User login

MedPAC eyes ‘incident to’ billing

WASHINGTON – Should Medicare abandon “incident to” billing for advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) and physician assistants (PAs) as part of its move away from fee-for-service payment? Some of the experts on the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission think so.

A proposal presented at a recent MedPAC meeting would eliminate “incident to” billing – a payment policy under which an APRN or PA delivers the care but the claim is filed under a physician’s National Provider Identifier (NPI) and is paid at the Medicare physician fee schedule rate. Instead, APRNs and PAs would file claims under their own NPI and be paid at 85% of the physician fee schedule rate for any claims associated with an episode of care.

About 40% of evaluation and management (E&M) office visits conducted by APRNs on established patients were likely billed “incident to” in 2016, as were about 30% of such visits performed by PAs, MedPAC staff estimated.

“To put these numbers in context, we think that the rates of ‘incident to’ billing for NPs [nurse practitioners] and PAs mean that roughly 5% of all E&M office visits billed by physicians were likely performed by an NP or PA in 2018,” Brian O’Donnell, MedPAC policy analyst, told commissioners.

One reason for eliminating “incident to” billing is that it “obscure[s] the number of services actually furnished by NPs and PAs,” Mr. O’Donnell said. “Given the rapidly expanding number of NPs and PAs, Medicare’s ‘incident to’ rules could apply to an increasing number of services.”

MedPAC commissioner Kathy Buto, former vice president of global health policy at Johnson & Johnson, expressed support for the idea but raised a red flag that the system could be manipulated so that APRN/PA claims could still be paid at 100% of the fee schedule rate.

Commissioner Bruce Pyenson, principal and consulting actuary of Milliman in New York, suggested that APRN and PA claims should be paid at 100% of the fee schedule, mirroring other Medicare efforts to achieve site-neutral payments.

Similarly, commissioner Amy Bricker, vice president of supply chain strategy at Express Scripts, St. Louis, said that while she generally does not favor redistributing program savings, if APRN and PA claims were paid at 85%, the saving generated should go back to physicians who would otherwise lose money.

That change in revenue was a key concern for Michael Munger, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

“We have a policy on ‘incident to’ billing at the academy,” Dr. Munger said in an interview. “It says that services that are delegated to and provided by nonphysician providers under physician supervision must be provided with the same quality and should be reimbursed at the same level as services directly provided by a physician.”

He said that lowering APRNs and PAs payments to 85% of what physicians make would impact doctors in a negative way, but if the elimination of “incident to” came with a recommendation that they be paid the same as physicians, it “would be less problematic.”

Dr. Munger described primary care as a team sport, and “this is certainly going to be felt in terms of the overall mission of delivering quality care.”

Access to care also could be reduced along with the reduced payment level, he added.

“You have to make business decisions at the end of the day,” he said. “You need to make sure that you can have adequate revenue to offset expenses, and if you are going to take a 15% cut in your revenue in, you have to look at where your expenses are, and obviously salary is your No. 1 expense. If you are not able to count on this revenue and you can’t afford to have NPs and PAs as part of the team, it is going to become an access issue for patients.”

Potential access and quality issues also resonated with the American Osteopathic Association.

“You really could see the elimination of the physician element from that practice environment and that would be to the detriment of patients,” David Pugach, AOA senior vice president of public policy, said in an interview. “Right now, you have the ability for incident billing, which requires the active participation of a physician in the management of patient care. If you end that practice, you are essentially removing the physician from the equation, and that really is an access issue; it’s a safety issue; and it’s a quality issue.”

He also noted that sometimes there is overutilization of diagnostic services with APRNs and PAs, and while costs may be saved by paying for those clinicians at less than the rate of physicians, the overutilization of other services by them could end up offsetting the savings.

“We have some significant concerns,” Mr. Pugach said.

The American Academy of Physician Assistants echoed some concerns expressed by MedPAC commissioners and staff.

“What we feel strongly about is the fact that one of the problems of ‘incident to’ is that it hides the practitioners, in this case the PA who actually renders the service,” Michael Powe, AAPA vice president of reimbursement and professional advocacy, said in an interview.

“We think that’s inappropriate for a number of reasons,” he continued. “Clearly from the issue of trying to figure who’s doing what, who saw the patient, what the quality of care happens to be, we think that PAs ought to be recognized ... and not hidden which happens under the ‘incident to’ methodology.”

He said that transparency helps determine where primary care needs are, whether they are being met, and it helps with determining network adequacy.

“So there are a number of good reasons why the accuracy and transparency should be there whether or not ‘incident to’ goes away.”

Jennifer Winter, committee chair for public education for the Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants, agreed.*

Eliminating “incident to” would grant greater visibility of PA practice “because right now, some of what we do is hidden by what the physician does” because it is billed under the physician and you can’t see what the PA is doing, especially if there is an adverse event, said Ms. Winter, who practices in Olympia, Wash. “It confounds trying to collect data on outcomes.”

She also noted that some physicians might not want to hire an NP or PA “because they can hire a physician and get 100%, but they are also going to have to pay that physician at a physician rate.”

Ms. Winter said that PAs and nurse practitioners should be getting 100% of the pay as they are doing essentially the same work that physicians would be doing.

MedPAC staffers also recommended that APRNs and PAs more clearly identify the specialty that they work in, something they do not currently have to do, to allow for more transparency and accurate data on the work that these types of clinicians are performing.

*An earlier version of this story misspelled Ms. Winter's name.

WASHINGTON – Should Medicare abandon “incident to” billing for advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) and physician assistants (PAs) as part of its move away from fee-for-service payment? Some of the experts on the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission think so.

A proposal presented at a recent MedPAC meeting would eliminate “incident to” billing – a payment policy under which an APRN or PA delivers the care but the claim is filed under a physician’s National Provider Identifier (NPI) and is paid at the Medicare physician fee schedule rate. Instead, APRNs and PAs would file claims under their own NPI and be paid at 85% of the physician fee schedule rate for any claims associated with an episode of care.

About 40% of evaluation and management (E&M) office visits conducted by APRNs on established patients were likely billed “incident to” in 2016, as were about 30% of such visits performed by PAs, MedPAC staff estimated.

“To put these numbers in context, we think that the rates of ‘incident to’ billing for NPs [nurse practitioners] and PAs mean that roughly 5% of all E&M office visits billed by physicians were likely performed by an NP or PA in 2018,” Brian O’Donnell, MedPAC policy analyst, told commissioners.

One reason for eliminating “incident to” billing is that it “obscure[s] the number of services actually furnished by NPs and PAs,” Mr. O’Donnell said. “Given the rapidly expanding number of NPs and PAs, Medicare’s ‘incident to’ rules could apply to an increasing number of services.”

MedPAC commissioner Kathy Buto, former vice president of global health policy at Johnson & Johnson, expressed support for the idea but raised a red flag that the system could be manipulated so that APRN/PA claims could still be paid at 100% of the fee schedule rate.

Commissioner Bruce Pyenson, principal and consulting actuary of Milliman in New York, suggested that APRN and PA claims should be paid at 100% of the fee schedule, mirroring other Medicare efforts to achieve site-neutral payments.

Similarly, commissioner Amy Bricker, vice president of supply chain strategy at Express Scripts, St. Louis, said that while she generally does not favor redistributing program savings, if APRN and PA claims were paid at 85%, the saving generated should go back to physicians who would otherwise lose money.

That change in revenue was a key concern for Michael Munger, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

“We have a policy on ‘incident to’ billing at the academy,” Dr. Munger said in an interview. “It says that services that are delegated to and provided by nonphysician providers under physician supervision must be provided with the same quality and should be reimbursed at the same level as services directly provided by a physician.”

He said that lowering APRNs and PAs payments to 85% of what physicians make would impact doctors in a negative way, but if the elimination of “incident to” came with a recommendation that they be paid the same as physicians, it “would be less problematic.”

Dr. Munger described primary care as a team sport, and “this is certainly going to be felt in terms of the overall mission of delivering quality care.”

Access to care also could be reduced along with the reduced payment level, he added.

“You have to make business decisions at the end of the day,” he said. “You need to make sure that you can have adequate revenue to offset expenses, and if you are going to take a 15% cut in your revenue in, you have to look at where your expenses are, and obviously salary is your No. 1 expense. If you are not able to count on this revenue and you can’t afford to have NPs and PAs as part of the team, it is going to become an access issue for patients.”

Potential access and quality issues also resonated with the American Osteopathic Association.

“You really could see the elimination of the physician element from that practice environment and that would be to the detriment of patients,” David Pugach, AOA senior vice president of public policy, said in an interview. “Right now, you have the ability for incident billing, which requires the active participation of a physician in the management of patient care. If you end that practice, you are essentially removing the physician from the equation, and that really is an access issue; it’s a safety issue; and it’s a quality issue.”

He also noted that sometimes there is overutilization of diagnostic services with APRNs and PAs, and while costs may be saved by paying for those clinicians at less than the rate of physicians, the overutilization of other services by them could end up offsetting the savings.

“We have some significant concerns,” Mr. Pugach said.

The American Academy of Physician Assistants echoed some concerns expressed by MedPAC commissioners and staff.

“What we feel strongly about is the fact that one of the problems of ‘incident to’ is that it hides the practitioners, in this case the PA who actually renders the service,” Michael Powe, AAPA vice president of reimbursement and professional advocacy, said in an interview.

“We think that’s inappropriate for a number of reasons,” he continued. “Clearly from the issue of trying to figure who’s doing what, who saw the patient, what the quality of care happens to be, we think that PAs ought to be recognized ... and not hidden which happens under the ‘incident to’ methodology.”

He said that transparency helps determine where primary care needs are, whether they are being met, and it helps with determining network adequacy.

“So there are a number of good reasons why the accuracy and transparency should be there whether or not ‘incident to’ goes away.”

Jennifer Winter, committee chair for public education for the Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants, agreed.*

Eliminating “incident to” would grant greater visibility of PA practice “because right now, some of what we do is hidden by what the physician does” because it is billed under the physician and you can’t see what the PA is doing, especially if there is an adverse event, said Ms. Winter, who practices in Olympia, Wash. “It confounds trying to collect data on outcomes.”

She also noted that some physicians might not want to hire an NP or PA “because they can hire a physician and get 100%, but they are also going to have to pay that physician at a physician rate.”

Ms. Winter said that PAs and nurse practitioners should be getting 100% of the pay as they are doing essentially the same work that physicians would be doing.

MedPAC staffers also recommended that APRNs and PAs more clearly identify the specialty that they work in, something they do not currently have to do, to allow for more transparency and accurate data on the work that these types of clinicians are performing.

*An earlier version of this story misspelled Ms. Winter's name.

WASHINGTON – Should Medicare abandon “incident to” billing for advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) and physician assistants (PAs) as part of its move away from fee-for-service payment? Some of the experts on the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission think so.

A proposal presented at a recent MedPAC meeting would eliminate “incident to” billing – a payment policy under which an APRN or PA delivers the care but the claim is filed under a physician’s National Provider Identifier (NPI) and is paid at the Medicare physician fee schedule rate. Instead, APRNs and PAs would file claims under their own NPI and be paid at 85% of the physician fee schedule rate for any claims associated with an episode of care.

About 40% of evaluation and management (E&M) office visits conducted by APRNs on established patients were likely billed “incident to” in 2016, as were about 30% of such visits performed by PAs, MedPAC staff estimated.

“To put these numbers in context, we think that the rates of ‘incident to’ billing for NPs [nurse practitioners] and PAs mean that roughly 5% of all E&M office visits billed by physicians were likely performed by an NP or PA in 2018,” Brian O’Donnell, MedPAC policy analyst, told commissioners.

One reason for eliminating “incident to” billing is that it “obscure[s] the number of services actually furnished by NPs and PAs,” Mr. O’Donnell said. “Given the rapidly expanding number of NPs and PAs, Medicare’s ‘incident to’ rules could apply to an increasing number of services.”

MedPAC commissioner Kathy Buto, former vice president of global health policy at Johnson & Johnson, expressed support for the idea but raised a red flag that the system could be manipulated so that APRN/PA claims could still be paid at 100% of the fee schedule rate.

Commissioner Bruce Pyenson, principal and consulting actuary of Milliman in New York, suggested that APRN and PA claims should be paid at 100% of the fee schedule, mirroring other Medicare efforts to achieve site-neutral payments.

Similarly, commissioner Amy Bricker, vice president of supply chain strategy at Express Scripts, St. Louis, said that while she generally does not favor redistributing program savings, if APRN and PA claims were paid at 85%, the saving generated should go back to physicians who would otherwise lose money.

That change in revenue was a key concern for Michael Munger, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

“We have a policy on ‘incident to’ billing at the academy,” Dr. Munger said in an interview. “It says that services that are delegated to and provided by nonphysician providers under physician supervision must be provided with the same quality and should be reimbursed at the same level as services directly provided by a physician.”

He said that lowering APRNs and PAs payments to 85% of what physicians make would impact doctors in a negative way, but if the elimination of “incident to” came with a recommendation that they be paid the same as physicians, it “would be less problematic.”

Dr. Munger described primary care as a team sport, and “this is certainly going to be felt in terms of the overall mission of delivering quality care.”

Access to care also could be reduced along with the reduced payment level, he added.

“You have to make business decisions at the end of the day,” he said. “You need to make sure that you can have adequate revenue to offset expenses, and if you are going to take a 15% cut in your revenue in, you have to look at where your expenses are, and obviously salary is your No. 1 expense. If you are not able to count on this revenue and you can’t afford to have NPs and PAs as part of the team, it is going to become an access issue for patients.”

Potential access and quality issues also resonated with the American Osteopathic Association.

“You really could see the elimination of the physician element from that practice environment and that would be to the detriment of patients,” David Pugach, AOA senior vice president of public policy, said in an interview. “Right now, you have the ability for incident billing, which requires the active participation of a physician in the management of patient care. If you end that practice, you are essentially removing the physician from the equation, and that really is an access issue; it’s a safety issue; and it’s a quality issue.”

He also noted that sometimes there is overutilization of diagnostic services with APRNs and PAs, and while costs may be saved by paying for those clinicians at less than the rate of physicians, the overutilization of other services by them could end up offsetting the savings.

“We have some significant concerns,” Mr. Pugach said.

The American Academy of Physician Assistants echoed some concerns expressed by MedPAC commissioners and staff.

“What we feel strongly about is the fact that one of the problems of ‘incident to’ is that it hides the practitioners, in this case the PA who actually renders the service,” Michael Powe, AAPA vice president of reimbursement and professional advocacy, said in an interview.

“We think that’s inappropriate for a number of reasons,” he continued. “Clearly from the issue of trying to figure who’s doing what, who saw the patient, what the quality of care happens to be, we think that PAs ought to be recognized ... and not hidden which happens under the ‘incident to’ methodology.”

He said that transparency helps determine where primary care needs are, whether they are being met, and it helps with determining network adequacy.

“So there are a number of good reasons why the accuracy and transparency should be there whether or not ‘incident to’ goes away.”

Jennifer Winter, committee chair for public education for the Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants, agreed.*

Eliminating “incident to” would grant greater visibility of PA practice “because right now, some of what we do is hidden by what the physician does” because it is billed under the physician and you can’t see what the PA is doing, especially if there is an adverse event, said Ms. Winter, who practices in Olympia, Wash. “It confounds trying to collect data on outcomes.”

She also noted that some physicians might not want to hire an NP or PA “because they can hire a physician and get 100%, but they are also going to have to pay that physician at a physician rate.”

Ms. Winter said that PAs and nurse practitioners should be getting 100% of the pay as they are doing essentially the same work that physicians would be doing.

MedPAC staffers also recommended that APRNs and PAs more clearly identify the specialty that they work in, something they do not currently have to do, to allow for more transparency and accurate data on the work that these types of clinicians are performing.

*An earlier version of this story misspelled Ms. Winter's name.

REPORTING FROM A MEDPAC MEETING

Implementing the VA/DoD Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Clinical Practice Guideline (FULL)

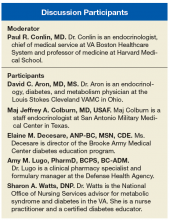

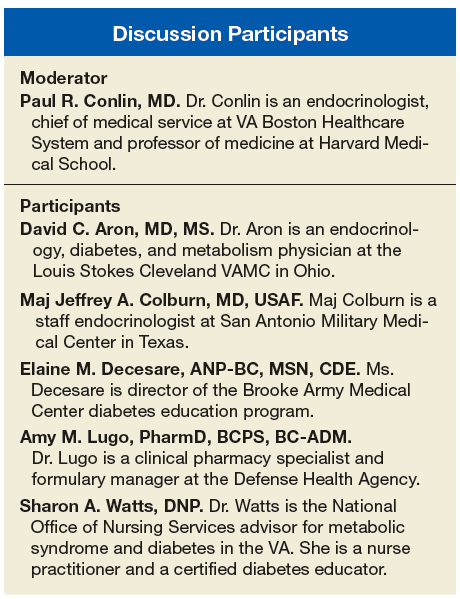

Paul Conlin, MD. Thank you all for joining us to talk about the recently released VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Primary Care (CPG). We’ve gathered together a group of experts who were part of the CPG development committee. We’re going to talk about some topics that were highlighted in the CPG that might provide additional detail to those in primary-care practices and help them in their management of patients with diabetes.

A unique feature of the VA/DoD CPG is that it emphasizes shared decision making as an important tool that clinicians should employ in their patient encounters. Dr. Watts, health care providers may wonder how they can make time for an intervention involving shared decision making using the SHARE approach, (ie, seek, help, assess, reach, and evaluate). Can you give us some advice on this?

Sharon Watts, DNP. Shared decision making is really crucial to success in diabetes. It’s been around for a while. We are trying to make an emphasis on this. The SHARE approach is from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The AHRQ has a wealth of information on its website. What AHRQ emphasizes is making it brief but conversational when you’re using the SHARE approach with your patient. Most importantly, the patient needs to be in the center of this dialogue, expressing his or her values and preferences of what’s most important to the whole team. This is a team effort. It’s not just with a provider. That’s where providers get overwhelmed. You can ask your nurse to advise the patient to write down 1 or 2 questions that are really important about diabetes before they come to see you, before the encounter. We can refer patients to diabetes classes where a lot of this information is given. The patient can talk to the dietitian or the pharmacist. There’s a whole team out there that will help in SHARE decision making. It’s crucial in the end for the provider to help the patient reach the decision and determine how best to treat the diabetes with them.

Dr. Conlin. Can you give a brief description of the key components of the SHARE approach?

Dr. Watts. Breaking it down simply, providers can start off by asking permission to go over the condition or treatment options because this immediately sets the stage as a signal to the patient that they are important in controlling the dialogue. It’s not the provider giving a discourse. You’re asking for permission. The next step would be to explore the benefits and risks of any course taken. Use decision aids if you have them. Keep in mind your patient’s current health literacy, numeracy, and other limitations.

Next ask about values, preferences, or barriers to whatever treatment you’re talking about. For instance, will this work with your work schedule?

Then the last thing would be ask what the patient wants to do next. Reach a decision on treatment, whatever it is, and make sure that you revisit that decision. Follow up later to see if it’s really working.

Dr. Conlin. If I’m a busy clinician and I have a limited amount of time with a patient, when are the appropriate times to employ the SHARE approach? Can I break it into components, where I address some elements during one visit and other elements in another visit?

Dr. Watts. Absolutely. It can be spread out. Your team is probably already providing information that will help in the SHARE approach. Just chart that you’ve done it. We know the SHARE approach is important because people tend to be adherent if they came up with part of the plan.

Dr. Conlin. Where does diabetes self-management education and diabetes self-management support fall into this framework?

Dr. Watts. Diabetes is a complex disease for providers and for the team and even more so for our patients. Invite them to diabetes classes. There’s so much to understand. The classes go over medications and blood sugar ranges, though you still may have to review it with the patient in your office. It saves the provider time if you have an informed and activated patient. It’s the same with sending a patient to a dietitian. I do all of the above.

Dr. Conlin. Many providers may not be familiar with this type of approach. How can I tell whether or not I’m doing it correctly?

Dr. Watts. The AHRQ website has conversation starters (www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/tools/index.html). Then make sure when you are with the patient to use Teach-Back. Have that conversation and say, “I want to make sure I understood correctly what we decided would work best for you.” Ask patients to say in their own words what they understand. Then I think you’re off to a great start.

Dr. Conlin. Many patients tend to be deferential to their health care providers. They were brought up in an era where they needed to listen to and respect clinicians rather than participate in discussions about their ongoing care. How do you engage with these patients?

Dr. Watts. That is a tough one. Before the patient leaves the office, I ask them: Are there any barriers? Does this work for your schedule? Is this a preference and value that you have? Is there anything that might get in the way of this working when you go home? I try to pull out a little bit more, making sure to give them some decision aids and revisit it at the next visit to make sure it’s working.

Dr. Conlin. We’ll now turn to a discussion of using hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measurements in clinical practice. Dr. Aron, what factors can impact the relationship between HbA1c and blood glucose? How should we use HbA1c in the treatment of patients who come from varied ethnic and racial backgrounds, where the relationship to average blood glucose may be different?

David C. Aron, MD, MS. The identification of HbA1c has been a tremendous advance in our ability to manage patients with diabetes. It represents an average blood glucose over the preceding 3 months but like everything in this world, it has issues. One is the fact that there is a certain degree of inaccuracy in measurement, and that’s true of any measurement that you make of anything. Just as you allow a little bit of wiggle room when you’re driving down the New Jersey Turnpike and watching your speedometer, which is not 100% accurate. It says you are going 65 but it could, for example be 68 or 62. You don’t want to go too fast or you’ll get a speeding ticket. You don’t want to go too slowly or the person behind you will start honking at you. You want to be at the speed limit plus or minus. The first thing to think about in using HbA1c is the issue of accuracy. Rather than choose a specific target number, health care providers should choose a range between this and that. There’ll be more detail on that later.

The second thing is that part of the degree to which HbA1c represents the average blood glucose depends on a lot of factors, and some of these factors are things that we can do absolutely nothing about because we are born with them. African Americans tend to have higher HbA1c levels than do whites for the same glucose. That difference is as much as 0.4. An HbA1c of 6.2 in African Americans gets you a 5.8 in whites for the same average blood glucose. Similarly, Native Americans have somewhat higher HbA1c, although not quite as high as African Americans. Hispanics and Asians do as well, so you have to take your patient’s ethnicity into account.

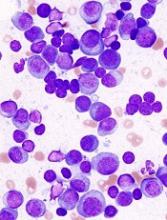

The second has to do with the way that HbA1c is measured and the fact that there are many things that can affect the measurement. An HbA1c is dependent upon the lifespan of the red blood cell, so if there are alterations in red cell lifespan or if someone has anemia, that can affect HbA1c. Certain hemoglobin variants, for example, hemoglobin F, which is typically elevated in someone with thalassemia, migrates with some assays in the same place as thalassemia, so the assay can’t tell the difference between thalassemia and hemoglobin F. There are drugs and other conditions that can also affect HbA1c. You should think about HbA1c as a guide, but no number should be considered to be written in stone.

Dr. Conlin. I can imagine that this would be particularly important if you were using HbA1c as a criterion for diagnosing diabetes.

Dr. Aron. Quite right. The effects of race and ethnicity on HbA1c account for one of the differences between the VA/DoD guidelines and those of the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Dr. Conlin. Isn’t < 8% HbA1c a national performance measure that people are asked to adhere to?

Dr. Aron. Not in the VA. In fact, the only performance measure that the VA has with a target is percent of patients with HbA1c > 9%, and we don’t want any of those or very few of them anyway. We have specifically avoided targets like < 8% HbA1c or < 7% HbA1c, which was prevalent some years ago, because the choice of HbA1c is very dependent upon the needs and desires of the individual patient. The VA has had stratified targets based on life expectancy and complications going back more than 15 years.

Dr. Conlin. Another issue that can confuse clinicians is when the HbA1c is in the target range but actually reflects an average of glucose levels that are at times very high and very low. How do we address this problem clinically?

Dr. Aron. In managing patients, you use whatever data you can get. The HbA1c gives you a general indication of average blood glucose, but particularly for those patients who are on insulin, it’s not a complete substitute for measuring blood glucose at appropriate times and taking the degree of glucose variability into account. We don’t want patients getting hypoglycemic, and particularly if they’re elderly, falling, or getting into a car accident. Similarly, we don’t want people to have very high blood sugars, even for limited periods of time, because they can lead to dehydration and other symptoms as well. We use a combination of both HbA1c and individual measures of blood glucose, like finger-stick blood sugar testing, typically.

Dr. Conlin. The VA/DoD CPG differs from other published guidelines in that we proposed patients are treated to HbA1c target ranges, whereas most other guidelines propose upper limits or threshold values, such as the HbA1c should be < 7% or < 8% but without lower bounds. Dr. Colburn, what are the target ranges that are recommended in the CPG? How were they determined?

Maj. Jeffrey A. Colburn, MD. It may be helpful to pull up the Determination of Average Target HbA1c Level Over Time table (page S17), which lays out risk for patients of treatment as well as the benefits of treatment. We first look at the patient’s state of health and whether they have a major comorbidity, a physiologic age that could be high risk, or advanced physiologic age with a diminished life expectancy. In controlling the levels of glucose, we’re often trying to benefit the microvascular health of the patient, realizing also that eventually poor management over time will lead to macrovascular disease as well. The main things that we see in child data is that the benefits of tight glucose control for younger patients with shorter duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the prevention of retinopathy, nephropathy, and peripheral neuropathy. Those patients that already have advanced microvascular disease are less likely to benefit from tight control. Trying to push glucose very low can harm the patient. It’s a delicate balance between the possible benefit vs the real harm.

The major trials are the ADVANCE, ACCORD, and the VADT trial, which was done in a VA population. To generalize the results, you are looking at an intensive control, which was trying to keep the HbA1c in general down below the 7% threshold. The patients enrolled in those trials all had microvascular and macrovascular disease and typically longer durations of diabetes at the time of the study. The studies revealed that we were not preventing macrovascular disease, heart attacks, strokes, the types of things that kill patients with diabetes. Individuals at higher HbA1c levels that went down to better HbA1c levels saw some improvement in the microvascular risk. Individuals already at the lower end didn’t see as much improvement. What we saw though that was surprising and concerning was that hypoglycemia, particularly severe hypoglycemia in the VADT trial was a lot more frequent when you try and target the HbA1c on the lower end. Because of these findings, we proposed the table with a set of ranges. As Dr. Aron noted, HbA1c is not a perfect test. It does have some variance in the number it presents. The CPG proposed to give individuals target ranges. They should be individualized based upon physiologic age, comorbidities, and life expectancy.

A criticism of the table that I commonly hear is what’s the magic crystal ball for determining somebody’s life expectancy? We don’t have one. This is a clinician’s judgment. The findings might actually change over time with the patient. A target HbA1c range is something that should be adapted and evolve along with the clinician and patient experience of the diabetes.

There are other important studies. For example, the UKPDS trials that included patients with shorter durations of diabetes and lesser disease to try and get their HbA1c levels on the lower end. We included that in the chart. Another concept we put forward is the idea of relative risk (RR) vs absolute risk. The RR reduction doesn’t speak to what the actual beginning risk is lowered to for a patient. The UKPDS is often cited for RR reduction of microvascular disease as 37% when an HbA1c of 7.9% is targeted down to 7.0%. The absolute risk reduction is actually 5 with the number needed to treat to do so is 20 patients. When we present the data, we give it a fair shake. We want individuals to guide therapy that is going to be both beneficial to preventing outcomes but also not harmful to the patient. I would highly recommend clinicians and patients look at this table together when making their decisions.

Dr. Conlin. In the VA/DoD CPG, the HbA1c target range for individuals with limited life expectancy extends to 9%. That may seem high for some, since most other guidelines propose lower HbA1c levels. How strong are the data that a person with limited life expectancy, say with end-stage renal disease or advanced complications, could be treated to a range of 8% to 9%? Shouldn’t lower levels actually improve life expectancy in such people?

Dr. Colburn. There’s much less data to support this level, which is why it’s cited in CPG as having weaker evidence. The reason it’s proposed is the experience of the workgroup and the evidence that is available of a high risk for patients with low life expectancy when they reduce their HbA1c greatly. One of the concerns about being at that level might be the real issue of renal glycosuria for individuals when their blood glucose is reaching above 180 mg/dL, which correlates to the 8% to 9% HbA1c range. You may have renal loss and risk of dehydration. It is an area where the clinician should be cautious in monitoring a patient in the 8% to 9% HbA1c range. With that being said, a patient who is having a lot of challenges in their health and extremely advanced conditions could be in that range. We would not expect a reversing of a micro- or macrovascular disease with glycemia control. We’re not going to go back from that level of disease they have. The idea about keeping them there is to prevent the risks of overtreatment and harm to the patient.

Dr. Conlin. Since patients with diabetes can progress over their lifetime from no complications to mild-to-moderate complications to advanced complications, how does the HbA1c target range evolve as a patient’s condition changes?

Dr. Colburn. As we check for evidence of microvascular disease or neuropathy signs, that evidence often is good for discussion between the clinician and patient to advise them that better control early on may help stem off or reverse some of that change. As those changes solidify, the patient is challenged by microvascular conditions. I would entertain allowing more relaxed HbA1c ranges to prevent harm to the patient given that we’re not going back. But you have to be careful. We have to consider benefits to the patient and the challenges for controlling glucose.

I hope that this table doesn’t make providers throw up their hands and give up. It’s meant to start a conversation on safety and benefits. With newer agents coming out that can help us control glucose quite well, without as much hypoglycemia risk, clinicians and patients potentially can try and get that HbA1c into a well-managed range.

Dr. Conlin. The CPG discusses various treatment options that might be available for patients who require pharmacologic therapy. The number of agents available is growing quite markedly. Dr. Colburn, can you describe how the CPG put together the pharmacologic therapy preferences.

Dr. Colburn. The CPG expressively stayed away from trying to promote specific regimens of medications. For example, other guidelines promote starting with certain agents followed by a second-line agent by a third-line agents. The concern that we had about that approach is that the medication landscape is rapidly evolving. The options available to clinicians and patients are really diverse at this moment, and the data are not concrete regarding what works best for a single patient.

Rather than trying to go from one agent to the next, we thought it best to discuss with patients using the SHARE decision-making model, the adverse effects (AEs) and relative benefits that are involved with each medication class to determine what might be best for the person. We have many new agents with evidence for possible reductions in cardiovascular outcomes outside of their glycemic control properties. As those evidences promote a potentially better option for a patient, we wanted to allow the room in management to make a decision together. I will say the CPG as well as all of the other applicable diabetes guidelines for T2DM promote metformin as the first therapy to consider for somebody with newly diagnosed T2DM because of safety and availability and the benefit that’s seen with that medication class. We ask clinicians to access the AHRQ website for updates as the medicines evolve.

In a rapidly changing landscape with new drugs coming into the market, each agency has on their individual website information about individual agents and their formulary status, criteria for use, and prior authorization requirements. We refer clinicians to the appropriate website for more information.

Dr. Conlin. There are a series of new medications that have recently come to market that seem to mitigate risk for hypoglycemia. Dr. Lugo, which treatment options carry greater risk? Which treatment options seem to have lesser risk for hypoglycemia?

Amy M. Lugo, PharmD. Insulin and the sulfonylureas have the highest risk of hypoglycemia. The sulfonylureas have fallen out of favor somewhat. One reason is that there are many newer agents that do not cause weight gain or increase the risk of hypoglycemia. Some of the newer insulins may have a lower risk of hypoglycemia and nocturnal hypoglycemia, in particular; however, it is difficult to conclude emphatically that one basal insulin analog is less likely to cause clinically relevant severe or nocturnal hypoglycemia events. This is due to the differences in the definitions of hypoglycemia used in the individual clinical trials, the open label study designs, and the different primary endpoints.

Dr. Conlin. How much affect on HbA1c might I expect to see using SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists? What would be some of the potential AEs I have to be aware of and therefore could counsel patients about?

Dr. Lugo. Let’s start with SGLT2 inhibitors. It depends on whether they are used as monotherapy or in combination. We prefer that patients start on metformin unless they have a contraindication. When used as monotherapy, the SGLT2s may decrease HbA1c from 0.4% to 1% from baseline. When combined with additional agents, they can have > 1% improvement in HbA1c from baseline. There are no head-to-head trials between any of the SGLT2 inhibitors. We cannot say that one is more efficacious than another in lowering HbA1c. The most common AEs include genital mycotic infections and urinary tract infections. The SGLT2 inhibitors also should be avoided in renal impairment. There was a recent FDA safety alert for the class for risk of ketoacidosis. Additionally, the FDA warned that patients with a history of bladder cancer should avoid dapagliflozin, and canagliflozin has a warning for increased risk of bone fractures, amputation, and decreased bone density.

Other actions of the SGLT2 inhibitors include a reduction in triglycerides and a modest increase in both low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. The SGLT2 inhibitors also slightly decrease systolic blood pressure (by 4 mm Hg to 6 mm Hg) and body weight (reduction of 1.8 kg)

The GLP-1s are likely to be more efficacious in reducing HbA1c. Typically we see 1% or greater lowering in HbA1c from baseline. As a class, the GLP-1 agonists have a lower risk of hypoglycemia; however, the risk increases when combined with sulfonylureas or insulin. The dose of insulin or sulfonylurea will likely need to be decreased when used concomitantly.

Patients are likely to experience weight loss when on a GLP-1 agonist, which is a great benefit. Gastrointestinal AEs such as nausea are common. Adverse effects may differ somewhat between the agents.

Dr. Conlin. Patients’ experience of care is integral to their engagement with treatment as well as their adherence. Ms. Decesare, what are patients looking for from their health care team?

Elaine M. Decesare. Patients are looking for a knowledgeable and compassionate health care team that has a consistent approach and a consistent message and that the team is updated on the knowledge of appropriate treatments and appropriate lifestyle modifications and targets for the care of diabetes.

Also, I think that the team needs to have some empathy for the challenges of living with diabetes. It’s a 24-hour-a-day disorder, 7 days a week. They can’t take vacation from it. They just can’t take a pill and forget about it. It’s a fairly demanding disorder, and sometimes just acknowledging that with the patient can help you with the dialog.

The second thing I think patients want is an effective treatment plan that’s tailored to their needs and lifestyles. That goes in with the shared decision-making approach, but the plan itself really has to be likely to achieve the targets and the goals that you’ve set up. Sometimes I see patients who are doing all they can with their lifestyle changes, but they can’t get to goal, because there isn’t enough medication in the plan. The plan has to be adequate so that the patient can manage their diabetes. In the shared approach, the patient has to buy in to the plan. With the shared decision making they’re more likely to take the plan on as their plan.

Dr. Conlin. How do you respond to patients who feel treatment burnout from having a new dietary plan, an exercise program, regular monitoring of glucose through finger sticks, and in many cases multiple medications and or injections, while potentially not achieving the goals that you and the patient have arrived at?

Ms. Decesare. First, I want to assess their mood. Sometimes patients are depressed, and they actually need help with that. If they have trouble with just the management, we do have behavioral health psychologists on our team that work with patients to get through some of the barriers and discuss some of the feelings that they have about diabetes and diabetes management.

Sometimes we look at the plan again and see if there’s something we can do to make the plan easier. Occasionally, something has happened in their life. Maybe they’re taking care of an elderly parent or they’ve had other health problems that have come about that we need to reassess the plan and make sure that it’s actually doable for them at this point in time.

Certainly diabetes self-management education can be helpful. Some of those approaches can be helpful for finding something that’s going to work for patients in the long run, because it can be a very difficult disorder to manage as time goes on.

Dr. Colburn. Type 2 DM disproportionately affects individuals who are ≥ 65 years compared with younger individuals. Such older patients also are more likely to have cognitive impairment or visual issues. How do we best manage such patients?

Ms. Decesare. When I’m looking at the care plan, social support is very important. If someone has social support and they have a spouse or a son or daughter or someone else that can help them with their diabetes, we oftentimes will get them involved with the plan, as long as it’s fine with the patient, to offer some help, especially with the patients with cognitive problems, because sometimes the patients just cognitively cannot manage diabetes on their own. Prandial insulin could be a really dangerous product for someone who has cognitive disease.

I think you have to look at all the resources that are available. Sometimes you have to change your HbA1c target range to something that’s going to be manageable for that patient at that time. It might not be perfect, but it would be better to have no hypoglycemia rather than a real aggressive HbA1c target or a target range, if that’s what’s going to keep the patient safe.

Dr. Conlin. We thank our discussants for sharing very practical advice on how to implement the CPG. We hope this information supports clinicians as they develop treatment plans based on each patient's unique characteristics and goals of care.

Paul Conlin, MD. Thank you all for joining us to talk about the recently released VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Primary Care (CPG). We’ve gathered together a group of experts who were part of the CPG development committee. We’re going to talk about some topics that were highlighted in the CPG that might provide additional detail to those in primary-care practices and help them in their management of patients with diabetes.

A unique feature of the VA/DoD CPG is that it emphasizes shared decision making as an important tool that clinicians should employ in their patient encounters. Dr. Watts, health care providers may wonder how they can make time for an intervention involving shared decision making using the SHARE approach, (ie, seek, help, assess, reach, and evaluate). Can you give us some advice on this?

Sharon Watts, DNP. Shared decision making is really crucial to success in diabetes. It’s been around for a while. We are trying to make an emphasis on this. The SHARE approach is from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The AHRQ has a wealth of information on its website. What AHRQ emphasizes is making it brief but conversational when you’re using the SHARE approach with your patient. Most importantly, the patient needs to be in the center of this dialogue, expressing his or her values and preferences of what’s most important to the whole team. This is a team effort. It’s not just with a provider. That’s where providers get overwhelmed. You can ask your nurse to advise the patient to write down 1 or 2 questions that are really important about diabetes before they come to see you, before the encounter. We can refer patients to diabetes classes where a lot of this information is given. The patient can talk to the dietitian or the pharmacist. There’s a whole team out there that will help in SHARE decision making. It’s crucial in the end for the provider to help the patient reach the decision and determine how best to treat the diabetes with them.

Dr. Conlin. Can you give a brief description of the key components of the SHARE approach?

Dr. Watts. Breaking it down simply, providers can start off by asking permission to go over the condition or treatment options because this immediately sets the stage as a signal to the patient that they are important in controlling the dialogue. It’s not the provider giving a discourse. You’re asking for permission. The next step would be to explore the benefits and risks of any course taken. Use decision aids if you have them. Keep in mind your patient’s current health literacy, numeracy, and other limitations.

Next ask about values, preferences, or barriers to whatever treatment you’re talking about. For instance, will this work with your work schedule?

Then the last thing would be ask what the patient wants to do next. Reach a decision on treatment, whatever it is, and make sure that you revisit that decision. Follow up later to see if it’s really working.

Dr. Conlin. If I’m a busy clinician and I have a limited amount of time with a patient, when are the appropriate times to employ the SHARE approach? Can I break it into components, where I address some elements during one visit and other elements in another visit?

Dr. Watts. Absolutely. It can be spread out. Your team is probably already providing information that will help in the SHARE approach. Just chart that you’ve done it. We know the SHARE approach is important because people tend to be adherent if they came up with part of the plan.

Dr. Conlin. Where does diabetes self-management education and diabetes self-management support fall into this framework?

Dr. Watts. Diabetes is a complex disease for providers and for the team and even more so for our patients. Invite them to diabetes classes. There’s so much to understand. The classes go over medications and blood sugar ranges, though you still may have to review it with the patient in your office. It saves the provider time if you have an informed and activated patient. It’s the same with sending a patient to a dietitian. I do all of the above.

Dr. Conlin. Many providers may not be familiar with this type of approach. How can I tell whether or not I’m doing it correctly?

Dr. Watts. The AHRQ website has conversation starters (www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/tools/index.html). Then make sure when you are with the patient to use Teach-Back. Have that conversation and say, “I want to make sure I understood correctly what we decided would work best for you.” Ask patients to say in their own words what they understand. Then I think you’re off to a great start.

Dr. Conlin. Many patients tend to be deferential to their health care providers. They were brought up in an era where they needed to listen to and respect clinicians rather than participate in discussions about their ongoing care. How do you engage with these patients?

Dr. Watts. That is a tough one. Before the patient leaves the office, I ask them: Are there any barriers? Does this work for your schedule? Is this a preference and value that you have? Is there anything that might get in the way of this working when you go home? I try to pull out a little bit more, making sure to give them some decision aids and revisit it at the next visit to make sure it’s working.

Dr. Conlin. We’ll now turn to a discussion of using hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measurements in clinical practice. Dr. Aron, what factors can impact the relationship between HbA1c and blood glucose? How should we use HbA1c in the treatment of patients who come from varied ethnic and racial backgrounds, where the relationship to average blood glucose may be different?

David C. Aron, MD, MS. The identification of HbA1c has been a tremendous advance in our ability to manage patients with diabetes. It represents an average blood glucose over the preceding 3 months but like everything in this world, it has issues. One is the fact that there is a certain degree of inaccuracy in measurement, and that’s true of any measurement that you make of anything. Just as you allow a little bit of wiggle room when you’re driving down the New Jersey Turnpike and watching your speedometer, which is not 100% accurate. It says you are going 65 but it could, for example be 68 or 62. You don’t want to go too fast or you’ll get a speeding ticket. You don’t want to go too slowly or the person behind you will start honking at you. You want to be at the speed limit plus or minus. The first thing to think about in using HbA1c is the issue of accuracy. Rather than choose a specific target number, health care providers should choose a range between this and that. There’ll be more detail on that later.

The second thing is that part of the degree to which HbA1c represents the average blood glucose depends on a lot of factors, and some of these factors are things that we can do absolutely nothing about because we are born with them. African Americans tend to have higher HbA1c levels than do whites for the same glucose. That difference is as much as 0.4. An HbA1c of 6.2 in African Americans gets you a 5.8 in whites for the same average blood glucose. Similarly, Native Americans have somewhat higher HbA1c, although not quite as high as African Americans. Hispanics and Asians do as well, so you have to take your patient’s ethnicity into account.

The second has to do with the way that HbA1c is measured and the fact that there are many things that can affect the measurement. An HbA1c is dependent upon the lifespan of the red blood cell, so if there are alterations in red cell lifespan or if someone has anemia, that can affect HbA1c. Certain hemoglobin variants, for example, hemoglobin F, which is typically elevated in someone with thalassemia, migrates with some assays in the same place as thalassemia, so the assay can’t tell the difference between thalassemia and hemoglobin F. There are drugs and other conditions that can also affect HbA1c. You should think about HbA1c as a guide, but no number should be considered to be written in stone.

Dr. Conlin. I can imagine that this would be particularly important if you were using HbA1c as a criterion for diagnosing diabetes.

Dr. Aron. Quite right. The effects of race and ethnicity on HbA1c account for one of the differences between the VA/DoD guidelines and those of the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Dr. Conlin. Isn’t < 8% HbA1c a national performance measure that people are asked to adhere to?

Dr. Aron. Not in the VA. In fact, the only performance measure that the VA has with a target is percent of patients with HbA1c > 9%, and we don’t want any of those or very few of them anyway. We have specifically avoided targets like < 8% HbA1c or < 7% HbA1c, which was prevalent some years ago, because the choice of HbA1c is very dependent upon the needs and desires of the individual patient. The VA has had stratified targets based on life expectancy and complications going back more than 15 years.

Dr. Conlin. Another issue that can confuse clinicians is when the HbA1c is in the target range but actually reflects an average of glucose levels that are at times very high and very low. How do we address this problem clinically?

Dr. Aron. In managing patients, you use whatever data you can get. The HbA1c gives you a general indication of average blood glucose, but particularly for those patients who are on insulin, it’s not a complete substitute for measuring blood glucose at appropriate times and taking the degree of glucose variability into account. We don’t want patients getting hypoglycemic, and particularly if they’re elderly, falling, or getting into a car accident. Similarly, we don’t want people to have very high blood sugars, even for limited periods of time, because they can lead to dehydration and other symptoms as well. We use a combination of both HbA1c and individual measures of blood glucose, like finger-stick blood sugar testing, typically.

Dr. Conlin. The VA/DoD CPG differs from other published guidelines in that we proposed patients are treated to HbA1c target ranges, whereas most other guidelines propose upper limits or threshold values, such as the HbA1c should be < 7% or < 8% but without lower bounds. Dr. Colburn, what are the target ranges that are recommended in the CPG? How were they determined?

Maj. Jeffrey A. Colburn, MD. It may be helpful to pull up the Determination of Average Target HbA1c Level Over Time table (page S17), which lays out risk for patients of treatment as well as the benefits of treatment. We first look at the patient’s state of health and whether they have a major comorbidity, a physiologic age that could be high risk, or advanced physiologic age with a diminished life expectancy. In controlling the levels of glucose, we’re often trying to benefit the microvascular health of the patient, realizing also that eventually poor management over time will lead to macrovascular disease as well. The main things that we see in child data is that the benefits of tight glucose control for younger patients with shorter duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the prevention of retinopathy, nephropathy, and peripheral neuropathy. Those patients that already have advanced microvascular disease are less likely to benefit from tight control. Trying to push glucose very low can harm the patient. It’s a delicate balance between the possible benefit vs the real harm.

The major trials are the ADVANCE, ACCORD, and the VADT trial, which was done in a VA population. To generalize the results, you are looking at an intensive control, which was trying to keep the HbA1c in general down below the 7% threshold. The patients enrolled in those trials all had microvascular and macrovascular disease and typically longer durations of diabetes at the time of the study. The studies revealed that we were not preventing macrovascular disease, heart attacks, strokes, the types of things that kill patients with diabetes. Individuals at higher HbA1c levels that went down to better HbA1c levels saw some improvement in the microvascular risk. Individuals already at the lower end didn’t see as much improvement. What we saw though that was surprising and concerning was that hypoglycemia, particularly severe hypoglycemia in the VADT trial was a lot more frequent when you try and target the HbA1c on the lower end. Because of these findings, we proposed the table with a set of ranges. As Dr. Aron noted, HbA1c is not a perfect test. It does have some variance in the number it presents. The CPG proposed to give individuals target ranges. They should be individualized based upon physiologic age, comorbidities, and life expectancy.

A criticism of the table that I commonly hear is what’s the magic crystal ball for determining somebody’s life expectancy? We don’t have one. This is a clinician’s judgment. The findings might actually change over time with the patient. A target HbA1c range is something that should be adapted and evolve along with the clinician and patient experience of the diabetes.

There are other important studies. For example, the UKPDS trials that included patients with shorter durations of diabetes and lesser disease to try and get their HbA1c levels on the lower end. We included that in the chart. Another concept we put forward is the idea of relative risk (RR) vs absolute risk. The RR reduction doesn’t speak to what the actual beginning risk is lowered to for a patient. The UKPDS is often cited for RR reduction of microvascular disease as 37% when an HbA1c of 7.9% is targeted down to 7.0%. The absolute risk reduction is actually 5 with the number needed to treat to do so is 20 patients. When we present the data, we give it a fair shake. We want individuals to guide therapy that is going to be both beneficial to preventing outcomes but also not harmful to the patient. I would highly recommend clinicians and patients look at this table together when making their decisions.

Dr. Conlin. In the VA/DoD CPG, the HbA1c target range for individuals with limited life expectancy extends to 9%. That may seem high for some, since most other guidelines propose lower HbA1c levels. How strong are the data that a person with limited life expectancy, say with end-stage renal disease or advanced complications, could be treated to a range of 8% to 9%? Shouldn’t lower levels actually improve life expectancy in such people?

Dr. Colburn. There’s much less data to support this level, which is why it’s cited in CPG as having weaker evidence. The reason it’s proposed is the experience of the workgroup and the evidence that is available of a high risk for patients with low life expectancy when they reduce their HbA1c greatly. One of the concerns about being at that level might be the real issue of renal glycosuria for individuals when their blood glucose is reaching above 180 mg/dL, which correlates to the 8% to 9% HbA1c range. You may have renal loss and risk of dehydration. It is an area where the clinician should be cautious in monitoring a patient in the 8% to 9% HbA1c range. With that being said, a patient who is having a lot of challenges in their health and extremely advanced conditions could be in that range. We would not expect a reversing of a micro- or macrovascular disease with glycemia control. We’re not going to go back from that level of disease they have. The idea about keeping them there is to prevent the risks of overtreatment and harm to the patient.

Dr. Conlin. Since patients with diabetes can progress over their lifetime from no complications to mild-to-moderate complications to advanced complications, how does the HbA1c target range evolve as a patient’s condition changes?

Dr. Colburn. As we check for evidence of microvascular disease or neuropathy signs, that evidence often is good for discussion between the clinician and patient to advise them that better control early on may help stem off or reverse some of that change. As those changes solidify, the patient is challenged by microvascular conditions. I would entertain allowing more relaxed HbA1c ranges to prevent harm to the patient given that we’re not going back. But you have to be careful. We have to consider benefits to the patient and the challenges for controlling glucose.

I hope that this table doesn’t make providers throw up their hands and give up. It’s meant to start a conversation on safety and benefits. With newer agents coming out that can help us control glucose quite well, without as much hypoglycemia risk, clinicians and patients potentially can try and get that HbA1c into a well-managed range.

Dr. Conlin. The CPG discusses various treatment options that might be available for patients who require pharmacologic therapy. The number of agents available is growing quite markedly. Dr. Colburn, can you describe how the CPG put together the pharmacologic therapy preferences.

Dr. Colburn. The CPG expressively stayed away from trying to promote specific regimens of medications. For example, other guidelines promote starting with certain agents followed by a second-line agent by a third-line agents. The concern that we had about that approach is that the medication landscape is rapidly evolving. The options available to clinicians and patients are really diverse at this moment, and the data are not concrete regarding what works best for a single patient.

Rather than trying to go from one agent to the next, we thought it best to discuss with patients using the SHARE decision-making model, the adverse effects (AEs) and relative benefits that are involved with each medication class to determine what might be best for the person. We have many new agents with evidence for possible reductions in cardiovascular outcomes outside of their glycemic control properties. As those evidences promote a potentially better option for a patient, we wanted to allow the room in management to make a decision together. I will say the CPG as well as all of the other applicable diabetes guidelines for T2DM promote metformin as the first therapy to consider for somebody with newly diagnosed T2DM because of safety and availability and the benefit that’s seen with that medication class. We ask clinicians to access the AHRQ website for updates as the medicines evolve.

In a rapidly changing landscape with new drugs coming into the market, each agency has on their individual website information about individual agents and their formulary status, criteria for use, and prior authorization requirements. We refer clinicians to the appropriate website for more information.

Dr. Conlin. There are a series of new medications that have recently come to market that seem to mitigate risk for hypoglycemia. Dr. Lugo, which treatment options carry greater risk? Which treatment options seem to have lesser risk for hypoglycemia?

Amy M. Lugo, PharmD. Insulin and the sulfonylureas have the highest risk of hypoglycemia. The sulfonylureas have fallen out of favor somewhat. One reason is that there are many newer agents that do not cause weight gain or increase the risk of hypoglycemia. Some of the newer insulins may have a lower risk of hypoglycemia and nocturnal hypoglycemia, in particular; however, it is difficult to conclude emphatically that one basal insulin analog is less likely to cause clinically relevant severe or nocturnal hypoglycemia events. This is due to the differences in the definitions of hypoglycemia used in the individual clinical trials, the open label study designs, and the different primary endpoints.

Dr. Conlin. How much affect on HbA1c might I expect to see using SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists? What would be some of the potential AEs I have to be aware of and therefore could counsel patients about?

Dr. Lugo. Let’s start with SGLT2 inhibitors. It depends on whether they are used as monotherapy or in combination. We prefer that patients start on metformin unless they have a contraindication. When used as monotherapy, the SGLT2s may decrease HbA1c from 0.4% to 1% from baseline. When combined with additional agents, they can have > 1% improvement in HbA1c from baseline. There are no head-to-head trials between any of the SGLT2 inhibitors. We cannot say that one is more efficacious than another in lowering HbA1c. The most common AEs include genital mycotic infections and urinary tract infections. The SGLT2 inhibitors also should be avoided in renal impairment. There was a recent FDA safety alert for the class for risk of ketoacidosis. Additionally, the FDA warned that patients with a history of bladder cancer should avoid dapagliflozin, and canagliflozin has a warning for increased risk of bone fractures, amputation, and decreased bone density.

Other actions of the SGLT2 inhibitors include a reduction in triglycerides and a modest increase in both low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. The SGLT2 inhibitors also slightly decrease systolic blood pressure (by 4 mm Hg to 6 mm Hg) and body weight (reduction of 1.8 kg)

The GLP-1s are likely to be more efficacious in reducing HbA1c. Typically we see 1% or greater lowering in HbA1c from baseline. As a class, the GLP-1 agonists have a lower risk of hypoglycemia; however, the risk increases when combined with sulfonylureas or insulin. The dose of insulin or sulfonylurea will likely need to be decreased when used concomitantly.

Patients are likely to experience weight loss when on a GLP-1 agonist, which is a great benefit. Gastrointestinal AEs such as nausea are common. Adverse effects may differ somewhat between the agents.

Dr. Conlin. Patients’ experience of care is integral to their engagement with treatment as well as their adherence. Ms. Decesare, what are patients looking for from their health care team?

Elaine M. Decesare. Patients are looking for a knowledgeable and compassionate health care team that has a consistent approach and a consistent message and that the team is updated on the knowledge of appropriate treatments and appropriate lifestyle modifications and targets for the care of diabetes.

Also, I think that the team needs to have some empathy for the challenges of living with diabetes. It’s a 24-hour-a-day disorder, 7 days a week. They can’t take vacation from it. They just can’t take a pill and forget about it. It’s a fairly demanding disorder, and sometimes just acknowledging that with the patient can help you with the dialog.

The second thing I think patients want is an effective treatment plan that’s tailored to their needs and lifestyles. That goes in with the shared decision-making approach, but the plan itself really has to be likely to achieve the targets and the goals that you’ve set up. Sometimes I see patients who are doing all they can with their lifestyle changes, but they can’t get to goal, because there isn’t enough medication in the plan. The plan has to be adequate so that the patient can manage their diabetes. In the shared approach, the patient has to buy in to the plan. With the shared decision making they’re more likely to take the plan on as their plan.

Dr. Conlin. How do you respond to patients who feel treatment burnout from having a new dietary plan, an exercise program, regular monitoring of glucose through finger sticks, and in many cases multiple medications and or injections, while potentially not achieving the goals that you and the patient have arrived at?

Ms. Decesare. First, I want to assess their mood. Sometimes patients are depressed, and they actually need help with that. If they have trouble with just the management, we do have behavioral health psychologists on our team that work with patients to get through some of the barriers and discuss some of the feelings that they have about diabetes and diabetes management.

Sometimes we look at the plan again and see if there’s something we can do to make the plan easier. Occasionally, something has happened in their life. Maybe they’re taking care of an elderly parent or they’ve had other health problems that have come about that we need to reassess the plan and make sure that it’s actually doable for them at this point in time.

Certainly diabetes self-management education can be helpful. Some of those approaches can be helpful for finding something that’s going to work for patients in the long run, because it can be a very difficult disorder to manage as time goes on.

Dr. Colburn. Type 2 DM disproportionately affects individuals who are ≥ 65 years compared with younger individuals. Such older patients also are more likely to have cognitive impairment or visual issues. How do we best manage such patients?

Ms. Decesare. When I’m looking at the care plan, social support is very important. If someone has social support and they have a spouse or a son or daughter or someone else that can help them with their diabetes, we oftentimes will get them involved with the plan, as long as it’s fine with the patient, to offer some help, especially with the patients with cognitive problems, because sometimes the patients just cognitively cannot manage diabetes on their own. Prandial insulin could be a really dangerous product for someone who has cognitive disease.

I think you have to look at all the resources that are available. Sometimes you have to change your HbA1c target range to something that’s going to be manageable for that patient at that time. It might not be perfect, but it would be better to have no hypoglycemia rather than a real aggressive HbA1c target or a target range, if that’s what’s going to keep the patient safe.

Dr. Conlin. We thank our discussants for sharing very practical advice on how to implement the CPG. We hope this information supports clinicians as they develop treatment plans based on each patient's unique characteristics and goals of care.

Paul Conlin, MD. Thank you all for joining us to talk about the recently released VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Primary Care (CPG). We’ve gathered together a group of experts who were part of the CPG development committee. We’re going to talk about some topics that were highlighted in the CPG that might provide additional detail to those in primary-care practices and help them in their management of patients with diabetes.

A unique feature of the VA/DoD CPG is that it emphasizes shared decision making as an important tool that clinicians should employ in their patient encounters. Dr. Watts, health care providers may wonder how they can make time for an intervention involving shared decision making using the SHARE approach, (ie, seek, help, assess, reach, and evaluate). Can you give us some advice on this?

Sharon Watts, DNP. Shared decision making is really crucial to success in diabetes. It’s been around for a while. We are trying to make an emphasis on this. The SHARE approach is from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The AHRQ has a wealth of information on its website. What AHRQ emphasizes is making it brief but conversational when you’re using the SHARE approach with your patient. Most importantly, the patient needs to be in the center of this dialogue, expressing his or her values and preferences of what’s most important to the whole team. This is a team effort. It’s not just with a provider. That’s where providers get overwhelmed. You can ask your nurse to advise the patient to write down 1 or 2 questions that are really important about diabetes before they come to see you, before the encounter. We can refer patients to diabetes classes where a lot of this information is given. The patient can talk to the dietitian or the pharmacist. There’s a whole team out there that will help in SHARE decision making. It’s crucial in the end for the provider to help the patient reach the decision and determine how best to treat the diabetes with them.

Dr. Conlin. Can you give a brief description of the key components of the SHARE approach?

Dr. Watts. Breaking it down simply, providers can start off by asking permission to go over the condition or treatment options because this immediately sets the stage as a signal to the patient that they are important in controlling the dialogue. It’s not the provider giving a discourse. You’re asking for permission. The next step would be to explore the benefits and risks of any course taken. Use decision aids if you have them. Keep in mind your patient’s current health literacy, numeracy, and other limitations.

Next ask about values, preferences, or barriers to whatever treatment you’re talking about. For instance, will this work with your work schedule?

Then the last thing would be ask what the patient wants to do next. Reach a decision on treatment, whatever it is, and make sure that you revisit that decision. Follow up later to see if it’s really working.

Dr. Conlin. If I’m a busy clinician and I have a limited amount of time with a patient, when are the appropriate times to employ the SHARE approach? Can I break it into components, where I address some elements during one visit and other elements in another visit?

Dr. Watts. Absolutely. It can be spread out. Your team is probably already providing information that will help in the SHARE approach. Just chart that you’ve done it. We know the SHARE approach is important because people tend to be adherent if they came up with part of the plan.

Dr. Conlin. Where does diabetes self-management education and diabetes self-management support fall into this framework?

Dr. Watts. Diabetes is a complex disease for providers and for the team and even more so for our patients. Invite them to diabetes classes. There’s so much to understand. The classes go over medications and blood sugar ranges, though you still may have to review it with the patient in your office. It saves the provider time if you have an informed and activated patient. It’s the same with sending a patient to a dietitian. I do all of the above.

Dr. Conlin. Many providers may not be familiar with this type of approach. How can I tell whether or not I’m doing it correctly?

Dr. Watts. The AHRQ website has conversation starters (www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/tools/index.html). Then make sure when you are with the patient to use Teach-Back. Have that conversation and say, “I want to make sure I understood correctly what we decided would work best for you.” Ask patients to say in their own words what they understand. Then I think you’re off to a great start.

Dr. Conlin. Many patients tend to be deferential to their health care providers. They were brought up in an era where they needed to listen to and respect clinicians rather than participate in discussions about their ongoing care. How do you engage with these patients?

Dr. Watts. That is a tough one. Before the patient leaves the office, I ask them: Are there any barriers? Does this work for your schedule? Is this a preference and value that you have? Is there anything that might get in the way of this working when you go home? I try to pull out a little bit more, making sure to give them some decision aids and revisit it at the next visit to make sure it’s working.

Dr. Conlin. We’ll now turn to a discussion of using hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measurements in clinical practice. Dr. Aron, what factors can impact the relationship between HbA1c and blood glucose? How should we use HbA1c in the treatment of patients who come from varied ethnic and racial backgrounds, where the relationship to average blood glucose may be different?