User login

Screening and counseling interventions to prevent peripartum depression: A practical approach

Perinatal depression is an episode of major or minor depression that occurs during pregnancy or in the 12 months after birth; it affects about 10% of new mothers.1 Perinatal depression adversely impacts mothers, children, and their families. Pregnant women with depression are at increased risk for preterm birth and low birth weight.2 Infants of mothers with postpartum depression have reduced bonding, lower rates of breastfeeding, delayed cognitive and social development, and an increased risk of future mental health issues.3 Timely treatment of perinatal depression can improve health outcomes for the woman, her children, and their family.

Clinicians follow current screening recommendations

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently recommends that ObGynsscreen all pregnant women for depression and anxiety symptoms at least once during the perinatal period.1 Many practices use the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) during pregnancy and postpartum. Women who screen positive are referred to mental health clinicians or have treatment initiated by their primary obstetrician.

Clinicians have been phenomenally successful in screening for perinatal depression. In a recent study from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 98% of pregnant women were screened for perinatal depression, and a diagnosis of depression was made in 12%.4 Of note, only 47% of women who screened positive for depression initiated treatment, although 82% of women with the most severe symptoms initiated treatment. These data demonstrate that ObGyns consistently screen pregnant women for depression but, due to patient and system issues, treatment of all screen-positive women remains a yet unattained goal.5,6

New USPSTF guideline: Identify women at risk for perinatal depression and refer for counseling

In 2016 the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended that pregnant and postpartum women be screened for depression with adequate systems in place to ensure diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up.7 The 2016 USPSTF recommendation was consistent with prior guidelines from both the American Academy of Pediatrics in 20108 and ACOG in 2015.9

Now, the USPSTF is making a bold new recommendation, jumping ahead of professional societies: screen pregnant women to identify those at risk for perinatal depression and refer them for counseling (B recommendation; net benefit is moderate).10,11 The USPSTF recommendation is based on growing literature that shows counseling women at risk for perinatal depression reduces the risk of having an episode of major depression by 40%.11 Both interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy have been reported to be effective for preventing perinatal depression.12,13

As an example of the relevant literature, in one trial performed in Rhode Island, women who were 20 to 35 weeks pregnant with a high score (≥27) on the Cooper Survey Questionnaire and on public assistance were randomized to counseling or usual care. The counseling intervention involved 4 small group (2 to 5 women) sessions of 90 minutes and one individual session of 50 minutes.14 The treatment focused on managing the transition to motherhood, developing a support system, improving communication skills to manage conflict, goal setting, and identifying psychosocial supports for new mothers. At 6 months after birth, a depressive episode had occurred in 31% of the control women and 16% of the women who had experienced the intervention (P = .041). At 12 months after birth, a depressive episode had occurred in 40% of control women and 26% of women in the intervention group (P = .052).

Of note, most cases of postpartum depression were diagnosed more than 3 months after birth, a time when new mothers generally no longer are receiving regular postpartum care by an obstetrician. The timing of the diagnosis of perinatal depression indicates that an effective handoff between the obstetrician and primary care and/or mental health clinicians is of great importance. The investigators concluded that pregnant women at very high risk for perinatal depression who receive interpersonal therapy have a lower rate of a postpartum depressive episode than women receiving usual care.14

Pregnancy, delivery, and the first year following birth are stressful for many women and their families. Women who are young, poor, and with minimal social supports are at especially high risk for developing perinatal depression. However, it will be challenging for obstetric practices to rapidly implement the new USPSTF recommendations because there is no professional consensus on how to screen women to identify those at high risk for perinatal depression, and mental health resources to care for the screen-positive women are not sufficient.

Continue to: Challenges to implementing new USPSTF guideline...

Challenges to implementing new USPSTF guideline

Obstetricians have had great success in screening for perinatal depression because validated screening tools are available. Professional societies need to reach a consensus on recommending a specific screening tool for perinatal depression risk that can be used in all obstetric practices.

- personal history of depression

- current depressive symptoms that do not reach a diagnostic threshold

- low income

- all adolescents

- all single mothers

- recent exposure to intimate partner violence

- elevated anxiety symptoms

- a history of significant negative life events.

For many obstetricians, most of their pregnant patients meet the USPSTF criteria for being at high risk for perinatal depression and, per the guideline, these women should have a counseling intervention.

For many health systems, the resources available to provide mental health services are very limited. If most pregnant women need a counseling intervention, the health system must evolve to meet this need. In addition, risk factors for perinatal depression are also risk factors for having difficulty in participating in mental health interventions due to limitations, such as lack of transportation, social support, and money.4

Fortunately, clinicians from many backgrounds, including psychologists, social workers, nurse practitioners, and public health workers have the experience and/or training to provide the counseling interventions that have been shown to reduce the risk of perinatal depression. Health systems will need to tap all these resources to accommodate the large numbers of pregnant women who will be referred for counseling interventions. Pilot projects using electronic interventions, including telephone counseling, smartphone apps, and internet programs show promise.15,16 Electronic interventions have the potential to reach many pregnant women without over-taxing limited mental health resources.

A practical approach

Identify women at the greatest risk for perinatal depression and focus counseling interventions on this group. In my opinion, implementation of the USPSTF recommendation will take time. A practical approach would be to implement them in a staged sequence, focusing first on the women at highest risk, later extending the program to women at lesser risk. The two factors that confer the greatest risk of perinatal depression are a personal history of depression and high depression symptoms that do not meet criteria for depression.17 Many women with depression who take antidepressants discontinue their medications during pregnancy. These women are at very high risk for perinatal depression and deserve extra attention.18

Continue to: To identify women with a prior personal history of depression...

To identify women with a prior personal history of depression, it may be helpful to ask open-ended questions about a past diagnosis of depression or a mood disorder or use of antidepressant medications. To identify women with the greatest depression symptoms, utilize a lower cut-off for screening positive in the Edinburgh questionnaire. Practices that use an EPDS screen-positive score of 13 or greater could reduce the cut-off to 10 or 11, which would increase the number of women referred for evaluation and treatment.19

Clinical judgment and screening

Screening for prevalent depression and screening for women at increased risk for perinatal depression is challenging. ACOG highlights two important clinical issues1:

“Women with current depression or anxiety, a history of perinatal mood disorders, risk factors for perinatal mood disorders or suicidal thoughts warrant particularly close monitoring, evaluation and assessment.”

When screening for perinatal depression, screening test results should be interpreted within the clinical context. “A normal score for a tearful patient with a flat affect does not exclude depression; an elevated score in the context of an acute stressful event may resolve with close follow-up.”

In addition, women who screen-positive for prevalent depression and are subsequently evaluated by a mental health specialist may be identified as having mental health problems such as an anxiety disorder, substance misuse, or borderline personality disorder.20

Policy changes that support pregnant women and mothers could help to reduce the stress of pregnancy, birth, and childrearing, thereby reducing the risk of perinatal depression. The United States stands alone among rich nations in not providing paid parental leave. Paid maternity and parental leave would help many families respond more effectively to the initial stresses of parenthood.21 For women and families living in poverty, improved social support, including secure housing, protection from abusive partners, transportation resources, and access to healthy foods likely will reduce both stress and the risk of depression.

The ultimate goal: A healthy pregnancy

Clinicians have been phenomenally successful in screening for perinatal depression. The new USPSTF recommendation adds the prevention of perinatal depression to the goals of a healthy pregnancy. This recommendation builds upon the foundation of screening for acute illness (depression), pivoting to the public health perspective of disease prevention.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening for perinatal depression. ACOG Committee Opinion No 757. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e208-e212.

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, et al. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012-1024.

- Pearlstein T, Howard M, Salisbury A, et al. Postpartum depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:357-364.

- Avalos LA, Raine-Bennett T, Chen H, et al. Improved perinatal depression screening, treatment and outcomes with a universal obstetric program. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:917-925.

- Cox EQ, Sowa NA, Meltzer-Brody SE, et al. The perinatal depression treatment cascade: baby steps toward improving outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:1189-1200.

- Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, et al. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;33:143-161.

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for depression in adults. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

- Earls MF. Committee on Psychological Aspects of Child and Family Health. American Academy of Pediatrics. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1032-1039.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No 630. Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1268-1271.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations statement. JAMA. 2019;321:580-587.

- O’Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger ML, et al. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;321:588-601.

- Sockol LE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women. J Affective Disorders. 2018;232:316-328.

- Sockol LE. A systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating and preventing perinatal depression. J Affective Disorders. 2015;177:7-21.

- Zlotnick C, Tzilos G, Miller I, et al. Randomized controlled trial to prevent postpartum depression in mothers on public assistance. J Affective Disorders. 2016;189:263-268.

- Haga SM, Drozd F, Lisoy C, et al. Mamma Mia—a randomized controlled trial of an internet-based intervention for perinatal depression. Psycholog Med. 2018;1-9.

- Shorey S, Ng YM, Ng ED, et al. Effectiveness of a technology-based supportive educational parenting program on parent outcomes (Part 1): Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e10816.

- Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295:499-507.

- Goodman JH. Women’s attitudes, preferences and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth. 2009;36:60-69.

- Smith-Nielsen J, Matthey S, Lange T, Vaever MS. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale against both DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:393.

- Judd F, Lorimer S, Thomson RH, et al. Screening for depression with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and finding borderline personality disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;Epub Oct 12. doi: 10.1177/0004867418804067.

- Diamond R. Promoting sensible parenting policies. Leading by example. JAMA. 2019;321:645- 646.

Perinatal depression is an episode of major or minor depression that occurs during pregnancy or in the 12 months after birth; it affects about 10% of new mothers.1 Perinatal depression adversely impacts mothers, children, and their families. Pregnant women with depression are at increased risk for preterm birth and low birth weight.2 Infants of mothers with postpartum depression have reduced bonding, lower rates of breastfeeding, delayed cognitive and social development, and an increased risk of future mental health issues.3 Timely treatment of perinatal depression can improve health outcomes for the woman, her children, and their family.

Clinicians follow current screening recommendations

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently recommends that ObGynsscreen all pregnant women for depression and anxiety symptoms at least once during the perinatal period.1 Many practices use the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) during pregnancy and postpartum. Women who screen positive are referred to mental health clinicians or have treatment initiated by their primary obstetrician.

Clinicians have been phenomenally successful in screening for perinatal depression. In a recent study from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 98% of pregnant women were screened for perinatal depression, and a diagnosis of depression was made in 12%.4 Of note, only 47% of women who screened positive for depression initiated treatment, although 82% of women with the most severe symptoms initiated treatment. These data demonstrate that ObGyns consistently screen pregnant women for depression but, due to patient and system issues, treatment of all screen-positive women remains a yet unattained goal.5,6

New USPSTF guideline: Identify women at risk for perinatal depression and refer for counseling

In 2016 the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended that pregnant and postpartum women be screened for depression with adequate systems in place to ensure diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up.7 The 2016 USPSTF recommendation was consistent with prior guidelines from both the American Academy of Pediatrics in 20108 and ACOG in 2015.9

Now, the USPSTF is making a bold new recommendation, jumping ahead of professional societies: screen pregnant women to identify those at risk for perinatal depression and refer them for counseling (B recommendation; net benefit is moderate).10,11 The USPSTF recommendation is based on growing literature that shows counseling women at risk for perinatal depression reduces the risk of having an episode of major depression by 40%.11 Both interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy have been reported to be effective for preventing perinatal depression.12,13

As an example of the relevant literature, in one trial performed in Rhode Island, women who were 20 to 35 weeks pregnant with a high score (≥27) on the Cooper Survey Questionnaire and on public assistance were randomized to counseling or usual care. The counseling intervention involved 4 small group (2 to 5 women) sessions of 90 minutes and one individual session of 50 minutes.14 The treatment focused on managing the transition to motherhood, developing a support system, improving communication skills to manage conflict, goal setting, and identifying psychosocial supports for new mothers. At 6 months after birth, a depressive episode had occurred in 31% of the control women and 16% of the women who had experienced the intervention (P = .041). At 12 months after birth, a depressive episode had occurred in 40% of control women and 26% of women in the intervention group (P = .052).

Of note, most cases of postpartum depression were diagnosed more than 3 months after birth, a time when new mothers generally no longer are receiving regular postpartum care by an obstetrician. The timing of the diagnosis of perinatal depression indicates that an effective handoff between the obstetrician and primary care and/or mental health clinicians is of great importance. The investigators concluded that pregnant women at very high risk for perinatal depression who receive interpersonal therapy have a lower rate of a postpartum depressive episode than women receiving usual care.14

Pregnancy, delivery, and the first year following birth are stressful for many women and their families. Women who are young, poor, and with minimal social supports are at especially high risk for developing perinatal depression. However, it will be challenging for obstetric practices to rapidly implement the new USPSTF recommendations because there is no professional consensus on how to screen women to identify those at high risk for perinatal depression, and mental health resources to care for the screen-positive women are not sufficient.

Continue to: Challenges to implementing new USPSTF guideline...

Challenges to implementing new USPSTF guideline

Obstetricians have had great success in screening for perinatal depression because validated screening tools are available. Professional societies need to reach a consensus on recommending a specific screening tool for perinatal depression risk that can be used in all obstetric practices.

- personal history of depression

- current depressive symptoms that do not reach a diagnostic threshold

- low income

- all adolescents

- all single mothers

- recent exposure to intimate partner violence

- elevated anxiety symptoms

- a history of significant negative life events.

For many obstetricians, most of their pregnant patients meet the USPSTF criteria for being at high risk for perinatal depression and, per the guideline, these women should have a counseling intervention.

For many health systems, the resources available to provide mental health services are very limited. If most pregnant women need a counseling intervention, the health system must evolve to meet this need. In addition, risk factors for perinatal depression are also risk factors for having difficulty in participating in mental health interventions due to limitations, such as lack of transportation, social support, and money.4

Fortunately, clinicians from many backgrounds, including psychologists, social workers, nurse practitioners, and public health workers have the experience and/or training to provide the counseling interventions that have been shown to reduce the risk of perinatal depression. Health systems will need to tap all these resources to accommodate the large numbers of pregnant women who will be referred for counseling interventions. Pilot projects using electronic interventions, including telephone counseling, smartphone apps, and internet programs show promise.15,16 Electronic interventions have the potential to reach many pregnant women without over-taxing limited mental health resources.

A practical approach

Identify women at the greatest risk for perinatal depression and focus counseling interventions on this group. In my opinion, implementation of the USPSTF recommendation will take time. A practical approach would be to implement them in a staged sequence, focusing first on the women at highest risk, later extending the program to women at lesser risk. The two factors that confer the greatest risk of perinatal depression are a personal history of depression and high depression symptoms that do not meet criteria for depression.17 Many women with depression who take antidepressants discontinue their medications during pregnancy. These women are at very high risk for perinatal depression and deserve extra attention.18

Continue to: To identify women with a prior personal history of depression...

To identify women with a prior personal history of depression, it may be helpful to ask open-ended questions about a past diagnosis of depression or a mood disorder or use of antidepressant medications. To identify women with the greatest depression symptoms, utilize a lower cut-off for screening positive in the Edinburgh questionnaire. Practices that use an EPDS screen-positive score of 13 or greater could reduce the cut-off to 10 or 11, which would increase the number of women referred for evaluation and treatment.19

Clinical judgment and screening

Screening for prevalent depression and screening for women at increased risk for perinatal depression is challenging. ACOG highlights two important clinical issues1:

“Women with current depression or anxiety, a history of perinatal mood disorders, risk factors for perinatal mood disorders or suicidal thoughts warrant particularly close monitoring, evaluation and assessment.”

When screening for perinatal depression, screening test results should be interpreted within the clinical context. “A normal score for a tearful patient with a flat affect does not exclude depression; an elevated score in the context of an acute stressful event may resolve with close follow-up.”

In addition, women who screen-positive for prevalent depression and are subsequently evaluated by a mental health specialist may be identified as having mental health problems such as an anxiety disorder, substance misuse, or borderline personality disorder.20

Policy changes that support pregnant women and mothers could help to reduce the stress of pregnancy, birth, and childrearing, thereby reducing the risk of perinatal depression. The United States stands alone among rich nations in not providing paid parental leave. Paid maternity and parental leave would help many families respond more effectively to the initial stresses of parenthood.21 For women and families living in poverty, improved social support, including secure housing, protection from abusive partners, transportation resources, and access to healthy foods likely will reduce both stress and the risk of depression.

The ultimate goal: A healthy pregnancy

Clinicians have been phenomenally successful in screening for perinatal depression. The new USPSTF recommendation adds the prevention of perinatal depression to the goals of a healthy pregnancy. This recommendation builds upon the foundation of screening for acute illness (depression), pivoting to the public health perspective of disease prevention.

Perinatal depression is an episode of major or minor depression that occurs during pregnancy or in the 12 months after birth; it affects about 10% of new mothers.1 Perinatal depression adversely impacts mothers, children, and their families. Pregnant women with depression are at increased risk for preterm birth and low birth weight.2 Infants of mothers with postpartum depression have reduced bonding, lower rates of breastfeeding, delayed cognitive and social development, and an increased risk of future mental health issues.3 Timely treatment of perinatal depression can improve health outcomes for the woman, her children, and their family.

Clinicians follow current screening recommendations

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently recommends that ObGynsscreen all pregnant women for depression and anxiety symptoms at least once during the perinatal period.1 Many practices use the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) during pregnancy and postpartum. Women who screen positive are referred to mental health clinicians or have treatment initiated by their primary obstetrician.

Clinicians have been phenomenally successful in screening for perinatal depression. In a recent study from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 98% of pregnant women were screened for perinatal depression, and a diagnosis of depression was made in 12%.4 Of note, only 47% of women who screened positive for depression initiated treatment, although 82% of women with the most severe symptoms initiated treatment. These data demonstrate that ObGyns consistently screen pregnant women for depression but, due to patient and system issues, treatment of all screen-positive women remains a yet unattained goal.5,6

New USPSTF guideline: Identify women at risk for perinatal depression and refer for counseling

In 2016 the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended that pregnant and postpartum women be screened for depression with adequate systems in place to ensure diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up.7 The 2016 USPSTF recommendation was consistent with prior guidelines from both the American Academy of Pediatrics in 20108 and ACOG in 2015.9

Now, the USPSTF is making a bold new recommendation, jumping ahead of professional societies: screen pregnant women to identify those at risk for perinatal depression and refer them for counseling (B recommendation; net benefit is moderate).10,11 The USPSTF recommendation is based on growing literature that shows counseling women at risk for perinatal depression reduces the risk of having an episode of major depression by 40%.11 Both interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy have been reported to be effective for preventing perinatal depression.12,13

As an example of the relevant literature, in one trial performed in Rhode Island, women who were 20 to 35 weeks pregnant with a high score (≥27) on the Cooper Survey Questionnaire and on public assistance were randomized to counseling or usual care. The counseling intervention involved 4 small group (2 to 5 women) sessions of 90 minutes and one individual session of 50 minutes.14 The treatment focused on managing the transition to motherhood, developing a support system, improving communication skills to manage conflict, goal setting, and identifying psychosocial supports for new mothers. At 6 months after birth, a depressive episode had occurred in 31% of the control women and 16% of the women who had experienced the intervention (P = .041). At 12 months after birth, a depressive episode had occurred in 40% of control women and 26% of women in the intervention group (P = .052).

Of note, most cases of postpartum depression were diagnosed more than 3 months after birth, a time when new mothers generally no longer are receiving regular postpartum care by an obstetrician. The timing of the diagnosis of perinatal depression indicates that an effective handoff between the obstetrician and primary care and/or mental health clinicians is of great importance. The investigators concluded that pregnant women at very high risk for perinatal depression who receive interpersonal therapy have a lower rate of a postpartum depressive episode than women receiving usual care.14

Pregnancy, delivery, and the first year following birth are stressful for many women and their families. Women who are young, poor, and with minimal social supports are at especially high risk for developing perinatal depression. However, it will be challenging for obstetric practices to rapidly implement the new USPSTF recommendations because there is no professional consensus on how to screen women to identify those at high risk for perinatal depression, and mental health resources to care for the screen-positive women are not sufficient.

Continue to: Challenges to implementing new USPSTF guideline...

Challenges to implementing new USPSTF guideline

Obstetricians have had great success in screening for perinatal depression because validated screening tools are available. Professional societies need to reach a consensus on recommending a specific screening tool for perinatal depression risk that can be used in all obstetric practices.

- personal history of depression

- current depressive symptoms that do not reach a diagnostic threshold

- low income

- all adolescents

- all single mothers

- recent exposure to intimate partner violence

- elevated anxiety symptoms

- a history of significant negative life events.

For many obstetricians, most of their pregnant patients meet the USPSTF criteria for being at high risk for perinatal depression and, per the guideline, these women should have a counseling intervention.

For many health systems, the resources available to provide mental health services are very limited. If most pregnant women need a counseling intervention, the health system must evolve to meet this need. In addition, risk factors for perinatal depression are also risk factors for having difficulty in participating in mental health interventions due to limitations, such as lack of transportation, social support, and money.4

Fortunately, clinicians from many backgrounds, including psychologists, social workers, nurse practitioners, and public health workers have the experience and/or training to provide the counseling interventions that have been shown to reduce the risk of perinatal depression. Health systems will need to tap all these resources to accommodate the large numbers of pregnant women who will be referred for counseling interventions. Pilot projects using electronic interventions, including telephone counseling, smartphone apps, and internet programs show promise.15,16 Electronic interventions have the potential to reach many pregnant women without over-taxing limited mental health resources.

A practical approach

Identify women at the greatest risk for perinatal depression and focus counseling interventions on this group. In my opinion, implementation of the USPSTF recommendation will take time. A practical approach would be to implement them in a staged sequence, focusing first on the women at highest risk, later extending the program to women at lesser risk. The two factors that confer the greatest risk of perinatal depression are a personal history of depression and high depression symptoms that do not meet criteria for depression.17 Many women with depression who take antidepressants discontinue their medications during pregnancy. These women are at very high risk for perinatal depression and deserve extra attention.18

Continue to: To identify women with a prior personal history of depression...

To identify women with a prior personal history of depression, it may be helpful to ask open-ended questions about a past diagnosis of depression or a mood disorder or use of antidepressant medications. To identify women with the greatest depression symptoms, utilize a lower cut-off for screening positive in the Edinburgh questionnaire. Practices that use an EPDS screen-positive score of 13 or greater could reduce the cut-off to 10 or 11, which would increase the number of women referred for evaluation and treatment.19

Clinical judgment and screening

Screening for prevalent depression and screening for women at increased risk for perinatal depression is challenging. ACOG highlights two important clinical issues1:

“Women with current depression or anxiety, a history of perinatal mood disorders, risk factors for perinatal mood disorders or suicidal thoughts warrant particularly close monitoring, evaluation and assessment.”

When screening for perinatal depression, screening test results should be interpreted within the clinical context. “A normal score for a tearful patient with a flat affect does not exclude depression; an elevated score in the context of an acute stressful event may resolve with close follow-up.”

In addition, women who screen-positive for prevalent depression and are subsequently evaluated by a mental health specialist may be identified as having mental health problems such as an anxiety disorder, substance misuse, or borderline personality disorder.20

Policy changes that support pregnant women and mothers could help to reduce the stress of pregnancy, birth, and childrearing, thereby reducing the risk of perinatal depression. The United States stands alone among rich nations in not providing paid parental leave. Paid maternity and parental leave would help many families respond more effectively to the initial stresses of parenthood.21 For women and families living in poverty, improved social support, including secure housing, protection from abusive partners, transportation resources, and access to healthy foods likely will reduce both stress and the risk of depression.

The ultimate goal: A healthy pregnancy

Clinicians have been phenomenally successful in screening for perinatal depression. The new USPSTF recommendation adds the prevention of perinatal depression to the goals of a healthy pregnancy. This recommendation builds upon the foundation of screening for acute illness (depression), pivoting to the public health perspective of disease prevention.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening for perinatal depression. ACOG Committee Opinion No 757. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e208-e212.

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, et al. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012-1024.

- Pearlstein T, Howard M, Salisbury A, et al. Postpartum depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:357-364.

- Avalos LA, Raine-Bennett T, Chen H, et al. Improved perinatal depression screening, treatment and outcomes with a universal obstetric program. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:917-925.

- Cox EQ, Sowa NA, Meltzer-Brody SE, et al. The perinatal depression treatment cascade: baby steps toward improving outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:1189-1200.

- Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, et al. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;33:143-161.

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for depression in adults. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

- Earls MF. Committee on Psychological Aspects of Child and Family Health. American Academy of Pediatrics. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1032-1039.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No 630. Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1268-1271.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations statement. JAMA. 2019;321:580-587.

- O’Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger ML, et al. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;321:588-601.

- Sockol LE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women. J Affective Disorders. 2018;232:316-328.

- Sockol LE. A systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating and preventing perinatal depression. J Affective Disorders. 2015;177:7-21.

- Zlotnick C, Tzilos G, Miller I, et al. Randomized controlled trial to prevent postpartum depression in mothers on public assistance. J Affective Disorders. 2016;189:263-268.

- Haga SM, Drozd F, Lisoy C, et al. Mamma Mia—a randomized controlled trial of an internet-based intervention for perinatal depression. Psycholog Med. 2018;1-9.

- Shorey S, Ng YM, Ng ED, et al. Effectiveness of a technology-based supportive educational parenting program on parent outcomes (Part 1): Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e10816.

- Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295:499-507.

- Goodman JH. Women’s attitudes, preferences and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth. 2009;36:60-69.

- Smith-Nielsen J, Matthey S, Lange T, Vaever MS. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale against both DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:393.

- Judd F, Lorimer S, Thomson RH, et al. Screening for depression with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and finding borderline personality disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;Epub Oct 12. doi: 10.1177/0004867418804067.

- Diamond R. Promoting sensible parenting policies. Leading by example. JAMA. 2019;321:645- 646.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening for perinatal depression. ACOG Committee Opinion No 757. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e208-e212.

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, et al. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012-1024.

- Pearlstein T, Howard M, Salisbury A, et al. Postpartum depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:357-364.

- Avalos LA, Raine-Bennett T, Chen H, et al. Improved perinatal depression screening, treatment and outcomes with a universal obstetric program. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:917-925.

- Cox EQ, Sowa NA, Meltzer-Brody SE, et al. The perinatal depression treatment cascade: baby steps toward improving outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:1189-1200.

- Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, et al. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;33:143-161.

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for depression in adults. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

- Earls MF. Committee on Psychological Aspects of Child and Family Health. American Academy of Pediatrics. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1032-1039.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No 630. Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1268-1271.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations statement. JAMA. 2019;321:580-587.

- O’Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger ML, et al. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;321:588-601.

- Sockol LE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women. J Affective Disorders. 2018;232:316-328.

- Sockol LE. A systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating and preventing perinatal depression. J Affective Disorders. 2015;177:7-21.

- Zlotnick C, Tzilos G, Miller I, et al. Randomized controlled trial to prevent postpartum depression in mothers on public assistance. J Affective Disorders. 2016;189:263-268.

- Haga SM, Drozd F, Lisoy C, et al. Mamma Mia—a randomized controlled trial of an internet-based intervention for perinatal depression. Psycholog Med. 2018;1-9.

- Shorey S, Ng YM, Ng ED, et al. Effectiveness of a technology-based supportive educational parenting program on parent outcomes (Part 1): Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e10816.

- Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295:499-507.

- Goodman JH. Women’s attitudes, preferences and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth. 2009;36:60-69.

- Smith-Nielsen J, Matthey S, Lange T, Vaever MS. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale against both DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:393.

- Judd F, Lorimer S, Thomson RH, et al. Screening for depression with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and finding borderline personality disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;Epub Oct 12. doi: 10.1177/0004867418804067.

- Diamond R. Promoting sensible parenting policies. Leading by example. JAMA. 2019;321:645- 646.

Highlighting the value in high-value care

Helping consumers learn

Hospitalists can have a role in helping patients choose and receive high-value care from the vast array of health care choices they face. Helping them use quality and cost reports is one way to do that, according to a recent editorial by Jeffrey T. Kullgren, MD, MS, MPH.

We know that if consumers used public reporting of quality and costs to choose facilities that generate the best health outcomes for the resources utilized, it might improve the overall value of health care spending. But most people choose health care services based on personal recommendations or the requirements of their insurance network. Even if they wanted to use reports of quality or cost, the information in these reports is meant for providers and would likely be unhelpful for consumers.

Research suggests that different presentation of the information could make a difference. “Simpler presentations of information in public reports may be more likely to help consumers choose higher-value providers and facilities,” Dr. Kullgren said.

He concluded that consumers may also need additional incentives, “such as financial incentives to encourage high-value choices or programs that educate consumers about how to use cost and quality information when seeking care,” he said.

There’s an opportunity for hospitalists to help consumers learn to use that information. “This strategy would approach consumerism as a teachable health behavior and could be particularly helpful for consumers with ongoing medical needs who face high cost sharing,” he wrote.

“Some hospitalists may be involved in the implementation of programs to publicly report quality and costs for their institutions,” he said. “Others may treat patients who have chosen hospitals based on publicly reported information, or patients who might be interested in using such information to choose sites of postdischarge outpatient care. In each of these cases, it is important for hospitalists to understand the opportunities and limits of such public reports so as to best help patients receive high-value care.”

Reference

Kullgren JT. Helping consumers make high value health care choices: The devil is in the details. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4). http://www.hsr.org/hsr/abstract.jsp?aid=53301961729.

Helping consumers learn

Helping consumers learn

Hospitalists can have a role in helping patients choose and receive high-value care from the vast array of health care choices they face. Helping them use quality and cost reports is one way to do that, according to a recent editorial by Jeffrey T. Kullgren, MD, MS, MPH.

We know that if consumers used public reporting of quality and costs to choose facilities that generate the best health outcomes for the resources utilized, it might improve the overall value of health care spending. But most people choose health care services based on personal recommendations or the requirements of their insurance network. Even if they wanted to use reports of quality or cost, the information in these reports is meant for providers and would likely be unhelpful for consumers.

Research suggests that different presentation of the information could make a difference. “Simpler presentations of information in public reports may be more likely to help consumers choose higher-value providers and facilities,” Dr. Kullgren said.

He concluded that consumers may also need additional incentives, “such as financial incentives to encourage high-value choices or programs that educate consumers about how to use cost and quality information when seeking care,” he said.

There’s an opportunity for hospitalists to help consumers learn to use that information. “This strategy would approach consumerism as a teachable health behavior and could be particularly helpful for consumers with ongoing medical needs who face high cost sharing,” he wrote.

“Some hospitalists may be involved in the implementation of programs to publicly report quality and costs for their institutions,” he said. “Others may treat patients who have chosen hospitals based on publicly reported information, or patients who might be interested in using such information to choose sites of postdischarge outpatient care. In each of these cases, it is important for hospitalists to understand the opportunities and limits of such public reports so as to best help patients receive high-value care.”

Reference

Kullgren JT. Helping consumers make high value health care choices: The devil is in the details. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4). http://www.hsr.org/hsr/abstract.jsp?aid=53301961729.

Hospitalists can have a role in helping patients choose and receive high-value care from the vast array of health care choices they face. Helping them use quality and cost reports is one way to do that, according to a recent editorial by Jeffrey T. Kullgren, MD, MS, MPH.

We know that if consumers used public reporting of quality and costs to choose facilities that generate the best health outcomes for the resources utilized, it might improve the overall value of health care spending. But most people choose health care services based on personal recommendations or the requirements of their insurance network. Even if they wanted to use reports of quality or cost, the information in these reports is meant for providers and would likely be unhelpful for consumers.

Research suggests that different presentation of the information could make a difference. “Simpler presentations of information in public reports may be more likely to help consumers choose higher-value providers and facilities,” Dr. Kullgren said.

He concluded that consumers may also need additional incentives, “such as financial incentives to encourage high-value choices or programs that educate consumers about how to use cost and quality information when seeking care,” he said.

There’s an opportunity for hospitalists to help consumers learn to use that information. “This strategy would approach consumerism as a teachable health behavior and could be particularly helpful for consumers with ongoing medical needs who face high cost sharing,” he wrote.

“Some hospitalists may be involved in the implementation of programs to publicly report quality and costs for their institutions,” he said. “Others may treat patients who have chosen hospitals based on publicly reported information, or patients who might be interested in using such information to choose sites of postdischarge outpatient care. In each of these cases, it is important for hospitalists to understand the opportunities and limits of such public reports so as to best help patients receive high-value care.”

Reference

Kullgren JT. Helping consumers make high value health care choices: The devil is in the details. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4). http://www.hsr.org/hsr/abstract.jsp?aid=53301961729.

Following pelvic floor surgery, patients value functional goals

TUCSON, ARIZ. – according to results of a new study. Such negative reactions occur more frequently as time passes and may be related to incongruent patient expectations, which may in turn affect physician-patient communication.

“We must bridge the gap between expectations and the occurrence of an unanticipated problem. What this study highlights is a need for counseling beyond the traditional complications, and more discussion about the possibility of failure in terms of the things that the patients identify as important,” Brenna McGuire, MD, a resident at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said while presenting the results at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

The work highlights the need to look at outcomes in a different way, said Vivian Sung, MD, who was not involved in the research and was a discussant following the presentation. “Most of our studies are designed with methodology to emphasize efficacy and often secondary outcomes to capture complications and adverse events. But there is a gray area. It’s something that’s evolving, and we’re getting better at,” Dr. Sung, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Brown University and a urogynecologist at Women and Infants Hospital, both in Providence, R.I., said in an interview.

The success of a procedure is typically evaluated by determining incontinence during an office visit, but the problem may not be occurring at that particular moment, and the patient may not be happy with the overall outcome. “Sometimes you can fix one problem, and the other problems become more prominent, or new problems develop. [Incontinence alone is] not a perfect picture or what the patient was envisioning her outcome to be,” Dr. Sung said.

Expectations can potentially be better managed through better patient counseling, but that’s not a simple fix either, she noted. Most surgeons counsel patients on negative outcomes, but adverse events with a 5%-10% probability may fail to make an impression. “Really, the rate is zero or 100%. It’s not that it doesn’t seem like a meaningful complication, it’s just that it doesn’t seem like it will happen to you. And then when it does, it can be very devastating depending on what it is and what your expectation was.”

Dr. McGuire and her associates followed 20 women (mean age, 55 years; 50% non-Hispanic white, 25% Hispanic, 25% Native American) at a single institution in New Mexico who underwent surgeries for pelvic floor disorders. They interviewed each participant before and after surgery, at 4-6 weeks, and 6 months after surgery, asking them to rank adverse events at each time point.

Before surgery, patients expressed concerns about postoperative pain, injury, and catheter issues. At 6-8 weeks, the chief concerns were daily activities, sexual activity, and symptom reduction. At 6 months, incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and mental health issues predominated. In other words, concerns migrated from traditional complications to functional outcomes over time.

At the 6-8 week interview, a representative quote was: “It’s the fact that it didn’t work. It’s the fact that I’m still suffering from all the same symptoms.” At 6 months, another quote was: “I hate this so much. It really does impact my life negatively. It affects my work, it affects everything, and makes me very angry.”

Traditional adverse events such as pain and infection dropped in frequency between the preoperative interview and the 6-month interview from 7.5%-10.0% to 2.5%-5.0% by 6 months. However, functional outcomes were a different matter: Concerns about a failed surgery increased from 10% to 25%, sexual dysfunction from 4% to 8%, and effect on daily function from 4% to 11%.

The study was funded by the University of New Mexico. Dr. McGuire and Dr. Sung reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McGuire B et al. SGS 2019, Abstract 01.

TUCSON, ARIZ. – according to results of a new study. Such negative reactions occur more frequently as time passes and may be related to incongruent patient expectations, which may in turn affect physician-patient communication.

“We must bridge the gap between expectations and the occurrence of an unanticipated problem. What this study highlights is a need for counseling beyond the traditional complications, and more discussion about the possibility of failure in terms of the things that the patients identify as important,” Brenna McGuire, MD, a resident at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said while presenting the results at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

The work highlights the need to look at outcomes in a different way, said Vivian Sung, MD, who was not involved in the research and was a discussant following the presentation. “Most of our studies are designed with methodology to emphasize efficacy and often secondary outcomes to capture complications and adverse events. But there is a gray area. It’s something that’s evolving, and we’re getting better at,” Dr. Sung, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Brown University and a urogynecologist at Women and Infants Hospital, both in Providence, R.I., said in an interview.

The success of a procedure is typically evaluated by determining incontinence during an office visit, but the problem may not be occurring at that particular moment, and the patient may not be happy with the overall outcome. “Sometimes you can fix one problem, and the other problems become more prominent, or new problems develop. [Incontinence alone is] not a perfect picture or what the patient was envisioning her outcome to be,” Dr. Sung said.

Expectations can potentially be better managed through better patient counseling, but that’s not a simple fix either, she noted. Most surgeons counsel patients on negative outcomes, but adverse events with a 5%-10% probability may fail to make an impression. “Really, the rate is zero or 100%. It’s not that it doesn’t seem like a meaningful complication, it’s just that it doesn’t seem like it will happen to you. And then when it does, it can be very devastating depending on what it is and what your expectation was.”

Dr. McGuire and her associates followed 20 women (mean age, 55 years; 50% non-Hispanic white, 25% Hispanic, 25% Native American) at a single institution in New Mexico who underwent surgeries for pelvic floor disorders. They interviewed each participant before and after surgery, at 4-6 weeks, and 6 months after surgery, asking them to rank adverse events at each time point.

Before surgery, patients expressed concerns about postoperative pain, injury, and catheter issues. At 6-8 weeks, the chief concerns were daily activities, sexual activity, and symptom reduction. At 6 months, incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and mental health issues predominated. In other words, concerns migrated from traditional complications to functional outcomes over time.

At the 6-8 week interview, a representative quote was: “It’s the fact that it didn’t work. It’s the fact that I’m still suffering from all the same symptoms.” At 6 months, another quote was: “I hate this so much. It really does impact my life negatively. It affects my work, it affects everything, and makes me very angry.”

Traditional adverse events such as pain and infection dropped in frequency between the preoperative interview and the 6-month interview from 7.5%-10.0% to 2.5%-5.0% by 6 months. However, functional outcomes were a different matter: Concerns about a failed surgery increased from 10% to 25%, sexual dysfunction from 4% to 8%, and effect on daily function from 4% to 11%.

The study was funded by the University of New Mexico. Dr. McGuire and Dr. Sung reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McGuire B et al. SGS 2019, Abstract 01.

TUCSON, ARIZ. – according to results of a new study. Such negative reactions occur more frequently as time passes and may be related to incongruent patient expectations, which may in turn affect physician-patient communication.

“We must bridge the gap between expectations and the occurrence of an unanticipated problem. What this study highlights is a need for counseling beyond the traditional complications, and more discussion about the possibility of failure in terms of the things that the patients identify as important,” Brenna McGuire, MD, a resident at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said while presenting the results at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

The work highlights the need to look at outcomes in a different way, said Vivian Sung, MD, who was not involved in the research and was a discussant following the presentation. “Most of our studies are designed with methodology to emphasize efficacy and often secondary outcomes to capture complications and adverse events. But there is a gray area. It’s something that’s evolving, and we’re getting better at,” Dr. Sung, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Brown University and a urogynecologist at Women and Infants Hospital, both in Providence, R.I., said in an interview.

The success of a procedure is typically evaluated by determining incontinence during an office visit, but the problem may not be occurring at that particular moment, and the patient may not be happy with the overall outcome. “Sometimes you can fix one problem, and the other problems become more prominent, or new problems develop. [Incontinence alone is] not a perfect picture or what the patient was envisioning her outcome to be,” Dr. Sung said.

Expectations can potentially be better managed through better patient counseling, but that’s not a simple fix either, she noted. Most surgeons counsel patients on negative outcomes, but adverse events with a 5%-10% probability may fail to make an impression. “Really, the rate is zero or 100%. It’s not that it doesn’t seem like a meaningful complication, it’s just that it doesn’t seem like it will happen to you. And then when it does, it can be very devastating depending on what it is and what your expectation was.”

Dr. McGuire and her associates followed 20 women (mean age, 55 years; 50% non-Hispanic white, 25% Hispanic, 25% Native American) at a single institution in New Mexico who underwent surgeries for pelvic floor disorders. They interviewed each participant before and after surgery, at 4-6 weeks, and 6 months after surgery, asking them to rank adverse events at each time point.

Before surgery, patients expressed concerns about postoperative pain, injury, and catheter issues. At 6-8 weeks, the chief concerns were daily activities, sexual activity, and symptom reduction. At 6 months, incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and mental health issues predominated. In other words, concerns migrated from traditional complications to functional outcomes over time.

At the 6-8 week interview, a representative quote was: “It’s the fact that it didn’t work. It’s the fact that I’m still suffering from all the same symptoms.” At 6 months, another quote was: “I hate this so much. It really does impact my life negatively. It affects my work, it affects everything, and makes me very angry.”

Traditional adverse events such as pain and infection dropped in frequency between the preoperative interview and the 6-month interview from 7.5%-10.0% to 2.5%-5.0% by 6 months. However, functional outcomes were a different matter: Concerns about a failed surgery increased from 10% to 25%, sexual dysfunction from 4% to 8%, and effect on daily function from 4% to 11%.

The study was funded by the University of New Mexico. Dr. McGuire and Dr. Sung reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McGuire B et al. SGS 2019, Abstract 01.

REPORTING FROM SGS 2019

Mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide found equal as induction therapy in pediatric lupus nephritis

according to findings in the real-world U.K. Juvenile Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Cohort Study.

The study involved 34 patients who received mycophenolate mofetil and 17 who received IV cyclophosphamide as induction therapy for proliferative lupus nephritis in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (JSLE). Along with her coinvestigators, first author Eve M.D. Smith, MD, PhD, of the University of Liverpool (England) and Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, described it as the largest study to date investigating induction treatments for proliferative lupus nephritis in JSLE.

The patients were aged 16 years or younger at diagnosis and monitored during 2006-2018 as part of the U.K. JSLE Cohort Study. They met four or more American College of Rheumatology SLE classification criteria and had a renal biopsy result demonstrating proliferative lupus nephritis, defined as class III or IV lupus nephritis by the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society. Within the mycophenolate group, half received oral prednisolone only and half received both IV methylprednisolone and oral prednisolone, whereas 2 in the cyclophosphamide group received oral prednisolone only and 15 received both IV methylprednisolone and oral prednisolone.

All the patient demographic factors at baseline – including gender, ethnicity, age at diagnosis, and age at lupus nephritis onset – were similar in both treatment groups.

The investigators detected no significant differences between the two treatment groups at 4-8 and 10-14 months post renal biopsy and last follow-up in renal pediatric British Isles Lupus Assessment Grade scores, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, serum creatinine, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anti-double stranded DNA antibody, Complement 3 levels, and patient/physician global scores. JSLE-related damage on the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Standardized Damage Index also was no different between the groups after a median 13 months following renal biopsy. Lupus nephritis became inactive in 82%-85% of each group, taking a median of 262 days with mycophenolate and 151 days with IV cyclophosphamide, while flares occurred in 69% treated with mycophenolate at a median of 451 days and in 50% with cyclophosphamide at a median of 343 days.

“Results from the presented study highlight the need for prospective comparison of mycophenolate mofetil versus IV cyclophosphamide induction treatment to better inform lupus nephritis treatment protocols for children, especially given IV cyclophosphamide’s poor safety profile,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Smith EMD et al. Lupus. 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1177/0961203319836712.

according to findings in the real-world U.K. Juvenile Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Cohort Study.

The study involved 34 patients who received mycophenolate mofetil and 17 who received IV cyclophosphamide as induction therapy for proliferative lupus nephritis in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (JSLE). Along with her coinvestigators, first author Eve M.D. Smith, MD, PhD, of the University of Liverpool (England) and Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, described it as the largest study to date investigating induction treatments for proliferative lupus nephritis in JSLE.

The patients were aged 16 years or younger at diagnosis and monitored during 2006-2018 as part of the U.K. JSLE Cohort Study. They met four or more American College of Rheumatology SLE classification criteria and had a renal biopsy result demonstrating proliferative lupus nephritis, defined as class III or IV lupus nephritis by the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society. Within the mycophenolate group, half received oral prednisolone only and half received both IV methylprednisolone and oral prednisolone, whereas 2 in the cyclophosphamide group received oral prednisolone only and 15 received both IV methylprednisolone and oral prednisolone.

All the patient demographic factors at baseline – including gender, ethnicity, age at diagnosis, and age at lupus nephritis onset – were similar in both treatment groups.

The investigators detected no significant differences between the two treatment groups at 4-8 and 10-14 months post renal biopsy and last follow-up in renal pediatric British Isles Lupus Assessment Grade scores, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, serum creatinine, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anti-double stranded DNA antibody, Complement 3 levels, and patient/physician global scores. JSLE-related damage on the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Standardized Damage Index also was no different between the groups after a median 13 months following renal biopsy. Lupus nephritis became inactive in 82%-85% of each group, taking a median of 262 days with mycophenolate and 151 days with IV cyclophosphamide, while flares occurred in 69% treated with mycophenolate at a median of 451 days and in 50% with cyclophosphamide at a median of 343 days.

“Results from the presented study highlight the need for prospective comparison of mycophenolate mofetil versus IV cyclophosphamide induction treatment to better inform lupus nephritis treatment protocols for children, especially given IV cyclophosphamide’s poor safety profile,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Smith EMD et al. Lupus. 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1177/0961203319836712.

according to findings in the real-world U.K. Juvenile Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Cohort Study.

The study involved 34 patients who received mycophenolate mofetil and 17 who received IV cyclophosphamide as induction therapy for proliferative lupus nephritis in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (JSLE). Along with her coinvestigators, first author Eve M.D. Smith, MD, PhD, of the University of Liverpool (England) and Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, described it as the largest study to date investigating induction treatments for proliferative lupus nephritis in JSLE.

The patients were aged 16 years or younger at diagnosis and monitored during 2006-2018 as part of the U.K. JSLE Cohort Study. They met four or more American College of Rheumatology SLE classification criteria and had a renal biopsy result demonstrating proliferative lupus nephritis, defined as class III or IV lupus nephritis by the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society. Within the mycophenolate group, half received oral prednisolone only and half received both IV methylprednisolone and oral prednisolone, whereas 2 in the cyclophosphamide group received oral prednisolone only and 15 received both IV methylprednisolone and oral prednisolone.

All the patient demographic factors at baseline – including gender, ethnicity, age at diagnosis, and age at lupus nephritis onset – were similar in both treatment groups.

The investigators detected no significant differences between the two treatment groups at 4-8 and 10-14 months post renal biopsy and last follow-up in renal pediatric British Isles Lupus Assessment Grade scores, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, serum creatinine, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anti-double stranded DNA antibody, Complement 3 levels, and patient/physician global scores. JSLE-related damage on the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Standardized Damage Index also was no different between the groups after a median 13 months following renal biopsy. Lupus nephritis became inactive in 82%-85% of each group, taking a median of 262 days with mycophenolate and 151 days with IV cyclophosphamide, while flares occurred in 69% treated with mycophenolate at a median of 451 days and in 50% with cyclophosphamide at a median of 343 days.

“Results from the presented study highlight the need for prospective comparison of mycophenolate mofetil versus IV cyclophosphamide induction treatment to better inform lupus nephritis treatment protocols for children, especially given IV cyclophosphamide’s poor safety profile,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Smith EMD et al. Lupus. 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1177/0961203319836712.

FROM LUPUS

Asymptomatic Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumor

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) were first described in 1996.1 They comprise a family of rare mesenchymal neoplasms that have a unique characteristic of staining positive for melanocytic and smooth muscle markers on immunohistochemistry.2 These neoplasms have been described in many areas of the body including the uterus, bladder, heart, pancreas, and prostate. The majority of PEComas are extracutaneous, with only 8% of reported cases originating on the skin.3 A case of primary cutaneous PEComa (pcPEComa) was described in 2003.4 The primary cutaneous form is extremely rare.3,5-7

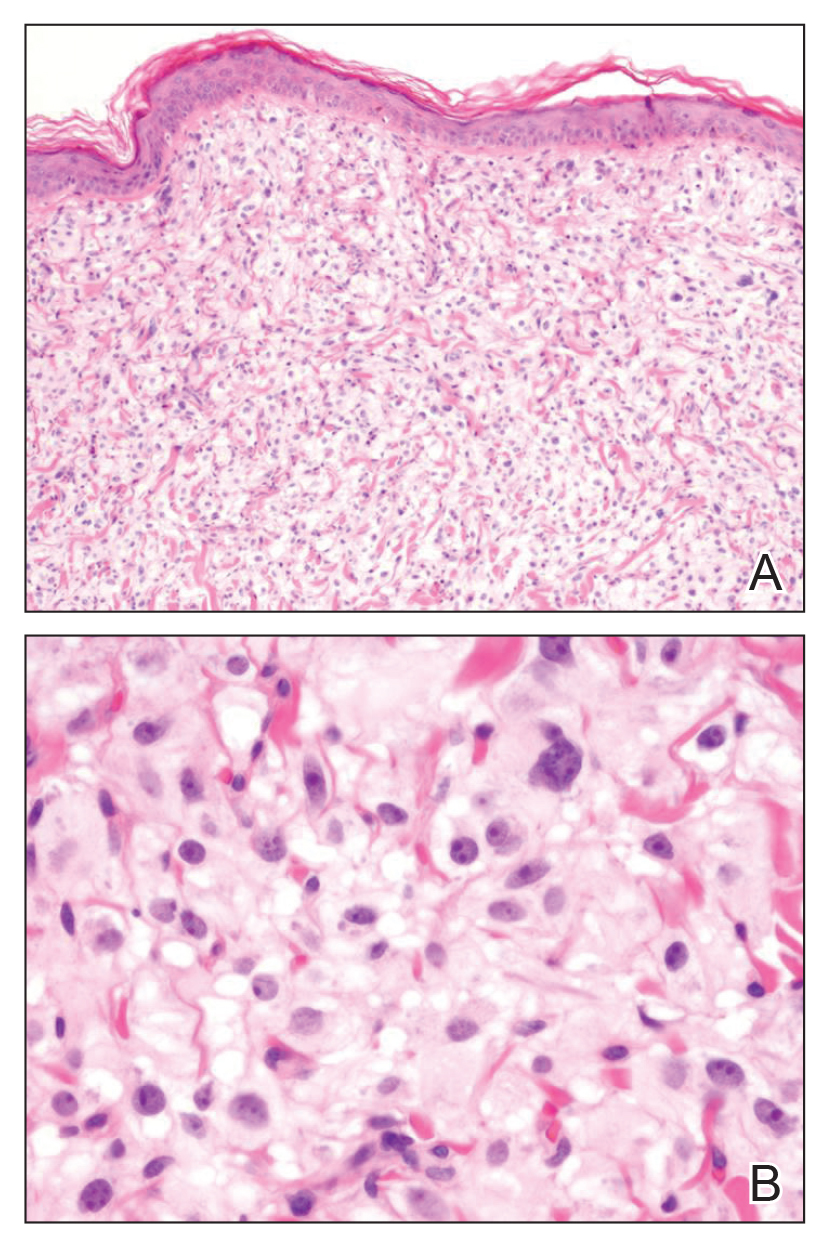

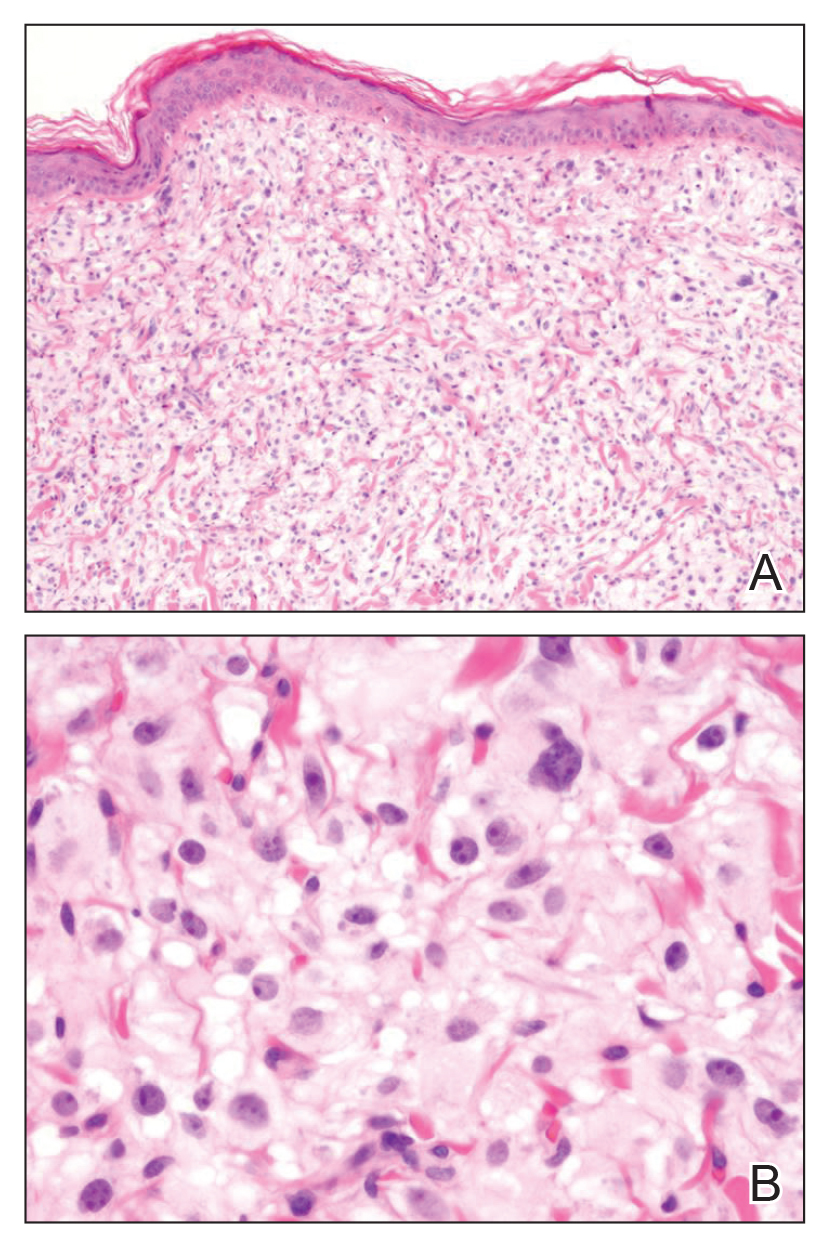

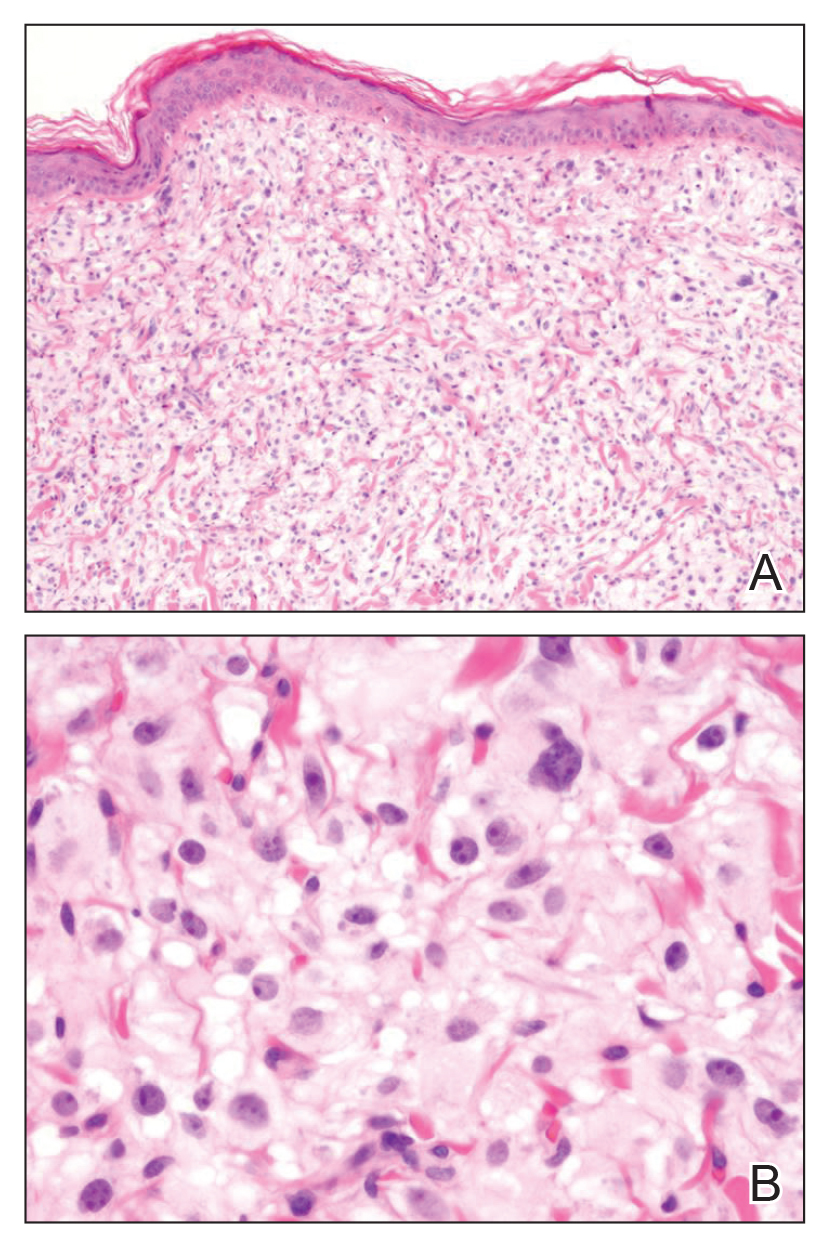

A broad deep shave biopsy was performed in our patient in an attempt to sample the entire lesion. Histopathologic examination of the nodule demonstrated a dermal neoplasm comprised of a diffuse proliferation of large polygonal cells with abundant clear cytoplasm, fine chromatin, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1A). Higher-power magnification showed moderate nuclear pleomorphism and only rare mitotic figures (Figure 1B).

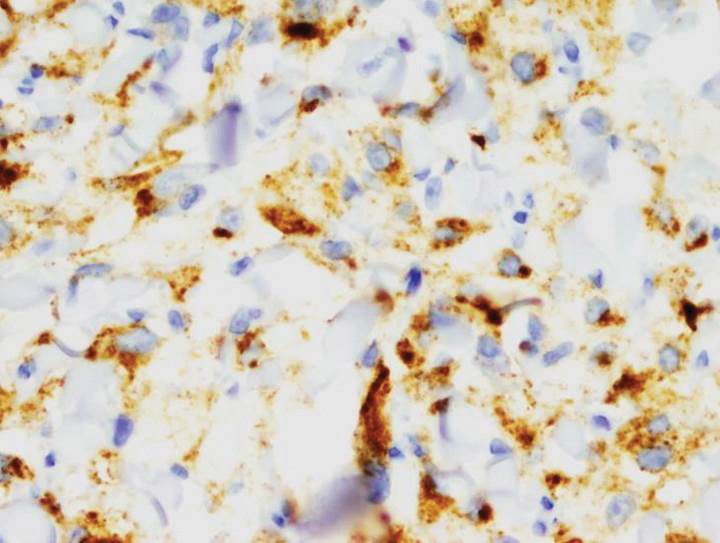

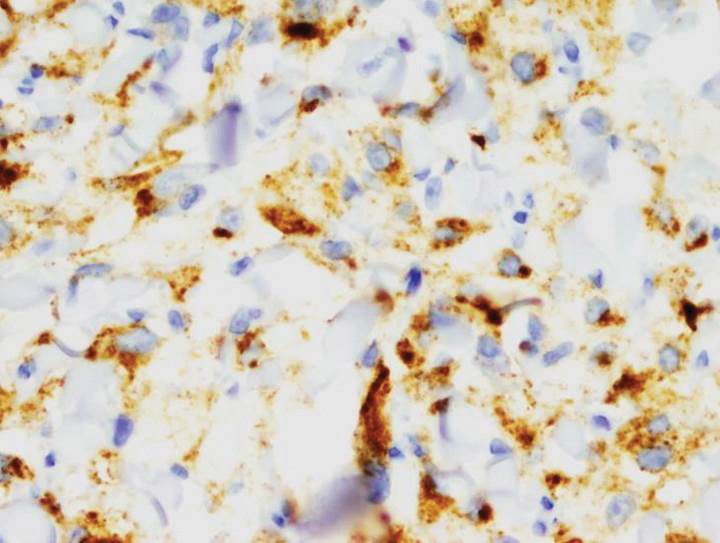

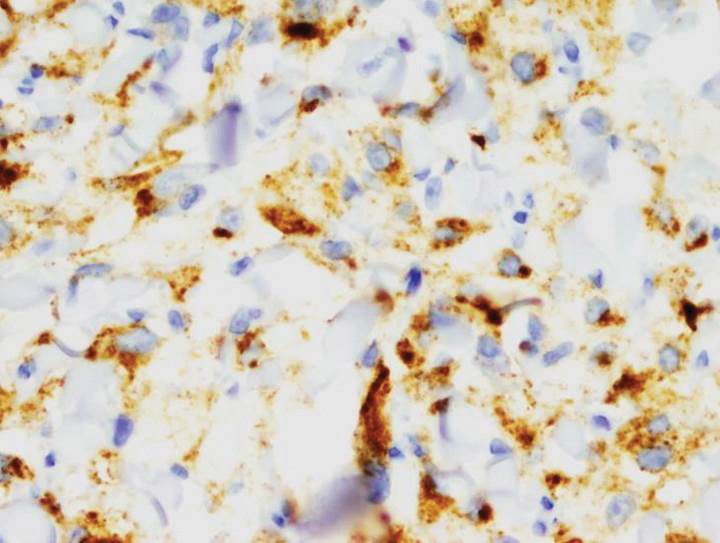

Immunohistochemical staining revealed positivity for myomelanocytic markers with positivity for human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45)(Figure 2) and desmin (not shown). Additionally, the tumor was positive for CD163 and negative for smooth muscle actin, cytokeratin, and S-100 protein.

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors are characterized histologically as mesenchymal neoplasms containing large epithelioid to spindled cells with a slightly granular, vacuolated cytoplasm. These cells often are found in close proximity to vascular structures.3,5,8 The hallmark of PEComas is the expression of both melanocytic and muscle markers.3,8 A review of staining patterns of pcPEComas emphasized that immunophenotypes between visceral and primary cutaneous forms may vary considerably.3,5,8 The most consistent and sensitive melanocytic marker is HMB-45 (88%-92% positive).3,8 Positive Melan-A staining varies in the literature from 0% to 50% of cases.3 Our patient's neoplasm expressed the characteristic myomelanocytic immunophenotype with both HMB-45 and desmin positivity.

Given the histologic characteristics, these lesions can be mistaken for melanocytic and other nonmelanocytic tumors with a clear cell morphology such as balloon cell nevus, hypomelanotic blue nevus, and melanoma.2,3 A pigmented case of pcPEComa was reported in 2015 and was originally diagnosed as metastatic melanoma.6 Unlike pcPEComa, melanoma usually stains positive with S-100 protein in up to 99% of cases8 and is negative for muscle markers; however, a case series reported S-100 protein positivity in 38% of pcPEComas.3 Nonmelanocytic neoplasms in the histologic differential diagnosis include clear cell sarcoma and clear cell renal cell carcinoma, both of which show immunoreactivity for cytokeratin.9

Histologic criteria exist for establishing malignancy potential for visceral PEComas but not for pcPEComas, though it has been suggested that the same malignancy criteria should be applied to pcPEComas.3,9 Features associated with malignancy include size greater than 8 cm, mitotic activity greater than 1 mitosis per 50 high-power fields, infiltrative growth pattern, high nuclear grade, necrosis, and vascular invasion. Based on these criteria, fulfilling 2 or more features technically classifies the lesion as malignant, 1 feature classifies it as uncertain malignant potential, and a lack of these features renders the lesion benign.9

The overwhelming majority of pcPEComas are considered benign. One case of pcPEComa was considered malignant with a high mitotic rate (5 mitoses per 10 high-power fields) and nuclear atypia.10 Further workup with thoracic computed tomography and positron emission tomography-computed tomography was negative for metastasis. Treatment with wide excision and radiotherapy was performed with no sign of recurrence at 24-month follow-up.10

Although pcPEComas arising from the dermis seem to be benign overall, PEComas originating from the subcutaneous tissue may have greater malignancy potential. Two cases of subcutaneous PEComas presenting as nodules resulted in metastasis; one case had local nodal metastasis and another developed metastasis to the lungs months later.10,11

- Zamboni G, Pea M, Martignoni G, et al. Clear cell “sugar” tumorof the pancreas. a novel member of the family of lesions characterizedby the presence of perivascular epithelioid cells. Am J Surg Pathol.1996;20:722-730.

- Folpe AK, Wiatkowski D. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms: pathology and pathogenesis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1-15.

- Charli-Joseph Y, Saggini A, Vemula S, et al. Primary cutaneous perivascularepithelioid cell tumor: a clinicopathological and molecular reappraisal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1127-1136.

- Crowson AN, Taylor JR, Magro CM. Cutaneous clear cell myomelanocytictumor-perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: first reported case. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:90A.

- Chaplin A, Conrad D, Tatlidil C, et al. Primary cutaneous PEComa. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:310-312.

- Navale P, Asgari M, Chen S. Pigmented perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:866-869.

- Ieremia E, Robson A. Cutaneous PEComa. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:E198-E201.

- Calder K, Schlauder S, Morgan M. Malignant perivascularepithelioid cell tumor (‘PEComa’): a case report and literature review of cutaneous/subcutaneous presentations. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:499-503.

- Folpe A, Mentzel T, Lehr H, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005; 29:1558-1575.

- Greveling K, Winnepenninckx V, Nagtzaam I, et al. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: a case report of a cutaneous tumor on the cheek of a male patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E262-E264.

- Shon W, Kim J, Sukov W, et al. Malignant TFE3-rearranged perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) presenting as a subcutaneous mass. Br J Dermatol. 2015;174:617-620.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumor

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) were first described in 1996.1 They comprise a family of rare mesenchymal neoplasms that have a unique characteristic of staining positive for melanocytic and smooth muscle markers on immunohistochemistry.2 These neoplasms have been described in many areas of the body including the uterus, bladder, heart, pancreas, and prostate. The majority of PEComas are extracutaneous, with only 8% of reported cases originating on the skin.3 A case of primary cutaneous PEComa (pcPEComa) was described in 2003.4 The primary cutaneous form is extremely rare.3,5-7

A broad deep shave biopsy was performed in our patient in an attempt to sample the entire lesion. Histopathologic examination of the nodule demonstrated a dermal neoplasm comprised of a diffuse proliferation of large polygonal cells with abundant clear cytoplasm, fine chromatin, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1A). Higher-power magnification showed moderate nuclear pleomorphism and only rare mitotic figures (Figure 1B).

Immunohistochemical staining revealed positivity for myomelanocytic markers with positivity for human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45)(Figure 2) and desmin (not shown). Additionally, the tumor was positive for CD163 and negative for smooth muscle actin, cytokeratin, and S-100 protein.

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors are characterized histologically as mesenchymal neoplasms containing large epithelioid to spindled cells with a slightly granular, vacuolated cytoplasm. These cells often are found in close proximity to vascular structures.3,5,8 The hallmark of PEComas is the expression of both melanocytic and muscle markers.3,8 A review of staining patterns of pcPEComas emphasized that immunophenotypes between visceral and primary cutaneous forms may vary considerably.3,5,8 The most consistent and sensitive melanocytic marker is HMB-45 (88%-92% positive).3,8 Positive Melan-A staining varies in the literature from 0% to 50% of cases.3 Our patient's neoplasm expressed the characteristic myomelanocytic immunophenotype with both HMB-45 and desmin positivity.

Given the histologic characteristics, these lesions can be mistaken for melanocytic and other nonmelanocytic tumors with a clear cell morphology such as balloon cell nevus, hypomelanotic blue nevus, and melanoma.2,3 A pigmented case of pcPEComa was reported in 2015 and was originally diagnosed as metastatic melanoma.6 Unlike pcPEComa, melanoma usually stains positive with S-100 protein in up to 99% of cases8 and is negative for muscle markers; however, a case series reported S-100 protein positivity in 38% of pcPEComas.3 Nonmelanocytic neoplasms in the histologic differential diagnosis include clear cell sarcoma and clear cell renal cell carcinoma, both of which show immunoreactivity for cytokeratin.9

Histologic criteria exist for establishing malignancy potential for visceral PEComas but not for pcPEComas, though it has been suggested that the same malignancy criteria should be applied to pcPEComas.3,9 Features associated with malignancy include size greater than 8 cm, mitotic activity greater than 1 mitosis per 50 high-power fields, infiltrative growth pattern, high nuclear grade, necrosis, and vascular invasion. Based on these criteria, fulfilling 2 or more features technically classifies the lesion as malignant, 1 feature classifies it as uncertain malignant potential, and a lack of these features renders the lesion benign.9

The overwhelming majority of pcPEComas are considered benign. One case of pcPEComa was considered malignant with a high mitotic rate (5 mitoses per 10 high-power fields) and nuclear atypia.10 Further workup with thoracic computed tomography and positron emission tomography-computed tomography was negative for metastasis. Treatment with wide excision and radiotherapy was performed with no sign of recurrence at 24-month follow-up.10