User login

Albuminuria linked to higher CVD risk in diabetes

BARCELONA – Fewer than half the adults in Denmark with type 2 diabetes in 2015 had a recent assessment for albuminuria, and those who underwent testing and had albuminuria had a greater than 50% increased rate of incident heart failure, MI, stroke, or all-cause death during 4-year follow-up, in a study of more than 74,000 Danish residents.

Even those in this study with type 2 diabetes but without albuminuria had a 19% rate of these adverse outcomes, highlighting the “substantial” cardiovascular disease risk faced by people with type 2 diabetes even without a clear indication of nephropathy, Saaima Parveen, MD, a cardiology researcher at Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital in Copenhagen, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This high rate of heart failure, MI, stroke, or death even in the absence of what is conventionally defined as albuminuria – a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) of at least 30 mg/g – suggests that this threshold for albuminuria may be too high, commented Luis M. Ruilope, MD, professor of public health and preventive medicine at Autonoma University, Madrid, who was not involved with the Danish study.

The study reported by Dr. Parveen “is very important because it shows that the risk of events is high not only in people with diabetes with albuminuria, but also in those without albuminuria,” Dr. Ruilope said in an interview.

The profile of albuminuria as a risk marker for people with type 2 diabetes spiked following the 2021 U.S. approval of finerenone (Kerendia) as an agent specifically targeted to adults with type 2 diabetes and albuminuria. (Finerenone gained marketing approval by in Europe in February 2022 under the same brand name.)

A lower threshold for albuminuria?

“Even patients with a UACR of 10-29 mg/g have risk and should be considered for finerenone treatment, said Dr. Ruilope. “People with type 2 diabetes with a UACR of 10-29 mg/g could explain” the high background risk shown by Dr. Parveen in her reported data. “In people with type 2 diabetes and a UACR of 10-29 mg/g we also see progression of kidney disease, but it’s slower” than in those who meet the current, standard threshold for albuminuria.

Dr. Ruilope was a coinvestigator for both of the finerenone pivotal trials, FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD. Although the design of both these studies specified enrollment of people with type 2 diabetes and a UACR of at least 30 mg/g, a few hundred of the total combined enrollment of more than 13,000 patients had UACR values below this level, and analysis of this subgroup could provide some important insights into the value of finerenone for people with “high normal” albuminuria, he said.

The study led by Dr. Parveen used data routinely collected in Danish national records and focused on all Danish adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes as of Jan. 1, 2015, who also had information in their records for a UACR and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) within the preceding year.

The records showed that only 47% of these people had a UACR value during this time frame, and that 57% had a recent measure of their eGFR, despite prevailing recommendations for routine and regular measurements of these parameters for all people with type 2 diabetes.

Dr. Parveen hypothesized that UACR measurement may lag for several reasons, such as reliance by primary care physicians on urine dipstick assessments, which preclude calculation of a UACR, poor adherence to regular medical assessment by people in low socioeconomic groups, and medical examination done outside of morning time periods, which is the best time of day for assessing UACR.

More albuminuria measurement needed in primary care

“Measurement of albuminuria in people with type 2 diabetes is improving in Europe, but is not yet at the level that’s needed,” commented Dr. Ruilope. “We are pushing to have it done more often in primary care practices,” he said.

Among the 74,014 people with type 2 diabetes who had the measurement records that allowed for their inclusion in the study, 40% had albuminuria and 60% did not.

During 4 years of follow-up, the incidence of heart failure, MI, stroke, or all-cause death was 28.6% in those with albuminuria and 18.7% among those without albuminuria, reported Dr. Parveen.

The rates for each event type in those with albuminuria were 7.0% for heart failure, 4.4% for MI, 7.6% for stroke, and 16.6% for all-cause death (each patient could tally more than one type of event). Among those without albuminuria, the rates were 4.0%, 3.2%, 5.5%, and 9.3%, respectively.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Parveen and Dr. Ruilope had no disclosures.

BARCELONA – Fewer than half the adults in Denmark with type 2 diabetes in 2015 had a recent assessment for albuminuria, and those who underwent testing and had albuminuria had a greater than 50% increased rate of incident heart failure, MI, stroke, or all-cause death during 4-year follow-up, in a study of more than 74,000 Danish residents.

Even those in this study with type 2 diabetes but without albuminuria had a 19% rate of these adverse outcomes, highlighting the “substantial” cardiovascular disease risk faced by people with type 2 diabetes even without a clear indication of nephropathy, Saaima Parveen, MD, a cardiology researcher at Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital in Copenhagen, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This high rate of heart failure, MI, stroke, or death even in the absence of what is conventionally defined as albuminuria – a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) of at least 30 mg/g – suggests that this threshold for albuminuria may be too high, commented Luis M. Ruilope, MD, professor of public health and preventive medicine at Autonoma University, Madrid, who was not involved with the Danish study.

The study reported by Dr. Parveen “is very important because it shows that the risk of events is high not only in people with diabetes with albuminuria, but also in those without albuminuria,” Dr. Ruilope said in an interview.

The profile of albuminuria as a risk marker for people with type 2 diabetes spiked following the 2021 U.S. approval of finerenone (Kerendia) as an agent specifically targeted to adults with type 2 diabetes and albuminuria. (Finerenone gained marketing approval by in Europe in February 2022 under the same brand name.)

A lower threshold for albuminuria?

“Even patients with a UACR of 10-29 mg/g have risk and should be considered for finerenone treatment, said Dr. Ruilope. “People with type 2 diabetes with a UACR of 10-29 mg/g could explain” the high background risk shown by Dr. Parveen in her reported data. “In people with type 2 diabetes and a UACR of 10-29 mg/g we also see progression of kidney disease, but it’s slower” than in those who meet the current, standard threshold for albuminuria.

Dr. Ruilope was a coinvestigator for both of the finerenone pivotal trials, FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD. Although the design of both these studies specified enrollment of people with type 2 diabetes and a UACR of at least 30 mg/g, a few hundred of the total combined enrollment of more than 13,000 patients had UACR values below this level, and analysis of this subgroup could provide some important insights into the value of finerenone for people with “high normal” albuminuria, he said.

The study led by Dr. Parveen used data routinely collected in Danish national records and focused on all Danish adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes as of Jan. 1, 2015, who also had information in their records for a UACR and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) within the preceding year.

The records showed that only 47% of these people had a UACR value during this time frame, and that 57% had a recent measure of their eGFR, despite prevailing recommendations for routine and regular measurements of these parameters for all people with type 2 diabetes.

Dr. Parveen hypothesized that UACR measurement may lag for several reasons, such as reliance by primary care physicians on urine dipstick assessments, which preclude calculation of a UACR, poor adherence to regular medical assessment by people in low socioeconomic groups, and medical examination done outside of morning time periods, which is the best time of day for assessing UACR.

More albuminuria measurement needed in primary care

“Measurement of albuminuria in people with type 2 diabetes is improving in Europe, but is not yet at the level that’s needed,” commented Dr. Ruilope. “We are pushing to have it done more often in primary care practices,” he said.

Among the 74,014 people with type 2 diabetes who had the measurement records that allowed for their inclusion in the study, 40% had albuminuria and 60% did not.

During 4 years of follow-up, the incidence of heart failure, MI, stroke, or all-cause death was 28.6% in those with albuminuria and 18.7% among those without albuminuria, reported Dr. Parveen.

The rates for each event type in those with albuminuria were 7.0% for heart failure, 4.4% for MI, 7.6% for stroke, and 16.6% for all-cause death (each patient could tally more than one type of event). Among those without albuminuria, the rates were 4.0%, 3.2%, 5.5%, and 9.3%, respectively.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Parveen and Dr. Ruilope had no disclosures.

BARCELONA – Fewer than half the adults in Denmark with type 2 diabetes in 2015 had a recent assessment for albuminuria, and those who underwent testing and had albuminuria had a greater than 50% increased rate of incident heart failure, MI, stroke, or all-cause death during 4-year follow-up, in a study of more than 74,000 Danish residents.

Even those in this study with type 2 diabetes but without albuminuria had a 19% rate of these adverse outcomes, highlighting the “substantial” cardiovascular disease risk faced by people with type 2 diabetes even without a clear indication of nephropathy, Saaima Parveen, MD, a cardiology researcher at Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital in Copenhagen, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This high rate of heart failure, MI, stroke, or death even in the absence of what is conventionally defined as albuminuria – a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) of at least 30 mg/g – suggests that this threshold for albuminuria may be too high, commented Luis M. Ruilope, MD, professor of public health and preventive medicine at Autonoma University, Madrid, who was not involved with the Danish study.

The study reported by Dr. Parveen “is very important because it shows that the risk of events is high not only in people with diabetes with albuminuria, but also in those without albuminuria,” Dr. Ruilope said in an interview.

The profile of albuminuria as a risk marker for people with type 2 diabetes spiked following the 2021 U.S. approval of finerenone (Kerendia) as an agent specifically targeted to adults with type 2 diabetes and albuminuria. (Finerenone gained marketing approval by in Europe in February 2022 under the same brand name.)

A lower threshold for albuminuria?

“Even patients with a UACR of 10-29 mg/g have risk and should be considered for finerenone treatment, said Dr. Ruilope. “People with type 2 diabetes with a UACR of 10-29 mg/g could explain” the high background risk shown by Dr. Parveen in her reported data. “In people with type 2 diabetes and a UACR of 10-29 mg/g we also see progression of kidney disease, but it’s slower” than in those who meet the current, standard threshold for albuminuria.

Dr. Ruilope was a coinvestigator for both of the finerenone pivotal trials, FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD. Although the design of both these studies specified enrollment of people with type 2 diabetes and a UACR of at least 30 mg/g, a few hundred of the total combined enrollment of more than 13,000 patients had UACR values below this level, and analysis of this subgroup could provide some important insights into the value of finerenone for people with “high normal” albuminuria, he said.

The study led by Dr. Parveen used data routinely collected in Danish national records and focused on all Danish adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes as of Jan. 1, 2015, who also had information in their records for a UACR and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) within the preceding year.

The records showed that only 47% of these people had a UACR value during this time frame, and that 57% had a recent measure of their eGFR, despite prevailing recommendations for routine and regular measurements of these parameters for all people with type 2 diabetes.

Dr. Parveen hypothesized that UACR measurement may lag for several reasons, such as reliance by primary care physicians on urine dipstick assessments, which preclude calculation of a UACR, poor adherence to regular medical assessment by people in low socioeconomic groups, and medical examination done outside of morning time periods, which is the best time of day for assessing UACR.

More albuminuria measurement needed in primary care

“Measurement of albuminuria in people with type 2 diabetes is improving in Europe, but is not yet at the level that’s needed,” commented Dr. Ruilope. “We are pushing to have it done more often in primary care practices,” he said.

Among the 74,014 people with type 2 diabetes who had the measurement records that allowed for their inclusion in the study, 40% had albuminuria and 60% did not.

During 4 years of follow-up, the incidence of heart failure, MI, stroke, or all-cause death was 28.6% in those with albuminuria and 18.7% among those without albuminuria, reported Dr. Parveen.

The rates for each event type in those with albuminuria were 7.0% for heart failure, 4.4% for MI, 7.6% for stroke, and 16.6% for all-cause death (each patient could tally more than one type of event). Among those without albuminuria, the rates were 4.0%, 3.2%, 5.5%, and 9.3%, respectively.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Parveen and Dr. Ruilope had no disclosures.

AT ESC CONGRESS 2022

DANCAVAS misses primary endpoint but hints at benefit from comprehensive CV screening

Comprehensive image-based cardiovascular screening in men aged 65-74 years did not significantly reduce all-cause mortality in a new Danish study, although there were strong suggestions of benefit in some cardiovascular endpoints in the whole group and also in mortality in those aged younger than 70.

The DANCAVAS study was presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, being held in Barcelona. It was also simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“I do believe there is something in this study,” lead investigator Axel Diederichsen, PhD, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, told this news organization.

“We can decrease all-cause mortality by screening in men younger than 70. That’s amazing, I think. And in the entire group the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality/MI/stroke was significantly reduced by 7%.”

He pointed out that only 63% of the screening group actually attended the tests. “So that 63% had to account for the difference of 100% of the screening group, with an all-cause mortality endpoint. That is very ambitious. But even so, we were very close to meeting the all-cause mortality primary endpoint.”

Dr. Diederichsen believes the data could support such cardiovascular screening in men younger than 70. “In Denmark, I think this would be feasible, and our study suggests it would be cost effective compared to cancer screening,” he said.

Noting that Denmark has a relatively healthy population with good routine care, he added: “In other countries where it can be more difficult to access care or where cardiovascular health is not so good, such a screening program would probably have a greater effect.”

The population-based DANCAVAS trial randomly assigned 46,611 Danish men aged 65-74 years in a 1:2 ratio to undergo screening (invited group) or not to undergo screening (control group) for subclinical cardiovascular disease.

Screening included non-contrast electrocardiography-gated CT to determine the coronary-artery calcium score and to detect aneurysms and atrial fibrillation; ankle–brachial blood-pressure measurements to detect peripheral artery disease and hypertension; and a blood sample to detect diabetes and hypercholesterolemia. Of the 16,736 men who were invited to the screening group, 10,471 (62.6%) actually attended for the screening.

In intention-to-treat analyses, after a median follow-up of 5.6 years, the primary endpoint (all cause death) had occurred in 2,106 men (12.6%) in the invited group and 3,915 men (13.1%) in the control group (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.90-1.00; P = .06).

The hazard ratio for stroke in the invited group, compared with the control group, was 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.86-0.99); for MI, 0.91 (95% CI, 0.81-1.03); for aortic dissection, 0.95 (95% CI, 0.61-1.49); and for aortic rupture, 0.81 (95% CI, 0.49-1.35).

The post-hoc composite endpoint of all-cause mortality/stroke/MI was reduced by 7%, with a hazard ratio of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.89-0.97).

There were no significant between-group differences in safety outcomes.

Subgroup analysis showed that the primary outcome of all-cause mortality was significantly reduced in men invited to screening who were aged 65-69 years (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.83-0.96), with no effect in men aged 70-74.

Other findings showed that in the group invited to screening, there was a large increase in use of antiplatelet medication (HR, 3.12) and in lipid lowering agents (HR, 2.54) but no difference in use of anticoagulants, antihypertensives, and diabetes drugs or in coronary or aortic revascularization.

In terms of cost-effectiveness, the total additional health care costs were €207 ($206 U.S.) per person in the invited group, which included the screening, medication, and all physician and hospital visits.

The quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained per person was 0.023, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of €9,075 ($9,043) per QALY in the whole cohort and €3,860 ($3,846) in the men aged 65-69.

Dr. Diederichsen said these figures compared favorably to cancer screening, with breast cancer screening having a cost-effectiveness ratio of €22,000 ($21,923) per QALY.

“This study is a step in the right direction,” Dr. Diederichsen said in an interview. But governments will have to decide if they want to spend public money on this type of screening. I would like this to happen. We can make a case for it with this data.”

He said the study had also collected some data on younger men – aged 60-64 – and in a small group of women, which has not been analyzed yet. “We would like to look at this to help us formulate recommendations,” he added.

Increased medical therapy

Designated discussant of the study at the ESC session, Harriette Van Spall, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., congratulated the DANCAVAS investigators for the trial, which she said was “implemented perfectly.”

“This is the kind of trial that is very difficult to run but comes from a big body of research from this remarkable group,” she commented.

Dr. Van Spall pointed out that it looked likely that any benefits from the screening approach were brought about by increased use of medical therapy alone (antiplatelet and lipid-lowering drugs). She added that the lack of an active screening comparator group made it unclear whether full CT imaging is more effective than active screening for traditional risk factors or assessment of global cardiovascular risk scores, and there was a missed opportunity to screen for and treat cigarette smoking in the intervention group.

“Aspects of the screening such as a full CT could be considered resource-intensive and not feasible in some health care systems. A strength of restricting the abdominal aorta iliac screening to a risk-enriched group – perhaps cigarette smokers – could have conserved additional resources,” she suggested.

Because 37% of the invited group did not attend for screening and at baseline these non-attendees had more comorbidities, this may have caused a bias in the intention to treat analysis toward the control group, thus underestimating the benefit of screening. There is therefore a role for a secondary on-treatment analysis, she noted.

Dr. Van Spall also pointed out that because of the population involved in this study, inferences can only be made to Danish men aged 65-74.

Noting that cardiovascular disease is relevant to everyone, accounting for 24% of deaths in Danish females and 25% of deaths in Danish males, she asked the investigators to consider eliminating sex-based eligibility criteria in their next big cardiovascular prevention trial.

Susanna Price, MD, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, and cochair of the ESC session at which DANCAVAS was presented, described the study as “really interesting” and useful in planning future screening approaches.

“Although the primary endpoint was neutral, and so the results may not change practice at this time, it should promote a look at different predefined endpoints in a larger population, including both men and women, to see what the best screening interventions would be,” she commented.

“What is interesting is that we are seeing huge amounts of money being spent on acute cardiac patients after having an event, but here we are beginning to shift the focus on how to prevent cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. That is starting to be the trend in cardiovascular medicine.”

Also commenting for this news organization, Dipti Itchhaporia, MD, University of California, Irvine, and immediate past president of the American College of Cardiology, said: “This study is asking the important question of whether comprehensive cardiovascular screening is needed, but I don’t think it has fully given the answer, although there did appear to be some benefit in those under 70.”

Dr. Itchhaporia questioned whether the 5-year follow up was long enough to show the true benefit of screening, and she suggested that a different approach with a longer monitoring period may have been better to detect AFib.

The DANCAVAS study was supported by the Southern Region of Denmark, the Danish Heart Foundation, and the Danish Independent Research Councils.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comprehensive image-based cardiovascular screening in men aged 65-74 years did not significantly reduce all-cause mortality in a new Danish study, although there were strong suggestions of benefit in some cardiovascular endpoints in the whole group and also in mortality in those aged younger than 70.

The DANCAVAS study was presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, being held in Barcelona. It was also simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“I do believe there is something in this study,” lead investigator Axel Diederichsen, PhD, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, told this news organization.

“We can decrease all-cause mortality by screening in men younger than 70. That’s amazing, I think. And in the entire group the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality/MI/stroke was significantly reduced by 7%.”

He pointed out that only 63% of the screening group actually attended the tests. “So that 63% had to account for the difference of 100% of the screening group, with an all-cause mortality endpoint. That is very ambitious. But even so, we were very close to meeting the all-cause mortality primary endpoint.”

Dr. Diederichsen believes the data could support such cardiovascular screening in men younger than 70. “In Denmark, I think this would be feasible, and our study suggests it would be cost effective compared to cancer screening,” he said.

Noting that Denmark has a relatively healthy population with good routine care, he added: “In other countries where it can be more difficult to access care or where cardiovascular health is not so good, such a screening program would probably have a greater effect.”

The population-based DANCAVAS trial randomly assigned 46,611 Danish men aged 65-74 years in a 1:2 ratio to undergo screening (invited group) or not to undergo screening (control group) for subclinical cardiovascular disease.

Screening included non-contrast electrocardiography-gated CT to determine the coronary-artery calcium score and to detect aneurysms and atrial fibrillation; ankle–brachial blood-pressure measurements to detect peripheral artery disease and hypertension; and a blood sample to detect diabetes and hypercholesterolemia. Of the 16,736 men who were invited to the screening group, 10,471 (62.6%) actually attended for the screening.

In intention-to-treat analyses, after a median follow-up of 5.6 years, the primary endpoint (all cause death) had occurred in 2,106 men (12.6%) in the invited group and 3,915 men (13.1%) in the control group (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.90-1.00; P = .06).

The hazard ratio for stroke in the invited group, compared with the control group, was 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.86-0.99); for MI, 0.91 (95% CI, 0.81-1.03); for aortic dissection, 0.95 (95% CI, 0.61-1.49); and for aortic rupture, 0.81 (95% CI, 0.49-1.35).

The post-hoc composite endpoint of all-cause mortality/stroke/MI was reduced by 7%, with a hazard ratio of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.89-0.97).

There were no significant between-group differences in safety outcomes.

Subgroup analysis showed that the primary outcome of all-cause mortality was significantly reduced in men invited to screening who were aged 65-69 years (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.83-0.96), with no effect in men aged 70-74.

Other findings showed that in the group invited to screening, there was a large increase in use of antiplatelet medication (HR, 3.12) and in lipid lowering agents (HR, 2.54) but no difference in use of anticoagulants, antihypertensives, and diabetes drugs or in coronary or aortic revascularization.

In terms of cost-effectiveness, the total additional health care costs were €207 ($206 U.S.) per person in the invited group, which included the screening, medication, and all physician and hospital visits.

The quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained per person was 0.023, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of €9,075 ($9,043) per QALY in the whole cohort and €3,860 ($3,846) in the men aged 65-69.

Dr. Diederichsen said these figures compared favorably to cancer screening, with breast cancer screening having a cost-effectiveness ratio of €22,000 ($21,923) per QALY.

“This study is a step in the right direction,” Dr. Diederichsen said in an interview. But governments will have to decide if they want to spend public money on this type of screening. I would like this to happen. We can make a case for it with this data.”

He said the study had also collected some data on younger men – aged 60-64 – and in a small group of women, which has not been analyzed yet. “We would like to look at this to help us formulate recommendations,” he added.

Increased medical therapy

Designated discussant of the study at the ESC session, Harriette Van Spall, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., congratulated the DANCAVAS investigators for the trial, which she said was “implemented perfectly.”

“This is the kind of trial that is very difficult to run but comes from a big body of research from this remarkable group,” she commented.

Dr. Van Spall pointed out that it looked likely that any benefits from the screening approach were brought about by increased use of medical therapy alone (antiplatelet and lipid-lowering drugs). She added that the lack of an active screening comparator group made it unclear whether full CT imaging is more effective than active screening for traditional risk factors or assessment of global cardiovascular risk scores, and there was a missed opportunity to screen for and treat cigarette smoking in the intervention group.

“Aspects of the screening such as a full CT could be considered resource-intensive and not feasible in some health care systems. A strength of restricting the abdominal aorta iliac screening to a risk-enriched group – perhaps cigarette smokers – could have conserved additional resources,” she suggested.

Because 37% of the invited group did not attend for screening and at baseline these non-attendees had more comorbidities, this may have caused a bias in the intention to treat analysis toward the control group, thus underestimating the benefit of screening. There is therefore a role for a secondary on-treatment analysis, she noted.

Dr. Van Spall also pointed out that because of the population involved in this study, inferences can only be made to Danish men aged 65-74.

Noting that cardiovascular disease is relevant to everyone, accounting for 24% of deaths in Danish females and 25% of deaths in Danish males, she asked the investigators to consider eliminating sex-based eligibility criteria in their next big cardiovascular prevention trial.

Susanna Price, MD, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, and cochair of the ESC session at which DANCAVAS was presented, described the study as “really interesting” and useful in planning future screening approaches.

“Although the primary endpoint was neutral, and so the results may not change practice at this time, it should promote a look at different predefined endpoints in a larger population, including both men and women, to see what the best screening interventions would be,” she commented.

“What is interesting is that we are seeing huge amounts of money being spent on acute cardiac patients after having an event, but here we are beginning to shift the focus on how to prevent cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. That is starting to be the trend in cardiovascular medicine.”

Also commenting for this news organization, Dipti Itchhaporia, MD, University of California, Irvine, and immediate past president of the American College of Cardiology, said: “This study is asking the important question of whether comprehensive cardiovascular screening is needed, but I don’t think it has fully given the answer, although there did appear to be some benefit in those under 70.”

Dr. Itchhaporia questioned whether the 5-year follow up was long enough to show the true benefit of screening, and she suggested that a different approach with a longer monitoring period may have been better to detect AFib.

The DANCAVAS study was supported by the Southern Region of Denmark, the Danish Heart Foundation, and the Danish Independent Research Councils.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comprehensive image-based cardiovascular screening in men aged 65-74 years did not significantly reduce all-cause mortality in a new Danish study, although there were strong suggestions of benefit in some cardiovascular endpoints in the whole group and also in mortality in those aged younger than 70.

The DANCAVAS study was presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, being held in Barcelona. It was also simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“I do believe there is something in this study,” lead investigator Axel Diederichsen, PhD, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, told this news organization.

“We can decrease all-cause mortality by screening in men younger than 70. That’s amazing, I think. And in the entire group the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality/MI/stroke was significantly reduced by 7%.”

He pointed out that only 63% of the screening group actually attended the tests. “So that 63% had to account for the difference of 100% of the screening group, with an all-cause mortality endpoint. That is very ambitious. But even so, we were very close to meeting the all-cause mortality primary endpoint.”

Dr. Diederichsen believes the data could support such cardiovascular screening in men younger than 70. “In Denmark, I think this would be feasible, and our study suggests it would be cost effective compared to cancer screening,” he said.

Noting that Denmark has a relatively healthy population with good routine care, he added: “In other countries where it can be more difficult to access care or where cardiovascular health is not so good, such a screening program would probably have a greater effect.”

The population-based DANCAVAS trial randomly assigned 46,611 Danish men aged 65-74 years in a 1:2 ratio to undergo screening (invited group) or not to undergo screening (control group) for subclinical cardiovascular disease.

Screening included non-contrast electrocardiography-gated CT to determine the coronary-artery calcium score and to detect aneurysms and atrial fibrillation; ankle–brachial blood-pressure measurements to detect peripheral artery disease and hypertension; and a blood sample to detect diabetes and hypercholesterolemia. Of the 16,736 men who were invited to the screening group, 10,471 (62.6%) actually attended for the screening.

In intention-to-treat analyses, after a median follow-up of 5.6 years, the primary endpoint (all cause death) had occurred in 2,106 men (12.6%) in the invited group and 3,915 men (13.1%) in the control group (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.90-1.00; P = .06).

The hazard ratio for stroke in the invited group, compared with the control group, was 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.86-0.99); for MI, 0.91 (95% CI, 0.81-1.03); for aortic dissection, 0.95 (95% CI, 0.61-1.49); and for aortic rupture, 0.81 (95% CI, 0.49-1.35).

The post-hoc composite endpoint of all-cause mortality/stroke/MI was reduced by 7%, with a hazard ratio of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.89-0.97).

There were no significant between-group differences in safety outcomes.

Subgroup analysis showed that the primary outcome of all-cause mortality was significantly reduced in men invited to screening who were aged 65-69 years (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.83-0.96), with no effect in men aged 70-74.

Other findings showed that in the group invited to screening, there was a large increase in use of antiplatelet medication (HR, 3.12) and in lipid lowering agents (HR, 2.54) but no difference in use of anticoagulants, antihypertensives, and diabetes drugs or in coronary or aortic revascularization.

In terms of cost-effectiveness, the total additional health care costs were €207 ($206 U.S.) per person in the invited group, which included the screening, medication, and all physician and hospital visits.

The quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained per person was 0.023, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of €9,075 ($9,043) per QALY in the whole cohort and €3,860 ($3,846) in the men aged 65-69.

Dr. Diederichsen said these figures compared favorably to cancer screening, with breast cancer screening having a cost-effectiveness ratio of €22,000 ($21,923) per QALY.

“This study is a step in the right direction,” Dr. Diederichsen said in an interview. But governments will have to decide if they want to spend public money on this type of screening. I would like this to happen. We can make a case for it with this data.”

He said the study had also collected some data on younger men – aged 60-64 – and in a small group of women, which has not been analyzed yet. “We would like to look at this to help us formulate recommendations,” he added.

Increased medical therapy

Designated discussant of the study at the ESC session, Harriette Van Spall, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., congratulated the DANCAVAS investigators for the trial, which she said was “implemented perfectly.”

“This is the kind of trial that is very difficult to run but comes from a big body of research from this remarkable group,” she commented.

Dr. Van Spall pointed out that it looked likely that any benefits from the screening approach were brought about by increased use of medical therapy alone (antiplatelet and lipid-lowering drugs). She added that the lack of an active screening comparator group made it unclear whether full CT imaging is more effective than active screening for traditional risk factors or assessment of global cardiovascular risk scores, and there was a missed opportunity to screen for and treat cigarette smoking in the intervention group.

“Aspects of the screening such as a full CT could be considered resource-intensive and not feasible in some health care systems. A strength of restricting the abdominal aorta iliac screening to a risk-enriched group – perhaps cigarette smokers – could have conserved additional resources,” she suggested.

Because 37% of the invited group did not attend for screening and at baseline these non-attendees had more comorbidities, this may have caused a bias in the intention to treat analysis toward the control group, thus underestimating the benefit of screening. There is therefore a role for a secondary on-treatment analysis, she noted.

Dr. Van Spall also pointed out that because of the population involved in this study, inferences can only be made to Danish men aged 65-74.

Noting that cardiovascular disease is relevant to everyone, accounting for 24% of deaths in Danish females and 25% of deaths in Danish males, she asked the investigators to consider eliminating sex-based eligibility criteria in their next big cardiovascular prevention trial.

Susanna Price, MD, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, and cochair of the ESC session at which DANCAVAS was presented, described the study as “really interesting” and useful in planning future screening approaches.

“Although the primary endpoint was neutral, and so the results may not change practice at this time, it should promote a look at different predefined endpoints in a larger population, including both men and women, to see what the best screening interventions would be,” she commented.

“What is interesting is that we are seeing huge amounts of money being spent on acute cardiac patients after having an event, but here we are beginning to shift the focus on how to prevent cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. That is starting to be the trend in cardiovascular medicine.”

Also commenting for this news organization, Dipti Itchhaporia, MD, University of California, Irvine, and immediate past president of the American College of Cardiology, said: “This study is asking the important question of whether comprehensive cardiovascular screening is needed, but I don’t think it has fully given the answer, although there did appear to be some benefit in those under 70.”

Dr. Itchhaporia questioned whether the 5-year follow up was long enough to show the true benefit of screening, and she suggested that a different approach with a longer monitoring period may have been better to detect AFib.

The DANCAVAS study was supported by the Southern Region of Denmark, the Danish Heart Foundation, and the Danish Independent Research Councils.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ESC CONGRESS 2022

PCI fails to beat OMT in ischemic cardiomyopathy: REVIVED-BCIS2

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with optimal medical therapy (OMT) does not prolong survival or improve ventricular function, compared with OMT alone, in patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy, according to results from the REVIVED-BCIS2 trial.

The primary composite outcome of all-cause death or heart failure hospitalization occurred in 37.2% of the PCI group and 38% of the OMT group (hazard ratio, 0.99; P = .96) over a median of 3.4 years follow-up. The treatment effect was consistent across all subgroups.

There were no significant differences in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at 6 and 12 months.

Quality of life scores favored PCI early on, but there was catch-up over time with medical therapy, and this advantage disappeared by 2 years, principal investigator Divaka Perera, MD, King’s College London, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“The takeaway is that we should not be offering PCI to patients who have stable, well-medicated left ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Perera told this news organization. “But we should still consider revascularization in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes or who have lots of angina, because they were not included in the trial.”

The study, published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine, provides the first randomized evidence on PCI for ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Revascularization guidelines in the United States make no recommendation for PCI, whereas those in Europe recommend coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) first for patients with multivessel disease (class 1); they have a class 2a, level of evidence C indication for PCI in select patients. U.S. and European heart failure guidelines also support guideline directed therapy and CABG in select patients with ejection fractions of 35% or less.

This guidance is based on consensus opinion and the STICH trial, in which CABG plus OMT failed to provide a mortality benefit over OMT alone at 5 years but improved survival at 10 years in the extension STICHES study.

“Medical therapy for heart failure works, and this trial’s results are another important reminder of that,” said Eric Velazquez, MD, who led STICH and was invited to comment on the findings.

Mortality will only get better with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors, he noted, which were not included in the trial. Utilization of ACE inhibitors/ARBs/ARNIs and beta-blockers was similar to STICH and excellent in REVIVED. “They did do a better job in utilization of ICD and CRTs than the STICH trial, and I think that needs to be explored further about the impact of those changes.”

Nevertheless, ischemic cardiomyopathy patients have “unacceptably high mortality,” with the observed mortality about 20% at 3 years and about 35% at 5 years, said Dr. Velazquez, with Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

In most heart failure trials, HF hospitalization drives the primary composite endpoint, but the opposite was true here and in STICH, he observed. “You had twice the risk of dying during the 3.4 years than you did of being hospitalized for heart failure, and ... that is [an important] distinction we must realize is evident in our ischemic cardiomyopathy patients.”

The findings will likely not lead to a change in the guidelines, he added. “I think we continue as status quo for now and get more data.”

Despite the lack of randomized evidence, he cautioned that PCI is increasingly performed in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, with registry data suggesting nearly 60% of patients received the procedure.

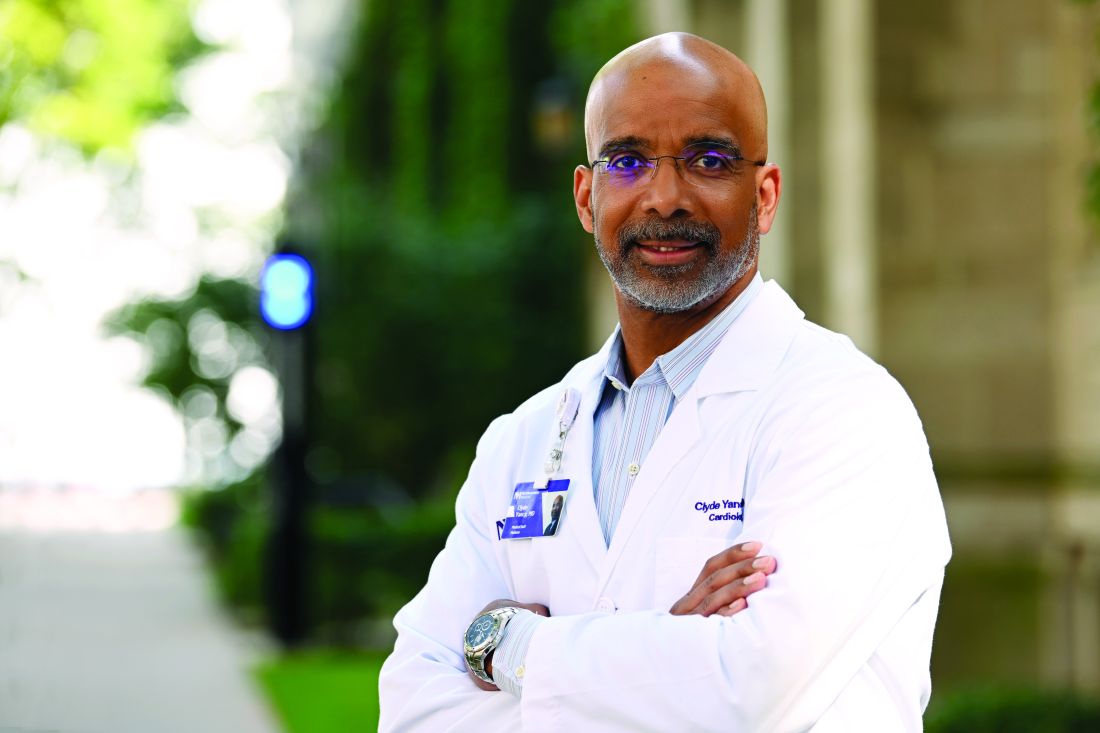

Reached for comment, Clyde Yancy, MD, chief of cardiology and vice dean of diversity & inclusion at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, said, “For now, the current guidelines are correct. Best application of guideline-directed medical and device therapy is the gold standard for heart failure, and that includes heart failure due to ischemic etiologies.

“Do these data resolve the question of revascularization in the setting of coronary disease and reduced EF heart failure? Hardly,” he added. “Clinical judgment must prevail, and where appropriate, coronary revascularization remains a consideration. But it is not a panacea.”

Detailed results

Between August 2013 and March 2020, REVIVED-BCIS2 enrolled 700 patients at 40 U.K. centers who had an LVEF of 35% or less, extensive CAD (defined by a British Cardiovascular Intervention Society myocardial Jeopardy Score [BCIS-JS] of at least 6), and viability in at least four myocardial segments amenable to PCI. Patients were evenly randomly assigned to individually adjusted pharmacologic and device therapy for heart failure alone or with PCI.

The average age was about 70, only 12.3% women, 344 patients had 2-vessel CAD, and 281 had 3-vessel CAD. The mean LVEF was 27% and median BCIS-JS score 10.

During follow-up, which reached 8.5 years in some patients due to the long enrollment, 31.7% of patients in the PCI group and 32.6% patients in the OMT group died from any cause and 14.7% and 15.3%, respectively, were admitted for heart failure.

LVEF improved by 1.8% at 6 months and 2% at 12 months in the PCI group and by 3.4% and 1.1%, respectively, in the OMT group. The mean between-group difference was –1.6% at 6 months and 0.9% at 12 months.

With regard to quality of life, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary score favored the PCI group by 6.5 points at 6 months and by 4.5 points at 12 months, but by 24 months the between-group difference was 2.6 points (95% confidence interval, –0.7 to 5.8). Scores on the EuroQol Group 5-Dimensions 5-Level Questionnaire followed a similar pattern.

Unplanned revascularization was more common in the OMT group (HR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.13-0.53). Acute myocardial infarction rates were similar in the two groups (HR, 1.01, 95% CI, 0.64-1.60), with the PCI group having more periprocedural infarcts and slightly fewer spontaneous infarcts.

Possible reasons for the discordant results between STICH and REVIVED are the threefold excess mortality within 30 days of CABG, whereas no such early hit occurred with PCI, lead investigator Dr. Perera said in an interview. Medical therapy has also evolved over time and REVIVED enrolled a more “real-world” population, with a median age close to 70 years versus 59 in STICH.

‘Modest’ degree of CAD?

An accompanying editorial, however, points out that despite considerable ventricular dysfunction, about half the patients in REVIVED had only 2-vessel disease and a median of two lesions treated.

“This relatively modest degree of coronary artery disease seems unusual for patients selected to undergo revascularization with the hope of restoring or normalizing ventricular function,” writes Ajay Kirtane, MD, from Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.

He said more details are needed on completeness of the revascularization, severity of stenosis, physiologic assessment of the lesion and, “most importantly, the correlation of stenosis with previous ischemic or viability testing.”

Asked about the editorial, Dr. Perera agreed that information on the type of revascularization and myocardial viability are important and said they hope to share analyses of the only recently unblinded data at the American College of Cardiology meeting next spring. Importantly, about 71% of viability testing was done by cardiac MR and the rest largely by dobutamine stress echocardiogram.

He disagreed, however, that participants had relatively modest CAD based on the 2- or 3-vessel classification and said the median score on the more granular BCIS-JS was 10, with maximum 12 indicating the entire myocardium is supplied by diseased vessels.

The trial also included almost 100 patients with left main disease, a group not included in previous medical therapy trials, including STICH and ISCHEMIA, Dr. Perera noted. “So, I think it was pretty, pretty severe coronary disease but a cohort that was better treated medically.”

George Dangas, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the study provides valuable information but also expressed concerns that the chronic heart failure in the trial was much more advanced than the CAD.

“Symptoms are low level, and this is predominantly related to CHF, and if you manage the CHF the best way with advanced therapies, assist device or transplant or any other way, that might take priority over the CAD lesions,” said Dr. Dangas, who was not associated with REVIVED. “I would expect CAD lesions would have more importance if we move into the class 3 or higher of symptomatology, and, again in this study, that was not [present] in over 70% of the patients.”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research’s Health Technology Assessment Program. Dr. Perera, Dr. Velazquez, and Dr. Dangas report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Kirtane reports grants, nonfinancial support and other from Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Abiomed, CathWorks, Siemens, Philips, ReCor Medical, Cardiovascular Systems, Amgen, and Chiesi. He reports grants and other from Neurotronic, Magental Medical, Canon, SoniVie, Shockwave Medical, and Merck. He also reports nonfinancial support from Opsens, Zoll, Regeneron, Biotronik, and Bolt Medical, and personal fees from IMDS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with optimal medical therapy (OMT) does not prolong survival or improve ventricular function, compared with OMT alone, in patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy, according to results from the REVIVED-BCIS2 trial.

The primary composite outcome of all-cause death or heart failure hospitalization occurred in 37.2% of the PCI group and 38% of the OMT group (hazard ratio, 0.99; P = .96) over a median of 3.4 years follow-up. The treatment effect was consistent across all subgroups.

There were no significant differences in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at 6 and 12 months.

Quality of life scores favored PCI early on, but there was catch-up over time with medical therapy, and this advantage disappeared by 2 years, principal investigator Divaka Perera, MD, King’s College London, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“The takeaway is that we should not be offering PCI to patients who have stable, well-medicated left ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Perera told this news organization. “But we should still consider revascularization in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes or who have lots of angina, because they were not included in the trial.”

The study, published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine, provides the first randomized evidence on PCI for ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Revascularization guidelines in the United States make no recommendation for PCI, whereas those in Europe recommend coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) first for patients with multivessel disease (class 1); they have a class 2a, level of evidence C indication for PCI in select patients. U.S. and European heart failure guidelines also support guideline directed therapy and CABG in select patients with ejection fractions of 35% or less.

This guidance is based on consensus opinion and the STICH trial, in which CABG plus OMT failed to provide a mortality benefit over OMT alone at 5 years but improved survival at 10 years in the extension STICHES study.

“Medical therapy for heart failure works, and this trial’s results are another important reminder of that,” said Eric Velazquez, MD, who led STICH and was invited to comment on the findings.

Mortality will only get better with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors, he noted, which were not included in the trial. Utilization of ACE inhibitors/ARBs/ARNIs and beta-blockers was similar to STICH and excellent in REVIVED. “They did do a better job in utilization of ICD and CRTs than the STICH trial, and I think that needs to be explored further about the impact of those changes.”

Nevertheless, ischemic cardiomyopathy patients have “unacceptably high mortality,” with the observed mortality about 20% at 3 years and about 35% at 5 years, said Dr. Velazquez, with Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

In most heart failure trials, HF hospitalization drives the primary composite endpoint, but the opposite was true here and in STICH, he observed. “You had twice the risk of dying during the 3.4 years than you did of being hospitalized for heart failure, and ... that is [an important] distinction we must realize is evident in our ischemic cardiomyopathy patients.”

The findings will likely not lead to a change in the guidelines, he added. “I think we continue as status quo for now and get more data.”

Despite the lack of randomized evidence, he cautioned that PCI is increasingly performed in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, with registry data suggesting nearly 60% of patients received the procedure.

Reached for comment, Clyde Yancy, MD, chief of cardiology and vice dean of diversity & inclusion at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, said, “For now, the current guidelines are correct. Best application of guideline-directed medical and device therapy is the gold standard for heart failure, and that includes heart failure due to ischemic etiologies.

“Do these data resolve the question of revascularization in the setting of coronary disease and reduced EF heart failure? Hardly,” he added. “Clinical judgment must prevail, and where appropriate, coronary revascularization remains a consideration. But it is not a panacea.”

Detailed results

Between August 2013 and March 2020, REVIVED-BCIS2 enrolled 700 patients at 40 U.K. centers who had an LVEF of 35% or less, extensive CAD (defined by a British Cardiovascular Intervention Society myocardial Jeopardy Score [BCIS-JS] of at least 6), and viability in at least four myocardial segments amenable to PCI. Patients were evenly randomly assigned to individually adjusted pharmacologic and device therapy for heart failure alone or with PCI.

The average age was about 70, only 12.3% women, 344 patients had 2-vessel CAD, and 281 had 3-vessel CAD. The mean LVEF was 27% and median BCIS-JS score 10.

During follow-up, which reached 8.5 years in some patients due to the long enrollment, 31.7% of patients in the PCI group and 32.6% patients in the OMT group died from any cause and 14.7% and 15.3%, respectively, were admitted for heart failure.

LVEF improved by 1.8% at 6 months and 2% at 12 months in the PCI group and by 3.4% and 1.1%, respectively, in the OMT group. The mean between-group difference was –1.6% at 6 months and 0.9% at 12 months.

With regard to quality of life, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary score favored the PCI group by 6.5 points at 6 months and by 4.5 points at 12 months, but by 24 months the between-group difference was 2.6 points (95% confidence interval, –0.7 to 5.8). Scores on the EuroQol Group 5-Dimensions 5-Level Questionnaire followed a similar pattern.

Unplanned revascularization was more common in the OMT group (HR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.13-0.53). Acute myocardial infarction rates were similar in the two groups (HR, 1.01, 95% CI, 0.64-1.60), with the PCI group having more periprocedural infarcts and slightly fewer spontaneous infarcts.

Possible reasons for the discordant results between STICH and REVIVED are the threefold excess mortality within 30 days of CABG, whereas no such early hit occurred with PCI, lead investigator Dr. Perera said in an interview. Medical therapy has also evolved over time and REVIVED enrolled a more “real-world” population, with a median age close to 70 years versus 59 in STICH.

‘Modest’ degree of CAD?

An accompanying editorial, however, points out that despite considerable ventricular dysfunction, about half the patients in REVIVED had only 2-vessel disease and a median of two lesions treated.

“This relatively modest degree of coronary artery disease seems unusual for patients selected to undergo revascularization with the hope of restoring or normalizing ventricular function,” writes Ajay Kirtane, MD, from Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.

He said more details are needed on completeness of the revascularization, severity of stenosis, physiologic assessment of the lesion and, “most importantly, the correlation of stenosis with previous ischemic or viability testing.”

Asked about the editorial, Dr. Perera agreed that information on the type of revascularization and myocardial viability are important and said they hope to share analyses of the only recently unblinded data at the American College of Cardiology meeting next spring. Importantly, about 71% of viability testing was done by cardiac MR and the rest largely by dobutamine stress echocardiogram.

He disagreed, however, that participants had relatively modest CAD based on the 2- or 3-vessel classification and said the median score on the more granular BCIS-JS was 10, with maximum 12 indicating the entire myocardium is supplied by diseased vessels.

The trial also included almost 100 patients with left main disease, a group not included in previous medical therapy trials, including STICH and ISCHEMIA, Dr. Perera noted. “So, I think it was pretty, pretty severe coronary disease but a cohort that was better treated medically.”

George Dangas, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the study provides valuable information but also expressed concerns that the chronic heart failure in the trial was much more advanced than the CAD.

“Symptoms are low level, and this is predominantly related to CHF, and if you manage the CHF the best way with advanced therapies, assist device or transplant or any other way, that might take priority over the CAD lesions,” said Dr. Dangas, who was not associated with REVIVED. “I would expect CAD lesions would have more importance if we move into the class 3 or higher of symptomatology, and, again in this study, that was not [present] in over 70% of the patients.”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research’s Health Technology Assessment Program. Dr. Perera, Dr. Velazquez, and Dr. Dangas report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Kirtane reports grants, nonfinancial support and other from Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Abiomed, CathWorks, Siemens, Philips, ReCor Medical, Cardiovascular Systems, Amgen, and Chiesi. He reports grants and other from Neurotronic, Magental Medical, Canon, SoniVie, Shockwave Medical, and Merck. He also reports nonfinancial support from Opsens, Zoll, Regeneron, Biotronik, and Bolt Medical, and personal fees from IMDS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with optimal medical therapy (OMT) does not prolong survival or improve ventricular function, compared with OMT alone, in patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy, according to results from the REVIVED-BCIS2 trial.

The primary composite outcome of all-cause death or heart failure hospitalization occurred in 37.2% of the PCI group and 38% of the OMT group (hazard ratio, 0.99; P = .96) over a median of 3.4 years follow-up. The treatment effect was consistent across all subgroups.

There were no significant differences in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at 6 and 12 months.

Quality of life scores favored PCI early on, but there was catch-up over time with medical therapy, and this advantage disappeared by 2 years, principal investigator Divaka Perera, MD, King’s College London, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“The takeaway is that we should not be offering PCI to patients who have stable, well-medicated left ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Perera told this news organization. “But we should still consider revascularization in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes or who have lots of angina, because they were not included in the trial.”

The study, published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine, provides the first randomized evidence on PCI for ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Revascularization guidelines in the United States make no recommendation for PCI, whereas those in Europe recommend coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) first for patients with multivessel disease (class 1); they have a class 2a, level of evidence C indication for PCI in select patients. U.S. and European heart failure guidelines also support guideline directed therapy and CABG in select patients with ejection fractions of 35% or less.

This guidance is based on consensus opinion and the STICH trial, in which CABG plus OMT failed to provide a mortality benefit over OMT alone at 5 years but improved survival at 10 years in the extension STICHES study.

“Medical therapy for heart failure works, and this trial’s results are another important reminder of that,” said Eric Velazquez, MD, who led STICH and was invited to comment on the findings.

Mortality will only get better with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors, he noted, which were not included in the trial. Utilization of ACE inhibitors/ARBs/ARNIs and beta-blockers was similar to STICH and excellent in REVIVED. “They did do a better job in utilization of ICD and CRTs than the STICH trial, and I think that needs to be explored further about the impact of those changes.”

Nevertheless, ischemic cardiomyopathy patients have “unacceptably high mortality,” with the observed mortality about 20% at 3 years and about 35% at 5 years, said Dr. Velazquez, with Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

In most heart failure trials, HF hospitalization drives the primary composite endpoint, but the opposite was true here and in STICH, he observed. “You had twice the risk of dying during the 3.4 years than you did of being hospitalized for heart failure, and ... that is [an important] distinction we must realize is evident in our ischemic cardiomyopathy patients.”

The findings will likely not lead to a change in the guidelines, he added. “I think we continue as status quo for now and get more data.”

Despite the lack of randomized evidence, he cautioned that PCI is increasingly performed in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, with registry data suggesting nearly 60% of patients received the procedure.

Reached for comment, Clyde Yancy, MD, chief of cardiology and vice dean of diversity & inclusion at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, said, “For now, the current guidelines are correct. Best application of guideline-directed medical and device therapy is the gold standard for heart failure, and that includes heart failure due to ischemic etiologies.

“Do these data resolve the question of revascularization in the setting of coronary disease and reduced EF heart failure? Hardly,” he added. “Clinical judgment must prevail, and where appropriate, coronary revascularization remains a consideration. But it is not a panacea.”

Detailed results

Between August 2013 and March 2020, REVIVED-BCIS2 enrolled 700 patients at 40 U.K. centers who had an LVEF of 35% or less, extensive CAD (defined by a British Cardiovascular Intervention Society myocardial Jeopardy Score [BCIS-JS] of at least 6), and viability in at least four myocardial segments amenable to PCI. Patients were evenly randomly assigned to individually adjusted pharmacologic and device therapy for heart failure alone or with PCI.

The average age was about 70, only 12.3% women, 344 patients had 2-vessel CAD, and 281 had 3-vessel CAD. The mean LVEF was 27% and median BCIS-JS score 10.

During follow-up, which reached 8.5 years in some patients due to the long enrollment, 31.7% of patients in the PCI group and 32.6% patients in the OMT group died from any cause and 14.7% and 15.3%, respectively, were admitted for heart failure.

LVEF improved by 1.8% at 6 months and 2% at 12 months in the PCI group and by 3.4% and 1.1%, respectively, in the OMT group. The mean between-group difference was –1.6% at 6 months and 0.9% at 12 months.

With regard to quality of life, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary score favored the PCI group by 6.5 points at 6 months and by 4.5 points at 12 months, but by 24 months the between-group difference was 2.6 points (95% confidence interval, –0.7 to 5.8). Scores on the EuroQol Group 5-Dimensions 5-Level Questionnaire followed a similar pattern.

Unplanned revascularization was more common in the OMT group (HR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.13-0.53). Acute myocardial infarction rates were similar in the two groups (HR, 1.01, 95% CI, 0.64-1.60), with the PCI group having more periprocedural infarcts and slightly fewer spontaneous infarcts.

Possible reasons for the discordant results between STICH and REVIVED are the threefold excess mortality within 30 days of CABG, whereas no such early hit occurred with PCI, lead investigator Dr. Perera said in an interview. Medical therapy has also evolved over time and REVIVED enrolled a more “real-world” population, with a median age close to 70 years versus 59 in STICH.

‘Modest’ degree of CAD?

An accompanying editorial, however, points out that despite considerable ventricular dysfunction, about half the patients in REVIVED had only 2-vessel disease and a median of two lesions treated.

“This relatively modest degree of coronary artery disease seems unusual for patients selected to undergo revascularization with the hope of restoring or normalizing ventricular function,” writes Ajay Kirtane, MD, from Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.

He said more details are needed on completeness of the revascularization, severity of stenosis, physiologic assessment of the lesion and, “most importantly, the correlation of stenosis with previous ischemic or viability testing.”

Asked about the editorial, Dr. Perera agreed that information on the type of revascularization and myocardial viability are important and said they hope to share analyses of the only recently unblinded data at the American College of Cardiology meeting next spring. Importantly, about 71% of viability testing was done by cardiac MR and the rest largely by dobutamine stress echocardiogram.

He disagreed, however, that participants had relatively modest CAD based on the 2- or 3-vessel classification and said the median score on the more granular BCIS-JS was 10, with maximum 12 indicating the entire myocardium is supplied by diseased vessels.

The trial also included almost 100 patients with left main disease, a group not included in previous medical therapy trials, including STICH and ISCHEMIA, Dr. Perera noted. “So, I think it was pretty, pretty severe coronary disease but a cohort that was better treated medically.”

George Dangas, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the study provides valuable information but also expressed concerns that the chronic heart failure in the trial was much more advanced than the CAD.

“Symptoms are low level, and this is predominantly related to CHF, and if you manage the CHF the best way with advanced therapies, assist device or transplant or any other way, that might take priority over the CAD lesions,” said Dr. Dangas, who was not associated with REVIVED. “I would expect CAD lesions would have more importance if we move into the class 3 or higher of symptomatology, and, again in this study, that was not [present] in over 70% of the patients.”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research’s Health Technology Assessment Program. Dr. Perera, Dr. Velazquez, and Dr. Dangas report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Kirtane reports grants, nonfinancial support and other from Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Abiomed, CathWorks, Siemens, Philips, ReCor Medical, Cardiovascular Systems, Amgen, and Chiesi. He reports grants and other from Neurotronic, Magental Medical, Canon, SoniVie, Shockwave Medical, and Merck. He also reports nonfinancial support from Opsens, Zoll, Regeneron, Biotronik, and Bolt Medical, and personal fees from IMDS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2022

In blinded trial, artificial intelligence beats sonographers for echo accuracy

Video-based artificial intelligence provided a more accurate and consistent reading of echocardiograms than did experienced sonographers in a blinded trial, a result suggesting that this technology is no longer experimental.

“We are planning to deploy this at Cedars, so this is essentially ready for use,” said David Ouyang, MD, who is affiliated with the Cedars-Sinai Medical School and is an instructor of cardiology at the University of California, both in Los Angeles.

The primary outcome of this trial, called EchoNet-RCT, was the proportion of cases in which cardiologists changed the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) reading by more than 5%. They were blinded to the origin of the reports.

This endpoint was reached in 27.2% of reports generated by sonographers but just 16.8% of reports generated by AI, a mean difference of 10.5% (P < .001).

The AI tested in the trial is called EchoNet-Dynamic. It employs a video-based deep learning algorithm that permits beat-by-beat evaluation of ejection fraction. The specifics of this system were described in a study published 2 years ago in Nature. In that evaluation of the model training set, the absolute error rate was 6% in the more than 10,000 annotated echocardiogram videos.

Echo-Net is first blinded AI echo trial

Although AI is already being employed for image evaluation in many areas of medicine, the EchoNet-RCT study “is the first blinded trial of AI in cardiology,” Dr. Ouyang said. Indeed, he noted that no prior study has even been randomized.

After a run-in period, 3,495 echocardiograms were randomizly assigned to be read by AI or by a sonographer. The reports generated by these two approaches were then evaluated by the blinded cardiologists. The sonographers and the cardiologists participating in this study had a mean of 14.1 years and 12.7 years of experience, respectively.

Each reading by both sonographers and AI was based on a single beat, but this presumably was a relative handicap for the potential advantage of AI technology, which is capable of evaluating ejection fraction across multiple cardiac cycles. The evaluation of multiple cycles has been shown previously to improve accuracy, but it is tedious and not commonly performed in routine practice, according to Dr. Ouyang.

AI favored for all major endpoints

The superiority of AI was calculated after noninferiority was demonstrated. AI also showed superiority for the secondary safety outcome which involved a test-retest evaluation. Historical AI and sonographer echocardiogram reports were again blindly assessed. Although the retest variability was lower for both (6.29% vs. 7.23%), the difference was still highly significant in favor of AI (P < .001)

The relative efficiency of AI to sonographer assessment was also tested and showed meaningful reductions in work time. While AI eliminates the labor of the sonographer completely (0 vs. a median of 119 seconds, P < .001), it was also associated with a highly significant reduction in median cardiologist time spent on echo evaluation (54 vs. 64 seconds, P < .001).

Assuming that AI is integrated into the routine workflow of a busy center, AI “could be very effective at not only improving the quality of echo reading output but also increasing efficiencies in time and effort spent by sonographers and cardiologists by simplifying otherwise tedious but important tasks,” Dr. Ouyang said.

The trial enrolled a relatively typical population. The median age was 66 years, 57% were male, and comorbidities such as diabetes and chronic kidney disease were common. When AI was compared with sonographer evaluation in groups stratified by these variables as well as by race, image quality, and location of the evaluation (inpatient vs. outpatient), the advantage of AI was consistent.

Cardiologists cannot detect AI-read echos

Identifying potential limitations of this study, James D. Thomas, MD, professor of medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, pointed out that it was a single-center trial, and he questioned a potential bias from cardiologists able to guess accurately which of the reports they were evaluating were generated by AI.

Dr. Ouyang acknowledged that this study was limited to patients at UCLA, but he pointed out that the training model was developed at Stanford (Calif.) University, so there were two sets of patients involved in testing the machine learning algorithm. He also noted that it was exceptionally large, providing a robust dataset.

As for the bias, this was evaluated as predefined endpoint.

“We asked the cardiologists to tell us [whether] they knew which reports were generated by AI,” Dr. Ouyang said. In 43% of cases, they reported they were not sure. However, when they did express confidence that the report was generated by AI, they were correct in only 32% of the cases and incorrect in 24%. Dr. Ouyang suggested these numbers argue against a substantial role for a bias affecting the trial results.

Dr. Thomas, who has an interest in the role of AI for cardiology, cautioned that there are “technical, privacy, commercial, maintenance, and regulatory barriers” that must be circumvented before AI is widely incorporated into clinical practice, but he praised this blinded trial for advancing the field. Even accounting for any limitations, he clearly shared Dr. Ouyang’s enthusiasm about the future of AI for EF assessment.

Dr. Ouyang reports financial relationships with EchoIQ, Ultromics, and InVision. Dr. Thomas reports financial relationships with Abbott, GE, egnite, EchoIQ, and Caption Health.

Video-based artificial intelligence provided a more accurate and consistent reading of echocardiograms than did experienced sonographers in a blinded trial, a result suggesting that this technology is no longer experimental.

“We are planning to deploy this at Cedars, so this is essentially ready for use,” said David Ouyang, MD, who is affiliated with the Cedars-Sinai Medical School and is an instructor of cardiology at the University of California, both in Los Angeles.

The primary outcome of this trial, called EchoNet-RCT, was the proportion of cases in which cardiologists changed the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) reading by more than 5%. They were blinded to the origin of the reports.

This endpoint was reached in 27.2% of reports generated by sonographers but just 16.8% of reports generated by AI, a mean difference of 10.5% (P < .001).

The AI tested in the trial is called EchoNet-Dynamic. It employs a video-based deep learning algorithm that permits beat-by-beat evaluation of ejection fraction. The specifics of this system were described in a study published 2 years ago in Nature. In that evaluation of the model training set, the absolute error rate was 6% in the more than 10,000 annotated echocardiogram videos.

Echo-Net is first blinded AI echo trial

Although AI is already being employed for image evaluation in many areas of medicine, the EchoNet-RCT study “is the first blinded trial of AI in cardiology,” Dr. Ouyang said. Indeed, he noted that no prior study has even been randomized.

After a run-in period, 3,495 echocardiograms were randomizly assigned to be read by AI or by a sonographer. The reports generated by these two approaches were then evaluated by the blinded cardiologists. The sonographers and the cardiologists participating in this study had a mean of 14.1 years and 12.7 years of experience, respectively.

Each reading by both sonographers and AI was based on a single beat, but this presumably was a relative handicap for the potential advantage of AI technology, which is capable of evaluating ejection fraction across multiple cardiac cycles. The evaluation of multiple cycles has been shown previously to improve accuracy, but it is tedious and not commonly performed in routine practice, according to Dr. Ouyang.

AI favored for all major endpoints

The superiority of AI was calculated after noninferiority was demonstrated. AI also showed superiority for the secondary safety outcome which involved a test-retest evaluation. Historical AI and sonographer echocardiogram reports were again blindly assessed. Although the retest variability was lower for both (6.29% vs. 7.23%), the difference was still highly significant in favor of AI (P < .001)

The relative efficiency of AI to sonographer assessment was also tested and showed meaningful reductions in work time. While AI eliminates the labor of the sonographer completely (0 vs. a median of 119 seconds, P < .001), it was also associated with a highly significant reduction in median cardiologist time spent on echo evaluation (54 vs. 64 seconds, P < .001).

Assuming that AI is integrated into the routine workflow of a busy center, AI “could be very effective at not only improving the quality of echo reading output but also increasing efficiencies in time and effort spent by sonographers and cardiologists by simplifying otherwise tedious but important tasks,” Dr. Ouyang said.

The trial enrolled a relatively typical population. The median age was 66 years, 57% were male, and comorbidities such as diabetes and chronic kidney disease were common. When AI was compared with sonographer evaluation in groups stratified by these variables as well as by race, image quality, and location of the evaluation (inpatient vs. outpatient), the advantage of AI was consistent.

Cardiologists cannot detect AI-read echos

Identifying potential limitations of this study, James D. Thomas, MD, professor of medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, pointed out that it was a single-center trial, and he questioned a potential bias from cardiologists able to guess accurately which of the reports they were evaluating were generated by AI.

Dr. Ouyang acknowledged that this study was limited to patients at UCLA, but he pointed out that the training model was developed at Stanford (Calif.) University, so there were two sets of patients involved in testing the machine learning algorithm. He also noted that it was exceptionally large, providing a robust dataset.

As for the bias, this was evaluated as predefined endpoint.

“We asked the cardiologists to tell us [whether] they knew which reports were generated by AI,” Dr. Ouyang said. In 43% of cases, they reported they were not sure. However, when they did express confidence that the report was generated by AI, they were correct in only 32% of the cases and incorrect in 24%. Dr. Ouyang suggested these numbers argue against a substantial role for a bias affecting the trial results.

Dr. Thomas, who has an interest in the role of AI for cardiology, cautioned that there are “technical, privacy, commercial, maintenance, and regulatory barriers” that must be circumvented before AI is widely incorporated into clinical practice, but he praised this blinded trial for advancing the field. Even accounting for any limitations, he clearly shared Dr. Ouyang’s enthusiasm about the future of AI for EF assessment.