User login

Things We Do for No Reason: Hospitalization for the Evaluation of Patients with Low-Risk Chest Pain

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Chest pain is one of the most common complaints among patients presenting to the emergency department. Moreover, at least 30% of patients who present with chest pain are admitted for observation, and >70% of those admitted with chest pain undergo cardiac stress testing (CST) during hospitalization. Several clinical risk prediction models have validated evaluation processes for managing patients with chest pain, helping to identify those at a low risk of major adverse cardiac events. Among these, the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction or HEART score can identify patients safe to be discharged with outpatient CST within 72 h. It is unnecessary to hospitalize all low-risk patients for cardiac testing because it may expose them to needless risk and avoidable care costs, with little additional benefit.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 60-year-old man with a history of osteoarthritis and depression presented to our emergency department (ED) with a 1-month history of left-sided chest pain that was present both at rest and exertion. There were no aggravating or relieving factors for the pain and no associated shortness of breath, diaphoresis, nausea, or lightheadedness. He smoked a half pack of cigarettes daily for 5 years in his twenties. The patient was taking aspirin 81 mg daily and paroxetine 40 mg daily, which he had been taking for 10 years. There was a family history of coronary artery disease in his mother, father, and sister. On examination, he was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 138/78 mm Hg and a heart rate of 62 beats/min; he appeared well, with no abnormal cardiopulmonary findings. Investigation revealed a normal initial troponin I level (<0.034 mg/mL) and normal electrocardiogram (ECG) with normal sinus rhythm (75 beats/min), normal axis, no ST changes, and no Q waves. He was therefore admitted to the hospital for further evaluation.

BACKGROUND

Each year, >7 million patients visit ED for chest pain in the United States,1 with approximately 13% diagnosed with acute coronary syndromes (ACSs).2 Over 30% of patients who present to ED with chest pain are hospitalized for observation, symptom evaluation, and risk stratification.3 In 2012, the mean Medicare reimbursement cost was $1,741 for in-hospital observation,4 with up to 70% of admitted patients undergoing cardiac stress testing (CST) before discharge.5

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK HOSPITALIZATION IS HELPFUL FOR THE EVALUATION OF LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN

A scientific statement by the American Heart Association in 2010 recommended that patients considered to be at low risk for ACS after initial evaluation (based on presenting symptoms, past history, ECG findings, and initial cardiac biomarkers) should undergo CST within 72 h (preferably within 24 h) of presentation to provoke ischemia or detect anatomic coronary artery disease.6 Early exercise treadmill testing as part of an accelerated diagnostic pathway can also reduce the length of stays (LOS) in hospital and lower the medical costs.7 Moreover, when there is noncompliance or poor accessibility, failure to pursue early exercise testing in a hospital could result in a loss of patients to follow-up. Hospitalization for testing through accelerated diagnostic pathways may improve access to care and reduce clinical and legal risks associated with a major adverse cardiac event (MACE).

WHY HOSPITALIZATION FOR THE EVALUATION OF LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN IS UNNECESSARY FOR MANY PATIENTS

Clinical Risk Prediction Models

When a patient initially presents with chest pain, it should be determined if the symptoms are related to ACS or some other diagnosis. Hospitalization is required for patients with ACS but may not be for those without ACS and those with a low risk of inducible ischemia. Clinical risk scores and risk prediction models, such as the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) and HEART scores, have been used in accelerated diagnostic protocols to determine a patient’s likelihood of having ACS. Several large trials of these clinical risk prediction models have validated the processes for evaluating patients with chest pain.

The TIMI risk score, the most well-known model, assesses risk based on the presence or absence of 7 characteristics (Appendix 1). It should be noted that the patient population studied for initial validation of this model comprised high-risk patients with unstable angina or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction who would benefit from early or urgent invasive therapy.8 In this population, TIMI scores of 0-1 are associated with low risk, with a 4.7% risk of ACS at 14 days.8 In another study of patients presenting to ED with undifferentiated chest pain and a TIMI score of zero, the risk of MACE at 30 days was approximately 2%.9

The HEART score is also used for patients presenting to ED with undifferentiated chest pain and assesses 5 separate variables scored 0–2 (Appendix 2). The original research gave a score of 2 to a troponin I level greater than twice the upper limit of the normal level,10 whereas a subsequent validation study gave a score of 2 to a troponin I or T level greater than or equal to 3 times the upper limit of the normal level.11 Patients are considered at low, intermediate, and high risk based on scores of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–10, respectively.10,11 Backus et al. performed a prospective randomized trial of 2388 patients who presented to ED with chest pain to validate the HEART score and compare it to the TIMI risk score. The HEART score performed better than the TIMI risk score in low-risk patients, with TIMI scores of 0-1 and HEART scores of 0–3 having a 6-week MACE risk of 2.8% and 1.7%, respectively.11

A HEART pathway was developed that combines the HEART score with serial troponin I assays assessed at the time of initial presentation and approximately 3 h later.12 Mahler et al. randomized 282 patients presenting to ED with chest pain to either the HEART pathway or conventional care. Patients with low-risk HEART scores and an abnormal troponin I level were admitted for cardiology consultation, whereas discharge was recommended for those with low scores and a normal troponin I level. Despite nearly 20% of the study cohort having a history of myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting, approximately 40% of patients in the HEART pathway were identified as low risk, increasing early discharge rates by 21.3% and decreasing the average LOS by 12 h. No low-risk patient suffered a MACE within 30 days, and the HEART pathway had a sensitivity and a negative predictive value of approximately 99%.

Costs and Harms of Hospitalization for Cardiac Testing

Hospitalization carries measurable risks.13,14 Between 2008 and 2013, Weinstock et al. evaluated the outcom

Outpatient CST can be reliably and safely performed for patients with chest pain.16-18 There is no clear evidence that earlier CST leads to improved patient outcomes, and CST in the absence of acute ischemia (or ACS) increases the rates of angiography and revascularization without improvements in the rate of myocardial infarction.19-21 Given the costs of in-hospital observation4 and the dubious benefits of providing CST for patients with low-risk chest pain, admitting all patients with low-risk chest pain exposes them to costs and harms with little potential benefit.

WHEN HOSPITALIZATION MAY BE REASONABLE TO EVALUATE LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN

Patients presenting with chest pain with either dynamic ECG changes or an elevated troponin level require hospitalization for further ACS diagnosis and treatment. When ACS cannot be clearly diagnosed at the initial evaluation, healthcare providers should use clinical risk prediction models to stratify patients. Those deemed to be at an intermediate or high risk by these models should be hospitalized for further evaluation, as should those at low risk but for whom access to outpatient follow-up is difficult (eg, those without health insurance).

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD OF HOSPITALIZATION FOR LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN

A complete history and physical examination, along with ECG and cardiac biomarker testing, are required for all patients presenting with chest pain. Validated clinical risk prediction models should then be used to determine the likelihood of a cardiac event. Fanaroff et al. reported that low-risk HEART scores of 0–3 and TIMI scores of 0-1 gave positive likelihood ratios of 0.2 and 0.31, respectively.22 Using a pre-test probability of 13%, as reported by Bhuiya et al.,2 the likelihood of ACS or MACE within 6 weeks is 2.9% for patients with low-risk HEART scores and 4.4% for those with low-risk TIMI scores.22 These risk prediction models allow clinicians to provide a shared decision-making plan with the patient and discuss the risks and benefits of in-hospital versus outpatient cardiac testing, especially among patients with access to appropriate outpatient follow-up.23 Low-risk patients can be referred for outpatient testing within 72 h, reducing hospitalization-associated costs and harms.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Patients presenting with chest pain should undergo a complete history taking and physical examination, as well as ECG and cardiac biomarker testing (eg, troponin I level at presentation and approximately 3 h later).

- Clinical risk prediction models, such as TIMI or HEART scores, should then be used to determine the risk of MACE.

- Patients at a low risk may be safely discharged with outpatient CST performed within 72 h.

- Patients at an intermediate or high risk of MACE should be hospitalized for further evaluation, as should those with low-risk chest pain who are unable to attend follow-up for outpatient CST within 72 h.

- Clinicians should provide a shared decision-making plan with each patient, taking care to discuss the risks and benefits of in-hospital versus outpatient CST.

CONCLUSION

The risk of MACE should be assessed in all patients presenting to ED with low-risk chest pain to avoid unnecessary hospitalization that exposes them to potential costs and harms with few additional benefits. If the risk scoring system was applied to the patient described in our original clinical scenario, he would have had a HEART score of 3 (ie, 1 point for a moderately suspicious history, 1 point for the age of 60 years, and 1 point for a positive family history) and a TIMI score of 1 (ie, 1 point for aspirin use within past 7 days). Therefore, he could be stratified as having a low-risk presentation. With a second negative troponin I test at 3 h, discharge from ED with timely outpatient CST within 72 h would be an appropriate management strategy.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing [email protected].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

1. Centers for Disease Control. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2011 Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2011_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2015.

2. Bhuiya FA, Pitts SR, McCaig LF. Emergency department visits for chest pain and abdominal pain: United States, 1999-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;(43):1-8. PubMed

3. Cotterill PG, Deb P, Shrank WH, Pines JM. Variation in chest pain emergency department admission rates and acute myocardial infarction and death within 30 days in the Medicare population. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(8):955-964. PubMed

4. Wright S. Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries, OEI-02-12-00040. 2013. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2017.

5. Penumetsa SC, Mallidi J, Friderici JL, Hiser W, Rothberg MB. Outcomes of patients admitted for observation of chest pain. Arch Inter Med. 2012;172(11):873-877. PubMed

6. Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Bluemke DA, et al. Testing of low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(17):1756-1776. PubMed

7. Hutter AM, Jr., Amsterdam EA, Jaffe AS. 31st Bethesda Conference. Emergency Cardiac Care. Task force 2: Acute coronary syndromes: Section 2B--Chest discomfort evaluation in the hospital. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(4):853-862. PubMed

8. Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000;284(7):835-842. PubMed

9. Pollack CV, Jr., Sites FD, Shofer FS, Sease KL, Hollander JE. Application of the TIMI risk score for unstable angina and non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome to an unselected emergency department chest pain population. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(1):13-18. PubMed

10. Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. Neth Heart J. 2008; 16(6):191-196. PubMed

11. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2153-2158. PubMed

12. Mahler SA, Riley RF, Hiestand BC, et al. The HEART Pathway randomized trial: identifying emergency department patients with acute chest pain for early discharge. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(2):195-203. PubMed

13. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Inter Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. PubMed

14. James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128. PubMed

15. Weinstock MB, Weingart S, Orth F, et al. Risk for clinically relevant adverse cardiac events in patients with chest pain at hospital admission. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1207-1212. PubMed

16. Meyer MC, Mooney RP, Sekera AK. A critical pathway for patients with acute chest pain and low risk for short-term adverse cardiac events: role of outpatient stress testing. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(5):427-435. PubMed

17. Lai C, Noeller TP, Schmidt K, King P, Emerman CL. Short-term risk after initial observation for chest pain. J Emerg Med. 2003;25(4):357-362. PubMed

18. Scheuermeyer FX, Innes G, Grafstein E, et al. Safety and efficiency of a chest pain diagnostic algorithm with selective outpatient stress testing for emergency department patients with potential ischemic chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(4):256-264 e253. PubMed

19. Safavi KC, Li SX, Dharmarajan K, et al. Hospital variation in the use of noninvasive cardiac imaging and its association with downstream testing, interventions, and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):546-553. PubMed

20. Foy AJ, Liu G, Davidson WR, Jr., Sciamanna C, Leslie DL. Comparative effectiveness of diagnostic testing strategies in emergency department patients with chest pain: an analysis of downstream testing, interventions, and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(3):428-436. PubMed

21. Sandhu AT, Heidenreich PA, Bhattacharya J, Bundorf MK. Cardiovascular testing and clinical outcomes in emergency department patients with chest pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1175-1182. PubMed

22. Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA, Simel DL, Newby LK. Does this patient with chest pain have acute coronary syndrome?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA. 2015;314(18):1955-1965. PubMed

23. Hess EP, Hollander JE, Schaffer JT, et al. Shared decision making in patients with low risk chest pain: prospective randomized pragmatic trial. BMJ. 2016;355:i6165. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Chest pain is one of the most common complaints among patients presenting to the emergency department. Moreover, at least 30% of patients who present with chest pain are admitted for observation, and >70% of those admitted with chest pain undergo cardiac stress testing (CST) during hospitalization. Several clinical risk prediction models have validated evaluation processes for managing patients with chest pain, helping to identify those at a low risk of major adverse cardiac events. Among these, the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction or HEART score can identify patients safe to be discharged with outpatient CST within 72 h. It is unnecessary to hospitalize all low-risk patients for cardiac testing because it may expose them to needless risk and avoidable care costs, with little additional benefit.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 60-year-old man with a history of osteoarthritis and depression presented to our emergency department (ED) with a 1-month history of left-sided chest pain that was present both at rest and exertion. There were no aggravating or relieving factors for the pain and no associated shortness of breath, diaphoresis, nausea, or lightheadedness. He smoked a half pack of cigarettes daily for 5 years in his twenties. The patient was taking aspirin 81 mg daily and paroxetine 40 mg daily, which he had been taking for 10 years. There was a family history of coronary artery disease in his mother, father, and sister. On examination, he was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 138/78 mm Hg and a heart rate of 62 beats/min; he appeared well, with no abnormal cardiopulmonary findings. Investigation revealed a normal initial troponin I level (<0.034 mg/mL) and normal electrocardiogram (ECG) with normal sinus rhythm (75 beats/min), normal axis, no ST changes, and no Q waves. He was therefore admitted to the hospital for further evaluation.

BACKGROUND

Each year, >7 million patients visit ED for chest pain in the United States,1 with approximately 13% diagnosed with acute coronary syndromes (ACSs).2 Over 30% of patients who present to ED with chest pain are hospitalized for observation, symptom evaluation, and risk stratification.3 In 2012, the mean Medicare reimbursement cost was $1,741 for in-hospital observation,4 with up to 70% of admitted patients undergoing cardiac stress testing (CST) before discharge.5

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK HOSPITALIZATION IS HELPFUL FOR THE EVALUATION OF LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN

A scientific statement by the American Heart Association in 2010 recommended that patients considered to be at low risk for ACS after initial evaluation (based on presenting symptoms, past history, ECG findings, and initial cardiac biomarkers) should undergo CST within 72 h (preferably within 24 h) of presentation to provoke ischemia or detect anatomic coronary artery disease.6 Early exercise treadmill testing as part of an accelerated diagnostic pathway can also reduce the length of stays (LOS) in hospital and lower the medical costs.7 Moreover, when there is noncompliance or poor accessibility, failure to pursue early exercise testing in a hospital could result in a loss of patients to follow-up. Hospitalization for testing through accelerated diagnostic pathways may improve access to care and reduce clinical and legal risks associated with a major adverse cardiac event (MACE).

WHY HOSPITALIZATION FOR THE EVALUATION OF LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN IS UNNECESSARY FOR MANY PATIENTS

Clinical Risk Prediction Models

When a patient initially presents with chest pain, it should be determined if the symptoms are related to ACS or some other diagnosis. Hospitalization is required for patients with ACS but may not be for those without ACS and those with a low risk of inducible ischemia. Clinical risk scores and risk prediction models, such as the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) and HEART scores, have been used in accelerated diagnostic protocols to determine a patient’s likelihood of having ACS. Several large trials of these clinical risk prediction models have validated the processes for evaluating patients with chest pain.

The TIMI risk score, the most well-known model, assesses risk based on the presence or absence of 7 characteristics (Appendix 1). It should be noted that the patient population studied for initial validation of this model comprised high-risk patients with unstable angina or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction who would benefit from early or urgent invasive therapy.8 In this population, TIMI scores of 0-1 are associated with low risk, with a 4.7% risk of ACS at 14 days.8 In another study of patients presenting to ED with undifferentiated chest pain and a TIMI score of zero, the risk of MACE at 30 days was approximately 2%.9

The HEART score is also used for patients presenting to ED with undifferentiated chest pain and assesses 5 separate variables scored 0–2 (Appendix 2). The original research gave a score of 2 to a troponin I level greater than twice the upper limit of the normal level,10 whereas a subsequent validation study gave a score of 2 to a troponin I or T level greater than or equal to 3 times the upper limit of the normal level.11 Patients are considered at low, intermediate, and high risk based on scores of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–10, respectively.10,11 Backus et al. performed a prospective randomized trial of 2388 patients who presented to ED with chest pain to validate the HEART score and compare it to the TIMI risk score. The HEART score performed better than the TIMI risk score in low-risk patients, with TIMI scores of 0-1 and HEART scores of 0–3 having a 6-week MACE risk of 2.8% and 1.7%, respectively.11

A HEART pathway was developed that combines the HEART score with serial troponin I assays assessed at the time of initial presentation and approximately 3 h later.12 Mahler et al. randomized 282 patients presenting to ED with chest pain to either the HEART pathway or conventional care. Patients with low-risk HEART scores and an abnormal troponin I level were admitted for cardiology consultation, whereas discharge was recommended for those with low scores and a normal troponin I level. Despite nearly 20% of the study cohort having a history of myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting, approximately 40% of patients in the HEART pathway were identified as low risk, increasing early discharge rates by 21.3% and decreasing the average LOS by 12 h. No low-risk patient suffered a MACE within 30 days, and the HEART pathway had a sensitivity and a negative predictive value of approximately 99%.

Costs and Harms of Hospitalization for Cardiac Testing

Hospitalization carries measurable risks.13,14 Between 2008 and 2013, Weinstock et al. evaluated the outcom

Outpatient CST can be reliably and safely performed for patients with chest pain.16-18 There is no clear evidence that earlier CST leads to improved patient outcomes, and CST in the absence of acute ischemia (or ACS) increases the rates of angiography and revascularization without improvements in the rate of myocardial infarction.19-21 Given the costs of in-hospital observation4 and the dubious benefits of providing CST for patients with low-risk chest pain, admitting all patients with low-risk chest pain exposes them to costs and harms with little potential benefit.

WHEN HOSPITALIZATION MAY BE REASONABLE TO EVALUATE LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN

Patients presenting with chest pain with either dynamic ECG changes or an elevated troponin level require hospitalization for further ACS diagnosis and treatment. When ACS cannot be clearly diagnosed at the initial evaluation, healthcare providers should use clinical risk prediction models to stratify patients. Those deemed to be at an intermediate or high risk by these models should be hospitalized for further evaluation, as should those at low risk but for whom access to outpatient follow-up is difficult (eg, those without health insurance).

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD OF HOSPITALIZATION FOR LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN

A complete history and physical examination, along with ECG and cardiac biomarker testing, are required for all patients presenting with chest pain. Validated clinical risk prediction models should then be used to determine the likelihood of a cardiac event. Fanaroff et al. reported that low-risk HEART scores of 0–3 and TIMI scores of 0-1 gave positive likelihood ratios of 0.2 and 0.31, respectively.22 Using a pre-test probability of 13%, as reported by Bhuiya et al.,2 the likelihood of ACS or MACE within 6 weeks is 2.9% for patients with low-risk HEART scores and 4.4% for those with low-risk TIMI scores.22 These risk prediction models allow clinicians to provide a shared decision-making plan with the patient and discuss the risks and benefits of in-hospital versus outpatient cardiac testing, especially among patients with access to appropriate outpatient follow-up.23 Low-risk patients can be referred for outpatient testing within 72 h, reducing hospitalization-associated costs and harms.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Patients presenting with chest pain should undergo a complete history taking and physical examination, as well as ECG and cardiac biomarker testing (eg, troponin I level at presentation and approximately 3 h later).

- Clinical risk prediction models, such as TIMI or HEART scores, should then be used to determine the risk of MACE.

- Patients at a low risk may be safely discharged with outpatient CST performed within 72 h.

- Patients at an intermediate or high risk of MACE should be hospitalized for further evaluation, as should those with low-risk chest pain who are unable to attend follow-up for outpatient CST within 72 h.

- Clinicians should provide a shared decision-making plan with each patient, taking care to discuss the risks and benefits of in-hospital versus outpatient CST.

CONCLUSION

The risk of MACE should be assessed in all patients presenting to ED with low-risk chest pain to avoid unnecessary hospitalization that exposes them to potential costs and harms with few additional benefits. If the risk scoring system was applied to the patient described in our original clinical scenario, he would have had a HEART score of 3 (ie, 1 point for a moderately suspicious history, 1 point for the age of 60 years, and 1 point for a positive family history) and a TIMI score of 1 (ie, 1 point for aspirin use within past 7 days). Therefore, he could be stratified as having a low-risk presentation. With a second negative troponin I test at 3 h, discharge from ED with timely outpatient CST within 72 h would be an appropriate management strategy.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing [email protected].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Chest pain is one of the most common complaints among patients presenting to the emergency department. Moreover, at least 30% of patients who present with chest pain are admitted for observation, and >70% of those admitted with chest pain undergo cardiac stress testing (CST) during hospitalization. Several clinical risk prediction models have validated evaluation processes for managing patients with chest pain, helping to identify those at a low risk of major adverse cardiac events. Among these, the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction or HEART score can identify patients safe to be discharged with outpatient CST within 72 h. It is unnecessary to hospitalize all low-risk patients for cardiac testing because it may expose them to needless risk and avoidable care costs, with little additional benefit.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 60-year-old man with a history of osteoarthritis and depression presented to our emergency department (ED) with a 1-month history of left-sided chest pain that was present both at rest and exertion. There were no aggravating or relieving factors for the pain and no associated shortness of breath, diaphoresis, nausea, or lightheadedness. He smoked a half pack of cigarettes daily for 5 years in his twenties. The patient was taking aspirin 81 mg daily and paroxetine 40 mg daily, which he had been taking for 10 years. There was a family history of coronary artery disease in his mother, father, and sister. On examination, he was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 138/78 mm Hg and a heart rate of 62 beats/min; he appeared well, with no abnormal cardiopulmonary findings. Investigation revealed a normal initial troponin I level (<0.034 mg/mL) and normal electrocardiogram (ECG) with normal sinus rhythm (75 beats/min), normal axis, no ST changes, and no Q waves. He was therefore admitted to the hospital for further evaluation.

BACKGROUND

Each year, >7 million patients visit ED for chest pain in the United States,1 with approximately 13% diagnosed with acute coronary syndromes (ACSs).2 Over 30% of patients who present to ED with chest pain are hospitalized for observation, symptom evaluation, and risk stratification.3 In 2012, the mean Medicare reimbursement cost was $1,741 for in-hospital observation,4 with up to 70% of admitted patients undergoing cardiac stress testing (CST) before discharge.5

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK HOSPITALIZATION IS HELPFUL FOR THE EVALUATION OF LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN

A scientific statement by the American Heart Association in 2010 recommended that patients considered to be at low risk for ACS after initial evaluation (based on presenting symptoms, past history, ECG findings, and initial cardiac biomarkers) should undergo CST within 72 h (preferably within 24 h) of presentation to provoke ischemia or detect anatomic coronary artery disease.6 Early exercise treadmill testing as part of an accelerated diagnostic pathway can also reduce the length of stays (LOS) in hospital and lower the medical costs.7 Moreover, when there is noncompliance or poor accessibility, failure to pursue early exercise testing in a hospital could result in a loss of patients to follow-up. Hospitalization for testing through accelerated diagnostic pathways may improve access to care and reduce clinical and legal risks associated with a major adverse cardiac event (MACE).

WHY HOSPITALIZATION FOR THE EVALUATION OF LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN IS UNNECESSARY FOR MANY PATIENTS

Clinical Risk Prediction Models

When a patient initially presents with chest pain, it should be determined if the symptoms are related to ACS or some other diagnosis. Hospitalization is required for patients with ACS but may not be for those without ACS and those with a low risk of inducible ischemia. Clinical risk scores and risk prediction models, such as the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) and HEART scores, have been used in accelerated diagnostic protocols to determine a patient’s likelihood of having ACS. Several large trials of these clinical risk prediction models have validated the processes for evaluating patients with chest pain.

The TIMI risk score, the most well-known model, assesses risk based on the presence or absence of 7 characteristics (Appendix 1). It should be noted that the patient population studied for initial validation of this model comprised high-risk patients with unstable angina or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction who would benefit from early or urgent invasive therapy.8 In this population, TIMI scores of 0-1 are associated with low risk, with a 4.7% risk of ACS at 14 days.8 In another study of patients presenting to ED with undifferentiated chest pain and a TIMI score of zero, the risk of MACE at 30 days was approximately 2%.9

The HEART score is also used for patients presenting to ED with undifferentiated chest pain and assesses 5 separate variables scored 0–2 (Appendix 2). The original research gave a score of 2 to a troponin I level greater than twice the upper limit of the normal level,10 whereas a subsequent validation study gave a score of 2 to a troponin I or T level greater than or equal to 3 times the upper limit of the normal level.11 Patients are considered at low, intermediate, and high risk based on scores of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–10, respectively.10,11 Backus et al. performed a prospective randomized trial of 2388 patients who presented to ED with chest pain to validate the HEART score and compare it to the TIMI risk score. The HEART score performed better than the TIMI risk score in low-risk patients, with TIMI scores of 0-1 and HEART scores of 0–3 having a 6-week MACE risk of 2.8% and 1.7%, respectively.11

A HEART pathway was developed that combines the HEART score with serial troponin I assays assessed at the time of initial presentation and approximately 3 h later.12 Mahler et al. randomized 282 patients presenting to ED with chest pain to either the HEART pathway or conventional care. Patients with low-risk HEART scores and an abnormal troponin I level were admitted for cardiology consultation, whereas discharge was recommended for those with low scores and a normal troponin I level. Despite nearly 20% of the study cohort having a history of myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting, approximately 40% of patients in the HEART pathway were identified as low risk, increasing early discharge rates by 21.3% and decreasing the average LOS by 12 h. No low-risk patient suffered a MACE within 30 days, and the HEART pathway had a sensitivity and a negative predictive value of approximately 99%.

Costs and Harms of Hospitalization for Cardiac Testing

Hospitalization carries measurable risks.13,14 Between 2008 and 2013, Weinstock et al. evaluated the outcom

Outpatient CST can be reliably and safely performed for patients with chest pain.16-18 There is no clear evidence that earlier CST leads to improved patient outcomes, and CST in the absence of acute ischemia (or ACS) increases the rates of angiography and revascularization without improvements in the rate of myocardial infarction.19-21 Given the costs of in-hospital observation4 and the dubious benefits of providing CST for patients with low-risk chest pain, admitting all patients with low-risk chest pain exposes them to costs and harms with little potential benefit.

WHEN HOSPITALIZATION MAY BE REASONABLE TO EVALUATE LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN

Patients presenting with chest pain with either dynamic ECG changes or an elevated troponin level require hospitalization for further ACS diagnosis and treatment. When ACS cannot be clearly diagnosed at the initial evaluation, healthcare providers should use clinical risk prediction models to stratify patients. Those deemed to be at an intermediate or high risk by these models should be hospitalized for further evaluation, as should those at low risk but for whom access to outpatient follow-up is difficult (eg, those without health insurance).

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD OF HOSPITALIZATION FOR LOW-RISK CHEST PAIN

A complete history and physical examination, along with ECG and cardiac biomarker testing, are required for all patients presenting with chest pain. Validated clinical risk prediction models should then be used to determine the likelihood of a cardiac event. Fanaroff et al. reported that low-risk HEART scores of 0–3 and TIMI scores of 0-1 gave positive likelihood ratios of 0.2 and 0.31, respectively.22 Using a pre-test probability of 13%, as reported by Bhuiya et al.,2 the likelihood of ACS or MACE within 6 weeks is 2.9% for patients with low-risk HEART scores and 4.4% for those with low-risk TIMI scores.22 These risk prediction models allow clinicians to provide a shared decision-making plan with the patient and discuss the risks and benefits of in-hospital versus outpatient cardiac testing, especially among patients with access to appropriate outpatient follow-up.23 Low-risk patients can be referred for outpatient testing within 72 h, reducing hospitalization-associated costs and harms.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Patients presenting with chest pain should undergo a complete history taking and physical examination, as well as ECG and cardiac biomarker testing (eg, troponin I level at presentation and approximately 3 h later).

- Clinical risk prediction models, such as TIMI or HEART scores, should then be used to determine the risk of MACE.

- Patients at a low risk may be safely discharged with outpatient CST performed within 72 h.

- Patients at an intermediate or high risk of MACE should be hospitalized for further evaluation, as should those with low-risk chest pain who are unable to attend follow-up for outpatient CST within 72 h.

- Clinicians should provide a shared decision-making plan with each patient, taking care to discuss the risks and benefits of in-hospital versus outpatient CST.

CONCLUSION

The risk of MACE should be assessed in all patients presenting to ED with low-risk chest pain to avoid unnecessary hospitalization that exposes them to potential costs and harms with few additional benefits. If the risk scoring system was applied to the patient described in our original clinical scenario, he would have had a HEART score of 3 (ie, 1 point for a moderately suspicious history, 1 point for the age of 60 years, and 1 point for a positive family history) and a TIMI score of 1 (ie, 1 point for aspirin use within past 7 days). Therefore, he could be stratified as having a low-risk presentation. With a second negative troponin I test at 3 h, discharge from ED with timely outpatient CST within 72 h would be an appropriate management strategy.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing [email protected].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

1. Centers for Disease Control. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2011 Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2011_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2015.

2. Bhuiya FA, Pitts SR, McCaig LF. Emergency department visits for chest pain and abdominal pain: United States, 1999-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;(43):1-8. PubMed

3. Cotterill PG, Deb P, Shrank WH, Pines JM. Variation in chest pain emergency department admission rates and acute myocardial infarction and death within 30 days in the Medicare population. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(8):955-964. PubMed

4. Wright S. Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries, OEI-02-12-00040. 2013. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2017.

5. Penumetsa SC, Mallidi J, Friderici JL, Hiser W, Rothberg MB. Outcomes of patients admitted for observation of chest pain. Arch Inter Med. 2012;172(11):873-877. PubMed

6. Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Bluemke DA, et al. Testing of low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(17):1756-1776. PubMed

7. Hutter AM, Jr., Amsterdam EA, Jaffe AS. 31st Bethesda Conference. Emergency Cardiac Care. Task force 2: Acute coronary syndromes: Section 2B--Chest discomfort evaluation in the hospital. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(4):853-862. PubMed

8. Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000;284(7):835-842. PubMed

9. Pollack CV, Jr., Sites FD, Shofer FS, Sease KL, Hollander JE. Application of the TIMI risk score for unstable angina and non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome to an unselected emergency department chest pain population. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(1):13-18. PubMed

10. Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. Neth Heart J. 2008; 16(6):191-196. PubMed

11. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2153-2158. PubMed

12. Mahler SA, Riley RF, Hiestand BC, et al. The HEART Pathway randomized trial: identifying emergency department patients with acute chest pain for early discharge. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(2):195-203. PubMed

13. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Inter Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. PubMed

14. James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128. PubMed

15. Weinstock MB, Weingart S, Orth F, et al. Risk for clinically relevant adverse cardiac events in patients with chest pain at hospital admission. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1207-1212. PubMed

16. Meyer MC, Mooney RP, Sekera AK. A critical pathway for patients with acute chest pain and low risk for short-term adverse cardiac events: role of outpatient stress testing. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(5):427-435. PubMed

17. Lai C, Noeller TP, Schmidt K, King P, Emerman CL. Short-term risk after initial observation for chest pain. J Emerg Med. 2003;25(4):357-362. PubMed

18. Scheuermeyer FX, Innes G, Grafstein E, et al. Safety and efficiency of a chest pain diagnostic algorithm with selective outpatient stress testing for emergency department patients with potential ischemic chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(4):256-264 e253. PubMed

19. Safavi KC, Li SX, Dharmarajan K, et al. Hospital variation in the use of noninvasive cardiac imaging and its association with downstream testing, interventions, and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):546-553. PubMed

20. Foy AJ, Liu G, Davidson WR, Jr., Sciamanna C, Leslie DL. Comparative effectiveness of diagnostic testing strategies in emergency department patients with chest pain: an analysis of downstream testing, interventions, and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(3):428-436. PubMed

21. Sandhu AT, Heidenreich PA, Bhattacharya J, Bundorf MK. Cardiovascular testing and clinical outcomes in emergency department patients with chest pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1175-1182. PubMed

22. Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA, Simel DL, Newby LK. Does this patient with chest pain have acute coronary syndrome?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA. 2015;314(18):1955-1965. PubMed

23. Hess EP, Hollander JE, Schaffer JT, et al. Shared decision making in patients with low risk chest pain: prospective randomized pragmatic trial. BMJ. 2016;355:i6165. PubMed

1. Centers for Disease Control. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2011 Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2011_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2015.

2. Bhuiya FA, Pitts SR, McCaig LF. Emergency department visits for chest pain and abdominal pain: United States, 1999-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;(43):1-8. PubMed

3. Cotterill PG, Deb P, Shrank WH, Pines JM. Variation in chest pain emergency department admission rates and acute myocardial infarction and death within 30 days in the Medicare population. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(8):955-964. PubMed

4. Wright S. Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries, OEI-02-12-00040. 2013. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2017.

5. Penumetsa SC, Mallidi J, Friderici JL, Hiser W, Rothberg MB. Outcomes of patients admitted for observation of chest pain. Arch Inter Med. 2012;172(11):873-877. PubMed

6. Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Bluemke DA, et al. Testing of low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(17):1756-1776. PubMed

7. Hutter AM, Jr., Amsterdam EA, Jaffe AS. 31st Bethesda Conference. Emergency Cardiac Care. Task force 2: Acute coronary syndromes: Section 2B--Chest discomfort evaluation in the hospital. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(4):853-862. PubMed

8. Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000;284(7):835-842. PubMed

9. Pollack CV, Jr., Sites FD, Shofer FS, Sease KL, Hollander JE. Application of the TIMI risk score for unstable angina and non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome to an unselected emergency department chest pain population. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(1):13-18. PubMed

10. Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. Neth Heart J. 2008; 16(6):191-196. PubMed

11. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2153-2158. PubMed

12. Mahler SA, Riley RF, Hiestand BC, et al. The HEART Pathway randomized trial: identifying emergency department patients with acute chest pain for early discharge. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(2):195-203. PubMed

13. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Inter Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. PubMed

14. James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128. PubMed

15. Weinstock MB, Weingart S, Orth F, et al. Risk for clinically relevant adverse cardiac events in patients with chest pain at hospital admission. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1207-1212. PubMed

16. Meyer MC, Mooney RP, Sekera AK. A critical pathway for patients with acute chest pain and low risk for short-term adverse cardiac events: role of outpatient stress testing. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(5):427-435. PubMed

17. Lai C, Noeller TP, Schmidt K, King P, Emerman CL. Short-term risk after initial observation for chest pain. J Emerg Med. 2003;25(4):357-362. PubMed

18. Scheuermeyer FX, Innes G, Grafstein E, et al. Safety and efficiency of a chest pain diagnostic algorithm with selective outpatient stress testing for emergency department patients with potential ischemic chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(4):256-264 e253. PubMed

19. Safavi KC, Li SX, Dharmarajan K, et al. Hospital variation in the use of noninvasive cardiac imaging and its association with downstream testing, interventions, and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):546-553. PubMed

20. Foy AJ, Liu G, Davidson WR, Jr., Sciamanna C, Leslie DL. Comparative effectiveness of diagnostic testing strategies in emergency department patients with chest pain: an analysis of downstream testing, interventions, and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(3):428-436. PubMed

21. Sandhu AT, Heidenreich PA, Bhattacharya J, Bundorf MK. Cardiovascular testing and clinical outcomes in emergency department patients with chest pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1175-1182. PubMed

22. Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA, Simel DL, Newby LK. Does this patient with chest pain have acute coronary syndrome?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA. 2015;314(18):1955-1965. PubMed

23. Hess EP, Hollander JE, Schaffer JT, et al. Shared decision making in patients with low risk chest pain: prospective randomized pragmatic trial. BMJ. 2016;355:i6165. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Numeracy, Health Literacy, Cognition, and 30-Day Readmissions among Patients with Heart Failure

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

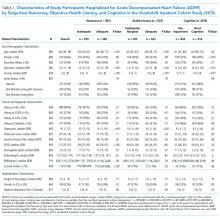

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.

Only 1 other study has examined the effect of numeracy on readmission risk among patients hospitalized for HF. In this multicenter prospective study, McNaughton et al.37 found low numeracy to be associated with higher odds of recidivism to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days. Our findings may differ from theirs for a few reasons. First, their study had a significantly higher percentage of individuals with low numeracy (55%) compared with ours (33.9%). This may be because they did not exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and their patient population was of lower socioeconomic status (SES) than ours. Low SES is associated with higher 30-day readmissions among HF patients1,10 throughout the literature, and low numeracy is associated with low SES in other diseases.13,38,39 Finally, they studied recidivism, which was defined as any unplanned return to the ED or hospital within 30 days of the index ED visit for acute HF. We only focused on 30-day readmissions, which also may explain why our results differed.

We found that health literacy was not associated with 30-day readmissions, which is consistent with the literature. Although an association between health literacy and mortality exists among adults with HF, several studies have not found an association between health literacy and 30- and 90-day readmission among adults hospitalized for HF.8,9,40 Although we found an association between objective health literacy and 30-day readmission in unadjusted analyses, we did not find one in the multivariable model. This, along with our numeracy finding, suggests that numeracy and literacy may not be driving the 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF.

We examined cognition alongside numeracy and literacy because it is a prevalent condition among HF patients and because it is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with HF, including readmission.41,42 Studies have shown that HF preferentially affects certain cognitive domains,43 some of which are vital to HF self-care activities. We found that 53% of patients had any cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the literature of adults hospitalized for ADHF.44,45 Cognitive impairment was not, however, associated with 30-day readmissions. There may be a couple reasons for this. First, we measured cognitive impairment with the SPMSQ, which, although widely used and well-validated, does not assess executive function, the domain most commonly affected in HF patients with cognitive impairment.46 Second, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those with delirium were excluded from this study, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in readmission by this factor.

As in prior studies, we found that a history of DM and more hospitalizations in the prior year were independently associated with 30-day readmissions in fully adjusted models. Like other studies, in adjusted models, we found that LVEF and a history of HF were not independently associated with 30-day readmission.47-49 This, however, is not surprising because recent studies have shown that, although HF patients are at risk for multiple hospitalizations, early readmission after a hospitalization for ADHF specifically is often because of reasons unrelated to HF or a non-cardiovascular cause in general.50,51

Although a negative study, several important themes emerged. First, while we were able to assess numeracy, health literacy, and cognition, none of these measures were HF-specific. It is possible that we did not see an effect on readmission because our instruments failed to assess domains specific to HF, such as monitoring weight changes, following a low-salt diet, and interpreting blood pressure. Currently, however, no HF-specific objective numeracy measure exists. With respect to health literacy, only 1 HF-specific measure exists,52 although it was only recently developed and validated. Second, while numeracy may not be a driving influence of all-cause 30-day readmissions, it may be associated with other health behaviors and quality metrics that we did not examine here, such as self-care, medication adherence, and HF-specific readmissions. Third, it is likely that the progression of HF itself, as well as the clinical management of patients following discharge, contribute significantly to 30-day readmissions. Increased attention to predischarge processes for HF patients occurred at VUMC during the study period; close follow-up and evidence-directed therapies may have mitigated some of the expected associations. Finally, we were not able to assess numeracy of participants’ primary caregivers who may help patients at home, especially postdischarge. Though a number of studies have examined the role of family caregivers in the management of HF,53,54 none have examined numeracy levels of caregivers in the context of HF, and this may be worth doing in future studies.

Overall, our study has several strengths. The size of the cohort is large and there were high response rates during the follow-up period. Unlike other HF readmission studies, VICS accounts for readmissions to outside hospitals. Approximately 35% of all hospitalizations in VICS are to outside facilities. Thus, the ascertainment of readmissions to hospitals other than Vanderbilt is more comprehensive than if readmissions to VUMC were only considered. We were able to include a number of clinical comorbidities, laboratory and diagnostic tests from the index admission, and hospitalization characteristics in our analyses. Finally, we performed additional analyses to investigate the correlation between numeracy, literacy, and cognition; ultimately, we found that the majority of these correlations were weak, which supports our ability to study them simultaneously among VICS participants.

Nonetheless, we note some limitations. Although we captured readmissions to outside hospitals, the study took place at a single referral center in Tennessee. Though patients were diverse in age and comorbidities, they were mostly white and of higher SES. Finally, we used home status as a proxy for social support, which may underestimate the support that home care workers provide.

In conclusion, in this prospective longitudinal study of adults hospitalized with ADHF, inadequate numeracy was present in more than a third of patients, and low health literacy was present in roughly a quarter of patients. Neither numeracy nor health literacy, however, were associated with 30-day readmissions in adjusted analyses. Any cognitive impairment, although present in roughly one-half of patients, was not associated with 30-day readmission either. Our findings suggest that other influences may play a more dominant role in determining 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for ADHF than inadequate numeracy, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment as assessed here.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109388) and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors’ funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. Dr. Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Mixon has a VA Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award at the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA 12-168). This material was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 20, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Disclosure

Dr. Kripalani reports personal fees from Verustat, personal fees from SAI Interactive, and equity from Bioscape Digital, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Rothman and Dr. Wallston report personal fees from EdLogics outside of the submitted work. All of the other authors have nothing to disclose

1. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch of Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371-1386. PubMed

33. Bohannon AD, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Hanlon JT, Blazer DG. Relationship of race/ethnicity and blood pressure to change in cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):424-429. PubMed

38. Abdel-Kader K, Dew MA, Bhatnagar M, et al. Numeracy Skills in CKD: Correlates and Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(9):1566-1573. PubMed

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.