User login

Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia During Orthopedic Surgery

ABSTRACT

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is a significant problem in patients undergoing either emergency or elective orthopedic surgery, and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Though in general the incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in postoperative recovery rooms has been decreasing over the last 2 decades, it still remains a significant risk in certain specialty practices, such as orthopedic surgery. This review article summarizes the currently available evidence on the incidence, risk factors, and complications of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Also, the effective preventive strategies in dealing with inadvertent perioperative hypothermia are reviewed and essential clinical guidelines to be followed are summarized.

Continue to: Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia...

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia, defined as an involuntary drop in core body temperature to <35°C (95°F), is a condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1 This phenomenon has been reported in both emergency orthopedic admissions, such as fracture management, as well as in the elective setting such as arthroscopy, arthroplasty, and spine surgery.

In a study conducted in the United Kingdom including 781 elderly patients with a mean age of 80 years who presented with hip fractures, the 30-day mortality rate was 15.3% in patients who were admitted with a tympanic temperature of <36.5°C and only 5.1% in patients who maintained a tympanic temperature of 36.5°C to 37.5°C (odds ratio, 2.8; P > .0005).2 For an even better perspective, this analysis can be compared with the UK National Hip Fracture Database of 2013, which reported a 30-day mortality of 8.2% in patients who were admitted to the National Health Service with a diagnosis of hip fracture.3

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is also a common phenomenon during elective orthopedic hospital admissions. An Australian audit, which included 5050 postoperative patients, looked into the association between inadvertent perioperative hypothermia and mortality based on diagnostic criteria classifying mild hypothermia as a core temperature of <36°C and severe hypothermia as a core temperature of <35°C.4 The authors found that mild and severe hypothermia was experienced by 36% and 6% of patients, respectively. In-hospital mortality was 5.6% for normothermic patients, 8.9% for all hypothermic patients (P < .001), and 14.7% for severely hypothermic patients (P < .001). For a decrease of 1°C in core body temperature from <36°C to <35°C (but >34°C), there were higher odds of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-2.60).

The physiologic response to hypothermia is to decrease heat loss by cutaneous and peripheral vasoconstriction and increase heat production by increasing the metabolic rate (eg, shivering and shifting to anaerobic metabolism). This response is blunted to a variable extent in perioperative patients for several reasons, including the effect of anesthetic drugs and old age.5

Maintenance of core body temperature >36°C is now a measured standard of perioperative care. A performance measure for perioperative temperature management was developed by the American Medical Association Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA-PCPI).6 To achieve this performance measure, mandatory documentation of use of active warming intraoperatively or a record of at least 1 body temperature ≥96.8°F (36°C) within 30 minutes immediately prior to and 15 minutes immediately after anesthesia end time is necessary. This performance measure is also endorsed by the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP-Inf-10) and National Quality Forum (NQF).6

Continue to: Overall, in the last 2 decades...

Overall, in the last 2 decades, the incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia has decreased, mainly due to aggressive intraoperative management.7 In spite of this, studies have shown that perioperative hypothermia remains a significant problem in patients undergoing orthopedic procedures. In a recent community hospital study conducted by the National Association for Healthcare Quality that included 4124 orthopedic patients undergoing elective surgery, it was shown that, in spite of 99% compliance to the AMA-PCPI recommendation, 7.7% of orthopedic patients were found to be hypothermic.6

Management of hypothermia has long been an integral component of “damage control surgery” and resuscitation during polytrauma, which aims to aggressively minimize hypovolemic shock and limit the development of the lethal triad of hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis.8 However, critical references to prevention and management of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia are lacking in the orthopedic literature on elective surgical procedures. This review aims to bridge this knowledge gap.

Unless otherwise specified, inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in this article refers to the core body temperature. In contrast, peripheral/limb hypothermia refers primarily to the effect of tourniquet application to the involved limb and the effect after deflation of the tourniquet on core body temperature.

RISK FACTORS

There are several measurable risk factors that can contribute to inadvertent perioperative hypothermia, which can be subdivided into 3 groups: patient-related risk factors, anesthesia-related risk factors, and procedure-related risk factors (Table 1).5,9-11 It is important to note that in any given patient a combination of 2 or more risk factors predisposes them to developing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Conceptualizing the etiology of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in this way helps to plan a multipronged strategy to prevent it from occurring in the first place. Some of the important risk factors for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia are discussed below.

Table 1. Risk Factors for Perioperative Hypothermia

Patient-Related Risk Factors | Anesthesia-Related Risk Factors | Procedure-Specific Risk Factors |

|

|

|

To identify patient-related risk factors, researchers from the University of Louisville conducted a study including 2138 operative patients who became hypothermic after admission, of whom 27% underwent orthopedic and spine procedures.9 The patient-related risk factors identified were a high severity of illness on admission (odds ratio, 2.81; 95% CI, 2.28-3.47), presence of a neurological disorder such as Alzheimer’s disease (odds ratio, 1.71; 95% CI,1.06-2.78), male sex (odds ratio, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.36-2.01), age >65 years (odds ratio, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.33-1.96), recent weight loss (odds ratio, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.04-2.48), anemia (odds ratio, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.12-1.98), and chronic renal failure (odds ratio, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.07-1.92). Interestingly, diabetes mellitus without end-stage organ failure was not found to be a significant risk factor (odds ratio, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.75). It is also important to note that some of these risk factors identified to contribute to perioperative hypothermia are dependent on each other and others are independent of each other. For example, chronic renal failure and anemia are dependent risk factors. In contrast, age >65 years and low body mass index as risk factors of perioperative hypothermia are independent of each other.

Continue to: The second subgroup of risk factors...

The second subgroup of risk factors for perioperative hypothermia is related to anesthesia. The effect of general and regional anesthesia on perioperative core temperature is significantly different, both in terms of intraoperative thermoregulation and postoperative recovery.12 Intraoperatively, the core body temperature during the first 2 hours of general anesthesia decreases at a rate of 1.3°C per hour due to loss of thermoregulatory cutaneous and peripheral vasoconstrictive responses resulting in heat loss exceeding metabolic heat production. However, the core temperature remains virtually constant during the subsequent 3 hours due to the return of the thermoregulatory response, which causes cutaneous and peripheral vasoconstriction and increased metabolic heat production. Postoperative recovery from the hypothermia induced by general anesthesia is significantly faster than from that induced by regional anesthesia.13

The effect of regional hypothermia on core body temperature is more complex because it must be considered in addition to the effect of an associated procedure-related variable (ie, tourniquet application). If a tourniquet is not used during a surgery with regional anesthesia, a linear decrease in core temperature follows until recovery, due to increased blood flow from the loss of sympathetic peripheral vasoconstrictive response with resultant core-to-peripheral heat redistribution to the exposed operating limb. If a tourniquet is used during surgery with regional anesthesia, there will be no significant effect of the exposed operating limb on core temperature, as there is no blood flow between them. However, once the tourniquet is deflated, the core body temperature will be affected significantly as a result of core-to-peripheral distribution of heat to the operated limb with the return of blood flow. This fall in core body temperature after tourniquet deflation can be prevented by active forced-air warming initiated from the beginning of surgery.10 The extent and rate of development of peripheral/limb hypothermia during surgery (and its subsequent effect on core body temperature) depends on several factors, including the operating room ambient temperature, duration of tourniquet application, and temperature of the irrigation fluid. Postoperative recovery from the hypothermia induced by regional anesthesia takes longer than from that induced by general anesthesia because of the prolonged period of loss of vasoconstrictive response.

The third subgroup of risk factors associated with perioperative hypothermia is procedure related. Several procedure-specific risk factors for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia during arthroscopic surgery are identified, including prolonged operating time, low blood pressure during the procedure, and low temperature of the irrigation fluid.11 It is logical to extrapolate the importance of these risk factors to other orthopedic procedures which also require prolonged operating times, are performed under hypotension, or expose the patient to irrigation fluid that is at a low temperature. Understanding the importance of each of these procedure-related risk factors is the most important from the perspective of the orthopedic surgeon when compared to the rest of the subgroups of risk factors for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia as he/she is directly responsible for them.

The ambient operating room temperature has traditionally been considered a risk factor for inadvertent hypothermia in perioperative patients, but evidence is available to the contrary. The recommended ambient room temperature as per the clinical guideline published by the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN) is 20°C to 24°C (68°F-75°F).14 The ambient temperature can have a significant effect on peripheral/limb hypothermia when operating on a limb with a tourniquet inflated, as the limb has no blood supply to distribute heat from the core to the periphery. However, the direct effect of ambient room temperature on the patient’s core body temperature is unlikely to be clinically significant if standard active warming interventions are implemented.15

COMPLICATIONS

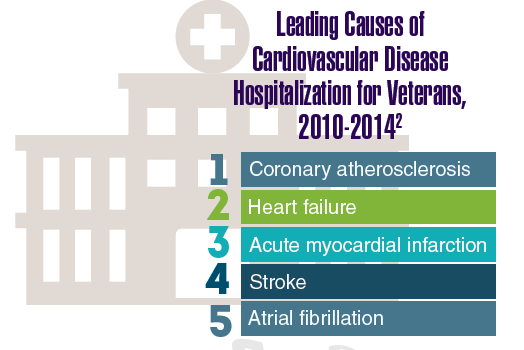

The increased incidence of mortality due to inadvertent hypothermia in the perioperative period has already been discussed. Several other complications of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia include increased incidence of coagulopathy, acidosis, stroke, sepsis, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, surgical site infections, altered drug metabolism, and longer hospital stays.8,9,16-18 Hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis have long been recognized as a lethal triad more commonly seen in polytrauma patients than in elective orthopedic surgery, as this occurs at extremes of temperature, usually <32°C. When compared with patients who did not develop perioperative hypothermia, patients who developed hypothermia during elective operations were shown to experience an overall doubled complication rate (13.9% vs 26.3%; P < .001) of which the incidence of stroke (1.0% vs 6.5%; P < .001), pneumonia (1.3% vs 5.1%; P < .001), and sepsis (2.6% vs 7.5%; P < .001) were much more likely than myocardial infarction (1.1% vs 3.3%; P = .01) and wound infection (3.3% vs 5.0%; P = .14).9

Continue to: Prevention...

PREVENTION

Prevention of perioperative hypothermia is a core measure to improve the outcome after ambulatory and fast-track orthopedic surgery and rehabilitation. Preventive strategies for perioperative hypothermia can be grouped into passive heat retention methods and active external warming methods (Table 2). Passive methods aim to maintain body temperature by decreasing the heat loss by radiation (eg, reflective blanket), conduction (eg, layered cotton blankets and padding the operating table), or convection (eg, heat and humidity exchanger in the breathing circuits) to the surrounding environment. Active patient heating methods aim to bring in heat from the source to the patient’s body using conduction (eg, Hot Dog® [Eden Augustine Temperature Management]) or convection (eg, Bair Hugger® [Arizant Healthcare]) techniques.

Table 2. Methods to Prevent Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia

Passive Heat-Retention Methods | Active External Warming Methods |

| Conduction techniques:

Convection techniques:

|

Active patient warming is superior to passive heat retention methods. A recent Cochrane study assessed the effects of standard care (ie, use of layered clothing and warm blankets, etc.) and addition of extra thermal insulation by reflective blankets or active forced air warming to standard care on the perioperative core body temperature.19 They concluded that there is no clear benefit of addition of extra thermal insulation by reflective blankets compared with standard care alone. Also, forced-air warming in addition to standard care appeared to maintain core temperature better than standard care alone, by between 0.5°C and 1°C, but the clinical importance of this difference could not be inferred, as none of the included studies in this meta-analysis documented major cardiovascular outcomes.

Several clinical guidelines have been developed by not-for-profit, government, and professional organizations aimed at prevention of perioperative hypothermia as primary or secondary outcome. A clinical guideline was published by ASPAN in 2001 for assessment, prevention, and intervention in unplanned perioperative hypothermia.14 Cost and time effectiveness of the ASPAN Hypothermia Guideline was published in 2008.20 The assessment guideline includes identification of risk factors, repeated pre-/intra-/postoperative temperature measurement, and repeated clinical evaluation of the patient’s status. The preventive guideline is to maintain an ambient temperature of 20°C to 24°C (68°F-75°F) and use appropriate passive patient warming methods pre-, intra-, and postoperatively. Intervention in the form of active patient heating is advised only if the patient develops hypothermia in spite of the above-mentioned standard preventive measures. But many orthopedic ambulatory surgery centers currently use active patient warming as both a preventive and an intervention strategy.

Active patient warming by conduction devices occurs by direct physical contact with the device, which is set at a higher temperature, whereas heat transfer from the convection device to the patient occurs by a physical medium such as forced air or circulating water that moves in between the device and the patient. Any recommendation for use of a specific technique of active patient warming (ie, by the use of a conduction device or a convection device) should only be given after comparing evidence on 3 critical aspects: efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness.

The heating efficacy and core rewarming rates of conduction and convection devices have been compared in the literature. Full-body forced-air heating with the Bair Hugger® and full-body resistive polymer heating with the Hot Dog® in healthy volunteers were found to be similar.21 Also, in a randomized study conducted on 80 orthopedic patients undergoing surgery, resistive polymer warming performed as efficiently as forced-air warming in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery.22

Continue to: Secondly, the safety of convection...

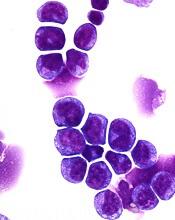

Secondly, the safety of convection devices such as the Bair Hugger® has been under intense scrutiny based on the evidence that it disrupts the laminar airflow in the operating theater.23-26 This disruption in laminar air flow has been shown to cause emission of significant levels of airborne contaminants of size >0.3 μm (germ size).27 Isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus were detected in 13.5%, 3.9%, and 1.9% of forced-air blowers, respectively.28 However, the clinical effect on the rate of deep joint infection due to the disruption of laminar air flow has been examined in only 1 study. McGovern and colleagues29 reported a significant increase in deep joint infection during a period when forced air warming was used compared to a period when conductive fabric warming was used (odds ratio, 3.8; P = .024) and recommended air-free warming by a conduction device over forced-air warming for orthopedic procedures. Unfortunately, the prophylactic antibiotic regimen was not kept constant during their study period. During an overlapping time frame during which they shifted from the use of a convection device (Bair Hugger®) to a conduction device (Hot Dog®), they also changed their antibiotic regimen from gentamicin 4.5 mg/kg intravenous (IV) to gentamicin 3 mg/kg IV plus teicoplanin 400 mg IV. This change in antibiotic regimen is a major confounding factor that calls into question the validity of the conclusions drawn by the authors.

Finally, the cost effectiveness of conduction and convection devices has never been studied. Hence, based on the current evidence, it is not possible to recommend a particular type of active patient-warming device.

CONCLUSION

Orthopedic surgeons should be aware that inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is a common phenomenon in perioperative patients. It must be recognized that the maintenance of perioperative normothermia during all major orthopedic surgical procedures is desirable, as inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is shown to be associated with increased mortality and systemic morbidity, such as stroke and sepsis. Compliance with the current clinical guidelines for assessment, prevention, and treatment of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia will minimize, if not eliminate, such risk. We recommend the following essential clinical guidelines to prevent inadvertent perioperative hypothermia (Table 3). Identification of patient-, anesthesia-, and procedure-related risk factors is an integral component of assessment of the risk of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. In order to achieve full compliance with implementation of active patient warming during surgery, it is prudent to make active warming information a part of the surgical timeout checklist. Irrespective of the presence of risk factors, passive heat retention methods should be part of perioperative management of patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery to prevent inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. In addition, there should be a minimum threshold to utilize active patient-warming techniques, especially in patients with inherent risk factors and surgeries that take >30 minutes of operating time, either under regional or general anesthesia. As there are concerns about safety issues with the use of convection devices, we believe a multicenter randomized controlled trial is warranted.

Table 3. Recommended Essential Clinical Guidelines for Prevention of Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia

|

- Brown DJ, Brugger H, Boyd J, Paal P. Accidental Hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1930-1938. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1114208.

- Uzoigwe CE, Khan A, Smith RP, et al. Hypothermia and low body temperature are common and associated with high mortality in hip fracture patients. Hip Int. 2014; 24(3):237-242. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000124.

- Johansen A, Wakeman R, Boulton C, Plant F, Roberts J, Williams A. National Hip Fracture Database: National Report 2013. London, UK: National Hip Fracture Database, Royal College of Physicians; 2013.

- Karalapillai D, Story DA, Calzavacca, Licari E, Liu YL, Hart GK. Inadvertent hypothermia and mortality in postoperative intensive care patients: retrospective audit of 5050 patients. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(9):968-972. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05989.x.

- Horosz B, Malec-Milewska M. Inadvertent intraoperative hypothermia. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2013;45(1):38-43. doi:10.5603/AIT.2013.0009.

- Steelman VM, Perkhounkova YS, Lemke JH. The gap between compliance with the quality performance measure "perioperative temperature management” and normothermia. J Healthc Qual. 2014;37(6):333-341. doi:10.1111/jhq.12063.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia: The Management of Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia in Adults. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008.

- Carlino W. Damage control resuscitation from major haemorrhage in polytrauma. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(2):137-141. doi:10.1007/s00590-013-1172-7.

- Billeter AT, Hohmann SF, Druen D, Cannon R, Polk HC Jr. Unintentional perioperative hypothermia is associated with severe complications and high mortality in elective operations. Surgery. 2014;156(5):1245-1252. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.024.

- Kim YS, Jeon YS, Lee JA, et al. Intra-operative warming with a forced-air warmer in preventing hypothermia after tourniquet deflation in elderly patients. J Int Med Res. 2009;37(5):1457-1464. doi:10.1177/147323000903700521.

- Parodi D, Tobar C, Valderrama J, et al. Hip arthroscopy and hypothermia. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):924-928. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2011.12.012.

- Kurz A, Sessler DI, Christensen R, Dechert M. Heat balance and distribution during the core-temperature plateau in anesthetized humans. Anesthesiology. 1995;83(3):491-499.

- Vaughan MS, Vaughan RW, Cork RC. Postoperative hypothermia in adults: relationship of age, anesthesia, and shivering to rewarming. Anesth Analg. 1981;60(10):746-751.

- American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses. Clinical guideline for the prevention of unplanned perioperative hypothermia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2001;16(5):305-314.

- Inaba K, Berg R, Barmparas G, et al. Prospective evaluation of ambient operating room temperature on the core temperature of injured patients undergoing emergent surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6):1478-1483. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182781db3.

- Barie PS. Surgical site infections: epidemiology and prevention. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2002;3 Suppl 1:S9-S21. doi:10.1089/sur.2002.3.s1-9.

- Jeran L. Patient temperature: an introduction to the clinical guideline for the prevention of unplanned perioperative hypothermia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2001;16(5):303-304.

- Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. Study of Wound Infection and Temperature Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(19):1209-1215.

- Alderson P, Campbell G, Smith AF, Warttig S, Nicholson A, Lewis SR. Thermal insulation for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD009908. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009908.pub2.

- Berry D, Wick C, Magons P. A clinical evaluation of the cost and time effectiveness of the ASPAN Hypothermia Guideline. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(1):24-35. doi:10.1016/j.jopan.2007.09.010.

- Kimberger O, Held C, Stadelmann K et al. Resistive polymer versus forced-air warming: comparable heat transfer and core rewarming rates in volunteers. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(5):1621-1626. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181845502.

- Brandt S, Oguz R, Hüttner H, et al. Resistive-polymer versus forced-air warming: comparable efficacy in orthopedic patients. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(3):834-838. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cb3f5f.

- Legg AJ, Hammer AJ. Forced-air patient warming blankets disrupt unidirectional airflow. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(3):407-410. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B3.29121.

- Dasari KB, Albrecht M, Harper M. Effect of forced-air warming on the performance of operating theatre laminar flow ventilation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(3):244-249. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06983.x.

- Belani KG, Albrecht M, McGovern PD, Reed M, Nachtsheim C. Patient warming excess heat: the effects on orthopedic operating room ventilation performance. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(2):406-411. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31825f81e2.

- Legg AJ, Cannon T, Hammer AJ. Do forced air patient-warming devices disrupt unidirectional downward airflow? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(2):254-256. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B2.27562.

- Albrecht M, Gaithier RL, Belani K, Litchy M, Leaper D. Forced-air warming blowers: An evaluation of filtration adequacy and airborne contamination emissions in the operating room. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(4):321-328. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2010.06.011.

- Reed M, Kimberger O, McGovern PD, Albrecht MC. Forced-air warming design: evaluation of intake filtration, internal microbial buildup, and airborne-contamination emissions. AANA J. 2013;81(4):275-280.

- McGovern PD, Albercht M, Belani KG, et al. Forced-air warming and ultra-clean ventilation do not mix: an investigation of theatre ventilation, patient warming and joint replacement infection in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Br.2011;93(11):1537-1544. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B11.27124.

ABSTRACT

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is a significant problem in patients undergoing either emergency or elective orthopedic surgery, and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Though in general the incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in postoperative recovery rooms has been decreasing over the last 2 decades, it still remains a significant risk in certain specialty practices, such as orthopedic surgery. This review article summarizes the currently available evidence on the incidence, risk factors, and complications of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Also, the effective preventive strategies in dealing with inadvertent perioperative hypothermia are reviewed and essential clinical guidelines to be followed are summarized.

Continue to: Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia...

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia, defined as an involuntary drop in core body temperature to <35°C (95°F), is a condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1 This phenomenon has been reported in both emergency orthopedic admissions, such as fracture management, as well as in the elective setting such as arthroscopy, arthroplasty, and spine surgery.

In a study conducted in the United Kingdom including 781 elderly patients with a mean age of 80 years who presented with hip fractures, the 30-day mortality rate was 15.3% in patients who were admitted with a tympanic temperature of <36.5°C and only 5.1% in patients who maintained a tympanic temperature of 36.5°C to 37.5°C (odds ratio, 2.8; P > .0005).2 For an even better perspective, this analysis can be compared with the UK National Hip Fracture Database of 2013, which reported a 30-day mortality of 8.2% in patients who were admitted to the National Health Service with a diagnosis of hip fracture.3

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is also a common phenomenon during elective orthopedic hospital admissions. An Australian audit, which included 5050 postoperative patients, looked into the association between inadvertent perioperative hypothermia and mortality based on diagnostic criteria classifying mild hypothermia as a core temperature of <36°C and severe hypothermia as a core temperature of <35°C.4 The authors found that mild and severe hypothermia was experienced by 36% and 6% of patients, respectively. In-hospital mortality was 5.6% for normothermic patients, 8.9% for all hypothermic patients (P < .001), and 14.7% for severely hypothermic patients (P < .001). For a decrease of 1°C in core body temperature from <36°C to <35°C (but >34°C), there were higher odds of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-2.60).

The physiologic response to hypothermia is to decrease heat loss by cutaneous and peripheral vasoconstriction and increase heat production by increasing the metabolic rate (eg, shivering and shifting to anaerobic metabolism). This response is blunted to a variable extent in perioperative patients for several reasons, including the effect of anesthetic drugs and old age.5

Maintenance of core body temperature >36°C is now a measured standard of perioperative care. A performance measure for perioperative temperature management was developed by the American Medical Association Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA-PCPI).6 To achieve this performance measure, mandatory documentation of use of active warming intraoperatively or a record of at least 1 body temperature ≥96.8°F (36°C) within 30 minutes immediately prior to and 15 minutes immediately after anesthesia end time is necessary. This performance measure is also endorsed by the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP-Inf-10) and National Quality Forum (NQF).6

Continue to: Overall, in the last 2 decades...

Overall, in the last 2 decades, the incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia has decreased, mainly due to aggressive intraoperative management.7 In spite of this, studies have shown that perioperative hypothermia remains a significant problem in patients undergoing orthopedic procedures. In a recent community hospital study conducted by the National Association for Healthcare Quality that included 4124 orthopedic patients undergoing elective surgery, it was shown that, in spite of 99% compliance to the AMA-PCPI recommendation, 7.7% of orthopedic patients were found to be hypothermic.6

Management of hypothermia has long been an integral component of “damage control surgery” and resuscitation during polytrauma, which aims to aggressively minimize hypovolemic shock and limit the development of the lethal triad of hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis.8 However, critical references to prevention and management of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia are lacking in the orthopedic literature on elective surgical procedures. This review aims to bridge this knowledge gap.

Unless otherwise specified, inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in this article refers to the core body temperature. In contrast, peripheral/limb hypothermia refers primarily to the effect of tourniquet application to the involved limb and the effect after deflation of the tourniquet on core body temperature.

RISK FACTORS

There are several measurable risk factors that can contribute to inadvertent perioperative hypothermia, which can be subdivided into 3 groups: patient-related risk factors, anesthesia-related risk factors, and procedure-related risk factors (Table 1).5,9-11 It is important to note that in any given patient a combination of 2 or more risk factors predisposes them to developing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Conceptualizing the etiology of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in this way helps to plan a multipronged strategy to prevent it from occurring in the first place. Some of the important risk factors for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia are discussed below.

Table 1. Risk Factors for Perioperative Hypothermia

Patient-Related Risk Factors | Anesthesia-Related Risk Factors | Procedure-Specific Risk Factors |

|

|

|

To identify patient-related risk factors, researchers from the University of Louisville conducted a study including 2138 operative patients who became hypothermic after admission, of whom 27% underwent orthopedic and spine procedures.9 The patient-related risk factors identified were a high severity of illness on admission (odds ratio, 2.81; 95% CI, 2.28-3.47), presence of a neurological disorder such as Alzheimer’s disease (odds ratio, 1.71; 95% CI,1.06-2.78), male sex (odds ratio, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.36-2.01), age >65 years (odds ratio, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.33-1.96), recent weight loss (odds ratio, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.04-2.48), anemia (odds ratio, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.12-1.98), and chronic renal failure (odds ratio, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.07-1.92). Interestingly, diabetes mellitus without end-stage organ failure was not found to be a significant risk factor (odds ratio, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.75). It is also important to note that some of these risk factors identified to contribute to perioperative hypothermia are dependent on each other and others are independent of each other. For example, chronic renal failure and anemia are dependent risk factors. In contrast, age >65 years and low body mass index as risk factors of perioperative hypothermia are independent of each other.

Continue to: The second subgroup of risk factors...

The second subgroup of risk factors for perioperative hypothermia is related to anesthesia. The effect of general and regional anesthesia on perioperative core temperature is significantly different, both in terms of intraoperative thermoregulation and postoperative recovery.12 Intraoperatively, the core body temperature during the first 2 hours of general anesthesia decreases at a rate of 1.3°C per hour due to loss of thermoregulatory cutaneous and peripheral vasoconstrictive responses resulting in heat loss exceeding metabolic heat production. However, the core temperature remains virtually constant during the subsequent 3 hours due to the return of the thermoregulatory response, which causes cutaneous and peripheral vasoconstriction and increased metabolic heat production. Postoperative recovery from the hypothermia induced by general anesthesia is significantly faster than from that induced by regional anesthesia.13

The effect of regional hypothermia on core body temperature is more complex because it must be considered in addition to the effect of an associated procedure-related variable (ie, tourniquet application). If a tourniquet is not used during a surgery with regional anesthesia, a linear decrease in core temperature follows until recovery, due to increased blood flow from the loss of sympathetic peripheral vasoconstrictive response with resultant core-to-peripheral heat redistribution to the exposed operating limb. If a tourniquet is used during surgery with regional anesthesia, there will be no significant effect of the exposed operating limb on core temperature, as there is no blood flow between them. However, once the tourniquet is deflated, the core body temperature will be affected significantly as a result of core-to-peripheral distribution of heat to the operated limb with the return of blood flow. This fall in core body temperature after tourniquet deflation can be prevented by active forced-air warming initiated from the beginning of surgery.10 The extent and rate of development of peripheral/limb hypothermia during surgery (and its subsequent effect on core body temperature) depends on several factors, including the operating room ambient temperature, duration of tourniquet application, and temperature of the irrigation fluid. Postoperative recovery from the hypothermia induced by regional anesthesia takes longer than from that induced by general anesthesia because of the prolonged period of loss of vasoconstrictive response.

The third subgroup of risk factors associated with perioperative hypothermia is procedure related. Several procedure-specific risk factors for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia during arthroscopic surgery are identified, including prolonged operating time, low blood pressure during the procedure, and low temperature of the irrigation fluid.11 It is logical to extrapolate the importance of these risk factors to other orthopedic procedures which also require prolonged operating times, are performed under hypotension, or expose the patient to irrigation fluid that is at a low temperature. Understanding the importance of each of these procedure-related risk factors is the most important from the perspective of the orthopedic surgeon when compared to the rest of the subgroups of risk factors for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia as he/she is directly responsible for them.

The ambient operating room temperature has traditionally been considered a risk factor for inadvertent hypothermia in perioperative patients, but evidence is available to the contrary. The recommended ambient room temperature as per the clinical guideline published by the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN) is 20°C to 24°C (68°F-75°F).14 The ambient temperature can have a significant effect on peripheral/limb hypothermia when operating on a limb with a tourniquet inflated, as the limb has no blood supply to distribute heat from the core to the periphery. However, the direct effect of ambient room temperature on the patient’s core body temperature is unlikely to be clinically significant if standard active warming interventions are implemented.15

COMPLICATIONS

The increased incidence of mortality due to inadvertent hypothermia in the perioperative period has already been discussed. Several other complications of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia include increased incidence of coagulopathy, acidosis, stroke, sepsis, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, surgical site infections, altered drug metabolism, and longer hospital stays.8,9,16-18 Hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis have long been recognized as a lethal triad more commonly seen in polytrauma patients than in elective orthopedic surgery, as this occurs at extremes of temperature, usually <32°C. When compared with patients who did not develop perioperative hypothermia, patients who developed hypothermia during elective operations were shown to experience an overall doubled complication rate (13.9% vs 26.3%; P < .001) of which the incidence of stroke (1.0% vs 6.5%; P < .001), pneumonia (1.3% vs 5.1%; P < .001), and sepsis (2.6% vs 7.5%; P < .001) were much more likely than myocardial infarction (1.1% vs 3.3%; P = .01) and wound infection (3.3% vs 5.0%; P = .14).9

Continue to: Prevention...

PREVENTION

Prevention of perioperative hypothermia is a core measure to improve the outcome after ambulatory and fast-track orthopedic surgery and rehabilitation. Preventive strategies for perioperative hypothermia can be grouped into passive heat retention methods and active external warming methods (Table 2). Passive methods aim to maintain body temperature by decreasing the heat loss by radiation (eg, reflective blanket), conduction (eg, layered cotton blankets and padding the operating table), or convection (eg, heat and humidity exchanger in the breathing circuits) to the surrounding environment. Active patient heating methods aim to bring in heat from the source to the patient’s body using conduction (eg, Hot Dog® [Eden Augustine Temperature Management]) or convection (eg, Bair Hugger® [Arizant Healthcare]) techniques.

Table 2. Methods to Prevent Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia

Passive Heat-Retention Methods | Active External Warming Methods |

| Conduction techniques:

Convection techniques:

|

Active patient warming is superior to passive heat retention methods. A recent Cochrane study assessed the effects of standard care (ie, use of layered clothing and warm blankets, etc.) and addition of extra thermal insulation by reflective blankets or active forced air warming to standard care on the perioperative core body temperature.19 They concluded that there is no clear benefit of addition of extra thermal insulation by reflective blankets compared with standard care alone. Also, forced-air warming in addition to standard care appeared to maintain core temperature better than standard care alone, by between 0.5°C and 1°C, but the clinical importance of this difference could not be inferred, as none of the included studies in this meta-analysis documented major cardiovascular outcomes.

Several clinical guidelines have been developed by not-for-profit, government, and professional organizations aimed at prevention of perioperative hypothermia as primary or secondary outcome. A clinical guideline was published by ASPAN in 2001 for assessment, prevention, and intervention in unplanned perioperative hypothermia.14 Cost and time effectiveness of the ASPAN Hypothermia Guideline was published in 2008.20 The assessment guideline includes identification of risk factors, repeated pre-/intra-/postoperative temperature measurement, and repeated clinical evaluation of the patient’s status. The preventive guideline is to maintain an ambient temperature of 20°C to 24°C (68°F-75°F) and use appropriate passive patient warming methods pre-, intra-, and postoperatively. Intervention in the form of active patient heating is advised only if the patient develops hypothermia in spite of the above-mentioned standard preventive measures. But many orthopedic ambulatory surgery centers currently use active patient warming as both a preventive and an intervention strategy.

Active patient warming by conduction devices occurs by direct physical contact with the device, which is set at a higher temperature, whereas heat transfer from the convection device to the patient occurs by a physical medium such as forced air or circulating water that moves in between the device and the patient. Any recommendation for use of a specific technique of active patient warming (ie, by the use of a conduction device or a convection device) should only be given after comparing evidence on 3 critical aspects: efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness.

The heating efficacy and core rewarming rates of conduction and convection devices have been compared in the literature. Full-body forced-air heating with the Bair Hugger® and full-body resistive polymer heating with the Hot Dog® in healthy volunteers were found to be similar.21 Also, in a randomized study conducted on 80 orthopedic patients undergoing surgery, resistive polymer warming performed as efficiently as forced-air warming in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery.22

Continue to: Secondly, the safety of convection...

Secondly, the safety of convection devices such as the Bair Hugger® has been under intense scrutiny based on the evidence that it disrupts the laminar airflow in the operating theater.23-26 This disruption in laminar air flow has been shown to cause emission of significant levels of airborne contaminants of size >0.3 μm (germ size).27 Isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus were detected in 13.5%, 3.9%, and 1.9% of forced-air blowers, respectively.28 However, the clinical effect on the rate of deep joint infection due to the disruption of laminar air flow has been examined in only 1 study. McGovern and colleagues29 reported a significant increase in deep joint infection during a period when forced air warming was used compared to a period when conductive fabric warming was used (odds ratio, 3.8; P = .024) and recommended air-free warming by a conduction device over forced-air warming for orthopedic procedures. Unfortunately, the prophylactic antibiotic regimen was not kept constant during their study period. During an overlapping time frame during which they shifted from the use of a convection device (Bair Hugger®) to a conduction device (Hot Dog®), they also changed their antibiotic regimen from gentamicin 4.5 mg/kg intravenous (IV) to gentamicin 3 mg/kg IV plus teicoplanin 400 mg IV. This change in antibiotic regimen is a major confounding factor that calls into question the validity of the conclusions drawn by the authors.

Finally, the cost effectiveness of conduction and convection devices has never been studied. Hence, based on the current evidence, it is not possible to recommend a particular type of active patient-warming device.

CONCLUSION

Orthopedic surgeons should be aware that inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is a common phenomenon in perioperative patients. It must be recognized that the maintenance of perioperative normothermia during all major orthopedic surgical procedures is desirable, as inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is shown to be associated with increased mortality and systemic morbidity, such as stroke and sepsis. Compliance with the current clinical guidelines for assessment, prevention, and treatment of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia will minimize, if not eliminate, such risk. We recommend the following essential clinical guidelines to prevent inadvertent perioperative hypothermia (Table 3). Identification of patient-, anesthesia-, and procedure-related risk factors is an integral component of assessment of the risk of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. In order to achieve full compliance with implementation of active patient warming during surgery, it is prudent to make active warming information a part of the surgical timeout checklist. Irrespective of the presence of risk factors, passive heat retention methods should be part of perioperative management of patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery to prevent inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. In addition, there should be a minimum threshold to utilize active patient-warming techniques, especially in patients with inherent risk factors and surgeries that take >30 minutes of operating time, either under regional or general anesthesia. As there are concerns about safety issues with the use of convection devices, we believe a multicenter randomized controlled trial is warranted.

Table 3. Recommended Essential Clinical Guidelines for Prevention of Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia

|

ABSTRACT

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is a significant problem in patients undergoing either emergency or elective orthopedic surgery, and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Though in general the incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in postoperative recovery rooms has been decreasing over the last 2 decades, it still remains a significant risk in certain specialty practices, such as orthopedic surgery. This review article summarizes the currently available evidence on the incidence, risk factors, and complications of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Also, the effective preventive strategies in dealing with inadvertent perioperative hypothermia are reviewed and essential clinical guidelines to be followed are summarized.

Continue to: Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia...

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia, defined as an involuntary drop in core body temperature to <35°C (95°F), is a condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1 This phenomenon has been reported in both emergency orthopedic admissions, such as fracture management, as well as in the elective setting such as arthroscopy, arthroplasty, and spine surgery.

In a study conducted in the United Kingdom including 781 elderly patients with a mean age of 80 years who presented with hip fractures, the 30-day mortality rate was 15.3% in patients who were admitted with a tympanic temperature of <36.5°C and only 5.1% in patients who maintained a tympanic temperature of 36.5°C to 37.5°C (odds ratio, 2.8; P > .0005).2 For an even better perspective, this analysis can be compared with the UK National Hip Fracture Database of 2013, which reported a 30-day mortality of 8.2% in patients who were admitted to the National Health Service with a diagnosis of hip fracture.3

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is also a common phenomenon during elective orthopedic hospital admissions. An Australian audit, which included 5050 postoperative patients, looked into the association between inadvertent perioperative hypothermia and mortality based on diagnostic criteria classifying mild hypothermia as a core temperature of <36°C and severe hypothermia as a core temperature of <35°C.4 The authors found that mild and severe hypothermia was experienced by 36% and 6% of patients, respectively. In-hospital mortality was 5.6% for normothermic patients, 8.9% for all hypothermic patients (P < .001), and 14.7% for severely hypothermic patients (P < .001). For a decrease of 1°C in core body temperature from <36°C to <35°C (but >34°C), there were higher odds of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-2.60).

The physiologic response to hypothermia is to decrease heat loss by cutaneous and peripheral vasoconstriction and increase heat production by increasing the metabolic rate (eg, shivering and shifting to anaerobic metabolism). This response is blunted to a variable extent in perioperative patients for several reasons, including the effect of anesthetic drugs and old age.5

Maintenance of core body temperature >36°C is now a measured standard of perioperative care. A performance measure for perioperative temperature management was developed by the American Medical Association Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA-PCPI).6 To achieve this performance measure, mandatory documentation of use of active warming intraoperatively or a record of at least 1 body temperature ≥96.8°F (36°C) within 30 minutes immediately prior to and 15 minutes immediately after anesthesia end time is necessary. This performance measure is also endorsed by the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP-Inf-10) and National Quality Forum (NQF).6

Continue to: Overall, in the last 2 decades...

Overall, in the last 2 decades, the incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia has decreased, mainly due to aggressive intraoperative management.7 In spite of this, studies have shown that perioperative hypothermia remains a significant problem in patients undergoing orthopedic procedures. In a recent community hospital study conducted by the National Association for Healthcare Quality that included 4124 orthopedic patients undergoing elective surgery, it was shown that, in spite of 99% compliance to the AMA-PCPI recommendation, 7.7% of orthopedic patients were found to be hypothermic.6

Management of hypothermia has long been an integral component of “damage control surgery” and resuscitation during polytrauma, which aims to aggressively minimize hypovolemic shock and limit the development of the lethal triad of hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis.8 However, critical references to prevention and management of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia are lacking in the orthopedic literature on elective surgical procedures. This review aims to bridge this knowledge gap.

Unless otherwise specified, inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in this article refers to the core body temperature. In contrast, peripheral/limb hypothermia refers primarily to the effect of tourniquet application to the involved limb and the effect after deflation of the tourniquet on core body temperature.

RISK FACTORS

There are several measurable risk factors that can contribute to inadvertent perioperative hypothermia, which can be subdivided into 3 groups: patient-related risk factors, anesthesia-related risk factors, and procedure-related risk factors (Table 1).5,9-11 It is important to note that in any given patient a combination of 2 or more risk factors predisposes them to developing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Conceptualizing the etiology of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in this way helps to plan a multipronged strategy to prevent it from occurring in the first place. Some of the important risk factors for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia are discussed below.

Table 1. Risk Factors for Perioperative Hypothermia

Patient-Related Risk Factors | Anesthesia-Related Risk Factors | Procedure-Specific Risk Factors |

|

|

|

To identify patient-related risk factors, researchers from the University of Louisville conducted a study including 2138 operative patients who became hypothermic after admission, of whom 27% underwent orthopedic and spine procedures.9 The patient-related risk factors identified were a high severity of illness on admission (odds ratio, 2.81; 95% CI, 2.28-3.47), presence of a neurological disorder such as Alzheimer’s disease (odds ratio, 1.71; 95% CI,1.06-2.78), male sex (odds ratio, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.36-2.01), age >65 years (odds ratio, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.33-1.96), recent weight loss (odds ratio, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.04-2.48), anemia (odds ratio, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.12-1.98), and chronic renal failure (odds ratio, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.07-1.92). Interestingly, diabetes mellitus without end-stage organ failure was not found to be a significant risk factor (odds ratio, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.75). It is also important to note that some of these risk factors identified to contribute to perioperative hypothermia are dependent on each other and others are independent of each other. For example, chronic renal failure and anemia are dependent risk factors. In contrast, age >65 years and low body mass index as risk factors of perioperative hypothermia are independent of each other.

Continue to: The second subgroup of risk factors...

The second subgroup of risk factors for perioperative hypothermia is related to anesthesia. The effect of general and regional anesthesia on perioperative core temperature is significantly different, both in terms of intraoperative thermoregulation and postoperative recovery.12 Intraoperatively, the core body temperature during the first 2 hours of general anesthesia decreases at a rate of 1.3°C per hour due to loss of thermoregulatory cutaneous and peripheral vasoconstrictive responses resulting in heat loss exceeding metabolic heat production. However, the core temperature remains virtually constant during the subsequent 3 hours due to the return of the thermoregulatory response, which causes cutaneous and peripheral vasoconstriction and increased metabolic heat production. Postoperative recovery from the hypothermia induced by general anesthesia is significantly faster than from that induced by regional anesthesia.13

The effect of regional hypothermia on core body temperature is more complex because it must be considered in addition to the effect of an associated procedure-related variable (ie, tourniquet application). If a tourniquet is not used during a surgery with regional anesthesia, a linear decrease in core temperature follows until recovery, due to increased blood flow from the loss of sympathetic peripheral vasoconstrictive response with resultant core-to-peripheral heat redistribution to the exposed operating limb. If a tourniquet is used during surgery with regional anesthesia, there will be no significant effect of the exposed operating limb on core temperature, as there is no blood flow between them. However, once the tourniquet is deflated, the core body temperature will be affected significantly as a result of core-to-peripheral distribution of heat to the operated limb with the return of blood flow. This fall in core body temperature after tourniquet deflation can be prevented by active forced-air warming initiated from the beginning of surgery.10 The extent and rate of development of peripheral/limb hypothermia during surgery (and its subsequent effect on core body temperature) depends on several factors, including the operating room ambient temperature, duration of tourniquet application, and temperature of the irrigation fluid. Postoperative recovery from the hypothermia induced by regional anesthesia takes longer than from that induced by general anesthesia because of the prolonged period of loss of vasoconstrictive response.

The third subgroup of risk factors associated with perioperative hypothermia is procedure related. Several procedure-specific risk factors for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia during arthroscopic surgery are identified, including prolonged operating time, low blood pressure during the procedure, and low temperature of the irrigation fluid.11 It is logical to extrapolate the importance of these risk factors to other orthopedic procedures which also require prolonged operating times, are performed under hypotension, or expose the patient to irrigation fluid that is at a low temperature. Understanding the importance of each of these procedure-related risk factors is the most important from the perspective of the orthopedic surgeon when compared to the rest of the subgroups of risk factors for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia as he/she is directly responsible for them.

The ambient operating room temperature has traditionally been considered a risk factor for inadvertent hypothermia in perioperative patients, but evidence is available to the contrary. The recommended ambient room temperature as per the clinical guideline published by the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN) is 20°C to 24°C (68°F-75°F).14 The ambient temperature can have a significant effect on peripheral/limb hypothermia when operating on a limb with a tourniquet inflated, as the limb has no blood supply to distribute heat from the core to the periphery. However, the direct effect of ambient room temperature on the patient’s core body temperature is unlikely to be clinically significant if standard active warming interventions are implemented.15

COMPLICATIONS

The increased incidence of mortality due to inadvertent hypothermia in the perioperative period has already been discussed. Several other complications of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia include increased incidence of coagulopathy, acidosis, stroke, sepsis, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, surgical site infections, altered drug metabolism, and longer hospital stays.8,9,16-18 Hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis have long been recognized as a lethal triad more commonly seen in polytrauma patients than in elective orthopedic surgery, as this occurs at extremes of temperature, usually <32°C. When compared with patients who did not develop perioperative hypothermia, patients who developed hypothermia during elective operations were shown to experience an overall doubled complication rate (13.9% vs 26.3%; P < .001) of which the incidence of stroke (1.0% vs 6.5%; P < .001), pneumonia (1.3% vs 5.1%; P < .001), and sepsis (2.6% vs 7.5%; P < .001) were much more likely than myocardial infarction (1.1% vs 3.3%; P = .01) and wound infection (3.3% vs 5.0%; P = .14).9

Continue to: Prevention...

PREVENTION

Prevention of perioperative hypothermia is a core measure to improve the outcome after ambulatory and fast-track orthopedic surgery and rehabilitation. Preventive strategies for perioperative hypothermia can be grouped into passive heat retention methods and active external warming methods (Table 2). Passive methods aim to maintain body temperature by decreasing the heat loss by radiation (eg, reflective blanket), conduction (eg, layered cotton blankets and padding the operating table), or convection (eg, heat and humidity exchanger in the breathing circuits) to the surrounding environment. Active patient heating methods aim to bring in heat from the source to the patient’s body using conduction (eg, Hot Dog® [Eden Augustine Temperature Management]) or convection (eg, Bair Hugger® [Arizant Healthcare]) techniques.

Table 2. Methods to Prevent Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia

Passive Heat-Retention Methods | Active External Warming Methods |

| Conduction techniques:

Convection techniques:

|

Active patient warming is superior to passive heat retention methods. A recent Cochrane study assessed the effects of standard care (ie, use of layered clothing and warm blankets, etc.) and addition of extra thermal insulation by reflective blankets or active forced air warming to standard care on the perioperative core body temperature.19 They concluded that there is no clear benefit of addition of extra thermal insulation by reflective blankets compared with standard care alone. Also, forced-air warming in addition to standard care appeared to maintain core temperature better than standard care alone, by between 0.5°C and 1°C, but the clinical importance of this difference could not be inferred, as none of the included studies in this meta-analysis documented major cardiovascular outcomes.

Several clinical guidelines have been developed by not-for-profit, government, and professional organizations aimed at prevention of perioperative hypothermia as primary or secondary outcome. A clinical guideline was published by ASPAN in 2001 for assessment, prevention, and intervention in unplanned perioperative hypothermia.14 Cost and time effectiveness of the ASPAN Hypothermia Guideline was published in 2008.20 The assessment guideline includes identification of risk factors, repeated pre-/intra-/postoperative temperature measurement, and repeated clinical evaluation of the patient’s status. The preventive guideline is to maintain an ambient temperature of 20°C to 24°C (68°F-75°F) and use appropriate passive patient warming methods pre-, intra-, and postoperatively. Intervention in the form of active patient heating is advised only if the patient develops hypothermia in spite of the above-mentioned standard preventive measures. But many orthopedic ambulatory surgery centers currently use active patient warming as both a preventive and an intervention strategy.

Active patient warming by conduction devices occurs by direct physical contact with the device, which is set at a higher temperature, whereas heat transfer from the convection device to the patient occurs by a physical medium such as forced air or circulating water that moves in between the device and the patient. Any recommendation for use of a specific technique of active patient warming (ie, by the use of a conduction device or a convection device) should only be given after comparing evidence on 3 critical aspects: efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness.

The heating efficacy and core rewarming rates of conduction and convection devices have been compared in the literature. Full-body forced-air heating with the Bair Hugger® and full-body resistive polymer heating with the Hot Dog® in healthy volunteers were found to be similar.21 Also, in a randomized study conducted on 80 orthopedic patients undergoing surgery, resistive polymer warming performed as efficiently as forced-air warming in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery.22

Continue to: Secondly, the safety of convection...

Secondly, the safety of convection devices such as the Bair Hugger® has been under intense scrutiny based on the evidence that it disrupts the laminar airflow in the operating theater.23-26 This disruption in laminar air flow has been shown to cause emission of significant levels of airborne contaminants of size >0.3 μm (germ size).27 Isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus were detected in 13.5%, 3.9%, and 1.9% of forced-air blowers, respectively.28 However, the clinical effect on the rate of deep joint infection due to the disruption of laminar air flow has been examined in only 1 study. McGovern and colleagues29 reported a significant increase in deep joint infection during a period when forced air warming was used compared to a period when conductive fabric warming was used (odds ratio, 3.8; P = .024) and recommended air-free warming by a conduction device over forced-air warming for orthopedic procedures. Unfortunately, the prophylactic antibiotic regimen was not kept constant during their study period. During an overlapping time frame during which they shifted from the use of a convection device (Bair Hugger®) to a conduction device (Hot Dog®), they also changed their antibiotic regimen from gentamicin 4.5 mg/kg intravenous (IV) to gentamicin 3 mg/kg IV plus teicoplanin 400 mg IV. This change in antibiotic regimen is a major confounding factor that calls into question the validity of the conclusions drawn by the authors.

Finally, the cost effectiveness of conduction and convection devices has never been studied. Hence, based on the current evidence, it is not possible to recommend a particular type of active patient-warming device.

CONCLUSION

Orthopedic surgeons should be aware that inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is a common phenomenon in perioperative patients. It must be recognized that the maintenance of perioperative normothermia during all major orthopedic surgical procedures is desirable, as inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is shown to be associated with increased mortality and systemic morbidity, such as stroke and sepsis. Compliance with the current clinical guidelines for assessment, prevention, and treatment of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia will minimize, if not eliminate, such risk. We recommend the following essential clinical guidelines to prevent inadvertent perioperative hypothermia (Table 3). Identification of patient-, anesthesia-, and procedure-related risk factors is an integral component of assessment of the risk of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. In order to achieve full compliance with implementation of active patient warming during surgery, it is prudent to make active warming information a part of the surgical timeout checklist. Irrespective of the presence of risk factors, passive heat retention methods should be part of perioperative management of patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery to prevent inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. In addition, there should be a minimum threshold to utilize active patient-warming techniques, especially in patients with inherent risk factors and surgeries that take >30 minutes of operating time, either under regional or general anesthesia. As there are concerns about safety issues with the use of convection devices, we believe a multicenter randomized controlled trial is warranted.

Table 3. Recommended Essential Clinical Guidelines for Prevention of Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia

|

- Brown DJ, Brugger H, Boyd J, Paal P. Accidental Hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1930-1938. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1114208.

- Uzoigwe CE, Khan A, Smith RP, et al. Hypothermia and low body temperature are common and associated with high mortality in hip fracture patients. Hip Int. 2014; 24(3):237-242. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000124.

- Johansen A, Wakeman R, Boulton C, Plant F, Roberts J, Williams A. National Hip Fracture Database: National Report 2013. London, UK: National Hip Fracture Database, Royal College of Physicians; 2013.

- Karalapillai D, Story DA, Calzavacca, Licari E, Liu YL, Hart GK. Inadvertent hypothermia and mortality in postoperative intensive care patients: retrospective audit of 5050 patients. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(9):968-972. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05989.x.

- Horosz B, Malec-Milewska M. Inadvertent intraoperative hypothermia. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2013;45(1):38-43. doi:10.5603/AIT.2013.0009.

- Steelman VM, Perkhounkova YS, Lemke JH. The gap between compliance with the quality performance measure "perioperative temperature management” and normothermia. J Healthc Qual. 2014;37(6):333-341. doi:10.1111/jhq.12063.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia: The Management of Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia in Adults. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008.

- Carlino W. Damage control resuscitation from major haemorrhage in polytrauma. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(2):137-141. doi:10.1007/s00590-013-1172-7.

- Billeter AT, Hohmann SF, Druen D, Cannon R, Polk HC Jr. Unintentional perioperative hypothermia is associated with severe complications and high mortality in elective operations. Surgery. 2014;156(5):1245-1252. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.024.

- Kim YS, Jeon YS, Lee JA, et al. Intra-operative warming with a forced-air warmer in preventing hypothermia after tourniquet deflation in elderly patients. J Int Med Res. 2009;37(5):1457-1464. doi:10.1177/147323000903700521.

- Parodi D, Tobar C, Valderrama J, et al. Hip arthroscopy and hypothermia. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):924-928. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2011.12.012.

- Kurz A, Sessler DI, Christensen R, Dechert M. Heat balance and distribution during the core-temperature plateau in anesthetized humans. Anesthesiology. 1995;83(3):491-499.

- Vaughan MS, Vaughan RW, Cork RC. Postoperative hypothermia in adults: relationship of age, anesthesia, and shivering to rewarming. Anesth Analg. 1981;60(10):746-751.

- American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses. Clinical guideline for the prevention of unplanned perioperative hypothermia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2001;16(5):305-314.

- Inaba K, Berg R, Barmparas G, et al. Prospective evaluation of ambient operating room temperature on the core temperature of injured patients undergoing emergent surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6):1478-1483. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182781db3.

- Barie PS. Surgical site infections: epidemiology and prevention. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2002;3 Suppl 1:S9-S21. doi:10.1089/sur.2002.3.s1-9.

- Jeran L. Patient temperature: an introduction to the clinical guideline for the prevention of unplanned perioperative hypothermia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2001;16(5):303-304.

- Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. Study of Wound Infection and Temperature Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(19):1209-1215.

- Alderson P, Campbell G, Smith AF, Warttig S, Nicholson A, Lewis SR. Thermal insulation for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD009908. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009908.pub2.

- Berry D, Wick C, Magons P. A clinical evaluation of the cost and time effectiveness of the ASPAN Hypothermia Guideline. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(1):24-35. doi:10.1016/j.jopan.2007.09.010.

- Kimberger O, Held C, Stadelmann K et al. Resistive polymer versus forced-air warming: comparable heat transfer and core rewarming rates in volunteers. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(5):1621-1626. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181845502.

- Brandt S, Oguz R, Hüttner H, et al. Resistive-polymer versus forced-air warming: comparable efficacy in orthopedic patients. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(3):834-838. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cb3f5f.

- Legg AJ, Hammer AJ. Forced-air patient warming blankets disrupt unidirectional airflow. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(3):407-410. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B3.29121.

- Dasari KB, Albrecht M, Harper M. Effect of forced-air warming on the performance of operating theatre laminar flow ventilation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(3):244-249. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06983.x.

- Belani KG, Albrecht M, McGovern PD, Reed M, Nachtsheim C. Patient warming excess heat: the effects on orthopedic operating room ventilation performance. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(2):406-411. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31825f81e2.

- Legg AJ, Cannon T, Hammer AJ. Do forced air patient-warming devices disrupt unidirectional downward airflow? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(2):254-256. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B2.27562.

- Albrecht M, Gaithier RL, Belani K, Litchy M, Leaper D. Forced-air warming blowers: An evaluation of filtration adequacy and airborne contamination emissions in the operating room. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(4):321-328. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2010.06.011.

- Reed M, Kimberger O, McGovern PD, Albrecht MC. Forced-air warming design: evaluation of intake filtration, internal microbial buildup, and airborne-contamination emissions. AANA J. 2013;81(4):275-280.

- McGovern PD, Albercht M, Belani KG, et al. Forced-air warming and ultra-clean ventilation do not mix: an investigation of theatre ventilation, patient warming and joint replacement infection in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Br.2011;93(11):1537-1544. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B11.27124.

- Brown DJ, Brugger H, Boyd J, Paal P. Accidental Hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1930-1938. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1114208.

- Uzoigwe CE, Khan A, Smith RP, et al. Hypothermia and low body temperature are common and associated with high mortality in hip fracture patients. Hip Int. 2014; 24(3):237-242. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000124.

- Johansen A, Wakeman R, Boulton C, Plant F, Roberts J, Williams A. National Hip Fracture Database: National Report 2013. London, UK: National Hip Fracture Database, Royal College of Physicians; 2013.

- Karalapillai D, Story DA, Calzavacca, Licari E, Liu YL, Hart GK. Inadvertent hypothermia and mortality in postoperative intensive care patients: retrospective audit of 5050 patients. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(9):968-972. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05989.x.

- Horosz B, Malec-Milewska M. Inadvertent intraoperative hypothermia. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2013;45(1):38-43. doi:10.5603/AIT.2013.0009.

- Steelman VM, Perkhounkova YS, Lemke JH. The gap between compliance with the quality performance measure "perioperative temperature management” and normothermia. J Healthc Qual. 2014;37(6):333-341. doi:10.1111/jhq.12063.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia: The Management of Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia in Adults. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008.

- Carlino W. Damage control resuscitation from major haemorrhage in polytrauma. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(2):137-141. doi:10.1007/s00590-013-1172-7.

- Billeter AT, Hohmann SF, Druen D, Cannon R, Polk HC Jr. Unintentional perioperative hypothermia is associated with severe complications and high mortality in elective operations. Surgery. 2014;156(5):1245-1252. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.024.

- Kim YS, Jeon YS, Lee JA, et al. Intra-operative warming with a forced-air warmer in preventing hypothermia after tourniquet deflation in elderly patients. J Int Med Res. 2009;37(5):1457-1464. doi:10.1177/147323000903700521.

- Parodi D, Tobar C, Valderrama J, et al. Hip arthroscopy and hypothermia. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):924-928. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2011.12.012.

- Kurz A, Sessler DI, Christensen R, Dechert M. Heat balance and distribution during the core-temperature plateau in anesthetized humans. Anesthesiology. 1995;83(3):491-499.

- Vaughan MS, Vaughan RW, Cork RC. Postoperative hypothermia in adults: relationship of age, anesthesia, and shivering to rewarming. Anesth Analg. 1981;60(10):746-751.

- American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses. Clinical guideline for the prevention of unplanned perioperative hypothermia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2001;16(5):305-314.

- Inaba K, Berg R, Barmparas G, et al. Prospective evaluation of ambient operating room temperature on the core temperature of injured patients undergoing emergent surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6):1478-1483. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182781db3.

- Barie PS. Surgical site infections: epidemiology and prevention. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2002;3 Suppl 1:S9-S21. doi:10.1089/sur.2002.3.s1-9.

- Jeran L. Patient temperature: an introduction to the clinical guideline for the prevention of unplanned perioperative hypothermia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2001;16(5):303-304.

- Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. Study of Wound Infection and Temperature Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(19):1209-1215.

- Alderson P, Campbell G, Smith AF, Warttig S, Nicholson A, Lewis SR. Thermal insulation for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD009908. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009908.pub2.

- Berry D, Wick C, Magons P. A clinical evaluation of the cost and time effectiveness of the ASPAN Hypothermia Guideline. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(1):24-35. doi:10.1016/j.jopan.2007.09.010.

- Kimberger O, Held C, Stadelmann K et al. Resistive polymer versus forced-air warming: comparable heat transfer and core rewarming rates in volunteers. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(5):1621-1626. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181845502.

- Brandt S, Oguz R, Hüttner H, et al. Resistive-polymer versus forced-air warming: comparable efficacy in orthopedic patients. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(3):834-838. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cb3f5f.

- Legg AJ, Hammer AJ. Forced-air patient warming blankets disrupt unidirectional airflow. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(3):407-410. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B3.29121.

- Dasari KB, Albrecht M, Harper M. Effect of forced-air warming on the performance of operating theatre laminar flow ventilation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(3):244-249. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06983.x.

- Belani KG, Albrecht M, McGovern PD, Reed M, Nachtsheim C. Patient warming excess heat: the effects on orthopedic operating room ventilation performance. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(2):406-411. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31825f81e2.

- Legg AJ, Cannon T, Hammer AJ. Do forced air patient-warming devices disrupt unidirectional downward airflow? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(2):254-256. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B2.27562.

- Albrecht M, Gaithier RL, Belani K, Litchy M, Leaper D. Forced-air warming blowers: An evaluation of filtration adequacy and airborne contamination emissions in the operating room. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(4):321-328. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2010.06.011.

- Reed M, Kimberger O, McGovern PD, Albrecht MC. Forced-air warming design: evaluation of intake filtration, internal microbial buildup, and airborne-contamination emissions. AANA J. 2013;81(4):275-280.

- McGovern PD, Albercht M, Belani KG, et al. Forced-air warming and ultra-clean ventilation do not mix: an investigation of theatre ventilation, patient warming and joint replacement infection in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Br.2011;93(11):1537-1544. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B11.27124.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia, defined as an involuntary drop in core body temperature to <35°C (95°F), is a condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

- Maintenance of core body temperature >36°C is now a measured standard of perioperative care.

- Overall, in the last 2 decades, the incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia has decreased, mainly due to aggressive intraoperative management.