User login

Low-normal thyroid function tied to advanced fibrosis

Advanced fibrosis affected 5.9% of adults with low-normal thyroid function or subclinical hypothyroidism – more than double the prevalence among adults with strict-normal thyroid function (2.8%; P less than .001), according to the results of a large survey study.

Based on these findings, therapy to improve low thyroid function might help prevent advanced fibrosis secondary to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, wrote Donghee Kim, MD, PhD, of Stanford University (Calif.), together with his associates in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Prior research has linked low-normal thyroid function with obesity, cardiometabolic diseases, and fractures. For this study, Dr. Kim and his coinvestigators analyzed data from 7,259 adults who lacked major etiologies of chronic liver disease and were included in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey between 2007 and 2012.

After accounting for demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical variables, the odds of biopsy-confirmed advanced fibrosis were 100% higher in adults with low-normal thyroid function or subclinical hypothyroidism, compared with adults with strict-normal thyroid function (odds ratio, 2.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-3.3). The prevalence and odds of advanced fibrosis was similar in each of these two subgroups. Furthermore, low thyroid function remained strongly linked with advanced fibrosis after accounting for insulin resistance using data from fasting subjects (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2-4.4).

Previously, Dr. Kim and his coinvestigators found a strong link between biopsy-proven advanced fibrosis and low-normal thyroid function or subclinical hypothyroidism among adults in Korea. “These [new] results are consistent with our previous observations in [an] Asian population, and show their generalizability to the Western world across all ethnicities.”

The researchers did not acknowledge external funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kim D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov 17. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.024.

Advanced fibrosis affected 5.9% of adults with low-normal thyroid function or subclinical hypothyroidism – more than double the prevalence among adults with strict-normal thyroid function (2.8%; P less than .001), according to the results of a large survey study.

Based on these findings, therapy to improve low thyroid function might help prevent advanced fibrosis secondary to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, wrote Donghee Kim, MD, PhD, of Stanford University (Calif.), together with his associates in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Prior research has linked low-normal thyroid function with obesity, cardiometabolic diseases, and fractures. For this study, Dr. Kim and his coinvestigators analyzed data from 7,259 adults who lacked major etiologies of chronic liver disease and were included in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey between 2007 and 2012.

After accounting for demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical variables, the odds of biopsy-confirmed advanced fibrosis were 100% higher in adults with low-normal thyroid function or subclinical hypothyroidism, compared with adults with strict-normal thyroid function (odds ratio, 2.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-3.3). The prevalence and odds of advanced fibrosis was similar in each of these two subgroups. Furthermore, low thyroid function remained strongly linked with advanced fibrosis after accounting for insulin resistance using data from fasting subjects (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2-4.4).

Previously, Dr. Kim and his coinvestigators found a strong link between biopsy-proven advanced fibrosis and low-normal thyroid function or subclinical hypothyroidism among adults in Korea. “These [new] results are consistent with our previous observations in [an] Asian population, and show their generalizability to the Western world across all ethnicities.”

The researchers did not acknowledge external funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kim D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov 17. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.024.

Advanced fibrosis affected 5.9% of adults with low-normal thyroid function or subclinical hypothyroidism – more than double the prevalence among adults with strict-normal thyroid function (2.8%; P less than .001), according to the results of a large survey study.

Based on these findings, therapy to improve low thyroid function might help prevent advanced fibrosis secondary to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, wrote Donghee Kim, MD, PhD, of Stanford University (Calif.), together with his associates in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Prior research has linked low-normal thyroid function with obesity, cardiometabolic diseases, and fractures. For this study, Dr. Kim and his coinvestigators analyzed data from 7,259 adults who lacked major etiologies of chronic liver disease and were included in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey between 2007 and 2012.

After accounting for demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical variables, the odds of biopsy-confirmed advanced fibrosis were 100% higher in adults with low-normal thyroid function or subclinical hypothyroidism, compared with adults with strict-normal thyroid function (odds ratio, 2.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-3.3). The prevalence and odds of advanced fibrosis was similar in each of these two subgroups. Furthermore, low thyroid function remained strongly linked with advanced fibrosis after accounting for insulin resistance using data from fasting subjects (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2-4.4).

Previously, Dr. Kim and his coinvestigators found a strong link between biopsy-proven advanced fibrosis and low-normal thyroid function or subclinical hypothyroidism among adults in Korea. “These [new] results are consistent with our previous observations in [an] Asian population, and show their generalizability to the Western world across all ethnicities.”

The researchers did not acknowledge external funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kim D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov 17. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.024.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Low-normal thyroid function correlates significantly with advanced fibrosis.

Major finding: In all, 5.9% of adults with low-normal thyroid function had advanced fibrosis, compared with 2.8% of individuals with strict-normal thyroid function (P less than .001).

Study details: A study of 7,259 adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2007-2012).

Disclosures: The investigators did not acknowledge funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kim D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov 17. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.024.

ICYMI: Caplacizumab benefits patients with acquired TTP

and were 1.55 times more likely to achieve platelet normalization, compared with placebo, according to results of the double-blind, controlled HERCULES trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Jan 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806311).

Patients taking caplacizumab also had a 74% lower incidence of a composite outcome that included TTP-related deaths, recurrence of TTP, or a major thromboembolic event.

We covered this story at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology before it was published in the journal. Find our coverage at the link below.

and were 1.55 times more likely to achieve platelet normalization, compared with placebo, according to results of the double-blind, controlled HERCULES trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Jan 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806311).

Patients taking caplacizumab also had a 74% lower incidence of a composite outcome that included TTP-related deaths, recurrence of TTP, or a major thromboembolic event.

We covered this story at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology before it was published in the journal. Find our coverage at the link below.

and were 1.55 times more likely to achieve platelet normalization, compared with placebo, according to results of the double-blind, controlled HERCULES trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Jan 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806311).

Patients taking caplacizumab also had a 74% lower incidence of a composite outcome that included TTP-related deaths, recurrence of TTP, or a major thromboembolic event.

We covered this story at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology before it was published in the journal. Find our coverage at the link below.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Secondhand vaping aerosols linked to childhood asthma exacerbations

Just like exposure to secondhand smoke, , according to a review of the 11,830 kids with asthma in the 2016 Florida Youth Tobacco survey.

Every year, the Florida Department of Health surveys public school children aged 11-17 years about various tobacco issues. In 2016, almost 12% of the asthmatic children in the survey said they vaped. Almost half were exposed to secondhand smoke, and a third reported exposure to secondhand vaping aerosols within the past 30 days. Overall, 21% reported an asthma attack in the past 12 months.

Using data from the Florida survey, the investigators crunched the numbers and found that secondhand aerosol exposure increased the odds of an asthma attack by 27%, independent of exposure to secondhand smoke and whether children smoked or vaped themselves (adjusted odds ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.47).

“Health professionals may wish to counsel asthmatic youth and their families regarding the potential risks of ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery system] use and exposure to ENDS aerosols.” Providers “may also consider including ENDS aerosol exposure as a possible trigger in asthma self-management/action plans and updating asthma home environment assessments to include exposure to ENDS aerosols,” said investigators led by medical student Jennifer Bayly, a research fellow at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in Bethesda, Md.

About 4% of adults in the United States and 11% of high school students vape, and almost 10% of U.S. adolescents reported living with an ENDS user in 2014. Given the data, “it is likely that a substantial number of asthmatic youth are exposed,” the investigators said.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence linking e-cigarettes to asthma. There’s moderate evidence for increased cough and wheezing in adolescents who use e-cigarettes, plus an association with e-cigarette use and increased asthma exacerbations. The new study, however, is likely the first to look specifically at secondhand exposure among asthmatic children. Ingredients in vaping aerosols, including flavorings, propylene glycol, and vegetable glycerin, are physiologically active in the lungs, and may be lung irritants.

Overall, about half of the respondents were female, and two-thirds were 11-13 years old. About a third identified as Hispanic, a third as white, and just over a fifth as black. Three-quarters of the sample lived in large or midsized metropolitan areas, and close to two-thirds in stand-alone homes. Participants were considered exposed to secondhand aerosols if they reported that in the past month they were in a room or car with someone who was vaping.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bayly JE et al. CHEST®. 2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.005.

Just like exposure to secondhand smoke, , according to a review of the 11,830 kids with asthma in the 2016 Florida Youth Tobacco survey.

Every year, the Florida Department of Health surveys public school children aged 11-17 years about various tobacco issues. In 2016, almost 12% of the asthmatic children in the survey said they vaped. Almost half were exposed to secondhand smoke, and a third reported exposure to secondhand vaping aerosols within the past 30 days. Overall, 21% reported an asthma attack in the past 12 months.

Using data from the Florida survey, the investigators crunched the numbers and found that secondhand aerosol exposure increased the odds of an asthma attack by 27%, independent of exposure to secondhand smoke and whether children smoked or vaped themselves (adjusted odds ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.47).

“Health professionals may wish to counsel asthmatic youth and their families regarding the potential risks of ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery system] use and exposure to ENDS aerosols.” Providers “may also consider including ENDS aerosol exposure as a possible trigger in asthma self-management/action plans and updating asthma home environment assessments to include exposure to ENDS aerosols,” said investigators led by medical student Jennifer Bayly, a research fellow at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in Bethesda, Md.

About 4% of adults in the United States and 11% of high school students vape, and almost 10% of U.S. adolescents reported living with an ENDS user in 2014. Given the data, “it is likely that a substantial number of asthmatic youth are exposed,” the investigators said.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence linking e-cigarettes to asthma. There’s moderate evidence for increased cough and wheezing in adolescents who use e-cigarettes, plus an association with e-cigarette use and increased asthma exacerbations. The new study, however, is likely the first to look specifically at secondhand exposure among asthmatic children. Ingredients in vaping aerosols, including flavorings, propylene glycol, and vegetable glycerin, are physiologically active in the lungs, and may be lung irritants.

Overall, about half of the respondents were female, and two-thirds were 11-13 years old. About a third identified as Hispanic, a third as white, and just over a fifth as black. Three-quarters of the sample lived in large or midsized metropolitan areas, and close to two-thirds in stand-alone homes. Participants were considered exposed to secondhand aerosols if they reported that in the past month they were in a room or car with someone who was vaping.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bayly JE et al. CHEST®. 2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.005.

Just like exposure to secondhand smoke, , according to a review of the 11,830 kids with asthma in the 2016 Florida Youth Tobacco survey.

Every year, the Florida Department of Health surveys public school children aged 11-17 years about various tobacco issues. In 2016, almost 12% of the asthmatic children in the survey said they vaped. Almost half were exposed to secondhand smoke, and a third reported exposure to secondhand vaping aerosols within the past 30 days. Overall, 21% reported an asthma attack in the past 12 months.

Using data from the Florida survey, the investigators crunched the numbers and found that secondhand aerosol exposure increased the odds of an asthma attack by 27%, independent of exposure to secondhand smoke and whether children smoked or vaped themselves (adjusted odds ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.47).

“Health professionals may wish to counsel asthmatic youth and their families regarding the potential risks of ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery system] use and exposure to ENDS aerosols.” Providers “may also consider including ENDS aerosol exposure as a possible trigger in asthma self-management/action plans and updating asthma home environment assessments to include exposure to ENDS aerosols,” said investigators led by medical student Jennifer Bayly, a research fellow at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in Bethesda, Md.

About 4% of adults in the United States and 11% of high school students vape, and almost 10% of U.S. adolescents reported living with an ENDS user in 2014. Given the data, “it is likely that a substantial number of asthmatic youth are exposed,” the investigators said.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence linking e-cigarettes to asthma. There’s moderate evidence for increased cough and wheezing in adolescents who use e-cigarettes, plus an association with e-cigarette use and increased asthma exacerbations. The new study, however, is likely the first to look specifically at secondhand exposure among asthmatic children. Ingredients in vaping aerosols, including flavorings, propylene glycol, and vegetable glycerin, are physiologically active in the lungs, and may be lung irritants.

Overall, about half of the respondents were female, and two-thirds were 11-13 years old. About a third identified as Hispanic, a third as white, and just over a fifth as black. Three-quarters of the sample lived in large or midsized metropolitan areas, and close to two-thirds in stand-alone homes. Participants were considered exposed to secondhand aerosols if they reported that in the past month they were in a room or car with someone who was vaping.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bayly JE et al. CHEST®. 2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.005.

FROM CHEST®

Key clinical point: It’s important to screen asthmatic children for exposure to secondhand vaping aerosols, and minimize exposure.

Major finding: Secondhand aerosols increased the odds of an asthma attack 27%, independent of exposure to secondhand smoke and whether children smoked or vaped themselves.

Study details: Analysis of 11,830 children with asthma in the 2016 Florida Youth Tobacco survey.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

Source: Bayly JE et al. CHEST®. 2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.005.

Health and Economic Burden of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in the United States and Its Impact on Veterans

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. NAFLD also is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and all-cause mortality.1-3 As the leading cause of liver disease in the US and globally, NAFLD is strongly associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome, with the rising prevalence of NAFLD closely mirroring the epidemic of obesity and T2DM.4,5 The unrelenting increase of NAFLD prevalence has led to a significant rise in associated health care and economic burdens, compounded by the boom in childhood obesity and an aging population. In this review, we will discuss the epidemiology and economic burden of NAFLD in the US and how it affects veteran health.

NAFLD Definition

NAFLD is defined as the presence of > 5% of hepatic steatosis in the absence of excessive alcohol use, steatosis-inducing medication, or other concurrent chronic liver diseases.

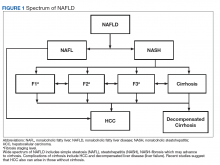

Compared with patients with NAFL, patients with NASH are at a much higher risk of developing fibrosis (scarring of the liver) and cirrhosis (significant scarring with distorted liver architecture). Patients with either NAFL or NASH, with or without advanced fibrosis, also can develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Severity of liver fibrosis (ie, fibrosis stage) is the most important predictor of liver-associated mortality and all-cause mortality; those with significant fibrosis (≥ F2 stage of fibrosis) are more likely to die of liver disease or to undergo a liver transplant compared with those with earlier stages of disease (ie, stages 0 to F1). Those with advanced scarring or cirrhosis (≥ F3 stage of fibrosis) exhibit an even higher risk of death or liver transplantation.6

NAFLD is a slow and often progressive disease. Time to progression between each stage of fibrosis is about 7 years; however, there has been a documented subset of patients with rapid progression to advanced fibrosis.7 The risk factors associated with this increased risk of fibrosis progression remain poorly understood.

Prevalence

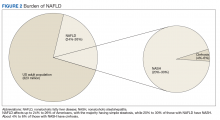

The prevalence of NAFLD in the US is about 24% to 26%—about 85 million Americans. Up to 20% to 30% of these cases (about 17-25 million Americans) are thought to have NASH (Figure 2).

Although liver biopsy remains the current gold standard for diagnosis and histopathologic staging of NAFLD, alternatives to liver biopsy include elastography techniques (ie, transient elastography using Fibroscan[Paris, France], shear wave elastography using Supersonic Image Aixplorer [Weston, FL], and magnetic resonance elastography), magnetic resonance spectroscopy, liver enzymes, and noninvasive simple and complex (serologic) scoring systems such as the Fatty Liver Index. Among these, liver enzymes and serologic scores are most likely to underestimate NAFLD disease burden. Transient elastographyis widely used because the test is easy to perform, noninvasive, and reliably estimates the degree of liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD by measuring the speed of a mechanically induced shear wave using pulse-echo ultrasonic acquisitions in a much larger portion of the tissue (about 100 times more than a liver biopsy core). Transient elastography also can objectively quantify the amount of liver fat by measuring a 3.5 MHz ultrasound coefficient of attenuation or controlled attenuation parameter (CAP). This correlates with the degree of liver fat, and a higher CAP level reflects a greater degree of steatosis.

The largest study of US veterans utilized abnormal (ie, elevated) liver enzymes as the diagnostic criteria and reviewed nearly 10 million veterans who were followed between 2003 and 2011. Investigators reported a NAFLD prevalence of 13.6% in this population and noted an overall increase in NAFLD prevalence from 6.3% in 2003 to 17.6% in 2011, which highlights the continued growth in NAFLD clinical burden.10 This study, however, is likely to have underestimated the prevalence of NAFLD among veterans because liver enzymes are often normal among those with NAFLD (ie, low sensitivity), and the prevalence of obesity and T2DM are significantly higher in the veteran population vs the general population.

Incidence

There are limited studies on NAFLD incidence. The largest study of US veterans to date used liver enzymes as its diagnostic criteria and reported an annual NAFLD incidence of 2 to 3 per 100 persons (over 9 years from 2003 to 2011).10 There are a few studies from Asia and Europe, and a recent pooled meta-analysis of these studies reported the incidence of NAFLD in Asia to be 52.3 per 1,000 person-years; the incidence in Western countries was 28 per 1,000 person-years.5 These variances may be explained, in part, to disparities in race/background. For example, Hispanics and South Asians (ie, people from Bangladesh, India, or Pakistan) are at higher risk for NAFLD/NASH.11 These findings reinforce the need for further studies to better estimate the true incidence of NAFLD among veterans.

Chronic Liver Disease, Cirrhosis, and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The prevalence of NASH cirrhosis also has been evaluated using serologic scores, such as aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database was reviewed, and data for adults in 2 separate periods were analyzed (1999-2002 and 2009-2012) and the prevalence of NASH cirrhosis was noted to have increased 2.5-fold over the period (0.072% vs 0.178%, P < .05).11 Based on data from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database from 2006 to 2014, about 15% of cirrhosis cases were attributed to NAFLD, and about 24% each were attributed to hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcoholic liver disease.12 A review of about 60,000 veterans with cirrhosis between 2001 and 2013 revealed a prevalence of NAFLD-related cirrhosis of about 15%, while 48% were attributed to HCV.13 In contrast to the continued increase in NAFLD prevalence, the number of patients with HCV-associated liver disease has been in gradual decline since the advent of direct acting antiviral medications in 2011.12

Based on data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the number of patients awaiting liver transplant due to NAFLD nearly tripled from 2004 to 2013, and in 2013 NAFLD became the second leading disease among waitlisted patients for liver transplantation.14 Dynamic Markov modeling predicts that cases of decompensated NASH cirrhosis (ie, liver failure) will rise by 161%, from about 144,000 to 376,000 cases over the next 15 years.8 These projections predict that NAFLD will overtake HCV as the leading cause of chronic liver disease among patients awaiting a liver transplant and will pose a significant clinical and economic burden in the coming years.

Aside from cirrhosis due to NAFLD, NAFLD-related HCC has been on the rise and has overtaken HCV-related HCC. UNOS data from 2003 to 2015 have shown a 2-fold decline in liver transplantation for HCV-associated HCC; however, the same period saw a 10-fold increase in liver transplantation for NAFLD-associated HCC.15,16 This trend in NAFLD-related HCC is expected to grow from 5,000 to 6,000 cases in 2005 to 45,000 cases by 2025.9 More surprisingly, studies from the US veteran population have reported that patients with NAFLD-related HCC are less likely to have cirrhosis compared with patients with HCV- or alcohol-related HCC.17 Among all US veterans who developed HCC in the absence of cirrhosis between 2005 and 2010, NAFLD and metabolic syndrome seemed to be the leading risk factors for development of HCC.18 These trends raise concern for the rise in noncirrhotic HCC in the NAFLD population and highlight the need to improve current screening guidelines for this subset of patients.

Economic Burden

With such a heavy clinical burden and a projected increase in volume over the next decade, NAFLD is expected to have a similarly exponential impact on the economic burden. A review of 976 Medicare beneficiaries with NAFLD who were hospitalized from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2010, noted a median annual total payment of about $11,000, with significantly lower payment for patients without cirrhosis compared with those with cirrhosis ($10,146 vs $18,804, P < .01).19 Another review of 29,528 Medicare beneficiaries with NAFLD who sought outpatient care between 2005 and 2010 saw a rise in mean yearly charges in 2005 of $2,624 ± 3,308 to $3,608 ± 5,132 in 2010 (P < .05).20

To place these costs in perspective, Allen and colleagues reviewed a large national claims database of individuals enrolled with private and Medicare advantage health plans.21 Comparing patients with NAFLD with a control matched group with similar metabolic comorbidities the study revealed annual median outpatient care costs of $5,363 for the patients with NAFLD with Medicare advantage plans, which was significantly higher than $4,111 for the control group. Projection models based on similar Medicare beneficiaries estimate a rise in annual US economic burden to $103 billion from direct medical care costs alone and another $188 billion in societal costs related to NAFLD.22 New NASH/antifibrotic therapies are being evaluated in clinical trials and are expected to lead to even higher costs. Given the similarities in the trends of NAFLD prevalence between veterans and the general population, it is anticipated that a similar growth and burden in health care utilization cost will affect the VHA.

Association With Other Chronic Medical Conditions

NAFLD is closely associated with metabolic syndrome (Figure 3). Concurrent diagnosis of NAFLD in patients with existing T2DM is associated with poor glycemic control, progressive diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, increased risk of cardiovascular complications, and a 2-fold increase in all-cause mortality.1-3

Similar associations have been described between NAFLD and other metabolic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, hypothyroidism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and chronic kidney disease.31 Identifying patients with NAFLD may help with screening for the above metabolic diseases because patients with NAFLD (by comparison with patients with non-NAFLD) are at higher risk for diabetic, cardiovascular, and pulmonary complications and may warrant a more intensive treatment approach.

Conclusion

A leading cause of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis in the US, NAFLD is independently associated with metabolic syndrome and all-cause mortality. The number of veterans with NAFLD is expected to grow significantly over the coming years given the ongoing epidemic of adult and childhood obesity and T2DM. It is associated with many other medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease and complications, incident metabolic diseases, and may progress to liver cirrhosis and cirrhosis associated complications like HCC and liver failure. The current lack of any approved drug treatment for NASH/fibrosis and the shortage of organs for liver transplant emphasize the need for comprehensive primary prevention measures to reduce the future health and economic costs associated with NAFLD.

There is a growing need to address the epidemic of metabolic syndrome, as heralded by the World Health Organization in its 2013 global action plan. To address this multifaceted disease, initial approach should be to improve NAFLD education among veterans, beginning with the primary care teams and extending to specialty care, including hepatologists. Future steps also should include the development of a comprehensive metabolic/NAFLD clinic in all US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers that integrates multidisciplinary care, point-of-care evaluation (eg, elastography staging of disease), and access to clinical trials, and have NAFLD care/outcome as a key performance target for all providers.

1. Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1212-1218.

2. Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease and proliferative/laser-treated retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2008;51(3):444-450.

3. Adams LA, Harmsen S, St Sauver JL, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of death among patients with diabetes: a community-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010. 105(7):1567-1573.

4. Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(11):686-690.

5. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73-84.

6. Angulo P, Machado MV, Diehl AM. Fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35(2):132-145.

7. Satapathy SK, Sanyal AJ. Epidemiology and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35(3):221-235.

8. Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):896-904.

9. Ahmed O, Liu L, Gayed A, et al. The changing face of hepatocellular carcinoma: forecasting prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatitis C cirrhosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018. In press.

10. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, Yu X, White D, El-Serag HB. Trends in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a United States cohort of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):301-308.

11. Kabbany MN, Conjeevaram Selvakumar PK, Watt K, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-associated cirrhosis in the United States: an analysis of national health and nutrition examination survey data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(4):581-587.

12. Goldberg D, Ditah IC, Saeian K, et al. Changes in the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and alcoholic liver disease among patients with cirrhosis or liver failure on the waitlist for liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1090-1099.

13. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-1482.

14. Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):547-555.

15. Belli LS, Perricone G, Adam R, et al; all the contributing centers (www.eltr.org) and the European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). Impact of DAAs on liver transplantation: major effects on the evolution of indications and results. An ELITA study based on the ELTR registry. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):810-817.

16. Flemming JA, Kim WR, Brosgart CL, Terrault NA. Reduction in liver transplant wait-listing in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2017;65(3):804-812.

17. Mittal S, Sada YH, El-Serag HB, et al. Temporal trends of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the Veteran Affairs population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(3):594-601.

18. Mittal S, El-Serag HB, Sada YH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in United States veterans is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):124-131.e1.

19. Sayiner M, Otgonsuren M, Cable R. Variables associated with inpatient and outpatient resource utilization among medicare beneficiaries with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with or without cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(3):254-260.

20. Younossi ZM, Zheng L, Stepanova M, Henry L, Venkatesan C, Mishra A. Trends in outpatient resource utilizations and outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):222-227.

21. Allen AM, Van Houten HK, Sangaralingham LR, Talwalkar JA, McCoy RG. Healthcare cost and utilization in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: real-world data from a large US claims database. Hepatology. 2018;68(6):2230-2238.

22. Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, et al. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1577-1586.

23. Armstrong MJ, Hazlehurst JM, Parker R, et al. Severe asymptomatic non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in routine diabetes care; a multi-disciplinary team approach to diagnosis and management. QJM. 2014;107(1):33-41.

24. Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology. 2006;44(4):865-873.

25. Kim D, Choi SY, Park EH, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with coronary artery calcification. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):605-613.

26. Stepanova M, Younossi ZM. Independent association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease in the US population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(6):646-650.

27. Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(14):1341-1350.

28. Mir HM, Stepanova M, Afendy H, Cable R, Younossi ZM. Association of sleep disorders with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a population-based study. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3(3):181-185.

29. Agrawal S, Duseja A, Aggarwal A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is an important predictor of hepatic fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a tertiary care center. Hepatol Int. 2015;9(2):283-291.

30. Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with fatty liver and abnormal liver enzymes: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2013;23(11):1815-1825.

31. Armstrong MJ, Adams LA, Canbay A, Syn WK. Extrahepatic complications of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1174-1197.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. NAFLD also is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and all-cause mortality.1-3 As the leading cause of liver disease in the US and globally, NAFLD is strongly associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome, with the rising prevalence of NAFLD closely mirroring the epidemic of obesity and T2DM.4,5 The unrelenting increase of NAFLD prevalence has led to a significant rise in associated health care and economic burdens, compounded by the boom in childhood obesity and an aging population. In this review, we will discuss the epidemiology and economic burden of NAFLD in the US and how it affects veteran health.

NAFLD Definition

NAFLD is defined as the presence of > 5% of hepatic steatosis in the absence of excessive alcohol use, steatosis-inducing medication, or other concurrent chronic liver diseases.

Compared with patients with NAFL, patients with NASH are at a much higher risk of developing fibrosis (scarring of the liver) and cirrhosis (significant scarring with distorted liver architecture). Patients with either NAFL or NASH, with or without advanced fibrosis, also can develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Severity of liver fibrosis (ie, fibrosis stage) is the most important predictor of liver-associated mortality and all-cause mortality; those with significant fibrosis (≥ F2 stage of fibrosis) are more likely to die of liver disease or to undergo a liver transplant compared with those with earlier stages of disease (ie, stages 0 to F1). Those with advanced scarring or cirrhosis (≥ F3 stage of fibrosis) exhibit an even higher risk of death or liver transplantation.6

NAFLD is a slow and often progressive disease. Time to progression between each stage of fibrosis is about 7 years; however, there has been a documented subset of patients with rapid progression to advanced fibrosis.7 The risk factors associated with this increased risk of fibrosis progression remain poorly understood.

Prevalence

The prevalence of NAFLD in the US is about 24% to 26%—about 85 million Americans. Up to 20% to 30% of these cases (about 17-25 million Americans) are thought to have NASH (Figure 2).

Although liver biopsy remains the current gold standard for diagnosis and histopathologic staging of NAFLD, alternatives to liver biopsy include elastography techniques (ie, transient elastography using Fibroscan[Paris, France], shear wave elastography using Supersonic Image Aixplorer [Weston, FL], and magnetic resonance elastography), magnetic resonance spectroscopy, liver enzymes, and noninvasive simple and complex (serologic) scoring systems such as the Fatty Liver Index. Among these, liver enzymes and serologic scores are most likely to underestimate NAFLD disease burden. Transient elastographyis widely used because the test is easy to perform, noninvasive, and reliably estimates the degree of liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD by measuring the speed of a mechanically induced shear wave using pulse-echo ultrasonic acquisitions in a much larger portion of the tissue (about 100 times more than a liver biopsy core). Transient elastography also can objectively quantify the amount of liver fat by measuring a 3.5 MHz ultrasound coefficient of attenuation or controlled attenuation parameter (CAP). This correlates with the degree of liver fat, and a higher CAP level reflects a greater degree of steatosis.

The largest study of US veterans utilized abnormal (ie, elevated) liver enzymes as the diagnostic criteria and reviewed nearly 10 million veterans who were followed between 2003 and 2011. Investigators reported a NAFLD prevalence of 13.6% in this population and noted an overall increase in NAFLD prevalence from 6.3% in 2003 to 17.6% in 2011, which highlights the continued growth in NAFLD clinical burden.10 This study, however, is likely to have underestimated the prevalence of NAFLD among veterans because liver enzymes are often normal among those with NAFLD (ie, low sensitivity), and the prevalence of obesity and T2DM are significantly higher in the veteran population vs the general population.

Incidence

There are limited studies on NAFLD incidence. The largest study of US veterans to date used liver enzymes as its diagnostic criteria and reported an annual NAFLD incidence of 2 to 3 per 100 persons (over 9 years from 2003 to 2011).10 There are a few studies from Asia and Europe, and a recent pooled meta-analysis of these studies reported the incidence of NAFLD in Asia to be 52.3 per 1,000 person-years; the incidence in Western countries was 28 per 1,000 person-years.5 These variances may be explained, in part, to disparities in race/background. For example, Hispanics and South Asians (ie, people from Bangladesh, India, or Pakistan) are at higher risk for NAFLD/NASH.11 These findings reinforce the need for further studies to better estimate the true incidence of NAFLD among veterans.

Chronic Liver Disease, Cirrhosis, and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The prevalence of NASH cirrhosis also has been evaluated using serologic scores, such as aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database was reviewed, and data for adults in 2 separate periods were analyzed (1999-2002 and 2009-2012) and the prevalence of NASH cirrhosis was noted to have increased 2.5-fold over the period (0.072% vs 0.178%, P < .05).11 Based on data from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database from 2006 to 2014, about 15% of cirrhosis cases were attributed to NAFLD, and about 24% each were attributed to hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcoholic liver disease.12 A review of about 60,000 veterans with cirrhosis between 2001 and 2013 revealed a prevalence of NAFLD-related cirrhosis of about 15%, while 48% were attributed to HCV.13 In contrast to the continued increase in NAFLD prevalence, the number of patients with HCV-associated liver disease has been in gradual decline since the advent of direct acting antiviral medications in 2011.12

Based on data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the number of patients awaiting liver transplant due to NAFLD nearly tripled from 2004 to 2013, and in 2013 NAFLD became the second leading disease among waitlisted patients for liver transplantation.14 Dynamic Markov modeling predicts that cases of decompensated NASH cirrhosis (ie, liver failure) will rise by 161%, from about 144,000 to 376,000 cases over the next 15 years.8 These projections predict that NAFLD will overtake HCV as the leading cause of chronic liver disease among patients awaiting a liver transplant and will pose a significant clinical and economic burden in the coming years.

Aside from cirrhosis due to NAFLD, NAFLD-related HCC has been on the rise and has overtaken HCV-related HCC. UNOS data from 2003 to 2015 have shown a 2-fold decline in liver transplantation for HCV-associated HCC; however, the same period saw a 10-fold increase in liver transplantation for NAFLD-associated HCC.15,16 This trend in NAFLD-related HCC is expected to grow from 5,000 to 6,000 cases in 2005 to 45,000 cases by 2025.9 More surprisingly, studies from the US veteran population have reported that patients with NAFLD-related HCC are less likely to have cirrhosis compared with patients with HCV- or alcohol-related HCC.17 Among all US veterans who developed HCC in the absence of cirrhosis between 2005 and 2010, NAFLD and metabolic syndrome seemed to be the leading risk factors for development of HCC.18 These trends raise concern for the rise in noncirrhotic HCC in the NAFLD population and highlight the need to improve current screening guidelines for this subset of patients.

Economic Burden

With such a heavy clinical burden and a projected increase in volume over the next decade, NAFLD is expected to have a similarly exponential impact on the economic burden. A review of 976 Medicare beneficiaries with NAFLD who were hospitalized from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2010, noted a median annual total payment of about $11,000, with significantly lower payment for patients without cirrhosis compared with those with cirrhosis ($10,146 vs $18,804, P < .01).19 Another review of 29,528 Medicare beneficiaries with NAFLD who sought outpatient care between 2005 and 2010 saw a rise in mean yearly charges in 2005 of $2,624 ± 3,308 to $3,608 ± 5,132 in 2010 (P < .05).20

To place these costs in perspective, Allen and colleagues reviewed a large national claims database of individuals enrolled with private and Medicare advantage health plans.21 Comparing patients with NAFLD with a control matched group with similar metabolic comorbidities the study revealed annual median outpatient care costs of $5,363 for the patients with NAFLD with Medicare advantage plans, which was significantly higher than $4,111 for the control group. Projection models based on similar Medicare beneficiaries estimate a rise in annual US economic burden to $103 billion from direct medical care costs alone and another $188 billion in societal costs related to NAFLD.22 New NASH/antifibrotic therapies are being evaluated in clinical trials and are expected to lead to even higher costs. Given the similarities in the trends of NAFLD prevalence between veterans and the general population, it is anticipated that a similar growth and burden in health care utilization cost will affect the VHA.

Association With Other Chronic Medical Conditions

NAFLD is closely associated with metabolic syndrome (Figure 3). Concurrent diagnosis of NAFLD in patients with existing T2DM is associated with poor glycemic control, progressive diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, increased risk of cardiovascular complications, and a 2-fold increase in all-cause mortality.1-3

Similar associations have been described between NAFLD and other metabolic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, hypothyroidism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and chronic kidney disease.31 Identifying patients with NAFLD may help with screening for the above metabolic diseases because patients with NAFLD (by comparison with patients with non-NAFLD) are at higher risk for diabetic, cardiovascular, and pulmonary complications and may warrant a more intensive treatment approach.

Conclusion

A leading cause of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis in the US, NAFLD is independently associated with metabolic syndrome and all-cause mortality. The number of veterans with NAFLD is expected to grow significantly over the coming years given the ongoing epidemic of adult and childhood obesity and T2DM. It is associated with many other medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease and complications, incident metabolic diseases, and may progress to liver cirrhosis and cirrhosis associated complications like HCC and liver failure. The current lack of any approved drug treatment for NASH/fibrosis and the shortage of organs for liver transplant emphasize the need for comprehensive primary prevention measures to reduce the future health and economic costs associated with NAFLD.

There is a growing need to address the epidemic of metabolic syndrome, as heralded by the World Health Organization in its 2013 global action plan. To address this multifaceted disease, initial approach should be to improve NAFLD education among veterans, beginning with the primary care teams and extending to specialty care, including hepatologists. Future steps also should include the development of a comprehensive metabolic/NAFLD clinic in all US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers that integrates multidisciplinary care, point-of-care evaluation (eg, elastography staging of disease), and access to clinical trials, and have NAFLD care/outcome as a key performance target for all providers.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. NAFLD also is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and all-cause mortality.1-3 As the leading cause of liver disease in the US and globally, NAFLD is strongly associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome, with the rising prevalence of NAFLD closely mirroring the epidemic of obesity and T2DM.4,5 The unrelenting increase of NAFLD prevalence has led to a significant rise in associated health care and economic burdens, compounded by the boom in childhood obesity and an aging population. In this review, we will discuss the epidemiology and economic burden of NAFLD in the US and how it affects veteran health.

NAFLD Definition

NAFLD is defined as the presence of > 5% of hepatic steatosis in the absence of excessive alcohol use, steatosis-inducing medication, or other concurrent chronic liver diseases.

Compared with patients with NAFL, patients with NASH are at a much higher risk of developing fibrosis (scarring of the liver) and cirrhosis (significant scarring with distorted liver architecture). Patients with either NAFL or NASH, with or without advanced fibrosis, also can develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Severity of liver fibrosis (ie, fibrosis stage) is the most important predictor of liver-associated mortality and all-cause mortality; those with significant fibrosis (≥ F2 stage of fibrosis) are more likely to die of liver disease or to undergo a liver transplant compared with those with earlier stages of disease (ie, stages 0 to F1). Those with advanced scarring or cirrhosis (≥ F3 stage of fibrosis) exhibit an even higher risk of death or liver transplantation.6

NAFLD is a slow and often progressive disease. Time to progression between each stage of fibrosis is about 7 years; however, there has been a documented subset of patients with rapid progression to advanced fibrosis.7 The risk factors associated with this increased risk of fibrosis progression remain poorly understood.

Prevalence

The prevalence of NAFLD in the US is about 24% to 26%—about 85 million Americans. Up to 20% to 30% of these cases (about 17-25 million Americans) are thought to have NASH (Figure 2).

Although liver biopsy remains the current gold standard for diagnosis and histopathologic staging of NAFLD, alternatives to liver biopsy include elastography techniques (ie, transient elastography using Fibroscan[Paris, France], shear wave elastography using Supersonic Image Aixplorer [Weston, FL], and magnetic resonance elastography), magnetic resonance spectroscopy, liver enzymes, and noninvasive simple and complex (serologic) scoring systems such as the Fatty Liver Index. Among these, liver enzymes and serologic scores are most likely to underestimate NAFLD disease burden. Transient elastographyis widely used because the test is easy to perform, noninvasive, and reliably estimates the degree of liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD by measuring the speed of a mechanically induced shear wave using pulse-echo ultrasonic acquisitions in a much larger portion of the tissue (about 100 times more than a liver biopsy core). Transient elastography also can objectively quantify the amount of liver fat by measuring a 3.5 MHz ultrasound coefficient of attenuation or controlled attenuation parameter (CAP). This correlates with the degree of liver fat, and a higher CAP level reflects a greater degree of steatosis.

The largest study of US veterans utilized abnormal (ie, elevated) liver enzymes as the diagnostic criteria and reviewed nearly 10 million veterans who were followed between 2003 and 2011. Investigators reported a NAFLD prevalence of 13.6% in this population and noted an overall increase in NAFLD prevalence from 6.3% in 2003 to 17.6% in 2011, which highlights the continued growth in NAFLD clinical burden.10 This study, however, is likely to have underestimated the prevalence of NAFLD among veterans because liver enzymes are often normal among those with NAFLD (ie, low sensitivity), and the prevalence of obesity and T2DM are significantly higher in the veteran population vs the general population.

Incidence

There are limited studies on NAFLD incidence. The largest study of US veterans to date used liver enzymes as its diagnostic criteria and reported an annual NAFLD incidence of 2 to 3 per 100 persons (over 9 years from 2003 to 2011).10 There are a few studies from Asia and Europe, and a recent pooled meta-analysis of these studies reported the incidence of NAFLD in Asia to be 52.3 per 1,000 person-years; the incidence in Western countries was 28 per 1,000 person-years.5 These variances may be explained, in part, to disparities in race/background. For example, Hispanics and South Asians (ie, people from Bangladesh, India, or Pakistan) are at higher risk for NAFLD/NASH.11 These findings reinforce the need for further studies to better estimate the true incidence of NAFLD among veterans.

Chronic Liver Disease, Cirrhosis, and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The prevalence of NASH cirrhosis also has been evaluated using serologic scores, such as aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database was reviewed, and data for adults in 2 separate periods were analyzed (1999-2002 and 2009-2012) and the prevalence of NASH cirrhosis was noted to have increased 2.5-fold over the period (0.072% vs 0.178%, P < .05).11 Based on data from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database from 2006 to 2014, about 15% of cirrhosis cases were attributed to NAFLD, and about 24% each were attributed to hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcoholic liver disease.12 A review of about 60,000 veterans with cirrhosis between 2001 and 2013 revealed a prevalence of NAFLD-related cirrhosis of about 15%, while 48% were attributed to HCV.13 In contrast to the continued increase in NAFLD prevalence, the number of patients with HCV-associated liver disease has been in gradual decline since the advent of direct acting antiviral medications in 2011.12

Based on data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the number of patients awaiting liver transplant due to NAFLD nearly tripled from 2004 to 2013, and in 2013 NAFLD became the second leading disease among waitlisted patients for liver transplantation.14 Dynamic Markov modeling predicts that cases of decompensated NASH cirrhosis (ie, liver failure) will rise by 161%, from about 144,000 to 376,000 cases over the next 15 years.8 These projections predict that NAFLD will overtake HCV as the leading cause of chronic liver disease among patients awaiting a liver transplant and will pose a significant clinical and economic burden in the coming years.

Aside from cirrhosis due to NAFLD, NAFLD-related HCC has been on the rise and has overtaken HCV-related HCC. UNOS data from 2003 to 2015 have shown a 2-fold decline in liver transplantation for HCV-associated HCC; however, the same period saw a 10-fold increase in liver transplantation for NAFLD-associated HCC.15,16 This trend in NAFLD-related HCC is expected to grow from 5,000 to 6,000 cases in 2005 to 45,000 cases by 2025.9 More surprisingly, studies from the US veteran population have reported that patients with NAFLD-related HCC are less likely to have cirrhosis compared with patients with HCV- or alcohol-related HCC.17 Among all US veterans who developed HCC in the absence of cirrhosis between 2005 and 2010, NAFLD and metabolic syndrome seemed to be the leading risk factors for development of HCC.18 These trends raise concern for the rise in noncirrhotic HCC in the NAFLD population and highlight the need to improve current screening guidelines for this subset of patients.

Economic Burden

With such a heavy clinical burden and a projected increase in volume over the next decade, NAFLD is expected to have a similarly exponential impact on the economic burden. A review of 976 Medicare beneficiaries with NAFLD who were hospitalized from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2010, noted a median annual total payment of about $11,000, with significantly lower payment for patients without cirrhosis compared with those with cirrhosis ($10,146 vs $18,804, P < .01).19 Another review of 29,528 Medicare beneficiaries with NAFLD who sought outpatient care between 2005 and 2010 saw a rise in mean yearly charges in 2005 of $2,624 ± 3,308 to $3,608 ± 5,132 in 2010 (P < .05).20

To place these costs in perspective, Allen and colleagues reviewed a large national claims database of individuals enrolled with private and Medicare advantage health plans.21 Comparing patients with NAFLD with a control matched group with similar metabolic comorbidities the study revealed annual median outpatient care costs of $5,363 for the patients with NAFLD with Medicare advantage plans, which was significantly higher than $4,111 for the control group. Projection models based on similar Medicare beneficiaries estimate a rise in annual US economic burden to $103 billion from direct medical care costs alone and another $188 billion in societal costs related to NAFLD.22 New NASH/antifibrotic therapies are being evaluated in clinical trials and are expected to lead to even higher costs. Given the similarities in the trends of NAFLD prevalence between veterans and the general population, it is anticipated that a similar growth and burden in health care utilization cost will affect the VHA.

Association With Other Chronic Medical Conditions

NAFLD is closely associated with metabolic syndrome (Figure 3). Concurrent diagnosis of NAFLD in patients with existing T2DM is associated with poor glycemic control, progressive diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, increased risk of cardiovascular complications, and a 2-fold increase in all-cause mortality.1-3

Similar associations have been described between NAFLD and other metabolic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, hypothyroidism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and chronic kidney disease.31 Identifying patients with NAFLD may help with screening for the above metabolic diseases because patients with NAFLD (by comparison with patients with non-NAFLD) are at higher risk for diabetic, cardiovascular, and pulmonary complications and may warrant a more intensive treatment approach.

Conclusion

A leading cause of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis in the US, NAFLD is independently associated with metabolic syndrome and all-cause mortality. The number of veterans with NAFLD is expected to grow significantly over the coming years given the ongoing epidemic of adult and childhood obesity and T2DM. It is associated with many other medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease and complications, incident metabolic diseases, and may progress to liver cirrhosis and cirrhosis associated complications like HCC and liver failure. The current lack of any approved drug treatment for NASH/fibrosis and the shortage of organs for liver transplant emphasize the need for comprehensive primary prevention measures to reduce the future health and economic costs associated with NAFLD.

There is a growing need to address the epidemic of metabolic syndrome, as heralded by the World Health Organization in its 2013 global action plan. To address this multifaceted disease, initial approach should be to improve NAFLD education among veterans, beginning with the primary care teams and extending to specialty care, including hepatologists. Future steps also should include the development of a comprehensive metabolic/NAFLD clinic in all US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers that integrates multidisciplinary care, point-of-care evaluation (eg, elastography staging of disease), and access to clinical trials, and have NAFLD care/outcome as a key performance target for all providers.

1. Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1212-1218.

2. Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease and proliferative/laser-treated retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2008;51(3):444-450.

3. Adams LA, Harmsen S, St Sauver JL, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of death among patients with diabetes: a community-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010. 105(7):1567-1573.

4. Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(11):686-690.

5. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73-84.

6. Angulo P, Machado MV, Diehl AM. Fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35(2):132-145.

7. Satapathy SK, Sanyal AJ. Epidemiology and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35(3):221-235.

8. Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):896-904.

9. Ahmed O, Liu L, Gayed A, et al. The changing face of hepatocellular carcinoma: forecasting prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatitis C cirrhosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018. In press.

10. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, Yu X, White D, El-Serag HB. Trends in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a United States cohort of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):301-308.

11. Kabbany MN, Conjeevaram Selvakumar PK, Watt K, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-associated cirrhosis in the United States: an analysis of national health and nutrition examination survey data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(4):581-587.

12. Goldberg D, Ditah IC, Saeian K, et al. Changes in the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and alcoholic liver disease among patients with cirrhosis or liver failure on the waitlist for liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1090-1099.

13. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-1482.

14. Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):547-555.

15. Belli LS, Perricone G, Adam R, et al; all the contributing centers (www.eltr.org) and the European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). Impact of DAAs on liver transplantation: major effects on the evolution of indications and results. An ELITA study based on the ELTR registry. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):810-817.

16. Flemming JA, Kim WR, Brosgart CL, Terrault NA. Reduction in liver transplant wait-listing in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2017;65(3):804-812.

17. Mittal S, Sada YH, El-Serag HB, et al. Temporal trends of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the Veteran Affairs population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(3):594-601.

18. Mittal S, El-Serag HB, Sada YH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in United States veterans is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):124-131.e1.

19. Sayiner M, Otgonsuren M, Cable R. Variables associated with inpatient and outpatient resource utilization among medicare beneficiaries with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with or without cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(3):254-260.

20. Younossi ZM, Zheng L, Stepanova M, Henry L, Venkatesan C, Mishra A. Trends in outpatient resource utilizations and outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):222-227.

21. Allen AM, Van Houten HK, Sangaralingham LR, Talwalkar JA, McCoy RG. Healthcare cost and utilization in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: real-world data from a large US claims database. Hepatology. 2018;68(6):2230-2238.

22. Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, et al. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1577-1586.

23. Armstrong MJ, Hazlehurst JM, Parker R, et al. Severe asymptomatic non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in routine diabetes care; a multi-disciplinary team approach to diagnosis and management. QJM. 2014;107(1):33-41.

24. Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology. 2006;44(4):865-873.

25. Kim D, Choi SY, Park EH, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with coronary artery calcification. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):605-613.

26. Stepanova M, Younossi ZM. Independent association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease in the US population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(6):646-650.

27. Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(14):1341-1350.

28. Mir HM, Stepanova M, Afendy H, Cable R, Younossi ZM. Association of sleep disorders with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a population-based study. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3(3):181-185.

29. Agrawal S, Duseja A, Aggarwal A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is an important predictor of hepatic fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a tertiary care center. Hepatol Int. 2015;9(2):283-291.

30. Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with fatty liver and abnormal liver enzymes: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2013;23(11):1815-1825.

31. Armstrong MJ, Adams LA, Canbay A, Syn WK. Extrahepatic complications of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1174-1197.

1. Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1212-1218.

2. Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease and proliferative/laser-treated retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2008;51(3):444-450.

3. Adams LA, Harmsen S, St Sauver JL, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of death among patients with diabetes: a community-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010. 105(7):1567-1573.

4. Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(11):686-690.

5. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73-84.

6. Angulo P, Machado MV, Diehl AM. Fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35(2):132-145.

7. Satapathy SK, Sanyal AJ. Epidemiology and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35(3):221-235.

8. Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):896-904.

9. Ahmed O, Liu L, Gayed A, et al. The changing face of hepatocellular carcinoma: forecasting prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatitis C cirrhosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018. In press.

10. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, Yu X, White D, El-Serag HB. Trends in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a United States cohort of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):301-308.

11. Kabbany MN, Conjeevaram Selvakumar PK, Watt K, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-associated cirrhosis in the United States: an analysis of national health and nutrition examination survey data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(4):581-587.

12. Goldberg D, Ditah IC, Saeian K, et al. Changes in the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and alcoholic liver disease among patients with cirrhosis or liver failure on the waitlist for liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1090-1099.

13. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-1482.

14. Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):547-555.

15. Belli LS, Perricone G, Adam R, et al; all the contributing centers (www.eltr.org) and the European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). Impact of DAAs on liver transplantation: major effects on the evolution of indications and results. An ELITA study based on the ELTR registry. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):810-817.

16. Flemming JA, Kim WR, Brosgart CL, Terrault NA. Reduction in liver transplant wait-listing in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2017;65(3):804-812.

17. Mittal S, Sada YH, El-Serag HB, et al. Temporal trends of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the Veteran Affairs population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(3):594-601.

18. Mittal S, El-Serag HB, Sada YH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in United States veterans is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):124-131.e1.

19. Sayiner M, Otgonsuren M, Cable R. Variables associated with inpatient and outpatient resource utilization among medicare beneficiaries with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with or without cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(3):254-260.

20. Younossi ZM, Zheng L, Stepanova M, Henry L, Venkatesan C, Mishra A. Trends in outpatient resource utilizations and outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(3):222-227.

21. Allen AM, Van Houten HK, Sangaralingham LR, Talwalkar JA, McCoy RG. Healthcare cost and utilization in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: real-world data from a large US claims database. Hepatology. 2018;68(6):2230-2238.

22. Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, et al. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1577-1586.

23. Armstrong MJ, Hazlehurst JM, Parker R, et al. Severe asymptomatic non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in routine diabetes care; a multi-disciplinary team approach to diagnosis and management. QJM. 2014;107(1):33-41.

24. Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology. 2006;44(4):865-873.

25. Kim D, Choi SY, Park EH, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with coronary artery calcification. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):605-613.

26. Stepanova M, Younossi ZM. Independent association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease in the US population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(6):646-650.

27. Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(14):1341-1350.

28. Mir HM, Stepanova M, Afendy H, Cable R, Younossi ZM. Association of sleep disorders with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a population-based study. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3(3):181-185.

29. Agrawal S, Duseja A, Aggarwal A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is an important predictor of hepatic fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a tertiary care center. Hepatol Int. 2015;9(2):283-291.

30. Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with fatty liver and abnormal liver enzymes: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2013;23(11):1815-1825.

31. Armstrong MJ, Adams LA, Canbay A, Syn WK. Extrahepatic complications of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1174-1197.

Hospitalist movers and shakers – January 2019

The Michigan chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine has named Peter Watson, MD, SFHM, as state Hospitalist of the Year. Dr. Watson is the vice president of care management and outcomes for Health Alliance Plan (HAP) in Detroit. The Michigan chapter cited Dr. Watson’s leadership in hospital medicine and “generosity of spirit” as reasons for his selection.

Dr. Watson oversees nurses, social workers, and support staff while also serving as HAP Midwest Health Plan’s medical director. He’s a founding member of the Michigan SHM chapter, which he formerly represented as president.

Dr. Watson spent 11 years overseeing the Henry Ford Medical Group’s hospitalist program prior to joining HAP, and still works as an attending hospitalist for Henry Ford.

Hyung (Harry) Cho, MD, was named the inaugural chief value officer for NYC Health + Hospitals, which includes 11 hospitals in New York and is the largest public health system in the United States. He will oversee systemwide initiatives in value improvement and the reduction of unnecessary testing and treatment.

Prior to this appointment, Dr. Cho served as an academic hospitalist at Mount Sinai Hospital for 7 years, leading high-value care initiatives. Currently, he is a senior fellow with the Lown Institute in Brookline, Mass., and director of quality improvement implementation for the High Value Practice Academic Alliance.

Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, has been promoted to executive director at Huntington (N.Y.) Hospital. Dr. Fitterman has been a long-time physician and administrator at Huntington, serving previously as vice chair of medicine as well as head of hospitalists.

Dr. Fitterman has served as president of SHM’s Long Island chapter.

Previously, Dr. Fitterman was chief resident at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and he remains an associate professor at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y.

Allen Kachalia, MD, was named director of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality and senior vice president of patient safety and quality for Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. Dr. Kachalia is a general internist who has been an active academic hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Kachalia will oversee patient safety and quality across all of Hopkins Medicine, with a focus on ending preventable harm, improving outcomes and patient experience, and reducing waste in the system’s delivery of care. He also will guide academic efforts for the Armstrong Institute, formed recently thanks to a $10 million gift.

In addition to his hospitalist work, Dr. Kachalia comes to Hopkins after serving as chief quality officer and vice president of quality and safety at Brigham Health.

Riane Dodge, PA, has been elevated to director of clinical education in physician assistant studies at Clarkson University, Potsdam, N.Y. The veteran physician assistant previously worked as a hospitalist in the Claxton Hepburn Medical Center in Ogdensburg, N.Y. There, she cared for patients in acute rehab, mental health, and on regular medical floors.

Dodge also has a background in urgent care and family medicine, and has experience as an emergency department technician.

BUSINESS MOVES

Surgical Affiliates of Sacramento, a surgical hospitalist provider with expertise in trauma, orthopedic, neurosurgery, and general surgery for hospital systems, has added partnerships with Christus Spohn Hospital South and Christus Spohn Hospital Shoreline in Corpus Christi, Texas.

Surgical Affiliates’ hospitalist system will provide round-the-clock emergency orthopedic surgery service to adult and pediatric patients in the two hospitals. With Surgical Affiliates’ help, Christus Spohn facilities will be able to cover its own patients, as well as those requiring transfer from regional hospitals.

Hospitalist surgeons will handle emergency surgeries and patient surgery consultations. Clinics will be provided at each facility to care for patients after they are discharged.

The Michigan chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine has named Peter Watson, MD, SFHM, as state Hospitalist of the Year. Dr. Watson is the vice president of care management and outcomes for Health Alliance Plan (HAP) in Detroit. The Michigan chapter cited Dr. Watson’s leadership in hospital medicine and “generosity of spirit” as reasons for his selection.

Dr. Watson oversees nurses, social workers, and support staff while also serving as HAP Midwest Health Plan’s medical director. He’s a founding member of the Michigan SHM chapter, which he formerly represented as president.

Dr. Watson spent 11 years overseeing the Henry Ford Medical Group’s hospitalist program prior to joining HAP, and still works as an attending hospitalist for Henry Ford.

Hyung (Harry) Cho, MD, was named the inaugural chief value officer for NYC Health + Hospitals, which includes 11 hospitals in New York and is the largest public health system in the United States. He will oversee systemwide initiatives in value improvement and the reduction of unnecessary testing and treatment.

Prior to this appointment, Dr. Cho served as an academic hospitalist at Mount Sinai Hospital for 7 years, leading high-value care initiatives. Currently, he is a senior fellow with the Lown Institute in Brookline, Mass., and director of quality improvement implementation for the High Value Practice Academic Alliance.

Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, has been promoted to executive director at Huntington (N.Y.) Hospital. Dr. Fitterman has been a long-time physician and administrator at Huntington, serving previously as vice chair of medicine as well as head of hospitalists.

Dr. Fitterman has served as president of SHM’s Long Island chapter.

Previously, Dr. Fitterman was chief resident at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and he remains an associate professor at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y.