User login

What we know and don’t know about virus variants and vaccines

About 20 states across the country have detected the more transmissible B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2 variant to date. Given the unknowns of the emerging situation, experts with the Infectious Diseases Society of America addressed vaccine effectiveness, how well equipped the United States is to track new mutations, and shared their impressions of President Joe Biden’s COVID-19 executive orders.

One of the major concerns remains the ability of COVID-19 vaccines to work on new strains. “All of our vaccines target the spike protein and try to elicit neutralizing antibodies that bind to that protein,” Mirella Salvatore, MD, assistant professor of medicine and population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said during an IDSA press briefing on Thursday.

The B.1.1.7 mutation occurs in the “very important” spike protein, a component of the SARS-CoV-2 virus necessary for binding, which allows the virus to enter cells, added Dr. Salvatore, an IDSA fellow.

The evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 should be capable of producing one or two mutations per month. However, the B.1.1.7 variant surprised investigators in the United Kingdom when they first discovered the strain had 17 mutations, Dr. Salvatore said.

It’s still unknown why this particular strain is more transmissible, but Dr. Salvatore speculated that the mutation gives the virus an advantage and increases binding, allowing it to enter cells more easily. She added that the mutations might have arisen among immunocompromised people infected with SARS-CoV-2, but “that is just a hypothesis.”

On a positive note, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, another IDSA fellow, explained at the briefing that the existing vaccines target more than one location on the virus’ spike protein. Therefore, “if there is a mutation that changes one structure of the spike protein, there will be other areas where the binding can occur.”

This polyclonal response “is why the vaccine can still be effective against this virus,” added Dr. Edwards, scientific director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program and professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Dr. Salvatore emphasized that, although the new variant is more transmissible, it doesn’t appear to be more lethal. “This might affect overall mortality but not for the individual who gets the infection.”

Staying one step ahead

When asked for assurance that COVID-19 vaccines will work against emerging variants, Dr. Edwards said, “It may be we will have to change the vaccine so it is more responsive to new variants, but at this point that does not seem to be the case.”

Should the vaccines require an update, the messenger RNA vaccines have an advantage – researchers can rapidly revise them. “All you need to do is put all the little nucleotides together,” Dr. Edwards said.

“A number of us are looking at how this will work, and we look to influenza,” she added. Dr. Edwards drew an analogy to choosing – and sometimes updating – the influenza strains each year for the annual flu vaccine. With appropriate funding, the same system could be replicated to address any evolving changes to SARS-CoV-2.

On funding, Dr. Salvatore said more money would be required to optimize the surveillance system for emerging strains in the United States.

“We actually have this system – there is a wonderful network that sequences the influenza strains,” she said. “The structure exists, we just need the funding.”

“The CDC is getting the system tooled up to get more viruses to be sequenced,” Dr. Edwards said.

Both experts praised the CDC for its website with up-to-date surveillance information on emerging strains of SARS-CoV-2.

President Biden’s backing of science

A reporter asked each infectious disease expert to share their impression of President Biden’s newly signed COVID-19 executive orders.

“The biggest takeaway is the role of science and the lessons we’ve learned from masks, handwashing, and distancing,” Dr. Edwards said. “We need to heed the advice ... [especially] with a variant that is more contagious.

“It is encouraging that science will be listened to – that is the overall message,” she added.

Dr. Salvatore agreed, saying that the orders give “the feeling that we can now act by following science.”

“We have plenty of papers that show the effectiveness of masking,” for example, she said. Dr. Salvatore acknowledged that there are “a lot of contrasting ideas about masking” across the United States but stressed their importance.

“We should follow measures that we know work,” she said.

Both experts said more research is needed to stay ahead of this evolving scenario. “We still need a lot of basic science showing how this virus replicates in the cell,” Dr. Salvatore said. “We need to really characterize all these mutations and their functions.”

“We need to be concerned, do follow-up studies,” she added, “but we don’t need to panic.”

This article was based on an Infectious Diseases Society of America Media Briefing on Jan. 21, 2021. Dr. Salvatore disclosed that she is a site principal investigator on a study from Verily Life Sciences/Brin Foundation on Predictors of Severe COVID-19 Outcomes and principal investigator for an investigator-initiated study sponsored by Genentech on combination therapy in influenza. Dr. Edwards disclosed National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants; consulting for Bionet and IBM; and being a member of data safety and monitoring committees for Sanofi, X-4 Pharma, Seqirus, Moderna, Pfizer, and Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 20 states across the country have detected the more transmissible B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2 variant to date. Given the unknowns of the emerging situation, experts with the Infectious Diseases Society of America addressed vaccine effectiveness, how well equipped the United States is to track new mutations, and shared their impressions of President Joe Biden’s COVID-19 executive orders.

One of the major concerns remains the ability of COVID-19 vaccines to work on new strains. “All of our vaccines target the spike protein and try to elicit neutralizing antibodies that bind to that protein,” Mirella Salvatore, MD, assistant professor of medicine and population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said during an IDSA press briefing on Thursday.

The B.1.1.7 mutation occurs in the “very important” spike protein, a component of the SARS-CoV-2 virus necessary for binding, which allows the virus to enter cells, added Dr. Salvatore, an IDSA fellow.

The evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 should be capable of producing one or two mutations per month. However, the B.1.1.7 variant surprised investigators in the United Kingdom when they first discovered the strain had 17 mutations, Dr. Salvatore said.

It’s still unknown why this particular strain is more transmissible, but Dr. Salvatore speculated that the mutation gives the virus an advantage and increases binding, allowing it to enter cells more easily. She added that the mutations might have arisen among immunocompromised people infected with SARS-CoV-2, but “that is just a hypothesis.”

On a positive note, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, another IDSA fellow, explained at the briefing that the existing vaccines target more than one location on the virus’ spike protein. Therefore, “if there is a mutation that changes one structure of the spike protein, there will be other areas where the binding can occur.”

This polyclonal response “is why the vaccine can still be effective against this virus,” added Dr. Edwards, scientific director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program and professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Dr. Salvatore emphasized that, although the new variant is more transmissible, it doesn’t appear to be more lethal. “This might affect overall mortality but not for the individual who gets the infection.”

Staying one step ahead

When asked for assurance that COVID-19 vaccines will work against emerging variants, Dr. Edwards said, “It may be we will have to change the vaccine so it is more responsive to new variants, but at this point that does not seem to be the case.”

Should the vaccines require an update, the messenger RNA vaccines have an advantage – researchers can rapidly revise them. “All you need to do is put all the little nucleotides together,” Dr. Edwards said.

“A number of us are looking at how this will work, and we look to influenza,” she added. Dr. Edwards drew an analogy to choosing – and sometimes updating – the influenza strains each year for the annual flu vaccine. With appropriate funding, the same system could be replicated to address any evolving changes to SARS-CoV-2.

On funding, Dr. Salvatore said more money would be required to optimize the surveillance system for emerging strains in the United States.

“We actually have this system – there is a wonderful network that sequences the influenza strains,” she said. “The structure exists, we just need the funding.”

“The CDC is getting the system tooled up to get more viruses to be sequenced,” Dr. Edwards said.

Both experts praised the CDC for its website with up-to-date surveillance information on emerging strains of SARS-CoV-2.

President Biden’s backing of science

A reporter asked each infectious disease expert to share their impression of President Biden’s newly signed COVID-19 executive orders.

“The biggest takeaway is the role of science and the lessons we’ve learned from masks, handwashing, and distancing,” Dr. Edwards said. “We need to heed the advice ... [especially] with a variant that is more contagious.

“It is encouraging that science will be listened to – that is the overall message,” she added.

Dr. Salvatore agreed, saying that the orders give “the feeling that we can now act by following science.”

“We have plenty of papers that show the effectiveness of masking,” for example, she said. Dr. Salvatore acknowledged that there are “a lot of contrasting ideas about masking” across the United States but stressed their importance.

“We should follow measures that we know work,” she said.

Both experts said more research is needed to stay ahead of this evolving scenario. “We still need a lot of basic science showing how this virus replicates in the cell,” Dr. Salvatore said. “We need to really characterize all these mutations and their functions.”

“We need to be concerned, do follow-up studies,” she added, “but we don’t need to panic.”

This article was based on an Infectious Diseases Society of America Media Briefing on Jan. 21, 2021. Dr. Salvatore disclosed that she is a site principal investigator on a study from Verily Life Sciences/Brin Foundation on Predictors of Severe COVID-19 Outcomes and principal investigator for an investigator-initiated study sponsored by Genentech on combination therapy in influenza. Dr. Edwards disclosed National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants; consulting for Bionet and IBM; and being a member of data safety and monitoring committees for Sanofi, X-4 Pharma, Seqirus, Moderna, Pfizer, and Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 20 states across the country have detected the more transmissible B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2 variant to date. Given the unknowns of the emerging situation, experts with the Infectious Diseases Society of America addressed vaccine effectiveness, how well equipped the United States is to track new mutations, and shared their impressions of President Joe Biden’s COVID-19 executive orders.

One of the major concerns remains the ability of COVID-19 vaccines to work on new strains. “All of our vaccines target the spike protein and try to elicit neutralizing antibodies that bind to that protein,” Mirella Salvatore, MD, assistant professor of medicine and population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said during an IDSA press briefing on Thursday.

The B.1.1.7 mutation occurs in the “very important” spike protein, a component of the SARS-CoV-2 virus necessary for binding, which allows the virus to enter cells, added Dr. Salvatore, an IDSA fellow.

The evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 should be capable of producing one or two mutations per month. However, the B.1.1.7 variant surprised investigators in the United Kingdom when they first discovered the strain had 17 mutations, Dr. Salvatore said.

It’s still unknown why this particular strain is more transmissible, but Dr. Salvatore speculated that the mutation gives the virus an advantage and increases binding, allowing it to enter cells more easily. She added that the mutations might have arisen among immunocompromised people infected with SARS-CoV-2, but “that is just a hypothesis.”

On a positive note, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, another IDSA fellow, explained at the briefing that the existing vaccines target more than one location on the virus’ spike protein. Therefore, “if there is a mutation that changes one structure of the spike protein, there will be other areas where the binding can occur.”

This polyclonal response “is why the vaccine can still be effective against this virus,” added Dr. Edwards, scientific director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program and professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Dr. Salvatore emphasized that, although the new variant is more transmissible, it doesn’t appear to be more lethal. “This might affect overall mortality but not for the individual who gets the infection.”

Staying one step ahead

When asked for assurance that COVID-19 vaccines will work against emerging variants, Dr. Edwards said, “It may be we will have to change the vaccine so it is more responsive to new variants, but at this point that does not seem to be the case.”

Should the vaccines require an update, the messenger RNA vaccines have an advantage – researchers can rapidly revise them. “All you need to do is put all the little nucleotides together,” Dr. Edwards said.

“A number of us are looking at how this will work, and we look to influenza,” she added. Dr. Edwards drew an analogy to choosing – and sometimes updating – the influenza strains each year for the annual flu vaccine. With appropriate funding, the same system could be replicated to address any evolving changes to SARS-CoV-2.

On funding, Dr. Salvatore said more money would be required to optimize the surveillance system for emerging strains in the United States.

“We actually have this system – there is a wonderful network that sequences the influenza strains,” she said. “The structure exists, we just need the funding.”

“The CDC is getting the system tooled up to get more viruses to be sequenced,” Dr. Edwards said.

Both experts praised the CDC for its website with up-to-date surveillance information on emerging strains of SARS-CoV-2.

President Biden’s backing of science

A reporter asked each infectious disease expert to share their impression of President Biden’s newly signed COVID-19 executive orders.

“The biggest takeaway is the role of science and the lessons we’ve learned from masks, handwashing, and distancing,” Dr. Edwards said. “We need to heed the advice ... [especially] with a variant that is more contagious.

“It is encouraging that science will be listened to – that is the overall message,” she added.

Dr. Salvatore agreed, saying that the orders give “the feeling that we can now act by following science.”

“We have plenty of papers that show the effectiveness of masking,” for example, she said. Dr. Salvatore acknowledged that there are “a lot of contrasting ideas about masking” across the United States but stressed their importance.

“We should follow measures that we know work,” she said.

Both experts said more research is needed to stay ahead of this evolving scenario. “We still need a lot of basic science showing how this virus replicates in the cell,” Dr. Salvatore said. “We need to really characterize all these mutations and their functions.”

“We need to be concerned, do follow-up studies,” she added, “but we don’t need to panic.”

This article was based on an Infectious Diseases Society of America Media Briefing on Jan. 21, 2021. Dr. Salvatore disclosed that she is a site principal investigator on a study from Verily Life Sciences/Brin Foundation on Predictors of Severe COVID-19 Outcomes and principal investigator for an investigator-initiated study sponsored by Genentech on combination therapy in influenza. Dr. Edwards disclosed National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants; consulting for Bionet and IBM; and being a member of data safety and monitoring committees for Sanofi, X-4 Pharma, Seqirus, Moderna, Pfizer, and Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dermatologist survey spotlights psoriasis care deficiencies in reproductive-age women

In a , Jenny Murase, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“In Germany, the UK, and the United States, dermatologists face challenges in discussing pregnancy and child-bearing aspiration with women of reproductive age, in recommending compatible treatments during pregnancy, and engaging patients in the shared decision-making process. These challenges may exist due to suboptimal knowledge, skills, confidence, and attitude in respective areas of care,” said Dr. Murase, a dermatologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and coeditor-in-chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

These shortcomings were documented in a survey, which began with Dr. Murase and her coinvestigators conducting detailed, 45-minute-long, semistructured telephone interviews with 24 dermatologists in the three countries. Those interviews provided the basis for subsequent development of a 20-minute online survey on psoriasis and pregnancy completed by 167 American, German, and UK dermatologists. The survey incorporated multiple choice questions and quantitative rating scales.

“Participants expressed challenges engaging in family planning counseling and reproductive health care as part of risk assessments for psoriasis,” Dr. Murase said.

Among the key findings:

- Forty-seven percent of respondents considered their knowledge of the impact of psoriasis on women’s reproductive health to be suboptimal. This knowledge gap was most common among American dermatologists, 59% of whom rated themselves as having suboptimal knowledge, and least common among German practitioners, only 27% of whom reported deficiencies in this area.

Fifty percent of dermatologists rated themselves as having suboptimal skills in discussing contraceptive methods with their psoriasis patients of childbearing potential.

- Forty-eight percent of respondents – and 59% of the American dermatologists – indicated they prefer to leave pregnancy-related discussions to ob.gyns.

- Fifty-five percent of dermatologists had only limited knowledge of the safety data and indications for prescribing biologic therapies before, during, and after pregnancy. Respondents gave themselves an average score of 58 out of 100 in terms of their confidence in prescribing biologics during pregnancy, compared to 74 out of 100 when prescribing before or after pregnancy.

- Forty-eight percent of participants indicated they had suboptimal skills in helping patients counter obstacles to treatment adherence.

Consideration of treatment of psoriasis in pregnancy requires balancing potential medication risks to the fetus versus the possible maternal and fetal harms of under- or nontreatment of their chronic inflammatory skin disease. It’s a matter that calls for shared decision-making between dermatologist and patient. But the survey showed that shared decision-making was often poorly integrated into clinical practice. Ninety-seven percent of the U.S. dermatologists were unaware of the existence of shared decision-making practice guidelines or models, as were 80% of UK respondents and 85% of the Germans. Of the relatively few dermatologists who were aware of such guidance, nearly half dismissed it as inapplicable to their clinical practice. More than one-third of respondents admitted having suboptimal skills in assessing their patients’ desired level of involvement in medical decisions. And one-third of the German dermatologists and roughly one-quarter of those from the United States and United Kingdom reported feeling pressure to make treatment decisions quickly and without patient input.

Dr. Murase added that the survey findings make a strong case for future interventions designed to help dermatologists appreciate the value of shared decision-making and develop the requisite patient-engagement skills. Dr. Murase reported serving as a paid consultant to UCB Pharma, which funded the survey via an educational grant.

In a , Jenny Murase, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“In Germany, the UK, and the United States, dermatologists face challenges in discussing pregnancy and child-bearing aspiration with women of reproductive age, in recommending compatible treatments during pregnancy, and engaging patients in the shared decision-making process. These challenges may exist due to suboptimal knowledge, skills, confidence, and attitude in respective areas of care,” said Dr. Murase, a dermatologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and coeditor-in-chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

These shortcomings were documented in a survey, which began with Dr. Murase and her coinvestigators conducting detailed, 45-minute-long, semistructured telephone interviews with 24 dermatologists in the three countries. Those interviews provided the basis for subsequent development of a 20-minute online survey on psoriasis and pregnancy completed by 167 American, German, and UK dermatologists. The survey incorporated multiple choice questions and quantitative rating scales.

“Participants expressed challenges engaging in family planning counseling and reproductive health care as part of risk assessments for psoriasis,” Dr. Murase said.

Among the key findings:

- Forty-seven percent of respondents considered their knowledge of the impact of psoriasis on women’s reproductive health to be suboptimal. This knowledge gap was most common among American dermatologists, 59% of whom rated themselves as having suboptimal knowledge, and least common among German practitioners, only 27% of whom reported deficiencies in this area.

Fifty percent of dermatologists rated themselves as having suboptimal skills in discussing contraceptive methods with their psoriasis patients of childbearing potential.

- Forty-eight percent of respondents – and 59% of the American dermatologists – indicated they prefer to leave pregnancy-related discussions to ob.gyns.

- Fifty-five percent of dermatologists had only limited knowledge of the safety data and indications for prescribing biologic therapies before, during, and after pregnancy. Respondents gave themselves an average score of 58 out of 100 in terms of their confidence in prescribing biologics during pregnancy, compared to 74 out of 100 when prescribing before or after pregnancy.

- Forty-eight percent of participants indicated they had suboptimal skills in helping patients counter obstacles to treatment adherence.

Consideration of treatment of psoriasis in pregnancy requires balancing potential medication risks to the fetus versus the possible maternal and fetal harms of under- or nontreatment of their chronic inflammatory skin disease. It’s a matter that calls for shared decision-making between dermatologist and patient. But the survey showed that shared decision-making was often poorly integrated into clinical practice. Ninety-seven percent of the U.S. dermatologists were unaware of the existence of shared decision-making practice guidelines or models, as were 80% of UK respondents and 85% of the Germans. Of the relatively few dermatologists who were aware of such guidance, nearly half dismissed it as inapplicable to their clinical practice. More than one-third of respondents admitted having suboptimal skills in assessing their patients’ desired level of involvement in medical decisions. And one-third of the German dermatologists and roughly one-quarter of those from the United States and United Kingdom reported feeling pressure to make treatment decisions quickly and without patient input.

Dr. Murase added that the survey findings make a strong case for future interventions designed to help dermatologists appreciate the value of shared decision-making and develop the requisite patient-engagement skills. Dr. Murase reported serving as a paid consultant to UCB Pharma, which funded the survey via an educational grant.

In a , Jenny Murase, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“In Germany, the UK, and the United States, dermatologists face challenges in discussing pregnancy and child-bearing aspiration with women of reproductive age, in recommending compatible treatments during pregnancy, and engaging patients in the shared decision-making process. These challenges may exist due to suboptimal knowledge, skills, confidence, and attitude in respective areas of care,” said Dr. Murase, a dermatologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and coeditor-in-chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

These shortcomings were documented in a survey, which began with Dr. Murase and her coinvestigators conducting detailed, 45-minute-long, semistructured telephone interviews with 24 dermatologists in the three countries. Those interviews provided the basis for subsequent development of a 20-minute online survey on psoriasis and pregnancy completed by 167 American, German, and UK dermatologists. The survey incorporated multiple choice questions and quantitative rating scales.

“Participants expressed challenges engaging in family planning counseling and reproductive health care as part of risk assessments for psoriasis,” Dr. Murase said.

Among the key findings:

- Forty-seven percent of respondents considered their knowledge of the impact of psoriasis on women’s reproductive health to be suboptimal. This knowledge gap was most common among American dermatologists, 59% of whom rated themselves as having suboptimal knowledge, and least common among German practitioners, only 27% of whom reported deficiencies in this area.

Fifty percent of dermatologists rated themselves as having suboptimal skills in discussing contraceptive methods with their psoriasis patients of childbearing potential.

- Forty-eight percent of respondents – and 59% of the American dermatologists – indicated they prefer to leave pregnancy-related discussions to ob.gyns.

- Fifty-five percent of dermatologists had only limited knowledge of the safety data and indications for prescribing biologic therapies before, during, and after pregnancy. Respondents gave themselves an average score of 58 out of 100 in terms of their confidence in prescribing biologics during pregnancy, compared to 74 out of 100 when prescribing before or after pregnancy.

- Forty-eight percent of participants indicated they had suboptimal skills in helping patients counter obstacles to treatment adherence.

Consideration of treatment of psoriasis in pregnancy requires balancing potential medication risks to the fetus versus the possible maternal and fetal harms of under- or nontreatment of their chronic inflammatory skin disease. It’s a matter that calls for shared decision-making between dermatologist and patient. But the survey showed that shared decision-making was often poorly integrated into clinical practice. Ninety-seven percent of the U.S. dermatologists were unaware of the existence of shared decision-making practice guidelines or models, as were 80% of UK respondents and 85% of the Germans. Of the relatively few dermatologists who were aware of such guidance, nearly half dismissed it as inapplicable to their clinical practice. More than one-third of respondents admitted having suboptimal skills in assessing their patients’ desired level of involvement in medical decisions. And one-third of the German dermatologists and roughly one-quarter of those from the United States and United Kingdom reported feeling pressure to make treatment decisions quickly and without patient input.

Dr. Murase added that the survey findings make a strong case for future interventions designed to help dermatologists appreciate the value of shared decision-making and develop the requisite patient-engagement skills. Dr. Murase reported serving as a paid consultant to UCB Pharma, which funded the survey via an educational grant.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

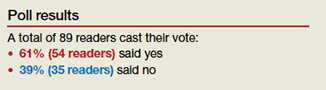

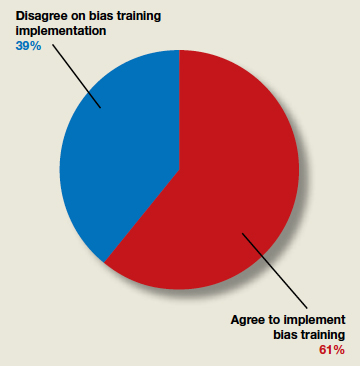

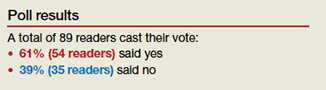

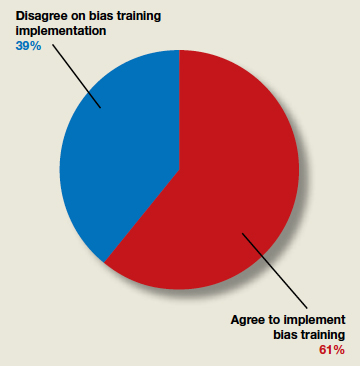

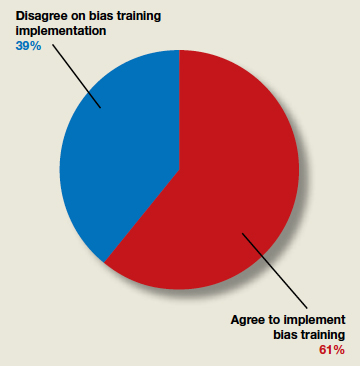

Do ObGyns agree that bias training and inclusion and diversity policies should be implemented?

In their column, “Physician leadership: Racial disparities and racism. Where do we go from here?” (August 2020), Biftu Mengesha, MD, MAS; Kavita Shah Arora, MD, MBE, MS; and Barbara Levy, MD, stated that, “The COVID-19 pandemic…has highlighted the continued poor outcomes our health and health care systems create for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities.” They implored readers to “advocate as physicians and leaders in our settings for every policy, practice, and procedure to be scrutinized using an antiracist lens” and set out action items for doing so. OBG Management followed up with a poll for readers: “Should institutions implement implicit bias training and policies for inclusion and diversity to address health care inequities?”

In their column, “Physician leadership: Racial disparities and racism. Where do we go from here?” (August 2020), Biftu Mengesha, MD, MAS; Kavita Shah Arora, MD, MBE, MS; and Barbara Levy, MD, stated that, “The COVID-19 pandemic…has highlighted the continued poor outcomes our health and health care systems create for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities.” They implored readers to “advocate as physicians and leaders in our settings for every policy, practice, and procedure to be scrutinized using an antiracist lens” and set out action items for doing so. OBG Management followed up with a poll for readers: “Should institutions implement implicit bias training and policies for inclusion and diversity to address health care inequities?”

In their column, “Physician leadership: Racial disparities and racism. Where do we go from here?” (August 2020), Biftu Mengesha, MD, MAS; Kavita Shah Arora, MD, MBE, MS; and Barbara Levy, MD, stated that, “The COVID-19 pandemic…has highlighted the continued poor outcomes our health and health care systems create for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities.” They implored readers to “advocate as physicians and leaders in our settings for every policy, practice, and procedure to be scrutinized using an antiracist lens” and set out action items for doing so. OBG Management followed up with a poll for readers: “Should institutions implement implicit bias training and policies for inclusion and diversity to address health care inequities?”

Timing of Complete Revascularization in Patients With STEMI

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the effect of the timing of nonculprit-lesion percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Design. Planned substudy of an international, multicenter, randomized controlled trial blinded to outcome.

Setting and participants. Among 4041 patients with STEMI who had multivessel coronary disease, randomization to nonculprit PCI versus culprit-only PCI was stratified according to intended timing of nonculprit lesion PCI. A total of 2702 patients with intended timing of nonculprit PCI during the index hospitalization and 1339 patients with intended timing of nonculprit PCI after the index hospitalization within 45 days were included.

Main outcome measures. The first co-primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular (CV) death or myocardial infarction (MI).

Main results. In both groups, the composite endpoint of CV death or MI was reduced with complete revascularization compared to the culprit-only strategy (index hospitalization: hazard ratio [HR], 0.77, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59-1.00; after hospital discharge: HR, 0.69, 95% CI, 0.49-0.97; interaction, P = 0.62). Landmark analyses demonstrated a HR of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.59-1.24) during the first 45 days and 0.69 (95% CI,0.54-0.89) from 45 days to the end of follow-up for intended nonculprit lesion PCI versus culprit-lesion-only PCI.

Conclusion. Among patients with STEMI and multivessel disease, the benefit of complete revascularization over culprit-lesion-only PCI was consistent, irrespective of the investigator-determined timing of staged nonculprit lesion intervention.

Commentary

Patients presenting with STEMI often have multivessel disease.1 Although the question of whether to revascularize the nonculprit vessel has been controversial, multiple contemporary studies have reported benefit of nonculprit-vessel revascularization compared to the culprit-only strategy.2-5 Compared to these previous medium-sized randomized controlled trials that included ischemia-driven revascularization as a composite endpoint, the COMPETE trial was unique in that it enrolled a large number of patients and reported a benefit in hard outcomes of a composite of CV death or MI.6

As the previous studies point toward the benefit of complete revascularization in patients presenting with STEMI, another important question has been the optimal timing of nonculprit vessel revascularization. Operators have 3 possible options: during the index procedure as primary PCI, as a staged procedure during the index admission, or as a staged procedure as an outpatient following discharge. Timing of nonculprit PCI has been inconsistent in the previous studies. For example, in the PRAMI trial, nonculprit PCI was performed during the index procedure,2 while in the CvPRIT and COMPARE ACUTE trials, the nonculprit PCI was performed during the index procedure or as a staged procedure during the same admission at the operator’s discretion.3,5

In this context, the COMPLETE investigators report their findings of the prespecified substudy regarding the timing of staged nonculprit vessel PCI. In the COMPLETE trial, 4041 patients were stratified by intended timing of nonculprit lesion PCI (2702 patients during index hospitalization, 1339 after discharge), which was predetermined by the operator prior to the randomization. Among the patients with intended staged nonculprit PCI during index hospitalization, the incidence of the first co-primary outcome of CV death or MI was 2.7% per year in patients with complete revascularization, as compared to 3.5% per year in patients with culprit-lesion only PCI (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.59-1.00). Similarly, in patients with intended nonculprit PCI after the index hospitalization, the incidence of the first co-primary outcome of CV death or MI was 2.7% per year in patients randomized to complete revascularization, as compared to 3.9% per year in patients with culprit-lesion-only PCI (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.49-0.97). These findings were similar for the second co-primary outcome of CV death, MI, or ischemia-driven revascularization (3.0% vs 6.6% per year for intended timing of nonculprit PCI during index admission, and 3.1% vs 5.4% per year for intended timing of nonculprit PCI after discharge, both favoring complete revascularization).

The investigators also performed a landmark analysis before and after 45 days of randomization. Within the first 45 days, CV death or MI occurred in 2.5% of the complete revascularization group and 3.0% of the culprit-lesion-only PCI group (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.59-1.24). On the other hand, during the interval from 45 days to the end of the study, CV death or MI occurred in 5.5% in the complete revascularization group and 7.8% in the culprit-lesion-only group (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54-0.89).

There were a number of strengths of the COMPLETE study, as we have previously described, such as multiple patients enrolled, contemporary therapy with high use of radial access, mandated use of fractional flow reserve for 50% to 69% stenosis lesions, and low cross-over rate.7 In addition, the current substudy is unique and important, as it was the first study to systematically evaluate the timing of the staged PCI. In addition to their finding of consistent benefit between staged procedure before or after discharge, the results from their landmark analysis suggest that the benefit of complete revascularization accumulates over the long term rather than the short term.

The main limitation of the COMPLETE study is that it was not adequately powered to find statistical differences in each subgroup studied. In addition, since all nonculprit PCIs were staged in this study, nonculprit PCI performed during the index procedure cannot be assessed.

Nevertheless, the finding of similar benefit of complete revascularization regardless of the timing of the staged PCI has clinical implication for practicing interventional cardiologists and patients presenting with STEMI. For example, if the patient presents with hemodynamically stable STEMI on a Friday, the patient can potentially be safely discharged over the weekend and return for a staged PCI as an outpatient instead of staying extra days for an inpatient staged PCI. Whether this approach may improve the patient satisfaction and hospital resource utilization will require further study.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In patients presenting with hemodynamically stable STEMI, staged complete revascularization can be performed during the admission or after discharge within 45 days.

—Taishi Hirai, MD

1. Park DW, Clare RM, Schulte PJ, et al. Extent, location, and clinical significance of non-infarct-related coronary artery disease among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014;312:2019-2027.

2. Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1115-1123.

3. Gershlick AH, Khan JN, Kelly DJ, et al. Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:963-972.

4. Engstrom T, Kelbaek H, Helqvist S, et al. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9994):665-671.

5. Smits PC, Abdel-Wahab M, Neumann FJ, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided multivessel angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1234-1244.

6. Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al. Complete revascularization with multivessel pci for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1411-1421.

7. Hirai T, Blair JEA. Nonculprit lesion PCI strategies in patients with STEMI without cardiogenic shock. J Clin Outcomes Management. 2020;27:7-9.

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the effect of the timing of nonculprit-lesion percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Design. Planned substudy of an international, multicenter, randomized controlled trial blinded to outcome.

Setting and participants. Among 4041 patients with STEMI who had multivessel coronary disease, randomization to nonculprit PCI versus culprit-only PCI was stratified according to intended timing of nonculprit lesion PCI. A total of 2702 patients with intended timing of nonculprit PCI during the index hospitalization and 1339 patients with intended timing of nonculprit PCI after the index hospitalization within 45 days were included.

Main outcome measures. The first co-primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular (CV) death or myocardial infarction (MI).

Main results. In both groups, the composite endpoint of CV death or MI was reduced with complete revascularization compared to the culprit-only strategy (index hospitalization: hazard ratio [HR], 0.77, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59-1.00; after hospital discharge: HR, 0.69, 95% CI, 0.49-0.97; interaction, P = 0.62). Landmark analyses demonstrated a HR of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.59-1.24) during the first 45 days and 0.69 (95% CI,0.54-0.89) from 45 days to the end of follow-up for intended nonculprit lesion PCI versus culprit-lesion-only PCI.

Conclusion. Among patients with STEMI and multivessel disease, the benefit of complete revascularization over culprit-lesion-only PCI was consistent, irrespective of the investigator-determined timing of staged nonculprit lesion intervention.

Commentary

Patients presenting with STEMI often have multivessel disease.1 Although the question of whether to revascularize the nonculprit vessel has been controversial, multiple contemporary studies have reported benefit of nonculprit-vessel revascularization compared to the culprit-only strategy.2-5 Compared to these previous medium-sized randomized controlled trials that included ischemia-driven revascularization as a composite endpoint, the COMPETE trial was unique in that it enrolled a large number of patients and reported a benefit in hard outcomes of a composite of CV death or MI.6

As the previous studies point toward the benefit of complete revascularization in patients presenting with STEMI, another important question has been the optimal timing of nonculprit vessel revascularization. Operators have 3 possible options: during the index procedure as primary PCI, as a staged procedure during the index admission, or as a staged procedure as an outpatient following discharge. Timing of nonculprit PCI has been inconsistent in the previous studies. For example, in the PRAMI trial, nonculprit PCI was performed during the index procedure,2 while in the CvPRIT and COMPARE ACUTE trials, the nonculprit PCI was performed during the index procedure or as a staged procedure during the same admission at the operator’s discretion.3,5

In this context, the COMPLETE investigators report their findings of the prespecified substudy regarding the timing of staged nonculprit vessel PCI. In the COMPLETE trial, 4041 patients were stratified by intended timing of nonculprit lesion PCI (2702 patients during index hospitalization, 1339 after discharge), which was predetermined by the operator prior to the randomization. Among the patients with intended staged nonculprit PCI during index hospitalization, the incidence of the first co-primary outcome of CV death or MI was 2.7% per year in patients with complete revascularization, as compared to 3.5% per year in patients with culprit-lesion only PCI (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.59-1.00). Similarly, in patients with intended nonculprit PCI after the index hospitalization, the incidence of the first co-primary outcome of CV death or MI was 2.7% per year in patients randomized to complete revascularization, as compared to 3.9% per year in patients with culprit-lesion-only PCI (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.49-0.97). These findings were similar for the second co-primary outcome of CV death, MI, or ischemia-driven revascularization (3.0% vs 6.6% per year for intended timing of nonculprit PCI during index admission, and 3.1% vs 5.4% per year for intended timing of nonculprit PCI after discharge, both favoring complete revascularization).

The investigators also performed a landmark analysis before and after 45 days of randomization. Within the first 45 days, CV death or MI occurred in 2.5% of the complete revascularization group and 3.0% of the culprit-lesion-only PCI group (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.59-1.24). On the other hand, during the interval from 45 days to the end of the study, CV death or MI occurred in 5.5% in the complete revascularization group and 7.8% in the culprit-lesion-only group (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54-0.89).

There were a number of strengths of the COMPLETE study, as we have previously described, such as multiple patients enrolled, contemporary therapy with high use of radial access, mandated use of fractional flow reserve for 50% to 69% stenosis lesions, and low cross-over rate.7 In addition, the current substudy is unique and important, as it was the first study to systematically evaluate the timing of the staged PCI. In addition to their finding of consistent benefit between staged procedure before or after discharge, the results from their landmark analysis suggest that the benefit of complete revascularization accumulates over the long term rather than the short term.

The main limitation of the COMPLETE study is that it was not adequately powered to find statistical differences in each subgroup studied. In addition, since all nonculprit PCIs were staged in this study, nonculprit PCI performed during the index procedure cannot be assessed.

Nevertheless, the finding of similar benefit of complete revascularization regardless of the timing of the staged PCI has clinical implication for practicing interventional cardiologists and patients presenting with STEMI. For example, if the patient presents with hemodynamically stable STEMI on a Friday, the patient can potentially be safely discharged over the weekend and return for a staged PCI as an outpatient instead of staying extra days for an inpatient staged PCI. Whether this approach may improve the patient satisfaction and hospital resource utilization will require further study.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In patients presenting with hemodynamically stable STEMI, staged complete revascularization can be performed during the admission or after discharge within 45 days.

—Taishi Hirai, MD

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the effect of the timing of nonculprit-lesion percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Design. Planned substudy of an international, multicenter, randomized controlled trial blinded to outcome.

Setting and participants. Among 4041 patients with STEMI who had multivessel coronary disease, randomization to nonculprit PCI versus culprit-only PCI was stratified according to intended timing of nonculprit lesion PCI. A total of 2702 patients with intended timing of nonculprit PCI during the index hospitalization and 1339 patients with intended timing of nonculprit PCI after the index hospitalization within 45 days were included.

Main outcome measures. The first co-primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular (CV) death or myocardial infarction (MI).

Main results. In both groups, the composite endpoint of CV death or MI was reduced with complete revascularization compared to the culprit-only strategy (index hospitalization: hazard ratio [HR], 0.77, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59-1.00; after hospital discharge: HR, 0.69, 95% CI, 0.49-0.97; interaction, P = 0.62). Landmark analyses demonstrated a HR of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.59-1.24) during the first 45 days and 0.69 (95% CI,0.54-0.89) from 45 days to the end of follow-up for intended nonculprit lesion PCI versus culprit-lesion-only PCI.

Conclusion. Among patients with STEMI and multivessel disease, the benefit of complete revascularization over culprit-lesion-only PCI was consistent, irrespective of the investigator-determined timing of staged nonculprit lesion intervention.

Commentary

Patients presenting with STEMI often have multivessel disease.1 Although the question of whether to revascularize the nonculprit vessel has been controversial, multiple contemporary studies have reported benefit of nonculprit-vessel revascularization compared to the culprit-only strategy.2-5 Compared to these previous medium-sized randomized controlled trials that included ischemia-driven revascularization as a composite endpoint, the COMPETE trial was unique in that it enrolled a large number of patients and reported a benefit in hard outcomes of a composite of CV death or MI.6

As the previous studies point toward the benefit of complete revascularization in patients presenting with STEMI, another important question has been the optimal timing of nonculprit vessel revascularization. Operators have 3 possible options: during the index procedure as primary PCI, as a staged procedure during the index admission, or as a staged procedure as an outpatient following discharge. Timing of nonculprit PCI has been inconsistent in the previous studies. For example, in the PRAMI trial, nonculprit PCI was performed during the index procedure,2 while in the CvPRIT and COMPARE ACUTE trials, the nonculprit PCI was performed during the index procedure or as a staged procedure during the same admission at the operator’s discretion.3,5

In this context, the COMPLETE investigators report their findings of the prespecified substudy regarding the timing of staged nonculprit vessel PCI. In the COMPLETE trial, 4041 patients were stratified by intended timing of nonculprit lesion PCI (2702 patients during index hospitalization, 1339 after discharge), which was predetermined by the operator prior to the randomization. Among the patients with intended staged nonculprit PCI during index hospitalization, the incidence of the first co-primary outcome of CV death or MI was 2.7% per year in patients with complete revascularization, as compared to 3.5% per year in patients with culprit-lesion only PCI (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.59-1.00). Similarly, in patients with intended nonculprit PCI after the index hospitalization, the incidence of the first co-primary outcome of CV death or MI was 2.7% per year in patients randomized to complete revascularization, as compared to 3.9% per year in patients with culprit-lesion-only PCI (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.49-0.97). These findings were similar for the second co-primary outcome of CV death, MI, or ischemia-driven revascularization (3.0% vs 6.6% per year for intended timing of nonculprit PCI during index admission, and 3.1% vs 5.4% per year for intended timing of nonculprit PCI after discharge, both favoring complete revascularization).

The investigators also performed a landmark analysis before and after 45 days of randomization. Within the first 45 days, CV death or MI occurred in 2.5% of the complete revascularization group and 3.0% of the culprit-lesion-only PCI group (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.59-1.24). On the other hand, during the interval from 45 days to the end of the study, CV death or MI occurred in 5.5% in the complete revascularization group and 7.8% in the culprit-lesion-only group (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54-0.89).

There were a number of strengths of the COMPLETE study, as we have previously described, such as multiple patients enrolled, contemporary therapy with high use of radial access, mandated use of fractional flow reserve for 50% to 69% stenosis lesions, and low cross-over rate.7 In addition, the current substudy is unique and important, as it was the first study to systematically evaluate the timing of the staged PCI. In addition to their finding of consistent benefit between staged procedure before or after discharge, the results from their landmark analysis suggest that the benefit of complete revascularization accumulates over the long term rather than the short term.

The main limitation of the COMPLETE study is that it was not adequately powered to find statistical differences in each subgroup studied. In addition, since all nonculprit PCIs were staged in this study, nonculprit PCI performed during the index procedure cannot be assessed.

Nevertheless, the finding of similar benefit of complete revascularization regardless of the timing of the staged PCI has clinical implication for practicing interventional cardiologists and patients presenting with STEMI. For example, if the patient presents with hemodynamically stable STEMI on a Friday, the patient can potentially be safely discharged over the weekend and return for a staged PCI as an outpatient instead of staying extra days for an inpatient staged PCI. Whether this approach may improve the patient satisfaction and hospital resource utilization will require further study.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In patients presenting with hemodynamically stable STEMI, staged complete revascularization can be performed during the admission or after discharge within 45 days.

—Taishi Hirai, MD

1. Park DW, Clare RM, Schulte PJ, et al. Extent, location, and clinical significance of non-infarct-related coronary artery disease among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014;312:2019-2027.

2. Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1115-1123.

3. Gershlick AH, Khan JN, Kelly DJ, et al. Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:963-972.

4. Engstrom T, Kelbaek H, Helqvist S, et al. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9994):665-671.

5. Smits PC, Abdel-Wahab M, Neumann FJ, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided multivessel angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1234-1244.

6. Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al. Complete revascularization with multivessel pci for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1411-1421.

7. Hirai T, Blair JEA. Nonculprit lesion PCI strategies in patients with STEMI without cardiogenic shock. J Clin Outcomes Management. 2020;27:7-9.

1. Park DW, Clare RM, Schulte PJ, et al. Extent, location, and clinical significance of non-infarct-related coronary artery disease among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014;312:2019-2027.

2. Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1115-1123.

3. Gershlick AH, Khan JN, Kelly DJ, et al. Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:963-972.

4. Engstrom T, Kelbaek H, Helqvist S, et al. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9994):665-671.

5. Smits PC, Abdel-Wahab M, Neumann FJ, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided multivessel angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1234-1244.

6. Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al. Complete revascularization with multivessel pci for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1411-1421.

7. Hirai T, Blair JEA. Nonculprit lesion PCI strategies in patients with STEMI without cardiogenic shock. J Clin Outcomes Management. 2020;27:7-9.

Blood biomarker may predict Alzheimer’s disease progression

new research suggests.

In a study of more than 1,000 participants, changes over time in levels of p-tau181 were associated with prospective neurodegeneration and cognitive decline characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. These results have implications for investigative trials as well as clinical practice, the investigators noted.

Like p-tau181, neurofilament light chain (NfL) is associated with imaging markers of degeneration and cognitive decline; in contrast to the findings related to p-tau181, however, the associations between NfL and these outcomes are not specific to Alzheimer’s disease. Using both biomarkers could improve prediction of outcomes and patient monitoring, according to the researchers.

“These findings demonstrate that p-tau181 and NfL in blood have individual and complementary potential roles in the diagnosis and the monitoring of neurodegenerative disease,” said coinvestigator Michael Schöll, PhD, senior lecturer in psychiatry and neurochemistry at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden).

“With the reservation that we did not assess domain-specific cognitive impairment, p-tau181 was also more strongly associated with cognitive decline than was NfL,” Dr. Schöll added.

The findings were published online Jan. 11 in JAMA Neurology.

Biomarker-tracked neurodegeneration

Monitoring a patient’s neurodegenerative changes is important for tracking Alzheimer’s disease progression. Although clinicians can detect amyloid-beta and tau pathology using PET and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers, the widespread use of the latter has been hampered by cost and limited availability of necessary equipment. The use of blood-based biomarkers is not limited in these ways, and so they could aid in diagnosis and patient monitoring.

Previous studies have suggested that p-tau181 is a marker of Alzheimer’s disease status.

In the current study, investigators examined whether baseline and longitudinal levels of p-tau181 in plasma were associated with progressive neurodegeneration related to the disease. They analyzed data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, a multicenter study designed to identify biomarkers for the detection and tracking of Alzheimer’s disease.

The researchers selected data for cognitively unimpaired and cognitively impaired participants who participated in the initiative between Feb. 1, 2007, and June 6, 2016. Participants were eligible for inclusion if plasma p-tau181 and NfL data were available for them and if they had undergone at least one 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET scan or structural T1 MRI at the same study visit. Most had also undergone imaging with 18florbetapir, which detects amyloid-beta.

A single-molecule array was used to analyze concentrations of p-tau181 and NfL in participants’ blood samples. Outliers for p-tau181 and NfL concentrations were excluded from further analysis. Using participants’ FDG-PET scans, the investigators measured glucose hypometabolism characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. They used T1-weighted MRI scans to measure gray-matter volume.

Cognitively unimpaired participants responded to the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite, a measure designed to detect early cognitive changes in cognitively normal patients with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Cognitively impaired participants underwent the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale with 13 tasks to assess the severity of cognitive impairment.

The researchers included 1,113 participants (54% men; 89% non-Hispanic Whites; mean age, 74 years) in their analysis. In all, 378 participants were cognitively unimpaired, and 735 were cognitively impaired. Of the latter group, 73% had mild cognitive impairment, and 27% had Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

Atrophy predictor

Results showed that higher plasma p-tau181 levels at baseline were associated with more rapid progression of hypometabolism and atrophy in areas vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease among cognitively impaired participants (FDG-PET standardized uptake value ratio change, r = –0.28; P < .001; gray-matter volume change, r = –0.28; P < .001).

The association with atrophy progression in cognitively impaired participants was stronger for p-tau181 than for NfL.

Plasma p-tau181 levels at baseline also predicted atrophy in temporoparietal regions vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease among cognitively unimpaired participants (r = –0.11; P = .03). NfL, however, was associated with progressive atrophy in frontal regions among cognitively unimpaired participants.

At baseline, plasma p-tau181 levels were associated with prospective cognitive decline in both the cognitively unimpaired group (r = −0.12; P = .04) and the cognitively impaired group (r = 0.35; P < .001). However, plasma NfL was linked to cognitive decline only among those who were cognitively impaired (r = 0.26; P < .001).

Additional analyses showed that p-tau181, unlike NfL, was associated with hypometabolism and atrophy only in participants with amyloid-beta, regardless of cognitive status.

Between 25% and 45% of the association between baseline p-tau181 level and cognitive decline was mediated by baseline imaging markers of neurodegeneration. This finding suggests that another factor, such as regional tau pathology, might have an independent and direct effect on cognition, Dr. Schöll noted.

Furthermore, changes over time in p-tau181 levels were associated with cognitive decline in the cognitively unimpaired (r = –0.24; P < .001) and cognitively impaired (r = 0.34; P < .001) participants. Longitudinal changes in this biomarker also were associated with a prospective decrease in glucose metabolism in cognitively unimpaired (r = –0.05; P = .48) and cognitively impaired (r = –0.27; P < .001) participants, but the association was only significant in the latter group.

Changes over time in p-tau181 levels were linked to prospective decreases in gray-matter volume in brain regions highly characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease in those who were cognitively unimpaired (r = –0.19; P < .001) and those who were cognitively impaired (r = –0.31, P < .001). However, these associations were obtained only in patients with amyloid-beta.

Dr. Schöll noted that blood-based biomarkers that are sensitive to Alzheimer’s disease could greatly expand patients’ access to a diagnostic workup and could improve screening for clinical trials.

“While the final validation of the existence and the monitoring of potential changes of neuropathology in vivo is likely to be conducted using neuroimaging modalities such as PET, our results suggest that at least a part of these examinations could be replaced by regular blood tests,” Dr. Schöll said.

Lead author Alexis Moscoso, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in psychiatry and neurochemistry at the University of Gothenburg, reported that the researchers will continue validating blood-based biomarkers, especially against established and well-validated neuroimaging methods. “We are also hoping to be able to compare existing and novel blood-based Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers head to head to establish the individual roles each of these play in the research and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Moscoso said.

‘Outstanding study’

Commenting on the findings, David S. Knopman, MD, professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that this is “an outstanding study” because of its large number of participants and because the investigators are “world leaders in the technology of measuring plasma p-tau and NfL.”

Dr. Knopman, who was not involved with the research, noted that the study had no substantive weaknesses.

“The biggest advantages of a blood-based biomarker over CSF- and PET-based biomarkers of Alzheimer disease are the obvious ones of accessibility, cost, portability, and ease of repeatability,” he said.

“As CSF and PET exams are largely limited to major medical centers, valid blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer disease that are reasonably specific make large-scale epidemiological studies that investigate dementia etiologies in rural or urban and diverse communities feasible,” he added.

Whereas p-tau181 appears to be specific for plaque and tangle disease, NfL is a nonspecific marker of neurodegeneration.

“Each has a role that could be valuable, depending on the circumstance,” said Dr. Knopman. “Plasma NfL has already proved itself useful in frontotemporal degeneration and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, for example.”

He noted that future studies should examine how closely p-tau181 and NfL align with more granular and direct measures of Alzheimer’s disease–related brain pathologies.

“There has got to be some loss of fidelity in detecting abnormality in going from brain tissue to blood, which might siphon off some time-related and severity-related information,” said Dr. Knopman.

“The exact role that plasma p-tau and NfL will play remains to be seen, because the diagnostic information that these biomarkers provide is contingent on the existence of interventions that require specific or nonspecific information about progressive neurodegeneration due to Alzheimer disease,” he added.

The study was funded by grants from the Spanish Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Brightfocus Foundation, the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation, and the Swedish Brain Foundation. Dr. Schöll reported serving on a scientific advisory board for Servier on matters unrelated to this study. Dr. Moscoso and Dr. Knopman have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In a study of more than 1,000 participants, changes over time in levels of p-tau181 were associated with prospective neurodegeneration and cognitive decline characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. These results have implications for investigative trials as well as clinical practice, the investigators noted.

Like p-tau181, neurofilament light chain (NfL) is associated with imaging markers of degeneration and cognitive decline; in contrast to the findings related to p-tau181, however, the associations between NfL and these outcomes are not specific to Alzheimer’s disease. Using both biomarkers could improve prediction of outcomes and patient monitoring, according to the researchers.

“These findings demonstrate that p-tau181 and NfL in blood have individual and complementary potential roles in the diagnosis and the monitoring of neurodegenerative disease,” said coinvestigator Michael Schöll, PhD, senior lecturer in psychiatry and neurochemistry at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden).

“With the reservation that we did not assess domain-specific cognitive impairment, p-tau181 was also more strongly associated with cognitive decline than was NfL,” Dr. Schöll added.

The findings were published online Jan. 11 in JAMA Neurology.

Biomarker-tracked neurodegeneration

Monitoring a patient’s neurodegenerative changes is important for tracking Alzheimer’s disease progression. Although clinicians can detect amyloid-beta and tau pathology using PET and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers, the widespread use of the latter has been hampered by cost and limited availability of necessary equipment. The use of blood-based biomarkers is not limited in these ways, and so they could aid in diagnosis and patient monitoring.

Previous studies have suggested that p-tau181 is a marker of Alzheimer’s disease status.

In the current study, investigators examined whether baseline and longitudinal levels of p-tau181 in plasma were associated with progressive neurodegeneration related to the disease. They analyzed data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, a multicenter study designed to identify biomarkers for the detection and tracking of Alzheimer’s disease.

The researchers selected data for cognitively unimpaired and cognitively impaired participants who participated in the initiative between Feb. 1, 2007, and June 6, 2016. Participants were eligible for inclusion if plasma p-tau181 and NfL data were available for them and if they had undergone at least one 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET scan or structural T1 MRI at the same study visit. Most had also undergone imaging with 18florbetapir, which detects amyloid-beta.

A single-molecule array was used to analyze concentrations of p-tau181 and NfL in participants’ blood samples. Outliers for p-tau181 and NfL concentrations were excluded from further analysis. Using participants’ FDG-PET scans, the investigators measured glucose hypometabolism characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. They used T1-weighted MRI scans to measure gray-matter volume.

Cognitively unimpaired participants responded to the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite, a measure designed to detect early cognitive changes in cognitively normal patients with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Cognitively impaired participants underwent the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale with 13 tasks to assess the severity of cognitive impairment.

The researchers included 1,113 participants (54% men; 89% non-Hispanic Whites; mean age, 74 years) in their analysis. In all, 378 participants were cognitively unimpaired, and 735 were cognitively impaired. Of the latter group, 73% had mild cognitive impairment, and 27% had Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

Atrophy predictor

Results showed that higher plasma p-tau181 levels at baseline were associated with more rapid progression of hypometabolism and atrophy in areas vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease among cognitively impaired participants (FDG-PET standardized uptake value ratio change, r = –0.28; P < .001; gray-matter volume change, r = –0.28; P < .001).

The association with atrophy progression in cognitively impaired participants was stronger for p-tau181 than for NfL.

Plasma p-tau181 levels at baseline also predicted atrophy in temporoparietal regions vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease among cognitively unimpaired participants (r = –0.11; P = .03). NfL, however, was associated with progressive atrophy in frontal regions among cognitively unimpaired participants.

At baseline, plasma p-tau181 levels were associated with prospective cognitive decline in both the cognitively unimpaired group (r = −0.12; P = .04) and the cognitively impaired group (r = 0.35; P < .001). However, plasma NfL was linked to cognitive decline only among those who were cognitively impaired (r = 0.26; P < .001).

Additional analyses showed that p-tau181, unlike NfL, was associated with hypometabolism and atrophy only in participants with amyloid-beta, regardless of cognitive status.

Between 25% and 45% of the association between baseline p-tau181 level and cognitive decline was mediated by baseline imaging markers of neurodegeneration. This finding suggests that another factor, such as regional tau pathology, might have an independent and direct effect on cognition, Dr. Schöll noted.

Furthermore, changes over time in p-tau181 levels were associated with cognitive decline in the cognitively unimpaired (r = –0.24; P < .001) and cognitively impaired (r = 0.34; P < .001) participants. Longitudinal changes in this biomarker also were associated with a prospective decrease in glucose metabolism in cognitively unimpaired (r = –0.05; P = .48) and cognitively impaired (r = –0.27; P < .001) participants, but the association was only significant in the latter group.

Changes over time in p-tau181 levels were linked to prospective decreases in gray-matter volume in brain regions highly characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease in those who were cognitively unimpaired (r = –0.19; P < .001) and those who were cognitively impaired (r = –0.31, P < .001). However, these associations were obtained only in patients with amyloid-beta.

Dr. Schöll noted that blood-based biomarkers that are sensitive to Alzheimer’s disease could greatly expand patients’ access to a diagnostic workup and could improve screening for clinical trials.

“While the final validation of the existence and the monitoring of potential changes of neuropathology in vivo is likely to be conducted using neuroimaging modalities such as PET, our results suggest that at least a part of these examinations could be replaced by regular blood tests,” Dr. Schöll said.

Lead author Alexis Moscoso, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in psychiatry and neurochemistry at the University of Gothenburg, reported that the researchers will continue validating blood-based biomarkers, especially against established and well-validated neuroimaging methods. “We are also hoping to be able to compare existing and novel blood-based Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers head to head to establish the individual roles each of these play in the research and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Moscoso said.

‘Outstanding study’

Commenting on the findings, David S. Knopman, MD, professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that this is “an outstanding study” because of its large number of participants and because the investigators are “world leaders in the technology of measuring plasma p-tau and NfL.”

Dr. Knopman, who was not involved with the research, noted that the study had no substantive weaknesses.

“The biggest advantages of a blood-based biomarker over CSF- and PET-based biomarkers of Alzheimer disease are the obvious ones of accessibility, cost, portability, and ease of repeatability,” he said.

“As CSF and PET exams are largely limited to major medical centers, valid blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer disease that are reasonably specific make large-scale epidemiological studies that investigate dementia etiologies in rural or urban and diverse communities feasible,” he added.

Whereas p-tau181 appears to be specific for plaque and tangle disease, NfL is a nonspecific marker of neurodegeneration.

“Each has a role that could be valuable, depending on the circumstance,” said Dr. Knopman. “Plasma NfL has already proved itself useful in frontotemporal degeneration and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, for example.”

He noted that future studies should examine how closely p-tau181 and NfL align with more granular and direct measures of Alzheimer’s disease–related brain pathologies.

“There has got to be some loss of fidelity in detecting abnormality in going from brain tissue to blood, which might siphon off some time-related and severity-related information,” said Dr. Knopman.

“The exact role that plasma p-tau and NfL will play remains to be seen, because the diagnostic information that these biomarkers provide is contingent on the existence of interventions that require specific or nonspecific information about progressive neurodegeneration due to Alzheimer disease,” he added.

The study was funded by grants from the Spanish Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Brightfocus Foundation, the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation, and the Swedish Brain Foundation. Dr. Schöll reported serving on a scientific advisory board for Servier on matters unrelated to this study. Dr. Moscoso and Dr. Knopman have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In a study of more than 1,000 participants, changes over time in levels of p-tau181 were associated with prospective neurodegeneration and cognitive decline characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. These results have implications for investigative trials as well as clinical practice, the investigators noted.

Like p-tau181, neurofilament light chain (NfL) is associated with imaging markers of degeneration and cognitive decline; in contrast to the findings related to p-tau181, however, the associations between NfL and these outcomes are not specific to Alzheimer’s disease. Using both biomarkers could improve prediction of outcomes and patient monitoring, according to the researchers.

“These findings demonstrate that p-tau181 and NfL in blood have individual and complementary potential roles in the diagnosis and the monitoring of neurodegenerative disease,” said coinvestigator Michael Schöll, PhD, senior lecturer in psychiatry and neurochemistry at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden).

“With the reservation that we did not assess domain-specific cognitive impairment, p-tau181 was also more strongly associated with cognitive decline than was NfL,” Dr. Schöll added.

The findings were published online Jan. 11 in JAMA Neurology.

Biomarker-tracked neurodegeneration

Monitoring a patient’s neurodegenerative changes is important for tracking Alzheimer’s disease progression. Although clinicians can detect amyloid-beta and tau pathology using PET and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers, the widespread use of the latter has been hampered by cost and limited availability of necessary equipment. The use of blood-based biomarkers is not limited in these ways, and so they could aid in diagnosis and patient monitoring.

Previous studies have suggested that p-tau181 is a marker of Alzheimer’s disease status.

In the current study, investigators examined whether baseline and longitudinal levels of p-tau181 in plasma were associated with progressive neurodegeneration related to the disease. They analyzed data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, a multicenter study designed to identify biomarkers for the detection and tracking of Alzheimer’s disease.

The researchers selected data for cognitively unimpaired and cognitively impaired participants who participated in the initiative between Feb. 1, 2007, and June 6, 2016. Participants were eligible for inclusion if plasma p-tau181 and NfL data were available for them and if they had undergone at least one 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET scan or structural T1 MRI at the same study visit. Most had also undergone imaging with 18florbetapir, which detects amyloid-beta.

A single-molecule array was used to analyze concentrations of p-tau181 and NfL in participants’ blood samples. Outliers for p-tau181 and NfL concentrations were excluded from further analysis. Using participants’ FDG-PET scans, the investigators measured glucose hypometabolism characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. They used T1-weighted MRI scans to measure gray-matter volume.

Cognitively unimpaired participants responded to the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite, a measure designed to detect early cognitive changes in cognitively normal patients with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Cognitively impaired participants underwent the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale with 13 tasks to assess the severity of cognitive impairment.

The researchers included 1,113 participants (54% men; 89% non-Hispanic Whites; mean age, 74 years) in their analysis. In all, 378 participants were cognitively unimpaired, and 735 were cognitively impaired. Of the latter group, 73% had mild cognitive impairment, and 27% had Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

Atrophy predictor