User login

Men die more often than women after bariatric surgery

Men had a much higher rate of death following bariatric surgery performed in Austria during 2010-2018, compared with women in a retrospective analysis of nearly 20,000 patients based on health insurance records.

The reason may be that men undergoing bariatric surgery have “worse overall health at the time of surgery” than women, Hannes Beiglböck, MD, suggested at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The results also showed that “men tend to be older [at time of surgery] and that might have the biggest impact on outcomes after bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Beiglböck, a researcher in the division of endocrinology and metabolism at the Medical University of Vienna.

The findings confirm those of prior studies in various worldwide locations, he noted; that is, men undergoing bariatric surgery tend to be older than women and have more comorbidities and perioperative mortality.

Dr. Beiglböck also highlighted earlier reports that indicate “profound” sex-specific differences in why patients undergo bariatric surgery, with men often driven by a medical condition and women motivated by appearance.

Hence, for men, it may be important to focus on preoperative counseling to try to get them to think about bariatric surgery earlier, “which may improve their postsurgical mortality rate,” he observed.

Nearly threefold higher mortality among men

Dr. Beiglböck and associates used medical claims data filed with the Austrian health system, which includes nearly all residents. In 2010-2018, 19,901 Austrian patients underwent bariatric surgery, and researchers tracked their outcomes for a median of 5.4 years, through April 2020.

During the 9-year period, 74% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery were women, again, a finding consistent with prior reports from other countries.

The 5,220 men were an average of 41.8 years old, with 65% undergoing gastric bypass and 30% gastric banding. The 14,681 women were an average of 40.1 years old, with 70% undergoing gastric bypass and 22% gastric banding.

During follow-up, 367 patients (1.8%) died. Among men, the overall mortality rate was 2.6-fold higher, compared with women (1.3% vs. 3.4%) and average mortality per year was 2.8-fold higher (0.64% vs. 0.24%).

The rate of death on the day of surgery among men also substantially exceeded that of women (0.29% vs. 0.05%), as did death within 30 days of surgery (0.48% vs. 0.08%). All of these between-sex differences were significant.

Baseline prevalence of four categories of comorbidities and how these differed by sex among patients who died during follow-up was also examined. Underlying cardiovascular disease was prevalent in 299 patients (81% of the deceased group), 200 (54%) had a psychiatric disorder, 138 (38%) had diabetes, and 132 (36%) had a malignancy.

The prevalence of cardiovascular disease and psychiatric disorders was roughly the same in men and women. Men had a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes, and a higher proportion of women had a malignancy.

Consistent with U.S. studies

A U.S. report in 2015 documented a higher prevalence of comorbidities and more severe illness among men undergoing bariatric surgery, compared with women, noted session chair Zhila Semnani-Azad, PhD, a researcher in the department of nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health in Boston.

“I think the [Austrian] data presented have relevance to the U.S. population,” Dr. Semnani-Azad said in an interview.

“The main limitation of these univariate analyses is they don’t account for potential confounding variables that could affect the association, such as lifestyle variables, age, and family history. There is always potential for other variables” to influence apparent sex-specific associations, she commented. Another limitation is the small total number of deaths analyzed, at 367.

“These results are a good starting point for future studies. More work is needed to better understand the impact of comorbidities and sex on postsurgical mortality,” Dr. Semnani-Azad concluded.

Dr. Beiglböck and Dr. Semnani-Azad have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Men had a much higher rate of death following bariatric surgery performed in Austria during 2010-2018, compared with women in a retrospective analysis of nearly 20,000 patients based on health insurance records.

The reason may be that men undergoing bariatric surgery have “worse overall health at the time of surgery” than women, Hannes Beiglböck, MD, suggested at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The results also showed that “men tend to be older [at time of surgery] and that might have the biggest impact on outcomes after bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Beiglböck, a researcher in the division of endocrinology and metabolism at the Medical University of Vienna.

The findings confirm those of prior studies in various worldwide locations, he noted; that is, men undergoing bariatric surgery tend to be older than women and have more comorbidities and perioperative mortality.

Dr. Beiglböck also highlighted earlier reports that indicate “profound” sex-specific differences in why patients undergo bariatric surgery, with men often driven by a medical condition and women motivated by appearance.

Hence, for men, it may be important to focus on preoperative counseling to try to get them to think about bariatric surgery earlier, “which may improve their postsurgical mortality rate,” he observed.

Nearly threefold higher mortality among men

Dr. Beiglböck and associates used medical claims data filed with the Austrian health system, which includes nearly all residents. In 2010-2018, 19,901 Austrian patients underwent bariatric surgery, and researchers tracked their outcomes for a median of 5.4 years, through April 2020.

During the 9-year period, 74% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery were women, again, a finding consistent with prior reports from other countries.

The 5,220 men were an average of 41.8 years old, with 65% undergoing gastric bypass and 30% gastric banding. The 14,681 women were an average of 40.1 years old, with 70% undergoing gastric bypass and 22% gastric banding.

During follow-up, 367 patients (1.8%) died. Among men, the overall mortality rate was 2.6-fold higher, compared with women (1.3% vs. 3.4%) and average mortality per year was 2.8-fold higher (0.64% vs. 0.24%).

The rate of death on the day of surgery among men also substantially exceeded that of women (0.29% vs. 0.05%), as did death within 30 days of surgery (0.48% vs. 0.08%). All of these between-sex differences were significant.

Baseline prevalence of four categories of comorbidities and how these differed by sex among patients who died during follow-up was also examined. Underlying cardiovascular disease was prevalent in 299 patients (81% of the deceased group), 200 (54%) had a psychiatric disorder, 138 (38%) had diabetes, and 132 (36%) had a malignancy.

The prevalence of cardiovascular disease and psychiatric disorders was roughly the same in men and women. Men had a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes, and a higher proportion of women had a malignancy.

Consistent with U.S. studies

A U.S. report in 2015 documented a higher prevalence of comorbidities and more severe illness among men undergoing bariatric surgery, compared with women, noted session chair Zhila Semnani-Azad, PhD, a researcher in the department of nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health in Boston.

“I think the [Austrian] data presented have relevance to the U.S. population,” Dr. Semnani-Azad said in an interview.

“The main limitation of these univariate analyses is they don’t account for potential confounding variables that could affect the association, such as lifestyle variables, age, and family history. There is always potential for other variables” to influence apparent sex-specific associations, she commented. Another limitation is the small total number of deaths analyzed, at 367.

“These results are a good starting point for future studies. More work is needed to better understand the impact of comorbidities and sex on postsurgical mortality,” Dr. Semnani-Azad concluded.

Dr. Beiglböck and Dr. Semnani-Azad have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Men had a much higher rate of death following bariatric surgery performed in Austria during 2010-2018, compared with women in a retrospective analysis of nearly 20,000 patients based on health insurance records.

The reason may be that men undergoing bariatric surgery have “worse overall health at the time of surgery” than women, Hannes Beiglböck, MD, suggested at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The results also showed that “men tend to be older [at time of surgery] and that might have the biggest impact on outcomes after bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Beiglböck, a researcher in the division of endocrinology and metabolism at the Medical University of Vienna.

The findings confirm those of prior studies in various worldwide locations, he noted; that is, men undergoing bariatric surgery tend to be older than women and have more comorbidities and perioperative mortality.

Dr. Beiglböck also highlighted earlier reports that indicate “profound” sex-specific differences in why patients undergo bariatric surgery, with men often driven by a medical condition and women motivated by appearance.

Hence, for men, it may be important to focus on preoperative counseling to try to get them to think about bariatric surgery earlier, “which may improve their postsurgical mortality rate,” he observed.

Nearly threefold higher mortality among men

Dr. Beiglböck and associates used medical claims data filed with the Austrian health system, which includes nearly all residents. In 2010-2018, 19,901 Austrian patients underwent bariatric surgery, and researchers tracked their outcomes for a median of 5.4 years, through April 2020.

During the 9-year period, 74% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery were women, again, a finding consistent with prior reports from other countries.

The 5,220 men were an average of 41.8 years old, with 65% undergoing gastric bypass and 30% gastric banding. The 14,681 women were an average of 40.1 years old, with 70% undergoing gastric bypass and 22% gastric banding.

During follow-up, 367 patients (1.8%) died. Among men, the overall mortality rate was 2.6-fold higher, compared with women (1.3% vs. 3.4%) and average mortality per year was 2.8-fold higher (0.64% vs. 0.24%).

The rate of death on the day of surgery among men also substantially exceeded that of women (0.29% vs. 0.05%), as did death within 30 days of surgery (0.48% vs. 0.08%). All of these between-sex differences were significant.

Baseline prevalence of four categories of comorbidities and how these differed by sex among patients who died during follow-up was also examined. Underlying cardiovascular disease was prevalent in 299 patients (81% of the deceased group), 200 (54%) had a psychiatric disorder, 138 (38%) had diabetes, and 132 (36%) had a malignancy.

The prevalence of cardiovascular disease and psychiatric disorders was roughly the same in men and women. Men had a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes, and a higher proportion of women had a malignancy.

Consistent with U.S. studies

A U.S. report in 2015 documented a higher prevalence of comorbidities and more severe illness among men undergoing bariatric surgery, compared with women, noted session chair Zhila Semnani-Azad, PhD, a researcher in the department of nutrition at Harvard School of Public Health in Boston.

“I think the [Austrian] data presented have relevance to the U.S. population,” Dr. Semnani-Azad said in an interview.

“The main limitation of these univariate analyses is they don’t account for potential confounding variables that could affect the association, such as lifestyle variables, age, and family history. There is always potential for other variables” to influence apparent sex-specific associations, she commented. Another limitation is the small total number of deaths analyzed, at 367.

“These results are a good starting point for future studies. More work is needed to better understand the impact of comorbidities and sex on postsurgical mortality,” Dr. Semnani-Azad concluded.

Dr. Beiglböck and Dr. Semnani-Azad have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASD 2021

Botanical Briefs: Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis)

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) is a member of the family Papaveraceae.1 This North American plant commonly is found in widespread distribution from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Florida and from the Great Lakes to Mississippi.2 Historically, Native Americans used bloodroot as a skin dye and as a medicine for many ailments.3

Bloodroot blooms for only a few days, starting in March, and fruits in June. The flowers comprise 8 to 10 white petals, surrounding a bed of yellow stamens (Figure). The plant thrives in wooded areas and grows to 12 inches tall. In its off-season, the plant remains dormant and can survive below-freezing temperatures.4

Chemical Constituents

Bloodroot gets its colloquial name from its red sap, which is released when the plant’s rhizome is cut. This sap contains a high concentration of alkaloids that are used for protection against predators. The rhizome itself has a rusty, red-brown color; the roots are a brighter red-orange.4

The rhizome of S canadensis contains the highest concentration of active alkaloids; the roots also contain these chemicals, though to a lesser degree; and the leaves, flowers, and fruits harvest approximately 1% of the alkaloids found in the roots.4 The concentration of alkaloids can vary from one plant to the next, depending on environmental conditions.5,6

The major alkaloids in S canadensis include both quaternary benzophenanthridine alkaloids (eg, sanguinarine, chelerythrine, sanguilutine, chelilutine, sanguirubine, chelirubine) and protopin alkaloids (eg, protopine, allocryptopine).3,7 Of these, sanguinarine and chelerythrine typically are the most potent.1 Oral ingestion or topical application of these molecules can have therapeutic and toxic effects.8

Biophysiological Effects

Bloodroot has been shown to have remarkable antimicrobial effects.9 The plant produces hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion.10 These mediators cause oxidative stress, thus inducing destruction of cellular DNA and the cell membrane.11 Although these effects can be helpful when fighting infection, they are not necessarily selective against healthy cells.12

Alkaloids of bloodroot also have cardiovascular therapeutic effects. Sanguinarine blocks angiotensin II and causes vasodilation, thus helping treat hypertension.13 It also acts as an inotrope by blocking the Na+/K+ ATPase pump. These effects in a patient who is already taking digoxin can cause notable cardiotoxicity because the 2 drugs share a mechanism of action.14

Chelerythrine blocks production of cyclooxygenase 2 and prostaglandin E2.15 This pathway modification results in anti-inflammatory effects that can help treat arthritis, edema, and other inflammatory conditions.16 Moreover, sanguinarine has demonstrated efficacy in numerous anticancer pathways,17 including downregulation of intercellular adhesion molecules, vascular cell adhesion molecules, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).18-20 Blocking VEGF is one way to inhibit angiogenesis,21 which is upregulated in tumor formation, thus sanguinarine can have an antiproliferative anticancer effect.22 Sanguinarine also upregulates molecules such as nuclear factor–κB and the protease enzymes known as caspases to cause proapoptotic effects, furthering its antitumor potential.23,24

Treatment of Dermatologic Conditions

The initial technique of Mohs micrographic surgery employed a chemopaste that utilized an extract of S canadensis to preserve tissue.25 Outside the dermatologist’s office, bloodroot is used as a topical home remedy for a variety of cutaneous conditions, including cancer, skin tags, and warts.26 Bloodroot is advertised as black salve, an alternative anticancer treatment.27,28

As useful as this natural agent sounds, it has a pitfall: The alkaloids of S canadensis are nonspecific in their cytotoxicity, damaging neoplastic and healthy tissue.29 This cytotoxic effect can cause escharification through diffuse tissue destruction and has been observed to result in formation of a keloid scar.30 The alkaloids in black salve also have been shown to cause skin erosions and cellular atypia.28,31 Therefore, the utility of this escharotic in medical treatment is limited.32 Fortuitously, oral antibiotics and wound care can help address this adverse effect.28

Bloodroot was once used as a mouth rinse and toothpaste to treat gingivitis, but this application was later associated with oral leukoplakia, a premalignant condition.33 Leukoplakia associated with S canadensis extract often is unremitting. Immediate discontinuation of the offending agent produces little regression, suggesting that cellular damage is irreversible.34

Final Thoughts

Although bloodroot demonstrates efficacy as a phytotherapeutic, it does come with notable toxicity. Physicians should warn patients of the unwanted cosmetic effects of black salve, especially oral products that incorporate sanguinarine. Adverse effects on the oropharynx can be irreversible, though the eschar associated with black salve can be treated with a topical or oral corticosteroid.29

- Vogel M, Lawson M, Sippl W, et al. Structure and mechanism of sanguinarine reductase, an enzyme of alkaloid detoxification. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18397-18406. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.088989

- Maranda EL, Wang MX, Cortizo J, et al. Flower power—the versatility of bloodroot. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:824. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5522

- Setzer WN. The phytochemistry of Cherokee aromatic medicinal plants. Medicines (Basel). 2018;5:121. doi:10.3390/medicines5040121

- Croaker A, King GJ, Pyne JH, et al. Sanguinaria canadensis: traditional medicine, phytochemical composition, biological activities and current uses. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1414. doi:10.3390/ijms17091414

- Graf TN, Levine KE, Andrews ME, et al. Variability in the yield of benzophenanthridine alkaloids in wildcrafted vs cultivated bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2007; 55:1205-1211. doi:10.1021/jf062498f

- Bennett BC, Bell CR, Boulware RT. Geographic variation in alkaloid content of Sanguinaria canadensis (Papaveraceae). Rhodora. 1990;92:57-69.

- Leaver CA, Yuan H, Wallen GR. Apoptotic activities of Sanguinaria canadensis: primary human keratinocytes, C-33A, and human papillomavirus HeLa cervical cancer lines. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2018;17:32-37.

- Kutchan TM. Molecular genetics of plant alkaloid biosynthesis. In: Cordell GA, ed. The Alkaloids. Vol 50. Elsevier Science Publishing Co, Inc; 1997:257-316.

- Obiang-Obounou BW, Kang O-H, Choi J-G, et al. The mechanism of action of sanguinarine against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Toxicol Sci. 2011;36:277-283. doi:10.2131/jts.36.277

- Z˙abka A, Winnicki K, Polit JT, et al. Sanguinarine-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis-like programmed cell death (AL-PCD) in root meristem cells of Allium cepa. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;112:193-206. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.01.004

- Kumar GS, Hazra S. Sanguinarine, a promising anticancer therapeutic: photochemical and nucleic acid binding properties. RSC Advances. 2014;4:56518-56531.

- Ping G, Wang Y, Shen L, et al. Highly efficient complexation of sanguinarine alkaloid by carboxylatopillar[6]arene: pKa shift, increased solubility and enhanced antibacterial activity. Chemical Commun (Camb). 2017;53:7381-7384. doi:10.1039/c7cc02799k

- Caballero-George C, Vanderheyden PM, Solis PN, et al. Biological screening of selected medicinal Panamanian plants by radioligand-binding techniques. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:59-70. doi:10.1078/0944-7113-00011

- Seifen E, Adams RJ, Riemer RK. Sanguinarine: a positive inotropic alkaloid which inhibits cardiac Na+, K+-ATPase. Eur J Pharmacol. 1979;60:373-377. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(79)90245-0

- Debprasad C, Hemanta M, Paromita B, et al. Inhibition of NO2, PGE2, TNF-α, and iNOS EXpression by Shorea robusta L.: an ethnomedicine used for anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012; 2012:254849. doi:10.1155/2012/254849

- Melov S, Ravenscroft J, Malik S, et al. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science. 2000;289:1567-1569. doi:10.1126/science.289.5484.1567

- Basu P, Kumar GS. Sanguinarine and its role in chronic diseases. In: Gupta SC, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB, eds. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology: Anti-inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases. Vol 928. Springer International Publishing; 2016:155-172.

- Alasvand M, Assadollahi V, Ambra R, et al. Antiangiogenic effect of alkaloids. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:9475908. doi:10.1155/2019/9475908

- Basini G, Santini SE, Bussolati S, et al. The plant alkaloid sanguinarine is a potential inhibitor of follicular angiogenesis. J Reprod Dev. 2007;53:573-579. doi:10.1262/jrd.18126

- Xu J-Y, Meng Q-H, Chong Y, et al. Sanguinarine is a novel VEGF inhibitor involved in the suppression of angiogenesis and cell migration. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:331-336. doi:10.3892/mco.2012.41

- Lu K, Bhat M, Basu S. Plants and their active compounds: natural molecules to target angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2016;19:287-295. doi:10.1007/s10456-016-9512-y

- Achkar IW, Mraiche F, Mohammad RM, et al. Anticancer potential of sanguinarine for various human malignancies. Future Med Chem. 2017;9:933-950. doi:10.4155/fmc-2017-0041

- Lee TK, Park C, Jeong S-J, et al. Sanguinarine induces apoptosis of human oral squamous cell carcinoma KB cells via inactivation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Drug Dev Res. 2016;77:227-240. doi:10.1002/ddr.21315

- Gaziano R, Moroni G, Buè C, et al. Antitumor effects of the benzophenanthridine alkaloid sanguinarine: evidence and perspectives. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:30-39. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v8.i1.30

- Mohs FE. Chemosurgery for skin cancer: fixed tissue and fresh tissue techniques. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:211-215.

- Affleck AG, Varma S. A case of do-it-yourself Mohs’ surgery using bloodroot obtained from the internet. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1078-1079. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08180.x

- Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E154-E155. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.031

- Osswald SS, Elston DM, Farley MF, et al. Self-treatment of a basal cell carcinoma with “black and yellow salve.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:508-510. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.007

- Schlichte MJ, Downing CP, Ramirez-Fort M, et al. Bloodroot associated eschar. Dermatol Online J. 2015;20:13030/qt05r0r2wr.

- Wang MZ, Warshaw EM. Bloodroot. Dermatitis. 2012;23:281-283. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e318273a4dd

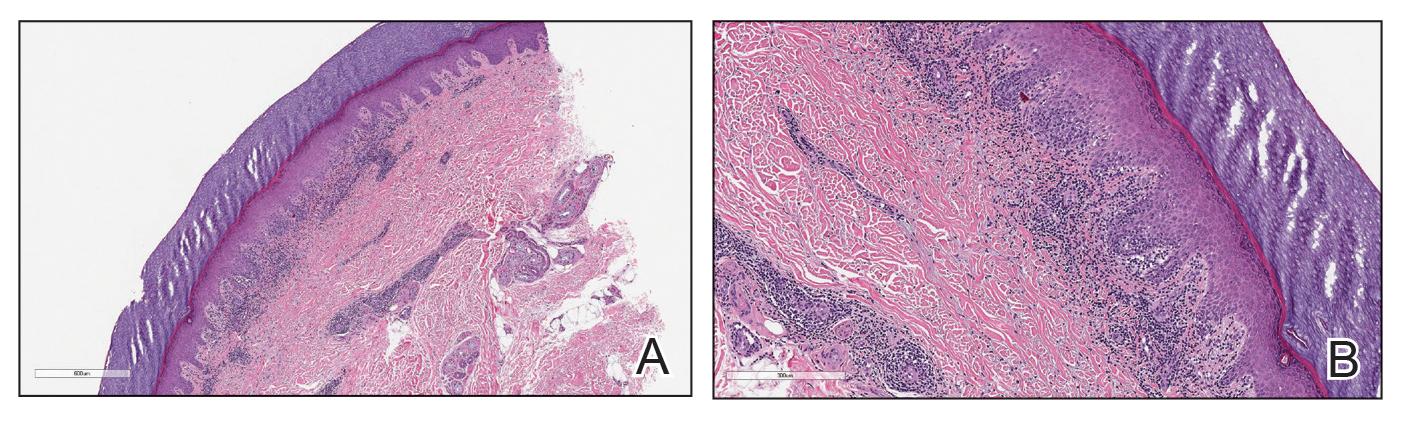

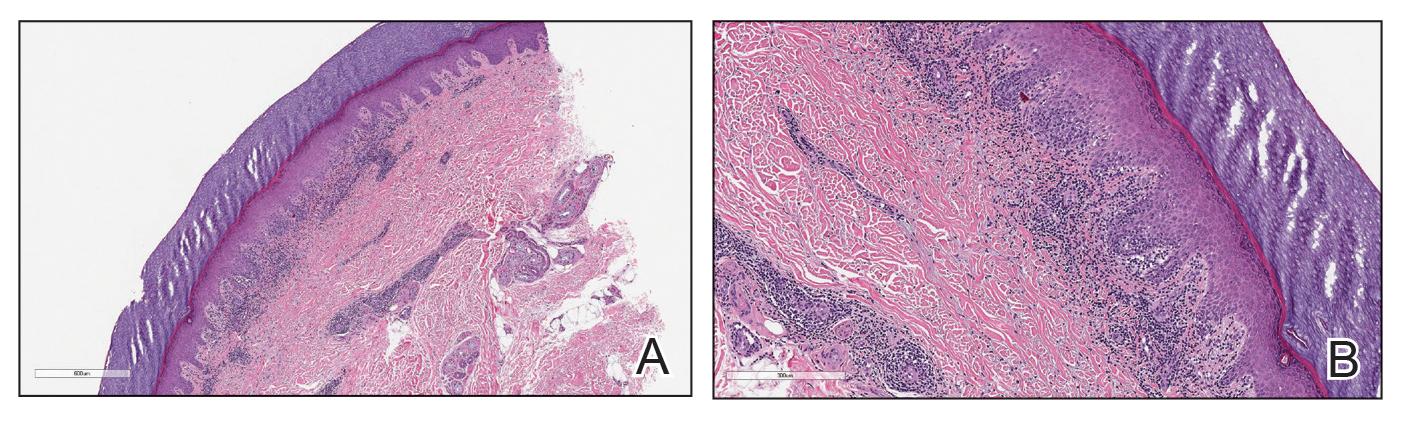

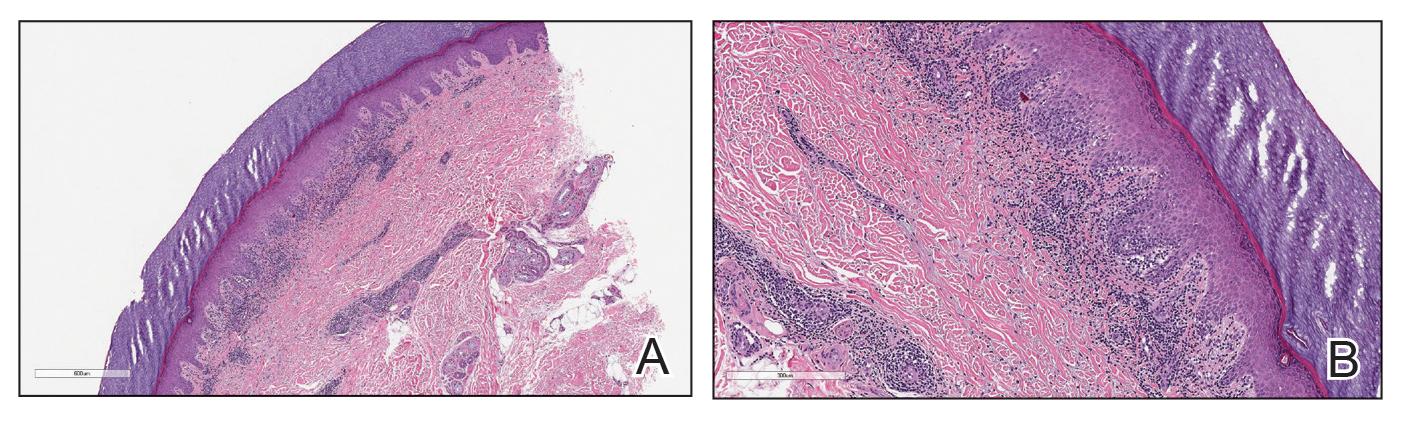

- Tan JM, Peters P, Ong N, et al. Histopathological features after topical black salve application. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:75-76.

- Hou JL, Brewer JD. Black salve and bloodroot extract in dermatologic conditions. Cutis. 2015;95:309-311.

- Eversole LR, Eversole GM, Kopcik J. Sanguinaria-associated oral leukoplakia: comparison with other benign and dysplastic leukoplakic lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:455-464. doi:10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70125-9

- Mascarenhas AK, Allen CM, Moeschberger ML. The association between Viadent® use and oral leukoplakia—results of a matched case-control study. J Public Health Dent. 2002;62:158-162. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2002.tb03437.x

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) is a member of the family Papaveraceae.1 This North American plant commonly is found in widespread distribution from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Florida and from the Great Lakes to Mississippi.2 Historically, Native Americans used bloodroot as a skin dye and as a medicine for many ailments.3

Bloodroot blooms for only a few days, starting in March, and fruits in June. The flowers comprise 8 to 10 white petals, surrounding a bed of yellow stamens (Figure). The plant thrives in wooded areas and grows to 12 inches tall. In its off-season, the plant remains dormant and can survive below-freezing temperatures.4

Chemical Constituents

Bloodroot gets its colloquial name from its red sap, which is released when the plant’s rhizome is cut. This sap contains a high concentration of alkaloids that are used for protection against predators. The rhizome itself has a rusty, red-brown color; the roots are a brighter red-orange.4

The rhizome of S canadensis contains the highest concentration of active alkaloids; the roots also contain these chemicals, though to a lesser degree; and the leaves, flowers, and fruits harvest approximately 1% of the alkaloids found in the roots.4 The concentration of alkaloids can vary from one plant to the next, depending on environmental conditions.5,6

The major alkaloids in S canadensis include both quaternary benzophenanthridine alkaloids (eg, sanguinarine, chelerythrine, sanguilutine, chelilutine, sanguirubine, chelirubine) and protopin alkaloids (eg, protopine, allocryptopine).3,7 Of these, sanguinarine and chelerythrine typically are the most potent.1 Oral ingestion or topical application of these molecules can have therapeutic and toxic effects.8

Biophysiological Effects

Bloodroot has been shown to have remarkable antimicrobial effects.9 The plant produces hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion.10 These mediators cause oxidative stress, thus inducing destruction of cellular DNA and the cell membrane.11 Although these effects can be helpful when fighting infection, they are not necessarily selective against healthy cells.12

Alkaloids of bloodroot also have cardiovascular therapeutic effects. Sanguinarine blocks angiotensin II and causes vasodilation, thus helping treat hypertension.13 It also acts as an inotrope by blocking the Na+/K+ ATPase pump. These effects in a patient who is already taking digoxin can cause notable cardiotoxicity because the 2 drugs share a mechanism of action.14

Chelerythrine blocks production of cyclooxygenase 2 and prostaglandin E2.15 This pathway modification results in anti-inflammatory effects that can help treat arthritis, edema, and other inflammatory conditions.16 Moreover, sanguinarine has demonstrated efficacy in numerous anticancer pathways,17 including downregulation of intercellular adhesion molecules, vascular cell adhesion molecules, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).18-20 Blocking VEGF is one way to inhibit angiogenesis,21 which is upregulated in tumor formation, thus sanguinarine can have an antiproliferative anticancer effect.22 Sanguinarine also upregulates molecules such as nuclear factor–κB and the protease enzymes known as caspases to cause proapoptotic effects, furthering its antitumor potential.23,24

Treatment of Dermatologic Conditions

The initial technique of Mohs micrographic surgery employed a chemopaste that utilized an extract of S canadensis to preserve tissue.25 Outside the dermatologist’s office, bloodroot is used as a topical home remedy for a variety of cutaneous conditions, including cancer, skin tags, and warts.26 Bloodroot is advertised as black salve, an alternative anticancer treatment.27,28

As useful as this natural agent sounds, it has a pitfall: The alkaloids of S canadensis are nonspecific in their cytotoxicity, damaging neoplastic and healthy tissue.29 This cytotoxic effect can cause escharification through diffuse tissue destruction and has been observed to result in formation of a keloid scar.30 The alkaloids in black salve also have been shown to cause skin erosions and cellular atypia.28,31 Therefore, the utility of this escharotic in medical treatment is limited.32 Fortuitously, oral antibiotics and wound care can help address this adverse effect.28

Bloodroot was once used as a mouth rinse and toothpaste to treat gingivitis, but this application was later associated with oral leukoplakia, a premalignant condition.33 Leukoplakia associated with S canadensis extract often is unremitting. Immediate discontinuation of the offending agent produces little regression, suggesting that cellular damage is irreversible.34

Final Thoughts

Although bloodroot demonstrates efficacy as a phytotherapeutic, it does come with notable toxicity. Physicians should warn patients of the unwanted cosmetic effects of black salve, especially oral products that incorporate sanguinarine. Adverse effects on the oropharynx can be irreversible, though the eschar associated with black salve can be treated with a topical or oral corticosteroid.29

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) is a member of the family Papaveraceae.1 This North American plant commonly is found in widespread distribution from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Florida and from the Great Lakes to Mississippi.2 Historically, Native Americans used bloodroot as a skin dye and as a medicine for many ailments.3

Bloodroot blooms for only a few days, starting in March, and fruits in June. The flowers comprise 8 to 10 white petals, surrounding a bed of yellow stamens (Figure). The plant thrives in wooded areas and grows to 12 inches tall. In its off-season, the plant remains dormant and can survive below-freezing temperatures.4

Chemical Constituents

Bloodroot gets its colloquial name from its red sap, which is released when the plant’s rhizome is cut. This sap contains a high concentration of alkaloids that are used for protection against predators. The rhizome itself has a rusty, red-brown color; the roots are a brighter red-orange.4

The rhizome of S canadensis contains the highest concentration of active alkaloids; the roots also contain these chemicals, though to a lesser degree; and the leaves, flowers, and fruits harvest approximately 1% of the alkaloids found in the roots.4 The concentration of alkaloids can vary from one plant to the next, depending on environmental conditions.5,6

The major alkaloids in S canadensis include both quaternary benzophenanthridine alkaloids (eg, sanguinarine, chelerythrine, sanguilutine, chelilutine, sanguirubine, chelirubine) and protopin alkaloids (eg, protopine, allocryptopine).3,7 Of these, sanguinarine and chelerythrine typically are the most potent.1 Oral ingestion or topical application of these molecules can have therapeutic and toxic effects.8

Biophysiological Effects

Bloodroot has been shown to have remarkable antimicrobial effects.9 The plant produces hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion.10 These mediators cause oxidative stress, thus inducing destruction of cellular DNA and the cell membrane.11 Although these effects can be helpful when fighting infection, they are not necessarily selective against healthy cells.12

Alkaloids of bloodroot also have cardiovascular therapeutic effects. Sanguinarine blocks angiotensin II and causes vasodilation, thus helping treat hypertension.13 It also acts as an inotrope by blocking the Na+/K+ ATPase pump. These effects in a patient who is already taking digoxin can cause notable cardiotoxicity because the 2 drugs share a mechanism of action.14

Chelerythrine blocks production of cyclooxygenase 2 and prostaglandin E2.15 This pathway modification results in anti-inflammatory effects that can help treat arthritis, edema, and other inflammatory conditions.16 Moreover, sanguinarine has demonstrated efficacy in numerous anticancer pathways,17 including downregulation of intercellular adhesion molecules, vascular cell adhesion molecules, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).18-20 Blocking VEGF is one way to inhibit angiogenesis,21 which is upregulated in tumor formation, thus sanguinarine can have an antiproliferative anticancer effect.22 Sanguinarine also upregulates molecules such as nuclear factor–κB and the protease enzymes known as caspases to cause proapoptotic effects, furthering its antitumor potential.23,24

Treatment of Dermatologic Conditions

The initial technique of Mohs micrographic surgery employed a chemopaste that utilized an extract of S canadensis to preserve tissue.25 Outside the dermatologist’s office, bloodroot is used as a topical home remedy for a variety of cutaneous conditions, including cancer, skin tags, and warts.26 Bloodroot is advertised as black salve, an alternative anticancer treatment.27,28

As useful as this natural agent sounds, it has a pitfall: The alkaloids of S canadensis are nonspecific in their cytotoxicity, damaging neoplastic and healthy tissue.29 This cytotoxic effect can cause escharification through diffuse tissue destruction and has been observed to result in formation of a keloid scar.30 The alkaloids in black salve also have been shown to cause skin erosions and cellular atypia.28,31 Therefore, the utility of this escharotic in medical treatment is limited.32 Fortuitously, oral antibiotics and wound care can help address this adverse effect.28

Bloodroot was once used as a mouth rinse and toothpaste to treat gingivitis, but this application was later associated with oral leukoplakia, a premalignant condition.33 Leukoplakia associated with S canadensis extract often is unremitting. Immediate discontinuation of the offending agent produces little regression, suggesting that cellular damage is irreversible.34

Final Thoughts

Although bloodroot demonstrates efficacy as a phytotherapeutic, it does come with notable toxicity. Physicians should warn patients of the unwanted cosmetic effects of black salve, especially oral products that incorporate sanguinarine. Adverse effects on the oropharynx can be irreversible, though the eschar associated with black salve can be treated with a topical or oral corticosteroid.29

- Vogel M, Lawson M, Sippl W, et al. Structure and mechanism of sanguinarine reductase, an enzyme of alkaloid detoxification. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18397-18406. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.088989

- Maranda EL, Wang MX, Cortizo J, et al. Flower power—the versatility of bloodroot. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:824. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5522

- Setzer WN. The phytochemistry of Cherokee aromatic medicinal plants. Medicines (Basel). 2018;5:121. doi:10.3390/medicines5040121

- Croaker A, King GJ, Pyne JH, et al. Sanguinaria canadensis: traditional medicine, phytochemical composition, biological activities and current uses. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1414. doi:10.3390/ijms17091414

- Graf TN, Levine KE, Andrews ME, et al. Variability in the yield of benzophenanthridine alkaloids in wildcrafted vs cultivated bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2007; 55:1205-1211. doi:10.1021/jf062498f

- Bennett BC, Bell CR, Boulware RT. Geographic variation in alkaloid content of Sanguinaria canadensis (Papaveraceae). Rhodora. 1990;92:57-69.

- Leaver CA, Yuan H, Wallen GR. Apoptotic activities of Sanguinaria canadensis: primary human keratinocytes, C-33A, and human papillomavirus HeLa cervical cancer lines. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2018;17:32-37.

- Kutchan TM. Molecular genetics of plant alkaloid biosynthesis. In: Cordell GA, ed. The Alkaloids. Vol 50. Elsevier Science Publishing Co, Inc; 1997:257-316.

- Obiang-Obounou BW, Kang O-H, Choi J-G, et al. The mechanism of action of sanguinarine against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Toxicol Sci. 2011;36:277-283. doi:10.2131/jts.36.277

- Z˙abka A, Winnicki K, Polit JT, et al. Sanguinarine-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis-like programmed cell death (AL-PCD) in root meristem cells of Allium cepa. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;112:193-206. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.01.004

- Kumar GS, Hazra S. Sanguinarine, a promising anticancer therapeutic: photochemical and nucleic acid binding properties. RSC Advances. 2014;4:56518-56531.

- Ping G, Wang Y, Shen L, et al. Highly efficient complexation of sanguinarine alkaloid by carboxylatopillar[6]arene: pKa shift, increased solubility and enhanced antibacterial activity. Chemical Commun (Camb). 2017;53:7381-7384. doi:10.1039/c7cc02799k

- Caballero-George C, Vanderheyden PM, Solis PN, et al. Biological screening of selected medicinal Panamanian plants by radioligand-binding techniques. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:59-70. doi:10.1078/0944-7113-00011

- Seifen E, Adams RJ, Riemer RK. Sanguinarine: a positive inotropic alkaloid which inhibits cardiac Na+, K+-ATPase. Eur J Pharmacol. 1979;60:373-377. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(79)90245-0

- Debprasad C, Hemanta M, Paromita B, et al. Inhibition of NO2, PGE2, TNF-α, and iNOS EXpression by Shorea robusta L.: an ethnomedicine used for anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012; 2012:254849. doi:10.1155/2012/254849

- Melov S, Ravenscroft J, Malik S, et al. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science. 2000;289:1567-1569. doi:10.1126/science.289.5484.1567

- Basu P, Kumar GS. Sanguinarine and its role in chronic diseases. In: Gupta SC, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB, eds. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology: Anti-inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases. Vol 928. Springer International Publishing; 2016:155-172.

- Alasvand M, Assadollahi V, Ambra R, et al. Antiangiogenic effect of alkaloids. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:9475908. doi:10.1155/2019/9475908

- Basini G, Santini SE, Bussolati S, et al. The plant alkaloid sanguinarine is a potential inhibitor of follicular angiogenesis. J Reprod Dev. 2007;53:573-579. doi:10.1262/jrd.18126

- Xu J-Y, Meng Q-H, Chong Y, et al. Sanguinarine is a novel VEGF inhibitor involved in the suppression of angiogenesis and cell migration. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:331-336. doi:10.3892/mco.2012.41

- Lu K, Bhat M, Basu S. Plants and their active compounds: natural molecules to target angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2016;19:287-295. doi:10.1007/s10456-016-9512-y

- Achkar IW, Mraiche F, Mohammad RM, et al. Anticancer potential of sanguinarine for various human malignancies. Future Med Chem. 2017;9:933-950. doi:10.4155/fmc-2017-0041

- Lee TK, Park C, Jeong S-J, et al. Sanguinarine induces apoptosis of human oral squamous cell carcinoma KB cells via inactivation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Drug Dev Res. 2016;77:227-240. doi:10.1002/ddr.21315

- Gaziano R, Moroni G, Buè C, et al. Antitumor effects of the benzophenanthridine alkaloid sanguinarine: evidence and perspectives. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:30-39. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v8.i1.30

- Mohs FE. Chemosurgery for skin cancer: fixed tissue and fresh tissue techniques. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:211-215.

- Affleck AG, Varma S. A case of do-it-yourself Mohs’ surgery using bloodroot obtained from the internet. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1078-1079. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08180.x

- Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E154-E155. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.031

- Osswald SS, Elston DM, Farley MF, et al. Self-treatment of a basal cell carcinoma with “black and yellow salve.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:508-510. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.007

- Schlichte MJ, Downing CP, Ramirez-Fort M, et al. Bloodroot associated eschar. Dermatol Online J. 2015;20:13030/qt05r0r2wr.

- Wang MZ, Warshaw EM. Bloodroot. Dermatitis. 2012;23:281-283. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e318273a4dd

- Tan JM, Peters P, Ong N, et al. Histopathological features after topical black salve application. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:75-76.

- Hou JL, Brewer JD. Black salve and bloodroot extract in dermatologic conditions. Cutis. 2015;95:309-311.

- Eversole LR, Eversole GM, Kopcik J. Sanguinaria-associated oral leukoplakia: comparison with other benign and dysplastic leukoplakic lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:455-464. doi:10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70125-9

- Mascarenhas AK, Allen CM, Moeschberger ML. The association between Viadent® use and oral leukoplakia—results of a matched case-control study. J Public Health Dent. 2002;62:158-162. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2002.tb03437.x

- Vogel M, Lawson M, Sippl W, et al. Structure and mechanism of sanguinarine reductase, an enzyme of alkaloid detoxification. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18397-18406. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.088989

- Maranda EL, Wang MX, Cortizo J, et al. Flower power—the versatility of bloodroot. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:824. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5522

- Setzer WN. The phytochemistry of Cherokee aromatic medicinal plants. Medicines (Basel). 2018;5:121. doi:10.3390/medicines5040121

- Croaker A, King GJ, Pyne JH, et al. Sanguinaria canadensis: traditional medicine, phytochemical composition, biological activities and current uses. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1414. doi:10.3390/ijms17091414

- Graf TN, Levine KE, Andrews ME, et al. Variability in the yield of benzophenanthridine alkaloids in wildcrafted vs cultivated bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2007; 55:1205-1211. doi:10.1021/jf062498f

- Bennett BC, Bell CR, Boulware RT. Geographic variation in alkaloid content of Sanguinaria canadensis (Papaveraceae). Rhodora. 1990;92:57-69.

- Leaver CA, Yuan H, Wallen GR. Apoptotic activities of Sanguinaria canadensis: primary human keratinocytes, C-33A, and human papillomavirus HeLa cervical cancer lines. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2018;17:32-37.

- Kutchan TM. Molecular genetics of plant alkaloid biosynthesis. In: Cordell GA, ed. The Alkaloids. Vol 50. Elsevier Science Publishing Co, Inc; 1997:257-316.

- Obiang-Obounou BW, Kang O-H, Choi J-G, et al. The mechanism of action of sanguinarine against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Toxicol Sci. 2011;36:277-283. doi:10.2131/jts.36.277

- Z˙abka A, Winnicki K, Polit JT, et al. Sanguinarine-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis-like programmed cell death (AL-PCD) in root meristem cells of Allium cepa. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;112:193-206. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.01.004

- Kumar GS, Hazra S. Sanguinarine, a promising anticancer therapeutic: photochemical and nucleic acid binding properties. RSC Advances. 2014;4:56518-56531.

- Ping G, Wang Y, Shen L, et al. Highly efficient complexation of sanguinarine alkaloid by carboxylatopillar[6]arene: pKa shift, increased solubility and enhanced antibacterial activity. Chemical Commun (Camb). 2017;53:7381-7384. doi:10.1039/c7cc02799k

- Caballero-George C, Vanderheyden PM, Solis PN, et al. Biological screening of selected medicinal Panamanian plants by radioligand-binding techniques. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:59-70. doi:10.1078/0944-7113-00011

- Seifen E, Adams RJ, Riemer RK. Sanguinarine: a positive inotropic alkaloid which inhibits cardiac Na+, K+-ATPase. Eur J Pharmacol. 1979;60:373-377. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(79)90245-0

- Debprasad C, Hemanta M, Paromita B, et al. Inhibition of NO2, PGE2, TNF-α, and iNOS EXpression by Shorea robusta L.: an ethnomedicine used for anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012; 2012:254849. doi:10.1155/2012/254849

- Melov S, Ravenscroft J, Malik S, et al. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science. 2000;289:1567-1569. doi:10.1126/science.289.5484.1567

- Basu P, Kumar GS. Sanguinarine and its role in chronic diseases. In: Gupta SC, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB, eds. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology: Anti-inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases. Vol 928. Springer International Publishing; 2016:155-172.

- Alasvand M, Assadollahi V, Ambra R, et al. Antiangiogenic effect of alkaloids. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:9475908. doi:10.1155/2019/9475908

- Basini G, Santini SE, Bussolati S, et al. The plant alkaloid sanguinarine is a potential inhibitor of follicular angiogenesis. J Reprod Dev. 2007;53:573-579. doi:10.1262/jrd.18126

- Xu J-Y, Meng Q-H, Chong Y, et al. Sanguinarine is a novel VEGF inhibitor involved in the suppression of angiogenesis and cell migration. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:331-336. doi:10.3892/mco.2012.41

- Lu K, Bhat M, Basu S. Plants and their active compounds: natural molecules to target angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2016;19:287-295. doi:10.1007/s10456-016-9512-y

- Achkar IW, Mraiche F, Mohammad RM, et al. Anticancer potential of sanguinarine for various human malignancies. Future Med Chem. 2017;9:933-950. doi:10.4155/fmc-2017-0041

- Lee TK, Park C, Jeong S-J, et al. Sanguinarine induces apoptosis of human oral squamous cell carcinoma KB cells via inactivation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Drug Dev Res. 2016;77:227-240. doi:10.1002/ddr.21315

- Gaziano R, Moroni G, Buè C, et al. Antitumor effects of the benzophenanthridine alkaloid sanguinarine: evidence and perspectives. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:30-39. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v8.i1.30

- Mohs FE. Chemosurgery for skin cancer: fixed tissue and fresh tissue techniques. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:211-215.

- Affleck AG, Varma S. A case of do-it-yourself Mohs’ surgery using bloodroot obtained from the internet. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1078-1079. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08180.x

- Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E154-E155. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.031

- Osswald SS, Elston DM, Farley MF, et al. Self-treatment of a basal cell carcinoma with “black and yellow salve.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:508-510. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.007

- Schlichte MJ, Downing CP, Ramirez-Fort M, et al. Bloodroot associated eschar. Dermatol Online J. 2015;20:13030/qt05r0r2wr.

- Wang MZ, Warshaw EM. Bloodroot. Dermatitis. 2012;23:281-283. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e318273a4dd

- Tan JM, Peters P, Ong N, et al. Histopathological features after topical black salve application. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:75-76.

- Hou JL, Brewer JD. Black salve and bloodroot extract in dermatologic conditions. Cutis. 2015;95:309-311.

- Eversole LR, Eversole GM, Kopcik J. Sanguinaria-associated oral leukoplakia: comparison with other benign and dysplastic leukoplakic lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:455-464. doi:10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70125-9

- Mascarenhas AK, Allen CM, Moeschberger ML. The association between Viadent® use and oral leukoplakia—results of a matched case-control study. J Public Health Dent. 2002;62:158-162. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2002.tb03437.x

Practice Points

- Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) is a plant historically used in Mohs micrographic surgery as chemopaste.

- Bloodroot has been shown to have remarkable antimicrobial effects.

- The alkaloids of S canadensis are nonspecific in their cytotoxicity, damaging both neoplastic and healthy tissue. They have been shown to cause skin erosions and cellular atypia.

Skin of Color in Preclinical Medical Education: A Cross-Institutional Comparison and A Call to Action

A ccording to the US Census Bureau, more than half of all Americans are projected to belong to a minority group, defined as any group other than non-Hispanic White alone, by 2044. 1 Consequently, the United States rapidly is becoming a country in which the majority of citizens will have skin of color. Individuals with skin of color are of diverse ethnic backgrounds and include people of African, Latin American, Native American, Pacific Islander, and Asian descent, as well as interethnic backgrounds. 2 Throughout the country, dermatologists along with primary care practitioners may be confronted with certain cutaneous conditions that have varying disease presentations or processes in patients with skin of color. It also is important to note that racial categories are socially rather than biologically constructed, and the term skin of color includes a wide variety of diverse skin types. Nevertheless, the current literature thoroughly supports unique pathophysiologic differences in skin of color as well as variations in disease manifestation compared to White patients. 3-5 For example, the increased lability of melanosomes in skin of color patients, which increases their risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, has been well documented. 5-7 There are various dermatologic conditions that also occur with higher frequency and manifest uniquely in people with darker, more pigmented skin, 7-9 and dermatologists, along with primary care physicians, should feel prepared to recognize and address them.

Extensive evidence also indicates that there are unique aspects to consider while managing certain skin diseases in patients with skin of color.8,10,11 Consequently, as noted on the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) website, “[a]n increase in the body of dermatological literature concerning skin of color as well as the advancement of both basic science and clinical investigational research is necessary to meet the needs of the expanding skin of color population.”2 In the meantime, current knowledge regarding cutaneous conditions that diversely or disproportionately affect skin of color should be actively disseminated to physicians in training. Although patients with skin of color should always have access to comprehensive care and knowledgeable practitioners, the current changes in national and regional demographics further underscore the need for a more thorough understanding of skin of color with regard to disease pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.

Several studies have found that medical students in the United States are minimally exposed to dermatology in general compared to other clinical specialties,12-14 which can easily lead to the underrecognition of disorders that may uniquely or disproportionately affect individuals with pigmented skin. Recent data showed that medical schools typically required fewer than 10 hours of dermatology instruction,12 and on average, dermatologic training made up less than 1% of a medical student’s undergraduate medical education.13,15,16 Consequently, less than 40% of primary care residents felt that their medical school curriculum adequately prepared them to manage common skin conditions.14 Although not all physicians should be expected to fully grasp the complexities of skin of color and its diagnostic and therapeutic implications, both practicing and training dermatologists have acknowledged a lack of exposure to skin of color. In one study, approximately 47% of dermatologists and dermatology residents reported that their medical training (medical school and/or residency) was inadequate in training them on skin conditions in Black patients. Furthermore, many who felt their training was lacking in skin of color identified the need for greater exposure to Black patients and training materials.15 The absence of comprehensive medical education regarding skin of color ultimately can be a disadvantage for both practitioners and patients, resulting in poorer outcomes. Furthermore, underrepresentation of skin of color may persist beyond undergraduate and graduate medical education. There also is evidence to suggest that noninclusion of skin of color pervades foundational dermatologic educational resources, including commonly used textbooks as well as continuing medical education disseminated at national conferences and meetings.17 Taken together, these findings highlight the need for more diverse and representative exposure to skin of color throughout medical training, which begins with a diverse inclusive undergraduate medical education in dermatology.

The objective of this study was to determine if the preclinical dermatology curriculum at 3 US medical schools provided adequate representation of skin of color patients in their didactic presentation slides.

Methods

Participants—Three US medical schools, a blend of private and public medical schools located across different geographic boundaries, agreed to participate in the study. All 3 institutions were current members of the American Medical Association (AMA) Accelerating Change in Medical Education consortium, whose primary goal is to create the medical school of the future and transform physician training.18 All 32 member institutions of the AMA consortium were contacted to request their participation in the study. As part of the consortium, these institutions have vowed to collectively work to develop and share the best models for educational advancement to improve care for patients, populations, and communities18 and would expectedly provide a more racially and ethnically inclusive curriculum than an institution not accountable to a group dedicated to identifying the best ways to deliver care for increasingly diverse communities.

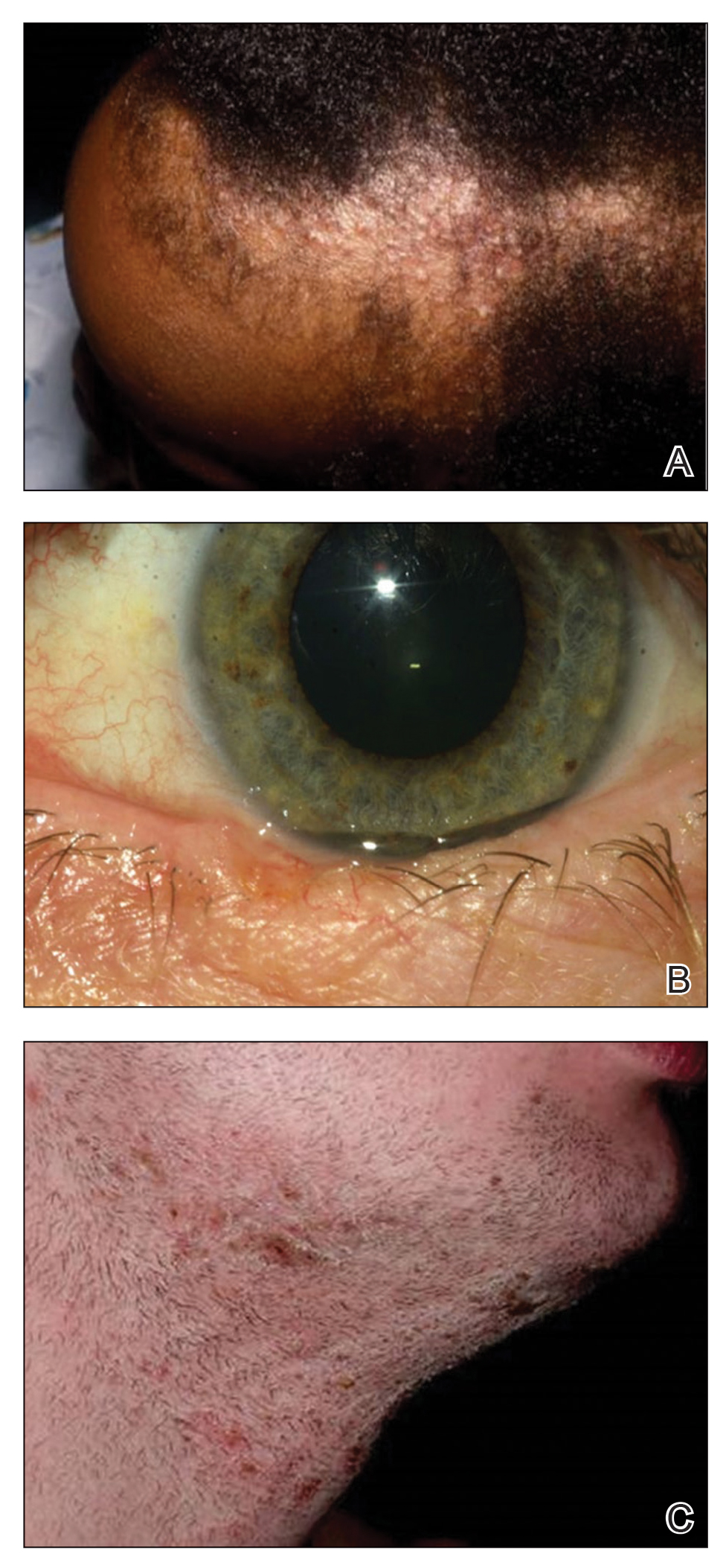

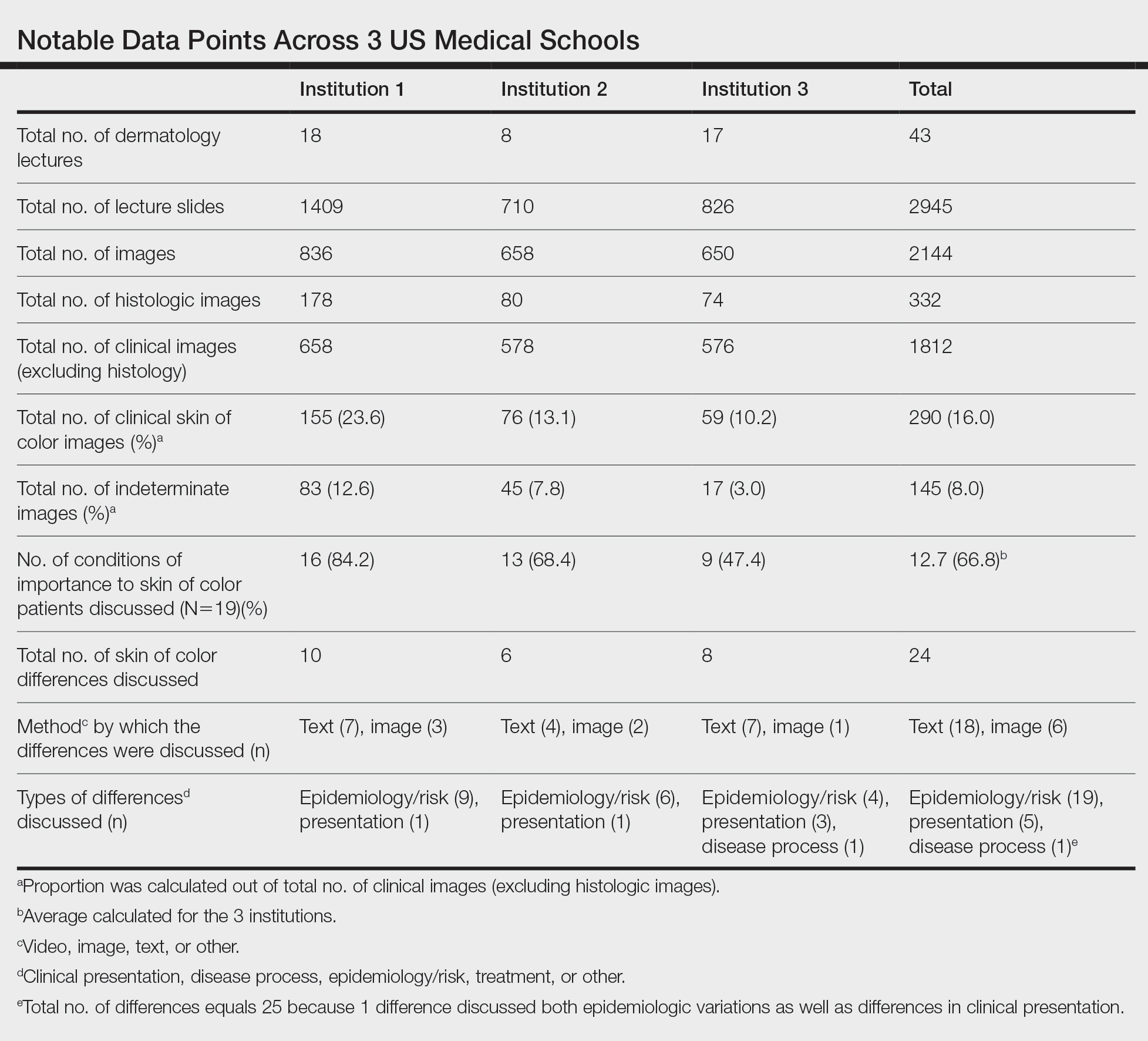

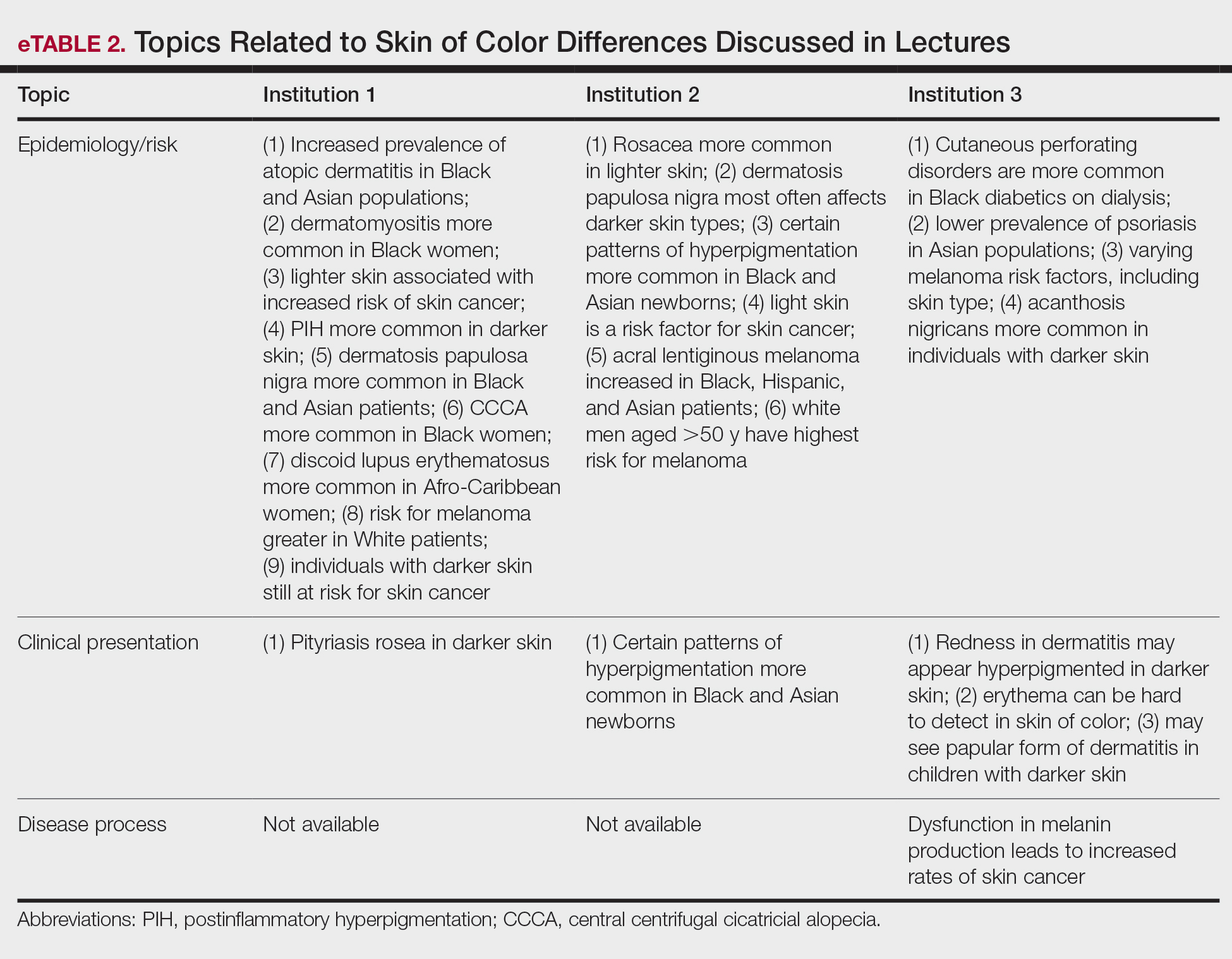

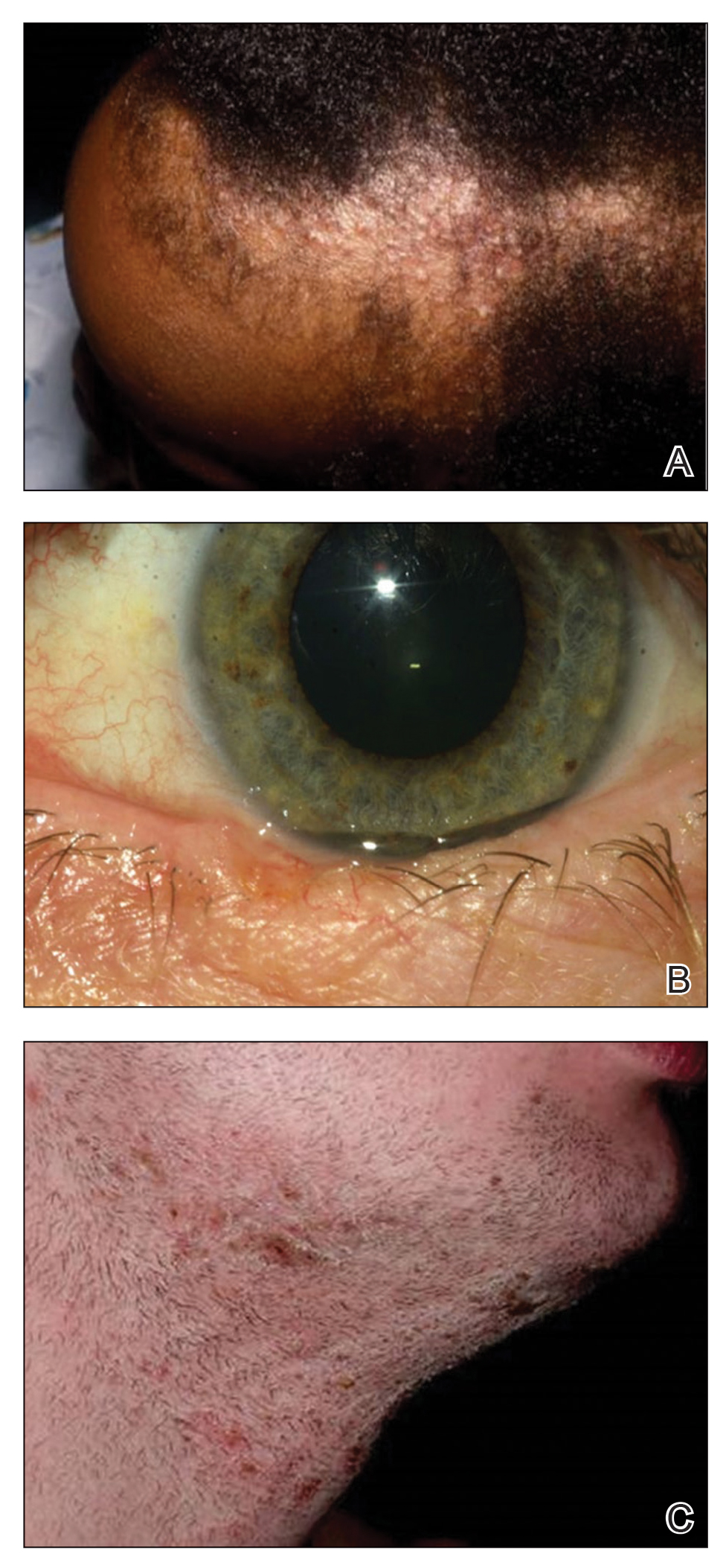

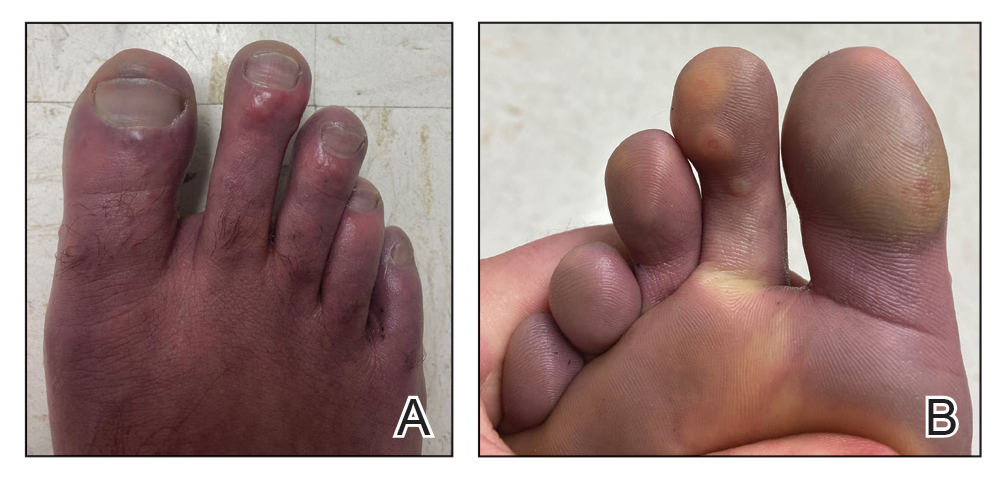

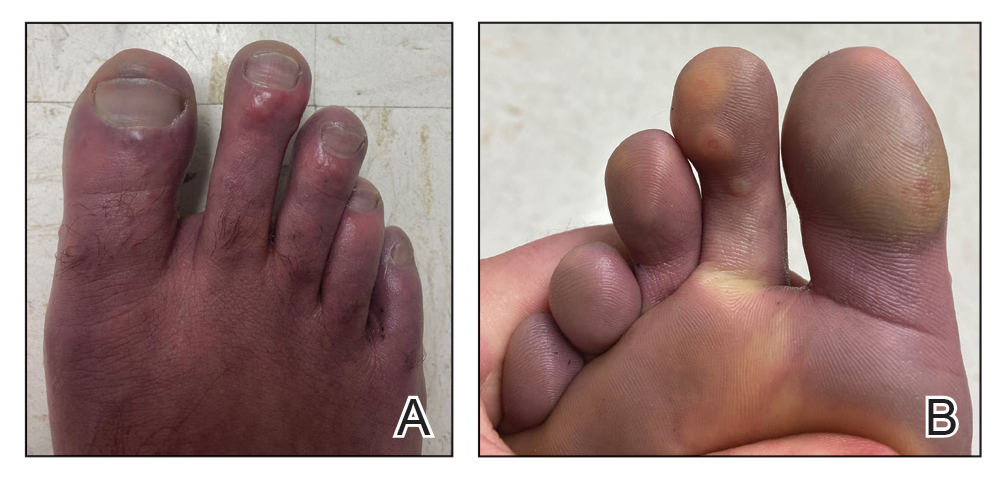

Data Collection—Lectures were included if they were presented during dermatology preclinical courses in the 2015 to 2016 academic year. An uninvolved third party removed the names and identities of instructors to preserve anonymity. Two independent coders from different institutions extracted the data—lecture title, total number of clinical and histologic images, and number of skin of color images—from each of the anonymized lectures using a standardized coding form. We documented differences in skin of color noted in lectures and the disease context for the discussed differences, such as variations in clinical presentation, disease process, epidemiology/risk, and treatment between different skin phenotypes or ethnic groups. Photographs in which the coders were unable to differentiate whether the patient had skin of color were designated as indeterminate or unclear. Photographs appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI19 were categorically designated as skin of color, and those appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were described as not skin of color; however, images appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin type III often were classified as not skin of color or indeterminate and occasionally skin of color. The Figure shows examples of images classified as skin of color, indeterminate, and not skin of color. Photographs often were classified as indeterminate due to poor lighting, close-up view photographs, or highlighted pathology obscuring the surrounding skin. We excluded duplicate photographs and histologic images from the analyses.

We also reviewed 19 conditions previously highlighted by the SOCS as areas of importance to skin of color patients.20 The coders tracked how many of these conditions were noted in each lecture. Duplicate discussion of these conditions was not included in the analyses. Any discrepancies between coders were resolved through additional slide review and discussion. The final coded data with the agreed upon changes were used for statistical analyses. Recent national demographic data from the US Census Bureau in 2019 describe approximately 39.9% of the population as belonging to racial/ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic/Latinx White.21 Consequently, the standard for adequate representation for skin of color photographs was set at 35% for the purpose of this study.

Results

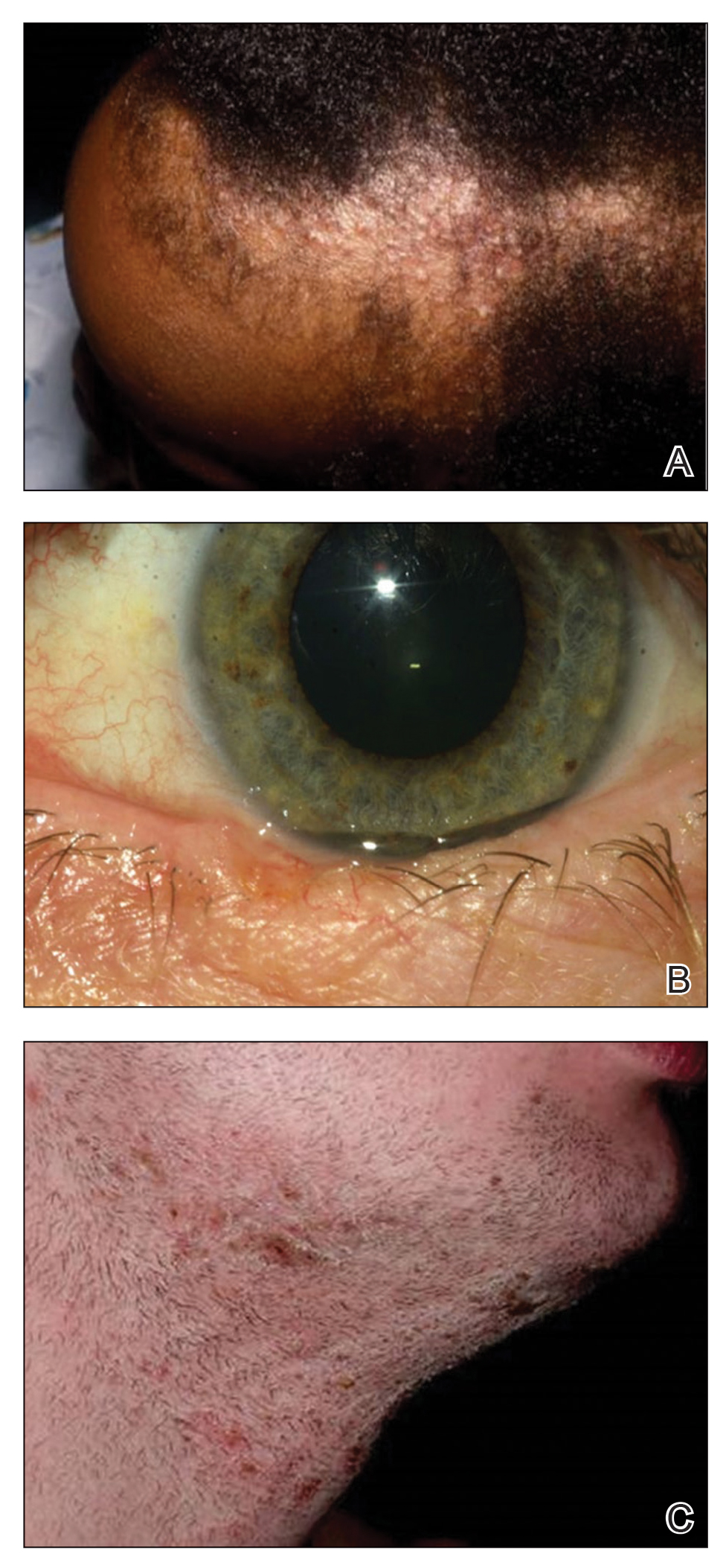

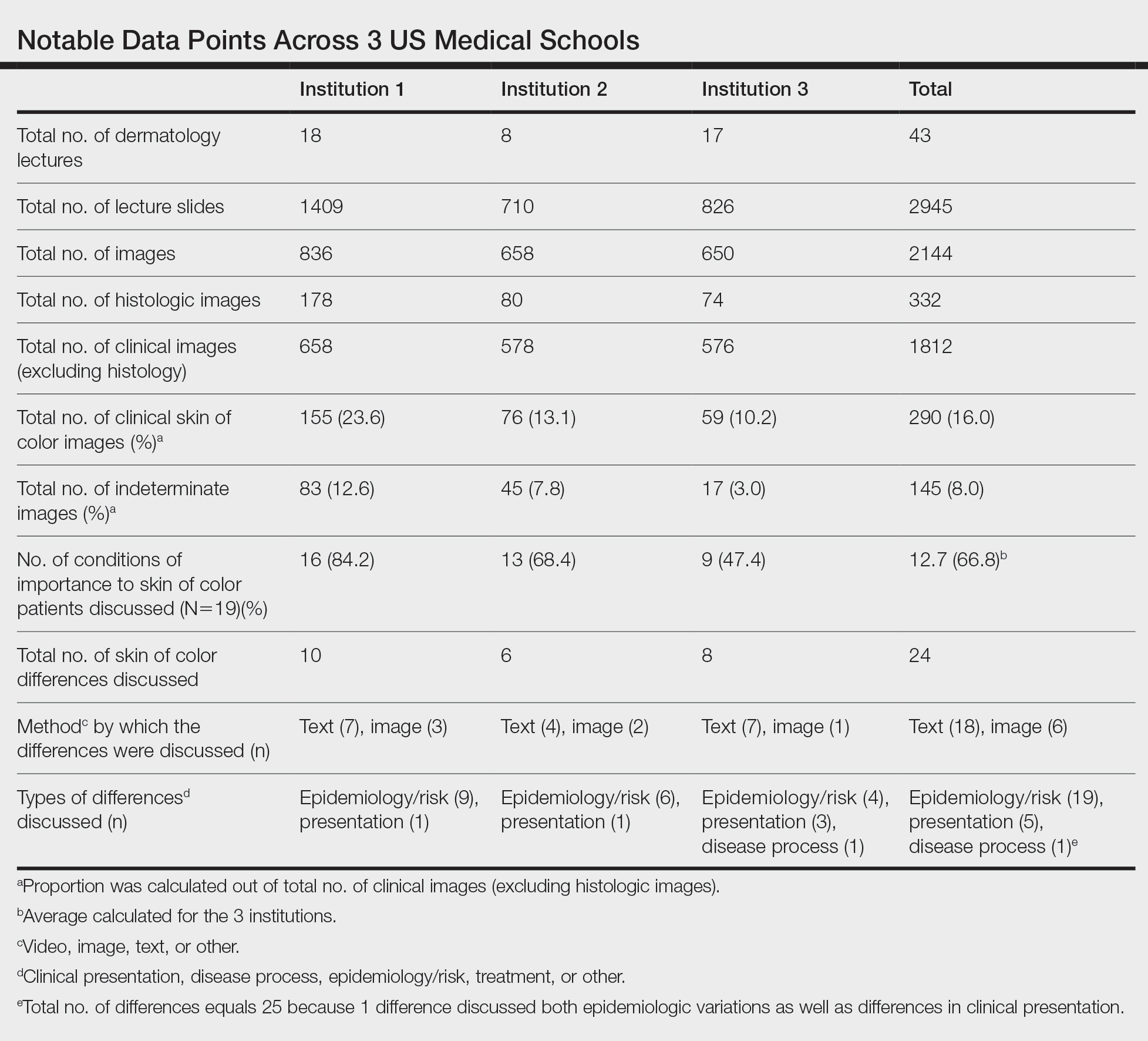

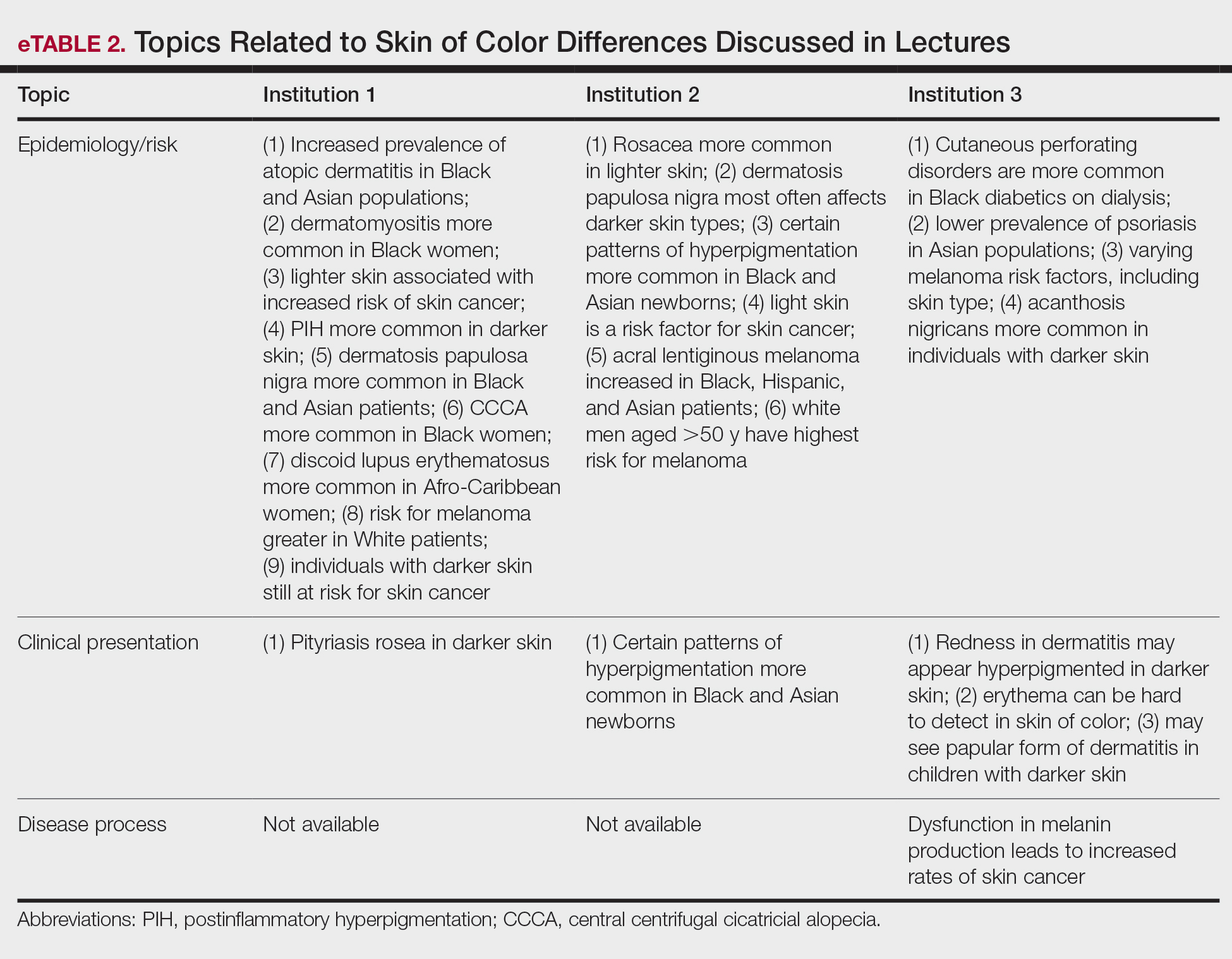

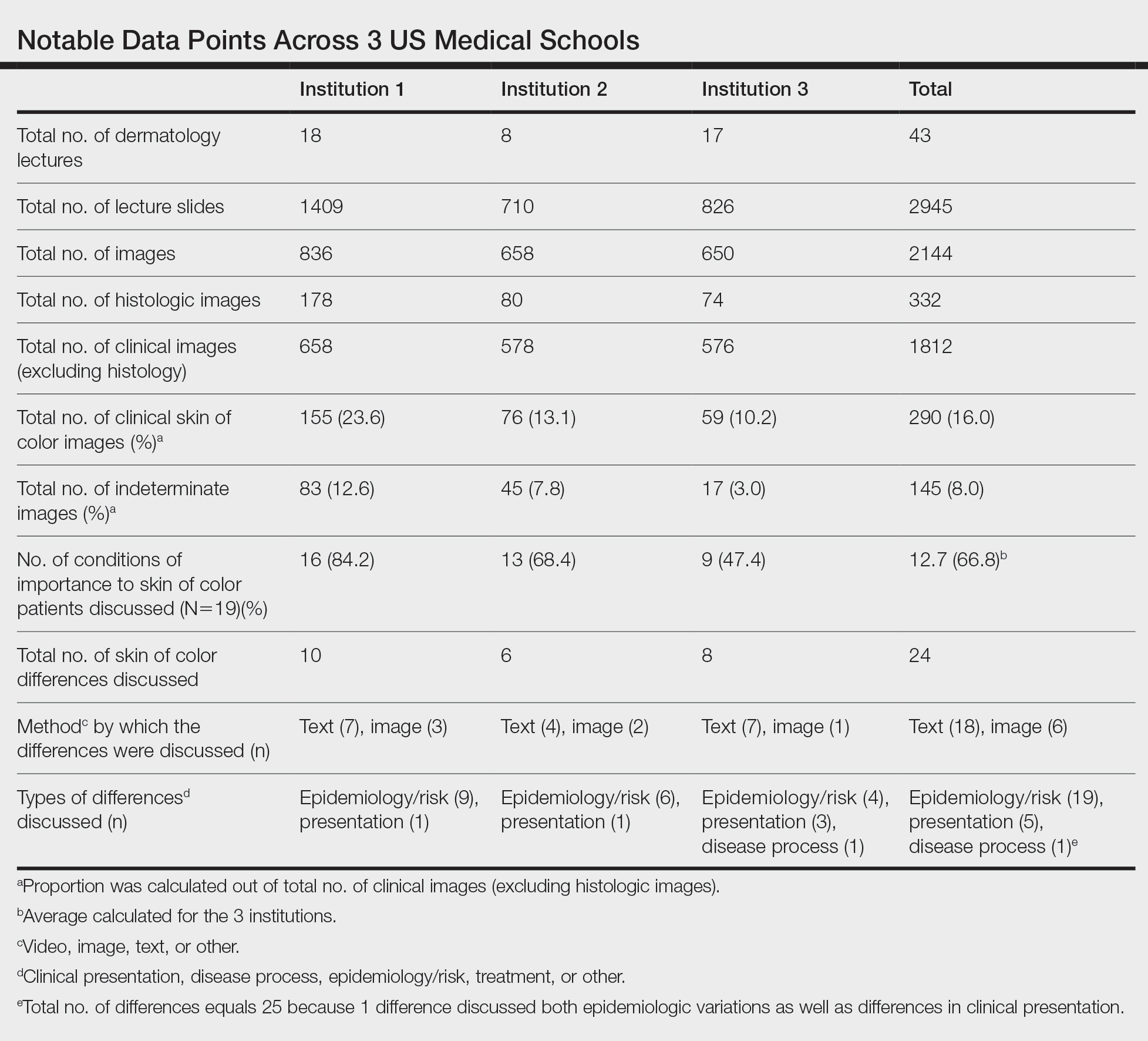

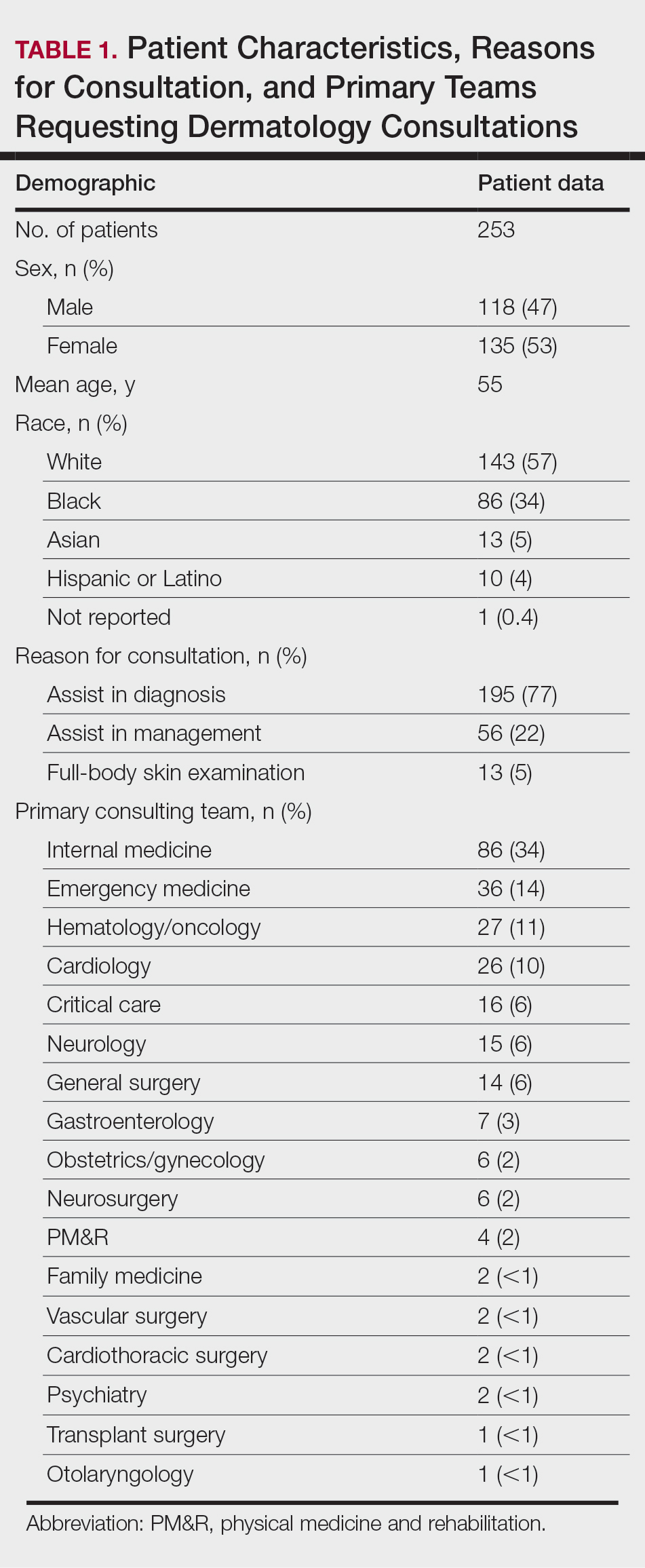

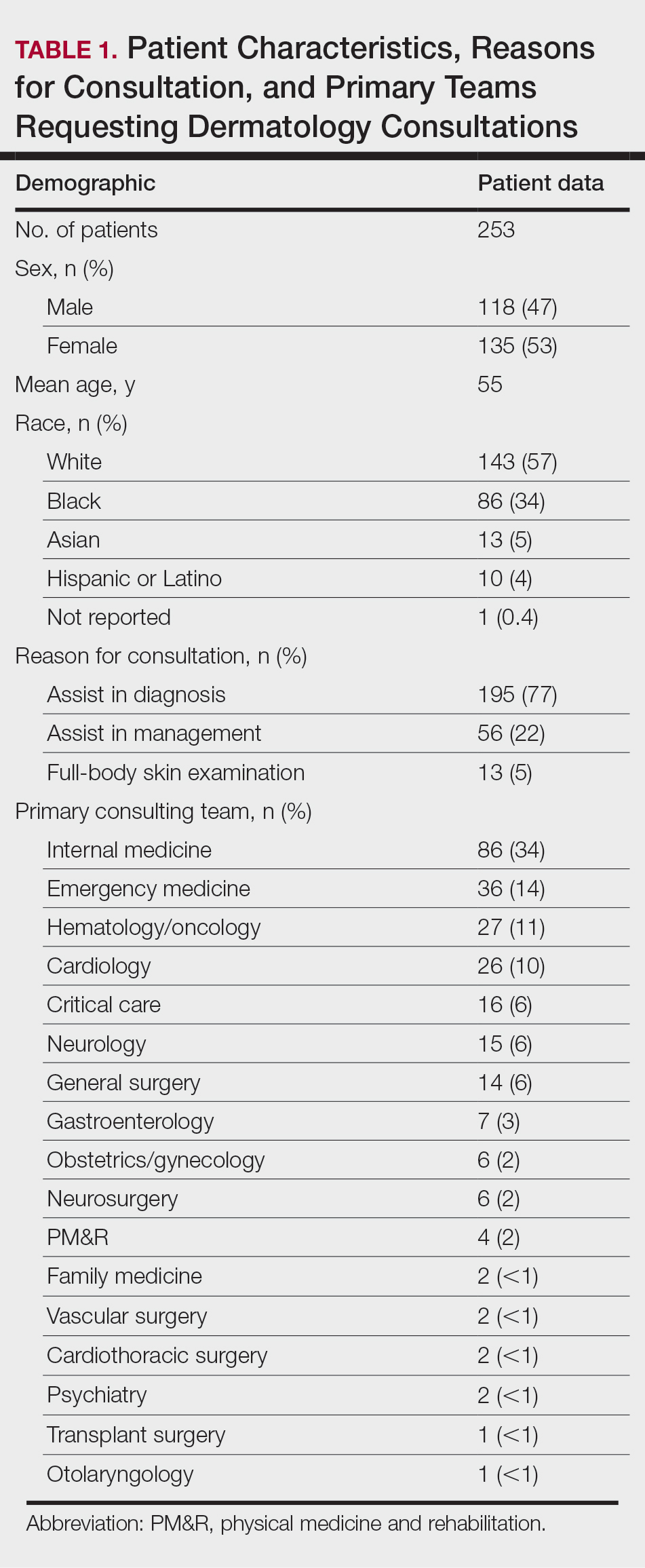

Across all 3 institutions included in the study, the proportion of the total number of clinical photographs showing skin of color was 16% (290/1812). Eight percent of the total photographs (145/1812) were noted to be indeterminate (Table). For institution 1, 23.6% of photographs (155/658) showed skin of color, and 12.6% (83/658) were indeterminate. For institution 2, 13.1% (76/578) showed skin of color and 7.8% (45/578) were indeterminate. For institution 3, 10.2% (59/576) showed skin of color and 3% (17/576) were indeterminate.

Institutions 1, 2, and 3 had 18, 8, and 17 total dermatology lectures, respectively. Of the 19 conditions designated as areas of importance to skin of color patients by the SOCS, 16 (84.2%) were discussed by institution 1, 11 (57.9%) by institution 2, and 9 (47.4%) by institution 3 (eTable 1). Institution 3 did not include photographs of skin of color patients in its acne, psoriasis, or cutaneous malignancy lectures. Institution 1 also did not include any skin of color patients in its malignancy lecture. Lectures that focused on pigmentary disorders, atopic dermatitis, infectious conditions, and benign cutaneous neoplasms were more likely to display photographs of skin of color patients; for example, lectures that discussed infectious conditions, such as superficial mycoses, herpes viruses, human papillomavirus, syphilis, and atypical mycobacterial infections, were consistently among those with higher proportions of photographs of skin of color patients.

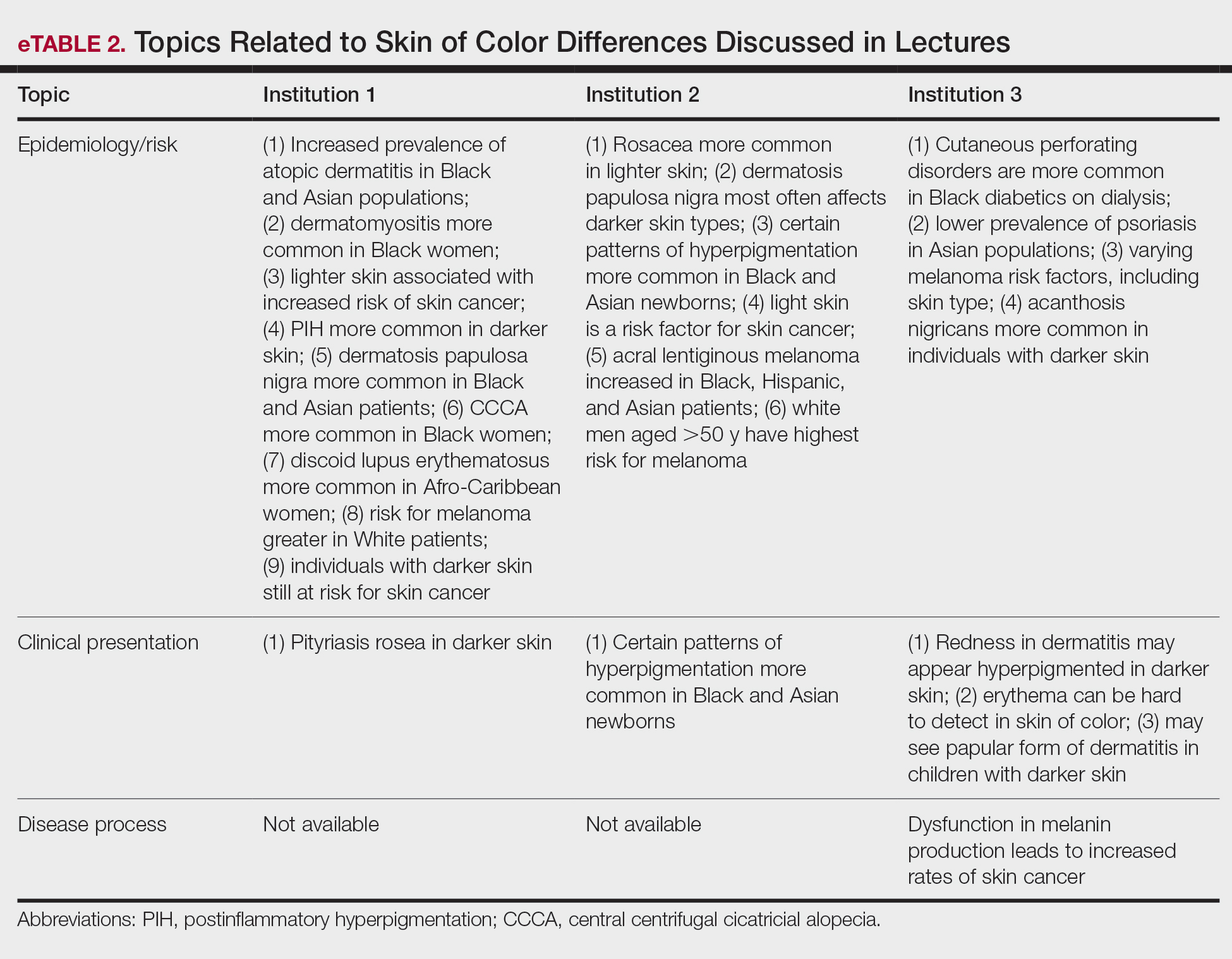

Throughout the entire preclinical dermatology course at all 3 institutions, of 2945 lecture slides, only 24 (0.8%) unique differences were noted between skin color and non–skin of color patients, with 10 total differences noted by institution 1, 6 by institution 2, and 8 by institution 3 (Table). The majority of these differences (19/24) were related to epidemiologic differences in prevalence among varying racial/ethnic groups, with only 5 instances highlighting differences in clinical presentation. There was only a single instance that elaborated on the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of the discussed difference. Of all 24 unique differences discussed, 8 were related to skin cancer, 3 were related to dermatitis, and 2 were related to the difference in manifestation of erythema in patients with darker skin (eTable 2).

Comment

The results of this study demonstrated that skin of color is underrepresented in the preclinical dermatology curriculum at these 3 institutions. Although only 16% of all included clinical photographs were of skin of color, individuals with skin of color will soon represent more than half of the total US population within the next 2 decades.1 To increase representation of skin of color patients, teaching faculty should consciously and deliberately include more photographs of skin of color patients for a wider variety of common conditions, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, in addition to those that tend to disparately affect skin of color patients, such as pseudofolliculitis barbae or melasma. Furthermore, they also can incorporate more detailed discussions about important differences seen in skin of color patients.

More Skin of Color Photographs in Psoriasis Lectures—At institution 3, there were no skin of color patients included in the psoriasis lecture, even though there is considerable data in the literature indicating notable differences in the clinical presentation, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in skin of color patients.11,22 There are multiple nuances in psoriasis manifestation in patients with skin of color, including less-conspicuous erythema in darker skin, higher degrees of dyspigmentation, and greater body surface area involvement. For Black patients with scalp psoriasis, the impact of hair texture, styling practices, and washing frequency are additional considerations that may impact disease severity and selection of topical therapy.11 The lack of inclusion of any skin of color patients in the psoriasis lecture at one institution further underscores the pressing need to prioritize communities of color in medical education.

More Skin of Color Photographs in Cutaneous Malignancy Lectures—Similarly, while a lecturer at institution 2 noted that acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for a considerable proportion of melanoma among skin of color patients,23 there was no mention of how melanoma generally is substantially more deadly in this population, potentially due to decreased awareness and inconsistent screening.24 Furthermore, at institutions 1 and 3, there were no photographs or discussion of skin of color patients during the cutaneous malignancy lectures. Evidence shows that more emphasis is needed for melanoma screening and awareness in skin of color populations to improve survival outcomes,24 and this begins with educating not only future dermatologists but all future physicians as well. The failure to include photographs of skin of color patients in discussions or lectures regarding cutaneous malignancies may serve to further perpetuate the harmful misperception that individuals with skin of color are unaffected by skin cancer.25,26

Analysis of Skin of Color Photographs in Infectious Disease Lectures—In addition, lectures discussing infectious etiologies were among those with the highest proportion of skin of color photographs. This relatively disproportionate representation of skin of color compared to the other lectures may contribute to the development of harmful stereotypes or the stigmatization of skin of color patients. Although skin of color should continue to be represented in similar lectures, teaching faculty should remain mindful of the potential unintended impact from lectures including relatively disproportionate amounts of skin of color, particularly when other lectures may have sparse to absent representation of skin of color.

More Photographs Available for Education—Overall, our findings may help to inform changes to preclinical dermatology medical education at other institutions to create more inclusive and representative curricula for skin of color patients. The ability of instructors to provide visual representation of various dermatologic conditions may be limited by the photographs available in certain textbooks with few examples of patients with skin of color; however, concerns regarding the lack of skin of color representation in dermatology training is not a novel discussion.17 Although it is the responsibility of all dermatologists to advocate for the inclusion of skin of color, many dermatologists of color have been leading the way in this movement for decades, publishing several textbooks to document various skin conditions in those with darker skin types and discuss unique considerations for patients with skin of color.27-29 Images from these textbooks can be utilized by programs to increase representation of skin of color in dermatology training. There also are multiple expanding online dermatologic databases, such as VisualDx, with an increasing focus on skin of color patients, some of which allow users to filter images by degree of skin pigmentation.30 Moreover, instructors also can work to diversify their curricula by highlighting more of the SOCS conditions of importance to skin of color patients, which have since been renamed and highlighted on the Patient Dermatology Education section of the SOCS website.20 These conditions, while not completely comprehensive, provide a useful starting point for medical educators to reevaluate for potential areas of improvement and inclusion.

There are several potential strategies that can be used to better represent skin of color in dermatologic preclinical medical education, including increasing awareness, especially among dermatology teaching faculty, of existing disparities in the representation of skin of color in the preclinical curricula. Additionally, all dermatology teaching materials could be reviewed at the department level prior to being disseminated to medical students to assess for instances in which skin of color could be prioritized for discussion or varying disease presentations in skin of color could be demonstrated. Finally, teaching faculty may consider photographing more clinical images of their skin of color patients to further develop a catalog of diverse images that can be used to teach students.

Study Limitations—Our study was unable to account for verbal discussion of skin of color not otherwise denoted or captured in lecture slides. Additional limitations include the utilization of Fitzpatrick skin types to describe and differentiate varying skin tones, as the Fitzpatrick scale originally was developed as a method to describe an individual’s response to UV exposure.19 The inability to further delineate the representation of darker skin types, such as those that may be classified as Fitzpatrick skin types V or VI,19 compared to those with lighter skin of color also was a limiting factor. This study was unable to assess for discussion of other common conditions affecting skin of color patients that were not listed as one of the priority conditions by SOCS. Photographs that were designated as indeterminate were difficult to elucidate as skin of color; however, it is possible that instructors may have verbally described these images as skin of color during lectures. Nonetheless, it may be beneficial for learners if teaching faculty were to clearly label instances where skin of color patients are shown or when notable differences are present.

Conclusion

Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of audio data from lectures, syllabi, and small group teaching materials from preclinical courses to more accurately assess representation of skin of color in dermatology training. Additionally, future studies also may expand to include images from lectures of overlapping clinical specialties, particularly infectious disease and rheumatology, to provide a broader assessment of skin of color exposure. Furthermore, repeat assessment may be beneficial to assess the longitudinal effectiveness of curricular changes at the institutions included in this study, comparing older lectures to more recent, updated lectures. This study also may be replicated at other medical schools to allow for wider comparison of curricula.

Acknowledgment—The authors wish to thank the institutions that offered and agreed to participate in this study with the hopes of improving medical education.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. United States Census Bureau website. Published March 2015. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- Learn more about SOCS. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed September 14, 2021. http://skinofcolorsociety.org/about-socs/

- Taylor SC. Skin of color: biology, structure, function, and implications for dermatologic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(suppl 2):S41-S62.

- Berardesca E, Maibach H. Ethnic skin: overview of structure and function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 6):S139-S142.

- Callender VD, Surin-Lord SS, Davis EC, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:87-99.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:20-31.

- Grimes PE, Stockton T. Pigmentary disorders in blacks. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:271-281.

- Halder RM, Nootheti PK. Ethnic skin disorders overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 6):S143-S148.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Callender VD. Acne in ethnic skin: special considerations for therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:184-195.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.

- Ramsay DL, Mayer F. National survey of undergraduate dermatologic medical education. Arch Dermatol.1985;121:1529-1530.

- Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, et al. Medical school dermatology curriculum: are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:23-29.

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii.

- Knable A, Hood AF, Pearson TG. Undergraduate medical education in dermatology: report from the AAD Interdisciplinary Education Committee, Subcommittee on Undergraduate Medical Education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:467-470.

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690.

- Skochelak SE, Stack SJ. Creating the medical schools of the future. Acad Med. 2017;92:16-19.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Skin of Color Society. Patient dermatology education. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/patient-dermatology-education

- QuickFacts: United States. US Census Bureau website. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US#

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423.

- Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427-434.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Pipitone M, Robinson JK, Camara C, et al. Skin cancer awareness in suburban employees: a Hispanic perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:118-123.

- Imahiyerobo-Ip J, Ip I, Jamal S, et al. Skin cancer awareness in communities of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:198-200.

- Taylor SSC, Serrano AMA, Kelly AP, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Dadzie OE, Petit A, Alexis AF, eds. Ethnic Dermatology: Principles and Practice. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

- Jackson-Richards D, Pandya AG, eds. Dermatology Atlas for Skin of Color. Springer; 2014.

- VisualDx. New VisualDx feature: skin of color sort. Published October 14, 2020. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.visualdx.com/blog/new-visualdx-feature-skin-of-color-sort/

A ccording to the US Census Bureau, more than half of all Americans are projected to belong to a minority group, defined as any group other than non-Hispanic White alone, by 2044. 1 Consequently, the United States rapidly is becoming a country in which the majority of citizens will have skin of color. Individuals with skin of color are of diverse ethnic backgrounds and include people of African, Latin American, Native American, Pacific Islander, and Asian descent, as well as interethnic backgrounds. 2 Throughout the country, dermatologists along with primary care practitioners may be confronted with certain cutaneous conditions that have varying disease presentations or processes in patients with skin of color. It also is important to note that racial categories are socially rather than biologically constructed, and the term skin of color includes a wide variety of diverse skin types. Nevertheless, the current literature thoroughly supports unique pathophysiologic differences in skin of color as well as variations in disease manifestation compared to White patients. 3-5 For example, the increased lability of melanosomes in skin of color patients, which increases their risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, has been well documented. 5-7 There are various dermatologic conditions that also occur with higher frequency and manifest uniquely in people with darker, more pigmented skin, 7-9 and dermatologists, along with primary care physicians, should feel prepared to recognize and address them.

Extensive evidence also indicates that there are unique aspects to consider while managing certain skin diseases in patients with skin of color.8,10,11 Consequently, as noted on the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) website, “[a]n increase in the body of dermatological literature concerning skin of color as well as the advancement of both basic science and clinical investigational research is necessary to meet the needs of the expanding skin of color population.”2 In the meantime, current knowledge regarding cutaneous conditions that diversely or disproportionately affect skin of color should be actively disseminated to physicians in training. Although patients with skin of color should always have access to comprehensive care and knowledgeable practitioners, the current changes in national and regional demographics further underscore the need for a more thorough understanding of skin of color with regard to disease pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.

Several studies have found that medical students in the United States are minimally exposed to dermatology in general compared to other clinical specialties,12-14 which can easily lead to the underrecognition of disorders that may uniquely or disproportionately affect individuals with pigmented skin. Recent data showed that medical schools typically required fewer than 10 hours of dermatology instruction,12 and on average, dermatologic training made up less than 1% of a medical student’s undergraduate medical education.13,15,16 Consequently, less than 40% of primary care residents felt that their medical school curriculum adequately prepared them to manage common skin conditions.14 Although not all physicians should be expected to fully grasp the complexities of skin of color and its diagnostic and therapeutic implications, both practicing and training dermatologists have acknowledged a lack of exposure to skin of color. In one study, approximately 47% of dermatologists and dermatology residents reported that their medical training (medical school and/or residency) was inadequate in training them on skin conditions in Black patients. Furthermore, many who felt their training was lacking in skin of color identified the need for greater exposure to Black patients and training materials.15 The absence of comprehensive medical education regarding skin of color ultimately can be a disadvantage for both practitioners and patients, resulting in poorer outcomes. Furthermore, underrepresentation of skin of color may persist beyond undergraduate and graduate medical education. There also is evidence to suggest that noninclusion of skin of color pervades foundational dermatologic educational resources, including commonly used textbooks as well as continuing medical education disseminated at national conferences and meetings.17 Taken together, these findings highlight the need for more diverse and representative exposure to skin of color throughout medical training, which begins with a diverse inclusive undergraduate medical education in dermatology.

The objective of this study was to determine if the preclinical dermatology curriculum at 3 US medical schools provided adequate representation of skin of color patients in their didactic presentation slides.

Methods

Participants—Three US medical schools, a blend of private and public medical schools located across different geographic boundaries, agreed to participate in the study. All 3 institutions were current members of the American Medical Association (AMA) Accelerating Change in Medical Education consortium, whose primary goal is to create the medical school of the future and transform physician training.18 All 32 member institutions of the AMA consortium were contacted to request their participation in the study. As part of the consortium, these institutions have vowed to collectively work to develop and share the best models for educational advancement to improve care for patients, populations, and communities18 and would expectedly provide a more racially and ethnically inclusive curriculum than an institution not accountable to a group dedicated to identifying the best ways to deliver care for increasingly diverse communities.

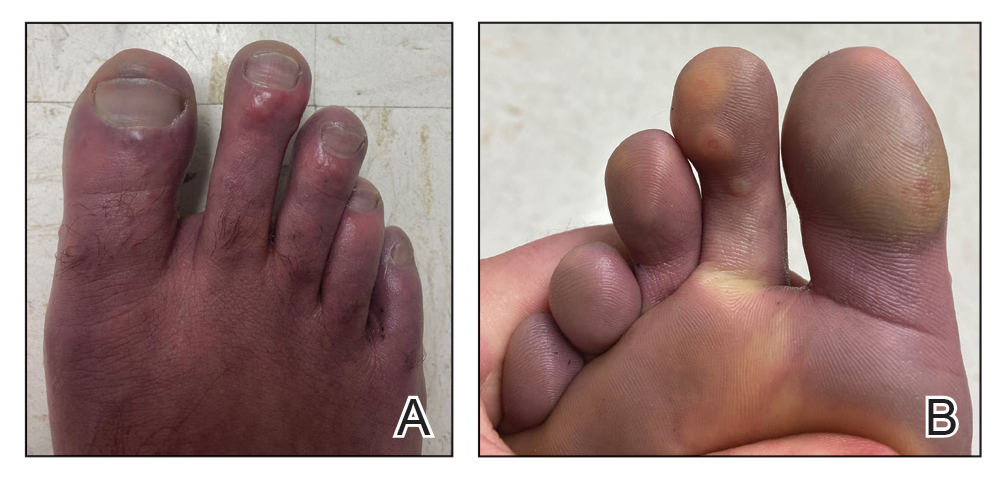

Data Collection—Lectures were included if they were presented during dermatology preclinical courses in the 2015 to 2016 academic year. An uninvolved third party removed the names and identities of instructors to preserve anonymity. Two independent coders from different institutions extracted the data—lecture title, total number of clinical and histologic images, and number of skin of color images—from each of the anonymized lectures using a standardized coding form. We documented differences in skin of color noted in lectures and the disease context for the discussed differences, such as variations in clinical presentation, disease process, epidemiology/risk, and treatment between different skin phenotypes or ethnic groups. Photographs in which the coders were unable to differentiate whether the patient had skin of color were designated as indeterminate or unclear. Photographs appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI19 were categorically designated as skin of color, and those appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were described as not skin of color; however, images appearing to represent Fitzpatrick skin type III often were classified as not skin of color or indeterminate and occasionally skin of color. The Figure shows examples of images classified as skin of color, indeterminate, and not skin of color. Photographs often were classified as indeterminate due to poor lighting, close-up view photographs, or highlighted pathology obscuring the surrounding skin. We excluded duplicate photographs and histologic images from the analyses.

We also reviewed 19 conditions previously highlighted by the SOCS as areas of importance to skin of color patients.20 The coders tracked how many of these conditions were noted in each lecture. Duplicate discussion of these conditions was not included in the analyses. Any discrepancies between coders were resolved through additional slide review and discussion. The final coded data with the agreed upon changes were used for statistical analyses. Recent national demographic data from the US Census Bureau in 2019 describe approximately 39.9% of the population as belonging to racial/ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic/Latinx White.21 Consequently, the standard for adequate representation for skin of color photographs was set at 35% for the purpose of this study.

Results

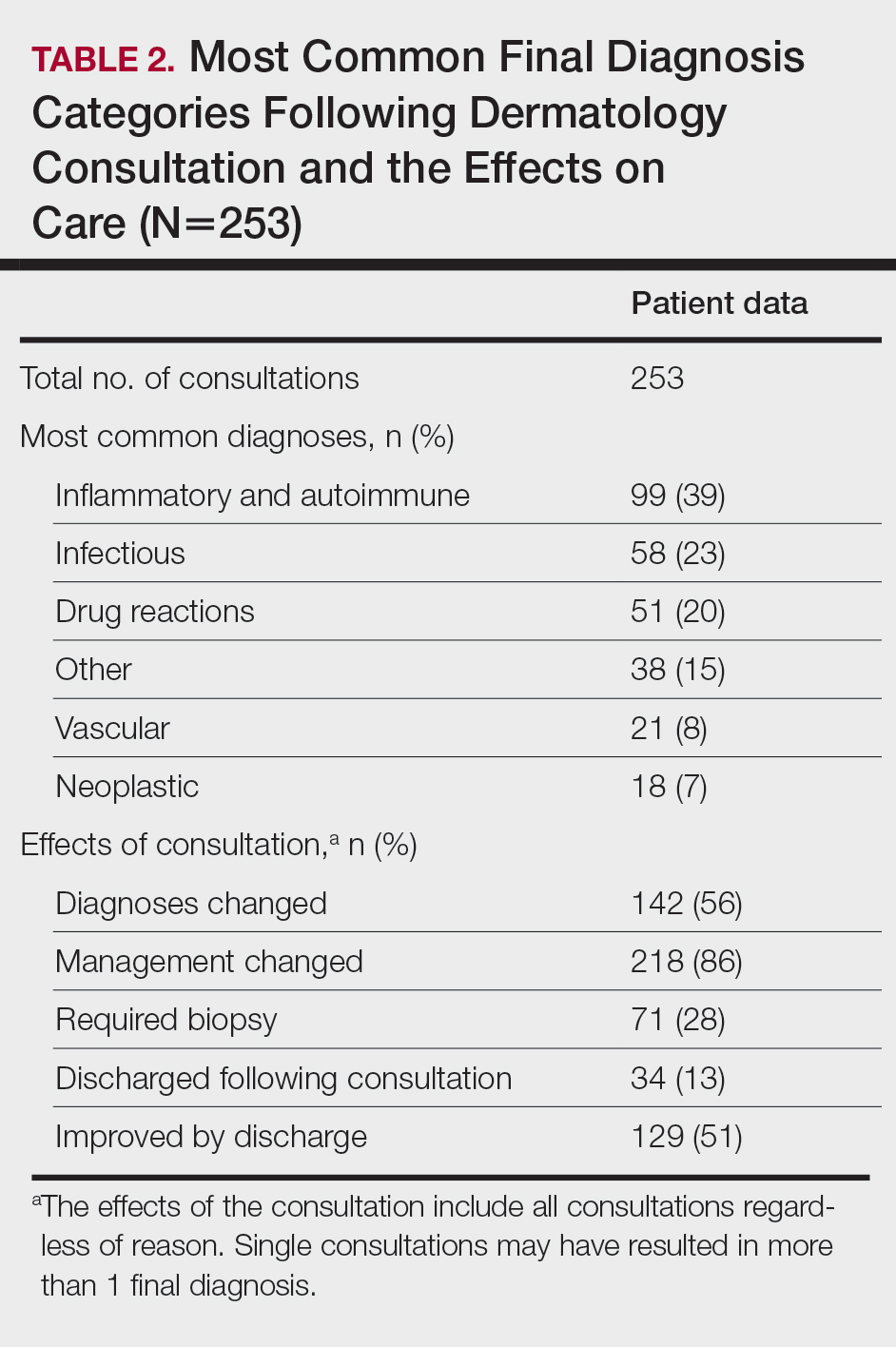

Across all 3 institutions included in the study, the proportion of the total number of clinical photographs showing skin of color was 16% (290/1812). Eight percent of the total photographs (145/1812) were noted to be indeterminate (Table). For institution 1, 23.6% of photographs (155/658) showed skin of color, and 12.6% (83/658) were indeterminate. For institution 2, 13.1% (76/578) showed skin of color and 7.8% (45/578) were indeterminate. For institution 3, 10.2% (59/576) showed skin of color and 3% (17/576) were indeterminate.