User login

CHMP backs expanded approval of tocilizumab

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the approved use of tocilizumab (RoActemra).

The recommendation is for tocilizumab to treat adults and pediatric patients age 2 and older who have severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome (CRS) induced by chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The CHMP’s recommendation will be reviewed by the European Commission, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission usually makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

Tocilizumab is a humanized interleukin-6 receptor antagonist marketed by Roche Registration GmbH.

The drug is already approved by the European Commission to treat rheumatoid arthritis, active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and juvenile idiopathic polyarthritis.

The CHMP’s recommendation to expand the approved use of tocilizumab is supported by results from a retrospective analysis of data from clinical trials of CAR T-cell therapies in patients with hematologic malignancies.

For this analysis, researchers assessed 45 pediatric and adult patients treated with tocilizumab, with or without additional high-dose corticosteroids, for severe or life-threatening CRS.

Thirty-one patients (69%) achieved a response, defined as resolution of CRS within 14 days of the first dose of tocilizumab.

No more than 2 doses of tocilizumab were needed, and no drugs other than tocilizumab and corticosteroids were used for treatment.

No adverse reactions related to tocilizumab were reported.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the approved use of tocilizumab (RoActemra).

The recommendation is for tocilizumab to treat adults and pediatric patients age 2 and older who have severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome (CRS) induced by chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The CHMP’s recommendation will be reviewed by the European Commission, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission usually makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

Tocilizumab is a humanized interleukin-6 receptor antagonist marketed by Roche Registration GmbH.

The drug is already approved by the European Commission to treat rheumatoid arthritis, active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and juvenile idiopathic polyarthritis.

The CHMP’s recommendation to expand the approved use of tocilizumab is supported by results from a retrospective analysis of data from clinical trials of CAR T-cell therapies in patients with hematologic malignancies.

For this analysis, researchers assessed 45 pediatric and adult patients treated with tocilizumab, with or without additional high-dose corticosteroids, for severe or life-threatening CRS.

Thirty-one patients (69%) achieved a response, defined as resolution of CRS within 14 days of the first dose of tocilizumab.

No more than 2 doses of tocilizumab were needed, and no drugs other than tocilizumab and corticosteroids were used for treatment.

No adverse reactions related to tocilizumab were reported.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the approved use of tocilizumab (RoActemra).

The recommendation is for tocilizumab to treat adults and pediatric patients age 2 and older who have severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome (CRS) induced by chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The CHMP’s recommendation will be reviewed by the European Commission, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission usually makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

Tocilizumab is a humanized interleukin-6 receptor antagonist marketed by Roche Registration GmbH.

The drug is already approved by the European Commission to treat rheumatoid arthritis, active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and juvenile idiopathic polyarthritis.

The CHMP’s recommendation to expand the approved use of tocilizumab is supported by results from a retrospective analysis of data from clinical trials of CAR T-cell therapies in patients with hematologic malignancies.

For this analysis, researchers assessed 45 pediatric and adult patients treated with tocilizumab, with or without additional high-dose corticosteroids, for severe or life-threatening CRS.

Thirty-one patients (69%) achieved a response, defined as resolution of CRS within 14 days of the first dose of tocilizumab.

No more than 2 doses of tocilizumab were needed, and no drugs other than tocilizumab and corticosteroids were used for treatment.

No adverse reactions related to tocilizumab were reported.

FDA lifts hold on trial of MYC inhibitor

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the clinical hold on a phase 1b trial of APTO-253.

APTO-253 is a small molecule that inhibits expression of the c-Myc oncogene without causing general myelosuppression of the bone marrow, according to Aptose Biosciences Inc., the company developing the drug.

Aptose was testing APTO-253 in a phase 1b trial of patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) before the FDA put the trial on hold in November 2015.

The hold was placed after an event that occurred during dosing at a clinical site. The event was stoppage of an intravenous infusion pump that was caused by back pressure resulting from clogging of the in-line filter.

Aptose said no drug-related serious adverse events were reported, and the observed pharmacokinetic levels in patients treated with APTO-253 were within the expected range.

However, a review revealed concerns about the documentation records of the manufacturing procedures associated with APTO-253. So Aptose voluntarily stopped dosing in the phase 1b trial, and the FDA placed the trial on hold.

A root cause investigation revealed that the event with the infusion pump resulted from chemistry and manufacturing-based issues.

Therefore, Aptose developed a new formulation of APTO-253 that did not cause filter clogging or pump stoppage during simulated infusion studies.

Now that the FDA has lifted the hold on the phase 1b trial, Aptose said screening and dosing will resume “as soon as practicable.”

“We are eager to return APTO-253 back into the clinic,” said William G. Rice, PhD, chairman, president and chief executive officer of Aptose.

“Our understanding of this molecule has evolved dramatically, and we are excited to deliver a MYC gene expression inhibitor to patients with debilitating hematologic malignancies.”

The phase 1b trial is designed to assess the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy of APTO-253 as a single agent and determine the recommended phase 2 dose of the drug.

APTO-253 will be administered once weekly, over a 28-day cycle. The dose-escalation cohort of the study could potentially enroll up to 20 patients with relapsed or refractory AML or high-risk MDS. The study is designed to then transition, as appropriate, to single-agent expansion cohorts in AML and MDS.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the clinical hold on a phase 1b trial of APTO-253.

APTO-253 is a small molecule that inhibits expression of the c-Myc oncogene without causing general myelosuppression of the bone marrow, according to Aptose Biosciences Inc., the company developing the drug.

Aptose was testing APTO-253 in a phase 1b trial of patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) before the FDA put the trial on hold in November 2015.

The hold was placed after an event that occurred during dosing at a clinical site. The event was stoppage of an intravenous infusion pump that was caused by back pressure resulting from clogging of the in-line filter.

Aptose said no drug-related serious adverse events were reported, and the observed pharmacokinetic levels in patients treated with APTO-253 were within the expected range.

However, a review revealed concerns about the documentation records of the manufacturing procedures associated with APTO-253. So Aptose voluntarily stopped dosing in the phase 1b trial, and the FDA placed the trial on hold.

A root cause investigation revealed that the event with the infusion pump resulted from chemistry and manufacturing-based issues.

Therefore, Aptose developed a new formulation of APTO-253 that did not cause filter clogging or pump stoppage during simulated infusion studies.

Now that the FDA has lifted the hold on the phase 1b trial, Aptose said screening and dosing will resume “as soon as practicable.”

“We are eager to return APTO-253 back into the clinic,” said William G. Rice, PhD, chairman, president and chief executive officer of Aptose.

“Our understanding of this molecule has evolved dramatically, and we are excited to deliver a MYC gene expression inhibitor to patients with debilitating hematologic malignancies.”

The phase 1b trial is designed to assess the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy of APTO-253 as a single agent and determine the recommended phase 2 dose of the drug.

APTO-253 will be administered once weekly, over a 28-day cycle. The dose-escalation cohort of the study could potentially enroll up to 20 patients with relapsed or refractory AML or high-risk MDS. The study is designed to then transition, as appropriate, to single-agent expansion cohorts in AML and MDS.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the clinical hold on a phase 1b trial of APTO-253.

APTO-253 is a small molecule that inhibits expression of the c-Myc oncogene without causing general myelosuppression of the bone marrow, according to Aptose Biosciences Inc., the company developing the drug.

Aptose was testing APTO-253 in a phase 1b trial of patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) before the FDA put the trial on hold in November 2015.

The hold was placed after an event that occurred during dosing at a clinical site. The event was stoppage of an intravenous infusion pump that was caused by back pressure resulting from clogging of the in-line filter.

Aptose said no drug-related serious adverse events were reported, and the observed pharmacokinetic levels in patients treated with APTO-253 were within the expected range.

However, a review revealed concerns about the documentation records of the manufacturing procedures associated with APTO-253. So Aptose voluntarily stopped dosing in the phase 1b trial, and the FDA placed the trial on hold.

A root cause investigation revealed that the event with the infusion pump resulted from chemistry and manufacturing-based issues.

Therefore, Aptose developed a new formulation of APTO-253 that did not cause filter clogging or pump stoppage during simulated infusion studies.

Now that the FDA has lifted the hold on the phase 1b trial, Aptose said screening and dosing will resume “as soon as practicable.”

“We are eager to return APTO-253 back into the clinic,” said William G. Rice, PhD, chairman, president and chief executive officer of Aptose.

“Our understanding of this molecule has evolved dramatically, and we are excited to deliver a MYC gene expression inhibitor to patients with debilitating hematologic malignancies.”

The phase 1b trial is designed to assess the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy of APTO-253 as a single agent and determine the recommended phase 2 dose of the drug.

APTO-253 will be administered once weekly, over a 28-day cycle. The dose-escalation cohort of the study could potentially enroll up to 20 patients with relapsed or refractory AML or high-risk MDS. The study is designed to then transition, as appropriate, to single-agent expansion cohorts in AML and MDS.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: What to do about missed doses

Antipsychotic agents are the mainstay of treatment for patients with schizophrenia,1-3 and when taken regularly, they can greatly improve patient outcomes. Unfortunately, many studies have documented poor adherence to antipsychotic regimens in patients with schizophrenia, which often leads to an exacerbation of symptoms and preventable hospitalizations.4-8 In order to improve adherence, many clinicians prescribe long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs).

LAIAs help improve adherence, but these benefits are seen only in patients who receive their injections within a specific time frame.9-11 LAIAs administered outside of this time frame (missed doses) can lead to reoccurrence or exacerbation of symptoms. This article explains how to adequately manage missed LAIA doses.

First-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics

Two first-generation antipsychotics are available as a long-acting injectable formulation: haloperidol decanoate and fluphenazine decanoate. Due to the increased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms, use of these agents have decreased, and they are often less preferred than second-generation LAIAs. Furthermore, unlike many of the newer second-generation LAIAs, first-generation LAIAs lack literature on how to manage missed doses. Therefore, clinicians should analyze the pharmacokinetic properties of these agents (Table 112-28), as well as the patient’s medical history and clinical presentation, in order to determine how best to address missed doses.

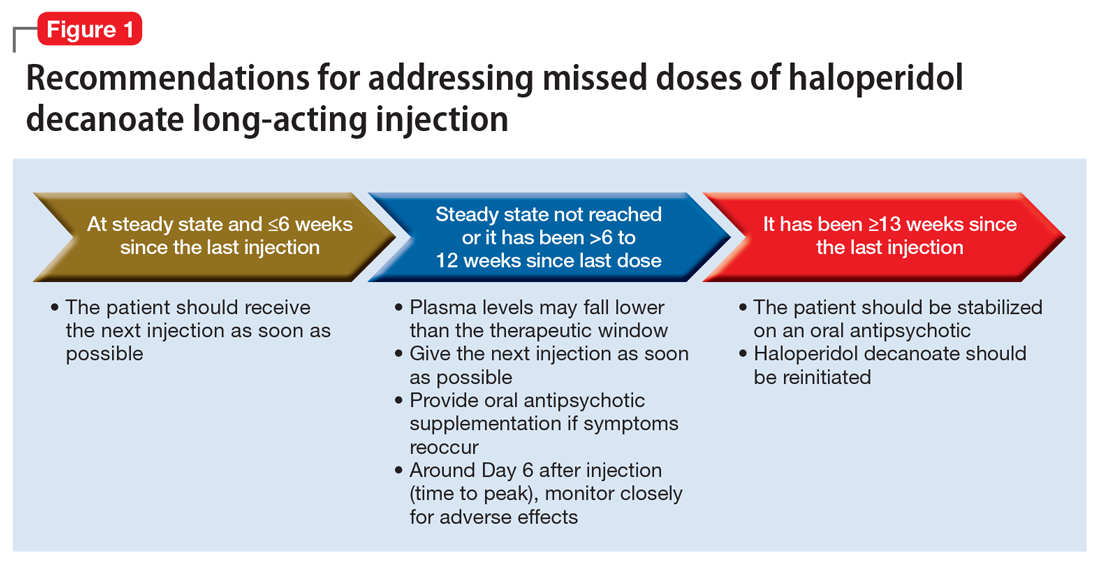

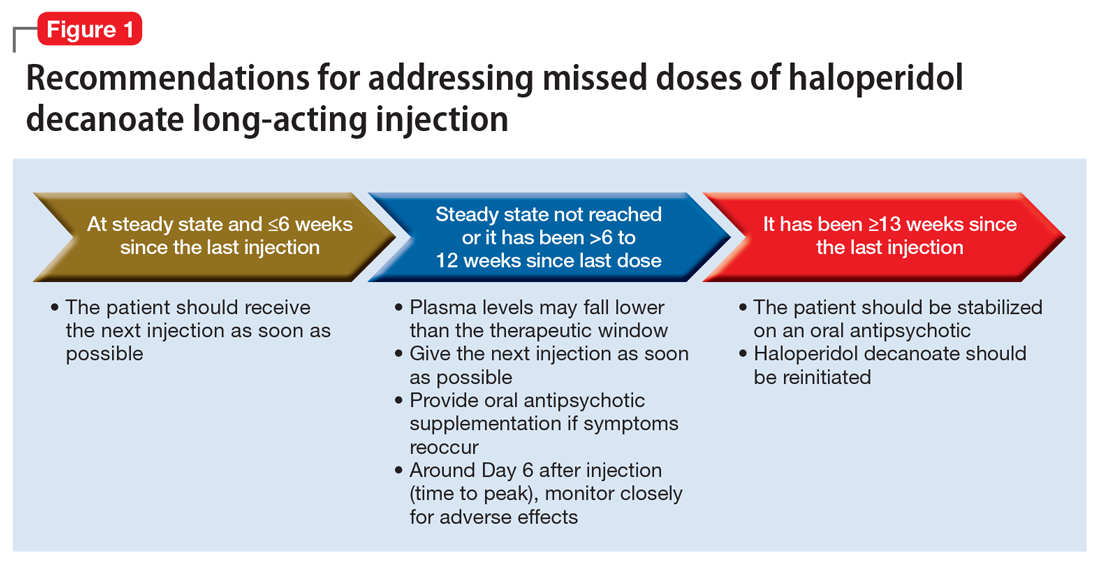

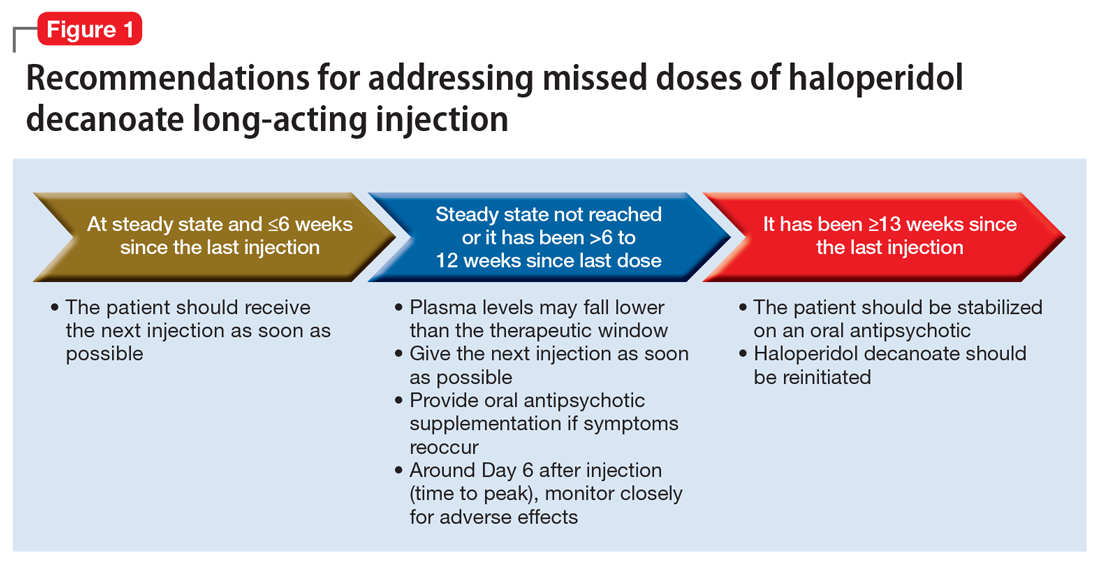

Haloperidol decanoate plasma concentrations peak approximately 6 days after the injection.12 The medication has a half-life of 3 weeks. One study found that haloperidol plasma concentrations were detectable 13 weeks after the discontinuation of haloperidol decanoate.17 This same study also found that the change in plasma levels from 3 to 6 weeks after the last dose was minimal.17 Based on these findings, Figure 1 summarizes our recommendations for addressing missed haloperidol decanoate doses.

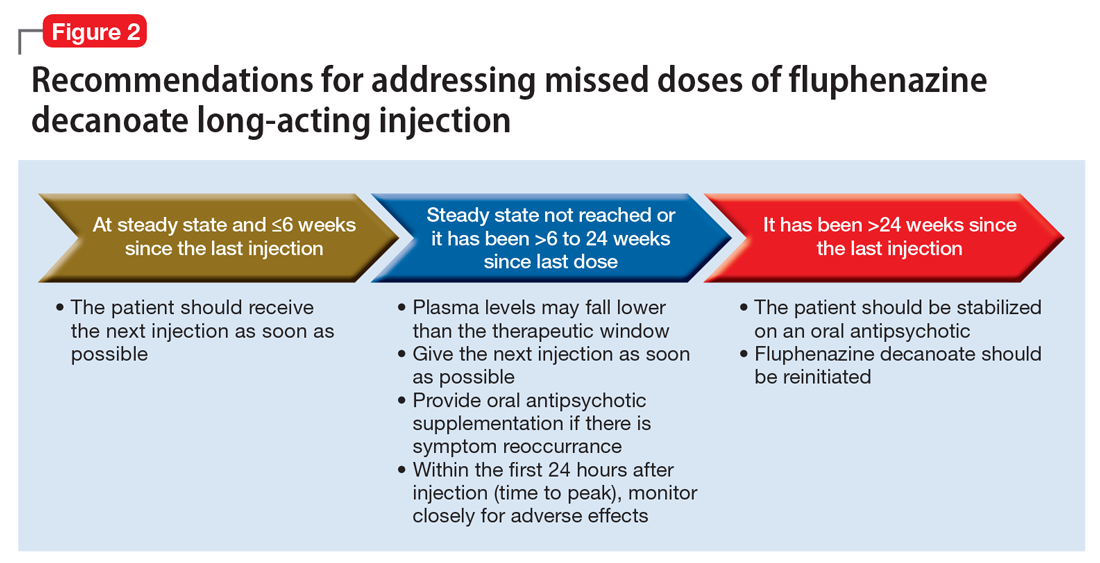

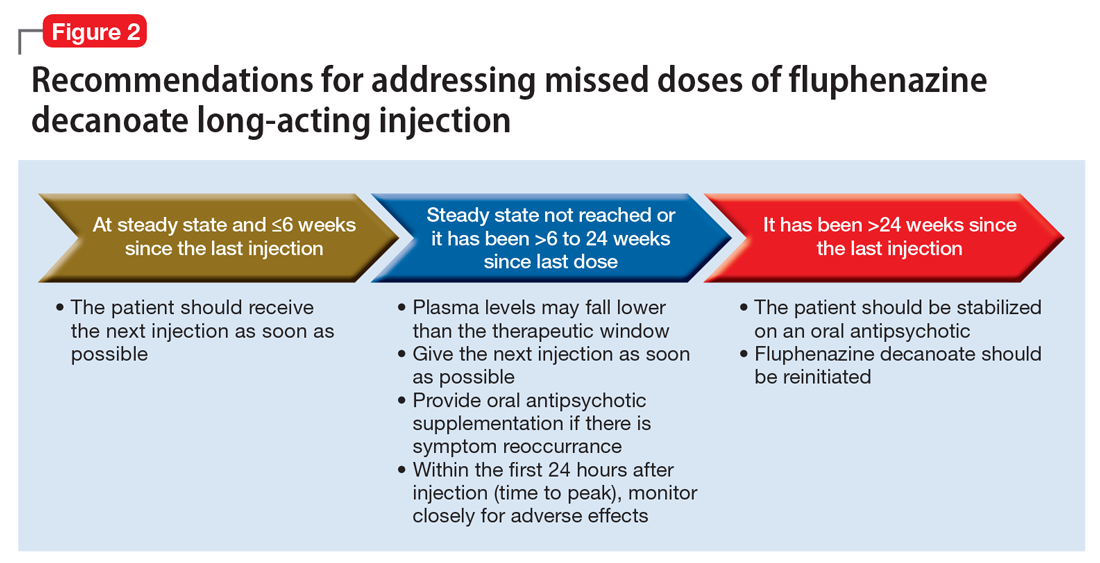

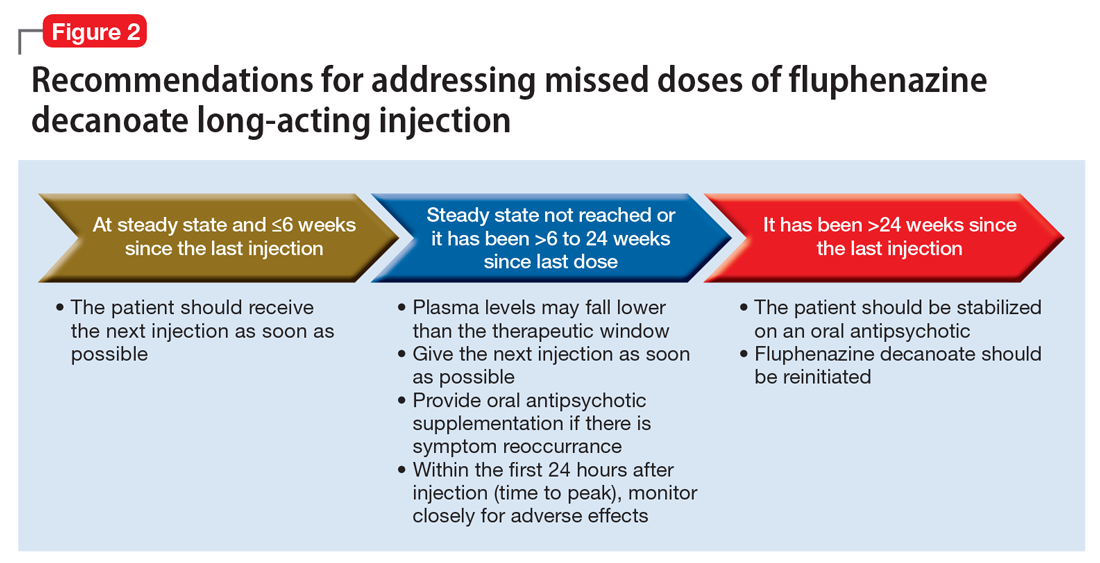

Fluphenazine decanoate levels peak 24 hours after the injection.18 An estimated therapeutic range for fluphenazine is 0.2 to 2 ng/mL.21-25 One study that evaluated fluphenazine decanoate levels following discontinuation after reaching steady state found there was no significant difference in plasma levels 6 weeks after the last dose of fluphenazine, but a significant decrease in levels 8 to 12 weeks after the last dose.26 Other studies found that fluphenazine levels were detectable 21 to 24 weeks following fluphenazine decanoate discontinuation.27,28 Based on these findings, Figure 2 summarizes our recommendations for addressing missed fluphenazine decanoate doses.

Continue to: Second-generation LAIAs

Second-generation LAIAs

Six second-generation LAIAs are available in the United States. Compared with the first-generation LAIAs, second-generation LAIAs have more extensive guidance on how to address missed doses.

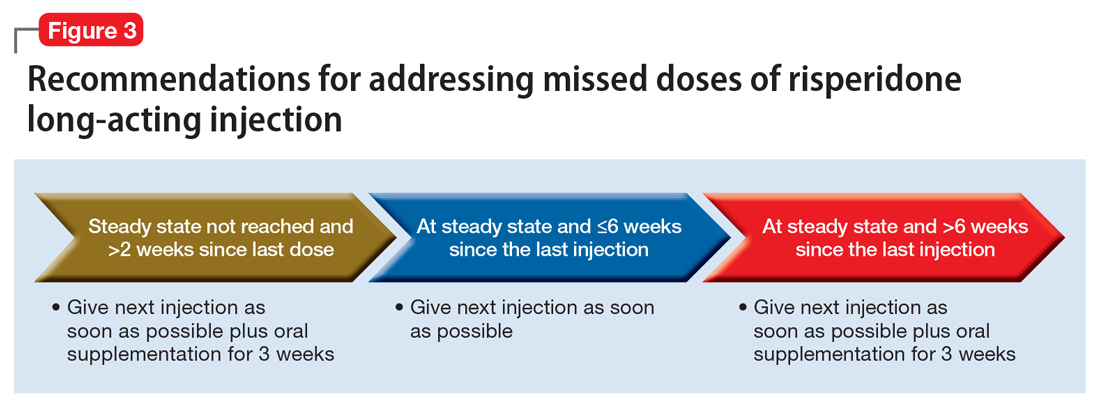

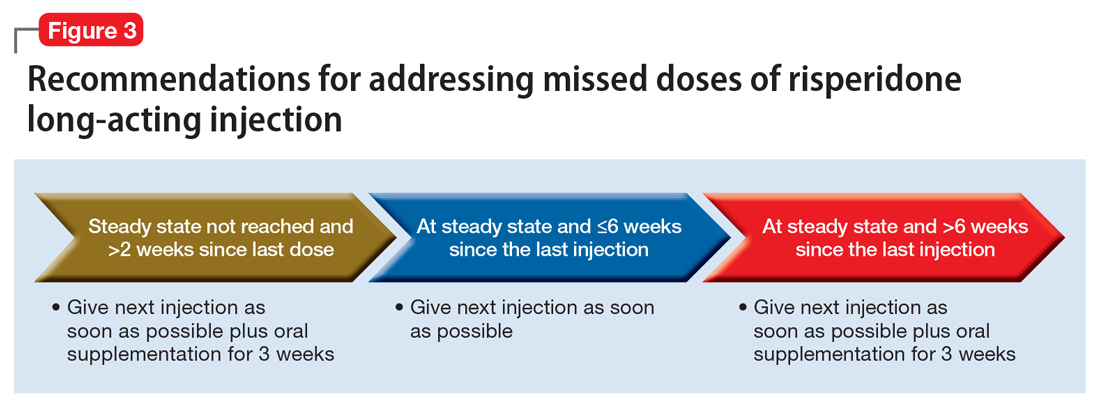

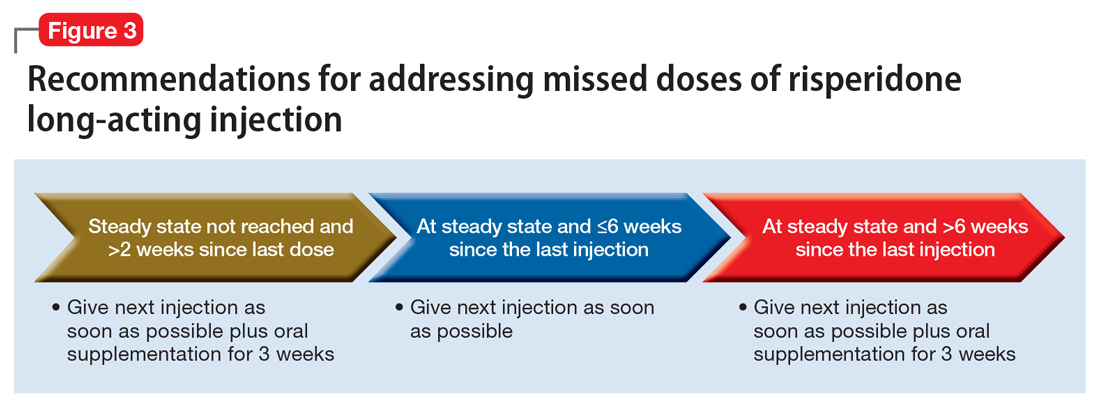

Risperidone long-acting injection. When addressing missed doses of risperidone long-acting injection, first determine whether the medication has reached steady state. Steady state occurs approximately after the fourth consecutive injection (approximately 2 months).29

If a patient missed a dose but has not reached steady state, he or she should receive the next dose as well as oral antipsychotic supplementation for 3 weeks.30 If the patient has reached steady state and if it has been ≤6 weeks since the last injection, give the next injection as soon as possible. However, if steady state has been reached and it has been >6 weeks since the last injection, give the next injection, along with 3 weeks of oral antipsychotic supplementation (Figure 3).

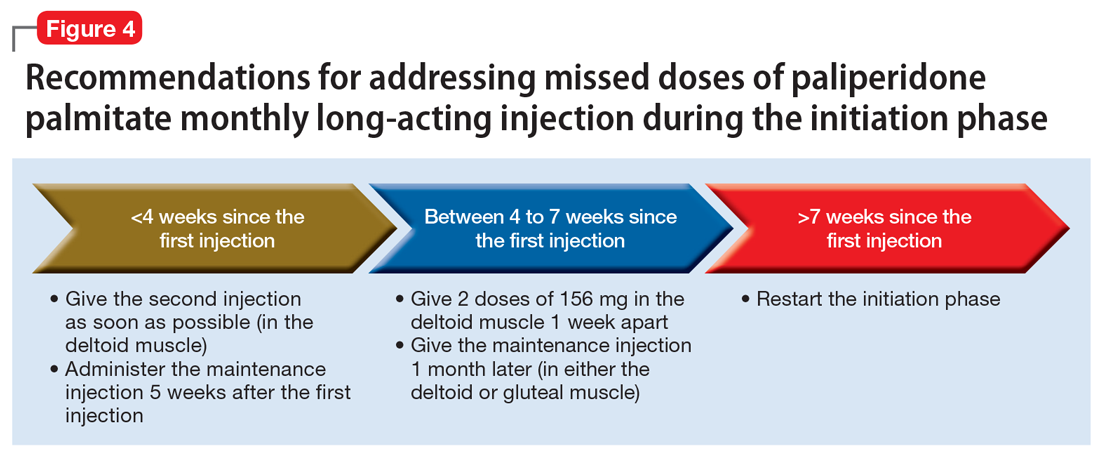

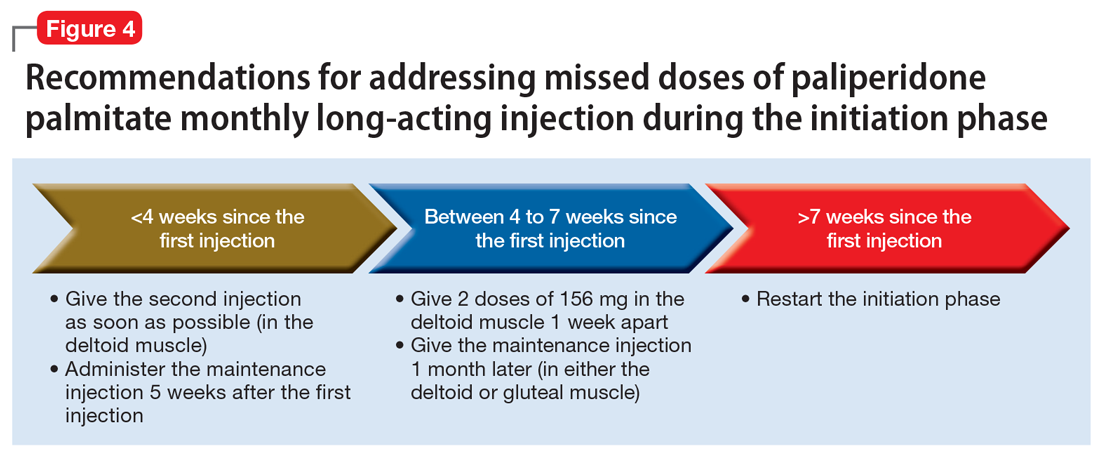

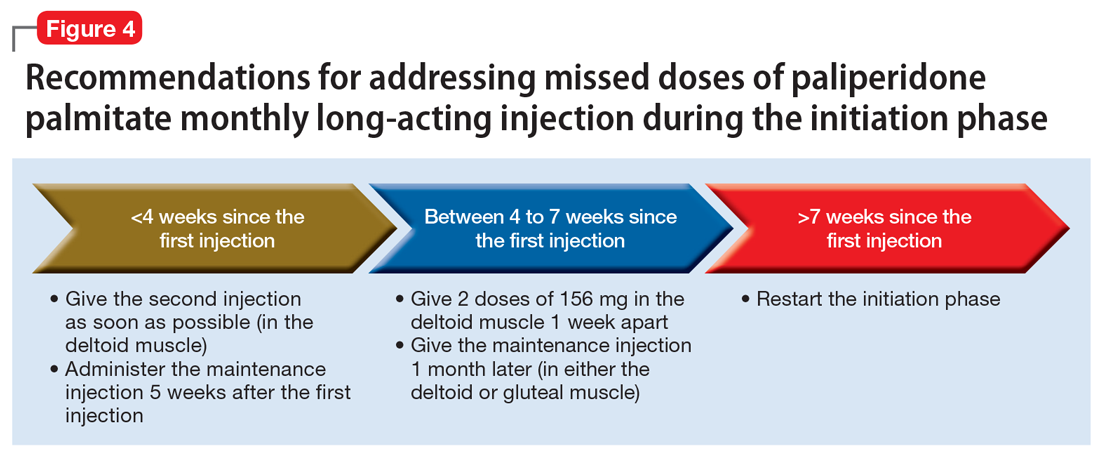

Paliperidone palmitate monthly long-acting injection. Once the initiation dosing phase of paliperidone palmitate monthly long-acting injection (PP1M) is completed, the maintenance dose is administered every 4 weeks. When addressing missed doses of PP1M, first determine whether the patient is in the initiation or maintenance dosing phase.31

Initiation phase. Patients are in the initiation dosing phase during the first 2 injections of PP1M. During the initiation phase, the patient first receives 234 mg and then 156 mg 1 week later, both in the deltoid muscle. One month later, the patient receives a maintenance dose of PP1M (in the deltoid or gluteal muscle). The second initiation injection may be given 4 days before or after the scheduled administration date. The initiation doses should be adjusted in patients with mild renal function (creatinine clearance 50 to 80 mL/min).31 Figure 4 summarizes the guidance for addressing a missed or delayed second injection during the initiation phase.

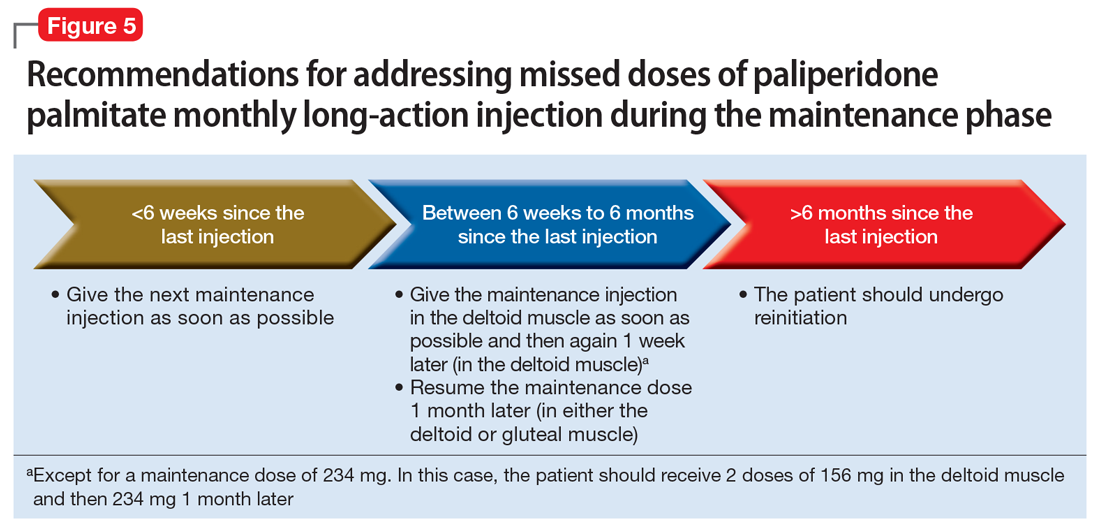

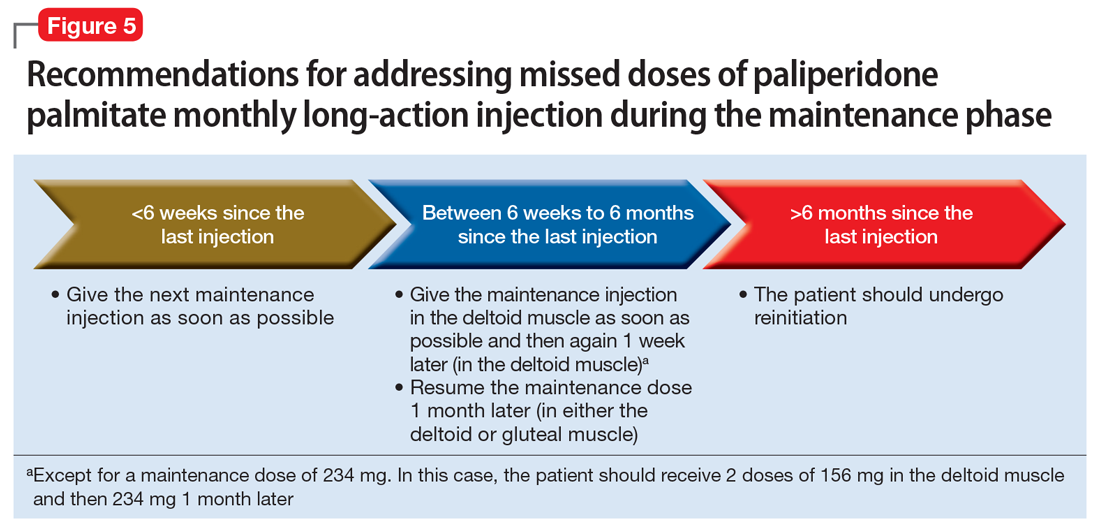

Continue to: Maintenance phase

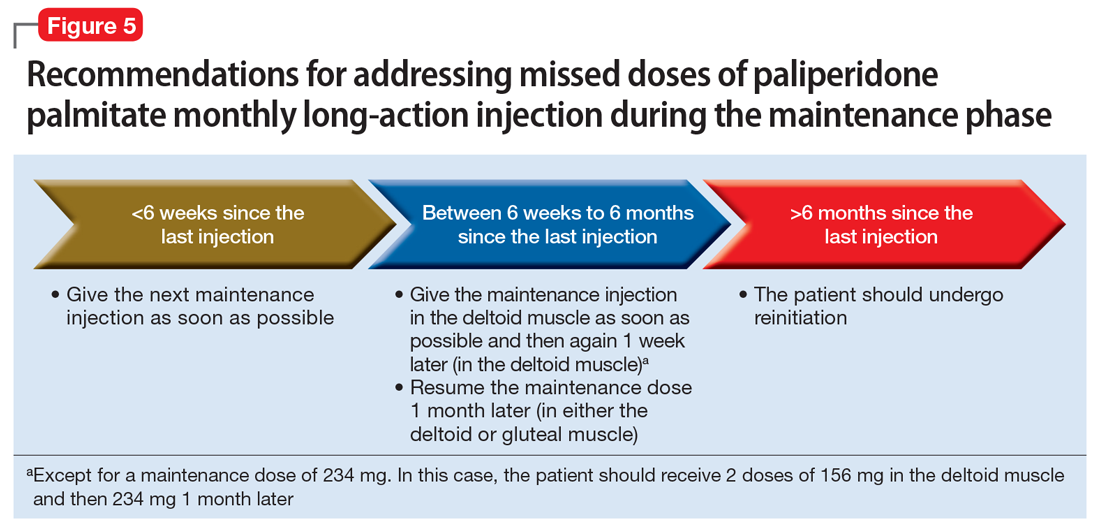

Maintenance phase. During the maintenance phase, PP1M can be administered 7 days before or after the monthly due date. If the patient has missed a maintenance injection and it has been <6 weeks since the last dose, the maintenance injection can be given as soon as possible (Figure 5).31 If it has been 6 weeks to 6 months since the last injection, the patient should receive their prescribed maintenance dose as soon as possible and the same dose 1 week later, with both injections in the deltoid muscle. Following the second dose, the patient can resume their regular monthly maintenance schedule, in either the deltoid or gluteal muscle. For example, if the patient was maintained on 117 mg of PP1M and it had been 8 weeks since the last injection, the patient should receive 117 mg immediately, then 117 mg 1 week later, then 117 mg 1 month later. An exception to this is if a patient’s maintenance dose is 234 mg monthly. In this case, the patient should receive 156 mg of PP1M immediately, then 156 mg 1 week later, and then 234 mg 1 month later.31 If it has been >6 months since the last dose, the patient should start the initiation schedule as if he or she were receiving a new medication.31

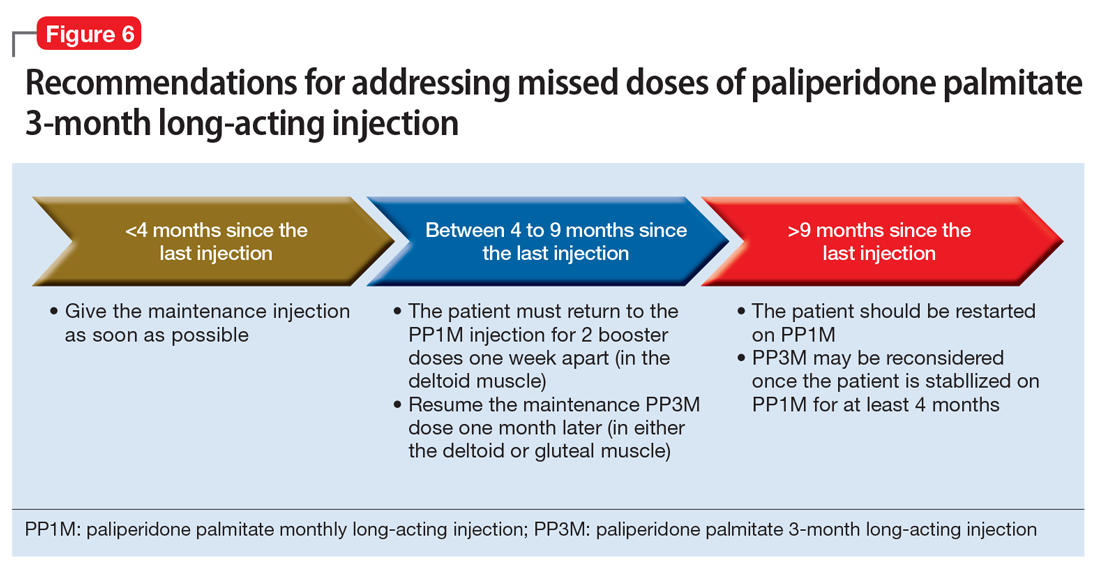

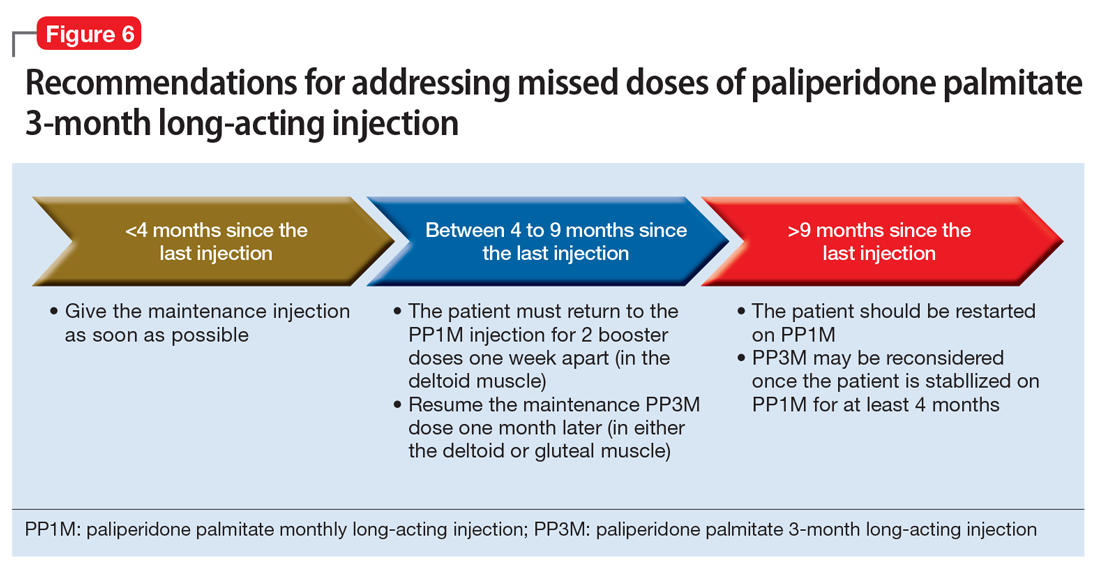

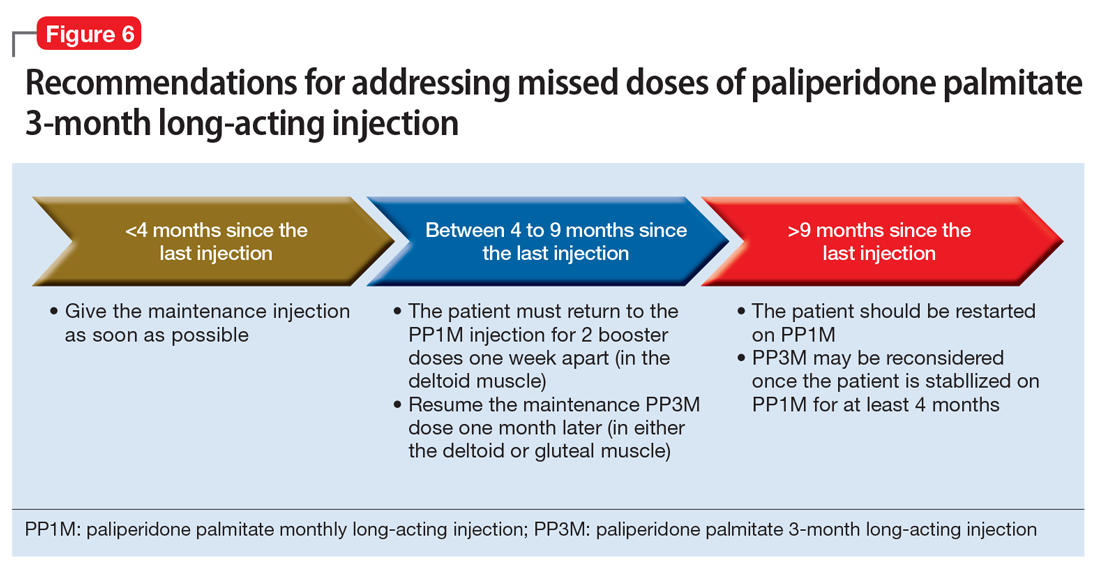

Paliperidone palmitate 3-month long-acting injection (PP3M) should be administered every 3 months. This injection can be given 2 weeks before or after the date of the scheduled dose.32

If the patient missed an injection and it has been <4 months since the last dose, the next scheduled dose should be given as soon as possible.32 If it has been 4 to 9 months since the last dose, the patient must return to PP1M for 2 booster injections 1 week apart. The dose of these PP1M booster injections depends on the dose of PP3M that the patient had been stabilized on:

- 78 mg if stabilized on 273 mg

- 117 mg if stabilized on 410 mg

- 156 mg if stabilized on 546 mg or 819 mg.32

After the second booster dose, PP3M can be restarted 1 month later.32 If it has been >9 months since the last PP3M dose, the patient should be restarted on PP1M. PP3M can be reconsidered once the patient has been stabilized on PP1M for ≥4 months (Figure 6).32

Continue to: Aripiprazole long-acting injection

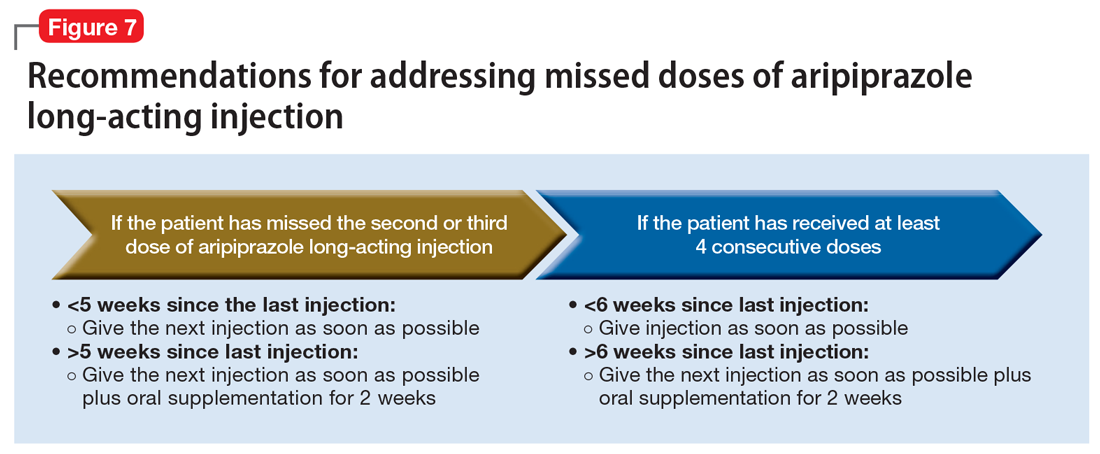

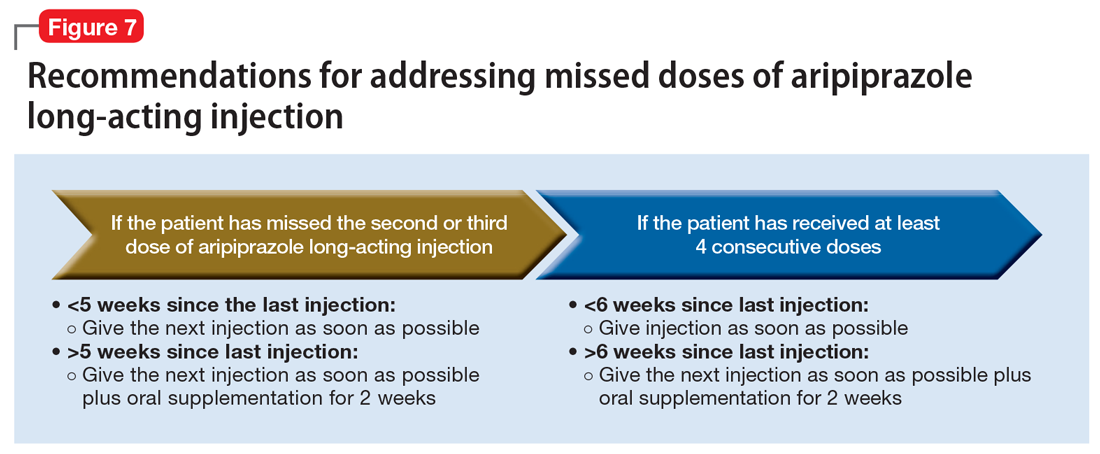

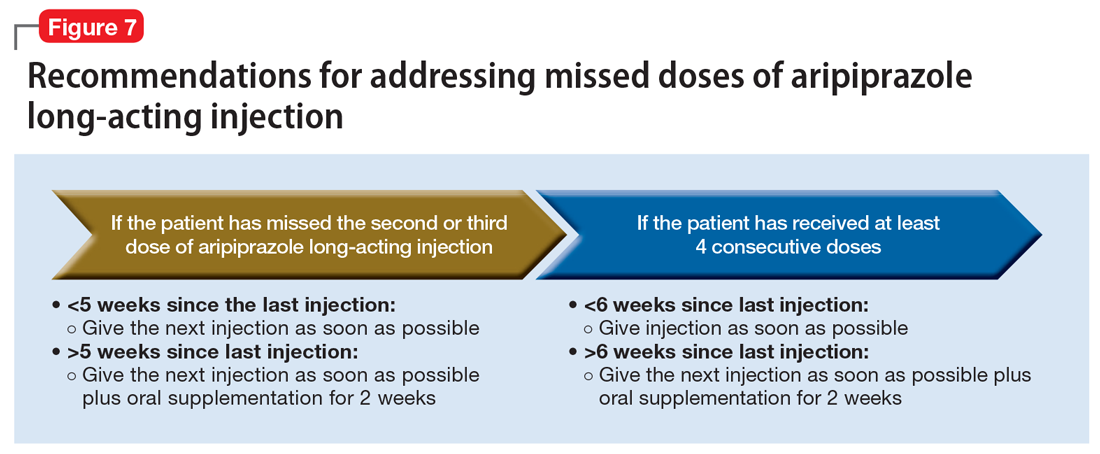

Aripiprazole long-acting injection is administered every 4 weeks. If a patient misses an injection, first determine how many consecutive doses he or she has received.33 If the patient has missed the second or third injection, and it has been <5 weeks since the last dose, give the next injection as soon as possible. If it has been >5 weeks, give the next injection as soon as possible, plus oral aripiprazole supplementation for 2 weeks (Figure 7).

If the patient has received ≥4 consecutive doses and misses a dose and it has been <6 weeks since the last dose, administer an injection as soon as possible. If it has been >6 weeks since the last dose, give the next injection as soon as possible, plus with oral aripiprazole supplementation for 2 weeks.

Aripiprazole lauroxil long-acting injection. Depending on the dose, aripiprazole lauroxil can be administered monthly, every 6 weeks, or every 2 months. Aripiprazole lauroxil can be administered 14 days before or after the scheduled dose.34

The guidance for addressing missed or delayed doses of aripiprazole lauroxil differs depending on the dose the patient is stabilized on, and how long it has been since the last injection. Figure 8 summarizes how missed injections should be managed. When oral aripiprazole supplementation is needed, the following doses should be used:

- 10 mg/d if stabilized on 441 mg every month

- 15 mg/d if stabilized on 662 mg every month, 882 mg every 6 weeks, or 1,064 mg every 2 months

- 20 mg/d if stabilized on 882 mg every month.34

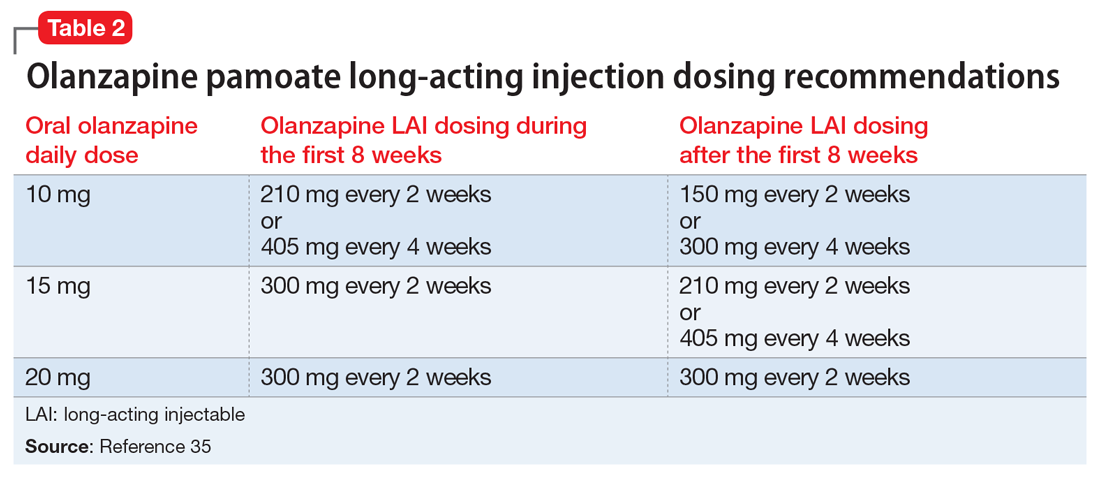

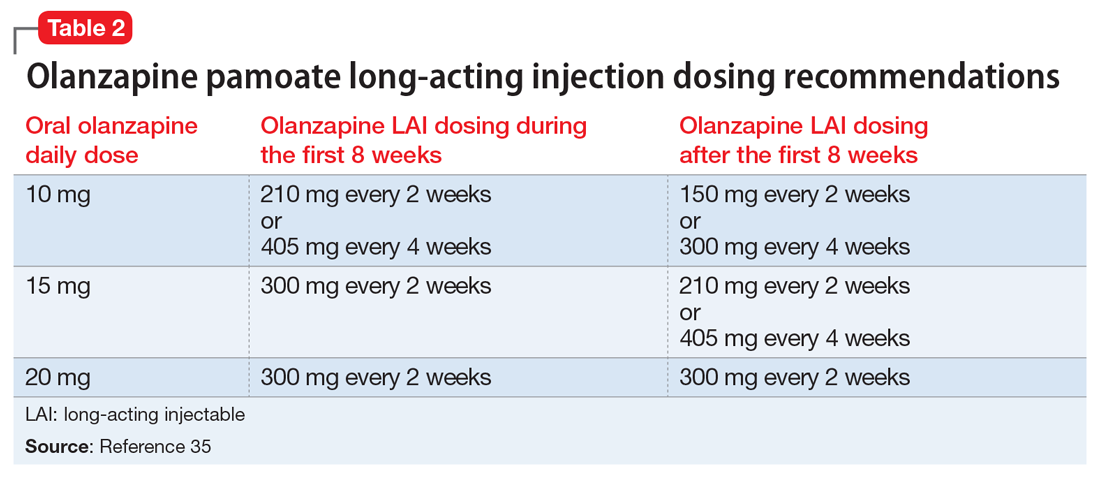

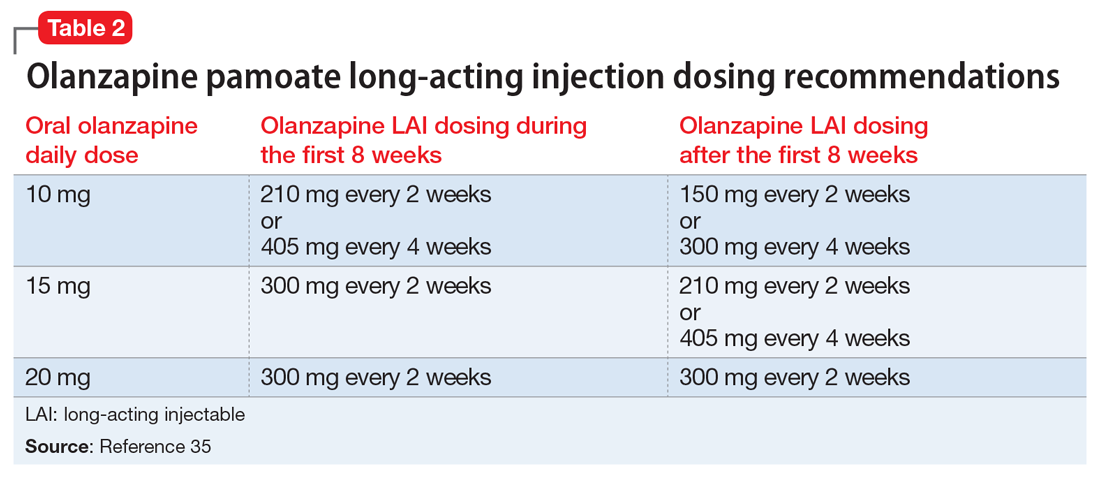

Olanzapine pamoate long-acting injection is a unique LAIA because it requires prescribers and patients to participate in a risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) program due the risk of post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome. It is administered every 2 to 4 weeks, with loading doses given for the first 2 months of treatment (Table 235). After 2 months, the patient can proceed to the maintenance dosing regimen.

Continue to: Currently, there is no concrete guidance...

Currently, there is no concrete guidance on how to address missed doses of olanzapine long-acting injection; however, the pharmacokinetics of this formulation allow flexibility in dosing intervals. Therapeutic levels are present after the first injection, and the medication reaches steady-state levels in 3 months.35-37 As a result of its specific formulation, olanzapine pamoate long-acting injection provides sustained olanzapine pamoate plasma concentrations between injections, and has a half-life of 30 days.35 Consequently, therapeutic levels of the medication are still present 2 to 4 weeks after an injection.37 Additionally, clinically relevant plasma concentrations may be present 2 to 3 months after the last injection.36

In light of this information, if a patient has not reached steady state and has missed an injection, he or she should receive the recommended loading dose schedule. If the patient has reached steady state and it has been ≤2 months since the last dose, he or she should receive the next dose as soon as possible. If steady state has been reached and it has been >2 months since the last injection, the patient should receive the recommended loading dosing for 2 months (Figure 9). Because of the risk of post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome, and because therapeutic levels are achieved after the first injection, oral olanzapine supplementation is not recommended.

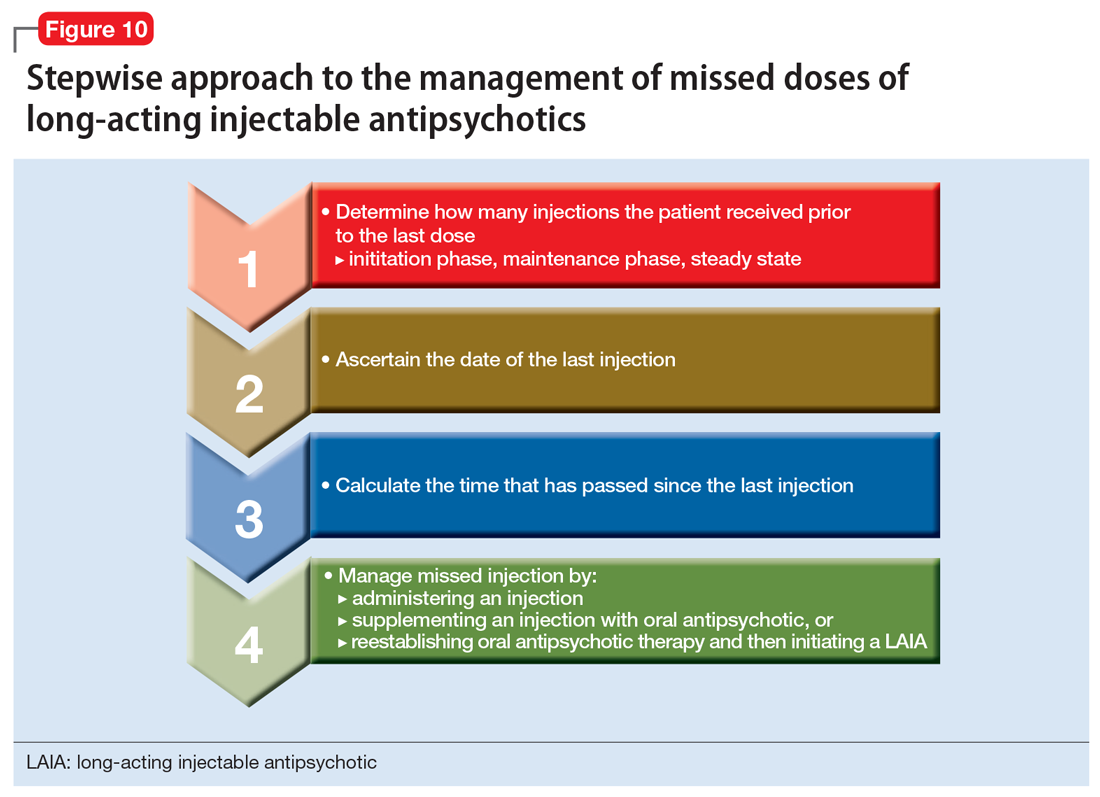

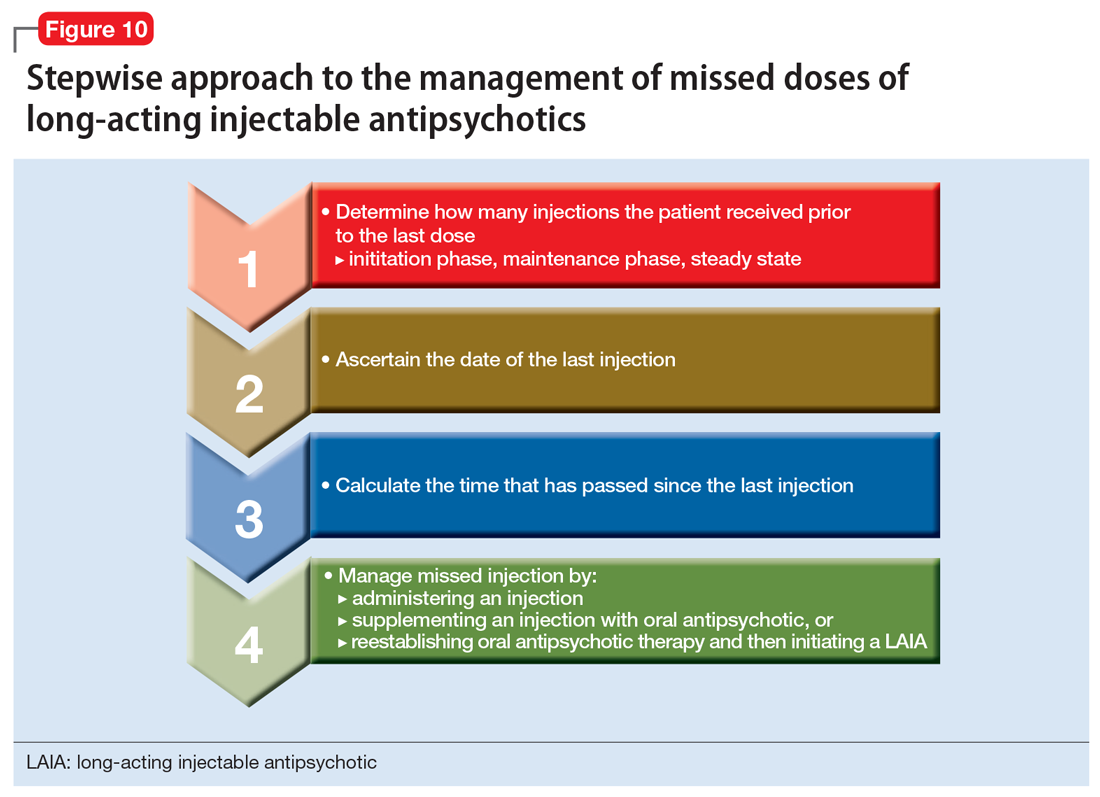

Use a stepwise approach

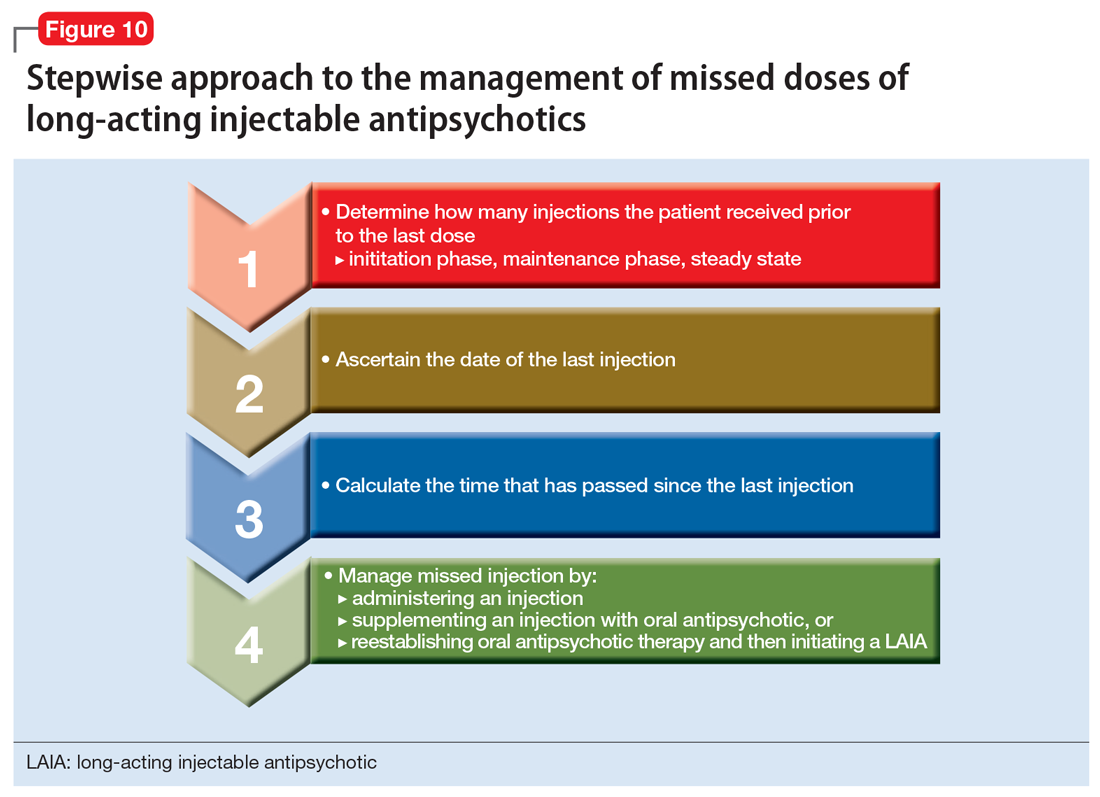

In general, clinicians can use a stepwise approach to managing missed doses of LAIAs (Figure 10). First, establish the number of LAIA doses the patient had received prior to the last dose, and whether these injections were administered on schedule. This will help you determine if the patient is in the initiation or maintenance phase and/or has reached steady state. The second step is to establish the date of the last injection. Use objective tools, such as pharmacy records or the medical chart, to determine the date of the last injection, rather than relying on patient reporting. For the third step, calculate the time that has passed since the last LAIA dose. Once you have completed these steps, use the specific medication recommendations described in this article to address the missed dose.

Continue to: Address barriers to adherence

Address barriers to adherence

When addressing missed LAIA doses, be sure to identify any barriers that may have led to a missed injection. These might include:

- bothersome adverse effects

- transportation difficulties

- issues with insurance/medication coverage

- comorbidities (ie, alcohol/substance use disorders)

- cognitive and functional impairment caused by the patient’s illness

- difficulty with keeping track of appointments.

Clinicians can work closely with patients and/or caregivers to address any barriers to ensure that patients receive their injections in a timely fashion.

The goal: Reducing relapse

LAIAs improve medication adherence. Although nonadherence is less frequent with LAIAs than with oral antipsychotics, when a LAIA dose is missed, it is important to properly follow a stepwise approach based on the unique properties of the specific LAIA prescribed. Proper management of LAIA missed doses can prevent relapse and reoccurrence of schizophrenia symptoms, thus possibly avoiding future hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Tschosik, JD, Mary Collen O’Rourke, MD, and Amanda Holloway, MD, for their assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Although long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs) greatly assist with adherence, these agents are effective only when missed doses are avoided. When addressing missed LAIA doses, use a stepwise approach that takes into consideration the unique properties of the specific LAIA prescribed.

Related Resources

- Haddad P, Lambert T, Lauriello J, eds. Antipsychotic long-acting injections. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Diefenderfer LA. When should you consider combining 2 long-acting injectable antipsychotics? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):42-46.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole long-acting injection • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil long-acting injection • Aristada

Fluphenazine decanoate • Prolixin decanoate

Haloperidol decanoate • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine pamoate long-acting injection • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone palmitate monthly long-acting injection • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate 3-month long-acting injection • Invega Trinza

Risperidone long-acting injection • Risperdal Consta

1. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, et al. Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2):216-222.

2. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

3. Kane JM, Garcia-Ribera C. Clinical guideline recommendations for antipsychotic long-acting injections. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2009;195(52):S63-S67.

4. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(5):306-324.

5. Kishimoto T, Robenzadeh A, Leucht C, et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):192-213.

6. Andreasen NC. Symptoms, signs, and diagnosis of schizophrenia. Lancet. 1995;346(8973):477-481.

7. de Sena EP, Santos-Jesus R, Miranda-Scippa Â, et al. Relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a comparison between risperidone and haloperidol. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2003;25(4):220-223.

8. Chue P. Long-acting risperidone injection: efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(1):13-39.

9. Lafeuille MH, Frois C, Cloutier M, et al. Factors associated with adherence to the HEDIS Quality Measure in medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(7):399-410.

10. Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957-965.

11. Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, et al. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):754-768.

12. Haldol Decanoate injection [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

13. Magliozzi JR, Hollister LE, Arnold KV, et al. Relationship of serum haloperidol levels to clinical response in schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(3):365-367.

14. Mavroidis ML, Kanter DR, Hirschowitz J, et al. Clinical response and plasma haloperidol levels in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1983;81(4):354-356.

15. Reyntigens AJ, Heykants JJ, Woestenborghs RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol decanoate. A 2-year follow-up. Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 1982;17(4):238-246.

16. Jann MW, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the depot antipsychotics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10(4):315-333.

17. Chang WH, Lin SK, Juang DJ, et al. Prolonged haloperidol and reduced haloperidol plasma concentrations after decanoate withdrawal. Schizophr Res. 1993;9(1):35-40.

18. Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW. Future of depot neuroleptic therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic approaches. J Clin Psychiatry.1984;45(5 pt 2):50-58.

19. Marder SR, Hawes EM, Van Putten T, et al. Fluphenazine plasma levels in patients receiving low and conventional doses of fluphenazine decanoate. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1986;88(4):480-483.

20. Marder SR, Hubbard JW, Van Putten T, et al. Pharmacokinetics of long-acting injectable neuroleptic drugs: clinical implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1989;98(4):433-439.

21. Mavroidis ML, Kanter DR, Hirschowitz J, et al. Fluphenazine plasma levels and clinical response. J Clin Psychiatry. 1984;45(9):370-373.

22. Balant-Gorgia AE, Balant LP, Andreoli A. Pharmacokinetic optimisation of the treatment of psychosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;25(3):217-236.

23. Van Putten T, Marder SR, Wirshing WC, et al. Neuroleptic plasma levels. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(2):197-216.

24. Dahl SG. Plasma level monitoring of antipsychotic drugs. Clinical utility. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1986;11(1):36-61.

25. Miller RS, Peterson GM, McLean S, et al. Monitoring plasma levels of fluphenazine during chronic therapy with fluphenazine decanoate. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1995;20(2):55-62.

26. Gitlin MJ, Midha KK, Fogelson D, et al. Persistence of fluphenazine in plasma after decanoate withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988;8(1):53-56.

27. Wistedt B, Wiles D, Kolakowska T. Slow decline of plasma drug and prolactin levels after discontinuation of chronic treatment with depot neuroleptics. Lancet. 1981;1(8230):1163.

28. Wistedt B, Jørgensen A, Wiles D. A depot neuroleptic withdrawal study. Plasma concentration of fluphenazine and flupenthixol and relapse frequency. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1982;78(4):301-304.

29. Risperdal Consta [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

30. Marder SR, Conley R, Ereshefsky L, et al. Clinical guidelines: dosing and switching strategies for long-acting risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 16):41-46.

31. Invega Sustenna [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

32. Invega Trinza [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

33. Abilify Maintena [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; December 2016.

34. Artistada [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes, Inc.; June 2017.

35. Zyprexa Relprevv [package insert]. Indianapolis; IN: Eli Lilly and Co.; February 2017.

36. Heres S, Kraemer S, Bergstrom RF, et al. Pharmacokinetics of olanzapine long-acting injection: the clinical perspective. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(6):299-312.

37. Detke HC, Zhao F, Garhyan P, et al. Dose correspondence between olanzapine long-acting injection and oral olanzapine: recommendations for switching. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(1):35-42.

Antipsychotic agents are the mainstay of treatment for patients with schizophrenia,1-3 and when taken regularly, they can greatly improve patient outcomes. Unfortunately, many studies have documented poor adherence to antipsychotic regimens in patients with schizophrenia, which often leads to an exacerbation of symptoms and preventable hospitalizations.4-8 In order to improve adherence, many clinicians prescribe long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs).

LAIAs help improve adherence, but these benefits are seen only in patients who receive their injections within a specific time frame.9-11 LAIAs administered outside of this time frame (missed doses) can lead to reoccurrence or exacerbation of symptoms. This article explains how to adequately manage missed LAIA doses.

First-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics

Two first-generation antipsychotics are available as a long-acting injectable formulation: haloperidol decanoate and fluphenazine decanoate. Due to the increased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms, use of these agents have decreased, and they are often less preferred than second-generation LAIAs. Furthermore, unlike many of the newer second-generation LAIAs, first-generation LAIAs lack literature on how to manage missed doses. Therefore, clinicians should analyze the pharmacokinetic properties of these agents (Table 112-28), as well as the patient’s medical history and clinical presentation, in order to determine how best to address missed doses.

Haloperidol decanoate plasma concentrations peak approximately 6 days after the injection.12 The medication has a half-life of 3 weeks. One study found that haloperidol plasma concentrations were detectable 13 weeks after the discontinuation of haloperidol decanoate.17 This same study also found that the change in plasma levels from 3 to 6 weeks after the last dose was minimal.17 Based on these findings, Figure 1 summarizes our recommendations for addressing missed haloperidol decanoate doses.

Fluphenazine decanoate levels peak 24 hours after the injection.18 An estimated therapeutic range for fluphenazine is 0.2 to 2 ng/mL.21-25 One study that evaluated fluphenazine decanoate levels following discontinuation after reaching steady state found there was no significant difference in plasma levels 6 weeks after the last dose of fluphenazine, but a significant decrease in levels 8 to 12 weeks after the last dose.26 Other studies found that fluphenazine levels were detectable 21 to 24 weeks following fluphenazine decanoate discontinuation.27,28 Based on these findings, Figure 2 summarizes our recommendations for addressing missed fluphenazine decanoate doses.

Continue to: Second-generation LAIAs

Second-generation LAIAs

Six second-generation LAIAs are available in the United States. Compared with the first-generation LAIAs, second-generation LAIAs have more extensive guidance on how to address missed doses.

Risperidone long-acting injection. When addressing missed doses of risperidone long-acting injection, first determine whether the medication has reached steady state. Steady state occurs approximately after the fourth consecutive injection (approximately 2 months).29

If a patient missed a dose but has not reached steady state, he or she should receive the next dose as well as oral antipsychotic supplementation for 3 weeks.30 If the patient has reached steady state and if it has been ≤6 weeks since the last injection, give the next injection as soon as possible. However, if steady state has been reached and it has been >6 weeks since the last injection, give the next injection, along with 3 weeks of oral antipsychotic supplementation (Figure 3).

Paliperidone palmitate monthly long-acting injection. Once the initiation dosing phase of paliperidone palmitate monthly long-acting injection (PP1M) is completed, the maintenance dose is administered every 4 weeks. When addressing missed doses of PP1M, first determine whether the patient is in the initiation or maintenance dosing phase.31

Initiation phase. Patients are in the initiation dosing phase during the first 2 injections of PP1M. During the initiation phase, the patient first receives 234 mg and then 156 mg 1 week later, both in the deltoid muscle. One month later, the patient receives a maintenance dose of PP1M (in the deltoid or gluteal muscle). The second initiation injection may be given 4 days before or after the scheduled administration date. The initiation doses should be adjusted in patients with mild renal function (creatinine clearance 50 to 80 mL/min).31 Figure 4 summarizes the guidance for addressing a missed or delayed second injection during the initiation phase.

Continue to: Maintenance phase

Maintenance phase. During the maintenance phase, PP1M can be administered 7 days before or after the monthly due date. If the patient has missed a maintenance injection and it has been <6 weeks since the last dose, the maintenance injection can be given as soon as possible (Figure 5).31 If it has been 6 weeks to 6 months since the last injection, the patient should receive their prescribed maintenance dose as soon as possible and the same dose 1 week later, with both injections in the deltoid muscle. Following the second dose, the patient can resume their regular monthly maintenance schedule, in either the deltoid or gluteal muscle. For example, if the patient was maintained on 117 mg of PP1M and it had been 8 weeks since the last injection, the patient should receive 117 mg immediately, then 117 mg 1 week later, then 117 mg 1 month later. An exception to this is if a patient’s maintenance dose is 234 mg monthly. In this case, the patient should receive 156 mg of PP1M immediately, then 156 mg 1 week later, and then 234 mg 1 month later.31 If it has been >6 months since the last dose, the patient should start the initiation schedule as if he or she were receiving a new medication.31

Paliperidone palmitate 3-month long-acting injection (PP3M) should be administered every 3 months. This injection can be given 2 weeks before or after the date of the scheduled dose.32

If the patient missed an injection and it has been <4 months since the last dose, the next scheduled dose should be given as soon as possible.32 If it has been 4 to 9 months since the last dose, the patient must return to PP1M for 2 booster injections 1 week apart. The dose of these PP1M booster injections depends on the dose of PP3M that the patient had been stabilized on:

- 78 mg if stabilized on 273 mg

- 117 mg if stabilized on 410 mg

- 156 mg if stabilized on 546 mg or 819 mg.32

After the second booster dose, PP3M can be restarted 1 month later.32 If it has been >9 months since the last PP3M dose, the patient should be restarted on PP1M. PP3M can be reconsidered once the patient has been stabilized on PP1M for ≥4 months (Figure 6).32

Continue to: Aripiprazole long-acting injection

Aripiprazole long-acting injection is administered every 4 weeks. If a patient misses an injection, first determine how many consecutive doses he or she has received.33 If the patient has missed the second or third injection, and it has been <5 weeks since the last dose, give the next injection as soon as possible. If it has been >5 weeks, give the next injection as soon as possible, plus oral aripiprazole supplementation for 2 weeks (Figure 7).

If the patient has received ≥4 consecutive doses and misses a dose and it has been <6 weeks since the last dose, administer an injection as soon as possible. If it has been >6 weeks since the last dose, give the next injection as soon as possible, plus with oral aripiprazole supplementation for 2 weeks.

Aripiprazole lauroxil long-acting injection. Depending on the dose, aripiprazole lauroxil can be administered monthly, every 6 weeks, or every 2 months. Aripiprazole lauroxil can be administered 14 days before or after the scheduled dose.34

The guidance for addressing missed or delayed doses of aripiprazole lauroxil differs depending on the dose the patient is stabilized on, and how long it has been since the last injection. Figure 8 summarizes how missed injections should be managed. When oral aripiprazole supplementation is needed, the following doses should be used:

- 10 mg/d if stabilized on 441 mg every month

- 15 mg/d if stabilized on 662 mg every month, 882 mg every 6 weeks, or 1,064 mg every 2 months

- 20 mg/d if stabilized on 882 mg every month.34

Olanzapine pamoate long-acting injection is a unique LAIA because it requires prescribers and patients to participate in a risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) program due the risk of post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome. It is administered every 2 to 4 weeks, with loading doses given for the first 2 months of treatment (Table 235). After 2 months, the patient can proceed to the maintenance dosing regimen.

Continue to: Currently, there is no concrete guidance...

Currently, there is no concrete guidance on how to address missed doses of olanzapine long-acting injection; however, the pharmacokinetics of this formulation allow flexibility in dosing intervals. Therapeutic levels are present after the first injection, and the medication reaches steady-state levels in 3 months.35-37 As a result of its specific formulation, olanzapine pamoate long-acting injection provides sustained olanzapine pamoate plasma concentrations between injections, and has a half-life of 30 days.35 Consequently, therapeutic levels of the medication are still present 2 to 4 weeks after an injection.37 Additionally, clinically relevant plasma concentrations may be present 2 to 3 months after the last injection.36

In light of this information, if a patient has not reached steady state and has missed an injection, he or she should receive the recommended loading dose schedule. If the patient has reached steady state and it has been ≤2 months since the last dose, he or she should receive the next dose as soon as possible. If steady state has been reached and it has been >2 months since the last injection, the patient should receive the recommended loading dosing for 2 months (Figure 9). Because of the risk of post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome, and because therapeutic levels are achieved after the first injection, oral olanzapine supplementation is not recommended.

Use a stepwise approach

In general, clinicians can use a stepwise approach to managing missed doses of LAIAs (Figure 10). First, establish the number of LAIA doses the patient had received prior to the last dose, and whether these injections were administered on schedule. This will help you determine if the patient is in the initiation or maintenance phase and/or has reached steady state. The second step is to establish the date of the last injection. Use objective tools, such as pharmacy records or the medical chart, to determine the date of the last injection, rather than relying on patient reporting. For the third step, calculate the time that has passed since the last LAIA dose. Once you have completed these steps, use the specific medication recommendations described in this article to address the missed dose.

Continue to: Address barriers to adherence

Address barriers to adherence

When addressing missed LAIA doses, be sure to identify any barriers that may have led to a missed injection. These might include:

- bothersome adverse effects

- transportation difficulties

- issues with insurance/medication coverage

- comorbidities (ie, alcohol/substance use disorders)

- cognitive and functional impairment caused by the patient’s illness

- difficulty with keeping track of appointments.

Clinicians can work closely with patients and/or caregivers to address any barriers to ensure that patients receive their injections in a timely fashion.

The goal: Reducing relapse

LAIAs improve medication adherence. Although nonadherence is less frequent with LAIAs than with oral antipsychotics, when a LAIA dose is missed, it is important to properly follow a stepwise approach based on the unique properties of the specific LAIA prescribed. Proper management of LAIA missed doses can prevent relapse and reoccurrence of schizophrenia symptoms, thus possibly avoiding future hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Tschosik, JD, Mary Collen O’Rourke, MD, and Amanda Holloway, MD, for their assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Although long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs) greatly assist with adherence, these agents are effective only when missed doses are avoided. When addressing missed LAIA doses, use a stepwise approach that takes into consideration the unique properties of the specific LAIA prescribed.

Related Resources

- Haddad P, Lambert T, Lauriello J, eds. Antipsychotic long-acting injections. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Diefenderfer LA. When should you consider combining 2 long-acting injectable antipsychotics? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):42-46.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole long-acting injection • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil long-acting injection • Aristada

Fluphenazine decanoate • Prolixin decanoate

Haloperidol decanoate • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine pamoate long-acting injection • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone palmitate monthly long-acting injection • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate 3-month long-acting injection • Invega Trinza

Risperidone long-acting injection • Risperdal Consta

Antipsychotic agents are the mainstay of treatment for patients with schizophrenia,1-3 and when taken regularly, they can greatly improve patient outcomes. Unfortunately, many studies have documented poor adherence to antipsychotic regimens in patients with schizophrenia, which often leads to an exacerbation of symptoms and preventable hospitalizations.4-8 In order to improve adherence, many clinicians prescribe long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs).

LAIAs help improve adherence, but these benefits are seen only in patients who receive their injections within a specific time frame.9-11 LAIAs administered outside of this time frame (missed doses) can lead to reoccurrence or exacerbation of symptoms. This article explains how to adequately manage missed LAIA doses.

First-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics

Two first-generation antipsychotics are available as a long-acting injectable formulation: haloperidol decanoate and fluphenazine decanoate. Due to the increased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms, use of these agents have decreased, and they are often less preferred than second-generation LAIAs. Furthermore, unlike many of the newer second-generation LAIAs, first-generation LAIAs lack literature on how to manage missed doses. Therefore, clinicians should analyze the pharmacokinetic properties of these agents (Table 112-28), as well as the patient’s medical history and clinical presentation, in order to determine how best to address missed doses.

Haloperidol decanoate plasma concentrations peak approximately 6 days after the injection.12 The medication has a half-life of 3 weeks. One study found that haloperidol plasma concentrations were detectable 13 weeks after the discontinuation of haloperidol decanoate.17 This same study also found that the change in plasma levels from 3 to 6 weeks after the last dose was minimal.17 Based on these findings, Figure 1 summarizes our recommendations for addressing missed haloperidol decanoate doses.

Fluphenazine decanoate levels peak 24 hours after the injection.18 An estimated therapeutic range for fluphenazine is 0.2 to 2 ng/mL.21-25 One study that evaluated fluphenazine decanoate levels following discontinuation after reaching steady state found there was no significant difference in plasma levels 6 weeks after the last dose of fluphenazine, but a significant decrease in levels 8 to 12 weeks after the last dose.26 Other studies found that fluphenazine levels were detectable 21 to 24 weeks following fluphenazine decanoate discontinuation.27,28 Based on these findings, Figure 2 summarizes our recommendations for addressing missed fluphenazine decanoate doses.

Continue to: Second-generation LAIAs

Second-generation LAIAs

Six second-generation LAIAs are available in the United States. Compared with the first-generation LAIAs, second-generation LAIAs have more extensive guidance on how to address missed doses.

Risperidone long-acting injection. When addressing missed doses of risperidone long-acting injection, first determine whether the medication has reached steady state. Steady state occurs approximately after the fourth consecutive injection (approximately 2 months).29

If a patient missed a dose but has not reached steady state, he or she should receive the next dose as well as oral antipsychotic supplementation for 3 weeks.30 If the patient has reached steady state and if it has been ≤6 weeks since the last injection, give the next injection as soon as possible. However, if steady state has been reached and it has been >6 weeks since the last injection, give the next injection, along with 3 weeks of oral antipsychotic supplementation (Figure 3).

Paliperidone palmitate monthly long-acting injection. Once the initiation dosing phase of paliperidone palmitate monthly long-acting injection (PP1M) is completed, the maintenance dose is administered every 4 weeks. When addressing missed doses of PP1M, first determine whether the patient is in the initiation or maintenance dosing phase.31

Initiation phase. Patients are in the initiation dosing phase during the first 2 injections of PP1M. During the initiation phase, the patient first receives 234 mg and then 156 mg 1 week later, both in the deltoid muscle. One month later, the patient receives a maintenance dose of PP1M (in the deltoid or gluteal muscle). The second initiation injection may be given 4 days before or after the scheduled administration date. The initiation doses should be adjusted in patients with mild renal function (creatinine clearance 50 to 80 mL/min).31 Figure 4 summarizes the guidance for addressing a missed or delayed second injection during the initiation phase.

Continue to: Maintenance phase

Maintenance phase. During the maintenance phase, PP1M can be administered 7 days before or after the monthly due date. If the patient has missed a maintenance injection and it has been <6 weeks since the last dose, the maintenance injection can be given as soon as possible (Figure 5).31 If it has been 6 weeks to 6 months since the last injection, the patient should receive their prescribed maintenance dose as soon as possible and the same dose 1 week later, with both injections in the deltoid muscle. Following the second dose, the patient can resume their regular monthly maintenance schedule, in either the deltoid or gluteal muscle. For example, if the patient was maintained on 117 mg of PP1M and it had been 8 weeks since the last injection, the patient should receive 117 mg immediately, then 117 mg 1 week later, then 117 mg 1 month later. An exception to this is if a patient’s maintenance dose is 234 mg monthly. In this case, the patient should receive 156 mg of PP1M immediately, then 156 mg 1 week later, and then 234 mg 1 month later.31 If it has been >6 months since the last dose, the patient should start the initiation schedule as if he or she were receiving a new medication.31

Paliperidone palmitate 3-month long-acting injection (PP3M) should be administered every 3 months. This injection can be given 2 weeks before or after the date of the scheduled dose.32

If the patient missed an injection and it has been <4 months since the last dose, the next scheduled dose should be given as soon as possible.32 If it has been 4 to 9 months since the last dose, the patient must return to PP1M for 2 booster injections 1 week apart. The dose of these PP1M booster injections depends on the dose of PP3M that the patient had been stabilized on:

- 78 mg if stabilized on 273 mg

- 117 mg if stabilized on 410 mg

- 156 mg if stabilized on 546 mg or 819 mg.32

After the second booster dose, PP3M can be restarted 1 month later.32 If it has been >9 months since the last PP3M dose, the patient should be restarted on PP1M. PP3M can be reconsidered once the patient has been stabilized on PP1M for ≥4 months (Figure 6).32

Continue to: Aripiprazole long-acting injection

Aripiprazole long-acting injection is administered every 4 weeks. If a patient misses an injection, first determine how many consecutive doses he or she has received.33 If the patient has missed the second or third injection, and it has been <5 weeks since the last dose, give the next injection as soon as possible. If it has been >5 weeks, give the next injection as soon as possible, plus oral aripiprazole supplementation for 2 weeks (Figure 7).

If the patient has received ≥4 consecutive doses and misses a dose and it has been <6 weeks since the last dose, administer an injection as soon as possible. If it has been >6 weeks since the last dose, give the next injection as soon as possible, plus with oral aripiprazole supplementation for 2 weeks.

Aripiprazole lauroxil long-acting injection. Depending on the dose, aripiprazole lauroxil can be administered monthly, every 6 weeks, or every 2 months. Aripiprazole lauroxil can be administered 14 days before or after the scheduled dose.34

The guidance for addressing missed or delayed doses of aripiprazole lauroxil differs depending on the dose the patient is stabilized on, and how long it has been since the last injection. Figure 8 summarizes how missed injections should be managed. When oral aripiprazole supplementation is needed, the following doses should be used:

- 10 mg/d if stabilized on 441 mg every month

- 15 mg/d if stabilized on 662 mg every month, 882 mg every 6 weeks, or 1,064 mg every 2 months

- 20 mg/d if stabilized on 882 mg every month.34

Olanzapine pamoate long-acting injection is a unique LAIA because it requires prescribers and patients to participate in a risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) program due the risk of post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome. It is administered every 2 to 4 weeks, with loading doses given for the first 2 months of treatment (Table 235). After 2 months, the patient can proceed to the maintenance dosing regimen.

Continue to: Currently, there is no concrete guidance...

Currently, there is no concrete guidance on how to address missed doses of olanzapine long-acting injection; however, the pharmacokinetics of this formulation allow flexibility in dosing intervals. Therapeutic levels are present after the first injection, and the medication reaches steady-state levels in 3 months.35-37 As a result of its specific formulation, olanzapine pamoate long-acting injection provides sustained olanzapine pamoate plasma concentrations between injections, and has a half-life of 30 days.35 Consequently, therapeutic levels of the medication are still present 2 to 4 weeks after an injection.37 Additionally, clinically relevant plasma concentrations may be present 2 to 3 months after the last injection.36

In light of this information, if a patient has not reached steady state and has missed an injection, he or she should receive the recommended loading dose schedule. If the patient has reached steady state and it has been ≤2 months since the last dose, he or she should receive the next dose as soon as possible. If steady state has been reached and it has been >2 months since the last injection, the patient should receive the recommended loading dosing for 2 months (Figure 9). Because of the risk of post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome, and because therapeutic levels are achieved after the first injection, oral olanzapine supplementation is not recommended.

Use a stepwise approach

In general, clinicians can use a stepwise approach to managing missed doses of LAIAs (Figure 10). First, establish the number of LAIA doses the patient had received prior to the last dose, and whether these injections were administered on schedule. This will help you determine if the patient is in the initiation or maintenance phase and/or has reached steady state. The second step is to establish the date of the last injection. Use objective tools, such as pharmacy records or the medical chart, to determine the date of the last injection, rather than relying on patient reporting. For the third step, calculate the time that has passed since the last LAIA dose. Once you have completed these steps, use the specific medication recommendations described in this article to address the missed dose.

Continue to: Address barriers to adherence

Address barriers to adherence

When addressing missed LAIA doses, be sure to identify any barriers that may have led to a missed injection. These might include:

- bothersome adverse effects

- transportation difficulties

- issues with insurance/medication coverage

- comorbidities (ie, alcohol/substance use disorders)

- cognitive and functional impairment caused by the patient’s illness

- difficulty with keeping track of appointments.

Clinicians can work closely with patients and/or caregivers to address any barriers to ensure that patients receive their injections in a timely fashion.

The goal: Reducing relapse

LAIAs improve medication adherence. Although nonadherence is less frequent with LAIAs than with oral antipsychotics, when a LAIA dose is missed, it is important to properly follow a stepwise approach based on the unique properties of the specific LAIA prescribed. Proper management of LAIA missed doses can prevent relapse and reoccurrence of schizophrenia symptoms, thus possibly avoiding future hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Tschosik, JD, Mary Collen O’Rourke, MD, and Amanda Holloway, MD, for their assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Although long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs) greatly assist with adherence, these agents are effective only when missed doses are avoided. When addressing missed LAIA doses, use a stepwise approach that takes into consideration the unique properties of the specific LAIA prescribed.

Related Resources

- Haddad P, Lambert T, Lauriello J, eds. Antipsychotic long-acting injections. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Diefenderfer LA. When should you consider combining 2 long-acting injectable antipsychotics? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):42-46.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole long-acting injection • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil long-acting injection • Aristada

Fluphenazine decanoate • Prolixin decanoate

Haloperidol decanoate • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine pamoate long-acting injection • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone palmitate monthly long-acting injection • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate 3-month long-acting injection • Invega Trinza

Risperidone long-acting injection • Risperdal Consta

1. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, et al. Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2):216-222.

2. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

3. Kane JM, Garcia-Ribera C. Clinical guideline recommendations for antipsychotic long-acting injections. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2009;195(52):S63-S67.

4. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(5):306-324.

5. Kishimoto T, Robenzadeh A, Leucht C, et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):192-213.

6. Andreasen NC. Symptoms, signs, and diagnosis of schizophrenia. Lancet. 1995;346(8973):477-481.

7. de Sena EP, Santos-Jesus R, Miranda-Scippa Â, et al. Relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a comparison between risperidone and haloperidol. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2003;25(4):220-223.

8. Chue P. Long-acting risperidone injection: efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(1):13-39.

9. Lafeuille MH, Frois C, Cloutier M, et al. Factors associated with adherence to the HEDIS Quality Measure in medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(7):399-410.

10. Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957-965.

11. Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, et al. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):754-768.

12. Haldol Decanoate injection [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

13. Magliozzi JR, Hollister LE, Arnold KV, et al. Relationship of serum haloperidol levels to clinical response in schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(3):365-367.

14. Mavroidis ML, Kanter DR, Hirschowitz J, et al. Clinical response and plasma haloperidol levels in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1983;81(4):354-356.

15. Reyntigens AJ, Heykants JJ, Woestenborghs RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol decanoate. A 2-year follow-up. Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 1982;17(4):238-246.

16. Jann MW, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the depot antipsychotics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10(4):315-333.

17. Chang WH, Lin SK, Juang DJ, et al. Prolonged haloperidol and reduced haloperidol plasma concentrations after decanoate withdrawal. Schizophr Res. 1993;9(1):35-40.

18. Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW. Future of depot neuroleptic therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic approaches. J Clin Psychiatry.1984;45(5 pt 2):50-58.

19. Marder SR, Hawes EM, Van Putten T, et al. Fluphenazine plasma levels in patients receiving low and conventional doses of fluphenazine decanoate. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1986;88(4):480-483.

20. Marder SR, Hubbard JW, Van Putten T, et al. Pharmacokinetics of long-acting injectable neuroleptic drugs: clinical implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1989;98(4):433-439.

21. Mavroidis ML, Kanter DR, Hirschowitz J, et al. Fluphenazine plasma levels and clinical response. J Clin Psychiatry. 1984;45(9):370-373.

22. Balant-Gorgia AE, Balant LP, Andreoli A. Pharmacokinetic optimisation of the treatment of psychosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;25(3):217-236.

23. Van Putten T, Marder SR, Wirshing WC, et al. Neuroleptic plasma levels. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(2):197-216.

24. Dahl SG. Plasma level monitoring of antipsychotic drugs. Clinical utility. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1986;11(1):36-61.

25. Miller RS, Peterson GM, McLean S, et al. Monitoring plasma levels of fluphenazine during chronic therapy with fluphenazine decanoate. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1995;20(2):55-62.

26. Gitlin MJ, Midha KK, Fogelson D, et al. Persistence of fluphenazine in plasma after decanoate withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988;8(1):53-56.

27. Wistedt B, Wiles D, Kolakowska T. Slow decline of plasma drug and prolactin levels after discontinuation of chronic treatment with depot neuroleptics. Lancet. 1981;1(8230):1163.

28. Wistedt B, Jørgensen A, Wiles D. A depot neuroleptic withdrawal study. Plasma concentration of fluphenazine and flupenthixol and relapse frequency. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1982;78(4):301-304.

29. Risperdal Consta [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

30. Marder SR, Conley R, Ereshefsky L, et al. Clinical guidelines: dosing and switching strategies for long-acting risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 16):41-46.

31. Invega Sustenna [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

32. Invega Trinza [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

33. Abilify Maintena [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; December 2016.

34. Artistada [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes, Inc.; June 2017.

35. Zyprexa Relprevv [package insert]. Indianapolis; IN: Eli Lilly and Co.; February 2017.

36. Heres S, Kraemer S, Bergstrom RF, et al. Pharmacokinetics of olanzapine long-acting injection: the clinical perspective. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(6):299-312.

37. Detke HC, Zhao F, Garhyan P, et al. Dose correspondence between olanzapine long-acting injection and oral olanzapine: recommendations for switching. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(1):35-42.

1. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, et al. Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2):216-222.

2. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

3. Kane JM, Garcia-Ribera C. Clinical guideline recommendations for antipsychotic long-acting injections. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2009;195(52):S63-S67.

4. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(5):306-324.

5. Kishimoto T, Robenzadeh A, Leucht C, et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):192-213.

6. Andreasen NC. Symptoms, signs, and diagnosis of schizophrenia. Lancet. 1995;346(8973):477-481.

7. de Sena EP, Santos-Jesus R, Miranda-Scippa Â, et al. Relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a comparison between risperidone and haloperidol. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2003;25(4):220-223.

8. Chue P. Long-acting risperidone injection: efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(1):13-39.

9. Lafeuille MH, Frois C, Cloutier M, et al. Factors associated with adherence to the HEDIS Quality Measure in medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(7):399-410.

10. Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957-965.

11. Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, et al. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):754-768.

12. Haldol Decanoate injection [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

13. Magliozzi JR, Hollister LE, Arnold KV, et al. Relationship of serum haloperidol levels to clinical response in schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(3):365-367.

14. Mavroidis ML, Kanter DR, Hirschowitz J, et al. Clinical response and plasma haloperidol levels in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1983;81(4):354-356.

15. Reyntigens AJ, Heykants JJ, Woestenborghs RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol decanoate. A 2-year follow-up. Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 1982;17(4):238-246.

16. Jann MW, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the depot antipsychotics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10(4):315-333.

17. Chang WH, Lin SK, Juang DJ, et al. Prolonged haloperidol and reduced haloperidol plasma concentrations after decanoate withdrawal. Schizophr Res. 1993;9(1):35-40.

18. Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW. Future of depot neuroleptic therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic approaches. J Clin Psychiatry.1984;45(5 pt 2):50-58.

19. Marder SR, Hawes EM, Van Putten T, et al. Fluphenazine plasma levels in patients receiving low and conventional doses of fluphenazine decanoate. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1986;88(4):480-483.

20. Marder SR, Hubbard JW, Van Putten T, et al. Pharmacokinetics of long-acting injectable neuroleptic drugs: clinical implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1989;98(4):433-439.

21. Mavroidis ML, Kanter DR, Hirschowitz J, et al. Fluphenazine plasma levels and clinical response. J Clin Psychiatry. 1984;45(9):370-373.

22. Balant-Gorgia AE, Balant LP, Andreoli A. Pharmacokinetic optimisation of the treatment of psychosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;25(3):217-236.

23. Van Putten T, Marder SR, Wirshing WC, et al. Neuroleptic plasma levels. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(2):197-216.

24. Dahl SG. Plasma level monitoring of antipsychotic drugs. Clinical utility. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1986;11(1):36-61.

25. Miller RS, Peterson GM, McLean S, et al. Monitoring plasma levels of fluphenazine during chronic therapy with fluphenazine decanoate. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1995;20(2):55-62.

26. Gitlin MJ, Midha KK, Fogelson D, et al. Persistence of fluphenazine in plasma after decanoate withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988;8(1):53-56.

27. Wistedt B, Wiles D, Kolakowska T. Slow decline of plasma drug and prolactin levels after discontinuation of chronic treatment with depot neuroleptics. Lancet. 1981;1(8230):1163.

28. Wistedt B, Jørgensen A, Wiles D. A depot neuroleptic withdrawal study. Plasma concentration of fluphenazine and flupenthixol and relapse frequency. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1982;78(4):301-304.

29. Risperdal Consta [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

30. Marder SR, Conley R, Ereshefsky L, et al. Clinical guidelines: dosing and switching strategies for long-acting risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 16):41-46.

31. Invega Sustenna [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

32. Invega Trinza [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; February 2017.

33. Abilify Maintena [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; December 2016.

34. Artistada [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes, Inc.; June 2017.

35. Zyprexa Relprevv [package insert]. Indianapolis; IN: Eli Lilly and Co.; February 2017.

36. Heres S, Kraemer S, Bergstrom RF, et al. Pharmacokinetics of olanzapine long-acting injection: the clinical perspective. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(6):299-312.

37. Detke HC, Zhao F, Garhyan P, et al. Dose correspondence between olanzapine long-acting injection and oral olanzapine: recommendations for switching. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(1):35-42.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: Monotherapy, or combination therapy?

More than 5 million older Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias—and this number is estimated to rise to almost 14 million by 2050.1 Dementia is associated with high costs for the patient, family, and society. In 2017, nearly 16.1 million caregivers assisted older adults with dementia, devoting more than 18.2 billion hours per year in care.1 In the United States, the cost of caring for individuals with dementia is expected to reach $277 billion in 2018. Additionally, Medicare and Medicaid are expected to pay 67% of the estimated 2018 cost, and 22% is expected to come out of the pockets of patients and their caregivers.1

Although dementia is often viewed as a memory loss disease, neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) are common. NPS includes distressing behaviors, such as aggression and wandering, that increase caregiver burden, escalate the cost of care, and contribute to premature institutionalization. This article examines the evidence for the use of a combination of a cholinesterase inhibitor and memantine vs use of either medication alone for treating NPS of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia.

First, rule out reversible causes of NPS

There are no disease-modifying treatments for dementia1; therefore, clinicians focus on decreasing patients’ suffering and improving their quality of life. Nearly all patients with dementia will develop at least one NPS. These commonly include auditory and visual hallucinations, delusions, depression, anxiety, psychosis, psychomotor agitation, aggression, apathy, repetitive questioning, wandering, socially or sexually inappropriate behaviors, and sleep disturbances.2 The underlying cause of these behaviors may be neurobiological,3 an acute medical condition, unmet needs or a pre-existing personality disorder, or other psychiatric illness.2 Because of this complexity, there is no specific treatment for NPS of dementia. Treatment should begin with an assessment to rule out potentially reversible causes of NPS, such as a urinary tract infection, environmental triggers, unmet needs, or untreated psychiatric illness. For mild to moderate NPS, short-term behavioral interventions, followed by pharmacologic interventions, are used. For moderate to severe NPS, pharmacologic interventions and behavioral interventions are often used simultaneously.

Pharmacologic options for treating NPS

The classes of medications frequently used to treat NPS include antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and memory-enhancing, dementia-specific agents (cholinesterase inhibitors and the N-methyl-

Antipsychotic medications are typically reserved for treating specific non-cognitive NPS, such as psychosis and/or severe agitated behavior that causes significant distress. Atypical antipsychotics,

The mood stabilizers valproate

Continue to: Evidence for dementia-specific medications

Evidence for dementia-specific medications

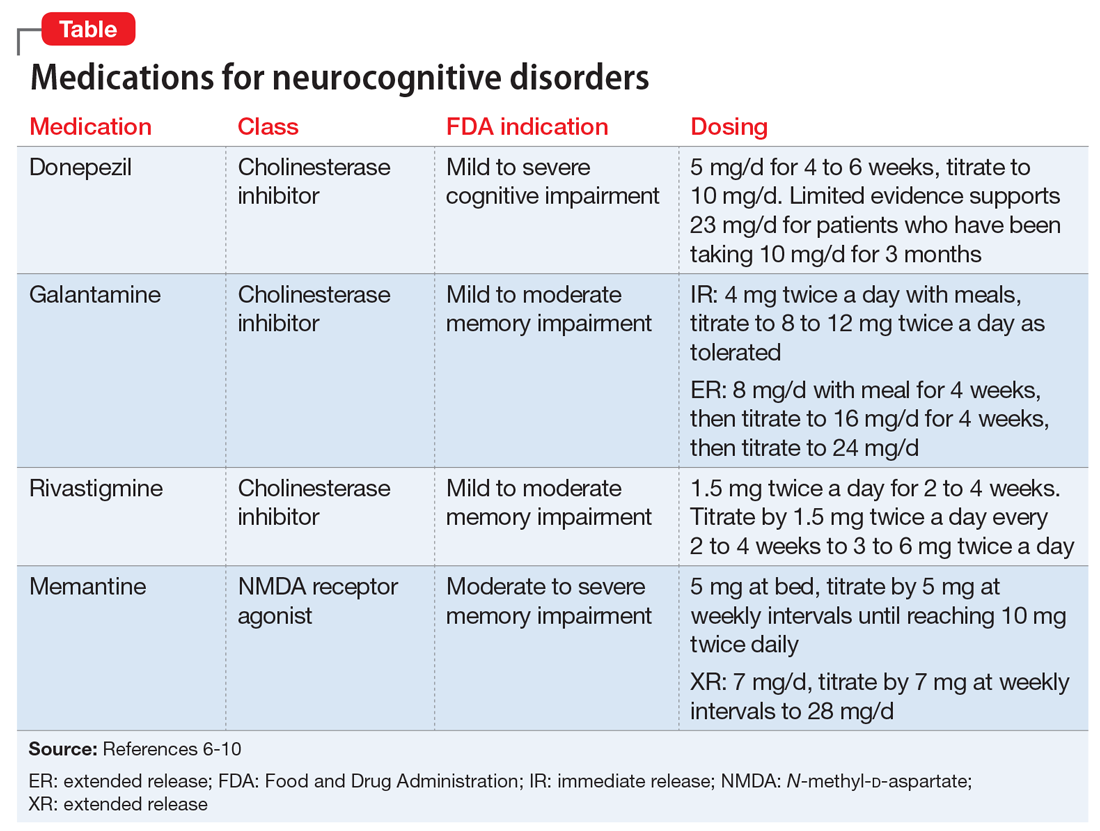

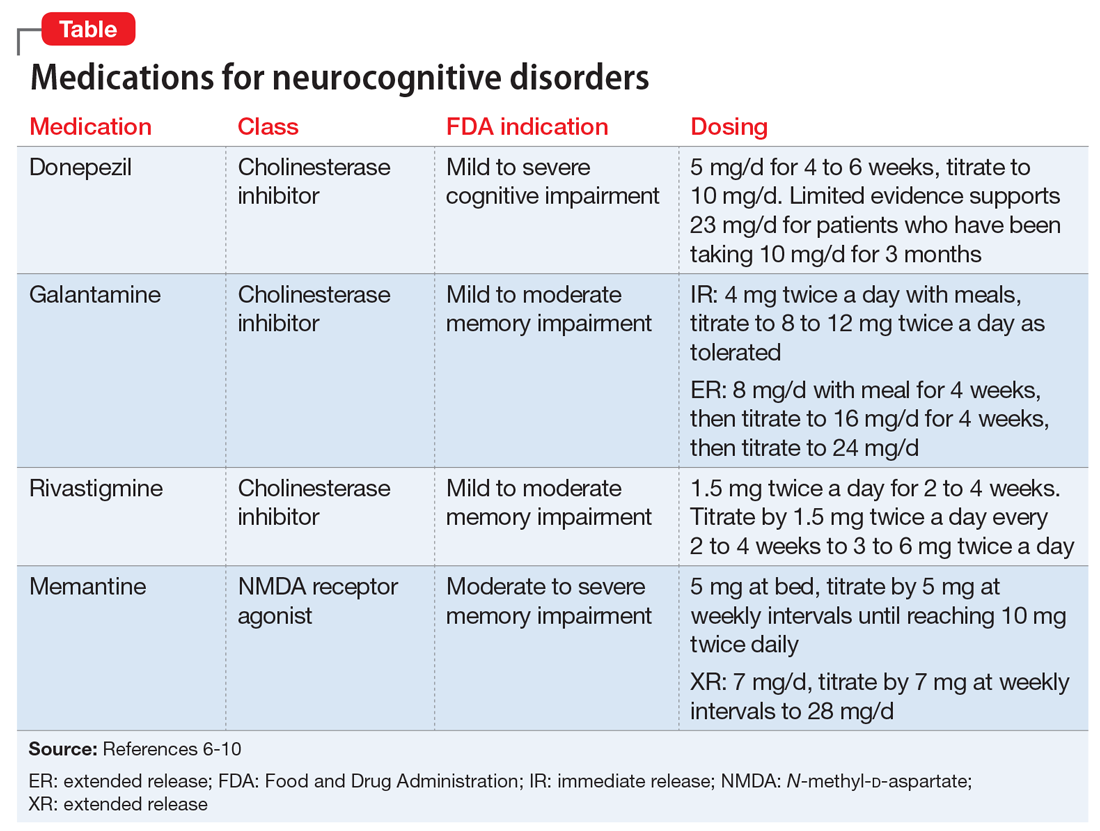

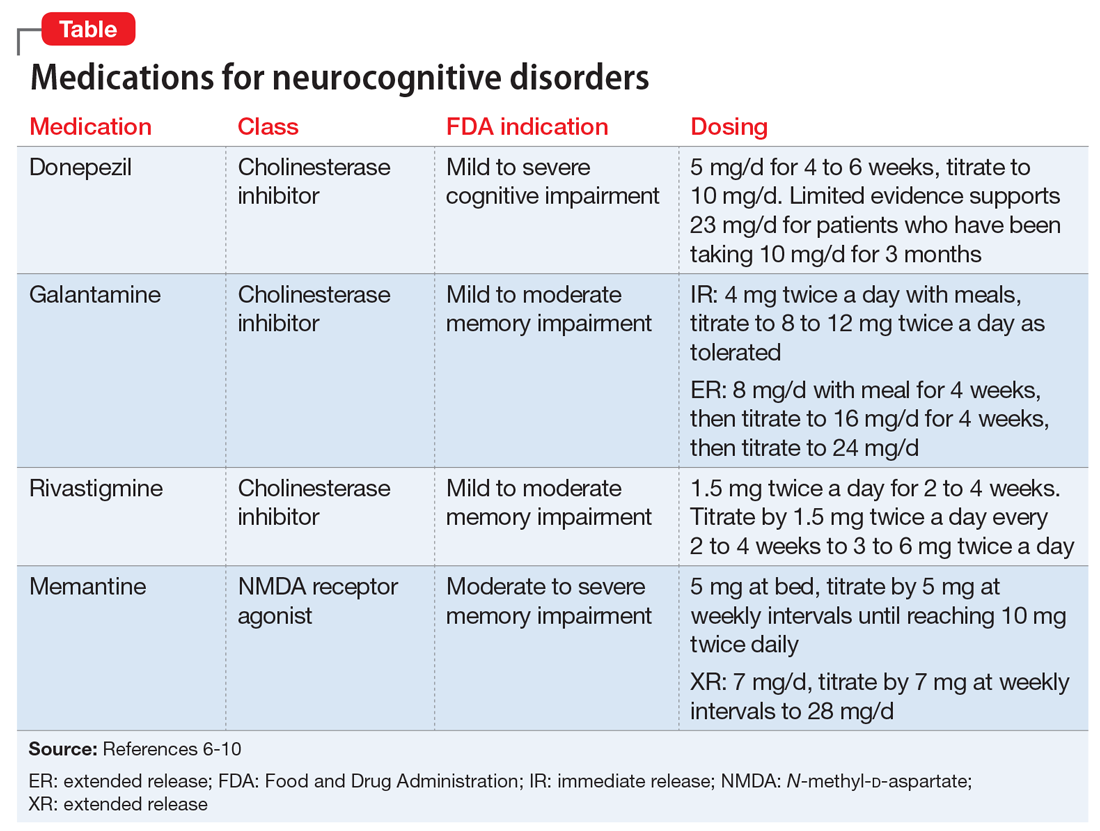

An alternative to the above pharmacologic options is treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor and/or memantine. Among cholinesterase inhibitors

Few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine have focused on improvement of NPS as a primary outcome measure, but some RCTs have used treatment of NPS as a secondary outcome.4 Most RCT data for using medications for NPS have come from small studies that lasted 17 days to 28 weeks and had design limitations. Most meta-analyses and review articles exclude trials if they do not evaluate NPS as a primary outcome, and most RCTs have only included NPS as a secondary outcome. We hypothesize that this is because NPS is conceptualized as a psychiatric condition, while dementia is codified as a neurologic condition. The reality is that dementia is a neuropsychiatric condition. This artificial divergence complicates both the evaluation and treatment of patients with dementia, who almost always have NPS. Medication trials focused on the neurologic components for primary outcomes contribute to the confusion and difficulty of building an evidence base around the treatment of NPS in Alzheimer’s disease. Patients with severe NPS are seldom included in RCTs.

A cholinesterase inhibitor, memantine, or both?

In the absence of extended RCTs, attention turns to the opinions of panels of experts examining available data.

The 2012 Fourth Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia12 recommended a trial of a cholinesterase inhibitor in most patients with Alzheimer’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease combined with another type of dementia. The panel did not find enough evidence to recommend for or against the use of cholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine for the treatment of NPS as a primary indication. However, they warned of the risks of discontinuing a cholinesterase inhibitor and suggested a slow taper and monitoring, with consideration of restarting the medication if there is notable functional or behavioral decline.

Continue to: In 2015, the European Neurological Society and the European Federation of Neurological Societies...

In 2015, the European Neurological Society and the European Federation of Neurological Societies (now combined into the European Academy of Neurology) found a moderate benefit for using cholinesterase inhibitors to treat problematic behaviors in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.13 They found the evidence weak only when they included consideration of cognitive benefits. For patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease, the Academy endorsed the combination of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine.13

The United Kingdom National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline on dementia is updated every 1 to 3 years based on evolving evidence for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and related symptoms. In 2016, NICE updated its guideline to recommend the use of a cholinesterase inhibitor for patients with mild to severe Alzheimer’s disease and memantine for those with severe Alzheimer’s disease.14 NICE specifically noted that it could not endorse the use of a cholinesterase inhibitor for severe dementia because that indication is not approved in the United Kingdom, even though there is evidence for this use. The NICE guidelines recommend use of cholinesterase inhibitors for the non-cognitive and/or behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, or mixed dementia after failure or intolerance of an antipsychotic medication. They recommend memantine if there is a failure to respond or intolerance of a cholinesterase inhibitor. The NICE guideline did not address concomitant use of a cholinesterase inhibitor with memantine.

The 2017 guideline published by the British Association for Psychopharmacology states that combination therapy (a cholinesterase inhibitor plus memantine) “may” be beneficial. The group noted that while studies were well-designed, sample sizes were small and not based on clinically representative samples.15

Both available evidence and published guidelines suggest that combination treatment for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease may slow the worsening of symptoms or prevent the emergence of NPS better than either medication could accomplish alone. Slowing symptom progression could potentially decrease the cost of in-home care and delay institutionalization.