms likely to be C. difficile infection was a nucleic acid amplification test, or a multistep algorithm, rather than a toxin test alone.

The guidelines committee also strongly advised against repeat testing within 7 days during the same episode of diarrhea, and against testing stool from asymptomatic patients, except for the purpose of epidemiologic study. They also noted there was insufficient evidence for the use of biologic markers such as fecal lactoferrin as an adjunct to testing.

The guidelines’ authors found there was not enough evidence to recommend discontinuing proton pump inhibitors to reduce the incidence of C. difficile infection, despite epidemiologic evidence of an association between proton pump inhibitor use and C. difficile infection. Similarly, there was a lack of evidence for the use of probiotics for primary prevention, but the authors noted that meta-analyses suggest probiotics may help prevent C. difficile infection in patients on antibiotics without a history of C. difficile infection.

With respect to antibiotic treatment, they recommended that patients diagnosed with C. difficile infection should first discontinue the inciting antibiotic treatment and then begin therapy with either vancomycin or fidaxomicin. For recurrent infection, they advised a tapered and pulsed regimen of oral vancomycin or a 10-day course of fidaxomicin. If patients had received metronidazole for the primary episode, they should be given a standard 10-day course of vancomycin for recurrent infection, the authors said.

In terms of diagnosis and management of pediatric C. difficile, the guidelines advised against routinely testing infants under 2 years of age with diarrhea, as the rate of C. difficile colonization even among asymptomatic infants can be higher than 40%. Even in children older than age 2, there was only a “weak” recommendation for C. difficile testing in patients with prolonged or worsening diarrhea and other risk factors such as inflammatory bowel disease or recent antibiotic exposure.

Children with a first episode or first recurrence of nonsevere C. difficile should be treated with either metronidazole or vancomycin, the authors wrote, but in the case of more severe illness or second recurrence, oral vancomycin was preferred over metronidazole.

The authors also suggested clinicians consider FMTs for children with recurrent infection that had failed to respond to antibiotics, but noted the quality of evidence for this was very low.

The guidelines were funded by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Six authors declared grants, consultancies, board positions, and other payments from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work. One author also held patents relating to the treatment and prevention of C. difficile infection.

SOURCE: McDonald CL et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085.

.

The updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children, published in the Feb. 15 edition of Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085), address changes in management and diagnosis of the infection, and include recommendations for pediatric infection. The guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America were lasted published in 2010.

One of the strongest recommendations was on the use of FMTs to treat recurrent C. difficile infection after the failure of antibiotic therapy.

“Anecdotal treatment success rates of fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent CDI [C. difficile infection] have been high regardless of route of instillation of feces, and have ranged between 77% and 94% with administration via the proximal small bowel; the highest success rates (80%-100%) have been associated with instillation of feces via the colon,” they wrote.

The guidelines also addressed what the authors described as the “evolving controversy” over the best methods for diagnosis, pointing out that there is little consensus about the best laboratory testing method.

“Given these various conundrums and the paucity of large prospective studies, the recommendations, while strong in some instances, are based upon a very low to low quality of evidence,” the authors said.

That aside, they advised that patients with unexplained and new-onset diarrhea (three or more unformed stools in 24 hours) were the preferred target population for testing for C. difficile infection. The most sensitive method of diagnosis in patients with clinical symptoms likely to be C. difficile infection was a nucleic acid amplification test, or a multistep algorithm, rather than a toxin test alone.

The guidelines committee also strongly advised against repeat testing within 7 days during the same episode of diarrhea, and against testing stool from asymptomatic patients, except for the purpose of epidemiologic study. They also noted there was insufficient evidence for the use of biologic markers such as fecal lactoferrin as an adjunct to testing.

The guidelines’ authors found there was not enough evidence to recommend discontinuing proton pump inhibitors to reduce the incidence of C. difficile infection, despite epidemiologic evidence of an association between proton pump inhibitor use and C. difficile infection. Similarly, there was a lack of evidence for the use of probiotics for primary prevention, but the authors noted that meta-analyses suggest probiotics may help prevent C. difficile infection in patients on antibiotics without a history of C. difficile infection.

With respect to antibiotic treatment, they recommended that patients diagnosed with C. difficile infection should first discontinue the inciting antibiotic treatment and then begin therapy with either vancomycin or fidaxomicin. For recurrent infection, they advised a tapered and pulsed regimen of oral vancomycin or a 10-day course of fidaxomicin. If patients had received metronidazole for the primary episode, they should be given a standard 10-day course of vancomycin for recurrent infection, the authors said.

In terms of diagnosis and management of pediatric C. difficile, the guidelines advised against routinely testing infants under 2 years of age with diarrhea, as the rate of C. difficile colonization even among asymptomatic infants can be higher than 40%. Even in children older than age 2, there was only a “weak” recommendation for C. difficile testing in patients with prolonged or worsening diarrhea and other risk factors such as inflammatory bowel disease or recent antibiotic exposure.

Children with a first episode or first recurrence of nonsevere C. difficile should be treated with either metronidazole or vancomycin, the authors wrote, but in the case of more severe illness or second recurrence, oral vancomycin was preferred over metronidazole.

The authors also suggested clinicians consider FMTs for children with recurrent infection that had failed to respond to antibiotics, but noted the quality of evidence for this was very low.

The guidelines were funded by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Six authors declared grants, consultancies, board positions, and other payments from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work. One author also held patents relating to the treatment and prevention of C. difficile infection.

SOURCE: McDonald CL et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085.

.

The updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children, published in the Feb. 15 edition of Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085), address changes in management and diagnosis of the infection, and include recommendations for pediatric infection. The guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America were lasted published in 2010.

One of the strongest recommendations was on the use of FMTs to treat recurrent C. difficile infection after the failure of antibiotic therapy.

“Anecdotal treatment success rates of fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent CDI [C. difficile infection] have been high regardless of route of instillation of feces, and have ranged between 77% and 94% with administration via the proximal small bowel; the highest success rates (80%-100%) have been associated with instillation of feces via the colon,” they wrote.

The guidelines also addressed what the authors described as the “evolving controversy” over the best methods for diagnosis, pointing out that there is little consensus about the best laboratory testing method.

“Given these various conundrums and the paucity of large prospective studies, the recommendations, while strong in some instances, are based upon a very low to low quality of evidence,” the authors said.

That aside, they advised that patients with unexplained and new-onset diarrhea (three or more unformed stools in 24 hours) were the preferred target population for testing for C. difficile infection. The most sensitive method of diagnosis in patients with clinical symptoms likely to be C. difficile infection was a nucleic acid amplification test, or a multistep algorithm, rather than a toxin test alone.

The guidelines committee also strongly advised against repeat testing within 7 days during the same episode of diarrhea, and against testing stool from asymptomatic patients, except for the purpose of epidemiologic study. They also noted there was insufficient evidence for the use of biologic markers such as fecal lactoferrin as an adjunct to testing.

The guidelines’ authors found there was not enough evidence to recommend discontinuing proton pump inhibitors to reduce the incidence of C. difficile infection, despite epidemiologic evidence of an association between proton pump inhibitor use and C. difficile infection. Similarly, there was a lack of evidence for the use of probiotics for primary prevention, but the authors noted that meta-analyses suggest probiotics may help prevent C. difficile infection in patients on antibiotics without a history of C. difficile infection.

With respect to antibiotic treatment, they recommended that patients diagnosed with C. difficile infection should first discontinue the inciting antibiotic treatment and then begin therapy with either vancomycin or fidaxomicin. For recurrent infection, they advised a tapered and pulsed regimen of oral vancomycin or a 10-day course of fidaxomicin. If patients had received metronidazole for the primary episode, they should be given a standard 10-day course of vancomycin for recurrent infection, the authors said.

In terms of diagnosis and management of pediatric C. difficile, the guidelines advised against routinely testing infants under 2 years of age with diarrhea, as the rate of C. difficile colonization even among asymptomatic infants can be higher than 40%. Even in children older than age 2, there was only a “weak” recommendation for C. difficile testing in patients with prolonged or worsening diarrhea and other risk factors such as inflammatory bowel disease or recent antibiotic exposure.

Children with a first episode or first recurrence of nonsevere C. difficile should be treated with either metronidazole or vancomycin, the authors wrote, but in the case of more severe illness or second recurrence, oral vancomycin was preferred over metronidazole.

The authors also suggested clinicians consider FMTs for children with recurrent infection that had failed to respond to antibiotics, but noted the quality of evidence for this was very low.

The guidelines were funded by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Six authors declared grants, consultancies, board positions, and other payments from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work. One author also held patents relating to the treatment and prevention of C. difficile infection.

SOURCE: McDonald CL et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Fecal microbiota transplants should be considered for use in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection that has not responded to antibiotic therapy.

Major finding: One of the strongest recommendations in the new guidelines on C. difficile infection is to consider use of fecal microbiota transplants in patients with recurrent infection.

Data source: Clinical practice guidelines.

Disclosures: The guidelines were funded by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Six authors declared grants, consultancies, board positions, and other payments from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work. One author also held patents relating to the treatment and prevention of C. difficile infection.

Source: McDonald CL et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085.

CPR decision support videos can serve as a supplement to CPR preference discussions for inpatients

Clinical question: Does the use of a CPR decision support video impact patients’ code status preferences?

Background: Discussions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation are an important aspect of inpatient care but may be difficult to complete for several reasons, including poor patient understanding of the CPR process and its expected outcomes. This study sought to evaluate the impact of a CPR decision support video on patient CPR preferences.

Setting: General medicine wards at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs from Sept. 28, 2015, to Oct. 23, 2015.

Synopsis: One hundred and nineteen patients older than 65 were randomized to receive standard care plus viewing a CPR decision support video or standard care alone. The primary outcome was patient code status preference. Patients completed a survey assessing trust in their care team.

Among the patients who viewed the video, 37% chose full code, compared with 71% of patients in the usual care arm. Patients who viewed the video were more likely to choose DNR/DNI (56%, compared with 17% in the control group). There was no significant difference in patient trust of the care team.

Study conclusions are limited by a study population consisting predominantly of white males. Though the study was randomized, it was not blinded.

Bottom line: A CPR decision support video led to a decrease in full code preference and an increase in DNR/DNI preference among hospitalized patients.

Citation: Merino AM et al. A randomized controlled trial of a CPR decision support video for patients admitted to the general medicine service. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):700-4.

Dr. Rodriguez is a hospitalist and a clinical informatics fellow, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Clinical question: Does the use of a CPR decision support video impact patients’ code status preferences?

Background: Discussions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation are an important aspect of inpatient care but may be difficult to complete for several reasons, including poor patient understanding of the CPR process and its expected outcomes. This study sought to evaluate the impact of a CPR decision support video on patient CPR preferences.

Setting: General medicine wards at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs from Sept. 28, 2015, to Oct. 23, 2015.

Synopsis: One hundred and nineteen patients older than 65 were randomized to receive standard care plus viewing a CPR decision support video or standard care alone. The primary outcome was patient code status preference. Patients completed a survey assessing trust in their care team.

Among the patients who viewed the video, 37% chose full code, compared with 71% of patients in the usual care arm. Patients who viewed the video were more likely to choose DNR/DNI (56%, compared with 17% in the control group). There was no significant difference in patient trust of the care team.

Study conclusions are limited by a study population consisting predominantly of white males. Though the study was randomized, it was not blinded.

Bottom line: A CPR decision support video led to a decrease in full code preference and an increase in DNR/DNI preference among hospitalized patients.

Citation: Merino AM et al. A randomized controlled trial of a CPR decision support video for patients admitted to the general medicine service. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):700-4.

Dr. Rodriguez is a hospitalist and a clinical informatics fellow, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Clinical question: Does the use of a CPR decision support video impact patients’ code status preferences?

Background: Discussions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation are an important aspect of inpatient care but may be difficult to complete for several reasons, including poor patient understanding of the CPR process and its expected outcomes. This study sought to evaluate the impact of a CPR decision support video on patient CPR preferences.

Setting: General medicine wards at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs from Sept. 28, 2015, to Oct. 23, 2015.

Synopsis: One hundred and nineteen patients older than 65 were randomized to receive standard care plus viewing a CPR decision support video or standard care alone. The primary outcome was patient code status preference. Patients completed a survey assessing trust in their care team.

Among the patients who viewed the video, 37% chose full code, compared with 71% of patients in the usual care arm. Patients who viewed the video were more likely to choose DNR/DNI (56%, compared with 17% in the control group). There was no significant difference in patient trust of the care team.

Study conclusions are limited by a study population consisting predominantly of white males. Though the study was randomized, it was not blinded.

Bottom line: A CPR decision support video led to a decrease in full code preference and an increase in DNR/DNI preference among hospitalized patients.

Citation: Merino AM et al. A randomized controlled trial of a CPR decision support video for patients admitted to the general medicine service. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):700-4.

Dr. Rodriguez is a hospitalist and a clinical informatics fellow, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Consent and DNR orders

Question: Paramedics brought an unconscious 70-year-old man to a Florida hospital emergency department. The patient had the words “Do Not Resuscitate” tattooed onto his chest. No one accompanied him, and he had no identifications on his person. His blood alcohol level was elevated, and a few hours after his arrival, he lapsed into severe metabolic acidosis and hypotensive shock. The treating team decided to enter a DNR order, and the patient died shortly thereafter without benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Which of the following is best?

A. An ethics consult may suggest honoring the patient’s DNR wishes, as it is reasonable to infer that the tattoo expressed an authentic preference.

B. It has been said, but remains debatable, that tattoos might represent “permanent reminders of regretted decisions made while the person was intoxicated.”

C. An earlier case report in the literature cautioned that the tattooed expression of a DNR request did not reflect that particular patient’s current wishes.

D. If this patient’s Florida Department of Health out-of-hospital DNR order confirms his DNR preference, then it is appropriate to withhold resuscitation.

E. All are correct.

ANSWER: E. The above hypothetical situation is modified from a recent case report in the correspondence section of the New England Journal of Medicine.1 It can be read as offering a sharp and dramatic focus on the issue of consent surrounding decisions to withhold CPR.

In 1983, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine supported DNR protocols (“no code”) based on three value considerations: self-determination, well-being, and equity.2

The physician is obligated to discuss with the patient or surrogate the procedure, risks, and benefits of CPR so that an informed choice can be made. DNR means that, in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest, no CPR efforts would be undertaken. DNR orders are not exclusive to the in-hospital setting, as some states, for example, Florida and Texas, have also enacted statutes that allow such orders to be valid outside the hospital.

Critics lament that problems – many surrounding the consent issue – continue to plague DNR orders.3 Discussions are often vague, and they may not meet the threshold of informed consent requirements, because they frequently omit risks and complications. A resident, rather than the attending physician, typically performs this important task. This is compounded by ill-timed discussions and wrong assumptions about patients’ preferences, which may in fact be ignored.4

Physicians sometimes extrapolate DNR orders to limit other treatments. Or, they perform CPR in contraindicated situations such as terminal illnesses, where death is expected, which amounts to “a positive violation of an individual’s right to die with dignity.” In some situations, physicians are known to override a patient’s DNR request.

Take the operating-room conundrum. There, the immediate availability of drugs, heightened skills, and in-place procedures significantly improve survival following a cardiopulmonary arrest. Studies show a 50% survival rate, versus 8%-14% elsewhere in the hospital. A Swedish study showed that 65% of the patients who had a cardiac arrest perioperatively were successfully resuscitated. When anesthesia caused the arrest, for example, esophageal intubation, disconnection from mechanical ventilation, or prolonged exposure to high concentrations of anesthetics, the recovery rate jumped to 92%.

Terminally ill patients typically disavow CPR when choosing a palliative course of action. However, surgery can be a part of palliation. In 1991, approximately 15% of patients with DNR orders had a surgical procedure, with most interventions targeting comfort and/or nursing care. When a terminally ill patient with a DNR order undergoes surgery, how should physicians deal with the patient’s no-code status, especially if an iatrogenic cardiac arrest should occur?

Because overriding a patient’s DNR wish violates the right of self-determination, a reasonable rule is to require the surgeon and/or anesthesiologist to discuss preoperatively the increased risk of a cardiac arrest during surgery, as well as the markedly improved chance of a successful resuscitation. The patient will then decide whether to retain his/her original DNR intent, or to suspend its execution in the perioperative period.5

What about iatrogenesis?

In 1999, David Casarett, MD, and Lainie F. Ross, MD, PhD, assessed whether physicians were more likely to override a DNR order if a hypothetical cardiac arrest was caused iatrogenically.6 Their survey revealed that 69% of physicians were very likely to do so. The authors suggested three explanations: 1) concern for malpractice litigation, 2) feelings of guilt or responsibility, and 3) the belief that patients do not consider the possibility of an iatrogenic cardiac arrest when they consent to a DNR order. Physicians may also believe a “properly negotiated DNR order does not apply to all foreseeable circumstances.”

However, some ethicists believe that an iatrogenic mishap does not make it permissible to override a patient’s prior refusal of treatment, because errors should not alter ethical obligations to respect a patient’s wishes to forgo treatment, including CPR.

Can a DNR order exist if it is against a patient’s wishes?7 In Gilgunn v. Massachusetts General Hospital, a 71-year-old diabetic woman with heart disease, breast cancer, and a hip fracture suffered two grand mal seizures and lapsed into a coma.8 Her daughter was the surrogate decision maker, and she made it clear that her mother always said she wanted everything done. After several weeks, the physicians decided that further treatment would be futile.

The chair of the ethics committee felt that the daughter’s opinion was not relevant because CPR was not a genuine therapeutic option and would be “medically contraindicated, inhumane, and unethical.” Accordingly, the attending physician entered a DNR order despite strong protest from the daughter. The patient died shortly thereafter without receiving CPR, and the daughter filed a negligence lawsuit against the hospital.

Still, there are state and federal statutes touching on DNR orders that warrant careful attention. For example, New York Public Health Law Section 2962, paragraph 1, states: “Every person admitted to a hospital shall be presumed to consent to the administration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the event of cardiac or respiratory arrest, unless there is consent to the issuance of an order not to resuscitate ...” This raises the question as to whether it is ever legally permissible in New York to enter a unilateral DNR order against the wishes of the patient.

And the federal “anti-dumping” law governing emergency treatment, widely known as EMTALA (Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act), requires all emergency departments to provide treatment necessary to prevent the material deterioration of the individual’s condition. This would always include the use of CPR unless specifically rejected by the patient or surrogate, as the law does not contain a “standard of care” or “futility” exception.9

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 30;377(22):2192-3.

2. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Deciding to Forego Life-Sustaining Treatment. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1983.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Jul;26(7):791-7.

4. JAMA. 1995 Nov 22-29;274(20):1591-8.

5. Hawaii Med J. 2001 Mar;60(3):64-7.

6. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jun 26;336(26):1908-10.

7. Tan SY. Futility and DNR Orders. Internal Medicine News, March 21, 2014.

8. Gilgunn v. Mass. General Hosp. No. 92-4820 (Mass. Super Ct. Apr. 21, 1995).

9. In re Baby K, 16 F.3d 590 (4th Cir. 1994).

Question: Paramedics brought an unconscious 70-year-old man to a Florida hospital emergency department. The patient had the words “Do Not Resuscitate” tattooed onto his chest. No one accompanied him, and he had no identifications on his person. His blood alcohol level was elevated, and a few hours after his arrival, he lapsed into severe metabolic acidosis and hypotensive shock. The treating team decided to enter a DNR order, and the patient died shortly thereafter without benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Which of the following is best?

A. An ethics consult may suggest honoring the patient’s DNR wishes, as it is reasonable to infer that the tattoo expressed an authentic preference.

B. It has been said, but remains debatable, that tattoos might represent “permanent reminders of regretted decisions made while the person was intoxicated.”

C. An earlier case report in the literature cautioned that the tattooed expression of a DNR request did not reflect that particular patient’s current wishes.

D. If this patient’s Florida Department of Health out-of-hospital DNR order confirms his DNR preference, then it is appropriate to withhold resuscitation.

E. All are correct.

ANSWER: E. The above hypothetical situation is modified from a recent case report in the correspondence section of the New England Journal of Medicine.1 It can be read as offering a sharp and dramatic focus on the issue of consent surrounding decisions to withhold CPR.

In 1983, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine supported DNR protocols (“no code”) based on three value considerations: self-determination, well-being, and equity.2

The physician is obligated to discuss with the patient or surrogate the procedure, risks, and benefits of CPR so that an informed choice can be made. DNR means that, in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest, no CPR efforts would be undertaken. DNR orders are not exclusive to the in-hospital setting, as some states, for example, Florida and Texas, have also enacted statutes that allow such orders to be valid outside the hospital.

Critics lament that problems – many surrounding the consent issue – continue to plague DNR orders.3 Discussions are often vague, and they may not meet the threshold of informed consent requirements, because they frequently omit risks and complications. A resident, rather than the attending physician, typically performs this important task. This is compounded by ill-timed discussions and wrong assumptions about patients’ preferences, which may in fact be ignored.4

Physicians sometimes extrapolate DNR orders to limit other treatments. Or, they perform CPR in contraindicated situations such as terminal illnesses, where death is expected, which amounts to “a positive violation of an individual’s right to die with dignity.” In some situations, physicians are known to override a patient’s DNR request.

Take the operating-room conundrum. There, the immediate availability of drugs, heightened skills, and in-place procedures significantly improve survival following a cardiopulmonary arrest. Studies show a 50% survival rate, versus 8%-14% elsewhere in the hospital. A Swedish study showed that 65% of the patients who had a cardiac arrest perioperatively were successfully resuscitated. When anesthesia caused the arrest, for example, esophageal intubation, disconnection from mechanical ventilation, or prolonged exposure to high concentrations of anesthetics, the recovery rate jumped to 92%.

Terminally ill patients typically disavow CPR when choosing a palliative course of action. However, surgery can be a part of palliation. In 1991, approximately 15% of patients with DNR orders had a surgical procedure, with most interventions targeting comfort and/or nursing care. When a terminally ill patient with a DNR order undergoes surgery, how should physicians deal with the patient’s no-code status, especially if an iatrogenic cardiac arrest should occur?

Because overriding a patient’s DNR wish violates the right of self-determination, a reasonable rule is to require the surgeon and/or anesthesiologist to discuss preoperatively the increased risk of a cardiac arrest during surgery, as well as the markedly improved chance of a successful resuscitation. The patient will then decide whether to retain his/her original DNR intent, or to suspend its execution in the perioperative period.5

What about iatrogenesis?

In 1999, David Casarett, MD, and Lainie F. Ross, MD, PhD, assessed whether physicians were more likely to override a DNR order if a hypothetical cardiac arrest was caused iatrogenically.6 Their survey revealed that 69% of physicians were very likely to do so. The authors suggested three explanations: 1) concern for malpractice litigation, 2) feelings of guilt or responsibility, and 3) the belief that patients do not consider the possibility of an iatrogenic cardiac arrest when they consent to a DNR order. Physicians may also believe a “properly negotiated DNR order does not apply to all foreseeable circumstances.”

However, some ethicists believe that an iatrogenic mishap does not make it permissible to override a patient’s prior refusal of treatment, because errors should not alter ethical obligations to respect a patient’s wishes to forgo treatment, including CPR.

Can a DNR order exist if it is against a patient’s wishes?7 In Gilgunn v. Massachusetts General Hospital, a 71-year-old diabetic woman with heart disease, breast cancer, and a hip fracture suffered two grand mal seizures and lapsed into a coma.8 Her daughter was the surrogate decision maker, and she made it clear that her mother always said she wanted everything done. After several weeks, the physicians decided that further treatment would be futile.

The chair of the ethics committee felt that the daughter’s opinion was not relevant because CPR was not a genuine therapeutic option and would be “medically contraindicated, inhumane, and unethical.” Accordingly, the attending physician entered a DNR order despite strong protest from the daughter. The patient died shortly thereafter without receiving CPR, and the daughter filed a negligence lawsuit against the hospital.

Still, there are state and federal statutes touching on DNR orders that warrant careful attention. For example, New York Public Health Law Section 2962, paragraph 1, states: “Every person admitted to a hospital shall be presumed to consent to the administration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the event of cardiac or respiratory arrest, unless there is consent to the issuance of an order not to resuscitate ...” This raises the question as to whether it is ever legally permissible in New York to enter a unilateral DNR order against the wishes of the patient.

And the federal “anti-dumping” law governing emergency treatment, widely known as EMTALA (Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act), requires all emergency departments to provide treatment necessary to prevent the material deterioration of the individual’s condition. This would always include the use of CPR unless specifically rejected by the patient or surrogate, as the law does not contain a “standard of care” or “futility” exception.9

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 30;377(22):2192-3.

2. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Deciding to Forego Life-Sustaining Treatment. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1983.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Jul;26(7):791-7.

4. JAMA. 1995 Nov 22-29;274(20):1591-8.

5. Hawaii Med J. 2001 Mar;60(3):64-7.

6. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jun 26;336(26):1908-10.

7. Tan SY. Futility and DNR Orders. Internal Medicine News, March 21, 2014.

8. Gilgunn v. Mass. General Hosp. No. 92-4820 (Mass. Super Ct. Apr. 21, 1995).

9. In re Baby K, 16 F.3d 590 (4th Cir. 1994).

Question: Paramedics brought an unconscious 70-year-old man to a Florida hospital emergency department. The patient had the words “Do Not Resuscitate” tattooed onto his chest. No one accompanied him, and he had no identifications on his person. His blood alcohol level was elevated, and a few hours after his arrival, he lapsed into severe metabolic acidosis and hypotensive shock. The treating team decided to enter a DNR order, and the patient died shortly thereafter without benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Which of the following is best?

A. An ethics consult may suggest honoring the patient’s DNR wishes, as it is reasonable to infer that the tattoo expressed an authentic preference.

B. It has been said, but remains debatable, that tattoos might represent “permanent reminders of regretted decisions made while the person was intoxicated.”

C. An earlier case report in the literature cautioned that the tattooed expression of a DNR request did not reflect that particular patient’s current wishes.

D. If this patient’s Florida Department of Health out-of-hospital DNR order confirms his DNR preference, then it is appropriate to withhold resuscitation.

E. All are correct.

ANSWER: E. The above hypothetical situation is modified from a recent case report in the correspondence section of the New England Journal of Medicine.1 It can be read as offering a sharp and dramatic focus on the issue of consent surrounding decisions to withhold CPR.

In 1983, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine supported DNR protocols (“no code”) based on three value considerations: self-determination, well-being, and equity.2

The physician is obligated to discuss with the patient or surrogate the procedure, risks, and benefits of CPR so that an informed choice can be made. DNR means that, in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest, no CPR efforts would be undertaken. DNR orders are not exclusive to the in-hospital setting, as some states, for example, Florida and Texas, have also enacted statutes that allow such orders to be valid outside the hospital.

Critics lament that problems – many surrounding the consent issue – continue to plague DNR orders.3 Discussions are often vague, and they may not meet the threshold of informed consent requirements, because they frequently omit risks and complications. A resident, rather than the attending physician, typically performs this important task. This is compounded by ill-timed discussions and wrong assumptions about patients’ preferences, which may in fact be ignored.4

Physicians sometimes extrapolate DNR orders to limit other treatments. Or, they perform CPR in contraindicated situations such as terminal illnesses, where death is expected, which amounts to “a positive violation of an individual’s right to die with dignity.” In some situations, physicians are known to override a patient’s DNR request.

Take the operating-room conundrum. There, the immediate availability of drugs, heightened skills, and in-place procedures significantly improve survival following a cardiopulmonary arrest. Studies show a 50% survival rate, versus 8%-14% elsewhere in the hospital. A Swedish study showed that 65% of the patients who had a cardiac arrest perioperatively were successfully resuscitated. When anesthesia caused the arrest, for example, esophageal intubation, disconnection from mechanical ventilation, or prolonged exposure to high concentrations of anesthetics, the recovery rate jumped to 92%.

Terminally ill patients typically disavow CPR when choosing a palliative course of action. However, surgery can be a part of palliation. In 1991, approximately 15% of patients with DNR orders had a surgical procedure, with most interventions targeting comfort and/or nursing care. When a terminally ill patient with a DNR order undergoes surgery, how should physicians deal with the patient’s no-code status, especially if an iatrogenic cardiac arrest should occur?

Because overriding a patient’s DNR wish violates the right of self-determination, a reasonable rule is to require the surgeon and/or anesthesiologist to discuss preoperatively the increased risk of a cardiac arrest during surgery, as well as the markedly improved chance of a successful resuscitation. The patient will then decide whether to retain his/her original DNR intent, or to suspend its execution in the perioperative period.5

What about iatrogenesis?

In 1999, David Casarett, MD, and Lainie F. Ross, MD, PhD, assessed whether physicians were more likely to override a DNR order if a hypothetical cardiac arrest was caused iatrogenically.6 Their survey revealed that 69% of physicians were very likely to do so. The authors suggested three explanations: 1) concern for malpractice litigation, 2) feelings of guilt or responsibility, and 3) the belief that patients do not consider the possibility of an iatrogenic cardiac arrest when they consent to a DNR order. Physicians may also believe a “properly negotiated DNR order does not apply to all foreseeable circumstances.”

However, some ethicists believe that an iatrogenic mishap does not make it permissible to override a patient’s prior refusal of treatment, because errors should not alter ethical obligations to respect a patient’s wishes to forgo treatment, including CPR.

Can a DNR order exist if it is against a patient’s wishes?7 In Gilgunn v. Massachusetts General Hospital, a 71-year-old diabetic woman with heart disease, breast cancer, and a hip fracture suffered two grand mal seizures and lapsed into a coma.8 Her daughter was the surrogate decision maker, and she made it clear that her mother always said she wanted everything done. After several weeks, the physicians decided that further treatment would be futile.

The chair of the ethics committee felt that the daughter’s opinion was not relevant because CPR was not a genuine therapeutic option and would be “medically contraindicated, inhumane, and unethical.” Accordingly, the attending physician entered a DNR order despite strong protest from the daughter. The patient died shortly thereafter without receiving CPR, and the daughter filed a negligence lawsuit against the hospital.

Still, there are state and federal statutes touching on DNR orders that warrant careful attention. For example, New York Public Health Law Section 2962, paragraph 1, states: “Every person admitted to a hospital shall be presumed to consent to the administration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the event of cardiac or respiratory arrest, unless there is consent to the issuance of an order not to resuscitate ...” This raises the question as to whether it is ever legally permissible in New York to enter a unilateral DNR order against the wishes of the patient.

And the federal “anti-dumping” law governing emergency treatment, widely known as EMTALA (Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act), requires all emergency departments to provide treatment necessary to prevent the material deterioration of the individual’s condition. This would always include the use of CPR unless specifically rejected by the patient or surrogate, as the law does not contain a “standard of care” or “futility” exception.9

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 30;377(22):2192-3.

2. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Deciding to Forego Life-Sustaining Treatment. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1983.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Jul;26(7):791-7.

4. JAMA. 1995 Nov 22-29;274(20):1591-8.

5. Hawaii Med J. 2001 Mar;60(3):64-7.

6. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jun 26;336(26):1908-10.

7. Tan SY. Futility and DNR Orders. Internal Medicine News, March 21, 2014.

8. Gilgunn v. Mass. General Hosp. No. 92-4820 (Mass. Super Ct. Apr. 21, 1995).

9. In re Baby K, 16 F.3d 590 (4th Cir. 1994).

Radiation exposure in MICU may exceed recommended limit

according to results of a recent observational study.

These “substantial” radiation doses in some patients suggest that efforts are warranted to “justify, restrict and optimize” the use of radiological resources when possible, said Sudhir Krishnan, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and his coauthors.

The retrospective, observational study included 4,155 adult admissions to a medical intensive care unit (MICU) at an academic medical center in 2013. Investigators calculated the cumulative effective dose (CED) of radiation based on reported ionizing radiological studies for each patient.

With a median length of stay of just 6.4 days, a total of 131 admissions (3%) accrued a CED of radiation of at least 50 millisieverts (mSv), the annual limit recommended by the National Commission on Radiation Protection, and 47 of those patients (1%) accrued a CED of radiation of at least 100 mSv, the 5-year cumulative exposure limit, the authors reported.

These findings suggest that “MICU patients could be subjected to radiation doses in a matter of days that are equivalent to or more than [the] CED observed in patients with chronic diseases and patients with trauma,” wrote Dr. Krishnan and his coauthors.

As hypothesized, patients with higher severity of illness scores (APACHE III scores) received a higher CED of radiation, according to the report. Using a multivariable linear regression model, investigators found that higher CED was predicted by higher APACHE III scores, sepsis, longer MICU stay, and gastrointestinal disorders and bleeding.

CT scans were the most common source of radiation exposure in patients who exceeded a 50 mSv of radiation, accounting for 49% of the total accrued dose, with interventional radiology accounting for 38%, authors reported.

Despite concerns about “the statistical risk of latent radiogenic cancer,” radiologic studies performed in the critically ill have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality, the authors acknowledged in a discussion of the results.

“This understandably shifts the risk-benefit ratio towards radiation exposure,” the researchers wrote. “However, complacency in this regard cannot be entirely justified.”

Of the patients in the study who were exposed to a CED of at least 50 mSv, 81% survived the hospital admission and could be subjected to even more radiation as a part of ongoing medical care, they noted.

“Robust tools for monitoring CED prospectively per episode of clinical care, counseling patients exposed to high doses of radiation, and prospective studies exploring radiogenic risk associated with medical radiation are urgently required,” the authors said.

Dr. Krishnan and his coauthors reported no significant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Krishnan S et al. Chest. 2018 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.019.

according to results of a recent observational study.

These “substantial” radiation doses in some patients suggest that efforts are warranted to “justify, restrict and optimize” the use of radiological resources when possible, said Sudhir Krishnan, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and his coauthors.

The retrospective, observational study included 4,155 adult admissions to a medical intensive care unit (MICU) at an academic medical center in 2013. Investigators calculated the cumulative effective dose (CED) of radiation based on reported ionizing radiological studies for each patient.

With a median length of stay of just 6.4 days, a total of 131 admissions (3%) accrued a CED of radiation of at least 50 millisieverts (mSv), the annual limit recommended by the National Commission on Radiation Protection, and 47 of those patients (1%) accrued a CED of radiation of at least 100 mSv, the 5-year cumulative exposure limit, the authors reported.

These findings suggest that “MICU patients could be subjected to radiation doses in a matter of days that are equivalent to or more than [the] CED observed in patients with chronic diseases and patients with trauma,” wrote Dr. Krishnan and his coauthors.

As hypothesized, patients with higher severity of illness scores (APACHE III scores) received a higher CED of radiation, according to the report. Using a multivariable linear regression model, investigators found that higher CED was predicted by higher APACHE III scores, sepsis, longer MICU stay, and gastrointestinal disorders and bleeding.

CT scans were the most common source of radiation exposure in patients who exceeded a 50 mSv of radiation, accounting for 49% of the total accrued dose, with interventional radiology accounting for 38%, authors reported.

Despite concerns about “the statistical risk of latent radiogenic cancer,” radiologic studies performed in the critically ill have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality, the authors acknowledged in a discussion of the results.

“This understandably shifts the risk-benefit ratio towards radiation exposure,” the researchers wrote. “However, complacency in this regard cannot be entirely justified.”

Of the patients in the study who were exposed to a CED of at least 50 mSv, 81% survived the hospital admission and could be subjected to even more radiation as a part of ongoing medical care, they noted.

“Robust tools for monitoring CED prospectively per episode of clinical care, counseling patients exposed to high doses of radiation, and prospective studies exploring radiogenic risk associated with medical radiation are urgently required,” the authors said.

Dr. Krishnan and his coauthors reported no significant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Krishnan S et al. Chest. 2018 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.019.

according to results of a recent observational study.

These “substantial” radiation doses in some patients suggest that efforts are warranted to “justify, restrict and optimize” the use of radiological resources when possible, said Sudhir Krishnan, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and his coauthors.

The retrospective, observational study included 4,155 adult admissions to a medical intensive care unit (MICU) at an academic medical center in 2013. Investigators calculated the cumulative effective dose (CED) of radiation based on reported ionizing radiological studies for each patient.

With a median length of stay of just 6.4 days, a total of 131 admissions (3%) accrued a CED of radiation of at least 50 millisieverts (mSv), the annual limit recommended by the National Commission on Radiation Protection, and 47 of those patients (1%) accrued a CED of radiation of at least 100 mSv, the 5-year cumulative exposure limit, the authors reported.

These findings suggest that “MICU patients could be subjected to radiation doses in a matter of days that are equivalent to or more than [the] CED observed in patients with chronic diseases and patients with trauma,” wrote Dr. Krishnan and his coauthors.

As hypothesized, patients with higher severity of illness scores (APACHE III scores) received a higher CED of radiation, according to the report. Using a multivariable linear regression model, investigators found that higher CED was predicted by higher APACHE III scores, sepsis, longer MICU stay, and gastrointestinal disorders and bleeding.

CT scans were the most common source of radiation exposure in patients who exceeded a 50 mSv of radiation, accounting for 49% of the total accrued dose, with interventional radiology accounting for 38%, authors reported.

Despite concerns about “the statistical risk of latent radiogenic cancer,” radiologic studies performed in the critically ill have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality, the authors acknowledged in a discussion of the results.

“This understandably shifts the risk-benefit ratio towards radiation exposure,” the researchers wrote. “However, complacency in this regard cannot be entirely justified.”

Of the patients in the study who were exposed to a CED of at least 50 mSv, 81% survived the hospital admission and could be subjected to even more radiation as a part of ongoing medical care, they noted.

“Robust tools for monitoring CED prospectively per episode of clinical care, counseling patients exposed to high doses of radiation, and prospective studies exploring radiogenic risk associated with medical radiation are urgently required,” the authors said.

Dr. Krishnan and his coauthors reported no significant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Krishnan S et al. Chest. 2018 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.019.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Patients admitted to MICUs may be exposed to doses of radiation that are substantial and may exceed federal occupational health limits.

Major finding: In a short span of time (median 6.4 days length of stay), 3% of MICU patients received a cumulative dose of radiation that exceeded the U.S. recommended limit, and 1% accrued enough exposure to exceed the 5-year cumulative limit.

Data source: A retrospective, observational study including 4,155 adult admissions to the MICU at an academic medical center in 2013.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no significant conflicts of interest.

Source: Krishnan S et al. Chest. 2018 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.019.

Evidence-based care processes decrease mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia

Clinical questions: What are the trends in patient outcome for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB)? Does the use of evidence-based care processes decrease mortality in SAB?

Background: SAB is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Prior research has demonstrated that several evidence-based interventions, namely appropriate antibiotics, echocardiography, and infectious disease consults, have been associated with improved outcomes. The use of these interventions in clinical practice and their large-scale impact on SAB mortality is not known.

Setting: Veterans Health Administration acute care hospitals in the continental United States from January 1, 2003, to Dec. 31, 2014.

Synopsis: This study used the Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure to identify 36,868 patients across 124 acute care hospitals with a first episode of SAB. Use of evidence-based care processes (specifically appropriate antibiotic use, echocardiography, and infectious disease consults) and patient mortality were recorded.

All-cause 30-day mortality decreased 25.7% in 2003 to 16.5% in 2014. Concurrently, the rate of evidence-based care processes increased from 2003 to 2014. There was lower risk-adjusted mortality when patients received all three evidence-based care processes compared to those who received none, with an odds ratio of 0.33 (95% confidence interval, 0.30-0.37); 57.3% of the decrease in mortality was attributable to use of all three evidence-based care processes.

Given the observational nature of the study, unmeasured confounders were not considered. Generalizability of the study is limited since the patients were primarily men.

Bottom line: The use of evidence-based care processes (appropriate antibiotic use, echocardiography, and infectious disease consultation) was associated with decreased SAB mortality.

Citation: Goto M et al. Association of evidence-based care processes with mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia at Veterans Health Administration hospitals, 2003-2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1489-97.

Dr. Rodriguez is a hospitalist and a clinical informatics fellow, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Clinical questions: What are the trends in patient outcome for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB)? Does the use of evidence-based care processes decrease mortality in SAB?

Background: SAB is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Prior research has demonstrated that several evidence-based interventions, namely appropriate antibiotics, echocardiography, and infectious disease consults, have been associated with improved outcomes. The use of these interventions in clinical practice and their large-scale impact on SAB mortality is not known.

Setting: Veterans Health Administration acute care hospitals in the continental United States from January 1, 2003, to Dec. 31, 2014.

Synopsis: This study used the Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure to identify 36,868 patients across 124 acute care hospitals with a first episode of SAB. Use of evidence-based care processes (specifically appropriate antibiotic use, echocardiography, and infectious disease consults) and patient mortality were recorded.

All-cause 30-day mortality decreased 25.7% in 2003 to 16.5% in 2014. Concurrently, the rate of evidence-based care processes increased from 2003 to 2014. There was lower risk-adjusted mortality when patients received all three evidence-based care processes compared to those who received none, with an odds ratio of 0.33 (95% confidence interval, 0.30-0.37); 57.3% of the decrease in mortality was attributable to use of all three evidence-based care processes.

Given the observational nature of the study, unmeasured confounders were not considered. Generalizability of the study is limited since the patients were primarily men.

Bottom line: The use of evidence-based care processes (appropriate antibiotic use, echocardiography, and infectious disease consultation) was associated with decreased SAB mortality.

Citation: Goto M et al. Association of evidence-based care processes with mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia at Veterans Health Administration hospitals, 2003-2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1489-97.

Dr. Rodriguez is a hospitalist and a clinical informatics fellow, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Clinical questions: What are the trends in patient outcome for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB)? Does the use of evidence-based care processes decrease mortality in SAB?

Background: SAB is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Prior research has demonstrated that several evidence-based interventions, namely appropriate antibiotics, echocardiography, and infectious disease consults, have been associated with improved outcomes. The use of these interventions in clinical practice and their large-scale impact on SAB mortality is not known.

Setting: Veterans Health Administration acute care hospitals in the continental United States from January 1, 2003, to Dec. 31, 2014.

Synopsis: This study used the Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure to identify 36,868 patients across 124 acute care hospitals with a first episode of SAB. Use of evidence-based care processes (specifically appropriate antibiotic use, echocardiography, and infectious disease consults) and patient mortality were recorded.