User login

Study finds pain perception disconnect during vascular laser procedures

DENVER – There is an apparent disconnect between the level of periprocedural pain experienced by patients during vascular laser procedures and what device manufacturers say that level of pain should be, results from a retrospective study showed.

“Although there is an abundance of research on how pain signals are transmitted in the nervous system and how pain is perceived among certain patient demographics, there is not much known about how pain perception differs from that put forth by industry,” Lauren Bonati, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “This study is unique because we are questioning not whether pain perception is reproducible between patients, but rather if it reflects what industry and device manufacturers are telling us.”

Dr. Bonati, a dermatologist at Edwards, Colo.–based Mountain Dermatology Specialists, and her colleagues collected median and mode pain scores from a past clinical trial that investigated a dual wavelength laser used for different types of treatments. “The treatment type (laser wavelength and treatment area) was largely based on the severity of facial redness for each individual patient,” she explained. “The options were spot treatment, nose and cheeks, or a global facial treatment with either wavelength.” The researchers reviewed industry-provided materials to determine language regarding procedural pain, and they interviewed the clinical trial’s principal investigator about how pain expectations were set during the trial. Next, they transferred subject-reported pain scores and verbal pain descriptors to the validated Numerical Rating Scale and the Verbal Rating Scale, for comparison.

In all, 85 procedural pain scores were collected from 22 subject charts. The researchers found that the average procedural pain scores for treatment types reported by subjects were translated to entirely different verbal and numerical categories of pain from those described by industry materials. “It was surprising to see how vague pain descriptions can be in device manuals and industry materials, if even addressed at all,” Dr. Bonati said.

She advised clinicians to be wary of whom they rely on for information related to pain expectations. “Also, remember that wrongly set pain expectations can have physiologic and emotional effects that may positively or negatively impact patient experience,” Dr. Bonati said.

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was a review of a previously conducted clinical trial, “which is not a perfect representation of real-life clinic.”

She reported having no conflicts of interest.

DENVER – There is an apparent disconnect between the level of periprocedural pain experienced by patients during vascular laser procedures and what device manufacturers say that level of pain should be, results from a retrospective study showed.

“Although there is an abundance of research on how pain signals are transmitted in the nervous system and how pain is perceived among certain patient demographics, there is not much known about how pain perception differs from that put forth by industry,” Lauren Bonati, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “This study is unique because we are questioning not whether pain perception is reproducible between patients, but rather if it reflects what industry and device manufacturers are telling us.”

Dr. Bonati, a dermatologist at Edwards, Colo.–based Mountain Dermatology Specialists, and her colleagues collected median and mode pain scores from a past clinical trial that investigated a dual wavelength laser used for different types of treatments. “The treatment type (laser wavelength and treatment area) was largely based on the severity of facial redness for each individual patient,” she explained. “The options were spot treatment, nose and cheeks, or a global facial treatment with either wavelength.” The researchers reviewed industry-provided materials to determine language regarding procedural pain, and they interviewed the clinical trial’s principal investigator about how pain expectations were set during the trial. Next, they transferred subject-reported pain scores and verbal pain descriptors to the validated Numerical Rating Scale and the Verbal Rating Scale, for comparison.

In all, 85 procedural pain scores were collected from 22 subject charts. The researchers found that the average procedural pain scores for treatment types reported by subjects were translated to entirely different verbal and numerical categories of pain from those described by industry materials. “It was surprising to see how vague pain descriptions can be in device manuals and industry materials, if even addressed at all,” Dr. Bonati said.

She advised clinicians to be wary of whom they rely on for information related to pain expectations. “Also, remember that wrongly set pain expectations can have physiologic and emotional effects that may positively or negatively impact patient experience,” Dr. Bonati said.

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was a review of a previously conducted clinical trial, “which is not a perfect representation of real-life clinic.”

She reported having no conflicts of interest.

DENVER – There is an apparent disconnect between the level of periprocedural pain experienced by patients during vascular laser procedures and what device manufacturers say that level of pain should be, results from a retrospective study showed.

“Although there is an abundance of research on how pain signals are transmitted in the nervous system and how pain is perceived among certain patient demographics, there is not much known about how pain perception differs from that put forth by industry,” Lauren Bonati, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “This study is unique because we are questioning not whether pain perception is reproducible between patients, but rather if it reflects what industry and device manufacturers are telling us.”

Dr. Bonati, a dermatologist at Edwards, Colo.–based Mountain Dermatology Specialists, and her colleagues collected median and mode pain scores from a past clinical trial that investigated a dual wavelength laser used for different types of treatments. “The treatment type (laser wavelength and treatment area) was largely based on the severity of facial redness for each individual patient,” she explained. “The options were spot treatment, nose and cheeks, or a global facial treatment with either wavelength.” The researchers reviewed industry-provided materials to determine language regarding procedural pain, and they interviewed the clinical trial’s principal investigator about how pain expectations were set during the trial. Next, they transferred subject-reported pain scores and verbal pain descriptors to the validated Numerical Rating Scale and the Verbal Rating Scale, for comparison.

In all, 85 procedural pain scores were collected from 22 subject charts. The researchers found that the average procedural pain scores for treatment types reported by subjects were translated to entirely different verbal and numerical categories of pain from those described by industry materials. “It was surprising to see how vague pain descriptions can be in device manuals and industry materials, if even addressed at all,” Dr. Bonati said.

She advised clinicians to be wary of whom they rely on for information related to pain expectations. “Also, remember that wrongly set pain expectations can have physiologic and emotional effects that may positively or negatively impact patient experience,” Dr. Bonati said.

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was a review of a previously conducted clinical trial, “which is not a perfect representation of real-life clinic.”

She reported having no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM ASLMS 2019

Key clinical point: Industry-provided materials failed to capture the range of procedural pain scores reported by patients undergoing a variety of vascular laser procedures.

Major finding: The average procedural pain scores for treatment types reported by subjects were translated to entirely different verbal and numerical categories of pain from those described by industry materials.

Study details: A retrospective evaluation of 85 procedural pain scores collected from 22 subject charts.

Disclosures: Dr. Bonati reported having no financial disclosures.

Trofinetide may benefit patients with Rett syndrome

Furthermore, the treatment is safe and well tolerated, according to results published online ahead of print March 27 in Neurology.

“These are very promising data for the Rett community that is currently without any [Food and Drug Administration]–approved treatment option,” Daniel Glaze, MD, said in a press release from Acadia Pharmaceuticals, which is developing trofinetide.

In 2017, a phase 2 study indicated that the drug was safe and tolerable when administered in doses of 70 mg/kg b.i.d. to adolescent and adult females with Rett syndrome. The study also provided initial evidence of the drug’s efficacy. Dr. Glaze, professor of pediatrics and neurology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and his colleagues decided to conduct a larger phase 2 study that examined higher doses and a longer treatment duration.

The researchers first enrolled 62 participants in the study, all of whom received placebo b.i.d. for 14 days. They next randomized participants in equal groups to placebo or one of three twice-daily doses of trofinetide (i.e., 50 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 200 mg/kg). After a blinded review of safety and tolerability data, Dr. Glaze and his colleagues enrolled 20 more participants and randomized them in equal groups to placebo or 200 mg/kg b.i.d. of trofinetide. This modification in study design was intended to increase the likelihood of detecting a clinical benefit. Randomized, double-blind treatment lasted for 42 days. Participants presented for a final visit at approximately 10 days after the treatment period ended.

A total of 82 girls aged 5-15 years participated in the study. They all met the 2010 diagnostic criteria for classic Rett syndrome, had a documented pathogenic MECP2 variant, were in the postregression stage of the syndrome, and had been stable on pharmacologic and behavioral treatments for at least 4 weeks. The sample’s mean age was 9.7 years, 94% were white, and mean weight was 26.1 kg. The treatment groups’ demographic characteristics were balanced.

All three doses of trofinetide were safe and tolerable. One participant in the 200-mg/kg b.i.d. group was withdrawn from the study at her parents’ request. Serious adverse events occurred in one control participant, one receiving the 100-mg/kg b.i.d. dose, and one receiving the 200-mg/kg b.i.d. dose. These serious adverse events were considered unrelated to study medication and resolved by the study’s end. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, vomiting, upper respiratory tract infection, and pyrexia. Most were mild or moderate and considered unrelated to trofinetide.

The 200-mg/kg b.i.d. dose of trofinetide significantly improved outcomes on the Rett Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire (RSBQ), Clinical Global Impression Scale–Improvement (CGI-I), and Rett Syndrome Domain Specific Concerns (RTT-DSC), compared with placebo. The change of the median RTT-DSC score was 15%, and the change of the mean RSBQ score was 16%. More than 20% of participants receiving 200 mg/kg b.i.d. of trofinetide were rated much improved on the CGI-I, compared with less than 5% of controls.

“Overall, the observed clinical improvement in the present pediatric trial was more manifest than in the previous trial, with younger age (i.e., greater neuroplasticity), higher doses (i.e., higher drug exposure), and longer drug treatment duration (i.e., 28 days in Rett-001 vs. 42 days in Rett-002) as potential contributors,” said Dr. Glaze and his colleagues. “Future studies aiming at replicating the results of this pediatric trial would benefit from including the RSBQ as a primary endpoint and should also consider evaluating RSBQ subscales such as the General Mood.”

Neuren Pharmaceuticals and Rettsyndrome.org funded the study. Dr. Glaze is a consultant to Neuren Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Glaze DG et al. Neurology. 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007316.

Furthermore, the treatment is safe and well tolerated, according to results published online ahead of print March 27 in Neurology.

“These are very promising data for the Rett community that is currently without any [Food and Drug Administration]–approved treatment option,” Daniel Glaze, MD, said in a press release from Acadia Pharmaceuticals, which is developing trofinetide.

In 2017, a phase 2 study indicated that the drug was safe and tolerable when administered in doses of 70 mg/kg b.i.d. to adolescent and adult females with Rett syndrome. The study also provided initial evidence of the drug’s efficacy. Dr. Glaze, professor of pediatrics and neurology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and his colleagues decided to conduct a larger phase 2 study that examined higher doses and a longer treatment duration.

The researchers first enrolled 62 participants in the study, all of whom received placebo b.i.d. for 14 days. They next randomized participants in equal groups to placebo or one of three twice-daily doses of trofinetide (i.e., 50 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 200 mg/kg). After a blinded review of safety and tolerability data, Dr. Glaze and his colleagues enrolled 20 more participants and randomized them in equal groups to placebo or 200 mg/kg b.i.d. of trofinetide. This modification in study design was intended to increase the likelihood of detecting a clinical benefit. Randomized, double-blind treatment lasted for 42 days. Participants presented for a final visit at approximately 10 days after the treatment period ended.

A total of 82 girls aged 5-15 years participated in the study. They all met the 2010 diagnostic criteria for classic Rett syndrome, had a documented pathogenic MECP2 variant, were in the postregression stage of the syndrome, and had been stable on pharmacologic and behavioral treatments for at least 4 weeks. The sample’s mean age was 9.7 years, 94% were white, and mean weight was 26.1 kg. The treatment groups’ demographic characteristics were balanced.

All three doses of trofinetide were safe and tolerable. One participant in the 200-mg/kg b.i.d. group was withdrawn from the study at her parents’ request. Serious adverse events occurred in one control participant, one receiving the 100-mg/kg b.i.d. dose, and one receiving the 200-mg/kg b.i.d. dose. These serious adverse events were considered unrelated to study medication and resolved by the study’s end. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, vomiting, upper respiratory tract infection, and pyrexia. Most were mild or moderate and considered unrelated to trofinetide.

The 200-mg/kg b.i.d. dose of trofinetide significantly improved outcomes on the Rett Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire (RSBQ), Clinical Global Impression Scale–Improvement (CGI-I), and Rett Syndrome Domain Specific Concerns (RTT-DSC), compared with placebo. The change of the median RTT-DSC score was 15%, and the change of the mean RSBQ score was 16%. More than 20% of participants receiving 200 mg/kg b.i.d. of trofinetide were rated much improved on the CGI-I, compared with less than 5% of controls.

“Overall, the observed clinical improvement in the present pediatric trial was more manifest than in the previous trial, with younger age (i.e., greater neuroplasticity), higher doses (i.e., higher drug exposure), and longer drug treatment duration (i.e., 28 days in Rett-001 vs. 42 days in Rett-002) as potential contributors,” said Dr. Glaze and his colleagues. “Future studies aiming at replicating the results of this pediatric trial would benefit from including the RSBQ as a primary endpoint and should also consider evaluating RSBQ subscales such as the General Mood.”

Neuren Pharmaceuticals and Rettsyndrome.org funded the study. Dr. Glaze is a consultant to Neuren Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Glaze DG et al. Neurology. 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007316.

Furthermore, the treatment is safe and well tolerated, according to results published online ahead of print March 27 in Neurology.

“These are very promising data for the Rett community that is currently without any [Food and Drug Administration]–approved treatment option,” Daniel Glaze, MD, said in a press release from Acadia Pharmaceuticals, which is developing trofinetide.

In 2017, a phase 2 study indicated that the drug was safe and tolerable when administered in doses of 70 mg/kg b.i.d. to adolescent and adult females with Rett syndrome. The study also provided initial evidence of the drug’s efficacy. Dr. Glaze, professor of pediatrics and neurology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and his colleagues decided to conduct a larger phase 2 study that examined higher doses and a longer treatment duration.

The researchers first enrolled 62 participants in the study, all of whom received placebo b.i.d. for 14 days. They next randomized participants in equal groups to placebo or one of three twice-daily doses of trofinetide (i.e., 50 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 200 mg/kg). After a blinded review of safety and tolerability data, Dr. Glaze and his colleagues enrolled 20 more participants and randomized them in equal groups to placebo or 200 mg/kg b.i.d. of trofinetide. This modification in study design was intended to increase the likelihood of detecting a clinical benefit. Randomized, double-blind treatment lasted for 42 days. Participants presented for a final visit at approximately 10 days after the treatment period ended.

A total of 82 girls aged 5-15 years participated in the study. They all met the 2010 diagnostic criteria for classic Rett syndrome, had a documented pathogenic MECP2 variant, were in the postregression stage of the syndrome, and had been stable on pharmacologic and behavioral treatments for at least 4 weeks. The sample’s mean age was 9.7 years, 94% were white, and mean weight was 26.1 kg. The treatment groups’ demographic characteristics were balanced.

All three doses of trofinetide were safe and tolerable. One participant in the 200-mg/kg b.i.d. group was withdrawn from the study at her parents’ request. Serious adverse events occurred in one control participant, one receiving the 100-mg/kg b.i.d. dose, and one receiving the 200-mg/kg b.i.d. dose. These serious adverse events were considered unrelated to study medication and resolved by the study’s end. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, vomiting, upper respiratory tract infection, and pyrexia. Most were mild or moderate and considered unrelated to trofinetide.

The 200-mg/kg b.i.d. dose of trofinetide significantly improved outcomes on the Rett Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire (RSBQ), Clinical Global Impression Scale–Improvement (CGI-I), and Rett Syndrome Domain Specific Concerns (RTT-DSC), compared with placebo. The change of the median RTT-DSC score was 15%, and the change of the mean RSBQ score was 16%. More than 20% of participants receiving 200 mg/kg b.i.d. of trofinetide were rated much improved on the CGI-I, compared with less than 5% of controls.

“Overall, the observed clinical improvement in the present pediatric trial was more manifest than in the previous trial, with younger age (i.e., greater neuroplasticity), higher doses (i.e., higher drug exposure), and longer drug treatment duration (i.e., 28 days in Rett-001 vs. 42 days in Rett-002) as potential contributors,” said Dr. Glaze and his colleagues. “Future studies aiming at replicating the results of this pediatric trial would benefit from including the RSBQ as a primary endpoint and should also consider evaluating RSBQ subscales such as the General Mood.”

Neuren Pharmaceuticals and Rettsyndrome.org funded the study. Dr. Glaze is a consultant to Neuren Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Glaze DG et al. Neurology. 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007316.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Trofinetide provides clinically meaningful improvements in core symptoms of Rett syndrome.

Major finding: The 200 mg/kg b.i.d. dose of trofinetide improved outcomes on the Rett Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire by 16%.

Study details: A phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 82 children and adolescents with Rett syndrome.

Disclosures: Neuren Pharmaceuticals and Rettsyndrome.org funded the study.

Source: Glaze DG et al. Neurology. 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007316.

Proinflammatory diet may not trigger adult psoriasis, PsA, or AD

reported Alanna C. Bridgman of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and her associates.

In a large, retrospective cohort study among women from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS-II), including 85,185 psoriasis participants and 63,443 atopic dermatitis participants, Ms. Bridgman and her associates sought to determine whether proinflammatory diet increased the risk of incident psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or atopic dermatitis. Clinicians administered food frequency questionnaires every 4 years beginning in 1991 among female nurses aged 25-42 years.

Food groups included in the evaluation were those most predictive of three plasma markers of inflammation: interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and tumor necrosis factor–alpha R2 (TNF-R2). Proinflammatory foods included processed meat, red meat, organ meat, white fish, vegetables other than leafy green and dark yellow, refined grains, low- and high-energy drinks, and tomatoes. Anti-inflammatory foods included beer, wine, tea, coffee, dark yellow and green leafy vegetables, snacks such as popcorn and crackers, fruit juice, and pizza.

No association was found between proinflammatory diet and increased likelihood for incident psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or atopic dermatitis. Although proinflammatory dietary patterns were associated with psoriatic arthritis in the age-adjusted model, the hazard ratio was attenuated and found to be no longer statistically significant after adjustment for important confounders such as body mass index. In addition, no significant relationship between atopic dermatitis and proinflammatory diet was observed, they reported. The study was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Ms. Bridgman and her associates measured dietary patterns using the Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP); dietary patterns measuring high on the EDIP scale were associated with higher levels of TNF-alpha, TNF-alpha R1, TNF-alpha R2, CRP, IL-6, and adiponectin. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are Th1- and Th17-mediated diseases that exhibit higher serum levels of IL-6, CRP, and TNF-alpha, unlike atopic dermatitis, which is primarily a Th2-mediated condition featuring reduced involvement of the Th1/Th17 inflammatory cytokines.

Because a goal of the EDIP score was to “account for the overall effect of dietary patterns,” the researchers included in their analysis only those food groups that “explain the maximal variation in the three noted inflammatory biomarkers.”

All patients included in the study were questioned at baseline regarding their height and race/ethnicity. Weight, smoking status, and physical activity, and diagnoses of hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and asthma were monitored biennially.

Overall, patients with higher EDIP scores were found to have higher BMI, lower physical activity, and alcohol use, as well as increased rates of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension.

“Though we found no convincing evidence for an association with EDIP score for any of the investigated diseases, the results followed an internal pattern consistent with our hypotheses that higher EDIP scores would have more of an association with psoriatic disease than with atopic dermatitis,” the researchers wrote.

Citing recent evidence gathered in studies, such as the French NutriNet-Santé study, which demonstrated proinflammatory effects similar to those measured with the EDIP in cases where there was low adherence to the Mediterranean diet, the authors attributed their contradictory findings to “important methodological differences.” Unlike the NutriNet-Santé study, which classified psoriasis by severity, Ms. Bridgman and her colleagues examined the overall risk of incident psoriasis. “It is possible that a dietary index associated with more Th-2 inflammation would yield different results,” they noted.

The large sample size, prospectively collected dietary, and psoriatic disease data, as well as the ability to adjust for important confounding factors, were included among the strengths of the study.

That the participants were limited to U.S. women could be considered a limitation because the results may not be generalizable to other populations. The results also may not be relevant to child-onset disease because the patient population included only cases of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Questionnaire-based diagnoses increase the likelihood of misclassification, so “dilution of the case pool with false-positive cases would bias our results towards the null,” they added.

Ultimately, the authors noted that proinflammatory diet may be associated with other health risks, but these do not warrant counseling patients concerning their possible impact in cases of psoriatic disease or atopic dermatitis.

The study was funded by Brown University department of dermatology and from Regeneron, Sanofi, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Cancer Institute. Two coauthors, one of whom has a patent pending for the nix-tix tick remover, disclosed ties with various companies.

SOURCE: Bridgman AC et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 21. pii: S0190-9622(19)30329-9.

reported Alanna C. Bridgman of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and her associates.

In a large, retrospective cohort study among women from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS-II), including 85,185 psoriasis participants and 63,443 atopic dermatitis participants, Ms. Bridgman and her associates sought to determine whether proinflammatory diet increased the risk of incident psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or atopic dermatitis. Clinicians administered food frequency questionnaires every 4 years beginning in 1991 among female nurses aged 25-42 years.

Food groups included in the evaluation were those most predictive of three plasma markers of inflammation: interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and tumor necrosis factor–alpha R2 (TNF-R2). Proinflammatory foods included processed meat, red meat, organ meat, white fish, vegetables other than leafy green and dark yellow, refined grains, low- and high-energy drinks, and tomatoes. Anti-inflammatory foods included beer, wine, tea, coffee, dark yellow and green leafy vegetables, snacks such as popcorn and crackers, fruit juice, and pizza.

No association was found between proinflammatory diet and increased likelihood for incident psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or atopic dermatitis. Although proinflammatory dietary patterns were associated with psoriatic arthritis in the age-adjusted model, the hazard ratio was attenuated and found to be no longer statistically significant after adjustment for important confounders such as body mass index. In addition, no significant relationship between atopic dermatitis and proinflammatory diet was observed, they reported. The study was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Ms. Bridgman and her associates measured dietary patterns using the Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP); dietary patterns measuring high on the EDIP scale were associated with higher levels of TNF-alpha, TNF-alpha R1, TNF-alpha R2, CRP, IL-6, and adiponectin. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are Th1- and Th17-mediated diseases that exhibit higher serum levels of IL-6, CRP, and TNF-alpha, unlike atopic dermatitis, which is primarily a Th2-mediated condition featuring reduced involvement of the Th1/Th17 inflammatory cytokines.

Because a goal of the EDIP score was to “account for the overall effect of dietary patterns,” the researchers included in their analysis only those food groups that “explain the maximal variation in the three noted inflammatory biomarkers.”

All patients included in the study were questioned at baseline regarding their height and race/ethnicity. Weight, smoking status, and physical activity, and diagnoses of hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and asthma were monitored biennially.

Overall, patients with higher EDIP scores were found to have higher BMI, lower physical activity, and alcohol use, as well as increased rates of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension.

“Though we found no convincing evidence for an association with EDIP score for any of the investigated diseases, the results followed an internal pattern consistent with our hypotheses that higher EDIP scores would have more of an association with psoriatic disease than with atopic dermatitis,” the researchers wrote.

Citing recent evidence gathered in studies, such as the French NutriNet-Santé study, which demonstrated proinflammatory effects similar to those measured with the EDIP in cases where there was low adherence to the Mediterranean diet, the authors attributed their contradictory findings to “important methodological differences.” Unlike the NutriNet-Santé study, which classified psoriasis by severity, Ms. Bridgman and her colleagues examined the overall risk of incident psoriasis. “It is possible that a dietary index associated with more Th-2 inflammation would yield different results,” they noted.

The large sample size, prospectively collected dietary, and psoriatic disease data, as well as the ability to adjust for important confounding factors, were included among the strengths of the study.

That the participants were limited to U.S. women could be considered a limitation because the results may not be generalizable to other populations. The results also may not be relevant to child-onset disease because the patient population included only cases of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Questionnaire-based diagnoses increase the likelihood of misclassification, so “dilution of the case pool with false-positive cases would bias our results towards the null,” they added.

Ultimately, the authors noted that proinflammatory diet may be associated with other health risks, but these do not warrant counseling patients concerning their possible impact in cases of psoriatic disease or atopic dermatitis.

The study was funded by Brown University department of dermatology and from Regeneron, Sanofi, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Cancer Institute. Two coauthors, one of whom has a patent pending for the nix-tix tick remover, disclosed ties with various companies.

SOURCE: Bridgman AC et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 21. pii: S0190-9622(19)30329-9.

reported Alanna C. Bridgman of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and her associates.

In a large, retrospective cohort study among women from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS-II), including 85,185 psoriasis participants and 63,443 atopic dermatitis participants, Ms. Bridgman and her associates sought to determine whether proinflammatory diet increased the risk of incident psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or atopic dermatitis. Clinicians administered food frequency questionnaires every 4 years beginning in 1991 among female nurses aged 25-42 years.

Food groups included in the evaluation were those most predictive of three plasma markers of inflammation: interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and tumor necrosis factor–alpha R2 (TNF-R2). Proinflammatory foods included processed meat, red meat, organ meat, white fish, vegetables other than leafy green and dark yellow, refined grains, low- and high-energy drinks, and tomatoes. Anti-inflammatory foods included beer, wine, tea, coffee, dark yellow and green leafy vegetables, snacks such as popcorn and crackers, fruit juice, and pizza.

No association was found between proinflammatory diet and increased likelihood for incident psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or atopic dermatitis. Although proinflammatory dietary patterns were associated with psoriatic arthritis in the age-adjusted model, the hazard ratio was attenuated and found to be no longer statistically significant after adjustment for important confounders such as body mass index. In addition, no significant relationship between atopic dermatitis and proinflammatory diet was observed, they reported. The study was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Ms. Bridgman and her associates measured dietary patterns using the Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP); dietary patterns measuring high on the EDIP scale were associated with higher levels of TNF-alpha, TNF-alpha R1, TNF-alpha R2, CRP, IL-6, and adiponectin. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are Th1- and Th17-mediated diseases that exhibit higher serum levels of IL-6, CRP, and TNF-alpha, unlike atopic dermatitis, which is primarily a Th2-mediated condition featuring reduced involvement of the Th1/Th17 inflammatory cytokines.

Because a goal of the EDIP score was to “account for the overall effect of dietary patterns,” the researchers included in their analysis only those food groups that “explain the maximal variation in the three noted inflammatory biomarkers.”

All patients included in the study were questioned at baseline regarding their height and race/ethnicity. Weight, smoking status, and physical activity, and diagnoses of hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and asthma were monitored biennially.

Overall, patients with higher EDIP scores were found to have higher BMI, lower physical activity, and alcohol use, as well as increased rates of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension.

“Though we found no convincing evidence for an association with EDIP score for any of the investigated diseases, the results followed an internal pattern consistent with our hypotheses that higher EDIP scores would have more of an association with psoriatic disease than with atopic dermatitis,” the researchers wrote.

Citing recent evidence gathered in studies, such as the French NutriNet-Santé study, which demonstrated proinflammatory effects similar to those measured with the EDIP in cases where there was low adherence to the Mediterranean diet, the authors attributed their contradictory findings to “important methodological differences.” Unlike the NutriNet-Santé study, which classified psoriasis by severity, Ms. Bridgman and her colleagues examined the overall risk of incident psoriasis. “It is possible that a dietary index associated with more Th-2 inflammation would yield different results,” they noted.

The large sample size, prospectively collected dietary, and psoriatic disease data, as well as the ability to adjust for important confounding factors, were included among the strengths of the study.

That the participants were limited to U.S. women could be considered a limitation because the results may not be generalizable to other populations. The results also may not be relevant to child-onset disease because the patient population included only cases of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Questionnaire-based diagnoses increase the likelihood of misclassification, so “dilution of the case pool with false-positive cases would bias our results towards the null,” they added.

Ultimately, the authors noted that proinflammatory diet may be associated with other health risks, but these do not warrant counseling patients concerning their possible impact in cases of psoriatic disease or atopic dermatitis.

The study was funded by Brown University department of dermatology and from Regeneron, Sanofi, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Cancer Institute. Two coauthors, one of whom has a patent pending for the nix-tix tick remover, disclosed ties with various companies.

SOURCE: Bridgman AC et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 21. pii: S0190-9622(19)30329-9.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Study results may not be generalizable to other study populations.

Major finding: No association was found between proinflammatory diet and increased likelihood for incident psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or atopic dermatitis in adult women.

Study details: Large retrospective cohort study of 85,185 psoriasis subjects and 63,443 atopic dermatitis subjects.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Brown University department of dermatology and from Regeneron, Sanofi, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Cancer Institute. Two coauthors, one of whom has a patent pending for the nix-tix tick remover, disclosed ties with various companies. Source: Bridgman AC et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 21. pii: S0190-9622(19)30329-9.

Flu shot can be given irrespective of the time of last methotrexate dose

Immune response to influenza vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis patients taking methotrexate appears to depend most on stopping the next two weekly doses of the drug rather than any effect from the timing of the last dose, new research concludes.

The new finding, reported in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, stems from a post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled trial that Jin Kyun Park, MD, of Seoul (Korea) National University, and his colleagues had conducted earlier on immune response when patients stopped methotrexate for either 2 or 4 weeks after vaccination. While the main endpoint of that study showed no difference in the improvement in vaccine response with either stopping methotrexate for 2 or 4 weeks and no increase in disease activity with stopping for 2 weeks, it was unclear whether the timing of the last dose mattered when stopping for 2 weeks.

In a bid to identify the optimal time between the last dose of methotrexate and administration of a flu vaccine, Dr. Park and his colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of the trial, which involved 316 patients with RA receiving methotrexate for 6 weeks or longer to continue (n = 156) or to hold methotrexate (n = 160) for 2 weeks after receiving a quadrivalent influenza vaccine containing H1N1, H3N2, B-Yamagata, and B-Victoria.

The study authors defined a positive vaccine response as a fourfold or greater increase in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer. A satisfactory vaccine response was a positive response to two or more of four vaccine antigens.

Patients who stopped taking methotrexate were divided into eight subgroups according to the number of days between their last dose and their vaccination.

The research team reported that response to vaccine, fold increase in HI antibody titers, and postvaccination seroprotection rates were not associated with the time between the last methotrexate dose and the time of vaccination.

However, they conceded that “the absence of impact of the number of days between the last methotrexate dose and vaccination could be due to the small patient numbers in eight subgroups.”

Vaccine response also did not differ between patients who received the influenza vaccination within 3 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 65) and those who received it between 4-7 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 95).

Furthermore, RA disease activity, seropositivity, or use of conventional or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs did not have an impact on methotrexate discontinuation.

The authors concluded that vaccinations could be given irrespective of the time of the last methotrexate dose, and patients should be advised to skip two weekly doses following vaccination.

“This supports the notion that the effects of methotrexate on humeral immunity occur rapidly, despite the delayed effects on arthritis; therefore, the absence of methotrexate during the first 2 weeks postvaccination is critical for humoral immunity,” they wrote.

The study was sponsored by GC Pharma. One author disclosed serving as a consultant to Pfizer and receiving research grants from GC Pharma and Hanmi Pharma.

SOURCE: Park JK et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215187.

Immune response to influenza vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis patients taking methotrexate appears to depend most on stopping the next two weekly doses of the drug rather than any effect from the timing of the last dose, new research concludes.

The new finding, reported in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, stems from a post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled trial that Jin Kyun Park, MD, of Seoul (Korea) National University, and his colleagues had conducted earlier on immune response when patients stopped methotrexate for either 2 or 4 weeks after vaccination. While the main endpoint of that study showed no difference in the improvement in vaccine response with either stopping methotrexate for 2 or 4 weeks and no increase in disease activity with stopping for 2 weeks, it was unclear whether the timing of the last dose mattered when stopping for 2 weeks.

In a bid to identify the optimal time between the last dose of methotrexate and administration of a flu vaccine, Dr. Park and his colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of the trial, which involved 316 patients with RA receiving methotrexate for 6 weeks or longer to continue (n = 156) or to hold methotrexate (n = 160) for 2 weeks after receiving a quadrivalent influenza vaccine containing H1N1, H3N2, B-Yamagata, and B-Victoria.

The study authors defined a positive vaccine response as a fourfold or greater increase in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer. A satisfactory vaccine response was a positive response to two or more of four vaccine antigens.

Patients who stopped taking methotrexate were divided into eight subgroups according to the number of days between their last dose and their vaccination.

The research team reported that response to vaccine, fold increase in HI antibody titers, and postvaccination seroprotection rates were not associated with the time between the last methotrexate dose and the time of vaccination.

However, they conceded that “the absence of impact of the number of days between the last methotrexate dose and vaccination could be due to the small patient numbers in eight subgroups.”

Vaccine response also did not differ between patients who received the influenza vaccination within 3 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 65) and those who received it between 4-7 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 95).

Furthermore, RA disease activity, seropositivity, or use of conventional or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs did not have an impact on methotrexate discontinuation.

The authors concluded that vaccinations could be given irrespective of the time of the last methotrexate dose, and patients should be advised to skip two weekly doses following vaccination.

“This supports the notion that the effects of methotrexate on humeral immunity occur rapidly, despite the delayed effects on arthritis; therefore, the absence of methotrexate during the first 2 weeks postvaccination is critical for humoral immunity,” they wrote.

The study was sponsored by GC Pharma. One author disclosed serving as a consultant to Pfizer and receiving research grants from GC Pharma and Hanmi Pharma.

SOURCE: Park JK et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215187.

Immune response to influenza vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis patients taking methotrexate appears to depend most on stopping the next two weekly doses of the drug rather than any effect from the timing of the last dose, new research concludes.

The new finding, reported in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, stems from a post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled trial that Jin Kyun Park, MD, of Seoul (Korea) National University, and his colleagues had conducted earlier on immune response when patients stopped methotrexate for either 2 or 4 weeks after vaccination. While the main endpoint of that study showed no difference in the improvement in vaccine response with either stopping methotrexate for 2 or 4 weeks and no increase in disease activity with stopping for 2 weeks, it was unclear whether the timing of the last dose mattered when stopping for 2 weeks.

In a bid to identify the optimal time between the last dose of methotrexate and administration of a flu vaccine, Dr. Park and his colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of the trial, which involved 316 patients with RA receiving methotrexate for 6 weeks or longer to continue (n = 156) or to hold methotrexate (n = 160) for 2 weeks after receiving a quadrivalent influenza vaccine containing H1N1, H3N2, B-Yamagata, and B-Victoria.

The study authors defined a positive vaccine response as a fourfold or greater increase in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer. A satisfactory vaccine response was a positive response to two or more of four vaccine antigens.

Patients who stopped taking methotrexate were divided into eight subgroups according to the number of days between their last dose and their vaccination.

The research team reported that response to vaccine, fold increase in HI antibody titers, and postvaccination seroprotection rates were not associated with the time between the last methotrexate dose and the time of vaccination.

However, they conceded that “the absence of impact of the number of days between the last methotrexate dose and vaccination could be due to the small patient numbers in eight subgroups.”

Vaccine response also did not differ between patients who received the influenza vaccination within 3 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 65) and those who received it between 4-7 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 95).

Furthermore, RA disease activity, seropositivity, or use of conventional or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs did not have an impact on methotrexate discontinuation.

The authors concluded that vaccinations could be given irrespective of the time of the last methotrexate dose, and patients should be advised to skip two weekly doses following vaccination.

“This supports the notion that the effects of methotrexate on humeral immunity occur rapidly, despite the delayed effects on arthritis; therefore, the absence of methotrexate during the first 2 weeks postvaccination is critical for humoral immunity,” they wrote.

The study was sponsored by GC Pharma. One author disclosed serving as a consultant to Pfizer and receiving research grants from GC Pharma and Hanmi Pharma.

SOURCE: Park JK et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215187.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Response to vaccine, fold increase in HI antibody titers, and postvaccination seroprotection rates were not associated with the time between the last methotrexate dose and the time of vaccination.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled trial involving 316 patients with rheumatoid arthritis who continued or stopped methotrexate for 2 weeks following influenza vaccination.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by GC Pharma. One author disclosed serving as a consultant to Pfizer and receiving research grants from GC Pharma and Hanmi Pharma.

Source: Park JK et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215187

Investigative magnetic device found effective for skin tightening in a small study

DENVER – Patients treated with results from a small trial showed.

“There are many different modalities for tissue tightening, including lights, radiofrequency, ultrasound and thermal energy,” Jerome M. Garden, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The idea behind all of these technologies is to heat up the skin’s collagen and to stimulate further collagen production, which can then result in improved skin tightening and textural improvement.”

In a trial conducted at the Chicago-based Physicians Laser and Dermatology Institute, Dr. Garden and his colleagues evaluated a new technology for tissue tightening that involves magnetic energy. Developed by Rocky Mountain Biosystems and BioFusionary Corp., the investigative device produces a magnetic field in the targeted tissue, which then results in the heating and eventual tightening of the tissue. “By using magnetic energy, which relies on the polarity of the molecules, it allows for a safe way to target specifically the polar dermis, without heating the relatively dry epidermis or nonpolar adipose layer, resulting in a more tolerable and potentially safer alternative to tissue tightening,” said Dr. Garden, a dermatologist who is the director of the Physicians Laser and Dermatology Institute.

For the trial, 20 patients with facial and upper skin laxity underwent a mean of 4.3 treatment sessions with the 27MHz magnetic device that used a 3-cm spot size, with a minimum of 4 weeks between each session. No anesthetics or analgesics were used. “No gels or skin prep was performed before the treatment, other than a gentle soap beforehand,” Dr. Garden said. “A bland moisturizer was applied to the treated skin after treatments.” The majority of patients (85%) had paid for their procedures (a price comparable to other skin-tightening procedures), and two board-certified dermatologists evaluated both before and after photographs for overall improvement of skin laxity and texture. Follow-ups were done 2-4 months after the last treatment. The observers were not informed which photographs were before or after.

Dr. Garden reported that the observers correctly chose 19 out of 20 patients’ before and after photographs, and they rated the mean grade level of improvement as 43%. Nearly half of the patients (48%) were graded at 50% or greater improvement. At the same time, patients rated their own improvement as a mean 6.5 out of 10. Nearly half of patients graded their outcome at 7 or better, which was designated as “very satisfied.” The procedures were well tolerated, Dr. Garden said, and the most common side effects were minor transient erythema and edema. The erythema generally faded after 2-4 hours, and the mild edema lasted up to 24 hours.

“Magnetic energy is a new technology that can be used to treat lower face and neck laxity,” said Dr. Garden, who is also a professor of clinical dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago. “We only treated patients with skin types I-IV, but we feel that this technology is likely safe for higher skin types as well.”

Rocky Mountain Biosystems and BioFusionary Corp. provided the device used for the study. Dr. Garden and his colleagues are currently extending the ongoing trial. He reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – Patients treated with results from a small trial showed.

“There are many different modalities for tissue tightening, including lights, radiofrequency, ultrasound and thermal energy,” Jerome M. Garden, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The idea behind all of these technologies is to heat up the skin’s collagen and to stimulate further collagen production, which can then result in improved skin tightening and textural improvement.”

In a trial conducted at the Chicago-based Physicians Laser and Dermatology Institute, Dr. Garden and his colleagues evaluated a new technology for tissue tightening that involves magnetic energy. Developed by Rocky Mountain Biosystems and BioFusionary Corp., the investigative device produces a magnetic field in the targeted tissue, which then results in the heating and eventual tightening of the tissue. “By using magnetic energy, which relies on the polarity of the molecules, it allows for a safe way to target specifically the polar dermis, without heating the relatively dry epidermis or nonpolar adipose layer, resulting in a more tolerable and potentially safer alternative to tissue tightening,” said Dr. Garden, a dermatologist who is the director of the Physicians Laser and Dermatology Institute.

For the trial, 20 patients with facial and upper skin laxity underwent a mean of 4.3 treatment sessions with the 27MHz magnetic device that used a 3-cm spot size, with a minimum of 4 weeks between each session. No anesthetics or analgesics were used. “No gels or skin prep was performed before the treatment, other than a gentle soap beforehand,” Dr. Garden said. “A bland moisturizer was applied to the treated skin after treatments.” The majority of patients (85%) had paid for their procedures (a price comparable to other skin-tightening procedures), and two board-certified dermatologists evaluated both before and after photographs for overall improvement of skin laxity and texture. Follow-ups were done 2-4 months after the last treatment. The observers were not informed which photographs were before or after.

Dr. Garden reported that the observers correctly chose 19 out of 20 patients’ before and after photographs, and they rated the mean grade level of improvement as 43%. Nearly half of the patients (48%) were graded at 50% or greater improvement. At the same time, patients rated their own improvement as a mean 6.5 out of 10. Nearly half of patients graded their outcome at 7 or better, which was designated as “very satisfied.” The procedures were well tolerated, Dr. Garden said, and the most common side effects were minor transient erythema and edema. The erythema generally faded after 2-4 hours, and the mild edema lasted up to 24 hours.

“Magnetic energy is a new technology that can be used to treat lower face and neck laxity,” said Dr. Garden, who is also a professor of clinical dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago. “We only treated patients with skin types I-IV, but we feel that this technology is likely safe for higher skin types as well.”

Rocky Mountain Biosystems and BioFusionary Corp. provided the device used for the study. Dr. Garden and his colleagues are currently extending the ongoing trial. He reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – Patients treated with results from a small trial showed.

“There are many different modalities for tissue tightening, including lights, radiofrequency, ultrasound and thermal energy,” Jerome M. Garden, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The idea behind all of these technologies is to heat up the skin’s collagen and to stimulate further collagen production, which can then result in improved skin tightening and textural improvement.”

In a trial conducted at the Chicago-based Physicians Laser and Dermatology Institute, Dr. Garden and his colleagues evaluated a new technology for tissue tightening that involves magnetic energy. Developed by Rocky Mountain Biosystems and BioFusionary Corp., the investigative device produces a magnetic field in the targeted tissue, which then results in the heating and eventual tightening of the tissue. “By using magnetic energy, which relies on the polarity of the molecules, it allows for a safe way to target specifically the polar dermis, without heating the relatively dry epidermis or nonpolar adipose layer, resulting in a more tolerable and potentially safer alternative to tissue tightening,” said Dr. Garden, a dermatologist who is the director of the Physicians Laser and Dermatology Institute.

For the trial, 20 patients with facial and upper skin laxity underwent a mean of 4.3 treatment sessions with the 27MHz magnetic device that used a 3-cm spot size, with a minimum of 4 weeks between each session. No anesthetics or analgesics were used. “No gels or skin prep was performed before the treatment, other than a gentle soap beforehand,” Dr. Garden said. “A bland moisturizer was applied to the treated skin after treatments.” The majority of patients (85%) had paid for their procedures (a price comparable to other skin-tightening procedures), and two board-certified dermatologists evaluated both before and after photographs for overall improvement of skin laxity and texture. Follow-ups were done 2-4 months after the last treatment. The observers were not informed which photographs were before or after.

Dr. Garden reported that the observers correctly chose 19 out of 20 patients’ before and after photographs, and they rated the mean grade level of improvement as 43%. Nearly half of the patients (48%) were graded at 50% or greater improvement. At the same time, patients rated their own improvement as a mean 6.5 out of 10. Nearly half of patients graded their outcome at 7 or better, which was designated as “very satisfied.” The procedures were well tolerated, Dr. Garden said, and the most common side effects were minor transient erythema and edema. The erythema generally faded after 2-4 hours, and the mild edema lasted up to 24 hours.

“Magnetic energy is a new technology that can be used to treat lower face and neck laxity,” said Dr. Garden, who is also a professor of clinical dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago. “We only treated patients with skin types I-IV, but we feel that this technology is likely safe for higher skin types as well.”

Rocky Mountain Biosystems and BioFusionary Corp. provided the device used for the study. Dr. Garden and his colleagues are currently extending the ongoing trial. He reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ASLMS 2019

Key clinical point: A device that delivers high magnetic energy was found safe and effective for treatment of skin laxity.

Major finding: Following treatment, dermatologists graded nearly half of the patients (48%) at 50% or greater improvement.

Study details: A single-center trial of 20 patients with facial and upper skin laxity who underwent a mean of 4.3 treatment sessions.

Disclosures: Rocky Mountain Biosystems and BioFusionary Corp. provided the device used for the study. Dr. Garden reported having no financial disclosures.

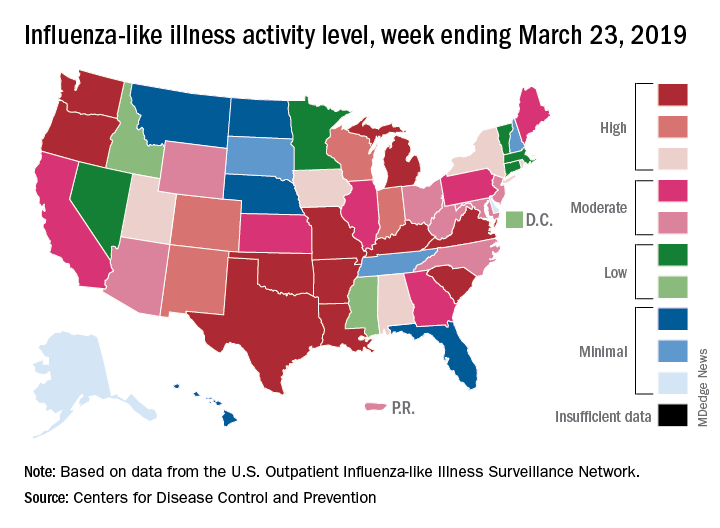

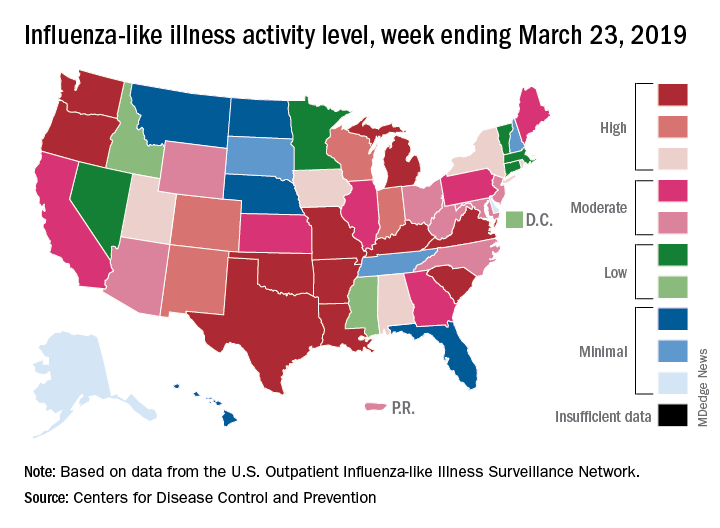

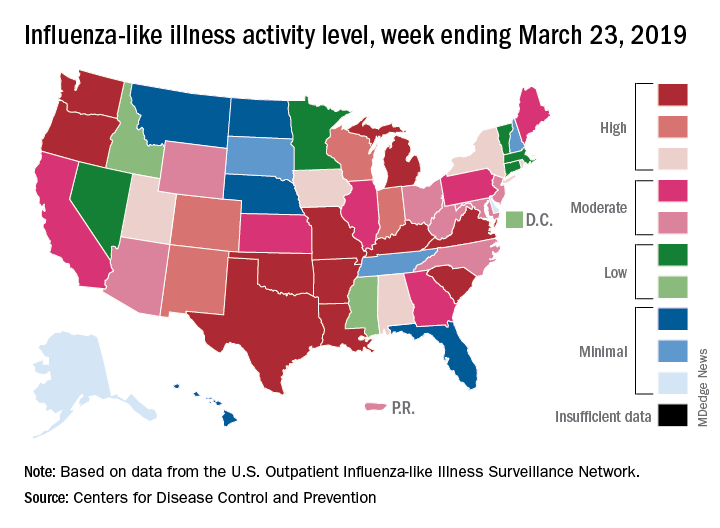

2018-2019 flu season: Going but not gone yet

The 2018-2019 flu season again showed real signs of ending as influenza activity levels dropped during the week ending March 23, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Despite those declines, however, current levels of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity are still elevated enough that the CDC issued a health advisory on March 28 to inform clinicians about the “increasing proportion of activity due to influenza A(H3N2) viruses, continued circulation of influenza A(H1N1) viruses, and low levels of influenza B viruses.”

The CDC’s weekly flu report, released March 29, does show that the overall burden is improving. The national proportion of outpatient visits for ILI dropped from 4.3% for the week ending March 16 to 3.8% for the latest reporting week, the CDC’s influenza division reported. The figure for March 16 was originally reported to be 4.4% but was revised in the new report.

The length of this years’ flu season, when measured as the number of weeks at or above the baseline level of 2.2%, is now 18 weeks. By this measure, the last five seasons have averaged 16 weeks, the CDC noted.

Influenza was considered widespread in 34 states and Puerto Rico for the week ending March 23, down from 44 states the previous week. The number of states at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale dropped from 20 to 11, and those in the high range (8-10) dropped from 26 to 20, data from the CDC’s Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network show.

There was one flu-related pediatric death during the week of March 23 but none reported from earlier weeks, which brings the total to 77 for the 2018-2019 season, the CDC said.

The 2018-2019 flu season again showed real signs of ending as influenza activity levels dropped during the week ending March 23, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Despite those declines, however, current levels of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity are still elevated enough that the CDC issued a health advisory on March 28 to inform clinicians about the “increasing proportion of activity due to influenza A(H3N2) viruses, continued circulation of influenza A(H1N1) viruses, and low levels of influenza B viruses.”

The CDC’s weekly flu report, released March 29, does show that the overall burden is improving. The national proportion of outpatient visits for ILI dropped from 4.3% for the week ending March 16 to 3.8% for the latest reporting week, the CDC’s influenza division reported. The figure for March 16 was originally reported to be 4.4% but was revised in the new report.

The length of this years’ flu season, when measured as the number of weeks at or above the baseline level of 2.2%, is now 18 weeks. By this measure, the last five seasons have averaged 16 weeks, the CDC noted.

Influenza was considered widespread in 34 states and Puerto Rico for the week ending March 23, down from 44 states the previous week. The number of states at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale dropped from 20 to 11, and those in the high range (8-10) dropped from 26 to 20, data from the CDC’s Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network show.

There was one flu-related pediatric death during the week of March 23 but none reported from earlier weeks, which brings the total to 77 for the 2018-2019 season, the CDC said.

The 2018-2019 flu season again showed real signs of ending as influenza activity levels dropped during the week ending March 23, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Despite those declines, however, current levels of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity are still elevated enough that the CDC issued a health advisory on March 28 to inform clinicians about the “increasing proportion of activity due to influenza A(H3N2) viruses, continued circulation of influenza A(H1N1) viruses, and low levels of influenza B viruses.”

The CDC’s weekly flu report, released March 29, does show that the overall burden is improving. The national proportion of outpatient visits for ILI dropped from 4.3% for the week ending March 16 to 3.8% for the latest reporting week, the CDC’s influenza division reported. The figure for March 16 was originally reported to be 4.4% but was revised in the new report.

The length of this years’ flu season, when measured as the number of weeks at or above the baseline level of 2.2%, is now 18 weeks. By this measure, the last five seasons have averaged 16 weeks, the CDC noted.

Influenza was considered widespread in 34 states and Puerto Rico for the week ending March 23, down from 44 states the previous week. The number of states at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale dropped from 20 to 11, and those in the high range (8-10) dropped from 26 to 20, data from the CDC’s Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network show.

There was one flu-related pediatric death during the week of March 23 but none reported from earlier weeks, which brings the total to 77 for the 2018-2019 season, the CDC said.

New renal, CV disease indication sought for canagliflozin

Janssen has announced that it has submitted a supplemental new drug application to the Food and Drug Administration to add an indication for canagliflozin (Invokana). The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 is currently indicated, in addition to diet and exercise, for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. However, in hopes of reducing the risks of end-stage kidney disease and of renal or cardiovascular death, according to a press release from the manufacturer.

If approved, canagliflozin will be the first diabetes medicine for the treatment of people living with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease, according to the press release.

The application was based on the results of the phase 3 CREDENCE trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of 4,401 patients with type 2 diabetes, stage 2 or 3 chronic kidney disease, and macroalbuminuria. The patients received standard of care as well. The trial was stopped early, in July 2018, because it had met the prespecified criteria for efficacy. Data from the trial will be presented in mid-April at the annual meeting of the International Society of Nephrology World Congress of Nephrology in Melbourne.

Canagliflozin is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2), patients with end-stage renal disease, or patients on dialysis. Serious side effects associated with canagliflozin include ketoacidosis, kidney problems, hyperkalemia, serious urinary tract infections, and hypoglycemia. The most common side effects are yeast infections of the vagina or penis, and changes in urination.

The full prescribing information for canagliflozin is available on the FDA website.

Janssen has announced that it has submitted a supplemental new drug application to the Food and Drug Administration to add an indication for canagliflozin (Invokana). The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 is currently indicated, in addition to diet and exercise, for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. However, in hopes of reducing the risks of end-stage kidney disease and of renal or cardiovascular death, according to a press release from the manufacturer.

If approved, canagliflozin will be the first diabetes medicine for the treatment of people living with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease, according to the press release.

The application was based on the results of the phase 3 CREDENCE trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of 4,401 patients with type 2 diabetes, stage 2 or 3 chronic kidney disease, and macroalbuminuria. The patients received standard of care as well. The trial was stopped early, in July 2018, because it had met the prespecified criteria for efficacy. Data from the trial will be presented in mid-April at the annual meeting of the International Society of Nephrology World Congress of Nephrology in Melbourne.

Canagliflozin is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2), patients with end-stage renal disease, or patients on dialysis. Serious side effects associated with canagliflozin include ketoacidosis, kidney problems, hyperkalemia, serious urinary tract infections, and hypoglycemia. The most common side effects are yeast infections of the vagina or penis, and changes in urination.

The full prescribing information for canagliflozin is available on the FDA website.

Janssen has announced that it has submitted a supplemental new drug application to the Food and Drug Administration to add an indication for canagliflozin (Invokana). The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 is currently indicated, in addition to diet and exercise, for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. However, in hopes of reducing the risks of end-stage kidney disease and of renal or cardiovascular death, according to a press release from the manufacturer.

If approved, canagliflozin will be the first diabetes medicine for the treatment of people living with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease, according to the press release.

The application was based on the results of the phase 3 CREDENCE trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of 4,401 patients with type 2 diabetes, stage 2 or 3 chronic kidney disease, and macroalbuminuria. The patients received standard of care as well. The trial was stopped early, in July 2018, because it had met the prespecified criteria for efficacy. Data from the trial will be presented in mid-April at the annual meeting of the International Society of Nephrology World Congress of Nephrology in Melbourne.

Canagliflozin is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2), patients with end-stage renal disease, or patients on dialysis. Serious side effects associated with canagliflozin include ketoacidosis, kidney problems, hyperkalemia, serious urinary tract infections, and hypoglycemia. The most common side effects are yeast infections of the vagina or penis, and changes in urination.

The full prescribing information for canagliflozin is available on the FDA website.

HM19 Day One highlights: Pulmonary, critical care, and perioperative care updates (VIDEO)

Marina Farah, MD, MHA, and Kranthi Sitammagari, MD, editorial board members for The Hospitalist, discuss Day One highlights from HM19.

Marina Farah, MD, MHA, and Kranthi Sitammagari, MD, editorial board members for The Hospitalist, discuss Day One highlights from HM19.

Marina Farah, MD, MHA, and Kranthi Sitammagari, MD, editorial board members for The Hospitalist, discuss Day One highlights from HM19.

At what diameter does a scar form after a full-thickness wound?

DENVER – A clinically identifiable scar occurs after full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter, while wounds of smaller diameter heal with no clinically perceptible scar.

The findings come from a “The broader purpose of this work is to contribute to the development of techniques for harvesting skin tissue with less morbidity than conventional methods,” lead study author Amanda H. Champlain, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The size threshold at which a full-thickness skin wound can heal without scarring had not been determined prior to this study.”

Dr. Champlain, a fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and The Wellman Center for Photomedicine, both in Boston, and her colleagues designed a way to evaluate healing responses and safety after collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin. According to the study abstract, the concept “is based on fractional photothermolysis in which a multitude of small, full-thickness thermal burns are produced by a laser on the skin with rapid healing and no scarring.” Measures included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), donor site pain scale, subject satisfaction survey, and an assessment of side effects, clinical photographs, and histology.

Preliminary data are available for five subjects. The POSAS-Observer scale ranges from 5 to 50 while the POSAS-Patient scale ranges from 6 to 60. The researchers observed that average final POSAS-Observer scores were 5.6 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 5.2 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 7.0 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.8 for scars 600 mcm in diameter, 8.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 9.6 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 13.2 for those 2 mm in diameter. Meanwhile, the average final POSAS-Subject scores were 6.0 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 6.0 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 6.6 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.4 for those 600 mcm in diameter, 7.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 7.4 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 10.0 for those 2 mm in diameter.

The maximum donor site pain reported was 4 out of 10 in one subject. “The procedure was very well tolerated by the subjects,” Dr. Champlain said. “They healed quickly, and the majority were happy with the cosmetic outcome regardless of the diameter of the microbiopsy used.”

The most common side effects of the study procedures included mild bleeding, scabbing, redness, and hyper/hypopigmentation. “The majority of study participants strongly agree that the study procedure was safe, tolerable, and cosmetically sound,” she said.

Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

DENVER – A clinically identifiable scar occurs after full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter, while wounds of smaller diameter heal with no clinically perceptible scar.

The findings come from a “The broader purpose of this work is to contribute to the development of techniques for harvesting skin tissue with less morbidity than conventional methods,” lead study author Amanda H. Champlain, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The size threshold at which a full-thickness skin wound can heal without scarring had not been determined prior to this study.”

Dr. Champlain, a fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and The Wellman Center for Photomedicine, both in Boston, and her colleagues designed a way to evaluate healing responses and safety after collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin. According to the study abstract, the concept “is based on fractional photothermolysis in which a multitude of small, full-thickness thermal burns are produced by a laser on the skin with rapid healing and no scarring.” Measures included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), donor site pain scale, subject satisfaction survey, and an assessment of side effects, clinical photographs, and histology.

Preliminary data are available for five subjects. The POSAS-Observer scale ranges from 5 to 50 while the POSAS-Patient scale ranges from 6 to 60. The researchers observed that average final POSAS-Observer scores were 5.6 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 5.2 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 7.0 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.8 for scars 600 mcm in diameter, 8.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 9.6 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 13.2 for those 2 mm in diameter. Meanwhile, the average final POSAS-Subject scores were 6.0 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 6.0 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 6.6 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.4 for those 600 mcm in diameter, 7.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 7.4 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 10.0 for those 2 mm in diameter.

The maximum donor site pain reported was 4 out of 10 in one subject. “The procedure was very well tolerated by the subjects,” Dr. Champlain said. “They healed quickly, and the majority were happy with the cosmetic outcome regardless of the diameter of the microbiopsy used.”

The most common side effects of the study procedures included mild bleeding, scabbing, redness, and hyper/hypopigmentation. “The majority of study participants strongly agree that the study procedure was safe, tolerable, and cosmetically sound,” she said.

Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

DENVER – A clinically identifiable scar occurs after full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter, while wounds of smaller diameter heal with no clinically perceptible scar.

The findings come from a “The broader purpose of this work is to contribute to the development of techniques for harvesting skin tissue with less morbidity than conventional methods,” lead study author Amanda H. Champlain, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The size threshold at which a full-thickness skin wound can heal without scarring had not been determined prior to this study.”

Dr. Champlain, a fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and The Wellman Center for Photomedicine, both in Boston, and her colleagues designed a way to evaluate healing responses and safety after collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin. According to the study abstract, the concept “is based on fractional photothermolysis in which a multitude of small, full-thickness thermal burns are produced by a laser on the skin with rapid healing and no scarring.” Measures included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), donor site pain scale, subject satisfaction survey, and an assessment of side effects, clinical photographs, and histology.

Preliminary data are available for five subjects. The POSAS-Observer scale ranges from 5 to 50 while the POSAS-Patient scale ranges from 6 to 60. The researchers observed that average final POSAS-Observer scores were 5.6 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 5.2 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 7.0 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.8 for scars 600 mcm in diameter, 8.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 9.6 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 13.2 for those 2 mm in diameter. Meanwhile, the average final POSAS-Subject scores were 6.0 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 6.0 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 6.6 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.4 for those 600 mcm in diameter, 7.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 7.4 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 10.0 for those 2 mm in diameter.

The maximum donor site pain reported was 4 out of 10 in one subject. “The procedure was very well tolerated by the subjects,” Dr. Champlain said. “They healed quickly, and the majority were happy with the cosmetic outcome regardless of the diameter of the microbiopsy used.”

The most common side effects of the study procedures included mild bleeding, scabbing, redness, and hyper/hypopigmentation. “The majority of study participants strongly agree that the study procedure was safe, tolerable, and cosmetically sound,” she said.

Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

REPORTING FROM ASLMS 2019

Key clinical point: Collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin is safe and highly tolerable.

Major finding: Full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter heal with a clinically identifiable scar.

Study details: A pilot trial in five individuals that set out to determine the biopsy size limit at which healing occurs without a scar, as well as demonstrate the safety of performing multiple skin microbiopsies.

Disclosures: Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

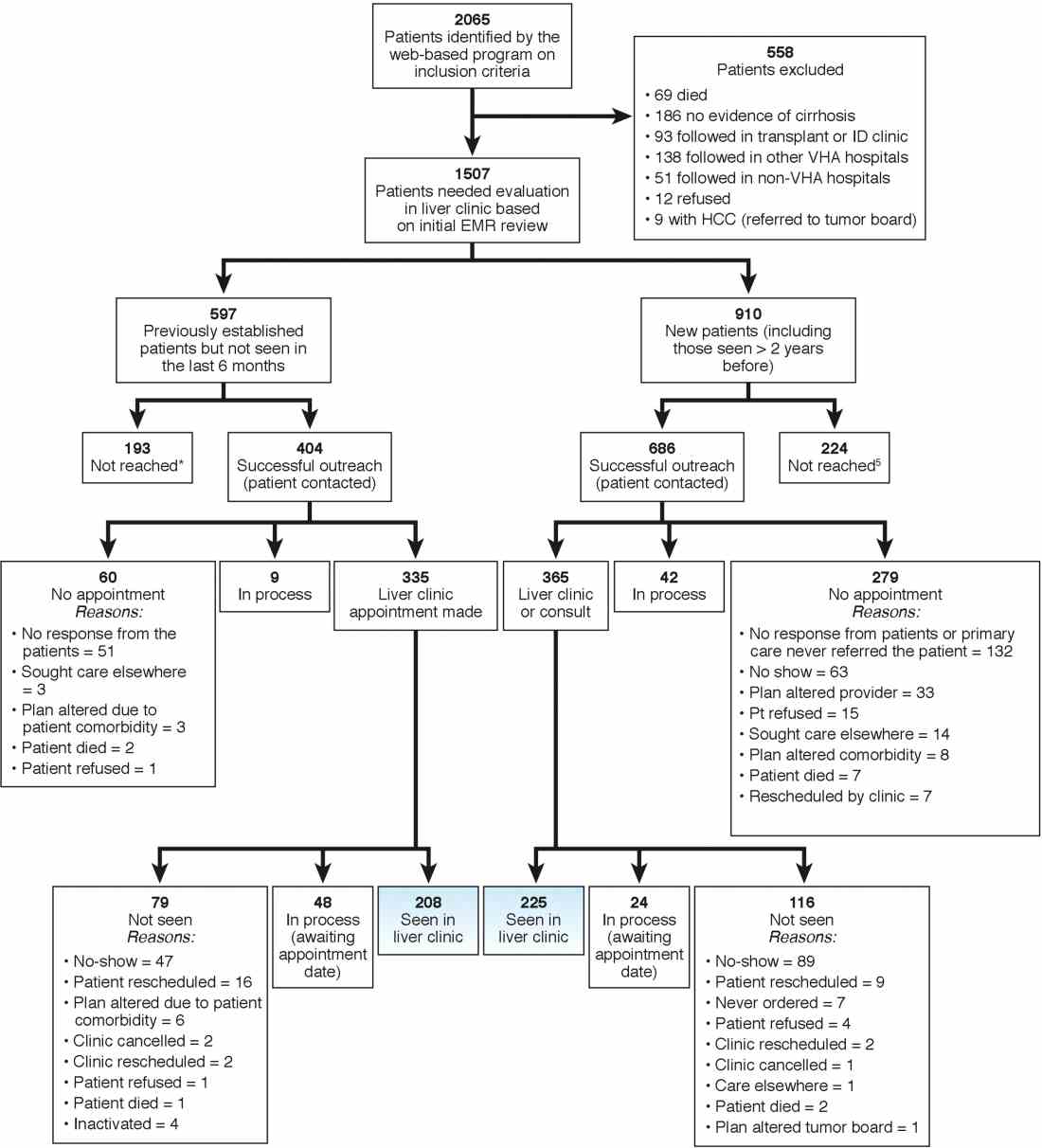

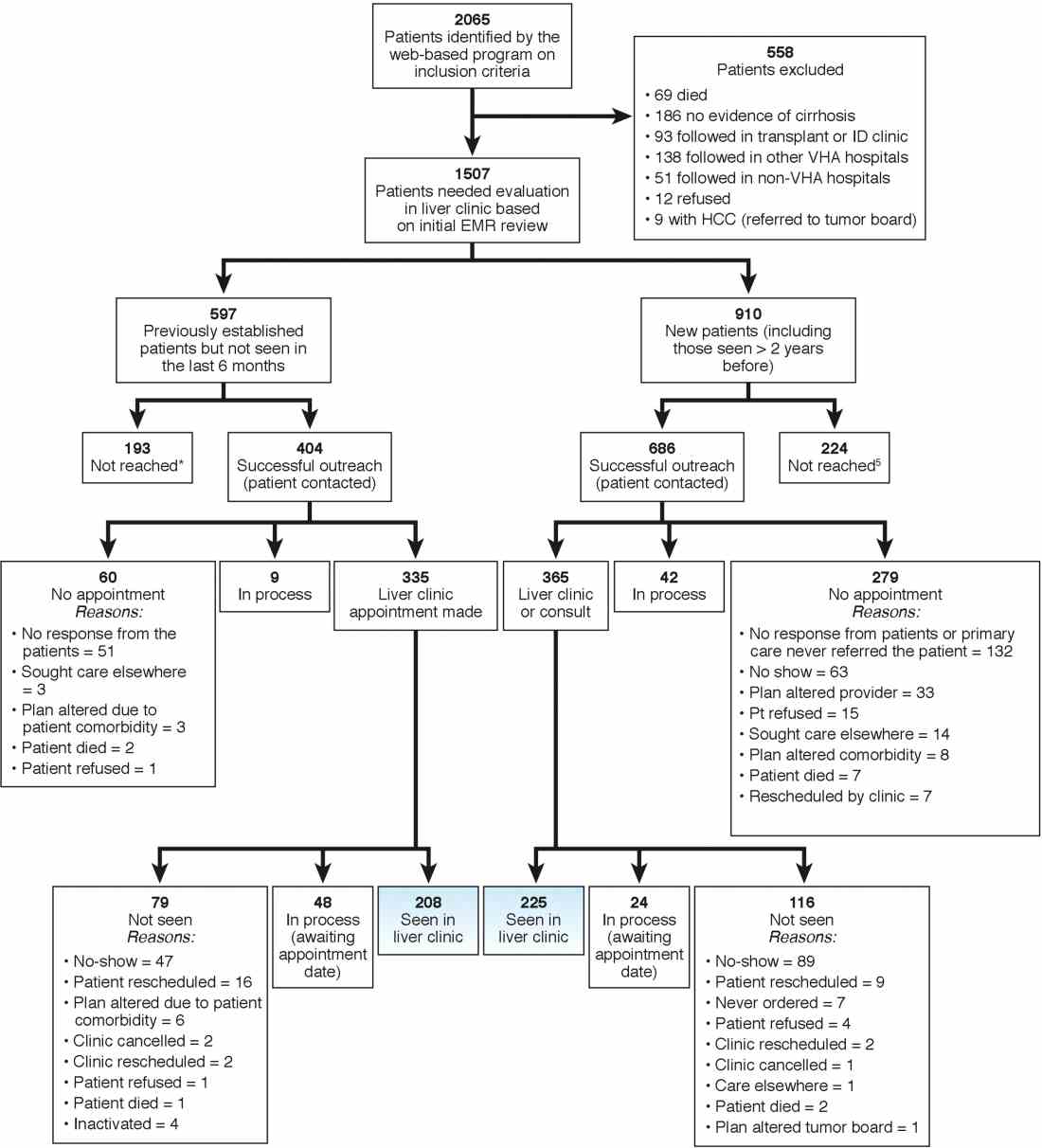

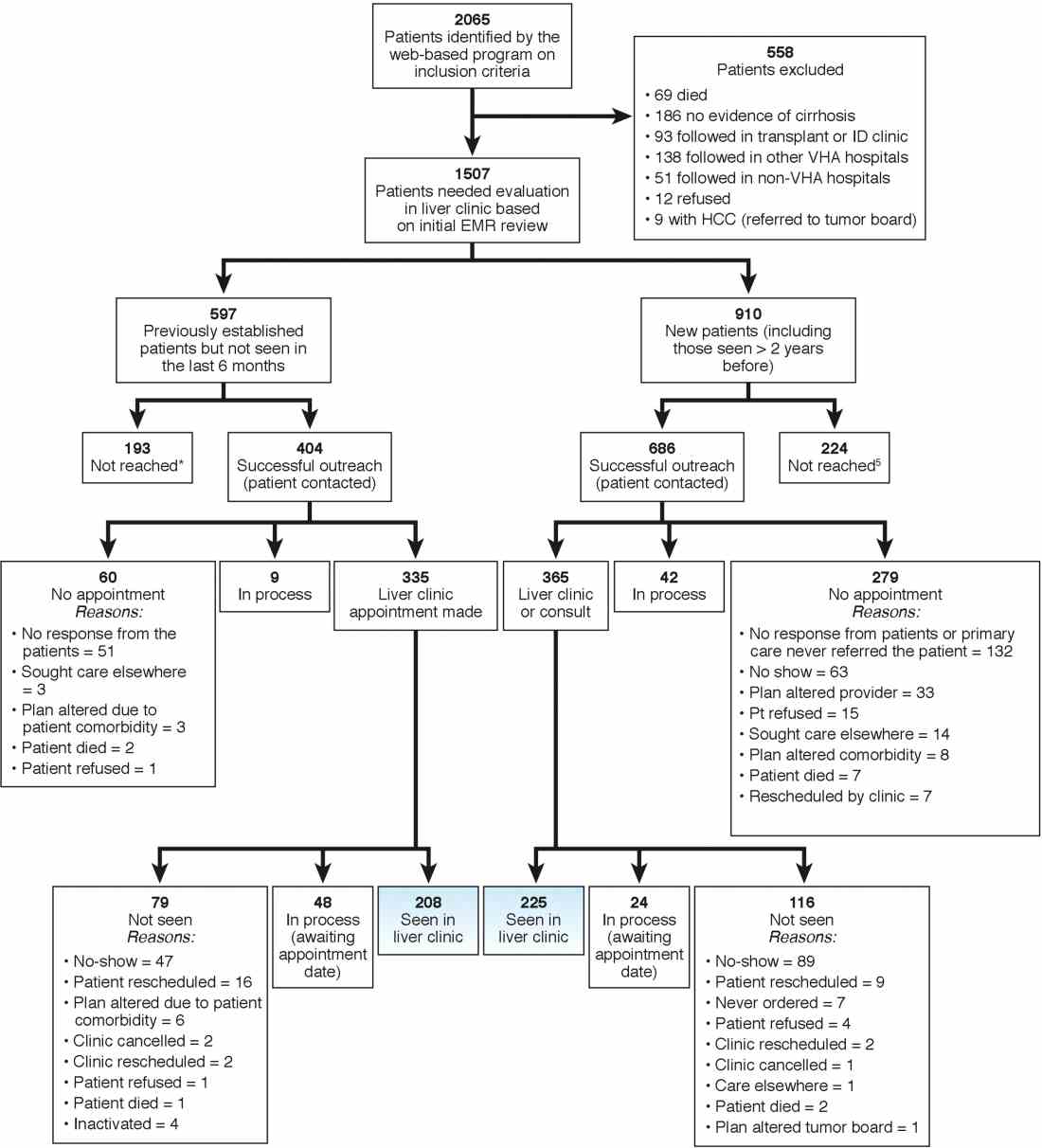

Implementation of a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system