User login

‘Regionalized’ care tied to better survival in tough cancer

The Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) Gastric-Esophageal Cancer Program was established in 2016 to consolidate the care of patients with gastric cancer and increase physician specialization and standardization.

In a retrospective study, Kaiser Permanente investigators compared the outcomes of the 942 patients diagnosed before the regional gastric cancer team was established with the outcomes of the 487 patients treated after it was implemented. Overall, the transformation appears to enhance the delivery of care and improves clinical and oncologic outcomes.

For example, among 394 patients who received curative-intent surgery, overall survival at 2 years increased from 72.7% before the program to 85.5% afterward.

“The regionalized gastric cancer program combines the benefits of community-based care, which is local and convenient, with the expertise of a specialized cancer center,” said coauthor Lisa Herrinton, PhD, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente division of research, in a statement.

She added that, in their integrated care system, “it is easy for the different physicians that treat cancer patients – including surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, among others – to come together and collaborate and tie their work flows together.”

The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Gastric cancer accounts for about 27,600 cases diagnosed annually in the United States, but the overall 5-year survival is still only 32%. About half of the cases are locoregional (stage I-III) and potentially eligible for curative-intent surgery and adjuvant therapy, the authors pointed out in the study.

As compared with North America, the incidence rate is five to six times higher in East Asia, but they have developed better surveillance for early detection and treatment is highly effective, as the increased incidence allows oncologists and surgeons to achieve greater specialization. Laparoscopic gastrectomy and extended (D2) lymph node dissection are more commonly performed in East Asia as compared with the United States, and surgical outcomes appear to be better in East Asia.

Regionalizing care

The rationale for regionalizing care was that increasing and concentrating the volume of cases to a specific location would make it more possible to introduce new surgical procedures as well as allow medical oncologists to uniformly introduce and standardize the use of the newest chemotherapy regimens.

Prior to regionalization, gastric cancer surgery was performed at 19 medical centers in the Kaiser system. Now, curative-intent laparoscopic gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy or esophagojejunostomy and side-to-side jejunojejunostomy is subsequently performed at only two centers by five surgeons.

“The two centers were selected based on how skilled the surgeons were at performing advanced minimally invasive oncologic surgery,” said lead author Swee H. Teh, MD, surgical director, gastric cancer surgery, Kaiser Permanente Northern California. “We also looked at the center’s retrospective gastrectomy outcomes and the strength of the leadership that would be collaborating with the regional multidisciplinary team.”

Dr. Teh said in an interview that it was imperative that their regional gastric cancer centers have surgeons highly skilled in advanced minimally invasive gastrointestinal surgery. “This is a newer technique and not one of our more senior surgeons had been trained in [it],” he said. “With this change, some surgeons were now no longer performing gastric cancer surgery.”

Not only were the centers selected based on the surgical skills of the surgeons already there, but they also took into account the locations and geographical membership distribution. “We have found that our patients’ traveling distance to receive surgical care has not changed significantly,” Dr. Teh said.

Improved outcomes

The cohort included 1,429 eligible patients all stages of gastric cancer; one-third were treated after regionalization, 650 had stage I-III disease, and 394 underwent curative-intent surgery.

Overall survival at 2 years was 32.8% pre- and 37.3% post regionalization (P = .20) for all stages of cancer; stage I-III cases with or without surgery, 55.6% and 61.1%, respectively (P = .25); and among all surgery patients, 72.7% and 85.5%, respectively (P < .03).

Among patients who underwent surgery, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy increased from 35% to 66% (P < .0001), as did laparoscopic gastrectomy from 18% to 92% (P < .0001), and D2 lymphadenectomy from 2% to 80% (P < .0001). In addition, dissection of 15 or more lymph nodes also rose from 61% to 95% (P < .0001). Post regionalization, the resection margin was more often negative, and the resection less often involved other organs.

The median length of hospitalization declined from 7 to 3 days (P < .001) after regionalization but all-cause readmissions and reoperation at 30 and 90 days were similar in both cohorts. The risk of bowel obstruction was less frequent post regionalization (P = .01 at both 30 and 90 days), as was risk of infection (P = .03 at 30 days and P = .01 at 90 days).

The risk of one or more serious adverse events was also lower (P < .01), and 30-day mortality did not change (pre 0.7% and post 0.0%, P = .34).

Generalizability may not be feasible

But although this was successful for Kaiser, the authors note that a key limitation of the study is generalizability – and that regionalization may not be feasible in many U.S. settings.

“There needs to be a standardized workflow that all stakeholders agree upon,” Dr. Teh explained. “For example, in our gastric cancer staging pathway, all patients who are considered candidates for surgery have four staging tests: CT scan, PET scan and endoscopic ultrasound [EUS], and staging laparoscopy.”

Another important aspect is that in order to make sure the workflow is smooth and timely, all subspecialties responsible for the staging modalities need to create a “special access.” What this means, he continued, is for example, that the radiology department must ensure that these patients will have their CT scan and PET scans promptly. “Similarly, the GI department must provide quick access to EUS, and the surgery department must quickly provide a staging laparoscopy,” Dr. Teh said. “We have been extremely successful in achieving this goal.”

Dr. Teh also noted that a skilled patient navigator and a team where each member brings high-level expertise and experience to the table are also necessary. And innovative technology is also needed.

“We use artificial intelligence to identify all newly diagnosed cases of gastric [cancer], and within 24 hours of a patient’s diagnosis, a notification is sent to entire team about this new patient,” he added. “We also use AI to extract data to create a dashboard that will track each patient’s progress and outcomes, so that the results are accessible to every member of the team. The innovative technology has also helped us build a comprehensive survivorship program.”

They also noted in their study that European and Canadian systems, as well as the Department of Veterans Affairs, could probably implement components of this, including enhanced recovery after surgery.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Teh and Dr. Herrinton have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) Gastric-Esophageal Cancer Program was established in 2016 to consolidate the care of patients with gastric cancer and increase physician specialization and standardization.

In a retrospective study, Kaiser Permanente investigators compared the outcomes of the 942 patients diagnosed before the regional gastric cancer team was established with the outcomes of the 487 patients treated after it was implemented. Overall, the transformation appears to enhance the delivery of care and improves clinical and oncologic outcomes.

For example, among 394 patients who received curative-intent surgery, overall survival at 2 years increased from 72.7% before the program to 85.5% afterward.

“The regionalized gastric cancer program combines the benefits of community-based care, which is local and convenient, with the expertise of a specialized cancer center,” said coauthor Lisa Herrinton, PhD, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente division of research, in a statement.

She added that, in their integrated care system, “it is easy for the different physicians that treat cancer patients – including surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, among others – to come together and collaborate and tie their work flows together.”

The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Gastric cancer accounts for about 27,600 cases diagnosed annually in the United States, but the overall 5-year survival is still only 32%. About half of the cases are locoregional (stage I-III) and potentially eligible for curative-intent surgery and adjuvant therapy, the authors pointed out in the study.

As compared with North America, the incidence rate is five to six times higher in East Asia, but they have developed better surveillance for early detection and treatment is highly effective, as the increased incidence allows oncologists and surgeons to achieve greater specialization. Laparoscopic gastrectomy and extended (D2) lymph node dissection are more commonly performed in East Asia as compared with the United States, and surgical outcomes appear to be better in East Asia.

Regionalizing care

The rationale for regionalizing care was that increasing and concentrating the volume of cases to a specific location would make it more possible to introduce new surgical procedures as well as allow medical oncologists to uniformly introduce and standardize the use of the newest chemotherapy regimens.

Prior to regionalization, gastric cancer surgery was performed at 19 medical centers in the Kaiser system. Now, curative-intent laparoscopic gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy or esophagojejunostomy and side-to-side jejunojejunostomy is subsequently performed at only two centers by five surgeons.

“The two centers were selected based on how skilled the surgeons were at performing advanced minimally invasive oncologic surgery,” said lead author Swee H. Teh, MD, surgical director, gastric cancer surgery, Kaiser Permanente Northern California. “We also looked at the center’s retrospective gastrectomy outcomes and the strength of the leadership that would be collaborating with the regional multidisciplinary team.”

Dr. Teh said in an interview that it was imperative that their regional gastric cancer centers have surgeons highly skilled in advanced minimally invasive gastrointestinal surgery. “This is a newer technique and not one of our more senior surgeons had been trained in [it],” he said. “With this change, some surgeons were now no longer performing gastric cancer surgery.”

Not only were the centers selected based on the surgical skills of the surgeons already there, but they also took into account the locations and geographical membership distribution. “We have found that our patients’ traveling distance to receive surgical care has not changed significantly,” Dr. Teh said.

Improved outcomes

The cohort included 1,429 eligible patients all stages of gastric cancer; one-third were treated after regionalization, 650 had stage I-III disease, and 394 underwent curative-intent surgery.

Overall survival at 2 years was 32.8% pre- and 37.3% post regionalization (P = .20) for all stages of cancer; stage I-III cases with or without surgery, 55.6% and 61.1%, respectively (P = .25); and among all surgery patients, 72.7% and 85.5%, respectively (P < .03).

Among patients who underwent surgery, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy increased from 35% to 66% (P < .0001), as did laparoscopic gastrectomy from 18% to 92% (P < .0001), and D2 lymphadenectomy from 2% to 80% (P < .0001). In addition, dissection of 15 or more lymph nodes also rose from 61% to 95% (P < .0001). Post regionalization, the resection margin was more often negative, and the resection less often involved other organs.

The median length of hospitalization declined from 7 to 3 days (P < .001) after regionalization but all-cause readmissions and reoperation at 30 and 90 days were similar in both cohorts. The risk of bowel obstruction was less frequent post regionalization (P = .01 at both 30 and 90 days), as was risk of infection (P = .03 at 30 days and P = .01 at 90 days).

The risk of one or more serious adverse events was also lower (P < .01), and 30-day mortality did not change (pre 0.7% and post 0.0%, P = .34).

Generalizability may not be feasible

But although this was successful for Kaiser, the authors note that a key limitation of the study is generalizability – and that regionalization may not be feasible in many U.S. settings.

“There needs to be a standardized workflow that all stakeholders agree upon,” Dr. Teh explained. “For example, in our gastric cancer staging pathway, all patients who are considered candidates for surgery have four staging tests: CT scan, PET scan and endoscopic ultrasound [EUS], and staging laparoscopy.”

Another important aspect is that in order to make sure the workflow is smooth and timely, all subspecialties responsible for the staging modalities need to create a “special access.” What this means, he continued, is for example, that the radiology department must ensure that these patients will have their CT scan and PET scans promptly. “Similarly, the GI department must provide quick access to EUS, and the surgery department must quickly provide a staging laparoscopy,” Dr. Teh said. “We have been extremely successful in achieving this goal.”

Dr. Teh also noted that a skilled patient navigator and a team where each member brings high-level expertise and experience to the table are also necessary. And innovative technology is also needed.

“We use artificial intelligence to identify all newly diagnosed cases of gastric [cancer], and within 24 hours of a patient’s diagnosis, a notification is sent to entire team about this new patient,” he added. “We also use AI to extract data to create a dashboard that will track each patient’s progress and outcomes, so that the results are accessible to every member of the team. The innovative technology has also helped us build a comprehensive survivorship program.”

They also noted in their study that European and Canadian systems, as well as the Department of Veterans Affairs, could probably implement components of this, including enhanced recovery after surgery.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Teh and Dr. Herrinton have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) Gastric-Esophageal Cancer Program was established in 2016 to consolidate the care of patients with gastric cancer and increase physician specialization and standardization.

In a retrospective study, Kaiser Permanente investigators compared the outcomes of the 942 patients diagnosed before the regional gastric cancer team was established with the outcomes of the 487 patients treated after it was implemented. Overall, the transformation appears to enhance the delivery of care and improves clinical and oncologic outcomes.

For example, among 394 patients who received curative-intent surgery, overall survival at 2 years increased from 72.7% before the program to 85.5% afterward.

“The regionalized gastric cancer program combines the benefits of community-based care, which is local and convenient, with the expertise of a specialized cancer center,” said coauthor Lisa Herrinton, PhD, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente division of research, in a statement.

She added that, in their integrated care system, “it is easy for the different physicians that treat cancer patients – including surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, among others – to come together and collaborate and tie their work flows together.”

The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Gastric cancer accounts for about 27,600 cases diagnosed annually in the United States, but the overall 5-year survival is still only 32%. About half of the cases are locoregional (stage I-III) and potentially eligible for curative-intent surgery and adjuvant therapy, the authors pointed out in the study.

As compared with North America, the incidence rate is five to six times higher in East Asia, but they have developed better surveillance for early detection and treatment is highly effective, as the increased incidence allows oncologists and surgeons to achieve greater specialization. Laparoscopic gastrectomy and extended (D2) lymph node dissection are more commonly performed in East Asia as compared with the United States, and surgical outcomes appear to be better in East Asia.

Regionalizing care

The rationale for regionalizing care was that increasing and concentrating the volume of cases to a specific location would make it more possible to introduce new surgical procedures as well as allow medical oncologists to uniformly introduce and standardize the use of the newest chemotherapy regimens.

Prior to regionalization, gastric cancer surgery was performed at 19 medical centers in the Kaiser system. Now, curative-intent laparoscopic gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy or esophagojejunostomy and side-to-side jejunojejunostomy is subsequently performed at only two centers by five surgeons.

“The two centers were selected based on how skilled the surgeons were at performing advanced minimally invasive oncologic surgery,” said lead author Swee H. Teh, MD, surgical director, gastric cancer surgery, Kaiser Permanente Northern California. “We also looked at the center’s retrospective gastrectomy outcomes and the strength of the leadership that would be collaborating with the regional multidisciplinary team.”

Dr. Teh said in an interview that it was imperative that their regional gastric cancer centers have surgeons highly skilled in advanced minimally invasive gastrointestinal surgery. “This is a newer technique and not one of our more senior surgeons had been trained in [it],” he said. “With this change, some surgeons were now no longer performing gastric cancer surgery.”

Not only were the centers selected based on the surgical skills of the surgeons already there, but they also took into account the locations and geographical membership distribution. “We have found that our patients’ traveling distance to receive surgical care has not changed significantly,” Dr. Teh said.

Improved outcomes

The cohort included 1,429 eligible patients all stages of gastric cancer; one-third were treated after regionalization, 650 had stage I-III disease, and 394 underwent curative-intent surgery.

Overall survival at 2 years was 32.8% pre- and 37.3% post regionalization (P = .20) for all stages of cancer; stage I-III cases with or without surgery, 55.6% and 61.1%, respectively (P = .25); and among all surgery patients, 72.7% and 85.5%, respectively (P < .03).

Among patients who underwent surgery, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy increased from 35% to 66% (P < .0001), as did laparoscopic gastrectomy from 18% to 92% (P < .0001), and D2 lymphadenectomy from 2% to 80% (P < .0001). In addition, dissection of 15 or more lymph nodes also rose from 61% to 95% (P < .0001). Post regionalization, the resection margin was more often negative, and the resection less often involved other organs.

The median length of hospitalization declined from 7 to 3 days (P < .001) after regionalization but all-cause readmissions and reoperation at 30 and 90 days were similar in both cohorts. The risk of bowel obstruction was less frequent post regionalization (P = .01 at both 30 and 90 days), as was risk of infection (P = .03 at 30 days and P = .01 at 90 days).

The risk of one or more serious adverse events was also lower (P < .01), and 30-day mortality did not change (pre 0.7% and post 0.0%, P = .34).

Generalizability may not be feasible

But although this was successful for Kaiser, the authors note that a key limitation of the study is generalizability – and that regionalization may not be feasible in many U.S. settings.

“There needs to be a standardized workflow that all stakeholders agree upon,” Dr. Teh explained. “For example, in our gastric cancer staging pathway, all patients who are considered candidates for surgery have four staging tests: CT scan, PET scan and endoscopic ultrasound [EUS], and staging laparoscopy.”

Another important aspect is that in order to make sure the workflow is smooth and timely, all subspecialties responsible for the staging modalities need to create a “special access.” What this means, he continued, is for example, that the radiology department must ensure that these patients will have their CT scan and PET scans promptly. “Similarly, the GI department must provide quick access to EUS, and the surgery department must quickly provide a staging laparoscopy,” Dr. Teh said. “We have been extremely successful in achieving this goal.”

Dr. Teh also noted that a skilled patient navigator and a team where each member brings high-level expertise and experience to the table are also necessary. And innovative technology is also needed.

“We use artificial intelligence to identify all newly diagnosed cases of gastric [cancer], and within 24 hours of a patient’s diagnosis, a notification is sent to entire team about this new patient,” he added. “We also use AI to extract data to create a dashboard that will track each patient’s progress and outcomes, so that the results are accessible to every member of the team. The innovative technology has also helped us build a comprehensive survivorship program.”

They also noted in their study that European and Canadian systems, as well as the Department of Veterans Affairs, could probably implement components of this, including enhanced recovery after surgery.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Teh and Dr. Herrinton have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: A Supplement to Dermatology News

Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: A Supplement to Dermatology News 2021

- Psoriasis severity redefined by expert group

- Mitigating PSA risk with biologic therapy

- Lack of diversity seen in psoriasis trials

- PSA Comorbidities effect on treatment responses

With Commentaries by Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE and Alan Menter, MD

And more…

Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: A Supplement to Dermatology News 2021

- Psoriasis severity redefined by expert group

- Mitigating PSA risk with biologic therapy

- Lack of diversity seen in psoriasis trials

- PSA Comorbidities effect on treatment responses

With Commentaries by Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE and Alan Menter, MD

And more…

Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: A Supplement to Dermatology News 2021

- Psoriasis severity redefined by expert group

- Mitigating PSA risk with biologic therapy

- Lack of diversity seen in psoriasis trials

- PSA Comorbidities effect on treatment responses

With Commentaries by Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE and Alan Menter, MD

And more…

Luminal, basal groupings could change metastatic prostate cancer treatment

.

Furthermore, the classification is “an important step toward better personalizing therapy for men with mCRPC,” write investigators led by Rahul Aggarwal, MD, a genitourinary oncologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

The classification is already of clinical importance in localized disease for prognosis and guides treatment, but has not until now been examined in mCRPC, they point out.

That’s probably because of the difficulty of biopsying prostate metastases, which often reside in the bone, the team adds.

The team retrospectively reviewed genetic and clinical information from 634 men in four clinical trial cohorts; 45% had tumors classified as luminal and 55% were classified as basal, based on increased or decreased expression of luminal and basal gene signatures. Treatment in the cohorts was at physicians’ discretion.

Much of what the team found is similar to what’s been reported for localized disease. Namely, “that patients with luminal tumors should be considered for androgen-signaling inhibitor [ASI] therapy, and those with basal tumors could be considered for chemotherapeutic approaches given the similarity to small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer and the diminished benefit of androgen-signaling inhibitors,” Dr. Aggarwal and colleagues write.

Stunningly and consistent with dependence on oncogenic androgen-receptor signaling in luminal tumors, luminal patients had significantly better survival when they were treated with ASIs instead of chemotherapy, with a median overall survival of 32 vs. 8.7 months (hazard ratio, 0.27; P < .001).

Notably, luminal tumors demonstrated an increased expression of androgen-signaling genes and obtained preferential benefit for ASI therapy, compared with basal tumors.

The basal subtype included but was not exclusive to small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer (SCNC), “which raises the potential that non-SCNC basal tumors (the majority) may share enough similarity with their SCNC counterparts that similar chemotherapy-based treatment strategies may be effective, especially given the diminished benefit of ASI therapy,” the team writes.

Overall, the investigators say the findings “warrant further validation in larger prospective cohorts and clinical trials.”

Possibly practice changing

Rodwell Mabaera, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., agreed with investigators about the potential impact of the basal/luminal classifications in an accompanying editorial.

“These subtypes represent a potentially powerful tool for personalized therapeutic decision-making that may improve outcomes in mCRPC,” he writes.

Dr. Mabaera notes that “the worst survival outcome was seen among patients with luminal tumors treated with chemotherapy, suggesting a potential negative effect of chemotherapy in this subgroup.”

The authors “appropriately concluded that use of ASI would be recommended in this population. ... If confirmed, these results would be practice changing for choice of treatment in [the] luminal subtype of mCRPC.”

In basal tumors, the investigators identified genetic changes for resistance to androgen-receptor antagonists and increased dependence on DNA damage-repair pathways. That opens “the prospect that PARP inhibitors,” which block cancer cells from repairing DNA, “may be effective in this subgroup of patients,” Dr. Mabaera said.

The basal/luminal treatment duality may not completely apply, however.

That’s because there was a trend toward improved survival with ASI treatment in basal tumors (HR, 0.62; P = .07), which suggests there may still be a subset of basal tumors that are dependent on androgen pathway signaling and would benefit from ASI therapy, he said.

Regarding the difficulty of biopsying mCRPC metastases, the investigators noted that the limited intraindividual variability in biopsy results supports “the feasibility of classifying patients on [the] basis of a single biopsy of a metastatic tumor.”

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program, the National Cancer Institute, and others. Dr. Aggarwal has served as a paid consultant to and/or has received research funding from a number of companies, including Janssen, Merck, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Mabaera has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Furthermore, the classification is “an important step toward better personalizing therapy for men with mCRPC,” write investigators led by Rahul Aggarwal, MD, a genitourinary oncologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

The classification is already of clinical importance in localized disease for prognosis and guides treatment, but has not until now been examined in mCRPC, they point out.

That’s probably because of the difficulty of biopsying prostate metastases, which often reside in the bone, the team adds.

The team retrospectively reviewed genetic and clinical information from 634 men in four clinical trial cohorts; 45% had tumors classified as luminal and 55% were classified as basal, based on increased or decreased expression of luminal and basal gene signatures. Treatment in the cohorts was at physicians’ discretion.

Much of what the team found is similar to what’s been reported for localized disease. Namely, “that patients with luminal tumors should be considered for androgen-signaling inhibitor [ASI] therapy, and those with basal tumors could be considered for chemotherapeutic approaches given the similarity to small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer and the diminished benefit of androgen-signaling inhibitors,” Dr. Aggarwal and colleagues write.

Stunningly and consistent with dependence on oncogenic androgen-receptor signaling in luminal tumors, luminal patients had significantly better survival when they were treated with ASIs instead of chemotherapy, with a median overall survival of 32 vs. 8.7 months (hazard ratio, 0.27; P < .001).

Notably, luminal tumors demonstrated an increased expression of androgen-signaling genes and obtained preferential benefit for ASI therapy, compared with basal tumors.

The basal subtype included but was not exclusive to small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer (SCNC), “which raises the potential that non-SCNC basal tumors (the majority) may share enough similarity with their SCNC counterparts that similar chemotherapy-based treatment strategies may be effective, especially given the diminished benefit of ASI therapy,” the team writes.

Overall, the investigators say the findings “warrant further validation in larger prospective cohorts and clinical trials.”

Possibly practice changing

Rodwell Mabaera, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., agreed with investigators about the potential impact of the basal/luminal classifications in an accompanying editorial.

“These subtypes represent a potentially powerful tool for personalized therapeutic decision-making that may improve outcomes in mCRPC,” he writes.

Dr. Mabaera notes that “the worst survival outcome was seen among patients with luminal tumors treated with chemotherapy, suggesting a potential negative effect of chemotherapy in this subgroup.”

The authors “appropriately concluded that use of ASI would be recommended in this population. ... If confirmed, these results would be practice changing for choice of treatment in [the] luminal subtype of mCRPC.”

In basal tumors, the investigators identified genetic changes for resistance to androgen-receptor antagonists and increased dependence on DNA damage-repair pathways. That opens “the prospect that PARP inhibitors,” which block cancer cells from repairing DNA, “may be effective in this subgroup of patients,” Dr. Mabaera said.

The basal/luminal treatment duality may not completely apply, however.

That’s because there was a trend toward improved survival with ASI treatment in basal tumors (HR, 0.62; P = .07), which suggests there may still be a subset of basal tumors that are dependent on androgen pathway signaling and would benefit from ASI therapy, he said.

Regarding the difficulty of biopsying mCRPC metastases, the investigators noted that the limited intraindividual variability in biopsy results supports “the feasibility of classifying patients on [the] basis of a single biopsy of a metastatic tumor.”

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program, the National Cancer Institute, and others. Dr. Aggarwal has served as a paid consultant to and/or has received research funding from a number of companies, including Janssen, Merck, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Mabaera has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Furthermore, the classification is “an important step toward better personalizing therapy for men with mCRPC,” write investigators led by Rahul Aggarwal, MD, a genitourinary oncologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

The classification is already of clinical importance in localized disease for prognosis and guides treatment, but has not until now been examined in mCRPC, they point out.

That’s probably because of the difficulty of biopsying prostate metastases, which often reside in the bone, the team adds.

The team retrospectively reviewed genetic and clinical information from 634 men in four clinical trial cohorts; 45% had tumors classified as luminal and 55% were classified as basal, based on increased or decreased expression of luminal and basal gene signatures. Treatment in the cohorts was at physicians’ discretion.

Much of what the team found is similar to what’s been reported for localized disease. Namely, “that patients with luminal tumors should be considered for androgen-signaling inhibitor [ASI] therapy, and those with basal tumors could be considered for chemotherapeutic approaches given the similarity to small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer and the diminished benefit of androgen-signaling inhibitors,” Dr. Aggarwal and colleagues write.

Stunningly and consistent with dependence on oncogenic androgen-receptor signaling in luminal tumors, luminal patients had significantly better survival when they were treated with ASIs instead of chemotherapy, with a median overall survival of 32 vs. 8.7 months (hazard ratio, 0.27; P < .001).

Notably, luminal tumors demonstrated an increased expression of androgen-signaling genes and obtained preferential benefit for ASI therapy, compared with basal tumors.

The basal subtype included but was not exclusive to small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer (SCNC), “which raises the potential that non-SCNC basal tumors (the majority) may share enough similarity with their SCNC counterparts that similar chemotherapy-based treatment strategies may be effective, especially given the diminished benefit of ASI therapy,” the team writes.

Overall, the investigators say the findings “warrant further validation in larger prospective cohorts and clinical trials.”

Possibly practice changing

Rodwell Mabaera, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., agreed with investigators about the potential impact of the basal/luminal classifications in an accompanying editorial.

“These subtypes represent a potentially powerful tool for personalized therapeutic decision-making that may improve outcomes in mCRPC,” he writes.

Dr. Mabaera notes that “the worst survival outcome was seen among patients with luminal tumors treated with chemotherapy, suggesting a potential negative effect of chemotherapy in this subgroup.”

The authors “appropriately concluded that use of ASI would be recommended in this population. ... If confirmed, these results would be practice changing for choice of treatment in [the] luminal subtype of mCRPC.”

In basal tumors, the investigators identified genetic changes for resistance to androgen-receptor antagonists and increased dependence on DNA damage-repair pathways. That opens “the prospect that PARP inhibitors,” which block cancer cells from repairing DNA, “may be effective in this subgroup of patients,” Dr. Mabaera said.

The basal/luminal treatment duality may not completely apply, however.

That’s because there was a trend toward improved survival with ASI treatment in basal tumors (HR, 0.62; P = .07), which suggests there may still be a subset of basal tumors that are dependent on androgen pathway signaling and would benefit from ASI therapy, he said.

Regarding the difficulty of biopsying mCRPC metastases, the investigators noted that the limited intraindividual variability in biopsy results supports “the feasibility of classifying patients on [the] basis of a single biopsy of a metastatic tumor.”

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program, the National Cancer Institute, and others. Dr. Aggarwal has served as a paid consultant to and/or has received research funding from a number of companies, including Janssen, Merck, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Mabaera has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

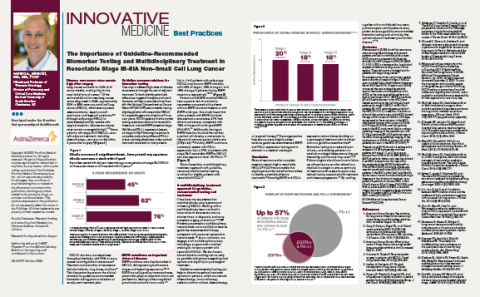

The Importance of Guideline-Recommended Biomarker Testing and Multidisciplinary Treatment in Resectable Stage IB-IIIA Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Genes related to osteosarcoma survival identified

When they combined them into a risk score and added one additional factor – metastases at diagnosis – the model was an “excellent” predictor of 1-year survival, the team said (area under the curve, 0.947; 95% confidence interval, 0.832-0.972).

“The survival-associated” immune-related genes (IRGs) “examined in this study have potential for identifying prognosis in osteosarcoma and may be clinically useful as relevant clinical biomarkers and candidate targets for anticancer therapy,” said investigators led by Wangmi Liu, MD, of Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

They explained that it’s often difficult to distinguish high- and low-risk patients at osteosarcoma diagnosis. To address the issue, they analyzed the genomic signatures of 84 patients in the Cancer Genome Atlas and their associated clinical information.

The team split their subjects evenly into high-risk and low-risk groups based on a score developed from their genetic signatures. A total of 26 patients in the high-risk group (61.9%) died over a median follow up of 4.1 years versus only 1 (2.4%) in the low-risk group.

The risk score also correlated positively with B-cell tumor infiltration, and negatively with infiltration of CD8 T cells and macrophages.

Overall, 16 genes were significantly up-regulated, and 187 genes were significantly down-regulated in the high-risk group, including three survival-associated IRGs: CCL2, CD79A, and FPR1.

The differentially expressed genes were most significantly associated with transmembrane signaling receptor activity and inflammatory response. The team noted that “it has been reported that inflammatory response plays a critical role in tumor initiation, promotion, malignant conversion, invasion, and metastases.”

Of the 14 survival-associated IRGs, 5 have been reported before in osteosarcoma. The other nine were deduced from computational analysis and may be potential treatment targets, including bone morphogenetic protein 8b (BMP8b). Another member of the BMP family, BMP9, has been shown to promote the proliferation of osteosarcoma cells, “which is similar to this study’s finding that BMP8b was a risk factor in osteosarcoma. Therefore, the role of BMP8b in osteosarcoma needs further research,” the team said.

“Because the database provides limited clinical information, other important factors, such as staging and grading, were not included in our analysis. Therefore, extrapolation based on the findings must be done very carefully,” they cautioned.

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and others. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

When they combined them into a risk score and added one additional factor – metastases at diagnosis – the model was an “excellent” predictor of 1-year survival, the team said (area under the curve, 0.947; 95% confidence interval, 0.832-0.972).

“The survival-associated” immune-related genes (IRGs) “examined in this study have potential for identifying prognosis in osteosarcoma and may be clinically useful as relevant clinical biomarkers and candidate targets for anticancer therapy,” said investigators led by Wangmi Liu, MD, of Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

They explained that it’s often difficult to distinguish high- and low-risk patients at osteosarcoma diagnosis. To address the issue, they analyzed the genomic signatures of 84 patients in the Cancer Genome Atlas and their associated clinical information.

The team split their subjects evenly into high-risk and low-risk groups based on a score developed from their genetic signatures. A total of 26 patients in the high-risk group (61.9%) died over a median follow up of 4.1 years versus only 1 (2.4%) in the low-risk group.

The risk score also correlated positively with B-cell tumor infiltration, and negatively with infiltration of CD8 T cells and macrophages.

Overall, 16 genes were significantly up-regulated, and 187 genes were significantly down-regulated in the high-risk group, including three survival-associated IRGs: CCL2, CD79A, and FPR1.

The differentially expressed genes were most significantly associated with transmembrane signaling receptor activity and inflammatory response. The team noted that “it has been reported that inflammatory response plays a critical role in tumor initiation, promotion, malignant conversion, invasion, and metastases.”

Of the 14 survival-associated IRGs, 5 have been reported before in osteosarcoma. The other nine were deduced from computational analysis and may be potential treatment targets, including bone morphogenetic protein 8b (BMP8b). Another member of the BMP family, BMP9, has been shown to promote the proliferation of osteosarcoma cells, “which is similar to this study’s finding that BMP8b was a risk factor in osteosarcoma. Therefore, the role of BMP8b in osteosarcoma needs further research,” the team said.

“Because the database provides limited clinical information, other important factors, such as staging and grading, were not included in our analysis. Therefore, extrapolation based on the findings must be done very carefully,” they cautioned.

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and others. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

When they combined them into a risk score and added one additional factor – metastases at diagnosis – the model was an “excellent” predictor of 1-year survival, the team said (area under the curve, 0.947; 95% confidence interval, 0.832-0.972).

“The survival-associated” immune-related genes (IRGs) “examined in this study have potential for identifying prognosis in osteosarcoma and may be clinically useful as relevant clinical biomarkers and candidate targets for anticancer therapy,” said investigators led by Wangmi Liu, MD, of Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

They explained that it’s often difficult to distinguish high- and low-risk patients at osteosarcoma diagnosis. To address the issue, they analyzed the genomic signatures of 84 patients in the Cancer Genome Atlas and their associated clinical information.

The team split their subjects evenly into high-risk and low-risk groups based on a score developed from their genetic signatures. A total of 26 patients in the high-risk group (61.9%) died over a median follow up of 4.1 years versus only 1 (2.4%) in the low-risk group.

The risk score also correlated positively with B-cell tumor infiltration, and negatively with infiltration of CD8 T cells and macrophages.

Overall, 16 genes were significantly up-regulated, and 187 genes were significantly down-regulated in the high-risk group, including three survival-associated IRGs: CCL2, CD79A, and FPR1.

The differentially expressed genes were most significantly associated with transmembrane signaling receptor activity and inflammatory response. The team noted that “it has been reported that inflammatory response plays a critical role in tumor initiation, promotion, malignant conversion, invasion, and metastases.”

Of the 14 survival-associated IRGs, 5 have been reported before in osteosarcoma. The other nine were deduced from computational analysis and may be potential treatment targets, including bone morphogenetic protein 8b (BMP8b). Another member of the BMP family, BMP9, has been shown to promote the proliferation of osteosarcoma cells, “which is similar to this study’s finding that BMP8b was a risk factor in osteosarcoma. Therefore, the role of BMP8b in osteosarcoma needs further research,” the team said.

“Because the database provides limited clinical information, other important factors, such as staging and grading, were not included in our analysis. Therefore, extrapolation based on the findings must be done very carefully,” they cautioned.

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and others. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

MRI screening cost effective for women with dense breasts

Alternatively, if a woman worries that the 4-year screening interval is too long, screening mammography may be offered every 2 years, with MRI screening offered for the second 2-year interval, according to the findings. This strategy would still require the patient to undergo MRI breast cancer screening every 4 years.

“MRI is more effective not only for selected patients. It is actually more effective than mammography for all women,” editorialist Christiane Kuhl, MD, PhD, University of Aachen (Germany), said in an interview.

“But the superior diagnostic accuracy of MRI is more often needed for women who are at higher risk for breast cancer, and therefore the cost-effectiveness is easier to achieve in women who are at higher risk,” she added.

The study was published online Sept. 29 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

DENSE trial

The simulation model used for the study was based on results from the Dense Tissue and Early Breast Neoplasm Screening (DENSE) trial, which showed that additional MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue led to significantly fewer interval cancers in comparison with mammography alone (P < .001). In the DENSE trial, MRI participants underwent mammography plus MRI at 2-year intervals; the control group underwent mammography alone at 2-year intervals.

In the current study, “screening strategies varied in the number of MRIs and mammograms offered to women aged 50-75 years,” explains Amarens Geuzinge, MSc, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues, “and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated ... with a willingness-to-pay threshold of 22,000 euros (>$25,000 U.S.),” the investigators add.

Analyses indicated that screening every 2 years with mammography alone cost the least of all strategies that were evaluated, but it also resulted in the lowest number of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) – in other words, it delivered the least amount of benefit for patients, coauthor Eveline Heijnsdijk, PhD, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, explained to this news organization.

Offering an additional MRI every 2 years resulted in the highest costs but not the highest number of QALYs and was inferior to the other screening strategies analyzed, she added. Alternating mammography with MRI breast cancer screening, each conducted every 2 years, came close to providing the same benefits to patients as the every-4-year MRI screening strategy, Dr. Heijnsdijk noted.

However, when the authors applied the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) threshold, MRI screening every 4 years yielded the highest acceptable incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), at 15,620 euros per QALYs, whereas screening every 3 years with MRI alone yielded an ICER of 37,181 euros per QALY.

If decision-makers are willing to pay more than 22,000 euros per QALY gained, “MRI every 2 or 3 years can also become cost effective,” the authors add.

Asked how acceptable MRI screening might be if performed only once every 4 years, Dr. Heijnsdijk noted that, in another of their studies, most of the women who had undergone MRI screening for breast cancer said that they would do so again. “MRI is not a pleasant test, but mammography is also not a pleasant test,” she said.

“So many women prefer MRI above mammography, especially because the detection rate with MRI is better than mammography,” she noted. Dr. Heijnsdijk also said that the percentage of women with extremely dense breasts who would be candidates for MRI screening is small – no more than 10% of women.

At a unit cost of slightly under 300 euros for MRI screening – compared with about 100 euros for screening mammography in the Netherlands – the cost of offering 10% of women MRI instead of mammography might increase, but any additional screening costs could be offset by reductions in the need to treat late-stage breast cancer more aggressively.

‘Interval’ cancers

Commenting further on the study, Dr. Kuhl pointed out that from 25% to 45% of cancers that occur in women who have undergone screening mammography are diagnosed as “interval” cancers, even among women who participate in the best mammography programs. “For a long time, people argued that these interval cancers developed only after the last respective mammogram, but that’s not true at all, because we know that with MRI screening, we can reduce the interval cancer rate down to zero,” Dr. Kuhl emphasized.

This is partially explained by the fact that mammography is “particularly blind” when it comes to detecting rapidly growing tumors. “The fact is that mammography has a modality-inherent tendency to preferentially detect slow-growing cancers, whereas rapidly growing tumors are indistinguishable from ubiquitous benign changes like cysts. [This] is why women who undergo screening mammography are frequently not diagnosed with the cancers that we really need to find,” she said.

Although there is ample talk about overdiagnosis when it comes to screening mammography, the overwhelmingly important problem is underdiagnosis. Even in exemplary mammography screening programs, at least 20% of tumors that are diagnosed on mammography have already advanced to a stage that is too late, Dr. Kuhl noted.

This means that at least half of women do not benefit from screening mammography nearly to the extent that they – and their health care practitioners – believe they should, she added. Dr. Kuhl underscored that this does not mean that clinicians should abandon screening mammography.

What it does mean is that physicians need to abandon the one-size-fits-all approach to screening mammography and start stratifying women on the basis of their individual risk of developing breast cancer by taking a family or personal history. Most women do undergo screening mammography at least once, Dr. Kuhl pointed out. From that mammogram, physicians can use information on breast density and breast architecture to better determine individual risk.

“We have good ideas about how to achieve risk stratification, but we’re not using them, because as long as mammography is the answer for everybody, there isn’t much motivation to dig deeper into the issue of how to determine risk,” Dr. Kuhl said.

“But we have to ensure the early diagnosis of aggressive cancers, and it’s exactly MRI that can do this, and we should start with women with very dense breasts because they are doubly underserved by mammography,” she said.

The study was supported by the University Medical Center Utrecht, Bayer HealthCare Medical Care, Matakina, and others. Ms. Geuzinge, Dr. Heijnsdijk, and Dr. Kuhl have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alternatively, if a woman worries that the 4-year screening interval is too long, screening mammography may be offered every 2 years, with MRI screening offered for the second 2-year interval, according to the findings. This strategy would still require the patient to undergo MRI breast cancer screening every 4 years.

“MRI is more effective not only for selected patients. It is actually more effective than mammography for all women,” editorialist Christiane Kuhl, MD, PhD, University of Aachen (Germany), said in an interview.

“But the superior diagnostic accuracy of MRI is more often needed for women who are at higher risk for breast cancer, and therefore the cost-effectiveness is easier to achieve in women who are at higher risk,” she added.

The study was published online Sept. 29 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

DENSE trial

The simulation model used for the study was based on results from the Dense Tissue and Early Breast Neoplasm Screening (DENSE) trial, which showed that additional MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue led to significantly fewer interval cancers in comparison with mammography alone (P < .001). In the DENSE trial, MRI participants underwent mammography plus MRI at 2-year intervals; the control group underwent mammography alone at 2-year intervals.

In the current study, “screening strategies varied in the number of MRIs and mammograms offered to women aged 50-75 years,” explains Amarens Geuzinge, MSc, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues, “and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated ... with a willingness-to-pay threshold of 22,000 euros (>$25,000 U.S.),” the investigators add.

Analyses indicated that screening every 2 years with mammography alone cost the least of all strategies that were evaluated, but it also resulted in the lowest number of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) – in other words, it delivered the least amount of benefit for patients, coauthor Eveline Heijnsdijk, PhD, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, explained to this news organization.

Offering an additional MRI every 2 years resulted in the highest costs but not the highest number of QALYs and was inferior to the other screening strategies analyzed, she added. Alternating mammography with MRI breast cancer screening, each conducted every 2 years, came close to providing the same benefits to patients as the every-4-year MRI screening strategy, Dr. Heijnsdijk noted.

However, when the authors applied the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) threshold, MRI screening every 4 years yielded the highest acceptable incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), at 15,620 euros per QALYs, whereas screening every 3 years with MRI alone yielded an ICER of 37,181 euros per QALY.

If decision-makers are willing to pay more than 22,000 euros per QALY gained, “MRI every 2 or 3 years can also become cost effective,” the authors add.

Asked how acceptable MRI screening might be if performed only once every 4 years, Dr. Heijnsdijk noted that, in another of their studies, most of the women who had undergone MRI screening for breast cancer said that they would do so again. “MRI is not a pleasant test, but mammography is also not a pleasant test,” she said.

“So many women prefer MRI above mammography, especially because the detection rate with MRI is better than mammography,” she noted. Dr. Heijnsdijk also said that the percentage of women with extremely dense breasts who would be candidates for MRI screening is small – no more than 10% of women.

At a unit cost of slightly under 300 euros for MRI screening – compared with about 100 euros for screening mammography in the Netherlands – the cost of offering 10% of women MRI instead of mammography might increase, but any additional screening costs could be offset by reductions in the need to treat late-stage breast cancer more aggressively.

‘Interval’ cancers

Commenting further on the study, Dr. Kuhl pointed out that from 25% to 45% of cancers that occur in women who have undergone screening mammography are diagnosed as “interval” cancers, even among women who participate in the best mammography programs. “For a long time, people argued that these interval cancers developed only after the last respective mammogram, but that’s not true at all, because we know that with MRI screening, we can reduce the interval cancer rate down to zero,” Dr. Kuhl emphasized.

This is partially explained by the fact that mammography is “particularly blind” when it comes to detecting rapidly growing tumors. “The fact is that mammography has a modality-inherent tendency to preferentially detect slow-growing cancers, whereas rapidly growing tumors are indistinguishable from ubiquitous benign changes like cysts. [This] is why women who undergo screening mammography are frequently not diagnosed with the cancers that we really need to find,” she said.

Although there is ample talk about overdiagnosis when it comes to screening mammography, the overwhelmingly important problem is underdiagnosis. Even in exemplary mammography screening programs, at least 20% of tumors that are diagnosed on mammography have already advanced to a stage that is too late, Dr. Kuhl noted.

This means that at least half of women do not benefit from screening mammography nearly to the extent that they – and their health care practitioners – believe they should, she added. Dr. Kuhl underscored that this does not mean that clinicians should abandon screening mammography.

What it does mean is that physicians need to abandon the one-size-fits-all approach to screening mammography and start stratifying women on the basis of their individual risk of developing breast cancer by taking a family or personal history. Most women do undergo screening mammography at least once, Dr. Kuhl pointed out. From that mammogram, physicians can use information on breast density and breast architecture to better determine individual risk.

“We have good ideas about how to achieve risk stratification, but we’re not using them, because as long as mammography is the answer for everybody, there isn’t much motivation to dig deeper into the issue of how to determine risk,” Dr. Kuhl said.

“But we have to ensure the early diagnosis of aggressive cancers, and it’s exactly MRI that can do this, and we should start with women with very dense breasts because they are doubly underserved by mammography,” she said.

The study was supported by the University Medical Center Utrecht, Bayer HealthCare Medical Care, Matakina, and others. Ms. Geuzinge, Dr. Heijnsdijk, and Dr. Kuhl have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alternatively, if a woman worries that the 4-year screening interval is too long, screening mammography may be offered every 2 years, with MRI screening offered for the second 2-year interval, according to the findings. This strategy would still require the patient to undergo MRI breast cancer screening every 4 years.

“MRI is more effective not only for selected patients. It is actually more effective than mammography for all women,” editorialist Christiane Kuhl, MD, PhD, University of Aachen (Germany), said in an interview.

“But the superior diagnostic accuracy of MRI is more often needed for women who are at higher risk for breast cancer, and therefore the cost-effectiveness is easier to achieve in women who are at higher risk,” she added.

The study was published online Sept. 29 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

DENSE trial

The simulation model used for the study was based on results from the Dense Tissue and Early Breast Neoplasm Screening (DENSE) trial, which showed that additional MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue led to significantly fewer interval cancers in comparison with mammography alone (P < .001). In the DENSE trial, MRI participants underwent mammography plus MRI at 2-year intervals; the control group underwent mammography alone at 2-year intervals.

In the current study, “screening strategies varied in the number of MRIs and mammograms offered to women aged 50-75 years,” explains Amarens Geuzinge, MSc, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues, “and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated ... with a willingness-to-pay threshold of 22,000 euros (>$25,000 U.S.),” the investigators add.

Analyses indicated that screening every 2 years with mammography alone cost the least of all strategies that were evaluated, but it also resulted in the lowest number of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) – in other words, it delivered the least amount of benefit for patients, coauthor Eveline Heijnsdijk, PhD, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, explained to this news organization.

Offering an additional MRI every 2 years resulted in the highest costs but not the highest number of QALYs and was inferior to the other screening strategies analyzed, she added. Alternating mammography with MRI breast cancer screening, each conducted every 2 years, came close to providing the same benefits to patients as the every-4-year MRI screening strategy, Dr. Heijnsdijk noted.

However, when the authors applied the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) threshold, MRI screening every 4 years yielded the highest acceptable incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), at 15,620 euros per QALYs, whereas screening every 3 years with MRI alone yielded an ICER of 37,181 euros per QALY.

If decision-makers are willing to pay more than 22,000 euros per QALY gained, “MRI every 2 or 3 years can also become cost effective,” the authors add.

Asked how acceptable MRI screening might be if performed only once every 4 years, Dr. Heijnsdijk noted that, in another of their studies, most of the women who had undergone MRI screening for breast cancer said that they would do so again. “MRI is not a pleasant test, but mammography is also not a pleasant test,” she said.

“So many women prefer MRI above mammography, especially because the detection rate with MRI is better than mammography,” she noted. Dr. Heijnsdijk also said that the percentage of women with extremely dense breasts who would be candidates for MRI screening is small – no more than 10% of women.

At a unit cost of slightly under 300 euros for MRI screening – compared with about 100 euros for screening mammography in the Netherlands – the cost of offering 10% of women MRI instead of mammography might increase, but any additional screening costs could be offset by reductions in the need to treat late-stage breast cancer more aggressively.

‘Interval’ cancers

Commenting further on the study, Dr. Kuhl pointed out that from 25% to 45% of cancers that occur in women who have undergone screening mammography are diagnosed as “interval” cancers, even among women who participate in the best mammography programs. “For a long time, people argued that these interval cancers developed only after the last respective mammogram, but that’s not true at all, because we know that with MRI screening, we can reduce the interval cancer rate down to zero,” Dr. Kuhl emphasized.

This is partially explained by the fact that mammography is “particularly blind” when it comes to detecting rapidly growing tumors. “The fact is that mammography has a modality-inherent tendency to preferentially detect slow-growing cancers, whereas rapidly growing tumors are indistinguishable from ubiquitous benign changes like cysts. [This] is why women who undergo screening mammography are frequently not diagnosed with the cancers that we really need to find,” she said.

Although there is ample talk about overdiagnosis when it comes to screening mammography, the overwhelmingly important problem is underdiagnosis. Even in exemplary mammography screening programs, at least 20% of tumors that are diagnosed on mammography have already advanced to a stage that is too late, Dr. Kuhl noted.

This means that at least half of women do not benefit from screening mammography nearly to the extent that they – and their health care practitioners – believe they should, she added. Dr. Kuhl underscored that this does not mean that clinicians should abandon screening mammography.

What it does mean is that physicians need to abandon the one-size-fits-all approach to screening mammography and start stratifying women on the basis of their individual risk of developing breast cancer by taking a family or personal history. Most women do undergo screening mammography at least once, Dr. Kuhl pointed out. From that mammogram, physicians can use information on breast density and breast architecture to better determine individual risk.

“We have good ideas about how to achieve risk stratification, but we’re not using them, because as long as mammography is the answer for everybody, there isn’t much motivation to dig deeper into the issue of how to determine risk,” Dr. Kuhl said.

“But we have to ensure the early diagnosis of aggressive cancers, and it’s exactly MRI that can do this, and we should start with women with very dense breasts because they are doubly underserved by mammography,” she said.

The study was supported by the University Medical Center Utrecht, Bayer HealthCare Medical Care, Matakina, and others. Ms. Geuzinge, Dr. Heijnsdijk, and Dr. Kuhl have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: CML October 2021

Ponatinib is most likely the most powerful tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved for the relapsed or refractory chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) after two lines of therapy. In the original PACE study, ponatinib showed deep and durable responses, but arterial occlusive events (AOE) emerged as notable adverse events. Post hoc analyses indicated that AOEs were dose dependent and recommendations to lower the dose from 45 mg to 30 mg after achieving complete cytogenic response (CCR) and to 15 mg after achieving major molecular response (MMR) were used in an attempt to minimize the cardiovascular toxicities. The question remained regarding the optimal dose of ponatinib in terms of efficacy and toxicity. Cortes et al (Blood 2021 Aug 18.) reported the results of the OPTIC trial where patients with chronic phase CML (CP-CML), resistant/intolerant to at least 2 prior BCR-ABL1 TKIs or with a BCR-ABL1T315I mutation, were randomized 1:1:1 to receive 3 different doses of ponatinib daily (45, 30, or 15 mg). Patients who received 45 mg or 30 mg daily reduced their dose to 15 mg upon achievement of response (BCR-ABL1IS transcript levels ≤1%). The primary endpoint (BCR-ABL1IS transcript levels ≤1%) was achieved at 12 months in 44.1%, 29.0%, and 23.1% in the 3 cohorts, respectively. Independently confirmed grade 3/4 treatment-emergent AOEs occurred in 5, 5, and 3 patients in the 3 cohorts, respectively. In conclusion, the optimal benefit:risk outcomes occurred with the 45 mg starting dose reduced to 15 mg upon achievement of response.

New drugs with alternative mechanisms of action are always welcome for the treatment of resistant or intolerant CP-CML. Asciminib is a first-in-class STAMP (Specifically Targeting the ABL Myristoyl Pocket) inhibitor with the potential to overcome resistance or intolerance to approved TKIs. Rea et al (Blood 2021 Aug 18) reported the results of the ASCEMBL trial that compare 40 mg twice daily asciminib vs. bosutinib in patients with CP-CML refractory to >2 previous lines of therapy. The rates of MMR at week 24 in patients receiving asciminib and bosutinib were 25.5% and 13.2%, respectively (difference 12.2%; P = .029). The bosutinib arm, compared to the asciminib arm, had a more frequent occurrence of grade 3 or higher adverse events (AE; 60.5% vs. 50.6%) and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation (21.1% vs. 5.8%). This will be another important alternative for CP-CML patients failing 2 lines of therapy; however, it is still unclear if the drug may be superior to ponatinib in the same setting.

In the new era of COVID-19, patients with hematologic malignancies are at an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19) and an adverse outcome. However, is unclear if this can be seen across the board in all type of hematologic malignancies, as a low mortality rate has been described in patients with CP-CML, suggesting that TKIs may have a protective role against severe COVID-19. Bonifacio et al (Cancer Med 2021 Aug 31) conducted a cross-sectional study of 564 consecutive patients with CML who were tested for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM antibodies at their first outpatient visit between May and early November 2020 in 5 hematologic centers representative of 3 Italian regions. Interestingly, the serological prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CML after the first pandemic wave was similar to that in the general population. The data confirm mild SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CML and suggest that patients with CML succeed to mount an antibody response after exposure to SARS-CoV-2 similar to the general population.

Ponatinib is most likely the most powerful tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved for the relapsed or refractory chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) after two lines of therapy. In the original PACE study, ponatinib showed deep and durable responses, but arterial occlusive events (AOE) emerged as notable adverse events. Post hoc analyses indicated that AOEs were dose dependent and recommendations to lower the dose from 45 mg to 30 mg after achieving complete cytogenic response (CCR) and to 15 mg after achieving major molecular response (MMR) were used in an attempt to minimize the cardiovascular toxicities. The question remained regarding the optimal dose of ponatinib in terms of efficacy and toxicity. Cortes et al (Blood 2021 Aug 18.) reported the results of the OPTIC trial where patients with chronic phase CML (CP-CML), resistant/intolerant to at least 2 prior BCR-ABL1 TKIs or with a BCR-ABL1T315I mutation, were randomized 1:1:1 to receive 3 different doses of ponatinib daily (45, 30, or 15 mg). Patients who received 45 mg or 30 mg daily reduced their dose to 15 mg upon achievement of response (BCR-ABL1IS transcript levels ≤1%). The primary endpoint (BCR-ABL1IS transcript levels ≤1%) was achieved at 12 months in 44.1%, 29.0%, and 23.1% in the 3 cohorts, respectively. Independently confirmed grade 3/4 treatment-emergent AOEs occurred in 5, 5, and 3 patients in the 3 cohorts, respectively. In conclusion, the optimal benefit:risk outcomes occurred with the 45 mg starting dose reduced to 15 mg upon achievement of response.

New drugs with alternative mechanisms of action are always welcome for the treatment of resistant or intolerant CP-CML. Asciminib is a first-in-class STAMP (Specifically Targeting the ABL Myristoyl Pocket) inhibitor with the potential to overcome resistance or intolerance to approved TKIs. Rea et al (Blood 2021 Aug 18) reported the results of the ASCEMBL trial that compare 40 mg twice daily asciminib vs. bosutinib in patients with CP-CML refractory to >2 previous lines of therapy. The rates of MMR at week 24 in patients receiving asciminib and bosutinib were 25.5% and 13.2%, respectively (difference 12.2%; P = .029). The bosutinib arm, compared to the asciminib arm, had a more frequent occurrence of grade 3 or higher adverse events (AE; 60.5% vs. 50.6%) and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation (21.1% vs. 5.8%). This will be another important alternative for CP-CML patients failing 2 lines of therapy; however, it is still unclear if the drug may be superior to ponatinib in the same setting.

In the new era of COVID-19, patients with hematologic malignancies are at an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19) and an adverse outcome. However, is unclear if this can be seen across the board in all type of hematologic malignancies, as a low mortality rate has been described in patients with CP-CML, suggesting that TKIs may have a protective role against severe COVID-19. Bonifacio et al (Cancer Med 2021 Aug 31) conducted a cross-sectional study of 564 consecutive patients with CML who were tested for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM antibodies at their first outpatient visit between May and early November 2020 in 5 hematologic centers representative of 3 Italian regions. Interestingly, the serological prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CML after the first pandemic wave was similar to that in the general population. The data confirm mild SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CML and suggest that patients with CML succeed to mount an antibody response after exposure to SARS-CoV-2 similar to the general population.

Ponatinib is most likely the most powerful tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved for the relapsed or refractory chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) after two lines of therapy. In the original PACE study, ponatinib showed deep and durable responses, but arterial occlusive events (AOE) emerged as notable adverse events. Post hoc analyses indicated that AOEs were dose dependent and recommendations to lower the dose from 45 mg to 30 mg after achieving complete cytogenic response (CCR) and to 15 mg after achieving major molecular response (MMR) were used in an attempt to minimize the cardiovascular toxicities. The question remained regarding the optimal dose of ponatinib in terms of efficacy and toxicity. Cortes et al (Blood 2021 Aug 18.) reported the results of the OPTIC trial where patients with chronic phase CML (CP-CML), resistant/intolerant to at least 2 prior BCR-ABL1 TKIs or with a BCR-ABL1T315I mutation, were randomized 1:1:1 to receive 3 different doses of ponatinib daily (45, 30, or 15 mg). Patients who received 45 mg or 30 mg daily reduced their dose to 15 mg upon achievement of response (BCR-ABL1IS transcript levels ≤1%). The primary endpoint (BCR-ABL1IS transcript levels ≤1%) was achieved at 12 months in 44.1%, 29.0%, and 23.1% in the 3 cohorts, respectively. Independently confirmed grade 3/4 treatment-emergent AOEs occurred in 5, 5, and 3 patients in the 3 cohorts, respectively. In conclusion, the optimal benefit:risk outcomes occurred with the 45 mg starting dose reduced to 15 mg upon achievement of response.

New drugs with alternative mechanisms of action are always welcome for the treatment of resistant or intolerant CP-CML. Asciminib is a first-in-class STAMP (Specifically Targeting the ABL Myristoyl Pocket) inhibitor with the potential to overcome resistance or intolerance to approved TKIs. Rea et al (Blood 2021 Aug 18) reported the results of the ASCEMBL trial that compare 40 mg twice daily asciminib vs. bosutinib in patients with CP-CML refractory to >2 previous lines of therapy. The rates of MMR at week 24 in patients receiving asciminib and bosutinib were 25.5% and 13.2%, respectively (difference 12.2%; P = .029). The bosutinib arm, compared to the asciminib arm, had a more frequent occurrence of grade 3 or higher adverse events (AE; 60.5% vs. 50.6%) and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation (21.1% vs. 5.8%). This will be another important alternative for CP-CML patients failing 2 lines of therapy; however, it is still unclear if the drug may be superior to ponatinib in the same setting.

In the new era of COVID-19, patients with hematologic malignancies are at an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19) and an adverse outcome. However, is unclear if this can be seen across the board in all type of hematologic malignancies, as a low mortality rate has been described in patients with CP-CML, suggesting that TKIs may have a protective role against severe COVID-19. Bonifacio et al (Cancer Med 2021 Aug 31) conducted a cross-sectional study of 564 consecutive patients with CML who were tested for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM antibodies at their first outpatient visit between May and early November 2020 in 5 hematologic centers representative of 3 Italian regions. Interestingly, the serological prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CML after the first pandemic wave was similar to that in the general population. The data confirm mild SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CML and suggest that patients with CML succeed to mount an antibody response after exposure to SARS-CoV-2 similar to the general population.

COVID-19: Two more cases of mucosal skin ulcers reported in male teens

Irish A similar case in an adolescent, also with ulcers affecting the mouth and penis, was reported earlier in 2021 in the United States.

“Our cases show that a swab for COVID-19 can be added to the list of investigations for mucosal and cutaneous rashes in children and probably adults,” said dermatologist Stephanie Bowe, MD, of South Infirmary-Victoria University Hospital in Cork, Ireland, in an interview. “Our patients seemed to improve with IV steroids, but there is not enough data to recommend them to all patients or for use in the different cutaneous presentations associated with COVID-19.”

The new case reports were presented at the 2021 meeting of the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology and published in Pediatric Dermatology.

Researchers have noted that skin disorders linked to COVID-19 infection are different than those in adults. In children, the conditions include morbilliform rash, pernio-like acral lesions, urticaria, macular erythema, vesicular eruption, papulosquamous eruption, and retiform purpura. “The pathogenesis of each is not fully understood but likely related to the inflammatory response to COVID-19 and the various pathways within the body, which become activated,” Dr. Bowe said.

The first patient, a 17-year-old boy, presented at clinic 6 days after he’d been confirmed to be infected with COVID-19 and 8 days after developing fever and cough. “He had a 2-day history of conjunctivitis and ulceration of his oral mucosa, erythematous circumferential erosions of the glans penis with no other cutaneous findings,” the authors write in the report.

The boy “was distressed and embarrassed about his genital ulceration and also found eating very painful due to his oral ulceration,” Dr. Bowe said.

The second patient, a 14-year-old boy, was hospitalized 7 days after a positive COVID-19 test and 9 days after developing cough and fever. “He had a 5-day history of ulceration of the oral mucosa with mild conjunctivitis,” the authors wrote. “Ulceration of the glans penis developed on day 2 of admission.”