User login

Rituximab Still Proves Safe Long Term

Rituximab, a B-cell–depleting agent, has been found safe and effective in clinical trials of patients with multiple sclerosis and patients with rheumatoid arthritis, among others. However, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and malignancies have been reported in patients with lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus who also received multiple immunosuppressive therapies, say researchers from Wayne State University in Michigan and University of Chicago in Illinois. In studies with ocrelizumab, which also depletes B-cells, adverse effects (AEs) have included infections, such as, herpes virus-associated infection, and neoplasms.

Although most research has found rituximab and ocrelizumab safe and effective, there is a “paucity of literature” on the safety of continuous B-cell depletion over a long period, the researchers say. They conducted a retrospective study involving 29 patients with immune-mediated neurologic disorders who received continuous cycles of rituximab infusions every 6 to 9 months for up to 7 years. Although small, the study was longer than the trials with ocrelizumab in multiple sclerosis . The mean duration of treatment was 51 months; with a mean of 9 treatment cycles.

The researchers found a low incidence of adverse events and prolonged rituximab-induced B-cell depletion did not lead to any life-threatening AEs, including malignancy. Overall, 32 AEs were reported. Four were serious; 3 were noted after 9 cycles (48 months), and 1 after 11 cycles (60 months). There were no cases of PML or malignancies. Repeated rituximab infusions were well tolerated The rate of AEs remained low over the 7-year observation period.

Source:

Memon AB, Javed A, Caon C, et al. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0190425.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190425.

Rituximab, a B-cell–depleting agent, has been found safe and effective in clinical trials of patients with multiple sclerosis and patients with rheumatoid arthritis, among others. However, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and malignancies have been reported in patients with lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus who also received multiple immunosuppressive therapies, say researchers from Wayne State University in Michigan and University of Chicago in Illinois. In studies with ocrelizumab, which also depletes B-cells, adverse effects (AEs) have included infections, such as, herpes virus-associated infection, and neoplasms.

Although most research has found rituximab and ocrelizumab safe and effective, there is a “paucity of literature” on the safety of continuous B-cell depletion over a long period, the researchers say. They conducted a retrospective study involving 29 patients with immune-mediated neurologic disorders who received continuous cycles of rituximab infusions every 6 to 9 months for up to 7 years. Although small, the study was longer than the trials with ocrelizumab in multiple sclerosis . The mean duration of treatment was 51 months; with a mean of 9 treatment cycles.

The researchers found a low incidence of adverse events and prolonged rituximab-induced B-cell depletion did not lead to any life-threatening AEs, including malignancy. Overall, 32 AEs were reported. Four were serious; 3 were noted after 9 cycles (48 months), and 1 after 11 cycles (60 months). There were no cases of PML or malignancies. Repeated rituximab infusions were well tolerated The rate of AEs remained low over the 7-year observation period.

Source:

Memon AB, Javed A, Caon C, et al. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0190425.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190425.

Rituximab, a B-cell–depleting agent, has been found safe and effective in clinical trials of patients with multiple sclerosis and patients with rheumatoid arthritis, among others. However, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and malignancies have been reported in patients with lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus who also received multiple immunosuppressive therapies, say researchers from Wayne State University in Michigan and University of Chicago in Illinois. In studies with ocrelizumab, which also depletes B-cells, adverse effects (AEs) have included infections, such as, herpes virus-associated infection, and neoplasms.

Although most research has found rituximab and ocrelizumab safe and effective, there is a “paucity of literature” on the safety of continuous B-cell depletion over a long period, the researchers say. They conducted a retrospective study involving 29 patients with immune-mediated neurologic disorders who received continuous cycles of rituximab infusions every 6 to 9 months for up to 7 years. Although small, the study was longer than the trials with ocrelizumab in multiple sclerosis . The mean duration of treatment was 51 months; with a mean of 9 treatment cycles.

The researchers found a low incidence of adverse events and prolonged rituximab-induced B-cell depletion did not lead to any life-threatening AEs, including malignancy. Overall, 32 AEs were reported. Four were serious; 3 were noted after 9 cycles (48 months), and 1 after 11 cycles (60 months). There were no cases of PML or malignancies. Repeated rituximab infusions were well tolerated The rate of AEs remained low over the 7-year observation period.

Source:

Memon AB, Javed A, Caon C, et al. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0190425.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190425.

VIP an unwelcome contributor to eosinophilic esophagitis

Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) appears to play an important role in the pathology of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) by recruiting mast cells and eosinophils that contribute to EoE’s hallmark symptoms of dysphagia and esophageal dysmotility, investigators reported in the February issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Blocking one of three VIP receptors – chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 (CRTH2) – could reduce eosinophil infiltration and mast cell numbers in the esophagus, wrote Alok K. Verma, PhD, a postodoctoral fellow at Tulane University in New Orleans, and his colleagues.

“We suggest that inhibiting the VIP–CRTH2 axis may ameliorate the dysphagia, stricture, and motility dysfunction of chronic EoE,” they wrote in a research letter to Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Several cytokines and chemokines, notably interleukin-5 and eotaxin-3, have been fingered as suspects in eosinophil infiltration, but whether chemokines other than eotaxin play a role has not been well documented, the investigators noted.

They hypothesized that VIP may be a chemoattractant that draws eosinophils into perineural areas of the muscular mucosa of the esophagus.

To test this idea, they looked at VIP-expression in samples from patients both with and without EoE and found that VIP expression was low among controls (without EoE); they also found that eosinophils were seen to accumulate near VIP-expressing nerve cells in biopsy samples from patients with EoE.

When they performed in vitro studies of VIP binding and immunologic functions, they found that eosinophils primarily express the CRTH2 receptor rather than the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 (VPAC-1) or VPAC-2.

They also demonstrated that VIP’s effects on eosinophil motility was similar to that of eotaxin and that, when they pretreated eosinophils with a CRTH2 inhibitor, esoinophil motility was hampered.

The investigators next looked at biopsy specimens from patients with EoE and found that eosinophils that express CRTH2 accumulated in the epithelial mucosa.

To see whether (as they and other researchers had suspected) VIP and its interaction with the CRTH2 receptor might play a role in mast cell recruitment, they performed immunofluorescence analyses and confirmed the presence of the CRTH2 receptor on tryptase-positive mast cells in the esophageal mucosa of patients with EoE.

“These findings suggest that, similar to eosinophils, mast cells accumulate via interaction of the CRTH2 receptor with neutrally derived VIP,” they wrote.

Finally, to see whether a reduction in peak eosinophil levels in patients with EoE with a CRTH2 antagonist – as seen in prior studies – could also ameliorate the negative effects of mast cells on esophageal function, they looked at the effects of CRTH2 inhibition in a mouse model of human EoE.

They found that, in the mice treated with a CRTH2 blocker, each segment of the esophagus had significant reductions in both eosinophil infiltration and mast cell numbers (P less than .05 for each).

The work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Tulane Edward G. Schlieder Educational Foundation. Senior author Anil Mishra, PhD, disclosed serving as a consultant for Axcan Pharma, Aptalis, Elite Biosciences, Calypso Biotech SA, and Enumeral Biomedical. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Verma AK et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5[1]:99-100.e7.

The rapid increase in the incidence of pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) draws immediate attention to the importance of studying the mechanisms underlying this detrimental condition. The lack of preventive or curative therapies for EoE further underscores the importance of research that addresses gaps in our understanding of how eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus is regulated on the molecular and cellular level. EoE is classified as an allergic immune disorder of the gastrointestinal tract and is characterized by eosinophil-rich, chronic Th2-type inflammation of the esophagus.

In this recent publication, the laboratory of Anil Mishra, PhD, showed that vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) serves as a potent chemoattractant for eosinophils and promotes accumulation of these innate immune cells adjacent to nerve cells in the muscular mucosa. Increased VIP expression was documented in EoE patients when compared to controls, and the authors identified the chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule expressed on Th2 lymphocytes (CRTH2) as a main binding receptor for VIP. Interestingly, CRTH2 was not only found to be expressed on eosinophils but also on tissue mast cells – another innate immune cell type that significantly contributes to the inflammatory tissue infiltrate in EoE patients. Based on the human findings, the authors tested whether VIP plays a major role in recruiting eosinophils and mast cells to the inflamed esophagus and whether CRTH2 blockade can modulate experimental EoE. Indeed, EoE pathology improved in animals that were treated with a CRTH2 antagonist.

In conclusion, these observations suggest that inhibiting the VIP-CRTH2 axis may serve as a therapeutic intervention pathway to ameliorate innate tissue inflammation in EoE patients.

Edda Fiebiger, PhD, is in the department of pediatrics in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as in the department of medicine at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. She had no disclosures.

The rapid increase in the incidence of pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) draws immediate attention to the importance of studying the mechanisms underlying this detrimental condition. The lack of preventive or curative therapies for EoE further underscores the importance of research that addresses gaps in our understanding of how eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus is regulated on the molecular and cellular level. EoE is classified as an allergic immune disorder of the gastrointestinal tract and is characterized by eosinophil-rich, chronic Th2-type inflammation of the esophagus.

In this recent publication, the laboratory of Anil Mishra, PhD, showed that vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) serves as a potent chemoattractant for eosinophils and promotes accumulation of these innate immune cells adjacent to nerve cells in the muscular mucosa. Increased VIP expression was documented in EoE patients when compared to controls, and the authors identified the chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule expressed on Th2 lymphocytes (CRTH2) as a main binding receptor for VIP. Interestingly, CRTH2 was not only found to be expressed on eosinophils but also on tissue mast cells – another innate immune cell type that significantly contributes to the inflammatory tissue infiltrate in EoE patients. Based on the human findings, the authors tested whether VIP plays a major role in recruiting eosinophils and mast cells to the inflamed esophagus and whether CRTH2 blockade can modulate experimental EoE. Indeed, EoE pathology improved in animals that were treated with a CRTH2 antagonist.

In conclusion, these observations suggest that inhibiting the VIP-CRTH2 axis may serve as a therapeutic intervention pathway to ameliorate innate tissue inflammation in EoE patients.

Edda Fiebiger, PhD, is in the department of pediatrics in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as in the department of medicine at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. She had no disclosures.

The rapid increase in the incidence of pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) draws immediate attention to the importance of studying the mechanisms underlying this detrimental condition. The lack of preventive or curative therapies for EoE further underscores the importance of research that addresses gaps in our understanding of how eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus is regulated on the molecular and cellular level. EoE is classified as an allergic immune disorder of the gastrointestinal tract and is characterized by eosinophil-rich, chronic Th2-type inflammation of the esophagus.

In this recent publication, the laboratory of Anil Mishra, PhD, showed that vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) serves as a potent chemoattractant for eosinophils and promotes accumulation of these innate immune cells adjacent to nerve cells in the muscular mucosa. Increased VIP expression was documented in EoE patients when compared to controls, and the authors identified the chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule expressed on Th2 lymphocytes (CRTH2) as a main binding receptor for VIP. Interestingly, CRTH2 was not only found to be expressed on eosinophils but also on tissue mast cells – another innate immune cell type that significantly contributes to the inflammatory tissue infiltrate in EoE patients. Based on the human findings, the authors tested whether VIP plays a major role in recruiting eosinophils and mast cells to the inflamed esophagus and whether CRTH2 blockade can modulate experimental EoE. Indeed, EoE pathology improved in animals that were treated with a CRTH2 antagonist.

In conclusion, these observations suggest that inhibiting the VIP-CRTH2 axis may serve as a therapeutic intervention pathway to ameliorate innate tissue inflammation in EoE patients.

Edda Fiebiger, PhD, is in the department of pediatrics in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as in the department of medicine at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. She had no disclosures.

Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) appears to play an important role in the pathology of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) by recruiting mast cells and eosinophils that contribute to EoE’s hallmark symptoms of dysphagia and esophageal dysmotility, investigators reported in the February issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Blocking one of three VIP receptors – chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 (CRTH2) – could reduce eosinophil infiltration and mast cell numbers in the esophagus, wrote Alok K. Verma, PhD, a postodoctoral fellow at Tulane University in New Orleans, and his colleagues.

“We suggest that inhibiting the VIP–CRTH2 axis may ameliorate the dysphagia, stricture, and motility dysfunction of chronic EoE,” they wrote in a research letter to Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Several cytokines and chemokines, notably interleukin-5 and eotaxin-3, have been fingered as suspects in eosinophil infiltration, but whether chemokines other than eotaxin play a role has not been well documented, the investigators noted.

They hypothesized that VIP may be a chemoattractant that draws eosinophils into perineural areas of the muscular mucosa of the esophagus.

To test this idea, they looked at VIP-expression in samples from patients both with and without EoE and found that VIP expression was low among controls (without EoE); they also found that eosinophils were seen to accumulate near VIP-expressing nerve cells in biopsy samples from patients with EoE.

When they performed in vitro studies of VIP binding and immunologic functions, they found that eosinophils primarily express the CRTH2 receptor rather than the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 (VPAC-1) or VPAC-2.

They also demonstrated that VIP’s effects on eosinophil motility was similar to that of eotaxin and that, when they pretreated eosinophils with a CRTH2 inhibitor, esoinophil motility was hampered.

The investigators next looked at biopsy specimens from patients with EoE and found that eosinophils that express CRTH2 accumulated in the epithelial mucosa.

To see whether (as they and other researchers had suspected) VIP and its interaction with the CRTH2 receptor might play a role in mast cell recruitment, they performed immunofluorescence analyses and confirmed the presence of the CRTH2 receptor on tryptase-positive mast cells in the esophageal mucosa of patients with EoE.

“These findings suggest that, similar to eosinophils, mast cells accumulate via interaction of the CRTH2 receptor with neutrally derived VIP,” they wrote.

Finally, to see whether a reduction in peak eosinophil levels in patients with EoE with a CRTH2 antagonist – as seen in prior studies – could also ameliorate the negative effects of mast cells on esophageal function, they looked at the effects of CRTH2 inhibition in a mouse model of human EoE.

They found that, in the mice treated with a CRTH2 blocker, each segment of the esophagus had significant reductions in both eosinophil infiltration and mast cell numbers (P less than .05 for each).

The work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Tulane Edward G. Schlieder Educational Foundation. Senior author Anil Mishra, PhD, disclosed serving as a consultant for Axcan Pharma, Aptalis, Elite Biosciences, Calypso Biotech SA, and Enumeral Biomedical. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Verma AK et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5[1]:99-100.e7.

Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) appears to play an important role in the pathology of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) by recruiting mast cells and eosinophils that contribute to EoE’s hallmark symptoms of dysphagia and esophageal dysmotility, investigators reported in the February issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Blocking one of three VIP receptors – chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 (CRTH2) – could reduce eosinophil infiltration and mast cell numbers in the esophagus, wrote Alok K. Verma, PhD, a postodoctoral fellow at Tulane University in New Orleans, and his colleagues.

“We suggest that inhibiting the VIP–CRTH2 axis may ameliorate the dysphagia, stricture, and motility dysfunction of chronic EoE,” they wrote in a research letter to Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Several cytokines and chemokines, notably interleukin-5 and eotaxin-3, have been fingered as suspects in eosinophil infiltration, but whether chemokines other than eotaxin play a role has not been well documented, the investigators noted.

They hypothesized that VIP may be a chemoattractant that draws eosinophils into perineural areas of the muscular mucosa of the esophagus.

To test this idea, they looked at VIP-expression in samples from patients both with and without EoE and found that VIP expression was low among controls (without EoE); they also found that eosinophils were seen to accumulate near VIP-expressing nerve cells in biopsy samples from patients with EoE.

When they performed in vitro studies of VIP binding and immunologic functions, they found that eosinophils primarily express the CRTH2 receptor rather than the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 (VPAC-1) or VPAC-2.

They also demonstrated that VIP’s effects on eosinophil motility was similar to that of eotaxin and that, when they pretreated eosinophils with a CRTH2 inhibitor, esoinophil motility was hampered.

The investigators next looked at biopsy specimens from patients with EoE and found that eosinophils that express CRTH2 accumulated in the epithelial mucosa.

To see whether (as they and other researchers had suspected) VIP and its interaction with the CRTH2 receptor might play a role in mast cell recruitment, they performed immunofluorescence analyses and confirmed the presence of the CRTH2 receptor on tryptase-positive mast cells in the esophageal mucosa of patients with EoE.

“These findings suggest that, similar to eosinophils, mast cells accumulate via interaction of the CRTH2 receptor with neutrally derived VIP,” they wrote.

Finally, to see whether a reduction in peak eosinophil levels in patients with EoE with a CRTH2 antagonist – as seen in prior studies – could also ameliorate the negative effects of mast cells on esophageal function, they looked at the effects of CRTH2 inhibition in a mouse model of human EoE.

They found that, in the mice treated with a CRTH2 blocker, each segment of the esophagus had significant reductions in both eosinophil infiltration and mast cell numbers (P less than .05 for each).

The work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Tulane Edward G. Schlieder Educational Foundation. Senior author Anil Mishra, PhD, disclosed serving as a consultant for Axcan Pharma, Aptalis, Elite Biosciences, Calypso Biotech SA, and Enumeral Biomedical. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Verma AK et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5[1]:99-100.e7.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: VIP appears to play an important role in the pathogenesis of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

Major finding: Neurally derived VIP and its interaction with the CRTH2 receptor appear to recruit eosinophils and mast cells into the esophageal mucosa.

Data source: In vitro studies of human EoE biopsy samples and in vivo studies in mouse models of EoE.

Disclosures: The work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Tulane Edward G. Schlieder Educational Foundation. Senior author Anil Mishra, PhD, disclosed serving as a consultant for Axcan Pharma, Aptalis, Elite Biosciences, Calypso Biotech SA, and Enumeral Biomedical. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Source: Verma AK et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5[1]:99-100.e7.

Benzodiazepines: Sensible prescribing in light of the risks

As a group, anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the Unites States, affecting 40 million adults. There is a nearly 30% lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in the general population.1 DSM-5 anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), panic disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. Although DSM-IV-TR also classified obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as anxiety disorders, these diagnoses were reclassified in DSM-5. Anxiety also is a frequent symptom of many other psychiatric disorders, especially major depressive disorder.

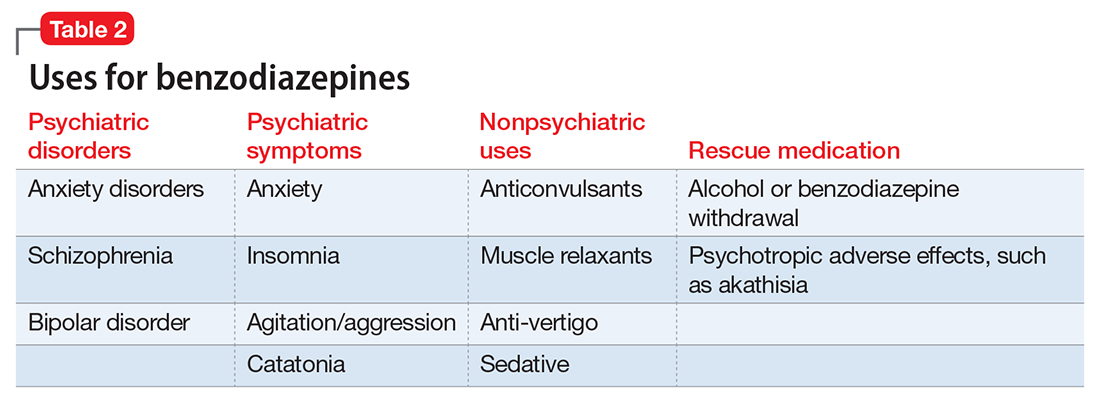

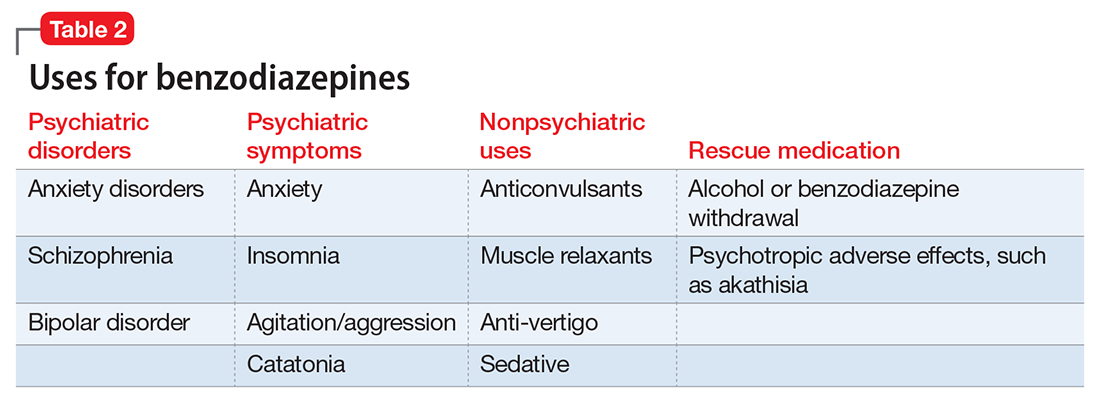

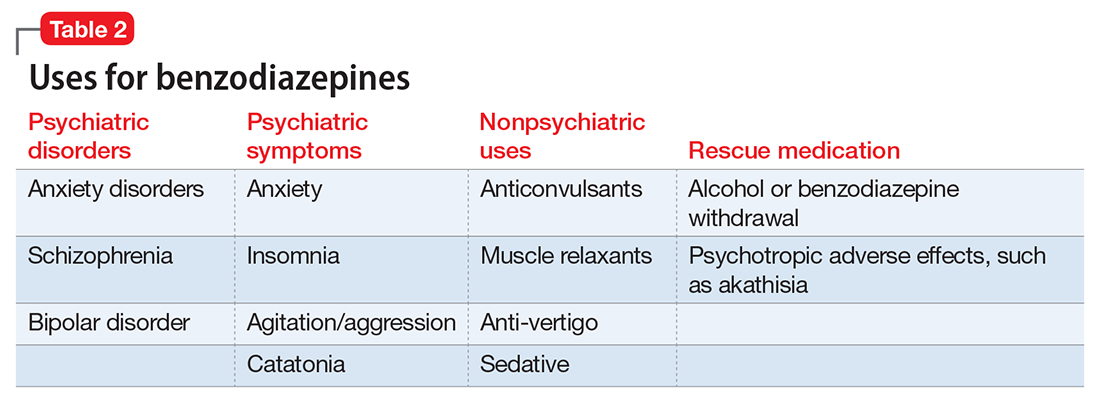

Although benzodiazepines have many potential uses, they also carry risks that prescribers should recognize. This article reviews some of the risks of benzodiazepine use, identifies patients with higher risks of adverse effects, and presents a practical approach to prescribing these medications.

A wide range of risks

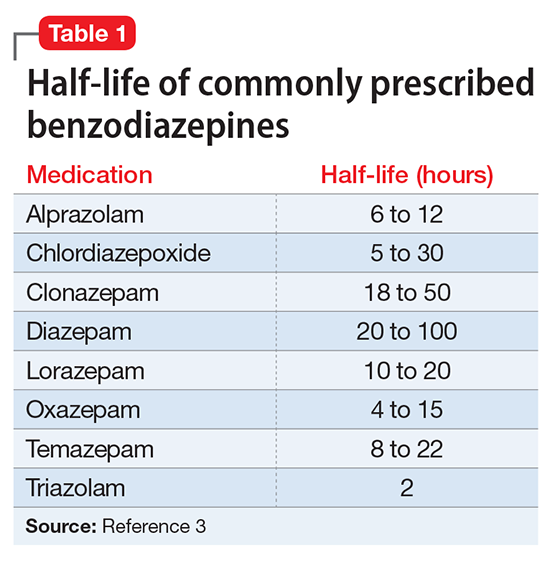

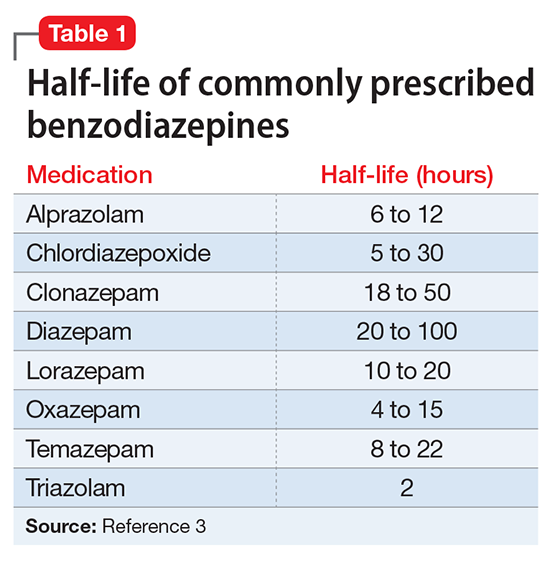

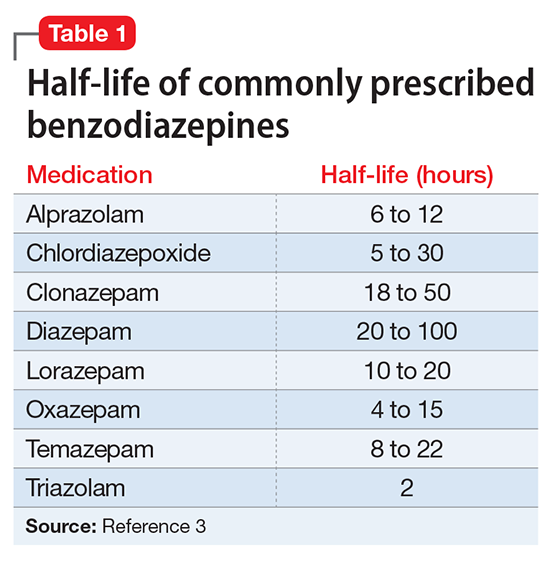

Abuse and addiction. Perhaps the most commonly recognized risk associated with benzodiazepine use is the potential for abuse and addiction.4 Prolonged benzodiazepine use typically results in physiologic tolerance, requiring higher dosing to achieve the same initial effect.5 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recognize the potential for benzodiazepine use to result in symptoms of dependence, including cravings and withdrawal, stating that “with ongoing use, all benzodiazepines will produce physiological dependence in most patients.”6 High-potency, short-acting compounds such as alprazolam have a higher risk for dependence, toxicity, and abuse.7 However, long-acting benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) also can be habit-forming.8 Because of these properties, it is generally advisable to avoid prescribing benzodiazepines (and short-acting compounds in particular) when treating patients with current or past substance use disorders, except when treating withdrawal.9

Limited efficacy for other disorders. Although benzodiazepines can help reduce anxiety in patients with anxiety disorders, they have shown less promise in treating other disorders in which anxiety is a common symptom. Treating PTSD with benzodiazepines does not appear to offer any advantage over placebo, and may even result in increased symptoms over time.10,11 There is limited evidence supporting the use of benzodiazepines to treat OCD.12,13 Patients with borderline personality disorder who are treated with benzodiazepines may experience an increase in behavioral dysregulation.14

Physical ailments. Benzodiazepines can affect comorbid physical ailments. One study found that long-term benzodiazepine use among patients with comorbid pain disorders was correlated with high utilization of medical services and high disability levels.15 Benzodiazepine use also has been associated with an increased risk of exacerbating respiratory conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,16 and increased risk of pneumonia.17,18

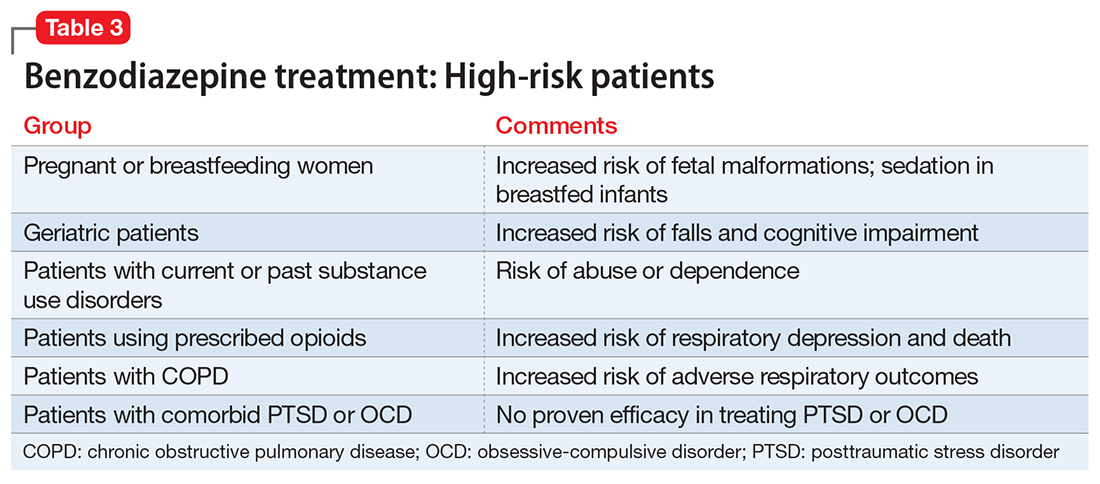

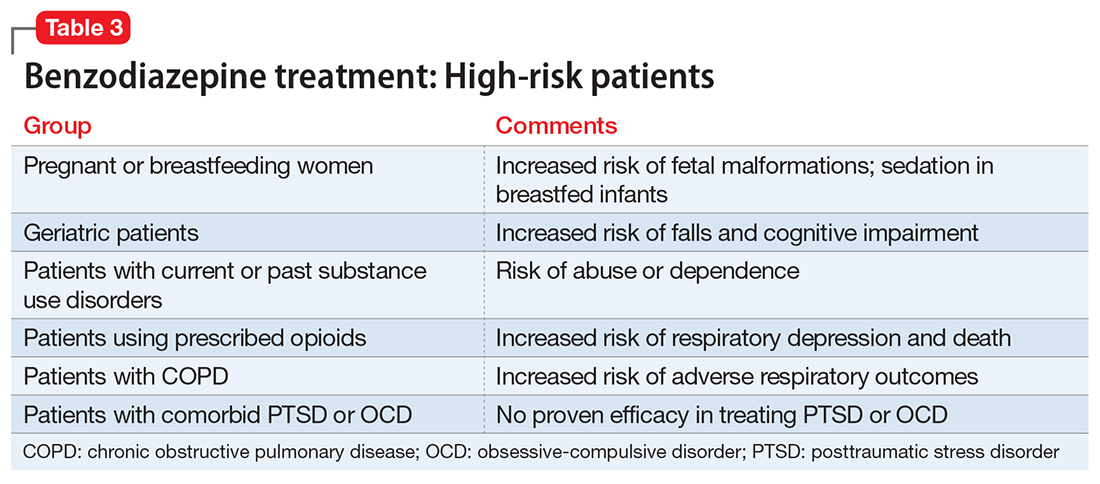

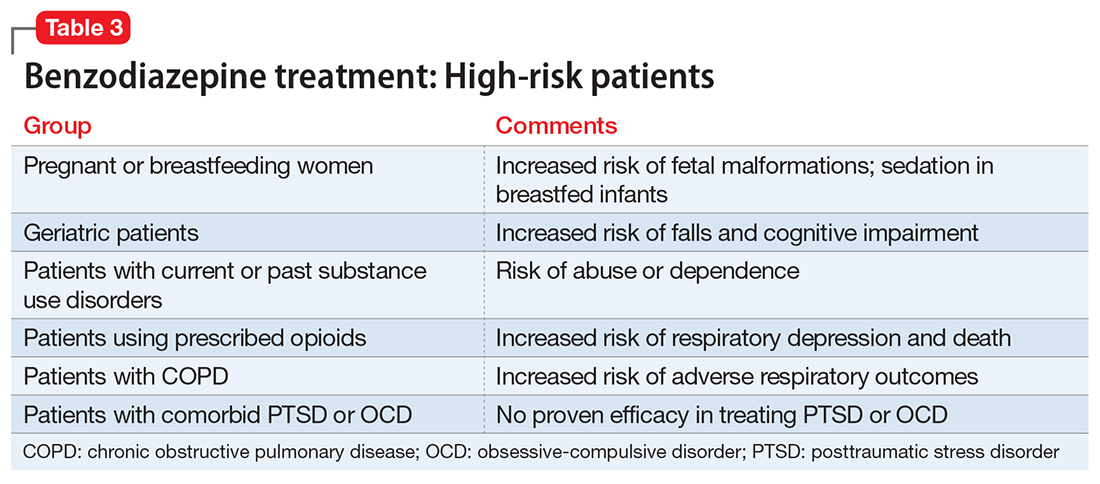

Pregnancy and breastfeeding. Benzodiazepines carry risks for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Benzodiazepine use during pregnancy may increase the relative risk of major malformations and oral clefts. It also may result in neonatal lethargy, sedation, and weight loss. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can occur in the neonate.19 Benzodiazepines are secreted in breast milk and can result in sedation among breastfed infants.20

Geriatric patients. Older adults may be particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults recommends against prescribing benzodiazepines to geriatric patients.21 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with an increased risk for falls among older adults,22,23 with an increased risk of fractures24 that can be fatal.25 Benzodiazepines also have been associated with an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and dementia.26,27 Despite the documented risks of using benzodiazepines in geriatric patients, benzodiazepines continue to be frequently prescribed to this age group.28,29 One study found that the rate of prescribing benzodiazepines by primary care physicians increased from 2003 to 2012, primarily among older adults with no diagnosis of pain or a psychiatric disorder.30

Mortality. Benzodiazepine use also carries an increased risk of mortality. Benzodiazepine users are at increased risk of motor vehicle accidents because of difficulty maintaining road position.31 Some research has shown that patients with schizophrenia treated with benzodiazepines have an increased risk of death compared with those who are prescribed antipsychotics or antidepressants.32 Another study showed that patients with schizophrenia who were prescribed benzodiazepines had a greater risk of death by suicide and accidental poisoning.33 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with suicidal ideation and an increased risk of suicide.34 Prescription opioids and benzodiazepines are the top 2 causes of overdose-related deaths (benzodiazepines are involved in approximately 31% of fatal overdoses35), and from 2002 to 2015 there was a 4.3-fold increase in deaths from benzodiazepine overdose in the United States.36 CDC guidelines recommend against co-prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines because of the risk of death by respiratory depression.37 As of August 2016, the FDA required black-box warnings for opioids and benzodiazepines regarding the risk of respiratory depression and death when these agents are used in combination, noting that “If these medicines are prescribed together, limit the dosages and duration of each drug to the minimum possible while achieving the desired clinical effect.”38,39

A sensible approach to prescribing

Given the risks posed by benzodiazepines, what would constitute a sensible approach to their use? Clearly, there are some patients for whom benzodiazepine use should be minimized or avoided (Table 3). In a patient who is deemed a good candidate for benzodiazepines, a long-acting agent may be preferable because of the increased risk of dependence associated with short-acting compounds. Start with a low dose, and use the lowest dose that adequately treats the patient’s symptoms.40 Using scheduled rather than “as-needed” dosing may help reduce behavioral escape patterns that reinforce anxiety and dependence in the long term.

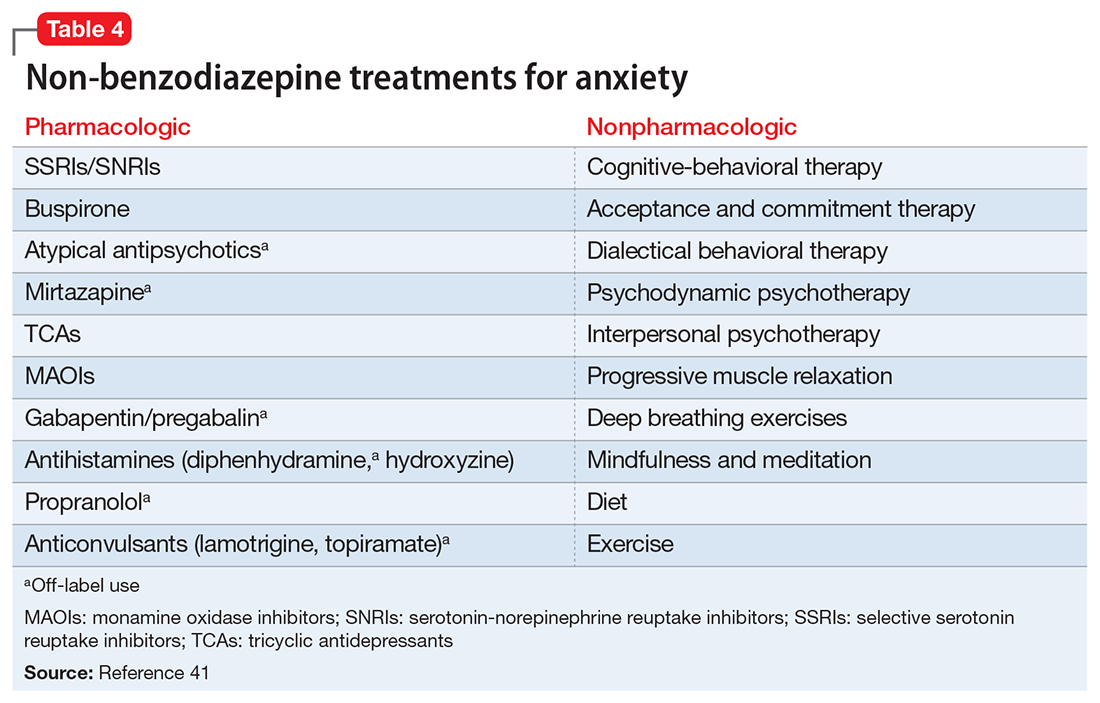

Before starting a patient on a benzodiazepine, discuss with him (her) the risks of use and an exit plan to discontinue the medication. For example, a benzodiazepine may be prescribed at the same time as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), with the goal of weaning off the benzodiazepine once the SSRI has achieved efficacy.6 Inform the patient that prescribing or treatment may be terminated if it is discovered that the patient is abusing or diverting the medication (regularly reviewing the state prescription monitoring program database can help determine if this has occurred). Strongly consider using non-benzodiazepine treatments for anxiety with (or eventually in place of) benzodiazepines (Table 441).

Reducing or stopping benzodiazepines can be challenging.42 Patients often are reluctant to stop such medications, and abrupt cessation can cause severe withdrawal. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can be severe or even fatal. Therefore, a safe and collaborative approach to reducing or stopping benzodiazepines is necessary. A starting point might be to review the risks associated with benzodiazepine use with the patient and ask about the frequency of use. Discuss with the patient a slow taper, perhaps reducing the dose by 10% to 25% increments weekly to biweekly.43,44 Less motivated patients may require a slower taper, more time, or repeated discussions. When starting a dose reduction, notify the patient that some rebound anxiety or insomnia are to be expected. With any progress the patient makes toward reducing his usage, congratulate him on such progress.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Balon R, Fava GA, Rickels K. Need for a realistic appraisal of benzodiazepines. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):243-244.

3. Ashton CH. Benzodiazepine equivalence table. http://www.benzo.org.uk/bzequiv.htm. Revised April 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Commonly abused drugs. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/commonly_abused_drugs_3.pdf. Revised January 2016. Accessed January 9, 2018.

5. Licata SC, Rowlett JK. Abuse and dependence liability of benzodiazepine-type drugs: GABA(A) receptor modulation and beyond. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90(1):74-89.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, second edition. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed May 3, 2017.

7. Salzman C. The APA Task Force report on benzodiazepine dependence, toxicity, and abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(2):151-152.

8. Bushnell GA, Stürmer T, Gaynes BN, et al. Simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use and subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in adults with depression, United States, 2001-2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):747-755.

9. O’Brien PL, Karnell LH, Gokhale M, et al. Prescribing of benzodiazepines and opioids to individuals with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:223-230.

10. Mellman TA, Bustamante V, David D, et al. Hypnotic medication in the aftermath of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1183-1184.

11. Gelpin E, Bonne O, Peri T, et al. Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(9):390-394.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd.pdf. Published July 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

13. Abdel-Ahad P, Kazour F. Non-antidepressant pharmacological treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a comprehensive review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10(2):97-111.

14. Gardner DL, Cowdry RW. Alprazolam-induced dyscontrol in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(1):98-100.

15. Ciccone DS, Just N, Bandilla EB, et al. Psychological correlates of opioid use in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain: a preliminary test of the downhill spiral hypothesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(3):180-192.

16. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

17. Obiora E, Hubbard R, Sanders RD, et al. The impact of benzodiazepines on occurrence of pneumonia and mortality from pneumonia: a nested case-control and survival analysis in a population-based cohort. Thorax. 2013;68(2):163-170.

18. Taipale H, Tolppanen AM, Koponen M, et al. Risk of pneumonia associated with incident benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling adults with Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2017;189(14):E519-E529.

19. Iqbal MM, Sobhan T, Ryals T. Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant. Psychiatric Serv. 2002;53:39-49.

20. U.S. National Library of Medicine, TOXNET Toxicology Data Network. Lactmed: alprazolam. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search2/r?dbs+lactmed:@term+@DOCNO+335. Accessed May 3, 2017.

21. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

22. Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falls in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):682-685.

23. Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952-1960.

24. Bolton JM, Morin SN, Majumdar SR, et al. Association of mental disorders and related medication use with risk for major osteoporotic fractures. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):641-648.

25. Pariente A, Dartiques JF, Benichou J, et al. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(1):61-70.

26. Lagnaoui R, Tournier M, Moride Y, et al. The risk of cognitive impairment in older community-dwelling women after benzodiazepine use. Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):226-228.

27. Billioti de Gage S, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6231.

28. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142.

29. Maust DT, Kales HC, Wiechers IR, et al. No end in sight: benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2546-2553.

30. Maust DT, Blow FC, Wiechers IR, et al. National trends in antidepressant, benzodiazepine, and other sedative-hypnotic treatment of older adults in psychiatric and primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(4):e363-e371.

31. Rapoport MJ, Lanctôt KL, Streiner DL, et al. Benzodiazepine use and driving: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(5):663-673.

32. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

33. Fontanella CA, Campo JV, Phillips GS, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of mortality among patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):661-667.

34. McCall WV, Benca RM, Rosenguist PB, et al. Hypnotic medications and suicide: risk, mechanisms, mitigation, and the FDA. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(1):18-25.

35. Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, et al. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):686-688.

36. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Updated September 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

37. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(1):1-49.

38. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use [press release]. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm518697.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

39. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm518473.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

40. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Controlled drugs: safe use and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng46/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-2427186353. Published April 2016. Accessed July 25, 2017.

41. Stahl SM. Anxiety disorders and anxiolytics. In: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:721-772.

42. Paquin AM, Zimmerman K, Rudolph JL. Risk versus risk: a review of benzodiazepine reduction in older adults. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(7):919-934.

43. Nardi AE, Freire RC, Valença AM, et al. Tapering clonazepam in patients with panic disorder after at least 3 years of treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):290-293.

44. Tampi R. How to wean geriatric patients off benzodiazepines. Psychiatric News. http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.PP3b6. Published March 18, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

As a group, anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the Unites States, affecting 40 million adults. There is a nearly 30% lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in the general population.1 DSM-5 anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), panic disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. Although DSM-IV-TR also classified obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as anxiety disorders, these diagnoses were reclassified in DSM-5. Anxiety also is a frequent symptom of many other psychiatric disorders, especially major depressive disorder.

Although benzodiazepines have many potential uses, they also carry risks that prescribers should recognize. This article reviews some of the risks of benzodiazepine use, identifies patients with higher risks of adverse effects, and presents a practical approach to prescribing these medications.

A wide range of risks

Abuse and addiction. Perhaps the most commonly recognized risk associated with benzodiazepine use is the potential for abuse and addiction.4 Prolonged benzodiazepine use typically results in physiologic tolerance, requiring higher dosing to achieve the same initial effect.5 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recognize the potential for benzodiazepine use to result in symptoms of dependence, including cravings and withdrawal, stating that “with ongoing use, all benzodiazepines will produce physiological dependence in most patients.”6 High-potency, short-acting compounds such as alprazolam have a higher risk for dependence, toxicity, and abuse.7 However, long-acting benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) also can be habit-forming.8 Because of these properties, it is generally advisable to avoid prescribing benzodiazepines (and short-acting compounds in particular) when treating patients with current or past substance use disorders, except when treating withdrawal.9

Limited efficacy for other disorders. Although benzodiazepines can help reduce anxiety in patients with anxiety disorders, they have shown less promise in treating other disorders in which anxiety is a common symptom. Treating PTSD with benzodiazepines does not appear to offer any advantage over placebo, and may even result in increased symptoms over time.10,11 There is limited evidence supporting the use of benzodiazepines to treat OCD.12,13 Patients with borderline personality disorder who are treated with benzodiazepines may experience an increase in behavioral dysregulation.14

Physical ailments. Benzodiazepines can affect comorbid physical ailments. One study found that long-term benzodiazepine use among patients with comorbid pain disorders was correlated with high utilization of medical services and high disability levels.15 Benzodiazepine use also has been associated with an increased risk of exacerbating respiratory conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,16 and increased risk of pneumonia.17,18

Pregnancy and breastfeeding. Benzodiazepines carry risks for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Benzodiazepine use during pregnancy may increase the relative risk of major malformations and oral clefts. It also may result in neonatal lethargy, sedation, and weight loss. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can occur in the neonate.19 Benzodiazepines are secreted in breast milk and can result in sedation among breastfed infants.20

Geriatric patients. Older adults may be particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults recommends against prescribing benzodiazepines to geriatric patients.21 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with an increased risk for falls among older adults,22,23 with an increased risk of fractures24 that can be fatal.25 Benzodiazepines also have been associated with an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and dementia.26,27 Despite the documented risks of using benzodiazepines in geriatric patients, benzodiazepines continue to be frequently prescribed to this age group.28,29 One study found that the rate of prescribing benzodiazepines by primary care physicians increased from 2003 to 2012, primarily among older adults with no diagnosis of pain or a psychiatric disorder.30

Mortality. Benzodiazepine use also carries an increased risk of mortality. Benzodiazepine users are at increased risk of motor vehicle accidents because of difficulty maintaining road position.31 Some research has shown that patients with schizophrenia treated with benzodiazepines have an increased risk of death compared with those who are prescribed antipsychotics or antidepressants.32 Another study showed that patients with schizophrenia who were prescribed benzodiazepines had a greater risk of death by suicide and accidental poisoning.33 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with suicidal ideation and an increased risk of suicide.34 Prescription opioids and benzodiazepines are the top 2 causes of overdose-related deaths (benzodiazepines are involved in approximately 31% of fatal overdoses35), and from 2002 to 2015 there was a 4.3-fold increase in deaths from benzodiazepine overdose in the United States.36 CDC guidelines recommend against co-prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines because of the risk of death by respiratory depression.37 As of August 2016, the FDA required black-box warnings for opioids and benzodiazepines regarding the risk of respiratory depression and death when these agents are used in combination, noting that “If these medicines are prescribed together, limit the dosages and duration of each drug to the minimum possible while achieving the desired clinical effect.”38,39

A sensible approach to prescribing

Given the risks posed by benzodiazepines, what would constitute a sensible approach to their use? Clearly, there are some patients for whom benzodiazepine use should be minimized or avoided (Table 3). In a patient who is deemed a good candidate for benzodiazepines, a long-acting agent may be preferable because of the increased risk of dependence associated with short-acting compounds. Start with a low dose, and use the lowest dose that adequately treats the patient’s symptoms.40 Using scheduled rather than “as-needed” dosing may help reduce behavioral escape patterns that reinforce anxiety and dependence in the long term.

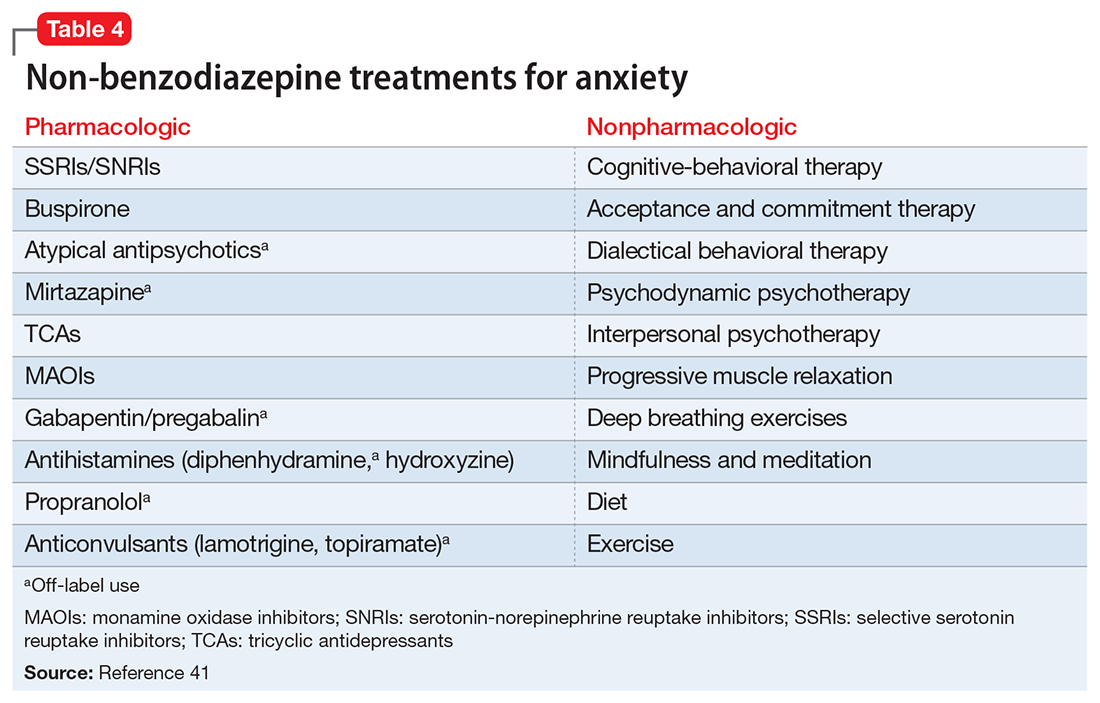

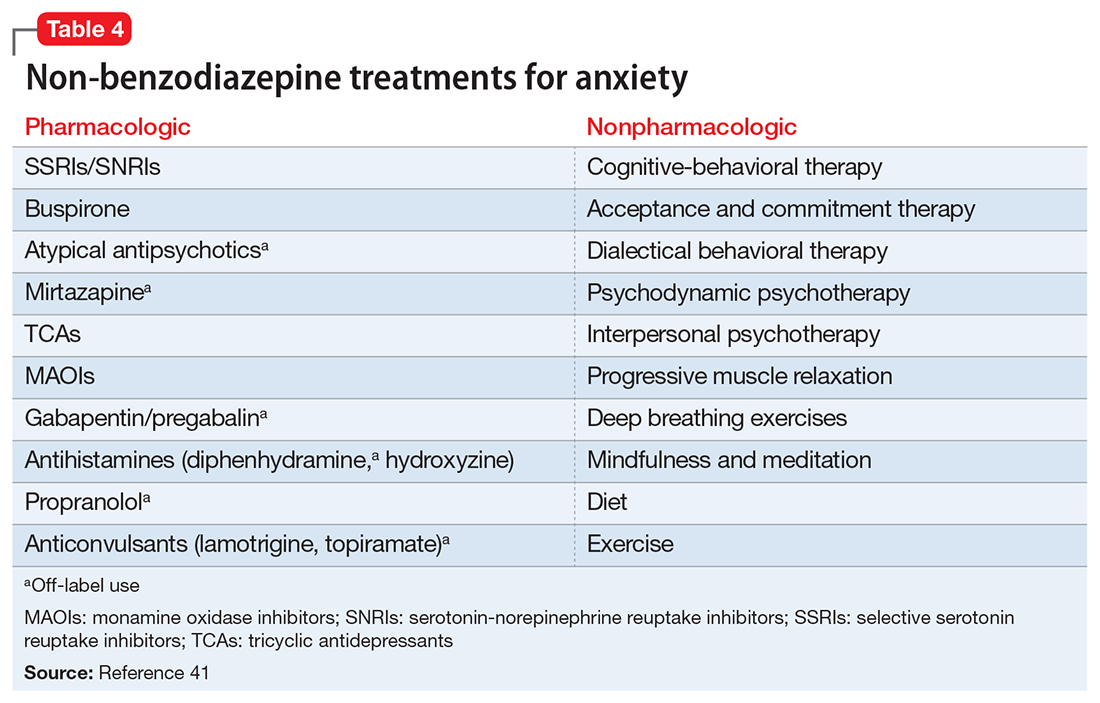

Before starting a patient on a benzodiazepine, discuss with him (her) the risks of use and an exit plan to discontinue the medication. For example, a benzodiazepine may be prescribed at the same time as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), with the goal of weaning off the benzodiazepine once the SSRI has achieved efficacy.6 Inform the patient that prescribing or treatment may be terminated if it is discovered that the patient is abusing or diverting the medication (regularly reviewing the state prescription monitoring program database can help determine if this has occurred). Strongly consider using non-benzodiazepine treatments for anxiety with (or eventually in place of) benzodiazepines (Table 441).

Reducing or stopping benzodiazepines can be challenging.42 Patients often are reluctant to stop such medications, and abrupt cessation can cause severe withdrawal. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can be severe or even fatal. Therefore, a safe and collaborative approach to reducing or stopping benzodiazepines is necessary. A starting point might be to review the risks associated with benzodiazepine use with the patient and ask about the frequency of use. Discuss with the patient a slow taper, perhaps reducing the dose by 10% to 25% increments weekly to biweekly.43,44 Less motivated patients may require a slower taper, more time, or repeated discussions. When starting a dose reduction, notify the patient that some rebound anxiety or insomnia are to be expected. With any progress the patient makes toward reducing his usage, congratulate him on such progress.

As a group, anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the Unites States, affecting 40 million adults. There is a nearly 30% lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in the general population.1 DSM-5 anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), panic disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. Although DSM-IV-TR also classified obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as anxiety disorders, these diagnoses were reclassified in DSM-5. Anxiety also is a frequent symptom of many other psychiatric disorders, especially major depressive disorder.

Although benzodiazepines have many potential uses, they also carry risks that prescribers should recognize. This article reviews some of the risks of benzodiazepine use, identifies patients with higher risks of adverse effects, and presents a practical approach to prescribing these medications.

A wide range of risks

Abuse and addiction. Perhaps the most commonly recognized risk associated with benzodiazepine use is the potential for abuse and addiction.4 Prolonged benzodiazepine use typically results in physiologic tolerance, requiring higher dosing to achieve the same initial effect.5 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recognize the potential for benzodiazepine use to result in symptoms of dependence, including cravings and withdrawal, stating that “with ongoing use, all benzodiazepines will produce physiological dependence in most patients.”6 High-potency, short-acting compounds such as alprazolam have a higher risk for dependence, toxicity, and abuse.7 However, long-acting benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) also can be habit-forming.8 Because of these properties, it is generally advisable to avoid prescribing benzodiazepines (and short-acting compounds in particular) when treating patients with current or past substance use disorders, except when treating withdrawal.9

Limited efficacy for other disorders. Although benzodiazepines can help reduce anxiety in patients with anxiety disorders, they have shown less promise in treating other disorders in which anxiety is a common symptom. Treating PTSD with benzodiazepines does not appear to offer any advantage over placebo, and may even result in increased symptoms over time.10,11 There is limited evidence supporting the use of benzodiazepines to treat OCD.12,13 Patients with borderline personality disorder who are treated with benzodiazepines may experience an increase in behavioral dysregulation.14

Physical ailments. Benzodiazepines can affect comorbid physical ailments. One study found that long-term benzodiazepine use among patients with comorbid pain disorders was correlated with high utilization of medical services and high disability levels.15 Benzodiazepine use also has been associated with an increased risk of exacerbating respiratory conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,16 and increased risk of pneumonia.17,18

Pregnancy and breastfeeding. Benzodiazepines carry risks for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Benzodiazepine use during pregnancy may increase the relative risk of major malformations and oral clefts. It also may result in neonatal lethargy, sedation, and weight loss. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can occur in the neonate.19 Benzodiazepines are secreted in breast milk and can result in sedation among breastfed infants.20

Geriatric patients. Older adults may be particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults recommends against prescribing benzodiazepines to geriatric patients.21 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with an increased risk for falls among older adults,22,23 with an increased risk of fractures24 that can be fatal.25 Benzodiazepines also have been associated with an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and dementia.26,27 Despite the documented risks of using benzodiazepines in geriatric patients, benzodiazepines continue to be frequently prescribed to this age group.28,29 One study found that the rate of prescribing benzodiazepines by primary care physicians increased from 2003 to 2012, primarily among older adults with no diagnosis of pain or a psychiatric disorder.30

Mortality. Benzodiazepine use also carries an increased risk of mortality. Benzodiazepine users are at increased risk of motor vehicle accidents because of difficulty maintaining road position.31 Some research has shown that patients with schizophrenia treated with benzodiazepines have an increased risk of death compared with those who are prescribed antipsychotics or antidepressants.32 Another study showed that patients with schizophrenia who were prescribed benzodiazepines had a greater risk of death by suicide and accidental poisoning.33 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with suicidal ideation and an increased risk of suicide.34 Prescription opioids and benzodiazepines are the top 2 causes of overdose-related deaths (benzodiazepines are involved in approximately 31% of fatal overdoses35), and from 2002 to 2015 there was a 4.3-fold increase in deaths from benzodiazepine overdose in the United States.36 CDC guidelines recommend against co-prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines because of the risk of death by respiratory depression.37 As of August 2016, the FDA required black-box warnings for opioids and benzodiazepines regarding the risk of respiratory depression and death when these agents are used in combination, noting that “If these medicines are prescribed together, limit the dosages and duration of each drug to the minimum possible while achieving the desired clinical effect.”38,39

A sensible approach to prescribing

Given the risks posed by benzodiazepines, what would constitute a sensible approach to their use? Clearly, there are some patients for whom benzodiazepine use should be minimized or avoided (Table 3). In a patient who is deemed a good candidate for benzodiazepines, a long-acting agent may be preferable because of the increased risk of dependence associated with short-acting compounds. Start with a low dose, and use the lowest dose that adequately treats the patient’s symptoms.40 Using scheduled rather than “as-needed” dosing may help reduce behavioral escape patterns that reinforce anxiety and dependence in the long term.

Before starting a patient on a benzodiazepine, discuss with him (her) the risks of use and an exit plan to discontinue the medication. For example, a benzodiazepine may be prescribed at the same time as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), with the goal of weaning off the benzodiazepine once the SSRI has achieved efficacy.6 Inform the patient that prescribing or treatment may be terminated if it is discovered that the patient is abusing or diverting the medication (regularly reviewing the state prescription monitoring program database can help determine if this has occurred). Strongly consider using non-benzodiazepine treatments for anxiety with (or eventually in place of) benzodiazepines (Table 441).

Reducing or stopping benzodiazepines can be challenging.42 Patients often are reluctant to stop such medications, and abrupt cessation can cause severe withdrawal. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can be severe or even fatal. Therefore, a safe and collaborative approach to reducing or stopping benzodiazepines is necessary. A starting point might be to review the risks associated with benzodiazepine use with the patient and ask about the frequency of use. Discuss with the patient a slow taper, perhaps reducing the dose by 10% to 25% increments weekly to biweekly.43,44 Less motivated patients may require a slower taper, more time, or repeated discussions. When starting a dose reduction, notify the patient that some rebound anxiety or insomnia are to be expected. With any progress the patient makes toward reducing his usage, congratulate him on such progress.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Balon R, Fava GA, Rickels K. Need for a realistic appraisal of benzodiazepines. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):243-244.

3. Ashton CH. Benzodiazepine equivalence table. http://www.benzo.org.uk/bzequiv.htm. Revised April 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Commonly abused drugs. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/commonly_abused_drugs_3.pdf. Revised January 2016. Accessed January 9, 2018.

5. Licata SC, Rowlett JK. Abuse and dependence liability of benzodiazepine-type drugs: GABA(A) receptor modulation and beyond. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90(1):74-89.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, second edition. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed May 3, 2017.

7. Salzman C. The APA Task Force report on benzodiazepine dependence, toxicity, and abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(2):151-152.

8. Bushnell GA, Stürmer T, Gaynes BN, et al. Simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use and subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in adults with depression, United States, 2001-2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):747-755.

9. O’Brien PL, Karnell LH, Gokhale M, et al. Prescribing of benzodiazepines and opioids to individuals with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:223-230.

10. Mellman TA, Bustamante V, David D, et al. Hypnotic medication in the aftermath of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1183-1184.

11. Gelpin E, Bonne O, Peri T, et al. Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(9):390-394.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd.pdf. Published July 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

13. Abdel-Ahad P, Kazour F. Non-antidepressant pharmacological treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a comprehensive review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10(2):97-111.

14. Gardner DL, Cowdry RW. Alprazolam-induced dyscontrol in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(1):98-100.

15. Ciccone DS, Just N, Bandilla EB, et al. Psychological correlates of opioid use in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain: a preliminary test of the downhill spiral hypothesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(3):180-192.

16. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

17. Obiora E, Hubbard R, Sanders RD, et al. The impact of benzodiazepines on occurrence of pneumonia and mortality from pneumonia: a nested case-control and survival analysis in a population-based cohort. Thorax. 2013;68(2):163-170.

18. Taipale H, Tolppanen AM, Koponen M, et al. Risk of pneumonia associated with incident benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling adults with Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2017;189(14):E519-E529.

19. Iqbal MM, Sobhan T, Ryals T. Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant. Psychiatric Serv. 2002;53:39-49.

20. U.S. National Library of Medicine, TOXNET Toxicology Data Network. Lactmed: alprazolam. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search2/r?dbs+lactmed:@term+@DOCNO+335. Accessed May 3, 2017.

21. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

22. Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falls in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):682-685.

23. Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952-1960.

24. Bolton JM, Morin SN, Majumdar SR, et al. Association of mental disorders and related medication use with risk for major osteoporotic fractures. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):641-648.

25. Pariente A, Dartiques JF, Benichou J, et al. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(1):61-70.

26. Lagnaoui R, Tournier M, Moride Y, et al. The risk of cognitive impairment in older community-dwelling women after benzodiazepine use. Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):226-228.

27. Billioti de Gage S, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6231.

28. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142.

29. Maust DT, Kales HC, Wiechers IR, et al. No end in sight: benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2546-2553.

30. Maust DT, Blow FC, Wiechers IR, et al. National trends in antidepressant, benzodiazepine, and other sedative-hypnotic treatment of older adults in psychiatric and primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(4):e363-e371.

31. Rapoport MJ, Lanctôt KL, Streiner DL, et al. Benzodiazepine use and driving: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(5):663-673.

32. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

33. Fontanella CA, Campo JV, Phillips GS, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of mortality among patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):661-667.

34. McCall WV, Benca RM, Rosenguist PB, et al. Hypnotic medications and suicide: risk, mechanisms, mitigation, and the FDA. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(1):18-25.

35. Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, et al. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):686-688.

36. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Updated September 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

37. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(1):1-49.

38. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use [press release]. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm518697.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

39. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm518473.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

40. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Controlled drugs: safe use and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng46/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-2427186353. Published April 2016. Accessed July 25, 2017.

41. Stahl SM. Anxiety disorders and anxiolytics. In: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:721-772.

42. Paquin AM, Zimmerman K, Rudolph JL. Risk versus risk: a review of benzodiazepine reduction in older adults. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(7):919-934.

43. Nardi AE, Freire RC, Valença AM, et al. Tapering clonazepam in patients with panic disorder after at least 3 years of treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):290-293.

44. Tampi R. How to wean geriatric patients off benzodiazepines. Psychiatric News. http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.PP3b6. Published March 18, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Balon R, Fava GA, Rickels K. Need for a realistic appraisal of benzodiazepines. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):243-244.

3. Ashton CH. Benzodiazepine equivalence table. http://www.benzo.org.uk/bzequiv.htm. Revised April 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Commonly abused drugs. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/commonly_abused_drugs_3.pdf. Revised January 2016. Accessed January 9, 2018.

5. Licata SC, Rowlett JK. Abuse and dependence liability of benzodiazepine-type drugs: GABA(A) receptor modulation and beyond. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90(1):74-89.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, second edition. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed May 3, 2017.

7. Salzman C. The APA Task Force report on benzodiazepine dependence, toxicity, and abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(2):151-152.

8. Bushnell GA, Stürmer T, Gaynes BN, et al. Simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use and subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in adults with depression, United States, 2001-2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):747-755.

9. O’Brien PL, Karnell LH, Gokhale M, et al. Prescribing of benzodiazepines and opioids to individuals with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:223-230.

10. Mellman TA, Bustamante V, David D, et al. Hypnotic medication in the aftermath of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1183-1184.

11. Gelpin E, Bonne O, Peri T, et al. Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(9):390-394.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd.pdf. Published July 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

13. Abdel-Ahad P, Kazour F. Non-antidepressant pharmacological treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a comprehensive review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10(2):97-111.

14. Gardner DL, Cowdry RW. Alprazolam-induced dyscontrol in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(1):98-100.

15. Ciccone DS, Just N, Bandilla EB, et al. Psychological correlates of opioid use in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain: a preliminary test of the downhill spiral hypothesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(3):180-192.

16. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

17. Obiora E, Hubbard R, Sanders RD, et al. The impact of benzodiazepines on occurrence of pneumonia and mortality from pneumonia: a nested case-control and survival analysis in a population-based cohort. Thorax. 2013;68(2):163-170.

18. Taipale H, Tolppanen AM, Koponen M, et al. Risk of pneumonia associated with incident benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling adults with Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2017;189(14):E519-E529.

19. Iqbal MM, Sobhan T, Ryals T. Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant. Psychiatric Serv. 2002;53:39-49.

20. U.S. National Library of Medicine, TOXNET Toxicology Data Network. Lactmed: alprazolam. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search2/r?dbs+lactmed:@term+@DOCNO+335. Accessed May 3, 2017.

21. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

22. Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falls in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):682-685.

23. Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952-1960.

24. Bolton JM, Morin SN, Majumdar SR, et al. Association of mental disorders and related medication use with risk for major osteoporotic fractures. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):641-648.

25. Pariente A, Dartiques JF, Benichou J, et al. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(1):61-70.

26. Lagnaoui R, Tournier M, Moride Y, et al. The risk of cognitive impairment in older community-dwelling women after benzodiazepine use. Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):226-228.

27. Billioti de Gage S, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6231.

28. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142.

29. Maust DT, Kales HC, Wiechers IR, et al. No end in sight: benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2546-2553.

30. Maust DT, Blow FC, Wiechers IR, et al. National trends in antidepressant, benzodiazepine, and other sedative-hypnotic treatment of older adults in psychiatric and primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(4):e363-e371.

31. Rapoport MJ, Lanctôt KL, Streiner DL, et al. Benzodiazepine use and driving: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(5):663-673.

32. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

33. Fontanella CA, Campo JV, Phillips GS, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of mortality among patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):661-667.

34. McCall WV, Benca RM, Rosenguist PB, et al. Hypnotic medications and suicide: risk, mechanisms, mitigation, and the FDA. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(1):18-25.

35. Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, et al. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):686-688.

36. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Updated September 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

37. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(1):1-49.

38. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use [press release]. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm518697.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

39. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm518473.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

40. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Controlled drugs: safe use and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng46/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-2427186353. Published April 2016. Accessed July 25, 2017.

41. Stahl SM. Anxiety disorders and anxiolytics. In: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:721-772.

42. Paquin AM, Zimmerman K, Rudolph JL. Risk versus risk: a review of benzodiazepine reduction in older adults. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(7):919-934.

43. Nardi AE, Freire RC, Valença AM, et al. Tapering clonazepam in patients with panic disorder after at least 3 years of treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):290-293.

44. Tampi R. How to wean geriatric patients off benzodiazepines. Psychiatric News. http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.PP3b6. Published March 18, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

Compulsive sexual behavior: A nonjudgmental approach

Compulsive sexual behavior (CSB), also referred to as sexual addiction or hypersexuality, is characterized by repetitive and intense preoccupations with sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors that are distressing to the individual and/or result in psychosocial impairment. Individuals with CSB often perceive their sexual behavior to be excessive but are unable to control it. CSB can involve fantasies and urges in addition to or in place of the behavior but must cause clinically significant distress and interference in daily life to qualify as a disorder.

Because of the lack of large-scale, population-based epidemiological studies assessing CSB, its true prevalence among adults is unknown. A study of 204 psychiatric inpatients found a current prevalence of 4.4%,1 while a university-based survey estimated the prevalence of CSB at approximately 2%.2 Others have estimated that the prevalence is between 3% to 6% of adults in the United States,3,4 with males comprising the majority (≥80%) of affected individuals.5

CSB usually develops during late adolescence/early adulthood, and most who present for treatment are male.5 Mood states, including depression, happiness, and loneliness, may trigger CSB.6 Many individuals report feelings of dissociation while engaging in CSB-related behaviors, whereas others report feeling important, powerful, excited, or gratified.

Why CSB is difficult to diagnose

Although CSB may be common, it usually goes undiagnosed. This potentially problematic behavior often is not diagnosed because of:

- Shame and secrecy. Embarrassment and shame, which are fundamental to CSB, appear to explain, in part, why few patients volunteer information regarding this behavior unless specifically asked.1

- Patient lack of knowledge. Patients often do not know that their behavior can be successfully treated.

- Clinician lack of knowledge. Few health care professionals have education or training in CSB. A lack of recognition of CSB also may be due to our limited understanding regarding the limits of sexual normality. In addition, the classification of CSB is unclear and not agreed upon (Box7-9), and moral judgments often are involved in understanding sexual behaviors.10

Box

Classifying compulsive sexual behavior

No consensus on diagnostic criteria

Accurately diagnosing CSB is difficult because of a lack of consensus about the diagnostic criteria for the disorder. Christenson et al11 developed an early set of criteria for CSB as part of a larger survey of impulse control disorders. They used the following 2 criteria to diagnose CSB: (1) excessive or uncontrolled sexual behavior(s) or sexual thoughts/urges to engage in behavior, and (2) these behaviors or thoughts/urges lead to significant distress, social or occupational impairment, or legal and financial consequences.11,12

During the DSM-5 revision process, a second approach to the diagnostic criteria was proposed for hypersexuality disorder. Under the proposed criteria for hypersexuality, a person would meet the diagnosis if ≥3 of the following were endorsed over a 6-month period: (a) time consumed by sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors repetitively interferes with other important (non-sexual) goals, activities, and obligations; (b) repetitively engaging in sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors in response to dysphoric mood states; (c) repetitively engaging in sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors in response to stressful life events; (d) repetitive but unsuccessful efforts to control or significantly reduce these sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors; and (e) repetitively engaging in sexual behaviors while disregarding the risk for physical or emotional harm to self or others.9

These 2 proposed approaches to diagnosis are somewhat similar. Both suggest that the core underlying issues involve sexual urges or behaviors that are difficult to control and that lead to psychosocial dysfunction. Differences in the criteria, however, could result in different rates of CSB diagnosis; therefore, further research will need to determine which diagnostic approach reflects the neurobiology underlying CSB.

Avoid misdiagnosis

Before making a diagnosis of CSB, it is important for clinicians to consider whether they are stigmatizing “negative consequences,” distress, or social impairment based on unconscious bias toward certain sexual behaviors. In addition, we need to ensure that we are not holding sex to different standards than other behaviors (for example, there are many things in life we do that result in negative consequences and yet do not classify as a mental disorder, such as indulging in less healthy food choices). Furthermore, excessive sexual behaviors might be associated with the normal coming out process for LGBTQ individuals, partner relationship problems, or sexual/gender identity. Therefore, the behavior needs to be assessed in the context of these psychosocial environmental factors.

Differential diagnosis

Various psychiatric disorders also may include excessive sexual behavior as part of their clinical presentation, and it is important to differentiate that behavior from CSB.

Bipolar disorder. Excessive sexual behavior can occur as part of a manic episode in bipolar disorder. If the problematic sexual behavior also occurs when the person’s mood is stable, the individual may have CSB and bipolar disorder. This distinction is important because the treatment for bipolar disorder is often different for CSB, because anticonvulsants have only case reports attesting to their use in CSB.

Substance abuse. Excessive sexual behavior can occur when a person is abusing substances, particularly stimulants such as cocaine and amphetamines.13 If the sexual behavior does not occur when the person is not using drugs, then the appropriate diagnosis would not likely be CSB.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Individuals with OCD often are preoccupied with sexual themes and feel that they think about sex excessively.14 Although patients with OCD may be preoccupied with thoughts of sex, the key difference is that persons with CSB report feeling excited by these thoughts and derive pleasure from the behavior, whereas the sexual thoughts of OCD are perceived as unpleasant.

Other disorders that may give rise to hypersexual behavior include neurocognitive disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, and depressive disorders.