User login

Rhabdomyolysis Occurring After Use of Cocaine Contaminated With Fentanyl Causing Bilateral Brachial Plexopathy

The brachial plexus is a group of interwoven nerves arising from the cervical spinal cord and coursing through the neck, shoulder, and axilla with terminal branches extending to the distal arm.1 Disorders of the brachial plexus are more rare than other isolated peripheral nerve disorders, trauma being the most common etiology.1 Traction, neoplasms, radiation exposure, external compression, and inflammatory processes, such as Parsonage-Turner syndrome, have also been described as less common etiologies.2

Rhabdomyolysis, a condition in which muscle breakdown occurs, is an uncommon and perhaps underrecognized cause of brachial plexopathy. Rhabdomyolysis is often caused by muscle overuse, trauma, prolonged immobilization, drugs, or toxins. Substances indicated as precipitating factors include alcohol, opioids, cocaine, and amphetamines.3,4 As rhabdomyolysis progresses, swelling and edema can compress surrounding structures. Therefore, in cases of rhabdomyolysis involving the muscles of the neck and shoulder girdle, external compression of the brachial plexus can potentially cause brachial plexopathy. Rare cases of this phenomenon occurring as a sequela of substance use have been described.1,5-9 Few cases have been reported in the literature.

The following case report describes a patient who

Case Presentation

A 68-year-old male patient with a history of polysubstance use disorder presented to the emergency department with complete loss of sensory and motor function of both arms. He had fallen asleep on his couch the previous evening with his arms crossed over his chest in the prone position.

On admission, the patient presented with an agitated mental status. The patient presented with 0/5 strength bilaterally in the upper extremities (UEs) accompanied by numbness and tingling. Radial pulses were palpable in both arms. All UE reflexes were absent, but patellar reflex was intact bilaterally. On hospital day 2, the patient was awake, alert, and oriented to person, place, and time and could provide a full history. The patient’s cranial nerves were intact with shoulder shrug testing mildly weak at 4/5 strength.

Serum electrolytes and glucose levels were normal. The creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level was elevated at 21,292 IU/L. Creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels were elevated at 1.7 mg/dL and 32 mg/dL, respectively. Serum B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c levels were normal.

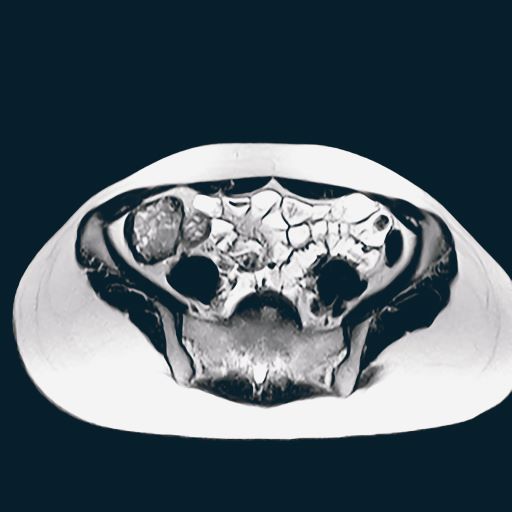

Due to the absence of evidence of spinal cord injury, presence of normal motor and sensory function of the lower extremities, an elevated CPK level, signal hyperintensities of the muscles of the shoulder girdle, and the patient’s history, the leading diagnosis at this time was brachial plexopathy secondary to focal rhabdomyolysis.

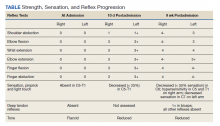

Over the next week, the patient regained some motor function of the left hand and some sensory function bilaterally. At 8 weeks postadmission, a nerve conduction study showed prolonged latencies in the median and ulnar nerves bilaterally. The following week, the patient reported pain in both shoulders (left greater than the right) as well as weakness of shoulder movement on the left greater than the right. There was pain in the right arm throughout. On examination, there was improved function of the arms distal to the elbow, which was better on the right side despite the associated pain (Table). There was atrophy of the left scapular muscles, hypothenar eminence, and deltoid muscle. There was weakness of the left triceps, with slight fourth and fifth finger flexion. The patient was unable to elevate or abduct the left shoulder but could elevate the right shoulder up to 45°. Sensation was decreased over the right outer arm and left posterior upper arm, with hypersensitivity in the right medial upper and lower arm. Deep tendon reflexes were absent in the upper arm aside from the biceps reflex (1+). All reflexes of the lower extremities were normal. It is interesting to note the relative greater improvement on the right despite the edema found on initial imaging being more prominent on the right.

Discussion

Rhabdomyolysis is a condition defined by myocyte necrosis that results in release of cellular contents and local edema. Inciting events may be traumatic, metabolic, ischemic, or substance induced. Common substances indicated include cocaine, amphetamines, acetaminophen, opioids, and alcohol.10 It classically presents with muscle pain and a marked elevation in serum CPK level, but other metabolic disturbances, acute kidney injury, or toxic hepatitis may also occur. A more uncommon sequela of rhabdomyolysis is plexopathy caused by edematous swelling and compression of the surrounding structures.

Rare cases of brachial plexopathy caused by rhabdomyolysis following substance use have been described. In many of these cases, rhabdomyolysis occurred after alcohol use with or without concurrent use of prescription opioids or heroin.7-9 One case following use of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamptamine (MDMA) and marijuana use was reported.1 Another case of concurrent brachial plexopathy and Horner syndrome in a 29-year-old male patient following ingestion of alcohol and opioids has also been described.5 The rate of occurrence of this phenomenon in the general population is unknown.

The pathophysiology of rhabdomyolysis caused by substance use has not been definitively identified, but it is hypothesized that the cause is 2-fold. The first insult is the direct toxicity of the substances to myocytes.8,9 The second factor is prolonged immobilization in a position that compresses the affected musculature and blood supply, causing both mechanical stress and ischemia to the muscles and brachial plexus. This prolonged immobilization can frequently follow use of substances, such as alcohol or opioids.9 Cases have been reported wherein rhabdomyolysis causing brachial plexopathy occurred despite relatively normal positioning of the arms and shoulders during sleep.9 In our case, the patient had fallen asleep with his arms crossed over his chest in the prone position with his head turned, though he could not recall to which side. Although he stated that he had slept in this position regularly, the effects of fentanyl may have prevented the patient from waking to adjust his posture. This position had potential to compress the musculature of the neck and shoulders and restrict blood flow, resulting in the focal rhabdomyolysis seen in this patient. In theory, the position could also cause a stretch injury of the brachial plexus, although a pure stretch injury would more likely present unilaterally and without evidence of rhabdomyolysis.

Chronic ethanol use may have been a major contributor by both sensitizing the muscles to toxicity of other substances and induction of CYP450 enzymes that are normally responsible for metabolizing other drugs.8 Alcohol also inhibits gluconeogenesis and leads to hyperpolarization of myocytes, further contributing to their susceptibility to damage.9 Our patient had a prior history of alcohol use years before this event, but not at the time of this event.

Our patient had other known risk factors for rhabdomyolysis, including his long-term statin therapy, but it is unclear whether these were contributing factors in his case.10 Of the medications that are known to cause rhabdomyolysis, statins are among the most commonly described, although the mechanism through which this process occurs is not clear. A case of rhabdomyolysis following use of cocaine and heroin in a patient on long-standing statin therapy has been described.13 Our review of the literature found no cases of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis associated with brachial plexopathy. It is possible that concurrent statin therapy has an additive effect to other substances in inducing rhabdomyolysis.

Parsonage-Turner syndrome, also known as neuralgic amyotrophy, should also be included in the differential diagnosis. While there have been multiple etiologies proposed for Parsonage-Turner syndrome, it is generally thought to begin as a primary inflammatory process targeting the brachial plexus. One case report describes Parsonage-Turner syndrome progressing to secondary rhabdomyolysis.6 In this case, no primary etiology was identified, so the Parsonage-Turner syndrome diagnosis was made with secondary rhabdomyolysis.6 We believe it is possible that this case and others may have been misdiagnosed as Parsonage-Turner syndrome.

Aside from physical rehabilitation programs, cases of plexopathy secondary to rhabdomyolysis similar to our patient have largely been treated with supportive therapy and symptom management. Pain management was the primary goal in this patient, which was achieved with moderate success using a combination of muscle relaxants, antiepileptics, tramadol, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Some surgical approaches have been reported in the literature. One case of rhabdomyolysis of the shoulder girdle causing a similar process benefitted from fasciotomy and surgical decompression.7 This patient had a complete recovery of all motor functions aside from shoulder abduction at 8 weeks postoperation, but neuropathic pain persisted in both arms. It is possible our patient may have benefitted from a similar treatment. Further research is necessary to determine the utility of this type of procedure when treating such cases.

Conclusions

This case report adds to the literature describing focal rhabdomyolysis causing secondary bilateral brachial plexopathy after substance use. Further research is needed to establish a definitive pathophysiology as well as treatment guidelines. Evidence-based treatment could mean better outcomes and quicker recoveries for future patients with this condition.

1. Eker Büyüks¸ireci D, Polat M, Zinnurog˘lu M, Cengiz B, Kaymak Karatas¸ GK. Bilateral pan-plexus lesion after substance use: A case report. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;65(4):411-414. doi:10.5606/tftrd.2019.3157

2. Rubin DI. Brachial and lumbosacral plexopathies: a review. Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2020;5:173-193. doi:10.1016/j.cnp.2020.07.005

3. Oshima Y. Characteristics of drug-associated rhabdomyolysis: analysis of 8,610 cases reported to the US Food and Drug Administration. Intern Med. 2011;50(8):845-853. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4484

4. Waldman W, Kabata PM, Dines AM, et al. Rhabdomyolysis related to acute recreational drug toxicity-a euro-den study. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246297. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246297

5. Lee SC, Geannette C, Wolfe SW, Feinberg JH, Sneag DB. Rhabdomyolysis resulting in concurrent Horner’s syndrome and brachial plexopathy: a case report. Skeletal Radiology. 2017;46(8):1131-1136. doi:10.1007/s00256-017-2634-5

6. Goetsch MR, Shen J, Jones JA, Memon A, Chatham W. Neuralgic amyotrophy presenting with multifocal myonecrosis and rhabdomyolysis. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7382. doi:10.7759/cureus.7382

7. Tonetti DA, Tarkin IS, Bandi K, Moossy JJ. Complete bilateral brachial plexus injury from rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome: surgical case report. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2019;17(2):E68-e72. doi:10.1093/ons/opy289

8. Riggs JE, Schochet SS Jr, Hogg JP. Focal rhabdomyolysis and brachial plexopathy: an association with heroin and chronic ethanol use. Mil Med. 1999;164(3):228-229.

9. Maddison P. Acute rhabdomyolysis and brachial plexopathy following alcohol ingestion. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25(2):283-285. doi:10.1002/mus.10021.abs

10. Giannoglou GD, Chatzizisis YS, Misirli G. The syndrome of rhabdomyolysis: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18(2):90-100. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2006.09.020

11. Meacham MC, Lynch KL, Coffin PO, Wade A, Wheeler E, Riley ED. Addressing overdose risk among unstably housed women in San Francisco, California: an examination of potential fentanyl contamination of multiple substances. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12954-020-00361-8

12. Klar SA, Brodkin E, Gibson E, et al. Notes from the field: furanyl-fentanyl overdose events caused by smoking contaminated crack cocaine - British Columbia, Canada, July 15-18, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(37):1015-1016. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6537a6

13. Mitaritonno M, Lupo M, Greco I, Mazza A, Cervellin G. Severe rhabdomyolysis induced by co-administration of cocaine and heroin in a 45 years old man treated with rosuvastatin: a case report. Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S1):e2021089. doi:10.23750/abm.v92iS1.8858

The brachial plexus is a group of interwoven nerves arising from the cervical spinal cord and coursing through the neck, shoulder, and axilla with terminal branches extending to the distal arm.1 Disorders of the brachial plexus are more rare than other isolated peripheral nerve disorders, trauma being the most common etiology.1 Traction, neoplasms, radiation exposure, external compression, and inflammatory processes, such as Parsonage-Turner syndrome, have also been described as less common etiologies.2

Rhabdomyolysis, a condition in which muscle breakdown occurs, is an uncommon and perhaps underrecognized cause of brachial plexopathy. Rhabdomyolysis is often caused by muscle overuse, trauma, prolonged immobilization, drugs, or toxins. Substances indicated as precipitating factors include alcohol, opioids, cocaine, and amphetamines.3,4 As rhabdomyolysis progresses, swelling and edema can compress surrounding structures. Therefore, in cases of rhabdomyolysis involving the muscles of the neck and shoulder girdle, external compression of the brachial plexus can potentially cause brachial plexopathy. Rare cases of this phenomenon occurring as a sequela of substance use have been described.1,5-9 Few cases have been reported in the literature.

The following case report describes a patient who

Case Presentation

A 68-year-old male patient with a history of polysubstance use disorder presented to the emergency department with complete loss of sensory and motor function of both arms. He had fallen asleep on his couch the previous evening with his arms crossed over his chest in the prone position.

On admission, the patient presented with an agitated mental status. The patient presented with 0/5 strength bilaterally in the upper extremities (UEs) accompanied by numbness and tingling. Radial pulses were palpable in both arms. All UE reflexes were absent, but patellar reflex was intact bilaterally. On hospital day 2, the patient was awake, alert, and oriented to person, place, and time and could provide a full history. The patient’s cranial nerves were intact with shoulder shrug testing mildly weak at 4/5 strength.

Serum electrolytes and glucose levels were normal. The creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level was elevated at 21,292 IU/L. Creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels were elevated at 1.7 mg/dL and 32 mg/dL, respectively. Serum B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c levels were normal.

Due to the absence of evidence of spinal cord injury, presence of normal motor and sensory function of the lower extremities, an elevated CPK level, signal hyperintensities of the muscles of the shoulder girdle, and the patient’s history, the leading diagnosis at this time was brachial plexopathy secondary to focal rhabdomyolysis.

Over the next week, the patient regained some motor function of the left hand and some sensory function bilaterally. At 8 weeks postadmission, a nerve conduction study showed prolonged latencies in the median and ulnar nerves bilaterally. The following week, the patient reported pain in both shoulders (left greater than the right) as well as weakness of shoulder movement on the left greater than the right. There was pain in the right arm throughout. On examination, there was improved function of the arms distal to the elbow, which was better on the right side despite the associated pain (Table). There was atrophy of the left scapular muscles, hypothenar eminence, and deltoid muscle. There was weakness of the left triceps, with slight fourth and fifth finger flexion. The patient was unable to elevate or abduct the left shoulder but could elevate the right shoulder up to 45°. Sensation was decreased over the right outer arm and left posterior upper arm, with hypersensitivity in the right medial upper and lower arm. Deep tendon reflexes were absent in the upper arm aside from the biceps reflex (1+). All reflexes of the lower extremities were normal. It is interesting to note the relative greater improvement on the right despite the edema found on initial imaging being more prominent on the right.

Discussion

Rhabdomyolysis is a condition defined by myocyte necrosis that results in release of cellular contents and local edema. Inciting events may be traumatic, metabolic, ischemic, or substance induced. Common substances indicated include cocaine, amphetamines, acetaminophen, opioids, and alcohol.10 It classically presents with muscle pain and a marked elevation in serum CPK level, but other metabolic disturbances, acute kidney injury, or toxic hepatitis may also occur. A more uncommon sequela of rhabdomyolysis is plexopathy caused by edematous swelling and compression of the surrounding structures.

Rare cases of brachial plexopathy caused by rhabdomyolysis following substance use have been described. In many of these cases, rhabdomyolysis occurred after alcohol use with or without concurrent use of prescription opioids or heroin.7-9 One case following use of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamptamine (MDMA) and marijuana use was reported.1 Another case of concurrent brachial plexopathy and Horner syndrome in a 29-year-old male patient following ingestion of alcohol and opioids has also been described.5 The rate of occurrence of this phenomenon in the general population is unknown.

The pathophysiology of rhabdomyolysis caused by substance use has not been definitively identified, but it is hypothesized that the cause is 2-fold. The first insult is the direct toxicity of the substances to myocytes.8,9 The second factor is prolonged immobilization in a position that compresses the affected musculature and blood supply, causing both mechanical stress and ischemia to the muscles and brachial plexus. This prolonged immobilization can frequently follow use of substances, such as alcohol or opioids.9 Cases have been reported wherein rhabdomyolysis causing brachial plexopathy occurred despite relatively normal positioning of the arms and shoulders during sleep.9 In our case, the patient had fallen asleep with his arms crossed over his chest in the prone position with his head turned, though he could not recall to which side. Although he stated that he had slept in this position regularly, the effects of fentanyl may have prevented the patient from waking to adjust his posture. This position had potential to compress the musculature of the neck and shoulders and restrict blood flow, resulting in the focal rhabdomyolysis seen in this patient. In theory, the position could also cause a stretch injury of the brachial plexus, although a pure stretch injury would more likely present unilaterally and without evidence of rhabdomyolysis.

Chronic ethanol use may have been a major contributor by both sensitizing the muscles to toxicity of other substances and induction of CYP450 enzymes that are normally responsible for metabolizing other drugs.8 Alcohol also inhibits gluconeogenesis and leads to hyperpolarization of myocytes, further contributing to their susceptibility to damage.9 Our patient had a prior history of alcohol use years before this event, but not at the time of this event.

Our patient had other known risk factors for rhabdomyolysis, including his long-term statin therapy, but it is unclear whether these were contributing factors in his case.10 Of the medications that are known to cause rhabdomyolysis, statins are among the most commonly described, although the mechanism through which this process occurs is not clear. A case of rhabdomyolysis following use of cocaine and heroin in a patient on long-standing statin therapy has been described.13 Our review of the literature found no cases of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis associated with brachial plexopathy. It is possible that concurrent statin therapy has an additive effect to other substances in inducing rhabdomyolysis.

Parsonage-Turner syndrome, also known as neuralgic amyotrophy, should also be included in the differential diagnosis. While there have been multiple etiologies proposed for Parsonage-Turner syndrome, it is generally thought to begin as a primary inflammatory process targeting the brachial plexus. One case report describes Parsonage-Turner syndrome progressing to secondary rhabdomyolysis.6 In this case, no primary etiology was identified, so the Parsonage-Turner syndrome diagnosis was made with secondary rhabdomyolysis.6 We believe it is possible that this case and others may have been misdiagnosed as Parsonage-Turner syndrome.

Aside from physical rehabilitation programs, cases of plexopathy secondary to rhabdomyolysis similar to our patient have largely been treated with supportive therapy and symptom management. Pain management was the primary goal in this patient, which was achieved with moderate success using a combination of muscle relaxants, antiepileptics, tramadol, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Some surgical approaches have been reported in the literature. One case of rhabdomyolysis of the shoulder girdle causing a similar process benefitted from fasciotomy and surgical decompression.7 This patient had a complete recovery of all motor functions aside from shoulder abduction at 8 weeks postoperation, but neuropathic pain persisted in both arms. It is possible our patient may have benefitted from a similar treatment. Further research is necessary to determine the utility of this type of procedure when treating such cases.

Conclusions

This case report adds to the literature describing focal rhabdomyolysis causing secondary bilateral brachial plexopathy after substance use. Further research is needed to establish a definitive pathophysiology as well as treatment guidelines. Evidence-based treatment could mean better outcomes and quicker recoveries for future patients with this condition.

The brachial plexus is a group of interwoven nerves arising from the cervical spinal cord and coursing through the neck, shoulder, and axilla with terminal branches extending to the distal arm.1 Disorders of the brachial plexus are more rare than other isolated peripheral nerve disorders, trauma being the most common etiology.1 Traction, neoplasms, radiation exposure, external compression, and inflammatory processes, such as Parsonage-Turner syndrome, have also been described as less common etiologies.2

Rhabdomyolysis, a condition in which muscle breakdown occurs, is an uncommon and perhaps underrecognized cause of brachial plexopathy. Rhabdomyolysis is often caused by muscle overuse, trauma, prolonged immobilization, drugs, or toxins. Substances indicated as precipitating factors include alcohol, opioids, cocaine, and amphetamines.3,4 As rhabdomyolysis progresses, swelling and edema can compress surrounding structures. Therefore, in cases of rhabdomyolysis involving the muscles of the neck and shoulder girdle, external compression of the brachial plexus can potentially cause brachial plexopathy. Rare cases of this phenomenon occurring as a sequela of substance use have been described.1,5-9 Few cases have been reported in the literature.

The following case report describes a patient who

Case Presentation

A 68-year-old male patient with a history of polysubstance use disorder presented to the emergency department with complete loss of sensory and motor function of both arms. He had fallen asleep on his couch the previous evening with his arms crossed over his chest in the prone position.

On admission, the patient presented with an agitated mental status. The patient presented with 0/5 strength bilaterally in the upper extremities (UEs) accompanied by numbness and tingling. Radial pulses were palpable in both arms. All UE reflexes were absent, but patellar reflex was intact bilaterally. On hospital day 2, the patient was awake, alert, and oriented to person, place, and time and could provide a full history. The patient’s cranial nerves were intact with shoulder shrug testing mildly weak at 4/5 strength.

Serum electrolytes and glucose levels were normal. The creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level was elevated at 21,292 IU/L. Creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels were elevated at 1.7 mg/dL and 32 mg/dL, respectively. Serum B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c levels were normal.

Due to the absence of evidence of spinal cord injury, presence of normal motor and sensory function of the lower extremities, an elevated CPK level, signal hyperintensities of the muscles of the shoulder girdle, and the patient’s history, the leading diagnosis at this time was brachial plexopathy secondary to focal rhabdomyolysis.

Over the next week, the patient regained some motor function of the left hand and some sensory function bilaterally. At 8 weeks postadmission, a nerve conduction study showed prolonged latencies in the median and ulnar nerves bilaterally. The following week, the patient reported pain in both shoulders (left greater than the right) as well as weakness of shoulder movement on the left greater than the right. There was pain in the right arm throughout. On examination, there was improved function of the arms distal to the elbow, which was better on the right side despite the associated pain (Table). There was atrophy of the left scapular muscles, hypothenar eminence, and deltoid muscle. There was weakness of the left triceps, with slight fourth and fifth finger flexion. The patient was unable to elevate or abduct the left shoulder but could elevate the right shoulder up to 45°. Sensation was decreased over the right outer arm and left posterior upper arm, with hypersensitivity in the right medial upper and lower arm. Deep tendon reflexes were absent in the upper arm aside from the biceps reflex (1+). All reflexes of the lower extremities were normal. It is interesting to note the relative greater improvement on the right despite the edema found on initial imaging being more prominent on the right.

Discussion

Rhabdomyolysis is a condition defined by myocyte necrosis that results in release of cellular contents and local edema. Inciting events may be traumatic, metabolic, ischemic, or substance induced. Common substances indicated include cocaine, amphetamines, acetaminophen, opioids, and alcohol.10 It classically presents with muscle pain and a marked elevation in serum CPK level, but other metabolic disturbances, acute kidney injury, or toxic hepatitis may also occur. A more uncommon sequela of rhabdomyolysis is plexopathy caused by edematous swelling and compression of the surrounding structures.

Rare cases of brachial plexopathy caused by rhabdomyolysis following substance use have been described. In many of these cases, rhabdomyolysis occurred after alcohol use with or without concurrent use of prescription opioids or heroin.7-9 One case following use of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamptamine (MDMA) and marijuana use was reported.1 Another case of concurrent brachial plexopathy and Horner syndrome in a 29-year-old male patient following ingestion of alcohol and opioids has also been described.5 The rate of occurrence of this phenomenon in the general population is unknown.

The pathophysiology of rhabdomyolysis caused by substance use has not been definitively identified, but it is hypothesized that the cause is 2-fold. The first insult is the direct toxicity of the substances to myocytes.8,9 The second factor is prolonged immobilization in a position that compresses the affected musculature and blood supply, causing both mechanical stress and ischemia to the muscles and brachial plexus. This prolonged immobilization can frequently follow use of substances, such as alcohol or opioids.9 Cases have been reported wherein rhabdomyolysis causing brachial plexopathy occurred despite relatively normal positioning of the arms and shoulders during sleep.9 In our case, the patient had fallen asleep with his arms crossed over his chest in the prone position with his head turned, though he could not recall to which side. Although he stated that he had slept in this position regularly, the effects of fentanyl may have prevented the patient from waking to adjust his posture. This position had potential to compress the musculature of the neck and shoulders and restrict blood flow, resulting in the focal rhabdomyolysis seen in this patient. In theory, the position could also cause a stretch injury of the brachial plexus, although a pure stretch injury would more likely present unilaterally and without evidence of rhabdomyolysis.

Chronic ethanol use may have been a major contributor by both sensitizing the muscles to toxicity of other substances and induction of CYP450 enzymes that are normally responsible for metabolizing other drugs.8 Alcohol also inhibits gluconeogenesis and leads to hyperpolarization of myocytes, further contributing to their susceptibility to damage.9 Our patient had a prior history of alcohol use years before this event, but not at the time of this event.

Our patient had other known risk factors for rhabdomyolysis, including his long-term statin therapy, but it is unclear whether these were contributing factors in his case.10 Of the medications that are known to cause rhabdomyolysis, statins are among the most commonly described, although the mechanism through which this process occurs is not clear. A case of rhabdomyolysis following use of cocaine and heroin in a patient on long-standing statin therapy has been described.13 Our review of the literature found no cases of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis associated with brachial plexopathy. It is possible that concurrent statin therapy has an additive effect to other substances in inducing rhabdomyolysis.

Parsonage-Turner syndrome, also known as neuralgic amyotrophy, should also be included in the differential diagnosis. While there have been multiple etiologies proposed for Parsonage-Turner syndrome, it is generally thought to begin as a primary inflammatory process targeting the brachial plexus. One case report describes Parsonage-Turner syndrome progressing to secondary rhabdomyolysis.6 In this case, no primary etiology was identified, so the Parsonage-Turner syndrome diagnosis was made with secondary rhabdomyolysis.6 We believe it is possible that this case and others may have been misdiagnosed as Parsonage-Turner syndrome.

Aside from physical rehabilitation programs, cases of plexopathy secondary to rhabdomyolysis similar to our patient have largely been treated with supportive therapy and symptom management. Pain management was the primary goal in this patient, which was achieved with moderate success using a combination of muscle relaxants, antiepileptics, tramadol, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Some surgical approaches have been reported in the literature. One case of rhabdomyolysis of the shoulder girdle causing a similar process benefitted from fasciotomy and surgical decompression.7 This patient had a complete recovery of all motor functions aside from shoulder abduction at 8 weeks postoperation, but neuropathic pain persisted in both arms. It is possible our patient may have benefitted from a similar treatment. Further research is necessary to determine the utility of this type of procedure when treating such cases.

Conclusions

This case report adds to the literature describing focal rhabdomyolysis causing secondary bilateral brachial plexopathy after substance use. Further research is needed to establish a definitive pathophysiology as well as treatment guidelines. Evidence-based treatment could mean better outcomes and quicker recoveries for future patients with this condition.

1. Eker Büyüks¸ireci D, Polat M, Zinnurog˘lu M, Cengiz B, Kaymak Karatas¸ GK. Bilateral pan-plexus lesion after substance use: A case report. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;65(4):411-414. doi:10.5606/tftrd.2019.3157

2. Rubin DI. Brachial and lumbosacral plexopathies: a review. Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2020;5:173-193. doi:10.1016/j.cnp.2020.07.005

3. Oshima Y. Characteristics of drug-associated rhabdomyolysis: analysis of 8,610 cases reported to the US Food and Drug Administration. Intern Med. 2011;50(8):845-853. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4484

4. Waldman W, Kabata PM, Dines AM, et al. Rhabdomyolysis related to acute recreational drug toxicity-a euro-den study. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246297. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246297

5. Lee SC, Geannette C, Wolfe SW, Feinberg JH, Sneag DB. Rhabdomyolysis resulting in concurrent Horner’s syndrome and brachial plexopathy: a case report. Skeletal Radiology. 2017;46(8):1131-1136. doi:10.1007/s00256-017-2634-5

6. Goetsch MR, Shen J, Jones JA, Memon A, Chatham W. Neuralgic amyotrophy presenting with multifocal myonecrosis and rhabdomyolysis. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7382. doi:10.7759/cureus.7382

7. Tonetti DA, Tarkin IS, Bandi K, Moossy JJ. Complete bilateral brachial plexus injury from rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome: surgical case report. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2019;17(2):E68-e72. doi:10.1093/ons/opy289

8. Riggs JE, Schochet SS Jr, Hogg JP. Focal rhabdomyolysis and brachial plexopathy: an association with heroin and chronic ethanol use. Mil Med. 1999;164(3):228-229.

9. Maddison P. Acute rhabdomyolysis and brachial plexopathy following alcohol ingestion. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25(2):283-285. doi:10.1002/mus.10021.abs

10. Giannoglou GD, Chatzizisis YS, Misirli G. The syndrome of rhabdomyolysis: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18(2):90-100. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2006.09.020

11. Meacham MC, Lynch KL, Coffin PO, Wade A, Wheeler E, Riley ED. Addressing overdose risk among unstably housed women in San Francisco, California: an examination of potential fentanyl contamination of multiple substances. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12954-020-00361-8

12. Klar SA, Brodkin E, Gibson E, et al. Notes from the field: furanyl-fentanyl overdose events caused by smoking contaminated crack cocaine - British Columbia, Canada, July 15-18, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(37):1015-1016. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6537a6

13. Mitaritonno M, Lupo M, Greco I, Mazza A, Cervellin G. Severe rhabdomyolysis induced by co-administration of cocaine and heroin in a 45 years old man treated with rosuvastatin: a case report. Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S1):e2021089. doi:10.23750/abm.v92iS1.8858

1. Eker Büyüks¸ireci D, Polat M, Zinnurog˘lu M, Cengiz B, Kaymak Karatas¸ GK. Bilateral pan-plexus lesion after substance use: A case report. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;65(4):411-414. doi:10.5606/tftrd.2019.3157

2. Rubin DI. Brachial and lumbosacral plexopathies: a review. Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2020;5:173-193. doi:10.1016/j.cnp.2020.07.005

3. Oshima Y. Characteristics of drug-associated rhabdomyolysis: analysis of 8,610 cases reported to the US Food and Drug Administration. Intern Med. 2011;50(8):845-853. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4484

4. Waldman W, Kabata PM, Dines AM, et al. Rhabdomyolysis related to acute recreational drug toxicity-a euro-den study. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246297. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246297

5. Lee SC, Geannette C, Wolfe SW, Feinberg JH, Sneag DB. Rhabdomyolysis resulting in concurrent Horner’s syndrome and brachial plexopathy: a case report. Skeletal Radiology. 2017;46(8):1131-1136. doi:10.1007/s00256-017-2634-5

6. Goetsch MR, Shen J, Jones JA, Memon A, Chatham W. Neuralgic amyotrophy presenting with multifocal myonecrosis and rhabdomyolysis. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7382. doi:10.7759/cureus.7382

7. Tonetti DA, Tarkin IS, Bandi K, Moossy JJ. Complete bilateral brachial plexus injury from rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome: surgical case report. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2019;17(2):E68-e72. doi:10.1093/ons/opy289

8. Riggs JE, Schochet SS Jr, Hogg JP. Focal rhabdomyolysis and brachial plexopathy: an association with heroin and chronic ethanol use. Mil Med. 1999;164(3):228-229.

9. Maddison P. Acute rhabdomyolysis and brachial plexopathy following alcohol ingestion. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25(2):283-285. doi:10.1002/mus.10021.abs

10. Giannoglou GD, Chatzizisis YS, Misirli G. The syndrome of rhabdomyolysis: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18(2):90-100. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2006.09.020

11. Meacham MC, Lynch KL, Coffin PO, Wade A, Wheeler E, Riley ED. Addressing overdose risk among unstably housed women in San Francisco, California: an examination of potential fentanyl contamination of multiple substances. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12954-020-00361-8

12. Klar SA, Brodkin E, Gibson E, et al. Notes from the field: furanyl-fentanyl overdose events caused by smoking contaminated crack cocaine - British Columbia, Canada, July 15-18, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(37):1015-1016. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6537a6

13. Mitaritonno M, Lupo M, Greco I, Mazza A, Cervellin G. Severe rhabdomyolysis induced by co-administration of cocaine and heroin in a 45 years old man treated with rosuvastatin: a case report. Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S1):e2021089. doi:10.23750/abm.v92iS1.8858

New National Lipid Association statement on statin intolerance

The U.S. National Lipid Association has issued a new scientific statement on the management of patients with statin intolerance, which recommends different strategies to help patients stay on statin medications, and also suggests alternatives that can be used in patients who really cannot tolerate statin drugs.

The statement was published online in the Journal of Clinical Lipidology.

It notes that, although statins are generally well tolerated, statin intolerance is reported in 5%-30% of patients and contributes to reduced statin adherence and persistence, as well as higher risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

The statement acknowledges the importance of identifying modifiable risk factors for statin intolerance and recognizes the possibility of a “nocebo” effect, basically the patient expectation of harm resulting in perceived side effects.

To identify a tolerable statin regimen, it recommends that clinicians consider using several different strategies (different statin, dose, and/or dosing frequency), and to classify a patient as having statin intolerance, a minimum of two statins should have been attempted, including at least one at the lowest-approved daily dosage.

The statement says that nonstatin therapy may be required for patients who cannot reach therapeutic objectives with lifestyle and maximal tolerated statin therapy, and in these cases, therapies with outcomes data from randomized trials showing reduced cardiovascular events are favored.

In high and very high-risk patients who are statin intolerant, clinicians should consider initiating nonstatin therapy while additional attempts are made to identify a tolerable statin in order to limit the time of exposure to elevated levels of atherogenic lipoproteins, it suggests.

“There is strong evidence that statins reduce risk of cardiovascular events particularly in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, but recent research shows that only about half of patients with ASCVD are on a statin,” Kevin C. Maki, PhD, coauthor of the statement and current president of the National Lipid Association, said in an interview.

“There is an urgent problem with underutilization of statins and undertreatment of ASCVD. And we know that perceived side effects associated with statins are a common reason for discontinuation of these drugs and the consequent failure to manage ASCVD adequately,” he said.

Dr. Maki noted that the NLA’s first message is that, when experiencing symptoms taking statins, a large majority of patients can still tolerate a statin. “They can try a different agent or a different dose. But for those who still can’t tolerate a statin, we then recommend nonstatin therapies and we favor those therapies with evidence from randomized trials.”

He pointed out that many patients who believe they are experiencing side effects from taking statins still experience the same effects on a placebo, a condition known as the nocebo effect.

“Several studies have shown that the nocebo effect is very common and accounts for more than half of perceived statin side effects. It is therefore estimated that many of the complaints of statin intolerance are probably not directly related to the pharmacodynamic actions of the drugs,” Dr. Maki said.

One recent study on the nocebo effect, the SAMSON study, suggested that 90% of symptoms attributed to statins were elicited by placebo tablets too.

But Dr. Maki added that it can be a losing battle for the clinician if patients think their symptoms are related to taking a statin.

“We suggest that clinicians inform patients that most people can tolerate a statin – maybe with a different agent or an alternative dose – and it is really important to lower LDL cholesterol as that will lower the risk of MI and stroke, so we need to find a regimen that works for each individual,” he said. “Most people can find a regimen that works. If this means taking a lower dose of a statin, they can take some additional therapy as well. This is a better situation than stopping taking statins altogether and allowing ASCVD to progress.”

Dr. Maki stressed that statins should still be the first choice as they are effective, taken orally, and inexpensive.

“Other medications do not have all these advantages. For example, PCSK9 inhibitors are very effective but they are expensive and injectable,” he noted. “And while ezetimibe [Zetia] is now generic so inexpensive, it has a more modest effect on LDL-lowering compared to statins, so by itself it is not normally enough for most patients to get to their target LDL, but it is an option for use in combination with a statin.”

He added that the NLA message is to do everything possible to keep patients on a statin, especially patients with preexisting ASCVD.

“We would like these patients to be on high-intensity statins. If they really can’t tolerate this, then they could be on a low-intensity statin plus an additional agent.”

Commenting on the NLA statement, SAMSON study coauthor James Howard, MB BChir, PhD, Imperial College London, said he had reservations about some of the recommendations.

“Whilst I think it is great news that the existence and importance of the nocebo effect is increasingly recognized in international guidelines and statements, I think we need to be very careful about recommending reduced doses and frequencies of statins,” Dr. Howard said.

“Studies such as SAMSON and StatinWISE indicate the vast majority of side effects reported by patients taking statins are not caused by the statin molecule, but instead are caused by either the nocebo effect, or ever-present background symptoms that are wrongly attributed to the statins,” he commented. “Therefore, to recommend that the correct approach in a patient with a history of MI suffering symptoms on 80 mg of atorvastatin is to reduce the dose or try alternate daily dosing. This reinforces the view that these drugs are side-effect prone and need to be carefully titrated.”

Dr. Howard suggested that patients should be educated on the possibility of the nocebo effect or background symptoms and encouraged to retrial statins at the same dose. “If that doesn’t work, then formal recording with a symptom diary might help patients recognize background symptoms,” he added.

Dr. Howard noted that, if symptoms still persist, an “n-of-1” trial could be conducted, in which the patient rotates between multiple periods of taking a statin and a placebo, but he acknowledged that this is expensive and time consuming.

Also commenting, Steve Nissen, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said he thought the NLA statement was “reasonable and thoughtful.”

“Regardless of whether the symptoms are due to the nocebo effect or not, some patients will just not take a statin no matter how hard you try to convince them to persevere, so we do need alternatives,” Dr. Nissen said.

He noted that current alternatives would include the PCSK9 inhibitors and ezetimibe, but a future candidate could be the oral bempedoic acid (Nexletol), which is currently being evaluated in a large outcomes trial (CLEAR Outcomes).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. National Lipid Association has issued a new scientific statement on the management of patients with statin intolerance, which recommends different strategies to help patients stay on statin medications, and also suggests alternatives that can be used in patients who really cannot tolerate statin drugs.

The statement was published online in the Journal of Clinical Lipidology.

It notes that, although statins are generally well tolerated, statin intolerance is reported in 5%-30% of patients and contributes to reduced statin adherence and persistence, as well as higher risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

The statement acknowledges the importance of identifying modifiable risk factors for statin intolerance and recognizes the possibility of a “nocebo” effect, basically the patient expectation of harm resulting in perceived side effects.

To identify a tolerable statin regimen, it recommends that clinicians consider using several different strategies (different statin, dose, and/or dosing frequency), and to classify a patient as having statin intolerance, a minimum of two statins should have been attempted, including at least one at the lowest-approved daily dosage.

The statement says that nonstatin therapy may be required for patients who cannot reach therapeutic objectives with lifestyle and maximal tolerated statin therapy, and in these cases, therapies with outcomes data from randomized trials showing reduced cardiovascular events are favored.

In high and very high-risk patients who are statin intolerant, clinicians should consider initiating nonstatin therapy while additional attempts are made to identify a tolerable statin in order to limit the time of exposure to elevated levels of atherogenic lipoproteins, it suggests.

“There is strong evidence that statins reduce risk of cardiovascular events particularly in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, but recent research shows that only about half of patients with ASCVD are on a statin,” Kevin C. Maki, PhD, coauthor of the statement and current president of the National Lipid Association, said in an interview.

“There is an urgent problem with underutilization of statins and undertreatment of ASCVD. And we know that perceived side effects associated with statins are a common reason for discontinuation of these drugs and the consequent failure to manage ASCVD adequately,” he said.

Dr. Maki noted that the NLA’s first message is that, when experiencing symptoms taking statins, a large majority of patients can still tolerate a statin. “They can try a different agent or a different dose. But for those who still can’t tolerate a statin, we then recommend nonstatin therapies and we favor those therapies with evidence from randomized trials.”

He pointed out that many patients who believe they are experiencing side effects from taking statins still experience the same effects on a placebo, a condition known as the nocebo effect.

“Several studies have shown that the nocebo effect is very common and accounts for more than half of perceived statin side effects. It is therefore estimated that many of the complaints of statin intolerance are probably not directly related to the pharmacodynamic actions of the drugs,” Dr. Maki said.

One recent study on the nocebo effect, the SAMSON study, suggested that 90% of symptoms attributed to statins were elicited by placebo tablets too.

But Dr. Maki added that it can be a losing battle for the clinician if patients think their symptoms are related to taking a statin.

“We suggest that clinicians inform patients that most people can tolerate a statin – maybe with a different agent or an alternative dose – and it is really important to lower LDL cholesterol as that will lower the risk of MI and stroke, so we need to find a regimen that works for each individual,” he said. “Most people can find a regimen that works. If this means taking a lower dose of a statin, they can take some additional therapy as well. This is a better situation than stopping taking statins altogether and allowing ASCVD to progress.”

Dr. Maki stressed that statins should still be the first choice as they are effective, taken orally, and inexpensive.

“Other medications do not have all these advantages. For example, PCSK9 inhibitors are very effective but they are expensive and injectable,” he noted. “And while ezetimibe [Zetia] is now generic so inexpensive, it has a more modest effect on LDL-lowering compared to statins, so by itself it is not normally enough for most patients to get to their target LDL, but it is an option for use in combination with a statin.”

He added that the NLA message is to do everything possible to keep patients on a statin, especially patients with preexisting ASCVD.

“We would like these patients to be on high-intensity statins. If they really can’t tolerate this, then they could be on a low-intensity statin plus an additional agent.”

Commenting on the NLA statement, SAMSON study coauthor James Howard, MB BChir, PhD, Imperial College London, said he had reservations about some of the recommendations.

“Whilst I think it is great news that the existence and importance of the nocebo effect is increasingly recognized in international guidelines and statements, I think we need to be very careful about recommending reduced doses and frequencies of statins,” Dr. Howard said.

“Studies such as SAMSON and StatinWISE indicate the vast majority of side effects reported by patients taking statins are not caused by the statin molecule, but instead are caused by either the nocebo effect, or ever-present background symptoms that are wrongly attributed to the statins,” he commented. “Therefore, to recommend that the correct approach in a patient with a history of MI suffering symptoms on 80 mg of atorvastatin is to reduce the dose or try alternate daily dosing. This reinforces the view that these drugs are side-effect prone and need to be carefully titrated.”

Dr. Howard suggested that patients should be educated on the possibility of the nocebo effect or background symptoms and encouraged to retrial statins at the same dose. “If that doesn’t work, then formal recording with a symptom diary might help patients recognize background symptoms,” he added.

Dr. Howard noted that, if symptoms still persist, an “n-of-1” trial could be conducted, in which the patient rotates between multiple periods of taking a statin and a placebo, but he acknowledged that this is expensive and time consuming.

Also commenting, Steve Nissen, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said he thought the NLA statement was “reasonable and thoughtful.”

“Regardless of whether the symptoms are due to the nocebo effect or not, some patients will just not take a statin no matter how hard you try to convince them to persevere, so we do need alternatives,” Dr. Nissen said.

He noted that current alternatives would include the PCSK9 inhibitors and ezetimibe, but a future candidate could be the oral bempedoic acid (Nexletol), which is currently being evaluated in a large outcomes trial (CLEAR Outcomes).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. National Lipid Association has issued a new scientific statement on the management of patients with statin intolerance, which recommends different strategies to help patients stay on statin medications, and also suggests alternatives that can be used in patients who really cannot tolerate statin drugs.

The statement was published online in the Journal of Clinical Lipidology.

It notes that, although statins are generally well tolerated, statin intolerance is reported in 5%-30% of patients and contributes to reduced statin adherence and persistence, as well as higher risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

The statement acknowledges the importance of identifying modifiable risk factors for statin intolerance and recognizes the possibility of a “nocebo” effect, basically the patient expectation of harm resulting in perceived side effects.

To identify a tolerable statin regimen, it recommends that clinicians consider using several different strategies (different statin, dose, and/or dosing frequency), and to classify a patient as having statin intolerance, a minimum of two statins should have been attempted, including at least one at the lowest-approved daily dosage.

The statement says that nonstatin therapy may be required for patients who cannot reach therapeutic objectives with lifestyle and maximal tolerated statin therapy, and in these cases, therapies with outcomes data from randomized trials showing reduced cardiovascular events are favored.

In high and very high-risk patients who are statin intolerant, clinicians should consider initiating nonstatin therapy while additional attempts are made to identify a tolerable statin in order to limit the time of exposure to elevated levels of atherogenic lipoproteins, it suggests.

“There is strong evidence that statins reduce risk of cardiovascular events particularly in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, but recent research shows that only about half of patients with ASCVD are on a statin,” Kevin C. Maki, PhD, coauthor of the statement and current president of the National Lipid Association, said in an interview.

“There is an urgent problem with underutilization of statins and undertreatment of ASCVD. And we know that perceived side effects associated with statins are a common reason for discontinuation of these drugs and the consequent failure to manage ASCVD adequately,” he said.

Dr. Maki noted that the NLA’s first message is that, when experiencing symptoms taking statins, a large majority of patients can still tolerate a statin. “They can try a different agent or a different dose. But for those who still can’t tolerate a statin, we then recommend nonstatin therapies and we favor those therapies with evidence from randomized trials.”

He pointed out that many patients who believe they are experiencing side effects from taking statins still experience the same effects on a placebo, a condition known as the nocebo effect.

“Several studies have shown that the nocebo effect is very common and accounts for more than half of perceived statin side effects. It is therefore estimated that many of the complaints of statin intolerance are probably not directly related to the pharmacodynamic actions of the drugs,” Dr. Maki said.

One recent study on the nocebo effect, the SAMSON study, suggested that 90% of symptoms attributed to statins were elicited by placebo tablets too.

But Dr. Maki added that it can be a losing battle for the clinician if patients think their symptoms are related to taking a statin.

“We suggest that clinicians inform patients that most people can tolerate a statin – maybe with a different agent or an alternative dose – and it is really important to lower LDL cholesterol as that will lower the risk of MI and stroke, so we need to find a regimen that works for each individual,” he said. “Most people can find a regimen that works. If this means taking a lower dose of a statin, they can take some additional therapy as well. This is a better situation than stopping taking statins altogether and allowing ASCVD to progress.”

Dr. Maki stressed that statins should still be the first choice as they are effective, taken orally, and inexpensive.

“Other medications do not have all these advantages. For example, PCSK9 inhibitors are very effective but they are expensive and injectable,” he noted. “And while ezetimibe [Zetia] is now generic so inexpensive, it has a more modest effect on LDL-lowering compared to statins, so by itself it is not normally enough for most patients to get to their target LDL, but it is an option for use in combination with a statin.”

He added that the NLA message is to do everything possible to keep patients on a statin, especially patients with preexisting ASCVD.

“We would like these patients to be on high-intensity statins. If they really can’t tolerate this, then they could be on a low-intensity statin plus an additional agent.”

Commenting on the NLA statement, SAMSON study coauthor James Howard, MB BChir, PhD, Imperial College London, said he had reservations about some of the recommendations.

“Whilst I think it is great news that the existence and importance of the nocebo effect is increasingly recognized in international guidelines and statements, I think we need to be very careful about recommending reduced doses and frequencies of statins,” Dr. Howard said.

“Studies such as SAMSON and StatinWISE indicate the vast majority of side effects reported by patients taking statins are not caused by the statin molecule, but instead are caused by either the nocebo effect, or ever-present background symptoms that are wrongly attributed to the statins,” he commented. “Therefore, to recommend that the correct approach in a patient with a history of MI suffering symptoms on 80 mg of atorvastatin is to reduce the dose or try alternate daily dosing. This reinforces the view that these drugs are side-effect prone and need to be carefully titrated.”

Dr. Howard suggested that patients should be educated on the possibility of the nocebo effect or background symptoms and encouraged to retrial statins at the same dose. “If that doesn’t work, then formal recording with a symptom diary might help patients recognize background symptoms,” he added.

Dr. Howard noted that, if symptoms still persist, an “n-of-1” trial could be conducted, in which the patient rotates between multiple periods of taking a statin and a placebo, but he acknowledged that this is expensive and time consuming.

Also commenting, Steve Nissen, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said he thought the NLA statement was “reasonable and thoughtful.”

“Regardless of whether the symptoms are due to the nocebo effect or not, some patients will just not take a statin no matter how hard you try to convince them to persevere, so we do need alternatives,” Dr. Nissen said.

He noted that current alternatives would include the PCSK9 inhibitors and ezetimibe, but a future candidate could be the oral bempedoic acid (Nexletol), which is currently being evaluated in a large outcomes trial (CLEAR Outcomes).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL LIPIDOLOGY

Pediatric hepatitis has not increased during pandemic: CDC

The number of pediatric hepatitis cases has remained steady since 2017, new research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests, despite the recent investigation into children with hepatitis of unknown cause. The study also found that there was no indication of elevated rates of adenovirus type 40/41 infection in children.

But Rohit Kohli, MBBS, MS, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, California, says that although the study is “well-designed and robust,” that does not mean that these hepatitis cases of unknown origin are no longer a concern. He was not involved with the CDC research. “As a clinician, I’m still worried,” he said. “Why I feel like this is not conclusive is that there are other data from entities like the United Kingdom Health Security Agency that are incongruent with [these findings],” he said.

The research was published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In November 2021, the Alabama Department of Public Health began an investigation with the CDC after a cluster of children were admitted to a children’s hospital in the state with severe hepatitis, who all tested positive for adenovirus. When the United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency announced an investigation into similar cases in early April 2022, the CDC decided to expand their search nationally.

Now, as of June 15, the agency is investigating 290 cases in 41 states and U.S. territories. Worldwide, 650 cases in 33 countries have been reported, according to the most recent update by the World Health Organization on May 27, 2022. At least 38 patients have needed liver transplants, and nine deaths have been reported to WHO.

In its most recent press call on the topic, the CDC announced that it’s aware of six deaths in the United States through May 20, 2022. The COVID-19 vaccine has been ruled out as a potential cause because the majority of affected children are unvaccinated or are too young to receive the vaccine. Adenovirus infection remains a leading suspect in these sick children because the virus has been detected in 60.8% of tested cases, WHO reports.

Investigators have detected an increase in reported pediatric hepatitis cases, compared with prior years in the United Kingdom, but it was not clear whether that same pattern would be found in the United States. Neither pediatric hepatitis nor adenovirus type 40/41 are reportable conditions in the United States. In the May 20 CDC press call, Umesh Parashar, MD, chief of the CDC’s Viral Gastroenteritis Branch, said that an estimated 1,500-2,000 children aged younger than 10 are hospitalized in the United States for hepatitis every year. “That’s a fairly large number,” he said, and it might make it difficult to detect a small increase in cases.

To better estimate trends in pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus infection in the United States, investigators collected available data on emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants associated with hepatitis in children as well as adenovirus stool testing results. Researchers used four large databases: the National Syndromic Surveillance Program; the Premier Healthcare Database Special Release; the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network; and Labcorp, which is a large commercial lab network.

To account for changes in health care utilization in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the team compared hepatitis-associated ED visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants from October 2021 to March 2022 versus the same months (January to March and October to December) in 2017, 2018, and 2019. For adenovirus stool testing, results from October 2021 to March 2022 were compared with the same calendar months (October to March) from 2017-2018, 2018-2019, and 2019-2020, to help control for seasonality.

Investigators found no statistically significant increases in the outcomes during October 2021 to March 2022 versus pre-pandemic years:

- Weekly ED visits with hepatitis-associated discharge codes

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalizations in children aged 0-4 years (22 vs. 19.5; P = .26)

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalization in children aged 5-11 years (12 vs. 10.5; P = .42)

- Monthly liver transplants (5 vs. 4; P = .19)

- Percentage of stool specimens positive for adenovirus types 40/41, though the number of specimens tested was highest in March 2022

The authors acknowledged that pediatric hepatitis is rare, so it may be difficult tease out small changes in the number of cases. Also, data on hospitalizations and liver transplants have a 2- to 3-month reporting delay, so the case counts for March 2022 “might be underreported,” they wrote. Mr. Kohli noted that because hepatitis and adenovirus are not reportable conditions, the analysis relied on retrospective data from insurance companies and electronic medical records. Retrospective data are inherently limited, compared with prospective analyses, he said, and it’s possible that certain cases could be included in more than one database and thus be double-counted, whereas other cases could be missed entirely.

These findings also conflict with data from the United Kingdom, which in May reported that the average number of hepatitis cases had increased, compared with previous years, he said. More data are needed, he said, and he is involved with a study with the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that is also collecting data to try to understand whether there has been an uptick in pediatric hepatitis cases. The study will collect patient data directly from hospitals as well as include additional pathology data, such as biopsy results.

“We should not be inhibited to look further academically – and public health–wise – while we take into cognizance this very good, robust attempt from the CDC,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of pediatric hepatitis cases has remained steady since 2017, new research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests, despite the recent investigation into children with hepatitis of unknown cause. The study also found that there was no indication of elevated rates of adenovirus type 40/41 infection in children.

But Rohit Kohli, MBBS, MS, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, California, says that although the study is “well-designed and robust,” that does not mean that these hepatitis cases of unknown origin are no longer a concern. He was not involved with the CDC research. “As a clinician, I’m still worried,” he said. “Why I feel like this is not conclusive is that there are other data from entities like the United Kingdom Health Security Agency that are incongruent with [these findings],” he said.

The research was published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In November 2021, the Alabama Department of Public Health began an investigation with the CDC after a cluster of children were admitted to a children’s hospital in the state with severe hepatitis, who all tested positive for adenovirus. When the United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency announced an investigation into similar cases in early April 2022, the CDC decided to expand their search nationally.

Now, as of June 15, the agency is investigating 290 cases in 41 states and U.S. territories. Worldwide, 650 cases in 33 countries have been reported, according to the most recent update by the World Health Organization on May 27, 2022. At least 38 patients have needed liver transplants, and nine deaths have been reported to WHO.

In its most recent press call on the topic, the CDC announced that it’s aware of six deaths in the United States through May 20, 2022. The COVID-19 vaccine has been ruled out as a potential cause because the majority of affected children are unvaccinated or are too young to receive the vaccine. Adenovirus infection remains a leading suspect in these sick children because the virus has been detected in 60.8% of tested cases, WHO reports.

Investigators have detected an increase in reported pediatric hepatitis cases, compared with prior years in the United Kingdom, but it was not clear whether that same pattern would be found in the United States. Neither pediatric hepatitis nor adenovirus type 40/41 are reportable conditions in the United States. In the May 20 CDC press call, Umesh Parashar, MD, chief of the CDC’s Viral Gastroenteritis Branch, said that an estimated 1,500-2,000 children aged younger than 10 are hospitalized in the United States for hepatitis every year. “That’s a fairly large number,” he said, and it might make it difficult to detect a small increase in cases.

To better estimate trends in pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus infection in the United States, investigators collected available data on emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants associated with hepatitis in children as well as adenovirus stool testing results. Researchers used four large databases: the National Syndromic Surveillance Program; the Premier Healthcare Database Special Release; the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network; and Labcorp, which is a large commercial lab network.

To account for changes in health care utilization in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the team compared hepatitis-associated ED visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants from October 2021 to March 2022 versus the same months (January to March and October to December) in 2017, 2018, and 2019. For adenovirus stool testing, results from October 2021 to March 2022 were compared with the same calendar months (October to March) from 2017-2018, 2018-2019, and 2019-2020, to help control for seasonality.

Investigators found no statistically significant increases in the outcomes during October 2021 to March 2022 versus pre-pandemic years:

- Weekly ED visits with hepatitis-associated discharge codes

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalizations in children aged 0-4 years (22 vs. 19.5; P = .26)

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalization in children aged 5-11 years (12 vs. 10.5; P = .42)

- Monthly liver transplants (5 vs. 4; P = .19)

- Percentage of stool specimens positive for adenovirus types 40/41, though the number of specimens tested was highest in March 2022

The authors acknowledged that pediatric hepatitis is rare, so it may be difficult tease out small changes in the number of cases. Also, data on hospitalizations and liver transplants have a 2- to 3-month reporting delay, so the case counts for March 2022 “might be underreported,” they wrote. Mr. Kohli noted that because hepatitis and adenovirus are not reportable conditions, the analysis relied on retrospective data from insurance companies and electronic medical records. Retrospective data are inherently limited, compared with prospective analyses, he said, and it’s possible that certain cases could be included in more than one database and thus be double-counted, whereas other cases could be missed entirely.

These findings also conflict with data from the United Kingdom, which in May reported that the average number of hepatitis cases had increased, compared with previous years, he said. More data are needed, he said, and he is involved with a study with the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that is also collecting data to try to understand whether there has been an uptick in pediatric hepatitis cases. The study will collect patient data directly from hospitals as well as include additional pathology data, such as biopsy results.

“We should not be inhibited to look further academically – and public health–wise – while we take into cognizance this very good, robust attempt from the CDC,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of pediatric hepatitis cases has remained steady since 2017, new research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests, despite the recent investigation into children with hepatitis of unknown cause. The study also found that there was no indication of elevated rates of adenovirus type 40/41 infection in children.

But Rohit Kohli, MBBS, MS, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, California, says that although the study is “well-designed and robust,” that does not mean that these hepatitis cases of unknown origin are no longer a concern. He was not involved with the CDC research. “As a clinician, I’m still worried,” he said. “Why I feel like this is not conclusive is that there are other data from entities like the United Kingdom Health Security Agency that are incongruent with [these findings],” he said.

The research was published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In November 2021, the Alabama Department of Public Health began an investigation with the CDC after a cluster of children were admitted to a children’s hospital in the state with severe hepatitis, who all tested positive for adenovirus. When the United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency announced an investigation into similar cases in early April 2022, the CDC decided to expand their search nationally.

Now, as of June 15, the agency is investigating 290 cases in 41 states and U.S. territories. Worldwide, 650 cases in 33 countries have been reported, according to the most recent update by the World Health Organization on May 27, 2022. At least 38 patients have needed liver transplants, and nine deaths have been reported to WHO.

In its most recent press call on the topic, the CDC announced that it’s aware of six deaths in the United States through May 20, 2022. The COVID-19 vaccine has been ruled out as a potential cause because the majority of affected children are unvaccinated or are too young to receive the vaccine. Adenovirus infection remains a leading suspect in these sick children because the virus has been detected in 60.8% of tested cases, WHO reports.

Investigators have detected an increase in reported pediatric hepatitis cases, compared with prior years in the United Kingdom, but it was not clear whether that same pattern would be found in the United States. Neither pediatric hepatitis nor adenovirus type 40/41 are reportable conditions in the United States. In the May 20 CDC press call, Umesh Parashar, MD, chief of the CDC’s Viral Gastroenteritis Branch, said that an estimated 1,500-2,000 children aged younger than 10 are hospitalized in the United States for hepatitis every year. “That’s a fairly large number,” he said, and it might make it difficult to detect a small increase in cases.

To better estimate trends in pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus infection in the United States, investigators collected available data on emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants associated with hepatitis in children as well as adenovirus stool testing results. Researchers used four large databases: the National Syndromic Surveillance Program; the Premier Healthcare Database Special Release; the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network; and Labcorp, which is a large commercial lab network.

To account for changes in health care utilization in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the team compared hepatitis-associated ED visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants from October 2021 to March 2022 versus the same months (January to March and October to December) in 2017, 2018, and 2019. For adenovirus stool testing, results from October 2021 to March 2022 were compared with the same calendar months (October to March) from 2017-2018, 2018-2019, and 2019-2020, to help control for seasonality.

Investigators found no statistically significant increases in the outcomes during October 2021 to March 2022 versus pre-pandemic years:

- Weekly ED visits with hepatitis-associated discharge codes

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalizations in children aged 0-4 years (22 vs. 19.5; P = .26)

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalization in children aged 5-11 years (12 vs. 10.5; P = .42)

- Monthly liver transplants (5 vs. 4; P = .19)

- Percentage of stool specimens positive for adenovirus types 40/41, though the number of specimens tested was highest in March 2022

The authors acknowledged that pediatric hepatitis is rare, so it may be difficult tease out small changes in the number of cases. Also, data on hospitalizations and liver transplants have a 2- to 3-month reporting delay, so the case counts for March 2022 “might be underreported,” they wrote. Mr. Kohli noted that because hepatitis and adenovirus are not reportable conditions, the analysis relied on retrospective data from insurance companies and electronic medical records. Retrospective data are inherently limited, compared with prospective analyses, he said, and it’s possible that certain cases could be included in more than one database and thus be double-counted, whereas other cases could be missed entirely.

These findings also conflict with data from the United Kingdom, which in May reported that the average number of hepatitis cases had increased, compared with previous years, he said. More data are needed, he said, and he is involved with a study with the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that is also collecting data to try to understand whether there has been an uptick in pediatric hepatitis cases. The study will collect patient data directly from hospitals as well as include additional pathology data, such as biopsy results.

“We should not be inhibited to look further academically – and public health–wise – while we take into cognizance this very good, robust attempt from the CDC,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MMWR

WHO to rename monkeypox because of stigma concerns

The virus has infected more than 1,600 people in 39 countries so far this year, the WHO said, including 32 countries where the virus isn’t typically detected.

“WHO is working with partners and experts from around the world on changing the name of monkeypox virus, its clades, and the disease it causes,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, the WHO’s director-general, said during a press briefing.

“We will make announcements about the new names as soon as possible,” he said.

Last week, more than 30 international scientists urged the public health community to change the name of the virus. The scientists posted a letter on June 10, which included support from the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, noting that the name should change with the ongoing transmission among humans this year.

“The prevailing perception in the international media and scientific literature is that MPXV is endemic in people in some African countries. However, it is well established that nearly all MPXV outbreaks in Africa prior to the 2022 outbreak have been the result of spillover from animals and humans and only rarely have there been reports of sustained human-to-human transmissions,” they wrote.

“In the context of the current global outbreak, continued reference to, and nomenclature of this virus being African is not only inaccurate but is also discriminatory and stigmatizing,” they added.