User login

Definitive diverticular hemorrhage: Diagnosis and management

Diverticular hemorrhage is the most common cause of colonic bleeding, accounting for 20%-65% of cases of severe lower intestinal bleeding in adults.1 Urgent colonoscopy after purging the colon of blood, clots, and stool is the most accurate method of diagnosing and guiding treatment of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.2-5 The diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage depends upon identification of some stigmata of recent hemorrhage (SRH) in a single diverticulum (TIC), which can include active arterial bleeding, oozing, non-bleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, or flat spot.2-4 Although other approaches, such as nuclear medicine scans and angiography of various types (CT, MRI, or standard angiography), for the early diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia are utilized in many medical centers, only active bleeding can be detected by these techniques. However, as subsequently discussed, this SRH is documented in only 26% of definitive diverticular bleeds found on urgent colonoscopy, so diagnostic yields of these techniques will be low.2-5

The diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia and diverticulosis, as well as triage of all of them to specific medical, endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical management, is facilitated by an urgent endoscopic approach.2-5 Patients who are diagnosed with definitive diverticular hemorrhage on colonoscopy represent about 30% of all true TIC bleeds when urgent colonoscopy is the management approach.2-5 That is because approximately 50% of all patients with colon diverticulosis and first presentation of severe hematochezia have incidental diverticulosis; they have colonic diverticulosis, but another site of bleeding is identified as the cause of hemorrhage in the gastrointestinal tract.2-4 Presumptive diverticular hemorrhage is diagnosed when colonic diverticulosis without TIC stigmata are found but no other GI bleeding source is found on colonoscopy, anoscopy, enteroscopy, or capsule endoscopy.2-5 In our experience with urgent colonoscopy, the presumptive diverticular bleed group accounts for about 70% of patients with documented diverticular hemorrhage (e.g., not including incidental diverticulosis bleeds but combining subgroups of patients with either definitive or presumptive TIC diagnoses as documented TIC hemorrhage).

Clinical presentation

Patients with diverticular hemorrhage present with severe, painless large volume hematochezia. Hematochezia may be self-limited and spontaneously resolve in 75%-80% of all patients but with high rebleeding rates up to 40%.5-7 Of all patients with diverticulosis, only about 3%-5% develop diverticular hemorrhage.8 Risk factors for diverticular hemorrhage include medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs, and anticoagulants) and other clinical factors, such as older age, low-fiber diet, and chronic constipation.9,10 On urgent colonoscopy, more than 70% of diverticulosis in U.S. patients are located anatomically in the descending colon or more distally. In contrast, about 60% of definitive diverticular hemorrhage cases in our experience had diverticula with stigmata identified at or proximal to the splenic flexure.2,4,11

Pathophysiology

Colonic diverticula are herniations of mucosa and submucosa with colonic arteries that penetrate the muscular wall. Bleeding can occur when there is asymmetric rupture of the vasa recta at either the base of the diverticulum or the neck.4 Thinning of the mucosa on the luminal surface (such as that resulting from impacted fecaliths and stool) can cause injury to the site of the penetrating vessels, resulting in hemorrhage.12

Initial management

Patients with acute, severe hematochezia should be triaged to an inpatient setting with a monitored bed. Admission to an intensive care unit should be considered for patients with hemodynamic instability, persistent bleeding, and/or significant comorbidities. Patients with TIC hemorrhage often require resuscitation with crystalloids and packed red blood cell transfusions for hemoglobin less than 8 g/dl.4 Unlike upper GI hemorrhage, which has been extensively reported on, data regarding a more restrictive transfusion threshold, compared with a liberal transfusion threshold, in lower intestinal bleeding are very limited. Correction of underlying coagulopathies is recommended but should be individualized, particularly in those patients on antithrombotic agents or with underlying bleeding disorders.

Urgent diagnosis and hemostasis

Urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours is the most accurate way to make a diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage and to effectively and safely treat them.2-4,10,11 For patients with severe hematochezia, when the colonoscopy is either not available in a medical center or does not reveal the source of bleeding, nuclear scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or interventional radiology [IR]) are recommended. CT angiography may be particularly helpful to diagnose patients with hemodynamic instability who are suspected to have active TIC bleeding and are not able to complete a bowel preparation. However, these imaging techniques require active bleeding at the time of the study to be diagnostic. This SRH is also uncommon for definitive diverticular hemorrhage, so the diagnostic yield is usually quite low.2-5,10,11 An additional limitation of scintigraphy and CT or MRI angiography is that, if active bleeding is found, some other type of treatment, such as colonoscopy, IR angiography, or surgery, will be required for definitive hemostasis.

For urgent colonoscopy, adequate colon preparation with a large volume preparation (6-8 liters of polyethylene glycol-based solution) is recommended to clear stool, blood, and clots to allow endoscopic visualization and localization of the bleeding source. Use of a nasogastric tube should be considered if the patient is unable to drink enough prep.2-4,13 Additionally, administration of a prokinetic agent, such as Metoclopramide, may improve gastric emptying and tolerance of the prep. During colonoscopy, careful inspection of the colonic mucosa during insertion and withdrawal is important since lesions may bleed intermittently and SRH can be missed. An adult or pediatric colonoscope with a large working channel (at least 3.3 mm) is recommended to facilitate suctioning of blood clots and stool, as well as allow the passage of endoscopic hemostasis accessories. Targeted water-jet irrigation, an expert colonoscopist, a cap attachment, and adequate colon preparation are all predictors for improved diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.4,14

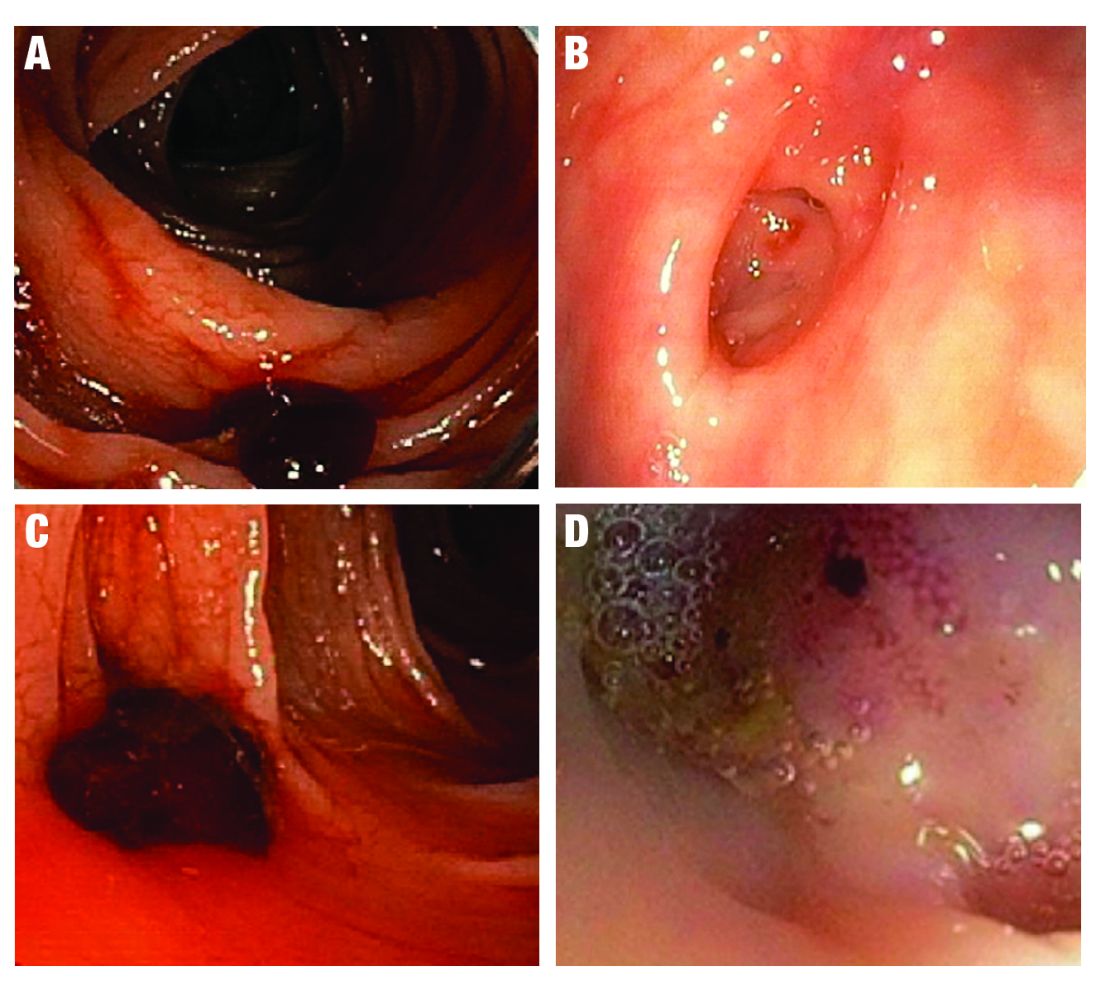

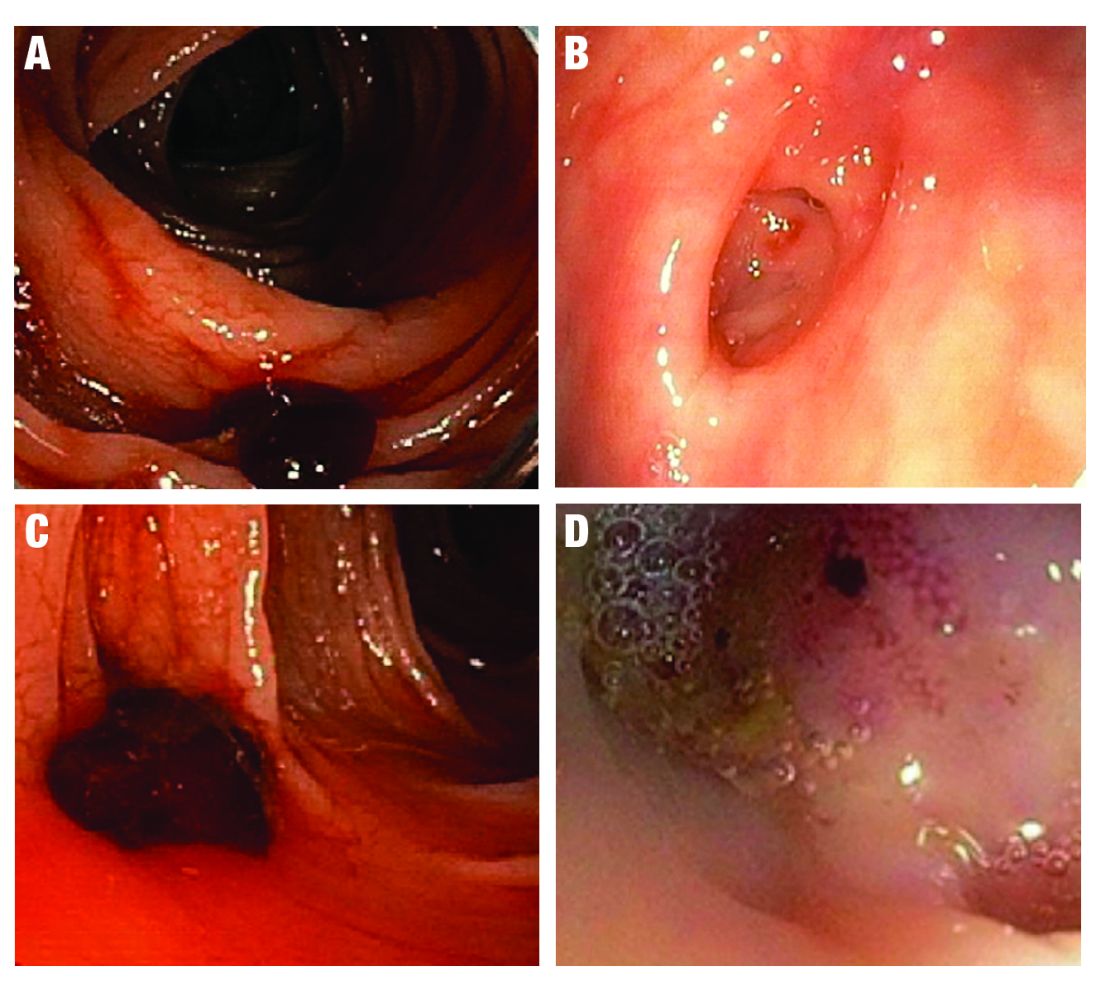

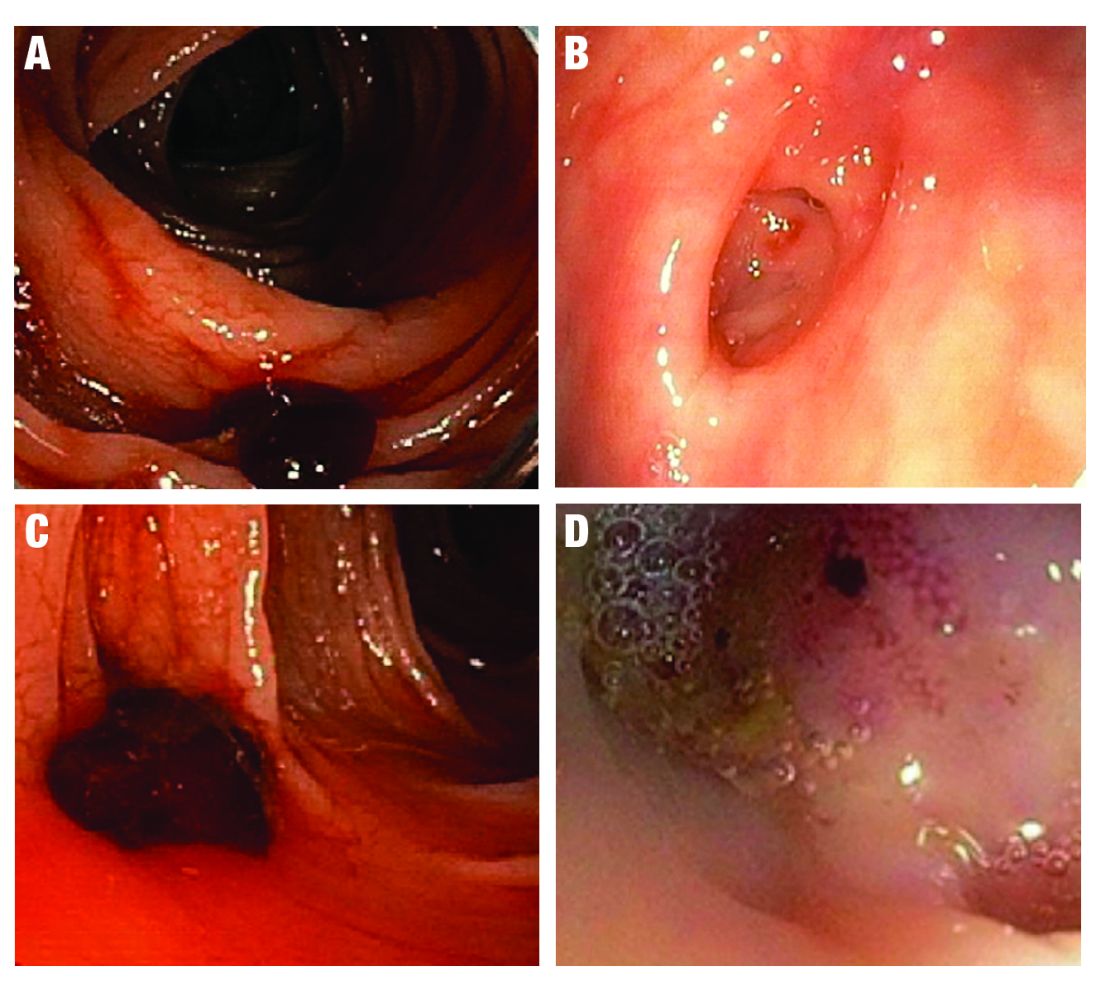

SRH in definitive TIC bleeds all have a high risk of TIC rebleeding,2-4,10,11 including active bleeding, nonbleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, and a flat spot (See Figure).

Based on CURE Hemostasis Group data of 118 definitive TIC bleeds, 26% had active bleeding, 24% had a nonbleeding visible vessel, 37% had an adherent clot, and 13% had a flat spot (with underlying arterial blood flow by Doppler probe monitoring).4 Approximately 50% of the SRH were found in the neck of the TIC and 50% at the base, with actively bleeding cases more often from the base. In CURE Doppler endoscopic probe studies, 90% of all stigmata had an underlying arterial blood flow detected with the Doppler probe.4,10 The Doppler probe is reported to be very useful for risk stratification and to confirm obliteration of the arterial blood flow underlying SRH for definitive hemostasis.4,10

Endoscopic treatment

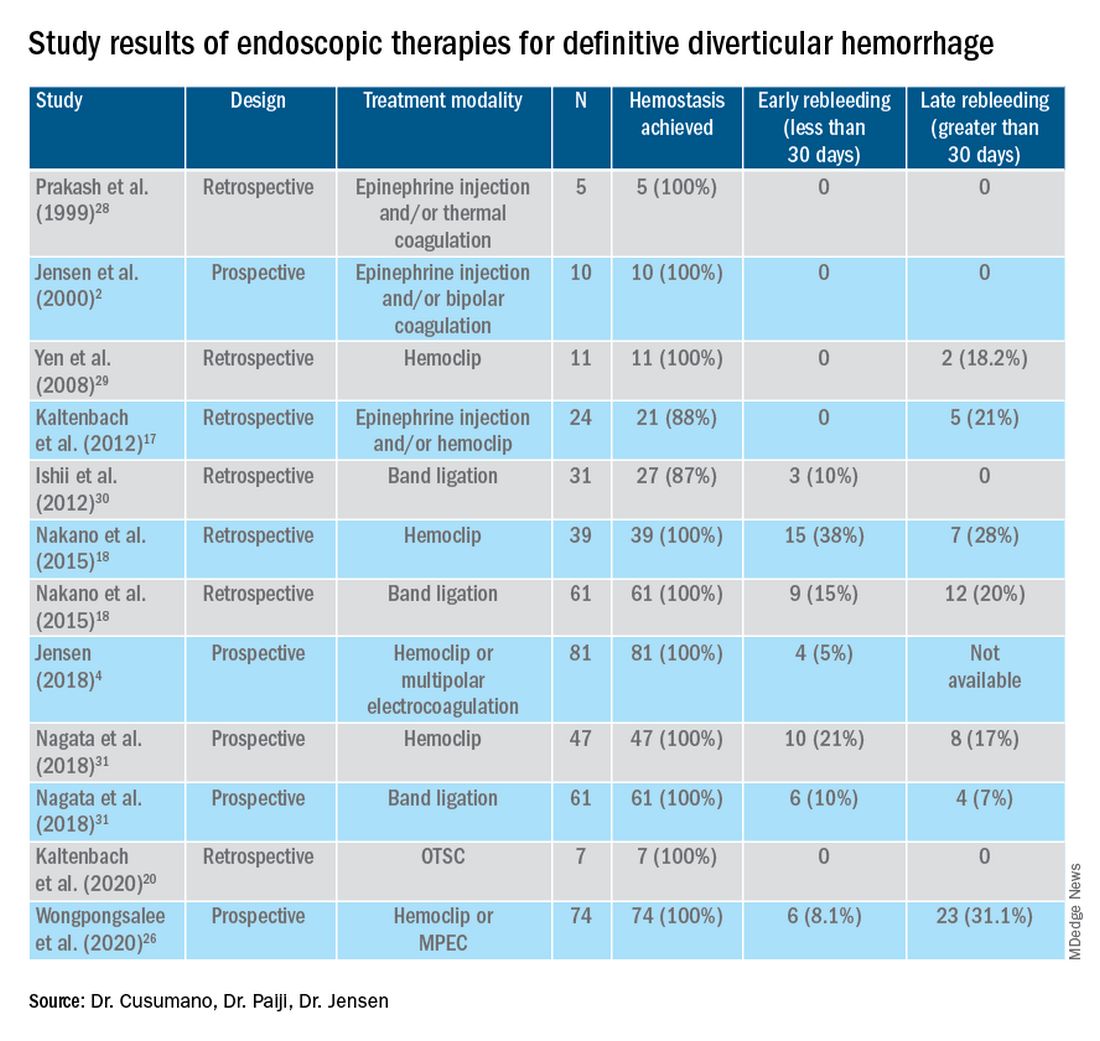

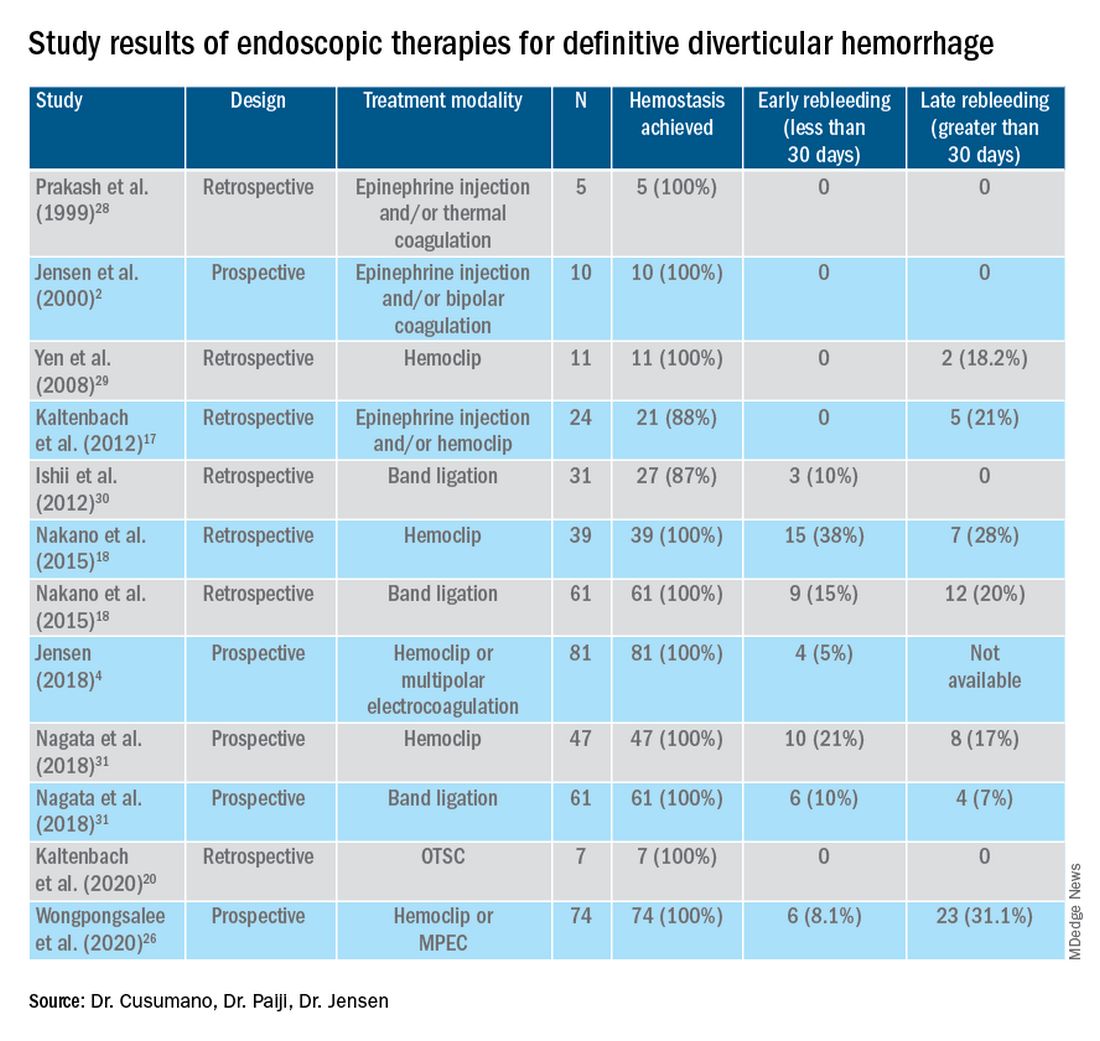

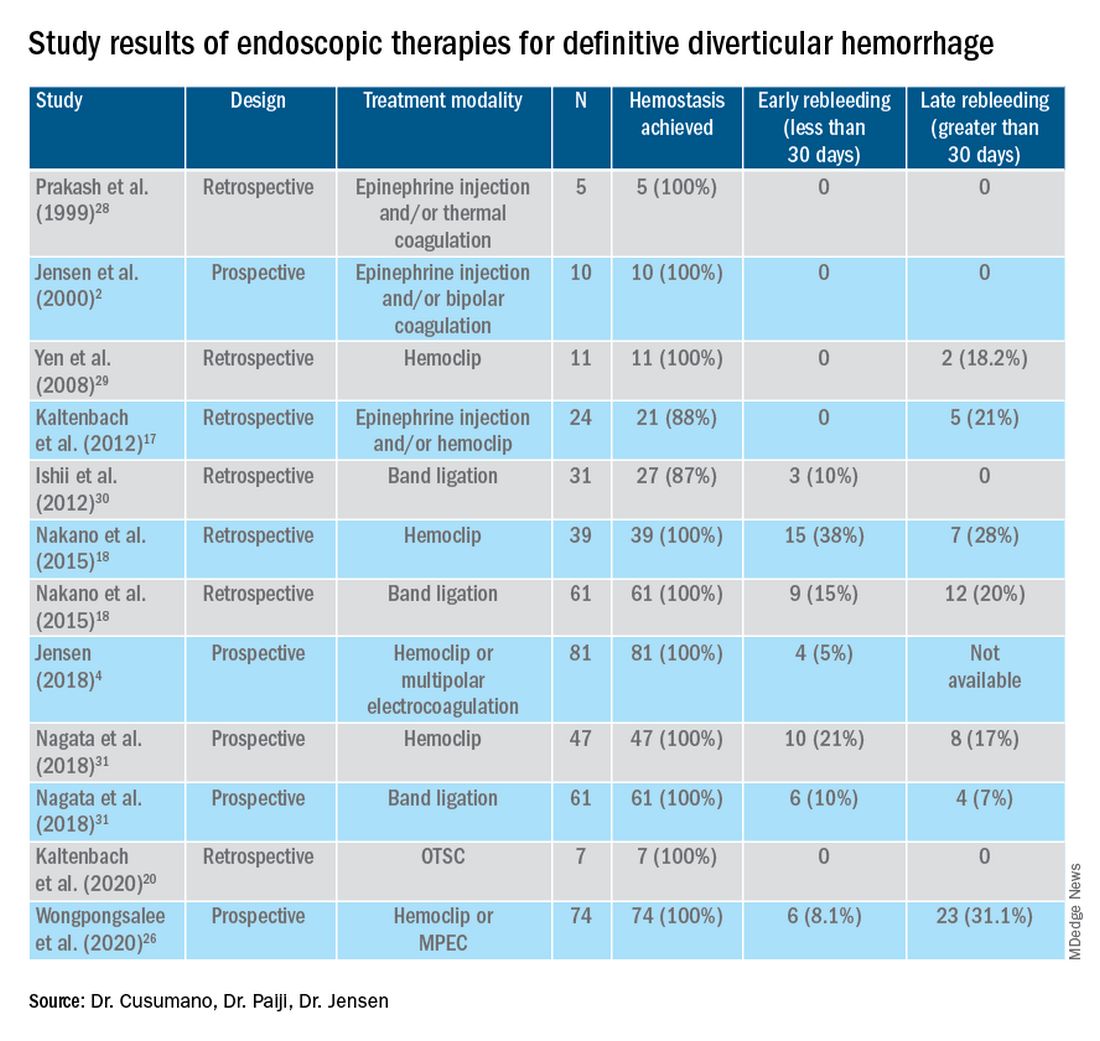

Given high rates of rebleeding with medical management alone, definitive TIC hemorrhage can be effectively and safely treated with endoscopic therapies once SRH are localized.4,10 Endoscopic therapies that have been reported in the literature include electrocoagulation, hemoclip, band ligation, and over-the-scope clip. Four-quadrant injection of 1:20,000 epinephrine around the SRH can improve visualization of SRH and provide temporary control of bleeding, but it should be combined with other modalities because of risk of rebleeding with epinephrine alone.15 Results from studies reporting rates of both early rebleeding (occurring within 30 days) and late rebleeding (occurring after 30 days) are listed in the Table.

Multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC), which utilizes a focal electric current to generate heat, can coaptively coagulate small TIC arteries.16 For SRH in the neck of TIC, MPEC is effective for coaptive coagulation at a power of 12-15 watts in 1-2 second pulses with moderate laterally applied tamponade pressure. MPEC should be avoided for treating SRH at the TIC base because of lack of muscularis propria and higher risk of perforation.

Hemoclip therapy has been reported to be safe and efficacious in treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage, by causing mechanical hemostasis with occlusion of the bleeding artery.16 Hemoclips are recommended to treat stigmata in the base of TICs and should be targeted on either side of visible vessel in order to occlude the artery underneath it.4,10 With a cap on the tip of the colonoscope, suctioning can evert TICs, allowing more precise placement of hemoclip on SRH in the base of the TIC.17 Hemoclip retention rates vary with different models and can range from less than 7 days to more than 4 weeks. Hemoclips can also mark the site if early rebleeding occurs; then, reintervention (e.g., repeat endoscopy or angioembolization) is facilitated.

Another treatment is endoscopic band ligation, which provides mechanical hemostasis. Endoscopic band ligation has been reported to be efficacious for TIC hemorrhage.18 Suctioning the TIC with the SRH into the distal cap and deploying a band leads to obliteration of vessels and potentially necrosis and disappearance of banded TIC.16 This technique carries a risk of perforation because of the thin walls of TICs. This risk may be higher for right-sided colon lesions since an exvivo colon specimen study reported serosal entrapment and inclusion of muscularis propria postband ligation, both of which may result in ischemia of intestinal wall and delayed perforation.19

Over-the-scope clip (OTSC) has been reported in case series for treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage. With a distal cap and large clip, suctioning can evert TICs and facilitate deployment over the SRH.20,21 OTSC can grasp an entire TIC with the SRH and obliterate the arterial blood flow with a single clip.20,21 No complications have been reported yet for treatment of TIC hemorrhage. However, the OTSC system is relatively expensive when compared with other modalities.

After endoscopic treatment is performed, four-quadrant spot tattooing is recommended adjacent to the TIC with the SRH. This step will facilitate localization and treatment in the case of TIC rebleeding.4,10

Outcomes following endoscopic treatment

Following endoscopic treatment, patients should be monitored for early and late rebleeding. In a pooled analysis of case series composed of 847 patients with TIC bleeding, among the 137 patients in which endoscopic hemostasis was initially achieved, early rebleeding occurred in 8% and late rebleeding occurred in 12% of patients.22 Risk factors for TIC rebleeding within 30 days were residual arterial blood flow following hemostasis and early reinitiation of antiplatelet agents.

Remote treatment of TIC hemorrhage distant from the SRH is a significant risk factor for early TIC rebleeding.4, 10 For example, using hemoclips to close the mouth of a TIC when active bleeding or an SRH is located in the TIC base often fails because arterial flow remains open in the base and the artery is larger there.4,10 This example highlights the importance of focal obliteration of arterial blood flow underlying SRH in order to achieve definitive hemostasis.4,10

Salvage treatments

For TIC hemorrhage that is not controlled by endoscopic therapy, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is recommended. If bleeding rate is high enough (at least 0.5 milliliters per minute) to be detected by angiography, TAE can serve as an effective method of diagnosis and immediate hemostasis.23 However, the most common major complication of embolization is intestinal ischemia. The incidence of intestinal ischemia has been reported as high as 10%, with highest risk with embolization of at least three vasa recta.24

Surgery is also recommended if TIC hemorrhage cannot be controlled with endoscopic therapy or TAE. Segmental colectomy is recommended if the bleeding site can be localized before surgery with colonoscopy or angiography resulting from significantly lower perioperative morbidity than subtotal colectomy.25 However, subtotal colectomy may be necessary if preoperative localization of bleeding is unsuccessful.

There are very few reports of short- or long-term results that compare endoscopy, TAE, and surgery for management of TIC bleeding. However, a recent retrospective study reported better outcomes with endoscopic treatment of definitive TIC bleeding.26 Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment had fewer RBC transfusions, shorter hospitalizations, and lower rates of postprocedure complications.

Management after cessation of hemorrhage

Medical management is important following an episode of TIC hemorrhage. A mainstay is daily fiber supplementation every morning and stool softener in the evening. Furthermore, patients are advised to drink an extra liter of fluids (not containing alcohol or caffeine) daily. By reducing colon transit time and increasing stool weight, these measures can help control constipation and prevent future complications of TIC disease.27

Patients with recurrent TIC hemorrhage should undergo evaluation for elective surgery, provided they are appropriate surgical candidates. If preoperative localization of bleeding site is successful, segmental colectomy is preferred. Segmental resection is associated with significantly decreased rebleeding rate, with lower rates of morbidity compared with subtotal colectomy.32

Chronic NSAIDs, aspirin, and antiplatelet drugs are risk factors for recurrent TIC hemorrhage, and avoiding these medications is recommended if possible.33,34 Although anticoagulants have shown to be associated with increased risk of all-cause gastrointestinal bleeding, these agents have not been shown to increase risk of recurrent TIC hemorrhage in recent large retrospective studies. Since antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents serve to reduce risk of thromboembolic events, the clinician who recommended these medications should be consulted after a TIC bleed to re-evaluate whether these medications can be discontinued or reduced in dose.

Conclusion

The most effective way to diagnose and treat definitive TIC hemorrhage is to perform an urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours to identify and treat TIC SRH. This procedure requires thoroughly cleansing the colon first, as well as an experienced colonoscopist who can identify and treat TIC SRH to obliterate arterial blood flow underneath SRH and achieve definitive TIC hemostasis. Other approaches to early diagnosis include nuclear medicine scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or IR). However, these techniques can only detect active bleeding which is documented in only 26% of colonoscopically diagnosed definitive TIC hemorrhages. So, the expected diagnostic yield of these tests will be low. When urgent colonoscopy fails to make a diagnosis or TIC bleeding continues, TAE and/or surgery are recommended. After definitive hemostasis of TIC hemorrhage and for long term management, control of constipation and discontinuation of chronic NSAIDs and antiplatelet drugs (if possible) are recommended to prevent recurrent TIC hemorrhage.

Dr. Cusumano and Dr. Paiji are fellow physicians in the Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases at University of California Los Angeles. Dr. Jensen is a professor of medicine in Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases and is with the CURE Digestive Diseases Research Center at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Calif. All authors declare that they have no competing interests or disclosures.

References

1. Longstreth GF. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(3):419-24.

2. Jensen DM et al. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(2):78-82.

3. Jensen DM et al. Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2001;3(4):192-8.

4. Jensen DM. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1570-3.

5. Zuckerman GR et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1999;49(2):228-38.

6. Stollman N et al. Lancet. 2004;363(9409):631-9.

7. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1994;220(5):653-6.

8. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1972;175(6):847-55.

9. Strate LL et al. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-10.

10. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016;83(2):416-23.

11. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7(3):477-98.

12. Maykel JA et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17(3):195-204.

13. Green BT et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2395-402.

14. Niikura R et al. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):e24-30.

15. Bloomfeld RS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(8):2367-72.

16. Parsi MA,et al. VideoGIE. 2019;4(7):285-99.

17. Kaltenbach T et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2012;10(2):131-7.

18. Nakano K et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E529-33.

19. Barker KB et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;62(2):224-7.

20. Kaltenbach T et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020;30(1):13-23.

21. Yamazaki K et al. VideoGIE. 2020;5(6):252-4.

22. Strate LL et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2010;8(4):333-43.

23. Evangelista et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(5):601-6.

24. Kodani M et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(6):824-30.

25. Mohammed et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31(4):243-50.

26. Wongpongsalee T et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020;91(6):AB471-2.

27. Böhm SK. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31(2):84-94.

28. Prakash C et al. Endoscopy. 1999;31(6):460-3.

29. Yen EF et al. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2008;53(9):2480-5.

30. Ishii N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75(2):382-7.

31. Nagata N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2018;88(5):841-53.e4.

32. Parkes BM et al. Am Surg. 1993;59(10):676-8.

33. Vajravelu RK et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1416-27.

34. Oakland K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7):1276-84.e3.

35. Yamada A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):116-20.

36. Coleman CI et al. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(1):53-63.

37. Holster IL et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-12.e15.

Diverticular hemorrhage is the most common cause of colonic bleeding, accounting for 20%-65% of cases of severe lower intestinal bleeding in adults.1 Urgent colonoscopy after purging the colon of blood, clots, and stool is the most accurate method of diagnosing and guiding treatment of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.2-5 The diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage depends upon identification of some stigmata of recent hemorrhage (SRH) in a single diverticulum (TIC), which can include active arterial bleeding, oozing, non-bleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, or flat spot.2-4 Although other approaches, such as nuclear medicine scans and angiography of various types (CT, MRI, or standard angiography), for the early diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia are utilized in many medical centers, only active bleeding can be detected by these techniques. However, as subsequently discussed, this SRH is documented in only 26% of definitive diverticular bleeds found on urgent colonoscopy, so diagnostic yields of these techniques will be low.2-5

The diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia and diverticulosis, as well as triage of all of them to specific medical, endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical management, is facilitated by an urgent endoscopic approach.2-5 Patients who are diagnosed with definitive diverticular hemorrhage on colonoscopy represent about 30% of all true TIC bleeds when urgent colonoscopy is the management approach.2-5 That is because approximately 50% of all patients with colon diverticulosis and first presentation of severe hematochezia have incidental diverticulosis; they have colonic diverticulosis, but another site of bleeding is identified as the cause of hemorrhage in the gastrointestinal tract.2-4 Presumptive diverticular hemorrhage is diagnosed when colonic diverticulosis without TIC stigmata are found but no other GI bleeding source is found on colonoscopy, anoscopy, enteroscopy, or capsule endoscopy.2-5 In our experience with urgent colonoscopy, the presumptive diverticular bleed group accounts for about 70% of patients with documented diverticular hemorrhage (e.g., not including incidental diverticulosis bleeds but combining subgroups of patients with either definitive or presumptive TIC diagnoses as documented TIC hemorrhage).

Clinical presentation

Patients with diverticular hemorrhage present with severe, painless large volume hematochezia. Hematochezia may be self-limited and spontaneously resolve in 75%-80% of all patients but with high rebleeding rates up to 40%.5-7 Of all patients with diverticulosis, only about 3%-5% develop diverticular hemorrhage.8 Risk factors for diverticular hemorrhage include medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs, and anticoagulants) and other clinical factors, such as older age, low-fiber diet, and chronic constipation.9,10 On urgent colonoscopy, more than 70% of diverticulosis in U.S. patients are located anatomically in the descending colon or more distally. In contrast, about 60% of definitive diverticular hemorrhage cases in our experience had diverticula with stigmata identified at or proximal to the splenic flexure.2,4,11

Pathophysiology

Colonic diverticula are herniations of mucosa and submucosa with colonic arteries that penetrate the muscular wall. Bleeding can occur when there is asymmetric rupture of the vasa recta at either the base of the diverticulum or the neck.4 Thinning of the mucosa on the luminal surface (such as that resulting from impacted fecaliths and stool) can cause injury to the site of the penetrating vessels, resulting in hemorrhage.12

Initial management

Patients with acute, severe hematochezia should be triaged to an inpatient setting with a monitored bed. Admission to an intensive care unit should be considered for patients with hemodynamic instability, persistent bleeding, and/or significant comorbidities. Patients with TIC hemorrhage often require resuscitation with crystalloids and packed red blood cell transfusions for hemoglobin less than 8 g/dl.4 Unlike upper GI hemorrhage, which has been extensively reported on, data regarding a more restrictive transfusion threshold, compared with a liberal transfusion threshold, in lower intestinal bleeding are very limited. Correction of underlying coagulopathies is recommended but should be individualized, particularly in those patients on antithrombotic agents or with underlying bleeding disorders.

Urgent diagnosis and hemostasis

Urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours is the most accurate way to make a diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage and to effectively and safely treat them.2-4,10,11 For patients with severe hematochezia, when the colonoscopy is either not available in a medical center or does not reveal the source of bleeding, nuclear scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or interventional radiology [IR]) are recommended. CT angiography may be particularly helpful to diagnose patients with hemodynamic instability who are suspected to have active TIC bleeding and are not able to complete a bowel preparation. However, these imaging techniques require active bleeding at the time of the study to be diagnostic. This SRH is also uncommon for definitive diverticular hemorrhage, so the diagnostic yield is usually quite low.2-5,10,11 An additional limitation of scintigraphy and CT or MRI angiography is that, if active bleeding is found, some other type of treatment, such as colonoscopy, IR angiography, or surgery, will be required for definitive hemostasis.

For urgent colonoscopy, adequate colon preparation with a large volume preparation (6-8 liters of polyethylene glycol-based solution) is recommended to clear stool, blood, and clots to allow endoscopic visualization and localization of the bleeding source. Use of a nasogastric tube should be considered if the patient is unable to drink enough prep.2-4,13 Additionally, administration of a prokinetic agent, such as Metoclopramide, may improve gastric emptying and tolerance of the prep. During colonoscopy, careful inspection of the colonic mucosa during insertion and withdrawal is important since lesions may bleed intermittently and SRH can be missed. An adult or pediatric colonoscope with a large working channel (at least 3.3 mm) is recommended to facilitate suctioning of blood clots and stool, as well as allow the passage of endoscopic hemostasis accessories. Targeted water-jet irrigation, an expert colonoscopist, a cap attachment, and adequate colon preparation are all predictors for improved diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.4,14

SRH in definitive TIC bleeds all have a high risk of TIC rebleeding,2-4,10,11 including active bleeding, nonbleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, and a flat spot (See Figure).

Based on CURE Hemostasis Group data of 118 definitive TIC bleeds, 26% had active bleeding, 24% had a nonbleeding visible vessel, 37% had an adherent clot, and 13% had a flat spot (with underlying arterial blood flow by Doppler probe monitoring).4 Approximately 50% of the SRH were found in the neck of the TIC and 50% at the base, with actively bleeding cases more often from the base. In CURE Doppler endoscopic probe studies, 90% of all stigmata had an underlying arterial blood flow detected with the Doppler probe.4,10 The Doppler probe is reported to be very useful for risk stratification and to confirm obliteration of the arterial blood flow underlying SRH for definitive hemostasis.4,10

Endoscopic treatment

Given high rates of rebleeding with medical management alone, definitive TIC hemorrhage can be effectively and safely treated with endoscopic therapies once SRH are localized.4,10 Endoscopic therapies that have been reported in the literature include electrocoagulation, hemoclip, band ligation, and over-the-scope clip. Four-quadrant injection of 1:20,000 epinephrine around the SRH can improve visualization of SRH and provide temporary control of bleeding, but it should be combined with other modalities because of risk of rebleeding with epinephrine alone.15 Results from studies reporting rates of both early rebleeding (occurring within 30 days) and late rebleeding (occurring after 30 days) are listed in the Table.

Multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC), which utilizes a focal electric current to generate heat, can coaptively coagulate small TIC arteries.16 For SRH in the neck of TIC, MPEC is effective for coaptive coagulation at a power of 12-15 watts in 1-2 second pulses with moderate laterally applied tamponade pressure. MPEC should be avoided for treating SRH at the TIC base because of lack of muscularis propria and higher risk of perforation.

Hemoclip therapy has been reported to be safe and efficacious in treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage, by causing mechanical hemostasis with occlusion of the bleeding artery.16 Hemoclips are recommended to treat stigmata in the base of TICs and should be targeted on either side of visible vessel in order to occlude the artery underneath it.4,10 With a cap on the tip of the colonoscope, suctioning can evert TICs, allowing more precise placement of hemoclip on SRH in the base of the TIC.17 Hemoclip retention rates vary with different models and can range from less than 7 days to more than 4 weeks. Hemoclips can also mark the site if early rebleeding occurs; then, reintervention (e.g., repeat endoscopy or angioembolization) is facilitated.

Another treatment is endoscopic band ligation, which provides mechanical hemostasis. Endoscopic band ligation has been reported to be efficacious for TIC hemorrhage.18 Suctioning the TIC with the SRH into the distal cap and deploying a band leads to obliteration of vessels and potentially necrosis and disappearance of banded TIC.16 This technique carries a risk of perforation because of the thin walls of TICs. This risk may be higher for right-sided colon lesions since an exvivo colon specimen study reported serosal entrapment and inclusion of muscularis propria postband ligation, both of which may result in ischemia of intestinal wall and delayed perforation.19

Over-the-scope clip (OTSC) has been reported in case series for treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage. With a distal cap and large clip, suctioning can evert TICs and facilitate deployment over the SRH.20,21 OTSC can grasp an entire TIC with the SRH and obliterate the arterial blood flow with a single clip.20,21 No complications have been reported yet for treatment of TIC hemorrhage. However, the OTSC system is relatively expensive when compared with other modalities.

After endoscopic treatment is performed, four-quadrant spot tattooing is recommended adjacent to the TIC with the SRH. This step will facilitate localization and treatment in the case of TIC rebleeding.4,10

Outcomes following endoscopic treatment

Following endoscopic treatment, patients should be monitored for early and late rebleeding. In a pooled analysis of case series composed of 847 patients with TIC bleeding, among the 137 patients in which endoscopic hemostasis was initially achieved, early rebleeding occurred in 8% and late rebleeding occurred in 12% of patients.22 Risk factors for TIC rebleeding within 30 days were residual arterial blood flow following hemostasis and early reinitiation of antiplatelet agents.

Remote treatment of TIC hemorrhage distant from the SRH is a significant risk factor for early TIC rebleeding.4, 10 For example, using hemoclips to close the mouth of a TIC when active bleeding or an SRH is located in the TIC base often fails because arterial flow remains open in the base and the artery is larger there.4,10 This example highlights the importance of focal obliteration of arterial blood flow underlying SRH in order to achieve definitive hemostasis.4,10

Salvage treatments

For TIC hemorrhage that is not controlled by endoscopic therapy, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is recommended. If bleeding rate is high enough (at least 0.5 milliliters per minute) to be detected by angiography, TAE can serve as an effective method of diagnosis and immediate hemostasis.23 However, the most common major complication of embolization is intestinal ischemia. The incidence of intestinal ischemia has been reported as high as 10%, with highest risk with embolization of at least three vasa recta.24

Surgery is also recommended if TIC hemorrhage cannot be controlled with endoscopic therapy or TAE. Segmental colectomy is recommended if the bleeding site can be localized before surgery with colonoscopy or angiography resulting from significantly lower perioperative morbidity than subtotal colectomy.25 However, subtotal colectomy may be necessary if preoperative localization of bleeding is unsuccessful.

There are very few reports of short- or long-term results that compare endoscopy, TAE, and surgery for management of TIC bleeding. However, a recent retrospective study reported better outcomes with endoscopic treatment of definitive TIC bleeding.26 Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment had fewer RBC transfusions, shorter hospitalizations, and lower rates of postprocedure complications.

Management after cessation of hemorrhage

Medical management is important following an episode of TIC hemorrhage. A mainstay is daily fiber supplementation every morning and stool softener in the evening. Furthermore, patients are advised to drink an extra liter of fluids (not containing alcohol or caffeine) daily. By reducing colon transit time and increasing stool weight, these measures can help control constipation and prevent future complications of TIC disease.27

Patients with recurrent TIC hemorrhage should undergo evaluation for elective surgery, provided they are appropriate surgical candidates. If preoperative localization of bleeding site is successful, segmental colectomy is preferred. Segmental resection is associated with significantly decreased rebleeding rate, with lower rates of morbidity compared with subtotal colectomy.32

Chronic NSAIDs, aspirin, and antiplatelet drugs are risk factors for recurrent TIC hemorrhage, and avoiding these medications is recommended if possible.33,34 Although anticoagulants have shown to be associated with increased risk of all-cause gastrointestinal bleeding, these agents have not been shown to increase risk of recurrent TIC hemorrhage in recent large retrospective studies. Since antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents serve to reduce risk of thromboembolic events, the clinician who recommended these medications should be consulted after a TIC bleed to re-evaluate whether these medications can be discontinued or reduced in dose.

Conclusion

The most effective way to diagnose and treat definitive TIC hemorrhage is to perform an urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours to identify and treat TIC SRH. This procedure requires thoroughly cleansing the colon first, as well as an experienced colonoscopist who can identify and treat TIC SRH to obliterate arterial blood flow underneath SRH and achieve definitive TIC hemostasis. Other approaches to early diagnosis include nuclear medicine scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or IR). However, these techniques can only detect active bleeding which is documented in only 26% of colonoscopically diagnosed definitive TIC hemorrhages. So, the expected diagnostic yield of these tests will be low. When urgent colonoscopy fails to make a diagnosis or TIC bleeding continues, TAE and/or surgery are recommended. After definitive hemostasis of TIC hemorrhage and for long term management, control of constipation and discontinuation of chronic NSAIDs and antiplatelet drugs (if possible) are recommended to prevent recurrent TIC hemorrhage.

Dr. Cusumano and Dr. Paiji are fellow physicians in the Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases at University of California Los Angeles. Dr. Jensen is a professor of medicine in Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases and is with the CURE Digestive Diseases Research Center at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Calif. All authors declare that they have no competing interests or disclosures.

References

1. Longstreth GF. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(3):419-24.

2. Jensen DM et al. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(2):78-82.

3. Jensen DM et al. Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2001;3(4):192-8.

4. Jensen DM. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1570-3.

5. Zuckerman GR et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1999;49(2):228-38.

6. Stollman N et al. Lancet. 2004;363(9409):631-9.

7. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1994;220(5):653-6.

8. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1972;175(6):847-55.

9. Strate LL et al. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-10.

10. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016;83(2):416-23.

11. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7(3):477-98.

12. Maykel JA et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17(3):195-204.

13. Green BT et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2395-402.

14. Niikura R et al. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):e24-30.

15. Bloomfeld RS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(8):2367-72.

16. Parsi MA,et al. VideoGIE. 2019;4(7):285-99.

17. Kaltenbach T et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2012;10(2):131-7.

18. Nakano K et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E529-33.

19. Barker KB et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;62(2):224-7.

20. Kaltenbach T et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020;30(1):13-23.

21. Yamazaki K et al. VideoGIE. 2020;5(6):252-4.

22. Strate LL et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2010;8(4):333-43.

23. Evangelista et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(5):601-6.

24. Kodani M et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(6):824-30.

25. Mohammed et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31(4):243-50.

26. Wongpongsalee T et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020;91(6):AB471-2.

27. Böhm SK. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31(2):84-94.

28. Prakash C et al. Endoscopy. 1999;31(6):460-3.

29. Yen EF et al. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2008;53(9):2480-5.

30. Ishii N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75(2):382-7.

31. Nagata N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2018;88(5):841-53.e4.

32. Parkes BM et al. Am Surg. 1993;59(10):676-8.

33. Vajravelu RK et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1416-27.

34. Oakland K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7):1276-84.e3.

35. Yamada A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):116-20.

36. Coleman CI et al. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(1):53-63.

37. Holster IL et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-12.e15.

Diverticular hemorrhage is the most common cause of colonic bleeding, accounting for 20%-65% of cases of severe lower intestinal bleeding in adults.1 Urgent colonoscopy after purging the colon of blood, clots, and stool is the most accurate method of diagnosing and guiding treatment of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.2-5 The diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage depends upon identification of some stigmata of recent hemorrhage (SRH) in a single diverticulum (TIC), which can include active arterial bleeding, oozing, non-bleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, or flat spot.2-4 Although other approaches, such as nuclear medicine scans and angiography of various types (CT, MRI, or standard angiography), for the early diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia are utilized in many medical centers, only active bleeding can be detected by these techniques. However, as subsequently discussed, this SRH is documented in only 26% of definitive diverticular bleeds found on urgent colonoscopy, so diagnostic yields of these techniques will be low.2-5

The diagnosis of patients with severe hematochezia and diverticulosis, as well as triage of all of them to specific medical, endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical management, is facilitated by an urgent endoscopic approach.2-5 Patients who are diagnosed with definitive diverticular hemorrhage on colonoscopy represent about 30% of all true TIC bleeds when urgent colonoscopy is the management approach.2-5 That is because approximately 50% of all patients with colon diverticulosis and first presentation of severe hematochezia have incidental diverticulosis; they have colonic diverticulosis, but another site of bleeding is identified as the cause of hemorrhage in the gastrointestinal tract.2-4 Presumptive diverticular hemorrhage is diagnosed when colonic diverticulosis without TIC stigmata are found but no other GI bleeding source is found on colonoscopy, anoscopy, enteroscopy, or capsule endoscopy.2-5 In our experience with urgent colonoscopy, the presumptive diverticular bleed group accounts for about 70% of patients with documented diverticular hemorrhage (e.g., not including incidental diverticulosis bleeds but combining subgroups of patients with either definitive or presumptive TIC diagnoses as documented TIC hemorrhage).

Clinical presentation

Patients with diverticular hemorrhage present with severe, painless large volume hematochezia. Hematochezia may be self-limited and spontaneously resolve in 75%-80% of all patients but with high rebleeding rates up to 40%.5-7 Of all patients with diverticulosis, only about 3%-5% develop diverticular hemorrhage.8 Risk factors for diverticular hemorrhage include medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs, and anticoagulants) and other clinical factors, such as older age, low-fiber diet, and chronic constipation.9,10 On urgent colonoscopy, more than 70% of diverticulosis in U.S. patients are located anatomically in the descending colon or more distally. In contrast, about 60% of definitive diverticular hemorrhage cases in our experience had diverticula with stigmata identified at or proximal to the splenic flexure.2,4,11

Pathophysiology

Colonic diverticula are herniations of mucosa and submucosa with colonic arteries that penetrate the muscular wall. Bleeding can occur when there is asymmetric rupture of the vasa recta at either the base of the diverticulum or the neck.4 Thinning of the mucosa on the luminal surface (such as that resulting from impacted fecaliths and stool) can cause injury to the site of the penetrating vessels, resulting in hemorrhage.12

Initial management

Patients with acute, severe hematochezia should be triaged to an inpatient setting with a monitored bed. Admission to an intensive care unit should be considered for patients with hemodynamic instability, persistent bleeding, and/or significant comorbidities. Patients with TIC hemorrhage often require resuscitation with crystalloids and packed red blood cell transfusions for hemoglobin less than 8 g/dl.4 Unlike upper GI hemorrhage, which has been extensively reported on, data regarding a more restrictive transfusion threshold, compared with a liberal transfusion threshold, in lower intestinal bleeding are very limited. Correction of underlying coagulopathies is recommended but should be individualized, particularly in those patients on antithrombotic agents or with underlying bleeding disorders.

Urgent diagnosis and hemostasis

Urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours is the most accurate way to make a diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage and to effectively and safely treat them.2-4,10,11 For patients with severe hematochezia, when the colonoscopy is either not available in a medical center or does not reveal the source of bleeding, nuclear scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or interventional radiology [IR]) are recommended. CT angiography may be particularly helpful to diagnose patients with hemodynamic instability who are suspected to have active TIC bleeding and are not able to complete a bowel preparation. However, these imaging techniques require active bleeding at the time of the study to be diagnostic. This SRH is also uncommon for definitive diverticular hemorrhage, so the diagnostic yield is usually quite low.2-5,10,11 An additional limitation of scintigraphy and CT or MRI angiography is that, if active bleeding is found, some other type of treatment, such as colonoscopy, IR angiography, or surgery, will be required for definitive hemostasis.

For urgent colonoscopy, adequate colon preparation with a large volume preparation (6-8 liters of polyethylene glycol-based solution) is recommended to clear stool, blood, and clots to allow endoscopic visualization and localization of the bleeding source. Use of a nasogastric tube should be considered if the patient is unable to drink enough prep.2-4,13 Additionally, administration of a prokinetic agent, such as Metoclopramide, may improve gastric emptying and tolerance of the prep. During colonoscopy, careful inspection of the colonic mucosa during insertion and withdrawal is important since lesions may bleed intermittently and SRH can be missed. An adult or pediatric colonoscope with a large working channel (at least 3.3 mm) is recommended to facilitate suctioning of blood clots and stool, as well as allow the passage of endoscopic hemostasis accessories. Targeted water-jet irrigation, an expert colonoscopist, a cap attachment, and adequate colon preparation are all predictors for improved diagnosis of definitive diverticular hemorrhage.4,14

SRH in definitive TIC bleeds all have a high risk of TIC rebleeding,2-4,10,11 including active bleeding, nonbleeding visible vessel, adherent clot, and a flat spot (See Figure).

Based on CURE Hemostasis Group data of 118 definitive TIC bleeds, 26% had active bleeding, 24% had a nonbleeding visible vessel, 37% had an adherent clot, and 13% had a flat spot (with underlying arterial blood flow by Doppler probe monitoring).4 Approximately 50% of the SRH were found in the neck of the TIC and 50% at the base, with actively bleeding cases more often from the base. In CURE Doppler endoscopic probe studies, 90% of all stigmata had an underlying arterial blood flow detected with the Doppler probe.4,10 The Doppler probe is reported to be very useful for risk stratification and to confirm obliteration of the arterial blood flow underlying SRH for definitive hemostasis.4,10

Endoscopic treatment

Given high rates of rebleeding with medical management alone, definitive TIC hemorrhage can be effectively and safely treated with endoscopic therapies once SRH are localized.4,10 Endoscopic therapies that have been reported in the literature include electrocoagulation, hemoclip, band ligation, and over-the-scope clip. Four-quadrant injection of 1:20,000 epinephrine around the SRH can improve visualization of SRH and provide temporary control of bleeding, but it should be combined with other modalities because of risk of rebleeding with epinephrine alone.15 Results from studies reporting rates of both early rebleeding (occurring within 30 days) and late rebleeding (occurring after 30 days) are listed in the Table.

Multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC), which utilizes a focal electric current to generate heat, can coaptively coagulate small TIC arteries.16 For SRH in the neck of TIC, MPEC is effective for coaptive coagulation at a power of 12-15 watts in 1-2 second pulses with moderate laterally applied tamponade pressure. MPEC should be avoided for treating SRH at the TIC base because of lack of muscularis propria and higher risk of perforation.

Hemoclip therapy has been reported to be safe and efficacious in treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage, by causing mechanical hemostasis with occlusion of the bleeding artery.16 Hemoclips are recommended to treat stigmata in the base of TICs and should be targeted on either side of visible vessel in order to occlude the artery underneath it.4,10 With a cap on the tip of the colonoscope, suctioning can evert TICs, allowing more precise placement of hemoclip on SRH in the base of the TIC.17 Hemoclip retention rates vary with different models and can range from less than 7 days to more than 4 weeks. Hemoclips can also mark the site if early rebleeding occurs; then, reintervention (e.g., repeat endoscopy or angioembolization) is facilitated.

Another treatment is endoscopic band ligation, which provides mechanical hemostasis. Endoscopic band ligation has been reported to be efficacious for TIC hemorrhage.18 Suctioning the TIC with the SRH into the distal cap and deploying a band leads to obliteration of vessels and potentially necrosis and disappearance of banded TIC.16 This technique carries a risk of perforation because of the thin walls of TICs. This risk may be higher for right-sided colon lesions since an exvivo colon specimen study reported serosal entrapment and inclusion of muscularis propria postband ligation, both of which may result in ischemia of intestinal wall and delayed perforation.19

Over-the-scope clip (OTSC) has been reported in case series for treatment of definitive TIC hemorrhage. With a distal cap and large clip, suctioning can evert TICs and facilitate deployment over the SRH.20,21 OTSC can grasp an entire TIC with the SRH and obliterate the arterial blood flow with a single clip.20,21 No complications have been reported yet for treatment of TIC hemorrhage. However, the OTSC system is relatively expensive when compared with other modalities.

After endoscopic treatment is performed, four-quadrant spot tattooing is recommended adjacent to the TIC with the SRH. This step will facilitate localization and treatment in the case of TIC rebleeding.4,10

Outcomes following endoscopic treatment

Following endoscopic treatment, patients should be monitored for early and late rebleeding. In a pooled analysis of case series composed of 847 patients with TIC bleeding, among the 137 patients in which endoscopic hemostasis was initially achieved, early rebleeding occurred in 8% and late rebleeding occurred in 12% of patients.22 Risk factors for TIC rebleeding within 30 days were residual arterial blood flow following hemostasis and early reinitiation of antiplatelet agents.

Remote treatment of TIC hemorrhage distant from the SRH is a significant risk factor for early TIC rebleeding.4, 10 For example, using hemoclips to close the mouth of a TIC when active bleeding or an SRH is located in the TIC base often fails because arterial flow remains open in the base and the artery is larger there.4,10 This example highlights the importance of focal obliteration of arterial blood flow underlying SRH in order to achieve definitive hemostasis.4,10

Salvage treatments

For TIC hemorrhage that is not controlled by endoscopic therapy, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is recommended. If bleeding rate is high enough (at least 0.5 milliliters per minute) to be detected by angiography, TAE can serve as an effective method of diagnosis and immediate hemostasis.23 However, the most common major complication of embolization is intestinal ischemia. The incidence of intestinal ischemia has been reported as high as 10%, with highest risk with embolization of at least three vasa recta.24

Surgery is also recommended if TIC hemorrhage cannot be controlled with endoscopic therapy or TAE. Segmental colectomy is recommended if the bleeding site can be localized before surgery with colonoscopy or angiography resulting from significantly lower perioperative morbidity than subtotal colectomy.25 However, subtotal colectomy may be necessary if preoperative localization of bleeding is unsuccessful.

There are very few reports of short- or long-term results that compare endoscopy, TAE, and surgery for management of TIC bleeding. However, a recent retrospective study reported better outcomes with endoscopic treatment of definitive TIC bleeding.26 Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment had fewer RBC transfusions, shorter hospitalizations, and lower rates of postprocedure complications.

Management after cessation of hemorrhage

Medical management is important following an episode of TIC hemorrhage. A mainstay is daily fiber supplementation every morning and stool softener in the evening. Furthermore, patients are advised to drink an extra liter of fluids (not containing alcohol or caffeine) daily. By reducing colon transit time and increasing stool weight, these measures can help control constipation and prevent future complications of TIC disease.27

Patients with recurrent TIC hemorrhage should undergo evaluation for elective surgery, provided they are appropriate surgical candidates. If preoperative localization of bleeding site is successful, segmental colectomy is preferred. Segmental resection is associated with significantly decreased rebleeding rate, with lower rates of morbidity compared with subtotal colectomy.32

Chronic NSAIDs, aspirin, and antiplatelet drugs are risk factors for recurrent TIC hemorrhage, and avoiding these medications is recommended if possible.33,34 Although anticoagulants have shown to be associated with increased risk of all-cause gastrointestinal bleeding, these agents have not been shown to increase risk of recurrent TIC hemorrhage in recent large retrospective studies. Since antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents serve to reduce risk of thromboembolic events, the clinician who recommended these medications should be consulted after a TIC bleed to re-evaluate whether these medications can be discontinued or reduced in dose.

Conclusion

The most effective way to diagnose and treat definitive TIC hemorrhage is to perform an urgent colonoscopy within 24 hours to identify and treat TIC SRH. This procedure requires thoroughly cleansing the colon first, as well as an experienced colonoscopist who can identify and treat TIC SRH to obliterate arterial blood flow underneath SRH and achieve definitive TIC hemostasis. Other approaches to early diagnosis include nuclear medicine scintigraphy or angiography (CT, MRI, or IR). However, these techniques can only detect active bleeding which is documented in only 26% of colonoscopically diagnosed definitive TIC hemorrhages. So, the expected diagnostic yield of these tests will be low. When urgent colonoscopy fails to make a diagnosis or TIC bleeding continues, TAE and/or surgery are recommended. After definitive hemostasis of TIC hemorrhage and for long term management, control of constipation and discontinuation of chronic NSAIDs and antiplatelet drugs (if possible) are recommended to prevent recurrent TIC hemorrhage.

Dr. Cusumano and Dr. Paiji are fellow physicians in the Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases at University of California Los Angeles. Dr. Jensen is a professor of medicine in Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases and is with the CURE Digestive Diseases Research Center at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Calif. All authors declare that they have no competing interests or disclosures.

References

1. Longstreth GF. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(3):419-24.

2. Jensen DM et al. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(2):78-82.

3. Jensen DM et al. Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2001;3(4):192-8.

4. Jensen DM. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1570-3.

5. Zuckerman GR et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1999;49(2):228-38.

6. Stollman N et al. Lancet. 2004;363(9409):631-9.

7. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1994;220(5):653-6.

8. McGuire HH et al. Ann Surg. 1972;175(6):847-55.

9. Strate LL et al. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-10.

10. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016;83(2):416-23.

11. Jensen DM et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7(3):477-98.

12. Maykel JA et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17(3):195-204.

13. Green BT et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2395-402.

14. Niikura R et al. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):e24-30.

15. Bloomfeld RS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(8):2367-72.

16. Parsi MA,et al. VideoGIE. 2019;4(7):285-99.

17. Kaltenbach T et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2012;10(2):131-7.

18. Nakano K et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E529-33.

19. Barker KB et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;62(2):224-7.

20. Kaltenbach T et al. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020;30(1):13-23.

21. Yamazaki K et al. VideoGIE. 2020;5(6):252-4.

22. Strate LL et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatol. 2010;8(4):333-43.

23. Evangelista et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(5):601-6.

24. Kodani M et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(6):824-30.

25. Mohammed et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31(4):243-50.

26. Wongpongsalee T et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020;91(6):AB471-2.

27. Böhm SK. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31(2):84-94.

28. Prakash C et al. Endoscopy. 1999;31(6):460-3.

29. Yen EF et al. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2008;53(9):2480-5.

30. Ishii N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75(2):382-7.

31. Nagata N et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2018;88(5):841-53.e4.

32. Parkes BM et al. Am Surg. 1993;59(10):676-8.

33. Vajravelu RK et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1416-27.

34. Oakland K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7):1276-84.e3.

35. Yamada A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):116-20.

36. Coleman CI et al. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(1):53-63.

37. Holster IL et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-12.e15.

Emerging realities

Dear colleagues,

Welcome to the November edition of The New Gastroenterologist! Our fall newsletter features a particularly interesting compilation of articles. As the pandemic lingers on, we are forced to face the realities of coexisting with COVID-19 as the virus certainly seems to be here to stay.

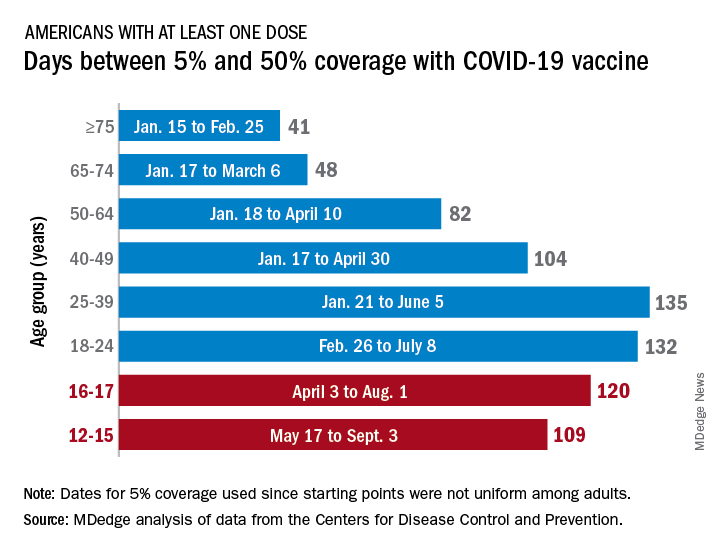

To protect against ongoing risk of exposure, health care workers and other high-risk subsets of patients are now being offered booster shots. For our patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on immune-modifying therapies, there has always been a question of vaccine efficacy. Dr. Freddy Caldera and Dr. Trevor Schell (University of Wisconsin-Madison) shed some much needed light on recommendations on the COVID-19 vaccine for IBD patients.

In April of 2021, a federal rule was implemented mandating that patients have immediate and free access to their electronic health information – which includes all documentation from their health care providers. Some physicians have been concerned about this practice, namely how patients will respond and whether this will increase the burden on clinicians. Clearly, this issue is multifaceted: Dr. Sachin Shah (University of Chicago) discusses the ethical implications from a clinical standpoint, while attorney Valerie Guttman Koch (University of Houston Law Center, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago) shares a riveting legal perspective.

Colonic diverticular bleeding is the most common etiology of overt lower gastrointestinal bleeding and one of the most frequent consults we receive as gastroenterologists. However, even with the use of colonoscopy, obtaining a definitive diagnosis can often be difficult. Our “In Focus” feature for November, is an excellent piece written by Dr. Vivy Cusumano, Dr. Christopher Paiji, and Dr. Dennis Jensen (all with University of California, Los Angeles), detailing the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment.

Navigating pregnancy and parental leave during training is difficult. Drs. Joy Liu, Keith Summa, Ronak Patel, Erica Donnan, Amanda Guentner, and Leila Kia (all with Northwestern University) share their program’s experience, providing incredibly helpful and practical recommendations for both gastroenterology trainees and fellowship directors.

The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists emerged against the backdrop of recent social and health care injustices. Dr. Kafayat Busari (Florida State University) and Dr. Alexandra Guillaume (Stony Brook University Hospital) discuss the critical importance and mission of this association and how it will help shape the field of gastroenterology in the years to come.

Medical pancreatology is a subspecialty that most gastroenterology fellows have little, if any, exposure to. In our post-fellowship pathways section, Dr. Sajan Nagpal (University of Chicago) details his own experiences in addition to discussing the important role of a medical pancreatologist within a gastroenterology division.

Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. Sanjay Sandhir (Dayton [Ohio] Gastroenterology), discusses the importance of education and screening for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

Welcome to the November edition of The New Gastroenterologist! Our fall newsletter features a particularly interesting compilation of articles. As the pandemic lingers on, we are forced to face the realities of coexisting with COVID-19 as the virus certainly seems to be here to stay.

To protect against ongoing risk of exposure, health care workers and other high-risk subsets of patients are now being offered booster shots. For our patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on immune-modifying therapies, there has always been a question of vaccine efficacy. Dr. Freddy Caldera and Dr. Trevor Schell (University of Wisconsin-Madison) shed some much needed light on recommendations on the COVID-19 vaccine for IBD patients.

In April of 2021, a federal rule was implemented mandating that patients have immediate and free access to their electronic health information – which includes all documentation from their health care providers. Some physicians have been concerned about this practice, namely how patients will respond and whether this will increase the burden on clinicians. Clearly, this issue is multifaceted: Dr. Sachin Shah (University of Chicago) discusses the ethical implications from a clinical standpoint, while attorney Valerie Guttman Koch (University of Houston Law Center, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago) shares a riveting legal perspective.

Colonic diverticular bleeding is the most common etiology of overt lower gastrointestinal bleeding and one of the most frequent consults we receive as gastroenterologists. However, even with the use of colonoscopy, obtaining a definitive diagnosis can often be difficult. Our “In Focus” feature for November, is an excellent piece written by Dr. Vivy Cusumano, Dr. Christopher Paiji, and Dr. Dennis Jensen (all with University of California, Los Angeles), detailing the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment.

Navigating pregnancy and parental leave during training is difficult. Drs. Joy Liu, Keith Summa, Ronak Patel, Erica Donnan, Amanda Guentner, and Leila Kia (all with Northwestern University) share their program’s experience, providing incredibly helpful and practical recommendations for both gastroenterology trainees and fellowship directors.

The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists emerged against the backdrop of recent social and health care injustices. Dr. Kafayat Busari (Florida State University) and Dr. Alexandra Guillaume (Stony Brook University Hospital) discuss the critical importance and mission of this association and how it will help shape the field of gastroenterology in the years to come.

Medical pancreatology is a subspecialty that most gastroenterology fellows have little, if any, exposure to. In our post-fellowship pathways section, Dr. Sajan Nagpal (University of Chicago) details his own experiences in addition to discussing the important role of a medical pancreatologist within a gastroenterology division.

Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. Sanjay Sandhir (Dayton [Ohio] Gastroenterology), discusses the importance of education and screening for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

Welcome to the November edition of The New Gastroenterologist! Our fall newsletter features a particularly interesting compilation of articles. As the pandemic lingers on, we are forced to face the realities of coexisting with COVID-19 as the virus certainly seems to be here to stay.

To protect against ongoing risk of exposure, health care workers and other high-risk subsets of patients are now being offered booster shots. For our patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on immune-modifying therapies, there has always been a question of vaccine efficacy. Dr. Freddy Caldera and Dr. Trevor Schell (University of Wisconsin-Madison) shed some much needed light on recommendations on the COVID-19 vaccine for IBD patients.

In April of 2021, a federal rule was implemented mandating that patients have immediate and free access to their electronic health information – which includes all documentation from their health care providers. Some physicians have been concerned about this practice, namely how patients will respond and whether this will increase the burden on clinicians. Clearly, this issue is multifaceted: Dr. Sachin Shah (University of Chicago) discusses the ethical implications from a clinical standpoint, while attorney Valerie Guttman Koch (University of Houston Law Center, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago) shares a riveting legal perspective.

Colonic diverticular bleeding is the most common etiology of overt lower gastrointestinal bleeding and one of the most frequent consults we receive as gastroenterologists. However, even with the use of colonoscopy, obtaining a definitive diagnosis can often be difficult. Our “In Focus” feature for November, is an excellent piece written by Dr. Vivy Cusumano, Dr. Christopher Paiji, and Dr. Dennis Jensen (all with University of California, Los Angeles), detailing the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment.

Navigating pregnancy and parental leave during training is difficult. Drs. Joy Liu, Keith Summa, Ronak Patel, Erica Donnan, Amanda Guentner, and Leila Kia (all with Northwestern University) share their program’s experience, providing incredibly helpful and practical recommendations for both gastroenterology trainees and fellowship directors.

The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists emerged against the backdrop of recent social and health care injustices. Dr. Kafayat Busari (Florida State University) and Dr. Alexandra Guillaume (Stony Brook University Hospital) discuss the critical importance and mission of this association and how it will help shape the field of gastroenterology in the years to come.

Medical pancreatology is a subspecialty that most gastroenterology fellows have little, if any, exposure to. In our post-fellowship pathways section, Dr. Sajan Nagpal (University of Chicago) details his own experiences in addition to discussing the important role of a medical pancreatologist within a gastroenterology division.

Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. Sanjay Sandhir (Dayton [Ohio] Gastroenterology), discusses the importance of education and screening for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

FDA not recognizing efficacy of psychopharmacologic therapies

Many years ago, drug development in psychiatry turned to control of specific symptoms across disorders rather than within disorders, but regulatory agencies are still not yet on board, according to an expert psychopharmacologist outlining the ongoing evolution at the virtual Psychopharmacology Update presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, sponsored by Medscape Live.

If this reorientation is going to lead to the broad indications the newer drugs likely deserve, which is control of specific types of symptoms regardless of the diagnosis, “we have to move the [Food and Drug Administration] along,” said Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, chairman of the Neuroscience Institute and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego.

On the side of drug development and clinical practice, the reorientation has already taken place. Dr. Stahl described numerous brain circuits known to produce symptoms when function is altered that are now treatment targets. This includes the ventral medial prefrontal cortex where deficient information processing leads to depression and the orbital frontal cortex where altered function leads to impulsivity.

“It is not like each part of the brain does a little bit of everything. Rather, each part of the brain has an assignment and duty and function,” Dr. Stahl explained. By addressing the disturbed signaling in brain circuits that lead to depression, impulsivity, agitation, or other symptoms, there is an opportunity for control, regardless of the psychiatric diagnosis with which the symptom is associated.

For example, Dr. Stahl predicted that pimavanserin, a highly selective 5-HT2A inverse agonist that is already approved for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease, is now likely to be approved for psychosis associated with other conditions on the basis of recent positive clinical studies in these other disorders.

Brexpiprazole, a serotonin-dopamine activity modulator already known to be useful for control of the agitation characteristic of schizophrenia, is now showing the same type of activity against agitation when it is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Again, Dr. Stahl thinks this drug is on course for an indication across diseases once studies are conducted in each disease individually.

Another drug being evaluated for agitation, the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist dextromethorphan bupropion, is also being tested for treatment of symptoms across multiple disorders, he reported.

However, the FDA has so far taken the position that each drug must be tested separately for a given symptom in each disorder for which it is being considered despite the underlying premise that it is the symptom, not the disease, that is important.

Unlike physiological diseases where symptoms, like a fever or abdominal cramps, are the product of a disease, psychiatric symptoms are the disease and a fundamental target – regardless of the DSM-based diagnosis.

To some degree, the symptoms of psychiatric disorders have always been the focus of treatment, but a pivot toward developing therapies that will control a symptom regardless of the underlying diagnosis is an important conceptual change. It is being made possible by advances in the detail with which the neuropathology of these symptoms is understood .

“By my count, 79 symptoms are described in DSM-5, but they are spread across hundreds of syndromes because they are grouped together in different ways,” Dr. Stahl observed.

He noted that clinicians make a diagnosis on the basis symptom groupings, but their interventions are selected to address the manifestations of the disease, not the disease itself.

“If you are a real psychopharmacologist treating real patients, you are treating the specific symptoms of the specific patient,” according to Dr. Stahl.

So far, the FDA has not made this leap, insisting on trials in these categorical disorders rather than permitting trial designs that allow benefit to be demonstrated against a symptom regardless of the syndrome with which it is associated.

Of egregious examples, Dr. Stahl recounted a recent trial of a 5-HT2 antagonist that looked so promising against psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease that the trialists enrolled patients with psychosis regardless of type of dementia, such as vascular dementia and Lewy body disease. The efficacy was impressive.

“It worked so well that they stopped the trial, but the FDA declined to approve it,” Dr. Stahl recounted. Despite clear evidence of benefit, the regulators insisted that the investigators needed to show a significant benefit in each condition individually.

While the trial investigators acknowledged that there was not enough power in the trial to show a statistically significant benefit in each category, they argued that the overall benefit and the consistent response across categories required them to stop the trial for ethical reasons.

“That’s your problem, the FDA said to the investigators,” according to Dr. Stahl.

The failure of the FDA to recognize the efficacy of psychopharmacologic therapies across symptoms regardless of the associated disease is a failure to stay current with an important evolution in medicine, Dr. Stahl indicated.

“What we have come to understand is the neurobiology of any given symptom is likely to be the same across disorders,” he said.

Agency’s arbitrary decisions cited

“I completely agree with Dr. Stahl,” said Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neuroscience, University of Cincinnati.

In addition to the fact that symptoms are present across multiple categories, many patients manifest multiple symptoms at one time, Dr. Nasrallah pointed out. For neurodegenerative disorders associated with psychosis, depression, anxiety, aggression, and other symptoms, it is already well known that the heterogeneous symptoms “cannot be treated with a single drug,” he said. Rather different drugs targeting each symptom individually is essential for effective management.

Dr. Nasrallah, who chaired the Psychopharmacology Update meeting, has made this point many times in the past, including in his role as the editor of Current Psychiatry. In one editorial 10 years ago, he wrote that “it makes little sense for the FDA to mandate that a drug must work for a DSM diagnosis instead of specific symptoms.”

“The FDA must update its old policy, which has led to the widespread off-label use of psychiatric drugs, an artificial concept, simply because the FDA arbitrarily decided a long time ago that new drugs must be approved for a specific DSM diagnosis,” Dr. Nasrallah said.

Dr. Stahl reported financial relationships with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies, including those that are involved in the development of drugs included in his talk. Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Many years ago, drug development in psychiatry turned to control of specific symptoms across disorders rather than within disorders, but regulatory agencies are still not yet on board, according to an expert psychopharmacologist outlining the ongoing evolution at the virtual Psychopharmacology Update presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, sponsored by Medscape Live.

If this reorientation is going to lead to the broad indications the newer drugs likely deserve, which is control of specific types of symptoms regardless of the diagnosis, “we have to move the [Food and Drug Administration] along,” said Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, chairman of the Neuroscience Institute and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego.

On the side of drug development and clinical practice, the reorientation has already taken place. Dr. Stahl described numerous brain circuits known to produce symptoms when function is altered that are now treatment targets. This includes the ventral medial prefrontal cortex where deficient information processing leads to depression and the orbital frontal cortex where altered function leads to impulsivity.

“It is not like each part of the brain does a little bit of everything. Rather, each part of the brain has an assignment and duty and function,” Dr. Stahl explained. By addressing the disturbed signaling in brain circuits that lead to depression, impulsivity, agitation, or other symptoms, there is an opportunity for control, regardless of the psychiatric diagnosis with which the symptom is associated.

For example, Dr. Stahl predicted that pimavanserin, a highly selective 5-HT2A inverse agonist that is already approved for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease, is now likely to be approved for psychosis associated with other conditions on the basis of recent positive clinical studies in these other disorders.

Brexpiprazole, a serotonin-dopamine activity modulator already known to be useful for control of the agitation characteristic of schizophrenia, is now showing the same type of activity against agitation when it is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Again, Dr. Stahl thinks this drug is on course for an indication across diseases once studies are conducted in each disease individually.

Another drug being evaluated for agitation, the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist dextromethorphan bupropion, is also being tested for treatment of symptoms across multiple disorders, he reported.

However, the FDA has so far taken the position that each drug must be tested separately for a given symptom in each disorder for which it is being considered despite the underlying premise that it is the symptom, not the disease, that is important.

Unlike physiological diseases where symptoms, like a fever or abdominal cramps, are the product of a disease, psychiatric symptoms are the disease and a fundamental target – regardless of the DSM-based diagnosis.

To some degree, the symptoms of psychiatric disorders have always been the focus of treatment, but a pivot toward developing therapies that will control a symptom regardless of the underlying diagnosis is an important conceptual change. It is being made possible by advances in the detail with which the neuropathology of these symptoms is understood .

“By my count, 79 symptoms are described in DSM-5, but they are spread across hundreds of syndromes because they are grouped together in different ways,” Dr. Stahl observed.

He noted that clinicians make a diagnosis on the basis symptom groupings, but their interventions are selected to address the manifestations of the disease, not the disease itself.

“If you are a real psychopharmacologist treating real patients, you are treating the specific symptoms of the specific patient,” according to Dr. Stahl.

So far, the FDA has not made this leap, insisting on trials in these categorical disorders rather than permitting trial designs that allow benefit to be demonstrated against a symptom regardless of the syndrome with which it is associated.

Of egregious examples, Dr. Stahl recounted a recent trial of a 5-HT2 antagonist that looked so promising against psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease that the trialists enrolled patients with psychosis regardless of type of dementia, such as vascular dementia and Lewy body disease. The efficacy was impressive.

“It worked so well that they stopped the trial, but the FDA declined to approve it,” Dr. Stahl recounted. Despite clear evidence of benefit, the regulators insisted that the investigators needed to show a significant benefit in each condition individually.

While the trial investigators acknowledged that there was not enough power in the trial to show a statistically significant benefit in each category, they argued that the overall benefit and the consistent response across categories required them to stop the trial for ethical reasons.

“That’s your problem, the FDA said to the investigators,” according to Dr. Stahl.