User login

Higher water intake linked to less hyperuricemia in gout

SAN DIEGO – While more hydration seems to improve gout, there’s little research into the connection between the two. Now, a new study suggests a strong link between low water consumption and hyperuricemia, a possible sign that boosting water intake will help some gout patients.

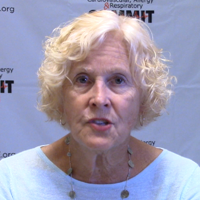

While it’s too early to confirm a clinically relevant connection, “there is a statistically significant inverse association between water consumption and high uric acid levels,” said Patricia Kachur, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at the University of Central Florida, Ocala (Fla.) Regional Medical Center. Dr. Kachur, who spoke about the findings in an interview, is lead author of a study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

An abstract presented at the 2009 ACR annual meeting reported fewer gout attacks (adjusted odds ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-0.90) in 535 gout patients who reported drinking more than eight glasses of water over a 24-hour period, compared with those who drank one or fewer.

For the new study, Dr. Kachur and her colleagues examined findings from 539 participants with gout (but not chronic kidney disease) out of 17,321 individuals who took part in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2009 to 2014.

Of the 539 participants, 39% were defined as having hyperuricemia (6.0 mg/dL or greater), with the rest having a low or normal level. Those with hyperuricemia were significantly more likely to be male and have obesity and hypertension.

The investigators defined high water intake as three or more liters of water per day for men and 2.2 or more liters for women. Of the 539 participants, 116 (22%) had high water intake.

The researchers found a lower risk of developing hyperuricemia in those with higher water intake, compared with those with lower intake (adjusted OR, 0.421; 95% CI, 0.262-0.679; P = .0007).

“These findings do not say anything about water and gout – not yet anyway,” Dr. Kachur said. “Rather there is a possibility that outpatient water intake has an association with lower uric acid levels in people afflicted by gout even after considering multiple other factors such as gender, race, BMI, age, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.”

Indeed, she and her colleagues decided against publishing the results of their 2009 study “because there is a major challenge in interpreting these data.”

“Given that people only consume a finite amount of liquids each day, is it that consuming more water is beneficial or that drinking less of ‘bad’ fluids (for example, sodas, sugar-sweetened juices) is beneficial? We were not able to disentangle this issue,” she explained.

Still, she said, there are explanations about why water intake could be beneficial for gout. “Intravascular volume depletion increases the concentration of serum urate, and increased serum urate beyond the saturation threshold can result in crystallization,” she said. “With heat-related dehydration, there may also be metabolic acidosis and/or electrolyte abnormalities that can lead to decreased urate secretion in renal tubules, and an acidic pH can decrease solubility of serum urate.”

Dr. Neogi does encourage appropriate gout patients to make sure they drink enough water, especially if it is hot. She cowrote a 2014 study that linked gout flares to high temperatures and extremes of humidity, which can lead to dehydration (Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Aug 15;180[4]:372-7).

“The amount of water intake that is beneficial for gout is not known, so patients should follow general recommendations for water intake. In addition, I strongly encourage patients with gout to avoid or limit the amount of liquid consumed in the form of regular sodas and sweetened drinks or juices, particularly those with high-fructose corn syrup, and alcohol,” she said. “With regards to tea or coffee, if patients drink either tea or coffee, they can continue to do so and to use only low-fat or nonfat milk and little or no sugar.”

Meanwhile, she said, “there are some data to suggest that cherry juice – true natural cherry juice from fruit, not ‘cherry drinks’ – can be beneficial for gout. We are formally testing cherry juice in a trial.”

What’s next for research into water intake and gout? “The clinical correlation is missing in the study,” said Dr. Kachur, lead author of the new study. “Targeted surveys of gout patients, hopefully followed by a randomized controlled trial regulating water intake, can help make those connections.”

Dr. Kachur and other study authors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Neogi reported having no relevant disclosures. No specific study funding was reported.

SAN DIEGO – While more hydration seems to improve gout, there’s little research into the connection between the two. Now, a new study suggests a strong link between low water consumption and hyperuricemia, a possible sign that boosting water intake will help some gout patients.

While it’s too early to confirm a clinically relevant connection, “there is a statistically significant inverse association between water consumption and high uric acid levels,” said Patricia Kachur, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at the University of Central Florida, Ocala (Fla.) Regional Medical Center. Dr. Kachur, who spoke about the findings in an interview, is lead author of a study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

An abstract presented at the 2009 ACR annual meeting reported fewer gout attacks (adjusted odds ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-0.90) in 535 gout patients who reported drinking more than eight glasses of water over a 24-hour period, compared with those who drank one or fewer.

For the new study, Dr. Kachur and her colleagues examined findings from 539 participants with gout (but not chronic kidney disease) out of 17,321 individuals who took part in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2009 to 2014.

Of the 539 participants, 39% were defined as having hyperuricemia (6.0 mg/dL or greater), with the rest having a low or normal level. Those with hyperuricemia were significantly more likely to be male and have obesity and hypertension.

The investigators defined high water intake as three or more liters of water per day for men and 2.2 or more liters for women. Of the 539 participants, 116 (22%) had high water intake.

The researchers found a lower risk of developing hyperuricemia in those with higher water intake, compared with those with lower intake (adjusted OR, 0.421; 95% CI, 0.262-0.679; P = .0007).

“These findings do not say anything about water and gout – not yet anyway,” Dr. Kachur said. “Rather there is a possibility that outpatient water intake has an association with lower uric acid levels in people afflicted by gout even after considering multiple other factors such as gender, race, BMI, age, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.”

Indeed, she and her colleagues decided against publishing the results of their 2009 study “because there is a major challenge in interpreting these data.”

“Given that people only consume a finite amount of liquids each day, is it that consuming more water is beneficial or that drinking less of ‘bad’ fluids (for example, sodas, sugar-sweetened juices) is beneficial? We were not able to disentangle this issue,” she explained.

Still, she said, there are explanations about why water intake could be beneficial for gout. “Intravascular volume depletion increases the concentration of serum urate, and increased serum urate beyond the saturation threshold can result in crystallization,” she said. “With heat-related dehydration, there may also be metabolic acidosis and/or electrolyte abnormalities that can lead to decreased urate secretion in renal tubules, and an acidic pH can decrease solubility of serum urate.”

Dr. Neogi does encourage appropriate gout patients to make sure they drink enough water, especially if it is hot. She cowrote a 2014 study that linked gout flares to high temperatures and extremes of humidity, which can lead to dehydration (Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Aug 15;180[4]:372-7).

“The amount of water intake that is beneficial for gout is not known, so patients should follow general recommendations for water intake. In addition, I strongly encourage patients with gout to avoid or limit the amount of liquid consumed in the form of regular sodas and sweetened drinks or juices, particularly those with high-fructose corn syrup, and alcohol,” she said. “With regards to tea or coffee, if patients drink either tea or coffee, they can continue to do so and to use only low-fat or nonfat milk and little or no sugar.”

Meanwhile, she said, “there are some data to suggest that cherry juice – true natural cherry juice from fruit, not ‘cherry drinks’ – can be beneficial for gout. We are formally testing cherry juice in a trial.”

What’s next for research into water intake and gout? “The clinical correlation is missing in the study,” said Dr. Kachur, lead author of the new study. “Targeted surveys of gout patients, hopefully followed by a randomized controlled trial regulating water intake, can help make those connections.”

Dr. Kachur and other study authors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Neogi reported having no relevant disclosures. No specific study funding was reported.

SAN DIEGO – While more hydration seems to improve gout, there’s little research into the connection between the two. Now, a new study suggests a strong link between low water consumption and hyperuricemia, a possible sign that boosting water intake will help some gout patients.

While it’s too early to confirm a clinically relevant connection, “there is a statistically significant inverse association between water consumption and high uric acid levels,” said Patricia Kachur, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at the University of Central Florida, Ocala (Fla.) Regional Medical Center. Dr. Kachur, who spoke about the findings in an interview, is lead author of a study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

An abstract presented at the 2009 ACR annual meeting reported fewer gout attacks (adjusted odds ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-0.90) in 535 gout patients who reported drinking more than eight glasses of water over a 24-hour period, compared with those who drank one or fewer.

For the new study, Dr. Kachur and her colleagues examined findings from 539 participants with gout (but not chronic kidney disease) out of 17,321 individuals who took part in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2009 to 2014.

Of the 539 participants, 39% were defined as having hyperuricemia (6.0 mg/dL or greater), with the rest having a low or normal level. Those with hyperuricemia were significantly more likely to be male and have obesity and hypertension.

The investigators defined high water intake as three or more liters of water per day for men and 2.2 or more liters for women. Of the 539 participants, 116 (22%) had high water intake.

The researchers found a lower risk of developing hyperuricemia in those with higher water intake, compared with those with lower intake (adjusted OR, 0.421; 95% CI, 0.262-0.679; P = .0007).

“These findings do not say anything about water and gout – not yet anyway,” Dr. Kachur said. “Rather there is a possibility that outpatient water intake has an association with lower uric acid levels in people afflicted by gout even after considering multiple other factors such as gender, race, BMI, age, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.”

Indeed, she and her colleagues decided against publishing the results of their 2009 study “because there is a major challenge in interpreting these data.”

“Given that people only consume a finite amount of liquids each day, is it that consuming more water is beneficial or that drinking less of ‘bad’ fluids (for example, sodas, sugar-sweetened juices) is beneficial? We were not able to disentangle this issue,” she explained.

Still, she said, there are explanations about why water intake could be beneficial for gout. “Intravascular volume depletion increases the concentration of serum urate, and increased serum urate beyond the saturation threshold can result in crystallization,” she said. “With heat-related dehydration, there may also be metabolic acidosis and/or electrolyte abnormalities that can lead to decreased urate secretion in renal tubules, and an acidic pH can decrease solubility of serum urate.”

Dr. Neogi does encourage appropriate gout patients to make sure they drink enough water, especially if it is hot. She cowrote a 2014 study that linked gout flares to high temperatures and extremes of humidity, which can lead to dehydration (Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Aug 15;180[4]:372-7).

“The amount of water intake that is beneficial for gout is not known, so patients should follow general recommendations for water intake. In addition, I strongly encourage patients with gout to avoid or limit the amount of liquid consumed in the form of regular sodas and sweetened drinks or juices, particularly those with high-fructose corn syrup, and alcohol,” she said. “With regards to tea or coffee, if patients drink either tea or coffee, they can continue to do so and to use only low-fat or nonfat milk and little or no sugar.”

Meanwhile, she said, “there are some data to suggest that cherry juice – true natural cherry juice from fruit, not ‘cherry drinks’ – can be beneficial for gout. We are formally testing cherry juice in a trial.”

What’s next for research into water intake and gout? “The clinical correlation is missing in the study,” said Dr. Kachur, lead author of the new study. “Targeted surveys of gout patients, hopefully followed by a randomized controlled trial regulating water intake, can help make those connections.”

Dr. Kachur and other study authors reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Neogi reported having no relevant disclosures. No specific study funding was reported.

AT ACR 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Gout patients with the highest water intake were less likely than others to have hyperuricemia (aOR, 0.421).

Data source: 539 participants with gout (but not chronic kidney disease) out of 17,321 in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009-2014.

Disclosures: The study authors reported having no relevant disclosures. No specific study funding was reported.

Robotic hysterectomy plus mini-lap outperformed open procedure

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Robotic hysterectomy combined with extraction of the uterus via mini-laparotomy led to significantly shorter lengths of stay, lower estimated blood loss, and fewer postoperative complications compared with open hysterectomy when the uterus weighed more than 250 grams.

Gynecologic surgeons are seeking ways to safely perform minimally invasive hysterectomy on patients with larger uteri in light of the 2014 Food and Drug Administration admonition regarding power morcellation. To this end, Natasha Gupta, MD, and her colleagues at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, retrospectively reviewed all patients with uterine sizes larger than 250 grams undergoing hysterectomy at their institution between 2012 and 2015.

“For the mini-laparotomy, the technique utilizes a customized incision connecting the two left port sites, followed by the removal of the specimen via this incision,” Dr. Gupta said at the AAGL Global Congress.

Patient factors and outcomes were compared via Student t-tests and Chi-square analysis.

Mean length of stay was significantly shorter for patients who underwent robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy, at 1.4 days vs. 5.4 days for those with open hysterectomy (P = .000) as was mean estimated blood loss – 119.9 mL vs. 547.5 mL, respectively (P = .000). Postoperative complications were seen in fewer patients who underwent robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy, 9 of 82 patients vs. 15 of 58 open hysterectomy patients.

Mean operative time was significantly longer in robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy patients – 191.6 minutes vs. 162.8 minutes (P = .005) – but that was expected, Dr. Gupta noted. Patient factors such as hypertension, diabetes, history of spontaneous vaginal delivery and/or cesarean delivery, and body mass index, as well as uterine pathology, were not significantly different between the groups.

“Mini-laparotomy combined with minimally invasive hysterectomy is a very safe and feasible technique for tissue extraction where contained morcellation is either not preferred or not available,” Dr. Gupta said.

Dr. Gupta reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Robotic hysterectomy combined with extraction of the uterus via mini-laparotomy led to significantly shorter lengths of stay, lower estimated blood loss, and fewer postoperative complications compared with open hysterectomy when the uterus weighed more than 250 grams.

Gynecologic surgeons are seeking ways to safely perform minimally invasive hysterectomy on patients with larger uteri in light of the 2014 Food and Drug Administration admonition regarding power morcellation. To this end, Natasha Gupta, MD, and her colleagues at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, retrospectively reviewed all patients with uterine sizes larger than 250 grams undergoing hysterectomy at their institution between 2012 and 2015.

“For the mini-laparotomy, the technique utilizes a customized incision connecting the two left port sites, followed by the removal of the specimen via this incision,” Dr. Gupta said at the AAGL Global Congress.

Patient factors and outcomes were compared via Student t-tests and Chi-square analysis.

Mean length of stay was significantly shorter for patients who underwent robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy, at 1.4 days vs. 5.4 days for those with open hysterectomy (P = .000) as was mean estimated blood loss – 119.9 mL vs. 547.5 mL, respectively (P = .000). Postoperative complications were seen in fewer patients who underwent robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy, 9 of 82 patients vs. 15 of 58 open hysterectomy patients.

Mean operative time was significantly longer in robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy patients – 191.6 minutes vs. 162.8 minutes (P = .005) – but that was expected, Dr. Gupta noted. Patient factors such as hypertension, diabetes, history of spontaneous vaginal delivery and/or cesarean delivery, and body mass index, as well as uterine pathology, were not significantly different between the groups.

“Mini-laparotomy combined with minimally invasive hysterectomy is a very safe and feasible technique for tissue extraction where contained morcellation is either not preferred or not available,” Dr. Gupta said.

Dr. Gupta reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Robotic hysterectomy combined with extraction of the uterus via mini-laparotomy led to significantly shorter lengths of stay, lower estimated blood loss, and fewer postoperative complications compared with open hysterectomy when the uterus weighed more than 250 grams.

Gynecologic surgeons are seeking ways to safely perform minimally invasive hysterectomy on patients with larger uteri in light of the 2014 Food and Drug Administration admonition regarding power morcellation. To this end, Natasha Gupta, MD, and her colleagues at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, retrospectively reviewed all patients with uterine sizes larger than 250 grams undergoing hysterectomy at their institution between 2012 and 2015.

“For the mini-laparotomy, the technique utilizes a customized incision connecting the two left port sites, followed by the removal of the specimen via this incision,” Dr. Gupta said at the AAGL Global Congress.

Patient factors and outcomes were compared via Student t-tests and Chi-square analysis.

Mean length of stay was significantly shorter for patients who underwent robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy, at 1.4 days vs. 5.4 days for those with open hysterectomy (P = .000) as was mean estimated blood loss – 119.9 mL vs. 547.5 mL, respectively (P = .000). Postoperative complications were seen in fewer patients who underwent robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy, 9 of 82 patients vs. 15 of 58 open hysterectomy patients.

Mean operative time was significantly longer in robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy patients – 191.6 minutes vs. 162.8 minutes (P = .005) – but that was expected, Dr. Gupta noted. Patient factors such as hypertension, diabetes, history of spontaneous vaginal delivery and/or cesarean delivery, and body mass index, as well as uterine pathology, were not significantly different between the groups.

“Mini-laparotomy combined with minimally invasive hysterectomy is a very safe and feasible technique for tissue extraction where contained morcellation is either not preferred or not available,” Dr. Gupta said.

Dr. Gupta reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

AT AAGL 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Mean length of stay was 1.4 days with robotic hysterectomy/mini-laparotomy vs. 5.4 days for open hysterectomy (P = .000).

Data source: A single-center retrospective review of all hysterectomies with uteri larger than 250 grams from the period of 2012-2015.

Disclosures: The study had no outside funding. Dr. Gupta reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Asymptomatic Pink Plaque on the Scapula

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma

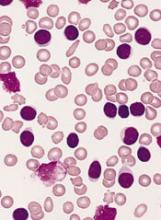

Immunohistochemistry revealed a nodular infiltrate consisting of small to large atypical lymphocytes forming an irregular germinal center with notably thinned mantle zones and lack of polarization (Figure, A). Atypical cells stained positively with Bcl-6, and CD20 was diffusely positive (Figure, B-D). Bcl-2 and CD3 colocalized to the reactive T-cell infiltrate, and CD10 was largely negative. Further workup with bone marrow biopsy and full-body positron emission tomography-computed tomography was unremarkable. Given these findings, a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) was made. At 1 month following radiation therapy, complete clinical clearance of the lymphoma was achieved.

Follicle center lymphoma, also known as cutaneous follicular lymphoma, is the most common subtype of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas, representing approximately 57% of cases.1 Follicle center lymphoma typically affects older, non-Hispanic white adults with a median age of onset of 60 years. It has a predilection for the head, neck, and trunk.2 Lesions present as solitary erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules, but they can more rarely be multifocal.3 Clinical diagnosis of FCL can be difficult, with papular lesions resembling acne, rosacea, folliculitis, or arthropod assault.4,5 As such, diagnosis of FCL typically relies on histopathologic analysis.

Histologically, FCL can present in several different patterns including follicular, nodular, diffuse, or a pleomorphic mix of these.2,6 The cells are comprised of germinal center B cells, staining positively for Bcl-6, CD20, and CD79a.7 Tumor cells do not exhibit the t(14;18) translocation seen in nodal follicular lymphomas.2,8 Unlike marginal zone lymphoma, FCL stains negatively for Bcl-2 and multiple myeloma 1/interferon regulatory factor 4 (MUM1/IRF-4).2,9 Forkhead box P1 (FOXP1) also is usually negative, but its presence can indicate a poorer prognosis.2 It is important to distinguish primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas from systemic B-cell lymphoma with secondary cutaneous involvement, as they have a different clinical prognosis and management course. Further workup includes bone marrow biopsy, serum analysis for clonal involvement, and positron emission tomography-computed tomography imaging. Follicle center lymphoma generally has an indolent disease course with a favorable 5-year survival rate of approximately 95%.6,8

Untreated lesions may enlarge slowly or even spontaneously involute.10 The histologic growth pattern and number of lesions do not affect prognosis, but presence on the legs has a 5-year survival rate of 41%.2 Extracutaneous dissemination can occur in 5% to 10% of cases.2 Given the slow progression of FCL, conservative management with observation is an option. However, curative treatment can be reasonably attempted for solitary lesions by excision or radiation. Treatment of FCL often can be complicated by its predilection for the head and neck. Other treatment modalities include topical steroids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and bexarotene.10 More generalized involvement may require systemic therapy with rituximab or chemotherapy. Recurrence after therapy is common, reported in 46.5% of patients, but does not affect prognosis.2

- Zinzani PL, Quaglino P, Pimpinelli N, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: The Italian Study Group for Cutaneous Lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1376-1382.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1-13.

- Grange F, Bekkenk MW, Wechsler J, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas: a European multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3602-3610.

- Soon CW, Pincus LB, Ai WZ, et al. Acneiform presentation of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:887-889.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: a report of 18 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Wilcox RA. CME information: cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Franco R, Fernandez-Vazquez A, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, et al. Cutaneous follicular B-cell lymphoma: description of a series of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:875-883.

- Kempf W, Denisjuk N, Kerl K, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:12-22; quiz 23.

- de Leval L HN, Longtine J, Ferry JA, et al. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas of follicular and marginal zone types: use of Bcl-6, CD10, Bcl-2, and CD21 in differential diagnosis and classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:732-741.

- Suárez AL, Querfeld C, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part II. therapy and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1-11.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma

Immunohistochemistry revealed a nodular infiltrate consisting of small to large atypical lymphocytes forming an irregular germinal center with notably thinned mantle zones and lack of polarization (Figure, A). Atypical cells stained positively with Bcl-6, and CD20 was diffusely positive (Figure, B-D). Bcl-2 and CD3 colocalized to the reactive T-cell infiltrate, and CD10 was largely negative. Further workup with bone marrow biopsy and full-body positron emission tomography-computed tomography was unremarkable. Given these findings, a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) was made. At 1 month following radiation therapy, complete clinical clearance of the lymphoma was achieved.

Follicle center lymphoma, also known as cutaneous follicular lymphoma, is the most common subtype of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas, representing approximately 57% of cases.1 Follicle center lymphoma typically affects older, non-Hispanic white adults with a median age of onset of 60 years. It has a predilection for the head, neck, and trunk.2 Lesions present as solitary erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules, but they can more rarely be multifocal.3 Clinical diagnosis of FCL can be difficult, with papular lesions resembling acne, rosacea, folliculitis, or arthropod assault.4,5 As such, diagnosis of FCL typically relies on histopathologic analysis.

Histologically, FCL can present in several different patterns including follicular, nodular, diffuse, or a pleomorphic mix of these.2,6 The cells are comprised of germinal center B cells, staining positively for Bcl-6, CD20, and CD79a.7 Tumor cells do not exhibit the t(14;18) translocation seen in nodal follicular lymphomas.2,8 Unlike marginal zone lymphoma, FCL stains negatively for Bcl-2 and multiple myeloma 1/interferon regulatory factor 4 (MUM1/IRF-4).2,9 Forkhead box P1 (FOXP1) also is usually negative, but its presence can indicate a poorer prognosis.2 It is important to distinguish primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas from systemic B-cell lymphoma with secondary cutaneous involvement, as they have a different clinical prognosis and management course. Further workup includes bone marrow biopsy, serum analysis for clonal involvement, and positron emission tomography-computed tomography imaging. Follicle center lymphoma generally has an indolent disease course with a favorable 5-year survival rate of approximately 95%.6,8

Untreated lesions may enlarge slowly or even spontaneously involute.10 The histologic growth pattern and number of lesions do not affect prognosis, but presence on the legs has a 5-year survival rate of 41%.2 Extracutaneous dissemination can occur in 5% to 10% of cases.2 Given the slow progression of FCL, conservative management with observation is an option. However, curative treatment can be reasonably attempted for solitary lesions by excision or radiation. Treatment of FCL often can be complicated by its predilection for the head and neck. Other treatment modalities include topical steroids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and bexarotene.10 More generalized involvement may require systemic therapy with rituximab or chemotherapy. Recurrence after therapy is common, reported in 46.5% of patients, but does not affect prognosis.2

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma

Immunohistochemistry revealed a nodular infiltrate consisting of small to large atypical lymphocytes forming an irregular germinal center with notably thinned mantle zones and lack of polarization (Figure, A). Atypical cells stained positively with Bcl-6, and CD20 was diffusely positive (Figure, B-D). Bcl-2 and CD3 colocalized to the reactive T-cell infiltrate, and CD10 was largely negative. Further workup with bone marrow biopsy and full-body positron emission tomography-computed tomography was unremarkable. Given these findings, a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) was made. At 1 month following radiation therapy, complete clinical clearance of the lymphoma was achieved.

Follicle center lymphoma, also known as cutaneous follicular lymphoma, is the most common subtype of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas, representing approximately 57% of cases.1 Follicle center lymphoma typically affects older, non-Hispanic white adults with a median age of onset of 60 years. It has a predilection for the head, neck, and trunk.2 Lesions present as solitary erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules, but they can more rarely be multifocal.3 Clinical diagnosis of FCL can be difficult, with papular lesions resembling acne, rosacea, folliculitis, or arthropod assault.4,5 As such, diagnosis of FCL typically relies on histopathologic analysis.

Histologically, FCL can present in several different patterns including follicular, nodular, diffuse, or a pleomorphic mix of these.2,6 The cells are comprised of germinal center B cells, staining positively for Bcl-6, CD20, and CD79a.7 Tumor cells do not exhibit the t(14;18) translocation seen in nodal follicular lymphomas.2,8 Unlike marginal zone lymphoma, FCL stains negatively for Bcl-2 and multiple myeloma 1/interferon regulatory factor 4 (MUM1/IRF-4).2,9 Forkhead box P1 (FOXP1) also is usually negative, but its presence can indicate a poorer prognosis.2 It is important to distinguish primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas from systemic B-cell lymphoma with secondary cutaneous involvement, as they have a different clinical prognosis and management course. Further workup includes bone marrow biopsy, serum analysis for clonal involvement, and positron emission tomography-computed tomography imaging. Follicle center lymphoma generally has an indolent disease course with a favorable 5-year survival rate of approximately 95%.6,8

Untreated lesions may enlarge slowly or even spontaneously involute.10 The histologic growth pattern and number of lesions do not affect prognosis, but presence on the legs has a 5-year survival rate of 41%.2 Extracutaneous dissemination can occur in 5% to 10% of cases.2 Given the slow progression of FCL, conservative management with observation is an option. However, curative treatment can be reasonably attempted for solitary lesions by excision or radiation. Treatment of FCL often can be complicated by its predilection for the head and neck. Other treatment modalities include topical steroids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and bexarotene.10 More generalized involvement may require systemic therapy with rituximab or chemotherapy. Recurrence after therapy is common, reported in 46.5% of patients, but does not affect prognosis.2

- Zinzani PL, Quaglino P, Pimpinelli N, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: The Italian Study Group for Cutaneous Lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1376-1382.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1-13.

- Grange F, Bekkenk MW, Wechsler J, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas: a European multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3602-3610.

- Soon CW, Pincus LB, Ai WZ, et al. Acneiform presentation of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:887-889.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: a report of 18 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Wilcox RA. CME information: cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Franco R, Fernandez-Vazquez A, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, et al. Cutaneous follicular B-cell lymphoma: description of a series of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:875-883.

- Kempf W, Denisjuk N, Kerl K, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:12-22; quiz 23.

- de Leval L HN, Longtine J, Ferry JA, et al. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas of follicular and marginal zone types: use of Bcl-6, CD10, Bcl-2, and CD21 in differential diagnosis and classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:732-741.

- Suárez AL, Querfeld C, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part II. therapy and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1-11.

- Zinzani PL, Quaglino P, Pimpinelli N, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: The Italian Study Group for Cutaneous Lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1376-1382.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1-13.

- Grange F, Bekkenk MW, Wechsler J, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas: a European multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3602-3610.

- Soon CW, Pincus LB, Ai WZ, et al. Acneiform presentation of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:887-889.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: a report of 18 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Wilcox RA. CME information: cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Franco R, Fernandez-Vazquez A, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, et al. Cutaneous follicular B-cell lymphoma: description of a series of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:875-883.

- Kempf W, Denisjuk N, Kerl K, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:12-22; quiz 23.

- de Leval L HN, Longtine J, Ferry JA, et al. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas of follicular and marginal zone types: use of Bcl-6, CD10, Bcl-2, and CD21 in differential diagnosis and classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:732-741.

- Suárez AL, Querfeld C, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part II. therapy and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1-11.

A 36-year-old man presented with a pink plaque on the right side of the scapula of 1 year's duration. The plaque had not grown and was completely asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed a violaceous, pink, 2-cm nodule with overlying telangiectasia. No other concerning lesions were identified on total-body skin examination. A punch biopsy was obtained.

GSI may boost BCMA CAR T-cell therapy efficacy in myeloma

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Gamma secretase inhibition may lead to improved outcomes in multiple myeloma patients treated with B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–specific CAR T-cell therapy, according to Margot J. Pont, PhD.

In a preclinical myeloma model, gamma secretase inhibition (GSI) increased antitumor efficacy of BCMA-specific chimeric antigen receptor modified T-cells (BCMA CAR T), Dr. Pont of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

BCMA is expressed in most multiple myeloma patients, and can be targeted by T cells that have been transduced with an anti-BCMA CAR. Other studies have shown efficacy of BCMA CAR T cells, and Dr. Pont and her colleagues have developed and optimized a CAR, based on a previously described single-chain variable fragment (scFv), that performs at least as well as a similar CAR developed previously by another group.

Previous studies have found that antigen down-regulation and escape can be an important escape mechanism by the tumor, so low-to-negative antigen expression could lead to failure in CAR T-cell recognition, resulting in relapse, she explained.

“We need the antigen density to be high enough,” she said, noting that BCMA, specifically, can be susceptible to antigen down-regulation, because its extracellular component is cleaved off the cell membrane by the enzyme gamma-secretase.

“That leads to two things: It reduces the surface expression of BCMA and it sheds soluble BCMA into the circulation, so you get high concentrations of soluble BCMA in the tumor microenvironment,” she said.

Inhibiting BCMA shedding with GSI can increase surface expression and reduce levels of soluble BCMA, thereby potentially enhancing the CAR activity.

First, soluble BCMA levels were measured in bone marrow sera from myeloma patients.

“We indeed saw high levels of soluble BCMA in these patients, and they roughly correlated with tumor burden. When culturing myeloma cell lines in vitro, we detected sBCMA in the culture supernatant within 24 hours,” Dr. Pont said, adding that the introduction of recombinant BCMA to the cultures showed that increasing levels of recombinant BCMA reduced staining of the CAR, demonstrating binding to the receptor.

Next, GSI was used to increase BCMA levels, and with increasing concentrations of the drug, BCMA surface expression was increased, she said, noting that this coincided with a reduction of soluble BCMA in the culture supernatant.

This also worked in patient samples, and was achieved with low doses of GSI, which upregulated surface BCMA levels on primary multiple myeloma by up to tenfold, she said.

In vivo testing of CAR T-cell efficacy was performed in tumor-bearing mice, which were treated with either BCMA-specific CAR T cells alone or in combination with GSI.

In this preclinical model of myeloma, RO4929097 increased BCMA on tumor cells in bone marrow and decreased soluble BCMA in peripheral blood. The myeloma-bearing mice treated with both BCMA CAR T cells and intermittent doses of RO4929097 experienced improved antitumor effects of the BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, as well as increased survival versus mice that did not receive RO4929097, she said.

“We’re currently optimizing these dosing regimens,” she said, concluding that “combining GSI and BCMA CAR T is an attractive option to improve the level of efficacy and prevent the outgrowth of BCMA-low tumor cells.”

Dr. Pont reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Gamma secretase inhibition may lead to improved outcomes in multiple myeloma patients treated with B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–specific CAR T-cell therapy, according to Margot J. Pont, PhD.

In a preclinical myeloma model, gamma secretase inhibition (GSI) increased antitumor efficacy of BCMA-specific chimeric antigen receptor modified T-cells (BCMA CAR T), Dr. Pont of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

BCMA is expressed in most multiple myeloma patients, and can be targeted by T cells that have been transduced with an anti-BCMA CAR. Other studies have shown efficacy of BCMA CAR T cells, and Dr. Pont and her colleagues have developed and optimized a CAR, based on a previously described single-chain variable fragment (scFv), that performs at least as well as a similar CAR developed previously by another group.

Previous studies have found that antigen down-regulation and escape can be an important escape mechanism by the tumor, so low-to-negative antigen expression could lead to failure in CAR T-cell recognition, resulting in relapse, she explained.

“We need the antigen density to be high enough,” she said, noting that BCMA, specifically, can be susceptible to antigen down-regulation, because its extracellular component is cleaved off the cell membrane by the enzyme gamma-secretase.

“That leads to two things: It reduces the surface expression of BCMA and it sheds soluble BCMA into the circulation, so you get high concentrations of soluble BCMA in the tumor microenvironment,” she said.

Inhibiting BCMA shedding with GSI can increase surface expression and reduce levels of soluble BCMA, thereby potentially enhancing the CAR activity.

First, soluble BCMA levels were measured in bone marrow sera from myeloma patients.

“We indeed saw high levels of soluble BCMA in these patients, and they roughly correlated with tumor burden. When culturing myeloma cell lines in vitro, we detected sBCMA in the culture supernatant within 24 hours,” Dr. Pont said, adding that the introduction of recombinant BCMA to the cultures showed that increasing levels of recombinant BCMA reduced staining of the CAR, demonstrating binding to the receptor.

Next, GSI was used to increase BCMA levels, and with increasing concentrations of the drug, BCMA surface expression was increased, she said, noting that this coincided with a reduction of soluble BCMA in the culture supernatant.

This also worked in patient samples, and was achieved with low doses of GSI, which upregulated surface BCMA levels on primary multiple myeloma by up to tenfold, she said.

In vivo testing of CAR T-cell efficacy was performed in tumor-bearing mice, which were treated with either BCMA-specific CAR T cells alone or in combination with GSI.

In this preclinical model of myeloma, RO4929097 increased BCMA on tumor cells in bone marrow and decreased soluble BCMA in peripheral blood. The myeloma-bearing mice treated with both BCMA CAR T cells and intermittent doses of RO4929097 experienced improved antitumor effects of the BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, as well as increased survival versus mice that did not receive RO4929097, she said.

“We’re currently optimizing these dosing regimens,” she said, concluding that “combining GSI and BCMA CAR T is an attractive option to improve the level of efficacy and prevent the outgrowth of BCMA-low tumor cells.”

Dr. Pont reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Gamma secretase inhibition may lead to improved outcomes in multiple myeloma patients treated with B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–specific CAR T-cell therapy, according to Margot J. Pont, PhD.

In a preclinical myeloma model, gamma secretase inhibition (GSI) increased antitumor efficacy of BCMA-specific chimeric antigen receptor modified T-cells (BCMA CAR T), Dr. Pont of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

BCMA is expressed in most multiple myeloma patients, and can be targeted by T cells that have been transduced with an anti-BCMA CAR. Other studies have shown efficacy of BCMA CAR T cells, and Dr. Pont and her colleagues have developed and optimized a CAR, based on a previously described single-chain variable fragment (scFv), that performs at least as well as a similar CAR developed previously by another group.

Previous studies have found that antigen down-regulation and escape can be an important escape mechanism by the tumor, so low-to-negative antigen expression could lead to failure in CAR T-cell recognition, resulting in relapse, she explained.

“We need the antigen density to be high enough,” she said, noting that BCMA, specifically, can be susceptible to antigen down-regulation, because its extracellular component is cleaved off the cell membrane by the enzyme gamma-secretase.

“That leads to two things: It reduces the surface expression of BCMA and it sheds soluble BCMA into the circulation, so you get high concentrations of soluble BCMA in the tumor microenvironment,” she said.

Inhibiting BCMA shedding with GSI can increase surface expression and reduce levels of soluble BCMA, thereby potentially enhancing the CAR activity.

First, soluble BCMA levels were measured in bone marrow sera from myeloma patients.

“We indeed saw high levels of soluble BCMA in these patients, and they roughly correlated with tumor burden. When culturing myeloma cell lines in vitro, we detected sBCMA in the culture supernatant within 24 hours,” Dr. Pont said, adding that the introduction of recombinant BCMA to the cultures showed that increasing levels of recombinant BCMA reduced staining of the CAR, demonstrating binding to the receptor.

Next, GSI was used to increase BCMA levels, and with increasing concentrations of the drug, BCMA surface expression was increased, she said, noting that this coincided with a reduction of soluble BCMA in the culture supernatant.

This also worked in patient samples, and was achieved with low doses of GSI, which upregulated surface BCMA levels on primary multiple myeloma by up to tenfold, she said.

In vivo testing of CAR T-cell efficacy was performed in tumor-bearing mice, which were treated with either BCMA-specific CAR T cells alone or in combination with GSI.

In this preclinical model of myeloma, RO4929097 increased BCMA on tumor cells in bone marrow and decreased soluble BCMA in peripheral blood. The myeloma-bearing mice treated with both BCMA CAR T cells and intermittent doses of RO4929097 experienced improved antitumor effects of the BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, as well as increased survival versus mice that did not receive RO4929097, she said.

“We’re currently optimizing these dosing regimens,” she said, concluding that “combining GSI and BCMA CAR T is an attractive option to improve the level of efficacy and prevent the outgrowth of BCMA-low tumor cells.”

Dr. Pont reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT SITC 2017

MACRA Monday: Pneumococcal vaccination

If you haven’t started reporting quality data for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), there’s still time to avoid a 4% cut to your Medicare payments.

Under the Pick Your Pace approach being offered this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows clinicians to test the system by reporting on one quality measure for one patient through paper-based claims. Be sure to append a Quality Data Code (QDC) to the claim form for care provided up to Dec. 31, 2017, in order to avoid a penalty in payment year 2019.

Consider this measure:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Measure #111: Pneumococcal Vaccination Status for Older Adults

This measure is aimed at capturing the percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have ever received a pneumococcal vaccine.

What you need to do: Review the medical record to find out if the patient has ever received a pneumococcal vaccine and if not, administer the vaccine.

Eligible cases include patients who were aged 65 years or older on the date of the encounter and a patient encounter during the performance period. Applicable codes include (CPT or HCPCS): 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350, G0402, G0438, G0439.

To get credit under MIPS, be sure to include a QDC that shows that you successfully performed the measure or had a good reason for not doing so. For instance, CPT II 4040F indicates that the pneumococcal vaccine was administered or previously received. Use exclusion code G9707 to indicate that the patient was not eligible because they received hospice services at any time during the measurement period.

CMS has a full list measures available for claims-based reporting at qpp.cms.gov. The American Medical Association has also created a step-by-step guide for reporting on one quality measure.

Certain clinicians are exempt from reporting and do not face a penalty under MIPS:

• Those who enrolled in Medicare for the first time during a performance period.

• Those who have Medicare Part B allowed charges of $30,000 or less.

• Those who have 100 or fewer Medicare Part B patients.

• Those who are significantly participating in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

If you haven’t started reporting quality data for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), there’s still time to avoid a 4% cut to your Medicare payments.

Under the Pick Your Pace approach being offered this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows clinicians to test the system by reporting on one quality measure for one patient through paper-based claims. Be sure to append a Quality Data Code (QDC) to the claim form for care provided up to Dec. 31, 2017, in order to avoid a penalty in payment year 2019.

Consider this measure:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Measure #111: Pneumococcal Vaccination Status for Older Adults

This measure is aimed at capturing the percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have ever received a pneumococcal vaccine.

What you need to do: Review the medical record to find out if the patient has ever received a pneumococcal vaccine and if not, administer the vaccine.

Eligible cases include patients who were aged 65 years or older on the date of the encounter and a patient encounter during the performance period. Applicable codes include (CPT or HCPCS): 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350, G0402, G0438, G0439.

To get credit under MIPS, be sure to include a QDC that shows that you successfully performed the measure or had a good reason for not doing so. For instance, CPT II 4040F indicates that the pneumococcal vaccine was administered or previously received. Use exclusion code G9707 to indicate that the patient was not eligible because they received hospice services at any time during the measurement period.

CMS has a full list measures available for claims-based reporting at qpp.cms.gov. The American Medical Association has also created a step-by-step guide for reporting on one quality measure.

Certain clinicians are exempt from reporting and do not face a penalty under MIPS:

• Those who enrolled in Medicare for the first time during a performance period.

• Those who have Medicare Part B allowed charges of $30,000 or less.

• Those who have 100 or fewer Medicare Part B patients.

• Those who are significantly participating in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

If you haven’t started reporting quality data for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), there’s still time to avoid a 4% cut to your Medicare payments.

Under the Pick Your Pace approach being offered this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows clinicians to test the system by reporting on one quality measure for one patient through paper-based claims. Be sure to append a Quality Data Code (QDC) to the claim form for care provided up to Dec. 31, 2017, in order to avoid a penalty in payment year 2019.

Consider this measure:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Measure #111: Pneumococcal Vaccination Status for Older Adults

This measure is aimed at capturing the percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have ever received a pneumococcal vaccine.

What you need to do: Review the medical record to find out if the patient has ever received a pneumococcal vaccine and if not, administer the vaccine.

Eligible cases include patients who were aged 65 years or older on the date of the encounter and a patient encounter during the performance period. Applicable codes include (CPT or HCPCS): 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350, G0402, G0438, G0439.

To get credit under MIPS, be sure to include a QDC that shows that you successfully performed the measure or had a good reason for not doing so. For instance, CPT II 4040F indicates that the pneumococcal vaccine was administered or previously received. Use exclusion code G9707 to indicate that the patient was not eligible because they received hospice services at any time during the measurement period.

CMS has a full list measures available for claims-based reporting at qpp.cms.gov. The American Medical Association has also created a step-by-step guide for reporting on one quality measure.

Certain clinicians are exempt from reporting and do not face a penalty under MIPS:

• Those who enrolled in Medicare for the first time during a performance period.

• Those who have Medicare Part B allowed charges of $30,000 or less.

• Those who have 100 or fewer Medicare Part B patients.

• Those who are significantly participating in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

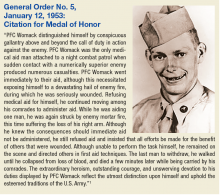

Bryant Homer Womack: Honoring Sacrifice

Bryant Homer Womack was born in 1931 and raised in Mill Spring in southwestern North Carolina. He and his 4 siblings grew up doing farmwork. Womack enjoyed the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. After completing high school, he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 and later deployed to Korea.

PFC Womack was assigned to the Medical Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. During a firefight near Sokso-ri, Korea, on March 12, 1952, his night combat patrol began taking heavy casualties. Womack exposed himself to enemy fire in order to treat his wounded. Although wounded, PFC Womack refused medical treatment and continued to provide aid to others. He was the last soldier to withdraw from the engagement and died of his wounds soon after. Not yet 21 at the time of his death, Womack was buried at Lebanon Methodist Church in his hometown.

PFC Womack received a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1953 (Sidebar) and Womack Army Community Hospital, located on Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina, was named for him in 1958. The first medical facility to serve Fort Bragg was constructed in September 1918 as a U.S. States Army Hospital. In June 1932, an 83-bed, 3-story hospital was built and designated Station Hospital One; it was closed in 1941. The building is now Headquarters for XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. Station Hospital Two and Station Hospital Three were cantonment style hospitals that replaced Station Hospital One. In 1949, the medical facilities were combined and became the U.S. Army Station Hospital.

On August 3, 1958, a new 9-story facility was opened and named Womack Army Community Hospital in honor of combat medic and Medal of Honor recipient PFC Bryant H. Womack. It was renamed the Womack Army Medical Center in 1991. This facility was the principal medical facility for the Fort Bragg community for more than 40 years.

In March, 2000, a new Womack Army Medical Center with more than 1 million square feet of space was dedicated. This new health care complex was part of the U.S. Army Medical Department’s plan to increase patient access to more medical and specialized resources at Fort Bragg.

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War. https://history.army.mil/moh/koreanwar.html#WOMACK. Updated April 2, 2014. Accessed October 12, 2017.

Bryant Homer Womack was born in 1931 and raised in Mill Spring in southwestern North Carolina. He and his 4 siblings grew up doing farmwork. Womack enjoyed the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. After completing high school, he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 and later deployed to Korea.

PFC Womack was assigned to the Medical Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. During a firefight near Sokso-ri, Korea, on March 12, 1952, his night combat patrol began taking heavy casualties. Womack exposed himself to enemy fire in order to treat his wounded. Although wounded, PFC Womack refused medical treatment and continued to provide aid to others. He was the last soldier to withdraw from the engagement and died of his wounds soon after. Not yet 21 at the time of his death, Womack was buried at Lebanon Methodist Church in his hometown.

PFC Womack received a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1953 (Sidebar) and Womack Army Community Hospital, located on Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina, was named for him in 1958. The first medical facility to serve Fort Bragg was constructed in September 1918 as a U.S. States Army Hospital. In June 1932, an 83-bed, 3-story hospital was built and designated Station Hospital One; it was closed in 1941. The building is now Headquarters for XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. Station Hospital Two and Station Hospital Three were cantonment style hospitals that replaced Station Hospital One. In 1949, the medical facilities were combined and became the U.S. Army Station Hospital.

On August 3, 1958, a new 9-story facility was opened and named Womack Army Community Hospital in honor of combat medic and Medal of Honor recipient PFC Bryant H. Womack. It was renamed the Womack Army Medical Center in 1991. This facility was the principal medical facility for the Fort Bragg community for more than 40 years.

In March, 2000, a new Womack Army Medical Center with more than 1 million square feet of space was dedicated. This new health care complex was part of the U.S. Army Medical Department’s plan to increase patient access to more medical and specialized resources at Fort Bragg.

Bryant Homer Womack was born in 1931 and raised in Mill Spring in southwestern North Carolina. He and his 4 siblings grew up doing farmwork. Womack enjoyed the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. After completing high school, he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 and later deployed to Korea.

PFC Womack was assigned to the Medical Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. During a firefight near Sokso-ri, Korea, on March 12, 1952, his night combat patrol began taking heavy casualties. Womack exposed himself to enemy fire in order to treat his wounded. Although wounded, PFC Womack refused medical treatment and continued to provide aid to others. He was the last soldier to withdraw from the engagement and died of his wounds soon after. Not yet 21 at the time of his death, Womack was buried at Lebanon Methodist Church in his hometown.

PFC Womack received a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1953 (Sidebar) and Womack Army Community Hospital, located on Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina, was named for him in 1958. The first medical facility to serve Fort Bragg was constructed in September 1918 as a U.S. States Army Hospital. In June 1932, an 83-bed, 3-story hospital was built and designated Station Hospital One; it was closed in 1941. The building is now Headquarters for XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. Station Hospital Two and Station Hospital Three were cantonment style hospitals that replaced Station Hospital One. In 1949, the medical facilities were combined and became the U.S. Army Station Hospital.

On August 3, 1958, a new 9-story facility was opened and named Womack Army Community Hospital in honor of combat medic and Medal of Honor recipient PFC Bryant H. Womack. It was renamed the Womack Army Medical Center in 1991. This facility was the principal medical facility for the Fort Bragg community for more than 40 years.

In March, 2000, a new Womack Army Medical Center with more than 1 million square feet of space was dedicated. This new health care complex was part of the U.S. Army Medical Department’s plan to increase patient access to more medical and specialized resources at Fort Bragg.

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War. https://history.army.mil/moh/koreanwar.html#WOMACK. Updated April 2, 2014. Accessed October 12, 2017.

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War. https://history.army.mil/moh/koreanwar.html#WOMACK. Updated April 2, 2014. Accessed October 12, 2017.

Team identifies genetic differences between MM patients

Researchers say they have identified significant genetic differences between African-American patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and Caucasian patients with the disease.

For example, the researchers found that African Americans were more likely to have mutations in BCL7A, BRWD3, and AUTS2, but Caucasians were more likely to have mutations in IRF4 and TP53.

“A cancer therapy that targets TP53 would not be as effective for African Americans with multiple myeloma as it would be for a white population because doctors would be trying to fix the wrong mutated gene,” said Zarko Manojlovic, PhD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Dr Manojlovic and his colleagues conducted this research and detailed the results in PLOS Genetics.

The researchers analyzed genetic sequencing data and clinical data from 718 MM patients participating in the MMRF CoMMpass Study.

Race was reported by the patients, but the researchers also used the genetic data to determine that 127 patients were of African descent and 591 were of European descent. The researchers noted that the mean European admixture among self-reported African Americans was 31% (range; 11%-67.8%). And the mean west-African admixture among self-reported Caucasians was 0.1% (range; 0-34.3).

The African-American patients were significantly more likely than the Caucasians to have early onset MM (at ages 40-49)—11% and 4.6%, respectively (P=0.004). And Caucasians were significantly more likely than African Americans to have late-onset MM (at ages 70-79)—22% and 14%, respectively (P=0.04).

There was no significant difference in overall survival based on race, age of onset, or MM karyotype in this population.

Mutations in the following genes occurred at significantly higher frequencies in African-American patients than in Caucasians: RYR1, RPL10, PTCHD3, BCL7A, SPEF2, MYH13, ABI3BP, BRWD3, GRM7, AUTS2, PARP4, PLD1, ANKRD26, DDX17, and STXBP4.

On the other hand, Caucasians had a significantly higher frequency of mutations in IRF4 and TP53. In fact, there was a TP53 somatic mutation frequency of 6.3% in Caucasians and 1.6% in African Americans (P=0.035).

“One of the most surprising discoveries from this large cohort is that cancers from patients of European descent were 6 times more likely than their African-descent counterparts to have mutations in TP53, a known tumor suppressor gene,” Dr Manojlovic said.

“Biologically speaking, higher mutation rates in this gene should lead to overall lower survival rates among patients of European descent, but that does not correlate with what we see in clinical outcomes. Going forward, we hope to functionally validate these results for more insight into the underlying biology.”

“We in the cancer genomics community have a responsibility to ensure that our studies represent true population diversity so we can understand the role of ancestry and biology in health outcomes,” added study author John D. Carpten, PhD, of the University of Southern California.

“The new candidate myeloma genes we identified in the African-American population may have been overlooked because of the lack of diversity in previous genomic efforts. There are clearly molecular differences between African-American and Caucasian multiple myeloma cases, and it will be critical to pursue these observations to better improve clinical management of the disease for all patients.” ![]()

Researchers say they have identified significant genetic differences between African-American patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and Caucasian patients with the disease.

For example, the researchers found that African Americans were more likely to have mutations in BCL7A, BRWD3, and AUTS2, but Caucasians were more likely to have mutations in IRF4 and TP53.

“A cancer therapy that targets TP53 would not be as effective for African Americans with multiple myeloma as it would be for a white population because doctors would be trying to fix the wrong mutated gene,” said Zarko Manojlovic, PhD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Dr Manojlovic and his colleagues conducted this research and detailed the results in PLOS Genetics.

The researchers analyzed genetic sequencing data and clinical data from 718 MM patients participating in the MMRF CoMMpass Study.

Race was reported by the patients, but the researchers also used the genetic data to determine that 127 patients were of African descent and 591 were of European descent. The researchers noted that the mean European admixture among self-reported African Americans was 31% (range; 11%-67.8%). And the mean west-African admixture among self-reported Caucasians was 0.1% (range; 0-34.3).

The African-American patients were significantly more likely than the Caucasians to have early onset MM (at ages 40-49)—11% and 4.6%, respectively (P=0.004). And Caucasians were significantly more likely than African Americans to have late-onset MM (at ages 70-79)—22% and 14%, respectively (P=0.04).

There was no significant difference in overall survival based on race, age of onset, or MM karyotype in this population.

Mutations in the following genes occurred at significantly higher frequencies in African-American patients than in Caucasians: RYR1, RPL10, PTCHD3, BCL7A, SPEF2, MYH13, ABI3BP, BRWD3, GRM7, AUTS2, PARP4, PLD1, ANKRD26, DDX17, and STXBP4.

On the other hand, Caucasians had a significantly higher frequency of mutations in IRF4 and TP53. In fact, there was a TP53 somatic mutation frequency of 6.3% in Caucasians and 1.6% in African Americans (P=0.035).

“One of the most surprising discoveries from this large cohort is that cancers from patients of European descent were 6 times more likely than their African-descent counterparts to have mutations in TP53, a known tumor suppressor gene,” Dr Manojlovic said.

“Biologically speaking, higher mutation rates in this gene should lead to overall lower survival rates among patients of European descent, but that does not correlate with what we see in clinical outcomes. Going forward, we hope to functionally validate these results for more insight into the underlying biology.”

“We in the cancer genomics community have a responsibility to ensure that our studies represent true population diversity so we can understand the role of ancestry and biology in health outcomes,” added study author John D. Carpten, PhD, of the University of Southern California.

“The new candidate myeloma genes we identified in the African-American population may have been overlooked because of the lack of diversity in previous genomic efforts. There are clearly molecular differences between African-American and Caucasian multiple myeloma cases, and it will be critical to pursue these observations to better improve clinical management of the disease for all patients.” ![]()

Researchers say they have identified significant genetic differences between African-American patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and Caucasian patients with the disease.

For example, the researchers found that African Americans were more likely to have mutations in BCL7A, BRWD3, and AUTS2, but Caucasians were more likely to have mutations in IRF4 and TP53.

“A cancer therapy that targets TP53 would not be as effective for African Americans with multiple myeloma as it would be for a white population because doctors would be trying to fix the wrong mutated gene,” said Zarko Manojlovic, PhD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Dr Manojlovic and his colleagues conducted this research and detailed the results in PLOS Genetics.

The researchers analyzed genetic sequencing data and clinical data from 718 MM patients participating in the MMRF CoMMpass Study.

Race was reported by the patients, but the researchers also used the genetic data to determine that 127 patients were of African descent and 591 were of European descent. The researchers noted that the mean European admixture among self-reported African Americans was 31% (range; 11%-67.8%). And the mean west-African admixture among self-reported Caucasians was 0.1% (range; 0-34.3).

The African-American patients were significantly more likely than the Caucasians to have early onset MM (at ages 40-49)—11% and 4.6%, respectively (P=0.004). And Caucasians were significantly more likely than African Americans to have late-onset MM (at ages 70-79)—22% and 14%, respectively (P=0.04).

There was no significant difference in overall survival based on race, age of onset, or MM karyotype in this population.

Mutations in the following genes occurred at significantly higher frequencies in African-American patients than in Caucasians: RYR1, RPL10, PTCHD3, BCL7A, SPEF2, MYH13, ABI3BP, BRWD3, GRM7, AUTS2, PARP4, PLD1, ANKRD26, DDX17, and STXBP4.

On the other hand, Caucasians had a significantly higher frequency of mutations in IRF4 and TP53. In fact, there was a TP53 somatic mutation frequency of 6.3% in Caucasians and 1.6% in African Americans (P=0.035).

“One of the most surprising discoveries from this large cohort is that cancers from patients of European descent were 6 times more likely than their African-descent counterparts to have mutations in TP53, a known tumor suppressor gene,” Dr Manojlovic said.

“Biologically speaking, higher mutation rates in this gene should lead to overall lower survival rates among patients of European descent, but that does not correlate with what we see in clinical outcomes. Going forward, we hope to functionally validate these results for more insight into the underlying biology.”

“We in the cancer genomics community have a responsibility to ensure that our studies represent true population diversity so we can understand the role of ancestry and biology in health outcomes,” added study author John D. Carpten, PhD, of the University of Southern California.

“The new candidate myeloma genes we identified in the African-American population may have been overlooked because of the lack of diversity in previous genomic efforts. There are clearly molecular differences between African-American and Caucasian multiple myeloma cases, and it will be critical to pursue these observations to better improve clinical management of the disease for all patients.” ![]()

Anaphylaxis Controversy and Consensus

Simplify Your Life; Pay Dues Invoice Online

Don't forget that the end of the year is the time to keep up to date with your SVS membership dues. Invoices were emailed to all members earlier this month and are due by Dec. 31.

It's simple to pay your 2018 dues online -- and there's no need to write out a check or find a stamp! Just log on to vascular.org/payinvoice. (While you're at it, please make sure your record is up to date.) You also can make a donation to the SVS Foundation at the same time. For membership help, e-mail the SVS membership department, or call 312-334-2313

Don't forget that the end of the year is the time to keep up to date with your SVS membership dues. Invoices were emailed to all members earlier this month and are due by Dec. 31.

It's simple to pay your 2018 dues online -- and there's no need to write out a check or find a stamp! Just log on to vascular.org/payinvoice. (While you're at it, please make sure your record is up to date.) You also can make a donation to the SVS Foundation at the same time. For membership help, e-mail the SVS membership department, or call 312-334-2313

Don't forget that the end of the year is the time to keep up to date with your SVS membership dues. Invoices were emailed to all members earlier this month and are due by Dec. 31.

It's simple to pay your 2018 dues online -- and there's no need to write out a check or find a stamp! Just log on to vascular.org/payinvoice. (While you're at it, please make sure your record is up to date.) You also can make a donation to the SVS Foundation at the same time. For membership help, e-mail the SVS membership department, or call 312-334-2313

How CLL patients weigh treatment efficacy, safety, and cost

New research suggests patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are willing to trade treatment efficacy for a reduced risk of side effects, but the cost of treatment may trump other factors.

The patients studied placed the highest value on treatments that deliver the longest progression-free survival (PFS), but the patients were also willing to swap some efficacy for a reduced risk of serious adverse events (AEs).

Study results also indicated that factoring out-of-pocket costs into the decision-making process can significantly influence a patient’s choice of treatment.

Carol Mansfield, PhD, of RTI Health Solutions in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, and her colleagues conducted this study and reported the results in Blood Advances. The study was supported by funding from Genentech, Inc., to RTI Health Solutions.

The researchers surveyed 384 patients with CLL. Patients were asked to choose between hypothetical treatment options, each of which was defined by 5 variable attributes—PFS, mode of administration, typical severity of diarrhea, chance of serious infection, and chance of organ damage.

The attribute patients ranked highest was a change in PFS from 10 months to 60 months. This was followed by a change in infection risk from 30% to 0%, a change in the risk of organ damage from 8% to 0%, a change in diarrhea from severe to none, and a change in the mode of administration from intravenous to oral.

On average, a gain in PFS of 35.9 months was needed for patients to accept a 30% risk of serious infection. A gain in PFS of 26.3 months was needed for patients to accept an 8% risk of organ damage.

A gain in PFS of 21.6 months was needed for patients to accept severe diarrhea. And a gain in PFS of 3.5 months was needed for patients to accept the change from a daily pill to intravenous administration for 6 months.

There were no significant differences in preferences among treatment-naïve patients, first-line patients, and relapsed/refractory patients.

Impact of cost

When the researchers conducted a supplemental cost analysis, they found that out-of-pocket cost had a substantial impact on treatment choice.

The cost analysis included 2 treatments—medicines A and B. Based on the prior analysis, the researchers predicted that 91% of patients would choose medicine B if cost were not a concern because B offered longer PFS than A.

“We used the results from the discrete-choice experiment to forecast the probability that a respondent would pick each hypothetical drug without any mention of cost and then compared that to the choices people made when out-of-pocket costs for these medicines were included,” Dr Mansfield explained.

Patients were asked to choose between medicines A and B under 2 circumstances in which B cost more than A.

When medicine B had a monthly out-of-pocket cost that was $75 more than medicine A, 50% of patients chose medicine A.

When medicine B had a monthly out-of-pocket cost that was $400 more than medicine A, 74% of patients chose medicine A.

“Cost is clearly something that has an impact,” Dr Mansfield said. “When patients get prescribed something they can’t afford, they have to make very difficult choices.”

Dr Mansfield and her colleagues believe their findings will help doctors and patients focus on treatments that account for a patient’s unique circumstances and goals.

“Patients don’t always know that they could be making these tradeoffs,” Dr Mansfield said. “We hope that our findings can help doctors to have frank discussions with their patients about the differences between treatments and how these might affect their lives.” ![]()

New research suggests patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are willing to trade treatment efficacy for a reduced risk of side effects, but the cost of treatment may trump other factors.

The patients studied placed the highest value on treatments that deliver the longest progression-free survival (PFS), but the patients were also willing to swap some efficacy for a reduced risk of serious adverse events (AEs).

Study results also indicated that factoring out-of-pocket costs into the decision-making process can significantly influence a patient’s choice of treatment.

Carol Mansfield, PhD, of RTI Health Solutions in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, and her colleagues conducted this study and reported the results in Blood Advances. The study was supported by funding from Genentech, Inc., to RTI Health Solutions.