User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Bad blood: Could brain bleeds be contagious?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

How do you tell if a condition is caused by an infection?

It seems like an obvious question, right? In the post–van Leeuwenhoek era we can look at whatever part of the body is diseased under a microscope and see microbes – you know, the usual suspects.

Except when we can’t. And there are plenty of cases where we can’t: where the microbe is too small to be seen without more advanced imaging techniques, like with viruses; or when the pathogen is sparsely populated or hard to culture, like Mycobacterium.

Finding out that a condition is the result of an infection is not only an exercise for 19th century physicians. After all, it was 2008 when Barry Marshall and Robin Warren won their Nobel Prize for proving that stomach ulcers, long thought to be due to “stress,” were actually caused by a tiny microbe called Helicobacter pylori.

And this week, we are looking at a study which, once again, begins to suggest that a condition thought to be more or less random – cerebral amyloid angiopathy – may actually be the result of an infectious disease.

We’re talking about this paper, appearing in JAMA, which is just a great example of old-fashioned shoe-leather epidemiology. But let’s get up to speed on cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) first.

CAA is characterized by the deposition of amyloid protein in the brain. While there are some genetic causes, they are quite rare, and most cases are thought to be idiopathic. Recent analyses suggest that somewhere between 5% and 7% of cognitively normal older adults have CAA, but the rate is much higher among those with intracerebral hemorrhage – brain bleeds. In fact, CAA is the second-most common cause of bleeding in the brain, second only to severe hypertension.

An article in Nature highlights cases that seemed to develop after the administration of cadaveric pituitary hormone.

Other studies have shown potential transmission via dura mater grafts and neurosurgical instruments. But despite those clues, no infectious organism has been identified. Some have suggested that the long latent period and difficulty of finding a responsible microbe points to a prion-like disease not yet known. But these studies are more or less case series. The new JAMA paper gives us, if not a smoking gun, a pretty decent set of fingerprints.

Here’s the idea: If CAA is caused by some infectious agent, it may be transmitted in the blood. We know that a decent percentage of people who have spontaneous brain bleeds have CAA. If those people donated blood in the past, maybe the people who received that blood would be at risk for brain bleeds too.

Of course, to really test that hypothesis, you’d need to know who every blood donor in a country was and every person who received that blood and all their subsequent diagnoses for basically their entire lives. No one has that kind of data, right?

Well, if you’ve been watching this space, you’ll know that a few countries do. Enter Sweden and Denmark, with their national electronic health record that captures all of this information, and much more, on every single person who lives or has lived in those countries since before 1970. Unbelievable.

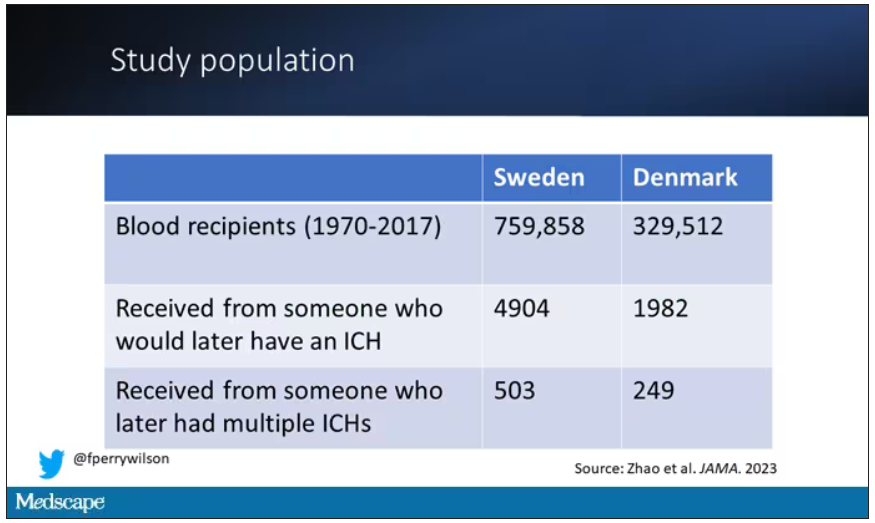

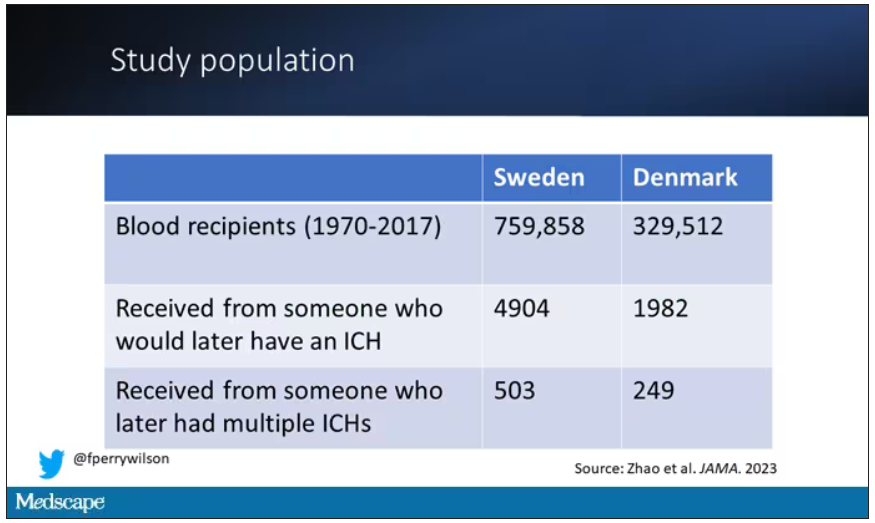

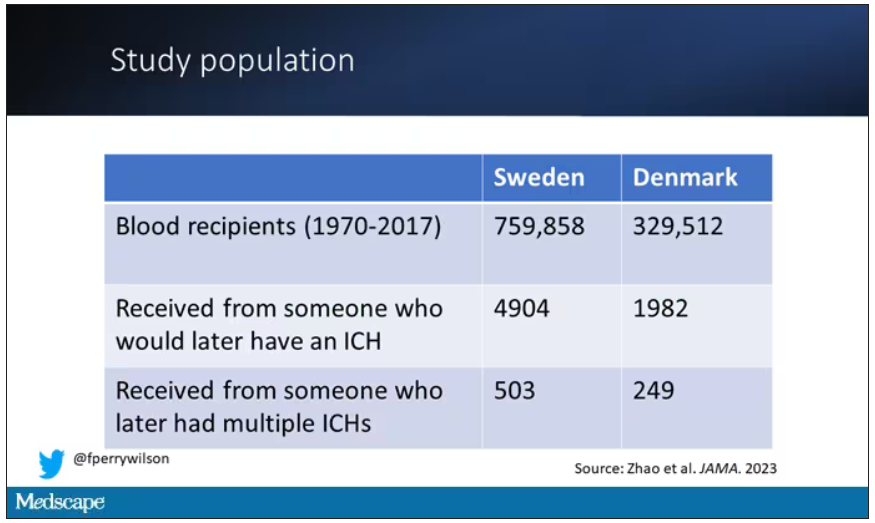

So that’s exactly what the researchers, led by Jingchen Zhao at Karolinska (Sweden) University, did. They identified roughly 760,000 individuals in Sweden and 330,000 people in Denmark who had received a blood transfusion between 1970 and 2017.

Of course, most of those blood donors – 99% of them, actually – never went on to have any bleeding in the brain. It is a rare thing, fortunately.

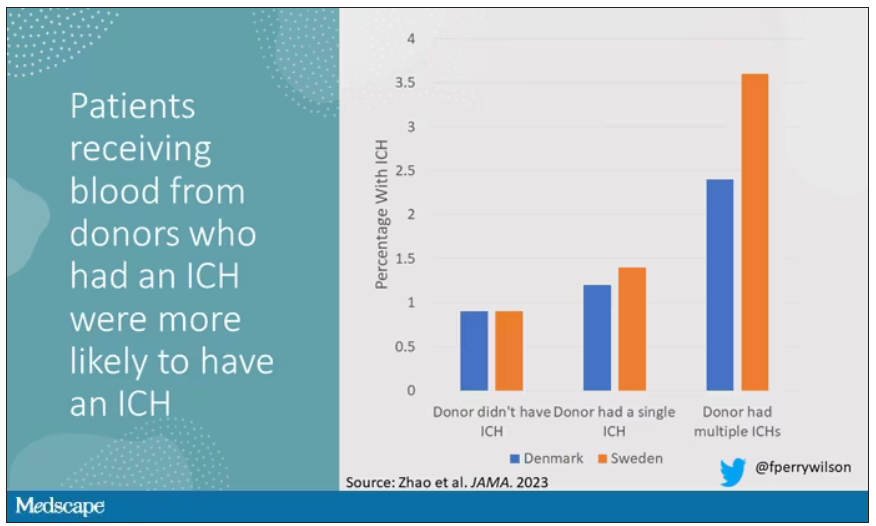

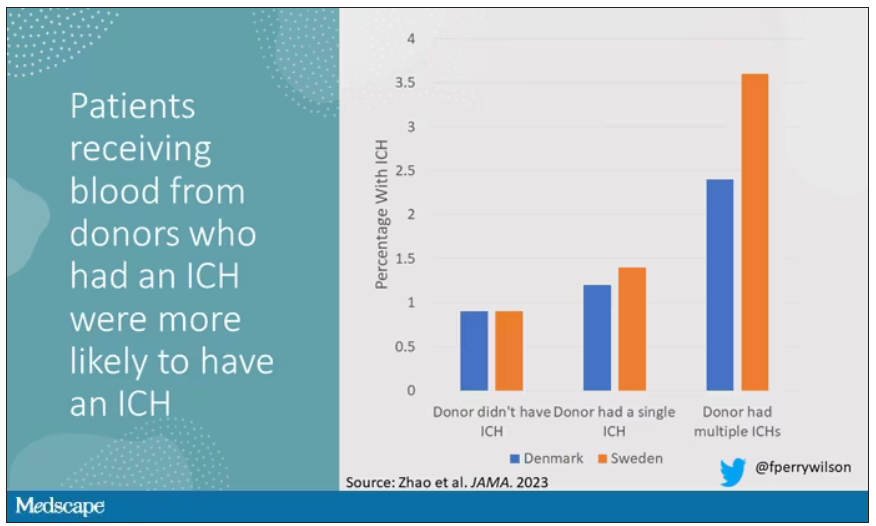

But some of the donors did, on average within about 5 years of the time they donated blood. The researchers characterized each donor as either never having a brain bleed, having a single bleed, or having multiple bleeds. The latter is most strongly associated with CAA.

The big question: Would recipients who got blood from individuals who later on had brain bleeds, have brain bleeds themselves?

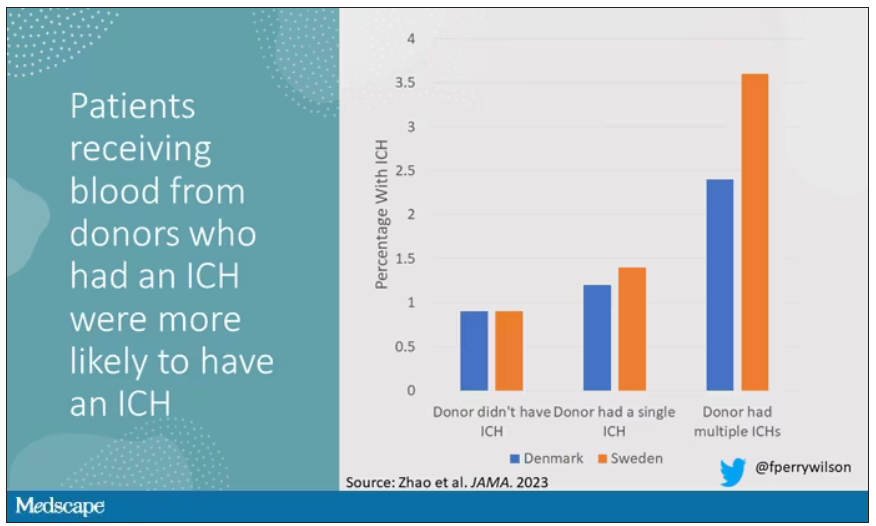

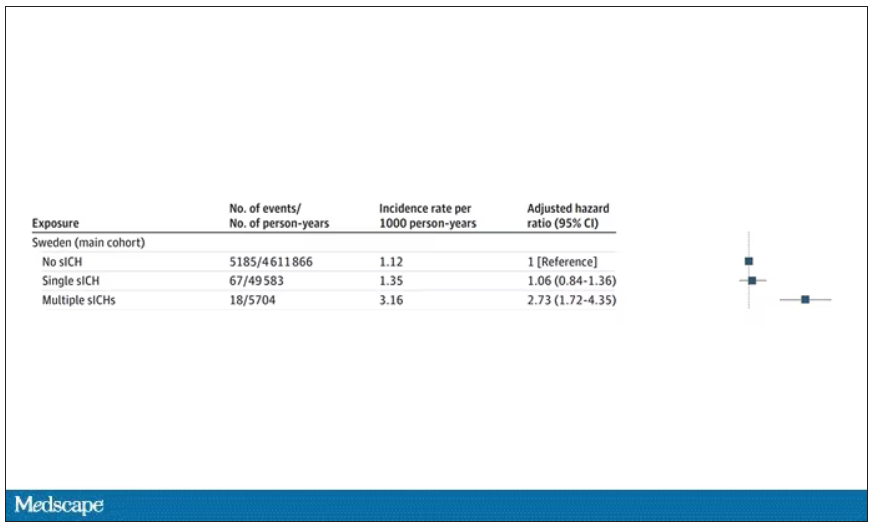

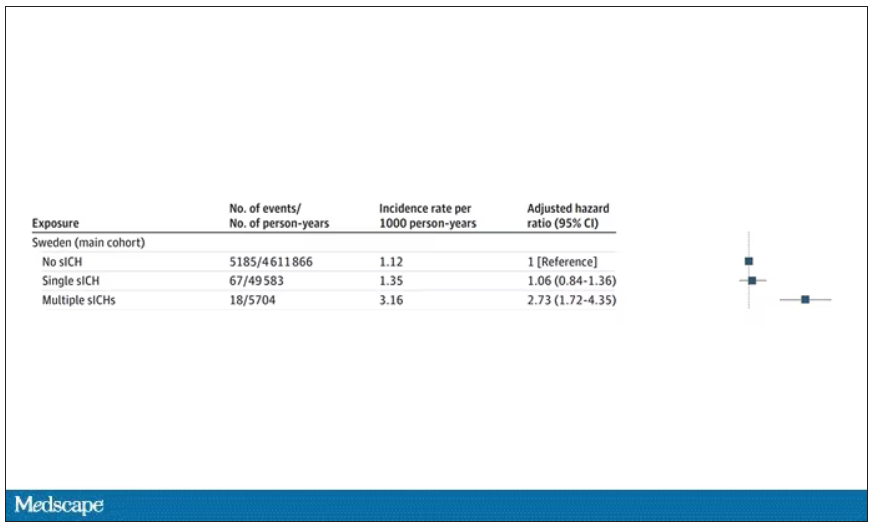

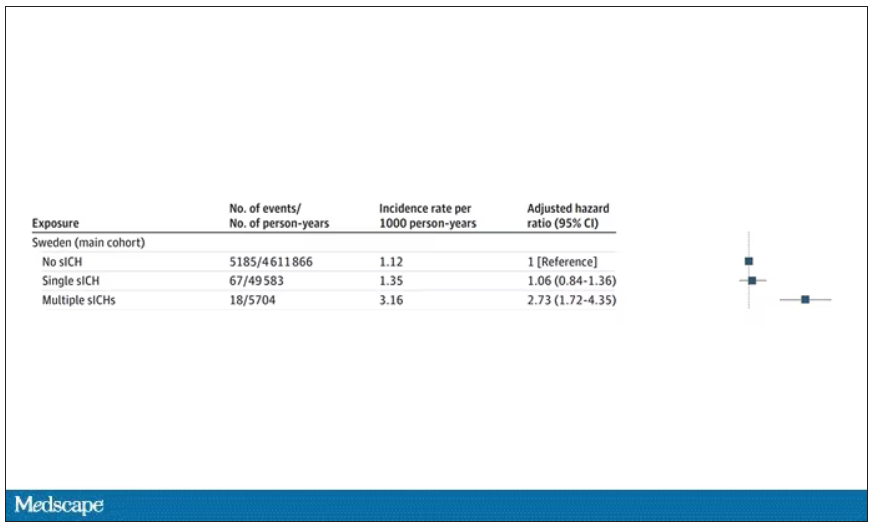

The answer is yes, though with an asterisk. You can see the results here. The risk of recipients having a brain bleed was lowest if the blood they received was from people who never had a brain bleed, higher if the individual had a single brain bleed, and highest if they got blood from a donor who would go on to have multiple brain bleeds.

All in all, individuals who received blood from someone who would later have multiple hemorrhages were three times more likely to themselves develop bleeds themselves. It’s fairly compelling evidence of a transmissible agent.

Of course, there are some potential confounders to consider here. Whose blood you get is not totally random. If, for example, people with type O blood are just more likely to have brain bleeds, then you could get results like this, as type O tends to donate to type O and both groups would have higher risk after donation. But the authors adjusted for blood type. They also adjusted for number of transfusions, calendar year, age, sex, and indication for transfusion.

Perhaps most compelling, and most clever, is that they used ischemic stroke as a negative control. Would people who received blood from someone who later had an ischemic stroke themselves be more likely to go on to have an ischemic stroke? No signal at all. It does not appear that there is a transmissible agent associated with ischemic stroke – only the brain bleeds.

I know what you’re thinking. What’s the agent? What’s the microbe, or virus, or prion, or toxin? The study gives us no insight there. These nationwide databases are awesome but they can only do so much. Because of the vagaries of medical coding and the difficulty of making the CAA diagnosis, the authors are using brain bleeds as a proxy here; we don’t even know for sure whether these were CAA-associated brain bleeds.

It’s also worth noting that there’s little we can do about this. None of the blood donors in this study had a brain bleed prior to donation; it’s not like we could screen people out of donating in the future. We have no test for whatever this agent is, if it even exists, nor do we have a potential treatment. Fortunately, whatever it is, it is extremely rare.

Still, this paper feels like a shot across the bow. At this point, the probability has shifted strongly away from CAA being a purely random disease and toward it being an infectious one. It may be time to round up some of the unusual suspects.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

How do you tell if a condition is caused by an infection?

It seems like an obvious question, right? In the post–van Leeuwenhoek era we can look at whatever part of the body is diseased under a microscope and see microbes – you know, the usual suspects.

Except when we can’t. And there are plenty of cases where we can’t: where the microbe is too small to be seen without more advanced imaging techniques, like with viruses; or when the pathogen is sparsely populated or hard to culture, like Mycobacterium.

Finding out that a condition is the result of an infection is not only an exercise for 19th century physicians. After all, it was 2008 when Barry Marshall and Robin Warren won their Nobel Prize for proving that stomach ulcers, long thought to be due to “stress,” were actually caused by a tiny microbe called Helicobacter pylori.

And this week, we are looking at a study which, once again, begins to suggest that a condition thought to be more or less random – cerebral amyloid angiopathy – may actually be the result of an infectious disease.

We’re talking about this paper, appearing in JAMA, which is just a great example of old-fashioned shoe-leather epidemiology. But let’s get up to speed on cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) first.

CAA is characterized by the deposition of amyloid protein in the brain. While there are some genetic causes, they are quite rare, and most cases are thought to be idiopathic. Recent analyses suggest that somewhere between 5% and 7% of cognitively normal older adults have CAA, but the rate is much higher among those with intracerebral hemorrhage – brain bleeds. In fact, CAA is the second-most common cause of bleeding in the brain, second only to severe hypertension.

An article in Nature highlights cases that seemed to develop after the administration of cadaveric pituitary hormone.

Other studies have shown potential transmission via dura mater grafts and neurosurgical instruments. But despite those clues, no infectious organism has been identified. Some have suggested that the long latent period and difficulty of finding a responsible microbe points to a prion-like disease not yet known. But these studies are more or less case series. The new JAMA paper gives us, if not a smoking gun, a pretty decent set of fingerprints.

Here’s the idea: If CAA is caused by some infectious agent, it may be transmitted in the blood. We know that a decent percentage of people who have spontaneous brain bleeds have CAA. If those people donated blood in the past, maybe the people who received that blood would be at risk for brain bleeds too.

Of course, to really test that hypothesis, you’d need to know who every blood donor in a country was and every person who received that blood and all their subsequent diagnoses for basically their entire lives. No one has that kind of data, right?

Well, if you’ve been watching this space, you’ll know that a few countries do. Enter Sweden and Denmark, with their national electronic health record that captures all of this information, and much more, on every single person who lives or has lived in those countries since before 1970. Unbelievable.

So that’s exactly what the researchers, led by Jingchen Zhao at Karolinska (Sweden) University, did. They identified roughly 760,000 individuals in Sweden and 330,000 people in Denmark who had received a blood transfusion between 1970 and 2017.

Of course, most of those blood donors – 99% of them, actually – never went on to have any bleeding in the brain. It is a rare thing, fortunately.

But some of the donors did, on average within about 5 years of the time they donated blood. The researchers characterized each donor as either never having a brain bleed, having a single bleed, or having multiple bleeds. The latter is most strongly associated with CAA.

The big question: Would recipients who got blood from individuals who later on had brain bleeds, have brain bleeds themselves?

The answer is yes, though with an asterisk. You can see the results here. The risk of recipients having a brain bleed was lowest if the blood they received was from people who never had a brain bleed, higher if the individual had a single brain bleed, and highest if they got blood from a donor who would go on to have multiple brain bleeds.

All in all, individuals who received blood from someone who would later have multiple hemorrhages were three times more likely to themselves develop bleeds themselves. It’s fairly compelling evidence of a transmissible agent.

Of course, there are some potential confounders to consider here. Whose blood you get is not totally random. If, for example, people with type O blood are just more likely to have brain bleeds, then you could get results like this, as type O tends to donate to type O and both groups would have higher risk after donation. But the authors adjusted for blood type. They also adjusted for number of transfusions, calendar year, age, sex, and indication for transfusion.

Perhaps most compelling, and most clever, is that they used ischemic stroke as a negative control. Would people who received blood from someone who later had an ischemic stroke themselves be more likely to go on to have an ischemic stroke? No signal at all. It does not appear that there is a transmissible agent associated with ischemic stroke – only the brain bleeds.

I know what you’re thinking. What’s the agent? What’s the microbe, or virus, or prion, or toxin? The study gives us no insight there. These nationwide databases are awesome but they can only do so much. Because of the vagaries of medical coding and the difficulty of making the CAA diagnosis, the authors are using brain bleeds as a proxy here; we don’t even know for sure whether these were CAA-associated brain bleeds.

It’s also worth noting that there’s little we can do about this. None of the blood donors in this study had a brain bleed prior to donation; it’s not like we could screen people out of donating in the future. We have no test for whatever this agent is, if it even exists, nor do we have a potential treatment. Fortunately, whatever it is, it is extremely rare.

Still, this paper feels like a shot across the bow. At this point, the probability has shifted strongly away from CAA being a purely random disease and toward it being an infectious one. It may be time to round up some of the unusual suspects.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

How do you tell if a condition is caused by an infection?

It seems like an obvious question, right? In the post–van Leeuwenhoek era we can look at whatever part of the body is diseased under a microscope and see microbes – you know, the usual suspects.

Except when we can’t. And there are plenty of cases where we can’t: where the microbe is too small to be seen without more advanced imaging techniques, like with viruses; or when the pathogen is sparsely populated or hard to culture, like Mycobacterium.

Finding out that a condition is the result of an infection is not only an exercise for 19th century physicians. After all, it was 2008 when Barry Marshall and Robin Warren won their Nobel Prize for proving that stomach ulcers, long thought to be due to “stress,” were actually caused by a tiny microbe called Helicobacter pylori.

And this week, we are looking at a study which, once again, begins to suggest that a condition thought to be more or less random – cerebral amyloid angiopathy – may actually be the result of an infectious disease.

We’re talking about this paper, appearing in JAMA, which is just a great example of old-fashioned shoe-leather epidemiology. But let’s get up to speed on cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) first.

CAA is characterized by the deposition of amyloid protein in the brain. While there are some genetic causes, they are quite rare, and most cases are thought to be idiopathic. Recent analyses suggest that somewhere between 5% and 7% of cognitively normal older adults have CAA, but the rate is much higher among those with intracerebral hemorrhage – brain bleeds. In fact, CAA is the second-most common cause of bleeding in the brain, second only to severe hypertension.

An article in Nature highlights cases that seemed to develop after the administration of cadaveric pituitary hormone.

Other studies have shown potential transmission via dura mater grafts and neurosurgical instruments. But despite those clues, no infectious organism has been identified. Some have suggested that the long latent period and difficulty of finding a responsible microbe points to a prion-like disease not yet known. But these studies are more or less case series. The new JAMA paper gives us, if not a smoking gun, a pretty decent set of fingerprints.

Here’s the idea: If CAA is caused by some infectious agent, it may be transmitted in the blood. We know that a decent percentage of people who have spontaneous brain bleeds have CAA. If those people donated blood in the past, maybe the people who received that blood would be at risk for brain bleeds too.

Of course, to really test that hypothesis, you’d need to know who every blood donor in a country was and every person who received that blood and all their subsequent diagnoses for basically their entire lives. No one has that kind of data, right?

Well, if you’ve been watching this space, you’ll know that a few countries do. Enter Sweden and Denmark, with their national electronic health record that captures all of this information, and much more, on every single person who lives or has lived in those countries since before 1970. Unbelievable.

So that’s exactly what the researchers, led by Jingchen Zhao at Karolinska (Sweden) University, did. They identified roughly 760,000 individuals in Sweden and 330,000 people in Denmark who had received a blood transfusion between 1970 and 2017.

Of course, most of those blood donors – 99% of them, actually – never went on to have any bleeding in the brain. It is a rare thing, fortunately.

But some of the donors did, on average within about 5 years of the time they donated blood. The researchers characterized each donor as either never having a brain bleed, having a single bleed, or having multiple bleeds. The latter is most strongly associated with CAA.

The big question: Would recipients who got blood from individuals who later on had brain bleeds, have brain bleeds themselves?

The answer is yes, though with an asterisk. You can see the results here. The risk of recipients having a brain bleed was lowest if the blood they received was from people who never had a brain bleed, higher if the individual had a single brain bleed, and highest if they got blood from a donor who would go on to have multiple brain bleeds.

All in all, individuals who received blood from someone who would later have multiple hemorrhages were three times more likely to themselves develop bleeds themselves. It’s fairly compelling evidence of a transmissible agent.

Of course, there are some potential confounders to consider here. Whose blood you get is not totally random. If, for example, people with type O blood are just more likely to have brain bleeds, then you could get results like this, as type O tends to donate to type O and both groups would have higher risk after donation. But the authors adjusted for blood type. They also adjusted for number of transfusions, calendar year, age, sex, and indication for transfusion.

Perhaps most compelling, and most clever, is that they used ischemic stroke as a negative control. Would people who received blood from someone who later had an ischemic stroke themselves be more likely to go on to have an ischemic stroke? No signal at all. It does not appear that there is a transmissible agent associated with ischemic stroke – only the brain bleeds.

I know what you’re thinking. What’s the agent? What’s the microbe, or virus, or prion, or toxin? The study gives us no insight there. These nationwide databases are awesome but they can only do so much. Because of the vagaries of medical coding and the difficulty of making the CAA diagnosis, the authors are using brain bleeds as a proxy here; we don’t even know for sure whether these were CAA-associated brain bleeds.

It’s also worth noting that there’s little we can do about this. None of the blood donors in this study had a brain bleed prior to donation; it’s not like we could screen people out of donating in the future. We have no test for whatever this agent is, if it even exists, nor do we have a potential treatment. Fortunately, whatever it is, it is extremely rare.

Still, this paper feels like a shot across the bow. At this point, the probability has shifted strongly away from CAA being a purely random disease and toward it being an infectious one. It may be time to round up some of the unusual suspects.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Disenfranchised grief: What it looks like, where it goes

What happens to grief when those around you don’t understand it? Where does it go? How do you process it?

Disenfranchised grief, when someone or society more generally doesn’t see a loss as worthy of mourning, can deprive people of experiencing or processing their sadness. This grief, which may be triggered by the death of an ex-spouse, a pet, a failed adoption, can be painful and long-lasting.

Suzanne Cole, MD: ‘I didn’t feel the right to grieve’

During the COVID-19 pandemic, my little sister unexpectedly died. Though she was not one of the nearly 7 million people who died of the virus, in 2021 she became another type of statistic: one of the 109,699 people in the United State who died from a drug overdose. Hers was from fentanyl laced with methamphetamines.

Her death unraveled me. I felt deep guilt that I could not pull her from the sweeping current that had wrenched her from mainstream society into the underbelly of sex work and toward the solace of mind-altering drugs.

But I did not feel the right to grieve for her as I have grieved for other loved ones who were not blamed for their exit from this world. My sister was living a sordid life on the fringes of society. My grief felt invalid, undeserved. Yet, in the eyes of other “upstanding citizens,” her life was not as worth grieving – or so I thought. I tucked my sorrow into a small corner of my soul so no one would see, and I carried on.

To this day, the shame I feel robbed me of the ability to freely talk about her or share the searing pain I feel. Tears still prick my eyes when I think of her, but I have become adept at swallowing them, shaking off the waves of grief as though nothing happened. Even now, I cannot shake the pervasive feeling that my silent tears don’t deserve to be wept.

Don S. Dizon, MD: Working through tragedy

As a medical student, I worked with an outpatient physician as part of a third-year rotation. When we met, the first thing that struck me was how disheveled he looked. His clothes were wrinkled, and his pants were baggy. He took cigarette breaks, which I found disturbing.

But I quickly came to admire him. Despite my first impression, he was the type of doctor I aspired to be. He didn’t need to look at a patient’s chart to recall who they were. He just knew them. He greeted patients warmly, asked about their family. He even remembered the special occasions his patients had mentioned since their past visit. He epitomized empathy and connectedness.

Spending one day in clinic brought to light the challenges of forming such bonds with patients. A man came into the cancer clinic reporting chest pain and was triaged to an exam room. Soon after, the patient was found unresponsive on the floor. Nurses were yelling for help, and the doctor ran in and started CPR while minutes ticked by waiting for an ambulance that could take him to the ED.

By the time help arrived, the patient was blue.

He had died in the clinic in the middle of the day, as the waiting room filled. After the body was taken away, the doctor went into the bathroom. About 20 minutes later, he came out, eyes bloodshot, and continued with the rest of his day, ensuring each patient was seen and cared for.

As a medical student, it hit me how hard it must be to see something so tragic like the end of a life and then continue with your day as if nothing had happened. This is an experience of grief I later came to know well after nearly 30 years treating patients with advanced cancers: compartmentalizing it and carrying on.

A space for grieving: The Schwartz Center Rounds

Disenfranchised grief, the grief that is hard to share and often seems wrong to feel in the first place, can be triggered in many situations. Losing a person others don’t believe deserve to be grieved, such as an abusive partner or someone who committed a crime; losing someone you cared for in a professional role; a loss experienced in a breakup or same-sex partnership, if that relationship was not accepted by one’s family; loss from infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, or failed adoption; loss that may be taboo or stigmatized, such as deaths via suicide or abortion; and loss of a job, home, or possession that you treasure.

Many of us have had similar situations or will, and the feeling that no one understands the need to mourn can be paralyzing and alienating. In the early days, intense, crushing feelings can cause intrusive, distracting thoughts, and over time, that grief can linger and find a permanent place in our minds.

More and more, though, we are being given opportunities to reflect on these sad moments.

The Schwartz Rounds are an example of such an opportunity. In these rounds, we gather to talk about the experience of caring for people, not the science of medicine.

During one particularly powerful rounds, I spoke to my colleagues about my initial meeting with a patient who was very sick. I detailed the experience of telling her children and her at that initial consult how I thought she was dying and that I did not recommend therapy. I remember how they cried. And I remembered how powerless I felt.

As I recalled that memory during Schwartz Rounds, I could not stop from crying. The unfairness of being a physician meeting someone for the first time and having to tell them such bad news overwhelmed me.

Even more poignant, I had the chance to reconnect with this woman’s children, who were present that day, not as audience members but as participants. Their presence may have brought my emotions to the surface more strongly. In that moment, I could show them the feelings I had bottled up for the sake of professionalism. Ultimately, I felt relieved, freer somehow, as if this burden my soul was carrying had been lifted.

Although we are both grateful for forums like this, these opportunities to share and express the grief we may have hidden away are not as common as they should be.

As physicians, we may express grief by shedding tears at the bedside of a patient nearing the end of life or through the anxiety we feel when our patient suffers a severe reaction to treatment. But we tend to put it away, to go on with our day, because there are others to be seen and cared for and more work to be done. Somehow, we move forward, shedding tears in one room and celebrating victories in another.

We need to create more spaces to express and feel grief, so we don’t get lost in it. Because understanding how grief impacts us, as people and as providers, is one of the most important realizations we can make as we go about our time-honored profession as healers.

Dr. Dizon is the director of women’s cancers at Lifespan Cancer Institute, director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Brown University, all in Providence. He reported conflicts of interest with Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Kazia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What happens to grief when those around you don’t understand it? Where does it go? How do you process it?

Disenfranchised grief, when someone or society more generally doesn’t see a loss as worthy of mourning, can deprive people of experiencing or processing their sadness. This grief, which may be triggered by the death of an ex-spouse, a pet, a failed adoption, can be painful and long-lasting.

Suzanne Cole, MD: ‘I didn’t feel the right to grieve’

During the COVID-19 pandemic, my little sister unexpectedly died. Though she was not one of the nearly 7 million people who died of the virus, in 2021 she became another type of statistic: one of the 109,699 people in the United State who died from a drug overdose. Hers was from fentanyl laced with methamphetamines.

Her death unraveled me. I felt deep guilt that I could not pull her from the sweeping current that had wrenched her from mainstream society into the underbelly of sex work and toward the solace of mind-altering drugs.

But I did not feel the right to grieve for her as I have grieved for other loved ones who were not blamed for their exit from this world. My sister was living a sordid life on the fringes of society. My grief felt invalid, undeserved. Yet, in the eyes of other “upstanding citizens,” her life was not as worth grieving – or so I thought. I tucked my sorrow into a small corner of my soul so no one would see, and I carried on.

To this day, the shame I feel robbed me of the ability to freely talk about her or share the searing pain I feel. Tears still prick my eyes when I think of her, but I have become adept at swallowing them, shaking off the waves of grief as though nothing happened. Even now, I cannot shake the pervasive feeling that my silent tears don’t deserve to be wept.

Don S. Dizon, MD: Working through tragedy

As a medical student, I worked with an outpatient physician as part of a third-year rotation. When we met, the first thing that struck me was how disheveled he looked. His clothes were wrinkled, and his pants were baggy. He took cigarette breaks, which I found disturbing.

But I quickly came to admire him. Despite my first impression, he was the type of doctor I aspired to be. He didn’t need to look at a patient’s chart to recall who they were. He just knew them. He greeted patients warmly, asked about their family. He even remembered the special occasions his patients had mentioned since their past visit. He epitomized empathy and connectedness.

Spending one day in clinic brought to light the challenges of forming such bonds with patients. A man came into the cancer clinic reporting chest pain and was triaged to an exam room. Soon after, the patient was found unresponsive on the floor. Nurses were yelling for help, and the doctor ran in and started CPR while minutes ticked by waiting for an ambulance that could take him to the ED.

By the time help arrived, the patient was blue.

He had died in the clinic in the middle of the day, as the waiting room filled. After the body was taken away, the doctor went into the bathroom. About 20 minutes later, he came out, eyes bloodshot, and continued with the rest of his day, ensuring each patient was seen and cared for.

As a medical student, it hit me how hard it must be to see something so tragic like the end of a life and then continue with your day as if nothing had happened. This is an experience of grief I later came to know well after nearly 30 years treating patients with advanced cancers: compartmentalizing it and carrying on.

A space for grieving: The Schwartz Center Rounds

Disenfranchised grief, the grief that is hard to share and often seems wrong to feel in the first place, can be triggered in many situations. Losing a person others don’t believe deserve to be grieved, such as an abusive partner or someone who committed a crime; losing someone you cared for in a professional role; a loss experienced in a breakup or same-sex partnership, if that relationship was not accepted by one’s family; loss from infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, or failed adoption; loss that may be taboo or stigmatized, such as deaths via suicide or abortion; and loss of a job, home, or possession that you treasure.

Many of us have had similar situations or will, and the feeling that no one understands the need to mourn can be paralyzing and alienating. In the early days, intense, crushing feelings can cause intrusive, distracting thoughts, and over time, that grief can linger and find a permanent place in our minds.

More and more, though, we are being given opportunities to reflect on these sad moments.

The Schwartz Rounds are an example of such an opportunity. In these rounds, we gather to talk about the experience of caring for people, not the science of medicine.

During one particularly powerful rounds, I spoke to my colleagues about my initial meeting with a patient who was very sick. I detailed the experience of telling her children and her at that initial consult how I thought she was dying and that I did not recommend therapy. I remember how they cried. And I remembered how powerless I felt.

As I recalled that memory during Schwartz Rounds, I could not stop from crying. The unfairness of being a physician meeting someone for the first time and having to tell them such bad news overwhelmed me.

Even more poignant, I had the chance to reconnect with this woman’s children, who were present that day, not as audience members but as participants. Their presence may have brought my emotions to the surface more strongly. In that moment, I could show them the feelings I had bottled up for the sake of professionalism. Ultimately, I felt relieved, freer somehow, as if this burden my soul was carrying had been lifted.

Although we are both grateful for forums like this, these opportunities to share and express the grief we may have hidden away are not as common as they should be.

As physicians, we may express grief by shedding tears at the bedside of a patient nearing the end of life or through the anxiety we feel when our patient suffers a severe reaction to treatment. But we tend to put it away, to go on with our day, because there are others to be seen and cared for and more work to be done. Somehow, we move forward, shedding tears in one room and celebrating victories in another.

We need to create more spaces to express and feel grief, so we don’t get lost in it. Because understanding how grief impacts us, as people and as providers, is one of the most important realizations we can make as we go about our time-honored profession as healers.

Dr. Dizon is the director of women’s cancers at Lifespan Cancer Institute, director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Brown University, all in Providence. He reported conflicts of interest with Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Kazia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What happens to grief when those around you don’t understand it? Where does it go? How do you process it?

Disenfranchised grief, when someone or society more generally doesn’t see a loss as worthy of mourning, can deprive people of experiencing or processing their sadness. This grief, which may be triggered by the death of an ex-spouse, a pet, a failed adoption, can be painful and long-lasting.

Suzanne Cole, MD: ‘I didn’t feel the right to grieve’

During the COVID-19 pandemic, my little sister unexpectedly died. Though she was not one of the nearly 7 million people who died of the virus, in 2021 she became another type of statistic: one of the 109,699 people in the United State who died from a drug overdose. Hers was from fentanyl laced with methamphetamines.

Her death unraveled me. I felt deep guilt that I could not pull her from the sweeping current that had wrenched her from mainstream society into the underbelly of sex work and toward the solace of mind-altering drugs.

But I did not feel the right to grieve for her as I have grieved for other loved ones who were not blamed for their exit from this world. My sister was living a sordid life on the fringes of society. My grief felt invalid, undeserved. Yet, in the eyes of other “upstanding citizens,” her life was not as worth grieving – or so I thought. I tucked my sorrow into a small corner of my soul so no one would see, and I carried on.

To this day, the shame I feel robbed me of the ability to freely talk about her or share the searing pain I feel. Tears still prick my eyes when I think of her, but I have become adept at swallowing them, shaking off the waves of grief as though nothing happened. Even now, I cannot shake the pervasive feeling that my silent tears don’t deserve to be wept.

Don S. Dizon, MD: Working through tragedy

As a medical student, I worked with an outpatient physician as part of a third-year rotation. When we met, the first thing that struck me was how disheveled he looked. His clothes were wrinkled, and his pants were baggy. He took cigarette breaks, which I found disturbing.

But I quickly came to admire him. Despite my first impression, he was the type of doctor I aspired to be. He didn’t need to look at a patient’s chart to recall who they were. He just knew them. He greeted patients warmly, asked about their family. He even remembered the special occasions his patients had mentioned since their past visit. He epitomized empathy and connectedness.

Spending one day in clinic brought to light the challenges of forming such bonds with patients. A man came into the cancer clinic reporting chest pain and was triaged to an exam room. Soon after, the patient was found unresponsive on the floor. Nurses were yelling for help, and the doctor ran in and started CPR while minutes ticked by waiting for an ambulance that could take him to the ED.

By the time help arrived, the patient was blue.

He had died in the clinic in the middle of the day, as the waiting room filled. After the body was taken away, the doctor went into the bathroom. About 20 minutes later, he came out, eyes bloodshot, and continued with the rest of his day, ensuring each patient was seen and cared for.

As a medical student, it hit me how hard it must be to see something so tragic like the end of a life and then continue with your day as if nothing had happened. This is an experience of grief I later came to know well after nearly 30 years treating patients with advanced cancers: compartmentalizing it and carrying on.

A space for grieving: The Schwartz Center Rounds

Disenfranchised grief, the grief that is hard to share and often seems wrong to feel in the first place, can be triggered in many situations. Losing a person others don’t believe deserve to be grieved, such as an abusive partner or someone who committed a crime; losing someone you cared for in a professional role; a loss experienced in a breakup or same-sex partnership, if that relationship was not accepted by one’s family; loss from infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, or failed adoption; loss that may be taboo or stigmatized, such as deaths via suicide or abortion; and loss of a job, home, or possession that you treasure.

Many of us have had similar situations or will, and the feeling that no one understands the need to mourn can be paralyzing and alienating. In the early days, intense, crushing feelings can cause intrusive, distracting thoughts, and over time, that grief can linger and find a permanent place in our minds.

More and more, though, we are being given opportunities to reflect on these sad moments.

The Schwartz Rounds are an example of such an opportunity. In these rounds, we gather to talk about the experience of caring for people, not the science of medicine.

During one particularly powerful rounds, I spoke to my colleagues about my initial meeting with a patient who was very sick. I detailed the experience of telling her children and her at that initial consult how I thought she was dying and that I did not recommend therapy. I remember how they cried. And I remembered how powerless I felt.

As I recalled that memory during Schwartz Rounds, I could not stop from crying. The unfairness of being a physician meeting someone for the first time and having to tell them such bad news overwhelmed me.

Even more poignant, I had the chance to reconnect with this woman’s children, who were present that day, not as audience members but as participants. Their presence may have brought my emotions to the surface more strongly. In that moment, I could show them the feelings I had bottled up for the sake of professionalism. Ultimately, I felt relieved, freer somehow, as if this burden my soul was carrying had been lifted.

Although we are both grateful for forums like this, these opportunities to share and express the grief we may have hidden away are not as common as they should be.

As physicians, we may express grief by shedding tears at the bedside of a patient nearing the end of life or through the anxiety we feel when our patient suffers a severe reaction to treatment. But we tend to put it away, to go on with our day, because there are others to be seen and cared for and more work to be done. Somehow, we move forward, shedding tears in one room and celebrating victories in another.

We need to create more spaces to express and feel grief, so we don’t get lost in it. Because understanding how grief impacts us, as people and as providers, is one of the most important realizations we can make as we go about our time-honored profession as healers.

Dr. Dizon is the director of women’s cancers at Lifespan Cancer Institute, director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Brown University, all in Providence. He reported conflicts of interest with Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Kazia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sedentary lifestyle tied to increased dementia risk

The study of nearly 50,000 adults in the UK Biobank shows that dementia risk increased 8% with 10 hours of sedentary time and 63% with 12 hours. That’s particularly concerning because Americans spend an average of 9.5 hours a day sitting.

Sleep wasn’t factored into the sedentary time and how someone accumulated the 10 hours – either in one continuous block or broken up throughout the day – was irrelevant.

“Our analysis cannot determine whether there is a causal link, so prescriptive conclusions are not really possible; however. I think it is very reasonable to conclude that sitting less and moving more may help reduce risk of dementia,” lead investigator David Raichlen, PhD, professor of biological sciences and anthropology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA.

A surprising find?

The study is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from the UK Biobank of 49,841 adults aged 60 years or older who wore an accelerometer on their wrists 24 hours a day for a week. Participants had no history of dementia when they wore the movement monitoring device.

Investigators used machine-based learning to determine sedentary time based on readings from the accelerometers. Sleep was not included as sedentary behavior.

Over a mean follow-up of 6.72 years, 414 participants were diagnosed with dementia.

Investigators found that dementia risk rises by 8% at 10 hours a day (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.08; P < .001) and 63% at 12 hours a day (aHR, 1.63; P < .001), compared with 9.27 hours a day. Those who logged 15 hours of sedentary behavior a day had more than triple the dementia risk (aHR, 3.21; P < .001).

Although previous studies had found that breaking up sedentary periods with short bursts of activity help offset some negative health effects of sitting, that wasn’t the case here. Dementia risk was elevated whether participants were sedentary for 10 uninterrupted hours or multiple sedentary periods that totaled 10 hours over the whole day.

“This was surprising,” Dr. Raichlen said. “We expected to find that patterns of sedentary behavior would play a role in risk of dementia, but once you take into account the daily volume of time spent sedentary, how you get there doesn’t seem to matter as much.”

The study did not examine how participants spent sedentary time, but an earlier study by Dr. Raichlen found that watching TV was associated with a greater risk of dementia in older adults, compared with working on a computer.

More research welcome

Dr. Raichlen noted that the number of dementia cases in the study is low and that the view of sedentary behavior is based on 1 week of accelerometer readings. A longitudinal study is needed to determine if the findings last over a longer time period.

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, senior director of scientific programs and outreach for the Alzheimer’s Association, says that earlier studies reported an association between sedentary time and dementia, so these results aren’t “particularly surprising.”

“However, reports that did not find an association have also been published, so additional research on possible associations is welcome,” she said.

It’s also important to note that this observational study doesn’t establish a causal relationship between inactivity and cognitive function, which Dr. Sexton said means the influence of other dementia risk factors that are also exacerbated by sedentary behavior can’t be ruled out.

“Although results remained significant after adjusting for several of these factors, further research is required to better understand the various elements that may influence the observed relationship,” noted Dr. Sexton, who was not part of the study. “Reverse causality – that changes in the brain related to dementia are causing the sedentary behavior – cannot be ruled out.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the state of Arizona, the Arizona Department of Health Services, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. Dr. Raichlen and Dr. Sexton report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study of nearly 50,000 adults in the UK Biobank shows that dementia risk increased 8% with 10 hours of sedentary time and 63% with 12 hours. That’s particularly concerning because Americans spend an average of 9.5 hours a day sitting.

Sleep wasn’t factored into the sedentary time and how someone accumulated the 10 hours – either in one continuous block or broken up throughout the day – was irrelevant.

“Our analysis cannot determine whether there is a causal link, so prescriptive conclusions are not really possible; however. I think it is very reasonable to conclude that sitting less and moving more may help reduce risk of dementia,” lead investigator David Raichlen, PhD, professor of biological sciences and anthropology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA.

A surprising find?

The study is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from the UK Biobank of 49,841 adults aged 60 years or older who wore an accelerometer on their wrists 24 hours a day for a week. Participants had no history of dementia when they wore the movement monitoring device.

Investigators used machine-based learning to determine sedentary time based on readings from the accelerometers. Sleep was not included as sedentary behavior.

Over a mean follow-up of 6.72 years, 414 participants were diagnosed with dementia.

Investigators found that dementia risk rises by 8% at 10 hours a day (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.08; P < .001) and 63% at 12 hours a day (aHR, 1.63; P < .001), compared with 9.27 hours a day. Those who logged 15 hours of sedentary behavior a day had more than triple the dementia risk (aHR, 3.21; P < .001).

Although previous studies had found that breaking up sedentary periods with short bursts of activity help offset some negative health effects of sitting, that wasn’t the case here. Dementia risk was elevated whether participants were sedentary for 10 uninterrupted hours or multiple sedentary periods that totaled 10 hours over the whole day.

“This was surprising,” Dr. Raichlen said. “We expected to find that patterns of sedentary behavior would play a role in risk of dementia, but once you take into account the daily volume of time spent sedentary, how you get there doesn’t seem to matter as much.”

The study did not examine how participants spent sedentary time, but an earlier study by Dr. Raichlen found that watching TV was associated with a greater risk of dementia in older adults, compared with working on a computer.

More research welcome

Dr. Raichlen noted that the number of dementia cases in the study is low and that the view of sedentary behavior is based on 1 week of accelerometer readings. A longitudinal study is needed to determine if the findings last over a longer time period.

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, senior director of scientific programs and outreach for the Alzheimer’s Association, says that earlier studies reported an association between sedentary time and dementia, so these results aren’t “particularly surprising.”

“However, reports that did not find an association have also been published, so additional research on possible associations is welcome,” she said.

It’s also important to note that this observational study doesn’t establish a causal relationship between inactivity and cognitive function, which Dr. Sexton said means the influence of other dementia risk factors that are also exacerbated by sedentary behavior can’t be ruled out.

“Although results remained significant after adjusting for several of these factors, further research is required to better understand the various elements that may influence the observed relationship,” noted Dr. Sexton, who was not part of the study. “Reverse causality – that changes in the brain related to dementia are causing the sedentary behavior – cannot be ruled out.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the state of Arizona, the Arizona Department of Health Services, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. Dr. Raichlen and Dr. Sexton report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study of nearly 50,000 adults in the UK Biobank shows that dementia risk increased 8% with 10 hours of sedentary time and 63% with 12 hours. That’s particularly concerning because Americans spend an average of 9.5 hours a day sitting.

Sleep wasn’t factored into the sedentary time and how someone accumulated the 10 hours – either in one continuous block or broken up throughout the day – was irrelevant.

“Our analysis cannot determine whether there is a causal link, so prescriptive conclusions are not really possible; however. I think it is very reasonable to conclude that sitting less and moving more may help reduce risk of dementia,” lead investigator David Raichlen, PhD, professor of biological sciences and anthropology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA.

A surprising find?

The study is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from the UK Biobank of 49,841 adults aged 60 years or older who wore an accelerometer on their wrists 24 hours a day for a week. Participants had no history of dementia when they wore the movement monitoring device.

Investigators used machine-based learning to determine sedentary time based on readings from the accelerometers. Sleep was not included as sedentary behavior.

Over a mean follow-up of 6.72 years, 414 participants were diagnosed with dementia.

Investigators found that dementia risk rises by 8% at 10 hours a day (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.08; P < .001) and 63% at 12 hours a day (aHR, 1.63; P < .001), compared with 9.27 hours a day. Those who logged 15 hours of sedentary behavior a day had more than triple the dementia risk (aHR, 3.21; P < .001).

Although previous studies had found that breaking up sedentary periods with short bursts of activity help offset some negative health effects of sitting, that wasn’t the case here. Dementia risk was elevated whether participants were sedentary for 10 uninterrupted hours or multiple sedentary periods that totaled 10 hours over the whole day.

“This was surprising,” Dr. Raichlen said. “We expected to find that patterns of sedentary behavior would play a role in risk of dementia, but once you take into account the daily volume of time spent sedentary, how you get there doesn’t seem to matter as much.”

The study did not examine how participants spent sedentary time, but an earlier study by Dr. Raichlen found that watching TV was associated with a greater risk of dementia in older adults, compared with working on a computer.

More research welcome

Dr. Raichlen noted that the number of dementia cases in the study is low and that the view of sedentary behavior is based on 1 week of accelerometer readings. A longitudinal study is needed to determine if the findings last over a longer time period.

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, senior director of scientific programs and outreach for the Alzheimer’s Association, says that earlier studies reported an association between sedentary time and dementia, so these results aren’t “particularly surprising.”

“However, reports that did not find an association have also been published, so additional research on possible associations is welcome,” she said.

It’s also important to note that this observational study doesn’t establish a causal relationship between inactivity and cognitive function, which Dr. Sexton said means the influence of other dementia risk factors that are also exacerbated by sedentary behavior can’t be ruled out.

“Although results remained significant after adjusting for several of these factors, further research is required to better understand the various elements that may influence the observed relationship,” noted Dr. Sexton, who was not part of the study. “Reverse causality – that changes in the brain related to dementia are causing the sedentary behavior – cannot be ruled out.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the state of Arizona, the Arizona Department of Health Services, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. Dr. Raichlen and Dr. Sexton report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

New COVID vaccines force bivalents out

COVID vaccines will have a new formulation in 2023, according to a decision announced by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, that will focus efforts on circulating variants. The move pushes last year’s bivalent vaccines out of circulation because they will no longer be authorized for use in the United States.

The updated mRNA vaccines for 2023-2024 are being revised to include a single component that corresponds to the Omicron variant XBB.1.5. Like the bivalents offered before, the new monovalents are being manufactured by Moderna and Pfizer.

The new vaccines are authorized for use in individuals age 6 months and older. And the new options are being developed using a similar process as previous formulations, according to the FDA.

Targeting circulating variants

In recent studies, regulators point out the extent of neutralization observed by the updated vaccines against currently circulating viral variants causing COVID-19, including EG.5, BA.2.86, appears to be of a similar magnitude to the extent of neutralization observed with previous versions of the vaccines against corresponding prior variants.

“This suggests that the vaccines are a good match for protecting against the currently circulating COVID-19 variants,” according to the report.

Hundreds of millions of people in the United States have already received previously approved mRNA COVID vaccines, according to regulators who say the benefit-to-risk profile is well understood as they move forward with new formulations.

“Vaccination remains critical to public health and continued protection against serious consequences of COVID-19, including hospitalization and death,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “The public can be assured that these updated vaccines have met the agency’s rigorous scientific standards for safety, effectiveness, and manufacturing quality. We very much encourage those who are eligible to consider getting vaccinated.”

Timing the effort

On Sept. 12 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that everyone 6 months and older get an updated COVID-19 vaccine. Updated vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna will be available later this week, according to the agency.

This article was updated 9/14/23.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID vaccines will have a new formulation in 2023, according to a decision announced by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, that will focus efforts on circulating variants. The move pushes last year’s bivalent vaccines out of circulation because they will no longer be authorized for use in the United States.

The updated mRNA vaccines for 2023-2024 are being revised to include a single component that corresponds to the Omicron variant XBB.1.5. Like the bivalents offered before, the new monovalents are being manufactured by Moderna and Pfizer.

The new vaccines are authorized for use in individuals age 6 months and older. And the new options are being developed using a similar process as previous formulations, according to the FDA.

Targeting circulating variants

In recent studies, regulators point out the extent of neutralization observed by the updated vaccines against currently circulating viral variants causing COVID-19, including EG.5, BA.2.86, appears to be of a similar magnitude to the extent of neutralization observed with previous versions of the vaccines against corresponding prior variants.

“This suggests that the vaccines are a good match for protecting against the currently circulating COVID-19 variants,” according to the report.

Hundreds of millions of people in the United States have already received previously approved mRNA COVID vaccines, according to regulators who say the benefit-to-risk profile is well understood as they move forward with new formulations.

“Vaccination remains critical to public health and continued protection against serious consequences of COVID-19, including hospitalization and death,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “The public can be assured that these updated vaccines have met the agency’s rigorous scientific standards for safety, effectiveness, and manufacturing quality. We very much encourage those who are eligible to consider getting vaccinated.”

Timing the effort

On Sept. 12 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that everyone 6 months and older get an updated COVID-19 vaccine. Updated vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna will be available later this week, according to the agency.

This article was updated 9/14/23.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID vaccines will have a new formulation in 2023, according to a decision announced by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, that will focus efforts on circulating variants. The move pushes last year’s bivalent vaccines out of circulation because they will no longer be authorized for use in the United States.

The updated mRNA vaccines for 2023-2024 are being revised to include a single component that corresponds to the Omicron variant XBB.1.5. Like the bivalents offered before, the new monovalents are being manufactured by Moderna and Pfizer.

The new vaccines are authorized for use in individuals age 6 months and older. And the new options are being developed using a similar process as previous formulations, according to the FDA.

Targeting circulating variants

In recent studies, regulators point out the extent of neutralization observed by the updated vaccines against currently circulating viral variants causing COVID-19, including EG.5, BA.2.86, appears to be of a similar magnitude to the extent of neutralization observed with previous versions of the vaccines against corresponding prior variants.

“This suggests that the vaccines are a good match for protecting against the currently circulating COVID-19 variants,” according to the report.

Hundreds of millions of people in the United States have already received previously approved mRNA COVID vaccines, according to regulators who say the benefit-to-risk profile is well understood as they move forward with new formulations.

“Vaccination remains critical to public health and continued protection against serious consequences of COVID-19, including hospitalization and death,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “The public can be assured that these updated vaccines have met the agency’s rigorous scientific standards for safety, effectiveness, and manufacturing quality. We very much encourage those who are eligible to consider getting vaccinated.”

Timing the effort

On Sept. 12 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that everyone 6 months and older get an updated COVID-19 vaccine. Updated vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna will be available later this week, according to the agency.

This article was updated 9/14/23.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Dusty, but still cool

When I was 16, keeping my car shiny was a priority. I washed it every weekend and waxed it once a month. I was pretty good at it and got paid to do the occasional job for a neighbor, too.

In college I was busier, and my car was back at the house, so it didn’t need to be washed as much.

In medical school I think I washed the car once a year. Residency was probably the same.

Today I realized I couldn’t remember when I last had it washed (at my age I don’t have time to do it myself). So I looked it up in Quicken: Nov. 14, 2018.

Really? I’ve gone almost 5 years without washing my car? I can’t even blame that on the pandemic.

I mean, I still like my car. It’s comfortable, has good air conditioning (in Phoenix that’s critical), and gets me where I want to go. At my age those things are what’s really important. It’s hard to believe that 40 years ago, keeping a polished car was the center of my existence. Of course, it probably still is for most guys that age.

It’s a reminder of how much things change as life goes by.

Here in my little corner of neurology, multiple sclerosis has gone from steroids for relapses, to a few injections of mild benefit, to a bunch of drugs that are, literally, game-changing for many patients. And the Big Four epilepsy drugs (Dilantin, Tegretol, Depakote, and Phenobarb) are slowly fading into the background.

But back to changing priorities – it’s the way life rewrites our plans at each step. From a freshly waxed car to good grades to mortgages to kids – and then watching as they wax their cars.

Suddenly my car looks dusty. Am I the same way? I’m certainly not 16 anymore. Realistically, the majority of my life and career are behind me now. That doesn’t mean I’m not still having fun, it’s just the truth. I try not to think about it that much, as doing so won’t change anything.

In all honesty, neither did washing my car. I mean, the car looked good, but did it make me one of the cool kids? Or get me a girlfriend? Or invited to THE parties? Not at all. Like so many things about appearances, very few of them really matter. There’s only so far that style will get you, compared with substance.

Which doesn’t change the fact that I need to wash my car. But procrastination is for another column.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

When I was 16, keeping my car shiny was a priority. I washed it every weekend and waxed it once a month. I was pretty good at it and got paid to do the occasional job for a neighbor, too.

In college I was busier, and my car was back at the house, so it didn’t need to be washed as much.

In medical school I think I washed the car once a year. Residency was probably the same.

Today I realized I couldn’t remember when I last had it washed (at my age I don’t have time to do it myself). So I looked it up in Quicken: Nov. 14, 2018.

Really? I’ve gone almost 5 years without washing my car? I can’t even blame that on the pandemic.

I mean, I still like my car. It’s comfortable, has good air conditioning (in Phoenix that’s critical), and gets me where I want to go. At my age those things are what’s really important. It’s hard to believe that 40 years ago, keeping a polished car was the center of my existence. Of course, it probably still is for most guys that age.

It’s a reminder of how much things change as life goes by.

Here in my little corner of neurology, multiple sclerosis has gone from steroids for relapses, to a few injections of mild benefit, to a bunch of drugs that are, literally, game-changing for many patients. And the Big Four epilepsy drugs (Dilantin, Tegretol, Depakote, and Phenobarb) are slowly fading into the background.

But back to changing priorities – it’s the way life rewrites our plans at each step. From a freshly waxed car to good grades to mortgages to kids – and then watching as they wax their cars.

Suddenly my car looks dusty. Am I the same way? I’m certainly not 16 anymore. Realistically, the majority of my life and career are behind me now. That doesn’t mean I’m not still having fun, it’s just the truth. I try not to think about it that much, as doing so won’t change anything.

In all honesty, neither did washing my car. I mean, the car looked good, but did it make me one of the cool kids? Or get me a girlfriend? Or invited to THE parties? Not at all. Like so many things about appearances, very few of them really matter. There’s only so far that style will get you, compared with substance.

Which doesn’t change the fact that I need to wash my car. But procrastination is for another column.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

When I was 16, keeping my car shiny was a priority. I washed it every weekend and waxed it once a month. I was pretty good at it and got paid to do the occasional job for a neighbor, too.

In college I was busier, and my car was back at the house, so it didn’t need to be washed as much.

In medical school I think I washed the car once a year. Residency was probably the same.

Today I realized I couldn’t remember when I last had it washed (at my age I don’t have time to do it myself). So I looked it up in Quicken: Nov. 14, 2018.

Really? I’ve gone almost 5 years without washing my car? I can’t even blame that on the pandemic.

I mean, I still like my car. It’s comfortable, has good air conditioning (in Phoenix that’s critical), and gets me where I want to go. At my age those things are what’s really important. It’s hard to believe that 40 years ago, keeping a polished car was the center of my existence. Of course, it probably still is for most guys that age.

It’s a reminder of how much things change as life goes by.

Here in my little corner of neurology, multiple sclerosis has gone from steroids for relapses, to a few injections of mild benefit, to a bunch of drugs that are, literally, game-changing for many patients. And the Big Four epilepsy drugs (Dilantin, Tegretol, Depakote, and Phenobarb) are slowly fading into the background.

But back to changing priorities – it’s the way life rewrites our plans at each step. From a freshly waxed car to good grades to mortgages to kids – and then watching as they wax their cars.

Suddenly my car looks dusty. Am I the same way? I’m certainly not 16 anymore. Realistically, the majority of my life and career are behind me now. That doesn’t mean I’m not still having fun, it’s just the truth. I try not to think about it that much, as doing so won’t change anything.

In all honesty, neither did washing my car. I mean, the car looked good, but did it make me one of the cool kids? Or get me a girlfriend? Or invited to THE parties? Not at all. Like so many things about appearances, very few of them really matter. There’s only so far that style will get you, compared with substance.

Which doesn’t change the fact that I need to wash my car. But procrastination is for another column.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Seeking help for burnout may be a gamble for doctors

By the end of 2021, Anuj Peddada, MD, had hit a wall. He couldn’t sleep, couldn’t concentrate, erupted in anger, and felt isolated personally and professionally. To temper pandemic-driven pressures, the Colorado radiation oncologist took an 8-week stress management and resiliency course, but the feelings kept creeping back.

Still, Dr. Peddada, in his own private practice, pushed through, working 60-hour weeks and carrying the workload of two physicians. It wasn’t until he caught himself making uncharacteristic medical errors, including radiation planning for the wrong site, that he knew he needed help – and possibly a temporary break from medicine.

There was just one hitch: He was closing his private practice to start a new in-house job with Centura Health, the Colorado Springs hospital he’d contracted with for over 20 years.

Given the long-standing relationship – Dr. Peddada’s image graced some of the company’s marketing billboards – he expected Centura would understand when, on his doctor’s recommendation, he requested a short-term medical leave that would delay his start date by 1 month.

Instead, Centura abruptly rescinded the employment offer, leaving Dr. Peddada jobless and with no recourse but to sue.

“I was blindsided. The hospital had a physician resiliency program that claimed to encourage physicians to seek help, [so] I thought they would be completely supportive and understanding,” Dr. Peddada said.

He told this news organization that he was naive to have been so honest with the hospital he’d long served as a contractor, including the decade-plus he›d spent directing its radiation oncology department.

“It is exceedingly painful to see hospital leadership use me in their advertisement[s] ... trying to profit off my reputation and work after devastating my career.”

The lawsuit Dr. Peddada filed in July in Colorado federal district court may offer a rare glimpse of the potential career ramifications of seeking help for physician burnout. Despite employers’ oft-stated support for physician wellness, Dr. Peddada’s experience may serve as a cautionary tale for doctors who are open about their struggles.

Centura Health did not respond to requests for comment. In court documents, the health system’s attorneys asked for more time to respond to Dr. Peddada’s complaint.

A plea for help

In the complaint, Dr. Peddada and his attorneys claim that Centura violated the state’s Anti-Discrimination Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) when it failed to offer reasonable accommodations after he began experiencing “physiological and psychological symptoms corresponding to burnout.”

Since 1999, Dr. Peddada had contracted exclusively with Centura to provide oncology services at its hospital, Penrose Cancer Center, and began covering a second Centura location in 2021. As medical director of Penrose’s radiation oncology department, he helped establish a community nurse navigator program and accounted for 75% of Centura’s radiation oncology referrals, according to the complaint.

But when his symptoms and fear for the safety of his patients became unbearable, Dr. Peddada requested an urgent evaluation from his primary care physician, who diagnosed him with “physician burnout” and recommended medical leave.

Shortly after presenting the leave request to Centura, rumors began circulating that he was having a “nervous breakdown,” the complaint noted. Dr. Peddada worried that perhaps his private health information was being shared with hospital employees.

After meeting with the hospital’s head of physician resiliency and agreeing to undergo a peer review evaluation by the Colorado Physician Health Program, which would decide the reinstatement timeline and if further therapy was necessary, Dr. Peddada was assured his leave would be approved.

Five days later, his job offer was revoked.

In an email from hospital leadership, the oncologist was informed that he had “declined employment” by failing to sign a revised employment contract sent to him 2 weeks prior when he was out of state on a preapproved vacation, according to the lawsuit.

The lawsuit alleges that Dr. Peddada was wrongfully discharged due to his disability after Centura “exploited [his] extensive patient base, referral network, and reputation to generate growth and profit.”

Colorado employment law attorney Deborah Yim, Esq., who is not involved in Peddada’s case, told this news organization that the ADA requires employers to provide reasonable accommodations for physical or mental impairments that substantially limit at least one major life activity, except when the request imposes an undue hardship on the employer.

“Depression and related mental health conditions would qualify, depending on the circumstances, and courts have certainly found them to be qualifying disabilities entitled to ADA protection in the past,” she said.

Not all employers are receptive to doctors’ needs, says the leadership team at Physicians Just Equity, an organization providing peer support to doctors experiencing workplace conflicts like discrimination and retaliation. They say that Dr. Peddada’s experience, where disclosing burnout results in being “ostracized, penalized, and ultimately ousted,” is the rule rather than the exception.

“Dr. Peddada’s case represents the unfortunate reality faced by many physicians in today’s clinical landscape,” the organization’s board of directors said in a written statement. “The imbalance of unreasonable professional demands, the lack of autonomy, moral injury, and disintegrating practice rewards is unsustainable for the medical professional.”

“Retaliation by employers after speaking up against this imbalance [and] requesting support and time to rejuvenate is a grave failure of health care systems that prioritize the business of delivering health care over the health, well-being, and satisfaction of their most valuable resource – the physician,” the board added in their statement.

Dr. Peddada has since closed his private practice and works as an independent contractor and consultant, his attorney, Iris Halpern, JD, said in an interview. She says Centura could have honored the accommodation request or suggested another option that met his needs, but “not only were they unsupportive, they terminated him.”

Ms. Yim says the parties will have opportunities to reach a settlement and resolve the dispute as the case works through the court system. Otherwise, Dr. Peddada and Centura may eventually head to trial.

Current state of physician burnout

The state of physician burnout is certainly a concerning one. More than half (53%) of physicians responding to this year’s Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report said they are burned out. Nearly one-quarter reported feeling depressed. Some of the top reasons they cited were too many bureaucratic tasks (61%), too many work hours (37%), and lack of autonomy (31%).

A 2022 study by the Mayo Clinic found a substantial increase in physician burnout in the first 2 years of the pandemic, with doctors reporting rising emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

Although burnout affects many physicians and is a priority focus of the National Academy of Medicine’s plan to restore workforce well-being, admitting it is often seen as taboo and can imperil a doctor’s career. In the Medscape report, for example, 39% of physicians said they would not even consider professional treatment for burnout, with many commenting that they would just deal with it themselves.

“Many physicians are frightened to take time out for self-care because [they] fear losing their job, being stigmatized, and potentially ending their careers,” said Dr. Peddada, adding that physicians are commonly asked questions about their mental health when applying for hospital privileges. He says this dynamic forces them to choose between getting help or ignoring their true feelings, leading to poor quality of care and patient safety risks.

Medical licensing boards probe physicians’ mental health, too. As part of its #FightingForDocs campaign, the American Medical Association hopes to remove the stigma around burnout and depression and advocates for licensing boards to revise questions that may discourage physicians from seeking assistance. The AMA recommends that physicians only disclose current physical or mental conditions affecting their ability to practice.

Pringl Miller, MD, founder and executive director of Physician Just Equity, told Medscape that improving physician wellness requires structural change.

“Physicians (who) experience burnout without the proper accommodations run the risk of personal harm, because most physicians will prioritize the health and well-being of their patients over themselves ... [resulting in] suboptimal and unsafe patient care,” she said.

Helping doctors regain a sense of purpose

One change involves reframing how the health care industry thinks about and approaches burnout, says Steven Siegel, MD, chief mental health and wellness officer with Keck Medicine of USC. He told this news organization that these discussions should enhance the physician’s sense of purpose.

“Some people treat burnout as a concrete disorder like cancer, instead of saying, ‘I’m feeling exhausted, demoralized, and don’t enjoy my job anymore. What can we do to restore my enthusiasm for work?’ ”