User login

Combatting Climate Change: 10 Interventions for Dermatologists to Consider for Sustainability

The impacts of anthropogenic climate change on human health are numerous and growing. The evidence that climate change is occurring due to the burning of fossil fuels is substantial, with a 2019 report elevating the data supporting anthropogenic climate change to a gold standard 5-sigma level of significance.1 In the peer-reviewed scientific literature, the consensus that humans are causing climate change is greater than 99%.2 Both the American Medical Association and the American College of Physicians have acknowledged the health impacts of climate change and importance for action. They encourage physicians to engage in environmentally sustainable practices and to advocate for effective climate change mitigation strategies.3,4 A survey of dermatologists also found that 99.3% (n=148) recognize climate change is occurring, and similarly high numbers are concerned about its health impacts.5

Notably, the health care industry must grapple not only with the health impacts of climate change but with the fact that the health care sector itself is responsible for a large amount of carbon emissions.6 The global health care industry as a whole produces enough carbon emissions to be ranked as the fifth largest emitting nation in the world.7 A quarter of these emissions are attributed to the US health care system.8,9 Climate science has shown we must limit CO2 emissions to avoid catastrophic climate change, with the sixth assessment report of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement targeting large emission reductions within the next decade.10 In August 2021, the US Department of Health and Human Services created the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity. Assistant Secretary for Health ADM Rachel L. Levine, MD, has committed to reducing the carbon emissions from the health care sector by 25% in the next decade, in line with scientific consensus regarding necessary changes.11

The dermatologic impacts of climate change are myriad. Rising temperatures, increasing air and water pollution, and stratospheric ozone depletion will lead to expanded geographic ranges of vector-borne diseases, worsening of chronic skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis/eczema and pemphigus, and increasing rates of skin cancer.12 For instance, warmer temperatures have allowed mosquitoes of the Aedes genus to infest new areas, leading to outbreaks of viral illnesses with cutaneous manifestations such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus in previously nonindigenous regions.13 Rising temperatures also have been associated with an expanding geographic range of tick- and sandfly-borne illnesses such as Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and cutaneous leishmaniasis.13,14 Additionally, short-term exposure to air pollution from wildfire smoke has been associated with an increased use of health care services by patients with atopic dermatitis.15 Increased levels of air pollutants also have been found to be associated with psoriasis flares as well as hyperpigmentation and wrinkle formation.16,17 Skin cancer incidence is predicted to rise due to increased UV radiation exposure secondary to stratospheric ozone depletion.18

Although the effects of climate change are significant and the magnitude of the climate crisis may feel overwhelming, it is essential to avoid doomerism and focus on meaningful impactful actions. Current CO2 emissions will remain in the atmosphere for hundreds to thousands of years, and the choices we make now commit future generations to live in a world shaped by our decisions. Importantly, there are impactful and low-cost, cost-effective, or cost-saving changes that can be made to mitigate the climate crisis. Herein, we provide 10 practical actionable interventions for dermatologists to help combat climate change.

10 Interventions for Dermatologists to Combat Climate Change

1. Consider switching to renewable sources of energy. Making this switch often is the most impactful decision a dermatologist can make to address climate change. The electricity sector is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the US health care system, and dermatology outpatient practices in particular have been observed to have a higher peak energy consumption than most other specialties studied.19,20 Many dermatology practices—both privately owned and academic—can switch to renewable energy seamlessly through power purchase agreements (PPAs), which are contracts between power providers and private entities to install renewable energy equipment or source renewable energy from offsite sources at a fixed rate. Using PPAs instead of traditional fossil fuel energy can provide cost savings as well as protect buyers from electrical price volatility. Numerous health care systems utilize PPAs such as Kaiser Permanente, Cleveland Clinic, and Rochester Regional Health. Additionally, dermatologists can directly purchase renewable energy equipment and eventually receive a return on investment from substantially lowered electric bills. It is important to note that the cost of commercial solar energy systems has decreased 69% since 2010 with further cost reductions predicted.21,22

2. Reduce standby power consumption. This refers to the use of electricity by a device when it appears to be off or is not in use, which can lead to considerable energy consumption and subsequently a larger carbon footprint for your practice. Ensuring electronics such as phone chargers, light fixtures, television screens, and computers are switched off prior to the end of the workday can make a large difference; for instance, a single radiology department at the University of Maryland (College Park, Maryland) found that if clinical workstations were shut down when not in use after an 8-hour workday, it would save 83,866 kWh of energy and $9225.33 per year.23 Additionally, using power strips with an automatic shutoff feature to shut off power to devices not in use provides a more convenient way to reduce standby power.

3. Optimize thermostat settings. An analysis of energy consumption in 157,000 US health care facilities found that space heating and cooling accounted for 40% of their total energy consumption.24 Thus, ensuring your thermostat and heating/cooling systems are working efficiently can conserve a substantial amount of energy. For maximum efficiency, it is recommended to set air conditioners to 74 °F (24 °C) and heaters to 68 °F (20 °C) or employ smart thermostats to optimally adjust temperatures when the office is not in use.25 In addition, routinely replacing or cleaning air conditioner filters can lower energy consumption by 5% to 15%.26 Similarly, improving insulation and ruggedization of both homes and offices may reduce heating and cooling waste and limit costs and emissions as a result.

4. Offer bicycle racks and charging ports for electric vehicles. In the United States, transportation generates more greenhouse gas emissions than any other source, primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels to power automobiles, trains, and planes. Because bicycles do not consume any fossil fuels and the use of electric vehicles has been found to result in substantial air pollution health benefits, encouraging the use of both can make a considerable positive impact on our climate.27 Providing these resources not only allows those who already travel sustainably to continue to do so but also serves as a reminder to your patients that sustainability is important to you as their health care provider. As electric vehicle sales continue to climb, infrastructure to support their use, including charging stations, will grow in importance. A physician’s office that offers a car-charging station may soon have a competitive advantage over others in the area.

5. Ensure properly regulated medical waste management. Regulated medical waste (also known as infectious medical waste or red bag waste) refers to health care–generated waste unsuitable for disposal in municipal solid waste systems due to concern for the spread of infectious or pathogenic materials. This waste largely is disposed via incineration, which harms the environment in a multitude of ways—both through harmful byproducts and from the CO2 emissions required to ship the waste to special processing facilities.28 Incineration of regulated medical waste emits potent toxins such as dioxins and furans as well as particulate matter, which contribute to air pollution. Ensuring only materials with infectious potential (as defined by each state’s Environmental Protection Agency) are disposed in regulated medical waste containers can dramatically reduce the harmful effects of incineration. Additionally, limiting regulated medical waste can be very cost-effective, as its disposal is 5- to 10-times more expensive than that of unregulated medical waste.29 Simple nudge measures such as educating staff about what waste goes in which receptacle, placing signage over the red bag waste to prompt staff to pause to consider if use of that bin is required before utilizing, using weights or clasps to make opening red bag waste containers slightly harder, and positioning different trash receptacles in different parts of examination rooms may help reduce inappropriate use of red bag waste.

6. Consider virtual platforms when possible. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual meeting platforms saw a considerable increase in usage by dermatologists. Teledermatology for patient care became much more widely adopted, and traditionally in-person meetings turned virtual.30 The reduction in emissions from these changes was remarkable. A recent study looking at the environmental impact of 3 months of teledermatology visits early during the COVID-19 pandemic found that 1476 teledermatology appointments saved 55,737 miles of car travel, equivalent to 15.37 metric tons of CO2.31 Whether for patient care when appropriate, academic conferences and continuing medical education credit, or for interviews (eg, medical students, residents, other staff), use of virtual platforms can reduce unnecessary travel and therefore substantially reduce travel-related emissions. When travel is unavoidable, consider exploring validated vetted companies that offer carbon offsets to reduce the harmful environmental impact of high-emission flights.

7. Limit use of single-use disposable items. Although single-use items such as examination gloves or needles are necessary in a dermatology practice, there are many opportunities to incorporate reusable items in your workplace. For instance, you can replace plastic cutlery and single-use plates in kitchen or dining areas with reusable alternatives. Additionally, using reusable isolation gowns instead of their single-use counterparts can help reduce waste; a reusable isolation gown system for providers including laundering services was found to consume 28% less energy and emit 30% fewer greenhouse gases than a single-use isolation gown system.32 Similarly, opting for reusable instruments instead of single-use instruments when possible also can help reduce your practice’s carbon footprint. Carefully evaluating each part of your “dermatology visit supply chain” may offer opportunities to utilize additional cost-saving, environmentally friendly options; for example, an individually plastic-wrapped Dermablade vs a bulk-packaged blade for shave biopsies has a higher cost and worse environmental impact. A single gauze often is sufficient for shave biopsies, but many practices open a plastic container of bulk gauze, much of which results in waste that too often is inappropriately disposed of as regulated medical waste despite not being saturated in blood/body fluids.

8. Educate on the effects of climate change. Dermatologists and other physicians have the unique opportunity to teach members of their community every day through patient care. Physicians are trusted messengers, and appropriately counseling patients regarding the risks of climate change and its effects on their dermatologic health is in line with both American Medical Association and American College of Physicians guidelines.3,4 For instance, patients with Lyme disease in Canada or Maine were unheard of a few decades ago, but now they are common; flares of atopic dermatitis in regions adjacent to recent wildfires may be attributable to harmful particulate matter resulting from fossil-fueled climate change and record droughts. Educating medical trainees on the impacts of climate change is just as vital, as it is a topic that often is neglected in medical school and residency curricula.33

9. Install water-efficient toilets and faucets. Anthropogenic climate change has been shown to increase the duration and intensity of droughts throughout the world.34 Much of the western United States also is experiencing record droughts. One way in which dermatology practices can work to combat droughts is through the use of water-conserving toilets, faucets, and urinals. Using water fixtures with the US Environmental Protection Agency’s WaterSense label is a convenient way to do so. The WaterSense label helps identify water fixtures certified to use at least 20% less water as well as save energy and decrease water costs.

10. Advocate through local and national organizations. There are numerous ways in which dermatologists can advocate for action against climate change. Joining professional organizations focused on addressing the climate crisis can help you connect with fellow dermatologists and physicians. The Expert Resource Group on Climate Change and Environmental Issues affiliated with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) is one such organization with many opportunities to raise awareness within the field of dermatology. The AAD recently joined the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health, an organization providing opportunities for policy and media outreach as well as research on climate change. Advocacy also can mean joining your local chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility or encouraging divestment from fossil fuel companies within your institution. Voicing support for climate change–focused lectures at events such as grand rounds and society meetings at the local, regional, and state-wide levels can help raise awareness. As the dermatologic effects of climate change grow, being knowledgeable of the views of future leaders in our specialty and country on this issue will become increasingly important.

Final Thoughts

In addition to the climate-friendly decisions one can make as a dermatologist, there are many personal lifestyle choices to consider. Small dietary changes such as limiting consumption of beef and minimizing food waste can have large downstream effects. Opting for transportation via train and limiting air travel are both impactful decisions in reducing CO2 emissions. Similarly, switching to an electric vehicle or vehicle with minimal emissions can work to reduce greenhouse gas accumulation. For additional resources, note the AAD has partnered with My Green Doctor, a nonprofit service for health care practices that includes practical cost-saving suggestions to support sustainability in physician practices.

A recent joint publication in more than 200 medical journals described climate change as the greatest threat to global public health.35 Climate change is having devastating effects on dermatologic health and will only continue to do so if not addressed now. Dermatologists have the opportunity to join with our colleagues in the house of medicine and to take action to fight climate change and mitigate the health impacts on our patients, the population, and future generations.

- Santer BD, Bonfils CJW, Fu Q, et al. Celebrating the anniversary of three key events in climate change science. Nat Clim Chang. 2019;9:180-182.

- Lynas M, Houlton BZ, Perry S. Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Environ Res Lett. 2021;16:114005.

- Crowley RA; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Climate change and health: a position paper of the American College of Physicians [published online April 19, 2016]. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:608-610. doi:10.7326/M15-2766

- Global climate change and human health H-135.398. American Medical Association website. Updated 2019. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/climate%20change?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-309.xml

- Mieczkowska K, Stringer T, Barbieri JS, et al. Surveying the attitudes of dermatologists regarding climate change. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:748-750.

- Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental impacts of the U.S. health care system and effects on public health. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157014

- Karliner J, Slotterback S, Boyd R, et al. Health care’s climate footprint: how the health sector contributes to the global climate crisis and opportunities for action. Health Care Without Harm website. Published September 2019. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_090619.pdf

- Pichler PP, Jaccard IS, Weisz U, et al. International comparison of health care carbon footprints. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14:064004.

- Solomon CG, LaRocque RC. Climate change—a health emergency. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:209-211. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1817067

- IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, et al, eds. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2021:3-32.

- Dzau VJ, Levine R, Barrett G, et al. Decarbonizing the U.S. Health Sector—a call to action [published online October 13, 2021]. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2117-2119. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2115675

- Silva GS, Rosenbach M. Climate change and dermatology: an introduction to a special topic, for this special issue. Int J Womens Dermatol 2021;7:3-7.

- Coates SJ, Norton SA. The effects of climate change on infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:8-16. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.005

- Andersen LK, Davis MD. Climate change and the epidemiology of selected tick-borne and mosquito-borne diseases: update from the International Society of Dermatology Climate Change Task Force [published online October 1, 2016]. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:252-259. doi:10.1111/ijd.13438

- Fadadu RP, Grimes B, Jewell NP, et al. Association of wildfire air pollution and health care use for atopic dermatitis and itch. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:658-666. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0179

- Bellinato F, Adami G, Vaienti S, et al. Association between short-term exposure to environmental air pollution and psoriasis flare. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:375-381. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.6019

- Krutmann J, Bouloc A, Sore G, et al. The skin aging exposome [published online September 28, 2016]. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;85:152-161.

- Parker ER. The influence of climate change on skin cancer incidence—a review of the evidence. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:17-27. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.003

- Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, et al. Health care pollution and public health damage in the United States: an update. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:2071-2079.

- Sheppy M, Pless S, Kung F. Healthcare energy end-use monitoring. US Department of Energy website. Published August 2014. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/09/f18/61064.pdf

- Feldman D, Ramasamy V, Fu R, et al. U.S. solar photovoltaic system and energy storage cost benchmark: Q1 2020. Published January 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/77324.pdf

- 22. Apostoleris H, Sgouridis S, Stefancich M, et al. Utility solar prices will continue to drop all over the world even without subsidies. Nat Energy. 2019;4:833-834.

- Prasanna PM, Siegel E, Kunce A. Greening radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8:780-784. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.07.017

- Bawaneh K, Nezami FG, Rasheduzzaman MD, et al. Energy consumption analysis and characterization of healthcare facilities in the United States. Energies. 2019;12:1-20. doi:10.3390/en12193775

- Blum S, Buckland M, Sack TL, et al. Greening the office: saving resources, saving money, and educating our patients [published online July 4, 2020]. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:112-116.

- Maintaining your air conditioner. US Department of Energy website. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/maintaining-your-air-conditioner

- Choma EF, Evans JS, Hammitt JK, et al. Assessing the health impacts of electric vehicles through air pollution in the United States [published online August 25, 2020]. Environ Int. 2020;144:106015.

- Windfeld ES, Brooks MS. Medical waste management—a review [published online August 22, 2015]. J Environ Manage. 2015;1;163:98-108. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.08.013

- Fathy R, Nelson CA, Barbieri JS. Combating climate change in the clinic: cost-effective strategies to decrease the carbon footprint of outpatient dermatologic practice. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:107-111.

- Pulsipher KJ, Presley CL, Rundle CW, et al. Teledermatology application use in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt1fs0m0tp.

- O’Connell G, O’Connor C, Murphy M. Every cloud has a silver lining: the environmental benefit of teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online July 9, 2021]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1589-1590. doi:10.1111/ced.14795

- Vozzola E, Overcash M, Griffing E. Environmental considerations in the selection of isolation gowns: a life cycle assessment of reusable and disposable alternatives [published online April 11, 2018]. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46:881-886. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2018.02.002

- Rabin BM, Laney EB, Philipsborn RP. The unique role of medical students in catalyzing climate change education [published online October 14, 2020]. J Med Educ Curric Dev. doi:10.1177/2382120520957653

- Chiang F, Mazdiyasni O, AghaKouchak A. Evidence of anthropogenic impacts on global drought frequency, duration, and intensity [published online May 12, 2021]. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2754. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22314-w

- Atwoli L, Baqui AH, Benfield T, et al. Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health [published online September 5, 2021]. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1134-1137. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2113200

The impacts of anthropogenic climate change on human health are numerous and growing. The evidence that climate change is occurring due to the burning of fossil fuels is substantial, with a 2019 report elevating the data supporting anthropogenic climate change to a gold standard 5-sigma level of significance.1 In the peer-reviewed scientific literature, the consensus that humans are causing climate change is greater than 99%.2 Both the American Medical Association and the American College of Physicians have acknowledged the health impacts of climate change and importance for action. They encourage physicians to engage in environmentally sustainable practices and to advocate for effective climate change mitigation strategies.3,4 A survey of dermatologists also found that 99.3% (n=148) recognize climate change is occurring, and similarly high numbers are concerned about its health impacts.5

Notably, the health care industry must grapple not only with the health impacts of climate change but with the fact that the health care sector itself is responsible for a large amount of carbon emissions.6 The global health care industry as a whole produces enough carbon emissions to be ranked as the fifth largest emitting nation in the world.7 A quarter of these emissions are attributed to the US health care system.8,9 Climate science has shown we must limit CO2 emissions to avoid catastrophic climate change, with the sixth assessment report of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement targeting large emission reductions within the next decade.10 In August 2021, the US Department of Health and Human Services created the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity. Assistant Secretary for Health ADM Rachel L. Levine, MD, has committed to reducing the carbon emissions from the health care sector by 25% in the next decade, in line with scientific consensus regarding necessary changes.11

The dermatologic impacts of climate change are myriad. Rising temperatures, increasing air and water pollution, and stratospheric ozone depletion will lead to expanded geographic ranges of vector-borne diseases, worsening of chronic skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis/eczema and pemphigus, and increasing rates of skin cancer.12 For instance, warmer temperatures have allowed mosquitoes of the Aedes genus to infest new areas, leading to outbreaks of viral illnesses with cutaneous manifestations such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus in previously nonindigenous regions.13 Rising temperatures also have been associated with an expanding geographic range of tick- and sandfly-borne illnesses such as Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and cutaneous leishmaniasis.13,14 Additionally, short-term exposure to air pollution from wildfire smoke has been associated with an increased use of health care services by patients with atopic dermatitis.15 Increased levels of air pollutants also have been found to be associated with psoriasis flares as well as hyperpigmentation and wrinkle formation.16,17 Skin cancer incidence is predicted to rise due to increased UV radiation exposure secondary to stratospheric ozone depletion.18

Although the effects of climate change are significant and the magnitude of the climate crisis may feel overwhelming, it is essential to avoid doomerism and focus on meaningful impactful actions. Current CO2 emissions will remain in the atmosphere for hundreds to thousands of years, and the choices we make now commit future generations to live in a world shaped by our decisions. Importantly, there are impactful and low-cost, cost-effective, or cost-saving changes that can be made to mitigate the climate crisis. Herein, we provide 10 practical actionable interventions for dermatologists to help combat climate change.

10 Interventions for Dermatologists to Combat Climate Change

1. Consider switching to renewable sources of energy. Making this switch often is the most impactful decision a dermatologist can make to address climate change. The electricity sector is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the US health care system, and dermatology outpatient practices in particular have been observed to have a higher peak energy consumption than most other specialties studied.19,20 Many dermatology practices—both privately owned and academic—can switch to renewable energy seamlessly through power purchase agreements (PPAs), which are contracts between power providers and private entities to install renewable energy equipment or source renewable energy from offsite sources at a fixed rate. Using PPAs instead of traditional fossil fuel energy can provide cost savings as well as protect buyers from electrical price volatility. Numerous health care systems utilize PPAs such as Kaiser Permanente, Cleveland Clinic, and Rochester Regional Health. Additionally, dermatologists can directly purchase renewable energy equipment and eventually receive a return on investment from substantially lowered electric bills. It is important to note that the cost of commercial solar energy systems has decreased 69% since 2010 with further cost reductions predicted.21,22

2. Reduce standby power consumption. This refers to the use of electricity by a device when it appears to be off or is not in use, which can lead to considerable energy consumption and subsequently a larger carbon footprint for your practice. Ensuring electronics such as phone chargers, light fixtures, television screens, and computers are switched off prior to the end of the workday can make a large difference; for instance, a single radiology department at the University of Maryland (College Park, Maryland) found that if clinical workstations were shut down when not in use after an 8-hour workday, it would save 83,866 kWh of energy and $9225.33 per year.23 Additionally, using power strips with an automatic shutoff feature to shut off power to devices not in use provides a more convenient way to reduce standby power.

3. Optimize thermostat settings. An analysis of energy consumption in 157,000 US health care facilities found that space heating and cooling accounted for 40% of their total energy consumption.24 Thus, ensuring your thermostat and heating/cooling systems are working efficiently can conserve a substantial amount of energy. For maximum efficiency, it is recommended to set air conditioners to 74 °F (24 °C) and heaters to 68 °F (20 °C) or employ smart thermostats to optimally adjust temperatures when the office is not in use.25 In addition, routinely replacing or cleaning air conditioner filters can lower energy consumption by 5% to 15%.26 Similarly, improving insulation and ruggedization of both homes and offices may reduce heating and cooling waste and limit costs and emissions as a result.

4. Offer bicycle racks and charging ports for electric vehicles. In the United States, transportation generates more greenhouse gas emissions than any other source, primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels to power automobiles, trains, and planes. Because bicycles do not consume any fossil fuels and the use of electric vehicles has been found to result in substantial air pollution health benefits, encouraging the use of both can make a considerable positive impact on our climate.27 Providing these resources not only allows those who already travel sustainably to continue to do so but also serves as a reminder to your patients that sustainability is important to you as their health care provider. As electric vehicle sales continue to climb, infrastructure to support their use, including charging stations, will grow in importance. A physician’s office that offers a car-charging station may soon have a competitive advantage over others in the area.

5. Ensure properly regulated medical waste management. Regulated medical waste (also known as infectious medical waste or red bag waste) refers to health care–generated waste unsuitable for disposal in municipal solid waste systems due to concern for the spread of infectious or pathogenic materials. This waste largely is disposed via incineration, which harms the environment in a multitude of ways—both through harmful byproducts and from the CO2 emissions required to ship the waste to special processing facilities.28 Incineration of regulated medical waste emits potent toxins such as dioxins and furans as well as particulate matter, which contribute to air pollution. Ensuring only materials with infectious potential (as defined by each state’s Environmental Protection Agency) are disposed in regulated medical waste containers can dramatically reduce the harmful effects of incineration. Additionally, limiting regulated medical waste can be very cost-effective, as its disposal is 5- to 10-times more expensive than that of unregulated medical waste.29 Simple nudge measures such as educating staff about what waste goes in which receptacle, placing signage over the red bag waste to prompt staff to pause to consider if use of that bin is required before utilizing, using weights or clasps to make opening red bag waste containers slightly harder, and positioning different trash receptacles in different parts of examination rooms may help reduce inappropriate use of red bag waste.

6. Consider virtual platforms when possible. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual meeting platforms saw a considerable increase in usage by dermatologists. Teledermatology for patient care became much more widely adopted, and traditionally in-person meetings turned virtual.30 The reduction in emissions from these changes was remarkable. A recent study looking at the environmental impact of 3 months of teledermatology visits early during the COVID-19 pandemic found that 1476 teledermatology appointments saved 55,737 miles of car travel, equivalent to 15.37 metric tons of CO2.31 Whether for patient care when appropriate, academic conferences and continuing medical education credit, or for interviews (eg, medical students, residents, other staff), use of virtual platforms can reduce unnecessary travel and therefore substantially reduce travel-related emissions. When travel is unavoidable, consider exploring validated vetted companies that offer carbon offsets to reduce the harmful environmental impact of high-emission flights.

7. Limit use of single-use disposable items. Although single-use items such as examination gloves or needles are necessary in a dermatology practice, there are many opportunities to incorporate reusable items in your workplace. For instance, you can replace plastic cutlery and single-use plates in kitchen or dining areas with reusable alternatives. Additionally, using reusable isolation gowns instead of their single-use counterparts can help reduce waste; a reusable isolation gown system for providers including laundering services was found to consume 28% less energy and emit 30% fewer greenhouse gases than a single-use isolation gown system.32 Similarly, opting for reusable instruments instead of single-use instruments when possible also can help reduce your practice’s carbon footprint. Carefully evaluating each part of your “dermatology visit supply chain” may offer opportunities to utilize additional cost-saving, environmentally friendly options; for example, an individually plastic-wrapped Dermablade vs a bulk-packaged blade for shave biopsies has a higher cost and worse environmental impact. A single gauze often is sufficient for shave biopsies, but many practices open a plastic container of bulk gauze, much of which results in waste that too often is inappropriately disposed of as regulated medical waste despite not being saturated in blood/body fluids.

8. Educate on the effects of climate change. Dermatologists and other physicians have the unique opportunity to teach members of their community every day through patient care. Physicians are trusted messengers, and appropriately counseling patients regarding the risks of climate change and its effects on their dermatologic health is in line with both American Medical Association and American College of Physicians guidelines.3,4 For instance, patients with Lyme disease in Canada or Maine were unheard of a few decades ago, but now they are common; flares of atopic dermatitis in regions adjacent to recent wildfires may be attributable to harmful particulate matter resulting from fossil-fueled climate change and record droughts. Educating medical trainees on the impacts of climate change is just as vital, as it is a topic that often is neglected in medical school and residency curricula.33

9. Install water-efficient toilets and faucets. Anthropogenic climate change has been shown to increase the duration and intensity of droughts throughout the world.34 Much of the western United States also is experiencing record droughts. One way in which dermatology practices can work to combat droughts is through the use of water-conserving toilets, faucets, and urinals. Using water fixtures with the US Environmental Protection Agency’s WaterSense label is a convenient way to do so. The WaterSense label helps identify water fixtures certified to use at least 20% less water as well as save energy and decrease water costs.

10. Advocate through local and national organizations. There are numerous ways in which dermatologists can advocate for action against climate change. Joining professional organizations focused on addressing the climate crisis can help you connect with fellow dermatologists and physicians. The Expert Resource Group on Climate Change and Environmental Issues affiliated with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) is one such organization with many opportunities to raise awareness within the field of dermatology. The AAD recently joined the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health, an organization providing opportunities for policy and media outreach as well as research on climate change. Advocacy also can mean joining your local chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility or encouraging divestment from fossil fuel companies within your institution. Voicing support for climate change–focused lectures at events such as grand rounds and society meetings at the local, regional, and state-wide levels can help raise awareness. As the dermatologic effects of climate change grow, being knowledgeable of the views of future leaders in our specialty and country on this issue will become increasingly important.

Final Thoughts

In addition to the climate-friendly decisions one can make as a dermatologist, there are many personal lifestyle choices to consider. Small dietary changes such as limiting consumption of beef and minimizing food waste can have large downstream effects. Opting for transportation via train and limiting air travel are both impactful decisions in reducing CO2 emissions. Similarly, switching to an electric vehicle or vehicle with minimal emissions can work to reduce greenhouse gas accumulation. For additional resources, note the AAD has partnered with My Green Doctor, a nonprofit service for health care practices that includes practical cost-saving suggestions to support sustainability in physician practices.

A recent joint publication in more than 200 medical journals described climate change as the greatest threat to global public health.35 Climate change is having devastating effects on dermatologic health and will only continue to do so if not addressed now. Dermatologists have the opportunity to join with our colleagues in the house of medicine and to take action to fight climate change and mitigate the health impacts on our patients, the population, and future generations.

The impacts of anthropogenic climate change on human health are numerous and growing. The evidence that climate change is occurring due to the burning of fossil fuels is substantial, with a 2019 report elevating the data supporting anthropogenic climate change to a gold standard 5-sigma level of significance.1 In the peer-reviewed scientific literature, the consensus that humans are causing climate change is greater than 99%.2 Both the American Medical Association and the American College of Physicians have acknowledged the health impacts of climate change and importance for action. They encourage physicians to engage in environmentally sustainable practices and to advocate for effective climate change mitigation strategies.3,4 A survey of dermatologists also found that 99.3% (n=148) recognize climate change is occurring, and similarly high numbers are concerned about its health impacts.5

Notably, the health care industry must grapple not only with the health impacts of climate change but with the fact that the health care sector itself is responsible for a large amount of carbon emissions.6 The global health care industry as a whole produces enough carbon emissions to be ranked as the fifth largest emitting nation in the world.7 A quarter of these emissions are attributed to the US health care system.8,9 Climate science has shown we must limit CO2 emissions to avoid catastrophic climate change, with the sixth assessment report of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement targeting large emission reductions within the next decade.10 In August 2021, the US Department of Health and Human Services created the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity. Assistant Secretary for Health ADM Rachel L. Levine, MD, has committed to reducing the carbon emissions from the health care sector by 25% in the next decade, in line with scientific consensus regarding necessary changes.11

The dermatologic impacts of climate change are myriad. Rising temperatures, increasing air and water pollution, and stratospheric ozone depletion will lead to expanded geographic ranges of vector-borne diseases, worsening of chronic skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis/eczema and pemphigus, and increasing rates of skin cancer.12 For instance, warmer temperatures have allowed mosquitoes of the Aedes genus to infest new areas, leading to outbreaks of viral illnesses with cutaneous manifestations such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus in previously nonindigenous regions.13 Rising temperatures also have been associated with an expanding geographic range of tick- and sandfly-borne illnesses such as Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and cutaneous leishmaniasis.13,14 Additionally, short-term exposure to air pollution from wildfire smoke has been associated with an increased use of health care services by patients with atopic dermatitis.15 Increased levels of air pollutants also have been found to be associated with psoriasis flares as well as hyperpigmentation and wrinkle formation.16,17 Skin cancer incidence is predicted to rise due to increased UV radiation exposure secondary to stratospheric ozone depletion.18

Although the effects of climate change are significant and the magnitude of the climate crisis may feel overwhelming, it is essential to avoid doomerism and focus on meaningful impactful actions. Current CO2 emissions will remain in the atmosphere for hundreds to thousands of years, and the choices we make now commit future generations to live in a world shaped by our decisions. Importantly, there are impactful and low-cost, cost-effective, or cost-saving changes that can be made to mitigate the climate crisis. Herein, we provide 10 practical actionable interventions for dermatologists to help combat climate change.

10 Interventions for Dermatologists to Combat Climate Change

1. Consider switching to renewable sources of energy. Making this switch often is the most impactful decision a dermatologist can make to address climate change. The electricity sector is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the US health care system, and dermatology outpatient practices in particular have been observed to have a higher peak energy consumption than most other specialties studied.19,20 Many dermatology practices—both privately owned and academic—can switch to renewable energy seamlessly through power purchase agreements (PPAs), which are contracts between power providers and private entities to install renewable energy equipment or source renewable energy from offsite sources at a fixed rate. Using PPAs instead of traditional fossil fuel energy can provide cost savings as well as protect buyers from electrical price volatility. Numerous health care systems utilize PPAs such as Kaiser Permanente, Cleveland Clinic, and Rochester Regional Health. Additionally, dermatologists can directly purchase renewable energy equipment and eventually receive a return on investment from substantially lowered electric bills. It is important to note that the cost of commercial solar energy systems has decreased 69% since 2010 with further cost reductions predicted.21,22

2. Reduce standby power consumption. This refers to the use of electricity by a device when it appears to be off or is not in use, which can lead to considerable energy consumption and subsequently a larger carbon footprint for your practice. Ensuring electronics such as phone chargers, light fixtures, television screens, and computers are switched off prior to the end of the workday can make a large difference; for instance, a single radiology department at the University of Maryland (College Park, Maryland) found that if clinical workstations were shut down when not in use after an 8-hour workday, it would save 83,866 kWh of energy and $9225.33 per year.23 Additionally, using power strips with an automatic shutoff feature to shut off power to devices not in use provides a more convenient way to reduce standby power.

3. Optimize thermostat settings. An analysis of energy consumption in 157,000 US health care facilities found that space heating and cooling accounted for 40% of their total energy consumption.24 Thus, ensuring your thermostat and heating/cooling systems are working efficiently can conserve a substantial amount of energy. For maximum efficiency, it is recommended to set air conditioners to 74 °F (24 °C) and heaters to 68 °F (20 °C) or employ smart thermostats to optimally adjust temperatures when the office is not in use.25 In addition, routinely replacing or cleaning air conditioner filters can lower energy consumption by 5% to 15%.26 Similarly, improving insulation and ruggedization of both homes and offices may reduce heating and cooling waste and limit costs and emissions as a result.

4. Offer bicycle racks and charging ports for electric vehicles. In the United States, transportation generates more greenhouse gas emissions than any other source, primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels to power automobiles, trains, and planes. Because bicycles do not consume any fossil fuels and the use of electric vehicles has been found to result in substantial air pollution health benefits, encouraging the use of both can make a considerable positive impact on our climate.27 Providing these resources not only allows those who already travel sustainably to continue to do so but also serves as a reminder to your patients that sustainability is important to you as their health care provider. As electric vehicle sales continue to climb, infrastructure to support their use, including charging stations, will grow in importance. A physician’s office that offers a car-charging station may soon have a competitive advantage over others in the area.

5. Ensure properly regulated medical waste management. Regulated medical waste (also known as infectious medical waste or red bag waste) refers to health care–generated waste unsuitable for disposal in municipal solid waste systems due to concern for the spread of infectious or pathogenic materials. This waste largely is disposed via incineration, which harms the environment in a multitude of ways—both through harmful byproducts and from the CO2 emissions required to ship the waste to special processing facilities.28 Incineration of regulated medical waste emits potent toxins such as dioxins and furans as well as particulate matter, which contribute to air pollution. Ensuring only materials with infectious potential (as defined by each state’s Environmental Protection Agency) are disposed in regulated medical waste containers can dramatically reduce the harmful effects of incineration. Additionally, limiting regulated medical waste can be very cost-effective, as its disposal is 5- to 10-times more expensive than that of unregulated medical waste.29 Simple nudge measures such as educating staff about what waste goes in which receptacle, placing signage over the red bag waste to prompt staff to pause to consider if use of that bin is required before utilizing, using weights or clasps to make opening red bag waste containers slightly harder, and positioning different trash receptacles in different parts of examination rooms may help reduce inappropriate use of red bag waste.

6. Consider virtual platforms when possible. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual meeting platforms saw a considerable increase in usage by dermatologists. Teledermatology for patient care became much more widely adopted, and traditionally in-person meetings turned virtual.30 The reduction in emissions from these changes was remarkable. A recent study looking at the environmental impact of 3 months of teledermatology visits early during the COVID-19 pandemic found that 1476 teledermatology appointments saved 55,737 miles of car travel, equivalent to 15.37 metric tons of CO2.31 Whether for patient care when appropriate, academic conferences and continuing medical education credit, or for interviews (eg, medical students, residents, other staff), use of virtual platforms can reduce unnecessary travel and therefore substantially reduce travel-related emissions. When travel is unavoidable, consider exploring validated vetted companies that offer carbon offsets to reduce the harmful environmental impact of high-emission flights.

7. Limit use of single-use disposable items. Although single-use items such as examination gloves or needles are necessary in a dermatology practice, there are many opportunities to incorporate reusable items in your workplace. For instance, you can replace plastic cutlery and single-use plates in kitchen or dining areas with reusable alternatives. Additionally, using reusable isolation gowns instead of their single-use counterparts can help reduce waste; a reusable isolation gown system for providers including laundering services was found to consume 28% less energy and emit 30% fewer greenhouse gases than a single-use isolation gown system.32 Similarly, opting for reusable instruments instead of single-use instruments when possible also can help reduce your practice’s carbon footprint. Carefully evaluating each part of your “dermatology visit supply chain” may offer opportunities to utilize additional cost-saving, environmentally friendly options; for example, an individually plastic-wrapped Dermablade vs a bulk-packaged blade for shave biopsies has a higher cost and worse environmental impact. A single gauze often is sufficient for shave biopsies, but many practices open a plastic container of bulk gauze, much of which results in waste that too often is inappropriately disposed of as regulated medical waste despite not being saturated in blood/body fluids.

8. Educate on the effects of climate change. Dermatologists and other physicians have the unique opportunity to teach members of their community every day through patient care. Physicians are trusted messengers, and appropriately counseling patients regarding the risks of climate change and its effects on their dermatologic health is in line with both American Medical Association and American College of Physicians guidelines.3,4 For instance, patients with Lyme disease in Canada or Maine were unheard of a few decades ago, but now they are common; flares of atopic dermatitis in regions adjacent to recent wildfires may be attributable to harmful particulate matter resulting from fossil-fueled climate change and record droughts. Educating medical trainees on the impacts of climate change is just as vital, as it is a topic that often is neglected in medical school and residency curricula.33

9. Install water-efficient toilets and faucets. Anthropogenic climate change has been shown to increase the duration and intensity of droughts throughout the world.34 Much of the western United States also is experiencing record droughts. One way in which dermatology practices can work to combat droughts is through the use of water-conserving toilets, faucets, and urinals. Using water fixtures with the US Environmental Protection Agency’s WaterSense label is a convenient way to do so. The WaterSense label helps identify water fixtures certified to use at least 20% less water as well as save energy and decrease water costs.

10. Advocate through local and national organizations. There are numerous ways in which dermatologists can advocate for action against climate change. Joining professional organizations focused on addressing the climate crisis can help you connect with fellow dermatologists and physicians. The Expert Resource Group on Climate Change and Environmental Issues affiliated with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) is one such organization with many opportunities to raise awareness within the field of dermatology. The AAD recently joined the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health, an organization providing opportunities for policy and media outreach as well as research on climate change. Advocacy also can mean joining your local chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility or encouraging divestment from fossil fuel companies within your institution. Voicing support for climate change–focused lectures at events such as grand rounds and society meetings at the local, regional, and state-wide levels can help raise awareness. As the dermatologic effects of climate change grow, being knowledgeable of the views of future leaders in our specialty and country on this issue will become increasingly important.

Final Thoughts

In addition to the climate-friendly decisions one can make as a dermatologist, there are many personal lifestyle choices to consider. Small dietary changes such as limiting consumption of beef and minimizing food waste can have large downstream effects. Opting for transportation via train and limiting air travel are both impactful decisions in reducing CO2 emissions. Similarly, switching to an electric vehicle or vehicle with minimal emissions can work to reduce greenhouse gas accumulation. For additional resources, note the AAD has partnered with My Green Doctor, a nonprofit service for health care practices that includes practical cost-saving suggestions to support sustainability in physician practices.

A recent joint publication in more than 200 medical journals described climate change as the greatest threat to global public health.35 Climate change is having devastating effects on dermatologic health and will only continue to do so if not addressed now. Dermatologists have the opportunity to join with our colleagues in the house of medicine and to take action to fight climate change and mitigate the health impacts on our patients, the population, and future generations.

- Santer BD, Bonfils CJW, Fu Q, et al. Celebrating the anniversary of three key events in climate change science. Nat Clim Chang. 2019;9:180-182.

- Lynas M, Houlton BZ, Perry S. Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Environ Res Lett. 2021;16:114005.

- Crowley RA; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Climate change and health: a position paper of the American College of Physicians [published online April 19, 2016]. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:608-610. doi:10.7326/M15-2766

- Global climate change and human health H-135.398. American Medical Association website. Updated 2019. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/climate%20change?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-309.xml

- Mieczkowska K, Stringer T, Barbieri JS, et al. Surveying the attitudes of dermatologists regarding climate change. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:748-750.

- Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental impacts of the U.S. health care system and effects on public health. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157014

- Karliner J, Slotterback S, Boyd R, et al. Health care’s climate footprint: how the health sector contributes to the global climate crisis and opportunities for action. Health Care Without Harm website. Published September 2019. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_090619.pdf

- Pichler PP, Jaccard IS, Weisz U, et al. International comparison of health care carbon footprints. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14:064004.

- Solomon CG, LaRocque RC. Climate change—a health emergency. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:209-211. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1817067

- IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, et al, eds. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2021:3-32.

- Dzau VJ, Levine R, Barrett G, et al. Decarbonizing the U.S. Health Sector—a call to action [published online October 13, 2021]. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2117-2119. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2115675

- Silva GS, Rosenbach M. Climate change and dermatology: an introduction to a special topic, for this special issue. Int J Womens Dermatol 2021;7:3-7.

- Coates SJ, Norton SA. The effects of climate change on infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:8-16. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.005

- Andersen LK, Davis MD. Climate change and the epidemiology of selected tick-borne and mosquito-borne diseases: update from the International Society of Dermatology Climate Change Task Force [published online October 1, 2016]. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:252-259. doi:10.1111/ijd.13438

- Fadadu RP, Grimes B, Jewell NP, et al. Association of wildfire air pollution and health care use for atopic dermatitis and itch. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:658-666. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0179

- Bellinato F, Adami G, Vaienti S, et al. Association between short-term exposure to environmental air pollution and psoriasis flare. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:375-381. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.6019

- Krutmann J, Bouloc A, Sore G, et al. The skin aging exposome [published online September 28, 2016]. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;85:152-161.

- Parker ER. The influence of climate change on skin cancer incidence—a review of the evidence. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:17-27. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.003

- Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, et al. Health care pollution and public health damage in the United States: an update. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:2071-2079.

- Sheppy M, Pless S, Kung F. Healthcare energy end-use monitoring. US Department of Energy website. Published August 2014. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/09/f18/61064.pdf

- Feldman D, Ramasamy V, Fu R, et al. U.S. solar photovoltaic system and energy storage cost benchmark: Q1 2020. Published January 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/77324.pdf

- 22. Apostoleris H, Sgouridis S, Stefancich M, et al. Utility solar prices will continue to drop all over the world even without subsidies. Nat Energy. 2019;4:833-834.

- Prasanna PM, Siegel E, Kunce A. Greening radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8:780-784. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.07.017

- Bawaneh K, Nezami FG, Rasheduzzaman MD, et al. Energy consumption analysis and characterization of healthcare facilities in the United States. Energies. 2019;12:1-20. doi:10.3390/en12193775

- Blum S, Buckland M, Sack TL, et al. Greening the office: saving resources, saving money, and educating our patients [published online July 4, 2020]. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:112-116.

- Maintaining your air conditioner. US Department of Energy website. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/maintaining-your-air-conditioner

- Choma EF, Evans JS, Hammitt JK, et al. Assessing the health impacts of electric vehicles through air pollution in the United States [published online August 25, 2020]. Environ Int. 2020;144:106015.

- Windfeld ES, Brooks MS. Medical waste management—a review [published online August 22, 2015]. J Environ Manage. 2015;1;163:98-108. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.08.013

- Fathy R, Nelson CA, Barbieri JS. Combating climate change in the clinic: cost-effective strategies to decrease the carbon footprint of outpatient dermatologic practice. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:107-111.

- Pulsipher KJ, Presley CL, Rundle CW, et al. Teledermatology application use in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt1fs0m0tp.

- O’Connell G, O’Connor C, Murphy M. Every cloud has a silver lining: the environmental benefit of teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online July 9, 2021]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1589-1590. doi:10.1111/ced.14795

- Vozzola E, Overcash M, Griffing E. Environmental considerations in the selection of isolation gowns: a life cycle assessment of reusable and disposable alternatives [published online April 11, 2018]. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46:881-886. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2018.02.002

- Rabin BM, Laney EB, Philipsborn RP. The unique role of medical students in catalyzing climate change education [published online October 14, 2020]. J Med Educ Curric Dev. doi:10.1177/2382120520957653

- Chiang F, Mazdiyasni O, AghaKouchak A. Evidence of anthropogenic impacts on global drought frequency, duration, and intensity [published online May 12, 2021]. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2754. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22314-w

- Atwoli L, Baqui AH, Benfield T, et al. Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health [published online September 5, 2021]. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1134-1137. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2113200

- Santer BD, Bonfils CJW, Fu Q, et al. Celebrating the anniversary of three key events in climate change science. Nat Clim Chang. 2019;9:180-182.

- Lynas M, Houlton BZ, Perry S. Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Environ Res Lett. 2021;16:114005.

- Crowley RA; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Climate change and health: a position paper of the American College of Physicians [published online April 19, 2016]. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:608-610. doi:10.7326/M15-2766

- Global climate change and human health H-135.398. American Medical Association website. Updated 2019. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/climate%20change?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-309.xml

- Mieczkowska K, Stringer T, Barbieri JS, et al. Surveying the attitudes of dermatologists regarding climate change. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:748-750.

- Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental impacts of the U.S. health care system and effects on public health. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157014

- Karliner J, Slotterback S, Boyd R, et al. Health care’s climate footprint: how the health sector contributes to the global climate crisis and opportunities for action. Health Care Without Harm website. Published September 2019. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_090619.pdf

- Pichler PP, Jaccard IS, Weisz U, et al. International comparison of health care carbon footprints. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14:064004.

- Solomon CG, LaRocque RC. Climate change—a health emergency. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:209-211. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1817067

- IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, et al, eds. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2021:3-32.

- Dzau VJ, Levine R, Barrett G, et al. Decarbonizing the U.S. Health Sector—a call to action [published online October 13, 2021]. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2117-2119. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2115675

- Silva GS, Rosenbach M. Climate change and dermatology: an introduction to a special topic, for this special issue. Int J Womens Dermatol 2021;7:3-7.

- Coates SJ, Norton SA. The effects of climate change on infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:8-16. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.005

- Andersen LK, Davis MD. Climate change and the epidemiology of selected tick-borne and mosquito-borne diseases: update from the International Society of Dermatology Climate Change Task Force [published online October 1, 2016]. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:252-259. doi:10.1111/ijd.13438

- Fadadu RP, Grimes B, Jewell NP, et al. Association of wildfire air pollution and health care use for atopic dermatitis and itch. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:658-666. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0179

- Bellinato F, Adami G, Vaienti S, et al. Association between short-term exposure to environmental air pollution and psoriasis flare. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:375-381. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.6019

- Krutmann J, Bouloc A, Sore G, et al. The skin aging exposome [published online September 28, 2016]. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;85:152-161.

- Parker ER. The influence of climate change on skin cancer incidence—a review of the evidence. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:17-27. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.003

- Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, et al. Health care pollution and public health damage in the United States: an update. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:2071-2079.

- Sheppy M, Pless S, Kung F. Healthcare energy end-use monitoring. US Department of Energy website. Published August 2014. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/09/f18/61064.pdf

- Feldman D, Ramasamy V, Fu R, et al. U.S. solar photovoltaic system and energy storage cost benchmark: Q1 2020. Published January 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/77324.pdf

- 22. Apostoleris H, Sgouridis S, Stefancich M, et al. Utility solar prices will continue to drop all over the world even without subsidies. Nat Energy. 2019;4:833-834.

- Prasanna PM, Siegel E, Kunce A. Greening radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8:780-784. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.07.017

- Bawaneh K, Nezami FG, Rasheduzzaman MD, et al. Energy consumption analysis and characterization of healthcare facilities in the United States. Energies. 2019;12:1-20. doi:10.3390/en12193775

- Blum S, Buckland M, Sack TL, et al. Greening the office: saving resources, saving money, and educating our patients [published online July 4, 2020]. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:112-116.

- Maintaining your air conditioner. US Department of Energy website. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/maintaining-your-air-conditioner

- Choma EF, Evans JS, Hammitt JK, et al. Assessing the health impacts of electric vehicles through air pollution in the United States [published online August 25, 2020]. Environ Int. 2020;144:106015.

- Windfeld ES, Brooks MS. Medical waste management—a review [published online August 22, 2015]. J Environ Manage. 2015;1;163:98-108. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.08.013

- Fathy R, Nelson CA, Barbieri JS. Combating climate change in the clinic: cost-effective strategies to decrease the carbon footprint of outpatient dermatologic practice. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:107-111.

- Pulsipher KJ, Presley CL, Rundle CW, et al. Teledermatology application use in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt1fs0m0tp.

- O’Connell G, O’Connor C, Murphy M. Every cloud has a silver lining: the environmental benefit of teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online July 9, 2021]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1589-1590. doi:10.1111/ced.14795

- Vozzola E, Overcash M, Griffing E. Environmental considerations in the selection of isolation gowns: a life cycle assessment of reusable and disposable alternatives [published online April 11, 2018]. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46:881-886. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2018.02.002

- Rabin BM, Laney EB, Philipsborn RP. The unique role of medical students in catalyzing climate change education [published online October 14, 2020]. J Med Educ Curric Dev. doi:10.1177/2382120520957653

- Chiang F, Mazdiyasni O, AghaKouchak A. Evidence of anthropogenic impacts on global drought frequency, duration, and intensity [published online May 12, 2021]. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2754. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22314-w

- Atwoli L, Baqui AH, Benfield T, et al. Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health [published online September 5, 2021]. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1134-1137. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2113200

Pigmented Papules on the Face, Neck, and Chest

The Diagnosis: Syringoma

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors with distinct histopathologic features, including the characteristic comma- or tadpole-shaped tail comprised of dilated cystic eccrine ducts. Clinically, syringomas typically present predominantly in the periorbital region in adolescent girls. They may present as solitary or multiple lesions, and sites such as the genital area, palms, scalp, and chest rarely can be involved.1 Eruptive syringoma is a clinical subtype of syringoma that is seen on the face, neck, chest, and axillae that predominantly occurs in females with skin of color in countries such as Asia and Africa before or during puberty.2,3 Lesions appear as small, flesh-colored or slightly pigmented, flat-topped papules.3 The condition can be cosmetically disfiguring and difficult to treat, especially in patients with darker skin.

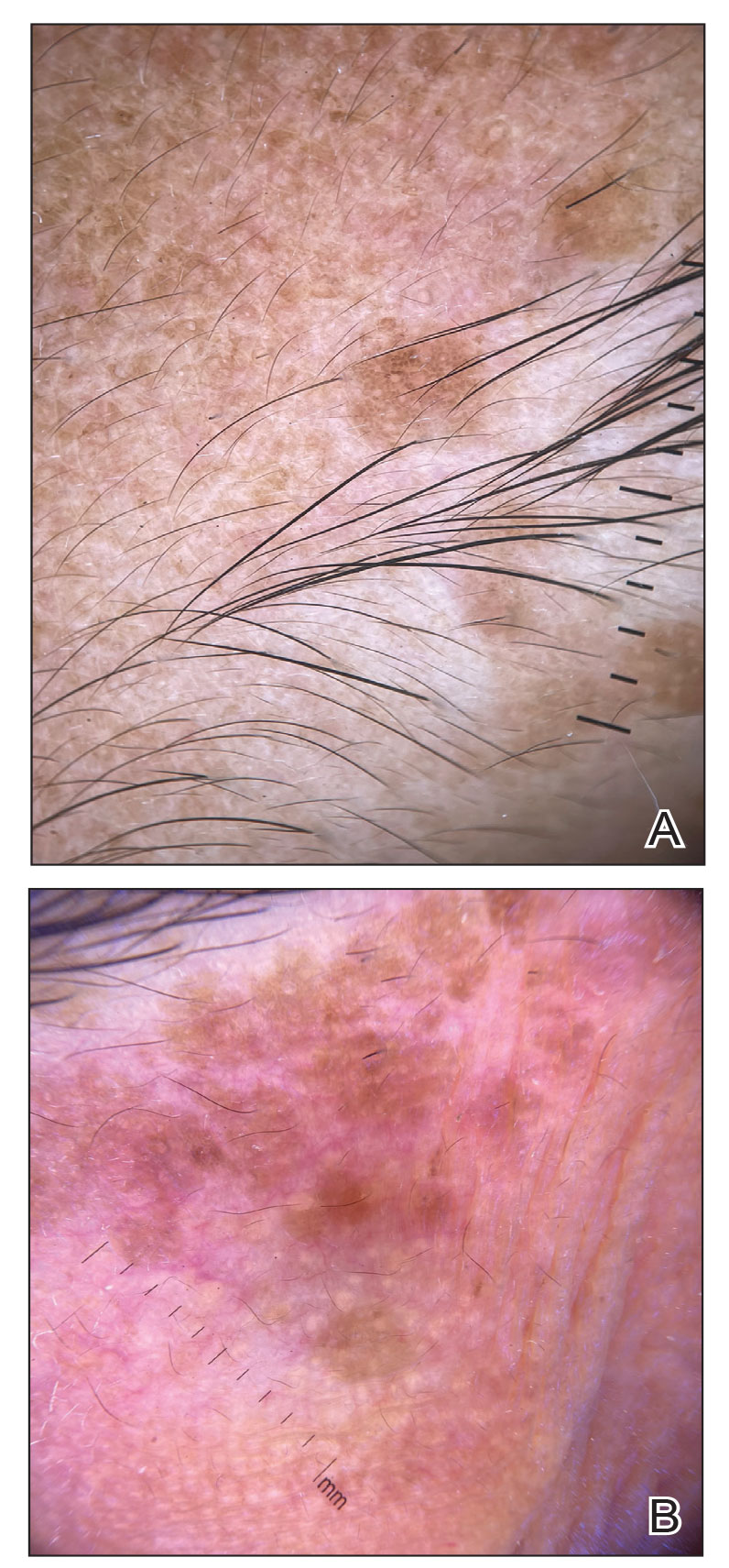

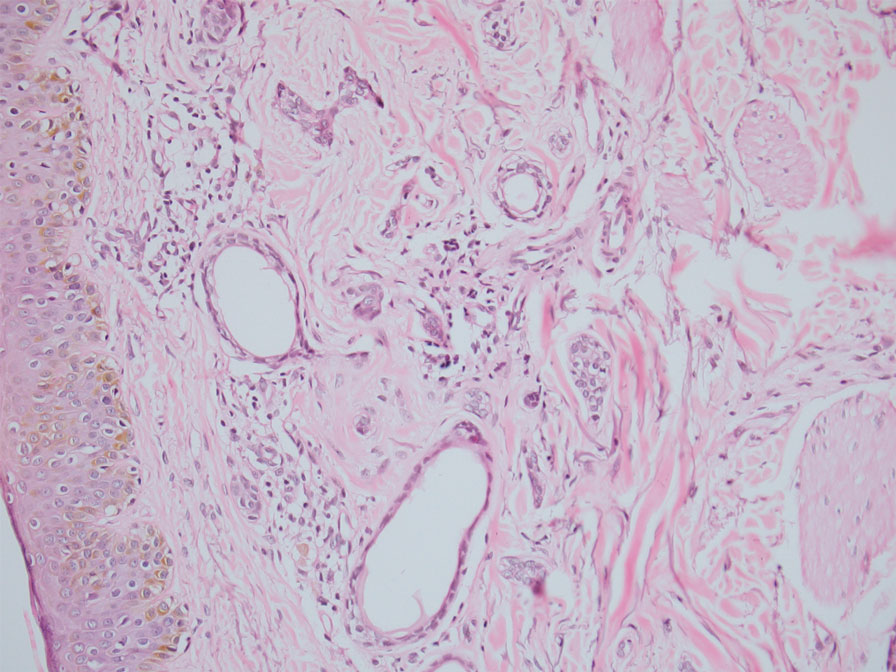

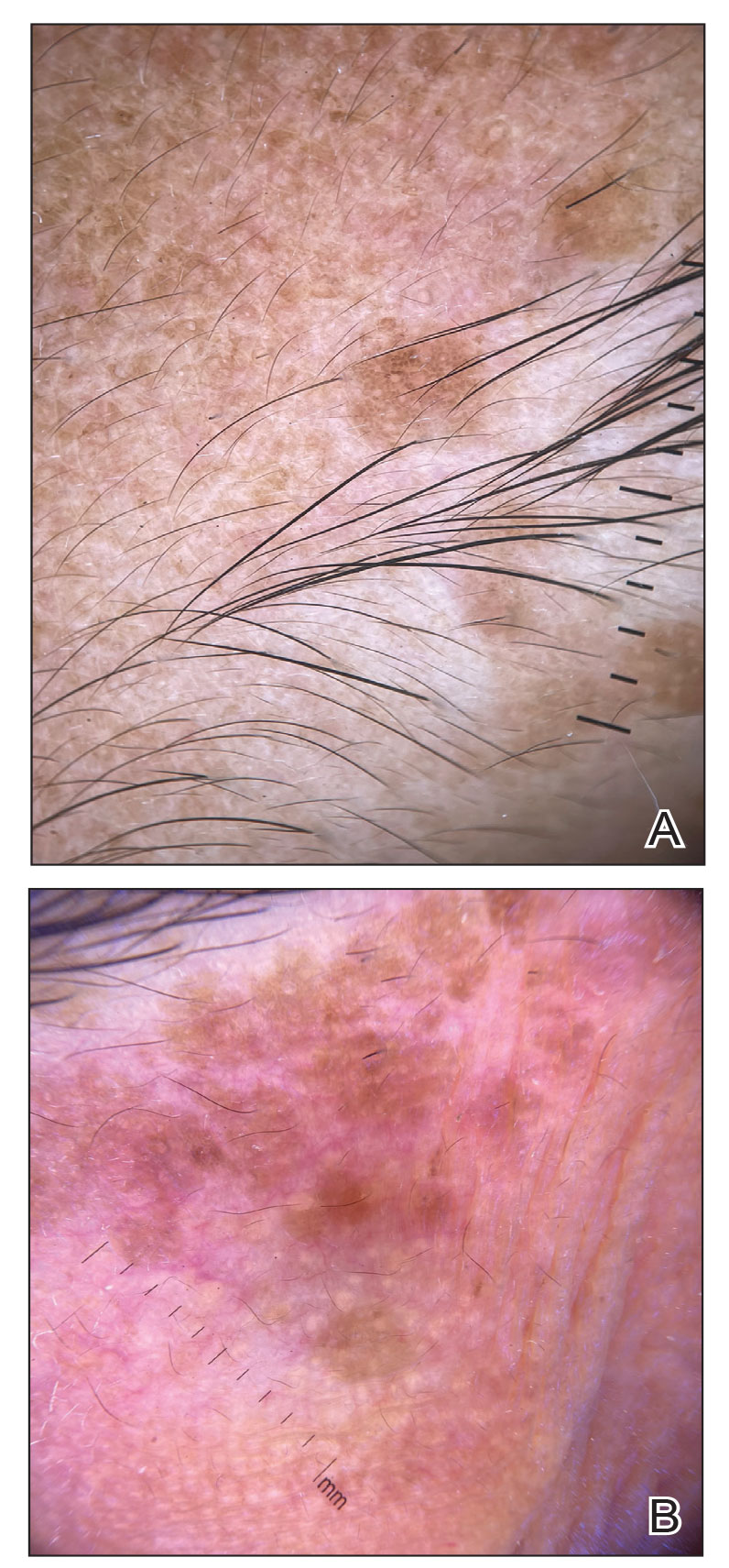

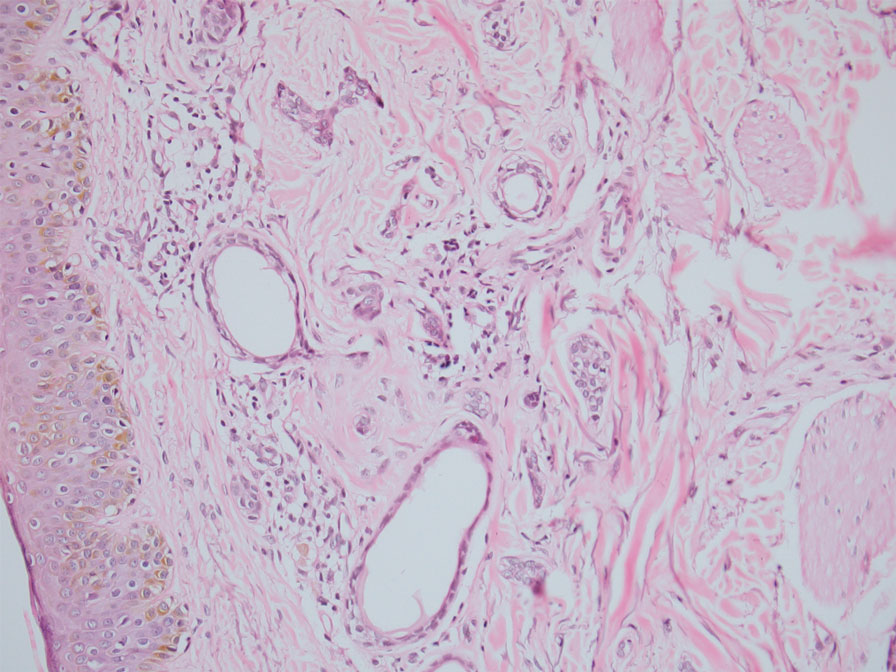

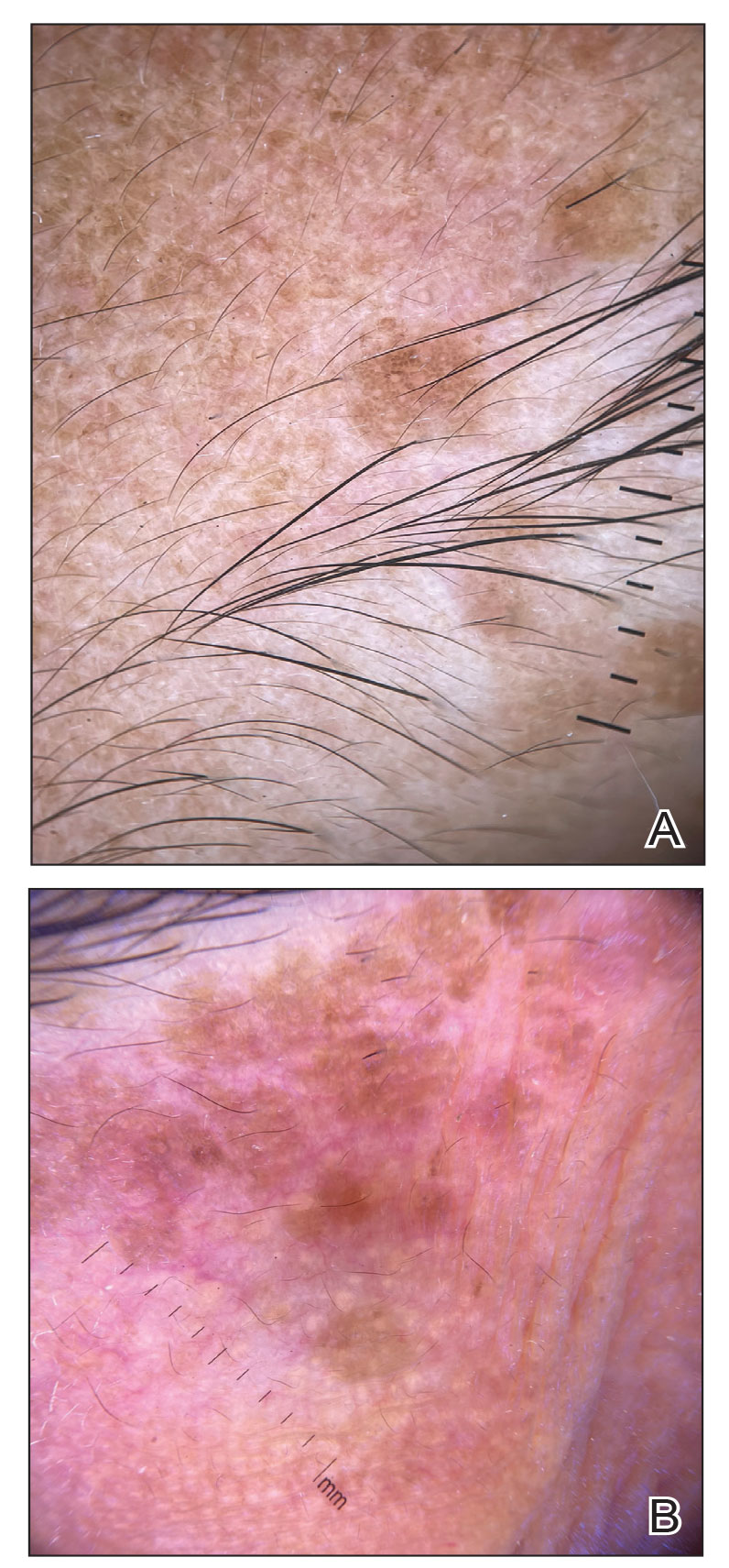

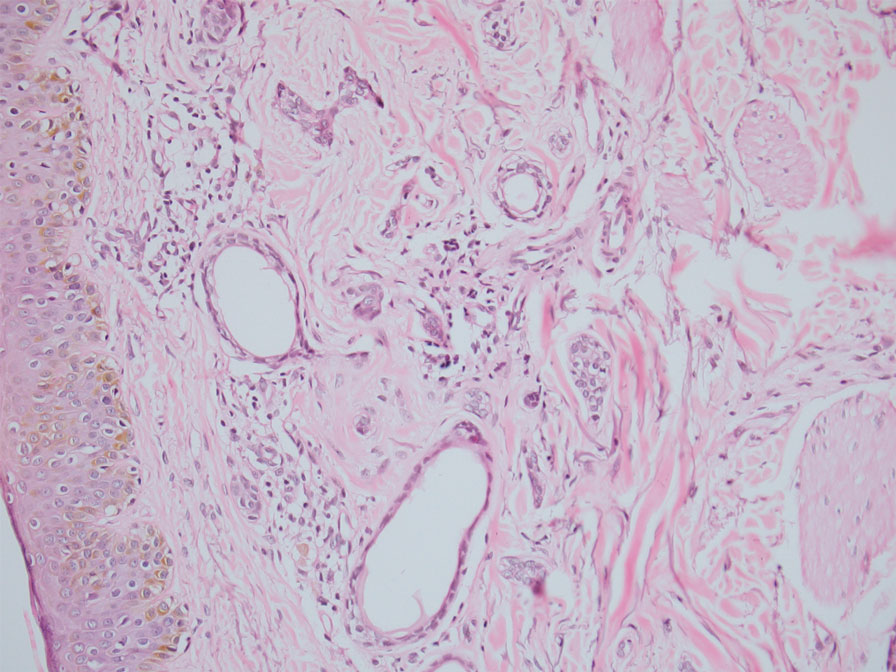

In our patient, dermoscopic evaluation revealed reticular light brown lines, structureless light brown areas, clustered brown dots, globules, and reticular vessels on a faint background (Figure 1A). Glittering yellow-whitish round structures over a fading pink-brown background also were seen at some sites (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of a neck lesion revealed an epidermis with focal acanthosis; the upper dermis had tumor islands and ducts with cells with round to vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. A well-circumscribed tumor in the dermis composed of tubules of varying sizes lined by cuboidal cells was seen, consistent with syringoma (Figure 2).

Dermoscopic features of syringomas have not been widely studied. Hayashi et al4 reported the dermoscopic features of unilateral linear syringomas as a delicate and faint reticular pigmentation network and multiple hypopigmented areas. Sakiyama et al5 also defined an incomplete pigment network with faint erythema in 2 eruptive syringoma cases.

Treatment of this condition is for cosmetic reasons only, and there are no reports of long-term morbidity associated with the disease.6,7 Multiple therapeutic options are available but are associated with complications such as hyperpigmentation and sclerosis in patients with skin of color due to the dermal location of these syringomas. Management of syringomas includes topical and surgical methods, including topical retinoids such as tretinoin and atropine solution 1%; surgical methods include dermabrasion, excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrofulguration, laser therapy, and chemical cautery. However, there is a substantial risk for recurrence with these treatment options. In a case series of 5 patients with periorbital syringomas, treatment using radiofrequency and a CO2 laser was performed with favorable outcomes, highlighting the use of combination therapies for treatment.8 Seo et al9 reported a retrospective case series of 92 patients with periorbital syringomas in which they treated one group with CO2 laser and the other with botulinum toxin A injection; CO2 laser combined with botulinum toxin A showed a greater effect than laser treatment alone. The differential diagnosis includes pigmented plane warts, sebaceous hyperplasia, eruptive xanthomas, and hidrocystomas. Pigmented plane warts characteristically present as flat-topped papules with small hemorrhagic dots or tiny pinpoint vessels on dermoscopy. In sebaceous hyperplasia, yellowish umbilicated papular lesions are seen with crown vessels on dermoscopy. Eruptive xanthomas usually are erythematous to yellow, dome-shaped papules that appear mainly over the extensor aspects of the extremities. Hidrocystoma presents as a solitary translucent larger syringomalike lesion commonly seen in the periorbital region and/or on the cheeks.

We report a case of widespread syringomas with multiple close mimickers such as pigmented plane warts; however, dermoscopy of the lesions helped to arrive at the diagnosis. Dermatologists should be aware of this condition and its benign nature to ensure correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234.e9-1240.e9.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Singh S, Tewari R, Gupta S. An unusual case of generalised eruptive syringoma in an adult male. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70:389-391.

- Hayashi Y, Tanaka M, Nakajima S, et al. Unilateral linear syringoma in a Japanese female: dermoscopic differentiation from lichen lanus linearis. Dermatol Rep. 2011;3:E42.

- Sakiyama M, Maeda M, Fujimoto N, et al. Eruptive syringoma localized in intertriginous areas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:72-73.

- Wang JI, Roenigk HH Jr. Treatment of multiple facial syringomas with the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:136-139.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Hasson A, Farias MM, Nicklas C, et al. Periorbital syringoma treated with radiofrequency and carbon dioxide (CO2) laser in 5 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:879-880.

- Seo HM, Choi JY, Min J, et al. Carbon dioxide laser combined with botulinum toxin A for patients with periorbital syringomas [published online March 31, 2016]. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:149-153.

The Diagnosis: Syringoma

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors with distinct histopathologic features, including the characteristic comma- or tadpole-shaped tail comprised of dilated cystic eccrine ducts. Clinically, syringomas typically present predominantly in the periorbital region in adolescent girls. They may present as solitary or multiple lesions, and sites such as the genital area, palms, scalp, and chest rarely can be involved.1 Eruptive syringoma is a clinical subtype of syringoma that is seen on the face, neck, chest, and axillae that predominantly occurs in females with skin of color in countries such as Asia and Africa before or during puberty.2,3 Lesions appear as small, flesh-colored or slightly pigmented, flat-topped papules.3 The condition can be cosmetically disfiguring and difficult to treat, especially in patients with darker skin.

In our patient, dermoscopic evaluation revealed reticular light brown lines, structureless light brown areas, clustered brown dots, globules, and reticular vessels on a faint background (Figure 1A). Glittering yellow-whitish round structures over a fading pink-brown background also were seen at some sites (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of a neck lesion revealed an epidermis with focal acanthosis; the upper dermis had tumor islands and ducts with cells with round to vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. A well-circumscribed tumor in the dermis composed of tubules of varying sizes lined by cuboidal cells was seen, consistent with syringoma (Figure 2).

Dermoscopic features of syringomas have not been widely studied. Hayashi et al4 reported the dermoscopic features of unilateral linear syringomas as a delicate and faint reticular pigmentation network and multiple hypopigmented areas. Sakiyama et al5 also defined an incomplete pigment network with faint erythema in 2 eruptive syringoma cases.

Treatment of this condition is for cosmetic reasons only, and there are no reports of long-term morbidity associated with the disease.6,7 Multiple therapeutic options are available but are associated with complications such as hyperpigmentation and sclerosis in patients with skin of color due to the dermal location of these syringomas. Management of syringomas includes topical and surgical methods, including topical retinoids such as tretinoin and atropine solution 1%; surgical methods include dermabrasion, excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrofulguration, laser therapy, and chemical cautery. However, there is a substantial risk for recurrence with these treatment options. In a case series of 5 patients with periorbital syringomas, treatment using radiofrequency and a CO2 laser was performed with favorable outcomes, highlighting the use of combination therapies for treatment.8 Seo et al9 reported a retrospective case series of 92 patients with periorbital syringomas in which they treated one group with CO2 laser and the other with botulinum toxin A injection; CO2 laser combined with botulinum toxin A showed a greater effect than laser treatment alone. The differential diagnosis includes pigmented plane warts, sebaceous hyperplasia, eruptive xanthomas, and hidrocystomas. Pigmented plane warts characteristically present as flat-topped papules with small hemorrhagic dots or tiny pinpoint vessels on dermoscopy. In sebaceous hyperplasia, yellowish umbilicated papular lesions are seen with crown vessels on dermoscopy. Eruptive xanthomas usually are erythematous to yellow, dome-shaped papules that appear mainly over the extensor aspects of the extremities. Hidrocystoma presents as a solitary translucent larger syringomalike lesion commonly seen in the periorbital region and/or on the cheeks.

We report a case of widespread syringomas with multiple close mimickers such as pigmented plane warts; however, dermoscopy of the lesions helped to arrive at the diagnosis. Dermatologists should be aware of this condition and its benign nature to ensure correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Syringoma

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors with distinct histopathologic features, including the characteristic comma- or tadpole-shaped tail comprised of dilated cystic eccrine ducts. Clinically, syringomas typically present predominantly in the periorbital region in adolescent girls. They may present as solitary or multiple lesions, and sites such as the genital area, palms, scalp, and chest rarely can be involved.1 Eruptive syringoma is a clinical subtype of syringoma that is seen on the face, neck, chest, and axillae that predominantly occurs in females with skin of color in countries such as Asia and Africa before or during puberty.2,3 Lesions appear as small, flesh-colored or slightly pigmented, flat-topped papules.3 The condition can be cosmetically disfiguring and difficult to treat, especially in patients with darker skin.

In our patient, dermoscopic evaluation revealed reticular light brown lines, structureless light brown areas, clustered brown dots, globules, and reticular vessels on a faint background (Figure 1A). Glittering yellow-whitish round structures over a fading pink-brown background also were seen at some sites (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of a neck lesion revealed an epidermis with focal acanthosis; the upper dermis had tumor islands and ducts with cells with round to vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. A well-circumscribed tumor in the dermis composed of tubules of varying sizes lined by cuboidal cells was seen, consistent with syringoma (Figure 2).

Dermoscopic features of syringomas have not been widely studied. Hayashi et al4 reported the dermoscopic features of unilateral linear syringomas as a delicate and faint reticular pigmentation network and multiple hypopigmented areas. Sakiyama et al5 also defined an incomplete pigment network with faint erythema in 2 eruptive syringoma cases.