User login

3D vs 2D mammography for detecting cancer in dense breasts

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

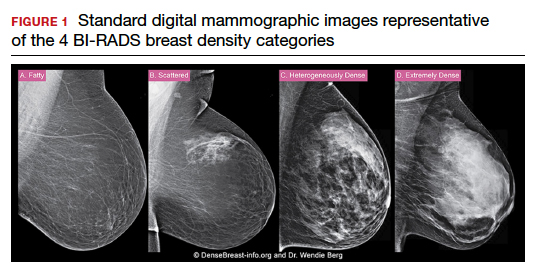

C. Overall, tomosynthesis depicts an additional 1 to 2 cancers per thousand women screened in the first round of screening when added to standard digital mammography;1-3 however, this improvement in cancer detection is only observed in women with fatty breasts (category A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (category B), and heterogeneously dense breasts (category C). Importantly, tomosynthesis does not significantly improve breast cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts (category D).2,4

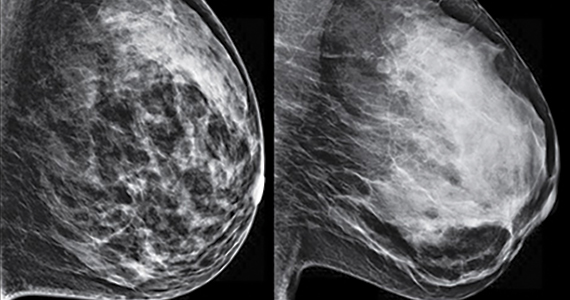

Digital breast tomosynthesis, also referred to as “3-dimensional mammography” (3D mammography) or tomosynthesis, uses a dedicated electronic detector system to obtain multiple projection images that are reconstructed by the computer to create thin slices or slabs of multiple slices of the breast. These slices can be individually “scrolled through” by the radiologist to reduce tissue overlap that may obscure breast cancers on a standard mammogram. While tomosynthesis improves breast cancer detection in women with fatty, scattered fibroglandular density, and heterogeneously dense breasts, there is very little soft tissue contrast in extremely dense breasts due to insufficient fat, and some cancers will remain hidden by dense tissue even on sliced images through the breast.

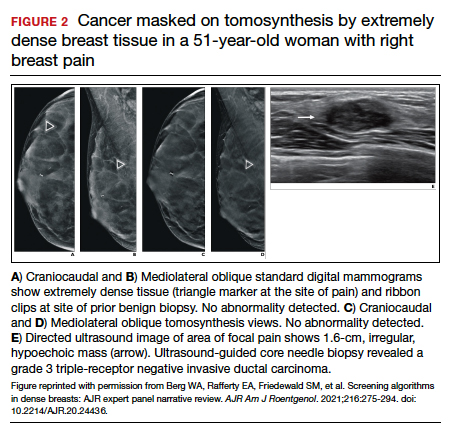

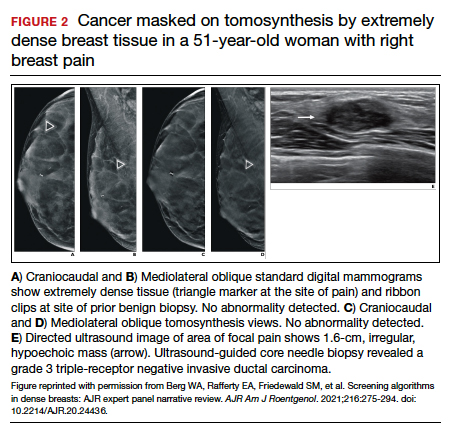

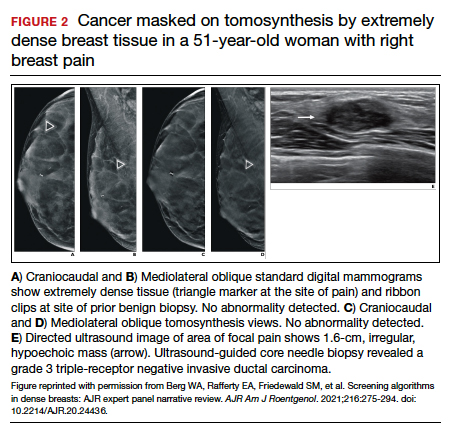

FIGURE 2 shows an example of cancer that was missed on tomosynthesis in a 51-year-old woman with extremely dense breasts and right breast pain. The cancer was masked by extremely dense tissue on standard digital mammography and tomosynthesis; no abnormalities were detected. Ultrasonography showed a 1.6-cm, irregular, hypoechoic mass at the site of pain, and biopsy revealed a grade 3 triple-receptor negative invasive ductal carcinoma.

In women with dense breasts, especially extremely dense breasts, supplemental screening beyond tomosynthesis should be considered. Although tomosynthesis doesn’t improve cancer detection in extremely dense breasts, it does reduce callbacks for additional testing in all breast densities compared with standard digital mammography. Callbacks are reduced from approximately 100‒120 per 1,000 women screened with standard digital mammography alone1,5 to an average of 80 per 1,000 women when tomosynthesis and standard mammography are interpreted together.1-3 ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295:285-293.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Niklason LT, et al. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology. 2019;291:23-30.

- Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011792.

- Lee CS, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, et al. Association of patient age with outcomes of current-era, large-scale screening mammography: analysis of data from the National Mammography Database. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1134-1136.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

C. Overall, tomosynthesis depicts an additional 1 to 2 cancers per thousand women screened in the first round of screening when added to standard digital mammography;1-3 however, this improvement in cancer detection is only observed in women with fatty breasts (category A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (category B), and heterogeneously dense breasts (category C). Importantly, tomosynthesis does not significantly improve breast cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts (category D).2,4

Digital breast tomosynthesis, also referred to as “3-dimensional mammography” (3D mammography) or tomosynthesis, uses a dedicated electronic detector system to obtain multiple projection images that are reconstructed by the computer to create thin slices or slabs of multiple slices of the breast. These slices can be individually “scrolled through” by the radiologist to reduce tissue overlap that may obscure breast cancers on a standard mammogram. While tomosynthesis improves breast cancer detection in women with fatty, scattered fibroglandular density, and heterogeneously dense breasts, there is very little soft tissue contrast in extremely dense breasts due to insufficient fat, and some cancers will remain hidden by dense tissue even on sliced images through the breast.

FIGURE 2 shows an example of cancer that was missed on tomosynthesis in a 51-year-old woman with extremely dense breasts and right breast pain. The cancer was masked by extremely dense tissue on standard digital mammography and tomosynthesis; no abnormalities were detected. Ultrasonography showed a 1.6-cm, irregular, hypoechoic mass at the site of pain, and biopsy revealed a grade 3 triple-receptor negative invasive ductal carcinoma.

In women with dense breasts, especially extremely dense breasts, supplemental screening beyond tomosynthesis should be considered. Although tomosynthesis doesn’t improve cancer detection in extremely dense breasts, it does reduce callbacks for additional testing in all breast densities compared with standard digital mammography. Callbacks are reduced from approximately 100‒120 per 1,000 women screened with standard digital mammography alone1,5 to an average of 80 per 1,000 women when tomosynthesis and standard mammography are interpreted together.1-3 ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

C. Overall, tomosynthesis depicts an additional 1 to 2 cancers per thousand women screened in the first round of screening when added to standard digital mammography;1-3 however, this improvement in cancer detection is only observed in women with fatty breasts (category A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (category B), and heterogeneously dense breasts (category C). Importantly, tomosynthesis does not significantly improve breast cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts (category D).2,4

Digital breast tomosynthesis, also referred to as “3-dimensional mammography” (3D mammography) or tomosynthesis, uses a dedicated electronic detector system to obtain multiple projection images that are reconstructed by the computer to create thin slices or slabs of multiple slices of the breast. These slices can be individually “scrolled through” by the radiologist to reduce tissue overlap that may obscure breast cancers on a standard mammogram. While tomosynthesis improves breast cancer detection in women with fatty, scattered fibroglandular density, and heterogeneously dense breasts, there is very little soft tissue contrast in extremely dense breasts due to insufficient fat, and some cancers will remain hidden by dense tissue even on sliced images through the breast.

FIGURE 2 shows an example of cancer that was missed on tomosynthesis in a 51-year-old woman with extremely dense breasts and right breast pain. The cancer was masked by extremely dense tissue on standard digital mammography and tomosynthesis; no abnormalities were detected. Ultrasonography showed a 1.6-cm, irregular, hypoechoic mass at the site of pain, and biopsy revealed a grade 3 triple-receptor negative invasive ductal carcinoma.

In women with dense breasts, especially extremely dense breasts, supplemental screening beyond tomosynthesis should be considered. Although tomosynthesis doesn’t improve cancer detection in extremely dense breasts, it does reduce callbacks for additional testing in all breast densities compared with standard digital mammography. Callbacks are reduced from approximately 100‒120 per 1,000 women screened with standard digital mammography alone1,5 to an average of 80 per 1,000 women when tomosynthesis and standard mammography are interpreted together.1-3 ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295:285-293.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Niklason LT, et al. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology. 2019;291:23-30.

- Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011792.

- Lee CS, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, et al. Association of patient age with outcomes of current-era, large-scale screening mammography: analysis of data from the National Mammography Database. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1134-1136.

- Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295:285-293.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Niklason LT, et al. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology. 2019;291:23-30.

- Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011792.

- Lee CS, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, et al. Association of patient age with outcomes of current-era, large-scale screening mammography: analysis of data from the National Mammography Database. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1134-1136.

Quiz developed in collaboration with

AGA Clinical Practice Guideline: Coagulation in cirrhosis

A clinical update from the American Gastroenterological Association focuses on bleeding and thrombosis-related questions in patients with cirrhosis. It provides guidance on test strategies for bleeding risk, preprocedure management of bleeding risk, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, screening for portal vein thrombosis (PVT), and anticoagulation therapies. It is aimed at primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and hepatologists, among other health care providers.

In cirrhosis, there are often changes to platelet (PLT) counts and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR), among other parameters, and historically these changes led to concerns that patients were at greater risk of bleeding or thrombosis. More recent evidence has led to a nuanced view. Neither factor necessarily suggests increased bleeding risk, and the severity of coagulopathy predicted by them does not predict the risk of bleeding complications.

Patients with cirrhosis are at greater risk of thrombosis, but clinicians may be hesitant to prescribe anticoagulants because of uncertain risk profiles, and test strategies employing PT/INR to estimate bleeding risk and track treatment endpoints in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists may not work in cirrhosis patients with alterations in procoagulant and anticoagulant measures. Recent efforts to address this led to testing of fibrin clot formation and lysis to better gauge the variety of abnormalities in cirrhosis patients.

The guideline, published in Gastroenterology, was informed by a technical review that focused on both bleeding-related and thrombosis-related questions. Bleeding-related questions included testing strategies and preprocedure prophylaxis to reduce bleeding risk. Thrombosis-related questions included whether VTE prophylaxis may be useful in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, whether patients should be screened for PVT, potential therapies for nontumoral PVT, and whether or not anticoagulation is safe and effective when atrial fibrillation is present alongside cirrhosis.

Because of a lack of evidence, the guideline provides no recommendations on visco-elastic testing for bleeding risk in advance of common gastrointestinal procedures for patients with stable cirrhosis. It recommends against use of extensive preprocedural testing, such as repeated PT/INR or PLT count testing.

The guideline also looked at whether preprocedural efforts to correct coagulation parameters could reduce bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis. It recommends against giving blood products ahead of the procedure for patients with stable cirrhosis without severe thrombocytopenia or severe coagulopathy. Such interventions can be considered for patients in the latter categories who are undergoing procedures with high bleeding risk after consideration of risks and benefits, and consultation with a hematologist.

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) are also not recommended in patients with thrombocytopenia and stable cirrhosis undergoing common procedures, but they can be considered for patients who are more concerned about reduction of bleeding events and less concerned about the risk of PVT.

Patients who are hospitalized and meet the requirements should receive VTE prophylaxis. Although there is little available evidence about the effects of thromboprophylaxis in patients with cirrhosis, there is strong evidence of benefit in acutely ill hospitalized patients, and patients with cirrhosis are believed to be at a similar risk of VTE. There is evidence of increased bleed risk, but this is of very low certainty.

PVT should not be routinely tested for, but such testing can be offered to patients with a high level of concern over PVT and are not as worried about potential harms of treatment. This recommendation does not apply to patients waiting for a liver transplant.

Patients with non-umoral PVT should receive anticoagulation therapy, but patients who have high levels of concern about bleeding risk from anticoagulation and put a lower value on possible benefits of anticoagulation may choose not to receive it.

The guideline recommends anticoagulation for patients with atrial fibrillation and cirrhosis who are indicated for it. Patients with more concern about the bleeding risk of anticoagulation and place lower value on the reduction in stroke risk may choose to not receive anticoagulation. This is particularly true for those with more advanced cirrhosis (Child-Turcotte-Pugh Class C) and/or low CHA2DS2-VASC scores.

Nearly all of the recommendations in the guideline are conditional, reflecting a lack of data and a range of knowledge gaps that need filling. The authors call for additional research to identify specific patients who are at high risk for bleeding or thrombosis “to appropriately provide prophylaxis using blood product transfusion or TPO-RAs in patients at risk for clinically significant bleeding, to screen for and treat PVT, and to prevent clinically significant thromboembolic events.”

The development of the guideline was funded fully by the AGA. Members of the panel submitted conflict of interest information, and these statements are maintained at AGA headquarters.

A clinical update from the American Gastroenterological Association focuses on bleeding and thrombosis-related questions in patients with cirrhosis. It provides guidance on test strategies for bleeding risk, preprocedure management of bleeding risk, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, screening for portal vein thrombosis (PVT), and anticoagulation therapies. It is aimed at primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and hepatologists, among other health care providers.

In cirrhosis, there are often changes to platelet (PLT) counts and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR), among other parameters, and historically these changes led to concerns that patients were at greater risk of bleeding or thrombosis. More recent evidence has led to a nuanced view. Neither factor necessarily suggests increased bleeding risk, and the severity of coagulopathy predicted by them does not predict the risk of bleeding complications.

Patients with cirrhosis are at greater risk of thrombosis, but clinicians may be hesitant to prescribe anticoagulants because of uncertain risk profiles, and test strategies employing PT/INR to estimate bleeding risk and track treatment endpoints in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists may not work in cirrhosis patients with alterations in procoagulant and anticoagulant measures. Recent efforts to address this led to testing of fibrin clot formation and lysis to better gauge the variety of abnormalities in cirrhosis patients.

The guideline, published in Gastroenterology, was informed by a technical review that focused on both bleeding-related and thrombosis-related questions. Bleeding-related questions included testing strategies and preprocedure prophylaxis to reduce bleeding risk. Thrombosis-related questions included whether VTE prophylaxis may be useful in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, whether patients should be screened for PVT, potential therapies for nontumoral PVT, and whether or not anticoagulation is safe and effective when atrial fibrillation is present alongside cirrhosis.

Because of a lack of evidence, the guideline provides no recommendations on visco-elastic testing for bleeding risk in advance of common gastrointestinal procedures for patients with stable cirrhosis. It recommends against use of extensive preprocedural testing, such as repeated PT/INR or PLT count testing.

The guideline also looked at whether preprocedural efforts to correct coagulation parameters could reduce bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis. It recommends against giving blood products ahead of the procedure for patients with stable cirrhosis without severe thrombocytopenia or severe coagulopathy. Such interventions can be considered for patients in the latter categories who are undergoing procedures with high bleeding risk after consideration of risks and benefits, and consultation with a hematologist.

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) are also not recommended in patients with thrombocytopenia and stable cirrhosis undergoing common procedures, but they can be considered for patients who are more concerned about reduction of bleeding events and less concerned about the risk of PVT.

Patients who are hospitalized and meet the requirements should receive VTE prophylaxis. Although there is little available evidence about the effects of thromboprophylaxis in patients with cirrhosis, there is strong evidence of benefit in acutely ill hospitalized patients, and patients with cirrhosis are believed to be at a similar risk of VTE. There is evidence of increased bleed risk, but this is of very low certainty.

PVT should not be routinely tested for, but such testing can be offered to patients with a high level of concern over PVT and are not as worried about potential harms of treatment. This recommendation does not apply to patients waiting for a liver transplant.

Patients with non-umoral PVT should receive anticoagulation therapy, but patients who have high levels of concern about bleeding risk from anticoagulation and put a lower value on possible benefits of anticoagulation may choose not to receive it.

The guideline recommends anticoagulation for patients with atrial fibrillation and cirrhosis who are indicated for it. Patients with more concern about the bleeding risk of anticoagulation and place lower value on the reduction in stroke risk may choose to not receive anticoagulation. This is particularly true for those with more advanced cirrhosis (Child-Turcotte-Pugh Class C) and/or low CHA2DS2-VASC scores.

Nearly all of the recommendations in the guideline are conditional, reflecting a lack of data and a range of knowledge gaps that need filling. The authors call for additional research to identify specific patients who are at high risk for bleeding or thrombosis “to appropriately provide prophylaxis using blood product transfusion or TPO-RAs in patients at risk for clinically significant bleeding, to screen for and treat PVT, and to prevent clinically significant thromboembolic events.”

The development of the guideline was funded fully by the AGA. Members of the panel submitted conflict of interest information, and these statements are maintained at AGA headquarters.

A clinical update from the American Gastroenterological Association focuses on bleeding and thrombosis-related questions in patients with cirrhosis. It provides guidance on test strategies for bleeding risk, preprocedure management of bleeding risk, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, screening for portal vein thrombosis (PVT), and anticoagulation therapies. It is aimed at primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and hepatologists, among other health care providers.

In cirrhosis, there are often changes to platelet (PLT) counts and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR), among other parameters, and historically these changes led to concerns that patients were at greater risk of bleeding or thrombosis. More recent evidence has led to a nuanced view. Neither factor necessarily suggests increased bleeding risk, and the severity of coagulopathy predicted by them does not predict the risk of bleeding complications.

Patients with cirrhosis are at greater risk of thrombosis, but clinicians may be hesitant to prescribe anticoagulants because of uncertain risk profiles, and test strategies employing PT/INR to estimate bleeding risk and track treatment endpoints in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists may not work in cirrhosis patients with alterations in procoagulant and anticoagulant measures. Recent efforts to address this led to testing of fibrin clot formation and lysis to better gauge the variety of abnormalities in cirrhosis patients.

The guideline, published in Gastroenterology, was informed by a technical review that focused on both bleeding-related and thrombosis-related questions. Bleeding-related questions included testing strategies and preprocedure prophylaxis to reduce bleeding risk. Thrombosis-related questions included whether VTE prophylaxis may be useful in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, whether patients should be screened for PVT, potential therapies for nontumoral PVT, and whether or not anticoagulation is safe and effective when atrial fibrillation is present alongside cirrhosis.

Because of a lack of evidence, the guideline provides no recommendations on visco-elastic testing for bleeding risk in advance of common gastrointestinal procedures for patients with stable cirrhosis. It recommends against use of extensive preprocedural testing, such as repeated PT/INR or PLT count testing.

The guideline also looked at whether preprocedural efforts to correct coagulation parameters could reduce bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis. It recommends against giving blood products ahead of the procedure for patients with stable cirrhosis without severe thrombocytopenia or severe coagulopathy. Such interventions can be considered for patients in the latter categories who are undergoing procedures with high bleeding risk after consideration of risks and benefits, and consultation with a hematologist.

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) are also not recommended in patients with thrombocytopenia and stable cirrhosis undergoing common procedures, but they can be considered for patients who are more concerned about reduction of bleeding events and less concerned about the risk of PVT.

Patients who are hospitalized and meet the requirements should receive VTE prophylaxis. Although there is little available evidence about the effects of thromboprophylaxis in patients with cirrhosis, there is strong evidence of benefit in acutely ill hospitalized patients, and patients with cirrhosis are believed to be at a similar risk of VTE. There is evidence of increased bleed risk, but this is of very low certainty.

PVT should not be routinely tested for, but such testing can be offered to patients with a high level of concern over PVT and are not as worried about potential harms of treatment. This recommendation does not apply to patients waiting for a liver transplant.

Patients with non-umoral PVT should receive anticoagulation therapy, but patients who have high levels of concern about bleeding risk from anticoagulation and put a lower value on possible benefits of anticoagulation may choose not to receive it.

The guideline recommends anticoagulation for patients with atrial fibrillation and cirrhosis who are indicated for it. Patients with more concern about the bleeding risk of anticoagulation and place lower value on the reduction in stroke risk may choose to not receive anticoagulation. This is particularly true for those with more advanced cirrhosis (Child-Turcotte-Pugh Class C) and/or low CHA2DS2-VASC scores.

Nearly all of the recommendations in the guideline are conditional, reflecting a lack of data and a range of knowledge gaps that need filling. The authors call for additional research to identify specific patients who are at high risk for bleeding or thrombosis “to appropriately provide prophylaxis using blood product transfusion or TPO-RAs in patients at risk for clinically significant bleeding, to screen for and treat PVT, and to prevent clinically significant thromboembolic events.”

The development of the guideline was funded fully by the AGA. Members of the panel submitted conflict of interest information, and these statements are maintained at AGA headquarters.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Renal denervation remains only promising, per latest meta-analysis

Questions remain despite efficacy

According to the latest meta-analysis of sham-controlled randomized trials, catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation produces clinically meaningful reductions in blood pressure with acceptable safety, but the strategy is not yet regarded as ready for prime time, according to a summary of the results to be presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

This meta-analysis was based on seven blinded trials, all of which associated denervation with a reduction in systolic ambulatory BP, according to Yousif Ahmad, BMBS, PhD, an interventional cardiologist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Although the BP-lowering advantage in two of these studies did not reach statistical significance, the other five did, and all the data moved in the same direction.

For ambulatory diastolic pressure, the effect was more modest. One of the studies showed essentially a neutral effect. The reductions were statistically significant in only two, but, again, the data moved in the same direction in six of the studies, and a random-effects analysis suggested that the reductions, although modest, were potentially meaningful, according to Dr. Ahmad.

Overall, at a mean follow-up of 4.5 months, the reductions in ambulatory systolic and diastolic BPs were 3.61 and 1.85 mm Hg, respectively. The benefit was about the same whether renal denervation was or was not performed on the background of antihypertensive drugs, which was permitted in five of the seven trials. In the other two, all patients were off hypertensive medication.

Office-based systolic reduction: 6 mm Hg

When the same analysis was performed for office-based BP reductions, which were available for five of the seven trials, the overall reductions based on the meta-analysis were 5.86 and 3.63 mm Hg for the systolic and diastolic pressures, respectively. Again, background antihypertensive therapy was not a factor.

Of the seven trials, three randomized fewer than 100 patients. The largest, SYMPLICITY HTN-3, randomized 491 patients in 2:1 ratio to denervation or sham.

Three of the studies in the meta-analysis were trials of the Symplicity flex device. Another two evaluated the Symplicity Spyral catheter. Both deliver radiofrequency energy to for denervation. The Paradise device, the focus of the remaining two trials, employs energy in the form of ultrasound.

According to Dr. Ahmad, adverse events regardless of device were rare and not more common among those in the active treatment arm than in those treated with a sham procedure. Although one of these trials, RADIANCE-HTN SOLO associated denervation with efficacy and safety out to 12 months , Dr. Ahmad concluded that the mean follow-up of 4.5 months is not sufficient to consider long-term effects.

More than 20 meta-analyses published so far

By one count, there have been more than 20 meta-analyses of renal denervation published previously yet this intervention is still considered “controversial,” according to Dr. Ahmad. Relative to the previous meta-analyses, this included the RADIANCE-HTN TRIO trial, which is the latest such sham-controlled study and added 136 patients to the dataset of high-quality trials.

Basically, the results led Dr. Ahmad to conclude that, although the treatment effect is modest, it could be valuable in specific groups of patients, such as those reluctant or unable to take multiple medications or any medications at all. In addition to generating more data on efficacy and safety, he said longer follow-up is also needed for calculations of cost-effectiveness. Larger-scale observational studies might be one way of collecting these data, he reported.

The results of this study were published online in JACC Cardiovascular Interventions with an accompanying editorial by David E. Kandzari, MD, director of interventional cardiology, Piedmont Hart Institute, Atlanta.

Commenting on the large pile of meta-analyses, sometimes published months apart, Dr. Kandzari explained that their “short half-life” is a product of the continuous updating of data with new trials. For a procedure that remains controversial, he said these constant relooks are inevitable.

“My point is that, with more studies, we can expect to see more meta-analyses. It is just the way this is going to work,” Dr. Kandzari said in an interview.

Individual study data also relevant

Even as the authors of these analyses attempt to cull the best data from the most rigorously performed trials, “we are also going to have to look at the individual studies, because of the differences in the trial designs, particularly the devices used,” according to Dr. Kandzari, who was the principle investigator of the sham-controlled SPYRAL HTN-ON MED trial.

So far, the data, despite some inconsistencies, have supported “clinically meaningful” BP reductions and acceptable safety regardless of the device used, according to Dr. Kandzari. Although he also agrees with the basic premise that more long-term data are needed to better determine how renal denervation should be applied in management of hypertension, he does think it will eventually find a role that is “complimentary to, rather than a replacement for, drugs.”

“The effect is modest, but keep in mind that the effect size is similar to that of a single oral medication, and there are some features, such as an always-on 24-hour effect that could be useful,” he said.

“We have enough of a signal to start thinking of how this will be enveloped into routine care,” he said.

But it is not ready yet. This was the point made by Dr. Ahmad, and it was seconded by Dr. Kandzari. One of the senior authors of the meta-analysis, Deepak Bhatt, MD, executive director of interventional cardiovascular programs, Brigham and Women’s Health, Boston, was also asked to weigh on when it will be ready for prime time.

“At a minimum, I would recommend completion of ongoing sham-controlled randomized trials before considering clinical use of renal denervation. Longer term safety and durability data, as well as data on cost-effectiveness, are all still needed – preferably from randomized trials as opposed to registries,” he said.

“Ideally, larger sham-controlled trials with longer follow-up and clinical endpoints, as opposed to only blood pressure measurements, would be performed, although I am not aware of any plans at present,” he added.

Dr. Ahmad reported no financial relationships relevant to this research. Dr. Bhatt has financial relationships with more than 30 pharmaceutical companies, including those developing products relevant to hypertension and renal denervation. Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Ablative Solutions and Medtronic.

Questions remain despite efficacy

Questions remain despite efficacy

According to the latest meta-analysis of sham-controlled randomized trials, catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation produces clinically meaningful reductions in blood pressure with acceptable safety, but the strategy is not yet regarded as ready for prime time, according to a summary of the results to be presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

This meta-analysis was based on seven blinded trials, all of which associated denervation with a reduction in systolic ambulatory BP, according to Yousif Ahmad, BMBS, PhD, an interventional cardiologist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Although the BP-lowering advantage in two of these studies did not reach statistical significance, the other five did, and all the data moved in the same direction.

For ambulatory diastolic pressure, the effect was more modest. One of the studies showed essentially a neutral effect. The reductions were statistically significant in only two, but, again, the data moved in the same direction in six of the studies, and a random-effects analysis suggested that the reductions, although modest, were potentially meaningful, according to Dr. Ahmad.

Overall, at a mean follow-up of 4.5 months, the reductions in ambulatory systolic and diastolic BPs were 3.61 and 1.85 mm Hg, respectively. The benefit was about the same whether renal denervation was or was not performed on the background of antihypertensive drugs, which was permitted in five of the seven trials. In the other two, all patients were off hypertensive medication.

Office-based systolic reduction: 6 mm Hg

When the same analysis was performed for office-based BP reductions, which were available for five of the seven trials, the overall reductions based on the meta-analysis were 5.86 and 3.63 mm Hg for the systolic and diastolic pressures, respectively. Again, background antihypertensive therapy was not a factor.

Of the seven trials, three randomized fewer than 100 patients. The largest, SYMPLICITY HTN-3, randomized 491 patients in 2:1 ratio to denervation or sham.

Three of the studies in the meta-analysis were trials of the Symplicity flex device. Another two evaluated the Symplicity Spyral catheter. Both deliver radiofrequency energy to for denervation. The Paradise device, the focus of the remaining two trials, employs energy in the form of ultrasound.

According to Dr. Ahmad, adverse events regardless of device were rare and not more common among those in the active treatment arm than in those treated with a sham procedure. Although one of these trials, RADIANCE-HTN SOLO associated denervation with efficacy and safety out to 12 months , Dr. Ahmad concluded that the mean follow-up of 4.5 months is not sufficient to consider long-term effects.

More than 20 meta-analyses published so far

By one count, there have been more than 20 meta-analyses of renal denervation published previously yet this intervention is still considered “controversial,” according to Dr. Ahmad. Relative to the previous meta-analyses, this included the RADIANCE-HTN TRIO trial, which is the latest such sham-controlled study and added 136 patients to the dataset of high-quality trials.

Basically, the results led Dr. Ahmad to conclude that, although the treatment effect is modest, it could be valuable in specific groups of patients, such as those reluctant or unable to take multiple medications or any medications at all. In addition to generating more data on efficacy and safety, he said longer follow-up is also needed for calculations of cost-effectiveness. Larger-scale observational studies might be one way of collecting these data, he reported.

The results of this study were published online in JACC Cardiovascular Interventions with an accompanying editorial by David E. Kandzari, MD, director of interventional cardiology, Piedmont Hart Institute, Atlanta.

Commenting on the large pile of meta-analyses, sometimes published months apart, Dr. Kandzari explained that their “short half-life” is a product of the continuous updating of data with new trials. For a procedure that remains controversial, he said these constant relooks are inevitable.

“My point is that, with more studies, we can expect to see more meta-analyses. It is just the way this is going to work,” Dr. Kandzari said in an interview.

Individual study data also relevant

Even as the authors of these analyses attempt to cull the best data from the most rigorously performed trials, “we are also going to have to look at the individual studies, because of the differences in the trial designs, particularly the devices used,” according to Dr. Kandzari, who was the principle investigator of the sham-controlled SPYRAL HTN-ON MED trial.

So far, the data, despite some inconsistencies, have supported “clinically meaningful” BP reductions and acceptable safety regardless of the device used, according to Dr. Kandzari. Although he also agrees with the basic premise that more long-term data are needed to better determine how renal denervation should be applied in management of hypertension, he does think it will eventually find a role that is “complimentary to, rather than a replacement for, drugs.”

“The effect is modest, but keep in mind that the effect size is similar to that of a single oral medication, and there are some features, such as an always-on 24-hour effect that could be useful,” he said.

“We have enough of a signal to start thinking of how this will be enveloped into routine care,” he said.

But it is not ready yet. This was the point made by Dr. Ahmad, and it was seconded by Dr. Kandzari. One of the senior authors of the meta-analysis, Deepak Bhatt, MD, executive director of interventional cardiovascular programs, Brigham and Women’s Health, Boston, was also asked to weigh on when it will be ready for prime time.

“At a minimum, I would recommend completion of ongoing sham-controlled randomized trials before considering clinical use of renal denervation. Longer term safety and durability data, as well as data on cost-effectiveness, are all still needed – preferably from randomized trials as opposed to registries,” he said.

“Ideally, larger sham-controlled trials with longer follow-up and clinical endpoints, as opposed to only blood pressure measurements, would be performed, although I am not aware of any plans at present,” he added.

Dr. Ahmad reported no financial relationships relevant to this research. Dr. Bhatt has financial relationships with more than 30 pharmaceutical companies, including those developing products relevant to hypertension and renal denervation. Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Ablative Solutions and Medtronic.

According to the latest meta-analysis of sham-controlled randomized trials, catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation produces clinically meaningful reductions in blood pressure with acceptable safety, but the strategy is not yet regarded as ready for prime time, according to a summary of the results to be presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

This meta-analysis was based on seven blinded trials, all of which associated denervation with a reduction in systolic ambulatory BP, according to Yousif Ahmad, BMBS, PhD, an interventional cardiologist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Although the BP-lowering advantage in two of these studies did not reach statistical significance, the other five did, and all the data moved in the same direction.

For ambulatory diastolic pressure, the effect was more modest. One of the studies showed essentially a neutral effect. The reductions were statistically significant in only two, but, again, the data moved in the same direction in six of the studies, and a random-effects analysis suggested that the reductions, although modest, were potentially meaningful, according to Dr. Ahmad.

Overall, at a mean follow-up of 4.5 months, the reductions in ambulatory systolic and diastolic BPs were 3.61 and 1.85 mm Hg, respectively. The benefit was about the same whether renal denervation was or was not performed on the background of antihypertensive drugs, which was permitted in five of the seven trials. In the other two, all patients were off hypertensive medication.

Office-based systolic reduction: 6 mm Hg

When the same analysis was performed for office-based BP reductions, which were available for five of the seven trials, the overall reductions based on the meta-analysis were 5.86 and 3.63 mm Hg for the systolic and diastolic pressures, respectively. Again, background antihypertensive therapy was not a factor.

Of the seven trials, three randomized fewer than 100 patients. The largest, SYMPLICITY HTN-3, randomized 491 patients in 2:1 ratio to denervation or sham.

Three of the studies in the meta-analysis were trials of the Symplicity flex device. Another two evaluated the Symplicity Spyral catheter. Both deliver radiofrequency energy to for denervation. The Paradise device, the focus of the remaining two trials, employs energy in the form of ultrasound.

According to Dr. Ahmad, adverse events regardless of device were rare and not more common among those in the active treatment arm than in those treated with a sham procedure. Although one of these trials, RADIANCE-HTN SOLO associated denervation with efficacy and safety out to 12 months , Dr. Ahmad concluded that the mean follow-up of 4.5 months is not sufficient to consider long-term effects.

More than 20 meta-analyses published so far

By one count, there have been more than 20 meta-analyses of renal denervation published previously yet this intervention is still considered “controversial,” according to Dr. Ahmad. Relative to the previous meta-analyses, this included the RADIANCE-HTN TRIO trial, which is the latest such sham-controlled study and added 136 patients to the dataset of high-quality trials.

Basically, the results led Dr. Ahmad to conclude that, although the treatment effect is modest, it could be valuable in specific groups of patients, such as those reluctant or unable to take multiple medications or any medications at all. In addition to generating more data on efficacy and safety, he said longer follow-up is also needed for calculations of cost-effectiveness. Larger-scale observational studies might be one way of collecting these data, he reported.

The results of this study were published online in JACC Cardiovascular Interventions with an accompanying editorial by David E. Kandzari, MD, director of interventional cardiology, Piedmont Hart Institute, Atlanta.

Commenting on the large pile of meta-analyses, sometimes published months apart, Dr. Kandzari explained that their “short half-life” is a product of the continuous updating of data with new trials. For a procedure that remains controversial, he said these constant relooks are inevitable.

“My point is that, with more studies, we can expect to see more meta-analyses. It is just the way this is going to work,” Dr. Kandzari said in an interview.

Individual study data also relevant

Even as the authors of these analyses attempt to cull the best data from the most rigorously performed trials, “we are also going to have to look at the individual studies, because of the differences in the trial designs, particularly the devices used,” according to Dr. Kandzari, who was the principle investigator of the sham-controlled SPYRAL HTN-ON MED trial.

So far, the data, despite some inconsistencies, have supported “clinically meaningful” BP reductions and acceptable safety regardless of the device used, according to Dr. Kandzari. Although he also agrees with the basic premise that more long-term data are needed to better determine how renal denervation should be applied in management of hypertension, he does think it will eventually find a role that is “complimentary to, rather than a replacement for, drugs.”

“The effect is modest, but keep in mind that the effect size is similar to that of a single oral medication, and there are some features, such as an always-on 24-hour effect that could be useful,” he said.

“We have enough of a signal to start thinking of how this will be enveloped into routine care,” he said.

But it is not ready yet. This was the point made by Dr. Ahmad, and it was seconded by Dr. Kandzari. One of the senior authors of the meta-analysis, Deepak Bhatt, MD, executive director of interventional cardiovascular programs, Brigham and Women’s Health, Boston, was also asked to weigh on when it will be ready for prime time.

“At a minimum, I would recommend completion of ongoing sham-controlled randomized trials before considering clinical use of renal denervation. Longer term safety and durability data, as well as data on cost-effectiveness, are all still needed – preferably from randomized trials as opposed to registries,” he said.

“Ideally, larger sham-controlled trials with longer follow-up and clinical endpoints, as opposed to only blood pressure measurements, would be performed, although I am not aware of any plans at present,” he added.

Dr. Ahmad reported no financial relationships relevant to this research. Dr. Bhatt has financial relationships with more than 30 pharmaceutical companies, including those developing products relevant to hypertension and renal denervation. Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Ablative Solutions and Medtronic.

FROM TCT 2021

James Bond taken down by an epidemiologist

No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die

Movie watching usually requires a certain suspension of disbelief, and it’s safe to say James Bond movies require this more than most. Between the impossible gadgets and ludicrous doomsday plans, very few have ever stopped to consider the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Now, however, Bond, James Bond, has met his most formidable opponent: Wouter Graumans, a graduate student in epidemiology from the Netherlands. During a foray to Burkina Faso to study infectious diseases, Mr. Graumans came down with a case of food poisoning, which led him to wonder how 007 is able to trot across this big world of ours without contracting so much as a sinus infection.

Because Mr. Graumans is a man of science and conviction, mere speculation wasn’t enough. He and a group of coauthors wrote an entire paper on the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Doing so required watching over 3,000 minutes of numerous movies and analyzing Bond’s 86 total trips to 46 different countries based on current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advice for travel to those countries. Time which, the authors state in the abstract, “could easily have been spent on more pressing societal issues or forms of relaxation that are more acceptable in academic circles.”

Naturally, Mr. Bond’s line of work entails exposure to unpleasant things, such as poison, dehydration, heatstroke, and dangerous wildlife (everything from ticks to crocodiles), though oddly enough he never succumbs to any of it. He’s also curiously immune to hangovers, despite rarely drinking anything nonalcoholic. There are also less obvious risks: For one, 007 rarely washes his hands. During one movie, he handles raw chicken to lure away a pack of crocodiles but fails to wash his hands afterward, leaving him at risk for multiple food-borne illnesses.

Of course, we must address the elephant in the bedroom: Mr. Bond’s numerous, er, encounters with women. One would imagine the biggest risk to those women would be from the various STDs that likely course through Bond’s body, but of the 27% who died shortly after … encountering … him, all involved violence, with disease playing no obvious role. Who knows, maybe he’s clean? Stranger things have happened.

The timing of this article may seem a bit suspicious. Was it a PR stunt by the studio? Rest assured, the authors addressed this, noting that they received no funding for the study, and that, “given the futility of its academic value, this is deemed entirely appropriate by all authors.” We love when a punchline writes itself.

How to see Atlanta on $688.35 a day

The world is always changing, so we have to change with it. This week, LOTME becomes a travel guide, and our first stop is the Big A, the Big Peach, Dogwood City, Empire City of the South, Wakanda.

There’s lots to do in Atlanta: Celebrate a World Series win, visit the College Football Hall of Fame or the World of Coca Cola, or take the Stranger Things/Upside Down film locations tour. Serious adventurers, however, get out of the city and go to Emory Decatur Hospital in – you guessed it – Decatur (unofficial motto: “Everything is Greater in Decatur”).

Find the emergency room and ask for Taylor Davis, who will be your personal guide. She’ll show you how to check in at the desk, sit in the waiting room for 7 hours, and then leave without seeing any medical personnel or receiving any sort of attention whatsoever. All the things she did when she went there in July for a head injury.

Ms. Davis told Fox5 Atlanta: “I didn’t get my vitals taken, nobody called my name. I wasn’t seen at all.”

But wait! There’s more! By booking your trip through LOTMEgo* and using the code “Decatur,” you’ll get the Taylor Davis special, which includes a bill/cover charge for $688.35 from the hospital. An Emory Healthcare patient financial services employee told Ms. Davis that “you get charged before you are seen. Not for being seen.”

If all this has you ready to hop in your car (really?), then check out LOTMEgo* on Twittbook and InstaTok. You’ll also find trick-or-treating tips and discounts on haunted hospital tours.

*Does not actually exist

Breaking down the hot flash

Do you ever wonder why we scramble for cold things when we’re feeling nauseous? Whether it’s the cool air that needs to hit your face in the car or a cold, damp towel on the back of your neck, scientists think it could possibly be an evolutionary mechanism at the cellular level.

Motion sickness it’s actually a battle of body temperature, according to an article from LiveScience. Capillaries in the skin dilate, allowing for more blood flow near the skin’s surface and causing core temperature to fall. Once body temperature drops, the hypothalamus, which regulates temperature, tries to do its job by raising body temperature. Thus the hot flash!

The cold compress and cool air help fight the battle by counteracting the hypothalamus, but why the drop in body temperature to begin with?

There are a few theories. Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, told LiveScience that the lack of oxygen needed in body tissue to survive at lower temperatures could be making it difficult to get oxygen to the body when a person is ill, and is “more likely an adaptive response influenced by poorly understood mechanisms at the cellular level.”

Another theory is that the nausea and body temperature shift is the body’s natural response to help people vomit.

Then there’s the theory of “defensive hypothermia,” which suggests that cold sweats are a possible mechanism to conserve energy so the body can fight off an intruder, which was supported by a 2014 study and a 2016 review.

It’s another one of the body’s many survival tricks.

Teachers were right: Pupils can do the math

Teachers liked to preach that we wouldn’t have calculators with us all the time, but that wound up not being true. Our phones have calculators at the press of a button. But maybe even calculators aren’t always needed because our pupils do more math than you think.

The pupil light reflex – constrict in light and dilate in darkness – is well known, but recent work shows that pupil size is also regulated by cognitive and perceptual factors. By presenting subjects with images of various numbers of dots and measuring pupil size, the investigators were able to show “that numerical information is intrinsically related to perception,” lead author Dr. Elisa Castaldi of Florence University noted in a written statement.

The researchers found that pupils are responsible for important survival techniques. Coauthor David Burr of the University of Sydney and the University of Florence gave an evolutionary perspective: “When we look around, we spontaneously perceive the form, size, movement and colour of a scene. Equally spontaneously, we perceive the number of items before us. This ability, shared with most other animals, is an evolutionary fundamental: It reveals immediately important quantities, such as how many apples there are on the tree, or how many enemies are attacking.”

Useful information, indeed, but our pupils seem to be more interested in the quantity of beers in the refrigerator.

No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die

Movie watching usually requires a certain suspension of disbelief, and it’s safe to say James Bond movies require this more than most. Between the impossible gadgets and ludicrous doomsday plans, very few have ever stopped to consider the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Now, however, Bond, James Bond, has met his most formidable opponent: Wouter Graumans, a graduate student in epidemiology from the Netherlands. During a foray to Burkina Faso to study infectious diseases, Mr. Graumans came down with a case of food poisoning, which led him to wonder how 007 is able to trot across this big world of ours without contracting so much as a sinus infection.

Because Mr. Graumans is a man of science and conviction, mere speculation wasn’t enough. He and a group of coauthors wrote an entire paper on the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Doing so required watching over 3,000 minutes of numerous movies and analyzing Bond’s 86 total trips to 46 different countries based on current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advice for travel to those countries. Time which, the authors state in the abstract, “could easily have been spent on more pressing societal issues or forms of relaxation that are more acceptable in academic circles.”

Naturally, Mr. Bond’s line of work entails exposure to unpleasant things, such as poison, dehydration, heatstroke, and dangerous wildlife (everything from ticks to crocodiles), though oddly enough he never succumbs to any of it. He’s also curiously immune to hangovers, despite rarely drinking anything nonalcoholic. There are also less obvious risks: For one, 007 rarely washes his hands. During one movie, he handles raw chicken to lure away a pack of crocodiles but fails to wash his hands afterward, leaving him at risk for multiple food-borne illnesses.

Of course, we must address the elephant in the bedroom: Mr. Bond’s numerous, er, encounters with women. One would imagine the biggest risk to those women would be from the various STDs that likely course through Bond’s body, but of the 27% who died shortly after … encountering … him, all involved violence, with disease playing no obvious role. Who knows, maybe he’s clean? Stranger things have happened.

The timing of this article may seem a bit suspicious. Was it a PR stunt by the studio? Rest assured, the authors addressed this, noting that they received no funding for the study, and that, “given the futility of its academic value, this is deemed entirely appropriate by all authors.” We love when a punchline writes itself.

How to see Atlanta on $688.35 a day

The world is always changing, so we have to change with it. This week, LOTME becomes a travel guide, and our first stop is the Big A, the Big Peach, Dogwood City, Empire City of the South, Wakanda.

There’s lots to do in Atlanta: Celebrate a World Series win, visit the College Football Hall of Fame or the World of Coca Cola, or take the Stranger Things/Upside Down film locations tour. Serious adventurers, however, get out of the city and go to Emory Decatur Hospital in – you guessed it – Decatur (unofficial motto: “Everything is Greater in Decatur”).

Find the emergency room and ask for Taylor Davis, who will be your personal guide. She’ll show you how to check in at the desk, sit in the waiting room for 7 hours, and then leave without seeing any medical personnel or receiving any sort of attention whatsoever. All the things she did when she went there in July for a head injury.

Ms. Davis told Fox5 Atlanta: “I didn’t get my vitals taken, nobody called my name. I wasn’t seen at all.”

But wait! There’s more! By booking your trip through LOTMEgo* and using the code “Decatur,” you’ll get the Taylor Davis special, which includes a bill/cover charge for $688.35 from the hospital. An Emory Healthcare patient financial services employee told Ms. Davis that “you get charged before you are seen. Not for being seen.”

If all this has you ready to hop in your car (really?), then check out LOTMEgo* on Twittbook and InstaTok. You’ll also find trick-or-treating tips and discounts on haunted hospital tours.

*Does not actually exist

Breaking down the hot flash

Do you ever wonder why we scramble for cold things when we’re feeling nauseous? Whether it’s the cool air that needs to hit your face in the car or a cold, damp towel on the back of your neck, scientists think it could possibly be an evolutionary mechanism at the cellular level.

Motion sickness it’s actually a battle of body temperature, according to an article from LiveScience. Capillaries in the skin dilate, allowing for more blood flow near the skin’s surface and causing core temperature to fall. Once body temperature drops, the hypothalamus, which regulates temperature, tries to do its job by raising body temperature. Thus the hot flash!

The cold compress and cool air help fight the battle by counteracting the hypothalamus, but why the drop in body temperature to begin with?

There are a few theories. Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, told LiveScience that the lack of oxygen needed in body tissue to survive at lower temperatures could be making it difficult to get oxygen to the body when a person is ill, and is “more likely an adaptive response influenced by poorly understood mechanisms at the cellular level.”

Another theory is that the nausea and body temperature shift is the body’s natural response to help people vomit.

Then there’s the theory of “defensive hypothermia,” which suggests that cold sweats are a possible mechanism to conserve energy so the body can fight off an intruder, which was supported by a 2014 study and a 2016 review.

It’s another one of the body’s many survival tricks.

Teachers were right: Pupils can do the math

Teachers liked to preach that we wouldn’t have calculators with us all the time, but that wound up not being true. Our phones have calculators at the press of a button. But maybe even calculators aren’t always needed because our pupils do more math than you think.

The pupil light reflex – constrict in light and dilate in darkness – is well known, but recent work shows that pupil size is also regulated by cognitive and perceptual factors. By presenting subjects with images of various numbers of dots and measuring pupil size, the investigators were able to show “that numerical information is intrinsically related to perception,” lead author Dr. Elisa Castaldi of Florence University noted in a written statement.

The researchers found that pupils are responsible for important survival techniques. Coauthor David Burr of the University of Sydney and the University of Florence gave an evolutionary perspective: “When we look around, we spontaneously perceive the form, size, movement and colour of a scene. Equally spontaneously, we perceive the number of items before us. This ability, shared with most other animals, is an evolutionary fundamental: It reveals immediately important quantities, such as how many apples there are on the tree, or how many enemies are attacking.”

Useful information, indeed, but our pupils seem to be more interested in the quantity of beers in the refrigerator.

No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die

Movie watching usually requires a certain suspension of disbelief, and it’s safe to say James Bond movies require this more than most. Between the impossible gadgets and ludicrous doomsday plans, very few have ever stopped to consider the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Now, however, Bond, James Bond, has met his most formidable opponent: Wouter Graumans, a graduate student in epidemiology from the Netherlands. During a foray to Burkina Faso to study infectious diseases, Mr. Graumans came down with a case of food poisoning, which led him to wonder how 007 is able to trot across this big world of ours without contracting so much as a sinus infection.

Because Mr. Graumans is a man of science and conviction, mere speculation wasn’t enough. He and a group of coauthors wrote an entire paper on the health risks of the James Bond universe.

Doing so required watching over 3,000 minutes of numerous movies and analyzing Bond’s 86 total trips to 46 different countries based on current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advice for travel to those countries. Time which, the authors state in the abstract, “could easily have been spent on more pressing societal issues or forms of relaxation that are more acceptable in academic circles.”

Naturally, Mr. Bond’s line of work entails exposure to unpleasant things, such as poison, dehydration, heatstroke, and dangerous wildlife (everything from ticks to crocodiles), though oddly enough he never succumbs to any of it. He’s also curiously immune to hangovers, despite rarely drinking anything nonalcoholic. There are also less obvious risks: For one, 007 rarely washes his hands. During one movie, he handles raw chicken to lure away a pack of crocodiles but fails to wash his hands afterward, leaving him at risk for multiple food-borne illnesses.

Of course, we must address the elephant in the bedroom: Mr. Bond’s numerous, er, encounters with women. One would imagine the biggest risk to those women would be from the various STDs that likely course through Bond’s body, but of the 27% who died shortly after … encountering … him, all involved violence, with disease playing no obvious role. Who knows, maybe he’s clean? Stranger things have happened.

The timing of this article may seem a bit suspicious. Was it a PR stunt by the studio? Rest assured, the authors addressed this, noting that they received no funding for the study, and that, “given the futility of its academic value, this is deemed entirely appropriate by all authors.” We love when a punchline writes itself.

How to see Atlanta on $688.35 a day

The world is always changing, so we have to change with it. This week, LOTME becomes a travel guide, and our first stop is the Big A, the Big Peach, Dogwood City, Empire City of the South, Wakanda.

There’s lots to do in Atlanta: Celebrate a World Series win, visit the College Football Hall of Fame or the World of Coca Cola, or take the Stranger Things/Upside Down film locations tour. Serious adventurers, however, get out of the city and go to Emory Decatur Hospital in – you guessed it – Decatur (unofficial motto: “Everything is Greater in Decatur”).

Find the emergency room and ask for Taylor Davis, who will be your personal guide. She’ll show you how to check in at the desk, sit in the waiting room for 7 hours, and then leave without seeing any medical personnel or receiving any sort of attention whatsoever. All the things she did when she went there in July for a head injury.

Ms. Davis told Fox5 Atlanta: “I didn’t get my vitals taken, nobody called my name. I wasn’t seen at all.”

But wait! There’s more! By booking your trip through LOTMEgo* and using the code “Decatur,” you’ll get the Taylor Davis special, which includes a bill/cover charge for $688.35 from the hospital. An Emory Healthcare patient financial services employee told Ms. Davis that “you get charged before you are seen. Not for being seen.”

If all this has you ready to hop in your car (really?), then check out LOTMEgo* on Twittbook and InstaTok. You’ll also find trick-or-treating tips and discounts on haunted hospital tours.

*Does not actually exist

Breaking down the hot flash

Do you ever wonder why we scramble for cold things when we’re feeling nauseous? Whether it’s the cool air that needs to hit your face in the car or a cold, damp towel on the back of your neck, scientists think it could possibly be an evolutionary mechanism at the cellular level.

Motion sickness it’s actually a battle of body temperature, according to an article from LiveScience. Capillaries in the skin dilate, allowing for more blood flow near the skin’s surface and causing core temperature to fall. Once body temperature drops, the hypothalamus, which regulates temperature, tries to do its job by raising body temperature. Thus the hot flash!

The cold compress and cool air help fight the battle by counteracting the hypothalamus, but why the drop in body temperature to begin with?

There are a few theories. Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, told LiveScience that the lack of oxygen needed in body tissue to survive at lower temperatures could be making it difficult to get oxygen to the body when a person is ill, and is “more likely an adaptive response influenced by poorly understood mechanisms at the cellular level.”

Another theory is that the nausea and body temperature shift is the body’s natural response to help people vomit.

Then there’s the theory of “defensive hypothermia,” which suggests that cold sweats are a possible mechanism to conserve energy so the body can fight off an intruder, which was supported by a 2014 study and a 2016 review.

It’s another one of the body’s many survival tricks.

Teachers were right: Pupils can do the math

Teachers liked to preach that we wouldn’t have calculators with us all the time, but that wound up not being true. Our phones have calculators at the press of a button. But maybe even calculators aren’t always needed because our pupils do more math than you think.

The pupil light reflex – constrict in light and dilate in darkness – is well known, but recent work shows that pupil size is also regulated by cognitive and perceptual factors. By presenting subjects with images of various numbers of dots and measuring pupil size, the investigators were able to show “that numerical information is intrinsically related to perception,” lead author Dr. Elisa Castaldi of Florence University noted in a written statement.

The researchers found that pupils are responsible for important survival techniques. Coauthor David Burr of the University of Sydney and the University of Florence gave an evolutionary perspective: “When we look around, we spontaneously perceive the form, size, movement and colour of a scene. Equally spontaneously, we perceive the number of items before us. This ability, shared with most other animals, is an evolutionary fundamental: It reveals immediately important quantities, such as how many apples there are on the tree, or how many enemies are attacking.”

Useful information, indeed, but our pupils seem to be more interested in the quantity of beers in the refrigerator.

New study ‘changes understanding of bone loss after menopause’

In the longest study of bone loss in postmenopausal women to date, on average, bone mineral density (BMD) at the femoral neck (the most common location for a hip fracture) had dropped by 10% in 25 years – less than expected based on shorter studies.

Specifically, average BMD loss at the femoral neck was 0.4% per year during 25 years in this new study from Finland, compared with a drop of 1.6% per year over 15 years reported in other cohorts.

Five-year BMD change appeared to predict long-term bone loss. However, certain women had faster bone loss, indicating that they should be followed more closely.

“Although the average bone loss was 10.1% ... there is a significant variation in the bone loss rate” among women in the study, senior author Joonas Sirola, MD, PhD, associate professor, University of Eastern Finland, and coauthor Heikki Kröger, MD, PhD, a professor at the same university, explained to this news organization in an email, so “women with fast bone loss should receive special attention.

The findings from the Kuopio Osteoporosis Risk Factor and Prevention study by Anna Moilanen and colleagues were published online October 19 in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Several factors might explain the lower than expected drop in femoral neck BMD (the site that is used to diagnose osteoporosis), Dr. Sirola and Dr. Kröger said. BMD depends on a person’s age, race, sex, and genes. And compared with other countries, people in Finland consume more dairy products, and more postmenopausal women there take hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

“If otherwise indicated, HRT seemed to effectively protect from bone loss,” the researchers noted.

Also, the number of women who smoked or used corticosteroids was low, so bone loss in other populations may be higher. Moreover, the women who completed the study may have been healthier to start with, so the results should be interpreted with caution, they urge.

Nevertheless, the study sheds light on long-term changes in BMD in postmenopausal women and “stresses the importance of high peak bone mass before menopause and keeping a healthy weight” during aging to protect bone health, they say.

Indeed the work “changes our understanding of bone loss in older women,” said Dr. Kröger in a press release from the university.

Check BMD every 5 years after menopause

Invited to comment, American Society of Bone and Mineral Research President Peter R. Ebeling, MD, who was not involved with the research, noted key findings are that the rate of femoral neck bone loss after perimenopause was far less than previously expected, and 5-year BMD change appeared to predict long-term bone loss in postmenopausal women.

“We know bone loss begins 1 year before menopause and accelerates over the next 5 years,” Dr. Ebeling, from Monash University, Melbourne, added in an email. “This study indicates some stabilization of bone loss thereafter with lesser effects of low estrogen levels on bone.”

“It probably means bone density does not need to be measured as frequently following the menopause transition and could be every 5 years, rather than every 2 years, if there was concern about continuing bone loss.”

Baseline risk factors and long-term changes in BMD

For the study, researchers examined the association between risk factors for bone loss and long-term changes in femoral neck BMD in 2,695 women living in Kuopio who were 47 to 56 years old in 1989. The women were a mean age of 53 years, and 62% were postmenopausal.

They answered questionnaires and had femoral neck BMD measured by DEXA every 5 years.

A total of 2,695, 2,583, 2,482, 2,135, 1,305, and 686 women were assessed at baseline and 5-, 10-, 15-, 20- and 25-year follow-ups, respectively, indicating significant study drop-out by 25 years.

By then, 17% of patients had died, 9% needed long-term care, some were unwilling to continue in the study, and others had factors that would have resulted in DEXA measurement errors (for example, hip implants, spine degeneration).

Researchers divided participants into quartiles of mean initial femoral neck BMD: 1.09 g/cm2, 0.97 g/cm2, 0.89 g/cm2, and 0.79 g/cm2, corresponding with quartiles 1 to 4 respectively (where quartile 1 had the highest initial femoral BMD and quartile 4 the lowest).

At 25 years, the mean femoral BMD had dropped to 0.97 g/cm2, 0.87 g/cm2, 0.80 g/cm2, and 0.73 g/cm2 in these respective quartiles.

Women lost 0.9%, 0.5%, 3.0%, and 1.0% of their initial BMD each year in quartiles 1 to 4, respectively.

And at 25 years, the women had lost 22.5%, 12.5%, 7.5%, and 2.5% of their initial BMD in the four quartiles, respectively.

Women in quartile 1 had the greatest drop in femoral BMD at 25 years, although their mean BMD at 25 years was higher than the mean initial BMD of the other women.

The prevalence of bone-affecting diseases, smoking, and use of vitamin D/calcium supplementation, corticosteroids, or alcohol was similar in the four quartiles and was not associated with significant differences in annual bone loss.

The most important protective factor was HRT

However, body mass index (BMI) and HRT were significantly different in the four quartiles.

On average, women in quartile 1 had a mean BMI of 26.7 kg/m2 at baseline and 27.8 kg/m2 at 25 years. Women in quartile 4 (lowest initial BMD and lowest drop in BMD) had a mean BMI of 24.9 kg/m2 at baseline and 28.4 kg/m2 at 25 years.

Women in quartile 4 (lowest initial BMD and lowest drop in BMD) were more likely to take HRT than women in quartile 1 (highest initial BMD and highest drop in BMD), at 41% versus 26%, respectively.

“The average decrease in bone mineral density was lower than has been assumed on the basis of earlier, shorter follow-ups where the bone loss rate at the femoral neck has been estimated to be even more than 20%,” Dr. Sirola commented in the press release.

“There were also surprisingly few risk factors affecting bone mineral density. The most significant factor protecting against bone loss was hormone replacement therapy. Weight gain during the follow-up also protected against bone loss,” Dr. Sirola added.

The study was funded by the Academy of Finland, Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, and the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation. The authors and Dr. Ebeling have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the longest study of bone loss in postmenopausal women to date, on average, bone mineral density (BMD) at the femoral neck (the most common location for a hip fracture) had dropped by 10% in 25 years – less than expected based on shorter studies.

Specifically, average BMD loss at the femoral neck was 0.4% per year during 25 years in this new study from Finland, compared with a drop of 1.6% per year over 15 years reported in other cohorts.

Five-year BMD change appeared to predict long-term bone loss. However, certain women had faster bone loss, indicating that they should be followed more closely.

“Although the average bone loss was 10.1% ... there is a significant variation in the bone loss rate” among women in the study, senior author Joonas Sirola, MD, PhD, associate professor, University of Eastern Finland, and coauthor Heikki Kröger, MD, PhD, a professor at the same university, explained to this news organization in an email, so “women with fast bone loss should receive special attention.

The findings from the Kuopio Osteoporosis Risk Factor and Prevention study by Anna Moilanen and colleagues were published online October 19 in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Several factors might explain the lower than expected drop in femoral neck BMD (the site that is used to diagnose osteoporosis), Dr. Sirola and Dr. Kröger said. BMD depends on a person’s age, race, sex, and genes. And compared with other countries, people in Finland consume more dairy products, and more postmenopausal women there take hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

“If otherwise indicated, HRT seemed to effectively protect from bone loss,” the researchers noted.

Also, the number of women who smoked or used corticosteroids was low, so bone loss in other populations may be higher. Moreover, the women who completed the study may have been healthier to start with, so the results should be interpreted with caution, they urge.

Nevertheless, the study sheds light on long-term changes in BMD in postmenopausal women and “stresses the importance of high peak bone mass before menopause and keeping a healthy weight” during aging to protect bone health, they say.

Indeed the work “changes our understanding of bone loss in older women,” said Dr. Kröger in a press release from the university.

Check BMD every 5 years after menopause

Invited to comment, American Society of Bone and Mineral Research President Peter R. Ebeling, MD, who was not involved with the research, noted key findings are that the rate of femoral neck bone loss after perimenopause was far less than previously expected, and 5-year BMD change appeared to predict long-term bone loss in postmenopausal women.

“We know bone loss begins 1 year before menopause and accelerates over the next 5 years,” Dr. Ebeling, from Monash University, Melbourne, added in an email. “This study indicates some stabilization of bone loss thereafter with lesser effects of low estrogen levels on bone.”

“It probably means bone density does not need to be measured as frequently following the menopause transition and could be every 5 years, rather than every 2 years, if there was concern about continuing bone loss.”

Baseline risk factors and long-term changes in BMD

For the study, researchers examined the association between risk factors for bone loss and long-term changes in femoral neck BMD in 2,695 women living in Kuopio who were 47 to 56 years old in 1989. The women were a mean age of 53 years, and 62% were postmenopausal.

They answered questionnaires and had femoral neck BMD measured by DEXA every 5 years.