User login

The impact of combining human and online supportive resources for prostate cancer patients

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in men. 1 Treatment choices for prostate cancer are perhaps more varied than for many other cancers, with surgery, external beam radiation therapy, and brachytherapy all widely used, a number of adjuvant and nonstandard therapy options available, as well as the possibility of not immediately treating the cancer – the “active surveillance” option.

Biochemical failure rates do not differ between the 3 main treatments,2 but each exposes patients to the risk of side effects, including impotence, incontinence, rectal injury, and operative mortality. Recovery can be gradual and will not always involve a return to baseline functioning.3 Quality-of-life comparisons observed covariate-controlled decreases in varying specific aspects of quality of life for each of the treatments.4

Surgery, brachytherapy, and external beam radiation therapy have each shown advantages over other treatments on at least some specific aspect, but disadvantages on others.4 Ongoing surveillance of a cancer left in place has become a more common option in part because of the disadvantages of traditional treatment and because of the growing recognition that sensitive diagnosis techniques often locate cancers that might not be life threatening. Recent reviews and reasonably long-term trials portray active surveillance as a valid alternative to surgery and radiation in many cases, with little difference in life expectancy and cancer-related quality of life, and possibly some reduction in health system cost.5-7

Prostate cancer patients cope with these uncertainties and decisions in many ways,8 often using multiple coping behaviors,9 but coping almost always includes seeking information and social support, as well as active problem-solving, to make informed treatment decisions consistent with their values.

Unfortunately, prostate patients often do not receive or use needed information. McGregor10 reported that patients were aware of their incomplete understanding of their disease and treatment options. Findings from several studies suggest that patients often perceive that clinicians inform them about the disease and treatment options but then send them home unprepared to deal with such things as incontinence or difficulties with sexual functioning.11

Similarly, previous research demonstrates the benefits of social support for prostate cancer patients who receive it, but also that overall they are underserved.12,13 Male cancer patients are generally far less likely to seek support and health information than are female patients. And when patients with prostate cancer do participate in online cancer support groups, they are more likely to exchange information, whereas breast cancer patients provide support for each other.14

Mentoring

Some responses to these knowledge and support gaps pair newly diagnosed patients with survivors willing to be a guide, coach, and a source of information, as in the American Cancer Society’s (ACS’s) Man-to-Man support groups.15 Peer mentors may have a sophisticated level of understanding from their own experiences with medical literature and the health care system, but this cannot be assumed. Another mentoring model is expert-based, exemplified by the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) cancer information specialist at the Cancer Information Service (CIS) and a similar system at the ACS. These telephone services allow for responsiveness to the caller’s needs, existing knowledge, and the caller’s readiness for information. The CIS specialist can also introduce important information the caller might not have known to ask about.16

However, not all problems presented by callers can be solved in a single conversation. Callers are encouraged to call back with additional questions or when their situation changes, but speaking with the same specialist is not facilitated, so it is hard for a second call to build upon the first. Combining the expertise of the cancer information specialist with the ongoing and proactive contact and support typical of the lay guide/mentor/navigator could be more effective. Here a CIS-trained information specialist called prostate patients multiple times over the intervention period to help them deal with information seeking and interpretation. In a previous study with breast cancer patients, a mentor of this sort improved patient information competence and emotional processing.17

Interactive resources

Online resources allow cancer patients self-paced and self-directed access to information and support anonymously and at any time. However, this can be more complicated than it might at first seem. With the complexities of the prostate cancer diagnosis, the multiple treatment options, and the uncertain but potentially serious effects of the treatments themselves, the amount of potentially relevant information is quite large. Then, because individuals will value differentially the attributes of treatments, their consequences, or even notions of risk and gain, a system must be able to respond appropriately to a range of very different people. Beyond this, as prostate cancer patients move from the shock of a cancer diagnosis to the problems of interpreting its details, to making treatment decisions, to dealing with problems of recovery, and then re-establishing what is a “new normal” for them, an individual’s demands on a system vary as well. Comprehensive and integrated systems of services meet the varying needs of their users at different times and different situations.18,19 The systems approach not only makes it far easier for users to find what they need, it may also encourage them to see connections between physical, emotional, and social aspects of their illness. Versions of the system used in the present study – CHESS, or Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System – have been effective supporting patients with AIDS and breast and lung cancers, and teens with asthma.16,20

Study goals and hypotheses

Given the success of the 2 aforementioned approaches, we wanted to compare how CHESS and ongoing contact with a human cancer information mentor in patients with prostate cancer would affect both several general aspects of quality of life and 1 specific to prostate cancer. We also examined differences in the patients’ information competence, quality of life, and social support. There was no a priori expectation that one intervention would be superior to the other, but any differences found could be important to policy decisions, given their quite-different cost and scalability.

More importantly, the primary hypothesis of the study was that patients with access to both CHESS and a mentor would experience substantially better outcomes than those with access to either intervention alone, because each had the potential to enhance the other’s benefits. For example, a patient could read CHESS material and come to the mentor much better prepared. By referring the user to specific parts of CHESS for basic information, the mentor could use calls to address more complex issues, or help interpret and evaluate difficult issues. In addition, because CHESS provides the mentor information about changes in the patient’s treatments, symptoms, and CHESS use, in the combined condition the cancer information mentor can know much more about the patient than when working alone. We also expected that the mentor would stimulate the kind of diverse use of CHESS services we have found to be most effective

Because both mentoring and CHESS have consistently produced positive quality of life effects on their own, compared to controls, there is no reasonable expectation that negative effects of a combined condition could occur and should be tested for. Thus, the study was powered for 1-tailed significance in the comparison between the combined condition and either intervention alone, a procedure used consistently in previous studies of CHESS components or combined conditions. However, since the research question comparing the 2 interventions alone had no such strong history it was tested 2-tailed.

Methods

Recruitment

Study recruitment was conducted from January 1, 2007 to September 30, 2008 at the University of Wisconsin’s Paul P Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center in Madison, Hartford Hospital’s Helen and Harry Gray Cancer Center in Hartford, Connecticut, and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

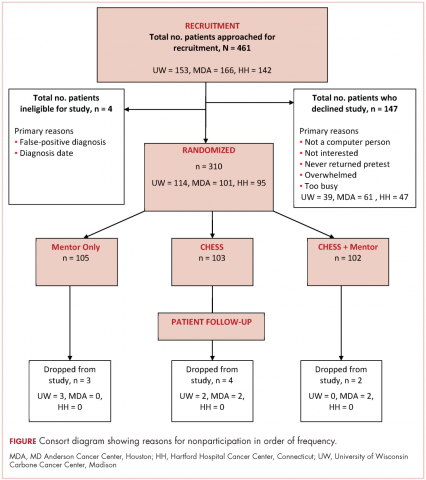

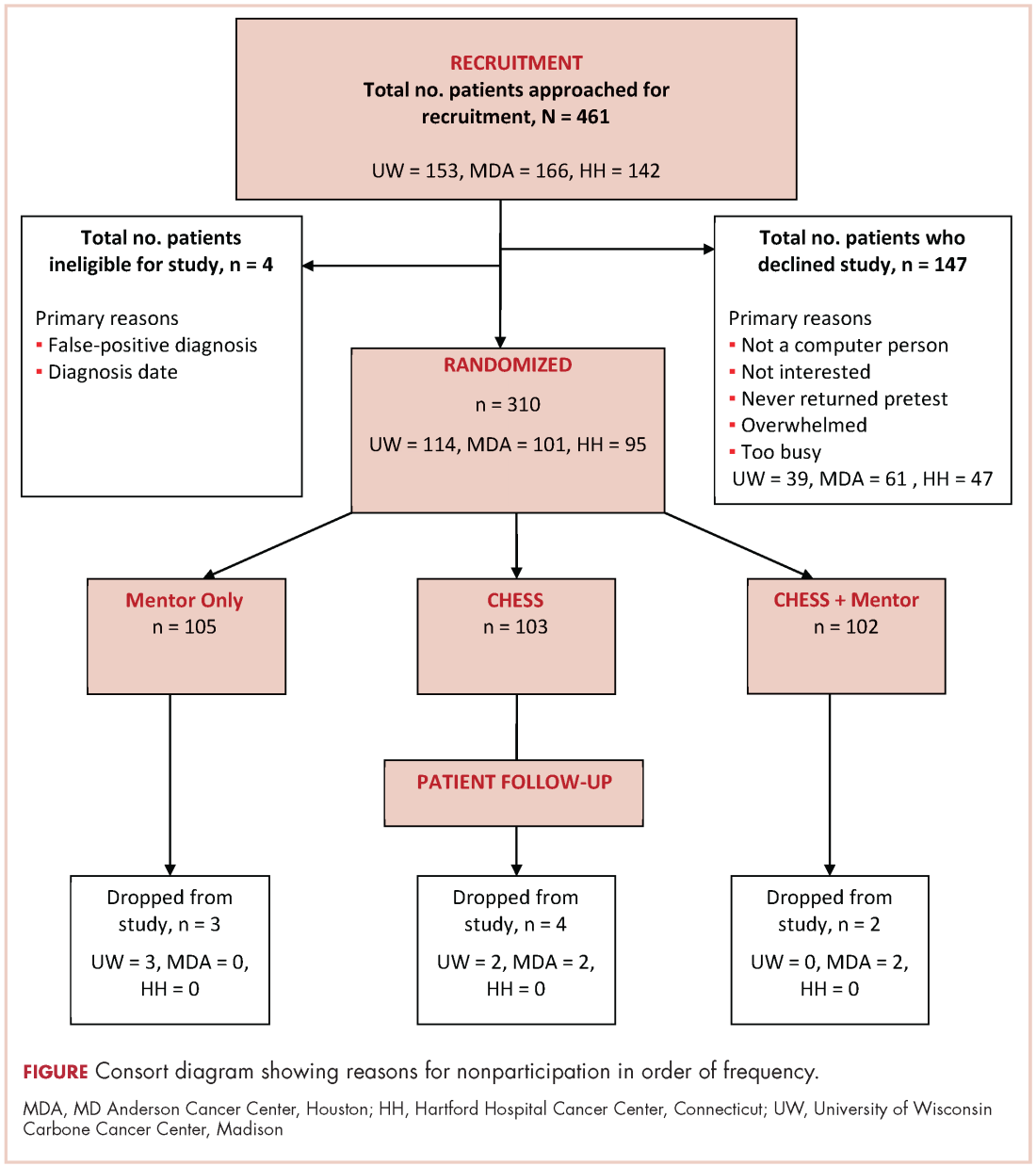

A total of 461 patients were invited to participate in the study. Of those patients, 147 declined to participate, 4 were excluded, and 310 were randomized to access to CHESS only, access to a human mentor only, or access to CHESS and a mentor (CHESS+Mentor) during the 6-month intervention period, which provided adequate power (>.80) for effects of moderate size (Figure 1). Randomization was done with a computer-generated list that site study managers accessed on a patient-by-patient basis, with experimental conditions blocked within sites.

Recruitment was done by posting brochures about the study at the relevant locations and devising standardized recruitment scripts for clinical staff to use when talking to patients about the study. Staff at all sites invited patients they thought might be eligible to learn more about the study. As appropriate, staff members then reviewed informed consent and HIPAA information, explained the interventions, answered patient questions, obtained written consent, collected complete patient contact and computer access information, and provided patients the baseline questionnaires.

The standard inclusion criteria were: men older than 17 years, being able to read and understand English, and being within 2 months of a diagnosis of primary prostate cancer (stage 1 or 2) at the time of recruitment. Despite the 2-month window, few men had begun treatment before pretest. Only 9 of the 310 participants reported having already had surgery (7 prostatectomies, 2 implants), so participants may be fairly characterized as beginning the study in time to benefit from interventions during most stages of their experience with prostate cancer.

Interventions

To provide an equal baseline, all of the participants were given access to the Internet, which is becoming a de facto standard for information access. Internet access charges were paid for all participants during the 6-month intervention period, and computers were loaned to those who did not have a personal computer. All of the participants were offered training on using the computer, particularly with Google search procedures so that they could access resources on prostate cancer.

Participants assigned to the CHESS or CHESS+Mentor conditions were also offered training in using CHESS (basically a guided tour), which typically took about 30 minutes on the telephone but was occasionally done in-person.

CHESS intervention. In creating CHESS for prostate cancer patients, a combination of patient needs assessments, focus groups with patients and family members, and clinician expertise helped us identify the needs, coping mechanisms, and relevant medical information to help patients respond to the disease. An article describing development of the CHESS Prostate Cancer Module22 presents how those different services address patient needs for information, communication, and support, or build skills.

Most of these services were present in CHESS for other diseases, but several were newly created to meet needs of prostate cancer patients and partners, such as a decision map tool and a module on managing sexual problems.22 Also, patients expressed frustration at being overwhelmed by the volume of information and said they would prefer to focus only on what was most relevant, so we created an alternative navigation structure on the CHESS homepage. Using terms suggested by focus groups of prostate cancer survivors and their spouses, we devised a navigation structure called Step-by-Step that identified 6 typical sequential steps of men’s experience with prostate cancer. Clicking on a step would take a patient to a menu focused on actions and considerations specific to that disease step, links to information most relevant at that step, and suggested questions to ask oneself and one’s doctor.

Mentor intervention. The cancer information mentor who made most of the calls to patients was an experienced information specialist with the Cancer Information Service and had served as the expert for the CHESS Ask an Expert service for 6 years. She was highly knowledgeable about prostate cancer and patient information needs. Her additional training for this study focused on taking advantage of repeated contacts with the participants and how to set limits to avoid any semblance of psychological counseling. At recruitment, we made clear that a male mentor was also available if the participant would prefer to discuss sensitive topics with another man. The male mentor was experienced in the Man-to-Man program and received additional training for this role, but he was used for only 1% of all contacts.

During calls, the mentor had Internet access to a range of NCI, ACS, and other resources. She could help interpret information the participant already possessed as well as refer him to other public resources, including those on the Internet. CHESS software designers created an additional interface for the mentor that handled call scheduling and allowed her to record the topics of conversations, her responses and recommendations, and her overall ratings of patient preparedness and satisfaction. Using this interface allowed the mentor to quickly review a participant’s status and focus the conversation on issues raised by past conversations or scheduled treatment events. The mentor calls were audiorecorded and reviewed frequently by the project director during the early months of intervention and less frequently thereafter to ensure adherence to the protocol.

The mentor telephoned weekly during the first month of intervention, then twice during the second month, and once a month during the final 4 months of the intervention (ie, 10 scheduled calls, though patients could also initiate additional calls). Calls were scheduled through a combination of telephone contact and e-mail according to the patient’s preference. Call length ranged from 5 minutes to an hour, with the average about 12 minutes (the first call tended to be considerably longer, and was scheduled for 45 minutes). About 10%-15% of participants in the Mentor conditions initiated calls to the mentor to obtain additional support, and about 15% of scheduled calls in fact took place as e-mail exchanges. A few calls were missed because of scheduling difficulties, and some participants stopped scheduling the last few calls, but the average number of full calls or e-mails was 6.41 per participant.

CHESS+Mentor intervention. For the CHESS+Mentor condition, the interactions and resources used were similar to those of the Mentor-only condition, but the interface also provided the mentor with a summary of the participant’s recent CHESS use and any concerns reported to CHESS, which helped the mentor assess knowledge and make tailored recommendations. The mentor could also refer participants to specific resources within CHESS, aided by knowledge of what parts of CHESS had or had not been used.

Assessment methods

Patients were given surveys at the baseline visit to complete and mail back to research staff before randomization. Follow-up surveys were mailed to patients at 2, 6, 12, and 24 weeks post intervention access, and patients returned the surveys by mail. Patient withdrawal rates were about 3%.

Measures

Outcomes. This study included 4 measures of quality of life (an average of relevant portions of the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life (WHOQOL) measure, Emotional and Functional Well-being, and a prostate-cancer specific index, the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC). We also tested group differences on 5 more specific outcomes that were likely to be proximal rather than distal effects of the interventions: Cancer Information Competence, Health care Competence, Social Support, Bonding (with other patients), and Positive Coping.

Quality of life. Quality of life was measured by combining the psychological, social, and overall dimensions of the WHOQOL measures.23 Each of the 11 items was assessed with a 5-point scale, and the mean of those answers was the overall score.

Emotional well-being. Respondents answered 6 items of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Prostate

Functional well-being. Respondents indicated how often they experienced each of the seven functional well-being subscale items of the FACT-Prostate.24

Prostate cancer patient functioning. We used the EPIC to measure of 3 of 4 domains of prostate cancer patient functioning: urinary, bowel, and sexual (omitting hormonal).25 The EPIC measures frequency and subjective degree of being a problem of several aspects in each domain. We then summed scores across the domains and transformed linearly to a 0-100 scale, with higher scores representing better functioning.

Cancer information competence. Five cancer information competence items, measured on a 5-point scale, assessed a participant’s perception about whether he could find and effectively and use health information, and were summed to create a single score.20

Social support. Six 5-point social support items assessed the informational and emotional support provided by friends, family, coworkers, and others, and were summed to create a single score.20

Health care competence. Five 5-point health care competence items assessed a patient’s comfort and activation level dealing with physicians and health care situations, and were summed to create a single score.20

Positive coping. Coping strategies were measured with the Brief Cope, a shorter version of the original 60-item COPE scale.26 Positive coping strategy, a predictor of positive adaptation in numerous coping contexts, was measured with the mean score of 4 scales (8 items in all): active coping, planning, positive reframing, and humor.

Bonding. Bonding with other prostate cancer patients was measured with five 5-point items about how frequently participants connected with and got information and support from other men with prostate cancer.27

User vs nonuser. Intent-to-treat analyses compared the assigned conditions. However, because CHESS use was self-selected and available at any time whereas mentor calls were scheduled and initiated by another person, the proportion actually using the interventions was quite different.

Since a participant assigned access to CHESS had to select the URL, even a single entry to the system was counted as use. Of 198 participants assigned to either the CHESS or CHESS+Mentor conditions, 43 (22%) never logged in and were classified as nonusers.

Because the mentor scheduled calls and attempted repeatedly to complete scheduled calls, the patient was in a reactive position, and the decision not to use the mentor’s services could come at the earliest at the end of a first completed call. However, after examining call notes and consulting with the mentors, it was clear that opting not to receive mentoring typically occurred at the second call. Furthermore, much (though not all) of the first call was typically taken up with getting acquainted and scheduling issues, so that defining “nonuse” as 2 or fewer completed calls was most faithful to what actually happened. Of 202 participants assigned access to a mentor, 16 (8%) were thus defined as nonusers.

Results

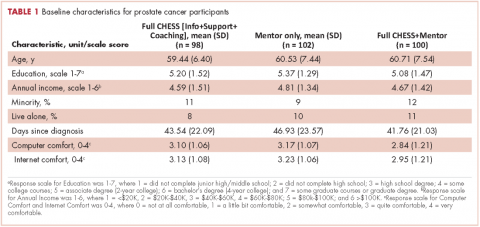

Overall, the participants were about 60 years of age and had some college education and middle-class incomes (Table 1). Only about 10% were minorities or lived alone, and their comfort using computers and the Internet was at or above the “quite comfortable” level. None of groups differed significantly from any other.

The 2 primary hypotheses of the study were that participants in the combined condition would manifest higher outcome scores than those with either intervention alone. Table 2 displays group means at 3 posttest intervals, controlling for theoretically chosen covariates (age, education, and minority status) and pretest levels of the dependent variable. The table also summarizes tests examining the hypotheses and the comparison of CHESS and Mentor conditions. The 4 quality-of-life scores appear first, followed by 5 more specific outcomes that are perhaps more proximal effects of these interventions.

The combined condition scored significantly higher than the CHESS-only condition on functional well-being at 3 months, on positive coping at 6 months, and on bonding at both 6 weeks and 6 months. The combined condition scored significantly higher than Mentor-only on health care competence and positive coping at 6 weeks, and on bonding at 6 months. This represents partial but scattered support for the hypotheses. And some comparisons of the combined condition with the Mentor-only condition showed reversals of the predicted relationship (although only cancer information competence at 3 months would have reached statistical significance in a 2-tailed test).

No directional hypotheses were made for the comparison of the 2 interventions (see Table 2 for the results of 2-tailed tests). Participants in the Mentor condition reported significantly higher functional well-being at 3 months, although there were 5 other comparisons in which the Mentor group scored higher at P < .10, and higher than the CHESS group on 22 of the 27 comparisons. Thus, it seemed that the Mentor condition alone might have been a somewhat stronger intervention than CHESS alone.

Discussion

We used a randomized control design to test whether combining computer-based and human interventions would provide greater benefits to prostate cancer patients than either alone, as previous research had shown for breast cancer patients.18 The computer-based resource was CHESS, a repeatedly evaluated integrated system combining information, social support, and interactive tools to help patients manage their response to disease. The human cancer information mentor intervention combined the expertise of NCI’s Cancer Information Service with the repeated contact more typical of peer mentoring. Previous research with breast cancer patients had shown both interventions to provide greater information, support, and quality-of-life benefits than Internet access alone.14 This study also compared outcomes obtained by the separate CHESS and Mentor conditions, but without predicting a direction of difference.

Tests at 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months after intervention found instances in which prostate cancer patients assigned to the combined CHESS+Mentor condition experienced more positive quality of life or other outcomes than those assigned to CHESS or Mentor alone, but those differences were scattered rather than consistent. In the direct comparisons of the separate CHESS and Mentor conditions, significance was even rarer, but outcome scores tended to be higher in the Mentor condition than in the CHESS condition.

We noted that differential uptake of the 2 interventions (92% for Mentor vs 78% for CHESS) made interpreting the intent-to-treat analyses problematic, as the mentor’s control of the call schedule meant that far more patients in that condition actually received at least some intervention than in the CHESS condition, where patients used or did not use CHESS entirely at their own volition. This could have biased results in several ways, such as by underestimating the efficacy of the CHESS condition alone and thus inflating the contrast between CHESS alone and CHESS+Mentor. Or the combined condition might have been less different than the Mentor-only condition than intended, thus making for a conservative test of that comparison. However, post hoc analyses of only those participants who had actually used their assigned interventions (and this led to some reclassification of those originally assigned to the CHESS+Mentor condition) produced results that were little different than the intent-to-treat analysis.

Thus, although the combined condition produced some small advantages over either intervention alone, these advantages did not live up to expectations or to previous experience with breast cancer patients.17 We expected the mentor to be able to reinforce and help interpret what the participants learned from CHESS and their clinicians, and also to advise and direct these patients to be much more effective users of CHESS and other resources. Similarly, we expected that CHESS would make patients much better prepared for mentoring, so that instead of dealing with routine information matters, the mentor could go into greater detail or deal with more complex issues. Their combined effect should have been much larger than each alone, and that was not the case. Perhaps from the prostate cancer patients’ perspective, the 2 interventions seemed to offer similar resources, and a patient benefitted from one or the other but expected no additional gain from attending to both.

The 2 interventions themselves seemed nearly equally effective. The Mentor intervention was significantly stronger than CHESS in only 1 of 27 tests in the intent-to-treat analysis and 2 in the analysis limited to intervention users.

These results for prostate cancer patients are somewhat weaker than those previously reported with breast cancer patients.17 It is possible that prostate cancer patients (or men in general) are less inclined to seek health information, support, and health self-management than breast cancer patients (or women in general), perhaps becaus

Although these interventions were experienced by prostate cancer patients in their homes in natural and familiar ways, any experimental manipulation must acknowledge possible problems with external validity. More important here, our recruitment procedures may have produced self-selection to enter or not enter the study in 2 ways that limit its applicability. First, although we thought that offering Internet access to all participants would make participation more likely, the most frequent reason men gave in declining to join the study was “not a computer person.” Our participants were certainly very comfortable with computers and the Internet, and most used them frequently even before the study. Second, it seems that, except for their prostate cancer, our sample was healthy in other respects, as indicated by the low number of other health care visits or surgeries/hospitalization they reported (and “overwhelmed” and “too busy,” 2 common reasons for declining study participations could also be coming from men with more comorbidities). Thus, our sample was probably more computer literate and healthier than the general population of prostate cancer patients.

Nonetheless, for policymakers deciding what information and support interventions to put in place for prostate cancer patients (or more generally for other cancer patients as well), these results have 2 implications. First, since the combination of the mentor and CHESS produced only small advantages over either alone, the extra effort of doing both seems clearly unwarranted for prostate cancer patients. The somewhat larger advantage of the combined intervention shown for breast cancer patients in previous studiesmight warrant using the combination in some circumstances, but even that is not clear-cut.

Finding that CHESS and the cancer information mentor separately provided essentially equal benefits might seem to suggest that they can be regarded as alternatives. However, computer-based services can be provided much more cheaply and scaled up far more readily than services dependent on one-on-one contacts by a highly trained professional. This may direct health care decision makers first toward computer-based services.

1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300.

2. Cozzarini C. Low-dose rate brachytherapy, radical prostatectomy, or external-beam radiation therapy for localized prostate carcinoma: The growing dilemma. European Urology. 2011;60(5):894-896.

3. Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250-1261.

4. Ferrer F, Guedea F, Pardo Y, et al. Quality of life impact of treatments for localized prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2013;108(2):306-313.

5. Cooperberg, MR, Carroll, PR, Klotz, L. Active Surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Onc. 2011;29:3669-3676.

6. Hamdy, FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1415-1424.

7. Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1425-37.

8. Lavery JF, Clarke VA. Prostate cancer: patients’ spouses’ coping and marital adjustment. Psychol Health Med. 1999;4(3):289-302.

9. Folkman S, Lazarus R. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J Pers Soc Psycol. 1985;48:150-170.

10. McGregor S. What information patients with localized prostate cancer hear and understand. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;49:273-278.

11. Steginga SK, Occhipinti S, Dunn J, Gardiner RA, Heathcote P, Yaxley J. (2001) The supportive care needs of men with prostate cancer (2000). Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):66-75.

12. Gregoire I, Kalogeropoulos D, Corcos J. The effectiveness of a professionally led support group for men with prostate cancer. Urologic Nurs. 1997;17(2):58-66.

13. Katz D, Koppie T, Wu D, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics and health related quality of life in men attending prostate cancer support groups. J Urol. 2002;168:2092-2096.

14. Klemm P, Hurst M, Dearholt S, Trone S. Gender differences on Internet cancer support groups. Comput Nurs. 1999;17(2):65-72.

15. Gray R, Fitch M, Phillips C, Labrecque M, Fergus K. Managing the impact of illness: the experiences of men with prostate cancer and their spouses. J Health Psychol. 2000;5(4):531-548.

16. Thomsen CA, Ter Maat J. Evaluating the Cancer Information Service: a model for health communications. Part 1. J Health Commun. 1998;3(suppl.):1-13.

17. Hawkins RP, Pingree S, Baker TB, et al. Integrating eHealth with human services for breast cancer patients. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(1):146-154.

18. Strecher V. Internet methods for delivering behavioral and health-related interventions. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;(3):53-76.

19. Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, McTavish F, et al. Internet-based interactive support for cancer patients: Are integrated systems better? J Commun. 2008;58(2):238-257.

20. Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg EW, et al. CHESS: Ten years of research and development in consumer health informatics for broad populations, including the underserved. Int J Med Inform. 2002;65(3):169-177.

21. Han JY, Hawkins RP, Shaw B, Pingree S, McTavish F, Gustafson D. Unraveling uses and effects of an interactive health communication system. J Broadcast Electron Media. 2009;53(1):1-22.

22. Van Bogaert D, Hawkins RP, Pingree S, Jarrard D. The development of an eHealth tool suite for prostate cancer patients and their partners. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(5):202-208.

23. The WHOQOL Group. Development of the WHOQOL: Rationale and current status. Int J Ment Health. 1994;23:24-56.

24. Esper P, Mo F, Chodak G, Sinner M, Cella D, Pienta KJ. Measuring quality of life in men with prostate cancer using the functional assessment of cancer therapy-prostate instrument. Urology. 1997;50:920-928.

25. Wei JT, Dunn R, Litwin M, Sandler H, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56:899-905.

26. Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4: 91-100.

27. Gustafson D, McTavish F, Stengle W, et al. Use and impact of eHealth System by low-income women with breast cancer. J Health Commun. 2005;10(suppl 1):219-234.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in men. 1 Treatment choices for prostate cancer are perhaps more varied than for many other cancers, with surgery, external beam radiation therapy, and brachytherapy all widely used, a number of adjuvant and nonstandard therapy options available, as well as the possibility of not immediately treating the cancer – the “active surveillance” option.

Biochemical failure rates do not differ between the 3 main treatments,2 but each exposes patients to the risk of side effects, including impotence, incontinence, rectal injury, and operative mortality. Recovery can be gradual and will not always involve a return to baseline functioning.3 Quality-of-life comparisons observed covariate-controlled decreases in varying specific aspects of quality of life for each of the treatments.4

Surgery, brachytherapy, and external beam radiation therapy have each shown advantages over other treatments on at least some specific aspect, but disadvantages on others.4 Ongoing surveillance of a cancer left in place has become a more common option in part because of the disadvantages of traditional treatment and because of the growing recognition that sensitive diagnosis techniques often locate cancers that might not be life threatening. Recent reviews and reasonably long-term trials portray active surveillance as a valid alternative to surgery and radiation in many cases, with little difference in life expectancy and cancer-related quality of life, and possibly some reduction in health system cost.5-7

Prostate cancer patients cope with these uncertainties and decisions in many ways,8 often using multiple coping behaviors,9 but coping almost always includes seeking information and social support, as well as active problem-solving, to make informed treatment decisions consistent with their values.

Unfortunately, prostate patients often do not receive or use needed information. McGregor10 reported that patients were aware of their incomplete understanding of their disease and treatment options. Findings from several studies suggest that patients often perceive that clinicians inform them about the disease and treatment options but then send them home unprepared to deal with such things as incontinence or difficulties with sexual functioning.11

Similarly, previous research demonstrates the benefits of social support for prostate cancer patients who receive it, but also that overall they are underserved.12,13 Male cancer patients are generally far less likely to seek support and health information than are female patients. And when patients with prostate cancer do participate in online cancer support groups, they are more likely to exchange information, whereas breast cancer patients provide support for each other.14

Mentoring

Some responses to these knowledge and support gaps pair newly diagnosed patients with survivors willing to be a guide, coach, and a source of information, as in the American Cancer Society’s (ACS’s) Man-to-Man support groups.15 Peer mentors may have a sophisticated level of understanding from their own experiences with medical literature and the health care system, but this cannot be assumed. Another mentoring model is expert-based, exemplified by the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) cancer information specialist at the Cancer Information Service (CIS) and a similar system at the ACS. These telephone services allow for responsiveness to the caller’s needs, existing knowledge, and the caller’s readiness for information. The CIS specialist can also introduce important information the caller might not have known to ask about.16

However, not all problems presented by callers can be solved in a single conversation. Callers are encouraged to call back with additional questions or when their situation changes, but speaking with the same specialist is not facilitated, so it is hard for a second call to build upon the first. Combining the expertise of the cancer information specialist with the ongoing and proactive contact and support typical of the lay guide/mentor/navigator could be more effective. Here a CIS-trained information specialist called prostate patients multiple times over the intervention period to help them deal with information seeking and interpretation. In a previous study with breast cancer patients, a mentor of this sort improved patient information competence and emotional processing.17

Interactive resources

Online resources allow cancer patients self-paced and self-directed access to information and support anonymously and at any time. However, this can be more complicated than it might at first seem. With the complexities of the prostate cancer diagnosis, the multiple treatment options, and the uncertain but potentially serious effects of the treatments themselves, the amount of potentially relevant information is quite large. Then, because individuals will value differentially the attributes of treatments, their consequences, or even notions of risk and gain, a system must be able to respond appropriately to a range of very different people. Beyond this, as prostate cancer patients move from the shock of a cancer diagnosis to the problems of interpreting its details, to making treatment decisions, to dealing with problems of recovery, and then re-establishing what is a “new normal” for them, an individual’s demands on a system vary as well. Comprehensive and integrated systems of services meet the varying needs of their users at different times and different situations.18,19 The systems approach not only makes it far easier for users to find what they need, it may also encourage them to see connections between physical, emotional, and social aspects of their illness. Versions of the system used in the present study – CHESS, or Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System – have been effective supporting patients with AIDS and breast and lung cancers, and teens with asthma.16,20

Study goals and hypotheses

Given the success of the 2 aforementioned approaches, we wanted to compare how CHESS and ongoing contact with a human cancer information mentor in patients with prostate cancer would affect both several general aspects of quality of life and 1 specific to prostate cancer. We also examined differences in the patients’ information competence, quality of life, and social support. There was no a priori expectation that one intervention would be superior to the other, but any differences found could be important to policy decisions, given their quite-different cost and scalability.

More importantly, the primary hypothesis of the study was that patients with access to both CHESS and a mentor would experience substantially better outcomes than those with access to either intervention alone, because each had the potential to enhance the other’s benefits. For example, a patient could read CHESS material and come to the mentor much better prepared. By referring the user to specific parts of CHESS for basic information, the mentor could use calls to address more complex issues, or help interpret and evaluate difficult issues. In addition, because CHESS provides the mentor information about changes in the patient’s treatments, symptoms, and CHESS use, in the combined condition the cancer information mentor can know much more about the patient than when working alone. We also expected that the mentor would stimulate the kind of diverse use of CHESS services we have found to be most effective

Because both mentoring and CHESS have consistently produced positive quality of life effects on their own, compared to controls, there is no reasonable expectation that negative effects of a combined condition could occur and should be tested for. Thus, the study was powered for 1-tailed significance in the comparison between the combined condition and either intervention alone, a procedure used consistently in previous studies of CHESS components or combined conditions. However, since the research question comparing the 2 interventions alone had no such strong history it was tested 2-tailed.

Methods

Recruitment

Study recruitment was conducted from January 1, 2007 to September 30, 2008 at the University of Wisconsin’s Paul P Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center in Madison, Hartford Hospital’s Helen and Harry Gray Cancer Center in Hartford, Connecticut, and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

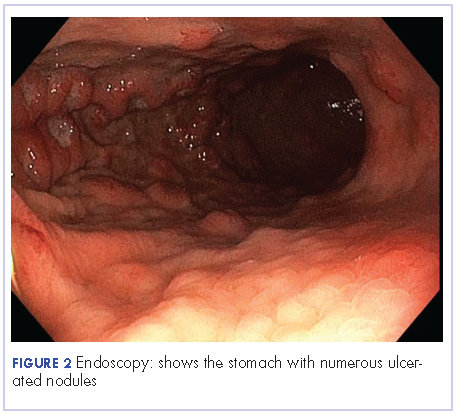

A total of 461 patients were invited to participate in the study. Of those patients, 147 declined to participate, 4 were excluded, and 310 were randomized to access to CHESS only, access to a human mentor only, or access to CHESS and a mentor (CHESS+Mentor) during the 6-month intervention period, which provided adequate power (>.80) for effects of moderate size (Figure 1). Randomization was done with a computer-generated list that site study managers accessed on a patient-by-patient basis, with experimental conditions blocked within sites.

Recruitment was done by posting brochures about the study at the relevant locations and devising standardized recruitment scripts for clinical staff to use when talking to patients about the study. Staff at all sites invited patients they thought might be eligible to learn more about the study. As appropriate, staff members then reviewed informed consent and HIPAA information, explained the interventions, answered patient questions, obtained written consent, collected complete patient contact and computer access information, and provided patients the baseline questionnaires.

The standard inclusion criteria were: men older than 17 years, being able to read and understand English, and being within 2 months of a diagnosis of primary prostate cancer (stage 1 or 2) at the time of recruitment. Despite the 2-month window, few men had begun treatment before pretest. Only 9 of the 310 participants reported having already had surgery (7 prostatectomies, 2 implants), so participants may be fairly characterized as beginning the study in time to benefit from interventions during most stages of their experience with prostate cancer.

Interventions

To provide an equal baseline, all of the participants were given access to the Internet, which is becoming a de facto standard for information access. Internet access charges were paid for all participants during the 6-month intervention period, and computers were loaned to those who did not have a personal computer. All of the participants were offered training on using the computer, particularly with Google search procedures so that they could access resources on prostate cancer.

Participants assigned to the CHESS or CHESS+Mentor conditions were also offered training in using CHESS (basically a guided tour), which typically took about 30 minutes on the telephone but was occasionally done in-person.

CHESS intervention. In creating CHESS for prostate cancer patients, a combination of patient needs assessments, focus groups with patients and family members, and clinician expertise helped us identify the needs, coping mechanisms, and relevant medical information to help patients respond to the disease. An article describing development of the CHESS Prostate Cancer Module22 presents how those different services address patient needs for information, communication, and support, or build skills.

Most of these services were present in CHESS for other diseases, but several were newly created to meet needs of prostate cancer patients and partners, such as a decision map tool and a module on managing sexual problems.22 Also, patients expressed frustration at being overwhelmed by the volume of information and said they would prefer to focus only on what was most relevant, so we created an alternative navigation structure on the CHESS homepage. Using terms suggested by focus groups of prostate cancer survivors and their spouses, we devised a navigation structure called Step-by-Step that identified 6 typical sequential steps of men’s experience with prostate cancer. Clicking on a step would take a patient to a menu focused on actions and considerations specific to that disease step, links to information most relevant at that step, and suggested questions to ask oneself and one’s doctor.

Mentor intervention. The cancer information mentor who made most of the calls to patients was an experienced information specialist with the Cancer Information Service and had served as the expert for the CHESS Ask an Expert service for 6 years. She was highly knowledgeable about prostate cancer and patient information needs. Her additional training for this study focused on taking advantage of repeated contacts with the participants and how to set limits to avoid any semblance of psychological counseling. At recruitment, we made clear that a male mentor was also available if the participant would prefer to discuss sensitive topics with another man. The male mentor was experienced in the Man-to-Man program and received additional training for this role, but he was used for only 1% of all contacts.

During calls, the mentor had Internet access to a range of NCI, ACS, and other resources. She could help interpret information the participant already possessed as well as refer him to other public resources, including those on the Internet. CHESS software designers created an additional interface for the mentor that handled call scheduling and allowed her to record the topics of conversations, her responses and recommendations, and her overall ratings of patient preparedness and satisfaction. Using this interface allowed the mentor to quickly review a participant’s status and focus the conversation on issues raised by past conversations or scheduled treatment events. The mentor calls were audiorecorded and reviewed frequently by the project director during the early months of intervention and less frequently thereafter to ensure adherence to the protocol.

The mentor telephoned weekly during the first month of intervention, then twice during the second month, and once a month during the final 4 months of the intervention (ie, 10 scheduled calls, though patients could also initiate additional calls). Calls were scheduled through a combination of telephone contact and e-mail according to the patient’s preference. Call length ranged from 5 minutes to an hour, with the average about 12 minutes (the first call tended to be considerably longer, and was scheduled for 45 minutes). About 10%-15% of participants in the Mentor conditions initiated calls to the mentor to obtain additional support, and about 15% of scheduled calls in fact took place as e-mail exchanges. A few calls were missed because of scheduling difficulties, and some participants stopped scheduling the last few calls, but the average number of full calls or e-mails was 6.41 per participant.

CHESS+Mentor intervention. For the CHESS+Mentor condition, the interactions and resources used were similar to those of the Mentor-only condition, but the interface also provided the mentor with a summary of the participant’s recent CHESS use and any concerns reported to CHESS, which helped the mentor assess knowledge and make tailored recommendations. The mentor could also refer participants to specific resources within CHESS, aided by knowledge of what parts of CHESS had or had not been used.

Assessment methods

Patients were given surveys at the baseline visit to complete and mail back to research staff before randomization. Follow-up surveys were mailed to patients at 2, 6, 12, and 24 weeks post intervention access, and patients returned the surveys by mail. Patient withdrawal rates were about 3%.

Measures

Outcomes. This study included 4 measures of quality of life (an average of relevant portions of the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life (WHOQOL) measure, Emotional and Functional Well-being, and a prostate-cancer specific index, the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC). We also tested group differences on 5 more specific outcomes that were likely to be proximal rather than distal effects of the interventions: Cancer Information Competence, Health care Competence, Social Support, Bonding (with other patients), and Positive Coping.

Quality of life. Quality of life was measured by combining the psychological, social, and overall dimensions of the WHOQOL measures.23 Each of the 11 items was assessed with a 5-point scale, and the mean of those answers was the overall score.

Emotional well-being. Respondents answered 6 items of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Prostate

Functional well-being. Respondents indicated how often they experienced each of the seven functional well-being subscale items of the FACT-Prostate.24

Prostate cancer patient functioning. We used the EPIC to measure of 3 of 4 domains of prostate cancer patient functioning: urinary, bowel, and sexual (omitting hormonal).25 The EPIC measures frequency and subjective degree of being a problem of several aspects in each domain. We then summed scores across the domains and transformed linearly to a 0-100 scale, with higher scores representing better functioning.

Cancer information competence. Five cancer information competence items, measured on a 5-point scale, assessed a participant’s perception about whether he could find and effectively and use health information, and were summed to create a single score.20

Social support. Six 5-point social support items assessed the informational and emotional support provided by friends, family, coworkers, and others, and were summed to create a single score.20

Health care competence. Five 5-point health care competence items assessed a patient’s comfort and activation level dealing with physicians and health care situations, and were summed to create a single score.20

Positive coping. Coping strategies were measured with the Brief Cope, a shorter version of the original 60-item COPE scale.26 Positive coping strategy, a predictor of positive adaptation in numerous coping contexts, was measured with the mean score of 4 scales (8 items in all): active coping, planning, positive reframing, and humor.

Bonding. Bonding with other prostate cancer patients was measured with five 5-point items about how frequently participants connected with and got information and support from other men with prostate cancer.27

User vs nonuser. Intent-to-treat analyses compared the assigned conditions. However, because CHESS use was self-selected and available at any time whereas mentor calls were scheduled and initiated by another person, the proportion actually using the interventions was quite different.

Since a participant assigned access to CHESS had to select the URL, even a single entry to the system was counted as use. Of 198 participants assigned to either the CHESS or CHESS+Mentor conditions, 43 (22%) never logged in and were classified as nonusers.

Because the mentor scheduled calls and attempted repeatedly to complete scheduled calls, the patient was in a reactive position, and the decision not to use the mentor’s services could come at the earliest at the end of a first completed call. However, after examining call notes and consulting with the mentors, it was clear that opting not to receive mentoring typically occurred at the second call. Furthermore, much (though not all) of the first call was typically taken up with getting acquainted and scheduling issues, so that defining “nonuse” as 2 or fewer completed calls was most faithful to what actually happened. Of 202 participants assigned access to a mentor, 16 (8%) were thus defined as nonusers.

Results

Overall, the participants were about 60 years of age and had some college education and middle-class incomes (Table 1). Only about 10% were minorities or lived alone, and their comfort using computers and the Internet was at or above the “quite comfortable” level. None of groups differed significantly from any other.

The 2 primary hypotheses of the study were that participants in the combined condition would manifest higher outcome scores than those with either intervention alone. Table 2 displays group means at 3 posttest intervals, controlling for theoretically chosen covariates (age, education, and minority status) and pretest levels of the dependent variable. The table also summarizes tests examining the hypotheses and the comparison of CHESS and Mentor conditions. The 4 quality-of-life scores appear first, followed by 5 more specific outcomes that are perhaps more proximal effects of these interventions.

The combined condition scored significantly higher than the CHESS-only condition on functional well-being at 3 months, on positive coping at 6 months, and on bonding at both 6 weeks and 6 months. The combined condition scored significantly higher than Mentor-only on health care competence and positive coping at 6 weeks, and on bonding at 6 months. This represents partial but scattered support for the hypotheses. And some comparisons of the combined condition with the Mentor-only condition showed reversals of the predicted relationship (although only cancer information competence at 3 months would have reached statistical significance in a 2-tailed test).

No directional hypotheses were made for the comparison of the 2 interventions (see Table 2 for the results of 2-tailed tests). Participants in the Mentor condition reported significantly higher functional well-being at 3 months, although there were 5 other comparisons in which the Mentor group scored higher at P < .10, and higher than the CHESS group on 22 of the 27 comparisons. Thus, it seemed that the Mentor condition alone might have been a somewhat stronger intervention than CHESS alone.

Discussion

We used a randomized control design to test whether combining computer-based and human interventions would provide greater benefits to prostate cancer patients than either alone, as previous research had shown for breast cancer patients.18 The computer-based resource was CHESS, a repeatedly evaluated integrated system combining information, social support, and interactive tools to help patients manage their response to disease. The human cancer information mentor intervention combined the expertise of NCI’s Cancer Information Service with the repeated contact more typical of peer mentoring. Previous research with breast cancer patients had shown both interventions to provide greater information, support, and quality-of-life benefits than Internet access alone.14 This study also compared outcomes obtained by the separate CHESS and Mentor conditions, but without predicting a direction of difference.

Tests at 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months after intervention found instances in which prostate cancer patients assigned to the combined CHESS+Mentor condition experienced more positive quality of life or other outcomes than those assigned to CHESS or Mentor alone, but those differences were scattered rather than consistent. In the direct comparisons of the separate CHESS and Mentor conditions, significance was even rarer, but outcome scores tended to be higher in the Mentor condition than in the CHESS condition.

We noted that differential uptake of the 2 interventions (92% for Mentor vs 78% for CHESS) made interpreting the intent-to-treat analyses problematic, as the mentor’s control of the call schedule meant that far more patients in that condition actually received at least some intervention than in the CHESS condition, where patients used or did not use CHESS entirely at their own volition. This could have biased results in several ways, such as by underestimating the efficacy of the CHESS condition alone and thus inflating the contrast between CHESS alone and CHESS+Mentor. Or the combined condition might have been less different than the Mentor-only condition than intended, thus making for a conservative test of that comparison. However, post hoc analyses of only those participants who had actually used their assigned interventions (and this led to some reclassification of those originally assigned to the CHESS+Mentor condition) produced results that were little different than the intent-to-treat analysis.

Thus, although the combined condition produced some small advantages over either intervention alone, these advantages did not live up to expectations or to previous experience with breast cancer patients.17 We expected the mentor to be able to reinforce and help interpret what the participants learned from CHESS and their clinicians, and also to advise and direct these patients to be much more effective users of CHESS and other resources. Similarly, we expected that CHESS would make patients much better prepared for mentoring, so that instead of dealing with routine information matters, the mentor could go into greater detail or deal with more complex issues. Their combined effect should have been much larger than each alone, and that was not the case. Perhaps from the prostate cancer patients’ perspective, the 2 interventions seemed to offer similar resources, and a patient benefitted from one or the other but expected no additional gain from attending to both.

The 2 interventions themselves seemed nearly equally effective. The Mentor intervention was significantly stronger than CHESS in only 1 of 27 tests in the intent-to-treat analysis and 2 in the analysis limited to intervention users.

These results for prostate cancer patients are somewhat weaker than those previously reported with breast cancer patients.17 It is possible that prostate cancer patients (or men in general) are less inclined to seek health information, support, and health self-management than breast cancer patients (or women in general), perhaps becaus

Although these interventions were experienced by prostate cancer patients in their homes in natural and familiar ways, any experimental manipulation must acknowledge possible problems with external validity. More important here, our recruitment procedures may have produced self-selection to enter or not enter the study in 2 ways that limit its applicability. First, although we thought that offering Internet access to all participants would make participation more likely, the most frequent reason men gave in declining to join the study was “not a computer person.” Our participants were certainly very comfortable with computers and the Internet, and most used them frequently even before the study. Second, it seems that, except for their prostate cancer, our sample was healthy in other respects, as indicated by the low number of other health care visits or surgeries/hospitalization they reported (and “overwhelmed” and “too busy,” 2 common reasons for declining study participations could also be coming from men with more comorbidities). Thus, our sample was probably more computer literate and healthier than the general population of prostate cancer patients.

Nonetheless, for policymakers deciding what information and support interventions to put in place for prostate cancer patients (or more generally for other cancer patients as well), these results have 2 implications. First, since the combination of the mentor and CHESS produced only small advantages over either alone, the extra effort of doing both seems clearly unwarranted for prostate cancer patients. The somewhat larger advantage of the combined intervention shown for breast cancer patients in previous studiesmight warrant using the combination in some circumstances, but even that is not clear-cut.

Finding that CHESS and the cancer information mentor separately provided essentially equal benefits might seem to suggest that they can be regarded as alternatives. However, computer-based services can be provided much more cheaply and scaled up far more readily than services dependent on one-on-one contacts by a highly trained professional. This may direct health care decision makers first toward computer-based services.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in men. 1 Treatment choices for prostate cancer are perhaps more varied than for many other cancers, with surgery, external beam radiation therapy, and brachytherapy all widely used, a number of adjuvant and nonstandard therapy options available, as well as the possibility of not immediately treating the cancer – the “active surveillance” option.

Biochemical failure rates do not differ between the 3 main treatments,2 but each exposes patients to the risk of side effects, including impotence, incontinence, rectal injury, and operative mortality. Recovery can be gradual and will not always involve a return to baseline functioning.3 Quality-of-life comparisons observed covariate-controlled decreases in varying specific aspects of quality of life for each of the treatments.4

Surgery, brachytherapy, and external beam radiation therapy have each shown advantages over other treatments on at least some specific aspect, but disadvantages on others.4 Ongoing surveillance of a cancer left in place has become a more common option in part because of the disadvantages of traditional treatment and because of the growing recognition that sensitive diagnosis techniques often locate cancers that might not be life threatening. Recent reviews and reasonably long-term trials portray active surveillance as a valid alternative to surgery and radiation in many cases, with little difference in life expectancy and cancer-related quality of life, and possibly some reduction in health system cost.5-7

Prostate cancer patients cope with these uncertainties and decisions in many ways,8 often using multiple coping behaviors,9 but coping almost always includes seeking information and social support, as well as active problem-solving, to make informed treatment decisions consistent with their values.

Unfortunately, prostate patients often do not receive or use needed information. McGregor10 reported that patients were aware of their incomplete understanding of their disease and treatment options. Findings from several studies suggest that patients often perceive that clinicians inform them about the disease and treatment options but then send them home unprepared to deal with such things as incontinence or difficulties with sexual functioning.11

Similarly, previous research demonstrates the benefits of social support for prostate cancer patients who receive it, but also that overall they are underserved.12,13 Male cancer patients are generally far less likely to seek support and health information than are female patients. And when patients with prostate cancer do participate in online cancer support groups, they are more likely to exchange information, whereas breast cancer patients provide support for each other.14

Mentoring

Some responses to these knowledge and support gaps pair newly diagnosed patients with survivors willing to be a guide, coach, and a source of information, as in the American Cancer Society’s (ACS’s) Man-to-Man support groups.15 Peer mentors may have a sophisticated level of understanding from their own experiences with medical literature and the health care system, but this cannot be assumed. Another mentoring model is expert-based, exemplified by the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) cancer information specialist at the Cancer Information Service (CIS) and a similar system at the ACS. These telephone services allow for responsiveness to the caller’s needs, existing knowledge, and the caller’s readiness for information. The CIS specialist can also introduce important information the caller might not have known to ask about.16

However, not all problems presented by callers can be solved in a single conversation. Callers are encouraged to call back with additional questions or when their situation changes, but speaking with the same specialist is not facilitated, so it is hard for a second call to build upon the first. Combining the expertise of the cancer information specialist with the ongoing and proactive contact and support typical of the lay guide/mentor/navigator could be more effective. Here a CIS-trained information specialist called prostate patients multiple times over the intervention period to help them deal with information seeking and interpretation. In a previous study with breast cancer patients, a mentor of this sort improved patient information competence and emotional processing.17

Interactive resources

Online resources allow cancer patients self-paced and self-directed access to information and support anonymously and at any time. However, this can be more complicated than it might at first seem. With the complexities of the prostate cancer diagnosis, the multiple treatment options, and the uncertain but potentially serious effects of the treatments themselves, the amount of potentially relevant information is quite large. Then, because individuals will value differentially the attributes of treatments, their consequences, or even notions of risk and gain, a system must be able to respond appropriately to a range of very different people. Beyond this, as prostate cancer patients move from the shock of a cancer diagnosis to the problems of interpreting its details, to making treatment decisions, to dealing with problems of recovery, and then re-establishing what is a “new normal” for them, an individual’s demands on a system vary as well. Comprehensive and integrated systems of services meet the varying needs of their users at different times and different situations.18,19 The systems approach not only makes it far easier for users to find what they need, it may also encourage them to see connections between physical, emotional, and social aspects of their illness. Versions of the system used in the present study – CHESS, or Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System – have been effective supporting patients with AIDS and breast and lung cancers, and teens with asthma.16,20

Study goals and hypotheses

Given the success of the 2 aforementioned approaches, we wanted to compare how CHESS and ongoing contact with a human cancer information mentor in patients with prostate cancer would affect both several general aspects of quality of life and 1 specific to prostate cancer. We also examined differences in the patients’ information competence, quality of life, and social support. There was no a priori expectation that one intervention would be superior to the other, but any differences found could be important to policy decisions, given their quite-different cost and scalability.

More importantly, the primary hypothesis of the study was that patients with access to both CHESS and a mentor would experience substantially better outcomes than those with access to either intervention alone, because each had the potential to enhance the other’s benefits. For example, a patient could read CHESS material and come to the mentor much better prepared. By referring the user to specific parts of CHESS for basic information, the mentor could use calls to address more complex issues, or help interpret and evaluate difficult issues. In addition, because CHESS provides the mentor information about changes in the patient’s treatments, symptoms, and CHESS use, in the combined condition the cancer information mentor can know much more about the patient than when working alone. We also expected that the mentor would stimulate the kind of diverse use of CHESS services we have found to be most effective

Because both mentoring and CHESS have consistently produced positive quality of life effects on their own, compared to controls, there is no reasonable expectation that negative effects of a combined condition could occur and should be tested for. Thus, the study was powered for 1-tailed significance in the comparison between the combined condition and either intervention alone, a procedure used consistently in previous studies of CHESS components or combined conditions. However, since the research question comparing the 2 interventions alone had no such strong history it was tested 2-tailed.

Methods

Recruitment

Study recruitment was conducted from January 1, 2007 to September 30, 2008 at the University of Wisconsin’s Paul P Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center in Madison, Hartford Hospital’s Helen and Harry Gray Cancer Center in Hartford, Connecticut, and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A total of 461 patients were invited to participate in the study. Of those patients, 147 declined to participate, 4 were excluded, and 310 were randomized to access to CHESS only, access to a human mentor only, or access to CHESS and a mentor (CHESS+Mentor) during the 6-month intervention period, which provided adequate power (>.80) for effects of moderate size (Figure 1). Randomization was done with a computer-generated list that site study managers accessed on a patient-by-patient basis, with experimental conditions blocked within sites.

Recruitment was done by posting brochures about the study at the relevant locations and devising standardized recruitment scripts for clinical staff to use when talking to patients about the study. Staff at all sites invited patients they thought might be eligible to learn more about the study. As appropriate, staff members then reviewed informed consent and HIPAA information, explained the interventions, answered patient questions, obtained written consent, collected complete patient contact and computer access information, and provided patients the baseline questionnaires.

The standard inclusion criteria were: men older than 17 years, being able to read and understand English, and being within 2 months of a diagnosis of primary prostate cancer (stage 1 or 2) at the time of recruitment. Despite the 2-month window, few men had begun treatment before pretest. Only 9 of the 310 participants reported having already had surgery (7 prostatectomies, 2 implants), so participants may be fairly characterized as beginning the study in time to benefit from interventions during most stages of their experience with prostate cancer.

Interventions

To provide an equal baseline, all of the participants were given access to the Internet, which is becoming a de facto standard for information access. Internet access charges were paid for all participants during the 6-month intervention period, and computers were loaned to those who did not have a personal computer. All of the participants were offered training on using the computer, particularly with Google search procedures so that they could access resources on prostate cancer.

Participants assigned to the CHESS or CHESS+Mentor conditions were also offered training in using CHESS (basically a guided tour), which typically took about 30 minutes on the telephone but was occasionally done in-person.

CHESS intervention. In creating CHESS for prostate cancer patients, a combination of patient needs assessments, focus groups with patients and family members, and clinician expertise helped us identify the needs, coping mechanisms, and relevant medical information to help patients respond to the disease. An article describing development of the CHESS Prostate Cancer Module22 presents how those different services address patient needs for information, communication, and support, or build skills.

Most of these services were present in CHESS for other diseases, but several were newly created to meet needs of prostate cancer patients and partners, such as a decision map tool and a module on managing sexual problems.22 Also, patients expressed frustration at being overwhelmed by the volume of information and said they would prefer to focus only on what was most relevant, so we created an alternative navigation structure on the CHESS homepage. Using terms suggested by focus groups of prostate cancer survivors and their spouses, we devised a navigation structure called Step-by-Step that identified 6 typical sequential steps of men’s experience with prostate cancer. Clicking on a step would take a patient to a menu focused on actions and considerations specific to that disease step, links to information most relevant at that step, and suggested questions to ask oneself and one’s doctor.

Mentor intervention. The cancer information mentor who made most of the calls to patients was an experienced information specialist with the Cancer Information Service and had served as the expert for the CHESS Ask an Expert service for 6 years. She was highly knowledgeable about prostate cancer and patient information needs. Her additional training for this study focused on taking advantage of repeated contacts with the participants and how to set limits to avoid any semblance of psychological counseling. At recruitment, we made clear that a male mentor was also available if the participant would prefer to discuss sensitive topics with another man. The male mentor was experienced in the Man-to-Man program and received additional training for this role, but he was used for only 1% of all contacts.

During calls, the mentor had Internet access to a range of NCI, ACS, and other resources. She could help interpret information the participant already possessed as well as refer him to other public resources, including those on the Internet. CHESS software designers created an additional interface for the mentor that handled call scheduling and allowed her to record the topics of conversations, her responses and recommendations, and her overall ratings of patient preparedness and satisfaction. Using this interface allowed the mentor to quickly review a participant’s status and focus the conversation on issues raised by past conversations or scheduled treatment events. The mentor calls were audiorecorded and reviewed frequently by the project director during the early months of intervention and less frequently thereafter to ensure adherence to the protocol.

The mentor telephoned weekly during the first month of intervention, then twice during the second month, and once a month during the final 4 months of the intervention (ie, 10 scheduled calls, though patients could also initiate additional calls). Calls were scheduled through a combination of telephone contact and e-mail according to the patient’s preference. Call length ranged from 5 minutes to an hour, with the average about 12 minutes (the first call tended to be considerably longer, and was scheduled for 45 minutes). About 10%-15% of participants in the Mentor conditions initiated calls to the mentor to obtain additional support, and about 15% of scheduled calls in fact took place as e-mail exchanges. A few calls were missed because of scheduling difficulties, and some participants stopped scheduling the last few calls, but the average number of full calls or e-mails was 6.41 per participant.

CHESS+Mentor intervention. For the CHESS+Mentor condition, the interactions and resources used were similar to those of the Mentor-only condition, but the interface also provided the mentor with a summary of the participant’s recent CHESS use and any concerns reported to CHESS, which helped the mentor assess knowledge and make tailored recommendations. The mentor could also refer participants to specific resources within CHESS, aided by knowledge of what parts of CHESS had or had not been used.

Assessment methods

Patients were given surveys at the baseline visit to complete and mail back to research staff before randomization. Follow-up surveys were mailed to patients at 2, 6, 12, and 24 weeks post intervention access, and patients returned the surveys by mail. Patient withdrawal rates were about 3%.

Measures

Outcomes. This study included 4 measures of quality of life (an average of relevant portions of the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life (WHOQOL) measure, Emotional and Functional Well-being, and a prostate-cancer specific index, the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC). We also tested group differences on 5 more specific outcomes that were likely to be proximal rather than distal effects of the interventions: Cancer Information Competence, Health care Competence, Social Support, Bonding (with other patients), and Positive Coping.

Quality of life. Quality of life was measured by combining the psychological, social, and overall dimensions of the WHOQOL measures.23 Each of the 11 items was assessed with a 5-point scale, and the mean of those answers was the overall score.

Emotional well-being. Respondents answered 6 items of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Prostate

Functional well-being. Respondents indicated how often they experienced each of the seven functional well-being subscale items of the FACT-Prostate.24

Prostate cancer patient functioning. We used the EPIC to measure of 3 of 4 domains of prostate cancer patient functioning: urinary, bowel, and sexual (omitting hormonal).25 The EPIC measures frequency and subjective degree of being a problem of several aspects in each domain. We then summed scores across the domains and transformed linearly to a 0-100 scale, with higher scores representing better functioning.

Cancer information competence. Five cancer information competence items, measured on a 5-point scale, assessed a participant’s perception about whether he could find and effectively and use health information, and were summed to create a single score.20

Social support. Six 5-point social support items assessed the informational and emotional support provided by friends, family, coworkers, and others, and were summed to create a single score.20

Health care competence. Five 5-point health care competence items assessed a patient’s comfort and activation level dealing with physicians and health care situations, and were summed to create a single score.20

Positive coping. Coping strategies were measured with the Brief Cope, a shorter version of the original 60-item COPE scale.26 Positive coping strategy, a predictor of positive adaptation in numerous coping contexts, was measured with the mean score of 4 scales (8 items in all): active coping, planning, positive reframing, and humor.

Bonding. Bonding with other prostate cancer patients was measured with five 5-point items about how frequently participants connected with and got information and support from other men with prostate cancer.27