User login

Updates on treatment/prevention of VTE in cancer patients

Updated clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism for patients with cancer, including those with cancer and COVID-19, have been released by the International Initiative on Thrombosis and Cancer (ITAC), an academic working group of VTE experts.

“Because patients with cancer have a baseline increased risk of VTE, compared with patients without cancer, the combination of both COVID-19 and cancer – and its effect on VTE risk and treatment – is of concern,” said the authors, led by Dominique Farge, MD, PhD, Nord Universite de Paris.

they added.

The new guidelines were published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“Cancer-associated VTE remains an important clinical problem, associated with increased morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Farge and colleagues observed.

“The ITAC guidelines’ companion free web-based mobile application will assist the practicing clinician with decision making at various levels to provide optimal care of patients with cancer to treat and prevent VTE,” they emphasized. More information is available at itaccme.com.

Cancer patients with COVID

The new section of the guidelines notes that the treatment and prevention of VTE for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 remain the same as for patients without COVID.

Whether or not cancer patients with COVID-19 are hospitalized, have been discharged, or are ambulatory, they should be assessed for the risk of VTE, as should any other patient. For cancer patients with COVID-19 who are hospitalized, pharmacologic prophylaxis should be given at the same dose and anticoagulant type as for hospitalized cancer patients who do not have COVID-19.

Following discharge, VTE prophylaxis is not advised for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, and routine primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE for ambulatory patients with COVID-19 is also not recommended, the authors noted.

Initial treatment of established VTE

Initial treatment of established VTE for up to 10 days of anticoagulation should include low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“A regimen of LMWH, taken once per day, is recommended unless a twice-per-day regimen is required because of patients’ characteristics,” the authors noted. These characteristics include a high risk of bleeding, moderate renal failure, and the need for technical intervention, including surgery.

If a twice-a-day regimen is required, only enoxaparin at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice daily can be used, the authors cautioned.

For patients with a low risk of gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding, rivaroxaban (Xarelto) or apixaban (Eliquis) can be given in the first 10 days, as well as edoxaban (Lixiana). The latter should be started after at least 5 days of parenteral anticoagulation, provided creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“Unfractionated heparin as well as fondaparinux (GlaxoSmithKline) can be also used for the initial treatment of established VTE when LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants are contraindicated,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Thrombolysis can be considered on a case-by-case basis, although physicians must pay attention to specific contraindications, especially bleeding risk.

“In the initial treatment of VTE, inferior vena cava filters might be considered when anticoagulant treatment is contraindicated or, in the case of pulmonary embolism, when recurrence occurs under optimal anticoagulation,” the authors noted.

Maintenance VTE treatment

For maintenance therapy, which the authors define as early maintenance for up to 6 months and long-term maintenance beyond 6 months, they point out that LMWHs are preferred over vitamin K antagonists for the treatment of VTE when the creatinine clearance is again at least 30 mL/min.

Any of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOAs) – edoxaban, rivaroxaban, or apixaban – is also recommended for the same patients, provided there is no risk of inducing a strong drug-drug interaction or GI absorption is impaired.

However, the DOAs should be used with caution for patients with GI malignancies, especially upper GI cancers, because data show there is an increased risk of GI bleeding with both edoxaban and rivaroxaban.

“LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants should be used for a minimum of 6 months to treat established VTE in patients with cancer,” the authors wrote.

“After 6 months, termination or continuation of anticoagulation (LMWH, direct oral anticoagulants, or vitamin K antagonists) should be based on individual evaluation of the benefit-risk ratio,” they added.

Treatment of VTE recurrence

The guideline authors explain that three options can be considered in the event of VTE recurrence. These include an increase in the LMWH dose by 20%-25%, or a switch to a DOA, or, if patients are taking a DOA, a switch to an LMWH. If the patient is taking a vitamin K antagonist, it can be switched to either an LMWH or a DOA.

For treatment of catheter-related thrombosis, anticoagulant treatment is recommended for a minimum of 3 months and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. In this setting, the LMWHs are recommended.

The central venous catheter can be kept in place if it is functional, well positioned, and is not infected, provided there is good resolution of symptoms under close surveillance while anticoagulants are being administered.

In surgically treated patients, the LMWH, given once a day, to patients with a serum creatinine concentration of at least 30 mL/min can be used to prevent VTE. Alternatively, VTE can be prevented by the use low-dose unfractionated heparin, given three times a day.

“Pharmacological prophylaxis should be started 2-12 h preoperatively and continued for at least 7–10 days,” Dr. Farge and colleagues advised. In this setting, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of fondaparinux or a DOA as an alternative to an LMWH for the prophylaxis of postoperative VTE. “Use of the highest prophylactic dose of LMWH to prevent postoperative VTE in patients with cancer is recommended,” the authors advised.

Furthermore, extended prophylaxis of at least 4 weeks with LMWH is advised to prevent postoperative VTE after major abdominal or pelvic surgery. Mechanical methods are not recommended except when pharmacologic methods are contraindicated. Inferior vena cava filters are also not recommended for routine prophylaxis.

Patients with reduced mobility

For medically treated hospitalized patients with cancer whose mobility is reduced, the authors recommend prophylaxis with either an LMWH or fondaparinux, provided their creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min. These patients can also be treated with unfractionated heparin, they add.

In contrast, DOAs are not recommended – at least not routinely – in this setting, the authors cautioned. Primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE with either LMWH or DOAs – either rivaroxaban or apixaban – is indicated in ambulatory patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy, provided they are at low risk of bleeding.

However, primary pharmacologic prophylaxis with LMWH is not recommended outside of a clinical trial for patients with locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer who are undergoing systemic anticancer therapy, even for patients who are at low risk of bleeding.

For ambulatory patients who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy and who are at intermediate risk of VTE, primary prophylaxis with rivaroxaban or apixaban is recommended for those with myeloma who are receiving immunomodulatory therapy plus steroids or other systemic therapies.

In this setting, oral anticoagulants should consist of a vitamin K antagonist, given at low or therapeutic doses, or apixaban, given at prophylactic doses. Alternatively, LMWH, given at prophylactic doses, or low-dose aspirin, given at a dose of 100 mg/day, can be used.

Catheter-related thrombosis

Use of anticoagulation for routine prophylaxis of catheter-related thrombosis is not recommended. Catheters should be inserted on the right side in the jugular vein, and the distal extremity of the central catheter should be located at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium. “In patients requiring central venous catheters, we suggest the use of implanted ports over peripheral inserted central catheter lines,” the authors noted.

The authors described a number of unique situations regarding the treatment of VTE. These situations include patients with a brain tumor, for whom treatment of established VTE should favor either LMWH or a DOA. The authors also recommended the use of LMWH or unfractionated heparin, started postoperatively, for the prevention of VTE for patients undergoing neurosurgery.

In contrast, pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE in medically treated patients with a brain tumor who are not undergoing neurosurgery is not recommended. “In the presence of severe renal failure...we suggest using unfractionated heparin followed by early vitamin K antagonists (possibly from day 1) or LMWH adjusted to anti-Xa concentration of the treatment of established VTE,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Anticoagulant treatment is also recommended for a minimum of 3 months for children with symptomatic catheter-related thrombosis and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. For children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are undergoing induction chemotherapy, LMWH is also recommended as thromboprophylaxis.

For children who require a central venous catheter, the authors suggested that physicians use implanted ports over peripherally inserted central lines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism for patients with cancer, including those with cancer and COVID-19, have been released by the International Initiative on Thrombosis and Cancer (ITAC), an academic working group of VTE experts.

“Because patients with cancer have a baseline increased risk of VTE, compared with patients without cancer, the combination of both COVID-19 and cancer – and its effect on VTE risk and treatment – is of concern,” said the authors, led by Dominique Farge, MD, PhD, Nord Universite de Paris.

they added.

The new guidelines were published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“Cancer-associated VTE remains an important clinical problem, associated with increased morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Farge and colleagues observed.

“The ITAC guidelines’ companion free web-based mobile application will assist the practicing clinician with decision making at various levels to provide optimal care of patients with cancer to treat and prevent VTE,” they emphasized. More information is available at itaccme.com.

Cancer patients with COVID

The new section of the guidelines notes that the treatment and prevention of VTE for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 remain the same as for patients without COVID.

Whether or not cancer patients with COVID-19 are hospitalized, have been discharged, or are ambulatory, they should be assessed for the risk of VTE, as should any other patient. For cancer patients with COVID-19 who are hospitalized, pharmacologic prophylaxis should be given at the same dose and anticoagulant type as for hospitalized cancer patients who do not have COVID-19.

Following discharge, VTE prophylaxis is not advised for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, and routine primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE for ambulatory patients with COVID-19 is also not recommended, the authors noted.

Initial treatment of established VTE

Initial treatment of established VTE for up to 10 days of anticoagulation should include low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“A regimen of LMWH, taken once per day, is recommended unless a twice-per-day regimen is required because of patients’ characteristics,” the authors noted. These characteristics include a high risk of bleeding, moderate renal failure, and the need for technical intervention, including surgery.

If a twice-a-day regimen is required, only enoxaparin at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice daily can be used, the authors cautioned.

For patients with a low risk of gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding, rivaroxaban (Xarelto) or apixaban (Eliquis) can be given in the first 10 days, as well as edoxaban (Lixiana). The latter should be started after at least 5 days of parenteral anticoagulation, provided creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“Unfractionated heparin as well as fondaparinux (GlaxoSmithKline) can be also used for the initial treatment of established VTE when LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants are contraindicated,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Thrombolysis can be considered on a case-by-case basis, although physicians must pay attention to specific contraindications, especially bleeding risk.

“In the initial treatment of VTE, inferior vena cava filters might be considered when anticoagulant treatment is contraindicated or, in the case of pulmonary embolism, when recurrence occurs under optimal anticoagulation,” the authors noted.

Maintenance VTE treatment

For maintenance therapy, which the authors define as early maintenance for up to 6 months and long-term maintenance beyond 6 months, they point out that LMWHs are preferred over vitamin K antagonists for the treatment of VTE when the creatinine clearance is again at least 30 mL/min.

Any of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOAs) – edoxaban, rivaroxaban, or apixaban – is also recommended for the same patients, provided there is no risk of inducing a strong drug-drug interaction or GI absorption is impaired.

However, the DOAs should be used with caution for patients with GI malignancies, especially upper GI cancers, because data show there is an increased risk of GI bleeding with both edoxaban and rivaroxaban.

“LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants should be used for a minimum of 6 months to treat established VTE in patients with cancer,” the authors wrote.

“After 6 months, termination or continuation of anticoagulation (LMWH, direct oral anticoagulants, or vitamin K antagonists) should be based on individual evaluation of the benefit-risk ratio,” they added.

Treatment of VTE recurrence

The guideline authors explain that three options can be considered in the event of VTE recurrence. These include an increase in the LMWH dose by 20%-25%, or a switch to a DOA, or, if patients are taking a DOA, a switch to an LMWH. If the patient is taking a vitamin K antagonist, it can be switched to either an LMWH or a DOA.

For treatment of catheter-related thrombosis, anticoagulant treatment is recommended for a minimum of 3 months and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. In this setting, the LMWHs are recommended.

The central venous catheter can be kept in place if it is functional, well positioned, and is not infected, provided there is good resolution of symptoms under close surveillance while anticoagulants are being administered.

In surgically treated patients, the LMWH, given once a day, to patients with a serum creatinine concentration of at least 30 mL/min can be used to prevent VTE. Alternatively, VTE can be prevented by the use low-dose unfractionated heparin, given three times a day.

“Pharmacological prophylaxis should be started 2-12 h preoperatively and continued for at least 7–10 days,” Dr. Farge and colleagues advised. In this setting, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of fondaparinux or a DOA as an alternative to an LMWH for the prophylaxis of postoperative VTE. “Use of the highest prophylactic dose of LMWH to prevent postoperative VTE in patients with cancer is recommended,” the authors advised.

Furthermore, extended prophylaxis of at least 4 weeks with LMWH is advised to prevent postoperative VTE after major abdominal or pelvic surgery. Mechanical methods are not recommended except when pharmacologic methods are contraindicated. Inferior vena cava filters are also not recommended for routine prophylaxis.

Patients with reduced mobility

For medically treated hospitalized patients with cancer whose mobility is reduced, the authors recommend prophylaxis with either an LMWH or fondaparinux, provided their creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min. These patients can also be treated with unfractionated heparin, they add.

In contrast, DOAs are not recommended – at least not routinely – in this setting, the authors cautioned. Primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE with either LMWH or DOAs – either rivaroxaban or apixaban – is indicated in ambulatory patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy, provided they are at low risk of bleeding.

However, primary pharmacologic prophylaxis with LMWH is not recommended outside of a clinical trial for patients with locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer who are undergoing systemic anticancer therapy, even for patients who are at low risk of bleeding.

For ambulatory patients who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy and who are at intermediate risk of VTE, primary prophylaxis with rivaroxaban or apixaban is recommended for those with myeloma who are receiving immunomodulatory therapy plus steroids or other systemic therapies.

In this setting, oral anticoagulants should consist of a vitamin K antagonist, given at low or therapeutic doses, or apixaban, given at prophylactic doses. Alternatively, LMWH, given at prophylactic doses, or low-dose aspirin, given at a dose of 100 mg/day, can be used.

Catheter-related thrombosis

Use of anticoagulation for routine prophylaxis of catheter-related thrombosis is not recommended. Catheters should be inserted on the right side in the jugular vein, and the distal extremity of the central catheter should be located at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium. “In patients requiring central venous catheters, we suggest the use of implanted ports over peripheral inserted central catheter lines,” the authors noted.

The authors described a number of unique situations regarding the treatment of VTE. These situations include patients with a brain tumor, for whom treatment of established VTE should favor either LMWH or a DOA. The authors also recommended the use of LMWH or unfractionated heparin, started postoperatively, for the prevention of VTE for patients undergoing neurosurgery.

In contrast, pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE in medically treated patients with a brain tumor who are not undergoing neurosurgery is not recommended. “In the presence of severe renal failure...we suggest using unfractionated heparin followed by early vitamin K antagonists (possibly from day 1) or LMWH adjusted to anti-Xa concentration of the treatment of established VTE,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Anticoagulant treatment is also recommended for a minimum of 3 months for children with symptomatic catheter-related thrombosis and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. For children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are undergoing induction chemotherapy, LMWH is also recommended as thromboprophylaxis.

For children who require a central venous catheter, the authors suggested that physicians use implanted ports over peripherally inserted central lines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism for patients with cancer, including those with cancer and COVID-19, have been released by the International Initiative on Thrombosis and Cancer (ITAC), an academic working group of VTE experts.

“Because patients with cancer have a baseline increased risk of VTE, compared with patients without cancer, the combination of both COVID-19 and cancer – and its effect on VTE risk and treatment – is of concern,” said the authors, led by Dominique Farge, MD, PhD, Nord Universite de Paris.

they added.

The new guidelines were published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“Cancer-associated VTE remains an important clinical problem, associated with increased morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Farge and colleagues observed.

“The ITAC guidelines’ companion free web-based mobile application will assist the practicing clinician with decision making at various levels to provide optimal care of patients with cancer to treat and prevent VTE,” they emphasized. More information is available at itaccme.com.

Cancer patients with COVID

The new section of the guidelines notes that the treatment and prevention of VTE for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 remain the same as for patients without COVID.

Whether or not cancer patients with COVID-19 are hospitalized, have been discharged, or are ambulatory, they should be assessed for the risk of VTE, as should any other patient. For cancer patients with COVID-19 who are hospitalized, pharmacologic prophylaxis should be given at the same dose and anticoagulant type as for hospitalized cancer patients who do not have COVID-19.

Following discharge, VTE prophylaxis is not advised for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, and routine primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE for ambulatory patients with COVID-19 is also not recommended, the authors noted.

Initial treatment of established VTE

Initial treatment of established VTE for up to 10 days of anticoagulation should include low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“A regimen of LMWH, taken once per day, is recommended unless a twice-per-day regimen is required because of patients’ characteristics,” the authors noted. These characteristics include a high risk of bleeding, moderate renal failure, and the need for technical intervention, including surgery.

If a twice-a-day regimen is required, only enoxaparin at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice daily can be used, the authors cautioned.

For patients with a low risk of gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding, rivaroxaban (Xarelto) or apixaban (Eliquis) can be given in the first 10 days, as well as edoxaban (Lixiana). The latter should be started after at least 5 days of parenteral anticoagulation, provided creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“Unfractionated heparin as well as fondaparinux (GlaxoSmithKline) can be also used for the initial treatment of established VTE when LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants are contraindicated,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Thrombolysis can be considered on a case-by-case basis, although physicians must pay attention to specific contraindications, especially bleeding risk.

“In the initial treatment of VTE, inferior vena cava filters might be considered when anticoagulant treatment is contraindicated or, in the case of pulmonary embolism, when recurrence occurs under optimal anticoagulation,” the authors noted.

Maintenance VTE treatment

For maintenance therapy, which the authors define as early maintenance for up to 6 months and long-term maintenance beyond 6 months, they point out that LMWHs are preferred over vitamin K antagonists for the treatment of VTE when the creatinine clearance is again at least 30 mL/min.

Any of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOAs) – edoxaban, rivaroxaban, or apixaban – is also recommended for the same patients, provided there is no risk of inducing a strong drug-drug interaction or GI absorption is impaired.

However, the DOAs should be used with caution for patients with GI malignancies, especially upper GI cancers, because data show there is an increased risk of GI bleeding with both edoxaban and rivaroxaban.

“LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants should be used for a minimum of 6 months to treat established VTE in patients with cancer,” the authors wrote.

“After 6 months, termination or continuation of anticoagulation (LMWH, direct oral anticoagulants, or vitamin K antagonists) should be based on individual evaluation of the benefit-risk ratio,” they added.

Treatment of VTE recurrence

The guideline authors explain that three options can be considered in the event of VTE recurrence. These include an increase in the LMWH dose by 20%-25%, or a switch to a DOA, or, if patients are taking a DOA, a switch to an LMWH. If the patient is taking a vitamin K antagonist, it can be switched to either an LMWH or a DOA.

For treatment of catheter-related thrombosis, anticoagulant treatment is recommended for a minimum of 3 months and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. In this setting, the LMWHs are recommended.

The central venous catheter can be kept in place if it is functional, well positioned, and is not infected, provided there is good resolution of symptoms under close surveillance while anticoagulants are being administered.

In surgically treated patients, the LMWH, given once a day, to patients with a serum creatinine concentration of at least 30 mL/min can be used to prevent VTE. Alternatively, VTE can be prevented by the use low-dose unfractionated heparin, given three times a day.

“Pharmacological prophylaxis should be started 2-12 h preoperatively and continued for at least 7–10 days,” Dr. Farge and colleagues advised. In this setting, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of fondaparinux or a DOA as an alternative to an LMWH for the prophylaxis of postoperative VTE. “Use of the highest prophylactic dose of LMWH to prevent postoperative VTE in patients with cancer is recommended,” the authors advised.

Furthermore, extended prophylaxis of at least 4 weeks with LMWH is advised to prevent postoperative VTE after major abdominal or pelvic surgery. Mechanical methods are not recommended except when pharmacologic methods are contraindicated. Inferior vena cava filters are also not recommended for routine prophylaxis.

Patients with reduced mobility

For medically treated hospitalized patients with cancer whose mobility is reduced, the authors recommend prophylaxis with either an LMWH or fondaparinux, provided their creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min. These patients can also be treated with unfractionated heparin, they add.

In contrast, DOAs are not recommended – at least not routinely – in this setting, the authors cautioned. Primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE with either LMWH or DOAs – either rivaroxaban or apixaban – is indicated in ambulatory patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy, provided they are at low risk of bleeding.

However, primary pharmacologic prophylaxis with LMWH is not recommended outside of a clinical trial for patients with locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer who are undergoing systemic anticancer therapy, even for patients who are at low risk of bleeding.

For ambulatory patients who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy and who are at intermediate risk of VTE, primary prophylaxis with rivaroxaban or apixaban is recommended for those with myeloma who are receiving immunomodulatory therapy plus steroids or other systemic therapies.

In this setting, oral anticoagulants should consist of a vitamin K antagonist, given at low or therapeutic doses, or apixaban, given at prophylactic doses. Alternatively, LMWH, given at prophylactic doses, or low-dose aspirin, given at a dose of 100 mg/day, can be used.

Catheter-related thrombosis

Use of anticoagulation for routine prophylaxis of catheter-related thrombosis is not recommended. Catheters should be inserted on the right side in the jugular vein, and the distal extremity of the central catheter should be located at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium. “In patients requiring central venous catheters, we suggest the use of implanted ports over peripheral inserted central catheter lines,” the authors noted.

The authors described a number of unique situations regarding the treatment of VTE. These situations include patients with a brain tumor, for whom treatment of established VTE should favor either LMWH or a DOA. The authors also recommended the use of LMWH or unfractionated heparin, started postoperatively, for the prevention of VTE for patients undergoing neurosurgery.

In contrast, pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE in medically treated patients with a brain tumor who are not undergoing neurosurgery is not recommended. “In the presence of severe renal failure...we suggest using unfractionated heparin followed by early vitamin K antagonists (possibly from day 1) or LMWH adjusted to anti-Xa concentration of the treatment of established VTE,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Anticoagulant treatment is also recommended for a minimum of 3 months for children with symptomatic catheter-related thrombosis and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. For children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are undergoing induction chemotherapy, LMWH is also recommended as thromboprophylaxis.

For children who require a central venous catheter, the authors suggested that physicians use implanted ports over peripherally inserted central lines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET ONCOLOGY

Firm Exophytic Tumor on the Shin

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

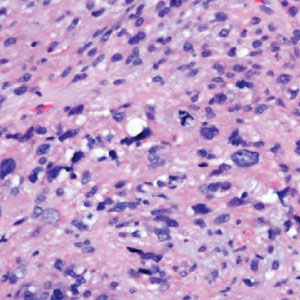

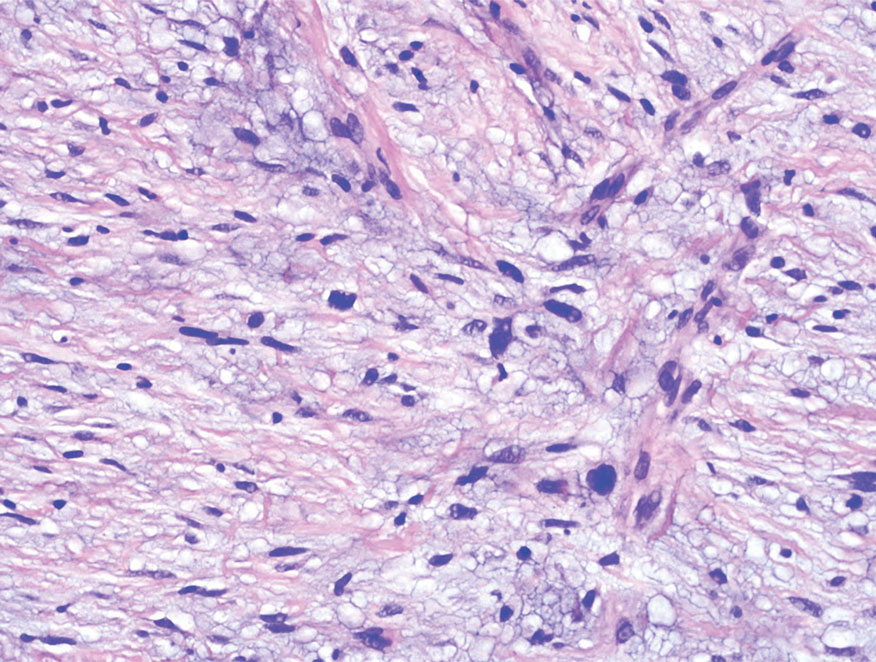

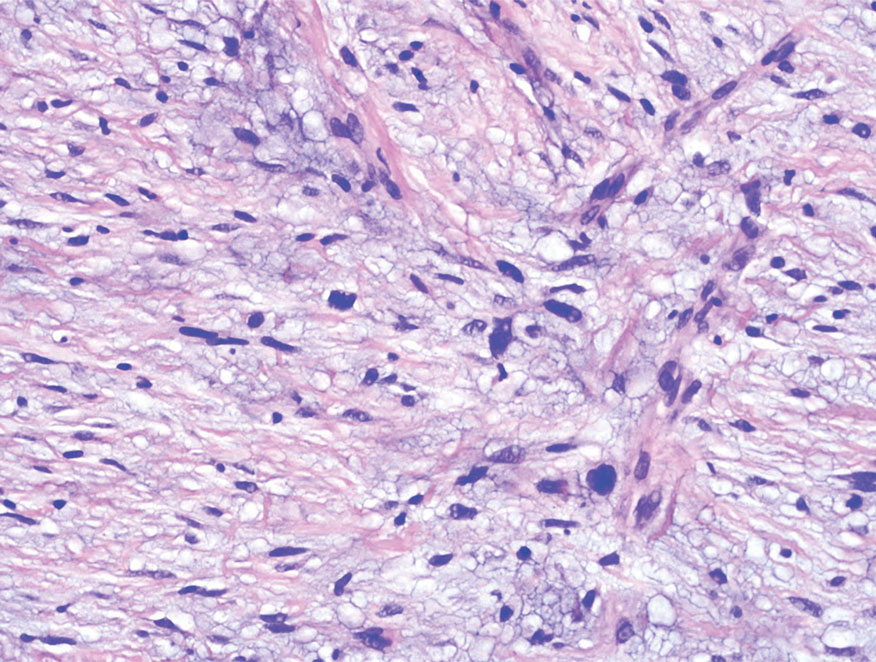

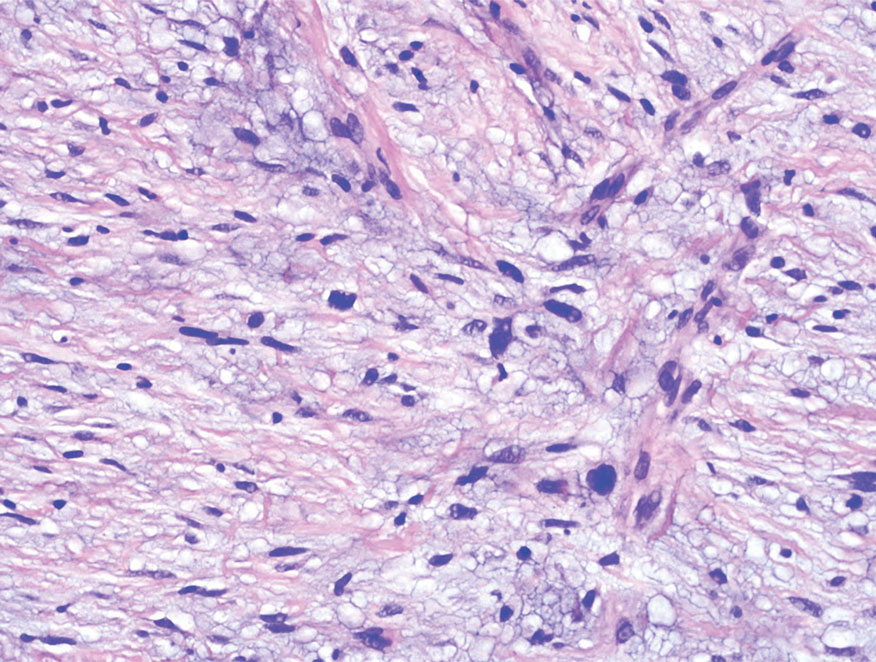

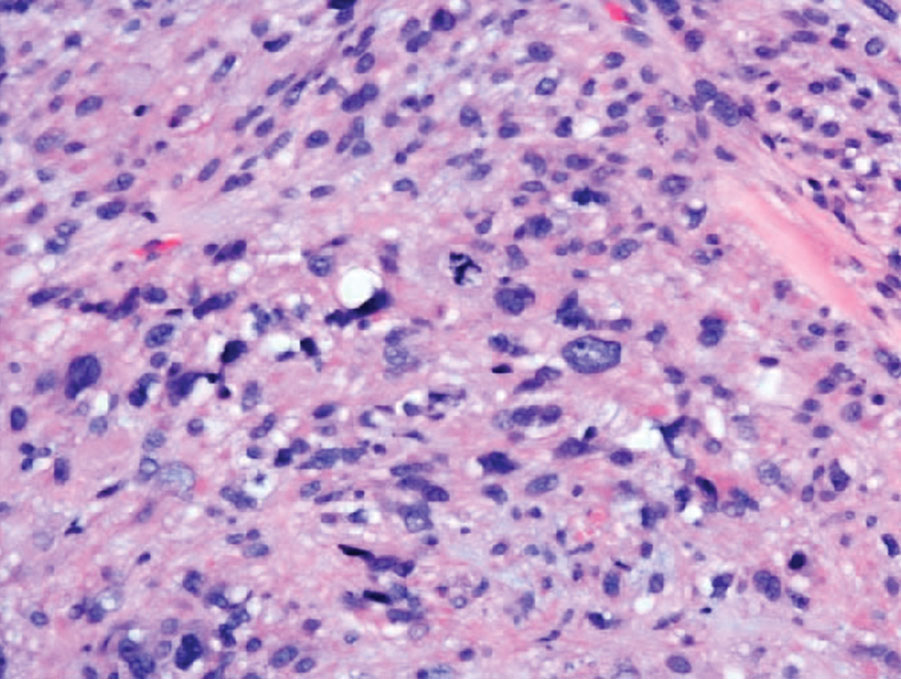

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

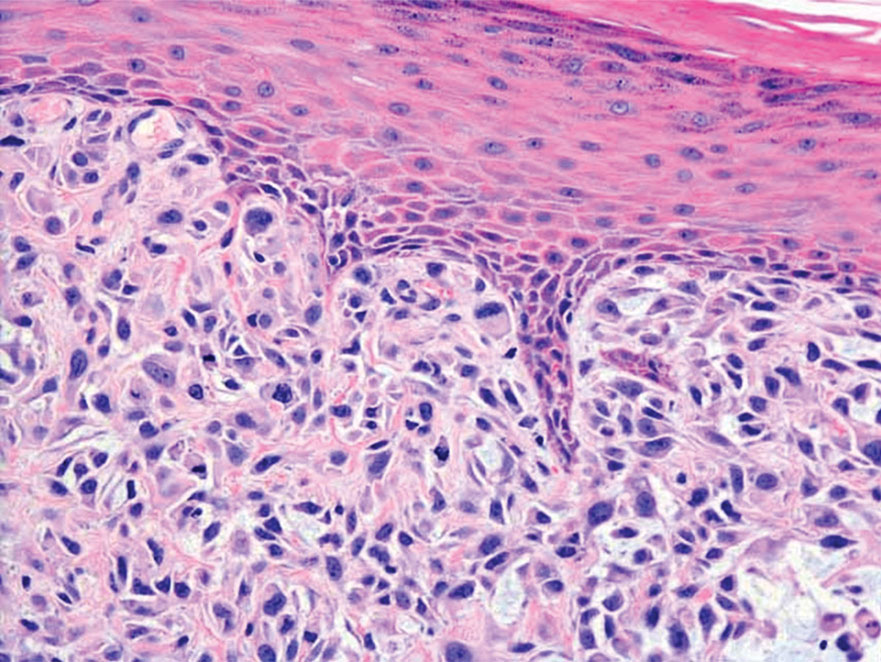

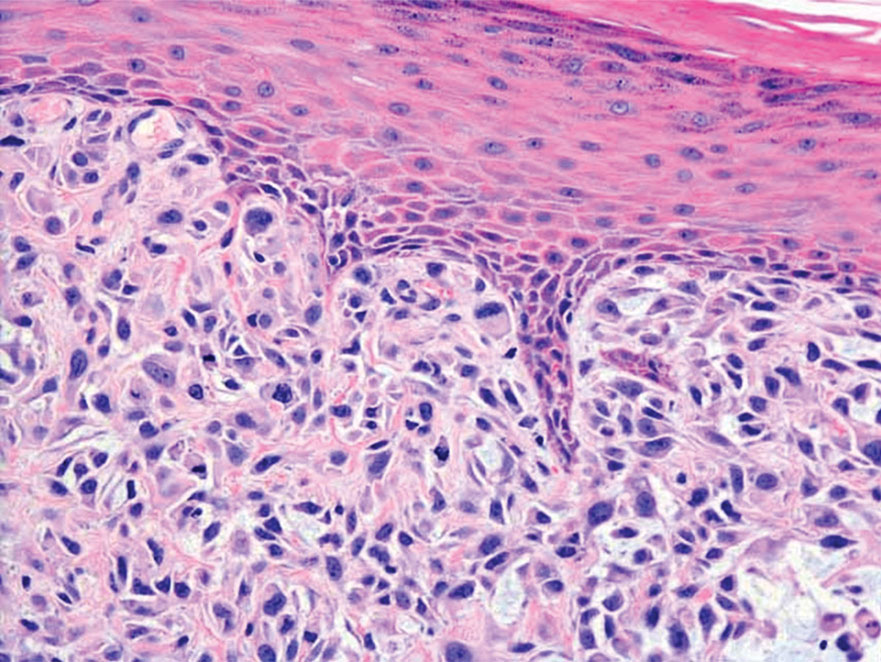

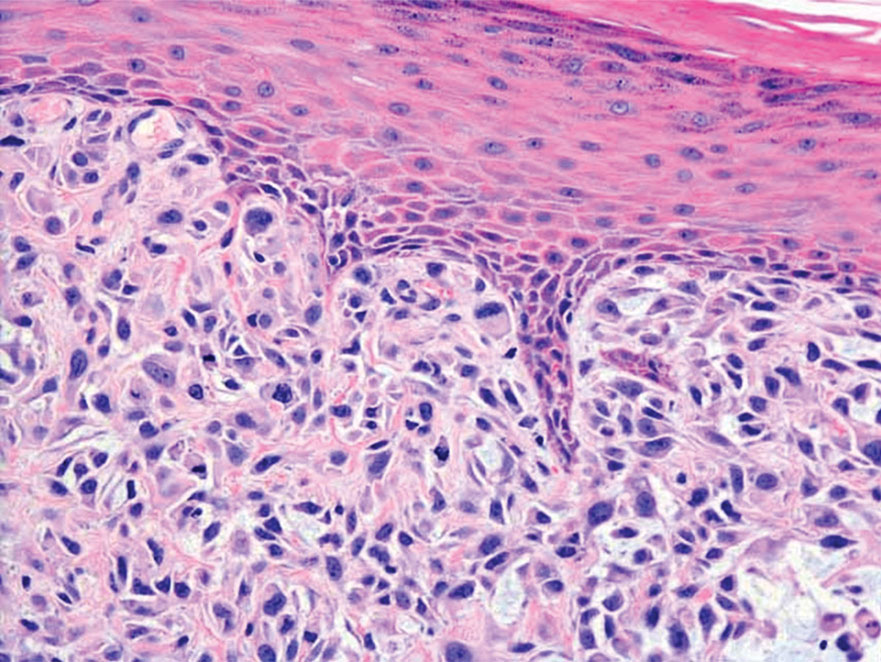

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

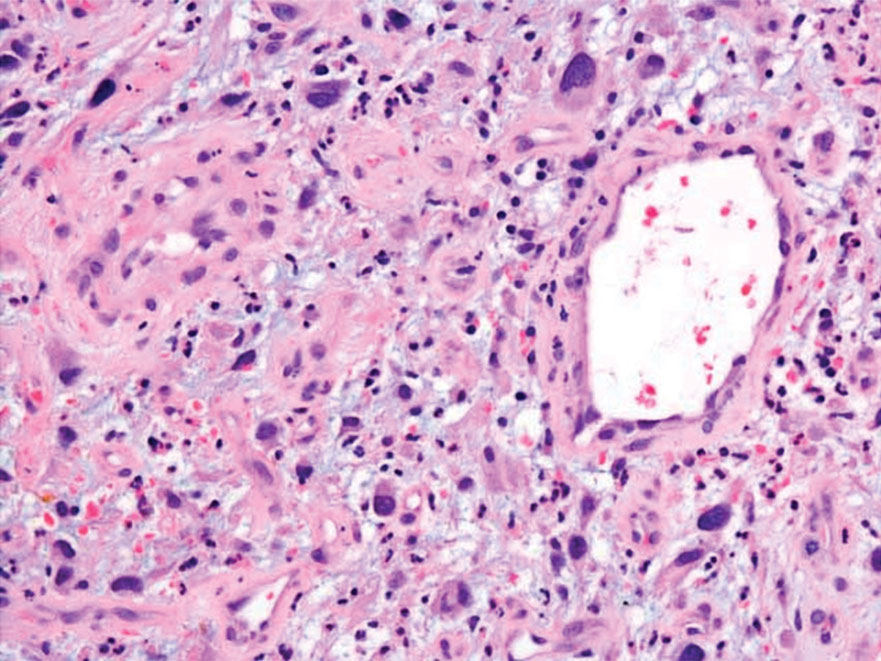

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

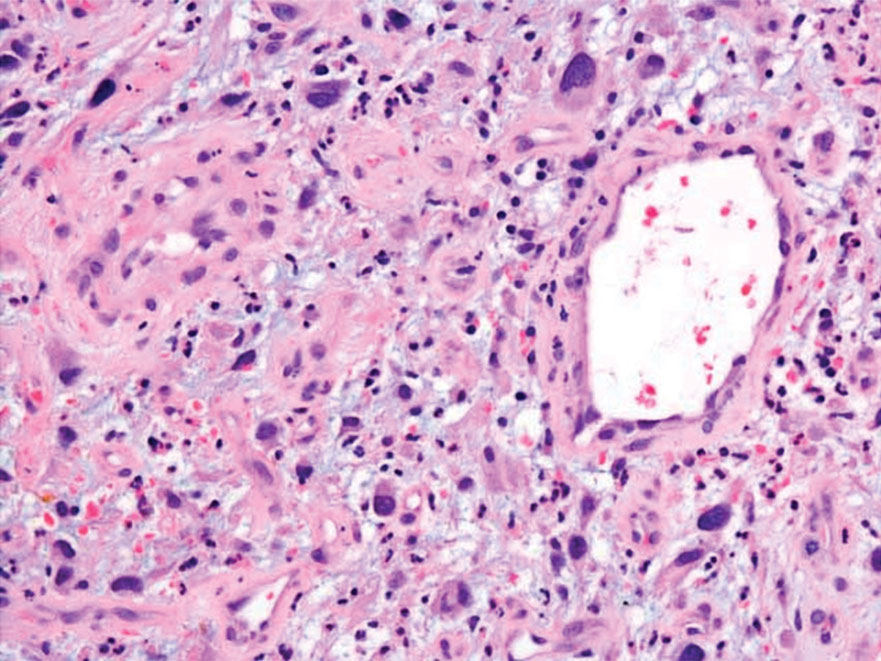

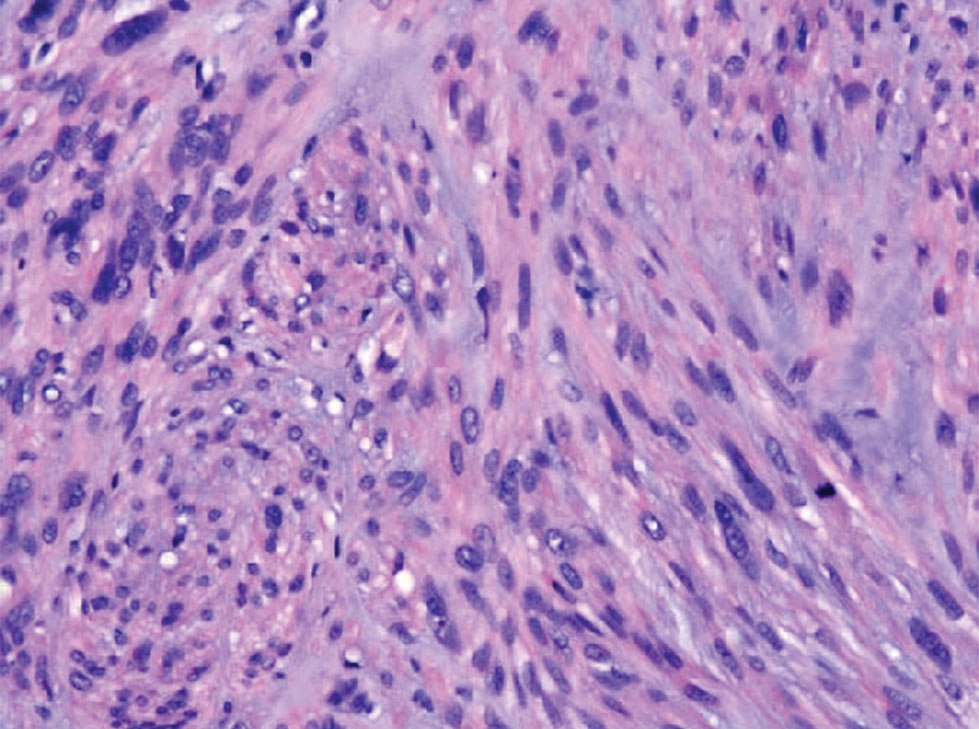

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

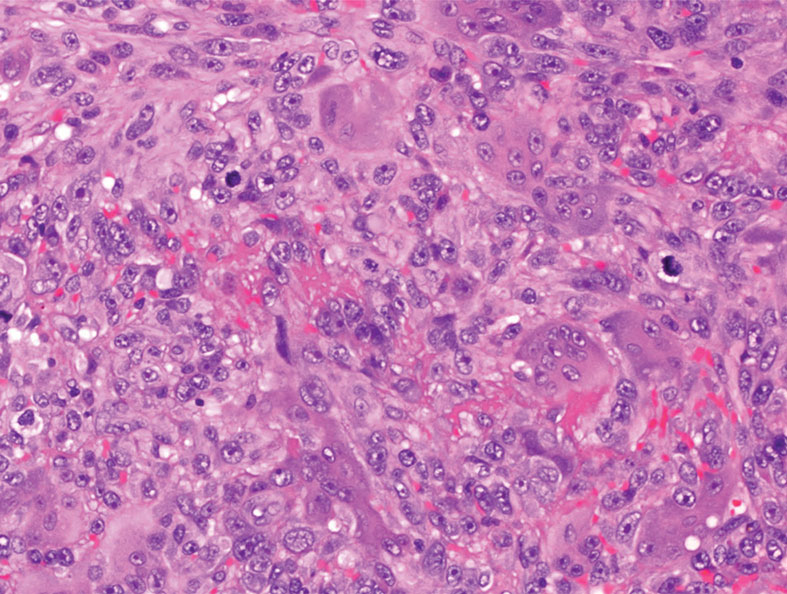

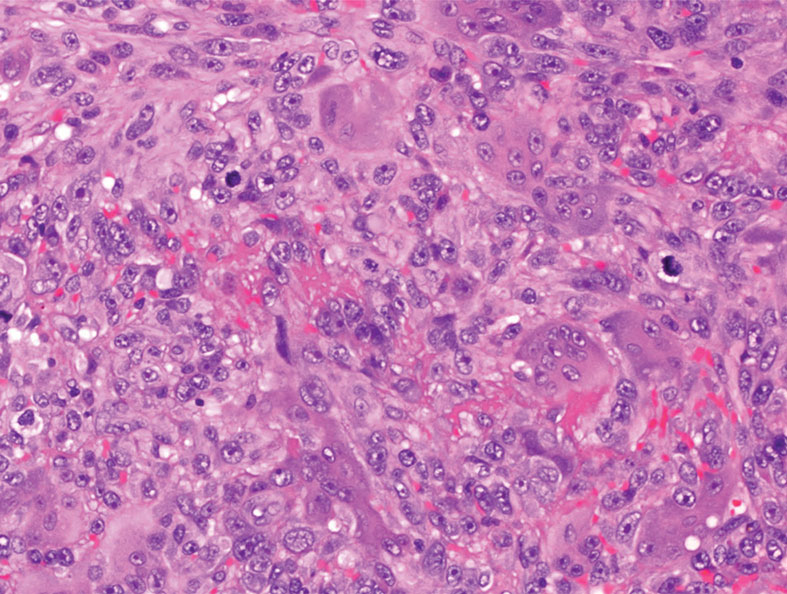

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

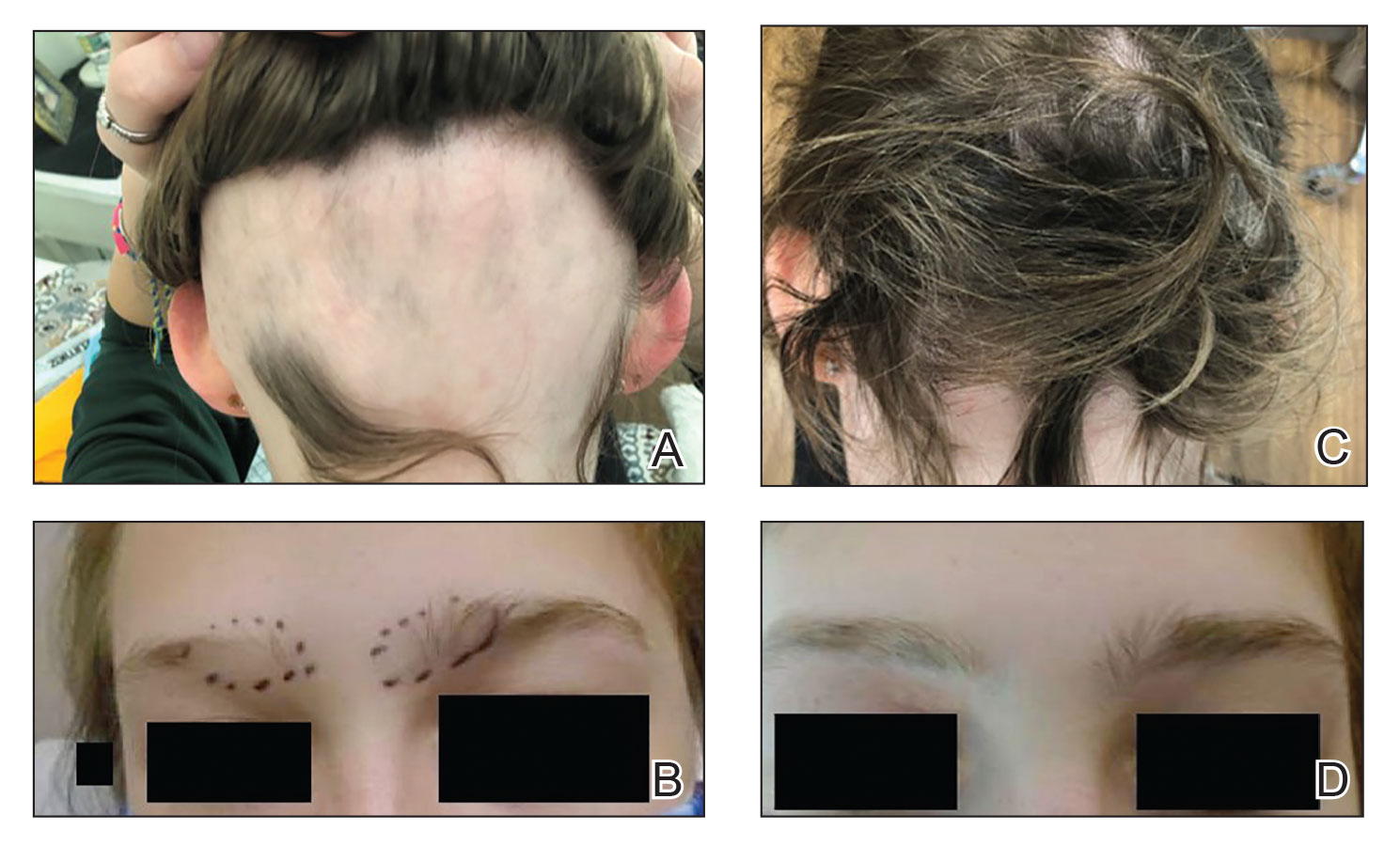

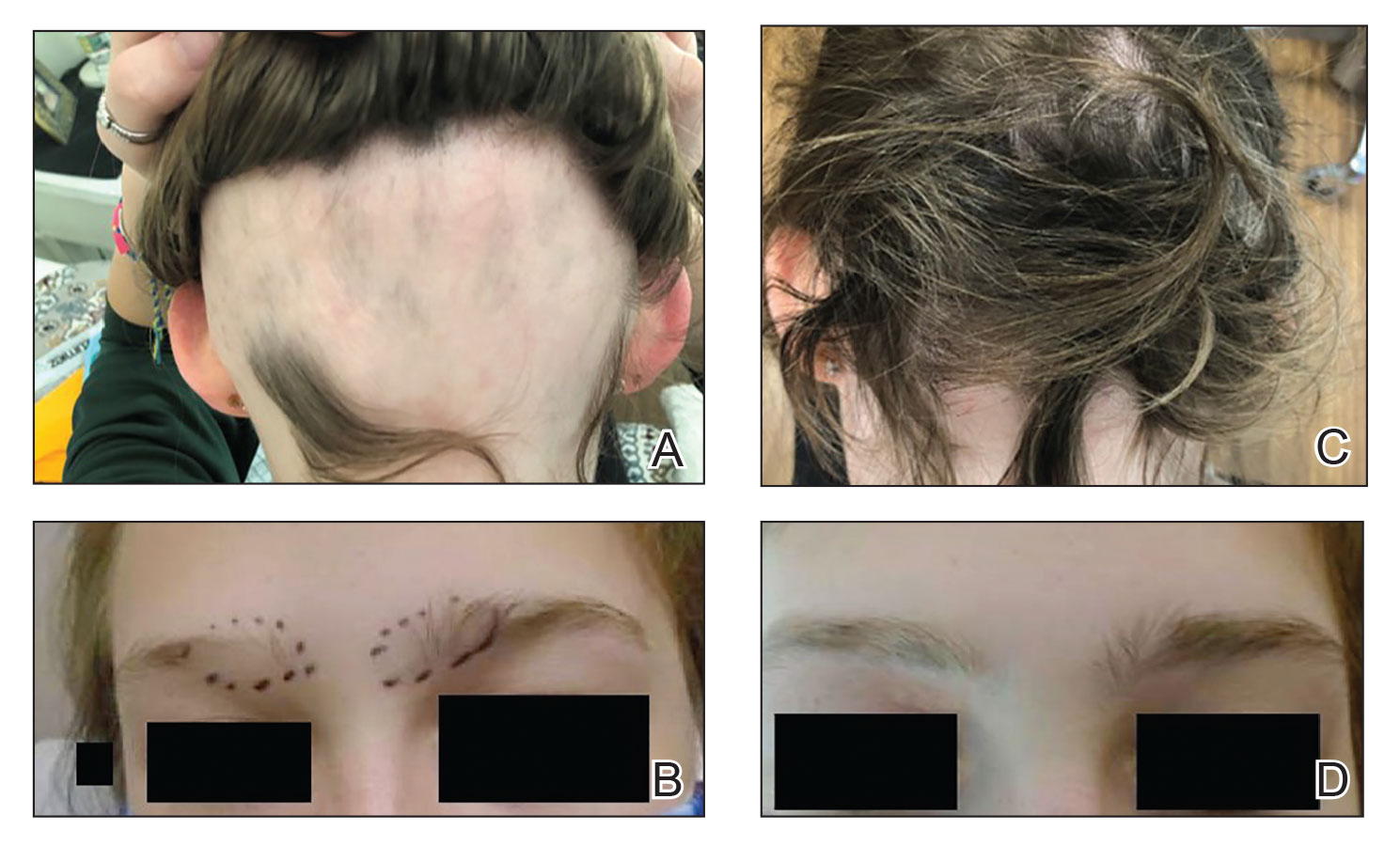

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

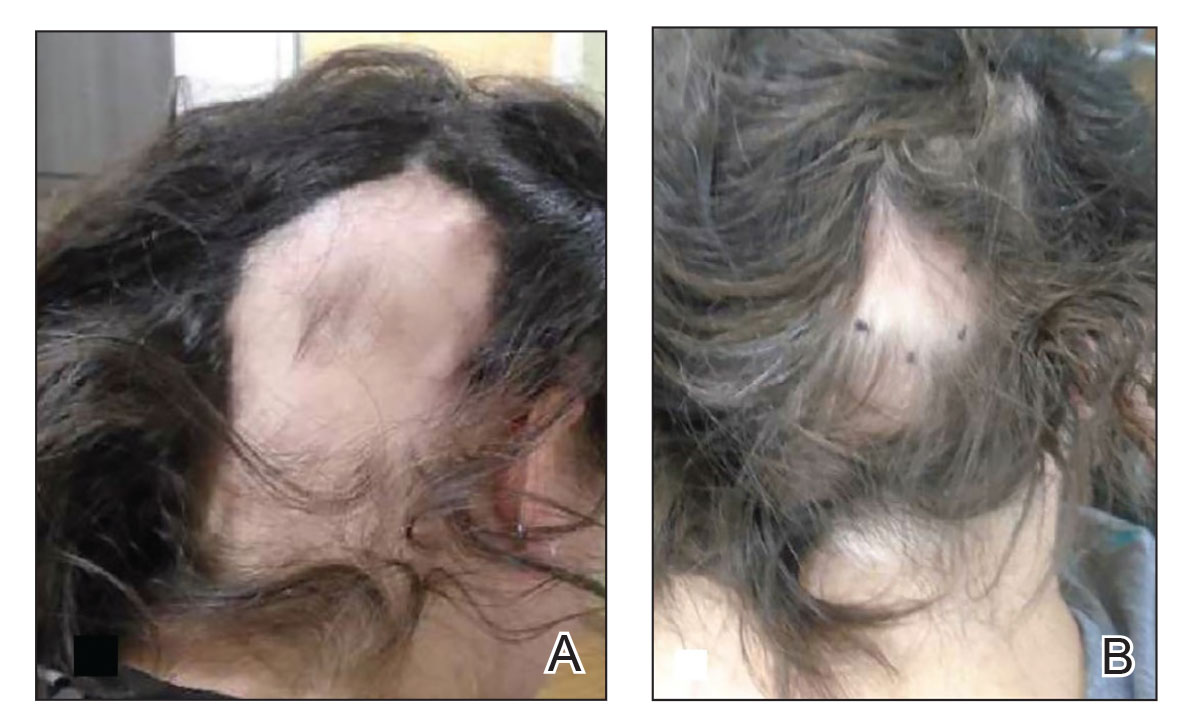

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

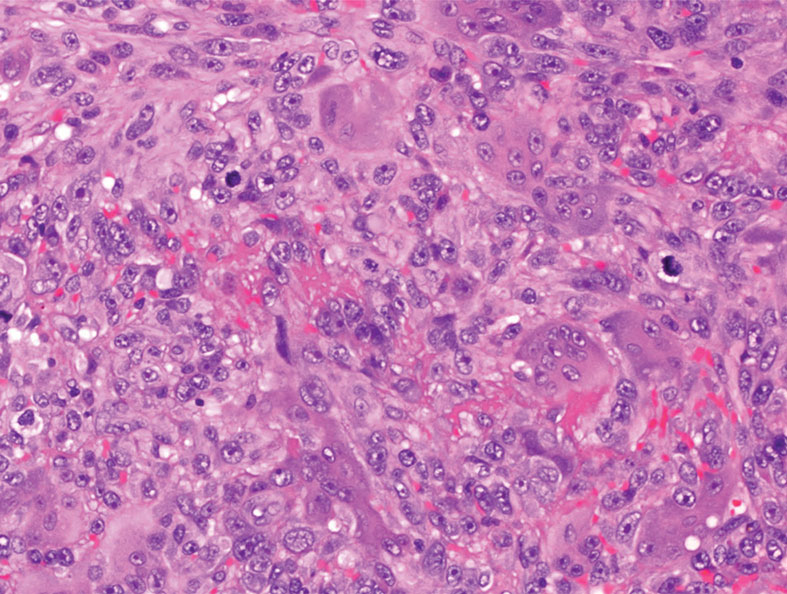

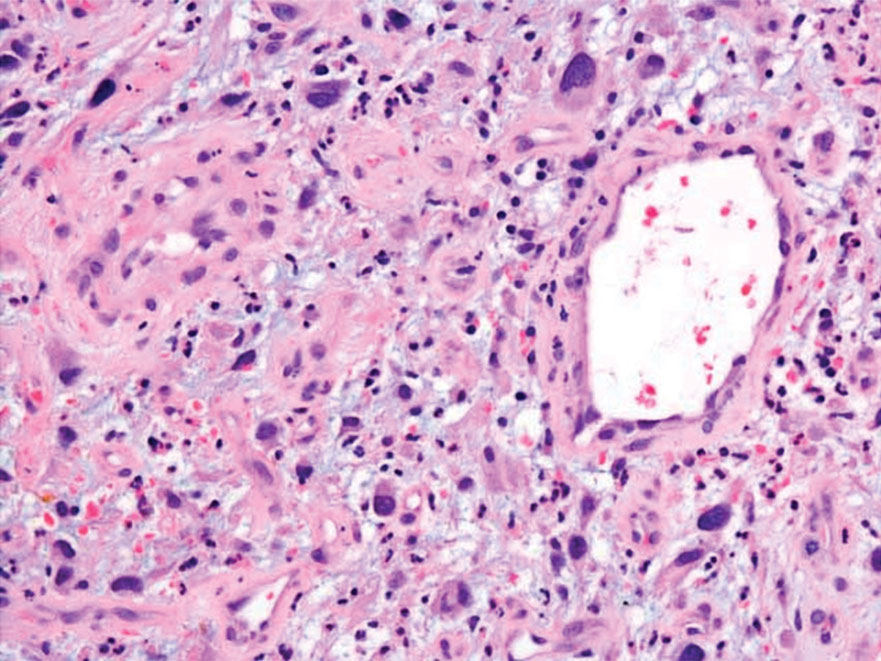

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

A 62-year-old man presented with a firm, exophytic, 2.8×1.5-cm tumor on the left shin of 6 to 7 years’ duration. An excisional biopsy was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.

Blood test for cancer available, but is it ready for prime time?

The Galleri blood test is being now offered by a number of United States health networks.

The company marketing the test, GRAIL, has established partnerships with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Mercy Health, Ochsner Health, Intermountain Healthcare, Community Health Network, Knight Cancer Institute at Oregon Health & Science University, Premier, and Cleveland Clinic, among others.

Cleveland Clinic’s Eric Klein, MD, emeritus chair of the Glickman Urological Kidney Institute, is enthusiastic about the test, describing it as a “game-changer” and emphasizing that it can detect many different cancers and at a very early stage.

“It completely changes the way we think about screening for cancer,” commented Jeff Venstrom, MD, chief medical officer at GRAIL. He joined the company because “there are not many things in life where you can be part of a disruptive paradigm and disruptive technology, and this really is disruptive,” he said in an interview.

‘The devil is in the details’

But there is some concern among clinicians that widespread clinical use of the test may be premature.

Having a blood test for multiple cancers is a “very good idea, and the scientific basis for this platform is sound,” commented Timothy R. Rebbeck, PhD, professor of cancer prevention, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Division of Population Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston.

“But the devil is in the details to ensure the test can accurately detect very early cancers and there is a pathway for subsequent workup (diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, etc.),” Dr. Rebbeck told this news organization.

Galleri is offering the test to individuals who are older than 50 and have a family history of cancer or those who are high risk for cancer or immunocompromised. They suggest that interested individuals get in touch with their health care professional, who then needs to register with GRAIL and order the test.

As well as needing a prescription, interested individuals will have to pay for it out of pocket, around $950. The test is not covered by medical insurance and is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Falls into primary care setting

Dr. Rebbeck commented that Galleri is a screening test for individuals who don’t have cancer, so the test is intended to fall into the primary care setting. But he warned that “clinical pathways are not yet in place (but are being developed) so that primary care providers can effectively use them.”

The test uses next-generation sequencing to analyze the arrangement of methyl groups on circulating tumor (or cell-free) DNA in a blood sample.

The methylation turns genes on or off, explains Cleveland Clinic’s Dr. Klein in his post. “It’s like fingerprints and how fingerprints tell the difference between two people,” he wrote. “The methylation patterns are fingerprints that are characteristic of each kind of cancer. They look one way for lung cancer and different for colon cancer.”

The test returns one of two possible results: either “positive, cancer signal detected” or “negative, no cancer signal detected.”

According to the company, when a cancer signal is detected, the Galleri test predicts the cancer signal origin “with high accuracy, to help guide the next steps to diagnosis.”

However, one problem for clinical practice is all the follow-up tests an individual may undergo if their test comes back positive, said Sameek Roychowdhury, MD, PhD, an oncologist with Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus.

“Not everybody will have an actual cancer, but they may undergo many tests, with a lot of stress and cost and still not find anything. I can tell you every time someone undergoes a test looking for cancer, that is not an easy day,” Dr. Roychowdhury said in an interview.

In a large-scale validation study, the Galleri test had a specificity of 99.5% (false-positive rate of 0.5%), meaning in roughly 200 people tested without cancer, only one person received a false-positive result (that is, “cancer signal detected” when cancer is not present).

The overall sensitivity of the test for any stage of cancer was 51.5%, although it was higher for later-stage cancers (77% for stage III and 90.1% for stage IV) and lower for early-stage cancers (16.8% for stage I and 40.4% for stage II).

Exacerbate health disparities?

In Dr. Rebbeck’s view, the characteristics of the test are still “relatively poor for detecting very early cancers, so it will need additional tweaking before it really achieves the goal of multi-cancer EARLY detection,” he said.

Dr. Venstrom acknowledges that the test is “not perfect yet” and says the company will continue to update and improve its performance. “We have some new data coming out in September,” he said.

Clinical data are being accumulated in the United Kingdom, where the Galleri test is being investigated in a large trial run by the National Health Service (NHS). The company recently announced that the enrollment of 140,000 healthy cancer-free volunteers aged 50-77 into this trial has now been completed and claimed this the largest-ever study of a multi-cancer early detection test.

Dr. Roychowdhury said he would encourage anyone interested in the test to join a clinical trial.

Another expert approached for comment last year, when GRAIL first started marketing the test, was in agreement. This test should be viewed as one that is still under clinical investigation, commented William Grady, MD, a member of the clinical research division and public health sciences division at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

“The Galleri test is still unproven in the clinical care setting and ... I am concerned that many of the results will be false-positives and will cause many unnecessary follow-up tests and imaging studies as well as anxiety in the people getting the test done,” Dr. Grady said.

Dr. Rebbeck said another issue that needs to be addressed is whether all populations will have access to and benefit from these types of blood tests to screen for cancer, given that they are expensive.

“There is a great danger – as we have seen with many other technological innovations – that the wealthy and connected benefit, but the majority of the population, and particularly those who are underserved, do not,” Dr. Rebbeck said.

“As a result, health disparities are created or exacerbated. This is something that needs to be addressed so that the future use of these tests will provide equitable benefits,” he added.

Dr. Rebbeck and Dr. Roychowdhury have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Venstrom is an employee of GRAIL.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Galleri blood test is being now offered by a number of United States health networks.

The company marketing the test, GRAIL, has established partnerships with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Mercy Health, Ochsner Health, Intermountain Healthcare, Community Health Network, Knight Cancer Institute at Oregon Health & Science University, Premier, and Cleveland Clinic, among others.

Cleveland Clinic’s Eric Klein, MD, emeritus chair of the Glickman Urological Kidney Institute, is enthusiastic about the test, describing it as a “game-changer” and emphasizing that it can detect many different cancers and at a very early stage.

“It completely changes the way we think about screening for cancer,” commented Jeff Venstrom, MD, chief medical officer at GRAIL. He joined the company because “there are not many things in life where you can be part of a disruptive paradigm and disruptive technology, and this really is disruptive,” he said in an interview.

‘The devil is in the details’

But there is some concern among clinicians that widespread clinical use of the test may be premature.

Having a blood test for multiple cancers is a “very good idea, and the scientific basis for this platform is sound,” commented Timothy R. Rebbeck, PhD, professor of cancer prevention, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Division of Population Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston.

“But the devil is in the details to ensure the test can accurately detect very early cancers and there is a pathway for subsequent workup (diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, etc.),” Dr. Rebbeck told this news organization.

Galleri is offering the test to individuals who are older than 50 and have a family history of cancer or those who are high risk for cancer or immunocompromised. They suggest that interested individuals get in touch with their health care professional, who then needs to register with GRAIL and order the test.

As well as needing a prescription, interested individuals will have to pay for it out of pocket, around $950. The test is not covered by medical insurance and is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Falls into primary care setting

Dr. Rebbeck commented that Galleri is a screening test for individuals who don’t have cancer, so the test is intended to fall into the primary care setting. But he warned that “clinical pathways are not yet in place (but are being developed) so that primary care providers can effectively use them.”

The test uses next-generation sequencing to analyze the arrangement of methyl groups on circulating tumor (or cell-free) DNA in a blood sample.

The methylation turns genes on or off, explains Cleveland Clinic’s Dr. Klein in his post. “It’s like fingerprints and how fingerprints tell the difference between two people,” he wrote. “The methylation patterns are fingerprints that are characteristic of each kind of cancer. They look one way for lung cancer and different for colon cancer.”

The test returns one of two possible results: either “positive, cancer signal detected” or “negative, no cancer signal detected.”

According to the company, when a cancer signal is detected, the Galleri test predicts the cancer signal origin “with high accuracy, to help guide the next steps to diagnosis.”

However, one problem for clinical practice is all the follow-up tests an individual may undergo if their test comes back positive, said Sameek Roychowdhury, MD, PhD, an oncologist with Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus.

“Not everybody will have an actual cancer, but they may undergo many tests, with a lot of stress and cost and still not find anything. I can tell you every time someone undergoes a test looking for cancer, that is not an easy day,” Dr. Roychowdhury said in an interview.

In a large-scale validation study, the Galleri test had a specificity of 99.5% (false-positive rate of 0.5%), meaning in roughly 200 people tested without cancer, only one person received a false-positive result (that is, “cancer signal detected” when cancer is not present).

The overall sensitivity of the test for any stage of cancer was 51.5%, although it was higher for later-stage cancers (77% for stage III and 90.1% for stage IV) and lower for early-stage cancers (16.8% for stage I and 40.4% for stage II).

Exacerbate health disparities?

In Dr. Rebbeck’s view, the characteristics of the test are still “relatively poor for detecting very early cancers, so it will need additional tweaking before it really achieves the goal of multi-cancer EARLY detection,” he said.

Dr. Venstrom acknowledges that the test is “not perfect yet” and says the company will continue to update and improve its performance. “We have some new data coming out in September,” he said.

Clinical data are being accumulated in the United Kingdom, where the Galleri test is being investigated in a large trial run by the National Health Service (NHS). The company recently announced that the enrollment of 140,000 healthy cancer-free volunteers aged 50-77 into this trial has now been completed and claimed this the largest-ever study of a multi-cancer early detection test.

Dr. Roychowdhury said he would encourage anyone interested in the test to join a clinical trial.

Another expert approached for comment last year, when GRAIL first started marketing the test, was in agreement. This test should be viewed as one that is still under clinical investigation, commented William Grady, MD, a member of the clinical research division and public health sciences division at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

“The Galleri test is still unproven in the clinical care setting and ... I am concerned that many of the results will be false-positives and will cause many unnecessary follow-up tests and imaging studies as well as anxiety in the people getting the test done,” Dr. Grady said.

Dr. Rebbeck said another issue that needs to be addressed is whether all populations will have access to and benefit from these types of blood tests to screen for cancer, given that they are expensive.

“There is a great danger – as we have seen with many other technological innovations – that the wealthy and connected benefit, but the majority of the population, and particularly those who are underserved, do not,” Dr. Rebbeck said.

“As a result, health disparities are created or exacerbated. This is something that needs to be addressed so that the future use of these tests will provide equitable benefits,” he added.

Dr. Rebbeck and Dr. Roychowdhury have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Venstrom is an employee of GRAIL.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Galleri blood test is being now offered by a number of United States health networks.

The company marketing the test, GRAIL, has established partnerships with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Mercy Health, Ochsner Health, Intermountain Healthcare, Community Health Network, Knight Cancer Institute at Oregon Health & Science University, Premier, and Cleveland Clinic, among others.

Cleveland Clinic’s Eric Klein, MD, emeritus chair of the Glickman Urological Kidney Institute, is enthusiastic about the test, describing it as a “game-changer” and emphasizing that it can detect many different cancers and at a very early stage.

“It completely changes the way we think about screening for cancer,” commented Jeff Venstrom, MD, chief medical officer at GRAIL. He joined the company because “there are not many things in life where you can be part of a disruptive paradigm and disruptive technology, and this really is disruptive,” he said in an interview.

‘The devil is in the details’

But there is some concern among clinicians that widespread clinical use of the test may be premature.

Having a blood test for multiple cancers is a “very good idea, and the scientific basis for this platform is sound,” commented Timothy R. Rebbeck, PhD, professor of cancer prevention, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Division of Population Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston.

“But the devil is in the details to ensure the test can accurately detect very early cancers and there is a pathway for subsequent workup (diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, etc.),” Dr. Rebbeck told this news organization.

Galleri is offering the test to individuals who are older than 50 and have a family history of cancer or those who are high risk for cancer or immunocompromised. They suggest that interested individuals get in touch with their health care professional, who then needs to register with GRAIL and order the test.

As well as needing a prescription, interested individuals will have to pay for it out of pocket, around $950. The test is not covered by medical insurance and is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Falls into primary care setting

Dr. Rebbeck commented that Galleri is a screening test for individuals who don’t have cancer, so the test is intended to fall into the primary care setting. But he warned that “clinical pathways are not yet in place (but are being developed) so that primary care providers can effectively use them.”

The test uses next-generation sequencing to analyze the arrangement of methyl groups on circulating tumor (or cell-free) DNA in a blood sample.

The methylation turns genes on or off, explains Cleveland Clinic’s Dr. Klein in his post. “It’s like fingerprints and how fingerprints tell the difference between two people,” he wrote. “The methylation patterns are fingerprints that are characteristic of each kind of cancer. They look one way for lung cancer and different for colon cancer.”

The test returns one of two possible results: either “positive, cancer signal detected” or “negative, no cancer signal detected.”

According to the company, when a cancer signal is detected, the Galleri test predicts the cancer signal origin “with high accuracy, to help guide the next steps to diagnosis.”

However, one problem for clinical practice is all the follow-up tests an individual may undergo if their test comes back positive, said Sameek Roychowdhury, MD, PhD, an oncologist with Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus.

“Not everybody will have an actual cancer, but they may undergo many tests, with a lot of stress and cost and still not find anything. I can tell you every time someone undergoes a test looking for cancer, that is not an easy day,” Dr. Roychowdhury said in an interview.

In a large-scale validation study, the Galleri test had a specificity of 99.5% (false-positive rate of 0.5%), meaning in roughly 200 people tested without cancer, only one person received a false-positive result (that is, “cancer signal detected” when cancer is not present).

The overall sensitivity of the test for any stage of cancer was 51.5%, although it was higher for later-stage cancers (77% for stage III and 90.1% for stage IV) and lower for early-stage cancers (16.8% for stage I and 40.4% for stage II).

Exacerbate health disparities?

In Dr. Rebbeck’s view, the characteristics of the test are still “relatively poor for detecting very early cancers, so it will need additional tweaking before it really achieves the goal of multi-cancer EARLY detection,” he said.

Dr. Venstrom acknowledges that the test is “not perfect yet” and says the company will continue to update and improve its performance. “We have some new data coming out in September,” he said.

Clinical data are being accumulated in the United Kingdom, where the Galleri test is being investigated in a large trial run by the National Health Service (NHS). The company recently announced that the enrollment of 140,000 healthy cancer-free volunteers aged 50-77 into this trial has now been completed and claimed this the largest-ever study of a multi-cancer early detection test.

Dr. Roychowdhury said he would encourage anyone interested in the test to join a clinical trial.

Another expert approached for comment last year, when GRAIL first started marketing the test, was in agreement. This test should be viewed as one that is still under clinical investigation, commented William Grady, MD, a member of the clinical research division and public health sciences division at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

“The Galleri test is still unproven in the clinical care setting and ... I am concerned that many of the results will be false-positives and will cause many unnecessary follow-up tests and imaging studies as well as anxiety in the people getting the test done,” Dr. Grady said.

Dr. Rebbeck said another issue that needs to be addressed is whether all populations will have access to and benefit from these types of blood tests to screen for cancer, given that they are expensive.

“There is a great danger – as we have seen with many other technological innovations – that the wealthy and connected benefit, but the majority of the population, and particularly those who are underserved, do not,” Dr. Rebbeck said.

“As a result, health disparities are created or exacerbated. This is something that needs to be addressed so that the future use of these tests will provide equitable benefits,” he added.

Dr. Rebbeck and Dr. Roychowdhury have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Venstrom is an employee of GRAIL.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA acts against sales of unapproved mole and skin tag products on Amazon, other sites

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.