User login

Investigators Use ARMSS Score to Predict Future MS-related Disability

Key clinical point: ARMSS-rate at 2 years accurately predicts disease course over the subsequent 8 years.

Major finding: ARMSS-rate at 2 years had an area under the curve of 0.921 for predicting the next 8 years of ARMSS-rate.

Study details: An analysis of data for 4,514 participants in the Swedish MS Registry.

Disclosures: Dr. Ramanujam had no conflicts of interest to disclose. He receives funding from the MultipleMS Project, which is part of the EU Horizon 2020 Framework.

Citation: Manouchehrinia A et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract 218.

Key clinical point: ARMSS-rate at 2 years accurately predicts disease course over the subsequent 8 years.

Major finding: ARMSS-rate at 2 years had an area under the curve of 0.921 for predicting the next 8 years of ARMSS-rate.

Study details: An analysis of data for 4,514 participants in the Swedish MS Registry.

Disclosures: Dr. Ramanujam had no conflicts of interest to disclose. He receives funding from the MultipleMS Project, which is part of the EU Horizon 2020 Framework.

Citation: Manouchehrinia A et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract 218.

Key clinical point: ARMSS-rate at 2 years accurately predicts disease course over the subsequent 8 years.

Major finding: ARMSS-rate at 2 years had an area under the curve of 0.921 for predicting the next 8 years of ARMSS-rate.

Study details: An analysis of data for 4,514 participants in the Swedish MS Registry.

Disclosures: Dr. Ramanujam had no conflicts of interest to disclose. He receives funding from the MultipleMS Project, which is part of the EU Horizon 2020 Framework.

Citation: Manouchehrinia A et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract 218.

Smoking Impairs Cognition and Shrinks Brain Volume in MS

Key clinical point: Patients with MS who quit smoking tobacco may experience improved cognitive function.

Major finding: Former smokers with MS scored an average of 3.6 points lower on the Processing Speed Test than never smokers, and current smokers scored 5.9 points lower.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 997 patients with MS who had cognitive function test scores and brain MRIs.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no relevant financial interests.

Citation: Alshehri E et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract P461.

Key clinical point: Patients with MS who quit smoking tobacco may experience improved cognitive function.

Major finding: Former smokers with MS scored an average of 3.6 points lower on the Processing Speed Test than never smokers, and current smokers scored 5.9 points lower.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 997 patients with MS who had cognitive function test scores and brain MRIs.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no relevant financial interests.

Citation: Alshehri E et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract P461.

Key clinical point: Patients with MS who quit smoking tobacco may experience improved cognitive function.

Major finding: Former smokers with MS scored an average of 3.6 points lower on the Processing Speed Test than never smokers, and current smokers scored 5.9 points lower.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 997 patients with MS who had cognitive function test scores and brain MRIs.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no relevant financial interests.

Citation: Alshehri E et al. ECTRIMS 2019. Abstract P461.

Adolescent Lung Inflammation May Trigger Later MS

Key clinical point: Inflammatory pulmonary events occurring at age 11-15 years may be a risk factor for subsequent multiple sclerosis.

Major finding: Swedes who experienced pneumonia at age 11-15 years had an adjusted 2.8-fold increased risk of MS later in life.

Study details: This Swedish national registry cohort study included 6,109 MS patients and 49,479 controls matched for age, gender, and locale.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research funding from F. Hoffmann–La Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca and serving on an advisory board for IQVIA.

Citation: Montgomery S. ECTRIMS 2019, Abstract 270.

Key clinical point: Inflammatory pulmonary events occurring at age 11-15 years may be a risk factor for subsequent multiple sclerosis.

Major finding: Swedes who experienced pneumonia at age 11-15 years had an adjusted 2.8-fold increased risk of MS later in life.

Study details: This Swedish national registry cohort study included 6,109 MS patients and 49,479 controls matched for age, gender, and locale.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research funding from F. Hoffmann–La Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca and serving on an advisory board for IQVIA.

Citation: Montgomery S. ECTRIMS 2019, Abstract 270.

Key clinical point: Inflammatory pulmonary events occurring at age 11-15 years may be a risk factor for subsequent multiple sclerosis.

Major finding: Swedes who experienced pneumonia at age 11-15 years had an adjusted 2.8-fold increased risk of MS later in life.

Study details: This Swedish national registry cohort study included 6,109 MS patients and 49,479 controls matched for age, gender, and locale.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research funding from F. Hoffmann–La Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca and serving on an advisory board for IQVIA.

Citation: Montgomery S. ECTRIMS 2019, Abstract 270.

EHR prompt significantly reduced telemetry monitoring during inpatient stays

Background: Prior studies have shown multifaceted interventions that include EHR prompts can reduce the utilization of telemetry monitoring, but it is unclear if EHR prompts alone can reduce utilization.

Study design: Cluster-randomized, control trial.

Setting: November 2016 and May 2017 at a tertiary care medical center on the general medicine service.

Synopsis: The authors designed an EHR prompt for patients ordered for telemetry. The prompt would request the team to either discontinue or continue telemetry. Half of the general medicine teams (representing 499 hospitalizations) were randomized to receive the intervention, and the other half of the general medicine teams (representing 567 hospitalizations) did not receive the intervention. In the intervention group, 62% of prompts were followed by a discontinuation of telemetry. This led to a 17% reduction in the mean hours of telemetry monitoring (50 hours in the control group and 41.3 hours in the intervention group; P = .001). There was no significant difference in the rate of rapid responses or medical emergencies between the two groups.

Bottom line: A targeted EHR prompt alone may lead to a reduction in the utilization of telemetry monitoring.

Citation: Najafi N et al. Assessment of a targeted electronic health record intervention to reduce telemetry duration: A cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Dec 10;179(1):11-5.

Dr. Biddick is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and instructor in medicine Harvard Medical School.

Background: Prior studies have shown multifaceted interventions that include EHR prompts can reduce the utilization of telemetry monitoring, but it is unclear if EHR prompts alone can reduce utilization.

Study design: Cluster-randomized, control trial.

Setting: November 2016 and May 2017 at a tertiary care medical center on the general medicine service.

Synopsis: The authors designed an EHR prompt for patients ordered for telemetry. The prompt would request the team to either discontinue or continue telemetry. Half of the general medicine teams (representing 499 hospitalizations) were randomized to receive the intervention, and the other half of the general medicine teams (representing 567 hospitalizations) did not receive the intervention. In the intervention group, 62% of prompts were followed by a discontinuation of telemetry. This led to a 17% reduction in the mean hours of telemetry monitoring (50 hours in the control group and 41.3 hours in the intervention group; P = .001). There was no significant difference in the rate of rapid responses or medical emergencies between the two groups.

Bottom line: A targeted EHR prompt alone may lead to a reduction in the utilization of telemetry monitoring.

Citation: Najafi N et al. Assessment of a targeted electronic health record intervention to reduce telemetry duration: A cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Dec 10;179(1):11-5.

Dr. Biddick is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and instructor in medicine Harvard Medical School.

Background: Prior studies have shown multifaceted interventions that include EHR prompts can reduce the utilization of telemetry monitoring, but it is unclear if EHR prompts alone can reduce utilization.

Study design: Cluster-randomized, control trial.

Setting: November 2016 and May 2017 at a tertiary care medical center on the general medicine service.

Synopsis: The authors designed an EHR prompt for patients ordered for telemetry. The prompt would request the team to either discontinue or continue telemetry. Half of the general medicine teams (representing 499 hospitalizations) were randomized to receive the intervention, and the other half of the general medicine teams (representing 567 hospitalizations) did not receive the intervention. In the intervention group, 62% of prompts were followed by a discontinuation of telemetry. This led to a 17% reduction in the mean hours of telemetry monitoring (50 hours in the control group and 41.3 hours in the intervention group; P = .001). There was no significant difference in the rate of rapid responses or medical emergencies between the two groups.

Bottom line: A targeted EHR prompt alone may lead to a reduction in the utilization of telemetry monitoring.

Citation: Najafi N et al. Assessment of a targeted electronic health record intervention to reduce telemetry duration: A cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Dec 10;179(1):11-5.

Dr. Biddick is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and instructor in medicine Harvard Medical School.

Pink Polycyclic Ulcerations on the Lower Back and Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

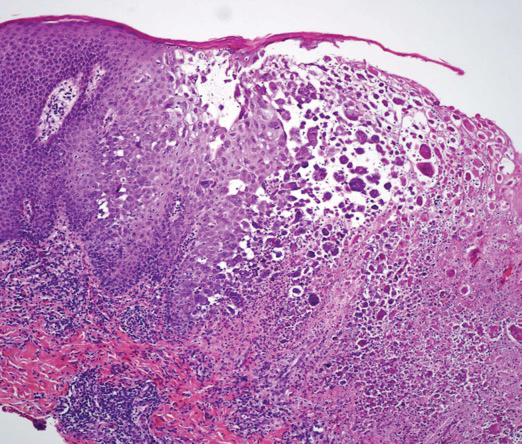

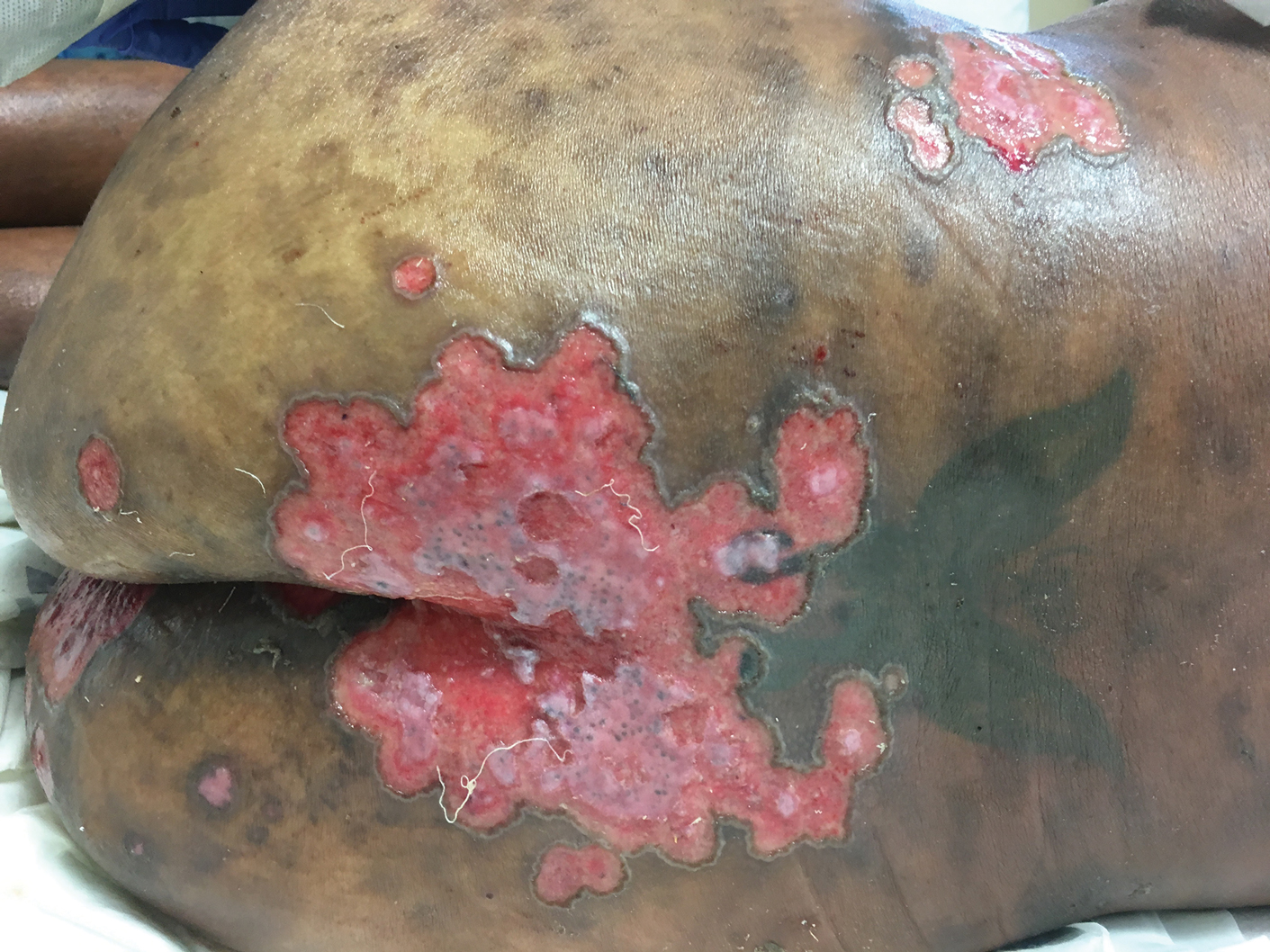

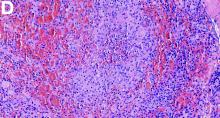

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

A 32-year-old woman with stage IV cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was admitted with pancytopenia and septic shock secondary to methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Dermatology was consulted regarding sacral ulcerations. The lesions were asymptomatic and had been slowly enlarging over the course of 1 month. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, pink, polycyclic ulcerations on the lower back and buttocks extending onto the perineum. There was no pain or tingling associated with the ulcerations. She denied a history of cold sore lesions on the lips or genitals. A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and histopathologic examination.

CBT and antidepressants have similar costs for major depressive disorder

according to a recent study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“In the absence of clear superiority of either treatment, shared decision making incorporating patient preferences is critical,” Eric L. Ross, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Ross and colleagues created a decision-analytic model for adults with major depressive disorder in the United States using age and gender data from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, and simulated a cohort consisting of 62.2% women with a mean age of 40.7 years. Patients underwent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or received a second-generation antidepressant (SGA) as first-line therapy, and the model calculated risks and benefits of each therapy as well as likelihood of remission and response using data from meta-analyses.

The researchers calculated the average quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) of both treatments at 1 years and 5 years. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was set at $100,000 or less per QALY for cost effectiveness, and the results were adjusted to 2014 U.S. dollars. Researchers also calculated the net monetary benefit of each treatment based on health and economic outcomes.

At 1 year, Dr. Ross and colleagues found quality-adjusted survival in patients who received CBT increased by 3 days (QALY, 0.008; 95% confidence interval, 0.013-0.025) compared with SGA, but there was a higher mean cost to the health care sector ($900; 95% CI, $500-$1,400) and to society ($1,500; 95% CI, $500-$2,500). CBT was not cost effective at 1 year, with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios in the health care sector of $119,000 per QALY and $186,000 per QALY to society, but the net monetary benefit confidence intervals in the health care sector ($2,400-$1,600) and in society ($3,400-$1,600) appear to show some cost effectiveness for CBT at 1 year, the researchers said.

Compared with SGA, there was an increase of 20 quality-adjusted life days in patients who received CBT at 5 years (QALY, 0.055; 95% CI, 0.044-0.160), and the cost for CBT treatment was reduced by $2,000. While CBT appeared to be cost saving in the base-case analysis, the researchers said there was some uncertainty in the cost effectiveness of CBT when they calculated the incremental net monetary benefit of CBT for the health care sector ($8,100-$21,700) and to society ($10,400-$25,300). In a sensitivity analysis, preference for SGA as a first-line therapy at 1 year was between 64% and 77%, while CBT became more preferred between 1.5 and 2 years, and had between a 73% and 87% preference range at 5 years.

In a related editorial, Mark Sinyor, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, said that although more longitudinal data are needed comparing outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder undergoing treatment with psychotherapy or medication, clinicians should act on what the current evidence shows about the effectiveness of CBT and SGA.

“It is increasingly evident that differences in effectiveness between CBT and SGAs are not substantial and that CBT has some advantages, including potentially lower long-term costs. These must be balanced with the advantages of SGAs, such as potentially more rapid action as well as efficacy across the full [major depressive disorder] severity spectrum,” he said.

Dr. Sinyor also called for CBT and SGA to be made available to all patients with major depressive disorder.

“Antidepressants for [major depressive disorder] are widely accessible in developed countries and that is important for our patients. If we are serious about providing evidence-based care, CBT must become equally available,” he said.

Neil Skolnik, MD, professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health, echoed the sentiment that CBT should be offered alongside antidepressants for treatment of major depressive disorder.

“CBT works as well or better than antidepressant medication, and since people learn skills that they can continue to use, it often has a long-lasting effect. In my experience, for people for whom CBT works – that is, for people who are seeing a therapist who use CBT as their technique and who are willing to put in the work it takes – CBT can be life changing,” he said in an interview. “So, I am not surprised, but I am happy to see the results of this study showing that CBT is cost effective.”

Dr. Skolnik emphasized that not every therapist offers CBT, so health care providers should be aware of the type of therapy they are referring their patients for and monitor that therapy when possible.

“We should talk to our patients, present them with options, and then decide together with our patients which approach is best for them,” Dr. Skolnik added. “Medications work, and for many this is a good choice. CBT works, and for many this is a good choice. For some patients, using both CBT and medications is the optimal choice. Both are about equally cost effective. We should discuss the options with our patients and decide the path forward together.”

This study was funded by grants from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development and the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Ross reported receiving a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. Two coauthors reported receiving grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Sinyor and Dr. Skolnik reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ross EL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M18-1480.

according to a recent study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“In the absence of clear superiority of either treatment, shared decision making incorporating patient preferences is critical,” Eric L. Ross, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Ross and colleagues created a decision-analytic model for adults with major depressive disorder in the United States using age and gender data from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, and simulated a cohort consisting of 62.2% women with a mean age of 40.7 years. Patients underwent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or received a second-generation antidepressant (SGA) as first-line therapy, and the model calculated risks and benefits of each therapy as well as likelihood of remission and response using data from meta-analyses.

The researchers calculated the average quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) of both treatments at 1 years and 5 years. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was set at $100,000 or less per QALY for cost effectiveness, and the results were adjusted to 2014 U.S. dollars. Researchers also calculated the net monetary benefit of each treatment based on health and economic outcomes.

At 1 year, Dr. Ross and colleagues found quality-adjusted survival in patients who received CBT increased by 3 days (QALY, 0.008; 95% confidence interval, 0.013-0.025) compared with SGA, but there was a higher mean cost to the health care sector ($900; 95% CI, $500-$1,400) and to society ($1,500; 95% CI, $500-$2,500). CBT was not cost effective at 1 year, with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios in the health care sector of $119,000 per QALY and $186,000 per QALY to society, but the net monetary benefit confidence intervals in the health care sector ($2,400-$1,600) and in society ($3,400-$1,600) appear to show some cost effectiveness for CBT at 1 year, the researchers said.

Compared with SGA, there was an increase of 20 quality-adjusted life days in patients who received CBT at 5 years (QALY, 0.055; 95% CI, 0.044-0.160), and the cost for CBT treatment was reduced by $2,000. While CBT appeared to be cost saving in the base-case analysis, the researchers said there was some uncertainty in the cost effectiveness of CBT when they calculated the incremental net monetary benefit of CBT for the health care sector ($8,100-$21,700) and to society ($10,400-$25,300). In a sensitivity analysis, preference for SGA as a first-line therapy at 1 year was between 64% and 77%, while CBT became more preferred between 1.5 and 2 years, and had between a 73% and 87% preference range at 5 years.

In a related editorial, Mark Sinyor, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, said that although more longitudinal data are needed comparing outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder undergoing treatment with psychotherapy or medication, clinicians should act on what the current evidence shows about the effectiveness of CBT and SGA.

“It is increasingly evident that differences in effectiveness between CBT and SGAs are not substantial and that CBT has some advantages, including potentially lower long-term costs. These must be balanced with the advantages of SGAs, such as potentially more rapid action as well as efficacy across the full [major depressive disorder] severity spectrum,” he said.

Dr. Sinyor also called for CBT and SGA to be made available to all patients with major depressive disorder.

“Antidepressants for [major depressive disorder] are widely accessible in developed countries and that is important for our patients. If we are serious about providing evidence-based care, CBT must become equally available,” he said.

Neil Skolnik, MD, professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health, echoed the sentiment that CBT should be offered alongside antidepressants for treatment of major depressive disorder.

“CBT works as well or better than antidepressant medication, and since people learn skills that they can continue to use, it often has a long-lasting effect. In my experience, for people for whom CBT works – that is, for people who are seeing a therapist who use CBT as their technique and who are willing to put in the work it takes – CBT can be life changing,” he said in an interview. “So, I am not surprised, but I am happy to see the results of this study showing that CBT is cost effective.”

Dr. Skolnik emphasized that not every therapist offers CBT, so health care providers should be aware of the type of therapy they are referring their patients for and monitor that therapy when possible.

“We should talk to our patients, present them with options, and then decide together with our patients which approach is best for them,” Dr. Skolnik added. “Medications work, and for many this is a good choice. CBT works, and for many this is a good choice. For some patients, using both CBT and medications is the optimal choice. Both are about equally cost effective. We should discuss the options with our patients and decide the path forward together.”

This study was funded by grants from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development and the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Ross reported receiving a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. Two coauthors reported receiving grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Sinyor and Dr. Skolnik reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ross EL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M18-1480.

according to a recent study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“In the absence of clear superiority of either treatment, shared decision making incorporating patient preferences is critical,” Eric L. Ross, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Ross and colleagues created a decision-analytic model for adults with major depressive disorder in the United States using age and gender data from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, and simulated a cohort consisting of 62.2% women with a mean age of 40.7 years. Patients underwent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or received a second-generation antidepressant (SGA) as first-line therapy, and the model calculated risks and benefits of each therapy as well as likelihood of remission and response using data from meta-analyses.

The researchers calculated the average quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) of both treatments at 1 years and 5 years. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was set at $100,000 or less per QALY for cost effectiveness, and the results were adjusted to 2014 U.S. dollars. Researchers also calculated the net monetary benefit of each treatment based on health and economic outcomes.

At 1 year, Dr. Ross and colleagues found quality-adjusted survival in patients who received CBT increased by 3 days (QALY, 0.008; 95% confidence interval, 0.013-0.025) compared with SGA, but there was a higher mean cost to the health care sector ($900; 95% CI, $500-$1,400) and to society ($1,500; 95% CI, $500-$2,500). CBT was not cost effective at 1 year, with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios in the health care sector of $119,000 per QALY and $186,000 per QALY to society, but the net monetary benefit confidence intervals in the health care sector ($2,400-$1,600) and in society ($3,400-$1,600) appear to show some cost effectiveness for CBT at 1 year, the researchers said.

Compared with SGA, there was an increase of 20 quality-adjusted life days in patients who received CBT at 5 years (QALY, 0.055; 95% CI, 0.044-0.160), and the cost for CBT treatment was reduced by $2,000. While CBT appeared to be cost saving in the base-case analysis, the researchers said there was some uncertainty in the cost effectiveness of CBT when they calculated the incremental net monetary benefit of CBT for the health care sector ($8,100-$21,700) and to society ($10,400-$25,300). In a sensitivity analysis, preference for SGA as a first-line therapy at 1 year was between 64% and 77%, while CBT became more preferred between 1.5 and 2 years, and had between a 73% and 87% preference range at 5 years.

In a related editorial, Mark Sinyor, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, said that although more longitudinal data are needed comparing outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder undergoing treatment with psychotherapy or medication, clinicians should act on what the current evidence shows about the effectiveness of CBT and SGA.

“It is increasingly evident that differences in effectiveness between CBT and SGAs are not substantial and that CBT has some advantages, including potentially lower long-term costs. These must be balanced with the advantages of SGAs, such as potentially more rapid action as well as efficacy across the full [major depressive disorder] severity spectrum,” he said.

Dr. Sinyor also called for CBT and SGA to be made available to all patients with major depressive disorder.

“Antidepressants for [major depressive disorder] are widely accessible in developed countries and that is important for our patients. If we are serious about providing evidence-based care, CBT must become equally available,” he said.

Neil Skolnik, MD, professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health, echoed the sentiment that CBT should be offered alongside antidepressants for treatment of major depressive disorder.

“CBT works as well or better than antidepressant medication, and since people learn skills that they can continue to use, it often has a long-lasting effect. In my experience, for people for whom CBT works – that is, for people who are seeing a therapist who use CBT as their technique and who are willing to put in the work it takes – CBT can be life changing,” he said in an interview. “So, I am not surprised, but I am happy to see the results of this study showing that CBT is cost effective.”

Dr. Skolnik emphasized that not every therapist offers CBT, so health care providers should be aware of the type of therapy they are referring their patients for and monitor that therapy when possible.

“We should talk to our patients, present them with options, and then decide together with our patients which approach is best for them,” Dr. Skolnik added. “Medications work, and for many this is a good choice. CBT works, and for many this is a good choice. For some patients, using both CBT and medications is the optimal choice. Both are about equally cost effective. We should discuss the options with our patients and decide the path forward together.”

This study was funded by grants from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development and the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Ross reported receiving a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. Two coauthors reported receiving grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Sinyor and Dr. Skolnik reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ross EL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M18-1480.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Treat or treat

In Charles M. Schulz’s “It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown,” the Peanuts gang goes trick or treating door to door. While everyone else gets candy, chewing gum, and chocolate bars, Charlie Brown just gets a bag of rocks. Everyone got treats except Charlie Brown, who only got tricks. Sometimes it seems that my patients are trick or treating, too. Sadly, the tricks come way too often.

Linus tried to avoid tricks by staking out a sincere pumpkin patch in the hope that the Great Pumpkin would rise and deliver him candy and toys. Alas, our patients sometimes sincerely believe things like alkalinization, naturopathy, and antineoplastons will deliver the treats they need to cure their cancer. They will be similarly disappointed.

Most patients depend on us to skew the treat to trick ratio favorably. They trust us to know what to recommend to lengthen life and reduce suffering. Their faith is both a profound privilege and a daunting responsibility.

My patient was hospitalized with hypercalcemia, the latest complication deriving from a decade of progressive multiple myeloma. He was on his 11th line of therapy complicated by at least a grade 3 neuropathy resulting in an unstable gait, chronic pain requiring opioid analgesia, two hospitalizations in the last year for severe infections, and venous thromboembolism on anticoagulation, all resulting in an ECOG performance status no better than a 2. He stabilized and then we needed to talk about next steps.

A clinical trial would be ideal, but he would be excluded from any that we have open and travel isn’t really an option for him. I could choose to treat him with selinexor. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration and has about a one-in-four chance of producing a short remission in a population of patients that would not include my patient. It also has a three-in-four chance of significant side effects. I could also create a combination regimen with drugs that he has already been exposed to, knowing that response is unlikely and side effects are certain.

This situation is not unique; in fact it is an all too frequent occurrence. The easiest path forward for me would be to recommend treatment. The patient expects treatment and would readily consent to whatever regimen I proposed. He would bear whatever side effects resulted as an expected consequence of therapy. On the surface, this easy path appears to be the proverbial “treat.” But really, further treatment is the “trick” because it is not known to prolong life and would certainly add side effects. The problem, of course, is knowing both when treats become tricks and how to let patients know this, too.

No one knows exactly when treats become tricks, least of all me. Every month I get a report updating me on the status of a former patient being treated elsewhere. This is someone who I thought had no more treatment options. I am humbled every time a colleague, or fellow, recommends a treatment I had never considered. I am not perfect; I do the best I can. My recommendation might be wrong.

Yet I have watched my patient steadily deteriorate and cognitively decline no matter what treatment I employed, whether or not the monoclonal spike decreased. There is no evidence that treatment under such circumstances benefits the patient at all. Moreover, I have sat through many morbidity and mortality conferences where the conclusion was that we should have consulted hospice sooner. Like so many hematologists and oncologists every day, I needed to have a goals-of-care conversation with my patient knowing that treatment could possibly help, but probably would not.

Crucial conversations like these are difficult for everybody. There are techniques to employ that my palliative care colleagues recommend. I tried to remember them as I started talking to my patient and his wife. He listened and clearly understood the gravity of the situation and the resulting poor prognosis regardless of treatment. I recommended hospice. He declined.

Getting to this point was uncomfortable enough, but then I came to a decision that I am still struggling with – acquiesce to his wishes and treat while feeling that I should not, or decline to treat further and transfer his care to someone more willing? This is not the kind of trick or treat I enjoy.

I look forward to the day when discussions of end of life are less awkward. Small movements have started to bring these conversations into the open. One such movement choreographs a dinner to encourage frank and open discussion of death (https://deathoverdinner.org/). Another reimagines the doula – a childbirth coach – as a coach at the end of life (https://www.agentlerparting.com/). Another provides a step-by-step approach to generating an end-of-life conversation (https://theconversationproject.org/). These, and many other efforts, did not occur in a vacuum. They emerged because of the growing recognition that the modern delivery of health care, and the culture it created, is inadequate for the end of life.

Until our culture changes, though, we are left with tough conversations and tougher decisions with our patients who are at the end of their cancer journey. I wish I could tell my junior colleagues that it gets easier with experience. In many ways it gets worse because of the long relationships we develop. As long as the rewards of treats are greater than the disappointments of tricks, though, I will continue trick or treating in my white coat costume.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He is a hematologist-oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

In Charles M. Schulz’s “It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown,” the Peanuts gang goes trick or treating door to door. While everyone else gets candy, chewing gum, and chocolate bars, Charlie Brown just gets a bag of rocks. Everyone got treats except Charlie Brown, who only got tricks. Sometimes it seems that my patients are trick or treating, too. Sadly, the tricks come way too often.

Linus tried to avoid tricks by staking out a sincere pumpkin patch in the hope that the Great Pumpkin would rise and deliver him candy and toys. Alas, our patients sometimes sincerely believe things like alkalinization, naturopathy, and antineoplastons will deliver the treats they need to cure their cancer. They will be similarly disappointed.

Most patients depend on us to skew the treat to trick ratio favorably. They trust us to know what to recommend to lengthen life and reduce suffering. Their faith is both a profound privilege and a daunting responsibility.

My patient was hospitalized with hypercalcemia, the latest complication deriving from a decade of progressive multiple myeloma. He was on his 11th line of therapy complicated by at least a grade 3 neuropathy resulting in an unstable gait, chronic pain requiring opioid analgesia, two hospitalizations in the last year for severe infections, and venous thromboembolism on anticoagulation, all resulting in an ECOG performance status no better than a 2. He stabilized and then we needed to talk about next steps.

A clinical trial would be ideal, but he would be excluded from any that we have open and travel isn’t really an option for him. I could choose to treat him with selinexor. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration and has about a one-in-four chance of producing a short remission in a population of patients that would not include my patient. It also has a three-in-four chance of significant side effects. I could also create a combination regimen with drugs that he has already been exposed to, knowing that response is unlikely and side effects are certain.

This situation is not unique; in fact it is an all too frequent occurrence. The easiest path forward for me would be to recommend treatment. The patient expects treatment and would readily consent to whatever regimen I proposed. He would bear whatever side effects resulted as an expected consequence of therapy. On the surface, this easy path appears to be the proverbial “treat.” But really, further treatment is the “trick” because it is not known to prolong life and would certainly add side effects. The problem, of course, is knowing both when treats become tricks and how to let patients know this, too.

No one knows exactly when treats become tricks, least of all me. Every month I get a report updating me on the status of a former patient being treated elsewhere. This is someone who I thought had no more treatment options. I am humbled every time a colleague, or fellow, recommends a treatment I had never considered. I am not perfect; I do the best I can. My recommendation might be wrong.

Yet I have watched my patient steadily deteriorate and cognitively decline no matter what treatment I employed, whether or not the monoclonal spike decreased. There is no evidence that treatment under such circumstances benefits the patient at all. Moreover, I have sat through many morbidity and mortality conferences where the conclusion was that we should have consulted hospice sooner. Like so many hematologists and oncologists every day, I needed to have a goals-of-care conversation with my patient knowing that treatment could possibly help, but probably would not.

Crucial conversations like these are difficult for everybody. There are techniques to employ that my palliative care colleagues recommend. I tried to remember them as I started talking to my patient and his wife. He listened and clearly understood the gravity of the situation and the resulting poor prognosis regardless of treatment. I recommended hospice. He declined.

Getting to this point was uncomfortable enough, but then I came to a decision that I am still struggling with – acquiesce to his wishes and treat while feeling that I should not, or decline to treat further and transfer his care to someone more willing? This is not the kind of trick or treat I enjoy.

I look forward to the day when discussions of end of life are less awkward. Small movements have started to bring these conversations into the open. One such movement choreographs a dinner to encourage frank and open discussion of death (https://deathoverdinner.org/). Another reimagines the doula – a childbirth coach – as a coach at the end of life (https://www.agentlerparting.com/). Another provides a step-by-step approach to generating an end-of-life conversation (https://theconversationproject.org/). These, and many other efforts, did not occur in a vacuum. They emerged because of the growing recognition that the modern delivery of health care, and the culture it created, is inadequate for the end of life.

Until our culture changes, though, we are left with tough conversations and tougher decisions with our patients who are at the end of their cancer journey. I wish I could tell my junior colleagues that it gets easier with experience. In many ways it gets worse because of the long relationships we develop. As long as the rewards of treats are greater than the disappointments of tricks, though, I will continue trick or treating in my white coat costume.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He is a hematologist-oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

In Charles M. Schulz’s “It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown,” the Peanuts gang goes trick or treating door to door. While everyone else gets candy, chewing gum, and chocolate bars, Charlie Brown just gets a bag of rocks. Everyone got treats except Charlie Brown, who only got tricks. Sometimes it seems that my patients are trick or treating, too. Sadly, the tricks come way too often.

Linus tried to avoid tricks by staking out a sincere pumpkin patch in the hope that the Great Pumpkin would rise and deliver him candy and toys. Alas, our patients sometimes sincerely believe things like alkalinization, naturopathy, and antineoplastons will deliver the treats they need to cure their cancer. They will be similarly disappointed.

Most patients depend on us to skew the treat to trick ratio favorably. They trust us to know what to recommend to lengthen life and reduce suffering. Their faith is both a profound privilege and a daunting responsibility.

My patient was hospitalized with hypercalcemia, the latest complication deriving from a decade of progressive multiple myeloma. He was on his 11th line of therapy complicated by at least a grade 3 neuropathy resulting in an unstable gait, chronic pain requiring opioid analgesia, two hospitalizations in the last year for severe infections, and venous thromboembolism on anticoagulation, all resulting in an ECOG performance status no better than a 2. He stabilized and then we needed to talk about next steps.

A clinical trial would be ideal, but he would be excluded from any that we have open and travel isn’t really an option for him. I could choose to treat him with selinexor. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration and has about a one-in-four chance of producing a short remission in a population of patients that would not include my patient. It also has a three-in-four chance of significant side effects. I could also create a combination regimen with drugs that he has already been exposed to, knowing that response is unlikely and side effects are certain.

This situation is not unique; in fact it is an all too frequent occurrence. The easiest path forward for me would be to recommend treatment. The patient expects treatment and would readily consent to whatever regimen I proposed. He would bear whatever side effects resulted as an expected consequence of therapy. On the surface, this easy path appears to be the proverbial “treat.” But really, further treatment is the “trick” because it is not known to prolong life and would certainly add side effects. The problem, of course, is knowing both when treats become tricks and how to let patients know this, too.

No one knows exactly when treats become tricks, least of all me. Every month I get a report updating me on the status of a former patient being treated elsewhere. This is someone who I thought had no more treatment options. I am humbled every time a colleague, or fellow, recommends a treatment I had never considered. I am not perfect; I do the best I can. My recommendation might be wrong.

Yet I have watched my patient steadily deteriorate and cognitively decline no matter what treatment I employed, whether or not the monoclonal spike decreased. There is no evidence that treatment under such circumstances benefits the patient at all. Moreover, I have sat through many morbidity and mortality conferences where the conclusion was that we should have consulted hospice sooner. Like so many hematologists and oncologists every day, I needed to have a goals-of-care conversation with my patient knowing that treatment could possibly help, but probably would not.

Crucial conversations like these are difficult for everybody. There are techniques to employ that my palliative care colleagues recommend. I tried to remember them as I started talking to my patient and his wife. He listened and clearly understood the gravity of the situation and the resulting poor prognosis regardless of treatment. I recommended hospice. He declined.

Getting to this point was uncomfortable enough, but then I came to a decision that I am still struggling with – acquiesce to his wishes and treat while feeling that I should not, or decline to treat further and transfer his care to someone more willing? This is not the kind of trick or treat I enjoy.

I look forward to the day when discussions of end of life are less awkward. Small movements have started to bring these conversations into the open. One such movement choreographs a dinner to encourage frank and open discussion of death (https://deathoverdinner.org/). Another reimagines the doula – a childbirth coach – as a coach at the end of life (https://www.agentlerparting.com/). Another provides a step-by-step approach to generating an end-of-life conversation (https://theconversationproject.org/). These, and many other efforts, did not occur in a vacuum. They emerged because of the growing recognition that the modern delivery of health care, and the culture it created, is inadequate for the end of life.

Until our culture changes, though, we are left with tough conversations and tougher decisions with our patients who are at the end of their cancer journey. I wish I could tell my junior colleagues that it gets easier with experience. In many ways it gets worse because of the long relationships we develop. As long as the rewards of treats are greater than the disappointments of tricks, though, I will continue trick or treating in my white coat costume.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He is a hematologist-oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

What is your diagnosis? - November 2019

Aseptic abscesses syndrome

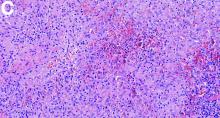

The clinical presentation with cervical feverish lymphadenopathy in a patient who underwent anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy was worrisome and suggestive of tuberculosis lymphadenitis. However, the ineffective antituberculosis treatment and the negative exploration for an etiology instead suggested another pathologic process. After antituberculosis treatment and because repeated negative results came from extensive searches for an infectious cause, a corticoid treatment was subsequently initiated. The clinical response was quick, with apyrexia, diminution of C-reactive protein at 10 mg/L, disappearance of the swelling, and complete healing of the fistula in 3 weeks (Figures E, F). This response to steroid treatment suggested an autoinflammatory pathologic process. Histology with epithelioid cell granuloma could evoke metastatic Crohn’s disease. However, this hypothesis was unlikely in this case because inside the granuloma was spotted noncaseous necrosis, and because symptoms occurred under infliximab treatment while the disease was well-controlled throughout the period in question. Furthermore, metastatic Crohn’s disease is usually localized in skin creases, such as the submammary fold, inguinal areas, and abdominal skinfold creases.1 In addition, we are not aware of any lymph node involvement described in literature.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome is a rare condition associated with Crohn’s disease first described in 1995 by André et al.2 Aseptic abscesses syndrome is an autoinflammatory disease involving neutrophils that is characterized by disseminated sterile purulent collections. An inflammatory bowel disease is associated in 70% of the cases.3 Aseptic abscesses are generally located in the spleen (90% of cases) and abdominal lymph nodes, but can also affect the liver, lung, pancreas, and superficial lymph nodes.3 Repeated bacteriologic tests are always negative. Fever is the most frequent clinical feature (90%) and persists despite antibiotic therapy, whereas symptoms can vary depending on the aseptic abscesses localization. Biochemical tests show an increased CRP and leukocyte count. Histologically, aseptic abscesses are well-limited nodular lesions measuring from a few millimeters to 7 cm and containing white pus. These abscesses are surrounded by epithelioid cell granulomatous reaction, inside of which can be found a noncaseous necrosis, unlike tuberculosis. Specific colorations are negative as well (Ziehl, periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott, and Whartin-Starry).

In subcutaneous node involvement, the main differential diagnosis is pyoderma gangrenosum, but abscesses are not surrounded by granulomatosis reaction in pyoderma gangrenosum. Limited forms can be treated by colchicine, thalidomide, or dapsone, but steroid therapy is almost always necessary, with a consistently favorable evolution. However, relapses occur in two-thirds of cases.

In conclusion, aseptic abscesses syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, which is rare and should be considered in a patient known for inflammatory bowel disease who develops fever and deep abscesses with negative results on repeated searches for infectious causes.3

References

1. Guest G.D. Fink R.L.W. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: case report of an unusual variant and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1764–6.

2. André M., Aumaitre O., Marcheix J.C. et al. Unexplained sterile systemic abscesses in Crohn’s disease: aseptic abscesses as a new entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1183–4.

3. André M.F.J., Piette J.-C., Kémény J.-L. et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145–61.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome

The clinical presentation with cervical feverish lymphadenopathy in a patient who underwent anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy was worrisome and suggestive of tuberculosis lymphadenitis. However, the ineffective antituberculosis treatment and the negative exploration for an etiology instead suggested another pathologic process. After antituberculosis treatment and because repeated negative results came from extensive searches for an infectious cause, a corticoid treatment was subsequently initiated. The clinical response was quick, with apyrexia, diminution of C-reactive protein at 10 mg/L, disappearance of the swelling, and complete healing of the fistula in 3 weeks (Figures E, F). This response to steroid treatment suggested an autoinflammatory pathologic process. Histology with epithelioid cell granuloma could evoke metastatic Crohn’s disease. However, this hypothesis was unlikely in this case because inside the granuloma was spotted noncaseous necrosis, and because symptoms occurred under infliximab treatment while the disease was well-controlled throughout the period in question. Furthermore, metastatic Crohn’s disease is usually localized in skin creases, such as the submammary fold, inguinal areas, and abdominal skinfold creases.1 In addition, we are not aware of any lymph node involvement described in literature.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome is a rare condition associated with Crohn’s disease first described in 1995 by André et al.2 Aseptic abscesses syndrome is an autoinflammatory disease involving neutrophils that is characterized by disseminated sterile purulent collections. An inflammatory bowel disease is associated in 70% of the cases.3 Aseptic abscesses are generally located in the spleen (90% of cases) and abdominal lymph nodes, but can also affect the liver, lung, pancreas, and superficial lymph nodes.3 Repeated bacteriologic tests are always negative. Fever is the most frequent clinical feature (90%) and persists despite antibiotic therapy, whereas symptoms can vary depending on the aseptic abscesses localization. Biochemical tests show an increased CRP and leukocyte count. Histologically, aseptic abscesses are well-limited nodular lesions measuring from a few millimeters to 7 cm and containing white pus. These abscesses are surrounded by epithelioid cell granulomatous reaction, inside of which can be found a noncaseous necrosis, unlike tuberculosis. Specific colorations are negative as well (Ziehl, periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott, and Whartin-Starry).

In subcutaneous node involvement, the main differential diagnosis is pyoderma gangrenosum, but abscesses are not surrounded by granulomatosis reaction in pyoderma gangrenosum. Limited forms can be treated by colchicine, thalidomide, or dapsone, but steroid therapy is almost always necessary, with a consistently favorable evolution. However, relapses occur in two-thirds of cases.

In conclusion, aseptic abscesses syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, which is rare and should be considered in a patient known for inflammatory bowel disease who develops fever and deep abscesses with negative results on repeated searches for infectious causes.3

References

1. Guest G.D. Fink R.L.W. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: case report of an unusual variant and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1764–6.

2. André M., Aumaitre O., Marcheix J.C. et al. Unexplained sterile systemic abscesses in Crohn’s disease: aseptic abscesses as a new entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1183–4.

3. André M.F.J., Piette J.-C., Kémény J.-L. et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145–61.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome

The clinical presentation with cervical feverish lymphadenopathy in a patient who underwent anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy was worrisome and suggestive of tuberculosis lymphadenitis. However, the ineffective antituberculosis treatment and the negative exploration for an etiology instead suggested another pathologic process. After antituberculosis treatment and because repeated negative results came from extensive searches for an infectious cause, a corticoid treatment was subsequently initiated. The clinical response was quick, with apyrexia, diminution of C-reactive protein at 10 mg/L, disappearance of the swelling, and complete healing of the fistula in 3 weeks (Figures E, F). This response to steroid treatment suggested an autoinflammatory pathologic process. Histology with epithelioid cell granuloma could evoke metastatic Crohn’s disease. However, this hypothesis was unlikely in this case because inside the granuloma was spotted noncaseous necrosis, and because symptoms occurred under infliximab treatment while the disease was well-controlled throughout the period in question. Furthermore, metastatic Crohn’s disease is usually localized in skin creases, such as the submammary fold, inguinal areas, and abdominal skinfold creases.1 In addition, we are not aware of any lymph node involvement described in literature.

Aseptic abscesses syndrome is a rare condition associated with Crohn’s disease first described in 1995 by André et al.2 Aseptic abscesses syndrome is an autoinflammatory disease involving neutrophils that is characterized by disseminated sterile purulent collections. An inflammatory bowel disease is associated in 70% of the cases.3 Aseptic abscesses are generally located in the spleen (90% of cases) and abdominal lymph nodes, but can also affect the liver, lung, pancreas, and superficial lymph nodes.3 Repeated bacteriologic tests are always negative. Fever is the most frequent clinical feature (90%) and persists despite antibiotic therapy, whereas symptoms can vary depending on the aseptic abscesses localization. Biochemical tests show an increased CRP and leukocyte count. Histologically, aseptic abscesses are well-limited nodular lesions measuring from a few millimeters to 7 cm and containing white pus. These abscesses are surrounded by epithelioid cell granulomatous reaction, inside of which can be found a noncaseous necrosis, unlike tuberculosis. Specific colorations are negative as well (Ziehl, periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott, and Whartin-Starry).

In subcutaneous node involvement, the main differential diagnosis is pyoderma gangrenosum, but abscesses are not surrounded by granulomatosis reaction in pyoderma gangrenosum. Limited forms can be treated by colchicine, thalidomide, or dapsone, but steroid therapy is almost always necessary, with a consistently favorable evolution. However, relapses occur in two-thirds of cases.

In conclusion, aseptic abscesses syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, which is rare and should be considered in a patient known for inflammatory bowel disease who develops fever and deep abscesses with negative results on repeated searches for infectious causes.3

References

1. Guest G.D. Fink R.L.W. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: case report of an unusual variant and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1764–6.

2. André M., Aumaitre O., Marcheix J.C. et al. Unexplained sterile systemic abscesses in Crohn’s disease: aseptic abscesses as a new entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1183–4.

3. André M.F.J., Piette J.-C., Kémény J.-L. et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145–61.

An 18-year-old man presented with feverish cervical swelling that had developed over a few weeks.

He had a prior history of severe Crohn's disease with perianal manifestation with spontaneous perforation and had required an ileocecal and jejunal resection 3 years before. Clinical remission was achieved after 1 year of combination therapy by infliximab and azathioprine, followed by infliximab alone.

Physical examination showed an elevated body temperature of 38.5°C, and cervical palpation identified 3 painful erythematous nodes (3 cm in the left level IIb; 1 cm in the right IIb; 1 cm right supraclavicular space; Figure A). The rest of the examination was normal, and he did not complain about his bowel movements. He stated that he had not been traveling recently, nor had he been in contact with any sick person.

Laboratory tests spotted elevated levels of C-reactive protein (95.5 mg/L). Interferon-gamma release assays QuantiFERON-TB Gold was normal. Fine-needle aspiration showed a purulent content with repeated bacteriologic culture and gram stain culture, both of which were negative. Specific culture and polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis were negative as well.

On computed tomography scan, the lymphadenitis showed liquid content with peripheral enhancement. One had an air-fluid level because of a spontaneous fistulization (Figure B). There were neither pulmonary abnormalities, mediastinal adenopathy, nor signs of Crohn's disease activity.

Histologic analysis of a lymph node excision showed epithelioid cell granuloma with noncaseous necrosis (Figure C, D).

Because the patient underwent anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy and despite the negative specific testing for tuberculosis, he was treated with probabilistic antituberculosis drugs for 6 months. Treatment proved ineffective and the patient's condition evolved with further fistulization and node size increase.

Considering the patient's medical history and evolution, what treatment should we consider, and what is the diagnosis?

November 2019

Q2. Correct answer: D

Rationale

HELLP syndrome is a multisystemic disorder that is characterized by the development of hemolytic anemia, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets. Most cases occur between 28 and 36 weeks of gestation, but it can also develop up to 1 week postpartum in 30% of cases.

Reference

Fitzpatrick KE, et al. Risk factors, management, and outcomes of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome and elevated liver enzymes, low platelets syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar;123(3):618-27.

Q2. Correct answer: D

Rationale

HELLP syndrome is a multisystemic disorder that is characterized by the development of hemolytic anemia, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets. Most cases occur between 28 and 36 weeks of gestation, but it can also develop up to 1 week postpartum in 30% of cases.

Reference

Fitzpatrick KE, et al. Risk factors, management, and outcomes of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome and elevated liver enzymes, low platelets syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar;123(3):618-27.

Q2. Correct answer: D

Rationale

HELLP syndrome is a multisystemic disorder that is characterized by the development of hemolytic anemia, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets. Most cases occur between 28 and 36 weeks of gestation, but it can also develop up to 1 week postpartum in 30% of cases.

Reference

Fitzpatrick KE, et al. Risk factors, management, and outcomes of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome and elevated liver enzymes, low platelets syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar;123(3):618-27.

Q2. A 29-year-old woman at 37 weeks gestation presents to the emergency room with right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting. She is diagnosed with preeclampsia. She is treated with intravenous magnesium, antihypertensive therapy, and labor is induced. Prior to delivery, laboratory values were as follows: aspartate aminotransferase, 240 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 220 U/L; total bilirubin, 1.8 mg/dL; hemoglobin, 10.1 g/dL; platelets, 110,000 microL. Forty-eight hours following delivery, she complained of worsening right upper quadrant pain and headache. Repeat laboratory values 48 hours postpartum were as follows: AST, 410 U/L; ALT, 390 U/L; total bilirubin, 5.1 mg/dL; hemoglobin, 7.9 g/dL; and platelets 75,000 microL.

November 2019

Q1. Correct answer: F

Rationale

There are a number of known risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma including PSC, choledochal cysts, obesity, chronic liver disease, toxins such as Thorotrast as well as liver flukes including those in the Opisthorchis and Clonorchis genus. While Fasciola does infect the liver, an association has not been reported with cholangiocarcinoma.

References

1. Fevery J, et al. Malignancies and mortality in 200 patients with primary sclerosering cholan¬gitis: a long-term single-centre study. Liver Int. 2012;32(2):214-22.

2. Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Cancer surveillance in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2011;54(5): 1842-52.

3. Williamson KD, Chapman RW. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a clinical update. Br Med Bull. 2015;114(1):53-64.

Q1. Correct answer: F

Rationale

There are a number of known risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma including PSC, choledochal cysts, obesity, chronic liver disease, toxins such as Thorotrast as well as liver flukes including those in the Opisthorchis and Clonorchis genus. While Fasciola does infect the liver, an association has not been reported with cholangiocarcinoma.

References

1. Fevery J, et al. Malignancies and mortality in 200 patients with primary sclerosering cholan¬gitis: a long-term single-centre study. Liver Int. 2012;32(2):214-22.

2. Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Cancer surveillance in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2011;54(5): 1842-52.

3. Williamson KD, Chapman RW. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a clinical update. Br Med Bull. 2015;114(1):53-64.

Q1. Correct answer: F

Rationale

There are a number of known risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma including PSC, choledochal cysts, obesity, chronic liver disease, toxins such as Thorotrast as well as liver flukes including those in the Opisthorchis and Clonorchis genus. While Fasciola does infect the liver, an association has not been reported with cholangiocarcinoma.

References

1. Fevery J, et al. Malignancies and mortality in 200 patients with primary sclerosering cholan¬gitis: a long-term single-centre study. Liver Int. 2012;32(2):214-22.

2. Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Cancer surveillance in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2011;54(5): 1842-52.

3. Williamson KD, Chapman RW. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a clinical update. Br Med Bull. 2015;114(1):53-64.

Q1. You are evaluating a 77-year-old man for obstructive jaundice and weight loss. The patient reports an approximate 25-pound weight loss over the last month. He denies abdominal pain. Labs reveal a total bilirubin of 17.5 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase of 441 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 60 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase of 70 IU/L, lipase of 41 U (ULN 50 U) and WBC of 8 × 109/L. A right upper quadrant ultrasound is obtained and shows intra- and extrahepatic biliary dilation up to 2 cm. A subsequent pancreas protocol CT is notable for narrowing of the mid bile duct with a normal downstream common bile duct. A mass is not visualized within the pancreas. CA 19-9 is elevated to 1900 U/mL and CEA is 8 ng/ mL. You are concerned for a possible extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.