User login

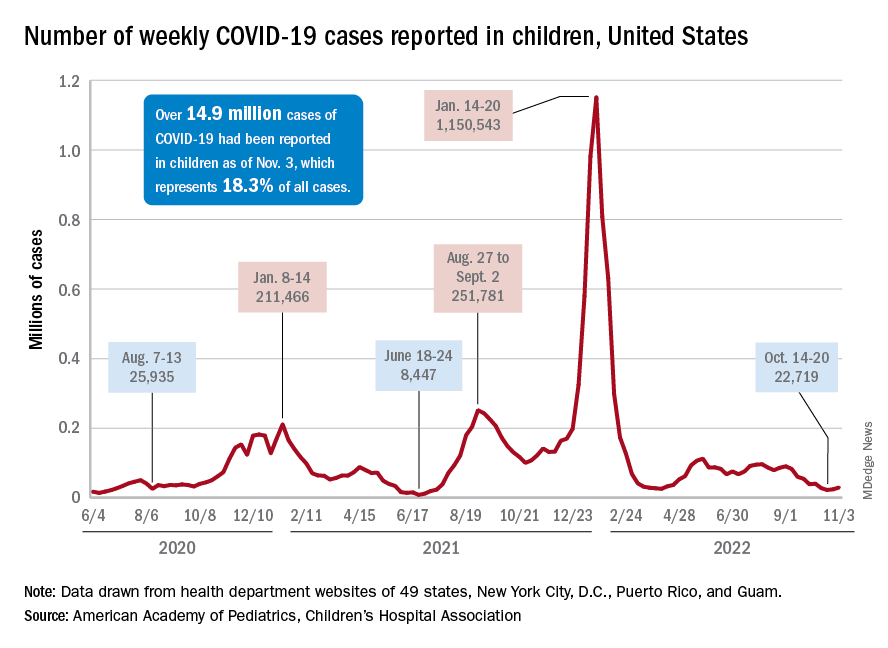

In Case You Missed It: COVID

Love them or hate them, masks in schools work

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The body of evidence for Paxlovid therapy

Dear Colleagues,

We have a mismatch. The evidence supporting treatment for Paxlovid is compelling for people aged 60 or over, but the older patients in the United States are much less likely to be treated. Not only was there a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of high-risk patients which showed 89% reduction of hospitalizations and deaths (median age, 45), but there have been multiple real-world effectiveness studies subsequently published that have partitioned the benefit for age 65 or older, such as the ones from Israel and Hong Kong (age 60+). Overall, the real-world effectiveness in the first month after treatment is at least as good, if not better, than in the high-risk randomized trial.

We’re doing the current survey to find out, but the most likely reasons include (1) lack of confidence of benefit; (2) medication interactions; and (3) concerns over rebound.

Let me address each of these briefly. The lack of confidence in benefit stems from the fact that the initial high-risk trial was in unvaccinated individuals. That concern can now be put aside because all of the several real-world studies confirming the protective benefit against hospitalizations and deaths are in people who have been vaccinated, and a significant proportion received booster shots.

The potential medication interactions due to the ritonavir component of the Paxlovid drug combination, attributable to its cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition, have been unduly emphasized. There are many drug-interaction checkers for Paxlovid, but this one from the University of Liverpool is user friendly, color- and icon-coded, and shows that the vast majority of interactions can be sidestepped by discontinuing the medication of concern for the length of the Paxlovid treatment, 5 days. The simple chart is provided in my recent substack newsletter.

As far as rebound, this problem has unfortunately been exaggerated because of lack of prospective systematic studies and appreciation that a positive test of clinical symptom rebound can occur without Paxlovid. There are soon to be multiple reports that the incidence of Paxlovid rebound is fairly low, in the range of 10%. That concern should not be a reason to withhold treatment.

Now the plot thickens. A new preprint report from the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the United States, looks at 90-day outcomes of about 9,000 Paxlovid-treated patients and approximately 47,000 controls. Not only was there a 26% reduction in long COVID, but of the breakdown of 12 organs/systems and symptoms, 10 of 12 were significantly reduced with Paxlovid, including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and neurocognitive impairment. There was also a 48% reduction in death and a 30% reduction in hospitalizations after the first 30 days. I have reviewed all of these data and put them in context in a recent newsletter. A key point is that the magnitude of benefit was unaffected by vaccination or booster status, or prior COVID infections, or unvaccinated status. Also, it was the same for men and women, as well as for age > 70 and age < 60. These findings all emphasize a new reason to be using Paxlovid therapy, and if replicated, Paxlovid may even be indicated for younger patients (who are at low risk for hospitalizations and deaths but at increased risk for long COVID).

In summary, for older patients, we should be thinking of why we should be using Paxlovid rather than the reason not to treat. We’ll be interested in the survey results to understand the mismatch better, and we look forward to your ideas and feedback to make better use of this treatment for the people who need it the most.

Sincerely yours, Eric J. Topol, MD

Dr. Topol reports no conflicts of interest with Pfizer; he receives no honoraria or speaker fees, does not serve in an advisory role, and has no financial association with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dear Colleagues,

We have a mismatch. The evidence supporting treatment for Paxlovid is compelling for people aged 60 or over, but the older patients in the United States are much less likely to be treated. Not only was there a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of high-risk patients which showed 89% reduction of hospitalizations and deaths (median age, 45), but there have been multiple real-world effectiveness studies subsequently published that have partitioned the benefit for age 65 or older, such as the ones from Israel and Hong Kong (age 60+). Overall, the real-world effectiveness in the first month after treatment is at least as good, if not better, than in the high-risk randomized trial.

We’re doing the current survey to find out, but the most likely reasons include (1) lack of confidence of benefit; (2) medication interactions; and (3) concerns over rebound.

Let me address each of these briefly. The lack of confidence in benefit stems from the fact that the initial high-risk trial was in unvaccinated individuals. That concern can now be put aside because all of the several real-world studies confirming the protective benefit against hospitalizations and deaths are in people who have been vaccinated, and a significant proportion received booster shots.

The potential medication interactions due to the ritonavir component of the Paxlovid drug combination, attributable to its cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition, have been unduly emphasized. There are many drug-interaction checkers for Paxlovid, but this one from the University of Liverpool is user friendly, color- and icon-coded, and shows that the vast majority of interactions can be sidestepped by discontinuing the medication of concern for the length of the Paxlovid treatment, 5 days. The simple chart is provided in my recent substack newsletter.

As far as rebound, this problem has unfortunately been exaggerated because of lack of prospective systematic studies and appreciation that a positive test of clinical symptom rebound can occur without Paxlovid. There are soon to be multiple reports that the incidence of Paxlovid rebound is fairly low, in the range of 10%. That concern should not be a reason to withhold treatment.

Now the plot thickens. A new preprint report from the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the United States, looks at 90-day outcomes of about 9,000 Paxlovid-treated patients and approximately 47,000 controls. Not only was there a 26% reduction in long COVID, but of the breakdown of 12 organs/systems and symptoms, 10 of 12 were significantly reduced with Paxlovid, including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and neurocognitive impairment. There was also a 48% reduction in death and a 30% reduction in hospitalizations after the first 30 days. I have reviewed all of these data and put them in context in a recent newsletter. A key point is that the magnitude of benefit was unaffected by vaccination or booster status, or prior COVID infections, or unvaccinated status. Also, it was the same for men and women, as well as for age > 70 and age < 60. These findings all emphasize a new reason to be using Paxlovid therapy, and if replicated, Paxlovid may even be indicated for younger patients (who are at low risk for hospitalizations and deaths but at increased risk for long COVID).

In summary, for older patients, we should be thinking of why we should be using Paxlovid rather than the reason not to treat. We’ll be interested in the survey results to understand the mismatch better, and we look forward to your ideas and feedback to make better use of this treatment for the people who need it the most.

Sincerely yours, Eric J. Topol, MD

Dr. Topol reports no conflicts of interest with Pfizer; he receives no honoraria or speaker fees, does not serve in an advisory role, and has no financial association with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dear Colleagues,

We have a mismatch. The evidence supporting treatment for Paxlovid is compelling for people aged 60 or over, but the older patients in the United States are much less likely to be treated. Not only was there a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of high-risk patients which showed 89% reduction of hospitalizations and deaths (median age, 45), but there have been multiple real-world effectiveness studies subsequently published that have partitioned the benefit for age 65 or older, such as the ones from Israel and Hong Kong (age 60+). Overall, the real-world effectiveness in the first month after treatment is at least as good, if not better, than in the high-risk randomized trial.

We’re doing the current survey to find out, but the most likely reasons include (1) lack of confidence of benefit; (2) medication interactions; and (3) concerns over rebound.

Let me address each of these briefly. The lack of confidence in benefit stems from the fact that the initial high-risk trial was in unvaccinated individuals. That concern can now be put aside because all of the several real-world studies confirming the protective benefit against hospitalizations and deaths are in people who have been vaccinated, and a significant proportion received booster shots.

The potential medication interactions due to the ritonavir component of the Paxlovid drug combination, attributable to its cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition, have been unduly emphasized. There are many drug-interaction checkers for Paxlovid, but this one from the University of Liverpool is user friendly, color- and icon-coded, and shows that the vast majority of interactions can be sidestepped by discontinuing the medication of concern for the length of the Paxlovid treatment, 5 days. The simple chart is provided in my recent substack newsletter.

As far as rebound, this problem has unfortunately been exaggerated because of lack of prospective systematic studies and appreciation that a positive test of clinical symptom rebound can occur without Paxlovid. There are soon to be multiple reports that the incidence of Paxlovid rebound is fairly low, in the range of 10%. That concern should not be a reason to withhold treatment.

Now the plot thickens. A new preprint report from the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the United States, looks at 90-day outcomes of about 9,000 Paxlovid-treated patients and approximately 47,000 controls. Not only was there a 26% reduction in long COVID, but of the breakdown of 12 organs/systems and symptoms, 10 of 12 were significantly reduced with Paxlovid, including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and neurocognitive impairment. There was also a 48% reduction in death and a 30% reduction in hospitalizations after the first 30 days. I have reviewed all of these data and put them in context in a recent newsletter. A key point is that the magnitude of benefit was unaffected by vaccination or booster status, or prior COVID infections, or unvaccinated status. Also, it was the same for men and women, as well as for age > 70 and age < 60. These findings all emphasize a new reason to be using Paxlovid therapy, and if replicated, Paxlovid may even be indicated for younger patients (who are at low risk for hospitalizations and deaths but at increased risk for long COVID).

In summary, for older patients, we should be thinking of why we should be using Paxlovid rather than the reason not to treat. We’ll be interested in the survey results to understand the mismatch better, and we look forward to your ideas and feedback to make better use of this treatment for the people who need it the most.

Sincerely yours, Eric J. Topol, MD

Dr. Topol reports no conflicts of interest with Pfizer; he receives no honoraria or speaker fees, does not serve in an advisory role, and has no financial association with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat COVID infection doubles mortality risk

Getting COVID-19 a second time doubles a person’s chance of dying and triples the likelihood of being hospitalized in the next 6 months, a new study found.

Vaccination and booster status did not improve survival or hospitalization rates among people who were infected more than once.

“Reinfection with COVID-19 increases the risk of both acute outcomes and long COVID,” study author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, told Reuters. “This was evident in unvaccinated, vaccinated and boosted people.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs data, including 443,588 people with a first infection of SARS-CoV-2, 40,947 people who were infected two or more times, and 5.3 million people who had not been infected with coronavirus, whose data served as the control group.

“During the past few months, there’s been an air of invincibility among people who have had COVID-19 or their vaccinations and boosters, and especially among people who have had an infection and also received vaccines; some people started to [refer] to these individuals as having a sort of superimmunity to the virus,” Dr. Al-Aly said in a press release from Washington University in St. Louis. “Without ambiguity, our research showed that getting an infection a second, third or fourth time contributes to additional health risks in the acute phase, meaning the first 30 days after infection, and in the months beyond, meaning the long COVID phase.”

Being infected with COVID-19 more than once also dramatically increased the risk of developing lung problems, heart conditions, or brain conditions. The heightened risks persisted for 6 months.

Researchers said a limitation of their study was that data primarily came from White males.

An expert not involved in the study told Reuters that the Veterans Affairs population does not reflect the general population. Patients at VA health facilities are generally older with more than normal health complications, said John Moore, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Dr. Al-Aly encouraged people to be vigilant as they plan for the holiday season, Reuters reported.

“We had started seeing a lot of patients coming to the clinic with an air of invincibility,” he told Reuters. “They wondered, ‘Does getting a reinfection really matter?’ The answer is yes, it absolutely does.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Getting COVID-19 a second time doubles a person’s chance of dying and triples the likelihood of being hospitalized in the next 6 months, a new study found.

Vaccination and booster status did not improve survival or hospitalization rates among people who were infected more than once.

“Reinfection with COVID-19 increases the risk of both acute outcomes and long COVID,” study author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, told Reuters. “This was evident in unvaccinated, vaccinated and boosted people.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs data, including 443,588 people with a first infection of SARS-CoV-2, 40,947 people who were infected two or more times, and 5.3 million people who had not been infected with coronavirus, whose data served as the control group.

“During the past few months, there’s been an air of invincibility among people who have had COVID-19 or their vaccinations and boosters, and especially among people who have had an infection and also received vaccines; some people started to [refer] to these individuals as having a sort of superimmunity to the virus,” Dr. Al-Aly said in a press release from Washington University in St. Louis. “Without ambiguity, our research showed that getting an infection a second, third or fourth time contributes to additional health risks in the acute phase, meaning the first 30 days after infection, and in the months beyond, meaning the long COVID phase.”

Being infected with COVID-19 more than once also dramatically increased the risk of developing lung problems, heart conditions, or brain conditions. The heightened risks persisted for 6 months.

Researchers said a limitation of their study was that data primarily came from White males.

An expert not involved in the study told Reuters that the Veterans Affairs population does not reflect the general population. Patients at VA health facilities are generally older with more than normal health complications, said John Moore, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Dr. Al-Aly encouraged people to be vigilant as they plan for the holiday season, Reuters reported.

“We had started seeing a lot of patients coming to the clinic with an air of invincibility,” he told Reuters. “They wondered, ‘Does getting a reinfection really matter?’ The answer is yes, it absolutely does.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Getting COVID-19 a second time doubles a person’s chance of dying and triples the likelihood of being hospitalized in the next 6 months, a new study found.

Vaccination and booster status did not improve survival or hospitalization rates among people who were infected more than once.

“Reinfection with COVID-19 increases the risk of both acute outcomes and long COVID,” study author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, told Reuters. “This was evident in unvaccinated, vaccinated and boosted people.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs data, including 443,588 people with a first infection of SARS-CoV-2, 40,947 people who were infected two or more times, and 5.3 million people who had not been infected with coronavirus, whose data served as the control group.

“During the past few months, there’s been an air of invincibility among people who have had COVID-19 or their vaccinations and boosters, and especially among people who have had an infection and also received vaccines; some people started to [refer] to these individuals as having a sort of superimmunity to the virus,” Dr. Al-Aly said in a press release from Washington University in St. Louis. “Without ambiguity, our research showed that getting an infection a second, third or fourth time contributes to additional health risks in the acute phase, meaning the first 30 days after infection, and in the months beyond, meaning the long COVID phase.”

Being infected with COVID-19 more than once also dramatically increased the risk of developing lung problems, heart conditions, or brain conditions. The heightened risks persisted for 6 months.

Researchers said a limitation of their study was that data primarily came from White males.

An expert not involved in the study told Reuters that the Veterans Affairs population does not reflect the general population. Patients at VA health facilities are generally older with more than normal health complications, said John Moore, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Dr. Al-Aly encouraged people to be vigilant as they plan for the holiday season, Reuters reported.

“We had started seeing a lot of patients coming to the clinic with an air of invincibility,” he told Reuters. “They wondered, ‘Does getting a reinfection really matter?’ The answer is yes, it absolutely does.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Third COVID booster benefits cancer patients

though this population still suffers higher risks than those of the general population, according to a new large-scale observational study out of the United Kingdom.

People living with lymphoma and those who underwent recent systemic anti-cancer treatment or radiotherapy are at the highest risk, according to study author Lennard Y.W. Lee, PhD. “Our study is the largest evaluation of a coronavirus third dose vaccine booster effectiveness in people living with cancer in the world. For the first time we have quantified the benefits of boosters for COVID-19 in cancer patients,” said Dr. Lee, UK COVID Cancer program lead and a medical oncologist at the University of Oxford, England.

The research was published in the November issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

Despite the encouraging numbers, those with cancer continue to have a more than threefold increased risk of both hospitalization and death from coronavirus compared to the general population. “More needs to be done to reduce this excess risk, like prophylactic antibody therapies,” Dr. Lee said.

Third dose efficacy was lower among cancer patients who had been diagnosed within the past 12 months, as well as those with lymphoma, and those who had undergone systemic anti-cancer therapy or radiotherapy within the past 12 months.

The increased vulnerability among individuals with cancer is likely due to compromised immune systems. “Patients with cancer often have impaired B and T cell function and this study provides the largest global clinical study showing the definitive meaningful clinical impact of this,” Dr. Lee said. The greater risk among those with lymphoma likely traces to aberrant white cells or immunosuppressant regimens, he said.

“Vaccination probably should be used in combination with new forms of prevention and in Europe the strategy of using prophylactic antibodies is going to provide additional levels of protection,” Dr. Lee said.

Overall, the study reveals the challenges that cancer patients face in a pandemic that remains a critical health concern, one that can seriously affect quality of life. “Many are still shielding, unable to see family or hug loved ones. Furthermore, looking beyond the direct health risks, there is also the mental health impact. Shielding for nearly 3 years is very difficult. It is important to realize that behind this large-scale study, which is the biggest in the world, there are real people. The pandemic still goes on for them as they remain at higher risk from COVID-19 and we must be aware of the impact on them,” Dr. Lee said.

The study included data from the United Kingdom’s third dose booster vaccine program, representing 361,098 individuals who participated from December 2020 through December 2021. It also include results from all coronavirus tests conducted in the United Kingdom during that period. Among the participants, 97.8% got the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine as a booster, while 1.5% received the Moderna vaccine. Overall, 8,371,139 individuals received a third dose booster, including 230,666 living with cancer. The researchers used a test-negative case-controlled analysis to estimate vaccine efficacy.

The booster shot had a 59.1% efficacy against breakthrough infections, 62.8% efficacy against symptomatic infections, 80.5% efficacy versus coronavirus hospitalization, and 94.5% efficacy against coronavirus death. Patients with solid tumors benefited from higher efficacy versus breakthrough infections 66.0% versus 53.2%) and symptomatic infections (69.6% versus 56.0%).

Patients with lymphoma experienced just a 10.5% efficacy of the primary dose vaccine versus breakthrough infections and 13.6% versus symptomatic infections, and this did not improve with a third dose. The benefit was greater for hospitalization (23.2%) and death (80.1%).

Despite the additional protection of a third dose, patients with cancer had a higher risk than the population control for coronavirus hospitalization (odds ratio, 3.38; P < .000001) and death (odds ratio, 3.01; P < .000001).

Dr. Lee has no relevant financial disclosures.

though this population still suffers higher risks than those of the general population, according to a new large-scale observational study out of the United Kingdom.

People living with lymphoma and those who underwent recent systemic anti-cancer treatment or radiotherapy are at the highest risk, according to study author Lennard Y.W. Lee, PhD. “Our study is the largest evaluation of a coronavirus third dose vaccine booster effectiveness in people living with cancer in the world. For the first time we have quantified the benefits of boosters for COVID-19 in cancer patients,” said Dr. Lee, UK COVID Cancer program lead and a medical oncologist at the University of Oxford, England.

The research was published in the November issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

Despite the encouraging numbers, those with cancer continue to have a more than threefold increased risk of both hospitalization and death from coronavirus compared to the general population. “More needs to be done to reduce this excess risk, like prophylactic antibody therapies,” Dr. Lee said.

Third dose efficacy was lower among cancer patients who had been diagnosed within the past 12 months, as well as those with lymphoma, and those who had undergone systemic anti-cancer therapy or radiotherapy within the past 12 months.

The increased vulnerability among individuals with cancer is likely due to compromised immune systems. “Patients with cancer often have impaired B and T cell function and this study provides the largest global clinical study showing the definitive meaningful clinical impact of this,” Dr. Lee said. The greater risk among those with lymphoma likely traces to aberrant white cells or immunosuppressant regimens, he said.

“Vaccination probably should be used in combination with new forms of prevention and in Europe the strategy of using prophylactic antibodies is going to provide additional levels of protection,” Dr. Lee said.

Overall, the study reveals the challenges that cancer patients face in a pandemic that remains a critical health concern, one that can seriously affect quality of life. “Many are still shielding, unable to see family or hug loved ones. Furthermore, looking beyond the direct health risks, there is also the mental health impact. Shielding for nearly 3 years is very difficult. It is important to realize that behind this large-scale study, which is the biggest in the world, there are real people. The pandemic still goes on for them as they remain at higher risk from COVID-19 and we must be aware of the impact on them,” Dr. Lee said.

The study included data from the United Kingdom’s third dose booster vaccine program, representing 361,098 individuals who participated from December 2020 through December 2021. It also include results from all coronavirus tests conducted in the United Kingdom during that period. Among the participants, 97.8% got the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine as a booster, while 1.5% received the Moderna vaccine. Overall, 8,371,139 individuals received a third dose booster, including 230,666 living with cancer. The researchers used a test-negative case-controlled analysis to estimate vaccine efficacy.

The booster shot had a 59.1% efficacy against breakthrough infections, 62.8% efficacy against symptomatic infections, 80.5% efficacy versus coronavirus hospitalization, and 94.5% efficacy against coronavirus death. Patients with solid tumors benefited from higher efficacy versus breakthrough infections 66.0% versus 53.2%) and symptomatic infections (69.6% versus 56.0%).

Patients with lymphoma experienced just a 10.5% efficacy of the primary dose vaccine versus breakthrough infections and 13.6% versus symptomatic infections, and this did not improve with a third dose. The benefit was greater for hospitalization (23.2%) and death (80.1%).

Despite the additional protection of a third dose, patients with cancer had a higher risk than the population control for coronavirus hospitalization (odds ratio, 3.38; P < .000001) and death (odds ratio, 3.01; P < .000001).

Dr. Lee has no relevant financial disclosures.

though this population still suffers higher risks than those of the general population, according to a new large-scale observational study out of the United Kingdom.

People living with lymphoma and those who underwent recent systemic anti-cancer treatment or radiotherapy are at the highest risk, according to study author Lennard Y.W. Lee, PhD. “Our study is the largest evaluation of a coronavirus third dose vaccine booster effectiveness in people living with cancer in the world. For the first time we have quantified the benefits of boosters for COVID-19 in cancer patients,” said Dr. Lee, UK COVID Cancer program lead and a medical oncologist at the University of Oxford, England.

The research was published in the November issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

Despite the encouraging numbers, those with cancer continue to have a more than threefold increased risk of both hospitalization and death from coronavirus compared to the general population. “More needs to be done to reduce this excess risk, like prophylactic antibody therapies,” Dr. Lee said.

Third dose efficacy was lower among cancer patients who had been diagnosed within the past 12 months, as well as those with lymphoma, and those who had undergone systemic anti-cancer therapy or radiotherapy within the past 12 months.

The increased vulnerability among individuals with cancer is likely due to compromised immune systems. “Patients with cancer often have impaired B and T cell function and this study provides the largest global clinical study showing the definitive meaningful clinical impact of this,” Dr. Lee said. The greater risk among those with lymphoma likely traces to aberrant white cells or immunosuppressant regimens, he said.

“Vaccination probably should be used in combination with new forms of prevention and in Europe the strategy of using prophylactic antibodies is going to provide additional levels of protection,” Dr. Lee said.

Overall, the study reveals the challenges that cancer patients face in a pandemic that remains a critical health concern, one that can seriously affect quality of life. “Many are still shielding, unable to see family or hug loved ones. Furthermore, looking beyond the direct health risks, there is also the mental health impact. Shielding for nearly 3 years is very difficult. It is important to realize that behind this large-scale study, which is the biggest in the world, there are real people. The pandemic still goes on for them as they remain at higher risk from COVID-19 and we must be aware of the impact on them,” Dr. Lee said.

The study included data from the United Kingdom’s third dose booster vaccine program, representing 361,098 individuals who participated from December 2020 through December 2021. It also include results from all coronavirus tests conducted in the United Kingdom during that period. Among the participants, 97.8% got the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine as a booster, while 1.5% received the Moderna vaccine. Overall, 8,371,139 individuals received a third dose booster, including 230,666 living with cancer. The researchers used a test-negative case-controlled analysis to estimate vaccine efficacy.

The booster shot had a 59.1% efficacy against breakthrough infections, 62.8% efficacy against symptomatic infections, 80.5% efficacy versus coronavirus hospitalization, and 94.5% efficacy against coronavirus death. Patients with solid tumors benefited from higher efficacy versus breakthrough infections 66.0% versus 53.2%) and symptomatic infections (69.6% versus 56.0%).

Patients with lymphoma experienced just a 10.5% efficacy of the primary dose vaccine versus breakthrough infections and 13.6% versus symptomatic infections, and this did not improve with a third dose. The benefit was greater for hospitalization (23.2%) and death (80.1%).

Despite the additional protection of a third dose, patients with cancer had a higher risk than the population control for coronavirus hospitalization (odds ratio, 3.38; P < .000001) and death (odds ratio, 3.01; P < .000001).

Dr. Lee has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CANCER

Liver disease-related deaths rise during pandemic

according to new findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Between 2019 and 2021, ALD-related deaths increased by 17.6% and NAFLD-related deaths increased by 14.5%, Yee Hui Yeo, MD, a resident physician and hepatology-focused investigator at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said at a preconference press briefing.

“Even before the pandemic, the mortality rates for these two diseases have been increasing, with NAFLD having an even steeper increasing trend,” he said. “During the pandemic, these two diseases had a significant surge.”

Recent U.S. liver disease death rates

Dr. Yeo and colleagues analyzed data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Vital Statistic System to estimate the age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR) of liver disease between 2010 and 2021, including ALD, NAFLD, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. Using prediction modeling analyses based on trends from 2010 to 2019, they predicted mortality rates for 2020-2021 and compared them with the observed rates to quantify the differences related to the pandemic.

Between 2010 and 2021, there were about 626,000 chronic liver disease–related deaths, including about 343,000 ALD-related deaths, 204,000 hepatitis C–related deaths, 58,000 NAFLD-related deaths, and 21,000 hepatitis B–related deaths.

For ALD-related deaths, the annual percentage change was 3.5% for 2010-2019 and 17.6% for 2019-2021. The observed ASMR in 2020 was significantly higher than predicted, at 15.7 deaths per 100,000 people versus 13.0 predicted from the 2010-2019 rate. The trend continued in 2021, with 17.4 deaths per 100,000 people versus 13.4 in the previous decade.

The highest numbers of ALD-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in Alaska, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and South Dakota.

For NAFLD-related deaths, the annual percentage change was 7.6% for 2010-2014, 11.8% for 2014-2019, and 14.5% for 2019-2021. The observed ASMR was also higher than predicted, at 3.1 deaths per 100,000 people versus 2.6 in 2020, as well as 3.4 versus 2.8 in 2021.

The highest numbers of NAFLD-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in Oklahoma, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia.

Hepatitis B and C gains lost in pandemic

In contrast, the annual percentage change in was –1.9% for hepatitis B and –2.8% for hepatitis C. After new treatment for hepatitis C emerged in 2013-2014, mortality rates were –7.8% for 2014-2019, Dr. Yeo noted.

“However, during the pandemic, we saw that this decrease has become a nonsignificant change,” he said. “That means our progress of the past 5 or 6 years has already stopped during the pandemic.”

By race and ethnicity, the increase in ALD-related mortality was most pronounced in non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Alaska Native/American Indian populations, Dr. Yeo said. Alaska Natives and American Indians had the highest annual percentage change, at 18%, followed by non-Hispanic Whites at 11.7% and non-Hispanic Blacks at 10.8%. There were no significant differences in race and ethnicity for NAFLD-related deaths, although all groups had major increases in recent years.

Biggest rise in young adults

By age, the increase in ALD-related mortality was particularly severe for ages 25-44, with an annual percentage change of 34.6% in 2019-2021, as compared with 13.7% for ages 45-64 and 12.6% for ages 65 and older.

For NAFLD-related deaths, another major increase was observed among ages 25-44, with an annual percentage change of 28.1% for 2019-2021, as compared with 12% for ages 65 and older and 7.4% for ages 45-64.

By sex, the ASMR increase in NAFLD-related mortality was steady throughout 2010-2021 for both men and women. In contrast, ALD-related death increased sharply between 2019 and 2021, with an annual percentage change of 19.1% for women and 16.7% for men.

“The increasing trend in mortality rates for ALD and NAFLD has been quite alarming, with disparities in age, race, and ethnicity,” Dr. Yeo said.

The study received no funding support. Some authors disclosed research funding, advisory board roles, and consulting fees with various pharmaceutical companies.

according to new findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Between 2019 and 2021, ALD-related deaths increased by 17.6% and NAFLD-related deaths increased by 14.5%, Yee Hui Yeo, MD, a resident physician and hepatology-focused investigator at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said at a preconference press briefing.

“Even before the pandemic, the mortality rates for these two diseases have been increasing, with NAFLD having an even steeper increasing trend,” he said. “During the pandemic, these two diseases had a significant surge.”

Recent U.S. liver disease death rates

Dr. Yeo and colleagues analyzed data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Vital Statistic System to estimate the age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR) of liver disease between 2010 and 2021, including ALD, NAFLD, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. Using prediction modeling analyses based on trends from 2010 to 2019, they predicted mortality rates for 2020-2021 and compared them with the observed rates to quantify the differences related to the pandemic.

Between 2010 and 2021, there were about 626,000 chronic liver disease–related deaths, including about 343,000 ALD-related deaths, 204,000 hepatitis C–related deaths, 58,000 NAFLD-related deaths, and 21,000 hepatitis B–related deaths.

For ALD-related deaths, the annual percentage change was 3.5% for 2010-2019 and 17.6% for 2019-2021. The observed ASMR in 2020 was significantly higher than predicted, at 15.7 deaths per 100,000 people versus 13.0 predicted from the 2010-2019 rate. The trend continued in 2021, with 17.4 deaths per 100,000 people versus 13.4 in the previous decade.

The highest numbers of ALD-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in Alaska, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and South Dakota.

For NAFLD-related deaths, the annual percentage change was 7.6% for 2010-2014, 11.8% for 2014-2019, and 14.5% for 2019-2021. The observed ASMR was also higher than predicted, at 3.1 deaths per 100,000 people versus 2.6 in 2020, as well as 3.4 versus 2.8 in 2021.

The highest numbers of NAFLD-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in Oklahoma, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia.

Hepatitis B and C gains lost in pandemic

In contrast, the annual percentage change in was –1.9% for hepatitis B and –2.8% for hepatitis C. After new treatment for hepatitis C emerged in 2013-2014, mortality rates were –7.8% for 2014-2019, Dr. Yeo noted.

“However, during the pandemic, we saw that this decrease has become a nonsignificant change,” he said. “That means our progress of the past 5 or 6 years has already stopped during the pandemic.”

By race and ethnicity, the increase in ALD-related mortality was most pronounced in non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Alaska Native/American Indian populations, Dr. Yeo said. Alaska Natives and American Indians had the highest annual percentage change, at 18%, followed by non-Hispanic Whites at 11.7% and non-Hispanic Blacks at 10.8%. There were no significant differences in race and ethnicity for NAFLD-related deaths, although all groups had major increases in recent years.

Biggest rise in young adults

By age, the increase in ALD-related mortality was particularly severe for ages 25-44, with an annual percentage change of 34.6% in 2019-2021, as compared with 13.7% for ages 45-64 and 12.6% for ages 65 and older.

For NAFLD-related deaths, another major increase was observed among ages 25-44, with an annual percentage change of 28.1% for 2019-2021, as compared with 12% for ages 65 and older and 7.4% for ages 45-64.

By sex, the ASMR increase in NAFLD-related mortality was steady throughout 2010-2021 for both men and women. In contrast, ALD-related death increased sharply between 2019 and 2021, with an annual percentage change of 19.1% for women and 16.7% for men.

“The increasing trend in mortality rates for ALD and NAFLD has been quite alarming, with disparities in age, race, and ethnicity,” Dr. Yeo said.

The study received no funding support. Some authors disclosed research funding, advisory board roles, and consulting fees with various pharmaceutical companies.

according to new findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Between 2019 and 2021, ALD-related deaths increased by 17.6% and NAFLD-related deaths increased by 14.5%, Yee Hui Yeo, MD, a resident physician and hepatology-focused investigator at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said at a preconference press briefing.

“Even before the pandemic, the mortality rates for these two diseases have been increasing, with NAFLD having an even steeper increasing trend,” he said. “During the pandemic, these two diseases had a significant surge.”

Recent U.S. liver disease death rates

Dr. Yeo and colleagues analyzed data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Vital Statistic System to estimate the age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR) of liver disease between 2010 and 2021, including ALD, NAFLD, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. Using prediction modeling analyses based on trends from 2010 to 2019, they predicted mortality rates for 2020-2021 and compared them with the observed rates to quantify the differences related to the pandemic.

Between 2010 and 2021, there were about 626,000 chronic liver disease–related deaths, including about 343,000 ALD-related deaths, 204,000 hepatitis C–related deaths, 58,000 NAFLD-related deaths, and 21,000 hepatitis B–related deaths.

For ALD-related deaths, the annual percentage change was 3.5% for 2010-2019 and 17.6% for 2019-2021. The observed ASMR in 2020 was significantly higher than predicted, at 15.7 deaths per 100,000 people versus 13.0 predicted from the 2010-2019 rate. The trend continued in 2021, with 17.4 deaths per 100,000 people versus 13.4 in the previous decade.

The highest numbers of ALD-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in Alaska, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and South Dakota.

For NAFLD-related deaths, the annual percentage change was 7.6% for 2010-2014, 11.8% for 2014-2019, and 14.5% for 2019-2021. The observed ASMR was also higher than predicted, at 3.1 deaths per 100,000 people versus 2.6 in 2020, as well as 3.4 versus 2.8 in 2021.

The highest numbers of NAFLD-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in Oklahoma, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia.

Hepatitis B and C gains lost in pandemic

In contrast, the annual percentage change in was –1.9% for hepatitis B and –2.8% for hepatitis C. After new treatment for hepatitis C emerged in 2013-2014, mortality rates were –7.8% for 2014-2019, Dr. Yeo noted.

“However, during the pandemic, we saw that this decrease has become a nonsignificant change,” he said. “That means our progress of the past 5 or 6 years has already stopped during the pandemic.”

By race and ethnicity, the increase in ALD-related mortality was most pronounced in non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Alaska Native/American Indian populations, Dr. Yeo said. Alaska Natives and American Indians had the highest annual percentage change, at 18%, followed by non-Hispanic Whites at 11.7% and non-Hispanic Blacks at 10.8%. There were no significant differences in race and ethnicity for NAFLD-related deaths, although all groups had major increases in recent years.

Biggest rise in young adults

By age, the increase in ALD-related mortality was particularly severe for ages 25-44, with an annual percentage change of 34.6% in 2019-2021, as compared with 13.7% for ages 45-64 and 12.6% for ages 65 and older.

For NAFLD-related deaths, another major increase was observed among ages 25-44, with an annual percentage change of 28.1% for 2019-2021, as compared with 12% for ages 65 and older and 7.4% for ages 45-64.

By sex, the ASMR increase in NAFLD-related mortality was steady throughout 2010-2021 for both men and women. In contrast, ALD-related death increased sharply between 2019 and 2021, with an annual percentage change of 19.1% for women and 16.7% for men.

“The increasing trend in mortality rates for ALD and NAFLD has been quite alarming, with disparities in age, race, and ethnicity,” Dr. Yeo said.

The study received no funding support. Some authors disclosed research funding, advisory board roles, and consulting fees with various pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE LIVER MEETING

Have you heard the one about the emergency dept. that called 911?

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.