User login

Renal denervation reduced BP in sham-controlled trials, meta-analysis shows

although previous investigations of the procedure have had conflicting results.

Renal sympathetic denervation (RSD) was associated with statistically significant reductions in blood pressure assessed by 24-hour ambulatory, daytime ambulatory, and office measurements in the analysis of six trials including a total of 977 participants.

However, the benefit was particularly pronounced in more recent randomized trials that had few patients with isolated systolic hypertension, had highly experienced operators; used more complete techniques of radiofrequency ablation, used novel approaches such as endovascular renal denervation, and used efficacy endpoints such as clinical outcomes, according to investigator Partha Sardar, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and his colleagues.

“Altogether, the present study affirms the safety and efficacy of renal denervation for blood pressure reduction, and highlights the importance of incorporating the previously described modifications in trial design,” wrote Dr. Sardar and his coauthors. The report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

While initial trials of catheter-based denervation of renal arteries were positive, three blinded randomized, controlled trials showed no difference in blood pressure between the procedure and a sham procedure, the investigators said. Those findings led to several small, sham-controlled trials that incorporated the aforementioned changes.

For the six trials combined in the meta-analysis, reductions in 24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure were significantly lower for RSD, with a weighted mean difference of –3.65 mm Hg (P less than .001), Dr. Sardar and his colleagues reported.

For the earlier trials, the average reductions in 24-hour ambulatory systolic and diastolic blood pressure were 2.23 and 0.66 for RSD and sham patients, respectively.

By contrast, in the second-generation trials, those blood pressure reductions were 4.85 for RSD and 2.98 mm Hg for sham, they said in the report, adding that the reduction in daytime ambulatory systolic blood pressure with RSD was significantly greater for the second-generation studies.

The second-generation studies excluded patients with isolated systolic hypertension, based in part on observations that RSD has a more pronounced impact on blood pressure with combined systolic and diastolic hypertension, according to the authors.

Moreover, the second-generation studies required that very experienced operators perform the procedures, incorporated advanced catheter and ablation techniques, less often used modified medication regimens, and set ambulatory blood pressure as the primary end point, they added.

“These results should inform the design and powering of larger, pivotal trials to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of RSD in patients with uncontrolled and resistant hypertension,” Dr. Sardar and his coauthors said.

Dr. Sardar reported no relevant financial disclosures, as did most of the coauthors. Three coauthors provided disclosures related to Regado Biosciences, Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Medtronic, and ReCor Medical, among others.

SOURCE: Sardar P et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(13):1633-42.

While questions remain about the future of renal sympathetic denervation for treatment of hypertension, the present meta-analysis provides “interesting” findings that confirm a benefit of the procedure, particularly in the more recent randomized trials, editorialists said.

“The evidence is now there to conclude that RSD does lower blood pressure in hypertensive patients,” Sverre E. Kjeldsen, MD, PhD, Fadl E.M. Fadl Elmula, MD, PhD, and Alexandre Persu, MD, PhD, wrote in their editorial. That conclusion makes sense in light of knowledge that sympathetic overactivity is a known contributor to hypertension pathogenesis.

Although the blood pressure benefits of RSD in the second-generation trials still seem “relatively modest” and equate roughly to the effect of one antihypertensive drug, the aggregate results mask a wide variation in individual patient response, with up to 30% of patients experiencing dramatic improvements after the procedure, they said.

Accordingly, one key research priority is to figure out what patient characteristics might be used to single out patients who are extreme responders to the therapy.

That kind of optimized patient selection, in tandem with technical improvements in the procedure, they said, may help break the “glass ceiling” in blood pressure reduction reported in randomized trials to date.

“Research on RSD still has good days to come, and patients may eventually benefit from this research effort,” Dr. Kjeldsen, Dr. Fadl Elmula, and Dr. Persu concluded.

Dr. Kjeldsen and Dr. Fadl Elmula are at Oslo University Hospital, Ullevaal, and the University of Oslo; Dr. Persu is at the Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels. The comments summarize an editorial accompanying the article by Sardar et al. (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.008). Dr. Kjeldsen reported disclosures related to Merck KGaA, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Sanofi, and Takeda.

While questions remain about the future of renal sympathetic denervation for treatment of hypertension, the present meta-analysis provides “interesting” findings that confirm a benefit of the procedure, particularly in the more recent randomized trials, editorialists said.

“The evidence is now there to conclude that RSD does lower blood pressure in hypertensive patients,” Sverre E. Kjeldsen, MD, PhD, Fadl E.M. Fadl Elmula, MD, PhD, and Alexandre Persu, MD, PhD, wrote in their editorial. That conclusion makes sense in light of knowledge that sympathetic overactivity is a known contributor to hypertension pathogenesis.

Although the blood pressure benefits of RSD in the second-generation trials still seem “relatively modest” and equate roughly to the effect of one antihypertensive drug, the aggregate results mask a wide variation in individual patient response, with up to 30% of patients experiencing dramatic improvements after the procedure, they said.

Accordingly, one key research priority is to figure out what patient characteristics might be used to single out patients who are extreme responders to the therapy.

That kind of optimized patient selection, in tandem with technical improvements in the procedure, they said, may help break the “glass ceiling” in blood pressure reduction reported in randomized trials to date.

“Research on RSD still has good days to come, and patients may eventually benefit from this research effort,” Dr. Kjeldsen, Dr. Fadl Elmula, and Dr. Persu concluded.

Dr. Kjeldsen and Dr. Fadl Elmula are at Oslo University Hospital, Ullevaal, and the University of Oslo; Dr. Persu is at the Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels. The comments summarize an editorial accompanying the article by Sardar et al. (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.008). Dr. Kjeldsen reported disclosures related to Merck KGaA, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Sanofi, and Takeda.

While questions remain about the future of renal sympathetic denervation for treatment of hypertension, the present meta-analysis provides “interesting” findings that confirm a benefit of the procedure, particularly in the more recent randomized trials, editorialists said.

“The evidence is now there to conclude that RSD does lower blood pressure in hypertensive patients,” Sverre E. Kjeldsen, MD, PhD, Fadl E.M. Fadl Elmula, MD, PhD, and Alexandre Persu, MD, PhD, wrote in their editorial. That conclusion makes sense in light of knowledge that sympathetic overactivity is a known contributor to hypertension pathogenesis.

Although the blood pressure benefits of RSD in the second-generation trials still seem “relatively modest” and equate roughly to the effect of one antihypertensive drug, the aggregate results mask a wide variation in individual patient response, with up to 30% of patients experiencing dramatic improvements after the procedure, they said.

Accordingly, one key research priority is to figure out what patient characteristics might be used to single out patients who are extreme responders to the therapy.

That kind of optimized patient selection, in tandem with technical improvements in the procedure, they said, may help break the “glass ceiling” in blood pressure reduction reported in randomized trials to date.

“Research on RSD still has good days to come, and patients may eventually benefit from this research effort,” Dr. Kjeldsen, Dr. Fadl Elmula, and Dr. Persu concluded.

Dr. Kjeldsen and Dr. Fadl Elmula are at Oslo University Hospital, Ullevaal, and the University of Oslo; Dr. Persu is at the Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels. The comments summarize an editorial accompanying the article by Sardar et al. (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.008). Dr. Kjeldsen reported disclosures related to Merck KGaA, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Sanofi, and Takeda.

although previous investigations of the procedure have had conflicting results.

Renal sympathetic denervation (RSD) was associated with statistically significant reductions in blood pressure assessed by 24-hour ambulatory, daytime ambulatory, and office measurements in the analysis of six trials including a total of 977 participants.

However, the benefit was particularly pronounced in more recent randomized trials that had few patients with isolated systolic hypertension, had highly experienced operators; used more complete techniques of radiofrequency ablation, used novel approaches such as endovascular renal denervation, and used efficacy endpoints such as clinical outcomes, according to investigator Partha Sardar, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and his colleagues.

“Altogether, the present study affirms the safety and efficacy of renal denervation for blood pressure reduction, and highlights the importance of incorporating the previously described modifications in trial design,” wrote Dr. Sardar and his coauthors. The report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

While initial trials of catheter-based denervation of renal arteries were positive, three blinded randomized, controlled trials showed no difference in blood pressure between the procedure and a sham procedure, the investigators said. Those findings led to several small, sham-controlled trials that incorporated the aforementioned changes.

For the six trials combined in the meta-analysis, reductions in 24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure were significantly lower for RSD, with a weighted mean difference of –3.65 mm Hg (P less than .001), Dr. Sardar and his colleagues reported.

For the earlier trials, the average reductions in 24-hour ambulatory systolic and diastolic blood pressure were 2.23 and 0.66 for RSD and sham patients, respectively.

By contrast, in the second-generation trials, those blood pressure reductions were 4.85 for RSD and 2.98 mm Hg for sham, they said in the report, adding that the reduction in daytime ambulatory systolic blood pressure with RSD was significantly greater for the second-generation studies.

The second-generation studies excluded patients with isolated systolic hypertension, based in part on observations that RSD has a more pronounced impact on blood pressure with combined systolic and diastolic hypertension, according to the authors.

Moreover, the second-generation studies required that very experienced operators perform the procedures, incorporated advanced catheter and ablation techniques, less often used modified medication regimens, and set ambulatory blood pressure as the primary end point, they added.

“These results should inform the design and powering of larger, pivotal trials to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of RSD in patients with uncontrolled and resistant hypertension,” Dr. Sardar and his coauthors said.

Dr. Sardar reported no relevant financial disclosures, as did most of the coauthors. Three coauthors provided disclosures related to Regado Biosciences, Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Medtronic, and ReCor Medical, among others.

SOURCE: Sardar P et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(13):1633-42.

although previous investigations of the procedure have had conflicting results.

Renal sympathetic denervation (RSD) was associated with statistically significant reductions in blood pressure assessed by 24-hour ambulatory, daytime ambulatory, and office measurements in the analysis of six trials including a total of 977 participants.

However, the benefit was particularly pronounced in more recent randomized trials that had few patients with isolated systolic hypertension, had highly experienced operators; used more complete techniques of radiofrequency ablation, used novel approaches such as endovascular renal denervation, and used efficacy endpoints such as clinical outcomes, according to investigator Partha Sardar, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and his colleagues.

“Altogether, the present study affirms the safety and efficacy of renal denervation for blood pressure reduction, and highlights the importance of incorporating the previously described modifications in trial design,” wrote Dr. Sardar and his coauthors. The report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

While initial trials of catheter-based denervation of renal arteries were positive, three blinded randomized, controlled trials showed no difference in blood pressure between the procedure and a sham procedure, the investigators said. Those findings led to several small, sham-controlled trials that incorporated the aforementioned changes.

For the six trials combined in the meta-analysis, reductions in 24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure were significantly lower for RSD, with a weighted mean difference of –3.65 mm Hg (P less than .001), Dr. Sardar and his colleagues reported.

For the earlier trials, the average reductions in 24-hour ambulatory systolic and diastolic blood pressure were 2.23 and 0.66 for RSD and sham patients, respectively.

By contrast, in the second-generation trials, those blood pressure reductions were 4.85 for RSD and 2.98 mm Hg for sham, they said in the report, adding that the reduction in daytime ambulatory systolic blood pressure with RSD was significantly greater for the second-generation studies.

The second-generation studies excluded patients with isolated systolic hypertension, based in part on observations that RSD has a more pronounced impact on blood pressure with combined systolic and diastolic hypertension, according to the authors.

Moreover, the second-generation studies required that very experienced operators perform the procedures, incorporated advanced catheter and ablation techniques, less often used modified medication regimens, and set ambulatory blood pressure as the primary end point, they added.

“These results should inform the design and powering of larger, pivotal trials to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of RSD in patients with uncontrolled and resistant hypertension,” Dr. Sardar and his coauthors said.

Dr. Sardar reported no relevant financial disclosures, as did most of the coauthors. Three coauthors provided disclosures related to Regado Biosciences, Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Medtronic, and ReCor Medical, among others.

SOURCE: Sardar P et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(13):1633-42.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Key clinical point: Renal sympathetic denervation significantly reduced blood pressure in randomized, sham-controlled trials.

Major finding: In second-generation trials of renal sympathetic denervation for hypertension therapy, 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure reductions were 4.85 for RSD and 2.98 mm Hg for sham.

Study details: Renal sympathetic denervation for treating hypertension was tested in six randomized, sham-controlled trials of 24-hour ambulatory, daytime ambulatory, and blood pressure office measurements including a total of 977 participants.

Disclosures: Dr. Sardar reported no relevant financial disclosures, as did most of the coauthors. Three coauthors provided disclosures related to Regado Biosciences, Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Medtronic, and ReCor Medical, among others.

Source: Sardar P et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(13):1633-42.

Society of Gynecologic Surgeons 2019 meeting: Daily reporting from Fellow Scholar

WEDNESDAY, 4/3/2019. DAY 4 OF SGS.

Sadly, the annual Society of Gynecologic Surgeons meeting is wrapping up, and we will soon be leaving sunny Tucson! The last morning of conference proceedings was jam-packed with more outstanding oral and video presentations. We heard about topics such as the burden of postoperative catheterization, dietary patterns associated with postoperative defecatory symptoms, and more surgical tips and tricks to take back to our own institutions. At the end of the morning, the Distinguished Surgeon award was presented to the talented and deserving J. Marion Sims Endowed Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at UAB Medicine in Birmingham Dr. Holly E. Richter. The SGS Presidential Gavel was then passed from current SGS President Dr. Rajiv Gala to the incoming 46th President Dr. Peter Rosenblatt, Director of the Urogynecology and Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery Division at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

#SGS2019 was an amazingly successful conference! Beautiful surroundings, emerging science and education, and respectful inquiry was plentiful. I enjoyed all of the networking, reconnecting, and relaxing, and could not ask for a better community of GYN surgeons to have shared this with. I can’t wait to return to Pittsburgh to implement all the new things that I have learned. Thanks to the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, OBG MANAGEMENT, and all the sponsors of the Fellows Scholar Program for supporting each of the scholars and this blog!

If you were at all intrigued by the happenings reported here, please consider attending the SGS meeting in 2020! The conference will be located in Jacksonville, Florida! See you there!

Thanks for following along! #SGS2019 out.

Continue to: TUESDAY, 4/2/19. DAY 3...

TUESDAY, 4/2/19. DAY 3.

The third day of the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons started off with several academic roundtables hosted by experts in the field. The general session got underway with more fantastic oral and video presentations and, as usual, plenty of lively discussion and education ensued! The 45th SGS President Dr. Rajiv Gala (@rgala_nola) gave his presidential address, where he spoke so genuinely about how SGS is looking forward in our field. After all, the best way to predict your future is to create it! Be on the lookout on Twitter for Dr. Gala’s selfie with his “SGS Family” that he took during his address!

This year’s Telinde Lecture was given by Dr. Marcela G. del Carmen, titled “Health Care Disparities in Gynecologic Oncology Surgery.” She gave an informative and eye-opening lecture on the disparities that still exist in our field, specifically in patients with cancer. The morning session was rounded out with a mentoring panel, featuring Drs. B. Star Hampton, Bobby Shull, Peggy Norton, Tom Nolan, and Deborah Myers. Plenty of sage advice was offered. Thanks to Dr. Shull for reminding us to “be gracious; kindness never goes out of style,” and to be “a citizen of the world.”

Conference goers took the afternoon to enjoy leisure activities in the beautiful Arizona surroundings, including mountain biking, yoga, golf, and poolside lounging. The evening was filled with the excitement of the annual “SGS Got Talent” show! Fabulous performances and delicious food and drinks were just half of the fun, though. The life-size play on hungry, hungry hippos—“Hungry, Hungry Surgeons”—competition was the hit of the night!

Tomorrow is the last day of #SGS2019. Be sure to follow along for the final day of coverage!

Continue to: MONDAY, 4/1/19. DAY 2...

MONDAY, 4/1/19. DAY 2.

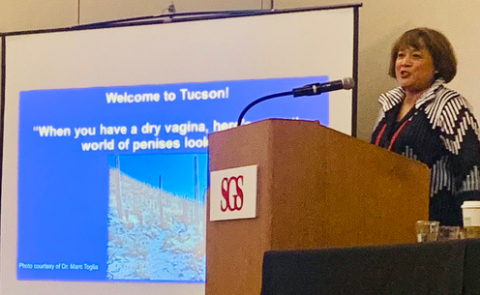

The first day of the general sessions started off with a cleverly titled breakfast symposium, “Postmenopausal sexuality: A bit dry but a must-have conversation,” by the brilliant and entertaining duo of Cheryl Iglesia (@cheryliglesia) and Sheryl Kingsberg (@SherylKingsburg) #CherylandSheryl.

Cheryl Iglesia, MD

The new members of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons were recognized, and there were several outstanding oral and video presentations throughout the morning. A range of topics were discussed, including vaginal surgery education, patient perspectives on adverse events, and postoperative pain management. In addition, Dr. Gary Dunnington (@GLDunnington), Chair of Surgery at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, gave the keynote lecture on “Measuring and improving performance in surgical training,” reminding us to continually strive for change.

After a brief lunch and stroll around the exhibit hall, the afternoon session kicked off with a special guest lecture on vaginal rejuvenation and energy-based therapies for female genital cosmetic surgery by Cheryl Iglesia (@cheryliglesia). Next, a distinguished panel of experts from all gynecologic subspecialties gave their opinions on “Working together to shape the future of gynecologic surgery.” What a treat to see such important topics discussed by all the giants of our field sitting in one room: Society of Gynecologic Surgeons President Rajiv Gala, MD; ACOG President Elect Ted Anderson, MD; American Urogynecologic Society President Geoffrey W. Cundiff, MD; Society of Gynecologic Oncology President Elect Warner Huh, MD; Society of Reproductive Surgeons Immediate Past President Samantha Pfeifer, MD; and AAGL President Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, MD.

Supplemented by popcorn, the Videofest featured a series of informative and impressive videos—from management of removal of the Essure hysteroscopic contraceptive device to tips and tricks to navigate a pelvic kidney. The Fellows’ Pelvic Research Network (FPRN), a network of fellows from both minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and urogynecology programs that facilitates multicenter research, met and discussed ongoing and upcoming studies. Exciting work is coming your way thanks to the collaboration of the FPRN!

We concluded an excellent first day of general sessions with an awards ceremony and President’s reception. It was an evening filled with networking, catching up with old colleagues, and meeting new friends. I look forward to another day of scholarship and education tomorrow! Follow @lauraknewcomb, @GynSurgery, and @MDedgeObGyn on Twitter for updates.

Continue to: SUNDAY, 3/31/19. DAY 1 AT SGS...

SUNDAY, 3/31/19. DAY 1 AT SGS.

Hello from Tucson! I woke up to a beautiful Arizona sunrise, with cacti as far as the eye can see; a great start to what is surely going to be an educational scientific conference of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons! Be sure to follow me on Twitter to stay in the loop real-time: @lauraknewcomb. And don’t forget to check out our conference hashtag #SGS2019.

Postgrad courses kick off

Quality improvement bootcamp

Dr. Bob Flora (@RFFlora) gave a great “Teach the Teacher” session, reviewing different methods for performing quality improvement projects in your own workspace, including the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Model for Improvement (www.IHI.org). We also had the opportunity to learn and play with QI Macros (KnowWare International Inc) and Lucid Chart (Lucid Software Inc) programs—which are excellent tools to assist in quality improvement data analysis and presentation. Try them out if you have never used them before!

Sex and surgery

The sex and surgery postgraduate course was a lively discussion centering on:

- the links between gynecologic surgery and sexual function

- how to measure sexual function and incorporate discussion into our pre- and post-operative counseling

- how to approach the patient with postoperative sexual concerns.

As surgeons, we admitted that an anatomic approach with surgery will not always be successful in treating sexual complaints, as sexuality encompasses psychological, social/cultural, interpersonal, and biological aspects. We agreed that further studies are needed to examine the issue, using sexual function as a primary endpoint, because the concern is of critical importance to our patients.

Social media workshop

The talented SGS Social Media Committee, including influencers Dr. Mireille Truong (@MIS_MDT) and Dr. Elisa Jorgensen (@ejiorgensenmd) gave us the run-down on how to host a successful Twitter journal club and how to be a responsible and influential influencer on various social media avenues. They encouraged us to take advantage of the virtual space that connects so many more people than we could interact with without it!

Hands-on laparoscopic suturing simulation

This course was an excellent comprehensive laparoscopic suturing course. It began with a detailed outline of basic principles and slowly built on these concepts until we were performing laparoscopic myomectomies on a high-fidelity model. We can’t wait to implement these principles in the operating room next week! Thanks to the talented faculty who taught all the tips and tricks of the experts!

Conservative and definitive surgical strategies for fibroid management

Drs. Megan Wasson (@WassonMegan), Arnold Advincula (@arnieadvincula), and others taught all the nuances of managing fibroids and difficult surgical cases. Participants learned several tips, tricks, and techniques to use to manage fibroids—for example the “bow and arrow” and “push and tuck” techniques when performing a hysteroscopic myomectomy with a resectoscope.

Women’s leadership forum

During the evening women’s leadership forum, Drs. Catherine Matthews and Kimberly Kenton (@KimKenton1) highlighted the differences between mentorship and sponsorship. While most female physicians identify meaningful mentorship relationships, women lack sponsorship to advance their careers. Furthermore, more women-to-women sponsorship relationships are needed to improve and achieve gender equality.

Lastly, we all enjoyed the Arizona sunset with a welcome reception on the lawn. It was a great first day and we are all looking forward to an exciting general session on Monday! Stay tuned for more!

#SGS2019 attendees enjoying the welcome reception

WEDNESDAY, 4/3/2019. DAY 4 OF SGS.

Sadly, the annual Society of Gynecologic Surgeons meeting is wrapping up, and we will soon be leaving sunny Tucson! The last morning of conference proceedings was jam-packed with more outstanding oral and video presentations. We heard about topics such as the burden of postoperative catheterization, dietary patterns associated with postoperative defecatory symptoms, and more surgical tips and tricks to take back to our own institutions. At the end of the morning, the Distinguished Surgeon award was presented to the talented and deserving J. Marion Sims Endowed Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at UAB Medicine in Birmingham Dr. Holly E. Richter. The SGS Presidential Gavel was then passed from current SGS President Dr. Rajiv Gala to the incoming 46th President Dr. Peter Rosenblatt, Director of the Urogynecology and Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery Division at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

#SGS2019 was an amazingly successful conference! Beautiful surroundings, emerging science and education, and respectful inquiry was plentiful. I enjoyed all of the networking, reconnecting, and relaxing, and could not ask for a better community of GYN surgeons to have shared this with. I can’t wait to return to Pittsburgh to implement all the new things that I have learned. Thanks to the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, OBG MANAGEMENT, and all the sponsors of the Fellows Scholar Program for supporting each of the scholars and this blog!

If you were at all intrigued by the happenings reported here, please consider attending the SGS meeting in 2020! The conference will be located in Jacksonville, Florida! See you there!

Thanks for following along! #SGS2019 out.

Continue to: TUESDAY, 4/2/19. DAY 3...

TUESDAY, 4/2/19. DAY 3.

The third day of the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons started off with several academic roundtables hosted by experts in the field. The general session got underway with more fantastic oral and video presentations and, as usual, plenty of lively discussion and education ensued! The 45th SGS President Dr. Rajiv Gala (@rgala_nola) gave his presidential address, where he spoke so genuinely about how SGS is looking forward in our field. After all, the best way to predict your future is to create it! Be on the lookout on Twitter for Dr. Gala’s selfie with his “SGS Family” that he took during his address!

This year’s Telinde Lecture was given by Dr. Marcela G. del Carmen, titled “Health Care Disparities in Gynecologic Oncology Surgery.” She gave an informative and eye-opening lecture on the disparities that still exist in our field, specifically in patients with cancer. The morning session was rounded out with a mentoring panel, featuring Drs. B. Star Hampton, Bobby Shull, Peggy Norton, Tom Nolan, and Deborah Myers. Plenty of sage advice was offered. Thanks to Dr. Shull for reminding us to “be gracious; kindness never goes out of style,” and to be “a citizen of the world.”

Conference goers took the afternoon to enjoy leisure activities in the beautiful Arizona surroundings, including mountain biking, yoga, golf, and poolside lounging. The evening was filled with the excitement of the annual “SGS Got Talent” show! Fabulous performances and delicious food and drinks were just half of the fun, though. The life-size play on hungry, hungry hippos—“Hungry, Hungry Surgeons”—competition was the hit of the night!

Tomorrow is the last day of #SGS2019. Be sure to follow along for the final day of coverage!

Continue to: MONDAY, 4/1/19. DAY 2...

MONDAY, 4/1/19. DAY 2.

The first day of the general sessions started off with a cleverly titled breakfast symposium, “Postmenopausal sexuality: A bit dry but a must-have conversation,” by the brilliant and entertaining duo of Cheryl Iglesia (@cheryliglesia) and Sheryl Kingsberg (@SherylKingsburg) #CherylandSheryl.

Cheryl Iglesia, MD

The new members of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons were recognized, and there were several outstanding oral and video presentations throughout the morning. A range of topics were discussed, including vaginal surgery education, patient perspectives on adverse events, and postoperative pain management. In addition, Dr. Gary Dunnington (@GLDunnington), Chair of Surgery at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, gave the keynote lecture on “Measuring and improving performance in surgical training,” reminding us to continually strive for change.

After a brief lunch and stroll around the exhibit hall, the afternoon session kicked off with a special guest lecture on vaginal rejuvenation and energy-based therapies for female genital cosmetic surgery by Cheryl Iglesia (@cheryliglesia). Next, a distinguished panel of experts from all gynecologic subspecialties gave their opinions on “Working together to shape the future of gynecologic surgery.” What a treat to see such important topics discussed by all the giants of our field sitting in one room: Society of Gynecologic Surgeons President Rajiv Gala, MD; ACOG President Elect Ted Anderson, MD; American Urogynecologic Society President Geoffrey W. Cundiff, MD; Society of Gynecologic Oncology President Elect Warner Huh, MD; Society of Reproductive Surgeons Immediate Past President Samantha Pfeifer, MD; and AAGL President Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, MD.

Supplemented by popcorn, the Videofest featured a series of informative and impressive videos—from management of removal of the Essure hysteroscopic contraceptive device to tips and tricks to navigate a pelvic kidney. The Fellows’ Pelvic Research Network (FPRN), a network of fellows from both minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and urogynecology programs that facilitates multicenter research, met and discussed ongoing and upcoming studies. Exciting work is coming your way thanks to the collaboration of the FPRN!

We concluded an excellent first day of general sessions with an awards ceremony and President’s reception. It was an evening filled with networking, catching up with old colleagues, and meeting new friends. I look forward to another day of scholarship and education tomorrow! Follow @lauraknewcomb, @GynSurgery, and @MDedgeObGyn on Twitter for updates.

Continue to: SUNDAY, 3/31/19. DAY 1 AT SGS...

SUNDAY, 3/31/19. DAY 1 AT SGS.

Hello from Tucson! I woke up to a beautiful Arizona sunrise, with cacti as far as the eye can see; a great start to what is surely going to be an educational scientific conference of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons! Be sure to follow me on Twitter to stay in the loop real-time: @lauraknewcomb. And don’t forget to check out our conference hashtag #SGS2019.

Postgrad courses kick off

Quality improvement bootcamp

Dr. Bob Flora (@RFFlora) gave a great “Teach the Teacher” session, reviewing different methods for performing quality improvement projects in your own workspace, including the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Model for Improvement (www.IHI.org). We also had the opportunity to learn and play with QI Macros (KnowWare International Inc) and Lucid Chart (Lucid Software Inc) programs—which are excellent tools to assist in quality improvement data analysis and presentation. Try them out if you have never used them before!

Sex and surgery

The sex and surgery postgraduate course was a lively discussion centering on:

- the links between gynecologic surgery and sexual function

- how to measure sexual function and incorporate discussion into our pre- and post-operative counseling

- how to approach the patient with postoperative sexual concerns.

As surgeons, we admitted that an anatomic approach with surgery will not always be successful in treating sexual complaints, as sexuality encompasses psychological, social/cultural, interpersonal, and biological aspects. We agreed that further studies are needed to examine the issue, using sexual function as a primary endpoint, because the concern is of critical importance to our patients.

Social media workshop

The talented SGS Social Media Committee, including influencers Dr. Mireille Truong (@MIS_MDT) and Dr. Elisa Jorgensen (@ejiorgensenmd) gave us the run-down on how to host a successful Twitter journal club and how to be a responsible and influential influencer on various social media avenues. They encouraged us to take advantage of the virtual space that connects so many more people than we could interact with without it!

Hands-on laparoscopic suturing simulation

This course was an excellent comprehensive laparoscopic suturing course. It began with a detailed outline of basic principles and slowly built on these concepts until we were performing laparoscopic myomectomies on a high-fidelity model. We can’t wait to implement these principles in the operating room next week! Thanks to the talented faculty who taught all the tips and tricks of the experts!

Conservative and definitive surgical strategies for fibroid management

Drs. Megan Wasson (@WassonMegan), Arnold Advincula (@arnieadvincula), and others taught all the nuances of managing fibroids and difficult surgical cases. Participants learned several tips, tricks, and techniques to use to manage fibroids—for example the “bow and arrow” and “push and tuck” techniques when performing a hysteroscopic myomectomy with a resectoscope.

Women’s leadership forum

During the evening women’s leadership forum, Drs. Catherine Matthews and Kimberly Kenton (@KimKenton1) highlighted the differences between mentorship and sponsorship. While most female physicians identify meaningful mentorship relationships, women lack sponsorship to advance their careers. Furthermore, more women-to-women sponsorship relationships are needed to improve and achieve gender equality.

Lastly, we all enjoyed the Arizona sunset with a welcome reception on the lawn. It was a great first day and we are all looking forward to an exciting general session on Monday! Stay tuned for more!

#SGS2019 attendees enjoying the welcome reception

WEDNESDAY, 4/3/2019. DAY 4 OF SGS.

Sadly, the annual Society of Gynecologic Surgeons meeting is wrapping up, and we will soon be leaving sunny Tucson! The last morning of conference proceedings was jam-packed with more outstanding oral and video presentations. We heard about topics such as the burden of postoperative catheterization, dietary patterns associated with postoperative defecatory symptoms, and more surgical tips and tricks to take back to our own institutions. At the end of the morning, the Distinguished Surgeon award was presented to the talented and deserving J. Marion Sims Endowed Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at UAB Medicine in Birmingham Dr. Holly E. Richter. The SGS Presidential Gavel was then passed from current SGS President Dr. Rajiv Gala to the incoming 46th President Dr. Peter Rosenblatt, Director of the Urogynecology and Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery Division at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

#SGS2019 was an amazingly successful conference! Beautiful surroundings, emerging science and education, and respectful inquiry was plentiful. I enjoyed all of the networking, reconnecting, and relaxing, and could not ask for a better community of GYN surgeons to have shared this with. I can’t wait to return to Pittsburgh to implement all the new things that I have learned. Thanks to the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, OBG MANAGEMENT, and all the sponsors of the Fellows Scholar Program for supporting each of the scholars and this blog!

If you were at all intrigued by the happenings reported here, please consider attending the SGS meeting in 2020! The conference will be located in Jacksonville, Florida! See you there!

Thanks for following along! #SGS2019 out.

Continue to: TUESDAY, 4/2/19. DAY 3...

TUESDAY, 4/2/19. DAY 3.

The third day of the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons started off with several academic roundtables hosted by experts in the field. The general session got underway with more fantastic oral and video presentations and, as usual, plenty of lively discussion and education ensued! The 45th SGS President Dr. Rajiv Gala (@rgala_nola) gave his presidential address, where he spoke so genuinely about how SGS is looking forward in our field. After all, the best way to predict your future is to create it! Be on the lookout on Twitter for Dr. Gala’s selfie with his “SGS Family” that he took during his address!

This year’s Telinde Lecture was given by Dr. Marcela G. del Carmen, titled “Health Care Disparities in Gynecologic Oncology Surgery.” She gave an informative and eye-opening lecture on the disparities that still exist in our field, specifically in patients with cancer. The morning session was rounded out with a mentoring panel, featuring Drs. B. Star Hampton, Bobby Shull, Peggy Norton, Tom Nolan, and Deborah Myers. Plenty of sage advice was offered. Thanks to Dr. Shull for reminding us to “be gracious; kindness never goes out of style,” and to be “a citizen of the world.”

Conference goers took the afternoon to enjoy leisure activities in the beautiful Arizona surroundings, including mountain biking, yoga, golf, and poolside lounging. The evening was filled with the excitement of the annual “SGS Got Talent” show! Fabulous performances and delicious food and drinks were just half of the fun, though. The life-size play on hungry, hungry hippos—“Hungry, Hungry Surgeons”—competition was the hit of the night!

Tomorrow is the last day of #SGS2019. Be sure to follow along for the final day of coverage!

Continue to: MONDAY, 4/1/19. DAY 2...

MONDAY, 4/1/19. DAY 2.

The first day of the general sessions started off with a cleverly titled breakfast symposium, “Postmenopausal sexuality: A bit dry but a must-have conversation,” by the brilliant and entertaining duo of Cheryl Iglesia (@cheryliglesia) and Sheryl Kingsberg (@SherylKingsburg) #CherylandSheryl.

Cheryl Iglesia, MD

The new members of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons were recognized, and there were several outstanding oral and video presentations throughout the morning. A range of topics were discussed, including vaginal surgery education, patient perspectives on adverse events, and postoperative pain management. In addition, Dr. Gary Dunnington (@GLDunnington), Chair of Surgery at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, gave the keynote lecture on “Measuring and improving performance in surgical training,” reminding us to continually strive for change.

After a brief lunch and stroll around the exhibit hall, the afternoon session kicked off with a special guest lecture on vaginal rejuvenation and energy-based therapies for female genital cosmetic surgery by Cheryl Iglesia (@cheryliglesia). Next, a distinguished panel of experts from all gynecologic subspecialties gave their opinions on “Working together to shape the future of gynecologic surgery.” What a treat to see such important topics discussed by all the giants of our field sitting in one room: Society of Gynecologic Surgeons President Rajiv Gala, MD; ACOG President Elect Ted Anderson, MD; American Urogynecologic Society President Geoffrey W. Cundiff, MD; Society of Gynecologic Oncology President Elect Warner Huh, MD; Society of Reproductive Surgeons Immediate Past President Samantha Pfeifer, MD; and AAGL President Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, MD.

Supplemented by popcorn, the Videofest featured a series of informative and impressive videos—from management of removal of the Essure hysteroscopic contraceptive device to tips and tricks to navigate a pelvic kidney. The Fellows’ Pelvic Research Network (FPRN), a network of fellows from both minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and urogynecology programs that facilitates multicenter research, met and discussed ongoing and upcoming studies. Exciting work is coming your way thanks to the collaboration of the FPRN!

We concluded an excellent first day of general sessions with an awards ceremony and President’s reception. It was an evening filled with networking, catching up with old colleagues, and meeting new friends. I look forward to another day of scholarship and education tomorrow! Follow @lauraknewcomb, @GynSurgery, and @MDedgeObGyn on Twitter for updates.

Continue to: SUNDAY, 3/31/19. DAY 1 AT SGS...

SUNDAY, 3/31/19. DAY 1 AT SGS.

Hello from Tucson! I woke up to a beautiful Arizona sunrise, with cacti as far as the eye can see; a great start to what is surely going to be an educational scientific conference of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons! Be sure to follow me on Twitter to stay in the loop real-time: @lauraknewcomb. And don’t forget to check out our conference hashtag #SGS2019.

Postgrad courses kick off

Quality improvement bootcamp

Dr. Bob Flora (@RFFlora) gave a great “Teach the Teacher” session, reviewing different methods for performing quality improvement projects in your own workspace, including the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Model for Improvement (www.IHI.org). We also had the opportunity to learn and play with QI Macros (KnowWare International Inc) and Lucid Chart (Lucid Software Inc) programs—which are excellent tools to assist in quality improvement data analysis and presentation. Try them out if you have never used them before!

Sex and surgery

The sex and surgery postgraduate course was a lively discussion centering on:

- the links between gynecologic surgery and sexual function

- how to measure sexual function and incorporate discussion into our pre- and post-operative counseling

- how to approach the patient with postoperative sexual concerns.

As surgeons, we admitted that an anatomic approach with surgery will not always be successful in treating sexual complaints, as sexuality encompasses psychological, social/cultural, interpersonal, and biological aspects. We agreed that further studies are needed to examine the issue, using sexual function as a primary endpoint, because the concern is of critical importance to our patients.

Social media workshop

The talented SGS Social Media Committee, including influencers Dr. Mireille Truong (@MIS_MDT) and Dr. Elisa Jorgensen (@ejiorgensenmd) gave us the run-down on how to host a successful Twitter journal club and how to be a responsible and influential influencer on various social media avenues. They encouraged us to take advantage of the virtual space that connects so many more people than we could interact with without it!

Hands-on laparoscopic suturing simulation

This course was an excellent comprehensive laparoscopic suturing course. It began with a detailed outline of basic principles and slowly built on these concepts until we were performing laparoscopic myomectomies on a high-fidelity model. We can’t wait to implement these principles in the operating room next week! Thanks to the talented faculty who taught all the tips and tricks of the experts!

Conservative and definitive surgical strategies for fibroid management

Drs. Megan Wasson (@WassonMegan), Arnold Advincula (@arnieadvincula), and others taught all the nuances of managing fibroids and difficult surgical cases. Participants learned several tips, tricks, and techniques to use to manage fibroids—for example the “bow and arrow” and “push and tuck” techniques when performing a hysteroscopic myomectomy with a resectoscope.

Women’s leadership forum

During the evening women’s leadership forum, Drs. Catherine Matthews and Kimberly Kenton (@KimKenton1) highlighted the differences between mentorship and sponsorship. While most female physicians identify meaningful mentorship relationships, women lack sponsorship to advance their careers. Furthermore, more women-to-women sponsorship relationships are needed to improve and achieve gender equality.

Lastly, we all enjoyed the Arizona sunset with a welcome reception on the lawn. It was a great first day and we are all looking forward to an exciting general session on Monday! Stay tuned for more!

#SGS2019 attendees enjoying the welcome reception

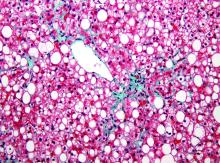

Novel microbiome signature may detect NAFLD-cirrhosis

according to results from a study published in Nature Communications.

“Limited data exist concerning the diagnostic accuracy of gut microbiome–derived signatures for detecting NAFLD-cirrhosis,” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, along with her colleagues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 203 patients with NAFLD. Data was collected from a twin and family cohort with a total of 98 probands that included the complete spectrum of the disease. In addition, 105 first-degree relatives of the probands were also included.

The team analyzed stool samples of participants using MRI and assessed whether the novel signature could accurately identify cirrhosis in NAFLD.

After analysis, the researchers found that in a specific cohort of probands, the microbial biomarker showed strong diagnostic accuracy for identifying cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.92). These findings were validated in another cohort of first-degree relatives of the proband group (AUROC, 0.87).

The authors acknowledged that a key limitation of the analysis was that it was only a single-center study. As a result, the widespread generalizability of the findings could be restricted.

“This conveniently assessed microbial biomarker could present an adjunct tool to current invasive approaches to determine stage of liver disease,” they concluded.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and Janssen. The authors reported financial affiliations with the American Gastroenterological Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Nat Commun. 2019 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9.

according to results from a study published in Nature Communications.

“Limited data exist concerning the diagnostic accuracy of gut microbiome–derived signatures for detecting NAFLD-cirrhosis,” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, along with her colleagues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 203 patients with NAFLD. Data was collected from a twin and family cohort with a total of 98 probands that included the complete spectrum of the disease. In addition, 105 first-degree relatives of the probands were also included.

The team analyzed stool samples of participants using MRI and assessed whether the novel signature could accurately identify cirrhosis in NAFLD.

After analysis, the researchers found that in a specific cohort of probands, the microbial biomarker showed strong diagnostic accuracy for identifying cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.92). These findings were validated in another cohort of first-degree relatives of the proband group (AUROC, 0.87).

The authors acknowledged that a key limitation of the analysis was that it was only a single-center study. As a result, the widespread generalizability of the findings could be restricted.

“This conveniently assessed microbial biomarker could present an adjunct tool to current invasive approaches to determine stage of liver disease,” they concluded.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and Janssen. The authors reported financial affiliations with the American Gastroenterological Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Nat Commun. 2019 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9.

according to results from a study published in Nature Communications.

“Limited data exist concerning the diagnostic accuracy of gut microbiome–derived signatures for detecting NAFLD-cirrhosis,” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, along with her colleagues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 203 patients with NAFLD. Data was collected from a twin and family cohort with a total of 98 probands that included the complete spectrum of the disease. In addition, 105 first-degree relatives of the probands were also included.

The team analyzed stool samples of participants using MRI and assessed whether the novel signature could accurately identify cirrhosis in NAFLD.

After analysis, the researchers found that in a specific cohort of probands, the microbial biomarker showed strong diagnostic accuracy for identifying cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.92). These findings were validated in another cohort of first-degree relatives of the proband group (AUROC, 0.87).

The authors acknowledged that a key limitation of the analysis was that it was only a single-center study. As a result, the widespread generalizability of the findings could be restricted.

“This conveniently assessed microbial biomarker could present an adjunct tool to current invasive approaches to determine stage of liver disease,” they concluded.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and Janssen. The authors reported financial affiliations with the American Gastroenterological Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Nat Commun. 2019 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

Bariatric surgery may be appropriate for class 1 obesity

LAS VEGAS – Once reserved for the most obese patients, bariatric surgery is on the road to becoming an option for millions of Americans who are just a step beyond overweight, even those with a body mass index as low as 30 kg/m2.

In regard to patients with lower levels of obesity, “we should be intervening in this chronic disease earlier rather than later,” said Stacy A. Brethauer, MD, professor of surgery at the Ohio State University, Columbus, in a presentation about new standards for bariatric surgery at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Bariatric treatment “should be offered after nonsurgical [weight-loss] therapy has failed,” he said. “That’s not where you stop. You continue to escalate as you would for heart disease or cancer.”

As Dr. Brethauer noted, research suggests that all categories of obesity – including so-called class 1 obesity (defined as a BMI from 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2) – boost the risk of multiple diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, pulmonary embolism, gallbladder disease, several types of cancer, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain.

“There is no question that class 1 obesity is clearly putting people at risk,” he said. “Ultimately, you can conclude from all this evidence that class 1 is a chronic disease, and it deserves to be treated effectively.”

There are, of course, various nonsurgical treatments for obesity, including diet and exercise and pharmacotherapy. However, systematic reviews have found that people find it extremely difficult to keep the weight off after 1 year regardless of the strategy they adopt.

Beyond a year, Dr. Brethauer said, “you get poor maintenance of weight control, and you get poor control of metabolic burden. You don’t have a durable efficacy.”

In the past, bariatric surgery wasn’t considered an option for patients with class 1 obesity. It’s traditionally been reserved for patients with BMIs at or above 35 kg/m2. But this standard has evolved in recent years.

In 2018, Dr. Brethauer coauthored an updated position statement by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery that encouraged bariatric surgery in certain mildly obese patients.

“For most people with class I obesity,” the statement on bariatric surgery states, “it is clear that the nonsurgical group of therapies will not provide a durable solution to their disease of obesity.”

The statement went on to say that “surgical intervention should be considered after failure of nonsurgical treatments” in the class 1 population.

Bariatric surgery in the class 1 population does more than reduce obesity, Dr. Brethauer said. “Over the last 5 years or so, a large body of literature has emerged,” he said, and both systematic reviews and randomized trails have shown significant postsurgery improvements in comorbidities such as diabetes.

“It’s important to emphasize that these patients don’t become underweight,” he said. “The body finds a healthy set point. They don’t become underweight or malnourished because you’re operating on a lower-weight group.”

Are weight-loss operations safe in class 1 patients? The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery statement says that research has found “bariatric surgery is associated with modest morbidity and very low mortality in patients with class I obesity.”

In fact, Dr. Brethauer said, the mortality rate in this population is “less than gallbladder surgery, less than hip surgery, less than hysterectomy, less than knee surgery – operations people are being referred for and undergoing all the time.”

He added: “The case can be made very clearly based on this data that these operations are safe in this patient population. Not only are they safe, they have durable and significant impact on comorbidities.”

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Brethauer discloses relationships with Medtronic (speaker) and GI Windows (consultant).

Review the AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper, which provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at http://ow.ly/WV8l30oeyYv.

LAS VEGAS – Once reserved for the most obese patients, bariatric surgery is on the road to becoming an option for millions of Americans who are just a step beyond overweight, even those with a body mass index as low as 30 kg/m2.

In regard to patients with lower levels of obesity, “we should be intervening in this chronic disease earlier rather than later,” said Stacy A. Brethauer, MD, professor of surgery at the Ohio State University, Columbus, in a presentation about new standards for bariatric surgery at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Bariatric treatment “should be offered after nonsurgical [weight-loss] therapy has failed,” he said. “That’s not where you stop. You continue to escalate as you would for heart disease or cancer.”

As Dr. Brethauer noted, research suggests that all categories of obesity – including so-called class 1 obesity (defined as a BMI from 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2) – boost the risk of multiple diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, pulmonary embolism, gallbladder disease, several types of cancer, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain.

“There is no question that class 1 obesity is clearly putting people at risk,” he said. “Ultimately, you can conclude from all this evidence that class 1 is a chronic disease, and it deserves to be treated effectively.”

There are, of course, various nonsurgical treatments for obesity, including diet and exercise and pharmacotherapy. However, systematic reviews have found that people find it extremely difficult to keep the weight off after 1 year regardless of the strategy they adopt.

Beyond a year, Dr. Brethauer said, “you get poor maintenance of weight control, and you get poor control of metabolic burden. You don’t have a durable efficacy.”

In the past, bariatric surgery wasn’t considered an option for patients with class 1 obesity. It’s traditionally been reserved for patients with BMIs at or above 35 kg/m2. But this standard has evolved in recent years.

In 2018, Dr. Brethauer coauthored an updated position statement by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery that encouraged bariatric surgery in certain mildly obese patients.

“For most people with class I obesity,” the statement on bariatric surgery states, “it is clear that the nonsurgical group of therapies will not provide a durable solution to their disease of obesity.”

The statement went on to say that “surgical intervention should be considered after failure of nonsurgical treatments” in the class 1 population.

Bariatric surgery in the class 1 population does more than reduce obesity, Dr. Brethauer said. “Over the last 5 years or so, a large body of literature has emerged,” he said, and both systematic reviews and randomized trails have shown significant postsurgery improvements in comorbidities such as diabetes.

“It’s important to emphasize that these patients don’t become underweight,” he said. “The body finds a healthy set point. They don’t become underweight or malnourished because you’re operating on a lower-weight group.”

Are weight-loss operations safe in class 1 patients? The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery statement says that research has found “bariatric surgery is associated with modest morbidity and very low mortality in patients with class I obesity.”

In fact, Dr. Brethauer said, the mortality rate in this population is “less than gallbladder surgery, less than hip surgery, less than hysterectomy, less than knee surgery – operations people are being referred for and undergoing all the time.”

He added: “The case can be made very clearly based on this data that these operations are safe in this patient population. Not only are they safe, they have durable and significant impact on comorbidities.”

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Brethauer discloses relationships with Medtronic (speaker) and GI Windows (consultant).

Review the AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper, which provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at http://ow.ly/WV8l30oeyYv.

LAS VEGAS – Once reserved for the most obese patients, bariatric surgery is on the road to becoming an option for millions of Americans who are just a step beyond overweight, even those with a body mass index as low as 30 kg/m2.

In regard to patients with lower levels of obesity, “we should be intervening in this chronic disease earlier rather than later,” said Stacy A. Brethauer, MD, professor of surgery at the Ohio State University, Columbus, in a presentation about new standards for bariatric surgery at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Bariatric treatment “should be offered after nonsurgical [weight-loss] therapy has failed,” he said. “That’s not where you stop. You continue to escalate as you would for heart disease or cancer.”

As Dr. Brethauer noted, research suggests that all categories of obesity – including so-called class 1 obesity (defined as a BMI from 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2) – boost the risk of multiple diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, pulmonary embolism, gallbladder disease, several types of cancer, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain.

“There is no question that class 1 obesity is clearly putting people at risk,” he said. “Ultimately, you can conclude from all this evidence that class 1 is a chronic disease, and it deserves to be treated effectively.”

There are, of course, various nonsurgical treatments for obesity, including diet and exercise and pharmacotherapy. However, systematic reviews have found that people find it extremely difficult to keep the weight off after 1 year regardless of the strategy they adopt.

Beyond a year, Dr. Brethauer said, “you get poor maintenance of weight control, and you get poor control of metabolic burden. You don’t have a durable efficacy.”

In the past, bariatric surgery wasn’t considered an option for patients with class 1 obesity. It’s traditionally been reserved for patients with BMIs at or above 35 kg/m2. But this standard has evolved in recent years.

In 2018, Dr. Brethauer coauthored an updated position statement by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery that encouraged bariatric surgery in certain mildly obese patients.

“For most people with class I obesity,” the statement on bariatric surgery states, “it is clear that the nonsurgical group of therapies will not provide a durable solution to their disease of obesity.”

The statement went on to say that “surgical intervention should be considered after failure of nonsurgical treatments” in the class 1 population.

Bariatric surgery in the class 1 population does more than reduce obesity, Dr. Brethauer said. “Over the last 5 years or so, a large body of literature has emerged,” he said, and both systematic reviews and randomized trails have shown significant postsurgery improvements in comorbidities such as diabetes.

“It’s important to emphasize that these patients don’t become underweight,” he said. “The body finds a healthy set point. They don’t become underweight or malnourished because you’re operating on a lower-weight group.”

Are weight-loss operations safe in class 1 patients? The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery statement says that research has found “bariatric surgery is associated with modest morbidity and very low mortality in patients with class I obesity.”

In fact, Dr. Brethauer said, the mortality rate in this population is “less than gallbladder surgery, less than hip surgery, less than hysterectomy, less than knee surgery – operations people are being referred for and undergoing all the time.”

He added: “The case can be made very clearly based on this data that these operations are safe in this patient population. Not only are they safe, they have durable and significant impact on comorbidities.”

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Brethauer discloses relationships with Medtronic (speaker) and GI Windows (consultant).

Review the AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper, which provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at http://ow.ly/WV8l30oeyYv.

REPORTING FROM MISS

FDA approves multiple ambrisentan generics for patients with PAH

The Food and Drug Administration has approved multiple generics for ambrisentan (Letairis) tablets, as well as their associated risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS), for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

A total of four generics were approved, licensed to Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Sun Pharma Global, Watson Laboratories, and Zydus Pharmaceuticals. All four were approved at 5-mg and 10-mg doses. According to the label, the most common adverse events associated with ambrisentan include peripheral edema, nasal congestion, sinusitis, and flushing.

In addition to the generics, the FDA also approved two shared system REMS programs for ambrisentan. The first, Ambrisentan REMS, includes the brand sponsor and three abbreviated new drug applications. The FDA also approved two shared system REMS programs for ambrisentan. The first, Ambrisentan REMS, is composed of the brand sponsor and three abbreviated new drug applications. The second, PS-Ambrisentan REMS, is a parallel system and currently is constituted by one abbreviated new drug application.

“With the approval of these first generics ... patients will now have access to additional products (brand-name and generic) and additional types of pharmacies to fill their prescriptions,” the FDA said.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved multiple generics for ambrisentan (Letairis) tablets, as well as their associated risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS), for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

A total of four generics were approved, licensed to Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Sun Pharma Global, Watson Laboratories, and Zydus Pharmaceuticals. All four were approved at 5-mg and 10-mg doses. According to the label, the most common adverse events associated with ambrisentan include peripheral edema, nasal congestion, sinusitis, and flushing.

In addition to the generics, the FDA also approved two shared system REMS programs for ambrisentan. The first, Ambrisentan REMS, includes the brand sponsor and three abbreviated new drug applications. The FDA also approved two shared system REMS programs for ambrisentan. The first, Ambrisentan REMS, is composed of the brand sponsor and three abbreviated new drug applications. The second, PS-Ambrisentan REMS, is a parallel system and currently is constituted by one abbreviated new drug application.

“With the approval of these first generics ... patients will now have access to additional products (brand-name and generic) and additional types of pharmacies to fill their prescriptions,” the FDA said.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved multiple generics for ambrisentan (Letairis) tablets, as well as their associated risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS), for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

A total of four generics were approved, licensed to Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Sun Pharma Global, Watson Laboratories, and Zydus Pharmaceuticals. All four were approved at 5-mg and 10-mg doses. According to the label, the most common adverse events associated with ambrisentan include peripheral edema, nasal congestion, sinusitis, and flushing.

In addition to the generics, the FDA also approved two shared system REMS programs for ambrisentan. The first, Ambrisentan REMS, includes the brand sponsor and three abbreviated new drug applications. The FDA also approved two shared system REMS programs for ambrisentan. The first, Ambrisentan REMS, is composed of the brand sponsor and three abbreviated new drug applications. The second, PS-Ambrisentan REMS, is a parallel system and currently is constituted by one abbreviated new drug application.

“With the approval of these first generics ... patients will now have access to additional products (brand-name and generic) and additional types of pharmacies to fill their prescriptions,” the FDA said.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

Anti-EGFR TKI, MET inhibitor team up against drug-resistant NSCLC

ATLANTA – About 10%-25% of patients with epithelial growth factor receptor–(EGFR) mutant non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have tumors with either MET amplification or another MET-based mechanism that leads to drug resistance.

In the TATTON trial, investigators are evaluating a combination of the EGFR-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) osimertinib (Tagrisso) with savolitinib, an investigational MET inhibitor, for safety and activity against MET-driven NSCLC in patients with disease that has progressed on one or more prior EGFR-targeted agents.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Lecia Sequist, MD, from the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, discusses early results with the osimertinib/savolitinib combination in patients with disease progression after a first and/or second-generation EGFR TKI, or after a third-generation agent.

Dr. Sequist said results of TATTON suggest that it may be possible to overcome MET-driven drug-resistance mechanisms.

The TATTON trial is sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Sequist reported serving as an advisory board member and receiving research support and honoraria from the company.

ATLANTA – About 10%-25% of patients with epithelial growth factor receptor–(EGFR) mutant non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have tumors with either MET amplification or another MET-based mechanism that leads to drug resistance.

In the TATTON trial, investigators are evaluating a combination of the EGFR-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) osimertinib (Tagrisso) with savolitinib, an investigational MET inhibitor, for safety and activity against MET-driven NSCLC in patients with disease that has progressed on one or more prior EGFR-targeted agents.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Lecia Sequist, MD, from the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, discusses early results with the osimertinib/savolitinib combination in patients with disease progression after a first and/or second-generation EGFR TKI, or after a third-generation agent.

Dr. Sequist said results of TATTON suggest that it may be possible to overcome MET-driven drug-resistance mechanisms.

The TATTON trial is sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Sequist reported serving as an advisory board member and receiving research support and honoraria from the company.

ATLANTA – About 10%-25% of patients with epithelial growth factor receptor–(EGFR) mutant non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have tumors with either MET amplification or another MET-based mechanism that leads to drug resistance.

In the TATTON trial, investigators are evaluating a combination of the EGFR-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) osimertinib (Tagrisso) with savolitinib, an investigational MET inhibitor, for safety and activity against MET-driven NSCLC in patients with disease that has progressed on one or more prior EGFR-targeted agents.

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Lecia Sequist, MD, from the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, discusses early results with the osimertinib/savolitinib combination in patients with disease progression after a first and/or second-generation EGFR TKI, or after a third-generation agent.

Dr. Sequist said results of TATTON suggest that it may be possible to overcome MET-driven drug-resistance mechanisms.

The TATTON trial is sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Sequist reported serving as an advisory board member and receiving research support and honoraria from the company.

REPORTING FROM AACR 2019

CAR T cells target HER2 expression in advanced sarcomas

ATLANTA – Sarcomas of bone and soft tissues are considered to be “antigenically cold” tumors, with few identifiable mutations that may be susceptible to targeted therapies.

Some sarcoma subtypes such as osteosarcoma and rhabomyosarcoma, however, frequently express the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 on tumor surfaces. Although HER2 expression in these tumors is at too low a level for HER2-targeted therapies such as trastuzumab (Herceptin), HER2 appears to be an opportunistic target for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, according to Shoba Navai, MD, from Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

In a video interview at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Dr. Navai describes her team’s early experience using a HER2-targeted CAR-T cell construct and preinfusion lymphodepletion in patients with advanced sarcomas.

Development of the CAR-T cell construct is supported by the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, Stand Up to Cancer, the St. Baldrick’s Foundation, Cookies for Kids’ Cancer, Alex’s Lemonade Stand, and a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Navai reported having no disclosures.

ATLANTA – Sarcomas of bone and soft tissues are considered to be “antigenically cold” tumors, with few identifiable mutations that may be susceptible to targeted therapies.

Some sarcoma subtypes such as osteosarcoma and rhabomyosarcoma, however, frequently express the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 on tumor surfaces. Although HER2 expression in these tumors is at too low a level for HER2-targeted therapies such as trastuzumab (Herceptin), HER2 appears to be an opportunistic target for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, according to Shoba Navai, MD, from Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

In a video interview at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Dr. Navai describes her team’s early experience using a HER2-targeted CAR-T cell construct and preinfusion lymphodepletion in patients with advanced sarcomas.

Development of the CAR-T cell construct is supported by the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, Stand Up to Cancer, the St. Baldrick’s Foundation, Cookies for Kids’ Cancer, Alex’s Lemonade Stand, and a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Navai reported having no disclosures.

ATLANTA – Sarcomas of bone and soft tissues are considered to be “antigenically cold” tumors, with few identifiable mutations that may be susceptible to targeted therapies.

Some sarcoma subtypes such as osteosarcoma and rhabomyosarcoma, however, frequently express the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 on tumor surfaces. Although HER2 expression in these tumors is at too low a level for HER2-targeted therapies such as trastuzumab (Herceptin), HER2 appears to be an opportunistic target for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, according to Shoba Navai, MD, from Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

In a video interview at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Dr. Navai describes her team’s early experience using a HER2-targeted CAR-T cell construct and preinfusion lymphodepletion in patients with advanced sarcomas.

Development of the CAR-T cell construct is supported by the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, Stand Up to Cancer, the St. Baldrick’s Foundation, Cookies for Kids’ Cancer, Alex’s Lemonade Stand, and a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Navai reported having no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM AACR 2019

FDA approves Mavenclad for treatment of relapsing MS

including relapsing/remitting and active secondary progressive disease.

The drug’s manufacturer, EMD Serono, said in a press release that cladribine is the first short-course oral therapy for such patients, and its use is generally recommended for patients who have had an inadequate response to, or are unable to tolerate, an alternate drug indicated for the treatment of MS. Cladribine is not recommended for use in patients with clinically isolated syndrome.

The agency’s decision is based on results from a clinical trial of 1,326 patients with relapsing MS who had experienced at least one relapse in the previous 12 months. Patients who received cladribine had significantly fewer relapses than did those who received placebo; the progression of disability was also significantly reduced in the cladribine group, compared with placebo, according to the FDA’s announcement.

The most common adverse events associated with cladribine include upper respiratory tract infections, headache, and decreased lymphocyte counts. In addition, the medication must be dispensed with a patient medication guide because the label includes a boxed warning for increased risk of malignancy and fetal harm. Other warnings include a risk for decreased lymphocyte count, hematologic toxicity and bone marrow suppression, and graft-versus-host-disease.

“We are committed to supporting the development of safe and effective treatments for patients with multiple sclerosis. The approval of Mavenclad represents an additional option for patients who have tried another treatment without success,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the division of neurology products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the announcement.