User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Abdominal fat linked to lower brain volume in midlife

In a large study of healthy middle-aged adults, greater visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat on abdominal MRI predicted brain atrophy on imaging, especially in women.

“The study shows that excess fat is bad for the brain and worse in women, including in Alzheimer’s disease risk regions,” lead author Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, Mo., said in an interview.

The study was published online in the journal Aging and Disease

Modifiable risk factor

Multiple studies have suggested a connection between body fat accumulation and increased dementia risk. But few have examined the relationship between types of fat (visceral and subcutaneous) and brain volume.

For the new study, 10,000 healthy adults aged 20-80 years (mean age, 52.9 years; 53% men) underwent a short whole-body MRI protocol. Regression analyses of abdominal fat types and normalized brain volumes were evaluated, controlling for age and sex.

The research team found that higher amounts of both visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat predicted lower total gray and white matter volume, as well as lower volume in the hippocampus, frontal cortex, and temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes.

“The findings are quite dramatic,” Dr. Raji told this news organization. “Overall, we found that both subcutaneous and visceral fat has similar levels of negative relationships with brain volumes.”

Women had a higher burden of brain atrophy with increased visceral fat than men. However, it’s difficult to place the sex differences in context because of the lack of prior work specifically investigating visceral fat, brain volume loss, and sex differences, the researchers caution.

They also note that while statistically significant relationships were observed between visceral fat levels and gray matter volume changes, their effect sizes were generally small.

“Thus, the statistical significance of this work is influenced by the large sample size and less so by large effect size in any given set of regions,” the investigators write.

Other limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the study, which precludes conclusions about causality. The analysis also did not account for other lifestyle factors such as physical activity, diet, and genetic variables.

The researchers call for further investigation “to better elucidate underlying mechanisms and discover possible interventions targeting abdominal fat reduction as a strategy to maintain brain health.”

‘Helpful addition to the literature’

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific programs and outreach, noted that “previous studies have linked obesity with cognitive decline and increased risk of dementia. Rather than using BMI as a proxy for body fat, the current study examined visceral and subcutaneous fat directly using imaging techniques.”

Dr. Sexton, who was not associated with this study, said the finding that increased body fat was associated with reduced brain volumes suggests “a possible mechanism to explain the previously reported associations between obesity and cognition.”

“Though some degree of atrophy and brain shrinkage is common with old age, awareness of this association is important because reduced brain volume may be associated with problems with thinking, memory, and performing everyday tasks, and because rates of obesity continue to rise in the United States, along with obesity-related conditions including heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer,” she added.

“While a helpful addition to the literature, the study does have important limitations. As an observational study, it cannot establish whether higher levels of body fat directly causes reduced brain volumes,” Dr. Sexton cautioned.

In addition, the study did not take into account important related factors like physical activity and diet, which may influence any relationship between body fat and brain volumes, she noted. “Overall, it is not just one factor that is important to consider when considering risk for cognitive decline and dementia, but multiple factors.

“Obesity and the location of body fat must be considered in combination with one’s total lived experience and habits, including physical activity, education, head injury, sleep, mental health, and the health of your heart/cardiovascular system and other key bodily systems,” Dr. Sexton said.

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial known as U.S. POINTER to see whether combining physical activity, healthy nutrition, social and intellectual challenges, and improved self-management of medical conditions can protect cognitive function in older adults who are at increased risk for cognitive decline.

This work was supported in part by Providence St. Joseph Health in Seattle; Saint John’s Health Center Foundation; Pacific Neuroscience Institute and Foundation; Will and Cary Singleton; and the McLoughlin family. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Voxelwise, Neurevolution, Pacific Neuroscience Institute Foundation, and Icometrix. Dr. Sexton reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large study of healthy middle-aged adults, greater visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat on abdominal MRI predicted brain atrophy on imaging, especially in women.

“The study shows that excess fat is bad for the brain and worse in women, including in Alzheimer’s disease risk regions,” lead author Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, Mo., said in an interview.

The study was published online in the journal Aging and Disease

Modifiable risk factor

Multiple studies have suggested a connection between body fat accumulation and increased dementia risk. But few have examined the relationship between types of fat (visceral and subcutaneous) and brain volume.

For the new study, 10,000 healthy adults aged 20-80 years (mean age, 52.9 years; 53% men) underwent a short whole-body MRI protocol. Regression analyses of abdominal fat types and normalized brain volumes were evaluated, controlling for age and sex.

The research team found that higher amounts of both visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat predicted lower total gray and white matter volume, as well as lower volume in the hippocampus, frontal cortex, and temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes.

“The findings are quite dramatic,” Dr. Raji told this news organization. “Overall, we found that both subcutaneous and visceral fat has similar levels of negative relationships with brain volumes.”

Women had a higher burden of brain atrophy with increased visceral fat than men. However, it’s difficult to place the sex differences in context because of the lack of prior work specifically investigating visceral fat, brain volume loss, and sex differences, the researchers caution.

They also note that while statistically significant relationships were observed between visceral fat levels and gray matter volume changes, their effect sizes were generally small.

“Thus, the statistical significance of this work is influenced by the large sample size and less so by large effect size in any given set of regions,” the investigators write.

Other limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the study, which precludes conclusions about causality. The analysis also did not account for other lifestyle factors such as physical activity, diet, and genetic variables.

The researchers call for further investigation “to better elucidate underlying mechanisms and discover possible interventions targeting abdominal fat reduction as a strategy to maintain brain health.”

‘Helpful addition to the literature’

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific programs and outreach, noted that “previous studies have linked obesity with cognitive decline and increased risk of dementia. Rather than using BMI as a proxy for body fat, the current study examined visceral and subcutaneous fat directly using imaging techniques.”

Dr. Sexton, who was not associated with this study, said the finding that increased body fat was associated with reduced brain volumes suggests “a possible mechanism to explain the previously reported associations between obesity and cognition.”

“Though some degree of atrophy and brain shrinkage is common with old age, awareness of this association is important because reduced brain volume may be associated with problems with thinking, memory, and performing everyday tasks, and because rates of obesity continue to rise in the United States, along with obesity-related conditions including heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer,” she added.

“While a helpful addition to the literature, the study does have important limitations. As an observational study, it cannot establish whether higher levels of body fat directly causes reduced brain volumes,” Dr. Sexton cautioned.

In addition, the study did not take into account important related factors like physical activity and diet, which may influence any relationship between body fat and brain volumes, she noted. “Overall, it is not just one factor that is important to consider when considering risk for cognitive decline and dementia, but multiple factors.

“Obesity and the location of body fat must be considered in combination with one’s total lived experience and habits, including physical activity, education, head injury, sleep, mental health, and the health of your heart/cardiovascular system and other key bodily systems,” Dr. Sexton said.

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial known as U.S. POINTER to see whether combining physical activity, healthy nutrition, social and intellectual challenges, and improved self-management of medical conditions can protect cognitive function in older adults who are at increased risk for cognitive decline.

This work was supported in part by Providence St. Joseph Health in Seattle; Saint John’s Health Center Foundation; Pacific Neuroscience Institute and Foundation; Will and Cary Singleton; and the McLoughlin family. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Voxelwise, Neurevolution, Pacific Neuroscience Institute Foundation, and Icometrix. Dr. Sexton reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large study of healthy middle-aged adults, greater visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat on abdominal MRI predicted brain atrophy on imaging, especially in women.

“The study shows that excess fat is bad for the brain and worse in women, including in Alzheimer’s disease risk regions,” lead author Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, Mo., said in an interview.

The study was published online in the journal Aging and Disease

Modifiable risk factor

Multiple studies have suggested a connection between body fat accumulation and increased dementia risk. But few have examined the relationship between types of fat (visceral and subcutaneous) and brain volume.

For the new study, 10,000 healthy adults aged 20-80 years (mean age, 52.9 years; 53% men) underwent a short whole-body MRI protocol. Regression analyses of abdominal fat types and normalized brain volumes were evaluated, controlling for age and sex.

The research team found that higher amounts of both visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat predicted lower total gray and white matter volume, as well as lower volume in the hippocampus, frontal cortex, and temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes.

“The findings are quite dramatic,” Dr. Raji told this news organization. “Overall, we found that both subcutaneous and visceral fat has similar levels of negative relationships with brain volumes.”

Women had a higher burden of brain atrophy with increased visceral fat than men. However, it’s difficult to place the sex differences in context because of the lack of prior work specifically investigating visceral fat, brain volume loss, and sex differences, the researchers caution.

They also note that while statistically significant relationships were observed between visceral fat levels and gray matter volume changes, their effect sizes were generally small.

“Thus, the statistical significance of this work is influenced by the large sample size and less so by large effect size in any given set of regions,” the investigators write.

Other limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the study, which precludes conclusions about causality. The analysis also did not account for other lifestyle factors such as physical activity, diet, and genetic variables.

The researchers call for further investigation “to better elucidate underlying mechanisms and discover possible interventions targeting abdominal fat reduction as a strategy to maintain brain health.”

‘Helpful addition to the literature’

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific programs and outreach, noted that “previous studies have linked obesity with cognitive decline and increased risk of dementia. Rather than using BMI as a proxy for body fat, the current study examined visceral and subcutaneous fat directly using imaging techniques.”

Dr. Sexton, who was not associated with this study, said the finding that increased body fat was associated with reduced brain volumes suggests “a possible mechanism to explain the previously reported associations between obesity and cognition.”

“Though some degree of atrophy and brain shrinkage is common with old age, awareness of this association is important because reduced brain volume may be associated with problems with thinking, memory, and performing everyday tasks, and because rates of obesity continue to rise in the United States, along with obesity-related conditions including heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer,” she added.

“While a helpful addition to the literature, the study does have important limitations. As an observational study, it cannot establish whether higher levels of body fat directly causes reduced brain volumes,” Dr. Sexton cautioned.

In addition, the study did not take into account important related factors like physical activity and diet, which may influence any relationship between body fat and brain volumes, she noted. “Overall, it is not just one factor that is important to consider when considering risk for cognitive decline and dementia, but multiple factors.

“Obesity and the location of body fat must be considered in combination with one’s total lived experience and habits, including physical activity, education, head injury, sleep, mental health, and the health of your heart/cardiovascular system and other key bodily systems,” Dr. Sexton said.

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial known as U.S. POINTER to see whether combining physical activity, healthy nutrition, social and intellectual challenges, and improved self-management of medical conditions can protect cognitive function in older adults who are at increased risk for cognitive decline.

This work was supported in part by Providence St. Joseph Health in Seattle; Saint John’s Health Center Foundation; Pacific Neuroscience Institute and Foundation; Will and Cary Singleton; and the McLoughlin family. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Voxelwise, Neurevolution, Pacific Neuroscience Institute Foundation, and Icometrix. Dr. Sexton reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AGING AND DISEASES

The magic of music

I’m really going to miss Jimmy Buffett.

I’ve liked his music as far back as I can remember, and was lucky enough to see him in person in the mid-90s.

I’ve written about music before, but its affect on us never fails to amaze me. Songs can be background noise conducive to getting things done. They can also be in the foreground, serving as a mental vacation (or accompanying a real one). They can transport you to another place, briefly clearing your head from the daily goings-on around you. Even if it’s just during the drive home, it’s a welcome escape to a virtual beach and tropical drink.

Songs can bring back memories of certain events or people that we link them to. My dad loved anything by Neil Diamond, and nothing brings back thoughts of Dad more than when my iTunes randomly picks “I Am ... I Said.” Or John Williams’ Star Wars theme, taking me back to the summer of 1977 when I sat, spellbound, by this incredible movie whose magic is still going strong two generations later.

It’s amazing how our brain tries to make music out of nothing. Even in silence we have ear worms, the songs stuck in our head for hours to days (recently I’ve had “I Sing the Body Electric” from the 1980 movie Fame playing in there).

My office is over an MRI scanner, so I can always hear the chiller pumps softly running in the background. Sometimes my brain will turn their rhythmic chirping into a song, altering the pace of the song to fit them. The soft clicking of the ceiling fan, in my home office, does the same thing (for some reason my brain usually tries to fit “Yellow Submarine” to that one, no idea why).

Music is a part of that mysterious essence that makes us human. It touches all of us in some way, which varies between people, songs, and artists.

Jimmy Buffet’s music has a vacation vibe. Songs of the Caribbean & Keys, beaches, bars, boats, and tropical drinks. The 4:12 running time of his most well-known song, “Margaritaville,” gives a brief respite from my day when it comes on.

He passes into the beyond, to the sadness of his family, friends, and fans. But, unlike people, music can be immortal, and so he lives on through his creations. Like, Bach, Lennon, Bowie, Joplin, Sousa, and too many others to count, his work – and the enjoyment we get from it – are a gift left behind for the future.

Tight lines, Jimmy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m really going to miss Jimmy Buffett.

I’ve liked his music as far back as I can remember, and was lucky enough to see him in person in the mid-90s.

I’ve written about music before, but its affect on us never fails to amaze me. Songs can be background noise conducive to getting things done. They can also be in the foreground, serving as a mental vacation (or accompanying a real one). They can transport you to another place, briefly clearing your head from the daily goings-on around you. Even if it’s just during the drive home, it’s a welcome escape to a virtual beach and tropical drink.

Songs can bring back memories of certain events or people that we link them to. My dad loved anything by Neil Diamond, and nothing brings back thoughts of Dad more than when my iTunes randomly picks “I Am ... I Said.” Or John Williams’ Star Wars theme, taking me back to the summer of 1977 when I sat, spellbound, by this incredible movie whose magic is still going strong two generations later.

It’s amazing how our brain tries to make music out of nothing. Even in silence we have ear worms, the songs stuck in our head for hours to days (recently I’ve had “I Sing the Body Electric” from the 1980 movie Fame playing in there).

My office is over an MRI scanner, so I can always hear the chiller pumps softly running in the background. Sometimes my brain will turn their rhythmic chirping into a song, altering the pace of the song to fit them. The soft clicking of the ceiling fan, in my home office, does the same thing (for some reason my brain usually tries to fit “Yellow Submarine” to that one, no idea why).

Music is a part of that mysterious essence that makes us human. It touches all of us in some way, which varies between people, songs, and artists.

Jimmy Buffet’s music has a vacation vibe. Songs of the Caribbean & Keys, beaches, bars, boats, and tropical drinks. The 4:12 running time of his most well-known song, “Margaritaville,” gives a brief respite from my day when it comes on.

He passes into the beyond, to the sadness of his family, friends, and fans. But, unlike people, music can be immortal, and so he lives on through his creations. Like, Bach, Lennon, Bowie, Joplin, Sousa, and too many others to count, his work – and the enjoyment we get from it – are a gift left behind for the future.

Tight lines, Jimmy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m really going to miss Jimmy Buffett.

I’ve liked his music as far back as I can remember, and was lucky enough to see him in person in the mid-90s.

I’ve written about music before, but its affect on us never fails to amaze me. Songs can be background noise conducive to getting things done. They can also be in the foreground, serving as a mental vacation (or accompanying a real one). They can transport you to another place, briefly clearing your head from the daily goings-on around you. Even if it’s just during the drive home, it’s a welcome escape to a virtual beach and tropical drink.

Songs can bring back memories of certain events or people that we link them to. My dad loved anything by Neil Diamond, and nothing brings back thoughts of Dad more than when my iTunes randomly picks “I Am ... I Said.” Or John Williams’ Star Wars theme, taking me back to the summer of 1977 when I sat, spellbound, by this incredible movie whose magic is still going strong two generations later.

It’s amazing how our brain tries to make music out of nothing. Even in silence we have ear worms, the songs stuck in our head for hours to days (recently I’ve had “I Sing the Body Electric” from the 1980 movie Fame playing in there).

My office is over an MRI scanner, so I can always hear the chiller pumps softly running in the background. Sometimes my brain will turn their rhythmic chirping into a song, altering the pace of the song to fit them. The soft clicking of the ceiling fan, in my home office, does the same thing (for some reason my brain usually tries to fit “Yellow Submarine” to that one, no idea why).

Music is a part of that mysterious essence that makes us human. It touches all of us in some way, which varies between people, songs, and artists.

Jimmy Buffet’s music has a vacation vibe. Songs of the Caribbean & Keys, beaches, bars, boats, and tropical drinks. The 4:12 running time of his most well-known song, “Margaritaville,” gives a brief respite from my day when it comes on.

He passes into the beyond, to the sadness of his family, friends, and fans. But, unlike people, music can be immortal, and so he lives on through his creations. Like, Bach, Lennon, Bowie, Joplin, Sousa, and too many others to count, his work – and the enjoyment we get from it – are a gift left behind for the future.

Tight lines, Jimmy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

MS drugs during pregnancy show no safety signals

AURORA, COLO. – Several drugs for multiple sclerosis (MS) that are contraindicated during pregnancy nevertheless have not shown concerning safety signals in a series of small studies presented as posters at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. The industry-sponsored research included an assessment of pregnancy and infant outcomes for cladribine, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, and ozanimod, all of which are not recommended during pregnancy based primarily on minimal data that suggests, but does not confirm, possible teratogenicity.

“When these new medications hit the market, maternal-fetal medicine physicians and obstetricians are left with very scant data on how to counsel patients, and it’s often based on theory, case reports, or animal studies,” said Teodora Kolarova, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at the University of Washington, Seattle, who was not involved in any of the research. “Although these sample sizes seem small, the population they are sampling from – patients with MS who take immunomodulators who then experience a pregnancy – is much smaller than all pregnant patients.”

Taken together, the findings suggest no increased risk of miscarriage or congenital malformation, compared with baseline risk, Dr. Kolarova said.

“As a whole, these studies are overall reassuring with, of course, some caveats, including timing of medication exposure, limited sample size, and limited outcome data,” Dr. Kolarova said. She noted that embryonic organ formation is complete by 10 weeks gestation, by which time an unplanned pregnancy may not have been recognized yet. “In the subset of patients in the studies that were exposed during the first trimester, there was no increase in congenital malformations from a baseline risk of about 2%-3% in the general population, which is helpful for patient counseling.”

Counseling during the childbearing years

That kind of counseling is important yet absent for many people capable of pregnancy, suggests separate research also presented at the conference by Suma Shah, MD, an associate professor of neurology at Duke University, Durham, N.C. Dr. Shah gave 13-question surveys to female MS patients of all ages at her institution and presented an analysis of data from 38 completed surveys. Among those taking disease-modifying therapies, their medications included ocrelizumab, rituximab, teriflunomide, fingolimod, fumarates, interferons, natalizumab, and cladribine.

“MS disproportionately impacts women among 20 to 40 years, and that’s a really big part of their childbearing years when there are big decisions being made about whether they’re going to choose to grow family or not,” said Dr. Shah. The average age of those who completed the survey was 44. Dr. Shah noted that a lot of research has looked at the safety of older disease-modifying agents in pregnancy, but that information doesn’t appear to be filtering down to patients. “What I really wanted to look at is what do our parent patients understand about whether or not they can even think about pregnancy – and there’s a lot of work to be done.”

Just under a third of survey respondents said they did not have as many children as they would like, and a quarter said they were told they couldn’t have children if they had a diagnosis of MS.

“That was a little heartbreaking to hear because that’s not the truth,” Dr. Shah said. She said it’s necessary to have a more detailed conversation looking at tailored decisions for patients. “Both of those things – patients not being able to grow their family to the number that they desire, and not feeling like they can grow a family – I would think in 2023 we would have come farther than that, and there’s still a lot of room there to improve.”

She advised clinicians not to assume that MS patients know what their options are regarding family planning. “There’s still a lot of room for conversations,” she said. She also explicitly recommends discussing family planning and pregnancy planning with every patient, no matter their gender, early and often.

Cladribine shows no miscarriage, malformations

Dr. Kolarova noted that one of the studies, on cladribine, had a fairly robust sample size with its 180 pregnancy exposures. In that study, led by Kerstin Hellwig, MD, of Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, data came from the global surveillance program MAPLE-MS, established to assess cladribine effects on pregnancy and infant outcomes. The researchers analyzed data from 76 mothers and 9 fathers who, at any time from 2017 to 2022, were taking cladribine during pregnancy or up to 6 months before pregnancy. Outcomes included live birth, miscarriage, stillbirth, elective abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and major congenital anomalies.

Just over half the mothers (53.9%) were exposed before pregnancy, and about a quarter (26.3%) were exposed during the first trimester. The timing was unknown for most of the other mothers (18.4%). Among the fathers, two-thirds (66.7%) were exposed before pregnancy, and one-third had unknown timing.

Among the 180 pregnancies in the maternal cohort, 42.2% had known outcomes. Nearly half the women (48.7%) taking cladribine had live births, 28.9% had elective abortions, and 21.1% had miscarriages. Only 9 of the 22 pregnancies in the paternal cohort had known outcomes, which included 88.9% live births and 11.1% miscarriages. None of the pregnancies resulted in stillbirth or in a live birth with major congenital anomalies.

”Robust conclusions cannot be made about the risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes with cladribine tablets, but no increase has been signaled thus far,” the researchers reported. ”It is necessary to counsel patients to prevent pregnancy and to use effective contraception during cladribine tablets intake and for at least 6 months after the last cladribine tablet intake in each treatment year.”

Emily Evans, MD, MBE, medical director at U.S. Neurology and Immunology in Rockland, Mass., speaking on behalf of the findings, said they were fairly encouraging.

“Of course, we don’t encourage patients to get pregnant within 6 months of their last dose of cladribine tablets,” Dr. Evans said, but “within those individuals who have gotten pregnant within 6 months of their last dose of cladribine, or who have fathered a child within 6 months of their last dose of cladribine tablets, we’re seeing overall encouraging outcomes. We’re specifically not seeing any differences in the rates of spontaneous abortions, and we’re not seeing any differences in the rates of congenital malformations.”

Ocrelizumab and ofatumumab: No infections so far

Current recommendations for ocrelizumab are to avoid pregnancy for 6 months after the last infusion and stop any breastfeeding during therapy. Yet these recommendations are only because of insufficient data rather than evidence of risk, according to Lana Zhovtis Ryerson, MD, of the NYU Multiple Sclerosis Comprehensive Care Center in New York. She and her colleagues identified all women of childbearing age who had received ocrelizumab within 1 year of pregnancy at their NYU institution. A retrospective chart review found 18 women, with an average age of 35, an average 11 years of an MS diagnosis, and an average 11 months taking ocrelizumab.

Among the 18 pregnancies, four women had a first trimester miscarriage, one had a second trimester miscarriage, and one had an abortion. The miscarriage rate could have been partly influenced by the older maternal population, the authors noted. Of the remaining 12 live births, one infant was premature at 34 weeks, and three infants stayed in NICU but were discharged within 2 weeks.

One patient experienced an MS relapse postpartum, despite receiving ocrelizumab within 45 days of delivery. Of the 16 women who agreed to participate in a Pregnancy Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) developed by the CDC, two women chose to breastfeed, and seven said their neurologist recommended against breastfeeding. None of the children’s pediatricians advised delaying vaccinations.

“This small sample observational study has not identified a potential additional risk with ocrelizumab for an adverse pregnancy outcome,” the authors concluded, but they added that ongoing studies, MINORE and SOPRANINO, can help guide future recommendations.

Though still limited, slightly more data exists on ofatumumab during pregnancy, including transient B-cell depletion and lymphopenia in infants whose mothers received anti-CD20 antibodies during pregnancy. However, research has found minimal IgG transfer in the first trimester, though it begins rising in the second trimester, and in utero ofatumumab exposure did not lead to any maternal toxicity or adverse prenatal or postnatal developmental effects in cynomolgus monkeys.

Riley Love, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, Weill Institute for Neuroscience, and her colleagues both prospectively and retrospectively examined pregnancy and infant outcomes for up to 1 year post partum in women with MS who took ofatumumab during pregnancy or in the 6 months leading up to pregnancy. Their population included 104 prospective cases, most of which (84%) included first trimester exposure, and 14 retrospective cases. One in five of the prospective cases occurred during a clinical trial, while the remaining 80% occurred in postmarketing surveillance.

The prospectively followed women were an average 32 years old and were an average 7 weeks pregnant at the time of reporting. Among the 106 fetuses (including two twin pregnancies), only 30 outcomes had data at the cutoff time, including 16 live births, 9 abortions, and 5 miscarriages. None of the live births had congenital anomalies or serious infections. Another 30 pregnancies were lost to follow-up, and 46 were ongoing.

In the 14 retrospective cases, 57% of women were exposed in the first trimester, and 43% were exposed leading up to pregnancy. Half the cases occurred during clinical trials, and half in postmarketing surveillance. The women were an average 32 years old and were an average 10 weeks pregnant at reporting. Among the 14 pregnancies, nine were miscarriages, one was aborted, and four were born live with no congenital anomalies.

The authors did not draw any conclusions from the findings; they cited too little data and an ongoing study by Novartis to investigate ofatumumab in pregnancy.

“Therapies such as ofatumumab and ocrelizumab can lead to increased risk of infection due to transient B-cell depletion in neonates, but the two studies looking at this did not demonstrate increased infectious morbidity for these infants,” Dr. Kolarova said. “As with all poster presentations, I look forward to reading the full papers once they are published as they will often include a lot more detail about when during pregnancy medication exposure occurred and more detailed outcome data that was assessed.”

Ozanimod outcomes within general population’s ‘expected ranges’

The final study looked at outcomes of pregnancies in people taking ozanimod and in the partners of people taking ozanimod in a clinical trial setting. The findings show low rates of miscarriage, preterm birth, and congenital anomalies that the authors concluded were within the typical range expected for the general population.

“While pregnancy should be avoided when taking and for 3 months after stopping ozanimod to allow for drug elimination, there is no evidence to date of increased occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes with ozanimod exposure during early pregnancy,” wrote Anthony Krakovich, of Bristol Myers Squibb in Princeton, N.J., and his associates.

Ozanimod is an oral sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor 1 and 5 modulator whose therapeutic mechanism is not fully understood “but may involve the reduction of lymphocyte migration into the central nervous system and intestine,” the authors wrote. S1P receptors are involved in vascular formation during embryogenesis, and animal studies in rats and rabbits have shown toxicity to the embryo and fetus from S1P receptor modulators, including death and malformations. S1P receptor modulator labels therefore note potential fetal risk and the need for effective contraception while taking the drug.

The study prospectively tracked clinical trial participants taking ozanimod as healthy volunteers or for relapsing MS, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease. Most of the participants who became pregnant (73%) had relapsing MS, while 18% had ulcerative colitis and 8% had Crohn’s disease.

In female patients receiving ozanimod, 78 pregnancies resulted in 12 miscarriages (including one twin), 15 abortions, and 42 live births, with 6 pregnancies ongoing at the time of reporting and no data available for the remaining 4 pregnancies. Among the 42 live births, 4 were premature but otherwise healthy, 1 had a duplex kidney, and the other 37 infants were typical with no apparent health concerns. These rates of miscarriage, preterm birth, and congenital anomalies were within the expected ranges for the general population, the researchers wrote.

The researchers also assessed pregnancy outcomes for partners of male participants taking ozanimod. The 29 partner pregnancies resulted in 21 live births and one miscarriage, with one pregnancy ongoing and no information available for the other seven. The live births included 5 premature infants (including twins), 13 typical and healthy infants, 1 with Hirschsprung’s disease, 1 with a congenital hydrocele, and 1 with a partial atrioventricular septal defect. Again, the researchers concluded that these rates were within the typical range for the general population and that “no teratogenicity was observed.”

“We often encourage patients with MS, regardless of disease activity and therapies, to seek preconception evaluations with Maternal-Fetal Medicine and their neurologists in order to make plans for pregnancy and postpartum care,” Dr. Kolarova said. “That being said, access to subspecialized health care is not available to all, and pregnancy prior to such consultation does occur. These studies provide novel information that we have not had access to in the past and can improve patient counseling regarding their risks and options.”

The study on cladribine was funded by Merck KGaA, at which two authors are employed. Dr. Hellwig reported consulting, speaker, and/or research support from Bayer, Biogen, Teva, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Schering Healthcare, Serono, and Merck, and one author is a former employee of EMD Serono. The study on ocrelizumab was funded by Genentech. Dr. Zhovtis Ryerson reported personal fees from Biogen, Genentech, and Novartis, and research grants from Biogen, Genentech, and CMSC. The other authors had no disclosures. The study on ofatumumab was funded by Novartis. Dr. Bove has received research funds from Biogen, Novartis, and Roche Genentech, and consulting fees from EMD Serono, Horizon, Janssen, and TG Therapeutics; she has an ownership interest in Global Consult MD. Five authors are Novartis employees. Her coauthors, including Dr. Hellwig, reported advisory, consulting, research, speaking, or traveling fees from Alexion, Bayer, Biogen, Celgene BMS, EMD Serono, Horizon, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Pfizer, Roche Genentech, Sanofi Genzyme, Schering Healthcare, Teva, TG Therapeutics, and Novartis. The study on ozanimod was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Krakovich and another author are employees and/or shareholders of Bristol Myers Squibb. The other authors reported consulting, speaking, advisory board, and/or research fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Arena, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelhei, Celgene, Celltrion, EXCEMED, Falk Benelux, Ferring, Forward Pharma, Genentech, Genzyme, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Pfizer, Prometheus Labs, Protagonist, Roche, Sanofi, Synthon, Takeda, and Teva. Dr. Kolarova had no disclosures. Dr. Shah has received research support from Biogen and VeraSci.

AURORA, COLO. – Several drugs for multiple sclerosis (MS) that are contraindicated during pregnancy nevertheless have not shown concerning safety signals in a series of small studies presented as posters at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. The industry-sponsored research included an assessment of pregnancy and infant outcomes for cladribine, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, and ozanimod, all of which are not recommended during pregnancy based primarily on minimal data that suggests, but does not confirm, possible teratogenicity.

“When these new medications hit the market, maternal-fetal medicine physicians and obstetricians are left with very scant data on how to counsel patients, and it’s often based on theory, case reports, or animal studies,” said Teodora Kolarova, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at the University of Washington, Seattle, who was not involved in any of the research. “Although these sample sizes seem small, the population they are sampling from – patients with MS who take immunomodulators who then experience a pregnancy – is much smaller than all pregnant patients.”

Taken together, the findings suggest no increased risk of miscarriage or congenital malformation, compared with baseline risk, Dr. Kolarova said.

“As a whole, these studies are overall reassuring with, of course, some caveats, including timing of medication exposure, limited sample size, and limited outcome data,” Dr. Kolarova said. She noted that embryonic organ formation is complete by 10 weeks gestation, by which time an unplanned pregnancy may not have been recognized yet. “In the subset of patients in the studies that were exposed during the first trimester, there was no increase in congenital malformations from a baseline risk of about 2%-3% in the general population, which is helpful for patient counseling.”

Counseling during the childbearing years

That kind of counseling is important yet absent for many people capable of pregnancy, suggests separate research also presented at the conference by Suma Shah, MD, an associate professor of neurology at Duke University, Durham, N.C. Dr. Shah gave 13-question surveys to female MS patients of all ages at her institution and presented an analysis of data from 38 completed surveys. Among those taking disease-modifying therapies, their medications included ocrelizumab, rituximab, teriflunomide, fingolimod, fumarates, interferons, natalizumab, and cladribine.

“MS disproportionately impacts women among 20 to 40 years, and that’s a really big part of their childbearing years when there are big decisions being made about whether they’re going to choose to grow family or not,” said Dr. Shah. The average age of those who completed the survey was 44. Dr. Shah noted that a lot of research has looked at the safety of older disease-modifying agents in pregnancy, but that information doesn’t appear to be filtering down to patients. “What I really wanted to look at is what do our parent patients understand about whether or not they can even think about pregnancy – and there’s a lot of work to be done.”

Just under a third of survey respondents said they did not have as many children as they would like, and a quarter said they were told they couldn’t have children if they had a diagnosis of MS.

“That was a little heartbreaking to hear because that’s not the truth,” Dr. Shah said. She said it’s necessary to have a more detailed conversation looking at tailored decisions for patients. “Both of those things – patients not being able to grow their family to the number that they desire, and not feeling like they can grow a family – I would think in 2023 we would have come farther than that, and there’s still a lot of room there to improve.”

She advised clinicians not to assume that MS patients know what their options are regarding family planning. “There’s still a lot of room for conversations,” she said. She also explicitly recommends discussing family planning and pregnancy planning with every patient, no matter their gender, early and often.

Cladribine shows no miscarriage, malformations

Dr. Kolarova noted that one of the studies, on cladribine, had a fairly robust sample size with its 180 pregnancy exposures. In that study, led by Kerstin Hellwig, MD, of Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, data came from the global surveillance program MAPLE-MS, established to assess cladribine effects on pregnancy and infant outcomes. The researchers analyzed data from 76 mothers and 9 fathers who, at any time from 2017 to 2022, were taking cladribine during pregnancy or up to 6 months before pregnancy. Outcomes included live birth, miscarriage, stillbirth, elective abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and major congenital anomalies.

Just over half the mothers (53.9%) were exposed before pregnancy, and about a quarter (26.3%) were exposed during the first trimester. The timing was unknown for most of the other mothers (18.4%). Among the fathers, two-thirds (66.7%) were exposed before pregnancy, and one-third had unknown timing.

Among the 180 pregnancies in the maternal cohort, 42.2% had known outcomes. Nearly half the women (48.7%) taking cladribine had live births, 28.9% had elective abortions, and 21.1% had miscarriages. Only 9 of the 22 pregnancies in the paternal cohort had known outcomes, which included 88.9% live births and 11.1% miscarriages. None of the pregnancies resulted in stillbirth or in a live birth with major congenital anomalies.

”Robust conclusions cannot be made about the risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes with cladribine tablets, but no increase has been signaled thus far,” the researchers reported. ”It is necessary to counsel patients to prevent pregnancy and to use effective contraception during cladribine tablets intake and for at least 6 months after the last cladribine tablet intake in each treatment year.”

Emily Evans, MD, MBE, medical director at U.S. Neurology and Immunology in Rockland, Mass., speaking on behalf of the findings, said they were fairly encouraging.

“Of course, we don’t encourage patients to get pregnant within 6 months of their last dose of cladribine tablets,” Dr. Evans said, but “within those individuals who have gotten pregnant within 6 months of their last dose of cladribine, or who have fathered a child within 6 months of their last dose of cladribine tablets, we’re seeing overall encouraging outcomes. We’re specifically not seeing any differences in the rates of spontaneous abortions, and we’re not seeing any differences in the rates of congenital malformations.”

Ocrelizumab and ofatumumab: No infections so far

Current recommendations for ocrelizumab are to avoid pregnancy for 6 months after the last infusion and stop any breastfeeding during therapy. Yet these recommendations are only because of insufficient data rather than evidence of risk, according to Lana Zhovtis Ryerson, MD, of the NYU Multiple Sclerosis Comprehensive Care Center in New York. She and her colleagues identified all women of childbearing age who had received ocrelizumab within 1 year of pregnancy at their NYU institution. A retrospective chart review found 18 women, with an average age of 35, an average 11 years of an MS diagnosis, and an average 11 months taking ocrelizumab.

Among the 18 pregnancies, four women had a first trimester miscarriage, one had a second trimester miscarriage, and one had an abortion. The miscarriage rate could have been partly influenced by the older maternal population, the authors noted. Of the remaining 12 live births, one infant was premature at 34 weeks, and three infants stayed in NICU but were discharged within 2 weeks.

One patient experienced an MS relapse postpartum, despite receiving ocrelizumab within 45 days of delivery. Of the 16 women who agreed to participate in a Pregnancy Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) developed by the CDC, two women chose to breastfeed, and seven said their neurologist recommended against breastfeeding. None of the children’s pediatricians advised delaying vaccinations.

“This small sample observational study has not identified a potential additional risk with ocrelizumab for an adverse pregnancy outcome,” the authors concluded, but they added that ongoing studies, MINORE and SOPRANINO, can help guide future recommendations.

Though still limited, slightly more data exists on ofatumumab during pregnancy, including transient B-cell depletion and lymphopenia in infants whose mothers received anti-CD20 antibodies during pregnancy. However, research has found minimal IgG transfer in the first trimester, though it begins rising in the second trimester, and in utero ofatumumab exposure did not lead to any maternal toxicity or adverse prenatal or postnatal developmental effects in cynomolgus monkeys.

Riley Love, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, Weill Institute for Neuroscience, and her colleagues both prospectively and retrospectively examined pregnancy and infant outcomes for up to 1 year post partum in women with MS who took ofatumumab during pregnancy or in the 6 months leading up to pregnancy. Their population included 104 prospective cases, most of which (84%) included first trimester exposure, and 14 retrospective cases. One in five of the prospective cases occurred during a clinical trial, while the remaining 80% occurred in postmarketing surveillance.

The prospectively followed women were an average 32 years old and were an average 7 weeks pregnant at the time of reporting. Among the 106 fetuses (including two twin pregnancies), only 30 outcomes had data at the cutoff time, including 16 live births, 9 abortions, and 5 miscarriages. None of the live births had congenital anomalies or serious infections. Another 30 pregnancies were lost to follow-up, and 46 were ongoing.

In the 14 retrospective cases, 57% of women were exposed in the first trimester, and 43% were exposed leading up to pregnancy. Half the cases occurred during clinical trials, and half in postmarketing surveillance. The women were an average 32 years old and were an average 10 weeks pregnant at reporting. Among the 14 pregnancies, nine were miscarriages, one was aborted, and four were born live with no congenital anomalies.

The authors did not draw any conclusions from the findings; they cited too little data and an ongoing study by Novartis to investigate ofatumumab in pregnancy.

“Therapies such as ofatumumab and ocrelizumab can lead to increased risk of infection due to transient B-cell depletion in neonates, but the two studies looking at this did not demonstrate increased infectious morbidity for these infants,” Dr. Kolarova said. “As with all poster presentations, I look forward to reading the full papers once they are published as they will often include a lot more detail about when during pregnancy medication exposure occurred and more detailed outcome data that was assessed.”

Ozanimod outcomes within general population’s ‘expected ranges’

The final study looked at outcomes of pregnancies in people taking ozanimod and in the partners of people taking ozanimod in a clinical trial setting. The findings show low rates of miscarriage, preterm birth, and congenital anomalies that the authors concluded were within the typical range expected for the general population.

“While pregnancy should be avoided when taking and for 3 months after stopping ozanimod to allow for drug elimination, there is no evidence to date of increased occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes with ozanimod exposure during early pregnancy,” wrote Anthony Krakovich, of Bristol Myers Squibb in Princeton, N.J., and his associates.

Ozanimod is an oral sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor 1 and 5 modulator whose therapeutic mechanism is not fully understood “but may involve the reduction of lymphocyte migration into the central nervous system and intestine,” the authors wrote. S1P receptors are involved in vascular formation during embryogenesis, and animal studies in rats and rabbits have shown toxicity to the embryo and fetus from S1P receptor modulators, including death and malformations. S1P receptor modulator labels therefore note potential fetal risk and the need for effective contraception while taking the drug.

The study prospectively tracked clinical trial participants taking ozanimod as healthy volunteers or for relapsing MS, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease. Most of the participants who became pregnant (73%) had relapsing MS, while 18% had ulcerative colitis and 8% had Crohn’s disease.

In female patients receiving ozanimod, 78 pregnancies resulted in 12 miscarriages (including one twin), 15 abortions, and 42 live births, with 6 pregnancies ongoing at the time of reporting and no data available for the remaining 4 pregnancies. Among the 42 live births, 4 were premature but otherwise healthy, 1 had a duplex kidney, and the other 37 infants were typical with no apparent health concerns. These rates of miscarriage, preterm birth, and congenital anomalies were within the expected ranges for the general population, the researchers wrote.

The researchers also assessed pregnancy outcomes for partners of male participants taking ozanimod. The 29 partner pregnancies resulted in 21 live births and one miscarriage, with one pregnancy ongoing and no information available for the other seven. The live births included 5 premature infants (including twins), 13 typical and healthy infants, 1 with Hirschsprung’s disease, 1 with a congenital hydrocele, and 1 with a partial atrioventricular septal defect. Again, the researchers concluded that these rates were within the typical range for the general population and that “no teratogenicity was observed.”

“We often encourage patients with MS, regardless of disease activity and therapies, to seek preconception evaluations with Maternal-Fetal Medicine and their neurologists in order to make plans for pregnancy and postpartum care,” Dr. Kolarova said. “That being said, access to subspecialized health care is not available to all, and pregnancy prior to such consultation does occur. These studies provide novel information that we have not had access to in the past and can improve patient counseling regarding their risks and options.”

The study on cladribine was funded by Merck KGaA, at which two authors are employed. Dr. Hellwig reported consulting, speaker, and/or research support from Bayer, Biogen, Teva, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Schering Healthcare, Serono, and Merck, and one author is a former employee of EMD Serono. The study on ocrelizumab was funded by Genentech. Dr. Zhovtis Ryerson reported personal fees from Biogen, Genentech, and Novartis, and research grants from Biogen, Genentech, and CMSC. The other authors had no disclosures. The study on ofatumumab was funded by Novartis. Dr. Bove has received research funds from Biogen, Novartis, and Roche Genentech, and consulting fees from EMD Serono, Horizon, Janssen, and TG Therapeutics; she has an ownership interest in Global Consult MD. Five authors are Novartis employees. Her coauthors, including Dr. Hellwig, reported advisory, consulting, research, speaking, or traveling fees from Alexion, Bayer, Biogen, Celgene BMS, EMD Serono, Horizon, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Pfizer, Roche Genentech, Sanofi Genzyme, Schering Healthcare, Teva, TG Therapeutics, and Novartis. The study on ozanimod was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Krakovich and another author are employees and/or shareholders of Bristol Myers Squibb. The other authors reported consulting, speaking, advisory board, and/or research fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Arena, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelhei, Celgene, Celltrion, EXCEMED, Falk Benelux, Ferring, Forward Pharma, Genentech, Genzyme, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Pfizer, Prometheus Labs, Protagonist, Roche, Sanofi, Synthon, Takeda, and Teva. Dr. Kolarova had no disclosures. Dr. Shah has received research support from Biogen and VeraSci.

AURORA, COLO. – Several drugs for multiple sclerosis (MS) that are contraindicated during pregnancy nevertheless have not shown concerning safety signals in a series of small studies presented as posters at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. The industry-sponsored research included an assessment of pregnancy and infant outcomes for cladribine, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, and ozanimod, all of which are not recommended during pregnancy based primarily on minimal data that suggests, but does not confirm, possible teratogenicity.

“When these new medications hit the market, maternal-fetal medicine physicians and obstetricians are left with very scant data on how to counsel patients, and it’s often based on theory, case reports, or animal studies,” said Teodora Kolarova, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at the University of Washington, Seattle, who was not involved in any of the research. “Although these sample sizes seem small, the population they are sampling from – patients with MS who take immunomodulators who then experience a pregnancy – is much smaller than all pregnant patients.”

Taken together, the findings suggest no increased risk of miscarriage or congenital malformation, compared with baseline risk, Dr. Kolarova said.

“As a whole, these studies are overall reassuring with, of course, some caveats, including timing of medication exposure, limited sample size, and limited outcome data,” Dr. Kolarova said. She noted that embryonic organ formation is complete by 10 weeks gestation, by which time an unplanned pregnancy may not have been recognized yet. “In the subset of patients in the studies that were exposed during the first trimester, there was no increase in congenital malformations from a baseline risk of about 2%-3% in the general population, which is helpful for patient counseling.”

Counseling during the childbearing years

That kind of counseling is important yet absent for many people capable of pregnancy, suggests separate research also presented at the conference by Suma Shah, MD, an associate professor of neurology at Duke University, Durham, N.C. Dr. Shah gave 13-question surveys to female MS patients of all ages at her institution and presented an analysis of data from 38 completed surveys. Among those taking disease-modifying therapies, their medications included ocrelizumab, rituximab, teriflunomide, fingolimod, fumarates, interferons, natalizumab, and cladribine.

“MS disproportionately impacts women among 20 to 40 years, and that’s a really big part of their childbearing years when there are big decisions being made about whether they’re going to choose to grow family or not,” said Dr. Shah. The average age of those who completed the survey was 44. Dr. Shah noted that a lot of research has looked at the safety of older disease-modifying agents in pregnancy, but that information doesn’t appear to be filtering down to patients. “What I really wanted to look at is what do our parent patients understand about whether or not they can even think about pregnancy – and there’s a lot of work to be done.”

Just under a third of survey respondents said they did not have as many children as they would like, and a quarter said they were told they couldn’t have children if they had a diagnosis of MS.

“That was a little heartbreaking to hear because that’s not the truth,” Dr. Shah said. She said it’s necessary to have a more detailed conversation looking at tailored decisions for patients. “Both of those things – patients not being able to grow their family to the number that they desire, and not feeling like they can grow a family – I would think in 2023 we would have come farther than that, and there’s still a lot of room there to improve.”

She advised clinicians not to assume that MS patients know what their options are regarding family planning. “There’s still a lot of room for conversations,” she said. She also explicitly recommends discussing family planning and pregnancy planning with every patient, no matter their gender, early and often.

Cladribine shows no miscarriage, malformations

Dr. Kolarova noted that one of the studies, on cladribine, had a fairly robust sample size with its 180 pregnancy exposures. In that study, led by Kerstin Hellwig, MD, of Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, data came from the global surveillance program MAPLE-MS, established to assess cladribine effects on pregnancy and infant outcomes. The researchers analyzed data from 76 mothers and 9 fathers who, at any time from 2017 to 2022, were taking cladribine during pregnancy or up to 6 months before pregnancy. Outcomes included live birth, miscarriage, stillbirth, elective abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and major congenital anomalies.

Just over half the mothers (53.9%) were exposed before pregnancy, and about a quarter (26.3%) were exposed during the first trimester. The timing was unknown for most of the other mothers (18.4%). Among the fathers, two-thirds (66.7%) were exposed before pregnancy, and one-third had unknown timing.

Among the 180 pregnancies in the maternal cohort, 42.2% had known outcomes. Nearly half the women (48.7%) taking cladribine had live births, 28.9% had elective abortions, and 21.1% had miscarriages. Only 9 of the 22 pregnancies in the paternal cohort had known outcomes, which included 88.9% live births and 11.1% miscarriages. None of the pregnancies resulted in stillbirth or in a live birth with major congenital anomalies.

”Robust conclusions cannot be made about the risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes with cladribine tablets, but no increase has been signaled thus far,” the researchers reported. ”It is necessary to counsel patients to prevent pregnancy and to use effective contraception during cladribine tablets intake and for at least 6 months after the last cladribine tablet intake in each treatment year.”

Emily Evans, MD, MBE, medical director at U.S. Neurology and Immunology in Rockland, Mass., speaking on behalf of the findings, said they were fairly encouraging.

“Of course, we don’t encourage patients to get pregnant within 6 months of their last dose of cladribine tablets,” Dr. Evans said, but “within those individuals who have gotten pregnant within 6 months of their last dose of cladribine, or who have fathered a child within 6 months of their last dose of cladribine tablets, we’re seeing overall encouraging outcomes. We’re specifically not seeing any differences in the rates of spontaneous abortions, and we’re not seeing any differences in the rates of congenital malformations.”

Ocrelizumab and ofatumumab: No infections so far

Current recommendations for ocrelizumab are to avoid pregnancy for 6 months after the last infusion and stop any breastfeeding during therapy. Yet these recommendations are only because of insufficient data rather than evidence of risk, according to Lana Zhovtis Ryerson, MD, of the NYU Multiple Sclerosis Comprehensive Care Center in New York. She and her colleagues identified all women of childbearing age who had received ocrelizumab within 1 year of pregnancy at their NYU institution. A retrospective chart review found 18 women, with an average age of 35, an average 11 years of an MS diagnosis, and an average 11 months taking ocrelizumab.

Among the 18 pregnancies, four women had a first trimester miscarriage, one had a second trimester miscarriage, and one had an abortion. The miscarriage rate could have been partly influenced by the older maternal population, the authors noted. Of the remaining 12 live births, one infant was premature at 34 weeks, and three infants stayed in NICU but were discharged within 2 weeks.

One patient experienced an MS relapse postpartum, despite receiving ocrelizumab within 45 days of delivery. Of the 16 women who agreed to participate in a Pregnancy Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) developed by the CDC, two women chose to breastfeed, and seven said their neurologist recommended against breastfeeding. None of the children’s pediatricians advised delaying vaccinations.

“This small sample observational study has not identified a potential additional risk with ocrelizumab for an adverse pregnancy outcome,” the authors concluded, but they added that ongoing studies, MINORE and SOPRANINO, can help guide future recommendations.

Though still limited, slightly more data exists on ofatumumab during pregnancy, including transient B-cell depletion and lymphopenia in infants whose mothers received anti-CD20 antibodies during pregnancy. However, research has found minimal IgG transfer in the first trimester, though it begins rising in the second trimester, and in utero ofatumumab exposure did not lead to any maternal toxicity or adverse prenatal or postnatal developmental effects in cynomolgus monkeys.

Riley Love, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, Weill Institute for Neuroscience, and her colleagues both prospectively and retrospectively examined pregnancy and infant outcomes for up to 1 year post partum in women with MS who took ofatumumab during pregnancy or in the 6 months leading up to pregnancy. Their population included 104 prospective cases, most of which (84%) included first trimester exposure, and 14 retrospective cases. One in five of the prospective cases occurred during a clinical trial, while the remaining 80% occurred in postmarketing surveillance.

The prospectively followed women were an average 32 years old and were an average 7 weeks pregnant at the time of reporting. Among the 106 fetuses (including two twin pregnancies), only 30 outcomes had data at the cutoff time, including 16 live births, 9 abortions, and 5 miscarriages. None of the live births had congenital anomalies or serious infections. Another 30 pregnancies were lost to follow-up, and 46 were ongoing.

In the 14 retrospective cases, 57% of women were exposed in the first trimester, and 43% were exposed leading up to pregnancy. Half the cases occurred during clinical trials, and half in postmarketing surveillance. The women were an average 32 years old and were an average 10 weeks pregnant at reporting. Among the 14 pregnancies, nine were miscarriages, one was aborted, and four were born live with no congenital anomalies.

The authors did not draw any conclusions from the findings; they cited too little data and an ongoing study by Novartis to investigate ofatumumab in pregnancy.

“Therapies such as ofatumumab and ocrelizumab can lead to increased risk of infection due to transient B-cell depletion in neonates, but the two studies looking at this did not demonstrate increased infectious morbidity for these infants,” Dr. Kolarova said. “As with all poster presentations, I look forward to reading the full papers once they are published as they will often include a lot more detail about when during pregnancy medication exposure occurred and more detailed outcome data that was assessed.”

Ozanimod outcomes within general population’s ‘expected ranges’

The final study looked at outcomes of pregnancies in people taking ozanimod and in the partners of people taking ozanimod in a clinical trial setting. The findings show low rates of miscarriage, preterm birth, and congenital anomalies that the authors concluded were within the typical range expected for the general population.

“While pregnancy should be avoided when taking and for 3 months after stopping ozanimod to allow for drug elimination, there is no evidence to date of increased occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes with ozanimod exposure during early pregnancy,” wrote Anthony Krakovich, of Bristol Myers Squibb in Princeton, N.J., and his associates.

Ozanimod is an oral sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor 1 and 5 modulator whose therapeutic mechanism is not fully understood “but may involve the reduction of lymphocyte migration into the central nervous system and intestine,” the authors wrote. S1P receptors are involved in vascular formation during embryogenesis, and animal studies in rats and rabbits have shown toxicity to the embryo and fetus from S1P receptor modulators, including death and malformations. S1P receptor modulator labels therefore note potential fetal risk and the need for effective contraception while taking the drug.

The study prospectively tracked clinical trial participants taking ozanimod as healthy volunteers or for relapsing MS, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease. Most of the participants who became pregnant (73%) had relapsing MS, while 18% had ulcerative colitis and 8% had Crohn’s disease.

In female patients receiving ozanimod, 78 pregnancies resulted in 12 miscarriages (including one twin), 15 abortions, and 42 live births, with 6 pregnancies ongoing at the time of reporting and no data available for the remaining 4 pregnancies. Among the 42 live births, 4 were premature but otherwise healthy, 1 had a duplex kidney, and the other 37 infants were typical with no apparent health concerns. These rates of miscarriage, preterm birth, and congenital anomalies were within the expected ranges for the general population, the researchers wrote.

The researchers also assessed pregnancy outcomes for partners of male participants taking ozanimod. The 29 partner pregnancies resulted in 21 live births and one miscarriage, with one pregnancy ongoing and no information available for the other seven. The live births included 5 premature infants (including twins), 13 typical and healthy infants, 1 with Hirschsprung’s disease, 1 with a congenital hydrocele, and 1 with a partial atrioventricular septal defect. Again, the researchers concluded that these rates were within the typical range for the general population and that “no teratogenicity was observed.”

“We often encourage patients with MS, regardless of disease activity and therapies, to seek preconception evaluations with Maternal-Fetal Medicine and their neurologists in order to make plans for pregnancy and postpartum care,” Dr. Kolarova said. “That being said, access to subspecialized health care is not available to all, and pregnancy prior to such consultation does occur. These studies provide novel information that we have not had access to in the past and can improve patient counseling regarding their risks and options.”

The study on cladribine was funded by Merck KGaA, at which two authors are employed. Dr. Hellwig reported consulting, speaker, and/or research support from Bayer, Biogen, Teva, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Schering Healthcare, Serono, and Merck, and one author is a former employee of EMD Serono. The study on ocrelizumab was funded by Genentech. Dr. Zhovtis Ryerson reported personal fees from Biogen, Genentech, and Novartis, and research grants from Biogen, Genentech, and CMSC. The other authors had no disclosures. The study on ofatumumab was funded by Novartis. Dr. Bove has received research funds from Biogen, Novartis, and Roche Genentech, and consulting fees from EMD Serono, Horizon, Janssen, and TG Therapeutics; she has an ownership interest in Global Consult MD. Five authors are Novartis employees. Her coauthors, including Dr. Hellwig, reported advisory, consulting, research, speaking, or traveling fees from Alexion, Bayer, Biogen, Celgene BMS, EMD Serono, Horizon, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Pfizer, Roche Genentech, Sanofi Genzyme, Schering Healthcare, Teva, TG Therapeutics, and Novartis. The study on ozanimod was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Krakovich and another author are employees and/or shareholders of Bristol Myers Squibb. The other authors reported consulting, speaking, advisory board, and/or research fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Arena, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelhei, Celgene, Celltrion, EXCEMED, Falk Benelux, Ferring, Forward Pharma, Genentech, Genzyme, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Pfizer, Prometheus Labs, Protagonist, Roche, Sanofi, Synthon, Takeda, and Teva. Dr. Kolarova had no disclosures. Dr. Shah has received research support from Biogen and VeraSci.

FROM CMSC 2023

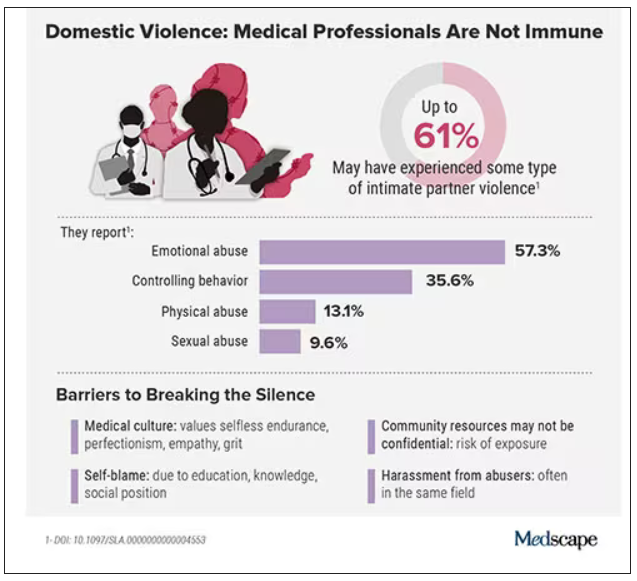

Domestic violence in health care is real and underreported

To protect survivors’ identities, some names have been changed or shortened.

Natasha Abadilla, MD, met the man who would become her abuser while working abroad for a public health nonprofit. When he began emotionally and physically abusing her, she did everything she could to hide it.

“My coworkers knew nothing of the abuse. I became an expert in applying makeup to hide the bruises,” recalls Dr. Abadilla, now a second-year resident and pediatric neurologist at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford.

Dr. Abadilla says she strongly identifies as a hard worker and – to this day – hopes her work did not falter despite her partner’s constant drain on her. But the impact of the abuse continued to affect her for years. Like many survivors of domestic violence, she struggled with PTSD and depression.

Health care workers are often the first point of contact for survivors of domestic violence. Experts and advocates continue to push for more training for clinicians to identify and respond to signs among their patients. Often missing from this conversation is the reality that those tasked with screening can also be victims of intimate partner violence themselves.

What’s more: The very strengths that medical professionals often pride themselves on – perfectionism, empathy, grit – can make it harder for them to identify abuse in their own relationships and push through humiliation and shame to seek help.

Dr. Abadilla is exceptional among survivors in the medical field. Rather than keep her experience quiet, she has shared it publicly.

Awareness, she believes, can save lives.

An understudied problem in an underserved group

The majority of research on health care workers in this area has focused on workplace violence, which 62% experience worldwide. But intimate partner violence remains understudied and underdiscussed. Some medical professionals are even saddled with a “double burden,” facing trauma at work and at home, note the authors of a 2022 meta-analysis published in the journal Trauma, Violence, & Abuse.

The problem has had dire consequences. In recent years, many health care workers have been killed by their abusers:

- In 2016, Casey M. Drawert, MD, a Texas-based critical care anesthesiologist, was fatally shot by her husband in a murder-suicide.

- In 2018, Tamara O’Neal, MD, an ER physician, and Dayna Less, a first-year pharmacy resident, were killed by Dr. O’Neal’s ex-fiancé at Mercy Hospital in Chicago.

- In 2019, Sarah Hawley, MD, a first-year University of Utah resident, was fatally shot by her boyfriend in a murder-suicide.

- In 2021, Moria Kinsey, a nurse practitioner in Tahlequah, Okla., was murdered by a physician.

- In July of 2023, Gwendolyn Lavonne Riddick, DO, an ob.gyn. in North Carolina, was fatally shot by the father of her 3-year-old son.

There are others.

In the wake of these tragedies, calls for health care workers to screen each other as well as patients have grown. But for an untold number of survivors, breaking the silence is still not possible due to concerns about their reputation, professional consequences, the threat of harassment from abusers who are often in the same field, a medical culture of selfless endurance, and a lack of appropriate resources.

While the vast majority have stayed silent, those who have spoken out say there’s a need for targeted interventions to educate medical professionals as well as more supportive policies throughout the health care system.

Are health care workers more at risk?

Although more studies are needed, research indicates health care workers experience domestic violence at rates comparable to those of other populations, whereas some data suggest rates may be higher.

In the United States, more than one in three women and one in four men experience some form of intimate partner violence in their lifetime. Similarly, a 2020 study found that 24% of 400 physicians responding to a survey reported a history of domestic violence, with 15% reporting verbal abuse, 8% reporting physical violence, 4% reporting sexual abuse, and 4% reporting stalking.

Meanwhile, in an anonymous survey completed by 882 practicing surgeons and trainees in the United States from late 2018 to early 2019, more than 60% reported experiencing some type of intimate partner violence, most commonly emotional abuse.

Recent studies in the United Kingdom, Australia, and elsewhere show that significant numbers of medical professionals are fighting this battle. A 2019 study of more than 2,000 nurses, midwives, and health care assistants in the United Kingdom found that nurses were three times more likely to experience domestic violence than the average person.

What would help solve this problem: More study of health care worker-survivors as a unique group with unique risk factors. In general, domestic violence is most prevalent among women and people in marginalized groups. But young adults, such as medical students and trainees, can face an increased risk due to economic strain. Major life changes, such as relocating for residency, can also drive up stress and fray social connections, further isolating victims.

Why it’s so much harder for medical professionals to reveal abuse

For medical professionals accustomed to being strong and forging on, identifying as a victim of abuse can seem like a personal contradiction. It can feel easier to separate their personal and professional lives rather than face a complex reality.

In a personal essay on KevinMD.com, medical student Chloe N. L. Lee describes this emotional turmoil. “As an aspiring psychiatrist, I questioned my character judgment (how did I end up with a misogynistic abuser?) and wondered if I ought to have known better. I worried that my colleagues would deem me unfit to care for patients. And I thought that this was not supposed to happen to women like me,” Ms. Lee writes.

Kimberly, a licensed therapist, experienced a similar pattern of self-blame when her partner began exhibiting violent behavior. “For a long time, I felt guilty because I said to myself, You’re a therapist. You’re supposed to know this,” she recalls. At the same time, she felt driven to help him and sought couples therapy as his violence escalated.

Whitney, a pharmacist, recognized the “hallmarks” of abuse in her relationship, but she coped by compartmentalizing. Whitney says she was vulnerable to her abuser as a young college student who struggled financially. As he showered her with gifts, she found herself waving away red flags like aggressiveness or overprotectiveness.