User login

High EZH2 expression a marker for death risk in RCC

In patients with localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC), tumor levels of the oncogenic protein EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2) were predictive of risk of RCC-specific death, including in patients considered at low or intermediate risk by a standard prognostic model.

Among nearly 2,000 tumors from patients with RCC in three different cohorts, the risks of both all-cause mortality and RCC-specific death were approximately double for patients with tumors that had high expression of EZH2 compared with those whose tumors expressed only low levels, reported Thai Huu Ho, MD, PhD, from the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, and colleagues.

Among patients deemed to be at low risk according to the Mayo Clinic stage, size, grade, and necrosis (SSIGN) score, high levels of EZH2 were associated with a sixfold increase in risk of death, the investigators wrote (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Oct 4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.3238).

“With the increasing incidence of small RCC tumors detected by cross-sectional imaging, our study emphasizes the clinical utility of a biomarker that is compatible with a single FFPE [formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded] slide that accurately predicts risk of RCC death beyond existing clinicopathologic models” they wrote.

EZH2 is a chromatin remodeler, a member of a family of proteins that are involved in epigenetic gene silencing. Although previous studies have explored potential associations between EZH2 expression and RCC outcomes, results have been conflicting, Dr. Ho and associates noted.

In hopes of getting a more definitive picture of the potential role of EZH2 as a prognostic biomarker for RCC, the investigators looked at the association between EZH2 expression and survival in tumors from 532 patients in the Cancer Genome Atlas (CGA) cohort, 122 patients from a University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas) cohort, and from 1,338 patients in a Mayo Clinic cohort.

In a model adjusted for age and SSIGN score, patients in the CGA cohort whose tumors had high levels of EZH2 expression had a hazard ratio (HR) for worse overall survival of 1.54 (P less than .028) compared with patients with low expression. Respective HRs for overall survival in the UT Southwestern and Mayo Cohorts were 2.16 (P = .034) and 1.43 (P = .00026).

When the researchers looked at RCC-specific survival in patients in the Mayo cohort, they found that those with the highest levels of EZH2 expression had a twofold risk for death vs. those with the lowest levels (HR 1.97, P less than .001).

They also found that patients with a low-risk SSIGN score who had high levels of EZH2 protein expression had an HR for RCC-specific death of 6.14, and that patients with intermediate-risk SSIGN scores has an HR for RCC-related death of 2.12 (P less than .001 for both comparisons).

The investigators noted that EZH2 enzymatic activity in RCC could potentially be targeted by EZH2 inhibitors such as tazemetostat.

“Further studies are required to determine how to better incorporate molecular biomarkers with prognostic information into surveillance guidelines and adjuvant clinical trials,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Mayo Clinic, Gerstner Family Career Development Award, National Cancer Institute, and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas. Dr. Ho and seven coauthors reported no relationships to disclose. The remaining investigators reported relationships with various companies.

In patients with localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC), tumor levels of the oncogenic protein EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2) were predictive of risk of RCC-specific death, including in patients considered at low or intermediate risk by a standard prognostic model.

Among nearly 2,000 tumors from patients with RCC in three different cohorts, the risks of both all-cause mortality and RCC-specific death were approximately double for patients with tumors that had high expression of EZH2 compared with those whose tumors expressed only low levels, reported Thai Huu Ho, MD, PhD, from the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, and colleagues.

Among patients deemed to be at low risk according to the Mayo Clinic stage, size, grade, and necrosis (SSIGN) score, high levels of EZH2 were associated with a sixfold increase in risk of death, the investigators wrote (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Oct 4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.3238).

“With the increasing incidence of small RCC tumors detected by cross-sectional imaging, our study emphasizes the clinical utility of a biomarker that is compatible with a single FFPE [formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded] slide that accurately predicts risk of RCC death beyond existing clinicopathologic models” they wrote.

EZH2 is a chromatin remodeler, a member of a family of proteins that are involved in epigenetic gene silencing. Although previous studies have explored potential associations between EZH2 expression and RCC outcomes, results have been conflicting, Dr. Ho and associates noted.

In hopes of getting a more definitive picture of the potential role of EZH2 as a prognostic biomarker for RCC, the investigators looked at the association between EZH2 expression and survival in tumors from 532 patients in the Cancer Genome Atlas (CGA) cohort, 122 patients from a University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas) cohort, and from 1,338 patients in a Mayo Clinic cohort.

In a model adjusted for age and SSIGN score, patients in the CGA cohort whose tumors had high levels of EZH2 expression had a hazard ratio (HR) for worse overall survival of 1.54 (P less than .028) compared with patients with low expression. Respective HRs for overall survival in the UT Southwestern and Mayo Cohorts were 2.16 (P = .034) and 1.43 (P = .00026).

When the researchers looked at RCC-specific survival in patients in the Mayo cohort, they found that those with the highest levels of EZH2 expression had a twofold risk for death vs. those with the lowest levels (HR 1.97, P less than .001).

They also found that patients with a low-risk SSIGN score who had high levels of EZH2 protein expression had an HR for RCC-specific death of 6.14, and that patients with intermediate-risk SSIGN scores has an HR for RCC-related death of 2.12 (P less than .001 for both comparisons).

The investigators noted that EZH2 enzymatic activity in RCC could potentially be targeted by EZH2 inhibitors such as tazemetostat.

“Further studies are required to determine how to better incorporate molecular biomarkers with prognostic information into surveillance guidelines and adjuvant clinical trials,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Mayo Clinic, Gerstner Family Career Development Award, National Cancer Institute, and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas. Dr. Ho and seven coauthors reported no relationships to disclose. The remaining investigators reported relationships with various companies.

In patients with localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC), tumor levels of the oncogenic protein EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2) were predictive of risk of RCC-specific death, including in patients considered at low or intermediate risk by a standard prognostic model.

Among nearly 2,000 tumors from patients with RCC in three different cohorts, the risks of both all-cause mortality and RCC-specific death were approximately double for patients with tumors that had high expression of EZH2 compared with those whose tumors expressed only low levels, reported Thai Huu Ho, MD, PhD, from the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, and colleagues.

Among patients deemed to be at low risk according to the Mayo Clinic stage, size, grade, and necrosis (SSIGN) score, high levels of EZH2 were associated with a sixfold increase in risk of death, the investigators wrote (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Oct 4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.3238).

“With the increasing incidence of small RCC tumors detected by cross-sectional imaging, our study emphasizes the clinical utility of a biomarker that is compatible with a single FFPE [formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded] slide that accurately predicts risk of RCC death beyond existing clinicopathologic models” they wrote.

EZH2 is a chromatin remodeler, a member of a family of proteins that are involved in epigenetic gene silencing. Although previous studies have explored potential associations between EZH2 expression and RCC outcomes, results have been conflicting, Dr. Ho and associates noted.

In hopes of getting a more definitive picture of the potential role of EZH2 as a prognostic biomarker for RCC, the investigators looked at the association between EZH2 expression and survival in tumors from 532 patients in the Cancer Genome Atlas (CGA) cohort, 122 patients from a University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas) cohort, and from 1,338 patients in a Mayo Clinic cohort.

In a model adjusted for age and SSIGN score, patients in the CGA cohort whose tumors had high levels of EZH2 expression had a hazard ratio (HR) for worse overall survival of 1.54 (P less than .028) compared with patients with low expression. Respective HRs for overall survival in the UT Southwestern and Mayo Cohorts were 2.16 (P = .034) and 1.43 (P = .00026).

When the researchers looked at RCC-specific survival in patients in the Mayo cohort, they found that those with the highest levels of EZH2 expression had a twofold risk for death vs. those with the lowest levels (HR 1.97, P less than .001).

They also found that patients with a low-risk SSIGN score who had high levels of EZH2 protein expression had an HR for RCC-specific death of 6.14, and that patients with intermediate-risk SSIGN scores has an HR for RCC-related death of 2.12 (P less than .001 for both comparisons).

The investigators noted that EZH2 enzymatic activity in RCC could potentially be targeted by EZH2 inhibitors such as tazemetostat.

“Further studies are required to determine how to better incorporate molecular biomarkers with prognostic information into surveillance guidelines and adjuvant clinical trials,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Mayo Clinic, Gerstner Family Career Development Award, National Cancer Institute, and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas. Dr. Ho and seven coauthors reported no relationships to disclose. The remaining investigators reported relationships with various companies.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: High levels of EZH2 were associated with worse survival of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Major finding: Patients with RCC who had high levels of EZH2 expression in tumors had about a 1.5-fold risk for all-cause mortality, and twofold risk for RCC-specific death.

Data source: Analysis of EZH2 gene and protein expression in tumors from 1,192 patients with RCC in three cohorts.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Mayo Clinic, Gerstner Family Career Development Award National Cancer Institute and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas. Dr. Ho and seven coauthors reported no relationships to disclose. The remaining investigators reported relationships with various companies.

VIDEO: New sexual desire drugs coming for women

PHILADELPHIA – Despite the slow start that flibanserin had since being approved to treat hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women in 2015, more drugs are in the pipeline to help women address low desire.

One drug – bremelanotide – has completed phase 3 trials and could be considered by the Food and Drug Administration as early as 2018, Sheryl A. Kingsberg, PhD, said during an interview at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Bremelanotide is a first-in-class melanocortin receptor 4 agonist being developed for premenopausal women to use on an as-needed basis and is delivered using a single-dose, auto injector.

Another drug, prasterone, is also being studied to treat HSDD. The intravaginal DHEA treatment is already approved to treat dyspareunia due to vulvovaginal atrophy in menopause. The manufacturer is beginning phase 3 trials for HSDD in postmenopausal women, said Dr. Kingsberg, who is chief of the division of behavioral medicine at MacDonald Women’s Hospital/University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and the president of NAMS.

Additional drugs are in earlier stages of development for HSDD. While flibanserin hasn’t been a blockbuster drug, its approval by the FDA paved the way for additional drug development in this area, Dr. Kingsberg said.

Dr. Kingsberg reported consultant/advisory board work for Amag Pharmaceuticals, Duchesnay, Emotional Brain, EndoCeutics, Materna Medical, Palatin Technologies, Pfizer, Shionogi, TherapeuticsMD, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, and Viveve. She is on the speakers bureau for Valeant Pharmaceuticals and owns stock in Viveve.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Despite the slow start that flibanserin had since being approved to treat hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women in 2015, more drugs are in the pipeline to help women address low desire.

One drug – bremelanotide – has completed phase 3 trials and could be considered by the Food and Drug Administration as early as 2018, Sheryl A. Kingsberg, PhD, said during an interview at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Bremelanotide is a first-in-class melanocortin receptor 4 agonist being developed for premenopausal women to use on an as-needed basis and is delivered using a single-dose, auto injector.

Another drug, prasterone, is also being studied to treat HSDD. The intravaginal DHEA treatment is already approved to treat dyspareunia due to vulvovaginal atrophy in menopause. The manufacturer is beginning phase 3 trials for HSDD in postmenopausal women, said Dr. Kingsberg, who is chief of the division of behavioral medicine at MacDonald Women’s Hospital/University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and the president of NAMS.

Additional drugs are in earlier stages of development for HSDD. While flibanserin hasn’t been a blockbuster drug, its approval by the FDA paved the way for additional drug development in this area, Dr. Kingsberg said.

Dr. Kingsberg reported consultant/advisory board work for Amag Pharmaceuticals, Duchesnay, Emotional Brain, EndoCeutics, Materna Medical, Palatin Technologies, Pfizer, Shionogi, TherapeuticsMD, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, and Viveve. She is on the speakers bureau for Valeant Pharmaceuticals and owns stock in Viveve.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Despite the slow start that flibanserin had since being approved to treat hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women in 2015, more drugs are in the pipeline to help women address low desire.

One drug – bremelanotide – has completed phase 3 trials and could be considered by the Food and Drug Administration as early as 2018, Sheryl A. Kingsberg, PhD, said during an interview at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Bremelanotide is a first-in-class melanocortin receptor 4 agonist being developed for premenopausal women to use on an as-needed basis and is delivered using a single-dose, auto injector.

Another drug, prasterone, is also being studied to treat HSDD. The intravaginal DHEA treatment is already approved to treat dyspareunia due to vulvovaginal atrophy in menopause. The manufacturer is beginning phase 3 trials for HSDD in postmenopausal women, said Dr. Kingsberg, who is chief of the division of behavioral medicine at MacDonald Women’s Hospital/University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and the president of NAMS.

Additional drugs are in earlier stages of development for HSDD. While flibanserin hasn’t been a blockbuster drug, its approval by the FDA paved the way for additional drug development in this area, Dr. Kingsberg said.

Dr. Kingsberg reported consultant/advisory board work for Amag Pharmaceuticals, Duchesnay, Emotional Brain, EndoCeutics, Materna Medical, Palatin Technologies, Pfizer, Shionogi, TherapeuticsMD, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, and Viveve. She is on the speakers bureau for Valeant Pharmaceuticals and owns stock in Viveve.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NAMS 2017

VIDEO: Dr. Andrew Kaunitz’s top lessons from NAMS 2017

PHILADELPHIA – Andrew Kaunitz, MD, the chair of the 2017 scientific program committee for the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, shared his top take-home messages from the meeting.

New anabolic medications that increase bone mineral density and dramatically reduce fracture risk are in the pipeline, Dr. Kaunitz, a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida, Jacksonville, said in a video interview.

Another finding from the meeting is that type 2 diabetes, despite being associated with an increased body mass index, actually elevates a woman’s risk for fracture. “That was something new for me, and I think it was something new for a lot of the practitioners attending the NAMS meeting,” Dr. Kaunitz said.

The meeting also offered tips for managing polycystic ovarian syndrome in women who are in midlife, including the importance of screening for diabetes and assessing for lipid disorders. Additionally, attendees learned about the management of migraines in menopausal women and older reproductive-age women.

A well-attended session on breast imaging explored how breast tomosynthesis can reduce false positives and recalls, as well as how new technology can reduce the radiation exposure associated with tomosynthesis. The session also featured evidence that screening mammography has lower-than-reported sensitivity, but offered a hopeful note on the promise of improved sensitivity through molecular breast imaging.

Dr. Kaunitz reported consultant/advisory board work for Allergan, Amag Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Mithra Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Shionogi. He has received grant/research support from Bayer, Radius Health, TherapeuticsMD, and Millendo Therapeutics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Andrew Kaunitz, MD, the chair of the 2017 scientific program committee for the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, shared his top take-home messages from the meeting.

New anabolic medications that increase bone mineral density and dramatically reduce fracture risk are in the pipeline, Dr. Kaunitz, a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida, Jacksonville, said in a video interview.

Another finding from the meeting is that type 2 diabetes, despite being associated with an increased body mass index, actually elevates a woman’s risk for fracture. “That was something new for me, and I think it was something new for a lot of the practitioners attending the NAMS meeting,” Dr. Kaunitz said.

The meeting also offered tips for managing polycystic ovarian syndrome in women who are in midlife, including the importance of screening for diabetes and assessing for lipid disorders. Additionally, attendees learned about the management of migraines in menopausal women and older reproductive-age women.

A well-attended session on breast imaging explored how breast tomosynthesis can reduce false positives and recalls, as well as how new technology can reduce the radiation exposure associated with tomosynthesis. The session also featured evidence that screening mammography has lower-than-reported sensitivity, but offered a hopeful note on the promise of improved sensitivity through molecular breast imaging.

Dr. Kaunitz reported consultant/advisory board work for Allergan, Amag Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Mithra Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Shionogi. He has received grant/research support from Bayer, Radius Health, TherapeuticsMD, and Millendo Therapeutics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Andrew Kaunitz, MD, the chair of the 2017 scientific program committee for the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, shared his top take-home messages from the meeting.

New anabolic medications that increase bone mineral density and dramatically reduce fracture risk are in the pipeline, Dr. Kaunitz, a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida, Jacksonville, said in a video interview.

Another finding from the meeting is that type 2 diabetes, despite being associated with an increased body mass index, actually elevates a woman’s risk for fracture. “That was something new for me, and I think it was something new for a lot of the practitioners attending the NAMS meeting,” Dr. Kaunitz said.

The meeting also offered tips for managing polycystic ovarian syndrome in women who are in midlife, including the importance of screening for diabetes and assessing for lipid disorders. Additionally, attendees learned about the management of migraines in menopausal women and older reproductive-age women.

A well-attended session on breast imaging explored how breast tomosynthesis can reduce false positives and recalls, as well as how new technology can reduce the radiation exposure associated with tomosynthesis. The session also featured evidence that screening mammography has lower-than-reported sensitivity, but offered a hopeful note on the promise of improved sensitivity through molecular breast imaging.

Dr. Kaunitz reported consultant/advisory board work for Allergan, Amag Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Mithra Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Shionogi. He has received grant/research support from Bayer, Radius Health, TherapeuticsMD, and Millendo Therapeutics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NAMS 2017

VIDEO: Does genitourinary syndrome of menopause capture all the symptoms?

PHILADELPHIA – Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) replaced vulvovaginal atrophy in 2014 as a way to describe the changes to the genital and urinary tracts after menopause, but preliminary research shows it may be missing some symptoms.

In 2015, Amanda Clark, MD, a urogynecologist at the Kaiser Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and her colleagues surveyed women aged 55 years and older about their vulvar, vaginal, urinary, and sexual symptoms within 2 weeks of a well-woman visit to their primary care physician or gynecologist in the Kaiser system. In total, 1,533 provided valid data.

The researchers then used factor analysis to see if the symptoms matched up with GSM. If GSM is a true syndrome and only a single syndrome, then all of the factors would fit together in a one-factor model, Dr. Clark explained at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. Instead, the researchers found that a three-factor model – with vulvovaginal symptoms of irritation and pain in one group, urinary symptoms in another group, and vaginal discharge and odor in a third group – fit best with the symptoms reported in their survey.

“This work is very preliminary and needs to be replicated in many other samples and looked at carefully,” Dr. Clark said in an interview. “But what we think is that genitourinary syndrome of menopause is a starting point.”

The study was funded by a Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change and the North American Menopause Society. Dr. Clark reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) replaced vulvovaginal atrophy in 2014 as a way to describe the changes to the genital and urinary tracts after menopause, but preliminary research shows it may be missing some symptoms.

In 2015, Amanda Clark, MD, a urogynecologist at the Kaiser Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and her colleagues surveyed women aged 55 years and older about their vulvar, vaginal, urinary, and sexual symptoms within 2 weeks of a well-woman visit to their primary care physician or gynecologist in the Kaiser system. In total, 1,533 provided valid data.

The researchers then used factor analysis to see if the symptoms matched up with GSM. If GSM is a true syndrome and only a single syndrome, then all of the factors would fit together in a one-factor model, Dr. Clark explained at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. Instead, the researchers found that a three-factor model – with vulvovaginal symptoms of irritation and pain in one group, urinary symptoms in another group, and vaginal discharge and odor in a third group – fit best with the symptoms reported in their survey.

“This work is very preliminary and needs to be replicated in many other samples and looked at carefully,” Dr. Clark said in an interview. “But what we think is that genitourinary syndrome of menopause is a starting point.”

The study was funded by a Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change and the North American Menopause Society. Dr. Clark reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) replaced vulvovaginal atrophy in 2014 as a way to describe the changes to the genital and urinary tracts after menopause, but preliminary research shows it may be missing some symptoms.

In 2015, Amanda Clark, MD, a urogynecologist at the Kaiser Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and her colleagues surveyed women aged 55 years and older about their vulvar, vaginal, urinary, and sexual symptoms within 2 weeks of a well-woman visit to their primary care physician or gynecologist in the Kaiser system. In total, 1,533 provided valid data.

The researchers then used factor analysis to see if the symptoms matched up with GSM. If GSM is a true syndrome and only a single syndrome, then all of the factors would fit together in a one-factor model, Dr. Clark explained at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. Instead, the researchers found that a three-factor model – with vulvovaginal symptoms of irritation and pain in one group, urinary symptoms in another group, and vaginal discharge and odor in a third group – fit best with the symptoms reported in their survey.

“This work is very preliminary and needs to be replicated in many other samples and looked at carefully,” Dr. Clark said in an interview. “But what we think is that genitourinary syndrome of menopause is a starting point.”

The study was funded by a Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change and the North American Menopause Society. Dr. Clark reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

AT NAMS 2017

Radial Shaft Stress Fracture in a Major League Pitcher

Take-Home Points

- Stress fractures should always be considered when dealing with overuse injuries.

- Radial shaft stress fractures in overhead throwing athletes are rare.

- Stress fractures can occur anywhere increased muscular forces exceed the bone’s ability to remodel.

- Proper imaging is necessary to make the diagnosis of a stress fracture.

- Nonoperative management of radial shaft stress fractures is an effective treatment.

In athletes, the incidence of stress fractures has been reported to be 1.4% to 4.4%.1 Stress fractures of the upper extremity are less common and not as well described as lower extremity stress fractures. Although data is lacking, stress fractures involving the upper extremity appear to account for <6% of all stress fractures.2 Stress fractures of the upper extremity, though rare, are being recognized more often in overhead athletes.3-6 In baseball pitchers, stress fractures most commonly occur in the olecranon but have also been found in the ribs, clavicle, humerus, and ulnar shaft.2,4,7-10 Stress fractures of the radius are a rare cause of forearm pain in athletes, and there are only a few case reports involving overhead athletes.4,11-15 To our knowledge, a stress fracture of the radial shaft has not been reported in a throwing athlete. Currently, there are no reports on stress fractures of the proximal radial shaft.16-18

In this article, we report the case of a radial shaft stress fracture that was causing forearm pain in a Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher. We also discuss the etiology, diagnosis, and management of stress fractures of the upper extremity of overhead throwing athletes. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 28-year-old right-hand-dominant MLB pitcher presented to the clinic with a 4-week history of right dorsal forearm pain that was refractory to a period of rest and physical therapy modalities. The pain radiated to the wrist and along the dorsal forearm. The pain started after the man attempted to develop a new pitch that required a significant amount of supination. The pain prevented him from pitching competitively. Indomethacin, diclofenac sodium topical gel, and methylprednisolone (Medrol Dosepak) reduced his symptoms only slightly.

Physical examination of the right elbow showed mild range of motion deficits; about 5° of extension and 5° of flexion were lacking. The patient had full pronation and supination. Palpation of the dorsal aspect of the forearm revealed marked tenderness in the area of the proximal radius. There was no tenderness over the posterior olecranon or the ulnar collateral ligament, and a moving valgus stress test was negative. No pain was elicited by resisted extension of the wrist or fingers. Motor innervation from the posterior interosseous nerve, anterior interosseous nerve, and ulnar nerve was intact with 5/5 strength, and there were no sensory deficits in the distribution of the radial, median, or ulnar nerves.

Discussion

Stress fractures account for 0.7% to 20% of sports medicine clinic injuries; <10% of all stress fractures involve the rib or upper extremity.4,6 When the intensity or frequency of physical activity is increased, as with overuse, bone resorption surpasses bone production, locally weakening the bone and making it prone to mechanical failure. Failure is thought to be induced by a combination of contractile muscular forces across damaged bone and increased mechanical loading caused by fatigue of supporting structures.5,6,19 These forces may have contributed to our baseball pitcher’s development of a stress fracture near the insertion of the supinator muscle in his throwing arm.

Given the insidious nature of stress fractures, the evaluating physician must have a high index of suspicion. Early recognition of a stress fracture is important in preventing further injury and allowing for early intervention, which is associated with faster healing.6,20 The clinical history often involves a change in training regimen within the weeks before pain onset. Furthermore, understanding the type of pitches used and the mechanics of each pitch can help with diagnosis. Often, pain increases as the inciting activity continues, and relief comes with rest. In an upper extremity examination, it is important to recall the usual stress fracture locations in throwers—the ribs, clavicle, humerus, ulnar shaft, and most often the olecranon—though the patient’s history often narrows the anatomical region of suspicion.2,4,7-10 Examination begins with inspection of the skin and soft tissues. Range of motion and strength testing results likely are normal throughout the upper extremity.3 Palpation over the suspected injury location often elicits pain and indicates further imaging is needed.6 The tuning fork test or the 3-point fulcrum test may elicit symptoms in occult fractures.3 Completing the assessment is a thorough neurovascular examination.

Insidious forearm pain requires a broad differential, including flexor-pronator mass or distal biceps injury, chronic exertional compartment syndrome, radial tunnel syndrome, intersection syndrome, pronator teres syndrome, anterior interosseous syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, musculocutaneous nerve compression, deep vein thrombosis of ulnar vein, and periostitis. Stress fractures distal to the elbow more commonly occur in weight-bearing athletes, though as this case shows it is important to consider stress fractures of the radius and ulna when evaluating forearm pain in a throwing athlete.21

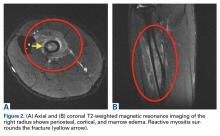

The first imaging examination for a suspected stress fracture is a radiograph, which can be normal in up to 90% of patients, as it initially was in our athlete’s case.22 Often, radiographic evidence takes 2 to 12 weeks to appear.5 Even then, radiographs may be positive in only 50% of cases.19 CT, often regarded as insensitive during the early stages, is useful in visualizing fracture lines in a suspicious location.19,22 Radionuclide uptake scanning is highly sensitive during the early stages of stress injury but is nonspecific and may indicate neoplasm or infection; in addition, up to 46% of abnormal foci are asymptomatic.19 MRI has sensitivity comparable to that of radionuclide scanning but also many advantages, including lack of ionizing radiation, improved spatial resolution, and ability to image bone and soft tissue simultaneously.19 In our patient’s case, the unusual stress fracture location potentially could have hindered identification of the cause of injury. The lesion was just distal to the field of view of a normal elbow MRI and was not detected until a dedicated forearm MRI was examined. Both MRI and CT helped in identifying the stress fracture, and CT was used to follow interval healing.

In baseball players, upper extremity stress fractures are often nonoperatively treated with throwing cessation for 4 to 6 weeks followed by participation in a structured rehabilitation program.4,5 The throwing program that we suggest, and that was used in this case, has 21 stages of progression in duration, distance, and velocity of throwing. The athlete advances from each stage on the basis of symptoms.23 Other issues that may be addressed are vitamin D and calcium status and any flawed throwing mechanics that may have predisposed the athlete to injury. Such mechanics are gradually corrected.

The literature suggests that appropriate nonoperative management of stress fractures allows for return to sport in 8 to 10 weeks. It is important to note that most of the literature on stress fractures involves the lower extremity, and that treatment and time to return to play are therefore better described for such fractures.6 More study and evaluation of upper extremity stress fractures are needed to make return-to-sport predictions more reliable and successful treatment modalities more unified for this patient population. Last, it is imperative that clinical examination and symptoms be correlated with serial imaging when deciding on return to play. Our patient took 12 weeks to return to high-level sport. He progressed pain-free through the throwing program and showed radiographic evidence of healing on follow-up CT.

Conclusion

Radial shaft stress fractures are rare in throwing athletes. However, with a thorough history, a physical examination, and appropriate imaging, the correct diagnosis can be made early on, and proper treatment can be started to facilitate return to sport. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a stress fracture in the radial shaft of a MLB pitcher. Although the radial shaft is an uncommon location for stress fractures, we should keep in mind that they can occur wherever increased muscular forces exceed the ability of native bone to remodel. After diagnosis, the fracture usually heals with nonoperative treatment, and healing is confirmed with follow-up imaging, as was done in our patient’s case. Improved prediction of time to return to play for upper extremity fractures, such as the radial stress fracture described in this article, requires more study.

1. Monteleone GP Jr. Stress fractures in the athlete. Orthop Clin North Am. 1995;26(3):423-432.

2. Iwamoto J, Takeda T. Stress fractures in athletes: review of 196 cases. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(3):273-278.

3. Miller TL, Kaeding CC. Upper-extremity stress fractures: distribution and causative activities in 70 patients. Orthopedics. 2012;35(9):789-793.

4. Jones GL. Upper extremity stress fractures. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(1):159-174.

5. Brooks AA. Stress fractures of the upper extremity. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20(3):613-620.

6. Fredericson M, Jennings F, Beaulieu C, Matheson GO. Stress fractures in athletes. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;17(5):309-325.

7. Gurtler R, Pavlov H, Torg JS. Stress fracture of the ipsilateral first rib in a pitcher. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(4):277-279.

8. Polu KR, Schenck RC Jr, Wirth MA, Greeson J, Cone RO 3rd, Rockwood CA Jr. Stress fracture of the humerus in a collegiate baseball pitcher. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(6):813-816.

9. Wu C, Chen Y. Stress fracture of the clavicle in a professional baseball player. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(2):164-167.

10. Schickendantz MS, Ho CP, Koh J. Stress injury of the proximal ulna in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(5):737-741.

11. Loosli AR, Leslie M. Stress fractures of the distal radius. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):523-524.

12. Inagaki H, Inoue G. Stress fracture of the scaphoid combined with the distal radial epiphysiolysis. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31(3):256-257.

13. Read MT. Stress fractures of the distal radius in adolescent gymnasts. Br J Sports Med. 1981;15(4):272-276.

14. Orloff AS, Resnick D. Fatigue fracture of the distal part of the radius in a pool player. Injury. 1986;17(6):418-419.

15. Eisenberg D, Kirchner SG, Green NE. Stress fracture of the distal radius caused by “wheelies.” South Med J. 1986;79(7):918-919.

16. Brukner P. Stress fractures of the upper limb. Sports Med. 1998;26(6):415-424.

17. Farquharson-Roberts MA, Fulford PC. Stress fracture of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980;62(2):194-195.

18. Orloff AS, Resnick D. Fatigue fracture of the distal part of the radius in a pool player. Injury. 1986;17(6):418-419.

19. Anderson MW. Imaging of upper extremity stress fractures in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(3):489-504.

20. Bennell K, Brukner P. Preventing and managing stress fractures in athletes. Phys Ther Sport. 2005;6(4):171-180.

21. Sinha AK, Kaeding CC, Wadley GM. Upper extremity stress fractures in athletes: clinical features of 44 cases. Clin J Sport Med. 1999;9(4):199-202.

22. Matheson GO, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Taunton JE, Lloyd-Smith DR, MacIntyre JG. Stress fractures in athletes. A study of 320 cases. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(1):46-58.

23. Kaplan L, Lesniak B, Baraga M, et al. Throwing program for baseball players. 2009. http://uhealthsportsmedicine.com/documents/UHealth_Throwing_Program.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2016.

Take-Home Points

- Stress fractures should always be considered when dealing with overuse injuries.

- Radial shaft stress fractures in overhead throwing athletes are rare.

- Stress fractures can occur anywhere increased muscular forces exceed the bone’s ability to remodel.

- Proper imaging is necessary to make the diagnosis of a stress fracture.

- Nonoperative management of radial shaft stress fractures is an effective treatment.

In athletes, the incidence of stress fractures has been reported to be 1.4% to 4.4%.1 Stress fractures of the upper extremity are less common and not as well described as lower extremity stress fractures. Although data is lacking, stress fractures involving the upper extremity appear to account for <6% of all stress fractures.2 Stress fractures of the upper extremity, though rare, are being recognized more often in overhead athletes.3-6 In baseball pitchers, stress fractures most commonly occur in the olecranon but have also been found in the ribs, clavicle, humerus, and ulnar shaft.2,4,7-10 Stress fractures of the radius are a rare cause of forearm pain in athletes, and there are only a few case reports involving overhead athletes.4,11-15 To our knowledge, a stress fracture of the radial shaft has not been reported in a throwing athlete. Currently, there are no reports on stress fractures of the proximal radial shaft.16-18

In this article, we report the case of a radial shaft stress fracture that was causing forearm pain in a Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher. We also discuss the etiology, diagnosis, and management of stress fractures of the upper extremity of overhead throwing athletes. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 28-year-old right-hand-dominant MLB pitcher presented to the clinic with a 4-week history of right dorsal forearm pain that was refractory to a period of rest and physical therapy modalities. The pain radiated to the wrist and along the dorsal forearm. The pain started after the man attempted to develop a new pitch that required a significant amount of supination. The pain prevented him from pitching competitively. Indomethacin, diclofenac sodium topical gel, and methylprednisolone (Medrol Dosepak) reduced his symptoms only slightly.

Physical examination of the right elbow showed mild range of motion deficits; about 5° of extension and 5° of flexion were lacking. The patient had full pronation and supination. Palpation of the dorsal aspect of the forearm revealed marked tenderness in the area of the proximal radius. There was no tenderness over the posterior olecranon or the ulnar collateral ligament, and a moving valgus stress test was negative. No pain was elicited by resisted extension of the wrist or fingers. Motor innervation from the posterior interosseous nerve, anterior interosseous nerve, and ulnar nerve was intact with 5/5 strength, and there were no sensory deficits in the distribution of the radial, median, or ulnar nerves.

Discussion

Stress fractures account for 0.7% to 20% of sports medicine clinic injuries; <10% of all stress fractures involve the rib or upper extremity.4,6 When the intensity or frequency of physical activity is increased, as with overuse, bone resorption surpasses bone production, locally weakening the bone and making it prone to mechanical failure. Failure is thought to be induced by a combination of contractile muscular forces across damaged bone and increased mechanical loading caused by fatigue of supporting structures.5,6,19 These forces may have contributed to our baseball pitcher’s development of a stress fracture near the insertion of the supinator muscle in his throwing arm.

Given the insidious nature of stress fractures, the evaluating physician must have a high index of suspicion. Early recognition of a stress fracture is important in preventing further injury and allowing for early intervention, which is associated with faster healing.6,20 The clinical history often involves a change in training regimen within the weeks before pain onset. Furthermore, understanding the type of pitches used and the mechanics of each pitch can help with diagnosis. Often, pain increases as the inciting activity continues, and relief comes with rest. In an upper extremity examination, it is important to recall the usual stress fracture locations in throwers—the ribs, clavicle, humerus, ulnar shaft, and most often the olecranon—though the patient’s history often narrows the anatomical region of suspicion.2,4,7-10 Examination begins with inspection of the skin and soft tissues. Range of motion and strength testing results likely are normal throughout the upper extremity.3 Palpation over the suspected injury location often elicits pain and indicates further imaging is needed.6 The tuning fork test or the 3-point fulcrum test may elicit symptoms in occult fractures.3 Completing the assessment is a thorough neurovascular examination.

Insidious forearm pain requires a broad differential, including flexor-pronator mass or distal biceps injury, chronic exertional compartment syndrome, radial tunnel syndrome, intersection syndrome, pronator teres syndrome, anterior interosseous syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, musculocutaneous nerve compression, deep vein thrombosis of ulnar vein, and periostitis. Stress fractures distal to the elbow more commonly occur in weight-bearing athletes, though as this case shows it is important to consider stress fractures of the radius and ulna when evaluating forearm pain in a throwing athlete.21

The first imaging examination for a suspected stress fracture is a radiograph, which can be normal in up to 90% of patients, as it initially was in our athlete’s case.22 Often, radiographic evidence takes 2 to 12 weeks to appear.5 Even then, radiographs may be positive in only 50% of cases.19 CT, often regarded as insensitive during the early stages, is useful in visualizing fracture lines in a suspicious location.19,22 Radionuclide uptake scanning is highly sensitive during the early stages of stress injury but is nonspecific and may indicate neoplasm or infection; in addition, up to 46% of abnormal foci are asymptomatic.19 MRI has sensitivity comparable to that of radionuclide scanning but also many advantages, including lack of ionizing radiation, improved spatial resolution, and ability to image bone and soft tissue simultaneously.19 In our patient’s case, the unusual stress fracture location potentially could have hindered identification of the cause of injury. The lesion was just distal to the field of view of a normal elbow MRI and was not detected until a dedicated forearm MRI was examined. Both MRI and CT helped in identifying the stress fracture, and CT was used to follow interval healing.

In baseball players, upper extremity stress fractures are often nonoperatively treated with throwing cessation for 4 to 6 weeks followed by participation in a structured rehabilitation program.4,5 The throwing program that we suggest, and that was used in this case, has 21 stages of progression in duration, distance, and velocity of throwing. The athlete advances from each stage on the basis of symptoms.23 Other issues that may be addressed are vitamin D and calcium status and any flawed throwing mechanics that may have predisposed the athlete to injury. Such mechanics are gradually corrected.

The literature suggests that appropriate nonoperative management of stress fractures allows for return to sport in 8 to 10 weeks. It is important to note that most of the literature on stress fractures involves the lower extremity, and that treatment and time to return to play are therefore better described for such fractures.6 More study and evaluation of upper extremity stress fractures are needed to make return-to-sport predictions more reliable and successful treatment modalities more unified for this patient population. Last, it is imperative that clinical examination and symptoms be correlated with serial imaging when deciding on return to play. Our patient took 12 weeks to return to high-level sport. He progressed pain-free through the throwing program and showed radiographic evidence of healing on follow-up CT.

Conclusion

Radial shaft stress fractures are rare in throwing athletes. However, with a thorough history, a physical examination, and appropriate imaging, the correct diagnosis can be made early on, and proper treatment can be started to facilitate return to sport. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a stress fracture in the radial shaft of a MLB pitcher. Although the radial shaft is an uncommon location for stress fractures, we should keep in mind that they can occur wherever increased muscular forces exceed the ability of native bone to remodel. After diagnosis, the fracture usually heals with nonoperative treatment, and healing is confirmed with follow-up imaging, as was done in our patient’s case. Improved prediction of time to return to play for upper extremity fractures, such as the radial stress fracture described in this article, requires more study.

Take-Home Points

- Stress fractures should always be considered when dealing with overuse injuries.

- Radial shaft stress fractures in overhead throwing athletes are rare.

- Stress fractures can occur anywhere increased muscular forces exceed the bone’s ability to remodel.

- Proper imaging is necessary to make the diagnosis of a stress fracture.

- Nonoperative management of radial shaft stress fractures is an effective treatment.

In athletes, the incidence of stress fractures has been reported to be 1.4% to 4.4%.1 Stress fractures of the upper extremity are less common and not as well described as lower extremity stress fractures. Although data is lacking, stress fractures involving the upper extremity appear to account for <6% of all stress fractures.2 Stress fractures of the upper extremity, though rare, are being recognized more often in overhead athletes.3-6 In baseball pitchers, stress fractures most commonly occur in the olecranon but have also been found in the ribs, clavicle, humerus, and ulnar shaft.2,4,7-10 Stress fractures of the radius are a rare cause of forearm pain in athletes, and there are only a few case reports involving overhead athletes.4,11-15 To our knowledge, a stress fracture of the radial shaft has not been reported in a throwing athlete. Currently, there are no reports on stress fractures of the proximal radial shaft.16-18

In this article, we report the case of a radial shaft stress fracture that was causing forearm pain in a Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher. We also discuss the etiology, diagnosis, and management of stress fractures of the upper extremity of overhead throwing athletes. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 28-year-old right-hand-dominant MLB pitcher presented to the clinic with a 4-week history of right dorsal forearm pain that was refractory to a period of rest and physical therapy modalities. The pain radiated to the wrist and along the dorsal forearm. The pain started after the man attempted to develop a new pitch that required a significant amount of supination. The pain prevented him from pitching competitively. Indomethacin, diclofenac sodium topical gel, and methylprednisolone (Medrol Dosepak) reduced his symptoms only slightly.

Physical examination of the right elbow showed mild range of motion deficits; about 5° of extension and 5° of flexion were lacking. The patient had full pronation and supination. Palpation of the dorsal aspect of the forearm revealed marked tenderness in the area of the proximal radius. There was no tenderness over the posterior olecranon or the ulnar collateral ligament, and a moving valgus stress test was negative. No pain was elicited by resisted extension of the wrist or fingers. Motor innervation from the posterior interosseous nerve, anterior interosseous nerve, and ulnar nerve was intact with 5/5 strength, and there were no sensory deficits in the distribution of the radial, median, or ulnar nerves.

Discussion

Stress fractures account for 0.7% to 20% of sports medicine clinic injuries; <10% of all stress fractures involve the rib or upper extremity.4,6 When the intensity or frequency of physical activity is increased, as with overuse, bone resorption surpasses bone production, locally weakening the bone and making it prone to mechanical failure. Failure is thought to be induced by a combination of contractile muscular forces across damaged bone and increased mechanical loading caused by fatigue of supporting structures.5,6,19 These forces may have contributed to our baseball pitcher’s development of a stress fracture near the insertion of the supinator muscle in his throwing arm.

Given the insidious nature of stress fractures, the evaluating physician must have a high index of suspicion. Early recognition of a stress fracture is important in preventing further injury and allowing for early intervention, which is associated with faster healing.6,20 The clinical history often involves a change in training regimen within the weeks before pain onset. Furthermore, understanding the type of pitches used and the mechanics of each pitch can help with diagnosis. Often, pain increases as the inciting activity continues, and relief comes with rest. In an upper extremity examination, it is important to recall the usual stress fracture locations in throwers—the ribs, clavicle, humerus, ulnar shaft, and most often the olecranon—though the patient’s history often narrows the anatomical region of suspicion.2,4,7-10 Examination begins with inspection of the skin and soft tissues. Range of motion and strength testing results likely are normal throughout the upper extremity.3 Palpation over the suspected injury location often elicits pain and indicates further imaging is needed.6 The tuning fork test or the 3-point fulcrum test may elicit symptoms in occult fractures.3 Completing the assessment is a thorough neurovascular examination.

Insidious forearm pain requires a broad differential, including flexor-pronator mass or distal biceps injury, chronic exertional compartment syndrome, radial tunnel syndrome, intersection syndrome, pronator teres syndrome, anterior interosseous syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, musculocutaneous nerve compression, deep vein thrombosis of ulnar vein, and periostitis. Stress fractures distal to the elbow more commonly occur in weight-bearing athletes, though as this case shows it is important to consider stress fractures of the radius and ulna when evaluating forearm pain in a throwing athlete.21

The first imaging examination for a suspected stress fracture is a radiograph, which can be normal in up to 90% of patients, as it initially was in our athlete’s case.22 Often, radiographic evidence takes 2 to 12 weeks to appear.5 Even then, radiographs may be positive in only 50% of cases.19 CT, often regarded as insensitive during the early stages, is useful in visualizing fracture lines in a suspicious location.19,22 Radionuclide uptake scanning is highly sensitive during the early stages of stress injury but is nonspecific and may indicate neoplasm or infection; in addition, up to 46% of abnormal foci are asymptomatic.19 MRI has sensitivity comparable to that of radionuclide scanning but also many advantages, including lack of ionizing radiation, improved spatial resolution, and ability to image bone and soft tissue simultaneously.19 In our patient’s case, the unusual stress fracture location potentially could have hindered identification of the cause of injury. The lesion was just distal to the field of view of a normal elbow MRI and was not detected until a dedicated forearm MRI was examined. Both MRI and CT helped in identifying the stress fracture, and CT was used to follow interval healing.

In baseball players, upper extremity stress fractures are often nonoperatively treated with throwing cessation for 4 to 6 weeks followed by participation in a structured rehabilitation program.4,5 The throwing program that we suggest, and that was used in this case, has 21 stages of progression in duration, distance, and velocity of throwing. The athlete advances from each stage on the basis of symptoms.23 Other issues that may be addressed are vitamin D and calcium status and any flawed throwing mechanics that may have predisposed the athlete to injury. Such mechanics are gradually corrected.

The literature suggests that appropriate nonoperative management of stress fractures allows for return to sport in 8 to 10 weeks. It is important to note that most of the literature on stress fractures involves the lower extremity, and that treatment and time to return to play are therefore better described for such fractures.6 More study and evaluation of upper extremity stress fractures are needed to make return-to-sport predictions more reliable and successful treatment modalities more unified for this patient population. Last, it is imperative that clinical examination and symptoms be correlated with serial imaging when deciding on return to play. Our patient took 12 weeks to return to high-level sport. He progressed pain-free through the throwing program and showed radiographic evidence of healing on follow-up CT.

Conclusion

Radial shaft stress fractures are rare in throwing athletes. However, with a thorough history, a physical examination, and appropriate imaging, the correct diagnosis can be made early on, and proper treatment can be started to facilitate return to sport. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a stress fracture in the radial shaft of a MLB pitcher. Although the radial shaft is an uncommon location for stress fractures, we should keep in mind that they can occur wherever increased muscular forces exceed the ability of native bone to remodel. After diagnosis, the fracture usually heals with nonoperative treatment, and healing is confirmed with follow-up imaging, as was done in our patient’s case. Improved prediction of time to return to play for upper extremity fractures, such as the radial stress fracture described in this article, requires more study.

1. Monteleone GP Jr. Stress fractures in the athlete. Orthop Clin North Am. 1995;26(3):423-432.

2. Iwamoto J, Takeda T. Stress fractures in athletes: review of 196 cases. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(3):273-278.

3. Miller TL, Kaeding CC. Upper-extremity stress fractures: distribution and causative activities in 70 patients. Orthopedics. 2012;35(9):789-793.

4. Jones GL. Upper extremity stress fractures. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(1):159-174.

5. Brooks AA. Stress fractures of the upper extremity. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20(3):613-620.

6. Fredericson M, Jennings F, Beaulieu C, Matheson GO. Stress fractures in athletes. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;17(5):309-325.

7. Gurtler R, Pavlov H, Torg JS. Stress fracture of the ipsilateral first rib in a pitcher. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(4):277-279.

8. Polu KR, Schenck RC Jr, Wirth MA, Greeson J, Cone RO 3rd, Rockwood CA Jr. Stress fracture of the humerus in a collegiate baseball pitcher. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(6):813-816.

9. Wu C, Chen Y. Stress fracture of the clavicle in a professional baseball player. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(2):164-167.

10. Schickendantz MS, Ho CP, Koh J. Stress injury of the proximal ulna in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(5):737-741.

11. Loosli AR, Leslie M. Stress fractures of the distal radius. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):523-524.

12. Inagaki H, Inoue G. Stress fracture of the scaphoid combined with the distal radial epiphysiolysis. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31(3):256-257.

13. Read MT. Stress fractures of the distal radius in adolescent gymnasts. Br J Sports Med. 1981;15(4):272-276.

14. Orloff AS, Resnick D. Fatigue fracture of the distal part of the radius in a pool player. Injury. 1986;17(6):418-419.

15. Eisenberg D, Kirchner SG, Green NE. Stress fracture of the distal radius caused by “wheelies.” South Med J. 1986;79(7):918-919.

16. Brukner P. Stress fractures of the upper limb. Sports Med. 1998;26(6):415-424.

17. Farquharson-Roberts MA, Fulford PC. Stress fracture of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980;62(2):194-195.

18. Orloff AS, Resnick D. Fatigue fracture of the distal part of the radius in a pool player. Injury. 1986;17(6):418-419.

19. Anderson MW. Imaging of upper extremity stress fractures in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(3):489-504.

20. Bennell K, Brukner P. Preventing and managing stress fractures in athletes. Phys Ther Sport. 2005;6(4):171-180.

21. Sinha AK, Kaeding CC, Wadley GM. Upper extremity stress fractures in athletes: clinical features of 44 cases. Clin J Sport Med. 1999;9(4):199-202.

22. Matheson GO, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Taunton JE, Lloyd-Smith DR, MacIntyre JG. Stress fractures in athletes. A study of 320 cases. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(1):46-58.

23. Kaplan L, Lesniak B, Baraga M, et al. Throwing program for baseball players. 2009. http://uhealthsportsmedicine.com/documents/UHealth_Throwing_Program.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2016.

1. Monteleone GP Jr. Stress fractures in the athlete. Orthop Clin North Am. 1995;26(3):423-432.

2. Iwamoto J, Takeda T. Stress fractures in athletes: review of 196 cases. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(3):273-278.

3. Miller TL, Kaeding CC. Upper-extremity stress fractures: distribution and causative activities in 70 patients. Orthopedics. 2012;35(9):789-793.

4. Jones GL. Upper extremity stress fractures. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(1):159-174.

5. Brooks AA. Stress fractures of the upper extremity. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20(3):613-620.

6. Fredericson M, Jennings F, Beaulieu C, Matheson GO. Stress fractures in athletes. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;17(5):309-325.

7. Gurtler R, Pavlov H, Torg JS. Stress fracture of the ipsilateral first rib in a pitcher. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(4):277-279.

8. Polu KR, Schenck RC Jr, Wirth MA, Greeson J, Cone RO 3rd, Rockwood CA Jr. Stress fracture of the humerus in a collegiate baseball pitcher. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(6):813-816.

9. Wu C, Chen Y. Stress fracture of the clavicle in a professional baseball player. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(2):164-167.

10. Schickendantz MS, Ho CP, Koh J. Stress injury of the proximal ulna in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(5):737-741.

11. Loosli AR, Leslie M. Stress fractures of the distal radius. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):523-524.

12. Inagaki H, Inoue G. Stress fracture of the scaphoid combined with the distal radial epiphysiolysis. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31(3):256-257.

13. Read MT. Stress fractures of the distal radius in adolescent gymnasts. Br J Sports Med. 1981;15(4):272-276.

14. Orloff AS, Resnick D. Fatigue fracture of the distal part of the radius in a pool player. Injury. 1986;17(6):418-419.

15. Eisenberg D, Kirchner SG, Green NE. Stress fracture of the distal radius caused by “wheelies.” South Med J. 1986;79(7):918-919.

16. Brukner P. Stress fractures of the upper limb. Sports Med. 1998;26(6):415-424.

17. Farquharson-Roberts MA, Fulford PC. Stress fracture of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980;62(2):194-195.

18. Orloff AS, Resnick D. Fatigue fracture of the distal part of the radius in a pool player. Injury. 1986;17(6):418-419.

19. Anderson MW. Imaging of upper extremity stress fractures in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25(3):489-504.

20. Bennell K, Brukner P. Preventing and managing stress fractures in athletes. Phys Ther Sport. 2005;6(4):171-180.

21. Sinha AK, Kaeding CC, Wadley GM. Upper extremity stress fractures in athletes: clinical features of 44 cases. Clin J Sport Med. 1999;9(4):199-202.

22. Matheson GO, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Taunton JE, Lloyd-Smith DR, MacIntyre JG. Stress fractures in athletes. A study of 320 cases. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(1):46-58.

23. Kaplan L, Lesniak B, Baraga M, et al. Throwing program for baseball players. 2009. http://uhealthsportsmedicine.com/documents/UHealth_Throwing_Program.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2016.

Information on Orthopedic Trauma Fellowships: Online Accessibility and Content

Take-Home Points

- The Internet is a popular resource for orthopedic fellowship applicants.

- 86% of OTF websites are accessible from Google and FREIDA.

- Accessible websites feature only 40% of fellowship applicant content.

- Accessibility and content of OTF websites are highly variable and largely deficient.

- Improvement of the accessibility and content of website information should be a future focus of OTF programs.

The Orthopaedic Trauma Fellowship Match facilitates the matching process for orthopedic residency graduates pursuing a career as orthopedic traumatologists. This match is supported by the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) and the San Francisco Matching Program (SFMP). Orthopedic trauma fellowship (OTF) programs are accredited by the OTA and may receive oversight by the American Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which defines uniform standards for fellowship training.1

Studies have found that the internet is an important and popular resource for applicants researching residency and fellowship programs.2-5 For many applicants, the internet is their initial and main source of information.5 Unfortunately, training programs do not have standardized website accessibility and content.

Few studies have addressed online content on orthopedic fellowship programs,4,6,7 and to our knowledge no one has studied online content on OTF programs. We conducted a study to assess the accessibility and ease of navigation of OTF websites and to evaluate the content on these sites. We wanted to identify content that applicants may reliably expect on OTF sites. Any deficits identified may be useful to fellowship programs and program directors interested in improving website quality. We hypothesized that the accessibility and content of online OTF content would be highly variable and largely deficient.

Methods

This study was conducted at New York University Hospital for Joint Diseases. On February 5, 2015, both the OTA database8 and the Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database (FREIDA)9 were accessed in order to create a comprehensive list of OTF programs. FREIDA, a catalog of all ACGME-accredited graduate medical education programs in the United States, is supported by the American Medical Association and provides cursory program information, including training program duration and number of positions per year.

The databases were reviewed for links to OTF program websites. An independent Google search for program websites was also initiated on February 5, 2015. The Google search was performed in the format “program name + orthopaedic trauma fellowship” to assess how accessible the program sites are from outside the 2 databases (OTA, FREIDA). Google was used because it is the most commonly used search engine.10 The first 25 search results were reviewed for links to OTF websites. Programs without accessible links to OTF websites—from the OTA database, from FREIDA, or from the Google search—were excluded from content assessment.

Accessible websites were electronically captured to ensure consistency of content during assessment. OTF site content was evaluated using methods described in similar investigations.4,5,11,12 In our dichotomous assessment of fellow education content, we awarded 1 point per content item on the website. The 10 education content items evaluated were call responsibilities, didactic instruction, journal club, research requirements, evaluation criteria, rotation schedule, operative experience, office/clinic experience, meetings attended, and courses attended. We also performed a dichotomous assessment of fellow recruitment content. The 10 recruitment content items evaluated were program description, application requirements, selection criteria, OTA link, SFMP link, location description, program contact information, fellow listing, faculty listing, and salary. Content items were chosen for evaluation on the basis of published OTF applicant experience.13 Percentages of education content, recruitment content, and total content were compared by program location, number of fellows, ACGME accreditation status,14 affiliation with a top 20 orthopedic hospital,15 and affiliation with a top 20 medical school,16 as in similar studies.7,17

Chi-square tests were used to compare content by fellowship location, number of fellows, ACGME accreditation status, affiliation with a top 20 orthopedic hospital, and affiliation with a top 20 medical school. For all tests, the significance level was set at P < .05.

Results

Of the 49 OTF programs identified with database queries, 9 appeared in both the OTA database and FREIDA, 39 appeared only in the OTA database, and 1 appeared only in FREIDA. There were 48 programs total in the OTA database and 10 total in FREIDA.

The OTA database had no OTF website links. Of the 10 OTF links in FREIDA, 3 (6%) were nonfunctioning, 6 (12%) had multiple steps for accessing program information, and 1 (2%) connected directly to program information. Therefore, FREIDA had a total of 7 accessible OTF links (14%). The independent Google search yielded website links for 42 (86%) of the 49 OTF programs. Five links (10%, 5/49) had multiple steps for accessing program information, and 37 links (76%, 37/49) connected directly to program information. The 7 OTF links accessible through FREIDA were accessible through Google as well. Table 1 summarizes the accessibility data.

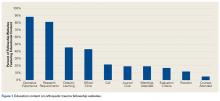

All 42 accessible OTF websites were assessed for content. On average, these sites had 40% (range, 0%-75%) of the total assessed content. Mean (SD) education content score was 3.6 (2.2) out of 10. Operative experience (88%) and research requirements (81%) were the most consistently presented education items. Didactic learning (45%) and description of common office/clinic cases (43%) were next. Less than 5% of the sites had content on the training courses (eg, sponsored fracture courses) attended by fellows. Figure 1 summarizes the education items on the OTF websites.

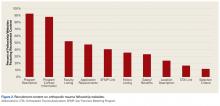

Mean (SD) recruitment content score was 4.4 (2.2) out of 10. Program description (93%) and program contact information (88%) were the most consistently presented recruitment items. Clinical faculty (52%) and current and/or prior fellows (36%) were next. Fellow selection criteria appeared least often (12%). Figure 2 summarizes the recruitment items on the OTF websites.

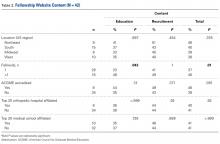

Thirty-six percent of OTF programs with accessible websites were in the southern United States. However, there were no significant differences in online content between OTF program locations. Websites of programs with >1 fellow had significantly more education content (48% vs 33%; P = .043) and total content (46% vs 37%; P = .01) than websites of programs with 1 fellow. ACGME accreditation status, affiliation with a top 20 orthopedic hospital, and affiliation with a top 20 medical school did not have a significant effect on OTF website content. Table 2 summarizes OTF website content by location, number of fellows, top 20 orthopedic hospital affiliation, and top 20 medical school affiliation.

Discussion

We conducted this study to assess the accessibility of OTF program websites and to evaluate the content of the sites. Our hypothesis, that the accessibility and content of online OTF content would be highly variable and largely deficient, was supported by our findings. We found that the OTA database had no OTF website links and that FREIDA links connected directly to only 2% of OTF sites. The majority of OTF sites were accessed from the Google search, which had direct links to 76% of the OTF programs.

Other studies have had similar findings regarding the accessibility of fellowship websites. Mulcahey and colleagues6 evaluated sports medicine fellowship websites for accessibility and content, and found that the website of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine directly linked to fellowship information for only 3% of programs; a Google search yielded direct links to 71% of program websites. Davidson and colleagues4 examined the quality and accessibility of online information on pediatric orthopedic fellowships and found no program links on the website of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America; a Google search yielded direct links to 68% of programs. Silvestre and colleagues7 assessed spine fellowship information on the Internet. The North American Spine Society website had working links to only 3% of fellowship sites, and FREIDA connected to only 6% of sites.

Content scores in our study were highly variable. Mean education and recruitment content scores were 3.6 (range, 0-9) and 4.4 (range, 0-10), respectively. Operative experience (88%) and program description (93%) were the most frequently presented education and recruitment items, respectively. Consistency in presenting program descriptions on OTF websites was slightly poorer than that in other orthopedic specialties. Sports medicine, pediatric orthopedic, and spine fellowship websites provided program descriptions for fellowship recruitment.4,6,7 Nevertheless, overall content scores in our study and in the aforementioned studies were similarly poor.

In our study, OTF websites showed no significant differences in content scores for program location, ACGME accreditation status, affiliation with a top 20 orthopedic hospital, or affiliation with a top 20 medical school. Lack of a significant effect of medical school or orthopedic hospital affiliation suggests academic prestige does not play a large role in attempts by OTF websites to attract applicants. However, programs with >1 fellow had significantly more education and total content than programs with 1 fellow. Results from a comparable study support this finding. Silvestre and colleagues18 assessed the accessibility of online plastic surgery residency content. Programs with 3 or 4 residents had significantly more online education content than programs with 1 resident. This finding may relate to the cost efficiency of developing low-cost websites to attract applicants to multiple positions.7

Despite lacking links to OTF websites, the OTA database had a large amount of content on 98% (48/49) of OTFs. In addition to presenting the content that we assessed in this study, the OTA database provided the number of inpatient beds at the primary teaching hospital, the annual number of emergency department visits, the annual number of trauma admissions, and the annual number of orthopedic trauma procedures. This standardized information may be very helpful to fellowship applicants and may be an important adjunct to fellowship websites.

FREIDA provided similar content, but accessible links were found for only 14% of the assessed programs. Although the deficiency in accessible OTF links in the OTA database and FREIDA is not well understood, it is important. The results of our study and of similar studies suggest that the listing of active fellowship program links on society websites would benefit orthopedic fellowship applicants, likely fostering a better understanding and a more efficient review of available programs. In addition, links on society websites afford fellowship directors the means to efficiently publicize their programs to large numbers of potential applicants, who likely use society websites as an initial informational resource.

Our study had limitations. First, its findings are subject to the dynamism of the internet, and OTF information may have been updated after this investigation was conducted. Second, our study did not rank-order accessible links, which may have provided more information on the efficiency of using Internet search engines in a review of OTF programs. In addition, our study involved dichotomous assessment of OTF content. Multichotomous evaluation may have further elucidated the quality of website information. Last, our study evaluated websites only for US-based OTF programs. Inclusion of international OTF programs, though outside the scope of this study, may have yielded different findings.

Conclusion

Our results highlight the difficulties that OTF applicants may experience in gathering fellowship information online. OTF website accessibility and content were found to be highly variable and largely deficient. Comparing our findings with those of similar studies revealed that fellowship websites generally provided little information that orthopedic specialty applicants could use. OTF programs should focus on improving their website accessibility and content.

1. Daniels AH, Grabel Z, DiGiovanni CW. ACGME accreditation of orthopaedic surgery subspecialty fellowship training programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(11):e94.

2. Reilly EF, Leibrandt TJ, Zonno AJ, Simpson MC, Morris JB. General surgery residency program websites: usefulness and usability for resident applicants. Curr Surg. 2004;61(2):236-240.

3. Perron AD, Brady WJ. Sources of information on emergency medicine residency programs. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(12):1462-1463.

4. Davidson AR, Murphy RF, Spence DD, Kelly DM, Warner WC Jr, Sawyer JR. Accessibility and quality of online information for pediatric orthopaedic surgery fellowships. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(8):831-834.

5. Rozental TD, Lonner JH, Parekh SG. The internet as a communication tool for academic orthopaedic surgery departments in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(7):987-991.

6. Mulcahey MK, Gosselin MM, Fadale PD. Evaluation of the content and accessibility of web sites for accredited orthopaedic sports medicine fellowships. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(12):e85.

7. Silvestre J, Guzman JZ, Skovrlj B, et al. The internet as a communication tool for orthopedic spine fellowships in the United States. Spine J. 2015;15(4):655-661.

8. Orthopaedic Trauma Association. Orthopaedic trauma fellowship directory. http://spec.ota.org/education/fellowshipcenter/fellowship_dir/dir_summary.cfm. Accessed February 5, 2015.

9. Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database. Orthopaedic trauma fellowship programs. https://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida/user/search/programSearch.do. Accessed February 5, 2015.

10. Experian Hitwise. Search engine analysis. http://www.experian.com/marketing-services/online-trends-search-engine.html. Accessed February 5, 2015.

11. Hinds RM, Klifto CS, Naik AA, Sapienza A, Capo JT. Hand society and matching program web sites provide poor access to information regarding hand surgery fellowship. J Hand Microsurg. 2016;8(2):91-95.

12. Hinds RM, Danna NR, Capo JT, Mroczek KJ. Foot and ankle fellowship websites: An assessment of accessibility and quality. Foot Ankle Spec. 2017;10(4):302-307.

13. Griffin SM, Stoneback JW. Navigating the Orthopaedic Trauma Fellowship Match from a candidate’s perspective. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25(suppl 3):S101-S103.

14. American Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accredited orthopaedic trauma fellowship programs. https://www.acgme.org/ads/Public/Programs/Search?specialtyId=49&orgCode=&city=. Accessed February 5, 2015.

15. US News & World Report. Best hospitals for orthopedics. http://health.usnews.com/best-hospitals/rankings/orthopedics. Accessed February 5, 2015.