User login

The Expanded Timed Get Up and Go Test Predicts MS Disability

PARIS—The Expanded Timed Get Up and Go (ETGUG) may be a more sensitive predictor of disability in multiple sclerosis (MS) than the Timed 25-Foot Walk (T25FW), according to research presented at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting.

The 355 study participants were part of the New York State MS Consortium, a 20-year longitudinal registry. The researchers compared the ETGUG, T25FW, and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) using Spearman’s Rank correlations. They performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses with 80% specificity to determine the ETGUG and T25FW cutoff score and associated sensitivity predicting an EDSS score of 4.0 or greater.

Of the 355 participants, 121 (34.1%) had an EDSS score of 4.0 or higher. Both ETGUG and T25FW were highly correlated with EDSS. Correlations with EDSS were stronger for ETGUG and T25FW among subjects with an EDSS score of 4.0 or greater than among people with MS with EDSS scores of less than 4.0. At the predetermined specificity, an ETGUG score of 23.5 seconds or more had a 91.7% sensitivity of identifying subjects with an EDSS of 4.0 or greater. Completing the T25FW in 6.4 seconds or more, however, had a lower sensitivity of 82.7%.

“Prospectively captured data are required to determine the sensitivity of the ETGUG to longitudinal change and its usefulness in predicting disability progression and risk of falling, especially in the patients with higher disability,” said the researchers.

PARIS—The Expanded Timed Get Up and Go (ETGUG) may be a more sensitive predictor of disability in multiple sclerosis (MS) than the Timed 25-Foot Walk (T25FW), according to research presented at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting.

The 355 study participants were part of the New York State MS Consortium, a 20-year longitudinal registry. The researchers compared the ETGUG, T25FW, and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) using Spearman’s Rank correlations. They performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses with 80% specificity to determine the ETGUG and T25FW cutoff score and associated sensitivity predicting an EDSS score of 4.0 or greater.

Of the 355 participants, 121 (34.1%) had an EDSS score of 4.0 or higher. Both ETGUG and T25FW were highly correlated with EDSS. Correlations with EDSS were stronger for ETGUG and T25FW among subjects with an EDSS score of 4.0 or greater than among people with MS with EDSS scores of less than 4.0. At the predetermined specificity, an ETGUG score of 23.5 seconds or more had a 91.7% sensitivity of identifying subjects with an EDSS of 4.0 or greater. Completing the T25FW in 6.4 seconds or more, however, had a lower sensitivity of 82.7%.

“Prospectively captured data are required to determine the sensitivity of the ETGUG to longitudinal change and its usefulness in predicting disability progression and risk of falling, especially in the patients with higher disability,” said the researchers.

PARIS—The Expanded Timed Get Up and Go (ETGUG) may be a more sensitive predictor of disability in multiple sclerosis (MS) than the Timed 25-Foot Walk (T25FW), according to research presented at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting.

The 355 study participants were part of the New York State MS Consortium, a 20-year longitudinal registry. The researchers compared the ETGUG, T25FW, and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) using Spearman’s Rank correlations. They performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses with 80% specificity to determine the ETGUG and T25FW cutoff score and associated sensitivity predicting an EDSS score of 4.0 or greater.

Of the 355 participants, 121 (34.1%) had an EDSS score of 4.0 or higher. Both ETGUG and T25FW were highly correlated with EDSS. Correlations with EDSS were stronger for ETGUG and T25FW among subjects with an EDSS score of 4.0 or greater than among people with MS with EDSS scores of less than 4.0. At the predetermined specificity, an ETGUG score of 23.5 seconds or more had a 91.7% sensitivity of identifying subjects with an EDSS of 4.0 or greater. Completing the T25FW in 6.4 seconds or more, however, had a lower sensitivity of 82.7%.

“Prospectively captured data are required to determine the sensitivity of the ETGUG to longitudinal change and its usefulness in predicting disability progression and risk of falling, especially in the patients with higher disability,” said the researchers.

Long-Term Outcomes of Neuromyelitis Optica

PARIS—Among patients with neuromyelitis optica (NMO), early disability predicts late disability, consistent with favorable effects of early treatment on disability, according to a literature review presented at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting. Additionally, outcomes are worse in nonwhite patients and Hispanic patients. Visual outcomes are worse in young-onset NMO, and motor outcomes are worse in late-onset NMO.

Noting that there is limited literature regarding long-term outcomes in NMO spectrum disorder (NMOSD) since the discovery of aquaporin-4 immunoglobulin G (AQP4–IgG), Zahra Nasr, a medical student at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran, and colleagues sought to perform a systematic literature review on long-term outcomes in NMOSD in the era of AQP4-IgG.

The researchers conducted a database search that included studies in Cochrane Collaboration Database, PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Knowledge, and Embase through April 2017. They used the search terms “neuromyelitis optica” or “Devic’s disease,” and “clinical features,” “outcome,” “natural history,” “prognosis,” “mortality,” “morbidity,” “incidence,” “prevalence,” “epidemiology,” and “demography.” They included in their analysis English language studies that used 1999, 2006, or 2015 Wingerchuk criteria and reported AQP4-IgG status.

Twenty percent to 30% of patients had residual motor and visual disability after the initial attack; early disability was positively associated with long-term disability. After five to six years, 11% to 18% of individuals had visual acuity of 20/200 or less in at least one eye, and 7% to 23% were wheelchair confined.

Nonwhite patients and Hispanic patients had higher relapse rates and worse outcomes. Younger patients and men had worse visual outcomes, whereas older patients had poor motor outcomes. In addition, long-term immunosuppressive treatment reduced attack-related disability. AQP4-IgG serostatus was not associated with outcome.

Survival improved in contemporary studies (91% to 98% survival after five years), compared with survival reported prior to the discovery of AQP4-IgG (68% to 75% survival). A higher attack frequency during the first two years, older age at onset, lack of recovery from first attack, blindness, and history of other autoimmune disease were associated with higher mortality rates, but race, gender, and type of attack at onset were not.

The researchers concluded that contemporary studies report more favorable outcomes than pre-AQP4-IgG series.

PARIS—Among patients with neuromyelitis optica (NMO), early disability predicts late disability, consistent with favorable effects of early treatment on disability, according to a literature review presented at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting. Additionally, outcomes are worse in nonwhite patients and Hispanic patients. Visual outcomes are worse in young-onset NMO, and motor outcomes are worse in late-onset NMO.

Noting that there is limited literature regarding long-term outcomes in NMO spectrum disorder (NMOSD) since the discovery of aquaporin-4 immunoglobulin G (AQP4–IgG), Zahra Nasr, a medical student at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran, and colleagues sought to perform a systematic literature review on long-term outcomes in NMOSD in the era of AQP4-IgG.

The researchers conducted a database search that included studies in Cochrane Collaboration Database, PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Knowledge, and Embase through April 2017. They used the search terms “neuromyelitis optica” or “Devic’s disease,” and “clinical features,” “outcome,” “natural history,” “prognosis,” “mortality,” “morbidity,” “incidence,” “prevalence,” “epidemiology,” and “demography.” They included in their analysis English language studies that used 1999, 2006, or 2015 Wingerchuk criteria and reported AQP4-IgG status.

Twenty percent to 30% of patients had residual motor and visual disability after the initial attack; early disability was positively associated with long-term disability. After five to six years, 11% to 18% of individuals had visual acuity of 20/200 or less in at least one eye, and 7% to 23% were wheelchair confined.

Nonwhite patients and Hispanic patients had higher relapse rates and worse outcomes. Younger patients and men had worse visual outcomes, whereas older patients had poor motor outcomes. In addition, long-term immunosuppressive treatment reduced attack-related disability. AQP4-IgG serostatus was not associated with outcome.

Survival improved in contemporary studies (91% to 98% survival after five years), compared with survival reported prior to the discovery of AQP4-IgG (68% to 75% survival). A higher attack frequency during the first two years, older age at onset, lack of recovery from first attack, blindness, and history of other autoimmune disease were associated with higher mortality rates, but race, gender, and type of attack at onset were not.

The researchers concluded that contemporary studies report more favorable outcomes than pre-AQP4-IgG series.

PARIS—Among patients with neuromyelitis optica (NMO), early disability predicts late disability, consistent with favorable effects of early treatment on disability, according to a literature review presented at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting. Additionally, outcomes are worse in nonwhite patients and Hispanic patients. Visual outcomes are worse in young-onset NMO, and motor outcomes are worse in late-onset NMO.

Noting that there is limited literature regarding long-term outcomes in NMO spectrum disorder (NMOSD) since the discovery of aquaporin-4 immunoglobulin G (AQP4–IgG), Zahra Nasr, a medical student at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran, and colleagues sought to perform a systematic literature review on long-term outcomes in NMOSD in the era of AQP4-IgG.

The researchers conducted a database search that included studies in Cochrane Collaboration Database, PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Knowledge, and Embase through April 2017. They used the search terms “neuromyelitis optica” or “Devic’s disease,” and “clinical features,” “outcome,” “natural history,” “prognosis,” “mortality,” “morbidity,” “incidence,” “prevalence,” “epidemiology,” and “demography.” They included in their analysis English language studies that used 1999, 2006, or 2015 Wingerchuk criteria and reported AQP4-IgG status.

Twenty percent to 30% of patients had residual motor and visual disability after the initial attack; early disability was positively associated with long-term disability. After five to six years, 11% to 18% of individuals had visual acuity of 20/200 or less in at least one eye, and 7% to 23% were wheelchair confined.

Nonwhite patients and Hispanic patients had higher relapse rates and worse outcomes. Younger patients and men had worse visual outcomes, whereas older patients had poor motor outcomes. In addition, long-term immunosuppressive treatment reduced attack-related disability. AQP4-IgG serostatus was not associated with outcome.

Survival improved in contemporary studies (91% to 98% survival after five years), compared with survival reported prior to the discovery of AQP4-IgG (68% to 75% survival). A higher attack frequency during the first two years, older age at onset, lack of recovery from first attack, blindness, and history of other autoimmune disease were associated with higher mortality rates, but race, gender, and type of attack at onset were not.

The researchers concluded that contemporary studies report more favorable outcomes than pre-AQP4-IgG series.

Autoimmune endocrinopathies spike after celiac disease diagnosis

ORLANDO – Patients diagnosed with celiac disease subsequently showed a high incidence of autoimmune endocrinopathies in a review of 249 patients in a longitudinal, population-based database.

The finding that celiac disease patients developed autoimmune endocrinopathies (AE) at a rate of 9.14 cases per person-year of follow-up suggests that “screening for AEs is recommended in treated celiac disease patients,” Imad Absah, MD, said at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

Autoimmune thyroid disorders are the screening focus, and Dr. Asbah recommended a screening interval of every 2 years. Among the 14 patients in the review who developed an AE following a diagnosis of celiac disease, the two most common conditions were Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (4 patients) and hypothyroidism (4 patients), said Dr. Absah, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. One additional patient developed Graves disease.

He also suggested screening for type 1 diabetes in patients who show symptoms of diabetes. In the review, one patient developed type 1 diabetes following an index diagnosis of celiac disease.

His study used data collected in the Rochester Epidemiology Project on residents of Olmsted County, Minn. during 1997-2015. The database included 90 children and 159 adults less than 80 years old diagnosed with celiac disease after they entered the study. The children averaged 9 years old, and the adults averaged 32 years old; about two-thirds were girls or women.

Fifty-four of these people (22%) had been diagnosed with an AE prior to developing celiac disease, and then an additional 20 people (8%) had an incident AE during an average 5.7 years of follow-up for the children and an average 8.5 years of follow-up among the adults. Six of these 20 patients also had a different AE prior to their celiac disease diagnosis. Dr. Absah censored out these six patients and focused his analysis on the 14 patients with no AE prior to developing celiac disease. The incidence rate in both subgroups was 7%, which worked out to an overall incidence rate of 9.14 cases of AE for every person-year of follow-up in newly diagnosed patients with celiac disease.

Finding similar incidence rates among both children and adults suggests that “the length of gluten exposure prior to celiac disease did not affect the risk for an AE,” Dr. Absah said.

Dr. Absah had no relevant disclosures.

This article was updated 10/30/17.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Patients diagnosed with celiac disease subsequently showed a high incidence of autoimmune endocrinopathies in a review of 249 patients in a longitudinal, population-based database.

The finding that celiac disease patients developed autoimmune endocrinopathies (AE) at a rate of 9.14 cases per person-year of follow-up suggests that “screening for AEs is recommended in treated celiac disease patients,” Imad Absah, MD, said at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

Autoimmune thyroid disorders are the screening focus, and Dr. Asbah recommended a screening interval of every 2 years. Among the 14 patients in the review who developed an AE following a diagnosis of celiac disease, the two most common conditions were Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (4 patients) and hypothyroidism (4 patients), said Dr. Absah, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. One additional patient developed Graves disease.

He also suggested screening for type 1 diabetes in patients who show symptoms of diabetes. In the review, one patient developed type 1 diabetes following an index diagnosis of celiac disease.

His study used data collected in the Rochester Epidemiology Project on residents of Olmsted County, Minn. during 1997-2015. The database included 90 children and 159 adults less than 80 years old diagnosed with celiac disease after they entered the study. The children averaged 9 years old, and the adults averaged 32 years old; about two-thirds were girls or women.

Fifty-four of these people (22%) had been diagnosed with an AE prior to developing celiac disease, and then an additional 20 people (8%) had an incident AE during an average 5.7 years of follow-up for the children and an average 8.5 years of follow-up among the adults. Six of these 20 patients also had a different AE prior to their celiac disease diagnosis. Dr. Absah censored out these six patients and focused his analysis on the 14 patients with no AE prior to developing celiac disease. The incidence rate in both subgroups was 7%, which worked out to an overall incidence rate of 9.14 cases of AE for every person-year of follow-up in newly diagnosed patients with celiac disease.

Finding similar incidence rates among both children and adults suggests that “the length of gluten exposure prior to celiac disease did not affect the risk for an AE,” Dr. Absah said.

Dr. Absah had no relevant disclosures.

This article was updated 10/30/17.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Patients diagnosed with celiac disease subsequently showed a high incidence of autoimmune endocrinopathies in a review of 249 patients in a longitudinal, population-based database.

The finding that celiac disease patients developed autoimmune endocrinopathies (AE) at a rate of 9.14 cases per person-year of follow-up suggests that “screening for AEs is recommended in treated celiac disease patients,” Imad Absah, MD, said at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

Autoimmune thyroid disorders are the screening focus, and Dr. Asbah recommended a screening interval of every 2 years. Among the 14 patients in the review who developed an AE following a diagnosis of celiac disease, the two most common conditions were Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (4 patients) and hypothyroidism (4 patients), said Dr. Absah, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. One additional patient developed Graves disease.

He also suggested screening for type 1 diabetes in patients who show symptoms of diabetes. In the review, one patient developed type 1 diabetes following an index diagnosis of celiac disease.

His study used data collected in the Rochester Epidemiology Project on residents of Olmsted County, Minn. during 1997-2015. The database included 90 children and 159 adults less than 80 years old diagnosed with celiac disease after they entered the study. The children averaged 9 years old, and the adults averaged 32 years old; about two-thirds were girls or women.

Fifty-four of these people (22%) had been diagnosed with an AE prior to developing celiac disease, and then an additional 20 people (8%) had an incident AE during an average 5.7 years of follow-up for the children and an average 8.5 years of follow-up among the adults. Six of these 20 patients also had a different AE prior to their celiac disease diagnosis. Dr. Absah censored out these six patients and focused his analysis on the 14 patients with no AE prior to developing celiac disease. The incidence rate in both subgroups was 7%, which worked out to an overall incidence rate of 9.14 cases of AE for every person-year of follow-up in newly diagnosed patients with celiac disease.

Finding similar incidence rates among both children and adults suggests that “the length of gluten exposure prior to celiac disease did not affect the risk for an AE,” Dr. Absah said.

Dr. Absah had no relevant disclosures.

This article was updated 10/30/17.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE WORLD CONGRESS OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Following celiac disease diagnosis, the annual incidence of autoimmune endocrinopathies was 0.9%.

Data source: Review of 249 patients diagnosed with celiac disease in the Rochester Epidemiology Project database.

Disclosures: Dr. Absah had no disclosures.

What Is the Prevalence of Truly Benign MS?

PARIS—Benign multiple sclerosis (MS) appears to be rare. Its estimated prevalence is less than 4%, according to a study described at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting.

The existence of benign MS has been proposed, but it remains controversial. Neurologists are uncertain about the frequency and pathologic explanation for a favorable outcome in MS. Identifying and studying individuals with benign MS would have “considerable implications for patient management and for our understanding of the biology of the disease,” said Emma Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in the Division of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom, and colleagues.

Most definitions of benign MS are focused on walking ability after 10 or 15 years, despite the far wider effects of MS on ability. Dr. Tallantyre and colleagues screened a prevalent population of more than 2,000 people with MS and found 275 individuals who had unlimited walking ability after 15 or more years from onset. The investigators undertook detailed assessments of 56 of the individuals within this group (ie, those recorded to have unlimited walking ability after the longest disease durations). Assessment incorporated scores of cognition, fatigue, mood, vision, bladder symptoms, and arm and leg function.

All patients were considered to have relapsing-remitting MS, but they showed a wide range of relapse frequency and severity. In a group of 32 patients who fulfilled a contemporary definition of benign MS based on the Expanded Disability Status Scale, the researchers considered less than 25% to be truly benign, which was defined as having normal function in all domains. Patient-reported scores of MS impact correlated strongly with the outcomes of clinical assessment, but patients’ own perceptions of their condition was more benign than clinicians’ perceptions.

MR imaging was used to explore the biology underlying benign MS using a global approach and a tract-based approach. The study provides early insights into the phenotypic and imaging characteristics of benign MS and could provide information about the biologic mechanisms of a favorable outcome in MS, said Dr. Tallantyre.

PARIS—Benign multiple sclerosis (MS) appears to be rare. Its estimated prevalence is less than 4%, according to a study described at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting.

The existence of benign MS has been proposed, but it remains controversial. Neurologists are uncertain about the frequency and pathologic explanation for a favorable outcome in MS. Identifying and studying individuals with benign MS would have “considerable implications for patient management and for our understanding of the biology of the disease,” said Emma Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in the Division of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom, and colleagues.

Most definitions of benign MS are focused on walking ability after 10 or 15 years, despite the far wider effects of MS on ability. Dr. Tallantyre and colleagues screened a prevalent population of more than 2,000 people with MS and found 275 individuals who had unlimited walking ability after 15 or more years from onset. The investigators undertook detailed assessments of 56 of the individuals within this group (ie, those recorded to have unlimited walking ability after the longest disease durations). Assessment incorporated scores of cognition, fatigue, mood, vision, bladder symptoms, and arm and leg function.

All patients were considered to have relapsing-remitting MS, but they showed a wide range of relapse frequency and severity. In a group of 32 patients who fulfilled a contemporary definition of benign MS based on the Expanded Disability Status Scale, the researchers considered less than 25% to be truly benign, which was defined as having normal function in all domains. Patient-reported scores of MS impact correlated strongly with the outcomes of clinical assessment, but patients’ own perceptions of their condition was more benign than clinicians’ perceptions.

MR imaging was used to explore the biology underlying benign MS using a global approach and a tract-based approach. The study provides early insights into the phenotypic and imaging characteristics of benign MS and could provide information about the biologic mechanisms of a favorable outcome in MS, said Dr. Tallantyre.

PARIS—Benign multiple sclerosis (MS) appears to be rare. Its estimated prevalence is less than 4%, according to a study described at the Seventh Joint ECTRIMS–ACTRIMS Meeting.

The existence of benign MS has been proposed, but it remains controversial. Neurologists are uncertain about the frequency and pathologic explanation for a favorable outcome in MS. Identifying and studying individuals with benign MS would have “considerable implications for patient management and for our understanding of the biology of the disease,” said Emma Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in the Division of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom, and colleagues.

Most definitions of benign MS are focused on walking ability after 10 or 15 years, despite the far wider effects of MS on ability. Dr. Tallantyre and colleagues screened a prevalent population of more than 2,000 people with MS and found 275 individuals who had unlimited walking ability after 15 or more years from onset. The investigators undertook detailed assessments of 56 of the individuals within this group (ie, those recorded to have unlimited walking ability after the longest disease durations). Assessment incorporated scores of cognition, fatigue, mood, vision, bladder symptoms, and arm and leg function.

All patients were considered to have relapsing-remitting MS, but they showed a wide range of relapse frequency and severity. In a group of 32 patients who fulfilled a contemporary definition of benign MS based on the Expanded Disability Status Scale, the researchers considered less than 25% to be truly benign, which was defined as having normal function in all domains. Patient-reported scores of MS impact correlated strongly with the outcomes of clinical assessment, but patients’ own perceptions of their condition was more benign than clinicians’ perceptions.

MR imaging was used to explore the biology underlying benign MS using a global approach and a tract-based approach. The study provides early insights into the phenotypic and imaging characteristics of benign MS and could provide information about the biologic mechanisms of a favorable outcome in MS, said Dr. Tallantyre.

Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon), installed as 98th ACS President

Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon) the John F. and Carolyn Bookout Distinguished Endowed Chair and chair, department of surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, was installed as President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) at the October 22 Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA.

Read more about Dr. Bass, Dr. Mabry, and Dr. Pruitt in the November Bulletin at URL TO COME

Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon) the John F. and Carolyn Bookout Distinguished Endowed Chair and chair, department of surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, was installed as President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) at the October 22 Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA.

Read more about Dr. Bass, Dr. Mabry, and Dr. Pruitt in the November Bulletin at URL TO COME

Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon) the John F. and Carolyn Bookout Distinguished Endowed Chair and chair, department of surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, TX, was installed as President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) at the October 22 Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA.

Read more about Dr. Bass, Dr. Mabry, and Dr. Pruitt in the November Bulletin at URL TO COME

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker Award presented to Dr. Kuy

At the Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) presented the 2017 Dr. Mary Edwards Walker Inspiring Women in Surgery Award to SreyRam Kuy, MD, MHS, FACS. This award was established by the ACS Women in Surgery Committee (WiSC) and is presented annually at the Clinical Congress in recognition of an individual’s significant contributions to the advancement of women in the field of surgery.

The award is named in honor of Mary Edwards Walker, MD. Dr. Walker volunteered to serve with the Union Army at the outbreak of the American Civil War and was the first female surgeon ever employed by the U.S. Army. Dr. Walker is the only woman to have ever received the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest U.S. Armed Forces decoration for bravery. Through Dr. Walker’s example of perseverance, excellence, and pioneering behavior, she paved the way for today’s women surgeons.

Dr. Kuy’s career embodies the spirit of this award and demonstrates her personal determination, professional excellence, and commitment to public service.

Inspiration to practice

Dr. Kuy was born in a labor camp in Cambodia in 1978 during the Cambodian genocide known as the Killing Fields. Following the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge, her family fled to a refugee camp in Thailand where Dr. Kuy, her sister, and her mother were severely injured by a grenade. All three lives were saved by surgeons volunteering at the refugee camp. These volunteer surgeons helped inspire Dr. Kuy to pursue a career in medicine.

Her family moved to the U.S. in 1981 and settled in Oregon. Dr. Kuy attended Oregon State University, Corvallis, and went on to complete medical school at Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland. She earned her master’s degree in health policy, public health, and outcomes research at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, as a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar.

An accomplished early career

As associate chief of staff, Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, Houston, TX, Dr. Kuy oversees 5,000 staff in a complex VA hospital with the busiest emergency department and operating rooms in the VA system. Dr. Kuy previously served as chief medical officer for Medicaid in the Louisiana Department of Health, Baton Rouge. Under her leadership, Louisiana was the first state to develop a Zika prevention strategy for pregnant Medicaid patients. Dr. Kuy also led initiatives that enabled women with breast cancer to have access to reconstructive surgery and testing, led efforts to coordinate medical disaster relief efforts during the historic Louisiana flooding of 2016, and led Louisiana Medicaid’s initiative to tackle the opioid epidemic.

Dr. Kuy developed statewide health performance metrics, pay-for-performance incentives, and novel Medicaid Expansion Early Wins measures, which enabled the state of Louisiana to assess how access to care directly affects lives. Before serving as Chief Medical Officer for Louisiana Medicaid, Dr. Kuy served in numerous leadership roles in the VA system, including the following: director, Center for Innovations in Quality, Outcomes and Patient Safety; assistant chief, general surgery; and chair, Systems Redesign Committee. She also was a member, Quality, Safety & Value Board, Overton Brooks VA Medical Center, Shreveport, LA.

Dr. Kuy’s successful efforts to reduce patient mortality and morbidity and decrease adverse events were profiled by the VA National Center for Patient Safety. Her work in increasing veterans’ access to care through clinic efficiency was profiled by the Association for VA Surgeons, and the templates she developed were disseminated for implementation at VA medical centers across the country. Dr. Kuy has served on the National Quality Forum, the National Board of Medical Examiners, and the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education.

In 2017, Dr. Kuy was selected to be a Presidential Leadership Scholar, a joint, bipartisan leadership program taught by Presidents George W. Bush, William J. Clinton, and George H. W. Bush. She subsequently delivered the keynote commencement address at the Bush Institute. Dr. Kuy received the Greater Baton Rouge Business Report’s 40 Under 40 Award for her work to improve health care quality in the Louisiana Medicaid population, the Ford Foundation’s Gerald E. Bruce Community Service Award for her work serving veterans, and Random Acts’ Caught in the Act national public service award. Dr. Kuy also was selected for the Early Career Achievement Award in 2017 by Oregon Health & Sciences University School of Medicine.

Dr. Kuy is grateful for the many incredible mentors and teachers who have inspired her on her journey, and she is proud to be a part of the surgical family. She has dedicated her career to improving the quality of medical care and increasing the public’s access to quality care. The College is proud to have Dr. Kuy as a member and looks forward to what challenges she will tackle next.

At the Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) presented the 2017 Dr. Mary Edwards Walker Inspiring Women in Surgery Award to SreyRam Kuy, MD, MHS, FACS. This award was established by the ACS Women in Surgery Committee (WiSC) and is presented annually at the Clinical Congress in recognition of an individual’s significant contributions to the advancement of women in the field of surgery.

The award is named in honor of Mary Edwards Walker, MD. Dr. Walker volunteered to serve with the Union Army at the outbreak of the American Civil War and was the first female surgeon ever employed by the U.S. Army. Dr. Walker is the only woman to have ever received the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest U.S. Armed Forces decoration for bravery. Through Dr. Walker’s example of perseverance, excellence, and pioneering behavior, she paved the way for today’s women surgeons.

Dr. Kuy’s career embodies the spirit of this award and demonstrates her personal determination, professional excellence, and commitment to public service.

Inspiration to practice

Dr. Kuy was born in a labor camp in Cambodia in 1978 during the Cambodian genocide known as the Killing Fields. Following the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge, her family fled to a refugee camp in Thailand where Dr. Kuy, her sister, and her mother were severely injured by a grenade. All three lives were saved by surgeons volunteering at the refugee camp. These volunteer surgeons helped inspire Dr. Kuy to pursue a career in medicine.

Her family moved to the U.S. in 1981 and settled in Oregon. Dr. Kuy attended Oregon State University, Corvallis, and went on to complete medical school at Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland. She earned her master’s degree in health policy, public health, and outcomes research at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, as a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar.

An accomplished early career

As associate chief of staff, Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, Houston, TX, Dr. Kuy oversees 5,000 staff in a complex VA hospital with the busiest emergency department and operating rooms in the VA system. Dr. Kuy previously served as chief medical officer for Medicaid in the Louisiana Department of Health, Baton Rouge. Under her leadership, Louisiana was the first state to develop a Zika prevention strategy for pregnant Medicaid patients. Dr. Kuy also led initiatives that enabled women with breast cancer to have access to reconstructive surgery and testing, led efforts to coordinate medical disaster relief efforts during the historic Louisiana flooding of 2016, and led Louisiana Medicaid’s initiative to tackle the opioid epidemic.

Dr. Kuy developed statewide health performance metrics, pay-for-performance incentives, and novel Medicaid Expansion Early Wins measures, which enabled the state of Louisiana to assess how access to care directly affects lives. Before serving as Chief Medical Officer for Louisiana Medicaid, Dr. Kuy served in numerous leadership roles in the VA system, including the following: director, Center for Innovations in Quality, Outcomes and Patient Safety; assistant chief, general surgery; and chair, Systems Redesign Committee. She also was a member, Quality, Safety & Value Board, Overton Brooks VA Medical Center, Shreveport, LA.

Dr. Kuy’s successful efforts to reduce patient mortality and morbidity and decrease adverse events were profiled by the VA National Center for Patient Safety. Her work in increasing veterans’ access to care through clinic efficiency was profiled by the Association for VA Surgeons, and the templates she developed were disseminated for implementation at VA medical centers across the country. Dr. Kuy has served on the National Quality Forum, the National Board of Medical Examiners, and the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education.

In 2017, Dr. Kuy was selected to be a Presidential Leadership Scholar, a joint, bipartisan leadership program taught by Presidents George W. Bush, William J. Clinton, and George H. W. Bush. She subsequently delivered the keynote commencement address at the Bush Institute. Dr. Kuy received the Greater Baton Rouge Business Report’s 40 Under 40 Award for her work to improve health care quality in the Louisiana Medicaid population, the Ford Foundation’s Gerald E. Bruce Community Service Award for her work serving veterans, and Random Acts’ Caught in the Act national public service award. Dr. Kuy also was selected for the Early Career Achievement Award in 2017 by Oregon Health & Sciences University School of Medicine.

Dr. Kuy is grateful for the many incredible mentors and teachers who have inspired her on her journey, and she is proud to be a part of the surgical family. She has dedicated her career to improving the quality of medical care and increasing the public’s access to quality care. The College is proud to have Dr. Kuy as a member and looks forward to what challenges she will tackle next.

At the Convocation Ceremony at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) presented the 2017 Dr. Mary Edwards Walker Inspiring Women in Surgery Award to SreyRam Kuy, MD, MHS, FACS. This award was established by the ACS Women in Surgery Committee (WiSC) and is presented annually at the Clinical Congress in recognition of an individual’s significant contributions to the advancement of women in the field of surgery.

The award is named in honor of Mary Edwards Walker, MD. Dr. Walker volunteered to serve with the Union Army at the outbreak of the American Civil War and was the first female surgeon ever employed by the U.S. Army. Dr. Walker is the only woman to have ever received the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest U.S. Armed Forces decoration for bravery. Through Dr. Walker’s example of perseverance, excellence, and pioneering behavior, she paved the way for today’s women surgeons.

Dr. Kuy’s career embodies the spirit of this award and demonstrates her personal determination, professional excellence, and commitment to public service.

Inspiration to practice

Dr. Kuy was born in a labor camp in Cambodia in 1978 during the Cambodian genocide known as the Killing Fields. Following the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge, her family fled to a refugee camp in Thailand where Dr. Kuy, her sister, and her mother were severely injured by a grenade. All three lives were saved by surgeons volunteering at the refugee camp. These volunteer surgeons helped inspire Dr. Kuy to pursue a career in medicine.

Her family moved to the U.S. in 1981 and settled in Oregon. Dr. Kuy attended Oregon State University, Corvallis, and went on to complete medical school at Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland. She earned her master’s degree in health policy, public health, and outcomes research at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, as a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar.

An accomplished early career

As associate chief of staff, Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, Houston, TX, Dr. Kuy oversees 5,000 staff in a complex VA hospital with the busiest emergency department and operating rooms in the VA system. Dr. Kuy previously served as chief medical officer for Medicaid in the Louisiana Department of Health, Baton Rouge. Under her leadership, Louisiana was the first state to develop a Zika prevention strategy for pregnant Medicaid patients. Dr. Kuy also led initiatives that enabled women with breast cancer to have access to reconstructive surgery and testing, led efforts to coordinate medical disaster relief efforts during the historic Louisiana flooding of 2016, and led Louisiana Medicaid’s initiative to tackle the opioid epidemic.

Dr. Kuy developed statewide health performance metrics, pay-for-performance incentives, and novel Medicaid Expansion Early Wins measures, which enabled the state of Louisiana to assess how access to care directly affects lives. Before serving as Chief Medical Officer for Louisiana Medicaid, Dr. Kuy served in numerous leadership roles in the VA system, including the following: director, Center for Innovations in Quality, Outcomes and Patient Safety; assistant chief, general surgery; and chair, Systems Redesign Committee. She also was a member, Quality, Safety & Value Board, Overton Brooks VA Medical Center, Shreveport, LA.

Dr. Kuy’s successful efforts to reduce patient mortality and morbidity and decrease adverse events were profiled by the VA National Center for Patient Safety. Her work in increasing veterans’ access to care through clinic efficiency was profiled by the Association for VA Surgeons, and the templates she developed were disseminated for implementation at VA medical centers across the country. Dr. Kuy has served on the National Quality Forum, the National Board of Medical Examiners, and the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education.

In 2017, Dr. Kuy was selected to be a Presidential Leadership Scholar, a joint, bipartisan leadership program taught by Presidents George W. Bush, William J. Clinton, and George H. W. Bush. She subsequently delivered the keynote commencement address at the Bush Institute. Dr. Kuy received the Greater Baton Rouge Business Report’s 40 Under 40 Award for her work to improve health care quality in the Louisiana Medicaid population, the Ford Foundation’s Gerald E. Bruce Community Service Award for her work serving veterans, and Random Acts’ Caught in the Act national public service award. Dr. Kuy also was selected for the Early Career Achievement Award in 2017 by Oregon Health & Sciences University School of Medicine.

Dr. Kuy is grateful for the many incredible mentors and teachers who have inspired her on her journey, and she is proud to be a part of the surgical family. She has dedicated her career to improving the quality of medical care and increasing the public’s access to quality care. The College is proud to have Dr. Kuy as a member and looks forward to what challenges she will tackle next.

Lawmakers Participate in ACS Bleeding Control Training

Leaders of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) hosted a Stop the Bleed® training program on Capitol Hill October 12 for members of Congress and their staffs. The congressional event focused on how early intervention from a Stop the Bleed-trained individual can save the life of someone suffering from a bleeding injury. Participants came to learn more about the ACS’ efforts with Stop the Bleed and engage in the hands-on training in how to control bleeding. The training was led by ACS Fellows, including Lenworth M. Jacobs, Jr., MD, MPH, FACS; Leonard J. Weireter, Jr., MD, FACS; Mark L. Gestring, MD, FACS; John H. Armstrong, MD, FACS; Joseph V. Sakran, MD, MPH, MPA, FACS; and Jack Sava, MD, FACS. Congressional guests included Reps. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA); Phil Roe, MD (R-TN); Raul Ruiz, MD (D-CA); and Brad Wenstrup, DPM (R-OH), who provided opening remarks.

Members of Congress and their staff left the program with a better understanding of how to become life-saving immediate responders and the value of Stop the Bleed training. In addition to promoting Stop the Bleed training, the College also is advocating for widespread access to bleeding control education before federal and state lawmakers.

For more information about ACS trauma advocacy, contact Justin Rosen, Congressional Lobbyist, at [email protected] or 202-672-1528. For more information about the Stop the Bleed program, visit BleedingControl.org.

Leaders of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) hosted a Stop the Bleed® training program on Capitol Hill October 12 for members of Congress and their staffs. The congressional event focused on how early intervention from a Stop the Bleed-trained individual can save the life of someone suffering from a bleeding injury. Participants came to learn more about the ACS’ efforts with Stop the Bleed and engage in the hands-on training in how to control bleeding. The training was led by ACS Fellows, including Lenworth M. Jacobs, Jr., MD, MPH, FACS; Leonard J. Weireter, Jr., MD, FACS; Mark L. Gestring, MD, FACS; John H. Armstrong, MD, FACS; Joseph V. Sakran, MD, MPH, MPA, FACS; and Jack Sava, MD, FACS. Congressional guests included Reps. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA); Phil Roe, MD (R-TN); Raul Ruiz, MD (D-CA); and Brad Wenstrup, DPM (R-OH), who provided opening remarks.

Members of Congress and their staff left the program with a better understanding of how to become life-saving immediate responders and the value of Stop the Bleed training. In addition to promoting Stop the Bleed training, the College also is advocating for widespread access to bleeding control education before federal and state lawmakers.

For more information about ACS trauma advocacy, contact Justin Rosen, Congressional Lobbyist, at [email protected] or 202-672-1528. For more information about the Stop the Bleed program, visit BleedingControl.org.

Leaders of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) hosted a Stop the Bleed® training program on Capitol Hill October 12 for members of Congress and their staffs. The congressional event focused on how early intervention from a Stop the Bleed-trained individual can save the life of someone suffering from a bleeding injury. Participants came to learn more about the ACS’ efforts with Stop the Bleed and engage in the hands-on training in how to control bleeding. The training was led by ACS Fellows, including Lenworth M. Jacobs, Jr., MD, MPH, FACS; Leonard J. Weireter, Jr., MD, FACS; Mark L. Gestring, MD, FACS; John H. Armstrong, MD, FACS; Joseph V. Sakran, MD, MPH, MPA, FACS; and Jack Sava, MD, FACS. Congressional guests included Reps. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA); Phil Roe, MD (R-TN); Raul Ruiz, MD (D-CA); and Brad Wenstrup, DPM (R-OH), who provided opening remarks.

Members of Congress and their staff left the program with a better understanding of how to become life-saving immediate responders and the value of Stop the Bleed training. In addition to promoting Stop the Bleed training, the College also is advocating for widespread access to bleeding control education before federal and state lawmakers.

For more information about ACS trauma advocacy, contact Justin Rosen, Congressional Lobbyist, at [email protected] or 202-672-1528. For more information about the Stop the Bleed program, visit BleedingControl.org.

Read the November Bulletin : Should your health care system invest in an ambulatory surgical center

The November issue of the Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons is now available online at bulletin.facs.org. This month’s Bulletin includes the following features, columns, and new stories, among others:

Features

• Frank R. Lewis, Jr., MD, FACS: 15 years of visionary leadership at the American Board of Surgery

• A history of health information technology and the future of interoperability

Columns

• Looking forward: Health care reform

• What surgeons should know about...The New Medicare Card Project

• ACS NSQIP best practices case studies: Quality improvement in imaging strategies for pediatric appendicitis

News

• Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon), installed as 98th ACS President

• Honorary Fellowship in the ACS awarded to 10 prominent surgeons

• Call for nominations for the ACS Board of Regents and ACS Officers-Elect

The Bulletin is available in a variety of digital formats to satisfy every reader’s preference, including an interactive version and a smartphone app. Go to the Bulletin website at bulletin.facs.org to connect to any of these versions or to read the articles directly online.

The November issue of the Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons is now available online at bulletin.facs.org. This month’s Bulletin includes the following features, columns, and new stories, among others:

Features

• Frank R. Lewis, Jr., MD, FACS: 15 years of visionary leadership at the American Board of Surgery

• A history of health information technology and the future of interoperability

Columns

• Looking forward: Health care reform

• What surgeons should know about...The New Medicare Card Project

• ACS NSQIP best practices case studies: Quality improvement in imaging strategies for pediatric appendicitis

News

• Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon), installed as 98th ACS President

• Honorary Fellowship in the ACS awarded to 10 prominent surgeons

• Call for nominations for the ACS Board of Regents and ACS Officers-Elect

The Bulletin is available in a variety of digital formats to satisfy every reader’s preference, including an interactive version and a smartphone app. Go to the Bulletin website at bulletin.facs.org to connect to any of these versions or to read the articles directly online.

The November issue of the Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons is now available online at bulletin.facs.org. This month’s Bulletin includes the following features, columns, and new stories, among others:

Features

• Frank R. Lewis, Jr., MD, FACS: 15 years of visionary leadership at the American Board of Surgery

• A history of health information technology and the future of interoperability

Columns

• Looking forward: Health care reform

• What surgeons should know about...The New Medicare Card Project

• ACS NSQIP best practices case studies: Quality improvement in imaging strategies for pediatric appendicitis

News

• Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, FRCS(Hon), installed as 98th ACS President

• Honorary Fellowship in the ACS awarded to 10 prominent surgeons

• Call for nominations for the ACS Board of Regents and ACS Officers-Elect

The Bulletin is available in a variety of digital formats to satisfy every reader’s preference, including an interactive version and a smartphone app. Go to the Bulletin website at bulletin.facs.org to connect to any of these versions or to read the articles directly online.

Psoriasis patients face higher risk of alcohol-related death – but lower suicide risk

GENEVA – Psoriasis patients are roughly two-thirds more likely to die of alcohol-related causes than their peers in the general population, Rosa Parisi, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Indeed, alcohol-related mortality appears to be an important contributor to the long-recognized elevated risk of premature mortality in patients who’ve been diagnosed with psoriasis, according to Dr. Parisi of the University of Manchester (England), who presented the results of a retrospective cohort study of alcohol-related deaths. The reasons for psoriasis patients’ increased risk of early mortality have been unclear, although it’s well established that psoriasis is associated with increased rates of unhealthy behaviors, including smoking and high alcohol consumption.

The study of alcohol-related deaths utilized a database of 398 primary care practices in England. The study population consisted of 55,537 patients diagnosed with psoriasis in 1998-2014 and 854,314 controls without psoriasis who were matched based on age, sex, and membership in the same primary care practice.

During a median 4.4 years of follow-up, the rate of deaths directly attributable to alcohol consumption was 4.8 per 10,000 person-years in the psoriasis group and 2.5 per 10,000 person-years in controls. Nearly two-thirds of the alcohol-related deaths were recorded as due to alcoholic liver disease and 24% to hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis; 8% were attributed to mental and behavioral disorders due to alcohol.

In an analysis adjusted for socioeconomic status, the risk for alcohol-related death was increased 1.58-fold in the psoriasis group, compared with controls. Upon exclusion of all subjects who’d been on methotrexate on the grounds that the drug interacts with alcohol to accelerate liver damage, having psoriasis was associated with a 1.66-fold increased risk of alcohol-related death.

Such deaths occurred in women with psoriasis at a median age of 55 – a full 5 years younger than alcohol-related deaths in nonpsoriatic women. The age gap was smaller in men.

Medical records indicated that 82.2% of psoriasis patients who died of alcohol-related causes had previously been coded by their primary care practitioner as a heavy drinker, as were 75.5% of those without psoriasis who died of similar causes. Yet fewer than 11% of the psoriasis patients and controls who experienced alcohol-related mortality had ever received a prescription for a medication for alcohol dependence, such as disulfiram. Psychologic support for alcohol dependence had been offered within the primary care practices for only 19.7% of psoriasis patients with an alcohol-related death and 14.4% of controls.

These statistics contain an important message for clinicians, Dr. Parisi said.

“Alcohol misuse often remains unidentified and undertreated in primary care. Health care practitioners should be more aware of the psychologic difficulties of people with psoriasis. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test screening tool, which has been developed by the World Health Organization, should be implemented in both primary and secondary care to detect alcohol misuse in psoriasis patients,” she asserted.

Elsewhere at the meeting, she presented a study on the risks of suicide and nonfatal deliberate self-harm among psoriasis patients. She utilized the same database of 398 English primary care medical practices. This analysis included 56,961 psoriasis patients and 876,919 matched controls.

The suicide rate was 1.1 per 10,000 person-years in the psoriasis group and 1.5 per 10,000 person-years in controls. In a proportional hazard analysis adjusted for socioeconomic status, psoriasis patients were at a significant 41% lower risk of suicide than their nonpsoriatic peers. Breaking down the data further based upon age at diagnosis of psoriasis, patients diagnosed before age 40 were at a nonsignificant 8% lower risk of suicide, while those diagnosed at age 40 years or older experienced a highly significant 62% reduction in risk of suicide, compared with controls.

This was the case even though the psoriasis group had a significantly greater prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities overall, by a margin of 29.2% versus 26.4%.

The analysis of risk of nonfatal deliberate self-harm was done after excluding all individuals in the suicide study who had a baseline history of self-harm. This resulted in a study population of 54,709 psoriasis patients and 813,699 controls matched by age, sex, and primary care practice. Bottom line: There was no evidence of an association between having a diagnosis of psoriasis and nonfatal deliberate self-harm. The rates – 18.9 events per 10,000 person-years in the psoriasis group and 16.3 per 10,000 person-years in controls – were closely similar after adjusting for socioeconomic status.

Simultaneous with her EADV presentation on alcohol-related deaths in psoriasis patients, Dr. Parisi’s study was published online (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Sep 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3225).

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentations.

GENEVA – Psoriasis patients are roughly two-thirds more likely to die of alcohol-related causes than their peers in the general population, Rosa Parisi, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Indeed, alcohol-related mortality appears to be an important contributor to the long-recognized elevated risk of premature mortality in patients who’ve been diagnosed with psoriasis, according to Dr. Parisi of the University of Manchester (England), who presented the results of a retrospective cohort study of alcohol-related deaths. The reasons for psoriasis patients’ increased risk of early mortality have been unclear, although it’s well established that psoriasis is associated with increased rates of unhealthy behaviors, including smoking and high alcohol consumption.

The study of alcohol-related deaths utilized a database of 398 primary care practices in England. The study population consisted of 55,537 patients diagnosed with psoriasis in 1998-2014 and 854,314 controls without psoriasis who were matched based on age, sex, and membership in the same primary care practice.

During a median 4.4 years of follow-up, the rate of deaths directly attributable to alcohol consumption was 4.8 per 10,000 person-years in the psoriasis group and 2.5 per 10,000 person-years in controls. Nearly two-thirds of the alcohol-related deaths were recorded as due to alcoholic liver disease and 24% to hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis; 8% were attributed to mental and behavioral disorders due to alcohol.

In an analysis adjusted for socioeconomic status, the risk for alcohol-related death was increased 1.58-fold in the psoriasis group, compared with controls. Upon exclusion of all subjects who’d been on methotrexate on the grounds that the drug interacts with alcohol to accelerate liver damage, having psoriasis was associated with a 1.66-fold increased risk of alcohol-related death.

Such deaths occurred in women with psoriasis at a median age of 55 – a full 5 years younger than alcohol-related deaths in nonpsoriatic women. The age gap was smaller in men.

Medical records indicated that 82.2% of psoriasis patients who died of alcohol-related causes had previously been coded by their primary care practitioner as a heavy drinker, as were 75.5% of those without psoriasis who died of similar causes. Yet fewer than 11% of the psoriasis patients and controls who experienced alcohol-related mortality had ever received a prescription for a medication for alcohol dependence, such as disulfiram. Psychologic support for alcohol dependence had been offered within the primary care practices for only 19.7% of psoriasis patients with an alcohol-related death and 14.4% of controls.

These statistics contain an important message for clinicians, Dr. Parisi said.

“Alcohol misuse often remains unidentified and undertreated in primary care. Health care practitioners should be more aware of the psychologic difficulties of people with psoriasis. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test screening tool, which has been developed by the World Health Organization, should be implemented in both primary and secondary care to detect alcohol misuse in psoriasis patients,” she asserted.

Elsewhere at the meeting, she presented a study on the risks of suicide and nonfatal deliberate self-harm among psoriasis patients. She utilized the same database of 398 English primary care medical practices. This analysis included 56,961 psoriasis patients and 876,919 matched controls.

The suicide rate was 1.1 per 10,000 person-years in the psoriasis group and 1.5 per 10,000 person-years in controls. In a proportional hazard analysis adjusted for socioeconomic status, psoriasis patients were at a significant 41% lower risk of suicide than their nonpsoriatic peers. Breaking down the data further based upon age at diagnosis of psoriasis, patients diagnosed before age 40 were at a nonsignificant 8% lower risk of suicide, while those diagnosed at age 40 years or older experienced a highly significant 62% reduction in risk of suicide, compared with controls.

This was the case even though the psoriasis group had a significantly greater prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities overall, by a margin of 29.2% versus 26.4%.

The analysis of risk of nonfatal deliberate self-harm was done after excluding all individuals in the suicide study who had a baseline history of self-harm. This resulted in a study population of 54,709 psoriasis patients and 813,699 controls matched by age, sex, and primary care practice. Bottom line: There was no evidence of an association between having a diagnosis of psoriasis and nonfatal deliberate self-harm. The rates – 18.9 events per 10,000 person-years in the psoriasis group and 16.3 per 10,000 person-years in controls – were closely similar after adjusting for socioeconomic status.

Simultaneous with her EADV presentation on alcohol-related deaths in psoriasis patients, Dr. Parisi’s study was published online (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Sep 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3225).

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentations.

GENEVA – Psoriasis patients are roughly two-thirds more likely to die of alcohol-related causes than their peers in the general population, Rosa Parisi, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Indeed, alcohol-related mortality appears to be an important contributor to the long-recognized elevated risk of premature mortality in patients who’ve been diagnosed with psoriasis, according to Dr. Parisi of the University of Manchester (England), who presented the results of a retrospective cohort study of alcohol-related deaths. The reasons for psoriasis patients’ increased risk of early mortality have been unclear, although it’s well established that psoriasis is associated with increased rates of unhealthy behaviors, including smoking and high alcohol consumption.

The study of alcohol-related deaths utilized a database of 398 primary care practices in England. The study population consisted of 55,537 patients diagnosed with psoriasis in 1998-2014 and 854,314 controls without psoriasis who were matched based on age, sex, and membership in the same primary care practice.

During a median 4.4 years of follow-up, the rate of deaths directly attributable to alcohol consumption was 4.8 per 10,000 person-years in the psoriasis group and 2.5 per 10,000 person-years in controls. Nearly two-thirds of the alcohol-related deaths were recorded as due to alcoholic liver disease and 24% to hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis; 8% were attributed to mental and behavioral disorders due to alcohol.

In an analysis adjusted for socioeconomic status, the risk for alcohol-related death was increased 1.58-fold in the psoriasis group, compared with controls. Upon exclusion of all subjects who’d been on methotrexate on the grounds that the drug interacts with alcohol to accelerate liver damage, having psoriasis was associated with a 1.66-fold increased risk of alcohol-related death.

Such deaths occurred in women with psoriasis at a median age of 55 – a full 5 years younger than alcohol-related deaths in nonpsoriatic women. The age gap was smaller in men.

Medical records indicated that 82.2% of psoriasis patients who died of alcohol-related causes had previously been coded by their primary care practitioner as a heavy drinker, as were 75.5% of those without psoriasis who died of similar causes. Yet fewer than 11% of the psoriasis patients and controls who experienced alcohol-related mortality had ever received a prescription for a medication for alcohol dependence, such as disulfiram. Psychologic support for alcohol dependence had been offered within the primary care practices for only 19.7% of psoriasis patients with an alcohol-related death and 14.4% of controls.

These statistics contain an important message for clinicians, Dr. Parisi said.

“Alcohol misuse often remains unidentified and undertreated in primary care. Health care practitioners should be more aware of the psychologic difficulties of people with psoriasis. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test screening tool, which has been developed by the World Health Organization, should be implemented in both primary and secondary care to detect alcohol misuse in psoriasis patients,” she asserted.

Elsewhere at the meeting, she presented a study on the risks of suicide and nonfatal deliberate self-harm among psoriasis patients. She utilized the same database of 398 English primary care medical practices. This analysis included 56,961 psoriasis patients and 876,919 matched controls.

The suicide rate was 1.1 per 10,000 person-years in the psoriasis group and 1.5 per 10,000 person-years in controls. In a proportional hazard analysis adjusted for socioeconomic status, psoriasis patients were at a significant 41% lower risk of suicide than their nonpsoriatic peers. Breaking down the data further based upon age at diagnosis of psoriasis, patients diagnosed before age 40 were at a nonsignificant 8% lower risk of suicide, while those diagnosed at age 40 years or older experienced a highly significant 62% reduction in risk of suicide, compared with controls.

This was the case even though the psoriasis group had a significantly greater prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities overall, by a margin of 29.2% versus 26.4%.

The analysis of risk of nonfatal deliberate self-harm was done after excluding all individuals in the suicide study who had a baseline history of self-harm. This resulted in a study population of 54,709 psoriasis patients and 813,699 controls matched by age, sex, and primary care practice. Bottom line: There was no evidence of an association between having a diagnosis of psoriasis and nonfatal deliberate self-harm. The rates – 18.9 events per 10,000 person-years in the psoriasis group and 16.3 per 10,000 person-years in controls – were closely similar after adjusting for socioeconomic status.

Simultaneous with her EADV presentation on alcohol-related deaths in psoriasis patients, Dr. Parisi’s study was published online (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Sep 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3225).

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentations.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Psoriasis patients who had never been on methotrexate had a 66% higher rate of alcohol-related death than matched controls without psoriasis.

Data source: This retrospective cohort study of alcohol-related deaths included 55,537 psoriasis patients and 854,314 controls without psoriasis matched based on age, sex, and membership in the same primary care practice.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

Given the recent rise in marijuana legalization efforts and an overall increase in the prevalence of marijuana use, it is becoming increasingly important to recognize conditions that are associated with its use. Data obtained from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health show the prevalence of marijuana use within the past month among those surveyed was 8.4% in 2014. This represents a 35% increase from the same study in 2002. Based on this survey, 2.5 million people (or ~7,000 per day) used marijuana for the first time.1

Following the liberalization of marijuana in Colorado, the prevalence of presentation to the emergency department (ED) for cyclic vomiting nearly doubled.2 During the 2016 election season, several states included legislation that increased access to marijuana on the ballot, most of which passed. There are now 28 states plus the District of Columbia that permit medical marijuana usage, and 8 of those states and the District of Columbia have laws allowing for recreational use of marijuana.3

First described in a case series by Allen and colleagues in 2004, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is indicated by recurrent episodes of nausea and vomiting with vague abdominal pain and compulsive hot bathing in the setting of chronic, often daily, cannabis use.4 A case of a middle-aged veteran with chronic marijuana use and recurrent, self-limited nausea and vomiting is presented here.

Case Presentation

A 45-year-old man presented to the ED with a 5-day history of persistent nausea and vomiting that began abruptly. The symptoms had been constant since onset, resulting in very little oral intake. The patient reported no hematemesis or coffee ground emesis. He noted a drop in his urine output over the previous 2 days. He also reported abdominal pain associated with the nausea. The patient characterized his pain as “dull and achy” diffuse pain that was partially relieved with emesis. His bowel movements had been regular, and he reported no diarrhea, fever, chills, or other constitutional symptoms. Additional 10-point review of systems was otherwise negative. The patient reported smoking marijuana multiple times daily for many years. The patient reported he had not used alcohol for several months.

A physical exam showed a pale and diaphoretic patient. Vital signs were significant for mild hypertension (150/75), but the patient was afebrile with a normal heart rate. An abdominal exam revealed a nontender, nondistended abdomen with no signs of rebound or guarding. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable. An initial workup showed a mild elevation of serum creatinine to 1.36 mg/dL (baseline is 1.10 mg/dL). Other workups, including complete blood count (CBC) with differential, complete metabolic panel, lipase, amylase, and urine analysis, were all unremarkable.

The patient’s urine drug screen (UDS) was positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). A computed tomography (CT) scan of his abdomen and pelvis with contrast was unremarkable. The patient was admitted for his inability to tolerate oral intake and dehydration and treated supportively with IV fluids and antiemetics.

Overnight, the nursing staff reported that the patient took multiple, prolonged hot showers. Upon further questioning, he reported the hot showers significantly helped the nausea and abdominal pain. He had learned this behavior after experiencing previous episodes of self-limited nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Extensive review of his medical record revealed that the patient had, in fact, presented to the ED with similar symptoms 11 times in the prior 8 years. He was admitted on 8 occasions over that time frame. The typical hospital course included supportive care with antiemetics and IV fluids. The patient’s symptoms typically resolved within 24 to 72 hours of hospitalization. Previous evaluations included additional unremarkable CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis. The patient also had received 2 esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs), one 2 years prior and the other 5 years prior. Both EGDs showed only mild gastritis. On every check during the previous 8 years, the patient’s UDS was positive for THC.

Most of his previous admissions were attributed to viral gastroenteritis due to the self-limited nature of the symptoms. Other admissions were attributed to alcohol-induced gastritis. However, after abstaining from alcohol for long periods, the patient had continued recurrence of the symptoms and increased frequency of presentations to the ED.

The characteristics, signs, and symptoms of CHS were discussed with the patient. The patient strongly felt as though these symptoms aligned with his clinical course over the prior 8 years. At time of writing, the patient had gone 20 months without requiring hospitalization; however, he had a recent relapse of marijuana use and subsequently required hospitalization.

Discussion

As in this case, CHS often presents with refractory, self-limited nausea and vomiting with vague abdominal pain that is temporarily relieved by hot baths or showers. In the largest case series, it was noted the average age was 32 years, and the majority of subjects used marijuana at least weekly for > 2 years.5 Many studies categorize CHS into 3 phases: prodromal, hyperemetic, and recovery.

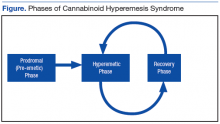

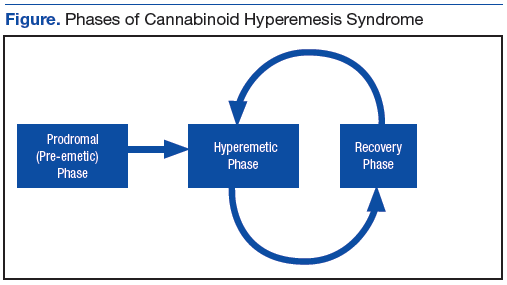

The prodromal, or preemetic phase, is characterized by early morning nausea without emesis and abdominal discomfort. The hyperemetic phase begins when the patient accesses the health care system via either the ED or primary care physician. This phase is characterized by intractable nausea and vomiting and may be associated with mild diffuse abdominal pain. The nausea and vomiting typically do not respond to antiemetic medications. Patients in this stage also develop a compulsive behavior of hot showers that temporarily relieve the symptoms. These behaviors are thought to be learned through their cyclical periods of emesis and may not be present during the first few hyperemetic phases. During the recovery phase, the patient returns to a baseline state of health and often ceases utilizing the hot shower. The recovery phase can last weeks to months despite continued cannabis use prior to returning to the hyperemetic phase (Figure).6,7

Simonetto and colleagues proposed clinical criteria for the diagnosis of CHS based on their case series as well as on previously proposed criteria presented by Sontineni and colleagues.5,8 Long-term cannabis use is required for the diagnosis. In the Simonetto and colleagues case series, the majority of patients developed symptoms within the first 5 years of cannabis use; however, Soriano and colleagues conducted a smaller case series that showed that the majority of subjects used marijuana for roughly 16 years prior to the onset of vomiting.5,7

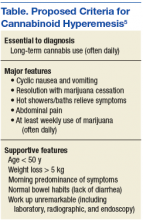

The major CHS features that suggest the diagnosis are severe cyclic nausea and vomiting, relief of symptoms with abstinence from cannabis, temporary symptom relief with hot bathing, abdominal pain, and at least weekly use of marijuana. Other supportive features include aged < 50 years, weight loss > 5 kg, symptoms that are worse in the morning, normal bowel habits, and negative evaluation, including laboratory, radiography, and endoscopy (Table).5

Treatment often is supportive with emphasis placed on marijuana cessation. Intravenous fluids often are used due to dehydration from the emesis. The use of antiemetics, such as 5-HT3 (eg, ondansetron), D2 (eg, prochlorperazine), H1 (eg, promethazine), or neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists (eg, aprepitant) can be tried, but these therapies often are ineffective. Diet can be advanced as the patient tolerates. Given that many patients are found to have a mild gastritis, H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors may be used. Extensive counseling on marijuana cessation is needed as it is the only therapy shown to have prolonged relief of the hyperemetic phase.6 The length of cessation from marijuana for resolution of the cyclical hyperemesis varies from 1 to 3 months. Returning to marijuana use often results in the returning of CHS.5

The pathophysiology of CHS is largely unknown; however, there are several hypothesized mechanisms. Many theorize that due to the lipophilicity and long half-life of THC, a primary compound in marijuana, it accumulates in the body over time.4,6 It is thought that this accumulation may cause toxicity in both the gastrointestinal tract as well as in the brain. Central effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis may play a major role, and the reason for the symptom relief of hot baths is due to a change in thermoregulation in the hypothalamus.5 One interesting mechanism relates to CB1 receptor activation and vasodilation within the gastrointestinal tract due to chronic THC accumulation. The relief of the abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting with hot showers can be secondary to the vasodilation of the skin, causing a redistribution from the gut. This theorized mechanism has been referred to as “cutaneous steal.”9

Conclusion

With the increased prevalence of marijuana use in the U.S. over the past decade and reform in legislation taking place over the next couple of years, it is increasingly important to be able to recognize CHS to avoid frequent hospital utilization and repeated costly evaluations. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is recognized by the triad of chronic cannabis use, cyclical hyperemesis, and compulsive hot bathing.4

The syndrome has 3 phases. In the prodromal phase the patient has morning predominance of nausea, usually without emesis. This is followed by the hyperemesis phase, which is characterized by hyperemesis, vague abdominal pain, and learned compulsive hot bathing.

The third phase is the recovery phase, which is a return to normal behavior. During the recovery phase, if patients cease marijuana use, they remain asymptomatic; however, if patients continue to use marijuana, they often have recurrence of the hyperemesis phase.5 The diagnosis of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is difficult as it is a diagnosis of exclusion. Patients may present to the ED many times prior to diagnosis. With the changing climate of marijuana laws, it is an important condition to consider when establishing a differential. More studies will be required to evaluate the overall prevalence of this condition as well as if there are any changes following the liberalization of marijuana laws in many states.

1. Azofeifa A, Mattson ME, Schauer G, McAfee T, Grant A, Lyerla R. National estimates of marijuana use and related indicators - National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2002-2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(11):1-28.

2. Kim HS, Anderson JD, Saghafi O, Heard KJ, Monte AA. Cyclic vomiting presentations following marijuana liberalization in Colorado. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(6):694-699.

3. National Conference of State Legislatures. State medical marijuana laws. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx. Updated July 7, 2017. Accessed August 3, 2017.

4. Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, Twartz JC. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut. 2004;53(11):1566-1570.

5. Simonetto DA, Oxentenko AS, Herman ML, Szostek JH. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: a case series of 98 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):114-119.

6. Galli JA, Sawaya RA, Friedenberg FK. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(4):241-249.