User login

AHA/ACC issues first comprehensive guidance on chest pain

Clinicians should use standardized risk assessments, clinical pathways, and tools to evaluate and communicate with patients who present with chest pain (angina), advises a joint clinical practice guideline released by American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

While evaluation of chest pain has been covered in previous guidelines, this is the first comprehensive guideline from the AHA and ACC focused exclusively on the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain.

“As our imaging technologies have evolved, we needed a contemporary approach to which patients need further testing, and which do not, in addition to what testing is effective,” Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, and chair of the guideline writing group, said in an interview.

“Our hope is that we have provided an evidence-based approach to evaluating patients that will assist all of us who manage, diagnose, and treat patients who experience chest pain,” said Dr. Gulati, who is also president-elect of the American Society for Preventive Cardiology.

The guideline was simultaneously published online Oct. 28, 2021, in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

‘Atypical’ is out, ‘noncardiac’ is in

Each year, chest pain sends more than 6.5 million adults to the ED and more than 4 million to outpatient clinics in the United States.

Yet, among all patients who come to the ED, only 5% will have acute coronary syndrome (ACS). More than half will ultimately have a noncardiac reason for their chest pain, including respiratory, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, psychological, or other causes.

The guideline says evaluating the severity and the cause of chest pain is essential and advises using standard risk assessments to determine if a patient is at low, intermediate, or high risk for having a cardiac event.

“I hope clinicians take from our guidelines the understanding that low-risk patients often do not need additional testing. And if we communicate this effectively with our patients – incorporating shared decision-making into our practice – we can reduce ‘overtesting’ in low-risk patients,” Dr. Gulati said in an interview.

The guideline notes that women are unique when presenting with ACS symptoms. While chest pain is the dominant and most common symptom for both men and women, women may be more likely to also have symptoms such as nausea and shortness of breath.

The guideline also encourages using the term “noncardiac” if heart disease is not suspected in a patient with angina and says the term “atypical” is a “misleading” descriptor of chest pain and should not be used.

“Words matter, and we need to move away from describing chest pain as ‘atypical’ because it has resulted in confusion when these words are used,” Dr. Gulati stressed.

“Rather than meaning a different way of presenting, it has taken on a meaning to imply it is not cardiac. It is more useful to talk about the probability of the pain being cardiac vs noncardiac,” Dr. Gulati explained.

No one best test for everyone

There is also a focus on evaluation of patients with chest pain who present to the ED. The initial goals of ED physicians should be to identify if there are life-threatening causes and to determine if there is a need for hospital admission or testing, the guideline states.

Thorough screening in the ED may help determine who is at high risk versus intermediate or low risk for a cardiac event. An individual deemed to be at low risk may be referred for additional evaluation in an outpatient setting rather than being admitted to the hospital, the authors wrote.

High-sensitivity cardiac troponins are the “preferred standard” for establishing a biomarker diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, allowing for more accurate detection and exclusion of myocardial injury, they added.

“While there is no one ‘best test’ for every patient, the guideline emphasizes the tests that may be most appropriate, depending on the individual situation, and which ones won’t provide additional information; therefore, these tests should not be done just for the sake of doing them,” Dr. Gulati said in a news release.

“Appropriate testing is also dependent upon the technology and screening devices that are available at the hospital or healthcare center where the patient is receiving care. All imaging modalities highlighted in the guideline have an important role in the assessment of chest pain to help determine the underlying cause, with the goal of preventing a serious cardiac event,” Dr. Gulati added.

The guideline was prepared on behalf of and approved by the AHA and ACC Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Five other partnering organizations participated in and approved the guideline: the American Society of Echocardiography, the American College of Chest Physicians, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.

The writing group included representatives from each of the partnering organizations and experts in the field (cardiac intensivists, cardiac interventionalists, cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, emergency physicians, and epidemiologists), as well as a lay/patient representative.

The research had no commercial funding.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians should use standardized risk assessments, clinical pathways, and tools to evaluate and communicate with patients who present with chest pain (angina), advises a joint clinical practice guideline released by American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

While evaluation of chest pain has been covered in previous guidelines, this is the first comprehensive guideline from the AHA and ACC focused exclusively on the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain.

“As our imaging technologies have evolved, we needed a contemporary approach to which patients need further testing, and which do not, in addition to what testing is effective,” Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, and chair of the guideline writing group, said in an interview.

“Our hope is that we have provided an evidence-based approach to evaluating patients that will assist all of us who manage, diagnose, and treat patients who experience chest pain,” said Dr. Gulati, who is also president-elect of the American Society for Preventive Cardiology.

The guideline was simultaneously published online Oct. 28, 2021, in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

‘Atypical’ is out, ‘noncardiac’ is in

Each year, chest pain sends more than 6.5 million adults to the ED and more than 4 million to outpatient clinics in the United States.

Yet, among all patients who come to the ED, only 5% will have acute coronary syndrome (ACS). More than half will ultimately have a noncardiac reason for their chest pain, including respiratory, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, psychological, or other causes.

The guideline says evaluating the severity and the cause of chest pain is essential and advises using standard risk assessments to determine if a patient is at low, intermediate, or high risk for having a cardiac event.

“I hope clinicians take from our guidelines the understanding that low-risk patients often do not need additional testing. And if we communicate this effectively with our patients – incorporating shared decision-making into our practice – we can reduce ‘overtesting’ in low-risk patients,” Dr. Gulati said in an interview.

The guideline notes that women are unique when presenting with ACS symptoms. While chest pain is the dominant and most common symptom for both men and women, women may be more likely to also have symptoms such as nausea and shortness of breath.

The guideline also encourages using the term “noncardiac” if heart disease is not suspected in a patient with angina and says the term “atypical” is a “misleading” descriptor of chest pain and should not be used.

“Words matter, and we need to move away from describing chest pain as ‘atypical’ because it has resulted in confusion when these words are used,” Dr. Gulati stressed.

“Rather than meaning a different way of presenting, it has taken on a meaning to imply it is not cardiac. It is more useful to talk about the probability of the pain being cardiac vs noncardiac,” Dr. Gulati explained.

No one best test for everyone

There is also a focus on evaluation of patients with chest pain who present to the ED. The initial goals of ED physicians should be to identify if there are life-threatening causes and to determine if there is a need for hospital admission or testing, the guideline states.

Thorough screening in the ED may help determine who is at high risk versus intermediate or low risk for a cardiac event. An individual deemed to be at low risk may be referred for additional evaluation in an outpatient setting rather than being admitted to the hospital, the authors wrote.

High-sensitivity cardiac troponins are the “preferred standard” for establishing a biomarker diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, allowing for more accurate detection and exclusion of myocardial injury, they added.

“While there is no one ‘best test’ for every patient, the guideline emphasizes the tests that may be most appropriate, depending on the individual situation, and which ones won’t provide additional information; therefore, these tests should not be done just for the sake of doing them,” Dr. Gulati said in a news release.

“Appropriate testing is also dependent upon the technology and screening devices that are available at the hospital or healthcare center where the patient is receiving care. All imaging modalities highlighted in the guideline have an important role in the assessment of chest pain to help determine the underlying cause, with the goal of preventing a serious cardiac event,” Dr. Gulati added.

The guideline was prepared on behalf of and approved by the AHA and ACC Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Five other partnering organizations participated in and approved the guideline: the American Society of Echocardiography, the American College of Chest Physicians, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.

The writing group included representatives from each of the partnering organizations and experts in the field (cardiac intensivists, cardiac interventionalists, cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, emergency physicians, and epidemiologists), as well as a lay/patient representative.

The research had no commercial funding.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians should use standardized risk assessments, clinical pathways, and tools to evaluate and communicate with patients who present with chest pain (angina), advises a joint clinical practice guideline released by American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

While evaluation of chest pain has been covered in previous guidelines, this is the first comprehensive guideline from the AHA and ACC focused exclusively on the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain.

“As our imaging technologies have evolved, we needed a contemporary approach to which patients need further testing, and which do not, in addition to what testing is effective,” Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, and chair of the guideline writing group, said in an interview.

“Our hope is that we have provided an evidence-based approach to evaluating patients that will assist all of us who manage, diagnose, and treat patients who experience chest pain,” said Dr. Gulati, who is also president-elect of the American Society for Preventive Cardiology.

The guideline was simultaneously published online Oct. 28, 2021, in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

‘Atypical’ is out, ‘noncardiac’ is in

Each year, chest pain sends more than 6.5 million adults to the ED and more than 4 million to outpatient clinics in the United States.

Yet, among all patients who come to the ED, only 5% will have acute coronary syndrome (ACS). More than half will ultimately have a noncardiac reason for their chest pain, including respiratory, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, psychological, or other causes.

The guideline says evaluating the severity and the cause of chest pain is essential and advises using standard risk assessments to determine if a patient is at low, intermediate, or high risk for having a cardiac event.

“I hope clinicians take from our guidelines the understanding that low-risk patients often do not need additional testing. And if we communicate this effectively with our patients – incorporating shared decision-making into our practice – we can reduce ‘overtesting’ in low-risk patients,” Dr. Gulati said in an interview.

The guideline notes that women are unique when presenting with ACS symptoms. While chest pain is the dominant and most common symptom for both men and women, women may be more likely to also have symptoms such as nausea and shortness of breath.

The guideline also encourages using the term “noncardiac” if heart disease is not suspected in a patient with angina and says the term “atypical” is a “misleading” descriptor of chest pain and should not be used.

“Words matter, and we need to move away from describing chest pain as ‘atypical’ because it has resulted in confusion when these words are used,” Dr. Gulati stressed.

“Rather than meaning a different way of presenting, it has taken on a meaning to imply it is not cardiac. It is more useful to talk about the probability of the pain being cardiac vs noncardiac,” Dr. Gulati explained.

No one best test for everyone

There is also a focus on evaluation of patients with chest pain who present to the ED. The initial goals of ED physicians should be to identify if there are life-threatening causes and to determine if there is a need for hospital admission or testing, the guideline states.

Thorough screening in the ED may help determine who is at high risk versus intermediate or low risk for a cardiac event. An individual deemed to be at low risk may be referred for additional evaluation in an outpatient setting rather than being admitted to the hospital, the authors wrote.

High-sensitivity cardiac troponins are the “preferred standard” for establishing a biomarker diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, allowing for more accurate detection and exclusion of myocardial injury, they added.

“While there is no one ‘best test’ for every patient, the guideline emphasizes the tests that may be most appropriate, depending on the individual situation, and which ones won’t provide additional information; therefore, these tests should not be done just for the sake of doing them,” Dr. Gulati said in a news release.

“Appropriate testing is also dependent upon the technology and screening devices that are available at the hospital or healthcare center where the patient is receiving care. All imaging modalities highlighted in the guideline have an important role in the assessment of chest pain to help determine the underlying cause, with the goal of preventing a serious cardiac event,” Dr. Gulati added.

The guideline was prepared on behalf of and approved by the AHA and ACC Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Five other partnering organizations participated in and approved the guideline: the American Society of Echocardiography, the American College of Chest Physicians, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.

The writing group included representatives from each of the partnering organizations and experts in the field (cardiac intensivists, cardiac interventionalists, cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, emergency physicians, and epidemiologists), as well as a lay/patient representative.

The research had no commercial funding.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

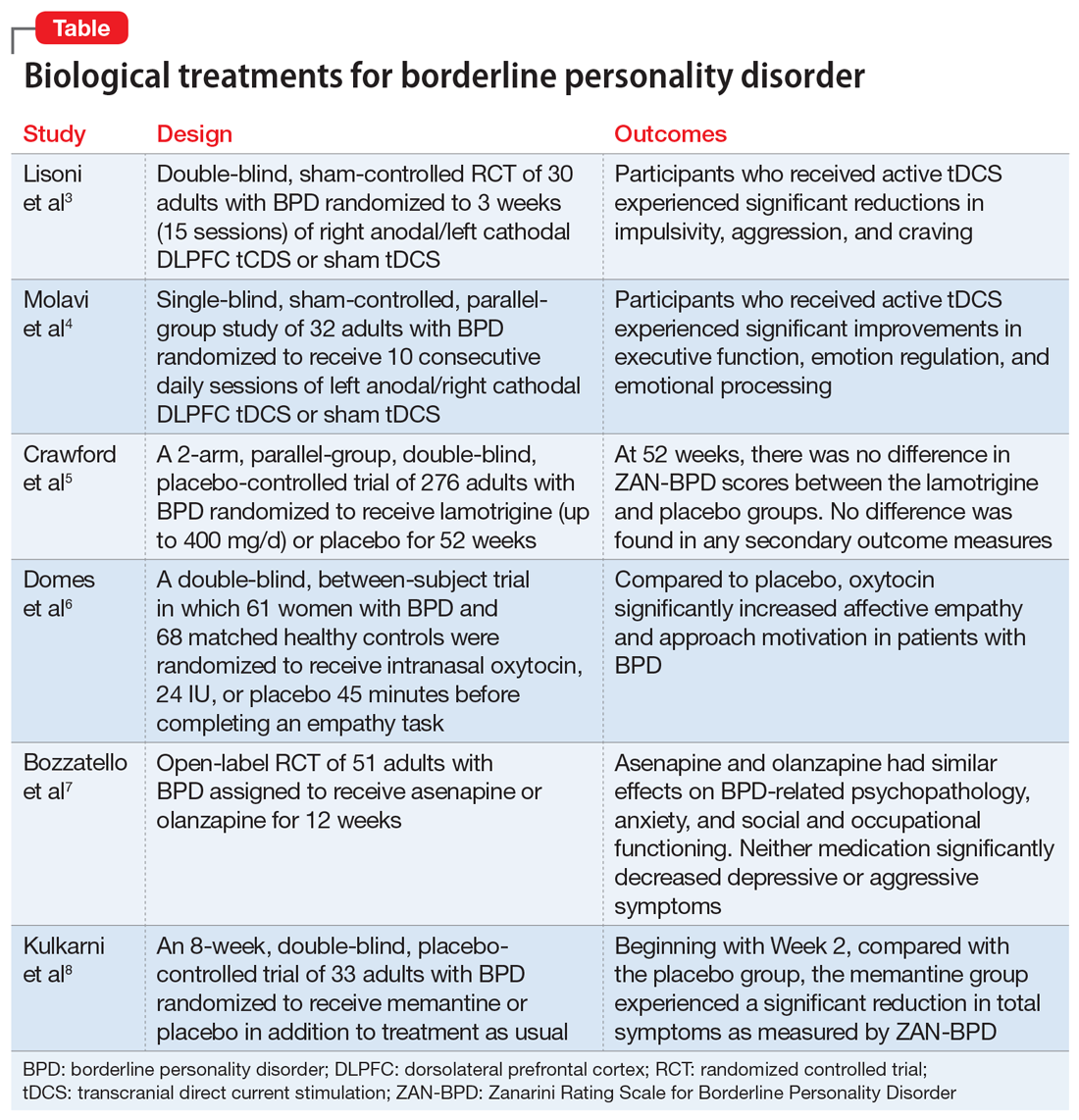

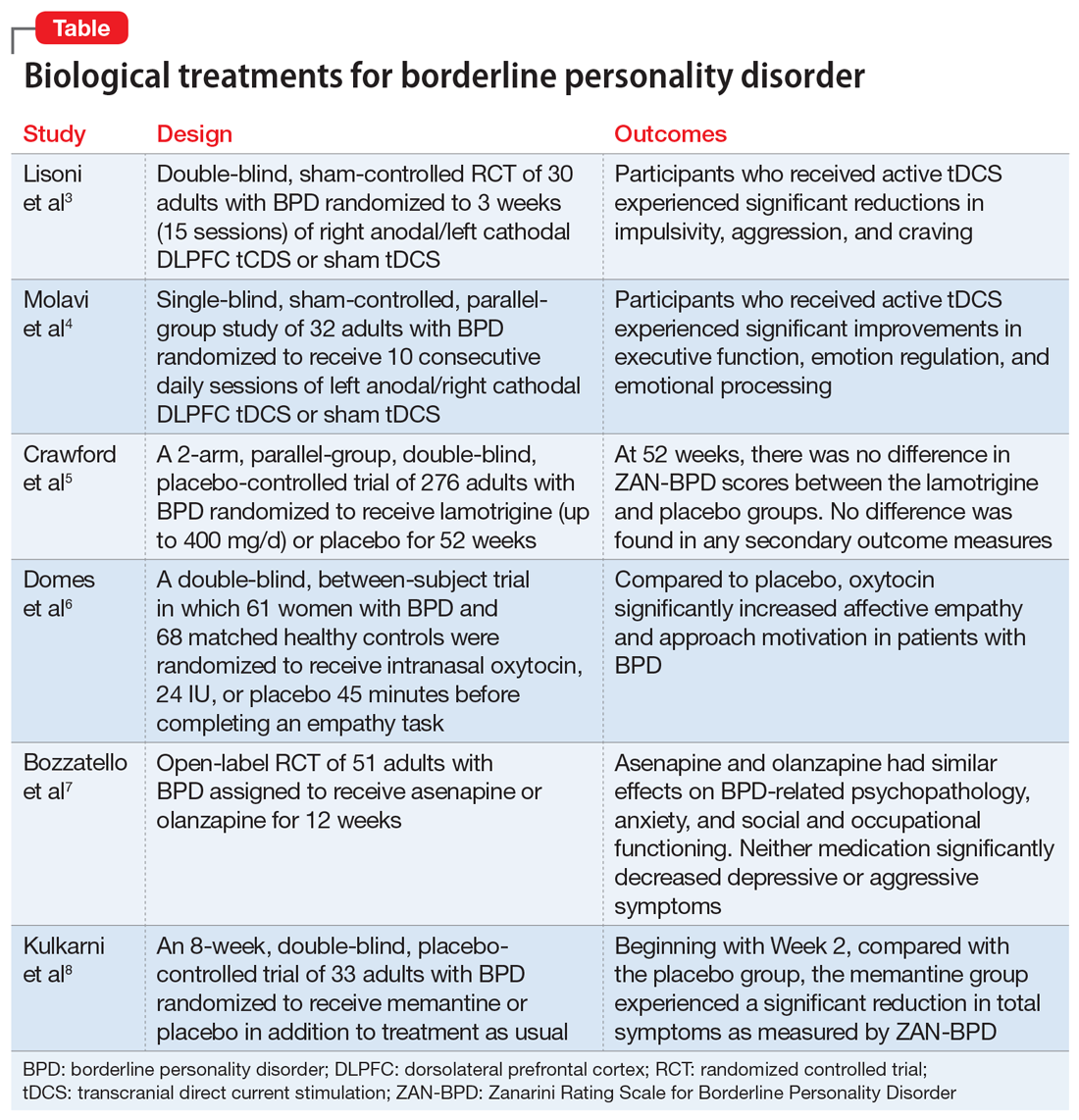

Borderline personality disorder: 6 studies of biological interventions

FIRST OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is marked by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior, often resulting in problems in relationships. BPD is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 Patients with BPD tend to use more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or those with major depressive disorder (MDD).2 However, there has been little consensus on the best treatment(s) for this serious and debilitating disorder, and some clinicians view BPD as difficult to treat.

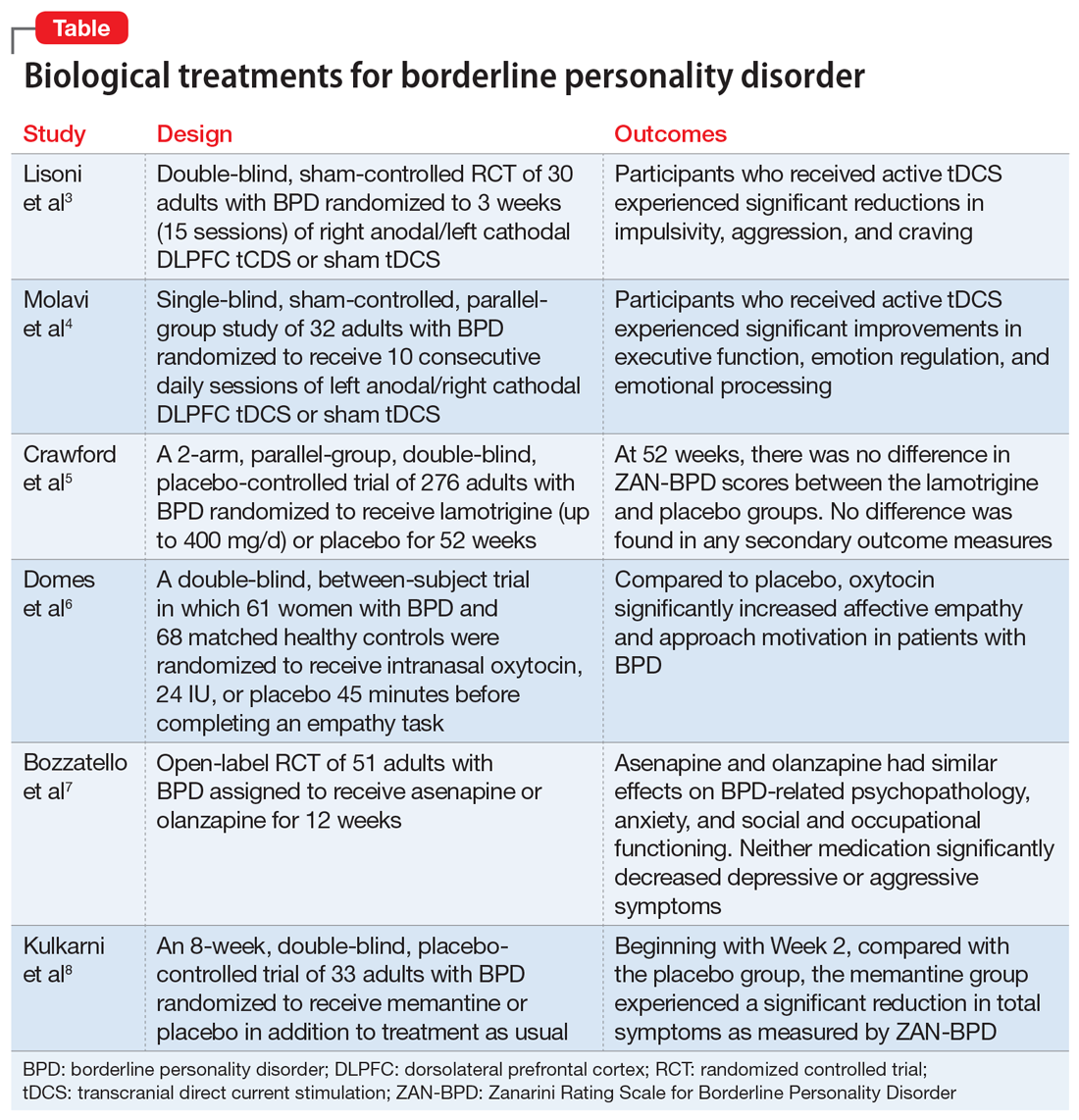

Current treatments for BPD include psychological and pharmacological interventions. Neuromodulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, may also positively affect BPD symptomatology. In recent years, there have been some promising findings in the treatment of BPD. In this 2-part article, we focus on current (within the last 5 years) findings from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of BPD treatments. Here in Part 1, we focus on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions (Table,3-8). In Part 2, we will focus on RCTs that investigated psychological interventions.

1. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

Impulsivity has been described as the core feature of BPD that best explains its behavioral, cognitive, and clinical manifestations. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the role of the prefrontal cortex in modulating impulsivity. Dysfunction of the

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In a double-blind, sham-controlled trial, adults who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD were randomized to 3 weeks (15 sessions) of right anodal/left cathodal DLPFC tCDS (n = 15) or sham tDCS (n = 15). This study included patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorders. Discontinuation or alteration of existing medications was not allowed.

- The presence, severity, and change over time of BPD core symptoms was assessed at baseline and after 3 weeks using several clinical scales, self-questionnaires, and neuropsychological tests, including the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BP-AQ), Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Irritability-Depression Anxiety Scale (IDA), Visual Analog Scales (VAS), and Iowa Gambling Task.

Outcomes

- Participants in the active tDCS group experienced significant reductions in impulsivity, aggression, and craving as measured by the BIS-11, BP-AQ, and VAS.

- Compared to the sham group, the active tDCS group had greater reductions in HAM-D and BDI scores.

- HAM-A and IDA scores were improved in both groups, although the active tDCS group showed greater reductions in IDA scores compared with the sham group.

- As measured by DERS, active tDCS did not improve affective dysregulation more than sham tDCS.

Conclusions/limitations

- Bilateral tDCS targeting the right DLPFC with anodal stimulation is a safe, well-tolerated technique that may modulate core dimensions of BPD, including impulsivity, aggression, and craving.

- Excitatory anodal stimulation of the right DLFPC coupled with inhibitory cathodal stimulation on the left DLPFC may be an effective montage for targeting impulsivity in patients with BPD.

- Study limitations include a small sample size, use of targeted questionnaires only, inclusion of patients with BPD who also had certain comorbid psychiatric disorders, lack of analysis of the contributions of medications, lack of functional neuroimaging, and lack of a follow-up phase.

2. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

Emotional dysregulation is considered a core feature of BPD psychopathology and is closely associated with executive dysfunction and cognitive control. Manifestations of executive dysfunction include aggressiveness, impulsive decision-making, disinhibition, and self-destructive behaviors. Neuroimaging of patients with BPD has shown enhanced activity in the insula, posterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala, with reduced activity in the medial PFC, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, and DLPFC. Molavi et al4 postulated that increasing DLPFC activation with left anodal tDCS would result in improved executive functioning and emotion dysregulation in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In this single-blind, sham-controlled, parallel-group study, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were randomized to receive 10 consecutive daily sessions of left anodal/right cathodal DLPFC tDCS (n = 16) or sham tDCS (n = 16).

- The effect of tDCS on executive dysfunction, emotion dysregulation, and emotional processing was measured using the Executive Skills Questionnaire for Adults (ESQ), Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), and Emotional Processing Scale (EPS). Measurements occurred at baseline and after 10 sessions of active or sham tDCS.

Outcomes

- Participants who received active tDCS experienced significant improvements in ESQ overall score and most of the executive function domains measured by the ESQ.

- Those in the active tDCS group also experienced significant improvement in emotion regulation as measured by the cognitive reappraisal subscale (but not the expressive suppression subscale) of the ERQ after the intervention.

- Overall emotional processing as measured by the EPS was significantly improved in the active tDCS group following the intervention.

Conclusions/limitations

- Repeated bilateral left anodal/right cathodal tDCS stimulation of the DLPFC significantly improved executive functioning and aspects of emotion regulation and emotional processing in patients with BPD. This improvement was presumed to be the result of increased activity of left DLPFC.

- Study limitations include a single-blind design, lack of follow-up to assess durability and stability of response over time, reliance on self-report measures, lack of functional neuroimaging, and limited focality of tDCS.

3. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

One of the hallmark symptoms of BPD is mood dysregulation. Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of mood stabilizers for BPD despite limited quality evidence of effectiveness and a lack of FDA-approved medications with this indication. In this RCT, Crawford et al5 examined whether lamotrigine is a clinically effective and cost-effective treatment for people with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In this 2-arm, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 276 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to receive lamotrigine (up to 400 mg/d) or placebo for 52 weeks.

- The primary outcome was the score on the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) at 52 weeks. Secondary outcomes included depressive symptoms, deliberate self-harm, social functioning, health-related quality of life, resource use and costs, treatment adverse effects, and adverse events. These were assessed using the BDI; Acts of Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; Social Functioning Questionnaire; Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test; and the EQ-5D-3L.

Outcomes

- Mean ZAN-BPD score decreased at 12 weeks in both groups, after which time the score remained stable.

- There was no difference in ZAN-BPD scores at 52 weeks between treatment arms. No difference was found in any secondary outcome measures.

- Difference in costs between groups was not significant.

Conclusions/limitations

- There was no evidence that lamotrigine led to clinical improvements in BPD symptomatology, social functioning, health-related quality of life, or substance use.

- Lamotrigine is neither clinically effective nor a cost-effective use of resources in the treatment of BPD.

- Limitations include a low level of adherence.

4. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

A core feature of BPD is impairment in empathy; adequate empathy is required for intact social functioning. Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that helps regulate complex social cognition and behavior. Prior research has found that oxytocin administration enhances emotion regulation and empathy. Women with BPD have been observed to have lower levels of oxytocin. Domes et al6 conducted an RCT to see if oxytocin could have a beneficial effect on social approach and social cognition in women with BPD.

Study design

- In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, between-subject trial, 61 women who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD and 68 matched healthy controls were randomized to receive intranasal oxytocin, 24 IU, or placebo 45 minutes before completing an empathy task.

- An extended version of the Multifaceted Empathy Test was used to assess empathy and approach motivation.

Outcomes

- For cognitive empathy, patients with BPD exhibited significantly lower overall performance compared to controls. There was no effect of oxytocin on this performance in either group.

- Patients with BPD had significantly lower affective empathy compared with controls. After oxytocin administration, patients with BPD had significantly higher affective empathy than those with BPD who received placebo, reaching the level of healthy controls who received placebo.

- For positive stimuli, patients with BPD showed lower affective empathy than controls. Oxytocin treatment increased affective empathy in both groups.

- For negative stimuli, oxytocin increased affective empathy more in patients with BPD than in controls.

- Patients with BPD demonstrated less approach motivation than controls. Oxytocin increased approach motivation more in patients with BPD than in controls. For approach motivation toward positive stimuli, oxytocin had a significant effect on patients with BPD.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations...

Conclusions/limitations

- Patients with BPD showed reduced cognitive and affective empathy and less approach behavior motivation than healthy controls.

- Patients with BPD who received oxytocin attained a level of affective empathy and approach motivation similar to that of healthy controls who received placebo. For positive stimuli, both groups exhibited comparable improvements from oxytocin. For negative stimuli, patients with BPD patients showed significant improvement with oxytocin, whereas healthy controls received no such benefit.

- Limitations include the use of self-report scales, lack of a control group, and inclusion of patients using psychotherapeutic medications. The study lacks generalizability because only women were included; the effect of exogenous oxytocin on men may differ.

5. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

The last decade has seen a noticeable shift in clinical practice from the use of antidepressants to mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in the treatment of BPD. Studies have demonstrated therapeutic effects of antipsychotic drugs across a wide range of BPD symptoms. Among SGAs, olanzapine is the most extensively studied across case reports, open-label studies, and RCTs of patients with BPD. In an RCT, Bozzatello et al7 compared the efficacy and tolerability of asenapine to olanzapine.

Study design

- In this open-label RCT, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were assigned to receive asenapine (n = 25) or olanzapine (n = 26) for 12 weeks.

- Study measurements included the Clinical Global Impression Scale, Severity item, HAM-D, HAM-A, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI), BIS-11, Modified Overt Aggression Scale, and Dosage Record Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale.

Outcomes

- Asenapine and olanzapine had similar effects on BPD-related psychopathology, anxiety, and social and occupational functioning.

- Neither medication significantly decreased depressive or aggressive symptoms.

- Asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the affective instability score of the BPDSI.

- Akathisia and restlessness/anxiety were more common with asenapine, and somnolence and fatigue were more common with olanzapine.

Conclusions/limitations

- The overall efficacy of asenapine was not different from olanzapine, and both medications were well-tolerated.

- Neither medication led to an improvement in depression or aggression, but asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the severity of affective instability.

- Limitations include an open-label design, lack of placebo group, small sample size, high drop-out rate, exclusion of participants with co-occurring MDD and substance abuse/dependence, lack of data on prior pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies, and lack of power to detect a difference on the dissociation/paranoid ideation item of BPDSI.

6. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

It has been hypothesized that glutamate dysregulation and excitotoxicity are crucial to the development of the cognitive disturbances that underlie BPD. As such, glutamate modulators such as memantine hold promise for the treatment of BPD. In this RCT, Kulkarni et al8 examined the efficacy and tolerability of memantine compared with treatment as usual in patients with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, adults diagnosed with BPD according to the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients were randomized to receive memantine (n = 17) or placebo (n = 16) in addition to treatment as usual. Treatment as usual included the use of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics as well as psychotherapy and other psychosocial interventions.

- Patients were initiated on placebo or memantine, 10 mg/d. Memantine was increased to 20 mg/d after 7 days.

- ZAN-BPD score was the primary outcome and was measured at baseline and 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. An adverse effects questionnaire was administered every 2 weeks to assess tolerability.

Outcomes

- During the first 2 weeks of treatment, there were no significant improvements in ZAN-BPD score in the memantine group compared with the placebo group.

- Beginning with Week 2, compared with the placebo group, the memantine group experienced a significant reduction in total symptoms as measured by ZAN-BPD.

- There were no statistically significant differences in adverse events between groups.

Conclusions/limitations

- Memantine appears to be a well-tolerated treatment option for patients with BPD and merits further study.

- Limitations include a small sample size, and an inability to reach plateau of ZAN-BPD total score in either group. Also, there is considerable individual variability in memantine steady-state plasma concentrations, but plasma levels were not measured in this study.

Bottom Line

Findings from small randomized controlled trials suggest that transcranial direct current stimulation, oxytocin, asenapine, olanzapine, and memantine may have beneficial effects on some core symptoms of borderline personality disorder. These findings need to be replicated in larger studies.

1. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TM, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159:276-283.

2. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:295-302.

3. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

4. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

5. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

6. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

7. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

8. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

FIRST OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is marked by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior, often resulting in problems in relationships. BPD is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 Patients with BPD tend to use more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or those with major depressive disorder (MDD).2 However, there has been little consensus on the best treatment(s) for this serious and debilitating disorder, and some clinicians view BPD as difficult to treat.

Current treatments for BPD include psychological and pharmacological interventions. Neuromodulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, may also positively affect BPD symptomatology. In recent years, there have been some promising findings in the treatment of BPD. In this 2-part article, we focus on current (within the last 5 years) findings from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of BPD treatments. Here in Part 1, we focus on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions (Table,3-8). In Part 2, we will focus on RCTs that investigated psychological interventions.

1. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

Impulsivity has been described as the core feature of BPD that best explains its behavioral, cognitive, and clinical manifestations. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the role of the prefrontal cortex in modulating impulsivity. Dysfunction of the

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In a double-blind, sham-controlled trial, adults who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD were randomized to 3 weeks (15 sessions) of right anodal/left cathodal DLPFC tCDS (n = 15) or sham tDCS (n = 15). This study included patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorders. Discontinuation or alteration of existing medications was not allowed.

- The presence, severity, and change over time of BPD core symptoms was assessed at baseline and after 3 weeks using several clinical scales, self-questionnaires, and neuropsychological tests, including the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BP-AQ), Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Irritability-Depression Anxiety Scale (IDA), Visual Analog Scales (VAS), and Iowa Gambling Task.

Outcomes

- Participants in the active tDCS group experienced significant reductions in impulsivity, aggression, and craving as measured by the BIS-11, BP-AQ, and VAS.

- Compared to the sham group, the active tDCS group had greater reductions in HAM-D and BDI scores.

- HAM-A and IDA scores were improved in both groups, although the active tDCS group showed greater reductions in IDA scores compared with the sham group.

- As measured by DERS, active tDCS did not improve affective dysregulation more than sham tDCS.

Conclusions/limitations

- Bilateral tDCS targeting the right DLPFC with anodal stimulation is a safe, well-tolerated technique that may modulate core dimensions of BPD, including impulsivity, aggression, and craving.

- Excitatory anodal stimulation of the right DLFPC coupled with inhibitory cathodal stimulation on the left DLPFC may be an effective montage for targeting impulsivity in patients with BPD.

- Study limitations include a small sample size, use of targeted questionnaires only, inclusion of patients with BPD who also had certain comorbid psychiatric disorders, lack of analysis of the contributions of medications, lack of functional neuroimaging, and lack of a follow-up phase.

2. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

Emotional dysregulation is considered a core feature of BPD psychopathology and is closely associated with executive dysfunction and cognitive control. Manifestations of executive dysfunction include aggressiveness, impulsive decision-making, disinhibition, and self-destructive behaviors. Neuroimaging of patients with BPD has shown enhanced activity in the insula, posterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala, with reduced activity in the medial PFC, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, and DLPFC. Molavi et al4 postulated that increasing DLPFC activation with left anodal tDCS would result in improved executive functioning and emotion dysregulation in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In this single-blind, sham-controlled, parallel-group study, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were randomized to receive 10 consecutive daily sessions of left anodal/right cathodal DLPFC tDCS (n = 16) or sham tDCS (n = 16).

- The effect of tDCS on executive dysfunction, emotion dysregulation, and emotional processing was measured using the Executive Skills Questionnaire for Adults (ESQ), Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), and Emotional Processing Scale (EPS). Measurements occurred at baseline and after 10 sessions of active or sham tDCS.

Outcomes

- Participants who received active tDCS experienced significant improvements in ESQ overall score and most of the executive function domains measured by the ESQ.

- Those in the active tDCS group also experienced significant improvement in emotion regulation as measured by the cognitive reappraisal subscale (but not the expressive suppression subscale) of the ERQ after the intervention.

- Overall emotional processing as measured by the EPS was significantly improved in the active tDCS group following the intervention.

Conclusions/limitations

- Repeated bilateral left anodal/right cathodal tDCS stimulation of the DLPFC significantly improved executive functioning and aspects of emotion regulation and emotional processing in patients with BPD. This improvement was presumed to be the result of increased activity of left DLPFC.

- Study limitations include a single-blind design, lack of follow-up to assess durability and stability of response over time, reliance on self-report measures, lack of functional neuroimaging, and limited focality of tDCS.

3. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

One of the hallmark symptoms of BPD is mood dysregulation. Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of mood stabilizers for BPD despite limited quality evidence of effectiveness and a lack of FDA-approved medications with this indication. In this RCT, Crawford et al5 examined whether lamotrigine is a clinically effective and cost-effective treatment for people with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In this 2-arm, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 276 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to receive lamotrigine (up to 400 mg/d) or placebo for 52 weeks.

- The primary outcome was the score on the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) at 52 weeks. Secondary outcomes included depressive symptoms, deliberate self-harm, social functioning, health-related quality of life, resource use and costs, treatment adverse effects, and adverse events. These were assessed using the BDI; Acts of Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; Social Functioning Questionnaire; Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test; and the EQ-5D-3L.

Outcomes

- Mean ZAN-BPD score decreased at 12 weeks in both groups, after which time the score remained stable.

- There was no difference in ZAN-BPD scores at 52 weeks between treatment arms. No difference was found in any secondary outcome measures.

- Difference in costs between groups was not significant.

Conclusions/limitations

- There was no evidence that lamotrigine led to clinical improvements in BPD symptomatology, social functioning, health-related quality of life, or substance use.

- Lamotrigine is neither clinically effective nor a cost-effective use of resources in the treatment of BPD.

- Limitations include a low level of adherence.

4. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

A core feature of BPD is impairment in empathy; adequate empathy is required for intact social functioning. Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that helps regulate complex social cognition and behavior. Prior research has found that oxytocin administration enhances emotion regulation and empathy. Women with BPD have been observed to have lower levels of oxytocin. Domes et al6 conducted an RCT to see if oxytocin could have a beneficial effect on social approach and social cognition in women with BPD.

Study design

- In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, between-subject trial, 61 women who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD and 68 matched healthy controls were randomized to receive intranasal oxytocin, 24 IU, or placebo 45 minutes before completing an empathy task.

- An extended version of the Multifaceted Empathy Test was used to assess empathy and approach motivation.

Outcomes

- For cognitive empathy, patients with BPD exhibited significantly lower overall performance compared to controls. There was no effect of oxytocin on this performance in either group.

- Patients with BPD had significantly lower affective empathy compared with controls. After oxytocin administration, patients with BPD had significantly higher affective empathy than those with BPD who received placebo, reaching the level of healthy controls who received placebo.

- For positive stimuli, patients with BPD showed lower affective empathy than controls. Oxytocin treatment increased affective empathy in both groups.

- For negative stimuli, oxytocin increased affective empathy more in patients with BPD than in controls.

- Patients with BPD demonstrated less approach motivation than controls. Oxytocin increased approach motivation more in patients with BPD than in controls. For approach motivation toward positive stimuli, oxytocin had a significant effect on patients with BPD.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations...

Conclusions/limitations

- Patients with BPD showed reduced cognitive and affective empathy and less approach behavior motivation than healthy controls.

- Patients with BPD who received oxytocin attained a level of affective empathy and approach motivation similar to that of healthy controls who received placebo. For positive stimuli, both groups exhibited comparable improvements from oxytocin. For negative stimuli, patients with BPD patients showed significant improvement with oxytocin, whereas healthy controls received no such benefit.

- Limitations include the use of self-report scales, lack of a control group, and inclusion of patients using psychotherapeutic medications. The study lacks generalizability because only women were included; the effect of exogenous oxytocin on men may differ.

5. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

The last decade has seen a noticeable shift in clinical practice from the use of antidepressants to mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in the treatment of BPD. Studies have demonstrated therapeutic effects of antipsychotic drugs across a wide range of BPD symptoms. Among SGAs, olanzapine is the most extensively studied across case reports, open-label studies, and RCTs of patients with BPD. In an RCT, Bozzatello et al7 compared the efficacy and tolerability of asenapine to olanzapine.

Study design

- In this open-label RCT, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were assigned to receive asenapine (n = 25) or olanzapine (n = 26) for 12 weeks.

- Study measurements included the Clinical Global Impression Scale, Severity item, HAM-D, HAM-A, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI), BIS-11, Modified Overt Aggression Scale, and Dosage Record Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale.

Outcomes

- Asenapine and olanzapine had similar effects on BPD-related psychopathology, anxiety, and social and occupational functioning.

- Neither medication significantly decreased depressive or aggressive symptoms.

- Asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the affective instability score of the BPDSI.

- Akathisia and restlessness/anxiety were more common with asenapine, and somnolence and fatigue were more common with olanzapine.

Conclusions/limitations

- The overall efficacy of asenapine was not different from olanzapine, and both medications were well-tolerated.

- Neither medication led to an improvement in depression or aggression, but asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the severity of affective instability.

- Limitations include an open-label design, lack of placebo group, small sample size, high drop-out rate, exclusion of participants with co-occurring MDD and substance abuse/dependence, lack of data on prior pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies, and lack of power to detect a difference on the dissociation/paranoid ideation item of BPDSI.

6. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

It has been hypothesized that glutamate dysregulation and excitotoxicity are crucial to the development of the cognitive disturbances that underlie BPD. As such, glutamate modulators such as memantine hold promise for the treatment of BPD. In this RCT, Kulkarni et al8 examined the efficacy and tolerability of memantine compared with treatment as usual in patients with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, adults diagnosed with BPD according to the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients were randomized to receive memantine (n = 17) or placebo (n = 16) in addition to treatment as usual. Treatment as usual included the use of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics as well as psychotherapy and other psychosocial interventions.

- Patients were initiated on placebo or memantine, 10 mg/d. Memantine was increased to 20 mg/d after 7 days.

- ZAN-BPD score was the primary outcome and was measured at baseline and 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. An adverse effects questionnaire was administered every 2 weeks to assess tolerability.

Outcomes

- During the first 2 weeks of treatment, there were no significant improvements in ZAN-BPD score in the memantine group compared with the placebo group.

- Beginning with Week 2, compared with the placebo group, the memantine group experienced a significant reduction in total symptoms as measured by ZAN-BPD.

- There were no statistically significant differences in adverse events between groups.

Conclusions/limitations

- Memantine appears to be a well-tolerated treatment option for patients with BPD and merits further study.

- Limitations include a small sample size, and an inability to reach plateau of ZAN-BPD total score in either group. Also, there is considerable individual variability in memantine steady-state plasma concentrations, but plasma levels were not measured in this study.

Bottom Line

Findings from small randomized controlled trials suggest that transcranial direct current stimulation, oxytocin, asenapine, olanzapine, and memantine may have beneficial effects on some core symptoms of borderline personality disorder. These findings need to be replicated in larger studies.

FIRST OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is marked by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior, often resulting in problems in relationships. BPD is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 Patients with BPD tend to use more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or those with major depressive disorder (MDD).2 However, there has been little consensus on the best treatment(s) for this serious and debilitating disorder, and some clinicians view BPD as difficult to treat.

Current treatments for BPD include psychological and pharmacological interventions. Neuromodulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, may also positively affect BPD symptomatology. In recent years, there have been some promising findings in the treatment of BPD. In this 2-part article, we focus on current (within the last 5 years) findings from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of BPD treatments. Here in Part 1, we focus on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions (Table,3-8). In Part 2, we will focus on RCTs that investigated psychological interventions.

1. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

Impulsivity has been described as the core feature of BPD that best explains its behavioral, cognitive, and clinical manifestations. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the role of the prefrontal cortex in modulating impulsivity. Dysfunction of the

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In a double-blind, sham-controlled trial, adults who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD were randomized to 3 weeks (15 sessions) of right anodal/left cathodal DLPFC tCDS (n = 15) or sham tDCS (n = 15). This study included patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorders. Discontinuation or alteration of existing medications was not allowed.

- The presence, severity, and change over time of BPD core symptoms was assessed at baseline and after 3 weeks using several clinical scales, self-questionnaires, and neuropsychological tests, including the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BP-AQ), Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Irritability-Depression Anxiety Scale (IDA), Visual Analog Scales (VAS), and Iowa Gambling Task.

Outcomes

- Participants in the active tDCS group experienced significant reductions in impulsivity, aggression, and craving as measured by the BIS-11, BP-AQ, and VAS.

- Compared to the sham group, the active tDCS group had greater reductions in HAM-D and BDI scores.

- HAM-A and IDA scores were improved in both groups, although the active tDCS group showed greater reductions in IDA scores compared with the sham group.

- As measured by DERS, active tDCS did not improve affective dysregulation more than sham tDCS.

Conclusions/limitations

- Bilateral tDCS targeting the right DLPFC with anodal stimulation is a safe, well-tolerated technique that may modulate core dimensions of BPD, including impulsivity, aggression, and craving.

- Excitatory anodal stimulation of the right DLFPC coupled with inhibitory cathodal stimulation on the left DLPFC may be an effective montage for targeting impulsivity in patients with BPD.

- Study limitations include a small sample size, use of targeted questionnaires only, inclusion of patients with BPD who also had certain comorbid psychiatric disorders, lack of analysis of the contributions of medications, lack of functional neuroimaging, and lack of a follow-up phase.

2. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

Emotional dysregulation is considered a core feature of BPD psychopathology and is closely associated with executive dysfunction and cognitive control. Manifestations of executive dysfunction include aggressiveness, impulsive decision-making, disinhibition, and self-destructive behaviors. Neuroimaging of patients with BPD has shown enhanced activity in the insula, posterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala, with reduced activity in the medial PFC, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, and DLPFC. Molavi et al4 postulated that increasing DLPFC activation with left anodal tDCS would result in improved executive functioning and emotion dysregulation in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In this single-blind, sham-controlled, parallel-group study, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were randomized to receive 10 consecutive daily sessions of left anodal/right cathodal DLPFC tDCS (n = 16) or sham tDCS (n = 16).

- The effect of tDCS on executive dysfunction, emotion dysregulation, and emotional processing was measured using the Executive Skills Questionnaire for Adults (ESQ), Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), and Emotional Processing Scale (EPS). Measurements occurred at baseline and after 10 sessions of active or sham tDCS.

Outcomes

- Participants who received active tDCS experienced significant improvements in ESQ overall score and most of the executive function domains measured by the ESQ.

- Those in the active tDCS group also experienced significant improvement in emotion regulation as measured by the cognitive reappraisal subscale (but not the expressive suppression subscale) of the ERQ after the intervention.

- Overall emotional processing as measured by the EPS was significantly improved in the active tDCS group following the intervention.

Conclusions/limitations

- Repeated bilateral left anodal/right cathodal tDCS stimulation of the DLPFC significantly improved executive functioning and aspects of emotion regulation and emotional processing in patients with BPD. This improvement was presumed to be the result of increased activity of left DLPFC.

- Study limitations include a single-blind design, lack of follow-up to assess durability and stability of response over time, reliance on self-report measures, lack of functional neuroimaging, and limited focality of tDCS.

3. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

One of the hallmark symptoms of BPD is mood dysregulation. Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of mood stabilizers for BPD despite limited quality evidence of effectiveness and a lack of FDA-approved medications with this indication. In this RCT, Crawford et al5 examined whether lamotrigine is a clinically effective and cost-effective treatment for people with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In this 2-arm, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 276 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to receive lamotrigine (up to 400 mg/d) or placebo for 52 weeks.

- The primary outcome was the score on the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) at 52 weeks. Secondary outcomes included depressive symptoms, deliberate self-harm, social functioning, health-related quality of life, resource use and costs, treatment adverse effects, and adverse events. These were assessed using the BDI; Acts of Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; Social Functioning Questionnaire; Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test; and the EQ-5D-3L.

Outcomes

- Mean ZAN-BPD score decreased at 12 weeks in both groups, after which time the score remained stable.

- There was no difference in ZAN-BPD scores at 52 weeks between treatment arms. No difference was found in any secondary outcome measures.

- Difference in costs between groups was not significant.

Conclusions/limitations

- There was no evidence that lamotrigine led to clinical improvements in BPD symptomatology, social functioning, health-related quality of life, or substance use.

- Lamotrigine is neither clinically effective nor a cost-effective use of resources in the treatment of BPD.

- Limitations include a low level of adherence.

4. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

A core feature of BPD is impairment in empathy; adequate empathy is required for intact social functioning. Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that helps regulate complex social cognition and behavior. Prior research has found that oxytocin administration enhances emotion regulation and empathy. Women with BPD have been observed to have lower levels of oxytocin. Domes et al6 conducted an RCT to see if oxytocin could have a beneficial effect on social approach and social cognition in women with BPD.

Study design

- In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, between-subject trial, 61 women who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD and 68 matched healthy controls were randomized to receive intranasal oxytocin, 24 IU, or placebo 45 minutes before completing an empathy task.

- An extended version of the Multifaceted Empathy Test was used to assess empathy and approach motivation.

Outcomes

- For cognitive empathy, patients with BPD exhibited significantly lower overall performance compared to controls. There was no effect of oxytocin on this performance in either group.

- Patients with BPD had significantly lower affective empathy compared with controls. After oxytocin administration, patients with BPD had significantly higher affective empathy than those with BPD who received placebo, reaching the level of healthy controls who received placebo.

- For positive stimuli, patients with BPD showed lower affective empathy than controls. Oxytocin treatment increased affective empathy in both groups.

- For negative stimuli, oxytocin increased affective empathy more in patients with BPD than in controls.

- Patients with BPD demonstrated less approach motivation than controls. Oxytocin increased approach motivation more in patients with BPD than in controls. For approach motivation toward positive stimuli, oxytocin had a significant effect on patients with BPD.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations...

Conclusions/limitations

- Patients with BPD showed reduced cognitive and affective empathy and less approach behavior motivation than healthy controls.

- Patients with BPD who received oxytocin attained a level of affective empathy and approach motivation similar to that of healthy controls who received placebo. For positive stimuli, both groups exhibited comparable improvements from oxytocin. For negative stimuli, patients with BPD patients showed significant improvement with oxytocin, whereas healthy controls received no such benefit.

- Limitations include the use of self-report scales, lack of a control group, and inclusion of patients using psychotherapeutic medications. The study lacks generalizability because only women were included; the effect of exogenous oxytocin on men may differ.

5. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

The last decade has seen a noticeable shift in clinical practice from the use of antidepressants to mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in the treatment of BPD. Studies have demonstrated therapeutic effects of antipsychotic drugs across a wide range of BPD symptoms. Among SGAs, olanzapine is the most extensively studied across case reports, open-label studies, and RCTs of patients with BPD. In an RCT, Bozzatello et al7 compared the efficacy and tolerability of asenapine to olanzapine.

Study design

- In this open-label RCT, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were assigned to receive asenapine (n = 25) or olanzapine (n = 26) for 12 weeks.

- Study measurements included the Clinical Global Impression Scale, Severity item, HAM-D, HAM-A, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI), BIS-11, Modified Overt Aggression Scale, and Dosage Record Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale.

Outcomes

- Asenapine and olanzapine had similar effects on BPD-related psychopathology, anxiety, and social and occupational functioning.

- Neither medication significantly decreased depressive or aggressive symptoms.

- Asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the affective instability score of the BPDSI.

- Akathisia and restlessness/anxiety were more common with asenapine, and somnolence and fatigue were more common with olanzapine.

Conclusions/limitations

- The overall efficacy of asenapine was not different from olanzapine, and both medications were well-tolerated.

- Neither medication led to an improvement in depression or aggression, but asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the severity of affective instability.

- Limitations include an open-label design, lack of placebo group, small sample size, high drop-out rate, exclusion of participants with co-occurring MDD and substance abuse/dependence, lack of data on prior pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies, and lack of power to detect a difference on the dissociation/paranoid ideation item of BPDSI.

6. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

It has been hypothesized that glutamate dysregulation and excitotoxicity are crucial to the development of the cognitive disturbances that underlie BPD. As such, glutamate modulators such as memantine hold promise for the treatment of BPD. In this RCT, Kulkarni et al8 examined the efficacy and tolerability of memantine compared with treatment as usual in patients with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, adults diagnosed with BPD according to the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients were randomized to receive memantine (n = 17) or placebo (n = 16) in addition to treatment as usual. Treatment as usual included the use of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics as well as psychotherapy and other psychosocial interventions.

- Patients were initiated on placebo or memantine, 10 mg/d. Memantine was increased to 20 mg/d after 7 days.

- ZAN-BPD score was the primary outcome and was measured at baseline and 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. An adverse effects questionnaire was administered every 2 weeks to assess tolerability.

Outcomes

- During the first 2 weeks of treatment, there were no significant improvements in ZAN-BPD score in the memantine group compared with the placebo group.

- Beginning with Week 2, compared with the placebo group, the memantine group experienced a significant reduction in total symptoms as measured by ZAN-BPD.

- There were no statistically significant differences in adverse events between groups.

Conclusions/limitations

- Memantine appears to be a well-tolerated treatment option for patients with BPD and merits further study.

- Limitations include a small sample size, and an inability to reach plateau of ZAN-BPD total score in either group. Also, there is considerable individual variability in memantine steady-state plasma concentrations, but plasma levels were not measured in this study.

Bottom Line

Findings from small randomized controlled trials suggest that transcranial direct current stimulation, oxytocin, asenapine, olanzapine, and memantine may have beneficial effects on some core symptoms of borderline personality disorder. These findings need to be replicated in larger studies.

1. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TM, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159:276-283.

2. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:295-302.

3. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

4. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

5. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

6. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

7. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

8. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

1. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TM, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159:276-283.

2. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:295-302.

3. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

4. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

5. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

6. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

7. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

8. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

Service animals and emotional support animals: Should you write that letter?

For centuries, animals, especially dogs, have assisted humans in a variety of ways in their daily lives. Animals that assist people with disabilities fall into 2 broad categories: disability service animals, and emotional support animals (ESAs). Often there is confusion in how these categories differ because of the animal’s role and the laws related to them.

This article describes the differences between disability service animals and ESAs, and outlines the forensic and ethical concerns you should consider before agreeing to write a letter for a patient outlining their need for a disability service animal or ESA. A letter may protect a patient and their service animal or ESA in situations where laws and regulations typically prohibit animals, such as on a flight or when renting an apartment or house. Note that a description of how to conduct the formal patient evaluation before writing a verification letter is beyond the scope of this article.

The differences between disability service animals and ESAs

Purpose and training. Disability service animals, or service animals, are dogs of any breed (and in some cases miniature horses) that are specially trained to perform tasks for an individual with a disability (physical, sensory, psychiatric, intellectual, or other mental disability).1-3 These tasks must be directly related to the individual’s disability.1,2 On the other hand, ESAs, which can be any species of animal, provide support and minimize the impact of an individual’s emotional or psychological disability based on their presence alone. Unlike disability service animals, ESAs are not trained to perform a specific task or duty.2,3

There is no legal requirement for service animals to know specific commands, and professional training is not required—individuals can train the animals themselves.1 Service animals, mainly dogs, can be trained to perform numerous tasks, including4:

- attending to an individual’s mobility and activities of daily living

- guiding an individual who is deaf or hearing impaired

- helping to remind an individual to take their medications

- assisting an individual during and/or after a seizure

- alerting individuals with diabetes in advance of low or high blood sugar episodes

- supporting an individual with autism

- assisting an individual with a psychiatric or mental disability

- applying sensory commands such as lying on the person or resting their head on the individual’s lap to help the individual regain behavioral control.

Service dog verification works via an honor system, which can be problematic, especially in the case of psychiatric service dogs, whose handlers may not have a visible disability (Box 11,5).

Box 1

In the United States, there is no national service dog certification program—meaning there is no official test that a dog has to pass in order to obtain formal recognition as a service animal—nor is there a central and mandatory service dog registry.5 Instead, service dog verification works through an honor system, which can be problematic.5 In many states, misrepresenting one’s dog as a service dog is considered a misdemeanor.5 Unfortunately, other than the guidance set forth by the Americans with Disabilities Act, there are no criteria by which one can recognize a genuine service dog vs one being passed off as a service dog.5

In situations in public settings where it is not obvious or there’s doubt that the dog is a service animal (such as when a person visits a restaurant or store), employees are not allowed to request documentation for the dog, require the dog demonstrate its task, or inquire about the nature of the person’s disability.1

However, they can ask 2 questions1:

1. Is the animal required because of a disability?

2. What work or task has the animal been trained to perform?

Legal protections. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), individuals with disabilities can bring their service animals into buildings or facilities where members of the public, program participants, clients, customers, patrons, or invitees are allowed.2 This does not include private clubs, religious organizations, or places of worship that are not open to the public.6,7 ESAs do not qualify as service animals under the ADA and are not given the same legal accommodations as service animals.1,3 Although ESAs were initially covered by the Air Carrier Access Act, they are no longer allowed in aircraft cabins after the US Department of Transportation revised this Act’s regulations in December 2020. ESAs are covered under the Fair Housing Act. Box 21-3,6-15 further discusses these laws and protections.

Evidence.

Due to the difficulty in reconciling inconsistent definitions for ESAs, there is limited high-quality data pertaining to the potential benefits and risks of ESAs.9 Currently, ESAs are not an evidence-based treatment for psychiatric disorders. To date, a handful of small studies have focused on ESAs. However, data from actual tests of the clinical risks and benefits of ESAs do not exist.9 In practice, ESAs are equivalent to pets. It stands to reason that similar to pets, ESAs could reduce loneliness, improve life satisfaction, and provide a sense of well-being.9 A systematic review suggested that pets provide benefits to patients with mental health conditions “through the intensity of connectivity with their owners and the contribution they make to emotional support in times of crises together with their ability to help manage symptoms when they arise.”18 In response to a congressional mandate, the US Department of Veterans Affairs launched a multi-site study from December 2014 to June 2019 to examine how limitations on activity and quality of life in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder are impacted by the provision of a service dog vs an emotional support dog.19 As of October 14, 2021, results had not been published.19

Continue to: What’s in a disability service animal/ESA letter?

What’s in a disability service animal/ESA letter?

If you decide to write a letter advocating for your patient to have a service animal or ESA, the letter should appear on letterhead, be written by a licensed mental health professional, and include the following2,20: