User login

Which agent is best for neuromyelitis optica?

The Alexion-sponsored study was presented at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS) by Dean Wingerchuk, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Other experts in the field have highlighted limitations to the analysis and pointed out that all three agents are very effective in treating AQP4+ NMOSD, and many other considerations need to be taken into account as well as time to first relapse when selecting a therapy, leaving the door open for all three agents.

Dr. Wingerchuk explained that NMOSD is a rare severely disabling complement-mediated autoimmune neuroinflammatory disease of the central nervous system, characterized by devastating and unpredictable attacks (relapses) that can cause immediate and irreversible damage.

There are three recently approved monoclonal antibody treatment options in the United States for adults with AQP4+ NMOSD: eculizumab (Soliris, Alexion), inebilizumab (Uplizna, Horizon), and satralizumab (Enspryng, Genentech). A comparison of the relative treatment effects of these drugs would facilitate the treatment selection process, Dr. Wingerchuk said.

The objective of this study was to perform an indirect treatment comparison on the efficacy of these three FDA-approved treatment options for adults with AQP4+ NMOSD, in the absence of any head-to-head studies.

Using published data from randomized controlled trials, which were identified by a systematic literature review in September 2020, the researchers performed a Bayesian network meta-analysis to estimate the relative effects between eculizumab, inebilizumab, and satralizumab.

Network meta-analyses were performed for clinically relevant subpopulations based on three treatment networks: (1) patients who received monotherapy with one of the monoclonal antibodies or in combination with an immunosuppressant therapy; (2) patients who received monotherapy with the monoclonal antibody alone; and (3) patients who received a combination of both the monoclonal antibody and immunosuppressant therapy.

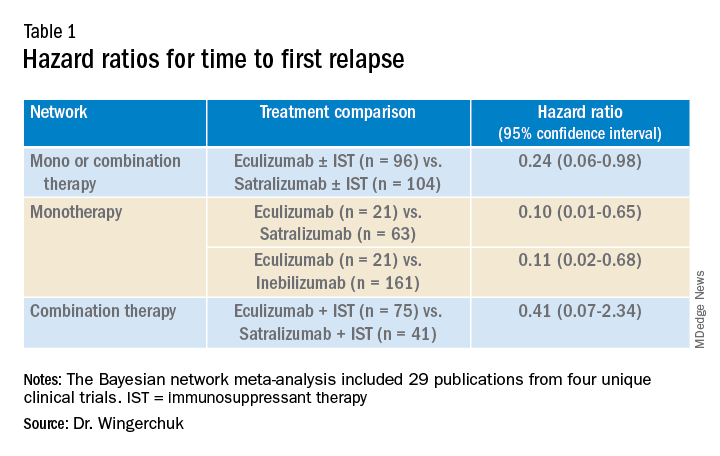

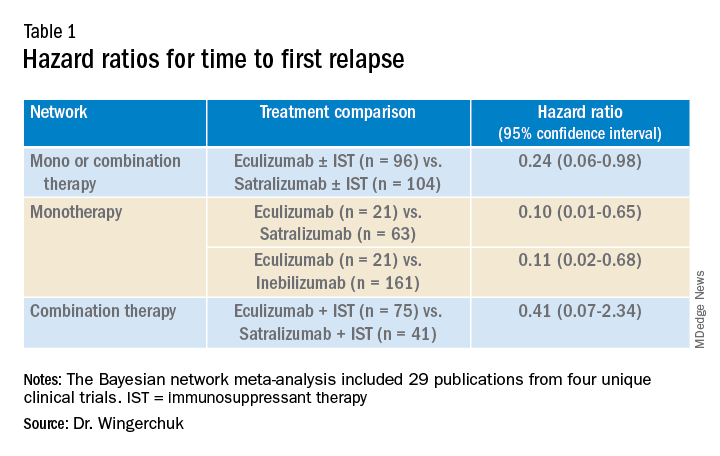

Time to first relapse was the primary efficacy outcome assessed. Relative treatment effects were expressed as hazard ratios and the probability that a treatment was the best at delaying time to first relapse was also evaluated.

In the systematic literature review, 29 publications from four unique clinical trials were identified and include in the network meta-analysis. These included publications from congress proceedings and peer-reviewed journals.

The four clinical trials were the N-MOmentum trial of inebilizumab versus placebo; the PREVENT trial of eculizumab with or without immunosuppressant therapy versus placebo with or without immunosuppressant therapy; the SAkuraSky trial of satralizumab plus immunosuppressant therapy versus placebo plus immunosuppressant therapy; and the SAkuraStar trial of satralizumab versus placebo.

Results showed that for the first analysis of mono or combination therapy, patients treated with eculizumab with or without immunosuppressant therapy were 76% less likely to experience a first relapse when compared with patients treated with satralizumab with or without immunosuppressant therapy.

In the monotherapy network, patients on eculizumab were 90% less likely to experience a first relapse when compared with patients treated with satralizumab, and patients on eculizumab were 89% less likely to experience a first relapse when compared with patients treated with inebilizumab.

In the third network analysis – a comparison of eculizumab plus immunosuppressant therapy with inebilizumab plus immunosuppressant therapy (Table 1) – the point estimate appeared to favor eculizumab but the confidence intervals were wide and not significant.

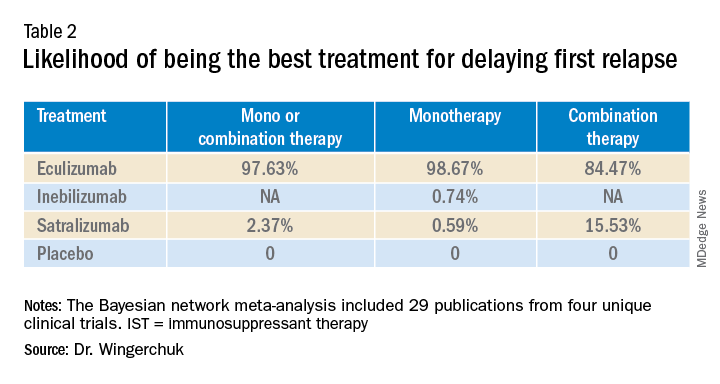

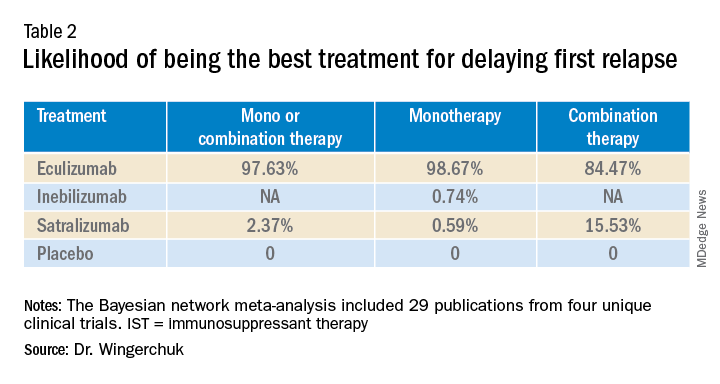

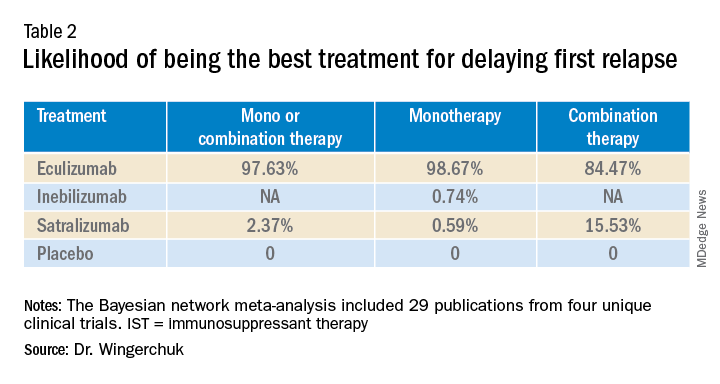

A subsequent analysis looked at the rank order of the best treatment option, with eculizumab coming out first in all three networks (Table 2).

Dr. Wingerchuk acknowledged that there were many limitations to this study, including that analyses for annualized relapse rate, disability, and quality of life were not included because of a lack of consistent outcome reporting by AQP4+ status in the randomized trials.

Safety outcomes were excluded because of a lack of standardized baseline risks and inconsistent reporting by AQP4+ status across trials.

Because this study focused on drugs approved in the United States in a rare disease area, there were a limited number of studies with intervention effects.

There were differences in follow-up durations across the different trials, with N-MOmentum having a follow-up of 197 days compared with 144 weeks for other trials.

“In the absence of head-to-head trials, this network meta-analysis provides important evidence on the relative efficacy of eculizumab versus satralizumab or inebilizumab for the treatment of patients with AQP4+ NMOSD, with significant differences in two out of the three treatment comparison scenarios observed,” Dr. Wingerchuk concluded.

“Based on current evidence, monotherapy and mono-combination therapy with eculizumab appear to more efficacious at preventing relapses than satralizumab or inebilizumab for the treatment of adults with AQP4+ NMOSD. These findings appear to suggest that C5 complement inhibition with treatments such as eculizumab appear to prevent relapses more effectively than other mechanisms involving IL-6 receptor or CD19 inhibition among adults with AQP4+ NMOSD,” he added.

Experts respond

Commenting on the study, several experts in the field provided some balancing views.

Bruce Cree, MD, University of California San Francisco, who was the chief investigator of the N-MOmentum study with inebilizumab, said he was skeptical about this new indirect comparison. “The results of this study seem too good to be true; a 90% difference between agents has to be an overestimate,” he said.

“We know from independent studies that all three drugs are very effective. If we take each trial separately, eculizumab reduced attack risk by 90% versus placebo; and the other two drugs by 77% to 78% versus placebo. For eculizumab to be 90% better than inebilizumab or satralizumab its basically like saying these drugs perform like placebo, but we know that is not the case,” Dr. Cree argued.

He pointed out that when comparing results across studies there are many factors that have to be considered, including the different patient populations included in the different studies, with the characteristic of each population in each trial being unique to that dataset.

In addition, Dr. Cree suggested that all the studies included in the comparison were relatively small for this type of analysis. “Normally this type of analysis is done with much larger studies, so the resulting database is closer to a representation of the disease state itself,” he said.

Dr. Cree also questioned the role of the sponsor in this meta-analysis. “The analysis was sponsored by Alexion and several coauthors were employees of Alexion. There was not much description available of how the statistics were done. I am concerned that the company was involved in the analysis, which could introduce bias. I look forward to seeing details of the statistical methodology,” he said.

“This is definitely a provocative study. They have thrown down the gauntlet. If they are so confident in the results they should now do a head-to-head study to back this result up. If they don’t do that, then I think physicians should ignore it as there are just too many problems with this analysis,” Dr. Cree stated.

Dr. Cree acknowledged that when looking at the four trials separately, eculizumab does look a little better than the other two agents in delaying time to first relapse. “But there are some caveats. Despite a larger reduction in relapse rate there was no reduction in disability in the eculizumab trial. Whereas the inebilizumab trial did show a reduction in disability. And while the PREVENT trial with eculizumab was a good study, during the course of the trial the definition of clinical relapse was changed, and as a consequence that increased the product’s performance – that’s a little bit curious,” he added.

How to choose?

On how to choose between the three agents, Dr. Cree said they are all “extraordinarily effective” at reducing relapse activity. “They are all ‘home run’ products, but they have differences in safety,” he said.

“Inebilizumab is linked to hypogammaglobulinemia over time – we haven’t seen an increase in infection risk linked to this, but with enough time, I would expect that there probably will be. But inebilizumab is a B-cell-depleting agent like the agents used in MS, and we now have a lot of experiences with this type of product, which gives us more confidence on the safety profile,” Dr. Cree noted.

“Eculizumab was linked to a risk of meningococcal meningitis and other bacterial infections, and satralizumab seems to [be] overall well tolerated with no obvious safety concerns to date, but the studies have been quite small,” he added.

On routes of administration and frequency of dosing, Dr. Cree pointed out that while all three drugs have an intensive loading schedule, for maintenance, eculizumab needs to be given as an IV infusion every 2 weeks. Inebilizumab needs just two infusions per year for maintenance, while satralizumab is given by subcutaneous injection once per month.

“It may be that eculizumab could be used at the time of an acute attack but then treatment could be switched to one of the other two for long-term maintenance,” he suggested.

But Dr. Cree pointed out that the biggest challenge for all three agents is access. “The costs are astronomically high ($200,000-$770,000). They are prohibitively expensive and very few insurance companies are covering them.”

Also commenting, Brian Weinshenker, MD, from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who was a member of the attack adjudication committee for both PREVENT and N-MOmentum studies, pointed out that as well as differences in the populations enrolled, and study designs, the studies with the three different drugs also had differences in attack adjudication criteria.

“These factors make it very difficult to compare across studies, which is what was done in this analysis, so I would be reluctant to reach many conclusions about differences.”

Dr. Weinshenker added: “All three treatments provided strong benefit. We are still learning about long-term benefits, but emerging data have suggested that all three seem to provide persistent benefits for the length of the open-label extension study. We don’t have much evidence about the severity of the attacks that did occur, although some limited data suggest that both eculizumab and inebilizumab reduce attack severity.”

Dennis Bourdette, MD, professor emeritus, department of neurology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who was not involved in any of the studies, said he thought the new analysis was “a worthwhile effort to determine the relative effectiveness of the three different drugs in treating AQP4+ NMOSD.

“Given the rarity of APQ4+ NMOSD, it will be difficult to perform randomized head-to-head clinical trials of the agents, so this type of comparison is the best we can do at this time,” he said.

While Dr. Bourdette feels this study supports the notion that eculizumab is more effective at delaying time to first relapse than inebilizumab and satralizumab, he does not believe the results should have a major impact on decisions about which agent to use in clinical practice.

“A difference in delaying time to first relapse tells us little about the relative effectiveness of the long-term benefit of these [agents], particularly with regards to permanent disability or frequency of relapses. However, it is possible that the difference reflects the efficacy kinetics of the agents with eculizumab working faster than the other two agents, which would be useful in making a decision about a patient with very active NMOSD where one wants to get the disease under control as quickly as possible,” Dr. Bourdette noted.

But he added that neurologists should also consider safety profile, convenience, and contraindications. “Eculizumab is clearly less convenient in terms of dosing schedule than the other two agents, and patient convenience is important for long-term compliance.”

Dr. Bourdette pointed out that another consideration is prior treatment. “Many patients with NMOSD will receive the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab – which depletes B cells – off label. Inebilizumab also depletes B cells, so a patient who has had continued NMOSD disease activity on rituximab probably should not be treated with inebilizumab, making eculizumab or satralizumab preferable,” he suggested.

Finally, Dr. Bourdette highlighted the sponsorship of the current study by the manufacturer of eculizumab, Alexion, and that all of the authors have some financial relationship with Alexion as described in their disclosures. “Whether this resulted in any biases about the design, conduct, or interpretation of the study is uncertain but is always a concern,” he said.

Company statements

The companies selling inebilizumab and satralizumab sent statements on the new analysis and repeated many of the above points.

Genentech noted that new longer-term data presented at ECTRIMS show that satralizumab is effective in significantly reducing relapses over 4 years of treatment in people with AQP4+ NMOSD, with a favorable safety profile both as a monotherapy and in conjunction with immunosuppressive therapy. More than 70% of people treated with satralizumab remained relapse free after 4 years in the SAkuraStar (73%) and SAkuraSky (71%) open-label extension studies, and 90% and 91%, respectively, were free from severe relapse, the company reported.

Horizon said: “We are confident in the efficacy and safety of Uplizna (inebilizumab) – a convenient, twice-annual monotherapy – that was studied in the largest randomized, placebo-controlled, global trial of a monotherapy in NMOSD. The endpoints in this trial were prospectively defined and assessed by an adjudication committee as published in The Lancet, with long-term follow-up data now published in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal that further support the efficacy and safety.”

The current study was funded by Alexion–AstraZeneca Rare Disease. Dr. Wingerchuk has participated on data safety monitoring or advisory boards for Roche, Viela Bio, Genentech, Biogen, Reistone, TG Therapeutics, Celgene, Novartis, and Alexion–AstraZeneca Rare Disease. He has received grants for clinical trials through Alexion–AstraZeneca Rare Disease and Terumo BCT, and has been paid consulting fees by Mitsubishi Tanabe. Several coauthors of this study are employees of Alexion Pharmaceutics. Dr. Cree was principal investigator on the N-MOmentum study with inebilizumab. He has a grant from Genentech for MS research, and has consulted for Alexion in the past. Dr. Weinshenker has served as a member of the attack adjudication committee for both PREVENT and N-MOmentum studies and has financial relationships with the manufacturers of all three drugs. Dr. Bourdette has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Alexion-sponsored study was presented at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS) by Dean Wingerchuk, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Other experts in the field have highlighted limitations to the analysis and pointed out that all three agents are very effective in treating AQP4+ NMOSD, and many other considerations need to be taken into account as well as time to first relapse when selecting a therapy, leaving the door open for all three agents.

Dr. Wingerchuk explained that NMOSD is a rare severely disabling complement-mediated autoimmune neuroinflammatory disease of the central nervous system, characterized by devastating and unpredictable attacks (relapses) that can cause immediate and irreversible damage.

There are three recently approved monoclonal antibody treatment options in the United States for adults with AQP4+ NMOSD: eculizumab (Soliris, Alexion), inebilizumab (Uplizna, Horizon), and satralizumab (Enspryng, Genentech). A comparison of the relative treatment effects of these drugs would facilitate the treatment selection process, Dr. Wingerchuk said.

The objective of this study was to perform an indirect treatment comparison on the efficacy of these three FDA-approved treatment options for adults with AQP4+ NMOSD, in the absence of any head-to-head studies.

Using published data from randomized controlled trials, which were identified by a systematic literature review in September 2020, the researchers performed a Bayesian network meta-analysis to estimate the relative effects between eculizumab, inebilizumab, and satralizumab.

Network meta-analyses were performed for clinically relevant subpopulations based on three treatment networks: (1) patients who received monotherapy with one of the monoclonal antibodies or in combination with an immunosuppressant therapy; (2) patients who received monotherapy with the monoclonal antibody alone; and (3) patients who received a combination of both the monoclonal antibody and immunosuppressant therapy.

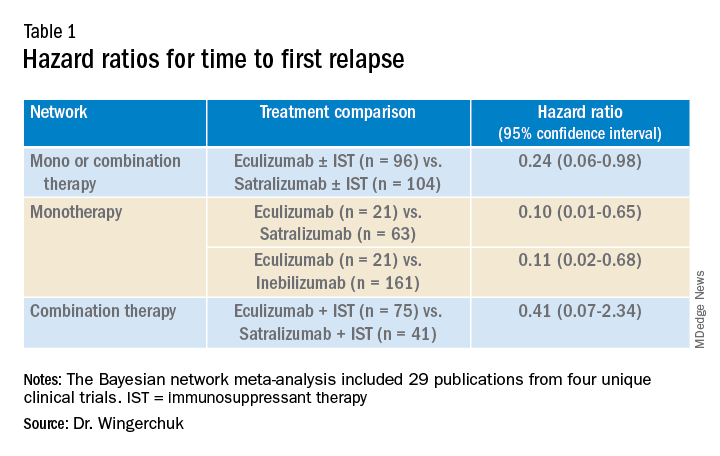

Time to first relapse was the primary efficacy outcome assessed. Relative treatment effects were expressed as hazard ratios and the probability that a treatment was the best at delaying time to first relapse was also evaluated.

In the systematic literature review, 29 publications from four unique clinical trials were identified and include in the network meta-analysis. These included publications from congress proceedings and peer-reviewed journals.

The four clinical trials were the N-MOmentum trial of inebilizumab versus placebo; the PREVENT trial of eculizumab with or without immunosuppressant therapy versus placebo with or without immunosuppressant therapy; the SAkuraSky trial of satralizumab plus immunosuppressant therapy versus placebo plus immunosuppressant therapy; and the SAkuraStar trial of satralizumab versus placebo.

Results showed that for the first analysis of mono or combination therapy, patients treated with eculizumab with or without immunosuppressant therapy were 76% less likely to experience a first relapse when compared with patients treated with satralizumab with or without immunosuppressant therapy.

In the monotherapy network, patients on eculizumab were 90% less likely to experience a first relapse when compared with patients treated with satralizumab, and patients on eculizumab were 89% less likely to experience a first relapse when compared with patients treated with inebilizumab.

In the third network analysis – a comparison of eculizumab plus immunosuppressant therapy with inebilizumab plus immunosuppressant therapy (Table 1) – the point estimate appeared to favor eculizumab but the confidence intervals were wide and not significant.

A subsequent analysis looked at the rank order of the best treatment option, with eculizumab coming out first in all three networks (Table 2).

Dr. Wingerchuk acknowledged that there were many limitations to this study, including that analyses for annualized relapse rate, disability, and quality of life were not included because of a lack of consistent outcome reporting by AQP4+ status in the randomized trials.

Safety outcomes were excluded because of a lack of standardized baseline risks and inconsistent reporting by AQP4+ status across trials.

Because this study focused on drugs approved in the United States in a rare disease area, there were a limited number of studies with intervention effects.

There were differences in follow-up durations across the different trials, with N-MOmentum having a follow-up of 197 days compared with 144 weeks for other trials.

“In the absence of head-to-head trials, this network meta-analysis provides important evidence on the relative efficacy of eculizumab versus satralizumab or inebilizumab for the treatment of patients with AQP4+ NMOSD, with significant differences in two out of the three treatment comparison scenarios observed,” Dr. Wingerchuk concluded.

“Based on current evidence, monotherapy and mono-combination therapy with eculizumab appear to more efficacious at preventing relapses than satralizumab or inebilizumab for the treatment of adults with AQP4+ NMOSD. These findings appear to suggest that C5 complement inhibition with treatments such as eculizumab appear to prevent relapses more effectively than other mechanisms involving IL-6 receptor or CD19 inhibition among adults with AQP4+ NMOSD,” he added.

Experts respond

Commenting on the study, several experts in the field provided some balancing views.

Bruce Cree, MD, University of California San Francisco, who was the chief investigator of the N-MOmentum study with inebilizumab, said he was skeptical about this new indirect comparison. “The results of this study seem too good to be true; a 90% difference between agents has to be an overestimate,” he said.

“We know from independent studies that all three drugs are very effective. If we take each trial separately, eculizumab reduced attack risk by 90% versus placebo; and the other two drugs by 77% to 78% versus placebo. For eculizumab to be 90% better than inebilizumab or satralizumab its basically like saying these drugs perform like placebo, but we know that is not the case,” Dr. Cree argued.

He pointed out that when comparing results across studies there are many factors that have to be considered, including the different patient populations included in the different studies, with the characteristic of each population in each trial being unique to that dataset.

In addition, Dr. Cree suggested that all the studies included in the comparison were relatively small for this type of analysis. “Normally this type of analysis is done with much larger studies, so the resulting database is closer to a representation of the disease state itself,” he said.

Dr. Cree also questioned the role of the sponsor in this meta-analysis. “The analysis was sponsored by Alexion and several coauthors were employees of Alexion. There was not much description available of how the statistics were done. I am concerned that the company was involved in the analysis, which could introduce bias. I look forward to seeing details of the statistical methodology,” he said.

“This is definitely a provocative study. They have thrown down the gauntlet. If they are so confident in the results they should now do a head-to-head study to back this result up. If they don’t do that, then I think physicians should ignore it as there are just too many problems with this analysis,” Dr. Cree stated.

Dr. Cree acknowledged that when looking at the four trials separately, eculizumab does look a little better than the other two agents in delaying time to first relapse. “But there are some caveats. Despite a larger reduction in relapse rate there was no reduction in disability in the eculizumab trial. Whereas the inebilizumab trial did show a reduction in disability. And while the PREVENT trial with eculizumab was a good study, during the course of the trial the definition of clinical relapse was changed, and as a consequence that increased the product’s performance – that’s a little bit curious,” he added.

How to choose?

On how to choose between the three agents, Dr. Cree said they are all “extraordinarily effective” at reducing relapse activity. “They are all ‘home run’ products, but they have differences in safety,” he said.

“Inebilizumab is linked to hypogammaglobulinemia over time – we haven’t seen an increase in infection risk linked to this, but with enough time, I would expect that there probably will be. But inebilizumab is a B-cell-depleting agent like the agents used in MS, and we now have a lot of experiences with this type of product, which gives us more confidence on the safety profile,” Dr. Cree noted.

“Eculizumab was linked to a risk of meningococcal meningitis and other bacterial infections, and satralizumab seems to [be] overall well tolerated with no obvious safety concerns to date, but the studies have been quite small,” he added.

On routes of administration and frequency of dosing, Dr. Cree pointed out that while all three drugs have an intensive loading schedule, for maintenance, eculizumab needs to be given as an IV infusion every 2 weeks. Inebilizumab needs just two infusions per year for maintenance, while satralizumab is given by subcutaneous injection once per month.

“It may be that eculizumab could be used at the time of an acute attack but then treatment could be switched to one of the other two for long-term maintenance,” he suggested.

But Dr. Cree pointed out that the biggest challenge for all three agents is access. “The costs are astronomically high ($200,000-$770,000). They are prohibitively expensive and very few insurance companies are covering them.”

Also commenting, Brian Weinshenker, MD, from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who was a member of the attack adjudication committee for both PREVENT and N-MOmentum studies, pointed out that as well as differences in the populations enrolled, and study designs, the studies with the three different drugs also had differences in attack adjudication criteria.

“These factors make it very difficult to compare across studies, which is what was done in this analysis, so I would be reluctant to reach many conclusions about differences.”

Dr. Weinshenker added: “All three treatments provided strong benefit. We are still learning about long-term benefits, but emerging data have suggested that all three seem to provide persistent benefits for the length of the open-label extension study. We don’t have much evidence about the severity of the attacks that did occur, although some limited data suggest that both eculizumab and inebilizumab reduce attack severity.”

Dennis Bourdette, MD, professor emeritus, department of neurology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who was not involved in any of the studies, said he thought the new analysis was “a worthwhile effort to determine the relative effectiveness of the three different drugs in treating AQP4+ NMOSD.

“Given the rarity of APQ4+ NMOSD, it will be difficult to perform randomized head-to-head clinical trials of the agents, so this type of comparison is the best we can do at this time,” he said.

While Dr. Bourdette feels this study supports the notion that eculizumab is more effective at delaying time to first relapse than inebilizumab and satralizumab, he does not believe the results should have a major impact on decisions about which agent to use in clinical practice.

“A difference in delaying time to first relapse tells us little about the relative effectiveness of the long-term benefit of these [agents], particularly with regards to permanent disability or frequency of relapses. However, it is possible that the difference reflects the efficacy kinetics of the agents with eculizumab working faster than the other two agents, which would be useful in making a decision about a patient with very active NMOSD where one wants to get the disease under control as quickly as possible,” Dr. Bourdette noted.

But he added that neurologists should also consider safety profile, convenience, and contraindications. “Eculizumab is clearly less convenient in terms of dosing schedule than the other two agents, and patient convenience is important for long-term compliance.”

Dr. Bourdette pointed out that another consideration is prior treatment. “Many patients with NMOSD will receive the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab – which depletes B cells – off label. Inebilizumab also depletes B cells, so a patient who has had continued NMOSD disease activity on rituximab probably should not be treated with inebilizumab, making eculizumab or satralizumab preferable,” he suggested.

Finally, Dr. Bourdette highlighted the sponsorship of the current study by the manufacturer of eculizumab, Alexion, and that all of the authors have some financial relationship with Alexion as described in their disclosures. “Whether this resulted in any biases about the design, conduct, or interpretation of the study is uncertain but is always a concern,” he said.

Company statements

The companies selling inebilizumab and satralizumab sent statements on the new analysis and repeated many of the above points.

Genentech noted that new longer-term data presented at ECTRIMS show that satralizumab is effective in significantly reducing relapses over 4 years of treatment in people with AQP4+ NMOSD, with a favorable safety profile both as a monotherapy and in conjunction with immunosuppressive therapy. More than 70% of people treated with satralizumab remained relapse free after 4 years in the SAkuraStar (73%) and SAkuraSky (71%) open-label extension studies, and 90% and 91%, respectively, were free from severe relapse, the company reported.

Horizon said: “We are confident in the efficacy and safety of Uplizna (inebilizumab) – a convenient, twice-annual monotherapy – that was studied in the largest randomized, placebo-controlled, global trial of a monotherapy in NMOSD. The endpoints in this trial were prospectively defined and assessed by an adjudication committee as published in The Lancet, with long-term follow-up data now published in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal that further support the efficacy and safety.”

The current study was funded by Alexion–AstraZeneca Rare Disease. Dr. Wingerchuk has participated on data safety monitoring or advisory boards for Roche, Viela Bio, Genentech, Biogen, Reistone, TG Therapeutics, Celgene, Novartis, and Alexion–AstraZeneca Rare Disease. He has received grants for clinical trials through Alexion–AstraZeneca Rare Disease and Terumo BCT, and has been paid consulting fees by Mitsubishi Tanabe. Several coauthors of this study are employees of Alexion Pharmaceutics. Dr. Cree was principal investigator on the N-MOmentum study with inebilizumab. He has a grant from Genentech for MS research, and has consulted for Alexion in the past. Dr. Weinshenker has served as a member of the attack adjudication committee for both PREVENT and N-MOmentum studies and has financial relationships with the manufacturers of all three drugs. Dr. Bourdette has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Alexion-sponsored study was presented at the annual meeting of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS) by Dean Wingerchuk, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Other experts in the field have highlighted limitations to the analysis and pointed out that all three agents are very effective in treating AQP4+ NMOSD, and many other considerations need to be taken into account as well as time to first relapse when selecting a therapy, leaving the door open for all three agents.

Dr. Wingerchuk explained that NMOSD is a rare severely disabling complement-mediated autoimmune neuroinflammatory disease of the central nervous system, characterized by devastating and unpredictable attacks (relapses) that can cause immediate and irreversible damage.

There are three recently approved monoclonal antibody treatment options in the United States for adults with AQP4+ NMOSD: eculizumab (Soliris, Alexion), inebilizumab (Uplizna, Horizon), and satralizumab (Enspryng, Genentech). A comparison of the relative treatment effects of these drugs would facilitate the treatment selection process, Dr. Wingerchuk said.

The objective of this study was to perform an indirect treatment comparison on the efficacy of these three FDA-approved treatment options for adults with AQP4+ NMOSD, in the absence of any head-to-head studies.

Using published data from randomized controlled trials, which were identified by a systematic literature review in September 2020, the researchers performed a Bayesian network meta-analysis to estimate the relative effects between eculizumab, inebilizumab, and satralizumab.

Network meta-analyses were performed for clinically relevant subpopulations based on three treatment networks: (1) patients who received monotherapy with one of the monoclonal antibodies or in combination with an immunosuppressant therapy; (2) patients who received monotherapy with the monoclonal antibody alone; and (3) patients who received a combination of both the monoclonal antibody and immunosuppressant therapy.

Time to first relapse was the primary efficacy outcome assessed. Relative treatment effects were expressed as hazard ratios and the probability that a treatment was the best at delaying time to first relapse was also evaluated.

In the systematic literature review, 29 publications from four unique clinical trials were identified and include in the network meta-analysis. These included publications from congress proceedings and peer-reviewed journals.

The four clinical trials were the N-MOmentum trial of inebilizumab versus placebo; the PREVENT trial of eculizumab with or without immunosuppressant therapy versus placebo with or without immunosuppressant therapy; the SAkuraSky trial of satralizumab plus immunosuppressant therapy versus placebo plus immunosuppressant therapy; and the SAkuraStar trial of satralizumab versus placebo.

Results showed that for the first analysis of mono or combination therapy, patients treated with eculizumab with or without immunosuppressant therapy were 76% less likely to experience a first relapse when compared with patients treated with satralizumab with or without immunosuppressant therapy.

In the monotherapy network, patients on eculizumab were 90% less likely to experience a first relapse when compared with patients treated with satralizumab, and patients on eculizumab were 89% less likely to experience a first relapse when compared with patients treated with inebilizumab.

In the third network analysis – a comparison of eculizumab plus immunosuppressant therapy with inebilizumab plus immunosuppressant therapy (Table 1) – the point estimate appeared to favor eculizumab but the confidence intervals were wide and not significant.

A subsequent analysis looked at the rank order of the best treatment option, with eculizumab coming out first in all three networks (Table 2).

Dr. Wingerchuk acknowledged that there were many limitations to this study, including that analyses for annualized relapse rate, disability, and quality of life were not included because of a lack of consistent outcome reporting by AQP4+ status in the randomized trials.

Safety outcomes were excluded because of a lack of standardized baseline risks and inconsistent reporting by AQP4+ status across trials.

Because this study focused on drugs approved in the United States in a rare disease area, there were a limited number of studies with intervention effects.

There were differences in follow-up durations across the different trials, with N-MOmentum having a follow-up of 197 days compared with 144 weeks for other trials.

“In the absence of head-to-head trials, this network meta-analysis provides important evidence on the relative efficacy of eculizumab versus satralizumab or inebilizumab for the treatment of patients with AQP4+ NMOSD, with significant differences in two out of the three treatment comparison scenarios observed,” Dr. Wingerchuk concluded.

“Based on current evidence, monotherapy and mono-combination therapy with eculizumab appear to more efficacious at preventing relapses than satralizumab or inebilizumab for the treatment of adults with AQP4+ NMOSD. These findings appear to suggest that C5 complement inhibition with treatments such as eculizumab appear to prevent relapses more effectively than other mechanisms involving IL-6 receptor or CD19 inhibition among adults with AQP4+ NMOSD,” he added.

Experts respond

Commenting on the study, several experts in the field provided some balancing views.

Bruce Cree, MD, University of California San Francisco, who was the chief investigator of the N-MOmentum study with inebilizumab, said he was skeptical about this new indirect comparison. “The results of this study seem too good to be true; a 90% difference between agents has to be an overestimate,” he said.

“We know from independent studies that all three drugs are very effective. If we take each trial separately, eculizumab reduced attack risk by 90% versus placebo; and the other two drugs by 77% to 78% versus placebo. For eculizumab to be 90% better than inebilizumab or satralizumab its basically like saying these drugs perform like placebo, but we know that is not the case,” Dr. Cree argued.

He pointed out that when comparing results across studies there are many factors that have to be considered, including the different patient populations included in the different studies, with the characteristic of each population in each trial being unique to that dataset.

In addition, Dr. Cree suggested that all the studies included in the comparison were relatively small for this type of analysis. “Normally this type of analysis is done with much larger studies, so the resulting database is closer to a representation of the disease state itself,” he said.

Dr. Cree also questioned the role of the sponsor in this meta-analysis. “The analysis was sponsored by Alexion and several coauthors were employees of Alexion. There was not much description available of how the statistics were done. I am concerned that the company was involved in the analysis, which could introduce bias. I look forward to seeing details of the statistical methodology,” he said.

“This is definitely a provocative study. They have thrown down the gauntlet. If they are so confident in the results they should now do a head-to-head study to back this result up. If they don’t do that, then I think physicians should ignore it as there are just too many problems with this analysis,” Dr. Cree stated.

Dr. Cree acknowledged that when looking at the four trials separately, eculizumab does look a little better than the other two agents in delaying time to first relapse. “But there are some caveats. Despite a larger reduction in relapse rate there was no reduction in disability in the eculizumab trial. Whereas the inebilizumab trial did show a reduction in disability. And while the PREVENT trial with eculizumab was a good study, during the course of the trial the definition of clinical relapse was changed, and as a consequence that increased the product’s performance – that’s a little bit curious,” he added.

How to choose?

On how to choose between the three agents, Dr. Cree said they are all “extraordinarily effective” at reducing relapse activity. “They are all ‘home run’ products, but they have differences in safety,” he said.

“Inebilizumab is linked to hypogammaglobulinemia over time – we haven’t seen an increase in infection risk linked to this, but with enough time, I would expect that there probably will be. But inebilizumab is a B-cell-depleting agent like the agents used in MS, and we now have a lot of experiences with this type of product, which gives us more confidence on the safety profile,” Dr. Cree noted.

“Eculizumab was linked to a risk of meningococcal meningitis and other bacterial infections, and satralizumab seems to [be] overall well tolerated with no obvious safety concerns to date, but the studies have been quite small,” he added.

On routes of administration and frequency of dosing, Dr. Cree pointed out that while all three drugs have an intensive loading schedule, for maintenance, eculizumab needs to be given as an IV infusion every 2 weeks. Inebilizumab needs just two infusions per year for maintenance, while satralizumab is given by subcutaneous injection once per month.

“It may be that eculizumab could be used at the time of an acute attack but then treatment could be switched to one of the other two for long-term maintenance,” he suggested.

But Dr. Cree pointed out that the biggest challenge for all three agents is access. “The costs are astronomically high ($200,000-$770,000). They are prohibitively expensive and very few insurance companies are covering them.”

Also commenting, Brian Weinshenker, MD, from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who was a member of the attack adjudication committee for both PREVENT and N-MOmentum studies, pointed out that as well as differences in the populations enrolled, and study designs, the studies with the three different drugs also had differences in attack adjudication criteria.

“These factors make it very difficult to compare across studies, which is what was done in this analysis, so I would be reluctant to reach many conclusions about differences.”

Dr. Weinshenker added: “All three treatments provided strong benefit. We are still learning about long-term benefits, but emerging data have suggested that all three seem to provide persistent benefits for the length of the open-label extension study. We don’t have much evidence about the severity of the attacks that did occur, although some limited data suggest that both eculizumab and inebilizumab reduce attack severity.”

Dennis Bourdette, MD, professor emeritus, department of neurology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who was not involved in any of the studies, said he thought the new analysis was “a worthwhile effort to determine the relative effectiveness of the three different drugs in treating AQP4+ NMOSD.

“Given the rarity of APQ4+ NMOSD, it will be difficult to perform randomized head-to-head clinical trials of the agents, so this type of comparison is the best we can do at this time,” he said.

While Dr. Bourdette feels this study supports the notion that eculizumab is more effective at delaying time to first relapse than inebilizumab and satralizumab, he does not believe the results should have a major impact on decisions about which agent to use in clinical practice.

“A difference in delaying time to first relapse tells us little about the relative effectiveness of the long-term benefit of these [agents], particularly with regards to permanent disability or frequency of relapses. However, it is possible that the difference reflects the efficacy kinetics of the agents with eculizumab working faster than the other two agents, which would be useful in making a decision about a patient with very active NMOSD where one wants to get the disease under control as quickly as possible,” Dr. Bourdette noted.

But he added that neurologists should also consider safety profile, convenience, and contraindications. “Eculizumab is clearly less convenient in terms of dosing schedule than the other two agents, and patient convenience is important for long-term compliance.”

Dr. Bourdette pointed out that another consideration is prior treatment. “Many patients with NMOSD will receive the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab – which depletes B cells – off label. Inebilizumab also depletes B cells, so a patient who has had continued NMOSD disease activity on rituximab probably should not be treated with inebilizumab, making eculizumab or satralizumab preferable,” he suggested.

Finally, Dr. Bourdette highlighted the sponsorship of the current study by the manufacturer of eculizumab, Alexion, and that all of the authors have some financial relationship with Alexion as described in their disclosures. “Whether this resulted in any biases about the design, conduct, or interpretation of the study is uncertain but is always a concern,” he said.

Company statements

The companies selling inebilizumab and satralizumab sent statements on the new analysis and repeated many of the above points.

Genentech noted that new longer-term data presented at ECTRIMS show that satralizumab is effective in significantly reducing relapses over 4 years of treatment in people with AQP4+ NMOSD, with a favorable safety profile both as a monotherapy and in conjunction with immunosuppressive therapy. More than 70% of people treated with satralizumab remained relapse free after 4 years in the SAkuraStar (73%) and SAkuraSky (71%) open-label extension studies, and 90% and 91%, respectively, were free from severe relapse, the company reported.

Horizon said: “We are confident in the efficacy and safety of Uplizna (inebilizumab) – a convenient, twice-annual monotherapy – that was studied in the largest randomized, placebo-controlled, global trial of a monotherapy in NMOSD. The endpoints in this trial were prospectively defined and assessed by an adjudication committee as published in The Lancet, with long-term follow-up data now published in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal that further support the efficacy and safety.”

The current study was funded by Alexion–AstraZeneca Rare Disease. Dr. Wingerchuk has participated on data safety monitoring or advisory boards for Roche, Viela Bio, Genentech, Biogen, Reistone, TG Therapeutics, Celgene, Novartis, and Alexion–AstraZeneca Rare Disease. He has received grants for clinical trials through Alexion–AstraZeneca Rare Disease and Terumo BCT, and has been paid consulting fees by Mitsubishi Tanabe. Several coauthors of this study are employees of Alexion Pharmaceutics. Dr. Cree was principal investigator on the N-MOmentum study with inebilizumab. He has a grant from Genentech for MS research, and has consulted for Alexion in the past. Dr. Weinshenker has served as a member of the attack adjudication committee for both PREVENT and N-MOmentum studies and has financial relationships with the manufacturers of all three drugs. Dr. Bourdette has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ECTRIMS 2021

Clinicians underprescribe behavior therapy for preschool ADHD

The majority of families of preschool children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were not offered behavior therapy as a first-line treatment, according to data from nearly 200 children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current clinical practice guidelines recommend parent training in behavior management (PTBM) as a first-line treatment for children aged 4-5 years diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity or impulsivity, but data on how well primary care providers follow this recommendation in practice are lacking, wrote Yair Bannett, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

To investigate the rates of PTBM recommendations, the researchers reviewed electronic health records for 22,714 children aged 48-71 months who had at least two visits to any 1 of 10 primary care practices in a California pediatric health network between Oct. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2019. Children with an autism diagnosis were excluded; ADHD-related visits were identified via ADHD diagnosis codes or symptom-level diagnosis codes.

In the study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, 192 children (1%) had either an ADHD diagnosis or ADHD symptoms; of these, 21 (11%) received referrals for PTBM during ADHD-related primary care visits. Records showed an additional 55 patients (29%) had a mention of counseling on PTBM by a primary care provider, including handouts.

PCPs prescribed ADHD medications for 32 children; 9 of these had documented PTBM recommendations, and in 4 cases, the PCPs recommended PTBM before prescribing a first medication.

A majority (73%) of the children were male, 64% were privately insured, 56% had subspecialists involved in their care, and 17% were prescribed ADHD medications (88% of which were stimulants).

In a multivariate analysis, children with public insurance were significantly less likely to receive a PTBM recommendation than were those with private insurance (adjusted relative risk 0.87).

The most common recommendation overall was routine/habit modifications (for 79 children), such as reducing sugar or adding supplements to the diet; improving sleep hygiene; and limiting screen time.

The low rates of PTBM among publicly insured patients in particular highlight the need to identify factors behind disparities in recommended treatments, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on primary care provider documentation during the study period and the inclusion only of medical record reviews with diagnostic codes for ADHD, the researchers noted. Further studies beyond a single health care system are needed to assess generalizability, they added.

However, the results present an opportunity for primary care providers to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines and establish behavioral treatment at an early age to mitigate long-term morbidity, they concluded.

Low rates highlight barriers and opportunities

“We were surprised to find very low rates of documented recommendations for behavioral treatment mentioned by PCPs,” Dr. Bannett said in an interview. The researchers were surprised that recommendations for changes in daily routines and habits, such as reduced sugar intake, regular exercise, better sleep, and reduced screen time, were the most common recommendations for families of children presenting with symptoms of ADHD. “Though these are good recommendations that can support the general health of any young child, there is no evidence to support their benefit in alleviating symptoms of ADHD,” he said.

Dr. Bannett acknowledged the challenge for pediatricians to stay current on where and how families can access this type of behavioral treatment, but the evidence supports behavior therapy over medication in preschool children, he said.

“I think that it is important for primary care clinicians to know that there are options for parent training in behavioral management for both privately and publicly insured patients,” said Dr. Bannett. “In California, for example, parent training programs are offered through county mental health services. In some counties, there are other organizations that offer parent training for underserved populations and those with public insurance,” he said.

Dr. Bannett noted that online treatments, including behavioral treatments, may be possible for some families.

He cited Triple P, an evidence-based curriculum for parent training in behavior management, which offers an online course for parents at triplep-parenting.com, and an online parent training course offered through the CHADD website (chadd.org/parent-to-parent/).

Dr. Bannett noted that the researchers are planning a follow-up study to investigate the reasons behind the low referral rates for PTBM. “A known barrier is the limited availability of therapists who can provide this type of therapy,” Dr. Bannett said. “Research is needed on the effectiveness of online versions of parent training, which can overcome some of the access barriers many families experience,” he added.

“Additionally, since behavioral treatment requires a significant effort on the part of the parents and caregivers, who often are not able to complete the therapy, there is a need for research on ways to enhance parent and family engagement and participation in these important evidence-based treatments,” as well as a need to research ways to increase adherence to evidence-based practices, said Dr. Bannett. “We are currently planning intervention studies that will enhance primary care clinicians’ knowledge and clinical practice; for example, decision support tools in the electronic health record, and up-to-date information about available resources and behavioral therapists in their community that they can share with families,” he said.

Barriers make it difficult to adhere to guidelines

The study authors missed a significant element of the AAP guidelines by failing to acknowledge the extensive accompanying section on barriers to adoption, which details why most pediatricians in clinical practice do not prescribe PTBM, Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“Academically, it is a wonderful article,” said Dr. Lessin, who was a member of the authoring committee of the AAP guidelines and a major contributor to the section on barriers. The AAP guidelines recommend PTBM because it is evidence based, but the barrier section is essential to understanding that this evidence-based recommendation is nearly impossible to follow in real-world clinical practice, he emphasized.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents,” published in October of 2019 in Pediatrics, included a full subsection on barriers as to why the guidelines might not be followed in many cases in a real-world setting, and the study authors failed to acknowledge this section and its implications, said Dr. Lessin. Notably, the barriers section was originally published in Pediatrics under a Supplemental Data tab that might easily be overlooked by someone reviewing the main practice guideline recommendations, he said.

In most areas of the country, PTBM is simply unavailable, Dr. Lessin said.

There is a dearth of mental health providers in the United States in general, and “a monstrous shortage of mental health practitioners for young children,” he said. Children in underserved areas barely have access to a medical home, let alone mental health subspecialists, he added.

Even in areas where specialized behavior therapy may be available, it can be prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patients, Dr. Lessin noted. Insurance does not cover this type of behavior therapy, and most mental health professionals don’t accept Medicaid, nor commercial insurance, he said.

“I don’t even bother with those referrals, because they are not available,” said Dr. Lessin. The take-home message is that most community-based pediatricians are not following the guidelines because the barriers are so enormous, he said.

The study was supported by a research grant from the Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and salary support through the Instructor Support Program at the department of pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, to Dr. Bannett. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

The majority of families of preschool children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were not offered behavior therapy as a first-line treatment, according to data from nearly 200 children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current clinical practice guidelines recommend parent training in behavior management (PTBM) as a first-line treatment for children aged 4-5 years diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity or impulsivity, but data on how well primary care providers follow this recommendation in practice are lacking, wrote Yair Bannett, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

To investigate the rates of PTBM recommendations, the researchers reviewed electronic health records for 22,714 children aged 48-71 months who had at least two visits to any 1 of 10 primary care practices in a California pediatric health network between Oct. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2019. Children with an autism diagnosis were excluded; ADHD-related visits were identified via ADHD diagnosis codes or symptom-level diagnosis codes.

In the study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, 192 children (1%) had either an ADHD diagnosis or ADHD symptoms; of these, 21 (11%) received referrals for PTBM during ADHD-related primary care visits. Records showed an additional 55 patients (29%) had a mention of counseling on PTBM by a primary care provider, including handouts.

PCPs prescribed ADHD medications for 32 children; 9 of these had documented PTBM recommendations, and in 4 cases, the PCPs recommended PTBM before prescribing a first medication.

A majority (73%) of the children were male, 64% were privately insured, 56% had subspecialists involved in their care, and 17% were prescribed ADHD medications (88% of which were stimulants).

In a multivariate analysis, children with public insurance were significantly less likely to receive a PTBM recommendation than were those with private insurance (adjusted relative risk 0.87).

The most common recommendation overall was routine/habit modifications (for 79 children), such as reducing sugar or adding supplements to the diet; improving sleep hygiene; and limiting screen time.

The low rates of PTBM among publicly insured patients in particular highlight the need to identify factors behind disparities in recommended treatments, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on primary care provider documentation during the study period and the inclusion only of medical record reviews with diagnostic codes for ADHD, the researchers noted. Further studies beyond a single health care system are needed to assess generalizability, they added.

However, the results present an opportunity for primary care providers to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines and establish behavioral treatment at an early age to mitigate long-term morbidity, they concluded.

Low rates highlight barriers and opportunities

“We were surprised to find very low rates of documented recommendations for behavioral treatment mentioned by PCPs,” Dr. Bannett said in an interview. The researchers were surprised that recommendations for changes in daily routines and habits, such as reduced sugar intake, regular exercise, better sleep, and reduced screen time, were the most common recommendations for families of children presenting with symptoms of ADHD. “Though these are good recommendations that can support the general health of any young child, there is no evidence to support their benefit in alleviating symptoms of ADHD,” he said.

Dr. Bannett acknowledged the challenge for pediatricians to stay current on where and how families can access this type of behavioral treatment, but the evidence supports behavior therapy over medication in preschool children, he said.

“I think that it is important for primary care clinicians to know that there are options for parent training in behavioral management for both privately and publicly insured patients,” said Dr. Bannett. “In California, for example, parent training programs are offered through county mental health services. In some counties, there are other organizations that offer parent training for underserved populations and those with public insurance,” he said.

Dr. Bannett noted that online treatments, including behavioral treatments, may be possible for some families.

He cited Triple P, an evidence-based curriculum for parent training in behavior management, which offers an online course for parents at triplep-parenting.com, and an online parent training course offered through the CHADD website (chadd.org/parent-to-parent/).

Dr. Bannett noted that the researchers are planning a follow-up study to investigate the reasons behind the low referral rates for PTBM. “A known barrier is the limited availability of therapists who can provide this type of therapy,” Dr. Bannett said. “Research is needed on the effectiveness of online versions of parent training, which can overcome some of the access barriers many families experience,” he added.

“Additionally, since behavioral treatment requires a significant effort on the part of the parents and caregivers, who often are not able to complete the therapy, there is a need for research on ways to enhance parent and family engagement and participation in these important evidence-based treatments,” as well as a need to research ways to increase adherence to evidence-based practices, said Dr. Bannett. “We are currently planning intervention studies that will enhance primary care clinicians’ knowledge and clinical practice; for example, decision support tools in the electronic health record, and up-to-date information about available resources and behavioral therapists in their community that they can share with families,” he said.

Barriers make it difficult to adhere to guidelines

The study authors missed a significant element of the AAP guidelines by failing to acknowledge the extensive accompanying section on barriers to adoption, which details why most pediatricians in clinical practice do not prescribe PTBM, Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“Academically, it is a wonderful article,” said Dr. Lessin, who was a member of the authoring committee of the AAP guidelines and a major contributor to the section on barriers. The AAP guidelines recommend PTBM because it is evidence based, but the barrier section is essential to understanding that this evidence-based recommendation is nearly impossible to follow in real-world clinical practice, he emphasized.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents,” published in October of 2019 in Pediatrics, included a full subsection on barriers as to why the guidelines might not be followed in many cases in a real-world setting, and the study authors failed to acknowledge this section and its implications, said Dr. Lessin. Notably, the barriers section was originally published in Pediatrics under a Supplemental Data tab that might easily be overlooked by someone reviewing the main practice guideline recommendations, he said.

In most areas of the country, PTBM is simply unavailable, Dr. Lessin said.

There is a dearth of mental health providers in the United States in general, and “a monstrous shortage of mental health practitioners for young children,” he said. Children in underserved areas barely have access to a medical home, let alone mental health subspecialists, he added.

Even in areas where specialized behavior therapy may be available, it can be prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patients, Dr. Lessin noted. Insurance does not cover this type of behavior therapy, and most mental health professionals don’t accept Medicaid, nor commercial insurance, he said.

“I don’t even bother with those referrals, because they are not available,” said Dr. Lessin. The take-home message is that most community-based pediatricians are not following the guidelines because the barriers are so enormous, he said.

The study was supported by a research grant from the Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and salary support through the Instructor Support Program at the department of pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, to Dr. Bannett. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

The majority of families of preschool children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were not offered behavior therapy as a first-line treatment, according to data from nearly 200 children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current clinical practice guidelines recommend parent training in behavior management (PTBM) as a first-line treatment for children aged 4-5 years diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity or impulsivity, but data on how well primary care providers follow this recommendation in practice are lacking, wrote Yair Bannett, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

To investigate the rates of PTBM recommendations, the researchers reviewed electronic health records for 22,714 children aged 48-71 months who had at least two visits to any 1 of 10 primary care practices in a California pediatric health network between Oct. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2019. Children with an autism diagnosis were excluded; ADHD-related visits were identified via ADHD diagnosis codes or symptom-level diagnosis codes.

In the study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, 192 children (1%) had either an ADHD diagnosis or ADHD symptoms; of these, 21 (11%) received referrals for PTBM during ADHD-related primary care visits. Records showed an additional 55 patients (29%) had a mention of counseling on PTBM by a primary care provider, including handouts.

PCPs prescribed ADHD medications for 32 children; 9 of these had documented PTBM recommendations, and in 4 cases, the PCPs recommended PTBM before prescribing a first medication.

A majority (73%) of the children were male, 64% were privately insured, 56% had subspecialists involved in their care, and 17% were prescribed ADHD medications (88% of which were stimulants).

In a multivariate analysis, children with public insurance were significantly less likely to receive a PTBM recommendation than were those with private insurance (adjusted relative risk 0.87).

The most common recommendation overall was routine/habit modifications (for 79 children), such as reducing sugar or adding supplements to the diet; improving sleep hygiene; and limiting screen time.

The low rates of PTBM among publicly insured patients in particular highlight the need to identify factors behind disparities in recommended treatments, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on primary care provider documentation during the study period and the inclusion only of medical record reviews with diagnostic codes for ADHD, the researchers noted. Further studies beyond a single health care system are needed to assess generalizability, they added.

However, the results present an opportunity for primary care providers to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines and establish behavioral treatment at an early age to mitigate long-term morbidity, they concluded.

Low rates highlight barriers and opportunities

“We were surprised to find very low rates of documented recommendations for behavioral treatment mentioned by PCPs,” Dr. Bannett said in an interview. The researchers were surprised that recommendations for changes in daily routines and habits, such as reduced sugar intake, regular exercise, better sleep, and reduced screen time, were the most common recommendations for families of children presenting with symptoms of ADHD. “Though these are good recommendations that can support the general health of any young child, there is no evidence to support their benefit in alleviating symptoms of ADHD,” he said.

Dr. Bannett acknowledged the challenge for pediatricians to stay current on where and how families can access this type of behavioral treatment, but the evidence supports behavior therapy over medication in preschool children, he said.

“I think that it is important for primary care clinicians to know that there are options for parent training in behavioral management for both privately and publicly insured patients,” said Dr. Bannett. “In California, for example, parent training programs are offered through county mental health services. In some counties, there are other organizations that offer parent training for underserved populations and those with public insurance,” he said.

Dr. Bannett noted that online treatments, including behavioral treatments, may be possible for some families.

He cited Triple P, an evidence-based curriculum for parent training in behavior management, which offers an online course for parents at triplep-parenting.com, and an online parent training course offered through the CHADD website (chadd.org/parent-to-parent/).

Dr. Bannett noted that the researchers are planning a follow-up study to investigate the reasons behind the low referral rates for PTBM. “A known barrier is the limited availability of therapists who can provide this type of therapy,” Dr. Bannett said. “Research is needed on the effectiveness of online versions of parent training, which can overcome some of the access barriers many families experience,” he added.

“Additionally, since behavioral treatment requires a significant effort on the part of the parents and caregivers, who often are not able to complete the therapy, there is a need for research on ways to enhance parent and family engagement and participation in these important evidence-based treatments,” as well as a need to research ways to increase adherence to evidence-based practices, said Dr. Bannett. “We are currently planning intervention studies that will enhance primary care clinicians’ knowledge and clinical practice; for example, decision support tools in the electronic health record, and up-to-date information about available resources and behavioral therapists in their community that they can share with families,” he said.

Barriers make it difficult to adhere to guidelines

The study authors missed a significant element of the AAP guidelines by failing to acknowledge the extensive accompanying section on barriers to adoption, which details why most pediatricians in clinical practice do not prescribe PTBM, Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“Academically, it is a wonderful article,” said Dr. Lessin, who was a member of the authoring committee of the AAP guidelines and a major contributor to the section on barriers. The AAP guidelines recommend PTBM because it is evidence based, but the barrier section is essential to understanding that this evidence-based recommendation is nearly impossible to follow in real-world clinical practice, he emphasized.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents,” published in October of 2019 in Pediatrics, included a full subsection on barriers as to why the guidelines might not be followed in many cases in a real-world setting, and the study authors failed to acknowledge this section and its implications, said Dr. Lessin. Notably, the barriers section was originally published in Pediatrics under a Supplemental Data tab that might easily be overlooked by someone reviewing the main practice guideline recommendations, he said.

In most areas of the country, PTBM is simply unavailable, Dr. Lessin said.

There is a dearth of mental health providers in the United States in general, and “a monstrous shortage of mental health practitioners for young children,” he said. Children in underserved areas barely have access to a medical home, let alone mental health subspecialists, he added.

Even in areas where specialized behavior therapy may be available, it can be prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patients, Dr. Lessin noted. Insurance does not cover this type of behavior therapy, and most mental health professionals don’t accept Medicaid, nor commercial insurance, he said.

“I don’t even bother with those referrals, because they are not available,” said Dr. Lessin. The take-home message is that most community-based pediatricians are not following the guidelines because the barriers are so enormous, he said.

The study was supported by a research grant from the Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and salary support through the Instructor Support Program at the department of pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, to Dr. Bannett. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Novel blood-based panel highly effective for early-stage HCC

A blood-based biomarker panel that includes DNA and protein markers featured a 71% sensitivity at 90% specificity for the detection of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) compared with the GALAD (gender, age, a-fetoprotein [AFP], Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive AFP [AFP-L3], and des-gamma-carboxy-prothrombin [DCP]) score or AFP alone, according to research findings. The panel reportedly performed well in certain subgroups based on sex, presence of cirrhosis, and liver disease etiology.

The study, which included inpatients with HCC and controls without HCC but underlying liver disease, suggests the panel could be utilized in the detection of early stage disease in patients with well-established risk factors for HCC. Ultimately, this may lead to earlier treatment initiation and potentially improved clinical outcomes.

“A blood-based marker panel that detects early-stage HCC with higher sensitivity than current biomarker-based approaches could substantially benefit patients undergoing HCC surveillance,” wrote study authors Naga Chalasani, MD, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, and colleagues. Their report is in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

HCC, which accounts for most primary liver cancers, generally occurs in patients with several established risk factors, including alcoholic liver disease or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as well as chronic hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection. Current guidelines, such as those from the European Association for the Study of the Liver and those from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, recommend surveillance of at-risk patients every 6 months by ultrasound with or without AFP measurement. When caught early, HCC is typically treatable and is associated with a higher rate of survival compared with late-stage disease. According to Dr. Chalasani and colleagues, however, the effectiveness of current recommended surveillance for very early stage or early stage HCC is poor, characterized by a 45% sensitivity for ultrasound and a 63% sensitivity for ultrasound coupled with AFP measurement.

The investigators of the multicenter, case-control study collected blood specimens from 135 patients with HCC as well as 302 age-matched controls with underlying liver disease but no HCC. Very early or early stage disease was seen in approximately 56.3% of patients with HCC, and intermediate, advanced, or terminal stage disease was seen in 43.7% of patients.

To predict cases of HCC, the researchers used a logistic regression algorithm to analyze 10 methylated DNA markers (MDMs) associated with HCC, methylated B3GALT6 (reference DNA marker), and 3 candidate proteins. Finally, the researchers compared the accuracy of the developed blood-based biomarker panel with other blood-based biomarkers – including the GALAD, AFP, AFP-L3, DCP – for the detection of HCC.

The multitarget HCC panel included 3 MDMs – HOXA1, EMX1, and TSPYL5. In addition, the panel included methylation reference marker B3GALT6 and the protein markers AFP and AFP-L3. The biomarker panel featured a higher sensitivity (71%; 95% confidence interval, 60-81) at 90% specificity for the detection of early stage HCC compared with the GALAD score (41%; 95% CI, 30-53) or AFP ≥ 7.32 ng/mL (45%; 95% CI, 33-57). The area under the curve for the novel HCC panel for the detection of any stage HCC was 0.92 vs. 0.87 for the GALAD and 0.81 for the AFP measurement alone. The researchers found that the performance of the test was similar between men and women in terms of sensitivity (79% and 84%, respectively). Moreover, the panel performed similarly well among subgroups based on presence of cirrhosis and liver disease etiology.

A potential limitation of this study was the inclusion of controls who were largely confirmed HCC negative by ultrasound, a technique that lacks sensitivity for detecting early stage HCC, the researchers noted. Given this limitation, the researchers suggest that some of the control participants may have had underlying HCC that was missed by ultrasound. Furthermore, the findings indicate that the cross-sectional nature of the study may also mean some of the control participants had HCCs that were undetectable at initial screening.

Despite the limitations of the study, the researchers reported that the novel, blood-based marker panel’s sensitivity for detecting early stage HCC likely supports its use “among at-risk patients to enhance HCC surveillance and improve early cancer detection.”

The study was funded by the Exact Sciences Corporation. The researchers reported conflicts of interest with several pharmaceutical companies.

A blood-based biomarker panel that includes DNA and protein markers featured a 71% sensitivity at 90% specificity for the detection of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) compared with the GALAD (gender, age, a-fetoprotein [AFP], Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive AFP [AFP-L3], and des-gamma-carboxy-prothrombin [DCP]) score or AFP alone, according to research findings. The panel reportedly performed well in certain subgroups based on sex, presence of cirrhosis, and liver disease etiology.

The study, which included inpatients with HCC and controls without HCC but underlying liver disease, suggests the panel could be utilized in the detection of early stage disease in patients with well-established risk factors for HCC. Ultimately, this may lead to earlier treatment initiation and potentially improved clinical outcomes.

“A blood-based marker panel that detects early-stage HCC with higher sensitivity than current biomarker-based approaches could substantially benefit patients undergoing HCC surveillance,” wrote study authors Naga Chalasani, MD, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, and colleagues. Their report is in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

HCC, which accounts for most primary liver cancers, generally occurs in patients with several established risk factors, including alcoholic liver disease or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as well as chronic hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection. Current guidelines, such as those from the European Association for the Study of the Liver and those from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, recommend surveillance of at-risk patients every 6 months by ultrasound with or without AFP measurement. When caught early, HCC is typically treatable and is associated with a higher rate of survival compared with late-stage disease. According to Dr. Chalasani and colleagues, however, the effectiveness of current recommended surveillance for very early stage or early stage HCC is poor, characterized by a 45% sensitivity for ultrasound and a 63% sensitivity for ultrasound coupled with AFP measurement.