User login

‘Push the bar higher’: New statement on type 1 diabetes in adults

A newly published consensus statement on the management of type 1 diabetes in adults addresses the unique clinical needs of the population compared with those of children with type 1 diabetes or adults with type 2 diabetes.

“The focus on adults is kind of new and it is important. ... I do think it’s a bit of a forgotten population. Whenever we talk about diabetes in adults it’s assumed to be about type 2,” document coauthor M. Sue Kirkman, MD, said in an interview.

The document covers diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, goals and targets, schedule of care, self-management education and lifestyle, glucose monitoring, insulin therapy, hypoglycemia, psychosocial care, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), pancreas transplant/islet cell transplantation, adjunctive therapies, special populations (pregnant, older, hospitalized), and emergent and future perspectives.

Initially presented in draft form in June at the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 81st scientific sessions, the final version of the joint ADA/EASD statement was presented Oct. 1 at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and simultaneously published in Diabetologia and Diabetes Care.

“We are aware of the many and rapid advances in the diagnosis and treatment of type 1 diabetes ... However, despite these advances, there is also a growing recognition of the psychosocial burden of living with type 1 diabetes,” writing group cochair Richard I.G. Holt, MB BChir, PhD, professor of diabetes and endocrinology at the University of Southampton, England, said when introducing the 90-minute EASD session.

“Although there is guidance for the management of type 1 diabetes, the aim of this report is to highlight the major areas that health care professionals should consider when managing adults with type 1 diabetes,” he added.

Noting that the joint EASD/ADA consensus report on type 2 diabetes has been “highly influential,” Dr. Holt said, “EASD and ADA recognized the need to develop a comparable consensus report specifically addressing type 1 diabetes.”

The overriding goals, Dr. Holt said, are to “support people with type 1 diabetes to live a long and healthy life” with four specific strategies: delivery of insulin to keep glucose levels as close to target as possible to prevent complications while minimizing hypoglycemia and preventing DKA; managing cardiovascular risk factors; minimizing psychosocial burden; and promoting psychological well-being.

Diagnostic algorithm

Another coauthor, J. Hans de Vries, MD, PhD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Amsterdam, explained the recommended approach to distinguishing type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes or monogenic diabetes in adults, which is often a clinical challenge.

This also was the topic prompting the most questions during the EASD session.

“Especially in adults, misdiagnosis of type of diabetes is common, occurring in up to 40% of patients diagnosed after the age of 30 years,” Dr. de Vries said.

Among the many reasons for the confusion are that C-peptide levels, a reflection of endogenous insulin secretion, can still be relatively high at the time of clinical onset of type 1 diabetes, but islet antibodies don’t have 100% positive predictive value.

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are increasingly seen at younger ages, and DKA can occur in type 2 diabetes (“ketosis-prone”). In addition, monogenic forms of diabetes can be disguised as type 1 diabetes.

“So, we thought there was a need for a diagnostic algorithm,” Dr. de Vries said, adding that the algorithm – displayed as a graphic in the statement – is only for adults in whom type 1 diabetes is suspected, not other types. Also, it’s based on data from White European populations.

The first step is to test islet autoantibodies. If positive, the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes can be made. If negative and the person is younger than 35 years and without signs of type 2 diabetes, testing C-peptide is advised. If that’s below 200 pmol/L, type 1 diabetes is the diagnosis. If above 200 pmol/L, genetic testing for monogenic diabetes is advised. If there are signs of type 2 diabetes and/or the person is over age 35, type 2 diabetes is the most likely diagnosis.

And if uncertainty remains, the recommendation is to try noninsulin therapy and retest C-peptide again in 3 years, as by that time it will be below 200 pmol/L in a person with type 1 diabetes.

Dr. Kirkman commented regarding the algorithm: “It’s very much from a European population perspective. In some ways that’s a limitation, especially in the U.S. where the population is diverse, but I do think it’s still useful to help guide people through how to think about somebody who presents as an adult where it’s not obviously type 2 or type 1 ... There is a lot of in-between stuff.”

Psychosocial support: Essential but often overlooked

Frank J. Snoek, PhD, professor of psychology at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Vrije Universiteit, presented the section on behavioral and psychosocial care. He pointed out that diabetes-related emotional distress is reported by 20%-40% of adults with type 1 diabetes, and that the risk of such distress is especially high at the time of diagnosis and when complications develop.

About 15% of people with type 1 diabetes have depression, which is linked to elevated A1c levels, increased complication risk, and mortality. Anxiety also is very common and linked with diabetes-specific fears including hypoglycemia. Eating disorders are more prevalent among people with type 1 diabetes than in the general population and can further complicate diabetes management.

Recommendations include periodic evaluation of psychological health and social barriers to self-management and having clear referral pathways and access to psychological or psychiatric care for individuals in need. “All members of the diabetes care team have a responsibility when it comes to offering psychosocial support as part of ongoing diabetes care and education.”

Dr. Kirkman had identified this section as noteworthy: “I think the focus on psychosocial care and making that an ongoing part of diabetes care and assessment is important.”

More data needed on diets, many other areas

During the discussion, several attendees asked about low-carbohydrate diets, embraced by many individuals with type 1 diabetes.

The document states: “While low-carbohydrate and very low-carbohydrate eating patterns have become increasingly popular and reduce A1c levels in the short term, it is important to incorporate these in conjunction with healthy eating guidelines. Additional components of the meal, including high fat and/or high protein, may contribute to delayed hyperglycemia and the need for insulin dose adjustments. Since this is highly variable between individuals, postprandial glucose measurements for up to 3 hours or more may be needed to determine initial dose adjustments.”

Beyond that, Tomasz Klupa, MD, PhD, of the department of metabolic diseases, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, responded: “We don’t have much data on low-carb diets in type 1 diabetes. ... Compliance to those diets is pretty poor. We don’t have long-term follow-up and the studies are simply not conclusive. Initial results do show reductions in body weight and A1c, but with time the compliance goes down dramatically.”

“Certainly, when we think of low-carb diets, we have to meet our patients where they are,” said Amy Hess-Fischl, a nutritionist and certified diabetes care and education specialist at the University of Chicago. “We don’t have enough data to really say there’s positive long-term evidence. But we can find a happy medium to find some benefits in glycemic and weight control. ... It’s really that collaboration with that person to identify what’s going to work for them in a healthy way.”

The EASD session concluded with writing group cochair Anne L. Peters, MD, director of clinical diabetes programs at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, summing up the many other knowledge gaps, including personalizing use of diabetes technology, the problems of health disparities and lack of access to care, and the feasibility of prevention and/or cure.

She observed: “There is no one-size-fits-all approach to diabetes care, and the more we can individualize our approaches, the more successful we are likely to be. ... Hopefully this consensus statement has pushed the bar a bit higher, telling the powers that be that people with type 1 diabetes need and deserve the best.

“We have a very long way to go before all of our patients reach their goals and health equity is achieved. ... We need to provide each and every person the access to the care we describe in this consensus statement, so that all can prosper and thrive and look forward to a long and healthy life lived with type 1 diabetes.”

Dr. Holt has financial relationships with Novo Nordisk, Abbott, Eli Lilly, Otsuka, and Roche. Dr. de Vries has financial relationships with Afon, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Adocia, and Zealand Pharma. Ms. Hess-Fischl has financial relationships with Abbott Diabetes Care and Xeris. Dr. Klupa has financial relationships with numerous drug and device companies. Dr. Snoek has financial relationships with Abbott, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Peters has financial relationships with Abbott Diabetes Care, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Insulet, Novo Nordisk, Medscape, and Zealand Pharmaceuticals. She holds stock options in Omada Health and Livongo and is a special government employee of the Food and Drug Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A newly published consensus statement on the management of type 1 diabetes in adults addresses the unique clinical needs of the population compared with those of children with type 1 diabetes or adults with type 2 diabetes.

“The focus on adults is kind of new and it is important. ... I do think it’s a bit of a forgotten population. Whenever we talk about diabetes in adults it’s assumed to be about type 2,” document coauthor M. Sue Kirkman, MD, said in an interview.

The document covers diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, goals and targets, schedule of care, self-management education and lifestyle, glucose monitoring, insulin therapy, hypoglycemia, psychosocial care, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), pancreas transplant/islet cell transplantation, adjunctive therapies, special populations (pregnant, older, hospitalized), and emergent and future perspectives.

Initially presented in draft form in June at the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 81st scientific sessions, the final version of the joint ADA/EASD statement was presented Oct. 1 at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and simultaneously published in Diabetologia and Diabetes Care.

“We are aware of the many and rapid advances in the diagnosis and treatment of type 1 diabetes ... However, despite these advances, there is also a growing recognition of the psychosocial burden of living with type 1 diabetes,” writing group cochair Richard I.G. Holt, MB BChir, PhD, professor of diabetes and endocrinology at the University of Southampton, England, said when introducing the 90-minute EASD session.

“Although there is guidance for the management of type 1 diabetes, the aim of this report is to highlight the major areas that health care professionals should consider when managing adults with type 1 diabetes,” he added.

Noting that the joint EASD/ADA consensus report on type 2 diabetes has been “highly influential,” Dr. Holt said, “EASD and ADA recognized the need to develop a comparable consensus report specifically addressing type 1 diabetes.”

The overriding goals, Dr. Holt said, are to “support people with type 1 diabetes to live a long and healthy life” with four specific strategies: delivery of insulin to keep glucose levels as close to target as possible to prevent complications while minimizing hypoglycemia and preventing DKA; managing cardiovascular risk factors; minimizing psychosocial burden; and promoting psychological well-being.

Diagnostic algorithm

Another coauthor, J. Hans de Vries, MD, PhD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Amsterdam, explained the recommended approach to distinguishing type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes or monogenic diabetes in adults, which is often a clinical challenge.

This also was the topic prompting the most questions during the EASD session.

“Especially in adults, misdiagnosis of type of diabetes is common, occurring in up to 40% of patients diagnosed after the age of 30 years,” Dr. de Vries said.

Among the many reasons for the confusion are that C-peptide levels, a reflection of endogenous insulin secretion, can still be relatively high at the time of clinical onset of type 1 diabetes, but islet antibodies don’t have 100% positive predictive value.

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are increasingly seen at younger ages, and DKA can occur in type 2 diabetes (“ketosis-prone”). In addition, monogenic forms of diabetes can be disguised as type 1 diabetes.

“So, we thought there was a need for a diagnostic algorithm,” Dr. de Vries said, adding that the algorithm – displayed as a graphic in the statement – is only for adults in whom type 1 diabetes is suspected, not other types. Also, it’s based on data from White European populations.

The first step is to test islet autoantibodies. If positive, the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes can be made. If negative and the person is younger than 35 years and without signs of type 2 diabetes, testing C-peptide is advised. If that’s below 200 pmol/L, type 1 diabetes is the diagnosis. If above 200 pmol/L, genetic testing for monogenic diabetes is advised. If there are signs of type 2 diabetes and/or the person is over age 35, type 2 diabetes is the most likely diagnosis.

And if uncertainty remains, the recommendation is to try noninsulin therapy and retest C-peptide again in 3 years, as by that time it will be below 200 pmol/L in a person with type 1 diabetes.

Dr. Kirkman commented regarding the algorithm: “It’s very much from a European population perspective. In some ways that’s a limitation, especially in the U.S. where the population is diverse, but I do think it’s still useful to help guide people through how to think about somebody who presents as an adult where it’s not obviously type 2 or type 1 ... There is a lot of in-between stuff.”

Psychosocial support: Essential but often overlooked

Frank J. Snoek, PhD, professor of psychology at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Vrije Universiteit, presented the section on behavioral and psychosocial care. He pointed out that diabetes-related emotional distress is reported by 20%-40% of adults with type 1 diabetes, and that the risk of such distress is especially high at the time of diagnosis and when complications develop.

About 15% of people with type 1 diabetes have depression, which is linked to elevated A1c levels, increased complication risk, and mortality. Anxiety also is very common and linked with diabetes-specific fears including hypoglycemia. Eating disorders are more prevalent among people with type 1 diabetes than in the general population and can further complicate diabetes management.

Recommendations include periodic evaluation of psychological health and social barriers to self-management and having clear referral pathways and access to psychological or psychiatric care for individuals in need. “All members of the diabetes care team have a responsibility when it comes to offering psychosocial support as part of ongoing diabetes care and education.”

Dr. Kirkman had identified this section as noteworthy: “I think the focus on psychosocial care and making that an ongoing part of diabetes care and assessment is important.”

More data needed on diets, many other areas

During the discussion, several attendees asked about low-carbohydrate diets, embraced by many individuals with type 1 diabetes.

The document states: “While low-carbohydrate and very low-carbohydrate eating patterns have become increasingly popular and reduce A1c levels in the short term, it is important to incorporate these in conjunction with healthy eating guidelines. Additional components of the meal, including high fat and/or high protein, may contribute to delayed hyperglycemia and the need for insulin dose adjustments. Since this is highly variable between individuals, postprandial glucose measurements for up to 3 hours or more may be needed to determine initial dose adjustments.”

Beyond that, Tomasz Klupa, MD, PhD, of the department of metabolic diseases, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, responded: “We don’t have much data on low-carb diets in type 1 diabetes. ... Compliance to those diets is pretty poor. We don’t have long-term follow-up and the studies are simply not conclusive. Initial results do show reductions in body weight and A1c, but with time the compliance goes down dramatically.”

“Certainly, when we think of low-carb diets, we have to meet our patients where they are,” said Amy Hess-Fischl, a nutritionist and certified diabetes care and education specialist at the University of Chicago. “We don’t have enough data to really say there’s positive long-term evidence. But we can find a happy medium to find some benefits in glycemic and weight control. ... It’s really that collaboration with that person to identify what’s going to work for them in a healthy way.”

The EASD session concluded with writing group cochair Anne L. Peters, MD, director of clinical diabetes programs at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, summing up the many other knowledge gaps, including personalizing use of diabetes technology, the problems of health disparities and lack of access to care, and the feasibility of prevention and/or cure.

She observed: “There is no one-size-fits-all approach to diabetes care, and the more we can individualize our approaches, the more successful we are likely to be. ... Hopefully this consensus statement has pushed the bar a bit higher, telling the powers that be that people with type 1 diabetes need and deserve the best.

“We have a very long way to go before all of our patients reach their goals and health equity is achieved. ... We need to provide each and every person the access to the care we describe in this consensus statement, so that all can prosper and thrive and look forward to a long and healthy life lived with type 1 diabetes.”

Dr. Holt has financial relationships with Novo Nordisk, Abbott, Eli Lilly, Otsuka, and Roche. Dr. de Vries has financial relationships with Afon, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Adocia, and Zealand Pharma. Ms. Hess-Fischl has financial relationships with Abbott Diabetes Care and Xeris. Dr. Klupa has financial relationships with numerous drug and device companies. Dr. Snoek has financial relationships with Abbott, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Peters has financial relationships with Abbott Diabetes Care, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Insulet, Novo Nordisk, Medscape, and Zealand Pharmaceuticals. She holds stock options in Omada Health and Livongo and is a special government employee of the Food and Drug Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A newly published consensus statement on the management of type 1 diabetes in adults addresses the unique clinical needs of the population compared with those of children with type 1 diabetes or adults with type 2 diabetes.

“The focus on adults is kind of new and it is important. ... I do think it’s a bit of a forgotten population. Whenever we talk about diabetes in adults it’s assumed to be about type 2,” document coauthor M. Sue Kirkman, MD, said in an interview.

The document covers diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, goals and targets, schedule of care, self-management education and lifestyle, glucose monitoring, insulin therapy, hypoglycemia, psychosocial care, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), pancreas transplant/islet cell transplantation, adjunctive therapies, special populations (pregnant, older, hospitalized), and emergent and future perspectives.

Initially presented in draft form in June at the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 81st scientific sessions, the final version of the joint ADA/EASD statement was presented Oct. 1 at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and simultaneously published in Diabetologia and Diabetes Care.

“We are aware of the many and rapid advances in the diagnosis and treatment of type 1 diabetes ... However, despite these advances, there is also a growing recognition of the psychosocial burden of living with type 1 diabetes,” writing group cochair Richard I.G. Holt, MB BChir, PhD, professor of diabetes and endocrinology at the University of Southampton, England, said when introducing the 90-minute EASD session.

“Although there is guidance for the management of type 1 diabetes, the aim of this report is to highlight the major areas that health care professionals should consider when managing adults with type 1 diabetes,” he added.

Noting that the joint EASD/ADA consensus report on type 2 diabetes has been “highly influential,” Dr. Holt said, “EASD and ADA recognized the need to develop a comparable consensus report specifically addressing type 1 diabetes.”

The overriding goals, Dr. Holt said, are to “support people with type 1 diabetes to live a long and healthy life” with four specific strategies: delivery of insulin to keep glucose levels as close to target as possible to prevent complications while minimizing hypoglycemia and preventing DKA; managing cardiovascular risk factors; minimizing psychosocial burden; and promoting psychological well-being.

Diagnostic algorithm

Another coauthor, J. Hans de Vries, MD, PhD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Amsterdam, explained the recommended approach to distinguishing type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes or monogenic diabetes in adults, which is often a clinical challenge.

This also was the topic prompting the most questions during the EASD session.

“Especially in adults, misdiagnosis of type of diabetes is common, occurring in up to 40% of patients diagnosed after the age of 30 years,” Dr. de Vries said.

Among the many reasons for the confusion are that C-peptide levels, a reflection of endogenous insulin secretion, can still be relatively high at the time of clinical onset of type 1 diabetes, but islet antibodies don’t have 100% positive predictive value.

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are increasingly seen at younger ages, and DKA can occur in type 2 diabetes (“ketosis-prone”). In addition, monogenic forms of diabetes can be disguised as type 1 diabetes.

“So, we thought there was a need for a diagnostic algorithm,” Dr. de Vries said, adding that the algorithm – displayed as a graphic in the statement – is only for adults in whom type 1 diabetes is suspected, not other types. Also, it’s based on data from White European populations.

The first step is to test islet autoantibodies. If positive, the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes can be made. If negative and the person is younger than 35 years and without signs of type 2 diabetes, testing C-peptide is advised. If that’s below 200 pmol/L, type 1 diabetes is the diagnosis. If above 200 pmol/L, genetic testing for monogenic diabetes is advised. If there are signs of type 2 diabetes and/or the person is over age 35, type 2 diabetes is the most likely diagnosis.

And if uncertainty remains, the recommendation is to try noninsulin therapy and retest C-peptide again in 3 years, as by that time it will be below 200 pmol/L in a person with type 1 diabetes.

Dr. Kirkman commented regarding the algorithm: “It’s very much from a European population perspective. In some ways that’s a limitation, especially in the U.S. where the population is diverse, but I do think it’s still useful to help guide people through how to think about somebody who presents as an adult where it’s not obviously type 2 or type 1 ... There is a lot of in-between stuff.”

Psychosocial support: Essential but often overlooked

Frank J. Snoek, PhD, professor of psychology at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Vrije Universiteit, presented the section on behavioral and psychosocial care. He pointed out that diabetes-related emotional distress is reported by 20%-40% of adults with type 1 diabetes, and that the risk of such distress is especially high at the time of diagnosis and when complications develop.

About 15% of people with type 1 diabetes have depression, which is linked to elevated A1c levels, increased complication risk, and mortality. Anxiety also is very common and linked with diabetes-specific fears including hypoglycemia. Eating disorders are more prevalent among people with type 1 diabetes than in the general population and can further complicate diabetes management.

Recommendations include periodic evaluation of psychological health and social barriers to self-management and having clear referral pathways and access to psychological or psychiatric care for individuals in need. “All members of the diabetes care team have a responsibility when it comes to offering psychosocial support as part of ongoing diabetes care and education.”

Dr. Kirkman had identified this section as noteworthy: “I think the focus on psychosocial care and making that an ongoing part of diabetes care and assessment is important.”

More data needed on diets, many other areas

During the discussion, several attendees asked about low-carbohydrate diets, embraced by many individuals with type 1 diabetes.

The document states: “While low-carbohydrate and very low-carbohydrate eating patterns have become increasingly popular and reduce A1c levels in the short term, it is important to incorporate these in conjunction with healthy eating guidelines. Additional components of the meal, including high fat and/or high protein, may contribute to delayed hyperglycemia and the need for insulin dose adjustments. Since this is highly variable between individuals, postprandial glucose measurements for up to 3 hours or more may be needed to determine initial dose adjustments.”

Beyond that, Tomasz Klupa, MD, PhD, of the department of metabolic diseases, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, responded: “We don’t have much data on low-carb diets in type 1 diabetes. ... Compliance to those diets is pretty poor. We don’t have long-term follow-up and the studies are simply not conclusive. Initial results do show reductions in body weight and A1c, but with time the compliance goes down dramatically.”

“Certainly, when we think of low-carb diets, we have to meet our patients where they are,” said Amy Hess-Fischl, a nutritionist and certified diabetes care and education specialist at the University of Chicago. “We don’t have enough data to really say there’s positive long-term evidence. But we can find a happy medium to find some benefits in glycemic and weight control. ... It’s really that collaboration with that person to identify what’s going to work for them in a healthy way.”

The EASD session concluded with writing group cochair Anne L. Peters, MD, director of clinical diabetes programs at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, summing up the many other knowledge gaps, including personalizing use of diabetes technology, the problems of health disparities and lack of access to care, and the feasibility of prevention and/or cure.

She observed: “There is no one-size-fits-all approach to diabetes care, and the more we can individualize our approaches, the more successful we are likely to be. ... Hopefully this consensus statement has pushed the bar a bit higher, telling the powers that be that people with type 1 diabetes need and deserve the best.

“We have a very long way to go before all of our patients reach their goals and health equity is achieved. ... We need to provide each and every person the access to the care we describe in this consensus statement, so that all can prosper and thrive and look forward to a long and healthy life lived with type 1 diabetes.”

Dr. Holt has financial relationships with Novo Nordisk, Abbott, Eli Lilly, Otsuka, and Roche. Dr. de Vries has financial relationships with Afon, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Adocia, and Zealand Pharma. Ms. Hess-Fischl has financial relationships with Abbott Diabetes Care and Xeris. Dr. Klupa has financial relationships with numerous drug and device companies. Dr. Snoek has financial relationships with Abbott, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Peters has financial relationships with Abbott Diabetes Care, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Insulet, Novo Nordisk, Medscape, and Zealand Pharmaceuticals. She holds stock options in Omada Health and Livongo and is a special government employee of the Food and Drug Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASD 2021

Paraneoplastic Signs in Bladder Transitional Cell Carcinoma: An Unusual Presentation

To the Editor:

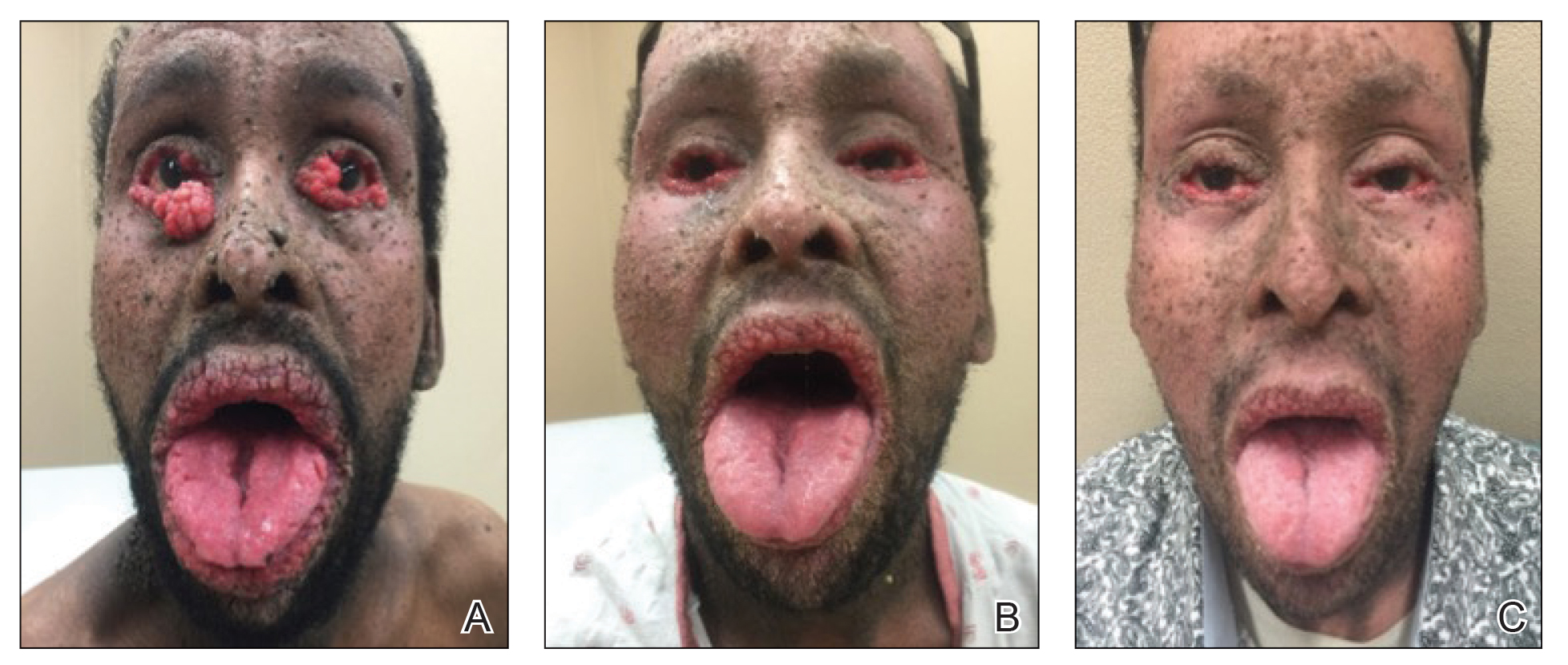

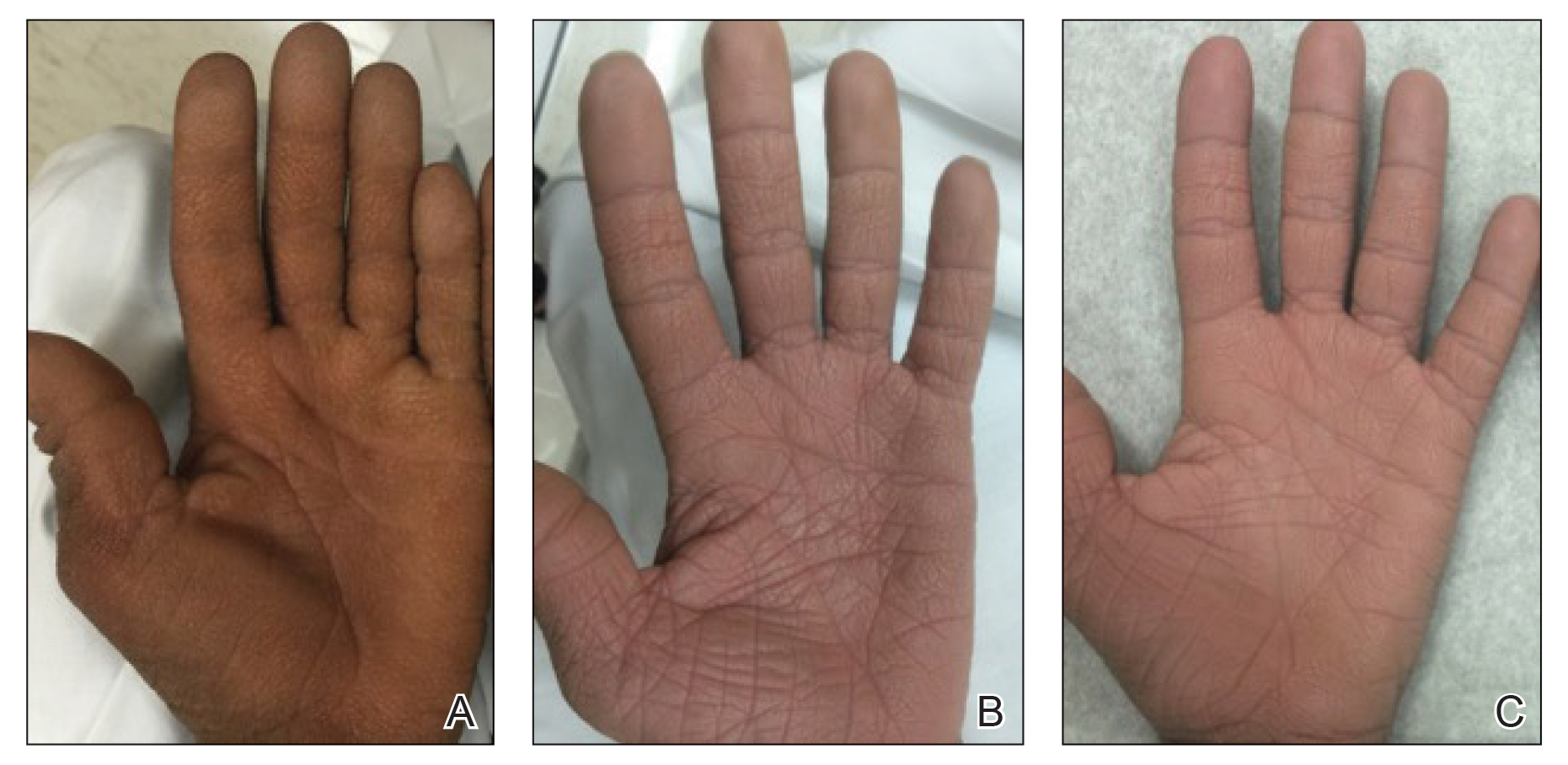

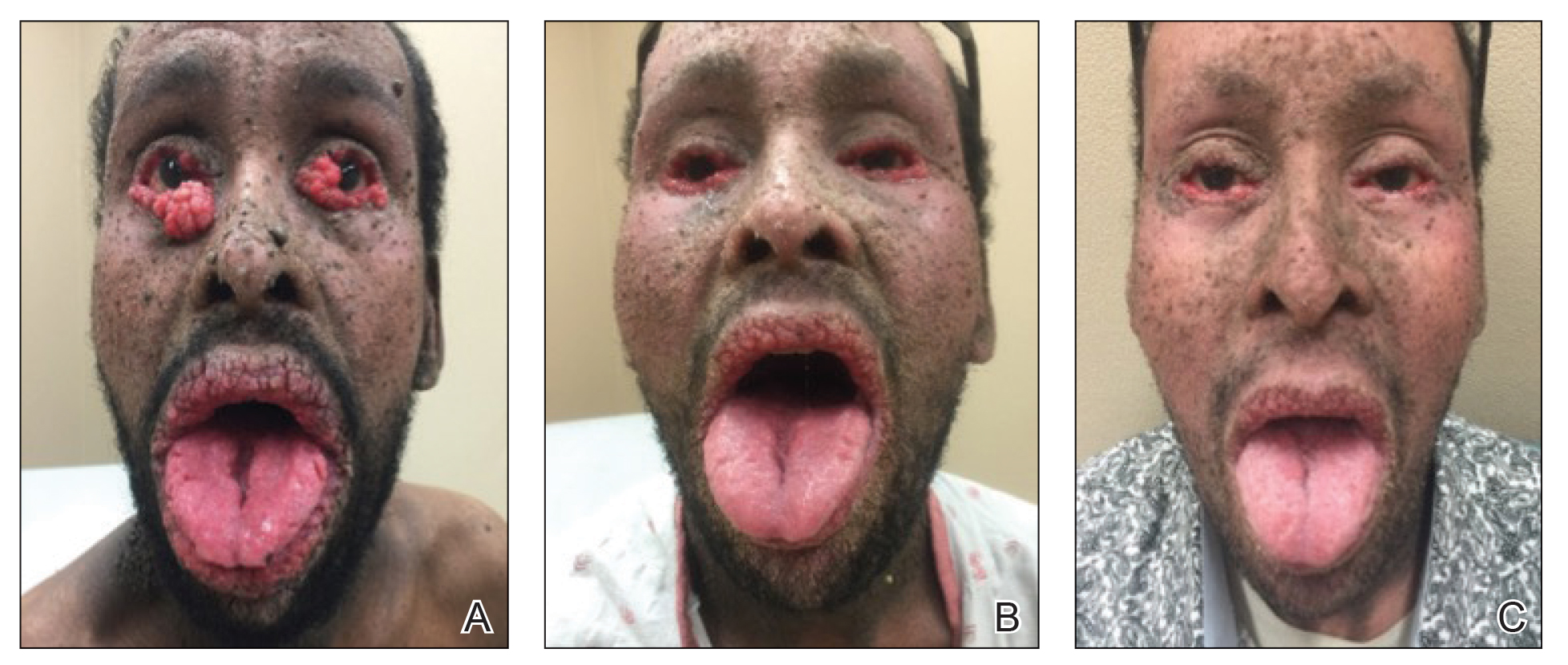

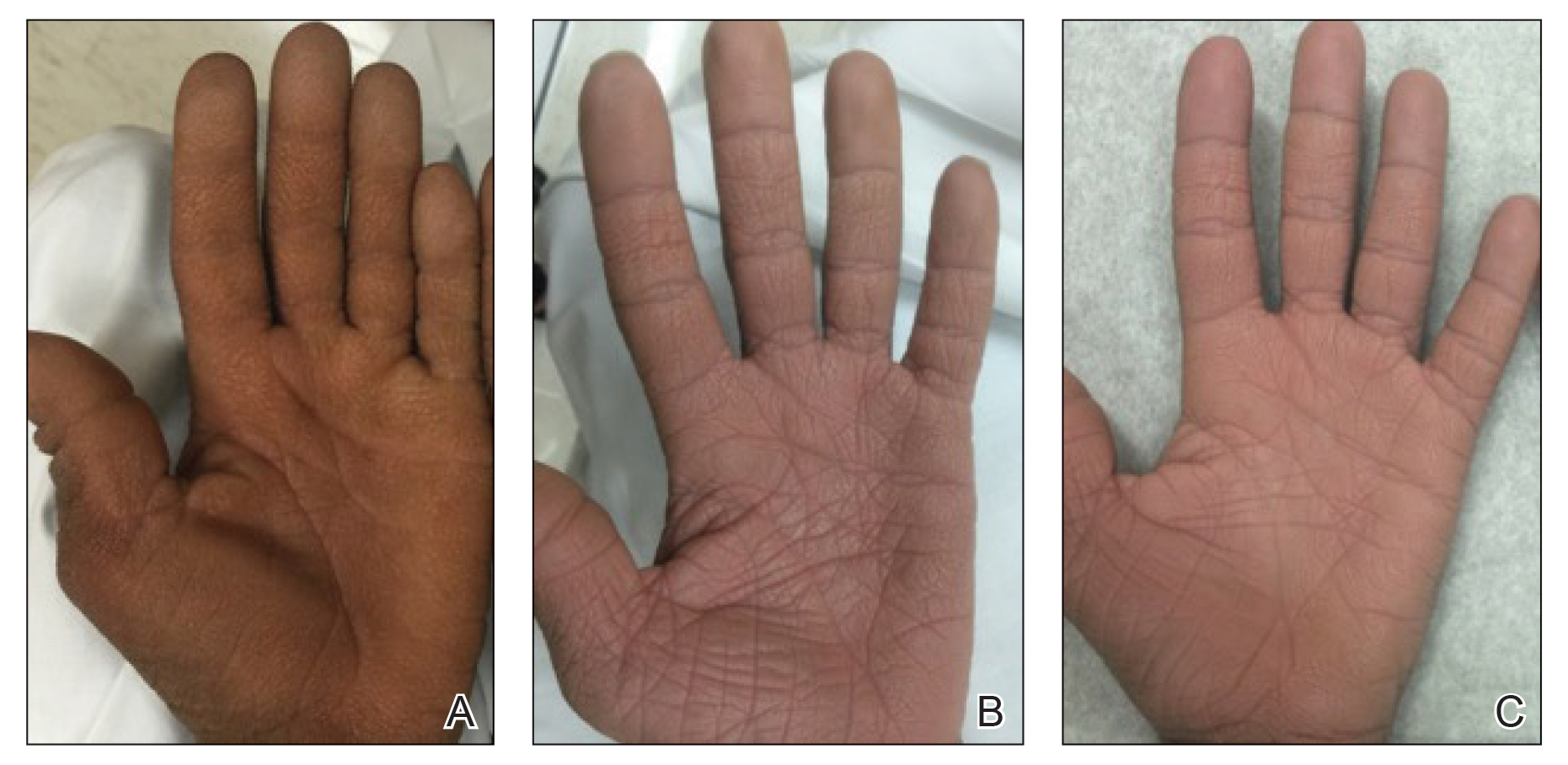

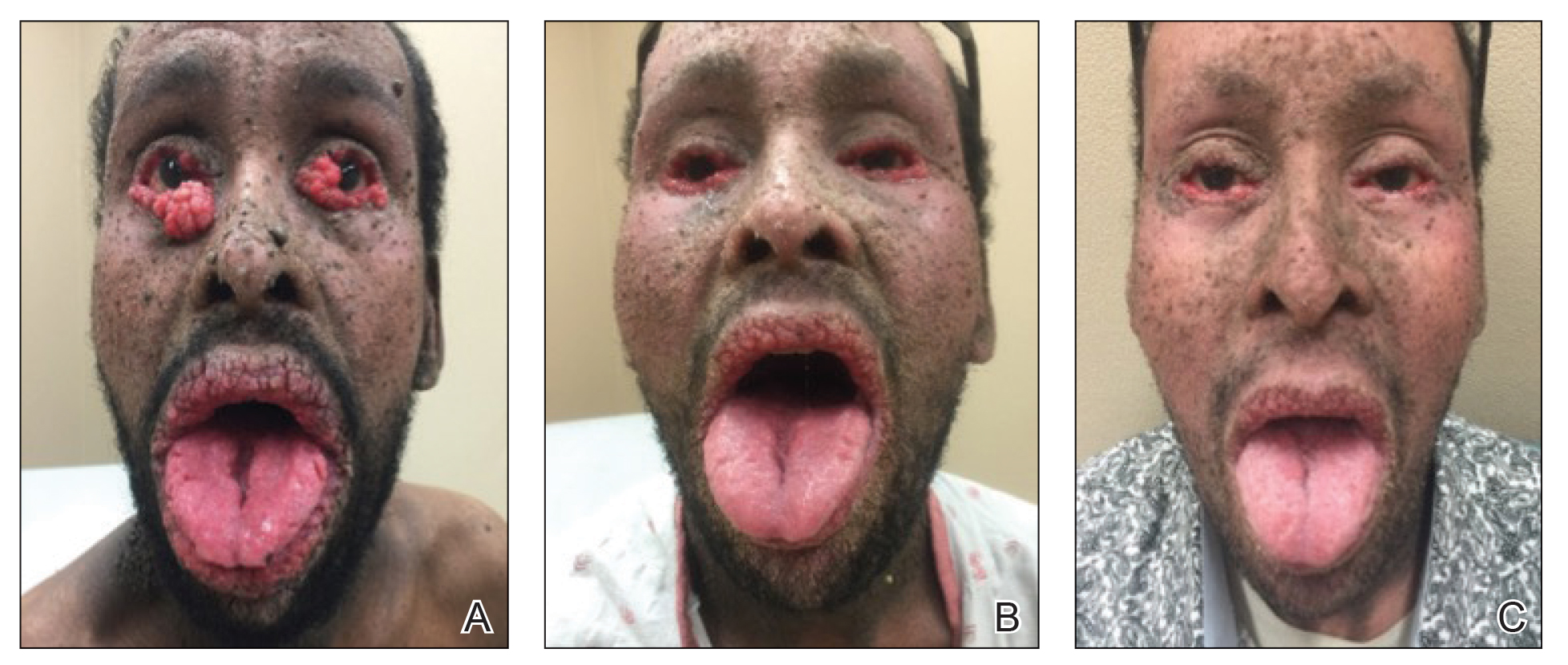

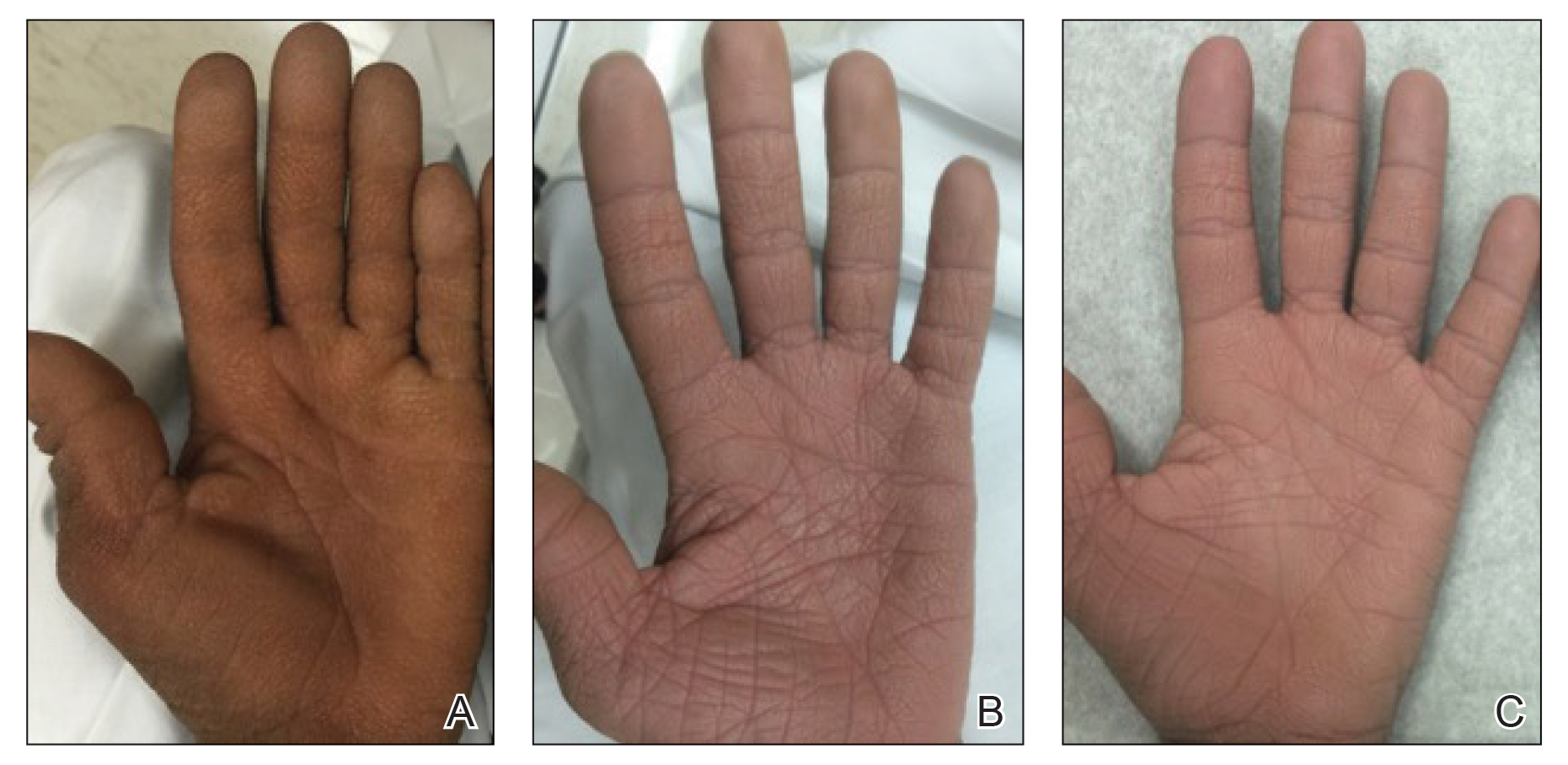

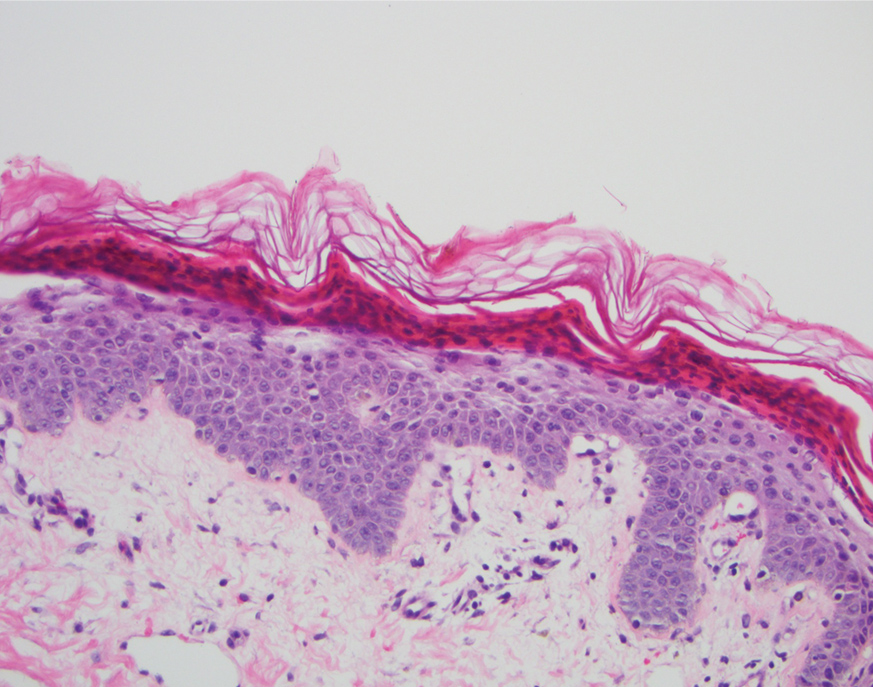

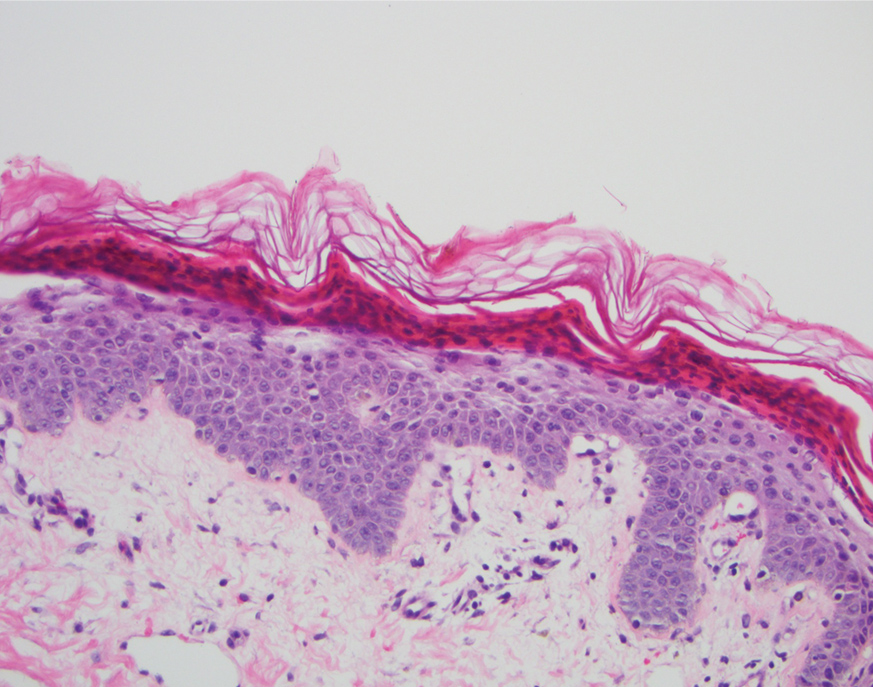

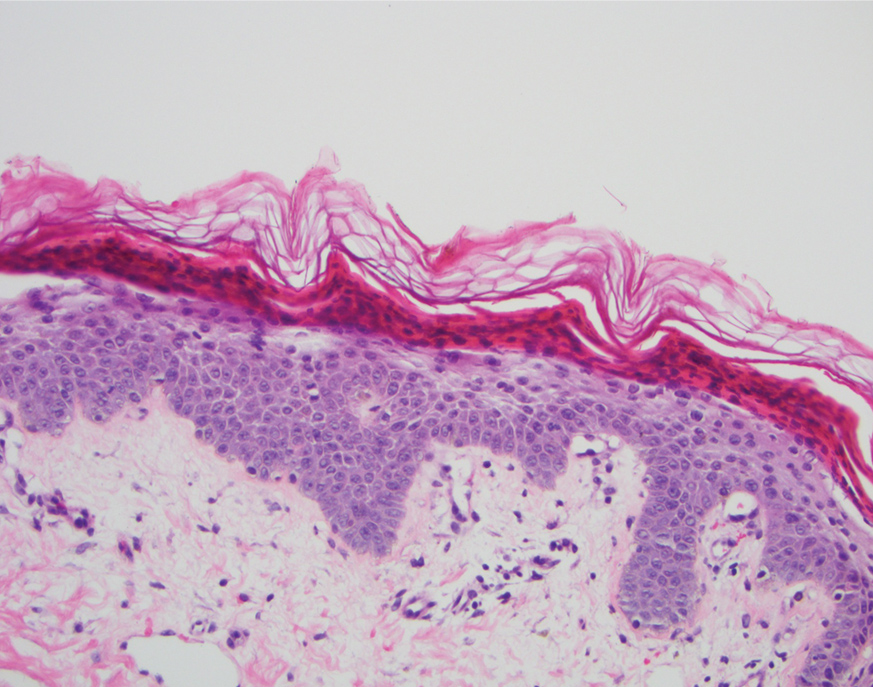

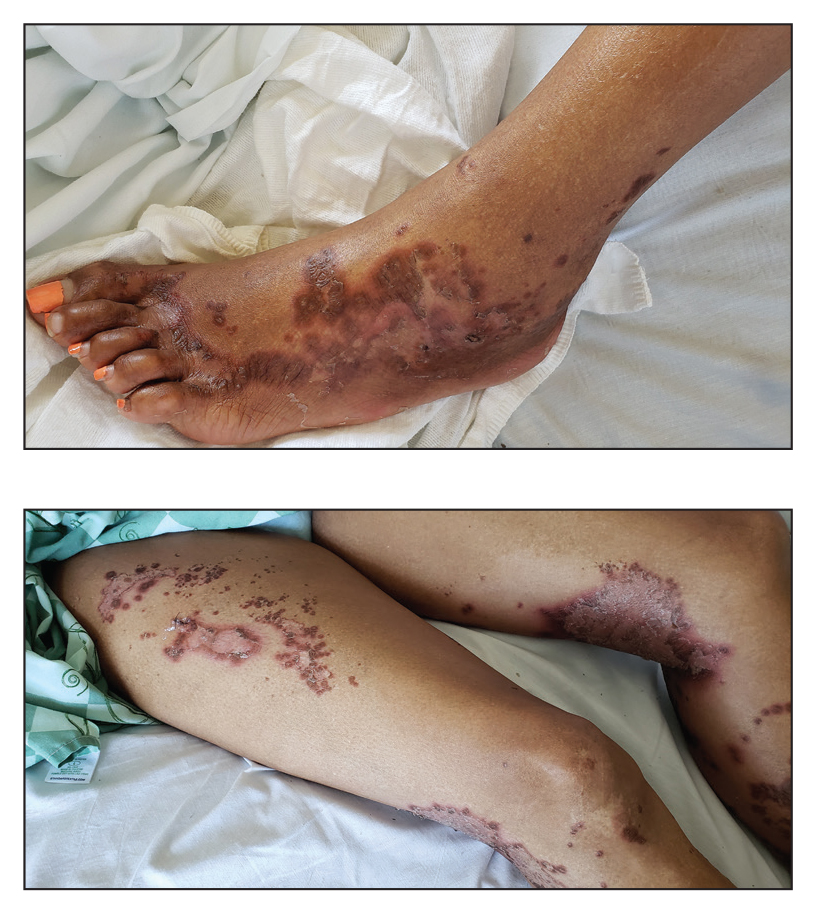

A 40-year-old Somalian man presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the eyelids, tongue, lips, and hands of 8 years’ duration. He was a former refugee who had faced considerable stigma from his community due to his appearance. A review of systems was remarkable for decreased appetite but no weight loss. He reported no abdominal distention, early satiety, or urinary symptoms, and he had no personal history of diabetes mellitus or obesity. Physical examination demonstrated hyperpigmented velvety plaques in all skin folds and on the genitalia. Massive papillomatosis of the eyelid margins, tongue, and lips also was noted (Figure 1A). Flesh-colored papules also were scattered across the face. Punctate, flesh-colored papules were present on the volar and palmar hands (Figure 2A). Histopathology demonstrated pronounced papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with negative human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 and HPV-18 DNA studies. Given the appearance of malignant acanthosis nigricans with oral and conjunctival features, cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms, concern for underlying malignancy was high. Malignancy workup, including upper and lower endoscopy as well as serial computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, was unrevealing.

Laboratory investigation revealed a positive Schistosoma IgG antibody (0.38 geometric mean egg count) and peripheral eosinophilia (1.09 ×103/μL), which normalized after praziquantel therapy. With no malignancy identified over the preceding 6-month period, treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily was initiated based on limited literature support.1-3 Treatment led to reduction in the size and number of papillomas (Figure 1B) and tripe palms (Figure 2B) with increased mobility of hands, lips, and tongue. The patient underwent oculoplastic surgery to reduce the papilloma burden along the eyelid margins. Subsequent cystoscopy 9 months after the initial presentation revealed low-grade transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Intraoperative mitomycin C led to tumor shrinkage and, with continued treatment with daily acitretin, dramatic improvement of all cutaneous and mucosal symptoms (Figure 1C and Figure 2C). To date, his cutaneous symptoms have resolved.

This case demonstrated a unique presentation of multiple paraneoplastic signs in bladder transitional cell carcinoma. The presence of malignant acanthosis nigricans (including oral and conjunctival involvement), cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms have been individually documented in various types of gastric malignancies.4 Acanthosis nigricans often is secondary to diabetes and obesity, presenting with diffuse, thickened, velvety plaques in the flexural areas. Malignant acanthosis nigricans is a rare, rapidly progressive condition that often presents over a period of weeks to months; it almost always is associated with internal malignancies. It often has more extensive involvement, extending beyond the flexural areas, than typical acanthosis nigricans.4 Oral involvement can be either hypertrophic or papillomatous; papillomatosis of the oral mucosa was reported in over 40% of malignant acanthosis nigricans cases (N=200).5 Cases with conjunctival involvement are less common.6 Although malignant acanthosis nigricans often is codiagnosed with a malignancy, it can precede the cancer diagnosis in some cases.7,8 A majority of cases are associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.4 Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis also is a rare paraneoplastic condition that most commonly is associated with gastric adenocarcinomas. Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis often presents rapidly as verrucous growths on cutaneous surfaces (including the hands and face) but also can affect mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and conjunctiva.9-11 Tripe palms are characterized by exaggerated dermatoglyphics with diffuse palmar ridging and hyperkeratosis. Tripe palms most often are associated with pulmonary malignancies. When tripe palms are present with malignant acanthosis nigricans, they reflect up to a one-third incidence of gastrointestinal malignancy.12,13

Despite the individual presentation of these paraneoplastic signs in a variety of malignancies, synchronous presentation is rare. A brief literature review only identified 6 cases of concurrent acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis with an underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.1,11,14-17 Two additional reports described tripe palms with oral acanthosis nigricans and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis in metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma and renal urothelial carcinoma.2,18 An additional case of all 3 paraneoplastic conditions was reported in the setting of metastatic cervical cancer (HPV positive).19 Per a recent case report and literature review,20 there have only been 8 cases of acanthosis nigricans reported in bladder transitional cell carcinoma,20-27 half of which have included oral malignant acanthosis nigricans.20-23 Only one report of concurrent cutaneous and oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and triple palms in the setting of bladder cancer has been reported.20 Given the extensive conjunctival involvement and cutaneous papillomatosis in our patient, ours is a rarely reported case of concurrent malignant mucocutaneous acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive papillomatosis in transitional cell bladder carcinoma. We believe it is imperative to consider the role of this malignancy as a cause of these paraneoplastic conditions.

Although these paraneoplastic conditions rarely co-occur, our case further offers a common molecular pathway for these conditions.28 In these paraneoplastic conditions, the stimulating factor is thought to be tumor growth factor α, which is structurally related to epidermal growth factor (EGF). Epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) are found in the basal layer of the epidermis, where activation stimulates keratinocyte growth and leads to the cutaneous manifestation of symptoms.28 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations are found in most noninvasive transitional cell tumors of the bladder.29 The fibroblast growth factor pathway is distinctly different from the tumor growth factor α and EGF pathways.30 However, this association with transitional cell carcinoma suggests that fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 also may be implicated in these paraneoplastic conditions.

Our patient responded well to treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily. The mechanism of action of retinoids involves inducing mitotic activity and desmosomal shedding.31 Retinoids downregulate EGFR expression and activation in EGF-stimulated cells.32 We hypothesize that these oral retinoids decreased the growth stimulus and thereby improved cutaneous signs in the setting of our patient’s transitional cell cancer. Although definitive therapy is malignancy management, our case highlights the utility of adjunctive measures such as oral retinoids and surgical debulking. While previous cases have reported use of retinoids at a lower dosage than used in this case, oral lesions often have only been mildly improved with little impact on other cutaneous symptoms.1,2 In one case of malignant acanthosis nigricans and oral papillomatosis, isotretinoin 25 mg once every 2 to 3 days led to a moderate decrease in hyperkeratosis and papillomas, but the patient was lost to follow-up.3 Our case highlights the use of higher daily doses of oral retinoids for over 9 months, resulting in marked improvement in both the mucosal and cutaneous symptoms of acanthosis nigricans, progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms. Therefore, oral acitretin should be considered as adjuvant therapy for these paraneoplastic conditions.

By reporting this case, we hope to demonstrate the importance of considering other forms of malignancies in the presence of paraneoplastic conditions. Although gastric malignancies more commonly are associated with these conditions, bladder carcinomas also can present with cutaneous manifestations. The presence of these paraneoplastic conditions alone or together rarely is reported in urologic cancers and generally is considered to be an indicator of poor prognosis. Paraneoplastic conditions often develop rapidly and occur in very advanced malignancies.4 The disfiguring presentation in our case also had unusual diagnostic challenges. The presence of these conditions for 8 years and nonmetastatic advanced malignancy suggest a more indolent process and that these signs are not always an indicator of poor prognosis. Future patients with these paraneoplastic conditions may benefit from both a thorough malignancy screen, including cystoscopy, and high daily doses of oral retinoids.

- Stawczyk-Macieja M, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Nowicki R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:56-58.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong W-S. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Swineford SL, Drucker CR. Palliative treatment of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans and oral florid papillomatosis with retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1151-1153.

- Wick MR, Patterson JW. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes [published online January 31, 2019]. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36:211-228.

- Tyler MT, Ficarra G, Silverman S, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with florid papillary oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:445-449.

- Zhang X, Liu R, Liu Y, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: a case report. BMC Ophthalmology. 2020;20:1-4.

- Curth HO. Dermatoses and malignant internal tumours. Arch Dermatol Syphil. 1955;71:95-107.

- Krawczyk M, Mykala-Cies´la J, Kolodziej-Jaskula A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

- Singhi MK, Gupta LK, Bansal M, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis with adenocarcinoma of stomach in a 35 year old male. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:195-196.

- Klieb HB, Avon SL, Gilbert J, et al. Florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis: mucocutaneous markers of an underlying gastric malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E218-E219.

- Yang YH, Zhang RZ, Kang DH, et al. Three paraneoplastic signs in the same patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18966.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Chantarojanasiri T, Buranathawornsom A, Sirinawasatien A. Diffuse esophageal squamous papillomatosis: a rare disease associated with acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:702-706.

- Muhammad R, Iftikhar N, Sarfraz T, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an indicator of internal malignancy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:888-890.

- Brinca A, Cardoso JC, Brites MM, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis and acanthosis nigricans maligna revealing gastric adenocarcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:573-577.

- Vilas-Sueiro A, Suárez-Amor O, Monteagudo B, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis, and tripe palms in a man with gastric adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:438-439.

- Paravina M, Ljubisavljevic´ D. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma—a case report. Serbian J Dermatology Venereol. 2015;7:5-14.

- Kleikamp S, Böhm M, Frosch P, et al. Acanthosis nigricans, papillomatosis mucosae and “tripe” palms in a patient with metastasized gastric carcinoma [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:1209-1213.

- Mikhail GR, Fachnie DM, Drukker BH, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:201-202.

- Zhang R, Jiang M, Lei W, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with recurrent bladder cancer: a case report and review of literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:951.

- Olek-Hrab K, Silny W, Zaba R, et al. Co-occurrence of acanthosis nigricans and bladder adenocarcinoma-case report. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2013;17:327-330.

- Canjuga I, Mravak-Stipetic´ M, Kopic´V, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans: case report and comparison with literature reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2008;16:91-95.

- Cairo F, Rubino I, Rotundo R, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans as a marker of internal malignancy. a case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1271-1275.

- Möhrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Singh GK, Sen D, Mulajker DS, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:722-725.

- Gohji K, Hasunuma Y, Gotoh A, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:433-435.

- Pinto WBVR, Badia BML, Souza PVS, et al. Paraneoplastic motor neuronopathy and malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2019;77:527.

- Koyama S, Ikeda K, Sato M, et al. Transforming growth factor–alpha (TGF-alpha)-producing gastric carcinoma with acanthosis nigricans: an endocrine effect of TGF alpha in the pathogenesis of cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome and epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:71-77.

- Billerey C, Chopin D, Aubriot-Lorton MH, et al. Frequent FGFR3 mutations in papillary non-invasive bladder (pTa) tumors. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1955-1959.

- Lee C-J, Lee M-H, Cho Y-Y. Fibroblast and epidermal growth factors utilize different signaling pathways to induce anchorage-independent cell transformation in JB6 Cl41 mouse skin epidermal cells. J Cancer Prev. 2014;19:199-208.

- Darmstadt GL, Yokel BK, Horn TD. Treatment of acanthosis nigricans with tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1139-1140.

- Sah JF, Eckert RL, Chandraratna RA, et al. Retinoids suppress epidermal growth factor–associated cell proliferation by inhibiting epidermal growth factor receptor–dependent ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9728-9735.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old Somalian man presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the eyelids, tongue, lips, and hands of 8 years’ duration. He was a former refugee who had faced considerable stigma from his community due to his appearance. A review of systems was remarkable for decreased appetite but no weight loss. He reported no abdominal distention, early satiety, or urinary symptoms, and he had no personal history of diabetes mellitus or obesity. Physical examination demonstrated hyperpigmented velvety plaques in all skin folds and on the genitalia. Massive papillomatosis of the eyelid margins, tongue, and lips also was noted (Figure 1A). Flesh-colored papules also were scattered across the face. Punctate, flesh-colored papules were present on the volar and palmar hands (Figure 2A). Histopathology demonstrated pronounced papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with negative human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 and HPV-18 DNA studies. Given the appearance of malignant acanthosis nigricans with oral and conjunctival features, cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms, concern for underlying malignancy was high. Malignancy workup, including upper and lower endoscopy as well as serial computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, was unrevealing.

Laboratory investigation revealed a positive Schistosoma IgG antibody (0.38 geometric mean egg count) and peripheral eosinophilia (1.09 ×103/μL), which normalized after praziquantel therapy. With no malignancy identified over the preceding 6-month period, treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily was initiated based on limited literature support.1-3 Treatment led to reduction in the size and number of papillomas (Figure 1B) and tripe palms (Figure 2B) with increased mobility of hands, lips, and tongue. The patient underwent oculoplastic surgery to reduce the papilloma burden along the eyelid margins. Subsequent cystoscopy 9 months after the initial presentation revealed low-grade transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Intraoperative mitomycin C led to tumor shrinkage and, with continued treatment with daily acitretin, dramatic improvement of all cutaneous and mucosal symptoms (Figure 1C and Figure 2C). To date, his cutaneous symptoms have resolved.

This case demonstrated a unique presentation of multiple paraneoplastic signs in bladder transitional cell carcinoma. The presence of malignant acanthosis nigricans (including oral and conjunctival involvement), cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms have been individually documented in various types of gastric malignancies.4 Acanthosis nigricans often is secondary to diabetes and obesity, presenting with diffuse, thickened, velvety plaques in the flexural areas. Malignant acanthosis nigricans is a rare, rapidly progressive condition that often presents over a period of weeks to months; it almost always is associated with internal malignancies. It often has more extensive involvement, extending beyond the flexural areas, than typical acanthosis nigricans.4 Oral involvement can be either hypertrophic or papillomatous; papillomatosis of the oral mucosa was reported in over 40% of malignant acanthosis nigricans cases (N=200).5 Cases with conjunctival involvement are less common.6 Although malignant acanthosis nigricans often is codiagnosed with a malignancy, it can precede the cancer diagnosis in some cases.7,8 A majority of cases are associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.4 Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis also is a rare paraneoplastic condition that most commonly is associated with gastric adenocarcinomas. Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis often presents rapidly as verrucous growths on cutaneous surfaces (including the hands and face) but also can affect mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and conjunctiva.9-11 Tripe palms are characterized by exaggerated dermatoglyphics with diffuse palmar ridging and hyperkeratosis. Tripe palms most often are associated with pulmonary malignancies. When tripe palms are present with malignant acanthosis nigricans, they reflect up to a one-third incidence of gastrointestinal malignancy.12,13

Despite the individual presentation of these paraneoplastic signs in a variety of malignancies, synchronous presentation is rare. A brief literature review only identified 6 cases of concurrent acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis with an underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.1,11,14-17 Two additional reports described tripe palms with oral acanthosis nigricans and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis in metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma and renal urothelial carcinoma.2,18 An additional case of all 3 paraneoplastic conditions was reported in the setting of metastatic cervical cancer (HPV positive).19 Per a recent case report and literature review,20 there have only been 8 cases of acanthosis nigricans reported in bladder transitional cell carcinoma,20-27 half of which have included oral malignant acanthosis nigricans.20-23 Only one report of concurrent cutaneous and oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and triple palms in the setting of bladder cancer has been reported.20 Given the extensive conjunctival involvement and cutaneous papillomatosis in our patient, ours is a rarely reported case of concurrent malignant mucocutaneous acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive papillomatosis in transitional cell bladder carcinoma. We believe it is imperative to consider the role of this malignancy as a cause of these paraneoplastic conditions.

Although these paraneoplastic conditions rarely co-occur, our case further offers a common molecular pathway for these conditions.28 In these paraneoplastic conditions, the stimulating factor is thought to be tumor growth factor α, which is structurally related to epidermal growth factor (EGF). Epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) are found in the basal layer of the epidermis, where activation stimulates keratinocyte growth and leads to the cutaneous manifestation of symptoms.28 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations are found in most noninvasive transitional cell tumors of the bladder.29 The fibroblast growth factor pathway is distinctly different from the tumor growth factor α and EGF pathways.30 However, this association with transitional cell carcinoma suggests that fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 also may be implicated in these paraneoplastic conditions.

Our patient responded well to treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily. The mechanism of action of retinoids involves inducing mitotic activity and desmosomal shedding.31 Retinoids downregulate EGFR expression and activation in EGF-stimulated cells.32 We hypothesize that these oral retinoids decreased the growth stimulus and thereby improved cutaneous signs in the setting of our patient’s transitional cell cancer. Although definitive therapy is malignancy management, our case highlights the utility of adjunctive measures such as oral retinoids and surgical debulking. While previous cases have reported use of retinoids at a lower dosage than used in this case, oral lesions often have only been mildly improved with little impact on other cutaneous symptoms.1,2 In one case of malignant acanthosis nigricans and oral papillomatosis, isotretinoin 25 mg once every 2 to 3 days led to a moderate decrease in hyperkeratosis and papillomas, but the patient was lost to follow-up.3 Our case highlights the use of higher daily doses of oral retinoids for over 9 months, resulting in marked improvement in both the mucosal and cutaneous symptoms of acanthosis nigricans, progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms. Therefore, oral acitretin should be considered as adjuvant therapy for these paraneoplastic conditions.

By reporting this case, we hope to demonstrate the importance of considering other forms of malignancies in the presence of paraneoplastic conditions. Although gastric malignancies more commonly are associated with these conditions, bladder carcinomas also can present with cutaneous manifestations. The presence of these paraneoplastic conditions alone or together rarely is reported in urologic cancers and generally is considered to be an indicator of poor prognosis. Paraneoplastic conditions often develop rapidly and occur in very advanced malignancies.4 The disfiguring presentation in our case also had unusual diagnostic challenges. The presence of these conditions for 8 years and nonmetastatic advanced malignancy suggest a more indolent process and that these signs are not always an indicator of poor prognosis. Future patients with these paraneoplastic conditions may benefit from both a thorough malignancy screen, including cystoscopy, and high daily doses of oral retinoids.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old Somalian man presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the eyelids, tongue, lips, and hands of 8 years’ duration. He was a former refugee who had faced considerable stigma from his community due to his appearance. A review of systems was remarkable for decreased appetite but no weight loss. He reported no abdominal distention, early satiety, or urinary symptoms, and he had no personal history of diabetes mellitus or obesity. Physical examination demonstrated hyperpigmented velvety plaques in all skin folds and on the genitalia. Massive papillomatosis of the eyelid margins, tongue, and lips also was noted (Figure 1A). Flesh-colored papules also were scattered across the face. Punctate, flesh-colored papules were present on the volar and palmar hands (Figure 2A). Histopathology demonstrated pronounced papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with negative human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 and HPV-18 DNA studies. Given the appearance of malignant acanthosis nigricans with oral and conjunctival features, cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms, concern for underlying malignancy was high. Malignancy workup, including upper and lower endoscopy as well as serial computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, was unrevealing.

Laboratory investigation revealed a positive Schistosoma IgG antibody (0.38 geometric mean egg count) and peripheral eosinophilia (1.09 ×103/μL), which normalized after praziquantel therapy. With no malignancy identified over the preceding 6-month period, treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily was initiated based on limited literature support.1-3 Treatment led to reduction in the size and number of papillomas (Figure 1B) and tripe palms (Figure 2B) with increased mobility of hands, lips, and tongue. The patient underwent oculoplastic surgery to reduce the papilloma burden along the eyelid margins. Subsequent cystoscopy 9 months after the initial presentation revealed low-grade transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Intraoperative mitomycin C led to tumor shrinkage and, with continued treatment with daily acitretin, dramatic improvement of all cutaneous and mucosal symptoms (Figure 1C and Figure 2C). To date, his cutaneous symptoms have resolved.

This case demonstrated a unique presentation of multiple paraneoplastic signs in bladder transitional cell carcinoma. The presence of malignant acanthosis nigricans (including oral and conjunctival involvement), cutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms have been individually documented in various types of gastric malignancies.4 Acanthosis nigricans often is secondary to diabetes and obesity, presenting with diffuse, thickened, velvety plaques in the flexural areas. Malignant acanthosis nigricans is a rare, rapidly progressive condition that often presents over a period of weeks to months; it almost always is associated with internal malignancies. It often has more extensive involvement, extending beyond the flexural areas, than typical acanthosis nigricans.4 Oral involvement can be either hypertrophic or papillomatous; papillomatosis of the oral mucosa was reported in over 40% of malignant acanthosis nigricans cases (N=200).5 Cases with conjunctival involvement are less common.6 Although malignant acanthosis nigricans often is codiagnosed with a malignancy, it can precede the cancer diagnosis in some cases.7,8 A majority of cases are associated with adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.4 Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis also is a rare paraneoplastic condition that most commonly is associated with gastric adenocarcinomas. Progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis often presents rapidly as verrucous growths on cutaneous surfaces (including the hands and face) but also can affect mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and conjunctiva.9-11 Tripe palms are characterized by exaggerated dermatoglyphics with diffuse palmar ridging and hyperkeratosis. Tripe palms most often are associated with pulmonary malignancies. When tripe palms are present with malignant acanthosis nigricans, they reflect up to a one-third incidence of gastrointestinal malignancy.12,13

Despite the individual presentation of these paraneoplastic signs in a variety of malignancies, synchronous presentation is rare. A brief literature review only identified 6 cases of concurrent acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis with an underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.1,11,14-17 Two additional reports described tripe palms with oral acanthosis nigricans and progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis in metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma and renal urothelial carcinoma.2,18 An additional case of all 3 paraneoplastic conditions was reported in the setting of metastatic cervical cancer (HPV positive).19 Per a recent case report and literature review,20 there have only been 8 cases of acanthosis nigricans reported in bladder transitional cell carcinoma,20-27 half of which have included oral malignant acanthosis nigricans.20-23 Only one report of concurrent cutaneous and oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and triple palms in the setting of bladder cancer has been reported.20 Given the extensive conjunctival involvement and cutaneous papillomatosis in our patient, ours is a rarely reported case of concurrent malignant mucocutaneous acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms, and progressive papillomatosis in transitional cell bladder carcinoma. We believe it is imperative to consider the role of this malignancy as a cause of these paraneoplastic conditions.

Although these paraneoplastic conditions rarely co-occur, our case further offers a common molecular pathway for these conditions.28 In these paraneoplastic conditions, the stimulating factor is thought to be tumor growth factor α, which is structurally related to epidermal growth factor (EGF). Epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) are found in the basal layer of the epidermis, where activation stimulates keratinocyte growth and leads to the cutaneous manifestation of symptoms.28 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations are found in most noninvasive transitional cell tumors of the bladder.29 The fibroblast growth factor pathway is distinctly different from the tumor growth factor α and EGF pathways.30 However, this association with transitional cell carcinoma suggests that fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 also may be implicated in these paraneoplastic conditions.

Our patient responded well to treatment with acitretin 50 mg daily. The mechanism of action of retinoids involves inducing mitotic activity and desmosomal shedding.31 Retinoids downregulate EGFR expression and activation in EGF-stimulated cells.32 We hypothesize that these oral retinoids decreased the growth stimulus and thereby improved cutaneous signs in the setting of our patient’s transitional cell cancer. Although definitive therapy is malignancy management, our case highlights the utility of adjunctive measures such as oral retinoids and surgical debulking. While previous cases have reported use of retinoids at a lower dosage than used in this case, oral lesions often have only been mildly improved with little impact on other cutaneous symptoms.1,2 In one case of malignant acanthosis nigricans and oral papillomatosis, isotretinoin 25 mg once every 2 to 3 days led to a moderate decrease in hyperkeratosis and papillomas, but the patient was lost to follow-up.3 Our case highlights the use of higher daily doses of oral retinoids for over 9 months, resulting in marked improvement in both the mucosal and cutaneous symptoms of acanthosis nigricans, progressive mucocutaneous papillomatosis, and tripe palms. Therefore, oral acitretin should be considered as adjuvant therapy for these paraneoplastic conditions.

By reporting this case, we hope to demonstrate the importance of considering other forms of malignancies in the presence of paraneoplastic conditions. Although gastric malignancies more commonly are associated with these conditions, bladder carcinomas also can present with cutaneous manifestations. The presence of these paraneoplastic conditions alone or together rarely is reported in urologic cancers and generally is considered to be an indicator of poor prognosis. Paraneoplastic conditions often develop rapidly and occur in very advanced malignancies.4 The disfiguring presentation in our case also had unusual diagnostic challenges. The presence of these conditions for 8 years and nonmetastatic advanced malignancy suggest a more indolent process and that these signs are not always an indicator of poor prognosis. Future patients with these paraneoplastic conditions may benefit from both a thorough malignancy screen, including cystoscopy, and high daily doses of oral retinoids.

- Stawczyk-Macieja M, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Nowicki R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:56-58.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong W-S. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Swineford SL, Drucker CR. Palliative treatment of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans and oral florid papillomatosis with retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1151-1153.

- Wick MR, Patterson JW. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes [published online January 31, 2019]. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36:211-228.

- Tyler MT, Ficarra G, Silverman S, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with florid papillary oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:445-449.

- Zhang X, Liu R, Liu Y, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: a case report. BMC Ophthalmology. 2020;20:1-4.

- Curth HO. Dermatoses and malignant internal tumours. Arch Dermatol Syphil. 1955;71:95-107.

- Krawczyk M, Mykala-Cies´la J, Kolodziej-Jaskula A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

- Singhi MK, Gupta LK, Bansal M, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis with adenocarcinoma of stomach in a 35 year old male. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:195-196.

- Klieb HB, Avon SL, Gilbert J, et al. Florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis: mucocutaneous markers of an underlying gastric malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E218-E219.

- Yang YH, Zhang RZ, Kang DH, et al. Three paraneoplastic signs in the same patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18966.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Chantarojanasiri T, Buranathawornsom A, Sirinawasatien A. Diffuse esophageal squamous papillomatosis: a rare disease associated with acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:702-706.

- Muhammad R, Iftikhar N, Sarfraz T, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an indicator of internal malignancy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:888-890.

- Brinca A, Cardoso JC, Brites MM, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis and acanthosis nigricans maligna revealing gastric adenocarcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:573-577.

- Vilas-Sueiro A, Suárez-Amor O, Monteagudo B, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis, and tripe palms in a man with gastric adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:438-439.

- Paravina M, Ljubisavljevic´ D. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma—a case report. Serbian J Dermatology Venereol. 2015;7:5-14.

- Kleikamp S, Böhm M, Frosch P, et al. Acanthosis nigricans, papillomatosis mucosae and “tripe” palms in a patient with metastasized gastric carcinoma [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:1209-1213.

- Mikhail GR, Fachnie DM, Drukker BH, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:201-202.

- Zhang R, Jiang M, Lei W, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with recurrent bladder cancer: a case report and review of literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:951.

- Olek-Hrab K, Silny W, Zaba R, et al. Co-occurrence of acanthosis nigricans and bladder adenocarcinoma-case report. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2013;17:327-330.

- Canjuga I, Mravak-Stipetic´ M, Kopic´V, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans: case report and comparison with literature reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2008;16:91-95.

- Cairo F, Rubino I, Rotundo R, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans as a marker of internal malignancy. a case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1271-1275.

- Möhrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Singh GK, Sen D, Mulajker DS, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:722-725.

- Gohji K, Hasunuma Y, Gotoh A, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:433-435.

- Pinto WBVR, Badia BML, Souza PVS, et al. Paraneoplastic motor neuronopathy and malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2019;77:527.

- Koyama S, Ikeda K, Sato M, et al. Transforming growth factor–alpha (TGF-alpha)-producing gastric carcinoma with acanthosis nigricans: an endocrine effect of TGF alpha in the pathogenesis of cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome and epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:71-77.

- Billerey C, Chopin D, Aubriot-Lorton MH, et al. Frequent FGFR3 mutations in papillary non-invasive bladder (pTa) tumors. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1955-1959.

- Lee C-J, Lee M-H, Cho Y-Y. Fibroblast and epidermal growth factors utilize different signaling pathways to induce anchorage-independent cell transformation in JB6 Cl41 mouse skin epidermal cells. J Cancer Prev. 2014;19:199-208.

- Darmstadt GL, Yokel BK, Horn TD. Treatment of acanthosis nigricans with tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1139-1140.

- Sah JF, Eckert RL, Chandraratna RA, et al. Retinoids suppress epidermal growth factor–associated cell proliferation by inhibiting epidermal growth factor receptor–dependent ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9728-9735.

- Stawczyk-Macieja M, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Nowicki R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:56-58.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong W-S. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Swineford SL, Drucker CR. Palliative treatment of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans and oral florid papillomatosis with retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1151-1153.

- Wick MR, Patterson JW. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes [published online January 31, 2019]. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36:211-228.

- Tyler MT, Ficarra G, Silverman S, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with florid papillary oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:445-449.

- Zhang X, Liu R, Liu Y, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: a case report. BMC Ophthalmology. 2020;20:1-4.

- Curth HO. Dermatoses and malignant internal tumours. Arch Dermatol Syphil. 1955;71:95-107.

- Krawczyk M, Mykala-Cies´la J, Kolodziej-Jaskula A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:180-183.

- Singhi MK, Gupta LK, Bansal M, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis with adenocarcinoma of stomach in a 35 year old male. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:195-196.

- Klieb HB, Avon SL, Gilbert J, et al. Florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis: mucocutaneous markers of an underlying gastric malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E218-E219.

- Yang YH, Zhang RZ, Kang DH, et al. Three paraneoplastic signs in the same patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18966.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Chantarojanasiri T, Buranathawornsom A, Sirinawasatien A. Diffuse esophageal squamous papillomatosis: a rare disease associated with acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:702-706.

- Muhammad R, Iftikhar N, Sarfraz T, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an indicator of internal malignancy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:888-890.

- Brinca A, Cardoso JC, Brites MM, et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis and acanthosis nigricans maligna revealing gastric adenocarcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:573-577.

- Vilas-Sueiro A, Suárez-Amor O, Monteagudo B, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis, and tripe palms in a man with gastric adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:438-439.

- Paravina M, Ljubisavljevic´ D. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, florid cutaneous papillomatosis and tripe palms syndrome associated with gastric adenocarcinoma—a case report. Serbian J Dermatology Venereol. 2015;7:5-14.

- Kleikamp S, Böhm M, Frosch P, et al. Acanthosis nigricans, papillomatosis mucosae and “tripe” palms in a patient with metastasized gastric carcinoma [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:1209-1213.

- Mikhail GR, Fachnie DM, Drukker BH, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:201-202.

- Zhang R, Jiang M, Lei W, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans with recurrent bladder cancer: a case report and review of literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:951.

- Olek-Hrab K, Silny W, Zaba R, et al. Co-occurrence of acanthosis nigricans and bladder adenocarcinoma-case report. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2013;17:327-330.

- Canjuga I, Mravak-Stipetic´ M, Kopic´V, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans: case report and comparison with literature reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2008;16:91-95.

- Cairo F, Rubino I, Rotundo R, et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans as a marker of internal malignancy. a case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1271-1275.

- Möhrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Singh GK, Sen D, Mulajker DS, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:722-725.

- Gohji K, Hasunuma Y, Gotoh A, et al. Acanthosis nigricans associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:433-435.

- Pinto WBVR, Badia BML, Souza PVS, et al. Paraneoplastic motor neuronopathy and malignant acanthosis nigricans. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2019;77:527.

- Koyama S, Ikeda K, Sato M, et al. Transforming growth factor–alpha (TGF-alpha)-producing gastric carcinoma with acanthosis nigricans: an endocrine effect of TGF alpha in the pathogenesis of cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome and epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:71-77.

- Billerey C, Chopin D, Aubriot-Lorton MH, et al. Frequent FGFR3 mutations in papillary non-invasive bladder (pTa) tumors. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1955-1959.

- Lee C-J, Lee M-H, Cho Y-Y. Fibroblast and epidermal growth factors utilize different signaling pathways to induce anchorage-independent cell transformation in JB6 Cl41 mouse skin epidermal cells. J Cancer Prev. 2014;19:199-208.

- Darmstadt GL, Yokel BK, Horn TD. Treatment of acanthosis nigricans with tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1139-1140.

- Sah JF, Eckert RL, Chandraratna RA, et al. Retinoids suppress epidermal growth factor–associated cell proliferation by inhibiting epidermal growth factor receptor–dependent ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9728-9735.

Practice Points

- Paraneoplastic conditions may present secondary to urologic malignancy. Providers should perform thorough malignancy screening, including urologic cystoscopy, in patients presenting with paraneoplastic signs and no identified malignancy.

- Oral retinoids, such as acitretin, may be used as an adjuvant treatment to treat paraneoplastic cutaneous symptoms. The definitive treatment is malignancy management.

Cold viruses thrived in kids as other viruses faded in 2020

The common-cold viruses rhinovirus (RV) and enterovirus (EV) continued to circulate among children during the COVID-19 pandemic while there were sharp declines in influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and other respiratory viruses, new data indicate.

Researchers used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network. The cases involved 37,676 children in seven geographically diverse U.S. medical centers between December 2016 and January 2021. Patients presented to emergency departments or were hospitalized with RV, EV, and other acute respiratory viruses.

The investigators found that the percentage of children in whom RV/EV was detected from March 2020 to January 2021 was similar to the percentage during the same months in 2017-2018 and 2019-2020. However, the proportion of children infected with influenza, RSV, and other respiratory viruses combined dropped significantly in comparison to the three prior seasons.

Danielle Rankin, MPH, lead author of the study and a doctoral candidate in pediatric infectious disease at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., presented the study on Sept. 30 during a press conference at IDWeek 2021, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Reasoning for rhinovirus and enterovirus circulation is unknown but may be attributed to a number of factors, such as different transmission routes or the prolonged survival of the virus on surfaces,” Ms. Rankin said. “Improved understanding of these persistent factors of RV/EV and the role of nonpharmaceutical interventions on transmission dynamics can further guide future prevention recommendations and guidelines.”

Coauthor Claire Midgley, PhD, an epidemiologist in the Division of Viral Diseases at the CDC, told reporters that further studies will assess why RV and EV remained during the pandemic and which virus types within the RV/EV group persisted.

“We do know that the virus can spread through secretions on people’s hands,” she said. “Washing kids’ hands regularly and trying not to touch your face where possible is a really effective way to prevent transmission,” Dr. Midgley said.

“The more we understand about all of these factors, the better we can inform prevention measures.”

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, chief, division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that rhinoviruses can persist in the nose for a very long time, especially in younger children, which increases the opportunities for transmission.

“Very young children who are unable to wear masks or are unlikely to wear them well may be acting as the reservoir, allowing transmission in households,” he said. “There is also an enormous pool of diverse rhinoviruses, so past colds provide limited immunity, as everyone has found out from experience.”

Martha Perry, MD, associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and chief of adolescent medicine, told this news organization that some of the differences in the prevalence of viruses may be because of their seasonality.

“Times when there were more mask mandates were times when RSV and influenza are more prevalent,” said Dr. Perry, who was not involved with the study. “We were masking more intently during those times, and there was loosening of restrictions when we see more enterovirus, particularly because that tends to be more of a summer/fall virus.”

She agreed that the differences may result from the way the viruses are transmitted.

“Perhaps masks were helping with RSV and influenza, but perhaps there was not as much hand washing or cleansing as needed to prevent the spread of rhinovirus and enterovirus, because those are viruses that require a bit more hand washing,” Dr. Perry said. “They are less aerosolized and better spread with hand-to-hand contact.”

Dr. Perry added that on the flip side, “it’s really exciting that there are ways we can prevent RSV and influenza, which tend to cause more severe infection.”

Ms. Rankin said limitations of the study include the fact that from March 2020 to January 2021, health care–seeking behaviors may have changed because of the pandemic and that the study does not include the frequency of respiratory viruses in the outpatient setting.

The sharp 2020-2021 decline in RSV reported in the study may have reversed after many of the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted this summer.

This news organization reported in June of this year that the CDC has issued a health advisory to notify clinicians and caregivers about an increase in cases of interseasonal RSV in parts of the southern United States.

The CDC has urged broader testing for RSV among patients presenting with acute respiratory illness who test negative for SARS-CoV-2.

The study’s authors, Ms. Pavia, and Dr. Perry have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The common-cold viruses rhinovirus (RV) and enterovirus (EV) continued to circulate among children during the COVID-19 pandemic while there were sharp declines in influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and other respiratory viruses, new data indicate.

Researchers used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network. The cases involved 37,676 children in seven geographically diverse U.S. medical centers between December 2016 and January 2021. Patients presented to emergency departments or were hospitalized with RV, EV, and other acute respiratory viruses.

The investigators found that the percentage of children in whom RV/EV was detected from March 2020 to January 2021 was similar to the percentage during the same months in 2017-2018 and 2019-2020. However, the proportion of children infected with influenza, RSV, and other respiratory viruses combined dropped significantly in comparison to the three prior seasons.

Danielle Rankin, MPH, lead author of the study and a doctoral candidate in pediatric infectious disease at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., presented the study on Sept. 30 during a press conference at IDWeek 2021, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.