User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

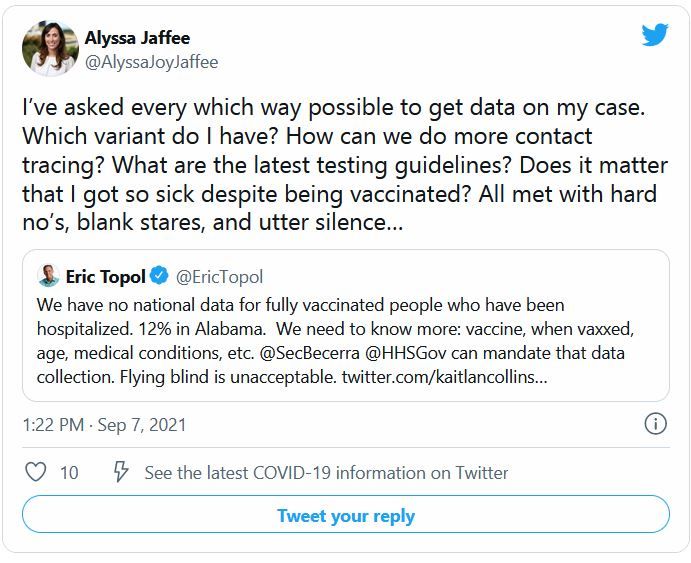

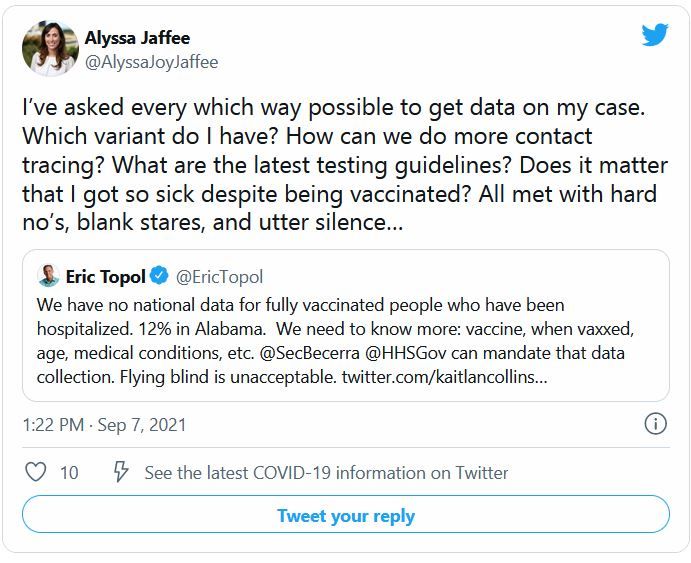

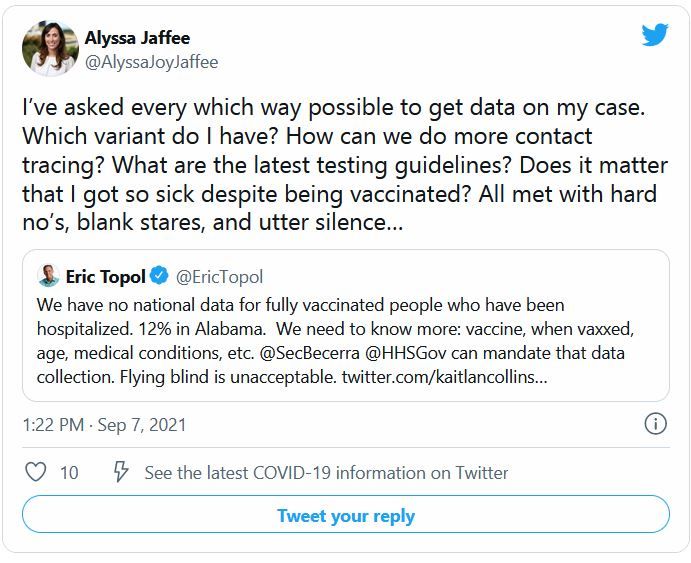

COVID vaccine preprint study prompts Twitter outrage

A preprint study finding that the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA COVID vaccine is associated with an increased risk for cardiac adverse events in teenage boys has elicited a firestorm on Twitter. Although some people issued thoughtful critiques, others lobbed insults against the authors, and still others accused them of either being antivaccine or stoking the fires of the vaccine skeptic movement.

The controversy began soon after the study was posted online September 8 on medRxiv. The authors conclude that for boys, the risk for a cardiac adverse event or hospitalization after the second dose of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine was “considerably higher” than the 120-day risk for hospitalization for COVID-19, “even at times of peak disease prevalence.” This was especially true for those aged 12 to 15 years and even those with no underlying health conditions.

The conclusion – as well as the paper’s source, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), and its methodology, modeled after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assessment of the database – did not sit well with many.

“Your methodology hugely overestimates risk, which many commentators who are specialists in the field have highlighted,” tweeted Deepti Gurdasani, senior lecturer in epidemiology at Queen Mary University of London. “Why make this claim when you must know it’s wrong?”

“The authors don’t know what they are doing and they are following their own ideology,” tweeted Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, in the cardiology division. Dr. Ziaeian also tweeted, “I believe the CDC is doing honest work and not dredging slop like you are.”

“Holy shit. Truly terrible methods in that paper,” tweeted Michael Mina, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and immunologist at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, more bluntly.

Some pointed out that VAERS is often used by vaccine skeptics to spread misinformation. “‘Dumpster diving’ describes studies using #VAERS by authors (almost always antivaxxers) who don’t understand its limitations,” tweeted David Gorski, MD, PhD, the editor of Science-Based Medicine, who says in his Twitter bio that he “exposes quackery.”

Added Dr. Gorski: “Doctors fell into this trap with their study suggesting #CovidVaccine is more dangerous to children than #COVID19.”

Dr. Gorski said he did not think that the authors were antivaccine. But, he tweeted, “I’d argue that at least one of the authors (Stevenson) is grossly unqualified to analyze the data. Mandrola? Marginal. The other two *might* be qualified in public health/epi, but they clearly either had no clue about #VAERS limitations or didn’t take them seriously enough.”

Two of the authors, John Mandrola, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist who is also a columnist for Medscape, and Tracy Beth Hoeg, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and sports medicine specialist, told this news organization that their estimates are not definitive, owing to the nature of the VAERS database.

“I want to emphasize that our signal is hypothesis-generating,” said Dr. Mandrola. “There’s obviously more research that needs to be done.”

“I don’t think it should be used to establish a for-certain rate,” said Dr. Hoeg, about the study. “It’s not a perfect way of establishing what the rate of cardiac adverse events was, but it gives you an estimate, and generally with VAERS, it’s a significant underestimate.”

Both Dr. Hoeg and Dr. Mandrola said their analysis showed enough of a signal that it warranted a rush to publish. “We felt that it was super time-sensitive,” Dr. Mandrola said.

Vaccine risks versus COVID harm

The authors searched the VAERS system for children aged 12 to 17 years who had received one or two doses of an mRNA vaccine and had symptoms of myocarditis, pericarditis, myopericarditis, or chest pain, and also troponin levels available in the lab data.

Of the 257 patients they examined, 211 had peak troponin values available for analysis. All but one received the Pfizer vaccine. Results were stratified by age and sex.

The authors found that the rates of cardiac adverse events (CAEs) after dose 1 were 12.0 per million for 12- to 15-year-old boys and 8.2 per million for 16- and 17-year-old boys, compared with 0.0 per million and 2.0 per million for girls the same ages.

The estimates for the 12- to 15-year-old boys were 22% to 150% higher than what the CDC had previously reported.

After the second dose, the rate of CAEs for boys 12 to 15 years was 162.2 per million (143% to 280% higher than the CDC estimate) and for boys 16 and 17 years, it was 94.0 per million, or 30% to 40% higher than CDC estimate.

Dr. Mandrola said he and his colleagues found potentially more cases by using slightly broader search terms than those employed by the CDC but agreed with some critics that a limitation was that they did not call the reporting physicians, as is typical with CDC follow-up on VAERS reports.

The authors point to troponin levels as valid indicators of myocardial damage. Peak troponin levels exceeded 2 ng/mL in 71% of the 12- to 15-year-olds and 82% of 16- and 17-year-olds.

The study shows that for boys 12 to 15 years with no comorbidities, the risk for a CAE after the second dose would be 22.8 times higher than the risk for hospitalization for COVID-19 during periods of low disease burden, 6.0 times higher during periods of moderate transmission, and 4.3 times higher during periods of high transmission.

The authors acknowledge in the paper that their analysis “does not take into account any benefits the vaccine provides against transmission to others, long-term COVID-19 disease risk, or protection from nonsevere COVID-19 symptoms.”

Both Dr. Mandrola and Dr. Hoeg told this news organization that they are currently recalculating their estimates because of the rising numbers of pediatric hospitalizations from the Delta variant surge.

Paper rejected by journals

Dr. Hoeg said in an interview that the paper went through peer-review at three journals but was rejected by all three, for reasons that were not made clear.

She and the other authors incorporated the reviewers’ feedback at each turn and included all of their suggestions in the paper that was ultimately uploaded to medRxiv, said Dr. Hoeg.

They decided to put it out as a preprint after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued its data and then a warning on June 25 about myocarditis with use of the Pfizer vaccine in children 12 to 15 years of age.

The preprint study was picked up by some media outlets, including The Telegraph and The Guardian newspapers, and tweeted out by vaccine skeptics like Robert W. Malone, MD.

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Georgia), an outspoken vaccine skeptic, tweeted out the Guardian story saying that the findings mean “there is every reason to stop the covid vaccine mandates.”

Dr. Gorski noted in tweets and in a blog post that one of the paper’s coauthors, Josh Stevenson, is part of Rational Ground, a group that supports the Great Barrington Declaration and is against lockdowns and mask mandates.

Mr. Stevenson did not disclose his affiliation in the paper, and Dr. Hoeg said in an interview that she was unaware of the group and Mr. Stevenson’s association with it and that she did not have the impression that he was altering the data to show any bias.

Both Dr. Mandrola and Dr. Hoeg said they are provaccine and that they were dismayed to find their work being used to support any agenda. “It’s very frustrating,” said Dr. Hoeg, adding that she understands that “when you publish research on a controversial topic, people are going to take it and use it for their agendas.”

Some on Twitter blamed the open and free-wheeling nature of preprints.

Harlan Krumholz, MD, SM, the Harold H. Hines, junior professor of medicine and public health at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., which oversees medRxiv, tweeted, “Do you get that the discussion about the preprint is exactly the purpose of #preprints. So that way when someone claims something, you can look at the source and experts can comment.”

But Dr. Ziaeian tweeted back, “Preprints like this one can be weaponized to stir anti-vaccine lies and damage public health.”

In turn, the Yale physician replied, “Unfortunately these days, almost anything can be weaponized, distorted, misunderstood.” Dr. Krumholz added: “There is no question that this preprint is worthy of deep vetting and discussion. But there is a #preprint artifact to examine.”

Measured support

Some clinicians signaled their support for open debate and the preprint’s findings.

“I’ve been very critical of preprints that are too quickly disseminated in the media, and this one is no exception,” tweeted Walid Gellad, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “On the other hand, I think the vitriol directed at these authors is wrong,” he added.

“Like it or not, the issue of myocarditis in kids is an issue. Other countries have made vaccination decisions because of this issue, not because they’re driven by some ideology,” he tweeted.

Dr. Gellad also notes that the FDA has estimated the risk could be as high as one in 5,000 and that the preprint numbers could actually be underestimates.

In a long thread, Frank Han, MD, an adult congenital and pediatric cardiologist at the University of Illinois, tweets that relying on the VAERS reports might be faulty and that advanced cardiac imaging – guided by strict criteria – is the best way to determine myocarditis. And, he tweeted, “Physician review of VAERS reports really matters.”

Dr. Han concluded that vaccination “trades in a significant risk with a much smaller risk. That’s what counts in the end.”

In a response, Dr. Mandrola called Han’s tweets “reasoned criticism of our analysis.” He adds that his and Dr. Hoeg’s study have limits, but “our point is not to avoid protecting kids, but how to do so most safely.”

Both Dr. Mandrola and Dr. Hoeg said they welcomed critiques, but they felt blindsided by the vehemence of some of the Twitter debate.

“Some of the vitriol was surprising,” Dr. Mandrola said. “I kind of have this naive notion that people would assume that we’re not bad people,” he added.

However, Dr. Mandrola is known on Twitter for sometimes being highly critical of other researchers’ work, referring to some studies as “howlers,” and has in the past called out others for citing those papers.

Dr. Hoeg said she found critiques about weaknesses in the methods to be helpful. But she said many tweets were “attacking us as people, or not really attacking anything about our study, but just attacking the finding,” which does not help anyone “figure out what we should do about the safety signal or how we can research it further.”

Said Dr. Mandrola: “Why would we just ignore that and go forward with two-shot vaccination as a mandate when other countries are looking at other strategies?”

He noted that the United Kingdom has announced that children 12 to 15 years of age should receive just one shot of the mRNA vaccines instead of two because of the risk for myocarditis. Sixteen- to 18-year-olds have already been advised to get only one dose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A preprint study finding that the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA COVID vaccine is associated with an increased risk for cardiac adverse events in teenage boys has elicited a firestorm on Twitter. Although some people issued thoughtful critiques, others lobbed insults against the authors, and still others accused them of either being antivaccine or stoking the fires of the vaccine skeptic movement.

The controversy began soon after the study was posted online September 8 on medRxiv. The authors conclude that for boys, the risk for a cardiac adverse event or hospitalization after the second dose of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine was “considerably higher” than the 120-day risk for hospitalization for COVID-19, “even at times of peak disease prevalence.” This was especially true for those aged 12 to 15 years and even those with no underlying health conditions.

The conclusion – as well as the paper’s source, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), and its methodology, modeled after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assessment of the database – did not sit well with many.

“Your methodology hugely overestimates risk, which many commentators who are specialists in the field have highlighted,” tweeted Deepti Gurdasani, senior lecturer in epidemiology at Queen Mary University of London. “Why make this claim when you must know it’s wrong?”

“The authors don’t know what they are doing and they are following their own ideology,” tweeted Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, in the cardiology division. Dr. Ziaeian also tweeted, “I believe the CDC is doing honest work and not dredging slop like you are.”

“Holy shit. Truly terrible methods in that paper,” tweeted Michael Mina, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and immunologist at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, more bluntly.

Some pointed out that VAERS is often used by vaccine skeptics to spread misinformation. “‘Dumpster diving’ describes studies using #VAERS by authors (almost always antivaxxers) who don’t understand its limitations,” tweeted David Gorski, MD, PhD, the editor of Science-Based Medicine, who says in his Twitter bio that he “exposes quackery.”

Added Dr. Gorski: “Doctors fell into this trap with their study suggesting #CovidVaccine is more dangerous to children than #COVID19.”

Dr. Gorski said he did not think that the authors were antivaccine. But, he tweeted, “I’d argue that at least one of the authors (Stevenson) is grossly unqualified to analyze the data. Mandrola? Marginal. The other two *might* be qualified in public health/epi, but they clearly either had no clue about #VAERS limitations or didn’t take them seriously enough.”

Two of the authors, John Mandrola, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist who is also a columnist for Medscape, and Tracy Beth Hoeg, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and sports medicine specialist, told this news organization that their estimates are not definitive, owing to the nature of the VAERS database.

“I want to emphasize that our signal is hypothesis-generating,” said Dr. Mandrola. “There’s obviously more research that needs to be done.”

“I don’t think it should be used to establish a for-certain rate,” said Dr. Hoeg, about the study. “It’s not a perfect way of establishing what the rate of cardiac adverse events was, but it gives you an estimate, and generally with VAERS, it’s a significant underestimate.”

Both Dr. Hoeg and Dr. Mandrola said their analysis showed enough of a signal that it warranted a rush to publish. “We felt that it was super time-sensitive,” Dr. Mandrola said.

Vaccine risks versus COVID harm

The authors searched the VAERS system for children aged 12 to 17 years who had received one or two doses of an mRNA vaccine and had symptoms of myocarditis, pericarditis, myopericarditis, or chest pain, and also troponin levels available in the lab data.

Of the 257 patients they examined, 211 had peak troponin values available for analysis. All but one received the Pfizer vaccine. Results were stratified by age and sex.

The authors found that the rates of cardiac adverse events (CAEs) after dose 1 were 12.0 per million for 12- to 15-year-old boys and 8.2 per million for 16- and 17-year-old boys, compared with 0.0 per million and 2.0 per million for girls the same ages.

The estimates for the 12- to 15-year-old boys were 22% to 150% higher than what the CDC had previously reported.

After the second dose, the rate of CAEs for boys 12 to 15 years was 162.2 per million (143% to 280% higher than the CDC estimate) and for boys 16 and 17 years, it was 94.0 per million, or 30% to 40% higher than CDC estimate.

Dr. Mandrola said he and his colleagues found potentially more cases by using slightly broader search terms than those employed by the CDC but agreed with some critics that a limitation was that they did not call the reporting physicians, as is typical with CDC follow-up on VAERS reports.

The authors point to troponin levels as valid indicators of myocardial damage. Peak troponin levels exceeded 2 ng/mL in 71% of the 12- to 15-year-olds and 82% of 16- and 17-year-olds.

The study shows that for boys 12 to 15 years with no comorbidities, the risk for a CAE after the second dose would be 22.8 times higher than the risk for hospitalization for COVID-19 during periods of low disease burden, 6.0 times higher during periods of moderate transmission, and 4.3 times higher during periods of high transmission.

The authors acknowledge in the paper that their analysis “does not take into account any benefits the vaccine provides against transmission to others, long-term COVID-19 disease risk, or protection from nonsevere COVID-19 symptoms.”

Both Dr. Mandrola and Dr. Hoeg told this news organization that they are currently recalculating their estimates because of the rising numbers of pediatric hospitalizations from the Delta variant surge.

Paper rejected by journals

Dr. Hoeg said in an interview that the paper went through peer-review at three journals but was rejected by all three, for reasons that were not made clear.

She and the other authors incorporated the reviewers’ feedback at each turn and included all of their suggestions in the paper that was ultimately uploaded to medRxiv, said Dr. Hoeg.

They decided to put it out as a preprint after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued its data and then a warning on June 25 about myocarditis with use of the Pfizer vaccine in children 12 to 15 years of age.

The preprint study was picked up by some media outlets, including The Telegraph and The Guardian newspapers, and tweeted out by vaccine skeptics like Robert W. Malone, MD.

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Georgia), an outspoken vaccine skeptic, tweeted out the Guardian story saying that the findings mean “there is every reason to stop the covid vaccine mandates.”

Dr. Gorski noted in tweets and in a blog post that one of the paper’s coauthors, Josh Stevenson, is part of Rational Ground, a group that supports the Great Barrington Declaration and is against lockdowns and mask mandates.

Mr. Stevenson did not disclose his affiliation in the paper, and Dr. Hoeg said in an interview that she was unaware of the group and Mr. Stevenson’s association with it and that she did not have the impression that he was altering the data to show any bias.

Both Dr. Mandrola and Dr. Hoeg said they are provaccine and that they were dismayed to find their work being used to support any agenda. “It’s very frustrating,” said Dr. Hoeg, adding that she understands that “when you publish research on a controversial topic, people are going to take it and use it for their agendas.”

Some on Twitter blamed the open and free-wheeling nature of preprints.

Harlan Krumholz, MD, SM, the Harold H. Hines, junior professor of medicine and public health at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., which oversees medRxiv, tweeted, “Do you get that the discussion about the preprint is exactly the purpose of #preprints. So that way when someone claims something, you can look at the source and experts can comment.”

But Dr. Ziaeian tweeted back, “Preprints like this one can be weaponized to stir anti-vaccine lies and damage public health.”

In turn, the Yale physician replied, “Unfortunately these days, almost anything can be weaponized, distorted, misunderstood.” Dr. Krumholz added: “There is no question that this preprint is worthy of deep vetting and discussion. But there is a #preprint artifact to examine.”

Measured support

Some clinicians signaled their support for open debate and the preprint’s findings.

“I’ve been very critical of preprints that are too quickly disseminated in the media, and this one is no exception,” tweeted Walid Gellad, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “On the other hand, I think the vitriol directed at these authors is wrong,” he added.

“Like it or not, the issue of myocarditis in kids is an issue. Other countries have made vaccination decisions because of this issue, not because they’re driven by some ideology,” he tweeted.

Dr. Gellad also notes that the FDA has estimated the risk could be as high as one in 5,000 and that the preprint numbers could actually be underestimates.

In a long thread, Frank Han, MD, an adult congenital and pediatric cardiologist at the University of Illinois, tweets that relying on the VAERS reports might be faulty and that advanced cardiac imaging – guided by strict criteria – is the best way to determine myocarditis. And, he tweeted, “Physician review of VAERS reports really matters.”

Dr. Han concluded that vaccination “trades in a significant risk with a much smaller risk. That’s what counts in the end.”

In a response, Dr. Mandrola called Han’s tweets “reasoned criticism of our analysis.” He adds that his and Dr. Hoeg’s study have limits, but “our point is not to avoid protecting kids, but how to do so most safely.”

Both Dr. Mandrola and Dr. Hoeg said they welcomed critiques, but they felt blindsided by the vehemence of some of the Twitter debate.

“Some of the vitriol was surprising,” Dr. Mandrola said. “I kind of have this naive notion that people would assume that we’re not bad people,” he added.

However, Dr. Mandrola is known on Twitter for sometimes being highly critical of other researchers’ work, referring to some studies as “howlers,” and has in the past called out others for citing those papers.

Dr. Hoeg said she found critiques about weaknesses in the methods to be helpful. But she said many tweets were “attacking us as people, or not really attacking anything about our study, but just attacking the finding,” which does not help anyone “figure out what we should do about the safety signal or how we can research it further.”

Said Dr. Mandrola: “Why would we just ignore that and go forward with two-shot vaccination as a mandate when other countries are looking at other strategies?”

He noted that the United Kingdom has announced that children 12 to 15 years of age should receive just one shot of the mRNA vaccines instead of two because of the risk for myocarditis. Sixteen- to 18-year-olds have already been advised to get only one dose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A preprint study finding that the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA COVID vaccine is associated with an increased risk for cardiac adverse events in teenage boys has elicited a firestorm on Twitter. Although some people issued thoughtful critiques, others lobbed insults against the authors, and still others accused them of either being antivaccine or stoking the fires of the vaccine skeptic movement.

The controversy began soon after the study was posted online September 8 on medRxiv. The authors conclude that for boys, the risk for a cardiac adverse event or hospitalization after the second dose of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine was “considerably higher” than the 120-day risk for hospitalization for COVID-19, “even at times of peak disease prevalence.” This was especially true for those aged 12 to 15 years and even those with no underlying health conditions.

The conclusion – as well as the paper’s source, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), and its methodology, modeled after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assessment of the database – did not sit well with many.

“Your methodology hugely overestimates risk, which many commentators who are specialists in the field have highlighted,” tweeted Deepti Gurdasani, senior lecturer in epidemiology at Queen Mary University of London. “Why make this claim when you must know it’s wrong?”

“The authors don’t know what they are doing and they are following their own ideology,” tweeted Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, in the cardiology division. Dr. Ziaeian also tweeted, “I believe the CDC is doing honest work and not dredging slop like you are.”

“Holy shit. Truly terrible methods in that paper,” tweeted Michael Mina, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and immunologist at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, more bluntly.

Some pointed out that VAERS is often used by vaccine skeptics to spread misinformation. “‘Dumpster diving’ describes studies using #VAERS by authors (almost always antivaxxers) who don’t understand its limitations,” tweeted David Gorski, MD, PhD, the editor of Science-Based Medicine, who says in his Twitter bio that he “exposes quackery.”

Added Dr. Gorski: “Doctors fell into this trap with their study suggesting #CovidVaccine is more dangerous to children than #COVID19.”

Dr. Gorski said he did not think that the authors were antivaccine. But, he tweeted, “I’d argue that at least one of the authors (Stevenson) is grossly unqualified to analyze the data. Mandrola? Marginal. The other two *might* be qualified in public health/epi, but they clearly either had no clue about #VAERS limitations or didn’t take them seriously enough.”

Two of the authors, John Mandrola, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist who is also a columnist for Medscape, and Tracy Beth Hoeg, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and sports medicine specialist, told this news organization that their estimates are not definitive, owing to the nature of the VAERS database.

“I want to emphasize that our signal is hypothesis-generating,” said Dr. Mandrola. “There’s obviously more research that needs to be done.”

“I don’t think it should be used to establish a for-certain rate,” said Dr. Hoeg, about the study. “It’s not a perfect way of establishing what the rate of cardiac adverse events was, but it gives you an estimate, and generally with VAERS, it’s a significant underestimate.”

Both Dr. Hoeg and Dr. Mandrola said their analysis showed enough of a signal that it warranted a rush to publish. “We felt that it was super time-sensitive,” Dr. Mandrola said.

Vaccine risks versus COVID harm

The authors searched the VAERS system for children aged 12 to 17 years who had received one or two doses of an mRNA vaccine and had symptoms of myocarditis, pericarditis, myopericarditis, or chest pain, and also troponin levels available in the lab data.

Of the 257 patients they examined, 211 had peak troponin values available for analysis. All but one received the Pfizer vaccine. Results were stratified by age and sex.

The authors found that the rates of cardiac adverse events (CAEs) after dose 1 were 12.0 per million for 12- to 15-year-old boys and 8.2 per million for 16- and 17-year-old boys, compared with 0.0 per million and 2.0 per million for girls the same ages.

The estimates for the 12- to 15-year-old boys were 22% to 150% higher than what the CDC had previously reported.

After the second dose, the rate of CAEs for boys 12 to 15 years was 162.2 per million (143% to 280% higher than the CDC estimate) and for boys 16 and 17 years, it was 94.0 per million, or 30% to 40% higher than CDC estimate.

Dr. Mandrola said he and his colleagues found potentially more cases by using slightly broader search terms than those employed by the CDC but agreed with some critics that a limitation was that they did not call the reporting physicians, as is typical with CDC follow-up on VAERS reports.

The authors point to troponin levels as valid indicators of myocardial damage. Peak troponin levels exceeded 2 ng/mL in 71% of the 12- to 15-year-olds and 82% of 16- and 17-year-olds.

The study shows that for boys 12 to 15 years with no comorbidities, the risk for a CAE after the second dose would be 22.8 times higher than the risk for hospitalization for COVID-19 during periods of low disease burden, 6.0 times higher during periods of moderate transmission, and 4.3 times higher during periods of high transmission.

The authors acknowledge in the paper that their analysis “does not take into account any benefits the vaccine provides against transmission to others, long-term COVID-19 disease risk, or protection from nonsevere COVID-19 symptoms.”

Both Dr. Mandrola and Dr. Hoeg told this news organization that they are currently recalculating their estimates because of the rising numbers of pediatric hospitalizations from the Delta variant surge.

Paper rejected by journals

Dr. Hoeg said in an interview that the paper went through peer-review at three journals but was rejected by all three, for reasons that were not made clear.

She and the other authors incorporated the reviewers’ feedback at each turn and included all of their suggestions in the paper that was ultimately uploaded to medRxiv, said Dr. Hoeg.

They decided to put it out as a preprint after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued its data and then a warning on June 25 about myocarditis with use of the Pfizer vaccine in children 12 to 15 years of age.

The preprint study was picked up by some media outlets, including The Telegraph and The Guardian newspapers, and tweeted out by vaccine skeptics like Robert W. Malone, MD.

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Georgia), an outspoken vaccine skeptic, tweeted out the Guardian story saying that the findings mean “there is every reason to stop the covid vaccine mandates.”

Dr. Gorski noted in tweets and in a blog post that one of the paper’s coauthors, Josh Stevenson, is part of Rational Ground, a group that supports the Great Barrington Declaration and is against lockdowns and mask mandates.

Mr. Stevenson did not disclose his affiliation in the paper, and Dr. Hoeg said in an interview that she was unaware of the group and Mr. Stevenson’s association with it and that she did not have the impression that he was altering the data to show any bias.

Both Dr. Mandrola and Dr. Hoeg said they are provaccine and that they were dismayed to find their work being used to support any agenda. “It’s very frustrating,” said Dr. Hoeg, adding that she understands that “when you publish research on a controversial topic, people are going to take it and use it for their agendas.”

Some on Twitter blamed the open and free-wheeling nature of preprints.

Harlan Krumholz, MD, SM, the Harold H. Hines, junior professor of medicine and public health at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., which oversees medRxiv, tweeted, “Do you get that the discussion about the preprint is exactly the purpose of #preprints. So that way when someone claims something, you can look at the source and experts can comment.”

But Dr. Ziaeian tweeted back, “Preprints like this one can be weaponized to stir anti-vaccine lies and damage public health.”

In turn, the Yale physician replied, “Unfortunately these days, almost anything can be weaponized, distorted, misunderstood.” Dr. Krumholz added: “There is no question that this preprint is worthy of deep vetting and discussion. But there is a #preprint artifact to examine.”

Measured support

Some clinicians signaled their support for open debate and the preprint’s findings.

“I’ve been very critical of preprints that are too quickly disseminated in the media, and this one is no exception,” tweeted Walid Gellad, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “On the other hand, I think the vitriol directed at these authors is wrong,” he added.

“Like it or not, the issue of myocarditis in kids is an issue. Other countries have made vaccination decisions because of this issue, not because they’re driven by some ideology,” he tweeted.

Dr. Gellad also notes that the FDA has estimated the risk could be as high as one in 5,000 and that the preprint numbers could actually be underestimates.

In a long thread, Frank Han, MD, an adult congenital and pediatric cardiologist at the University of Illinois, tweets that relying on the VAERS reports might be faulty and that advanced cardiac imaging – guided by strict criteria – is the best way to determine myocarditis. And, he tweeted, “Physician review of VAERS reports really matters.”

Dr. Han concluded that vaccination “trades in a significant risk with a much smaller risk. That’s what counts in the end.”

In a response, Dr. Mandrola called Han’s tweets “reasoned criticism of our analysis.” He adds that his and Dr. Hoeg’s study have limits, but “our point is not to avoid protecting kids, but how to do so most safely.”

Both Dr. Mandrola and Dr. Hoeg said they welcomed critiques, but they felt blindsided by the vehemence of some of the Twitter debate.

“Some of the vitriol was surprising,” Dr. Mandrola said. “I kind of have this naive notion that people would assume that we’re not bad people,” he added.

However, Dr. Mandrola is known on Twitter for sometimes being highly critical of other researchers’ work, referring to some studies as “howlers,” and has in the past called out others for citing those papers.

Dr. Hoeg said she found critiques about weaknesses in the methods to be helpful. But she said many tweets were “attacking us as people, or not really attacking anything about our study, but just attacking the finding,” which does not help anyone “figure out what we should do about the safety signal or how we can research it further.”

Said Dr. Mandrola: “Why would we just ignore that and go forward with two-shot vaccination as a mandate when other countries are looking at other strategies?”

He noted that the United Kingdom has announced that children 12 to 15 years of age should receive just one shot of the mRNA vaccines instead of two because of the risk for myocarditis. Sixteen- to 18-year-olds have already been advised to get only one dose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Three ‘bad news’ payment changes coming soon for physicians

Physicians are bracing for upcoming changes in reimbursement that may start within a few months. As doctors gear up for another wave of COVID, payment trends may not be the top priority, but some “uh oh” announcements in the fall of 2021 could have far-reaching implications that could affect your future.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a proposed rule in the summer covering key aspects of physician payment. Although the rule contained some small bright lights, the most important changes proposed were far from welcome.

Here’s what could be in store:

1. The highly anticipated Medicare Physician Fee Schedule ruling confirmed a sweeping payment cut. The drive to maintain budget neutrality forced the federal agency to reduce Medicare payments, on average, by nearly 4%. Many physicians are outraged at the proposed cut.

2. More bad news for 2022: Sequestration will be back. Sequestration is the mandatory, pesky, negative 2% adjustment on all Medicare payments. It had been put on hold and is set to return at the beginning of 2022.

Essentially, sequestration reduces what Medicare pays its providers for health services, but Medicare beneficiaries bear no responsibility for the cost difference. To prevent further debt, CMS imposes financially on hospitals, physicians, and other health care providers.

The Health Resources and Services Administration has funds remaining to reimburse for all COVID-related testing, treatment, and vaccines provided to uninsured individuals. You can apply and be reimbursed at Medicare rates for these services when COVID is the primary diagnosis (or secondary in the case of pregnancy). Patients need not be American citizens for you to get paid.

3. Down to a nail-biter: The final ruling is expected in early November. The situation smacks of earlier days when physicians clung to a precipice, waiting in anticipation for a legislative body to save them from the dreaded income plunge. Indeed, we are slipping back to the decade-long period when Congress kept coming to the rescue simply to maintain the status quo.

Many anticipate a last-minute Congressional intervention to save the day, particularly in the midst of another COVID spike. The promises of a stable reimbursement system made possible by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act have been far from realized, and there are signs that the payment landscape is in the midst of a fundamental transformation.

Other changes proposed in the 1,747-page ruling include:

Positive:

- More telehealth services will be covered by Medicare, including home visits.

- Tele–mental health services got a big boost; many restrictions were removed so that now the patient’s home is considered a permissible originating site. It also allows for audio-only (no visual required) encounters; the audio-only allowance will extend to opioid use disorder treatment services. Phone treatment is covered.

- Permanent adoption of G2252: The 11- to 20-minute virtual check-in code wasn’t just a one-time payment but will be reimbursed in perpetuity.

- Boosts in reimbursement for chronic care and principal care management codes, which range on the basis of service but indicate a commitment to pay for care coordination.

- Clarification of roles and billing opportunities for split/shared visits, which occur if a physician and advanced practice provider see the same patient on a particular day. Prepare for new coding rules to include a modifier. Previously, the rules for billing were muddled, so transparency helps guide payment opportunities.

- Delay of the appropriate use criteria for advanced imaging for 1 (more) year, a welcome postponement of the ruling that carries a significant administrative burden.

- Physician assistants will be able to bill Medicare directly, and referrals to be made to medical nutrition therapy by a nontreating physician.

- A new approach to patient cost-sharing for colorectal cancer screenings will be phased in. This area has caused problems in the past when the physician identifies a need for additional services (for example, polyp removal by a gastroenterologist during routine colonoscopy).

Not positive:

- Which specialties benefit and which get zapped? The anticipated impact by specialty ranges from hits to interventional radiologists (–9%) and vascular surgeons (–8%), to increases for family practitioners, hand surgeons, endocrinologists, and geriatricians, each estimated to gain a modest 2%. (The exception is portable x-ray supplier, with an estimated increase of 10%.) All other specialties fall in between.

- The proposed conversion factor for 2022 is $33.58, a 3.75% drop from the 2021 conversion factor of $34.89.

The proposed ruling also covered the Quality Payment Program, the overarching program of which the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is the main track for participation. The proposal incorporates additional episode-based cost measures as well as updates to quality indicators and improvement activities.

MIPS penalties. The stakes are higher now, with 9% penalties on the table for nonparticipants. The government offers physicians the ability to officially get out of the program in 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby staving off the steep penalty. The option, which is available through the end of the year, requires a simple application that can be completed on behalf of the entire practice. If you want out, now is the time to find and fill out that application.

Exempt from technology requirements. If the proposal is accepted, small practices – defined by CMS as 15 eligible clinicians or fewer – won’t have to file an annual application to reweight the “promoting interoperability” portion of the program. If acknowledged, small practices will automatically be exempt from the program’s technology section. That’s a big plus, as one of the many chief complaints from small practices is the onus of meeting the technology requirements, which include a security risk analysis, bi-directional health information exchange, public health reporting, and patient access to health information. Meeting the requirements is no small feat. That will only affect future years, so be sure to apply in 2021 if applicable for your practice.

Changes in MIPS. MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) are anticipated for 2023, with the government releasing details about proposed models for heart disease, rheumatology, joint repair, and more. The MVPs are slated to take over the traditional MIPS by 2027.

The program will shift to 30% of your score coming from the “cost” category, which is based on the government’s analysis of a physician’s claims – and, if attributed, the claims of the patients for whom you care. This area is tricky to manage, but recognize that the costs under scrutiny are the expenses paid by Medicare on behalf of its patients.

In essence, Medicare is measuring the cost of your patients as compared with your colleagues’ costs (in the form of specialty-based benchmarks). Therefore, if you’re referring, or ordering, a more costly set of diagnostic tests, assessments, or interventions than your peers, you’ll be dinged.

However, physicians are more likely this year to flat out reject participation in the federal payment program. Payouts have been paltry and dismal to date, and the buzz is that physicians just don’t consider it worth the effort. Of course, clearing the threshold (which is proposed at 70 points next year) is a must to avoid the penalty, but don’t go crazy to get a perfect score as it won’t count for much. 2022 is the final year that there are any monies for exceptional performance.

Considering that the payouts for exceptional performance have been less than 2% for several years now, it’s hard to justify dedicating resources to achieve perfection. Experts believe that even exceptional performance will only be worth pennies in bonus payments.

The fear of the stick, therefore, may be the only motivation. And that is subjective, as physicians weigh the effort required versus just taking the hit on the penalty. But the penalty is substantial, and so even without the incentive, it’s important to participate at least at the threshold.

Fewer cost-sharing waivers. While the federal government’s payment policies have a major impact on reimbursement, other forces may have broader implications. Commercial payers have rolled back cost-sharing waivers, bringing to light the significant financial responsibility that patients have for their health care in the form of deductibles, coinsurance, and so forth.

More than a third of Americans had trouble paying their health care bills before the pandemic; as patients catch up with services that were postponed or delayed because of the pandemic, this may expose challenges for you. Patients with unpaid bills translate into your financial burden.

Virtual-first health plans. Patients may be seeking alternatives to avoid the frustrating cycle of unpaid medical bills. This may be a factor propelling another trend: Lower-cost virtual-first health plans such as Alignment Health have taken hold in the market. As the name implies, insurance coverage features telehealth that extends to in-person services if necessary.

These disruptors may have their hands at least somewhat tied, however. The market may not be able to fully embrace telemedicine until state licensure is addressed. Despite the federal regulatory relaxations, states still control the distribution of medical care through licensure requirements. Many are rolling back their pandemic-based emergency orders and only allowing licensed physicians to see patients in their state, even over telemedicine.

While seemingly frustrating for physicians who want to see patients over state lines, the delays imposed by states may actually have a welcome effect. If licensure migrates to the federal level, there are many implications. For the purposes of this article, the competitive landscape will become incredibly aggressive. You will need to compete with Amazon Care, Walmart, Cigna, and many other well-funded national players that would love nothing more than to launch a campaign to target the entire nation. Investors are eager to capture part of the nearly quarter-trillion-dollar market, with telemedicine at 38 times prepandemic levels and no signs of abating.

Increased competition for insurers. While the proposed drop in Medicare reimbursement is frustrating, keep a pulse on the fact that your patients may soon be lured by vendors like Amazon and others eager to gain access to physician payments. Instead of analyzing Federal Registers in the future, we may be assessing stock prices.

Consider, therefore, how to ensure that your digital front door is at least available, if not wide open, in the meantime. The nature of physician payments is surely changing.

Ms. Woodcock is president of Woodcock & Associates, Atlanta. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians are bracing for upcoming changes in reimbursement that may start within a few months. As doctors gear up for another wave of COVID, payment trends may not be the top priority, but some “uh oh” announcements in the fall of 2021 could have far-reaching implications that could affect your future.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a proposed rule in the summer covering key aspects of physician payment. Although the rule contained some small bright lights, the most important changes proposed were far from welcome.

Here’s what could be in store:

1. The highly anticipated Medicare Physician Fee Schedule ruling confirmed a sweeping payment cut. The drive to maintain budget neutrality forced the federal agency to reduce Medicare payments, on average, by nearly 4%. Many physicians are outraged at the proposed cut.

2. More bad news for 2022: Sequestration will be back. Sequestration is the mandatory, pesky, negative 2% adjustment on all Medicare payments. It had been put on hold and is set to return at the beginning of 2022.

Essentially, sequestration reduces what Medicare pays its providers for health services, but Medicare beneficiaries bear no responsibility for the cost difference. To prevent further debt, CMS imposes financially on hospitals, physicians, and other health care providers.

The Health Resources and Services Administration has funds remaining to reimburse for all COVID-related testing, treatment, and vaccines provided to uninsured individuals. You can apply and be reimbursed at Medicare rates for these services when COVID is the primary diagnosis (or secondary in the case of pregnancy). Patients need not be American citizens for you to get paid.

3. Down to a nail-biter: The final ruling is expected in early November. The situation smacks of earlier days when physicians clung to a precipice, waiting in anticipation for a legislative body to save them from the dreaded income plunge. Indeed, we are slipping back to the decade-long period when Congress kept coming to the rescue simply to maintain the status quo.

Many anticipate a last-minute Congressional intervention to save the day, particularly in the midst of another COVID spike. The promises of a stable reimbursement system made possible by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act have been far from realized, and there are signs that the payment landscape is in the midst of a fundamental transformation.

Other changes proposed in the 1,747-page ruling include:

Positive:

- More telehealth services will be covered by Medicare, including home visits.

- Tele–mental health services got a big boost; many restrictions were removed so that now the patient’s home is considered a permissible originating site. It also allows for audio-only (no visual required) encounters; the audio-only allowance will extend to opioid use disorder treatment services. Phone treatment is covered.

- Permanent adoption of G2252: The 11- to 20-minute virtual check-in code wasn’t just a one-time payment but will be reimbursed in perpetuity.

- Boosts in reimbursement for chronic care and principal care management codes, which range on the basis of service but indicate a commitment to pay for care coordination.

- Clarification of roles and billing opportunities for split/shared visits, which occur if a physician and advanced practice provider see the same patient on a particular day. Prepare for new coding rules to include a modifier. Previously, the rules for billing were muddled, so transparency helps guide payment opportunities.

- Delay of the appropriate use criteria for advanced imaging for 1 (more) year, a welcome postponement of the ruling that carries a significant administrative burden.

- Physician assistants will be able to bill Medicare directly, and referrals to be made to medical nutrition therapy by a nontreating physician.

- A new approach to patient cost-sharing for colorectal cancer screenings will be phased in. This area has caused problems in the past when the physician identifies a need for additional services (for example, polyp removal by a gastroenterologist during routine colonoscopy).

Not positive:

- Which specialties benefit and which get zapped? The anticipated impact by specialty ranges from hits to interventional radiologists (–9%) and vascular surgeons (–8%), to increases for family practitioners, hand surgeons, endocrinologists, and geriatricians, each estimated to gain a modest 2%. (The exception is portable x-ray supplier, with an estimated increase of 10%.) All other specialties fall in between.

- The proposed conversion factor for 2022 is $33.58, a 3.75% drop from the 2021 conversion factor of $34.89.

The proposed ruling also covered the Quality Payment Program, the overarching program of which the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is the main track for participation. The proposal incorporates additional episode-based cost measures as well as updates to quality indicators and improvement activities.

MIPS penalties. The stakes are higher now, with 9% penalties on the table for nonparticipants. The government offers physicians the ability to officially get out of the program in 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby staving off the steep penalty. The option, which is available through the end of the year, requires a simple application that can be completed on behalf of the entire practice. If you want out, now is the time to find and fill out that application.

Exempt from technology requirements. If the proposal is accepted, small practices – defined by CMS as 15 eligible clinicians or fewer – won’t have to file an annual application to reweight the “promoting interoperability” portion of the program. If acknowledged, small practices will automatically be exempt from the program’s technology section. That’s a big plus, as one of the many chief complaints from small practices is the onus of meeting the technology requirements, which include a security risk analysis, bi-directional health information exchange, public health reporting, and patient access to health information. Meeting the requirements is no small feat. That will only affect future years, so be sure to apply in 2021 if applicable for your practice.

Changes in MIPS. MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) are anticipated for 2023, with the government releasing details about proposed models for heart disease, rheumatology, joint repair, and more. The MVPs are slated to take over the traditional MIPS by 2027.

The program will shift to 30% of your score coming from the “cost” category, which is based on the government’s analysis of a physician’s claims – and, if attributed, the claims of the patients for whom you care. This area is tricky to manage, but recognize that the costs under scrutiny are the expenses paid by Medicare on behalf of its patients.

In essence, Medicare is measuring the cost of your patients as compared with your colleagues’ costs (in the form of specialty-based benchmarks). Therefore, if you’re referring, or ordering, a more costly set of diagnostic tests, assessments, or interventions than your peers, you’ll be dinged.

However, physicians are more likely this year to flat out reject participation in the federal payment program. Payouts have been paltry and dismal to date, and the buzz is that physicians just don’t consider it worth the effort. Of course, clearing the threshold (which is proposed at 70 points next year) is a must to avoid the penalty, but don’t go crazy to get a perfect score as it won’t count for much. 2022 is the final year that there are any monies for exceptional performance.

Considering that the payouts for exceptional performance have been less than 2% for several years now, it’s hard to justify dedicating resources to achieve perfection. Experts believe that even exceptional performance will only be worth pennies in bonus payments.

The fear of the stick, therefore, may be the only motivation. And that is subjective, as physicians weigh the effort required versus just taking the hit on the penalty. But the penalty is substantial, and so even without the incentive, it’s important to participate at least at the threshold.

Fewer cost-sharing waivers. While the federal government’s payment policies have a major impact on reimbursement, other forces may have broader implications. Commercial payers have rolled back cost-sharing waivers, bringing to light the significant financial responsibility that patients have for their health care in the form of deductibles, coinsurance, and so forth.

More than a third of Americans had trouble paying their health care bills before the pandemic; as patients catch up with services that were postponed or delayed because of the pandemic, this may expose challenges for you. Patients with unpaid bills translate into your financial burden.

Virtual-first health plans. Patients may be seeking alternatives to avoid the frustrating cycle of unpaid medical bills. This may be a factor propelling another trend: Lower-cost virtual-first health plans such as Alignment Health have taken hold in the market. As the name implies, insurance coverage features telehealth that extends to in-person services if necessary.

These disruptors may have their hands at least somewhat tied, however. The market may not be able to fully embrace telemedicine until state licensure is addressed. Despite the federal regulatory relaxations, states still control the distribution of medical care through licensure requirements. Many are rolling back their pandemic-based emergency orders and only allowing licensed physicians to see patients in their state, even over telemedicine.

While seemingly frustrating for physicians who want to see patients over state lines, the delays imposed by states may actually have a welcome effect. If licensure migrates to the federal level, there are many implications. For the purposes of this article, the competitive landscape will become incredibly aggressive. You will need to compete with Amazon Care, Walmart, Cigna, and many other well-funded national players that would love nothing more than to launch a campaign to target the entire nation. Investors are eager to capture part of the nearly quarter-trillion-dollar market, with telemedicine at 38 times prepandemic levels and no signs of abating.

Increased competition for insurers. While the proposed drop in Medicare reimbursement is frustrating, keep a pulse on the fact that your patients may soon be lured by vendors like Amazon and others eager to gain access to physician payments. Instead of analyzing Federal Registers in the future, we may be assessing stock prices.

Consider, therefore, how to ensure that your digital front door is at least available, if not wide open, in the meantime. The nature of physician payments is surely changing.

Ms. Woodcock is president of Woodcock & Associates, Atlanta. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians are bracing for upcoming changes in reimbursement that may start within a few months. As doctors gear up for another wave of COVID, payment trends may not be the top priority, but some “uh oh” announcements in the fall of 2021 could have far-reaching implications that could affect your future.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a proposed rule in the summer covering key aspects of physician payment. Although the rule contained some small bright lights, the most important changes proposed were far from welcome.

Here’s what could be in store:

1. The highly anticipated Medicare Physician Fee Schedule ruling confirmed a sweeping payment cut. The drive to maintain budget neutrality forced the federal agency to reduce Medicare payments, on average, by nearly 4%. Many physicians are outraged at the proposed cut.

2. More bad news for 2022: Sequestration will be back. Sequestration is the mandatory, pesky, negative 2% adjustment on all Medicare payments. It had been put on hold and is set to return at the beginning of 2022.

Essentially, sequestration reduces what Medicare pays its providers for health services, but Medicare beneficiaries bear no responsibility for the cost difference. To prevent further debt, CMS imposes financially on hospitals, physicians, and other health care providers.

The Health Resources and Services Administration has funds remaining to reimburse for all COVID-related testing, treatment, and vaccines provided to uninsured individuals. You can apply and be reimbursed at Medicare rates for these services when COVID is the primary diagnosis (or secondary in the case of pregnancy). Patients need not be American citizens for you to get paid.

3. Down to a nail-biter: The final ruling is expected in early November. The situation smacks of earlier days when physicians clung to a precipice, waiting in anticipation for a legislative body to save them from the dreaded income plunge. Indeed, we are slipping back to the decade-long period when Congress kept coming to the rescue simply to maintain the status quo.

Many anticipate a last-minute Congressional intervention to save the day, particularly in the midst of another COVID spike. The promises of a stable reimbursement system made possible by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act have been far from realized, and there are signs that the payment landscape is in the midst of a fundamental transformation.

Other changes proposed in the 1,747-page ruling include:

Positive:

- More telehealth services will be covered by Medicare, including home visits.

- Tele–mental health services got a big boost; many restrictions were removed so that now the patient’s home is considered a permissible originating site. It also allows for audio-only (no visual required) encounters; the audio-only allowance will extend to opioid use disorder treatment services. Phone treatment is covered.

- Permanent adoption of G2252: The 11- to 20-minute virtual check-in code wasn’t just a one-time payment but will be reimbursed in perpetuity.

- Boosts in reimbursement for chronic care and principal care management codes, which range on the basis of service but indicate a commitment to pay for care coordination.

- Clarification of roles and billing opportunities for split/shared visits, which occur if a physician and advanced practice provider see the same patient on a particular day. Prepare for new coding rules to include a modifier. Previously, the rules for billing were muddled, so transparency helps guide payment opportunities.

- Delay of the appropriate use criteria for advanced imaging for 1 (more) year, a welcome postponement of the ruling that carries a significant administrative burden.

- Physician assistants will be able to bill Medicare directly, and referrals to be made to medical nutrition therapy by a nontreating physician.

- A new approach to patient cost-sharing for colorectal cancer screenings will be phased in. This area has caused problems in the past when the physician identifies a need for additional services (for example, polyp removal by a gastroenterologist during routine colonoscopy).

Not positive:

- Which specialties benefit and which get zapped? The anticipated impact by specialty ranges from hits to interventional radiologists (–9%) and vascular surgeons (–8%), to increases for family practitioners, hand surgeons, endocrinologists, and geriatricians, each estimated to gain a modest 2%. (The exception is portable x-ray supplier, with an estimated increase of 10%.) All other specialties fall in between.

- The proposed conversion factor for 2022 is $33.58, a 3.75% drop from the 2021 conversion factor of $34.89.

The proposed ruling also covered the Quality Payment Program, the overarching program of which the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is the main track for participation. The proposal incorporates additional episode-based cost measures as well as updates to quality indicators and improvement activities.

MIPS penalties. The stakes are higher now, with 9% penalties on the table for nonparticipants. The government offers physicians the ability to officially get out of the program in 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby staving off the steep penalty. The option, which is available through the end of the year, requires a simple application that can be completed on behalf of the entire practice. If you want out, now is the time to find and fill out that application.

Exempt from technology requirements. If the proposal is accepted, small practices – defined by CMS as 15 eligible clinicians or fewer – won’t have to file an annual application to reweight the “promoting interoperability” portion of the program. If acknowledged, small practices will automatically be exempt from the program’s technology section. That’s a big plus, as one of the many chief complaints from small practices is the onus of meeting the technology requirements, which include a security risk analysis, bi-directional health information exchange, public health reporting, and patient access to health information. Meeting the requirements is no small feat. That will only affect future years, so be sure to apply in 2021 if applicable for your practice.

Changes in MIPS. MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) are anticipated for 2023, with the government releasing details about proposed models for heart disease, rheumatology, joint repair, and more. The MVPs are slated to take over the traditional MIPS by 2027.

The program will shift to 30% of your score coming from the “cost” category, which is based on the government’s analysis of a physician’s claims – and, if attributed, the claims of the patients for whom you care. This area is tricky to manage, but recognize that the costs under scrutiny are the expenses paid by Medicare on behalf of its patients.

In essence, Medicare is measuring the cost of your patients as compared with your colleagues’ costs (in the form of specialty-based benchmarks). Therefore, if you’re referring, or ordering, a more costly set of diagnostic tests, assessments, or interventions than your peers, you’ll be dinged.

However, physicians are more likely this year to flat out reject participation in the federal payment program. Payouts have been paltry and dismal to date, and the buzz is that physicians just don’t consider it worth the effort. Of course, clearing the threshold (which is proposed at 70 points next year) is a must to avoid the penalty, but don’t go crazy to get a perfect score as it won’t count for much. 2022 is the final year that there are any monies for exceptional performance.

Considering that the payouts for exceptional performance have been less than 2% for several years now, it’s hard to justify dedicating resources to achieve perfection. Experts believe that even exceptional performance will only be worth pennies in bonus payments.

The fear of the stick, therefore, may be the only motivation. And that is subjective, as physicians weigh the effort required versus just taking the hit on the penalty. But the penalty is substantial, and so even without the incentive, it’s important to participate at least at the threshold.

Fewer cost-sharing waivers. While the federal government’s payment policies have a major impact on reimbursement, other forces may have broader implications. Commercial payers have rolled back cost-sharing waivers, bringing to light the significant financial responsibility that patients have for their health care in the form of deductibles, coinsurance, and so forth.

More than a third of Americans had trouble paying their health care bills before the pandemic; as patients catch up with services that were postponed or delayed because of the pandemic, this may expose challenges for you. Patients with unpaid bills translate into your financial burden.

Virtual-first health plans. Patients may be seeking alternatives to avoid the frustrating cycle of unpaid medical bills. This may be a factor propelling another trend: Lower-cost virtual-first health plans such as Alignment Health have taken hold in the market. As the name implies, insurance coverage features telehealth that extends to in-person services if necessary.

These disruptors may have their hands at least somewhat tied, however. The market may not be able to fully embrace telemedicine until state licensure is addressed. Despite the federal regulatory relaxations, states still control the distribution of medical care through licensure requirements. Many are rolling back their pandemic-based emergency orders and only allowing licensed physicians to see patients in their state, even over telemedicine.

While seemingly frustrating for physicians who want to see patients over state lines, the delays imposed by states may actually have a welcome effect. If licensure migrates to the federal level, there are many implications. For the purposes of this article, the competitive landscape will become incredibly aggressive. You will need to compete with Amazon Care, Walmart, Cigna, and many other well-funded national players that would love nothing more than to launch a campaign to target the entire nation. Investors are eager to capture part of the nearly quarter-trillion-dollar market, with telemedicine at 38 times prepandemic levels and no signs of abating.

Increased competition for insurers. While the proposed drop in Medicare reimbursement is frustrating, keep a pulse on the fact that your patients may soon be lured by vendors like Amazon and others eager to gain access to physician payments. Instead of analyzing Federal Registers in the future, we may be assessing stock prices.

Consider, therefore, how to ensure that your digital front door is at least available, if not wide open, in the meantime. The nature of physician payments is surely changing.

Ms. Woodcock is president of Woodcock & Associates, Atlanta. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID wars, part nine: The rise of iodine

Onions and iodine and COVID, oh my!

As surely as the sun rises, anti-vaxxers will come up with some wacky and dangerous new idea to prevent COVID. While perhaps nothing will top horse medication, gargling iodine (or spraying it into the nose) is also not a great idea.

Multiple social media posts have extolled the virtues of gargling Betadine (povidone iodine), which is a TOPICAL disinfectant commonly used in EDs and operating rooms. One post cited a paper by a Bangladeshi plastic surgeon who hypothesized on the subject, and if that’s not a peer-reviewed, rigorously researched source, we don’t know what is.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, actual medical experts do not recommend using Betadine to prevent COVID. Ingesting it can cause iodine poisoning and plenty of nasty GI side effects; while Betadine does make a diluted product safe for gargling use (used for the treatment of sore throats), it has not shown any effectiveness against viruses or COVID in particular.

A New York ED doctor summed it up best in the Rolling Stone article when he was told anti-vaxxers were gargling iodine: He offered a choice four-letter expletive, then said, “Of course they are.”

But wait! We’ve got a two-for-one deal on dubious COVID cures this week. Health experts in Myanmar (Burma to all the “Seinfeld” fans) and Thailand have been combating social media posts claiming that onion fumes will cure COVID. All you need to do is slice an onion in half, sniff it for a while, then chew on a second onion, and your COVID will be cured!

In what is surely the most radical understatement of the year, a professor in the department of preventive and social medicine at Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, said in the AFP article that there is “no solid evidence” to support onion sniffing from “any clinical research.”

We’re just going to assume the expletives that surely followed were kept off the record.

Pro-Trump state governor encourages vaccination

Clearly, the politics of COVID-19 have been working against the science of COVID-19. Politicians can’t, or won’t, agree on what to do about it, and many prominent Republicans have been actively resisting vaccine and mask mandates.

There is at least one Republican governor who has wholeheartedly encouraged vaccination in his pro-Trump state. We’re talking about Gov. Jim Justice of West Virginia, and not for the first time.

The Washington Post has detailed his efforts to promote the COVID vaccine, and we would like to share a couple of examples.

In June he suggested that people who didn’t get vaccinated were “entering the death drawing.” He followed that by saying, “If I knew for certain that there was going to be eight or nine people die by next Tuesday, and I could be one of them if I don’t take the vaccine ... What in the world do you think I would do? I mean, I would run over top of somebody.”

More recently, Gov. Justice took on vaccine conspiracy theories.

“For God’s sakes a livin’, how difficult is this to understand? Why in the world do we have to come up with these crazy ideas – and they’re crazy ideas – that the vaccine’s got something in it and it’s tracing people wherever they go? And the very same people that are saying that are carrying their cellphones around. I mean, come on. Come on.”

Nuff said.

Jet lag may be a gut feeling

After a week-long vacation halfway around the world, it’s time to go back to your usual routine and time zone. But don’t forget about that free souvenir, jet lag. A disrupted circadian rhythm can be a real bummer, but researchers may have found the fix in your belly.

In a study funded by the U.S. Navy, researchers at the University of Colorado, Boulder, looked into how the presence of a prebiotic in one’s diet can have on the disrupted biological clocks. They’re not the same as probiotics, which help you stay regular in another way. Prebiotics work as food to help the good gut bacteria you already have. An earlier study had suggested that prebiotics may have a positive effect on the brain.

To test the theory, the researchers gave one group of rats their regular food while another group received food with two different prebiotics. After manipulating the rats’ light-dark cycle for 8 weeks to give the illusion of traveling to a time zone 12 hours ahead every week, they found that the rats who ate the prebiotics were able to bounce back faster.

The possibility of ingesting something to keep your body clock regular sounds like a dream, but the researchers don’t really advise you to snatch all the supplements you can at your local pharmacy just yet.

“If you know you are going to come into a challenge, you could take a look at some of the prebiotics that are available. Just realize that they are not customized yet, so it might work for you but it won’t work for your neighbor,” said senior author Monika Fleshner.

Until there’s more conclusive research, just be good to your bacteria.

How to make stuff up and influence people

You’ve probably heard that we use only 10% of our brain. It’s right up there with “the Earth is flat” and “an apple a day keeps the doctor away.”

The idea that we use only 10% of our brains can probably be traced back to the early 1900s, suggests Discover magazine, when psychologist William James wrote, “Compared with what we ought to be, we are only half awake. Our fires are damped, our drafts are checked. We are making use of only a small part of our possible mental and physical resources.”

There are many different takes on it, but it is indeed a myth that we use only 10% of our brains. Dale Carnegie, the public speaking teacher, seems to be the one who put the specific number of 10% on James’ idea in his 1936 book, “How to Win Friends and Influence People.”

“We think that people are excited by this pseudo fact because it’s very optimistic,” neuroscientist Sandra Aamodt told Discover. “Wouldn’t we all love to think our brains had some giant pool of untapped potential that we’re not using?”

The reality is, we do use our whole brain. Functional MRI shows that different parts of the brain are used for different things such as language and memories. “Not all at the same time, of course. But every part of the brain has a job to do,” the Discover article explained.

There are many things we don’t know about how the brain works, but at least you know you use more than 10%. After all, a brain just told you so.

Onions and iodine and COVID, oh my!

As surely as the sun rises, anti-vaxxers will come up with some wacky and dangerous new idea to prevent COVID. While perhaps nothing will top horse medication, gargling iodine (or spraying it into the nose) is also not a great idea.

Multiple social media posts have extolled the virtues of gargling Betadine (povidone iodine), which is a TOPICAL disinfectant commonly used in EDs and operating rooms. One post cited a paper by a Bangladeshi plastic surgeon who hypothesized on the subject, and if that’s not a peer-reviewed, rigorously researched source, we don’t know what is.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, actual medical experts do not recommend using Betadine to prevent COVID. Ingesting it can cause iodine poisoning and plenty of nasty GI side effects; while Betadine does make a diluted product safe for gargling use (used for the treatment of sore throats), it has not shown any effectiveness against viruses or COVID in particular.

A New York ED doctor summed it up best in the Rolling Stone article when he was told anti-vaxxers were gargling iodine: He offered a choice four-letter expletive, then said, “Of course they are.”

But wait! We’ve got a two-for-one deal on dubious COVID cures this week. Health experts in Myanmar (Burma to all the “Seinfeld” fans) and Thailand have been combating social media posts claiming that onion fumes will cure COVID. All you need to do is slice an onion in half, sniff it for a while, then chew on a second onion, and your COVID will be cured!

In what is surely the most radical understatement of the year, a professor in the department of preventive and social medicine at Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, said in the AFP article that there is “no solid evidence” to support onion sniffing from “any clinical research.”

We’re just going to assume the expletives that surely followed were kept off the record.

Pro-Trump state governor encourages vaccination

Clearly, the politics of COVID-19 have been working against the science of COVID-19. Politicians can’t, or won’t, agree on what to do about it, and many prominent Republicans have been actively resisting vaccine and mask mandates.

There is at least one Republican governor who has wholeheartedly encouraged vaccination in his pro-Trump state. We’re talking about Gov. Jim Justice of West Virginia, and not for the first time.

The Washington Post has detailed his efforts to promote the COVID vaccine, and we would like to share a couple of examples.

In June he suggested that people who didn’t get vaccinated were “entering the death drawing.” He followed that by saying, “If I knew for certain that there was going to be eight or nine people die by next Tuesday, and I could be one of them if I don’t take the vaccine ... What in the world do you think I would do? I mean, I would run over top of somebody.”

More recently, Gov. Justice took on vaccine conspiracy theories.

“For God’s sakes a livin’, how difficult is this to understand? Why in the world do we have to come up with these crazy ideas – and they’re crazy ideas – that the vaccine’s got something in it and it’s tracing people wherever they go? And the very same people that are saying that are carrying their cellphones around. I mean, come on. Come on.”

Nuff said.

Jet lag may be a gut feeling

After a week-long vacation halfway around the world, it’s time to go back to your usual routine and time zone. But don’t forget about that free souvenir, jet lag. A disrupted circadian rhythm can be a real bummer, but researchers may have found the fix in your belly.

In a study funded by the U.S. Navy, researchers at the University of Colorado, Boulder, looked into how the presence of a prebiotic in one’s diet can have on the disrupted biological clocks. They’re not the same as probiotics, which help you stay regular in another way. Prebiotics work as food to help the good gut bacteria you already have. An earlier study had suggested that prebiotics may have a positive effect on the brain.