User login

Stressed about weight gain? Well, stress causes weight gain

Stress, meet weight gain. Weight gain, meet stress

You’re not eating differently and you’re keeping active, but your waistline is expanding. How is that happening? Since eating healthy and exercising shouldn’t make you gain weight, there may be a hidden factor getting in your way. Stress. The one thing that can have a grip on your circadian rhythm stronger than any bodybuilder.

Investigators at Weill Cornell Medicine published two mouse studies that suggest stress and other factors that throw the body’s circadian clocks out of rhythm may contribute to weight gain.

In the first study, the researchers imitated disruptive condition effects like high cortisol exposure and chronic stress by implanting pellets under the skin that released glucocorticoid at a constant rate for 21 days. Mice that received the pellets had twice as much white and brown fat, as well as much higher insulin levels, regardless of their unchanged and still-healthy diet.

In the second study, they used tagged proteins as markers to monitor the daily fluctuations of a protein that regulates fat cell production and circadian gene expression in mouse fat cell precursors. The results showed “that fat cell precursors commit to becoming fat cells only during the circadian cycle phase corresponding to evening in humans,” they said in a written statement.

“Every cell in our body has an intrinsic cell clock, just like the fat cells, and we have a master clock in our brain, which controls hormone secretion,” said senior author Mary Teruel of Cornell University. “A lot of forces are working against a healthy metabolism when we are out of circadian rhythm. The more we understand, the more likely we will be able to do something about it.”

So if you’re stressing out that the scale is or isn’t moving in the direction you want, you could be standing in your own way. Take a chill pill.

Who can smell cancer? The locust nose

If you need to smell some gas, there’s nothing better than a nose. Just ask a scientist: “Noses are still state of the art,” said Debajit Saha, PhD, of Michigan State University. “There’s really nothing like them when it comes to gas sensing.”

And when it comes to noses, dogs are best, right? After all, there’s a reason we don’t have bomb-sniffing wombats and drug-sniffing ostriches. Dogs are better. Better, but not perfect. And if they’re not perfect, then human technology can do better.

Enter the electronic nose. Which is better than dogs … except that it isn’t. “People have been working on ‘electronic noses’ for more than 15 years, but they’re still not close to achieving what biology can do seamlessly,” Dr. Saha explained in a statement from the university.

Which brings us back to dogs. If you want to detect early-stage cancer using smell, you go to the dogs, right? Nope.

Here’s Christopher Contag, PhD, also of Michigan State, who recruited Dr. Saha to the university: “I told him, ‘When you come here, we’ll detect cancer. I’m sure your locusts can do it.’ ”

Yes, locusts. Dr. Contag and his research team were looking at mouth cancers and noticed that different cell lines had different appearances. Then they discovered that those different-looking cell lines produced different metabolites, some of which were volatile.

Enter Dr. Saha’s locusts. They were able to tell the difference between normal cells and cancer cells and could even distinguish between the different cell lines. And how they were able to share this information? Not voluntarily, that’s for sure. The researchers attached electrodes to the insects’ brains and recorded their responses to gas samples from both healthy and cancer cells. Those brain signals were then used to create chemical profiles of the different cells. Piece of cake.

The whole getting-electrodes-attached-to-their-brains thing seemed at least a bit ethically ambiguous, so we contacted the locusts’ PR office, which offered some positive spin: “Humans get their early cancer detection and we get that whole swarms-that-devour-entire-countrysides thing off our backs. Win win.”

Bad news for vampires everywhere

Pop culture has been extraordinarily kind to the vampire. A few hundred years ago, vampires were demon-possessed, often-inhuman monsters. Now? They’re suave, sophisticated, beautiful, and oh-so dramatic and angst-filled about their “curse.” Drink a little human blood, live and look young forever. Such monsters they are.

It does make sense in a morbid sort of way. An old person receiving the blood of the young does seem like a good idea for rejuvenation, right? A team of Ukrainian researchers sought to find out, conducting a study in which older mice were linked with young mice via heterochronic parabiosis. For 3 months, old-young mice pairs were surgically connected and shared blood. After 3 months, the mice were disconnected from each other and the effects of the blood link were studied.

For all the vampire enthusiasts out there, we have bad news and worse news. The bad news first: The older mice received absolutely no benefit from heterochronic parabiosis. No youthfulness, no increased lifespan, nothing. The worse news is that the younger mice were adversely affected by the older blood. They aged more and experienced a shortened lifespan, even after the connection was severed. The old blood, according to the investigators, contains factors capable of inducing aging in younger mice, but the opposite is not true. Further research into aging, they added, should focus on suppressing the aging factors in older blood.

Of note, the paper was written by doctors who are currently refugees, fleeing the war in Ukraine. We don’t want to speculate on the true cause of the war, but we’re onto you, Putin. We know you wanted the vampire research for yourself, but it won’t work. Your dream of becoming Vlad “Dracula” Putin will never come to pass.

Hearing is not always believing

Have you ever heard yourself on a voice mail, or from a recording you did at work? No matter how good you sound, you still might feel like the recording sounds nothing like you. It may even cause low self-esteem for those who don’t like how their voice sounds or don’t recognize it when it’s played back to them.

Since one possible symptom of schizophrenia is not recognizing one’s own speech and having a false sense of control over actions, and those with schizophrenia may hallucinate or hear voices, not being able to recognize their own voices may be alarming.

A recent study on the sense of agency, or sense of control, involved having volunteers speak with different pitches in their voices and then having it played back to them to gauge their reactions.

“Our results demonstrate that hearing one’s own voice is a critical factor to increased self-agency over speech. In other words, we do not strongly feel that ‘I’ am generating the speech if we hear someone else’s voice as an outcome of the speech. Our study provides empirical evidence of the tight link between the sense of agency and self-voice identity,” lead author Ryu Ohata, PhD, of the University of Tokyo, said in a written statement.

As social interaction becomes more digital through platforms such as FaceTime, Zoom, and voicemail, especially since the pandemic has promoted social distancing, it makes sense that people may be more aware and more surprised by how they sound on recordings.

So, if you ever promised someone something that you don’t want to do, and they play it back to you from the recording you made, maybe you can just say you don’t recognize the voice. And if it’s not you, then you don’t have to do it.

Stress, meet weight gain. Weight gain, meet stress

You’re not eating differently and you’re keeping active, but your waistline is expanding. How is that happening? Since eating healthy and exercising shouldn’t make you gain weight, there may be a hidden factor getting in your way. Stress. The one thing that can have a grip on your circadian rhythm stronger than any bodybuilder.

Investigators at Weill Cornell Medicine published two mouse studies that suggest stress and other factors that throw the body’s circadian clocks out of rhythm may contribute to weight gain.

In the first study, the researchers imitated disruptive condition effects like high cortisol exposure and chronic stress by implanting pellets under the skin that released glucocorticoid at a constant rate for 21 days. Mice that received the pellets had twice as much white and brown fat, as well as much higher insulin levels, regardless of their unchanged and still-healthy diet.

In the second study, they used tagged proteins as markers to monitor the daily fluctuations of a protein that regulates fat cell production and circadian gene expression in mouse fat cell precursors. The results showed “that fat cell precursors commit to becoming fat cells only during the circadian cycle phase corresponding to evening in humans,” they said in a written statement.

“Every cell in our body has an intrinsic cell clock, just like the fat cells, and we have a master clock in our brain, which controls hormone secretion,” said senior author Mary Teruel of Cornell University. “A lot of forces are working against a healthy metabolism when we are out of circadian rhythm. The more we understand, the more likely we will be able to do something about it.”

So if you’re stressing out that the scale is or isn’t moving in the direction you want, you could be standing in your own way. Take a chill pill.

Who can smell cancer? The locust nose

If you need to smell some gas, there’s nothing better than a nose. Just ask a scientist: “Noses are still state of the art,” said Debajit Saha, PhD, of Michigan State University. “There’s really nothing like them when it comes to gas sensing.”

And when it comes to noses, dogs are best, right? After all, there’s a reason we don’t have bomb-sniffing wombats and drug-sniffing ostriches. Dogs are better. Better, but not perfect. And if they’re not perfect, then human technology can do better.

Enter the electronic nose. Which is better than dogs … except that it isn’t. “People have been working on ‘electronic noses’ for more than 15 years, but they’re still not close to achieving what biology can do seamlessly,” Dr. Saha explained in a statement from the university.

Which brings us back to dogs. If you want to detect early-stage cancer using smell, you go to the dogs, right? Nope.

Here’s Christopher Contag, PhD, also of Michigan State, who recruited Dr. Saha to the university: “I told him, ‘When you come here, we’ll detect cancer. I’m sure your locusts can do it.’ ”

Yes, locusts. Dr. Contag and his research team were looking at mouth cancers and noticed that different cell lines had different appearances. Then they discovered that those different-looking cell lines produced different metabolites, some of which were volatile.

Enter Dr. Saha’s locusts. They were able to tell the difference between normal cells and cancer cells and could even distinguish between the different cell lines. And how they were able to share this information? Not voluntarily, that’s for sure. The researchers attached electrodes to the insects’ brains and recorded their responses to gas samples from both healthy and cancer cells. Those brain signals were then used to create chemical profiles of the different cells. Piece of cake.

The whole getting-electrodes-attached-to-their-brains thing seemed at least a bit ethically ambiguous, so we contacted the locusts’ PR office, which offered some positive spin: “Humans get their early cancer detection and we get that whole swarms-that-devour-entire-countrysides thing off our backs. Win win.”

Bad news for vampires everywhere

Pop culture has been extraordinarily kind to the vampire. A few hundred years ago, vampires were demon-possessed, often-inhuman monsters. Now? They’re suave, sophisticated, beautiful, and oh-so dramatic and angst-filled about their “curse.” Drink a little human blood, live and look young forever. Such monsters they are.

It does make sense in a morbid sort of way. An old person receiving the blood of the young does seem like a good idea for rejuvenation, right? A team of Ukrainian researchers sought to find out, conducting a study in which older mice were linked with young mice via heterochronic parabiosis. For 3 months, old-young mice pairs were surgically connected and shared blood. After 3 months, the mice were disconnected from each other and the effects of the blood link were studied.

For all the vampire enthusiasts out there, we have bad news and worse news. The bad news first: The older mice received absolutely no benefit from heterochronic parabiosis. No youthfulness, no increased lifespan, nothing. The worse news is that the younger mice were adversely affected by the older blood. They aged more and experienced a shortened lifespan, even after the connection was severed. The old blood, according to the investigators, contains factors capable of inducing aging in younger mice, but the opposite is not true. Further research into aging, they added, should focus on suppressing the aging factors in older blood.

Of note, the paper was written by doctors who are currently refugees, fleeing the war in Ukraine. We don’t want to speculate on the true cause of the war, but we’re onto you, Putin. We know you wanted the vampire research for yourself, but it won’t work. Your dream of becoming Vlad “Dracula” Putin will never come to pass.

Hearing is not always believing

Have you ever heard yourself on a voice mail, or from a recording you did at work? No matter how good you sound, you still might feel like the recording sounds nothing like you. It may even cause low self-esteem for those who don’t like how their voice sounds or don’t recognize it when it’s played back to them.

Since one possible symptom of schizophrenia is not recognizing one’s own speech and having a false sense of control over actions, and those with schizophrenia may hallucinate or hear voices, not being able to recognize their own voices may be alarming.

A recent study on the sense of agency, or sense of control, involved having volunteers speak with different pitches in their voices and then having it played back to them to gauge their reactions.

“Our results demonstrate that hearing one’s own voice is a critical factor to increased self-agency over speech. In other words, we do not strongly feel that ‘I’ am generating the speech if we hear someone else’s voice as an outcome of the speech. Our study provides empirical evidence of the tight link between the sense of agency and self-voice identity,” lead author Ryu Ohata, PhD, of the University of Tokyo, said in a written statement.

As social interaction becomes more digital through platforms such as FaceTime, Zoom, and voicemail, especially since the pandemic has promoted social distancing, it makes sense that people may be more aware and more surprised by how they sound on recordings.

So, if you ever promised someone something that you don’t want to do, and they play it back to you from the recording you made, maybe you can just say you don’t recognize the voice. And if it’s not you, then you don’t have to do it.

Stress, meet weight gain. Weight gain, meet stress

You’re not eating differently and you’re keeping active, but your waistline is expanding. How is that happening? Since eating healthy and exercising shouldn’t make you gain weight, there may be a hidden factor getting in your way. Stress. The one thing that can have a grip on your circadian rhythm stronger than any bodybuilder.

Investigators at Weill Cornell Medicine published two mouse studies that suggest stress and other factors that throw the body’s circadian clocks out of rhythm may contribute to weight gain.

In the first study, the researchers imitated disruptive condition effects like high cortisol exposure and chronic stress by implanting pellets under the skin that released glucocorticoid at a constant rate for 21 days. Mice that received the pellets had twice as much white and brown fat, as well as much higher insulin levels, regardless of their unchanged and still-healthy diet.

In the second study, they used tagged proteins as markers to monitor the daily fluctuations of a protein that regulates fat cell production and circadian gene expression in mouse fat cell precursors. The results showed “that fat cell precursors commit to becoming fat cells only during the circadian cycle phase corresponding to evening in humans,” they said in a written statement.

“Every cell in our body has an intrinsic cell clock, just like the fat cells, and we have a master clock in our brain, which controls hormone secretion,” said senior author Mary Teruel of Cornell University. “A lot of forces are working against a healthy metabolism when we are out of circadian rhythm. The more we understand, the more likely we will be able to do something about it.”

So if you’re stressing out that the scale is or isn’t moving in the direction you want, you could be standing in your own way. Take a chill pill.

Who can smell cancer? The locust nose

If you need to smell some gas, there’s nothing better than a nose. Just ask a scientist: “Noses are still state of the art,” said Debajit Saha, PhD, of Michigan State University. “There’s really nothing like them when it comes to gas sensing.”

And when it comes to noses, dogs are best, right? After all, there’s a reason we don’t have bomb-sniffing wombats and drug-sniffing ostriches. Dogs are better. Better, but not perfect. And if they’re not perfect, then human technology can do better.

Enter the electronic nose. Which is better than dogs … except that it isn’t. “People have been working on ‘electronic noses’ for more than 15 years, but they’re still not close to achieving what biology can do seamlessly,” Dr. Saha explained in a statement from the university.

Which brings us back to dogs. If you want to detect early-stage cancer using smell, you go to the dogs, right? Nope.

Here’s Christopher Contag, PhD, also of Michigan State, who recruited Dr. Saha to the university: “I told him, ‘When you come here, we’ll detect cancer. I’m sure your locusts can do it.’ ”

Yes, locusts. Dr. Contag and his research team were looking at mouth cancers and noticed that different cell lines had different appearances. Then they discovered that those different-looking cell lines produced different metabolites, some of which were volatile.

Enter Dr. Saha’s locusts. They were able to tell the difference between normal cells and cancer cells and could even distinguish between the different cell lines. And how they were able to share this information? Not voluntarily, that’s for sure. The researchers attached electrodes to the insects’ brains and recorded their responses to gas samples from both healthy and cancer cells. Those brain signals were then used to create chemical profiles of the different cells. Piece of cake.

The whole getting-electrodes-attached-to-their-brains thing seemed at least a bit ethically ambiguous, so we contacted the locusts’ PR office, which offered some positive spin: “Humans get their early cancer detection and we get that whole swarms-that-devour-entire-countrysides thing off our backs. Win win.”

Bad news for vampires everywhere

Pop culture has been extraordinarily kind to the vampire. A few hundred years ago, vampires were demon-possessed, often-inhuman monsters. Now? They’re suave, sophisticated, beautiful, and oh-so dramatic and angst-filled about their “curse.” Drink a little human blood, live and look young forever. Such monsters they are.

It does make sense in a morbid sort of way. An old person receiving the blood of the young does seem like a good idea for rejuvenation, right? A team of Ukrainian researchers sought to find out, conducting a study in which older mice were linked with young mice via heterochronic parabiosis. For 3 months, old-young mice pairs were surgically connected and shared blood. After 3 months, the mice were disconnected from each other and the effects of the blood link were studied.

For all the vampire enthusiasts out there, we have bad news and worse news. The bad news first: The older mice received absolutely no benefit from heterochronic parabiosis. No youthfulness, no increased lifespan, nothing. The worse news is that the younger mice were adversely affected by the older blood. They aged more and experienced a shortened lifespan, even after the connection was severed. The old blood, according to the investigators, contains factors capable of inducing aging in younger mice, but the opposite is not true. Further research into aging, they added, should focus on suppressing the aging factors in older blood.

Of note, the paper was written by doctors who are currently refugees, fleeing the war in Ukraine. We don’t want to speculate on the true cause of the war, but we’re onto you, Putin. We know you wanted the vampire research for yourself, but it won’t work. Your dream of becoming Vlad “Dracula” Putin will never come to pass.

Hearing is not always believing

Have you ever heard yourself on a voice mail, or from a recording you did at work? No matter how good you sound, you still might feel like the recording sounds nothing like you. It may even cause low self-esteem for those who don’t like how their voice sounds or don’t recognize it when it’s played back to them.

Since one possible symptom of schizophrenia is not recognizing one’s own speech and having a false sense of control over actions, and those with schizophrenia may hallucinate or hear voices, not being able to recognize their own voices may be alarming.

A recent study on the sense of agency, or sense of control, involved having volunteers speak with different pitches in their voices and then having it played back to them to gauge their reactions.

“Our results demonstrate that hearing one’s own voice is a critical factor to increased self-agency over speech. In other words, we do not strongly feel that ‘I’ am generating the speech if we hear someone else’s voice as an outcome of the speech. Our study provides empirical evidence of the tight link between the sense of agency and self-voice identity,” lead author Ryu Ohata, PhD, of the University of Tokyo, said in a written statement.

As social interaction becomes more digital through platforms such as FaceTime, Zoom, and voicemail, especially since the pandemic has promoted social distancing, it makes sense that people may be more aware and more surprised by how they sound on recordings.

So, if you ever promised someone something that you don’t want to do, and they play it back to you from the recording you made, maybe you can just say you don’t recognize the voice. And if it’s not you, then you don’t have to do it.

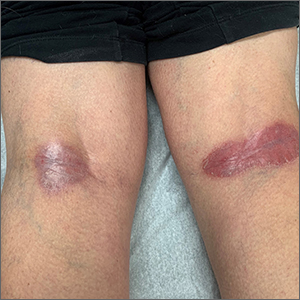

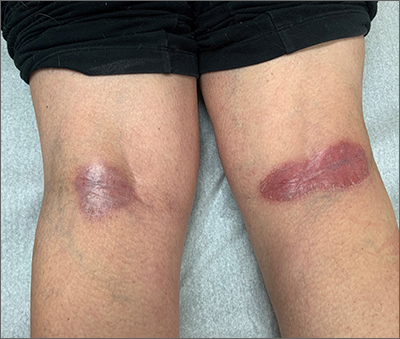

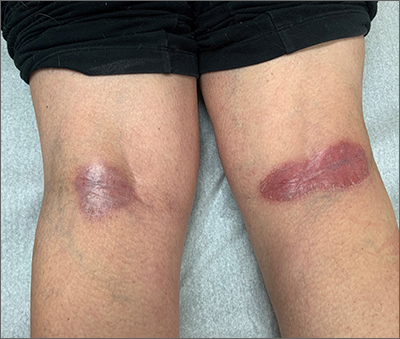

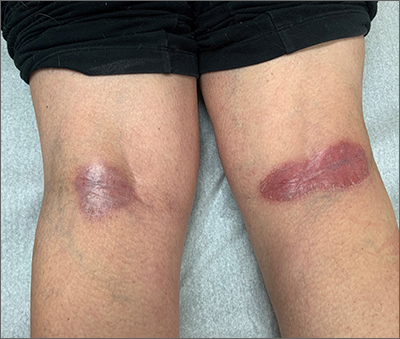

Popliteal plaques

Both a Wood lamp examination and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep returned negative results. Those findings, combined with the patient’s month-long antifungal medication adherence, helped to rule out other diagnoses. Based on history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a skin infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium minutissimum1 that usually manifests in moist intertriginous areas. Sometimes it is secondary to fungal or yeast infections, local skin irritation due to friction, or due to maceration of the skin from persistent moisture. The Wood lamp examination can show coral-red fluorescence in erythrasma, but recent bathing (as in this case) may limit this finding.1

The differential diagnosis of erythematous plaques in an intertriginous area includes inverse psoriasis. However, this patient had no nail changes, joint difficulties, or other rashes consistent with psoriasis. Macerated, erythematous inflammatory changes in intertriginous areas are always concerning for fungal infections (eg, yeast infection, tinea corporis), especially with the presence of any scale. In this case, the patient’s medication regimen helped to rule out these types of conditions.

First-line therapy for erythrasma includes topical antibiotics: clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, and fusidic acid. Systemic antibiotics in the tetracycline family and macrolides may also be used but have a higher risk of adverse effects. Keeping the affected area dry is a useful adjunct to pharmacologic therapy.

The patient was treated with topical clindamycin bid for 7 days. By her 2-month follow-up appointment, there were no residual skin changes. Had the plaques persisted, the possibility of inverse psoriasis would have been revisited, with either presumptive treatment prescribed or biopsy performed to establish the diagnosis.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

Both a Wood lamp examination and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep returned negative results. Those findings, combined with the patient’s month-long antifungal medication adherence, helped to rule out other diagnoses. Based on history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a skin infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium minutissimum1 that usually manifests in moist intertriginous areas. Sometimes it is secondary to fungal or yeast infections, local skin irritation due to friction, or due to maceration of the skin from persistent moisture. The Wood lamp examination can show coral-red fluorescence in erythrasma, but recent bathing (as in this case) may limit this finding.1

The differential diagnosis of erythematous plaques in an intertriginous area includes inverse psoriasis. However, this patient had no nail changes, joint difficulties, or other rashes consistent with psoriasis. Macerated, erythematous inflammatory changes in intertriginous areas are always concerning for fungal infections (eg, yeast infection, tinea corporis), especially with the presence of any scale. In this case, the patient’s medication regimen helped to rule out these types of conditions.

First-line therapy for erythrasma includes topical antibiotics: clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, and fusidic acid. Systemic antibiotics in the tetracycline family and macrolides may also be used but have a higher risk of adverse effects. Keeping the affected area dry is a useful adjunct to pharmacologic therapy.

The patient was treated with topical clindamycin bid for 7 days. By her 2-month follow-up appointment, there were no residual skin changes. Had the plaques persisted, the possibility of inverse psoriasis would have been revisited, with either presumptive treatment prescribed or biopsy performed to establish the diagnosis.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Both a Wood lamp examination and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep returned negative results. Those findings, combined with the patient’s month-long antifungal medication adherence, helped to rule out other diagnoses. Based on history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a skin infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium minutissimum1 that usually manifests in moist intertriginous areas. Sometimes it is secondary to fungal or yeast infections, local skin irritation due to friction, or due to maceration of the skin from persistent moisture. The Wood lamp examination can show coral-red fluorescence in erythrasma, but recent bathing (as in this case) may limit this finding.1

The differential diagnosis of erythematous plaques in an intertriginous area includes inverse psoriasis. However, this patient had no nail changes, joint difficulties, or other rashes consistent with psoriasis. Macerated, erythematous inflammatory changes in intertriginous areas are always concerning for fungal infections (eg, yeast infection, tinea corporis), especially with the presence of any scale. In this case, the patient’s medication regimen helped to rule out these types of conditions.

First-line therapy for erythrasma includes topical antibiotics: clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, and fusidic acid. Systemic antibiotics in the tetracycline family and macrolides may also be used but have a higher risk of adverse effects. Keeping the affected area dry is a useful adjunct to pharmacologic therapy.

The patient was treated with topical clindamycin bid for 7 days. By her 2-month follow-up appointment, there were no residual skin changes. Had the plaques persisted, the possibility of inverse psoriasis would have been revisited, with either presumptive treatment prescribed or biopsy performed to establish the diagnosis.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

1. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

Plasma biomarkers predict COVID’s neurological sequelae

SAN DIEGO – Even after recovery of an acute COVID-19 infection, some patients experience extended or even long-term symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. Some of these symptoms are neurological: headaches, brain fog, cognitive impairment, loss of taste or smell, and even cerebrovascular complications such stroke. There are even hints that COVID-19 infection could lead to future neurodegeneration.

Those issues have prompted efforts to identify biomarkers that can help track and monitor neurological complications of COVID-19. “Throughout the course of the pandemic, it has become apparent that COVID-19 can cause various neurological symptoms. Because of this, ,” Jennifer Cooper said during a lecture at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. She presented new research suggesting that neurofilament light (NfL) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) may prove useful.

Ms. Cooper is a master’s degree student at the University of British Columbia and Canada.

Looking for sensitivity and specificity in plasma biomarkers

The researchers turned to plasma-based markers because they can reflect underlying pathology in the central nervous system. They focused on NfL, which reflects axonal damage, and GFAP, which is a marker of astrocyte activation.

The researchers analyzed data from 209 patients with COVID-19 who were admitted to the Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital intensive care unit. Sixty-four percent were male, and the median age was 61 years. Sixty percent were ventilated, and 17% died.

The researchers determined if an individual patient’s biomarker level at hospital admission fell within a normal biomarker reference interval. A total of 53% had NfL levels outside the normal range, and 42% had GFAP levels outside the normal range. In addition, 31% of patients had both GFAP and NfL levels outside of the normal range.

Among all patients, 12% experienced ischemia, 4% hemorrhage, 2% seizures, and 10% degeneration.

At admission, NfL predicted a neurological complication with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.702. GFAP had an AUC of 0.722. In combination, they had an AUC of 0.743. At 1 week, NfL had an AUC of 0.802, GFAP an AUC of 0.733, and the combination an AUC of 0.812.

Using age-specific cutoff values, the researchers found increased risks for neurological complications at admission (NfL odds ratio [OR], 2.9; GFAP OR, 1.6; combined OR, 2.1) and at 1 week (NfL OR, not significant; GFAP OR, 4.8; combined OR, 6.6). “We can see that both NFL and GFAP have utility in detecting neurological complications. And combining both of our markers improves detection at both time points. NfL is a marker that provides more sensitivity, where in this cohort GFAP is a marker that provides a little bit more specificity,” said Ms. Cooper.

Will additional biomarkers help?

The researchers are continuing to follow up patients at 6 months and 18 months post diagnosis, using neuropsychiatric tests and additional biomarker analysis, as well as PET and MRI scans. The patient sample is being expanded to those in the general hospital ward and some who were not hospitalized.

During the Q&A session, Ms. Cooper was asked if the group had collected reference data from patients who were admitted to the ICU with non-COVID disease. She responded that the group has some of that data, but as the pandemic went on they had difficulty finding patients who had never been infected with COVID to serve as reliable controls. To date, they have identified 33 controls who had a respiratory condition when admitted to the ICU. “What we see is the neurological biomarker levels in COVID are slightly lower than those with another respiratory condition in the ICU. But the data has a massive spread and the significance is very small between the two groups,” said Ms. Cooper.

Unanswered questions

The study is interesting, but leaves a lot of unanswered questions, according to Wiesje van der Flier, PhD, who moderated the session where the study was presented. “There are a lot of unknowns still: Will [the biomarkers] become normal again, once the COVID is over? Also, there was an increased risk, but it was not a one-to-one correspondence, so you can also have the increased markers but not have the neurological signs or symptoms. So I thought there were lots of questions as well,” said Dr. van der Flier, professor of neurology at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

She noted that researchers at her institution in Amsterdam have observed similar relationships, and that the associations between neurological complications and plasma biomarkers over time will be an important topic of study.

The work could provide more information on neurological manifestations of long COVID, such as long-haul fatigue. “You might also think that’s some response in their brain. It would be great if we could actually capture that [using biomarkers],” said Dr. van der Flier.

Ms. Cooper and Dr. van der Flier have no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Even after recovery of an acute COVID-19 infection, some patients experience extended or even long-term symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. Some of these symptoms are neurological: headaches, brain fog, cognitive impairment, loss of taste or smell, and even cerebrovascular complications such stroke. There are even hints that COVID-19 infection could lead to future neurodegeneration.

Those issues have prompted efforts to identify biomarkers that can help track and monitor neurological complications of COVID-19. “Throughout the course of the pandemic, it has become apparent that COVID-19 can cause various neurological symptoms. Because of this, ,” Jennifer Cooper said during a lecture at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. She presented new research suggesting that neurofilament light (NfL) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) may prove useful.

Ms. Cooper is a master’s degree student at the University of British Columbia and Canada.

Looking for sensitivity and specificity in plasma biomarkers

The researchers turned to plasma-based markers because they can reflect underlying pathology in the central nervous system. They focused on NfL, which reflects axonal damage, and GFAP, which is a marker of astrocyte activation.

The researchers analyzed data from 209 patients with COVID-19 who were admitted to the Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital intensive care unit. Sixty-four percent were male, and the median age was 61 years. Sixty percent were ventilated, and 17% died.

The researchers determined if an individual patient’s biomarker level at hospital admission fell within a normal biomarker reference interval. A total of 53% had NfL levels outside the normal range, and 42% had GFAP levels outside the normal range. In addition, 31% of patients had both GFAP and NfL levels outside of the normal range.

Among all patients, 12% experienced ischemia, 4% hemorrhage, 2% seizures, and 10% degeneration.

At admission, NfL predicted a neurological complication with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.702. GFAP had an AUC of 0.722. In combination, they had an AUC of 0.743. At 1 week, NfL had an AUC of 0.802, GFAP an AUC of 0.733, and the combination an AUC of 0.812.

Using age-specific cutoff values, the researchers found increased risks for neurological complications at admission (NfL odds ratio [OR], 2.9; GFAP OR, 1.6; combined OR, 2.1) and at 1 week (NfL OR, not significant; GFAP OR, 4.8; combined OR, 6.6). “We can see that both NFL and GFAP have utility in detecting neurological complications. And combining both of our markers improves detection at both time points. NfL is a marker that provides more sensitivity, where in this cohort GFAP is a marker that provides a little bit more specificity,” said Ms. Cooper.

Will additional biomarkers help?

The researchers are continuing to follow up patients at 6 months and 18 months post diagnosis, using neuropsychiatric tests and additional biomarker analysis, as well as PET and MRI scans. The patient sample is being expanded to those in the general hospital ward and some who were not hospitalized.

During the Q&A session, Ms. Cooper was asked if the group had collected reference data from patients who were admitted to the ICU with non-COVID disease. She responded that the group has some of that data, but as the pandemic went on they had difficulty finding patients who had never been infected with COVID to serve as reliable controls. To date, they have identified 33 controls who had a respiratory condition when admitted to the ICU. “What we see is the neurological biomarker levels in COVID are slightly lower than those with another respiratory condition in the ICU. But the data has a massive spread and the significance is very small between the two groups,” said Ms. Cooper.

Unanswered questions

The study is interesting, but leaves a lot of unanswered questions, according to Wiesje van der Flier, PhD, who moderated the session where the study was presented. “There are a lot of unknowns still: Will [the biomarkers] become normal again, once the COVID is over? Also, there was an increased risk, but it was not a one-to-one correspondence, so you can also have the increased markers but not have the neurological signs or symptoms. So I thought there were lots of questions as well,” said Dr. van der Flier, professor of neurology at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

She noted that researchers at her institution in Amsterdam have observed similar relationships, and that the associations between neurological complications and plasma biomarkers over time will be an important topic of study.

The work could provide more information on neurological manifestations of long COVID, such as long-haul fatigue. “You might also think that’s some response in their brain. It would be great if we could actually capture that [using biomarkers],” said Dr. van der Flier.

Ms. Cooper and Dr. van der Flier have no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Even after recovery of an acute COVID-19 infection, some patients experience extended or even long-term symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. Some of these symptoms are neurological: headaches, brain fog, cognitive impairment, loss of taste or smell, and even cerebrovascular complications such stroke. There are even hints that COVID-19 infection could lead to future neurodegeneration.

Those issues have prompted efforts to identify biomarkers that can help track and monitor neurological complications of COVID-19. “Throughout the course of the pandemic, it has become apparent that COVID-19 can cause various neurological symptoms. Because of this, ,” Jennifer Cooper said during a lecture at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. She presented new research suggesting that neurofilament light (NfL) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) may prove useful.

Ms. Cooper is a master’s degree student at the University of British Columbia and Canada.

Looking for sensitivity and specificity in plasma biomarkers

The researchers turned to plasma-based markers because they can reflect underlying pathology in the central nervous system. They focused on NfL, which reflects axonal damage, and GFAP, which is a marker of astrocyte activation.

The researchers analyzed data from 209 patients with COVID-19 who were admitted to the Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital intensive care unit. Sixty-four percent were male, and the median age was 61 years. Sixty percent were ventilated, and 17% died.

The researchers determined if an individual patient’s biomarker level at hospital admission fell within a normal biomarker reference interval. A total of 53% had NfL levels outside the normal range, and 42% had GFAP levels outside the normal range. In addition, 31% of patients had both GFAP and NfL levels outside of the normal range.

Among all patients, 12% experienced ischemia, 4% hemorrhage, 2% seizures, and 10% degeneration.

At admission, NfL predicted a neurological complication with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.702. GFAP had an AUC of 0.722. In combination, they had an AUC of 0.743. At 1 week, NfL had an AUC of 0.802, GFAP an AUC of 0.733, and the combination an AUC of 0.812.

Using age-specific cutoff values, the researchers found increased risks for neurological complications at admission (NfL odds ratio [OR], 2.9; GFAP OR, 1.6; combined OR, 2.1) and at 1 week (NfL OR, not significant; GFAP OR, 4.8; combined OR, 6.6). “We can see that both NFL and GFAP have utility in detecting neurological complications. And combining both of our markers improves detection at both time points. NfL is a marker that provides more sensitivity, where in this cohort GFAP is a marker that provides a little bit more specificity,” said Ms. Cooper.

Will additional biomarkers help?

The researchers are continuing to follow up patients at 6 months and 18 months post diagnosis, using neuropsychiatric tests and additional biomarker analysis, as well as PET and MRI scans. The patient sample is being expanded to those in the general hospital ward and some who were not hospitalized.

During the Q&A session, Ms. Cooper was asked if the group had collected reference data from patients who were admitted to the ICU with non-COVID disease. She responded that the group has some of that data, but as the pandemic went on they had difficulty finding patients who had never been infected with COVID to serve as reliable controls. To date, they have identified 33 controls who had a respiratory condition when admitted to the ICU. “What we see is the neurological biomarker levels in COVID are slightly lower than those with another respiratory condition in the ICU. But the data has a massive spread and the significance is very small between the two groups,” said Ms. Cooper.

Unanswered questions

The study is interesting, but leaves a lot of unanswered questions, according to Wiesje van der Flier, PhD, who moderated the session where the study was presented. “There are a lot of unknowns still: Will [the biomarkers] become normal again, once the COVID is over? Also, there was an increased risk, but it was not a one-to-one correspondence, so you can also have the increased markers but not have the neurological signs or symptoms. So I thought there were lots of questions as well,” said Dr. van der Flier, professor of neurology at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

She noted that researchers at her institution in Amsterdam have observed similar relationships, and that the associations between neurological complications and plasma biomarkers over time will be an important topic of study.

The work could provide more information on neurological manifestations of long COVID, such as long-haul fatigue. “You might also think that’s some response in their brain. It would be great if we could actually capture that [using biomarkers],” said Dr. van der Flier.

Ms. Cooper and Dr. van der Flier have no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAIC 2022

Cardiorespiratory fitness key to longevity for all?

Cardiorespiratory fitness emerged as a stronger predictor of all-cause mortality than did any traditional risk factor across the spectrum of age, sex, and race in a modeling study that included more than 750,000 U.S. veterans.

In addition, mortality risk was cut in half if individuals achieved a moderate cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) level – that is, by meeting the current U.S. physical activity recommendations of 150 minutes per week, the authors note.

Furthermore, contrary to some previous research, “extremely high” fitness was not associated with an increased risk for mortality in the study, published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“This study has been 15 years in the making,” lead author Peter Kokkinos, PhD, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J., and the VA Medical Center, Washington, told this news organization. “We waited until we had the computer power and the right people to really assess this. We wanted to be very liberal in excluding patients we thought might contaminate the results, such as those with cardiovascular disease in the 6 months prior to a stress test.”

Figuring the time was right, the team analyzed data from the VA’s Exercise Testing and Health Outcomes Study (ETHOS) on individuals aged 30-95 years who underwent exercise treadmill tests between 1999 and 2020.

After exclusions, 750,302 individuals (from among 822,995) were included: 6.5% were women; 73.7% were White individuals; 19% were African American individuals; 4.7% were Hispanic individuals; and 2.1% were Native American, Asian, or Hawaiian individuals. Septuagenarians made up 14.7% of the cohort, and octogenarians made up 3.6%.

CRF categories for age and sex were determined by the peak metabolic equivalent of task (MET) achieved during the treadmill test. One MET is the energy spent at rest – that is the basal metabolic rate.

Although some physicians may resist putting patients through a stress test, “the amount of information we get from it is incredible,” Dr. Kokkinos noted. “We get blood pressure, we get heart rate, we get a response if you’re not doing exercise. This tells us a lot more than having you sit around so we can measure resting heart rate and blood pressure.”

Lowest mortality at 14.0 METs

During a median follow-up of 10.2 years (7,803,861 person-years), 23% of participants died, for an average of 22.4 events per 1,000 person-years.

Higher exercise capacity was inversely related to mortality risk across the cohort and within each age category. Specifically, every 1 MET increase in exercise capacity yielded an adjusted hazard ratio for mortality of 0.86 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-0.87; P < .001) for the entire cohort and similar HRs by sex and race.

The mortality risk for the least-fit individuals (20th percentile) was fourfold higher than for extremely fit individuals (HR, 4.09; 95% CI, 3.90-4.20), with the lowest mortality risk at about 14.0 METs for both men (HR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.23-0.25) and women (HR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.17-0.29). Extremely high CRF did not increase the risk.

In addition, at 20 years of follow-up, about 80% of men and 95% of women in the highest CRF category (98th percentile) were alive vs. less than 40% of men and approximately 75% of women in the least fit CRF category.

“We know CRF declines by 1% per year after age 30,” Dr. Kokkinos said. “But the age-related decline is cut in half if you are fit, meaning that an expected 10% decline over a decade will be only a 5% decline if you stay active. We cannot stop or reverse the decline, but we can kind of put the brakes on, and that’s a reason for clinicians to continue to encourage fitness.”

Indeed, “improving CRF should be considered a target in CVD prevention, similar to improving lipids, blood sugar, blood pressure, and weight,” Carl J. Lavie, MD, Ochsner Health, New Orleans, and colleagues affirm in a related editorial.

‘A difficult battle’

But that may not happen any time soon. “Unfortunately, despite having been recognized in an American Heart Association scientific statement as a clinical vital sign, aerobic fitness is undervalued and underutilized,” Claudio Gil Araújo, MD, PhD, research director of the Exercise Medicine Clinic-CLINIMEX, Rio de Janeiro, told this news organization.

Dr. Araújo led a recent study showing that the ability to stand on one leg for at least 10 seconds is strongly linked to the risk for death over the next 7 years.

Although physicians should be encouraging fitness, he said that “a substantial part of health professionals are physically unfit and feel uncomfortable talking about and prescribing exercise for their patients. Also, physicians tend to be better trained in treating diseases (using medications and/or prescribing procedures) than in preventing diseases by stimulating adoption of healthy habits. So, this a long road and a difficult battle.”

Nonetheless, he added, “Darwin said a long time ago that only the fittest will survive. If Darwin could read this study, he would surely smile.”

No commercial funding or conflicts of interest related to the study were reported. Dr. Lavie previously served as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health on their PAI (Personalized Activity Intelligence) applications.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiorespiratory fitness emerged as a stronger predictor of all-cause mortality than did any traditional risk factor across the spectrum of age, sex, and race in a modeling study that included more than 750,000 U.S. veterans.

In addition, mortality risk was cut in half if individuals achieved a moderate cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) level – that is, by meeting the current U.S. physical activity recommendations of 150 minutes per week, the authors note.

Furthermore, contrary to some previous research, “extremely high” fitness was not associated with an increased risk for mortality in the study, published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“This study has been 15 years in the making,” lead author Peter Kokkinos, PhD, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J., and the VA Medical Center, Washington, told this news organization. “We waited until we had the computer power and the right people to really assess this. We wanted to be very liberal in excluding patients we thought might contaminate the results, such as those with cardiovascular disease in the 6 months prior to a stress test.”

Figuring the time was right, the team analyzed data from the VA’s Exercise Testing and Health Outcomes Study (ETHOS) on individuals aged 30-95 years who underwent exercise treadmill tests between 1999 and 2020.

After exclusions, 750,302 individuals (from among 822,995) were included: 6.5% were women; 73.7% were White individuals; 19% were African American individuals; 4.7% were Hispanic individuals; and 2.1% were Native American, Asian, or Hawaiian individuals. Septuagenarians made up 14.7% of the cohort, and octogenarians made up 3.6%.

CRF categories for age and sex were determined by the peak metabolic equivalent of task (MET) achieved during the treadmill test. One MET is the energy spent at rest – that is the basal metabolic rate.

Although some physicians may resist putting patients through a stress test, “the amount of information we get from it is incredible,” Dr. Kokkinos noted. “We get blood pressure, we get heart rate, we get a response if you’re not doing exercise. This tells us a lot more than having you sit around so we can measure resting heart rate and blood pressure.”

Lowest mortality at 14.0 METs

During a median follow-up of 10.2 years (7,803,861 person-years), 23% of participants died, for an average of 22.4 events per 1,000 person-years.

Higher exercise capacity was inversely related to mortality risk across the cohort and within each age category. Specifically, every 1 MET increase in exercise capacity yielded an adjusted hazard ratio for mortality of 0.86 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-0.87; P < .001) for the entire cohort and similar HRs by sex and race.

The mortality risk for the least-fit individuals (20th percentile) was fourfold higher than for extremely fit individuals (HR, 4.09; 95% CI, 3.90-4.20), with the lowest mortality risk at about 14.0 METs for both men (HR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.23-0.25) and women (HR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.17-0.29). Extremely high CRF did not increase the risk.

In addition, at 20 years of follow-up, about 80% of men and 95% of women in the highest CRF category (98th percentile) were alive vs. less than 40% of men and approximately 75% of women in the least fit CRF category.

“We know CRF declines by 1% per year after age 30,” Dr. Kokkinos said. “But the age-related decline is cut in half if you are fit, meaning that an expected 10% decline over a decade will be only a 5% decline if you stay active. We cannot stop or reverse the decline, but we can kind of put the brakes on, and that’s a reason for clinicians to continue to encourage fitness.”

Indeed, “improving CRF should be considered a target in CVD prevention, similar to improving lipids, blood sugar, blood pressure, and weight,” Carl J. Lavie, MD, Ochsner Health, New Orleans, and colleagues affirm in a related editorial.

‘A difficult battle’

But that may not happen any time soon. “Unfortunately, despite having been recognized in an American Heart Association scientific statement as a clinical vital sign, aerobic fitness is undervalued and underutilized,” Claudio Gil Araújo, MD, PhD, research director of the Exercise Medicine Clinic-CLINIMEX, Rio de Janeiro, told this news organization.

Dr. Araújo led a recent study showing that the ability to stand on one leg for at least 10 seconds is strongly linked to the risk for death over the next 7 years.

Although physicians should be encouraging fitness, he said that “a substantial part of health professionals are physically unfit and feel uncomfortable talking about and prescribing exercise for their patients. Also, physicians tend to be better trained in treating diseases (using medications and/or prescribing procedures) than in preventing diseases by stimulating adoption of healthy habits. So, this a long road and a difficult battle.”

Nonetheless, he added, “Darwin said a long time ago that only the fittest will survive. If Darwin could read this study, he would surely smile.”

No commercial funding or conflicts of interest related to the study were reported. Dr. Lavie previously served as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health on their PAI (Personalized Activity Intelligence) applications.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiorespiratory fitness emerged as a stronger predictor of all-cause mortality than did any traditional risk factor across the spectrum of age, sex, and race in a modeling study that included more than 750,000 U.S. veterans.

In addition, mortality risk was cut in half if individuals achieved a moderate cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) level – that is, by meeting the current U.S. physical activity recommendations of 150 minutes per week, the authors note.

Furthermore, contrary to some previous research, “extremely high” fitness was not associated with an increased risk for mortality in the study, published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“This study has been 15 years in the making,” lead author Peter Kokkinos, PhD, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J., and the VA Medical Center, Washington, told this news organization. “We waited until we had the computer power and the right people to really assess this. We wanted to be very liberal in excluding patients we thought might contaminate the results, such as those with cardiovascular disease in the 6 months prior to a stress test.”

Figuring the time was right, the team analyzed data from the VA’s Exercise Testing and Health Outcomes Study (ETHOS) on individuals aged 30-95 years who underwent exercise treadmill tests between 1999 and 2020.

After exclusions, 750,302 individuals (from among 822,995) were included: 6.5% were women; 73.7% were White individuals; 19% were African American individuals; 4.7% were Hispanic individuals; and 2.1% were Native American, Asian, or Hawaiian individuals. Septuagenarians made up 14.7% of the cohort, and octogenarians made up 3.6%.

CRF categories for age and sex were determined by the peak metabolic equivalent of task (MET) achieved during the treadmill test. One MET is the energy spent at rest – that is the basal metabolic rate.

Although some physicians may resist putting patients through a stress test, “the amount of information we get from it is incredible,” Dr. Kokkinos noted. “We get blood pressure, we get heart rate, we get a response if you’re not doing exercise. This tells us a lot more than having you sit around so we can measure resting heart rate and blood pressure.”

Lowest mortality at 14.0 METs

During a median follow-up of 10.2 years (7,803,861 person-years), 23% of participants died, for an average of 22.4 events per 1,000 person-years.

Higher exercise capacity was inversely related to mortality risk across the cohort and within each age category. Specifically, every 1 MET increase in exercise capacity yielded an adjusted hazard ratio for mortality of 0.86 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-0.87; P < .001) for the entire cohort and similar HRs by sex and race.

The mortality risk for the least-fit individuals (20th percentile) was fourfold higher than for extremely fit individuals (HR, 4.09; 95% CI, 3.90-4.20), with the lowest mortality risk at about 14.0 METs for both men (HR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.23-0.25) and women (HR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.17-0.29). Extremely high CRF did not increase the risk.

In addition, at 20 years of follow-up, about 80% of men and 95% of women in the highest CRF category (98th percentile) were alive vs. less than 40% of men and approximately 75% of women in the least fit CRF category.

“We know CRF declines by 1% per year after age 30,” Dr. Kokkinos said. “But the age-related decline is cut in half if you are fit, meaning that an expected 10% decline over a decade will be only a 5% decline if you stay active. We cannot stop or reverse the decline, but we can kind of put the brakes on, and that’s a reason for clinicians to continue to encourage fitness.”

Indeed, “improving CRF should be considered a target in CVD prevention, similar to improving lipids, blood sugar, blood pressure, and weight,” Carl J. Lavie, MD, Ochsner Health, New Orleans, and colleagues affirm in a related editorial.

‘A difficult battle’

But that may not happen any time soon. “Unfortunately, despite having been recognized in an American Heart Association scientific statement as a clinical vital sign, aerobic fitness is undervalued and underutilized,” Claudio Gil Araújo, MD, PhD, research director of the Exercise Medicine Clinic-CLINIMEX, Rio de Janeiro, told this news organization.

Dr. Araújo led a recent study showing that the ability to stand on one leg for at least 10 seconds is strongly linked to the risk for death over the next 7 years.

Although physicians should be encouraging fitness, he said that “a substantial part of health professionals are physically unfit and feel uncomfortable talking about and prescribing exercise for their patients. Also, physicians tend to be better trained in treating diseases (using medications and/or prescribing procedures) than in preventing diseases by stimulating adoption of healthy habits. So, this a long road and a difficult battle.”

Nonetheless, he added, “Darwin said a long time ago that only the fittest will survive. If Darwin could read this study, he would surely smile.”

No commercial funding or conflicts of interest related to the study were reported. Dr. Lavie previously served as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health on their PAI (Personalized Activity Intelligence) applications.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

In MCI, combo training boosts effect

SAN DIEGO – The findings were drawn from an unusual study design that split patients into five groups, one of which included both interventions.

After the study was completed, researchers collapsed the groups into a single analysis to compare the different regimens, according to Manuel Montero-Odasso, MD, PhD, who presented the work at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. He is a geriatrician at Parkwood Institute, London, Ont.

Two previous trials looked at whether the combination of exercise plus cognitive training could outperform either intervention alone. In both, the combination improved cognition but not as much as either intervention alone. “So it seemed that when they combine it, they didn’t do as well,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso. Those findings left doubt about whether or not there is synergism between the two approaches.

Sequential, not simultaneous

A possible explanation for the finding is that patients who are doing both cognitive training and physical exercise simultaneously might not be able to focus enough on either task to do get the maximum benefit. “When we try to combine concurrently, participants or patients cannot focus and do enough progression in both at the same time. That’s the reason we designed the trial in a way that the interventions were sequential. You got a very good quality (cognitive) training, and later you got the exercise,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso.

In the new study, patients receiving both interventions conducted the cognitive training first, then did physical exercises 30 minutes later. “The practical message is that you should follow a program. Something I see in my patients, when they do the two things at the same time, they don’t pay enough attention,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso.

The researchers added vitamin D to the regimen as there have been small studies reporting that vitamin D supplementation can lead to greater muscle mass resulting from exercise.

The study included 176 patients aged 60-85 with MCI. The researchers excluded patients already participating in an active exercise program with a personal trainer, as well as those taking vitamin D at doses higher than 1,000 IU/day.

Over 20 weeks, the randomized groups included combination exercise and cognitive training with vitamin D (10,000 IU three times per week), exercise and cognitive training with placebo, exercise with a cognitive control and vitamin D, exercise with a cognitive control and placebo, and an exercise control (balance and toning) with cognitive control and placebo.

The interventions were completed three times per week. Cognitive training employed a tablet with multifunctional tasks and memory components. It was adaptive, becoming more difficult as patients improved or simplifying the task if a patient struggled. The exercise component included 40 minutes of progressive, supervised resistance training, followed by 20 minutes of aerobic exercise.

Compared with the double-placebo group, the double-intervention group had significant improvement in cognitive performance. “Exercise alone without cognitive training shows an effect, but that effect was lower than a combination with cognitive training,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso.

The combined groups had medium effect sizes on cognition when combined with vitamin D (Cohen’s d, 0.65; P = .003) and with vitamin D placebo (Cohen’s d, 0.58; P = .013). There were nonsignificant improvements in the exercise and vitamin D group (Cohen’s d, 0.30; P = .241) and the exercise plus placebo group (Cohen’s d, 0.42; P = .139)

After collapsing the arms, the researchers found that the exercise plus cognitive training regimen had an effect size of 0.62 (P = .002), while exercise alone only trended toward improvement and with a small effect size (Cohen’s d, 0.36; P = .13). There was no apparent effect of vitamin D supplementation, though Dr. Montero-Odasso pointed out that most participants were taking vitamin D supplements before study entry and had normal to high serum levels of vitamin D.

‘Optimistic’ results

The study was limited by an inability to retain patients due to the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a dropout rate of 17%.

“I think the idea of combining risk reduction strategies together in a population and individuals with MCI is really exciting. These are optimistic results. You certainly need to look into a larger and more diverse population as it goes forward,” said Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, who was asked to comment on the study.

She noted that the study looked at all-cause cognitive impairment. It would be interesting, Dr. Snyder said, to see how individuals with different underlying conditions handle the combination intervention.

The researchers are now in the planning stage of the Synergic 2 trial, which will incorporate exercise and cognitive training, plus diet and sleep counseling. It will be conducted virtually, involving one-to-one interactions with coaches.

Dr. Montero-Odasso and Dr. Snyder have no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The findings were drawn from an unusual study design that split patients into five groups, one of which included both interventions.

After the study was completed, researchers collapsed the groups into a single analysis to compare the different regimens, according to Manuel Montero-Odasso, MD, PhD, who presented the work at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. He is a geriatrician at Parkwood Institute, London, Ont.

Two previous trials looked at whether the combination of exercise plus cognitive training could outperform either intervention alone. In both, the combination improved cognition but not as much as either intervention alone. “So it seemed that when they combine it, they didn’t do as well,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso. Those findings left doubt about whether or not there is synergism between the two approaches.

Sequential, not simultaneous

A possible explanation for the finding is that patients who are doing both cognitive training and physical exercise simultaneously might not be able to focus enough on either task to do get the maximum benefit. “When we try to combine concurrently, participants or patients cannot focus and do enough progression in both at the same time. That’s the reason we designed the trial in a way that the interventions were sequential. You got a very good quality (cognitive) training, and later you got the exercise,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso.

In the new study, patients receiving both interventions conducted the cognitive training first, then did physical exercises 30 minutes later. “The practical message is that you should follow a program. Something I see in my patients, when they do the two things at the same time, they don’t pay enough attention,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso.

The researchers added vitamin D to the regimen as there have been small studies reporting that vitamin D supplementation can lead to greater muscle mass resulting from exercise.

The study included 176 patients aged 60-85 with MCI. The researchers excluded patients already participating in an active exercise program with a personal trainer, as well as those taking vitamin D at doses higher than 1,000 IU/day.

Over 20 weeks, the randomized groups included combination exercise and cognitive training with vitamin D (10,000 IU three times per week), exercise and cognitive training with placebo, exercise with a cognitive control and vitamin D, exercise with a cognitive control and placebo, and an exercise control (balance and toning) with cognitive control and placebo.

The interventions were completed three times per week. Cognitive training employed a tablet with multifunctional tasks and memory components. It was adaptive, becoming more difficult as patients improved or simplifying the task if a patient struggled. The exercise component included 40 minutes of progressive, supervised resistance training, followed by 20 minutes of aerobic exercise.

Compared with the double-placebo group, the double-intervention group had significant improvement in cognitive performance. “Exercise alone without cognitive training shows an effect, but that effect was lower than a combination with cognitive training,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso.

The combined groups had medium effect sizes on cognition when combined with vitamin D (Cohen’s d, 0.65; P = .003) and with vitamin D placebo (Cohen’s d, 0.58; P = .013). There were nonsignificant improvements in the exercise and vitamin D group (Cohen’s d, 0.30; P = .241) and the exercise plus placebo group (Cohen’s d, 0.42; P = .139)

After collapsing the arms, the researchers found that the exercise plus cognitive training regimen had an effect size of 0.62 (P = .002), while exercise alone only trended toward improvement and with a small effect size (Cohen’s d, 0.36; P = .13). There was no apparent effect of vitamin D supplementation, though Dr. Montero-Odasso pointed out that most participants were taking vitamin D supplements before study entry and had normal to high serum levels of vitamin D.

‘Optimistic’ results

The study was limited by an inability to retain patients due to the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a dropout rate of 17%.

“I think the idea of combining risk reduction strategies together in a population and individuals with MCI is really exciting. These are optimistic results. You certainly need to look into a larger and more diverse population as it goes forward,” said Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, who was asked to comment on the study.

She noted that the study looked at all-cause cognitive impairment. It would be interesting, Dr. Snyder said, to see how individuals with different underlying conditions handle the combination intervention.

The researchers are now in the planning stage of the Synergic 2 trial, which will incorporate exercise and cognitive training, plus diet and sleep counseling. It will be conducted virtually, involving one-to-one interactions with coaches.

Dr. Montero-Odasso and Dr. Snyder have no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The findings were drawn from an unusual study design that split patients into five groups, one of which included both interventions.

After the study was completed, researchers collapsed the groups into a single analysis to compare the different regimens, according to Manuel Montero-Odasso, MD, PhD, who presented the work at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. He is a geriatrician at Parkwood Institute, London, Ont.

Two previous trials looked at whether the combination of exercise plus cognitive training could outperform either intervention alone. In both, the combination improved cognition but not as much as either intervention alone. “So it seemed that when they combine it, they didn’t do as well,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso. Those findings left doubt about whether or not there is synergism between the two approaches.

Sequential, not simultaneous

A possible explanation for the finding is that patients who are doing both cognitive training and physical exercise simultaneously might not be able to focus enough on either task to do get the maximum benefit. “When we try to combine concurrently, participants or patients cannot focus and do enough progression in both at the same time. That’s the reason we designed the trial in a way that the interventions were sequential. You got a very good quality (cognitive) training, and later you got the exercise,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso.

In the new study, patients receiving both interventions conducted the cognitive training first, then did physical exercises 30 minutes later. “The practical message is that you should follow a program. Something I see in my patients, when they do the two things at the same time, they don’t pay enough attention,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso.

The researchers added vitamin D to the regimen as there have been small studies reporting that vitamin D supplementation can lead to greater muscle mass resulting from exercise.

The study included 176 patients aged 60-85 with MCI. The researchers excluded patients already participating in an active exercise program with a personal trainer, as well as those taking vitamin D at doses higher than 1,000 IU/day.

Over 20 weeks, the randomized groups included combination exercise and cognitive training with vitamin D (10,000 IU three times per week), exercise and cognitive training with placebo, exercise with a cognitive control and vitamin D, exercise with a cognitive control and placebo, and an exercise control (balance and toning) with cognitive control and placebo.

The interventions were completed three times per week. Cognitive training employed a tablet with multifunctional tasks and memory components. It was adaptive, becoming more difficult as patients improved or simplifying the task if a patient struggled. The exercise component included 40 minutes of progressive, supervised resistance training, followed by 20 minutes of aerobic exercise.

Compared with the double-placebo group, the double-intervention group had significant improvement in cognitive performance. “Exercise alone without cognitive training shows an effect, but that effect was lower than a combination with cognitive training,” said Dr. Montero-Odasso.

The combined groups had medium effect sizes on cognition when combined with vitamin D (Cohen’s d, 0.65; P = .003) and with vitamin D placebo (Cohen’s d, 0.58; P = .013). There were nonsignificant improvements in the exercise and vitamin D group (Cohen’s d, 0.30; P = .241) and the exercise plus placebo group (Cohen’s d, 0.42; P = .139)

After collapsing the arms, the researchers found that the exercise plus cognitive training regimen had an effect size of 0.62 (P = .002), while exercise alone only trended toward improvement and with a small effect size (Cohen’s d, 0.36; P = .13). There was no apparent effect of vitamin D supplementation, though Dr. Montero-Odasso pointed out that most participants were taking vitamin D supplements before study entry and had normal to high serum levels of vitamin D.

‘Optimistic’ results

The study was limited by an inability to retain patients due to the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a dropout rate of 17%.

“I think the idea of combining risk reduction strategies together in a population and individuals with MCI is really exciting. These are optimistic results. You certainly need to look into a larger and more diverse population as it goes forward,” said Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, who was asked to comment on the study.

She noted that the study looked at all-cause cognitive impairment. It would be interesting, Dr. Snyder said, to see how individuals with different underlying conditions handle the combination intervention.

The researchers are now in the planning stage of the Synergic 2 trial, which will incorporate exercise and cognitive training, plus diet and sleep counseling. It will be conducted virtually, involving one-to-one interactions with coaches.

Dr. Montero-Odasso and Dr. Snyder have no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAIC 2022

Stopping JIA drugs? Many can regain control after a flare

About two-thirds of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) were able to return to an inactive disease state within 12 months after a flare occurred when they took a break from medication, and slightly more than half – 55% – reached this state within 6 months, according to findings from registry data examined in a study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

Sarah Ringold, MD, MS, of the Seattle Children’s Hospital, and coauthors used data from participants in the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Registry to track what happened to patients when they took a break from antirheumatic drugs. They described their paper as being the first to use a large multicenter database such as the CARRA Registry to focus on JIA outcomes after medication discontinuation and flare, to describe flare severity after medication discontinuation, and to report patterns of medication use for flares.

“To date, JIA studies have established that flares after medication discontinuation are common but have generated conflicting data regarding flare risk factors,” Dr. Ringold and coauthors wrote. “Since it is not yet possible to predict reliably which children will successfully discontinue medication, families and physicians face uncertainty when deciding to stop medications, and there is significant variation in approach.”

The study will be “very helpful” to physicians working with parents and patients to make decisions about discontinuing medications, said Grant Schulert, MD, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, who was not involved with the study.

“It gives some numbers to help us have those conversations,” he said in an interview.

But interpreting those numbers still will present parents with a challenge, Dr. Schulert said.

“You can say: ‘The glass is half full; 55% of them could go back into remission in 6 months, a little bit higher in a year,’ ” he said. “Or the glass is half empty; some of them, even at a year, are still not back in remission.”

But “patients aren’t a statistic. They’re each one person,” he said. “They’re going to be in one of those two situations.”