User login

Disparity in endometrial cancer outcomes: What can we do?

While the incidence of most cancers is falling, endometrial cancer rates continue to rise, in large part because of increasing life expectancy and obesity rates. However, what is even more alarming is the observation that there is a clear disparity in outcomes between black and white women with this disease. But there are things that all health care providers, including nononcologists, can do to help to overcome this disparity.

Black women are nearly twice as likely as non-Hispanic white women to die from the endometrial cancer. The 5-year survival for stage III and IV cancer is 43% for non-Hispanic white women, yet only 25% for black women.1 For a long time, this survival disparity was assumed to be a function of the more aggressive cancer histologies, such as serous, which are more commonly seen in black women. These high-grade cancers are more likely to present in advanced stages and with poorer responses to treatments; however, the predisposition to aggressive cancers tells only part of the story of racial disparities in endometrial cancer and their presentation at later stages. Indeed, fueling the problem are the findings that black women report symptoms less, experience more delays in diagnosis or more frequent deviations from guideline-directed diagnostics, undergo more morbid surgical approaches, receive less surgical staging, are enrolled less in clinical trials, have lower socioeconomic status and lower rates of health insurance, and receive less differential administration of adjuvant therapies, as well as have a background of higher all-cause mortality and comorbidities. While this array of contributing factors may seem overwhelming, it also can be considered a guide for health care providers because most of these factors, unlike histologic cell type, are modifiable, and it is important that we all consider what role we can play in dismantling them.

Black women are less likely to receive guideline-recommended care upon presentation. Research by Kemi M. Doll, MD, from the University of Washington, Seattle, demonstrated that, among women with endometrial cancers, black women were less likely to have documented histories of postmenopausal bleeding within 2 years of the diagnosis, presumably because of factors related to underreporting and inadequate ascertainment by medical professionals of whether or not they had experienced postmenopausal bleeding.2 Additionally, when postmenopausal bleeding was reported by these women, they were less likely to receive the appropriate diagnostic work-up as described by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines, and their bleeding was more likely to be ascribed to nonmalignant pathologies. Her work raises the important question about how black women view the health care profession and their willingness to engage early in good faith that their concerns will be met. These concerns are understandable given the documented different responsiveness of providers to black patients’ symptoms such as pain.3

both of which are considered the standard of care.1,4 Lower rates of minimally invasive surgery expose black women to increased morbidity and are deleterious to quality of life, return to work, and functionality. If surgical staging is omitted, which is more common for these women, clinicians are less able to appropriately prescribe adjuvant therapies which might prevent lethal recurrences from unrecognized advanced cancer or they may overtreat early-stage cancers with adjuvant therapy to make up for gaps in staging information.1,5 However, adjuvant therapy is not a benign intervention, and itself is associated with morbidity.

As mentioned earlier, black women are at a higher risk for developing more aggressive cancer subtypes, and this phenomenon may appear unmodifiable. However, important research is looking at the concept of epigenetics and how modifiable environmental factors may contribute to the development of more aggressive types of cancer through gene expression. Additionally, differences in the gene mutations and gene expression of cancers more frequently acquired by black women may negatively influence how these cancers respond to conventional therapies. In the GOG210 study, which evaluated the outcomes of women with comprehensively staged endometrial cancer, black women demonstrated worse survival from cancer, even though they were more likely to receive chemotherapy.5 One explanation for this finding is that these women’s cancers were less responsive to conventional chemotherapy agents.

This raises a critical issue of disparity in clinical trial inclusion. Black women are underrepresented in clinical trials in the United States. There is a dark history in medical research and minority populations, particularly African American populations, which continues to be remembered and felt. However, not all of this underrepresentation may be from unwillingness to participate: For black women, issues of lack of access to or being considered for clinical trials is also a factor. But without adequate representation in trials of novel agents, we will not know whether they are effective for all populations, and indeed it would appear that we should not assume they are equally effective based on the results to date.

So how can we all individually help to overcome these disparities in endometrial cancer outcomes? To begin with, it is important to acknowledge that black women commonly report negative experiences with reproductive health care. From early in their lives, we must sensitively engage all of our patients and ensure they all feel heard and valued. They should know that their symptoms, including pain or bleeding, are taken and treated seriously. If we can do better with this throughout a woman’s earlier reproductive health care experiences, perhaps later in her life, when she experiences postmenopausal bleeding, she will feel comfortable raising this issue with her health care provider who in turn must take this symptom seriously and expeditiously engage all of the appropriate diagnostic resources. Health care delivery is about more than simply offering the best treatment. We also are responsible for education and shared decision making to ensure that we can deliver the best treatment.

We also can support organizations such as ECANA (Endometrial Cancer Action Network for African Americans) which serves to inform black women in their communities about the threat that endometrial cancer plays and empowers them through education about its symptoms and the need to seek care.

Systematically we must ensure black women have access to the same standards in surgical and nonsurgical management of these cancers. This includes referral of all women with cancer, including minorities, to high-volume centers with oncology specialists and explaining to those who may be reluctant to travel that this is associated with improved outcomes in the short and long term. We also must actively consider our black patients for clinical trials, sensitively educate them about their benefits, and overcome barriers to access. One simple way to do this is to explain that the treatments that we have developed for endometrial cancer have mostly been tested on white women, which may explain in part why they do not work so well for nonwhite women.

The racial disparity in endometrial cancer outcomes cannot entirely be attributed to the passive phenomenon of patient and tumor genetics, particularly with consideration that race is a social construct rather than a biological phenomenon. We can all make a difference through advocacy, access, education, and heightened awareness to combat this inequity and overcome these disparate outcomes.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Oct;143(1):98-104.

2. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec;219(6):593.e1-14.

3. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Jun 1;30(16):1980-8.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):526-34.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;219(5):459.e1-11.

While the incidence of most cancers is falling, endometrial cancer rates continue to rise, in large part because of increasing life expectancy and obesity rates. However, what is even more alarming is the observation that there is a clear disparity in outcomes between black and white women with this disease. But there are things that all health care providers, including nononcologists, can do to help to overcome this disparity.

Black women are nearly twice as likely as non-Hispanic white women to die from the endometrial cancer. The 5-year survival for stage III and IV cancer is 43% for non-Hispanic white women, yet only 25% for black women.1 For a long time, this survival disparity was assumed to be a function of the more aggressive cancer histologies, such as serous, which are more commonly seen in black women. These high-grade cancers are more likely to present in advanced stages and with poorer responses to treatments; however, the predisposition to aggressive cancers tells only part of the story of racial disparities in endometrial cancer and their presentation at later stages. Indeed, fueling the problem are the findings that black women report symptoms less, experience more delays in diagnosis or more frequent deviations from guideline-directed diagnostics, undergo more morbid surgical approaches, receive less surgical staging, are enrolled less in clinical trials, have lower socioeconomic status and lower rates of health insurance, and receive less differential administration of adjuvant therapies, as well as have a background of higher all-cause mortality and comorbidities. While this array of contributing factors may seem overwhelming, it also can be considered a guide for health care providers because most of these factors, unlike histologic cell type, are modifiable, and it is important that we all consider what role we can play in dismantling them.

Black women are less likely to receive guideline-recommended care upon presentation. Research by Kemi M. Doll, MD, from the University of Washington, Seattle, demonstrated that, among women with endometrial cancers, black women were less likely to have documented histories of postmenopausal bleeding within 2 years of the diagnosis, presumably because of factors related to underreporting and inadequate ascertainment by medical professionals of whether or not they had experienced postmenopausal bleeding.2 Additionally, when postmenopausal bleeding was reported by these women, they were less likely to receive the appropriate diagnostic work-up as described by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines, and their bleeding was more likely to be ascribed to nonmalignant pathologies. Her work raises the important question about how black women view the health care profession and their willingness to engage early in good faith that their concerns will be met. These concerns are understandable given the documented different responsiveness of providers to black patients’ symptoms such as pain.3

both of which are considered the standard of care.1,4 Lower rates of minimally invasive surgery expose black women to increased morbidity and are deleterious to quality of life, return to work, and functionality. If surgical staging is omitted, which is more common for these women, clinicians are less able to appropriately prescribe adjuvant therapies which might prevent lethal recurrences from unrecognized advanced cancer or they may overtreat early-stage cancers with adjuvant therapy to make up for gaps in staging information.1,5 However, adjuvant therapy is not a benign intervention, and itself is associated with morbidity.

As mentioned earlier, black women are at a higher risk for developing more aggressive cancer subtypes, and this phenomenon may appear unmodifiable. However, important research is looking at the concept of epigenetics and how modifiable environmental factors may contribute to the development of more aggressive types of cancer through gene expression. Additionally, differences in the gene mutations and gene expression of cancers more frequently acquired by black women may negatively influence how these cancers respond to conventional therapies. In the GOG210 study, which evaluated the outcomes of women with comprehensively staged endometrial cancer, black women demonstrated worse survival from cancer, even though they were more likely to receive chemotherapy.5 One explanation for this finding is that these women’s cancers were less responsive to conventional chemotherapy agents.

This raises a critical issue of disparity in clinical trial inclusion. Black women are underrepresented in clinical trials in the United States. There is a dark history in medical research and minority populations, particularly African American populations, which continues to be remembered and felt. However, not all of this underrepresentation may be from unwillingness to participate: For black women, issues of lack of access to or being considered for clinical trials is also a factor. But without adequate representation in trials of novel agents, we will not know whether they are effective for all populations, and indeed it would appear that we should not assume they are equally effective based on the results to date.

So how can we all individually help to overcome these disparities in endometrial cancer outcomes? To begin with, it is important to acknowledge that black women commonly report negative experiences with reproductive health care. From early in their lives, we must sensitively engage all of our patients and ensure they all feel heard and valued. They should know that their symptoms, including pain or bleeding, are taken and treated seriously. If we can do better with this throughout a woman’s earlier reproductive health care experiences, perhaps later in her life, when she experiences postmenopausal bleeding, she will feel comfortable raising this issue with her health care provider who in turn must take this symptom seriously and expeditiously engage all of the appropriate diagnostic resources. Health care delivery is about more than simply offering the best treatment. We also are responsible for education and shared decision making to ensure that we can deliver the best treatment.

We also can support organizations such as ECANA (Endometrial Cancer Action Network for African Americans) which serves to inform black women in their communities about the threat that endometrial cancer plays and empowers them through education about its symptoms and the need to seek care.

Systematically we must ensure black women have access to the same standards in surgical and nonsurgical management of these cancers. This includes referral of all women with cancer, including minorities, to high-volume centers with oncology specialists and explaining to those who may be reluctant to travel that this is associated with improved outcomes in the short and long term. We also must actively consider our black patients for clinical trials, sensitively educate them about their benefits, and overcome barriers to access. One simple way to do this is to explain that the treatments that we have developed for endometrial cancer have mostly been tested on white women, which may explain in part why they do not work so well for nonwhite women.

The racial disparity in endometrial cancer outcomes cannot entirely be attributed to the passive phenomenon of patient and tumor genetics, particularly with consideration that race is a social construct rather than a biological phenomenon. We can all make a difference through advocacy, access, education, and heightened awareness to combat this inequity and overcome these disparate outcomes.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Oct;143(1):98-104.

2. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec;219(6):593.e1-14.

3. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Jun 1;30(16):1980-8.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):526-34.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;219(5):459.e1-11.

While the incidence of most cancers is falling, endometrial cancer rates continue to rise, in large part because of increasing life expectancy and obesity rates. However, what is even more alarming is the observation that there is a clear disparity in outcomes between black and white women with this disease. But there are things that all health care providers, including nononcologists, can do to help to overcome this disparity.

Black women are nearly twice as likely as non-Hispanic white women to die from the endometrial cancer. The 5-year survival for stage III and IV cancer is 43% for non-Hispanic white women, yet only 25% for black women.1 For a long time, this survival disparity was assumed to be a function of the more aggressive cancer histologies, such as serous, which are more commonly seen in black women. These high-grade cancers are more likely to present in advanced stages and with poorer responses to treatments; however, the predisposition to aggressive cancers tells only part of the story of racial disparities in endometrial cancer and their presentation at later stages. Indeed, fueling the problem are the findings that black women report symptoms less, experience more delays in diagnosis or more frequent deviations from guideline-directed diagnostics, undergo more morbid surgical approaches, receive less surgical staging, are enrolled less in clinical trials, have lower socioeconomic status and lower rates of health insurance, and receive less differential administration of adjuvant therapies, as well as have a background of higher all-cause mortality and comorbidities. While this array of contributing factors may seem overwhelming, it also can be considered a guide for health care providers because most of these factors, unlike histologic cell type, are modifiable, and it is important that we all consider what role we can play in dismantling them.

Black women are less likely to receive guideline-recommended care upon presentation. Research by Kemi M. Doll, MD, from the University of Washington, Seattle, demonstrated that, among women with endometrial cancers, black women were less likely to have documented histories of postmenopausal bleeding within 2 years of the diagnosis, presumably because of factors related to underreporting and inadequate ascertainment by medical professionals of whether or not they had experienced postmenopausal bleeding.2 Additionally, when postmenopausal bleeding was reported by these women, they were less likely to receive the appropriate diagnostic work-up as described by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines, and their bleeding was more likely to be ascribed to nonmalignant pathologies. Her work raises the important question about how black women view the health care profession and their willingness to engage early in good faith that their concerns will be met. These concerns are understandable given the documented different responsiveness of providers to black patients’ symptoms such as pain.3

both of which are considered the standard of care.1,4 Lower rates of minimally invasive surgery expose black women to increased morbidity and are deleterious to quality of life, return to work, and functionality. If surgical staging is omitted, which is more common for these women, clinicians are less able to appropriately prescribe adjuvant therapies which might prevent lethal recurrences from unrecognized advanced cancer or they may overtreat early-stage cancers with adjuvant therapy to make up for gaps in staging information.1,5 However, adjuvant therapy is not a benign intervention, and itself is associated with morbidity.

As mentioned earlier, black women are at a higher risk for developing more aggressive cancer subtypes, and this phenomenon may appear unmodifiable. However, important research is looking at the concept of epigenetics and how modifiable environmental factors may contribute to the development of more aggressive types of cancer through gene expression. Additionally, differences in the gene mutations and gene expression of cancers more frequently acquired by black women may negatively influence how these cancers respond to conventional therapies. In the GOG210 study, which evaluated the outcomes of women with comprehensively staged endometrial cancer, black women demonstrated worse survival from cancer, even though they were more likely to receive chemotherapy.5 One explanation for this finding is that these women’s cancers were less responsive to conventional chemotherapy agents.

This raises a critical issue of disparity in clinical trial inclusion. Black women are underrepresented in clinical trials in the United States. There is a dark history in medical research and minority populations, particularly African American populations, which continues to be remembered and felt. However, not all of this underrepresentation may be from unwillingness to participate: For black women, issues of lack of access to or being considered for clinical trials is also a factor. But without adequate representation in trials of novel agents, we will not know whether they are effective for all populations, and indeed it would appear that we should not assume they are equally effective based on the results to date.

So how can we all individually help to overcome these disparities in endometrial cancer outcomes? To begin with, it is important to acknowledge that black women commonly report negative experiences with reproductive health care. From early in their lives, we must sensitively engage all of our patients and ensure they all feel heard and valued. They should know that their symptoms, including pain or bleeding, are taken and treated seriously. If we can do better with this throughout a woman’s earlier reproductive health care experiences, perhaps later in her life, when she experiences postmenopausal bleeding, she will feel comfortable raising this issue with her health care provider who in turn must take this symptom seriously and expeditiously engage all of the appropriate diagnostic resources. Health care delivery is about more than simply offering the best treatment. We also are responsible for education and shared decision making to ensure that we can deliver the best treatment.

We also can support organizations such as ECANA (Endometrial Cancer Action Network for African Americans) which serves to inform black women in their communities about the threat that endometrial cancer plays and empowers them through education about its symptoms and the need to seek care.

Systematically we must ensure black women have access to the same standards in surgical and nonsurgical management of these cancers. This includes referral of all women with cancer, including minorities, to high-volume centers with oncology specialists and explaining to those who may be reluctant to travel that this is associated with improved outcomes in the short and long term. We also must actively consider our black patients for clinical trials, sensitively educate them about their benefits, and overcome barriers to access. One simple way to do this is to explain that the treatments that we have developed for endometrial cancer have mostly been tested on white women, which may explain in part why they do not work so well for nonwhite women.

The racial disparity in endometrial cancer outcomes cannot entirely be attributed to the passive phenomenon of patient and tumor genetics, particularly with consideration that race is a social construct rather than a biological phenomenon. We can all make a difference through advocacy, access, education, and heightened awareness to combat this inequity and overcome these disparate outcomes.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Oct;143(1):98-104.

2. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec;219(6):593.e1-14.

3. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Jun 1;30(16):1980-8.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):526-34.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;219(5):459.e1-11.

Could the biosimilar market stall before it ever really started?

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – If the United States does not step up and create a thriving biosimilars market soon, it risks destroying the market not only domestically but internationally as well.

This was the warning Gillian Woollett, senior vice president at Avalere, provided to attendees at the annual meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy.

She prefaced her warning by quoting Alex Azar, secretary of Health & Human Services, who said that those “trying to hold back biosimilars are simply on the wrong side of history,” though Ms. Woollett said they “may be on the right side of the current economic model in the United States.”

And despite the probusiness, procompetition philosophy of current HHS leadership, there has been very little movement on creating a competitive market for biosimilars in the United States, evidenced by the very expensive regulatory requirements that biosimilar manufacturers need to meet in order to get products to market.

“It’s not that we won’t have competition in the U.S.,” she said. “I think we will. We do have that innovation. ... It’s just that biosimilars may not ultimately be part of that competition. And for that, we will pay a price, and I actually think the whole world will pay a price because if we are not providing the [return on investment], I am not sure the other markets can sustain it.”

One issue biosimilars have is the lack of recognition of the value that they bring.

“That biosimilars offer the same clinical outcomes at a lower price is yet to be a recognized value,” she said. “To me that’s a really surprising situation in the United States.”

Ms. Woollett continued: “It’s not even acknowledged as a basic truth in the United States, which again suggests the business model may not be there for biosimilars.”

Ms. Woollett disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to her presentation.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – If the United States does not step up and create a thriving biosimilars market soon, it risks destroying the market not only domestically but internationally as well.

This was the warning Gillian Woollett, senior vice president at Avalere, provided to attendees at the annual meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy.

She prefaced her warning by quoting Alex Azar, secretary of Health & Human Services, who said that those “trying to hold back biosimilars are simply on the wrong side of history,” though Ms. Woollett said they “may be on the right side of the current economic model in the United States.”

And despite the probusiness, procompetition philosophy of current HHS leadership, there has been very little movement on creating a competitive market for biosimilars in the United States, evidenced by the very expensive regulatory requirements that biosimilar manufacturers need to meet in order to get products to market.

“It’s not that we won’t have competition in the U.S.,” she said. “I think we will. We do have that innovation. ... It’s just that biosimilars may not ultimately be part of that competition. And for that, we will pay a price, and I actually think the whole world will pay a price because if we are not providing the [return on investment], I am not sure the other markets can sustain it.”

One issue biosimilars have is the lack of recognition of the value that they bring.

“That biosimilars offer the same clinical outcomes at a lower price is yet to be a recognized value,” she said. “To me that’s a really surprising situation in the United States.”

Ms. Woollett continued: “It’s not even acknowledged as a basic truth in the United States, which again suggests the business model may not be there for biosimilars.”

Ms. Woollett disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to her presentation.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – If the United States does not step up and create a thriving biosimilars market soon, it risks destroying the market not only domestically but internationally as well.

This was the warning Gillian Woollett, senior vice president at Avalere, provided to attendees at the annual meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy.

She prefaced her warning by quoting Alex Azar, secretary of Health & Human Services, who said that those “trying to hold back biosimilars are simply on the wrong side of history,” though Ms. Woollett said they “may be on the right side of the current economic model in the United States.”

And despite the probusiness, procompetition philosophy of current HHS leadership, there has been very little movement on creating a competitive market for biosimilars in the United States, evidenced by the very expensive regulatory requirements that biosimilar manufacturers need to meet in order to get products to market.

“It’s not that we won’t have competition in the U.S.,” she said. “I think we will. We do have that innovation. ... It’s just that biosimilars may not ultimately be part of that competition. And for that, we will pay a price, and I actually think the whole world will pay a price because if we are not providing the [return on investment], I am not sure the other markets can sustain it.”

One issue biosimilars have is the lack of recognition of the value that they bring.

“That biosimilars offer the same clinical outcomes at a lower price is yet to be a recognized value,” she said. “To me that’s a really surprising situation in the United States.”

Ms. Woollett continued: “It’s not even acknowledged as a basic truth in the United States, which again suggests the business model may not be there for biosimilars.”

Ms. Woollett disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to her presentation.

REPORTING FROM AMCP NEXUS 2019

Premiums down slightly for 2020 plans on HealthCare.gov

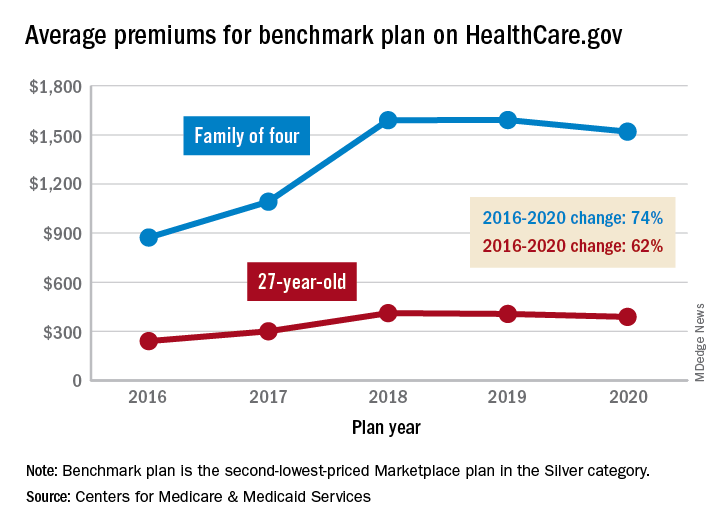

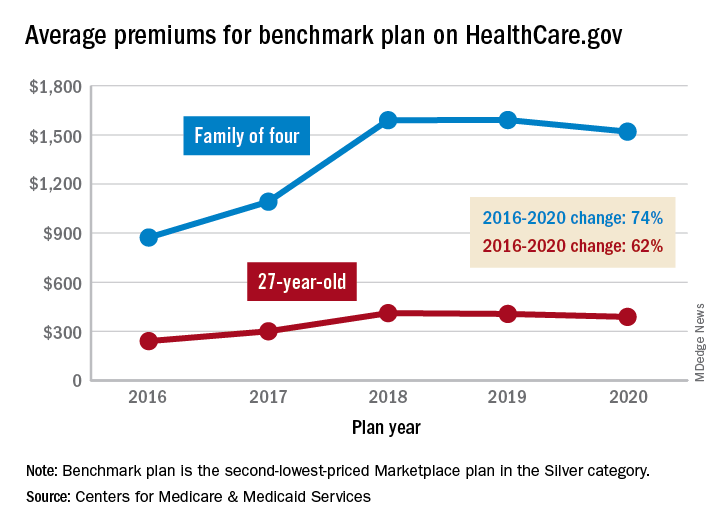

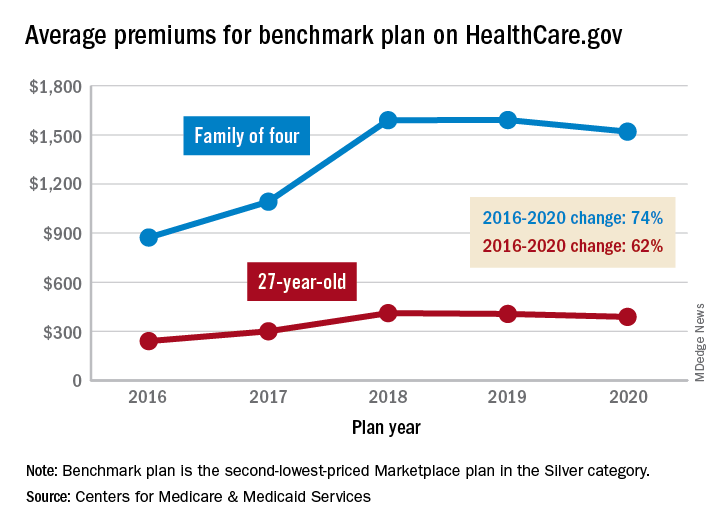

The average family of four will see a 4% drop in its premium for a benchmark plan on the HealthCare.gov Marketplace in 2020, compared with 2019, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

That family’s $1,520 premium for coverage next year will, however, be 74% higher than the average of $873 for the same plan in 2016. The situation is similar for a single person with a benchmark plan – defined as the second-lowest-priced Marketplace health insurance plan in the Silver category. The average premium for a 27-year-old, $388, for coverage in 2020 also will be 4% lower than in 2019, but that’s still 62% higher than in 2016, CMS said in a recent report.

The 4% average reductions for 2020 follow a 1% decrease for a 27-year-old on the benchmark plan and a $1 increase for a family of four between 2018 and 2019. “We have been committed to taking every step possible to lower premiums and provide more choices. A second year of declining premiums and expanding choice is proof that our actions to promote more stability are working. But premiums are still too high for people without subsidies,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a statement.

Consumers looking for health care coverage on 1 of the 38 state exchanges during the upcoming open enrollment period (Nov. 1 to Dec. 15) also will have more choices. The average number of qualified health plans available to enrollees will be 37.9 for the 2020 plan year, compared with 25.9 for 2019 and 24.8 in 2018. The number of companies issuing those plans also rose for the second consecutive year, going from 132 for the 2018 plan year to 155 in 2019 and 175 in 2020, CMS reported.

The average family of four will see a 4% drop in its premium for a benchmark plan on the HealthCare.gov Marketplace in 2020, compared with 2019, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

That family’s $1,520 premium for coverage next year will, however, be 74% higher than the average of $873 for the same plan in 2016. The situation is similar for a single person with a benchmark plan – defined as the second-lowest-priced Marketplace health insurance plan in the Silver category. The average premium for a 27-year-old, $388, for coverage in 2020 also will be 4% lower than in 2019, but that’s still 62% higher than in 2016, CMS said in a recent report.

The 4% average reductions for 2020 follow a 1% decrease for a 27-year-old on the benchmark plan and a $1 increase for a family of four between 2018 and 2019. “We have been committed to taking every step possible to lower premiums and provide more choices. A second year of declining premiums and expanding choice is proof that our actions to promote more stability are working. But premiums are still too high for people without subsidies,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a statement.

Consumers looking for health care coverage on 1 of the 38 state exchanges during the upcoming open enrollment period (Nov. 1 to Dec. 15) also will have more choices. The average number of qualified health plans available to enrollees will be 37.9 for the 2020 plan year, compared with 25.9 for 2019 and 24.8 in 2018. The number of companies issuing those plans also rose for the second consecutive year, going from 132 for the 2018 plan year to 155 in 2019 and 175 in 2020, CMS reported.

The average family of four will see a 4% drop in its premium for a benchmark plan on the HealthCare.gov Marketplace in 2020, compared with 2019, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

That family’s $1,520 premium for coverage next year will, however, be 74% higher than the average of $873 for the same plan in 2016. The situation is similar for a single person with a benchmark plan – defined as the second-lowest-priced Marketplace health insurance plan in the Silver category. The average premium for a 27-year-old, $388, for coverage in 2020 also will be 4% lower than in 2019, but that’s still 62% higher than in 2016, CMS said in a recent report.

The 4% average reductions for 2020 follow a 1% decrease for a 27-year-old on the benchmark plan and a $1 increase for a family of four between 2018 and 2019. “We have been committed to taking every step possible to lower premiums and provide more choices. A second year of declining premiums and expanding choice is proof that our actions to promote more stability are working. But premiums are still too high for people without subsidies,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a statement.

Consumers looking for health care coverage on 1 of the 38 state exchanges during the upcoming open enrollment period (Nov. 1 to Dec. 15) also will have more choices. The average number of qualified health plans available to enrollees will be 37.9 for the 2020 plan year, compared with 25.9 for 2019 and 24.8 in 2018. The number of companies issuing those plans also rose for the second consecutive year, going from 132 for the 2018 plan year to 155 in 2019 and 175 in 2020, CMS reported.

Telemedicine migraine consults effective for management

Key clinical point: Follow-up consultations with migraine patients via telemedicine are effective and can increase physician productivity and patient convenience.

Major finding: Migraine disability assessment improved by an average of 24 points in the telemedicine patients and by 19 points in the control group.

Study details: A single-center, randomized study with 40 migraine patients.

Disclosures: The study received partial funding from Merck.

Citation: Friedman DI. Headache. 2019 June;59(S1):1-208, LBOR01

Key clinical point: Follow-up consultations with migraine patients via telemedicine are effective and can increase physician productivity and patient convenience.

Major finding: Migraine disability assessment improved by an average of 24 points in the telemedicine patients and by 19 points in the control group.

Study details: A single-center, randomized study with 40 migraine patients.

Disclosures: The study received partial funding from Merck.

Citation: Friedman DI. Headache. 2019 June;59(S1):1-208, LBOR01

Key clinical point: Follow-up consultations with migraine patients via telemedicine are effective and can increase physician productivity and patient convenience.

Major finding: Migraine disability assessment improved by an average of 24 points in the telemedicine patients and by 19 points in the control group.

Study details: A single-center, randomized study with 40 migraine patients.

Disclosures: The study received partial funding from Merck.

Citation: Friedman DI. Headache. 2019 June;59(S1):1-208, LBOR01

Vestibular migraine: New study may help in diagnosis

Key clinical point: Loudness discomfort levels and temporal auditory processing may help diagnosis patients with vestibular migraine (VM).

Major finding: VM patients experienced response latencies with longer frequencies and a lower noise tolerance, compared with patients without migraine. The statistically significant findings showed that “the frequency following response latencies were significantly longer in the patients with vestibular migraine than in the control group, suggesting altered pure tone temporal processing, which may also affect the processing of complex sounds,” noted the investigators. “The lower discomfort thresholds suggest the presence of mild hyperacusis, in concordance with other previous studies.”

Study details: Fifty-four women were split up into two groups: 29 women with VM and 25 healthy women without migraine.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Citation: Takeuti AA, et al. BMC Neurol. 2019 Jun 27;19(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1368-5.

Key clinical point: Loudness discomfort levels and temporal auditory processing may help diagnosis patients with vestibular migraine (VM).

Major finding: VM patients experienced response latencies with longer frequencies and a lower noise tolerance, compared with patients without migraine. The statistically significant findings showed that “the frequency following response latencies were significantly longer in the patients with vestibular migraine than in the control group, suggesting altered pure tone temporal processing, which may also affect the processing of complex sounds,” noted the investigators. “The lower discomfort thresholds suggest the presence of mild hyperacusis, in concordance with other previous studies.”

Study details: Fifty-four women were split up into two groups: 29 women with VM and 25 healthy women without migraine.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Citation: Takeuti AA, et al. BMC Neurol. 2019 Jun 27;19(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1368-5.

Key clinical point: Loudness discomfort levels and temporal auditory processing may help diagnosis patients with vestibular migraine (VM).

Major finding: VM patients experienced response latencies with longer frequencies and a lower noise tolerance, compared with patients without migraine. The statistically significant findings showed that “the frequency following response latencies were significantly longer in the patients with vestibular migraine than in the control group, suggesting altered pure tone temporal processing, which may also affect the processing of complex sounds,” noted the investigators. “The lower discomfort thresholds suggest the presence of mild hyperacusis, in concordance with other previous studies.”

Study details: Fifty-four women were split up into two groups: 29 women with VM and 25 healthy women without migraine.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Citation: Takeuti AA, et al. BMC Neurol. 2019 Jun 27;19(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1368-5.

Economic burden of cycling through migraine preventive medications

Key clinical point: Patients that cycle through migraine preventive medications have a higher economic burden.

Major finding: Migraine patients cycling through more than two preventive migraine medications (PMMs) had an increased financial burden, compared with patients that received their initial medication class. “Mean all-cause total direct costs, including prescription costs, were significantly higher in PMM2 ($13,429) and PMM3 ($18,394) subgroups versus the persistent subgroup ($11,941),” noted the investigators

Study details: This was a retrospective observational study of 55,402 adult patients with migraine beginning their first PMM: antidepressants, antiepileptics, beta blockers, or neurotoxins. Patients had to have continuous medical and prescription enrollment for 12 months to be included in the study.

Disclosures: Eli Lilly and Company funded and designed the study. All study investigators reported being employees and stockholders of Eli Lily and Company.

Citation: Ford JH, et al. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019 Jan;25(1):46-59. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2018.18058.

Key clinical point: Patients that cycle through migraine preventive medications have a higher economic burden.

Major finding: Migraine patients cycling through more than two preventive migraine medications (PMMs) had an increased financial burden, compared with patients that received their initial medication class. “Mean all-cause total direct costs, including prescription costs, were significantly higher in PMM2 ($13,429) and PMM3 ($18,394) subgroups versus the persistent subgroup ($11,941),” noted the investigators

Study details: This was a retrospective observational study of 55,402 adult patients with migraine beginning their first PMM: antidepressants, antiepileptics, beta blockers, or neurotoxins. Patients had to have continuous medical and prescription enrollment for 12 months to be included in the study.

Disclosures: Eli Lilly and Company funded and designed the study. All study investigators reported being employees and stockholders of Eli Lily and Company.

Citation: Ford JH, et al. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019 Jan;25(1):46-59. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2018.18058.

Key clinical point: Patients that cycle through migraine preventive medications have a higher economic burden.

Major finding: Migraine patients cycling through more than two preventive migraine medications (PMMs) had an increased financial burden, compared with patients that received their initial medication class. “Mean all-cause total direct costs, including prescription costs, were significantly higher in PMM2 ($13,429) and PMM3 ($18,394) subgroups versus the persistent subgroup ($11,941),” noted the investigators

Study details: This was a retrospective observational study of 55,402 adult patients with migraine beginning their first PMM: antidepressants, antiepileptics, beta blockers, or neurotoxins. Patients had to have continuous medical and prescription enrollment for 12 months to be included in the study.

Disclosures: Eli Lilly and Company funded and designed the study. All study investigators reported being employees and stockholders of Eli Lily and Company.

Citation: Ford JH, et al. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019 Jan;25(1):46-59. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2018.18058.

COGS update shows viability of endophenotypes in schizophrenia research

Lead author Tiffany A. Greenwood, PhD, noted that clinically diverse schizophrenia patients often are grouped together to get large sample sizes for genome-wide association studies, which can miss specific features of the heterogeneous disorder. Instead, in phase 2 of the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia (COGS) study, Dr. Greenwood and associates sought to connect features clustered into endophenotypes with certain genetic regions of interest.

“As stable biomarkers of the underlying brain dysfunctions, endophenotypes hold promise for parsing clinical heterogeneity of schizophrenia and refining the genetic signal,” they wrote. The study was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Using this approach among 1,533 participants, they found seven regions exceeding the conventional genome-wide association significance of P less than 5 x 10–8, including regions associated with the endophenotypes of face memory (chromosome 3p21; effect size, –0.72; P = 4.2 x 10–8), antisaccade task (chromosome 9q31; effect size, –0.24; P = 3.5 x 10–8), and abstraction and mental flexibility (chromosome 10q23; effect size, –0.56; P = 1.5 x 10–8).

Those endophenotypes and genes intersect theoretical molecular and biological processes that have been identified in other research and could explain underlying mechanisms of schizophrenia. For example, research has suggested that NRG3, which is near the region associated with abstraction and mental flexibility, and affects certain cellular signaling pathways, could be a locus of susceptibility; in particular, some variants of NRG3 have been associated with cognitive and psychotic symptom severity in previous research.

“Although shared genetic substrates appear likely, this is not a study of schizophrenia but rather a study of neurophysiological and neurocognitive deficits that occur in the general population but are more pronounced in the context of schizophrenia and have implications for treatment,” wrote Dr. Greenwood, of the University of California, San Diego, and associates.

One limitation of the study is that, as investigators have demonstrated elsewhere, P values can prove highly variable over the course of replication studies, so the significance thresholds shown in this study still could run the risk of hiding false positives or negatives.

“As many of the 11 endophenotypes have been endorsed as targets for the development of novel treatments for schizophrenia, a better understanding of the corresponding cellular and molecular processes may pave the way for precision-based medicine in schizophrenia and perhaps other psychiatric illnesses with a shared genetic liability,” Dr. Greenwood and associates concluded.

SOURCE: Greenwood TA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2850.

Lead author Tiffany A. Greenwood, PhD, noted that clinically diverse schizophrenia patients often are grouped together to get large sample sizes for genome-wide association studies, which can miss specific features of the heterogeneous disorder. Instead, in phase 2 of the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia (COGS) study, Dr. Greenwood and associates sought to connect features clustered into endophenotypes with certain genetic regions of interest.

“As stable biomarkers of the underlying brain dysfunctions, endophenotypes hold promise for parsing clinical heterogeneity of schizophrenia and refining the genetic signal,” they wrote. The study was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Using this approach among 1,533 participants, they found seven regions exceeding the conventional genome-wide association significance of P less than 5 x 10–8, including regions associated with the endophenotypes of face memory (chromosome 3p21; effect size, –0.72; P = 4.2 x 10–8), antisaccade task (chromosome 9q31; effect size, –0.24; P = 3.5 x 10–8), and abstraction and mental flexibility (chromosome 10q23; effect size, –0.56; P = 1.5 x 10–8).

Those endophenotypes and genes intersect theoretical molecular and biological processes that have been identified in other research and could explain underlying mechanisms of schizophrenia. For example, research has suggested that NRG3, which is near the region associated with abstraction and mental flexibility, and affects certain cellular signaling pathways, could be a locus of susceptibility; in particular, some variants of NRG3 have been associated with cognitive and psychotic symptom severity in previous research.

“Although shared genetic substrates appear likely, this is not a study of schizophrenia but rather a study of neurophysiological and neurocognitive deficits that occur in the general population but are more pronounced in the context of schizophrenia and have implications for treatment,” wrote Dr. Greenwood, of the University of California, San Diego, and associates.

One limitation of the study is that, as investigators have demonstrated elsewhere, P values can prove highly variable over the course of replication studies, so the significance thresholds shown in this study still could run the risk of hiding false positives or negatives.

“As many of the 11 endophenotypes have been endorsed as targets for the development of novel treatments for schizophrenia, a better understanding of the corresponding cellular and molecular processes may pave the way for precision-based medicine in schizophrenia and perhaps other psychiatric illnesses with a shared genetic liability,” Dr. Greenwood and associates concluded.

SOURCE: Greenwood TA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2850.

Lead author Tiffany A. Greenwood, PhD, noted that clinically diverse schizophrenia patients often are grouped together to get large sample sizes for genome-wide association studies, which can miss specific features of the heterogeneous disorder. Instead, in phase 2 of the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia (COGS) study, Dr. Greenwood and associates sought to connect features clustered into endophenotypes with certain genetic regions of interest.

“As stable biomarkers of the underlying brain dysfunctions, endophenotypes hold promise for parsing clinical heterogeneity of schizophrenia and refining the genetic signal,” they wrote. The study was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Using this approach among 1,533 participants, they found seven regions exceeding the conventional genome-wide association significance of P less than 5 x 10–8, including regions associated with the endophenotypes of face memory (chromosome 3p21; effect size, –0.72; P = 4.2 x 10–8), antisaccade task (chromosome 9q31; effect size, –0.24; P = 3.5 x 10–8), and abstraction and mental flexibility (chromosome 10q23; effect size, –0.56; P = 1.5 x 10–8).

Those endophenotypes and genes intersect theoretical molecular and biological processes that have been identified in other research and could explain underlying mechanisms of schizophrenia. For example, research has suggested that NRG3, which is near the region associated with abstraction and mental flexibility, and affects certain cellular signaling pathways, could be a locus of susceptibility; in particular, some variants of NRG3 have been associated with cognitive and psychotic symptom severity in previous research.

“Although shared genetic substrates appear likely, this is not a study of schizophrenia but rather a study of neurophysiological and neurocognitive deficits that occur in the general population but are more pronounced in the context of schizophrenia and have implications for treatment,” wrote Dr. Greenwood, of the University of California, San Diego, and associates.

One limitation of the study is that, as investigators have demonstrated elsewhere, P values can prove highly variable over the course of replication studies, so the significance thresholds shown in this study still could run the risk of hiding false positives or negatives.

“As many of the 11 endophenotypes have been endorsed as targets for the development of novel treatments for schizophrenia, a better understanding of the corresponding cellular and molecular processes may pave the way for precision-based medicine in schizophrenia and perhaps other psychiatric illnesses with a shared genetic liability,” Dr. Greenwood and associates concluded.

SOURCE: Greenwood TA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2850.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

‘How did I get cancer?’

We are 20 minutes into the visit. My patient is 77 years old, a retired school administrator. She was sent to the oncology clinic for a new diagnosis of lung cancer with metastases to the liver and bones.

I was asking my usual questions – how did this all begin? – and I was hearing the usual answers. The cough that didn’t get better with antibiotics. The unintentional weight loss. The chest x-ray that looked “fuzzy.”

I continue: How many packs of cigarettes a day, and for how many years? Any family history of cancer?

These were my standard questions. They were met by hers: “How did I get this?”

I recently hosted a podcast on common, difficult questions we hear in hematology and oncology. How long do I have to live? What would you do if this were your family member?

This was another. There are variations to be sure. How, why, why me, what did I do, what didn’t I do, did my doctor miss it, if I had this or that test would they have caught it sooner?

When I was an internist, I talked about prevention. Meeting a new patient meant sizing them up for risk factors. In their habits I saw opportunities for healthier choices. In their family histories I gathered warning signs.

Now, I ask the same probing questions, but the purpose is not the same. Smoking, alcohol, family history, I ask these of everyone, I reassure them. It’s no longer about assessing risk. It’s not to place blame. But they read into the fact that I am asking, because they have asked themselves the same.

They ask why.

I try not to overdo the pity. I say that I’m sorry this is happening, but I don’t dwell. What I want to convey is the opposite – it’s normalcy. What I want to convey is: I’ve seen this a million times. This is where we are, and here is where we go. We don’t dwell or regret or wonder what if. My patients don’t want sympathy – at least, not from their doctor. They want a plan.

They ask: How did I get this?

It’s bad luck, I say. It’s a genetic mutation causing a cell to replicate.

My answers do not always satisfy their questions. Because it’s not a question seeking an informational answer. The truth is, medically and existentially, I don’t know. None of us do. The question is an existential itch no medical jargon can scratch.

I have a modern Hippocratic oath tacked to a wall in my room. “I will prevent disease whenever I can, because prevention is preferable to cure,” it says. True, but that offers little solace to those who already have the illness. Yes, we need prevention. And we need a path forward when tragedy has already struck.

I am humbled when I meet a new cancer patient because the visit is a metaphor for a nonjudgmental life. There’s something beautiful about meeting someone exactly where they are, where decisions made in the past are as irrelevant to me now as they were to the cancer.

When they inevitably ask “how did I get this?” and I answer, what I’m really saying is this: I don’t care what you did, or didn’t do, or how we got here. But we are here, and so I am here with you, and from now on the only place we care about is here and now, the only direction forward.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz and listen to her each week on the Blood & Cancer podcast.

We are 20 minutes into the visit. My patient is 77 years old, a retired school administrator. She was sent to the oncology clinic for a new diagnosis of lung cancer with metastases to the liver and bones.

I was asking my usual questions – how did this all begin? – and I was hearing the usual answers. The cough that didn’t get better with antibiotics. The unintentional weight loss. The chest x-ray that looked “fuzzy.”

I continue: How many packs of cigarettes a day, and for how many years? Any family history of cancer?

These were my standard questions. They were met by hers: “How did I get this?”

I recently hosted a podcast on common, difficult questions we hear in hematology and oncology. How long do I have to live? What would you do if this were your family member?

This was another. There are variations to be sure. How, why, why me, what did I do, what didn’t I do, did my doctor miss it, if I had this or that test would they have caught it sooner?

When I was an internist, I talked about prevention. Meeting a new patient meant sizing them up for risk factors. In their habits I saw opportunities for healthier choices. In their family histories I gathered warning signs.

Now, I ask the same probing questions, but the purpose is not the same. Smoking, alcohol, family history, I ask these of everyone, I reassure them. It’s no longer about assessing risk. It’s not to place blame. But they read into the fact that I am asking, because they have asked themselves the same.

They ask why.

I try not to overdo the pity. I say that I’m sorry this is happening, but I don’t dwell. What I want to convey is the opposite – it’s normalcy. What I want to convey is: I’ve seen this a million times. This is where we are, and here is where we go. We don’t dwell or regret or wonder what if. My patients don’t want sympathy – at least, not from their doctor. They want a plan.

They ask: How did I get this?

It’s bad luck, I say. It’s a genetic mutation causing a cell to replicate.

My answers do not always satisfy their questions. Because it’s not a question seeking an informational answer. The truth is, medically and existentially, I don’t know. None of us do. The question is an existential itch no medical jargon can scratch.

I have a modern Hippocratic oath tacked to a wall in my room. “I will prevent disease whenever I can, because prevention is preferable to cure,” it says. True, but that offers little solace to those who already have the illness. Yes, we need prevention. And we need a path forward when tragedy has already struck.

I am humbled when I meet a new cancer patient because the visit is a metaphor for a nonjudgmental life. There’s something beautiful about meeting someone exactly where they are, where decisions made in the past are as irrelevant to me now as they were to the cancer.

When they inevitably ask “how did I get this?” and I answer, what I’m really saying is this: I don’t care what you did, or didn’t do, or how we got here. But we are here, and so I am here with you, and from now on the only place we care about is here and now, the only direction forward.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz and listen to her each week on the Blood & Cancer podcast.

We are 20 minutes into the visit. My patient is 77 years old, a retired school administrator. She was sent to the oncology clinic for a new diagnosis of lung cancer with metastases to the liver and bones.

I was asking my usual questions – how did this all begin? – and I was hearing the usual answers. The cough that didn’t get better with antibiotics. The unintentional weight loss. The chest x-ray that looked “fuzzy.”

I continue: How many packs of cigarettes a day, and for how many years? Any family history of cancer?

These were my standard questions. They were met by hers: “How did I get this?”

I recently hosted a podcast on common, difficult questions we hear in hematology and oncology. How long do I have to live? What would you do if this were your family member?

This was another. There are variations to be sure. How, why, why me, what did I do, what didn’t I do, did my doctor miss it, if I had this or that test would they have caught it sooner?

When I was an internist, I talked about prevention. Meeting a new patient meant sizing them up for risk factors. In their habits I saw opportunities for healthier choices. In their family histories I gathered warning signs.

Now, I ask the same probing questions, but the purpose is not the same. Smoking, alcohol, family history, I ask these of everyone, I reassure them. It’s no longer about assessing risk. It’s not to place blame. But they read into the fact that I am asking, because they have asked themselves the same.

They ask why.

I try not to overdo the pity. I say that I’m sorry this is happening, but I don’t dwell. What I want to convey is the opposite – it’s normalcy. What I want to convey is: I’ve seen this a million times. This is where we are, and here is where we go. We don’t dwell or regret or wonder what if. My patients don’t want sympathy – at least, not from their doctor. They want a plan.

They ask: How did I get this?

It’s bad luck, I say. It’s a genetic mutation causing a cell to replicate.

My answers do not always satisfy their questions. Because it’s not a question seeking an informational answer. The truth is, medically and existentially, I don’t know. None of us do. The question is an existential itch no medical jargon can scratch.

I have a modern Hippocratic oath tacked to a wall in my room. “I will prevent disease whenever I can, because prevention is preferable to cure,” it says. True, but that offers little solace to those who already have the illness. Yes, we need prevention. And we need a path forward when tragedy has already struck.

I am humbled when I meet a new cancer patient because the visit is a metaphor for a nonjudgmental life. There’s something beautiful about meeting someone exactly where they are, where decisions made in the past are as irrelevant to me now as they were to the cancer.

When they inevitably ask “how did I get this?” and I answer, what I’m really saying is this: I don’t care what you did, or didn’t do, or how we got here. But we are here, and so I am here with you, and from now on the only place we care about is here and now, the only direction forward.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz and listen to her each week on the Blood & Cancer podcast.

STI update: Testing, treatment, and emerging threats

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are still increasing in incidence and probably will continue to do so in the near future. Moreover, drug-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae are emerging, as are less-known organisms such as Mycoplasma genitalium.

Now the good news: new tests for STIs are available or are coming! Based on nucleic acid amplification, these tests can be performed at the point of care, so that patients can leave the clinic with an accurate diagnosis and proper treatment for themselves and their sexual partners. Also, the tests can be run on samples collected by the patients themselves, either swabs or urine collections, eliminating the need for invasive sampling and making doctor-shy patients more likely to come in to be treated.1 We hope that by using these sensitive and accurate tests we can begin to bend the upward curve of STIs and be better antimicrobial stewards.2

This article reviews current issues surrounding STI control, and provides detailed guidance on recognizing, testing for, and treating gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and M genitalium infection.

STI RATES ARE HIGH AND RISING

STIs are among the most common acute infectious diseases worldwide, with an estimated 1 million new curable cases every day.3 Further, STIs have major impacts on sexual, reproductive, and psychological health.

In the United States, rates of reportable STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis) are rising.4 In addition, more-sensitive tests for trichomoniasis, which is not a reportable infection in any state, have revealed it to be more prevalent than previously thought.5

BARRIERS AND CHALLENGES TO DIAGNOSIS

The medical system does not fully meet the needs of some populations, including young people and men who have sex with men, regarding their sexual and reproductive health.

Ongoing barriers among young people include reluctance to use available health services, limited access to STI testing, worries about confidentiality, and the shame and stigma associated with STIs.6

Men who have sex with men have a higher incidence of STIs than other groups. Since STIs are associated with a higher risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, it is important to detect, diagnose, and manage STIs in this group—and in all high-risk groups. Rectal STIs are an independent risk factor for incident HIV infection.7 In addition, many men who have sex with men face challenges navigating the emotional, physical, and cognitive aspects of adolescence, a voyage further complicated by mental health issues, unprotected sexual encounters, and substance abuse in many, especially among minority youth.8 These same factors also impair their ability to access resources for preventing and treating HIV and other STIs.

STI diagnosis is often missed

Most people who have STIs feel no symptoms, which increases the importance of risk-based screening to detect these infections.9,10 In many other cases, STIs manifest with nonspecific genitourinary symptoms that are mistaken for urinary tract infection. Tomas et al11 found that of 264 women who presented to an emergency department with genitourinary symptoms or were being treated for urinary tract infection, 175 were given a diagnosis of a urinary tract infection. Of these, 100 (57%) were treated without performing a urine culture; 60 (23%) of the 264 women had 1 or more positive STI tests, 22 (37%) of whom did not receive treatment for an STI.

Poor follow-up of patients and partners

Patients with STIs need to be retested 3 months after treatment to make sure the treatment was effective. Another reason for follow-up is that these patients are at higher risk of another infection within a year.12

Although treating patients’ partners has been shown to reduce reinfection rates, fewer than one-third of STIs (including HIV infections) were recognized through partner notification between 2010 and 2012 in a Dutch study, in men who have sex with men and in women.13 Challenges included partners who could not be identified among men who have sex with men, failure of heterosexual men to notify their partners, and lower rates of partner notification for HIV.

In the United States, “expedited partner therapy” allows healthcare providers to provide a prescription or medications to partners of patients diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea without examining the partner.14 While this approach is legal in most states, implementation can be challenging.15

STI EVALUATION

History and physical examination

A complete sexual history helps in estimating the patient’s risk of an STI and applying appropriate risk-based screening. Factors such as sexual practices, use of barrier protection, and history of STIs should be discussed.

Physical examination is also important. Although some patients may experience discomfort during a genital or pelvic examination, omitting this step may lead to missed diagnoses in women with STIs.16

Laboratory testing

Laboratory testing for STIs helps ensure accurate diagnosis and treatment. Empiric treatment without testing could give a patient a false sense of health by missing an infection that is not currently causing symptoms but that could later worsen or have lasting complications. Failure to test patients also misses the opportunity for partner notification, linkage to services, and follow-up testing.

Many of the most common STIs, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis, can be detected using vaginal, cervical, or urethral swabs or first-catch urine (from the initial urine stream). In studies that compared various sampling methods,17 self-collected urine samples for gonorrhea in men were nearly as good as clinician-collected swabs of the urethra. In women, self-collected vaginal swabs for gonorrhea and chlamydia were nearly as good as clinician-collected vaginal swabs. While urine specimens are acceptable for chlamydia testing in women, their sensitivity may be slightly lower than with vaginal and endocervical swab specimens.18,19

A major advantage of urine specimens for STI testing is that collection is noninvasive and is therefore more likely to be acceptable to patients. Urine testing can also be conducted in a variety of nonclinical settings such as health fairs, pharmacy-based screening programs, and express STI testing sites, thus increasing availability.

To prevent further transmission and morbidity and to aid in public health efforts, it is critical to recognize the cause of infectious cervicitis and urethritis and to screen for STIs according to guidelines.12 Table 1 summarizes current screening and laboratory testing recommendations.

GONORRHEA AND CHLAMYDIA

Gonorrhea and chlamydia are the 2 most frequently reported STIs in the United States, with more than 550,000 cases of gonorrhea and 1.7 million cases of chlamydia reported in 2017.4

Both infections present similarly: cervicitis or urethritis characterized by discharge (mucopurulent discharge with gonorrhea) and dysuria. Untreated, they can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, inflammation, and infertility.

Extragenital infections can be asymptomatic or cause exudative pharyngitis or proctitis. Most people in whom chlamydia is detected from pharyngeal specimens are asymptomatic. When pharyngeal symptoms exist secondary to gonorrheal infection, they typically include sore throat and pharyngeal exudates. However, Komaroff et al,20 in a study of 192 men and women who presented with sore throat, found that only 2 (1%) tested positive for N gonorrhoeae.

Screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia

Best practices include screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia as follows21–23:

- Every year in sexually active women through age 25 (including during pregnancy) and in older women who have risk factors for infection12

- At least every year in men who have sex with men, at all sites of sexual contact (urethra, pharynx, rectum), along with testing for HIV and syphilis

- Every 3 to 6 months in men who have sex with men who have multiple or anonymous partners, who are sexually active and use illicit drugs, or who have partners who use illicit drugs

- Possibly every year in young men who live in high-prevalence areas or who are seen in certain clinical settings, such as STI and adolescent clinics.

Specimens. A vaginal swab is preferred for screening in women. Several studies have shown that self-collected swabs have clinical sensitivity and specificity comparable to that of provider-collected samples.17,24 First-catch urine or endocervical swabs have similar performance characteristics and are also acceptable. In men, urethral swabs or first-catch urine samples are appropriate for screening for urogenital infections.

Testing methods. Testing for both pathogens should be done simultaneously with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). Commercially available NAATs are more sensitive than culture and antigen testing for detecting gonorrhea and chlamydia.25–27

Most assays are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for testing vaginal, urethral, cervical, and urine specimens. Until recently, no commercial assay was cleared for testing extragenital sites, but recommendations for screening extragenital sites prompted many clinical laboratories to validate throat and rectal swabs for use with NAATs, which are more sensitive than culture at these sites.25,28 The recent FDA approval of extragenital specimen types for 2 commercially available assays may increase the availability of testing for these sites.

Data on the utility of NAATs for detecting chlamydia and gonorrhea in children are limited, and many clinical laboratories have not validated molecular methods for testing in children. Current guidelines specific to this population should be followed regarding test methods and preferred specimen types.12,29,30

Although gonococcal infection is usually diagnosed with culture-independent molecular methods, antimicrobial resistance is emerging. Thus, failure of the combination of ceftriaxone and azithromycin should prompt culture-based follow-up testing to determine antimicrobial susceptibility.

Strategies for treatment and control

Historically, people treated for gonorrhea have been treated for chlamydia at the same time, as these diseases tend to go together. This can be with a single intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone for the gonorrhea plus a single oral dose of azithromycin for the chlamydia.12 For patients who have only gonorrhea, this double regimen may help prevent the development of resistant gonorrhea strains.

All the patient’s sexual partners in the previous 60 days should be tested and treated, and expedited partner therapy should be offered if possible. Patients should be advised to have no sexual contact until they complete the treatment, or 7 days after single-dose treatment. Testing should be repeated 3 months after treatment.

M GENITALIUM IS EMERGING

A member of the Mycoplasmataceae family, M genitalium was originally identified as a pathogen in the early 1980s but has only recently emerged as an important cause of STI. Studies indicate that it is responsible for 10% to 20% of cases of nongonococcal urethritis and 10% to 30% of cases of cervicitis.31–33 Additionally, 2% to 22% of cases of pelvic inflammatory disease have evidence of M genitalium.34,35

However, data on M genitalium prevalence are suspect because the organism is hard to identify—lacking a cell wall, it is undetectable by Gram stain.36 Although it has been isolated in respiratory and synovial fluids, it has so far been recognized to be clinically important only in the urogenital tract. It can persist for years in infected patients by exploiting specialized cell-surface structures to invade cells.36 Once inside a cell, it triggers secretion of mycoplasmal toxins and destructive metabolites such as hydrogen peroxide, evading the host immune system as it does so.37

Testing guidelines for M genitalium

Current guidelines do not recommend routine screening for M genitalium, and no commercial test was available until recently.12 Although evidence suggests that M genitalium is independently associated with preterm birth and miscarriages,38 routine screening of pregnant women is not recommended.12

Testing for M genitalium should be considered in cases of persistent or recurrent nongonococcal urethritis in patients who test negative for gonorrhea and chlamydia or for whom treatment has failed.12 Many isolates exhibit genotypic resistance to macrolide antibiotics, which are often the first-line therapy for nongonococcal urethritis.39

Further study is needed to evaluate the potential impact of routine screening for M genitalium on the reproductive and sexual health of at-risk populations.

Diagnostic tests for M genitalium

Awareness of M genitalium as a cause of nongonococcal urethritis has been hampered by a dearth of diagnostic tests.40 The organism’s fastidious requirements and extremely slow growth preclude culture as a practical method of diagnosis.41 Serologic assays are dogged by cross-reactivity and poor sensitivity.42,43 Thus, molecular assays for detecting M genitalium and associated resistance markers are preferred for diagnosis.12

Several molecular tests are approved, available, and in use in Europe for diagnosing M genitalium infection,40 and in January 2019 the FDA approved a molecular test that can detect M genitalium in urine specimens and vaginal, endocervical, urethral, and penile meatal swabs. Although vaginal swabs are preferred for this assay because they have higher sensitivity (92% for provider-collected and 99% for patient-collected swabs), urine specimens are acceptable, with a sensitivity of 78%.44

At least 1 company is seeking FDA clearance for another molecular diagnostic assay for detecting M genitalium and markers of macrolide resistance in urine and genital swab specimens. Such assays may facilitate appropriate treatment.

Clinicians should stay abreast of diagnostic testing options, which are likely to become more readily available soon.

A high rate of macrolide resistance

Because M genitalium lacks a cell wall, antibiotics such as beta-lactams that target cell wall synthesis are ineffective.

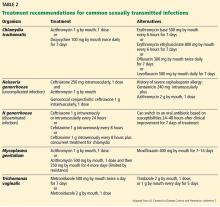

Regimens for treating M genitalium are outlined in Table 2.12 Azithromycin is more effective than doxycycline. However, as many as 50% of strains were macrolide-resistant in a cohort of US female patients.45 Given the high incidence of treatment failure with azithromycin 1 g, it is thought that this regimen might select for resistance. For cases in which symptoms persist, a 1- to 2-week course of moxifloxacin is recommended.12 However, this has not been validated by clinical trials, and failures of the 7-day regimen have been reported.46

Partners of patients who test positive for M genitalium should also be tested and undergo clinically applicable screening for nongonococcal urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.12

TRICHOMONIASIS

Trichomoniasis, caused by the parasite Trichomonas vaginalis, is the most prevalent nonviral STI in the United States. It disproportionately affects black women, in whom the prevalence is 13%, compared with 1% in non-Hispanic white women.47 It is also present in 26% of women with symptoms who are seen in STI clinics and is highly prevalent in incarcerated populations. It is uncommon in men who have sex with men.48

In men, trichomoniasis manifests as urethritis, epididymitis, or prostatitis. While most infected women have no symptoms, they may experience vaginitis with discharge that is diffuse, frothy, pruritic, malodorous, or yellow-green. Vaginal and cervical erythema (“strawberry cervix”) can also occur.

Screening for trichomoniasis

Current guidelines of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend testing for T vaginalis in women who have symptoms and routinely screening in women who are HIV-positive, regardless of symptoms. There is no evidence to support routine screening of pregnant women without symptoms, and pregnant women who do have symptoms should be evaluated according to the same guidelines as for nonpregnant women.12 Testing can be considered in patients who have no symptoms but who engage in high-risk behaviors and in areas of high prevalence.

A lack of studies using sensitive methods for T vaginalis detection has hampered a true estimation of disease burden and at-risk populations. Screening recommendations may evolve in upcoming clinical guidelines as the field advances.

As infection can recur, women should be retested 3 months after initial diagnosis.12

NAAT is the preferred test for trichomoniasis