User login

Resident doctor who attempted suicide three times fights for change

In early 2020, Justin Bullock, MD, MPH, did what few, if any, resident physicians have done: He published an honest account in the New England Journal of Medicine of a would-be suicide attempt during medical training.

In the article, Dr. Bullock matter-of-factly laid out how, in 2019, intern-year night shifts contributed to a depressive episode. For Dr. Bullock, who has a bipolar disorder, sleep dysregulation can be deadly. He had a plan for completing suicide, and this wouldn’t have been his first attempt. Thanks to his history and openness about his condition, Dr. Bullock had an experienced care team that helped him get to a psychiatric hospital before anything happened. While there for around 5 days, he wrote the bulk of the NEJM article.

The article took Dr. Bullock’s impact nationwide. On Twitter and in interviews, Dr. Bullock is an unapologetic advocate for accommodations for people in medicine with mental illness. “One of the things that inspired me to speak out early on is that I feel I stand in a place of so much privilege,” Dr. Bullock told this news organization. “I often feel this sense of ... ‘you have to speak up, Justin; no one else can.’ ”

Dr. Bullock’s activism is especially noteworthy, given that he is still establishing his career. In August, while an internal medicine resident at the University of California, San Francisco, he received a lifetime teaching award from UCSF because he had received three prior teaching awards; a recognition like this is considered rare someone so early in their career. Now in his final year of residency, he actively researches medical education, advocates for mental health support, and is working to become a leading voice on related issues.

“It seems to be working,” his older sister, Jacquis Mahoney, RN, said during a visit to the UCSF campus. Instead of any awkwardness, everyone is thrilled to learn that she is Justin’s sister. “There’s a lot of pride and excitement.”

Suicide attempts during medical training

Now 28, Dr. Bullock grew up in Detroit, with his mom and two older sisters. His father was incarcerated for much of Dr. Bullock’s childhood, in part because of his own bipolar disorder not being well controlled, Dr. Bullock said.

When he was younger, Dr. Bullock was the peacekeeper in the house between his two sisters, said Ms. Mahoney: “Justin was always very delicate and kind.”

He played soccer and ran track but also loved math and science. While outwardly accumulating an impressive resume, Dr. Bullock was internally struggling. In high school, he made what he now calls an “immature” attempt at suicide after coming out as gay to his family. While Dr. Bullock said he doesn’t necessarily dwell on the discrimination he has faced as a gay, Black man, his awareness of how others perceive and treat him because of his identity increases the background stress present in his daily life.

After high school, Dr. Bullock went to MIT in Boston, where he continued running and studied chemical-biological engineering. During college, Dr. Bullock thought he was going to have to withdraw from MIT because of his depression. Thankfully, he received counseling from student services and advice from a track coach who sat him down and talked about pragmatic solutions, like medication. “That was life-changing,” said Dr. Bullock.

When trying to decide between engineering and medicine, Dr. Bullock realized he preferred contemplating medical problems to engineering ones. So he applied to medical school. Dr. Bullock eventually ended up at UCSF, where he was selected to participate in the Program in Medical Education for the Urban Underserved, a 5-year track at the college for students committed to working with underserved communities.

By the time Dr. Bullock got to medical school, he was feeling good. In consultation with his psychiatrist, he thought it worthwhile to take a break from his medications. At that time, his diagnosis was major depressive disorder and he had only had one serious depressive episode, which didn’t necessarily indicate that he would need medication long-term, he said.

Dr. Bullock loved everything about medical school. “One day when I was in my first year of med school, I called my mom and said: ‘It’s like science summer camp but every day!’” he recalled.

Despite his enthusiasm, though, he began feeling something troubling. Recognizing the symptoms of early depression, Dr. Bullock restarted his medication. But this time, the same SSRI only made things worse. He went from sleeping 8 hours to 90 minutes a night. He felt angry. One day, he went on a furious 22-mile run. Plus, within the first 6 months of moving to San Francisco, Dr. Bullock was stopped by the police three different times while riding his bike. He attributes this to his race, which has only further added to his stress. In September 2015, during his second year of medical school, Dr. Bullock attempted suicide again. This time, he was intubated in the ED and rushed to the ICU.

He was given a new diagnosis: bipolar disorder. He changed medications and lived for a time with Ms. Mahoney and his other sister, who moved from Chicago to California to be with him. “My family has helped me a lot,” he said.

Dr. Bullock was initially not sure whether he would be able to return to school after his attempted suicide. Overall, UCSF was extremely supportive, he said. That came as a relief. Medical school was a grounding force in his life, not a destabilizing one: “If I had been pushed out, it would have been really harmful to me.”

Then Dr. Bullock started residency. The sleep disruption that comes with the night shift – the resident rite of passage – triggered another episode. At first, Dr. Bullock was overly productive; his mind was active and alert after staying up all night. He worked on new research during the day instead of sleeping.

Sleep disturbance is a hallmark symptom of bipolar disorder. “Justin should never be on a 24-hour call,” said Lisa Meeks, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and family medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and a leading scholar on disability advocacy for medical trainees. When he started residency, Dr. Bullock was open with his program director about his diagnosis and sought accommodations to go to therapy each week. But he didn’t try to get out of night shifts or 24-hour calls, despite his care team urging him to do so. “I have this sense of wanting to tough it out,” he said. He also felt guilty making his peers take on his share of those challenging shifts.

In December 2019, Dr. Bullock was voluntarily hospitalized for a few days and started writing the article that would later appear in NEJM. In January, a friend and UCSF medical student completed suicide. In March, the same month his NEJM article came out, Dr. Bullock attempted suicide again. This time, he quickly recognized that he was making a mistake and called an ambulance. “For me, as far as suicide attempts go, it’s the most positive one.”

Advocating for changes in medical training

Throughout his medical training, Dr. Bullock was always open about his struggles with his peers and with the administration. He shared his suicidal thoughts at a Mental Illness Among Us event during medical school. His story resonated with peers who were surprised that Dr. Bullock, who was thriving academically, could be struggling emotionally.

During residency, he led small group discussions and gave lectures at the medical school, including a talk about his attempts to create institutional change at UCSF, such as his public fight against the college’s Fitness for Duty (FFD) assessment process. That discussion earned him an Outstanding Lecturer award. Because it was the third award he had received from the medical school, Dr. Bullock also automatically earned a lifetime teaching award. When he told his mom, a teacher herself, about the award, she joked: “Are you old enough for ‘lifetime’ anything?”

Dr. Bullock has also spoken out and actively fought against the processes within the medical community that prevent people from coming forward until it is too late. Physicians and trainees often fear that if they seek mental health treatment, they will have to disclose that treatment to a potential employer or licensing board and then be barred from practicing medicine. Because he has been open about his mental health for so long, Dr. Bullock feels that he is in a position to push back against these norms. For example, in June he coauthored another article, this time for the Journal of Hospital Medicine, describing the traumatizing FFD assessment that followed his March 2020 suicide attempt.

In that article, Dr. Bullock wrote how no mental health professional served on the UCSF Physician Well Being Committee – comprising physicians and lawyers who evaluate physician impairment or potential physician impairment – that evaluated him. Dr. Bullock was referred to an outside psychiatrist. He also describes how he was forced to release all of his psychiatric records and undergo extensive drug testing, despite having no history of substance abuse. To return to work, he had to sign a contract, agreeing to be monitored and to attend a specific kind of therapy.

While steps like these can, in the right circumstances, protect both the public and doctors-in-training in important ways, they can also “be very punitive and isolating for someone going through a mental health crisis,” said Dr. Meeks. There were also no Black physicians or lawyers on the committee evaluating Dr. Bullock. “That was really egregious, when you look back.” Dr. Meeks is a coauthor on Dr. Bullock’s JHM article and a mentor and previous student disability officer at UCSF.

Dr. Bullock raised objections to UCSF administrators about how he felt that the committee was discriminating against him because of his mental illness despite assurances from the director of his program that there have never been any performance or professionalism concerns with him. He said the administrators told him he was the first person to question the FFD process. This isn’t surprising, given that all the power in such situations usually lies with the hospital and the administrators, whereas the resident or physician is worried about losing their job and their license, said Dr. Meeks.

Dr. Bullock contends that he’s in a unique position to speak out, considering his stellar academic and work records, openness about his mental illness before a crisis, access to quality mental health care, and extensive personal network among the UCSF administration. “I know that I hold power within my institution; I spoke out because I could,” Dr. Bullock said. In addition to writing an article about his experience, Dr. Bullock shared his story with a task force appointed by the medical staff president to review the Physician Well-Being Committee and the overall FFD process. Even before Dr. Bullock shared his story with the public, the task force had already been appointed as a result of the increased concern about physician mental health during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Michelle Guy, MD, clinical professor of medicine at UCSF, told this news organization.

Elizabeth Fernandez, a UCSF senior public information representative, declined to comment on Dr. Bullock’s specific experience as reported in the JHM. “As with every hospital accredited by the Joint Commission, UCSF Medical Center has a Physician Well Being Committee that provides resources for physicians who may need help with chemical dependency or mental illness,” Ms. Fernandez said.

“Our goal through this program is always, first, to provide the compassion and assistance our physicians need to address the issues they face and continue to pursue their careers. This program is entirely voluntary and is bound by federal and state laws and regulations to protect the confidentiality of its participants, while ensuring that – first and foremost – no one is harmed by the situation, including the participant.”

Overcoming stigma to change the system

All of the attention – from national media outlets such as Vox to struggling peers and others – is fulfilling, Dr. Bullock said. But it can also be overwhelming. “I have definitely been praised as ‘Black excellence,’ and that definitely has added to the pressure to keep going ... to keep pushing at times,” he said.

Ms. Mahoney added: “He’s willing to sacrifice himself in order to make a difference. He would be a sacrificial lamb” for the Black community, the gay community, or any minority community.

Despite these concerns and his past suicide attempts, colleagues feel that Dr. Bullock is in a strong place to make decisions. “I trust Justin to put the boundaries up when they are needed and to engage in a way that feels comfortable for him,” said Ms. Meeks. “He is someone who has incredible self-awareness.”

Dr. Bullock’s history isn’t just something he overcame: It’s something that makes him a better, more empathetic doctor, said Ms. Mahoney. He knows what it’s like to be hospitalized, to deal with the frustration of insurance, to navigate the complexity of the health care system as a patient, or to be facing a deep internal darkness. He “can genuinely hold that person’s hand and say: ‘I know what you’re going through and we’re going to work through this day by day,’ ” she said. “That is something he can bring that no other physician can bring.”

In his advocacy on Twitter, in lectures, and in conversations with UCSF administrators, Dr. Bullock is pushing for board licensing questions to be reformed so physicians are no longer penalized for seeking mental health treatment. He would also like residency programs to make it easier and less stigmatizing for trainees to receive accommodations for a disability or mental illness.

“They say one person can’t change a system,” said Dr. Meeks, “but I do think Justin is calling an awful lot of attention to the system and I do think there will be changes because of his advocacy.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In early 2020, Justin Bullock, MD, MPH, did what few, if any, resident physicians have done: He published an honest account in the New England Journal of Medicine of a would-be suicide attempt during medical training.

In the article, Dr. Bullock matter-of-factly laid out how, in 2019, intern-year night shifts contributed to a depressive episode. For Dr. Bullock, who has a bipolar disorder, sleep dysregulation can be deadly. He had a plan for completing suicide, and this wouldn’t have been his first attempt. Thanks to his history and openness about his condition, Dr. Bullock had an experienced care team that helped him get to a psychiatric hospital before anything happened. While there for around 5 days, he wrote the bulk of the NEJM article.

The article took Dr. Bullock’s impact nationwide. On Twitter and in interviews, Dr. Bullock is an unapologetic advocate for accommodations for people in medicine with mental illness. “One of the things that inspired me to speak out early on is that I feel I stand in a place of so much privilege,” Dr. Bullock told this news organization. “I often feel this sense of ... ‘you have to speak up, Justin; no one else can.’ ”

Dr. Bullock’s activism is especially noteworthy, given that he is still establishing his career. In August, while an internal medicine resident at the University of California, San Francisco, he received a lifetime teaching award from UCSF because he had received three prior teaching awards; a recognition like this is considered rare someone so early in their career. Now in his final year of residency, he actively researches medical education, advocates for mental health support, and is working to become a leading voice on related issues.

“It seems to be working,” his older sister, Jacquis Mahoney, RN, said during a visit to the UCSF campus. Instead of any awkwardness, everyone is thrilled to learn that she is Justin’s sister. “There’s a lot of pride and excitement.”

Suicide attempts during medical training

Now 28, Dr. Bullock grew up in Detroit, with his mom and two older sisters. His father was incarcerated for much of Dr. Bullock’s childhood, in part because of his own bipolar disorder not being well controlled, Dr. Bullock said.

When he was younger, Dr. Bullock was the peacekeeper in the house between his two sisters, said Ms. Mahoney: “Justin was always very delicate and kind.”

He played soccer and ran track but also loved math and science. While outwardly accumulating an impressive resume, Dr. Bullock was internally struggling. In high school, he made what he now calls an “immature” attempt at suicide after coming out as gay to his family. While Dr. Bullock said he doesn’t necessarily dwell on the discrimination he has faced as a gay, Black man, his awareness of how others perceive and treat him because of his identity increases the background stress present in his daily life.

After high school, Dr. Bullock went to MIT in Boston, where he continued running and studied chemical-biological engineering. During college, Dr. Bullock thought he was going to have to withdraw from MIT because of his depression. Thankfully, he received counseling from student services and advice from a track coach who sat him down and talked about pragmatic solutions, like medication. “That was life-changing,” said Dr. Bullock.

When trying to decide between engineering and medicine, Dr. Bullock realized he preferred contemplating medical problems to engineering ones. So he applied to medical school. Dr. Bullock eventually ended up at UCSF, where he was selected to participate in the Program in Medical Education for the Urban Underserved, a 5-year track at the college for students committed to working with underserved communities.

By the time Dr. Bullock got to medical school, he was feeling good. In consultation with his psychiatrist, he thought it worthwhile to take a break from his medications. At that time, his diagnosis was major depressive disorder and he had only had one serious depressive episode, which didn’t necessarily indicate that he would need medication long-term, he said.

Dr. Bullock loved everything about medical school. “One day when I was in my first year of med school, I called my mom and said: ‘It’s like science summer camp but every day!’” he recalled.

Despite his enthusiasm, though, he began feeling something troubling. Recognizing the symptoms of early depression, Dr. Bullock restarted his medication. But this time, the same SSRI only made things worse. He went from sleeping 8 hours to 90 minutes a night. He felt angry. One day, he went on a furious 22-mile run. Plus, within the first 6 months of moving to San Francisco, Dr. Bullock was stopped by the police three different times while riding his bike. He attributes this to his race, which has only further added to his stress. In September 2015, during his second year of medical school, Dr. Bullock attempted suicide again. This time, he was intubated in the ED and rushed to the ICU.

He was given a new diagnosis: bipolar disorder. He changed medications and lived for a time with Ms. Mahoney and his other sister, who moved from Chicago to California to be with him. “My family has helped me a lot,” he said.

Dr. Bullock was initially not sure whether he would be able to return to school after his attempted suicide. Overall, UCSF was extremely supportive, he said. That came as a relief. Medical school was a grounding force in his life, not a destabilizing one: “If I had been pushed out, it would have been really harmful to me.”

Then Dr. Bullock started residency. The sleep disruption that comes with the night shift – the resident rite of passage – triggered another episode. At first, Dr. Bullock was overly productive; his mind was active and alert after staying up all night. He worked on new research during the day instead of sleeping.

Sleep disturbance is a hallmark symptom of bipolar disorder. “Justin should never be on a 24-hour call,” said Lisa Meeks, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and family medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and a leading scholar on disability advocacy for medical trainees. When he started residency, Dr. Bullock was open with his program director about his diagnosis and sought accommodations to go to therapy each week. But he didn’t try to get out of night shifts or 24-hour calls, despite his care team urging him to do so. “I have this sense of wanting to tough it out,” he said. He also felt guilty making his peers take on his share of those challenging shifts.

In December 2019, Dr. Bullock was voluntarily hospitalized for a few days and started writing the article that would later appear in NEJM. In January, a friend and UCSF medical student completed suicide. In March, the same month his NEJM article came out, Dr. Bullock attempted suicide again. This time, he quickly recognized that he was making a mistake and called an ambulance. “For me, as far as suicide attempts go, it’s the most positive one.”

Advocating for changes in medical training

Throughout his medical training, Dr. Bullock was always open about his struggles with his peers and with the administration. He shared his suicidal thoughts at a Mental Illness Among Us event during medical school. His story resonated with peers who were surprised that Dr. Bullock, who was thriving academically, could be struggling emotionally.

During residency, he led small group discussions and gave lectures at the medical school, including a talk about his attempts to create institutional change at UCSF, such as his public fight against the college’s Fitness for Duty (FFD) assessment process. That discussion earned him an Outstanding Lecturer award. Because it was the third award he had received from the medical school, Dr. Bullock also automatically earned a lifetime teaching award. When he told his mom, a teacher herself, about the award, she joked: “Are you old enough for ‘lifetime’ anything?”

Dr. Bullock has also spoken out and actively fought against the processes within the medical community that prevent people from coming forward until it is too late. Physicians and trainees often fear that if they seek mental health treatment, they will have to disclose that treatment to a potential employer or licensing board and then be barred from practicing medicine. Because he has been open about his mental health for so long, Dr. Bullock feels that he is in a position to push back against these norms. For example, in June he coauthored another article, this time for the Journal of Hospital Medicine, describing the traumatizing FFD assessment that followed his March 2020 suicide attempt.

In that article, Dr. Bullock wrote how no mental health professional served on the UCSF Physician Well Being Committee – comprising physicians and lawyers who evaluate physician impairment or potential physician impairment – that evaluated him. Dr. Bullock was referred to an outside psychiatrist. He also describes how he was forced to release all of his psychiatric records and undergo extensive drug testing, despite having no history of substance abuse. To return to work, he had to sign a contract, agreeing to be monitored and to attend a specific kind of therapy.

While steps like these can, in the right circumstances, protect both the public and doctors-in-training in important ways, they can also “be very punitive and isolating for someone going through a mental health crisis,” said Dr. Meeks. There were also no Black physicians or lawyers on the committee evaluating Dr. Bullock. “That was really egregious, when you look back.” Dr. Meeks is a coauthor on Dr. Bullock’s JHM article and a mentor and previous student disability officer at UCSF.

Dr. Bullock raised objections to UCSF administrators about how he felt that the committee was discriminating against him because of his mental illness despite assurances from the director of his program that there have never been any performance or professionalism concerns with him. He said the administrators told him he was the first person to question the FFD process. This isn’t surprising, given that all the power in such situations usually lies with the hospital and the administrators, whereas the resident or physician is worried about losing their job and their license, said Dr. Meeks.

Dr. Bullock contends that he’s in a unique position to speak out, considering his stellar academic and work records, openness about his mental illness before a crisis, access to quality mental health care, and extensive personal network among the UCSF administration. “I know that I hold power within my institution; I spoke out because I could,” Dr. Bullock said. In addition to writing an article about his experience, Dr. Bullock shared his story with a task force appointed by the medical staff president to review the Physician Well-Being Committee and the overall FFD process. Even before Dr. Bullock shared his story with the public, the task force had already been appointed as a result of the increased concern about physician mental health during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Michelle Guy, MD, clinical professor of medicine at UCSF, told this news organization.

Elizabeth Fernandez, a UCSF senior public information representative, declined to comment on Dr. Bullock’s specific experience as reported in the JHM. “As with every hospital accredited by the Joint Commission, UCSF Medical Center has a Physician Well Being Committee that provides resources for physicians who may need help with chemical dependency or mental illness,” Ms. Fernandez said.

“Our goal through this program is always, first, to provide the compassion and assistance our physicians need to address the issues they face and continue to pursue their careers. This program is entirely voluntary and is bound by federal and state laws and regulations to protect the confidentiality of its participants, while ensuring that – first and foremost – no one is harmed by the situation, including the participant.”

Overcoming stigma to change the system

All of the attention – from national media outlets such as Vox to struggling peers and others – is fulfilling, Dr. Bullock said. But it can also be overwhelming. “I have definitely been praised as ‘Black excellence,’ and that definitely has added to the pressure to keep going ... to keep pushing at times,” he said.

Ms. Mahoney added: “He’s willing to sacrifice himself in order to make a difference. He would be a sacrificial lamb” for the Black community, the gay community, or any minority community.

Despite these concerns and his past suicide attempts, colleagues feel that Dr. Bullock is in a strong place to make decisions. “I trust Justin to put the boundaries up when they are needed and to engage in a way that feels comfortable for him,” said Ms. Meeks. “He is someone who has incredible self-awareness.”

Dr. Bullock’s history isn’t just something he overcame: It’s something that makes him a better, more empathetic doctor, said Ms. Mahoney. He knows what it’s like to be hospitalized, to deal with the frustration of insurance, to navigate the complexity of the health care system as a patient, or to be facing a deep internal darkness. He “can genuinely hold that person’s hand and say: ‘I know what you’re going through and we’re going to work through this day by day,’ ” she said. “That is something he can bring that no other physician can bring.”

In his advocacy on Twitter, in lectures, and in conversations with UCSF administrators, Dr. Bullock is pushing for board licensing questions to be reformed so physicians are no longer penalized for seeking mental health treatment. He would also like residency programs to make it easier and less stigmatizing for trainees to receive accommodations for a disability or mental illness.

“They say one person can’t change a system,” said Dr. Meeks, “but I do think Justin is calling an awful lot of attention to the system and I do think there will be changes because of his advocacy.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In early 2020, Justin Bullock, MD, MPH, did what few, if any, resident physicians have done: He published an honest account in the New England Journal of Medicine of a would-be suicide attempt during medical training.

In the article, Dr. Bullock matter-of-factly laid out how, in 2019, intern-year night shifts contributed to a depressive episode. For Dr. Bullock, who has a bipolar disorder, sleep dysregulation can be deadly. He had a plan for completing suicide, and this wouldn’t have been his first attempt. Thanks to his history and openness about his condition, Dr. Bullock had an experienced care team that helped him get to a psychiatric hospital before anything happened. While there for around 5 days, he wrote the bulk of the NEJM article.

The article took Dr. Bullock’s impact nationwide. On Twitter and in interviews, Dr. Bullock is an unapologetic advocate for accommodations for people in medicine with mental illness. “One of the things that inspired me to speak out early on is that I feel I stand in a place of so much privilege,” Dr. Bullock told this news organization. “I often feel this sense of ... ‘you have to speak up, Justin; no one else can.’ ”

Dr. Bullock’s activism is especially noteworthy, given that he is still establishing his career. In August, while an internal medicine resident at the University of California, San Francisco, he received a lifetime teaching award from UCSF because he had received three prior teaching awards; a recognition like this is considered rare someone so early in their career. Now in his final year of residency, he actively researches medical education, advocates for mental health support, and is working to become a leading voice on related issues.

“It seems to be working,” his older sister, Jacquis Mahoney, RN, said during a visit to the UCSF campus. Instead of any awkwardness, everyone is thrilled to learn that she is Justin’s sister. “There’s a lot of pride and excitement.”

Suicide attempts during medical training

Now 28, Dr. Bullock grew up in Detroit, with his mom and two older sisters. His father was incarcerated for much of Dr. Bullock’s childhood, in part because of his own bipolar disorder not being well controlled, Dr. Bullock said.

When he was younger, Dr. Bullock was the peacekeeper in the house between his two sisters, said Ms. Mahoney: “Justin was always very delicate and kind.”

He played soccer and ran track but also loved math and science. While outwardly accumulating an impressive resume, Dr. Bullock was internally struggling. In high school, he made what he now calls an “immature” attempt at suicide after coming out as gay to his family. While Dr. Bullock said he doesn’t necessarily dwell on the discrimination he has faced as a gay, Black man, his awareness of how others perceive and treat him because of his identity increases the background stress present in his daily life.

After high school, Dr. Bullock went to MIT in Boston, where he continued running and studied chemical-biological engineering. During college, Dr. Bullock thought he was going to have to withdraw from MIT because of his depression. Thankfully, he received counseling from student services and advice from a track coach who sat him down and talked about pragmatic solutions, like medication. “That was life-changing,” said Dr. Bullock.

When trying to decide between engineering and medicine, Dr. Bullock realized he preferred contemplating medical problems to engineering ones. So he applied to medical school. Dr. Bullock eventually ended up at UCSF, where he was selected to participate in the Program in Medical Education for the Urban Underserved, a 5-year track at the college for students committed to working with underserved communities.

By the time Dr. Bullock got to medical school, he was feeling good. In consultation with his psychiatrist, he thought it worthwhile to take a break from his medications. At that time, his diagnosis was major depressive disorder and he had only had one serious depressive episode, which didn’t necessarily indicate that he would need medication long-term, he said.

Dr. Bullock loved everything about medical school. “One day when I was in my first year of med school, I called my mom and said: ‘It’s like science summer camp but every day!’” he recalled.

Despite his enthusiasm, though, he began feeling something troubling. Recognizing the symptoms of early depression, Dr. Bullock restarted his medication. But this time, the same SSRI only made things worse. He went from sleeping 8 hours to 90 minutes a night. He felt angry. One day, he went on a furious 22-mile run. Plus, within the first 6 months of moving to San Francisco, Dr. Bullock was stopped by the police three different times while riding his bike. He attributes this to his race, which has only further added to his stress. In September 2015, during his second year of medical school, Dr. Bullock attempted suicide again. This time, he was intubated in the ED and rushed to the ICU.

He was given a new diagnosis: bipolar disorder. He changed medications and lived for a time with Ms. Mahoney and his other sister, who moved from Chicago to California to be with him. “My family has helped me a lot,” he said.

Dr. Bullock was initially not sure whether he would be able to return to school after his attempted suicide. Overall, UCSF was extremely supportive, he said. That came as a relief. Medical school was a grounding force in his life, not a destabilizing one: “If I had been pushed out, it would have been really harmful to me.”

Then Dr. Bullock started residency. The sleep disruption that comes with the night shift – the resident rite of passage – triggered another episode. At first, Dr. Bullock was overly productive; his mind was active and alert after staying up all night. He worked on new research during the day instead of sleeping.

Sleep disturbance is a hallmark symptom of bipolar disorder. “Justin should never be on a 24-hour call,” said Lisa Meeks, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and family medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and a leading scholar on disability advocacy for medical trainees. When he started residency, Dr. Bullock was open with his program director about his diagnosis and sought accommodations to go to therapy each week. But he didn’t try to get out of night shifts or 24-hour calls, despite his care team urging him to do so. “I have this sense of wanting to tough it out,” he said. He also felt guilty making his peers take on his share of those challenging shifts.

In December 2019, Dr. Bullock was voluntarily hospitalized for a few days and started writing the article that would later appear in NEJM. In January, a friend and UCSF medical student completed suicide. In March, the same month his NEJM article came out, Dr. Bullock attempted suicide again. This time, he quickly recognized that he was making a mistake and called an ambulance. “For me, as far as suicide attempts go, it’s the most positive one.”

Advocating for changes in medical training

Throughout his medical training, Dr. Bullock was always open about his struggles with his peers and with the administration. He shared his suicidal thoughts at a Mental Illness Among Us event during medical school. His story resonated with peers who were surprised that Dr. Bullock, who was thriving academically, could be struggling emotionally.

During residency, he led small group discussions and gave lectures at the medical school, including a talk about his attempts to create institutional change at UCSF, such as his public fight against the college’s Fitness for Duty (FFD) assessment process. That discussion earned him an Outstanding Lecturer award. Because it was the third award he had received from the medical school, Dr. Bullock also automatically earned a lifetime teaching award. When he told his mom, a teacher herself, about the award, she joked: “Are you old enough for ‘lifetime’ anything?”

Dr. Bullock has also spoken out and actively fought against the processes within the medical community that prevent people from coming forward until it is too late. Physicians and trainees often fear that if they seek mental health treatment, they will have to disclose that treatment to a potential employer or licensing board and then be barred from practicing medicine. Because he has been open about his mental health for so long, Dr. Bullock feels that he is in a position to push back against these norms. For example, in June he coauthored another article, this time for the Journal of Hospital Medicine, describing the traumatizing FFD assessment that followed his March 2020 suicide attempt.

In that article, Dr. Bullock wrote how no mental health professional served on the UCSF Physician Well Being Committee – comprising physicians and lawyers who evaluate physician impairment or potential physician impairment – that evaluated him. Dr. Bullock was referred to an outside psychiatrist. He also describes how he was forced to release all of his psychiatric records and undergo extensive drug testing, despite having no history of substance abuse. To return to work, he had to sign a contract, agreeing to be monitored and to attend a specific kind of therapy.

While steps like these can, in the right circumstances, protect both the public and doctors-in-training in important ways, they can also “be very punitive and isolating for someone going through a mental health crisis,” said Dr. Meeks. There were also no Black physicians or lawyers on the committee evaluating Dr. Bullock. “That was really egregious, when you look back.” Dr. Meeks is a coauthor on Dr. Bullock’s JHM article and a mentor and previous student disability officer at UCSF.

Dr. Bullock raised objections to UCSF administrators about how he felt that the committee was discriminating against him because of his mental illness despite assurances from the director of his program that there have never been any performance or professionalism concerns with him. He said the administrators told him he was the first person to question the FFD process. This isn’t surprising, given that all the power in such situations usually lies with the hospital and the administrators, whereas the resident or physician is worried about losing their job and their license, said Dr. Meeks.

Dr. Bullock contends that he’s in a unique position to speak out, considering his stellar academic and work records, openness about his mental illness before a crisis, access to quality mental health care, and extensive personal network among the UCSF administration. “I know that I hold power within my institution; I spoke out because I could,” Dr. Bullock said. In addition to writing an article about his experience, Dr. Bullock shared his story with a task force appointed by the medical staff president to review the Physician Well-Being Committee and the overall FFD process. Even before Dr. Bullock shared his story with the public, the task force had already been appointed as a result of the increased concern about physician mental health during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Michelle Guy, MD, clinical professor of medicine at UCSF, told this news organization.

Elizabeth Fernandez, a UCSF senior public information representative, declined to comment on Dr. Bullock’s specific experience as reported in the JHM. “As with every hospital accredited by the Joint Commission, UCSF Medical Center has a Physician Well Being Committee that provides resources for physicians who may need help with chemical dependency or mental illness,” Ms. Fernandez said.

“Our goal through this program is always, first, to provide the compassion and assistance our physicians need to address the issues they face and continue to pursue their careers. This program is entirely voluntary and is bound by federal and state laws and regulations to protect the confidentiality of its participants, while ensuring that – first and foremost – no one is harmed by the situation, including the participant.”

Overcoming stigma to change the system

All of the attention – from national media outlets such as Vox to struggling peers and others – is fulfilling, Dr. Bullock said. But it can also be overwhelming. “I have definitely been praised as ‘Black excellence,’ and that definitely has added to the pressure to keep going ... to keep pushing at times,” he said.

Ms. Mahoney added: “He’s willing to sacrifice himself in order to make a difference. He would be a sacrificial lamb” for the Black community, the gay community, or any minority community.

Despite these concerns and his past suicide attempts, colleagues feel that Dr. Bullock is in a strong place to make decisions. “I trust Justin to put the boundaries up when they are needed and to engage in a way that feels comfortable for him,” said Ms. Meeks. “He is someone who has incredible self-awareness.”

Dr. Bullock’s history isn’t just something he overcame: It’s something that makes him a better, more empathetic doctor, said Ms. Mahoney. He knows what it’s like to be hospitalized, to deal with the frustration of insurance, to navigate the complexity of the health care system as a patient, or to be facing a deep internal darkness. He “can genuinely hold that person’s hand and say: ‘I know what you’re going through and we’re going to work through this day by day,’ ” she said. “That is something he can bring that no other physician can bring.”

In his advocacy on Twitter, in lectures, and in conversations with UCSF administrators, Dr. Bullock is pushing for board licensing questions to be reformed so physicians are no longer penalized for seeking mental health treatment. He would also like residency programs to make it easier and less stigmatizing for trainees to receive accommodations for a disability or mental illness.

“They say one person can’t change a system,” said Dr. Meeks, “but I do think Justin is calling an awful lot of attention to the system and I do think there will be changes because of his advocacy.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Feds launch COVID-19 worker vaccine mandates

The Biden administration on Nov. 4 unveiled its rule to require most of the country’s larger employers to mandate workers be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but set a Jan. 4 deadline, avoiding the busy holiday season.

The White House also shifted the time lines for earlier mandates applying to federal workers and contractors to Jan. 4. And the same deadline applies to a new separate rule for health care workers.

The new rules are meant to preempt “any inconsistent state or local laws,” including bans and limits on employers’ authority to require vaccination, masks, or testing, the White House said in a statement.

The rule on employers from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will apply to organizations with 100 or more employees. These employers will need to make sure each worker is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis. The OSHA rule will also require that employers provide paid time for employees to get vaccinated and ensure that all unvaccinated workers wear a face mask in the workplace. This rule will cover 84 million employees. The OSHA rule will not apply to workplaces covered by either the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rule or the federal contractor vaccination requirement

“The virus will not go away by itself, or because we wish it away: We have to act,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “Vaccination is the single best pathway out of this pandemic.”

Mandates were not the preferred route to managing the pandemic, he said.

“Too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good,” he said. “So I instituted requirements – and they are working.”

The White House said 70% percent of U.S. adults are now fully vaccinated – up from less than 1% when Mr. Biden took office in January.

The CMS vaccine rule is meant to cover more than 17 million workers and about 76,000 medical care sites, including hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities. The rule will apply to employees whether their positions involve patient care or not.

Unlike the OSHA mandate, the one for health care workers will not offer the option of frequent COVID-19 testing instead of vaccination. There is a “higher bar” for health care workers, given their role in treating patients, so the mandate allows only for vaccination or limited exemptions, a senior administration official said on Nov. 3 during a call with reporters.

The CMS rule includes a “range of remedies,” including penalties and denial of payment for health care facilities that fail to meet the vaccine mandate. CMS could theoretically cut off hospitals and other medical organizations for failure to comply, but that would be a “last resort,” a senior administration official said. CMS will instead work with health care facilities to help them comply with the federal rule on vaccination of medical workers.

The new CMS rules apply only to Medicare- and Medicaid-certified centers and organizations. The rule does not directly apply to other health care entities, such as doctor’s offices, that are not regulated by CMS.

“Most states have separate licensing requirements for health care staff and health care providers that would be applicable to physician office staff and other staff in small health care entities that are not subject to vaccination requirements under this IFC,” CMS said in the rule.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Biden administration on Nov. 4 unveiled its rule to require most of the country’s larger employers to mandate workers be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but set a Jan. 4 deadline, avoiding the busy holiday season.

The White House also shifted the time lines for earlier mandates applying to federal workers and contractors to Jan. 4. And the same deadline applies to a new separate rule for health care workers.

The new rules are meant to preempt “any inconsistent state or local laws,” including bans and limits on employers’ authority to require vaccination, masks, or testing, the White House said in a statement.

The rule on employers from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will apply to organizations with 100 or more employees. These employers will need to make sure each worker is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis. The OSHA rule will also require that employers provide paid time for employees to get vaccinated and ensure that all unvaccinated workers wear a face mask in the workplace. This rule will cover 84 million employees. The OSHA rule will not apply to workplaces covered by either the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rule or the federal contractor vaccination requirement

“The virus will not go away by itself, or because we wish it away: We have to act,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “Vaccination is the single best pathway out of this pandemic.”

Mandates were not the preferred route to managing the pandemic, he said.

“Too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good,” he said. “So I instituted requirements – and they are working.”

The White House said 70% percent of U.S. adults are now fully vaccinated – up from less than 1% when Mr. Biden took office in January.

The CMS vaccine rule is meant to cover more than 17 million workers and about 76,000 medical care sites, including hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities. The rule will apply to employees whether their positions involve patient care or not.

Unlike the OSHA mandate, the one for health care workers will not offer the option of frequent COVID-19 testing instead of vaccination. There is a “higher bar” for health care workers, given their role in treating patients, so the mandate allows only for vaccination or limited exemptions, a senior administration official said on Nov. 3 during a call with reporters.

The CMS rule includes a “range of remedies,” including penalties and denial of payment for health care facilities that fail to meet the vaccine mandate. CMS could theoretically cut off hospitals and other medical organizations for failure to comply, but that would be a “last resort,” a senior administration official said. CMS will instead work with health care facilities to help them comply with the federal rule on vaccination of medical workers.

The new CMS rules apply only to Medicare- and Medicaid-certified centers and organizations. The rule does not directly apply to other health care entities, such as doctor’s offices, that are not regulated by CMS.

“Most states have separate licensing requirements for health care staff and health care providers that would be applicable to physician office staff and other staff in small health care entities that are not subject to vaccination requirements under this IFC,” CMS said in the rule.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Biden administration on Nov. 4 unveiled its rule to require most of the country’s larger employers to mandate workers be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but set a Jan. 4 deadline, avoiding the busy holiday season.

The White House also shifted the time lines for earlier mandates applying to federal workers and contractors to Jan. 4. And the same deadline applies to a new separate rule for health care workers.

The new rules are meant to preempt “any inconsistent state or local laws,” including bans and limits on employers’ authority to require vaccination, masks, or testing, the White House said in a statement.

The rule on employers from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will apply to organizations with 100 or more employees. These employers will need to make sure each worker is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis. The OSHA rule will also require that employers provide paid time for employees to get vaccinated and ensure that all unvaccinated workers wear a face mask in the workplace. This rule will cover 84 million employees. The OSHA rule will not apply to workplaces covered by either the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rule or the federal contractor vaccination requirement

“The virus will not go away by itself, or because we wish it away: We have to act,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “Vaccination is the single best pathway out of this pandemic.”

Mandates were not the preferred route to managing the pandemic, he said.

“Too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good,” he said. “So I instituted requirements – and they are working.”

The White House said 70% percent of U.S. adults are now fully vaccinated – up from less than 1% when Mr. Biden took office in January.

The CMS vaccine rule is meant to cover more than 17 million workers and about 76,000 medical care sites, including hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities. The rule will apply to employees whether their positions involve patient care or not.

Unlike the OSHA mandate, the one for health care workers will not offer the option of frequent COVID-19 testing instead of vaccination. There is a “higher bar” for health care workers, given their role in treating patients, so the mandate allows only for vaccination or limited exemptions, a senior administration official said on Nov. 3 during a call with reporters.

The CMS rule includes a “range of remedies,” including penalties and denial of payment for health care facilities that fail to meet the vaccine mandate. CMS could theoretically cut off hospitals and other medical organizations for failure to comply, but that would be a “last resort,” a senior administration official said. CMS will instead work with health care facilities to help them comply with the federal rule on vaccination of medical workers.

The new CMS rules apply only to Medicare- and Medicaid-certified centers and organizations. The rule does not directly apply to other health care entities, such as doctor’s offices, that are not regulated by CMS.

“Most states have separate licensing requirements for health care staff and health care providers that would be applicable to physician office staff and other staff in small health care entities that are not subject to vaccination requirements under this IFC,” CMS said in the rule.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

How to screen for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in an ObGyn practice

The prevalence of T2DM is on the rise in the United States, and T2DM is currently the 7th leading cause of death.1 In a study of 28,143 participants in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) who were 18 years or older, the prevalence of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 14.3% between 2000 and 2008.2 About 24% of the participants had undiagnosed diabetes prior to the testing they received as a study participant.2 People from minority groups have a higher rate of T2DM than non-Hispanic White people. Using data from 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes was highest among American Indians/Alaska Natives (14.7%), people of Hispanic origin (12.5%), and non-Hispanic Blacks (11.7%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians (9.2%) and non-Hispanic Whites (7.5%).1 Diabetes is a major risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure, retinopathy, peripheral vascular disease, and neuropathy.1 Early detection and treatment of both prediabetes and diabetes may improve health and reduce these preventable complications, saving lives, preventing heart and renal failure and blindness.

T2DM is caused by a combination of insulin resistance and insufficient pancreatic secretion of insulin to overcome the insulin resistance.3 In young adults with insulin resistance, pancreatic secretion of insulin is often sufficient to overcome the insulin resistance resulting in normal glucose levels and persistently increased insulin concentration. As individuals with insulin resistance age, pancreatic secretion of insulin may decline, resulting in insufficient production of insulin and rising glucose levels. Many individuals experience a prolonged stage of prediabetes that may be present for decades prior to transitioning to T2DM. In 2020, 35% of US adults were reported to have prediabetes.1

Screening for diabetes mellitus

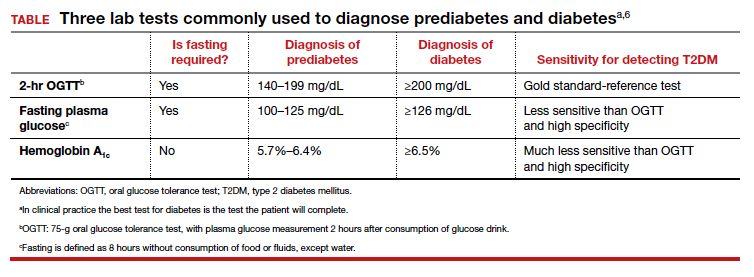

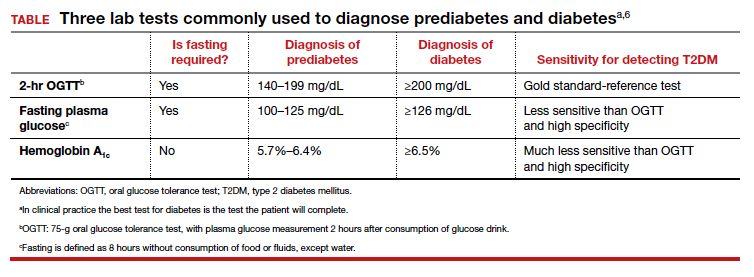

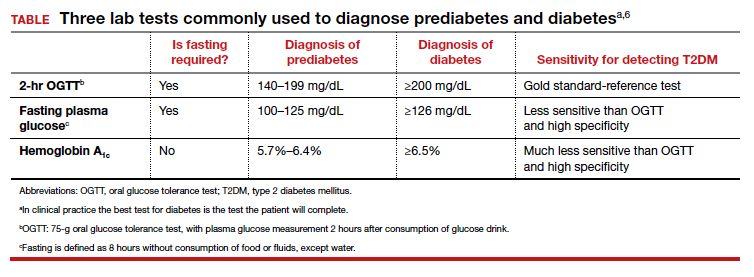

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently recommended that all adults aged 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese be screened for T2DM (B recommendation).4 Screening for diabetes will also result in detecting many people with prediabetes. The criteria for diagnosing diabetes and prediabetes are presented in the TABLE. Based on cohort studies, the USPSTF noted that screening every 3 years is a reasonable approach.4 They also recommended that people diagnosed with prediabetes should initiate preventive measures, including optimizing diet, weight loss, exercise, and in some cases, medication treatment such as metformin.5

Approaches to the diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes

Three laboratory tests are widely utilized for the diagnosis of prediabetes and diabetes: measurement of a plasma glucose 2 hours following consumption of oral glucose 75 g (2-hr oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT]), measurement of a fasting plasma glucose, and measurement of hemoglobin A1c (see Table).6In clinical practice, the best diabetes screening test is the test the patient will complete. Most evidence indicates that, compared with the 2-hr OGTT, a hemoglobin A1c measurement is specific for diagnosing T2DM, but not sensitive. In other words, if the hemoglobin A1c is ≥6.5%, the glucose measurement 2 hours following an OGTT will very likely be ≥200 mg/dL. But if the hemoglobin A1c is between 5.7% and 6.5%, the person might be diagnosed with T2DM if they had a 2-hr OGTT.6

In one study, 1,241 nondiabetic, overweight, or obese participants had all 3 tests to diagnose T2DM.7 The 2-hr OGTT diagnosed T2DM in 148 participants (12%). However, the hemoglobin A1c test only diagnosed T2DM in 78 of the 148 participants who were diagnosed with T2DM based on the 2-hr OGTT, missing 47% of the cases of T2DM. In this study, using the 2-hr OGTT as the “gold standard” reference test, the hemoglobin A1c test had a sensitivity of 53% and specificity of 97%.7

In clinical practice one approach is to explain to the patient the pros and cons of the 3 tests for T2DM and ask them to select the test they prefer to complete. In a high-risk population, including people with obesity, completing any of the 3 tests is better than not testing for diabetes. It also should be noted that, among people who have a normal body mass index (BMI), a “prediabetes” diagnosis is controversial. Compared with obese persons with prediabetes, people with a normal BMI and prediabetes diagnosed by a blood test progress to diabetes at a much lower rate. The value of diagnosing prediabetes after 70 years of age is also controversial because few people in this situation progress to diabetes.8 Clinicians should be cautious about diagnosing prediabetes in lean or elderly people.

The reliability of the hemoglobin A1c test is reduced in conditions associated with increased red blood cell turnover, including sickle cell disease, pregnancy (second and third trimesters), hemodialysis, recent blood transfusions or erythropoietin therapy. In these clinical situations, only blood glucose measurements should be used to diagnose prediabetes and T2DM.6 It should be noted that concordance among any of the 3 tests is not perfect.6

Continue to: A 2-step approach to diagnosing T2DM...

A 2-step approach to diagnosing T2DM

An alternative to relying on a single test for T2DM is to use a 2-step approach for screening. The first step is a hemoglobin A1c measurement, which neither requires fasting nor waiting for 2 hours for post–glucose load blood draw. If the hemoglobin A1c result is ≥6.5%, a T2DM diagnosis can be made, with no additional testing. If the hemoglobin A1c result is 5.7% to 6.4%, the person probably has either prediabetes or diabetes and can be offered a 2-hr OGTT to definitively determine if T2DM is the proper diagnosis. If the hemoglobin A1c test is <5.7%, it is unlikely that the person has T2DM or prediabetes at the time of the test. In this situation, the testing could be repeated in 3 years. Using a 2-step approach reduces the number of people who are tested with a 2-hr OGTT and detects more cases of T2DM than a 1-step approach that relies on a hemoglobin A1c measurement alone.

Treatment of prediabetes is warranted in people at high risk for developing diabetes

It is better to prevent diabetes among people with a high risk of diabetes than to treat diabetes once it is established. People with prediabetes who are overweight or obese are at high risk for developing diabetes. Prediabetes is diagnosed by a fasting plasma glucose level of 100 to 125 mg/dL or a hemoglobin A1c measurement of 5.7% to 6.4%.

High-quality randomized clinical trials have definitively demonstrated that, among people at high risk for developing diabetes, lifestyle modification and metformin treatment reduce the risk of developing diabetes. In the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) 3,234 people with a high risk of diabetes, mean BMI 34 kg/m2, were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups9:

- a control group

- metformin (850 mg twice daily) or

- lifestyle modification that included exercise (moderate intensity exercise for 150 minutes per week and weight loss (7% of body weight using a low-calorie, low-fat diet).

At 2.8 years of follow-up the incidence of diabetes was 11%, 7.8%, and 4.8% per 100 person-years in the people assigned to the control, metformin, and lifestyle modification groups, respectively.9 In the DPP study, compared with the control group, metformin was most effective in decreasing the risk of transitioning to diabetes in people who had a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 (53% reduction in risk) or a BMI from 30 to 35 kg/m2 (16% reduction in risk).9 Metformin was not as effective at preventing the transition to diabetes in people who had a normal BMI or who were overweight (3% reduction).9

In the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study, 522 obese people with impaired glucose tolerance were randomly assigned to lifestyle modification or a control group. After 4 years, the cumulative incidence of diabetes was 11% and 23% in the lifestyle modification and control groups, respectively.10 A meta-analysis of 23 randomized clinical trials reported that, among people with a high risk of developing diabetes, compared with no intervention (control group), lifestyle modification, including dieting, exercising, and weight loss significantly reduced the risk of developing diabetes (pooled relative risk [RR], 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.69‒0.88).5

In clinical practice, offering a patient at high risk for diabetes a suite of options, including5,9,10:

- a formal nutrition consult with the goal of targeting a 7% reduction in weight

- recommending moderate intensity exercise, 150 minutes weekly

- metformin treatment, if the patient is obese

would reduce the patient’s risk of developing diabetes.

Treatment of T2DM is complex

For people with T2DM, a widely recommended treatment goal is to reduce the hemoglobin A1c measurement to ≤7%. Initial treatment includes a comprehensive diabetes self-management education program, weight loss using diet and exercise, and metformin treatment. Metformin may be associated with an increased risk of lactic acidosis, especially in people with renal insufficiency. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends against initiating metformin therapy for people with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30 to 45 mL/min/1.73 m2. The FDA determined that metformin is contraindicated in people with an eGFR of <30 mL/min/1.73 m2.11 Many people with T2DM will require treatment with multiple pharmacologic agents to achieve a hemoglobin A1c ≤7%. In addition to metformin, pharmacologic agents used to treat T2DM include insulin, sulfonylureas, glucagon-like peptide-1(GLP-1) receptor agonists, a sodium glucose cotransporter (SGLT2) inhibitor, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, or an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor. Given the complexity of managing T2DM over a lifetime, most individuals with T2DM receive their diabetes care from a primary care clinician or subspecialist in endocrinology.

Experts predict that, within the next 8 years, the prevalence of obesity among adults in the United States will be approximately 50%.12 The US health care system has not been effective in controlling the obesity epidemic. Our failure to control the obesity epidemic will result in an increase in the prevalence of prediabetes and T2DM, leading to a rise in cardiovascular, renal, and eye disease. The diagnosis of prediabetes and diabetes is within the scope of practice of obstetrics and gynecology. The treatment of prediabetes is also within the scope of ObGyns, who have both expertise and familiarity in the diagnosis of gestational diabetes, a form of prediabetes. ●

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2021.

- Wang L, Li X, Wang Z, et al. Trends in prevalence of diabetes and control of risk factors in diabetes among U.S. adults, 1999-2018. JAMA. 2021;326:1-13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.9883.

- Type 2 diabetes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. . Last reviewed August 10, 2021 Accessed October 27, 2021.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prediabetes and diabetes. US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;326:736-743. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12531.

- Jonas D, Crotty K, Yun JD, et al. Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;326:744-760. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.10403.

- American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes‒2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S14-S31. doi: 10.2337/dc20-S002.

- Meijnikman AS, De Block CE, Dirinck E, et al. Not performing an OGTT results in significant under diagnosis of (pre)diabetes in a high-risk adult Caucasian population. Int J Obes. 2017;41:1615-1620. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.165.

- Rooney MR, Rawlings AM, Pankow JS, et al. Risk of progression to diabetes among older adults with prediabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:511-519. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8774.

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512.

- Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343-1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801.

- Glucophage [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol Meyers Squibb; April 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017020357s037s039,021202s021s023lbl.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2021.

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2019;381;2440-2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1917339.

The prevalence of T2DM is on the rise in the United States, and T2DM is currently the 7th leading cause of death.1 In a study of 28,143 participants in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) who were 18 years or older, the prevalence of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 14.3% between 2000 and 2008.2 About 24% of the participants had undiagnosed diabetes prior to the testing they received as a study participant.2 People from minority groups have a higher rate of T2DM than non-Hispanic White people. Using data from 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes was highest among American Indians/Alaska Natives (14.7%), people of Hispanic origin (12.5%), and non-Hispanic Blacks (11.7%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians (9.2%) and non-Hispanic Whites (7.5%).1 Diabetes is a major risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure, retinopathy, peripheral vascular disease, and neuropathy.1 Early detection and treatment of both prediabetes and diabetes may improve health and reduce these preventable complications, saving lives, preventing heart and renal failure and blindness.

T2DM is caused by a combination of insulin resistance and insufficient pancreatic secretion of insulin to overcome the insulin resistance.3 In young adults with insulin resistance, pancreatic secretion of insulin is often sufficient to overcome the insulin resistance resulting in normal glucose levels and persistently increased insulin concentration. As individuals with insulin resistance age, pancreatic secretion of insulin may decline, resulting in insufficient production of insulin and rising glucose levels. Many individuals experience a prolonged stage of prediabetes that may be present for decades prior to transitioning to T2DM. In 2020, 35% of US adults were reported to have prediabetes.1

Screening for diabetes mellitus

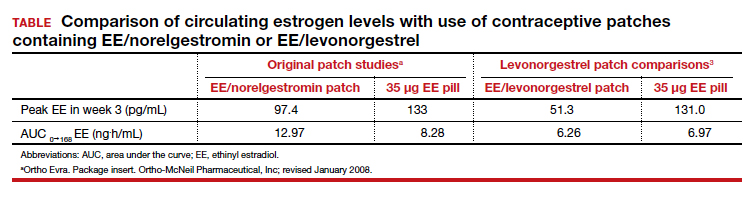

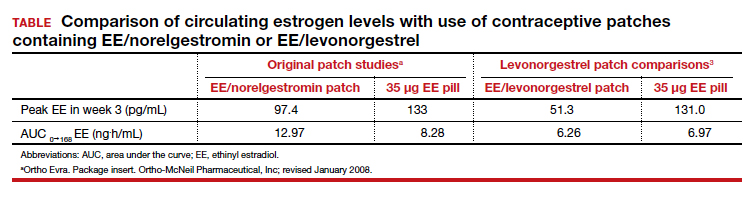

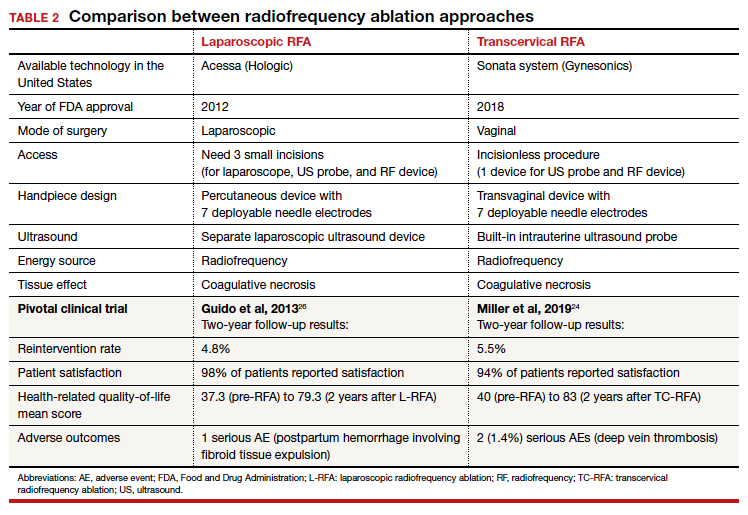

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently recommended that all adults aged 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese be screened for T2DM (B recommendation).4 Screening for diabetes will also result in detecting many people with prediabetes. The criteria for diagnosing diabetes and prediabetes are presented in the TABLE. Based on cohort studies, the USPSTF noted that screening every 3 years is a reasonable approach.4 They also recommended that people diagnosed with prediabetes should initiate preventive measures, including optimizing diet, weight loss, exercise, and in some cases, medication treatment such as metformin.5

Approaches to the diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes

Three laboratory tests are widely utilized for the diagnosis of prediabetes and diabetes: measurement of a plasma glucose 2 hours following consumption of oral glucose 75 g (2-hr oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT]), measurement of a fasting plasma glucose, and measurement of hemoglobin A1c (see Table).6In clinical practice, the best diabetes screening test is the test the patient will complete. Most evidence indicates that, compared with the 2-hr OGTT, a hemoglobin A1c measurement is specific for diagnosing T2DM, but not sensitive. In other words, if the hemoglobin A1c is ≥6.5%, the glucose measurement 2 hours following an OGTT will very likely be ≥200 mg/dL. But if the hemoglobin A1c is between 5.7% and 6.5%, the person might be diagnosed with T2DM if they had a 2-hr OGTT.6

In one study, 1,241 nondiabetic, overweight, or obese participants had all 3 tests to diagnose T2DM.7 The 2-hr OGTT diagnosed T2DM in 148 participants (12%). However, the hemoglobin A1c test only diagnosed T2DM in 78 of the 148 participants who were diagnosed with T2DM based on the 2-hr OGTT, missing 47% of the cases of T2DM. In this study, using the 2-hr OGTT as the “gold standard” reference test, the hemoglobin A1c test had a sensitivity of 53% and specificity of 97%.7

In clinical practice one approach is to explain to the patient the pros and cons of the 3 tests for T2DM and ask them to select the test they prefer to complete. In a high-risk population, including people with obesity, completing any of the 3 tests is better than not testing for diabetes. It also should be noted that, among people who have a normal body mass index (BMI), a “prediabetes” diagnosis is controversial. Compared with obese persons with prediabetes, people with a normal BMI and prediabetes diagnosed by a blood test progress to diabetes at a much lower rate. The value of diagnosing prediabetes after 70 years of age is also controversial because few people in this situation progress to diabetes.8 Clinicians should be cautious about diagnosing prediabetes in lean or elderly people.

The reliability of the hemoglobin A1c test is reduced in conditions associated with increased red blood cell turnover, including sickle cell disease, pregnancy (second and third trimesters), hemodialysis, recent blood transfusions or erythropoietin therapy. In these clinical situations, only blood glucose measurements should be used to diagnose prediabetes and T2DM.6 It should be noted that concordance among any of the 3 tests is not perfect.6

Continue to: A 2-step approach to diagnosing T2DM...

A 2-step approach to diagnosing T2DM

An alternative to relying on a single test for T2DM is to use a 2-step approach for screening. The first step is a hemoglobin A1c measurement, which neither requires fasting nor waiting for 2 hours for post–glucose load blood draw. If the hemoglobin A1c result is ≥6.5%, a T2DM diagnosis can be made, with no additional testing. If the hemoglobin A1c result is 5.7% to 6.4%, the person probably has either prediabetes or diabetes and can be offered a 2-hr OGTT to definitively determine if T2DM is the proper diagnosis. If the hemoglobin A1c test is <5.7%, it is unlikely that the person has T2DM or prediabetes at the time of the test. In this situation, the testing could be repeated in 3 years. Using a 2-step approach reduces the number of people who are tested with a 2-hr OGTT and detects more cases of T2DM than a 1-step approach that relies on a hemoglobin A1c measurement alone.

Treatment of prediabetes is warranted in people at high risk for developing diabetes

It is better to prevent diabetes among people with a high risk of diabetes than to treat diabetes once it is established. People with prediabetes who are overweight or obese are at high risk for developing diabetes. Prediabetes is diagnosed by a fasting plasma glucose level of 100 to 125 mg/dL or a hemoglobin A1c measurement of 5.7% to 6.4%.

High-quality randomized clinical trials have definitively demonstrated that, among people at high risk for developing diabetes, lifestyle modification and metformin treatment reduce the risk of developing diabetes. In the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) 3,234 people with a high risk of diabetes, mean BMI 34 kg/m2, were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups9:

- a control group

- metformin (850 mg twice daily) or

- lifestyle modification that included exercise (moderate intensity exercise for 150 minutes per week and weight loss (7% of body weight using a low-calorie, low-fat diet).

At 2.8 years of follow-up the incidence of diabetes was 11%, 7.8%, and 4.8% per 100 person-years in the people assigned to the control, metformin, and lifestyle modification groups, respectively.9 In the DPP study, compared with the control group, metformin was most effective in decreasing the risk of transitioning to diabetes in people who had a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 (53% reduction in risk) or a BMI from 30 to 35 kg/m2 (16% reduction in risk).9 Metformin was not as effective at preventing the transition to diabetes in people who had a normal BMI or who were overweight (3% reduction).9

In the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study, 522 obese people with impaired glucose tolerance were randomly assigned to lifestyle modification or a control group. After 4 years, the cumulative incidence of diabetes was 11% and 23% in the lifestyle modification and control groups, respectively.10 A meta-analysis of 23 randomized clinical trials reported that, among people with a high risk of developing diabetes, compared with no intervention (control group), lifestyle modification, including dieting, exercising, and weight loss significantly reduced the risk of developing diabetes (pooled relative risk [RR], 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.69‒0.88).5

In clinical practice, offering a patient at high risk for diabetes a suite of options, including5,9,10:

- a formal nutrition consult with the goal of targeting a 7% reduction in weight

- recommending moderate intensity exercise, 150 minutes weekly

- metformin treatment, if the patient is obese

would reduce the patient’s risk of developing diabetes.

Treatment of T2DM is complex

For people with T2DM, a widely recommended treatment goal is to reduce the hemoglobin A1c measurement to ≤7%. Initial treatment includes a comprehensive diabetes self-management education program, weight loss using diet and exercise, and metformin treatment. Metformin may be associated with an increased risk of lactic acidosis, especially in people with renal insufficiency. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends against initiating metformin therapy for people with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30 to 45 mL/min/1.73 m2. The FDA determined that metformin is contraindicated in people with an eGFR of <30 mL/min/1.73 m2.11 Many people with T2DM will require treatment with multiple pharmacologic agents to achieve a hemoglobin A1c ≤7%. In addition to metformin, pharmacologic agents used to treat T2DM include insulin, sulfonylureas, glucagon-like peptide-1(GLP-1) receptor agonists, a sodium glucose cotransporter (SGLT2) inhibitor, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, or an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor. Given the complexity of managing T2DM over a lifetime, most individuals with T2DM receive their diabetes care from a primary care clinician or subspecialist in endocrinology.

Experts predict that, within the next 8 years, the prevalence of obesity among adults in the United States will be approximately 50%.12 The US health care system has not been effective in controlling the obesity epidemic. Our failure to control the obesity epidemic will result in an increase in the prevalence of prediabetes and T2DM, leading to a rise in cardiovascular, renal, and eye disease. The diagnosis of prediabetes and diabetes is within the scope of practice of obstetrics and gynecology. The treatment of prediabetes is also within the scope of ObGyns, who have both expertise and familiarity in the diagnosis of gestational diabetes, a form of prediabetes. ●

The prevalence of T2DM is on the rise in the United States, and T2DM is currently the 7th leading cause of death.1 In a study of 28,143 participants in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) who were 18 years or older, the prevalence of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 14.3% between 2000 and 2008.2 About 24% of the participants had undiagnosed diabetes prior to the testing they received as a study participant.2 People from minority groups have a higher rate of T2DM than non-Hispanic White people. Using data from 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes was highest among American Indians/Alaska Natives (14.7%), people of Hispanic origin (12.5%), and non-Hispanic Blacks (11.7%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians (9.2%) and non-Hispanic Whites (7.5%).1 Diabetes is a major risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure, retinopathy, peripheral vascular disease, and neuropathy.1 Early detection and treatment of both prediabetes and diabetes may improve health and reduce these preventable complications, saving lives, preventing heart and renal failure and blindness.

T2DM is caused by a combination of insulin resistance and insufficient pancreatic secretion of insulin to overcome the insulin resistance.3 In young adults with insulin resistance, pancreatic secretion of insulin is often sufficient to overcome the insulin resistance resulting in normal glucose levels and persistently increased insulin concentration. As individuals with insulin resistance age, pancreatic secretion of insulin may decline, resulting in insufficient production of insulin and rising glucose levels. Many individuals experience a prolonged stage of prediabetes that may be present for decades prior to transitioning to T2DM. In 2020, 35% of US adults were reported to have prediabetes.1

Screening for diabetes mellitus