User login

Rheumatoid Arthritis vs Osteoarthritis: Comparison of Demographics and Trends of Joint Replacement Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample

ABSTRACT

Current literature regarding complications following total joint arthroplasty have primarily focused on patients with osteoarthritis (OA), with less emphasis on the trends and in-hospital outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients undergoing these procedures. The purpose of this study is to analyze the outcomes and trends of RA patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or total hip arthroplasty (THA) compared to OA patients.

Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2006 to 2011 was extracted using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for patients that received a TKA or THA. Outcome measures included cardiovascular complications, cerebrovascular complications, pulmonary complications, wound dehiscence, and infection. Inpatient and hospital demographics including primary diagnosis, age, gender, primary payer, hospital teaching status, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, hospital bed size, location, and median household income were analyzed.

Logistic regression analysis of OA vs RA patients with patient outcomes revealed that osteoarthritic THA candidates had lower risk for cardiovascular complications, pulmonary complications, wound dehiscence, infections, and systemic complications, compared to rheumatoid patients. There was a significantly elevated risk of cerebrovascular complication in osteoarthritic THA compared to RA THA. OA patients undergoing TKA had significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications. There were significant decreases in mechanical wounds, infection, and systemic complications in the OA TKA patients.

RA patients are at higher risk for postoperative infection, wound dehiscence, and systemic complications after TKA and THA compared to OA patients. These findings highlight the importance of preoperative medical clearance and management to optimize RA patients and improve the postoperative outcomes.

Continue to: RA is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease...

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that causes joint deterioration, leading to pain, disability, systemic complications, short lifespan, and decline in quality of life.1-3 The deterioration primarily affects the synovial membranes of joints, causing arthritis and resulting in extra-articular sequelae such as cardiovascular disease,4 pulmonary disease,5 and increased infection rates.3,6 RA is the most prevalent inflammatory arthritis worldwide and affects up to 50 cases per 100,000 in both the US and northern Europe.2,7-9 Although the gold standard of care for these patients is medical management with immunosuppressant drugs such as disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), total joint arthroplasty (TJA) remains an important tool in the management of joint deterioration in such patients.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) are common procedures utilized to treat disorders that cause joint pain and hindered joint mobility, including osteoarthritis (OA) and RA. Given the aging population, the amount of TKAs and THAs performed in the US has consistently increased each year, with the vast majority of this increase composed of patients with OA.10 As a result, previous studies investigated the trends and outcomes of these procedures in patients with OA, but relatively less is known about the outcomes and trends of patients with RA undergoing the same surgeries.

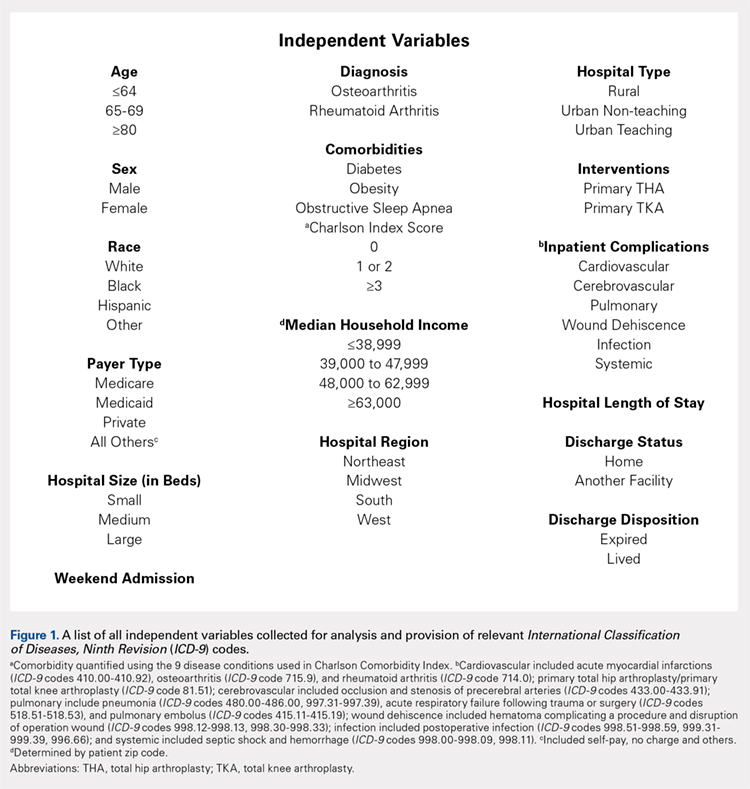

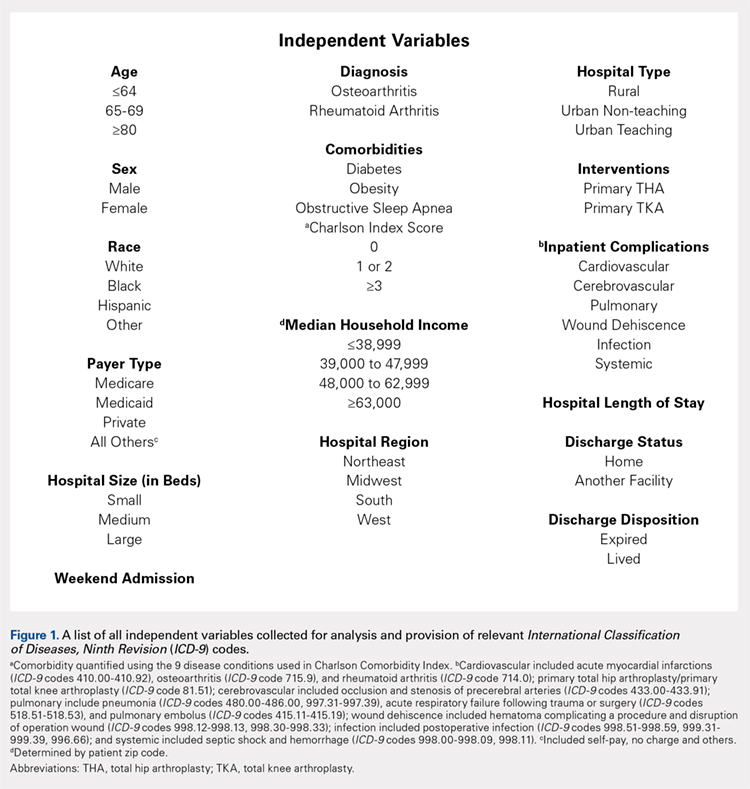

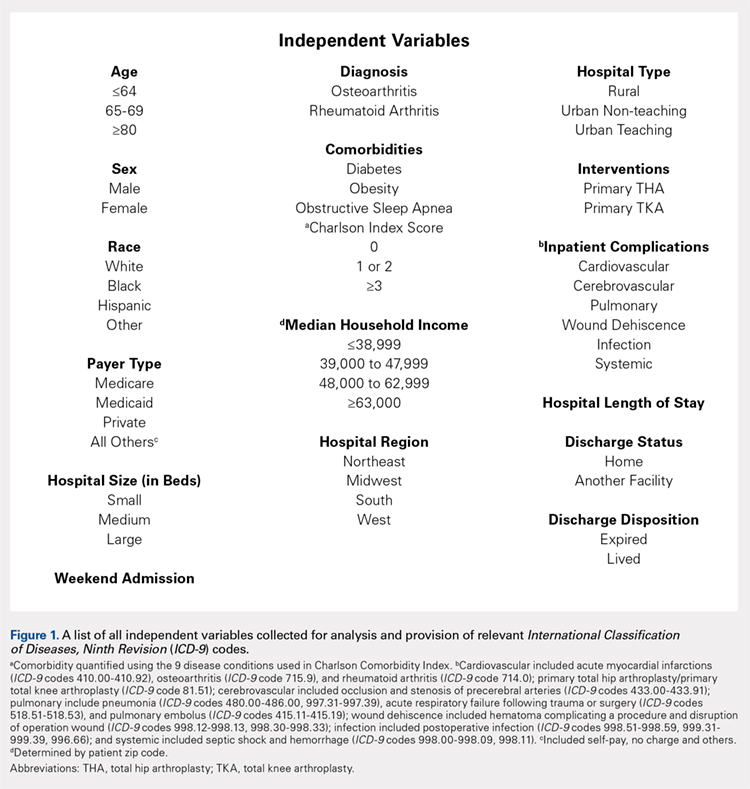

Given that RA is a fundamentally different condition with its own pathological characteristics, an understanding of how these differences may impact postoperative outcomes in patients with RA is important. This study aims to present a comparative analysis of the trends and postoperative outcomes between patients with RA and OA undergoing TKA and THA (Figure 1, Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Demographics of Total Knee Arthroplasty Patients Based on Primary Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis

| OA | RA | Total | P Value | |||

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | (RA vs OA) |

Age group |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

<64 years | 295,637 | 42.42 | 11,325 | 48.90 | 306,962 | 42.63 |

|

65 to 79 years | 329,034 | 47.22 | 10,055 | 43.42 | 339,089 | 47.09 |

|

≥80 years | 72,197 | 10.36 | 1780 | 7.69 | 73,977 | 10.27 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Male | 259,192 | 37.19 | 4887 | 21.12 | 264,079 | 36.68 |

|

Female | 435,855 | 62.54 | 18,248 | 78.88 | 454,103 | 63.07 |

|

Race |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

White | 468,632 | 67.25 | 14,532 | 77.18 | 483,164 | 67.10 |

|

Black | 39,691 | 5.7 | 2119 | 11.25 | 41,810 | 5.81 |

|

Hispanic | 28,573 | 4.1 | 1395 | 7.41 | 29,968 | 4.16 |

|

Other | 21,306 | 3.06 | 783 | 4.16 | 22,089 | 3.07 |

|

Region of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Northeast | 112,031 | 16.08 | 3417 | 14.75 | 115,448 | 16.03 |

|

Midwest | 192,595 | 27.64 | 5975 | 25.80 | 198,570 | 27.58 |

|

South | 257,855 | 37 | 9422 | 40.68 | 267,277 | 37.12 |

|

West | 134,387 | 19.28 | 4346 | 18.77 | 138,733 | 19.27 |

|

Location/teaching status of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Rural | 86,321 | 12.39 | 2709 | 11.79 | 89,030 | 12.36 |

|

Urban non-teaching | 333,043 | 47.79 | 10,905 | 47.46 | 343,948 | 47.77 |

|

Urban teaching | 273,326 | 39.22 | 9363 | 40.75 | 282,689 | 39.26 |

|

Hospital location |

|

|

|

|

|

| .0024 |

Rural | 86,321 | 12.39 | 2709 | 11.79 | 89,030 | 12.36 |

|

Urban | 606,369 | 87.01 | 20,268 | 88.21 | 626,637 | 87.03 |

|

Hospital teaching status |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Teaching | 409,465 | 58.76 | 13,275 | 57.78 | 422,740 | 58.71 |

|

Non-teaching | 283,225 | 40.64 | 9702 | 42.22 | 292,927 | 40.68 |

|

Comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obstructive sleep apnea | 65,342 | 9.38 | 1946 | 8.40 | 67,288 | 9.35 | <.0001 |

Diabetes | 147,292 | 21.14 | 4289 | 18.52 | 151,581 | 21.05 | <.0001 |

Obesity | 129,277 | 18.55 | 3730 | 16.11 | 133,007 | 18.47 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 2. Demographics of Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients Based on Primary Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis or Rheumatoid Arthritis

| OA | RA | Total | P Value | |||

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | (RA vs OA) |

Age group |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

<64 years | 133,645 | 45.18 | 4679 | 48.02 | 138,324 | 45.27 |

|

65 to 79 years | 123,628 | 41.8 | 3992 | 40.97 | 127,620 | 41.77 |

|

≥80 years | 38,513 | 13.02 | 1073 | 11.01 | 39,586 | 12.96 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Male | 129,708 | 43.85 | 2457 | 25.24 | 132,165 | 43.26 |

|

Female | 165,010 | 55.79 | 7278 | 74.76 | 172,288 | 56.39 |

|

Race |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

White | 207,005 | 69.98 | 6322 | 80.08 | 213,327 | 69.82 |

|

Black | 15,505 | 5.24 | 771 | 9.77 | 16,276 | 5.33 |

|

Hispanic | 6784 | 2.29 | 522 | 6.61 | 7306 | 2.39 |

|

Other | 7209 | 2.44 | 280 | 3.55 | 7489 | 2.45 |

|

Region of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Northeast | 58,525 | 19.79 | 1683 | 17.27 | 60,208 | 19.71 |

|

Midwest | 79,040 | 26.72 | 2446 | 25.10 | 81,486 | 26.67 |

|

South | 95,337 | 32.23 | 3716 | 38.14 | 99,053 | 32.42 |

|

West | 62,884 | 21.26 | 1899 | 19.49 | 64,783 | 21.20 |

|

Location/teaching status of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| .0065 |

Rural | 30,954 | 10.46 | 993 | 10.26 | 31,947 | 10.46 |

|

Urban non-teaching | 133,061 | 44.99 | 4245 | 43.87 | 137,306 | 44.94 |

|

Urban teaching | 130,150 | 44 | 4439 | 45.87 | 134,589 | 44.05 |

|

Hospital location |

|

|

|

|

|

| .4098 |

Rural | 30,954 | 10.46 | 993 | 10.26 | 31,947 | 10.46 |

|

Urban | 263,211 | 88.99 | 8684 | 89.74 | 271,895 | 88.99 |

|

Hospital teaching status |

|

|

|

|

|

| .0077 |

Teaching | 159,313 | 53.86 | 5108 | 52.78 | 164,421 | 53.82 |

|

Non-teaching | 134,852 | 45.59 | 4569 | 47.22 | 139,421 | 45.63 |

|

Comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obstructive sleep apnea | 19,760 | 6.68 | 573 | 5.88 | 20,333 | 6.65 | .0028 |

Diabetes | 41,929 | 14.18 | 1325 | 13.60 | 43,254 | 14.16 | .1077 |

Obesity | 38,808 | 13.12 | 1100 | 11.29 | 39,908 | 13.06 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

Exemptions were obtained from the Institutional Review Board. Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2006 to 2011 were extracted using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for patients that received primary TKA or THA, as well as their comorbid conditions. No patients or populations were excluded from the sampling process. A list of all independent variables collected for analysis and provision of relevant ICD-9 codes is included in Figure 1. The NIS is the largest all-payer stratified survey of inpatient care in the US healthcare system. As of 2011, each year provides information on approximately 8 million inpatient stays from about 1000 hospitals in 46 states. All discharges from sampled hospitals are also represented in the database. All patient information is protected, and all methods were conducted in accordance with the highest ethical standards of Human and Animal Rights Research.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

SAS 9.2 and PROC FREQ statistics software were used to generate P values (chi square result) and analyze the trends (Cochran-Armitage). Results were weighted utilizing standard discharge weights from the NIS to ensure accurate comparison of data from different time points. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to generate odds ratio and 95% confidence limits to assess outcomes across different demographic variables.

RESULTS

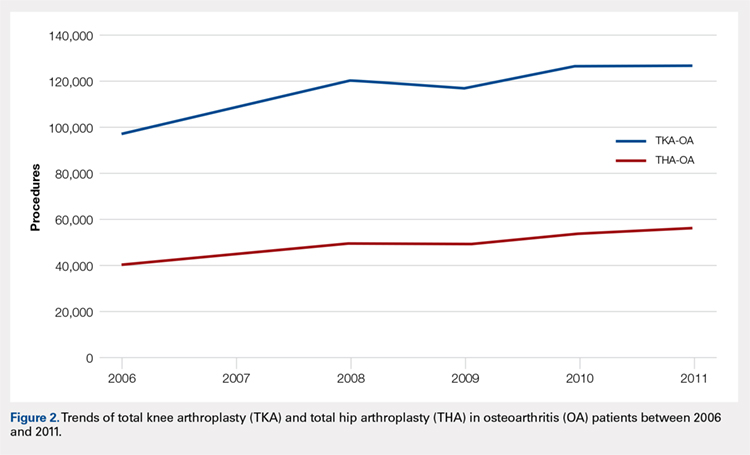

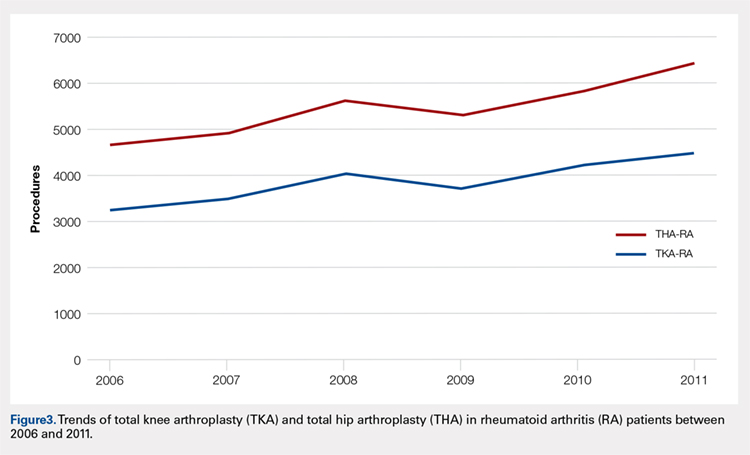

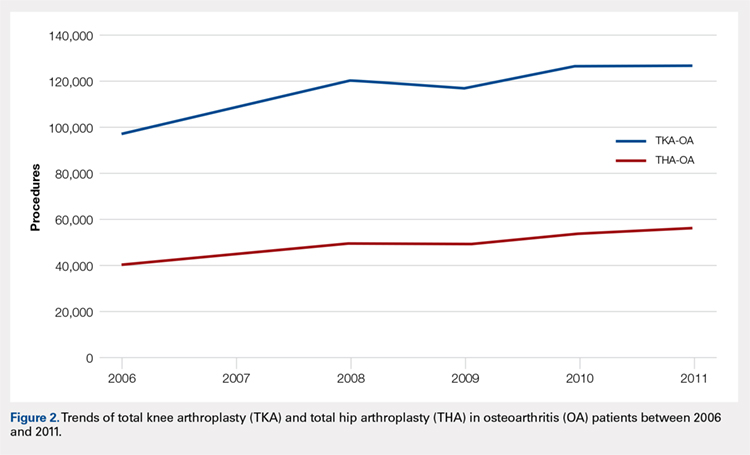

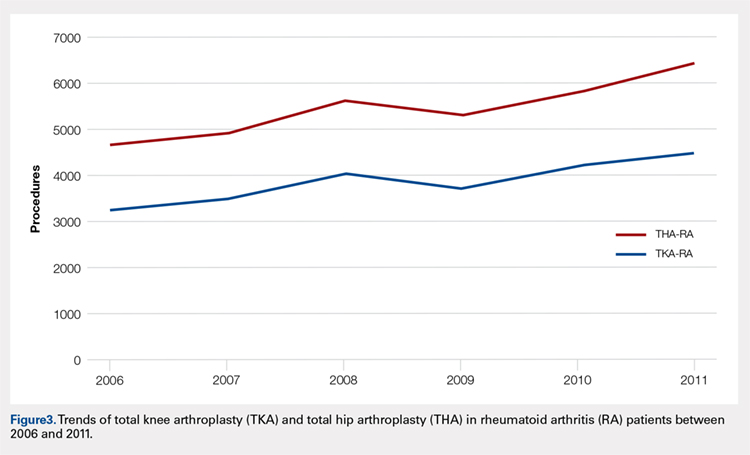

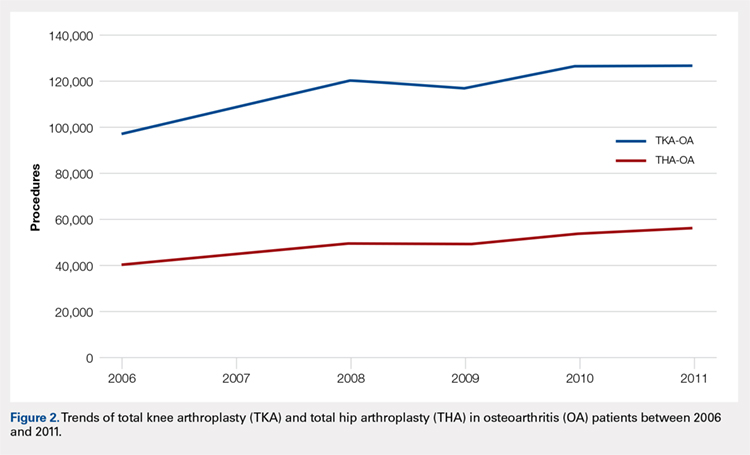

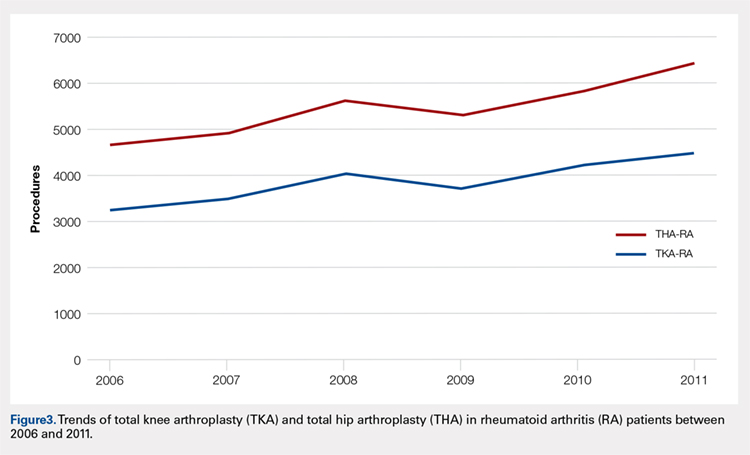

Data on 337,082 and 1,362,241 patients undergoing THA or TKA, respectively, between 2006 and 2011 were analyzed. Patients in both groups were further differentiated by a diagnosis of either OA or RA. OA was the most common diagnosis, constituting 96.8% of all arthritic THA and TKA patients. From 2006 to 2011, a 36% and 34% increase in total number of THAs and TKAs, respectively, were reported. The number of patients with OA undergoing THA and TKA steadily increased from 2006 to 2011 (Figure 2). The number of THA and TKA procedures in patients with RA followed a similar trend but at a comparatively slower rate (Figure 3). The TKA geographical trends mirrored those observed with THA. The majority of operations were performed at urban hospitals (89% THA, 87% TKA; P < .0001). Among patients with RA and OA, the majority of TKAs (47.77%; P < .0001) took place in urban non-teaching hospitals than in urban teaching hospitals (39.26%). This pattern was not the same for THA, with 44.94% being performed at urban teaching hospitals and 44.05% at urban non-teaching institutions (P < .0001). Rural hospitals accounted for a low percentage of operations for both procedures: 10.46% of THA and 12.36% of TKA (P < .0001). Large institutions (based on the number of beds) claimed the majority of cases (59% of THA and TKA).

Logistic regression analysis and odds ratios of patients with OA vs those with RA with patient outcomes adjusted for age, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, and gender revealed that patients with OA undergoing THA had lower risk for cardiovascular (0.674; confidence interval (CI) 0.587-0.774) and pulmonary complications (0.416; CI 0.384-0.450), wound dehiscence (0.647; CI 0.561-0.747), infections (0.258; CI 0.221-0.301), and systemic complications (0.625; CI 0.562-0.695) than patients with RA. Patients with OA exhibited statistically significantly higher odds of experiencing cerebrovascular complications after THA than those with RA (1.946; CI 1.673-2.236) (Table 3). In a similar logistic regression analysis of OA vs RA in TKA, which was adjusted for age, CCI score, and gender, patients with OA had significantly higher risk for cardiovascular (1.329; CI 1.069-1.651) and cerebrovascular complications (1.635; CI 1.375-1.943) than patients with RA. Significant decreases in wound dehiscence (0.757; CI 0.639-0.896), infection (0.331; CI 0.286-0.383), and systemic complication (0.641; CI 0.565-0.729) were noted in the patients with OA and TKA (Table 4).

Table 3. Odds Ratio for In-Hospital Complications Following THA for OA Patients vs RA Patients

| Odds Ratio | Confidence Limits |

Cardiovascular complication | .674 | .587-.744 |

Cerebrovascular complication | 1.946 | 1.673-2.236 |

Pulmonary complication | .416 | .384-.450 |

Wound dehiscence | .647 | .561-.747 |

Infection | .258 | .221-.301 |

Systemic complication | .625 | .562-.695 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; THA, total hip arthroplasty.

Table 4. Odds Ratio for In-Hospital Complications Following TKA for OA Patients vs RA Patients

| Odds Ratio | Confidence Limits |

Cardiovascular complication | 1.329 | 1.069-1.651 |

Cerebrovascular complication | 1.635 | 1.375-1.943 |

Pulmonary complication | 1.03 | .995-1.223 |

Wound dehiscence | .757 | .639-.896 |

Infection | .331 | .286-.383 |

Systemic complication | .641 | .565-.729 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION

Our results showed a continuous yearly increase from 2006 to 2011 in THA and TKA procedures at a rate of 36% and 34%, respectively; this result was consistent with existing literature.11 Despite a substantial increase in the amount of total THA and TKA procedures, the ratio of patients with RA undergoing these operations has decreased or remained nearly the same. Similar effects were found in Japan and the US when examining patients with RA undergoing TJA procedures between 2001 and 2007 and between 1992 and 2005, respectively.12-14 This observation may be explained by the advances and early initiation of pharmacologic treatment and the widespread use of DMARDs such as methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine, leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, and biological response modifiers TNF-α and interleukin-1.15 These medications have drastically improved survival rates of patients with RA with impressive capabilities in symptom relief.15 With the increasing use of DMARDs and aggressive treatment early on in the disease process, patients with RA are showing markedly slow progression of joint deterioration, leading to a decreased need for orthopedic intervention compared with the general population.13,15

When analyzing the complication rates for patients undergoing TKA and THA, we observed that patients with RA exhibited a significant increase in the rates of infections, wound dehiscence, and systemic complications prior to discharge from the hospital compared with the OA population. The increased risk of infections was reported in previous studies assessing postoperative complication rates in TJA.16,17 A study utilizing the Norwegian Arthroplasty Registry noted an increased risk of late infection in patients with RA, leading to increased rates of revision TJA in comparison with patients with OA.16 Another study, which was based on the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database, showed that patients with RA are at an increased risk of infection only after THA and interestingly not after TKA.17 Although our study did not identify the causes of the increased infection rate, the inherent nature of the disease and the immunomodulatory drugs used to treat it may contribute to this increased infectious risk in patients with RA.6,18 Immunosuppressive DMARDs are some of the widely used medications employed to treat RA and are prime suspects of causing increased infection rates.15 The perioperative use of MTX has not been shown to cause short-term increases in infection for patients undergoing orthopedic intervention, but leflunomide and TNF-α inhibitors have been shown to cause a significant several-fold increase in risk for surgical wound infections.19,20

All patients with RA presented with significant increases for infection, wound dehiscence, and systemic complications, whereas only patients with RA undergoing THA showed increased risk of pulmonary and cardiovascular complications when compared with patients with OA. Surprisingly, in TKA, patients with RA were at a significantly decreased risk of cardiovascular complications. This observation was interesting due to cardiovascular disease being one of RA's most notable extra-articular features.4,21

Patients with RA undergoing TJA also showed significantly lower cerebrovascular complications than patients with OA. The significant reduction in risk for these complications has not been previously reported in the current literature, and it was an unexpected finding as past studies have found an increased risk in cerebrovascular disease in patients with RA. RA is an inflammatory disease exhibiting the upregulation of procoagulation factors,22 so we expected patients with RA to be at an increased risk for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular complications over patients with OA. Although we are unsure why these results were observed, we postulate that pharmaceutical interventions may confer some protection to patients with RA. For example, aspirin is commonly utilized in RA for its protective anti-platelet effect23 and may be a contributing factor to why we found low postoperative complication rates in cerebrovascular disease. However, the reason why aspirin may be protective against cerebrovascular and not cardiovascular complications remains unclear. Moreover, most guidelines suggest that aspirin be stopped prior to surgery.24 Although patients with RA were younger than those with OA, age was accounted for when analyzing the data.

A major strength of the study was the large sample size and the adjustment of potential confounding variables when examining the difference in complications between RA and OA. It is also a national US study that utilizes a validated database. Given that the patient samples in the NIS are reported in a uniform and de-identified manner, the database is considered ideal and has been extensively used for retrospective large observational cohort studies.25 However, the study also had some limitations due to the retrospective and administrative nature of the NIS database. Only data concerning patient complications during their inpatient stay at the hospital were available. Patients who may develop complications following discharge were not included in the data, providing a very small window of time for analysis. Another limitation with the database was its lack of ability to identify the severity of each patient's disease process or the medical treatment they received perioperatively. Finally, no patient-reported outcomes were determined, which would provide information on whether these complications affect the patients’ postoperational satisfaction in regard to their pain and disability.

CONCLUSION

As RA patients continue to utilize joint arthroplasty to repair deteriorated joints, understanding of how the disease process and its medical management may impact patient outcomes is important. This article reports significantly higher postoperational infection rates in RA than in patients with OA, which may be due to the medical management of the disease. Although new medications have been introduced and are being used to treat patients with RA, they have not altered the complication rate following TJA in this patient population. Thus, surgeons and other members of the management team should be familiar with the common medical conditions, co-morbidities, and medical treatments/side effects that are encountered in patients with RA. Future studies should delve into possible differences in long-term outcomes of patients with RA undergoing TKA and THA, as well as whether certain perioperative strategies and therapies (medical or physical) may decrease complications and improve outcomes.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

- Myasoedova E, Davis JM 3rd, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis: rheumatoid arthritis and mortality. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(5):379-385. doi:10.1007/s11926-010-0117-y.

- Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423(6937):356-361. doi:10.1038/nature01661.

- Gullick NJ, Scott DL. Co-morbidities in established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(4):469-483. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2011.10.009.

- Masuda H, Miyazaki T, Shimada K, et al. Disease duration and severity impacts on long-term cardiovascular events in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Cardiol. 2014;64(5):366-370. doi:10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.02.018.

- Bongartz T, Nannini C, Medina-Velasquez YF, et al. Incidence and mortality of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum.2010;62(6):1583-1591. doi:10.1002/art.27405.

- Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2287-2293. doi:10.1002/art.10524.

- Rossini M, Rossi E, Bernardi D, et al. Prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(5):659664. doi:10.1007/s00296-014-2974-6.

- Alamanos Y, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA. Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis, based on the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;36(3):182-188. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.08.006.

- Carbonell J, Cobo T, Balsa A, Descalzo MA, Carmona L. The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Spain: results from a nationwide primary care registry. Rheumatology.2008;47(7):1088-1092. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken205.

- Skytta ET, Honkanen PB, Eskelinen A, Huhtala H, Remes V. Fewer and older patients with rheumatoid arthritis need total knee replacement. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41(5):345-349. doi:10.3109/03009742.2012.681061.

- Singh JA, Vessely MB, Harmsen WS, et al. A population-based study of trends in the use of total hip and total knee arthroplasty, 1969–2008. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(10):898-904. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0115.

- Momohara S, Inoue E, Ikari K, et al. Decrease in orthopaedic operations, including total joint replacements, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis between 2001 and 2007: data from Japanese outpatients in a single institute-based large observational cohort (IORRA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):312-313. doi:10.1136/ard.2009.107599.

- Jain A, Stein BE, Skolasky RL, Jones LC, Hungerford MW. Total joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a United States experience from 1992 through 2005. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):881-888. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2011.12.027.

- Mertelsmann-Voss C, Lyman S, Pan TJ, Goodman SM, Figgie MP, Mandl LA. US trends in rates of arthroplasty for inflammatory arthritis including rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66(6):1432-1439. doi:10.1002/art.38384.

- Howe CR, Gardner GC, Kadel NJ. Perioperative medication management for the patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(9):544-551. doi:10.5435/00124635-200609000-00004.

- Schrama JC, Espehaug B, Hallan G, et al. Risk of revision for infection in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with osteoarthritis: a prospective, population-based study on 108,786 hip and knee joint arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(4):473-479. doi:10.1002/acr.20036.

- Ravi B, Croxford R, Hollands S, et al. Increased risk of complications following total joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):254-263. doi:10.1002/art.38231.

- Au K, Reed G, Curtis JR, et al. High disease activity is associated with an increased risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):785-791. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.128637.

- Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295(19):2275-2285. doi:10.1001/jama.295.19.2275.

- Scherrer CB, Mannion AF, Kyburz D, Vogt M, Kramers-de Quervain IA. Infection risk after orthopedic surgery in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases treated with immunosuppressive drugs. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(12):2032-2040. doi:10.1002/acr.22077.

- Bacani AK, Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Heit JA, Matteson EL. Noncardiac vascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis: increase in venous thromboembolic events? Arthritis Rheum.2012;64(1):53-61. doi:10.1002/art.33322.

- Wallberg-Jonsson S, Dahlen GH, Nilsson TK, Ranby M, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S. Tissue plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and von Willebrand factor in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 1993;12(3):318324.

- van Heereveld HA, Laan RF, van den Hoogen FH, Malefijt MC, Novakova IR, van de Putte LB. Prevention of symptomatic thrombosis with short term (low molecular weight) heparin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after hip or knee replacement. Ann Rheum Dis.2001;60(10):974-976. doi:10.1136/ard.60.10.974.

- Mont MA, Jacobs JJ, Boggio LN, et al. Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg.2011;19(12):768-776.

- Bozic KJ, Bashyal RK, Anthony SG, Chiu V, Shulman B, Rubash HE. Is administratively coded comorbidity and complication data in total joint arthroplasty valid? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):201-205. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2352-1.

ABSTRACT

Current literature regarding complications following total joint arthroplasty have primarily focused on patients with osteoarthritis (OA), with less emphasis on the trends and in-hospital outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients undergoing these procedures. The purpose of this study is to analyze the outcomes and trends of RA patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or total hip arthroplasty (THA) compared to OA patients.

Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2006 to 2011 was extracted using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for patients that received a TKA or THA. Outcome measures included cardiovascular complications, cerebrovascular complications, pulmonary complications, wound dehiscence, and infection. Inpatient and hospital demographics including primary diagnosis, age, gender, primary payer, hospital teaching status, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, hospital bed size, location, and median household income were analyzed.

Logistic regression analysis of OA vs RA patients with patient outcomes revealed that osteoarthritic THA candidates had lower risk for cardiovascular complications, pulmonary complications, wound dehiscence, infections, and systemic complications, compared to rheumatoid patients. There was a significantly elevated risk of cerebrovascular complication in osteoarthritic THA compared to RA THA. OA patients undergoing TKA had significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications. There were significant decreases in mechanical wounds, infection, and systemic complications in the OA TKA patients.

RA patients are at higher risk for postoperative infection, wound dehiscence, and systemic complications after TKA and THA compared to OA patients. These findings highlight the importance of preoperative medical clearance and management to optimize RA patients and improve the postoperative outcomes.

Continue to: RA is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease...

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that causes joint deterioration, leading to pain, disability, systemic complications, short lifespan, and decline in quality of life.1-3 The deterioration primarily affects the synovial membranes of joints, causing arthritis and resulting in extra-articular sequelae such as cardiovascular disease,4 pulmonary disease,5 and increased infection rates.3,6 RA is the most prevalent inflammatory arthritis worldwide and affects up to 50 cases per 100,000 in both the US and northern Europe.2,7-9 Although the gold standard of care for these patients is medical management with immunosuppressant drugs such as disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), total joint arthroplasty (TJA) remains an important tool in the management of joint deterioration in such patients.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) are common procedures utilized to treat disorders that cause joint pain and hindered joint mobility, including osteoarthritis (OA) and RA. Given the aging population, the amount of TKAs and THAs performed in the US has consistently increased each year, with the vast majority of this increase composed of patients with OA.10 As a result, previous studies investigated the trends and outcomes of these procedures in patients with OA, but relatively less is known about the outcomes and trends of patients with RA undergoing the same surgeries.

Given that RA is a fundamentally different condition with its own pathological characteristics, an understanding of how these differences may impact postoperative outcomes in patients with RA is important. This study aims to present a comparative analysis of the trends and postoperative outcomes between patients with RA and OA undergoing TKA and THA (Figure 1, Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Demographics of Total Knee Arthroplasty Patients Based on Primary Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis

| OA | RA | Total | P Value | |||

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | (RA vs OA) |

Age group |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

<64 years | 295,637 | 42.42 | 11,325 | 48.90 | 306,962 | 42.63 |

|

65 to 79 years | 329,034 | 47.22 | 10,055 | 43.42 | 339,089 | 47.09 |

|

≥80 years | 72,197 | 10.36 | 1780 | 7.69 | 73,977 | 10.27 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Male | 259,192 | 37.19 | 4887 | 21.12 | 264,079 | 36.68 |

|

Female | 435,855 | 62.54 | 18,248 | 78.88 | 454,103 | 63.07 |

|

Race |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

White | 468,632 | 67.25 | 14,532 | 77.18 | 483,164 | 67.10 |

|

Black | 39,691 | 5.7 | 2119 | 11.25 | 41,810 | 5.81 |

|

Hispanic | 28,573 | 4.1 | 1395 | 7.41 | 29,968 | 4.16 |

|

Other | 21,306 | 3.06 | 783 | 4.16 | 22,089 | 3.07 |

|

Region of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Northeast | 112,031 | 16.08 | 3417 | 14.75 | 115,448 | 16.03 |

|

Midwest | 192,595 | 27.64 | 5975 | 25.80 | 198,570 | 27.58 |

|

South | 257,855 | 37 | 9422 | 40.68 | 267,277 | 37.12 |

|

West | 134,387 | 19.28 | 4346 | 18.77 | 138,733 | 19.27 |

|

Location/teaching status of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Rural | 86,321 | 12.39 | 2709 | 11.79 | 89,030 | 12.36 |

|

Urban non-teaching | 333,043 | 47.79 | 10,905 | 47.46 | 343,948 | 47.77 |

|

Urban teaching | 273,326 | 39.22 | 9363 | 40.75 | 282,689 | 39.26 |

|

Hospital location |

|

|

|

|

|

| .0024 |

Rural | 86,321 | 12.39 | 2709 | 11.79 | 89,030 | 12.36 |

|

Urban | 606,369 | 87.01 | 20,268 | 88.21 | 626,637 | 87.03 |

|

Hospital teaching status |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Teaching | 409,465 | 58.76 | 13,275 | 57.78 | 422,740 | 58.71 |

|

Non-teaching | 283,225 | 40.64 | 9702 | 42.22 | 292,927 | 40.68 |

|

Comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obstructive sleep apnea | 65,342 | 9.38 | 1946 | 8.40 | 67,288 | 9.35 | <.0001 |

Diabetes | 147,292 | 21.14 | 4289 | 18.52 | 151,581 | 21.05 | <.0001 |

Obesity | 129,277 | 18.55 | 3730 | 16.11 | 133,007 | 18.47 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 2. Demographics of Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients Based on Primary Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis or Rheumatoid Arthritis

| OA | RA | Total | P Value | |||

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | (RA vs OA) |

Age group |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

<64 years | 133,645 | 45.18 | 4679 | 48.02 | 138,324 | 45.27 |

|

65 to 79 years | 123,628 | 41.8 | 3992 | 40.97 | 127,620 | 41.77 |

|

≥80 years | 38,513 | 13.02 | 1073 | 11.01 | 39,586 | 12.96 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Male | 129,708 | 43.85 | 2457 | 25.24 | 132,165 | 43.26 |

|

Female | 165,010 | 55.79 | 7278 | 74.76 | 172,288 | 56.39 |

|

Race |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

White | 207,005 | 69.98 | 6322 | 80.08 | 213,327 | 69.82 |

|

Black | 15,505 | 5.24 | 771 | 9.77 | 16,276 | 5.33 |

|

Hispanic | 6784 | 2.29 | 522 | 6.61 | 7306 | 2.39 |

|

Other | 7209 | 2.44 | 280 | 3.55 | 7489 | 2.45 |

|

Region of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Northeast | 58,525 | 19.79 | 1683 | 17.27 | 60,208 | 19.71 |

|

Midwest | 79,040 | 26.72 | 2446 | 25.10 | 81,486 | 26.67 |

|

South | 95,337 | 32.23 | 3716 | 38.14 | 99,053 | 32.42 |

|

West | 62,884 | 21.26 | 1899 | 19.49 | 64,783 | 21.20 |

|

Location/teaching status of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| .0065 |

Rural | 30,954 | 10.46 | 993 | 10.26 | 31,947 | 10.46 |

|

Urban non-teaching | 133,061 | 44.99 | 4245 | 43.87 | 137,306 | 44.94 |

|

Urban teaching | 130,150 | 44 | 4439 | 45.87 | 134,589 | 44.05 |

|

Hospital location |

|

|

|

|

|

| .4098 |

Rural | 30,954 | 10.46 | 993 | 10.26 | 31,947 | 10.46 |

|

Urban | 263,211 | 88.99 | 8684 | 89.74 | 271,895 | 88.99 |

|

Hospital teaching status |

|

|

|

|

|

| .0077 |

Teaching | 159,313 | 53.86 | 5108 | 52.78 | 164,421 | 53.82 |

|

Non-teaching | 134,852 | 45.59 | 4569 | 47.22 | 139,421 | 45.63 |

|

Comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obstructive sleep apnea | 19,760 | 6.68 | 573 | 5.88 | 20,333 | 6.65 | .0028 |

Diabetes | 41,929 | 14.18 | 1325 | 13.60 | 43,254 | 14.16 | .1077 |

Obesity | 38,808 | 13.12 | 1100 | 11.29 | 39,908 | 13.06 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

Exemptions were obtained from the Institutional Review Board. Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2006 to 2011 were extracted using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for patients that received primary TKA or THA, as well as their comorbid conditions. No patients or populations were excluded from the sampling process. A list of all independent variables collected for analysis and provision of relevant ICD-9 codes is included in Figure 1. The NIS is the largest all-payer stratified survey of inpatient care in the US healthcare system. As of 2011, each year provides information on approximately 8 million inpatient stays from about 1000 hospitals in 46 states. All discharges from sampled hospitals are also represented in the database. All patient information is protected, and all methods were conducted in accordance with the highest ethical standards of Human and Animal Rights Research.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

SAS 9.2 and PROC FREQ statistics software were used to generate P values (chi square result) and analyze the trends (Cochran-Armitage). Results were weighted utilizing standard discharge weights from the NIS to ensure accurate comparison of data from different time points. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to generate odds ratio and 95% confidence limits to assess outcomes across different demographic variables.

RESULTS

Data on 337,082 and 1,362,241 patients undergoing THA or TKA, respectively, between 2006 and 2011 were analyzed. Patients in both groups were further differentiated by a diagnosis of either OA or RA. OA was the most common diagnosis, constituting 96.8% of all arthritic THA and TKA patients. From 2006 to 2011, a 36% and 34% increase in total number of THAs and TKAs, respectively, were reported. The number of patients with OA undergoing THA and TKA steadily increased from 2006 to 2011 (Figure 2). The number of THA and TKA procedures in patients with RA followed a similar trend but at a comparatively slower rate (Figure 3). The TKA geographical trends mirrored those observed with THA. The majority of operations were performed at urban hospitals (89% THA, 87% TKA; P < .0001). Among patients with RA and OA, the majority of TKAs (47.77%; P < .0001) took place in urban non-teaching hospitals than in urban teaching hospitals (39.26%). This pattern was not the same for THA, with 44.94% being performed at urban teaching hospitals and 44.05% at urban non-teaching institutions (P < .0001). Rural hospitals accounted for a low percentage of operations for both procedures: 10.46% of THA and 12.36% of TKA (P < .0001). Large institutions (based on the number of beds) claimed the majority of cases (59% of THA and TKA).

Logistic regression analysis and odds ratios of patients with OA vs those with RA with patient outcomes adjusted for age, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, and gender revealed that patients with OA undergoing THA had lower risk for cardiovascular (0.674; confidence interval (CI) 0.587-0.774) and pulmonary complications (0.416; CI 0.384-0.450), wound dehiscence (0.647; CI 0.561-0.747), infections (0.258; CI 0.221-0.301), and systemic complications (0.625; CI 0.562-0.695) than patients with RA. Patients with OA exhibited statistically significantly higher odds of experiencing cerebrovascular complications after THA than those with RA (1.946; CI 1.673-2.236) (Table 3). In a similar logistic regression analysis of OA vs RA in TKA, which was adjusted for age, CCI score, and gender, patients with OA had significantly higher risk for cardiovascular (1.329; CI 1.069-1.651) and cerebrovascular complications (1.635; CI 1.375-1.943) than patients with RA. Significant decreases in wound dehiscence (0.757; CI 0.639-0.896), infection (0.331; CI 0.286-0.383), and systemic complication (0.641; CI 0.565-0.729) were noted in the patients with OA and TKA (Table 4).

Table 3. Odds Ratio for In-Hospital Complications Following THA for OA Patients vs RA Patients

| Odds Ratio | Confidence Limits |

Cardiovascular complication | .674 | .587-.744 |

Cerebrovascular complication | 1.946 | 1.673-2.236 |

Pulmonary complication | .416 | .384-.450 |

Wound dehiscence | .647 | .561-.747 |

Infection | .258 | .221-.301 |

Systemic complication | .625 | .562-.695 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; THA, total hip arthroplasty.

Table 4. Odds Ratio for In-Hospital Complications Following TKA for OA Patients vs RA Patients

| Odds Ratio | Confidence Limits |

Cardiovascular complication | 1.329 | 1.069-1.651 |

Cerebrovascular complication | 1.635 | 1.375-1.943 |

Pulmonary complication | 1.03 | .995-1.223 |

Wound dehiscence | .757 | .639-.896 |

Infection | .331 | .286-.383 |

Systemic complication | .641 | .565-.729 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION

Our results showed a continuous yearly increase from 2006 to 2011 in THA and TKA procedures at a rate of 36% and 34%, respectively; this result was consistent with existing literature.11 Despite a substantial increase in the amount of total THA and TKA procedures, the ratio of patients with RA undergoing these operations has decreased or remained nearly the same. Similar effects were found in Japan and the US when examining patients with RA undergoing TJA procedures between 2001 and 2007 and between 1992 and 2005, respectively.12-14 This observation may be explained by the advances and early initiation of pharmacologic treatment and the widespread use of DMARDs such as methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine, leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, and biological response modifiers TNF-α and interleukin-1.15 These medications have drastically improved survival rates of patients with RA with impressive capabilities in symptom relief.15 With the increasing use of DMARDs and aggressive treatment early on in the disease process, patients with RA are showing markedly slow progression of joint deterioration, leading to a decreased need for orthopedic intervention compared with the general population.13,15

When analyzing the complication rates for patients undergoing TKA and THA, we observed that patients with RA exhibited a significant increase in the rates of infections, wound dehiscence, and systemic complications prior to discharge from the hospital compared with the OA population. The increased risk of infections was reported in previous studies assessing postoperative complication rates in TJA.16,17 A study utilizing the Norwegian Arthroplasty Registry noted an increased risk of late infection in patients with RA, leading to increased rates of revision TJA in comparison with patients with OA.16 Another study, which was based on the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database, showed that patients with RA are at an increased risk of infection only after THA and interestingly not after TKA.17 Although our study did not identify the causes of the increased infection rate, the inherent nature of the disease and the immunomodulatory drugs used to treat it may contribute to this increased infectious risk in patients with RA.6,18 Immunosuppressive DMARDs are some of the widely used medications employed to treat RA and are prime suspects of causing increased infection rates.15 The perioperative use of MTX has not been shown to cause short-term increases in infection for patients undergoing orthopedic intervention, but leflunomide and TNF-α inhibitors have been shown to cause a significant several-fold increase in risk for surgical wound infections.19,20

All patients with RA presented with significant increases for infection, wound dehiscence, and systemic complications, whereas only patients with RA undergoing THA showed increased risk of pulmonary and cardiovascular complications when compared with patients with OA. Surprisingly, in TKA, patients with RA were at a significantly decreased risk of cardiovascular complications. This observation was interesting due to cardiovascular disease being one of RA's most notable extra-articular features.4,21

Patients with RA undergoing TJA also showed significantly lower cerebrovascular complications than patients with OA. The significant reduction in risk for these complications has not been previously reported in the current literature, and it was an unexpected finding as past studies have found an increased risk in cerebrovascular disease in patients with RA. RA is an inflammatory disease exhibiting the upregulation of procoagulation factors,22 so we expected patients with RA to be at an increased risk for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular complications over patients with OA. Although we are unsure why these results were observed, we postulate that pharmaceutical interventions may confer some protection to patients with RA. For example, aspirin is commonly utilized in RA for its protective anti-platelet effect23 and may be a contributing factor to why we found low postoperative complication rates in cerebrovascular disease. However, the reason why aspirin may be protective against cerebrovascular and not cardiovascular complications remains unclear. Moreover, most guidelines suggest that aspirin be stopped prior to surgery.24 Although patients with RA were younger than those with OA, age was accounted for when analyzing the data.

A major strength of the study was the large sample size and the adjustment of potential confounding variables when examining the difference in complications between RA and OA. It is also a national US study that utilizes a validated database. Given that the patient samples in the NIS are reported in a uniform and de-identified manner, the database is considered ideal and has been extensively used for retrospective large observational cohort studies.25 However, the study also had some limitations due to the retrospective and administrative nature of the NIS database. Only data concerning patient complications during their inpatient stay at the hospital were available. Patients who may develop complications following discharge were not included in the data, providing a very small window of time for analysis. Another limitation with the database was its lack of ability to identify the severity of each patient's disease process or the medical treatment they received perioperatively. Finally, no patient-reported outcomes were determined, which would provide information on whether these complications affect the patients’ postoperational satisfaction in regard to their pain and disability.

CONCLUSION

As RA patients continue to utilize joint arthroplasty to repair deteriorated joints, understanding of how the disease process and its medical management may impact patient outcomes is important. This article reports significantly higher postoperational infection rates in RA than in patients with OA, which may be due to the medical management of the disease. Although new medications have been introduced and are being used to treat patients with RA, they have not altered the complication rate following TJA in this patient population. Thus, surgeons and other members of the management team should be familiar with the common medical conditions, co-morbidities, and medical treatments/side effects that are encountered in patients with RA. Future studies should delve into possible differences in long-term outcomes of patients with RA undergoing TKA and THA, as well as whether certain perioperative strategies and therapies (medical or physical) may decrease complications and improve outcomes.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

ABSTRACT

Current literature regarding complications following total joint arthroplasty have primarily focused on patients with osteoarthritis (OA), with less emphasis on the trends and in-hospital outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients undergoing these procedures. The purpose of this study is to analyze the outcomes and trends of RA patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or total hip arthroplasty (THA) compared to OA patients.

Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2006 to 2011 was extracted using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for patients that received a TKA or THA. Outcome measures included cardiovascular complications, cerebrovascular complications, pulmonary complications, wound dehiscence, and infection. Inpatient and hospital demographics including primary diagnosis, age, gender, primary payer, hospital teaching status, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, hospital bed size, location, and median household income were analyzed.

Logistic regression analysis of OA vs RA patients with patient outcomes revealed that osteoarthritic THA candidates had lower risk for cardiovascular complications, pulmonary complications, wound dehiscence, infections, and systemic complications, compared to rheumatoid patients. There was a significantly elevated risk of cerebrovascular complication in osteoarthritic THA compared to RA THA. OA patients undergoing TKA had significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications. There were significant decreases in mechanical wounds, infection, and systemic complications in the OA TKA patients.

RA patients are at higher risk for postoperative infection, wound dehiscence, and systemic complications after TKA and THA compared to OA patients. These findings highlight the importance of preoperative medical clearance and management to optimize RA patients and improve the postoperative outcomes.

Continue to: RA is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease...

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that causes joint deterioration, leading to pain, disability, systemic complications, short lifespan, and decline in quality of life.1-3 The deterioration primarily affects the synovial membranes of joints, causing arthritis and resulting in extra-articular sequelae such as cardiovascular disease,4 pulmonary disease,5 and increased infection rates.3,6 RA is the most prevalent inflammatory arthritis worldwide and affects up to 50 cases per 100,000 in both the US and northern Europe.2,7-9 Although the gold standard of care for these patients is medical management with immunosuppressant drugs such as disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), total joint arthroplasty (TJA) remains an important tool in the management of joint deterioration in such patients.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) are common procedures utilized to treat disorders that cause joint pain and hindered joint mobility, including osteoarthritis (OA) and RA. Given the aging population, the amount of TKAs and THAs performed in the US has consistently increased each year, with the vast majority of this increase composed of patients with OA.10 As a result, previous studies investigated the trends and outcomes of these procedures in patients with OA, but relatively less is known about the outcomes and trends of patients with RA undergoing the same surgeries.

Given that RA is a fundamentally different condition with its own pathological characteristics, an understanding of how these differences may impact postoperative outcomes in patients with RA is important. This study aims to present a comparative analysis of the trends and postoperative outcomes between patients with RA and OA undergoing TKA and THA (Figure 1, Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Demographics of Total Knee Arthroplasty Patients Based on Primary Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis

| OA | RA | Total | P Value | |||

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | (RA vs OA) |

Age group |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

<64 years | 295,637 | 42.42 | 11,325 | 48.90 | 306,962 | 42.63 |

|

65 to 79 years | 329,034 | 47.22 | 10,055 | 43.42 | 339,089 | 47.09 |

|

≥80 years | 72,197 | 10.36 | 1780 | 7.69 | 73,977 | 10.27 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Male | 259,192 | 37.19 | 4887 | 21.12 | 264,079 | 36.68 |

|

Female | 435,855 | 62.54 | 18,248 | 78.88 | 454,103 | 63.07 |

|

Race |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

White | 468,632 | 67.25 | 14,532 | 77.18 | 483,164 | 67.10 |

|

Black | 39,691 | 5.7 | 2119 | 11.25 | 41,810 | 5.81 |

|

Hispanic | 28,573 | 4.1 | 1395 | 7.41 | 29,968 | 4.16 |

|

Other | 21,306 | 3.06 | 783 | 4.16 | 22,089 | 3.07 |

|

Region of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Northeast | 112,031 | 16.08 | 3417 | 14.75 | 115,448 | 16.03 |

|

Midwest | 192,595 | 27.64 | 5975 | 25.80 | 198,570 | 27.58 |

|

South | 257,855 | 37 | 9422 | 40.68 | 267,277 | 37.12 |

|

West | 134,387 | 19.28 | 4346 | 18.77 | 138,733 | 19.27 |

|

Location/teaching status of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Rural | 86,321 | 12.39 | 2709 | 11.79 | 89,030 | 12.36 |

|

Urban non-teaching | 333,043 | 47.79 | 10,905 | 47.46 | 343,948 | 47.77 |

|

Urban teaching | 273,326 | 39.22 | 9363 | 40.75 | 282,689 | 39.26 |

|

Hospital location |

|

|

|

|

|

| .0024 |

Rural | 86,321 | 12.39 | 2709 | 11.79 | 89,030 | 12.36 |

|

Urban | 606,369 | 87.01 | 20,268 | 88.21 | 626,637 | 87.03 |

|

Hospital teaching status |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Teaching | 409,465 | 58.76 | 13,275 | 57.78 | 422,740 | 58.71 |

|

Non-teaching | 283,225 | 40.64 | 9702 | 42.22 | 292,927 | 40.68 |

|

Comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obstructive sleep apnea | 65,342 | 9.38 | 1946 | 8.40 | 67,288 | 9.35 | <.0001 |

Diabetes | 147,292 | 21.14 | 4289 | 18.52 | 151,581 | 21.05 | <.0001 |

Obesity | 129,277 | 18.55 | 3730 | 16.11 | 133,007 | 18.47 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 2. Demographics of Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients Based on Primary Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis or Rheumatoid Arthritis

| OA | RA | Total | P Value | |||

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | (RA vs OA) |

Age group |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

<64 years | 133,645 | 45.18 | 4679 | 48.02 | 138,324 | 45.27 |

|

65 to 79 years | 123,628 | 41.8 | 3992 | 40.97 | 127,620 | 41.77 |

|

≥80 years | 38,513 | 13.02 | 1073 | 11.01 | 39,586 | 12.96 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Male | 129,708 | 43.85 | 2457 | 25.24 | 132,165 | 43.26 |

|

Female | 165,010 | 55.79 | 7278 | 74.76 | 172,288 | 56.39 |

|

Race |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

White | 207,005 | 69.98 | 6322 | 80.08 | 213,327 | 69.82 |

|

Black | 15,505 | 5.24 | 771 | 9.77 | 16,276 | 5.33 |

|

Hispanic | 6784 | 2.29 | 522 | 6.61 | 7306 | 2.39 |

|

Other | 7209 | 2.44 | 280 | 3.55 | 7489 | 2.45 |

|

Region of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| <.0001 |

Northeast | 58,525 | 19.79 | 1683 | 17.27 | 60,208 | 19.71 |

|

Midwest | 79,040 | 26.72 | 2446 | 25.10 | 81,486 | 26.67 |

|

South | 95,337 | 32.23 | 3716 | 38.14 | 99,053 | 32.42 |

|

West | 62,884 | 21.26 | 1899 | 19.49 | 64,783 | 21.20 |

|

Location/teaching status of hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

| .0065 |

Rural | 30,954 | 10.46 | 993 | 10.26 | 31,947 | 10.46 |

|

Urban non-teaching | 133,061 | 44.99 | 4245 | 43.87 | 137,306 | 44.94 |

|

Urban teaching | 130,150 | 44 | 4439 | 45.87 | 134,589 | 44.05 |

|

Hospital location |

|

|

|

|

|

| .4098 |

Rural | 30,954 | 10.46 | 993 | 10.26 | 31,947 | 10.46 |

|

Urban | 263,211 | 88.99 | 8684 | 89.74 | 271,895 | 88.99 |

|

Hospital teaching status |

|

|

|

|

|

| .0077 |

Teaching | 159,313 | 53.86 | 5108 | 52.78 | 164,421 | 53.82 |

|

Non-teaching | 134,852 | 45.59 | 4569 | 47.22 | 139,421 | 45.63 |

|

Comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obstructive sleep apnea | 19,760 | 6.68 | 573 | 5.88 | 20,333 | 6.65 | .0028 |

Diabetes | 41,929 | 14.18 | 1325 | 13.60 | 43,254 | 14.16 | .1077 |

Obesity | 38,808 | 13.12 | 1100 | 11.29 | 39,908 | 13.06 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

Exemptions were obtained from the Institutional Review Board. Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2006 to 2011 were extracted using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for patients that received primary TKA or THA, as well as their comorbid conditions. No patients or populations were excluded from the sampling process. A list of all independent variables collected for analysis and provision of relevant ICD-9 codes is included in Figure 1. The NIS is the largest all-payer stratified survey of inpatient care in the US healthcare system. As of 2011, each year provides information on approximately 8 million inpatient stays from about 1000 hospitals in 46 states. All discharges from sampled hospitals are also represented in the database. All patient information is protected, and all methods were conducted in accordance with the highest ethical standards of Human and Animal Rights Research.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

SAS 9.2 and PROC FREQ statistics software were used to generate P values (chi square result) and analyze the trends (Cochran-Armitage). Results were weighted utilizing standard discharge weights from the NIS to ensure accurate comparison of data from different time points. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to generate odds ratio and 95% confidence limits to assess outcomes across different demographic variables.

RESULTS

Data on 337,082 and 1,362,241 patients undergoing THA or TKA, respectively, between 2006 and 2011 were analyzed. Patients in both groups were further differentiated by a diagnosis of either OA or RA. OA was the most common diagnosis, constituting 96.8% of all arthritic THA and TKA patients. From 2006 to 2011, a 36% and 34% increase in total number of THAs and TKAs, respectively, were reported. The number of patients with OA undergoing THA and TKA steadily increased from 2006 to 2011 (Figure 2). The number of THA and TKA procedures in patients with RA followed a similar trend but at a comparatively slower rate (Figure 3). The TKA geographical trends mirrored those observed with THA. The majority of operations were performed at urban hospitals (89% THA, 87% TKA; P < .0001). Among patients with RA and OA, the majority of TKAs (47.77%; P < .0001) took place in urban non-teaching hospitals than in urban teaching hospitals (39.26%). This pattern was not the same for THA, with 44.94% being performed at urban teaching hospitals and 44.05% at urban non-teaching institutions (P < .0001). Rural hospitals accounted for a low percentage of operations for both procedures: 10.46% of THA and 12.36% of TKA (P < .0001). Large institutions (based on the number of beds) claimed the majority of cases (59% of THA and TKA).

Logistic regression analysis and odds ratios of patients with OA vs those with RA with patient outcomes adjusted for age, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, and gender revealed that patients with OA undergoing THA had lower risk for cardiovascular (0.674; confidence interval (CI) 0.587-0.774) and pulmonary complications (0.416; CI 0.384-0.450), wound dehiscence (0.647; CI 0.561-0.747), infections (0.258; CI 0.221-0.301), and systemic complications (0.625; CI 0.562-0.695) than patients with RA. Patients with OA exhibited statistically significantly higher odds of experiencing cerebrovascular complications after THA than those with RA (1.946; CI 1.673-2.236) (Table 3). In a similar logistic regression analysis of OA vs RA in TKA, which was adjusted for age, CCI score, and gender, patients with OA had significantly higher risk for cardiovascular (1.329; CI 1.069-1.651) and cerebrovascular complications (1.635; CI 1.375-1.943) than patients with RA. Significant decreases in wound dehiscence (0.757; CI 0.639-0.896), infection (0.331; CI 0.286-0.383), and systemic complication (0.641; CI 0.565-0.729) were noted in the patients with OA and TKA (Table 4).

Table 3. Odds Ratio for In-Hospital Complications Following THA for OA Patients vs RA Patients

| Odds Ratio | Confidence Limits |

Cardiovascular complication | .674 | .587-.744 |

Cerebrovascular complication | 1.946 | 1.673-2.236 |

Pulmonary complication | .416 | .384-.450 |

Wound dehiscence | .647 | .561-.747 |

Infection | .258 | .221-.301 |

Systemic complication | .625 | .562-.695 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; THA, total hip arthroplasty.

Table 4. Odds Ratio for In-Hospital Complications Following TKA for OA Patients vs RA Patients

| Odds Ratio | Confidence Limits |

Cardiovascular complication | 1.329 | 1.069-1.651 |

Cerebrovascular complication | 1.635 | 1.375-1.943 |

Pulmonary complication | 1.03 | .995-1.223 |

Wound dehiscence | .757 | .639-.896 |

Infection | .331 | .286-.383 |

Systemic complication | .641 | .565-.729 |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION

Our results showed a continuous yearly increase from 2006 to 2011 in THA and TKA procedures at a rate of 36% and 34%, respectively; this result was consistent with existing literature.11 Despite a substantial increase in the amount of total THA and TKA procedures, the ratio of patients with RA undergoing these operations has decreased or remained nearly the same. Similar effects were found in Japan and the US when examining patients with RA undergoing TJA procedures between 2001 and 2007 and between 1992 and 2005, respectively.12-14 This observation may be explained by the advances and early initiation of pharmacologic treatment and the widespread use of DMARDs such as methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine, leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, and biological response modifiers TNF-α and interleukin-1.15 These medications have drastically improved survival rates of patients with RA with impressive capabilities in symptom relief.15 With the increasing use of DMARDs and aggressive treatment early on in the disease process, patients with RA are showing markedly slow progression of joint deterioration, leading to a decreased need for orthopedic intervention compared with the general population.13,15

When analyzing the complication rates for patients undergoing TKA and THA, we observed that patients with RA exhibited a significant increase in the rates of infections, wound dehiscence, and systemic complications prior to discharge from the hospital compared with the OA population. The increased risk of infections was reported in previous studies assessing postoperative complication rates in TJA.16,17 A study utilizing the Norwegian Arthroplasty Registry noted an increased risk of late infection in patients with RA, leading to increased rates of revision TJA in comparison with patients with OA.16 Another study, which was based on the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database, showed that patients with RA are at an increased risk of infection only after THA and interestingly not after TKA.17 Although our study did not identify the causes of the increased infection rate, the inherent nature of the disease and the immunomodulatory drugs used to treat it may contribute to this increased infectious risk in patients with RA.6,18 Immunosuppressive DMARDs are some of the widely used medications employed to treat RA and are prime suspects of causing increased infection rates.15 The perioperative use of MTX has not been shown to cause short-term increases in infection for patients undergoing orthopedic intervention, but leflunomide and TNF-α inhibitors have been shown to cause a significant several-fold increase in risk for surgical wound infections.19,20

All patients with RA presented with significant increases for infection, wound dehiscence, and systemic complications, whereas only patients with RA undergoing THA showed increased risk of pulmonary and cardiovascular complications when compared with patients with OA. Surprisingly, in TKA, patients with RA were at a significantly decreased risk of cardiovascular complications. This observation was interesting due to cardiovascular disease being one of RA's most notable extra-articular features.4,21

Patients with RA undergoing TJA also showed significantly lower cerebrovascular complications than patients with OA. The significant reduction in risk for these complications has not been previously reported in the current literature, and it was an unexpected finding as past studies have found an increased risk in cerebrovascular disease in patients with RA. RA is an inflammatory disease exhibiting the upregulation of procoagulation factors,22 so we expected patients with RA to be at an increased risk for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular complications over patients with OA. Although we are unsure why these results were observed, we postulate that pharmaceutical interventions may confer some protection to patients with RA. For example, aspirin is commonly utilized in RA for its protective anti-platelet effect23 and may be a contributing factor to why we found low postoperative complication rates in cerebrovascular disease. However, the reason why aspirin may be protective against cerebrovascular and not cardiovascular complications remains unclear. Moreover, most guidelines suggest that aspirin be stopped prior to surgery.24 Although patients with RA were younger than those with OA, age was accounted for when analyzing the data.

A major strength of the study was the large sample size and the adjustment of potential confounding variables when examining the difference in complications between RA and OA. It is also a national US study that utilizes a validated database. Given that the patient samples in the NIS are reported in a uniform and de-identified manner, the database is considered ideal and has been extensively used for retrospective large observational cohort studies.25 However, the study also had some limitations due to the retrospective and administrative nature of the NIS database. Only data concerning patient complications during their inpatient stay at the hospital were available. Patients who may develop complications following discharge were not included in the data, providing a very small window of time for analysis. Another limitation with the database was its lack of ability to identify the severity of each patient's disease process or the medical treatment they received perioperatively. Finally, no patient-reported outcomes were determined, which would provide information on whether these complications affect the patients’ postoperational satisfaction in regard to their pain and disability.

CONCLUSION

As RA patients continue to utilize joint arthroplasty to repair deteriorated joints, understanding of how the disease process and its medical management may impact patient outcomes is important. This article reports significantly higher postoperational infection rates in RA than in patients with OA, which may be due to the medical management of the disease. Although new medications have been introduced and are being used to treat patients with RA, they have not altered the complication rate following TJA in this patient population. Thus, surgeons and other members of the management team should be familiar with the common medical conditions, co-morbidities, and medical treatments/side effects that are encountered in patients with RA. Future studies should delve into possible differences in long-term outcomes of patients with RA undergoing TKA and THA, as well as whether certain perioperative strategies and therapies (medical or physical) may decrease complications and improve outcomes.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

- Myasoedova E, Davis JM 3rd, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis: rheumatoid arthritis and mortality. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(5):379-385. doi:10.1007/s11926-010-0117-y.

- Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423(6937):356-361. doi:10.1038/nature01661.

- Gullick NJ, Scott DL. Co-morbidities in established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(4):469-483. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2011.10.009.

- Masuda H, Miyazaki T, Shimada K, et al. Disease duration and severity impacts on long-term cardiovascular events in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Cardiol. 2014;64(5):366-370. doi:10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.02.018.

- Bongartz T, Nannini C, Medina-Velasquez YF, et al. Incidence and mortality of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum.2010;62(6):1583-1591. doi:10.1002/art.27405.

- Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2287-2293. doi:10.1002/art.10524.

- Rossini M, Rossi E, Bernardi D, et al. Prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(5):659664. doi:10.1007/s00296-014-2974-6.

- Alamanos Y, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA. Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis, based on the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;36(3):182-188. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.08.006.

- Carbonell J, Cobo T, Balsa A, Descalzo MA, Carmona L. The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Spain: results from a nationwide primary care registry. Rheumatology.2008;47(7):1088-1092. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken205.

- Skytta ET, Honkanen PB, Eskelinen A, Huhtala H, Remes V. Fewer and older patients with rheumatoid arthritis need total knee replacement. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41(5):345-349. doi:10.3109/03009742.2012.681061.

- Singh JA, Vessely MB, Harmsen WS, et al. A population-based study of trends in the use of total hip and total knee arthroplasty, 1969–2008. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(10):898-904. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0115.

- Momohara S, Inoue E, Ikari K, et al. Decrease in orthopaedic operations, including total joint replacements, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis between 2001 and 2007: data from Japanese outpatients in a single institute-based large observational cohort (IORRA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):312-313. doi:10.1136/ard.2009.107599.

- Jain A, Stein BE, Skolasky RL, Jones LC, Hungerford MW. Total joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a United States experience from 1992 through 2005. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):881-888. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2011.12.027.

- Mertelsmann-Voss C, Lyman S, Pan TJ, Goodman SM, Figgie MP, Mandl LA. US trends in rates of arthroplasty for inflammatory arthritis including rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66(6):1432-1439. doi:10.1002/art.38384.

- Howe CR, Gardner GC, Kadel NJ. Perioperative medication management for the patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(9):544-551. doi:10.5435/00124635-200609000-00004.

- Schrama JC, Espehaug B, Hallan G, et al. Risk of revision for infection in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with osteoarthritis: a prospective, population-based study on 108,786 hip and knee joint arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(4):473-479. doi:10.1002/acr.20036.

- Ravi B, Croxford R, Hollands S, et al. Increased risk of complications following total joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):254-263. doi:10.1002/art.38231.

- Au K, Reed G, Curtis JR, et al. High disease activity is associated with an increased risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):785-791. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.128637.

- Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295(19):2275-2285. doi:10.1001/jama.295.19.2275.

- Scherrer CB, Mannion AF, Kyburz D, Vogt M, Kramers-de Quervain IA. Infection risk after orthopedic surgery in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases treated with immunosuppressive drugs. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(12):2032-2040. doi:10.1002/acr.22077.

- Bacani AK, Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Heit JA, Matteson EL. Noncardiac vascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis: increase in venous thromboembolic events? Arthritis Rheum.2012;64(1):53-61. doi:10.1002/art.33322.

- Wallberg-Jonsson S, Dahlen GH, Nilsson TK, Ranby M, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S. Tissue plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and von Willebrand factor in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 1993;12(3):318324.

- van Heereveld HA, Laan RF, van den Hoogen FH, Malefijt MC, Novakova IR, van de Putte LB. Prevention of symptomatic thrombosis with short term (low molecular weight) heparin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after hip or knee replacement. Ann Rheum Dis.2001;60(10):974-976. doi:10.1136/ard.60.10.974.

- Mont MA, Jacobs JJ, Boggio LN, et al. Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg.2011;19(12):768-776.

- Bozic KJ, Bashyal RK, Anthony SG, Chiu V, Shulman B, Rubash HE. Is administratively coded comorbidity and complication data in total joint arthroplasty valid? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):201-205. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2352-1.

- Myasoedova E, Davis JM 3rd, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis: rheumatoid arthritis and mortality. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(5):379-385. doi:10.1007/s11926-010-0117-y.

- Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423(6937):356-361. doi:10.1038/nature01661.

- Gullick NJ, Scott DL. Co-morbidities in established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(4):469-483. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2011.10.009.

- Masuda H, Miyazaki T, Shimada K, et al. Disease duration and severity impacts on long-term cardiovascular events in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Cardiol. 2014;64(5):366-370. doi:10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.02.018.

- Bongartz T, Nannini C, Medina-Velasquez YF, et al. Incidence and mortality of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum.2010;62(6):1583-1591. doi:10.1002/art.27405.

- Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2287-2293. doi:10.1002/art.10524.

- Rossini M, Rossi E, Bernardi D, et al. Prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(5):659664. doi:10.1007/s00296-014-2974-6.

- Alamanos Y, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA. Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis, based on the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;36(3):182-188. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.08.006.

- Carbonell J, Cobo T, Balsa A, Descalzo MA, Carmona L. The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Spain: results from a nationwide primary care registry. Rheumatology.2008;47(7):1088-1092. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken205.

- Skytta ET, Honkanen PB, Eskelinen A, Huhtala H, Remes V. Fewer and older patients with rheumatoid arthritis need total knee replacement. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41(5):345-349. doi:10.3109/03009742.2012.681061.

- Singh JA, Vessely MB, Harmsen WS, et al. A population-based study of trends in the use of total hip and total knee arthroplasty, 1969–2008. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(10):898-904. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0115.

- Momohara S, Inoue E, Ikari K, et al. Decrease in orthopaedic operations, including total joint replacements, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis between 2001 and 2007: data from Japanese outpatients in a single institute-based large observational cohort (IORRA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):312-313. doi:10.1136/ard.2009.107599.

- Jain A, Stein BE, Skolasky RL, Jones LC, Hungerford MW. Total joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a United States experience from 1992 through 2005. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):881-888. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2011.12.027.

- Mertelsmann-Voss C, Lyman S, Pan TJ, Goodman SM, Figgie MP, Mandl LA. US trends in rates of arthroplasty for inflammatory arthritis including rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66(6):1432-1439. doi:10.1002/art.38384.

- Howe CR, Gardner GC, Kadel NJ. Perioperative medication management for the patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(9):544-551. doi:10.5435/00124635-200609000-00004.

- Schrama JC, Espehaug B, Hallan G, et al. Risk of revision for infection in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with osteoarthritis: a prospective, population-based study on 108,786 hip and knee joint arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(4):473-479. doi:10.1002/acr.20036.

- Ravi B, Croxford R, Hollands S, et al. Increased risk of complications following total joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):254-263. doi:10.1002/art.38231.

- Au K, Reed G, Curtis JR, et al. High disease activity is associated with an increased risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):785-791. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.128637.