User login

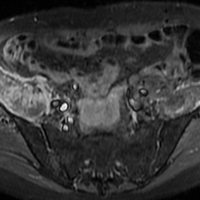

After 6 weeks, HealthCare.gov activity still ahead of last year

compared with the total at the end of week 4, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

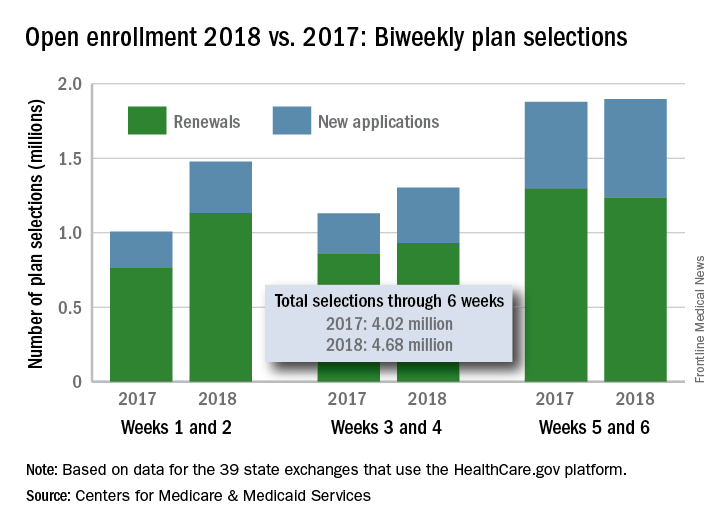

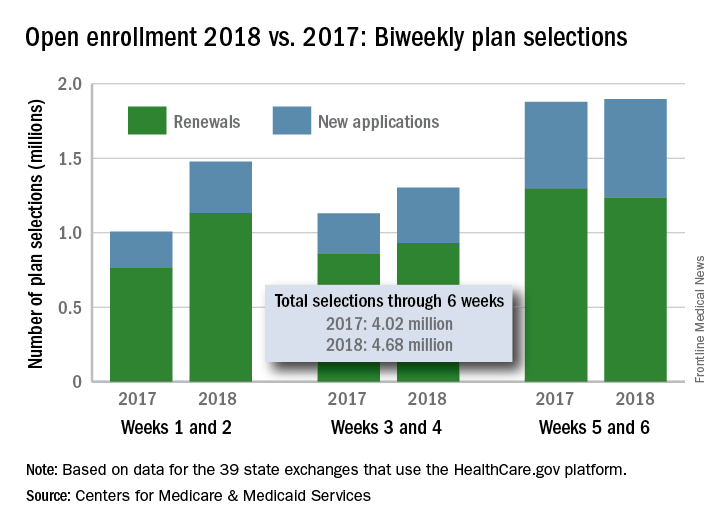

The 1.89 million plans that consumers selected over the 2-week period ending Dec. 9 brought this year’s total to 4.68 million after 6 weeks. That’s 16.5% higher than last year’s 6-week total of 4.02 million, but the difference has been getting smaller: After week 2 (enrollment figures were released only biweekly last year), the 2018 open season’s tally was higher than the 2017 open season’s week 2 tally by almost 47%, but after 4 weeks, the difference was only 30%, the CMS data show.

compared with the total at the end of week 4, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The 1.89 million plans that consumers selected over the 2-week period ending Dec. 9 brought this year’s total to 4.68 million after 6 weeks. That’s 16.5% higher than last year’s 6-week total of 4.02 million, but the difference has been getting smaller: After week 2 (enrollment figures were released only biweekly last year), the 2018 open season’s tally was higher than the 2017 open season’s week 2 tally by almost 47%, but after 4 weeks, the difference was only 30%, the CMS data show.

compared with the total at the end of week 4, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The 1.89 million plans that consumers selected over the 2-week period ending Dec. 9 brought this year’s total to 4.68 million after 6 weeks. That’s 16.5% higher than last year’s 6-week total of 4.02 million, but the difference has been getting smaller: After week 2 (enrollment figures were released only biweekly last year), the 2018 open season’s tally was higher than the 2017 open season’s week 2 tally by almost 47%, but after 4 weeks, the difference was only 30%, the CMS data show.

Carotid-axillary bypass for revascularization of the left subclavian artery in zone-2 TEVAR

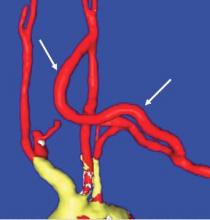

Stent-graft coverage of the left subclavian artery (LSA) is often performed during TEVAR treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies and, consequently, debranching of the LSA is frequently performed in such settings. The carotid-subclavian bypass (CSB) is undoubtedly the cervical bypass option preferred by most surgeons for this purpose.1,2 The technique was first described by Lyons and Galbraith in 1957,3 and popularized by Diethrich et al. who reported their large experience in a well-known article published 10 years later.4 In the ensuing decades, CSB became the overwhelming favorite of surgeons everywhere performing LSA revascularization for management of arterial occlusive disease and, more recently, in the context of zone-2 TEVAR. Well- documented good results would seem to justify such preference,5 but some level of concern has been voiced consistently over the years about some technical complexities and potential complications such as phrenic nerve and thoracic duct injuries.6 My own personal experience substantiated these reservations early on, prompting adoption of an alternative operative solution with use of the carotid-axillary bypass (CAB),7 an operation first reported by Shumacker in 1973.8 In my hands, it has produced equivalent results to the carotid-subclavian technique in terms of efficacy and durability, and with the additional appeal of distinct practical advantages – mainly because the axillary artery tends to be an easier vessel to expose and handle, and through the avoidance of complications resulting from damage to anatomical structures that are often in harm’s way when exposing the LSA.

Technical aspects

End-to-side anastomoses proximally and distally are constructed in routine manner (Fig. 2). We do not use carotid shunting for this procedure.

Occasionally one may want to combine a carotid endarterectomy with the cervical bypass, in which case the proximal vascular graft anastomosis is constructed at the endarterectomy site (Fig. 3). Close attention must be paid to careful length-tailoring the conduit to achieve the desirable gently curving course without undue tension or redundancy.

Proximal ligation of the LSA, often performed during the CSB, cannot be a component of the carotid-axillary operation because of inaccessibility. Some experts look upon this as a disadvantage, but I tend to view such limitation as advantageous because it eliminates the potential for a misplaced ligation distal to the left vertebral artery origin which present-day CTA studies show it to be the case more frequently than previously suspected. If interruption of the LSA is deemed necessary, it is arguably best to use an endovascular (retrograde trans-brachial) approach with precise deployment of a vascular plug device under angiographic guidance (Fig. 4). ■

Dr. Criado is at MedStar Union Memorial Hospital, Baltimore.

References

1. J Endovasc Ther 2002;9(suppl 2):1132-1138.

2. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:247-260.

3. Ann Surg 1957;146:487-494.

4. Am J Surg 1967;114:800-808.

5. J Vasc Surg 2008;48:555-560.

6. Ann Vasc Surg 2008;22:70-78.

7. J Vasc Surg 1995;22:717-723.

8. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1973;136:447-8.

9. J Vasc Surg 1999;30:1106-1112.

Stent-graft coverage of the left subclavian artery (LSA) is often performed during TEVAR treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies and, consequently, debranching of the LSA is frequently performed in such settings. The carotid-subclavian bypass (CSB) is undoubtedly the cervical bypass option preferred by most surgeons for this purpose.1,2 The technique was first described by Lyons and Galbraith in 1957,3 and popularized by Diethrich et al. who reported their large experience in a well-known article published 10 years later.4 In the ensuing decades, CSB became the overwhelming favorite of surgeons everywhere performing LSA revascularization for management of arterial occlusive disease and, more recently, in the context of zone-2 TEVAR. Well- documented good results would seem to justify such preference,5 but some level of concern has been voiced consistently over the years about some technical complexities and potential complications such as phrenic nerve and thoracic duct injuries.6 My own personal experience substantiated these reservations early on, prompting adoption of an alternative operative solution with use of the carotid-axillary bypass (CAB),7 an operation first reported by Shumacker in 1973.8 In my hands, it has produced equivalent results to the carotid-subclavian technique in terms of efficacy and durability, and with the additional appeal of distinct practical advantages – mainly because the axillary artery tends to be an easier vessel to expose and handle, and through the avoidance of complications resulting from damage to anatomical structures that are often in harm’s way when exposing the LSA.

Technical aspects

End-to-side anastomoses proximally and distally are constructed in routine manner (Fig. 2). We do not use carotid shunting for this procedure.

Occasionally one may want to combine a carotid endarterectomy with the cervical bypass, in which case the proximal vascular graft anastomosis is constructed at the endarterectomy site (Fig. 3). Close attention must be paid to careful length-tailoring the conduit to achieve the desirable gently curving course without undue tension or redundancy.

Proximal ligation of the LSA, often performed during the CSB, cannot be a component of the carotid-axillary operation because of inaccessibility. Some experts look upon this as a disadvantage, but I tend to view such limitation as advantageous because it eliminates the potential for a misplaced ligation distal to the left vertebral artery origin which present-day CTA studies show it to be the case more frequently than previously suspected. If interruption of the LSA is deemed necessary, it is arguably best to use an endovascular (retrograde trans-brachial) approach with precise deployment of a vascular plug device under angiographic guidance (Fig. 4). ■

Dr. Criado is at MedStar Union Memorial Hospital, Baltimore.

References

1. J Endovasc Ther 2002;9(suppl 2):1132-1138.

2. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:247-260.

3. Ann Surg 1957;146:487-494.

4. Am J Surg 1967;114:800-808.

5. J Vasc Surg 2008;48:555-560.

6. Ann Vasc Surg 2008;22:70-78.

7. J Vasc Surg 1995;22:717-723.

8. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1973;136:447-8.

9. J Vasc Surg 1999;30:1106-1112.

Stent-graft coverage of the left subclavian artery (LSA) is often performed during TEVAR treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies and, consequently, debranching of the LSA is frequently performed in such settings. The carotid-subclavian bypass (CSB) is undoubtedly the cervical bypass option preferred by most surgeons for this purpose.1,2 The technique was first described by Lyons and Galbraith in 1957,3 and popularized by Diethrich et al. who reported their large experience in a well-known article published 10 years later.4 In the ensuing decades, CSB became the overwhelming favorite of surgeons everywhere performing LSA revascularization for management of arterial occlusive disease and, more recently, in the context of zone-2 TEVAR. Well- documented good results would seem to justify such preference,5 but some level of concern has been voiced consistently over the years about some technical complexities and potential complications such as phrenic nerve and thoracic duct injuries.6 My own personal experience substantiated these reservations early on, prompting adoption of an alternative operative solution with use of the carotid-axillary bypass (CAB),7 an operation first reported by Shumacker in 1973.8 In my hands, it has produced equivalent results to the carotid-subclavian technique in terms of efficacy and durability, and with the additional appeal of distinct practical advantages – mainly because the axillary artery tends to be an easier vessel to expose and handle, and through the avoidance of complications resulting from damage to anatomical structures that are often in harm’s way when exposing the LSA.

Technical aspects

End-to-side anastomoses proximally and distally are constructed in routine manner (Fig. 2). We do not use carotid shunting for this procedure.

Occasionally one may want to combine a carotid endarterectomy with the cervical bypass, in which case the proximal vascular graft anastomosis is constructed at the endarterectomy site (Fig. 3). Close attention must be paid to careful length-tailoring the conduit to achieve the desirable gently curving course without undue tension or redundancy.

Proximal ligation of the LSA, often performed during the CSB, cannot be a component of the carotid-axillary operation because of inaccessibility. Some experts look upon this as a disadvantage, but I tend to view such limitation as advantageous because it eliminates the potential for a misplaced ligation distal to the left vertebral artery origin which present-day CTA studies show it to be the case more frequently than previously suspected. If interruption of the LSA is deemed necessary, it is arguably best to use an endovascular (retrograde trans-brachial) approach with precise deployment of a vascular plug device under angiographic guidance (Fig. 4). ■

Dr. Criado is at MedStar Union Memorial Hospital, Baltimore.

References

1. J Endovasc Ther 2002;9(suppl 2):1132-1138.

2. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:247-260.

3. Ann Surg 1957;146:487-494.

4. Am J Surg 1967;114:800-808.

5. J Vasc Surg 2008;48:555-560.

6. Ann Vasc Surg 2008;22:70-78.

7. J Vasc Surg 1995;22:717-723.

8. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1973;136:447-8.

9. J Vasc Surg 1999;30:1106-1112.

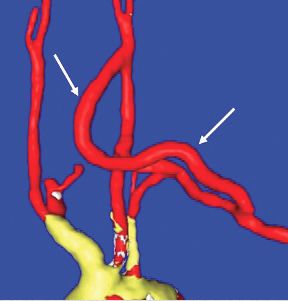

Tips and Tricks: Dealing with a troublesome peritoneal dialysis catheter

When faced with a poorly performing or nonfunctional peritoneal dialysis catheter, there is a very simple trick to make laparoscopic exploration easier. Prep the catheter into the field and take extra care to prep the cover of the catheter. It is usually easier to remove the extended portion of the catheter (A) and just leave the shorter piece (B).

As soon as the port is in, simply switch the CO2 over to it from the catheter. This technique comes in handy quite often, as many patients with difficult PD catheters have undergone multiple explorations or laparoscopies. Not rocket science, but it can definitely save you and the patient some difficulty!

Dr. Rigberg is Clinical Professor of Surgery and Program Director, University of California, Los Angeles, Division of Vascular Surgery, and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

When faced with a poorly performing or nonfunctional peritoneal dialysis catheter, there is a very simple trick to make laparoscopic exploration easier. Prep the catheter into the field and take extra care to prep the cover of the catheter. It is usually easier to remove the extended portion of the catheter (A) and just leave the shorter piece (B).

As soon as the port is in, simply switch the CO2 over to it from the catheter. This technique comes in handy quite often, as many patients with difficult PD catheters have undergone multiple explorations or laparoscopies. Not rocket science, but it can definitely save you and the patient some difficulty!

Dr. Rigberg is Clinical Professor of Surgery and Program Director, University of California, Los Angeles, Division of Vascular Surgery, and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

When faced with a poorly performing or nonfunctional peritoneal dialysis catheter, there is a very simple trick to make laparoscopic exploration easier. Prep the catheter into the field and take extra care to prep the cover of the catheter. It is usually easier to remove the extended portion of the catheter (A) and just leave the shorter piece (B).

As soon as the port is in, simply switch the CO2 over to it from the catheter. This technique comes in handy quite often, as many patients with difficult PD catheters have undergone multiple explorations or laparoscopies. Not rocket science, but it can definitely save you and the patient some difficulty!

Dr. Rigberg is Clinical Professor of Surgery and Program Director, University of California, Los Angeles, Division of Vascular Surgery, and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The men and women of vascular surgery

From the Editor

Recent news events have detailed the many humiliations and abuses, both verbal and physical, that women, and some men, have to endure in the workforce. It would not surprise me if some vascular surgeons admit that they have heard of similar instances of egregious behavior occurring in our workplaces. The people that have been impacted have predominantly been women and have come from all walks of life. They have been patients, colleagues, our employees or those of the many institutions in which we work. Unfortunately, the demands of our profession and the pace of our lives may diminish our relationships with these persons. This facelessness and disconnection may allow some surgeons to justify their poor behavior whereas others may not realize that they are negatively impacting these individuals’ lives. The fact that these injustices persist is made more upsetting because we are so indebted for all that these nurses, technologists, office personnel, and even patients, do for us.

Just think how much we owe the nurses on the hospital floors. It is to nurses that we entrust the postoperative care of our patients. They make sure to call us when they detect that a pulse is weakening or suddenly absent, or that a neck is expanding as a hematoma threatens breathing. They timely diagnose a retroperitoneal bleed that may endanger the patient’s life. Dialysis nurses notify us that a puncture looks like it may suddenly bleed out. Our patients’ lives are often entirely dependent on the astute observation of an accomplished nurse.

And what about the operating nurses and scrub technicians? They lay out our surgical tray perfectly with all the tools that we are wont to use. They are there to assist when a sudden event requires the steady hand of an observant nurse who knows just what instrument we need without us having to ask. When you are in a difficult area, an encouraging word will often inspire the confidence required to accomplish a successful outcome. When a procedure is going poorly and tension mounts, their silence accepts our sometimes curt requests. There is a bond that develops between two professionals who recognize each other’s expertise.

Vascular technologists work tirelessly, often in darkened rooms, frequently under challenging positions straining eyes and limbs to detect pathology that may be life or limb saving. Their diagnostic acumen can be the difference between a subsequent procedure’s success or failure. Indeed, the vascular surgeon has to make the final interpretation, but if the technologist fails to show the pathology, even the most erudite physician may miss the diagnosis.

Front-desk personnel who sit at check-in and check-out in an office are the face of our practice. Their friendly attitude welcomes our patients and reassures them that they have come to a well-run, professional workplace. A smiling, personal greeting will calm even the most worried patient. Of course, their attention to detail assures that collections will not be misplaced.

Our office nurses exude compassion for the many patients who face immense hurdles in living with vascular disease. They assist in teaching wound care, explain medications, and help in arranging social services. They cry with those that have recently lost a spouse or child and get excited to hear of the birth of a patient’s grandchild. Without their organizational skills, office hours would be interminable, and patients who are kept waiting would complain, or worse, leave the practice. They have learned to laugh at the same joke that they have heard us tell innumerable times, and to ignore the sometimes lousy mood we may bring into the office after a brutal night on call.

The spouses or significant others of our patients also play an important role since it is often from them that we get the most accurate history. They will ask to speak to us privately to make sure we do not cause despair when we discuss treatment options or to ensure that we firmly admonish their loved one to stop smoking, exercise or watch their weight. Unfortunately, they will sometimes have to accept a disparaging remark or gesture from their “spouse” to make sure that we are supplied all the necessary information to come to an appropriate diagnosis.

I can go on about other medical personnel that contribute to our success, but I believe I have made the point. The men and women with whom we interact as vascular surgeons deserve the same respect we grant ourselves. Any insult to them demeans not only the recipient but more so the abuser and those of us who stand by silently.

Finally, there are many female colleagues whose interest and drive has allowed them to not only break into but achieve leadership positions in a specialty that was almost uniformly male and unwelcoming. Their aptitudes and attitudes have broadened the specialty’s ability to help our patients. However, recently the news has been replete with evidence that women have been abused as they tried to enter other male-dominated professions and so it is likely that this has happened in ours.

Other recent news items suggest that these physical and emotional abuses are inflicted not only on women but also men. We may never know the scope of this mistreatment, but we must assure that it stops immediately.

Ethical behavior must be gender neutral. Further, condescending attitudes, cruel language, and a lack of appreciation sometimes can be as damaging as physical or sexual abuse and must be abolished from our workplace. ■

From the Editor

Recent news events have detailed the many humiliations and abuses, both verbal and physical, that women, and some men, have to endure in the workforce. It would not surprise me if some vascular surgeons admit that they have heard of similar instances of egregious behavior occurring in our workplaces. The people that have been impacted have predominantly been women and have come from all walks of life. They have been patients, colleagues, our employees or those of the many institutions in which we work. Unfortunately, the demands of our profession and the pace of our lives may diminish our relationships with these persons. This facelessness and disconnection may allow some surgeons to justify their poor behavior whereas others may not realize that they are negatively impacting these individuals’ lives. The fact that these injustices persist is made more upsetting because we are so indebted for all that these nurses, technologists, office personnel, and even patients, do for us.

Just think how much we owe the nurses on the hospital floors. It is to nurses that we entrust the postoperative care of our patients. They make sure to call us when they detect that a pulse is weakening or suddenly absent, or that a neck is expanding as a hematoma threatens breathing. They timely diagnose a retroperitoneal bleed that may endanger the patient’s life. Dialysis nurses notify us that a puncture looks like it may suddenly bleed out. Our patients’ lives are often entirely dependent on the astute observation of an accomplished nurse.

And what about the operating nurses and scrub technicians? They lay out our surgical tray perfectly with all the tools that we are wont to use. They are there to assist when a sudden event requires the steady hand of an observant nurse who knows just what instrument we need without us having to ask. When you are in a difficult area, an encouraging word will often inspire the confidence required to accomplish a successful outcome. When a procedure is going poorly and tension mounts, their silence accepts our sometimes curt requests. There is a bond that develops between two professionals who recognize each other’s expertise.

Vascular technologists work tirelessly, often in darkened rooms, frequently under challenging positions straining eyes and limbs to detect pathology that may be life or limb saving. Their diagnostic acumen can be the difference between a subsequent procedure’s success or failure. Indeed, the vascular surgeon has to make the final interpretation, but if the technologist fails to show the pathology, even the most erudite physician may miss the diagnosis.

Front-desk personnel who sit at check-in and check-out in an office are the face of our practice. Their friendly attitude welcomes our patients and reassures them that they have come to a well-run, professional workplace. A smiling, personal greeting will calm even the most worried patient. Of course, their attention to detail assures that collections will not be misplaced.

Our office nurses exude compassion for the many patients who face immense hurdles in living with vascular disease. They assist in teaching wound care, explain medications, and help in arranging social services. They cry with those that have recently lost a spouse or child and get excited to hear of the birth of a patient’s grandchild. Without their organizational skills, office hours would be interminable, and patients who are kept waiting would complain, or worse, leave the practice. They have learned to laugh at the same joke that they have heard us tell innumerable times, and to ignore the sometimes lousy mood we may bring into the office after a brutal night on call.

The spouses or significant others of our patients also play an important role since it is often from them that we get the most accurate history. They will ask to speak to us privately to make sure we do not cause despair when we discuss treatment options or to ensure that we firmly admonish their loved one to stop smoking, exercise or watch their weight. Unfortunately, they will sometimes have to accept a disparaging remark or gesture from their “spouse” to make sure that we are supplied all the necessary information to come to an appropriate diagnosis.

I can go on about other medical personnel that contribute to our success, but I believe I have made the point. The men and women with whom we interact as vascular surgeons deserve the same respect we grant ourselves. Any insult to them demeans not only the recipient but more so the abuser and those of us who stand by silently.

Finally, there are many female colleagues whose interest and drive has allowed them to not only break into but achieve leadership positions in a specialty that was almost uniformly male and unwelcoming. Their aptitudes and attitudes have broadened the specialty’s ability to help our patients. However, recently the news has been replete with evidence that women have been abused as they tried to enter other male-dominated professions and so it is likely that this has happened in ours.

Other recent news items suggest that these physical and emotional abuses are inflicted not only on women but also men. We may never know the scope of this mistreatment, but we must assure that it stops immediately.

Ethical behavior must be gender neutral. Further, condescending attitudes, cruel language, and a lack of appreciation sometimes can be as damaging as physical or sexual abuse and must be abolished from our workplace. ■

From the Editor

Recent news events have detailed the many humiliations and abuses, both verbal and physical, that women, and some men, have to endure in the workforce. It would not surprise me if some vascular surgeons admit that they have heard of similar instances of egregious behavior occurring in our workplaces. The people that have been impacted have predominantly been women and have come from all walks of life. They have been patients, colleagues, our employees or those of the many institutions in which we work. Unfortunately, the demands of our profession and the pace of our lives may diminish our relationships with these persons. This facelessness and disconnection may allow some surgeons to justify their poor behavior whereas others may not realize that they are negatively impacting these individuals’ lives. The fact that these injustices persist is made more upsetting because we are so indebted for all that these nurses, technologists, office personnel, and even patients, do for us.

Just think how much we owe the nurses on the hospital floors. It is to nurses that we entrust the postoperative care of our patients. They make sure to call us when they detect that a pulse is weakening or suddenly absent, or that a neck is expanding as a hematoma threatens breathing. They timely diagnose a retroperitoneal bleed that may endanger the patient’s life. Dialysis nurses notify us that a puncture looks like it may suddenly bleed out. Our patients’ lives are often entirely dependent on the astute observation of an accomplished nurse.

And what about the operating nurses and scrub technicians? They lay out our surgical tray perfectly with all the tools that we are wont to use. They are there to assist when a sudden event requires the steady hand of an observant nurse who knows just what instrument we need without us having to ask. When you are in a difficult area, an encouraging word will often inspire the confidence required to accomplish a successful outcome. When a procedure is going poorly and tension mounts, their silence accepts our sometimes curt requests. There is a bond that develops between two professionals who recognize each other’s expertise.

Vascular technologists work tirelessly, often in darkened rooms, frequently under challenging positions straining eyes and limbs to detect pathology that may be life or limb saving. Their diagnostic acumen can be the difference between a subsequent procedure’s success or failure. Indeed, the vascular surgeon has to make the final interpretation, but if the technologist fails to show the pathology, even the most erudite physician may miss the diagnosis.

Front-desk personnel who sit at check-in and check-out in an office are the face of our practice. Their friendly attitude welcomes our patients and reassures them that they have come to a well-run, professional workplace. A smiling, personal greeting will calm even the most worried patient. Of course, their attention to detail assures that collections will not be misplaced.

Our office nurses exude compassion for the many patients who face immense hurdles in living with vascular disease. They assist in teaching wound care, explain medications, and help in arranging social services. They cry with those that have recently lost a spouse or child and get excited to hear of the birth of a patient’s grandchild. Without their organizational skills, office hours would be interminable, and patients who are kept waiting would complain, or worse, leave the practice. They have learned to laugh at the same joke that they have heard us tell innumerable times, and to ignore the sometimes lousy mood we may bring into the office after a brutal night on call.

The spouses or significant others of our patients also play an important role since it is often from them that we get the most accurate history. They will ask to speak to us privately to make sure we do not cause despair when we discuss treatment options or to ensure that we firmly admonish their loved one to stop smoking, exercise or watch their weight. Unfortunately, they will sometimes have to accept a disparaging remark or gesture from their “spouse” to make sure that we are supplied all the necessary information to come to an appropriate diagnosis.

I can go on about other medical personnel that contribute to our success, but I believe I have made the point. The men and women with whom we interact as vascular surgeons deserve the same respect we grant ourselves. Any insult to them demeans not only the recipient but more so the abuser and those of us who stand by silently.

Finally, there are many female colleagues whose interest and drive has allowed them to not only break into but achieve leadership positions in a specialty that was almost uniformly male and unwelcoming. Their aptitudes and attitudes have broadened the specialty’s ability to help our patients. However, recently the news has been replete with evidence that women have been abused as they tried to enter other male-dominated professions and so it is likely that this has happened in ours.

Other recent news items suggest that these physical and emotional abuses are inflicted not only on women but also men. We may never know the scope of this mistreatment, but we must assure that it stops immediately.

Ethical behavior must be gender neutral. Further, condescending attitudes, cruel language, and a lack of appreciation sometimes can be as damaging as physical or sexual abuse and must be abolished from our workplace. ■

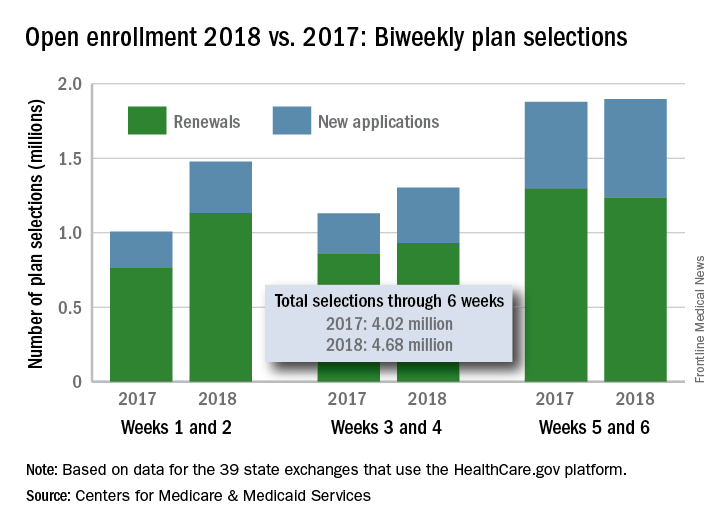

Should carotid body tumors be embolized preoperatively?

Preop embolization is safe and effective

To embolize or not to embolize ... that is the question when it comes to the management of carotid body tumors. Carotid body tumors (CBTs) are rare benign neoplasms that are almost always nonfunctional and account for up to 80% of all head and neck paragangliomas. Radiographic characteristics include tumor location at the carotid bifurcation, splaying apart the internal and external carotid arteries. Surgical resection is the mainstay of definitive treatment and is preferably performed at diagnosis. CBTs are categorized based upon their involvement with surrounding structures: Shamblin I tumors are small, without encasement of the carotid arteries; Shamblin II tumors partially encase the vessels; and Shamblin III tumors completely encase the vessels. When it comes to operative complications, advanced Shamblin stage is associated with a higher rate of cranial nerve injury when the tumor is resected.1

Pertinent to the technical aspects of surgical resection, CBTs are characteristically encased with an elaborate network of friable vessels which may contribute to significant intraoperative bleeding, especially with resection of larger tumors. The blood supply to CBTs typically originates from the branches of the external carotid artery. These branches may be sacrificed with minimal consequence using preoperative embolization. This common practice is felt by many to facilitate safe resection while minimizing intraoperative blood loss. Although the reduction of blood loss has not been observed universally, there is enough evidence of this in the literature to support the use of selective preoperative embolization. Several embolic agents have been described in this setting, including polyvinyl alcohol particles (150-1000 microns), polymerized glue (n-butyl cyanoacrylate), and more recently, ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx, ev3, Irvine, Calif.). Risks of complications related to CBT embolization in experienced hands are quite low with no adverse events reported in a number of reports describing the technique.2,3

Although embolization is argued to decrease blood loss, its impact on rates of neurologic complications is admittedly insignificant. One might question the added cost of the embolization procedure in the current atmosphere of focus on cost-containment, but this may be defrayed by lower rates of postoperative hematoma and operative times. Although blood loss has been shown to be decreased in a number of reports, translating this to decreased need for transfusion has unfortunately yet to be demonstrated. Until large-volume prospective randomized studies of the outcomes associated with preoperative embolization of CBTs are available, its use should be considered mainly when risks of blood loss are significant in advanced stage tumors and only if the associated complication risks associated with its use can be kept to acceptably low rates. As with other adjunctive procedures whose merit has not yet been convincingly sorted out in the available data, personal experience and preference often play a role in the decision making process we all face. For those who have experienced the added challenge of the meticulous dissection of the CBT in the face of a bloodied field, having such tools as embolization at our fingertips is a reassuring adjunct to be considered.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:64-8S.

2. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2008;1(2):37-41.

3. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1594-97.

4. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:979-89.

5. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;43:457-61.

Too many downsides

As vascular surgeons, we are frequently confronting situations where the “best” approach to a problem is far from established. The evidence to make a clinical decision may simply not exist, and we need to choose a course of therapy based more on personal preference than science. Such is the case with preoperative embolization for the resection of carotid body tumors (CBT).

It has been over 35 years since the technique for preoperative embolization of CBT was described, the aim being reduction in blood loss, decreased operative time, and improved visualization for safer tumor resection. This is based on the fact that most of the arterial supply to these tumors arises from external carotid branches (particularly the ascending pharyngeal), and these that can be safely sacrificed. Although this technique is certainly now a standard part of treatment for many vascular surgeons, the evidence of benefit is certainly not overwhelming, and like all interventions, nothing comes without risks.

So what are the downsides of preoperative embolization? The cost of the procedure itself is not insignificant, in some cases doubling the expense of the intervention. And there can also be organizational issues with coordinating the time in the endovascular suite versus the operating room. In my experience, we have taken patients directly from embolization for the CBT resection, and there are frequently delays and transport issues. Although advocates may claim decreased operative time as a benefit of embolization, this is attained at an overall increase in anesthetic time for the combined procedures. If a day or two separates the procedures, some patients do report the pain or fevers that can accompany any tumor embolization.

While the above may be nuisances, there are serious adverse effects from preoperative embolization as well. A review of 11 studies of preoperative embolization for CBT found a 2.5% rate of complications, including temporary aphasia, vocal cord paralysis, and arterial dissection. Stroke with permanent deficit has also been reported secondary to CBT embolization. Access site hematoma has also been reported as with any catheter-based intervention.

With regards to “selective” preoperative embolization, the literature again offers a mixed bag. Many advocates of embolization rely upon the Shamblin classification for selecting candidates, reserving embolization for Shamblin II and III tumors. However, the extent of carotid involvement is sometimes a surgical diagnosis. Although size of tumor generally correlates with Shamblin class, even smaller tumors can demonstrate arterial wall involvement. Abu-Ghanem provides a succinct review of the uncertainty regarding size, Shamblin class, and the impact these have on cranial nerve injury.2 The bottom line is that there is no data-based algorithm for deciding whom to select for preoperative embolization.

In the absence of compelling data for the use of preoperative embolization, this technique is difficult to recommend. There are undoubtedly cases with giant CBTs where a surgeon will want to take advantage of any preoperative adjuvant therapy that is available. However, for the vast majority of CBTs, the important principles are to stay in the correct plane, identify and protect the nerves at risk, and control the tumor blood supply in a systematic fashion. In the absence of a forthcoming randomized prospective study to evaluate preoperative embolization for CBT resection, I will rely on the wisdom of my mentor, Dr. Wesley Moore. He never utilized preoperative embolization for these cases. At least not that he will admit to me.

References

1. Surgery. 1980;87:459-464.

2. Head Neck. 2016;38:E2386-E2394.

3. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:1081-91.

4. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:942-950.

Preop embolization is safe and effective

To embolize or not to embolize ... that is the question when it comes to the management of carotid body tumors. Carotid body tumors (CBTs) are rare benign neoplasms that are almost always nonfunctional and account for up to 80% of all head and neck paragangliomas. Radiographic characteristics include tumor location at the carotid bifurcation, splaying apart the internal and external carotid arteries. Surgical resection is the mainstay of definitive treatment and is preferably performed at diagnosis. CBTs are categorized based upon their involvement with surrounding structures: Shamblin I tumors are small, without encasement of the carotid arteries; Shamblin II tumors partially encase the vessels; and Shamblin III tumors completely encase the vessels. When it comes to operative complications, advanced Shamblin stage is associated with a higher rate of cranial nerve injury when the tumor is resected.1

Pertinent to the technical aspects of surgical resection, CBTs are characteristically encased with an elaborate network of friable vessels which may contribute to significant intraoperative bleeding, especially with resection of larger tumors. The blood supply to CBTs typically originates from the branches of the external carotid artery. These branches may be sacrificed with minimal consequence using preoperative embolization. This common practice is felt by many to facilitate safe resection while minimizing intraoperative blood loss. Although the reduction of blood loss has not been observed universally, there is enough evidence of this in the literature to support the use of selective preoperative embolization. Several embolic agents have been described in this setting, including polyvinyl alcohol particles (150-1000 microns), polymerized glue (n-butyl cyanoacrylate), and more recently, ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx, ev3, Irvine, Calif.). Risks of complications related to CBT embolization in experienced hands are quite low with no adverse events reported in a number of reports describing the technique.2,3

Although embolization is argued to decrease blood loss, its impact on rates of neurologic complications is admittedly insignificant. One might question the added cost of the embolization procedure in the current atmosphere of focus on cost-containment, but this may be defrayed by lower rates of postoperative hematoma and operative times. Although blood loss has been shown to be decreased in a number of reports, translating this to decreased need for transfusion has unfortunately yet to be demonstrated. Until large-volume prospective randomized studies of the outcomes associated with preoperative embolization of CBTs are available, its use should be considered mainly when risks of blood loss are significant in advanced stage tumors and only if the associated complication risks associated with its use can be kept to acceptably low rates. As with other adjunctive procedures whose merit has not yet been convincingly sorted out in the available data, personal experience and preference often play a role in the decision making process we all face. For those who have experienced the added challenge of the meticulous dissection of the CBT in the face of a bloodied field, having such tools as embolization at our fingertips is a reassuring adjunct to be considered.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:64-8S.

2. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2008;1(2):37-41.

3. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1594-97.

4. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:979-89.

5. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;43:457-61.

Too many downsides

As vascular surgeons, we are frequently confronting situations where the “best” approach to a problem is far from established. The evidence to make a clinical decision may simply not exist, and we need to choose a course of therapy based more on personal preference than science. Such is the case with preoperative embolization for the resection of carotid body tumors (CBT).

It has been over 35 years since the technique for preoperative embolization of CBT was described, the aim being reduction in blood loss, decreased operative time, and improved visualization for safer tumor resection. This is based on the fact that most of the arterial supply to these tumors arises from external carotid branches (particularly the ascending pharyngeal), and these that can be safely sacrificed. Although this technique is certainly now a standard part of treatment for many vascular surgeons, the evidence of benefit is certainly not overwhelming, and like all interventions, nothing comes without risks.

So what are the downsides of preoperative embolization? The cost of the procedure itself is not insignificant, in some cases doubling the expense of the intervention. And there can also be organizational issues with coordinating the time in the endovascular suite versus the operating room. In my experience, we have taken patients directly from embolization for the CBT resection, and there are frequently delays and transport issues. Although advocates may claim decreased operative time as a benefit of embolization, this is attained at an overall increase in anesthetic time for the combined procedures. If a day or two separates the procedures, some patients do report the pain or fevers that can accompany any tumor embolization.

While the above may be nuisances, there are serious adverse effects from preoperative embolization as well. A review of 11 studies of preoperative embolization for CBT found a 2.5% rate of complications, including temporary aphasia, vocal cord paralysis, and arterial dissection. Stroke with permanent deficit has also been reported secondary to CBT embolization. Access site hematoma has also been reported as with any catheter-based intervention.

With regards to “selective” preoperative embolization, the literature again offers a mixed bag. Many advocates of embolization rely upon the Shamblin classification for selecting candidates, reserving embolization for Shamblin II and III tumors. However, the extent of carotid involvement is sometimes a surgical diagnosis. Although size of tumor generally correlates with Shamblin class, even smaller tumors can demonstrate arterial wall involvement. Abu-Ghanem provides a succinct review of the uncertainty regarding size, Shamblin class, and the impact these have on cranial nerve injury.2 The bottom line is that there is no data-based algorithm for deciding whom to select for preoperative embolization.

In the absence of compelling data for the use of preoperative embolization, this technique is difficult to recommend. There are undoubtedly cases with giant CBTs where a surgeon will want to take advantage of any preoperative adjuvant therapy that is available. However, for the vast majority of CBTs, the important principles are to stay in the correct plane, identify and protect the nerves at risk, and control the tumor blood supply in a systematic fashion. In the absence of a forthcoming randomized prospective study to evaluate preoperative embolization for CBT resection, I will rely on the wisdom of my mentor, Dr. Wesley Moore. He never utilized preoperative embolization for these cases. At least not that he will admit to me.

References

1. Surgery. 1980;87:459-464.

2. Head Neck. 2016;38:E2386-E2394.

3. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:1081-91.

4. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:942-950.

Preop embolization is safe and effective

To embolize or not to embolize ... that is the question when it comes to the management of carotid body tumors. Carotid body tumors (CBTs) are rare benign neoplasms that are almost always nonfunctional and account for up to 80% of all head and neck paragangliomas. Radiographic characteristics include tumor location at the carotid bifurcation, splaying apart the internal and external carotid arteries. Surgical resection is the mainstay of definitive treatment and is preferably performed at diagnosis. CBTs are categorized based upon their involvement with surrounding structures: Shamblin I tumors are small, without encasement of the carotid arteries; Shamblin II tumors partially encase the vessels; and Shamblin III tumors completely encase the vessels. When it comes to operative complications, advanced Shamblin stage is associated with a higher rate of cranial nerve injury when the tumor is resected.1

Pertinent to the technical aspects of surgical resection, CBTs are characteristically encased with an elaborate network of friable vessels which may contribute to significant intraoperative bleeding, especially with resection of larger tumors. The blood supply to CBTs typically originates from the branches of the external carotid artery. These branches may be sacrificed with minimal consequence using preoperative embolization. This common practice is felt by many to facilitate safe resection while minimizing intraoperative blood loss. Although the reduction of blood loss has not been observed universally, there is enough evidence of this in the literature to support the use of selective preoperative embolization. Several embolic agents have been described in this setting, including polyvinyl alcohol particles (150-1000 microns), polymerized glue (n-butyl cyanoacrylate), and more recently, ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx, ev3, Irvine, Calif.). Risks of complications related to CBT embolization in experienced hands are quite low with no adverse events reported in a number of reports describing the technique.2,3

Although embolization is argued to decrease blood loss, its impact on rates of neurologic complications is admittedly insignificant. One might question the added cost of the embolization procedure in the current atmosphere of focus on cost-containment, but this may be defrayed by lower rates of postoperative hematoma and operative times. Although blood loss has been shown to be decreased in a number of reports, translating this to decreased need for transfusion has unfortunately yet to be demonstrated. Until large-volume prospective randomized studies of the outcomes associated with preoperative embolization of CBTs are available, its use should be considered mainly when risks of blood loss are significant in advanced stage tumors and only if the associated complication risks associated with its use can be kept to acceptably low rates. As with other adjunctive procedures whose merit has not yet been convincingly sorted out in the available data, personal experience and preference often play a role in the decision making process we all face. For those who have experienced the added challenge of the meticulous dissection of the CBT in the face of a bloodied field, having such tools as embolization at our fingertips is a reassuring adjunct to be considered.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:64-8S.

2. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2008;1(2):37-41.

3. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1594-97.

4. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:979-89.

5. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;43:457-61.

Too many downsides

As vascular surgeons, we are frequently confronting situations where the “best” approach to a problem is far from established. The evidence to make a clinical decision may simply not exist, and we need to choose a course of therapy based more on personal preference than science. Such is the case with preoperative embolization for the resection of carotid body tumors (CBT).

It has been over 35 years since the technique for preoperative embolization of CBT was described, the aim being reduction in blood loss, decreased operative time, and improved visualization for safer tumor resection. This is based on the fact that most of the arterial supply to these tumors arises from external carotid branches (particularly the ascending pharyngeal), and these that can be safely sacrificed. Although this technique is certainly now a standard part of treatment for many vascular surgeons, the evidence of benefit is certainly not overwhelming, and like all interventions, nothing comes without risks.

So what are the downsides of preoperative embolization? The cost of the procedure itself is not insignificant, in some cases doubling the expense of the intervention. And there can also be organizational issues with coordinating the time in the endovascular suite versus the operating room. In my experience, we have taken patients directly from embolization for the CBT resection, and there are frequently delays and transport issues. Although advocates may claim decreased operative time as a benefit of embolization, this is attained at an overall increase in anesthetic time for the combined procedures. If a day or two separates the procedures, some patients do report the pain or fevers that can accompany any tumor embolization.

While the above may be nuisances, there are serious adverse effects from preoperative embolization as well. A review of 11 studies of preoperative embolization for CBT found a 2.5% rate of complications, including temporary aphasia, vocal cord paralysis, and arterial dissection. Stroke with permanent deficit has also been reported secondary to CBT embolization. Access site hematoma has also been reported as with any catheter-based intervention.

With regards to “selective” preoperative embolization, the literature again offers a mixed bag. Many advocates of embolization rely upon the Shamblin classification for selecting candidates, reserving embolization for Shamblin II and III tumors. However, the extent of carotid involvement is sometimes a surgical diagnosis. Although size of tumor generally correlates with Shamblin class, even smaller tumors can demonstrate arterial wall involvement. Abu-Ghanem provides a succinct review of the uncertainty regarding size, Shamblin class, and the impact these have on cranial nerve injury.2 The bottom line is that there is no data-based algorithm for deciding whom to select for preoperative embolization.

In the absence of compelling data for the use of preoperative embolization, this technique is difficult to recommend. There are undoubtedly cases with giant CBTs where a surgeon will want to take advantage of any preoperative adjuvant therapy that is available. However, for the vast majority of CBTs, the important principles are to stay in the correct plane, identify and protect the nerves at risk, and control the tumor blood supply in a systematic fashion. In the absence of a forthcoming randomized prospective study to evaluate preoperative embolization for CBT resection, I will rely on the wisdom of my mentor, Dr. Wesley Moore. He never utilized preoperative embolization for these cases. At least not that he will admit to me.

References

1. Surgery. 1980;87:459-464.

2. Head Neck. 2016;38:E2386-E2394.

3. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:1081-91.

4. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:942-950.

It’s time for us to talk about guns

Studies have shown that most of you already have deep-seated beliefs regarding guns. Some of you would frame the issue as Gun Rights, others as Gun Violence. I am not here to change your opinion. I am not in the habit of wasting my time. Logic has been drained from this discussion and emotion infused. As vascular surgeons, it is far past time to overcome these limitations and join the national discussion. Opinions and consensus statements have already been rendered from the American College of Surgeons, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and even the American College of Phlebology. Where does the SVS stand?

In January 2013, the Board of Directors of the SVS voted to support the ACS Statement on Firearm Injuries. There is virtually no public record of this endorsement, it does not appear on the SVS website and it was essentially ignored by the public.

Even the diligent National Rifle Association (NRA) left the SVS off their list of “National Organizations with Anti-Gun Policies” (Ed note: for more information, see “The Evolution of the NRA and Our Modern Gun Debate” at www.vascularspecialistonline.com).

We need to do better. If we are truly an independent specialty it is time to behave as such. Vascular surgeons are on the front lines of this battle. We have cared for the injured, revived the dying, and bear witness to the dead. To not have a voice and be counted is a disservice to our patients and ourselves.

What can be done to reduce gun violence? In Australia, between 1979 and 1996, there were 13 mass shootings. After a semiautomatic weapon ban was instituted in 1996 there have been none. The U.S. ban on military style weapons lapsed in 2004. While it is difficult to characterize “mass shootings” in a country our size, there certainly seems to be an increase since then. If defined as “four or more shot and/or killed in a single event, at the same general time and location not including the shooter,” then we have seen 275 mass shootings this year as of Oct. 5, 2017.

The other statistics are familiar and sobering. More Americans have died from guns since 1968 than have died in all the wars since our country’s inception. The United States accounts for 91% of gun deaths of children among developed countries. Our casualty figures more closely mirror Somalia and Honduras, not Britain or Germany.

Contemporary, large-scale research in limiting gun violence is essentially nonexistent since a 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded study found a link between keeping a gun in the home with an increased risk of homicide. Quick to respond, Congress passed the 1996 Dickey Amendment that prohibits the CDC from funding efforts that “advocate or promote gun control.” This amendment has been renewed every year despite the author of the bill, Representative Jay Dickey, expressing regret for halting all gun research, stating that was not his intention. Rep. Dickey died earlier this year.

In the U.S., gun laws have actually relaxed over time. In 1988, 18 states had laws allowing civilians to carry concealed hand guns in public places, now this practice is legal in 40 states. In a 2008 landmark decision, the Supreme Court struck down a personal handgun ban in the District of Columbia. The Second Amendment rights afforded to a “well-regulated militia” to “keep and bear arms” were now extended to private individuals. Guns are clearly more prevalent and available in the U.S. than ever before.

The congressional ban on firearms research now extends to all Department of Health and Human Services agencies, including the NIH. We need the Dickey Amendment lifted so we can study the relationship of gun ownership and crime. As physicians, we need to deal from an informed, intelligent position and not an emotional one.

Over 50 medical societies, comprising essentially every physician in the U.S., have released statements on gun violence. The AMA has labeled it a “public health crisis.” The ACS stated, in the aftermath of the Las Vegas shooting, “It is important that the American College of Surgeons, whose Fellows care for the victims of these events, be part of the solution.”

Aside from ethical or moral obligations, why should we dive into this quagmire? Most of us are already represented in the discussion through other groups. The answer lies in our identity. If vascular surgery is to become a truly independent specialty, we can’t hide behind the ACS or the AMA when the politics become sticky.

To protect the 30,000 people who die from aneurysm rupture yearly we literally forced an act of Congress. Where do we stand on the more than 33,000 people who die yearly from gun violence? For vascular surgery to have a true public presence, we must be prepared to enter the most public of all discussions.

Luckily, there is already a pathway to consensus. The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS COT) surveyed its members and found that only 15% had no strong opinions on firearms. Just over 50% felt that guns were important for personal safety and defense, while 30% felt the large number of guns in the U.S. was a threat to safety.

Individuals who felt that firearms were important were most likely to associate guns with personal freedom, while those who felt they were a threat were most likely to associate guns with violence.

To further the discussion, the emotional battle between personal freedom and violence needed to be minimized. In doing so, the ACS COT was able to produce a consensus statement despite the seemingly diametrically opposed opinions of its members.

An independent specialty needs an independent voice. If we don’t know our own position, obviously the public doesn’t either.

As a starting point, here is the ACS Statement on Firearms Injuries:

Because violence inflicted by guns continues to be a daily event in the United States and mass casualties involving firearms threaten the health and safety of the public, the American College of Surgeons supports:

1. Legislation banning civilian access to assault weapons, large ammunition clips, and munitions designed for military and law enforcement agencies.

2. Enhancing mandatory background checks for the purchase of firearms to include gun shows and auctions.

3. Assuring that health care professionals can fulfill their role in preventing firearm injuries by health screening, patient counseling, and referral to mental health services for those with behavioral medical conditions. 4. Developing and promoting proactive programs directed at improving safe gun storage and the teaching of nonviolent conflict resolution for a culture that often glorifies guns and violence in media and gaming.

5. Evidence-based research on firearm injury and the creation of a national firearm injury database to inform federal health policy.

Selected References

1) Gun Violence Research: History of Federal Funding Freeze (www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2013/02/gun-violence.aspx)

2) Childhood Firearm Injuries in the United States (www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2013/02/gun-violence.aspx)

3) Gun Violence Letter to the U.S. House of Representatives (2013) (www.acponline.org/acp_policy/letters/gun_violence_letter_house_2013.pdf)

4) Survey of American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma members on firearm injury: Consensus and opportunities (2016) (www.facs.org).

5) American College of Surgeons Statement on Firearm Injuries (www.facs.org)

Studies have shown that most of you already have deep-seated beliefs regarding guns. Some of you would frame the issue as Gun Rights, others as Gun Violence. I am not here to change your opinion. I am not in the habit of wasting my time. Logic has been drained from this discussion and emotion infused. As vascular surgeons, it is far past time to overcome these limitations and join the national discussion. Opinions and consensus statements have already been rendered from the American College of Surgeons, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and even the American College of Phlebology. Where does the SVS stand?

In January 2013, the Board of Directors of the SVS voted to support the ACS Statement on Firearm Injuries. There is virtually no public record of this endorsement, it does not appear on the SVS website and it was essentially ignored by the public.

Even the diligent National Rifle Association (NRA) left the SVS off their list of “National Organizations with Anti-Gun Policies” (Ed note: for more information, see “The Evolution of the NRA and Our Modern Gun Debate” at www.vascularspecialistonline.com).

We need to do better. If we are truly an independent specialty it is time to behave as such. Vascular surgeons are on the front lines of this battle. We have cared for the injured, revived the dying, and bear witness to the dead. To not have a voice and be counted is a disservice to our patients and ourselves.

What can be done to reduce gun violence? In Australia, between 1979 and 1996, there were 13 mass shootings. After a semiautomatic weapon ban was instituted in 1996 there have been none. The U.S. ban on military style weapons lapsed in 2004. While it is difficult to characterize “mass shootings” in a country our size, there certainly seems to be an increase since then. If defined as “four or more shot and/or killed in a single event, at the same general time and location not including the shooter,” then we have seen 275 mass shootings this year as of Oct. 5, 2017.

The other statistics are familiar and sobering. More Americans have died from guns since 1968 than have died in all the wars since our country’s inception. The United States accounts for 91% of gun deaths of children among developed countries. Our casualty figures more closely mirror Somalia and Honduras, not Britain or Germany.

Contemporary, large-scale research in limiting gun violence is essentially nonexistent since a 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded study found a link between keeping a gun in the home with an increased risk of homicide. Quick to respond, Congress passed the 1996 Dickey Amendment that prohibits the CDC from funding efforts that “advocate or promote gun control.” This amendment has been renewed every year despite the author of the bill, Representative Jay Dickey, expressing regret for halting all gun research, stating that was not his intention. Rep. Dickey died earlier this year.

In the U.S., gun laws have actually relaxed over time. In 1988, 18 states had laws allowing civilians to carry concealed hand guns in public places, now this practice is legal in 40 states. In a 2008 landmark decision, the Supreme Court struck down a personal handgun ban in the District of Columbia. The Second Amendment rights afforded to a “well-regulated militia” to “keep and bear arms” were now extended to private individuals. Guns are clearly more prevalent and available in the U.S. than ever before.

The congressional ban on firearms research now extends to all Department of Health and Human Services agencies, including the NIH. We need the Dickey Amendment lifted so we can study the relationship of gun ownership and crime. As physicians, we need to deal from an informed, intelligent position and not an emotional one.

Over 50 medical societies, comprising essentially every physician in the U.S., have released statements on gun violence. The AMA has labeled it a “public health crisis.” The ACS stated, in the aftermath of the Las Vegas shooting, “It is important that the American College of Surgeons, whose Fellows care for the victims of these events, be part of the solution.”

Aside from ethical or moral obligations, why should we dive into this quagmire? Most of us are already represented in the discussion through other groups. The answer lies in our identity. If vascular surgery is to become a truly independent specialty, we can’t hide behind the ACS or the AMA when the politics become sticky.

To protect the 30,000 people who die from aneurysm rupture yearly we literally forced an act of Congress. Where do we stand on the more than 33,000 people who die yearly from gun violence? For vascular surgery to have a true public presence, we must be prepared to enter the most public of all discussions.

Luckily, there is already a pathway to consensus. The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS COT) surveyed its members and found that only 15% had no strong opinions on firearms. Just over 50% felt that guns were important for personal safety and defense, while 30% felt the large number of guns in the U.S. was a threat to safety.

Individuals who felt that firearms were important were most likely to associate guns with personal freedom, while those who felt they were a threat were most likely to associate guns with violence.

To further the discussion, the emotional battle between personal freedom and violence needed to be minimized. In doing so, the ACS COT was able to produce a consensus statement despite the seemingly diametrically opposed opinions of its members.

An independent specialty needs an independent voice. If we don’t know our own position, obviously the public doesn’t either.

As a starting point, here is the ACS Statement on Firearms Injuries:

Because violence inflicted by guns continues to be a daily event in the United States and mass casualties involving firearms threaten the health and safety of the public, the American College of Surgeons supports:

1. Legislation banning civilian access to assault weapons, large ammunition clips, and munitions designed for military and law enforcement agencies.

2. Enhancing mandatory background checks for the purchase of firearms to include gun shows and auctions.

3. Assuring that health care professionals can fulfill their role in preventing firearm injuries by health screening, patient counseling, and referral to mental health services for those with behavioral medical conditions. 4. Developing and promoting proactive programs directed at improving safe gun storage and the teaching of nonviolent conflict resolution for a culture that often glorifies guns and violence in media and gaming.

5. Evidence-based research on firearm injury and the creation of a national firearm injury database to inform federal health policy.

Selected References

1) Gun Violence Research: History of Federal Funding Freeze (www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2013/02/gun-violence.aspx)

2) Childhood Firearm Injuries in the United States (www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2013/02/gun-violence.aspx)

3) Gun Violence Letter to the U.S. House of Representatives (2013) (www.acponline.org/acp_policy/letters/gun_violence_letter_house_2013.pdf)

4) Survey of American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma members on firearm injury: Consensus and opportunities (2016) (www.facs.org).

5) American College of Surgeons Statement on Firearm Injuries (www.facs.org)

Studies have shown that most of you already have deep-seated beliefs regarding guns. Some of you would frame the issue as Gun Rights, others as Gun Violence. I am not here to change your opinion. I am not in the habit of wasting my time. Logic has been drained from this discussion and emotion infused. As vascular surgeons, it is far past time to overcome these limitations and join the national discussion. Opinions and consensus statements have already been rendered from the American College of Surgeons, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and even the American College of Phlebology. Where does the SVS stand?

In January 2013, the Board of Directors of the SVS voted to support the ACS Statement on Firearm Injuries. There is virtually no public record of this endorsement, it does not appear on the SVS website and it was essentially ignored by the public.

Even the diligent National Rifle Association (NRA) left the SVS off their list of “National Organizations with Anti-Gun Policies” (Ed note: for more information, see “The Evolution of the NRA and Our Modern Gun Debate” at www.vascularspecialistonline.com).

We need to do better. If we are truly an independent specialty it is time to behave as such. Vascular surgeons are on the front lines of this battle. We have cared for the injured, revived the dying, and bear witness to the dead. To not have a voice and be counted is a disservice to our patients and ourselves.

What can be done to reduce gun violence? In Australia, between 1979 and 1996, there were 13 mass shootings. After a semiautomatic weapon ban was instituted in 1996 there have been none. The U.S. ban on military style weapons lapsed in 2004. While it is difficult to characterize “mass shootings” in a country our size, there certainly seems to be an increase since then. If defined as “four or more shot and/or killed in a single event, at the same general time and location not including the shooter,” then we have seen 275 mass shootings this year as of Oct. 5, 2017.

The other statistics are familiar and sobering. More Americans have died from guns since 1968 than have died in all the wars since our country’s inception. The United States accounts for 91% of gun deaths of children among developed countries. Our casualty figures more closely mirror Somalia and Honduras, not Britain or Germany.

Contemporary, large-scale research in limiting gun violence is essentially nonexistent since a 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded study found a link between keeping a gun in the home with an increased risk of homicide. Quick to respond, Congress passed the 1996 Dickey Amendment that prohibits the CDC from funding efforts that “advocate or promote gun control.” This amendment has been renewed every year despite the author of the bill, Representative Jay Dickey, expressing regret for halting all gun research, stating that was not his intention. Rep. Dickey died earlier this year.

In the U.S., gun laws have actually relaxed over time. In 1988, 18 states had laws allowing civilians to carry concealed hand guns in public places, now this practice is legal in 40 states. In a 2008 landmark decision, the Supreme Court struck down a personal handgun ban in the District of Columbia. The Second Amendment rights afforded to a “well-regulated militia” to “keep and bear arms” were now extended to private individuals. Guns are clearly more prevalent and available in the U.S. than ever before.

The congressional ban on firearms research now extends to all Department of Health and Human Services agencies, including the NIH. We need the Dickey Amendment lifted so we can study the relationship of gun ownership and crime. As physicians, we need to deal from an informed, intelligent position and not an emotional one.

Over 50 medical societies, comprising essentially every physician in the U.S., have released statements on gun violence. The AMA has labeled it a “public health crisis.” The ACS stated, in the aftermath of the Las Vegas shooting, “It is important that the American College of Surgeons, whose Fellows care for the victims of these events, be part of the solution.”

Aside from ethical or moral obligations, why should we dive into this quagmire? Most of us are already represented in the discussion through other groups. The answer lies in our identity. If vascular surgery is to become a truly independent specialty, we can’t hide behind the ACS or the AMA when the politics become sticky.

To protect the 30,000 people who die from aneurysm rupture yearly we literally forced an act of Congress. Where do we stand on the more than 33,000 people who die yearly from gun violence? For vascular surgery to have a true public presence, we must be prepared to enter the most public of all discussions.

Luckily, there is already a pathway to consensus. The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS COT) surveyed its members and found that only 15% had no strong opinions on firearms. Just over 50% felt that guns were important for personal safety and defense, while 30% felt the large number of guns in the U.S. was a threat to safety.

Individuals who felt that firearms were important were most likely to associate guns with personal freedom, while those who felt they were a threat were most likely to associate guns with violence.

To further the discussion, the emotional battle between personal freedom and violence needed to be minimized. In doing so, the ACS COT was able to produce a consensus statement despite the seemingly diametrically opposed opinions of its members.

An independent specialty needs an independent voice. If we don’t know our own position, obviously the public doesn’t either.

As a starting point, here is the ACS Statement on Firearms Injuries:

Because violence inflicted by guns continues to be a daily event in the United States and mass casualties involving firearms threaten the health and safety of the public, the American College of Surgeons supports:

1. Legislation banning civilian access to assault weapons, large ammunition clips, and munitions designed for military and law enforcement agencies.

2. Enhancing mandatory background checks for the purchase of firearms to include gun shows and auctions.

3. Assuring that health care professionals can fulfill their role in preventing firearm injuries by health screening, patient counseling, and referral to mental health services for those with behavioral medical conditions. 4. Developing and promoting proactive programs directed at improving safe gun storage and the teaching of nonviolent conflict resolution for a culture that often glorifies guns and violence in media and gaming.

5. Evidence-based research on firearm injury and the creation of a national firearm injury database to inform federal health policy.

Selected References

1) Gun Violence Research: History of Federal Funding Freeze (www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2013/02/gun-violence.aspx)

2) Childhood Firearm Injuries in the United States (www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2013/02/gun-violence.aspx)

3) Gun Violence Letter to the U.S. House of Representatives (2013) (www.acponline.org/acp_policy/letters/gun_violence_letter_house_2013.pdf)

4) Survey of American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma members on firearm injury: Consensus and opportunities (2016) (www.facs.org).

5) American College of Surgeons Statement on Firearm Injuries (www.facs.org)

Open vs. endo repair for ruptured AAA

Open repair should be offered to all patients with rAAA

With the advent of endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms (EVAR), the treatment of elective AAAs was revolutionized. Since ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (rAAAs) carry a higher morbidity and mortality than elective AAA repair the use of EVAR has been advocated for these patients.1 Dr. Aziz contends that EVAR should be utilized in all patients presenting with a rAAA. It is my contention that endovascular repair cannot replace open aneurysm repair in all situations. The best treatment option should be offered taking patient and institutional considerations into account. Forcing a given procedure and trying to “make it work” is not best for the patient.

In a systematic literature review of patients presenting with rAAAs, selection bias regarding treatment choice (EVAR vs. open repair) was found consistently.2 In an effort to show that EVAR is superior to open repair for rAAA, Hinchliffe et al. published a randomized trial that showed no difference in 30-day mortality (53%) in each treatment group.3 The AJAX trial randomized 116 patients and did not show benefit for EVAR with respect to 30-day morbidity or mortality.4 The ECAR trial randomized 107 patients and also failed to show a difference in mortality between EVAR and open techniques for rAAA.5

Determining suitability for EVAR includes assessing diameter of the neck of the aneurysm, angulation, size of iliac arteries, presence of atherosclerotic occlusive disease, presence of accessory renal arteries, and presence of concurrent aneurysms of the iliac arteries.7,8 In the IMPROVE trial, patients were randomized depending on anatomic suitability for EVAR.9 Anatomy was determined by imaging in those patients stable enough to undergo preoperative computed tomography angiogram (CTA). Therefore, given anatomic differences, patients presenting with rAAA were not randomized without significant treatment bias.

A true pararenal or paravisceral rupture certainly elevates the complexity of the case. Open repair can deal with this difficult challenge by adapting additional established techniques to the situation. Although some authors have advocated EVAR for rAAA using snorkels and chimneys, these techniques may not be appropriate in the treatment of rAAA in most institutions.10 These procedures take longer, require considerable experience and resources and are therefore not appropriate in unstable patients. No randomized control trial exists at this time to address superiority of EVAR to open repair in patients with complex anatomy.

Patients presenting with rAAA that have had prior endovascular intervention also pose complex anatomic and technical challenges.11 These patients can present with hemodynamic instability and rupture but now are complicated by having device failure. Salvage using endovascular means may not be possible. The risk of re-intervention with endovascular repair for rAAA is much higher than with open repair.12