User login

Early Diagnosis and Management of Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a delayed movement disorder resulting from treatment with dopamine receptor–blocking medications, Dr Karen Anderson of Georgetown University School of Medicine explains. TD is most commonly associated with long-term use of antipsychotic drugs.

TD is characterized by involuntary, jerking movements of the tongue, lips, face, trunk, extremities, or the whole body. Although its characteristic movements are sometimes viewed as cosmetic, TD can interfere with patients’ quality of life and add to the stigma of mental illness.

The sooner TD is diagnosed, the more likely it is for patients to achieve remission spontaneously and without treatment. To that end, patients who are prescribed antipsychotic medication should be evaluated at baseline and regularly thereafter using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), which rates abnormal movements.

The optimal first step in TD management is to stop the dopamine receptor–blocking medication, but this option may not be possible in patients with chronic conditions, such as manic depression and schizophrenia. In these patients, dose reduction or switching to a newer antipsychotic may provide relief.

Two vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors are approved to treat TD and have been found to not worsen patients’ underlying psychiatric condition. Dr Anderson cautions that patients treated with a VMAT2 inhibitor will require monitoring because side effects of these agents include suicidal ideation.

--

Karen Anderson, MD, Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Georgetown University School of Medicine; Washington, DC

Karen Anderson, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Neurocrine; Teva

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a delayed movement disorder resulting from treatment with dopamine receptor–blocking medications, Dr Karen Anderson of Georgetown University School of Medicine explains. TD is most commonly associated with long-term use of antipsychotic drugs.

TD is characterized by involuntary, jerking movements of the tongue, lips, face, trunk, extremities, or the whole body. Although its characteristic movements are sometimes viewed as cosmetic, TD can interfere with patients’ quality of life and add to the stigma of mental illness.

The sooner TD is diagnosed, the more likely it is for patients to achieve remission spontaneously and without treatment. To that end, patients who are prescribed antipsychotic medication should be evaluated at baseline and regularly thereafter using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), which rates abnormal movements.

The optimal first step in TD management is to stop the dopamine receptor–blocking medication, but this option may not be possible in patients with chronic conditions, such as manic depression and schizophrenia. In these patients, dose reduction or switching to a newer antipsychotic may provide relief.

Two vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors are approved to treat TD and have been found to not worsen patients’ underlying psychiatric condition. Dr Anderson cautions that patients treated with a VMAT2 inhibitor will require monitoring because side effects of these agents include suicidal ideation.

--

Karen Anderson, MD, Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Georgetown University School of Medicine; Washington, DC

Karen Anderson, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Neurocrine; Teva

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a delayed movement disorder resulting from treatment with dopamine receptor–blocking medications, Dr Karen Anderson of Georgetown University School of Medicine explains. TD is most commonly associated with long-term use of antipsychotic drugs.

TD is characterized by involuntary, jerking movements of the tongue, lips, face, trunk, extremities, or the whole body. Although its characteristic movements are sometimes viewed as cosmetic, TD can interfere with patients’ quality of life and add to the stigma of mental illness.

The sooner TD is diagnosed, the more likely it is for patients to achieve remission spontaneously and without treatment. To that end, patients who are prescribed antipsychotic medication should be evaluated at baseline and regularly thereafter using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), which rates abnormal movements.

The optimal first step in TD management is to stop the dopamine receptor–blocking medication, but this option may not be possible in patients with chronic conditions, such as manic depression and schizophrenia. In these patients, dose reduction or switching to a newer antipsychotic may provide relief.

Two vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors are approved to treat TD and have been found to not worsen patients’ underlying psychiatric condition. Dr Anderson cautions that patients treated with a VMAT2 inhibitor will require monitoring because side effects of these agents include suicidal ideation.

--

Karen Anderson, MD, Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Georgetown University School of Medicine; Washington, DC

Karen Anderson, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Neurocrine; Teva

PAH care turns corner with new therapies, intensified monitoring

Aggressive up-front combination therapy, more lofty treatment goals, and earlier and more frequent reassessments to guide treatment are improving care of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) while at the same time making it more complex.

A larger number of oral and generic treatment options have in some respects ushered in more management ease. But overall, “I don’t know if management of these patients has ever been more complicated, given the treatment options and strategies,” said Murali M. Chakinala, MD, professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis. “We’re always thinking through approaches.”

Diagnosis continues to be challenging given the rarity of PAH and its nonspecific presentation – and in some cases it’s now harder. Experts such as Dr. Chakinala are seeing increasing number of aging patients with left heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and other comorbidities who have significant precapillary pulmonary hypertension and who exhibit hemodynamics consistent with PAH, or group 1 PH.

The question experts face is, do such patients have “true PAH,” as do a reported 25-50 people per million, or do they have another type of PH in the classification schema – or a mixture?

Deciding which patients “really fit into group 1 and should be managed like group 1,” Dr. Chakinala said, requires clinical acumen and has important implications, as patients with PAH are the main beneficiaries of vasodilator therapy. Most other patients with PH will not respond to or tolerate such treatment.

“These older patients may be getting PAH through different mechanisms than our younger patients, but because we define PAH through hemodynamic criteria and by ruling out other obvious explanations, they all get lumped together,” said Dr. Chakinala. “We need to parse these patients out better in the future, much like our oncology colleagues are doing.”

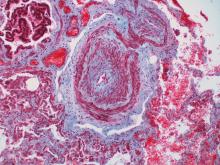

Personalized medicine hopefully is the next horizon for this condition, characterized by severe remodeling of the distal pulmonary arteries. Researchers are pushing to achieve deep phenotyping, identify biomarkers and improve risk assessment tools.

And with 80 or so centers now accredited by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association as Pulmonary Hypertension Care Centers, referred patients are accessing clinical trials of new nonvasodilatory drugs. Currently available therapies improve hemodynamics and symptoms, and can slow disease progression, but are not truly disease modifying, sources say.

“The endothelin, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin pathways have been exhaustively studied and we now have great drugs for those pathways,” said Dr. Chakinala, who leads the PHA’s scientific leadership council. But “we’re not going to put a greater dent into this disease until we have new drugs that work on different biologic pathways.”

Diagnostic challenges

The diagnosis of PAH – a remarkably heterogeneous condition that encompasses heritable forms and idiopathic forms, and that comprises a broad mix of predisposing conditions and exposures, from scleroderma to methamphetamine use – is still too often missed or delayed. Delayed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of PAH and other types of PH have been reported in up to 85% of at-risk patients, according to a 2016 literature review.

Being able to pivot from thinking about common pulmonary ailments or heart failure to considering PAH is a key part of earlier diagnosis and better treatment outcomes. “If someone has unexplained dyspnea or if they’re treated for other lung diseases and are not improving, think about a screening echocardiogram,” said Timothy L. Williamson, MD, vice president of quality and safety and a pulmonary and critical care physician at the University of Kansas Health Center, Kansas City.

One of the most common reasons Dr. Chakinala sees for missed diagnoses are right heart catheterizations that are incomplete or misinterpreted. (Right heart catheterizations are required to confirm the diagnosis.) “One can’t simply measure pressures and stop,” he said. “We need the full hemodynamic profile to know that it’s truly precapillary PAH ... and we need proper interpretation of [elements like] the waveforms.”

The 2019 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension shifted the definition of PH from an arbitrarily defined mean pulmonary arterial pressure of at least 25 mm Hg at rest (as measured by right heart catheterization) to a more scientifically determined mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg.

The classification document also requires pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of at least 3 Wood units in the definition of all forms of precapillary PH. PAH specifically is defined as the presence of mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg, PVR of at least 3 Wood units, and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure 15 mm Hg or less.

Trends in treatment

The value of initial combination therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor in treatment-naive PAH was cemented in 2015 by the AMBITION trial. The primary endpoint (death, PAH hospitalization, or unsatisfactory clinical response) occurred in 18%, 34%, and 28% of patients who were randomized, respectively, to combination therapy, monotherapy with the ERA ambrisentan, or monotherapy with the PDE-5 inhibitor tadalafil – and in 31% of the two monotherapy groups combined.

The trial reported a 50% reduction in the primary endpoint in the combination-therapy group versus the pooled monotherapy group, as well as greater reductions in N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, more satisfactory clinical response and greater improvement in 6-minute walking distance.

In practice, a minority of patients – typically older patients with multiple comorbidities – still receive initial monotherapy with sequential add-on therapies based on tolerance, but “for the most part PAH patients will start on combination therapy, most commonly with a ERA and PDE5 inhibitor,” Dr. Chakinala said.

For patients who are not improving on the ERA-PDE5 inhibitor approach – typically those who remain in the intermediate-risk category for intermediate-term mortality – substitution of the PDE5 inhibitor with the soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator riociguat may be considered, he and Dr. Williamson said. Clinical improvement with this substitution was demonstrated in the REPLACE trial.

Experts at PH care centers are also utilizing triple therapy for patients who do not improve to low-risk status after 2-4 months of dual combination therapy. The availability of oral prostacyclin analogues (selexipag and treprostinil) makes it easier to consider adding these agents early on, Dr. Chakinala and Dr. Richardson said.

Patients who fall into the high-risk category, at any point, are still best managed with parenteral prostacyclin analogues, Dr. Chakinala said.

In general, said Dr. Williamson, who also directs the University of Kansas Pulmonary Hypertension Comprehensive Care Center, “the PH community tends to be fairly aggressive up front, and with a low threshold for using prostacyclin analogues.”

The agents are “always part of the picture for someone who is really ill, in functional class IV, or has really impaired right ventricular function,” he said. “And we’re finding increased roles in patients who are not as ill but still have decompensated right ventricular dysfunction. It’s something we now consider.”

Recently published research on up-front oral triple therapy suggests possible benefit for some patients – but it’s far from conclusive, said Dr. Chakinala. The TRITON study randomized treatment-naive patients to the traditional ERA-PDE5 combination and either oral selexipag (a selective prostacyclin receptor agonist) or placebo as a third agent. It found no significant difference in reduction in PVR, the primary outcome, at week 26. However, the authors reported a “possible signal” for improved long-term outcomes with triple therapy.

“Based on this best evidence from a randomized clinical trial, I think it’s unfair to say that all patients should be on triple combination therapy right out of the gate,” he said. “Having said that, more recent [European] data showed that two drugs fell short of the mark in some patients, with high rates of clinical progression. And even in AMBITION, there were a number of patients in the combination arm who didn’t have a robust response.”

A 2021 retrospective analysis from the French Pulmonary Hypertension Registry – one of the European studies – assessed survival with monotherapy, dual therapy, or triple-combination therapy (two orals with a parenteral prostacyclin), and found no difference between monotherapy and dual therapy in high-risk patients.

Experts have been upping the ante, therefore, on early assessment and frequent reassessment of treatment response. Not long ago, patients were typically reassessed 6-12 months after the initiation of treatment. Now, experts at the PH care centers want to assess patients at 3-4 months and adjust or intensify treatment regimens for those who don’t yet qualify as low risk using a multidimensional risk score calculator.

The REVEAL (Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Management) risk score calculator, for instance, predicts the probability of 1-year survival and assigns patients to a strata of risk level based on either 12 or 6 variables (for the full or “lite” versions).]

Even better monitoring and risk assessment is needed, however, to “help sift out which patients are not improving enough on initial therapy or who are starting to fall off after being on a regimen for a period of time,” Dr. Chakinala said.

Today, with a network of accredited centers of expertise and a desire and need for many patients to remain close to home, Dr. Chakinala encourages finding a balance. Well-resourced clinicians can strive for early diagnosis and management – potentially initiating ERA–PDE-5 inhibitor combination therapy – but still should collaborate with PH experts.

“It’s a good idea to comanage these patients and let the experts see them periodically to help you determine when your patient may be declining,” he said. “The timetable for reassessment, the complexity of the reassessment, and the need to escalate to more advanced therapies has never been more important.”

Research highlights

Therapies that target inflammation and altered metabolism – including metformin – are among those being investigated for PAH. So are therapies targeting dysfunctional bone morphogenetic protein pathway signaling, which has been shown to be associated with hereditary, idiopathic, and likely other forms of PAH; one such drug, called sotatercept, is currently at the phase 3 trial stage.

Most promising for PAH may be the research efforts involving deep phenotyping, said Andrew J. Sweatt, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and the Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease.

“It’s where a lot of research is headed – deep phenotyping to deconstruct the molecular and clinical heterogeneity that exists within PAH ... to detect distinct subphenotypes of patients who would respond to particular therapies,” said Dr. Sweatt, who led a review of PH clinical research presented at the 2020 American Thoracic Society International Conference

“Right now, we largely treat all patients the same ... [while] we know that patients have a wide response to therapies and there’s a lot of clinical heterogeneity in how their disease evolves over time,” he said.

Data from a large National Institutes of Health–funded multicenter phenotyping study of PH is being analyzed and should yield findings and publications starting this year, said Anna R. Hemnes, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and an investigator with the initiative, coined “Redefining Pulmonary Hypertension through Pulmonary Disease Phenomics (PVDOMICS).”

Patients have undergone advanced imaging (for example, echocardiography, cardiac MRI, chest CT, ventilation/perfusion scans), advanced testing through right heart catheterization, body composition testing, quality of life questionnaires, and blood draws that have been analyzed for DNA and RNA expression, proteomics, and metabolomics, said Dr. Hemnes, assistant director of Vanderbilt’s Pulmonary Vascular Center.

The initiative aims to refine the classification of all kinds of PH and “to bring precision medicine to the field so we’re no longer characterizing somebody [based on imaging] and right heart catheterization, but we also incorporating molecular pieces and biomarkers into the diagnostic evaluation,” she said.

In the short term, the results of deep phenotyping should “allow us to be more effective with our therapy recommendations,” Dr. Hemnes said. “Then hopefully in the longer term, [identified biomarkers] will help us to develop new, more effective therapies.”

Dr. Sweatt and Dr. Williamson reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Hemnes reported that she holds stock in Tenax (which is studying a tyrosine kinase inhibitor for PAH) and serves as a consultant for Acceleron, Bayer, GossamerBio, United Therapeutics, and Janssen. She also receives research funding from Imara. Dr. Chakinala reported that he is an investigator on clinical trials for a number of pharmaceutical companies. He also serves on advisory boards for Phase Bio, Liquidia/Rare Gen, Bayer, Janssen, Trio Health Analytics, and Aerovate.

Aggressive up-front combination therapy, more lofty treatment goals, and earlier and more frequent reassessments to guide treatment are improving care of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) while at the same time making it more complex.

A larger number of oral and generic treatment options have in some respects ushered in more management ease. But overall, “I don’t know if management of these patients has ever been more complicated, given the treatment options and strategies,” said Murali M. Chakinala, MD, professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis. “We’re always thinking through approaches.”

Diagnosis continues to be challenging given the rarity of PAH and its nonspecific presentation – and in some cases it’s now harder. Experts such as Dr. Chakinala are seeing increasing number of aging patients with left heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and other comorbidities who have significant precapillary pulmonary hypertension and who exhibit hemodynamics consistent with PAH, or group 1 PH.

The question experts face is, do such patients have “true PAH,” as do a reported 25-50 people per million, or do they have another type of PH in the classification schema – or a mixture?

Deciding which patients “really fit into group 1 and should be managed like group 1,” Dr. Chakinala said, requires clinical acumen and has important implications, as patients with PAH are the main beneficiaries of vasodilator therapy. Most other patients with PH will not respond to or tolerate such treatment.

“These older patients may be getting PAH through different mechanisms than our younger patients, but because we define PAH through hemodynamic criteria and by ruling out other obvious explanations, they all get lumped together,” said Dr. Chakinala. “We need to parse these patients out better in the future, much like our oncology colleagues are doing.”

Personalized medicine hopefully is the next horizon for this condition, characterized by severe remodeling of the distal pulmonary arteries. Researchers are pushing to achieve deep phenotyping, identify biomarkers and improve risk assessment tools.

And with 80 or so centers now accredited by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association as Pulmonary Hypertension Care Centers, referred patients are accessing clinical trials of new nonvasodilatory drugs. Currently available therapies improve hemodynamics and symptoms, and can slow disease progression, but are not truly disease modifying, sources say.

“The endothelin, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin pathways have been exhaustively studied and we now have great drugs for those pathways,” said Dr. Chakinala, who leads the PHA’s scientific leadership council. But “we’re not going to put a greater dent into this disease until we have new drugs that work on different biologic pathways.”

Diagnostic challenges

The diagnosis of PAH – a remarkably heterogeneous condition that encompasses heritable forms and idiopathic forms, and that comprises a broad mix of predisposing conditions and exposures, from scleroderma to methamphetamine use – is still too often missed or delayed. Delayed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of PAH and other types of PH have been reported in up to 85% of at-risk patients, according to a 2016 literature review.

Being able to pivot from thinking about common pulmonary ailments or heart failure to considering PAH is a key part of earlier diagnosis and better treatment outcomes. “If someone has unexplained dyspnea or if they’re treated for other lung diseases and are not improving, think about a screening echocardiogram,” said Timothy L. Williamson, MD, vice president of quality and safety and a pulmonary and critical care physician at the University of Kansas Health Center, Kansas City.

One of the most common reasons Dr. Chakinala sees for missed diagnoses are right heart catheterizations that are incomplete or misinterpreted. (Right heart catheterizations are required to confirm the diagnosis.) “One can’t simply measure pressures and stop,” he said. “We need the full hemodynamic profile to know that it’s truly precapillary PAH ... and we need proper interpretation of [elements like] the waveforms.”

The 2019 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension shifted the definition of PH from an arbitrarily defined mean pulmonary arterial pressure of at least 25 mm Hg at rest (as measured by right heart catheterization) to a more scientifically determined mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg.

The classification document also requires pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of at least 3 Wood units in the definition of all forms of precapillary PH. PAH specifically is defined as the presence of mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg, PVR of at least 3 Wood units, and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure 15 mm Hg or less.

Trends in treatment

The value of initial combination therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor in treatment-naive PAH was cemented in 2015 by the AMBITION trial. The primary endpoint (death, PAH hospitalization, or unsatisfactory clinical response) occurred in 18%, 34%, and 28% of patients who were randomized, respectively, to combination therapy, monotherapy with the ERA ambrisentan, or monotherapy with the PDE-5 inhibitor tadalafil – and in 31% of the two monotherapy groups combined.

The trial reported a 50% reduction in the primary endpoint in the combination-therapy group versus the pooled monotherapy group, as well as greater reductions in N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, more satisfactory clinical response and greater improvement in 6-minute walking distance.

In practice, a minority of patients – typically older patients with multiple comorbidities – still receive initial monotherapy with sequential add-on therapies based on tolerance, but “for the most part PAH patients will start on combination therapy, most commonly with a ERA and PDE5 inhibitor,” Dr. Chakinala said.

For patients who are not improving on the ERA-PDE5 inhibitor approach – typically those who remain in the intermediate-risk category for intermediate-term mortality – substitution of the PDE5 inhibitor with the soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator riociguat may be considered, he and Dr. Williamson said. Clinical improvement with this substitution was demonstrated in the REPLACE trial.

Experts at PH care centers are also utilizing triple therapy for patients who do not improve to low-risk status after 2-4 months of dual combination therapy. The availability of oral prostacyclin analogues (selexipag and treprostinil) makes it easier to consider adding these agents early on, Dr. Chakinala and Dr. Richardson said.

Patients who fall into the high-risk category, at any point, are still best managed with parenteral prostacyclin analogues, Dr. Chakinala said.

In general, said Dr. Williamson, who also directs the University of Kansas Pulmonary Hypertension Comprehensive Care Center, “the PH community tends to be fairly aggressive up front, and with a low threshold for using prostacyclin analogues.”

The agents are “always part of the picture for someone who is really ill, in functional class IV, or has really impaired right ventricular function,” he said. “And we’re finding increased roles in patients who are not as ill but still have decompensated right ventricular dysfunction. It’s something we now consider.”

Recently published research on up-front oral triple therapy suggests possible benefit for some patients – but it’s far from conclusive, said Dr. Chakinala. The TRITON study randomized treatment-naive patients to the traditional ERA-PDE5 combination and either oral selexipag (a selective prostacyclin receptor agonist) or placebo as a third agent. It found no significant difference in reduction in PVR, the primary outcome, at week 26. However, the authors reported a “possible signal” for improved long-term outcomes with triple therapy.

“Based on this best evidence from a randomized clinical trial, I think it’s unfair to say that all patients should be on triple combination therapy right out of the gate,” he said. “Having said that, more recent [European] data showed that two drugs fell short of the mark in some patients, with high rates of clinical progression. And even in AMBITION, there were a number of patients in the combination arm who didn’t have a robust response.”

A 2021 retrospective analysis from the French Pulmonary Hypertension Registry – one of the European studies – assessed survival with monotherapy, dual therapy, or triple-combination therapy (two orals with a parenteral prostacyclin), and found no difference between monotherapy and dual therapy in high-risk patients.

Experts have been upping the ante, therefore, on early assessment and frequent reassessment of treatment response. Not long ago, patients were typically reassessed 6-12 months after the initiation of treatment. Now, experts at the PH care centers want to assess patients at 3-4 months and adjust or intensify treatment regimens for those who don’t yet qualify as low risk using a multidimensional risk score calculator.

The REVEAL (Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Management) risk score calculator, for instance, predicts the probability of 1-year survival and assigns patients to a strata of risk level based on either 12 or 6 variables (for the full or “lite” versions).]

Even better monitoring and risk assessment is needed, however, to “help sift out which patients are not improving enough on initial therapy or who are starting to fall off after being on a regimen for a period of time,” Dr. Chakinala said.

Today, with a network of accredited centers of expertise and a desire and need for many patients to remain close to home, Dr. Chakinala encourages finding a balance. Well-resourced clinicians can strive for early diagnosis and management – potentially initiating ERA–PDE-5 inhibitor combination therapy – but still should collaborate with PH experts.

“It’s a good idea to comanage these patients and let the experts see them periodically to help you determine when your patient may be declining,” he said. “The timetable for reassessment, the complexity of the reassessment, and the need to escalate to more advanced therapies has never been more important.”

Research highlights

Therapies that target inflammation and altered metabolism – including metformin – are among those being investigated for PAH. So are therapies targeting dysfunctional bone morphogenetic protein pathway signaling, which has been shown to be associated with hereditary, idiopathic, and likely other forms of PAH; one such drug, called sotatercept, is currently at the phase 3 trial stage.

Most promising for PAH may be the research efforts involving deep phenotyping, said Andrew J. Sweatt, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and the Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease.

“It’s where a lot of research is headed – deep phenotyping to deconstruct the molecular and clinical heterogeneity that exists within PAH ... to detect distinct subphenotypes of patients who would respond to particular therapies,” said Dr. Sweatt, who led a review of PH clinical research presented at the 2020 American Thoracic Society International Conference

“Right now, we largely treat all patients the same ... [while] we know that patients have a wide response to therapies and there’s a lot of clinical heterogeneity in how their disease evolves over time,” he said.

Data from a large National Institutes of Health–funded multicenter phenotyping study of PH is being analyzed and should yield findings and publications starting this year, said Anna R. Hemnes, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and an investigator with the initiative, coined “Redefining Pulmonary Hypertension through Pulmonary Disease Phenomics (PVDOMICS).”

Patients have undergone advanced imaging (for example, echocardiography, cardiac MRI, chest CT, ventilation/perfusion scans), advanced testing through right heart catheterization, body composition testing, quality of life questionnaires, and blood draws that have been analyzed for DNA and RNA expression, proteomics, and metabolomics, said Dr. Hemnes, assistant director of Vanderbilt’s Pulmonary Vascular Center.

The initiative aims to refine the classification of all kinds of PH and “to bring precision medicine to the field so we’re no longer characterizing somebody [based on imaging] and right heart catheterization, but we also incorporating molecular pieces and biomarkers into the diagnostic evaluation,” she said.

In the short term, the results of deep phenotyping should “allow us to be more effective with our therapy recommendations,” Dr. Hemnes said. “Then hopefully in the longer term, [identified biomarkers] will help us to develop new, more effective therapies.”

Dr. Sweatt and Dr. Williamson reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Hemnes reported that she holds stock in Tenax (which is studying a tyrosine kinase inhibitor for PAH) and serves as a consultant for Acceleron, Bayer, GossamerBio, United Therapeutics, and Janssen. She also receives research funding from Imara. Dr. Chakinala reported that he is an investigator on clinical trials for a number of pharmaceutical companies. He also serves on advisory boards for Phase Bio, Liquidia/Rare Gen, Bayer, Janssen, Trio Health Analytics, and Aerovate.

Aggressive up-front combination therapy, more lofty treatment goals, and earlier and more frequent reassessments to guide treatment are improving care of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) while at the same time making it more complex.

A larger number of oral and generic treatment options have in some respects ushered in more management ease. But overall, “I don’t know if management of these patients has ever been more complicated, given the treatment options and strategies,” said Murali M. Chakinala, MD, professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis. “We’re always thinking through approaches.”

Diagnosis continues to be challenging given the rarity of PAH and its nonspecific presentation – and in some cases it’s now harder. Experts such as Dr. Chakinala are seeing increasing number of aging patients with left heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and other comorbidities who have significant precapillary pulmonary hypertension and who exhibit hemodynamics consistent with PAH, or group 1 PH.

The question experts face is, do such patients have “true PAH,” as do a reported 25-50 people per million, or do they have another type of PH in the classification schema – or a mixture?

Deciding which patients “really fit into group 1 and should be managed like group 1,” Dr. Chakinala said, requires clinical acumen and has important implications, as patients with PAH are the main beneficiaries of vasodilator therapy. Most other patients with PH will not respond to or tolerate such treatment.

“These older patients may be getting PAH through different mechanisms than our younger patients, but because we define PAH through hemodynamic criteria and by ruling out other obvious explanations, they all get lumped together,” said Dr. Chakinala. “We need to parse these patients out better in the future, much like our oncology colleagues are doing.”

Personalized medicine hopefully is the next horizon for this condition, characterized by severe remodeling of the distal pulmonary arteries. Researchers are pushing to achieve deep phenotyping, identify biomarkers and improve risk assessment tools.

And with 80 or so centers now accredited by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association as Pulmonary Hypertension Care Centers, referred patients are accessing clinical trials of new nonvasodilatory drugs. Currently available therapies improve hemodynamics and symptoms, and can slow disease progression, but are not truly disease modifying, sources say.

“The endothelin, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin pathways have been exhaustively studied and we now have great drugs for those pathways,” said Dr. Chakinala, who leads the PHA’s scientific leadership council. But “we’re not going to put a greater dent into this disease until we have new drugs that work on different biologic pathways.”

Diagnostic challenges

The diagnosis of PAH – a remarkably heterogeneous condition that encompasses heritable forms and idiopathic forms, and that comprises a broad mix of predisposing conditions and exposures, from scleroderma to methamphetamine use – is still too often missed or delayed. Delayed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of PAH and other types of PH have been reported in up to 85% of at-risk patients, according to a 2016 literature review.

Being able to pivot from thinking about common pulmonary ailments or heart failure to considering PAH is a key part of earlier diagnosis and better treatment outcomes. “If someone has unexplained dyspnea or if they’re treated for other lung diseases and are not improving, think about a screening echocardiogram,” said Timothy L. Williamson, MD, vice president of quality and safety and a pulmonary and critical care physician at the University of Kansas Health Center, Kansas City.

One of the most common reasons Dr. Chakinala sees for missed diagnoses are right heart catheterizations that are incomplete or misinterpreted. (Right heart catheterizations are required to confirm the diagnosis.) “One can’t simply measure pressures and stop,” he said. “We need the full hemodynamic profile to know that it’s truly precapillary PAH ... and we need proper interpretation of [elements like] the waveforms.”

The 2019 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension shifted the definition of PH from an arbitrarily defined mean pulmonary arterial pressure of at least 25 mm Hg at rest (as measured by right heart catheterization) to a more scientifically determined mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg.

The classification document also requires pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of at least 3 Wood units in the definition of all forms of precapillary PH. PAH specifically is defined as the presence of mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg, PVR of at least 3 Wood units, and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure 15 mm Hg or less.

Trends in treatment

The value of initial combination therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor in treatment-naive PAH was cemented in 2015 by the AMBITION trial. The primary endpoint (death, PAH hospitalization, or unsatisfactory clinical response) occurred in 18%, 34%, and 28% of patients who were randomized, respectively, to combination therapy, monotherapy with the ERA ambrisentan, or monotherapy with the PDE-5 inhibitor tadalafil – and in 31% of the two monotherapy groups combined.

The trial reported a 50% reduction in the primary endpoint in the combination-therapy group versus the pooled monotherapy group, as well as greater reductions in N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, more satisfactory clinical response and greater improvement in 6-minute walking distance.

In practice, a minority of patients – typically older patients with multiple comorbidities – still receive initial monotherapy with sequential add-on therapies based on tolerance, but “for the most part PAH patients will start on combination therapy, most commonly with a ERA and PDE5 inhibitor,” Dr. Chakinala said.

For patients who are not improving on the ERA-PDE5 inhibitor approach – typically those who remain in the intermediate-risk category for intermediate-term mortality – substitution of the PDE5 inhibitor with the soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator riociguat may be considered, he and Dr. Williamson said. Clinical improvement with this substitution was demonstrated in the REPLACE trial.

Experts at PH care centers are also utilizing triple therapy for patients who do not improve to low-risk status after 2-4 months of dual combination therapy. The availability of oral prostacyclin analogues (selexipag and treprostinil) makes it easier to consider adding these agents early on, Dr. Chakinala and Dr. Richardson said.

Patients who fall into the high-risk category, at any point, are still best managed with parenteral prostacyclin analogues, Dr. Chakinala said.

In general, said Dr. Williamson, who also directs the University of Kansas Pulmonary Hypertension Comprehensive Care Center, “the PH community tends to be fairly aggressive up front, and with a low threshold for using prostacyclin analogues.”

The agents are “always part of the picture for someone who is really ill, in functional class IV, or has really impaired right ventricular function,” he said. “And we’re finding increased roles in patients who are not as ill but still have decompensated right ventricular dysfunction. It’s something we now consider.”

Recently published research on up-front oral triple therapy suggests possible benefit for some patients – but it’s far from conclusive, said Dr. Chakinala. The TRITON study randomized treatment-naive patients to the traditional ERA-PDE5 combination and either oral selexipag (a selective prostacyclin receptor agonist) or placebo as a third agent. It found no significant difference in reduction in PVR, the primary outcome, at week 26. However, the authors reported a “possible signal” for improved long-term outcomes with triple therapy.

“Based on this best evidence from a randomized clinical trial, I think it’s unfair to say that all patients should be on triple combination therapy right out of the gate,” he said. “Having said that, more recent [European] data showed that two drugs fell short of the mark in some patients, with high rates of clinical progression. And even in AMBITION, there were a number of patients in the combination arm who didn’t have a robust response.”

A 2021 retrospective analysis from the French Pulmonary Hypertension Registry – one of the European studies – assessed survival with monotherapy, dual therapy, or triple-combination therapy (two orals with a parenteral prostacyclin), and found no difference between monotherapy and dual therapy in high-risk patients.

Experts have been upping the ante, therefore, on early assessment and frequent reassessment of treatment response. Not long ago, patients were typically reassessed 6-12 months after the initiation of treatment. Now, experts at the PH care centers want to assess patients at 3-4 months and adjust or intensify treatment regimens for those who don’t yet qualify as low risk using a multidimensional risk score calculator.

The REVEAL (Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Management) risk score calculator, for instance, predicts the probability of 1-year survival and assigns patients to a strata of risk level based on either 12 or 6 variables (for the full or “lite” versions).]

Even better monitoring and risk assessment is needed, however, to “help sift out which patients are not improving enough on initial therapy or who are starting to fall off after being on a regimen for a period of time,” Dr. Chakinala said.

Today, with a network of accredited centers of expertise and a desire and need for many patients to remain close to home, Dr. Chakinala encourages finding a balance. Well-resourced clinicians can strive for early diagnosis and management – potentially initiating ERA–PDE-5 inhibitor combination therapy – but still should collaborate with PH experts.

“It’s a good idea to comanage these patients and let the experts see them periodically to help you determine when your patient may be declining,” he said. “The timetable for reassessment, the complexity of the reassessment, and the need to escalate to more advanced therapies has never been more important.”

Research highlights

Therapies that target inflammation and altered metabolism – including metformin – are among those being investigated for PAH. So are therapies targeting dysfunctional bone morphogenetic protein pathway signaling, which has been shown to be associated with hereditary, idiopathic, and likely other forms of PAH; one such drug, called sotatercept, is currently at the phase 3 trial stage.

Most promising for PAH may be the research efforts involving deep phenotyping, said Andrew J. Sweatt, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and the Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease.

“It’s where a lot of research is headed – deep phenotyping to deconstruct the molecular and clinical heterogeneity that exists within PAH ... to detect distinct subphenotypes of patients who would respond to particular therapies,” said Dr. Sweatt, who led a review of PH clinical research presented at the 2020 American Thoracic Society International Conference

“Right now, we largely treat all patients the same ... [while] we know that patients have a wide response to therapies and there’s a lot of clinical heterogeneity in how their disease evolves over time,” he said.

Data from a large National Institutes of Health–funded multicenter phenotyping study of PH is being analyzed and should yield findings and publications starting this year, said Anna R. Hemnes, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and an investigator with the initiative, coined “Redefining Pulmonary Hypertension through Pulmonary Disease Phenomics (PVDOMICS).”

Patients have undergone advanced imaging (for example, echocardiography, cardiac MRI, chest CT, ventilation/perfusion scans), advanced testing through right heart catheterization, body composition testing, quality of life questionnaires, and blood draws that have been analyzed for DNA and RNA expression, proteomics, and metabolomics, said Dr. Hemnes, assistant director of Vanderbilt’s Pulmonary Vascular Center.

The initiative aims to refine the classification of all kinds of PH and “to bring precision medicine to the field so we’re no longer characterizing somebody [based on imaging] and right heart catheterization, but we also incorporating molecular pieces and biomarkers into the diagnostic evaluation,” she said.

In the short term, the results of deep phenotyping should “allow us to be more effective with our therapy recommendations,” Dr. Hemnes said. “Then hopefully in the longer term, [identified biomarkers] will help us to develop new, more effective therapies.”

Dr. Sweatt and Dr. Williamson reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Hemnes reported that she holds stock in Tenax (which is studying a tyrosine kinase inhibitor for PAH) and serves as a consultant for Acceleron, Bayer, GossamerBio, United Therapeutics, and Janssen. She also receives research funding from Imara. Dr. Chakinala reported that he is an investigator on clinical trials for a number of pharmaceutical companies. He also serves on advisory boards for Phase Bio, Liquidia/Rare Gen, Bayer, Janssen, Trio Health Analytics, and Aerovate.

Multifactorial Effects of Endometriosis as a Chronic Systemic Disease

Can you talk about your research thus far and what your overall lab work has shown regarding endometriosis as a chronic systemic disease?

Dr. Flores: Endometriosis has traditionally been characterized by its pelvic manifestation however, it is important to understand that it is profoundly more than a pelvic disease—it is a chronic, systemic disease with multifactorial effects throughout the body.

We and other groups have found increased expression of several inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis. Our lab has found that compared to women without endometriosis, women with endometriosis not only have certain inflammatory cytokines elevated but also have altered expression of microRNAs. MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that bind to and modulate translation of mRNA. To help determine whether these miRNAs were involved in mediating increased expression of inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis, we then transfected these miRNAs into a macrophage cell line, and again found altered inflammatory cytokine expression. We and others have also found a role for stem cells (from bone marrow and other sources) in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. In addition, we have found that in endometriosis, women have a low body-mass index and altered metabolism, which is related to induction of induction of hepatic (anorexigenic) gene expression and microRNA-mediated changes in adipocyte (metabolic) gene expression. Furthermore, we have found altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered pain sensitization. Taken together, this work helps provide support for the systemic nature of endometriosis.

How can your findings in this space help us in diagnosing clinically and ultimately avoid diagnostic delay?

Dr. Flores: It’s about understanding that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disease and understanding that endometriosis is leading to inflammation and altered expression of miRNAs which allows endometriosis to have long-range effects. For example, women with endometriosis commonly have anxiety and depression and low BMI. As mentioned earlier, we have found that in a murine model of endometriosis, there is altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered metabolism in a murine model of endometriosis. Other groups have also found changes in brain volume in these same areas in women with endometriosis, and we have seen low BMI in women with endometriosis. In fact, a common misconception was that being thin was a risk factor for endometriosis, however we have found that the endometriosis itself, is causing women alteration in genes associated with metabolism.

With respect to the endometrium, in addition to being a pelvic pain disorder, we also see that women with endometriosis have a higher likelihood of having infertility. And we think that's in part because one, just like the lesions can be resistant to progesterone, the endometrium of these women can also be resistant to progesterone. Progesterone is necessary for decidualization/implantation. We have also seen that stem cells can be recruited and ultimately incorrectly incorporated into the endometrium, which may also contribute to infertility in women with endometriosis.

If we can understand this multifactorial nature of endometriosis, I think this will help us not only shift toward diagnosing endometriosis clinically, but also avoid diagnostic delay. If we can understand that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disorder, but that It can also involve altered mood, bowel/bladder symptoms, inflammation, altered metabolism and/or cause infertility, I think that will ultimately help us to diagnosing earlier.

In addition, we can also utilize pelvic pain symptomatology to help with diagnosis as well. We can ask about cyclic pelvic pain that's been getting progressively worse over the years, not responding to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Also, in understanding that endometriosis can affect other organs, asking about cyclic pain/symptoms in other areas, such as cyclical bowel or bladder symptoms.

Thinking about the fact that if you do have a patient like that, you're seeing that they have altered mood symptoms, or alterations in inflammatory markers. Maybe that will help us shift from a disease that was typically only considered to be diagnosed by surgery, by switching to a clinical diagnosis for endometriosis. Doing that will hopefully help avoid diagnostic delay.

If we understand that while we typically describe endometriosis as causing cyclic pain symptoms, sometimes because of the existing diagnostic delay, ultimately women can present with chronic pelvic pain. Thus, it's also important to ask patients presenting with chronic pelvic pain what the symptoms were like beforehand (i.e., was the pain cyclic and progressively worsening over the years/before it became chronic) doing so will also help in terms of diagnosing sooner.

Lastly, circulating miRNAs have been considered promising biomarker candidates because they are stable in circulation and have highly specific expression profiles. We have found that the combination of several miRNAs reliably distinguished endometriosis patients from controls, and a prospective, blinded study showed that the combination of several miRNAs could be used to accurately identify patients with endometriosis, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.93.

Roughly 11%, or more than 6.5 million, women in the United States between the ages of 15–44 years, may have endometriosis. Is this disease more common in any particular age range or ethnicity?

Dr. Flores: We’re actually actively investigating that right now. And I think what makes it challenging, especially with respect to the age range, is now we're -- I think in part because of so much more awareness and more research is being done looking at this disease as a chronic systemic disease-- we're now starting to see/diagnose adolescents with endometriosis.

I think as we start gathering more information about these individuals, we'll be able to better say if there is a particular age range. Right now, we usually say it's in the reproductive years, however for some women it may be later if they were not diagnosed earlier. Conversely, some who are hopefully reading this, and also who conduct research on endometriosis, may be able to diagnose someone earlier that may have been missed until they were in their 30s or 40s, for example.

With respect to ethnicity, I'm the task force leader for diversity, equity, and inclusion in research and recruitment. This is something that I'm actively starting to work on, as are other groups. I don't have the answer for that yet, but as we continue to collect more data, we will have more information on this.

What are some of the existing hormonal therapies you rely upon as well as the biomarkers in predicting response to treatment, and are there any new research or treatments on the horizon?

Dr. Flores: I'll first start by telling you a bit about our existing treatment regimens, and then how I decide who would benefit from a given one. First line has always been progestin-based therapy, either in the form of a combined oral contraceptive pill or as progesterone only pills. However, up to 1/3 of women fail progestin-based therapy—this is termed progesterone resistance.

When progestin-based therapies fail, we then rely on other agents that are focused more on estrogen deprivation because, while we don't know the complete etiology of endometriosis, we do know that it is estrogen-dependent. There are two classes— gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and GnRH antagonists. The agonist binds to the GnRH receptors, and initially can cause a flare effect due to its agonist properties, initially stimulate release of estradiol, and ultimately the GnRH receptor becomes downregulated and estradiol is decreased to the menopausal range. As a result we routinely provided add-back therapy with norethindrone to help prevent hot flashes and ensure bone protection.

Within the past three years, there has been a new oral GnRH receptor antagonist approved for treating endometriosis. The medication is available as a once a day or twice a day dosing regimen. As this is a GnRH antagonist, upon binding to the GnRH receptor, it blocks receptor activity, thus avoiding the flare affect; essentially, within 24 hours, there is a decrease in estradiol production.

As two doses are available, you can tailor how much you dial down estrogen for a given patient. The low dose lowers estradiol to a range of 40 picograms while the high (twice a day) dosing lowers your estrogen to about 6 picograms. Also, although it was not studied originally in terms of giving add-back therapy for the higher dose, given the safety (and effectiveness) of add-back therapy with GnRH agonists we are using the same norethindrone add-back therapy for women who are taking the GnRH receptor antagonist.

The next question is, how do we decide which medication a given patient receives? To answer that, I will tell you a bit about my precision-based medicine research. As mentioned before, while progestin-based therapy is first-line, failure rates are high, and unfortunately, we previously have not been able to identify who will or will not respond to first-line therapy. As such, I decided to assess progesterone receptor expression in endometriotic lesions from women who had undergone surgery for endometriosis, and determine whether progesterone receptor expression levels in lesions could be used to predict response to progestin-based therapy. I found that in women that had high levels of the progesterone receptor, they responded completely to progestin-based therapy-- there was a 100% response rate to progestin-based therapy. This is in sharp contrast to women who had low PR expression, where there was only a 6% response rate to progestin-based therapy.

While this is great with respect to being able to predict who will or will not respond to first line therapy, the one limitation is that would mean that women have to undergo surgery in order to determine progesterone receptor status/response to progestin-based therapy. However, given that within two to five years following surgery, up to 50% of women will have recurrence of pain symptoms, where I see my test coming into play is postoperatively. This is because many times , women who had pain, or who were failing a given agent, are placed back on that same medical therapy they were failing after surgery. Usually that was a progestin. Therefore, instead of putting them on that same therapy that they were failing, we can use my test to place them on an alternative therapy (such as a GnRH analogue) that more specifically targets estradiol production.

In terms of future directions with respect to treatment, there is a microRNA that has been found to be low in women with endometriosis—miRNALet-7b. In a murine model of endometriosis, we have found that if we supplement with Let-7, there is decreased inflammation and decreased lesion size of endometriosis. We have also found that supplementing miRNA Let-7b in human endometriotic lesions results in decreased inflammation in cell culture.

That would be future directions in terms of focusing on microRNAs and seeing how we can manipulate those to essentially block inflammation and lesion growth. Furthermore, such treatment would be non-hormonal, which would be a novel therapeutic approach.

As-Sanie S, Harris RE, Napadow V, et al. Changes in regional gray matter volume in women with chronic pelvic pain: a voxel-based morphometry study. Pain. 2012;153(5):1006-1014.

Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What's the delay? A qualitative study of women's experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1296-1301

Cosar E, Mamillapalli R, Ersoy GS, Cho S, Seifer B, Taylor HS. Serum microRNAs as diagnostic markers of endometriosis: a comprehensive array-based analysis. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(2):402-409.

Flores VA, Vanhie A, Dang T, Taylor HS. Progesterone Receptor Status Predicts Response to Progestin Therapy in Endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Dec 1;103(12):4561-4568

Goetz TG, Mamillapalli R, Taylor HS. Low Body Mass Index in Endometriosis Is Promoted by Hepatic Metabolic Gene Dysregulation in Mice. Biol Reprod. 2016;95(6):115.

Li T, et al. Endometriosis alters brain electrophysiology, gene expression and increases pain sensitization, anxiety, and depression in female mice. Biol Reprod. 2018;99(2):349-359.

Moustafa S, Burn M, Mamillapalli R, Nematian S, Flores V, Taylor HS. Accurate diagnosis of endometriosis using serum microRNAs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(4):557.e1-557.e11.

Nematian SE, et al. Systemic Inflammation Induced by microRNAs: Endometriosis-Derived Alterations in Circulating microRNA 125b-5p and Let-7b-5p Regulate Macrophage Cytokine Production. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(1):64-74.

Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366-373.e8.

Rogers PA, D'Hooghe TM, Fazleabas A, et al. Defining future directions for endometriosis research: workshop report from the 2011 World Congress of Endometriosis In Montpellier, France. Reprod Sci. 2013;20(5):483-499.

Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet. 2021 Feb 27

Zolbin MM, et al. Adipocyte alterations in endometriosis: reduced numbers of stem cells and microRNA induced alterations in adipocyte metabolic gene expression. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17(1):36.

Can you talk about your research thus far and what your overall lab work has shown regarding endometriosis as a chronic systemic disease?

Dr. Flores: Endometriosis has traditionally been characterized by its pelvic manifestation however, it is important to understand that it is profoundly more than a pelvic disease—it is a chronic, systemic disease with multifactorial effects throughout the body.

We and other groups have found increased expression of several inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis. Our lab has found that compared to women without endometriosis, women with endometriosis not only have certain inflammatory cytokines elevated but also have altered expression of microRNAs. MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that bind to and modulate translation of mRNA. To help determine whether these miRNAs were involved in mediating increased expression of inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis, we then transfected these miRNAs into a macrophage cell line, and again found altered inflammatory cytokine expression. We and others have also found a role for stem cells (from bone marrow and other sources) in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. In addition, we have found that in endometriosis, women have a low body-mass index and altered metabolism, which is related to induction of induction of hepatic (anorexigenic) gene expression and microRNA-mediated changes in adipocyte (metabolic) gene expression. Furthermore, we have found altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered pain sensitization. Taken together, this work helps provide support for the systemic nature of endometriosis.

How can your findings in this space help us in diagnosing clinically and ultimately avoid diagnostic delay?

Dr. Flores: It’s about understanding that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disease and understanding that endometriosis is leading to inflammation and altered expression of miRNAs which allows endometriosis to have long-range effects. For example, women with endometriosis commonly have anxiety and depression and low BMI. As mentioned earlier, we have found that in a murine model of endometriosis, there is altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered metabolism in a murine model of endometriosis. Other groups have also found changes in brain volume in these same areas in women with endometriosis, and we have seen low BMI in women with endometriosis. In fact, a common misconception was that being thin was a risk factor for endometriosis, however we have found that the endometriosis itself, is causing women alteration in genes associated with metabolism.

With respect to the endometrium, in addition to being a pelvic pain disorder, we also see that women with endometriosis have a higher likelihood of having infertility. And we think that's in part because one, just like the lesions can be resistant to progesterone, the endometrium of these women can also be resistant to progesterone. Progesterone is necessary for decidualization/implantation. We have also seen that stem cells can be recruited and ultimately incorrectly incorporated into the endometrium, which may also contribute to infertility in women with endometriosis.

If we can understand this multifactorial nature of endometriosis, I think this will help us not only shift toward diagnosing endometriosis clinically, but also avoid diagnostic delay. If we can understand that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disorder, but that It can also involve altered mood, bowel/bladder symptoms, inflammation, altered metabolism and/or cause infertility, I think that will ultimately help us to diagnosing earlier.

In addition, we can also utilize pelvic pain symptomatology to help with diagnosis as well. We can ask about cyclic pelvic pain that's been getting progressively worse over the years, not responding to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Also, in understanding that endometriosis can affect other organs, asking about cyclic pain/symptoms in other areas, such as cyclical bowel or bladder symptoms.

Thinking about the fact that if you do have a patient like that, you're seeing that they have altered mood symptoms, or alterations in inflammatory markers. Maybe that will help us shift from a disease that was typically only considered to be diagnosed by surgery, by switching to a clinical diagnosis for endometriosis. Doing that will hopefully help avoid diagnostic delay.

If we understand that while we typically describe endometriosis as causing cyclic pain symptoms, sometimes because of the existing diagnostic delay, ultimately women can present with chronic pelvic pain. Thus, it's also important to ask patients presenting with chronic pelvic pain what the symptoms were like beforehand (i.e., was the pain cyclic and progressively worsening over the years/before it became chronic) doing so will also help in terms of diagnosing sooner.

Lastly, circulating miRNAs have been considered promising biomarker candidates because they are stable in circulation and have highly specific expression profiles. We have found that the combination of several miRNAs reliably distinguished endometriosis patients from controls, and a prospective, blinded study showed that the combination of several miRNAs could be used to accurately identify patients with endometriosis, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.93.

Roughly 11%, or more than 6.5 million, women in the United States between the ages of 15–44 years, may have endometriosis. Is this disease more common in any particular age range or ethnicity?

Dr. Flores: We’re actually actively investigating that right now. And I think what makes it challenging, especially with respect to the age range, is now we're -- I think in part because of so much more awareness and more research is being done looking at this disease as a chronic systemic disease-- we're now starting to see/diagnose adolescents with endometriosis.

I think as we start gathering more information about these individuals, we'll be able to better say if there is a particular age range. Right now, we usually say it's in the reproductive years, however for some women it may be later if they were not diagnosed earlier. Conversely, some who are hopefully reading this, and also who conduct research on endometriosis, may be able to diagnose someone earlier that may have been missed until they were in their 30s or 40s, for example.

With respect to ethnicity, I'm the task force leader for diversity, equity, and inclusion in research and recruitment. This is something that I'm actively starting to work on, as are other groups. I don't have the answer for that yet, but as we continue to collect more data, we will have more information on this.

What are some of the existing hormonal therapies you rely upon as well as the biomarkers in predicting response to treatment, and are there any new research or treatments on the horizon?

Dr. Flores: I'll first start by telling you a bit about our existing treatment regimens, and then how I decide who would benefit from a given one. First line has always been progestin-based therapy, either in the form of a combined oral contraceptive pill or as progesterone only pills. However, up to 1/3 of women fail progestin-based therapy—this is termed progesterone resistance.

When progestin-based therapies fail, we then rely on other agents that are focused more on estrogen deprivation because, while we don't know the complete etiology of endometriosis, we do know that it is estrogen-dependent. There are two classes— gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and GnRH antagonists. The agonist binds to the GnRH receptors, and initially can cause a flare effect due to its agonist properties, initially stimulate release of estradiol, and ultimately the GnRH receptor becomes downregulated and estradiol is decreased to the menopausal range. As a result we routinely provided add-back therapy with norethindrone to help prevent hot flashes and ensure bone protection.

Within the past three years, there has been a new oral GnRH receptor antagonist approved for treating endometriosis. The medication is available as a once a day or twice a day dosing regimen. As this is a GnRH antagonist, upon binding to the GnRH receptor, it blocks receptor activity, thus avoiding the flare affect; essentially, within 24 hours, there is a decrease in estradiol production.

As two doses are available, you can tailor how much you dial down estrogen for a given patient. The low dose lowers estradiol to a range of 40 picograms while the high (twice a day) dosing lowers your estrogen to about 6 picograms. Also, although it was not studied originally in terms of giving add-back therapy for the higher dose, given the safety (and effectiveness) of add-back therapy with GnRH agonists we are using the same norethindrone add-back therapy for women who are taking the GnRH receptor antagonist.

The next question is, how do we decide which medication a given patient receives? To answer that, I will tell you a bit about my precision-based medicine research. As mentioned before, while progestin-based therapy is first-line, failure rates are high, and unfortunately, we previously have not been able to identify who will or will not respond to first-line therapy. As such, I decided to assess progesterone receptor expression in endometriotic lesions from women who had undergone surgery for endometriosis, and determine whether progesterone receptor expression levels in lesions could be used to predict response to progestin-based therapy. I found that in women that had high levels of the progesterone receptor, they responded completely to progestin-based therapy-- there was a 100% response rate to progestin-based therapy. This is in sharp contrast to women who had low PR expression, where there was only a 6% response rate to progestin-based therapy.

While this is great with respect to being able to predict who will or will not respond to first line therapy, the one limitation is that would mean that women have to undergo surgery in order to determine progesterone receptor status/response to progestin-based therapy. However, given that within two to five years following surgery, up to 50% of women will have recurrence of pain symptoms, where I see my test coming into play is postoperatively. This is because many times , women who had pain, or who were failing a given agent, are placed back on that same medical therapy they were failing after surgery. Usually that was a progestin. Therefore, instead of putting them on that same therapy that they were failing, we can use my test to place them on an alternative therapy (such as a GnRH analogue) that more specifically targets estradiol production.

In terms of future directions with respect to treatment, there is a microRNA that has been found to be low in women with endometriosis—miRNALet-7b. In a murine model of endometriosis, we have found that if we supplement with Let-7, there is decreased inflammation and decreased lesion size of endometriosis. We have also found that supplementing miRNA Let-7b in human endometriotic lesions results in decreased inflammation in cell culture.

That would be future directions in terms of focusing on microRNAs and seeing how we can manipulate those to essentially block inflammation and lesion growth. Furthermore, such treatment would be non-hormonal, which would be a novel therapeutic approach.

Can you talk about your research thus far and what your overall lab work has shown regarding endometriosis as a chronic systemic disease?

Dr. Flores: Endometriosis has traditionally been characterized by its pelvic manifestation however, it is important to understand that it is profoundly more than a pelvic disease—it is a chronic, systemic disease with multifactorial effects throughout the body.

We and other groups have found increased expression of several inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis. Our lab has found that compared to women without endometriosis, women with endometriosis not only have certain inflammatory cytokines elevated but also have altered expression of microRNAs. MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that bind to and modulate translation of mRNA. To help determine whether these miRNAs were involved in mediating increased expression of inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis, we then transfected these miRNAs into a macrophage cell line, and again found altered inflammatory cytokine expression. We and others have also found a role for stem cells (from bone marrow and other sources) in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. In addition, we have found that in endometriosis, women have a low body-mass index and altered metabolism, which is related to induction of induction of hepatic (anorexigenic) gene expression and microRNA-mediated changes in adipocyte (metabolic) gene expression. Furthermore, we have found altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered pain sensitization. Taken together, this work helps provide support for the systemic nature of endometriosis.

How can your findings in this space help us in diagnosing clinically and ultimately avoid diagnostic delay?

Dr. Flores: It’s about understanding that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disease and understanding that endometriosis is leading to inflammation and altered expression of miRNAs which allows endometriosis to have long-range effects. For example, women with endometriosis commonly have anxiety and depression and low BMI. As mentioned earlier, we have found that in a murine model of endometriosis, there is altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered metabolism in a murine model of endometriosis. Other groups have also found changes in brain volume in these same areas in women with endometriosis, and we have seen low BMI in women with endometriosis. In fact, a common misconception was that being thin was a risk factor for endometriosis, however we have found that the endometriosis itself, is causing women alteration in genes associated with metabolism.

With respect to the endometrium, in addition to being a pelvic pain disorder, we also see that women with endometriosis have a higher likelihood of having infertility. And we think that's in part because one, just like the lesions can be resistant to progesterone, the endometrium of these women can also be resistant to progesterone. Progesterone is necessary for decidualization/implantation. We have also seen that stem cells can be recruited and ultimately incorrectly incorporated into the endometrium, which may also contribute to infertility in women with endometriosis.

If we can understand this multifactorial nature of endometriosis, I think this will help us not only shift toward diagnosing endometriosis clinically, but also avoid diagnostic delay. If we can understand that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disorder, but that It can also involve altered mood, bowel/bladder symptoms, inflammation, altered metabolism and/or cause infertility, I think that will ultimately help us to diagnosing earlier.

In addition, we can also utilize pelvic pain symptomatology to help with diagnosis as well. We can ask about cyclic pelvic pain that's been getting progressively worse over the years, not responding to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Also, in understanding that endometriosis can affect other organs, asking about cyclic pain/symptoms in other areas, such as cyclical bowel or bladder symptoms.

Thinking about the fact that if you do have a patient like that, you're seeing that they have altered mood symptoms, or alterations in inflammatory markers. Maybe that will help us shift from a disease that was typically only considered to be diagnosed by surgery, by switching to a clinical diagnosis for endometriosis. Doing that will hopefully help avoid diagnostic delay.

If we understand that while we typically describe endometriosis as causing cyclic pain symptoms, sometimes because of the existing diagnostic delay, ultimately women can present with chronic pelvic pain. Thus, it's also important to ask patients presenting with chronic pelvic pain what the symptoms were like beforehand (i.e., was the pain cyclic and progressively worsening over the years/before it became chronic) doing so will also help in terms of diagnosing sooner.

Lastly, circulating miRNAs have been considered promising biomarker candidates because they are stable in circulation and have highly specific expression profiles. We have found that the combination of several miRNAs reliably distinguished endometriosis patients from controls, and a prospective, blinded study showed that the combination of several miRNAs could be used to accurately identify patients with endometriosis, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.93.

Roughly 11%, or more than 6.5 million, women in the United States between the ages of 15–44 years, may have endometriosis. Is this disease more common in any particular age range or ethnicity?

Dr. Flores: We’re actually actively investigating that right now. And I think what makes it challenging, especially with respect to the age range, is now we're -- I think in part because of so much more awareness and more research is being done looking at this disease as a chronic systemic disease-- we're now starting to see/diagnose adolescents with endometriosis.

I think as we start gathering more information about these individuals, we'll be able to better say if there is a particular age range. Right now, we usually say it's in the reproductive years, however for some women it may be later if they were not diagnosed earlier. Conversely, some who are hopefully reading this, and also who conduct research on endometriosis, may be able to diagnose someone earlier that may have been missed until they were in their 30s or 40s, for example.

With respect to ethnicity, I'm the task force leader for diversity, equity, and inclusion in research and recruitment. This is something that I'm actively starting to work on, as are other groups. I don't have the answer for that yet, but as we continue to collect more data, we will have more information on this.

What are some of the existing hormonal therapies you rely upon as well as the biomarkers in predicting response to treatment, and are there any new research or treatments on the horizon?

Dr. Flores: I'll first start by telling you a bit about our existing treatment regimens, and then how I decide who would benefit from a given one. First line has always been progestin-based therapy, either in the form of a combined oral contraceptive pill or as progesterone only pills. However, up to 1/3 of women fail progestin-based therapy—this is termed progesterone resistance.