User login

U.K. variant spreading in the U.S. as COVID mutations raise stakes

The U.K.’s B117 variant is circulating in at least 24 states, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 variant surveillance. The CDC projects that the U.K. variant will become the dominant strain in the United States by March.

From any vantage point, the United Kingdom appears to be in the crosshairs of COVID-19: Weeks after a new, highly contagious variant emerged that fueled a surge in cases and fresh lockdowns, the United Kingdom was revealed to have the world’s highest coronavirus death rate.

But the United Kingdom also has a not-so-secret weapon of its own: A genomic sequencing program widely believed to be the most coordinated and advanced any nation has forged. In the vise grip of the virus, the Brits have gleaned key insights into the behavior and consequences of SARS-CoV-2.

But B117 is also notable for what it is missing: In this case, producing a negative result on certain polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests in the spike protein, or S-gene.

One of the S-gene mutations specific to the variant deletes two amino acids, causing that portion of the PCR test to show up negative. The coincidental finding known as an S-gene target failure has become an integral proxy to help track where and when the variant is spreading in the United Kingdom, where about 5% of samples from COVID-19–infected patients are sequenced, said Sharon Peacock, PhD, executive director and chair of the COVID-19 Genomics U.K. Consortium.

That same tactic could prove valuable to clinicians similarly overwhelmed with cases and deaths but lacking high-level sequencing information on the virus, Dr. Peacock said in an interview. A British report released Friday stated that there is a “realistic possibility” that the variant has a higher death rate than other cases of SARS-CoV-2.

“In this particular variant, a deletion in the genome leads to one part of the diagnostic test failing,” Dr. Peacock explained. “Several targets are positive, but this is negative. In the U.K., this has been used as a surrogate marker.”

Targeting an invisible adversary

B117 is not the only variant that produces this result, Dr. Peacock cautioned, “but in screening for it, you can have this in mind.”

“Since the U.K. is sequencing about 5% of the cases they detect, this gives them really important clues about what’s happening there,” said Anderson Brito, PhD, a virologist and postdoctoral researcher at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., where investigators are creating custom PCR tests to detect the B117 variant.

Dr. Brito, who lived in the United Kingdom for 4 years while studying for his doctorate at Imperial College London, said a “major advantage” is the more unified process to collect and sequence samples. Crucial information – including the date and place of collection – comes with each sample, which fuels not only sequencing, but an epidemiologic perspective.

“They’re not in the dark at all,” Dr. Brito said in an interview. “I think no other country in the world knows better which virus lineages are circulating.”

The CDC launched the SPHERES consortium in May 2020 to coordinate the sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 genomes across the United States.

But American genomic efforts are “not as centralized,” said Dr. Brito, whose lab detected the first two cases of the U.K. variant in Connecticut on Jan. 6. “We struggle to get samples, because they’re decentralized to a level where there’s little coordination between hospitals and research centers. They’re not as connected as in the U.K. If we just get a sample and it has no date of collection and no origin information, for example, it’s basically useless.”

Global genomic collaborations include GISAID, an international database where researchers share new genomes from various coronaviruses. As of mid-January, the United States had submitted about 68,000 sequences to GISAID, adding about 3,000 new samples every week and expecting even more from commercial labs in coming days, according to the CDC.

“The U.K. is definitely much more on top of looking for variants as they pop up,” said Gigi Gronvall, PhD, an immunologist and senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. “The U.S. has now turned that up.”

Warning from British scientists to the world

Despite these genomic accomplishments, some British scientists said they have regrets too, wishing they’d known just how rapidly SARS-CoV-2 was actually spreading a year ago, when it hit western Europe.

That information was crucial not only for preventive efforts, but because viruses inevitably mutate faster the more people who are infected, said Igor Rudan, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Global Health Research at University of Edinburgh.

“Italy showed us just how fast it was spreading and how deadly it is for the very old and people with multiple comorbidities,” said Dr. Rudan, who also editor in chief of the Journal of Global Health. “We wish we knew it was spreading so fast, and we wish we knew the threshold of cases we could allow to be infected before the virus would mutate.”

More mutations mean more new strains of SARS-CoV-2, Dr. Rudan said in an interview. “We’ve reached that threshold now and will see more of these mutations.”

Despite its current struggles, the United Kingdom is reaching beyond tracking its new variant’s spread and trying to identify new mutations that might change the way the virus behaves.

Three features of any emerging variant are particularly important, Dr. Peacock explained: Is it more transmissible? Is it more lethal? And does it cut the ability of natural- or vaccine-induced immunity to protect people from infection?

“We need to sequence people coming to the hospital who are sicker,” said Dr. Peacock, also a professor of public health and microbiology at the University of Cambridge (England). “Also, if anyone has the infection after they’ve already been sick or had the vaccine, we really want to know what that looks like” genomically.

SARS-CoV-2 has already logged more than 4,000 mutations, Dr. Peacock said. But “knowing that viruses mutate all the time is not sufficient reason not to look. We really want to know if mutations lead to changes in amino acids, and if that can lead to changes in functionality.”

For the moment, however, experts say they’re relieved that the U.K. strain doesn’t seem able to evade COVID-19 vaccines or render them less effective.

“Even though mutations are common, those able to change the viral coding are rare,” Dr. Brito explained. If necessary, vaccines could be tweaked to replace the spike gene sequence “within a matter of weeks. We already do this for flu vaccines. Every year, we have to monitor variants of the virus circulating to develop a vaccine that covers most of them. If we end up having to do it for SARS-CoV-2, I would not be surprised.”

But variant-fueled increases in infections will require more people to be vaccinated before herd immunity can be achieved, Dr. Rudan warned. “If it spreads faster, we’ll need to vaccinate probably 85% of people versus 70% to reach herd immunity.”

One lesson the COVID-19 pandemic has driven home “is to always be on your guard about what happens next,” Dr. Peacock said. Although confident about the genomic efforts in the United Kingdom to date, she and her colleagues feel they’re still reaching for a complete understanding of the evolutionary changes of the virus.

“We’re ahead of the curve right now, but we want to get in front of the curve,” Dr. Peacock said. “It’s essential to get ahead of what might be around the corner because we don’t know how the virus is going to evolve.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.K.’s B117 variant is circulating in at least 24 states, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 variant surveillance. The CDC projects that the U.K. variant will become the dominant strain in the United States by March.

From any vantage point, the United Kingdom appears to be in the crosshairs of COVID-19: Weeks after a new, highly contagious variant emerged that fueled a surge in cases and fresh lockdowns, the United Kingdom was revealed to have the world’s highest coronavirus death rate.

But the United Kingdom also has a not-so-secret weapon of its own: A genomic sequencing program widely believed to be the most coordinated and advanced any nation has forged. In the vise grip of the virus, the Brits have gleaned key insights into the behavior and consequences of SARS-CoV-2.

But B117 is also notable for what it is missing: In this case, producing a negative result on certain polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests in the spike protein, or S-gene.

One of the S-gene mutations specific to the variant deletes two amino acids, causing that portion of the PCR test to show up negative. The coincidental finding known as an S-gene target failure has become an integral proxy to help track where and when the variant is spreading in the United Kingdom, where about 5% of samples from COVID-19–infected patients are sequenced, said Sharon Peacock, PhD, executive director and chair of the COVID-19 Genomics U.K. Consortium.

That same tactic could prove valuable to clinicians similarly overwhelmed with cases and deaths but lacking high-level sequencing information on the virus, Dr. Peacock said in an interview. A British report released Friday stated that there is a “realistic possibility” that the variant has a higher death rate than other cases of SARS-CoV-2.

“In this particular variant, a deletion in the genome leads to one part of the diagnostic test failing,” Dr. Peacock explained. “Several targets are positive, but this is negative. In the U.K., this has been used as a surrogate marker.”

Targeting an invisible adversary

B117 is not the only variant that produces this result, Dr. Peacock cautioned, “but in screening for it, you can have this in mind.”

“Since the U.K. is sequencing about 5% of the cases they detect, this gives them really important clues about what’s happening there,” said Anderson Brito, PhD, a virologist and postdoctoral researcher at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., where investigators are creating custom PCR tests to detect the B117 variant.

Dr. Brito, who lived in the United Kingdom for 4 years while studying for his doctorate at Imperial College London, said a “major advantage” is the more unified process to collect and sequence samples. Crucial information – including the date and place of collection – comes with each sample, which fuels not only sequencing, but an epidemiologic perspective.

“They’re not in the dark at all,” Dr. Brito said in an interview. “I think no other country in the world knows better which virus lineages are circulating.”

The CDC launched the SPHERES consortium in May 2020 to coordinate the sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 genomes across the United States.

But American genomic efforts are “not as centralized,” said Dr. Brito, whose lab detected the first two cases of the U.K. variant in Connecticut on Jan. 6. “We struggle to get samples, because they’re decentralized to a level where there’s little coordination between hospitals and research centers. They’re not as connected as in the U.K. If we just get a sample and it has no date of collection and no origin information, for example, it’s basically useless.”

Global genomic collaborations include GISAID, an international database where researchers share new genomes from various coronaviruses. As of mid-January, the United States had submitted about 68,000 sequences to GISAID, adding about 3,000 new samples every week and expecting even more from commercial labs in coming days, according to the CDC.

“The U.K. is definitely much more on top of looking for variants as they pop up,” said Gigi Gronvall, PhD, an immunologist and senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. “The U.S. has now turned that up.”

Warning from British scientists to the world

Despite these genomic accomplishments, some British scientists said they have regrets too, wishing they’d known just how rapidly SARS-CoV-2 was actually spreading a year ago, when it hit western Europe.

That information was crucial not only for preventive efforts, but because viruses inevitably mutate faster the more people who are infected, said Igor Rudan, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Global Health Research at University of Edinburgh.

“Italy showed us just how fast it was spreading and how deadly it is for the very old and people with multiple comorbidities,” said Dr. Rudan, who also editor in chief of the Journal of Global Health. “We wish we knew it was spreading so fast, and we wish we knew the threshold of cases we could allow to be infected before the virus would mutate.”

More mutations mean more new strains of SARS-CoV-2, Dr. Rudan said in an interview. “We’ve reached that threshold now and will see more of these mutations.”

Despite its current struggles, the United Kingdom is reaching beyond tracking its new variant’s spread and trying to identify new mutations that might change the way the virus behaves.

Three features of any emerging variant are particularly important, Dr. Peacock explained: Is it more transmissible? Is it more lethal? And does it cut the ability of natural- or vaccine-induced immunity to protect people from infection?

“We need to sequence people coming to the hospital who are sicker,” said Dr. Peacock, also a professor of public health and microbiology at the University of Cambridge (England). “Also, if anyone has the infection after they’ve already been sick or had the vaccine, we really want to know what that looks like” genomically.

SARS-CoV-2 has already logged more than 4,000 mutations, Dr. Peacock said. But “knowing that viruses mutate all the time is not sufficient reason not to look. We really want to know if mutations lead to changes in amino acids, and if that can lead to changes in functionality.”

For the moment, however, experts say they’re relieved that the U.K. strain doesn’t seem able to evade COVID-19 vaccines or render them less effective.

“Even though mutations are common, those able to change the viral coding are rare,” Dr. Brito explained. If necessary, vaccines could be tweaked to replace the spike gene sequence “within a matter of weeks. We already do this for flu vaccines. Every year, we have to monitor variants of the virus circulating to develop a vaccine that covers most of them. If we end up having to do it for SARS-CoV-2, I would not be surprised.”

But variant-fueled increases in infections will require more people to be vaccinated before herd immunity can be achieved, Dr. Rudan warned. “If it spreads faster, we’ll need to vaccinate probably 85% of people versus 70% to reach herd immunity.”

One lesson the COVID-19 pandemic has driven home “is to always be on your guard about what happens next,” Dr. Peacock said. Although confident about the genomic efforts in the United Kingdom to date, she and her colleagues feel they’re still reaching for a complete understanding of the evolutionary changes of the virus.

“We’re ahead of the curve right now, but we want to get in front of the curve,” Dr. Peacock said. “It’s essential to get ahead of what might be around the corner because we don’t know how the virus is going to evolve.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.K.’s B117 variant is circulating in at least 24 states, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 variant surveillance. The CDC projects that the U.K. variant will become the dominant strain in the United States by March.

From any vantage point, the United Kingdom appears to be in the crosshairs of COVID-19: Weeks after a new, highly contagious variant emerged that fueled a surge in cases and fresh lockdowns, the United Kingdom was revealed to have the world’s highest coronavirus death rate.

But the United Kingdom also has a not-so-secret weapon of its own: A genomic sequencing program widely believed to be the most coordinated and advanced any nation has forged. In the vise grip of the virus, the Brits have gleaned key insights into the behavior and consequences of SARS-CoV-2.

But B117 is also notable for what it is missing: In this case, producing a negative result on certain polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests in the spike protein, or S-gene.

One of the S-gene mutations specific to the variant deletes two amino acids, causing that portion of the PCR test to show up negative. The coincidental finding known as an S-gene target failure has become an integral proxy to help track where and when the variant is spreading in the United Kingdom, where about 5% of samples from COVID-19–infected patients are sequenced, said Sharon Peacock, PhD, executive director and chair of the COVID-19 Genomics U.K. Consortium.

That same tactic could prove valuable to clinicians similarly overwhelmed with cases and deaths but lacking high-level sequencing information on the virus, Dr. Peacock said in an interview. A British report released Friday stated that there is a “realistic possibility” that the variant has a higher death rate than other cases of SARS-CoV-2.

“In this particular variant, a deletion in the genome leads to one part of the diagnostic test failing,” Dr. Peacock explained. “Several targets are positive, but this is negative. In the U.K., this has been used as a surrogate marker.”

Targeting an invisible adversary

B117 is not the only variant that produces this result, Dr. Peacock cautioned, “but in screening for it, you can have this in mind.”

“Since the U.K. is sequencing about 5% of the cases they detect, this gives them really important clues about what’s happening there,” said Anderson Brito, PhD, a virologist and postdoctoral researcher at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., where investigators are creating custom PCR tests to detect the B117 variant.

Dr. Brito, who lived in the United Kingdom for 4 years while studying for his doctorate at Imperial College London, said a “major advantage” is the more unified process to collect and sequence samples. Crucial information – including the date and place of collection – comes with each sample, which fuels not only sequencing, but an epidemiologic perspective.

“They’re not in the dark at all,” Dr. Brito said in an interview. “I think no other country in the world knows better which virus lineages are circulating.”

The CDC launched the SPHERES consortium in May 2020 to coordinate the sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 genomes across the United States.

But American genomic efforts are “not as centralized,” said Dr. Brito, whose lab detected the first two cases of the U.K. variant in Connecticut on Jan. 6. “We struggle to get samples, because they’re decentralized to a level where there’s little coordination between hospitals and research centers. They’re not as connected as in the U.K. If we just get a sample and it has no date of collection and no origin information, for example, it’s basically useless.”

Global genomic collaborations include GISAID, an international database where researchers share new genomes from various coronaviruses. As of mid-January, the United States had submitted about 68,000 sequences to GISAID, adding about 3,000 new samples every week and expecting even more from commercial labs in coming days, according to the CDC.

“The U.K. is definitely much more on top of looking for variants as they pop up,” said Gigi Gronvall, PhD, an immunologist and senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. “The U.S. has now turned that up.”

Warning from British scientists to the world

Despite these genomic accomplishments, some British scientists said they have regrets too, wishing they’d known just how rapidly SARS-CoV-2 was actually spreading a year ago, when it hit western Europe.

That information was crucial not only for preventive efforts, but because viruses inevitably mutate faster the more people who are infected, said Igor Rudan, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Global Health Research at University of Edinburgh.

“Italy showed us just how fast it was spreading and how deadly it is for the very old and people with multiple comorbidities,” said Dr. Rudan, who also editor in chief of the Journal of Global Health. “We wish we knew it was spreading so fast, and we wish we knew the threshold of cases we could allow to be infected before the virus would mutate.”

More mutations mean more new strains of SARS-CoV-2, Dr. Rudan said in an interview. “We’ve reached that threshold now and will see more of these mutations.”

Despite its current struggles, the United Kingdom is reaching beyond tracking its new variant’s spread and trying to identify new mutations that might change the way the virus behaves.

Three features of any emerging variant are particularly important, Dr. Peacock explained: Is it more transmissible? Is it more lethal? And does it cut the ability of natural- or vaccine-induced immunity to protect people from infection?

“We need to sequence people coming to the hospital who are sicker,” said Dr. Peacock, also a professor of public health and microbiology at the University of Cambridge (England). “Also, if anyone has the infection after they’ve already been sick or had the vaccine, we really want to know what that looks like” genomically.

SARS-CoV-2 has already logged more than 4,000 mutations, Dr. Peacock said. But “knowing that viruses mutate all the time is not sufficient reason not to look. We really want to know if mutations lead to changes in amino acids, and if that can lead to changes in functionality.”

For the moment, however, experts say they’re relieved that the U.K. strain doesn’t seem able to evade COVID-19 vaccines or render them less effective.

“Even though mutations are common, those able to change the viral coding are rare,” Dr. Brito explained. If necessary, vaccines could be tweaked to replace the spike gene sequence “within a matter of weeks. We already do this for flu vaccines. Every year, we have to monitor variants of the virus circulating to develop a vaccine that covers most of them. If we end up having to do it for SARS-CoV-2, I would not be surprised.”

But variant-fueled increases in infections will require more people to be vaccinated before herd immunity can be achieved, Dr. Rudan warned. “If it spreads faster, we’ll need to vaccinate probably 85% of people versus 70% to reach herd immunity.”

One lesson the COVID-19 pandemic has driven home “is to always be on your guard about what happens next,” Dr. Peacock said. Although confident about the genomic efforts in the United Kingdom to date, she and her colleagues feel they’re still reaching for a complete understanding of the evolutionary changes of the virus.

“We’re ahead of the curve right now, but we want to get in front of the curve,” Dr. Peacock said. “It’s essential to get ahead of what might be around the corner because we don’t know how the virus is going to evolve.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

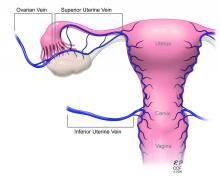

Male Genital Examinations: Special Considerations and Pearls for Dermatologists

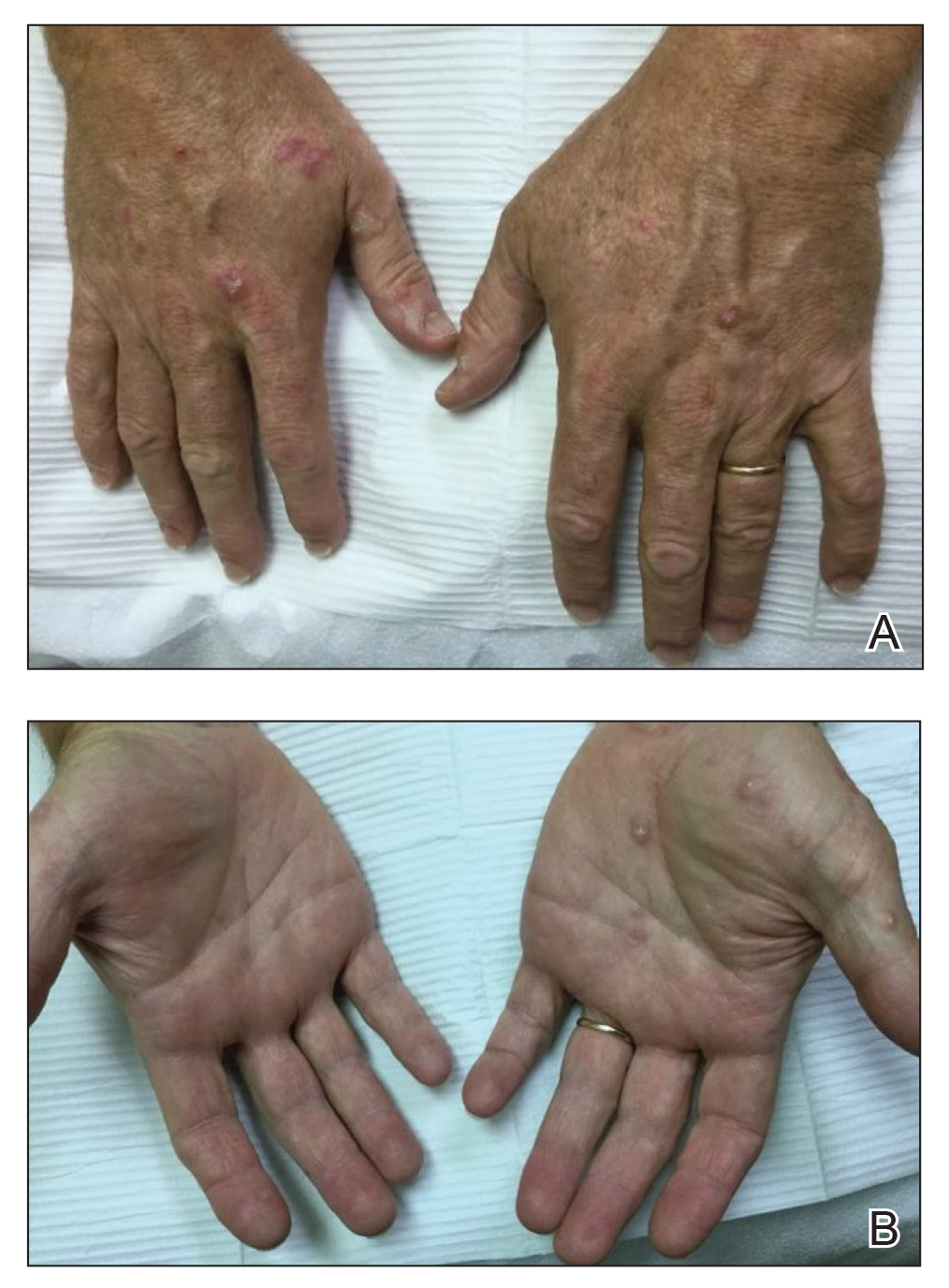

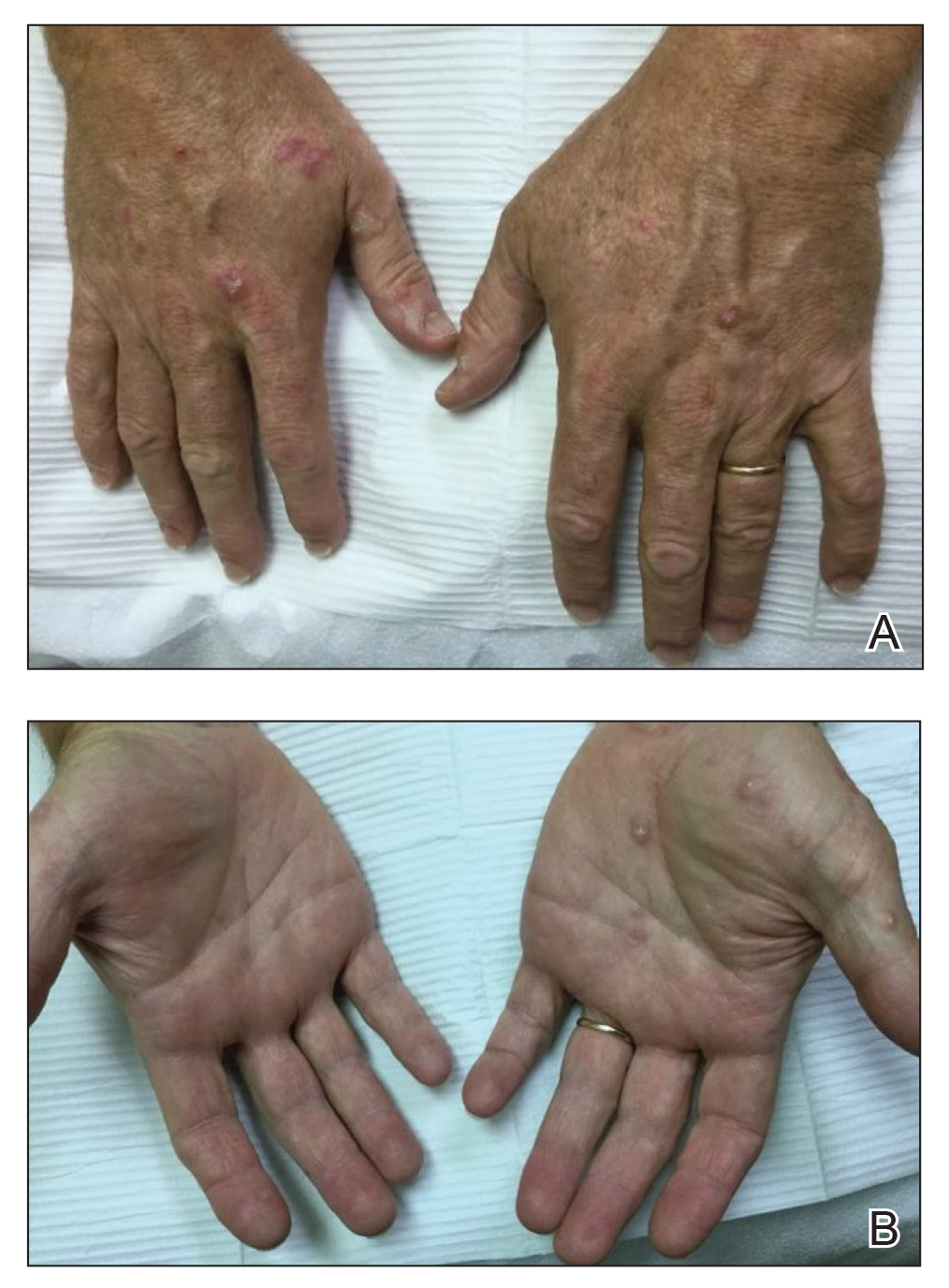

Men have unique dermatologic needs yet are significantly less likely than women to visit a dermatologist’s office.1 Male patients might have preconceived notions about the nature of dermatology visits and necessary areas of the body to be examined: For example, male patients might associate the genital examination with a urologist and not expect a dermatologist to complete such a seemingly private examination.2

Genital examinations are currently underperformed: Only one-quarter of dermatologists report examining a male patient’s genitals at most or all visits.3 In this commentary, we discuss the importance of genital examinations in men’s dermatology, specific issues that can arise, and strategies to enhance the quality and frequency of genital examinations in male patients.

Invaluable Aspect of Care

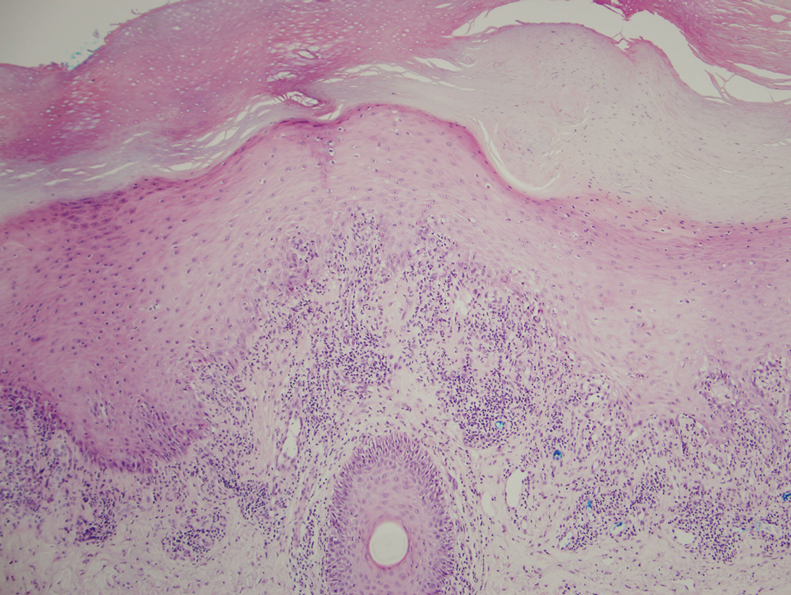

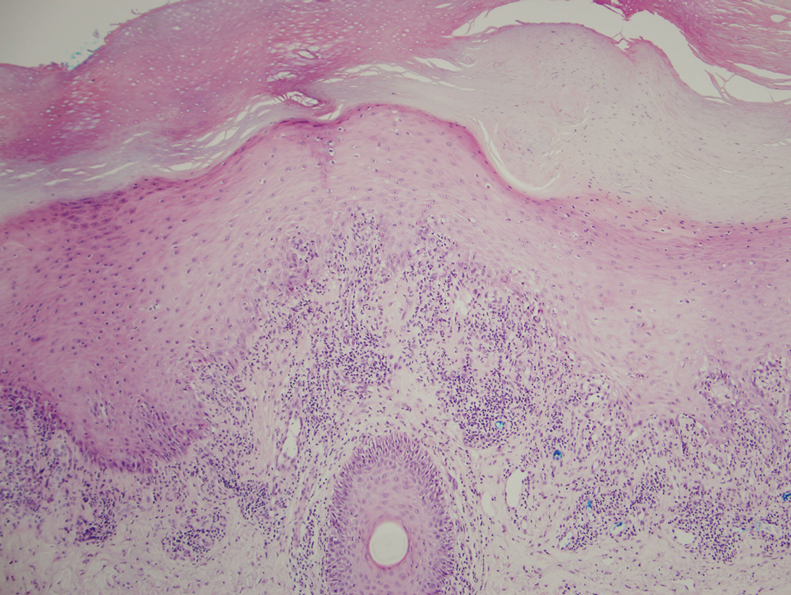

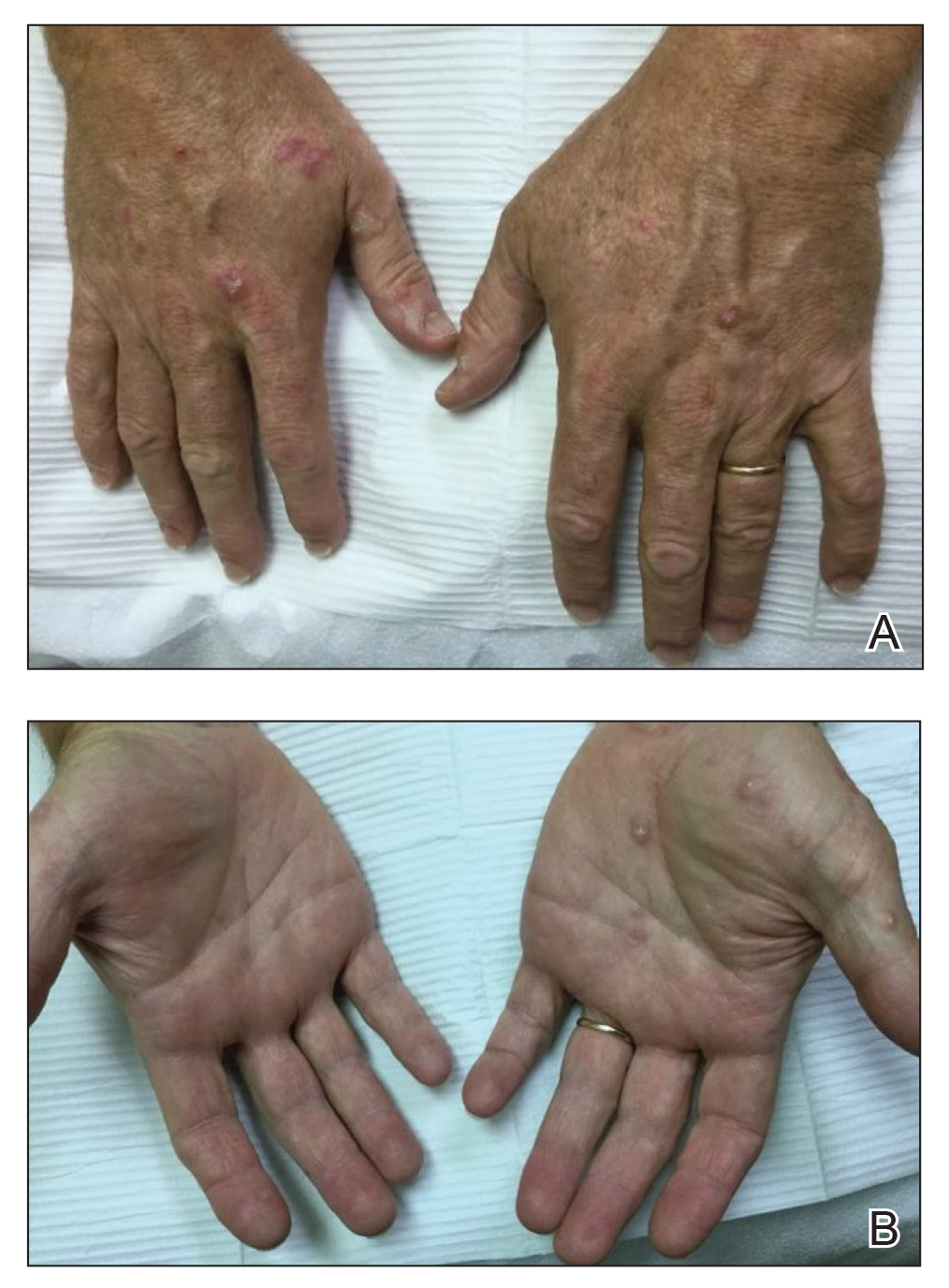

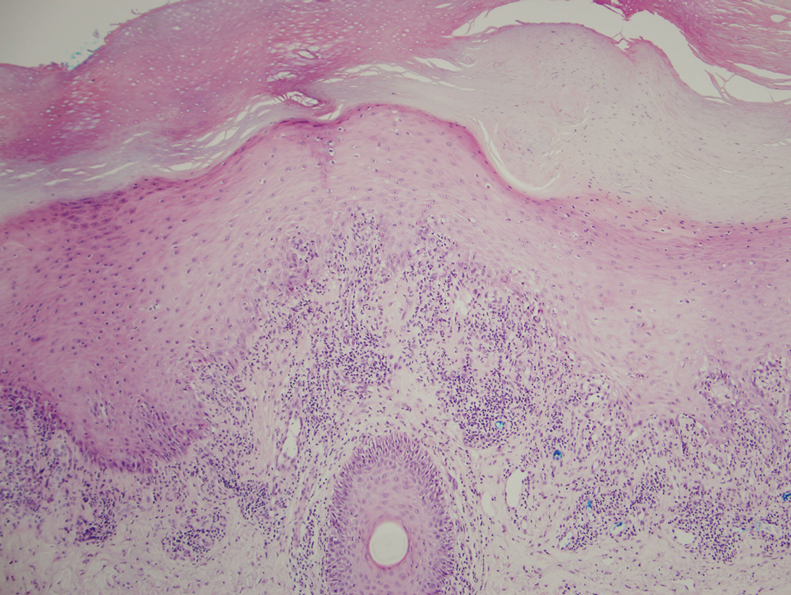

Thorough inspection of a male patient’s genital region is an important part of conducting a total-body skin examination (TBSE) for routine surveillance and evaluation of genital dermatoses. Sexually transmitted infections, warts, and other common lesions can be missed in diagnosis without careful inspection of the genital region. Additionally, scrotal malignancies, such as primary and metastatic melanoma and basal cell carcinoma, though rare, might be overlooked until symptoms become severe.4,5

There is no substitute for a physical examination but, in certain circumstances, it might be appropriate for a dermatologist to ask a patient if he has concerning lesions on his genitals. However, patients often are unsure of worrisome signs, and areas of the perineum might not be easily visible to a patient. Genital inspection during the physical examination allows for a teachable moment, during which the dermatologist can educate the patient about benign lesions and variants, such as pearly penile papules, seborrheic keratoses, and sebaceous cysts.6 These lesions might not require intervention but should be monitored for atypical features or infection.6

Also, the dermatologist might incidentally discover transmissible lesions, such as condylomata caused by human papillomavirus, which has been shown to be present in approximately 50% of men in the United States7—many of whom are unaware. Inflammatory dermatoses, such as psoriasis, often affect the genitals and go unnoticed; prompt intervention can decrease the likelihood of complications.6

Protocol for Genital Examinations

To examine the genitals, all surfaces of the penis, scrotum, and perineum should be evaluated, with anatomic and pathologic variants noted. The patient or physician should stretch the penis, maneuvering it in multiple directions so that all aspects can be examined. In uncircumcised men, the foreskin should be retracted so that the head of the penis can be examined, followed by replacement of the foreskin by the patient.8 The scrotum also should be examined and lifted to fully view the perineum.

Providers should not grasp the penis with the whole hand but use the thumb and first finger to hold the head of the penis to maneuver it.8 Similarly, using the back of the hand and fingers to manipulate the genitals establishes boundaries and sets a clinical tone for the examination.

Unintentional Erection

Unique to the male dermatologic examination is the unintentional patient erection; a physician might be unsure of how to approach such a potentially awkward situation. An erection is not always an indication of sexual arousal; rather, it can reflect an autonomic reflex in response to physical stimulation. Erections occur commonly in health care settings, especially if the genitals are being manipulated.9

Generally, the course of action here depends on the patient’s response.10 For patients who appear unbothered, it might be appropriate to ignore the erection and proceed with the examination, especially if the physician is not actively examining the genital region. If the patient appears embarrassed, the physician can say “This is completely normal” or “Random erections are common” to normalize the situation. Joking or laughing should be avoided. For a patient who appears upset, the physician can step outside the room for a brief period to give the patient privacy, then re-enter and ask him if he is comfortable continuing with the examination.

When a patient develops an erection, the physician might become uncomfortable and, consciously or subconsciously, increase the pace of the examination, which is a natural tendency, but expediency at the expense of comprehensive care is inappropriate.

Examiner’s Body Language and Tone

Throughout the genital examination, the physician should be mindful of their comments and body language to avoid exacerbating patient vulnerability. Using anatomic terms, rather than colloquial ones, to describe the genitalia is advised to prevent misunderstanding and maintain a professional clinical environment. Providers should be prepared to explain anatomic terms because some patients are not familiar with medical terminology.

Presence of a Chaperone

Involving a chaperone, as recommended by the American Medical Association, might make a patient more comfortable and alleviate potential misunderstanding. Still, physicians should be aware that some patients might feel uncomfortable with a chaperone, interpreting their presence as an expectation of impropriety.11 Universal offering of a chaperone to all patients, regardless of the gender of the physician, as well as appropriate signage in the clinical environment, normalizes chaperone invitation and use.

Other Helpful Considerations

Various strategies in the male genital examination can increase patient and physician comfort and improve care:

- The patient should be offered a gown before a TBSE or any skin examination during which the genitals will be examined.

- The patient should be allowed to keep his shorts or underwear on to avoid the feeling of being naked, which can provoke anxiety. Prior to beginning the examination, disclose that it will include “under the covered areas.”

- Ask the patient for permission to conduct the examination, enumerate the steps, and provide a rationale for a genital examination. These steps help gain cooperation, alleviate anticipation, and prevent surprise.

- To increase the patient’s comfort level, he can be asked whether he prefers to be examined supine or standing.

- Consider allowing the patient, himself, to expose and manipulate his genitals during the examination to increase his involvement and sense of autonomy.

- For genital examinations, patients often prefer that the examiner be a physician of the same gender. Accommodating a patient’s request regarding the examiner’s gender might not always be possible, but the medical practice should make an honest attempt to oblige.

Lastly, providers should be cognizant of the needs of male sexual and gender minority populations (ie, gay, bisexual, transgender/gender diverse, queer or questioning, intersex, and asexual persons). For example, transgender women might retain male anatomy or have surgical alteration of the genital region that also requires evaluation. In such patient populations, the genital examination is equally important to evaluate for dermatologic conditions that require treatment.

Final Thoughts

The male genital examination is an important component of the TBSE, as dermatologists can recognize lesions before symptoms present. Robust educational methods for trainees and practitioners in dermatology are lacking, and development of curricula might be beneficial to increase comfort in performing the genital examination. Still, use of the procedures described in this commentary can normalize the men’s genital examination, optimize the physical examination, and improve men’s overall dermatologic health.

- Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, et al. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1286-1291.

- Brezinski EA, Harskamp CT, Ledo L, et al. Public perception of dermatologists and comparison with other medical specialties: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:875-881.

- Rieder EA, Mu EW, Wang J, et al. Dermatologist practices during total body skin examinations: a survey study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:516-520.

- Gonzalez CD, Hawkes JE, Bowles TL. Malignant melanoma scrotal metastasis: the importance of the genital examination. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:10-12.

- Solimani F, Juratli H, Hoch M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma of the scrotum: an important but easily overlooked entity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E254-E255.

- Gabrielson AT, Le TV, Fontenot C, et al. Male genital dermatology: a primer for the sexual medicine physician. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7:71-83.

- Han JJ, Beltran TH, Song JW, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus vaccination rates among US adult men: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:810-816.

- Albaugh JA, Kellogg-Spadt S. Genital and dermatologic examination. part II: the male patient. Urol Nurs. 2003;23:366-367.

- Dean RC, Lue TF. Physiology of penile erection and pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 2005;32:379-395.

- Norwick P, Weston GK, Grant-Kels JM. Erection ethics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1225.

- Vogel L. Chaperones: friend or foe, and to whom? CMAJ. 2012;184:642-643.

Men have unique dermatologic needs yet are significantly less likely than women to visit a dermatologist’s office.1 Male patients might have preconceived notions about the nature of dermatology visits and necessary areas of the body to be examined: For example, male patients might associate the genital examination with a urologist and not expect a dermatologist to complete such a seemingly private examination.2

Genital examinations are currently underperformed: Only one-quarter of dermatologists report examining a male patient’s genitals at most or all visits.3 In this commentary, we discuss the importance of genital examinations in men’s dermatology, specific issues that can arise, and strategies to enhance the quality and frequency of genital examinations in male patients.

Invaluable Aspect of Care

Thorough inspection of a male patient’s genital region is an important part of conducting a total-body skin examination (TBSE) for routine surveillance and evaluation of genital dermatoses. Sexually transmitted infections, warts, and other common lesions can be missed in diagnosis without careful inspection of the genital region. Additionally, scrotal malignancies, such as primary and metastatic melanoma and basal cell carcinoma, though rare, might be overlooked until symptoms become severe.4,5

There is no substitute for a physical examination but, in certain circumstances, it might be appropriate for a dermatologist to ask a patient if he has concerning lesions on his genitals. However, patients often are unsure of worrisome signs, and areas of the perineum might not be easily visible to a patient. Genital inspection during the physical examination allows for a teachable moment, during which the dermatologist can educate the patient about benign lesions and variants, such as pearly penile papules, seborrheic keratoses, and sebaceous cysts.6 These lesions might not require intervention but should be monitored for atypical features or infection.6

Also, the dermatologist might incidentally discover transmissible lesions, such as condylomata caused by human papillomavirus, which has been shown to be present in approximately 50% of men in the United States7—many of whom are unaware. Inflammatory dermatoses, such as psoriasis, often affect the genitals and go unnoticed; prompt intervention can decrease the likelihood of complications.6

Protocol for Genital Examinations

To examine the genitals, all surfaces of the penis, scrotum, and perineum should be evaluated, with anatomic and pathologic variants noted. The patient or physician should stretch the penis, maneuvering it in multiple directions so that all aspects can be examined. In uncircumcised men, the foreskin should be retracted so that the head of the penis can be examined, followed by replacement of the foreskin by the patient.8 The scrotum also should be examined and lifted to fully view the perineum.

Providers should not grasp the penis with the whole hand but use the thumb and first finger to hold the head of the penis to maneuver it.8 Similarly, using the back of the hand and fingers to manipulate the genitals establishes boundaries and sets a clinical tone for the examination.

Unintentional Erection

Unique to the male dermatologic examination is the unintentional patient erection; a physician might be unsure of how to approach such a potentially awkward situation. An erection is not always an indication of sexual arousal; rather, it can reflect an autonomic reflex in response to physical stimulation. Erections occur commonly in health care settings, especially if the genitals are being manipulated.9

Generally, the course of action here depends on the patient’s response.10 For patients who appear unbothered, it might be appropriate to ignore the erection and proceed with the examination, especially if the physician is not actively examining the genital region. If the patient appears embarrassed, the physician can say “This is completely normal” or “Random erections are common” to normalize the situation. Joking or laughing should be avoided. For a patient who appears upset, the physician can step outside the room for a brief period to give the patient privacy, then re-enter and ask him if he is comfortable continuing with the examination.

When a patient develops an erection, the physician might become uncomfortable and, consciously or subconsciously, increase the pace of the examination, which is a natural tendency, but expediency at the expense of comprehensive care is inappropriate.

Examiner’s Body Language and Tone

Throughout the genital examination, the physician should be mindful of their comments and body language to avoid exacerbating patient vulnerability. Using anatomic terms, rather than colloquial ones, to describe the genitalia is advised to prevent misunderstanding and maintain a professional clinical environment. Providers should be prepared to explain anatomic terms because some patients are not familiar with medical terminology.

Presence of a Chaperone

Involving a chaperone, as recommended by the American Medical Association, might make a patient more comfortable and alleviate potential misunderstanding. Still, physicians should be aware that some patients might feel uncomfortable with a chaperone, interpreting their presence as an expectation of impropriety.11 Universal offering of a chaperone to all patients, regardless of the gender of the physician, as well as appropriate signage in the clinical environment, normalizes chaperone invitation and use.

Other Helpful Considerations

Various strategies in the male genital examination can increase patient and physician comfort and improve care:

- The patient should be offered a gown before a TBSE or any skin examination during which the genitals will be examined.

- The patient should be allowed to keep his shorts or underwear on to avoid the feeling of being naked, which can provoke anxiety. Prior to beginning the examination, disclose that it will include “under the covered areas.”

- Ask the patient for permission to conduct the examination, enumerate the steps, and provide a rationale for a genital examination. These steps help gain cooperation, alleviate anticipation, and prevent surprise.

- To increase the patient’s comfort level, he can be asked whether he prefers to be examined supine or standing.

- Consider allowing the patient, himself, to expose and manipulate his genitals during the examination to increase his involvement and sense of autonomy.

- For genital examinations, patients often prefer that the examiner be a physician of the same gender. Accommodating a patient’s request regarding the examiner’s gender might not always be possible, but the medical practice should make an honest attempt to oblige.

Lastly, providers should be cognizant of the needs of male sexual and gender minority populations (ie, gay, bisexual, transgender/gender diverse, queer or questioning, intersex, and asexual persons). For example, transgender women might retain male anatomy or have surgical alteration of the genital region that also requires evaluation. In such patient populations, the genital examination is equally important to evaluate for dermatologic conditions that require treatment.

Final Thoughts

The male genital examination is an important component of the TBSE, as dermatologists can recognize lesions before symptoms present. Robust educational methods for trainees and practitioners in dermatology are lacking, and development of curricula might be beneficial to increase comfort in performing the genital examination. Still, use of the procedures described in this commentary can normalize the men’s genital examination, optimize the physical examination, and improve men’s overall dermatologic health.

Men have unique dermatologic needs yet are significantly less likely than women to visit a dermatologist’s office.1 Male patients might have preconceived notions about the nature of dermatology visits and necessary areas of the body to be examined: For example, male patients might associate the genital examination with a urologist and not expect a dermatologist to complete such a seemingly private examination.2

Genital examinations are currently underperformed: Only one-quarter of dermatologists report examining a male patient’s genitals at most or all visits.3 In this commentary, we discuss the importance of genital examinations in men’s dermatology, specific issues that can arise, and strategies to enhance the quality and frequency of genital examinations in male patients.

Invaluable Aspect of Care

Thorough inspection of a male patient’s genital region is an important part of conducting a total-body skin examination (TBSE) for routine surveillance and evaluation of genital dermatoses. Sexually transmitted infections, warts, and other common lesions can be missed in diagnosis without careful inspection of the genital region. Additionally, scrotal malignancies, such as primary and metastatic melanoma and basal cell carcinoma, though rare, might be overlooked until symptoms become severe.4,5

There is no substitute for a physical examination but, in certain circumstances, it might be appropriate for a dermatologist to ask a patient if he has concerning lesions on his genitals. However, patients often are unsure of worrisome signs, and areas of the perineum might not be easily visible to a patient. Genital inspection during the physical examination allows for a teachable moment, during which the dermatologist can educate the patient about benign lesions and variants, such as pearly penile papules, seborrheic keratoses, and sebaceous cysts.6 These lesions might not require intervention but should be monitored for atypical features or infection.6

Also, the dermatologist might incidentally discover transmissible lesions, such as condylomata caused by human papillomavirus, which has been shown to be present in approximately 50% of men in the United States7—many of whom are unaware. Inflammatory dermatoses, such as psoriasis, often affect the genitals and go unnoticed; prompt intervention can decrease the likelihood of complications.6

Protocol for Genital Examinations

To examine the genitals, all surfaces of the penis, scrotum, and perineum should be evaluated, with anatomic and pathologic variants noted. The patient or physician should stretch the penis, maneuvering it in multiple directions so that all aspects can be examined. In uncircumcised men, the foreskin should be retracted so that the head of the penis can be examined, followed by replacement of the foreskin by the patient.8 The scrotum also should be examined and lifted to fully view the perineum.

Providers should not grasp the penis with the whole hand but use the thumb and first finger to hold the head of the penis to maneuver it.8 Similarly, using the back of the hand and fingers to manipulate the genitals establishes boundaries and sets a clinical tone for the examination.

Unintentional Erection

Unique to the male dermatologic examination is the unintentional patient erection; a physician might be unsure of how to approach such a potentially awkward situation. An erection is not always an indication of sexual arousal; rather, it can reflect an autonomic reflex in response to physical stimulation. Erections occur commonly in health care settings, especially if the genitals are being manipulated.9

Generally, the course of action here depends on the patient’s response.10 For patients who appear unbothered, it might be appropriate to ignore the erection and proceed with the examination, especially if the physician is not actively examining the genital region. If the patient appears embarrassed, the physician can say “This is completely normal” or “Random erections are common” to normalize the situation. Joking or laughing should be avoided. For a patient who appears upset, the physician can step outside the room for a brief period to give the patient privacy, then re-enter and ask him if he is comfortable continuing with the examination.

When a patient develops an erection, the physician might become uncomfortable and, consciously or subconsciously, increase the pace of the examination, which is a natural tendency, but expediency at the expense of comprehensive care is inappropriate.

Examiner’s Body Language and Tone

Throughout the genital examination, the physician should be mindful of their comments and body language to avoid exacerbating patient vulnerability. Using anatomic terms, rather than colloquial ones, to describe the genitalia is advised to prevent misunderstanding and maintain a professional clinical environment. Providers should be prepared to explain anatomic terms because some patients are not familiar with medical terminology.

Presence of a Chaperone

Involving a chaperone, as recommended by the American Medical Association, might make a patient more comfortable and alleviate potential misunderstanding. Still, physicians should be aware that some patients might feel uncomfortable with a chaperone, interpreting their presence as an expectation of impropriety.11 Universal offering of a chaperone to all patients, regardless of the gender of the physician, as well as appropriate signage in the clinical environment, normalizes chaperone invitation and use.

Other Helpful Considerations

Various strategies in the male genital examination can increase patient and physician comfort and improve care:

- The patient should be offered a gown before a TBSE or any skin examination during which the genitals will be examined.

- The patient should be allowed to keep his shorts or underwear on to avoid the feeling of being naked, which can provoke anxiety. Prior to beginning the examination, disclose that it will include “under the covered areas.”

- Ask the patient for permission to conduct the examination, enumerate the steps, and provide a rationale for a genital examination. These steps help gain cooperation, alleviate anticipation, and prevent surprise.

- To increase the patient’s comfort level, he can be asked whether he prefers to be examined supine or standing.

- Consider allowing the patient, himself, to expose and manipulate his genitals during the examination to increase his involvement and sense of autonomy.

- For genital examinations, patients often prefer that the examiner be a physician of the same gender. Accommodating a patient’s request regarding the examiner’s gender might not always be possible, but the medical practice should make an honest attempt to oblige.

Lastly, providers should be cognizant of the needs of male sexual and gender minority populations (ie, gay, bisexual, transgender/gender diverse, queer or questioning, intersex, and asexual persons). For example, transgender women might retain male anatomy or have surgical alteration of the genital region that also requires evaluation. In such patient populations, the genital examination is equally important to evaluate for dermatologic conditions that require treatment.

Final Thoughts

The male genital examination is an important component of the TBSE, as dermatologists can recognize lesions before symptoms present. Robust educational methods for trainees and practitioners in dermatology are lacking, and development of curricula might be beneficial to increase comfort in performing the genital examination. Still, use of the procedures described in this commentary can normalize the men’s genital examination, optimize the physical examination, and improve men’s overall dermatologic health.

- Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, et al. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1286-1291.

- Brezinski EA, Harskamp CT, Ledo L, et al. Public perception of dermatologists and comparison with other medical specialties: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:875-881.

- Rieder EA, Mu EW, Wang J, et al. Dermatologist practices during total body skin examinations: a survey study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:516-520.

- Gonzalez CD, Hawkes JE, Bowles TL. Malignant melanoma scrotal metastasis: the importance of the genital examination. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:10-12.

- Solimani F, Juratli H, Hoch M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma of the scrotum: an important but easily overlooked entity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E254-E255.

- Gabrielson AT, Le TV, Fontenot C, et al. Male genital dermatology: a primer for the sexual medicine physician. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7:71-83.

- Han JJ, Beltran TH, Song JW, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus vaccination rates among US adult men: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:810-816.

- Albaugh JA, Kellogg-Spadt S. Genital and dermatologic examination. part II: the male patient. Urol Nurs. 2003;23:366-367.

- Dean RC, Lue TF. Physiology of penile erection and pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 2005;32:379-395.

- Norwick P, Weston GK, Grant-Kels JM. Erection ethics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1225.

- Vogel L. Chaperones: friend or foe, and to whom? CMAJ. 2012;184:642-643.

- Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, et al. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1286-1291.

- Brezinski EA, Harskamp CT, Ledo L, et al. Public perception of dermatologists and comparison with other medical specialties: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:875-881.

- Rieder EA, Mu EW, Wang J, et al. Dermatologist practices during total body skin examinations: a survey study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:516-520.

- Gonzalez CD, Hawkes JE, Bowles TL. Malignant melanoma scrotal metastasis: the importance of the genital examination. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:10-12.

- Solimani F, Juratli H, Hoch M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma of the scrotum: an important but easily overlooked entity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E254-E255.

- Gabrielson AT, Le TV, Fontenot C, et al. Male genital dermatology: a primer for the sexual medicine physician. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7:71-83.

- Han JJ, Beltran TH, Song JW, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus vaccination rates among US adult men: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:810-816.

- Albaugh JA, Kellogg-Spadt S. Genital and dermatologic examination. part II: the male patient. Urol Nurs. 2003;23:366-367.

- Dean RC, Lue TF. Physiology of penile erection and pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 2005;32:379-395.

- Norwick P, Weston GK, Grant-Kels JM. Erection ethics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1225.

- Vogel L. Chaperones: friend or foe, and to whom? CMAJ. 2012;184:642-643.

Practice Points

- Genital examinations are an important aspect of comprehensive dermatologic care for male patients.

- Unintentional patient erections are unique to male patients and should be addressed professionally, depending on the patient’s reaction.

- In addition to being mindful of body language and tone, dermatologists may consider involving a chaperone when performing genital examinations to optimize patient experience.

Brazilian researchers tracking reinfection by new virus variant

Just as Brazil surpassed 200,000 deaths from COVID-19 on Jan. 7, news from Bahia added another layer of concern: A platform case report in a preprint detailed the first case of reinfection in that state, apparently caused by a new strain, one having the E484K mutation.

That variant, now called Brazil P.1, has migrated to the United States. The Minnesota Department of Health announced on Jan. 25 the nation’s first known COVID-19 case associated with it.

The mutation is located in the protein gene of the virus’ spike, which forms the crown structure of coronaviruses and is responsible for the virus’ binding to human cells. The E484K mutation is now the focus because it’s associated with mutations that escape the immune system’s neutralizing antibodies.

“This mutation is at the center of worldwide concern, and it is the first time that it has appeared in a reinfection,” the study’s first author, Bruno Solano de Freitas Souza, MD, a researcher at the Salvador regional unit of Instituto D’Or of Teaching and Research, based at Hospital São Rafael, Salvador, Brazil, explained in an interview.

“We will wait for the sample from Bahia to confirm the case from the perspective of the Ministry of Health’s surveillance network,” said Fernando Motta, PhD, deputy head of the Laboratory for Respiratory Virus and Measles at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, which acts as a national reference center for respiratory viruses with the Brazilian Ministry of Health (MS) and as a reference for the World Health Organization.

A case of reinfection

The case patient that led to the alarm was a 45-year-old woman who is a health care executive. She had no comorbidities. The team had been following health care professionals and patients who had tested positive on reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing more than once to understand whether they represented cases of prolonged viral persistence or new infections.

The woman had symptoms of viral infection on two occasions (May 26 and Oct. 26). On both occasions, results of RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 on nasopharyngeal samples were positive. In the first episode, the patient had diarrhea, myalgia, asthenia, and odynophagia for about 7 days. She returned to activities 21 days later. In the second episode, she had more severe symptoms that lasted longer, but she still did not require hospitalization.

“It was the first confirmed case of reinfection in Bahia, and in the second episode, we observed a mutation that could have an impact on the ability of antibodies to neutralize the virus,” Dr. Souza said. “The research continues with the investigation of cases in which the patient has a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR more than once in an interval greater than 45 days, to have a higher level of evidence.”

He stressed that “it is very important to reinforce measures to control the pandemic, social distance, use of masks, and speed up vaccination to be able to control the circulation of the virus, while monitoring the evolution of it.”

On alert for more cases

A person who twice tests positive for SARS-CoV-2 on real-time RT-PCR is suspected of having been reinfected, provided 90 or more days have elapsed between the two episodes, regardless of the condition observed. To confirm the suspected case, the samples must be sent to reference laboratories according to a plan established by the Ministry of Health in Brazil.

A health professional living in the Brazilian city of Natal represented the first confirmed case of reinfection by the new coronavirus in Brazil. That case was announced on Dec. 10, 2020.

“We communicated this case of reinfection to the MS in early December 2020. And the second sample already had the E484K mutation on the spike, as in the case of Bahia,” said Dr. Motta.

The first step in differentiating reinfection from persistence is to observe differences in the genotyping of the virus. For the technique to be successful, Dr. Souza said, researchers need a large amount of viral genetic material, which usually cannot be obtained.

“That is why there are many more suspected than confirmed cases,” Dr. Souza explained. He admitted that, although there are few cases, “it is increasingly clear that reinfection is a reality.”

Markers of mutations

What worried the researchers most was not only the possibility of reinfection but also the fact that preliminary analyses showed a specific mutation.

“The E484K mutation is present in a group of variants identified in South Africa that have been associated with increased infectivity and has been observed in a strain recently described in Brazil,” Dr. Souza said.

Mutations are expected, appear spontaneously, and in most cases have no effects on transmission or clinical outcome – they are simply used as markers and are useful for contact tracing or studying transmission routes. But some mutations can last because they provide an advantage for the pathogen, even if only momentary. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, mutations in the protein spike gene (S) are relevant because they may give clues to that advantage – as well as to changes in infectivity, transmission potential, antibodies, and response to vaccines.

A variant of the virus that has eight changes that affect the protein S gene – and several others in different genes – is behind the increase in the number of cases in London and southeastern England. Researchers from the University of São Paulo identified one of the factors that made this new variant – classified as B.1.1.7 – more infectious.

With bioinformatics tools, they found that the protein S gene in the new viral strain has a stronger molecular interaction with the ACE2 receptor, which is on the surface of human cells and to which the virus binds, making infection possible. The variant has already spread to the rest of the world, and the first two cases have been confirmed in Brazil by the Adolf Lutz Institute.

The alert for a new variant in Africa – similar to B.1.1.7 in the United Kingdom in that it carries nine changes in protein S at position 501 – was made by the Brazilian virologist Tulio de Oliveira, PhD.

“We found that this strain seems to be spreading much faster,” Dr. Oliveira, who is with the University of KwaZulu Natal, told the journal Science. His work first alerted British scientists to the importance of the position N501Y.

“The new variants just described in the United Kingdom and South Africa are slightly more transmissible and have already been identified in cases imported into Brazil,” Dr. Motta said. “Unfortunately, we believe it is only a matter of time before it becomes indigenous.”

The viral family grows

Viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 are classified into strains on the basis of small differences in their genetic material. Since Dec. 26, 2020, in addition to the British and South African variants, it appears the Carioca lineage also is a player.

In a preprint article, researchers analyzed the evolution of the epidemic in Rio de Janeiro from April 2020 until just before the new increase in incidence in December. They compared the complete sequences of the viral genome of 180 patients from different municipalities. The study, which is being jointly conducted by members of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and the National Laboratory for Scientific Computing, identified a new variant of SARS-CoV-2 that has five unique mutations (from one of the predominant strains). Concern arose because, in addition to those five genetic changes, many of the samples had a sixth – the well-known E484K mutation.

“The three lines – the U.K., South Africa, and Brazil – were almost synchronous publications, but there is no clear evidence that they have any kind of common ancestry,” Carolina M. Voloch, PhD, the article’s first author and a biologist and researcher at the Molecular Virology Laboratory and associate professor in the department of genetics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, said in an interview.

Dr. Voloch’s research focuses on the use of bioinformatics tools to study the molecular, phylogenetic, and genomic evolution of viruses.

“The emergence of new strains is common for viruses,” she said. “It can be happening anywhere in the world at any time.”

She stressed that identifying when mutations emerge will help to define the new Brazilian lineage. Researchers are working to determine whether the neutralizing antibodies of patients who have been infected with other strains respond to this Rio de Janeiro strain.

“We hope to soon be sharing these results,” Dr. Voloch said.

The article’s authors estimated that the new strain likely appeared in early July. They say more analysis is needed to predict whether the changes have a major effect on viral infectivity, the host’s immune response, or the severity of the disease. Asked about the lineage that caused the reinfection in Bahia, Dr. Voloch said she hadn’t yet contacted the authors to conduct a joint analysis but added that the data disclosed in the preprint would not represent the same variant.

“There are only two of the five mutations that characterize the Rio de Janeiro lineage. However, it has the E484K mutation that is present in more than 94% of the samples of the new variant of Rio,” she said.

She added that there’s a possibility of reinfection by the lineage that’s circulating in Rio de Janeiro and in other states, as well as countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan.

“The Carioca virus is being exported to the rest of the world,” Dr. Voloch said.

Virus’ diversity still unknown

Researchers now know that SARS-CoV-2 probably circulated silently in Brazil as early as February 2020 and reached all the nation’s regions before air travel was restricted. Since the first half of 2020, there have been two predominant strains.

“More than a dozen strains have been identified in Brazil, but more important than counting strains to identify the speed with which they arise – which is directly associated with the rate of infection, which is very high in the country,” said Dr. Motta.

The so-called variant of Rio de Janeiro, he said, has also been detected in other states in four regions of Brazil. The key to documenting variants is to get a more representative sample with genomes from other parts of the country.

As of Jan. 10, a total of 347,000 complete genome sequences had been shared globally through open databases since SARS-CoV-2 was first identified, but the contribution of countries is uneven. Although the cost and complexity of genetic sequencing has dropped significantly over time, effective sequencing programs still require substantial investments in personnel, equipment, reagents, and bioinformatics infrastructure.

According to Dr. Voloch, it will only be possible to combat the new coronavirus by knowing its diversity and understanding how it evolves. The Fiocruz Genomic Network has made an infographic available so researchers can track the strains circulating in Brazil. It›s the result of collaboration between researchers from Fiocruz and the GISAID Initiative, an international partnership that promotes rapid data sharing.

As of Jan. 5, researchers in Brazil had studied 1,897 genomes – not nearly enough.

“In Brazil, there is little testing and even less sequencing,” lamented Dr. Souza.

“In the U.K., 1 in 600 cases is sequenced. In Brazil it is less than 1 in 10 million cases,” Dr. Voloch added.

So far, no decisive factors for public health, such as greater virulence or greater transmissibility, have been identified in any of the strains established in Brazil. The million-dollar question is whether the emergence of new strains could have an impact on the effectiveness of vaccines being administered today.

“In one way or another, the vaccine is our best bet ever, even if in the future we identify escapist mutants and have to modify it,” Dr. Motta said. “It is what we do annually with influenza.”

Dr. Voloch, Dr. Motta, and Dr. Souza disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on the Portuguese edition of Medscape.com.

Just as Brazil surpassed 200,000 deaths from COVID-19 on Jan. 7, news from Bahia added another layer of concern: A platform case report in a preprint detailed the first case of reinfection in that state, apparently caused by a new strain, one having the E484K mutation.

That variant, now called Brazil P.1, has migrated to the United States. The Minnesota Department of Health announced on Jan. 25 the nation’s first known COVID-19 case associated with it.

The mutation is located in the protein gene of the virus’ spike, which forms the crown structure of coronaviruses and is responsible for the virus’ binding to human cells. The E484K mutation is now the focus because it’s associated with mutations that escape the immune system’s neutralizing antibodies.

“This mutation is at the center of worldwide concern, and it is the first time that it has appeared in a reinfection,” the study’s first author, Bruno Solano de Freitas Souza, MD, a researcher at the Salvador regional unit of Instituto D’Or of Teaching and Research, based at Hospital São Rafael, Salvador, Brazil, explained in an interview.

“We will wait for the sample from Bahia to confirm the case from the perspective of the Ministry of Health’s surveillance network,” said Fernando Motta, PhD, deputy head of the Laboratory for Respiratory Virus and Measles at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, which acts as a national reference center for respiratory viruses with the Brazilian Ministry of Health (MS) and as a reference for the World Health Organization.

A case of reinfection

The case patient that led to the alarm was a 45-year-old woman who is a health care executive. She had no comorbidities. The team had been following health care professionals and patients who had tested positive on reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing more than once to understand whether they represented cases of prolonged viral persistence or new infections.

The woman had symptoms of viral infection on two occasions (May 26 and Oct. 26). On both occasions, results of RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 on nasopharyngeal samples were positive. In the first episode, the patient had diarrhea, myalgia, asthenia, and odynophagia for about 7 days. She returned to activities 21 days later. In the second episode, she had more severe symptoms that lasted longer, but she still did not require hospitalization.

“It was the first confirmed case of reinfection in Bahia, and in the second episode, we observed a mutation that could have an impact on the ability of antibodies to neutralize the virus,” Dr. Souza said. “The research continues with the investigation of cases in which the patient has a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR more than once in an interval greater than 45 days, to have a higher level of evidence.”

He stressed that “it is very important to reinforce measures to control the pandemic, social distance, use of masks, and speed up vaccination to be able to control the circulation of the virus, while monitoring the evolution of it.”

On alert for more cases

A person who twice tests positive for SARS-CoV-2 on real-time RT-PCR is suspected of having been reinfected, provided 90 or more days have elapsed between the two episodes, regardless of the condition observed. To confirm the suspected case, the samples must be sent to reference laboratories according to a plan established by the Ministry of Health in Brazil.

A health professional living in the Brazilian city of Natal represented the first confirmed case of reinfection by the new coronavirus in Brazil. That case was announced on Dec. 10, 2020.

“We communicated this case of reinfection to the MS in early December 2020. And the second sample already had the E484K mutation on the spike, as in the case of Bahia,” said Dr. Motta.

The first step in differentiating reinfection from persistence is to observe differences in the genotyping of the virus. For the technique to be successful, Dr. Souza said, researchers need a large amount of viral genetic material, which usually cannot be obtained.

“That is why there are many more suspected than confirmed cases,” Dr. Souza explained. He admitted that, although there are few cases, “it is increasingly clear that reinfection is a reality.”

Markers of mutations

What worried the researchers most was not only the possibility of reinfection but also the fact that preliminary analyses showed a specific mutation.

“The E484K mutation is present in a group of variants identified in South Africa that have been associated with increased infectivity and has been observed in a strain recently described in Brazil,” Dr. Souza said.

Mutations are expected, appear spontaneously, and in most cases have no effects on transmission or clinical outcome – they are simply used as markers and are useful for contact tracing or studying transmission routes. But some mutations can last because they provide an advantage for the pathogen, even if only momentary. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, mutations in the protein spike gene (S) are relevant because they may give clues to that advantage – as well as to changes in infectivity, transmission potential, antibodies, and response to vaccines.

A variant of the virus that has eight changes that affect the protein S gene – and several others in different genes – is behind the increase in the number of cases in London and southeastern England. Researchers from the University of São Paulo identified one of the factors that made this new variant – classified as B.1.1.7 – more infectious.

With bioinformatics tools, they found that the protein S gene in the new viral strain has a stronger molecular interaction with the ACE2 receptor, which is on the surface of human cells and to which the virus binds, making infection possible. The variant has already spread to the rest of the world, and the first two cases have been confirmed in Brazil by the Adolf Lutz Institute.

The alert for a new variant in Africa – similar to B.1.1.7 in the United Kingdom in that it carries nine changes in protein S at position 501 – was made by the Brazilian virologist Tulio de Oliveira, PhD.

“We found that this strain seems to be spreading much faster,” Dr. Oliveira, who is with the University of KwaZulu Natal, told the journal Science. His work first alerted British scientists to the importance of the position N501Y.

“The new variants just described in the United Kingdom and South Africa are slightly more transmissible and have already been identified in cases imported into Brazil,” Dr. Motta said. “Unfortunately, we believe it is only a matter of time before it becomes indigenous.”

The viral family grows

Viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 are classified into strains on the basis of small differences in their genetic material. Since Dec. 26, 2020, in addition to the British and South African variants, it appears the Carioca lineage also is a player.

In a preprint article, researchers analyzed the evolution of the epidemic in Rio de Janeiro from April 2020 until just before the new increase in incidence in December. They compared the complete sequences of the viral genome of 180 patients from different municipalities. The study, which is being jointly conducted by members of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and the National Laboratory for Scientific Computing, identified a new variant of SARS-CoV-2 that has five unique mutations (from one of the predominant strains). Concern arose because, in addition to those five genetic changes, many of the samples had a sixth – the well-known E484K mutation.

“The three lines – the U.K., South Africa, and Brazil – were almost synchronous publications, but there is no clear evidence that they have any kind of common ancestry,” Carolina M. Voloch, PhD, the article’s first author and a biologist and researcher at the Molecular Virology Laboratory and associate professor in the department of genetics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, said in an interview.

Dr. Voloch’s research focuses on the use of bioinformatics tools to study the molecular, phylogenetic, and genomic evolution of viruses.

“The emergence of new strains is common for viruses,” she said. “It can be happening anywhere in the world at any time.”

She stressed that identifying when mutations emerge will help to define the new Brazilian lineage. Researchers are working to determine whether the neutralizing antibodies of patients who have been infected with other strains respond to this Rio de Janeiro strain.

“We hope to soon be sharing these results,” Dr. Voloch said.

The article’s authors estimated that the new strain likely appeared in early July. They say more analysis is needed to predict whether the changes have a major effect on viral infectivity, the host’s immune response, or the severity of the disease. Asked about the lineage that caused the reinfection in Bahia, Dr. Voloch said she hadn’t yet contacted the authors to conduct a joint analysis but added that the data disclosed in the preprint would not represent the same variant.

“There are only two of the five mutations that characterize the Rio de Janeiro lineage. However, it has the E484K mutation that is present in more than 94% of the samples of the new variant of Rio,” she said.

She added that there’s a possibility of reinfection by the lineage that’s circulating in Rio de Janeiro and in other states, as well as countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan.

“The Carioca virus is being exported to the rest of the world,” Dr. Voloch said.

Virus’ diversity still unknown

Researchers now know that SARS-CoV-2 probably circulated silently in Brazil as early as February 2020 and reached all the nation’s regions before air travel was restricted. Since the first half of 2020, there have been two predominant strains.

“More than a dozen strains have been identified in Brazil, but more important than counting strains to identify the speed with which they arise – which is directly associated with the rate of infection, which is very high in the country,” said Dr. Motta.

The so-called variant of Rio de Janeiro, he said, has also been detected in other states in four regions of Brazil. The key to documenting variants is to get a more representative sample with genomes from other parts of the country.

As of Jan. 10, a total of 347,000 complete genome sequences had been shared globally through open databases since SARS-CoV-2 was first identified, but the contribution of countries is uneven. Although the cost and complexity of genetic sequencing has dropped significantly over time, effective sequencing programs still require substantial investments in personnel, equipment, reagents, and bioinformatics infrastructure.

According to Dr. Voloch, it will only be possible to combat the new coronavirus by knowing its diversity and understanding how it evolves. The Fiocruz Genomic Network has made an infographic available so researchers can track the strains circulating in Brazil. It›s the result of collaboration between researchers from Fiocruz and the GISAID Initiative, an international partnership that promotes rapid data sharing.

As of Jan. 5, researchers in Brazil had studied 1,897 genomes – not nearly enough.

“In Brazil, there is little testing and even less sequencing,” lamented Dr. Souza.

“In the U.K., 1 in 600 cases is sequenced. In Brazil it is less than 1 in 10 million cases,” Dr. Voloch added.

So far, no decisive factors for public health, such as greater virulence or greater transmissibility, have been identified in any of the strains established in Brazil. The million-dollar question is whether the emergence of new strains could have an impact on the effectiveness of vaccines being administered today.

“In one way or another, the vaccine is our best bet ever, even if in the future we identify escapist mutants and have to modify it,” Dr. Motta said. “It is what we do annually with influenza.”

Dr. Voloch, Dr. Motta, and Dr. Souza disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on the Portuguese edition of Medscape.com.

Just as Brazil surpassed 200,000 deaths from COVID-19 on Jan. 7, news from Bahia added another layer of concern: A platform case report in a preprint detailed the first case of reinfection in that state, apparently caused by a new strain, one having the E484K mutation.

That variant, now called Brazil P.1, has migrated to the United States. The Minnesota Department of Health announced on Jan. 25 the nation’s first known COVID-19 case associated with it.

The mutation is located in the protein gene of the virus’ spike, which forms the crown structure of coronaviruses and is responsible for the virus’ binding to human cells. The E484K mutation is now the focus because it’s associated with mutations that escape the immune system’s neutralizing antibodies.

“This mutation is at the center of worldwide concern, and it is the first time that it has appeared in a reinfection,” the study’s first author, Bruno Solano de Freitas Souza, MD, a researcher at the Salvador regional unit of Instituto D’Or of Teaching and Research, based at Hospital São Rafael, Salvador, Brazil, explained in an interview.

“We will wait for the sample from Bahia to confirm the case from the perspective of the Ministry of Health’s surveillance network,” said Fernando Motta, PhD, deputy head of the Laboratory for Respiratory Virus and Measles at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, which acts as a national reference center for respiratory viruses with the Brazilian Ministry of Health (MS) and as a reference for the World Health Organization.

A case of reinfection

The case patient that led to the alarm was a 45-year-old woman who is a health care executive. She had no comorbidities. The team had been following health care professionals and patients who had tested positive on reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing more than once to understand whether they represented cases of prolonged viral persistence or new infections.