User login

What's your diagnosis?

Sigmoid colon perforation secondary to transcutaneous epicardial pacer wires.

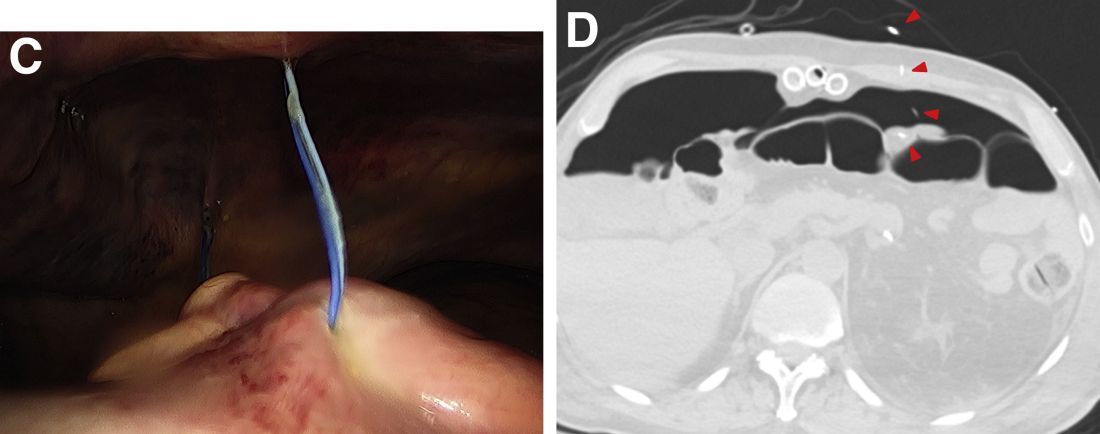

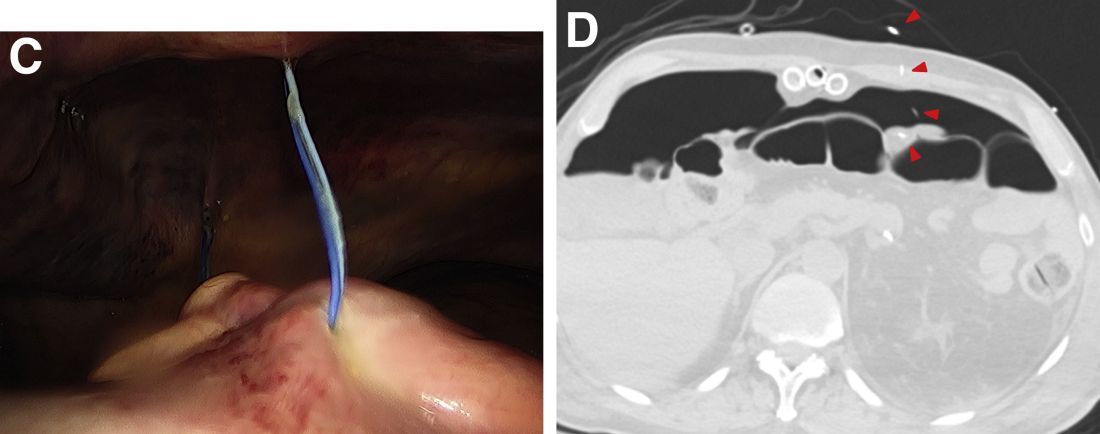

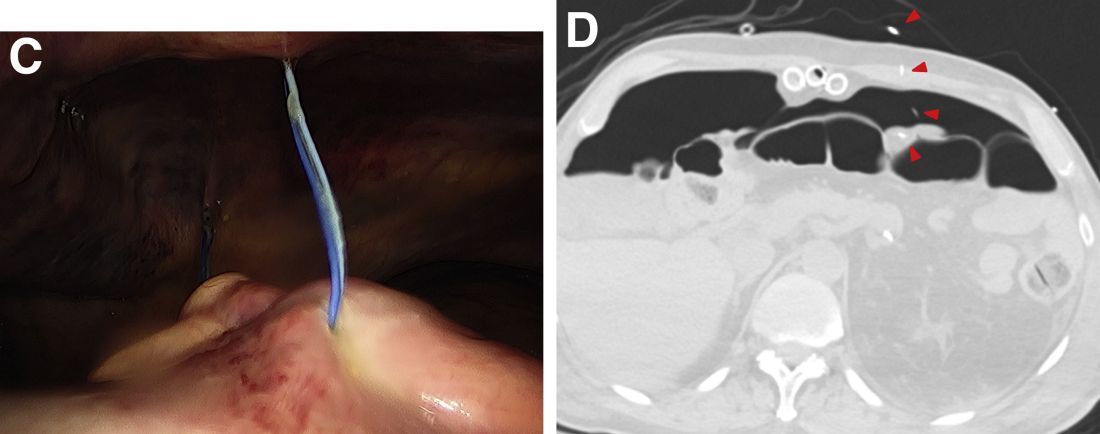

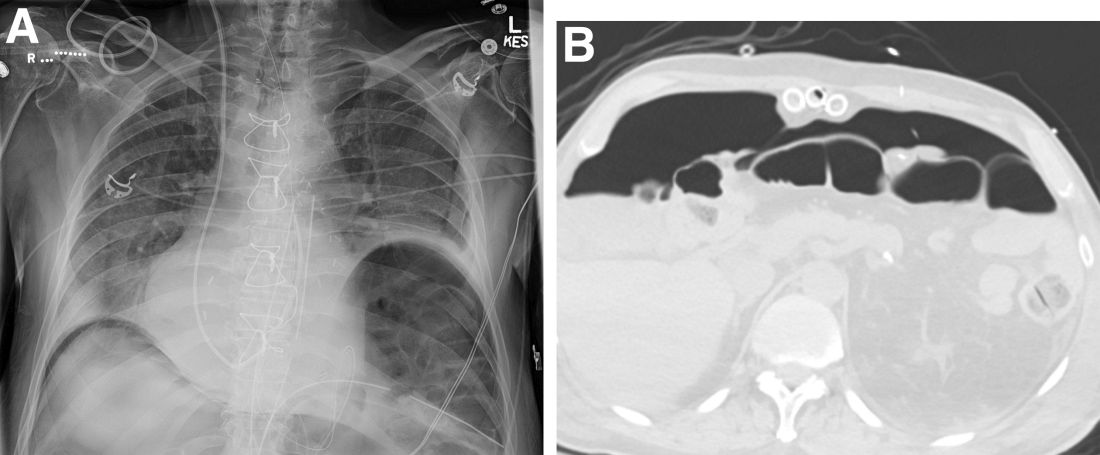

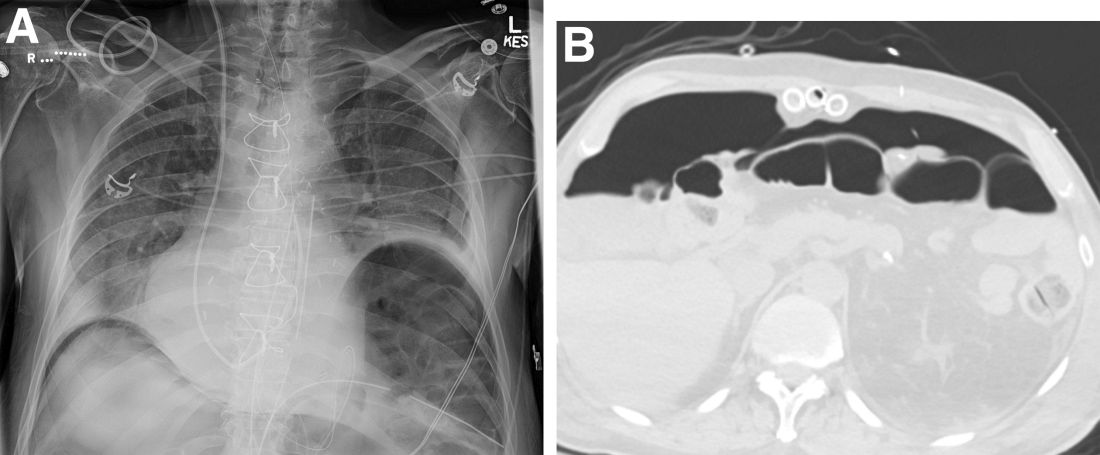

A plain film image (Figure A) shows diffusely dilated loops of bowel with subdiaphragmatic air concerning for GI viscous perforation. Dedicated cross-sectional imaging confirms intra-abdominal free air, and in representative cross section, the epicardial pacing wires can be visualized within the gastrointestinal lumen (Figure D, arrows). At the time of surgical consultation, the radiology report was notable for concern regarding possible disruption of peritoneum secondary to the difficult surgical chest tube placement in a patient with a high-riding left hemidiaphragm. Urgent laparoscopic exploration secondary to these findings unexpectedly revealed that the transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires had been inadvertently placed through the sigmoid colon (Figure C). The pacer wires were cut and removed intraoperatively. Unfortunately, 4 days after removal of pacer wires, the patient continued to have ongoing distension and was found to have sigmoid volvulus necessitating endoscopic decompression. After a prolonged hospitalization and recovery, he was discharged with a normal bowel pattern and tolerating oral intake to a skilled nursing facility.

Temporary transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires are often placed after complex cardiovascular surgical procedures. Complications from wire placement are thought to be relatively rare and are typically associated with migration into local structures after wire placement and infectious complications secondary to retained wires.1,2 Perforation of local structures during placement is less common, and GI viscous perforation in particular is not a well-characterized cause of associated morbidity.3

Our case demonstrates that, in patients with hemidiaphragm elevation, epicardial wire placement risks GI viscous perforation. Furthermore, given the frequency of concomitant surgical hardware in this patient population, identification of malpositioned epicardial wires on plain film and even cross-sectional imaging can be difficult and can delay diagnosis.

References

1. Del Nido P, Goldman BS. J Card Surg. 1989 Mar;4(1):99-103.

2. Kapoor A et al. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011 Jul;13(1):104-6.

3. Haba J et al. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2013 Feb;64(1):77-80.

Sigmoid colon perforation secondary to transcutaneous epicardial pacer wires.

A plain film image (Figure A) shows diffusely dilated loops of bowel with subdiaphragmatic air concerning for GI viscous perforation. Dedicated cross-sectional imaging confirms intra-abdominal free air, and in representative cross section, the epicardial pacing wires can be visualized within the gastrointestinal lumen (Figure D, arrows). At the time of surgical consultation, the radiology report was notable for concern regarding possible disruption of peritoneum secondary to the difficult surgical chest tube placement in a patient with a high-riding left hemidiaphragm. Urgent laparoscopic exploration secondary to these findings unexpectedly revealed that the transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires had been inadvertently placed through the sigmoid colon (Figure C). The pacer wires were cut and removed intraoperatively. Unfortunately, 4 days after removal of pacer wires, the patient continued to have ongoing distension and was found to have sigmoid volvulus necessitating endoscopic decompression. After a prolonged hospitalization and recovery, he was discharged with a normal bowel pattern and tolerating oral intake to a skilled nursing facility.

Temporary transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires are often placed after complex cardiovascular surgical procedures. Complications from wire placement are thought to be relatively rare and are typically associated with migration into local structures after wire placement and infectious complications secondary to retained wires.1,2 Perforation of local structures during placement is less common, and GI viscous perforation in particular is not a well-characterized cause of associated morbidity.3

Our case demonstrates that, in patients with hemidiaphragm elevation, epicardial wire placement risks GI viscous perforation. Furthermore, given the frequency of concomitant surgical hardware in this patient population, identification of malpositioned epicardial wires on plain film and even cross-sectional imaging can be difficult and can delay diagnosis.

References

1. Del Nido P, Goldman BS. J Card Surg. 1989 Mar;4(1):99-103.

2. Kapoor A et al. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011 Jul;13(1):104-6.

3. Haba J et al. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2013 Feb;64(1):77-80.

Sigmoid colon perforation secondary to transcutaneous epicardial pacer wires.

A plain film image (Figure A) shows diffusely dilated loops of bowel with subdiaphragmatic air concerning for GI viscous perforation. Dedicated cross-sectional imaging confirms intra-abdominal free air, and in representative cross section, the epicardial pacing wires can be visualized within the gastrointestinal lumen (Figure D, arrows). At the time of surgical consultation, the radiology report was notable for concern regarding possible disruption of peritoneum secondary to the difficult surgical chest tube placement in a patient with a high-riding left hemidiaphragm. Urgent laparoscopic exploration secondary to these findings unexpectedly revealed that the transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires had been inadvertently placed through the sigmoid colon (Figure C). The pacer wires were cut and removed intraoperatively. Unfortunately, 4 days after removal of pacer wires, the patient continued to have ongoing distension and was found to have sigmoid volvulus necessitating endoscopic decompression. After a prolonged hospitalization and recovery, he was discharged with a normal bowel pattern and tolerating oral intake to a skilled nursing facility.

Temporary transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires are often placed after complex cardiovascular surgical procedures. Complications from wire placement are thought to be relatively rare and are typically associated with migration into local structures after wire placement and infectious complications secondary to retained wires.1,2 Perforation of local structures during placement is less common, and GI viscous perforation in particular is not a well-characterized cause of associated morbidity.3

Our case demonstrates that, in patients with hemidiaphragm elevation, epicardial wire placement risks GI viscous perforation. Furthermore, given the frequency of concomitant surgical hardware in this patient population, identification of malpositioned epicardial wires on plain film and even cross-sectional imaging can be difficult and can delay diagnosis.

References

1. Del Nido P, Goldman BS. J Card Surg. 1989 Mar;4(1):99-103.

2. Kapoor A et al. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011 Jul;13(1):104-6.

3. Haba J et al. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2013 Feb;64(1):77-80.

Question: An 82-year-old man was admitted for urgent coronary artery bypass and concurrent mitral valve repair. Intraoperatively, he underwent cardiopulmonary bypass, epicardial pacing, and placement of two anterior mediastinal and one pleural chest tubes. After a relatively unremarkable initial postoperative course and nonnarcotic pain control, concern for ileus developed on postoperative day 4. A nasogastric tube was placed out of concern for worsening somnolence, nausea, and the inability to safely tolerate oral intake. The patient had been passing flatus but had yet to have a bowel movement since the operation. Physical examination at the time was notable for a soft abdomen with diffuse tenderness and voluntary guarding. Subsequent plain film imaging to confirm nasogastric tube placement (Figure A) and follow-up computed tomography imaging (Figure B) are shown.

What's the diagnosis?

A box of memories

My office’s storage room has an old bankers box, which has been there since I moved 8 years ago. Before that it was at my other office, behind an old desk. I had no idea what was in it, I always assumed office supplies, surplus drug company pens and sticky notes, who-knows-whats.

Last week I had one of those days where everyone cancels, so I decided to investigate the box.

It was packed with 10 years worth (2000-2010) of my secretary’s MRI scheduling sheets that had somehow escaped occasional shredding purges. So I sat down next to the office shredder to get rid of them.

As I fed the sheets in, the names jumped out at me. Some I have absolutely no recollection of. Others I still see today.

There were names of the long-deceased, bringing them back to me for the first time in years. There were others that I have no idea what happened to – they must have just stopped seeing me at some point, though for the life of me I can’t remember when, or why. Yet, in my mind, there they were, as if I’d just seen them yesterday. A few times I got curious enough to turn back to my computer and look up their charts, trying to remember their stories.

Then there were those I still remember clearly, every single detail of, in spite of the elapsed time. Something about their case or personality had indelibly etched them in my memory. A valuable lesson learned from them that had something or nothing to do with medicine that’s still with me.

Looking back, I’d guess I’ve seen roughly 15,000-20,000 patients over my career. Not nearly as many as my colleagues in general practice, but still quite a few. A decent sized basketball arena full.

The majority don’t stick with you. That’s the way it is in life.

The ones we didn’t know long – but who are still clearly remembered – are also valuable. In their own way, perhaps unknowingly, they made an impact that hopefully makes us better.

For that I’ll always be grateful to them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

My office’s storage room has an old bankers box, which has been there since I moved 8 years ago. Before that it was at my other office, behind an old desk. I had no idea what was in it, I always assumed office supplies, surplus drug company pens and sticky notes, who-knows-whats.

Last week I had one of those days where everyone cancels, so I decided to investigate the box.

It was packed with 10 years worth (2000-2010) of my secretary’s MRI scheduling sheets that had somehow escaped occasional shredding purges. So I sat down next to the office shredder to get rid of them.

As I fed the sheets in, the names jumped out at me. Some I have absolutely no recollection of. Others I still see today.

There were names of the long-deceased, bringing them back to me for the first time in years. There were others that I have no idea what happened to – they must have just stopped seeing me at some point, though for the life of me I can’t remember when, or why. Yet, in my mind, there they were, as if I’d just seen them yesterday. A few times I got curious enough to turn back to my computer and look up their charts, trying to remember their stories.

Then there were those I still remember clearly, every single detail of, in spite of the elapsed time. Something about their case or personality had indelibly etched them in my memory. A valuable lesson learned from them that had something or nothing to do with medicine that’s still with me.

Looking back, I’d guess I’ve seen roughly 15,000-20,000 patients over my career. Not nearly as many as my colleagues in general practice, but still quite a few. A decent sized basketball arena full.

The majority don’t stick with you. That’s the way it is in life.

The ones we didn’t know long – but who are still clearly remembered – are also valuable. In their own way, perhaps unknowingly, they made an impact that hopefully makes us better.

For that I’ll always be grateful to them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

My office’s storage room has an old bankers box, which has been there since I moved 8 years ago. Before that it was at my other office, behind an old desk. I had no idea what was in it, I always assumed office supplies, surplus drug company pens and sticky notes, who-knows-whats.

Last week I had one of those days where everyone cancels, so I decided to investigate the box.

It was packed with 10 years worth (2000-2010) of my secretary’s MRI scheduling sheets that had somehow escaped occasional shredding purges. So I sat down next to the office shredder to get rid of them.

As I fed the sheets in, the names jumped out at me. Some I have absolutely no recollection of. Others I still see today.

There were names of the long-deceased, bringing them back to me for the first time in years. There were others that I have no idea what happened to – they must have just stopped seeing me at some point, though for the life of me I can’t remember when, or why. Yet, in my mind, there they were, as if I’d just seen them yesterday. A few times I got curious enough to turn back to my computer and look up their charts, trying to remember their stories.

Then there were those I still remember clearly, every single detail of, in spite of the elapsed time. Something about their case or personality had indelibly etched them in my memory. A valuable lesson learned from them that had something or nothing to do with medicine that’s still with me.

Looking back, I’d guess I’ve seen roughly 15,000-20,000 patients over my career. Not nearly as many as my colleagues in general practice, but still quite a few. A decent sized basketball arena full.

The majority don’t stick with you. That’s the way it is in life.

The ones we didn’t know long – but who are still clearly remembered – are also valuable. In their own way, perhaps unknowingly, they made an impact that hopefully makes us better.

For that I’ll always be grateful to them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Without PrEP, a third of new HIV cases occur in MSM at low risk

Nearly one in three gay and bisexual men who were diagnosed with HIV at U.K. sexual health clinics didn’t meet the criteria for “high risk” that would signal to a clinician that they would be good candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

And that means that people who appear lower risk may still be good candidates for the HIV prevention pills, said Ann Sullivan, MD, consulting physician at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London.

“If people are coming forward for PrEP, they have self-identified that they need PrEP, [and] we should be allowing them to take PrEP,” said Dr. Sullivan at the 18th European AIDS Society Conference (EACS 2021). “We just need to trust patients. People know their risk, and we just have to accept that they know what they need best.”

And while this trial was made up of 95% gay and bisexual men, that ethos applies to every other group that could benefit from PrEP, including cisgender and transgender women and other gender-diverse people, Latinos, and Black Americans. In the United States, these groups make up nearly half of those who could benefit from PrEP under older guidelines but account for just 8% of people currently taking PrEP.

The finding also reinforces growing calls from health care providers to reduce gatekeeping around PrEP. For instance, there’s a move underway by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where drafts of updated PrEP guidelines call for clinicians to talk to any sexually active teenager and adult about PrEP.

For the PrEP Impact trial, gay and bisexual men who received sexual health care at UK National Health Service sexual health clinics were invited to enroll in the study based on national PrEP guidelines. Those guidelines included being a cisgender man who had had sex with men not currently living with HIV and reporting condomless anal sex in the last 3 months; having a male partner whose HIV status they don’t know or who doesn’t have an undetectable viral load and with whom they’ve had condomless anal sex; or someone who doesn’t reach those criteria but whom the clinician thinks would be a good candidate.

Between Oct. 2017 and Feb. 2020, a total of 17,770 gay and bisexual men and 503 transgender or nonbinary people enrolled in the trial and were paired with 97,098 gay and bisexual men who didn’t use PrEP. (Data from the transgender participants were reported in a separate presentation.) The median age was 27 years, with 14.4% of the cisgender gay men between the ages of 16 and 24. Three out of four cis men were White, most lived in London, and more than half came from very-low-income neighborhoods.

Participants and controls were assessed for whether they were at particularly high risk for acquiring HIV, such as having used PrEP, having had two or more HIV tests, having had a rectal bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI), or having had contact with someone with HIV or syphilis.

At the end of Feb. 2020, 24 cisgender men on PrEP had acquired HIV compared with 670 in the control group – an 87% reduction in HIV acquisition. Only one of those 24 cis men had lab-confirmed high adherence to PrEP. However, because the hair samples used to judge drug concentration weren’t long enough, Dr. Sullivan and colleagues were unable to assess whether the person really was fully adherent to treatment for the length of the trial.

But when they looked at the assessed behavior of people who acquired HIV, the two groups diverged. While a full 92% of people using PrEP had had STI diagnoses and other markers of increased risk, that was true for only 71% of people not taking PrEP. That meant, Dr. Sullivan said in an interview, that screening guidelines for PrEP were missing 29% of people with low assessed risk for HIV who nevertheless acquired the virus.

The findings led Antonio Urbina, MD, who both prescribes PrEP and manages Mount Sinai Medical Center’s PrEP program in New York, to the same conclusion that Dr. Sullivan and her team came to: that no screener is going to account for everything, and that there may be things that patients don’t want to tell their clinicians about their risk, either because of their own internalized stigma or their calculation that they aren’t comfortable enough with their providers to be honest.

“It reinforces to me that I need to ask more open-ended questions regarding risk and then just talk more about PrEP,” said Dr. Urbina, professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine. “Risk is dynamic and changes. And the great thing about PrEP is that if the risk goes up or down, if you have PrEP on board, you maintain this protection against HIV.”

An accompanying presentation on the transgender and nonbinary participants in the Impact Trial found that just one of 503 PrEP users acquired HIV. But here, too, there were people who could have benefited from PrEP but didn’t take it: Of the 477 trans and nonbinary participants who acted as controls, 97 were eligible by current guidelines but didn’t take PrEP. One in four of those declined the offer to take PrEP; the rest weren’t able to take it because they lived outside the treatment area. That, combined with a significantly lower likelihood that Black trans and nonbinary people took PrEP, indicated that work needs to be done to address the needs of people geographically and ethnically.

The data on gay men also raised the “who’s left out” issue for Gina Simoncini, MD, medical director for the Philadelphia AIDS Healthcare Foundation Healthcare Center. Dr. Simoncini previously taught attending physicians at Temple University how to prescribe PrEP and has done many grand rounds for primary care providers on how to manage PrEP.

“My biggest issue with this data is: What about the people who aren’t going to sexual health clinics?” she said. “What about the kid who’s 16 and maybe just barely putting his feet into the waters of sex and doesn’t feel quite comfortable going to a sexual health clinic? What about the trans Indian girl who can’t get to sexual health clinics because of family stigma and cultural stigma? The more we move toward primary care, the more people need to get on board with this.”

Dr. Sullivan reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Simoncini is an employee of AIDS Healthcare Foundation and has received advisory board fees from ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Urbina sits on the scientific advisory councils for Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, and Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly one in three gay and bisexual men who were diagnosed with HIV at U.K. sexual health clinics didn’t meet the criteria for “high risk” that would signal to a clinician that they would be good candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

And that means that people who appear lower risk may still be good candidates for the HIV prevention pills, said Ann Sullivan, MD, consulting physician at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London.

“If people are coming forward for PrEP, they have self-identified that they need PrEP, [and] we should be allowing them to take PrEP,” said Dr. Sullivan at the 18th European AIDS Society Conference (EACS 2021). “We just need to trust patients. People know their risk, and we just have to accept that they know what they need best.”

And while this trial was made up of 95% gay and bisexual men, that ethos applies to every other group that could benefit from PrEP, including cisgender and transgender women and other gender-diverse people, Latinos, and Black Americans. In the United States, these groups make up nearly half of those who could benefit from PrEP under older guidelines but account for just 8% of people currently taking PrEP.

The finding also reinforces growing calls from health care providers to reduce gatekeeping around PrEP. For instance, there’s a move underway by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where drafts of updated PrEP guidelines call for clinicians to talk to any sexually active teenager and adult about PrEP.

For the PrEP Impact trial, gay and bisexual men who received sexual health care at UK National Health Service sexual health clinics were invited to enroll in the study based on national PrEP guidelines. Those guidelines included being a cisgender man who had had sex with men not currently living with HIV and reporting condomless anal sex in the last 3 months; having a male partner whose HIV status they don’t know or who doesn’t have an undetectable viral load and with whom they’ve had condomless anal sex; or someone who doesn’t reach those criteria but whom the clinician thinks would be a good candidate.

Between Oct. 2017 and Feb. 2020, a total of 17,770 gay and bisexual men and 503 transgender or nonbinary people enrolled in the trial and were paired with 97,098 gay and bisexual men who didn’t use PrEP. (Data from the transgender participants were reported in a separate presentation.) The median age was 27 years, with 14.4% of the cisgender gay men between the ages of 16 and 24. Three out of four cis men were White, most lived in London, and more than half came from very-low-income neighborhoods.

Participants and controls were assessed for whether they were at particularly high risk for acquiring HIV, such as having used PrEP, having had two or more HIV tests, having had a rectal bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI), or having had contact with someone with HIV or syphilis.

At the end of Feb. 2020, 24 cisgender men on PrEP had acquired HIV compared with 670 in the control group – an 87% reduction in HIV acquisition. Only one of those 24 cis men had lab-confirmed high adherence to PrEP. However, because the hair samples used to judge drug concentration weren’t long enough, Dr. Sullivan and colleagues were unable to assess whether the person really was fully adherent to treatment for the length of the trial.

But when they looked at the assessed behavior of people who acquired HIV, the two groups diverged. While a full 92% of people using PrEP had had STI diagnoses and other markers of increased risk, that was true for only 71% of people not taking PrEP. That meant, Dr. Sullivan said in an interview, that screening guidelines for PrEP were missing 29% of people with low assessed risk for HIV who nevertheless acquired the virus.

The findings led Antonio Urbina, MD, who both prescribes PrEP and manages Mount Sinai Medical Center’s PrEP program in New York, to the same conclusion that Dr. Sullivan and her team came to: that no screener is going to account for everything, and that there may be things that patients don’t want to tell their clinicians about their risk, either because of their own internalized stigma or their calculation that they aren’t comfortable enough with their providers to be honest.

“It reinforces to me that I need to ask more open-ended questions regarding risk and then just talk more about PrEP,” said Dr. Urbina, professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine. “Risk is dynamic and changes. And the great thing about PrEP is that if the risk goes up or down, if you have PrEP on board, you maintain this protection against HIV.”

An accompanying presentation on the transgender and nonbinary participants in the Impact Trial found that just one of 503 PrEP users acquired HIV. But here, too, there were people who could have benefited from PrEP but didn’t take it: Of the 477 trans and nonbinary participants who acted as controls, 97 were eligible by current guidelines but didn’t take PrEP. One in four of those declined the offer to take PrEP; the rest weren’t able to take it because they lived outside the treatment area. That, combined with a significantly lower likelihood that Black trans and nonbinary people took PrEP, indicated that work needs to be done to address the needs of people geographically and ethnically.

The data on gay men also raised the “who’s left out” issue for Gina Simoncini, MD, medical director for the Philadelphia AIDS Healthcare Foundation Healthcare Center. Dr. Simoncini previously taught attending physicians at Temple University how to prescribe PrEP and has done many grand rounds for primary care providers on how to manage PrEP.

“My biggest issue with this data is: What about the people who aren’t going to sexual health clinics?” she said. “What about the kid who’s 16 and maybe just barely putting his feet into the waters of sex and doesn’t feel quite comfortable going to a sexual health clinic? What about the trans Indian girl who can’t get to sexual health clinics because of family stigma and cultural stigma? The more we move toward primary care, the more people need to get on board with this.”

Dr. Sullivan reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Simoncini is an employee of AIDS Healthcare Foundation and has received advisory board fees from ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Urbina sits on the scientific advisory councils for Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, and Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly one in three gay and bisexual men who were diagnosed with HIV at U.K. sexual health clinics didn’t meet the criteria for “high risk” that would signal to a clinician that they would be good candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

And that means that people who appear lower risk may still be good candidates for the HIV prevention pills, said Ann Sullivan, MD, consulting physician at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London.

“If people are coming forward for PrEP, they have self-identified that they need PrEP, [and] we should be allowing them to take PrEP,” said Dr. Sullivan at the 18th European AIDS Society Conference (EACS 2021). “We just need to trust patients. People know their risk, and we just have to accept that they know what they need best.”

And while this trial was made up of 95% gay and bisexual men, that ethos applies to every other group that could benefit from PrEP, including cisgender and transgender women and other gender-diverse people, Latinos, and Black Americans. In the United States, these groups make up nearly half of those who could benefit from PrEP under older guidelines but account for just 8% of people currently taking PrEP.

The finding also reinforces growing calls from health care providers to reduce gatekeeping around PrEP. For instance, there’s a move underway by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where drafts of updated PrEP guidelines call for clinicians to talk to any sexually active teenager and adult about PrEP.

For the PrEP Impact trial, gay and bisexual men who received sexual health care at UK National Health Service sexual health clinics were invited to enroll in the study based on national PrEP guidelines. Those guidelines included being a cisgender man who had had sex with men not currently living with HIV and reporting condomless anal sex in the last 3 months; having a male partner whose HIV status they don’t know or who doesn’t have an undetectable viral load and with whom they’ve had condomless anal sex; or someone who doesn’t reach those criteria but whom the clinician thinks would be a good candidate.

Between Oct. 2017 and Feb. 2020, a total of 17,770 gay and bisexual men and 503 transgender or nonbinary people enrolled in the trial and were paired with 97,098 gay and bisexual men who didn’t use PrEP. (Data from the transgender participants were reported in a separate presentation.) The median age was 27 years, with 14.4% of the cisgender gay men between the ages of 16 and 24. Three out of four cis men were White, most lived in London, and more than half came from very-low-income neighborhoods.

Participants and controls were assessed for whether they were at particularly high risk for acquiring HIV, such as having used PrEP, having had two or more HIV tests, having had a rectal bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI), or having had contact with someone with HIV or syphilis.

At the end of Feb. 2020, 24 cisgender men on PrEP had acquired HIV compared with 670 in the control group – an 87% reduction in HIV acquisition. Only one of those 24 cis men had lab-confirmed high adherence to PrEP. However, because the hair samples used to judge drug concentration weren’t long enough, Dr. Sullivan and colleagues were unable to assess whether the person really was fully adherent to treatment for the length of the trial.

But when they looked at the assessed behavior of people who acquired HIV, the two groups diverged. While a full 92% of people using PrEP had had STI diagnoses and other markers of increased risk, that was true for only 71% of people not taking PrEP. That meant, Dr. Sullivan said in an interview, that screening guidelines for PrEP were missing 29% of people with low assessed risk for HIV who nevertheless acquired the virus.

The findings led Antonio Urbina, MD, who both prescribes PrEP and manages Mount Sinai Medical Center’s PrEP program in New York, to the same conclusion that Dr. Sullivan and her team came to: that no screener is going to account for everything, and that there may be things that patients don’t want to tell their clinicians about their risk, either because of their own internalized stigma or their calculation that they aren’t comfortable enough with their providers to be honest.

“It reinforces to me that I need to ask more open-ended questions regarding risk and then just talk more about PrEP,” said Dr. Urbina, professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine. “Risk is dynamic and changes. And the great thing about PrEP is that if the risk goes up or down, if you have PrEP on board, you maintain this protection against HIV.”

An accompanying presentation on the transgender and nonbinary participants in the Impact Trial found that just one of 503 PrEP users acquired HIV. But here, too, there were people who could have benefited from PrEP but didn’t take it: Of the 477 trans and nonbinary participants who acted as controls, 97 were eligible by current guidelines but didn’t take PrEP. One in four of those declined the offer to take PrEP; the rest weren’t able to take it because they lived outside the treatment area. That, combined with a significantly lower likelihood that Black trans and nonbinary people took PrEP, indicated that work needs to be done to address the needs of people geographically and ethnically.

The data on gay men also raised the “who’s left out” issue for Gina Simoncini, MD, medical director for the Philadelphia AIDS Healthcare Foundation Healthcare Center. Dr. Simoncini previously taught attending physicians at Temple University how to prescribe PrEP and has done many grand rounds for primary care providers on how to manage PrEP.

“My biggest issue with this data is: What about the people who aren’t going to sexual health clinics?” she said. “What about the kid who’s 16 and maybe just barely putting his feet into the waters of sex and doesn’t feel quite comfortable going to a sexual health clinic? What about the trans Indian girl who can’t get to sexual health clinics because of family stigma and cultural stigma? The more we move toward primary care, the more people need to get on board with this.”

Dr. Sullivan reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Simoncini is an employee of AIDS Healthcare Foundation and has received advisory board fees from ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Urbina sits on the scientific advisory councils for Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, and Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-acting HIV ART: Lessons from a year of Cabenuva

One year into offering the first long-acting injectable HIV treatment to his patients, Jonathan Angel, MD, head of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Ottawa, reported that 15 of the 21 of patients who started on the regimen are still taking it, all with viral suppression. Those who weren’t cited a combination of inconvenience, injection site pain, and “injection fatigue.”

These are just a few things HIV providers are learning as they begin what Chloe Orkin, MD, professor of HIV medicine at Queen Mary University of London, called a paradigm shift to long-acting treatment, which may soon include not just shots but rings, implants, and microarray patches.

“It’s a paradigm shift, and we are at the very beginning of this paradigm shift,” said Dr. Orkin, commenting during the discussion session of the European AIDS Clinical Society 2021 annual meeting. “We’re having to change our model, and it’s challenging.”

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first long-acting injectable, a combination of cabotegravir and rilpivirine (CAB/RIL; Cabenuva, ViiV Healthcare) in January 2021. But it has been approved in Canada since March 2020 and available at Dr. Angel’s clinic since November 2020. It’s also available in Canada as an every-other-month shot. Injected into the buttocks, the shot was found to be noninferior to standard daily oral treatment in many studies, including the ATLAS, the ATLAS-2M – which tested the every-other-month approach – and FLAIR trials.

Dr. Angel’s clinic was part of all three of those trials, so his clinic has had 5 years’ experience preparing for the change in workflow and the new approach the shots require.

Of the 21 people Dr. Angel has treated, 11 were white Canadians, nine were Black African, and one was Indigenous Canadian, with women making up a third of the participants. Median age was 51 years, and all patients had had undetectable viral loads before beginning the regimen. (Studies of the drug’s effectiveness in people who struggle to take daily pills are still ongoing.)

Most of those 21 patients had had undetectable viral loads for more than 5 years, but a few had been undetectable for only 6 months before beginning the shots. Their immune systems were also healthy, with a median CD4 count of 618 cells/mcL. As in the clinical trials, none of the participants had experienced antiretroviral treatment failure. Because public health insurers in Canada have yet to approve the shots, Dr. Angel’s patients receiving Cabenuva also have private health insurance. Up to 90% of people in Canada receive pharmaceutical coverage through public insurance; therefore, the shot is not yet widely available.

Twenty patients switched from integrase-inhibitor regimens, and one had been receiving a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor–based regimen before starting Cabenuva.

And although the drug has not been approved for shot initiation this way, two patients requested – and Dr. Angel agreed – to start them on the shots without first doing a month of daily pills to check for safety.

“This is my conclusion from these data: the oral lead-in period is not necessary,” Dr. Angel said in his presentation at the meeting. “It can provide some comfort to either a physician or a patient, but it does not seem to be medically necessary.”

That approach is not without data to back it up. Research presented at HIV Glasgow 2020 showed that people who switched from daily oral dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine straight to the injections did so without problems.

At last clinic visit, 15 of those 21 were still receiving the shots. None have experienced treatment failure, and all were still virally suppressed. Four participants left the trials and one more person opted to return to daily pills, citing some level of what Dr. Angel called “injection fatigue.”

“Just as we use the term ‘pill fatigue’ for patients who are tired of taking pills, patients do get tired of coming in monthly for their visits and injections,” he said. They find the trip to the clinic for the intramuscular injections “inconvenient,” he said.

Unlike in the United States, where Cabenuva is approved for only monthly injections, Health Canada has already approved the shot for every-other-month injections, which Dr. Angel said may reduce the odds of injection fatigue.

Dr. Angel’s presentation drew comments, questions, and excitement from the crowd. Annemarie Wensing, MD, assistant professor of medicine at University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands), asked whether dispensing with the oral lead-in period could mean that these shots could be useful for people going on longer trips, people having surgeries where they can’t swallow pills, or in other scenarios.

“These are not hypothetical conversations,” Dr. Angel said. “I’m having these conversations with patients now – temporary use, they travel for 3 months and come back, can they go from injectable to oral to injectable.”

For now, he said, the answer is, “We’ll figure it out.”

Meanwhile, there’s another big question when it comes to injectables, said Marta Vas ylyev, MD, from Lviv (Ukraine) Regional AIDS Center: When will they be available to the people who might benefit most from them – people in resource-limited settings, people who so far have struggled to remember to take their pills every day?

For now, Dr. Angel replied, injectables continue to be a treatment only for those who are already doing well while receiving HIV treatment: those with already suppressed viral load, who are good at taking daily pills, and who are being treated at well-resourced clinics.

“There are huge obstacles to overcome if this is ever to be available [in resource-limited settings], and way more obstacles than there are with any oral therapies,” he said. “There’s not been much discussion here about the necessity of cold-chain requirements of pharmacies either centrally or locally, [or] the requirements of additional nurses or health care staff to administer the medication. So you’re looking at a very resource-intensive therapy, which now is fairly restrictive [as to] who will have access to it.”

Dr. Angel reports serving on advisory boards for ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences and has done contract research for ViiV Healthcare, Gilead, and Merck. Dr. Orkin has received research grants, fees as a consultant, travel sponsorship, and speaker fees from ViiV, Merck, and GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Vasylyev reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One year into offering the first long-acting injectable HIV treatment to his patients, Jonathan Angel, MD, head of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Ottawa, reported that 15 of the 21 of patients who started on the regimen are still taking it, all with viral suppression. Those who weren’t cited a combination of inconvenience, injection site pain, and “injection fatigue.”

These are just a few things HIV providers are learning as they begin what Chloe Orkin, MD, professor of HIV medicine at Queen Mary University of London, called a paradigm shift to long-acting treatment, which may soon include not just shots but rings, implants, and microarray patches.

“It’s a paradigm shift, and we are at the very beginning of this paradigm shift,” said Dr. Orkin, commenting during the discussion session of the European AIDS Clinical Society 2021 annual meeting. “We’re having to change our model, and it’s challenging.”

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first long-acting injectable, a combination of cabotegravir and rilpivirine (CAB/RIL; Cabenuva, ViiV Healthcare) in January 2021. But it has been approved in Canada since March 2020 and available at Dr. Angel’s clinic since November 2020. It’s also available in Canada as an every-other-month shot. Injected into the buttocks, the shot was found to be noninferior to standard daily oral treatment in many studies, including the ATLAS, the ATLAS-2M – which tested the every-other-month approach – and FLAIR trials.

Dr. Angel’s clinic was part of all three of those trials, so his clinic has had 5 years’ experience preparing for the change in workflow and the new approach the shots require.

Of the 21 people Dr. Angel has treated, 11 were white Canadians, nine were Black African, and one was Indigenous Canadian, with women making up a third of the participants. Median age was 51 years, and all patients had had undetectable viral loads before beginning the regimen. (Studies of the drug’s effectiveness in people who struggle to take daily pills are still ongoing.)

Most of those 21 patients had had undetectable viral loads for more than 5 years, but a few had been undetectable for only 6 months before beginning the shots. Their immune systems were also healthy, with a median CD4 count of 618 cells/mcL. As in the clinical trials, none of the participants had experienced antiretroviral treatment failure. Because public health insurers in Canada have yet to approve the shots, Dr. Angel’s patients receiving Cabenuva also have private health insurance. Up to 90% of people in Canada receive pharmaceutical coverage through public insurance; therefore, the shot is not yet widely available.

Twenty patients switched from integrase-inhibitor regimens, and one had been receiving a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor–based regimen before starting Cabenuva.

And although the drug has not been approved for shot initiation this way, two patients requested – and Dr. Angel agreed – to start them on the shots without first doing a month of daily pills to check for safety.

“This is my conclusion from these data: the oral lead-in period is not necessary,” Dr. Angel said in his presentation at the meeting. “It can provide some comfort to either a physician or a patient, but it does not seem to be medically necessary.”

That approach is not without data to back it up. Research presented at HIV Glasgow 2020 showed that people who switched from daily oral dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine straight to the injections did so without problems.

At last clinic visit, 15 of those 21 were still receiving the shots. None have experienced treatment failure, and all were still virally suppressed. Four participants left the trials and one more person opted to return to daily pills, citing some level of what Dr. Angel called “injection fatigue.”

“Just as we use the term ‘pill fatigue’ for patients who are tired of taking pills, patients do get tired of coming in monthly for their visits and injections,” he said. They find the trip to the clinic for the intramuscular injections “inconvenient,” he said.

Unlike in the United States, where Cabenuva is approved for only monthly injections, Health Canada has already approved the shot for every-other-month injections, which Dr. Angel said may reduce the odds of injection fatigue.

Dr. Angel’s presentation drew comments, questions, and excitement from the crowd. Annemarie Wensing, MD, assistant professor of medicine at University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands), asked whether dispensing with the oral lead-in period could mean that these shots could be useful for people going on longer trips, people having surgeries where they can’t swallow pills, or in other scenarios.

“These are not hypothetical conversations,” Dr. Angel said. “I’m having these conversations with patients now – temporary use, they travel for 3 months and come back, can they go from injectable to oral to injectable.”

For now, he said, the answer is, “We’ll figure it out.”

Meanwhile, there’s another big question when it comes to injectables, said Marta Vas ylyev, MD, from Lviv (Ukraine) Regional AIDS Center: When will they be available to the people who might benefit most from them – people in resource-limited settings, people who so far have struggled to remember to take their pills every day?

For now, Dr. Angel replied, injectables continue to be a treatment only for those who are already doing well while receiving HIV treatment: those with already suppressed viral load, who are good at taking daily pills, and who are being treated at well-resourced clinics.

“There are huge obstacles to overcome if this is ever to be available [in resource-limited settings], and way more obstacles than there are with any oral therapies,” he said. “There’s not been much discussion here about the necessity of cold-chain requirements of pharmacies either centrally or locally, [or] the requirements of additional nurses or health care staff to administer the medication. So you’re looking at a very resource-intensive therapy, which now is fairly restrictive [as to] who will have access to it.”

Dr. Angel reports serving on advisory boards for ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences and has done contract research for ViiV Healthcare, Gilead, and Merck. Dr. Orkin has received research grants, fees as a consultant, travel sponsorship, and speaker fees from ViiV, Merck, and GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Vasylyev reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One year into offering the first long-acting injectable HIV treatment to his patients, Jonathan Angel, MD, head of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Ottawa, reported that 15 of the 21 of patients who started on the regimen are still taking it, all with viral suppression. Those who weren’t cited a combination of inconvenience, injection site pain, and “injection fatigue.”

These are just a few things HIV providers are learning as they begin what Chloe Orkin, MD, professor of HIV medicine at Queen Mary University of London, called a paradigm shift to long-acting treatment, which may soon include not just shots but rings, implants, and microarray patches.

“It’s a paradigm shift, and we are at the very beginning of this paradigm shift,” said Dr. Orkin, commenting during the discussion session of the European AIDS Clinical Society 2021 annual meeting. “We’re having to change our model, and it’s challenging.”

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first long-acting injectable, a combination of cabotegravir and rilpivirine (CAB/RIL; Cabenuva, ViiV Healthcare) in January 2021. But it has been approved in Canada since March 2020 and available at Dr. Angel’s clinic since November 2020. It’s also available in Canada as an every-other-month shot. Injected into the buttocks, the shot was found to be noninferior to standard daily oral treatment in many studies, including the ATLAS, the ATLAS-2M – which tested the every-other-month approach – and FLAIR trials.

Dr. Angel’s clinic was part of all three of those trials, so his clinic has had 5 years’ experience preparing for the change in workflow and the new approach the shots require.

Of the 21 people Dr. Angel has treated, 11 were white Canadians, nine were Black African, and one was Indigenous Canadian, with women making up a third of the participants. Median age was 51 years, and all patients had had undetectable viral loads before beginning the regimen. (Studies of the drug’s effectiveness in people who struggle to take daily pills are still ongoing.)

Most of those 21 patients had had undetectable viral loads for more than 5 years, but a few had been undetectable for only 6 months before beginning the shots. Their immune systems were also healthy, with a median CD4 count of 618 cells/mcL. As in the clinical trials, none of the participants had experienced antiretroviral treatment failure. Because public health insurers in Canada have yet to approve the shots, Dr. Angel’s patients receiving Cabenuva also have private health insurance. Up to 90% of people in Canada receive pharmaceutical coverage through public insurance; therefore, the shot is not yet widely available.

Twenty patients switched from integrase-inhibitor regimens, and one had been receiving a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor–based regimen before starting Cabenuva.

And although the drug has not been approved for shot initiation this way, two patients requested – and Dr. Angel agreed – to start them on the shots without first doing a month of daily pills to check for safety.

“This is my conclusion from these data: the oral lead-in period is not necessary,” Dr. Angel said in his presentation at the meeting. “It can provide some comfort to either a physician or a patient, but it does not seem to be medically necessary.”

That approach is not without data to back it up. Research presented at HIV Glasgow 2020 showed that people who switched from daily oral dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine straight to the injections did so without problems.

At last clinic visit, 15 of those 21 were still receiving the shots. None have experienced treatment failure, and all were still virally suppressed. Four participants left the trials and one more person opted to return to daily pills, citing some level of what Dr. Angel called “injection fatigue.”

“Just as we use the term ‘pill fatigue’ for patients who are tired of taking pills, patients do get tired of coming in monthly for their visits and injections,” he said. They find the trip to the clinic for the intramuscular injections “inconvenient,” he said.

Unlike in the United States, where Cabenuva is approved for only monthly injections, Health Canada has already approved the shot for every-other-month injections, which Dr. Angel said may reduce the odds of injection fatigue.

Dr. Angel’s presentation drew comments, questions, and excitement from the crowd. Annemarie Wensing, MD, assistant professor of medicine at University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands), asked whether dispensing with the oral lead-in period could mean that these shots could be useful for people going on longer trips, people having surgeries where they can’t swallow pills, or in other scenarios.

“These are not hypothetical conversations,” Dr. Angel said. “I’m having these conversations with patients now – temporary use, they travel for 3 months and come back, can they go from injectable to oral to injectable.”

For now, he said, the answer is, “We’ll figure it out.”

Meanwhile, there’s another big question when it comes to injectables, said Marta Vas ylyev, MD, from Lviv (Ukraine) Regional AIDS Center: When will they be available to the people who might benefit most from them – people in resource-limited settings, people who so far have struggled to remember to take their pills every day?

For now, Dr. Angel replied, injectables continue to be a treatment only for those who are already doing well while receiving HIV treatment: those with already suppressed viral load, who are good at taking daily pills, and who are being treated at well-resourced clinics.

“There are huge obstacles to overcome if this is ever to be available [in resource-limited settings], and way more obstacles than there are with any oral therapies,” he said. “There’s not been much discussion here about the necessity of cold-chain requirements of pharmacies either centrally or locally, [or] the requirements of additional nurses or health care staff to administer the medication. So you’re looking at a very resource-intensive therapy, which now is fairly restrictive [as to] who will have access to it.”

Dr. Angel reports serving on advisory boards for ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences and has done contract research for ViiV Healthcare, Gilead, and Merck. Dr. Orkin has received research grants, fees as a consultant, travel sponsorship, and speaker fees from ViiV, Merck, and GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Vasylyev reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Neighborhood fast food restaurants linked to type 2 diabetes

new research indicates.

The national study of more than 4 million U.S. veterans also found the opposite association with supermarkets in suburban and rural communities but not others.

“Neighborhood food environment was associated with type 2 diabetes risk among U.S. veterans in multiple community types, suggesting potential avenues for action to address the burden of type 2 diabetes,” say Rania Kanchi, MPH, of the department of population health, New York University Langone Health, and colleagues.

Restriction of fast food establishments could benefit all types of communities, while interventions to increase supermarket availability could help minimize diabetes risk in suburban and rural communities, they stress.

“These actions, combined with increasing awareness of the risk of type 2 diabetes and the importance of healthy diet intake, might be associated with a decrease in the burden of type 2 diabetes among adults in the U.S.,” the researchers add.

The data were published online Oct. 29 in JAMA Network Open.

“The more we learn about the relationship between the food environment and chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes, the more policymakers can act by improving the mix of healthy food options sold in restaurants and food outlets, or by creating better zoning laws that promote optimal food options for residents,” commented Lorna Thorpe, PhD, MPH, professor in the department of population health at NYU Langone and senior author of the study in a press release.

In an accompanying editorial, Elham Hatef, MD, MPH, of the Center for Population Health IT at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, calls the study “a great example of the capabilities of [health information technology] to provide a comprehensive assessment of a person’s health, which goes beyond just documenting clinical diseases and medical interventions.”

Research has large geographic breadth

The study is notable for its large geographic breadth, say the researchers.

“Most studies that examine the built food environment and its relationship to chronic diseases have been much smaller or conducted in localized areas,” Ms. Kanchi said in the press statement.

“Our study design is national in scope and allowed us to identify the types of communities that people are living in, characterize their food environment, and observe what happens to them over time. The size of our cohort allows for geographic generalizability in a way that other studies do not,” Ms. Kanchi continued.

The research included data for 4,100,650 individuals from the Veterans Affairs electronic health records (EHRs) who didn’t have type 2 diabetes at baseline, between 2008 and 2016. After a median follow-up of 5.5 person-years, 13.2% developed type 2 diabetes. Cumulative incidence was greater among those who were older, those who were non-Hispanic Black compared with other races, and those with disabilities and lower incomes.

The proportion of adults with type 2 diabetes was highest among those living in high-density urban communities (14.3%), followed by low-density urban (13.1%), rural (13.2%), and suburban (12.6%) communities.

Overall, a 10% increase in the number of fast food restaurants compared with other food establishments in a given neighborhood was associated with a 1% increased risk for incident type 2 diabetes in high-density urban, low-density urban, and rural communities and a 2% increased risk in suburban communities.

In contrast, a 10% increase in supermarket density compared with other food stores was associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes in suburban and rural communities, but the association wasn’t significant elsewhere.

“Taken together, our findings suggest that policies specific to fast food restaurants, such as [those] ... restricting the siting of fast food restaurants and healthy beverage default laws, may be effective in reducing type 2 diabetes risk in all community types,” say the authors.

“In urban areas where population and retail density are growing, it will be even more important to focus on these policies,” they emphasize.

Great example of capabilities of health information technology

In the editorial, Dr. Hatef notes that methodological advances, such as natural language processing and machine learning, have enabled health systems to use real-world data such as the free-text notes in the EHR to identify patient-level risk factors for diseases or disease complications.

Such methods could be further used to “evaluate the associations between social needs and place-based [social determinants of health] and type 2 diabetes incidence and management,” Dr. Hatef adds.

And linkage of data from the EHR to such community-level data “would help to comprehensively assess and identify patients likely to experience type 2 diabetes and its complications as a result of their risk factors or characteristics of the neighborhoods where they reside.”

“This approach could foster collaborations between the health systems and at-risk communities they serve and help to reallocate health system resources to those in most need in the community to reduce the burden of type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions among racial minority groups and socioeconomically disadvantaged patients and to advance population health.”

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Aging, the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement program funded by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, the Urban Health Collaborative at Drexel University, and the Built Environment and Health Research Group at Columbia University. Ms. Kanchi and Dr. Hatef have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research indicates.

The national study of more than 4 million U.S. veterans also found the opposite association with supermarkets in suburban and rural communities but not others.

“Neighborhood food environment was associated with type 2 diabetes risk among U.S. veterans in multiple community types, suggesting potential avenues for action to address the burden of type 2 diabetes,” say Rania Kanchi, MPH, of the department of population health, New York University Langone Health, and colleagues.

Restriction of fast food establishments could benefit all types of communities, while interventions to increase supermarket availability could help minimize diabetes risk in suburban and rural communities, they stress.

“These actions, combined with increasing awareness of the risk of type 2 diabetes and the importance of healthy diet intake, might be associated with a decrease in the burden of type 2 diabetes among adults in the U.S.,” the researchers add.

The data were published online Oct. 29 in JAMA Network Open.

“The more we learn about the relationship between the food environment and chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes, the more policymakers can act by improving the mix of healthy food options sold in restaurants and food outlets, or by creating better zoning laws that promote optimal food options for residents,” commented Lorna Thorpe, PhD, MPH, professor in the department of population health at NYU Langone and senior author of the study in a press release.

In an accompanying editorial, Elham Hatef, MD, MPH, of the Center for Population Health IT at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, calls the study “a great example of the capabilities of [health information technology] to provide a comprehensive assessment of a person’s health, which goes beyond just documenting clinical diseases and medical interventions.”

Research has large geographic breadth

The study is notable for its large geographic breadth, say the researchers.

“Most studies that examine the built food environment and its relationship to chronic diseases have been much smaller or conducted in localized areas,” Ms. Kanchi said in the press statement.

“Our study design is national in scope and allowed us to identify the types of communities that people are living in, characterize their food environment, and observe what happens to them over time. The size of our cohort allows for geographic generalizability in a way that other studies do not,” Ms. Kanchi continued.

The research included data for 4,100,650 individuals from the Veterans Affairs electronic health records (EHRs) who didn’t have type 2 diabetes at baseline, between 2008 and 2016. After a median follow-up of 5.5 person-years, 13.2% developed type 2 diabetes. Cumulative incidence was greater among those who were older, those who were non-Hispanic Black compared with other races, and those with disabilities and lower incomes.

The proportion of adults with type 2 diabetes was highest among those living in high-density urban communities (14.3%), followed by low-density urban (13.1%), rural (13.2%), and suburban (12.6%) communities.

Overall, a 10% increase in the number of fast food restaurants compared with other food establishments in a given neighborhood was associated with a 1% increased risk for incident type 2 diabetes in high-density urban, low-density urban, and rural communities and a 2% increased risk in suburban communities.

In contrast, a 10% increase in supermarket density compared with other food stores was associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes in suburban and rural communities, but the association wasn’t significant elsewhere.

“Taken together, our findings suggest that policies specific to fast food restaurants, such as [those] ... restricting the siting of fast food restaurants and healthy beverage default laws, may be effective in reducing type 2 diabetes risk in all community types,” say the authors.

“In urban areas where population and retail density are growing, it will be even more important to focus on these policies,” they emphasize.

Great example of capabilities of health information technology

In the editorial, Dr. Hatef notes that methodological advances, such as natural language processing and machine learning, have enabled health systems to use real-world data such as the free-text notes in the EHR to identify patient-level risk factors for diseases or disease complications.

Such methods could be further used to “evaluate the associations between social needs and place-based [social determinants of health] and type 2 diabetes incidence and management,” Dr. Hatef adds.

And linkage of data from the EHR to such community-level data “would help to comprehensively assess and identify patients likely to experience type 2 diabetes and its complications as a result of their risk factors or characteristics of the neighborhoods where they reside.”

“This approach could foster collaborations between the health systems and at-risk communities they serve and help to reallocate health system resources to those in most need in the community to reduce the burden of type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions among racial minority groups and socioeconomically disadvantaged patients and to advance population health.”

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Aging, the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement program funded by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, the Urban Health Collaborative at Drexel University, and the Built Environment and Health Research Group at Columbia University. Ms. Kanchi and Dr. Hatef have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research indicates.

The national study of more than 4 million U.S. veterans also found the opposite association with supermarkets in suburban and rural communities but not others.

“Neighborhood food environment was associated with type 2 diabetes risk among U.S. veterans in multiple community types, suggesting potential avenues for action to address the burden of type 2 diabetes,” say Rania Kanchi, MPH, of the department of population health, New York University Langone Health, and colleagues.

Restriction of fast food establishments could benefit all types of communities, while interventions to increase supermarket availability could help minimize diabetes risk in suburban and rural communities, they stress.

“These actions, combined with increasing awareness of the risk of type 2 diabetes and the importance of healthy diet intake, might be associated with a decrease in the burden of type 2 diabetes among adults in the U.S.,” the researchers add.

The data were published online Oct. 29 in JAMA Network Open.

“The more we learn about the relationship between the food environment and chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes, the more policymakers can act by improving the mix of healthy food options sold in restaurants and food outlets, or by creating better zoning laws that promote optimal food options for residents,” commented Lorna Thorpe, PhD, MPH, professor in the department of population health at NYU Langone and senior author of the study in a press release.

In an accompanying editorial, Elham Hatef, MD, MPH, of the Center for Population Health IT at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, calls the study “a great example of the capabilities of [health information technology] to provide a comprehensive assessment of a person’s health, which goes beyond just documenting clinical diseases and medical interventions.”

Research has large geographic breadth

The study is notable for its large geographic breadth, say the researchers.

“Most studies that examine the built food environment and its relationship to chronic diseases have been much smaller or conducted in localized areas,” Ms. Kanchi said in the press statement.

“Our study design is national in scope and allowed us to identify the types of communities that people are living in, characterize their food environment, and observe what happens to them over time. The size of our cohort allows for geographic generalizability in a way that other studies do not,” Ms. Kanchi continued.

The research included data for 4,100,650 individuals from the Veterans Affairs electronic health records (EHRs) who didn’t have type 2 diabetes at baseline, between 2008 and 2016. After a median follow-up of 5.5 person-years, 13.2% developed type 2 diabetes. Cumulative incidence was greater among those who were older, those who were non-Hispanic Black compared with other races, and those with disabilities and lower incomes.

The proportion of adults with type 2 diabetes was highest among those living in high-density urban communities (14.3%), followed by low-density urban (13.1%), rural (13.2%), and suburban (12.6%) communities.

Overall, a 10% increase in the number of fast food restaurants compared with other food establishments in a given neighborhood was associated with a 1% increased risk for incident type 2 diabetes in high-density urban, low-density urban, and rural communities and a 2% increased risk in suburban communities.

In contrast, a 10% increase in supermarket density compared with other food stores was associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes in suburban and rural communities, but the association wasn’t significant elsewhere.

“Taken together, our findings suggest that policies specific to fast food restaurants, such as [those] ... restricting the siting of fast food restaurants and healthy beverage default laws, may be effective in reducing type 2 diabetes risk in all community types,” say the authors.

“In urban areas where population and retail density are growing, it will be even more important to focus on these policies,” they emphasize.

Great example of capabilities of health information technology

In the editorial, Dr. Hatef notes that methodological advances, such as natural language processing and machine learning, have enabled health systems to use real-world data such as the free-text notes in the EHR to identify patient-level risk factors for diseases or disease complications.

Such methods could be further used to “evaluate the associations between social needs and place-based [social determinants of health] and type 2 diabetes incidence and management,” Dr. Hatef adds.

And linkage of data from the EHR to such community-level data “would help to comprehensively assess and identify patients likely to experience type 2 diabetes and its complications as a result of their risk factors or characteristics of the neighborhoods where they reside.”

“This approach could foster collaborations between the health systems and at-risk communities they serve and help to reallocate health system resources to those in most need in the community to reduce the burden of type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions among racial minority groups and socioeconomically disadvantaged patients and to advance population health.”

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Aging, the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement program funded by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, the Urban Health Collaborative at Drexel University, and the Built Environment and Health Research Group at Columbia University. Ms. Kanchi and Dr. Hatef have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Multiple DMTs linked to alopecia, especially in women

a new study finds.

From 2009 to 2019, the Food and Drug Administration received 7,978 reports of new-onset alopecia in patients taking DMTs, particularly teriflunomide (3,255, 40.8%; 90% female), dimethyl fumarate (1,641, 20.6%; 89% female), natalizumab (955, 12.0%; 92% female), and fingolimod (776, 9.7% of the total reports; 93% female), several researchers reported at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC). Of these, only teriflunomide had previously been linked to alopecia, study coauthor Ahmed Obeidat, MD, PhD, a neurologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said in an interview.

“Our finding of frequent reports of alopecia on DMTs studied calls for further investigation into the subject,” Dr. Obeidat said. “Alopecia can cause deep personal impacts and can be a source of significant psychological concern for some patients.”

According to Dr. Obeidat, alopecia has been linked to the only a few DMTs – cladribine and the interferons – in addition to teriflunomide. “To our surprise, we received anecdotal reports of hair thinning from several of our MS patients treated with various other [DMTs]. Upon further investigation, we could not find substantial literature to explain this phenomenon which led us to conduct our investigation.”

Dr. Obeidat and colleagues identified DMT-related alopecia cases (18.3%) among 43,655 reports in the skin and subcutaneous tissue disorder category in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Other DMTs with more than 1 case report were interferon beta-1a (635, 8.0%; 92% female), glatiramer acetate (332, 4.2%; 87% female), ocrelizumab (142, 1.8%; 94% female), interferon beta-1b (126, 1.6%; 95% female), alemtuzumab (86, 1.1%; 88% female), cladribine (17, 0.2%; 65% female), and rituximab (10, 0.1%; 90% female).

The average age for the case reports varied from 42 to 51 years for most of the drugs except alemtuzumab (mean age, 40 years) and cladribine (average age, 38 years), which had low numbers of cases.

Siponimod (three cases) and ozanimod (no cases) were not included in the age and gender analyses.

Why do so many women seem to be affected, well beyond their percentage of MS cases overall? The answer is unclear, said medical student Mokshal H. Porwal, the study’s lead author. “There could be a biological explanation,” Mr. Porwal said, “or women may report cases more often: “Earlier studies suggested that alopecia may affect women more adversely in terms of body image as well as overall psychological well-being, compared to males.”

The researchers also noted that patients – not medical professionals – provided most of the case reports in the FDA database. “We believe this indicates that alopecia is a patient-centered concern that may have a larger impact on their lives than what the health care teams may perceive,” Mr. Porwal said. “Oftentimes, we as health care providers, look for the more acute and apparent adverse events, which can overshadow issues such as hair thinning/alopecia that could have even greater psychological impacts on our patients.”

Dr. Obeidat said there are still multiple mysteries about DMT and alopecia risk: the true incidence of cases per DMT or DMT class, the mechanism(s) behind a link, the permanent or transient nature of the alopecia cases, and the risk factors in individual patients.

Going forward, he said, “we advise clinicians to discuss hair thinning or alopecia as a possible side effect that has been reported in association with all DMTs in the real-world, postmarketing era.”

No study funding was reported. Dr. Obeidat reported various disclosures; the other authors reported no disclosures.

a new study finds.

From 2009 to 2019, the Food and Drug Administration received 7,978 reports of new-onset alopecia in patients taking DMTs, particularly teriflunomide (3,255, 40.8%; 90% female), dimethyl fumarate (1,641, 20.6%; 89% female), natalizumab (955, 12.0%; 92% female), and fingolimod (776, 9.7% of the total reports; 93% female), several researchers reported at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC). Of these, only teriflunomide had previously been linked to alopecia, study coauthor Ahmed Obeidat, MD, PhD, a neurologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said in an interview.

“Our finding of frequent reports of alopecia on DMTs studied calls for further investigation into the subject,” Dr. Obeidat said. “Alopecia can cause deep personal impacts and can be a source of significant psychological concern for some patients.”

According to Dr. Obeidat, alopecia has been linked to the only a few DMTs – cladribine and the interferons – in addition to teriflunomide. “To our surprise, we received anecdotal reports of hair thinning from several of our MS patients treated with various other [DMTs]. Upon further investigation, we could not find substantial literature to explain this phenomenon which led us to conduct our investigation.”

Dr. Obeidat and colleagues identified DMT-related alopecia cases (18.3%) among 43,655 reports in the skin and subcutaneous tissue disorder category in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Other DMTs with more than 1 case report were interferon beta-1a (635, 8.0%; 92% female), glatiramer acetate (332, 4.2%; 87% female), ocrelizumab (142, 1.8%; 94% female), interferon beta-1b (126, 1.6%; 95% female), alemtuzumab (86, 1.1%; 88% female), cladribine (17, 0.2%; 65% female), and rituximab (10, 0.1%; 90% female).

The average age for the case reports varied from 42 to 51 years for most of the drugs except alemtuzumab (mean age, 40 years) and cladribine (average age, 38 years), which had low numbers of cases.

Siponimod (three cases) and ozanimod (no cases) were not included in the age and gender analyses.

Why do so many women seem to be affected, well beyond their percentage of MS cases overall? The answer is unclear, said medical student Mokshal H. Porwal, the study’s lead author. “There could be a biological explanation,” Mr. Porwal said, “or women may report cases more often: “Earlier studies suggested that alopecia may affect women more adversely in terms of body image as well as overall psychological well-being, compared to males.”

The researchers also noted that patients – not medical professionals – provided most of the case reports in the FDA database. “We believe this indicates that alopecia is a patient-centered concern that may have a larger impact on their lives than what the health care teams may perceive,” Mr. Porwal said. “Oftentimes, we as health care providers, look for the more acute and apparent adverse events, which can overshadow issues such as hair thinning/alopecia that could have even greater psychological impacts on our patients.”

Dr. Obeidat said there are still multiple mysteries about DMT and alopecia risk: the true incidence of cases per DMT or DMT class, the mechanism(s) behind a link, the permanent or transient nature of the alopecia cases, and the risk factors in individual patients.

Going forward, he said, “we advise clinicians to discuss hair thinning or alopecia as a possible side effect that has been reported in association with all DMTs in the real-world, postmarketing era.”

No study funding was reported. Dr. Obeidat reported various disclosures; the other authors reported no disclosures.

a new study finds.