User login

The stigma toward BPD

In response to Dr. Mark Zimmerman’s article, “Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder” (

Why all the stigma? Because mental health professionals don’t have complete information. The assumption used to be that BPD was “intractable” with no treatment. Even if this were true, it still would not be a reason to fail to disclose a diagnosis, because in other fields of medicine, the concept of “therapeutic privilege” fell by the wayside long ago. However, we now know that in many individuals with BPD, symptoms improve over time, and there are several effective treatments.

In DSM-II, published in 1968, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was characterized as an “obsessive compulsive neurosis.” It was not reclassified as the current OCD diagnosis until DSM-III-R was published in 1987, after the FDA approved clomipramine. Why is this important? Because once people realized that there was a treatment, they started acknowledging OCD more often.

The first step in addressing the stigma toward BPD is that mental health professionals must recognize their own bias toward this diagnosis. We must be re-educated that this diagnosis carries hope, symptoms improve, and that there are effective treatments. This is how professionals will increase the recognition of BPD.

Assistant Professor and Compliance Officer

Department of Psychiatry

University of Florida

Clinic Director

UF Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic at Springhill Health Center

Gainesville, Florida

References

1. Unruh BT, Gunderson JG. “Good enough” psychiatric residency training in borderline personality disorder: challenges, choice points, and a model generalist curriculum. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2016;24(5):367-377.

2. Sheehan L, Nieweglowski K, Corrigan P. The stigma of personality disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(1):11.

Continue to: The author responds

The author responds

I agree with Dr. Shapiro that stigma by mental health clinicians contributes to the underdiagnosis of BPD. Mental health professions often hold a negative view of patients with personality disorders, particularly those with BPD, and see these patients as being more difficult to treat.1-3 They are the patients that some clinicians are reluctant to treat.3,4 Clinicians perceive patients with personality disorders as less mentally ill, more manipulative, and more able to control their behavior than patients with other psychiatric disorders.3,5 Consistent with this, clinicians have less sympathetic attitudes and behave less empathically toward patients with BPD.5,6 The term “borderline” also is sometimes used pejoratively to describe patients.1

As I described in my article, there are several possible reasons BPD is underdiagnosed. Foremost is that mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders are common in patients with BPD, and the symptoms of these other disorders are typically patients’ chief concerns when they present for treatment. Patients with BPD do not usually report the features of BPD—such as abandonment fears, chronic feelings of emptiness, or an identity disturbance—as their chief concerns. If they did, BPD would likely be easier to recognize. On a related note, clinicians do not have the time, or do not take the time, to conduct a thorough enough evaluation to diagnose BPD when it occurs in a patient who presents for treatment of a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, or substance use disorder. Our clinical research group found that when psychiatrists are presented with the results of a semi-structured interview, BPD is much more frequently diagnosed.7 Such a finding would not be expected if stigma was the primary or sole reason for underdiagnosis.

Dr. Shapiro highlights the clinical consequence of underrecognition and underdiagnosis: the underutilization of empirically supported psychotherapies for BPD. A corollary of underdiagnosing BPD is overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder and overprescription of medication.8

There are other consequences of bias and stigma toward BPD. Despite the high levels of psychosocial morbidity, reduced health-related quality of life, high utilization of services, and excess mortality associated with BPD, this disorder is not included in the Global Burden of Disease Study. Thus, the public health significance of BPD is less fully appreciated. Finally, there is evidence that the level of funding for research from the National Institutes of Health is not commensurate with the level of psychosocial morbidity, mortality, and health expenditures associated with the disorder.9 Thus, the stigma toward BPD exists in both clinical and research communities.

Mark Zimmerman, MD

Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior

Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Rhode Island Hospital

Providence, Rhode Island

References

1. Cleary M, Siegfried N, Walter G. Experience, knowledge and attitudes of mental health staff regarding clients with a borderline personality disorder. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2002;11(3):186-191.

2. Gallop R, Lancee WJ, Garfinkel P. How nursing staff respond to the label “borderline personality disorder.” Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(8):815-819.

3. Lewis G, Appleby L. Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:44-49.

4. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(3):67-74.

5. Markham D, Trower P. The effects of the psychiatric label ‘borderline personality disorder’ on nursing staff’s perceptions and causal attributions for challenging behaviours. Br J Clin Psychol. 2003;42(pt 3):243-256.

6. Fraser K, Gallop R. Nurses’ confirming/disconfirming responses to patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1993;7(6):336-341.

7. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Differences between clinical and research practices in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1570-1574.

8. Zimmerman M, Ruggero CJ, Chelminski I, et al. Is bipolar disorder overdiagnosed? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(6):935-940.

9. Zimmerman M, Gazarian D. Is research on borderline personality disorder underfunded by the National Institute of Health? Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(3):941-944.

In response to Dr. Mark Zimmerman’s article, “Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder” (

Why all the stigma? Because mental health professionals don’t have complete information. The assumption used to be that BPD was “intractable” with no treatment. Even if this were true, it still would not be a reason to fail to disclose a diagnosis, because in other fields of medicine, the concept of “therapeutic privilege” fell by the wayside long ago. However, we now know that in many individuals with BPD, symptoms improve over time, and there are several effective treatments.

In DSM-II, published in 1968, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was characterized as an “obsessive compulsive neurosis.” It was not reclassified as the current OCD diagnosis until DSM-III-R was published in 1987, after the FDA approved clomipramine. Why is this important? Because once people realized that there was a treatment, they started acknowledging OCD more often.

The first step in addressing the stigma toward BPD is that mental health professionals must recognize their own bias toward this diagnosis. We must be re-educated that this diagnosis carries hope, symptoms improve, and that there are effective treatments. This is how professionals will increase the recognition of BPD.

Assistant Professor and Compliance Officer

Department of Psychiatry

University of Florida

Clinic Director

UF Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic at Springhill Health Center

Gainesville, Florida

References

1. Unruh BT, Gunderson JG. “Good enough” psychiatric residency training in borderline personality disorder: challenges, choice points, and a model generalist curriculum. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2016;24(5):367-377.

2. Sheehan L, Nieweglowski K, Corrigan P. The stigma of personality disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(1):11.

Continue to: The author responds

The author responds

I agree with Dr. Shapiro that stigma by mental health clinicians contributes to the underdiagnosis of BPD. Mental health professions often hold a negative view of patients with personality disorders, particularly those with BPD, and see these patients as being more difficult to treat.1-3 They are the patients that some clinicians are reluctant to treat.3,4 Clinicians perceive patients with personality disorders as less mentally ill, more manipulative, and more able to control their behavior than patients with other psychiatric disorders.3,5 Consistent with this, clinicians have less sympathetic attitudes and behave less empathically toward patients with BPD.5,6 The term “borderline” also is sometimes used pejoratively to describe patients.1

As I described in my article, there are several possible reasons BPD is underdiagnosed. Foremost is that mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders are common in patients with BPD, and the symptoms of these other disorders are typically patients’ chief concerns when they present for treatment. Patients with BPD do not usually report the features of BPD—such as abandonment fears, chronic feelings of emptiness, or an identity disturbance—as their chief concerns. If they did, BPD would likely be easier to recognize. On a related note, clinicians do not have the time, or do not take the time, to conduct a thorough enough evaluation to diagnose BPD when it occurs in a patient who presents for treatment of a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, or substance use disorder. Our clinical research group found that when psychiatrists are presented with the results of a semi-structured interview, BPD is much more frequently diagnosed.7 Such a finding would not be expected if stigma was the primary or sole reason for underdiagnosis.

Dr. Shapiro highlights the clinical consequence of underrecognition and underdiagnosis: the underutilization of empirically supported psychotherapies for BPD. A corollary of underdiagnosing BPD is overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder and overprescription of medication.8

There are other consequences of bias and stigma toward BPD. Despite the high levels of psychosocial morbidity, reduced health-related quality of life, high utilization of services, and excess mortality associated with BPD, this disorder is not included in the Global Burden of Disease Study. Thus, the public health significance of BPD is less fully appreciated. Finally, there is evidence that the level of funding for research from the National Institutes of Health is not commensurate with the level of psychosocial morbidity, mortality, and health expenditures associated with the disorder.9 Thus, the stigma toward BPD exists in both clinical and research communities.

Mark Zimmerman, MD

Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior

Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Rhode Island Hospital

Providence, Rhode Island

References

1. Cleary M, Siegfried N, Walter G. Experience, knowledge and attitudes of mental health staff regarding clients with a borderline personality disorder. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2002;11(3):186-191.

2. Gallop R, Lancee WJ, Garfinkel P. How nursing staff respond to the label “borderline personality disorder.” Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(8):815-819.

3. Lewis G, Appleby L. Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:44-49.

4. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(3):67-74.

5. Markham D, Trower P. The effects of the psychiatric label ‘borderline personality disorder’ on nursing staff’s perceptions and causal attributions for challenging behaviours. Br J Clin Psychol. 2003;42(pt 3):243-256.

6. Fraser K, Gallop R. Nurses’ confirming/disconfirming responses to patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1993;7(6):336-341.

7. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Differences between clinical and research practices in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1570-1574.

8. Zimmerman M, Ruggero CJ, Chelminski I, et al. Is bipolar disorder overdiagnosed? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(6):935-940.

9. Zimmerman M, Gazarian D. Is research on borderline personality disorder underfunded by the National Institute of Health? Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(3):941-944.

In response to Dr. Mark Zimmerman’s article, “Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder” (

Why all the stigma? Because mental health professionals don’t have complete information. The assumption used to be that BPD was “intractable” with no treatment. Even if this were true, it still would not be a reason to fail to disclose a diagnosis, because in other fields of medicine, the concept of “therapeutic privilege” fell by the wayside long ago. However, we now know that in many individuals with BPD, symptoms improve over time, and there are several effective treatments.

In DSM-II, published in 1968, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was characterized as an “obsessive compulsive neurosis.” It was not reclassified as the current OCD diagnosis until DSM-III-R was published in 1987, after the FDA approved clomipramine. Why is this important? Because once people realized that there was a treatment, they started acknowledging OCD more often.

The first step in addressing the stigma toward BPD is that mental health professionals must recognize their own bias toward this diagnosis. We must be re-educated that this diagnosis carries hope, symptoms improve, and that there are effective treatments. This is how professionals will increase the recognition of BPD.

Assistant Professor and Compliance Officer

Department of Psychiatry

University of Florida

Clinic Director

UF Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic at Springhill Health Center

Gainesville, Florida

References

1. Unruh BT, Gunderson JG. “Good enough” psychiatric residency training in borderline personality disorder: challenges, choice points, and a model generalist curriculum. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2016;24(5):367-377.

2. Sheehan L, Nieweglowski K, Corrigan P. The stigma of personality disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(1):11.

Continue to: The author responds

The author responds

I agree with Dr. Shapiro that stigma by mental health clinicians contributes to the underdiagnosis of BPD. Mental health professions often hold a negative view of patients with personality disorders, particularly those with BPD, and see these patients as being more difficult to treat.1-3 They are the patients that some clinicians are reluctant to treat.3,4 Clinicians perceive patients with personality disorders as less mentally ill, more manipulative, and more able to control their behavior than patients with other psychiatric disorders.3,5 Consistent with this, clinicians have less sympathetic attitudes and behave less empathically toward patients with BPD.5,6 The term “borderline” also is sometimes used pejoratively to describe patients.1

As I described in my article, there are several possible reasons BPD is underdiagnosed. Foremost is that mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders are common in patients with BPD, and the symptoms of these other disorders are typically patients’ chief concerns when they present for treatment. Patients with BPD do not usually report the features of BPD—such as abandonment fears, chronic feelings of emptiness, or an identity disturbance—as their chief concerns. If they did, BPD would likely be easier to recognize. On a related note, clinicians do not have the time, or do not take the time, to conduct a thorough enough evaluation to diagnose BPD when it occurs in a patient who presents for treatment of a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, or substance use disorder. Our clinical research group found that when psychiatrists are presented with the results of a semi-structured interview, BPD is much more frequently diagnosed.7 Such a finding would not be expected if stigma was the primary or sole reason for underdiagnosis.

Dr. Shapiro highlights the clinical consequence of underrecognition and underdiagnosis: the underutilization of empirically supported psychotherapies for BPD. A corollary of underdiagnosing BPD is overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder and overprescription of medication.8

There are other consequences of bias and stigma toward BPD. Despite the high levels of psychosocial morbidity, reduced health-related quality of life, high utilization of services, and excess mortality associated with BPD, this disorder is not included in the Global Burden of Disease Study. Thus, the public health significance of BPD is less fully appreciated. Finally, there is evidence that the level of funding for research from the National Institutes of Health is not commensurate with the level of psychosocial morbidity, mortality, and health expenditures associated with the disorder.9 Thus, the stigma toward BPD exists in both clinical and research communities.

Mark Zimmerman, MD

Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior

Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Rhode Island Hospital

Providence, Rhode Island

References

1. Cleary M, Siegfried N, Walter G. Experience, knowledge and attitudes of mental health staff regarding clients with a borderline personality disorder. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2002;11(3):186-191.

2. Gallop R, Lancee WJ, Garfinkel P. How nursing staff respond to the label “borderline personality disorder.” Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(8):815-819.

3. Lewis G, Appleby L. Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:44-49.

4. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(3):67-74.

5. Markham D, Trower P. The effects of the psychiatric label ‘borderline personality disorder’ on nursing staff’s perceptions and causal attributions for challenging behaviours. Br J Clin Psychol. 2003;42(pt 3):243-256.

6. Fraser K, Gallop R. Nurses’ confirming/disconfirming responses to patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1993;7(6):336-341.

7. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Differences between clinical and research practices in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1570-1574.

8. Zimmerman M, Ruggero CJ, Chelminski I, et al. Is bipolar disorder overdiagnosed? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(6):935-940.

9. Zimmerman M, Gazarian D. Is research on borderline personality disorder underfunded by the National Institute of Health? Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(3):941-944.

Point-of-care ultrasound: Coming soon to primary care?

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been gaining greater traction in recent years as a way to quickly (and cost-effectively) assess for conditions including systolic dysfunction, pleural effusion, abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs), and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). It involves limited and specific ultrasound protocols performed at the bedside by the health care provider who is trying to answer a specific question and, thus, help guide treatment of the patient.

POCUS was first widely used by emergency physicians starting in the early 1990s with the widespread adoption of the Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) scan.1,2 Since that time, POCUS has expanded beyond trauma applications and into family medicine.

One study assessed physicians’ perceptions of POCUS after its integration into a military family medicine clinic. The study showed that physicians perceived POCUS to be relatively easy to use, not overly time consuming, and of high value to the practice.3 In fact, the literature tells us that POCUS can help decrease the cost of health care and improve outcomes,4-7 while requiring a relatively brief training period.

If residencies are any indication, POCUS may be headed your way

Ultrasound units are becoming smaller and more affordable, and medical schools are increasingly incorporating ultrasound curricula into medical student training.8 As of 2016, only 6% of practicing FPs reported using non-obstetric POCUS in their practices.9 Similarly, a survey from 2015 reported that only 2% of family medicine residency programs had established POCUS curricula.10 However, 50% of respondents in the 2015 survey reported early-stage development or interest in developing a POCUS curriculum.

Since then a validated family medicine residency curriculum has been published,11 and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recently released a POCUS Curriculum Guideline for residencies (https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint290D_POCUS.pdf).

[polldaddy:9928416]

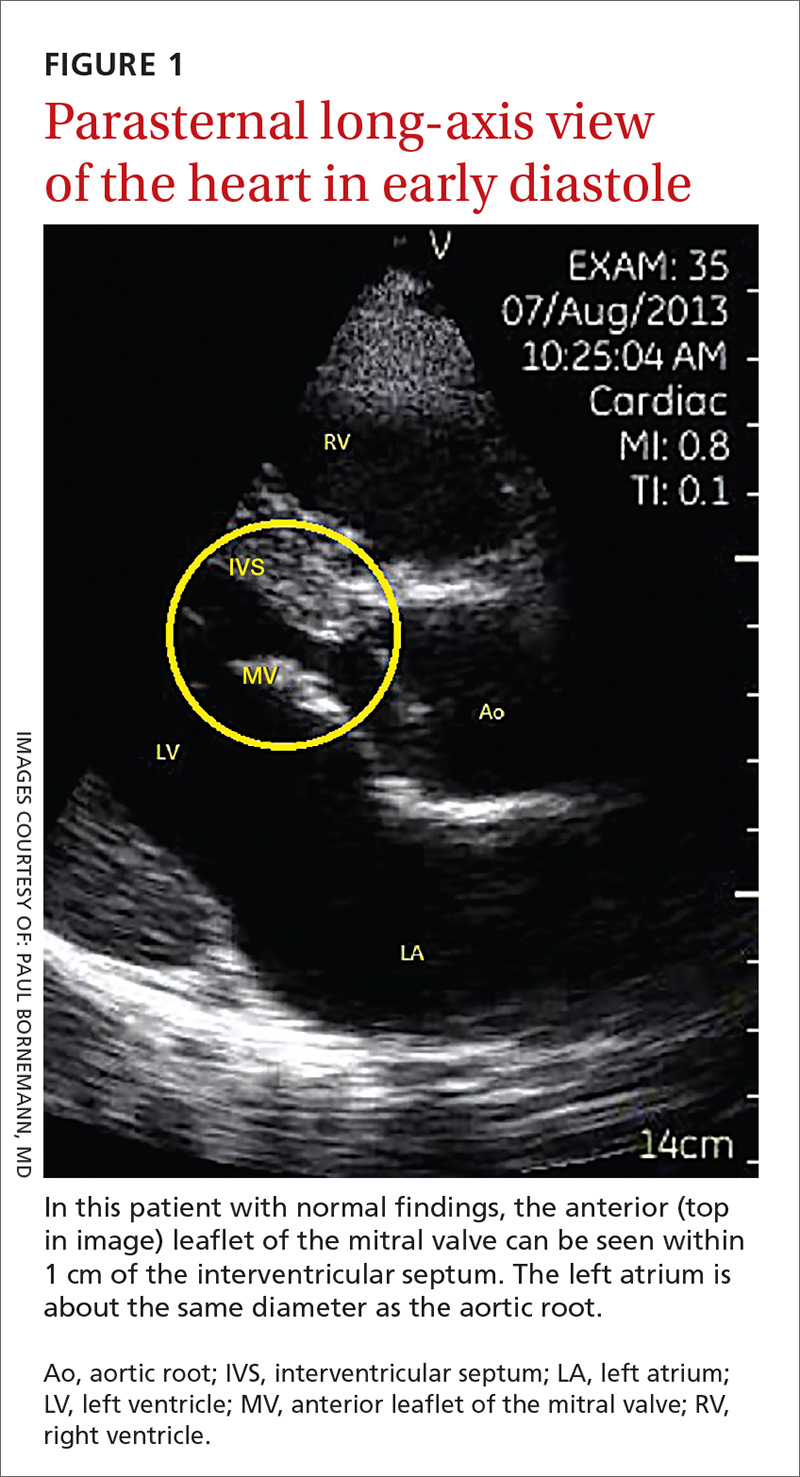

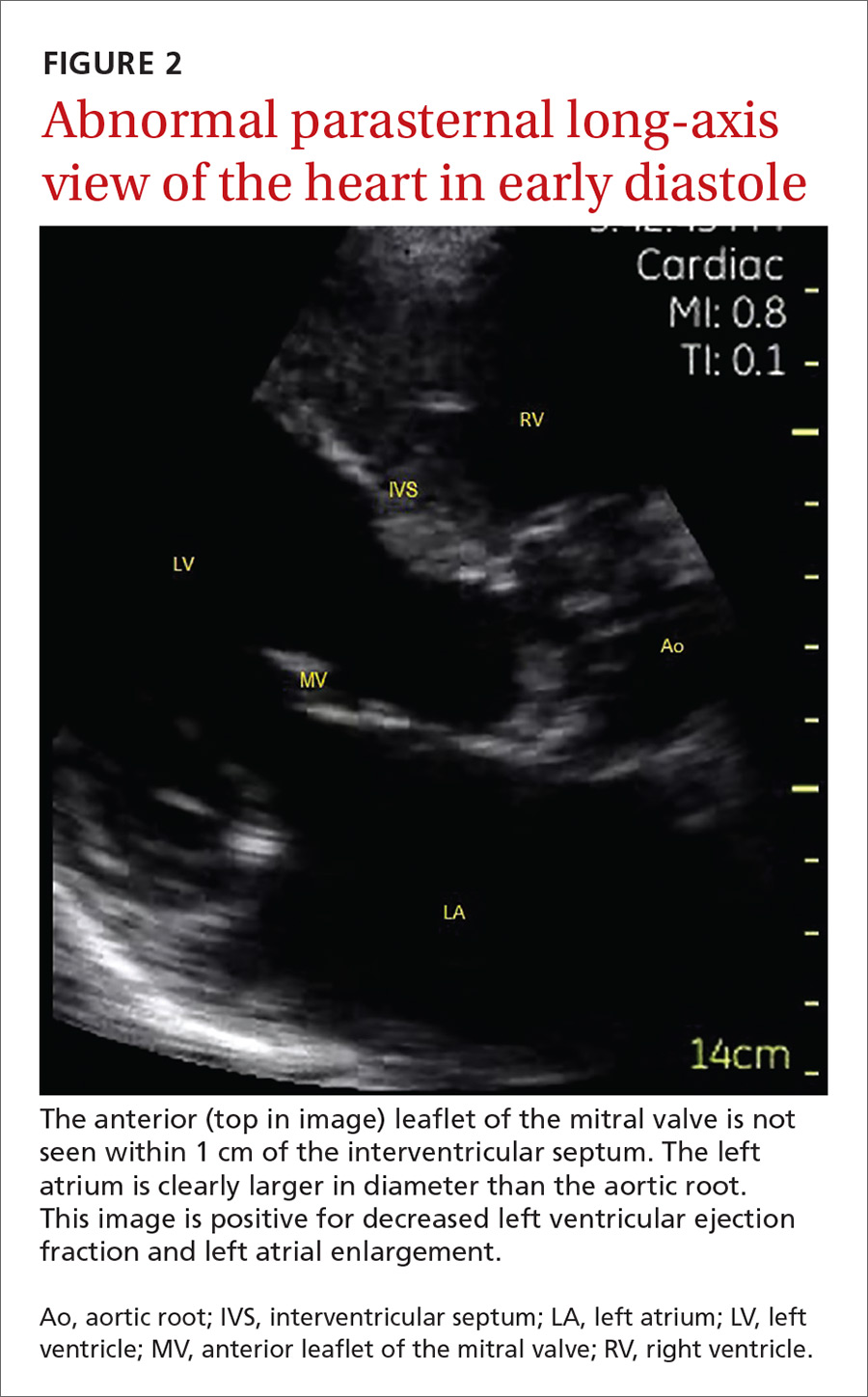

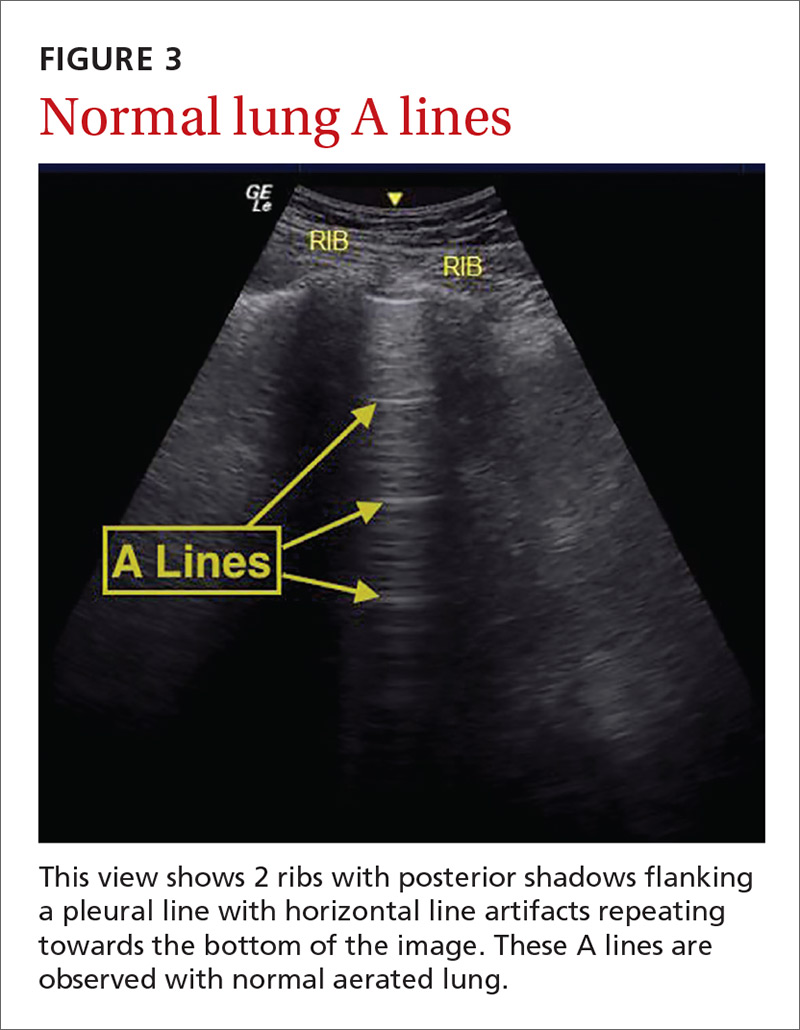

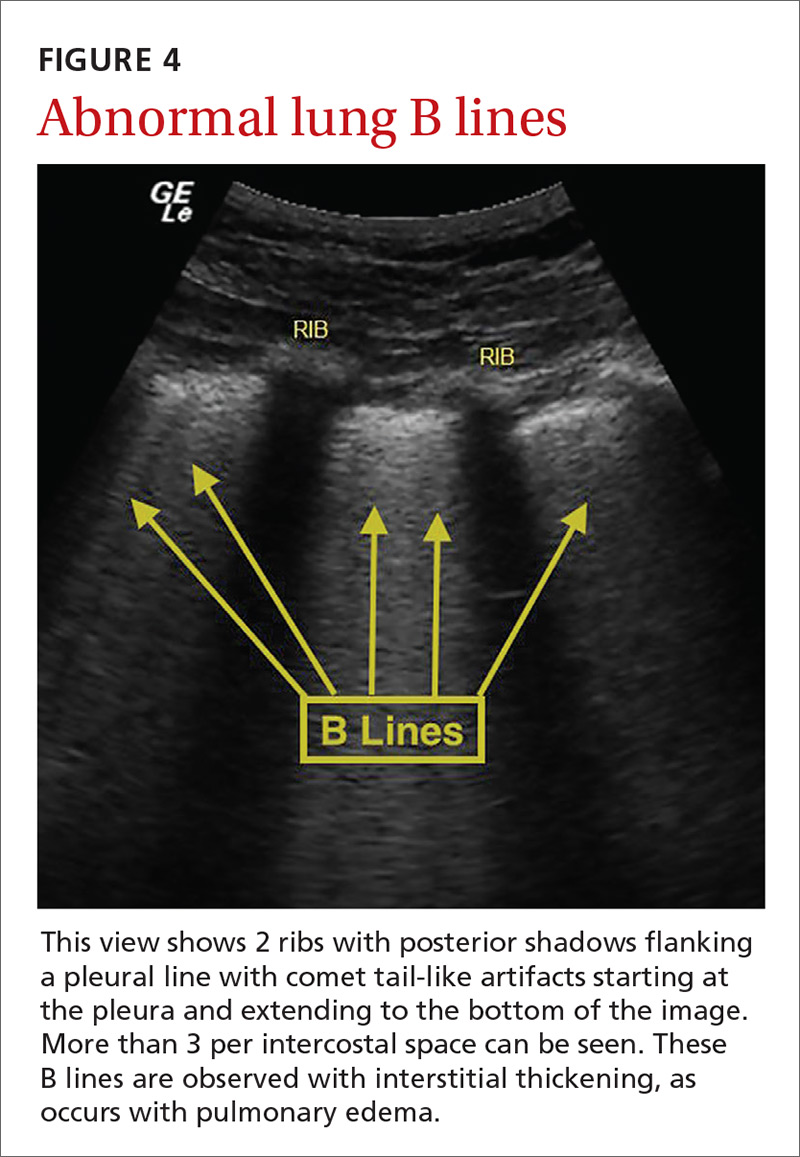

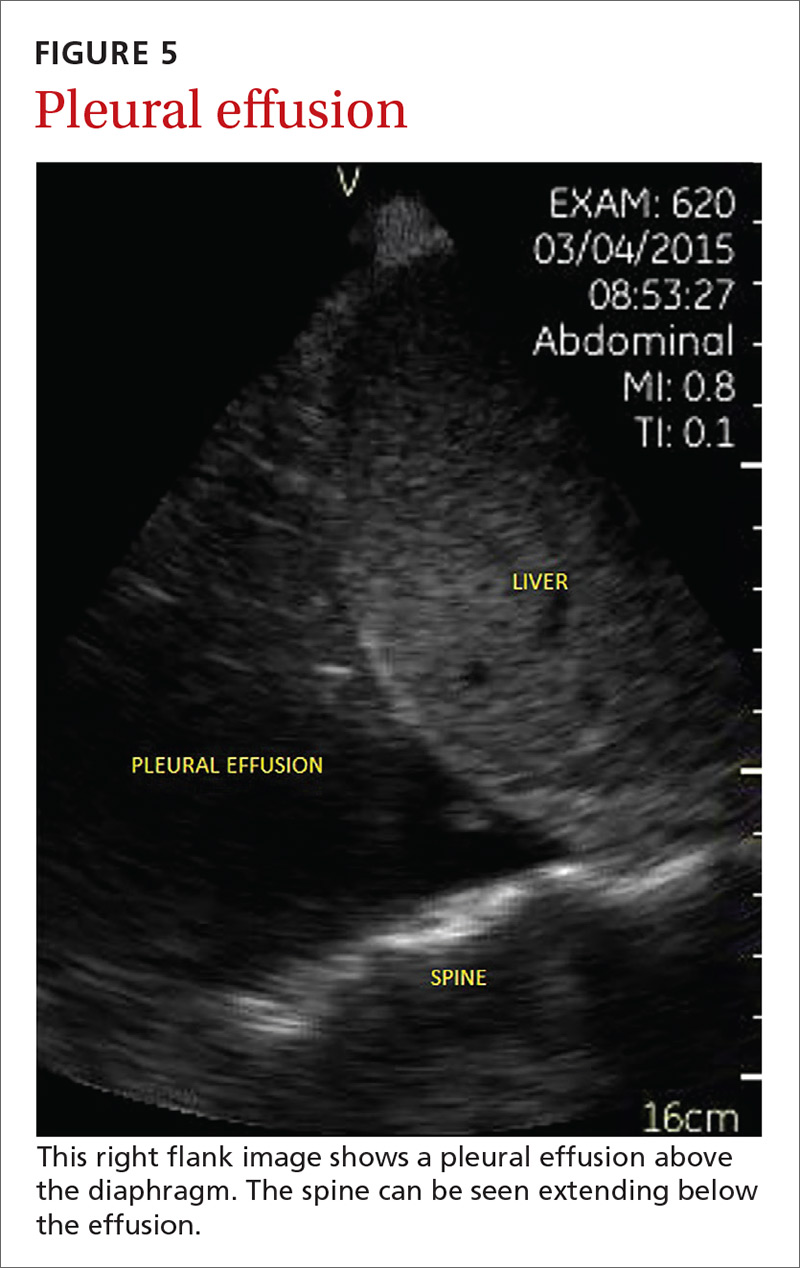

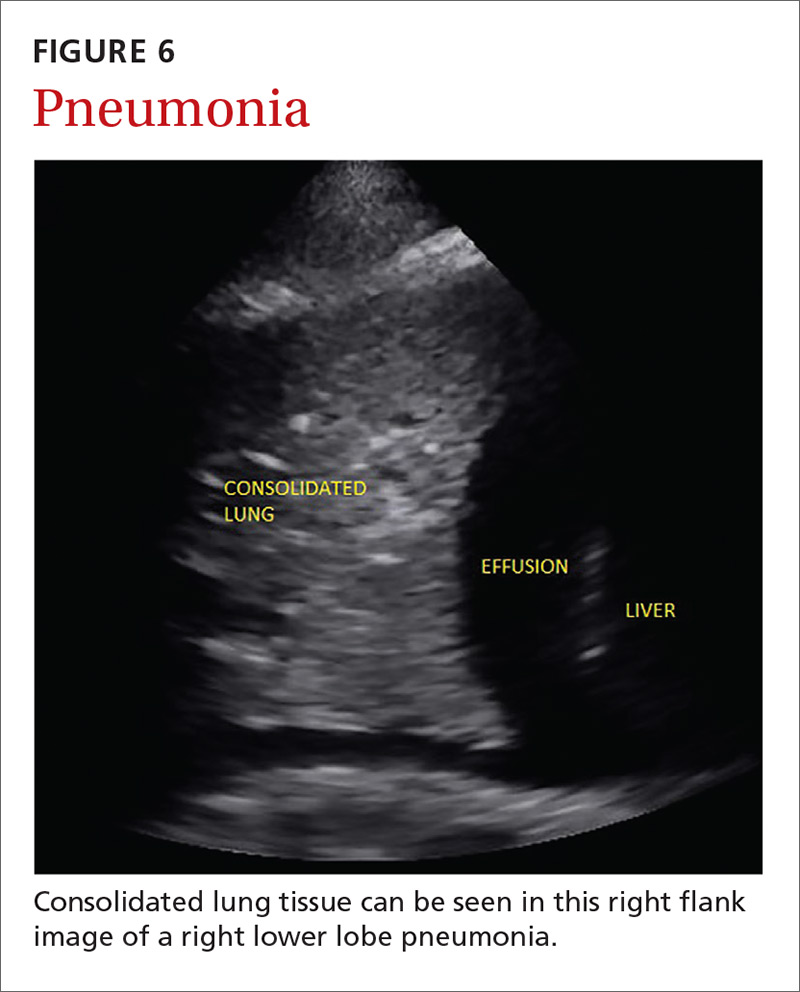

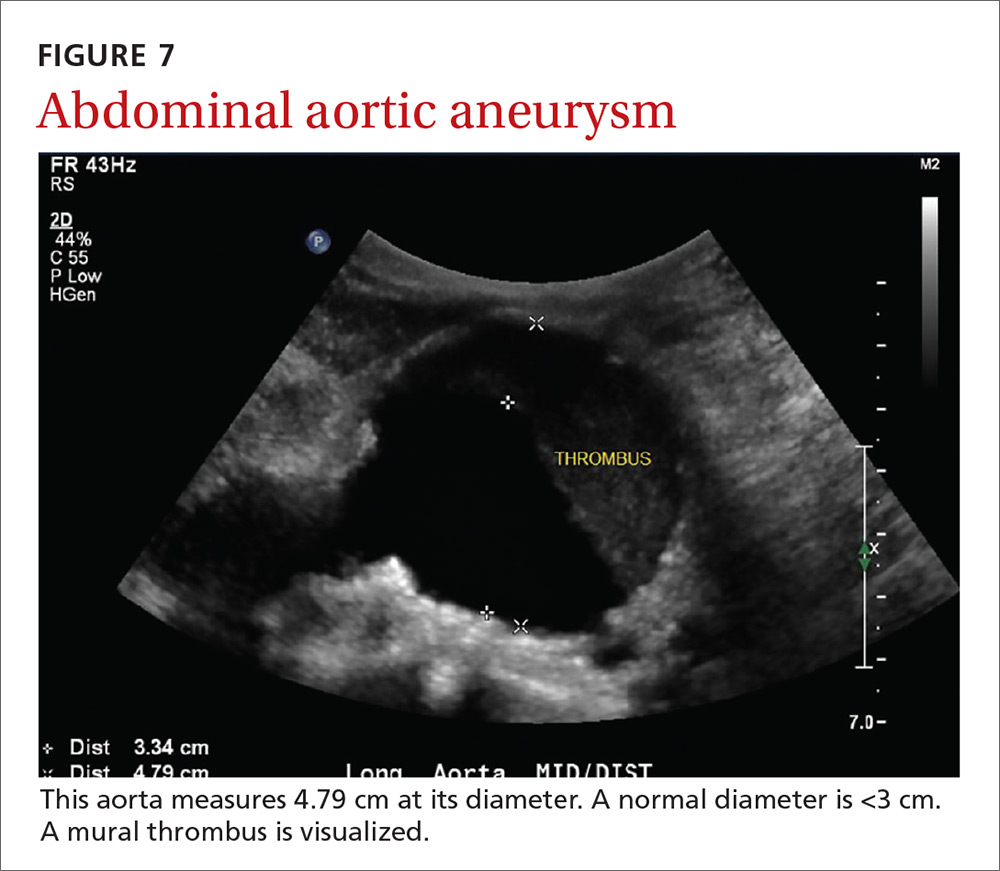

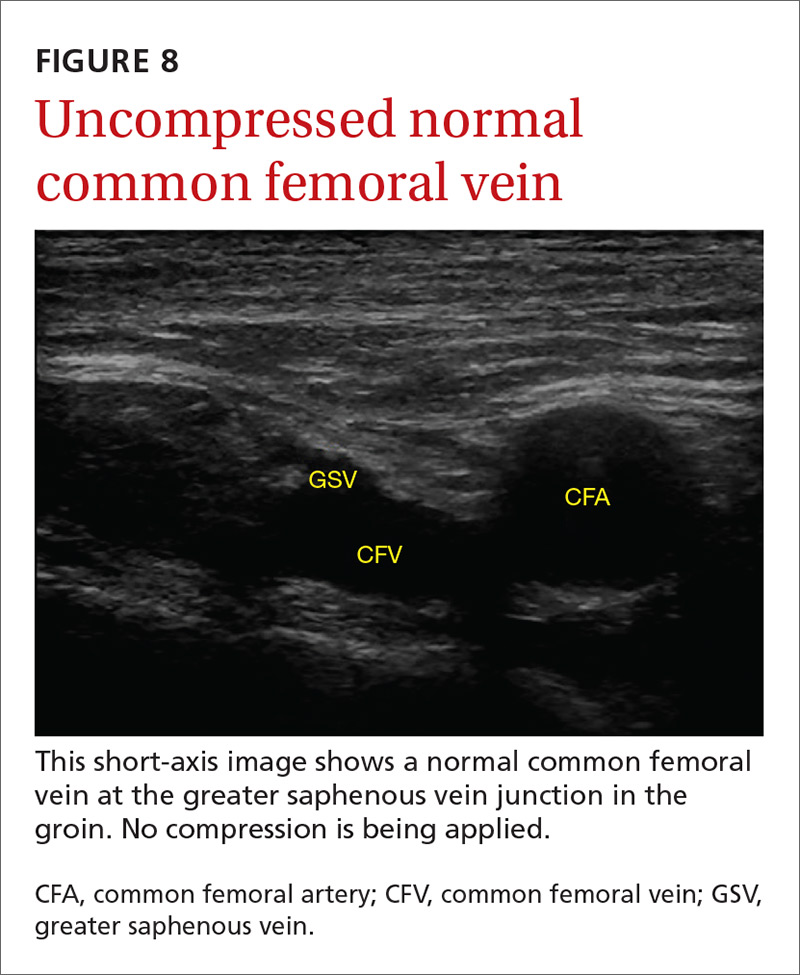

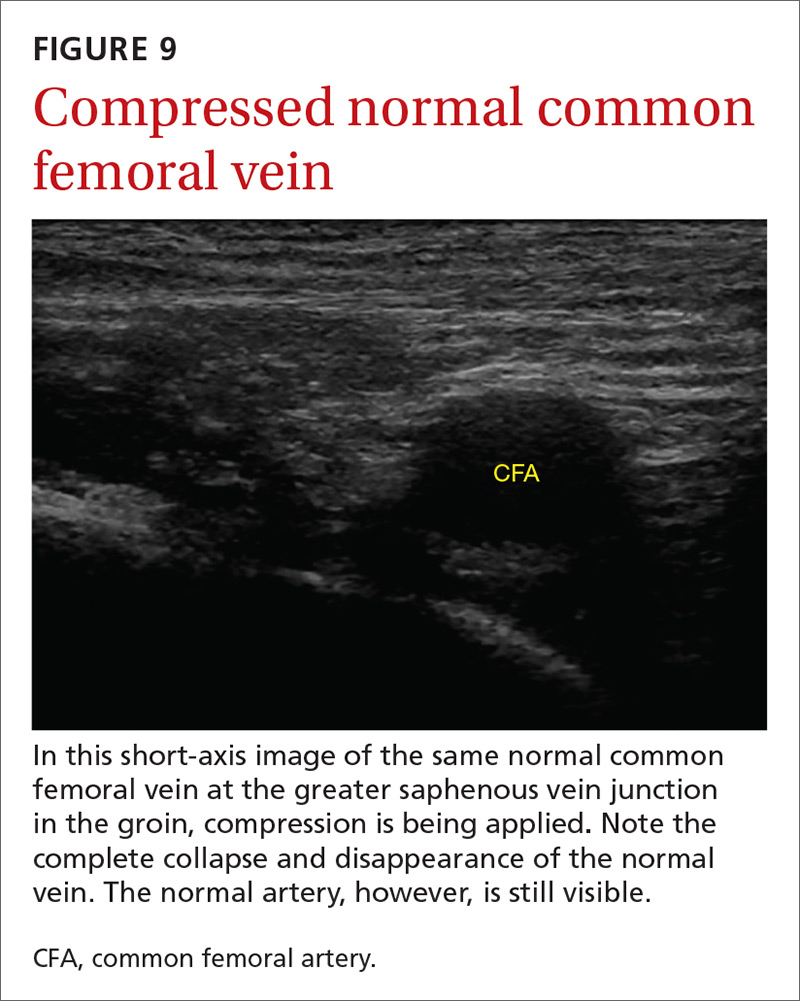

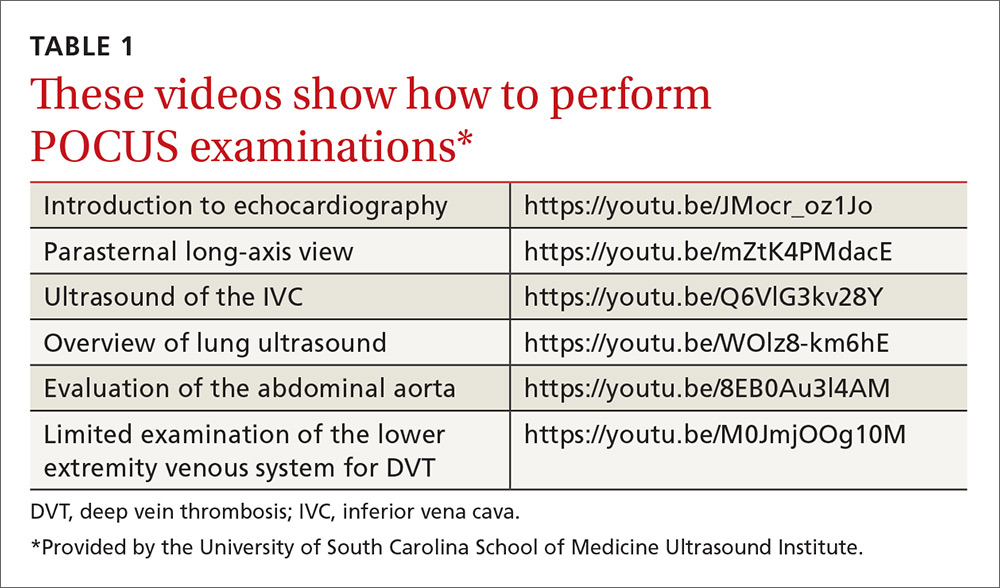

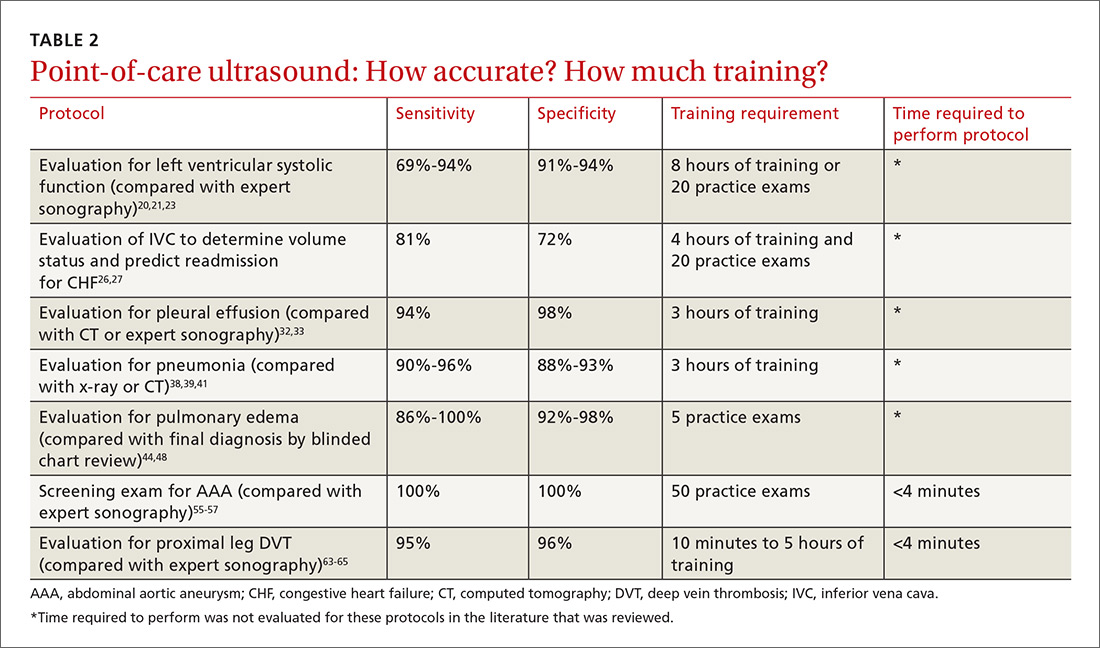

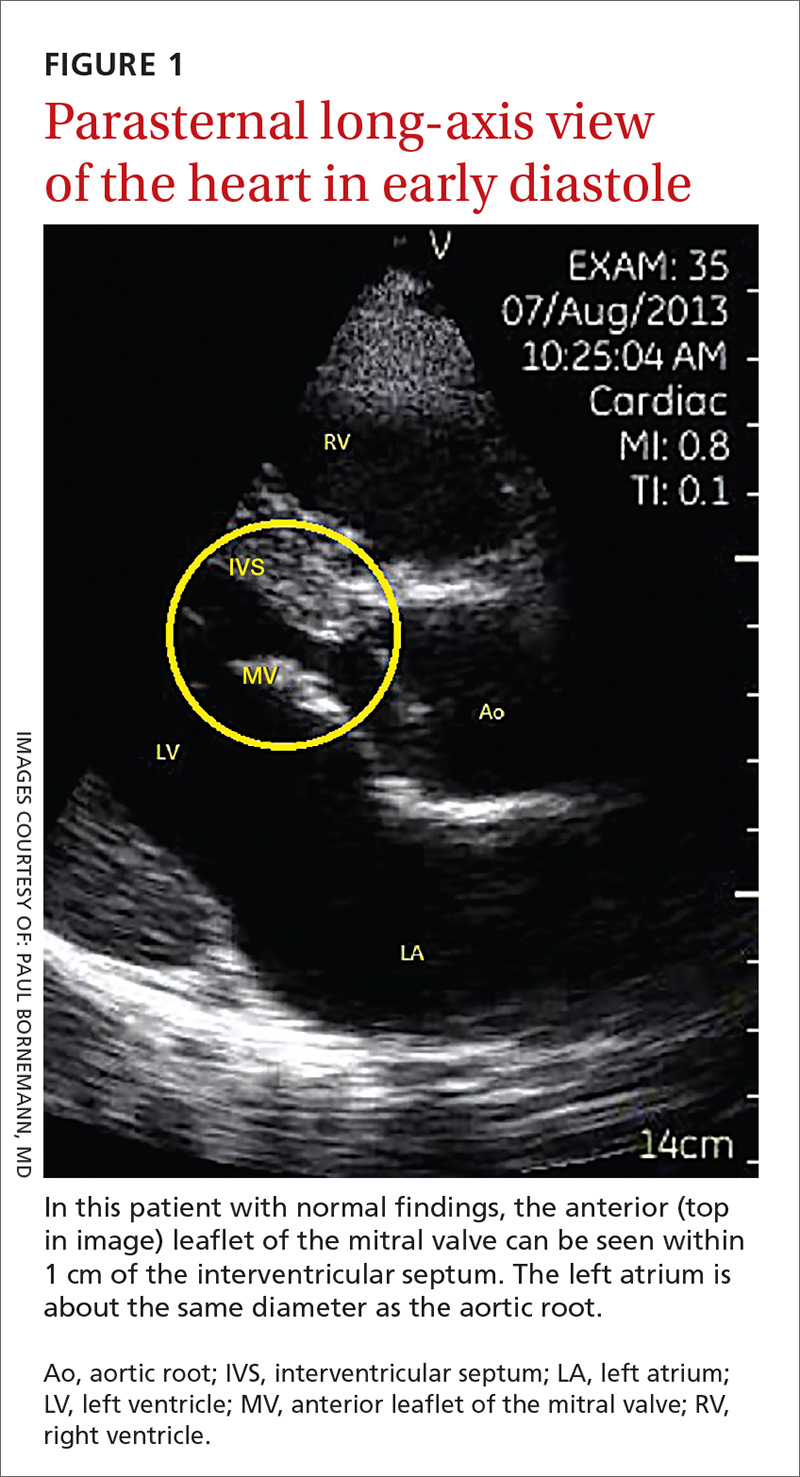

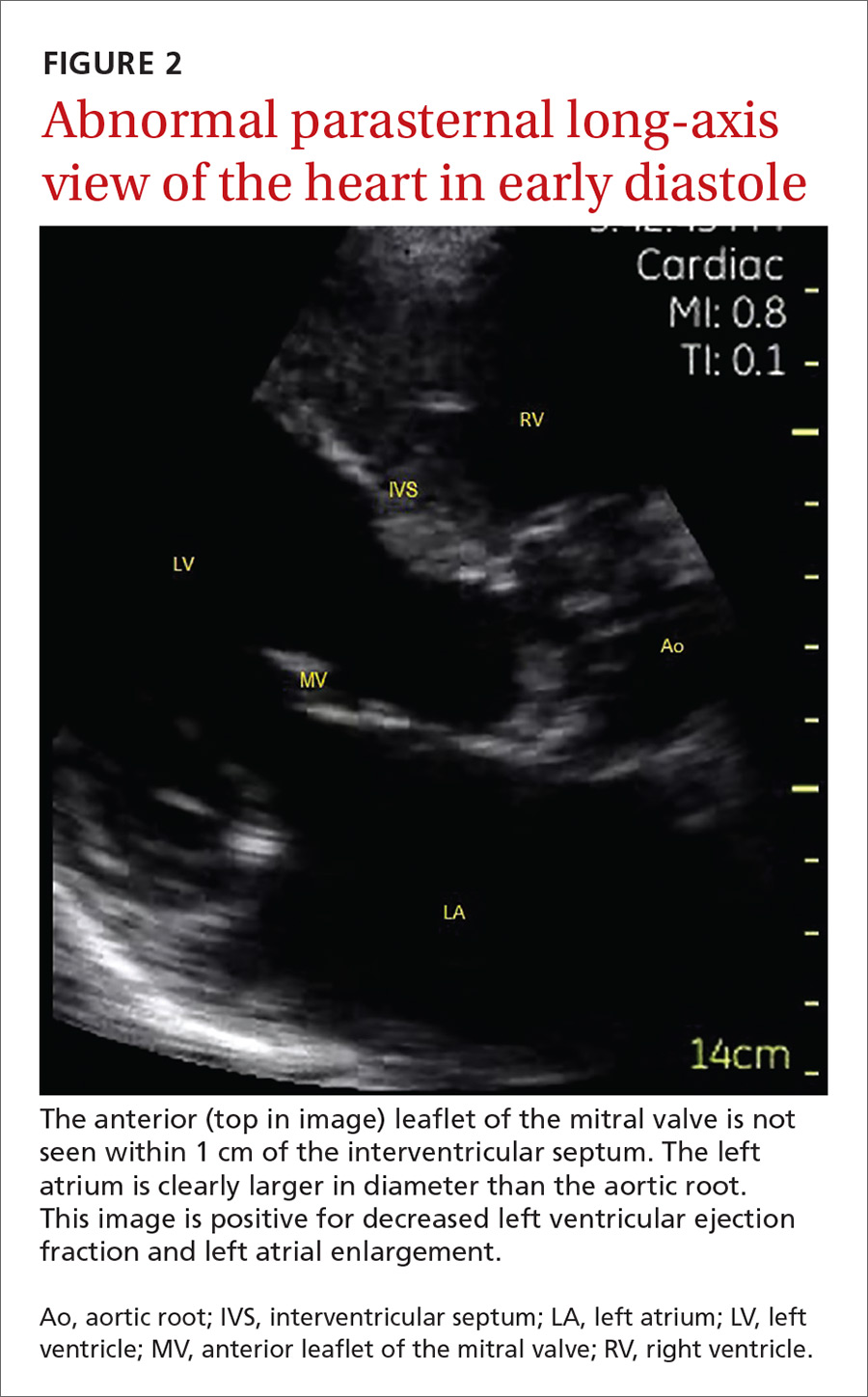

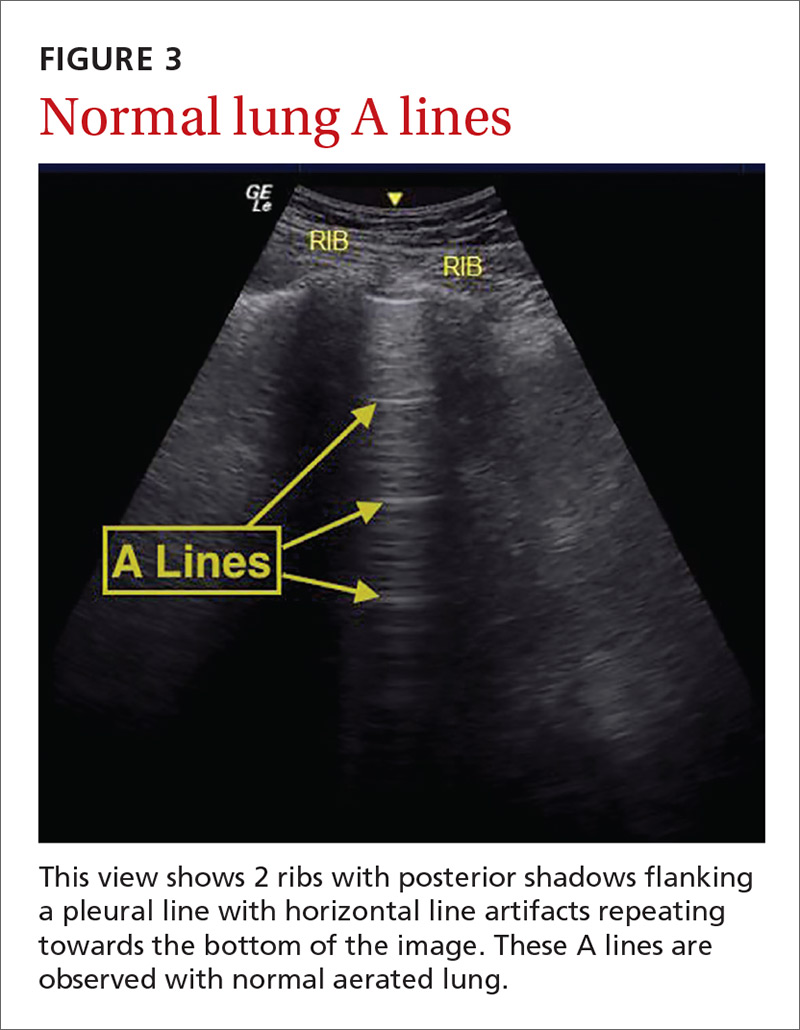

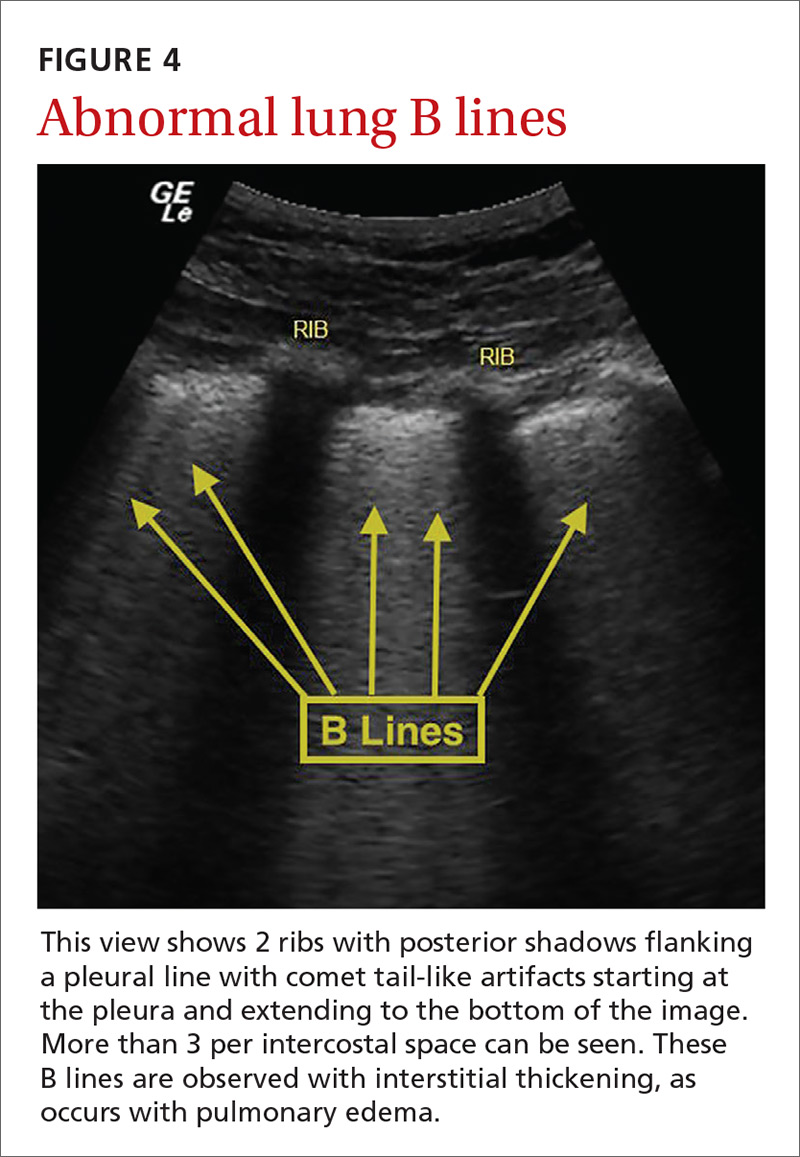

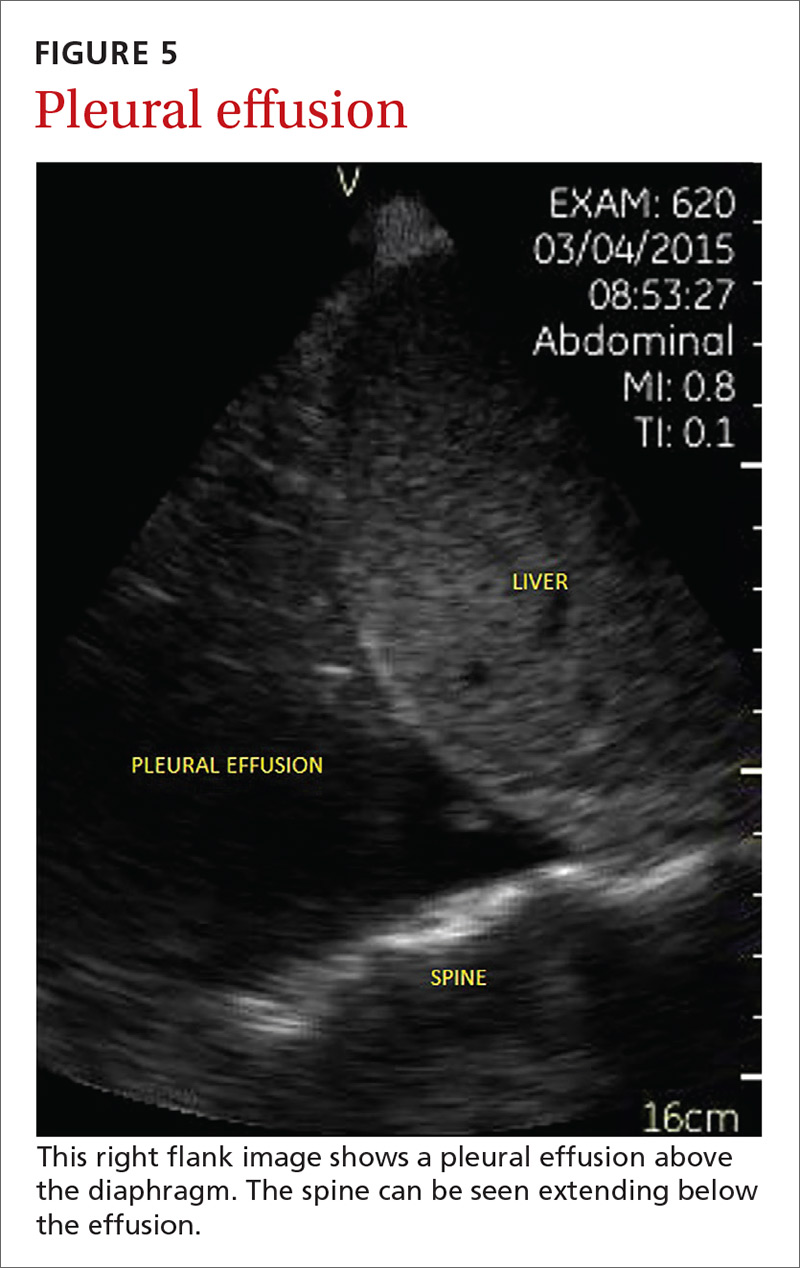

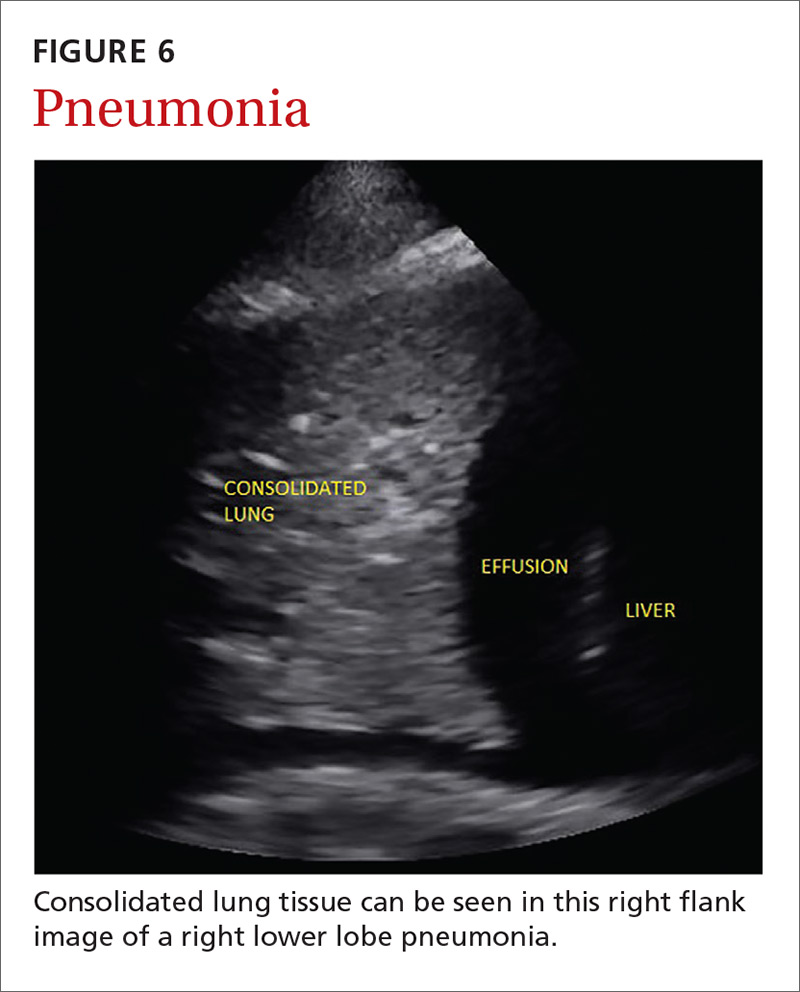

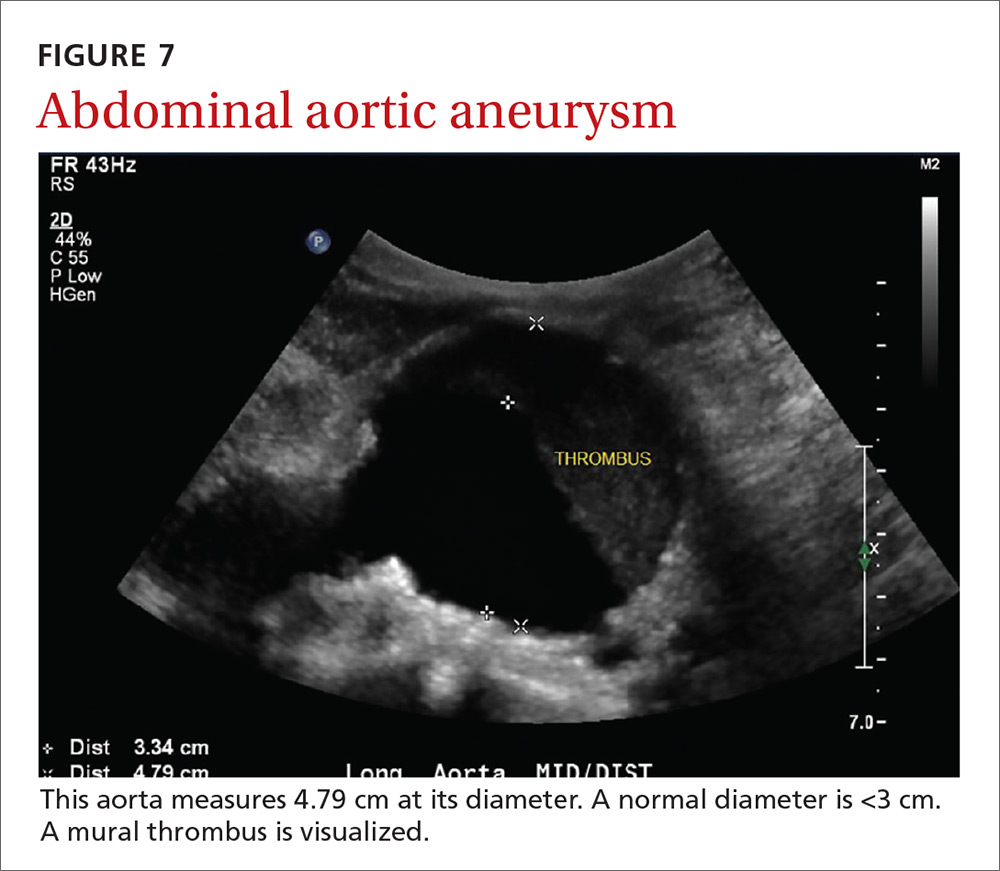

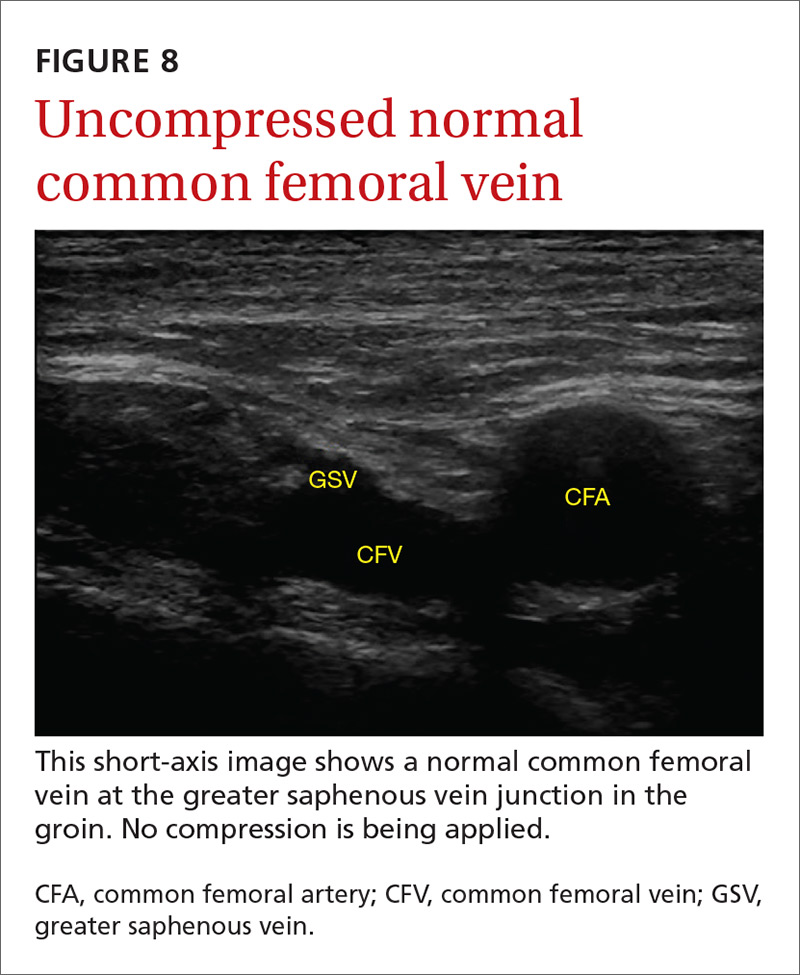

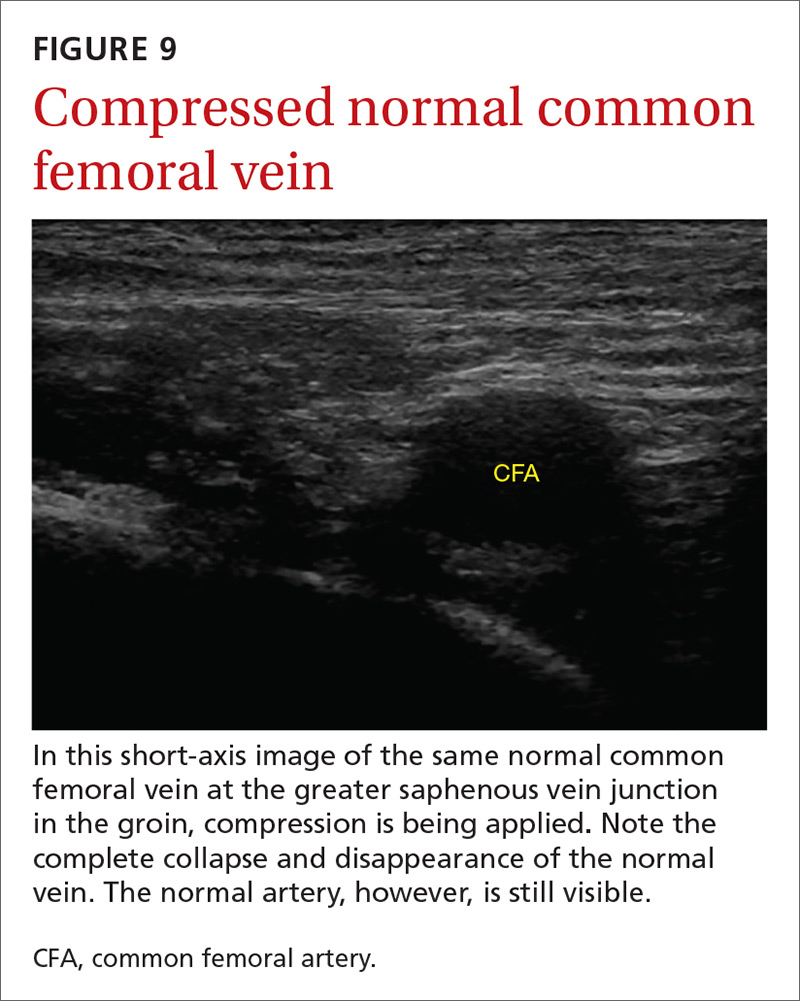

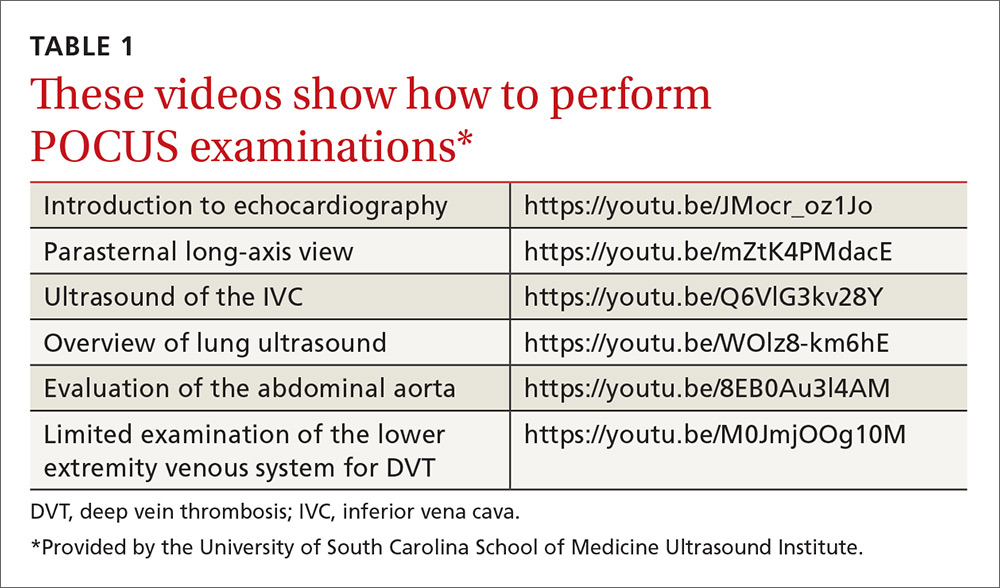

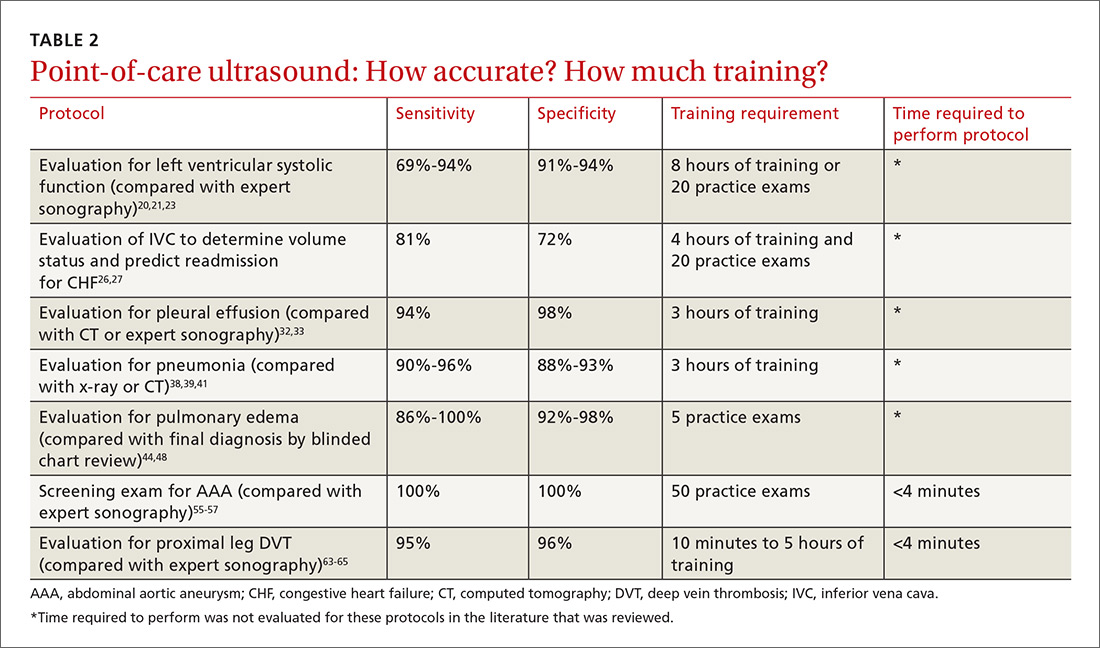

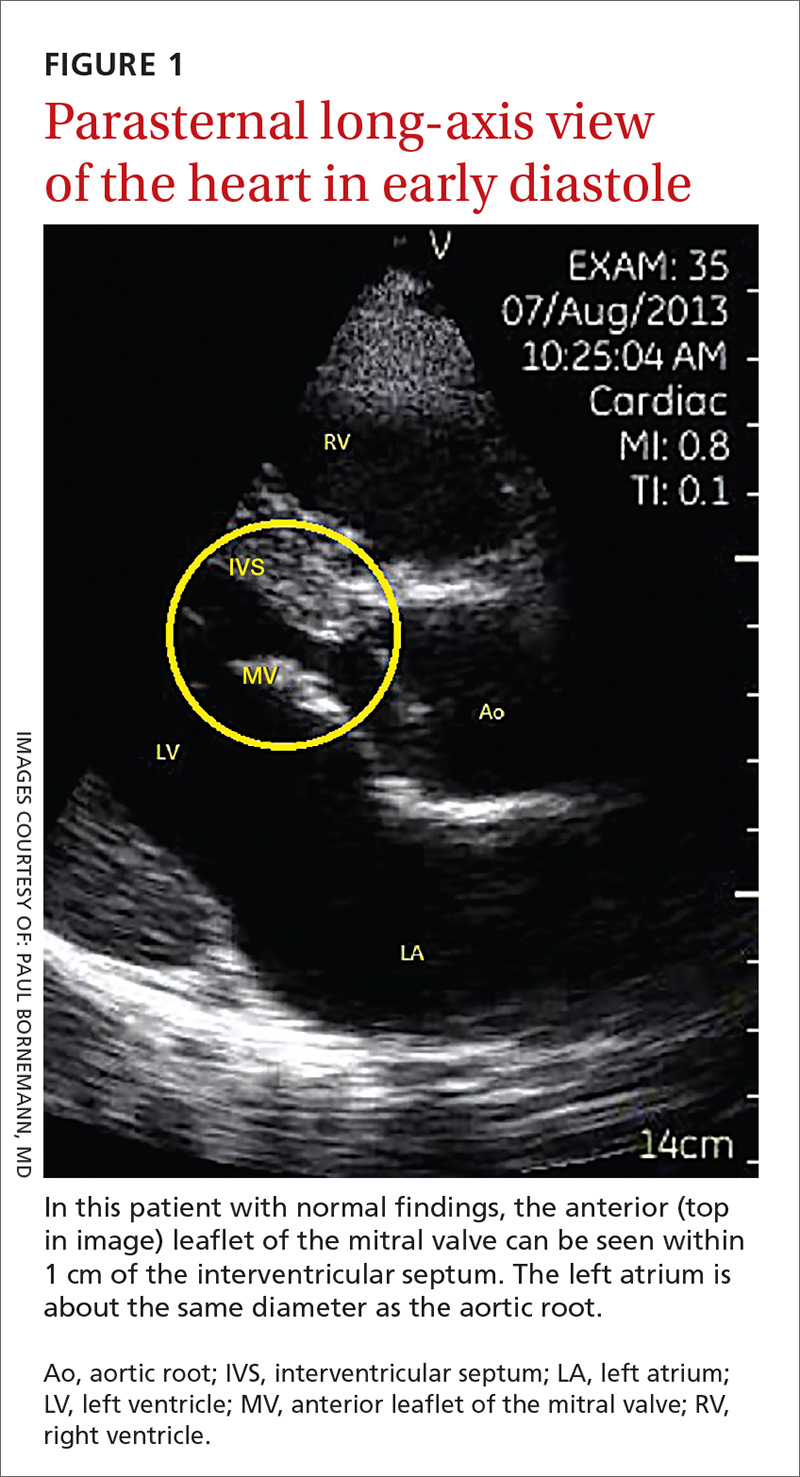

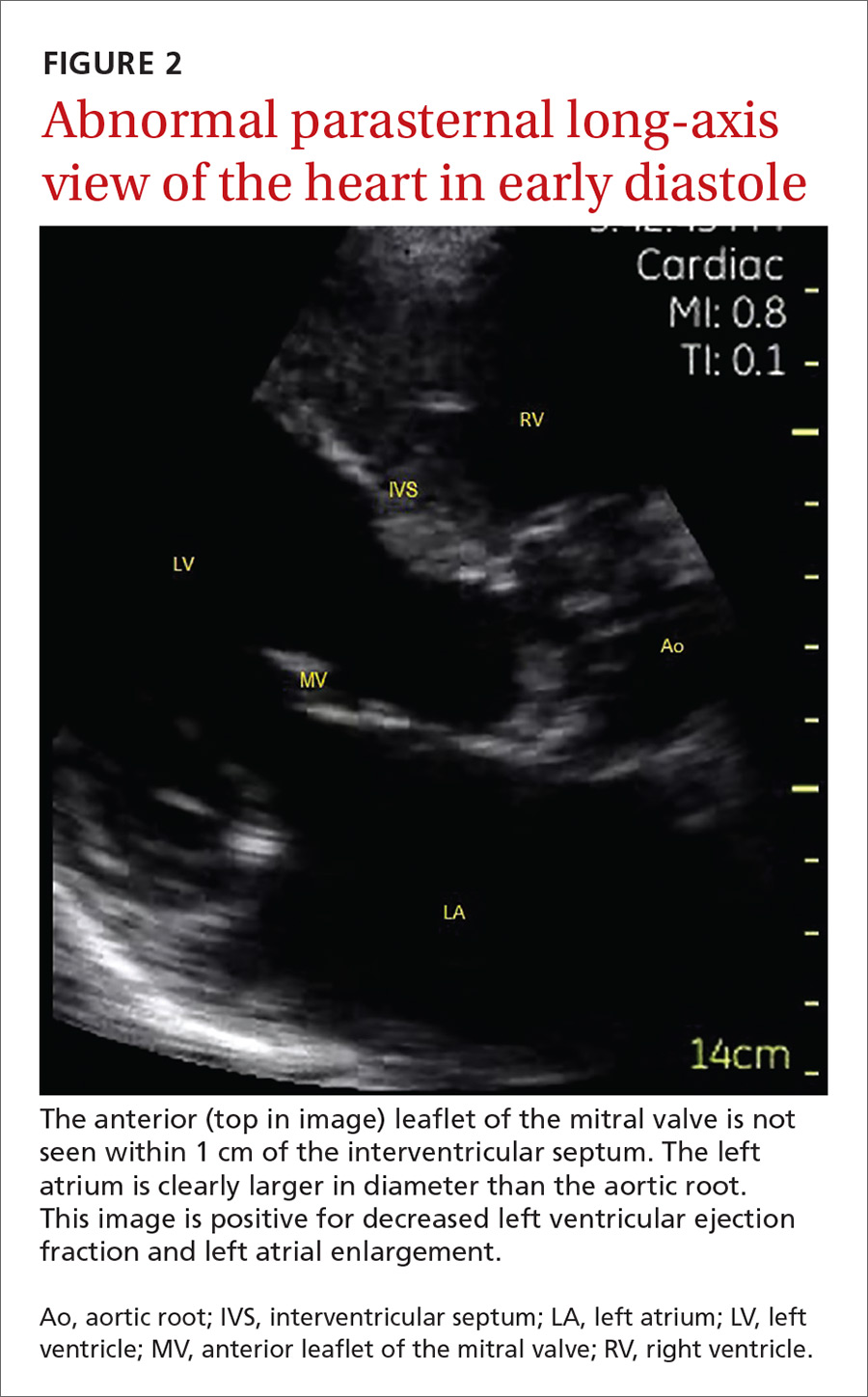

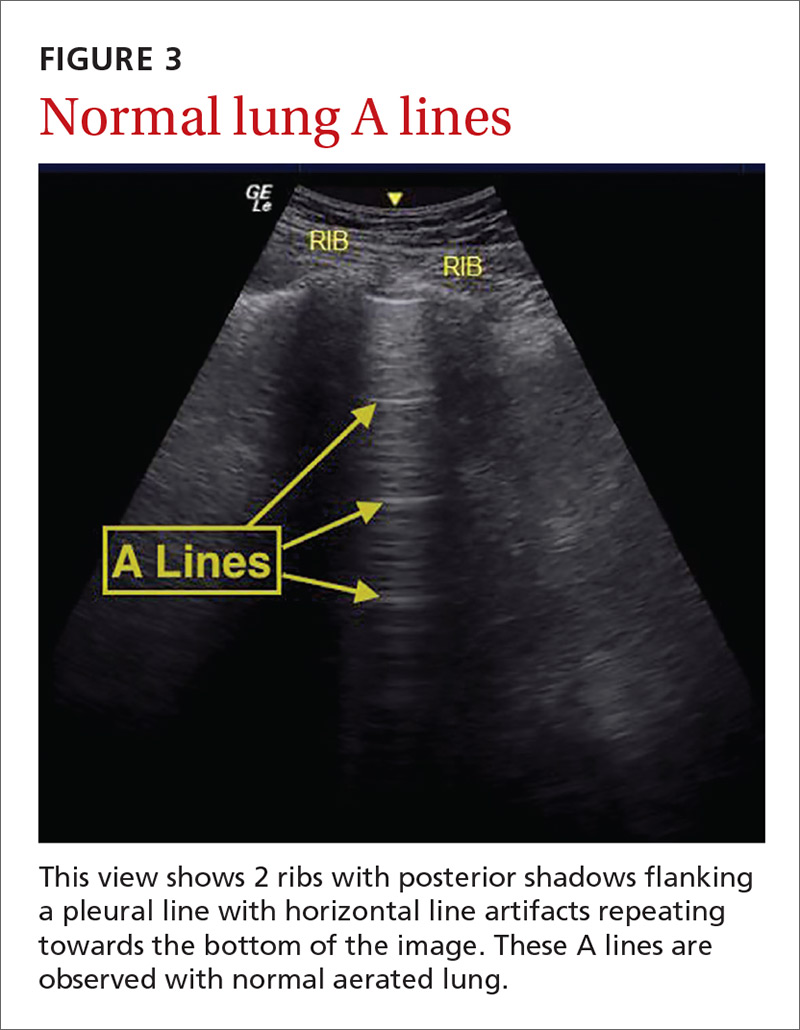

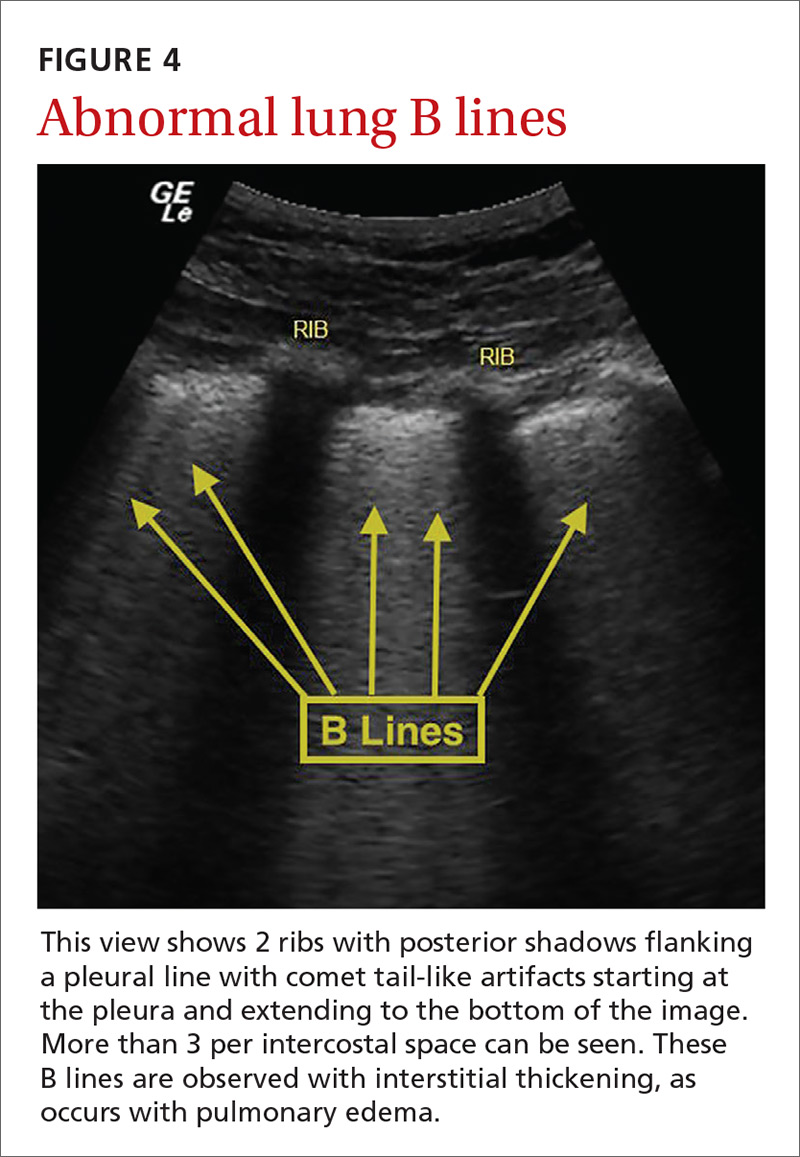

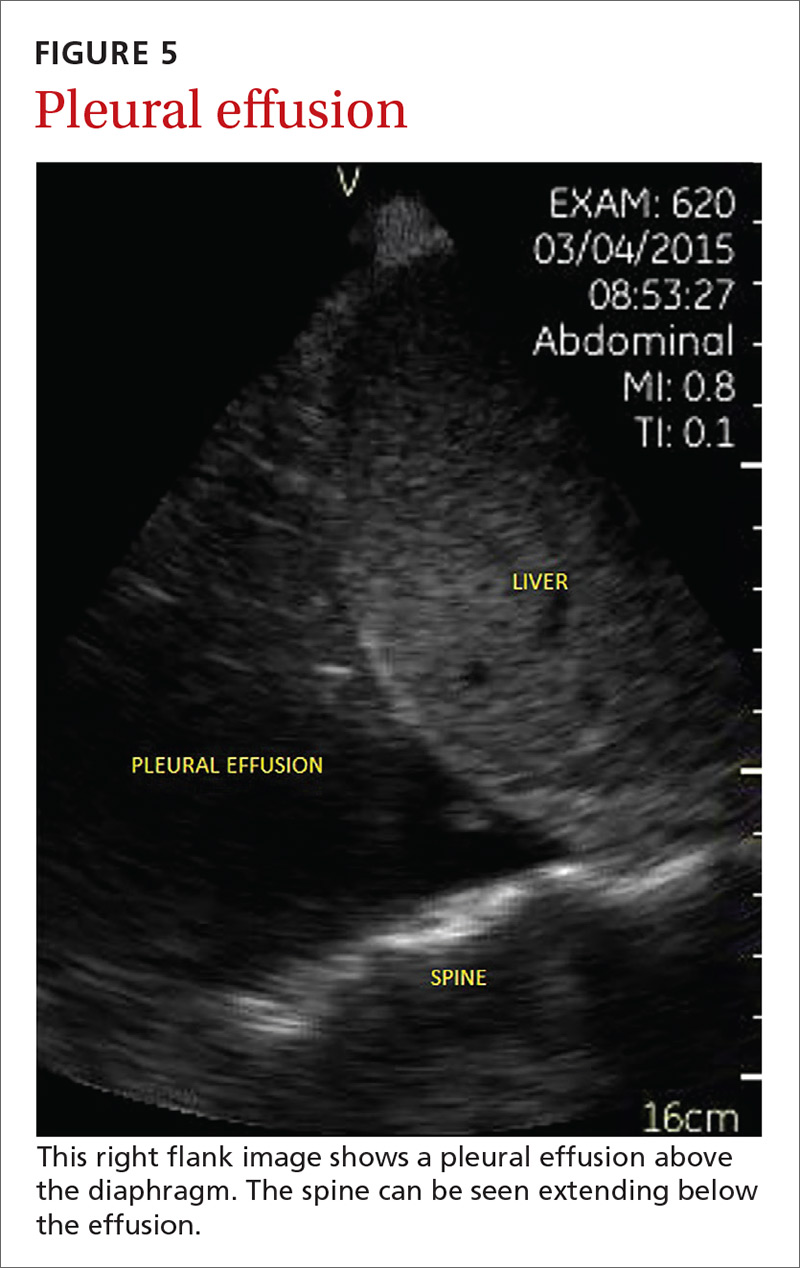

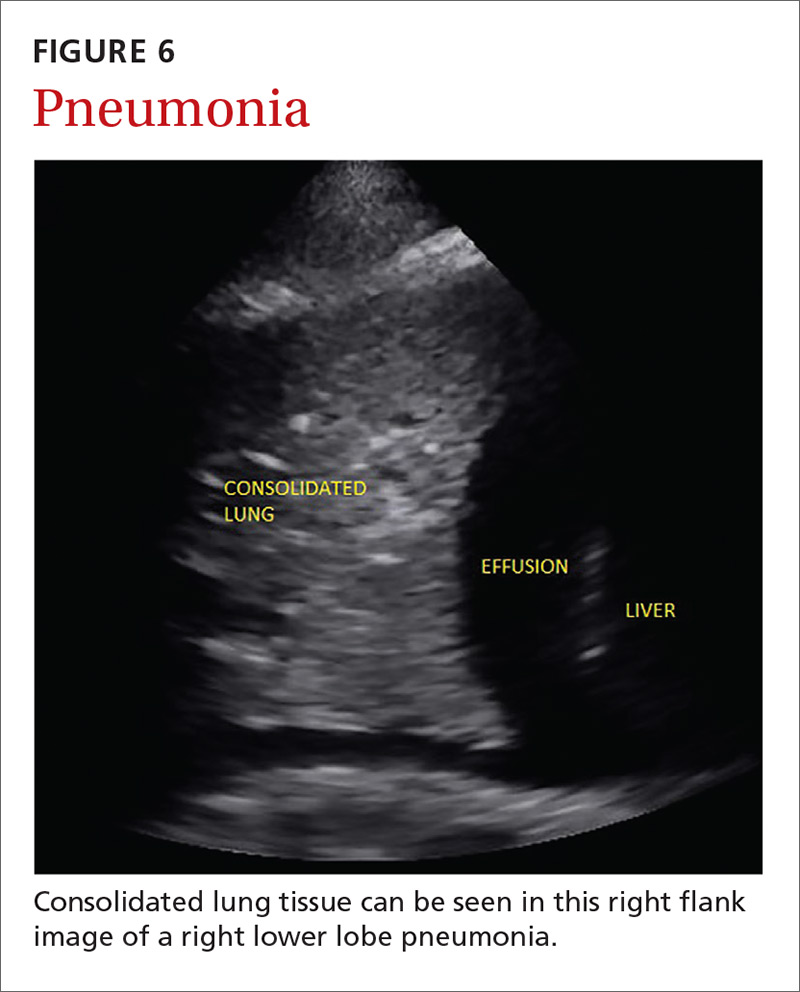

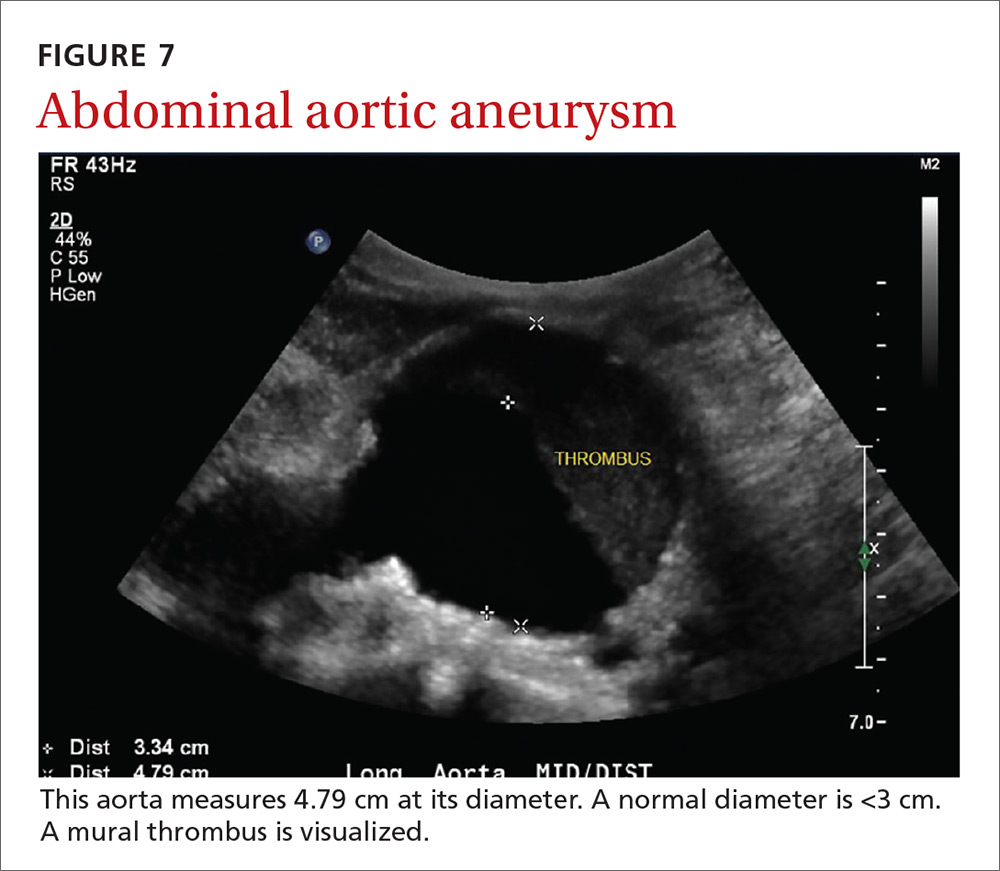

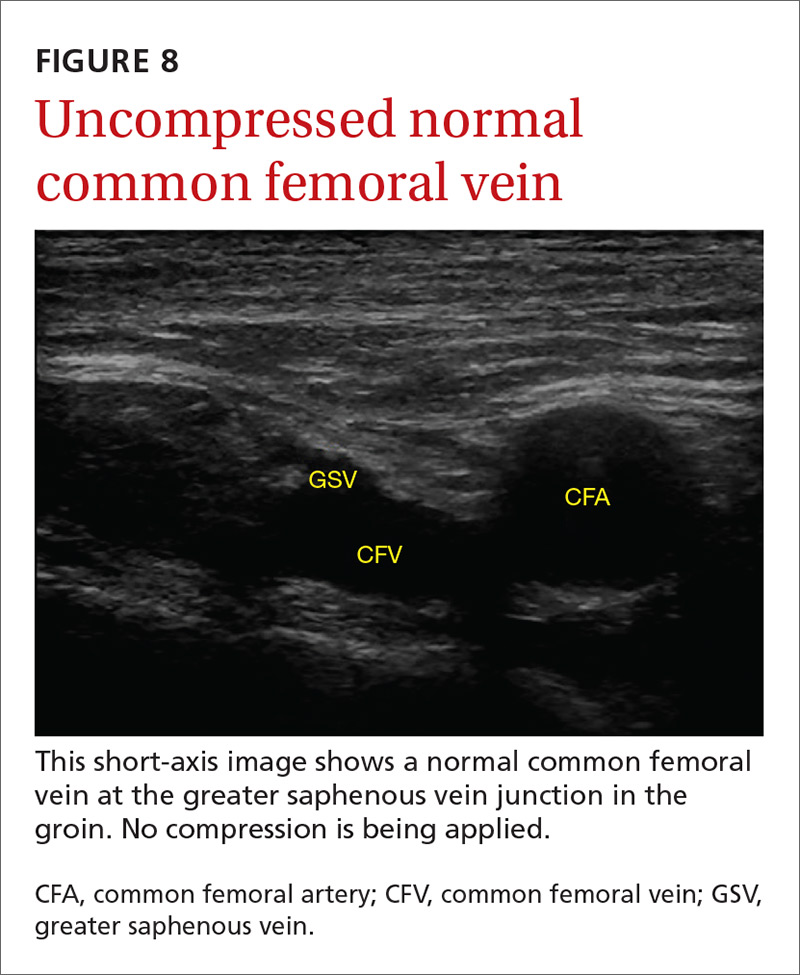

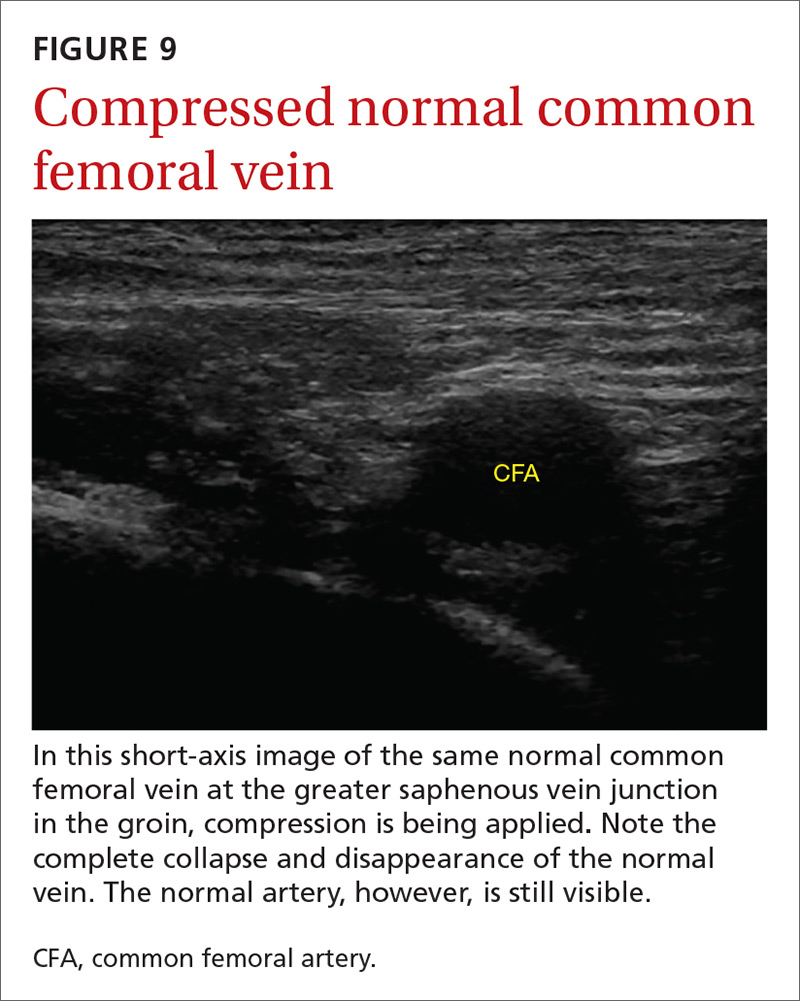

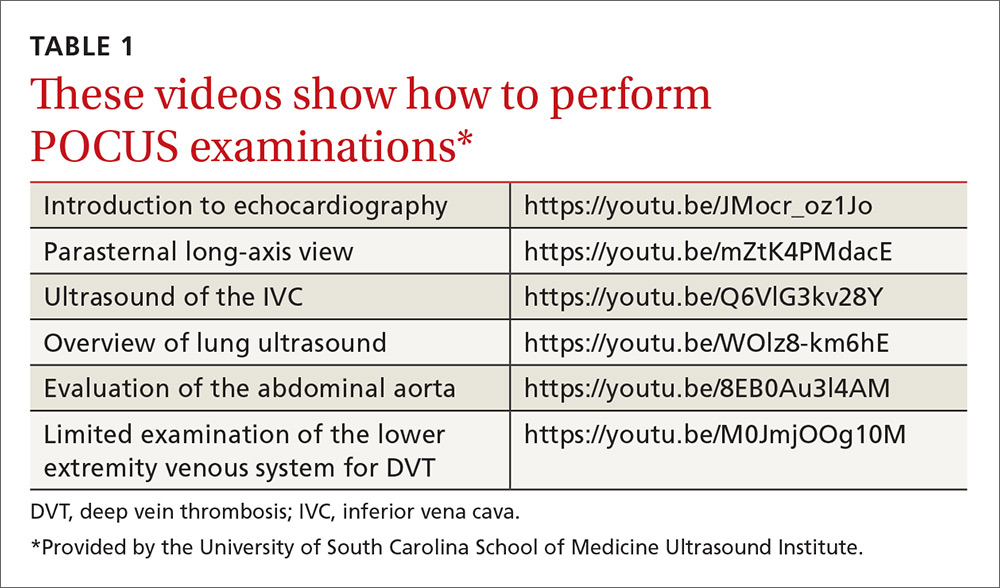

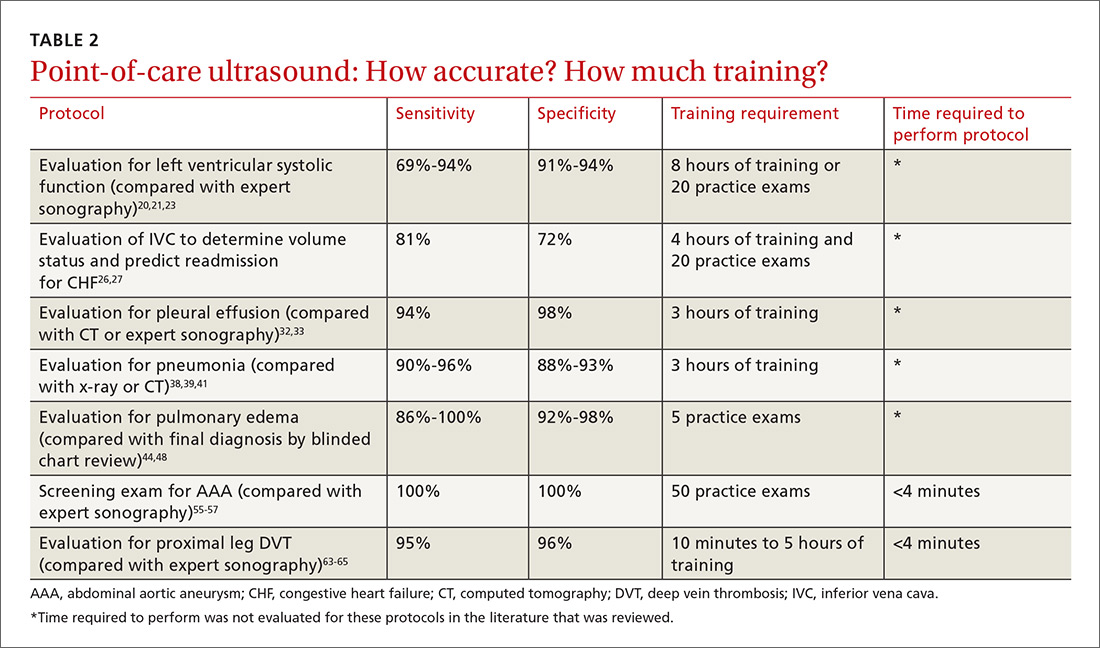

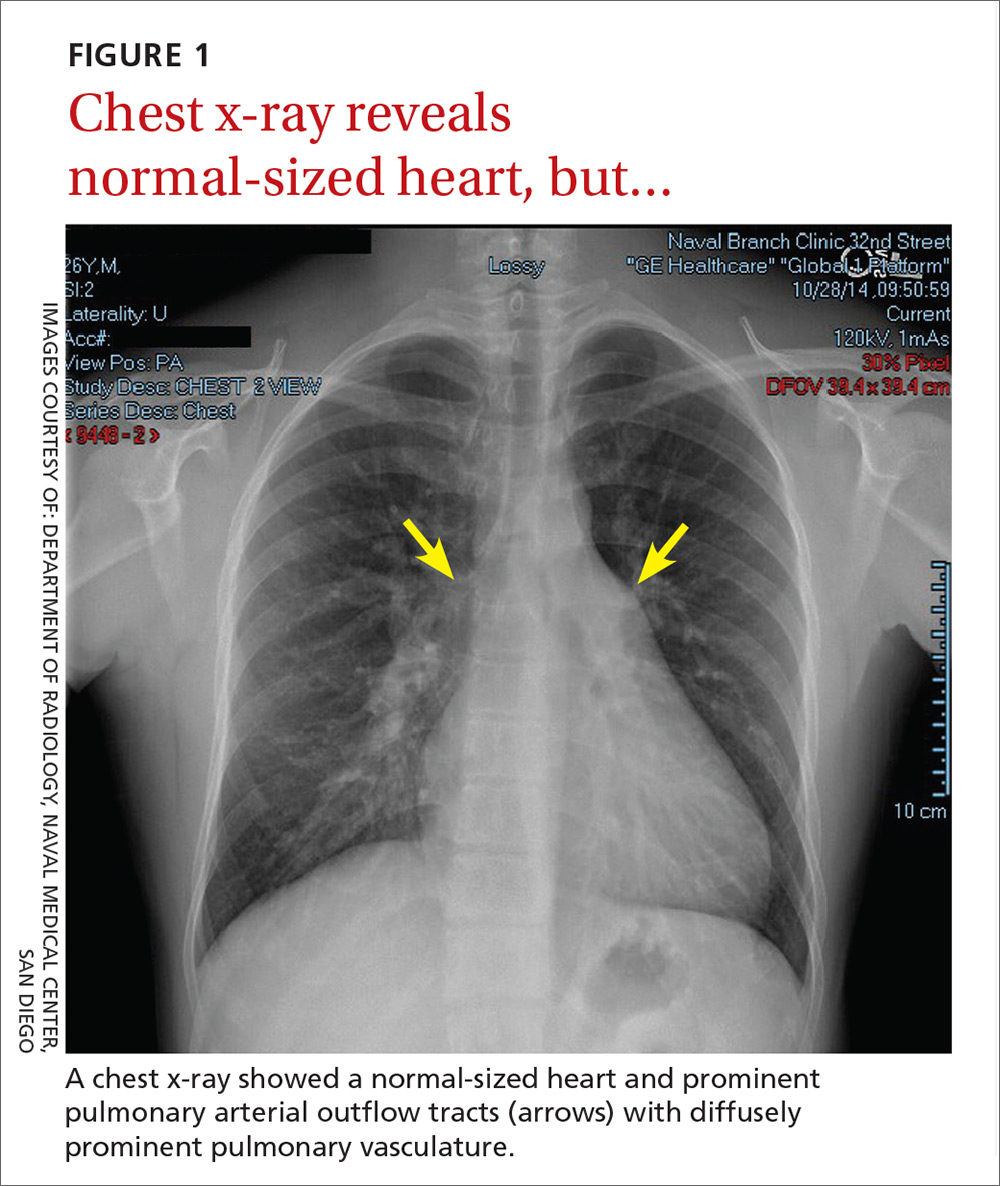

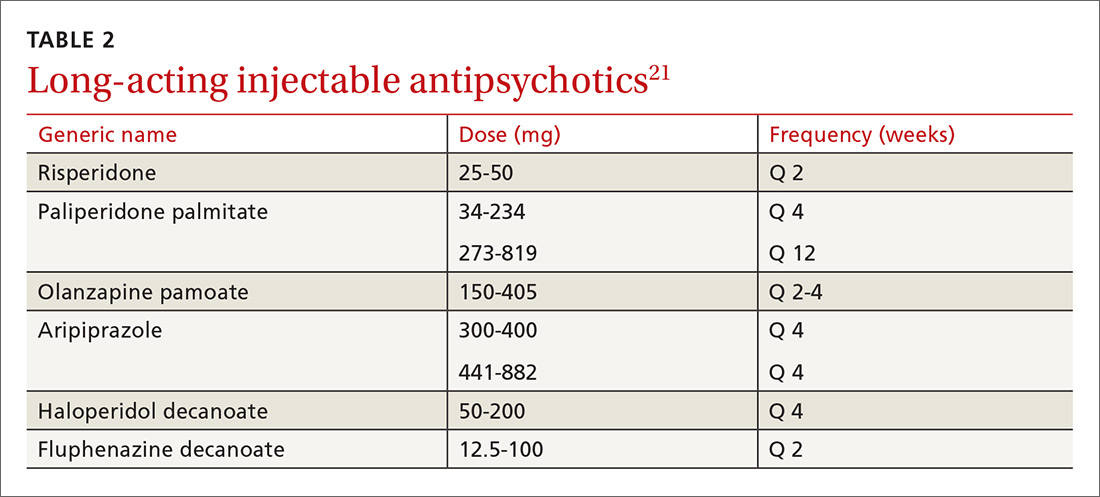

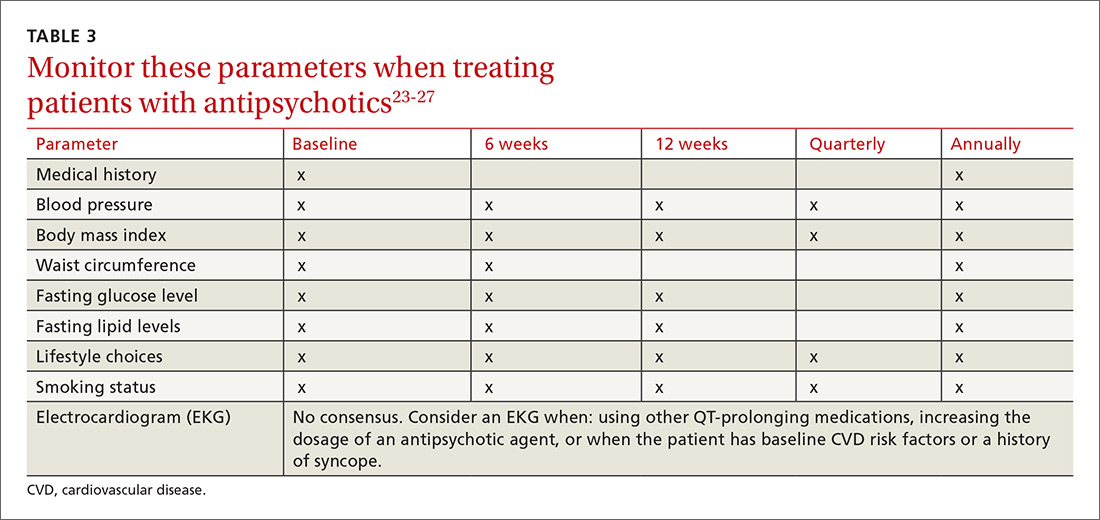

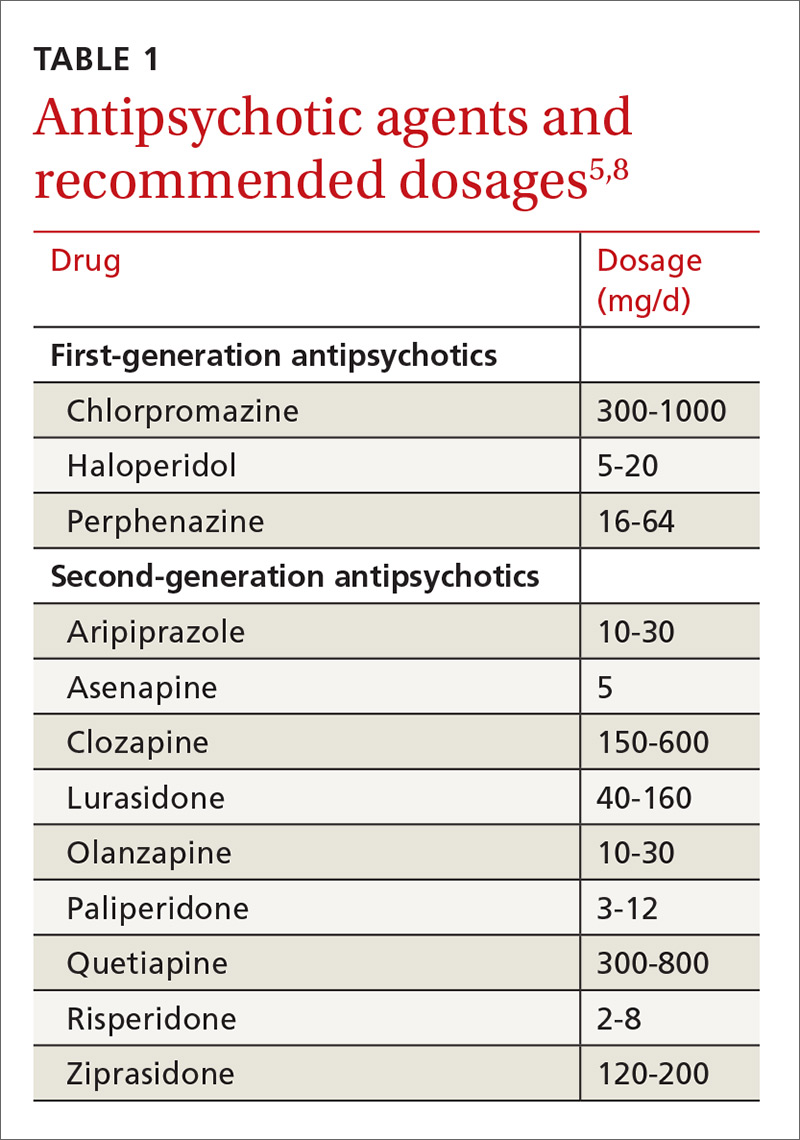

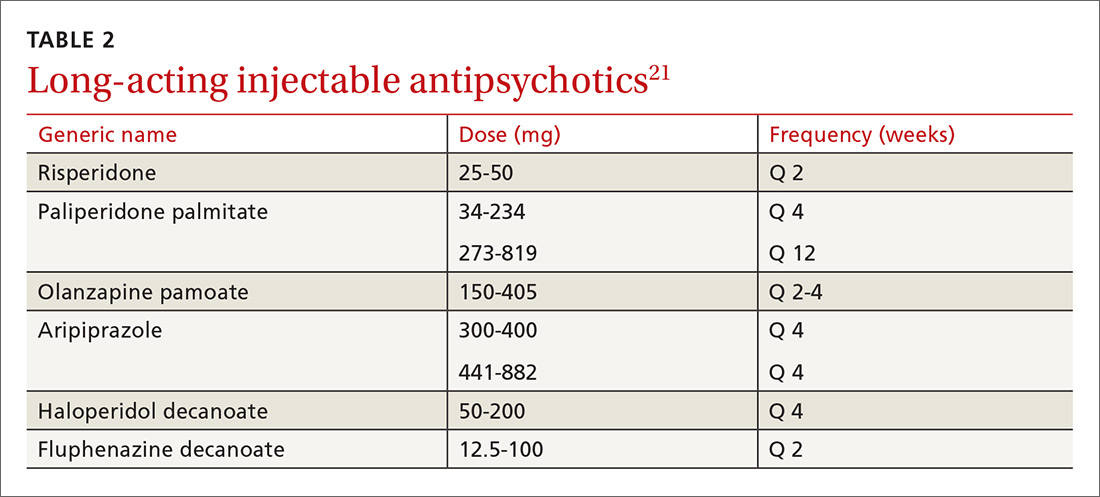

The potential applications of POCUS in family medicine are numerous and have been reviewed in several recent publications.12,13 In this article, we will review the evidence for the use of POCUS in 4 areas: the cardiovascular exam (FIGURES 1 and 2), the lung exam (FIGURES 3-6), the screening exam for AAAs (FIGURE 7), and the evaluation for DVT (FIGURES 8 and 9). (Obstetric and musculoskeletal applications have been sufficiently covered elsewhere.14-17) For all of these applications, POCUS is safe, accurate, and beneficial and can be performed with a relatively small amount of training by non-radiology specialists, including FPs (TABLEs 1 and 2).

Just 2 hours of cardio POCUS training enhanced Dx accuracy

The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) issued an expert consensus statement for focused cardiac ultrasound in 2013.18 The guideline supports non-cardiologists utilizing POCUS to assess for pericardial effusion and right and left ventricular enlargement, as well as to review global cardiac systolic function and intravascular volume status. Cardiovascular POCUS protocols are relatively easy to learn; even small amounts of training and practice can yield competency.

For example, a 2013 study showed that after 2 hours of training with a pocket ultrasound device, medical students and junior physicians inexperienced with POCUS were able to improve their diagnostic accuracy for heart failure from 50% to 75%.19 In another study, internal medicine residents with limited cardiac ultrasound training (ie, 20 practice exams) were able to detect decreased left ventricular ejection fraction using a handheld ultrasound device with 94% sensitivity and specificity in patients admitted to the hospital with acute decompensated heart failure.20 Similarly, after only 8 hours of training, a group of Norwegian general practitioners were able to obtain measurements of systolic function with a pocket ultrasound device that were not statistically different from a cardiologist’s measurements.21

In another study, rural FPs attended a 4-day course and then performed focused cardiac ultrasounds on primary care patients with a clinical indication for an echocardiogram.22 The scans were uploaded to a Web-based program for remote interpretation by a cardiologist. There was high concordance between the FPs’ interpretations of the focused cardiac ultrasounds and the cardiologist’s interpretations. Only 32% of the patients in the study group required a formal follow-up echocardiogram.

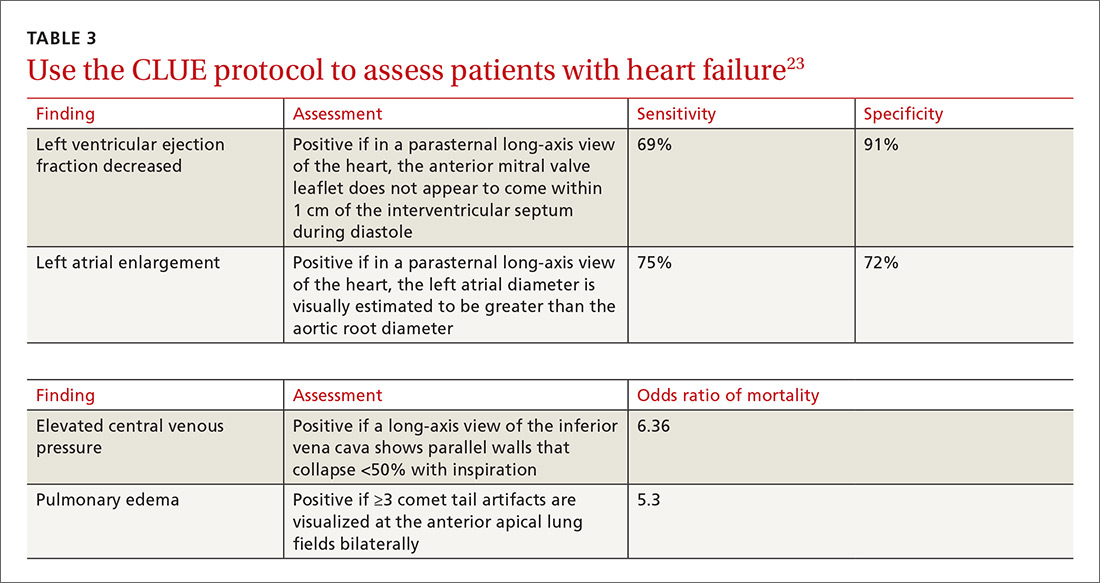

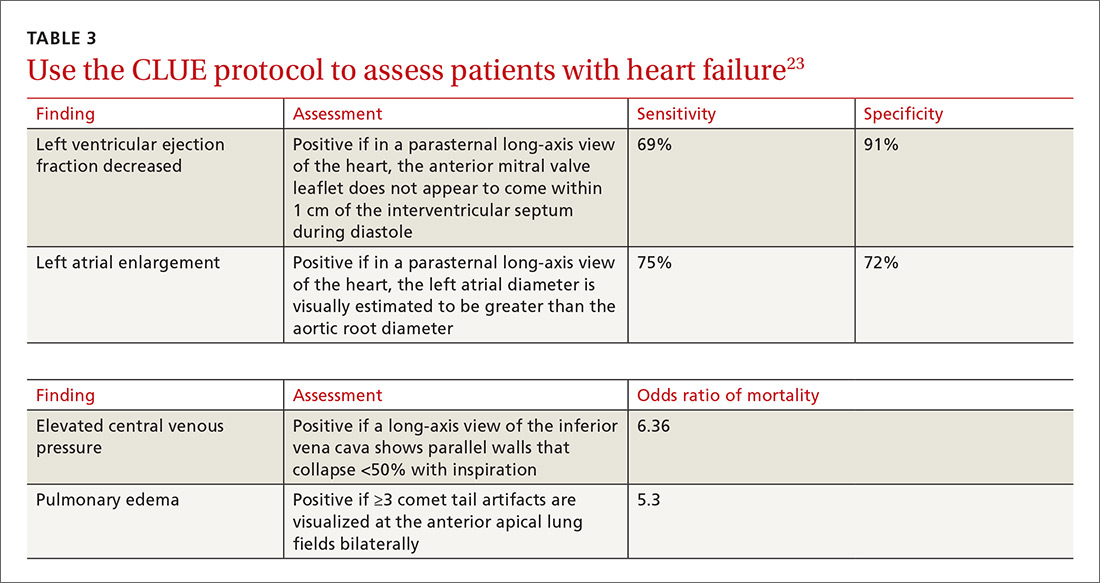

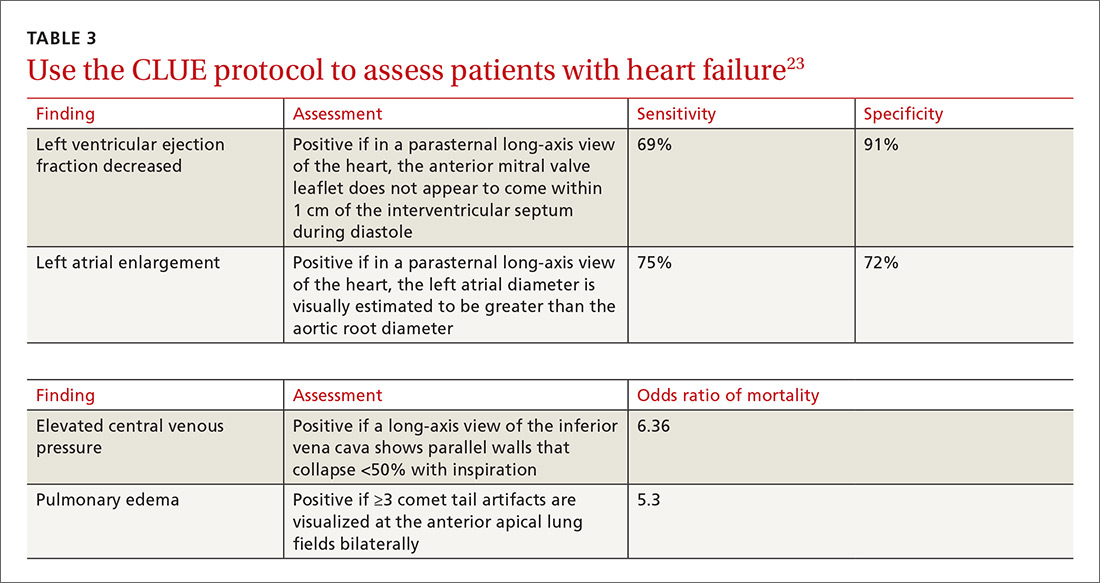

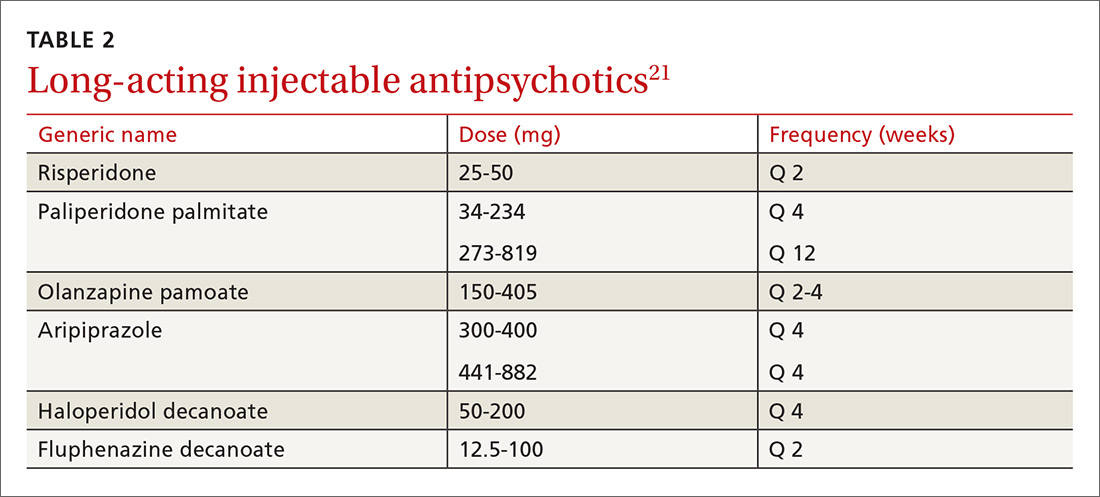

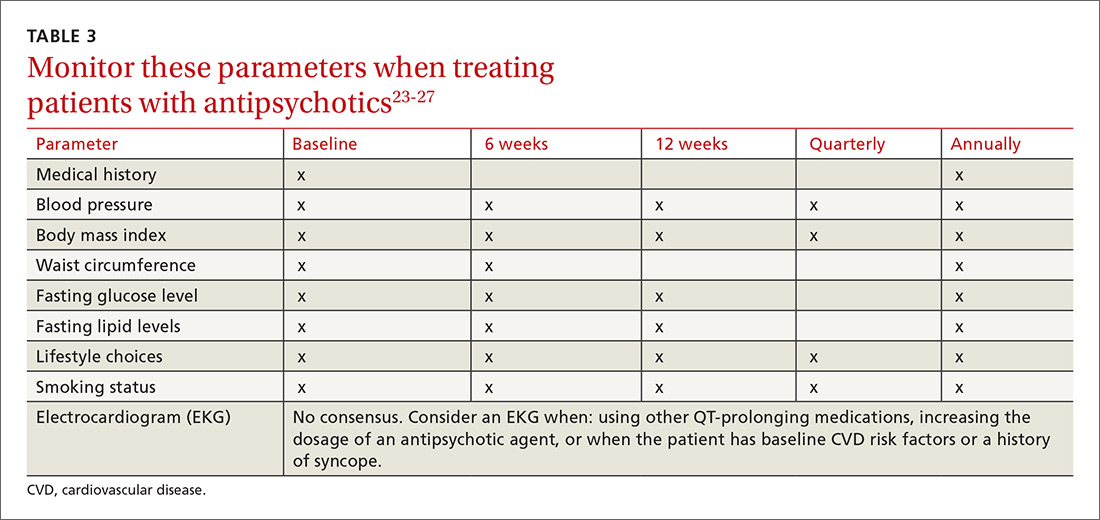

Kimura et al published a POCUS protocol for the rapid assessment of patients with heart failure, called the Cardiopulmonary Limited Ultrasound Exam (CLUE).23 The CLUE protocol utilizes 4 views to assess left ventricular systolic and diastolic function along with signs of pulmonary edema or systemic volume overload (TABLE 323). The presence of pulmonary edema or a plethoric inferior vena cava (IVC) was highly prognostic of in-hospital mortality. The CLUE protocol has been successfully used by novices including internal medicine residents after brief training (ie, up to 60 supervised scans) and can be performed in less than 5 minutes.24,25

Inpatient use. In addition to its use as an outpatient diagnostic tool, POCUS may be able to help guide therapy in patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure. Increasing collapse of the IVC directly correlates with the amount of fluid volume removed during hemodialysis.26 Goonewardena et al showed that IVC collapsibility was an independent predictor of 30-day hospital readmission even when demographics, signs and symptoms, and volume of diuresis were otherwise equal.27 However, whether the use of IVC collapsibility to guide management improves outcomes in heart failure remains to be validated in a prospective trial.

More sensitive, specific than x-rays for pulmonary diagnoses

The chest x-ray has traditionally been the imaging modality of choice to evaluate primary care pulmonary complaints. However, POCUS can be more sensitive and specific than a chest x-ray for evaluating several pulmonary diagnoses including pleural effusion, pneumonia, and pulmonary edema.

Pleural effusion can be difficult to detect with a physical exam alone. A systematic review showed that the physical exam is not sensitive for effusions <300 mL and can have even lower utility in obese patients.28 While an upright lateral chest x-ray can accurately detect effusions as small as 50 mL, portable x-rays have sensitivities of only 53% to 71% for small- or moderate-sized effusions.29,30 Ultrasound, however, has a sensitivity of 97% for small effusions.31

A 2016 meta-analysis showed that POCUS had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 98%, respectively, for pleural effusions, while chest x-ray had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 51% and 91%, respectively, when compared with computed tomography (CT) and expert sonography.32 POCUS evaluation for pleural effusion is technically simple, and at least one study showed that even novice users can achieve high diagnostic accuracy after only 3 hours of training.33

Pneumonia is the eighth leading cause of death in the United States and the single leading cause of infectious disease death in children worldwide.34-36 Pneumonia is a difficult diagnosis to make based on a history and physical examination alone, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends diagnostic imaging to make the diagnosis.37

The adult and pediatric literature clearly demonstrate that lung ultrasound is accurate at diagnosing pneumonia. In a 2015 meta-analysis of the pediatric literature, lung ultrasound had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 93% and positive and negative likelihood ratios of 15.3 and 0.06, respectively.38 In adults, a 2016 meta-analysis of lung ultrasound showed a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 88%, respectively, with positive and negative likelihood ratios of 6.6 and 0.08, respectively.39

In 2015, a prospective study compared the accuracy of lung ultrasound and chest x-ray using CT as the gold standard.40 Lung ultrasound had a significantly better sensitivity of 82% compared to a sensitivity of 64% for chest x-ray. Specificities were comparable at 94% for ultrasound and 90% for chest x-ray.40

At least one study found novice sonographers to be accurate with lung POCUS for the diagnosis of pneumonia after only two 90-minute training sessions.41 Moreover, ultrasound has a more favorable safety profile, greater portability, and lower cost compared with chest x-ray and CT.

Pulmonary edema. Lung ultrasound can identify interstitial pulmonary edema via artifacts called B lines, which are produced by the reverberation of sound waves from the pleura due to the widening of the fluid-filled interlobular septa. These are distinctly different from the A-line pattern of repeating horizontal lines that is seen with normal lungs, making lung ultrasound more accurate than chest x-ray for identification of pulmonary edema.42,43 When final diagnosis via blinded chart review is used as the reference standard, bilateral B lines on a lung ultrasound image have a sensitivity of 86% to 100% and a specificity of 92% to 98% for the diagnosis of pulmonary edema compared to chest x-ray’s sensitivity of 56.9% and specificity of 89.2%.44 There is also a linear correlation between the number of B lines present and the extent of pulmonary edema.42,45,46 The number of B lines decreases in real time as volume is removed in dialysis patients.47

POCUS evaluation for B lines can be learned very quickly. Exams of novices who have performed only 5 prior exams correlate highly with those of experts who have performed more than 100 exams.48

Simple, efficient screening method for abdominal aortic aneurysm

AAAs are present in up to 7% of men over the age of 50.49 The mortality rate of a ruptured AAA is as high as 80% to 95%.50 There is, however, a long prodromal period when interventions can make a significant difference, which is why accurate screening is so important.

AAA screening with ultrasound has been shown to decrease mortality.51 The current recommendation of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is a one-time AAA screening for all men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked (Grade B).52 Despite the recommendations of the USPSTF, screening rates are low. One study found that only 9% of eligible patients in primary care practices received appropriate screening.51

Ultrasound performed by specialists is known to be an excellent screening test for AAA with a sensitivity of 98.9% and a specificity of 99.9%.53 POCUS use by emergency medicine physicians for the evaluation of symptomatic AAA is well established in the literature. A meta-analysis including 7 studies and 655 patients showed a pooled sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 98%.54 Multiple studies also support primary care physicians performing POCUS AAA screening in the clinic setting.

For example, a 2012 prospective, observational study performed in Canada compared office-based ultrasound screening exams performed by a rural FP to scans performed in the hospital on the same patients.55 The physician completed 50 training examinations. The average discrepancy in aorta diameters between the 2 was only 2 mm, which is clinically insignificant, and the office-based scans had a sensitivity and specificity of 100%.

Similarly, a second FP study performed in Barcelona, showed that an FP who performed POCUS AAA screening had 100% concordance with a radiologist.56 Additionally, POCUS screening for AAA was not time consuming; it was performed in under 4 minutes per patient.55,57

Ruling out DVT

DVT is a relatively rare occurrence in the ambulatory setting. However, patients who present with a painful, swollen lower extremity are much more common, and DVT must be considered and ruled out in these situations.

Although isolated distal DVTs that occur in the calf veins are usually self-limited and have a very low risk of embolization, they can progress to proximal DVTs of the thigh veins up to 20% of time.58,59 Similarly, thrombophlebitis of the superficial lower extremity veins rarely embolizes, but can progress to a proximal DVT, especially if large segments are involved or if the segments are within 5 cm of the junction to the deep venous system.59 The risk of missing a proximal leg DVT is high because embolization occurs up to 60% of the time if the DVT is left untreated.60

The current standard for diagnosis of DVT is the lower extremity Doppler ultrasound examination, but obtaining same-day Doppler evaluations can be difficult in the ambulatory setting. In these instances, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that even low-risk patients receive anticoagulation pending the evaluation if it cannot be obtained in the first 24 hours.59 This approach not only increases the cost of care, but also exposes patients—many of whom will not be diagnosed with thrombosis in the end—to the risks of anticoagulation.

D-dimer blood tests have drawbacks, too. While a negative high-sensitivity D-dimer blood test in a patient with a low pre-test probability of DVT can effectively rule out a DVT, laboratory testing is not always immediately available in the ambulatory setting either.61 Additionally, false-positive rates are high, and positive D-dimer exams still require evaluation by Doppler ultrasound.

Given these limitations, performing an ultrasound at the bedside or in the exam room can allow for more timely and cost-effective care. In fact, research shows that a limited ultrasound, called the 2-region compression exam, which follows along the course of the common femoral vein and popliteal vein only, ignoring the femoral and calf veins, is highly accurate in assessing for proximal leg DVTs. As such, it has been adopted for POCUS use by emergency medicine physicians.62

Multiple studies show that physicians with minimal training can perform the 2-region compression exam with a high degree of accuracy when full-leg Doppler ultrasound was used as the gold standard.63,64 In these studies, hands-on training times ranged from only 10 minutes to 5 hours, and the exam could be performed in less than 4 minutes. A systematic review of 6 studies comparing emergency physician-performed ultrasound with radiology-performed ultrasound calculated an overall sensitivity of 0.95 (95% CI, 0.87-0.99) and specificity of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.87-0.99) for those performed by emergency physicians.65

The main concern with the 2-region compression exam is that it can miss a distal leg DVT. As stated earlier, distal DVTs are relatively benign and tend to resolve without treatment; however, up to 20% can progress to become a dangerous proximal leg DVT.58 Researchers have validated several methods by prospective trials to address this limitation.

Specifically, researchers have demonstrated that patients with a low pre-test probability of DVT per the Wells scoring system could have DVT effectively ruled out with a single 2-region compression ultrasound without further evaluation.66 In another study, researchers evaluated all patients (regardless of pretest probability) with a 2-point compression exam and found that those with negative exams could be followed with a second exam in 7 to 10 days without initiating anticoagulation. If the second one was negative, no further evaluation was needed.67,68

And finally, researchers demonstrated that a negative 2-point compression ultrasound in combination with a concurrent negative D-dimer test was effective at ruling out DVT, regardless of pre-test probability.69,70

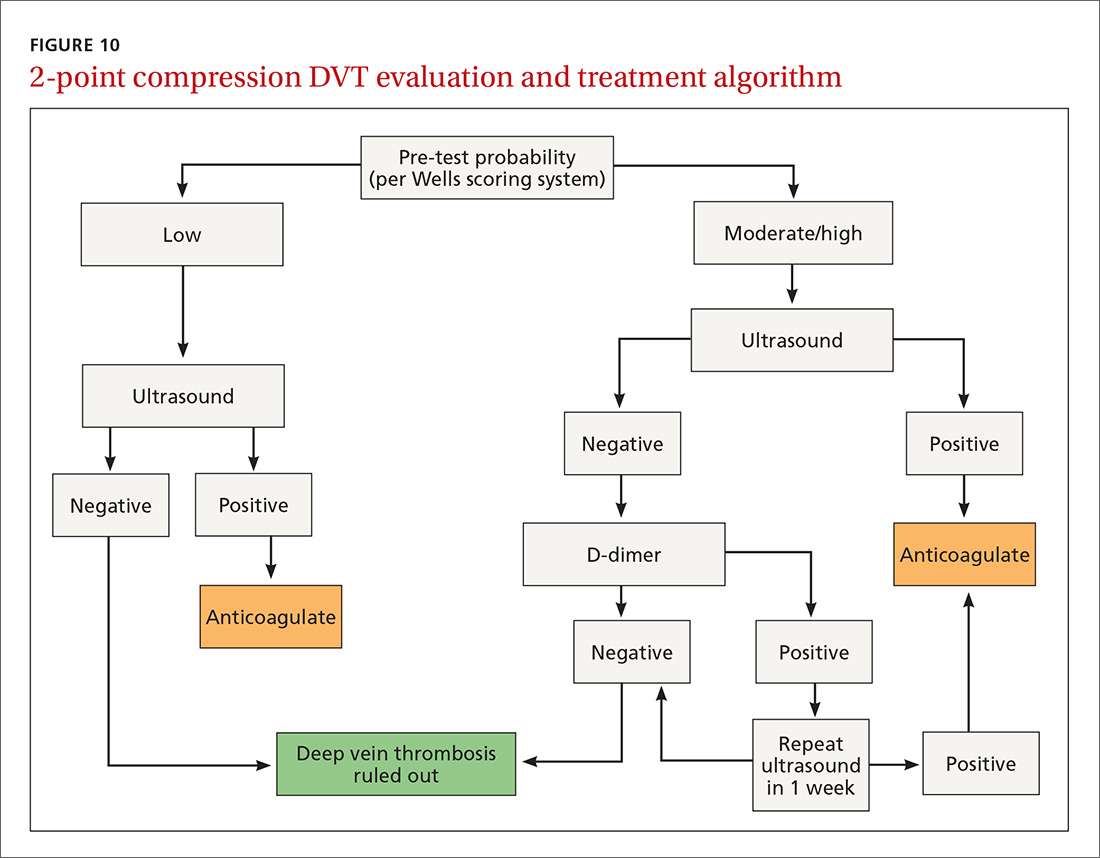

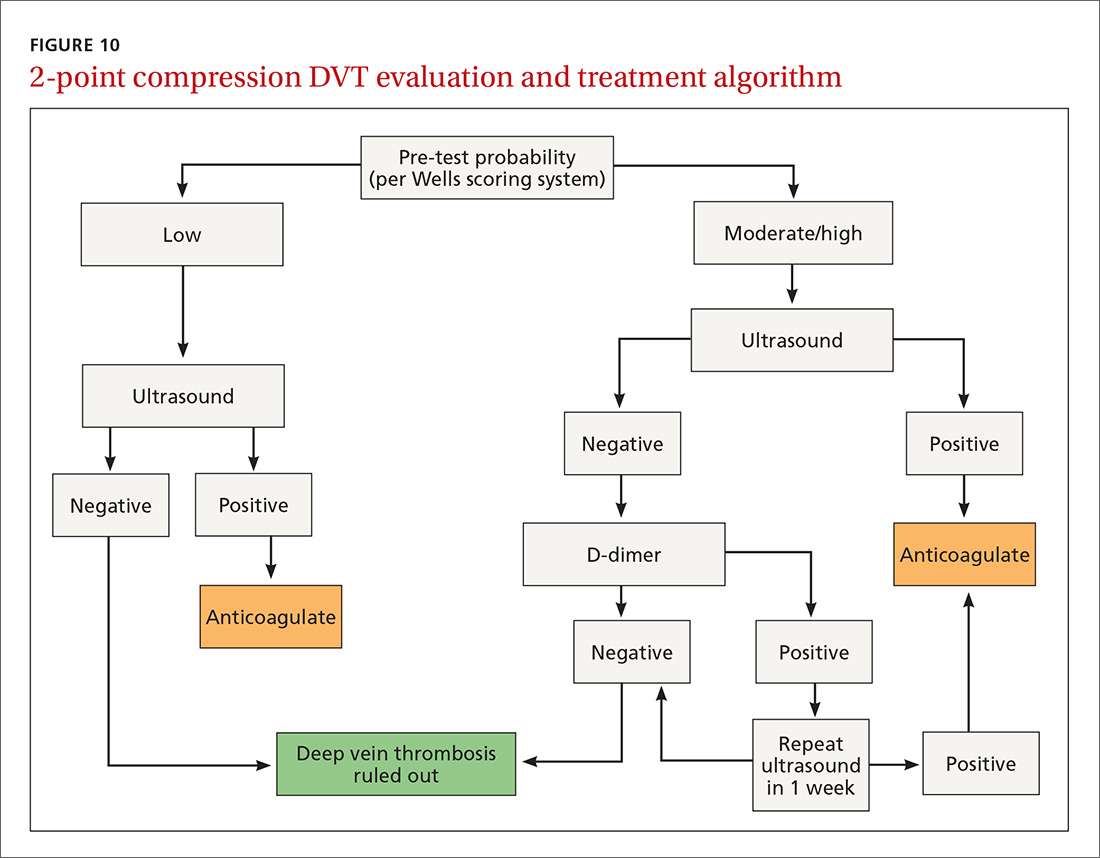

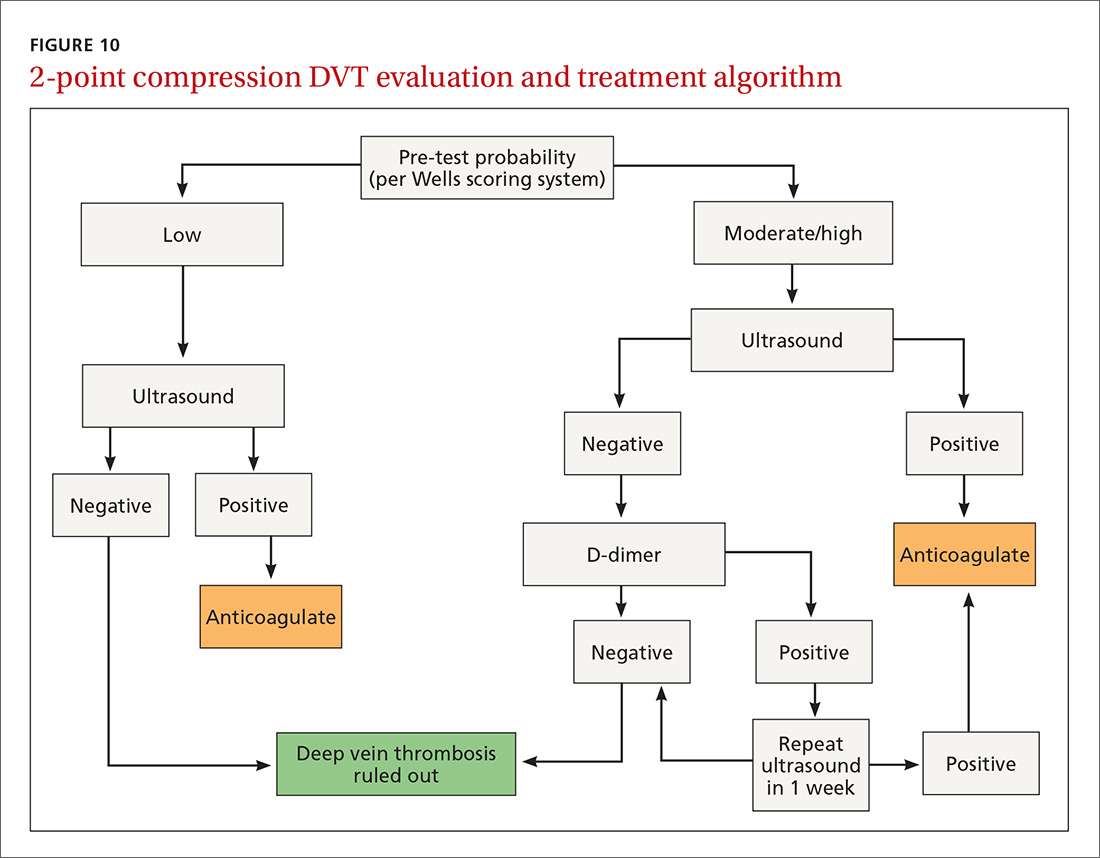

A preferred approach

Given this data and the fact that in the ambulatory setting it is often easier and faster to perform a 2-region compression examination than to obtain a D-dimer laboratory test or a formal full-leg Doppler ultrasound, what follows is our preferred approach to a patient with suspected DVT in the outpatient setting (FIGURE 10).

We first assess pre-test probability using the Wells scoring system. We then perform the 2-region compression ultrasound. If the patient has low pre-test risk according to the Wells score, we rule out DVT. If the patient has moderate or high risk with a negative 2-region compression ultrasound, the patient gets a D-dimer test. If the D-dimer test is negative, we rule out DVT. If the D-dimer test is positive, we schedule the patient for a repeat 2-region compression ultrasound in 7 to 10 days. If at any time the 2-region compression evaluation is positive, we treat the patient for DVT.

CORRESPONDENCE

Paul Bornemann, MD, Palmetto Health Family Medicine Residency, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 3209 Colonial Drive, Columbia, SC 29203; [email protected].

1. Hahn RG, Davies TC, Rodney WM. Diagnostic ultrasound in general practice. Fam Pract. 1988;5:129-135.

2. Deutchman ME, Hahn RG, Rodney WMM. Diagnostic ultrasound imaging by physicians of first contact: extending the family medicine experience into emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:594-596.

3. Bornemann P, Bornemann G. Military family physicians’ perceptions of a pocket point-of-care ultrasound device in clinical practice. Mil Med. 2014;179:1474-1477.

4. Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, et al. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1100-1110.

5. Parker L, Nazarian LN, Carrino JA, et al. Musculoskeletal imaging: medicare use, costs, and potential for cost substitution. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5:182-188.

6. Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, et al. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:332-339.

7. Calvert N, Hind D, McWilliams RG, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ultrasound locating devices for central venous access: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:1-84.

8. Hoppmann RA, Rao VV, Bell F, et al. The evolution of an integrated ultrasound curriculum (iUSC) for medical students: 9-year experience. Crit Ultrasound J. 2015;7:18.

9. Clinical procedures performed by physicians at their practice. American Academy of Family Physicians Member Census, December 31, 2016. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/about/the-aafp/family-medicine-facts/table-12(rev).html. Accessed June 26, 2017.

10. Hall JW, Holman H, Bornemann P, et al. Point of care ultrasound in family medicine residency programs: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2015;47:706-711.

11. Bornemann P. Assessment of a novel point-of-care ultrasound curriculum’s effect on competency measures in family medicine graduate medical education. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:1205-1211.

12. Steinmetz P, Oleskevich S. The benefits of doing ultrasound exams in your office. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:517-523.

13. Flick D. Bedside ultrasound education in family medicine. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:1369-1371.

14. Dresang LT, Rodney WM, Rodney KM. Prenatal ultrasound: a tale of two cities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:167-171.

15. Dresang LT, Rodney WM, Dees J. Teaching prenatal ultrasound to family medicine residents. Fam Med. 2004;36:98-107.

16. Rodney WM, Deutchman ME, Hartman KJ, et al. Obstetric ultrasound by family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1992;34:186-194.

17. Broadhurst NA, Simmons N. Musculoskeletal ultrasound - used to best advantage. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36:430-432.

18. Spencer KT, Kimura BJ, Korcarz CE, et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:567-581.

19. Panoulas VF, Daigeler AL, Malaweera AS, et al. Pocket-size hand-held cardiac ultrasound as an adjunct to clinical examination in the hands of medical students and junior doctors. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14:323-330.

20. Razi R, Estrada JR, Doll J, et al. Bedside hand-carried ultrasound by internal medicine residents versus traditional clinical assessment for the identification of systolic dysfunction in patients admitted with decompensated heart failure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:1319-1324.

21. Mjølstad OC, Snare SR, Folkvord L, et al. Assessment of left ventricular function by GPs using pocket-sized ultrasound. Fam Pract. 2012;29:534-540.

22. Evangelista A, Galuppo V, Méndez J, et al. Hand-held cardiac ultrasound screening performed by family doctors with remote expert support interpretation. Heart. 2016;102:376-382.

23. Kimura BJ, Yogo N, O’Connell CW, et al. Cardiopulmonary limited ultrasound examination for “quick-look” bedside application. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:586-590.

24. Kimura BJ, Amundson SA, Phan JN, et al. Observations during development of an internal medicine residency training program in cardiovascular limited ultrasound examination. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:537-542.

25. Kimura BJ, Shaw DJ, Amundson SA, et al. Cardiac limited ultrasound examination techniques to augment the bedside cardiac physical examination. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:1683-1690.

26. Brennan JM, Ronan A, Goonewardena S, et al. Handcarried ultrasound measurement of the inferior vena cava for assessment of intravascular volume status in the outpatient hemodialysis clinic. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:749-753.

27. Goonewardena SN, Gemignani A, Ronan A, et al. Comparison of hand-carried ultrasound assessment of the inferior vena cava and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide for predicting readmission after hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:595-601.

28. Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Straus SE. Does this patient have a pleural effusion? JAMA. 2009;301:309-317.

29. Blackmore CC, Black WC, Dallas RV, et al. Pleural fluid volume estimation: a chest radiograph prediction rule. Acad Radiol. 1996;3:103-109.

30. Kitazono MT, Lau CT, Parada AN, et al. Differentiation of pleural effusions from parenchymal opacities: accuracy of bedside chest radiography. Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:407-412.

31. Kalokairinou-Motogna M, Maratou K, Paianid I, et al. Application of color Doppler ultrasound in the study of small pleural effusion. Med Ultrason. 2010;12:12-16.

32. Yousefifard M, Baikpour M, Ghelichkhani P, et al. Screening performance characteristic of ultrasonography and radiography in detection of pleural effusion; a meta-analysis. Emerg (Tehran, Iran). 2016;4:1-10.

33. Begot E, Grumann A, Duvoid T, et al. Ultrasonographic identification and semiquantitative assessment of unloculated pleural effusions in critically ill patients by residents after a focused training. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1475-1480.

34. World Health Organization. Pneumonia. Fact Sheet No. 331. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs331/en/. Accessed June 26, 2017.

35. Gereige RS, Laufer PM. Pneumonia. Pediatr Rev. 2013;34:438-456.

36. National Center for Health Statistics. Leading causes of death. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm. Accessed July 2, 2017.

37. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-S72.

38. Pereda MA, Chavez MA, Hooper-Miele CC, et al. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135:714-722.

39. Xia Y, Ying Y, Wang S, et al. Effectiveness of lung ultrasonography for diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:2822-2831.

40. Nazerian P, Volpicelli G, Vanni S, et al. Accuracy of lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of consolidations when compared to chest computed tomography. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:620-625.

41. Filopei J, Siedenburg H, Rattner P, et al. Impact of pocket ultrasound use by internal medicine housestaff in the diagnosis of dyspnea. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:594-597.

42. Lichtenstein D, Mezière G. A lung ultrasound sign allowing bedside distinction between pulmonary edema and COPD: the comet-tail artifact. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:1331-1334.

43. Gargani L, Volpicelli G. How I do it: lung ultrasound. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014;12:25.

44. Martindale JL, Wakai A, Collins SP, et al. Diagnosing acute heart failure in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:223-242.

45. Volpicelli G, Mussa A, Garofalo G, et al. Bedside lung ultrasound in the assessment of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:689-696.

46. Picano E, Frassi F, Agricola E, et al. Ultrasound lung comets: a clinically useful sign of extravascular lung water. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:356-363.

47. Noble VE, Murray AF, Capp R, et al. Ultrasound assessment for extravascular lung water in patients undergoing hemodialysis: time course for resolution. Chest. 2009;135:1433-1439.

48. Gullett J, Donnelly JP, Sinert R, et al. Interobserver agreement in the evaluation of B-lines using bedside ultrasound. J Crit Care. 2015;30:1395-1399.

49. Guirguis-Blake JM, Beil TL, Sun X, et al. Primary Care Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Syntheses No. 109. Rockville, MD; 2014.

50. Metcalfe D, Holt PJE, Thompson MM. The management of abdominal aortic aneurysms. BMJ. 2011;342:d1384.

51. Thompson SG, Ashton HA, Gao L, et al. Final follow-up of the Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) randomized trial of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening. Brit J Surg. 2012;99:1649-1656.

52. LeFevre ML. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:281-290.

53. Lindholt JS, Vammen S, Juul S, et al. The validity of ultrasonographic scanning as screening method for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;17:472-475.

54. Rubano E, Mehta N, Caputo W, et al. Systematic review: emergency department bedside ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:128-138.

55. Blois B. Office-based ultrasound screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e172-e178.

56. Sisó-Almirall A, Gilabert Solé R, Bru Saumell C, et al. Feasibility of hand-held-ultrasonography in the screening of abdominal aortic aneurysms and abdominal aortic atherosclerosis. Med Clin (Barc). 2013;141:417-422.

57. Sisó-Almirall A, Kostov B, Navarro González M, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening program using hand-held ultrasound in primary healthcare. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176877.

58. Philbrick JT, Becker DM. Calf deep venous thrombosis: a wolf in sheep’s clothing? Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2131-2138.

59. Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e351S-418S.

60. Cushman M, Tsai AW, White RH, et al. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in two cohorts: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Am J Med. 2004;117:19-25.

61. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1227-1235.

62. Lensing AW, Prandoni P, Brandjes D, et al. Detection of deep-vein thrombosis by real-time B-mode ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:342-345.

63. Crisp JG, Lovato LM, Jang TB. Compression ultrasonography of the lower extremity with portable vascular ultrasonography can accurately detect deep venous thrombosis in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:601-610.

64. Blaivas M, Lambert MJ, Harwood RA, et al. Lower-extremity doppler for deep venous thrombosis—can emergency physicians be accurate and fast? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:120-126.

65. Burnside PR, Brown MD, Kline JA. Systematic review of emergency physician-performed ultrasonography for lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:493-498.

66. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Bormanis J, et al. Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep-vein thrombosis in clinical management. Lancet. 1997;350:1795-1798.

67. Birdwell BG, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL, et al. The clinical validity of normal compression ultrasonography in outpatients suspected of having deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:1-7.

68. Cogo A, Lensing AW, Koopman MM, et al. Compression ultrasonography for diagnostic management of patients with clinically suspected deep vein thrombosis: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 1998;316:17-20.

69. Tick LW, Ton E, Van Voorthuizen T, et al. Practical diagnostic management of patients with clinically suspected deep vein thrombosis by clinical probability test, compression ultrasonography, and D-dimer test. Am J Med. 2002;113:630-635.

70. Stevens

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been gaining greater traction in recent years as a way to quickly (and cost-effectively) assess for conditions including systolic dysfunction, pleural effusion, abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs), and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). It involves limited and specific ultrasound protocols performed at the bedside by the health care provider who is trying to answer a specific question and, thus, help guide treatment of the patient.

POCUS was first widely used by emergency physicians starting in the early 1990s with the widespread adoption of the Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) scan.1,2 Since that time, POCUS has expanded beyond trauma applications and into family medicine.

One study assessed physicians’ perceptions of POCUS after its integration into a military family medicine clinic. The study showed that physicians perceived POCUS to be relatively easy to use, not overly time consuming, and of high value to the practice.3 In fact, the literature tells us that POCUS can help decrease the cost of health care and improve outcomes,4-7 while requiring a relatively brief training period.

If residencies are any indication, POCUS may be headed your way

Ultrasound units are becoming smaller and more affordable, and medical schools are increasingly incorporating ultrasound curricula into medical student training.8 As of 2016, only 6% of practicing FPs reported using non-obstetric POCUS in their practices.9 Similarly, a survey from 2015 reported that only 2% of family medicine residency programs had established POCUS curricula.10 However, 50% of respondents in the 2015 survey reported early-stage development or interest in developing a POCUS curriculum.

Since then a validated family medicine residency curriculum has been published,11 and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recently released a POCUS Curriculum Guideline for residencies (https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint290D_POCUS.pdf).

[polldaddy:9928416]

The potential applications of POCUS in family medicine are numerous and have been reviewed in several recent publications.12,13 In this article, we will review the evidence for the use of POCUS in 4 areas: the cardiovascular exam (FIGURES 1 and 2), the lung exam (FIGURES 3-6), the screening exam for AAAs (FIGURE 7), and the evaluation for DVT (FIGURES 8 and 9). (Obstetric and musculoskeletal applications have been sufficiently covered elsewhere.14-17) For all of these applications, POCUS is safe, accurate, and beneficial and can be performed with a relatively small amount of training by non-radiology specialists, including FPs (TABLEs 1 and 2).

Just 2 hours of cardio POCUS training enhanced Dx accuracy

The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) issued an expert consensus statement for focused cardiac ultrasound in 2013.18 The guideline supports non-cardiologists utilizing POCUS to assess for pericardial effusion and right and left ventricular enlargement, as well as to review global cardiac systolic function and intravascular volume status. Cardiovascular POCUS protocols are relatively easy to learn; even small amounts of training and practice can yield competency.

For example, a 2013 study showed that after 2 hours of training with a pocket ultrasound device, medical students and junior physicians inexperienced with POCUS were able to improve their diagnostic accuracy for heart failure from 50% to 75%.19 In another study, internal medicine residents with limited cardiac ultrasound training (ie, 20 practice exams) were able to detect decreased left ventricular ejection fraction using a handheld ultrasound device with 94% sensitivity and specificity in patients admitted to the hospital with acute decompensated heart failure.20 Similarly, after only 8 hours of training, a group of Norwegian general practitioners were able to obtain measurements of systolic function with a pocket ultrasound device that were not statistically different from a cardiologist’s measurements.21

In another study, rural FPs attended a 4-day course and then performed focused cardiac ultrasounds on primary care patients with a clinical indication for an echocardiogram.22 The scans were uploaded to a Web-based program for remote interpretation by a cardiologist. There was high concordance between the FPs’ interpretations of the focused cardiac ultrasounds and the cardiologist’s interpretations. Only 32% of the patients in the study group required a formal follow-up echocardiogram.

Kimura et al published a POCUS protocol for the rapid assessment of patients with heart failure, called the Cardiopulmonary Limited Ultrasound Exam (CLUE).23 The CLUE protocol utilizes 4 views to assess left ventricular systolic and diastolic function along with signs of pulmonary edema or systemic volume overload (TABLE 323). The presence of pulmonary edema or a plethoric inferior vena cava (IVC) was highly prognostic of in-hospital mortality. The CLUE protocol has been successfully used by novices including internal medicine residents after brief training (ie, up to 60 supervised scans) and can be performed in less than 5 minutes.24,25

Inpatient use. In addition to its use as an outpatient diagnostic tool, POCUS may be able to help guide therapy in patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure. Increasing collapse of the IVC directly correlates with the amount of fluid volume removed during hemodialysis.26 Goonewardena et al showed that IVC collapsibility was an independent predictor of 30-day hospital readmission even when demographics, signs and symptoms, and volume of diuresis were otherwise equal.27 However, whether the use of IVC collapsibility to guide management improves outcomes in heart failure remains to be validated in a prospective trial.

More sensitive, specific than x-rays for pulmonary diagnoses

The chest x-ray has traditionally been the imaging modality of choice to evaluate primary care pulmonary complaints. However, POCUS can be more sensitive and specific than a chest x-ray for evaluating several pulmonary diagnoses including pleural effusion, pneumonia, and pulmonary edema.

Pleural effusion can be difficult to detect with a physical exam alone. A systematic review showed that the physical exam is not sensitive for effusions <300 mL and can have even lower utility in obese patients.28 While an upright lateral chest x-ray can accurately detect effusions as small as 50 mL, portable x-rays have sensitivities of only 53% to 71% for small- or moderate-sized effusions.29,30 Ultrasound, however, has a sensitivity of 97% for small effusions.31

A 2016 meta-analysis showed that POCUS had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 98%, respectively, for pleural effusions, while chest x-ray had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 51% and 91%, respectively, when compared with computed tomography (CT) and expert sonography.32 POCUS evaluation for pleural effusion is technically simple, and at least one study showed that even novice users can achieve high diagnostic accuracy after only 3 hours of training.33

Pneumonia is the eighth leading cause of death in the United States and the single leading cause of infectious disease death in children worldwide.34-36 Pneumonia is a difficult diagnosis to make based on a history and physical examination alone, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends diagnostic imaging to make the diagnosis.37

The adult and pediatric literature clearly demonstrate that lung ultrasound is accurate at diagnosing pneumonia. In a 2015 meta-analysis of the pediatric literature, lung ultrasound had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 93% and positive and negative likelihood ratios of 15.3 and 0.06, respectively.38 In adults, a 2016 meta-analysis of lung ultrasound showed a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 88%, respectively, with positive and negative likelihood ratios of 6.6 and 0.08, respectively.39

In 2015, a prospective study compared the accuracy of lung ultrasound and chest x-ray using CT as the gold standard.40 Lung ultrasound had a significantly better sensitivity of 82% compared to a sensitivity of 64% for chest x-ray. Specificities were comparable at 94% for ultrasound and 90% for chest x-ray.40

At least one study found novice sonographers to be accurate with lung POCUS for the diagnosis of pneumonia after only two 90-minute training sessions.41 Moreover, ultrasound has a more favorable safety profile, greater portability, and lower cost compared with chest x-ray and CT.

Pulmonary edema. Lung ultrasound can identify interstitial pulmonary edema via artifacts called B lines, which are produced by the reverberation of sound waves from the pleura due to the widening of the fluid-filled interlobular septa. These are distinctly different from the A-line pattern of repeating horizontal lines that is seen with normal lungs, making lung ultrasound more accurate than chest x-ray for identification of pulmonary edema.42,43 When final diagnosis via blinded chart review is used as the reference standard, bilateral B lines on a lung ultrasound image have a sensitivity of 86% to 100% and a specificity of 92% to 98% for the diagnosis of pulmonary edema compared to chest x-ray’s sensitivity of 56.9% and specificity of 89.2%.44 There is also a linear correlation between the number of B lines present and the extent of pulmonary edema.42,45,46 The number of B lines decreases in real time as volume is removed in dialysis patients.47

POCUS evaluation for B lines can be learned very quickly. Exams of novices who have performed only 5 prior exams correlate highly with those of experts who have performed more than 100 exams.48

Simple, efficient screening method for abdominal aortic aneurysm

AAAs are present in up to 7% of men over the age of 50.49 The mortality rate of a ruptured AAA is as high as 80% to 95%.50 There is, however, a long prodromal period when interventions can make a significant difference, which is why accurate screening is so important.

AAA screening with ultrasound has been shown to decrease mortality.51 The current recommendation of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is a one-time AAA screening for all men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked (Grade B).52 Despite the recommendations of the USPSTF, screening rates are low. One study found that only 9% of eligible patients in primary care practices received appropriate screening.51

Ultrasound performed by specialists is known to be an excellent screening test for AAA with a sensitivity of 98.9% and a specificity of 99.9%.53 POCUS use by emergency medicine physicians for the evaluation of symptomatic AAA is well established in the literature. A meta-analysis including 7 studies and 655 patients showed a pooled sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 98%.54 Multiple studies also support primary care physicians performing POCUS AAA screening in the clinic setting.

For example, a 2012 prospective, observational study performed in Canada compared office-based ultrasound screening exams performed by a rural FP to scans performed in the hospital on the same patients.55 The physician completed 50 training examinations. The average discrepancy in aorta diameters between the 2 was only 2 mm, which is clinically insignificant, and the office-based scans had a sensitivity and specificity of 100%.

Similarly, a second FP study performed in Barcelona, showed that an FP who performed POCUS AAA screening had 100% concordance with a radiologist.56 Additionally, POCUS screening for AAA was not time consuming; it was performed in under 4 minutes per patient.55,57

Ruling out DVT

DVT is a relatively rare occurrence in the ambulatory setting. However, patients who present with a painful, swollen lower extremity are much more common, and DVT must be considered and ruled out in these situations.

Although isolated distal DVTs that occur in the calf veins are usually self-limited and have a very low risk of embolization, they can progress to proximal DVTs of the thigh veins up to 20% of time.58,59 Similarly, thrombophlebitis of the superficial lower extremity veins rarely embolizes, but can progress to a proximal DVT, especially if large segments are involved or if the segments are within 5 cm of the junction to the deep venous system.59 The risk of missing a proximal leg DVT is high because embolization occurs up to 60% of the time if the DVT is left untreated.60

The current standard for diagnosis of DVT is the lower extremity Doppler ultrasound examination, but obtaining same-day Doppler evaluations can be difficult in the ambulatory setting. In these instances, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that even low-risk patients receive anticoagulation pending the evaluation if it cannot be obtained in the first 24 hours.59 This approach not only increases the cost of care, but also exposes patients—many of whom will not be diagnosed with thrombosis in the end—to the risks of anticoagulation.

D-dimer blood tests have drawbacks, too. While a negative high-sensitivity D-dimer blood test in a patient with a low pre-test probability of DVT can effectively rule out a DVT, laboratory testing is not always immediately available in the ambulatory setting either.61 Additionally, false-positive rates are high, and positive D-dimer exams still require evaluation by Doppler ultrasound.

Given these limitations, performing an ultrasound at the bedside or in the exam room can allow for more timely and cost-effective care. In fact, research shows that a limited ultrasound, called the 2-region compression exam, which follows along the course of the common femoral vein and popliteal vein only, ignoring the femoral and calf veins, is highly accurate in assessing for proximal leg DVTs. As such, it has been adopted for POCUS use by emergency medicine physicians.62

Multiple studies show that physicians with minimal training can perform the 2-region compression exam with a high degree of accuracy when full-leg Doppler ultrasound was used as the gold standard.63,64 In these studies, hands-on training times ranged from only 10 minutes to 5 hours, and the exam could be performed in less than 4 minutes. A systematic review of 6 studies comparing emergency physician-performed ultrasound with radiology-performed ultrasound calculated an overall sensitivity of 0.95 (95% CI, 0.87-0.99) and specificity of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.87-0.99) for those performed by emergency physicians.65

The main concern with the 2-region compression exam is that it can miss a distal leg DVT. As stated earlier, distal DVTs are relatively benign and tend to resolve without treatment; however, up to 20% can progress to become a dangerous proximal leg DVT.58 Researchers have validated several methods by prospective trials to address this limitation.

Specifically, researchers have demonstrated that patients with a low pre-test probability of DVT per the Wells scoring system could have DVT effectively ruled out with a single 2-region compression ultrasound without further evaluation.66 In another study, researchers evaluated all patients (regardless of pretest probability) with a 2-point compression exam and found that those with negative exams could be followed with a second exam in 7 to 10 days without initiating anticoagulation. If the second one was negative, no further evaluation was needed.67,68

And finally, researchers demonstrated that a negative 2-point compression ultrasound in combination with a concurrent negative D-dimer test was effective at ruling out DVT, regardless of pre-test probability.69,70

A preferred approach

Given this data and the fact that in the ambulatory setting it is often easier and faster to perform a 2-region compression examination than to obtain a D-dimer laboratory test or a formal full-leg Doppler ultrasound, what follows is our preferred approach to a patient with suspected DVT in the outpatient setting (FIGURE 10).

We first assess pre-test probability using the Wells scoring system. We then perform the 2-region compression ultrasound. If the patient has low pre-test risk according to the Wells score, we rule out DVT. If the patient has moderate or high risk with a negative 2-region compression ultrasound, the patient gets a D-dimer test. If the D-dimer test is negative, we rule out DVT. If the D-dimer test is positive, we schedule the patient for a repeat 2-region compression ultrasound in 7 to 10 days. If at any time the 2-region compression evaluation is positive, we treat the patient for DVT.

CORRESPONDENCE

Paul Bornemann, MD, Palmetto Health Family Medicine Residency, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 3209 Colonial Drive, Columbia, SC 29203; [email protected].

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been gaining greater traction in recent years as a way to quickly (and cost-effectively) assess for conditions including systolic dysfunction, pleural effusion, abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs), and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). It involves limited and specific ultrasound protocols performed at the bedside by the health care provider who is trying to answer a specific question and, thus, help guide treatment of the patient.

POCUS was first widely used by emergency physicians starting in the early 1990s with the widespread adoption of the Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) scan.1,2 Since that time, POCUS has expanded beyond trauma applications and into family medicine.

One study assessed physicians’ perceptions of POCUS after its integration into a military family medicine clinic. The study showed that physicians perceived POCUS to be relatively easy to use, not overly time consuming, and of high value to the practice.3 In fact, the literature tells us that POCUS can help decrease the cost of health care and improve outcomes,4-7 while requiring a relatively brief training period.

If residencies are any indication, POCUS may be headed your way

Ultrasound units are becoming smaller and more affordable, and medical schools are increasingly incorporating ultrasound curricula into medical student training.8 As of 2016, only 6% of practicing FPs reported using non-obstetric POCUS in their practices.9 Similarly, a survey from 2015 reported that only 2% of family medicine residency programs had established POCUS curricula.10 However, 50% of respondents in the 2015 survey reported early-stage development or interest in developing a POCUS curriculum.

Since then a validated family medicine residency curriculum has been published,11 and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recently released a POCUS Curriculum Guideline for residencies (https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint290D_POCUS.pdf).

[polldaddy:9928416]

The potential applications of POCUS in family medicine are numerous and have been reviewed in several recent publications.12,13 In this article, we will review the evidence for the use of POCUS in 4 areas: the cardiovascular exam (FIGURES 1 and 2), the lung exam (FIGURES 3-6), the screening exam for AAAs (FIGURE 7), and the evaluation for DVT (FIGURES 8 and 9). (Obstetric and musculoskeletal applications have been sufficiently covered elsewhere.14-17) For all of these applications, POCUS is safe, accurate, and beneficial and can be performed with a relatively small amount of training by non-radiology specialists, including FPs (TABLEs 1 and 2).

Just 2 hours of cardio POCUS training enhanced Dx accuracy

The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) issued an expert consensus statement for focused cardiac ultrasound in 2013.18 The guideline supports non-cardiologists utilizing POCUS to assess for pericardial effusion and right and left ventricular enlargement, as well as to review global cardiac systolic function and intravascular volume status. Cardiovascular POCUS protocols are relatively easy to learn; even small amounts of training and practice can yield competency.

For example, a 2013 study showed that after 2 hours of training with a pocket ultrasound device, medical students and junior physicians inexperienced with POCUS were able to improve their diagnostic accuracy for heart failure from 50% to 75%.19 In another study, internal medicine residents with limited cardiac ultrasound training (ie, 20 practice exams) were able to detect decreased left ventricular ejection fraction using a handheld ultrasound device with 94% sensitivity and specificity in patients admitted to the hospital with acute decompensated heart failure.20 Similarly, after only 8 hours of training, a group of Norwegian general practitioners were able to obtain measurements of systolic function with a pocket ultrasound device that were not statistically different from a cardiologist’s measurements.21

In another study, rural FPs attended a 4-day course and then performed focused cardiac ultrasounds on primary care patients with a clinical indication for an echocardiogram.22 The scans were uploaded to a Web-based program for remote interpretation by a cardiologist. There was high concordance between the FPs’ interpretations of the focused cardiac ultrasounds and the cardiologist’s interpretations. Only 32% of the patients in the study group required a formal follow-up echocardiogram.

Kimura et al published a POCUS protocol for the rapid assessment of patients with heart failure, called the Cardiopulmonary Limited Ultrasound Exam (CLUE).23 The CLUE protocol utilizes 4 views to assess left ventricular systolic and diastolic function along with signs of pulmonary edema or systemic volume overload (TABLE 323). The presence of pulmonary edema or a plethoric inferior vena cava (IVC) was highly prognostic of in-hospital mortality. The CLUE protocol has been successfully used by novices including internal medicine residents after brief training (ie, up to 60 supervised scans) and can be performed in less than 5 minutes.24,25

Inpatient use. In addition to its use as an outpatient diagnostic tool, POCUS may be able to help guide therapy in patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure. Increasing collapse of the IVC directly correlates with the amount of fluid volume removed during hemodialysis.26 Goonewardena et al showed that IVC collapsibility was an independent predictor of 30-day hospital readmission even when demographics, signs and symptoms, and volume of diuresis were otherwise equal.27 However, whether the use of IVC collapsibility to guide management improves outcomes in heart failure remains to be validated in a prospective trial.

More sensitive, specific than x-rays for pulmonary diagnoses

The chest x-ray has traditionally been the imaging modality of choice to evaluate primary care pulmonary complaints. However, POCUS can be more sensitive and specific than a chest x-ray for evaluating several pulmonary diagnoses including pleural effusion, pneumonia, and pulmonary edema.

Pleural effusion can be difficult to detect with a physical exam alone. A systematic review showed that the physical exam is not sensitive for effusions <300 mL and can have even lower utility in obese patients.28 While an upright lateral chest x-ray can accurately detect effusions as small as 50 mL, portable x-rays have sensitivities of only 53% to 71% for small- or moderate-sized effusions.29,30 Ultrasound, however, has a sensitivity of 97% for small effusions.31

A 2016 meta-analysis showed that POCUS had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 98%, respectively, for pleural effusions, while chest x-ray had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 51% and 91%, respectively, when compared with computed tomography (CT) and expert sonography.32 POCUS evaluation for pleural effusion is technically simple, and at least one study showed that even novice users can achieve high diagnostic accuracy after only 3 hours of training.33

Pneumonia is the eighth leading cause of death in the United States and the single leading cause of infectious disease death in children worldwide.34-36 Pneumonia is a difficult diagnosis to make based on a history and physical examination alone, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends diagnostic imaging to make the diagnosis.37

The adult and pediatric literature clearly demonstrate that lung ultrasound is accurate at diagnosing pneumonia. In a 2015 meta-analysis of the pediatric literature, lung ultrasound had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 93% and positive and negative likelihood ratios of 15.3 and 0.06, respectively.38 In adults, a 2016 meta-analysis of lung ultrasound showed a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 88%, respectively, with positive and negative likelihood ratios of 6.6 and 0.08, respectively.39

In 2015, a prospective study compared the accuracy of lung ultrasound and chest x-ray using CT as the gold standard.40 Lung ultrasound had a significantly better sensitivity of 82% compared to a sensitivity of 64% for chest x-ray. Specificities were comparable at 94% for ultrasound and 90% for chest x-ray.40

At least one study found novice sonographers to be accurate with lung POCUS for the diagnosis of pneumonia after only two 90-minute training sessions.41 Moreover, ultrasound has a more favorable safety profile, greater portability, and lower cost compared with chest x-ray and CT.

Pulmonary edema. Lung ultrasound can identify interstitial pulmonary edema via artifacts called B lines, which are produced by the reverberation of sound waves from the pleura due to the widening of the fluid-filled interlobular septa. These are distinctly different from the A-line pattern of repeating horizontal lines that is seen with normal lungs, making lung ultrasound more accurate than chest x-ray for identification of pulmonary edema.42,43 When final diagnosis via blinded chart review is used as the reference standard, bilateral B lines on a lung ultrasound image have a sensitivity of 86% to 100% and a specificity of 92% to 98% for the diagnosis of pulmonary edema compared to chest x-ray’s sensitivity of 56.9% and specificity of 89.2%.44 There is also a linear correlation between the number of B lines present and the extent of pulmonary edema.42,45,46 The number of B lines decreases in real time as volume is removed in dialysis patients.47

POCUS evaluation for B lines can be learned very quickly. Exams of novices who have performed only 5 prior exams correlate highly with those of experts who have performed more than 100 exams.48

Simple, efficient screening method for abdominal aortic aneurysm

AAAs are present in up to 7% of men over the age of 50.49 The mortality rate of a ruptured AAA is as high as 80% to 95%.50 There is, however, a long prodromal period when interventions can make a significant difference, which is why accurate screening is so important.

AAA screening with ultrasound has been shown to decrease mortality.51 The current recommendation of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is a one-time AAA screening for all men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked (Grade B).52 Despite the recommendations of the USPSTF, screening rates are low. One study found that only 9% of eligible patients in primary care practices received appropriate screening.51

Ultrasound performed by specialists is known to be an excellent screening test for AAA with a sensitivity of 98.9% and a specificity of 99.9%.53 POCUS use by emergency medicine physicians for the evaluation of symptomatic AAA is well established in the literature. A meta-analysis including 7 studies and 655 patients showed a pooled sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 98%.54 Multiple studies also support primary care physicians performing POCUS AAA screening in the clinic setting.

For example, a 2012 prospective, observational study performed in Canada compared office-based ultrasound screening exams performed by a rural FP to scans performed in the hospital on the same patients.55 The physician completed 50 training examinations. The average discrepancy in aorta diameters between the 2 was only 2 mm, which is clinically insignificant, and the office-based scans had a sensitivity and specificity of 100%.

Similarly, a second FP study performed in Barcelona, showed that an FP who performed POCUS AAA screening had 100% concordance with a radiologist.56 Additionally, POCUS screening for AAA was not time consuming; it was performed in under 4 minutes per patient.55,57

Ruling out DVT

DVT is a relatively rare occurrence in the ambulatory setting. However, patients who present with a painful, swollen lower extremity are much more common, and DVT must be considered and ruled out in these situations.

Although isolated distal DVTs that occur in the calf veins are usually self-limited and have a very low risk of embolization, they can progress to proximal DVTs of the thigh veins up to 20% of time.58,59 Similarly, thrombophlebitis of the superficial lower extremity veins rarely embolizes, but can progress to a proximal DVT, especially if large segments are involved or if the segments are within 5 cm of the junction to the deep venous system.59 The risk of missing a proximal leg DVT is high because embolization occurs up to 60% of the time if the DVT is left untreated.60

The current standard for diagnosis of DVT is the lower extremity Doppler ultrasound examination, but obtaining same-day Doppler evaluations can be difficult in the ambulatory setting. In these instances, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that even low-risk patients receive anticoagulation pending the evaluation if it cannot be obtained in the first 24 hours.59 This approach not only increases the cost of care, but also exposes patients—many of whom will not be diagnosed with thrombosis in the end—to the risks of anticoagulation.

D-dimer blood tests have drawbacks, too. While a negative high-sensitivity D-dimer blood test in a patient with a low pre-test probability of DVT can effectively rule out a DVT, laboratory testing is not always immediately available in the ambulatory setting either.61 Additionally, false-positive rates are high, and positive D-dimer exams still require evaluation by Doppler ultrasound.