User login

Is it time to abandon fasting for routine lipid testing?

Yes. The time has come to change the way we think about fasting before routine lipid testing. We now have robust evidence supporting the routine use of nonfasting lipid testing. Fasting lipid testing is rarely needed, but may be considered for patients with very high triglycerides or before starting treatment in patients with genetic lipid disorders. For most patients, nonfasting lipid testing is appropriate: it is evidence-based, safe, valid, and convenient. More widespread adoption of this strategy by US healthcare providers would improve quality of care and patient and clinician satisfaction.

GUIDELINES HAVE CHANGED

In 2014, the US Department of Veterans Affairs practice guidelines recommended nonfasting lipid testing for cardiovascular risk assessment.1 Other recent clinical guidelines and expert consensus statements from Europe and Canada now also recommend nonfasting lipid testing for most routine clinical evaluations.

Physiologically, we spend most of our lives in the nonfasting state, yet fasting lipid testing was standard practice advocated by earlier clinical guidelines. The rationale for fasting before measuring lipids was to reduce variability and to allow for a more accurate derivation of the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration using the Friedewald formula. There was also concern that an increase in triglyceride concentrations after consuming a fatty meal would reduce the validity of the results. However, numerous studies have found that the increase in plasma triglycerides after normal food intake is much less than that during a fat-tolerance test, making this less of a concern for most patients.2,3

In addition, recent studies suggest that postprandial effects do not diminish and may even strengthen the risk associations of lipids with cardiovascular disease, in particular for triglycerides.4 Moreover, in certain patients, such as those with metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, or certain genetic abnormalities, fasting can mask abnormalities in triglyceride-rich lipid metabolism, which may only be detected when triglycerides are measured in a nonfasting state. Nonfasting measurements may identify patients with elevated residual risk despite optimal guideline-based treatment.

Recently published recommendations for nonfasting lipid testing for routine assessments are summarized in Table 1.1,5–11

EFFECTS OF THE POSTPRANDIAL STATE ON LIPID LEVELS AND RISK ASSESSMENT

A common concern for clinicians who do not routinely order nonfasting lipid testing is the potential variability in lipid levels and interpretation of these values for treatment decisions. But in most circumstances the differences between fasting and nonfasting measurements are small and are not clinically relevant. Differences in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) are negligible; slightly lower levels are seen (up to −8 mg/dL) for nonfasting total cholesterol, LDL-C, and non-HDL-C compared with fasting levels; and differences are modest (up to 25 mg/dL higher) for triglycerides.5 These data should reassure clinicians who rely on lipid levels to guide management decisions.9

Cardiovascular risk assessment

Current algorithms for assessing risk of cardiovascular disease use total cholesterol and HDL-C, not triglycerides or LDL-C. Hence, eating has no effect on the risk estimates.

For clinicians who prefer an absolute lipid target for managing risk in patients on lipid-modifying therapy, a nonfasting LDL-C or non-HDL-C (or apolipoprotein B) may be used. The non-HDL-C level is a better risk marker than LDL-C, particularly in patients with low LDL-C or with triglyceride levels of 200 mg/dL or higher.12 Treatment goals for non-HDL-C are 30 mg/dL higher than for LDL-C (fasting or nonfasting). In addition, for these patients with low LDL-C or high triglycerides, a new LDL-C calculation method has more consistent results for fasting and nonfasting values than the commonly used Friedewald calculation.12

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING NONFASTING LIPID TESTING

The adequacy of nonfasting lipid testing for general screening for cardiovascular disease has been verified in large prospective studies over the past several decades.2,13,14 These studies evaluated cardiovascular event and mortality rates and found consistent associations of nonfasting lipid levels with cardiovascular disease. Studies that included both fasting and nonfasting patient populations found similar or occasionally even greater cardiovascular risk associations for nonfasting lipid measurements (including for LDL-C and triglycerides) compared with fasting lipid measurements.

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration14 reviewed the data from 68 studies in more than 300,000 people and found that the relationship between lipid levels and incident cardiovascular events was just as strong when nonfasting lipid values were used. In fact, at least 3 large statin trials reviewed (a total of 43,000 people) used nonfasting lipids.14

Genetic studies using mendelian randomization have also linked nonfasting triglyceride levels (and remnant cholesterol) to an increased risk of cardiovascular events and of death from any cause.15,16

Therefore, the evidence overall suggests that nonfasting lipid measurements are acceptable with respect to risk assessment, and indeed may be preferred in most instances, especially in patients with an atherogenic metabolic milieu that may otherwise be masked by the fasting state.

OTHER BENEFITS OF NONFASTING LIPID TESTING

Nonfasting lipid panels are more economical and safer for certain groups, such as elderly or diabetic patients. A pilot study17 found that up to 27.1% of patients with diabetes reported experiencing a fasting-evoked hypoglycemic event en route to testing because of fasting for blood work. These events are vastly underreported and add to patient morbidity that can easily be avoided by adopting nonfasting lipid testing.

No study has assessed the cost-effectiveness of fasting vs nonfasting lipid testing. It is common for patients to present for their office appointment without having obtained a fasting lipid panel simply because they forgot to fast and were turned away by the laboratory. Thus, management decisions during the visit are often deferred, and patients must return to the laboratory and reschedule follow-up visits. This is inefficient, increases outpatient waiting times, and also potentially deprives others of access to needed care. Laboratory workflow can also suffer from an influx of early morning visits for fasting tests, decreasing system efficiency. Decreased efficiency in multiple levels of the healthcare system leads to increased costs, burden on healthcare providers, and decreased patient and physician satisfaction.

GETTING WITH THE GUIDELINES

The 2002 National Cholesterol Education Program expert panel report18 and the 2013 joint cholesterol guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association9 both recommended that initial screening should involve fasting lipid testing, but they also allowed measuring nonfasting total cholesterol, HDL-C, and non-HDL-C.18 And internationally, there has been a shift in practice recommendations toward nonfasting lipids over the past 10 years (Table 1).

In 2014, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the UK National Clinical Guideline Centre, and the Joint British Societies said that fasting is no longer needed for routine testing.10 In 2016, the European Atherosclerosis Society and the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine recommended nonfasting lipid testing as the standard of care and provided clinically useful cut points for both fasting and nonfasting lipid measurements.5

In most guidelines, the threshold for elevated nonfasting triglycerides was defined as 175 mg/dL (≥ 2 mmol/L) or greater, and this level has been validated prospectively in a large study of US women.5,19 Repeat measurement of fasting triglycerides may be considered when nonfasting levels are greater than 400 mg/dL,5 although there is no consensus in the guidelines regarding when or if fasting triglycerides should be remeasured. (In the Danish experience,5 only 10% of patients have required repeat fasting values). In addition, the 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines6 removed fasting as a requirement. The 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society dyslipidemia guidelines7 reported that nonfasting lipid testing is a suitable alternative to fasting. Furthermore, the most recent revision of the European Society of Cardiology dyslipidemia guidelines8 acknowledged that nonfasting lipid panels are acceptable for screening and management of patients without severe hypertriglyceridemia or those with extremely low LDL-C levels.

LIMITATIONS OF THE EVIDENCE

To date, no study has assessed the predictive value of fasting vs nonfasting lipid measurements in the same individuals, and there have been no randomized outcomes trials or cost-effectiveness analyses. Ethnic variations in lipoproteins and nonfasting status also need to be investigated as nonfasting lipid testing becomes more universally accepted.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Robust evidence supports the routine use of nonfasting lipid testing, with fasting panels reserved potentially for patients with very high triglycerides and before starting treatment in those with genetic lipid disorders.

- For most patients, nonfasting tests are evidence-based, safe, valid, and convenient.

- More widespread adoption of this strategy by US healthcare providers would improve both quality of care and patient-clinician satisfaction.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines: the management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular risk reduction (lipids). 2014. www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/lipids. Accessed October 18, 2017.

- Langsted A, Freiberg JJ, Nordestgaard BG. Fasting and nonfasting lipid levels: influence of normal food intake on lipids, lipoproteins, apolipoproteins, and cardiovascular risk prediction. Circulation 2008; 118:2047–2056.

- Langsted A, Nordestgaard BG. Nonfasting lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins in individuals with and without diabetes: 58 434 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study. Clin Chem 2011; 57:482–489.

- Rifai N, Young IS, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Nonfasting sample for the determination of routine lipid profile: is it an idea whose time has come? Clin Chem 2016; 62:428–435.

- Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A, Mora S, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) and the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM) joint consensus initiative. Fasting is not routinely required for determination of a lipid profile: clinical and laboratory implications including flagging at desirable concentration cut-points-a joint consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:1944–1958.

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al; CHEP Guidelines Task Force. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2016; 32:569–588.

- Anderson TJ, Gregoire J, Pearson GJ, et al. 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol 2016; 32:1263–1282.

- Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al; Authors/Task Force Members; Additional Contributor. 2016 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:2999–3058.

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129(suppl):S1–S45.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. Clinical guideline CG181. Published July 2014. Updated September 2016. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181. Accessed October 18, 2017.

- Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract 2017; 23(suppl 2):1–87.

- Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Elshazly MB, et al. Friedewald-estimated versus directly measured low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and treatment implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62:732–739.

- Mora S, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Fasting compared with nonfasting lipids and apolipoproteins for predicting incident cardiovascular events. Circulation 2008; 118:993–1001.

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration; Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, Perry P, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA 2009; 302:1993–2000.

- Varbo A, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG. Remnant cholesterol as a causal risk factor for ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:427–436.

- Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg-Hansen A. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:32–41.

- Aldasouqi S, Corser W, Abela G, et al. Fasting for lipid profiles poses a high risk of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes: a pilot prevalence study in clinical practice. Int J Clin Med 2016; 7:1653–1667.

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002; 106:3143–3421.

- White KT, Moorthy MV, Akinkuolie AO, et al. Identifying an optimal cutpoint for the diagnosis of hypertriglyceridemia in the nonfasting state. Clin Chem 2015; 61:1156–1163.

Yes. The time has come to change the way we think about fasting before routine lipid testing. We now have robust evidence supporting the routine use of nonfasting lipid testing. Fasting lipid testing is rarely needed, but may be considered for patients with very high triglycerides or before starting treatment in patients with genetic lipid disorders. For most patients, nonfasting lipid testing is appropriate: it is evidence-based, safe, valid, and convenient. More widespread adoption of this strategy by US healthcare providers would improve quality of care and patient and clinician satisfaction.

GUIDELINES HAVE CHANGED

In 2014, the US Department of Veterans Affairs practice guidelines recommended nonfasting lipid testing for cardiovascular risk assessment.1 Other recent clinical guidelines and expert consensus statements from Europe and Canada now also recommend nonfasting lipid testing for most routine clinical evaluations.

Physiologically, we spend most of our lives in the nonfasting state, yet fasting lipid testing was standard practice advocated by earlier clinical guidelines. The rationale for fasting before measuring lipids was to reduce variability and to allow for a more accurate derivation of the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration using the Friedewald formula. There was also concern that an increase in triglyceride concentrations after consuming a fatty meal would reduce the validity of the results. However, numerous studies have found that the increase in plasma triglycerides after normal food intake is much less than that during a fat-tolerance test, making this less of a concern for most patients.2,3

In addition, recent studies suggest that postprandial effects do not diminish and may even strengthen the risk associations of lipids with cardiovascular disease, in particular for triglycerides.4 Moreover, in certain patients, such as those with metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, or certain genetic abnormalities, fasting can mask abnormalities in triglyceride-rich lipid metabolism, which may only be detected when triglycerides are measured in a nonfasting state. Nonfasting measurements may identify patients with elevated residual risk despite optimal guideline-based treatment.

Recently published recommendations for nonfasting lipid testing for routine assessments are summarized in Table 1.1,5–11

EFFECTS OF THE POSTPRANDIAL STATE ON LIPID LEVELS AND RISK ASSESSMENT

A common concern for clinicians who do not routinely order nonfasting lipid testing is the potential variability in lipid levels and interpretation of these values for treatment decisions. But in most circumstances the differences between fasting and nonfasting measurements are small and are not clinically relevant. Differences in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) are negligible; slightly lower levels are seen (up to −8 mg/dL) for nonfasting total cholesterol, LDL-C, and non-HDL-C compared with fasting levels; and differences are modest (up to 25 mg/dL higher) for triglycerides.5 These data should reassure clinicians who rely on lipid levels to guide management decisions.9

Cardiovascular risk assessment

Current algorithms for assessing risk of cardiovascular disease use total cholesterol and HDL-C, not triglycerides or LDL-C. Hence, eating has no effect on the risk estimates.

For clinicians who prefer an absolute lipid target for managing risk in patients on lipid-modifying therapy, a nonfasting LDL-C or non-HDL-C (or apolipoprotein B) may be used. The non-HDL-C level is a better risk marker than LDL-C, particularly in patients with low LDL-C or with triglyceride levels of 200 mg/dL or higher.12 Treatment goals for non-HDL-C are 30 mg/dL higher than for LDL-C (fasting or nonfasting). In addition, for these patients with low LDL-C or high triglycerides, a new LDL-C calculation method has more consistent results for fasting and nonfasting values than the commonly used Friedewald calculation.12

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING NONFASTING LIPID TESTING

The adequacy of nonfasting lipid testing for general screening for cardiovascular disease has been verified in large prospective studies over the past several decades.2,13,14 These studies evaluated cardiovascular event and mortality rates and found consistent associations of nonfasting lipid levels with cardiovascular disease. Studies that included both fasting and nonfasting patient populations found similar or occasionally even greater cardiovascular risk associations for nonfasting lipid measurements (including for LDL-C and triglycerides) compared with fasting lipid measurements.

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration14 reviewed the data from 68 studies in more than 300,000 people and found that the relationship between lipid levels and incident cardiovascular events was just as strong when nonfasting lipid values were used. In fact, at least 3 large statin trials reviewed (a total of 43,000 people) used nonfasting lipids.14

Genetic studies using mendelian randomization have also linked nonfasting triglyceride levels (and remnant cholesterol) to an increased risk of cardiovascular events and of death from any cause.15,16

Therefore, the evidence overall suggests that nonfasting lipid measurements are acceptable with respect to risk assessment, and indeed may be preferred in most instances, especially in patients with an atherogenic metabolic milieu that may otherwise be masked by the fasting state.

OTHER BENEFITS OF NONFASTING LIPID TESTING

Nonfasting lipid panels are more economical and safer for certain groups, such as elderly or diabetic patients. A pilot study17 found that up to 27.1% of patients with diabetes reported experiencing a fasting-evoked hypoglycemic event en route to testing because of fasting for blood work. These events are vastly underreported and add to patient morbidity that can easily be avoided by adopting nonfasting lipid testing.

No study has assessed the cost-effectiveness of fasting vs nonfasting lipid testing. It is common for patients to present for their office appointment without having obtained a fasting lipid panel simply because they forgot to fast and were turned away by the laboratory. Thus, management decisions during the visit are often deferred, and patients must return to the laboratory and reschedule follow-up visits. This is inefficient, increases outpatient waiting times, and also potentially deprives others of access to needed care. Laboratory workflow can also suffer from an influx of early morning visits for fasting tests, decreasing system efficiency. Decreased efficiency in multiple levels of the healthcare system leads to increased costs, burden on healthcare providers, and decreased patient and physician satisfaction.

GETTING WITH THE GUIDELINES

The 2002 National Cholesterol Education Program expert panel report18 and the 2013 joint cholesterol guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association9 both recommended that initial screening should involve fasting lipid testing, but they also allowed measuring nonfasting total cholesterol, HDL-C, and non-HDL-C.18 And internationally, there has been a shift in practice recommendations toward nonfasting lipids over the past 10 years (Table 1).

In 2014, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the UK National Clinical Guideline Centre, and the Joint British Societies said that fasting is no longer needed for routine testing.10 In 2016, the European Atherosclerosis Society and the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine recommended nonfasting lipid testing as the standard of care and provided clinically useful cut points for both fasting and nonfasting lipid measurements.5

In most guidelines, the threshold for elevated nonfasting triglycerides was defined as 175 mg/dL (≥ 2 mmol/L) or greater, and this level has been validated prospectively in a large study of US women.5,19 Repeat measurement of fasting triglycerides may be considered when nonfasting levels are greater than 400 mg/dL,5 although there is no consensus in the guidelines regarding when or if fasting triglycerides should be remeasured. (In the Danish experience,5 only 10% of patients have required repeat fasting values). In addition, the 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines6 removed fasting as a requirement. The 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society dyslipidemia guidelines7 reported that nonfasting lipid testing is a suitable alternative to fasting. Furthermore, the most recent revision of the European Society of Cardiology dyslipidemia guidelines8 acknowledged that nonfasting lipid panels are acceptable for screening and management of patients without severe hypertriglyceridemia or those with extremely low LDL-C levels.

LIMITATIONS OF THE EVIDENCE

To date, no study has assessed the predictive value of fasting vs nonfasting lipid measurements in the same individuals, and there have been no randomized outcomes trials or cost-effectiveness analyses. Ethnic variations in lipoproteins and nonfasting status also need to be investigated as nonfasting lipid testing becomes more universally accepted.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Robust evidence supports the routine use of nonfasting lipid testing, with fasting panels reserved potentially for patients with very high triglycerides and before starting treatment in those with genetic lipid disorders.

- For most patients, nonfasting tests are evidence-based, safe, valid, and convenient.

- More widespread adoption of this strategy by US healthcare providers would improve both quality of care and patient-clinician satisfaction.

Yes. The time has come to change the way we think about fasting before routine lipid testing. We now have robust evidence supporting the routine use of nonfasting lipid testing. Fasting lipid testing is rarely needed, but may be considered for patients with very high triglycerides or before starting treatment in patients with genetic lipid disorders. For most patients, nonfasting lipid testing is appropriate: it is evidence-based, safe, valid, and convenient. More widespread adoption of this strategy by US healthcare providers would improve quality of care and patient and clinician satisfaction.

GUIDELINES HAVE CHANGED

In 2014, the US Department of Veterans Affairs practice guidelines recommended nonfasting lipid testing for cardiovascular risk assessment.1 Other recent clinical guidelines and expert consensus statements from Europe and Canada now also recommend nonfasting lipid testing for most routine clinical evaluations.

Physiologically, we spend most of our lives in the nonfasting state, yet fasting lipid testing was standard practice advocated by earlier clinical guidelines. The rationale for fasting before measuring lipids was to reduce variability and to allow for a more accurate derivation of the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration using the Friedewald formula. There was also concern that an increase in triglyceride concentrations after consuming a fatty meal would reduce the validity of the results. However, numerous studies have found that the increase in plasma triglycerides after normal food intake is much less than that during a fat-tolerance test, making this less of a concern for most patients.2,3

In addition, recent studies suggest that postprandial effects do not diminish and may even strengthen the risk associations of lipids with cardiovascular disease, in particular for triglycerides.4 Moreover, in certain patients, such as those with metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, or certain genetic abnormalities, fasting can mask abnormalities in triglyceride-rich lipid metabolism, which may only be detected when triglycerides are measured in a nonfasting state. Nonfasting measurements may identify patients with elevated residual risk despite optimal guideline-based treatment.

Recently published recommendations for nonfasting lipid testing for routine assessments are summarized in Table 1.1,5–11

EFFECTS OF THE POSTPRANDIAL STATE ON LIPID LEVELS AND RISK ASSESSMENT

A common concern for clinicians who do not routinely order nonfasting lipid testing is the potential variability in lipid levels and interpretation of these values for treatment decisions. But in most circumstances the differences between fasting and nonfasting measurements are small and are not clinically relevant. Differences in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) are negligible; slightly lower levels are seen (up to −8 mg/dL) for nonfasting total cholesterol, LDL-C, and non-HDL-C compared with fasting levels; and differences are modest (up to 25 mg/dL higher) for triglycerides.5 These data should reassure clinicians who rely on lipid levels to guide management decisions.9

Cardiovascular risk assessment

Current algorithms for assessing risk of cardiovascular disease use total cholesterol and HDL-C, not triglycerides or LDL-C. Hence, eating has no effect on the risk estimates.

For clinicians who prefer an absolute lipid target for managing risk in patients on lipid-modifying therapy, a nonfasting LDL-C or non-HDL-C (or apolipoprotein B) may be used. The non-HDL-C level is a better risk marker than LDL-C, particularly in patients with low LDL-C or with triglyceride levels of 200 mg/dL or higher.12 Treatment goals for non-HDL-C are 30 mg/dL higher than for LDL-C (fasting or nonfasting). In addition, for these patients with low LDL-C or high triglycerides, a new LDL-C calculation method has more consistent results for fasting and nonfasting values than the commonly used Friedewald calculation.12

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING NONFASTING LIPID TESTING

The adequacy of nonfasting lipid testing for general screening for cardiovascular disease has been verified in large prospective studies over the past several decades.2,13,14 These studies evaluated cardiovascular event and mortality rates and found consistent associations of nonfasting lipid levels with cardiovascular disease. Studies that included both fasting and nonfasting patient populations found similar or occasionally even greater cardiovascular risk associations for nonfasting lipid measurements (including for LDL-C and triglycerides) compared with fasting lipid measurements.

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration14 reviewed the data from 68 studies in more than 300,000 people and found that the relationship between lipid levels and incident cardiovascular events was just as strong when nonfasting lipid values were used. In fact, at least 3 large statin trials reviewed (a total of 43,000 people) used nonfasting lipids.14

Genetic studies using mendelian randomization have also linked nonfasting triglyceride levels (and remnant cholesterol) to an increased risk of cardiovascular events and of death from any cause.15,16

Therefore, the evidence overall suggests that nonfasting lipid measurements are acceptable with respect to risk assessment, and indeed may be preferred in most instances, especially in patients with an atherogenic metabolic milieu that may otherwise be masked by the fasting state.

OTHER BENEFITS OF NONFASTING LIPID TESTING

Nonfasting lipid panels are more economical and safer for certain groups, such as elderly or diabetic patients. A pilot study17 found that up to 27.1% of patients with diabetes reported experiencing a fasting-evoked hypoglycemic event en route to testing because of fasting for blood work. These events are vastly underreported and add to patient morbidity that can easily be avoided by adopting nonfasting lipid testing.

No study has assessed the cost-effectiveness of fasting vs nonfasting lipid testing. It is common for patients to present for their office appointment without having obtained a fasting lipid panel simply because they forgot to fast and were turned away by the laboratory. Thus, management decisions during the visit are often deferred, and patients must return to the laboratory and reschedule follow-up visits. This is inefficient, increases outpatient waiting times, and also potentially deprives others of access to needed care. Laboratory workflow can also suffer from an influx of early morning visits for fasting tests, decreasing system efficiency. Decreased efficiency in multiple levels of the healthcare system leads to increased costs, burden on healthcare providers, and decreased patient and physician satisfaction.

GETTING WITH THE GUIDELINES

The 2002 National Cholesterol Education Program expert panel report18 and the 2013 joint cholesterol guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association9 both recommended that initial screening should involve fasting lipid testing, but they also allowed measuring nonfasting total cholesterol, HDL-C, and non-HDL-C.18 And internationally, there has been a shift in practice recommendations toward nonfasting lipids over the past 10 years (Table 1).

In 2014, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the UK National Clinical Guideline Centre, and the Joint British Societies said that fasting is no longer needed for routine testing.10 In 2016, the European Atherosclerosis Society and the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine recommended nonfasting lipid testing as the standard of care and provided clinically useful cut points for both fasting and nonfasting lipid measurements.5

In most guidelines, the threshold for elevated nonfasting triglycerides was defined as 175 mg/dL (≥ 2 mmol/L) or greater, and this level has been validated prospectively in a large study of US women.5,19 Repeat measurement of fasting triglycerides may be considered when nonfasting levels are greater than 400 mg/dL,5 although there is no consensus in the guidelines regarding when or if fasting triglycerides should be remeasured. (In the Danish experience,5 only 10% of patients have required repeat fasting values). In addition, the 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines6 removed fasting as a requirement. The 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society dyslipidemia guidelines7 reported that nonfasting lipid testing is a suitable alternative to fasting. Furthermore, the most recent revision of the European Society of Cardiology dyslipidemia guidelines8 acknowledged that nonfasting lipid panels are acceptable for screening and management of patients without severe hypertriglyceridemia or those with extremely low LDL-C levels.

LIMITATIONS OF THE EVIDENCE

To date, no study has assessed the predictive value of fasting vs nonfasting lipid measurements in the same individuals, and there have been no randomized outcomes trials or cost-effectiveness analyses. Ethnic variations in lipoproteins and nonfasting status also need to be investigated as nonfasting lipid testing becomes more universally accepted.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Robust evidence supports the routine use of nonfasting lipid testing, with fasting panels reserved potentially for patients with very high triglycerides and before starting treatment in those with genetic lipid disorders.

- For most patients, nonfasting tests are evidence-based, safe, valid, and convenient.

- More widespread adoption of this strategy by US healthcare providers would improve both quality of care and patient-clinician satisfaction.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines: the management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular risk reduction (lipids). 2014. www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/lipids. Accessed October 18, 2017.

- Langsted A, Freiberg JJ, Nordestgaard BG. Fasting and nonfasting lipid levels: influence of normal food intake on lipids, lipoproteins, apolipoproteins, and cardiovascular risk prediction. Circulation 2008; 118:2047–2056.

- Langsted A, Nordestgaard BG. Nonfasting lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins in individuals with and without diabetes: 58 434 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study. Clin Chem 2011; 57:482–489.

- Rifai N, Young IS, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Nonfasting sample for the determination of routine lipid profile: is it an idea whose time has come? Clin Chem 2016; 62:428–435.

- Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A, Mora S, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) and the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM) joint consensus initiative. Fasting is not routinely required for determination of a lipid profile: clinical and laboratory implications including flagging at desirable concentration cut-points-a joint consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:1944–1958.

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al; CHEP Guidelines Task Force. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2016; 32:569–588.

- Anderson TJ, Gregoire J, Pearson GJ, et al. 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol 2016; 32:1263–1282.

- Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al; Authors/Task Force Members; Additional Contributor. 2016 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:2999–3058.

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129(suppl):S1–S45.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. Clinical guideline CG181. Published July 2014. Updated September 2016. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181. Accessed October 18, 2017.

- Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract 2017; 23(suppl 2):1–87.

- Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Elshazly MB, et al. Friedewald-estimated versus directly measured low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and treatment implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62:732–739.

- Mora S, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Fasting compared with nonfasting lipids and apolipoproteins for predicting incident cardiovascular events. Circulation 2008; 118:993–1001.

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration; Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, Perry P, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA 2009; 302:1993–2000.

- Varbo A, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG. Remnant cholesterol as a causal risk factor for ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:427–436.

- Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg-Hansen A. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:32–41.

- Aldasouqi S, Corser W, Abela G, et al. Fasting for lipid profiles poses a high risk of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes: a pilot prevalence study in clinical practice. Int J Clin Med 2016; 7:1653–1667.

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002; 106:3143–3421.

- White KT, Moorthy MV, Akinkuolie AO, et al. Identifying an optimal cutpoint for the diagnosis of hypertriglyceridemia in the nonfasting state. Clin Chem 2015; 61:1156–1163.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines: the management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular risk reduction (lipids). 2014. www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/lipids. Accessed October 18, 2017.

- Langsted A, Freiberg JJ, Nordestgaard BG. Fasting and nonfasting lipid levels: influence of normal food intake on lipids, lipoproteins, apolipoproteins, and cardiovascular risk prediction. Circulation 2008; 118:2047–2056.

- Langsted A, Nordestgaard BG. Nonfasting lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins in individuals with and without diabetes: 58 434 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study. Clin Chem 2011; 57:482–489.

- Rifai N, Young IS, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Nonfasting sample for the determination of routine lipid profile: is it an idea whose time has come? Clin Chem 2016; 62:428–435.

- Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A, Mora S, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) and the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM) joint consensus initiative. Fasting is not routinely required for determination of a lipid profile: clinical and laboratory implications including flagging at desirable concentration cut-points-a joint consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:1944–1958.

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al; CHEP Guidelines Task Force. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2016; 32:569–588.

- Anderson TJ, Gregoire J, Pearson GJ, et al. 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol 2016; 32:1263–1282.

- Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al; Authors/Task Force Members; Additional Contributor. 2016 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:2999–3058.

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129(suppl):S1–S45.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. Clinical guideline CG181. Published July 2014. Updated September 2016. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181. Accessed October 18, 2017.

- Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract 2017; 23(suppl 2):1–87.

- Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Elshazly MB, et al. Friedewald-estimated versus directly measured low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and treatment implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62:732–739.

- Mora S, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Fasting compared with nonfasting lipids and apolipoproteins for predicting incident cardiovascular events. Circulation 2008; 118:993–1001.

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration; Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, Perry P, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA 2009; 302:1993–2000.

- Varbo A, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG. Remnant cholesterol as a causal risk factor for ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:427–436.

- Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg-Hansen A. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:32–41.

- Aldasouqi S, Corser W, Abela G, et al. Fasting for lipid profiles poses a high risk of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes: a pilot prevalence study in clinical practice. Int J Clin Med 2016; 7:1653–1667.

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002; 106:3143–3421.

- White KT, Moorthy MV, Akinkuolie AO, et al. Identifying an optimal cutpoint for the diagnosis of hypertriglyceridemia in the nonfasting state. Clin Chem 2015; 61:1156–1163.

It’s time to consider pharmacotherapy for obesity

The article in this issue by Bersoux et al on pharmacotherapy to manage obesity1 is apropos in light of a recent study2 showing that patients are filling 15 times more prescriptions for antidiabetic medications (excluding insulin) than for antiobesity drugs. What makes this finding significant is that nearly 3 times more adults meet the criteria for use of antiobesity drugs than for antidiabetic drugs—116 million vs 30 million, respectively.

This underuse of antiobesity medications has been noted in other studies. In 1 study,3 only about 2% of adults eligible for weight-loss drug therapy received a prescription. Conversely, about 86% of adults diagnosed with diabetes received antidiabetic medications.3

WEIGHT LOSS: IT'S IMPORTANT

This underuse of weight-loss drugs occurs despite our understanding that obesity is a risk factor for developing diabetes and that weight loss in obese patients reduces the risk.

The landmark Diabetes Prevention Program study found that even modest weight loss of 7% reduced the risk of developing diabetes by 58% in overweight and prediabetic individuals.4 Additionally, a 5% to 10% weight loss can lead to significant improvements in many comorbidities, including diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, sleep apnea, and fatty liver disease.

Antiobesity medications can help patients achieve weight-loss goals, especially if lifestyle and behavioral modifications alone have been unsuccessful. Data show that these drugs result in an average weight loss of 5% to 15% when added to diet and exercise.

BARRIERS TO PRESCRIBING WEIGHT-LOSS DRUGS

Why are practitioners reluctant to prescribe these drugs despite the worsening obesity epidemic and despite knowing that obesity is a risk factor for diabetes? Many of us who practice obesity medicine believe there are several reasons.

One barrier is the misconception that obesity does not warrant treatment with weight-loss medications, even though most practitioners will readily admit that patients cannot achieve effective, durable, and meaningful weight loss with behavioral changes and lifestyle modifications alone.

Other barriers stem from issues such as time constraints in the office, lack of training to treat this condition, and not enough data on the newer chronic weight-loss medications. And there are stringent requirements for patient follow-up once a medication has been initiated. Finally, it’s often difficult to obtain insurance coverage.

Addressing the barriers

Of these, I believe the biggest barrier for busy practitioners is finding the time and effort they need to devote to prescribing weight-loss medications. There are ways to address these issues.

Regarding time constraints, practitioners can discuss weight loss at follow-up visits and refer patients to obesity specialists. Regarding gaps in training and knowledge of obesity management, there are consensus guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and treatment of the overweight or obese individual.5–7 Guidelines provide extensive information on the pharmacologic treatment of obesity. These resources provide valuable evidence-based recommendations on how to manage this chronic disease.

ARMED WITH INFORMATION, PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

Bersoux et al provide another valuable resource for clinical use of weight-loss drugs.1 They accurately review the available medications, their mechanisms of action, dosing, efficacy, side effect profiles, and clinical indications. Their review is comprehensive in every aspect of this drug class.

This is important information for practitioners to have when considering prescribing antiobesity medications. It is especially important for primary care practitioners because of the large number of obese or overweight patients they treat.

Drug options have expanded

We did not always have this many drugs to choose from. As Bersoux et al note, practitioners had limited options for weight-loss medications during the 1990s and early 2000s, and several of those had to be taken off the market because of serious side effects. Then between 2012 and 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved 4 new medications, giving us a total of 6 weight-loss drugs. Those approvals greatly increased the available drug treatments, giving us much-needed options beyond lifestyle and behavioral modifications.

Although it is widely accepted that antiobesity drugs are underused, the study by Thomas et al was the first to quantify the extent of underuse, especially for the newer chronic weight-loss drugs.2 Their data show that only about 19% of antiobesity prescriptions were for the newer drugs while 74% were for the older but short-term medication phentermine.

Bersoux et al seem to encourage primary care physicians, or anyone caring for overweight or obese patients, to consider prescribing these treatments if nonpharmacologic options are unsuccessful. I agree with this concept because there are not enough specialists to care for the more than 116 million individuals who are potential candidates for antiobesity medications.

THE TIME HAS COME

This new class of medications has been strongly endorsed by the most prestigious organizations and societies involved in developing treatment guidelines for the overweight or obese patient. It is time for everyone who sees overweight or obese patients in daily practice to consider adopting chronic weight-loss medications as adjunctive therapy if lifestyle and behavioral strategies are ineffective.

- Bersoux S, Byun TH, Chaliki SS, Poole KJ Jr. Pharmacotherapy for obesity: what you need to know. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:951–958.

- Thomas CE, Mauer EA, Shukla AP, Rathi S, Aronne LJ. Low adoption of weight loss medications: a comparison of prescribing patterns of antiobesity pharmacotherapies and SGLT2s. Obesity 2016; 24:1955–1961.

- Samaranayake NR, Ong KL, Leung RY, Cheung BM. Management of obesity in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2007–2008. Ann Epidemiol 2012; 22:349–353.

- Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al; for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009; 374:1677–1686.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2985–3023.

- American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. AACE/ACE algorithm for the medical care of patients with obesity.

https://www.aace.com/files/final-appendix.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- Obesity Medicine Association. Obesity algorithm: 2016-2017.

https://obesitymedicine.org/obesity-algorithm/. Accessed October 3, 2017.

The article in this issue by Bersoux et al on pharmacotherapy to manage obesity1 is apropos in light of a recent study2 showing that patients are filling 15 times more prescriptions for antidiabetic medications (excluding insulin) than for antiobesity drugs. What makes this finding significant is that nearly 3 times more adults meet the criteria for use of antiobesity drugs than for antidiabetic drugs—116 million vs 30 million, respectively.

This underuse of antiobesity medications has been noted in other studies. In 1 study,3 only about 2% of adults eligible for weight-loss drug therapy received a prescription. Conversely, about 86% of adults diagnosed with diabetes received antidiabetic medications.3

WEIGHT LOSS: IT'S IMPORTANT

This underuse of weight-loss drugs occurs despite our understanding that obesity is a risk factor for developing diabetes and that weight loss in obese patients reduces the risk.

The landmark Diabetes Prevention Program study found that even modest weight loss of 7% reduced the risk of developing diabetes by 58% in overweight and prediabetic individuals.4 Additionally, a 5% to 10% weight loss can lead to significant improvements in many comorbidities, including diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, sleep apnea, and fatty liver disease.

Antiobesity medications can help patients achieve weight-loss goals, especially if lifestyle and behavioral modifications alone have been unsuccessful. Data show that these drugs result in an average weight loss of 5% to 15% when added to diet and exercise.

BARRIERS TO PRESCRIBING WEIGHT-LOSS DRUGS

Why are practitioners reluctant to prescribe these drugs despite the worsening obesity epidemic and despite knowing that obesity is a risk factor for diabetes? Many of us who practice obesity medicine believe there are several reasons.

One barrier is the misconception that obesity does not warrant treatment with weight-loss medications, even though most practitioners will readily admit that patients cannot achieve effective, durable, and meaningful weight loss with behavioral changes and lifestyle modifications alone.

Other barriers stem from issues such as time constraints in the office, lack of training to treat this condition, and not enough data on the newer chronic weight-loss medications. And there are stringent requirements for patient follow-up once a medication has been initiated. Finally, it’s often difficult to obtain insurance coverage.

Addressing the barriers

Of these, I believe the biggest barrier for busy practitioners is finding the time and effort they need to devote to prescribing weight-loss medications. There are ways to address these issues.

Regarding time constraints, practitioners can discuss weight loss at follow-up visits and refer patients to obesity specialists. Regarding gaps in training and knowledge of obesity management, there are consensus guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and treatment of the overweight or obese individual.5–7 Guidelines provide extensive information on the pharmacologic treatment of obesity. These resources provide valuable evidence-based recommendations on how to manage this chronic disease.

ARMED WITH INFORMATION, PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

Bersoux et al provide another valuable resource for clinical use of weight-loss drugs.1 They accurately review the available medications, their mechanisms of action, dosing, efficacy, side effect profiles, and clinical indications. Their review is comprehensive in every aspect of this drug class.

This is important information for practitioners to have when considering prescribing antiobesity medications. It is especially important for primary care practitioners because of the large number of obese or overweight patients they treat.

Drug options have expanded

We did not always have this many drugs to choose from. As Bersoux et al note, practitioners had limited options for weight-loss medications during the 1990s and early 2000s, and several of those had to be taken off the market because of serious side effects. Then between 2012 and 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved 4 new medications, giving us a total of 6 weight-loss drugs. Those approvals greatly increased the available drug treatments, giving us much-needed options beyond lifestyle and behavioral modifications.

Although it is widely accepted that antiobesity drugs are underused, the study by Thomas et al was the first to quantify the extent of underuse, especially for the newer chronic weight-loss drugs.2 Their data show that only about 19% of antiobesity prescriptions were for the newer drugs while 74% were for the older but short-term medication phentermine.

Bersoux et al seem to encourage primary care physicians, or anyone caring for overweight or obese patients, to consider prescribing these treatments if nonpharmacologic options are unsuccessful. I agree with this concept because there are not enough specialists to care for the more than 116 million individuals who are potential candidates for antiobesity medications.

THE TIME HAS COME

This new class of medications has been strongly endorsed by the most prestigious organizations and societies involved in developing treatment guidelines for the overweight or obese patient. It is time for everyone who sees overweight or obese patients in daily practice to consider adopting chronic weight-loss medications as adjunctive therapy if lifestyle and behavioral strategies are ineffective.

The article in this issue by Bersoux et al on pharmacotherapy to manage obesity1 is apropos in light of a recent study2 showing that patients are filling 15 times more prescriptions for antidiabetic medications (excluding insulin) than for antiobesity drugs. What makes this finding significant is that nearly 3 times more adults meet the criteria for use of antiobesity drugs than for antidiabetic drugs—116 million vs 30 million, respectively.

This underuse of antiobesity medications has been noted in other studies. In 1 study,3 only about 2% of adults eligible for weight-loss drug therapy received a prescription. Conversely, about 86% of adults diagnosed with diabetes received antidiabetic medications.3

WEIGHT LOSS: IT'S IMPORTANT

This underuse of weight-loss drugs occurs despite our understanding that obesity is a risk factor for developing diabetes and that weight loss in obese patients reduces the risk.

The landmark Diabetes Prevention Program study found that even modest weight loss of 7% reduced the risk of developing diabetes by 58% in overweight and prediabetic individuals.4 Additionally, a 5% to 10% weight loss can lead to significant improvements in many comorbidities, including diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, sleep apnea, and fatty liver disease.

Antiobesity medications can help patients achieve weight-loss goals, especially if lifestyle and behavioral modifications alone have been unsuccessful. Data show that these drugs result in an average weight loss of 5% to 15% when added to diet and exercise.

BARRIERS TO PRESCRIBING WEIGHT-LOSS DRUGS

Why are practitioners reluctant to prescribe these drugs despite the worsening obesity epidemic and despite knowing that obesity is a risk factor for diabetes? Many of us who practice obesity medicine believe there are several reasons.

One barrier is the misconception that obesity does not warrant treatment with weight-loss medications, even though most practitioners will readily admit that patients cannot achieve effective, durable, and meaningful weight loss with behavioral changes and lifestyle modifications alone.

Other barriers stem from issues such as time constraints in the office, lack of training to treat this condition, and not enough data on the newer chronic weight-loss medications. And there are stringent requirements for patient follow-up once a medication has been initiated. Finally, it’s often difficult to obtain insurance coverage.

Addressing the barriers

Of these, I believe the biggest barrier for busy practitioners is finding the time and effort they need to devote to prescribing weight-loss medications. There are ways to address these issues.

Regarding time constraints, practitioners can discuss weight loss at follow-up visits and refer patients to obesity specialists. Regarding gaps in training and knowledge of obesity management, there are consensus guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and treatment of the overweight or obese individual.5–7 Guidelines provide extensive information on the pharmacologic treatment of obesity. These resources provide valuable evidence-based recommendations on how to manage this chronic disease.

ARMED WITH INFORMATION, PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

Bersoux et al provide another valuable resource for clinical use of weight-loss drugs.1 They accurately review the available medications, their mechanisms of action, dosing, efficacy, side effect profiles, and clinical indications. Their review is comprehensive in every aspect of this drug class.

This is important information for practitioners to have when considering prescribing antiobesity medications. It is especially important for primary care practitioners because of the large number of obese or overweight patients they treat.

Drug options have expanded

We did not always have this many drugs to choose from. As Bersoux et al note, practitioners had limited options for weight-loss medications during the 1990s and early 2000s, and several of those had to be taken off the market because of serious side effects. Then between 2012 and 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved 4 new medications, giving us a total of 6 weight-loss drugs. Those approvals greatly increased the available drug treatments, giving us much-needed options beyond lifestyle and behavioral modifications.

Although it is widely accepted that antiobesity drugs are underused, the study by Thomas et al was the first to quantify the extent of underuse, especially for the newer chronic weight-loss drugs.2 Their data show that only about 19% of antiobesity prescriptions were for the newer drugs while 74% were for the older but short-term medication phentermine.

Bersoux et al seem to encourage primary care physicians, or anyone caring for overweight or obese patients, to consider prescribing these treatments if nonpharmacologic options are unsuccessful. I agree with this concept because there are not enough specialists to care for the more than 116 million individuals who are potential candidates for antiobesity medications.

THE TIME HAS COME

This new class of medications has been strongly endorsed by the most prestigious organizations and societies involved in developing treatment guidelines for the overweight or obese patient. It is time for everyone who sees overweight or obese patients in daily practice to consider adopting chronic weight-loss medications as adjunctive therapy if lifestyle and behavioral strategies are ineffective.

- Bersoux S, Byun TH, Chaliki SS, Poole KJ Jr. Pharmacotherapy for obesity: what you need to know. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:951–958.

- Thomas CE, Mauer EA, Shukla AP, Rathi S, Aronne LJ. Low adoption of weight loss medications: a comparison of prescribing patterns of antiobesity pharmacotherapies and SGLT2s. Obesity 2016; 24:1955–1961.

- Samaranayake NR, Ong KL, Leung RY, Cheung BM. Management of obesity in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2007–2008. Ann Epidemiol 2012; 22:349–353.

- Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al; for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009; 374:1677–1686.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2985–3023.

- American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. AACE/ACE algorithm for the medical care of patients with obesity.

https://www.aace.com/files/final-appendix.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- Obesity Medicine Association. Obesity algorithm: 2016-2017.

https://obesitymedicine.org/obesity-algorithm/. Accessed October 3, 2017.

- Bersoux S, Byun TH, Chaliki SS, Poole KJ Jr. Pharmacotherapy for obesity: what you need to know. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:951–958.

- Thomas CE, Mauer EA, Shukla AP, Rathi S, Aronne LJ. Low adoption of weight loss medications: a comparison of prescribing patterns of antiobesity pharmacotherapies and SGLT2s. Obesity 2016; 24:1955–1961.

- Samaranayake NR, Ong KL, Leung RY, Cheung BM. Management of obesity in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2007–2008. Ann Epidemiol 2012; 22:349–353.

- Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al; for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009; 374:1677–1686.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2985–3023.

- American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. AACE/ACE algorithm for the medical care of patients with obesity.

https://www.aace.com/files/final-appendix.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- Obesity Medicine Association. Obesity algorithm: 2016-2017.

https://obesitymedicine.org/obesity-algorithm/. Accessed October 3, 2017.

To have not and then to have: A challenging immune paradox

The successful interplay between the host defense system and infectious invaders depends on controlling the tissue damage that ensues from both the infection and the resultant inflammatory response. Even though an underactive immune system predisposes to unusual and potentially severe infections, an overly vigorous host response to infection can be as destructive as the infection itself. We can improve the outcome of some infections by introducing potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapy concurrent with appropriate anti-infective therapy. What initially seemed counterintuitive has become the standard of care in the treatment of bacterial and mycobacterial meningitis and severe Pneumocystis and bacterial pneumonias, and favorable data are accruing in other infections such as bacterial arthritis.

A twist on the above scenario can occur when an immunosuppressed patient with a partially controlled indolent infection has his or her immune system suddenly normalized due to successful treatment of the underlying cause of their immunodeficiency. This treatment may be the introduction of successful antiretroviral therapy against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), effective therapy of an immunosuppressing infection like tuberculosis, or withdrawal of an immunosuppressive anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drug. In this scenario, where the immune system is rapidly reconstituted and concurrently activated by the presence of persistent antigenic challenge or immunostimulatory molecules, a vigorous and clinically counterproductive inflammatory response may ensue, causing “collateral damage” to normal tissue. This immune reactivation syndrome may include fever, sweats, adenitis, and local tissue destruction at the site of infectious agents and associated phlogistic breakdown products. The result of this robust, tissue-injurious inflammatory response can be particularly devastating if it occurs in the brain or the retina, and may cause diagnostic confusion.

The trigger for this regional and systemic inflammatory response is multifactorial. It includes the newly recovered responsiveness to high levels of circulating cytokines, reaction to immune-stimulating fatty acids and other molecules released from dying mycobacteria (perhaps akin to the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction to rapidly dying spirochetes), and possibly an over-vigorous “rebooting” immune system if an appropriate regulatory cell network is yet to be reconstituted.

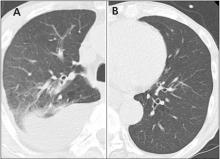

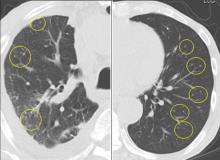

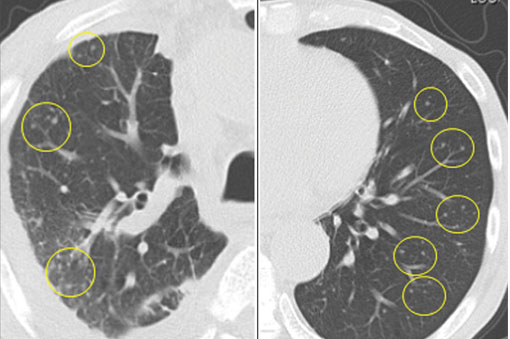

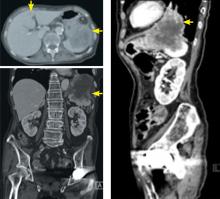

In this issue of the Journal, Hara et al provide images from a patient appropriately treated for tuberculosis who experienced continued systemic symptoms of infection with the appearance of new pulmonary lesions. The trigger was the withdrawal of the infliximab (anti-TNF) therapy he was taking for ulcerative colitis, which at face value might be expected to facilitate the successful treatment of his tuberculosis. This seemingly paradoxical reaction has been well described with the successful treatment of HIV-infected patients coinfected with mycobacteria (tuberculous or nontuberculous), cytomegalovirus, and herpes-associated Kaposi sarcoma and zoster. But as in this instructive description of a patient with an immune reactivation syndrome, it also occurs in the setting of non-HIV reversibly immunosuppressed patients.1,2 The syndrome is often recognized 1 to 2 months after immune reconstitution and the initiation of anti-infective therapy.

The treatment of this paradoxical reaction is (not so paradoxically) the administration of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs. The efficacy of corticosteroids has been demonstrated in a small placebo-controlled trial3 as well as in clinical practice. The mechanism driving this reaction may not be the same for all infections, and thus steroids may not be ideal treatment for all patients. There are reports of using infliximab to temper the immune reactivation syndrome in some patients who did not respond to corticosteroids.

There is no definitive confirmatory test for immune reactivation syndrome. And certainly in the case of known mycobacterial infection, we must ensure the absence of drug resistance and that the appropriate antibiotics are being used, and that no additional infection is present and untreated by the antimycobacterial therapy. While lymphocytosis and an overly robust tuberculin skin test response have been described in patients with tuberculosis experiencing an immune reactivation syndrome, this “paradoxical reaction” remains a clinical diagnosis, worth considering in the appropriate setting.

- Carvalho AC, De Iaco G, Saleri N, et al. Paradoxical reaction during tuberculosis treatment in HIV-seronegative patients. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42:893–895.

- Garcia Vidal C, Rodríguez Fernández S, Martínez Lacasa J, et al. Paradoxical response to antituberculous therapy in infliximab-treated patients with disseminated tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40:756–759.

- Meintjes G, Wilkinson RJ, Morroni C, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of prednisone for paradoxical TB-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS (London, England) 2010; 24:2381–2390.

The successful interplay between the host defense system and infectious invaders depends on controlling the tissue damage that ensues from both the infection and the resultant inflammatory response. Even though an underactive immune system predisposes to unusual and potentially severe infections, an overly vigorous host response to infection can be as destructive as the infection itself. We can improve the outcome of some infections by introducing potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapy concurrent with appropriate anti-infective therapy. What initially seemed counterintuitive has become the standard of care in the treatment of bacterial and mycobacterial meningitis and severe Pneumocystis and bacterial pneumonias, and favorable data are accruing in other infections such as bacterial arthritis.

A twist on the above scenario can occur when an immunosuppressed patient with a partially controlled indolent infection has his or her immune system suddenly normalized due to successful treatment of the underlying cause of their immunodeficiency. This treatment may be the introduction of successful antiretroviral therapy against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), effective therapy of an immunosuppressing infection like tuberculosis, or withdrawal of an immunosuppressive anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drug. In this scenario, where the immune system is rapidly reconstituted and concurrently activated by the presence of persistent antigenic challenge or immunostimulatory molecules, a vigorous and clinically counterproductive inflammatory response may ensue, causing “collateral damage” to normal tissue. This immune reactivation syndrome may include fever, sweats, adenitis, and local tissue destruction at the site of infectious agents and associated phlogistic breakdown products. The result of this robust, tissue-injurious inflammatory response can be particularly devastating if it occurs in the brain or the retina, and may cause diagnostic confusion.

The trigger for this regional and systemic inflammatory response is multifactorial. It includes the newly recovered responsiveness to high levels of circulating cytokines, reaction to immune-stimulating fatty acids and other molecules released from dying mycobacteria (perhaps akin to the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction to rapidly dying spirochetes), and possibly an over-vigorous “rebooting” immune system if an appropriate regulatory cell network is yet to be reconstituted.

In this issue of the Journal, Hara et al provide images from a patient appropriately treated for tuberculosis who experienced continued systemic symptoms of infection with the appearance of new pulmonary lesions. The trigger was the withdrawal of the infliximab (anti-TNF) therapy he was taking for ulcerative colitis, which at face value might be expected to facilitate the successful treatment of his tuberculosis. This seemingly paradoxical reaction has been well described with the successful treatment of HIV-infected patients coinfected with mycobacteria (tuberculous or nontuberculous), cytomegalovirus, and herpes-associated Kaposi sarcoma and zoster. But as in this instructive description of a patient with an immune reactivation syndrome, it also occurs in the setting of non-HIV reversibly immunosuppressed patients.1,2 The syndrome is often recognized 1 to 2 months after immune reconstitution and the initiation of anti-infective therapy.

The treatment of this paradoxical reaction is (not so paradoxically) the administration of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs. The efficacy of corticosteroids has been demonstrated in a small placebo-controlled trial3 as well as in clinical practice. The mechanism driving this reaction may not be the same for all infections, and thus steroids may not be ideal treatment for all patients. There are reports of using infliximab to temper the immune reactivation syndrome in some patients who did not respond to corticosteroids.

There is no definitive confirmatory test for immune reactivation syndrome. And certainly in the case of known mycobacterial infection, we must ensure the absence of drug resistance and that the appropriate antibiotics are being used, and that no additional infection is present and untreated by the antimycobacterial therapy. While lymphocytosis and an overly robust tuberculin skin test response have been described in patients with tuberculosis experiencing an immune reactivation syndrome, this “paradoxical reaction” remains a clinical diagnosis, worth considering in the appropriate setting.

The successful interplay between the host defense system and infectious invaders depends on controlling the tissue damage that ensues from both the infection and the resultant inflammatory response. Even though an underactive immune system predisposes to unusual and potentially severe infections, an overly vigorous host response to infection can be as destructive as the infection itself. We can improve the outcome of some infections by introducing potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapy concurrent with appropriate anti-infective therapy. What initially seemed counterintuitive has become the standard of care in the treatment of bacterial and mycobacterial meningitis and severe Pneumocystis and bacterial pneumonias, and favorable data are accruing in other infections such as bacterial arthritis.

A twist on the above scenario can occur when an immunosuppressed patient with a partially controlled indolent infection has his or her immune system suddenly normalized due to successful treatment of the underlying cause of their immunodeficiency. This treatment may be the introduction of successful antiretroviral therapy against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), effective therapy of an immunosuppressing infection like tuberculosis, or withdrawal of an immunosuppressive anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drug. In this scenario, where the immune system is rapidly reconstituted and concurrently activated by the presence of persistent antigenic challenge or immunostimulatory molecules, a vigorous and clinically counterproductive inflammatory response may ensue, causing “collateral damage” to normal tissue. This immune reactivation syndrome may include fever, sweats, adenitis, and local tissue destruction at the site of infectious agents and associated phlogistic breakdown products. The result of this robust, tissue-injurious inflammatory response can be particularly devastating if it occurs in the brain or the retina, and may cause diagnostic confusion.

The trigger for this regional and systemic inflammatory response is multifactorial. It includes the newly recovered responsiveness to high levels of circulating cytokines, reaction to immune-stimulating fatty acids and other molecules released from dying mycobacteria (perhaps akin to the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction to rapidly dying spirochetes), and possibly an over-vigorous “rebooting” immune system if an appropriate regulatory cell network is yet to be reconstituted.

In this issue of the Journal, Hara et al provide images from a patient appropriately treated for tuberculosis who experienced continued systemic symptoms of infection with the appearance of new pulmonary lesions. The trigger was the withdrawal of the infliximab (anti-TNF) therapy he was taking for ulcerative colitis, which at face value might be expected to facilitate the successful treatment of his tuberculosis. This seemingly paradoxical reaction has been well described with the successful treatment of HIV-infected patients coinfected with mycobacteria (tuberculous or nontuberculous), cytomegalovirus, and herpes-associated Kaposi sarcoma and zoster. But as in this instructive description of a patient with an immune reactivation syndrome, it also occurs in the setting of non-HIV reversibly immunosuppressed patients.1,2 The syndrome is often recognized 1 to 2 months after immune reconstitution and the initiation of anti-infective therapy.

The treatment of this paradoxical reaction is (not so paradoxically) the administration of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs. The efficacy of corticosteroids has been demonstrated in a small placebo-controlled trial3 as well as in clinical practice. The mechanism driving this reaction may not be the same for all infections, and thus steroids may not be ideal treatment for all patients. There are reports of using infliximab to temper the immune reactivation syndrome in some patients who did not respond to corticosteroids.

There is no definitive confirmatory test for immune reactivation syndrome. And certainly in the case of known mycobacterial infection, we must ensure the absence of drug resistance and that the appropriate antibiotics are being used, and that no additional infection is present and untreated by the antimycobacterial therapy. While lymphocytosis and an overly robust tuberculin skin test response have been described in patients with tuberculosis experiencing an immune reactivation syndrome, this “paradoxical reaction” remains a clinical diagnosis, worth considering in the appropriate setting.

- Carvalho AC, De Iaco G, Saleri N, et al. Paradoxical reaction during tuberculosis treatment in HIV-seronegative patients. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42:893–895.