User login

A Multi-Membership Approach for Attributing Patient-Level Outcomes to Providers in an Inpatient Setting

From Banner Health Corporation, Phoenix, AZ.

Background: Health care providers are routinely incentivized with pay-for-performance (P4P) metrics to increase the quality of care. In an inpatient setting, P4P models typically measure quality by attributing each patient’s outcome to a single provider even though many providers routinely care for the patient. This study investigates a new attribution approach aiming to distribute each outcome across all providers who provided care.

Methods: The methodology relies on a multi-membership model and is demonstrated in the Banner Health system using 3 clinical outcome measures (length of stay, 30-day readmissions, and mortality) and responses to 3 survey questions that measure a patient’s perception of their care. The new approach is compared to the “standard” method, which attributes each patient to only 1 provider.

Results: When ranking by clinical outcomes, both methods were concordant 72.1% to 82.1% of the time for top-half/bottom-half rankings, with a median percentile difference between 7 and 15. When ranking by survey scores, there was more agreement, with concordance between 84.1% and 86.6% and a median percentile difference between 11 and 13. Last, Pearson correlation coefficients of the paired percentiles ranged from 0.56 to 0.78.

Conclusion: The new approach provides a fairer solution when measuring provider performance.

Keywords: patient attribution; PAMM; PAPR; random effect model; pay for performance.

Providers practicing in hospitals are routinely evaluated based on their performance and, in many cases, are financially incentivized for a better-than-average performance within a pay-for-performance (P4P) model. The use of P4P models is based on the belief that they will “improve, motivate, and enhance providers to pursue aggressively and ultimately achieve the quality performance targets thus decreasing the number of medical errors with less malpractice events.”1 Although P4P models continue to be a movement in health care, they have been challenging to implement.

One concern involves the general quality of implementation, such as defining metrics and targets, setting payout amounts, managing technology and market conditions, and gauging the level of transparency to the provider.2 Another challenge, and the focus of this project, are concerns around measuring performance to avoid perceptions of unfairness. This concern can be minimized if the attribution is handled in a fairer way, by spreading it across all providers who affected the outcome, both in a positive or negative direction.3

To implement these models, the performance of providers needs to be measured and tracked periodically. This requires linking, or attributing, a patient’s outcome to a provider, which is almost always the attending or discharging provider (ie, a single provider).3 In this single-provider attribution approach, one provider will receive all the credit (good or bad) for their respective patients’ outcomes, even though the provider may have seen the patient only a fraction of the time during the hospitalization. Attributing outcomes—for example, length of stay (LOS), readmission rate, mortality rate, net promoter score (NPS)—using this approach reduces the validity of metrics designed to measure provider performance, especially in a rotating provider environment where many providers interact with and care for a patient. For example, the quality of providers’ interpersonal skills and competence were among the strongest determinants of patient satisfaction,4 but it is not credible that this is solely based on the last provider during a hospitalization.

Proportionally distributing the attribution of an outcome has been used successfully in other contexts. Typically, a statistical modeling approach using a multi-membership framework is used because it can handle the sometimes-complicated relationships within the hierarchy. It also allows for auxiliary variables to be introduced, which can help explain and control for exogenous effects.5-7 For example, in the education setting, standardized testing is administered to students at defined years of schooling: at grades 4, 8, and 10, for instance. The progress of students, measured as the academic gains between test years, are proportionally attributed to all the teachers who the student has had between the test years. These partial attributions are combined to evaluate an overall teacher performance.8,9

Although the multi-membership framework has been used in other industries, it has yet to be applied in measuring provider performance. The purpose of this project is to investigate the impact of using a multi-provider approach compared to the standard single-provider approach. The findings may lead to modifications in the way a provider’s performance is measured and, thus, how providers are compensated. A similar study investigated the impact of proportionally distributing patients’ outcomes across all rotating providers using a weighting method based on billing practices to measure the partial impact of each provider.3

This study is different in 2 fundamental ways. First, attribution is weighted based on the number of clinically documented interactions (via clinical notes) between a patient and all rotating providers during the hospitalization. Second, performance is measured via multi-membership models, which can estimate the effect (both positive and negative) that a provider has on an outcome, even when caring for a patient a fraction of the time during the hospitalization.

Methods

Setting

Banner Health is a non-profit, multi-hospital health care system across 6 states in the western United States that is uniquely positioned to study provider quality attribution models. It not only has a large number of providers and serves a broad patient population, but Banner Health also uses an instance of Cerner (Kansas City, MO), an enterprise-level electronic health record (EHR) system that connects all its facilities and allows for advanced analytics across its system.

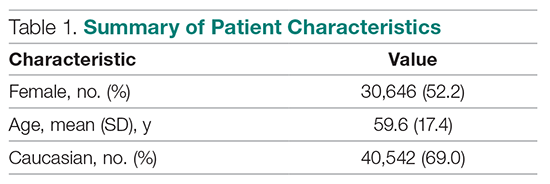

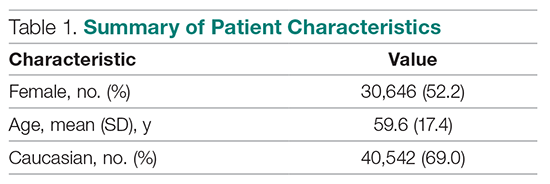

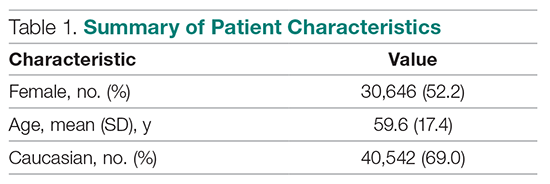

For this study, we included only general medicine and surgery patients admitted and discharged from the inpatient setting between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2018, who were between 18 and 89 years old at admission, and who had a LOS between 1 and 14 days. Visit- and patient-level data were collected from Cerner, while outcome data, and corresponding expected outcome data, were obtained from Premier, Inc. (Charlotte, NC) using their CareScience methodologies.10 To measure patient experience, response data were extracted from post-discharge surveys administered by InMoment (Salt Lake City, UT).

Provider Attribution Models

Provider Attribution by Physician of Record (PAPR). In the standard approach, denoted here as the PAPR model, 1 provider—typically the attending or discharging provider, which may be the same person—is attributed to the entire hospitalization. This provider is responsible for the patient’s care, and all patient outcomes are aggregated and attributed to the provider to gauge his or her performance. The PAPR model is the most popular form of attribution across many health care systems and is routinely used for P4P incentives.

In this study, the discharging provider was used when attributing hospitalizations using the PAPR model. Providers responsible for fewer than 12 discharges in the calendar year were excluded. Because of the directness of this type of attribution, the performance of 1 provider does not account for the performance of the other rotating providers during hospitalizations.

Provider Attribution by Multiple Membership (PAMM). In contrast, we introduce another attribution approach here that is designed to assign partial attribution to each provider who cares for the patient during the hospitalization. To aggregate the partial attributions, and possibly control for any exogenous or risk-based factors, a multiple-membership, or multi-member (MM), model is used. The MM model can measure the effect of a provider on an outcome even when the patient-to-provider relationship is complex, such as in a rotating provider environment.8

The purpose of this study is to compare attribution models and to determine whether there are meaningful differences between them. Therefore, for comparison purposes, the same discharging providers using the PAPR approach are eligible for the PAMM approach, so that both attribution models are using the same set of providers. All other providers are excluded because their performance would not be comparable to the PAPR approach.

While there are many ways to document provider-to-patient interactions, 2 methods are available in almost all health care systems. The first method is to link a provider’s billing charges to each patient-day combination. This approach limits the attribution to 1 provider per patient per day because multiple rotating providers cannot charge for the same patient-day combination.3 However, many providers interact with a patient on the same day, so using this approach excludes non-billed provider-to-patient interactions.

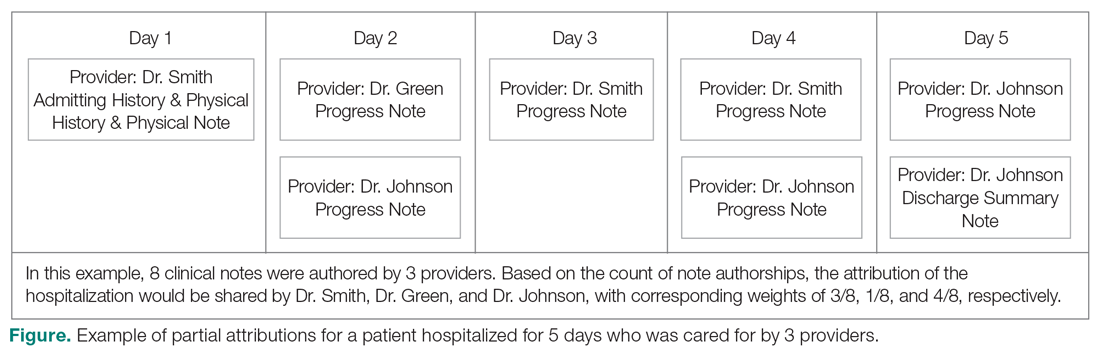

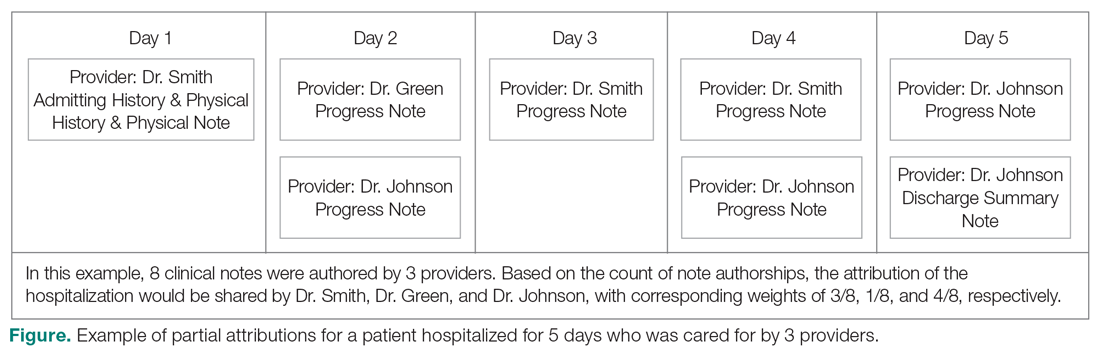

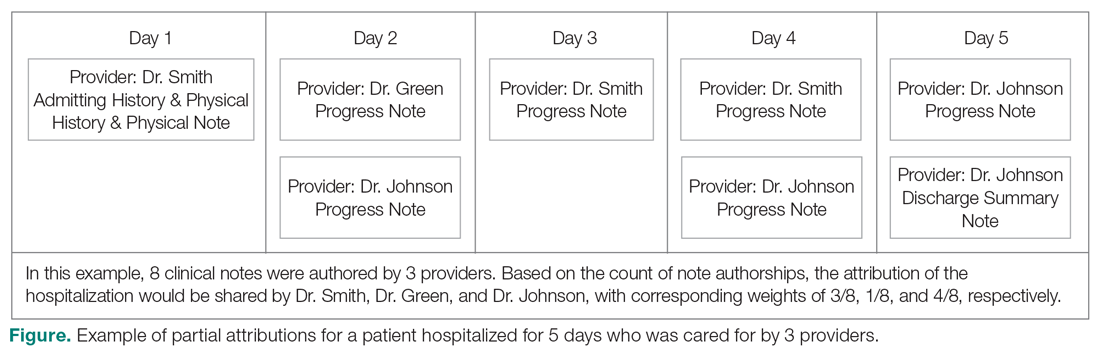

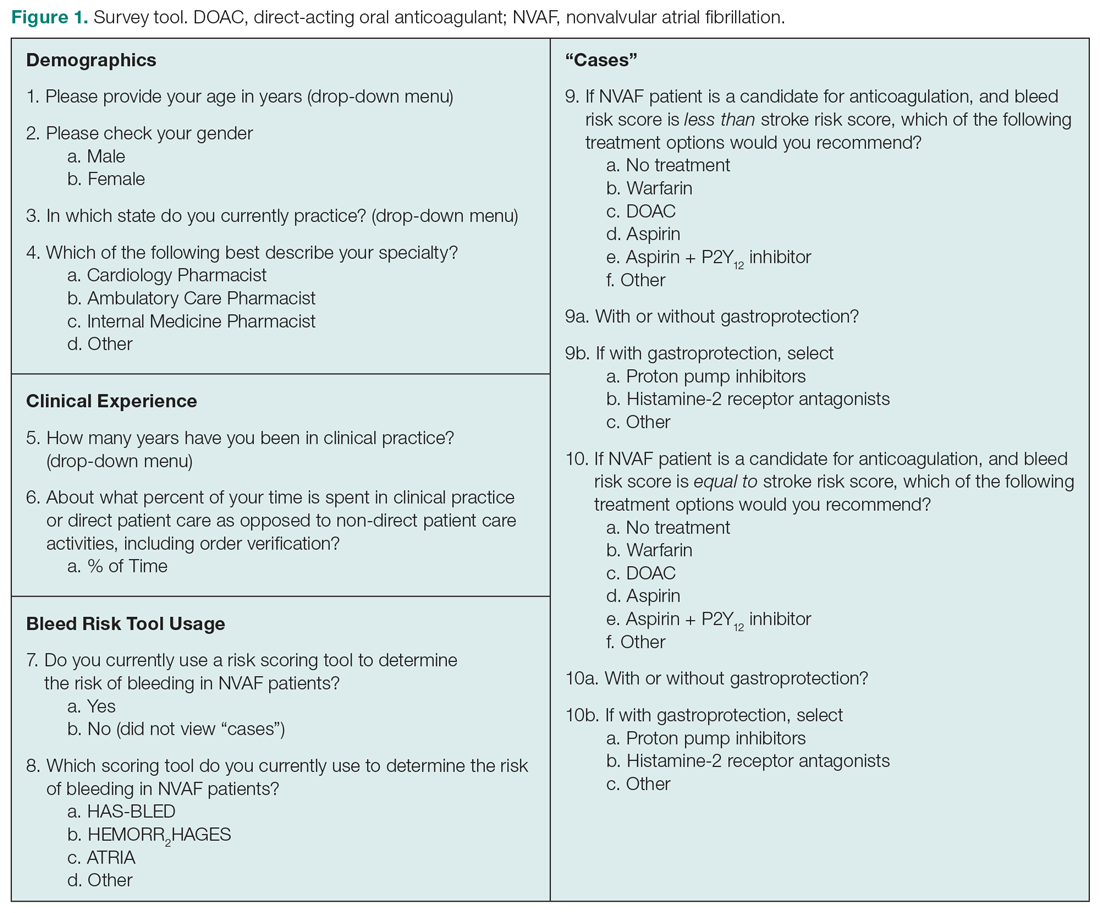

The second method, which was used in this study, relies on documented clinical notes within the EHR to determine how attribution is shared. In this approach, attribution is weighted based on the authorship of 3 types of eligible clinical notes: admitting history/physical notes (during admission), progress notes (during subsequent days), and discharge summary notes (during final discharge). This will (likely) result in many providers being linked to a patient on each day, which better reflects the clinical setting (Figure). Recently, clinical notes were used to attribute care of patients in an inpatient setting, and it was found that this approach provides a reliable way of tracking interactions and assigning ownership.11

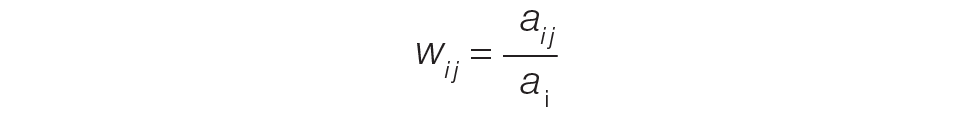

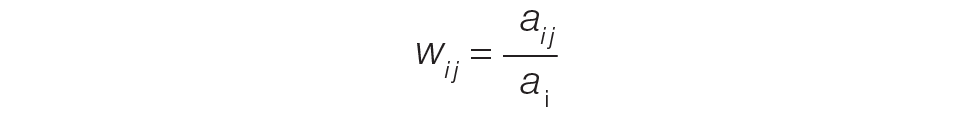

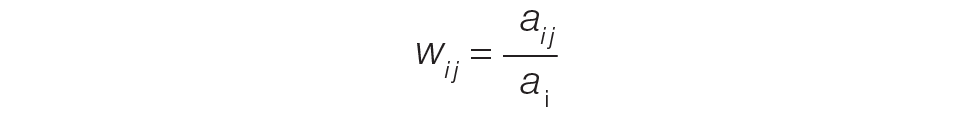

The provider-level attribution weights are based on the share of authorships of eligible note types. Specifically, for each provider j, let aij be the total count of eligible note types for hospitalization i authored by provider j, and let ai be the overall total count of eligible note types for hospitalization i. Then the attribution weight is

(Eq. 1)

for hospitalization i and provider j. Note that ∑jwij = 1: in other words, the total attribution, summed across all providers, is constrained to be 1 for each hospitalization.

Patient Outcomes

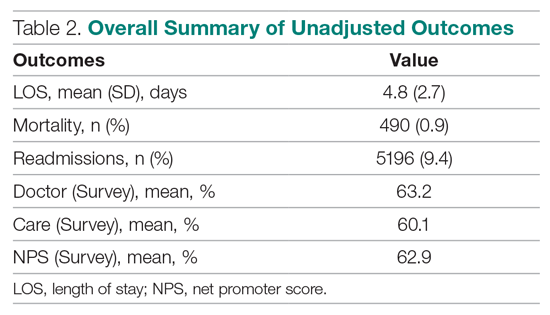

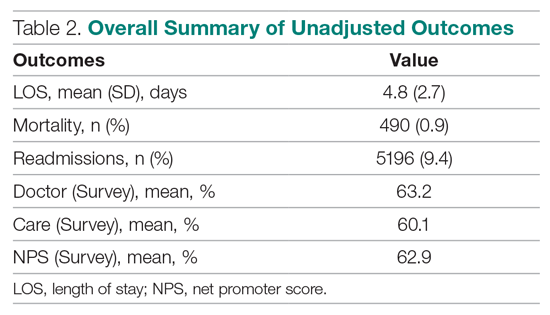

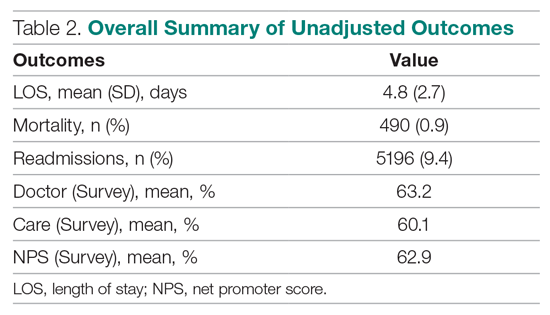

Outcomes were chosen based on their routine use in health care systems as standards when evaluating provider performance. This study included 6 outcomes: inpatient LOS, inpatient mortality, 30-day inpatient readmission, and patient responses from 3 survey questions. These outcomes can be collected without any manual chart reviews, and therefore are viewed as objective outcomes of provider performance.

Each outcome was aggregated for each provider using both attribution methods independently. For the PAPR method, observed-to-expected (OE) indices for LOS, mortality, and readmissions were calculated along with average patient survey scores. For the PAMM method, provider-level random effects from the fitted models were used. In both cases, the calculated measures were used for ranking purposes when determining top (or bottom) providers for each outcome.

Individual Provider Metrics for the PAPR Method

Inpatient LOS Index. Hospital inpatient LOS was measured as the number of days between admission date and discharge date. For each hospital visit, an expected LOS was determined using Premier’s CareScience Analytics (CSA) risk-adjustment methodology.10 The CSA methodology for LOS incorporates a patient’s clinical history, demographics, and visit-related administrative information.

Let nj be the number of hospitalizations attributed to provider j. Let oij and eij be the observed and expected LOS, respectively, for hospitalization i = 1,…,nj attributed to provider j. Then the inpatient LOS index for provider j is Lj = ∑ioij⁄∑ieij.

Inpatient Mortality Index. Inpatient mortality was defined as the death of the patient during hospitalization. For each hospitalization, an expected mortality probability was determined using Premier’s CSA risk-adjustment methodology.10 The CSA methodology for mortality incorporates a patient’s demographics and comorbidities.

Just as before, let nj be the number of hospitalizations attributed to provider j. Let mij = 1 if the patient died during hospitalization i = 1, … , nj attributed to provider j; mij = 0 otherwise. Let pij(m) be the corresponding expected mortality probability. Then the inpatient mortality index for provider j is Mj = ∑imij⁄∑ipij(m).

30-Day Inpatient Readmission Index. A 30-day inpatient readmission was defined as the event when a patient is discharged and readmits back into the inpatient setting within 30 days. The inclusion criteria defined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) all-cause hospital-wide readmission measure was used and, consequently, planned readmissions were excluded.12 Readmissions could occur at any Banner hospital, including the same hospital. For each hospital visit, an expected readmission probability was derived using Premier’s CSA risk-adjustment methodology.10 The CSA methodology for readmissions incorporates a patient’s clinical history, demographics, and visit-related administrative information.

Let nj be the number of hospitalizations attributed to provider j. Let rij = 1 if the patient had a readmission following hospitalization i = 1, … , nj attributed to provider j; rij = 0 otherwise. Let pij(r) be the corresponding expected readmission probability. Then the 30-day inpatient readmission index for provider j is Rj = ∑irij ⁄∑ipij(r).

Patient Survey Scores. The satisfaction of the patient’s experience during hospitalization was measured via post-discharge surveys administered by InMoment. Two survey questions were selected because they related directly to a provider’s interaction with the patient: “My interactions with doctors were excellent” (Doctor) and “I received the best possible care” (Care). A third question, “I would recommend this hospital to my family and friends,” was selected as a proxy measure of the overall experience and, in the aggregate, is referred to as the net promoter score (NPS).13,14 The responses were measured on an 11-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (0) to “Strongly Agree” (10); “N/A” or missing responses were excluded.

The Likert responses were coded to 3 discrete values as follows: if the value was between 0 and 6, then -1 (ie, detractor); between 7 and 8 (ie, neutral), then 0; otherwise 1 (ie, promoter). Averaging these coded responses results in a patient survey score for each question. Specifically, let nj be the number of hospitalizations attributed to provider j in which the patient responded to the survey question. Let sij ∈{−1, 0, 1} be the coded response linked to hospitalization i = 1, … , nj attributed to provider j. Then the patient experience score for provider j is Sj = ∑isij⁄nj.

Handling Ties in Provider Performance Measures. Because ties can occur in the PAPR approach for all measures, a tie-breaking strategy is needed. For LOS indices, ties are less likely because their numerator is strictly greater than 0, and expected LOS values are typically distinct enough. Indeed, no ties were found in this study for LOS indices. However, mortality and readmission indices can routinely result in ties when the best possible index is achieved, such as 0 deaths or readmissions among attributed hospitalizations. To help differentiate between those indices in the PAPR approach, the total estimated risk (denominator) was utilized as a secondary scoring criterion.

Mortality and readmission metrics were addressed by sorting first by the outcome (mortality index), and second by the denominator (total estimated risk). For example, if provider A has the same mortality rate as provider B, then provider A would be ranked higher if the denominator was larger, indicating a higher risk for mortality.

Similarly, it was very common for providers to have the same overall average rating for a survey question. Therefore, the denominator (number of respondents) was used to break ties. However, the denominator sorting was bidirectional. For example, if the tied score was positive (more promoters than detractors) for providers A and B, then provider A would be ranked higher if the denominator was larger. Conversely, if the tied score between providers A and B was neutral or negative (more detractors than promoters), then provider A would be ranked lower if the denominator was larger.

Individual Provider Metrics for the PAMM Method

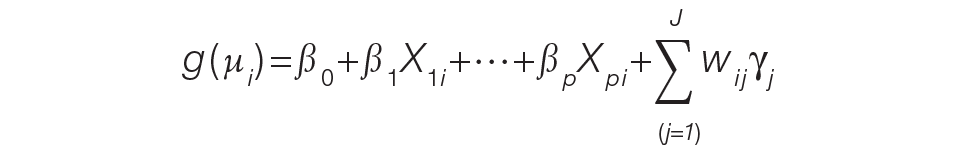

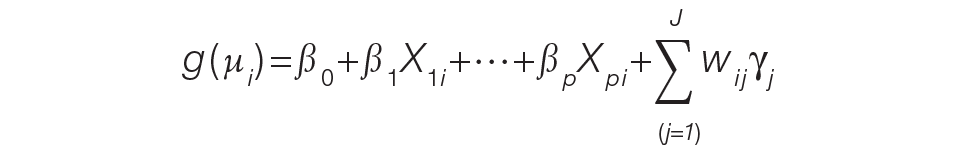

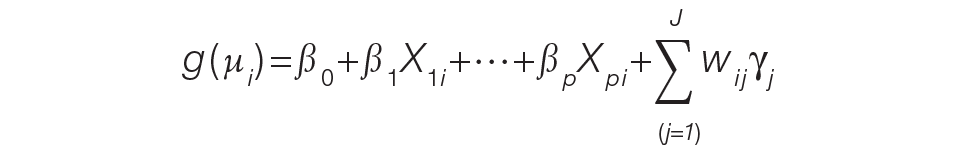

For the PAMM method, model-based metrics were derived using a MM model.8 Specifically, let J be the number of rotating providers in a health care system. Let Yi be an outcome of interest from hospitalization i, X1i, …, Xpi be fixed effects or covariates, and ß1, …, ßp be the coefficients for the respective covariates. Then the generalized MM statistical model is

(Eq. 2)

where g(μi ) is a link function between the mean of the outcome, μi, and its linear predictor, ß0, is the marginal intercept, wij represents the attribution weight of provider j on hospitalization i (described in Equation 1), and γj represents the random effect of provider j on the outcome with γj~N(0,σγ2).

For the mortality and readmission binary outcomes, logistic regression was performed using a logit link function, with the corresponding expected probability as the only fixed covariate. The expected probabilities were first converted into odds and then log-transformed before entering the model. For LOS, Poisson regression was performed using a log link function with the log-transformed expected LOS as the only fixed covariate. For coded patient experience responses, an ordered logistic regression was performed using a cumulative logit link function (no fixed effects were added).

MM Model-based Metrics. Each fitted MM model produces a predicted random effect for each provider. The provider-specific random effects can be interpreted as the unobserved influence of each provider on the outcome after controlling for any fixed effect included in the model. Therefore, the provider-specific random effects were used to evaluate the relative provider performance, which is analogous to the individual provider-level metrics used in the PAPR method.

Measuring provider performance using a MM model is more flexible and robust to outliers compared to the standard approach using OE indices or simple averages. First, although not investigated here, the effect of patient-, visit-, provider-, and/or temporal-level covariates can be controlled when evaluating provider performance. For example, a patient’s socioeconomic status, a provider’s workload, and seasonal factors can be added to the MM model. These external factors are not accounted for in OE indices.

Another advantage of using predicted random effects is the concept of “shrinkage.” The process of estimating random effects inherently accounts for small sample sizes (when providers do not treat a large enough sample of patients) and/or when there is a large ratio of patient variance to provider variance (for instance, when patient outcome variability is much higher compared to provider performance variability). In both cases, the estimation of the random effect is pulled ever closer to 0, signaling that the provider performance is closer to the population average. See Henderson15 and Mood16 for further details.

In contrast, OE indices can result in unreliable estimates when a provider has not cared for many patients. This is especially prevalent when the outcome is binary with a low probability of occurring, such as mortality. Indeed, provider-level mortality OE indices are routinely 0 when the patient counts are low, which skews performance rankings unfairly. Finally, OE indices also ignore the magnitude of the variance of an outcome between providers and patients, which can be large.

Comparison Methodology

In this study, we seek to compare the 2 methods of attribution, PAPR and PAMM, to determine whether there are meaningful differences between them when measuring provider performance. Using retrospective data described in the next section, each attribution method was used independently to derive provider-level metrics. To assess relative performance, percentiles were assigned to each provider based on their metric values so that, in the end, there were 2 percentile ranks for each provider for each metric.

Using these paired percentiles, we derived the following measures of concordance, similar to Herzke, Michtalik3: (1) the percent concordance measure—defined as the number of providers who landed in the top half (greater than the median) or bottom half under both attribution models—divided by the total number of providers; (2) the median of the absolute difference in percentiles under both attribution models; and (3) the Pearson correlation coefficient of the paired provider ranks. The first measure is a global measure of concordance between the 2 approaches and would be expected to be 50% by chance. The second measure gauges how an individual provider’s rank is affected by the change in attribution methodologies. The third measure is a statistical measure of linear correlation of the paired percentiles and was not included in the Herzke, Michtalik3 study.

All statistical analyses were performed on SAS (version 9.4; Cary, NC) and the MM models were fitted using PROC GLIMMIX with the EFFECT statement. The Banner Health Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

A total of

Multi-Membership Model Results

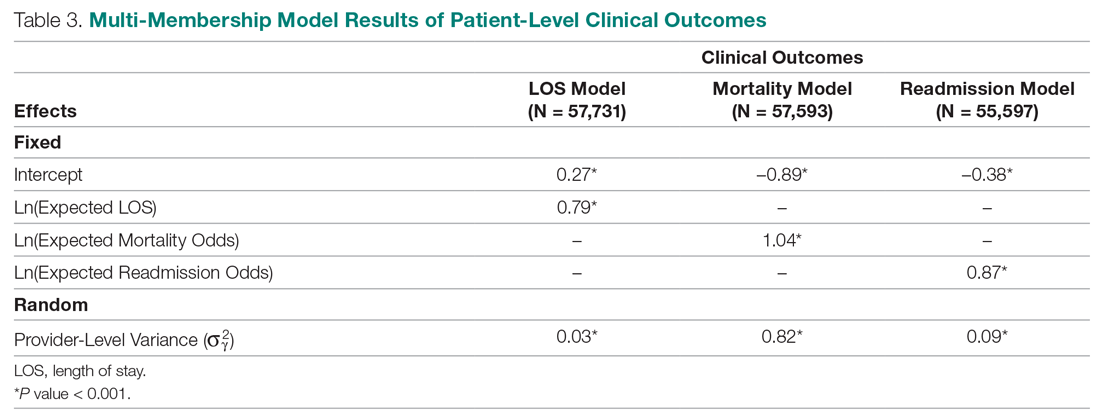

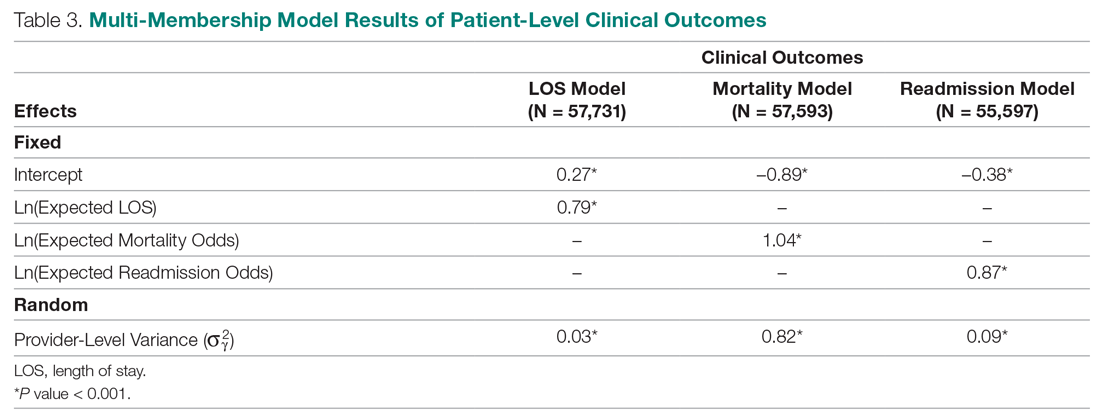

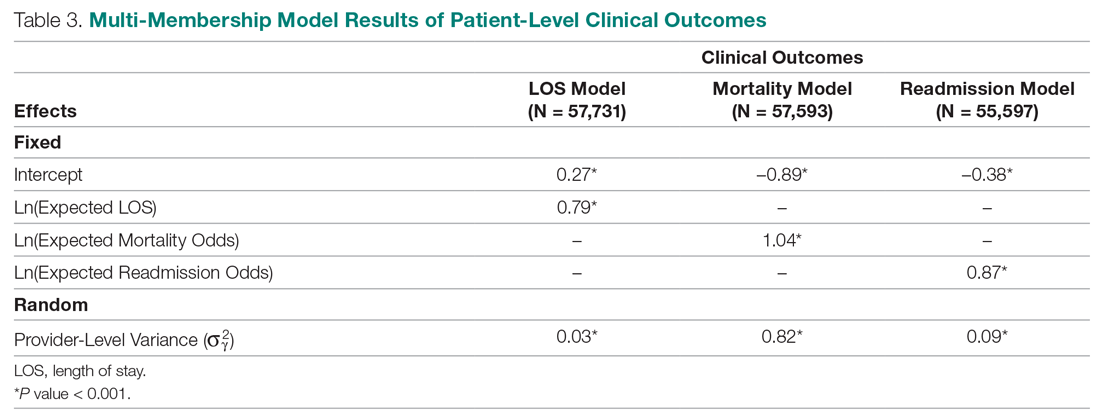

Table 3 displays the results after independently fitting MM models to each of the 3 clinical outcomes. Along with a marginal intercept, the only covariate in each model was the corresponding expected value after a transformation. This was added to use the same information that is typically used in OE indices, therefore allowing for a proper comparison between the 2 attribution methods. The provider-level variance represents the between-provider variation and measures the amount of influence providers have on the corresponding outcome after controlling for any covariates in the model. A provider-level variance of 0 would indicate that providers do not have any influence on the outcome. While the mortality and readmission model results can be compared to each other, the LOS model cannot given its different scale and transformation altogether.

The results in Table 3 suggest that each expected value covariate is highly correlated with its corresponding outcome, which is the anticipated conclusion given that they are constructed in this fashion. The estimated provider-level variances indicate that, after including an expected value in the model, providers have less of an influence on a patient’s LOS and likelihood of being readmitted. On the other hand, the results suggest that providers have much more influence on the likelihood of a patient dying in the hospital, even after controlling for an expected mortality covariate.

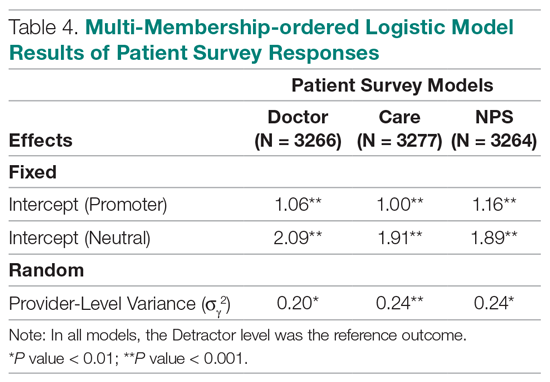

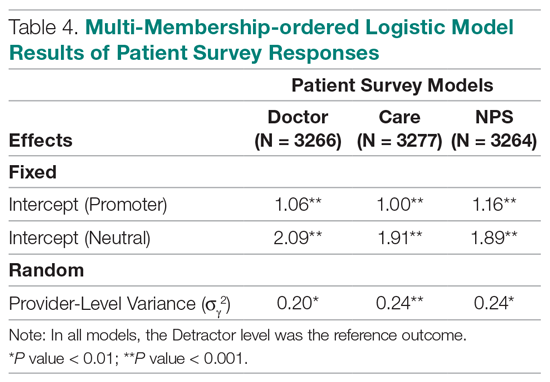

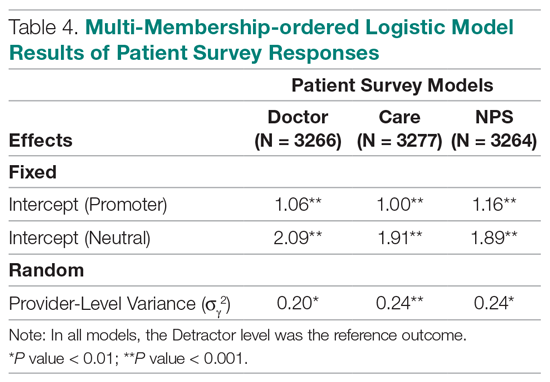

Table 4 shows the results after independently fitting MM-ordered logistic models to each of the 3 survey questions. The similar provider-level variances suggest that providers have the same influence on the patient’s perception of the quality of their interactions with the doctor (Doctor), the quality of the care they received (Care), and their likelihood to recommend a friend or family member to the hospital (NPS).

Comparison Results Between Both Attribution Methods

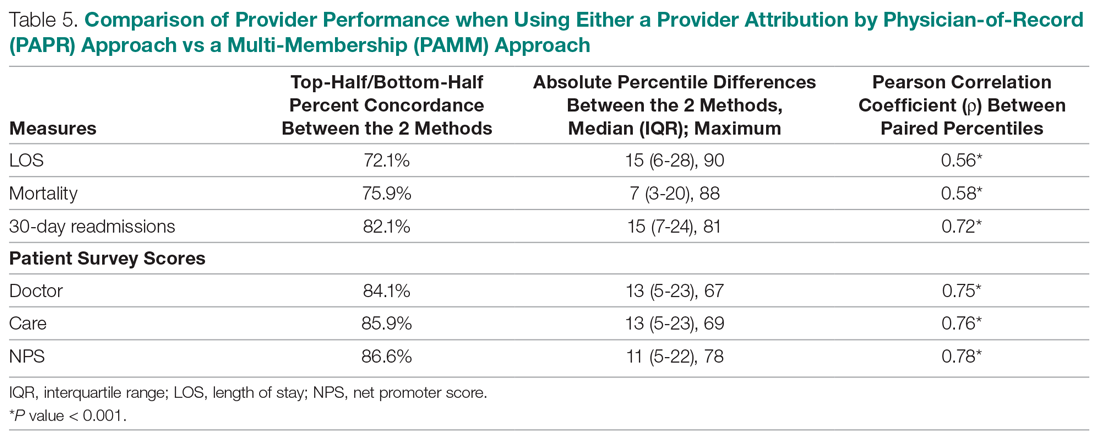

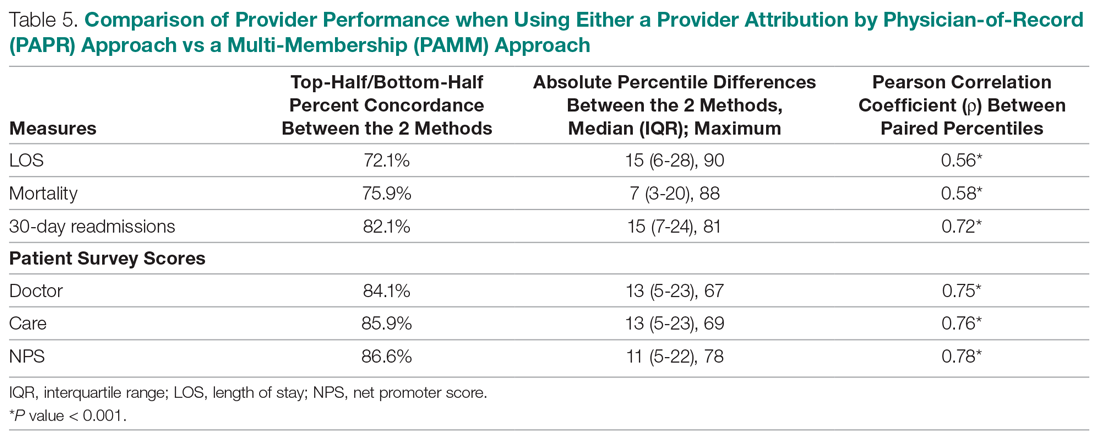

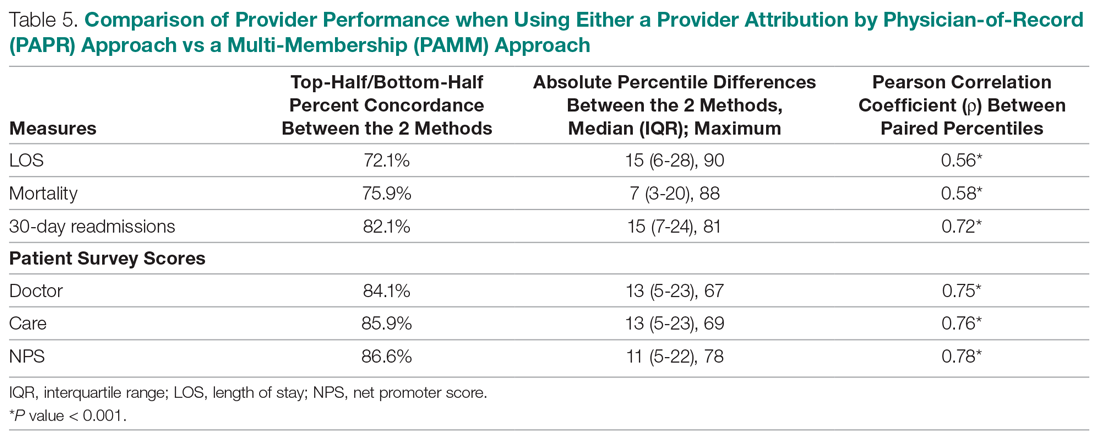

Table 5 compares the 2 attribution methods when ranking providers based on their performance on each outcome measure. The comparison metrics gauge how well the 2 methods agree overall (percent concordance), agree at the provider level (absolute percentile difference and interquartile range [IQR]), and how the paired percentiles linearly correlate to each other (Pearson correlation coefficient).

LOS, by a small margin, had the lowest concordance of clinical outcomes (72.1%), followed by mortality (75.9%) and readmissions (82.1%). Generally, the survey scores had higher percent concordance than the clinical outcome measures, with Doctor at 84.1%, Care at 85.9%, and NPS having the highest percent concordance at 86.6%. Given that by chance the percent concordance is expected to be 50%, there was notable discordance, especially with the clinical outcome measures. Using LOS performance as an example, one attribution methodology would rank a provider in the top half or bottom half, while the other attribution methodology would rank the same provider exactly the opposite way about 28% of the time.

The median absolute percentile difference between the 2 methods was more modest (between 7 and 15). Still, there were some providers whose performance ranking was heavily impacted by the attribution methodology that was used. This was especially true when evaluating performance for certain clinical measures, where the attribution method that was used could change the provider performance percentile by up to 90 levels.

The paired percentiles were positively correlated when ranking performance using any of the 6 measures. This suggests that both methodologies assess performance generally in the same direction, irrespective of the methodology and measure. We did not investigate more complex correlation measures and left this for future research.

It should be noted that ties occurred much more frequently with the PAPR method than when using PAMM and therefore required tie-breaking rules to be designed. Given the nature of OE indices, PAPR methodology is especially sensitive to ties whenever the measure includes counting the number of events (for example, mortality and readmissions) and whenever there are many providers with very few attributed patients. On the other hand, using the PAMM method is much more robust against ties given that the summation of all the weighted attributed outcomes will rarely result in ties, even with a nominal set of providers.

Discussion

In this study, the PAMM methodology was introduced and was used to assess relative provider performance on 3 clinical outcome measures and 3 patient survey scores. The new approach aims to distribute each outcome among all providers who provided care for a patient in an inpatient setting. Clinical notes were used to account for patient-to-provider interactions, and fitted MM statistical models were used to compute the effects that each provider had on each outcome. The provider effect was introduced as a random effect, and the set of predicted random effects was used to rank the performance of each provider.

The PAMM approach was compared to the more traditional methodology, PAPR, where each patient is attributed to only 1 provider: the discharging physician in this study. Using this approach, OE indices of clinical outcomes and averages of survey scores were used to rank the performance of each provider. This approach resulted in many ties, which were broken based on the number of hospitalizations, although other tie-breaking methods may be used in practice.

Both methodologies showed modest concordance with each other for the clinical outcomes, but higher concordance for the patient survey scores. This was also true when using the Pearson correlation coefficient to assess agreement. The 1 outcome measure that showed the least concordance and least linear correlation between methods was LOS, which would suggest that LOS performance is more sensitive to the attribution methodology that is used. However, it was the least concordant by a small margin.

Furthermore, although the medians of the absolute percentile differences were small, there were some providers who had large deviations, suggesting that some providers would move from being shown as high-performers to low-performers and vice versa based on the chosen attribution method. We investigated examples of this and determined that the root cause was the difference in effective sample sizes for a provider. For the PAPR method, the effective sample size is simply the number of hospitalizations attributed to the provider. For the PAMM method, the effective sample size is the sum of all non-zero weights across all hospitalizations where the provider cared for a patient. By and large, the PAMM methodology provides more information of the provider effect on an outcome than the PAPR approach because every provider-patient interaction is considered. For example, providers who do not routinely discharge patients, but often care for patients, will have rankings that differ dramatically between the 2 methods.

The PAMM methodology has many statistical advantages that were not fully utilized in this comparative study. For example, we did not include any covariates in the MM models except for the expected value of the outcome, when it was available. Still, it is known that other covariates can impact an outcome as well, such as the patient’s age, socioeconomic indicators, existing chronic conditions, and severity of hospitalization, which can be added to the MM models as fixed effects. In this way, the PAMM approach can control for these other covariates, which are typically outside of the control of providers but typically ignored using OE indices. Therefore, using the PAMM approach would provide a fairer comparison of provider performance.

Using the PAMM method, most providers had a large sample size to assess their performance once all the weighted interactions were included. Still, there were a few who did not care for many patients for a variety of reasons. In these scenarios, MM models “borrow” strength from other providers to produce a more robust predicted provider effect by using a weighted average between the overall population trend and the specific provider outcomes (see Rao and Molina17). As a result, PAMM is a more suitable approach when the sample sizes of patients attributed to providers can be small.

One of the most interesting findings of this study was the relative size of the provider-level variance to the size of the fixed effect in each model (Table 3). Except for mortality, these variances suggest that there is a small difference in performance from one provider to another. However, these should be interpreted as the variance when only 1 provider is involved in the care of a patient. When multiple providers are involved, using basic statistical theory, the overall provider-level variance will be σγ2 ∑wij2 (see Equation 2). For example, the estimated variance among providers for LOS was 0.03 (on a log scale), but, using the scenario in the Figure, the overall provider-level variance for this hospitalization will be 0.03 (0.3752 + 0.1252 + 0.52) = 0.012. Hence, the combined effect of providers on LOS is less than would be expected. Indeed, as more providers are involved with a patient’s care, the more their combined influence on an outcome is diluted.

In this study, the PAMM approach placed an equal weight on all provider-patient interactions via clinical note authorship, but that may not be optimal in some settings. For example, it may make more sense to set a higher weight on the provider who admitted or discharged the patient while placing less (or 0) weight on all other interactions. In the extreme, if the full weight were placed on 1 provider interaction (eg, during discharge, then the MM model would be reduced to a one-way random effects model. The flexibility of weighting interactions is a feature of the PAMM approach, but any weighting framework must be transparent to the providers before implementation.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the PAMM approach is a feasible option within a large health care organization. For P4P programs to be successful, providers must be able to trust that their performance will be fairly assessed and that all provider-patient interactions are captured to provide a full comparison amongst their peers. The PAMM methodology is one solution to spread the positive (and negative) outcomes across all providers who cared for a patient and therefore, if implemented, would add trust and fairness when measuring and assessing provider performance.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Barrie Bradley for his support in the initial stages of this research and Dr. Syed Ismail Jafri for his help and support on the standard approaches of assessing and measuring provider performances.

Corresponding author: Rachel Ginn, MS, Banner Health Corporation, 2901 N. Central Ave., Phoenix, AZ 85012; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Abduljawad A, Al-Assaf AF. Incentives for better performance in health care. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2011;11:201-206.

2. Milstein R, Schreyoegg J. Pay for performance in the inpatient sector: a review of 34 P4P programs in 14 OECD countries. Health Policy. 2016;120:1125-1140.

3. Herzke CA, Michtalik HJ, Durkin N, et al. A method for attributing patient-level metrics to rotating providers in an inpatient setting. J Hosp Med. 2018;13:470-475.

4. Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Savino MM, Amenta P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137:89-101.

5. Ballou D, Sanders W, Wright P. Controlling for student background in value-added assessment of teachers. J Educ Behav Stat. 2004;29:37-65.

6. Hill PW, Goldstein H. Multilevel modeling of educational data with cross-classification and missing identification for units. J Educ Behav Stat. 1998;23:117-128.

7. Rasbash J, Browne WJ. Handbook of Multilevel Analysis. Springer; 2007.

8. Brown WJ, Goldstein H, Rasbash J. Multiple membership multiple classification (MMMC) models. Statistical Modeling. 2001;1:103-124.

9. Sanders WL, Horn SP. The Tennessee Value-Added Assessment System (TVAAS)—mixed-model methodology in educational assessment. J Pers Eval Educ. 1994;8:299-311.

10. Kroch EA, Duan M. CareScience Risk Assessment Model: Hospital Performance Measurement. Premier, Inc., 2008. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/mortality/KrochRisk.htm

11. Schumacher DJ, Wu DTY, Meganathan K, et al. A feasibility study to attribute patients to primary interns on inpatient ward teams using electronic health record data. Acad Med. 2019;94:1376-1383.

12. Simoes J, Krumholz HM, Lin Z. Hospital-level 30-day risk-standardized readmission measure. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2018. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Downloads/Hospital-Wide-All-Cause-Readmission-Updates.zip

13. Krol MW, de Boer D, Delnoij DM, Rademakers JJDJM. The Net Promoter Score: an asset to patient experience surveys? Health Expect. 2015;18:3099-3109.

14. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001570.

15. Henderson CR. Sire evaluation and genetic trends. J Anim Sci. 1973;1973:10-41.

16. Mood AM. Introduction to the Theory of Statistics. McGraw-Hill; 1950:xiii, 433-xiii.

17. Rao JNK, Molina I. Small Area Estimation. Wiley; 2015.

From Banner Health Corporation, Phoenix, AZ.

Background: Health care providers are routinely incentivized with pay-for-performance (P4P) metrics to increase the quality of care. In an inpatient setting, P4P models typically measure quality by attributing each patient’s outcome to a single provider even though many providers routinely care for the patient. This study investigates a new attribution approach aiming to distribute each outcome across all providers who provided care.

Methods: The methodology relies on a multi-membership model and is demonstrated in the Banner Health system using 3 clinical outcome measures (length of stay, 30-day readmissions, and mortality) and responses to 3 survey questions that measure a patient’s perception of their care. The new approach is compared to the “standard” method, which attributes each patient to only 1 provider.

Results: When ranking by clinical outcomes, both methods were concordant 72.1% to 82.1% of the time for top-half/bottom-half rankings, with a median percentile difference between 7 and 15. When ranking by survey scores, there was more agreement, with concordance between 84.1% and 86.6% and a median percentile difference between 11 and 13. Last, Pearson correlation coefficients of the paired percentiles ranged from 0.56 to 0.78.

Conclusion: The new approach provides a fairer solution when measuring provider performance.

Keywords: patient attribution; PAMM; PAPR; random effect model; pay for performance.

Providers practicing in hospitals are routinely evaluated based on their performance and, in many cases, are financially incentivized for a better-than-average performance within a pay-for-performance (P4P) model. The use of P4P models is based on the belief that they will “improve, motivate, and enhance providers to pursue aggressively and ultimately achieve the quality performance targets thus decreasing the number of medical errors with less malpractice events.”1 Although P4P models continue to be a movement in health care, they have been challenging to implement.

One concern involves the general quality of implementation, such as defining metrics and targets, setting payout amounts, managing technology and market conditions, and gauging the level of transparency to the provider.2 Another challenge, and the focus of this project, are concerns around measuring performance to avoid perceptions of unfairness. This concern can be minimized if the attribution is handled in a fairer way, by spreading it across all providers who affected the outcome, both in a positive or negative direction.3

To implement these models, the performance of providers needs to be measured and tracked periodically. This requires linking, or attributing, a patient’s outcome to a provider, which is almost always the attending or discharging provider (ie, a single provider).3 In this single-provider attribution approach, one provider will receive all the credit (good or bad) for their respective patients’ outcomes, even though the provider may have seen the patient only a fraction of the time during the hospitalization. Attributing outcomes—for example, length of stay (LOS), readmission rate, mortality rate, net promoter score (NPS)—using this approach reduces the validity of metrics designed to measure provider performance, especially in a rotating provider environment where many providers interact with and care for a patient. For example, the quality of providers’ interpersonal skills and competence were among the strongest determinants of patient satisfaction,4 but it is not credible that this is solely based on the last provider during a hospitalization.

Proportionally distributing the attribution of an outcome has been used successfully in other contexts. Typically, a statistical modeling approach using a multi-membership framework is used because it can handle the sometimes-complicated relationships within the hierarchy. It also allows for auxiliary variables to be introduced, which can help explain and control for exogenous effects.5-7 For example, in the education setting, standardized testing is administered to students at defined years of schooling: at grades 4, 8, and 10, for instance. The progress of students, measured as the academic gains between test years, are proportionally attributed to all the teachers who the student has had between the test years. These partial attributions are combined to evaluate an overall teacher performance.8,9

Although the multi-membership framework has been used in other industries, it has yet to be applied in measuring provider performance. The purpose of this project is to investigate the impact of using a multi-provider approach compared to the standard single-provider approach. The findings may lead to modifications in the way a provider’s performance is measured and, thus, how providers are compensated. A similar study investigated the impact of proportionally distributing patients’ outcomes across all rotating providers using a weighting method based on billing practices to measure the partial impact of each provider.3

This study is different in 2 fundamental ways. First, attribution is weighted based on the number of clinically documented interactions (via clinical notes) between a patient and all rotating providers during the hospitalization. Second, performance is measured via multi-membership models, which can estimate the effect (both positive and negative) that a provider has on an outcome, even when caring for a patient a fraction of the time during the hospitalization.

Methods

Setting

Banner Health is a non-profit, multi-hospital health care system across 6 states in the western United States that is uniquely positioned to study provider quality attribution models. It not only has a large number of providers and serves a broad patient population, but Banner Health also uses an instance of Cerner (Kansas City, MO), an enterprise-level electronic health record (EHR) system that connects all its facilities and allows for advanced analytics across its system.

For this study, we included only general medicine and surgery patients admitted and discharged from the inpatient setting between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2018, who were between 18 and 89 years old at admission, and who had a LOS between 1 and 14 days. Visit- and patient-level data were collected from Cerner, while outcome data, and corresponding expected outcome data, were obtained from Premier, Inc. (Charlotte, NC) using their CareScience methodologies.10 To measure patient experience, response data were extracted from post-discharge surveys administered by InMoment (Salt Lake City, UT).

Provider Attribution Models

Provider Attribution by Physician of Record (PAPR). In the standard approach, denoted here as the PAPR model, 1 provider—typically the attending or discharging provider, which may be the same person—is attributed to the entire hospitalization. This provider is responsible for the patient’s care, and all patient outcomes are aggregated and attributed to the provider to gauge his or her performance. The PAPR model is the most popular form of attribution across many health care systems and is routinely used for P4P incentives.

In this study, the discharging provider was used when attributing hospitalizations using the PAPR model. Providers responsible for fewer than 12 discharges in the calendar year were excluded. Because of the directness of this type of attribution, the performance of 1 provider does not account for the performance of the other rotating providers during hospitalizations.

Provider Attribution by Multiple Membership (PAMM). In contrast, we introduce another attribution approach here that is designed to assign partial attribution to each provider who cares for the patient during the hospitalization. To aggregate the partial attributions, and possibly control for any exogenous or risk-based factors, a multiple-membership, or multi-member (MM), model is used. The MM model can measure the effect of a provider on an outcome even when the patient-to-provider relationship is complex, such as in a rotating provider environment.8

The purpose of this study is to compare attribution models and to determine whether there are meaningful differences between them. Therefore, for comparison purposes, the same discharging providers using the PAPR approach are eligible for the PAMM approach, so that both attribution models are using the same set of providers. All other providers are excluded because their performance would not be comparable to the PAPR approach.

While there are many ways to document provider-to-patient interactions, 2 methods are available in almost all health care systems. The first method is to link a provider’s billing charges to each patient-day combination. This approach limits the attribution to 1 provider per patient per day because multiple rotating providers cannot charge for the same patient-day combination.3 However, many providers interact with a patient on the same day, so using this approach excludes non-billed provider-to-patient interactions.

The second method, which was used in this study, relies on documented clinical notes within the EHR to determine how attribution is shared. In this approach, attribution is weighted based on the authorship of 3 types of eligible clinical notes: admitting history/physical notes (during admission), progress notes (during subsequent days), and discharge summary notes (during final discharge). This will (likely) result in many providers being linked to a patient on each day, which better reflects the clinical setting (Figure). Recently, clinical notes were used to attribute care of patients in an inpatient setting, and it was found that this approach provides a reliable way of tracking interactions and assigning ownership.11

The provider-level attribution weights are based on the share of authorships of eligible note types. Specifically, for each provider j, let aij be the total count of eligible note types for hospitalization i authored by provider j, and let ai be the overall total count of eligible note types for hospitalization i. Then the attribution weight is

(Eq. 1)

for hospitalization i and provider j. Note that ∑jwij = 1: in other words, the total attribution, summed across all providers, is constrained to be 1 for each hospitalization.

Patient Outcomes

Outcomes were chosen based on their routine use in health care systems as standards when evaluating provider performance. This study included 6 outcomes: inpatient LOS, inpatient mortality, 30-day inpatient readmission, and patient responses from 3 survey questions. These outcomes can be collected without any manual chart reviews, and therefore are viewed as objective outcomes of provider performance.

Each outcome was aggregated for each provider using both attribution methods independently. For the PAPR method, observed-to-expected (OE) indices for LOS, mortality, and readmissions were calculated along with average patient survey scores. For the PAMM method, provider-level random effects from the fitted models were used. In both cases, the calculated measures were used for ranking purposes when determining top (or bottom) providers for each outcome.

Individual Provider Metrics for the PAPR Method

Inpatient LOS Index. Hospital inpatient LOS was measured as the number of days between admission date and discharge date. For each hospital visit, an expected LOS was determined using Premier’s CareScience Analytics (CSA) risk-adjustment methodology.10 The CSA methodology for LOS incorporates a patient’s clinical history, demographics, and visit-related administrative information.

Let nj be the number of hospitalizations attributed to provider j. Let oij and eij be the observed and expected LOS, respectively, for hospitalization i = 1,…,nj attributed to provider j. Then the inpatient LOS index for provider j is Lj = ∑ioij⁄∑ieij.

Inpatient Mortality Index. Inpatient mortality was defined as the death of the patient during hospitalization. For each hospitalization, an expected mortality probability was determined using Premier’s CSA risk-adjustment methodology.10 The CSA methodology for mortality incorporates a patient’s demographics and comorbidities.

Just as before, let nj be the number of hospitalizations attributed to provider j. Let mij = 1 if the patient died during hospitalization i = 1, … , nj attributed to provider j; mij = 0 otherwise. Let pij(m) be the corresponding expected mortality probability. Then the inpatient mortality index for provider j is Mj = ∑imij⁄∑ipij(m).

30-Day Inpatient Readmission Index. A 30-day inpatient readmission was defined as the event when a patient is discharged and readmits back into the inpatient setting within 30 days. The inclusion criteria defined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) all-cause hospital-wide readmission measure was used and, consequently, planned readmissions were excluded.12 Readmissions could occur at any Banner hospital, including the same hospital. For each hospital visit, an expected readmission probability was derived using Premier’s CSA risk-adjustment methodology.10 The CSA methodology for readmissions incorporates a patient’s clinical history, demographics, and visit-related administrative information.

Let nj be the number of hospitalizations attributed to provider j. Let rij = 1 if the patient had a readmission following hospitalization i = 1, … , nj attributed to provider j; rij = 0 otherwise. Let pij(r) be the corresponding expected readmission probability. Then the 30-day inpatient readmission index for provider j is Rj = ∑irij ⁄∑ipij(r).

Patient Survey Scores. The satisfaction of the patient’s experience during hospitalization was measured via post-discharge surveys administered by InMoment. Two survey questions were selected because they related directly to a provider’s interaction with the patient: “My interactions with doctors were excellent” (Doctor) and “I received the best possible care” (Care). A third question, “I would recommend this hospital to my family and friends,” was selected as a proxy measure of the overall experience and, in the aggregate, is referred to as the net promoter score (NPS).13,14 The responses were measured on an 11-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (0) to “Strongly Agree” (10); “N/A” or missing responses were excluded.

The Likert responses were coded to 3 discrete values as follows: if the value was between 0 and 6, then -1 (ie, detractor); between 7 and 8 (ie, neutral), then 0; otherwise 1 (ie, promoter). Averaging these coded responses results in a patient survey score for each question. Specifically, let nj be the number of hospitalizations attributed to provider j in which the patient responded to the survey question. Let sij ∈{−1, 0, 1} be the coded response linked to hospitalization i = 1, … , nj attributed to provider j. Then the patient experience score for provider j is Sj = ∑isij⁄nj.

Handling Ties in Provider Performance Measures. Because ties can occur in the PAPR approach for all measures, a tie-breaking strategy is needed. For LOS indices, ties are less likely because their numerator is strictly greater than 0, and expected LOS values are typically distinct enough. Indeed, no ties were found in this study for LOS indices. However, mortality and readmission indices can routinely result in ties when the best possible index is achieved, such as 0 deaths or readmissions among attributed hospitalizations. To help differentiate between those indices in the PAPR approach, the total estimated risk (denominator) was utilized as a secondary scoring criterion.

Mortality and readmission metrics were addressed by sorting first by the outcome (mortality index), and second by the denominator (total estimated risk). For example, if provider A has the same mortality rate as provider B, then provider A would be ranked higher if the denominator was larger, indicating a higher risk for mortality.

Similarly, it was very common for providers to have the same overall average rating for a survey question. Therefore, the denominator (number of respondents) was used to break ties. However, the denominator sorting was bidirectional. For example, if the tied score was positive (more promoters than detractors) for providers A and B, then provider A would be ranked higher if the denominator was larger. Conversely, if the tied score between providers A and B was neutral or negative (more detractors than promoters), then provider A would be ranked lower if the denominator was larger.

Individual Provider Metrics for the PAMM Method

For the PAMM method, model-based metrics were derived using a MM model.8 Specifically, let J be the number of rotating providers in a health care system. Let Yi be an outcome of interest from hospitalization i, X1i, …, Xpi be fixed effects or covariates, and ß1, …, ßp be the coefficients for the respective covariates. Then the generalized MM statistical model is

(Eq. 2)

where g(μi ) is a link function between the mean of the outcome, μi, and its linear predictor, ß0, is the marginal intercept, wij represents the attribution weight of provider j on hospitalization i (described in Equation 1), and γj represents the random effect of provider j on the outcome with γj~N(0,σγ2).

For the mortality and readmission binary outcomes, logistic regression was performed using a logit link function, with the corresponding expected probability as the only fixed covariate. The expected probabilities were first converted into odds and then log-transformed before entering the model. For LOS, Poisson regression was performed using a log link function with the log-transformed expected LOS as the only fixed covariate. For coded patient experience responses, an ordered logistic regression was performed using a cumulative logit link function (no fixed effects were added).

MM Model-based Metrics. Each fitted MM model produces a predicted random effect for each provider. The provider-specific random effects can be interpreted as the unobserved influence of each provider on the outcome after controlling for any fixed effect included in the model. Therefore, the provider-specific random effects were used to evaluate the relative provider performance, which is analogous to the individual provider-level metrics used in the PAPR method.

Measuring provider performance using a MM model is more flexible and robust to outliers compared to the standard approach using OE indices or simple averages. First, although not investigated here, the effect of patient-, visit-, provider-, and/or temporal-level covariates can be controlled when evaluating provider performance. For example, a patient’s socioeconomic status, a provider’s workload, and seasonal factors can be added to the MM model. These external factors are not accounted for in OE indices.

Another advantage of using predicted random effects is the concept of “shrinkage.” The process of estimating random effects inherently accounts for small sample sizes (when providers do not treat a large enough sample of patients) and/or when there is a large ratio of patient variance to provider variance (for instance, when patient outcome variability is much higher compared to provider performance variability). In both cases, the estimation of the random effect is pulled ever closer to 0, signaling that the provider performance is closer to the population average. See Henderson15 and Mood16 for further details.

In contrast, OE indices can result in unreliable estimates when a provider has not cared for many patients. This is especially prevalent when the outcome is binary with a low probability of occurring, such as mortality. Indeed, provider-level mortality OE indices are routinely 0 when the patient counts are low, which skews performance rankings unfairly. Finally, OE indices also ignore the magnitude of the variance of an outcome between providers and patients, which can be large.

Comparison Methodology

In this study, we seek to compare the 2 methods of attribution, PAPR and PAMM, to determine whether there are meaningful differences between them when measuring provider performance. Using retrospective data described in the next section, each attribution method was used independently to derive provider-level metrics. To assess relative performance, percentiles were assigned to each provider based on their metric values so that, in the end, there were 2 percentile ranks for each provider for each metric.

Using these paired percentiles, we derived the following measures of concordance, similar to Herzke, Michtalik3: (1) the percent concordance measure—defined as the number of providers who landed in the top half (greater than the median) or bottom half under both attribution models—divided by the total number of providers; (2) the median of the absolute difference in percentiles under both attribution models; and (3) the Pearson correlation coefficient of the paired provider ranks. The first measure is a global measure of concordance between the 2 approaches and would be expected to be 50% by chance. The second measure gauges how an individual provider’s rank is affected by the change in attribution methodologies. The third measure is a statistical measure of linear correlation of the paired percentiles and was not included in the Herzke, Michtalik3 study.

All statistical analyses were performed on SAS (version 9.4; Cary, NC) and the MM models were fitted using PROC GLIMMIX with the EFFECT statement. The Banner Health Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

A total of

Multi-Membership Model Results

Table 3 displays the results after independently fitting MM models to each of the 3 clinical outcomes. Along with a marginal intercept, the only covariate in each model was the corresponding expected value after a transformation. This was added to use the same information that is typically used in OE indices, therefore allowing for a proper comparison between the 2 attribution methods. The provider-level variance represents the between-provider variation and measures the amount of influence providers have on the corresponding outcome after controlling for any covariates in the model. A provider-level variance of 0 would indicate that providers do not have any influence on the outcome. While the mortality and readmission model results can be compared to each other, the LOS model cannot given its different scale and transformation altogether.

The results in Table 3 suggest that each expected value covariate is highly correlated with its corresponding outcome, which is the anticipated conclusion given that they are constructed in this fashion. The estimated provider-level variances indicate that, after including an expected value in the model, providers have less of an influence on a patient’s LOS and likelihood of being readmitted. On the other hand, the results suggest that providers have much more influence on the likelihood of a patient dying in the hospital, even after controlling for an expected mortality covariate.

Table 4 shows the results after independently fitting MM-ordered logistic models to each of the 3 survey questions. The similar provider-level variances suggest that providers have the same influence on the patient’s perception of the quality of their interactions with the doctor (Doctor), the quality of the care they received (Care), and their likelihood to recommend a friend or family member to the hospital (NPS).

Comparison Results Between Both Attribution Methods

Table 5 compares the 2 attribution methods when ranking providers based on their performance on each outcome measure. The comparison metrics gauge how well the 2 methods agree overall (percent concordance), agree at the provider level (absolute percentile difference and interquartile range [IQR]), and how the paired percentiles linearly correlate to each other (Pearson correlation coefficient).

LOS, by a small margin, had the lowest concordance of clinical outcomes (72.1%), followed by mortality (75.9%) and readmissions (82.1%). Generally, the survey scores had higher percent concordance than the clinical outcome measures, with Doctor at 84.1%, Care at 85.9%, and NPS having the highest percent concordance at 86.6%. Given that by chance the percent concordance is expected to be 50%, there was notable discordance, especially with the clinical outcome measures. Using LOS performance as an example, one attribution methodology would rank a provider in the top half or bottom half, while the other attribution methodology would rank the same provider exactly the opposite way about 28% of the time.

The median absolute percentile difference between the 2 methods was more modest (between 7 and 15). Still, there were some providers whose performance ranking was heavily impacted by the attribution methodology that was used. This was especially true when evaluating performance for certain clinical measures, where the attribution method that was used could change the provider performance percentile by up to 90 levels.

The paired percentiles were positively correlated when ranking performance using any of the 6 measures. This suggests that both methodologies assess performance generally in the same direction, irrespective of the methodology and measure. We did not investigate more complex correlation measures and left this for future research.

It should be noted that ties occurred much more frequently with the PAPR method than when using PAMM and therefore required tie-breaking rules to be designed. Given the nature of OE indices, PAPR methodology is especially sensitive to ties whenever the measure includes counting the number of events (for example, mortality and readmissions) and whenever there are many providers with very few attributed patients. On the other hand, using the PAMM method is much more robust against ties given that the summation of all the weighted attributed outcomes will rarely result in ties, even with a nominal set of providers.

Discussion

In this study, the PAMM methodology was introduced and was used to assess relative provider performance on 3 clinical outcome measures and 3 patient survey scores. The new approach aims to distribute each outcome among all providers who provided care for a patient in an inpatient setting. Clinical notes were used to account for patient-to-provider interactions, and fitted MM statistical models were used to compute the effects that each provider had on each outcome. The provider effect was introduced as a random effect, and the set of predicted random effects was used to rank the performance of each provider.

The PAMM approach was compared to the more traditional methodology, PAPR, where each patient is attributed to only 1 provider: the discharging physician in this study. Using this approach, OE indices of clinical outcomes and averages of survey scores were used to rank the performance of each provider. This approach resulted in many ties, which were broken based on the number of hospitalizations, although other tie-breaking methods may be used in practice.

Both methodologies showed modest concordance with each other for the clinical outcomes, but higher concordance for the patient survey scores. This was also true when using the Pearson correlation coefficient to assess agreement. The 1 outcome measure that showed the least concordance and least linear correlation between methods was LOS, which would suggest that LOS performance is more sensitive to the attribution methodology that is used. However, it was the least concordant by a small margin.

Furthermore, although the medians of the absolute percentile differences were small, there were some providers who had large deviations, suggesting that some providers would move from being shown as high-performers to low-performers and vice versa based on the chosen attribution method. We investigated examples of this and determined that the root cause was the difference in effective sample sizes for a provider. For the PAPR method, the effective sample size is simply the number of hospitalizations attributed to the provider. For the PAMM method, the effective sample size is the sum of all non-zero weights across all hospitalizations where the provider cared for a patient. By and large, the PAMM methodology provides more information of the provider effect on an outcome than the PAPR approach because every provider-patient interaction is considered. For example, providers who do not routinely discharge patients, but often care for patients, will have rankings that differ dramatically between the 2 methods.

The PAMM methodology has many statistical advantages that were not fully utilized in this comparative study. For example, we did not include any covariates in the MM models except for the expected value of the outcome, when it was available. Still, it is known that other covariates can impact an outcome as well, such as the patient’s age, socioeconomic indicators, existing chronic conditions, and severity of hospitalization, which can be added to the MM models as fixed effects. In this way, the PAMM approach can control for these other covariates, which are typically outside of the control of providers but typically ignored using OE indices. Therefore, using the PAMM approach would provide a fairer comparison of provider performance.

Using the PAMM method, most providers had a large sample size to assess their performance once all the weighted interactions were included. Still, there were a few who did not care for many patients for a variety of reasons. In these scenarios, MM models “borrow” strength from other providers to produce a more robust predicted provider effect by using a weighted average between the overall population trend and the specific provider outcomes (see Rao and Molina17). As a result, PAMM is a more suitable approach when the sample sizes of patients attributed to providers can be small.

One of the most interesting findings of this study was the relative size of the provider-level variance to the size of the fixed effect in each model (Table 3). Except for mortality, these variances suggest that there is a small difference in performance from one provider to another. However, these should be interpreted as the variance when only 1 provider is involved in the care of a patient. When multiple providers are involved, using basic statistical theory, the overall provider-level variance will be σγ2 ∑wij2 (see Equation 2). For example, the estimated variance among providers for LOS was 0.03 (on a log scale), but, using the scenario in the Figure, the overall provider-level variance for this hospitalization will be 0.03 (0.3752 + 0.1252 + 0.52) = 0.012. Hence, the combined effect of providers on LOS is less than would be expected. Indeed, as more providers are involved with a patient’s care, the more their combined influence on an outcome is diluted.

In this study, the PAMM approach placed an equal weight on all provider-patient interactions via clinical note authorship, but that may not be optimal in some settings. For example, it may make more sense to set a higher weight on the provider who admitted or discharged the patient while placing less (or 0) weight on all other interactions. In the extreme, if the full weight were placed on 1 provider interaction (eg, during discharge, then the MM model would be reduced to a one-way random effects model. The flexibility of weighting interactions is a feature of the PAMM approach, but any weighting framework must be transparent to the providers before implementation.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the PAMM approach is a feasible option within a large health care organization. For P4P programs to be successful, providers must be able to trust that their performance will be fairly assessed and that all provider-patient interactions are captured to provide a full comparison amongst their peers. The PAMM methodology is one solution to spread the positive (and negative) outcomes across all providers who cared for a patient and therefore, if implemented, would add trust and fairness when measuring and assessing provider performance.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Barrie Bradley for his support in the initial stages of this research and Dr. Syed Ismail Jafri for his help and support on the standard approaches of assessing and measuring provider performances.

Corresponding author: Rachel Ginn, MS, Banner Health Corporation, 2901 N. Central Ave., Phoenix, AZ 85012; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From Banner Health Corporation, Phoenix, AZ.

Background: Health care providers are routinely incentivized with pay-for-performance (P4P) metrics to increase the quality of care. In an inpatient setting, P4P models typically measure quality by attributing each patient’s outcome to a single provider even though many providers routinely care for the patient. This study investigates a new attribution approach aiming to distribute each outcome across all providers who provided care.

Methods: The methodology relies on a multi-membership model and is demonstrated in the Banner Health system using 3 clinical outcome measures (length of stay, 30-day readmissions, and mortality) and responses to 3 survey questions that measure a patient’s perception of their care. The new approach is compared to the “standard” method, which attributes each patient to only 1 provider.

Results: When ranking by clinical outcomes, both methods were concordant 72.1% to 82.1% of the time for top-half/bottom-half rankings, with a median percentile difference between 7 and 15. When ranking by survey scores, there was more agreement, with concordance between 84.1% and 86.6% and a median percentile difference between 11 and 13. Last, Pearson correlation coefficients of the paired percentiles ranged from 0.56 to 0.78.

Conclusion: The new approach provides a fairer solution when measuring provider performance.

Keywords: patient attribution; PAMM; PAPR; random effect model; pay for performance.

Providers practicing in hospitals are routinely evaluated based on their performance and, in many cases, are financially incentivized for a better-than-average performance within a pay-for-performance (P4P) model. The use of P4P models is based on the belief that they will “improve, motivate, and enhance providers to pursue aggressively and ultimately achieve the quality performance targets thus decreasing the number of medical errors with less malpractice events.”1 Although P4P models continue to be a movement in health care, they have been challenging to implement.

One concern involves the general quality of implementation, such as defining metrics and targets, setting payout amounts, managing technology and market conditions, and gauging the level of transparency to the provider.2 Another challenge, and the focus of this project, are concerns around measuring performance to avoid perceptions of unfairness. This concern can be minimized if the attribution is handled in a fairer way, by spreading it across all providers who affected the outcome, both in a positive or negative direction.3

To implement these models, the performance of providers needs to be measured and tracked periodically. This requires linking, or attributing, a patient’s outcome to a provider, which is almost always the attending or discharging provider (ie, a single provider).3 In this single-provider attribution approach, one provider will receive all the credit (good or bad) for their respective patients’ outcomes, even though the provider may have seen the patient only a fraction of the time during the hospitalization. Attributing outcomes—for example, length of stay (LOS), readmission rate, mortality rate, net promoter score (NPS)—using this approach reduces the validity of metrics designed to measure provider performance, especially in a rotating provider environment where many providers interact with and care for a patient. For example, the quality of providers’ interpersonal skills and competence were among the strongest determinants of patient satisfaction,4 but it is not credible that this is solely based on the last provider during a hospitalization.

Proportionally distributing the attribution of an outcome has been used successfully in other contexts. Typically, a statistical modeling approach using a multi-membership framework is used because it can handle the sometimes-complicated relationships within the hierarchy. It also allows for auxiliary variables to be introduced, which can help explain and control for exogenous effects.5-7 For example, in the education setting, standardized testing is administered to students at defined years of schooling: at grades 4, 8, and 10, for instance. The progress of students, measured as the academic gains between test years, are proportionally attributed to all the teachers who the student has had between the test years. These partial attributions are combined to evaluate an overall teacher performance.8,9

Although the multi-membership framework has been used in other industries, it has yet to be applied in measuring provider performance. The purpose of this project is to investigate the impact of using a multi-provider approach compared to the standard single-provider approach. The findings may lead to modifications in the way a provider’s performance is measured and, thus, how providers are compensated. A similar study investigated the impact of proportionally distributing patients’ outcomes across all rotating providers using a weighting method based on billing practices to measure the partial impact of each provider.3

This study is different in 2 fundamental ways. First, attribution is weighted based on the number of clinically documented interactions (via clinical notes) between a patient and all rotating providers during the hospitalization. Second, performance is measured via multi-membership models, which can estimate the effect (both positive and negative) that a provider has on an outcome, even when caring for a patient a fraction of the time during the hospitalization.

Methods

Setting

Banner Health is a non-profit, multi-hospital health care system across 6 states in the western United States that is uniquely positioned to study provider quality attribution models. It not only has a large number of providers and serves a broad patient population, but Banner Health also uses an instance of Cerner (Kansas City, MO), an enterprise-level electronic health record (EHR) system that connects all its facilities and allows for advanced analytics across its system.

For this study, we included only general medicine and surgery patients admitted and discharged from the inpatient setting between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2018, who were between 18 and 89 years old at admission, and who had a LOS between 1 and 14 days. Visit- and patient-level data were collected from Cerner, while outcome data, and corresponding expected outcome data, were obtained from Premier, Inc. (Charlotte, NC) using their CareScience methodologies.10 To measure patient experience, response data were extracted from post-discharge surveys administered by InMoment (Salt Lake City, UT).

Provider Attribution Models

Provider Attribution by Physician of Record (PAPR). In the standard approach, denoted here as the PAPR model, 1 provider—typically the attending or discharging provider, which may be the same person—is attributed to the entire hospitalization. This provider is responsible for the patient’s care, and all patient outcomes are aggregated and attributed to the provider to gauge his or her performance. The PAPR model is the most popular form of attribution across many health care systems and is routinely used for P4P incentives.

In this study, the discharging provider was used when attributing hospitalizations using the PAPR model. Providers responsible for fewer than 12 discharges in the calendar year were excluded. Because of the directness of this type of attribution, the performance of 1 provider does not account for the performance of the other rotating providers during hospitalizations.

Provider Attribution by Multiple Membership (PAMM). In contrast, we introduce another attribution approach here that is designed to assign partial attribution to each provider who cares for the patient during the hospitalization. To aggregate the partial attributions, and possibly control for any exogenous or risk-based factors, a multiple-membership, or multi-member (MM), model is used. The MM model can measure the effect of a provider on an outcome even when the patient-to-provider relationship is complex, such as in a rotating provider environment.8

The purpose of this study is to compare attribution models and to determine whether there are meaningful differences between them. Therefore, for comparison purposes, the same discharging providers using the PAPR approach are eligible for the PAMM approach, so that both attribution models are using the same set of providers. All other providers are excluded because their performance would not be comparable to the PAPR approach.

While there are many ways to document provider-to-patient interactions, 2 methods are available in almost all health care systems. The first method is to link a provider’s billing charges to each patient-day combination. This approach limits the attribution to 1 provider per patient per day because multiple rotating providers cannot charge for the same patient-day combination.3 However, many providers interact with a patient on the same day, so using this approach excludes non-billed provider-to-patient interactions.

The second method, which was used in this study, relies on documented clinical notes within the EHR to determine how attribution is shared. In this approach, attribution is weighted based on the authorship of 3 types of eligible clinical notes: admitting history/physical notes (during admission), progress notes (during subsequent days), and discharge summary notes (during final discharge). This will (likely) result in many providers being linked to a patient on each day, which better reflects the clinical setting (Figure). Recently, clinical notes were used to attribute care of patients in an inpatient setting, and it was found that this approach provides a reliable way of tracking interactions and assigning ownership.11

The provider-level attribution weights are based on the share of authorships of eligible note types. Specifically, for each provider j, let aij be the total count of eligible note types for hospitalization i authored by provider j, and let ai be the overall total count of eligible note types for hospitalization i. Then the attribution weight is

(Eq. 1)

for hospitalization i and provider j. Note that ∑jwij = 1: in other words, the total attribution, summed across all providers, is constrained to be 1 for each hospitalization.

Patient Outcomes

Outcomes were chosen based on their routine use in health care systems as standards when evaluating provider performance. This study included 6 outcomes: inpatient LOS, inpatient mortality, 30-day inpatient readmission, and patient responses from 3 survey questions. These outcomes can be collected without any manual chart reviews, and therefore are viewed as objective outcomes of provider performance.