User login

A Randomized Cohort Controlled Trial to Compare Intern Sign-Out Training Interventions

Patient sign-outs are defined as the transition of patient care that includes the transfer of information, task accountability, and personal responsibility between providers.1-3 The adoption of mnemonics as a memory aid has been used to improve the transfer of patient information between providers.4 In the transfer of task accountability, providers transfer follow-up tasks to on-call or coverage providers and ensure that directives are understood. Joint task accountability is enhanced through collaborative giving and cross-checking of information received through assertive questioning to detect errors, and it also enables the receiver to codevelop an understanding of a patient’s condition.5-8 In the transfer of personal responsibility for the primary team’s patients, the provision of anticipatory guidance enables the coverage provider to have prospective information about potential, upcoming issues to facilitate care plans.6 Enabling coverage providers to anticipate overnight events helps them exercise responsibility for patients who are under their temporary care.2

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires residency programs to provide formal instruction on sign-outs.9 Yet, variability across training programs exists,8,10 with training emphasis on the transfer of information over accountability or responsibility.11 Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of sign-out training, such as the illness severity, patient summary, action list, situation awareness and contingency planning, and synthesis by reviewer (I-PASS) bundle.3 Yet, participation is far from 100% because the I-PASS bundle requires in-person workshops, e-learning platforms, organizational change campaigns, and faculty participation,12 involving resource and time commitments that few programs can afford. To address this issue, we seek to compare resource-efficient, knowledge-based, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training pedagogies. We focused on the evening sign-out because it is a high-risk period when care for inpatients is transferred to smaller coverage intern teams.

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

A prospective, randomized cohort trial of 4 training interventions was conducted at an internal medicine residency program at a Mid-Atlantic, academic, tertiary-care hospital with 1192 inpatient beds. The 52 interns admitted to the program were randomly assigned to 4 firms caring for up to 25 inpatients on each floor of the hospital. The case mix faced by each firm was similar because patients were randomly assigned to firms based on bed availability. Teams of 5 interns in each firm worked in 5-day duty cycles, during which each intern rotated as a night cover for his or her firm. Interns remain in their firm throughout their residency. Sign-outs were conducted face to face with a computer. Receivers printed sign-out sheets populated with patient information and took notes when senders communicated information from the computer. The hospital’s institutional review board approved this study.

Interventions

The firms were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 one-hour quality-improvement training interventions delivered at the same time and day in November 2014 at each firm’s office, located on different floors of the hospital. There was virtually no cross-talk among the firms in the first year, which ensured the integrity of the cohort randomization and interventions. Faculty from an affiliated business school of the academic center worked with attending physicians to train the firms.

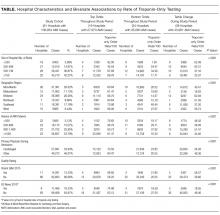

All interventions took 1 hour at noontime. Firm 1 (the control) received a didactic lecture on sign-out, which participants heard during orientation. Repeating that lecture reinforced their knowledge of sign-outs. Firm 2 was trained on the I-PASS mnemonic with a predictable progression of information elements to transfer.3,12 Interns role-played 3 scenarios to practice sign-out.3 They received skills feedback and a debriefing to link I-PASS with information elements to transfer. Firm 3 was dealt a policy mandate by the interns’ attending physician to perform specific tasks at sign-out. Senders were to provide the night cover with to-do tasks, and receivers were to actively discuss and verify these tasks to ensure task accountability.13 Firm 4 was trained on a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) protocol to identify and solve perceived barriers to sign-outs. Firm 4 agreed to solve the problem of the lack of care plans by the day team to the night cover. An ad hoc team in Firm 4 refined, pilot tested, and rolled out the solution within a month. Its protocol emphasized information on anticipated changes in patient status, providing contingency plans and their rationale as well as discussions to clarify care plans. Details of the 4 interventions are shown in the Table.

Data Collection Process

Outcomes

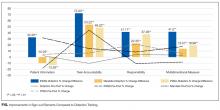

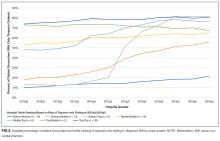

We measured improvements in sign-out quality by the mean percentage differences for each of the 3 dimensions of sign-out, as well as a multidimensional measure of sign-out comprising the 3 dimensions for each firm in 2 ways: (1) pre- and postintervention, and (2) vis-à-vis the control group postintervention.

Statistical Analysis

We factor analyzed the 17 sign-out elements using principal components analysis with varimax rotation to confirm their groupings within the 3 dimensions of sign-out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 (IBM, North Castle, NY). We calculated the mean percentage differences and used Student t tests to evaluate statistical differences at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Five hundred and sixty-three patient sign-outs were observed prior to the training interventions (κ = 0.646), and 620 patient sign-outs were observed after the interventions (κ = 0.648). Kappa values derived from SPSS were within acceptable interrater agreement ranges. Factor analysis of the 17 sign-out elements yielded 3 factors that we named patient information, task accountability, and responsibility, as shown in the supporting Table.

DISCUSSION

The results indicated that after only 1 hour of training, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training improved sign-out quality beyond knowledge-based didactics even though the number of sign-out elements taught in the latter 2 was lower than in the didactics group. Different training emphases influenced different dimensions of sign-out quality so that training interns to focus on task accountability or responsibility led to improvements in those dimensions only. The lower scores in other dimensions suggest potential risks in sign-out quality from focusing attention on 1 dimension at the expense of other dimensions. I-PASS, which covered the most sign-out elements and utilized 5 facilitators, led to the best overall improvement in sign-out quality, which is consistent with previous studies.3,12 We demonstrated that only 1 hour of training on the I-PASS mnemonics using video, role-playing, and feedback led to significant improvements. This approach is portable and easily applied to any program. Potential improvements in I-PASS training could be obtained by emphasizing task accountability and responsibility because the mandate and PDSA groups obtained higher scores than the I-PASS group in these dimensions.

Limitations

We measured sign-out quality in the evening at this site because it was at greatest risk for errors. Future studies should consider daytime sign-outs, interunit handoffs, and other hospital settings, such as community or rural hospitals and nonacute patient settings, to ascertain generalizability. Data were collected from observations, so Hawthorne effects may introduce bias. However, we believe that using a standardized checklist, a control group, and assessing relative changes minimized this risk. Although we observed almost 1200 patient sign-outs over 80 shift changes, we were not able to observe every intern in every firm. Finally, no sentinel events were reported during the study period, and we did not include other measures of clinical outcomes, which represent an opportunity for future researchers to test which specific sign-out elements or dimensions are related to clinical outcomes or are relevant to specific patient types.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that 1 hour of formal training can improve sign-out quality. Program directors should consider including I-PASS with additional focus on task accountability and personal responsibility in their sign-out training plans.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Darbyshire D, Gordon M, Baker P. Teaching handover of care to medical students. Clin Teach. 2013;10:32-37. PubMed

2. Lee SH, Phan PH, Dorman T, Weaver SJ, Pronovost PJ. Handoffs, safety culture, and practices: evidence from the hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMJ Health Serv Res. 2016;16:254. DOI 10.1186/s12913-016-1502-7. PubMed

3. Starmer AJ, O’Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, et al. Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I-PASS handoff curriculum: a multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014:89:876-884. PubMed

4. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Little BW. Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:196-204. PubMed

5. Cohen MD, Hilligoss B, Kajdacsy-Balla A. A handoff is not a telegram: an understanding of the patient is co-constructed. Crit Care. 2012;16:303. PubMed

6. McMullan A, Parush A, Momtahan K. Transferring patient care: patterns of synchronous bidisciplinary communication between physicians and nurses during handoffs in a critical care unit. J Perianesth Nurs. 2015;30:92-104. PubMed

7. Rayo MF, Mount-Campbell AF, O’Brien JM, et al. Interactive questioning in critical care during handovers: a transcript analysis of communication behaviours by physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:483-489. PubMed

8. Gordon M, Findley R. Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45:1081-1089. PubMed

9. Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES Jr; ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:e3. PubMed

10. Wohlauer MV, Arora VM, Horwitz LI, et al. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87:411-418. PubMed

11. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and attending physicians’ handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1775-1787. PubMed

12. Huth K, Hart F, Moreau K, et al. Real-world implementation of a standardized handover program (I-PASS) on a pediatric clinical teaching unit. Acad Ped. 2016;16:532-539. PubMed

13. Jonas E, Schulz-Hardt S, Frey D, Thelen N. Confirmation bias in sequential information search after preliminary decisions: An expansion of dissonance theoretical research on selective exposure to information. J Per Soc Psy. 2001;80:557-571. PubMed

14. Joint Commission. Improving handoff communications: Meeting national patient safety goal 2E. Jt Pers Patient Saf. 2006;6:9-15.

15. Improving Hand-off Communication. Joint Commission Resources. 2007. PubMed

Patient sign-outs are defined as the transition of patient care that includes the transfer of information, task accountability, and personal responsibility between providers.1-3 The adoption of mnemonics as a memory aid has been used to improve the transfer of patient information between providers.4 In the transfer of task accountability, providers transfer follow-up tasks to on-call or coverage providers and ensure that directives are understood. Joint task accountability is enhanced through collaborative giving and cross-checking of information received through assertive questioning to detect errors, and it also enables the receiver to codevelop an understanding of a patient’s condition.5-8 In the transfer of personal responsibility for the primary team’s patients, the provision of anticipatory guidance enables the coverage provider to have prospective information about potential, upcoming issues to facilitate care plans.6 Enabling coverage providers to anticipate overnight events helps them exercise responsibility for patients who are under their temporary care.2

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires residency programs to provide formal instruction on sign-outs.9 Yet, variability across training programs exists,8,10 with training emphasis on the transfer of information over accountability or responsibility.11 Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of sign-out training, such as the illness severity, patient summary, action list, situation awareness and contingency planning, and synthesis by reviewer (I-PASS) bundle.3 Yet, participation is far from 100% because the I-PASS bundle requires in-person workshops, e-learning platforms, organizational change campaigns, and faculty participation,12 involving resource and time commitments that few programs can afford. To address this issue, we seek to compare resource-efficient, knowledge-based, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training pedagogies. We focused on the evening sign-out because it is a high-risk period when care for inpatients is transferred to smaller coverage intern teams.

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

A prospective, randomized cohort trial of 4 training interventions was conducted at an internal medicine residency program at a Mid-Atlantic, academic, tertiary-care hospital with 1192 inpatient beds. The 52 interns admitted to the program were randomly assigned to 4 firms caring for up to 25 inpatients on each floor of the hospital. The case mix faced by each firm was similar because patients were randomly assigned to firms based on bed availability. Teams of 5 interns in each firm worked in 5-day duty cycles, during which each intern rotated as a night cover for his or her firm. Interns remain in their firm throughout their residency. Sign-outs were conducted face to face with a computer. Receivers printed sign-out sheets populated with patient information and took notes when senders communicated information from the computer. The hospital’s institutional review board approved this study.

Interventions

The firms were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 one-hour quality-improvement training interventions delivered at the same time and day in November 2014 at each firm’s office, located on different floors of the hospital. There was virtually no cross-talk among the firms in the first year, which ensured the integrity of the cohort randomization and interventions. Faculty from an affiliated business school of the academic center worked with attending physicians to train the firms.

All interventions took 1 hour at noontime. Firm 1 (the control) received a didactic lecture on sign-out, which participants heard during orientation. Repeating that lecture reinforced their knowledge of sign-outs. Firm 2 was trained on the I-PASS mnemonic with a predictable progression of information elements to transfer.3,12 Interns role-played 3 scenarios to practice sign-out.3 They received skills feedback and a debriefing to link I-PASS with information elements to transfer. Firm 3 was dealt a policy mandate by the interns’ attending physician to perform specific tasks at sign-out. Senders were to provide the night cover with to-do tasks, and receivers were to actively discuss and verify these tasks to ensure task accountability.13 Firm 4 was trained on a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) protocol to identify and solve perceived barriers to sign-outs. Firm 4 agreed to solve the problem of the lack of care plans by the day team to the night cover. An ad hoc team in Firm 4 refined, pilot tested, and rolled out the solution within a month. Its protocol emphasized information on anticipated changes in patient status, providing contingency plans and their rationale as well as discussions to clarify care plans. Details of the 4 interventions are shown in the Table.

Data Collection Process

Outcomes

We measured improvements in sign-out quality by the mean percentage differences for each of the 3 dimensions of sign-out, as well as a multidimensional measure of sign-out comprising the 3 dimensions for each firm in 2 ways: (1) pre- and postintervention, and (2) vis-à-vis the control group postintervention.

Statistical Analysis

We factor analyzed the 17 sign-out elements using principal components analysis with varimax rotation to confirm their groupings within the 3 dimensions of sign-out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 (IBM, North Castle, NY). We calculated the mean percentage differences and used Student t tests to evaluate statistical differences at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Five hundred and sixty-three patient sign-outs were observed prior to the training interventions (κ = 0.646), and 620 patient sign-outs were observed after the interventions (κ = 0.648). Kappa values derived from SPSS were within acceptable interrater agreement ranges. Factor analysis of the 17 sign-out elements yielded 3 factors that we named patient information, task accountability, and responsibility, as shown in the supporting Table.

DISCUSSION

The results indicated that after only 1 hour of training, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training improved sign-out quality beyond knowledge-based didactics even though the number of sign-out elements taught in the latter 2 was lower than in the didactics group. Different training emphases influenced different dimensions of sign-out quality so that training interns to focus on task accountability or responsibility led to improvements in those dimensions only. The lower scores in other dimensions suggest potential risks in sign-out quality from focusing attention on 1 dimension at the expense of other dimensions. I-PASS, which covered the most sign-out elements and utilized 5 facilitators, led to the best overall improvement in sign-out quality, which is consistent with previous studies.3,12 We demonstrated that only 1 hour of training on the I-PASS mnemonics using video, role-playing, and feedback led to significant improvements. This approach is portable and easily applied to any program. Potential improvements in I-PASS training could be obtained by emphasizing task accountability and responsibility because the mandate and PDSA groups obtained higher scores than the I-PASS group in these dimensions.

Limitations

We measured sign-out quality in the evening at this site because it was at greatest risk for errors. Future studies should consider daytime sign-outs, interunit handoffs, and other hospital settings, such as community or rural hospitals and nonacute patient settings, to ascertain generalizability. Data were collected from observations, so Hawthorne effects may introduce bias. However, we believe that using a standardized checklist, a control group, and assessing relative changes minimized this risk. Although we observed almost 1200 patient sign-outs over 80 shift changes, we were not able to observe every intern in every firm. Finally, no sentinel events were reported during the study period, and we did not include other measures of clinical outcomes, which represent an opportunity for future researchers to test which specific sign-out elements or dimensions are related to clinical outcomes or are relevant to specific patient types.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that 1 hour of formal training can improve sign-out quality. Program directors should consider including I-PASS with additional focus on task accountability and personal responsibility in their sign-out training plans.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Patient sign-outs are defined as the transition of patient care that includes the transfer of information, task accountability, and personal responsibility between providers.1-3 The adoption of mnemonics as a memory aid has been used to improve the transfer of patient information between providers.4 In the transfer of task accountability, providers transfer follow-up tasks to on-call or coverage providers and ensure that directives are understood. Joint task accountability is enhanced through collaborative giving and cross-checking of information received through assertive questioning to detect errors, and it also enables the receiver to codevelop an understanding of a patient’s condition.5-8 In the transfer of personal responsibility for the primary team’s patients, the provision of anticipatory guidance enables the coverage provider to have prospective information about potential, upcoming issues to facilitate care plans.6 Enabling coverage providers to anticipate overnight events helps them exercise responsibility for patients who are under their temporary care.2

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires residency programs to provide formal instruction on sign-outs.9 Yet, variability across training programs exists,8,10 with training emphasis on the transfer of information over accountability or responsibility.11 Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of sign-out training, such as the illness severity, patient summary, action list, situation awareness and contingency planning, and synthesis by reviewer (I-PASS) bundle.3 Yet, participation is far from 100% because the I-PASS bundle requires in-person workshops, e-learning platforms, organizational change campaigns, and faculty participation,12 involving resource and time commitments that few programs can afford. To address this issue, we seek to compare resource-efficient, knowledge-based, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training pedagogies. We focused on the evening sign-out because it is a high-risk period when care for inpatients is transferred to smaller coverage intern teams.

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

A prospective, randomized cohort trial of 4 training interventions was conducted at an internal medicine residency program at a Mid-Atlantic, academic, tertiary-care hospital with 1192 inpatient beds. The 52 interns admitted to the program were randomly assigned to 4 firms caring for up to 25 inpatients on each floor of the hospital. The case mix faced by each firm was similar because patients were randomly assigned to firms based on bed availability. Teams of 5 interns in each firm worked in 5-day duty cycles, during which each intern rotated as a night cover for his or her firm. Interns remain in their firm throughout their residency. Sign-outs were conducted face to face with a computer. Receivers printed sign-out sheets populated with patient information and took notes when senders communicated information from the computer. The hospital’s institutional review board approved this study.

Interventions

The firms were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 one-hour quality-improvement training interventions delivered at the same time and day in November 2014 at each firm’s office, located on different floors of the hospital. There was virtually no cross-talk among the firms in the first year, which ensured the integrity of the cohort randomization and interventions. Faculty from an affiliated business school of the academic center worked with attending physicians to train the firms.

All interventions took 1 hour at noontime. Firm 1 (the control) received a didactic lecture on sign-out, which participants heard during orientation. Repeating that lecture reinforced their knowledge of sign-outs. Firm 2 was trained on the I-PASS mnemonic with a predictable progression of information elements to transfer.3,12 Interns role-played 3 scenarios to practice sign-out.3 They received skills feedback and a debriefing to link I-PASS with information elements to transfer. Firm 3 was dealt a policy mandate by the interns’ attending physician to perform specific tasks at sign-out. Senders were to provide the night cover with to-do tasks, and receivers were to actively discuss and verify these tasks to ensure task accountability.13 Firm 4 was trained on a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) protocol to identify and solve perceived barriers to sign-outs. Firm 4 agreed to solve the problem of the lack of care plans by the day team to the night cover. An ad hoc team in Firm 4 refined, pilot tested, and rolled out the solution within a month. Its protocol emphasized information on anticipated changes in patient status, providing contingency plans and their rationale as well as discussions to clarify care plans. Details of the 4 interventions are shown in the Table.

Data Collection Process

Outcomes

We measured improvements in sign-out quality by the mean percentage differences for each of the 3 dimensions of sign-out, as well as a multidimensional measure of sign-out comprising the 3 dimensions for each firm in 2 ways: (1) pre- and postintervention, and (2) vis-à-vis the control group postintervention.

Statistical Analysis

We factor analyzed the 17 sign-out elements using principal components analysis with varimax rotation to confirm their groupings within the 3 dimensions of sign-out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 (IBM, North Castle, NY). We calculated the mean percentage differences and used Student t tests to evaluate statistical differences at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Five hundred and sixty-three patient sign-outs were observed prior to the training interventions (κ = 0.646), and 620 patient sign-outs were observed after the interventions (κ = 0.648). Kappa values derived from SPSS were within acceptable interrater agreement ranges. Factor analysis of the 17 sign-out elements yielded 3 factors that we named patient information, task accountability, and responsibility, as shown in the supporting Table.

DISCUSSION

The results indicated that after only 1 hour of training, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training improved sign-out quality beyond knowledge-based didactics even though the number of sign-out elements taught in the latter 2 was lower than in the didactics group. Different training emphases influenced different dimensions of sign-out quality so that training interns to focus on task accountability or responsibility led to improvements in those dimensions only. The lower scores in other dimensions suggest potential risks in sign-out quality from focusing attention on 1 dimension at the expense of other dimensions. I-PASS, which covered the most sign-out elements and utilized 5 facilitators, led to the best overall improvement in sign-out quality, which is consistent with previous studies.3,12 We demonstrated that only 1 hour of training on the I-PASS mnemonics using video, role-playing, and feedback led to significant improvements. This approach is portable and easily applied to any program. Potential improvements in I-PASS training could be obtained by emphasizing task accountability and responsibility because the mandate and PDSA groups obtained higher scores than the I-PASS group in these dimensions.

Limitations

We measured sign-out quality in the evening at this site because it was at greatest risk for errors. Future studies should consider daytime sign-outs, interunit handoffs, and other hospital settings, such as community or rural hospitals and nonacute patient settings, to ascertain generalizability. Data were collected from observations, so Hawthorne effects may introduce bias. However, we believe that using a standardized checklist, a control group, and assessing relative changes minimized this risk. Although we observed almost 1200 patient sign-outs over 80 shift changes, we were not able to observe every intern in every firm. Finally, no sentinel events were reported during the study period, and we did not include other measures of clinical outcomes, which represent an opportunity for future researchers to test which specific sign-out elements or dimensions are related to clinical outcomes or are relevant to specific patient types.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that 1 hour of formal training can improve sign-out quality. Program directors should consider including I-PASS with additional focus on task accountability and personal responsibility in their sign-out training plans.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Darbyshire D, Gordon M, Baker P. Teaching handover of care to medical students. Clin Teach. 2013;10:32-37. PubMed

2. Lee SH, Phan PH, Dorman T, Weaver SJ, Pronovost PJ. Handoffs, safety culture, and practices: evidence from the hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMJ Health Serv Res. 2016;16:254. DOI 10.1186/s12913-016-1502-7. PubMed

3. Starmer AJ, O’Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, et al. Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I-PASS handoff curriculum: a multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014:89:876-884. PubMed

4. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Little BW. Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:196-204. PubMed

5. Cohen MD, Hilligoss B, Kajdacsy-Balla A. A handoff is not a telegram: an understanding of the patient is co-constructed. Crit Care. 2012;16:303. PubMed

6. McMullan A, Parush A, Momtahan K. Transferring patient care: patterns of synchronous bidisciplinary communication between physicians and nurses during handoffs in a critical care unit. J Perianesth Nurs. 2015;30:92-104. PubMed

7. Rayo MF, Mount-Campbell AF, O’Brien JM, et al. Interactive questioning in critical care during handovers: a transcript analysis of communication behaviours by physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:483-489. PubMed

8. Gordon M, Findley R. Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45:1081-1089. PubMed

9. Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES Jr; ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:e3. PubMed

10. Wohlauer MV, Arora VM, Horwitz LI, et al. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87:411-418. PubMed

11. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and attending physicians’ handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1775-1787. PubMed

12. Huth K, Hart F, Moreau K, et al. Real-world implementation of a standardized handover program (I-PASS) on a pediatric clinical teaching unit. Acad Ped. 2016;16:532-539. PubMed

13. Jonas E, Schulz-Hardt S, Frey D, Thelen N. Confirmation bias in sequential information search after preliminary decisions: An expansion of dissonance theoretical research on selective exposure to information. J Per Soc Psy. 2001;80:557-571. PubMed

14. Joint Commission. Improving handoff communications: Meeting national patient safety goal 2E. Jt Pers Patient Saf. 2006;6:9-15.

15. Improving Hand-off Communication. Joint Commission Resources. 2007. PubMed

1. Darbyshire D, Gordon M, Baker P. Teaching handover of care to medical students. Clin Teach. 2013;10:32-37. PubMed

2. Lee SH, Phan PH, Dorman T, Weaver SJ, Pronovost PJ. Handoffs, safety culture, and practices: evidence from the hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMJ Health Serv Res. 2016;16:254. DOI 10.1186/s12913-016-1502-7. PubMed

3. Starmer AJ, O’Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, et al. Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I-PASS handoff curriculum: a multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014:89:876-884. PubMed

4. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Little BW. Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:196-204. PubMed

5. Cohen MD, Hilligoss B, Kajdacsy-Balla A. A handoff is not a telegram: an understanding of the patient is co-constructed. Crit Care. 2012;16:303. PubMed

6. McMullan A, Parush A, Momtahan K. Transferring patient care: patterns of synchronous bidisciplinary communication between physicians and nurses during handoffs in a critical care unit. J Perianesth Nurs. 2015;30:92-104. PubMed

7. Rayo MF, Mount-Campbell AF, O’Brien JM, et al. Interactive questioning in critical care during handovers: a transcript analysis of communication behaviours by physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:483-489. PubMed

8. Gordon M, Findley R. Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45:1081-1089. PubMed

9. Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES Jr; ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:e3. PubMed

10. Wohlauer MV, Arora VM, Horwitz LI, et al. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87:411-418. PubMed

11. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and attending physicians’ handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1775-1787. PubMed

12. Huth K, Hart F, Moreau K, et al. Real-world implementation of a standardized handover program (I-PASS) on a pediatric clinical teaching unit. Acad Ped. 2016;16:532-539. PubMed

13. Jonas E, Schulz-Hardt S, Frey D, Thelen N. Confirmation bias in sequential information search after preliminary decisions: An expansion of dissonance theoretical research on selective exposure to information. J Per Soc Psy. 2001;80:557-571. PubMed

14. Joint Commission. Improving handoff communications: Meeting national patient safety goal 2E. Jt Pers Patient Saf. 2006;6:9-15.

15. Improving Hand-off Communication. Joint Commission Resources. 2007. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Health Literacy and Hospital Length of Stay: An Inpatient Cohort Study

Health literacy (HL), defined as patients’ ability to understand health information and make health decisions,1 is a prevalent problem in the outpatient and inpatient settings.2,3 In both settings, low HL has adverse implications for self-care including interpreting health labels4 and taking medications correctly.5 Among outpatient cohorts, HL has been associated with worse outcomes and acute care utilization.6 Associations with low HL include increased hospitalizations,7 rehospitalizations,8,9 emergency department visits,10 and decreased preventative care use.11 Among the elderly, low HL is associated with increased mortality12 and decreased self-perception of health.13

A systematic review revealed that most high-quality HL outcome studies were conducted in the outpatient setting.6 There have been very few studies assessing effects of low HL in an acute-care setting.7,14 These studies have evaluated postdischarge outcomes, including admissions or readmissions,7-9 and medication knowledge.14 To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating associations between HL and hospital length of stay (LOS).

LOS has received much attention as providers and payers focus more on resource utilization and eliminating adverse effects of prolonged hospitalization.15 LOS is multifactorial, depending on clinical characteristics like disease severity, as well as on sociocultural, demographic, and geographic factors.16 Despite evidence that LOS reductions translate into improved resource allocation and potentially fewer complications, there remains a tension between the appropriate LOS and one that is too short for a given condition.17

Because low HL is associated with inefficient resource utilization, we hypothesized that low HL would be associated with increased LOS after controlling for illness severity. Our objectives were to evaluate the association between low HL and LOS and whether such an association was modified by illness severity and sociodemographics.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, Participants

An in-hospital, cohort study design of patients who were admitted or transferred to the general medicine service at the University of Chicago between October 2012 and November 2015 and screened for inclusion as part of a large, ongoing study of inpatient care quality was conducted.18 Exclusion criteria included observation status, age under 18 years, non-English speaking, and repeat participants. Those who died during hospitalization or whose discharge status was missing were excluded because the primary goal was to examine the association of HL and time to discharge, which could not be evaluated among those who died. We excluded participants with LOS >30 days to limit overly influential effects of extreme outliers (1% of the population).

Variables

HL was screened using the Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS), a validated, 3-question verbal survey not requiring adequate visual acuity to assess HL.19,20 The 3 questions are as follows: (1) “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?”, (2) “How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials?”, and (3) “How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information?” Responses to the questions were scored on a 5-point Likert scale in which higher scores corresponded to higher HL.21,22 The scores for each of the 3 questions were summed to yield a range between 3 and 15. On the individual questions, prior work has demonstrated improved test performance with a cutoff of ≤3, which corresponds to a response of “some of the time” or “somewhat”; therefore, when the 3 questions were summed together, scores of ≤9 were considered indicative of low HL.21,23

For severity of illness adjustment, we used relative weights derived from the 3M (3M, Maplewood, MN) All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG) classification system, which uses administrative data to classify the severity. The APR-DRG system assigns each admission to a DRG based on principal diagnosis; for each DRG, patients are then subdivided into 4 severity classes based on age, comorbidity, and interactions between these variables and the admitting diagnosis.24 Using the base DRG and severity score, the system assigns relative weights that reflect differences in expected hospital resource utilization.

LOS was derived from hospital administrative data and counted from the date of admission to the hospital. Participants who were discharged on the day of admission were counted as having an LOS of 1. Insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, no payer, private) also was obtained from administrative data. Age, sex (male or female), education (junior high or less, some high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, postgraduate), and race (black/African American, white, Asian or Pacific Islander [including Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, other Asian, Native Hawaiian, Guam/Chamorro, Samoan, other Pacific], American Indian or Alaskan Native, multiple race) were obtained from administrative data based on information provided by the patient. Participants with missing data on any of the sociodemographic variables or on the APR-DRG score were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

χ2 and 2-tailed t tests were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Multivariate linear regressions were employed to measure associations between the independent variables (HL, illness severity, race, gender, education, and insurance status) and the dependent variable, LOS. Independent variables were chosen for clinical significance and retained in the model regardless of statistical significance. The adjusted R2 values of models with and without the HL variable included were reported to provide information on the contribution of HL to the overall model.

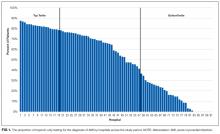

Because LOS was observed to be right skewed and residuals of the untransformed regression were observed to be non-normally distributed, the decision was made to natural log transform LOS, which is consistent with previous hospital LOS studies.16 Regression coefficients and confidence intervals were then transformed into percentage estimates using the following equation: 100(eβ–1). Adjusted R2 was reported for the transformed regression.

The APR-DRG relative weight was treated as a continuous variable. Sociodemographic variables were dichotomized as follows: female vs male; high school graduates vs not; African American vs not; Medicaid/no payer vs Medicare/private payer. Age was not included in the multivariate model because it has been incorporated into the weighted APR-DRG illness severity scores.

Each of the sociodemographic variables and the APR-DRG score were examined for effect modification via the same multivariate linear equation described above, with the addition of an interaction term. A separate regression was performed with an interaction term between age (dichotomized at ≥65) and HL to investigate whether age modified the association between HL and LOS. Finally, we explored whether effects were isolated to long vs short LOS by dividing the sample based on the mean LOS (≥6 days) and performing separate multivariate comparisons.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to exclude those with LOS greater than the 90th percentile and those with APR-DRG score greater than the 90th percentile; age was added to the model as a continuous variable to evaluate whether the illness severity score fully adjusted for the effects of age on LOS. Furthermore, we compared the participants with missing data to those with complete data across both dependent and independent variables. Alpha was set at 0.05; analyses were performed using Stata Version 14 (Stata, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 5983 participants met inclusion criteria and completed the HL assessment; of these participants, 75 (1%) died during hospitalization, 9 (0.2%) had missing discharge status, and 79 (1%) had LOS >30 days. Two hundred eighty (5%) were missing data on sociodemographic variables or APR-DRG score. Of the remaining (n = 5540), the mean age was 57 years (standard deviation [SD] = 19 years), over half of participants were female (57%), and the majority were African American (73%) and had graduated from high school (81%). The sample was divided into those with private insurance (25%), those with Medicare (46%), and those with Medicaid (26%); 2% had no payer. The mean APR-DRG score was 1.3 (SD = 1.2), and the scores ranged from 0.3 to 15.8.

On the BHLS screen for HL, 20% (1104/5540) had inadequate HL. Participants with low HL had higher weighted illness severity scores (average 1.4 vs 1.3; P = 0.003). Participants with low HL were also more likely to be 65 or older (55% vs 33%; P < 0.001), non-high school graduates (35% vs 15%; P < 0.001), and African American (78% vs 72%; P < 0.001), and to have Medicare or private insurance (75% vs 71%; P = 0.02). There was no significant difference with respect to gender (54% male vs 57% female; P = 0.1)

Finally, we compared the group with missing data (n = 280) to the group with complete data (n = 5540). The participants with missing data were more likely to have low HL (31% [86/280] vs 20%; P < 0.001) and to have Medicare or private insurance (82% [177/217] vs 72%; P = 0.002); however, they were not more likely to be 65 or older (40% [112/280] vs 37%; P = 0.3), high school graduates (88% [113/129] vs 81%; P = 0.06), African American (69% [177/256] vs 73%; P = 0.1), or female (57% [158/279] vs 57%; P = 1), nor were they more likely to have longer LOS (5.7 [n = 280] vs 5.5 days; P = 0.6) or higher illness severity scores (1.3 [n = 231] vs 1.3; P = 0.7).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the association between low HL and an important in-hospital outcome measure, hospital LOS. We found that low HL was associated with a longer hospital LOS, a result which remained significant when controlling for severity of illness and sociodemographic variables and when testing the model for sensitivity to the highest values of LOS and illness severity. Additionally, the association of HL with LOS appeared concentrated among participants with shorter LOS. Relative to other predictors, the contribution of HL to the overall LOS model was small, as evidenced by the change in adjusted R2 values with HL excluded.

Among the covariates, only gender modified the association between HL and LOS; the findings suggested that men were more susceptible to the effect of low HL on increased LOS. Illness severity and other sociodemographics, including age ≥65, did not appear to modify the association. We also found that being African American and having Medicaid or no insurance were associated with a significantly shorter LOS in multivariate analysis.

Previous work suggested that the adverse health effects of low HL may be mediated through several pathways, including health knowledge, self-efficacy, health skills, and illness stigma.25-27 The finding of a small but significant relationship between HL and LOS was not surprising given these known associations; nevertheless, there may be an additional patient-dependent effect of low HL on LOS not discovered here. For instance, patients with poor health knowledge and self-efficacy might stay in the hospital longer if they or their providers do not feel comfortable with their self-care ability.

This finding may be useful in developing hospital-based interventions. HL-specific interventions, several of which have been tested in the inpatient setting,14,28,29 have shown promise toward improving health knowledge,30 disease severity,31 and health resource utilization.32

Those with low HL may lack the self-efficacy to participate in discharge planning; in fact, previous work has related low HL to posthospital readmissions.8,9 Conversely, patients with low HL might struggle to engage in the inpatient milieu, advocating for shorter LOS if they feel alienated by the inpatient experience.

These possibilities show that LOS is a complex measure shown to depend on patient-level characteristics and on provider-based, geographical, and sociocultural factors.16,33 With these forces at play, additional effects of lower levels of HL may be lost without phenotyping patients by both level of HL and related characteristics, such as self-efficacy, health skills, and stigma. By gathering these additional data, future work should explore whether subpopulations of patients with low HL may be at risk for too-short vs too-long hospital admissions.

For instance, in this study, both race and Medicaid insurance were associated with shorter LOS. Being African American was associated with shorter LOS in our study but has been found to be associated with longer LOS in another study specifically focused on diabetes.34 Prior findings found uninsured patients have shorter LOS.35 Therefore, these findings in our study are difficult to explain without further work to understand whether there are health disparities in the way patients are cared for during hospitalization that may shorten or lengthen their LOS because of factors outside of their clinical need.

The finding that gender modified the effect of low HL on LOS was unexpected. There were similar proportions of men and women with low HL. There is evidence to support that women make the majority of health decisions for themselves and their familes36; therefore, there may be unmeasured aspects of HL that provide an advantage for female vs male inpatients. Furthermore, omitted confounders, such as social support, may not fully capture potential gender-related differences. Future work is needed to understand the role of gender in relationship to HL and LOS.

Limitations of this study include its observational, single-centered design with information derived from administrative data; positive and negative confounding cannot be ruled out. For instance, we did not control for complex aspects affecting LOS, such as discharge disposition and goals of care (eg, aggressive care after discharge vs hospice). To address this limitation, multivariate analyses were performed, which were adjusted for illness severity scores and took into account both comorbidity and severity of the current illness. Additionally, although it is important to study such populations, our largely urban, minority sample is not representative of the U.S. population, and within our large sample, there were participants with missing data who had lower HL on average, although this group represented only 5% of the sample. Finally, different HL tools have noncomplete concordance, which has been seen when comparing the BHLS with more objective tools.20,37 Furthermore, certain in-hospital clinical scenarios (eg, recent stroke or prolonged intensive care unit stay) may present unique challenges in establishing a baseline HL level. However, the BHLS was used in this study because of its greater feasibility.

In conclusion, this study is the first to evaluate the relationship between low HL and LOS. The findings suggest that HL may play a role in shaping outcomes in the inpatient setting and that targeting interventions toward screened patients may be a pathway toward mitigating adverse effects. Our findings need to be replicated in larger, more representative samples, and further work understanding subpopulations within the low HL population is needed. Future work should measure this association in diverse inpatient settings (eg, psychiatric, surgical, and specialty), in addition to assessing associations between HL and other important in-hospital outcome measures, including mortality and discharge disposition.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Hospitalist Project team for their assistance with data collection. The authors especially thank Chuanhong Liao and Ashley Snyder for assistance with statistical analyses; Andrea Flores, Ainoa Coltri, and Tom Best for their assistance with data management. The authors would also like to thank Nicole Twu for her help with preparing and editing the manuscript.

Disclosures

Dr. Jaffee was supported by a Calvin Fentress Research Fellowship and NIH R25MH094612. Dr. Press was supported by a career development award (NHLBI K23HL118151). This work was also supported by a seed grant from the Center for Health Administration Studies. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000.

2. “What Did the Doctor Say”? Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety. The Joint Commission; 2007.

3. Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. National Center for Education Statistics; 2006.

4. Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):887-894. PubMed

5. Kripalani S, Henderson LE, Chiu EY, Robertson R, Kolm P, Jacobson TA. Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):852-856. PubMed

6. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97-107. PubMed

7. Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS. Health literacy and the risk of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(12):791-798. PubMed

8. Mitchell SE, Sadikova E, Jack BW, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health literacy and 30-day postdischarge hospital utilization. J Health Commun. 2012;17(Suppl 3):325-338. PubMed

9. Jaffee EG, Arora VM, Matthiesen MI, Hariprasad SM, Meltzer DO, Press VG. Postdischarge Falls and Readmissions: Associations with Insufficient Vision and Low Health Literacy among Hospitalized Seniors. J Health Commun. 2016;21(sup2):135-140. PubMed

10. Hope CJ, Wu J, Tu W, Young J, Murray MD. Association of medication adherence, knowledge, and skills with emergency department visits by adults 50 years or older with congestive heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(19):2043-2049. PubMed

11. Bennett IM, Chen J, Soroui JS, White S. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):204-211. PubMed

12. Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA. Health literacy, cognitive abilities, and mortality among elderly persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):723-726. PubMed

13. Cho YI, Lee SY, Arozullah AM, Crittenden KS. Effects of health literacy on health status and health service utilization amongst the elderly. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1809-1816. PubMed

14. Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(8):980-986. PubMed

15. Soria-Aledo V, Carrillo-Alcaraz A, Campillo-Soto Á, et al. Associated factors and cost of inappropriate hospital admissions and stays in a second-level hospital. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(4):321-332. PubMed

16. Lu M, Sajobi T, Lucyk K, Lorenzetti D, Quan H. Systematic review of risk adjustment models of hospital length of stay (LOS). Med Care. 2015;53(4):355-365. PubMed

17. Clarke A, Rosen R. Length of stay. How short should hospital care be? Eur J Public Health. 2001;11(2):166-170. PubMed

18. Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866-874. PubMed

19. Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588-594. PubMed

20. Press VG, Shapiro MI, Mayo AM, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. More than meets the eye: relationship between low health literacy and poor vision in hospitalized patients. J Health Commun. 2013;18 Suppl 1:197-204. PubMed

21. Willens DE, Kripalani S, Schildcrout JS, et al. Association of brief health literacy screening and blood pressure in primary care. J Health Commun. 2013;18 Suppl 1:129-142. PubMed

22. Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, et al. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1695-1701. PubMed

23. Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561-566. PubMed

24. Averill RF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, et al. All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs): Methodology Overview. 3M Health Information Systems; 2003.

25. Waite KR, Paasche-Orlow M, Rintamaki LS, Davis TC, Wolf MS. Literacy, social stigma, and HIV medication adherence. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1367-1372. PubMed

26. Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31 Suppl 1:S19-26. PubMed

27. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2011;(199):1-941. PubMed

28. Kripalani S, Roumie CL, Dalal AK, et al. Effect of a pharmacist intervention on clinically important medication errors after hospital discharge: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):1-10. PubMed

29. Press VG, Arora VM, Shah LM, et al. Teaching the use of respiratory inhalers to hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1317-1325. PubMed

30. Sobel RM, Paasche-Orlow MK, Waite KR, Rittner SS, Wilson EAH, Wolf MS. Asthma 1-2-3: a low literacy multimedia tool to educate African American adults about asthma. J Community Health. 2009;34(4):321-327. PubMed

31. Rothman RL, DeWalt DA, Malone R, et al. Influence of patient literacy on the effectiveness of a primary care-based diabetes disease management program. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1711-1716. PubMed

32. DeWalt DA, Malone RM, Bryant ME, et al. A heart failure self-management

program for patients of all literacy levels: a randomized, controlled trial [ISRCTN11535170].

BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:30. PubMed

33. Hasan O, Orav EJ, Hicks LS. Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial

infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8):452-459. PubMed

34. Cook CB, Naylor DB, Hentz JG, et al. Disparities in diabetes-related hospitalizations:

relationship of age, sex, and race/ethnicity with hospital discharges, lengths

of stay, and direct inpatient charges. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):126-131. PubMed

35. Hadley J, Steinberg EP, Feder J. Comparison of uninsured and privately insured

hospital patients. Condition on admission, resource use, and outcome. JAMA.

1991;265(3):374-379. PubMed

36. Women’s Health Care Chartbook: Key Findings From the Kaiser Women’s

Health Survey. May 2011. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.

com/2013/01/8164.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

37. Louis AJ, Arora VM, Matthiesen MI, Meltzer DO, Press VG. Screening Hospitalized Patients for Low Health Literacy: Beyond the REALM of Possibility? PubMed

Health literacy (HL), defined as patients’ ability to understand health information and make health decisions,1 is a prevalent problem in the outpatient and inpatient settings.2,3 In both settings, low HL has adverse implications for self-care including interpreting health labels4 and taking medications correctly.5 Among outpatient cohorts, HL has been associated with worse outcomes and acute care utilization.6 Associations with low HL include increased hospitalizations,7 rehospitalizations,8,9 emergency department visits,10 and decreased preventative care use.11 Among the elderly, low HL is associated with increased mortality12 and decreased self-perception of health.13

A systematic review revealed that most high-quality HL outcome studies were conducted in the outpatient setting.6 There have been very few studies assessing effects of low HL in an acute-care setting.7,14 These studies have evaluated postdischarge outcomes, including admissions or readmissions,7-9 and medication knowledge.14 To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating associations between HL and hospital length of stay (LOS).

LOS has received much attention as providers and payers focus more on resource utilization and eliminating adverse effects of prolonged hospitalization.15 LOS is multifactorial, depending on clinical characteristics like disease severity, as well as on sociocultural, demographic, and geographic factors.16 Despite evidence that LOS reductions translate into improved resource allocation and potentially fewer complications, there remains a tension between the appropriate LOS and one that is too short for a given condition.17

Because low HL is associated with inefficient resource utilization, we hypothesized that low HL would be associated with increased LOS after controlling for illness severity. Our objectives were to evaluate the association between low HL and LOS and whether such an association was modified by illness severity and sociodemographics.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, Participants

An in-hospital, cohort study design of patients who were admitted or transferred to the general medicine service at the University of Chicago between October 2012 and November 2015 and screened for inclusion as part of a large, ongoing study of inpatient care quality was conducted.18 Exclusion criteria included observation status, age under 18 years, non-English speaking, and repeat participants. Those who died during hospitalization or whose discharge status was missing were excluded because the primary goal was to examine the association of HL and time to discharge, which could not be evaluated among those who died. We excluded participants with LOS >30 days to limit overly influential effects of extreme outliers (1% of the population).

Variables

HL was screened using the Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS), a validated, 3-question verbal survey not requiring adequate visual acuity to assess HL.19,20 The 3 questions are as follows: (1) “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?”, (2) “How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials?”, and (3) “How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information?” Responses to the questions were scored on a 5-point Likert scale in which higher scores corresponded to higher HL.21,22 The scores for each of the 3 questions were summed to yield a range between 3 and 15. On the individual questions, prior work has demonstrated improved test performance with a cutoff of ≤3, which corresponds to a response of “some of the time” or “somewhat”; therefore, when the 3 questions were summed together, scores of ≤9 were considered indicative of low HL.21,23

For severity of illness adjustment, we used relative weights derived from the 3M (3M, Maplewood, MN) All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG) classification system, which uses administrative data to classify the severity. The APR-DRG system assigns each admission to a DRG based on principal diagnosis; for each DRG, patients are then subdivided into 4 severity classes based on age, comorbidity, and interactions between these variables and the admitting diagnosis.24 Using the base DRG and severity score, the system assigns relative weights that reflect differences in expected hospital resource utilization.

LOS was derived from hospital administrative data and counted from the date of admission to the hospital. Participants who were discharged on the day of admission were counted as having an LOS of 1. Insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, no payer, private) also was obtained from administrative data. Age, sex (male or female), education (junior high or less, some high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, postgraduate), and race (black/African American, white, Asian or Pacific Islander [including Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, other Asian, Native Hawaiian, Guam/Chamorro, Samoan, other Pacific], American Indian or Alaskan Native, multiple race) were obtained from administrative data based on information provided by the patient. Participants with missing data on any of the sociodemographic variables or on the APR-DRG score were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

χ2 and 2-tailed t tests were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Multivariate linear regressions were employed to measure associations between the independent variables (HL, illness severity, race, gender, education, and insurance status) and the dependent variable, LOS. Independent variables were chosen for clinical significance and retained in the model regardless of statistical significance. The adjusted R2 values of models with and without the HL variable included were reported to provide information on the contribution of HL to the overall model.

Because LOS was observed to be right skewed and residuals of the untransformed regression were observed to be non-normally distributed, the decision was made to natural log transform LOS, which is consistent with previous hospital LOS studies.16 Regression coefficients and confidence intervals were then transformed into percentage estimates using the following equation: 100(eβ–1). Adjusted R2 was reported for the transformed regression.

The APR-DRG relative weight was treated as a continuous variable. Sociodemographic variables were dichotomized as follows: female vs male; high school graduates vs not; African American vs not; Medicaid/no payer vs Medicare/private payer. Age was not included in the multivariate model because it has been incorporated into the weighted APR-DRG illness severity scores.

Each of the sociodemographic variables and the APR-DRG score were examined for effect modification via the same multivariate linear equation described above, with the addition of an interaction term. A separate regression was performed with an interaction term between age (dichotomized at ≥65) and HL to investigate whether age modified the association between HL and LOS. Finally, we explored whether effects were isolated to long vs short LOS by dividing the sample based on the mean LOS (≥6 days) and performing separate multivariate comparisons.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to exclude those with LOS greater than the 90th percentile and those with APR-DRG score greater than the 90th percentile; age was added to the model as a continuous variable to evaluate whether the illness severity score fully adjusted for the effects of age on LOS. Furthermore, we compared the participants with missing data to those with complete data across both dependent and independent variables. Alpha was set at 0.05; analyses were performed using Stata Version 14 (Stata, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 5983 participants met inclusion criteria and completed the HL assessment; of these participants, 75 (1%) died during hospitalization, 9 (0.2%) had missing discharge status, and 79 (1%) had LOS >30 days. Two hundred eighty (5%) were missing data on sociodemographic variables or APR-DRG score. Of the remaining (n = 5540), the mean age was 57 years (standard deviation [SD] = 19 years), over half of participants were female (57%), and the majority were African American (73%) and had graduated from high school (81%). The sample was divided into those with private insurance (25%), those with Medicare (46%), and those with Medicaid (26%); 2% had no payer. The mean APR-DRG score was 1.3 (SD = 1.2), and the scores ranged from 0.3 to 15.8.

On the BHLS screen for HL, 20% (1104/5540) had inadequate HL. Participants with low HL had higher weighted illness severity scores (average 1.4 vs 1.3; P = 0.003). Participants with low HL were also more likely to be 65 or older (55% vs 33%; P < 0.001), non-high school graduates (35% vs 15%; P < 0.001), and African American (78% vs 72%; P < 0.001), and to have Medicare or private insurance (75% vs 71%; P = 0.02). There was no significant difference with respect to gender (54% male vs 57% female; P = 0.1)

Finally, we compared the group with missing data (n = 280) to the group with complete data (n = 5540). The participants with missing data were more likely to have low HL (31% [86/280] vs 20%; P < 0.001) and to have Medicare or private insurance (82% [177/217] vs 72%; P = 0.002); however, they were not more likely to be 65 or older (40% [112/280] vs 37%; P = 0.3), high school graduates (88% [113/129] vs 81%; P = 0.06), African American (69% [177/256] vs 73%; P = 0.1), or female (57% [158/279] vs 57%; P = 1), nor were they more likely to have longer LOS (5.7 [n = 280] vs 5.5 days; P = 0.6) or higher illness severity scores (1.3 [n = 231] vs 1.3; P = 0.7).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the association between low HL and an important in-hospital outcome measure, hospital LOS. We found that low HL was associated with a longer hospital LOS, a result which remained significant when controlling for severity of illness and sociodemographic variables and when testing the model for sensitivity to the highest values of LOS and illness severity. Additionally, the association of HL with LOS appeared concentrated among participants with shorter LOS. Relative to other predictors, the contribution of HL to the overall LOS model was small, as evidenced by the change in adjusted R2 values with HL excluded.

Among the covariates, only gender modified the association between HL and LOS; the findings suggested that men were more susceptible to the effect of low HL on increased LOS. Illness severity and other sociodemographics, including age ≥65, did not appear to modify the association. We also found that being African American and having Medicaid or no insurance were associated with a significantly shorter LOS in multivariate analysis.

Previous work suggested that the adverse health effects of low HL may be mediated through several pathways, including health knowledge, self-efficacy, health skills, and illness stigma.25-27 The finding of a small but significant relationship between HL and LOS was not surprising given these known associations; nevertheless, there may be an additional patient-dependent effect of low HL on LOS not discovered here. For instance, patients with poor health knowledge and self-efficacy might stay in the hospital longer if they or their providers do not feel comfortable with their self-care ability.

This finding may be useful in developing hospital-based interventions. HL-specific interventions, several of which have been tested in the inpatient setting,14,28,29 have shown promise toward improving health knowledge,30 disease severity,31 and health resource utilization.32

Those with low HL may lack the self-efficacy to participate in discharge planning; in fact, previous work has related low HL to posthospital readmissions.8,9 Conversely, patients with low HL might struggle to engage in the inpatient milieu, advocating for shorter LOS if they feel alienated by the inpatient experience.

These possibilities show that LOS is a complex measure shown to depend on patient-level characteristics and on provider-based, geographical, and sociocultural factors.16,33 With these forces at play, additional effects of lower levels of HL may be lost without phenotyping patients by both level of HL and related characteristics, such as self-efficacy, health skills, and stigma. By gathering these additional data, future work should explore whether subpopulations of patients with low HL may be at risk for too-short vs too-long hospital admissions.

For instance, in this study, both race and Medicaid insurance were associated with shorter LOS. Being African American was associated with shorter LOS in our study but has been found to be associated with longer LOS in another study specifically focused on diabetes.34 Prior findings found uninsured patients have shorter LOS.35 Therefore, these findings in our study are difficult to explain without further work to understand whether there are health disparities in the way patients are cared for during hospitalization that may shorten or lengthen their LOS because of factors outside of their clinical need.

The finding that gender modified the effect of low HL on LOS was unexpected. There were similar proportions of men and women with low HL. There is evidence to support that women make the majority of health decisions for themselves and their familes36; therefore, there may be unmeasured aspects of HL that provide an advantage for female vs male inpatients. Furthermore, omitted confounders, such as social support, may not fully capture potential gender-related differences. Future work is needed to understand the role of gender in relationship to HL and LOS.

Limitations of this study include its observational, single-centered design with information derived from administrative data; positive and negative confounding cannot be ruled out. For instance, we did not control for complex aspects affecting LOS, such as discharge disposition and goals of care (eg, aggressive care after discharge vs hospice). To address this limitation, multivariate analyses were performed, which were adjusted for illness severity scores and took into account both comorbidity and severity of the current illness. Additionally, although it is important to study such populations, our largely urban, minority sample is not representative of the U.S. population, and within our large sample, there were participants with missing data who had lower HL on average, although this group represented only 5% of the sample. Finally, different HL tools have noncomplete concordance, which has been seen when comparing the BHLS with more objective tools.20,37 Furthermore, certain in-hospital clinical scenarios (eg, recent stroke or prolonged intensive care unit stay) may present unique challenges in establishing a baseline HL level. However, the BHLS was used in this study because of its greater feasibility.

In conclusion, this study is the first to evaluate the relationship between low HL and LOS. The findings suggest that HL may play a role in shaping outcomes in the inpatient setting and that targeting interventions toward screened patients may be a pathway toward mitigating adverse effects. Our findings need to be replicated in larger, more representative samples, and further work understanding subpopulations within the low HL population is needed. Future work should measure this association in diverse inpatient settings (eg, psychiatric, surgical, and specialty), in addition to assessing associations between HL and other important in-hospital outcome measures, including mortality and discharge disposition.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Hospitalist Project team for their assistance with data collection. The authors especially thank Chuanhong Liao and Ashley Snyder for assistance with statistical analyses; Andrea Flores, Ainoa Coltri, and Tom Best for their assistance with data management. The authors would also like to thank Nicole Twu for her help with preparing and editing the manuscript.

Disclosures

Dr. Jaffee was supported by a Calvin Fentress Research Fellowship and NIH R25MH094612. Dr. Press was supported by a career development award (NHLBI K23HL118151). This work was also supported by a seed grant from the Center for Health Administration Studies. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Health literacy (HL), defined as patients’ ability to understand health information and make health decisions,1 is a prevalent problem in the outpatient and inpatient settings.2,3 In both settings, low HL has adverse implications for self-care including interpreting health labels4 and taking medications correctly.5 Among outpatient cohorts, HL has been associated with worse outcomes and acute care utilization.6 Associations with low HL include increased hospitalizations,7 rehospitalizations,8,9 emergency department visits,10 and decreased preventative care use.11 Among the elderly, low HL is associated with increased mortality12 and decreased self-perception of health.13

A systematic review revealed that most high-quality HL outcome studies were conducted in the outpatient setting.6 There have been very few studies assessing effects of low HL in an acute-care setting.7,14 These studies have evaluated postdischarge outcomes, including admissions or readmissions,7-9 and medication knowledge.14 To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating associations between HL and hospital length of stay (LOS).

LOS has received much attention as providers and payers focus more on resource utilization and eliminating adverse effects of prolonged hospitalization.15 LOS is multifactorial, depending on clinical characteristics like disease severity, as well as on sociocultural, demographic, and geographic factors.16 Despite evidence that LOS reductions translate into improved resource allocation and potentially fewer complications, there remains a tension between the appropriate LOS and one that is too short for a given condition.17

Because low HL is associated with inefficient resource utilization, we hypothesized that low HL would be associated with increased LOS after controlling for illness severity. Our objectives were to evaluate the association between low HL and LOS and whether such an association was modified by illness severity and sociodemographics.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, Participants

An in-hospital, cohort study design of patients who were admitted or transferred to the general medicine service at the University of Chicago between October 2012 and November 2015 and screened for inclusion as part of a large, ongoing study of inpatient care quality was conducted.18 Exclusion criteria included observation status, age under 18 years, non-English speaking, and repeat participants. Those who died during hospitalization or whose discharge status was missing were excluded because the primary goal was to examine the association of HL and time to discharge, which could not be evaluated among those who died. We excluded participants with LOS >30 days to limit overly influential effects of extreme outliers (1% of the population).

Variables

HL was screened using the Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS), a validated, 3-question verbal survey not requiring adequate visual acuity to assess HL.19,20 The 3 questions are as follows: (1) “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?”, (2) “How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials?”, and (3) “How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information?” Responses to the questions were scored on a 5-point Likert scale in which higher scores corresponded to higher HL.21,22 The scores for each of the 3 questions were summed to yield a range between 3 and 15. On the individual questions, prior work has demonstrated improved test performance with a cutoff of ≤3, which corresponds to a response of “some of the time” or “somewhat”; therefore, when the 3 questions were summed together, scores of ≤9 were considered indicative of low HL.21,23

For severity of illness adjustment, we used relative weights derived from the 3M (3M, Maplewood, MN) All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG) classification system, which uses administrative data to classify the severity. The APR-DRG system assigns each admission to a DRG based on principal diagnosis; for each DRG, patients are then subdivided into 4 severity classes based on age, comorbidity, and interactions between these variables and the admitting diagnosis.24 Using the base DRG and severity score, the system assigns relative weights that reflect differences in expected hospital resource utilization.