User login

Looking back to reflect on how far we’ve come

During the holiday break I took some time to organize a lot of old family pictures: deleting duplicates, merging those I pulled off my dad’s computer when he died (which was over 5 years ago), importing ones I took with old digital cameras that were in separate folders ... a bunch of stuff. Some were even childhood pics of me that had been scanned into digital formats. Lots of gigabytes. Lots of time spent watching the little “importing” wheel spin.

As I scrolled through them – literally 5,891 pics and 679 videos – I watched as it became more than a bunch of photos. I watched myself grow up, go through medical school, get married, raise a family. My hair went from brown to gray and receding. My kids went from toddlers to young adults about to leave for college.

It was the story of my life. Without meaning to, it’s what the pictures had become.

It was late at night, but I kept scrolling back and forth. My parents, wife, and others aged in front of me.

Looking in the mirror, or seeing others each day, we never notice the slow changes that time brings. You don’t really see it just thumbing through old photos, either.

But here, in the photos app (something entirely undreamed of in my childhood), I was watching it like it was a movie. Even childhood pictures of my parents. Them dating and getting married. Holding me after bringing me home from the hospital.

I’m certainly not the first to have these thoughts, nor will I be the last. We all go through life in a somewhat organized yet haphazard way, and only when looking backward do we really see how far we’ve come ... often realizing we’re past the halfway point.

Not that this is a bad thing. I mean, that’s life on Earth. It has its good and bad, and aging is part of the rules for all of us.

I suppose you could look at this in terms of our profession. We all (or at least most of us) start out as hospital patients. As we get older and become doctors, hopefully we need to see our own kind less often while at the same time seeing others as patients. As time goes by, most of us start to need to see doctors again, and as we retire and stop practicing medicine, we move back toward being patients ourselves.

For me, the pictures bring back memories and strike emotions in the way hearing or reading stories never can. They give new life to long-forgotten thoughts. Happy and sad, but overall a feeling of contentment that, so far, I feel like I’ve done more good than bad, more right than wrong.

I hope I always feel that way.

I hope everyone else does, too.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

During the holiday break I took some time to organize a lot of old family pictures: deleting duplicates, merging those I pulled off my dad’s computer when he died (which was over 5 years ago), importing ones I took with old digital cameras that were in separate folders ... a bunch of stuff. Some were even childhood pics of me that had been scanned into digital formats. Lots of gigabytes. Lots of time spent watching the little “importing” wheel spin.

As I scrolled through them – literally 5,891 pics and 679 videos – I watched as it became more than a bunch of photos. I watched myself grow up, go through medical school, get married, raise a family. My hair went from brown to gray and receding. My kids went from toddlers to young adults about to leave for college.

It was the story of my life. Without meaning to, it’s what the pictures had become.

It was late at night, but I kept scrolling back and forth. My parents, wife, and others aged in front of me.

Looking in the mirror, or seeing others each day, we never notice the slow changes that time brings. You don’t really see it just thumbing through old photos, either.

But here, in the photos app (something entirely undreamed of in my childhood), I was watching it like it was a movie. Even childhood pictures of my parents. Them dating and getting married. Holding me after bringing me home from the hospital.

I’m certainly not the first to have these thoughts, nor will I be the last. We all go through life in a somewhat organized yet haphazard way, and only when looking backward do we really see how far we’ve come ... often realizing we’re past the halfway point.

Not that this is a bad thing. I mean, that’s life on Earth. It has its good and bad, and aging is part of the rules for all of us.

I suppose you could look at this in terms of our profession. We all (or at least most of us) start out as hospital patients. As we get older and become doctors, hopefully we need to see our own kind less often while at the same time seeing others as patients. As time goes by, most of us start to need to see doctors again, and as we retire and stop practicing medicine, we move back toward being patients ourselves.

For me, the pictures bring back memories and strike emotions in the way hearing or reading stories never can. They give new life to long-forgotten thoughts. Happy and sad, but overall a feeling of contentment that, so far, I feel like I’ve done more good than bad, more right than wrong.

I hope I always feel that way.

I hope everyone else does, too.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

During the holiday break I took some time to organize a lot of old family pictures: deleting duplicates, merging those I pulled off my dad’s computer when he died (which was over 5 years ago), importing ones I took with old digital cameras that were in separate folders ... a bunch of stuff. Some were even childhood pics of me that had been scanned into digital formats. Lots of gigabytes. Lots of time spent watching the little “importing” wheel spin.

As I scrolled through them – literally 5,891 pics and 679 videos – I watched as it became more than a bunch of photos. I watched myself grow up, go through medical school, get married, raise a family. My hair went from brown to gray and receding. My kids went from toddlers to young adults about to leave for college.

It was the story of my life. Without meaning to, it’s what the pictures had become.

It was late at night, but I kept scrolling back and forth. My parents, wife, and others aged in front of me.

Looking in the mirror, or seeing others each day, we never notice the slow changes that time brings. You don’t really see it just thumbing through old photos, either.

But here, in the photos app (something entirely undreamed of in my childhood), I was watching it like it was a movie. Even childhood pictures of my parents. Them dating and getting married. Holding me after bringing me home from the hospital.

I’m certainly not the first to have these thoughts, nor will I be the last. We all go through life in a somewhat organized yet haphazard way, and only when looking backward do we really see how far we’ve come ... often realizing we’re past the halfway point.

Not that this is a bad thing. I mean, that’s life on Earth. It has its good and bad, and aging is part of the rules for all of us.

I suppose you could look at this in terms of our profession. We all (or at least most of us) start out as hospital patients. As we get older and become doctors, hopefully we need to see our own kind less often while at the same time seeing others as patients. As time goes by, most of us start to need to see doctors again, and as we retire and stop practicing medicine, we move back toward being patients ourselves.

For me, the pictures bring back memories and strike emotions in the way hearing or reading stories never can. They give new life to long-forgotten thoughts. Happy and sad, but overall a feeling of contentment that, so far, I feel like I’ve done more good than bad, more right than wrong.

I hope I always feel that way.

I hope everyone else does, too.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

End Tidal Capnography in the Emergency Department

Capnography is the measurement of the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (CO2) in exhaled air.1 It provides real-time information on ventilation (elimination of CO2), perfusion (CO2 transportation in vasculature), and metabolism (production of CO2 via cellular metabolism).2 The technology was originally developed in the 1970s to monitor general anesthesia patients; however, its reach has since broadened, with numerous applications currently in use and in development for the emergency provider (EP).3

Capnography exists in two configurations: a mainstream device that attaches directly to the hub of an endotracheal tube (ETT) and a side-stream device that measure levels via nasal or nasal-oral cannula.1,3

Qualitative monitors use a colorimetric device that monitors the end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) in exhaled gas and changes color depending on the amount of CO2 present.2,4 Expired CO2 and H20 form carbonic acid, causing the specially treated litmus paper inside the device to change from purple to yellow.2,4 Quantitative monitors display a capnogram, the waveform of expired CO2 as a function of time; as well as the capnometer, which depicts the numerical EtCO2 for each breath.4 In this overview, we will discuss the general interpretation of capnography and its specific uses in the ED.

The Capnogram

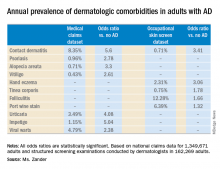

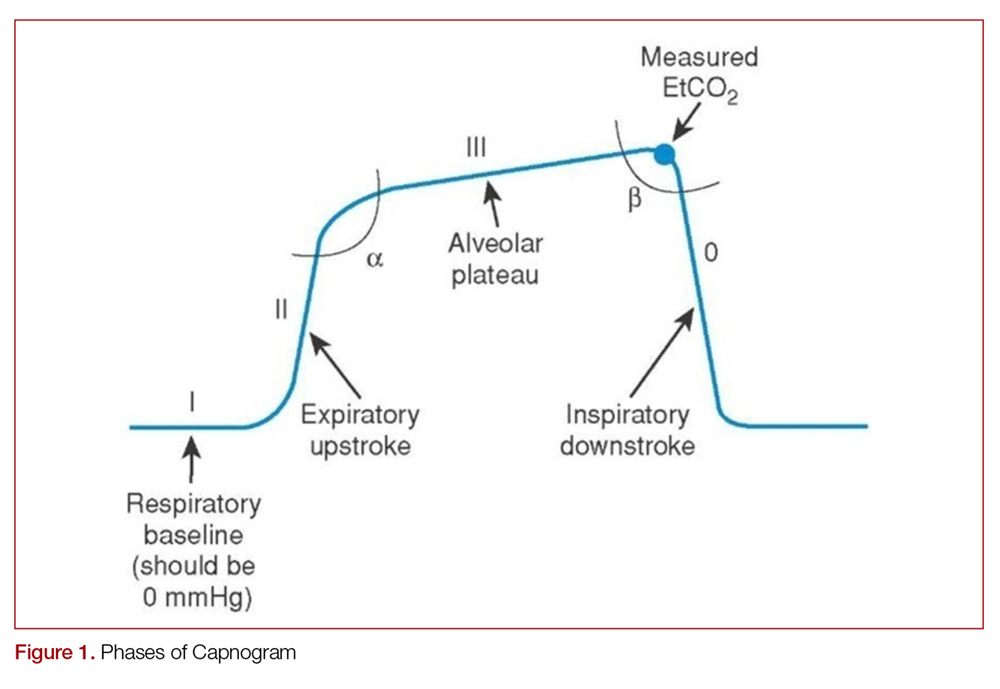

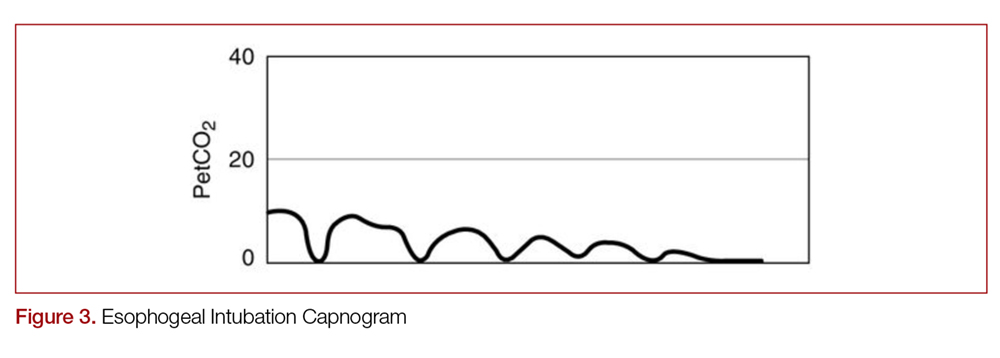

Just like the various stages of an electrocardiogram represent different phases of the cardiac cycle, different phases of a capnogram correspond to different phases of the respiratory cycle. Knowing how to analyze and interpret each phase will contribute to the utility of capnography. While there has been considerable ambiguity in the terminology related to the capnogram,5-7 the most frequently referenced capnogram terminology consists of the following phases (Figure 1):

Phase I: represents beginning of exhalation, where the dead space is cleared from the upper airway.2 This should be zero unless the patient is rebreathing CO2-laden expired gas from either artificially increased dead space or hypoventilation.2,8 A precipitous rise in both the baseline and EtCO2 may indicate contamination of the sensor, such as with secretions or water vapor.2,6

Phase II: rapid rise in exhaled as the CO2 from the alveoli reaches the sensor.4 This rise should be steep, particularly when ventilation to perfusion (V/Q) is well matched. More V/Q heterogeneity, such as with COPD or asthma, leads to a more gradual slope.9 A more gradual phase 2 slope may also indicate a delay in CO2 delivery to the sampling site, such as with bronchospasm or ETT kinking.2

Phase III: the expiratory plateau, which represents the CO2 concentration approaching equilibrium from alveoli to nose. The plateau should be nearly horizontal.2 If all alveoli had the same pCO2, this plateau would be perfectly flat, but spatial and temporal mismatch in alveolar V/Q ratios result in variable exhaled CO2. When there is substantial V/Q heterogeneity, the slope of the plateau will increase.1,2,6

Phase IV: the initiation of inspiration, which should be a nearly vertical drop to a baseline. If prolonged or bleeding into the expiratory phase, consider a leak in the expiratory portion of the circuit, such as an ETT tube cuff leak.2

Phase 0: the inspiratory segment

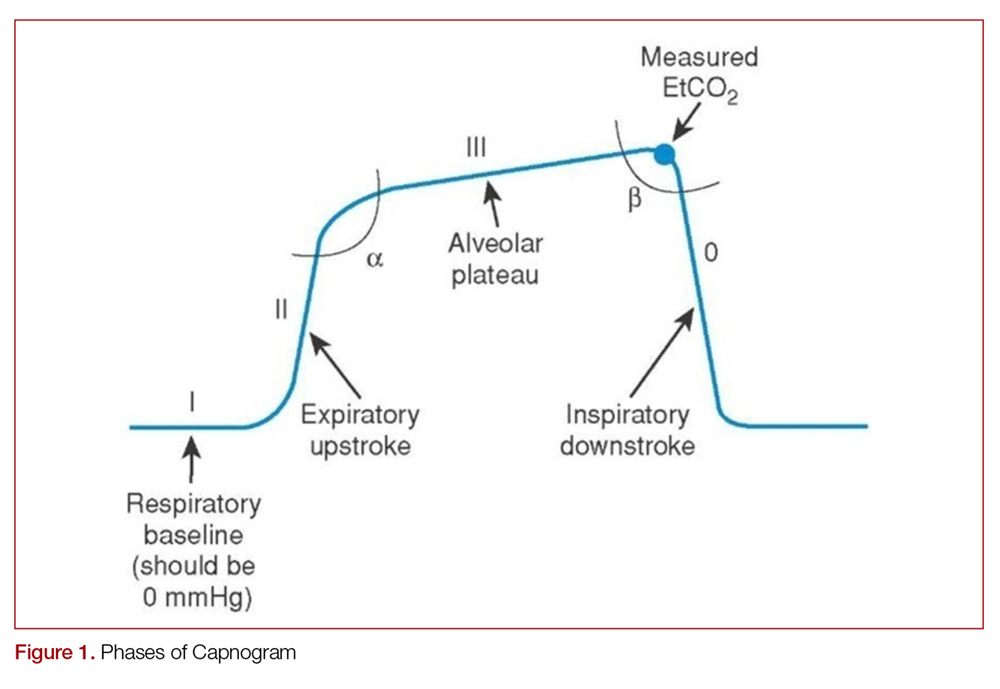

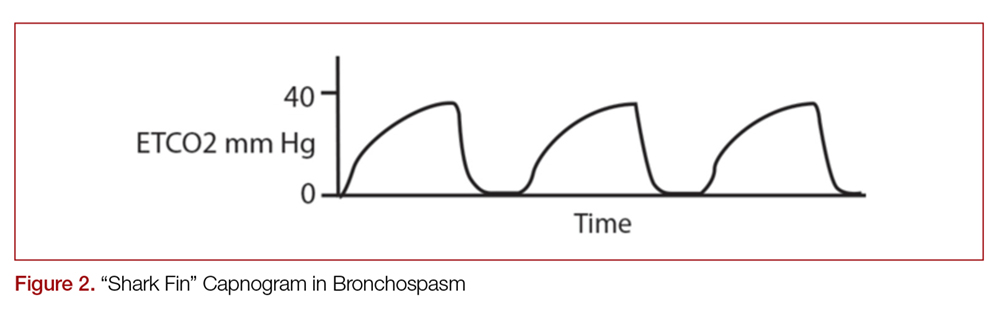

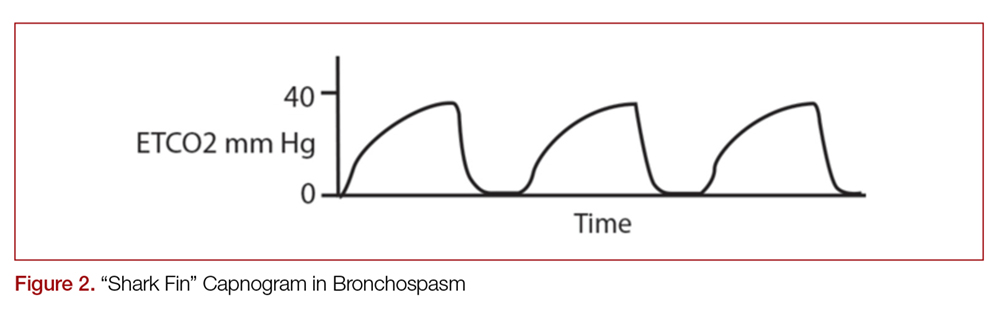

Another important part of the capnogram is the alpha angle. This is the angle of transition between Phase II and Phase III. The combination of a prolonged phase II and steeper phase III leads to a more obtuse alpha angle and will have a “shark-fin” appearance to the capnogram. This suggests an obstructive process, such as asthma or COPD (Figure 2).1,2,6

Standard Uses

Intubation

Capnography, along with visualizing ETT placement through the vocal cords, is the standard of care for confirming correct placement during intubation.4,10,11 Alternative signs of endotracheal intubation, such as chest wall movement, auscultation, condensation of water vapor in the tube lumen, or pulse oximetry, are less accurate.12

While not ideal, correct ETT placement can be confirmed qualitatively using a colorimetric device.13 Upon correct placement, the resultant exhalation of CO2 will change the paper color from purple to yellow (indicating EtCO2 values > 15 mm Hg).2,4 Without this color change, tube placement should be verified to rule out esophageal intubation. Unfortunately, qualitative capnography has false positives and negatives that limit its utility in the ED, and this method should be avoided if quantitative capnography is available.

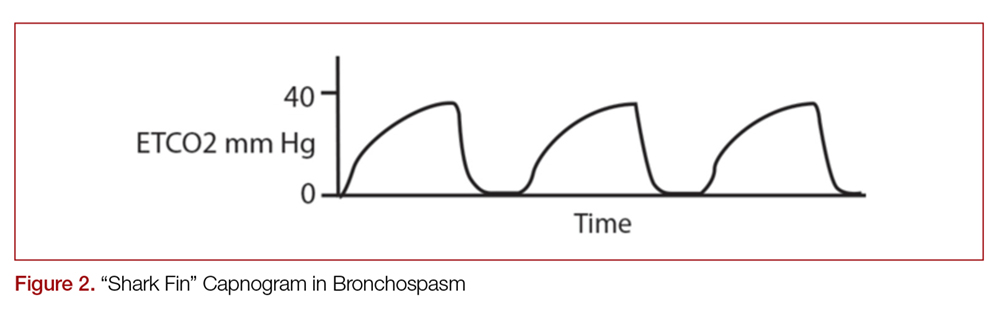

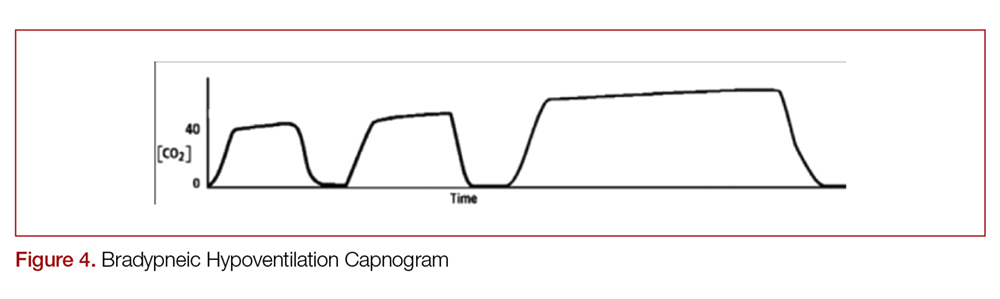

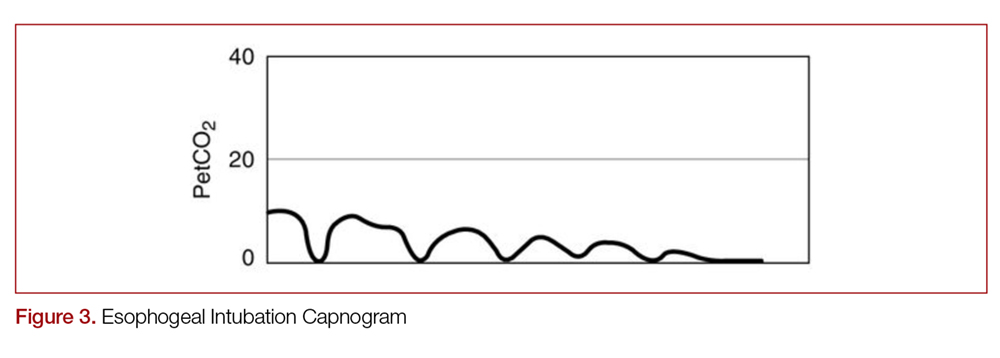

With quantitative capnography, obtaining the typical box-waveform on the capnogram reflects endotracheal intubation. In comparison, a flat capnogram is more indicative of an esophageal intubation (Figure 3).10 While other things may cause this waveform, such as technical malfunction or complete airway obstruction distal to the tube, tube placement confirmation to rule out esophageal intubation would be the first step to troubleshooting this waveform. In addition, if the ETT is placed in the hypopharynx above the vocal cords, the waveform may initially appear appropriate but will likely become erratic appearing over time.10

Quantitative capnography does have some limitations. For example, a main-stem bronchus intubation would still likely demonstrate normal-appearing capnography, so secondary strategies and a confirmatory chest x-ray are still indicated. False-negative ETCO2 readings can occur in low CO2 elimination states, such as cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolus, or pulmonary edema, while false-positives can theoretically occur after ingestion of large amounts of carbonated liquids or contamination of the sensor with stomach contents or acidic drugs.10 However, many of these misleading results can be caught by simply checking for an appropriate waveform.

Cardiac Arrest

Capnography has numerous uses in the monitoring, management, and prognostication of intubated patients in cardiac arrest.1,3,4,10,14 Under normal conditions, EtCO2 is 35-40 mm Hg. While the body still makes CO2 during cardiac arrest, it will not reach the alveoli without circulating blood.10 Without CPR, CO2 accumulates peripherally and won’t reach the lungs, causing EtCO2 to approach zero. This means that EtCO2 correlates directly with cardiac output during CPR, as long as ventilation remains constant.

This means the effectiveness of cardiac chest compression can be assessed in intubated patients using EtCO2, with higher values during CPR correlated with increased return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and survival.14-18 Using EtCO2 monitoring during cardiac arrest may improve outcomes,19 and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends monitoring capnography during cardiac arrest to assess compression efficacy.10,20 EtCO2 >20 mm Hg is considered optimal, while EtCO2 <10-15 mm Hg is considered suboptimal.4,10,16 In a recent meta-analysis, the average EtCO2 was 13.1 mm Hg in those who did not obtain ROSC, compared to 25.8 mm Hg in those who did.21 As such, goal EtCO2 for effective compressions may be even higher in future recommendations. If EtCO2 is low, either compression technique should be improved or a different operator should do compressions. Every 1 cm increase in depth will increase EtCO2 by approximately 1.4 mm Hg.16 Interestingly, compression rate is not a significant predictor of EtCO2 over the dynamic range of chest compression delivery.16

An abrupt increase in EtCO2 is an early indicator of ROSC.10,14-16,22,23 A return of a perfusing rhythm will increase cardiac output. This allows for accumulated peripheral CO2 to reach the lungs, subsequently causing a rapid rise in EtCO2.24 It is important to note that when it comes to evaluating for ROSC, the actual numbers are less important than the change from pre- to post-ROSC. Providers should look for a jump of at least 10 mm Hg on capnometry.4 Nevertheless, an abrupt rise in EtCO2 is a non-sensitive marker for ROSC (33%, 95% CI 22-47% in one multicenter cross-sectional study), meaning that the lack of an abrupt rise of EtCO2 may not necessarily mean a lack of ROSC.23

The EtCO2 level may help guide decision-making in assessing whether continued resuscitation in cardiac arrest is futile. Values <10 mm Hg after 20 minutes of active resuscitation have consistently demonstrated minimal chance of survival.17,25,26 In one study, an EtCO2 of <10 mm Hg at 20 minutes had a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 100% for death in PEA arrest.17 However, determination of the specific EtCO2 cutoff and the timing is still an area of research with a final consensus pending.17,18,25-30 One recent study suggested that even 3 min with EtCO2 <10 mm Hg could be an appropriate cutoff to cease resuscitation efforts.27

Unfortunately, there is a large amount of heterogeneity in the available literature using capnography to assess for ROSC and in guiding resuscitation efforts. EtCO2 should not be used as the only factor in the determination to cease resuscitation. In addition, the AHA recommends that EtCO2 for prognostication should be limited to intubated patients only.20

It is important to note that while cardiac output is the largest factor for EtCO2 in arrest, other physiologic and iatrogenic causes may affect EtCO2 during resuscitation. For example, there is considerable variation in EtCO2 with changes in ventilation rate.4 Measured CO2 may be significantly lower with manual instead of mechanical ventilation, likely due to over-ventilation that not only reduces alveolar CO2 but also causes excess intra-thoracic pressure, reducing venous return.21 For these reasons, use caution when using EtCO2 during manual ventilation of an intubated patient in cardiac arrest. In addition, administration of epinephrine may cause a small decrease in EtCO2, although the effect may vary for each individual.10,31 Sodium bicarbonate can also cause a transient increase in CO2 due to its conversion into CO2 and H2O.10

Procedural Sedation

Capnography is being used with increasing frequency to monitor patients during procedural sedation; it is now considered standard of care in many settings.32 Although rare, hypoventilation is a risk of procedural sedation.33 Typically, respiratory depression during procedural sedation is diagnosed with non-invasive pulse oximetry and visual inspection.34 However, capnography has been shown to identify respiratory depression, airway obstruction, apnea, and laryngospasm earlier than pulse oximetry, allowing the provider to intervene quicker.34,35 Unlike pulse oximetry, the capnogram also remains stable during patient motion and is reliable in low-perfusion states.36

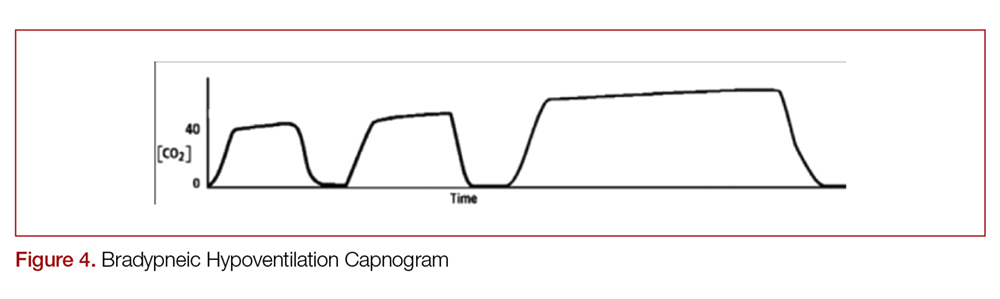

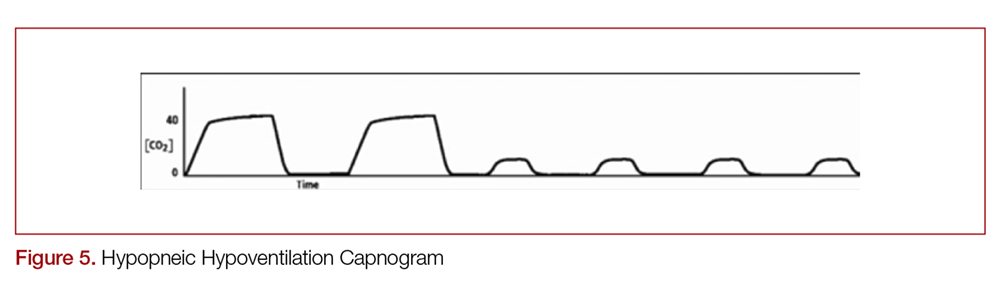

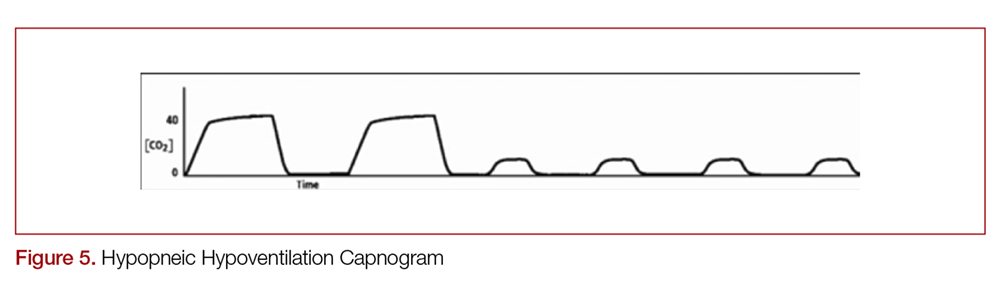

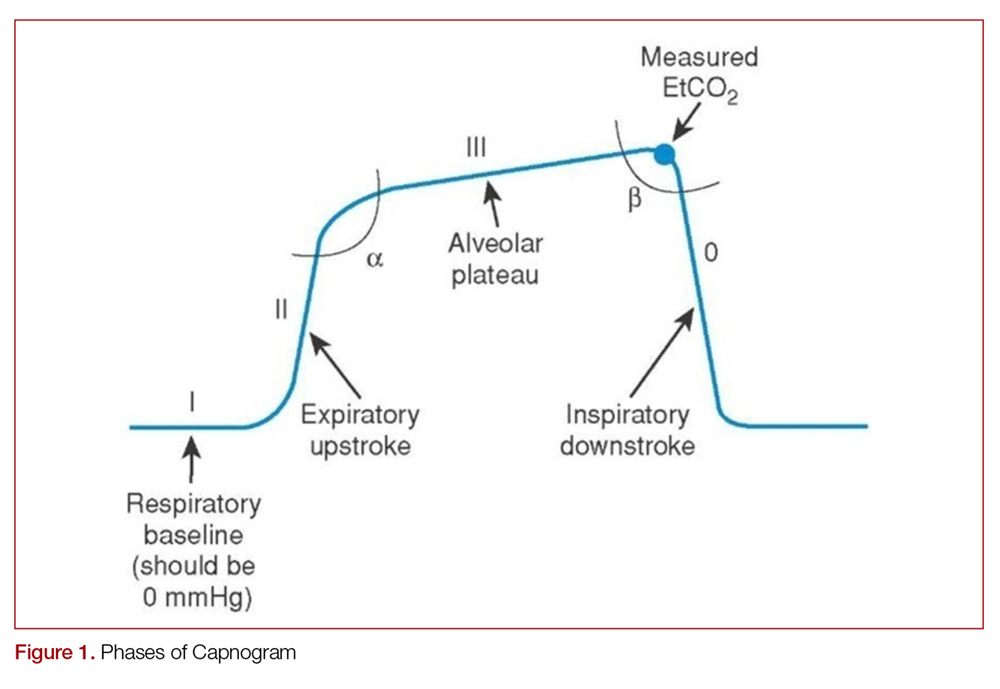

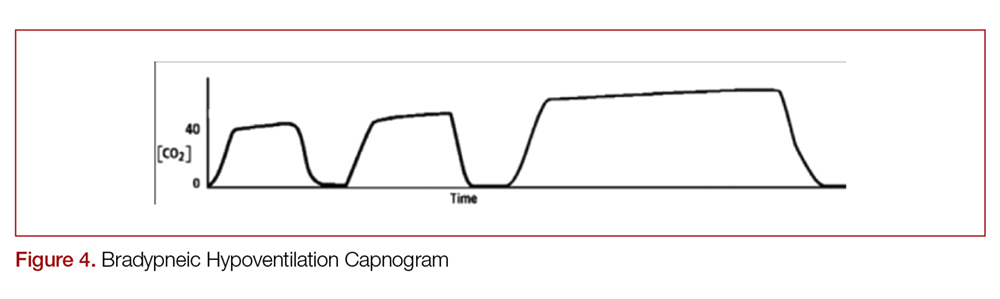

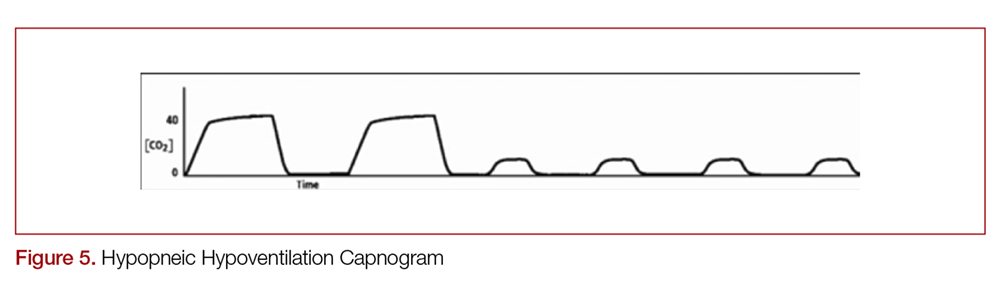

There are two distinct types of hypoventilation detected by capnography. Bradypneic hypoventilation (type 1), which is characterized by a decreased respiratory rate, results in a decreased expiratory time and a subsequent rise in EtCO2.36 This is depicted on capnography by a high EtCO2 and longer waveform, and is commonly observed after oversedation with opioids (Figure 4).36 In contrast, hypopneic hypoventilation (type 2) occurs with low tidal volumes but a normal respiratory rate.36 Type 2 is graphically represented by a suddenly lower ETCO2 with otherwise normal waveform and occurs most commonly with sedative-hypnotic drugs (Figure 5).36 Seeing either type during procedural sedation should alert the clinician to assess for airway obstruction, consider supplemental oxygen, cease drug administration or reduce dosing, and consider reversal if appropriate.36

There is some debate as to the utility of capnography for procedural sedation. While it is clear that capnography decreases the incidence of hypoxia, some studies suggest that it may not reduce patient-centered outcomes such as adverse respiratory events, neurologic injury, aspiration, or death compared to standard monitoring.35,37,38 However, pulse oximetry alone can suffer response delay, while EtCO2 can rapidly detect hypoventilation.39

Potential Uses/Applications

Respiratory Distress

Capnography can provide dynamic monitoring in patients with acute respiratory distress. Measuring EtCO2 with each breath provides instantaneous feedback on the clinical status of the patient and has numerous specific uses.1,3,4

Determining the etiology of respiratory distress in either the obtunded patient or those with multiple comorbidities can be a challenge. Vital sign abnormalities and physical exam findings can overlap in numerous conditions, which may only further obscure the diagnosis. Since different etiologies for respiratory disease require different management modalities, anything that can help clue in to the specific cause can be beneficial. As discussed above, obstructive diseases such as COPD or asthma demonstrate a “shark-fin appearance” on capnogram due to both V/Q heterogeneity and a prolonged expiratory phase due to airway constriction, which will contrast to the typical box-waveform in other conditions (Figure 2).1,2,6 Some studies have been able differentiate COPD from congestive heart failure (CHF) by waveform analysis alone, though this was primarily done via computer algorithms.40 Seeing the shark-fin (or the lack thereof) can help guide management of respiratory distress in conjunction with the remainder of the initial assessment.

Monitoring capnography can help with management and disposition in those with COPD or asthma. During exacerbations, EtCO2 levels may initially drop as the patient hyperventilates to compensate.1 It is not until ventilation becomes less effective that EtCO2 levels begin to rise. This may occur before hypoxia sets in and can prompt the clinician to escalate ventilation strategies. In addition, the normalization of the “shark-fin” obstructive pattern towards the more typical box-form wave may indicate effective treatment, though more data is needed before it can be recommended.41 One of the advantages of this technique would be that it is independent of patient effort, unlike peak-flow monitoring.

EtCO2 can be beneficial even before patients get to the ED. In one study, prehospital patients presenting with asthma or COPD who were found to have EtCO2 of >50 mm Hg or <28 mm Hg, representing the upper and lower limits in the study, had greater rates of intubation, critical care admission, and mortality.42 The patients in this cohort with higher EtCO2 were likely tiring after prolonged hyperventilation and therefore would be more likely to need ventilatory support. Those on the lower end were likely hyperventilating and had not yet tired out. It is important to note that while arrival EtCO2 levels may aid in determining the more critically ill, post-treatment levels were not found to have a statistical difference in determining disposition in patients with asthma or COPD.43

Caution is advised when attempting to use EtCO2 to approximate an arterial blood gas CO2 (PaCO2). While EtCO2 can correlate with PaCO2 within 5 mm Hg in greater than 80% of patients with dyspnea,44 large discrepancies are common depending on the disease state.45 In general, the EtCO2 should always be lower than the PaCO2 due to the contribution to the ETCO2 from dead space, which has a low CO2 content due to lack of perfusion.

Sepsis

EtCO2 may help identify septic patients given its inverse relationship with lactate levels.46-49 In conditions of poor tissue perfusion, lactate builds up. This begins to make the blood acidotic in the form of newly acquired anions, with a resultant anion gap metabolic acidosis. The body then tries to acutely compensate for this by hyperventilating, resulting in the observed lowering of EtCO2. Since lactate is a predictor of mortality in sepsis,50 and monitoring lactate clearance to evaluate resuscitation efforts in sepsis is recommended,51 EtCO2 could play a similar role. One group in particular has demonstrated that, when used with SIRS criteria, abnormally low prehospital EtCO2 levels is predictive of sepsis and inhospital mortality, and is more predictive than SIRS criteria alone.48,50 That said, EtCO2 was not associated with lactate temporally at 3 and 6 hours,51 so it should not be used to guide resuscitation like a lactate clearance. It appears that EtCO2 may be helpful for triage in sepsis, but more study is needed to determine the exact role particularly given most of the available research involves multiple studies from one group.47,48,52

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Initial bicarbonate levels and venous pH are associated with low EtCO2 readings in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).54,55 This could have many practical uses, in particular for patients presenting with hyperglycemia to rule out DKA. One study demonstrated that a blood glucose >250 mg/dL and capnography of >24.5 mm Hg had 90% sensitivity for excluding DKA.55 A value of 35 mm Hg or greater demonstrated 100% sensitivity for excluding DKA in patients with initial glucose >550 mg/dL,56 though this blood glucose is not practical, as this excludes many patients the EP would seek to rule out DKA (recall that blood glucose only has to be >250 mg/dL for the diagnosis). Smaller studies focused on the pediatric population found a 100% sensitivity marker for DKA varied from >30 to >36 mm Hg.57,58 Clearly a role exists, but no study has demonstrated sufficient sensitivity for ruling out DKA with EtCO2 and blood glucose alone within the framework of clinically relevant values.

Trauma

As described above, low EtCO2 is inversely correlated with lactate.46 Because of this, it could theoretically be a marker of hypoperfusion in trauma. Initial EtCO2 values <25 mm Hg have been associated with mortality and hemorrhage in intubated trauma patients,59 as well as mortality prior to discharge in nonintubated trauma patients.60 However, it did not demonstrate added clinical utility when combined with Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, systolic blood pressure, and age in predicting severe injury.61

Pulmonary Embolism

A pulmonary embolism (PE) causes a blockage in blood flow to alveoli, which results in a decrease in CO2 transportation to the alveoli and thus lower EtCO2, while also widening the gradient between PaCO2 and EtCO2.37 Because of this, it has a theoretical role in the diagnosis of PE, though numerous studies have demonstrated that EtCO2 alone is not sensitive nor specific enough for this role.62-66 In a recent meta-analysis, a pretest probability of 10% could lead to a posttest probability of 3% using capnography.62 While further study is needed before recommendation, this indicates that capnography could obviate the need for imaging in low to intermediate risk patients either after a positive D-Dimer or instead of obtaining a D-dimer.62-64

Triage

Simply measuring an initial EtCO2 as a triage vital sign may have added benefit to the EP, and consideration could be made for making this a policy in your ED. One study demonstrated that abnormal initial EtCO2 (outside of 35-45 mm Hg) was predictive of admisison (RR 2.5, 95% CI 1.5-4.0).67 An abnormal EtCO2 (outside of 31-41 mm Hg for this study) was 93% sensitive (95% CI 79-98%), with expectedly low specificity of 44% (95% CI 41-48%) for mortality prior to discharge.47 This potential vital sign may be treated similarly to tachycardia; while an abnormal heart rate should increase a clinician’s concern for a pathological condition, it needs to be taken in context of the situation to accurately interpret it.

Summary

Capnography has numerous uses in the ED in both intubated and spontaneously breathing patients. Quantitative capnography is the standard of care for confirming endotracheal intubation. It is recommended as an aide in maximizing chest compressions during cardiac arrest and can assist in prognostication. It rapidly identifies hypoventilation during procedural sedation. It also has many more potential applications that continue to be explored in areas such as respiratory distress, sepsis, trauma, DKA, and PE. Ultimately, capnography should always be used in association with the remainder of the clinical assessment.

- Manifold CA, Davids B, Villers LC, Wampler DA. Capnography for the nonintubated patient in the emergency setting. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(4):626-632.

- Ward K, Yealy DM. End-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring in emergency medicine, part 1: basic principles. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(6):628-636.

- Krauss B, Falk JL. Carbon dioxide monitoring (capnography). UpToDate. Waltham MA: UpToDate Inc. www.uptodate.com.

- Long B, Koyfman A, Michael AV. Capnography in the emergency department: a review of uses, waveforms, and limitations. J Emerg Med. 2017;(53)6:829-842.

- Shankar Kodali B. Capnography: A Comprehensive Educational Website. Boston, MA. www.capnography.com.

- Kodali B. Capnography outside the operating room. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:192-201.

- Bhavani, S. Defining segments and phases of a time capnogram. Anesth Analg. 2000;91(4):973-977.

- Petersson J, Glenny R. Gas exchange and ventilation-perfusion relationships in the lung. Eur Resp J. 2014;44(4):1023-1041.

- Nassar B, Schmidt GA. Capnography during critical illness. Chest. 2016;149(2):576-585.

- Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, et al. Part 8: Adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(18 suppl 3):S729-S767.

- Burns SM, Carpenter R, Blevins C, Bragg S, Marshall M, Browne L, et al. Detection of inadvertent airway intubation during gastric tube insertion: capnography versus a colorimetric carbon dioxide detector. Am J Crit Care. 2006:15(2):188-195.

- Goldberg JS, Rawle PR, Zehnder JL, Sladen RN. Colorimetric end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring for tracheal intubation. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1990:70(2):191-194.

- O'Flaherty D, Adams AP. The end-tidal carbon dioxide detector: assessment of a new method to distinguish oesophageal from tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 1990:45(8):653-655.

- Garnett AR, Ornato JP, Gonzalez ER, Johnson EB. End-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA. 1987;257:512-515.

- Falk JL, Rackow EC, Weil MH. End-tidal carbon dioxide concentration during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(10):607-611.

- Sheak KR, Wiebe DJ, Leary M, Babaeizadeh S, Yuen TC, Zive D, et al. Quantitative relationship between end-tidal carbon dioxide and CPR quality during both in-hospital and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2015;89:149-154.

- Levine RL, Wayne MA, Miller CC. End-tidal carbon dioxide and outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(5):301-306.

- Touma O, Davies M. The prognostic value of end tidal carbon dioxide during cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2013;84(11):1470-1479.

- Chen JJ, Lee YK, Hou SW, et al. End-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring may be associated with a higher possibility of return of spontaneous circulation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a population-based study. Scan J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23:104.

- Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW et al. Part 7: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2015;132(suppl 2):S315-S367.

- Hartmann SW, Farris RW, Di Gennaro JL, Roberts JS. Systematic review and meta-analysis of end-tidal carbon dioxide values associated with return of spontaneous circulation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Intensive Care Med. 2015;(30):426-435.

- Eckstein, M, Hatch, L, Malleck, J et al. EtCO2 as a predictor of survival in out-of hospital cardiac arrest. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;104:53-58.

- Lui CT, Poon KM, Tsui KL. Abrupt rise of end tidal carbon dioxide was a specific but non-sensitive marker of return of spontaneous circulation with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;104:53-58.

- Pokorna M, Necas E, Kratochvil J et al. A sudden increase in partial pressure end-tidal carbon dioxide at the moment of return of spontaneous circulation. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:614-621.

- Sanders A, Kern K, Otto C, et al. End-tidal carbon dixoide monitoring during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a prognostic indicator for survival. JAMA. 1989;262:1347-1351.

- Wayne M, Levine R, And Miller C. Use of end-tidal carbon dioxide to predict outcome in prehospital cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25(6):762-767.

- Poon KM, Lui CT, Tsui KL. Prognostication of out-of-hopsital cardiac arrest patients by 3-min end-tidal capnometry level in emergency department. Resuscitation. 2016;102:80-84.

- Einav S, Bromiker R, Weiniger C, Matot I. Mathematical modeling for prediction of survival from resuscitation based on computerized continuous capnography: proof of concept. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:468-475.

- Pearce A, Davis D, Minokadeh A, Sell R. Initial end-tidal carbon dioxide as a prognostic indicator for inpatient PEA arrest. Resuscitation. 2015;92:77-81.

- Akinci, E, Ramadan H, Yuzbasioglu Y, Coksun F. Comparison of end-tidal carbon dioxide levels with cardiopulmonary resuscitation success presented to emergency department with cardiopulmonary arrest. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30(1):16-21.

- Callaham M, Barton C, Matthay M. Effect of epinephrine on the ability of end-tidal carbon dioxide readings to predict initial resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 1992; 20:337-343.

- Wall BF, Magee K, Campbell SG, Zed PJ. Capnography versus standard monitoring for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017(3).

- Langhan ML, Shabanova V, Li FY, Bernstein SL, Shapiro ED. A randomized controlled trial of capnography during sedation in a pediatric emergency setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(1):25-30.

- Campbell SG, Magee KD, Zed PJ, Froese P, Etsell G, LaPierre A et al. End-tidal capnometry during emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia: a randomized, controlled study. World J Emerg Med. 2016;7(1):13.

- Waugh JB, Epps CA, Khodneva YA. Capnography enhances surveillance of respiratory events during procedural sedation: a meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2011;23(3):189-196.

- Krauss B, Hess DR. Capnography for procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(2):172-181.

- Deitch K, Miner J, Chudnofsky CR, Dominici P, Latta D. Does end tidal CO2 monitoring during emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia with propofol decrease the incidence of hypoxic events? A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(3):258-264.

- Godwin SA, Caro DA, Wolf SJ, Jagoda AS, Charles R, Marett BE, Moore J. Clinical policy: procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(2):177-196.

- Hamber EA, Bailey PI, James SW et al. Delays in the detection of hypoxemia due to site of pulse oximetry pulse placement. J Clin Anesth. 1999;11:113-118.

- Mieloszyk RJ, Vergehese GC, Deitch K, et al. Automated quantitative analysis of capnogram shape for COPD-normal and COPD-CHF classification. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2014;61:2882-2890.

- Howe TA, Jaalam K, R. Ahmad, Sheng CK, Ab Rahman NHN. The use of end-tidal capnography to monitor non-intubated patients presenting with acute exacerbation of asthma in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2011:41:581-589.

- Nagurka R, Bechmann S, Gluckman W et al. Utility of initial prehospital end-tidal carbon dioxide measurements to predict poor outcomes in adult asthmatic patients. Prehospital Emerg Care. 2014;18:180-184.

- Doğan NÖ, Şener A, Günaydın GP, İçme F, Çelik GK, Kavaklı HŞ, Temrel TA. The accuracy of mainstream end-tidal carbon dioxide levels to predict the severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations presented to the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(5):408-411.

- Cinar O, Acar YA, Arziman I, et al. Can mainstream end-tidal carbon dioxide measurement accurately predict the arterial carbon dioxide levels of patients with acute dyspnea in ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:358-361.

- Nassar BS, Schmidt GA. Capnography during critical illness. Chest. 2016:149(2):576-585.

- Caputo ND, Fraser RM, Paliga A et al. Nasal cannula end-tidal CO2 correlates with serum lactate levels and odds of operative intervention in penetrating trauma patients: a prospective cohort study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1202-1207.

- Hunter CL, Silvestri S, Ralls G, Bright S, Papa L. The sixth vital sign: prehospital end-tidal carbon dioxide predicts in-hospital mortality and metabolic disturbances. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(2):160-165.

- Hunter CL, Silvestri S, Dean M, Falk JL, Papa L. End-tidal carbon dioxide is associated with mortality and lactate in patients with suspected sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(1):64-71.

- McGillicuddy DC, Tang A, Cataldo L, et al. Evaluation of end-tidal carbon dioxide role in predicting elevated SOFA and lactic acidosis. Intern Emerg Med. 2009;4:41-44.

- Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D, Nathanson LA, Lisbon A, Wolfe RE, et al. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:524-528.

- Levy, MM, Evans LE, Rhodes A. The surviving sepsis campaign bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:997-1000.

- Hunter CL, Silvestri S, Ralls G et al. A prehospital screening tool utilizing end-tidal carbon dioxide predicts sepsis and severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:813-819.

- Guirgis FW, Williams DJ, Kalynych CJ, Hardy ME, Jones AE, Dodani S, Wears RL. End-tidal carbon dioxide as a goal of early sepsis therapy. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(11):1351-1356.

- Kartal M, Eray O, Rinnert S, Gosku E, Bektas F, Eken C. ETCO2: a predictive tool for excluding metabolic disturbances in nonintubated patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29: 65-69.

- Solmeinpur H, Taghizadieh A, Niafar M, Rahmani F, Golzari SE, Esfanjani RM. Predictive value of capnography for diagnosis in patients with suspected diabetic ketoacidosis in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14:590-594.

- Bou Chebl R, Madden B, Belsky J, Harmouche E, Yessayan L. Diagnostic value of end tidal capnography in patients with hyperglycemia in the emergency department. BMC Emerg Med. 2016;16:7.

- Fearon DM, Steele DW. End-tidal carbon dioxide predicts the presence and severity of acidosis in children with diabetes. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1373-1378.

- Gilhotra Y, Porter P. Predicting diabetic ketoacidosis in children by measuring end-tidal CO2 via non-invasive nasal capnography. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43:677-680.

- Dunham CM, Chirichella TJ, Gruber BS, et al. In emergently ventilated trauma patients, low end-tidal CO2 and low cardiac output are associated and correlate with hemodynamic instability, hemorrhage, abnormal pupils, and death. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013;13-20.

- Deakin CD, Sado DM, Coats TJ, Davies G. Prehospital end-tidal carbon dioxide concentration and outcome in major trauma. J Trauma.2004;57:65-68.

- Williams DJ, Guirgis FW, Morrissey TK, Wilkerson J, Wears RL, Kalynych C, Kerwin AJ, Godwin SA. End-tidal carbon dioxide and occult injury in trauma patients: ETCO2 does not rule out severe injury. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(11):2146-2149.

- Manara A, D’hoore W, Thys F. Capnography as a diagnostic tool for pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;52:584-591.

- Yoon YH, Lee SW, Jung DM et al. The additional use of end-tidal alveolar dead space fraction following D-dimer test to improve diagnostic accuracy for pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2010;27:663-667.

- Hemnes AR, Newman AL, Rosenbaum B, et al. Bedside end-tidal CO2 tension as a screening tool to exclude pulmonary embolism. Eur Resp J. 2010;35:735-741.

- Rias I Jacob B. Pulmonary embolism in Bradford, UK: role of end-tidal CO2 as a screening tool. Clin Med (Lond). 2014;14:128-133.

- Yuksel M, Pekdemir M, Yilmaz S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive end-tidal carbon dioxide measurement in emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Turk J Med Sci. 2016;46:84–90.

- Williams D, Morrissey T, Caro D, Wears R, Kalynyc C. Side-stream qunatitative end-tidal carbon dioxide measurement as a triage tool in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S212-S213.

Capnography is the measurement of the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (CO2) in exhaled air.1 It provides real-time information on ventilation (elimination of CO2), perfusion (CO2 transportation in vasculature), and metabolism (production of CO2 via cellular metabolism).2 The technology was originally developed in the 1970s to monitor general anesthesia patients; however, its reach has since broadened, with numerous applications currently in use and in development for the emergency provider (EP).3

Capnography exists in two configurations: a mainstream device that attaches directly to the hub of an endotracheal tube (ETT) and a side-stream device that measure levels via nasal or nasal-oral cannula.1,3

Qualitative monitors use a colorimetric device that monitors the end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) in exhaled gas and changes color depending on the amount of CO2 present.2,4 Expired CO2 and H20 form carbonic acid, causing the specially treated litmus paper inside the device to change from purple to yellow.2,4 Quantitative monitors display a capnogram, the waveform of expired CO2 as a function of time; as well as the capnometer, which depicts the numerical EtCO2 for each breath.4 In this overview, we will discuss the general interpretation of capnography and its specific uses in the ED.

The Capnogram

Just like the various stages of an electrocardiogram represent different phases of the cardiac cycle, different phases of a capnogram correspond to different phases of the respiratory cycle. Knowing how to analyze and interpret each phase will contribute to the utility of capnography. While there has been considerable ambiguity in the terminology related to the capnogram,5-7 the most frequently referenced capnogram terminology consists of the following phases (Figure 1):

Phase I: represents beginning of exhalation, where the dead space is cleared from the upper airway.2 This should be zero unless the patient is rebreathing CO2-laden expired gas from either artificially increased dead space or hypoventilation.2,8 A precipitous rise in both the baseline and EtCO2 may indicate contamination of the sensor, such as with secretions or water vapor.2,6

Phase II: rapid rise in exhaled as the CO2 from the alveoli reaches the sensor.4 This rise should be steep, particularly when ventilation to perfusion (V/Q) is well matched. More V/Q heterogeneity, such as with COPD or asthma, leads to a more gradual slope.9 A more gradual phase 2 slope may also indicate a delay in CO2 delivery to the sampling site, such as with bronchospasm or ETT kinking.2

Phase III: the expiratory plateau, which represents the CO2 concentration approaching equilibrium from alveoli to nose. The plateau should be nearly horizontal.2 If all alveoli had the same pCO2, this plateau would be perfectly flat, but spatial and temporal mismatch in alveolar V/Q ratios result in variable exhaled CO2. When there is substantial V/Q heterogeneity, the slope of the plateau will increase.1,2,6

Phase IV: the initiation of inspiration, which should be a nearly vertical drop to a baseline. If prolonged or bleeding into the expiratory phase, consider a leak in the expiratory portion of the circuit, such as an ETT tube cuff leak.2

Phase 0: the inspiratory segment

Another important part of the capnogram is the alpha angle. This is the angle of transition between Phase II and Phase III. The combination of a prolonged phase II and steeper phase III leads to a more obtuse alpha angle and will have a “shark-fin” appearance to the capnogram. This suggests an obstructive process, such as asthma or COPD (Figure 2).1,2,6

Standard Uses

Intubation

Capnography, along with visualizing ETT placement through the vocal cords, is the standard of care for confirming correct placement during intubation.4,10,11 Alternative signs of endotracheal intubation, such as chest wall movement, auscultation, condensation of water vapor in the tube lumen, or pulse oximetry, are less accurate.12

While not ideal, correct ETT placement can be confirmed qualitatively using a colorimetric device.13 Upon correct placement, the resultant exhalation of CO2 will change the paper color from purple to yellow (indicating EtCO2 values > 15 mm Hg).2,4 Without this color change, tube placement should be verified to rule out esophageal intubation. Unfortunately, qualitative capnography has false positives and negatives that limit its utility in the ED, and this method should be avoided if quantitative capnography is available.

With quantitative capnography, obtaining the typical box-waveform on the capnogram reflects endotracheal intubation. In comparison, a flat capnogram is more indicative of an esophageal intubation (Figure 3).10 While other things may cause this waveform, such as technical malfunction or complete airway obstruction distal to the tube, tube placement confirmation to rule out esophageal intubation would be the first step to troubleshooting this waveform. In addition, if the ETT is placed in the hypopharynx above the vocal cords, the waveform may initially appear appropriate but will likely become erratic appearing over time.10

Quantitative capnography does have some limitations. For example, a main-stem bronchus intubation would still likely demonstrate normal-appearing capnography, so secondary strategies and a confirmatory chest x-ray are still indicated. False-negative ETCO2 readings can occur in low CO2 elimination states, such as cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolus, or pulmonary edema, while false-positives can theoretically occur after ingestion of large amounts of carbonated liquids or contamination of the sensor with stomach contents or acidic drugs.10 However, many of these misleading results can be caught by simply checking for an appropriate waveform.

Cardiac Arrest

Capnography has numerous uses in the monitoring, management, and prognostication of intubated patients in cardiac arrest.1,3,4,10,14 Under normal conditions, EtCO2 is 35-40 mm Hg. While the body still makes CO2 during cardiac arrest, it will not reach the alveoli without circulating blood.10 Without CPR, CO2 accumulates peripherally and won’t reach the lungs, causing EtCO2 to approach zero. This means that EtCO2 correlates directly with cardiac output during CPR, as long as ventilation remains constant.

This means the effectiveness of cardiac chest compression can be assessed in intubated patients using EtCO2, with higher values during CPR correlated with increased return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and survival.14-18 Using EtCO2 monitoring during cardiac arrest may improve outcomes,19 and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends monitoring capnography during cardiac arrest to assess compression efficacy.10,20 EtCO2 >20 mm Hg is considered optimal, while EtCO2 <10-15 mm Hg is considered suboptimal.4,10,16 In a recent meta-analysis, the average EtCO2 was 13.1 mm Hg in those who did not obtain ROSC, compared to 25.8 mm Hg in those who did.21 As such, goal EtCO2 for effective compressions may be even higher in future recommendations. If EtCO2 is low, either compression technique should be improved or a different operator should do compressions. Every 1 cm increase in depth will increase EtCO2 by approximately 1.4 mm Hg.16 Interestingly, compression rate is not a significant predictor of EtCO2 over the dynamic range of chest compression delivery.16

An abrupt increase in EtCO2 is an early indicator of ROSC.10,14-16,22,23 A return of a perfusing rhythm will increase cardiac output. This allows for accumulated peripheral CO2 to reach the lungs, subsequently causing a rapid rise in EtCO2.24 It is important to note that when it comes to evaluating for ROSC, the actual numbers are less important than the change from pre- to post-ROSC. Providers should look for a jump of at least 10 mm Hg on capnometry.4 Nevertheless, an abrupt rise in EtCO2 is a non-sensitive marker for ROSC (33%, 95% CI 22-47% in one multicenter cross-sectional study), meaning that the lack of an abrupt rise of EtCO2 may not necessarily mean a lack of ROSC.23

The EtCO2 level may help guide decision-making in assessing whether continued resuscitation in cardiac arrest is futile. Values <10 mm Hg after 20 minutes of active resuscitation have consistently demonstrated minimal chance of survival.17,25,26 In one study, an EtCO2 of <10 mm Hg at 20 minutes had a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 100% for death in PEA arrest.17 However, determination of the specific EtCO2 cutoff and the timing is still an area of research with a final consensus pending.17,18,25-30 One recent study suggested that even 3 min with EtCO2 <10 mm Hg could be an appropriate cutoff to cease resuscitation efforts.27

Unfortunately, there is a large amount of heterogeneity in the available literature using capnography to assess for ROSC and in guiding resuscitation efforts. EtCO2 should not be used as the only factor in the determination to cease resuscitation. In addition, the AHA recommends that EtCO2 for prognostication should be limited to intubated patients only.20

It is important to note that while cardiac output is the largest factor for EtCO2 in arrest, other physiologic and iatrogenic causes may affect EtCO2 during resuscitation. For example, there is considerable variation in EtCO2 with changes in ventilation rate.4 Measured CO2 may be significantly lower with manual instead of mechanical ventilation, likely due to over-ventilation that not only reduces alveolar CO2 but also causes excess intra-thoracic pressure, reducing venous return.21 For these reasons, use caution when using EtCO2 during manual ventilation of an intubated patient in cardiac arrest. In addition, administration of epinephrine may cause a small decrease in EtCO2, although the effect may vary for each individual.10,31 Sodium bicarbonate can also cause a transient increase in CO2 due to its conversion into CO2 and H2O.10

Procedural Sedation

Capnography is being used with increasing frequency to monitor patients during procedural sedation; it is now considered standard of care in many settings.32 Although rare, hypoventilation is a risk of procedural sedation.33 Typically, respiratory depression during procedural sedation is diagnosed with non-invasive pulse oximetry and visual inspection.34 However, capnography has been shown to identify respiratory depression, airway obstruction, apnea, and laryngospasm earlier than pulse oximetry, allowing the provider to intervene quicker.34,35 Unlike pulse oximetry, the capnogram also remains stable during patient motion and is reliable in low-perfusion states.36

There are two distinct types of hypoventilation detected by capnography. Bradypneic hypoventilation (type 1), which is characterized by a decreased respiratory rate, results in a decreased expiratory time and a subsequent rise in EtCO2.36 This is depicted on capnography by a high EtCO2 and longer waveform, and is commonly observed after oversedation with opioids (Figure 4).36 In contrast, hypopneic hypoventilation (type 2) occurs with low tidal volumes but a normal respiratory rate.36 Type 2 is graphically represented by a suddenly lower ETCO2 with otherwise normal waveform and occurs most commonly with sedative-hypnotic drugs (Figure 5).36 Seeing either type during procedural sedation should alert the clinician to assess for airway obstruction, consider supplemental oxygen, cease drug administration or reduce dosing, and consider reversal if appropriate.36

There is some debate as to the utility of capnography for procedural sedation. While it is clear that capnography decreases the incidence of hypoxia, some studies suggest that it may not reduce patient-centered outcomes such as adverse respiratory events, neurologic injury, aspiration, or death compared to standard monitoring.35,37,38 However, pulse oximetry alone can suffer response delay, while EtCO2 can rapidly detect hypoventilation.39

Potential Uses/Applications

Respiratory Distress

Capnography can provide dynamic monitoring in patients with acute respiratory distress. Measuring EtCO2 with each breath provides instantaneous feedback on the clinical status of the patient and has numerous specific uses.1,3,4

Determining the etiology of respiratory distress in either the obtunded patient or those with multiple comorbidities can be a challenge. Vital sign abnormalities and physical exam findings can overlap in numerous conditions, which may only further obscure the diagnosis. Since different etiologies for respiratory disease require different management modalities, anything that can help clue in to the specific cause can be beneficial. As discussed above, obstructive diseases such as COPD or asthma demonstrate a “shark-fin appearance” on capnogram due to both V/Q heterogeneity and a prolonged expiratory phase due to airway constriction, which will contrast to the typical box-waveform in other conditions (Figure 2).1,2,6 Some studies have been able differentiate COPD from congestive heart failure (CHF) by waveform analysis alone, though this was primarily done via computer algorithms.40 Seeing the shark-fin (or the lack thereof) can help guide management of respiratory distress in conjunction with the remainder of the initial assessment.

Monitoring capnography can help with management and disposition in those with COPD or asthma. During exacerbations, EtCO2 levels may initially drop as the patient hyperventilates to compensate.1 It is not until ventilation becomes less effective that EtCO2 levels begin to rise. This may occur before hypoxia sets in and can prompt the clinician to escalate ventilation strategies. In addition, the normalization of the “shark-fin” obstructive pattern towards the more typical box-form wave may indicate effective treatment, though more data is needed before it can be recommended.41 One of the advantages of this technique would be that it is independent of patient effort, unlike peak-flow monitoring.

EtCO2 can be beneficial even before patients get to the ED. In one study, prehospital patients presenting with asthma or COPD who were found to have EtCO2 of >50 mm Hg or <28 mm Hg, representing the upper and lower limits in the study, had greater rates of intubation, critical care admission, and mortality.42 The patients in this cohort with higher EtCO2 were likely tiring after prolonged hyperventilation and therefore would be more likely to need ventilatory support. Those on the lower end were likely hyperventilating and had not yet tired out. It is important to note that while arrival EtCO2 levels may aid in determining the more critically ill, post-treatment levels were not found to have a statistical difference in determining disposition in patients with asthma or COPD.43

Caution is advised when attempting to use EtCO2 to approximate an arterial blood gas CO2 (PaCO2). While EtCO2 can correlate with PaCO2 within 5 mm Hg in greater than 80% of patients with dyspnea,44 large discrepancies are common depending on the disease state.45 In general, the EtCO2 should always be lower than the PaCO2 due to the contribution to the ETCO2 from dead space, which has a low CO2 content due to lack of perfusion.

Sepsis

EtCO2 may help identify septic patients given its inverse relationship with lactate levels.46-49 In conditions of poor tissue perfusion, lactate builds up. This begins to make the blood acidotic in the form of newly acquired anions, with a resultant anion gap metabolic acidosis. The body then tries to acutely compensate for this by hyperventilating, resulting in the observed lowering of EtCO2. Since lactate is a predictor of mortality in sepsis,50 and monitoring lactate clearance to evaluate resuscitation efforts in sepsis is recommended,51 EtCO2 could play a similar role. One group in particular has demonstrated that, when used with SIRS criteria, abnormally low prehospital EtCO2 levels is predictive of sepsis and inhospital mortality, and is more predictive than SIRS criteria alone.48,50 That said, EtCO2 was not associated with lactate temporally at 3 and 6 hours,51 so it should not be used to guide resuscitation like a lactate clearance. It appears that EtCO2 may be helpful for triage in sepsis, but more study is needed to determine the exact role particularly given most of the available research involves multiple studies from one group.47,48,52

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Initial bicarbonate levels and venous pH are associated with low EtCO2 readings in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).54,55 This could have many practical uses, in particular for patients presenting with hyperglycemia to rule out DKA. One study demonstrated that a blood glucose >250 mg/dL and capnography of >24.5 mm Hg had 90% sensitivity for excluding DKA.55 A value of 35 mm Hg or greater demonstrated 100% sensitivity for excluding DKA in patients with initial glucose >550 mg/dL,56 though this blood glucose is not practical, as this excludes many patients the EP would seek to rule out DKA (recall that blood glucose only has to be >250 mg/dL for the diagnosis). Smaller studies focused on the pediatric population found a 100% sensitivity marker for DKA varied from >30 to >36 mm Hg.57,58 Clearly a role exists, but no study has demonstrated sufficient sensitivity for ruling out DKA with EtCO2 and blood glucose alone within the framework of clinically relevant values.

Trauma

As described above, low EtCO2 is inversely correlated with lactate.46 Because of this, it could theoretically be a marker of hypoperfusion in trauma. Initial EtCO2 values <25 mm Hg have been associated with mortality and hemorrhage in intubated trauma patients,59 as well as mortality prior to discharge in nonintubated trauma patients.60 However, it did not demonstrate added clinical utility when combined with Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, systolic blood pressure, and age in predicting severe injury.61

Pulmonary Embolism

A pulmonary embolism (PE) causes a blockage in blood flow to alveoli, which results in a decrease in CO2 transportation to the alveoli and thus lower EtCO2, while also widening the gradient between PaCO2 and EtCO2.37 Because of this, it has a theoretical role in the diagnosis of PE, though numerous studies have demonstrated that EtCO2 alone is not sensitive nor specific enough for this role.62-66 In a recent meta-analysis, a pretest probability of 10% could lead to a posttest probability of 3% using capnography.62 While further study is needed before recommendation, this indicates that capnography could obviate the need for imaging in low to intermediate risk patients either after a positive D-Dimer or instead of obtaining a D-dimer.62-64

Triage

Simply measuring an initial EtCO2 as a triage vital sign may have added benefit to the EP, and consideration could be made for making this a policy in your ED. One study demonstrated that abnormal initial EtCO2 (outside of 35-45 mm Hg) was predictive of admisison (RR 2.5, 95% CI 1.5-4.0).67 An abnormal EtCO2 (outside of 31-41 mm Hg for this study) was 93% sensitive (95% CI 79-98%), with expectedly low specificity of 44% (95% CI 41-48%) for mortality prior to discharge.47 This potential vital sign may be treated similarly to tachycardia; while an abnormal heart rate should increase a clinician’s concern for a pathological condition, it needs to be taken in context of the situation to accurately interpret it.

Summary

Capnography has numerous uses in the ED in both intubated and spontaneously breathing patients. Quantitative capnography is the standard of care for confirming endotracheal intubation. It is recommended as an aide in maximizing chest compressions during cardiac arrest and can assist in prognostication. It rapidly identifies hypoventilation during procedural sedation. It also has many more potential applications that continue to be explored in areas such as respiratory distress, sepsis, trauma, DKA, and PE. Ultimately, capnography should always be used in association with the remainder of the clinical assessment.

Capnography is the measurement of the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (CO2) in exhaled air.1 It provides real-time information on ventilation (elimination of CO2), perfusion (CO2 transportation in vasculature), and metabolism (production of CO2 via cellular metabolism).2 The technology was originally developed in the 1970s to monitor general anesthesia patients; however, its reach has since broadened, with numerous applications currently in use and in development for the emergency provider (EP).3

Capnography exists in two configurations: a mainstream device that attaches directly to the hub of an endotracheal tube (ETT) and a side-stream device that measure levels via nasal or nasal-oral cannula.1,3

Qualitative monitors use a colorimetric device that monitors the end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) in exhaled gas and changes color depending on the amount of CO2 present.2,4 Expired CO2 and H20 form carbonic acid, causing the specially treated litmus paper inside the device to change from purple to yellow.2,4 Quantitative monitors display a capnogram, the waveform of expired CO2 as a function of time; as well as the capnometer, which depicts the numerical EtCO2 for each breath.4 In this overview, we will discuss the general interpretation of capnography and its specific uses in the ED.

The Capnogram

Just like the various stages of an electrocardiogram represent different phases of the cardiac cycle, different phases of a capnogram correspond to different phases of the respiratory cycle. Knowing how to analyze and interpret each phase will contribute to the utility of capnography. While there has been considerable ambiguity in the terminology related to the capnogram,5-7 the most frequently referenced capnogram terminology consists of the following phases (Figure 1):

Phase I: represents beginning of exhalation, where the dead space is cleared from the upper airway.2 This should be zero unless the patient is rebreathing CO2-laden expired gas from either artificially increased dead space or hypoventilation.2,8 A precipitous rise in both the baseline and EtCO2 may indicate contamination of the sensor, such as with secretions or water vapor.2,6

Phase II: rapid rise in exhaled as the CO2 from the alveoli reaches the sensor.4 This rise should be steep, particularly when ventilation to perfusion (V/Q) is well matched. More V/Q heterogeneity, such as with COPD or asthma, leads to a more gradual slope.9 A more gradual phase 2 slope may also indicate a delay in CO2 delivery to the sampling site, such as with bronchospasm or ETT kinking.2

Phase III: the expiratory plateau, which represents the CO2 concentration approaching equilibrium from alveoli to nose. The plateau should be nearly horizontal.2 If all alveoli had the same pCO2, this plateau would be perfectly flat, but spatial and temporal mismatch in alveolar V/Q ratios result in variable exhaled CO2. When there is substantial V/Q heterogeneity, the slope of the plateau will increase.1,2,6

Phase IV: the initiation of inspiration, which should be a nearly vertical drop to a baseline. If prolonged or bleeding into the expiratory phase, consider a leak in the expiratory portion of the circuit, such as an ETT tube cuff leak.2

Phase 0: the inspiratory segment

Another important part of the capnogram is the alpha angle. This is the angle of transition between Phase II and Phase III. The combination of a prolonged phase II and steeper phase III leads to a more obtuse alpha angle and will have a “shark-fin” appearance to the capnogram. This suggests an obstructive process, such as asthma or COPD (Figure 2).1,2,6

Standard Uses

Intubation

Capnography, along with visualizing ETT placement through the vocal cords, is the standard of care for confirming correct placement during intubation.4,10,11 Alternative signs of endotracheal intubation, such as chest wall movement, auscultation, condensation of water vapor in the tube lumen, or pulse oximetry, are less accurate.12

While not ideal, correct ETT placement can be confirmed qualitatively using a colorimetric device.13 Upon correct placement, the resultant exhalation of CO2 will change the paper color from purple to yellow (indicating EtCO2 values > 15 mm Hg).2,4 Without this color change, tube placement should be verified to rule out esophageal intubation. Unfortunately, qualitative capnography has false positives and negatives that limit its utility in the ED, and this method should be avoided if quantitative capnography is available.

With quantitative capnography, obtaining the typical box-waveform on the capnogram reflects endotracheal intubation. In comparison, a flat capnogram is more indicative of an esophageal intubation (Figure 3).10 While other things may cause this waveform, such as technical malfunction or complete airway obstruction distal to the tube, tube placement confirmation to rule out esophageal intubation would be the first step to troubleshooting this waveform. In addition, if the ETT is placed in the hypopharynx above the vocal cords, the waveform may initially appear appropriate but will likely become erratic appearing over time.10

Quantitative capnography does have some limitations. For example, a main-stem bronchus intubation would still likely demonstrate normal-appearing capnography, so secondary strategies and a confirmatory chest x-ray are still indicated. False-negative ETCO2 readings can occur in low CO2 elimination states, such as cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolus, or pulmonary edema, while false-positives can theoretically occur after ingestion of large amounts of carbonated liquids or contamination of the sensor with stomach contents or acidic drugs.10 However, many of these misleading results can be caught by simply checking for an appropriate waveform.

Cardiac Arrest

Capnography has numerous uses in the monitoring, management, and prognostication of intubated patients in cardiac arrest.1,3,4,10,14 Under normal conditions, EtCO2 is 35-40 mm Hg. While the body still makes CO2 during cardiac arrest, it will not reach the alveoli without circulating blood.10 Without CPR, CO2 accumulates peripherally and won’t reach the lungs, causing EtCO2 to approach zero. This means that EtCO2 correlates directly with cardiac output during CPR, as long as ventilation remains constant.

This means the effectiveness of cardiac chest compression can be assessed in intubated patients using EtCO2, with higher values during CPR correlated with increased return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and survival.14-18 Using EtCO2 monitoring during cardiac arrest may improve outcomes,19 and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends monitoring capnography during cardiac arrest to assess compression efficacy.10,20 EtCO2 >20 mm Hg is considered optimal, while EtCO2 <10-15 mm Hg is considered suboptimal.4,10,16 In a recent meta-analysis, the average EtCO2 was 13.1 mm Hg in those who did not obtain ROSC, compared to 25.8 mm Hg in those who did.21 As such, goal EtCO2 for effective compressions may be even higher in future recommendations. If EtCO2 is low, either compression technique should be improved or a different operator should do compressions. Every 1 cm increase in depth will increase EtCO2 by approximately 1.4 mm Hg.16 Interestingly, compression rate is not a significant predictor of EtCO2 over the dynamic range of chest compression delivery.16

An abrupt increase in EtCO2 is an early indicator of ROSC.10,14-16,22,23 A return of a perfusing rhythm will increase cardiac output. This allows for accumulated peripheral CO2 to reach the lungs, subsequently causing a rapid rise in EtCO2.24 It is important to note that when it comes to evaluating for ROSC, the actual numbers are less important than the change from pre- to post-ROSC. Providers should look for a jump of at least 10 mm Hg on capnometry.4 Nevertheless, an abrupt rise in EtCO2 is a non-sensitive marker for ROSC (33%, 95% CI 22-47% in one multicenter cross-sectional study), meaning that the lack of an abrupt rise of EtCO2 may not necessarily mean a lack of ROSC.23

The EtCO2 level may help guide decision-making in assessing whether continued resuscitation in cardiac arrest is futile. Values <10 mm Hg after 20 minutes of active resuscitation have consistently demonstrated minimal chance of survival.17,25,26 In one study, an EtCO2 of <10 mm Hg at 20 minutes had a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 100% for death in PEA arrest.17 However, determination of the specific EtCO2 cutoff and the timing is still an area of research with a final consensus pending.17,18,25-30 One recent study suggested that even 3 min with EtCO2 <10 mm Hg could be an appropriate cutoff to cease resuscitation efforts.27

Unfortunately, there is a large amount of heterogeneity in the available literature using capnography to assess for ROSC and in guiding resuscitation efforts. EtCO2 should not be used as the only factor in the determination to cease resuscitation. In addition, the AHA recommends that EtCO2 for prognostication should be limited to intubated patients only.20

It is important to note that while cardiac output is the largest factor for EtCO2 in arrest, other physiologic and iatrogenic causes may affect EtCO2 during resuscitation. For example, there is considerable variation in EtCO2 with changes in ventilation rate.4 Measured CO2 may be significantly lower with manual instead of mechanical ventilation, likely due to over-ventilation that not only reduces alveolar CO2 but also causes excess intra-thoracic pressure, reducing venous return.21 For these reasons, use caution when using EtCO2 during manual ventilation of an intubated patient in cardiac arrest. In addition, administration of epinephrine may cause a small decrease in EtCO2, although the effect may vary for each individual.10,31 Sodium bicarbonate can also cause a transient increase in CO2 due to its conversion into CO2 and H2O.10

Procedural Sedation

Capnography is being used with increasing frequency to monitor patients during procedural sedation; it is now considered standard of care in many settings.32 Although rare, hypoventilation is a risk of procedural sedation.33 Typically, respiratory depression during procedural sedation is diagnosed with non-invasive pulse oximetry and visual inspection.34 However, capnography has been shown to identify respiratory depression, airway obstruction, apnea, and laryngospasm earlier than pulse oximetry, allowing the provider to intervene quicker.34,35 Unlike pulse oximetry, the capnogram also remains stable during patient motion and is reliable in low-perfusion states.36

There are two distinct types of hypoventilation detected by capnography. Bradypneic hypoventilation (type 1), which is characterized by a decreased respiratory rate, results in a decreased expiratory time and a subsequent rise in EtCO2.36 This is depicted on capnography by a high EtCO2 and longer waveform, and is commonly observed after oversedation with opioids (Figure 4).36 In contrast, hypopneic hypoventilation (type 2) occurs with low tidal volumes but a normal respiratory rate.36 Type 2 is graphically represented by a suddenly lower ETCO2 with otherwise normal waveform and occurs most commonly with sedative-hypnotic drugs (Figure 5).36 Seeing either type during procedural sedation should alert the clinician to assess for airway obstruction, consider supplemental oxygen, cease drug administration or reduce dosing, and consider reversal if appropriate.36

There is some debate as to the utility of capnography for procedural sedation. While it is clear that capnography decreases the incidence of hypoxia, some studies suggest that it may not reduce patient-centered outcomes such as adverse respiratory events, neurologic injury, aspiration, or death compared to standard monitoring.35,37,38 However, pulse oximetry alone can suffer response delay, while EtCO2 can rapidly detect hypoventilation.39

Potential Uses/Applications

Respiratory Distress

Capnography can provide dynamic monitoring in patients with acute respiratory distress. Measuring EtCO2 with each breath provides instantaneous feedback on the clinical status of the patient and has numerous specific uses.1,3,4

Determining the etiology of respiratory distress in either the obtunded patient or those with multiple comorbidities can be a challenge. Vital sign abnormalities and physical exam findings can overlap in numerous conditions, which may only further obscure the diagnosis. Since different etiologies for respiratory disease require different management modalities, anything that can help clue in to the specific cause can be beneficial. As discussed above, obstructive diseases such as COPD or asthma demonstrate a “shark-fin appearance” on capnogram due to both V/Q heterogeneity and a prolonged expiratory phase due to airway constriction, which will contrast to the typical box-waveform in other conditions (Figure 2).1,2,6 Some studies have been able differentiate COPD from congestive heart failure (CHF) by waveform analysis alone, though this was primarily done via computer algorithms.40 Seeing the shark-fin (or the lack thereof) can help guide management of respiratory distress in conjunction with the remainder of the initial assessment.

Monitoring capnography can help with management and disposition in those with COPD or asthma. During exacerbations, EtCO2 levels may initially drop as the patient hyperventilates to compensate.1 It is not until ventilation becomes less effective that EtCO2 levels begin to rise. This may occur before hypoxia sets in and can prompt the clinician to escalate ventilation strategies. In addition, the normalization of the “shark-fin” obstructive pattern towards the more typical box-form wave may indicate effective treatment, though more data is needed before it can be recommended.41 One of the advantages of this technique would be that it is independent of patient effort, unlike peak-flow monitoring.

EtCO2 can be beneficial even before patients get to the ED. In one study, prehospital patients presenting with asthma or COPD who were found to have EtCO2 of >50 mm Hg or <28 mm Hg, representing the upper and lower limits in the study, had greater rates of intubation, critical care admission, and mortality.42 The patients in this cohort with higher EtCO2 were likely tiring after prolonged hyperventilation and therefore would be more likely to need ventilatory support. Those on the lower end were likely hyperventilating and had not yet tired out. It is important to note that while arrival EtCO2 levels may aid in determining the more critically ill, post-treatment levels were not found to have a statistical difference in determining disposition in patients with asthma or COPD.43

Caution is advised when attempting to use EtCO2 to approximate an arterial blood gas CO2 (PaCO2). While EtCO2 can correlate with PaCO2 within 5 mm Hg in greater than 80% of patients with dyspnea,44 large discrepancies are common depending on the disease state.45 In general, the EtCO2 should always be lower than the PaCO2 due to the contribution to the ETCO2 from dead space, which has a low CO2 content due to lack of perfusion.

Sepsis

EtCO2 may help identify septic patients given its inverse relationship with lactate levels.46-49 In conditions of poor tissue perfusion, lactate builds up. This begins to make the blood acidotic in the form of newly acquired anions, with a resultant anion gap metabolic acidosis. The body then tries to acutely compensate for this by hyperventilating, resulting in the observed lowering of EtCO2. Since lactate is a predictor of mortality in sepsis,50 and monitoring lactate clearance to evaluate resuscitation efforts in sepsis is recommended,51 EtCO2 could play a similar role. One group in particular has demonstrated that, when used with SIRS criteria, abnormally low prehospital EtCO2 levels is predictive of sepsis and inhospital mortality, and is more predictive than SIRS criteria alone.48,50 That said, EtCO2 was not associated with lactate temporally at 3 and 6 hours,51 so it should not be used to guide resuscitation like a lactate clearance. It appears that EtCO2 may be helpful for triage in sepsis, but more study is needed to determine the exact role particularly given most of the available research involves multiple studies from one group.47,48,52

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Initial bicarbonate levels and venous pH are associated with low EtCO2 readings in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).54,55 This could have many practical uses, in particular for patients presenting with hyperglycemia to rule out DKA. One study demonstrated that a blood glucose >250 mg/dL and capnography of >24.5 mm Hg had 90% sensitivity for excluding DKA.55 A value of 35 mm Hg or greater demonstrated 100% sensitivity for excluding DKA in patients with initial glucose >550 mg/dL,56 though this blood glucose is not practical, as this excludes many patients the EP would seek to rule out DKA (recall that blood glucose only has to be >250 mg/dL for the diagnosis). Smaller studies focused on the pediatric population found a 100% sensitivity marker for DKA varied from >30 to >36 mm Hg.57,58 Clearly a role exists, but no study has demonstrated sufficient sensitivity for ruling out DKA with EtCO2 and blood glucose alone within the framework of clinically relevant values.

Trauma

As described above, low EtCO2 is inversely correlated with lactate.46 Because of this, it could theoretically be a marker of hypoperfusion in trauma. Initial EtCO2 values <25 mm Hg have been associated with mortality and hemorrhage in intubated trauma patients,59 as well as mortality prior to discharge in nonintubated trauma patients.60 However, it did not demonstrate added clinical utility when combined with Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, systolic blood pressure, and age in predicting severe injury.61

Pulmonary Embolism

A pulmonary embolism (PE) causes a blockage in blood flow to alveoli, which results in a decrease in CO2 transportation to the alveoli and thus lower EtCO2, while also widening the gradient between PaCO2 and EtCO2.37 Because of this, it has a theoretical role in the diagnosis of PE, though numerous studies have demonstrated that EtCO2 alone is not sensitive nor specific enough for this role.62-66 In a recent meta-analysis, a pretest probability of 10% could lead to a posttest probability of 3% using capnography.62 While further study is needed before recommendation, this indicates that capnography could obviate the need for imaging in low to intermediate risk patients either after a positive D-Dimer or instead of obtaining a D-dimer.62-64

Triage