User login

Janssen/J&J COVID-19 vaccine cuts transmission, new data show

The single-dose vaccine reduces the risk of asymptomatic transmission by 74% at 71 days, compared with placebo, according to documents released today by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“The decrease in asymptomatic transmission is very welcome news too in curbing the spread of the virus,” Phyllis Tien, MD, told this news organization.

“While the earlier press release reported that the vaccine was effective against preventing severe COVID-19 disease, as well as hospitalizations and death, this new data shows that the vaccine can also decrease transmission, which is very important on a public health level,” said Dr. Tien, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of California, San Francisco.

“It is extremely important in terms of getting to herd immunity,” Paul Goepfert, MD, director of the Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic and infectious disease specialist at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, said in an interview. “It means that this vaccine is likely preventing subsequent transmission after a single dose, which could have huge implications once we get the majority of folks vaccinated.”

The FDA cautioned that the numbers of participants included in the study are relatively small and need to be verified. However, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine might not be the only product offering this advantage. Early data suggest that the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine also decreases transmission, providing further evidence that the protection offered by immunization goes beyond the individual.

The new analyses were provided by the FDA in advance of its review of the Janssen/Johnson & Johnson vaccine. The agency plans to fully address the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine at its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting on Friday, including evaluating its safety and efficacy.

The agency’s decision on whether or not to grant emergency use authorization (EUA) to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine could come as early as Friday evening or Saturday.

In addition to the newly released data, officials are likely to discuss phase 3 data, released Jan. 29, that reveal an 85% efficacy for the vaccine against severe COVID-19 illness globally, including data from South America, South Africa, and the United States. When the analysis was restricted to data from U.S. participants, the trial showed a 73% efficacy against moderate to severe COVID-19.

If and when the FDA grants an EUA, it remains unclear how much of the new vaccine will be immediately available. Initially, Johnson & Johnson predicted 18 million doses would be ready by the end of February, but others stated the figure will be closer to 2-4 million. The manufacturer’s contract with the U.S. government stipulates production of 100-million doses by the end of June.

Dr. Tien received support from Johnson & Johnson to conduct the J&J COVID-19 vaccine trial in the SF VA HealthCare System. Dr. Goepfert has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The single-dose vaccine reduces the risk of asymptomatic transmission by 74% at 71 days, compared with placebo, according to documents released today by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“The decrease in asymptomatic transmission is very welcome news too in curbing the spread of the virus,” Phyllis Tien, MD, told this news organization.

“While the earlier press release reported that the vaccine was effective against preventing severe COVID-19 disease, as well as hospitalizations and death, this new data shows that the vaccine can also decrease transmission, which is very important on a public health level,” said Dr. Tien, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of California, San Francisco.

“It is extremely important in terms of getting to herd immunity,” Paul Goepfert, MD, director of the Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic and infectious disease specialist at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, said in an interview. “It means that this vaccine is likely preventing subsequent transmission after a single dose, which could have huge implications once we get the majority of folks vaccinated.”

The FDA cautioned that the numbers of participants included in the study are relatively small and need to be verified. However, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine might not be the only product offering this advantage. Early data suggest that the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine also decreases transmission, providing further evidence that the protection offered by immunization goes beyond the individual.

The new analyses were provided by the FDA in advance of its review of the Janssen/Johnson & Johnson vaccine. The agency plans to fully address the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine at its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting on Friday, including evaluating its safety and efficacy.

The agency’s decision on whether or not to grant emergency use authorization (EUA) to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine could come as early as Friday evening or Saturday.

In addition to the newly released data, officials are likely to discuss phase 3 data, released Jan. 29, that reveal an 85% efficacy for the vaccine against severe COVID-19 illness globally, including data from South America, South Africa, and the United States. When the analysis was restricted to data from U.S. participants, the trial showed a 73% efficacy against moderate to severe COVID-19.

If and when the FDA grants an EUA, it remains unclear how much of the new vaccine will be immediately available. Initially, Johnson & Johnson predicted 18 million doses would be ready by the end of February, but others stated the figure will be closer to 2-4 million. The manufacturer’s contract with the U.S. government stipulates production of 100-million doses by the end of June.

Dr. Tien received support from Johnson & Johnson to conduct the J&J COVID-19 vaccine trial in the SF VA HealthCare System. Dr. Goepfert has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The single-dose vaccine reduces the risk of asymptomatic transmission by 74% at 71 days, compared with placebo, according to documents released today by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“The decrease in asymptomatic transmission is very welcome news too in curbing the spread of the virus,” Phyllis Tien, MD, told this news organization.

“While the earlier press release reported that the vaccine was effective against preventing severe COVID-19 disease, as well as hospitalizations and death, this new data shows that the vaccine can also decrease transmission, which is very important on a public health level,” said Dr. Tien, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of California, San Francisco.

“It is extremely important in terms of getting to herd immunity,” Paul Goepfert, MD, director of the Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic and infectious disease specialist at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, said in an interview. “It means that this vaccine is likely preventing subsequent transmission after a single dose, which could have huge implications once we get the majority of folks vaccinated.”

The FDA cautioned that the numbers of participants included in the study are relatively small and need to be verified. However, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine might not be the only product offering this advantage. Early data suggest that the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine also decreases transmission, providing further evidence that the protection offered by immunization goes beyond the individual.

The new analyses were provided by the FDA in advance of its review of the Janssen/Johnson & Johnson vaccine. The agency plans to fully address the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine at its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting on Friday, including evaluating its safety and efficacy.

The agency’s decision on whether or not to grant emergency use authorization (EUA) to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine could come as early as Friday evening or Saturday.

In addition to the newly released data, officials are likely to discuss phase 3 data, released Jan. 29, that reveal an 85% efficacy for the vaccine against severe COVID-19 illness globally, including data from South America, South Africa, and the United States. When the analysis was restricted to data from U.S. participants, the trial showed a 73% efficacy against moderate to severe COVID-19.

If and when the FDA grants an EUA, it remains unclear how much of the new vaccine will be immediately available. Initially, Johnson & Johnson predicted 18 million doses would be ready by the end of February, but others stated the figure will be closer to 2-4 million. The manufacturer’s contract with the U.S. government stipulates production of 100-million doses by the end of June.

Dr. Tien received support from Johnson & Johnson to conduct the J&J COVID-19 vaccine trial in the SF VA HealthCare System. Dr. Goepfert has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New data may help intercept head injuries in college football

Novel research from the Concussion Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium sheds new light on how to effectively reduce the incidence of concussion and head injury exposure in college football.

The study, led by neurotrauma experts Michael McCrea, PhD, and Brian Stemper, PhD, professors of neurosurgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, reports data from hundreds of college football players across five seasons and shows

The research also reveals that such injuries occur more often during practices than games.

“We think that with the findings from this paper, there’s a role for everybody to play in reducing injury,” Dr. McCrea said. “We hope these data help inform broad-based policy about practice and preseason training policies in collegiate football. We also think there’s a role for athletic administrators, coaches, and even athletes themselves.”

The study was published online Feb. 1 in JAMA Neurology.

More injuries in preseason

Concussion is one of the most common injuries in football. Beyond these harms are growing concerns that repetitive HIE may increase the risk of long-term neurologic health problems including chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

The CARE Consortium, which has been conducting research with college athletes across 26 sports and military cadets since 2014, has been interested in multiple facets of concussion and brain trauma.

“We’ve enrolled more than 50,000 athletes and service academy cadets into the consortium over the last 6 years to research all involved aspects including the clinical core, the imaging core, the blood biomarker core, and the genetic core, and we have a head impact measurement core.”

To investigate the pattern of concussion incidence across the football season in college players, the investigators used impact measurement technology across six Division I NCAA football programs participating in the CARE Consortium from 2015 to 2019.

A total of 658 players – all male, mean age 19 years – were fitted with the Head Impact Telemetry System (HITS) sensor arrays in their helmets to measure head impact frequency, location, and magnitude during play.

“This particular study had built-in algorithms that weeded out impacts that were below 10G of linear magnitude, because those have been determined not likely to be real impacts,” Dr. McCrea said.

Across the five seasons studied, 528,684 head impacts recorded met the quality standards for analysis. Players sustained a median of 415 (interquartile range [IQR], 190-727) impacts per season.

Of those, 68 players sustained a diagnosed concussion. In total, 48.5% of concussions occurred during preseason training, despite preseason representing only 20.8% of the football season. Total head injury exposure in the preseason occurred at twice the proportion of the regular season (324.9 vs. 162.4 impacts per team per day; mean difference, 162.6 impacts; 95% confidence interval, 110.9-214.3; P < .001).

“Preseason training often has a much higher intensity to it, in terms of the total hours, the actual training, and the heavy emphasis on full-contact drills like tackling and blocking,” said Dr. McCrea. “Even the volume of players that are participating is greater.”

Results also showed that in each of the five seasons, head injury exposure per athlete was highest in August (preseason) (median, 146.0 impacts; IQR, 63.0-247.8) and lowest in November (median, 80.0 impacts; IQR, 35.0-148.0). In the studied period, 72% of concussions and 66.9% of head injury exposure occurred in practice. Even within the regular season, total head injury exposure in practices was 84.2% higher than in games.

“This incredible dataset we have on head impact measurement also gives us the opportunity to compare it with our other research looking at the correlation between a single head impact and changes in brain structure and function on MRI, on blood biomarkers, giving us the ability to look at the connection between mechanism of effect of injury and recovery from injury,” said Dr. McCrea.

These findings also provide an opportunity to modify approaches to preseason training and football practices to keep players safer, said Dr. McCrea, noting that about half of the variance in head injury exposure is at the level of the individual athlete.

“With this large body of athletes we’ve instrumented, we can look at, for instance, all of the running backs and understand the athlete and what his head injury exposure looks like compared to all other running backs. If we find out that an athlete has a rate of head injury exposure that’s 300% higher than most other players that play the same position, we can take that data directly to the athlete to work on their technique and approach to the game.

“Every researcher wishes that their basic science or their clinical research findings will have some impact on the health and well-being of the population they’re studying. By modifying practices and preseason training, football teams could greatly reduce the risk of injury and exposure for their players, while still maintaining the competitive nature of game play,” he added.

Through a combination of policy and education, similar strategies could be implemented to help prevent concussion and HIE in high school and youth football too, said Dr. McCrea.

‘Shocking’ findings

In an accompanying editorial, Christopher J. Nowinski, PhD, of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, Boston, and Robert C. Cantu, MD, department of neurosurgery, Emerson Hospital, Concord, Massachusetts, said the findings could have significant policy implications and offer a valuable expansion of prior research.

“From 2005 to 2010, studies on college football revealed that about two-thirds of head impacts occurred in practice,” they noted. “We cited this data in 2010 when we proposed to the NFL Players Association that the most effective way to reduce the risks of negative neurological outcomes was to reduce hitting in practice. They agreed, and in 2011 collectively bargained for severe contact limits in practice, with 14 full-contact practices allowed during the 17-week season. Since that rule was implemented, only 18% of NFL concussions have occurred in practice.”

“Against this backdrop, the results of the study by McCrea et al. are shocking,” they added. “It reveals that college football players still experience 72% of their concussions and 67% of their total head injury exposure in practice.”

Even more shocking, noted Dr. Nowinski and Dr. Cantu, is that these numbers are almost certainly an underestimate of the dangers of practice.

“As a former college football player and a former team physician, respectively, we find this situation inexcusable. Concussions in games are inevitable, but concussions in practice are preventable,” they wrote.

“Laudably,” they added “the investigators call on the NCAA and football conferences to explore policy and rule changes to reduce concussion incidence and HIE and to create robust educational offerings to encourage change from coaches and college administrators.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Novel research from the Concussion Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium sheds new light on how to effectively reduce the incidence of concussion and head injury exposure in college football.

The study, led by neurotrauma experts Michael McCrea, PhD, and Brian Stemper, PhD, professors of neurosurgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, reports data from hundreds of college football players across five seasons and shows

The research also reveals that such injuries occur more often during practices than games.

“We think that with the findings from this paper, there’s a role for everybody to play in reducing injury,” Dr. McCrea said. “We hope these data help inform broad-based policy about practice and preseason training policies in collegiate football. We also think there’s a role for athletic administrators, coaches, and even athletes themselves.”

The study was published online Feb. 1 in JAMA Neurology.

More injuries in preseason

Concussion is one of the most common injuries in football. Beyond these harms are growing concerns that repetitive HIE may increase the risk of long-term neurologic health problems including chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

The CARE Consortium, which has been conducting research with college athletes across 26 sports and military cadets since 2014, has been interested in multiple facets of concussion and brain trauma.

“We’ve enrolled more than 50,000 athletes and service academy cadets into the consortium over the last 6 years to research all involved aspects including the clinical core, the imaging core, the blood biomarker core, and the genetic core, and we have a head impact measurement core.”

To investigate the pattern of concussion incidence across the football season in college players, the investigators used impact measurement technology across six Division I NCAA football programs participating in the CARE Consortium from 2015 to 2019.

A total of 658 players – all male, mean age 19 years – were fitted with the Head Impact Telemetry System (HITS) sensor arrays in their helmets to measure head impact frequency, location, and magnitude during play.

“This particular study had built-in algorithms that weeded out impacts that were below 10G of linear magnitude, because those have been determined not likely to be real impacts,” Dr. McCrea said.

Across the five seasons studied, 528,684 head impacts recorded met the quality standards for analysis. Players sustained a median of 415 (interquartile range [IQR], 190-727) impacts per season.

Of those, 68 players sustained a diagnosed concussion. In total, 48.5% of concussions occurred during preseason training, despite preseason representing only 20.8% of the football season. Total head injury exposure in the preseason occurred at twice the proportion of the regular season (324.9 vs. 162.4 impacts per team per day; mean difference, 162.6 impacts; 95% confidence interval, 110.9-214.3; P < .001).

“Preseason training often has a much higher intensity to it, in terms of the total hours, the actual training, and the heavy emphasis on full-contact drills like tackling and blocking,” said Dr. McCrea. “Even the volume of players that are participating is greater.”

Results also showed that in each of the five seasons, head injury exposure per athlete was highest in August (preseason) (median, 146.0 impacts; IQR, 63.0-247.8) and lowest in November (median, 80.0 impacts; IQR, 35.0-148.0). In the studied period, 72% of concussions and 66.9% of head injury exposure occurred in practice. Even within the regular season, total head injury exposure in practices was 84.2% higher than in games.

“This incredible dataset we have on head impact measurement also gives us the opportunity to compare it with our other research looking at the correlation between a single head impact and changes in brain structure and function on MRI, on blood biomarkers, giving us the ability to look at the connection between mechanism of effect of injury and recovery from injury,” said Dr. McCrea.

These findings also provide an opportunity to modify approaches to preseason training and football practices to keep players safer, said Dr. McCrea, noting that about half of the variance in head injury exposure is at the level of the individual athlete.

“With this large body of athletes we’ve instrumented, we can look at, for instance, all of the running backs and understand the athlete and what his head injury exposure looks like compared to all other running backs. If we find out that an athlete has a rate of head injury exposure that’s 300% higher than most other players that play the same position, we can take that data directly to the athlete to work on their technique and approach to the game.

“Every researcher wishes that their basic science or their clinical research findings will have some impact on the health and well-being of the population they’re studying. By modifying practices and preseason training, football teams could greatly reduce the risk of injury and exposure for their players, while still maintaining the competitive nature of game play,” he added.

Through a combination of policy and education, similar strategies could be implemented to help prevent concussion and HIE in high school and youth football too, said Dr. McCrea.

‘Shocking’ findings

In an accompanying editorial, Christopher J. Nowinski, PhD, of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, Boston, and Robert C. Cantu, MD, department of neurosurgery, Emerson Hospital, Concord, Massachusetts, said the findings could have significant policy implications and offer a valuable expansion of prior research.

“From 2005 to 2010, studies on college football revealed that about two-thirds of head impacts occurred in practice,” they noted. “We cited this data in 2010 when we proposed to the NFL Players Association that the most effective way to reduce the risks of negative neurological outcomes was to reduce hitting in practice. They agreed, and in 2011 collectively bargained for severe contact limits in practice, with 14 full-contact practices allowed during the 17-week season. Since that rule was implemented, only 18% of NFL concussions have occurred in practice.”

“Against this backdrop, the results of the study by McCrea et al. are shocking,” they added. “It reveals that college football players still experience 72% of their concussions and 67% of their total head injury exposure in practice.”

Even more shocking, noted Dr. Nowinski and Dr. Cantu, is that these numbers are almost certainly an underestimate of the dangers of practice.

“As a former college football player and a former team physician, respectively, we find this situation inexcusable. Concussions in games are inevitable, but concussions in practice are preventable,” they wrote.

“Laudably,” they added “the investigators call on the NCAA and football conferences to explore policy and rule changes to reduce concussion incidence and HIE and to create robust educational offerings to encourage change from coaches and college administrators.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Novel research from the Concussion Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium sheds new light on how to effectively reduce the incidence of concussion and head injury exposure in college football.

The study, led by neurotrauma experts Michael McCrea, PhD, and Brian Stemper, PhD, professors of neurosurgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, reports data from hundreds of college football players across five seasons and shows

The research also reveals that such injuries occur more often during practices than games.

“We think that with the findings from this paper, there’s a role for everybody to play in reducing injury,” Dr. McCrea said. “We hope these data help inform broad-based policy about practice and preseason training policies in collegiate football. We also think there’s a role for athletic administrators, coaches, and even athletes themselves.”

The study was published online Feb. 1 in JAMA Neurology.

More injuries in preseason

Concussion is one of the most common injuries in football. Beyond these harms are growing concerns that repetitive HIE may increase the risk of long-term neurologic health problems including chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

The CARE Consortium, which has been conducting research with college athletes across 26 sports and military cadets since 2014, has been interested in multiple facets of concussion and brain trauma.

“We’ve enrolled more than 50,000 athletes and service academy cadets into the consortium over the last 6 years to research all involved aspects including the clinical core, the imaging core, the blood biomarker core, and the genetic core, and we have a head impact measurement core.”

To investigate the pattern of concussion incidence across the football season in college players, the investigators used impact measurement technology across six Division I NCAA football programs participating in the CARE Consortium from 2015 to 2019.

A total of 658 players – all male, mean age 19 years – were fitted with the Head Impact Telemetry System (HITS) sensor arrays in their helmets to measure head impact frequency, location, and magnitude during play.

“This particular study had built-in algorithms that weeded out impacts that were below 10G of linear magnitude, because those have been determined not likely to be real impacts,” Dr. McCrea said.

Across the five seasons studied, 528,684 head impacts recorded met the quality standards for analysis. Players sustained a median of 415 (interquartile range [IQR], 190-727) impacts per season.

Of those, 68 players sustained a diagnosed concussion. In total, 48.5% of concussions occurred during preseason training, despite preseason representing only 20.8% of the football season. Total head injury exposure in the preseason occurred at twice the proportion of the regular season (324.9 vs. 162.4 impacts per team per day; mean difference, 162.6 impacts; 95% confidence interval, 110.9-214.3; P < .001).

“Preseason training often has a much higher intensity to it, in terms of the total hours, the actual training, and the heavy emphasis on full-contact drills like tackling and blocking,” said Dr. McCrea. “Even the volume of players that are participating is greater.”

Results also showed that in each of the five seasons, head injury exposure per athlete was highest in August (preseason) (median, 146.0 impacts; IQR, 63.0-247.8) and lowest in November (median, 80.0 impacts; IQR, 35.0-148.0). In the studied period, 72% of concussions and 66.9% of head injury exposure occurred in practice. Even within the regular season, total head injury exposure in practices was 84.2% higher than in games.

“This incredible dataset we have on head impact measurement also gives us the opportunity to compare it with our other research looking at the correlation between a single head impact and changes in brain structure and function on MRI, on blood biomarkers, giving us the ability to look at the connection between mechanism of effect of injury and recovery from injury,” said Dr. McCrea.

These findings also provide an opportunity to modify approaches to preseason training and football practices to keep players safer, said Dr. McCrea, noting that about half of the variance in head injury exposure is at the level of the individual athlete.

“With this large body of athletes we’ve instrumented, we can look at, for instance, all of the running backs and understand the athlete and what his head injury exposure looks like compared to all other running backs. If we find out that an athlete has a rate of head injury exposure that’s 300% higher than most other players that play the same position, we can take that data directly to the athlete to work on their technique and approach to the game.

“Every researcher wishes that their basic science or their clinical research findings will have some impact on the health and well-being of the population they’re studying. By modifying practices and preseason training, football teams could greatly reduce the risk of injury and exposure for their players, while still maintaining the competitive nature of game play,” he added.

Through a combination of policy and education, similar strategies could be implemented to help prevent concussion and HIE in high school and youth football too, said Dr. McCrea.

‘Shocking’ findings

In an accompanying editorial, Christopher J. Nowinski, PhD, of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, Boston, and Robert C. Cantu, MD, department of neurosurgery, Emerson Hospital, Concord, Massachusetts, said the findings could have significant policy implications and offer a valuable expansion of prior research.

“From 2005 to 2010, studies on college football revealed that about two-thirds of head impacts occurred in practice,” they noted. “We cited this data in 2010 when we proposed to the NFL Players Association that the most effective way to reduce the risks of negative neurological outcomes was to reduce hitting in practice. They agreed, and in 2011 collectively bargained for severe contact limits in practice, with 14 full-contact practices allowed during the 17-week season. Since that rule was implemented, only 18% of NFL concussions have occurred in practice.”

“Against this backdrop, the results of the study by McCrea et al. are shocking,” they added. “It reveals that college football players still experience 72% of their concussions and 67% of their total head injury exposure in practice.”

Even more shocking, noted Dr. Nowinski and Dr. Cantu, is that these numbers are almost certainly an underestimate of the dangers of practice.

“As a former college football player and a former team physician, respectively, we find this situation inexcusable. Concussions in games are inevitable, but concussions in practice are preventable,” they wrote.

“Laudably,” they added “the investigators call on the NCAA and football conferences to explore policy and rule changes to reduce concussion incidence and HIE and to create robust educational offerings to encourage change from coaches and college administrators.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

FPs need to remind patients they care for whole families

I think there are multiple factors explaining why the percentage of family physicians treating children declined again. Not the least of these is that pediatricians have a very limited scope of practice and need to market and attract patients, which they do quite a bit. There are even pediatric urgent care centers popping up all over the place now, some likely funded by venture capital just as other urgent care centers have been funded.

The loss of pediatric inpatient volume because of the effectiveness of vaccines that prevent many bacterial and viral illnesses means that fewer pediatric graduates are spending time in the hospital.

Family doctors used to retain their pediatric patients by delivering babies, seeing them in the newborn nursery, and beginning their relationship with the kids there. FPs are delivering fewer babies and the subsequent reduction in new kids in their practices has been a factor in this as well.

Finally, in multispecialty practices, pediatricians are employed there. Families immediately assume that their kids should be going to the pediatricians, not the family doctors. We need to keep talking up the fact that we take care of whole families to retain our pediatric practices.

Neil S. Calman, MD, is president and chief executive officer of the Institute for Family Health and is professor and chair of the Alfred and Gail Engelberg department of family medicine and community health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the Mount Sinai Health System, both in New York. Dr. Calman also serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News.

I think there are multiple factors explaining why the percentage of family physicians treating children declined again. Not the least of these is that pediatricians have a very limited scope of practice and need to market and attract patients, which they do quite a bit. There are even pediatric urgent care centers popping up all over the place now, some likely funded by venture capital just as other urgent care centers have been funded.

The loss of pediatric inpatient volume because of the effectiveness of vaccines that prevent many bacterial and viral illnesses means that fewer pediatric graduates are spending time in the hospital.

Family doctors used to retain their pediatric patients by delivering babies, seeing them in the newborn nursery, and beginning their relationship with the kids there. FPs are delivering fewer babies and the subsequent reduction in new kids in their practices has been a factor in this as well.

Finally, in multispecialty practices, pediatricians are employed there. Families immediately assume that their kids should be going to the pediatricians, not the family doctors. We need to keep talking up the fact that we take care of whole families to retain our pediatric practices.

Neil S. Calman, MD, is president and chief executive officer of the Institute for Family Health and is professor and chair of the Alfred and Gail Engelberg department of family medicine and community health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the Mount Sinai Health System, both in New York. Dr. Calman also serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News.

I think there are multiple factors explaining why the percentage of family physicians treating children declined again. Not the least of these is that pediatricians have a very limited scope of practice and need to market and attract patients, which they do quite a bit. There are even pediatric urgent care centers popping up all over the place now, some likely funded by venture capital just as other urgent care centers have been funded.

The loss of pediatric inpatient volume because of the effectiveness of vaccines that prevent many bacterial and viral illnesses means that fewer pediatric graduates are spending time in the hospital.

Family doctors used to retain their pediatric patients by delivering babies, seeing them in the newborn nursery, and beginning their relationship with the kids there. FPs are delivering fewer babies and the subsequent reduction in new kids in their practices has been a factor in this as well.

Finally, in multispecialty practices, pediatricians are employed there. Families immediately assume that their kids should be going to the pediatricians, not the family doctors. We need to keep talking up the fact that we take care of whole families to retain our pediatric practices.

Neil S. Calman, MD, is president and chief executive officer of the Institute for Family Health and is professor and chair of the Alfred and Gail Engelberg department of family medicine and community health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the Mount Sinai Health System, both in New York. Dr. Calman also serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News.

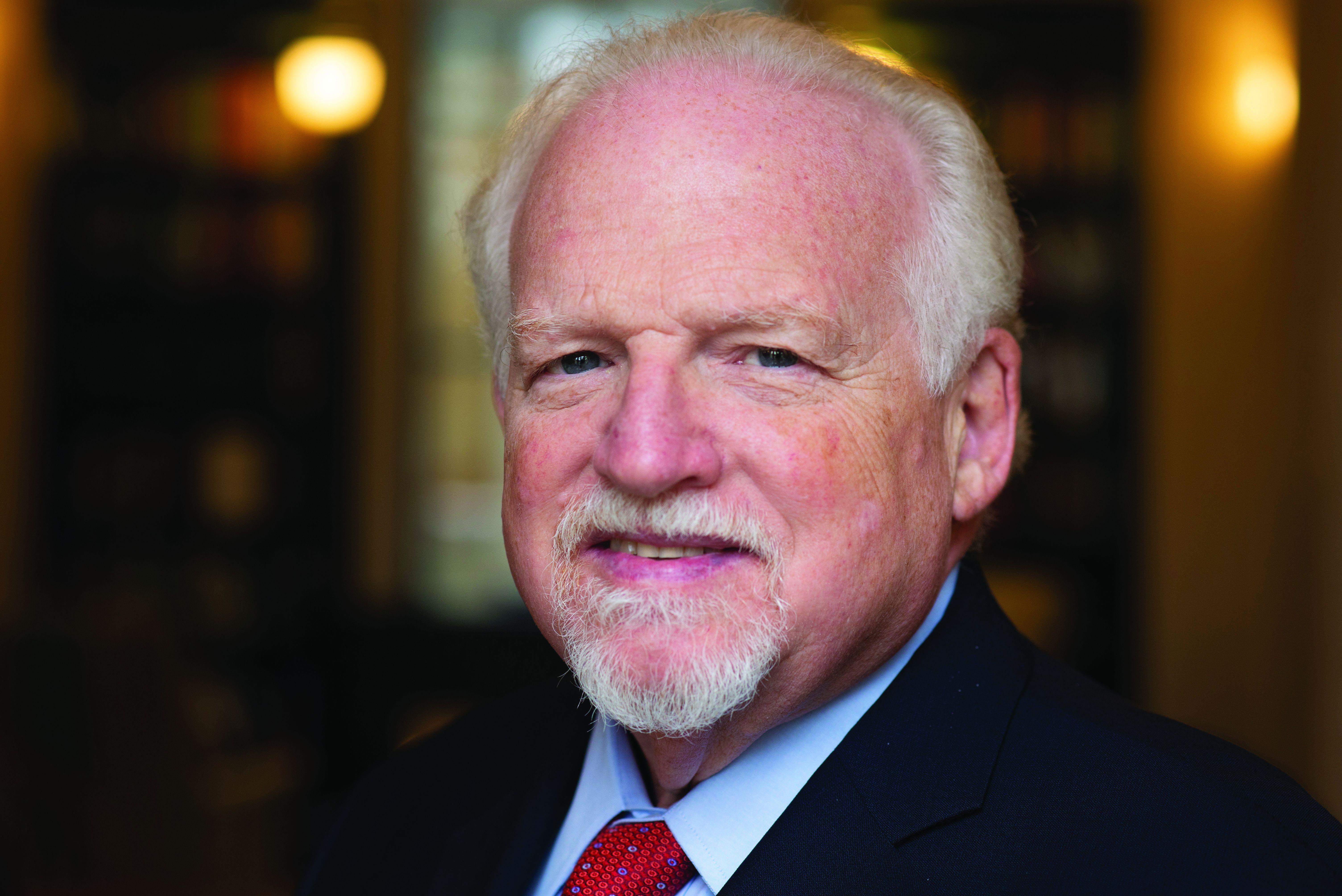

Ob.gyns. report high burnout prior to pandemic

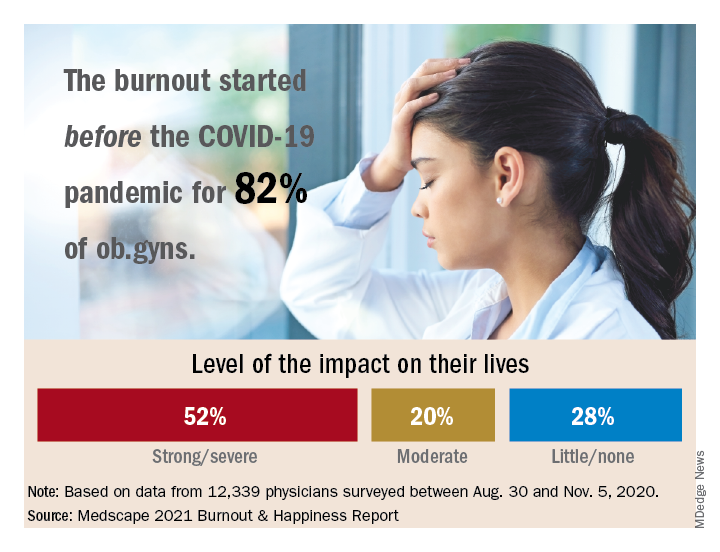

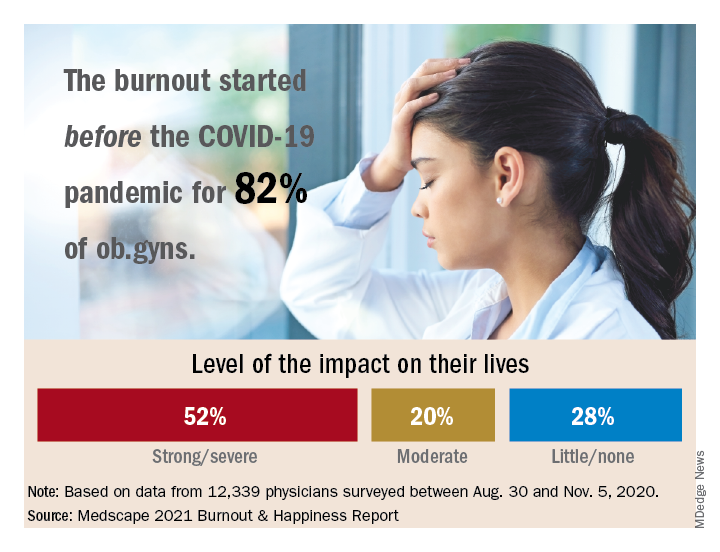

Among ob.gyns. who reported burnout in the past year, 82% say they felt burned out before the advent of the coronavirus pandemic, according the Medscape Obstetrician & Gynecologist Lifestyle, Happiness, & Burnout Report.

The past year brought unusual challenges to physicians in all specialties in different ways.

“Whether on the front lines of treating COVID-19 patients, pivoting from in-person to virtual care, or even having to shutter their practices, physicians faced an onslaught of crises, while political tensions, social unrest, and environmental concerns probably affected their lives outside of medicine,” wrote Keith L. Martin and Mary Lyn Koval, both of Medscape Business of Medicine, in the introduction to the report.

Although more physicians said their burnout began prior to the pandemic, 81% of ob.gyns. reported that they were happy outside of work prior to the pandemic. However, those reporting happiness outside of work dropped to 57% after the pandemic started.

“One does not have to do a ‘deep dive’ to understand the top reasons reported for burnout,” said Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of Fertility CARE: The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, in an interview. “Many conversations I have with colleagues are about the frustration of learning and managing electronic health records, insurance reimbursements, and a work-life balance. In addition, more physician practices are being purchased by hospitals or private-equity networks [that are] reducing and/or eliminating the autonomy of physicians.

“While all [respondents] exhibited a dramatic decline in ‘happiness’ prepandemic, compared with our current situation, ob.gyns. were no exception,” he added.

Burnout and suicidal thoughts

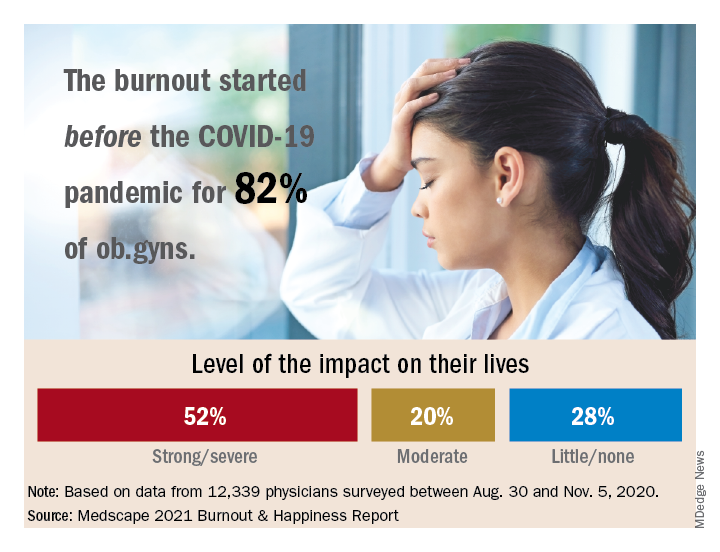

Overall, 26% of ob.gyn. survey respondents reported being burned out, 6% reported being depressed, and 18% reported being both burned out and depressed. Of those who reported burnout, 52% said burnout had “a strong or severe impact on my life,” while 20% reported a moderate impact and 28% reported little or no impact.

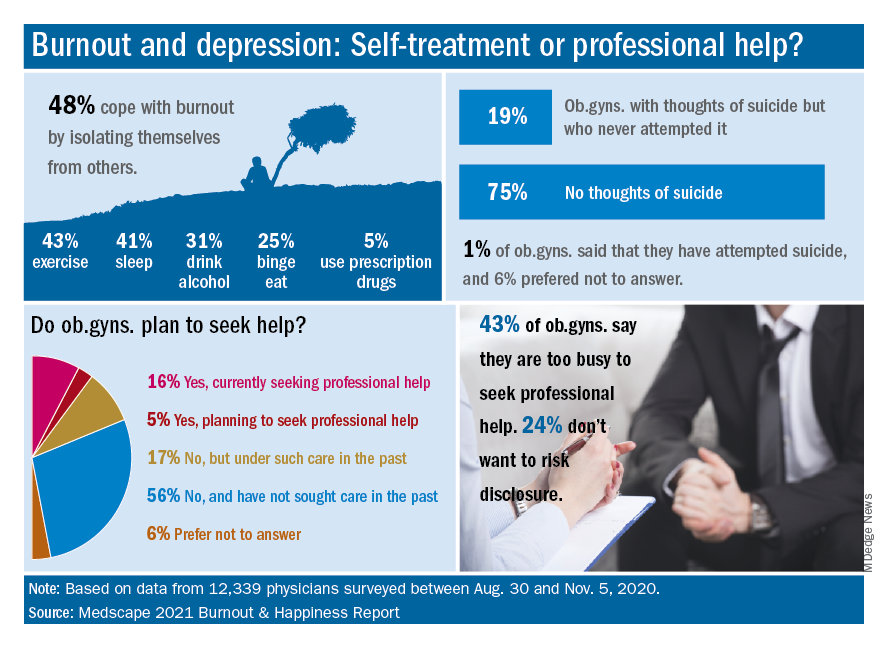

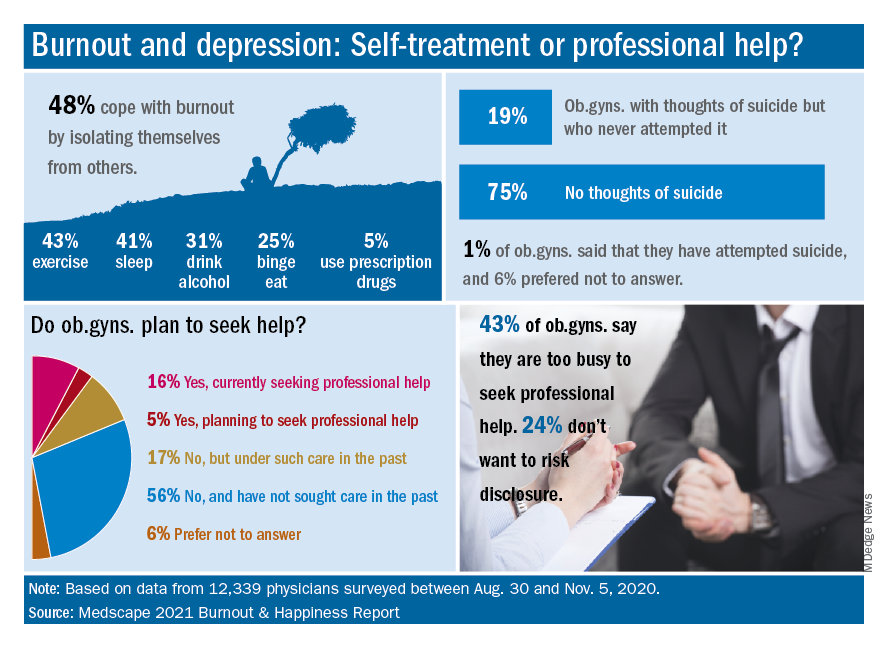

More than half (56%) of ob.gyns. who reported either depression or burnout said they had not sought professional help, although 17% reported receiving professional care in the past.

The main reason given for not seeking professional help was that burnout and depressive symptoms were not severe enough to merit it, according to 50% of respondents who reported burnout or depression but were not seeking help. In addition, 43% said they were too busy to seek help, 36% said they could deal with their symptoms without professional help, and 24% said they did not want to risk disclosure of their symptoms.

The most common cause of burnout was an overload of bureaucratic tasks, reported by 52% of respondents, followed by “lack of respect from administrators/employers, colleagues, or staff” (43%), and insufficient compensation or reimbursement (39%).

Notably, 19% of ob.gyns. reported suicidal thoughts, and 1% said they had attempted suicide.

“The most concerning statistic from this survey was in reference to suicidal ideation,” said Dr. Trolice. “Approximately one in five ob.gyns. have contemplated suicide, compared with 4.8% of adults age 18 and older in the U.S. reporting in 2019.”

Dr. Trolice said he was not surprised that relatively few ob.gyns. sought help for mental health issues. “Physicians are very private and usually do not seek help from colleagues, presumably from hubris. While this is unfortunate, all hospitals and health care organization should implement regular assessments of physicians’ health to ensure optimal performance from a professional and personal basis.”

Balance and self-care

The top workplace concern, by a large margin, was for work-life balance, reported by 44% of respondents, followed by compensation (19%), combining work and parenting (18%), and relationships with staff and colleagues (8%).

Approximately one-third (36%) of the ob.gyn. respondents said they made time to focus on personal well-being, compared with 35% of physicians overall. Although only 13% reported exercising every day, a total of 69% exercised at least twice a week, similar to the 70% of physicians overall who reported exercising at least twice a week.

“Work-life balance is high on the list of concerns, but physicians are split 50/50 on whether they would accept a salary reduction to improve this aspect of their lives,” Dr. Trolice said.

“Social relationships are a proven value to mental health, yet nearly 50% of ob.gyns. who reported feeling burnout use isolationism as their coping skill, citing a lack of severity to require treatment,” he noted. Nevertheless, more than 80% of responders were married and described their relationship as “good or very good.”

Address burnout at individual and organizational levels

“Sadly, the findings are not surprising,” said Iris Krisha, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, in an interview. “Burnout rates have been steadily increasing among physicians across all specialties.” Barriers to reducing burnout exist at the organizational and individual level, therefore strategies to reduce burnout should address individual and organizational solutions, Dr. Krishna emphasized. “At the organizational level, solutions may include developing manageable workloads, creating fair productivity targets, encouraging physician engagement in work structure, supporting flexible work schedules, and allowing for protected time for education and exercise. On the individual level, physicians can work to develop stress management strategies, engage in mindfulness and self-care.”

To reduce the burden of bureaucratic tasks, “health care organizations can work toward optimizing electronic medical records and hire staff to offload clerical work, and physicians can seek training in efficiency,” said Dr. Krishna. In addition, “health care organizations can reduce the stigma that may surround burnout or mental health issues, as well as promote a culture of wellness and resilience,” to help reduce and prevent burnout.

Find positivity and purpose

Improving the workplace experience so physicians feel engaged and in control as they navigate their many responsibilities may help reduce burnout, said Dr. Trolice. On the individual level, “finding your purpose to give you more meaning at work, discovering the power of hope to embrace optimism, and building friendships at work for greater engagement with others,” can help as well.

“In the face of adversity and setbacks, people in happier workplaces tend to be better at coping with and recovering from work pressure and at reconciling conflict,” Dr. Trolice emphasized. “The practice of medicine has dramatically changed for many physicians compared with the original expectations when they applied to medical school. Nevertheless, it behooves physician to adapt to 21st century medical care as they remind themselves of their purpose.”

The report included responses from 12,339 physicians across 29 specialties who completed a 10-minute online survey between Aug. 30 and Nov. 5, 2020. Participants were required to be practicing U.S. physicians.

Among ob.gyns. who reported burnout in the past year, 82% say they felt burned out before the advent of the coronavirus pandemic, according the Medscape Obstetrician & Gynecologist Lifestyle, Happiness, & Burnout Report.

The past year brought unusual challenges to physicians in all specialties in different ways.

“Whether on the front lines of treating COVID-19 patients, pivoting from in-person to virtual care, or even having to shutter their practices, physicians faced an onslaught of crises, while political tensions, social unrest, and environmental concerns probably affected their lives outside of medicine,” wrote Keith L. Martin and Mary Lyn Koval, both of Medscape Business of Medicine, in the introduction to the report.

Although more physicians said their burnout began prior to the pandemic, 81% of ob.gyns. reported that they were happy outside of work prior to the pandemic. However, those reporting happiness outside of work dropped to 57% after the pandemic started.

“One does not have to do a ‘deep dive’ to understand the top reasons reported for burnout,” said Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of Fertility CARE: The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, in an interview. “Many conversations I have with colleagues are about the frustration of learning and managing electronic health records, insurance reimbursements, and a work-life balance. In addition, more physician practices are being purchased by hospitals or private-equity networks [that are] reducing and/or eliminating the autonomy of physicians.

“While all [respondents] exhibited a dramatic decline in ‘happiness’ prepandemic, compared with our current situation, ob.gyns. were no exception,” he added.

Burnout and suicidal thoughts

Overall, 26% of ob.gyn. survey respondents reported being burned out, 6% reported being depressed, and 18% reported being both burned out and depressed. Of those who reported burnout, 52% said burnout had “a strong or severe impact on my life,” while 20% reported a moderate impact and 28% reported little or no impact.

More than half (56%) of ob.gyns. who reported either depression or burnout said they had not sought professional help, although 17% reported receiving professional care in the past.

The main reason given for not seeking professional help was that burnout and depressive symptoms were not severe enough to merit it, according to 50% of respondents who reported burnout or depression but were not seeking help. In addition, 43% said they were too busy to seek help, 36% said they could deal with their symptoms without professional help, and 24% said they did not want to risk disclosure of their symptoms.

The most common cause of burnout was an overload of bureaucratic tasks, reported by 52% of respondents, followed by “lack of respect from administrators/employers, colleagues, or staff” (43%), and insufficient compensation or reimbursement (39%).

Notably, 19% of ob.gyns. reported suicidal thoughts, and 1% said they had attempted suicide.

“The most concerning statistic from this survey was in reference to suicidal ideation,” said Dr. Trolice. “Approximately one in five ob.gyns. have contemplated suicide, compared with 4.8% of adults age 18 and older in the U.S. reporting in 2019.”

Dr. Trolice said he was not surprised that relatively few ob.gyns. sought help for mental health issues. “Physicians are very private and usually do not seek help from colleagues, presumably from hubris. While this is unfortunate, all hospitals and health care organization should implement regular assessments of physicians’ health to ensure optimal performance from a professional and personal basis.”

Balance and self-care

The top workplace concern, by a large margin, was for work-life balance, reported by 44% of respondents, followed by compensation (19%), combining work and parenting (18%), and relationships with staff and colleagues (8%).

Approximately one-third (36%) of the ob.gyn. respondents said they made time to focus on personal well-being, compared with 35% of physicians overall. Although only 13% reported exercising every day, a total of 69% exercised at least twice a week, similar to the 70% of physicians overall who reported exercising at least twice a week.

“Work-life balance is high on the list of concerns, but physicians are split 50/50 on whether they would accept a salary reduction to improve this aspect of their lives,” Dr. Trolice said.

“Social relationships are a proven value to mental health, yet nearly 50% of ob.gyns. who reported feeling burnout use isolationism as their coping skill, citing a lack of severity to require treatment,” he noted. Nevertheless, more than 80% of responders were married and described their relationship as “good or very good.”

Address burnout at individual and organizational levels

“Sadly, the findings are not surprising,” said Iris Krisha, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, in an interview. “Burnout rates have been steadily increasing among physicians across all specialties.” Barriers to reducing burnout exist at the organizational and individual level, therefore strategies to reduce burnout should address individual and organizational solutions, Dr. Krishna emphasized. “At the organizational level, solutions may include developing manageable workloads, creating fair productivity targets, encouraging physician engagement in work structure, supporting flexible work schedules, and allowing for protected time for education and exercise. On the individual level, physicians can work to develop stress management strategies, engage in mindfulness and self-care.”

To reduce the burden of bureaucratic tasks, “health care organizations can work toward optimizing electronic medical records and hire staff to offload clerical work, and physicians can seek training in efficiency,” said Dr. Krishna. In addition, “health care organizations can reduce the stigma that may surround burnout or mental health issues, as well as promote a culture of wellness and resilience,” to help reduce and prevent burnout.

Find positivity and purpose

Improving the workplace experience so physicians feel engaged and in control as they navigate their many responsibilities may help reduce burnout, said Dr. Trolice. On the individual level, “finding your purpose to give you more meaning at work, discovering the power of hope to embrace optimism, and building friendships at work for greater engagement with others,” can help as well.

“In the face of adversity and setbacks, people in happier workplaces tend to be better at coping with and recovering from work pressure and at reconciling conflict,” Dr. Trolice emphasized. “The practice of medicine has dramatically changed for many physicians compared with the original expectations when they applied to medical school. Nevertheless, it behooves physician to adapt to 21st century medical care as they remind themselves of their purpose.”

The report included responses from 12,339 physicians across 29 specialties who completed a 10-minute online survey between Aug. 30 and Nov. 5, 2020. Participants were required to be practicing U.S. physicians.

Among ob.gyns. who reported burnout in the past year, 82% say they felt burned out before the advent of the coronavirus pandemic, according the Medscape Obstetrician & Gynecologist Lifestyle, Happiness, & Burnout Report.

The past year brought unusual challenges to physicians in all specialties in different ways.

“Whether on the front lines of treating COVID-19 patients, pivoting from in-person to virtual care, or even having to shutter their practices, physicians faced an onslaught of crises, while political tensions, social unrest, and environmental concerns probably affected their lives outside of medicine,” wrote Keith L. Martin and Mary Lyn Koval, both of Medscape Business of Medicine, in the introduction to the report.

Although more physicians said their burnout began prior to the pandemic, 81% of ob.gyns. reported that they were happy outside of work prior to the pandemic. However, those reporting happiness outside of work dropped to 57% after the pandemic started.

“One does not have to do a ‘deep dive’ to understand the top reasons reported for burnout,” said Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of Fertility CARE: The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, in an interview. “Many conversations I have with colleagues are about the frustration of learning and managing electronic health records, insurance reimbursements, and a work-life balance. In addition, more physician practices are being purchased by hospitals or private-equity networks [that are] reducing and/or eliminating the autonomy of physicians.

“While all [respondents] exhibited a dramatic decline in ‘happiness’ prepandemic, compared with our current situation, ob.gyns. were no exception,” he added.

Burnout and suicidal thoughts

Overall, 26% of ob.gyn. survey respondents reported being burned out, 6% reported being depressed, and 18% reported being both burned out and depressed. Of those who reported burnout, 52% said burnout had “a strong or severe impact on my life,” while 20% reported a moderate impact and 28% reported little or no impact.

More than half (56%) of ob.gyns. who reported either depression or burnout said they had not sought professional help, although 17% reported receiving professional care in the past.

The main reason given for not seeking professional help was that burnout and depressive symptoms were not severe enough to merit it, according to 50% of respondents who reported burnout or depression but were not seeking help. In addition, 43% said they were too busy to seek help, 36% said they could deal with their symptoms without professional help, and 24% said they did not want to risk disclosure of their symptoms.

The most common cause of burnout was an overload of bureaucratic tasks, reported by 52% of respondents, followed by “lack of respect from administrators/employers, colleagues, or staff” (43%), and insufficient compensation or reimbursement (39%).

Notably, 19% of ob.gyns. reported suicidal thoughts, and 1% said they had attempted suicide.

“The most concerning statistic from this survey was in reference to suicidal ideation,” said Dr. Trolice. “Approximately one in five ob.gyns. have contemplated suicide, compared with 4.8% of adults age 18 and older in the U.S. reporting in 2019.”

Dr. Trolice said he was not surprised that relatively few ob.gyns. sought help for mental health issues. “Physicians are very private and usually do not seek help from colleagues, presumably from hubris. While this is unfortunate, all hospitals and health care organization should implement regular assessments of physicians’ health to ensure optimal performance from a professional and personal basis.”

Balance and self-care

The top workplace concern, by a large margin, was for work-life balance, reported by 44% of respondents, followed by compensation (19%), combining work and parenting (18%), and relationships with staff and colleagues (8%).

Approximately one-third (36%) of the ob.gyn. respondents said they made time to focus on personal well-being, compared with 35% of physicians overall. Although only 13% reported exercising every day, a total of 69% exercised at least twice a week, similar to the 70% of physicians overall who reported exercising at least twice a week.

“Work-life balance is high on the list of concerns, but physicians are split 50/50 on whether they would accept a salary reduction to improve this aspect of their lives,” Dr. Trolice said.

“Social relationships are a proven value to mental health, yet nearly 50% of ob.gyns. who reported feeling burnout use isolationism as their coping skill, citing a lack of severity to require treatment,” he noted. Nevertheless, more than 80% of responders were married and described their relationship as “good or very good.”

Address burnout at individual and organizational levels

“Sadly, the findings are not surprising,” said Iris Krisha, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, in an interview. “Burnout rates have been steadily increasing among physicians across all specialties.” Barriers to reducing burnout exist at the organizational and individual level, therefore strategies to reduce burnout should address individual and organizational solutions, Dr. Krishna emphasized. “At the organizational level, solutions may include developing manageable workloads, creating fair productivity targets, encouraging physician engagement in work structure, supporting flexible work schedules, and allowing for protected time for education and exercise. On the individual level, physicians can work to develop stress management strategies, engage in mindfulness and self-care.”

To reduce the burden of bureaucratic tasks, “health care organizations can work toward optimizing electronic medical records and hire staff to offload clerical work, and physicians can seek training in efficiency,” said Dr. Krishna. In addition, “health care organizations can reduce the stigma that may surround burnout or mental health issues, as well as promote a culture of wellness and resilience,” to help reduce and prevent burnout.

Find positivity and purpose

Improving the workplace experience so physicians feel engaged and in control as they navigate their many responsibilities may help reduce burnout, said Dr. Trolice. On the individual level, “finding your purpose to give you more meaning at work, discovering the power of hope to embrace optimism, and building friendships at work for greater engagement with others,” can help as well.

“In the face of adversity and setbacks, people in happier workplaces tend to be better at coping with and recovering from work pressure and at reconciling conflict,” Dr. Trolice emphasized. “The practice of medicine has dramatically changed for many physicians compared with the original expectations when they applied to medical school. Nevertheless, it behooves physician to adapt to 21st century medical care as they remind themselves of their purpose.”

The report included responses from 12,339 physicians across 29 specialties who completed a 10-minute online survey between Aug. 30 and Nov. 5, 2020. Participants were required to be practicing U.S. physicians.

Emerging treatments for molluscum contagiosum and acne show promise

, but that could soon change, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD.

“The treatment of molluscum is still an unmet need,” Dr. Kircik, clinical professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. However, a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been tested in phase 3 studies, is currently under FDA review. The manufacturer, Verrica Pharmaceuticals resubmitted a new drug application for the product, VP-102, in December 2020.

“VP-102 features a visualization agent so the injector can see which lesions have been treated, as well as a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children. Complete clearance at 12 weeks ranged from 46% to 54% of patients, while lesion count reduction compared with baseline ranged from 69% to 82%.”

Acne

In August, 2020, clascoterone 1% cream was approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older, a development that Dr. Kircik said “can be a game changer in acne treatment.” Clascoterone cream 1% exhibits strong, selective anti-androgen activity by targeting androgen receptors in the skin, not systemically. “It limits or blocks transcription of androgen responsive genes, but it also has an anti-inflammatory effect and an anti-sebum effect,” he explained.

According to results from two phase 3 trials of the product, a response of clear or almost clear on the IGA scale at week 12 was achieved in 18.4% of those on treatment vs. 9% of those on vehicle in one study (P less than .001) and 20.3% vs. 6.5%, respectively, in the second study (P less than .001). Clascoterone is also being evaluated for treating androgenetic alopecia.

In Dr. Kircik’s clinical experience, retinoids can be helpful for patients with moderate to severe acne. “We always use them for anticomedogenic effects, but we also know that they have anti-inflammatory effects,” he said. “They actually inhibit toll-like receptor activity. They also inhibit the AP-1 pathway by causing a reduction in inflammatory signaling associated with collagen degradation and scarring.”

The most recent retinoid to be approved for the topical treatment of acne was 0.005% trifarotene cream, in 2019, for patients aged 9 years and older. “But when we got the results, it was not that exciting,” a difference of about 3.6 (mean) inflammatory lesion reduction between the active and the vehicle arm, said Dr. Kircik, medical director of Physicians Skin Care in Louisville, Ky. “According to the package insert, treatment side effects included mild to moderate erythema in 59% of patients, scaling in 65%, dryness in 69%, and stinging/burning in 56%, which makes it difficult to use in our clinical practice.”

The drug was also tested for treating truncal acne. However, one comparative study showed that tazarotene 0.045% lotion spread an average of 36.7 square centimeters farther than the trifarotene cream, which makes the tazarotene lotion easier to use on the chest and back, he said.

Dr. Kircik also discussed 4% minocycline, a hydrophobic, topical foam formulation of minocycline that was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of moderate to severe acne, for patients aged 9 and older. In a 12-week study that involved 1,488 patients (mean age was about 20 years), investigators observed a 56% reduction in inflammatory lesion count among those treated with minocycline 4%, compared with 43% in the vehicle group.

Dr. Kircik, one of the authors of the study, noted that the hydrophobic composition of minocycline 4% allows for stable and efficient delivery of an inherently unstable active pharmaceutical ingredient such as minocycline. “It’s free of primary irritants such as surfactants and short chain alcohols, which makes it much more tolerable,” he said. “The unique physical foam characteristics facilitate ease of application and absorption at target sites.”

Dr. Kircik reported that he serves as a consultant and/or adviser to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, the manufacturer of trifarotene cream.

[email protected]

, but that could soon change, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD.

“The treatment of molluscum is still an unmet need,” Dr. Kircik, clinical professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. However, a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been tested in phase 3 studies, is currently under FDA review. The manufacturer, Verrica Pharmaceuticals resubmitted a new drug application for the product, VP-102, in December 2020.

“VP-102 features a visualization agent so the injector can see which lesions have been treated, as well as a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children. Complete clearance at 12 weeks ranged from 46% to 54% of patients, while lesion count reduction compared with baseline ranged from 69% to 82%.”

Acne

In August, 2020, clascoterone 1% cream was approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older, a development that Dr. Kircik said “can be a game changer in acne treatment.” Clascoterone cream 1% exhibits strong, selective anti-androgen activity by targeting androgen receptors in the skin, not systemically. “It limits or blocks transcription of androgen responsive genes, but it also has an anti-inflammatory effect and an anti-sebum effect,” he explained.

According to results from two phase 3 trials of the product, a response of clear or almost clear on the IGA scale at week 12 was achieved in 18.4% of those on treatment vs. 9% of those on vehicle in one study (P less than .001) and 20.3% vs. 6.5%, respectively, in the second study (P less than .001). Clascoterone is also being evaluated for treating androgenetic alopecia.

In Dr. Kircik’s clinical experience, retinoids can be helpful for patients with moderate to severe acne. “We always use them for anticomedogenic effects, but we also know that they have anti-inflammatory effects,” he said. “They actually inhibit toll-like receptor activity. They also inhibit the AP-1 pathway by causing a reduction in inflammatory signaling associated with collagen degradation and scarring.”

The most recent retinoid to be approved for the topical treatment of acne was 0.005% trifarotene cream, in 2019, for patients aged 9 years and older. “But when we got the results, it was not that exciting,” a difference of about 3.6 (mean) inflammatory lesion reduction between the active and the vehicle arm, said Dr. Kircik, medical director of Physicians Skin Care in Louisville, Ky. “According to the package insert, treatment side effects included mild to moderate erythema in 59% of patients, scaling in 65%, dryness in 69%, and stinging/burning in 56%, which makes it difficult to use in our clinical practice.”

The drug was also tested for treating truncal acne. However, one comparative study showed that tazarotene 0.045% lotion spread an average of 36.7 square centimeters farther than the trifarotene cream, which makes the tazarotene lotion easier to use on the chest and back, he said.

Dr. Kircik also discussed 4% minocycline, a hydrophobic, topical foam formulation of minocycline that was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of moderate to severe acne, for patients aged 9 and older. In a 12-week study that involved 1,488 patients (mean age was about 20 years), investigators observed a 56% reduction in inflammatory lesion count among those treated with minocycline 4%, compared with 43% in the vehicle group.

Dr. Kircik, one of the authors of the study, noted that the hydrophobic composition of minocycline 4% allows for stable and efficient delivery of an inherently unstable active pharmaceutical ingredient such as minocycline. “It’s free of primary irritants such as surfactants and short chain alcohols, which makes it much more tolerable,” he said. “The unique physical foam characteristics facilitate ease of application and absorption at target sites.”

Dr. Kircik reported that he serves as a consultant and/or adviser to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, the manufacturer of trifarotene cream.

[email protected]

, but that could soon change, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD.

“The treatment of molluscum is still an unmet need,” Dr. Kircik, clinical professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. However, a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been tested in phase 3 studies, is currently under FDA review. The manufacturer, Verrica Pharmaceuticals resubmitted a new drug application for the product, VP-102, in December 2020.

“VP-102 features a visualization agent so the injector can see which lesions have been treated, as well as a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children. Complete clearance at 12 weeks ranged from 46% to 54% of patients, while lesion count reduction compared with baseline ranged from 69% to 82%.”

Acne

In August, 2020, clascoterone 1% cream was approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older, a development that Dr. Kircik said “can be a game changer in acne treatment.” Clascoterone cream 1% exhibits strong, selective anti-androgen activity by targeting androgen receptors in the skin, not systemically. “It limits or blocks transcription of androgen responsive genes, but it also has an anti-inflammatory effect and an anti-sebum effect,” he explained.

According to results from two phase 3 trials of the product, a response of clear or almost clear on the IGA scale at week 12 was achieved in 18.4% of those on treatment vs. 9% of those on vehicle in one study (P less than .001) and 20.3% vs. 6.5%, respectively, in the second study (P less than .001). Clascoterone is also being evaluated for treating androgenetic alopecia.

In Dr. Kircik’s clinical experience, retinoids can be helpful for patients with moderate to severe acne. “We always use them for anticomedogenic effects, but we also know that they have anti-inflammatory effects,” he said. “They actually inhibit toll-like receptor activity. They also inhibit the AP-1 pathway by causing a reduction in inflammatory signaling associated with collagen degradation and scarring.”

The most recent retinoid to be approved for the topical treatment of acne was 0.005% trifarotene cream, in 2019, for patients aged 9 years and older. “But when we got the results, it was not that exciting,” a difference of about 3.6 (mean) inflammatory lesion reduction between the active and the vehicle arm, said Dr. Kircik, medical director of Physicians Skin Care in Louisville, Ky. “According to the package insert, treatment side effects included mild to moderate erythema in 59% of patients, scaling in 65%, dryness in 69%, and stinging/burning in 56%, which makes it difficult to use in our clinical practice.”

The drug was also tested for treating truncal acne. However, one comparative study showed that tazarotene 0.045% lotion spread an average of 36.7 square centimeters farther than the trifarotene cream, which makes the tazarotene lotion easier to use on the chest and back, he said.

Dr. Kircik also discussed 4% minocycline, a hydrophobic, topical foam formulation of minocycline that was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of moderate to severe acne, for patients aged 9 and older. In a 12-week study that involved 1,488 patients (mean age was about 20 years), investigators observed a 56% reduction in inflammatory lesion count among those treated with minocycline 4%, compared with 43% in the vehicle group.

Dr. Kircik, one of the authors of the study, noted that the hydrophobic composition of minocycline 4% allows for stable and efficient delivery of an inherently unstable active pharmaceutical ingredient such as minocycline. “It’s free of primary irritants such as surfactants and short chain alcohols, which makes it much more tolerable,” he said. “The unique physical foam characteristics facilitate ease of application and absorption at target sites.”

Dr. Kircik reported that he serves as a consultant and/or adviser to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, the manufacturer of trifarotene cream.

[email protected]

FROM ODAC 2021

Helping parents and children deal with a child’s limb deformity

After 15 years of limping and a gradual downhill slide in mobility, recreational walking had become uncomfortable enough that I’ve decided to shed my proudly worn cloak of denial and seek help. Even I could see that the x-ray made a total knee replacement the only option for some return to near normalcy. Scheduling a total knee replacement became a no-brainer.

My decision to accept the risks to reap the benefits of surgery is small potatoes compared with the decisions that the parents of a child born with a deformed lower extremity must face. In the Family Partnerships section of the February 2021 issue of Pediatrics you will find a heart-wrenching story of a family who embarked on what turned out to be painful and frustrating journey to lengthen their daughter’s congenitally deficient leg. In their own words, the mother and daughter describe how neither of them were prepared for the pain and life-altering complications the daughter has endured. Influenced by the optimism exuded by surgeons, the family gave little thought to the magnitude of the decision they were being asked to make. One has to wonder in retrospect if a well-timed amputation and prosthesis might have been a better decision. However, the thought of removing an extremity, even one that isn’t fully functional, is not one that most of us like to consider.

Over the last several decades I have read stories about people – usually athletes – born with short or deformed lower extremities who have faced the decision of amputation. I recall one college-age young man who despite his deformity and with the help of a prosthesis was a competitive multisport athlete. However, it became clear that his deformed foot was preventing him from accessing the most advanced prosthetic technology. Although he was highly motivated, he described his struggle with the decision to part with a portion of his body that despite its appearance and dysfunction had been with him since birth. On the other hand, I have read stories of young people who had become so frustrated by their deformity that they were more than eager to undergo amputation despite the concerns of their parents.

Early in my career I encountered a 3-year-old with phocomelia whose family was visiting from out of town and had come to our clinic because his older sibling was sick. The youngster, as I recall, had only one complete extremity, an arm. Like most 3-year-olds, he was driven to explore at breakneck speed. I will never forget watching him streak back and forth the length of our linoleum covered hallway like a crab skittering along the beach. His mother described how she and his well-meaning physicians were struggling unsuccessfully to get him to accept prostheses. Later I learned that his resistance is shared by many of the survivors of the thalidomide disaster who felt that the most frustrating period in their lives came when, again well-meaning, caregivers had tried to make them look and function more normally by fitting them with prostheses.

These anecdotal observations make clear a philosophy that we should have already internalized. In most clinic decisions the patient, pretty much regardless of age, should be a full participant in the process. And, to do this the patient and his or her family must be as informed as possible. Managing the aftermath of a traumatic amputation presents it own special set of challenges, but when it comes to elective amputation or prosthetic application for a congenital deficiency it is dangerous for us to insert our personal bias into the decision making.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

After 15 years of limping and a gradual downhill slide in mobility, recreational walking had become uncomfortable enough that I’ve decided to shed my proudly worn cloak of denial and seek help. Even I could see that the x-ray made a total knee replacement the only option for some return to near normalcy. Scheduling a total knee replacement became a no-brainer.

My decision to accept the risks to reap the benefits of surgery is small potatoes compared with the decisions that the parents of a child born with a deformed lower extremity must face. In the Family Partnerships section of the February 2021 issue of Pediatrics you will find a heart-wrenching story of a family who embarked on what turned out to be painful and frustrating journey to lengthen their daughter’s congenitally deficient leg. In their own words, the mother and daughter describe how neither of them were prepared for the pain and life-altering complications the daughter has endured. Influenced by the optimism exuded by surgeons, the family gave little thought to the magnitude of the decision they were being asked to make. One has to wonder in retrospect if a well-timed amputation and prosthesis might have been a better decision. However, the thought of removing an extremity, even one that isn’t fully functional, is not one that most of us like to consider.

Over the last several decades I have read stories about people – usually athletes – born with short or deformed lower extremities who have faced the decision of amputation. I recall one college-age young man who despite his deformity and with the help of a prosthesis was a competitive multisport athlete. However, it became clear that his deformed foot was preventing him from accessing the most advanced prosthetic technology. Although he was highly motivated, he described his struggle with the decision to part with a portion of his body that despite its appearance and dysfunction had been with him since birth. On the other hand, I have read stories of young people who had become so frustrated by their deformity that they were more than eager to undergo amputation despite the concerns of their parents.

Early in my career I encountered a 3-year-old with phocomelia whose family was visiting from out of town and had come to our clinic because his older sibling was sick. The youngster, as I recall, had only one complete extremity, an arm. Like most 3-year-olds, he was driven to explore at breakneck speed. I will never forget watching him streak back and forth the length of our linoleum covered hallway like a crab skittering along the beach. His mother described how she and his well-meaning physicians were struggling unsuccessfully to get him to accept prostheses. Later I learned that his resistance is shared by many of the survivors of the thalidomide disaster who felt that the most frustrating period in their lives came when, again well-meaning, caregivers had tried to make them look and function more normally by fitting them with prostheses.

These anecdotal observations make clear a philosophy that we should have already internalized. In most clinic decisions the patient, pretty much regardless of age, should be a full participant in the process. And, to do this the patient and his or her family must be as informed as possible. Managing the aftermath of a traumatic amputation presents it own special set of challenges, but when it comes to elective amputation or prosthetic application for a congenital deficiency it is dangerous for us to insert our personal bias into the decision making.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

After 15 years of limping and a gradual downhill slide in mobility, recreational walking had become uncomfortable enough that I’ve decided to shed my proudly worn cloak of denial and seek help. Even I could see that the x-ray made a total knee replacement the only option for some return to near normalcy. Scheduling a total knee replacement became a no-brainer.