User login

Doc’s misdiagnosis causes former firefighter to lose leg from flesh-eating bacterial infection

, as a story in the Pensacola News Journal indicates.

In September 2016, the former firefighter visited a hospital-affiliated urgent care center after he developed an ache and a blue discoloration in his right leg. Prior to this, the story says, he had been “exposed to the waters of Pensacola Bay,” which might have caused the infection.

At the urgent care center, he was examined by a primary care physician, who diagnosed him with an ankle sprain. Instructed to ice and elevate his leg, the former firefighter was given crutches and sent home.

The following day, still in pain, he visited a local podiatrist, who “immediately suspected ... [the patient] was suffering from an ongoing aggressive bacterial infection.” The podiatrist then arranged for the patient to be seen at a nearby hospital emergency department. There, doctors diagnosed a “necrotizing bacterial infection that need[ed] to be aggressively treated with antibodies and the removal of dead tissue.”

But despite their best efforts to control the infection and remove the necrotized tissue, the doctors eventually had to amputate the patient’s right leg above the knee.

The former firefighter and his wife then sued the primary care physician and the hospital where the physician worked.

After an 8-day civil trial, the jury awarded the plaintiff and his wife $6,805,071 and $787,371, respectively.

“What happened to [my clients] should never have happened,” said the attorney representing the plaintiffs.

The hospital declined to comment to the Pensacola News Journal about the case.

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, as a story in the Pensacola News Journal indicates.

In September 2016, the former firefighter visited a hospital-affiliated urgent care center after he developed an ache and a blue discoloration in his right leg. Prior to this, the story says, he had been “exposed to the waters of Pensacola Bay,” which might have caused the infection.

At the urgent care center, he was examined by a primary care physician, who diagnosed him with an ankle sprain. Instructed to ice and elevate his leg, the former firefighter was given crutches and sent home.

The following day, still in pain, he visited a local podiatrist, who “immediately suspected ... [the patient] was suffering from an ongoing aggressive bacterial infection.” The podiatrist then arranged for the patient to be seen at a nearby hospital emergency department. There, doctors diagnosed a “necrotizing bacterial infection that need[ed] to be aggressively treated with antibodies and the removal of dead tissue.”

But despite their best efforts to control the infection and remove the necrotized tissue, the doctors eventually had to amputate the patient’s right leg above the knee.

The former firefighter and his wife then sued the primary care physician and the hospital where the physician worked.

After an 8-day civil trial, the jury awarded the plaintiff and his wife $6,805,071 and $787,371, respectively.

“What happened to [my clients] should never have happened,” said the attorney representing the plaintiffs.

The hospital declined to comment to the Pensacola News Journal about the case.

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, as a story in the Pensacola News Journal indicates.

In September 2016, the former firefighter visited a hospital-affiliated urgent care center after he developed an ache and a blue discoloration in his right leg. Prior to this, the story says, he had been “exposed to the waters of Pensacola Bay,” which might have caused the infection.

At the urgent care center, he was examined by a primary care physician, who diagnosed him with an ankle sprain. Instructed to ice and elevate his leg, the former firefighter was given crutches and sent home.

The following day, still in pain, he visited a local podiatrist, who “immediately suspected ... [the patient] was suffering from an ongoing aggressive bacterial infection.” The podiatrist then arranged for the patient to be seen at a nearby hospital emergency department. There, doctors diagnosed a “necrotizing bacterial infection that need[ed] to be aggressively treated with antibodies and the removal of dead tissue.”

But despite their best efforts to control the infection and remove the necrotized tissue, the doctors eventually had to amputate the patient’s right leg above the knee.

The former firefighter and his wife then sued the primary care physician and the hospital where the physician worked.

After an 8-day civil trial, the jury awarded the plaintiff and his wife $6,805,071 and $787,371, respectively.

“What happened to [my clients] should never have happened,” said the attorney representing the plaintiffs.

The hospital declined to comment to the Pensacola News Journal about the case.

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA authorizes COVID vaccines in kids as young as 6 months

, one of the final steps in a long-awaited authorization process to extend protection to the youngest of Americans.

The agency’s move comes after a closely watched FDA advisory group vote earlier this week, which resulted in a unanimous vote in favor of the FDA authorizing both vaccines in this age group.

“The FDA’s evaluation and analysis of the safety, effectiveness, and manufacturing data of these vaccines was rigorous and comprehensive, supporting the EUAs,” the agency said in a news release.

The data show that the “known and potential benefits” of the vaccines outweigh any potential risks, the agency said.

The Moderna vaccine is authorized as a two-dose primary series in children 6 months to 17 years of age. The Pfizer vaccine is now authorized as a three-dose primary series in children 6 months up to 4 years of age. Pfizer’s vaccine was already authorized in children 5 years old and older.

Now all eyes are on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is expected to decide on the final regulatory hurdle at a meeting June 18. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has scheduled a vote on whether to give the vaccines the green light.

If ACIP gives the OK, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, is expected to issue recommendations for use shortly thereafter.

Following these final regulatory steps, parents could start bringing their children to pediatricians, family doctors, or local pharmacies for vaccination as early as June 20.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, one of the final steps in a long-awaited authorization process to extend protection to the youngest of Americans.

The agency’s move comes after a closely watched FDA advisory group vote earlier this week, which resulted in a unanimous vote in favor of the FDA authorizing both vaccines in this age group.

“The FDA’s evaluation and analysis of the safety, effectiveness, and manufacturing data of these vaccines was rigorous and comprehensive, supporting the EUAs,” the agency said in a news release.

The data show that the “known and potential benefits” of the vaccines outweigh any potential risks, the agency said.

The Moderna vaccine is authorized as a two-dose primary series in children 6 months to 17 years of age. The Pfizer vaccine is now authorized as a three-dose primary series in children 6 months up to 4 years of age. Pfizer’s vaccine was already authorized in children 5 years old and older.

Now all eyes are on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is expected to decide on the final regulatory hurdle at a meeting June 18. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has scheduled a vote on whether to give the vaccines the green light.

If ACIP gives the OK, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, is expected to issue recommendations for use shortly thereafter.

Following these final regulatory steps, parents could start bringing their children to pediatricians, family doctors, or local pharmacies for vaccination as early as June 20.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, one of the final steps in a long-awaited authorization process to extend protection to the youngest of Americans.

The agency’s move comes after a closely watched FDA advisory group vote earlier this week, which resulted in a unanimous vote in favor of the FDA authorizing both vaccines in this age group.

“The FDA’s evaluation and analysis of the safety, effectiveness, and manufacturing data of these vaccines was rigorous and comprehensive, supporting the EUAs,” the agency said in a news release.

The data show that the “known and potential benefits” of the vaccines outweigh any potential risks, the agency said.

The Moderna vaccine is authorized as a two-dose primary series in children 6 months to 17 years of age. The Pfizer vaccine is now authorized as a three-dose primary series in children 6 months up to 4 years of age. Pfizer’s vaccine was already authorized in children 5 years old and older.

Now all eyes are on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is expected to decide on the final regulatory hurdle at a meeting June 18. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has scheduled a vote on whether to give the vaccines the green light.

If ACIP gives the OK, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, is expected to issue recommendations for use shortly thereafter.

Following these final regulatory steps, parents could start bringing their children to pediatricians, family doctors, or local pharmacies for vaccination as early as June 20.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Anti-vaccine physician sentenced to prison for role in Capitol riot

Simone Gold, MD, JD, a leader in the anti-vaccine movement and founder of noted anti-vaccine group America’s Frontline Doctors, has been sentenced to 2 months in prison for her role in the storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021.

In March, As a part of the plea agreement, additional charges of obstructing an official proceeding and intent to disrupt the orderly conduct of government business were dropped. Although she insisted at the time that her actions were peaceful, Dr. Gold did admit, according to news reports, that she witnessed the assault of a police officer while inside the building.

America’s Frontline Doctors is an organization noted for spreading misinformation about COVID-19 and promoting unproven and potentially dangerous drugs, including ivermectin, for treating the illness. The group issued a statement saying that while Dr. Gold did express regret for “being involved in a situation that later became unpredictable,” her sentence is an example of “selective prosecution.”

“Dr. Gold remains committed to her advocacy for physicians’ free speech,” the statement noted, adding that Dr. Gold has been targeted by attacks attempting to “cancel” her since July 2020, when the California Medical Board threatened to revoke her license for what the statement calls an “unfounded claim” that she was sharing dangerous disinformation.

According to Associated Press reporting, U.S. District Judge Christopher Cooper did not consider Dr. Gold’s anti-vaccine activity when determining the sentence. However, Judge Cooper did say that Dr. Gold was not a “casual bystander” on January 6 and criticized the organization for misleading its supporters into believing that her prosecution was a politically motivated violation of her free-speech rights.

Prosecutors accused Dr. Gold of trying to profit from her crime, according to AP reports, noting in a court filing that America’s Frontline Doctors has raised more than $430,000 for her defense. “It beggars belief that [Dr.] Gold could have incurred anywhere near $430,000 in costs for her criminal defense: After all, she pleaded guilty – in the face of indisputable evidence – without filing a single motion.”

In the past, Dr. Gold has worked at Providence St. Joseph Medical Center, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles. These institutions have disassociated themselves from her. Her medical license remains active, but she noted on her website that she “voluntarily refused” to renew her board certification last year “due to the unethical behavior of the medical boards.” Dr. Gold is also a licensed attorney, having earned a law degree in health policy analysis at Stanford Law School.

The AP reports that since her arrest, Dr. Gold has moved from California to Florida.

In addition to the prison time, Judge Cooper ordered Dr. Gold to pay a $9,500 fine, and she will be subject to 12 months of supervised release after completing her sentence, according to media reports. At press time, the U.S. Department of Justice has not released an official announcement on the sentencing.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Simone Gold, MD, JD, a leader in the anti-vaccine movement and founder of noted anti-vaccine group America’s Frontline Doctors, has been sentenced to 2 months in prison for her role in the storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021.

In March, As a part of the plea agreement, additional charges of obstructing an official proceeding and intent to disrupt the orderly conduct of government business were dropped. Although she insisted at the time that her actions were peaceful, Dr. Gold did admit, according to news reports, that she witnessed the assault of a police officer while inside the building.

America’s Frontline Doctors is an organization noted for spreading misinformation about COVID-19 and promoting unproven and potentially dangerous drugs, including ivermectin, for treating the illness. The group issued a statement saying that while Dr. Gold did express regret for “being involved in a situation that later became unpredictable,” her sentence is an example of “selective prosecution.”

“Dr. Gold remains committed to her advocacy for physicians’ free speech,” the statement noted, adding that Dr. Gold has been targeted by attacks attempting to “cancel” her since July 2020, when the California Medical Board threatened to revoke her license for what the statement calls an “unfounded claim” that she was sharing dangerous disinformation.

According to Associated Press reporting, U.S. District Judge Christopher Cooper did not consider Dr. Gold’s anti-vaccine activity when determining the sentence. However, Judge Cooper did say that Dr. Gold was not a “casual bystander” on January 6 and criticized the organization for misleading its supporters into believing that her prosecution was a politically motivated violation of her free-speech rights.

Prosecutors accused Dr. Gold of trying to profit from her crime, according to AP reports, noting in a court filing that America’s Frontline Doctors has raised more than $430,000 for her defense. “It beggars belief that [Dr.] Gold could have incurred anywhere near $430,000 in costs for her criminal defense: After all, she pleaded guilty – in the face of indisputable evidence – without filing a single motion.”

In the past, Dr. Gold has worked at Providence St. Joseph Medical Center, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles. These institutions have disassociated themselves from her. Her medical license remains active, but she noted on her website that she “voluntarily refused” to renew her board certification last year “due to the unethical behavior of the medical boards.” Dr. Gold is also a licensed attorney, having earned a law degree in health policy analysis at Stanford Law School.

The AP reports that since her arrest, Dr. Gold has moved from California to Florida.

In addition to the prison time, Judge Cooper ordered Dr. Gold to pay a $9,500 fine, and she will be subject to 12 months of supervised release after completing her sentence, according to media reports. At press time, the U.S. Department of Justice has not released an official announcement on the sentencing.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Simone Gold, MD, JD, a leader in the anti-vaccine movement and founder of noted anti-vaccine group America’s Frontline Doctors, has been sentenced to 2 months in prison for her role in the storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021.

In March, As a part of the plea agreement, additional charges of obstructing an official proceeding and intent to disrupt the orderly conduct of government business were dropped. Although she insisted at the time that her actions were peaceful, Dr. Gold did admit, according to news reports, that she witnessed the assault of a police officer while inside the building.

America’s Frontline Doctors is an organization noted for spreading misinformation about COVID-19 and promoting unproven and potentially dangerous drugs, including ivermectin, for treating the illness. The group issued a statement saying that while Dr. Gold did express regret for “being involved in a situation that later became unpredictable,” her sentence is an example of “selective prosecution.”

“Dr. Gold remains committed to her advocacy for physicians’ free speech,” the statement noted, adding that Dr. Gold has been targeted by attacks attempting to “cancel” her since July 2020, when the California Medical Board threatened to revoke her license for what the statement calls an “unfounded claim” that she was sharing dangerous disinformation.

According to Associated Press reporting, U.S. District Judge Christopher Cooper did not consider Dr. Gold’s anti-vaccine activity when determining the sentence. However, Judge Cooper did say that Dr. Gold was not a “casual bystander” on January 6 and criticized the organization for misleading its supporters into believing that her prosecution was a politically motivated violation of her free-speech rights.

Prosecutors accused Dr. Gold of trying to profit from her crime, according to AP reports, noting in a court filing that America’s Frontline Doctors has raised more than $430,000 for her defense. “It beggars belief that [Dr.] Gold could have incurred anywhere near $430,000 in costs for her criminal defense: After all, she pleaded guilty – in the face of indisputable evidence – without filing a single motion.”

In the past, Dr. Gold has worked at Providence St. Joseph Medical Center, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles. These institutions have disassociated themselves from her. Her medical license remains active, but she noted on her website that she “voluntarily refused” to renew her board certification last year “due to the unethical behavior of the medical boards.” Dr. Gold is also a licensed attorney, having earned a law degree in health policy analysis at Stanford Law School.

The AP reports that since her arrest, Dr. Gold has moved from California to Florida.

In addition to the prison time, Judge Cooper ordered Dr. Gold to pay a $9,500 fine, and she will be subject to 12 months of supervised release after completing her sentence, according to media reports. At press time, the U.S. Department of Justice has not released an official announcement on the sentencing.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rheumatologic Perspective on Persistent Right-Hand Tenosynovitis Secondary to Mycobacterium marinum Infection

Rheumatologic conditions and infections may imitate each other, often making diagnosis challenging. Therefore, it is imperative to obtain adequate histories and have a keen eye for these potentially confounding differential diagnoses. Immunosuppressants used in managing rheumatologic etiologies have detrimental consequences in undiagnosed underlying infections. Consequently, worsening symptoms with standard therapy should raise awareness to a different diagnosis.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are slow-growing organisms difficult to yield in culture. Initial negative synovial fluid stains and cultures when suspecting NTM infectious arthritis or tenosynovitis should not exclude the diagnosis if there is a strong clinical scenario. The identification of Mycobacterium marinum (M marinum) infection in the hand is of utmost importance given that delayed treatment may cause significant and even permanent disability.

We present the case of a 73-year-old male patient with progressively worsening right-hand tenosynovitis who was evaluated for crystal-induced and sarcoid arthropathies in the setting of negative synovial biopsy cultures but was subsequently diagnosed with M marinum infectious tenosynovitis after a second surgical debridement.

Case Presentation

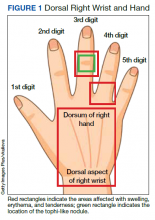

A 73-year-old male patient with history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, bilateral knee osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea, and posttraumatic stress disorder presented to the emergency department (ED) with right wrist swelling and pain for 4 days. The patient reported that he was working in his garden when symptoms started. He did not recall any skin abrasions or wounds, insect bites, thorn punctures, trauma, or exposure to swimming pools or fish tanks. Patient was afebrile, and vital signs were within normal range. On physical examination, there was erythema, swelling, and tenderness in the dorsum of the right hand and over the dorsal aspect of the fourth metacarpophalangeal joint (Figure 1). The skin was intact.

Symptoms had not responded to 7 days of cefalexin nor to a short course of oral steroids. Leukocytosis of 14.35 × 109/L (reference range, 3.90-9.90 × 109/L) with neutrophilia at 11.10 × 109/L (reference range, 1.73-6.37 × 109/L) was noted. Sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels were normal. Right-hand X-ray was remarkable for chondrocalcinosis in the triangular fibrocartilage. Right upper extremity magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed diffuse inflammation in the right wrist and hand (Figure 2). There was no evidence of septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. Consequently, orthopedic service recommended no surgical intervention. Additionally, the patient had preserved range of motion that further indicated tenosynovitis, which could be medically managed with antibiotics, rather than a septic joint.

One dose of IV piperacillin/tazobactam was given at the ED, and he was admitted to the internal medicine ward with right hand and wrist cellulitis and indolent suppurative tenosynovitis. Empiric IV ceftriaxone and vancomycin were started as per infectious disease (ID) service with adequate response defined as a reduction of the swelling, erythema, and tenderness of the right hand and wrist. Differential diagnosis included sporotrichosis, nocardia vs NTM infection.

Interventional radiology was consulted for right wrist drainage. However, only 1 mL of fluid was obtained. Synovial fluid was sent for cell count and differential, crystal analysis, bacterial cultures, fungal cultures, and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) stains and culture. Neutrophils were 43% and lymphocytes were 57%. Crystal analysis was negative. Bacterial culture and mycology were negative. AFB stain and culture results were negative after 6 weeks. Based on gardening history and risk of thorn exposure and low suspicion for common bacterial pathogens, ID service switched antibiotics to moxifloxacin, minocycline, and linezolid for broad coverage to complete 3 weeks as outpatient. The patient reported significantly improved pain and handgrip with notable decrease in swelling. Nonetheless, 3 weeks after completing antibiotics, the right-hand pain recurred, raising concern for complex regional syndrome vs crystalline arthropathy.

The patient was referred to rheumatology service for evaluation of crystal-induced arthropathy given chondrocalcinosis. Physical examination revealed right third proximal interphalangeal joint swelling and tenderness with overimposed tophilike nodule. No erythema or palpable effusions were appreciated. Range of motion was preserved. Laboratory workup showed resolved leukocytosis and neutrophilia, and normal sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein levels. Antinuclear antibody panel, rheumatoid factor, and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide levels were normal. Serum uric acid levels were 5.9 mg/dL. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HIV tests were negative. Short course of low-dose oral prednisone starting at 15 mg daily with tapering by 5 mg every 3 days was given for presumptive calcium pyrophosphate deposition vs gout. Nevertheless, right-hand swelling and pain worsened after steroids. Repeat right upper extremity MRI showed persistent soft tissue edema and inflammation along the dorsum of the hand extending to the digits, tenosynovitis, and fluid in the third metacarpophalangeal that could represent a superficial abscess. The patient was hospitalized given concerns of infection.

The relapse of tenosynovitis raised concerns for a persistent infection secondary to a fastidious organism, such as NTM. Thus, inquiries specifically pertaining to any contact with bodies of water were entertained. The patient remembered that he had gone scuba diving in the ocean weeks before symptom onset. This meant scuba diving could then be the inciting event rather than gardening, which placed NTM higher in the differential. ID service did not recommend antibiotics until new cultures were available. Orthopedic service was consulted for surgical debridement. The right dorsal hand, wrist, and distal forearm tendon sheaths were surgically opened to obtain a synovial biopsy.

Synovial fluid was sent for fungal, bacterial, and AFB cultures, and synovial biopsy for AFB stains, PCR amplification/sequencing assay, and cultures. Results showed nonnecrotizing granulomas and all cultures were negative (Figures 3, 4). Rheumatology was again consulted for evaluation for sarcoidosis given negative cultures and noncaseating granulomas. Review of systems was completely negative for sarcoidosis. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax did not show any pulmonary abnormalities, lymphadenopathy, and hilar adenopathy. Serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal. ID service recommended against empiric antibiotics given negative culture. Given persistent pain, and reported cases of isolated sarcoid tenosynovitis, low-dose oral prednisone 20 mg daily was given after clearance by ID service. Nonetheless, the right wrist and hand swelling, erythema, and tenderness relapsed with 1 dose of prednisone, leading to a repeat right upper extremity synovial biopsy due to high suspicion for persistent infection with a fastidious organism. New synovial tissue biopsy revealed fibro-adipose tissue with prominent vessels and fibrosis, nonnecrotizing, sarcoidlike granuloma with giant cell granulomatous reaction. The AFB and Grocott methenamine silver stains were negative. PCR was negative for AFB. No crystals were reported. After 5 weeks, the synovial biopsy culture was positive for M marinum. Patient was started on oral azithromycin 500 mg daily, rifabutin 300 mg daily, and ethambutol 15 mg/kg daily. At the time of this report, the patient was still completing antibiotic therapy with adequate response and undergoing occupational therapy rehabilitation (Figure 5).

Discussion

M marinum is an NTM found in bodies of water and marine settings. Infection arises after direct contact of lacerated skin with contaminated water. In a review article of 5 cases of M marinum tenosynovitis, they found that all individuals had wounds with exposure to fish or shrimp while in the water or while handling seafood.1 The incidence of this infection is infrequent, estimated to be 0.04 cases per 100,000, with only about 25% of these cases presenting as tenosynovitis.2 The incubation period ranges from 2 to 4 weeks.3 Late identification of this organism is common because of its slow development. For example, presentation from first exposure to symptom onset may take as long as 32 days.1 In addition, in the same review, surgical intervention occurred in 63 days.1 It has been reported that AFB stains are positive in just 9% of cases, which confounds diagnosis even more.4 After synovial tissue culture is obtained, it takes approximately 6 weeks for the organism to grow. Moreover, diagnosis may take longer if it is not suspected.5

Four types of M marinum infections have been described.5 The status of the immune system plays a role in how the manifestations present. The first type is limited, which is seen in immunocompetent persons, characterized by skin involvement, such as erythematous nodular lesions, that may improve on their own in months or years.4 Conversely, in immunosuppressed patients, the second type of infection may cause sporotrichoid spreading described as following lymphangitic pattern. The third type presents with musculoskeletal findings, such as arthritis, tenosynovitis, bursitis, or osteomyelitis, as seen in our patient. The fourth type consists of systemic manifestations.5 Medications that lower the immune system, such as corticosteroids, chemotherapy, and biologic disease modifying agents, may increase the risk for developing this entity.4 Specifically, antitumor necrosis factor inhibitors have been historically associated with mycobacterium infections.6

Patients are frequently diagnosed with soft tissue infection, such as abscesses or cellulitis, as in our case. They may at times be found to have other musculoskeletal conditions such as trigger finger.1 Other similar presenting entities are psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and remitting seronegative arthritis.4 These clinical resemblances complicate the scenario, especially when initial cultures are negative, as the treatment for these rheumatic diseases is immunosuppression, which adversely impact the fastidious infection. In our case, the improved swelling and range of motion after the 3-week course of empiric antibiotics for suppurative tenosynovitis was initially reassuring that the previous infection had been successfully treated. Subsequently, the presence of chondrocalcinosis in the triangular fibrocartilage in the right-hand X-rays, persistent pain, and the tophi-like appearance of the right third proximal interphalangeal nodule raised concerns for crystalline arthropathies, such as calcium pyrophosphate deposition vs gout. Nonetheless, given the lack of response to low-dose steroids, an ongoing infectious process was strongly considered.

Sarcoidosis was a concern after the first synovial biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas and negative stains and cultures. Sarcoid tenosynovitis is rare with only 22 cases described as per a 2015 report.7 Musculoskeletal involvement in sarcoidosis has been reported in 1 to 13% of sarcoid patients.7 Once again, unresponsiveness to steroids led to another synovial biopsy for culture due to potential infection. Akin to other cases, more than one surgical debridement was required to diagnose our patient.

Conclusions

Our case reinforces the vital role of history gathering in establishing diagnoses. It underscores the value of clinical suspicion especially in patients unresponsive to standard treatment for inflammatory arthritis, namely corticosteroids. Tissue biopsy with culture for AFB is crucial for accurate diagnosis in NTM infection, which may imitate rheumatic inflammatory arthritis. Clinicians should be keenly aware of this fastidious, indolent organism in the setting of persistent localized tenosynovitis.

1. Pang HN, Lee JY, Puhaindran ME, Tan SH, Tan AB, Yong FC. Mycobacterium marinum as a cause of chronic granulomatous tenosynovitis in the hand. J Infect. 2007;54(6):584-588. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.014

2. Wongworawat MD, Holtom P, Learch TJ, Fedenko A, Stevanovic MV. A prolonged case of Mycobacterium marinum flexor tenosynovitis: radiographic and histological correlation, and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32(9):542-545. doi:10.1007/s00256-003-0636-y

3. Schubert N, Schill T, Plüß M, Korsten P. Flare or foe? - Mycobacterium marinum infection mimicking rheumatoid arthritis tenosynovitis: case report and literature review. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4:11. Published 2020 Mar 16. doi:10.1186/s41927-020-0114-3

4. Lam A, Toma W, Schlesinger N. Mycobacterium marinum arthritis mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(4):817-819.

5. Hashish E, Merwad A, Elgaml S, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection in fish and man: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management; a review. Vet Q. 2018;38(1):35-46. doi:10.1080/01652176.2018.1447171

6. Thanou-Stavraki A, Sawalha AH, Crowson AN, Harley JB. Noodling and Mycobacterium marinum infection mimicking seronegative rheumatoid arthritis complicated by anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(1):160-164. doi:10.1002/acr.20303

7. Al-Ani Z, Oh TC, Macphie E, Woodruff MJ. Sarcoid tenosynovitis, rare presentation of a common disease. Case report and literature review. J Radiol Case Rep. 2015;9(8):16-23. Published 2015 Aug 31. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v9i8.2311

Rheumatologic conditions and infections may imitate each other, often making diagnosis challenging. Therefore, it is imperative to obtain adequate histories and have a keen eye for these potentially confounding differential diagnoses. Immunosuppressants used in managing rheumatologic etiologies have detrimental consequences in undiagnosed underlying infections. Consequently, worsening symptoms with standard therapy should raise awareness to a different diagnosis.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are slow-growing organisms difficult to yield in culture. Initial negative synovial fluid stains and cultures when suspecting NTM infectious arthritis or tenosynovitis should not exclude the diagnosis if there is a strong clinical scenario. The identification of Mycobacterium marinum (M marinum) infection in the hand is of utmost importance given that delayed treatment may cause significant and even permanent disability.

We present the case of a 73-year-old male patient with progressively worsening right-hand tenosynovitis who was evaluated for crystal-induced and sarcoid arthropathies in the setting of negative synovial biopsy cultures but was subsequently diagnosed with M marinum infectious tenosynovitis after a second surgical debridement.

Case Presentation

A 73-year-old male patient with history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, bilateral knee osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea, and posttraumatic stress disorder presented to the emergency department (ED) with right wrist swelling and pain for 4 days. The patient reported that he was working in his garden when symptoms started. He did not recall any skin abrasions or wounds, insect bites, thorn punctures, trauma, or exposure to swimming pools or fish tanks. Patient was afebrile, and vital signs were within normal range. On physical examination, there was erythema, swelling, and tenderness in the dorsum of the right hand and over the dorsal aspect of the fourth metacarpophalangeal joint (Figure 1). The skin was intact.

Symptoms had not responded to 7 days of cefalexin nor to a short course of oral steroids. Leukocytosis of 14.35 × 109/L (reference range, 3.90-9.90 × 109/L) with neutrophilia at 11.10 × 109/L (reference range, 1.73-6.37 × 109/L) was noted. Sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels were normal. Right-hand X-ray was remarkable for chondrocalcinosis in the triangular fibrocartilage. Right upper extremity magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed diffuse inflammation in the right wrist and hand (Figure 2). There was no evidence of septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. Consequently, orthopedic service recommended no surgical intervention. Additionally, the patient had preserved range of motion that further indicated tenosynovitis, which could be medically managed with antibiotics, rather than a septic joint.

One dose of IV piperacillin/tazobactam was given at the ED, and he was admitted to the internal medicine ward with right hand and wrist cellulitis and indolent suppurative tenosynovitis. Empiric IV ceftriaxone and vancomycin were started as per infectious disease (ID) service with adequate response defined as a reduction of the swelling, erythema, and tenderness of the right hand and wrist. Differential diagnosis included sporotrichosis, nocardia vs NTM infection.

Interventional radiology was consulted for right wrist drainage. However, only 1 mL of fluid was obtained. Synovial fluid was sent for cell count and differential, crystal analysis, bacterial cultures, fungal cultures, and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) stains and culture. Neutrophils were 43% and lymphocytes were 57%. Crystal analysis was negative. Bacterial culture and mycology were negative. AFB stain and culture results were negative after 6 weeks. Based on gardening history and risk of thorn exposure and low suspicion for common bacterial pathogens, ID service switched antibiotics to moxifloxacin, minocycline, and linezolid for broad coverage to complete 3 weeks as outpatient. The patient reported significantly improved pain and handgrip with notable decrease in swelling. Nonetheless, 3 weeks after completing antibiotics, the right-hand pain recurred, raising concern for complex regional syndrome vs crystalline arthropathy.

The patient was referred to rheumatology service for evaluation of crystal-induced arthropathy given chondrocalcinosis. Physical examination revealed right third proximal interphalangeal joint swelling and tenderness with overimposed tophilike nodule. No erythema or palpable effusions were appreciated. Range of motion was preserved. Laboratory workup showed resolved leukocytosis and neutrophilia, and normal sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein levels. Antinuclear antibody panel, rheumatoid factor, and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide levels were normal. Serum uric acid levels were 5.9 mg/dL. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HIV tests were negative. Short course of low-dose oral prednisone starting at 15 mg daily with tapering by 5 mg every 3 days was given for presumptive calcium pyrophosphate deposition vs gout. Nevertheless, right-hand swelling and pain worsened after steroids. Repeat right upper extremity MRI showed persistent soft tissue edema and inflammation along the dorsum of the hand extending to the digits, tenosynovitis, and fluid in the third metacarpophalangeal that could represent a superficial abscess. The patient was hospitalized given concerns of infection.

The relapse of tenosynovitis raised concerns for a persistent infection secondary to a fastidious organism, such as NTM. Thus, inquiries specifically pertaining to any contact with bodies of water were entertained. The patient remembered that he had gone scuba diving in the ocean weeks before symptom onset. This meant scuba diving could then be the inciting event rather than gardening, which placed NTM higher in the differential. ID service did not recommend antibiotics until new cultures were available. Orthopedic service was consulted for surgical debridement. The right dorsal hand, wrist, and distal forearm tendon sheaths were surgically opened to obtain a synovial biopsy.

Synovial fluid was sent for fungal, bacterial, and AFB cultures, and synovial biopsy for AFB stains, PCR amplification/sequencing assay, and cultures. Results showed nonnecrotizing granulomas and all cultures were negative (Figures 3, 4). Rheumatology was again consulted for evaluation for sarcoidosis given negative cultures and noncaseating granulomas. Review of systems was completely negative for sarcoidosis. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax did not show any pulmonary abnormalities, lymphadenopathy, and hilar adenopathy. Serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal. ID service recommended against empiric antibiotics given negative culture. Given persistent pain, and reported cases of isolated sarcoid tenosynovitis, low-dose oral prednisone 20 mg daily was given after clearance by ID service. Nonetheless, the right wrist and hand swelling, erythema, and tenderness relapsed with 1 dose of prednisone, leading to a repeat right upper extremity synovial biopsy due to high suspicion for persistent infection with a fastidious organism. New synovial tissue biopsy revealed fibro-adipose tissue with prominent vessels and fibrosis, nonnecrotizing, sarcoidlike granuloma with giant cell granulomatous reaction. The AFB and Grocott methenamine silver stains were negative. PCR was negative for AFB. No crystals were reported. After 5 weeks, the synovial biopsy culture was positive for M marinum. Patient was started on oral azithromycin 500 mg daily, rifabutin 300 mg daily, and ethambutol 15 mg/kg daily. At the time of this report, the patient was still completing antibiotic therapy with adequate response and undergoing occupational therapy rehabilitation (Figure 5).

Discussion

M marinum is an NTM found in bodies of water and marine settings. Infection arises after direct contact of lacerated skin with contaminated water. In a review article of 5 cases of M marinum tenosynovitis, they found that all individuals had wounds with exposure to fish or shrimp while in the water or while handling seafood.1 The incidence of this infection is infrequent, estimated to be 0.04 cases per 100,000, with only about 25% of these cases presenting as tenosynovitis.2 The incubation period ranges from 2 to 4 weeks.3 Late identification of this organism is common because of its slow development. For example, presentation from first exposure to symptom onset may take as long as 32 days.1 In addition, in the same review, surgical intervention occurred in 63 days.1 It has been reported that AFB stains are positive in just 9% of cases, which confounds diagnosis even more.4 After synovial tissue culture is obtained, it takes approximately 6 weeks for the organism to grow. Moreover, diagnosis may take longer if it is not suspected.5

Four types of M marinum infections have been described.5 The status of the immune system plays a role in how the manifestations present. The first type is limited, which is seen in immunocompetent persons, characterized by skin involvement, such as erythematous nodular lesions, that may improve on their own in months or years.4 Conversely, in immunosuppressed patients, the second type of infection may cause sporotrichoid spreading described as following lymphangitic pattern. The third type presents with musculoskeletal findings, such as arthritis, tenosynovitis, bursitis, or osteomyelitis, as seen in our patient. The fourth type consists of systemic manifestations.5 Medications that lower the immune system, such as corticosteroids, chemotherapy, and biologic disease modifying agents, may increase the risk for developing this entity.4 Specifically, antitumor necrosis factor inhibitors have been historically associated with mycobacterium infections.6

Patients are frequently diagnosed with soft tissue infection, such as abscesses or cellulitis, as in our case. They may at times be found to have other musculoskeletal conditions such as trigger finger.1 Other similar presenting entities are psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and remitting seronegative arthritis.4 These clinical resemblances complicate the scenario, especially when initial cultures are negative, as the treatment for these rheumatic diseases is immunosuppression, which adversely impact the fastidious infection. In our case, the improved swelling and range of motion after the 3-week course of empiric antibiotics for suppurative tenosynovitis was initially reassuring that the previous infection had been successfully treated. Subsequently, the presence of chondrocalcinosis in the triangular fibrocartilage in the right-hand X-rays, persistent pain, and the tophi-like appearance of the right third proximal interphalangeal nodule raised concerns for crystalline arthropathies, such as calcium pyrophosphate deposition vs gout. Nonetheless, given the lack of response to low-dose steroids, an ongoing infectious process was strongly considered.

Sarcoidosis was a concern after the first synovial biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas and negative stains and cultures. Sarcoid tenosynovitis is rare with only 22 cases described as per a 2015 report.7 Musculoskeletal involvement in sarcoidosis has been reported in 1 to 13% of sarcoid patients.7 Once again, unresponsiveness to steroids led to another synovial biopsy for culture due to potential infection. Akin to other cases, more than one surgical debridement was required to diagnose our patient.

Conclusions

Our case reinforces the vital role of history gathering in establishing diagnoses. It underscores the value of clinical suspicion especially in patients unresponsive to standard treatment for inflammatory arthritis, namely corticosteroids. Tissue biopsy with culture for AFB is crucial for accurate diagnosis in NTM infection, which may imitate rheumatic inflammatory arthritis. Clinicians should be keenly aware of this fastidious, indolent organism in the setting of persistent localized tenosynovitis.

Rheumatologic conditions and infections may imitate each other, often making diagnosis challenging. Therefore, it is imperative to obtain adequate histories and have a keen eye for these potentially confounding differential diagnoses. Immunosuppressants used in managing rheumatologic etiologies have detrimental consequences in undiagnosed underlying infections. Consequently, worsening symptoms with standard therapy should raise awareness to a different diagnosis.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are slow-growing organisms difficult to yield in culture. Initial negative synovial fluid stains and cultures when suspecting NTM infectious arthritis or tenosynovitis should not exclude the diagnosis if there is a strong clinical scenario. The identification of Mycobacterium marinum (M marinum) infection in the hand is of utmost importance given that delayed treatment may cause significant and even permanent disability.

We present the case of a 73-year-old male patient with progressively worsening right-hand tenosynovitis who was evaluated for crystal-induced and sarcoid arthropathies in the setting of negative synovial biopsy cultures but was subsequently diagnosed with M marinum infectious tenosynovitis after a second surgical debridement.

Case Presentation

A 73-year-old male patient with history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, bilateral knee osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea, and posttraumatic stress disorder presented to the emergency department (ED) with right wrist swelling and pain for 4 days. The patient reported that he was working in his garden when symptoms started. He did not recall any skin abrasions or wounds, insect bites, thorn punctures, trauma, or exposure to swimming pools or fish tanks. Patient was afebrile, and vital signs were within normal range. On physical examination, there was erythema, swelling, and tenderness in the dorsum of the right hand and over the dorsal aspect of the fourth metacarpophalangeal joint (Figure 1). The skin was intact.

Symptoms had not responded to 7 days of cefalexin nor to a short course of oral steroids. Leukocytosis of 14.35 × 109/L (reference range, 3.90-9.90 × 109/L) with neutrophilia at 11.10 × 109/L (reference range, 1.73-6.37 × 109/L) was noted. Sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels were normal. Right-hand X-ray was remarkable for chondrocalcinosis in the triangular fibrocartilage. Right upper extremity magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed diffuse inflammation in the right wrist and hand (Figure 2). There was no evidence of septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. Consequently, orthopedic service recommended no surgical intervention. Additionally, the patient had preserved range of motion that further indicated tenosynovitis, which could be medically managed with antibiotics, rather than a septic joint.

One dose of IV piperacillin/tazobactam was given at the ED, and he was admitted to the internal medicine ward with right hand and wrist cellulitis and indolent suppurative tenosynovitis. Empiric IV ceftriaxone and vancomycin were started as per infectious disease (ID) service with adequate response defined as a reduction of the swelling, erythema, and tenderness of the right hand and wrist. Differential diagnosis included sporotrichosis, nocardia vs NTM infection.

Interventional radiology was consulted for right wrist drainage. However, only 1 mL of fluid was obtained. Synovial fluid was sent for cell count and differential, crystal analysis, bacterial cultures, fungal cultures, and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) stains and culture. Neutrophils were 43% and lymphocytes were 57%. Crystal analysis was negative. Bacterial culture and mycology were negative. AFB stain and culture results were negative after 6 weeks. Based on gardening history and risk of thorn exposure and low suspicion for common bacterial pathogens, ID service switched antibiotics to moxifloxacin, minocycline, and linezolid for broad coverage to complete 3 weeks as outpatient. The patient reported significantly improved pain and handgrip with notable decrease in swelling. Nonetheless, 3 weeks after completing antibiotics, the right-hand pain recurred, raising concern for complex regional syndrome vs crystalline arthropathy.

The patient was referred to rheumatology service for evaluation of crystal-induced arthropathy given chondrocalcinosis. Physical examination revealed right third proximal interphalangeal joint swelling and tenderness with overimposed tophilike nodule. No erythema or palpable effusions were appreciated. Range of motion was preserved. Laboratory workup showed resolved leukocytosis and neutrophilia, and normal sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein levels. Antinuclear antibody panel, rheumatoid factor, and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide levels were normal. Serum uric acid levels were 5.9 mg/dL. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HIV tests were negative. Short course of low-dose oral prednisone starting at 15 mg daily with tapering by 5 mg every 3 days was given for presumptive calcium pyrophosphate deposition vs gout. Nevertheless, right-hand swelling and pain worsened after steroids. Repeat right upper extremity MRI showed persistent soft tissue edema and inflammation along the dorsum of the hand extending to the digits, tenosynovitis, and fluid in the third metacarpophalangeal that could represent a superficial abscess. The patient was hospitalized given concerns of infection.

The relapse of tenosynovitis raised concerns for a persistent infection secondary to a fastidious organism, such as NTM. Thus, inquiries specifically pertaining to any contact with bodies of water were entertained. The patient remembered that he had gone scuba diving in the ocean weeks before symptom onset. This meant scuba diving could then be the inciting event rather than gardening, which placed NTM higher in the differential. ID service did not recommend antibiotics until new cultures were available. Orthopedic service was consulted for surgical debridement. The right dorsal hand, wrist, and distal forearm tendon sheaths were surgically opened to obtain a synovial biopsy.

Synovial fluid was sent for fungal, bacterial, and AFB cultures, and synovial biopsy for AFB stains, PCR amplification/sequencing assay, and cultures. Results showed nonnecrotizing granulomas and all cultures were negative (Figures 3, 4). Rheumatology was again consulted for evaluation for sarcoidosis given negative cultures and noncaseating granulomas. Review of systems was completely negative for sarcoidosis. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax did not show any pulmonary abnormalities, lymphadenopathy, and hilar adenopathy. Serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal. ID service recommended against empiric antibiotics given negative culture. Given persistent pain, and reported cases of isolated sarcoid tenosynovitis, low-dose oral prednisone 20 mg daily was given after clearance by ID service. Nonetheless, the right wrist and hand swelling, erythema, and tenderness relapsed with 1 dose of prednisone, leading to a repeat right upper extremity synovial biopsy due to high suspicion for persistent infection with a fastidious organism. New synovial tissue biopsy revealed fibro-adipose tissue with prominent vessels and fibrosis, nonnecrotizing, sarcoidlike granuloma with giant cell granulomatous reaction. The AFB and Grocott methenamine silver stains were negative. PCR was negative for AFB. No crystals were reported. After 5 weeks, the synovial biopsy culture was positive for M marinum. Patient was started on oral azithromycin 500 mg daily, rifabutin 300 mg daily, and ethambutol 15 mg/kg daily. At the time of this report, the patient was still completing antibiotic therapy with adequate response and undergoing occupational therapy rehabilitation (Figure 5).

Discussion

M marinum is an NTM found in bodies of water and marine settings. Infection arises after direct contact of lacerated skin with contaminated water. In a review article of 5 cases of M marinum tenosynovitis, they found that all individuals had wounds with exposure to fish or shrimp while in the water or while handling seafood.1 The incidence of this infection is infrequent, estimated to be 0.04 cases per 100,000, with only about 25% of these cases presenting as tenosynovitis.2 The incubation period ranges from 2 to 4 weeks.3 Late identification of this organism is common because of its slow development. For example, presentation from first exposure to symptom onset may take as long as 32 days.1 In addition, in the same review, surgical intervention occurred in 63 days.1 It has been reported that AFB stains are positive in just 9% of cases, which confounds diagnosis even more.4 After synovial tissue culture is obtained, it takes approximately 6 weeks for the organism to grow. Moreover, diagnosis may take longer if it is not suspected.5

Four types of M marinum infections have been described.5 The status of the immune system plays a role in how the manifestations present. The first type is limited, which is seen in immunocompetent persons, characterized by skin involvement, such as erythematous nodular lesions, that may improve on their own in months or years.4 Conversely, in immunosuppressed patients, the second type of infection may cause sporotrichoid spreading described as following lymphangitic pattern. The third type presents with musculoskeletal findings, such as arthritis, tenosynovitis, bursitis, or osteomyelitis, as seen in our patient. The fourth type consists of systemic manifestations.5 Medications that lower the immune system, such as corticosteroids, chemotherapy, and biologic disease modifying agents, may increase the risk for developing this entity.4 Specifically, antitumor necrosis factor inhibitors have been historically associated with mycobacterium infections.6

Patients are frequently diagnosed with soft tissue infection, such as abscesses or cellulitis, as in our case. They may at times be found to have other musculoskeletal conditions such as trigger finger.1 Other similar presenting entities are psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and remitting seronegative arthritis.4 These clinical resemblances complicate the scenario, especially when initial cultures are negative, as the treatment for these rheumatic diseases is immunosuppression, which adversely impact the fastidious infection. In our case, the improved swelling and range of motion after the 3-week course of empiric antibiotics for suppurative tenosynovitis was initially reassuring that the previous infection had been successfully treated. Subsequently, the presence of chondrocalcinosis in the triangular fibrocartilage in the right-hand X-rays, persistent pain, and the tophi-like appearance of the right third proximal interphalangeal nodule raised concerns for crystalline arthropathies, such as calcium pyrophosphate deposition vs gout. Nonetheless, given the lack of response to low-dose steroids, an ongoing infectious process was strongly considered.

Sarcoidosis was a concern after the first synovial biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas and negative stains and cultures. Sarcoid tenosynovitis is rare with only 22 cases described as per a 2015 report.7 Musculoskeletal involvement in sarcoidosis has been reported in 1 to 13% of sarcoid patients.7 Once again, unresponsiveness to steroids led to another synovial biopsy for culture due to potential infection. Akin to other cases, more than one surgical debridement was required to diagnose our patient.

Conclusions

Our case reinforces the vital role of history gathering in establishing diagnoses. It underscores the value of clinical suspicion especially in patients unresponsive to standard treatment for inflammatory arthritis, namely corticosteroids. Tissue biopsy with culture for AFB is crucial for accurate diagnosis in NTM infection, which may imitate rheumatic inflammatory arthritis. Clinicians should be keenly aware of this fastidious, indolent organism in the setting of persistent localized tenosynovitis.

1. Pang HN, Lee JY, Puhaindran ME, Tan SH, Tan AB, Yong FC. Mycobacterium marinum as a cause of chronic granulomatous tenosynovitis in the hand. J Infect. 2007;54(6):584-588. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.014

2. Wongworawat MD, Holtom P, Learch TJ, Fedenko A, Stevanovic MV. A prolonged case of Mycobacterium marinum flexor tenosynovitis: radiographic and histological correlation, and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32(9):542-545. doi:10.1007/s00256-003-0636-y

3. Schubert N, Schill T, Plüß M, Korsten P. Flare or foe? - Mycobacterium marinum infection mimicking rheumatoid arthritis tenosynovitis: case report and literature review. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4:11. Published 2020 Mar 16. doi:10.1186/s41927-020-0114-3

4. Lam A, Toma W, Schlesinger N. Mycobacterium marinum arthritis mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(4):817-819.

5. Hashish E, Merwad A, Elgaml S, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection in fish and man: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management; a review. Vet Q. 2018;38(1):35-46. doi:10.1080/01652176.2018.1447171

6. Thanou-Stavraki A, Sawalha AH, Crowson AN, Harley JB. Noodling and Mycobacterium marinum infection mimicking seronegative rheumatoid arthritis complicated by anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(1):160-164. doi:10.1002/acr.20303

7. Al-Ani Z, Oh TC, Macphie E, Woodruff MJ. Sarcoid tenosynovitis, rare presentation of a common disease. Case report and literature review. J Radiol Case Rep. 2015;9(8):16-23. Published 2015 Aug 31. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v9i8.2311

1. Pang HN, Lee JY, Puhaindran ME, Tan SH, Tan AB, Yong FC. Mycobacterium marinum as a cause of chronic granulomatous tenosynovitis in the hand. J Infect. 2007;54(6):584-588. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.014

2. Wongworawat MD, Holtom P, Learch TJ, Fedenko A, Stevanovic MV. A prolonged case of Mycobacterium marinum flexor tenosynovitis: radiographic and histological correlation, and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32(9):542-545. doi:10.1007/s00256-003-0636-y

3. Schubert N, Schill T, Plüß M, Korsten P. Flare or foe? - Mycobacterium marinum infection mimicking rheumatoid arthritis tenosynovitis: case report and literature review. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4:11. Published 2020 Mar 16. doi:10.1186/s41927-020-0114-3

4. Lam A, Toma W, Schlesinger N. Mycobacterium marinum arthritis mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(4):817-819.

5. Hashish E, Merwad A, Elgaml S, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection in fish and man: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management; a review. Vet Q. 2018;38(1):35-46. doi:10.1080/01652176.2018.1447171

6. Thanou-Stavraki A, Sawalha AH, Crowson AN, Harley JB. Noodling and Mycobacterium marinum infection mimicking seronegative rheumatoid arthritis complicated by anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(1):160-164. doi:10.1002/acr.20303

7. Al-Ani Z, Oh TC, Macphie E, Woodruff MJ. Sarcoid tenosynovitis, rare presentation of a common disease. Case report and literature review. J Radiol Case Rep. 2015;9(8):16-23. Published 2015 Aug 31. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v9i8.2311

A doctor’s missed diagnosis results in mega award

, according to a story from WCCO CBS Minnesota, among other news outlets. The award has been called the largest judgment of its kind in Minnesota history.

In January 2017, Nepalese immigrant Anuj Thapa was playing in an indoor soccer game at St. Cloud State University when another player tackled him. His left leg badly injured, Mr. Thapa was taken by ambulance to CentraCare’s St. Cloud Hospital. The orthopedic surgeon on call that day was Chad Holien, MD, who is affiliated with St. Cloud Orthopedics, a private clinic in nearby Sartell, Minn. Following preparations, and with the help of a physician assistant, Dr. Holien operated on the patient’s broken leg.

But Mr. Thapa experienced post-surgical complications – severe pain, numbness, burning, and muscle issues. Despite the complications, he was discharged from the hospital that afternoon and sent home.

Six days later, Mr. Thapa returned to St. Cloud Hospital, still complaining of severe pain. A second orthopedic surgeon operated and found that Mr. Thapa had “acute compartment syndrome,” the result of internal pressure that had built up in his leg muscles.

Over time, Mr. Thapa underwent more than 20 surgeries on his leg to deal with the ongoing pain and other complications, according to WCCO.

In 2019, he filed a medical malpractice suit in U.S. district court against St. Cloud Orthopedics, the private practice that employed the surgeon and the PA. (Under Minnesota law, an employer is responsible for the actions of its employees.)

In his complaint, Mr. Thapa alleged that in treating him, “the defendants departed from accepted standards of medical practice.” Among other things, he claimed that Dr. Holien and the PA had not properly evaluated his postoperative symptoms, failed to diagnose and treat his compartment syndrome, and improperly discharged him from the hospital. These lapses, Mr. Thapa said, led to his “severe, permanent, and disabling injuries.”

The federal jury agreed. After a weeklong trial, it awarded the plaintiff $100 million for future “pain, disability, disfigurement, embarrassment, and emotional distress.” It also gave him $10 million for past suffering and a little more than $1 million for past and future medical bills.

In a postverdict statement, Mr. Thapa’s attorney said that, while the surgeon and PA are undoubtedly good providers, they made mistakes in this case.

A defense attorney for St. Cloud Orthopedics disputes this: “We maintain the care provided in this case was in accordance with accepted standards of care.”

At press time, the defense had not determined whether to appeal the jury’s $111 million verdict. “St. Cloud continues to support its providers,” said the clinic’s defense attorney. “We are evaluating our options regarding this verdict.”

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a story from WCCO CBS Minnesota, among other news outlets. The award has been called the largest judgment of its kind in Minnesota history.

In January 2017, Nepalese immigrant Anuj Thapa was playing in an indoor soccer game at St. Cloud State University when another player tackled him. His left leg badly injured, Mr. Thapa was taken by ambulance to CentraCare’s St. Cloud Hospital. The orthopedic surgeon on call that day was Chad Holien, MD, who is affiliated with St. Cloud Orthopedics, a private clinic in nearby Sartell, Minn. Following preparations, and with the help of a physician assistant, Dr. Holien operated on the patient’s broken leg.

But Mr. Thapa experienced post-surgical complications – severe pain, numbness, burning, and muscle issues. Despite the complications, he was discharged from the hospital that afternoon and sent home.

Six days later, Mr. Thapa returned to St. Cloud Hospital, still complaining of severe pain. A second orthopedic surgeon operated and found that Mr. Thapa had “acute compartment syndrome,” the result of internal pressure that had built up in his leg muscles.

Over time, Mr. Thapa underwent more than 20 surgeries on his leg to deal with the ongoing pain and other complications, according to WCCO.

In 2019, he filed a medical malpractice suit in U.S. district court against St. Cloud Orthopedics, the private practice that employed the surgeon and the PA. (Under Minnesota law, an employer is responsible for the actions of its employees.)

In his complaint, Mr. Thapa alleged that in treating him, “the defendants departed from accepted standards of medical practice.” Among other things, he claimed that Dr. Holien and the PA had not properly evaluated his postoperative symptoms, failed to diagnose and treat his compartment syndrome, and improperly discharged him from the hospital. These lapses, Mr. Thapa said, led to his “severe, permanent, and disabling injuries.”

The federal jury agreed. After a weeklong trial, it awarded the plaintiff $100 million for future “pain, disability, disfigurement, embarrassment, and emotional distress.” It also gave him $10 million for past suffering and a little more than $1 million for past and future medical bills.

In a postverdict statement, Mr. Thapa’s attorney said that, while the surgeon and PA are undoubtedly good providers, they made mistakes in this case.

A defense attorney for St. Cloud Orthopedics disputes this: “We maintain the care provided in this case was in accordance with accepted standards of care.”

At press time, the defense had not determined whether to appeal the jury’s $111 million verdict. “St. Cloud continues to support its providers,” said the clinic’s defense attorney. “We are evaluating our options regarding this verdict.”

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a story from WCCO CBS Minnesota, among other news outlets. The award has been called the largest judgment of its kind in Minnesota history.

In January 2017, Nepalese immigrant Anuj Thapa was playing in an indoor soccer game at St. Cloud State University when another player tackled him. His left leg badly injured, Mr. Thapa was taken by ambulance to CentraCare’s St. Cloud Hospital. The orthopedic surgeon on call that day was Chad Holien, MD, who is affiliated with St. Cloud Orthopedics, a private clinic in nearby Sartell, Minn. Following preparations, and with the help of a physician assistant, Dr. Holien operated on the patient’s broken leg.

But Mr. Thapa experienced post-surgical complications – severe pain, numbness, burning, and muscle issues. Despite the complications, he was discharged from the hospital that afternoon and sent home.

Six days later, Mr. Thapa returned to St. Cloud Hospital, still complaining of severe pain. A second orthopedic surgeon operated and found that Mr. Thapa had “acute compartment syndrome,” the result of internal pressure that had built up in his leg muscles.

Over time, Mr. Thapa underwent more than 20 surgeries on his leg to deal with the ongoing pain and other complications, according to WCCO.

In 2019, he filed a medical malpractice suit in U.S. district court against St. Cloud Orthopedics, the private practice that employed the surgeon and the PA. (Under Minnesota law, an employer is responsible for the actions of its employees.)

In his complaint, Mr. Thapa alleged that in treating him, “the defendants departed from accepted standards of medical practice.” Among other things, he claimed that Dr. Holien and the PA had not properly evaluated his postoperative symptoms, failed to diagnose and treat his compartment syndrome, and improperly discharged him from the hospital. These lapses, Mr. Thapa said, led to his “severe, permanent, and disabling injuries.”

The federal jury agreed. After a weeklong trial, it awarded the plaintiff $100 million for future “pain, disability, disfigurement, embarrassment, and emotional distress.” It also gave him $10 million for past suffering and a little more than $1 million for past and future medical bills.

In a postverdict statement, Mr. Thapa’s attorney said that, while the surgeon and PA are undoubtedly good providers, they made mistakes in this case.

A defense attorney for St. Cloud Orthopedics disputes this: “We maintain the care provided in this case was in accordance with accepted standards of care.”

At press time, the defense had not determined whether to appeal the jury’s $111 million verdict. “St. Cloud continues to support its providers,” said the clinic’s defense attorney. “We are evaluating our options regarding this verdict.”

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts elevate new drugs for diabetic kidney disease

ATLANTA – U.S. clinicians caring for people with diabetes should take a more aggressive approach to using combined medical treatments proven to slow the otherwise relentless progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to a new joint statement by the American Diabetes Association and a major international nephrology organization presented during the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

The statement elevates treatment with an agent from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class to first-line for people with diabetes and laboratory-based evidence of advancing CKD. It also re-emphasizes the key role of concurrent first-line treatment with a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker), metformin, and a statin.

The new statement also urges clinicians to rapidly add treatment with the new nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone (Kerendia) for further renal protection in the many patients suitable for treatment with this agent, and it recommends the second-line addition of a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist as the best add-on for any patient who needs additional glycemic control on top of metformin and an SGLT2 inhibitor.

The consensus joint statement with these updates came from a nine-member writing group assembled by the ADA and the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) organization.

“We’re going to try to make this feasible. We have to; I don’t think we have a choice,” commented Amy K. Mottl, MD, a nephrologist at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Mottl was not involved with writing the consensus statement but has been active in the Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative of the American Society of Nephrology, another group promoting a more aggressive multidrug-class approach to treating CKD in people with diabetes.

Wider use of costly drugs

Adoption of this evidence-based approach by U.S. clinicians will both increase the number of agents that many patients receive and drive a significant uptick in the cost and complexity of patient care, a consequence acknowledged by the authors of the joint statement as well as outside experts.

But they view this as unavoidable given what’s now known about the high incidence of worsening CKD in patients with diabetes and the types of interventions proven to blunt this.

Much of the financial implication stems from the price of agents from the new drug classes now emphasized in the consensus recommendations – SGLT2 inhibitors, finerenone, and GLP-1 receptor agonists. All these drugs currently remain on-patent with relatively expensive retail prices in the range of about $600 to $1,000/month.

Commenting on the cost concerns, Dr. Mottl highlighted that she currently has several patients in her practice on agents from two or more of these newer classes, and she has generally found it possible for patients to get much of their expenses covered by insurers and through drug-company assistance programs.

“The major gap is patients on Medicare,” she noted in an interview, because the Federal health insurance program does not allow beneficiaries to receive rebates for their drug costs. “The Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative is currently lobbying members of Congress to lift that barrier,” she emphasized.

Improved alignment

Details of the KDIGO recommendations feature in a guideline from that organization that appeared as a draft document online in March 2022. The ADA’s version recently appeared as an update to its Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2022, as reported by this news organization. A panel of five KDIGO representatives and four members appointed by the ADA produced the harmonization statement.

Recommendations from both organizations were largely in agreement at the outset, but following the panel’s review, the two groups are now “very well-aligned,” said Peter Rossing, MD, DMSc, a diabetologist and professor at the Steno Diabetes Center, Copenhagen, and a KDIGO representative to the writing committee, who presented the joint statement at the ADA meeting.

“These are very important drugs that are vastly underused,” commented Josef Coresh, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, who specializes in CKD and was not involved with the new statement.

“Coherence and simplicity are what we need so that there are no excuses about moving forward” with the recommended combination treatment, he stressed.

Moving too slow

“No one is resisting using these new medications, but they are just moving too slowly, and data now show that it’s moving more slowly in the United States than elsewhere. That may be partly because U.S. patients are charged much more for these drugs, and partly because U.S. health care is so much more fragmented,” Dr. Coresh said in an interview.

The new joint consensus statement may help, “but the fragmentation of the United States system and COVID-19 are big enemies” for any short-term increased use of the highlighted agents, he added.

Evidence for low U.S. use of SGLT2 inhibitors, finerenone, and GLP-1 receptor agonists is becoming well known.

Dr. Rossing cited a 2019 report from the CURE-CKD registry of more than 600,000 U.S. patients with CKD showing that less than 1% received an SGLT2 inhibitor and less than 1% a GLP-1 receptor agonist. Not all these patients had diabetes, but a subgroup analysis of those with diabetes, prediabetes, or hypertension showed that usage of each of these two classes remained at less than 1% even in this group.

A separate report at the ADA meeting documented that of more than 1.3 million people with type 2 diabetes in the U.S. Veterans Affairs Healthcare System during 2019 and 2020, just 10% received an SGLT2 inhibitor and 7% a GLP-1 receptor agonist. And this is in a setting where drug cost is not a limiting factor.

In addition to focusing on the updated scheme for drug intervention in the consensus statement, Dr. Rossing highlighted several other important points that the writing committee emphasized.

Lifestyle optimization is a core first-line element of managing patients with diabetes and CKD, including a healthy diet, exercise, smoking cessation, and weight control. Other key steps for management include optimization of blood pressure, glucose, and lipids. The statement also calls out a potentially helpful role for continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and CKD.

The statement notes that patients who also have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease usually qualify for and could potentially benefit from more intensified lipid management with ezetimibe or a PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) inhibitor, as well as a potential role for treatment with antiplatelet agents.

‘If you don’t screen, you won’t find it’

Dr. Rossing also stressed the importance of regular screening for the onset of advanced CKD in patients. Patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) drops below 60 mL/min/1.73m2, as well as those who develop microalbuminuria with a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio of at least 30 mg/g (30 mg/mmol), have a stage of CKD that warrants the drug interventions he outlined.

Guidelines from both the ADA and KDIGO were already in place, recommending annual screening of patients with diabetes for both these parameters starting at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes or 5 years following initial diagnosis of type 1 diabetes.

“If you don’t screen, you won’t find it, and you won’t be able to treat,” Dr. Rossing warned. He also highlighted the panel’s recommendation to treat these patients with an SGLT2 inhibitor as long as their eGFR is at least 20 mL/min/1.73m2. Treatment can then continue even when their eGFR drops lower.

Starting treatment with finerenone requires that patients have a normal level of serum potassium, he emphasized.

One reason for developing the new ADA and KDIGO statement is that “discrepancies in clinical practice guideline recommendations from various professional organizations add to confusion that impedes understanding of best practices,” write Katherine R. Tuttle, MD, and associates in a recent commentary.

The goal of the new statement is to harmonize and promote the shared recommendations of the two organizations, added Dr. Tuttle, who is executive director for research at Providence Healthcare, Spokane, Washington, and a KDIGO representative on the statement writing panel.