User login

How to address reviewer criticism

Authors of manuscripts typically receive one of three responses from journals: 1. Accepted as submitted; 2. Accepted pending revisions (major or minor); and 3. Rejected. Receiving an unconditional acceptance is an unusual fate worth documenting and celebrating. On the other hand, irreversible rejections are so common that authors need to get accustomed to them. Upon receiving an unqualified editorial rejection without a formal review (usually described as priority-related rejection), send the same manuscript out the next day to another journal (with electronic submissions you can do this on the same day).

If your manuscript is rejected after being reviewed, consider seriously the comments given and try to learn from them. Was your study design flawed? Do you need additional data? Were your analyses incomplete or did you employ suboptimal statistical methods? Was your interpretation of the findings far reaching and out of proportion to the actual data? Use this experience and feedback, revise your manuscript, and submit it to a different journal. It is not uncommon to encounter the same reviewer at the next journal; fixing major issues seems responsive and gets you in the door.

To receive a “conditional acceptance” or “rejection with hope” is the most likely “good” editorial response. Avoid a very quick response, because it may be hasty or create an impression of a hasty response. Because most manuscripts with substantial reviews are sent back to the reviewers, the turnaround time in most journals is several weeks and, therefore, there is little to be gained by sending the revised manuscript in 1 day rather than 1 week. The best course of action is to cool down for 1-2 days and then decide and draft responses in 1 week, including planned additional analyses. In the case of seemingly contradictory or numerous requests from reviewers, it is best to carefully examine clues from the editors or associate editors as to the nature and extent of the revision needed. In most instances, we draft the response letter before revising the manuscript. We use the draft letter to obtain specific input from other authors and ‘brainstorm’ about additional analyses that can best address reviewers concerns.

Do the best that you can to fully address all reviewers’ comments. Adequate time should be spent making real changes, including adding additional data or analyses to the manuscript, and taking utmost care in describing and highlighting these changes. If you believe that the reviewers missed a point that was already included in the paper, then point this out as politely as possible as part of the response letter (see below).

In addition to revising your manuscript, you will be asked to prepare a point-by-point response to each of the reviewers’ comments you receive. Thank the editors and reviewers sincerely for their comments and explain how changes based on the comments have made the paper better; they did spend time reviewing your manuscript, and they have not rejected it yet. Reviewers are usually recognized experts, or their apprentices, in the content or method of research employed in your paper. Reviewers are also likely to be authors on papers cited in your manuscript. Avoid unnecessary arguments when possible, especially about noncore issues or about changes that you already conceded. If you are compelled to contest any of the reviewers’ comments, provide substantial evidence that supports your position and be respectful with your responses. Address each comment separately, beginning with the comments raised by the editors followed by those from reviewer one, two, and so on. After each response, clearly point the reviewers and the editors to the revised sections in the manuscript. In case of similar comments, it is acceptable to direct the second (or the third) reviewer to your previous response. Provide new tables, figures, data elements, and references as part of the response letter to make it a stand-alone document. It can be difficult (and annoying) if the reviewer has to flip back and forth between documents to understand the full story.

Appealing editorial decisions consumes a lot of energy, annoys editors and reviewers, and is generally futile. If it is needed, then write a polite, brief appeal letter that summarizes the reasons for the appeal. The most common editorial response to an appeal, which usually follows a several-week delay, is an equally polite affirmation of the original decision. The second and arguably worse outcome is for the manuscript to be sent to two to three new reviewers with another rejection after a several-month delay.

Have colleagues read and comment on your revised paper and use these comments to improve the draft. There is evidence that writing groups are effective in providing suggestions for improving papers: A writing group also keeps the momentum going during the revision process. Setting realistic time lines with the coauthors of the paper is a useful strategy to maintain momentum during revisions.

Writing (and revising) papers can be a highly rewarding activity. Start early, plan carefully, and do not delay the process. Reviewers’ comments are mostly geared toward enhancing the manuscript. Take them seriously, address them fully, and you will have an improved (and we hope, an accepted) manuscript.

Additional reading

El-Serag HB. Writing and publishing scientific papers. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb;142(2):197-200. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.021. Epub 2011 Dec 16.

Downey SMet al. Manuscript development and publishing: A 5-step approach. Am J Med Sci. 2017 Feb;353(2):132-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.12.005. Epub 2016 Dec 9.

Sullivan GM. What to do when your paper is rejected. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:1-3. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00686.1

Kotz Det al. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part XII: responding to reviewers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:243. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.003. Epub 2014 Jan 9.

Dr. El-Serag is chairman of the Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; incoming president of the American Gastroenterological Association Institute; and past Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine and chief of the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Houston, and Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. This material is based on work supported by Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant (RP150587). The work is also supported in part by the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Authors of manuscripts typically receive one of three responses from journals: 1. Accepted as submitted; 2. Accepted pending revisions (major or minor); and 3. Rejected. Receiving an unconditional acceptance is an unusual fate worth documenting and celebrating. On the other hand, irreversible rejections are so common that authors need to get accustomed to them. Upon receiving an unqualified editorial rejection without a formal review (usually described as priority-related rejection), send the same manuscript out the next day to another journal (with electronic submissions you can do this on the same day).

If your manuscript is rejected after being reviewed, consider seriously the comments given and try to learn from them. Was your study design flawed? Do you need additional data? Were your analyses incomplete or did you employ suboptimal statistical methods? Was your interpretation of the findings far reaching and out of proportion to the actual data? Use this experience and feedback, revise your manuscript, and submit it to a different journal. It is not uncommon to encounter the same reviewer at the next journal; fixing major issues seems responsive and gets you in the door.

To receive a “conditional acceptance” or “rejection with hope” is the most likely “good” editorial response. Avoid a very quick response, because it may be hasty or create an impression of a hasty response. Because most manuscripts with substantial reviews are sent back to the reviewers, the turnaround time in most journals is several weeks and, therefore, there is little to be gained by sending the revised manuscript in 1 day rather than 1 week. The best course of action is to cool down for 1-2 days and then decide and draft responses in 1 week, including planned additional analyses. In the case of seemingly contradictory or numerous requests from reviewers, it is best to carefully examine clues from the editors or associate editors as to the nature and extent of the revision needed. In most instances, we draft the response letter before revising the manuscript. We use the draft letter to obtain specific input from other authors and ‘brainstorm’ about additional analyses that can best address reviewers concerns.

Do the best that you can to fully address all reviewers’ comments. Adequate time should be spent making real changes, including adding additional data or analyses to the manuscript, and taking utmost care in describing and highlighting these changes. If you believe that the reviewers missed a point that was already included in the paper, then point this out as politely as possible as part of the response letter (see below).

In addition to revising your manuscript, you will be asked to prepare a point-by-point response to each of the reviewers’ comments you receive. Thank the editors and reviewers sincerely for their comments and explain how changes based on the comments have made the paper better; they did spend time reviewing your manuscript, and they have not rejected it yet. Reviewers are usually recognized experts, or their apprentices, in the content or method of research employed in your paper. Reviewers are also likely to be authors on papers cited in your manuscript. Avoid unnecessary arguments when possible, especially about noncore issues or about changes that you already conceded. If you are compelled to contest any of the reviewers’ comments, provide substantial evidence that supports your position and be respectful with your responses. Address each comment separately, beginning with the comments raised by the editors followed by those from reviewer one, two, and so on. After each response, clearly point the reviewers and the editors to the revised sections in the manuscript. In case of similar comments, it is acceptable to direct the second (or the third) reviewer to your previous response. Provide new tables, figures, data elements, and references as part of the response letter to make it a stand-alone document. It can be difficult (and annoying) if the reviewer has to flip back and forth between documents to understand the full story.

Appealing editorial decisions consumes a lot of energy, annoys editors and reviewers, and is generally futile. If it is needed, then write a polite, brief appeal letter that summarizes the reasons for the appeal. The most common editorial response to an appeal, which usually follows a several-week delay, is an equally polite affirmation of the original decision. The second and arguably worse outcome is for the manuscript to be sent to two to three new reviewers with another rejection after a several-month delay.

Have colleagues read and comment on your revised paper and use these comments to improve the draft. There is evidence that writing groups are effective in providing suggestions for improving papers: A writing group also keeps the momentum going during the revision process. Setting realistic time lines with the coauthors of the paper is a useful strategy to maintain momentum during revisions.

Writing (and revising) papers can be a highly rewarding activity. Start early, plan carefully, and do not delay the process. Reviewers’ comments are mostly geared toward enhancing the manuscript. Take them seriously, address them fully, and you will have an improved (and we hope, an accepted) manuscript.

Additional reading

El-Serag HB. Writing and publishing scientific papers. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb;142(2):197-200. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.021. Epub 2011 Dec 16.

Downey SMet al. Manuscript development and publishing: A 5-step approach. Am J Med Sci. 2017 Feb;353(2):132-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.12.005. Epub 2016 Dec 9.

Sullivan GM. What to do when your paper is rejected. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:1-3. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00686.1

Kotz Det al. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part XII: responding to reviewers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:243. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.003. Epub 2014 Jan 9.

Dr. El-Serag is chairman of the Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; incoming president of the American Gastroenterological Association Institute; and past Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine and chief of the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Houston, and Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. This material is based on work supported by Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant (RP150587). The work is also supported in part by the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Authors of manuscripts typically receive one of three responses from journals: 1. Accepted as submitted; 2. Accepted pending revisions (major or minor); and 3. Rejected. Receiving an unconditional acceptance is an unusual fate worth documenting and celebrating. On the other hand, irreversible rejections are so common that authors need to get accustomed to them. Upon receiving an unqualified editorial rejection without a formal review (usually described as priority-related rejection), send the same manuscript out the next day to another journal (with electronic submissions you can do this on the same day).

If your manuscript is rejected after being reviewed, consider seriously the comments given and try to learn from them. Was your study design flawed? Do you need additional data? Were your analyses incomplete or did you employ suboptimal statistical methods? Was your interpretation of the findings far reaching and out of proportion to the actual data? Use this experience and feedback, revise your manuscript, and submit it to a different journal. It is not uncommon to encounter the same reviewer at the next journal; fixing major issues seems responsive and gets you in the door.

To receive a “conditional acceptance” or “rejection with hope” is the most likely “good” editorial response. Avoid a very quick response, because it may be hasty or create an impression of a hasty response. Because most manuscripts with substantial reviews are sent back to the reviewers, the turnaround time in most journals is several weeks and, therefore, there is little to be gained by sending the revised manuscript in 1 day rather than 1 week. The best course of action is to cool down for 1-2 days and then decide and draft responses in 1 week, including planned additional analyses. In the case of seemingly contradictory or numerous requests from reviewers, it is best to carefully examine clues from the editors or associate editors as to the nature and extent of the revision needed. In most instances, we draft the response letter before revising the manuscript. We use the draft letter to obtain specific input from other authors and ‘brainstorm’ about additional analyses that can best address reviewers concerns.

Do the best that you can to fully address all reviewers’ comments. Adequate time should be spent making real changes, including adding additional data or analyses to the manuscript, and taking utmost care in describing and highlighting these changes. If you believe that the reviewers missed a point that was already included in the paper, then point this out as politely as possible as part of the response letter (see below).

In addition to revising your manuscript, you will be asked to prepare a point-by-point response to each of the reviewers’ comments you receive. Thank the editors and reviewers sincerely for their comments and explain how changes based on the comments have made the paper better; they did spend time reviewing your manuscript, and they have not rejected it yet. Reviewers are usually recognized experts, or their apprentices, in the content or method of research employed in your paper. Reviewers are also likely to be authors on papers cited in your manuscript. Avoid unnecessary arguments when possible, especially about noncore issues or about changes that you already conceded. If you are compelled to contest any of the reviewers’ comments, provide substantial evidence that supports your position and be respectful with your responses. Address each comment separately, beginning with the comments raised by the editors followed by those from reviewer one, two, and so on. After each response, clearly point the reviewers and the editors to the revised sections in the manuscript. In case of similar comments, it is acceptable to direct the second (or the third) reviewer to your previous response. Provide new tables, figures, data elements, and references as part of the response letter to make it a stand-alone document. It can be difficult (and annoying) if the reviewer has to flip back and forth between documents to understand the full story.

Appealing editorial decisions consumes a lot of energy, annoys editors and reviewers, and is generally futile. If it is needed, then write a polite, brief appeal letter that summarizes the reasons for the appeal. The most common editorial response to an appeal, which usually follows a several-week delay, is an equally polite affirmation of the original decision. The second and arguably worse outcome is for the manuscript to be sent to two to three new reviewers with another rejection after a several-month delay.

Have colleagues read and comment on your revised paper and use these comments to improve the draft. There is evidence that writing groups are effective in providing suggestions for improving papers: A writing group also keeps the momentum going during the revision process. Setting realistic time lines with the coauthors of the paper is a useful strategy to maintain momentum during revisions.

Writing (and revising) papers can be a highly rewarding activity. Start early, plan carefully, and do not delay the process. Reviewers’ comments are mostly geared toward enhancing the manuscript. Take them seriously, address them fully, and you will have an improved (and we hope, an accepted) manuscript.

Additional reading

El-Serag HB. Writing and publishing scientific papers. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb;142(2):197-200. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.021. Epub 2011 Dec 16.

Downey SMet al. Manuscript development and publishing: A 5-step approach. Am J Med Sci. 2017 Feb;353(2):132-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.12.005. Epub 2016 Dec 9.

Sullivan GM. What to do when your paper is rejected. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:1-3. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00686.1

Kotz Det al. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part XII: responding to reviewers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:243. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.003. Epub 2014 Jan 9.

Dr. El-Serag is chairman of the Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; incoming president of the American Gastroenterological Association Institute; and past Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine and chief of the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Houston, and Editor in Chief, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. This material is based on work supported by Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas grant (RP150587). The work is also supported in part by the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Glucocorticoids plus tofacitinib may boost herpes zoster risk

Concomitant use of glucocorticoids with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis may double the risk of herpes zoster, but methotrexate does not appear to increase the risk, outcomes from a cohort study of 8,030 rheumatoid arthritis patients – including 222 cases of herpes zoster – suggest.

Using information from Medicare and MarketScan, researchers found that dual therapy with tofacitinib and glucocorticoids was associated with a 96% increase in the risk of herpes zoster, compared with monotherapy with the Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib (95% confidence interval, 33%-188%). The crude incidence rate in those taking concomitant tofacitinib and glucocorticoids was 6 cases per 100 patient-years, compared with an incidence rate of 3.4 cases per 100 patient-years with tofacitinib monotherapy.

However, the addition of methotrexate therapy to tofacitinib was not associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster, and the incidence rate in patients on this dual therapy was 3.7 cases per 100 patient-years, Jeffrey R. Curtis, MD, MS, MPH, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his coauthors reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

Women – who constituted 80% of the study population – showed a significantly increased risk of herpes zoster, as did older patients.

The study also found that individuals who had received the live herpes zoster vaccine showed a trend toward a decrease in risk.

“We saw a strong trend for decreased risk related to vaccination with the live agent (Zostavax); the concern with this form of vaccination is that any live vaccination is potentially dangerous in patients receiving potent immunosuppression,” Dr. Curtis and his associates wrote.

“The risks for disease flare, and potentially problematic tolerability related to a relatively high incidence of grade 3 (severe) systemic reactogenicity, may limit enthusiasm until specific data in an RA population is available,” they wrote. However, they noted that a randomized, controlled trial of the live virus vaccine was underway in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were being treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and suggested that vaccination should be considered in at-risk patients who didn’t have contraindications.

The authors noted that the effect of glucocorticoid exposure on herpes zoster risk in patients taking tofacitinib was similar to that seen in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or biologic therapies.

The study was partly funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Two authors declared research grants and other funding from the pharmaceutical industry, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Curtis J et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Oct 8. doi: 10.1002/acr.23769.

Concomitant use of glucocorticoids with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis may double the risk of herpes zoster, but methotrexate does not appear to increase the risk, outcomes from a cohort study of 8,030 rheumatoid arthritis patients – including 222 cases of herpes zoster – suggest.

Using information from Medicare and MarketScan, researchers found that dual therapy with tofacitinib and glucocorticoids was associated with a 96% increase in the risk of herpes zoster, compared with monotherapy with the Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib (95% confidence interval, 33%-188%). The crude incidence rate in those taking concomitant tofacitinib and glucocorticoids was 6 cases per 100 patient-years, compared with an incidence rate of 3.4 cases per 100 patient-years with tofacitinib monotherapy.

However, the addition of methotrexate therapy to tofacitinib was not associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster, and the incidence rate in patients on this dual therapy was 3.7 cases per 100 patient-years, Jeffrey R. Curtis, MD, MS, MPH, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his coauthors reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

Women – who constituted 80% of the study population – showed a significantly increased risk of herpes zoster, as did older patients.

The study also found that individuals who had received the live herpes zoster vaccine showed a trend toward a decrease in risk.

“We saw a strong trend for decreased risk related to vaccination with the live agent (Zostavax); the concern with this form of vaccination is that any live vaccination is potentially dangerous in patients receiving potent immunosuppression,” Dr. Curtis and his associates wrote.

“The risks for disease flare, and potentially problematic tolerability related to a relatively high incidence of grade 3 (severe) systemic reactogenicity, may limit enthusiasm until specific data in an RA population is available,” they wrote. However, they noted that a randomized, controlled trial of the live virus vaccine was underway in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were being treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and suggested that vaccination should be considered in at-risk patients who didn’t have contraindications.

The authors noted that the effect of glucocorticoid exposure on herpes zoster risk in patients taking tofacitinib was similar to that seen in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or biologic therapies.

The study was partly funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Two authors declared research grants and other funding from the pharmaceutical industry, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Curtis J et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Oct 8. doi: 10.1002/acr.23769.

Concomitant use of glucocorticoids with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis may double the risk of herpes zoster, but methotrexate does not appear to increase the risk, outcomes from a cohort study of 8,030 rheumatoid arthritis patients – including 222 cases of herpes zoster – suggest.

Using information from Medicare and MarketScan, researchers found that dual therapy with tofacitinib and glucocorticoids was associated with a 96% increase in the risk of herpes zoster, compared with monotherapy with the Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib (95% confidence interval, 33%-188%). The crude incidence rate in those taking concomitant tofacitinib and glucocorticoids was 6 cases per 100 patient-years, compared with an incidence rate of 3.4 cases per 100 patient-years with tofacitinib monotherapy.

However, the addition of methotrexate therapy to tofacitinib was not associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster, and the incidence rate in patients on this dual therapy was 3.7 cases per 100 patient-years, Jeffrey R. Curtis, MD, MS, MPH, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his coauthors reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

Women – who constituted 80% of the study population – showed a significantly increased risk of herpes zoster, as did older patients.

The study also found that individuals who had received the live herpes zoster vaccine showed a trend toward a decrease in risk.

“We saw a strong trend for decreased risk related to vaccination with the live agent (Zostavax); the concern with this form of vaccination is that any live vaccination is potentially dangerous in patients receiving potent immunosuppression,” Dr. Curtis and his associates wrote.

“The risks for disease flare, and potentially problematic tolerability related to a relatively high incidence of grade 3 (severe) systemic reactogenicity, may limit enthusiasm until specific data in an RA population is available,” they wrote. However, they noted that a randomized, controlled trial of the live virus vaccine was underway in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were being treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and suggested that vaccination should be considered in at-risk patients who didn’t have contraindications.

The authors noted that the effect of glucocorticoid exposure on herpes zoster risk in patients taking tofacitinib was similar to that seen in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or biologic therapies.

The study was partly funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Two authors declared research grants and other funding from the pharmaceutical industry, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Curtis J et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Oct 8. doi: 10.1002/acr.23769.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Patients treated with concomitant glucocorticoids and tofacitinib showed increased risk of herpes zoster.

Major finding: Concomitant use of glucocorticoids and tofacitinib is associated with nearly twofold increase in the risk of herpes zoster.

Study details: Cohort study using data from 8,030 rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Disclosures: The study was partly funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Two authors declared research grants and other funding from the pharmaceutical industry, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Curtis J et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Oct 8. doi: 10.1002/acr.23769.

Solitary Exophytic Plaque on the Left Groin

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

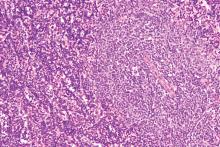

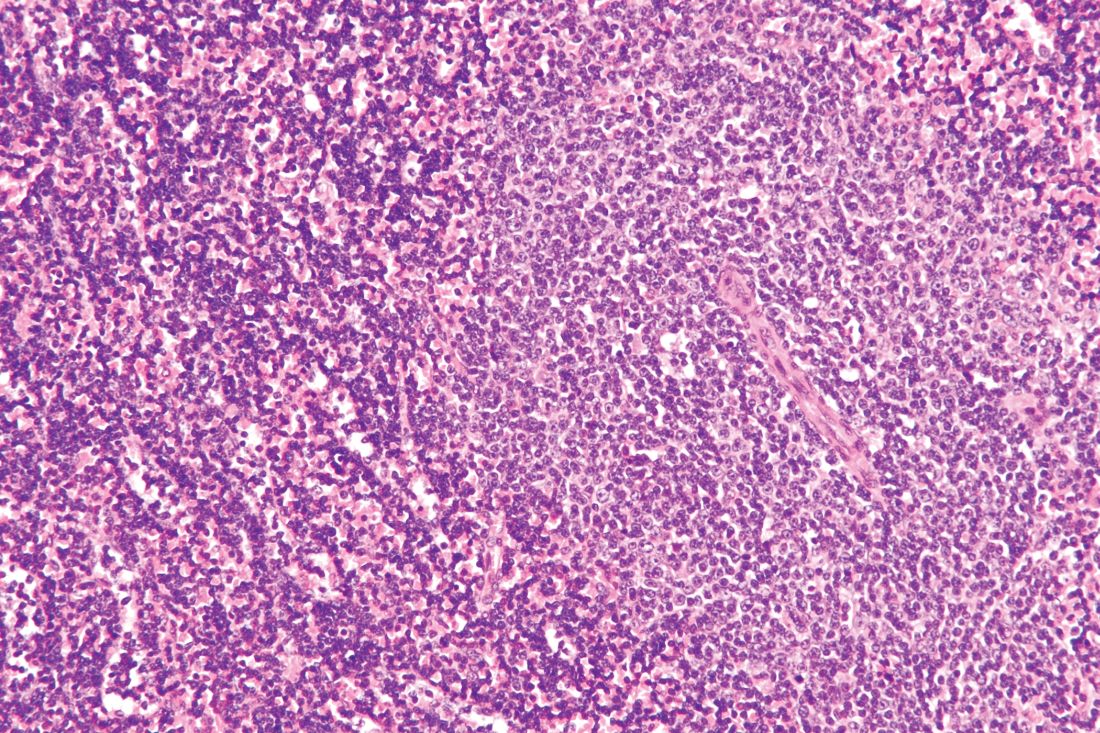

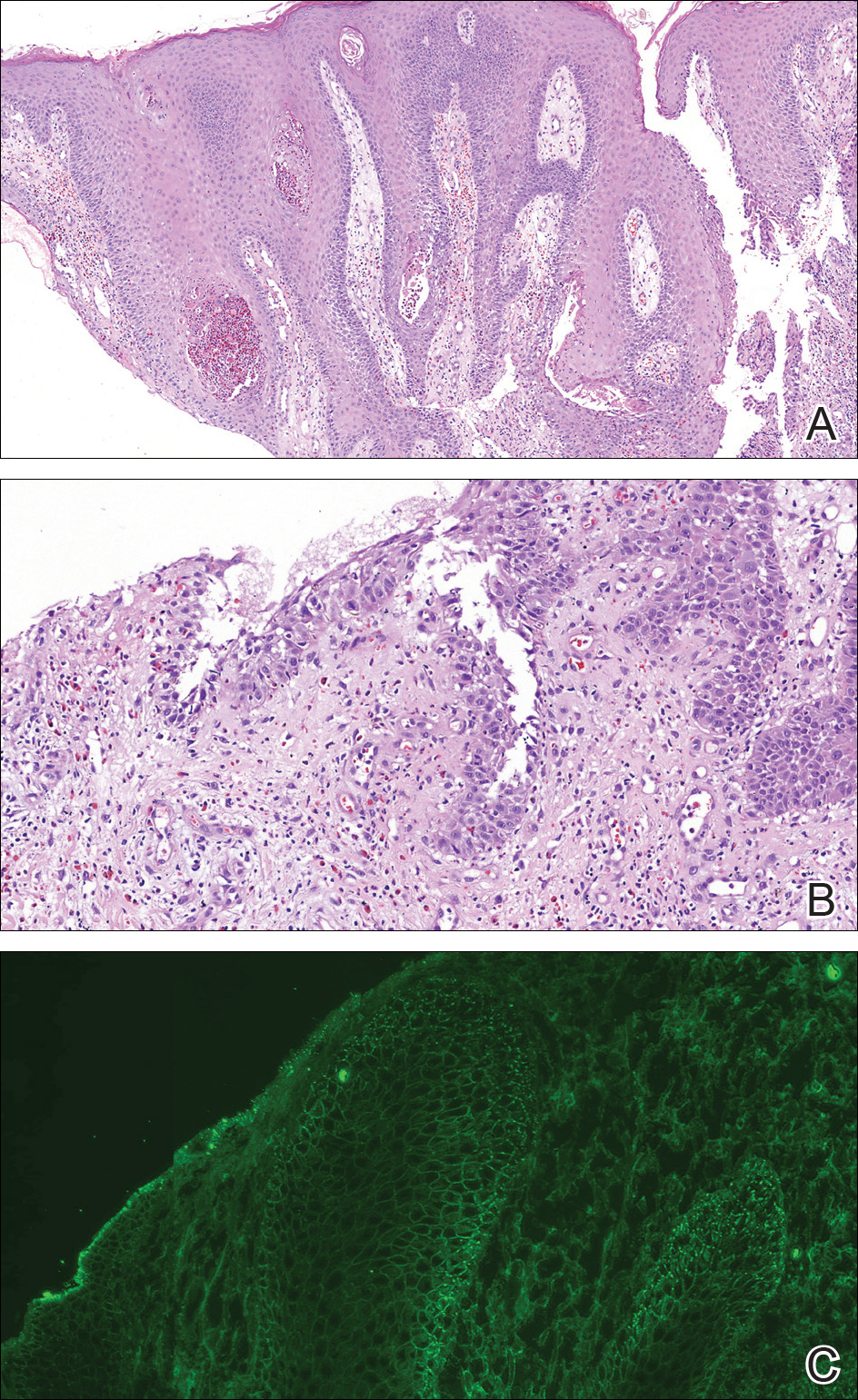

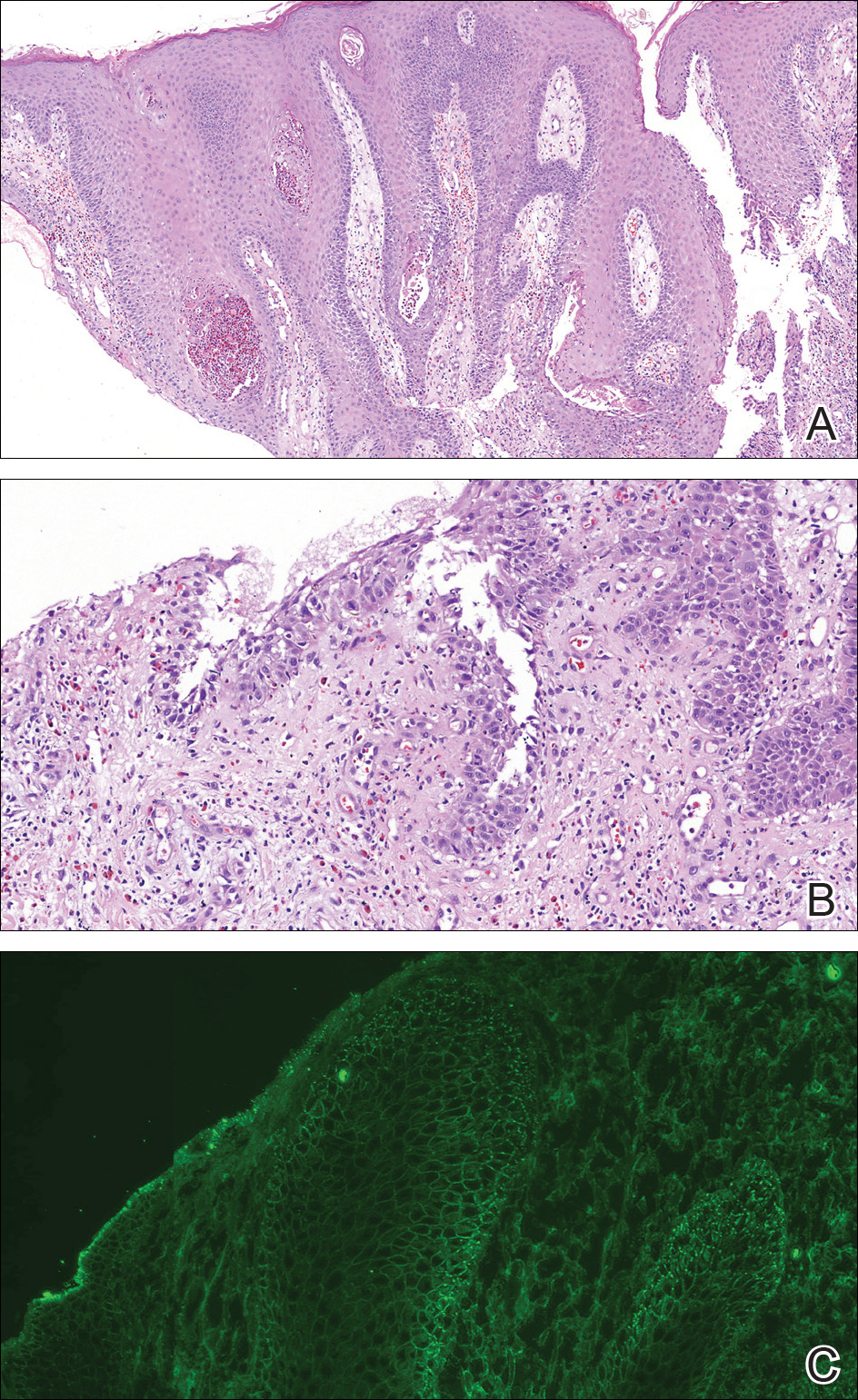

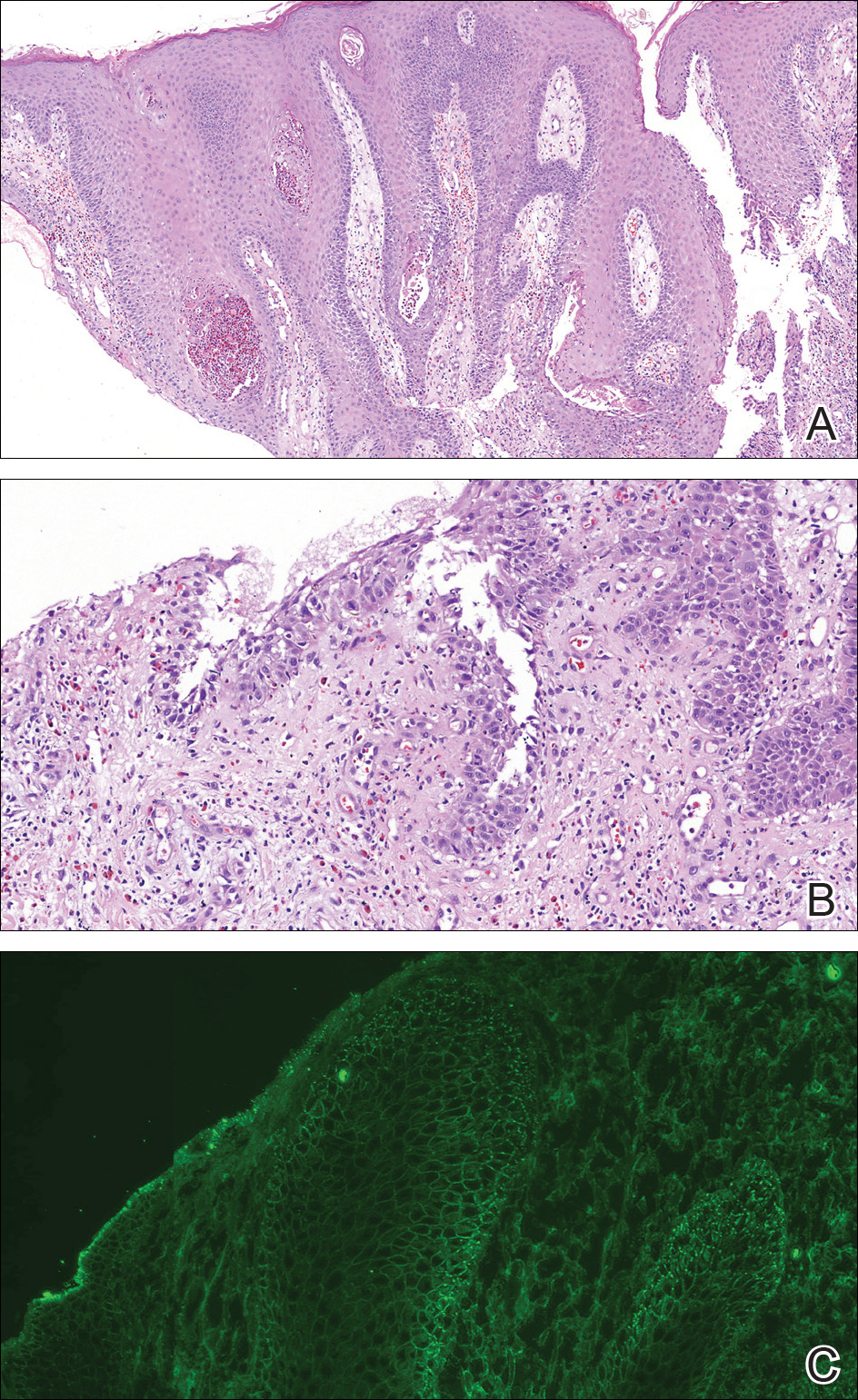

A punch biopsy was taken from the verrucous plaque, and microscopic examination demonstrated prominent epidermal hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses and a superficial dermatitis with abundant eosinophils (Figure 1A). Suprabasal acantholytic cleft formation was noted in a focal area (Figure 1B). Another punch biopsy was performed from the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination, which revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and C3 throughout the lower half of the epidermis (Figure 1C). Indirect immunofluorescence performed on monkey esophagus substrate showed circulating intercellular IgG antibodies in all the titers of up to 1/160 and an elevated level of IgG antidesmoglein 3 (anti-Dsg3) antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index value, >200 RU/mL [reference range, <20 RU/mL]).

Because there was a solitary lesion, the decision was made to perform local treatment. One intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection (20 mg/mL) resulted in remarkable flattening of the lesion (Figure 2). Subsequently, treatment was continued with clobetasol propionate ointment 3 times weekly for 1 month. During a follow-up period of 2 years, no signs of local relapse or new lesions elsewhere were noted, and the patient continued to be on long-term longitudinal evaluation.

Pemphigus vegetans (PV) is an uncommon variant of pemphigus, typically manifesting with vegetating erosions and plaques localized to the intertriginous areas of the body. Local factors such as semiocclusion, maceration, and/or bacterial or fungal colonization have been hypothesized to account for the distinctive localization and vegetation of the lesions.1,2 Traditionally, 2 clinical subtypes of PV have been described: (1) Hallopeau type presenting with pustules that later evolve into vegetating plaques, and (2) Neumann type that initially manifests as vesicles and bullae with a more disseminated distribution, transforming into hypertrophic masses with erosions.1-5 However, this distinction may not always be clear, and patients with features of both forms have been reported.2,5

At present, our case would best be regarded as a localized form of PV presenting with a solitary lesion. It may progress to more disseminated disease or remain localized during its course; the literature contains reports exemplifying both possibilities. In a large retrospective study from Tunisia encompassing almost 3 decades, the majority of the patients initially presented with unifocal involvement; however, the disease eventually became multifocal in almost all patients during the study period, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up.2 There also are reports of PV confined to a single anatomic site, such as the scalp, sole, or vulva, that remained localized for years.2,4,6,7 Involvement of the oral mucosa is an important finding of PV and the presenting concern in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 Interestingly, the oral mucosa was not involved in our patient despite the high titer of anti-Dsg3 antibody, which suggests the need for the presence of other factors for clinical expression of the disease.

Although PV is considered a vegetating clinicomorphologic variant of pemphigus vulgaris, PV is histopathologically distinguished from pemphigus vulgaris by the presence of epidermal hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses. Importantly, the epidermis displays signs of exuberant proliferation such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and/or papillomatosis of a varying degree.1,2,5 Of note, suprabasal acantholysis is usually overshadowed by the changes in PV and presents only focally, as in our patient. The most common autoantibody profile is IgG targeting Dsg3; however, a spectrum of other autoantibodies has been identified, such as IgG antidesmocollin 3, IgA anti-Dsg3, and IgG anti-Dsg1.8,9

The most important differential diagnosis of PV is pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. These 2 entities share many clinical and histopathological features; however, direct immunofluorescence is helpfulfor differentiation because it generally is negative in pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.2,10 Furthermore, there is a well-established association between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and inflammatory bowel disorders, whereas PV has anecdotally been linked to malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and heroin abuse.1,2,10 Our patient was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus and denied weight loss or loss of appetite. For those cases of PV involving a single anatomic site, the differential diagnosis is broader and encompasses dermatoses such as verrucae, syphilitic chancre, condylomata lata, granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus infection, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Treatment of PV is similar to pemphigus vulgaris and consists of a combination of systemic corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.1,5 On the other hand, more limited presentations of PV may be suitable for intralesional treatment with triamcinolone acetonide, thus avoiding potential adverse effects of systemic therapy.1,2 In our case with localized involvement, a favorable response was obtained with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and we plan to utilize systemic corticosteroids if the disease becomes generalized during follow-up.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Zaraa I, Sellami A, Bouguerra C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans: a clinical, histological, immunopathological and prognostic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1160-1167.

- Madan V, August PJ. Exophytic plaques, blisters, and mouth ulcers. pemphigus vegetans (PV), Neumann type. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:715-720.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Monshi B, Marker M, Feichtinger H, et al. Pemphigus vegetans--immunopathological findings in a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:179-183.

- Jain VK, Dixit VB, Mohan H. Pemphigus vegetans in an unusual site. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:352-353.

- Wong KT, Wong KK. A case of acantholytic dermatosis of the vulva with features of pemphigus vegetans. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:453-456.

- Morizane S, Yamamoto T, Hisamatsu Y, et al. Pemphigus vegetans with IgG and IgA antidesmoglein 3 antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1236-1237.

- Saruta H, Ishii N, Teye K, et al. Two cases of pemphigus vegetans with IgG anti-desmocollin 3 antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1209-1213.

- Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:266-269.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

A punch biopsy was taken from the verrucous plaque, and microscopic examination demonstrated prominent epidermal hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses and a superficial dermatitis with abundant eosinophils (Figure 1A). Suprabasal acantholytic cleft formation was noted in a focal area (Figure 1B). Another punch biopsy was performed from the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination, which revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and C3 throughout the lower half of the epidermis (Figure 1C). Indirect immunofluorescence performed on monkey esophagus substrate showed circulating intercellular IgG antibodies in all the titers of up to 1/160 and an elevated level of IgG antidesmoglein 3 (anti-Dsg3) antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index value, >200 RU/mL [reference range, <20 RU/mL]).

Because there was a solitary lesion, the decision was made to perform local treatment. One intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection (20 mg/mL) resulted in remarkable flattening of the lesion (Figure 2). Subsequently, treatment was continued with clobetasol propionate ointment 3 times weekly for 1 month. During a follow-up period of 2 years, no signs of local relapse or new lesions elsewhere were noted, and the patient continued to be on long-term longitudinal evaluation.

Pemphigus vegetans (PV) is an uncommon variant of pemphigus, typically manifesting with vegetating erosions and plaques localized to the intertriginous areas of the body. Local factors such as semiocclusion, maceration, and/or bacterial or fungal colonization have been hypothesized to account for the distinctive localization and vegetation of the lesions.1,2 Traditionally, 2 clinical subtypes of PV have been described: (1) Hallopeau type presenting with pustules that later evolve into vegetating plaques, and (2) Neumann type that initially manifests as vesicles and bullae with a more disseminated distribution, transforming into hypertrophic masses with erosions.1-5 However, this distinction may not always be clear, and patients with features of both forms have been reported.2,5

At present, our case would best be regarded as a localized form of PV presenting with a solitary lesion. It may progress to more disseminated disease or remain localized during its course; the literature contains reports exemplifying both possibilities. In a large retrospective study from Tunisia encompassing almost 3 decades, the majority of the patients initially presented with unifocal involvement; however, the disease eventually became multifocal in almost all patients during the study period, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up.2 There also are reports of PV confined to a single anatomic site, such as the scalp, sole, or vulva, that remained localized for years.2,4,6,7 Involvement of the oral mucosa is an important finding of PV and the presenting concern in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 Interestingly, the oral mucosa was not involved in our patient despite the high titer of anti-Dsg3 antibody, which suggests the need for the presence of other factors for clinical expression of the disease.

Although PV is considered a vegetating clinicomorphologic variant of pemphigus vulgaris, PV is histopathologically distinguished from pemphigus vulgaris by the presence of epidermal hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses. Importantly, the epidermis displays signs of exuberant proliferation such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and/or papillomatosis of a varying degree.1,2,5 Of note, suprabasal acantholysis is usually overshadowed by the changes in PV and presents only focally, as in our patient. The most common autoantibody profile is IgG targeting Dsg3; however, a spectrum of other autoantibodies has been identified, such as IgG antidesmocollin 3, IgA anti-Dsg3, and IgG anti-Dsg1.8,9

The most important differential diagnosis of PV is pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. These 2 entities share many clinical and histopathological features; however, direct immunofluorescence is helpfulfor differentiation because it generally is negative in pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.2,10 Furthermore, there is a well-established association between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and inflammatory bowel disorders, whereas PV has anecdotally been linked to malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and heroin abuse.1,2,10 Our patient was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus and denied weight loss or loss of appetite. For those cases of PV involving a single anatomic site, the differential diagnosis is broader and encompasses dermatoses such as verrucae, syphilitic chancre, condylomata lata, granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus infection, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Treatment of PV is similar to pemphigus vulgaris and consists of a combination of systemic corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.1,5 On the other hand, more limited presentations of PV may be suitable for intralesional treatment with triamcinolone acetonide, thus avoiding potential adverse effects of systemic therapy.1,2 In our case with localized involvement, a favorable response was obtained with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and we plan to utilize systemic corticosteroids if the disease becomes generalized during follow-up.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

A punch biopsy was taken from the verrucous plaque, and microscopic examination demonstrated prominent epidermal hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses and a superficial dermatitis with abundant eosinophils (Figure 1A). Suprabasal acantholytic cleft formation was noted in a focal area (Figure 1B). Another punch biopsy was performed from the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination, which revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and C3 throughout the lower half of the epidermis (Figure 1C). Indirect immunofluorescence performed on monkey esophagus substrate showed circulating intercellular IgG antibodies in all the titers of up to 1/160 and an elevated level of IgG antidesmoglein 3 (anti-Dsg3) antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index value, >200 RU/mL [reference range, <20 RU/mL]).

Because there was a solitary lesion, the decision was made to perform local treatment. One intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection (20 mg/mL) resulted in remarkable flattening of the lesion (Figure 2). Subsequently, treatment was continued with clobetasol propionate ointment 3 times weekly for 1 month. During a follow-up period of 2 years, no signs of local relapse or new lesions elsewhere were noted, and the patient continued to be on long-term longitudinal evaluation.

Pemphigus vegetans (PV) is an uncommon variant of pemphigus, typically manifesting with vegetating erosions and plaques localized to the intertriginous areas of the body. Local factors such as semiocclusion, maceration, and/or bacterial or fungal colonization have been hypothesized to account for the distinctive localization and vegetation of the lesions.1,2 Traditionally, 2 clinical subtypes of PV have been described: (1) Hallopeau type presenting with pustules that later evolve into vegetating plaques, and (2) Neumann type that initially manifests as vesicles and bullae with a more disseminated distribution, transforming into hypertrophic masses with erosions.1-5 However, this distinction may not always be clear, and patients with features of both forms have been reported.2,5

At present, our case would best be regarded as a localized form of PV presenting with a solitary lesion. It may progress to more disseminated disease or remain localized during its course; the literature contains reports exemplifying both possibilities. In a large retrospective study from Tunisia encompassing almost 3 decades, the majority of the patients initially presented with unifocal involvement; however, the disease eventually became multifocal in almost all patients during the study period, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up.2 There also are reports of PV confined to a single anatomic site, such as the scalp, sole, or vulva, that remained localized for years.2,4,6,7 Involvement of the oral mucosa is an important finding of PV and the presenting concern in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 Interestingly, the oral mucosa was not involved in our patient despite the high titer of anti-Dsg3 antibody, which suggests the need for the presence of other factors for clinical expression of the disease.

Although PV is considered a vegetating clinicomorphologic variant of pemphigus vulgaris, PV is histopathologically distinguished from pemphigus vulgaris by the presence of epidermal hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses. Importantly, the epidermis displays signs of exuberant proliferation such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and/or papillomatosis of a varying degree.1,2,5 Of note, suprabasal acantholysis is usually overshadowed by the changes in PV and presents only focally, as in our patient. The most common autoantibody profile is IgG targeting Dsg3; however, a spectrum of other autoantibodies has been identified, such as IgG antidesmocollin 3, IgA anti-Dsg3, and IgG anti-Dsg1.8,9

The most important differential diagnosis of PV is pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. These 2 entities share many clinical and histopathological features; however, direct immunofluorescence is helpfulfor differentiation because it generally is negative in pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.2,10 Furthermore, there is a well-established association between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and inflammatory bowel disorders, whereas PV has anecdotally been linked to malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and heroin abuse.1,2,10 Our patient was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus and denied weight loss or loss of appetite. For those cases of PV involving a single anatomic site, the differential diagnosis is broader and encompasses dermatoses such as verrucae, syphilitic chancre, condylomata lata, granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus infection, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Treatment of PV is similar to pemphigus vulgaris and consists of a combination of systemic corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.1,5 On the other hand, more limited presentations of PV may be suitable for intralesional treatment with triamcinolone acetonide, thus avoiding potential adverse effects of systemic therapy.1,2 In our case with localized involvement, a favorable response was obtained with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and we plan to utilize systemic corticosteroids if the disease becomes generalized during follow-up.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Zaraa I, Sellami A, Bouguerra C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans: a clinical, histological, immunopathological and prognostic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1160-1167.

- Madan V, August PJ. Exophytic plaques, blisters, and mouth ulcers. pemphigus vegetans (PV), Neumann type. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:715-720.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Monshi B, Marker M, Feichtinger H, et al. Pemphigus vegetans--immunopathological findings in a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:179-183.

- Jain VK, Dixit VB, Mohan H. Pemphigus vegetans in an unusual site. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:352-353.

- Wong KT, Wong KK. A case of acantholytic dermatosis of the vulva with features of pemphigus vegetans. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:453-456.

- Morizane S, Yamamoto T, Hisamatsu Y, et al. Pemphigus vegetans with IgG and IgA antidesmoglein 3 antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1236-1237.

- Saruta H, Ishii N, Teye K, et al. Two cases of pemphigus vegetans with IgG anti-desmocollin 3 antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1209-1213.

- Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:266-269.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Zaraa I, Sellami A, Bouguerra C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans: a clinical, histological, immunopathological and prognostic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1160-1167.

- Madan V, August PJ. Exophytic plaques, blisters, and mouth ulcers. pemphigus vegetans (PV), Neumann type. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:715-720.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Monshi B, Marker M, Feichtinger H, et al. Pemphigus vegetans--immunopathological findings in a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:179-183.

- Jain VK, Dixit VB, Mohan H. Pemphigus vegetans in an unusual site. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:352-353.

- Wong KT, Wong KK. A case of acantholytic dermatosis of the vulva with features of pemphigus vegetans. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:453-456.

- Morizane S, Yamamoto T, Hisamatsu Y, et al. Pemphigus vegetans with IgG and IgA antidesmoglein 3 antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1236-1237.

- Saruta H, Ishii N, Teye K, et al. Two cases of pemphigus vegetans with IgG anti-desmocollin 3 antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1209-1213.

- Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:266-269.

A 40-year-old otherwise healthy man presented with an exophytic plaque on the left groin of 1 month's duration. The lesion reportedly emerged as pustules that slowly expanded and coalesced. At an outside institution, cryotherapy was planned for a presumed diagnosis of condyloma acuminatum; however, the patient decided to get a second opinion. He denied recent intake of new drugs. Six months prior he had traveled to China and engaged in unprotected sexual intercourse. Physical examination revealed an approximately 4×2-cm exophytic plaque with a partially eroded and exudative surface on the left inguinal fold. Dermatologic examination, including the oral mucosa, was otherwise normal. Complete blood cell count and sexually transmitted disease panel were unremarkable.

CABG vs PCI, new index enhances cardiac CT, and more

, a new index stretches the prognostic power of cardiac CT, a weight-loss drug cuts new-onset diabetes, and a controversial diet score is validated.

Subscribe to Cardiocast wherever you get your podcasts:

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

, a new index stretches the prognostic power of cardiac CT, a weight-loss drug cuts new-onset diabetes, and a controversial diet score is validated.

Subscribe to Cardiocast wherever you get your podcasts:

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

, a new index stretches the prognostic power of cardiac CT, a weight-loss drug cuts new-onset diabetes, and a controversial diet score is validated.

Subscribe to Cardiocast wherever you get your podcasts:

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Junior faculty guide to preparing a research grant

A wise person once said, “Research is a marathon and not a sprint.” Grant writing is the training for the marathon, and it requires discipline and fortitude to succeed. We are junior faculty members with mentored career development awards who are transitioning to independence. Below, we provide for our junior faculty colleagues some tips that have helped us train for our marathon in research.

Identify great mentors

We all understand that outstanding mentorship is critical to success. With that said, we often struggle to understand what a good mentor is. In regard to grant writing, you need someone who is willing to use red ink. While positive reinforcement may be good for your self-esteem, your mentor needs to be critical so that you can learn how to present the best possible product. In return, you must be an invested mentee who is respectful of the mentor’s time, is prepared for meetings, and responds appropriately to feedback.

Attend workshops

Your home institution and professional societies hold outstanding workshops that provide didactic lessons on both the logistics and mechanics of grant writing and allow you to network with like-minded peers, potential mentors, and staff from the funding organization. One excellent example is the American Gastroenterological Association/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AGA/AASLD) Academic Skills workshop.

Decide on a grant mechanism

There are many different grants available through the government, industry, foundations, and your institution. Each grantor may have a variety of mechanisms from pilot awards to larger multiprovider and institution grants. Deciding which grants to apply for can be more of an art than it is a science. Research the opportunities available to you and develop a long-term plan with your mentors.

Start early and have a plan

An effective grant application is prepared in steps, and every step takes longer than anticipated. About 6 months prior to the deadline, read the instructions and consider using something like a Gantt chart to identify all required sections, special requirements (font, spacing, page limits), and anticipated time of completion. Then, structure a reasonable timeline – and stick to it! Remember to allow ample time for all sections, including the career development plan and research environment. Your institution will probably request the documents early, anywhere from 1 to 2 weeks prior to the deadline so that it can be circulated for institutional signatures. Steady progress wins most races.

Specific aims

There is no grant without a great idea, but not all great ideas are funded. So, the first step is to polish your idea, which must be clearly described on the Specific Aims page, which is a one-page summary that lays the framework for the rest of the grant. For the primary reviewers, it should entice them to read the proposal. For others on the review panel, it may be the only section of your grant that they read. Make sure it is clear and concise. If possible, construct a visually pleasing and easy-to-follow figure that encapsulates your proposal.

Circulate

Ideally, every section of the grant will be circulated but it is critical to have others review the Specific Aims at the very least. Ask not only your mentors and those in the field to critique but also those outside of your area and even your friends and unsuspecting family members; they may not know (or care) about the content but should be able to follow the flow and identify grammatical errors. Remember that everyone is busy, so give ample time for people to review the documents.

Read other proposals

Practice makes perfect. So you can either apply for many grants and make the mistakes yourself or read and review as many proposals as you can to learn from your colleagues’ successes and mistakes. Many institutions, mentors, and colleagues will provide copies of prior applications if you ask. Make sure you know which were successful and try to understand why the others were not successful.

When reading the aims and research strategy, pay close attention to how significance and innovation are detailed. Also, some things like the research environment, which is especially important for career development grants, may be directly applicable to your grant.

Help the reviewer

In general, reviewing grants is a voluntary undertaking. Imagine the reviewer reading your grant at a home filled with screaming children or, alternatively, flying in cramped quarters. Neither situation is stress-free, so put yourself in those positions and decide what you can do to make the reviewer’s job easier.

Use figures and tables to summarize the text, and consider coming back to the figure from your Specific Aims to refer to the specific parts of the proposal. You can decrease reviewer fatigue by using line breaks and fonts to break up sections and highlight important details. This will also be helpful to the reviewers on the panel who were not assigned to your grant and possibly first seeing it during the session.

Learn from rejection

You are either a savant or have not applied for enough grants if you have not received a rejection letter. Often, reviewers provide you with constructive comments, which (after a session of crying in the corner in a fetal position), you can use to improve your grant. Resubmission works!

Apply widely

Identify different possible grants, and work with your mentors on a strategy that allows you to make your idea versatile and package it for various funding mechanisms. Once you have a grant, you can tailor it to other grants as needed. However, remember that quantity does not replace quality, so many poor grants that are not funded will not replace one good one that is funded.

There are multiple approaches to training for the marathon of research, so these tips are not a comprehensive list or mandatory commandments. They have, however, proven invaluable to our mentors and us. Our institutions, societies and government agencies have identified the decline of young scientists and physician-scientists as a major leak in the research pipeline, so there are excellent funding mechanisms that are available to you. Good luck!

We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Weiss, MD, and Sumera Rizvi, MD, for their constructive comments.

Dr. Beyder is with the enteric neuroscience program, a consultant for the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physiology at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Twyman-Saint Victor is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

A wise person once said, “Research is a marathon and not a sprint.” Grant writing is the training for the marathon, and it requires discipline and fortitude to succeed. We are junior faculty members with mentored career development awards who are transitioning to independence. Below, we provide for our junior faculty colleagues some tips that have helped us train for our marathon in research.

Identify great mentors

We all understand that outstanding mentorship is critical to success. With that said, we often struggle to understand what a good mentor is. In regard to grant writing, you need someone who is willing to use red ink. While positive reinforcement may be good for your self-esteem, your mentor needs to be critical so that you can learn how to present the best possible product. In return, you must be an invested mentee who is respectful of the mentor’s time, is prepared for meetings, and responds appropriately to feedback.

Attend workshops

Your home institution and professional societies hold outstanding workshops that provide didactic lessons on both the logistics and mechanics of grant writing and allow you to network with like-minded peers, potential mentors, and staff from the funding organization. One excellent example is the American Gastroenterological Association/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AGA/AASLD) Academic Skills workshop.

Decide on a grant mechanism

There are many different grants available through the government, industry, foundations, and your institution. Each grantor may have a variety of mechanisms from pilot awards to larger multiprovider and institution grants. Deciding which grants to apply for can be more of an art than it is a science. Research the opportunities available to you and develop a long-term plan with your mentors.

Start early and have a plan

An effective grant application is prepared in steps, and every step takes longer than anticipated. About 6 months prior to the deadline, read the instructions and consider using something like a Gantt chart to identify all required sections, special requirements (font, spacing, page limits), and anticipated time of completion. Then, structure a reasonable timeline – and stick to it! Remember to allow ample time for all sections, including the career development plan and research environment. Your institution will probably request the documents early, anywhere from 1 to 2 weeks prior to the deadline so that it can be circulated for institutional signatures. Steady progress wins most races.

Specific aims

There is no grant without a great idea, but not all great ideas are funded. So, the first step is to polish your idea, which must be clearly described on the Specific Aims page, which is a one-page summary that lays the framework for the rest of the grant. For the primary reviewers, it should entice them to read the proposal. For others on the review panel, it may be the only section of your grant that they read. Make sure it is clear and concise. If possible, construct a visually pleasing and easy-to-follow figure that encapsulates your proposal.

Circulate

Ideally, every section of the grant will be circulated but it is critical to have others review the Specific Aims at the very least. Ask not only your mentors and those in the field to critique but also those outside of your area and even your friends and unsuspecting family members; they may not know (or care) about the content but should be able to follow the flow and identify grammatical errors. Remember that everyone is busy, so give ample time for people to review the documents.

Read other proposals

Practice makes perfect. So you can either apply for many grants and make the mistakes yourself or read and review as many proposals as you can to learn from your colleagues’ successes and mistakes. Many institutions, mentors, and colleagues will provide copies of prior applications if you ask. Make sure you know which were successful and try to understand why the others were not successful.

When reading the aims and research strategy, pay close attention to how significance and innovation are detailed. Also, some things like the research environment, which is especially important for career development grants, may be directly applicable to your grant.

Help the reviewer

In general, reviewing grants is a voluntary undertaking. Imagine the reviewer reading your grant at a home filled with screaming children or, alternatively, flying in cramped quarters. Neither situation is stress-free, so put yourself in those positions and decide what you can do to make the reviewer’s job easier.

Use figures and tables to summarize the text, and consider coming back to the figure from your Specific Aims to refer to the specific parts of the proposal. You can decrease reviewer fatigue by using line breaks and fonts to break up sections and highlight important details. This will also be helpful to the reviewers on the panel who were not assigned to your grant and possibly first seeing it during the session.

Learn from rejection

You are either a savant or have not applied for enough grants if you have not received a rejection letter. Often, reviewers provide you with constructive comments, which (after a session of crying in the corner in a fetal position), you can use to improve your grant. Resubmission works!

Apply widely

Identify different possible grants, and work with your mentors on a strategy that allows you to make your idea versatile and package it for various funding mechanisms. Once you have a grant, you can tailor it to other grants as needed. However, remember that quantity does not replace quality, so many poor grants that are not funded will not replace one good one that is funded.

There are multiple approaches to training for the marathon of research, so these tips are not a comprehensive list or mandatory commandments. They have, however, proven invaluable to our mentors and us. Our institutions, societies and government agencies have identified the decline of young scientists and physician-scientists as a major leak in the research pipeline, so there are excellent funding mechanisms that are available to you. Good luck!

We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Weiss, MD, and Sumera Rizvi, MD, for their constructive comments.

Dr. Beyder is with the enteric neuroscience program, a consultant for the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physiology at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Twyman-Saint Victor is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

A wise person once said, “Research is a marathon and not a sprint.” Grant writing is the training for the marathon, and it requires discipline and fortitude to succeed. We are junior faculty members with mentored career development awards who are transitioning to independence. Below, we provide for our junior faculty colleagues some tips that have helped us train for our marathon in research.

Identify great mentors

We all understand that outstanding mentorship is critical to success. With that said, we often struggle to understand what a good mentor is. In regard to grant writing, you need someone who is willing to use red ink. While positive reinforcement may be good for your self-esteem, your mentor needs to be critical so that you can learn how to present the best possible product. In return, you must be an invested mentee who is respectful of the mentor’s time, is prepared for meetings, and responds appropriately to feedback.

Attend workshops

Your home institution and professional societies hold outstanding workshops that provide didactic lessons on both the logistics and mechanics of grant writing and allow you to network with like-minded peers, potential mentors, and staff from the funding organization. One excellent example is the American Gastroenterological Association/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AGA/AASLD) Academic Skills workshop.

Decide on a grant mechanism

There are many different grants available through the government, industry, foundations, and your institution. Each grantor may have a variety of mechanisms from pilot awards to larger multiprovider and institution grants. Deciding which grants to apply for can be more of an art than it is a science. Research the opportunities available to you and develop a long-term plan with your mentors.

Start early and have a plan

An effective grant application is prepared in steps, and every step takes longer than anticipated. About 6 months prior to the deadline, read the instructions and consider using something like a Gantt chart to identify all required sections, special requirements (font, spacing, page limits), and anticipated time of completion. Then, structure a reasonable timeline – and stick to it! Remember to allow ample time for all sections, including the career development plan and research environment. Your institution will probably request the documents early, anywhere from 1 to 2 weeks prior to the deadline so that it can be circulated for institutional signatures. Steady progress wins most races.

Specific aims

There is no grant without a great idea, but not all great ideas are funded. So, the first step is to polish your idea, which must be clearly described on the Specific Aims page, which is a one-page summary that lays the framework for the rest of the grant. For the primary reviewers, it should entice them to read the proposal. For others on the review panel, it may be the only section of your grant that they read. Make sure it is clear and concise. If possible, construct a visually pleasing and easy-to-follow figure that encapsulates your proposal.

Circulate

Ideally, every section of the grant will be circulated but it is critical to have others review the Specific Aims at the very least. Ask not only your mentors and those in the field to critique but also those outside of your area and even your friends and unsuspecting family members; they may not know (or care) about the content but should be able to follow the flow and identify grammatical errors. Remember that everyone is busy, so give ample time for people to review the documents.

Read other proposals

Practice makes perfect. So you can either apply for many grants and make the mistakes yourself or read and review as many proposals as you can to learn from your colleagues’ successes and mistakes. Many institutions, mentors, and colleagues will provide copies of prior applications if you ask. Make sure you know which were successful and try to understand why the others were not successful.

When reading the aims and research strategy, pay close attention to how significance and innovation are detailed. Also, some things like the research environment, which is especially important for career development grants, may be directly applicable to your grant.

Help the reviewer

In general, reviewing grants is a voluntary undertaking. Imagine the reviewer reading your grant at a home filled with screaming children or, alternatively, flying in cramped quarters. Neither situation is stress-free, so put yourself in those positions and decide what you can do to make the reviewer’s job easier.

Use figures and tables to summarize the text, and consider coming back to the figure from your Specific Aims to refer to the specific parts of the proposal. You can decrease reviewer fatigue by using line breaks and fonts to break up sections and highlight important details. This will also be helpful to the reviewers on the panel who were not assigned to your grant and possibly first seeing it during the session.

Learn from rejection

You are either a savant or have not applied for enough grants if you have not received a rejection letter. Often, reviewers provide you with constructive comments, which (after a session of crying in the corner in a fetal position), you can use to improve your grant. Resubmission works!

Apply widely

Identify different possible grants, and work with your mentors on a strategy that allows you to make your idea versatile and package it for various funding mechanisms. Once you have a grant, you can tailor it to other grants as needed. However, remember that quantity does not replace quality, so many poor grants that are not funded will not replace one good one that is funded.

There are multiple approaches to training for the marathon of research, so these tips are not a comprehensive list or mandatory commandments. They have, however, proven invaluable to our mentors and us. Our institutions, societies and government agencies have identified the decline of young scientists and physician-scientists as a major leak in the research pipeline, so there are excellent funding mechanisms that are available to you. Good luck!

We would like to acknowledge Jennifer Weiss, MD, and Sumera Rizvi, MD, for their constructive comments.

Dr. Beyder is with the enteric neuroscience program, a consultant for the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physiology at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Twyman-Saint Victor is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Mepolizumab shows efficacy in bronchiectasis with eosinophilia

PARIS – according to a small case series of patients presented as a late-breaking study at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“The message is that it is important to think of all of the etiologies and treatable traits in patients with bronchiectasis, and do not forget eosinophilia, because this can be treated,” reported Jessica Rademacher, MD, of the Clinic for Pulmonology at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

Mepolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin-5, an important signaling protein for eosinophil recruitment, and is approved for use in asthma with eosinophilia. Larger, controlled trials are needed to confirm its efficacy in bronchiectasis, but the clinical improvements after 6 months of treatment in a series of 12 patients at Dr. Rademacher’s center were impressive.

Bronchiectasis patients were selected for treatment with mepolizumab if they had been poorly controlled on conventional therapies and they had an eosinophil count of greater than 300 cells/mm3. Of 328 patients with bronchiectasis that are being followed at Dr. Rademacher’s center, 7% met these criteria. Dr. Rademacher presented data on 12 who had been followed for at least 6 months.

In these patients, the median eosinophil count fell from a median baseline of 1,000 cells/mm3 to 100 cells/mm3 at 6 months (P = .0012). The median annualized rate of exacerbations fell from three per year to one per year, and the median Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale score fell from 2 to 0 (P = .004).

“There was a steroid-sparing effect in all seven patients who were taking oral corticosteroids at baseline. Five stopped oral steroids completely,” Dr. Rademacher reported.

A visual analog scale ranging from 1 to 10 with higher scores representing improvement showed patient-rated quality of life improved from 4 to 6.5 (P = .01). Dr. Rademacher emphasized this outcome because “improved quality of life is really what we are trying to achieve.”

Mepolizumab was well tolerated. In one patient who developed pneumonia, mepolizumab was discontinued, but it was restarted when the infection resolved, because the pneumonia was not considered mepolizumab related.

Although Dr. Rademacher acknowledged the possibility that at least some of the patients in this case series had overlapping asthma, she emphasized that they were selected from a referral population that had a comprehensive workup and that this overlap has been rarely reported.

There is evidence that anti–interleukin-5 therapies such as mepolizumab are effective in respiratory diseases when eosinophilia is present, according to Dr. Rademacher. For example, she cited reports of clinical improvement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and granulomatosis with polyangiitis patients with high eosinophil counts. In bronchiectasis, which has many causes, it may be particularly important to select relevant targets.

“There is an important variability in the presentation of bronchiectasis. Not all these patients have reduced lung function,” she said. Rather, the most significant symptoms for a patient may be sputum or cough. She suggested that the goals are to identify underlying causes of symptoms and which may be treatable.

According to these data, eosinophilia may be one of the treatable causes in a small but significant proportion of patients with bronchiectasis. A trial of mepolizumab may be reasonable in patients inadequately controlled on inhaled anti-inflammatory drugs. “If they do not profit from this therapy, then stop,” she added.

Dr. Rademacher acknowledged that data from this small case series are “not enough to say that [mepolizumab] is an option for these patients,” but she believes the consistency of benefit in this small series will encourage the trials needed to confirm that this approach is safe and effective.

Dr. Rademacher reported no disclosures relevant to the report.

PARIS – according to a small case series of patients presented as a late-breaking study at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“The message is that it is important to think of all of the etiologies and treatable traits in patients with bronchiectasis, and do not forget eosinophilia, because this can be treated,” reported Jessica Rademacher, MD, of the Clinic for Pulmonology at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

Mepolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin-5, an important signaling protein for eosinophil recruitment, and is approved for use in asthma with eosinophilia. Larger, controlled trials are needed to confirm its efficacy in bronchiectasis, but the clinical improvements after 6 months of treatment in a series of 12 patients at Dr. Rademacher’s center were impressive.

Bronchiectasis patients were selected for treatment with mepolizumab if they had been poorly controlled on conventional therapies and they had an eosinophil count of greater than 300 cells/mm3. Of 328 patients with bronchiectasis that are being followed at Dr. Rademacher’s center, 7% met these criteria. Dr. Rademacher presented data on 12 who had been followed for at least 6 months.

In these patients, the median eosinophil count fell from a median baseline of 1,000 cells/mm3 to 100 cells/mm3 at 6 months (P = .0012). The median annualized rate of exacerbations fell from three per year to one per year, and the median Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale score fell from 2 to 0 (P = .004).

“There was a steroid-sparing effect in all seven patients who were taking oral corticosteroids at baseline. Five stopped oral steroids completely,” Dr. Rademacher reported.

A visual analog scale ranging from 1 to 10 with higher scores representing improvement showed patient-rated quality of life improved from 4 to 6.5 (P = .01). Dr. Rademacher emphasized this outcome because “improved quality of life is really what we are trying to achieve.”

Mepolizumab was well tolerated. In one patient who developed pneumonia, mepolizumab was discontinued, but it was restarted when the infection resolved, because the pneumonia was not considered mepolizumab related.

Although Dr. Rademacher acknowledged the possibility that at least some of the patients in this case series had overlapping asthma, she emphasized that they were selected from a referral population that had a comprehensive workup and that this overlap has been rarely reported.

There is evidence that anti–interleukin-5 therapies such as mepolizumab are effective in respiratory diseases when eosinophilia is present, according to Dr. Rademacher. For example, she cited reports of clinical improvement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and granulomatosis with polyangiitis patients with high eosinophil counts. In bronchiectasis, which has many causes, it may be particularly important to select relevant targets.

“There is an important variability in the presentation of bronchiectasis. Not all these patients have reduced lung function,” she said. Rather, the most significant symptoms for a patient may be sputum or cough. She suggested that the goals are to identify underlying causes of symptoms and which may be treatable.