User login

Strategies to overcome the loss of port placement triangulation

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

This video is brought to you by

Clinical Challenges - November 2017 What's your diagnosis?

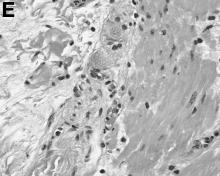

The diagnosis

Answer: Hepatic foregut duplication cyst and concurrent acute gangrenous cholecystitis

References

1. Imamoglu K.H., Walt, A.J. Duplication of the duodenum extending into liver. Am J Surg. 1977;133:628-32.

2. Seidman J.D., Yale-Loehr A.J., Beaver B., et al. Alimentary duplication presenting as an hepatic cyst in a neonate. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:695-8.

3. Vick D.J., Goodman Z.D., Deavers M.T., et al. Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst: A study of six cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:671-7.

The diagnosis

Answer: Hepatic foregut duplication cyst and concurrent acute gangrenous cholecystitis

References

1. Imamoglu K.H., Walt, A.J. Duplication of the duodenum extending into liver. Am J Surg. 1977;133:628-32.

2. Seidman J.D., Yale-Loehr A.J., Beaver B., et al. Alimentary duplication presenting as an hepatic cyst in a neonate. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:695-8.

3. Vick D.J., Goodman Z.D., Deavers M.T., et al. Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst: A study of six cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:671-7.

The diagnosis

Answer: Hepatic foregut duplication cyst and concurrent acute gangrenous cholecystitis

References

1. Imamoglu K.H., Walt, A.J. Duplication of the duodenum extending into liver. Am J Surg. 1977;133:628-32.

2. Seidman J.D., Yale-Loehr A.J., Beaver B., et al. Alimentary duplication presenting as an hepatic cyst in a neonate. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:695-8.

3. Vick D.J., Goodman Z.D., Deavers M.T., et al. Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst: A study of six cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:671-7.

By Ryan Law, MD, Thomas C. Smyrk, and Stephen C. Hauser. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144[3]:508, 658).

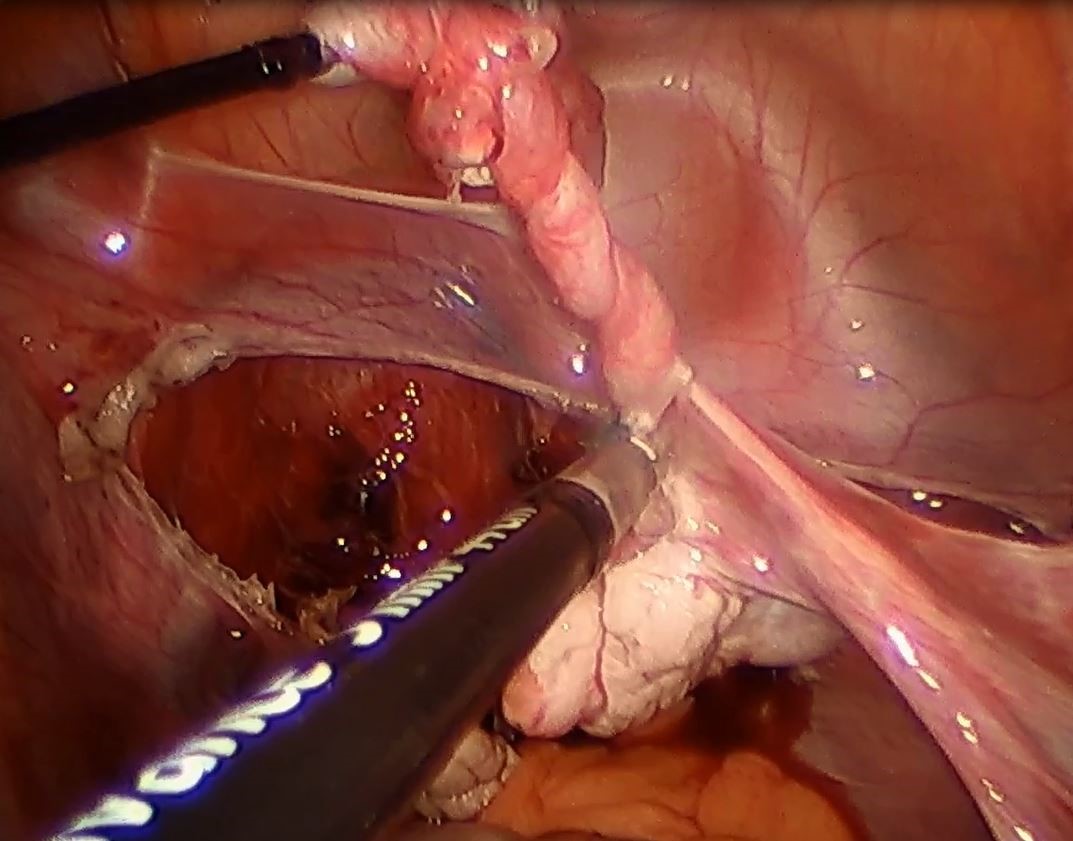

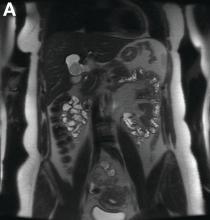

A 43-year-old woman presented with progressively worsening right upper-quadrant abdominal pain. The episodic pain occurred after high-fat meals and lasted from minutes to hours with accompanying nausea. Her previous medical history was notable for endometriosis. She denied other constitutional symptoms. Physical examination revealed no hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, right upper-quadrant mass, or stigmata of chronic liver disease.

Initial laboratory evaluation yielded normal white blood cell count and liver chemistries. Ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen all demonstrated a 2.0 × 4.1 × 3.9-cm, nonenhancing, elongated, cystic mass located superior to the gallbladder within the porta hepatis, with possible communication at the bile duct confluence and abutment of the right portal vein (Figure A). No definitive findings of acute cholecystitis were present.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with endoscopic ultrasonography was performed to further delineate the anatomy of the lesion. On endoscopic ultrasonography, the structure in question seemed to be embedded in the hepatic parenchyma with partial extension beyond the liver edge. Adherent debris was noted within the cystic structure. No lymphadenopathy was present. Cholangiography demonstrated filling of the lesion from a central right intrahepatic duct (Figure B). Attempts at cannulation of the cyst were unsuccessful.

The patient subsequently developed abnormal liver chemistries with continued right upper-quadrant pain. She was referred to an experienced hepatobiliary surgeon and underwent operative intervention. What is the diagnosis and how would you treat this patient?

Smell Test May Identify Increased Risk of Parkinson’s Disease

A smell test may identify people at increased risk of incident Parkinson’s disease as many as 10 years before diagnosis, according to research published in the October 3 issue of Neurology. The association between poor olfaction and incident Parkinson’s disease may be stronger among men than among women, and among whites than among blacks, and this possibility requires further investigation, said the authors.

“Earlier studies had shown prediction of Parkinson’s disease about four to five years after the smell test was taken,” said Honglei Chen, MD, PhD, Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine in East Lansing. “Our study shows that this test may be able to inform the risk much earlier than that.”

A Prospective Study of the Elderly

Dr. Chen and colleagues examined data for 1,510 white participants and 952 black participants in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. During clinical examinations in 1999 and 2000, the participants underwent the Brief Smell Identification Test (BSIT). The researchers followed the population until the date of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis, death, last contact, or August 31, 2012, whichever came first. Parkinson’s disease was diagnosed retrospectively using several data sources. Dr. Chen and colleagues used multivariable Cox models to estimate hazard ratios for Parkinson’s disease.

Participants’ mean age was 76. About 49% of participants were male, and approximately 39% of the population was black. During a mean follow-up duration of 9.8 years, the researchers identified 42 incident cases of Parkinson’s disease, including 30 white participants and 12 black participants.

Patients in the lowest tertile of BSIT scores (ie, those with the worst olfaction) were older and more likely to be male, black, and current smokers, compared with participants in the highest tertile of BSIT scores. Participants in the lowest BSIT tertile also were less likely to report education beyond high school or optimal health.

Olfaction Predicted Parkinson’s Disease

Overall, poor olfaction was associated with a higher risk of Parkinson’s disease. Compared with the highest BSIT tertile, the hazard ratio for Parkinson’s disease was 1.3 for the middle tertile and 4.8 for the lowest tertile. The association between olfaction and Parkinson’s disease was stronger among whites than among blacks, and stronger among men than among women.

Furthermore, the association between olfaction and Parkinson’s disease was significant for the first five years of follow-up, as well as for the period of follow-up after five years. In lagged analyses that excluded the first years of follow-up, the association remained similarly strong for the first six years of follow-up (hazard ratio, 4.1–5.0), after which point the hazard ratio decreased to 2.9.

“Previous studies have shown that black people are more likely to have a poor sense of smell than whites, and yet may be less likely to develop Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Chen. “We found no statistical significance for a link between poor sense of smell and Parkinson’s disease in blacks, but that may have been due to the small sample size. More research is needed to further investigate a possible link.”

Several Factors Could Explain Hyposmia

“The observation that black participants have higher prevalence of hyposmia yet lower incidence of Parkinson’s disease needs further clarification to determine whether this observation is simply methodologic … or if there is a true biologic explanation,” said Gene L. Bowman, ND, MPH, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Neurology at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, in an accompanying editorial.

One of the study’s limitations is that other factors besides neurodegeneration could explain hyposmia. The cause of the olfactory dysfunction observed in the study could be a subject for further research. “More granularity on the specific aspects of the smell tests that are impaired (eg, detection, identification, intensity) would help time-constrained clinicians focus on the most relevant tests,” Dr. Bowman concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Bowman GL. Biomarkers for early detection of Parkinson disease: a scent of consistency with olfactory dysfunction. Neurology. 2017;89(14):1432-1434.

Chen H, Shrestha S, Huang X, et al. Olfaction and incident Parkinson disease in US white and black older adults. Neurology. 2017

A smell test may identify people at increased risk of incident Parkinson’s disease as many as 10 years before diagnosis, according to research published in the October 3 issue of Neurology. The association between poor olfaction and incident Parkinson’s disease may be stronger among men than among women, and among whites than among blacks, and this possibility requires further investigation, said the authors.

“Earlier studies had shown prediction of Parkinson’s disease about four to five years after the smell test was taken,” said Honglei Chen, MD, PhD, Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine in East Lansing. “Our study shows that this test may be able to inform the risk much earlier than that.”

A Prospective Study of the Elderly

Dr. Chen and colleagues examined data for 1,510 white participants and 952 black participants in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. During clinical examinations in 1999 and 2000, the participants underwent the Brief Smell Identification Test (BSIT). The researchers followed the population until the date of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis, death, last contact, or August 31, 2012, whichever came first. Parkinson’s disease was diagnosed retrospectively using several data sources. Dr. Chen and colleagues used multivariable Cox models to estimate hazard ratios for Parkinson’s disease.

Participants’ mean age was 76. About 49% of participants were male, and approximately 39% of the population was black. During a mean follow-up duration of 9.8 years, the researchers identified 42 incident cases of Parkinson’s disease, including 30 white participants and 12 black participants.

Patients in the lowest tertile of BSIT scores (ie, those with the worst olfaction) were older and more likely to be male, black, and current smokers, compared with participants in the highest tertile of BSIT scores. Participants in the lowest BSIT tertile also were less likely to report education beyond high school or optimal health.

Olfaction Predicted Parkinson’s Disease

Overall, poor olfaction was associated with a higher risk of Parkinson’s disease. Compared with the highest BSIT tertile, the hazard ratio for Parkinson’s disease was 1.3 for the middle tertile and 4.8 for the lowest tertile. The association between olfaction and Parkinson’s disease was stronger among whites than among blacks, and stronger among men than among women.

Furthermore, the association between olfaction and Parkinson’s disease was significant for the first five years of follow-up, as well as for the period of follow-up after five years. In lagged analyses that excluded the first years of follow-up, the association remained similarly strong for the first six years of follow-up (hazard ratio, 4.1–5.0), after which point the hazard ratio decreased to 2.9.

“Previous studies have shown that black people are more likely to have a poor sense of smell than whites, and yet may be less likely to develop Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Chen. “We found no statistical significance for a link between poor sense of smell and Parkinson’s disease in blacks, but that may have been due to the small sample size. More research is needed to further investigate a possible link.”

Several Factors Could Explain Hyposmia

“The observation that black participants have higher prevalence of hyposmia yet lower incidence of Parkinson’s disease needs further clarification to determine whether this observation is simply methodologic … or if there is a true biologic explanation,” said Gene L. Bowman, ND, MPH, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Neurology at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, in an accompanying editorial.

One of the study’s limitations is that other factors besides neurodegeneration could explain hyposmia. The cause of the olfactory dysfunction observed in the study could be a subject for further research. “More granularity on the specific aspects of the smell tests that are impaired (eg, detection, identification, intensity) would help time-constrained clinicians focus on the most relevant tests,” Dr. Bowman concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Bowman GL. Biomarkers for early detection of Parkinson disease: a scent of consistency with olfactory dysfunction. Neurology. 2017;89(14):1432-1434.

Chen H, Shrestha S, Huang X, et al. Olfaction and incident Parkinson disease in US white and black older adults. Neurology. 2017

A smell test may identify people at increased risk of incident Parkinson’s disease as many as 10 years before diagnosis, according to research published in the October 3 issue of Neurology. The association between poor olfaction and incident Parkinson’s disease may be stronger among men than among women, and among whites than among blacks, and this possibility requires further investigation, said the authors.

“Earlier studies had shown prediction of Parkinson’s disease about four to five years after the smell test was taken,” said Honglei Chen, MD, PhD, Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine in East Lansing. “Our study shows that this test may be able to inform the risk much earlier than that.”

A Prospective Study of the Elderly

Dr. Chen and colleagues examined data for 1,510 white participants and 952 black participants in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. During clinical examinations in 1999 and 2000, the participants underwent the Brief Smell Identification Test (BSIT). The researchers followed the population until the date of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis, death, last contact, or August 31, 2012, whichever came first. Parkinson’s disease was diagnosed retrospectively using several data sources. Dr. Chen and colleagues used multivariable Cox models to estimate hazard ratios for Parkinson’s disease.

Participants’ mean age was 76. About 49% of participants were male, and approximately 39% of the population was black. During a mean follow-up duration of 9.8 years, the researchers identified 42 incident cases of Parkinson’s disease, including 30 white participants and 12 black participants.

Patients in the lowest tertile of BSIT scores (ie, those with the worst olfaction) were older and more likely to be male, black, and current smokers, compared with participants in the highest tertile of BSIT scores. Participants in the lowest BSIT tertile also were less likely to report education beyond high school or optimal health.

Olfaction Predicted Parkinson’s Disease

Overall, poor olfaction was associated with a higher risk of Parkinson’s disease. Compared with the highest BSIT tertile, the hazard ratio for Parkinson’s disease was 1.3 for the middle tertile and 4.8 for the lowest tertile. The association between olfaction and Parkinson’s disease was stronger among whites than among blacks, and stronger among men than among women.

Furthermore, the association between olfaction and Parkinson’s disease was significant for the first five years of follow-up, as well as for the period of follow-up after five years. In lagged analyses that excluded the first years of follow-up, the association remained similarly strong for the first six years of follow-up (hazard ratio, 4.1–5.0), after which point the hazard ratio decreased to 2.9.

“Previous studies have shown that black people are more likely to have a poor sense of smell than whites, and yet may be less likely to develop Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Chen. “We found no statistical significance for a link between poor sense of smell and Parkinson’s disease in blacks, but that may have been due to the small sample size. More research is needed to further investigate a possible link.”

Several Factors Could Explain Hyposmia

“The observation that black participants have higher prevalence of hyposmia yet lower incidence of Parkinson’s disease needs further clarification to determine whether this observation is simply methodologic … or if there is a true biologic explanation,” said Gene L. Bowman, ND, MPH, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Neurology at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, in an accompanying editorial.

One of the study’s limitations is that other factors besides neurodegeneration could explain hyposmia. The cause of the olfactory dysfunction observed in the study could be a subject for further research. “More granularity on the specific aspects of the smell tests that are impaired (eg, detection, identification, intensity) would help time-constrained clinicians focus on the most relevant tests,” Dr. Bowman concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Bowman GL. Biomarkers for early detection of Parkinson disease: a scent of consistency with olfactory dysfunction. Neurology. 2017;89(14):1432-1434.

Chen H, Shrestha S, Huang X, et al. Olfaction and incident Parkinson disease in US white and black older adults. Neurology. 2017

Endoscopic therapy effective for early cancer in Barrett’s esophagus

ORLANDO – Endoscopic therapy is as effective in Barrett’s esophagus patients with early cancer as in those with high-grade dysplasia, according to findings from an international multicenter consortium.

The findings suggest that invasive surgery may be avoidable in many Barrett’s esophagus patients with early cancer, Rajesh Krishnamoorthi, MD, of Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, reported at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

Further, after adjustment for age, sex, and Barrett’s esophagus length, there was no statistical difference in the CE-IM rate (hazard ratio, 1.15) or CE-D rate (HR, 1.21) between the two groups.

The rates of recurrent intestinal metaplasia (Re-IM) in the groups were also statistically similar at 43.9% and 34.7%, respectively, said Dr. Krishnamoorthi, whose work received a 2017 Esophagus Category Award at the meeting.

Endoscopic therapy is the treatment of choice for Barrett’s esophagus patients with high-grade dysplasia, and is also used in some cases as a noninvasive alternative to surgery in Barrett’s esophagus patients with intramucosal cancer. However, data comparing outcomes of endoscopic therapy for these two conditions are lacking.

For the current study, all subjects from the EET database of patients from 10 centers in the United States, Europe, and Australia with either intramucosal cancer or high-grade dysplasia who underwent endoscopic therapy since April 2012 were reviewed. The patients were treated with endoscopic mucosal resection if visible lesions were noted, and/or with mucosal ablation for the flat Barrett’s esophagus. Those who underwent at least four esophagogastroduodenoscopies with endoscopic therapy were included.

The median age of the patients was 66 years, 84% were men, and median Barrett’s esophagus segment length was 6 cm. Baseline characteristics did not differ between the groups, Dr. Krishnamoorthi noted.

Although limited by the relatively small number of patients in each study group, by the exclusion of patients who were lost to follow-up, and by the observational nature of the study, the findings could have implications for treatment selection in some patients with Barrett’s esophagus and early cancer.

“In this large well-defined cohort of Barrett’s patients, effectiveness of endoscopic therapy in intramucosal cancer is comparable to that of high-grade dysplasia. Consideration of endoscopic therapy in Barrett’s patients with early cancer could reduce the need for invasive surgery,” he concluded.

During a discussion period, however, it was pointed out that the centers involved in this study are “centers with a lot of expertise in this,” and that the generalizability of the findings to gastroenterology practices is something that should be looked at, especially considering that the diagnosis of intramucosal cancer “may not be uniformly accurate across the spectrum of gastroenterology practices.”

“I completely agree with that,” Dr. Krishnamoorthi said, adding that the diagnosis must be confirmed by a pathologist, and that the procedure should be performed by an endoscopist with extensive experience.

Dr. Krishnamoorthi reported having no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Endoscopic therapy is as effective in Barrett’s esophagus patients with early cancer as in those with high-grade dysplasia, according to findings from an international multicenter consortium.

The findings suggest that invasive surgery may be avoidable in many Barrett’s esophagus patients with early cancer, Rajesh Krishnamoorthi, MD, of Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, reported at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

Further, after adjustment for age, sex, and Barrett’s esophagus length, there was no statistical difference in the CE-IM rate (hazard ratio, 1.15) or CE-D rate (HR, 1.21) between the two groups.

The rates of recurrent intestinal metaplasia (Re-IM) in the groups were also statistically similar at 43.9% and 34.7%, respectively, said Dr. Krishnamoorthi, whose work received a 2017 Esophagus Category Award at the meeting.

Endoscopic therapy is the treatment of choice for Barrett’s esophagus patients with high-grade dysplasia, and is also used in some cases as a noninvasive alternative to surgery in Barrett’s esophagus patients with intramucosal cancer. However, data comparing outcomes of endoscopic therapy for these two conditions are lacking.

For the current study, all subjects from the EET database of patients from 10 centers in the United States, Europe, and Australia with either intramucosal cancer or high-grade dysplasia who underwent endoscopic therapy since April 2012 were reviewed. The patients were treated with endoscopic mucosal resection if visible lesions were noted, and/or with mucosal ablation for the flat Barrett’s esophagus. Those who underwent at least four esophagogastroduodenoscopies with endoscopic therapy were included.

The median age of the patients was 66 years, 84% were men, and median Barrett’s esophagus segment length was 6 cm. Baseline characteristics did not differ between the groups, Dr. Krishnamoorthi noted.

Although limited by the relatively small number of patients in each study group, by the exclusion of patients who were lost to follow-up, and by the observational nature of the study, the findings could have implications for treatment selection in some patients with Barrett’s esophagus and early cancer.

“In this large well-defined cohort of Barrett’s patients, effectiveness of endoscopic therapy in intramucosal cancer is comparable to that of high-grade dysplasia. Consideration of endoscopic therapy in Barrett’s patients with early cancer could reduce the need for invasive surgery,” he concluded.

During a discussion period, however, it was pointed out that the centers involved in this study are “centers with a lot of expertise in this,” and that the generalizability of the findings to gastroenterology practices is something that should be looked at, especially considering that the diagnosis of intramucosal cancer “may not be uniformly accurate across the spectrum of gastroenterology practices.”

“I completely agree with that,” Dr. Krishnamoorthi said, adding that the diagnosis must be confirmed by a pathologist, and that the procedure should be performed by an endoscopist with extensive experience.

Dr. Krishnamoorthi reported having no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Endoscopic therapy is as effective in Barrett’s esophagus patients with early cancer as in those with high-grade dysplasia, according to findings from an international multicenter consortium.

The findings suggest that invasive surgery may be avoidable in many Barrett’s esophagus patients with early cancer, Rajesh Krishnamoorthi, MD, of Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, reported at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

Further, after adjustment for age, sex, and Barrett’s esophagus length, there was no statistical difference in the CE-IM rate (hazard ratio, 1.15) or CE-D rate (HR, 1.21) between the two groups.

The rates of recurrent intestinal metaplasia (Re-IM) in the groups were also statistically similar at 43.9% and 34.7%, respectively, said Dr. Krishnamoorthi, whose work received a 2017 Esophagus Category Award at the meeting.

Endoscopic therapy is the treatment of choice for Barrett’s esophagus patients with high-grade dysplasia, and is also used in some cases as a noninvasive alternative to surgery in Barrett’s esophagus patients with intramucosal cancer. However, data comparing outcomes of endoscopic therapy for these two conditions are lacking.

For the current study, all subjects from the EET database of patients from 10 centers in the United States, Europe, and Australia with either intramucosal cancer or high-grade dysplasia who underwent endoscopic therapy since April 2012 were reviewed. The patients were treated with endoscopic mucosal resection if visible lesions were noted, and/or with mucosal ablation for the flat Barrett’s esophagus. Those who underwent at least four esophagogastroduodenoscopies with endoscopic therapy were included.

The median age of the patients was 66 years, 84% were men, and median Barrett’s esophagus segment length was 6 cm. Baseline characteristics did not differ between the groups, Dr. Krishnamoorthi noted.

Although limited by the relatively small number of patients in each study group, by the exclusion of patients who were lost to follow-up, and by the observational nature of the study, the findings could have implications for treatment selection in some patients with Barrett’s esophagus and early cancer.

“In this large well-defined cohort of Barrett’s patients, effectiveness of endoscopic therapy in intramucosal cancer is comparable to that of high-grade dysplasia. Consideration of endoscopic therapy in Barrett’s patients with early cancer could reduce the need for invasive surgery,” he concluded.

During a discussion period, however, it was pointed out that the centers involved in this study are “centers with a lot of expertise in this,” and that the generalizability of the findings to gastroenterology practices is something that should be looked at, especially considering that the diagnosis of intramucosal cancer “may not be uniformly accurate across the spectrum of gastroenterology practices.”

“I completely agree with that,” Dr. Krishnamoorthi said, adding that the diagnosis must be confirmed by a pathologist, and that the procedure should be performed by an endoscopist with extensive experience.

Dr. Krishnamoorthi reported having no disclosures.

AT THE 13th WORLD CONGRESS OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Outcomes did not differ significantly between Barrett’s esophagus patients with early cancer and those with high-grade dysplasia (hazard ratios for CE-IM and CE-D, respectively: 1.15, and 1.21).

Data source: Study of 276 patients from a prospective database.

Disclosures: Dr. Krishnamoorthi reported having no disclosures.

Quick Byte: Telemental health visits on the rise

Telemental health visits are on the rise.

In 2014, there were 5.3 and 11.8 telemental health visits per 100 rural beneficiaries with any mental illness or serious mental illness, respectively.

Reference

Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, et al. Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural Medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Aff. 2017 May 1;36(5):909-17. Accessed May 24, 2017.

Telemental health visits are on the rise.

In 2014, there were 5.3 and 11.8 telemental health visits per 100 rural beneficiaries with any mental illness or serious mental illness, respectively.

Reference

Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, et al. Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural Medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Aff. 2017 May 1;36(5):909-17. Accessed May 24, 2017.

Telemental health visits are on the rise.

In 2014, there were 5.3 and 11.8 telemental health visits per 100 rural beneficiaries with any mental illness or serious mental illness, respectively.

Reference

Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, et al. Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural Medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Aff. 2017 May 1;36(5):909-17. Accessed May 24, 2017.

Guidelines are not cookbooks

For many years I have counseled medical students and residents that half of what I was taught in medical school has since been proven obsolete or frankly wrong. I counsel them that I have no reason to believe that I am any better than my professors were. So I wish them luck sorting out what is true. Earlier in my career, that warning was mild hyperbole, but not anymore.

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) are the most common reason for an office visit during the winter. Bronchiolitis is the most frequent diagnosis for a winter admission of an infant to a community hospital. Pediatricians have nuanced assessments and many options when treating these diseases. Best practices have changed frequently over the past 3 decades, mostly by eliminating previously espoused treatments as ineffective. In infants and young children, those obsolete treatments include decongestants and cough suppressants for young children with common colds, inhaled beta-agonists and steroids for infants with bronchiolitis, and antibiotics for simple otitis media in older children. In other words, most of what I was originally taught.

There is a discontinuity between guidelines that forbid routine steroids and beta-agonists for bronchiolitis in infants, and guidelines that strongly prescribe steroids, metered dose inhalers, and asthma action plans for all discharged wheezers over age 2 years. When I worked as a hospitalist in the pulmonology department, I frequently diagnosed asthma under age 1 year. As a general pediatric hospitalist, one winter I twice ran afoul of a hospital quality metric that benchmarked 100% compliance with providing steroids, inhaled corticosteroids, and asthma action plans on discharge for all wheezers over age 2. Fortunately for both me and the quality team working on that quality dashboard, my thorough documentation of why I didn’t think a particular wheezer had asthma was detailed enough to satisfy peer review.

Historically, medical knowledge has been dependent upon these types of observation which then are taught to the next generation of physicians and, if confirmed repeatedly, become memes with some degree of reliability. An all-too-typical Cochrane library entry may challenge these memes by looking at 200 articles, finding 20 relevant studies, selecting only 2 underpowered studies as meeting their randomized controlled trial criteria, and then concluding that there is “insufficient evidence” to prove the treatment works. But absence of proof is not proof of absence. Twenty five years after coining the phrase “evidence-based medicine,” our medical knowledge base has not been purified.

In medicine, absolute certainty isn’t possible. Using 95% confidence intervals for a research paper does not even mean it is 95% likely to be right. So part of (which is tainted with confirmation bias.) It is a very imperfect art.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

For many years I have counseled medical students and residents that half of what I was taught in medical school has since been proven obsolete or frankly wrong. I counsel them that I have no reason to believe that I am any better than my professors were. So I wish them luck sorting out what is true. Earlier in my career, that warning was mild hyperbole, but not anymore.

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) are the most common reason for an office visit during the winter. Bronchiolitis is the most frequent diagnosis for a winter admission of an infant to a community hospital. Pediatricians have nuanced assessments and many options when treating these diseases. Best practices have changed frequently over the past 3 decades, mostly by eliminating previously espoused treatments as ineffective. In infants and young children, those obsolete treatments include decongestants and cough suppressants for young children with common colds, inhaled beta-agonists and steroids for infants with bronchiolitis, and antibiotics for simple otitis media in older children. In other words, most of what I was originally taught.

There is a discontinuity between guidelines that forbid routine steroids and beta-agonists for bronchiolitis in infants, and guidelines that strongly prescribe steroids, metered dose inhalers, and asthma action plans for all discharged wheezers over age 2 years. When I worked as a hospitalist in the pulmonology department, I frequently diagnosed asthma under age 1 year. As a general pediatric hospitalist, one winter I twice ran afoul of a hospital quality metric that benchmarked 100% compliance with providing steroids, inhaled corticosteroids, and asthma action plans on discharge for all wheezers over age 2. Fortunately for both me and the quality team working on that quality dashboard, my thorough documentation of why I didn’t think a particular wheezer had asthma was detailed enough to satisfy peer review.

Historically, medical knowledge has been dependent upon these types of observation which then are taught to the next generation of physicians and, if confirmed repeatedly, become memes with some degree of reliability. An all-too-typical Cochrane library entry may challenge these memes by looking at 200 articles, finding 20 relevant studies, selecting only 2 underpowered studies as meeting their randomized controlled trial criteria, and then concluding that there is “insufficient evidence” to prove the treatment works. But absence of proof is not proof of absence. Twenty five years after coining the phrase “evidence-based medicine,” our medical knowledge base has not been purified.

In medicine, absolute certainty isn’t possible. Using 95% confidence intervals for a research paper does not even mean it is 95% likely to be right. So part of (which is tainted with confirmation bias.) It is a very imperfect art.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

For many years I have counseled medical students and residents that half of what I was taught in medical school has since been proven obsolete or frankly wrong. I counsel them that I have no reason to believe that I am any better than my professors were. So I wish them luck sorting out what is true. Earlier in my career, that warning was mild hyperbole, but not anymore.

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) are the most common reason for an office visit during the winter. Bronchiolitis is the most frequent diagnosis for a winter admission of an infant to a community hospital. Pediatricians have nuanced assessments and many options when treating these diseases. Best practices have changed frequently over the past 3 decades, mostly by eliminating previously espoused treatments as ineffective. In infants and young children, those obsolete treatments include decongestants and cough suppressants for young children with common colds, inhaled beta-agonists and steroids for infants with bronchiolitis, and antibiotics for simple otitis media in older children. In other words, most of what I was originally taught.

There is a discontinuity between guidelines that forbid routine steroids and beta-agonists for bronchiolitis in infants, and guidelines that strongly prescribe steroids, metered dose inhalers, and asthma action plans for all discharged wheezers over age 2 years. When I worked as a hospitalist in the pulmonology department, I frequently diagnosed asthma under age 1 year. As a general pediatric hospitalist, one winter I twice ran afoul of a hospital quality metric that benchmarked 100% compliance with providing steroids, inhaled corticosteroids, and asthma action plans on discharge for all wheezers over age 2. Fortunately for both me and the quality team working on that quality dashboard, my thorough documentation of why I didn’t think a particular wheezer had asthma was detailed enough to satisfy peer review.

Historically, medical knowledge has been dependent upon these types of observation which then are taught to the next generation of physicians and, if confirmed repeatedly, become memes with some degree of reliability. An all-too-typical Cochrane library entry may challenge these memes by looking at 200 articles, finding 20 relevant studies, selecting only 2 underpowered studies as meeting their randomized controlled trial criteria, and then concluding that there is “insufficient evidence” to prove the treatment works. But absence of proof is not proof of absence. Twenty five years after coining the phrase “evidence-based medicine,” our medical knowledge base has not been purified.

In medicine, absolute certainty isn’t possible. Using 95% confidence intervals for a research paper does not even mean it is 95% likely to be right. So part of (which is tainted with confirmation bias.) It is a very imperfect art.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

“Great debates” at ACR 2017 address biosimilar switching, new curricular milestones

Two “Great Debates” at this year’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology in San Diego will center on important, but completely separate, issues in rheumatology: whether it is safe to switch to a biosimilar and the relevance of curricular milestones in rheumatology training.

At 2:30 p.m. on Sunday, Nov. 5, a session titled “Biosimilars ... To Switch or Not to Switch? That Is the Question“ will pit Jonathan Kay, MD, against Roy Fleischmann, MD, to try to sway the audience to their point of view in the face of a small evidence base about the consequences of switching.

Dr. Kay, the Timothy S. and Elaine L. Peterson Chair in Rheumatology and professor of medicine at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, where he directs clinical research in the division of rheumatology, will discuss and defend the usefulness of biosimilars for rheumatoid arthritis in his presentation, “The Data Supports That It Is Safe, Effective and Cost-Effective to Switch to a Biosimilar.” He has been greatly involved in clinical research on the development of biosimilars to treat rheumatic diseases in recent years.

In his presentation, “The Data Is Not Convincing. One Study Cannot Be Generalized to All Indications, and Some Studies Suggest That It Is Not Safe, Not Effective and Not Cost-Effective to Switch All Patients (YET) to a Biosimilar,” Dr. Fleischmann will discuss and defend the position that biosimilars are not yet well-enough researched to confidently allow switching. Dr. Fleischmann is clinical professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

At 7:30 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 6, two clinician-educators will advocate for opposing opinions in “The Great (Educational) Debate: Milestones: Meaningful vs. Millstone.” The debate will focus on the relative merits of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Next Accreditation System, which in 2013 led to a paradigm shift in how training programs approach curriculum development, and how both trainees and their programs are assessed.

Calvin Brown, MD, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology and director of the rheumatology training program at Northwestern University, Chicago, will describe the reported and perceived benefits of the milestones, while Simon Helfgott, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, will summarize the arguments that underlie the call for radical change in the milestones system of evaluation

Two “Great Debates” at this year’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology in San Diego will center on important, but completely separate, issues in rheumatology: whether it is safe to switch to a biosimilar and the relevance of curricular milestones in rheumatology training.

At 2:30 p.m. on Sunday, Nov. 5, a session titled “Biosimilars ... To Switch or Not to Switch? That Is the Question“ will pit Jonathan Kay, MD, against Roy Fleischmann, MD, to try to sway the audience to their point of view in the face of a small evidence base about the consequences of switching.

Dr. Kay, the Timothy S. and Elaine L. Peterson Chair in Rheumatology and professor of medicine at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, where he directs clinical research in the division of rheumatology, will discuss and defend the usefulness of biosimilars for rheumatoid arthritis in his presentation, “The Data Supports That It Is Safe, Effective and Cost-Effective to Switch to a Biosimilar.” He has been greatly involved in clinical research on the development of biosimilars to treat rheumatic diseases in recent years.

In his presentation, “The Data Is Not Convincing. One Study Cannot Be Generalized to All Indications, and Some Studies Suggest That It Is Not Safe, Not Effective and Not Cost-Effective to Switch All Patients (YET) to a Biosimilar,” Dr. Fleischmann will discuss and defend the position that biosimilars are not yet well-enough researched to confidently allow switching. Dr. Fleischmann is clinical professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

At 7:30 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 6, two clinician-educators will advocate for opposing opinions in “The Great (Educational) Debate: Milestones: Meaningful vs. Millstone.” The debate will focus on the relative merits of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Next Accreditation System, which in 2013 led to a paradigm shift in how training programs approach curriculum development, and how both trainees and their programs are assessed.

Calvin Brown, MD, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology and director of the rheumatology training program at Northwestern University, Chicago, will describe the reported and perceived benefits of the milestones, while Simon Helfgott, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, will summarize the arguments that underlie the call for radical change in the milestones system of evaluation

Two “Great Debates” at this year’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology in San Diego will center on important, but completely separate, issues in rheumatology: whether it is safe to switch to a biosimilar and the relevance of curricular milestones in rheumatology training.

At 2:30 p.m. on Sunday, Nov. 5, a session titled “Biosimilars ... To Switch or Not to Switch? That Is the Question“ will pit Jonathan Kay, MD, against Roy Fleischmann, MD, to try to sway the audience to their point of view in the face of a small evidence base about the consequences of switching.

Dr. Kay, the Timothy S. and Elaine L. Peterson Chair in Rheumatology and professor of medicine at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, where he directs clinical research in the division of rheumatology, will discuss and defend the usefulness of biosimilars for rheumatoid arthritis in his presentation, “The Data Supports That It Is Safe, Effective and Cost-Effective to Switch to a Biosimilar.” He has been greatly involved in clinical research on the development of biosimilars to treat rheumatic diseases in recent years.

In his presentation, “The Data Is Not Convincing. One Study Cannot Be Generalized to All Indications, and Some Studies Suggest That It Is Not Safe, Not Effective and Not Cost-Effective to Switch All Patients (YET) to a Biosimilar,” Dr. Fleischmann will discuss and defend the position that biosimilars are not yet well-enough researched to confidently allow switching. Dr. Fleischmann is clinical professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

At 7:30 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 6, two clinician-educators will advocate for opposing opinions in “The Great (Educational) Debate: Milestones: Meaningful vs. Millstone.” The debate will focus on the relative merits of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Next Accreditation System, which in 2013 led to a paradigm shift in how training programs approach curriculum development, and how both trainees and their programs are assessed.

Calvin Brown, MD, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology and director of the rheumatology training program at Northwestern University, Chicago, will describe the reported and perceived benefits of the milestones, while Simon Helfgott, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, will summarize the arguments that underlie the call for radical change in the milestones system of evaluation

FROM ACR 2017

Biofeedback significantly improves abdominal distension in small study

An electromyographic biofeedback program significantly improved abdominothoracic muscle control and abdominal distension compared with placebo in a randomized trial of patients fulfilling Rome III criteria for functional intestinal disorders.

Sensations of abdominal distension improved by 56% with biofeedback (standard deviation, 1%) versus 13% (SD, 8%) with placebo, wrote Elizabeth Barba, MD, of University Hospital Vall d’Hebron in Barcelona, and her associates. The study was published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.052). Biofeedback also led to a doubling of anterior wall muscle activity (101%; SD, 10%) compared with a 4% (SD, 2%) improvement with placebo. Finally, biofeedback lowered intercostal muscle activity by a mean of 45% (SD, 3%) compared with 5% (SD, 2%) with placebo (all P values less than .001).

“Biofeedback in this trial was applied using a complex technique that provided effective guidance to patients and allowed close control of the mechanistic effects of the intervention on postural tone,” the researchers noted. “Having proved the [efficacy] of this treatment, the next steps are to develop and then to properly validate a simpler technique for widespread application.”

Episodic abdominal distension is a primary reason for visiting gastroenterology clinics. Patients typically experience an objective, visible increase in girth with no detectable cause, although they often have irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, or both. Past work has linked abdominal distension with increased diaphragmatic tone and ventral protrusion and decreased muscle tone of the abdominal wall, the researchers noted.

Therefore, they developed an electromyography (EMG) biofeedback program to help patients learn to correct abdominothoracic muscular dystony. The trial comprised 48 patients (47 women and 1 man) ranging in age from 21 to 74 years. During each 30-minute session, patients sat upright in a quiet room while EMG recorded the activity of the intercostal muscles, anterior abdominal wall (external oblique, upper rectus, lower rectus, and internal oblique muscles), and diaphragm. Patients reported their sensation of abdominal distension on a visual rating scale ranging from 0 (no distension) to 6 (extreme distension). Those in the intervention group watched the EMG readout and were taught to reduce their intercostal and diaphragm activity while increasing the activity of the anterior abdominal muscles. Three training sessions occurred over 10 days and patients performed similar exercises at home for 5 minutes before each meal. Patients in the placebo group underwent the same instrumental interventions but did not watch the EMG recording, received no instructions about muscle control, and were given oral simethicone.

Symptoms associated with abdominal distension lessened by 57% (SD, 9%) in the biofeedback group and by 23% (4%) in the placebo group (P = .02). Treatment outcomes did not vary based on symptoms and there were no adverse effects of treatment, the researchers said. Furthermore, 19 patients in the placebo group who did not improve underwent biofeedback training and experienced benefits similar to those of the original intervention group. Sensations of abdominal distension and associated symptoms improved significantly immediately after biofeedback compared with baseline and continued to improve significantly over 6 months of follow-up.

The researchers described the complexity of the intervention, which, they acknowledged, would need to be simplified before it could be deployed widely. They measured the activity of the external oblique, upper rectus, lower rectus, and internal oblique muscles with bipolar leads, and recorded intercostal muscle activity by placing a monopolar electrode at the second intercostal space on the right midclavicular line, with a ground electrode over the central sternum. To verify correct placement, they recorded EMG responses to a Valsalva maneuver and a deep inhalation. They measured diaphragmatic activity by mounting electrodes on a polyvinyl tube, performing nasal intubation, and positioning the electrodes across the diaphragmatic hiatus under fluoroscopic control.

Funders included the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

An electromyographic biofeedback program significantly improved abdominothoracic muscle control and abdominal distension compared with placebo in a randomized trial of patients fulfilling Rome III criteria for functional intestinal disorders.

Sensations of abdominal distension improved by 56% with biofeedback (standard deviation, 1%) versus 13% (SD, 8%) with placebo, wrote Elizabeth Barba, MD, of University Hospital Vall d’Hebron in Barcelona, and her associates. The study was published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.052). Biofeedback also led to a doubling of anterior wall muscle activity (101%; SD, 10%) compared with a 4% (SD, 2%) improvement with placebo. Finally, biofeedback lowered intercostal muscle activity by a mean of 45% (SD, 3%) compared with 5% (SD, 2%) with placebo (all P values less than .001).

“Biofeedback in this trial was applied using a complex technique that provided effective guidance to patients and allowed close control of the mechanistic effects of the intervention on postural tone,” the researchers noted. “Having proved the [efficacy] of this treatment, the next steps are to develop and then to properly validate a simpler technique for widespread application.”

Episodic abdominal distension is a primary reason for visiting gastroenterology clinics. Patients typically experience an objective, visible increase in girth with no detectable cause, although they often have irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, or both. Past work has linked abdominal distension with increased diaphragmatic tone and ventral protrusion and decreased muscle tone of the abdominal wall, the researchers noted.

Therefore, they developed an electromyography (EMG) biofeedback program to help patients learn to correct abdominothoracic muscular dystony. The trial comprised 48 patients (47 women and 1 man) ranging in age from 21 to 74 years. During each 30-minute session, patients sat upright in a quiet room while EMG recorded the activity of the intercostal muscles, anterior abdominal wall (external oblique, upper rectus, lower rectus, and internal oblique muscles), and diaphragm. Patients reported their sensation of abdominal distension on a visual rating scale ranging from 0 (no distension) to 6 (extreme distension). Those in the intervention group watched the EMG readout and were taught to reduce their intercostal and diaphragm activity while increasing the activity of the anterior abdominal muscles. Three training sessions occurred over 10 days and patients performed similar exercises at home for 5 minutes before each meal. Patients in the placebo group underwent the same instrumental interventions but did not watch the EMG recording, received no instructions about muscle control, and were given oral simethicone.

Symptoms associated with abdominal distension lessened by 57% (SD, 9%) in the biofeedback group and by 23% (4%) in the placebo group (P = .02). Treatment outcomes did not vary based on symptoms and there were no adverse effects of treatment, the researchers said. Furthermore, 19 patients in the placebo group who did not improve underwent biofeedback training and experienced benefits similar to those of the original intervention group. Sensations of abdominal distension and associated symptoms improved significantly immediately after biofeedback compared with baseline and continued to improve significantly over 6 months of follow-up.

The researchers described the complexity of the intervention, which, they acknowledged, would need to be simplified before it could be deployed widely. They measured the activity of the external oblique, upper rectus, lower rectus, and internal oblique muscles with bipolar leads, and recorded intercostal muscle activity by placing a monopolar electrode at the second intercostal space on the right midclavicular line, with a ground electrode over the central sternum. To verify correct placement, they recorded EMG responses to a Valsalva maneuver and a deep inhalation. They measured diaphragmatic activity by mounting electrodes on a polyvinyl tube, performing nasal intubation, and positioning the electrodes across the diaphragmatic hiatus under fluoroscopic control.

Funders included the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

An electromyographic biofeedback program significantly improved abdominothoracic muscle control and abdominal distension compared with placebo in a randomized trial of patients fulfilling Rome III criteria for functional intestinal disorders.

Sensations of abdominal distension improved by 56% with biofeedback (standard deviation, 1%) versus 13% (SD, 8%) with placebo, wrote Elizabeth Barba, MD, of University Hospital Vall d’Hebron in Barcelona, and her associates. The study was published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.052). Biofeedback also led to a doubling of anterior wall muscle activity (101%; SD, 10%) compared with a 4% (SD, 2%) improvement with placebo. Finally, biofeedback lowered intercostal muscle activity by a mean of 45% (SD, 3%) compared with 5% (SD, 2%) with placebo (all P values less than .001).

“Biofeedback in this trial was applied using a complex technique that provided effective guidance to patients and allowed close control of the mechanistic effects of the intervention on postural tone,” the researchers noted. “Having proved the [efficacy] of this treatment, the next steps are to develop and then to properly validate a simpler technique for widespread application.”

Episodic abdominal distension is a primary reason for visiting gastroenterology clinics. Patients typically experience an objective, visible increase in girth with no detectable cause, although they often have irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, or both. Past work has linked abdominal distension with increased diaphragmatic tone and ventral protrusion and decreased muscle tone of the abdominal wall, the researchers noted.

Therefore, they developed an electromyography (EMG) biofeedback program to help patients learn to correct abdominothoracic muscular dystony. The trial comprised 48 patients (47 women and 1 man) ranging in age from 21 to 74 years. During each 30-minute session, patients sat upright in a quiet room while EMG recorded the activity of the intercostal muscles, anterior abdominal wall (external oblique, upper rectus, lower rectus, and internal oblique muscles), and diaphragm. Patients reported their sensation of abdominal distension on a visual rating scale ranging from 0 (no distension) to 6 (extreme distension). Those in the intervention group watched the EMG readout and were taught to reduce their intercostal and diaphragm activity while increasing the activity of the anterior abdominal muscles. Three training sessions occurred over 10 days and patients performed similar exercises at home for 5 minutes before each meal. Patients in the placebo group underwent the same instrumental interventions but did not watch the EMG recording, received no instructions about muscle control, and were given oral simethicone.

Symptoms associated with abdominal distension lessened by 57% (SD, 9%) in the biofeedback group and by 23% (4%) in the placebo group (P = .02). Treatment outcomes did not vary based on symptoms and there were no adverse effects of treatment, the researchers said. Furthermore, 19 patients in the placebo group who did not improve underwent biofeedback training and experienced benefits similar to those of the original intervention group. Sensations of abdominal distension and associated symptoms improved significantly immediately after biofeedback compared with baseline and continued to improve significantly over 6 months of follow-up.

The researchers described the complexity of the intervention, which, they acknowledged, would need to be simplified before it could be deployed widely. They measured the activity of the external oblique, upper rectus, lower rectus, and internal oblique muscles with bipolar leads, and recorded intercostal muscle activity by placing a monopolar electrode at the second intercostal space on the right midclavicular line, with a ground electrode over the central sternum. To verify correct placement, they recorded EMG responses to a Valsalva maneuver and a deep inhalation. They measured diaphragmatic activity by mounting electrodes on a polyvinyl tube, performing nasal intubation, and positioning the electrodes across the diaphragmatic hiatus under fluoroscopic control.

Funders included the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Biofeedback training significantly improved abdominal distension in patients with functional intestinal disorders.

Major finding: Subjective abdominal distension improved by 56% in the intervention group and by 13% in the placebo group (P less than .001).

Data source: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 48 patients meeting Rome III criteria for functional intestinal disorders.

Disclosures: Funders included the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and Instituto de Salud Carlos III. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Leadership hacks: structural tension

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

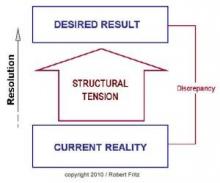

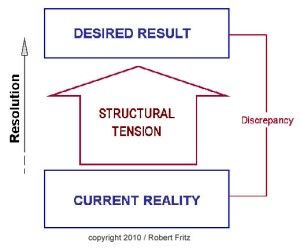

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

ECT patients do better when families attend sessions

NEW ORLEANS – In 2001, a patient at the Menninger Clinic, Houston, asked whether her husband could be with her during ECT treatments, so she’d feel safer.

He declined, but then she told her care team “the fact that you would allow that makes me feel entirely safe now,” recalled M. Justin Coffey, MD, medical director of Menninger’s Center for Brain Stimulation.

“She made her request partly in jest, but it was a great idea,” he said. Fast-forward 16 years, and it’s now standard practice at Menninger for patients to invite loved ones to ECT sessions. Sometimes they pick family members, other times a neighbor or even a pastor.

“One of the most powerful benefits we’ve seen is that the loved ones observing the treatment become thoroughly underwhelmed by what they see,” not much more than the patient under anesthesia. “At the same time, they are incredibly impressed by the expertise and competence of the team. They become ambassadors against stigma; I’ve got family members and patients now that join me in workshops talking about why ECT should be [used] more,” Dr. Coffey said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

The approach is catching on, including at the New York Community Hospital, Brooklyn, where it was implemented a few years ago. “It’s a wonderful thing to decrease patient anxiety and the stigma of treatment. You ask the patient’s permission, of course, and discuss with the family members what they are going to see. It demystifies the whole thing,” said Charles H. Kellner, MD, chief of electroconvulsive therapy at the hospital and a well-known ECT researcher.

Another benefit they’ve seen at Menninger is that patients come out of their postictal confusion sooner when there’s a familiar, comforting person in the room. That’s important, because the quicker patients reorient, the less likely they are to have retrograde memory problems, Dr. Coffey said.

Memory loss is perhaps the top fear people have about ECT, and it leads to the underuse of an otherwise safe and effective treatment for severe, refractory depression. Anterograde memory problems generally clear up in a few days, but retrograde problems can linger; memories formed within 3-6 months of ECT are the most vulnerable. It’s tough to pin down exactly how great the risk is because of variations in how ECT is performed from one center to the next.

“It’s always a risk-benefit decision,” Dr. Kellner said. “The vast majority of patients do not have profound memory trouble with ECT; it’s a temporary nuisance. I’d say maybe 10% or fewer have memory problems significant enough to stop treatment, or that really bother them.”

“The most important thing” when counseling patients “is not to promise anything, because you really don’t know how an individual is going to respond to ECT,” said Adriana P. Hermida, MD, a geriatric psychiatrist and ECT practitioner at Emory University, Atlanta.

In general, cognitive problems and memory loss are less likely with unilateral treatment than with bilateral, and least likely with ultra-brief unilateral treatment. Two sessions per week are less likely to cause problems than are the usual three, but treatment response isn’t as rapid. Also, giving more than two seizures per session increases the risk of medical and cognitive side effects, and isn’t recommended.

To manage the memory risk, cognitive function should be assessed before each session, not just by objective measures and patient report, but also by asking family members what they’ve noticed. “Many times patient do not report memory issues, but family members will,” Dr. Hermida said.

If there’s a problem, patients can switch to two sessions per week, for instance, or to ultra-brief unilateral ECT.

A few studies have suggested that cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine (Namenda) might attenuate cognitive side effects, but there’s not enough evidence to recommend their use, she said.

The speakers had no relevant industry disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – In 2001, a patient at the Menninger Clinic, Houston, asked whether her husband could be with her during ECT treatments, so she’d feel safer.

He declined, but then she told her care team “the fact that you would allow that makes me feel entirely safe now,” recalled M. Justin Coffey, MD, medical director of Menninger’s Center for Brain Stimulation.

“She made her request partly in jest, but it was a great idea,” he said. Fast-forward 16 years, and it’s now standard practice at Menninger for patients to invite loved ones to ECT sessions. Sometimes they pick family members, other times a neighbor or even a pastor.

“One of the most powerful benefits we’ve seen is that the loved ones observing the treatment become thoroughly underwhelmed by what they see,” not much more than the patient under anesthesia. “At the same time, they are incredibly impressed by the expertise and competence of the team. They become ambassadors against stigma; I’ve got family members and patients now that join me in workshops talking about why ECT should be [used] more,” Dr. Coffey said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

The approach is catching on, including at the New York Community Hospital, Brooklyn, where it was implemented a few years ago. “It’s a wonderful thing to decrease patient anxiety and the stigma of treatment. You ask the patient’s permission, of course, and discuss with the family members what they are going to see. It demystifies the whole thing,” said Charles H. Kellner, MD, chief of electroconvulsive therapy at the hospital and a well-known ECT researcher.

Another benefit they’ve seen at Menninger is that patients come out of their postictal confusion sooner when there’s a familiar, comforting person in the room. That’s important, because the quicker patients reorient, the less likely they are to have retrograde memory problems, Dr. Coffey said.

Memory loss is perhaps the top fear people have about ECT, and it leads to the underuse of an otherwise safe and effective treatment for severe, refractory depression. Anterograde memory problems generally clear up in a few days, but retrograde problems can linger; memories formed within 3-6 months of ECT are the most vulnerable. It’s tough to pin down exactly how great the risk is because of variations in how ECT is performed from one center to the next.

“It’s always a risk-benefit decision,” Dr. Kellner said. “The vast majority of patients do not have profound memory trouble with ECT; it’s a temporary nuisance. I’d say maybe 10% or fewer have memory problems significant enough to stop treatment, or that really bother them.”