User login

SEEDS for success: Lifestyle management in migraine

Migraine is the second leading cause of years of life lived with a disability globally.1 It affects people of all ages, but particularly during the years associated with the highest productivity in terms of work and family life.

Migraine is a genetic neurologic disease that can be influenced or triggered by environmental factors. However, triggers do not cause migraine. For example, stress does not cause migraine, but it can exacerbate it.

Primary care physicians can help patients reduce the likelihood of a migraine attack, the severity of symptoms, or both by offering lifestyle counseling centered around the mnemonic SEEDS: sleep, exercise, eat, diary, and stress. In this article, each factor is discussed individually for its current support in the literature along with best-practice recommendations.

S IS FOR SLEEP

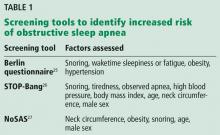

Before optimizing sleep hygiene, screen for sleep apnea, especially in those who have chronic daily headache upon awakening. An excellent tool is the STOP-Bang screening questionnaire5 (www.stopbang.ca/osa/screening.php). Patients respond “yes” or “no” to the following questions:

- Snoring: Do you snore loudly (louder than talking or loud enough to be heard through closed doors)?

- Tired: Do you often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during the daytime?

- Observed: Has anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep?

- Pressure: Do you have or are you being treated for high blood pressure?

- Body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2?

- Age over 50?

- Neck circumference larger than 40 cm (females) or 42 cm (males)?

- Gender—male?

Each “yes” answer is scored as 1 point. A score less than 3 indicates low risk of obstructive sleep apnea; 3 to 4 indicates moderate risk; and 5 or more indicates high risk. Optimization of sleep apnea with continuous positive airway pressure therapy can improve sleep apnea headache.6 The improved sleep from reduced arousals may also mitigate migraine symptoms.

Behavioral modification for sleep hygiene can convert chronic migraine to episodic migraine.7 One such program is stimulus control therapy, which focuses on using cues to initiate sleep (Table 1). Patients are encouraged to keep the bedroom quiet, dark, and cool, and to go to sleep at the same time every night. Importantly, the bed should be associated only with sleep. If patients are unable to fall asleep within 20 to 30 minutes, they should leave the room so they do not associate the bed with frustration and anxiety. Use of phones, tablets, and television in the bedroom is discouraged as these devices may make it more difficult to fall asleep.8

The next option is sleep restriction, which is useful for comorbid insomnia. Patients keep a sleep diary to better understand their sleep-wake cycle. The goal is 90% sleep efficiency, meaning that 90% of the time in bed (TIB) is spent asleep. For example, if the patient is in bed 8 hours but asleep only 4 hours, sleep efficiency is 50%. The goal is to reduce TIB to match the time asleep and to agree on a prescribed daily wake-up time. When the patient is consistently sleeping 90% of the TIB, add 30-minute increments until he or she is appropriately sleeping 7 to 8 hours at night.9 Naps are not recommended.

Let patients know that their migraine may worsen until a new routine sleep pattern emerges. This method is not recommended for patients with untreated sleep apnea.

E IS FOR EXERCISE

Exercise is broadly recommended for a healthy lifestyle; some evidence suggests that it can also be useful in the management of migraine.10 Low levels of physical activity and a sedentary lifestyle are associated with migraine.11 It is unclear if patients with migraine are less likely to exercise because they want to avoid triggering a migraine or if a sedentary lifestyle increases their risk.

Exercise has been studied for its prophylactic benefits in migraine, and one hypothesis relates to beta-endorphins. Levels of beta-endorphins are reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with migraine.12 Exercise programs may increase levels while reducing headache frequency and duration.13 One study showed that pain thresholds do not change with exercise programs, suggesting that it is avoidance behavior that is positively altered rather than the underlying pain pathways.14

A systematic review and meta-analysis based on 5 randomized controlled trials and 1 nonrandomized controlled clinical trial showed that exercise reduced monthly migraine days by only 0.6 (± 0.3) days, but the data also suggested that as the exercise intensity increased, so did the positive effects.10

Some data suggest that exercise may also reduce migraine duration and severity as well as the need for abortive medication.10 Two studies in this systematic review15,16 showed that exercise benefits were equivalent to those of migraine preventives such as amitriptyline and topiramate; the combination of amitriptyline and exercise was more beneficial than exercise alone. Multiple types of exercise were beneficial, including walking, jogging, cross-training, and cycling when done for least 6 weeks and for 30 to 50 minutes 3 to 5 times a week.

These findings are in line with the current recommendations for general health from the American College of Sports Medicine, ie, moderate to vigorous cardiorespiratory exercise for 30 to 60 minutes 3 to 5 times a week (or 150 minutes per week). The daily exercise can be continuous or done in intervals of less than 20 minutes. For those with a sedentary lifestyle, as is seen in a significant proportion of the migraine population, light to moderate exercise for less than 20 minutes is still beneficial.17

Based on this evidence, the best current recommendation for patients with migraine is to engage in graded moderate cardiorespiratory exercise, although any exercise is better than none. If a patient is sedentary or has poor exercise tolerance, or both, exercising once a week for shorter time periods may be a manageable place to start.

Some patients may identify exercise as a trigger or exacerbating factor in migraine. These patients may need appropriate prophylactic and abortive therapies before starting an exercise regimen.

THE SECOND E IS FOR EAT (FOOD AND DRINK)

Many patients believe that some foods trigger migraine attacks, but further study is needed. The most consistent food triggers appear to be red wine and caffeine (withdrawal).18,19 Interestingly, patients with migraine report low levels of alcohol consumption,20 but it is unclear if that is because alcohol has a protective effect or if patients avoid it.

Some patients may crave certain foods in the prodromal phase of an attack, eat the food, experience the attack, and falsely conclude that the food caused the attack.21 Premonitory symptoms include fatigue, cognitive changes, homeostatic changes, sensory hyperresponsiveness, and food cravings.21 It is difficult to distinguish between premonitory phase food cravings and true triggers because premonitory symptoms can precede headache by 48 to 72 hours, and the timing for a trigger to be considered causal is not known.22

Chocolate is often thought to be a migraine trigger, but the evidence argues against this and even suggests that sweet cravings are a part of the premonitory phase.23 Monosodium glutamate is often identified as a trigger as well, but the literature is inconsistent and does not support a causal relationship.24 Identifying true food triggers in migraine is difficult, and patients with migraine may have poor quality diets, with some foods acting as true triggers for certain patients.25 These possibilities have led to the development of many “migraine diets,” including elimination diets.

Elimination diets

Elimination diets involve avoiding specific food items over a period of time and then adding them back in one at a time to gauge whether they cause a reaction in the body. A number of these diets have been studied for their effects on headache and migraine:

Gluten-free diets restrict foods that contain wheat, rye, and barley. A systematic review of gluten-free diets in patients with celiac disease found that headache or migraine frequency decreased by 51.6% to 100% based on multiple cohort studies (N = 42,388).26 There are no studies on the use of a gluten-free diet for migraine in patients without celiac disease.

Immunoglobulin G-elimination diets restrict foods that serve as antigens for IgG. However, data supporting these diets are inconsistent. Two small randomized controlled trials found that the diets improved migraine symptoms, but a larger study found no improvement in the number of migraine days at 12 weeks, although there was an initially significant effect at 4 weeks.27–29

Antihistamine diets restrict foods that have high levels of histamines, including fermented dairy, vegetables, soy products, wine, beer, alcohol, and those that cause histamine release regardless of IgE testing results. A prospective single-arm study of antihistamine diets in patients with chronic headache reported symptom improvement, which could be applied to certain comorbidities such as mast cell activation syndrome.30 Another prospective nonrandomized controlled study eliminated foods based on positive IgE skin-prick testing for allergy in patients with recurrent migraine and found that it reduced headache frequency.31

Tyramine-free diets are often recommended due to the presumption that tyramine-containing foods (eg, aged cheese, cured or smoked meats and fish, and beer) are triggers. However, multiple studies have reviewed this theory with inconsistent results,32 and the only study of a tyramine-free diet was negative.33 In addition, commonly purported high-tyramine foods have lower tyramine levels than previously thought.34

Low-fat diets in migraine are supported by 2 small randomized controlled trials and a prospective study showing a decrease in symptom severity; the results for frequency are inconsistent.35–37

Low-glycemic index diets are supported in migraine by 1 randomized controlled trial that showed improvement in migraine frequency in a diet group and in a control group of patients who took a standard migraine-preventive medication to manage their symptoms.38

Other migraine diets

Diets high in certain foods or ingredient ratios, as opposed to elimination diets, have also been studied in patients with migraine. One promising diet containing high levels of omega-3 fatty acids and low levels of omega-6 fatty acids was shown in a systematic review to reduce the duration of migraine but not the frequency or severity.39 A more recent randomized controlled trial of this diet in chronic migraine also showed that it decreased migraine frequency.40

The ketogenic diet (high fat, low carbohydrate) had promising results in a randomized controlled trial in overweight women with migraine and in a prospective study.41,42 However, a prospective study of the Atkins diet in teenagers with chronic daily headaches showed no benefit.43 The ketogenic diet is difficult to follow and may work in part due to weight loss alone, although ketogenesis itself may also play a role.41,44

Sodium levels have been shown to be higher in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with migraine than in controls, particularly during an attack.45 For a prehypertensive population or an elderly population, a low-sodium diet may be beneficial based on 2 prospective trials.46,47 However, a younger female population without hypertension and low-to-normal body mass index had a reduced probability of migraine while consuming a high-sodium diet.48

Counseling about sodium intake should be tailored to specific patient populations. For example, a diet low in sodium may be appropriate for patients with vascular risk factors such as hypertension, whereas a high-sodium diet may be appropriate in patients with comorbidities like postural tachycardia syndrome or in those with a propensity for low blood pressure or low body mass index.

Encourage routine meals and hydration

The standard advice for patients with migraine is to consume regular meals. Headaches have been associated with fasting, and those with migraine are predisposed to attacks in the setting of fasting.49,50 Migraine is more common when meals are skipped, particularly breakfast.51

It is unclear how fasting lowers the migraine threshold. Nutritional studies show that skipping meals, particularly breakfast, increases low-grade inflammation and impairs glucose metabolism by affecting insulin and fat oxidation metabolism.52 However, hypoglycemia itself is not a consistent cause of headache or migraine attacks.53 As described above, a randomized controlled trial of a low-glycemic index diet actually decreased migraine frequency and severity.38 Skipping meals also reduces energy and is associated with reduced physical activity, perhaps leading to multiple compounding triggers that further lower the migraine threshold.54,55

When counseling patients about the need to eat breakfast, consider what they normally consume (eg, is breakfast just a cup of coffee?). Replacing simple carbohydrates with protein, fats, and fiber may be beneficial for general health, but the effects on migraine are not known, nor is the optimal composition of breakfast foods.55

The optimal timing of breakfast relative to awakening is also unclear, but in general, it should be eaten within 30 to 60 minutes of rising. Also consider patients’ work hours—delayed-phase or shift workers have altered sleep cycles.

Recommendations vary in regard to hydration. Headache is associated with fluid restriction and dehydration,56,57 but only a few studies suggest that rehydration and increased hydration status can improve migraine.58 In fact, a single post hoc analysis of a metoclopramide study showed that intravenous fluid alone for patients with migraine in the emergency room did not improve pain outcomes.59

The amount of water patients should drink daily in the setting of migraine is also unknown, but a study showed benefit with 4 L, which equates to a daily intake of 16 eight-ounce glasses.60 One review on general health that could be extrapolated given the low risk of the intervention indicated that 1.8 L daily (7 to 8 eight-ounce glasses) promoted a euhydration status in most people, although many factors contribute to hydration status.61

Caffeine intake is also a major consideration. Caffeine is a nonspecific adenosine receptor antagonist that modulates adenosine receptors like the pronociceptive 2A receptor, leading to changes integral to the neuropathophysiology of migraine.62 Caffeine has analgesic properties at doses greater than 65 to 200 mg and augments the effects of analgesics such as acetaminophen and aspirin. Chronic caffeine use can lead to withdrawal symptoms when intake is stopped abruptly; this is thought to be due to upregulation of adenosine receptors, but the effect varies based on genetic predisposition.19

The risk of chronic daily headache may relate to high use of caffeine preceding the onset of chronification, and caffeine abstinence may improve response to acute migraine treatment.19,63 There is a dose-dependent risk of headache.64,65 Current recommendations suggest limiting caffeine consumption to less than 200 mg per day or stopping caffeine consumption altogether based on the quantity required for caffeine-withdrawal headache.66 Varying the caffeine dose from day to day may also trigger headache due to the high sensitivity to caffeine withdrawal.

While many diets have shown potential benefit in patients with migraine, more studies are needed before any one “migraine diet” can be recommended. Caution should be taken, as there is risk of adverse effects from nutrient deficiencies or excess levels, especially if the patient is not under the care of a healthcare professional who is familiar with the diet.

Whether it is beneficial to avoid specific food triggers at this time is unclear and still controversial even within the migraine community because some of these foods may be misattributed as triggers instead of premonitory cravings driven by the hypothalamus. It is important to counsel patients with migraine to eat a healthy diet with consistent meals, to maintain adequate hydration, and to keep their caffeine intake low or at least consistent, although these teachings are predominantly based on limited studies with extrapolation from nutrition research.

D IS FOR DIARY

A headache diary is a recommended part of headache management and may enhance the accuracy of diagnosis and assist in treatment modifications. Paper and electronic diaries have been used. Electronic diaries may be more accurate for real-time use, but patients may be more likely to complete a paper one.67 Patients prefer electronic diaries over long paper forms,68 but a practical issue to consider is easy electronic access.

Patients can start keeping a headache diary before the initial consultation to assist with diagnosis, or early in their management. A first-appointment diary mailed with instructions is a feasible option.69 These types of diaries ask detailed questions to help diagnose all major primary headache types including menstrual migraine and to identify concomitant medication-overuse headache. Physicians and patients generally report improved communication with use of a diary.70

Some providers distinguish between a headache diary and a calendar. In standard practice, a headache diary is the general term referring to both, but the literature differentiates between the two. Both should at least include headache frequency, with possible inclusion of other factors such as headache duration, headache intensity, analgesic use, headache impact on function, and absenteeism. Potential triggers including menses can also be tracked. The calendar version can fit on a single page and can be used for simple tracking of headache frequency and analgesia use.

One of the simplest calendars to use is the “stoplight” calendar. Red days are when a patient is completely debilitated in bed. On a yellow day, function at work, school, or daily activities is significantly reduced by migraine, but the patient is not bedbound. A green day is when headache is present but function is not affected. No color is placed if the patient is 100% headache-free.

Acute treatment use can be written in or, to improve compliance, a checkmark can be placed on days of treatment. Patients who are tracking menses circle the days of menstruation. The calendar-diary should be brought to every appointment to track treatment response and medication use.

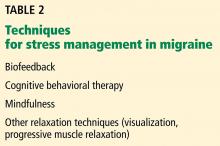

THE SECOND S IS FOR STRESS

Behavioral management such as cognitive behavioral therapy in migraine has been shown to decrease catastrophizing, migraine disability, and headache severity and frequency.74 Both depression and anxiety can improve along with migraine.75 Cognitive behavioral therapy can be provided in individualized sessions or group sessions, either in person or online.74,76,77 The effects become more prominent about 5 weeks into treatment.78

Biofeedback, which uses behavioral techniques paired with physiologic autonomic measures, has been extensively studied, and shows benefit in migraine, including in meta-analysis.79 The types of biofeedback measurements used include electromyography, electroencephalography, temperature, sweat sensors, heart rate, blood volume pulse feedback, and respiration bands. While biofeedback is generally done under the guidance of a therapist, it can still be useful with minimal therapist contact and supplemental audio.80

Mindfulness, or the awareness of thoughts, feelings, and sensations in the present moment without judgment, is a behavioral technique that can be done alone or paired with another technique. It is often taught through a mindfulness-based stress-reduction program, which relies on a standardized approach. A meta-analysis showed that mindfulness improves pain intensity, headache frequency, disability, self-efficacy, and quality of life.81 It may work by encouraging pain acceptance.82

Relaxation techniques are also employed in migraine management, either alone or in conjunction with techniques mentioned above, such as mindfulness. They include progressive muscle relaxation and deep breathing. Relaxation has been shown to be effective when done by professional trainers as well as lay trainers in both individual and group settings.83,84

In patients with intractable headache, more-intensive inpatient and outpatient programs have been tried. Inpatient admissions with multidisciplinary programs that include a focus on behavioral techniques often paired with lifestyle education and sometimes pharmacologic management can be beneficial.85,86 These programs have also been successfully conducted as multiple outpatient sessions.86–88

Stress management is an important aspect of migraine management. These treatments often involve homework and require active participation.

LIFESTYLE FOR ALL

All patients with migraine should initiate lifestyle modifications (see Advice to patients with migraine: SEEDS for success). Modifications with the highest level of evidence, specifically behavioral techniques, have had the most reproducible results. A headache diary is an essential tool to identify patterns and needs for optimization of acute or preventive treatment regimens. The strongest evidence is for the behavioral management techniques for stress reduction.

- GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017; 390(10100):1211–1259. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2

- Vgontzas A, Pavlovic JM. Sleep diorders and migraine: review of literature and potential pathophysiology mechanisms. Headache 2018; 58(7):1030–1039. doi:10.1111/head.13358

- Lund N, Westergaard ML, Barloese M, Glumer C, Jensen RH. Epidemiology of concurrent headache and sleep problems in Denmark. Cephalalgia 2014; 34(10):833–845. doi:10.1177/0333102414543332

- Woldeamanuel YW, Cowan RP. The impact of regular lifestyle behavior in migraine: a prevalence case-referent study. J Neurol 2016; 263(4):669–676. doi:10.1007/s00415-016-8031-5

- Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang questionnaire: a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2016; 149(3):631–638. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0903

- Johnson KG, Ziemba AM, Garb JL. Improvement in headaches with continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnea: a retrospective analysis. Headache 2013; 53(2):333–343. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02251.x

- Calhoun AH, Ford S. Behavioral sleep modification may revert transformed migraine to episodic migraine. Headache 2007; 47(8):1178–1183. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00780.x

- Calhoun AH, Ford S, Finkel AG, Kahn KA, Mann JD. The prevalence and spectrum of sleep problems in women with transformed migraine. Headache 2006; 46(4):604–610. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00410.x

- Rains JC. Optimizing circadian cycles and behavioral insomnia treatment in migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2008; 12(3):213–219. pmid:18796272

- Lemmens J, De Pauw J, Van Soom T, et al. The effect of aerobic exercise on the number of migraine days, duration and pain intensity in migraine: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Headache Pain 2019; 20(1):16. doi:10.1186/s10194-019-0961-8

- Amin FM, Aristeidou S, Baraldi C, et al; European Headache Federation School of Advanced Studies (EHF-SAS). The association between migraine and physical exercise. J Headache Pain 2018; 19(1):83. doi:10.1186/s10194-018-0902-y

- Genazzani AR, Nappi G, Facchinetti F, et al. Progressive impairment of CSF beta-EP levels in migraine sufferers. Pain 1984; 18:127-133. pmid:6324056

- Hindiyeh NA, Krusz JC, Cowan RP. Does exercise make migraines worse and tension type headaches better? Curr Pain Headache Rep 2013;17:380. pmid:24234818

- Kroll LS, Sjodahl Hammarlund C, Gard G, Jensen RH, Bendtsen L. Has aerobic exercise effect on pain perception in persons with migraine and coexisting tension-type headache and neck pain? A randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Eur J Pain 2018; 10:10. pmid:29635806

- Santiago MD, Carvalho Dde S, Gabbai AA, Pinto MM, Moutran AR, Villa TR. Amitriptyline and aerobic exercise or amitriptyline alone in the treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized comparative study. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2014; 72(11):851-855. pmid:25410451

- Varkey E, Cider A, Carlsson J, Linde M. Exercise as migraine prophylaxis: a randomized study using relaxation and topiramate as controls. Cephalalgia 2011; 31(14):1428-1438. pmid:21890526

- Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011; 43(7):1334-1359. pmid:21694556

- Guarnieri P, Radnitz CL, Blanchard EB. Assessment of dietary risk factors in chronic headache. Biofeedback Self Regul 1990; 15(1):15–25. pmid:2361144

- Shapiro RE. Caffeine and headaches. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2008; 12(4):311–315. pmid:18625110

- Yokoyama M, Yokoyama T, Funazu K, et al. Associations between headache and stress, alcohol drinking, exercise, sleep, and comorbid health conditions in a Japanese population. J Headache Pain 2009; 10(3):177–185. doi:10.1007/s10194-009-0113-7

- Karsan N, Bose P, Goadsby PJ. The migraine premonitory phase. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2018; 24(4, Headache):996–1008. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000624

- Pavlovic JM, Buse DC, Sollars CM, Haut S, Lipton RB. Trigger factors and premonitory features of migraine attacks: summary of studies. Headache 2014; 54(10):1670–1679. doi:10.1111/head.12468

- Marcus DA, Scharff L, Turk D, Gourley LM. A double-blind provocative study of chocolate as a trigger of headache. Cephalalgia 1997; 17(8):855–862. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1708855.x

- Obayashi Y, Nagamura Y. Does monosodium glutamate really cause headache? A systematic review of human studies. J Headache Pain 2016; 17:54. doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0639-4

- Evans EW, Lipton RB, Peterlin BL, et al. Dietary intake patterns and diet quality in a nationally representative sample of women with and without severe headache or migraine. Headache 2015; 55(4):550–561. doi:10.1111/head.12527

- Zis P, Julian T, Hadjivassiliou M. Headache associated with coeliac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2018; 10(10). doi:10.3390/nu10101445

- Alpay K, Ertas M, Orhan EK, Ustay DK, Lieners C, Baykan B. Diet restriction in migraine, based on IgG against foods: a clinical double-blind, randomised, cross-over trial. Cephalalgia 2010; 30(7):829–837. doi:10.1177/0333102410361404

- Aydinlar EI, Dikmen PY, Tiftikci A, et al. IgG-based elimination diet in migraine plus irritable bowel syndrome. Headache 2013; 53(3):514–525. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02296.x

- Mitchell N, Hewitt CE, Jayakody S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of food elimination diet based on IgG antibodies for the prevention of migraine like headaches. Nutr J 2011; 10:85. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-10-85

- Wantke F, Gotz M, Jarisch R. Histamine-free diet: treatment of choice for histamine-induced food intolerance and supporting treatment for chronic headaches. Clin Exp Allergy 1993; 23(12):982–985. pmid:10779289

- Mansfield LE, Vaughan TR, Waller SF, Haverly RW, Ting S. Food allergy and adult migraine: double-blind and mediator confirmation of an allergic etiology. Ann Allergy 1985; 55(2):126–129. pmid:4025956

- Kohlenberg RJ. Tyramine sensitivity in dietary migraine: a critical review. Headache 1982; 22(1):30–34. pmid:17152742

- Medina JL, Diamond S. The role of diet in migraine. Headache 1978; 18(1):31–34. pmid:649377

- Mosnaim AD, Freitag F, Ignacio R, et al. Apparent lack of correlation between tyramine and phenylethylamine content and the occurrence of food-precipitated migraine. Reexamination of a variety of food products frequently consumed in the United States and commonly restricted in tyramine-free diets. Headache Quarterly. Current Treatment and Research 1996; 7(3):239–249.

- Ferrara LA, Pacioni D, Di Fronzo V, et al. Low-lipid diet reduces frequency and severity of acute migraine attacks. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2015; 25(4):370–375. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2014.12.006

- Bic Z, Blix GG, Hopp HP, Leslie FM, Schell MJ. The influence of a low-fat diet on incidence and severity of migraine headaches. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 1999; 8(5):623–630. doi:10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.623

- Bunner AE, Agarwal U, Gonzales JF, Valente F, Barnard ND. Nutrition intervention for migraine: a randomized crossover trial. J Headache Pain 2014; 15:69. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-69

- Evcili G, Utku U, Ogun MN, Ozdemir G. Early and long period follow-up results of low glycemic index diet for migraine prophylaxis. Agri 2018; 30(1):8–11. doi:10.5505/agri.2017.62443

- Maghsoumi-Norouzabad L, Mansoori A, Abed R, Shishehbor F. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Neurosci 2018; 21(9):614–623. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2017.1344371

- Soares AA, Loucana PMC, Nasi EP, Sousa KMH, Sa OMS, Silva-Neto RP. A double- blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (OPFA Ω-3) for the prevention of migraine in chronic migraine patients using amitriptyline. Nutr Neurosci 2018; 21(3):219–223. doi:10.1080/1028415X.2016.1266133

- Di Lorenzo C, Coppola G, Sirianni G, et al. Migraine improvement during short lasting ketogenesis: a proof-of-concept study. Eur J Neurol 2015; 22(1):170–177. doi:10.1111/ene.12550

- Di Lorenzo C, Coppola G, Bracaglia M, et al. Cortical functional correlates of responsiveness to short-lasting preventive intervention with ketogenic diet in migraine: a multimodal evoked potentials study. J Headache Pain 2016; 17:58. doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0650-9

- Kossoff EH, Huffman J, Turner Z, Gladstein J. Use of the modified Atkins diet for adolescents with chronic daily headache. Cephalalgia 2010; 30(8):1014–1016. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.02016.x

- Slavin M, Ailani J. A clinical approach to addressing diet with migraine patients. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2017; 17(2):17. doi:10.1007/s11910-017-0721-6

- Amer M, Woodward M, Appel LJ. Effects of dietary sodium and the DASH diet on the occurrence of headaches: results from randomised multicentre DASH-sodium clinical trial. BMJ Open 2014; 4(12):e006671. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006671

- Chen L, Zhang Z, Chen W, Whelton PK, Appel LJ. Lower sodium intake and risk of headaches: results from the trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(7):1270–1275. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303143

- Pogoda JM, Gross NB, Arakaki X, Fonteh AN, Cowan RP, Harrington MG. Severe headache or migraine history is inversely correlated with dietary sodium intake: NHANES 1999–2004. Headache 2016; 56(4):688–698. doi:10.1111/head.12792

- Awada A, al Jumah M. The first-of-Ramadan headache. Headache 1999; 39(7):490–493. pmid:11279933

- Abu-Salameh I, Plakht Y, Ifergane G. Migraine exacerbation during Ramadan fasting. J Headache Pain 2010; 11(6):513–517. doi:10.1007/s10194-010-0242-z

- Nazari F, Safavi M, Mahmudi M. Migraine and its relation with lifestyle in women. Pain Pract 2010; 10(3):228–234. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00343.x

- Nas A, Mirza N, Hagele F, et al. Impact of breakfast skipping compared with dinner skipping on regulation of energy balance and metabolic risk. Am J Clin Nutr 2017; 105(6):1351–1361. doi:10.3945/ajcn.116.151332

- Torelli P, Manzoni GC. Fasting headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2010; 14(4):284–291. doi:10.1007/s11916-010-0119-5

- Yoshimura E, Hatamoto Y, Yonekura S, Tanaka H. Skipping breakfast reduces energy intake and physical activity in healthy women who are habitual breakfast eaters: a randomized crossover trial. Physiol Behav 2017; 174:89–94. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.008

- Pendergast FJ, Livingstone KM, Worsley A, McNaughton SA. Correlates of meal skipping in young adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016; 13(1):125. doi:10.1186/s12966-016-0451-1

- Maki KC, Phillips-Eakley AK, Smith KN. The effects of breakfast consumption and composition on metabolic wellness with a focus on carbohydrate metabolism. Adv Nutr 2016; 7(3):613S–621S. doi:10.3945/an.115.010314

- Shirreffs SM, Merson SJ, Fraser SM, Archer DT. The effects of fluid restriction on hydration status and subjective feelings in man. Br J Nutr 2004; 91(6):951–958. doi:10.1079/BJN20041149

- Blau JN. Water deprivation: a new migraine precipitant. Headache 2005; 45(6):757–759. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05143_3.x

- Price A, Burls A. Increased water intake to reduce headache: learning from a critical appraisal. J Eval Clin Pract 2015; 21(6):1212–1218. doi:10.1111/jep.12413

- Balbin JE, Nerenberg R, Baratloo A, Friedman BW. Intravenous fluids for migraine: a post hoc analysis of clinical trial data. Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34(4):713–716. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.12.080

- Spigt M, Weerkamp N, Troost J, van Schayck CP, Knottnerus JA. A randomized trial on the effects of regular water intake in patients with recurrent headaches. Fam Pract 2012; 29(4):370–375. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmr112

- Armstrong LE, Johnson EC. Water intake, water balance, and the elusive daily water requirement. Nutrients 2018; 10(12). doi:10.3390/nu10121928

- Fried NT, Elliott MB, Oshinsky ML. The role of adenosine signaling in headache: a review. Brain Sci 2017; 7(3). doi:10.3390/brainsci7030030

- Lee MJ, Choi HA, Choi H, Chung CS. Caffeine discontinuation improves acute migraine treatment: a prospective clinic-based study. J Headache Pain 2016; 17(1):71. doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0662-5

- Shirlow MJ, Mathers CD. A study of caffeine consumption and symptoms; indigestion, palpitations, tremor, headache and insomnia. Int J Epidemiol 1985; 14(2):239–248. doi:10.1093/ije/14.2.239

- Silverman K, Evans SM, Strain EC, Griffiths RR. Withdrawal syndrome after the double-blind cessation of caffeine consumption. N Engl J Med 1992; 327(16):1109–1114. doi:10.1056/NEJM199210153271601

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38(1):1–211. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202

- Krogh AB, Larsson B, Salvesen O, Linde M. A comparison between prospective Internet-based and paper diary recordings of headache among adolescents in the general population. Cephalalgia 2016; 36(4):335–345. doi:10.1177/0333102415591506

- Bandarian-Balooch S, Martin PR, McNally B, Brunelli A, Mackenzie S. Electronic-diary for recording headaches, triggers, and medication use: development and evaluation. Headache 2017; 57(10):1551–1569. doi:10.1111/head.13184

- Tassorelli C, Sances G, Allena M, et al. The usefulness and applicability of a basic headache diary before first consultation: results of a pilot study conducted in two centres. Cephalalgia 2008; 28(10):1023–1030. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01639.x

- Baos V, Ester F, Castellanos A, et al. Use of a structured migraine diary improves patient and physician communication about migraine disability and treatment outcomes. Int J Clin Pract 2005; 59(3):281–286. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00469.x

- Martin PR, MacLeod C. Behavioral management of headache triggers: avoidance of triggers is an inadequate strategy. Clin Psychol Rev 2009; 29(6):483–495. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.002

- Giannini G, Zanigni S, Grimaldi D, et al. Cephalalgiaphobia as a feature of high-frequency migraine: a pilot study. J Headache Pain 2013; 14:49. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-14-49

- Westergaard ML, Glumer C, Hansen EH, Jensen RH. Medication overuse, healthy lifestyle behaviour and stress in chronic headache: results from a population-based representative survey. Cephalalgia 2016; 36(1):15–28. doi:10.1177/0333102415578430

- Christiansen S, Jurgens TP, Klinger R. Outpatient combined group and individual cognitive-behavioral treatment for patients with migraine and tension-type headache in a routine clinical setting. Headache 2015; 55(8):1072–1091. doi:10.1111/head.12626

- Martin PR, Aiello R, Gilson K, Meadows G, Milgrom J, Reece J. Cognitive behavior therapy for comorbid migraine and/or tension-type headache and major depressive disorder: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2015; 73:8–18. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2015.07.005

- Nash JM, Park ER, Walker BB, Gordon N, Nicholson RA. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for disabling headache. Pain Med 2004; 5(2):178–186. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2004.04031.x

- Sorbi MJ, Balk Y, Kleiboer AM, Couturier EG. Follow-up over 20 months confirms gains of online behavioural training in frequent episodic migraine. Cephalalgia 2017; 37(3):236–250. doi:10.1177/0333102416657145

- Thorn BE, Pence LB, Ward LC, et al. A randomized clinical trial of targeted cognitive behavioral treatment to reduce catastrophizing in chronic headache sufferers. J Pain 2007; 8(12):938–949. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.010

- Nestoriuc Y, Martin A. Efficacy of biofeedback for migraine: a meta-analysis. Pain 2007; 128(1–2):111–127. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.007

- Blanchard EB, Appelbaum KA, Nicholson NL, et al. A controlled evaluation of the addition of cognitive therapy to a home-based biofeedback and relaxation treatment of vascular headache. Headache 1990; 30(6):371–376. pmid:2196240

- Gu Q, Hou JC, Fang XM. Mindfulness meditation for primary headache pain: a meta-analysis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2018; 131(7):829–838. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.228242

- Day MA, Thorn BE. The mediating role of pain acceptance during mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for headache. Complement Ther Med 2016; 25:51–54. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2016.01.002

- Williamson DA, Monguillot JE, Jarrell MP, Cohen RA, Pratt JM, Blouin DC. Relaxation for the treatment of headache. Controlled evaluation of two group programs. Behav Modif 1984; 8(3):407–424. doi:10.1177/01454455840083007

- Merelle SY, Sorbi MJ, Duivenvoorden HJ, Passchier J. Qualities and health of lay trainers with migraine for behavioral attack prevention. Headache 2010; 50(4):613–625. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01241.x

- Gaul C, van Doorn C, Webering N, et al. Clinical outcome of a headache-specific multidisciplinary treatment program and adherence to treatment recommendations in a tertiary headache center: an observational study. J Headache Pain 2011; 12(4):475–483. doi:10.1007/s10194-011-0348-y

- Wallasch TM, Kropp P. Multidisciplinary integrated headache care: a prospective 12-month follow-up observational study. J Headache Pain 2012; 13(7):521–529. doi:10.1007/s10194-012-0469-y

- Lemstra M, Stewart B, Olszynski WP. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary intervention in the treatment of migraine: a randomized clinical trial. Headache 2002; 42(9):845–854. pmid:12390609

- Krause SJ, Stillman MJ, Tepper DE, Zajac D. A prospective cohort study of outpatient interdisciplinary rehabilitation of chronic headache patients. Headache 2017; 57(3):428–440. doi:10.1111/head.13020

Migraine is the second leading cause of years of life lived with a disability globally.1 It affects people of all ages, but particularly during the years associated with the highest productivity in terms of work and family life.

Migraine is a genetic neurologic disease that can be influenced or triggered by environmental factors. However, triggers do not cause migraine. For example, stress does not cause migraine, but it can exacerbate it.

Primary care physicians can help patients reduce the likelihood of a migraine attack, the severity of symptoms, or both by offering lifestyle counseling centered around the mnemonic SEEDS: sleep, exercise, eat, diary, and stress. In this article, each factor is discussed individually for its current support in the literature along with best-practice recommendations.

S IS FOR SLEEP

Before optimizing sleep hygiene, screen for sleep apnea, especially in those who have chronic daily headache upon awakening. An excellent tool is the STOP-Bang screening questionnaire5 (www.stopbang.ca/osa/screening.php). Patients respond “yes” or “no” to the following questions:

- Snoring: Do you snore loudly (louder than talking or loud enough to be heard through closed doors)?

- Tired: Do you often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during the daytime?

- Observed: Has anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep?

- Pressure: Do you have or are you being treated for high blood pressure?

- Body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2?

- Age over 50?

- Neck circumference larger than 40 cm (females) or 42 cm (males)?

- Gender—male?

Each “yes” answer is scored as 1 point. A score less than 3 indicates low risk of obstructive sleep apnea; 3 to 4 indicates moderate risk; and 5 or more indicates high risk. Optimization of sleep apnea with continuous positive airway pressure therapy can improve sleep apnea headache.6 The improved sleep from reduced arousals may also mitigate migraine symptoms.

Behavioral modification for sleep hygiene can convert chronic migraine to episodic migraine.7 One such program is stimulus control therapy, which focuses on using cues to initiate sleep (Table 1). Patients are encouraged to keep the bedroom quiet, dark, and cool, and to go to sleep at the same time every night. Importantly, the bed should be associated only with sleep. If patients are unable to fall asleep within 20 to 30 minutes, they should leave the room so they do not associate the bed with frustration and anxiety. Use of phones, tablets, and television in the bedroom is discouraged as these devices may make it more difficult to fall asleep.8

The next option is sleep restriction, which is useful for comorbid insomnia. Patients keep a sleep diary to better understand their sleep-wake cycle. The goal is 90% sleep efficiency, meaning that 90% of the time in bed (TIB) is spent asleep. For example, if the patient is in bed 8 hours but asleep only 4 hours, sleep efficiency is 50%. The goal is to reduce TIB to match the time asleep and to agree on a prescribed daily wake-up time. When the patient is consistently sleeping 90% of the TIB, add 30-minute increments until he or she is appropriately sleeping 7 to 8 hours at night.9 Naps are not recommended.

Let patients know that their migraine may worsen until a new routine sleep pattern emerges. This method is not recommended for patients with untreated sleep apnea.

E IS FOR EXERCISE

Exercise is broadly recommended for a healthy lifestyle; some evidence suggests that it can also be useful in the management of migraine.10 Low levels of physical activity and a sedentary lifestyle are associated with migraine.11 It is unclear if patients with migraine are less likely to exercise because they want to avoid triggering a migraine or if a sedentary lifestyle increases their risk.

Exercise has been studied for its prophylactic benefits in migraine, and one hypothesis relates to beta-endorphins. Levels of beta-endorphins are reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with migraine.12 Exercise programs may increase levels while reducing headache frequency and duration.13 One study showed that pain thresholds do not change with exercise programs, suggesting that it is avoidance behavior that is positively altered rather than the underlying pain pathways.14

A systematic review and meta-analysis based on 5 randomized controlled trials and 1 nonrandomized controlled clinical trial showed that exercise reduced monthly migraine days by only 0.6 (± 0.3) days, but the data also suggested that as the exercise intensity increased, so did the positive effects.10

Some data suggest that exercise may also reduce migraine duration and severity as well as the need for abortive medication.10 Two studies in this systematic review15,16 showed that exercise benefits were equivalent to those of migraine preventives such as amitriptyline and topiramate; the combination of amitriptyline and exercise was more beneficial than exercise alone. Multiple types of exercise were beneficial, including walking, jogging, cross-training, and cycling when done for least 6 weeks and for 30 to 50 minutes 3 to 5 times a week.

These findings are in line with the current recommendations for general health from the American College of Sports Medicine, ie, moderate to vigorous cardiorespiratory exercise for 30 to 60 minutes 3 to 5 times a week (or 150 minutes per week). The daily exercise can be continuous or done in intervals of less than 20 minutes. For those with a sedentary lifestyle, as is seen in a significant proportion of the migraine population, light to moderate exercise for less than 20 minutes is still beneficial.17

Based on this evidence, the best current recommendation for patients with migraine is to engage in graded moderate cardiorespiratory exercise, although any exercise is better than none. If a patient is sedentary or has poor exercise tolerance, or both, exercising once a week for shorter time periods may be a manageable place to start.

Some patients may identify exercise as a trigger or exacerbating factor in migraine. These patients may need appropriate prophylactic and abortive therapies before starting an exercise regimen.

THE SECOND E IS FOR EAT (FOOD AND DRINK)

Many patients believe that some foods trigger migraine attacks, but further study is needed. The most consistent food triggers appear to be red wine and caffeine (withdrawal).18,19 Interestingly, patients with migraine report low levels of alcohol consumption,20 but it is unclear if that is because alcohol has a protective effect or if patients avoid it.

Some patients may crave certain foods in the prodromal phase of an attack, eat the food, experience the attack, and falsely conclude that the food caused the attack.21 Premonitory symptoms include fatigue, cognitive changes, homeostatic changes, sensory hyperresponsiveness, and food cravings.21 It is difficult to distinguish between premonitory phase food cravings and true triggers because premonitory symptoms can precede headache by 48 to 72 hours, and the timing for a trigger to be considered causal is not known.22

Chocolate is often thought to be a migraine trigger, but the evidence argues against this and even suggests that sweet cravings are a part of the premonitory phase.23 Monosodium glutamate is often identified as a trigger as well, but the literature is inconsistent and does not support a causal relationship.24 Identifying true food triggers in migraine is difficult, and patients with migraine may have poor quality diets, with some foods acting as true triggers for certain patients.25 These possibilities have led to the development of many “migraine diets,” including elimination diets.

Elimination diets

Elimination diets involve avoiding specific food items over a period of time and then adding them back in one at a time to gauge whether they cause a reaction in the body. A number of these diets have been studied for their effects on headache and migraine:

Gluten-free diets restrict foods that contain wheat, rye, and barley. A systematic review of gluten-free diets in patients with celiac disease found that headache or migraine frequency decreased by 51.6% to 100% based on multiple cohort studies (N = 42,388).26 There are no studies on the use of a gluten-free diet for migraine in patients without celiac disease.

Immunoglobulin G-elimination diets restrict foods that serve as antigens for IgG. However, data supporting these diets are inconsistent. Two small randomized controlled trials found that the diets improved migraine symptoms, but a larger study found no improvement in the number of migraine days at 12 weeks, although there was an initially significant effect at 4 weeks.27–29

Antihistamine diets restrict foods that have high levels of histamines, including fermented dairy, vegetables, soy products, wine, beer, alcohol, and those that cause histamine release regardless of IgE testing results. A prospective single-arm study of antihistamine diets in patients with chronic headache reported symptom improvement, which could be applied to certain comorbidities such as mast cell activation syndrome.30 Another prospective nonrandomized controlled study eliminated foods based on positive IgE skin-prick testing for allergy in patients with recurrent migraine and found that it reduced headache frequency.31

Tyramine-free diets are often recommended due to the presumption that tyramine-containing foods (eg, aged cheese, cured or smoked meats and fish, and beer) are triggers. However, multiple studies have reviewed this theory with inconsistent results,32 and the only study of a tyramine-free diet was negative.33 In addition, commonly purported high-tyramine foods have lower tyramine levels than previously thought.34

Low-fat diets in migraine are supported by 2 small randomized controlled trials and a prospective study showing a decrease in symptom severity; the results for frequency are inconsistent.35–37

Low-glycemic index diets are supported in migraine by 1 randomized controlled trial that showed improvement in migraine frequency in a diet group and in a control group of patients who took a standard migraine-preventive medication to manage their symptoms.38

Other migraine diets

Diets high in certain foods or ingredient ratios, as opposed to elimination diets, have also been studied in patients with migraine. One promising diet containing high levels of omega-3 fatty acids and low levels of omega-6 fatty acids was shown in a systematic review to reduce the duration of migraine but not the frequency or severity.39 A more recent randomized controlled trial of this diet in chronic migraine also showed that it decreased migraine frequency.40

The ketogenic diet (high fat, low carbohydrate) had promising results in a randomized controlled trial in overweight women with migraine and in a prospective study.41,42 However, a prospective study of the Atkins diet in teenagers with chronic daily headaches showed no benefit.43 The ketogenic diet is difficult to follow and may work in part due to weight loss alone, although ketogenesis itself may also play a role.41,44

Sodium levels have been shown to be higher in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with migraine than in controls, particularly during an attack.45 For a prehypertensive population or an elderly population, a low-sodium diet may be beneficial based on 2 prospective trials.46,47 However, a younger female population without hypertension and low-to-normal body mass index had a reduced probability of migraine while consuming a high-sodium diet.48

Counseling about sodium intake should be tailored to specific patient populations. For example, a diet low in sodium may be appropriate for patients with vascular risk factors such as hypertension, whereas a high-sodium diet may be appropriate in patients with comorbidities like postural tachycardia syndrome or in those with a propensity for low blood pressure or low body mass index.

Encourage routine meals and hydration

The standard advice for patients with migraine is to consume regular meals. Headaches have been associated with fasting, and those with migraine are predisposed to attacks in the setting of fasting.49,50 Migraine is more common when meals are skipped, particularly breakfast.51

It is unclear how fasting lowers the migraine threshold. Nutritional studies show that skipping meals, particularly breakfast, increases low-grade inflammation and impairs glucose metabolism by affecting insulin and fat oxidation metabolism.52 However, hypoglycemia itself is not a consistent cause of headache or migraine attacks.53 As described above, a randomized controlled trial of a low-glycemic index diet actually decreased migraine frequency and severity.38 Skipping meals also reduces energy and is associated with reduced physical activity, perhaps leading to multiple compounding triggers that further lower the migraine threshold.54,55

When counseling patients about the need to eat breakfast, consider what they normally consume (eg, is breakfast just a cup of coffee?). Replacing simple carbohydrates with protein, fats, and fiber may be beneficial for general health, but the effects on migraine are not known, nor is the optimal composition of breakfast foods.55

The optimal timing of breakfast relative to awakening is also unclear, but in general, it should be eaten within 30 to 60 minutes of rising. Also consider patients’ work hours—delayed-phase or shift workers have altered sleep cycles.

Recommendations vary in regard to hydration. Headache is associated with fluid restriction and dehydration,56,57 but only a few studies suggest that rehydration and increased hydration status can improve migraine.58 In fact, a single post hoc analysis of a metoclopramide study showed that intravenous fluid alone for patients with migraine in the emergency room did not improve pain outcomes.59

The amount of water patients should drink daily in the setting of migraine is also unknown, but a study showed benefit with 4 L, which equates to a daily intake of 16 eight-ounce glasses.60 One review on general health that could be extrapolated given the low risk of the intervention indicated that 1.8 L daily (7 to 8 eight-ounce glasses) promoted a euhydration status in most people, although many factors contribute to hydration status.61

Caffeine intake is also a major consideration. Caffeine is a nonspecific adenosine receptor antagonist that modulates adenosine receptors like the pronociceptive 2A receptor, leading to changes integral to the neuropathophysiology of migraine.62 Caffeine has analgesic properties at doses greater than 65 to 200 mg and augments the effects of analgesics such as acetaminophen and aspirin. Chronic caffeine use can lead to withdrawal symptoms when intake is stopped abruptly; this is thought to be due to upregulation of adenosine receptors, but the effect varies based on genetic predisposition.19

The risk of chronic daily headache may relate to high use of caffeine preceding the onset of chronification, and caffeine abstinence may improve response to acute migraine treatment.19,63 There is a dose-dependent risk of headache.64,65 Current recommendations suggest limiting caffeine consumption to less than 200 mg per day or stopping caffeine consumption altogether based on the quantity required for caffeine-withdrawal headache.66 Varying the caffeine dose from day to day may also trigger headache due to the high sensitivity to caffeine withdrawal.

While many diets have shown potential benefit in patients with migraine, more studies are needed before any one “migraine diet” can be recommended. Caution should be taken, as there is risk of adverse effects from nutrient deficiencies or excess levels, especially if the patient is not under the care of a healthcare professional who is familiar with the diet.

Whether it is beneficial to avoid specific food triggers at this time is unclear and still controversial even within the migraine community because some of these foods may be misattributed as triggers instead of premonitory cravings driven by the hypothalamus. It is important to counsel patients with migraine to eat a healthy diet with consistent meals, to maintain adequate hydration, and to keep their caffeine intake low or at least consistent, although these teachings are predominantly based on limited studies with extrapolation from nutrition research.

D IS FOR DIARY

A headache diary is a recommended part of headache management and may enhance the accuracy of diagnosis and assist in treatment modifications. Paper and electronic diaries have been used. Electronic diaries may be more accurate for real-time use, but patients may be more likely to complete a paper one.67 Patients prefer electronic diaries over long paper forms,68 but a practical issue to consider is easy electronic access.

Patients can start keeping a headache diary before the initial consultation to assist with diagnosis, or early in their management. A first-appointment diary mailed with instructions is a feasible option.69 These types of diaries ask detailed questions to help diagnose all major primary headache types including menstrual migraine and to identify concomitant medication-overuse headache. Physicians and patients generally report improved communication with use of a diary.70

Some providers distinguish between a headache diary and a calendar. In standard practice, a headache diary is the general term referring to both, but the literature differentiates between the two. Both should at least include headache frequency, with possible inclusion of other factors such as headache duration, headache intensity, analgesic use, headache impact on function, and absenteeism. Potential triggers including menses can also be tracked. The calendar version can fit on a single page and can be used for simple tracking of headache frequency and analgesia use.

One of the simplest calendars to use is the “stoplight” calendar. Red days are when a patient is completely debilitated in bed. On a yellow day, function at work, school, or daily activities is significantly reduced by migraine, but the patient is not bedbound. A green day is when headache is present but function is not affected. No color is placed if the patient is 100% headache-free.

Acute treatment use can be written in or, to improve compliance, a checkmark can be placed on days of treatment. Patients who are tracking menses circle the days of menstruation. The calendar-diary should be brought to every appointment to track treatment response and medication use.

THE SECOND S IS FOR STRESS

Behavioral management such as cognitive behavioral therapy in migraine has been shown to decrease catastrophizing, migraine disability, and headache severity and frequency.74 Both depression and anxiety can improve along with migraine.75 Cognitive behavioral therapy can be provided in individualized sessions or group sessions, either in person or online.74,76,77 The effects become more prominent about 5 weeks into treatment.78

Biofeedback, which uses behavioral techniques paired with physiologic autonomic measures, has been extensively studied, and shows benefit in migraine, including in meta-analysis.79 The types of biofeedback measurements used include electromyography, electroencephalography, temperature, sweat sensors, heart rate, blood volume pulse feedback, and respiration bands. While biofeedback is generally done under the guidance of a therapist, it can still be useful with minimal therapist contact and supplemental audio.80

Mindfulness, or the awareness of thoughts, feelings, and sensations in the present moment without judgment, is a behavioral technique that can be done alone or paired with another technique. It is often taught through a mindfulness-based stress-reduction program, which relies on a standardized approach. A meta-analysis showed that mindfulness improves pain intensity, headache frequency, disability, self-efficacy, and quality of life.81 It may work by encouraging pain acceptance.82

Relaxation techniques are also employed in migraine management, either alone or in conjunction with techniques mentioned above, such as mindfulness. They include progressive muscle relaxation and deep breathing. Relaxation has been shown to be effective when done by professional trainers as well as lay trainers in both individual and group settings.83,84

In patients with intractable headache, more-intensive inpatient and outpatient programs have been tried. Inpatient admissions with multidisciplinary programs that include a focus on behavioral techniques often paired with lifestyle education and sometimes pharmacologic management can be beneficial.85,86 These programs have also been successfully conducted as multiple outpatient sessions.86–88

Stress management is an important aspect of migraine management. These treatments often involve homework and require active participation.

LIFESTYLE FOR ALL

All patients with migraine should initiate lifestyle modifications (see Advice to patients with migraine: SEEDS for success). Modifications with the highest level of evidence, specifically behavioral techniques, have had the most reproducible results. A headache diary is an essential tool to identify patterns and needs for optimization of acute or preventive treatment regimens. The strongest evidence is for the behavioral management techniques for stress reduction.

Migraine is the second leading cause of years of life lived with a disability globally.1 It affects people of all ages, but particularly during the years associated with the highest productivity in terms of work and family life.

Migraine is a genetic neurologic disease that can be influenced or triggered by environmental factors. However, triggers do not cause migraine. For example, stress does not cause migraine, but it can exacerbate it.

Primary care physicians can help patients reduce the likelihood of a migraine attack, the severity of symptoms, or both by offering lifestyle counseling centered around the mnemonic SEEDS: sleep, exercise, eat, diary, and stress. In this article, each factor is discussed individually for its current support in the literature along with best-practice recommendations.

S IS FOR SLEEP

Before optimizing sleep hygiene, screen for sleep apnea, especially in those who have chronic daily headache upon awakening. An excellent tool is the STOP-Bang screening questionnaire5 (www.stopbang.ca/osa/screening.php). Patients respond “yes” or “no” to the following questions:

- Snoring: Do you snore loudly (louder than talking or loud enough to be heard through closed doors)?

- Tired: Do you often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during the daytime?

- Observed: Has anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep?

- Pressure: Do you have or are you being treated for high blood pressure?

- Body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2?

- Age over 50?

- Neck circumference larger than 40 cm (females) or 42 cm (males)?

- Gender—male?

Each “yes” answer is scored as 1 point. A score less than 3 indicates low risk of obstructive sleep apnea; 3 to 4 indicates moderate risk; and 5 or more indicates high risk. Optimization of sleep apnea with continuous positive airway pressure therapy can improve sleep apnea headache.6 The improved sleep from reduced arousals may also mitigate migraine symptoms.

Behavioral modification for sleep hygiene can convert chronic migraine to episodic migraine.7 One such program is stimulus control therapy, which focuses on using cues to initiate sleep (Table 1). Patients are encouraged to keep the bedroom quiet, dark, and cool, and to go to sleep at the same time every night. Importantly, the bed should be associated only with sleep. If patients are unable to fall asleep within 20 to 30 minutes, they should leave the room so they do not associate the bed with frustration and anxiety. Use of phones, tablets, and television in the bedroom is discouraged as these devices may make it more difficult to fall asleep.8

The next option is sleep restriction, which is useful for comorbid insomnia. Patients keep a sleep diary to better understand their sleep-wake cycle. The goal is 90% sleep efficiency, meaning that 90% of the time in bed (TIB) is spent asleep. For example, if the patient is in bed 8 hours but asleep only 4 hours, sleep efficiency is 50%. The goal is to reduce TIB to match the time asleep and to agree on a prescribed daily wake-up time. When the patient is consistently sleeping 90% of the TIB, add 30-minute increments until he or she is appropriately sleeping 7 to 8 hours at night.9 Naps are not recommended.

Let patients know that their migraine may worsen until a new routine sleep pattern emerges. This method is not recommended for patients with untreated sleep apnea.

E IS FOR EXERCISE

Exercise is broadly recommended for a healthy lifestyle; some evidence suggests that it can also be useful in the management of migraine.10 Low levels of physical activity and a sedentary lifestyle are associated with migraine.11 It is unclear if patients with migraine are less likely to exercise because they want to avoid triggering a migraine or if a sedentary lifestyle increases their risk.

Exercise has been studied for its prophylactic benefits in migraine, and one hypothesis relates to beta-endorphins. Levels of beta-endorphins are reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with migraine.12 Exercise programs may increase levels while reducing headache frequency and duration.13 One study showed that pain thresholds do not change with exercise programs, suggesting that it is avoidance behavior that is positively altered rather than the underlying pain pathways.14

A systematic review and meta-analysis based on 5 randomized controlled trials and 1 nonrandomized controlled clinical trial showed that exercise reduced monthly migraine days by only 0.6 (± 0.3) days, but the data also suggested that as the exercise intensity increased, so did the positive effects.10

Some data suggest that exercise may also reduce migraine duration and severity as well as the need for abortive medication.10 Two studies in this systematic review15,16 showed that exercise benefits were equivalent to those of migraine preventives such as amitriptyline and topiramate; the combination of amitriptyline and exercise was more beneficial than exercise alone. Multiple types of exercise were beneficial, including walking, jogging, cross-training, and cycling when done for least 6 weeks and for 30 to 50 minutes 3 to 5 times a week.

These findings are in line with the current recommendations for general health from the American College of Sports Medicine, ie, moderate to vigorous cardiorespiratory exercise for 30 to 60 minutes 3 to 5 times a week (or 150 minutes per week). The daily exercise can be continuous or done in intervals of less than 20 minutes. For those with a sedentary lifestyle, as is seen in a significant proportion of the migraine population, light to moderate exercise for less than 20 minutes is still beneficial.17

Based on this evidence, the best current recommendation for patients with migraine is to engage in graded moderate cardiorespiratory exercise, although any exercise is better than none. If a patient is sedentary or has poor exercise tolerance, or both, exercising once a week for shorter time periods may be a manageable place to start.

Some patients may identify exercise as a trigger or exacerbating factor in migraine. These patients may need appropriate prophylactic and abortive therapies before starting an exercise regimen.

THE SECOND E IS FOR EAT (FOOD AND DRINK)

Many patients believe that some foods trigger migraine attacks, but further study is needed. The most consistent food triggers appear to be red wine and caffeine (withdrawal).18,19 Interestingly, patients with migraine report low levels of alcohol consumption,20 but it is unclear if that is because alcohol has a protective effect or if patients avoid it.

Some patients may crave certain foods in the prodromal phase of an attack, eat the food, experience the attack, and falsely conclude that the food caused the attack.21 Premonitory symptoms include fatigue, cognitive changes, homeostatic changes, sensory hyperresponsiveness, and food cravings.21 It is difficult to distinguish between premonitory phase food cravings and true triggers because premonitory symptoms can precede headache by 48 to 72 hours, and the timing for a trigger to be considered causal is not known.22

Chocolate is often thought to be a migraine trigger, but the evidence argues against this and even suggests that sweet cravings are a part of the premonitory phase.23 Monosodium glutamate is often identified as a trigger as well, but the literature is inconsistent and does not support a causal relationship.24 Identifying true food triggers in migraine is difficult, and patients with migraine may have poor quality diets, with some foods acting as true triggers for certain patients.25 These possibilities have led to the development of many “migraine diets,” including elimination diets.

Elimination diets

Elimination diets involve avoiding specific food items over a period of time and then adding them back in one at a time to gauge whether they cause a reaction in the body. A number of these diets have been studied for their effects on headache and migraine:

Gluten-free diets restrict foods that contain wheat, rye, and barley. A systematic review of gluten-free diets in patients with celiac disease found that headache or migraine frequency decreased by 51.6% to 100% based on multiple cohort studies (N = 42,388).26 There are no studies on the use of a gluten-free diet for migraine in patients without celiac disease.

Immunoglobulin G-elimination diets restrict foods that serve as antigens for IgG. However, data supporting these diets are inconsistent. Two small randomized controlled trials found that the diets improved migraine symptoms, but a larger study found no improvement in the number of migraine days at 12 weeks, although there was an initially significant effect at 4 weeks.27–29

Antihistamine diets restrict foods that have high levels of histamines, including fermented dairy, vegetables, soy products, wine, beer, alcohol, and those that cause histamine release regardless of IgE testing results. A prospective single-arm study of antihistamine diets in patients with chronic headache reported symptom improvement, which could be applied to certain comorbidities such as mast cell activation syndrome.30 Another prospective nonrandomized controlled study eliminated foods based on positive IgE skin-prick testing for allergy in patients with recurrent migraine and found that it reduced headache frequency.31

Tyramine-free diets are often recommended due to the presumption that tyramine-containing foods (eg, aged cheese, cured or smoked meats and fish, and beer) are triggers. However, multiple studies have reviewed this theory with inconsistent results,32 and the only study of a tyramine-free diet was negative.33 In addition, commonly purported high-tyramine foods have lower tyramine levels than previously thought.34

Low-fat diets in migraine are supported by 2 small randomized controlled trials and a prospective study showing a decrease in symptom severity; the results for frequency are inconsistent.35–37

Low-glycemic index diets are supported in migraine by 1 randomized controlled trial that showed improvement in migraine frequency in a diet group and in a control group of patients who took a standard migraine-preventive medication to manage their symptoms.38

Other migraine diets

Diets high in certain foods or ingredient ratios, as opposed to elimination diets, have also been studied in patients with migraine. One promising diet containing high levels of omega-3 fatty acids and low levels of omega-6 fatty acids was shown in a systematic review to reduce the duration of migraine but not the frequency or severity.39 A more recent randomized controlled trial of this diet in chronic migraine also showed that it decreased migraine frequency.40

The ketogenic diet (high fat, low carbohydrate) had promising results in a randomized controlled trial in overweight women with migraine and in a prospective study.41,42 However, a prospective study of the Atkins diet in teenagers with chronic daily headaches showed no benefit.43 The ketogenic diet is difficult to follow and may work in part due to weight loss alone, although ketogenesis itself may also play a role.41,44

Sodium levels have been shown to be higher in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with migraine than in controls, particularly during an attack.45 For a prehypertensive population or an elderly population, a low-sodium diet may be beneficial based on 2 prospective trials.46,47 However, a younger female population without hypertension and low-to-normal body mass index had a reduced probability of migraine while consuming a high-sodium diet.48

Counseling about sodium intake should be tailored to specific patient populations. For example, a diet low in sodium may be appropriate for patients with vascular risk factors such as hypertension, whereas a high-sodium diet may be appropriate in patients with comorbidities like postural tachycardia syndrome or in those with a propensity for low blood pressure or low body mass index.

Encourage routine meals and hydration

The standard advice for patients with migraine is to consume regular meals. Headaches have been associated with fasting, and those with migraine are predisposed to attacks in the setting of fasting.49,50 Migraine is more common when meals are skipped, particularly breakfast.51

It is unclear how fasting lowers the migraine threshold. Nutritional studies show that skipping meals, particularly breakfast, increases low-grade inflammation and impairs glucose metabolism by affecting insulin and fat oxidation metabolism.52 However, hypoglycemia itself is not a consistent cause of headache or migraine attacks.53 As described above, a randomized controlled trial of a low-glycemic index diet actually decreased migraine frequency and severity.38 Skipping meals also reduces energy and is associated with reduced physical activity, perhaps leading to multiple compounding triggers that further lower the migraine threshold.54,55

When counseling patients about the need to eat breakfast, consider what they normally consume (eg, is breakfast just a cup of coffee?). Replacing simple carbohydrates with protein, fats, and fiber may be beneficial for general health, but the effects on migraine are not known, nor is the optimal composition of breakfast foods.55

The optimal timing of breakfast relative to awakening is also unclear, but in general, it should be eaten within 30 to 60 minutes of rising. Also consider patients’ work hours—delayed-phase or shift workers have altered sleep cycles.

Recommendations vary in regard to hydration. Headache is associated with fluid restriction and dehydration,56,57 but only a few studies suggest that rehydration and increased hydration status can improve migraine.58 In fact, a single post hoc analysis of a metoclopramide study showed that intravenous fluid alone for patients with migraine in the emergency room did not improve pain outcomes.59

The amount of water patients should drink daily in the setting of migraine is also unknown, but a study showed benefit with 4 L, which equates to a daily intake of 16 eight-ounce glasses.60 One review on general health that could be extrapolated given the low risk of the intervention indicated that 1.8 L daily (7 to 8 eight-ounce glasses) promoted a euhydration status in most people, although many factors contribute to hydration status.61

Caffeine intake is also a major consideration. Caffeine is a nonspecific adenosine receptor antagonist that modulates adenosine receptors like the pronociceptive 2A receptor, leading to changes integral to the neuropathophysiology of migraine.62 Caffeine has analgesic properties at doses greater than 65 to 200 mg and augments the effects of analgesics such as acetaminophen and aspirin. Chronic caffeine use can lead to withdrawal symptoms when intake is stopped abruptly; this is thought to be due to upregulation of adenosine receptors, but the effect varies based on genetic predisposition.19

The risk of chronic daily headache may relate to high use of caffeine preceding the onset of chronification, and caffeine abstinence may improve response to acute migraine treatment.19,63 There is a dose-dependent risk of headache.64,65 Current recommendations suggest limiting caffeine consumption to less than 200 mg per day or stopping caffeine consumption altogether based on the quantity required for caffeine-withdrawal headache.66 Varying the caffeine dose from day to day may also trigger headache due to the high sensitivity to caffeine withdrawal.

While many diets have shown potential benefit in patients with migraine, more studies are needed before any one “migraine diet” can be recommended. Caution should be taken, as there is risk of adverse effects from nutrient deficiencies or excess levels, especially if the patient is not under the care of a healthcare professional who is familiar with the diet.

Whether it is beneficial to avoid specific food triggers at this time is unclear and still controversial even within the migraine community because some of these foods may be misattributed as triggers instead of premonitory cravings driven by the hypothalamus. It is important to counsel patients with migraine to eat a healthy diet with consistent meals, to maintain adequate hydration, and to keep their caffeine intake low or at least consistent, although these teachings are predominantly based on limited studies with extrapolation from nutrition research.

D IS FOR DIARY

A headache diary is a recommended part of headache management and may enhance the accuracy of diagnosis and assist in treatment modifications. Paper and electronic diaries have been used. Electronic diaries may be more accurate for real-time use, but patients may be more likely to complete a paper one.67 Patients prefer electronic diaries over long paper forms,68 but a practical issue to consider is easy electronic access.

Patients can start keeping a headache diary before the initial consultation to assist with diagnosis, or early in their management. A first-appointment diary mailed with instructions is a feasible option.69 These types of diaries ask detailed questions to help diagnose all major primary headache types including menstrual migraine and to identify concomitant medication-overuse headache. Physicians and patients generally report improved communication with use of a diary.70